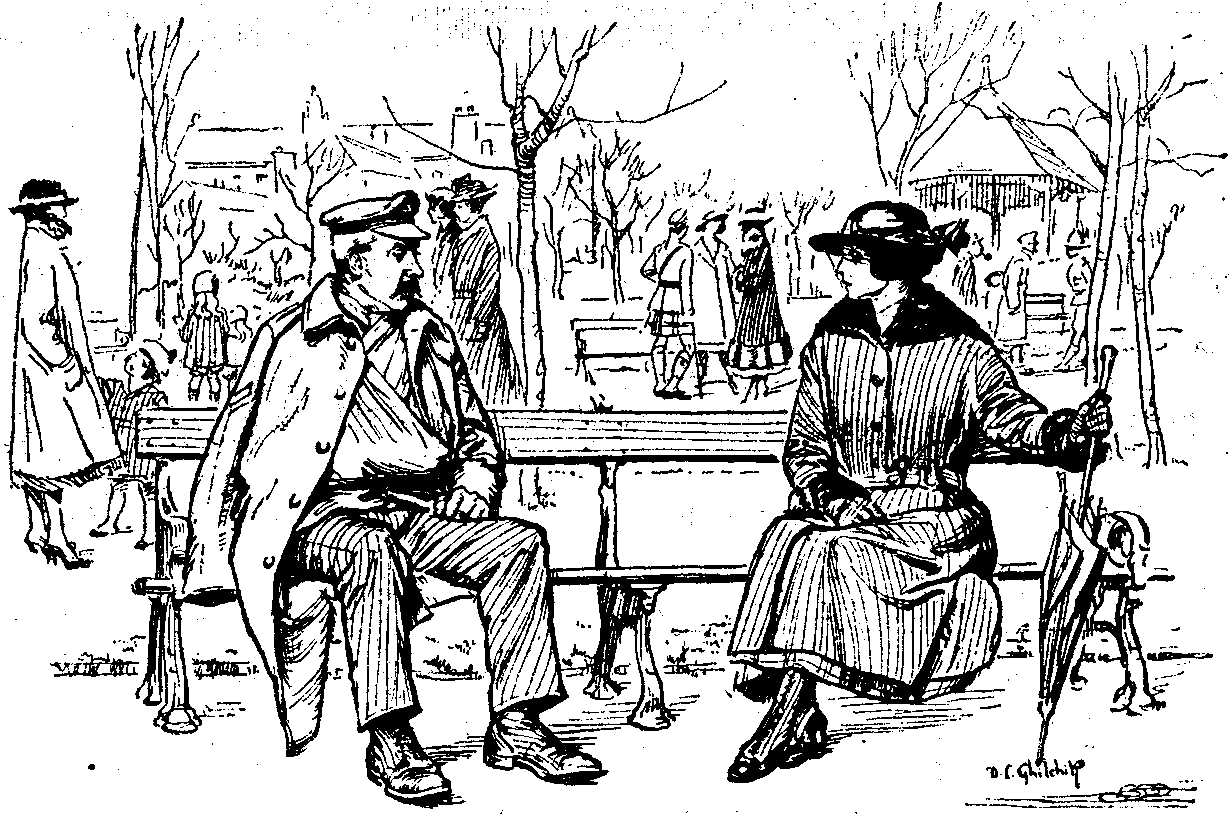

"I WISH MY HUSBAND HAD JOINED THEM PIVOTS INSTEAD OF THE

FOOSILEERS. HE'D 'A' BEEN DEMOBILISED BY NOW."

"I WISH MY HUSBAND HAD JOINED THEM PIVOTS INSTEAD OF THE

FOOSILEERS. HE'D 'A' BEEN DEMOBILISED BY NOW."A memorial to SIMON DE MONTFORT has been unveiled at Evesham, where he fell in 1265. A pathetic inquiry reaches us as to whether SIMON is yet demobilised.

We are informed that the project of adding a "Silence Room" to the National Liberal Club is to be resuscitated.

"Small one piece houses of concrete," says The National News, "are now quite common in America." The only complaint, it appears, is that some of them are just a trifle tight under the arms.

We hope that the proposed revival by a well-known theatre manager of The Sins of David so shortly after the General Election is not the work of a defeated Candidate.

"Some of the discredited Radical organs," says a contemporary, "are already toying with Bolshevism." A case of "Soviet qui peut."

The report that a number of distinguished Irish Unionists have been ordered to choose between the LORD-LIEUTENANT's Reconstruction Committee and the O.B.E. is causing anxiety in Dublin Club circles.

Weymouth Council has decided to change the name of Holstein Avenue. We deprecate these attempts to force the Peace Conference's hand.

Mr. HENRY FORD's new paper is called The Dearborn Independent. Most independent papers, it is noticed, are that.

"Why has the Government raised the price of new sharps?" asks "FARMER" in The Daily Mail. They may cost more, but they look to us like the same old sharps.

"Sensation-mongering" is the public's verdict on the startling report circulated last week that a Civil Servant had been seen running.

The National Potato Exhibition, it is announced, will in future be held at Birmingham. The League of Political Small Potatoes, on the other hand, has moved its permanent headquarters to Manchester.

There were 21,457 fewer paupers in London last week compared with the same period in 1915, it is stated. All we can say is, it isn't London's fault.

A correspondent, writing to a contemporary, thinks it should be illegal for one taxi-driver to talk to another in the streets. It would be interesting under these circumstances to see what happened if two rival cabs collided.

With reference to the Upper Norwood gentleman who is reported to have arrived home early one night last week, it is not true that he travelled by tube. He walked.

One thing after another. No sooner is influenza on the wane than we read of a serious outbreak of Jazz music in London.

We gather from the interviews appearing in the papers that Mr. PHILIP SNOWDEN is of the opinion that his defeat was due to the General Election.

We are asked to deny the rumour that the KAISER has offered to compete for The Daily Mail trans-Atlantic flight and has offered to forgo the prize.

Scientists are agreed, says Tit-Bits, that there is nothing to prevent people living for five hundred or even one thousand years. We feel, however, that in the case of certain very objectionable persons exemption might be given at the age of about forty years.

"Blwyddyn Newydd Dda i bawb Ohonynt" was the reported greeting sent by Mr. LLOYD GEORGE to his election agent. Other delegates to the Peace Conference are talking in the same truculent strain.

One of the men for whom our heart goes out in sympathy is a South Carolina farmer who has been in the habit of doctoring himself with the help of a medical book. When only fifty-five years of age he died of a misprint.

A prisoner charged at London Sessions with stealing was described as "one of a most daring and clever gang of thieves." It is said that he has asked counsel for permission to use this excellent testimonial on his note-headings.

An Irish farmer aged one hundred-and-four years, who took a prominent part in the General Election, has just died. This should be a lesson to people who meddle with politics.

"The current open secret in Society," says The Star, "is the engagement of Lady DIANA MANNERS, but when it will be announced only she herself will decide." This is extraordinary. A few weeks ago the decision would have rested with the newspapers.

There were 523 fewer books published last year than in the year before. This, we understand, is explained by the fact that Mr. CHARLES GARVICE and Mr. E. PHILLIPS OPPENHEIM each went to the theatre one night in the early autumn.

"I WISH MY HUSBAND HAD JOINED THEM PIVOTS INSTEAD OF THE

FOOSILEERS. HE'D 'A' BEEN DEMOBILISED BY NOW."

"I WISH MY HUSBAND HAD JOINED THEM PIVOTS INSTEAD OF THE

FOOSILEERS. HE'D 'A' BEEN DEMOBILISED BY NOW.""Traveller.—Wanted a pushing young man, to work through England and Scotland in barrel hoops."—Daily Telegraph.

"To these manifestations the President raised his hat, his smiling face indicating the measure of his pleasure at the leave-taking with the British public."—Daily Paper.

One of the things that might perhaps have been expressed differently.

The Bolshevist plan to conciliate Labour

Is based on the maxim of Beggar your Neighbour,

With the glorious result, when they share out the loot,

That ev'ry one's sure of possessing one boot.

By Salthouse Dock as I did pass one day not long ago,

I chanced to meet a sailorman that once I used to know;

His eye it had a roving gleam, his step was light and gay,

He looked like one just in from sea to blow a nine months' pay;

And as he passed athwart my hawse he hailed me long and loud:

"Oh, find me now a full saloon where I may stand the crowd;

I'm out to rouse the town this night as any man may be

That's just come off a salvage job, my lad, the same as me....

"Bringin' home the Rio Grande, her as used to be

Crack o' Moore, Mackellar's Line, back in ninety-three;

First of all the 'Frisco fleet, home in ninety-eight,

Ninety days to Carrick Roads from the Golden Gate;

Thirty shellbacks used to have all their work to do

Hauling them big yards of hers, heaving of her to

Down off Dago Ramirez, where the big winds blow,

Bringin' home the Rio Grande twenty years ago.

"We picked her up one morning homeward bound from Portland, Maine,

In a nine-knot grunting cargo tramp, by name the Crown o' Spain;

The day was breaking cold and dark and dirty as could be,

It was blowin' up for weather as we couldn't help but see.

