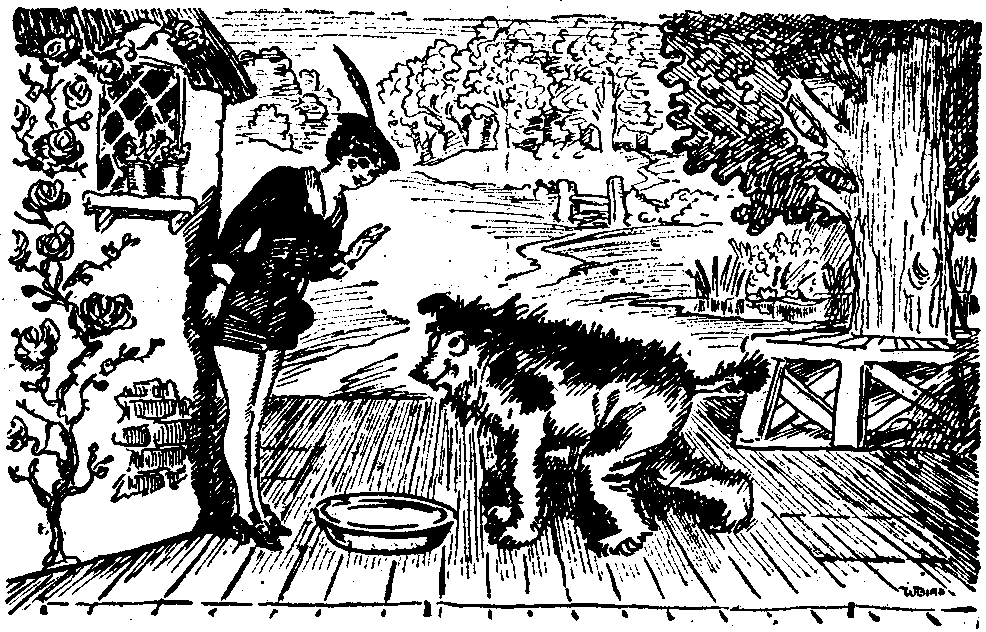

PANTOMIME FAUNA.

Extract from the note-book of the dramatic critic of "the Wampton Clarion":—

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 146., January 14, 1914, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol. 146., January 14, 1914 Author: Various Release Date: June 6, 2004 [EBook #12536] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, JANUARY 14, 1914 *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

We hear that the CHANCELLOR has, while in North Africa, been making a close study of camels, with a view to ascertaining the nature of the last straw which breaks their backs.

It is denied that Mr. LLOYD GEORGE, in order to give a practical demonstration of his belief in the disarmament idea, has given instructions that all precautions against attacks on him by Suffragettes are to be discontinued.

The Balkan situation is considered to have undergone a change for the worse owing to the purchase by Turkey of the Dreadnought Rio de Janeiro. For ourselves we cannot subscribe to this view. Is it likely that the Turks, after paying over £2,000,000 for her, will risk losing this valuable vessel in war?

On the day of the marriage of the Teuton Coal-King's daughter to Lord REDESDALE's son last week there was snow on the ground. The Coal-King must have shown up very well against it.

Sir REGINALD BRADE is to be the new permanent secretary at the War Office. Let's hope he has no connection with the firm of Gold Brade and Red Tape.

It has been discovered that members of a certain Eskimo tribe have an extra joint in their waists. The news has caused the greatest excitement among cannibal tribes all over the world, and it is expected that there will be a huge demand for these people. Where there are big families to feed the extra joint will be invaluable.

"OUR RESOLUTION IS TO GO FORWARD IN THE NEW YEAR." advertises the London General Omnibus Co. A capital idea, this. Vehicles which simply go backwards are never so satisfactory.

After one-hundred-and-fifty-years' careful consideration the War Office has given permission to the Black Watch and the King's Royal Rifle Corps to bear on their regimental colours the honorary distinction "North America, 1763-64," in recognition of services rendered during the war against the Red Indians.

