His Reverence. "DINNER, 7:30. I'LL GIVE YOU A QUARTER OF AN HOUR'S GRACE!"

His Irreverence. "THEN COMMENCE AT 7:30, AND I'LL BE THERE AT 7:45!"

This age has been called an Age of Progress, an Age of Reform, an Age of Intellect, an Age of Shams; everything in fact except an Age of Prizes. And yet, it is perhaps as an Age of Prizes that it is destined to be chiefly remembered. The humble but frantic solver of Acrostics has had his turn, the correct expounder of the law of Hard Cases has by this time established a complete code of etiquette; the doll-dresser, the epigram-maker, the teller of witty stories, the calculator who can discover by an instinct the number of letters in a given page of print, all have displayed their ingenuity, and have been magnificently rewarded by prizes varying in value from the mere publication of their names, up to a policy of life insurance, or a completely furnished mansion in Peckham Rye. In fact, it has been calculated by competent actuaries that taking a generation at about thirty-three years, and making every reasonable allowance for errors of postage, stoppage in transitu, fraudulent bankruptcies and unauthorised conversions, 120 per cent. of all persons alive in Great Britain and Ireland in any given day of twenty-four hours, must have received a prize of some sort.

Novelists, however, have not as yet received a prize of any sort, at least as novelists. The reproach is about to be removed. A prize of £1000 has been offered for the best novel by the Editor of a newspaper. The most distinguished writers are, so it is declared, entered for the Competition, but only the name of the prize-winner is to be revealed, only the prize-winning novel is to be published. Such at least has been the assurance given to all the eminent authors by the Editor in question. But Mr. Punch laughs at other people's assurances, and by means of powers conferred upon him by himself for that purpose, he has been able to obtain access to all the novels hitherto sent in, and will now publish a selection of Prize Novels, together with the names of their authors, and a few notes of his own, wherever the text may seem to require them.

In acting thus Mr. Punch feels, in the true spirit of the newest and the Reviewest of Reviews, that he is conferring a favour on the authors concerned by allowing them the publicity of these columns. Sometimes pruning and condensation may be necessary. The operation will be performed as kindly as circumstances permit. It is hardly necessary to add that Mr. Punch will give his own prize in his own way, and at his own time, to the author he may deem the best. And herewith Mr. Punch gives a specimen of—

[PREFATORY NOTE.—This Novel was carefully wrapped up in some odd leaves of MARK TWAIN'S Innocents Abroad, and was accompanied by a letter in which the author declared that the book was worth £3000, but that "to save any more blooming trouble," he would be willing to take the prize of £1000 by return of post, and say no more about it.—ED.]

It was all the Slavey what got us into the mess. Have you ever noticed what a way a Slavey has of snuffling and saying, "Lor, Sir, oo'd 'a thought it?" on the slightest provocation. She comes into your room just as you are about to fill your finest two-handed meerschaum with Navy-cut, and looks at you with a far-away look in her eyes, and a wisp of hair winding carelessly round the neck of her print dress. You murmur something in an insinuating way about that box of Vestas you bought last night from the blind man who stands outside "The Old King of Prussia" pub round the corner. Then one of her hairpins drops into the fireplace, and you rush to pick it up, and she rushes at the same moment, and your head goes crack against her head, and you see some stars, and a weary kind of sensation comes over you, and just as you feel inclined to send for the cat's-meat man down the next court to come and fetch you away to the Dogs' Home, in bounces your landlady, and with two or three "Well, I nevers!" and "There's an imperent 'ussey, for you!" nearly bursts the patent non-combustible bootlace you lent her last night to hang the brass locket round her neck by.

POTTLE says his landlady's different, but then POTTLE always was a rum 'un, and nobody knows what old rag-and-bone shop he gets his landladies from. I always get mine only at the best places, and advise everybody else to do the same. I mentioned this once to BILL MOSER, who looks after the calico department in the big store in the High Street, but he only sniffed, and said, "Garne, you don't know everythink!" which was rude of him. I might have given him one for himself just then, but I didn't. I always was a lamb; but I made up my mind that next time I go into the ham-and-beef shop kept by old Mother MOSER I'll say something about "'orses from Belgium" that the old lady won't like.

Did you ever go into a ham-and-beef shop? It's just like this. I went into MOSER'S last week. Just when I got in I tripped over some ribs of beef lying in the doorway, and before I had time to say I preferred my beef without any boot-blacking, I fell head-first against an immense sirloin on the parlour table. Mrs. MOSER called all the men who were loafing around, and all the boys and girls, and they carved away at the sirloin for five hours without being able to get my head out. At last an old gentleman, who was having his dinner there, said he couldn't bear whiskers served up as a vegetable with his beef. Then they knew they'd got near my face, so they sent away the Coroner and pulled me out, and when I got home my coat-tail pockets were full of old ham-bones. The boy did that—young varmint! I'll ham-bone him when I catch him next!

Let me see, what was I after? Oh, yes, I remember. I was going to tell you about our Slavey and the pretty pickle she got us into. I'm not sure it wasn't POTTLE'S fault. I said to him, just as he was wiping his mouth on the back of his hand after his fourth pint of shandy-gaff, "POTTLE, my boy," I said, "you're no end of a chap for shouting 'Cash forward!' so that all the girls in the shop hear you and say to one another, 'My, what a lovely voice that young POTTLE'S got!' But you're not much good at helping a pal to order a new coat, nor for the matter of that, in helping him to try it on." But POTTLE only hooked up his nose and looked scornful. Well, when the coat came home the Slavey brought it up, and put it on my best three-legged chair, and then flung out of the room with a toss of her head, as much as to say, "'Ere's extravagance!" First I looked at the coat, and then the coat seemed to look at me. Then I lifted it up and put it down again, and sent out for three-ha'porth of gin. Then I tackled the blooming thing again. One arm went in with a ten-horse power shove. Next I tried the other. After no end of fumbling I found the sleeve. "In you go!" I said to my arm, and in he went, only it happened to be the breast-pocket. I jammed, the pocket creaked, but I jammed hardest, and in went my fist, and out went the pocket.

Then I sat down, tired and sad, and the lodging-house cat came in and lapped up the milk for my tea, and MOSER'S bull-dog just looked me up, and went off with the left leg of my trousers, and the landlady's little boy peeped round the door and cried, "Oh, Mar, the poor gentleman's red in the face—I'm sure he's on fire!" And the local fire-brigade was called up, and they pumped on me for ten minutes, and then wrote "Inextinguishable" in their note-books, and went home; and all the time I couldn't move, because my arms were stuck tight in a coat two sizes too small for me.

The Slavey managed—

[No, thank you. No more.—ED.]

His Reverence. "DINNER, 7:30. I'LL GIVE YOU A QUARTER OF AN HOUR'S GRACE!"

His Irreverence. "THEN COMMENCE AT 7:30, AND I'LL BE THERE AT 7:45!"

FAVOURITE TOOL OF RAILWAY COMPANIES.—A Screw-Driver!