Her crew was gone the Lord knows where—and Fritz had left her too;

He must have took a scare and quit afore his job was through;

We tried to pass a hawser, but it warn't no kind o' good,

So we put a salvage crew aboard to save her if we could....

"Bringin' home the Rio Grande and her freight as well,

Half-a-score of steamboatmen cursin' her like hell,

Flounderin' in the flooded waist, scramblin' for a hold,

Hangin' on by teeth and toes, dippin' when she rolled;

Ginger Dan the donkeyman, Joe the 'doctor's' mate,

Lumpers off the water-front, greasers from the Plate,

That's the sort o' crowd we had to reef and steer and haul,

Bringin' home the Rio Grande—ship and freight and all.

"Our mate had served his time in sail, he was a bully boy,

It'd wake a corpse to hear him hail 'Foretopsail yard ahoy!'

He knew the ways o' squaresail and he knew the way to swear,

He'd got the habit of it here and there and everywhere;

He'd some samples from the Baltic and some more from Mozambique;

Chinook and Chink and double-Dutch and Mexican and Greek;

He'd a word or two in Russian, but he learned the best he'd got

Off a pious preachin' skipper—and he had to use the lot....

"Bringin' home the Rio Grande in a seven-days' gale,

Seven days and seven nights, the same as JONAH'S whale,

Standard compass gone to bits, steering all adrift,

Courses split and mainmast sprung, cargo on the shift ...

Not a chart in all the ship left to steer her by,

Not a glimpse of star or sun in the bloomin' sky ...

Two men at the jury wheel, kickin' like a mule,

Bringin' home the Rio Grande up to Liverpool.

"The seventh day off South Stack Light the sun began to shine;

Up come an Admiralty tug and offered us a line;

The mate he took the megaphone and leaned across the rail,

And this or something like it was the answer to her hail:

He'd take it very kindly if they'd tell us where we were,

And he hoped the War was going well, he'd got a brother there,

And he'd thought about their offer and he thanked them kindly too,

But since we'd brought her up so far, by God we'd see it through....

"Bringin' home the Rio Grande (and we done it too),

Courses split and mainmast sprung—half a watch for crew—

Bringin' home the Rio Grande and her freight as well,

Half-a-score of steamboatmen cursing her like hell—

Her as led the grain fleet home back in ninety-eight,

Ninety days to Carrick Roads from the Golden Gate—

Half-a-score of steamboatmen to steer and reef and haul,

Bringin' home the Rio Grande—ship and freight and all."

C.F.S.

To keep moth from a haggis, sprinkle well with prussic acid or cayenne pepper. Repeat three times daily. (This method has never been known to fail.)

An excellent germicide for wire-worm can be made with two parts carbolic acid and three parts castor-oil. Rub over the wire-worm with a soft rag and polish with a clean duster.

To remove dust from whiskers, soak whiskers in paraffin or petrol for half-an-hour and singe gently with lighted taper.

To clean a carpet, take a small wet tea-leaf and roll it well over the carpet. Then remove the tea-leaf and store in a dry place. Take the carpet to the cleaners and you will be surprised at the result.

An excellent trousers press can be made in the following manner: Get the local monumental mason to supply you with two slabs of granite measuring about six feet by two feet and weighing about seven hundredweight each. Place the trousers on top of one block of granite, place the other block on top of the trousers and secure with a couple of book-straps. Finish off with blue ribbon.—AUNT SADIE.

"America appealed to Ireland for help, and even sent a special Ambassador—the great Abraham Lincoln—to this country to state America's case before the Irish Parliament in the year 1771."—Dublin Evening Mail.

American papers please copy.

"The —— Chamber of Commerce have certainly made a capture in securing the services of Bragadier-General ——, District Director of the Ministry of Labour, for an address on 'Demobilisation and the Activities of the Appointments Department of the left eye, and after treatment was taken the Portsea Island Gas Company offices."—Provincial Paper.

We had heard there was some trouble over demobilisation, but had no idea it was as bad as this.

"Arrangements are being made in all the stations throughout India for the celebration of the signing of the armistice. In Simla the Commander-in-Chief will be present at a parade on the Ridge at 11.45 a.m., civilians in leaves dress assembling at 11.30."—Times of India.

It is pleasant to note that the establishment of the armistice brought about an immediate return, in Simla at least, to the conditions of Paradise.

The other day, while I was out for a ride, I happened to run up against my two Chinese acquaintances, Ah Sin and Dam Li, and I stopped to have a chat with them. After the usual greetings Dam Li remarked:—

"Hon'lable officer lookee too muchee sad."

"Allee same like littlee dog when 'nother big dog stealum bone," supplemented Ah Sin.

"I wasn't aware of it," I said shortly, a little hurt at the comparison.

"P'haps hon'lable officer losee lations allee same little dog," suggested Dam Li.

"Well," I admitted, "I have lost something—at least the Mess has. Only it isn't rations; it's a milk-jug."

This, our only article of plate, was a battered piece of treasure-trove salved from the ruins of a derelict village.

Dam Li was all sympathy.

"You talkee China boy. Him findum one time plenty quick," he announced confidently.

"All right," I said; "only you won't get anything just for trying, mind. You'll have to succeed."

"China boy no wantchee nothing," replied Dam Li reproachfully.

"Him only wantchee officer smile allee same like dog waggee tail when lations come back," added Ah Sin by way of embroidery.

"Thank you," I said gravely. "And when do you propose to start replacing my smile?"

Apparently there was no time like the present, so back we went to the Mess and they set to work. Their opening move was somewhat startling, even to me who knew them of old.

"Giveum China boy one piecee blead," commanded Dam Li.

"What for?" I demurred.

"China Boy eatum blead and talkee plenty good player [prayer]," said Ah Sin. "Then thief-man too muchee flighten' an' giveum back jug plenty dam quick."

"But why should he be afraid?" I asked.

Ah Sin was very patient with me.

"Players plenty stlong language talkee," he said. "S'pose thief-man not giveum back jug, belly get plenty too muchee fat ..."

"An' go bang allee same air-dlagon bomb," broke in Dam Li, rubbing his hands together at the prospect.

"Very well, you may have your loaf," said I, capitulating; and then rashly I added, "Is there anything else you'd like?"

"Beer makee players plenty much worser for thief-man," said Ah Sin ingratiatingly.

In the end I produced the beer as well as the bread and the incantations commenced. They consisted in getting outside my bread and beer, and in filling the intervals between mouthfuls with a copious barrage of Chinese, occasional prostrations and a considerable amount of laughter. This last aroused my suspicions and I asked what it meant.

"Thief-man keepee plenty big pain here," explained Dam Li, indicating the region to which the bread and beer had by now all descended. "Him topside mad this minute."

"Giveum back jug to-mollow," prophesied Ah Sin. "China boy come an' see," he added as he got up to go.

The morrow arrived and so did the Chinamen, but not the milk-jug. This seemed to cause Ah Sin and Dam Li the greatest surprise.

"Thief-man No. 1 stlong man," asserted the former.

"Wantchee extla double-lation players," agreed his companion.

"Hon'lable officer giveum China boy 'nother piece blead," suggested Ah Sin.

"An' baer," added Dam Li hastily.

Nosing an obvious conspiracy I at first refused. However I at length gave way on the understanding that there was on no account to be a third imposition. The rites of the day before were thereupon repeated.

When they were over Dam Li suddenly professed himself to be inspired.

"China boy seeum jug," he announced.

"Where?" I asked.

"Seeum box, plenty too muchee big," Dam Li went on in sepulchral tones; "jug inside box."

Ah Sin now joined in.

"Where isum box?" he asked excitedly.

"No savvy," replied Dam Li, shaking his head.

Ah Sin gazed wildly around. Seeing a box in the distance he rushed at it. Dam Li waved him back.

"That box no dam use," he stated.

Ah Sin tried again.

"P'haps him in dirty box," he suggested.

Dam Li rolled his eyes inwards, as one who consulted an oracle within.

"Jug inside dirty box," he agreed ultimately, pointing in its direction.

"Oh, in the dust-bin," I said. "Well, there's no harm in looking."

So look we did, and there, sure enough, it was. I picked it out and did some quick thinking.

"Now, when did you two ruffians put it there?" I asked sternly.

"Thief-man put it there," protested Dam Li, with a magnificent look of injured innocence.

"I know," said I. "Come on, now, tell me why you stole it, and, as you've brought it back again, I may let you off."

"China boy's lations too muchee few, him plenty hungly," said Ah Sin, seeing that the game was up.

"S'pose him sellum jug, buy plenty beer," confided Dam Li unblushingly.

"But hon'lable officer lookee too muchee sad, so China boy dam solly. Fetchee back jug," resumed Ah Sin.

As I had often gone out of my way to do the pair a good turn I was naturally pained at their ingratitude. Taking the jug, I turned away in silence and left them. Ah Sin pursued me.

"Hon'lable officer likee jug?" he asked.

Dam Li, who had followed, answered for me.

"Likee jug allee same China boy likee lations," he explained.

"An' China boy gottee lations, blead an' beer, allee same hon'lable officer gottee jug," continued Ah Sin.

"Then what more can wantchee?" concluded Dam Li triumphantly.

I surrendered unconditionally.