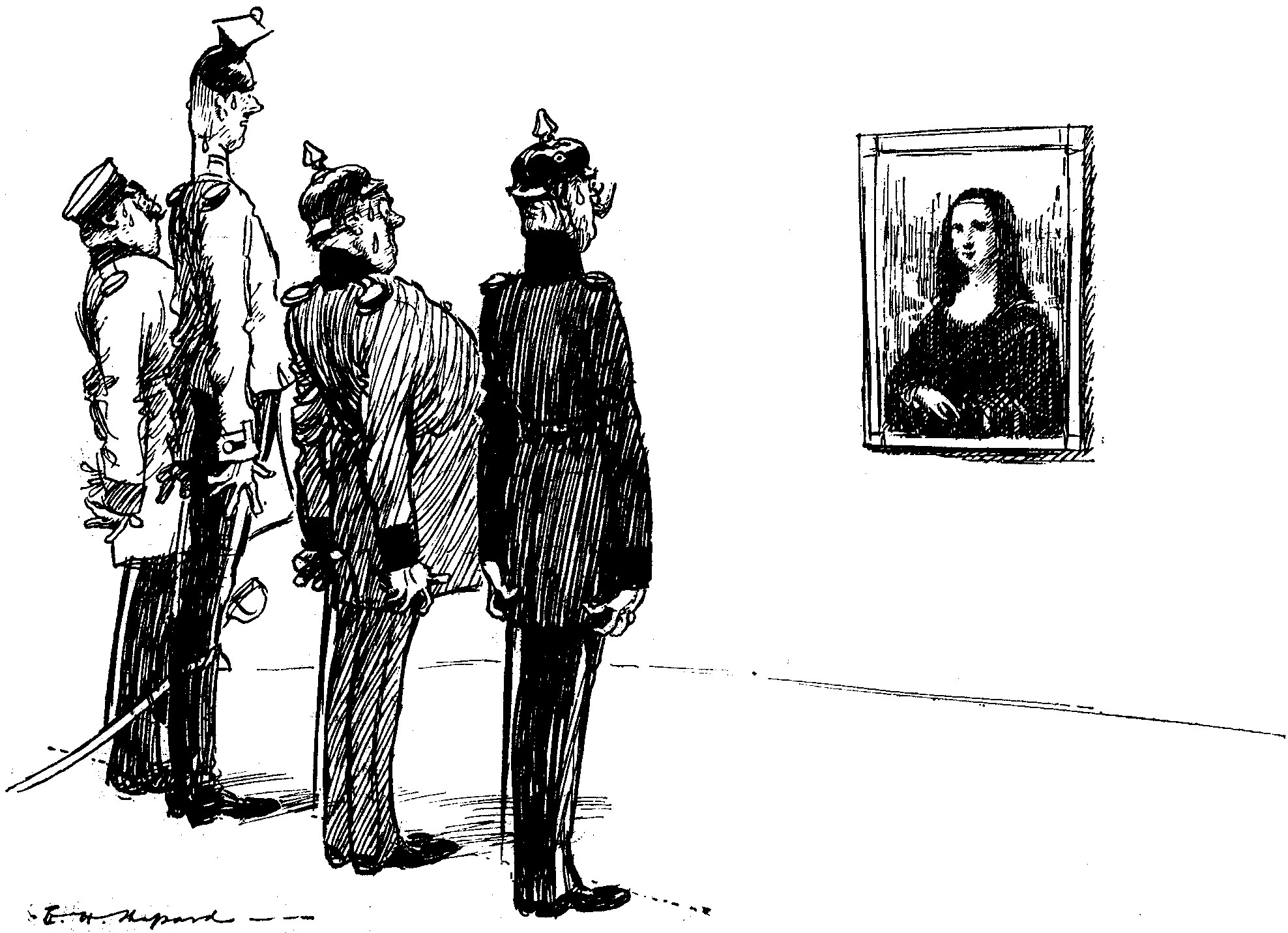

Not sixty people visited "La Gioconda" on one of the days after her return to Paris, when a charge of four shillings was made for admission, and, towards the end of the day, the smile is said to have worn a rather forced look.

"Who are the best selling modern authors?" asks a contemporary. We do not like to mention names, but, as readers, we have been sold by several popular writers lately.

We are not surprised that many persons are becoming rather disgusted with our little amateurish attempts at Winter. Thousands now go to Switzerland, and Sir ERNEST SHACKLETON is going even further afield. Meanwhile the Government does nothing to stem this emigration.

The boxing craze among the French continues. M. VEDRINES, the intrepid aviator, has taken it up and been practising on M. Roux's ears.

The German CROWN PRINCE has become a member of the Danzig Cabinet Makers' Union. Later on he hopes to become a Chancellor-maker.