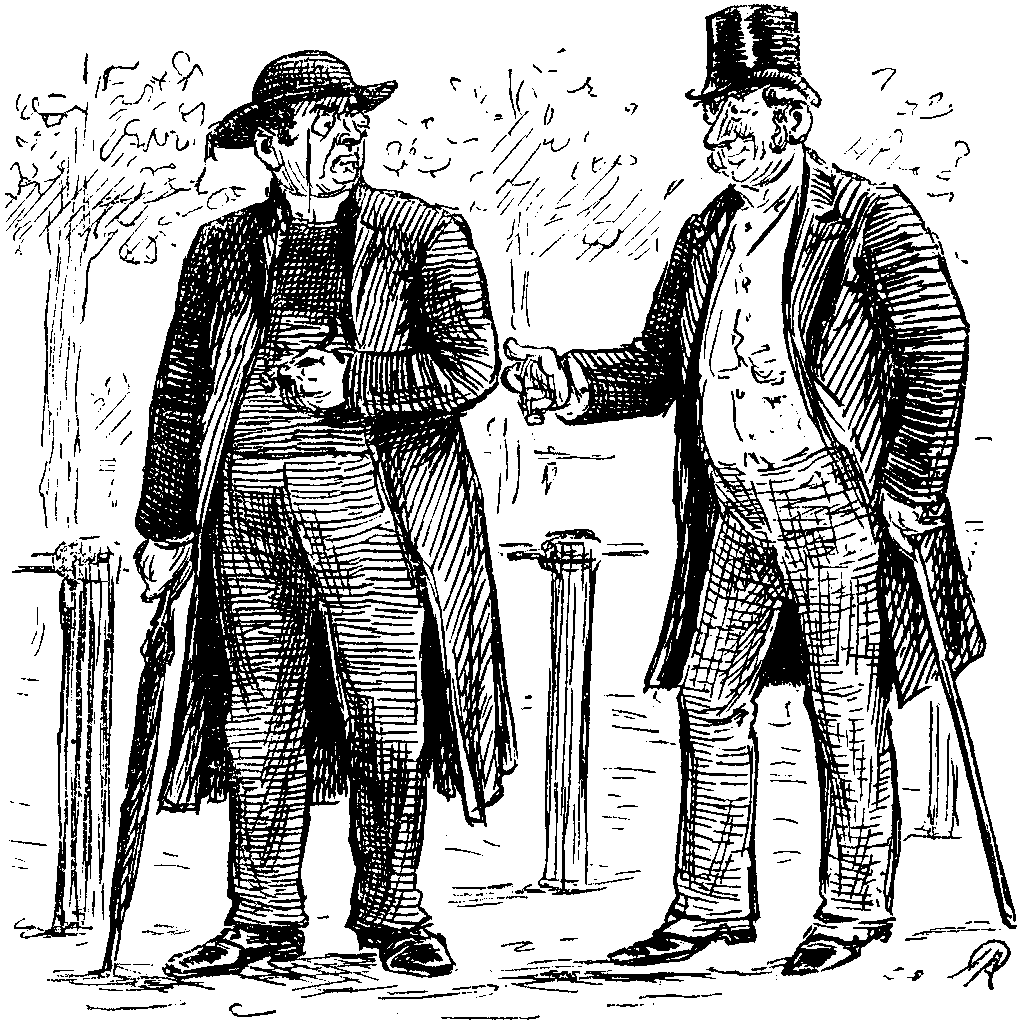

Mr. Bull (Paymaster). "WELL, WHAT DO YOU THINK OF IT?"

Mr. Punch (Umpire-in Chief). "FINE RIDER—FINE HORSE! BUT—AS A CAVALRY SOLDIER—HAS TO LEARN HIS BUSINESS!"

["How then about the British Cavalry of September, 1890? A spectator who has taken part in modern regular war, and has watched the manoeuvres, said one day to me when I accosted him, in an apologetic tone, 'I have hitherto done your Army injustice, I will not do so again; I had no idea how well your officers and your troopers ride,—they are very fine horsemen.' There he stopped; I waited for more, but he had ended; his silence was a crushing criticism, unintentionally too severe, but very true.... I assert, therefore, that at this moment, our Cavalry is inefficient, and not prepared for war."—The Times Military Correspondent.]

"Of all the recreations with which mortal man is blest"

(Says BALLIOL's Song) "fox-hunting still is pleasantest and best."

A Briton in the saddle is a picture, and our pride,

In scarlet or in uniform at least our lads can ride.

Away, away they go,

With a tally, tally-ho!

With a tally, tally, tally, tally, tally, tally-ho!

But riding, for our Cavalry, is, after all, not all.

To lead the field, to leap a fence, to bravely face a fall,

Are well enough. And first-rate stuff from the hunting-field may come,

But something more is wanted when Bellona beats her drum,

And calls our lads to go,

With a rally, rally-ho! &c.

Good men and rattling horses are not all that England needs;

She wants sound knowledge in the men, and training in the steeds.

Scouting and reconnaissance are not needed for the fox,

Nor "leading in big masses" for the furious final shocks,

When away the troopers go,

With a rally, rally, ho! &c.

But when a squadron charges on the real field of war,

Courage and a good seat alone will not go very far;

Our lads must "know their business," and their officers must "lead,"

Not with cross-country dash alone, but skill and prudent heed,

When away the troopers go,

With a rally, rally, ho! &c.

War's field will test the Cavalry, or clad in blue or red;

In all things they must "thorough" be, as well as thorough-bred.

"Heavy" or "light," they'll have to fight; not such mad, headlong fray,

As marked for fame with pride—and shame—that Balaklava day,

When away our lads did go,

With a rally, rally, ho! &c.

Eh? "Inefficient," Mr. BULL, "and not prepared for war?"

That judgment, if 'tis near the truth, on patriot souls must jar.

And Mr. Punch (Umpire-in-Chief) to JOHN (Paymaster), cries,

"You'll have to test the truth of this before the need arise

For our lads away to go.

With a rally, rally-ho!" &c

And since that Soldier's incomplete for Duty unprepared,

Although he's game to dare the worst that ever Briton dared,

To supplement our trooper's skill in saddle, pluck and dash,

You must have more manoeuvres, JOHN, and—if needs be,—more cash!

Then away away we'll go

With a tally rally-ho!

And never be afraid to face the strongest, fiercest foe.

The General-President had been established at the Elysée for some three months, when his aides-de-camp found their labours considerably increased. At all hours of the day and night they were called up to receive persons who desired an interview with their chief and master. As they had received strict orders from His Highness never to appear in anything but full uniform (cloth of gold tunics, silver-tissue trousers, and belts and epaulettes of diamonds) they spent most of their time in changing their costume.

"I am here to see anyone and everyone," said His Highness; "but I look to you, Gentlemen of the Ring, I should say Household, to see that I am disturbed by only those who have the right of entrée. And now, houp-là! You can go."

Thus dismissed, the unfortunate aides-de-camp could but bow, and retire in silence. But, though they gave no utterance to their thoughts, their reflections were of a painful character. They felt what with five reviews a day, to say nothing of what might be termed scenes in the circle (attendances at the Bois, dances at the Hôtel de Ville, and the like), their entire exhaustion was only a question of weeks, or even days.

One morning the General-President, weary of interviews, was about to retire into his salle-à-manger, there to discuss the twenty-five courses of his simple déjeuner à la fourchette, when he was stopped by a person in a garb more remarkable for its eccentricity than its richness. This person wore a coat with tails a yard long, enormous boots, a battered hat, and a red wig. A close observer would have doubted whether his nose was real or artificial. The strangely-garbed intruder bowed grotesquely.

"What do you want with me?" asked the General-President, sharply. "Do you not know I am busy?"

"Not too busy to see me," retorted the unwelcome guest, striking up a lively tune upon a banjo which he had concealed about his person while passing the Palace Guard, but which he now produced. "I pray you step with me a measure."

Thus courteously invited, His Highness could but comply, and for some ten minutes host and guest indulged in a breakdown.

"And now, what do you want with me?" asked the General-President when the dance had been brought to a satisfactory conclusion.

"My reward," was the prompt reply.

"Reward!" echoed His Highness. "Why, my good friend, I have refused a Royal Duke, an Imperial Prince, a Powerful Order, and any number of individuals, who have made a like demand."

"Ah! but they did not do so much for you as I did."

"Well, I don't know," returned the General-President, "but they parted with their gold pretty freely."

"Gold!" retorted the visitor, contemptuously, "I gave you more than gold. From me you had notes. Where would you have been without my songs?" He took off his false nose, and thus enabled the General-President to recognise the "Pride of the Music Halls!"

"You will find I am not ungrateful," said the Chief of the State, with difficulty suppressing his emotion.