Through the Channel's drift and toss

Swift your homing transports churn;

Soon for you the Southron Cross

High above your bows shall burn;

Soon beyond the rolling Bight

Gleam the Leeuwin's lance of light.

Rich reward your hearts shall hold,

None less dear if long delayed,

For with gifts of wattle-gold

Shall your country's debt be paid;

From her sunlight's golden store

She shall heal your hurts of war.

Ere the mantling Channel mist

Dim your distant decks and spars,

And your flag that victory kissed

And Valhalla hung with stars—

Crowd and watch our signal fly:

"Gallant hearts, good-bye! Good-bye!"

W.H.O.

"But most of the people aboard that car, if they had been truthfully outspoken, would probably have said, 'Dem's my sentiments.'"—Evening Paper.

"MARK OF CENTENARIAN.

"Mrs. Rachel ——, a former resident of this city, was the guest of honor at a dinner served yesterday at her son's home in Wilkinsburg, the occasion being the 92nd anniversary of her birth. Mrs. —— was born in Somerset County and resided in this city before the flood."—American Paper.

At first we thought the headline a little previous, but the last sentence shows that it is, on the contrary, decidedly belated.

Indignant Patriot (to Local Food Committee). "I WISH TO REPORT THAT THERE'S A GROCER IN THIS TOWN WHO IS SELLING BUTTER, SUGAR AND JAM WITHOUT COUPONS. HE—"

Food Committee (as one man, ecstatically). "WHICH IS HIS SHOP?"

Are you not, dear reader, a little tired of what is called "Literary Gossip"? Be frank. Aren't you? And have you not sometimes longed even more to know what the industrious fellows were not writing than what they were?

But suppose we could come across an authentic column like this?

Mr. KIPLING is putting the finishing touches to a new Jungle book. The first and second Jungle books have waited too long for this new companion; but it is now on its way. A friend of the author, who has been privileged to see an early copy, says that it is full of all the old enchantment.

Our Burwash correspondent informs us that, not content with the re-incarnation of Mowgli, Mr. KIPLING has completed a new romance of wandering life in India, not unlike Kim in treatment, to be entitled The Great Trunk Road.

An album has just come to light, the value of which is beyond computation. On the faded leaves of this book, which once belonged to Fanny Brawne, are inscribed three new poems in KEATS'S own hand. Not mere album verses, but poems of the highest importance, equal to rank to the Odes to the Grecian Urn and the Nightingale. The book itself will be sold by auction next week, but meanwhile the poems are to be issued in pamphlet form by Sir SIDNEY COLVIN.

An enterprising firm of publishers announces for immediate publication a volume by President WILSON, entitled From White House to Buckingham Palace. This work is in the form of a diary of singular frankness, and it contains some vivid accounts of conversations as well as the writer's honest opinion of some of the most prominent personages of the moment.

Admirers of O. HENRY will be excited to hear that a bundle of MS. stories in his best vein, some seventy-five all told (and how told!), has been discovered in a cupboard in one of his old lodgings: much as the manuscript of TENNYSON'S In Memoriam was found in his rooms in Mornington Crescent. How it happened that the historian of the joys and sorrows, the comedies and tragedies, of little old Baghdad-on-the-Subway neglected to send these tales to editors we shall never know, but he was always erratic. The book will be published at once, both in America and England.

After an interval of several years—far too many—Sir JAMES BARRIE has finished a new novel. With his customary reticence he withholds both the title and the subject; but the important thing is that the book is at the binders.

Having read those announcements I succumbed to precedent and woke up.

From a Japanese business circular:—

"Ladies and Gentlemen,—Congratulating upon the great victory of our Allies, we want to supply you Water Colour Pictures and Antique Prints fresh and much selected subjects painted by the most famous artists in Japan; so we long to have the honour to receive your favourable inspection and enjoy yourselves with triumphing victory for Our Lord's blessing in X'mas time."

"Surely with all the wars and rumours of wars all over the world, a little mare tact could have been displayed by the powers that be to keep the peace in the very centre of a British Protectorate."—Leader (East Africa).

The quality desired would appear to be the East African equivalent of horse sense.

That ass Ellis is a poor creature, and, like the poor, he is always with me. I think he is a punishment inflicted upon me for some past error.

A short time ago I caught the "flu." Naturally the first person I suspected was Ellis, but I am bound to confess that I have not been able to prove it. Indeed, when he followed me to hospital two days later and was put in the next bed, I felt justified in exonerating him altogether.

The first remark that he made, when he reached that stage of the complaint where you feel like making remarks, illustrates just the kind of man he is. He accused me of giving the thing to him!

I answered his outburst with the scorn it deserved.

"Preposterous," I said.

I added a few apposite remarks, to which he responded as best he could. But, medically speaking, I was two days senior to him, so that when the Sister heard the uproar and bustled up it was he who was forbidden to speak. She then proceeded to clinch the matter by inserting a thermometer in his mouth. I defy any man to argue under such a handicap.

I finished all I had to say and relapsed into an expectant silence. The Sister returned after a time, read the instrument and retired without a word. As she passed my bed I saw out of the corner of my eye that Ellis was watching feverishly. An inspiration seized me. I stopped her, and in a low voice asked if she had fed her rabbits. Sister isn't allowed to keep rabbits, but she does. As I hoped, she put a finger to her lips, nodded and walked away.

"Poor old man," I murmured vaguely to the ward in general. "A hundred-and-seven and still rising! Poor old Ellis!"

Ellis gave a little moan and collapsed under the bedclothes.

An hour later Burnett went his round. Burnett isn't the doctor, at least not the official one. I must tell you something about Burnett.

He is the grandfather of the ward. Though quite a young man he has grown fat through long lying in bed. He entered hospital, I understand, towards the end of 1914, suffering from influenza. Since then he has had a nibble at every imaginable disease, not to mention a number of imaginary ones as well. Regularly four times a day he would waddle round the ward in his dingy old dressing-gown, discussing symptoms with every cot. In exchange for your helping of pudding he would take your temperature and let you know the answer, and for a bunch of grapes he would tell you the probable course of your complaint and the odds against complete recovery. No one seemed to interfere with him. You see, Burnett was no longer a case; he was an institution.

He spent a long time by Ellis's bedside. I suspect Ellis wasn't feeling much like pudding at the moment. I couldn't hear very well what was going on, but Ellis was chattering as only Ellis can, and the comfortable Burnett was apparently soothing him with an occasional "All right, old man. I'll see what I can do for you."

At length the grapes were all consumed and the huge form of Burnett loomed above me.

"Why, Mr. L——," said the soothing voice, "I don't want to alarm you, but really—"

"Really what?" I cried, starting up in bed at the gravity of his tone.

"Well, you know—your colour; I perhaps—"

He fumbled in the folds of his voluminous gown and produced a small metal mirror. Then he seemed to change his mind and put it back again.

"I'd better not," he said softly to himself, and then louder to me, "Have you got a wife—or perhaps a mother?"

I am no coward, but I confess I was trembling by this time.

"Why?" I cried. "Do you think I ought to send for them?"

"Send for them?" he echoed. "Send for them? And you in the grip of C.S.M.! It would be sheer madness—murder!"

The cold sweat stood out upon my brow but I kept my head.

"Have an apple, won't you, Mr. Burnett?"

He selected the largest and began to munch it in silence—silence, that is, as far as talking was concerned.

"Tell me," I stammered; "wh—what is C.S.M.? And may I have a look at myself?"

He cogitated. "Shall I?" he muttered. "Yes, I think he ought to know." Then quite quietly, accompanied by the core of the apple, there fell from his lips the fatal words "Cerebro-spinal meningitis."

At the same time he handed me the glass and selected the next best apple.

I looked at myself. My hair stood straight on end; my face was whitish-yellow, my eyes blazed with unmistakable fever. A three-days' beard enhanced the horrible effect.

"Have you any pain—there?" One of his large soft hands gripped my side and pinched it hard, the other selected the third best apple.

"Yes," I groaned, "I had pain there."

"Ah!" he shook his head. "And there?" He sat down heavily on my right ankle. He is a ponderous man.

"Agony," I moaned.

"Ah! And something throbbing like a gong in the brain?" he inquired, tapping me on the head with the metal mirror.

I nodded dumbly. He rose, shrugging his shoulders.

"All the symptoms, I'm afraid. That's just how it took poor old Simpson. He had this very cot—let me see, back in '16, I suppose. I had it very slightly afterwards—it was touch and go; I was the only one they pulled through—but I only had it very slightly, you understand—not like that. But cheer up, old man. I've been told that a fellow got through it in the next ward—of course he's an idiot now, but he didn't die. I don't suppose you'll be wanting the rest of these apples, will you? All right, don't mention it;" and he passed on to the next cot.

[pg 39]When the proper doctor came round a few minutes later (Burnett says) he found his own thermometer quite inadequate and had to borrow the one that registers the heat of the ward. When he took it out of my mouth it wasn't far short of boiling-point, and he wrote straight off to The Lancet about it; also they had to get one of those lightning calculator chaps down to count my pulse.

Long before I came to, Ellis had been discharged, the ward had filled up with fresh cases (except Burnett, of course), and the armistice had been signed.

When I was well enough they handed me a letter which Ellis had left for me.

