The Grouser. "JUST OUR ROTTEN LUCK TO ARRIVE 'ERE ON

EARLY-CLOSING DAY."

The Grouser. "JUST OUR ROTTEN LUCK TO ARRIVE 'ERE ON

EARLY-CLOSING DAY.""Of course I cannot be in France and America at the same time," said Colonel ROOSEVELT to a New York interviewer. The EX-PRESIDENT is a very capable man and we can only conclude that he has not been really trying.

"The Church of to-morrow is not to be built up of prodigal sons," said a speaker at the Congregational Conference. Fatted calves will, however, continue to be a feature in Episcopal circles.

A Berlin coal merchant has been suspended from business for being rude to customers. It is obvious that the Prussian aristocracy will not abandon its prerogatives without a struggle.

The lack of food control in Ireland daily grows more scandalous. A Belfast constable has arrested a woman who was chewing four five-pound notes, and had already swallowed one.

An alien who was fined at Feltham police court embraced his solicitor and kissed him on the cheek. Some curiosity exists as to whether the act was intended as a reprisal.

The English Hymnal, says a morning paper, "contains forty English Traditional Melodies and three Welsh tunes." This attempt to sow dissension among the Allies can surely be traced to some enemy source.

Mr. GEORGE MOORE, the novelist, declares that ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON "was without merit for tale-telling." But how does Mr. GEORGE MOORE know?

"Is Pheasant Shooting Dangerous?" asks a weekly paper headline. We understand that many pheasants are of the opinion that it has its risks.

Only a little care is needed in the cooking of the marrow, says Mrs. MUDIE COOKE. But in eating it great caution should be taken not to swallow the marrow whole.

An applicant at the House of Commons' Appeal Tribunal stated that he had been wrongly described as a Member of Parliament. It is not known who first started the scandal.

HERR BATOCKI, Germany's first Food Dictator, is now on active service on the Western Front, where his remarks about the comparative dulness of the proceedings are a source of constant irritation to the Higher Command.

It is rumoured that the Carnegie Medal for Gallantry is to be awarded to the New York gentleman who has purchased Mr. EPSTEIN'S "Venus."

We understand that an enterprising firm of publishers is now negotiating for the production of a book written by "The German Prisoner Who Did Not Escape."

Four conscientious objectors at Newhaven have complained that their food often contains sandy substances. It seems a pity that the authorities cannot find some better way of getting a little grit into these poor fellows.

General SUKHOMLINOFF has appealed from his sentence of imprisonment for life. Some people don't know what gratitude is.

It is good to find that people exercise care in time of crisis. Told that enemy aircraft were on their way to London a dear old lady immediately rushed into her house and bolted the door.

Owing to a shortage of red paint, several London 'buses are being painted brown. Pedestrians who have only been knocked down by red-painted 'buses will of course now be able to start all over again.

We think it was in bad taste for Mr. BOTTOMLEY, just after saying that he had seen Mr. WINSTON CHURCHILL at the Front, to add, "I have Taken Risks."

Six little boa-constrictors have been born in the Zoological Gardens. A message has been despatched to Sir ARTHUR YAPP, urging the advisability of his addressing them at an early date.

To record the effect of meals on the physical condition of children, Leyton Council is erecting weighing machines in the feeding centres. Several altruistic youngsters, we are informed, have gallantly volunteered to demonstrate the effects of over-eating without regard to the consequences.

An allotment holder in Cambridgeshire has found a sovereign on a potato root. To its credit, however, it must be said that the potato was proceeding in the direction of the Local War Savings Association at the rate of several inches a day.

We are pleased to say that the Wimbledon gentleman who last week was inadvertently given a pound of sugar in mistake for tea is going on as well as can be expected, though he is still only allowed to see near relations.

"ANTIQUES.—All Lovers of the Genuine Antiques should not fail to see one of the best-selected Stocks of Genuine Antique Furniture, &c., including Stuart, Charles II., Tudor, Jacobean, Queen Anne, Chippendale, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, Adams, and Georgian periods.

FRESH GOODS EVERY DAY."

A new German Opera that we look forward to seeing: Die Gothädummerung.

"A man just under military age, with seven children, is ordered to join up."—Weekly Dispatch.

Such precocious parentage must be discouraged.

"HELSINGFORS, Sept. 28.—The Governor-General of Finland has ordered seals to be affixed to the doors of the Diet."—Times.

This seems superfluous. Seals have always been attached to a Fin Diet.

"A party of the Russians in their natural costumes have come to Portland to ply their trade as metal workers. They make a picturesque group, which a Press writer will try to describe to-morrow morning."—Portland Daily Press (U.S.A.).

We trust that he did not dwell unduly upon the scantiness of their attire.

[A few specimen conversations are here suggested as suitable for the conditions which we have lately experienced. The idea is to discourage the Hun by ignoring those conditions or explaining them away. For similar conversations in actual life blank verse would not of course be obligatory.]

A. Beautiful weather for the time of year!

B. A perfect spell, indeed, of halcyon calm,

Most grateful here in Town, and, what is more,

A priceless gift to our brave lads in France,

Whose need is sorer, being sick of mud.

A. They have our first thoughts ever, and, if Heaven

Had not enough good weather to go round,

Gladly I'd sacrifice this present boon

And welcome howling blizzards, hail and flood,

So they, out there, might still be warm and dry.

C. Have you observed the alien in our midst,

How strangely numerous he seems to-day,

Swarming like migrant swallows from the East?

D. I take it they would fain elude the net

Spread by Conscription's hands to haul them in.

All day they lurk in cover Houndsditch way,

Dodging the copper, and emerge at night

To snatch a breath of Occidental air

And drink the ozone of our Underground.

E. How glorious is the Milky Way just now!

F. True. In addition to the regular stars

I saw a number flash and disappear.

E. I too. A heavenly portent, let us hope,

Presaging triumph to our British arms.

G. Methought I heard yestreen a loudish noise

Closely resembling the report of guns.

H. Ay, you conjectured right. Those sounds arose

From anti-aircraft guns engaged in practice

Against the unlikely advent of the Hun.

One must be ready in a war like this

To face the most remote contingencies.

G. Something descended on the next back-yard,

Spoiling a dozen of my neighbour's tubers.

H. No doubt a live shell mixed among the blank;

Such oversights from time to time occur

Even in Potsdam, where the casual sausage

Perishes freely in a feu de joie.

J. We missed you badly at our board last night.

K. The loss was mine. I could not get a cab.

Whistling, as you're aware, is banned by law,

And when I went in person on the quest

The streets were void of taxis.

J. And to what

Do you attribute this unusual dearth?

K. The general rush to Halls of Mirth and Song,

Never so popular. The War goes well,

And London's millions needs must find a way

To vent their exaltation—else they burst.

J. But could you not have travelled by the Tube?

K. I did essay the Tube, but found it stuffed.

The atmosphere was solid as a cheese,

And I was loath to penetrate the crowd

Lest it should shove me from behind upon

The electric rail.

J. Can you account for that?

K. I should ascribe it to the harvest moon,

That wakes romance in Metropolitan breasts,

Drawing our young war-workers out of town

To seek the glamour of the country lanes

Under the silvery beams to lovers dear. O.S.

The fact that George had been eighteen months in Gallipoli, Egypt and France, without leave home till now, should have warned me. As it was I merely found myself gasping "Shell-shock!"