His Highness was as good as his word. The next night at the Café des Ambassadeurs there was a novel attraction. An old favourite was described in the affiches as le Due de Nouveau-Cirque.

The reception that old favourite received in the course of the evening was fairly, but not too cordial. But enthusiasm and hilarity reached fever-heat when, on turning his face from them, the audience discovered that their droll was wearing (in a somewhat grotesque fashion) the grand cordon of the Legion of Honour on his back! Then it was felt that France must be safe in the hands of a man whose sense of the fitness of things rivalled the taste of the pig whose soul soared above the charm of pearls!

ACT I.—A grand old Castle in the distance, with foreground of rude and rugged rocks. Around the rugged rocks a quaint funeral service. HENRY IRVING, "the Master" not only of Ravenswood, but the art of acting (as instanced by a score of fine impersonations), flouts the veteran comedian, HOWE; and, Howe attired? He is in some strange garb as a nondescript parson. Then "Master" (as the Sporting Times would irreverently speak of him) soliloquises over Master's father's coffin. Arrival of Sir William Ashton. Row and flashing of steel in torchlight. Appearance of one lovely beyond compare—ELLEN TERRY, otherwise Lucy Ashton; graceful as a Swan. Swan and Edgar. Curtain.

ACT II.—Library and Armoury. Convenient swords and loaded blunderbusses. Lord Keeper Ashton appears. Quite right that there should be the Keeper present, in view of Lucy subsequently going mad. Young Henry Ashton, the youth GORDON CRAIG, a lad of promise, and performance, has the entire stage to himself for full two minutes, to show what he can do with a speech descriptive of some pictures. Master alone with Keeper, suggests duel. Why arms in Library, unless duel? Fight about to commence according to Queensberry rules, when Master sees portrait. Whose? Lucy's? "No," says Master; "not to be taken in. I know LUCY'S picture; it was done by WARD." The Keeper explains that this is a portrait, not of the author of The History of Two Parliaments, and Fleecing Gideon, but of his daughter Lucy, which has never yet been seen in any exhibition or loan collection. "Oho," says Master, "then I won't fight a chap who has a daughter like that." Ha! Mad bull "heard without"—one of the "herd without,"—Master picks up blunderbuss, no blunder, makes a hit and saves a miss; i.e., Lucy. What shall he have who kills the bull with a bull 'it? Why, a tent at Cowshot, near Bisley.

Next Scene.—Wolf's Crag. Grand picture—thunder—music—Dr. MACKENZIE—Mr. MACINTOSH—"the two MACS"—doing excellent work in orchestra, and on stage—storm—Miss MARRIOTT admirable as old Witch—red light in fire-grate—blank verse by MERIVALE, and on we go to

ACT III.—A Scene never to be forgotten—the Mermaiden's Well (quite well, thank you), by HAWES CRAVEN, henceforth to be HAWES McCRAVENSWOOD. Pines, heather, sunlight, and two picturesque lovers, Master and Miss, exchanging vows. Master gloomy, Miss lively. Miss promises to become Missus. Enter Master's future Modern Mother-in-law. Intended to be vindictive, but really a comfortable and comely body. Might be Mrs. McBouncer in McBox and McCox. Naturally enough, off goes Master to France.

ACT IV.—Another splendid scene. Magnificently attired, Hayston of Bucklaw attempts to raise a laugh. Success. Mrs. Mac Bouncer coerces Lucy in white satin to sign the fatal contract that will settle Master. Ah! that awful laugh—far more tragic than the one secured by Bucklaw! It is Lucy going mad! She has already shown signs of incipient insanity by calling Mr. HOWE, otherwise Bide-the-Bent, a "holy Father,"—much to that excellent comedian's surprised content. Contract signed. Return of "Master." Dénoûment must be seen to be appreciated. Here McMERIVALE bids Sir WALTER good-bye, and finishes in his own way. Last scene of all, and the loveliest. The earliest rays of the sun shining on the advancing tide! Caleb picks up all that is left of "Master"—a feather! With Miss ELLEN, Master HENRY, McMARRIOTT, McMERIVALE, MACKINTOSH, MACKENZIE, and HAWES McCRAVENSWOOD, here is a success which the advancing tide of popular favour will float till Easter or longer, and will then leave a new feather in the cap of Master.

[The German Emperor is an accomplished Sportsman. He appears to be able to bring down his birds at will.—Daily News.]

Would you like to be an Emperor, and wear a golden crown,

With fifty different uniforms for every single day;

To make the nations shudder with the semblance of a frown,

And, if BISMARCKS should oppose you, just to order them away?

With your actions autocratic,

And your poses so dramatic;

Yours the honour and the glory, while the country pays the bill,

With your shouting sempiternal,

And your Grandmamma a Colonel,

And the power—which is best of all—to shoot your birds by will.

Then the joy of gallopading with a helmet and a sword,

While the thunder of your cannons wakes the echoes from afar.

And if, while you're in Germany, you happen to be bored,

Why, you rush away to Russia, and you call upon the CZAR.

With your wordy perorations,

And your peaceful proclamations,

While you grind the nation's manhood in your military mill.

And whenever skies look pleasant

Out you go and shoot a pheasant,

Or as many as you want to, with your double-barrelled will.

You can always flout your father, too—he's dead, but never mind;

He and all who dream as he did are much better in their graves.

And you cross the sea to Osborne, and, if Grandmamma be kind,

You become a British Admiral, and help to rule the waves;

With Jack Tars to say "Ay, Ay, Sir!"

To this nautical young Kaiser,

Who is like the waves he sails on, since he never can be still.

Who to every other blessing

Adds the proud one of possessing

A gun-replacing, bird-destroying, game-bag-filling will.

"HATS OFF!"—MR. EDWARD CROSSLEY, M.P., is to be congratulated on a narrow escape, according to the report in the Times last week. During service in the Free Church at Brodick, some portion of the ceiling gave way, Mr. CROSSLEY was covered with plaster—better to be covered with plaster before than after an accident—and "his hat was cut to pieces." From which it is to be inferred that "hats are much worn" during Divine service in the Free Church, as in the Synagogue. And so no fanatic can be admitted who has "a tile off." How fortunate for Mr. E. CROSSLEY that this ancient custom of the Hebrews is still observed in the Free Kirk. Since then Mr. CROSSLEY has bought a new tile, and is, therefore, perfectly re-covered.

The Baron says that he has scarcely been able to get through the first morning of The Last Days of Palmyra, which story, so far, reminds him—it being the fashion just now to mention Cardinal NEWMAN's works—of the latter's Callista. And à propos of Callista let me refer my readers to one of the best written articles on the Cardinal that I have seen. It is to be found in Good Words for October, and is by Mr. R.H. HUTTON. The Baron is coaching himself up for a visit to the Lyceum to see Ravenswood, of which, on all hands, he hears so much that is good. What a delightful scene where Caleb steals the wild-fowl from the spit, and the subsequent one, where Dame Lightbody cuffs the astonished little bairn's head! "As fresh to me," protests the Baron, "laughing in my chair, as I have been doing but a minute ago, as it was when I read it, the Council and Kirk-session only know how long ago!" And this farcical scene was considered so "grotesquely and absurdly extravagant" by Sir WALTER's contemporary critics (peace be to their hashes! Who were they? What were their names? Who cares?) that the great novelist actually explains how the incident was founded on one in real life.

Now to my books. Gadzooks, what's here? Another volume of Obiter Dicta? By one author this time, for if my memory fails me not, the previous little book was writ by two scribes. Well, no matter—or rather lots of matter—and by AUGUSTINE BIRRELL, who represents Obiter and Dicta too. With an unclassical false quantity anyone who so chooses to unscholarise himself, can speak of him as the O'Biter, so sharp and pungent are some of his remarks. Ah! here is something on LAMB. For me, quoth the Baron, LAMB is always in season, serve up the dish with what trimmings you may, but, if you please, no sauce. Size and shape are the only things against friend Obiter. It is not what this sort of book ought to be, portable and potable, like the craftily qualified contents of a pocket-flask, refreshing on a tedious journey. Had Obiter been the size of either The Handy Volume Shakspeare, or of Messrs. ROUTLEDGE'S Redbacks—both the Baron's prime favourites—the Baron would have been able to dip into it more frequently, as he would into that same pocket-flask aforementioned.