"DEAR L——" (it ran),—"Yes, the rabbits have had their food. The biggest of them swallowed it all most satisfactorily.

"Your loving ELLIS."

"AND I SUPPOSE YOU WILL BE DEMOBILISED AS SOON AS YOU GET OUT OF HOSPITAL?"

"OH, NO, MUM. YOU SEE, I WAS A SOLDIER IN CIVVY LIFE."

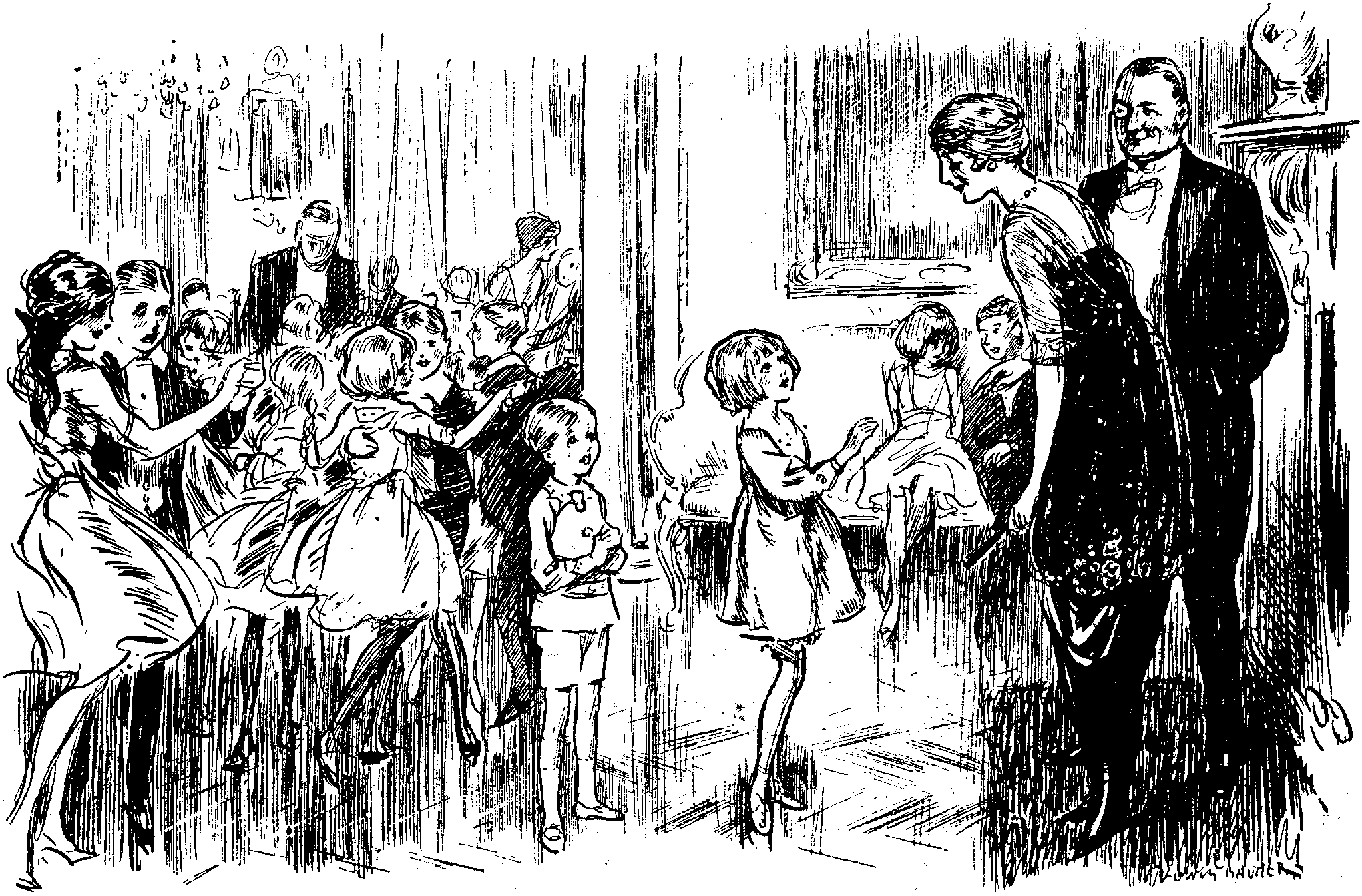

Hostess. "WHAT! GOING ALREADY, DEARS? IT'S VERY EARLY."

Little Girl. "YES—WE HAVE TO GO ON TO ANOTHER PARTY. WE'RE SORRY, BUT—YOU KNOW WHAT IT IS AT THIS TIME OF THE YEAR."

SHAKSPEARE on not the least surprising of Mr. LLOYD GEORGE'S appointments:—

"How now, Woolsack? what mutter you?"

I. Henry IV., ii. 4, 148.

We were discussing "slim" practices and the prevalence of the basic desire to get something for nothing.

"If honesty," said one of the company, "is truly the best policy, then there is a surfeit of the worst politician."

"Yes," said another, "and not only in the West. I assure you, speaking as the director of an insurance concern in Shanghai, that you have no monopoly in inventive chicanery. Insurance people must always be on their guard, but never more so than among the guileless Celestials. I can give you a case in point. Not long ago we received a visit from the wife of one of our policy-holders, saying that her husband was dead and claiming the money.

"'Certainly,' we said, 'the payment will be made, but only after the usual investigations,' and sent her back to her village. It is not that we were more suspicious of her than of anyone else, but such formalities are essential. In this case they turned out to be peculiarly necessary, for her husband was no more dead than you are.

"When she got back to him and explained that there is always 'a catch somewhere' in the insurance business, he took alarm. A prosecution might be awkward, and at any cost must be evaded. He therefore played a masterly card by writing the company a personal letter of explanation, which he pretended was despatched before his wife's return. The original is in Chinese, but I have an English translation in my pocket-book."

The pursuit of odd examples of the epistolary art being one of the principal occupations of my life, I secured a copy of the document, which in English runs thus:—

"To the —— Insurance Company, Shanghai.

"DEAR SIR,—When I died of a disease that came on suddenly an intelligent doctor was at once asked for. He forced some fluid into my mouth and made some injection on my body. He thus succeeded in bringing me to life again.

"The beneficiary came to your place yesterday. What did she say? Everything will be discussed after her return.

"Kindly give me your valuable assistance and reply by post.

"Yours faithfully, TSIN KOH."

On July 1st, 1916, the regiment, in company with several other regiments and sundry pieces of ordnance, attacked the Hun in the neighbourhood of the river Somme. A fortnight later the officers of B Company found themselves in a dug-out in a certain wood. It is now time to introduce Joshua.

Joshua was at that time our junior subaltern, and we called him Joshua after Sir JOSHUA REYNOLDS, on account of his artistic attainments, though portraits by the hand of our Joshua tended rather more in the direction of caricature than those I have seen by his illustrious namesake. Upon the wall of that dug-out in that wood, for instance, was displayed a crude though unmistakable portrait of our revered Brigadier, a fact of which we were but too conscious when our revered Brigadier paid us one night an unexpected visit.

A short conversation ensued, during which the Brigadier gave rein to a reprehensible passion he had for inquiring into the vie intime of junior officers. Just as he was leaving he turned to Joshua.

"Why do they call you 'Joshua'?" he asked. Joshua hesitated. His eyes rested for an infinitesimal moment on the portrait on the wall, then on the face of the Brigadier. He cursed me inwardly (as he told me afterwards) for having addressed him by this name in such strident tones just as the Brigadier was entering the dug-out; but for the credit of the British Officer I am happy to say that Joshua kept his head and showed that ready wit in an emergency which is the soldier's greatest virtue.

"Well, Sir," he said, "I—I think it's because JOSHUA was a great warrior."

"Ah, I hadn't thought of that," said the Brigadier as he took his departure, while I subsided in a fainting condition on to the floor of the dug-out and asked for brandy.

That night Joshua stopped a piece of shell with his head. We managed to get him back, but I did not like the look of him and I quite thought that his number was up. Before we pushed on next day I took down the portrait of the Brigadier and slipped it into my pocket-book. I had liked old Joshua well, and I thought I would keep this as a memento not only of his art but of his ability in spontaneous untruth.

That was, as I have said, in 1916. Much water had flowed between the banks of the river Somme before, in August, 1918, Joshua and I found ourselves in that neighbourhood once more.

But we did find ourselves there, for Joshua's head had proved tougher than we thought, and with an enthusiasm beyond praise he had recently wangled his return to the old regiment from a cushy Base job, and was helping to hasten what we hoped and firmly believed was Fritz's final "strategical retirement."

We had had three strenuous days, and now, while others carried on the good work, we were resting by chance in that very wood of which I have already spoken. I wandered forth at eventide over the familiar ground, which had lain for some time well within the German lines, and came suddenly upon the entrance to our old dug-out! I went down into it and found that, apart from a litter of empty ration-tins, it was unaltered. Then suddenly I bethought me of the caricature which still lay in my pocket-book. I had never told Joshua that I had kept it. It seemed a maudlin thing to have done and moreover might have given him an exaggerated idea of my opinion of his art. I took out the picture and looked at it. It had weathered two years of warfare fairly well. Then with an indelible pencil I scrawled below it—

"Sehr gute Bilde. F. Biermeister, 3 Preuss. Gard,"

a hazy recollection of school-German leading me to believe that "Sehr gute Bilde" meant "Very good picture." Then I pinned it up on the wall and went in search of Joshua.