We were walking in a crowded thoroughfare, and George was giving all the officers he met the cheeriest of "Good mornings." It took people in two ways. Those on leave, blushing to think they had so far forgotten their B.E.F. habits as to pass a brother-officer without some recognition, replied hastily by murmuring the conventional "How are you?" into some innocent civilian's face some yards behind us. Mere stay-at-homes, on the other hand, surprised into believing that they ought to know him, stopped and became quite effusive. As far as I can remember George accepted three invitations to dinner from total strangers rather than explain, and I was included in one of them.

We were for the play that night and I foresaw difficulties at the public telephone, and George's first remark of "Hullo, hullo, is that Signals? Put me through to His Majesty's," confirmed my apprehensions.

Half-an-hour of this kind of thing produced in me a strong desire for peace and seclusion. A taxi would have solved my difficulty (had I been able to solve the taxi difficulty first), but George himself anticipated me by suddenly holding up a private car and asking for a lift. I could have smiled at this further lapse had not the owner, a detestable club acquaintance whom I had been trying to keep at a distance for years, been the driver. He was delighted, and I was borne away conscious of twenty years' work undone by a single stroke.

Peace and seclusion at the club afforded no relief however. George was really very trying at tea. He accused the bread because the crust had not a hairy exterior (generally accumulated by its conveyance in a blanket or sandbag). He ridiculed the sugar ration—I don't believe he has ever been short in his life; and the resources of the place were unequal to the task of providing tea of sufficient strength to admit of the spoon being stood upright in it—a consistency to which, he said, he had grown accustomed. When I left him he was bullying the hall-porter of the club for a soft-nosed pencil; ink, he explained, being an abomination.

I also saw him pay 2½d. for a Daily Mail.

I got a letter from George just before he went back. He patronized me delightfully—seemed more than half a Colonial already. He said he was glad to have seen us all again, but was equally glad to be getting back, as he was beginning to feel a little homesick. He hinted we were dull dogs and treated people we didn't know like strangers. Didn't we ever cheer up? He became very unjust, I thought, when he said that France was at war, but that we had only an Army and Navy.

Incidentally I had to pay twopence on the letter, the postman insisting that George's neat signature in the bottom left-hand corner of the envelope was an insufficient substitute for a penny stamp.

"The raiders came in three suctions."—Evening News.

So that was what blocked the Tubes.

PRIME MINISTER. "YOU YOUNG RASCAL! I NEVER SAID THAT."

NEWSBOY. "WELL, I'LL LAY YER MEANT IT."

Keeper. "ANY BIRDS, SIR?"

Officer (fresh from France). "YES. THREE CRASHED; TWO DOWN OUT OF CONTROL."

MY DEAR CHARLES,—Here is a war, producing great men, and here am I writing to you from time to time about it and never mentioning one of them. I have touched upon Commanding Officers, Brigadiers, Divisional, Corps, even Army Commanders; I have gone so far as to mention the COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF once and I have mentioned myself very many times. But the really great men I have omitted. I mean the really, really great men, without whom the War could not possibly go on, and with whom, I am often led to suppose, the decision remains as to what day Peace shall be declared. Take the A.M.L.O. at —— for example.

Now, Charles, be it understood that I am not saying anything for or against the trade of Assisting Military Landing Officers; I have no feeling with regard to it one way or the other. For all I know it may require a technical knowledge so profound that any man who can master it is already half-way on the road to greatness. On the other hand, it may require no technical knowledge at all, and, the whole of a Military Landing Officer's duties being limited to watching other people working, the Assistant Military Landing Officer's task may consist of nothing more complicated than watching the Military Landing Officer watching the military land. If this is so, the work may be so simple that, once a man has satisfied the very rigid social test to be passed by all aspirants to so distinguished a position, he must simply be a silly ass if he doesn't automatically become a great man, after a walk or two up and down the quay. I repeat, I know nothing whatever of the calling of A.M.L.O., and I could not tell you without inquiry whether it is an ancient and honourable profession or an unscrupulous trade very jealously watched by the Law. I have some friends in it and I have many friends out of it, and the former should not be inflated with conceit nor the latter unduly depressed when I pronounce the deliberate opinion that the best known and greatest thing in the B.E.F. is without doubt the A.M.L.O. at ——.

Though it is months since I cast eyes on him, I can see him now, standing self-confidently on his own private quay, with the most chic of Virginian cigarettes smouldering between his aristocratic lips and the very latest and most elegant of Bond Street Khaki Neckwear distinguishing him from the mixed crowd about him. Every one else is distraught; even matured Generals, used to the simple and irresponsible task of commanding troops in action, are a little unnerved by the difficulties and intricacies of embarking oneself militarily. He on whom all the responsibility rests remains aloof. A smile, half cynical, plays across his proud face. He knows he has but to flick the ash from his cigarette and the Army will spring to attention and the Navy will get feverishly to work. He has but to express consent by the inclination of his head and sirens will blow, turbine engines will operate as they would never operate for anybody else, thousands of tons of shipping will rearrange itself, and even the sea will become less obstreperous and more circumspect in its demeanour, adjusting, if need be, its tides to suit his wishes.

I take it my condition is typical when I am "proceeding" (one will never come and go again in our time; one will always proceed)—when I am proceeding to the U.K. The whole thing is too good to believe, and I don't believe it till I have some written and omnipotent instructions, in my pocket and am actually moving towards the sea. The youngest and keenest schoolboy returning home for his holidays is a calm, collected, impassionate and even dismal man of the world compared to me. I see little and am impressed by nothing; all things and men are assumed to be good, and none [pg 251] of them is given the opportunity of proving itself to be the contrary. As for the A.M.L.O. at any other port but this one, I remark nothing about him except his princely generosity in letting me have an embarcation card. He is just one more good fellow in the long series of good fellows who have authorised my move. I am borne out to sea in a dream—a dream of England and all that England means to us, be that a wife or a reasonable breakfast at a reasonable hour. Not until I am on my way back does it occur to me that landing and transport officers have identities, and by that time I have lost all interest in transport and landing and officers and identities and everything else.

At the port of ——, however, it is very different. I may arrive on the quay in a dream, but I'm at once out of it when I have caught sight of Greatness sitting in its little hut with the ticket window firmly closed until the arrival of the hour before which he has disposed that it shall not open. Thoughts of home are gone; I can think of nothing but Him. When at last I have obtained his gracious, if reluctant, consent to my obeying the instructions I have, and have got on to the boat, I deposit my goods hurriedly, anywhere, and fight for a position by the bulwark nearest the quay, from which I may gaze at his august Excellency for the few remaining hours during which it is given us to linger in or near our well-beloved France.

How came it about, I ask myself, that the Right Man got to be in the Right Place? It cannot have been merely fortuitous that he was not thrust away into some such obscure job as the command of an Expeditionary Force or the control of the counsels of the Imperial General Staff. It must have been the deliberate choice of a wise chooser; Major-General Military Landing himself, the SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WAR on his own, even His MAJESTY in person? Or was a plebiscite taken through the length and breadth of the British Isles when I was elsewhere, and did Britain, thrilled to the core, clamour for him unanimously?

I watch him keep a perturbed and restless Major from the line waiting while he finishes his light-hearted badinage with a subordinate. It is altogether magnificent in its sheer sangfroid. Why is it that such a one is labelled merely A.M.L.O., when he should obviously be the M.L.O.? He has his subordinate, happily insignificant and obsequiously proud to serve. Let the subordinate be the a.m.l.o., and let It, Itself, be openly acknowledged to be It, Itself.