"Next, please!" BLACKIE'S Modern Cyclopedia. Vol. VII., so we're getting along. I'll just cast my eye over it; one eye, not two, says the Baron, out of compliment to the Cyclops. This Volume deals with the letters "P," "R," "S," and any person wishing to master a few really interesting subjects for dinner conversation will read and learn up all about Procyon, Pizemysi, and Pyrheliometer, Quotelet, Quintal, and Quito, Regulus, Ramazan, Rheumatism, Rhynchops, Rum-Shrub, and Rupar, Samoyedes, Semiquaver, Sahjehanpur, Silket, Sinter, and Size. When it is known what a gay conversationalist he is, he may induce some one to put him up for a cheery Club, where he will be Blackie-balled. Still, by studying the Cyclopedia carefully, with a view to being ready with words for charades and dumb-crambo during the festive Christmas-tide, he may once again achieve a certain amount of popularity, on which, as on fresh laurels, he had better retire.

"Next, please!" How Stanley Wrote his Darkest Africa. By Mr. E. MARSTON. A most interesting little book, published by SAMPSON LOW & Co., illustrated with excellent photographs, and with a couple of light easy sketches, by, I suppose, the Author, which makes the Baron regret that he didn't do more of them. "Buy it," says the Baron. The Baron recommends the perusal of this little book, if only to understand the full meaning of the old proverbial expression "Going on a wild-goose chase." The author is a wonderfully rapid-act traveller. He apparently can "run" round every principal city in Europe and see everything that's worth seeing in it in about an hour and a half at most. In this manner, and by not comprehending a word of the language wherever he is, or at all events only a very few of the words, he continues to pick up much curious information which probably would be novel to slower coaches than himself.

Interesting account of JOSEF ISRAELS in the Magazine of Art; but his portrait makes him look gigantic, which JOSEF is in Art, but not in stature. Those who "know not JOSEF," if any such there be, will learn much about him, and desire to know more. "Baroness," says the Baron, "you are right: let Hostesses and all dinner-givers read 'Some Humours of the Cuisine' in The Woman's World." The parodies of the style of Mr. PATER, and of a translation of a Tolstoian Romance in The Cornhill Magazine, are capital. In the same number, "Farmhouse Notes" are to The Baron like the Rule of Three in the ancient rhyme to the youthful student,—"it puzzles me." It includes a few anecdotes of some Farm'ous Persons; so perhaps the title is a crypto-punnygraph.

All Etonians should possess The English Illustrated Magazine (MACMILLAN'S), 1889-90, for the sake of the series of papers and the pictures of Eton College. There is also an interesting paper on the Beefsteak Room at the Lyceum by FREDERICK HAWKINS. Delightful Beefsteak Room! What pleasant little suppers—But no matter—my supper time is past—"Too late, too late, you cannot enter here," ought to be the warning inscribed over every Club or other supper-room, addressed chiefly to those who are of the Middle Ages, as is the mediæval

BARON DE BOOK-WORMS.

[The President of the British Pharmaceutical Conference lately drew attention to the prevalence of fashion in medicine.]

A fashion in physic, like fashions in frills:

The doctors at one time are mad upon pills;

And crystalline principles now have their day,

Where alkaloids once held an absolute sway.

The drugs of old times might be good, but it's true,

We discard them in favour of those that are new.

The salts and the senna have vanished, we fear,

As the poet has said, like the snows of last year;

And where is the mixture in boyhood we quaff'd,

That was known by the ominous name of Black Draught?

While Gregory's Powder has gone, we are told,

To the limbo of drugs that are worn out and old.

New fads and new fancies are reigning supreme,

And calomel one day will be but a dream;

While folks have asserted a chemist might toil

Through his shelves, and find out he had no castor oil;

While as to Infusions, they've long taken wings,

And they'd think you quite mad for prescribing such things.

The fashion to-day is a tincture so strong,

That, if dosing yourself, you are sure to go wrong.

What men learnt in the past they say brings them no pelf,

And the well-tried old remedies rest on the shelf.

But the patient may haply exclaim, "Don't be rash,

Lest your new-fangled physic should settle my hash!"

"TWINKLE, TWINKLE, LITTLE STAR!"—Professor JOHN TYNDALL wrote to T.W. RUSSELL last week commencing:—"Here, in the Alps, at the height of more than 7,000 feet above the sea, have I read your letter to the Times on 'the War in Tipperary.'" Prodigious! "7,000 feet" up in the air. "How's that for high?" as the Americans say. How misty his views must be in this cloudland—and that the Professor's writing should be above the heads of the people, goes without saying.

FEMALE ATHLETICISM.—If Ladies go in for "the gloves," not as formerly by the coward's blow on the lips of a sleeping victim—often uncommonly wide-awake—the noble art of self-defence can be taught under the head of "Millin-ery."

"CHANGE OF AIR—WANTED," by a party much broken up, a new tune to replace the "Boulanger March!" If the new tune cannot be found, we can at least suggest a change of title for the old one. So, instead of "En revenant de la Revue," let it be "En rêvant à la Revue." It should commence brilliantly, then intermediate variations, in which sharps and flats would play a considerable part, and, finally, after a chromatic scale, down not up, of accidentals, it should finish in the minor rallentando diminuendo, and end like the comic overture (whose we forget—HAYDN'S?), where all the performers sneak off, and the conductor is left alone in his glory.

The British Fire Brigade representatives took with them a dog, to be presented to President CARNOT. Why only one dog? Two fire-dogs are to be found on the hearth of every old French Château. Why only half do it?

[Major MARINDIN, in his Report to the Board of Trade on the railway collision at Eastleigh, attributes it to the engine-driver and stoker having "failed to keep a proper look-out." His opinion is, that both men were "asleep, or nearly so," owing to having been on duty for sixteen hours and a-half. "He expresses himself in very strong terms on the great danger to the public of working engine-drivers and firemen for too great a number of hours."—Daily Chronicle.]