Another impending apology? Headlines from The Daily Chronicle:—

"PNEUMONIA ON THE RAND.

DISCOVERY OF ITS CAUSE.

SIR ALMROTH WRIGHT'S

VACCINE TREATMENT."

Could frugality go further? At the golden wedding celebrations of a Southend couple, a packet of wedding cake was eaten which had been put away on their marriage day in 1863.

A soap combine, with a nominal capital of £35,000,000, is said to have been formed to exploit China; and the Mongols may yet cease to be a yellow race.

The latest tall story from America is to the effect that some burglars who broke into the Presbyterian church at Syracuse, New York, stole a parcel of sermons.

["It was better for a young mother to start her new chapter unhampered: the less she knew the better it was for her."—Mrs. Annie Swan.]

How do you take a baby up?

What does it like to eat?

Do you put rusks in a feeding cup?

Have you to mince its meat?

Haven't I heard them speak of pap?

Isn't there caudle too?

How do you keep the thing on your lap?

Why are its eyes askew?

Is it a touch of original sin

Causes an infant to squall,

Or trust misplaced in a safety-pin

Lost in the depths of a shawl?

When do you "shorten" a growing child

(Is it so much too long)?

Should legs be lopped or the scalp be filed?

Both in a sense seem wrong.

"Kitchy," I think I have heard them say;

What shall I make it kitch?

"Bo" I believe in a mystic way

Frightens or soothes, but which?

Didn't I see one once reversed,

Patted about the spine?

Is it the way they should all be nursed?

Will it agree with mine?

Surely its gums are strangely bare?

Why does it dribble so?

Will reason dawn in that glassy stare

If I dandle it briskly? OH!!!

Grandmothers! Mothers! or Instinct, you!

Haste with your secret lore!

What, oh what shall I, what shall I do?

Baby has crashed to the floor!

"They adjourned to the Village Hell, where each child was presented with a parcel of suitable clothing."—Tonbridge Free Press.

Asbestos, no doubt.

(Showing how Colonel VON REUTER, late of Zabern, appealed to his regiment to defend the honour of the Army. The following speech is based upon evidence given at the Strassburg trial.)

My Prussian braves, on whom devolves the mission

To vindicate our gallant Army's worth,

Upholding in its present proud position

The noblest fighting instrument on earth—

If, in your progress, any vile civilian

Declines the homage of the lifted hat,

Your business is to paint his chest vermilion—

Kindly attend to that.

Never leave barracks, when you go a-shopping,

Without an escort loaded up with lead;

Always maintain a desultory popping

At anyone who wags a wanton head;

If, as he passes, some low boy should whistle

With nose in air and shameless chin out-thrust,

Making your scandalised moustaches bristle—

Reduce the dog to dust.

I hear a sinister and shocking rumour

Touching the native tendency to chaff.

If you should meet with specimens of humour

See that our soldiers get the final laugh;

Fling the facetious corpses in the fountains

So as the red blood overflows the brink;

Keep on until the blue Alsatian mountains

Turn a reflective pink.

Should any female whom your shadow touches

Grudge you the glad, but deferential, eye;

Should any cripple fail to hold his crutches

At the salute as you go marching by;

Draw, in the KAISER's name—'tis rank high treason;

Stun them with sabre-strokes upon the poll;

Then dump them (giving no pedantic reason)

Down cellars with the coal.

Be on your guard against all people strolling

In ones or twos about the public square

Hard by your quarters; set your men patrolling;

Ask every knave what he is doing there;

And, if in your good wisdom you determine

To view their conduct in a dangerous light,

Bring the machine-guns out and blow the vermin

Into the Ewigkeit.

Enough! I leave our honour in your keeping.

What are your bright swords for except to slay?

Preserve their lustre; let me see them leaping

Out of their scabbards twenty times a day;

Unless we smash these craven churls like crockery

To prove our right of place within the sun,

Our martial prestige has become a mockery

And Deutschland's day is done!

O.S.

"The dancing, in the conventional bullet style, of Miss Sybil Roe, was quite good."—Wiltshire Times.

We confess that the bullet style is too fast for us.

"In all the best dress ateliers classic evening gowns are now being exhibited, and in many of these the lines of the corsage closely resemble the draperies to be seen on the Venus de Milo."—Daily Mail.

We must go and look at the Venus de Milo's corsage again.