By the way, where is his M.L.O.? Has anybody ever seen him? I haven't. Does he exist?... Has he been got rid of?

There is a convenient crevice between the quay and the boat with a convenient number of feet of water at the bottom of it. Is the M.L.O. down there, and is the "A.M.L.O." brassard but the modesty of true greatness?

If the M.L.O. has been thrown down there, who threw him?

Was it my idol, the A.M.L.O., in a moment of exasperation with his M.L.O.?

Or was it the M.L.O., in a moment of exasperation with my idol, the A.M.L.O.?

Old Lady. "IS THIS THE RESULT OF A BOMB, CONSTABLE?"

Constable (fed up). "BLESS YOU, NO, MA'AM. THE GENT THAT LIVES HERE'S GOT HAY FEVER."

"Naval Officer's (Minesweeping) Wife would be grateful for the opportunity of purchasing a Baby's Layette of good quality at a very reasonable price."—Morning Post.

Our congratulations to the mine sweeping wife upon having captured a Baby Mine.

Upon a marsh beside the sea,

With hawk and hound and vassals three,

Rode WILLIAM, Duke of NORMANDY,

The heir of Rover ROLLO;

And ever as his falcon flew

Quoth he: "Mark well, by St. MACLOU,

For where she hovers hasten you,

And where she falls I follow."

She rose into the misty sky,

A brooding menace hid on high,

Ere she dipped earthward suddenly

As dips the silver swallow;

Then, spurring through the rushes grey,

Cried WILLIAM, "Sirs, away, away!

For where she hovers is the prey,

And where she falls I follow."

Her marbled plume with crimson dight,

Seaward she soared, and bent her flight

Above the ridge of foaming white

Along the harbour hollow;

Then, looking grimly toward the strait,

Said WILLIAM, "Truly, soon or late,

There where she hovers is my fate,

And where she falls I follow."

"If you please, ma'am, that funny-looking gentleman with the long hair has brought his jug for some more water. And could you oblige him with a little pepper?"

"Certainly not," said my wife. "The man's a nuisance. He is not even respectable—looks like a gipsy or a disreputable artist. I'll speak to him myself." And she flounced out of the room.

I felt almost sorry for the man; but really the thing was overdone when, not content with overcrowding our village, these London people took to living in dug-outs on the common.

Matilda rushed back into the room with a metal jug in her hand.

"Oscar! It's old Sheffield plate, and there's a coat-of-arms on it. Turn up the heraldry book; look in the index for 'bears.' Perhaps they're somebody after all."

Matilda is a second cousin once removed of the Drewitts—one of the best baronetcies in England—and naturally we take an interest in Heraldry.

"Yes, here it is. A cave-bear rampant! Oscar, it's the crest of the Cave-Canems, one of the oldest families in Britain, if not the very oldest! Poor things, I feel so sorry for them. Perhaps I might offer him some vegetables."

"And to think of their having to live in a cave again after all these centuries," said my wife when she returned. "Isn't it pathetic? Oscar, don't you think we ought to call on them?"

We agreed that it was our duty to call on the distinguished cave-dwellers. But what ought we to wear? They dressed very simply; I had seen him in an old tweed suit and a soft felt hat.

"And his wife," Matilda said, "is positively dowdy. But that proves they are somebody. Only the very best people can afford to wear shabby clothes in these times."

We decided that in our case it was necessary to recognise the polite usages of society. So my wife wore her foliage green silk, and I my ordinary Sabbath attire.

A fragrant odour of vegetables cooking led us eventually to the little mound amidst the gorse where our aristocratic visitors were temporarily residing. There was some difficulty at first in attracting their attention, but this I overcame by tying our visiting-cards to a piece of string and dangling it down the tunnel that served as an entrance. After coughing several times I had a bite, and the cave-man showed himself.

"Hallo!" I heard him say, laughing, "it's the kind Philistines who gave us the vegetables." Then aloud, "Come in. Mind the steps."

I damaged my hat slightly against the roof, and I am afraid Matilda's dress suffered a little, but we managed to enter their dug-out. The place was faintly lighted by a sort of window overlooking the third hole of the deserted golf course. Our host introduced his wife.

"We were not really nervous," said the lady, "but a fragment of shell came through the studio window and destroyed a number of my husband's pictures. He is a painter of the Neo-Impressionistic School."

"What a shame!" said Matilda, taking up a canvas. "May I look? Oh! how pretty."

"My worst enemy has never called my work that," said the artist. "Perhaps you would appreciate it better if you held it the other way up."

It is at a moment like this that my wife shines.

"I should like to see it in a better light," she said. "But how interesting! Everyone paints now-a-days—even Royalty. My cousin, Sir Ethelwyn Drewitt, has done some charming water-colours of the family estates. Perhaps you know him?"

Our host shook his head.

"A very old family, like your own," said Matilda. "Our ancestors probably knew each other in the days of Stonehenge. I, of course, recognised the coat-of-arms on your plate."

"I am afraid you are in error," said the artist. "My name is Pitts. And I don't go back beyond my grandfather, who, honest man, kept a grocer's shop in Dulwich. The jug you've been admiring I bought in the Caledonian Cattle Market for fifteen shillings."

Matilda swooned. The air was certainly very close down there.

I Wish I did not dream of France

And spend my nights in mortal dread

On miry flats where whizz-bangs dance

And star-shells hover o'er my head,

And sometimes wake my anxious spouse

By making shrill excited rows

Because it seems a hundred "hows"

Are barraging the bed.

I never fight with tigers now

Or know the old nocturnal mares;

The house on fire, the frantic cow,

The cut-throat coming up the stairs

Would be a treat; I almost miss

That feeling of paralysis

With which one climbed a precipice

Or ran away from bears.

Nor do I dream the pleasant days

That sometimes soothe the worst of wars,

Of omelettes and estaminets

And smiling maids at cottage-doors;

But in a vague unbounded waste

For ever hide with futile haste

From 5.9's precisely placed,

And all the time it pours.

Yet, if I showed colossal phlegm

Or kept enormous crowds at bay,

And sometimes won the D.C.M.,

It might inspire me for the fray;

But, looking back, I do not seem

To recollect a single dream

In which I did not simply scream

And try to run away.

And when I wake with flesh that creeps

The only solace I can see

Is thinking, if the Prussian sleeps,

What hideous visions his must be!

Can all my dreams of gas and guns

Be half as rotten as the Hun's?

I like to think his blackest ones

Are when he dreams of me.

"Street lamp-posts in Chiswick are all being painted white by female labour."—Times.

The authorities were afraid, we understand, that if males were employed they would paint the town red.

"Four groups of raiders tried to attack London on Saturday night. If there were eight in each group, this meant thirty-two Gothas."—Evening Standard.

In view of the many loose and inaccurate assertions regarding the air-raids, it is agreeable to meet with a statement that may be unreservedly accepted.

Lodger (who has numbered his lumps of sugar with lead

pencil). "OH, MRS. JARVIS, I AM UNABLE TO FIND NUMBERS 3, 7 AND

18."

Lodger (who has numbered his lumps of sugar with lead

pencil). "OH, MRS. JARVIS, I AM UNABLE TO FIND NUMBERS 3, 7 AND

18."Once upon a time there was a sitting-room, in which, when everyone had gone to bed, the furniture, after its habit, used to talk. All furniture talks, although the only pieces with voices that we human beings can hear are clocks and wicker-chairs. Everyone has heard a little of the conversation of wicker-chairs, which usually turn upon the last person to be seated in them; but other furniture is more self-centered.