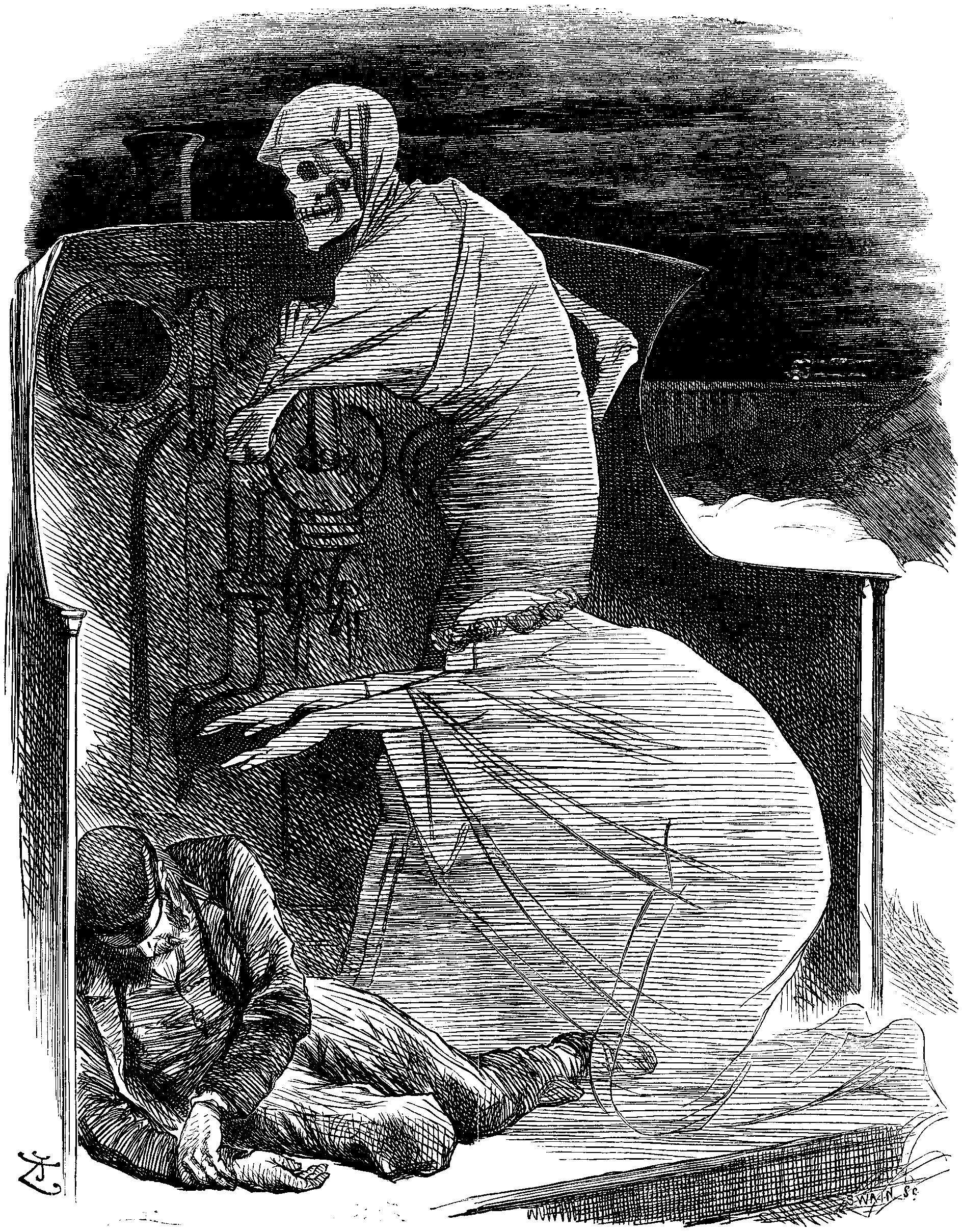

Who is in charge of the clattering train?

The axles creak, and the couplings strain.

Ten minutes behind at the Junction. Yes!

And we're twenty now to the bad—no less!

We must make it up on our flight to town.

Clatter and crash! That's the last train down,

Flashing by with a steamy trail.

Pile on the fuel! We must not fail.

At every mile we a minute must gain!

Who is in charge of the clattering train?

Why, flesh and blood, as a matter of course!

You may talk of iron, and prate of force;

But, after all, and do what you can,

The best—and cheapest—machine is Man!

Wealth knows it well, and the hucksters feel

'Tis safer to trust them to sinew than steel.

With a bit of brain, and a conscience, behind,

Muscle works better than steam or wind.

Better, and longer, and harder all round;

And cheap, so cheap! Men superabound

Men stalwart, vigilant, patient, bold;

The stokehole's heat and the crow's-nest's cold,

The choking dusk of the noisome mine,

The northern blast o'er the beating brine,

With dogged valour they coolly brave;

So on rattling rail, or on wind-scourged wave,

At engine lever, at furnace front,

Or steersman's wheel, they must bear the brunt

Of lonely vigil or lengthened strain.

Man is in charge of the thundering train!

Man, in the shape of a modest chap

In fustian trousers and greasy cap;

A trifle stolid, and something gruff,

Yet, though unpolished, of sturdy stuff.

With grave grey eyes, and a knitted brow,

The glare of sun and the gleam of snow

Those eyes have stared on this many a year.

The crow's-feet gather in mazes queer

About their corners most apt to choke

With grime of fuel and fume of smoke.

Little to tickle the artist taste—

An oil-can, a fist-full of "cotton waste,"

The lever's click and the furnace gleam,

And the mingled odour of oil and steam;

These are the matters that fill the brain

Of the Man in charge of the clattering train.

Only a Man, but away at his back,

In a dozen ears, on the steely track,

A hundred passengers place their trust

In this fellow of fustian, grease, and dust.

They cheerily chat, or they calmly sleep,

Sure that the driver his watch will keep

On the night-dark track, that he will not fail.

So the thud, thud, thud of wheel upon rail

The hiss of steam-spurts athwart the dark.

Lull them to confident drowsiness. Hark!

What is that sound? 'Tis the stertorous breath

Of a slumbering man,—and it smacks of death!

Full sixteen hours of continuous toil

Midst the fume of sulphur, the reek of oil,

Have told their tale on the man's tired brain,

And Death is in charge of the clattering train!

Sleep—Death's brother, as poets deem,

Stealeth soft to his side; a dream

Of home and rest on his spirit creeps,

That wearied man, as the engine leaps,

Throbbing, swaying along the line;

Those poppy-fingers his head incline

Lower, lower, in slumber's trance;

The shadows fleet, and the gas-gleams dance

Faster, faster in mazy flight,

As the engine flashes across the night.

Mortal muscle and human nerve

Cheap to purchase, and stout to serve.

Strained too fiercely will faint and swerve.

Over-weighted, and underpaid,

This human tool of exploiting Trade,

Though tougher than leather, tenser than steel.

Fails at last, for his senses reel,

His nerves collapse, and, with sleep-sealed eyes,

Prone and helpless a log he lies!

A hundred hearts beat placidly on,

Unwitting they that their warder's gone;

A hundred lips are babbling blithe,

Some seconds hence they in pain may writhe.

For the pace is hot, and the points are near,

And Sleep hath deadened the driver's ear;

And signals flash through the night in vain.

Death is in charge of the clattering train!

"WHAT TO DO WITH OUR GIRLS." (Paterfamilias's answer.)—Give them away! (Matrimonially, of course.)