"Do you remember that dug-out we used two years ago?" I asked when I had found him.

"I do," said Joshua. "It was there that I told old Turnips I was called Joshua after the O.C. Israelites at Jericho."

"That's the place," said I. "It's somewhere round here." And I led him unostentatiously in the right direction.

"There it is," he cried. "It all comes back to me. Got a flash-lamp?"

He disappeared below and I sat down and waited—waited for sounds of astonishment and joy from the bowels of the earth. But I waited in vain. Silence reigned. Then Joshua's head was thrust upwards.

"Biermeister!" he called. "You, Biermeister of the 3rd Prussian Guard, come away below here! There is one, Sir Joshua Reynolds, an artist, would have a word with you."

I shook my head sadly. Another of my little jokes had proved a dud. But I did not go below. Joshua is so rough sometimes.

To weep for the fallen who saved us is meet,

But it causes no kind of surprise

That RAMSAY MacDONALD'S and SNOWDEN'S defeat

Has dried many millions of eyes.

Weary of the labours of war-winning—

Downing mandarins in Downing Street,

Fixing brands of CAIN upon the sinning,

Bingeing up the Army and the Fleet;

Weary of dislodging Kings and Kaisers,

Wearier of his friends than of his foes,

Prompted by his medical advisers

He has wandered South to seek repose.

There to ease his cranial distension

He will lead the simple life, incog.,

Far from international dissension

Or upheavals of the under-dog;

Leaving all unread his weekly Hansard,

Studying only novels at his meals,

Leaving correspondence all unanswered,

Deaf to FOCH'S passionate appeals.

There, no longer rashly overtasking

Powers impaired by superhuman strain,

But amid exotic foliage basking,

He will rest his monumental brain,

Till refreshed, dæmonic and defiant,

Clad in dazzling amaranthine sheen,

He emerges like a godlike giant

Once again to dominate the scene.

There, recumbent in a chair with rockers,

Oft will he indulge in forty winks,

Or, attired in well-cut knickerbockers,

Decorate the landscape on the links;

Or, with arms upon his bosom folded,

He will stand as motionless as bronze,

While his features, classically moulded,

Hourly grow more like NAPOLEON'S.

What the Conference will do without him

Hardly can we venture to surmise;

Delegates who would not dare to flout him

Manifest their joy without disguise.

Freed from his relentless catechizing

WILSON goes out golfing all the day;

Printers, save for common advertising,

Sadly put their pica type away.

Still, although this act of self-seclusion

May create irreparable schism,

Whelm the Conference in dire confusion

And produce a cosmic cataclysm;

Let us, musing on his past achievement,

Bear with calm our soul-consuming grief

And condole in their supreme bereavement

With his Staff, deserted by their Chief.

"COWS, PIGS, ETC.

"GIRL (15), leaving school, desires position in nice office or bank."—Local Paper.

Much virtue in "etc."

"Mrs. Wilson waved her bouquet of orchards in salutation."—Local Paper.

So there is every reason to believe that the PRESIDENT'S visit was not fruitless.

"No one under 4ft. 9in. has any chance of securing admission to the London police."—Cork Constitution.

This will be a blow to some of our "bantams."

"Whether the rest of the journey be long or short, he would follow the same paths and continue to stand up for righteousness and liberty for the memocracy of this country."—Scotsman.

Is this another name for the woman's vote?

"The Telegraph Department notify that the delay in ordinary traffic to Madras is now normal."—Indian Paper.

In confirmation of the accuracy of the above statement an Indian correspondent writes that telegrams now reach their destination nearly as soon as letters.

There is a race of gentle folk

Who dwell in Chiswick, well content

In houses agéd as the oak,

But not unpleasing at the rent;

They look across the sunny stream

As Dr. JOHNSON used to look,

And all their lives are one long dream,

Though none of them has got a cook,

And there are whispers in the camp,

"It's jolly, but it is so damp."

But they are not exciting. No;

And you would find that Chiswick Mall

At half-past nine at night or so

Is far from being Bacchanal;

For, though there come from Chiswick Eyot

Soft sounds of something going on

Where the wild herons congregate

And revel madly with the swan,

You might suppose the people dead.

You mustn't; they have gone to bed.

No extra forces of police

Were needed here at Armistice;

No little European Peace

Could tamper with a peace like this.

Yet on the Eve of this New Year

A strange degrading thing occurred;

A startled Chiswick woke to hear

Such noise as she has never heard,

The sound of dance and singing at

About eleven. O my hat!

Yes, it was bad. But what is worse

They know not yet who broke the code,

And the dread Chiswick Fathers' curse

Still hovers sadly, unbestowed

Nay, there are wild false tales about

And hideous accusations made;

Men say old Piper led the rout

With that young fellow from "The Glade,"

While old maids murmur with a tear,

"I'm told it was the Rector, dear."

And since I would not see this shame

Be fastened on to guiltless men,

And hear that there are those who blame

The Editor at Number 10,

As having found the evil ones

And harboured them in his abode

And, after stimulants and buns,

Dragooned them, shouting, down the road

And carried on till two or three—

I say, O spare him; it was ME!

A.P.H.

"Lord Robert Cecil, who has been appointed to take charge of League of Notions questions at the peace conference."—Provincial Paper.

We don't like this cynicism.

"There is a 'suave qui peut' at the underground stations during the busiest hours."—Provincial Paper.

Personally we had not noticed it, being more struck (in the tenderer portions of our anatomy) by the "fortiter in re."

"The —— Mosquito Destroyer Coil. 1s. Perfectly Safe for mosquitoes."—Advt. in Burmese Paper.

"MORE LATE TRAINS. IMPROVED SERVICE ON G.E.R."—Times.

An aggrieved East Anglian writes to know how the trains can be made later than they are.

"WELCOME TO PRESIDENT WILSON, HONOURED CHIEF OF THE GREAT AMERICAN DEMOCRACY,

"To which we are attached by traditional lies."—Headline in Italian Paper.

Once more tradditore has turned traditore.

"At the doorway stood a Red Cross doctor, hypodermic needle in hand, ready to administer an injunction to relieve sufferers of their pain."—Daily Paper.

We thought it was only lawyers who believed in the tranquillizing effect of an injunction.

"FOR SALE.—A Chest C.B. Gelding. Aged 41/2 years. Height 14 feet 3 inches, Veterinary Certificate of soundness. Schooled since August. Very promising pony all round. Nice surefooted fencer. Price Rs. 650. Apply to Brigadier-General ——."—Indian Paper.

We gather that whatever he may have done in the past the gallant officer does not intend to "ride the high horse" any longer.

Mabel (on seeing some shoes of war-time quality

newly-arrived on approval). "MUMMIE, ARE THEY REAL

CARDBOARD?"

Mabel (on seeing some shoes of war-time quality

newly-arrived on approval). "MUMMIE, ARE THEY REAL

CARDBOARD?"Philip is a solicitor whose solicitations are confined to Hongkong and the Far East generally. Just now he is also a special constable, for the duration. He is other things as well, but the above should serve as a general introduction.

In his capacity as special constable he keeps an eagle eye upon the departing river steamers and the passengers purposing to travel in them, his idea being to detect them in the act of attempting to export opium without a permit, one of the deadly sins.

A little while ago Philip came into the possession of a dog of doubtful ancestry and antecedents, but reputed to be intelligent. It was called "Little Willie" because of its marked tendency to the predatory habit. His other leading characteristic was an inordinate craving for Punter's "Freak" biscuits.

One day Philip had a brain-wave. "I will teach Little Willie," he said, "to smell out opium concealed in passengers' luggage, and I shall acquire merit and the Superintendent of Imports and Exports will acquire opium." So he borrowed some opium from that official and concealed it about the house and in his office, and by-and-by what was required of him seemed to dawn on Little Willie, and every time he found a cache of the drug he was rewarded with a Punter's "Freak" biscuit.

At last his education was pronounced to be complete and Philip marched proudly down to the Canton wharf with the Opium Hound. There was a queue of passengers waiting to be allowed on board, and the ceremony of the examination of their baggage was going on. Little Willie was invited to take a hand, which he did in a rather perfunctory way, without any real interest in the proceedings. Indeed, his attention wandered to the doings of certain disreputable friends of his who had come down to the wharf in a spirit of curiosity, and Philip had to recall him to the matter in hand.

On a sudden a wonderful change came over the Opium Hound. A highly respectable old lady of the amah or domestic servant class came confidently along, carrying the customary round lacquered wooden box, a neat bundle and a huge umbrella. She was followed by a ragged coolie bearing a plethoric basket, lashed with a stout rope, but bulging in all directions. Little Willie sniffed once at the basket and stiffened. "Good dog," said Philip; "is that opium you have found?" The hound's tail wagged furiously, and he scratched at the basket in a paroxysm of excitement. The coolie dropped it and ran away. The amah waxed voluble and attacked Little Willie with the family umbrella. The hound grew more and more enthusiastic for the quest. Philip issued the fiat, "Open that basket, it contains opium," and struck an attitude.