On the night with which we are now concerned the first remark was made by the clock, who stated with a clarity only equalled by his brevity that it was one. An hour later he would probably be twice as voluble.

It was normally the signal for an outburst of comment and confidence; but let me first say that the house in which this sitting-room was situated belonged to an elderly gentleman and his wife, each conspicuous for peaceable kindliness. Neither would hurt a fly, but since they had grandsons fighting for England, honour and the world, it chanced that they were the incongruous possessors of quite a number of war relics, which included an inkstand made of a steel shell-top, copper shell-binding and cartridge-cases; a Turkish dud from Gallipoli to serve as a door-stop; a pencil-case made of an Austrian cartridge from the Carso; a cigarette-lighter made of English cartridge-cases; and several shell-cases transformed into vases for flowers. One of these at this moment contained some very beautiful late sweet peas, and the old gentleman had made a pleasant little joke, after dinner, about sweet peace blossoming in such a strange environment, and would probably make it again the next time they had guests.

You may be sure that, with the arrival of these souvenirs from such exciting parts, the conversation of the room became more interesting, although it may be that some of the stay-at-homes began after a while to feel a little out in the cold. What was an ordinary table to say when in competition with a .75 shell-case from the Battle of the Marne, or a mere Jubilee wedding-present against an inkstand composed of articles of destruction from Vimy Ridge, which had an irritating way of making the most of both its existences—reaping in two fields—by remarking, after a thrilling story of bloodshed, "But that's all behind me now. My new destiny is to prove the pen mightier than the sword"? Even though the Jubilee wedding-present came from Bond Street, and had once been picked up and set down again by QUEEN ALEXANDRA, what availed that? The souvenir held the floor.

Gradually the other occupants of the room had come to let the souvenirs uninterruptedly exchange war impressions and speculate as to how long it would last—a problem as to which they were not more exactly informed than many a human wiseacre. Under cover of this kind of talk, which is apt to become noisy, the humdrum of the others, the chairs and the table and the mantelpiece, and the pacific ornaments, and the mirror, could chat in their own mild way; the wicker-chair, for example, could wonder for the thousandth time how long it would be before the young Captain sat in it once more; and the mirror could remark that that would be a happy moment indeed when once again it held the reflections of the Lieutenant and his fiancée, who was one of the prettiest girls in the world.

"Do you think so?" the knob of the brass fender would inquire. "To me she seemed too fat and her mouth was very wide."

"But that's a fault," the tongs would reply, "that you find with every one."

To return to the night of which I want particularly to speak, no sooner had the clock made his monosyllabic utterance than "I am probably unique," the Vimy Ridge inkstand said.

"How?" the cigarette-lighter sharply [pg 254] inquired, uniqueness being one of his own chief claims to distinction.

"Strange," said the inkstand, "the blacksmith who made me was not blown to pieces. The usual thing is for the shell to be a live one, and no sooner does the blacksmith handle it than he and the soldiers who brought it and several onlookers go to glory. The papers are full of such incidents. But in my case—no. I remember," the inkstand was continuing—

"Oh, give us a rest," said the shell door-stop. "If you knew how tired I was of hearing about the War, when there's nothing to do for ever but stop in this stuffy room. And to me it's particularly galling, because I never exploded at all. I failed. For all the good we are any more, we—we warriors—we might as well be mouldy old fossils like the home-grown things in this room, who know of war or excitement absolutely nothing."

"That's where you're wrong," said a quiet voice.

"Who's speaking?" the shell asked.

"I am," said the door. "You're quite right about yourselves—you War souvenirs. You've done. You can still brag a bit, but that's all. You're out of it. Whereas I—I'm in it still. I can make people run for their lives."

"How?" asked the inkstand.

"Because whenever I bang," said the door, "they think I'm an air-raid."

Butler (the family having come down to the kitchen during an

air-raid). "'YSTERIA—WITHIN REASON—I DON'T OBJECT

TO. BUT WHAT I CAN'T STAND IS BRAVADO."

Butler (the family having come down to the kitchen during an

air-raid). "'YSTERIA—WITHIN REASON—I DON'T OBJECT

TO. BUT WHAT I CAN'T STAND IS BRAVADO."I found myself, some time ago,

Growing too fond of cuss-words, so

I made a vow to curb my passions

And put my angry tongue on rations.

As no Controller yet exists

To frame these necessary lists,

I had myself to pick and choose

The words that I could safely use.

Four verbs found favour in my sight,

Viz., "drat" and "dash" and "blow" and "blight";

While "blithering" and "blinkin'" were

My only adjectival pair.

I freely own that "dash" and "drat"

At times sound lamentably flat;

And "blight" and "blow" don't somehow seem

Quite adequate to every theme.

When you are wishful to be withering

'Tis hard to be confined to "blithering,"

And to express explosive thinkin'

One longs for some relief from "blinkin'."

Still Mr. BALFOUR, so I hear,

Seldom goes further than "O dear!"

While moments of annoyance draw

"Bother" at worst from BONAR LAW.

Hence, if our leaders in their style

Are able to suppress their bile,

And practise noble moderation

In comment and in objurgation,

Why should not I, a doggerel bard,

All futile expletives discard,

And discipline my restive soul

With salutary cuss-control?

From the Indian author of an Anglo-vernacular text-book:—

"As the book had to go through the press in haste I am sorry to write to you that there are some printers' devils, especially in English spelling."

"Nelson himself being a Suckling on his mother's side."—Observer.

We cannot know too much about the early history of our heroes.

"Captain William Redmond, son of Mr. John Redmond, has been awarded the D.S.O. He was commanding in a fierce fight and was blown out of a shell hole, sustaining a sprained knee and ankle. He rallied his men, and by promptly forming a defensive flank saved his part of the line."—Daily Express.

This must have been in Sir WALTER SCOTT'S proleptic mind when he wrote (in Rokeby):—

"Young Redmond, soil'd with smoke and blood,

Cheering his mates with heart and hand

Still to make good their desperate stand."

F.M. SIR DOUGLAS HAIG (sings). "O I'LL TAK' THE HIGH ROAD

AN' YE'LL TAK' THE LOW ROAD...."

[The enemy has been fighting desperately to prevent us from occupying the ridges above the Ypres-Menin road, and so forcing him to face the winter on the low ground.]

We live in a fortress on the crest of a hill overlooking a little Irish town, a centre of the pig and potheen industries. The fortress was, according to tradition, built by BRIAN BORU, renovated by Sir WALTER RALEIGH (the tobacconist, not the professor) and brought up to date by OLIVER CROMWELL. It has dungeons (for keeping the butter cool), loop-holes (through which to pour hot porridge on invaders), an oubliette (for bores) and a portcullis.

In spite of these conveniences our fortress is past its prime and a modern burglar would treat it as a joke. It is so weak in its joints that when the wind blows it shakes like a jelly, and we have to shave with safety-razors.

In a small villa opposite lives Freddy, our married subaltern, and Mrs. Freddy.

On a patch of turf up a neighbouring lane Oswald and Co. took up their residence this summer.

The troopers called him Oswald for some unknown reason, but I doubt if that was his baptismal name, and I doubt if he was ever baptized.

Oswald was a tall bony grizzled child of the Open.