|

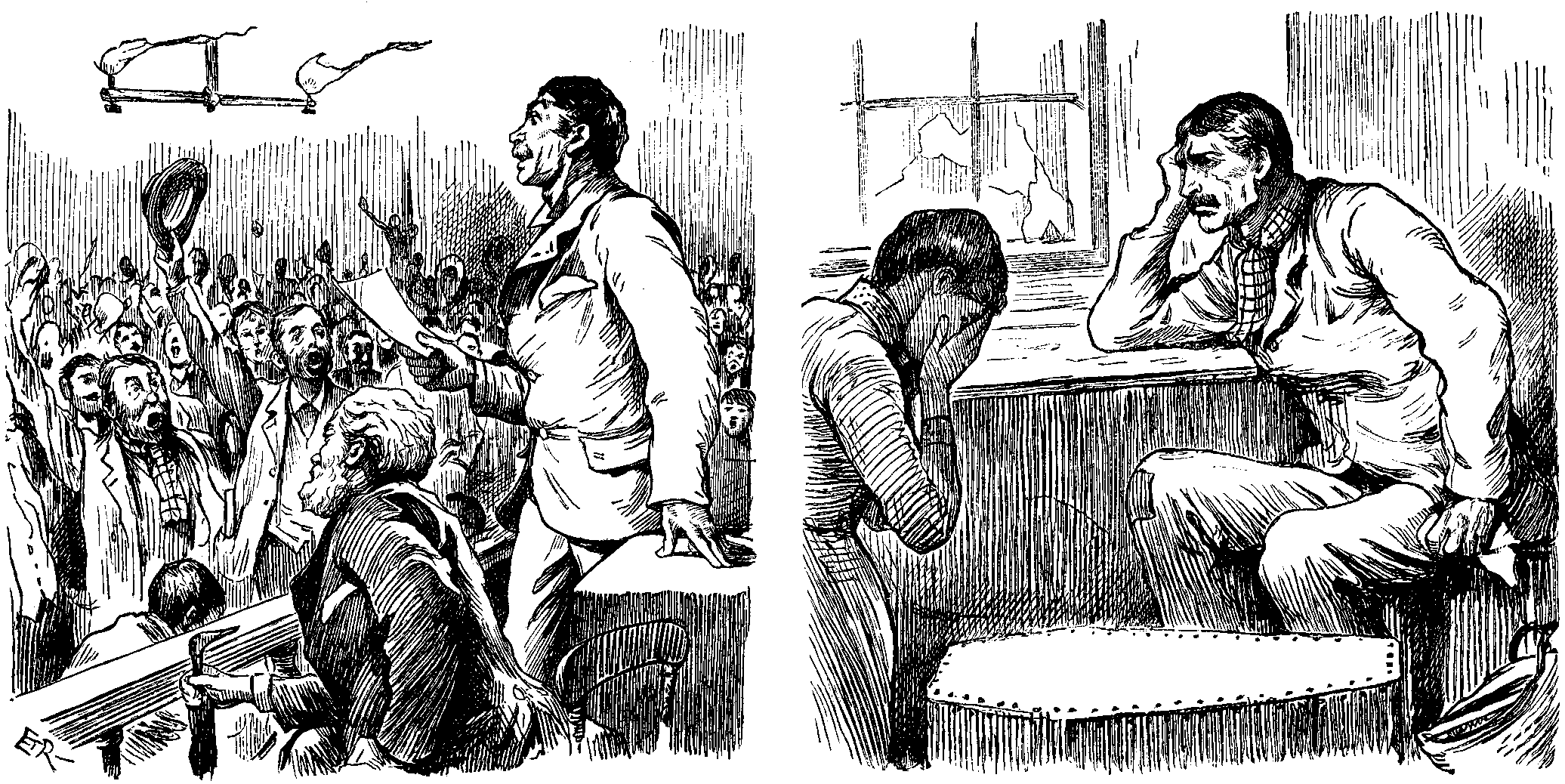

Mr. —— moved, "That this Mass-meeting pledges itself to support the efforts of Messrs. —— & Co.'s men, by joining the Union, and further pledges itself to take all legal efforts to prevent anyone obtaining a job there so long as the dispute lasts." The resolution was carried by acclamation. |

Coroner. How is it the child's father cannot get work? Witness. Because he has no Union card. Coroner. Then if men do not belong to the different Trades Unions they must starve.—Coroner's Inquest Report. |

["One of the most interesting exhibits (at the Royal Horticultural Society's Grape and Dahlia Show at Chiswick) were clusters of grapes with the scent and taste of strawberries and raspberries, as grown in Transatlantic hothouses."—Daily Paper.]

I'll tell thee everything I can;

There's little to relate:

I met a simple citizen

Of some "United State."

"Who are you, simple man?" I said,

"And how is it you live?"

And his answer seemed quite 'cute from one

So shy and sensitive.

He said, "I make electric cats

That prowl upon the leads,

To prey upon the brutes who raise

Mad music o'er our heads.

I also make all sorts of things

Which much convenience give;

In fact, I'm an inventor spry,

And that is how I live.

"And I am thinking of a plan

For artificial hens,

And automatic dairy-maids,

And self-propelling pens."

"Such things are stale," I made reply,

"They're old, and flat, and thin.

Tell me the last thing in your pate,

Or I will cave it in!"

His accents mild took up the tale:

He said, "I've tried to make

A sirloin out of turnips, and

A vegetable steak."

I shook him well, from side to side,

To stimulate his brain;

"You've got some newer dodge," I cried,

"And that you must explain."

He said, "I always willingly

Do anything to please.

What do you say to growing grapes

That taste like strawberr-ees!

They're showing off at Chiswick now,

As I a sinner am,

Some big black Hamburgs which, when pressed,

Taste just like raspberry jam."

So now whene'er I drink a glass

Of wine that seems like rum,

Or peel myself an orange that

Reminds me of a plum,

Or if I come across a peach

With flavour like a bilberry,

I weep, for it reminds me so

Of Chiswick's Grape and Dahlia Show,

And that 'cute man I used to know,

Who could at will transform a sloe

Into a thing with the aro-

-ma of all fruits known here below,

From apricot to mulberry.

According to a case about oysters—instead of a case, it ought to have been a barrel—heard before Mr. Alderman WILKIN,—and as the case may be still sub-Aldermanice, we have nothing to say as to its merits or demerits,—it appears, that in September, 1889, the price of Royal Whitstable Natives was 14s. per 100; i.e., 1s. 3d. for a baker's dozen of thirteen. Though why a baker should be allowed "a little one in," be it oysters or anything else, only Heaven and the erudite Editor of Notes and Queries know. But, without further allusion to the baker, who has just dropped in accidentally as he did into the conversation between Mrs. Bardell and Mrs. Cluppins, when Sam Weller joined in, and they all "got a talking," it is enough to make any oyster-lover's mouth water—no doubt the worthy Alderman's did water,—did water "like WILKIN!"—to hear that while everybody, including the worthy Alderman aforesaid, was paying 2s. 6d., and 3s., and even 3s. 6d. for real Natives, some people were gratifying their molluscous tastes at the small charge of One Shilling and Threepence for thirteen, or were getting six oysters and a half—the half be demm'd—for sixpence. Long time is it since we paid 1s. 3d. for Real Royal Natives. They may have left Whitstable at that price, but they never came to our Wits' Table at anything like that figure. Still, to the truly Christian mind it is pleasant, if not consoling, to know that some of our fellow-creatures, not generally so well-favoured as ourselves, should have been able to take advantage of the most favoured Native clause in the Oyster Season of 1889.

*** By the way, in answer to a Correspondent, who signs himself "AN ARTFUL DREDGER, WHO WISHES TO LIVE OUT OF TOWN," we beg to inform him that "Beds" is not a county specially celebrated for oysters.

Break, break, break!

On thy "Safety" swift, oh, "crack!"

And I would that my tongue could utter

My thoughts on the cyclist's track.

Oh, well for MECREDY, the "bhoy,"

That "records" for him won't stay;

And well for OSMOND and WOOD

That they break them every day.

And the "Safeties" still improve,

And their riders develope more skill;

And it's oh! for the records of yesterday!

To-morrow they'll all be nil!

Break! break! break!

On thy wheels, oh, S.B.C.!

But the grace of KEITH FALCONER, CORTIS, and KEEN,

Will they ever come back to me?

"SEQUEL to a Breach of Promise Case" is the heading to a paragraph in the Daily Telegraph, recording how Turner v. Avant was heard before Mr. Commissioner KERR, who adjourned the case for three weeks, because, as Mr. AGABEG, the Counsel for the Plaintiff, observed, without agabegging the question, they couldn't get any information essential to the proceedings as to the whereabouts of the Miss HAIRS, who, after failing in her action against Sir GEORGE ELLIOTT, M.P., gave up minding her own business, which she sold, and retired to the Continent; and Plaintiffs also wanted to know the present address of a certain, or uncertain, Mr. HOLLAND, somewhile Secretary to the Avant Company. Odd this. Not find Hairs in September! Cry "En Avant!" and let loose the harriers!—a suggestion that might have been appropriately made by the Commissioner whose name alone, with respect be it said, should qualify him for the Chief Magistracy in the Isle of Dogs. In the meantime the Plaintiffs have three weeks' adjournment in order to search the maps and find HOLLAND.

TITLED MONTHS.—In the list given by the Figaro of those present at Cardinal LAVIGERIE'S great anti-slavery function at Saint Sulpice was "un ancien ministre plénipotentiare le Baron d'Avril." What a set of new titles this suggests for any creation, of new Peers in England! Duke of DECEMBER! Earl of FEBRUARY! Of course, the nearest title to Baron D'AVRIL with us is the Earl of MARCH. The Marquis of MAY sounds nice; Lord AUGUST, Baron JULY; and, should a certain eminent ecclesiastical lawyer ever become a Law Lord, there will be yet another British cousin to Baron d'AVRIL and the Earl of MARCH in—Lord JEUNE.