The basket was solemnly unlashed amid the amah's shrill expostulations, and the contents soon flowed out upon the floor of the examination-hut. There was the usual conglomeration: Two pairs working trousers (blue cotton), two ditto jackets to match, one suit silk brocade for high days and holidays, two white aprons, three pairs Chinese shoes, three and a half pairs of Mississy's silk stockings, several mysterious under garments (from the same source); one cigarette tin containing sewing materials, buttons of all sorts and sizes [pg 46] nine empty cotton-reels, three spools from a sewing-machine, one pair nail-scissors (broken); one cigar-box containing several yards of tape (varying widths), cuttings of many different materials, one button-hook, one tin-opener and corkscrew combined, one silver thimble, one ditto (horn), one Chinese pipe; one packet of tea, one ditto sugar, one tin condensed milk (unopened), half a loaf of bread (very stale), two empty medicine bottles—but no opium!

Little Willie was nearly delirious by this time, and tried to get into the basket, which was now all but empty. The search continued, and two rolls of material were lifted out: five and a quarter yards of white calico and three yards of pink silk. This exposed the bottom of the basket, where lay a tin! Ah, the opium at last. Philip stepped forward and prised off the lid triumphantly.

The contents consisted solely of Punter's "Freak" biscuits.

Little Willie has been dismissed from his position as Opium Sleuth-hound.

"For Sale, owing to ill-health, Pedigree Flemish Stock."—Daily Paper.

Like the last rose of Summer

I'm left quite alone;

All my blooming companions

To Paris are flown—

Three daughters, two brothers,

Two sons and a niece

Have all gone to Paris

To speed up the Peace.

'Tis just the same story

Wherever I go,

There's hardly a soul left

For running the show—

Five thousand officials,

Not counting police,

Have all gone to Paris

To speed up the Peace.

There's calm in the City,

A hush in Whitehall—

A thousand fair typists

Have answered the call.

Henceforward their clicking

In London will cease—

They've all gone to Paris

To speed up the Peace.

P.S.

An expert accountant.

Has worked out the cost

Of the keep of officials

Who've recently crossed.

It must be Three Millions;

Mayhap 'twill increase

If the delegates dally

In speeding up Peace.

"THE THAMES RISING.

"LONDON MILK SUPPLY THREATENED."—Pall Mall Gazette.

A surprising change of affairs.

"Sprats in South London are 2½ lb. a lb."—Continental Daily Mail.

This may explain why our fishmonger's price is 2½ shillings a shillingsworth.

"The story of an ingenious robbery by three young boys was told to the Stockport magistrates to-day.

"The magistrates ordered them to receive the birch, usual way.—Reuter."—Provincial Paper.

It was kind of Reuter to add this detail.

"It is understood an order has been issued for the demobilisation of men called to the Colours under the last Military Service Act after they had attained the age of 441."—Provincial Paper.

There can't be very many of them; still it is good to know that the authorities have made a beginning.

The Knight-Errant. "MY DEAR LADY, I HAVE THE HAPPINESS OF RESCUING YOU FROM A GREAT PERIL."

The Lady (indignantly). "HOW DARE YOU ADDRESS ME, SIR, WITHOUT A PROPER INTRODUCTION?"

The Knight-Errant. "MADAM, IF YOU HAD SPOKEN SOONER I WOULD HAVE ASKED OUR FRIEND HERE TO FULFIL THAT NECESSARY SOCIAL OBLIGATION."

We are exceedingly pleased to note that our contemporary, The Pall Mall Gazette, preaches frugality in the most practical manner by providing a daily menu card, with helpful comments on the preparation of the viands. The time for an unrestricted dietary is still far off, and it is a work of national importance to encourage the thrifty use of what our contemporary calls "left-overs." Herein we are only following ancient and honourable precedent, one of the earliest lyrics in the language informing us that

"What they did not eat that day

The Queen next morning fried."

Our only fault with the P.M.G.'s chef is that he is inclined to err on the side of generosity. The dinner for January 6th, for instance, is composed of no fewer than four dishes, of which only one is a "left-over." The bill of fare opens with "Kipper meat on toast"; it proceeds with a fine crescendo to "Beef á la jardinière," followed by "Fried macaroni," and declining gracefully on "Cabinet pudding."

"Left-over meat," as our contemporary remarks, "is more of a problem nowadays than ever before, for, being generally imported, it is not so tender as the pre-war home-grown meat to begin with, and the small amounts that can be saved from the rationed joint rarely seem sufficient for another meal." An excellent plan, therefore, would be to provide all the members of the family with magnifying-glasses. It is easy to believe a thing to be large when it looks large. Also there is great virtue in calling a thing by a nutritious name. "Kipper on toast" is not nearly so rich in carbohydrates, calories and aplanatic amygdaloids as "Kipper meat." As for the preparation of "left-overs" in such a way as to render them both appetising and palatable, "all that need be done is to add a few vegetables and cook them over again." And herein, as our instructor most luminously observes, "lies one solution of the problem of quantity, for the amount of vegetables used, if not the meat, can be measured by the size of the family appetite." Once more the wisdom of the ancients comes to our help, for, as it has been said, "the less you eat the hungrier you are, and the hungrier you are the more you eat. Therefore the less you eat the more you eat." The instructions for the preparation of a sauce for the "Beef á la jardinière" seem to us rather lavish. It is suggested that we should give the whole a good brown colour by dissolving in it "a teaspoonful of any beef extract." Walnut juice is just as effective. If the "left-over" is made of "silver-side," the silver should be carefully extracted and sent to the Mint. The choice of the vegetables must of course depend on the idiosyncrasies of the family. In the best families the prejudice against parsnips is sometimes ineradicable. But if chopped up with kitten meat and onions their intrinsic savour is largely disguised. Fried macaroni, as the P.M.G. chef remarks in an inspired passage, is delicious if properly prepared with hot milk and quickly fried in hot fat. But, on the other hand, if treated with spermaceti or train-oil it loses much of its peninsular charm.

Cabinet pudding, if a "left-over," should perhaps be called "reconstruction pudding." Here again the amount of egg and sugar used must vary in a direct ratio with the size of the family appetite. Prepared to suit that of the family of the late Dr. TANNER, such a dinner as the above is not merely inexpensive, it costs nothing at all.

"All mules attached to the American Army in France have little khaki bags containing gas masks fastened to the collars of their harness. In the event of a gas attack these are slipped over their pleading noses."—Daily Paper.

This, we understand, is not what the drivers call them.

Our triumphal march into Germany having been arrested just west of the Meuse, Sir DOUGLAS HAIG (through the usual channels) gave me ten days' leave to visit the historic town of St. Omer. As I only asked for seven-days and he gave me ten I knew there was a catch somewhere. It appeared that the ten days was worked out on the idea that it would take me five days to get there and five to get back. Needless to say I ignored trains, which are a snare and delusion in these days. I lorry-hopped. Most people would think many times before lorry-hopping from Charleroi to Lille viâ Brussels and Tournai, but there is nothing that a man with a leave warrant in his pocket will not do—except perhaps save money.

It was during this leave that I barged right into GEORGE, "George" being our very own King, besides being Emperor of India.

To bridge the apparent gap between my arrival and the perturbing catastrophe referred to, it is only necessary to add that if you enter from the main route from Hazebrouck you will find just off the road a convoy of some sixty dear things seeing as much life as can be beheld while groping into the insides of the Red Cross motor ambulance which it is their job to feed, wash, coax and drive.

I have the entrée here (except when the relentless Miss Commanding Officer chases me out for breaking the two-and-a-half rules which govern the place), and when I admitted incautiously that the only place on the Front that I had not seen or been frightened at was Passchendaele, they smiled pityingly and promised to take me there on Sunday for a joy ride. Shades of 1917! What whirligigs of circumstance time and the armistice have brought us! It was in the joy ride we nearly upset a dynasty.

To accomplish the journey in greater comfort, Vee and her hut companion Sadie got hold of a perfectly good Colonel man who had a perfectly good car and had, moreover, a perfectly good excuse to go to Passchendaele (he was really going to Boulogne), but wanted to get a good flying start, and we set off. We were a perfectly organised unit, consisting of four sections (including two No. 2 Brownie Sections), A.S.C. complement (one lunch basket), Aid Post (bandage and thermometer, carried as a matter of course by Sadie, who thinks of these things), a Scotch dog (mascot) and a flask of similar nationality (medical comforts for the troops).

On our arrival at Ypres the traffic man held up his hand. That in itself would not have been important, for we have it on great authority that the blind eye may be employed on really special occasions, but the fellow stood determinedly in the middle of the road, and even traffic men, we have always insisted, should not be run over except on great provocation.

"All traffic stopped between 12 and 2," he said; "the KING is passing by."

We looked blankly at one another. I have an extraordinary respect for HIS MAJESTY, but I did wish that he did more of his work by aeroplane at times.

We ate sandwiches, selected and sited positions for sniping the royal progress with our No. 2 Brownies and photographed everything we saw, including an American cooker, the historic "Goldfish Chateau," and a Belgian leading a little pig, with the inscription, "The only good Bosch in the country"; but on the whole Ypres on a Sunday afternoon is hardly more exciting than the "great commercial centre" of Scotland.