Years ago he would have been dismissed briefly as a tramp, but we know better now; we have read our Georgian poets and we know that such folk do not perambulate the country stealing fowls and firing ricks from any dislike of settled labour, but because they have heard the call of far horizons, belles étoiles and great spaces.

The Co. consisted of a woolly donkey which carried Oswald's portmanteau when he trekked, and a hairy dog which provided him with company and conversation.

The donkey browsed, unfettered, about the roadside, taking the weather as it came; but Oswald and the dog, degenerates, sheltered under a wigwam of saplings and old sacks.

The wigwam being four feet long and Oswald six, he had to telescope like a tortoise to get fully under cover; sometimes he forgot his feet and left them outside all night in the dew, but, as he had no boots to spoil, this didn't matter much.

Not having any business to attend to he lay abed very late. Our troopers, riding at ease en route to the drill grounds, would toss their lighted cigarette-ends at the protruding bare feet. A grizzled head telescoping out of the other end of the wigwam and a husky voice calling down celestial fury upon them, would signalise a hit.

The Adjutant was for having Oswald moved on; we should be missing things presently, he warned—saddle-blankets, rifles, horses, perhaps the portcullis. However, the O.C. would have none of it; he maintained that this constant menace at our gates kept the sentries on the qui vive and accustomed them to practically Active Service conditions.

So all the summer the wigwam remained on the turf-patch and the sentries on the qui vive.

How Oswald existed is a mystery—probably on manna, for he toiled not neither span, and if he stole for a living it was not from us.

He spent his mornings in bed, his afternoons reclining on the bank behind his residence, puffing at his dudheen and watching our recruits going through the hoops with the amused contempt that a gentleman of leisure naturally feels for the working classes.

At the end of September, Freddy, the Benedick, finding himself in the orderly-room and forgetting what had brought him there, applied for leave as a matter of habit, and, walking out again, promptly forgot all about it. Freddy is given that way. Apparently [pg 257] the Orderly Room was finding time heavy on their hands that morning, for machinery was set in motion, and in due course the astonished Freddy discovered himself with permission to go to blazes for seven days and a warrant to London in his pocket.

He capered whooping home to his villa, told Mrs. Freddy to pack her toothbrush and come along, and the mail bore them hence. Next day the weather broke, the sky turned upside down and emptied itself upon us, the parade ground squelched if you trod on it, the gutters failed to cope with the rush of business, and the roads ran in spate.

The post-orderly, splashing back to barracks, reported the disappearance of Oswald and Co.

We determined that they must have been washed out to sea and pictured them astride the wigwam in a beam-roll off Kinsale, keeping a watchful eye for U-boats.

We had seven days of unrelieved downpour. On the morning of the eighth, Freddy and wife returned from leave, and, opening the front door of the villa—which they discovered they had forgotten to lock in the delirium of their departure—stepped within. At the same moment, Oswald, the hairy dog and the woolly donkey heard the call of the great spaces, and, opening the back door of the villa, stepped without and departed for haunts unknown.

Freddy in a high state of excitement came over to the Mess and told us all about it.

He himself had been all for slaying Oswald on the spot, he said, but Mrs. Freddy wouldn't hear of it.

"She says he hasn't stolen anything," Freddy explained. "She says he was only staying with us, in a manner of speaking, and was quite right to take his poor old dog and donkey under cover during that rotten weather, she says—so that's the end of it."

But it wasn't the end of it; Freddy had reckoned without his other O.C. Here was a heaven-sent opportunity of training the men under practically Active Service conditions, scouring the country after real game—Ho! toot the clarion, belt the drum! Boot and saddle! Hark away!

So now we are out scouring the country for Oswald and Co., one hundred men and horses, caparisoned like Christmas-trees, soaked to the skin, fed to the teeth. And Oswald and Co.—where are they? We cannot guess, and we are very very tired of practically Active Service conditions.

Oyez, Oyez, Oyez! Anyone finding three children of the Open answering to the description of our friends the enemy, and returning them, dead or alive, to our little fortress, will he handsomely and gratefully rewarded.

Earnest Lady. "OF COURSE I UNDERSTAND MEN MUST DRINK WHILE DOING SUCH HOT AND HEAVY WORK. BUT MUST IT BE BEER? CAN'T THEY DRINK WATER?"

Mechanic. "YES, LADY, THEY CAN DRINK WATER, BUT (confidentially) IT MAKES 'EM SO GIDDY."

"Boy, to heat at hearth and to strike occasionally."—Sheffield Daily Telegraph.

A case for the N.S.P.C.C.

Appended to a quotation from The Globe on German intrigues with the Vatican:—

"[NOTE: The above is obviously from the pen of Mr. L.J. Maxse, the editor of the National Review, who, as recently announced, has become associated with the editorial direction of the Pope.]"—Manchester Evening Chronicle.

In pursuance of this arrangement His Holiness will in future take the style of Pontifex Maxsemus.

"M. Kerensky has announced that all leaders of the revolt will be tried by court-martial, and has indicated that a determined end will be put to the present state of affairs by the most drastic means. Add Russian Fudge matter. utikwtStdheto"—Adelaide Register.

We have lately read a good deal of "Russian Fudge matter."

"PROMENADE CONCERTS, QUEEN'S HALL.

Sir Henry J. Wood, Conductor.

Mondays—Wagner. ——?——?—?——

Tuesdays—Russian. cymfwypo——

Wednesdays—Symphony. cmfwypemfwvfg

Thursdays—Popular. cmfwypemfwycppwf

Fridays—Beethoven. cmfwypemfwyy

Saturdays—Popular. cmfwypemf——"

The Star.

A sporting effort to reproduce the effect of the barrage obbligato.