[Several newspapers have been roused to a sense of their duties to their readers by the insurance competition between The Chronicle and The Mail. We make a few preliminary announcements of other insurance schemes which are not yet contemplated.]

VOTES FOR WOMEN.—A copy of the current issue nailed to your front door insures you absolutely against arson.

THE STAR.—All regular subscribers to The Star are insured with the proprietors of The Daily News for £1,000 in the event of being welshed on any race-course.

THE NATIONAL REVIEW.—Annual subscribers to The National Review are guaranteed £10,000 in the event of being (a) robbed on the highway by a member of the present Ministry; (b) defrauded by a member of the present Ministry; (c) having house burgled by member of the present Ministry; (d) having pocket picked by member of present Ministry; always excluding any act or acts done by the CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER in a strictly official capacity.

THE CHURCH TIMES.—All regular subscribers are insured for £500 against excommunication. £1,000 will be paid to the heirs or assigns of any reader who loses his head in a conflict with a Bishop (Deans, Rural Deans, Canons and Archdeacons being excepted from the benefit of this clause in the policy).

THE ENGLISH REVIEW.—Poetic contributors are insured for £500 in the event of a prosecution under the Blasphemy Laws.

THE DAILY EXPRESS.—You can sleep soundly in your bed, you can sleep soundly in your train, if the current issue of The Daily Express be on your person. All purchasers are insured for £10,000 against any conflagrations or explosions caused by bombs or combustibles dropped from German airships.

THE BRITISH WEEKLY.—All readers of The British Weekly are insured for £1,000 in the event of heart-failure caused by shock while reading the thrilling stories provided by SILAS, JOSEPH, TIMOTHY and JEREMIAH HOCKING.

THE RECORD.—£500 will be paid to any annual subscriber forcibly detained in a convent, provided that at the time of such detention a copy of the current issue of The Record be in his possession. £1,000 will be paid to the legal representatives of any reader burnt at the stake.

THE CRICCIETH CHRONICLE.—£3 a week for life, together with a poultry farm on a Sutherland deer-forest, to the owner of any shorn lamb which is found dead in a snow-drift with a copy of the current issue wrapt round it, to keep it warm.

The great world rolls on, but of the master-brains which direct its movement the man in the street knows nothing. He has never heard of the Clerk of the Portland Urban District Council; he is entirely ignorant of Army Order 701.

"Dear Sir" (writes the Clerk)—"A meeting of the Underhill Members of the Council will be held to-morrow (Saturday), at 3 o'clock p.m., in Spring Gardens (Fortuneswell) for the purpose of selecting a site for the Telegraph Post."

"With effect from 1st January, 1914" (says the Army Order) "rewigging of gun sponges will be done by the Ordnance Department instead of locally as at present."

"Inman was seen to greater advantage at yesterday afternoon's session in this match of 18,000 up, in Edinburgh, than on any previous day of the match, scoring 1,083 while Aiken was aggregating the mentally afflicted."—Nottingham Guardian.

One must amuse oneself somehow while the other man is at the table.

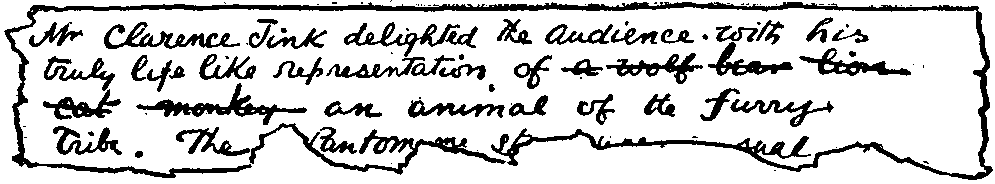

Amiable Uncle (doing some conjuring to amuse the children). "SEE, HERE I HAVE A BILLIARD BALL—I AM GOING TO TURN IT INTO SOMETHING ELSE."

First Bored Youngster (to second ditto). "WHY SHOULD HE? IT'S A VERY NICE BALL."

In view of The Daily Mail's praiseworthy efforts to instruct applicants for situations in the correct phrasing of letters to prospective employers, we propose to supply a similar long-felt want, and give a little advice as to the kind of letter it is desirable to enclose with contributions to periodicals.

Begin your letter in a friendly vein, hoping the Editor and his people are pretty well. Remember also that Editors like to know something of the characters and histories of their contributors. So let your communication include a résumé of your personal and literary career. Don't fall into the error of making your letter too concise.