NO MORE LAW OFFICERS!—"An Automatic Recorder on the Forth Bridge" was a heading to a paragraph in the St. James's last Saturday. The announcement must have startled Sir THOMAS CHAMBERS, Q.C. Heavens! If there is one Automatic Recorder in the North, why not another in the South? Automatic Recorders would be followed by Automatic Common Serjeants, and—Isn't it too awful!

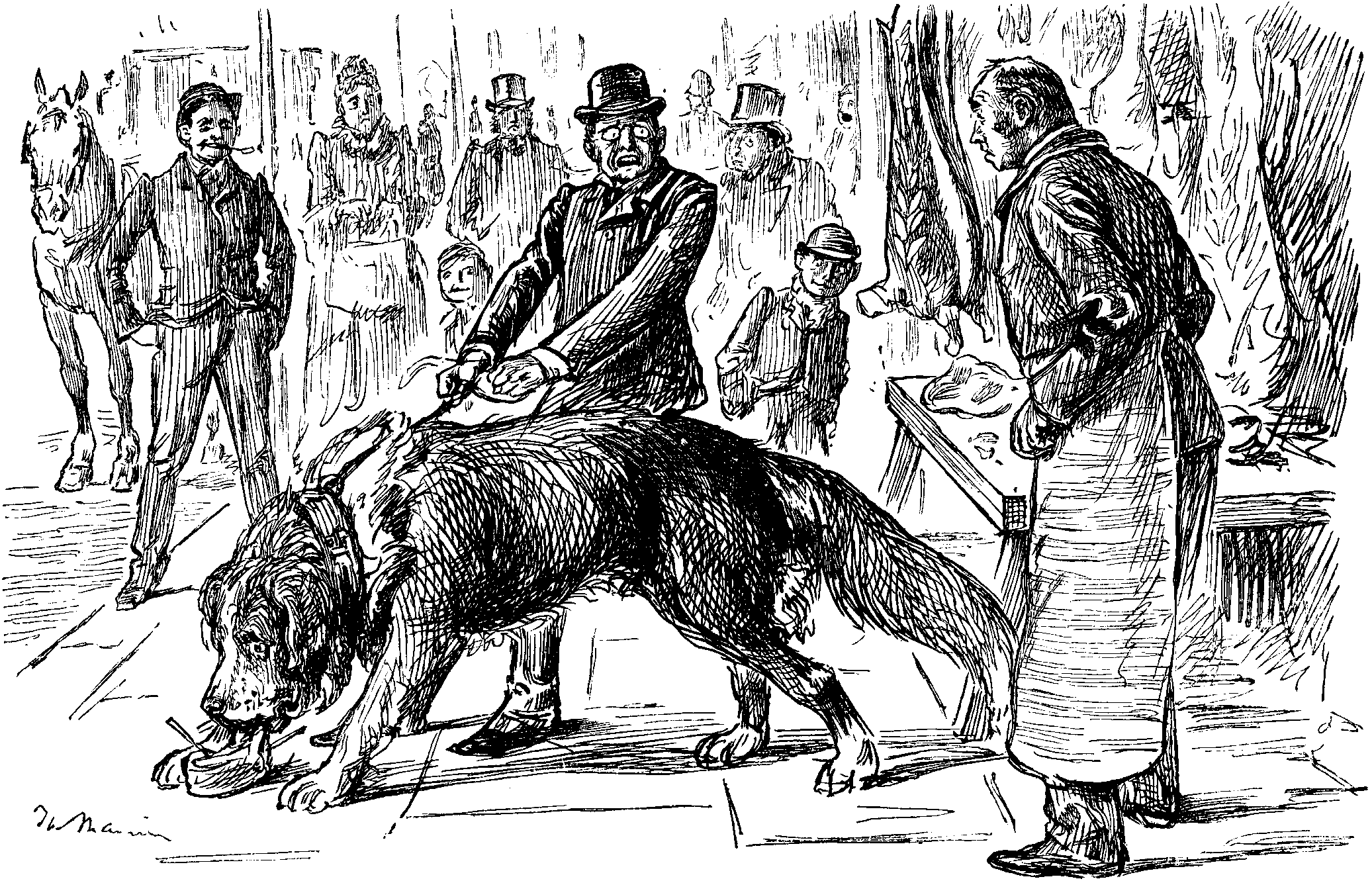

Yesterday morning LOO BOBBETT and BEN MOUSETRAP had an interview with Mr. PHEASANT, the Magistrate presiding in the North-West London Police Court. The approaches to the Court were crowded from an early hour. Amongst those in the street we noticed BILLY BLOWFROTH, and SAM SNEEZER, the well-known pot-boys from "The Glove and Wadding" and "The Tap o'Claret" Hotels, SHINY MOSES, AARON ISAACS, and SANDY the Sossidge (so-called by his friends on account of his appearance), the celebrated bankers from the West-end of Whitechapel, and a large gathering of the élite of the Lambeth Road. Inside the Court the company was, if possible, even more select. Mr. TITAN CHAPEL, the proprietor of the Featherbed Club, was the first to arrive in his private brougham, and he was followed at short intervals by the Earl of ARRIEMORE, Lord TRIMI GLOVESON, Mr. TOOWITH YEW, Mr. BRANDIC OHLD, Mr. SPLITTS ODER, Mr. GINCOCK TALE, and Mr. ANGUS TEWBER, with a heap more of the best known patrons of sport in the Metropolis. Little time was cut to waste in the preliminaries, and it was generally acknowledged at the end of the day that no prettier set-to had been witnessed for a long time than that which took place at the North-West London Police Court. We append below some of the more salient portions of the evidence.

Inspector Chizzlem. I produce a pair of gloves ordinarily used at London boxing matches. [Produces them from his waistcoat pocket.

Mr. Pheasant (the Magistrate). Pardon me. I don't quite understand. Were the gloves that you produce to be used at this particular competition?

Inspector Chizzlem. No, your Worship. These are one ounce gloves. The gloves with which these men were to fight are known as "feather-weight" gloves.

Mr. Pheasant. Ah, I see. Feather-weight, not feather-bed, I presume. (Loud Laughter, in which both the accused joined.) Have you the actual gloves with you?

Mr. Titan Chapel (from the Solicitor's table). I have brought them, Sir. Here—dear me, what can I have done with them? I thought I had them somewhere about me. (Pats his various pockets. A thought strikes him. He pulls out his watch.) Ah, of course, how foolish of me! I generally carry them in my watch-case.

[Opens watch, produces them, and hands them up to Magistrate.

Mr. Pheasant. Dear me!—so these are gloves. I know I am inexperienced in these matters, but they look to me rather like elastic bands. (Roars of laughter. Mr. PHEASANT tries them on.) However, they teem to fit very nicely. Yes, who is the next witness?

The Earl of Arriemore (entering the witness-box). I am, my noble sportsman.

Mr. Pheasant. Who are you?

The Earl of Arriemore. ARRIEMORE'S my name, yer Washup, wich I'm a bloomin' Lord.

Mr. Pheasant. Of course—of course. Now tell me, have you ever boxed at all yourself?

The Earl of Arriemore. Never, thwulp me, never! But I like to set the lads on to do a bit of millin' for me.

Mr. Pheasant. Quite so. Very right and proper. What do you say to the gloves produced by the inspector?

The Earl of Arriemore. Call them gloves? Why, I calls 'em woolsacks, that's what I calls 'em. [Much laughter.

Mr. Pheasant. No doubt, that would be so. But now with regard to these other gloves, do you say they would be calculated to deaden the force of a blow; in fact, to prevent such a contest from degenerating into a merely brutal exhibition, and to make it, as I understand it ought to be, a contest of pure skill?