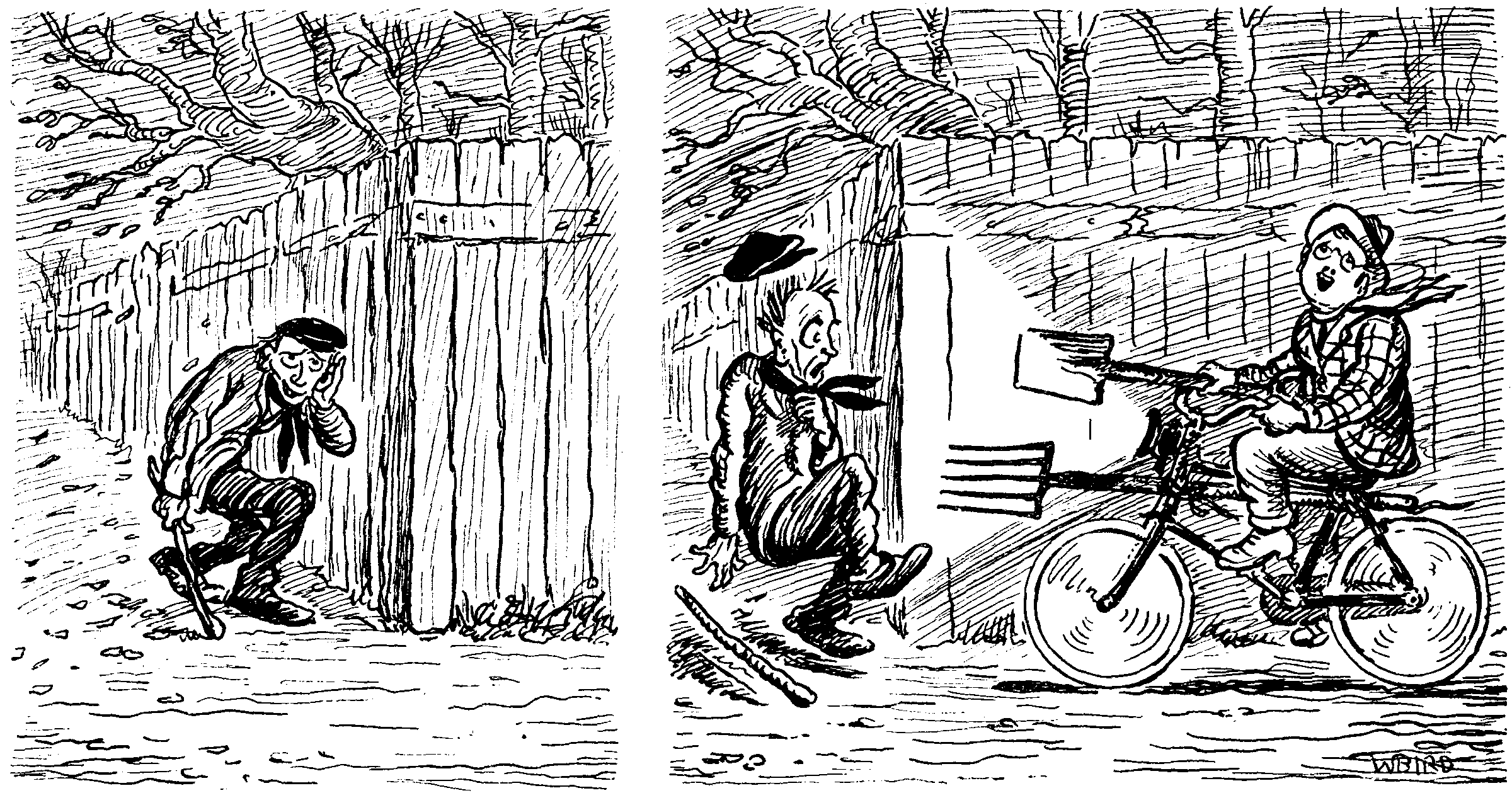

| Footpad. "I HEAR A CYCLIST COMING. I'LL UPSET HIS BIKE, AND THEN—" | BUT IT WAS MR. TUBER-CAINE, THE ALLOTMENT ENTHUSIAST, RETURNING FROM HIS LABOURS. |

Thomas (that may not be thine actual name

But it will serve as well as any other),

There be coarse souls to whom all flesh is game,

Who do not hail thee as a new-born brother

But merely as a thing at which to aim

Their fratricidal guns; they simply smother

The sense, which I for one cannot eschew,

Of soul relationship 'twixt man and gnu.

'Tis not, O surely not, for such as these

Those baby limbs are flung in lightsome capers;

Those puny bleatings were not meant to please

Facetious writers for the daily papers;

Let baser beasts inspire the obvious wheeze,

Wombats and wart-hogs, tortoises and tapirs;

These lack the subtle spell thy presence flings

About the spirit tuned to higher things.

Well could I picture thee, a dusky sprite,

With Dryad hoofs on Thracian ledges drumming,

When day is slipping from the arms of night

And all the hushed leaves whisper, "Pan is coming!"

And thou before him, leaping with delight,

Stirring all birds to song, all bees to humming

And buds to blossoming—but lo! at hand

A tablet reads, "C. Gnu. Nyassaland."

Thus they've described thy formidable sire,

A whiskered person with a chronic liver.

I feed him biscuits to appease his ire;

He eats the gift but fain would bite the giver.

His eye is red with reminiscent fire,

His thoughts are by the great Zambesi River

Where hides the hippopotam, huge as sin,

And slinking leopards with the dappled skin.

No couches of the nymph and Bassarid,

Or thymy meadows such as Simois glasses,

Lured his exulting feet, my jocund kid,

But veldt and kloof and waving jungle grasses,

Where lurk the python with unwinking lid,

And the lean lion, growling, as he passes,

His futile wrath against the hoarse baboons

That drape the rocks in chattering platoons.

Free of the waste he snuffed the breeze at morn,

The fleet-foot peer of sassaby and kudu;

The hunting leopard feared his bristling horn,

The foul hyæna voted him a hoodoo;

Browsing on tender grass and camel-thorn

He roamed the plains, as all right-minded gnu do;

But now he eats the bun of discontent

That once was lord of half a continent.

And thou, my child, to whom harsh fate has dealt

A captive's birthright—thou wilt never scamper

With wingéd feet across the windy veldt,

Where are no crowds to stare nor bars to hamper;

Thou wilt not ring upon the rhino's pelt

In wanton sport. But there—why put a damper

On thy young spirits by recounting what

Africa is but Regent's Park is not.

It would but grieve thee, and, moreover, I

Note that thy young attention's growing looser.

A piece of cake? O fie! my Thomas, fie!

The keeper said, "Please not to feed the gnu, Sir."

And yet it seems a shame to pass thee by

Without some slight confectionery douceur;

So here's a bun; and let this thought obtrude:

What matter freedom while there's lots of food!

"At St. Mary Abbot's, in Kensington, the organist played hymns for two hours during the Sunday raid, in which the congregation joined."—Daily Mirror.

The rumour that in consequence of the recent invasion of a popular sea-coast resort by denizens of the East End the local authorities have decided to change its name to "Brightchapel" is at present without foundation.

C. Officer. "NOW THEN, WHAT'S THE MEANING OF THIS?"

C. Painter. "I WAS TELLING 'IM 'E DIDN'T KNOW NOTHING ABOUT CAMERFLARGE, SIR, AND 'E SAYS, 'HO, DON'T I? I'LL SOON SHOW YER. I'LL MAKE YER SO'S YER OWN MOTHER WON'T KNOW YER'; AN' 'E UPS WITH THE PAINT-BUCKET ALL OVER ME, SIR."

A short while ago the following advertisement appeared in the "Personal" column of The Times:—

"Artist (33), literary, travelled, mentally isolated, would appreciate brilliant, interesting correspondents; writers' anonymity observed."

Now thereby hang many tales (none of them necessarily true). Here is one of them.

The Colonel of the Blank-blank Blankshires exclaimed (as all proper Colonels are expected to do), "Ha!" Carefully marking with a blue pencil a small paragraph on the front page of The Times, he threw it on the table among the attentive Mess and snorted.

"Ha! A Cuthbert—a genuine shirker! I think some of you might oblige the gentleman."

Then he stepped outside and went into the seventh edition of his impressionist sketch, "Farmyard of a French Farm," with lots of BBB pencil for the manure heap. He was a young C.O. and new to the regiment.

The Mess "carried on" the conversation.

"I'll write to the blighter," shouted the Junior Sub. "I'll be an awf'lly 'interesting correspondent.'"

"And a brilliant one?" queried the Major.

"A Verey brilliant one, Sir," asserted the Sub., giving a sample.

"This sort of slacker," said the Senior Captain bitterly, as with infinite toil he scraped the last of the glaze from the inside of the marmalade pot, "is the sort that doesn't realise that there's a war on."

"Don't you make any mistake," said the Major, "he knows, poor devil! I'm going to write to him and say, 'When I think of the incessant strain of the trench warfare carried on with inadequate support by you civilians of military age against the repeated brutal attacks of tribunals, I marvel at the indomitable pluck you display. In your place I should simply jack it up, plead ill-health and get into the Army."