The following suggestions may serve to indicate some of the lines of thought that you might follow:—

(1) State where you sent your first manuscript.

(2) What you thought of it, and of the Editor who returned it.

(3) Your height and chest measurement (an Editor likes to be on the safe side).

(4) State who persuaded you to take up literature, and give height and chest measurement of same.

(5) Give a short but optimistic description of your contribution, not to exceed in length the contribution itself.

(6) State whether literary genius is rife in your family or has been rife at any time since 1066.

(7) Give a list of journals to which you have already sent the enclosed contribution, and state your reasons for supposing that the Editors were misguided. Hint that perhaps, after all, their lack of enterprise was fortunate for the present recipient.

(8) Mention your hobbies and the different appointments you have held since the age of twelve, with names and addresses of employers. Also give your reasons for remaining as long as you did in each situation.

(9) State how long you have been a subscriber to the journal you are electing to honour, and whether you think it's worth the money. Point out any little improvements you consider desirable in its compilation, and mention other periodicals as perfect examples. Preface these remarks with some such phrase as this: "Pray don't think I want to teach you your business, but—"

(10) Give full list (names and addresses) of friends who have promised to buy the paper if your contribution appears.

(11) Give a brief outline, in faultless English, of your religious, political and police court convictions, your views on Mr. LLOYD GEORGE, and any ideas you may have about the Law of Copyright.

Finally, enclose a stamped and addressed envelope for the return of your article.

"It has always been supposed that Charles I. when Prince of Wales and travelling incognito with the Duke of Buckingham saw and fell in love with Marie Antoinette."

Not by us. We always supposed he fell in love with SARAH BERNHARDT.

We stood in a circle round the parrot's cage and gazed with interest at its occupant. She (Evangeline) was balancing easily on one leg, while with the other leg and her beak she tried to peel a monkey-nut. There are some of us who hate to be watched at meals, particularly when dealing with the dessert, but Evangeline is not of our number.

"There," said Mrs. Atherley, "isn't she a beauty?"

I felt that, as the last to be introduced, I ought to say something.

"What do you say to a parrot?" I whispered to Miss Atherley.

"Have a banana," suggested Archie.

"I believe you say, 'Scratch-a-poll,'" said Miss Atherley, "but I don't know why."

"Isn't that rather dangerous? Suppose it retorted 'Scratch your own,' I shouldn't know a bit how to go on."

"It can't talk," said Archie. "It's quite a baby—only seven months old. But it's no good showing it your watch; you must think of some other way of amusing it."

"Break it to me, Archie. Have I been asked down solely to amuse the parrot, or did any of you others want to see me?"

"Only the parrot," said Archie.

Evangeline paid no attention to us. She continued to wrestle with the monkey-nut. I should say that she was a bird not easily amused.

"Can't it really talk at all?" I asked Mrs. Atherley.

"Not yet. You see, she's only just come over from South America, and isn't used to the climate yet."

"Just the person you'd expect to talk a lot about the weather. I believe you've been had. Write a little note to the poulterers and ask if you can change it. You've got a bad one by mistake."

"We got it as a bird," said Mrs. Atherley with dignity, "not as a gramophone."

The next morning Evangeline was as silent as ever. Miss Atherley and I surveyed it after breakfast. It was still grappling with a monkey-nut, but no doubt a different one.

"Isn't it ever going to talk?" I asked. "Really, I thought parrots were continually chatting."

"Yes, but they have to be taught—just like you teach a baby."

"Are you sure? I quite see that you have to teach them any special things you want them to say, but I thought they were all born with a few simple obvious remarks, like 'Poor Polly,' or—or 'Dash LLOYD GEORGE.'"

"I don't think so," said Miss Atherley. "Not the green ones."

At dinner that evening, Mr. Atherley being now with us, the question of Evangeline's education was seriously considered.

"The only proper method," began Mr. Atherley—"By the way," he said, turning to me, "you don't know anything about parrots, do you?"

"No," I said. "You can go on quite safely."

"The only proper method of teaching a parrot—I got this from a man in the City this morning—is to give her a word at a time, and to go on repeating it over and over again until she's got hold of it."

"And after that the parrot goes on repeating it over and over again until you've got sick of it," said Archie.

"Then we shall have to be very careful what word we choose," said Mrs. Atherley.

"What is your favourite word?"