The Earl of Arriemore. That's just it. Why, two babbies might box with them gloves and do themselves no harm. And, as to skill, why it wants a lot of skill to hit with 'em at all.

[Winks at Lord TRIMI GLOVESON, who winks back.

Mr. Pheasant. Really? That is very interesting, very interesting indeed! I think perhaps the best plan will be for the two principals to accompany me into my private room, to give a practical exemplification of the manner in which such a contest is generally conducted. (At this point the learned Magistrate retired from the Bench, and was followed into his private room by LOO BOBBETT. BEN MOUSETRAP, and their Seconds. After an hour's interval, Mr. PHEASANT returned to the Bench alone.) I will give my decision at once. The prize must be handed over to Mr. MOUSETRAP. That last cross-counter of his fairly settled Mr. BOBBETT. I held the watch myself, and I know that he lay on the ground stunned for a full minute. (To the Usher.) Send the Divisional Surgeon into my room at once, and fetch an ambulance. The Court will now adjourn.

[Loud applause, which was instantly suppressed.

Mr. Pheasant (sternly). This Court is not a Prize-Ring.

First of all, the title of the piece is against it. The Struggle for Life suggests to the general British Public, unacquainted with the name of DAUDET, a melodrama of the type of Drink, in which a variety of characters should be engaged in the great struggle for existence. It is suggestive of strikes, the great struggle between Labour and Capital, between class and class, between principal and interest, between those with moral principles and those without them. It is suggestive of the very climax of melodramatic sensation, and, being suggestive of all this to the majority, the majority will be disappointed when it doesn't get all that this very responsible title has led them to expect. Those who know the French novel will be dissatisfied with the English adaptation of it, filtered, as it has been, through a French dramatic version of the story. So much for the title. For the play itself, as given by Messrs. BUCHANAN and HORNER,—the latter of whom, true to ancestral tradition, will have his finger in the pie,—it is but an ordinary drama, strongly reminding a public which knows its DICKENS of the story of Little Em'ly, with Vaillant for Old Peggotty, Lydie for Little Em'ly, Antonin Caussade for Ham, and Paul Astier for Steerforth. Perhaps it would be carrying the resemblance too far to see in Rosa Dartle, with her scorn For "that sort of creature," the germ of Esther de Sélény. Mix this with a situation from Le Monde où l'on s'ennuie, spoilt in the mixing, and there's the drama.

For the acting—it is admirable. Miss GENEVIEVE WARD is superb as Madame Paul Astier, and it is not her fault, but the misfortune of the part, that the wife of Paul is a woman old enough to be his mother, with whose sufferings—with her eyes wide open, having married a man of whose worthlessness she was aware,—it is impossible to feel very much sympathy. She is old enough to have known better. Mr. GEORGE ALEXANDER'S performance of the scoundrel Paul leaves little to be desired, but he must struggle for dear life against his—of course, unconscious—imitation of HENRY IRVING. Shut your eyes to the facts, occasionally, especially in the death-scene, and it is the voice of IRVING; open them, and it is ALEXANDER agonising. No one can care for the fine lady, statuesquely impersonated by Miss ALMA STANLEY, who yields as easily to Paul's seductive wooing as does Lady Anne to Richard the Third. After Miss WARD and Mr. ALEXANDER, the best performance is that of Miss GRAVES as Little Em'ly Lydie, and of Mr. FREDERICK KERR as Antonin Ham Caussade,—the last-named enlisting the genuine sympathy of the audience for a character which, in less able hands, might have bordered on the grotesque. The comic parts have simply been made bores by the adapters, and are not suited to the farcical couple, Miss KATE PHILLIPS and Mr. ALBERT CHEVALIER, who are cast for them. If this play is to struggle successfully for life, the weakest, that is, the comic element, should at once go to the wall, and the fittest alone, that is, the tragic, should survive. Also, as the play begins at the convenient hour of 8.45, it should end punctually at eleven. The only realistic scene is in Paul Astier's room, when he is dressing for dinner, and washes his hands with real soap, uses real towels, and puts real studs and links into his shirt, and then suddenly reminded, as it were, by a titter which pervades the house, that there are "ladies present," he disappears for a few seconds, and returns in his evening-dress trowsers and nice clean shirt, looking, except for the absence of braces, like a certain well-known haberdasher's pictorial advertisement. It is vastly to the credit of the management that all the articles of Paul's toilet, including Soap(!!), are not turned to pecuniary advantage in the advertisements on the programmes. But isn't it a chance lost in The Struggle for Life at the Avenue?

I have lately had the distinguished honour conferred upon me of being unanimously elected a Vestryman of the important Parish of Saint Michael-Shear-the-Hog, which I need hardly say is situate in the ancient and renowned City of London. I owe my election I believe, to the undoubted fact that I am what is called—I scarcely know why—a tooth-and-nail Conservative, no one of anything approaching to Radicalism being ever allowed to enter within the sacred precincts of our very select Body. Our number is small, but, I am informed, we represent the very pick of the Parish, and we have confided to us the somewhat desperate task of defending the funds entrusted to us, centuries ago, from the fierce attack of Commissioners with almost unlimited powers, but with little or no sympathy with the sacred wishes of deceased Parishioners.

Our contention is that wherever, from circumstances that our pious ancestors could not have foreseen, it has become simply impossible to carry out literally their instructions, the funds should be applied to strictly analogous purposes. For instance, now in a neighbouring Parish, I am not quite sure whether it is St. Margaret Moses, or St. Peter the Queer, a considerable sum was bequeathed by a pious parishioner in the reign of Queen MARY, of blessed memory, the income from which was to be applied to the purchasing of faggots for the burning of heretics, which it was probably considered would be a considerable saving to the funds of the Parish in question. At the present time, as we all know, although there are doubtless plenty of heretics, it has ceased to be the custom to burn them, so the bequest cannot be applied in accordance with the wishes of the pious founder. The important question therefore arises, how should the bequest be applied? Would it be believed that men are to be found, and men having authority, more's the pity, who can recommend its application to the education of the poor, to the providing of convalescent hospitals, or even the preservation of open spaces for the healthful enjoyment of the masses of the Metropolis! Yet such is the sad fact. My Vestry, I am proud to say, are unanimously of opinion that, in such a case as I have described, common sense and common justice would dictate that, as the intentions of the pious founder cannot be applied to the punishment of vice, it should be devoted to the reward of virtue, and this would be best accomplished by expending the fund in question in an annual banquet to those Vestrymen who attended the most assiduously to the arduous duties of their important office. JOSEPH GREENHORN.

[An Austrian physician, Dr. TERC, prescribes bee-stings as a cure for rheumatism!]

How cloth the little Busy Bee

Insert his poisoned stings,

And kill the keen rheumatic pain

That mortal muscle wrings!

Great Scott! It sounds so like a sell!

Bee-stings for rheumatiz?

As well try wasps to make one well.

That TERC must be a quiz.

Rather would I rheumatics bear

Than try the Busy Bee.

No, Austrian TERC, your cure may work!

But won't he tried on me!

"IL IRA LOIN."—Great day for England in general, and for London in particular, when AUGUSTUS GLOSSOP HARRIS,—the "Gloss-op"-portunely appears nothing without the gloss up-on him,—popularly known by the title of AUGUSTUS DRURIOLANUS, rode to the Embankment with his trumpeters,—it being infra dig. to be seen blowing one himself,—with his beautiful banners, and his footmen all in State liveries designed by LEWIS LE GRAND WINGFIELD, he himself (DRURIOLANUS, not LEWIS LE GRAND) being seated in his gorgeous new carriage; Sheriff FARMER, too, equally gorgeous, and equally new, but neither so grand nor so great as DRURIOLANUS The Magnificent. Then followed "the quaint ceremony of admission." Not "Free Admission," by any means, for no man can be a Sheriff of London for nothing. There were loud cheers, and a big Lunch. Ave Cæsar!

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.