"I've got an idea," said the Junior Sub., joyously.

"Consolidate it quickly," said the Adjutant, "and prepare to receive counter-attacks. Yes?"

"I've never yet been allowed to explain my side of that confounded affair of the revetments. I'll tell it all to Cuthbert. He'll sympathise with me. I'll tell him all that the C.O. said and all that I should have liked to say to the C.O. To pour out one's troubles into a travelled literary bosom—what a relief!"

"That's rather an idea," said the Senior Captain. "I nurse a private grief of my own beneath a camouflage of—of persiflage. I think I shall ask Cuthbert's opinion, as an artist, of a brother artist who himself does perfectly unrecognisable sketches of farm-yards"—he waved a golden-syrup spoon towards the Colonel and the manure-heap—"and yet demands a finnicking and altogether contemptible realism in the matter of trench maps. Pass the honey, please."

"It seems to me," said the Major reflectively as he rose from table, "that 'Artist, 33, literary, travelled, mentally isolated' (one) is going to be buried beneath the weight of the world's grievances—or the grievances of this battalion, at any rate."

"It's the same thing," observed the Senior Captain gloomily. "Isn't there any preserved ginger? Lord, what a Mess!"

Weary Williams, a time-expired [pg 260] Second Lieutenant—a ticket-of-leave man, as it were, without a ticket-of-leave—who had once commanded the remnants of two companies with honour but not with acknowledgment, poised a fountain-pen, inquiring casually, "What was it the C.O. said about the destruction of Ypres? Ah, yes" (and he began to write), "a Brobdingnagian act of brachycephalic brutality...."

At breakfast about a week later the Colonel seemed to be enjoying his immense pile of correspondence so heartily that many of the Mess, comparatively letterless as they were, directed glances of injured interest towards him—of rather deeper interest than was warranted by military discipline or civilian breeding (which are, of course, the same virtue in different forms).

Then, presently, as he put down one letter and opened another, the Major was seen to stiffen and the Junior Sub. to wilt. The attention of the table became as fixed and frigid as that of the midnight sentry at a loophole. The Colonel toyed happily with another letter (while the Senior Captain made a careful census of the grounds at the bottom of his coffee-cup), took the range of the manure-heap outside the window from the angles of the table-legs, rose, and departed with his correspondence, summoning Williams to follow him.

Outside the Weary One waited respectfully for the Colonel to speak.

"So you saw through my camouflage?" said the latter thoughtfully.

"Yes, Sir."

"How did you do it?"

"Well, Sir, to mention only the internal evidence—an 'Artist'"—Williams waved his hand expressively towards the manure-heap; "'thirty-three'—one of the youngest C.O.'s in the Army, I believe?" He bowed politely.

"Ha!" said the Colonel.

"'Literary'—I remember your stopping Captain Jones's leave for a split infinitive in a ration return. 'Travelled'—you have travelled in Turkey, I think, Sir?"

The Colonel, who had been blown out of a trench at Krithia, nodded shortly.

"'Mentally isolated'—I'm afraid, Sir, our Mess doesn't afford very much for a mind like yours to bite on. I'm afraid, too, that such correspondence as—as mine, for instance—can hardly be called either brilliant or interesting."

"I don't know," said the Colonel. "That was a very good bit about the destruction of Ypres. What was it?—Ha, yes—A Brobdingnagian act—"

"—of brachycephalic brutality, Sir. But that was not original."

"If you can't be original yourself," said the Colonel kindly, "the next best thing is to quote from those who can."

"That's what I thought, Sir."

"Ha! Well, of course the writers' anonymity must be observed—that's a point of honour. Still, I think, Williams—I have been asked to recommend an intelligent officer for a staff appointment—that if I were to name you I should not go far wrong. And—er—if you are ever asked for an opinion of the destruction of Ypres—"

"I shall remember to give the reference, Sir. Thank you, Sir."

On the tesselated slopes

Of the Isle of Tapioca,

Where the azure antelopes

Haunt the valley of Avoca,

Dwelt the maid Opoponax,

Only child of Brex Koax,

Far renowned in song and saga,

Ruler of ten million blacks,

Emperor of Larranaga.

She could play the loud jamboon

With a fervour corybantic;

She could hurl the macaroon

Far into the mid-Atlantic;

More self-helpful than a SMILES,

She could ride on crocodiles,

Catch the fleetest flying-fishes;

She could cook, like EUSTACE MILES,

Wondrous vegetarian dishes.

In the cool of eventide,

Gracefully festooned with myrtle,

In her sampan she would glide

Forth to spear the snapping turtle;

And her voice was blinding sweet,

Piercing as the parrakeet,

Fruity as old Manzanilla,

With a soupçon of the bleat

Of the African gorilla.

Eligible swains in shoals,

Victims to her fascination,

Toasted her in flowing bowls

Far beyond all computation;

There was valorous Hupu,

Xingalong and Timbalu,

And the peerless Popocotl,

Who had gained a triple blue

For his prowess with the bottle.

But Opoponax, whose mind

Soared above her native tutors,

Imperturbably declined

All these brave and dusky suitors.

Finally she hailed a tramp

And, contriving to decamp

To the shores of Patagonia,

Finding them too chill and damp,

Perished of acute pneumonia.

In an even darker doom

Tapioca's greatness ended,

For her father to the tomb

By swift leaps and bounds descended;

Xingalong and Timbalu

Both were slaughtered by Hupu,

Who was slain by Popocotl,

Who himself soon after slew

With an empty whisky bottle.

Every tale, we often hear,

Ought to have a wholesome moral;

And this truth is just as clear

In the land of palm and coral;

For this tragedy in tones

Louder than a megaphone's

Warns us that two things are risky,

If you dwell in torrid zones—

Change of climate, love of whisky.

From the window of an emporium of ivory articles:—

"Customers' Own Tusks Mounted."

"Daily morning housework; wanted at once, temporarily respectable person."—Middlesex County Times.

Everything is temporary in war-time.

From a drapery firm's advertisement:—

"We are the hub-bub of the Universe."

A distinct infringement of the KAISER'S prerogative.

"The pilot of the Sopwith single-seater aeroplane dropped his bombs and made off safely through a hail of anti-aircraft shells, but not before his observer had been wounded in the arm."—Daily Express.

It is inferred that the observer, in default of other accommodation, was seated upon the pilot's knee.

"Many an Englishman who disliked hunting or shooting in July, 1914, would have cheerfully pressed a button if he could thereby kill 100,000 Germans of military age in July, 1915."—The English Review.

But then, of course, there is no close time for Germans.

"We were pleased to meet here lately Captain ——, R.E., who has been in France since near a couple of years and has seen considerable service in H.M. forces. He left last week en route for la belle Francaise. We wish the gallant officer all future military success."—Scotch Paper.

Our best wishes for the lady, too.

"We have sunk more German submarines than ever before. The Admiralty has begun to see its way to reduce the danger to proportions, normal and negotiable, like other dangers. If that is done within the next months the British flee will have gained the most memorable, though the least evident, victory in all its annals."—Observer.

Good old insect! But what an odd way to spell it.

"IS IT SAFE NOW, MISTER?"

"YES—IT WAS ALL CLEAR AT 9.20."

"GOOD ON 'EM! JEST GAVE MY OLE MAN TIME TO GIT 'IS FINAL."