At intervals the Staff dashed up and spoke a word or two to the traffic man, but they departed again and nothing happened. We all had a turn at that traffic man, and what we don't know about his home life, pre-war and probable post-war troubles, isn't worth putting on any demobilisation paper. And each time we tackled him we got a different idea of the KING'S movements—HIS MAJESTY must have had an extraordinarily complex journey that day.

Suddenly we were free! The KING was going to lunch near the Cloth Hall and would not be by till 2.30 P.M. Knowing that any order emanating from a Staff is liable to instant cancellation we rushed back to the car and told the driver to "Go!" with the "G" hard, as in shell fire. Whether we went round or over the traffic man I don't know, but we slid with terrific speed into Ypres. Traffic was a little congested round the ruined cathedral, and we barged right up against a panting Ford, which had one lung completely gone and the other seemingly a little porous. A stream of traffic was coming down our side of the road; no matter, we must get on. Urged on by our advice the driver pulled out from behind the dying Ford and tried to pass. It was fearfully exciting. Some Staff on the bank began to wave to us. Thinking perhaps they knew some of us, or thought the girls looked nice, I smiled and nodded back. More Staff waved more arms. We were awfully pleased with our reception. Still three abreast on the road, the Ford having flickered up before death, we reached the crossroads as a large car with a flag on it came round the corner. The car stopped dead. So did we. The two cars glared at each other. The Ford writhed forward hideously in its death agony. I thought I felt funny, and when Vee whispered something about "the Royal Standard" I knew why. Royal Standard? Good Lord! I had visions of three laboriously acquired pips being torn from my sleeves by outraged authorities. The air was rent by my wild yell to our driver to go on—go on and carry the Ford with us on our bonnet if necessary.

What happened next is not very clear in my memory. I have a hazy picture of purple A.P.M.'s, of our GEORGE sitting calmly in a Rolls Royce, of irrepressible woman poking a No. 2 Brownie against the window of our car and trying to find a perfectly good king in a small viewfinder; of the Colonel on my right saluting, with a fearful waggle of the hand, without his hat on, that article having been simply swept off by my own tremendous "circular-motion-thumb-close-to-the-forefinger-touching-the-peak-of-the-cap, etc., etc." Through the haze I saw HIS MAJESTY graciously return our salute and I seem to recollect Vee taking his salute as a personal compliment to the feminine element in the car, and smiling back delightedly in return.

The next thing I remember was that the car had passed, the traffic man was gazing reproachfully at us, the Ford had expired and our chauffeur had stopped his engine. I don't know what Sadie did all this time, but since, from her position, she must have seen the whole thing in better perspective, I don't wonder the girl looked white.

Returning to consciousness I heard Vee utter a tremendous sigh of intense satisfaction.

"I sniped him," she said, and cuddled the No. 2 Brownie affectionately.

"Did you turn it round after the last one?" I asked suddenly.

"No, didn't you?"

And of course we hadn't. And there, in the undeveloped spool lies HIS MAJESTY superimposed on the back of the Bosch piglet we had photographed outside Ypres. Isn't that just the hardest of luck?

I'm going to ask if I can develop the film without running the risk of losing my commission. After all it's not so very inappropriate, is it?

L.

"Extensive floods are reported in the Home Counties. Mr. Noah —— had a narrow escape from drowning at —— on Saturday."—Scotch Paper.

And yet people say, "What's in a name?"

Nurse. "WHICH BABY HAVE YOU COME FOR?"

Little Girl. "THANK YOU, NURSE—I'M BEING SERVED."

If you can keep your courage and your curls up

When life a whirling chaos seems to be

Of amorous swains who want to ring their girls up

And get them through at once (as you for me);

If you can calm the weary and the waxy,

When no appeals, however nicely put,

Can lure from rank or pub. the ticking taxi,

And they, poor devils, have to go on foot;

If you can stem the rush of second-cousins,

Who crowd to get a glimpse of darling Fred,

When Father, Mother, Aunts and friends in dozens

Already form a circle round his bed;

If, in a word, you run a show amazing,

With precious little help to see you through it,

Yours is a temper far above all praising,

And—here we reach the point—I've seen you do it.

"Annie —— was fined £2 for failing to have the name attached to apples at a stall in —— Market. Mr. —— said the public were being wilfully kept in ignorance as to what they were buying."—Provincial Paper.

We think the Magistrate was rather pernickety. Most people know an apple when they see one, but the trouble in these days is to see one at all.

I admire all poilus, and especially did I admire Pierre. Once only did I find him at fault. It was one of my functions on a hospital ship plying between —— and —— to wheel about the more fortunate of the patients. On the occasion on which I met Pierre he was journeying to his mother in London and was temporarily engaged in the same pursuit. I beheld him approaching with his charge and immediately ported my helm. He bore down on his, keeping to his right, and we collided.

"Keep to your left, you fool!" I cried as the crash came.

"Mais non! le droit, M'sieur."

Here was a deadlock indeed. It was an English ship, therefore the English rule of the road should be maintained. On the other hand, the fact that we were still in French waters was in his favour. But my stubborn British will would not give way, and Heaven knows how long we should have remained there had not one of the invalids grunted, "Caan't thee keep t' the rule o' the waater?" and I saw a dignified way out of the difficulty. I withdrew to the right, and we passed on with no animosity towards one another. Still, it was a near thing for the Entente.

"The unfortunate lady was examining an unloaded pistol when it went off and caused instantaneous death."—Times of Ceylon.

In the circumstances we trust we are justified in thinking this tragic intelligence to be the result of a false report.

If Hubbard were not my friend I should describe him as one of the most amiable and most muddle-headed of mankind. Under the influence of his mind things that are quite clear become confused and lose themselves in long vistas of statement and sub-statement and sub-sub-statement, and a plain tale is darkened until at the end nothing is left of what it originally was. If you don't believe me listen to what follows.

We were sitting in the drawing-room one evening recently; the various topics of the day having been more or less exhausted, somebody proposed a round game as a diversion. Hubbard saw his chance and dashed in. "Yes, by Jove," he said, "let's have the new game of 'Likenesses;' it's a perfectly ripping game. I played it the other day and never laughed so much in my life."

"How do you play it?" I said.

"Oh," said Hubbard, "it's one of the easiest games in the world. All you have to do is to keep your mind clear and remember what you are driving at."

"Right," I said. "But what are you driving at?"

"Well," said Hubbard, "one of us goes out or stops his ears and the rest choose somebody."

"There's nothing very new about that," I said; "I've played it a thousand times."

"Wait a bit," said Hubbard, "and don't be so ready to plunge. I tell you this is an entirely new and original game."

"Let him," said somebody else, "get on with it in his own way or we shall be here till past midnight. Go ahead, Hubbard."

"Well," said Hubbard, "you choose somebody to be a likeness. When your man comes in again he begins to ask questions."

"Vegetable, animal or mineral," said Butterfield, "I knew it was."

"No, it isn't," said Hubbard. "The man who has gone out and has come in says to you, What food does the person you've chosen remind you of? and you say tapioca pudding or beef-steak and kidney pie."

"But," I said, "there's nobody in the whole wide world who reminds me of either of those things."

"Well, you can choose your own food," said Hubbard. "If you don't like tapioca pudding you can answer scrambled eggs. Only scrambled eggs must remind you of the person you have in your mind. Then you go on to the next man, and you ask him what cloth he reminds you of, and he answers tweed or Irish frieze or best Angola."

"Can anybody," said Butterfield, "tell me what 'best Angola' means? I've seen it often in my tailor's bills; mostly, I think, as waistcoats, but I've never known what it really is. If I had to guess now I should say it is something composed in equal parts of fancy waistcoats, tapioca pudding and scrambled eggs."

"Well, you'd be wrong," said Hubbard; "it's nothing of the sort. When you have got as far as scrambled eggs your man ought to begin to have a faint glimmering—"

"But," I said, "there's the tapioca pudding. What are you going to do with that? You can't be allowed to play fast and loose with that."

"Don't you see," said Hubbard, "that that's a mere example and now done with? Do please remember that we have got on to Irish frieze. You must allow me to explain the game in my own way. Now your man tackles the next person in turn. What building, he asks, does he remind you of? and the answer is Cologne Cathedral or the Bank of England."

"It would be difficult to choose anyone who reminded me of either of those celebrated structures," I said, "but I'll take the Bank of England for choice."

"But," said Hubbard, "you don't take either of them, you see it in a flash and it's gone."

"What do you see in a flash?" I said.

"The building that the man who has gone out and is asking questions in order to guess the person everybody is thinking of reminds you of," said Hubbard.

"Oh, yes. That makes it absolutely clear," said Butterfield. "Let's get to work. Personally I haven't got beyond scrambled eggs."

"And I am lost in tapioca," I said. "Let's get to bed." That's as far as Hubbard ever got with the explanation of his game. We left him struggling and went to bed.

All my life I've been a rover; I have ranged the wide world over,

And I've had the very devil of a time;

I've philandered through Alsatia with the nautch-girl and the geisha;

I have heard the bells of San Marino chime.

I've hobnobbed in Honolulu with the Zouave and the Zulu,

I have fought against the Turks at Spion Kop;

In a spirit of bravado I've accosted the MIKADO

And familiarly addressed him as "Old Top."

I've been captured by banditti, kissed a squaw in Salt Lake City,

Carved my name upon the tomb of LI HUNG CHANG,

And been overcome by toddy where the turbid Irrawaddy

Winds its way from Cincinnati to Penang.

I have crossed the far-famed ferry from Port Said to Pondicherry;

In a droschky shot the rapids at Hongkong;

I have pounded to a jelly dancing dervishes at Delhi,

And I've chased the chimpanzee at Chittagong.

I've smoked baksheesh in pagodas, stood a Dago Scotch-and-sodas,

Scaled the mighty Mississippi's snow-clad peaks,

Galloped madly on a llama through lagoons at Yokohama

And found rubies at Magillicuddy's Reeks.

Where the Tagus joins the Hooghly I have bowled the wily googly,

I have heard the howdah's howl at Hyderabad;

On a rickshaw I've gone sailing, with my boomerang impaling

Hooded cobras on the ice-floes off Bagdad.

I have slain the beri-beri with a ball from my knobkerry;

I have climbed the Pole and leapt across the Line;

I've seen seals in Abyssinia and volcanoes in Virginia,

And I've dived into the shark-infested Rhine.

From the pemmican's fierce claws and the tiffin's gaping jaws

I have never shrunk in abject terror yet;

In the jungle I have tracked them and attacked them and then hacked them

Into mincemeat with my trusty calumet.

I have interviewed the MULLAH, KRUGER, MENELIK, ABDULLAH,

LOBENGULA, SITTING BULL and Clan-na-Gael;

When I think of where I've been, what I've done and what I've seen,

I'm surprised that I'm alive to tell the tale.

Standing Lady. "MY HUSBAND WAS MADE A COLONEL JUST BEFORE THE ARMISTICE."

Seated ditto. "MY HUSBAND WOULD HAVE BEEN A GENERAL IF IT HADN'T BEEN FOR THE WAR."

Battle-books have already come to wear (even in so short a time) a strangely archaic aspect. But Through the Hindenburg Line (HODDER AND STOUGHTON) is, as its name tells you, nearer to date than most. The writer, Mr. F.A. MCKENZIE, was a Canadian war correspondent whom the Canadian Staff, believing (as he himself says) "that the right place for a war correspondent is where he can see what he is supposed to describe," allowed to live among the troops in the front line. As a result of this unusual privilege, his pictures of the great fights in the last stages of the War have the reality of personal experience. The actual smashing of the Line, for example, is an epic of heroism and achievement still hardly realised by people at home, who cling to an idea that the final victories were gained over an enemy enfeebled and at disadvantage. There are other chapters in the record that may perhaps hardly be welcomed at this moment by those amiable sentimentalists who would have us treat the enemy as a Bosch and a brother. The hospital raid at Etaples is one of them; when, even after the light of the burning huts had made ignorance impossible, the gentle Hun, swooping low, swept with machine-gun fire the nurses and doctors who were attempting to remove the wounded. That, I think, is a memory that will linger. Another picture, queerly disproportionate in the anger it excites, is that of the fruit garden in a great country house, with its wealth of famous old peach and pear trees still in place along the walls, but every one methodically sawn through. By comparison a trifling crime, but somehow I may forget other things more easily. One would welcome the revised judgment of Dr. SOLF upon this particular expression of the German spirit.

To those who have been persuaded by writers like Mr. H.G. WELLS that the horse has not and ought not to have any part in modern warfare, Captain SIDNEY GALTREY'S The Horse and the War ("COUNTRY LIFE") will come as a revelation. Mr. WELLS has said that the sight of a soldier wearing spurs makes him sick, or words to that effect; yet so neglectful were our military authorities of Mr. WELLS'S opinions and teaching that they went on steadily adding horses, many of them cavalry horses, to the Army. We began the War with twenty-five thousand horses, and we finished it with considerably more than a million, to say nothing of the mules, who diffused an air of cynical amusement over the military proceedings in which they were compelled to bear a part. This may conceivably be one more proof in Mr. WELLS'S eyes of our incurable stupidity. But those who have watched the work of our armies at close quarters will be the last to agree with him. Captain GALTREY in fact proves his case. He has an enthusiasm for horses and has written a most interesting book. The illustrations are excellent and appropriate, and the book is admirably got up.

Valour is apt to get the better of discretion in any novel that attempts to be quite up to date with a political subject. Mrs. TWEEDALE places The Veiled Woman (JENKINS) in some vague period later than August, 1914, largely in order to decry a Government that really by now one fails to [pg 52] identify, and to let off sundry feminist squibs and crackers which, in view of the present position of woman suffrage, can only be described as fireworks half-price on the 6th of November. Further, to get all my grumbles frankly over, she so constantly makes sweeping assertions against the other sex that even the most chivalrous of male reviewers may be inclined to kick. To hear a lady pronounce once or twice that the males of the species are obviously diminishing in stature and strength, or that the whole programme of the earth's return to the highest ideals is in woman's hands, may be good for the masculine soul, but after a while it brings up vividly BESANT'S story of The Revolt of Man—what happened then and just why. The claim to a monopoly of self-sacrifice in particular comes very badly in war-time. All the same, if you cut out this top-hamper the story of The Veiled Woman on its personal side is distinctly a good one. I wished the heroine had not spoiled her fine enthusiasms by mixing them so freely with a personal vendetta; but after all it is not the characterisation that intrigues one here. The plot—which I will not spoil by giving it away—goes excellently, and works up to a capital climax.

Mr. BOYD CABLE is the literary liaison officer between the Infantry and the Air Force. In the wonderful stories contained in Airmen O' War (MURRAY) his object is to make the armies on the ground understand what they owe to the armies of the air. If they suffer from a lack of understanding, this is not, I gather, likely to be removed by the airmen themselves, for they have evidently imbibed some of the spirit of our Navy and are magnificently reluctant to talk about their achievements. But this reticence has its dangers, and Mr. BOYD CABLE has set to work to remove them. Here he has written nothing for which he cannot find "an actual parallel fact." I honestly believe him and commend his book both to those who have a passion for tales of high adventure and also to those—if there are such—who need authentic instances of what our Airmen O' War have done for us.

The best I can honestly say of Tony Heron (COLLINS) is that it has all the makings of a good novel, but unfortunately stops there, unmade or rather unvitalized. It is the tale of a boy's upbringing by a sternly antagonistic father, of his growth to maturity, his love affairs, and in due course his relations with his own son. All the events happen that are proper to a scheme of this type; but somehow, despite the fact that Mr. C. KENNETT BURROW wields a practised and often picturesque pen, the whole affair remains a literary exercise and declines to come alive. Perhaps in justice I should except two characters, Roland, the sturdy-son born out of wedlock to Tony, and Phil, weakling child of old Heron by a second marriage. Both these and the relation of the pair to each other furnish a pleasant contrast to the anæmia which seems to affect the rest of the tale. Stay, there is yet another, Kenrick, the private tutor of Tony, whose treatment by the author is at least vigorous. I found him just a little surprising. A creature, we are told, over fond of good food and wine, who, dining with his pupil on the latter's sixteenth birthday and attempting convivial airs, is shown his place with a promptitude recalling the best manner of the eighteenth century. Subsequently, one gathers, he took to chronic alcoholism, combined with amateur blackmail; and a final appearance shows the fellow dribbling wine over the evening shirt, to whose wear the author is at pains to tell us he was unused. Clearly a low race, these tutors, about whom I seem hitherto to have been strangely misinformed.

Captain ROBERT B. ROSS has made excellent business of The Fifty-First in France (HODDER AND STOUGHTON). In any case there could be no doubts about the merits of this famous Scottish territorial division; it is one of the very many British divisions which has proved itself the best of all. I recall its first appearance at the Front as a constituted unit, and can speak to it that the impression its arrival caused was welcome and comforting. But our author is not only a soldier; he has also the literary art. Clearly he appreciates that a fine subject is not all that is wanted to make a good book; that one needs, for instance, the gift of observation, the power of conveying an impression, and a reserve of humour always ready at need. All these are his in abundance. His book treats of two earlier periods of the war; the second, the long-drawn offensive of the Somme, will make the most intimate appeal to men of his own and the other divisions involved. To those who knew the affair at first hand the story will recall much that they saw and felt themselves; often they will recognise a map-reading or will come across the name of a humble billet which they too regarded as a paradise replete with every modern comfort. Upon those who now learn it for the first time a deep and enduring impression will be produced. Captain Ross writes always with a due respect for the serious nature of his subject; but there are times when he breaks away from his military and literary discipline. There is for example, a moment when he dines well, "no more wisely than was desirable, no less wisely than was excusable." It must be added that the accompanying sketches are, if not of an ambitious order, yet of a certain merit. At any rate they assist.

"Cæsar autem erat imperator sui generis." "Now the Kaiser was a general of the pig tribe."

"As the President's steamer came alongside the officer shouted an inaudible order down a tube. There was a snap and a crash. A button was pressed, and, presto!"—Daily Paper.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK 10952 ***