Mr. STEPHEN McKENNA, with the blushing honours of Sonia still fresh upon him, has now turned his pen to a tale of farcical adventure, the result being Ninety-Six Hours' Leave (METHUEN), and I could find it in my heart to regret it. Because, to speak frankly, the present volume will do little to add to the reputation so deservedly won by the other. It is a tangle of complications, which, since they have nothing solid to rest upon, begin by baffling, and end by boring, the reader who strives to keep pace with them. A young officer, wishful to dine at a smart hotel and having no appropriate clothes, is struck with the idea of pretending to be a foreign royalty, and thus incapable of sartorial indiscretion. And, as all sorts of assassins and undesirable aliens happened to be waiting about to kill the man whose style he borrowed, you can make a fair guess at the subsequent action. There is much dialogue, most of it sparkling, though even here I have to report criticism from a young friend to whom I introduced the story. He said, "People don't talk like that really." Which happens to be undeniably true. Thus, while giving Mr. McKENNA credit for an active invention and some really writty turns of phrase, I fear I must repeat my warning that as a farceur he is below his best form.

The clever lady who elects to call herself "RICHARD DEHAN" has already secured a deserved reputation as a writer of short stories. Her new book, Under the Hermes (HEINEMANN), gives us a further selection of tales of various lengths, from one that is not quite a novel to others that are as brief as ten pages. The themes and settings are equally varied; but all—or almost all—show the writer at her best in the vigorous, swift and exciting development of some dramatic situation. The exception, I may say at once, is the title-tale, to my mind a stilted and—in a double sense—obviously "studio piece," quite unworthy of its position at the opening of so attractive a volume, where indeed it might easily discourage a questing reader. "Mr. DEHAN" is far more fairly represented by such brilliant little miniatures of historical romance as (to select three at random) "A Speaking Likeness," "A Game of Faro" and "The Vengeance of the Cherry Stone"—slight sketches ranging from France of the Revolution to mediæval Bologna, but each most effective in its vivid colouring and well-handled climax. Since one of these has lingered for many years in my recollection from some else-forgotten magazine, I suspect that most of the tales in the volume may be making a second appearance. If so, it is in every way deserved.

Trench Pictures from France (MELROSE) is by the late Major WILLIAM REDMOND, M.P., and The Ways of War (CONSTABLE) is by the late Professor T.M. KETTLE, M.P. Both these books are memorials raised to their authors by the pious zeal of relations and friends who thought it shame that so much nobility of purpose and generous ardour should go unrecorded in a tribute more permanent than the fleeting memories of contemporary survivors. Both WILLIE REDMOND and TOM KETTLE were Irishmen and members of the Nationalist Party and were to that extent foes of the British Government; yet, when they were [pg 262] compelled to look the Prussian menace in the face, neither the older man nor the younger hesitated for a moment. Each, though there were many reasons that might have pleaded against such a course, "joined up" in an Irish regiment, each in due time went to France and each made the supreme sacrifice, falling with his face to the foe. Neither doubted for a moment that he was serving the cause of Ireland in fighting against Prussianism and all that it implies. Their enthusiastic approval of the justice of our cause should be to us a great assurance. I knew them both and can say with the most complete sincerity that I never knew two men better loved by all who had to do with them or more worthy of this universal affection. It is in every way right that they should be commemorated for future generations. WILLIE REDMOND'S book consists of a series of sketches of the War contributed by him to The Daily Chronicle. They are written with great charm and, even in the gloomiest surroundings, reflect the sunny nature of the man. There is a most appreciative biographical memoir by E.M. SMITH-DAMPIER, and in an appendix will be found the memorable and splendid speech delivered by WILLIE REDMOND in the House of Commons on March 7th of this year—a true salutation in view of death. KETTLE'S book is in the main a reprint of articles that reveal a brilliant and versatile mind. Mrs. KETTLE contributes a very interesting and sympathetic account of her gallant husband's life. It would have been impossible for such a man not to have hated the German tyranny.

Mr. Stacy Aumonier takes for his theme the development of a clever neurotic, Arthur Gaffyn, who stands, in relation to normal life and normal feelings, Just Outside (METHUEN)—a common modern type, perhaps a commoner type in all ages than the obvious records show. The author handles with real subtlety the phases of Arthur's marriage with a woman much older than himself, a marriage in which the hunger of the woman for love was a greater factor than the not deeply stirred passion of the man. Then, with the appearance of the destined mate, beauty and youth and desire carry the day against duty, but neither callously nor flippantly. The insight and sympathy displayed in the analysis of motive are remarkable. The author has a real gift for portraiture. In particular he touches in his minor folk with extraordinarily deft defining lines. Perhaps in general there is a little hesitancy in craftsmanship, a slight quavering between the fashionable modern realism and an older romanticism. But the seriousness of his artistic intention, the solidity of his work (which is by no means to say stodginess, quite the contrary) will commend Mr. AUMONIER to all who care to listen to people who have the one thing necessary, something to say; and the other thing desirable, a pleasant way of saying it.

In its quiet unobtrusive way When Michael Came to Town (HUTCHINSON) is a most excellent specimen of Madame ALBANESI's art. No sound of war is to be heard in it, and when I think how completely some of our novelists have failed when trying to deal with contemporary events I cannot be too thankful that this novel is laid in a period before the Germans became an uncivilised nation. Olive, the heroine, a delightful girl, is the supposititious child of Sir James Wenborough, whose wife, in his absence and without his knowledge, secured her as a substitute for their own child, who died at its birth. The secret is disclosed by an unscrupulous minx, who uses the knowledge she has obtained to push her way into the Wenborough household. Men are not Madame ALBANESI'S strongest points, but in Roderick Guye and Michael Wenborough we have well-contrasted characters, and the worst that can be said of them is that they belong to rather stock types. Altogether a book which many people will describe as "perfectly sweet;" but, because of its sympathetic qualities and sound workmanship, it deserves a more distinctive label.

When the lean brown hero with the hawk lip extends an arm of steel from the six-cylinder Rolls-Royce in which he is lounging and snatches the beautiful mannequin from between the very jaws of an omnibus, we realise that we are in the presence of Romance in its purest form. A spin in the Park and a cosy dinner in a Soho restaurant are quite sufficient to convince hero and heroine that they are each other's own. Some novelists would let it go at that, but not Mr. ARTHUR APPLIN, who has only got to chapter II, and wishes to give us value for our money. What's to come is, as SHAKSPEARE says, still unsure, but apparently the heroine, who has gone to break the happy news to a poor but respectable aunt in Devonshire, is met at the country station by a chauffeur, who calls her "Lady Alice" and waves her towards a large Limousine. She knows she isn't Lady Alice and has no car to meet her, but she hops in nevertheless. She doesn't know where she is going, but she is on her way. There is a smash, and when the heroine comes to she is being called Lady Alice in an ancestral castle. Everything has been obliterated from her memory, including her own identity and that of the hero, and the author can now make a fresh start. If you wish to know how it all ends you must get The Woman Who Was Not (WARD, LOCK), but there is no compelling reason why you should.

"Monday commences the final week of Sir Thomas Beecham'sSeason of Nighty Promenade Concerts."

"Wensleydale Blue-Faced Sheep-Breeders' Show."

We cannot conceive why these breeders should look blue with prices at their present height.

"Before an interested and applauding public on the verandah of the Club-house Mrs. MacDonald, who had also provided tea, distributed the cups and other insignia of victory to the successful competitors."—Standard (Buenos Aires).