"Well, really—"

"Animal, vegetable or mineral?" asked Archie.

"This is quite impossible. Every word by itself seems so silly."

"Not 'home' and 'mother,'" I said reproachfully.

"You shall recite your little piece in the drawing-room afterwards," said Miss Atherley to me. "Think of something sensible now."

"Yes," said Mrs. Atherley. "What's the latest word from London?"

"Kikuyu."

"What?"

"I can't say it again," I protested.

"If you can't even say it twice, it's no good for Evangeline."

A thoughtful silence fell upon us.

"Have you fixed on a name for her yet?" Miss Atherley asked her mother.

"Evangeline, of course."

"No, I mean a name for her to call you. Because if she's going to call you 'Auntie' or 'Darling,' or whatever you decide on, you'd better start by teaching her that."

And then I had a brilliant idea.

"I've got the very word," I said. "It's 'hallo.' You see, it's a pleasant form of greeting to any stranger, and it will go perfectly with the next word that she's taught, whatever it may be."

"Supposing it's 'wardrobe,'" suggested Archie, "or 'sardine'?"

"Why not? 'Hallo, Sardine' is the perfect title for a revue. Witty, subtle, neat—probably the great brain of the Revue King has already evolved it, and is planning the opening scene."

"Yes, 'hallo' isn't at all bad," said Mr. Atherley. "Anyway, it's better than 'Poor Polly,' which is simply morbid. Let's fix on 'hallo.'"

"Good," said Mrs. Atherley.

Evangeline said nothing, being asleep under her blanket.

I was down first next morning, having forgotten to wind up my watch overnight. Longing for company I took the blanket off Evangeline's cage and introduced her to the world again. She stirred sleepily, opened her eyes and blinked at me.

"Hallo, Evangeline," I said.

She made no reply.

Suddenly a splendid scheme occurred to me. I would teach Evangeline her word now. How it would surprise the others when they came down and said "Hallo" to her, to find themselves promptly answered back!

"Evangeline," I said, "listen. Hallo, hallo, hallo, hallo." I stopped a moment and went on more slowly. "Hallo—hallo—hallo."

It was dull work.

"Hallo," I said, "hallo—hallo—hallo," and then very distinctly, "Hal-lo."

Evangeline looked at me with an utterly bored face.

"Hallo," I said, "hallo—hallo."

She picked up a monkey nut and ate it languidly.

"Hallo," I went on, "hallo, hallo ... hallo, hallo, HALLO, HALLO ... hallo, hallo—"

She dropped her nut and roused herself for a moment.

"Number engaged," she snapped, and took another nut.

You needn't believe this. The others didn't when I told them.

A.A.M.

From "Notes, Questions and Answers" in T.P.'s Weekly:—

"Author wanted, and where the whole poem can be found:—

"Drink to me only with thine eyes,

And I'll not ask for wine."

C.E.H.

[Herrick. A collected edition of the poems is published by J.M. Dent at 1s. net.—ED. N.Q.A.]"

Afterthought by ED. N.Q.A.: "At least I think it's HERRICK ... or WORDSWORTH ... but wait till the Editor comes back from Algiers. He's sure to know."

"Sir John Thornycroft kicked off in a football charity match at Bembridge, Isle of Wight, in which the combined ages of the players was 440 years."—Hull Daily Mail.

Why not?

"M. Timiriazeff, president of the Anglo-British Chamber of Commerce, followed with a speech."—Daily Telegraph.

We like his Anglo-British name.

[Some additional aspects of the fashionable topic that seem to have escaped the writers of similar articles in our contemporaries.]

For this game several players are required, who form themselves into one or more parties according to numbers. A player, preferably a woman, is selected as leader, and should possess nerve, coolness, and an authoritative voice. The object of the game is to secure (1) The best rooms; (2) Tables with a view; (3) The controlling interest in all projects of entertainment. It is an important advantage for the leader to have stayed in the hotel at least once previously. If she is able to announce on arrival, "Here we are as usual!" and to greet the proprietor and staff by name, this often gives an initial blow exceedingly hard to parry. English visitors have been proving very adept at the sport this season, with Americans a good second. The German game, on the contrary, is slower and less subtle.

An amusing game that has been very popular at many Swiss resorts lately, and one that calls for the qualifications of a quick brain and a keen eye. The universal adoption of sweaters and woollen caps makes the task of the players one of considerable difficulty. Envelope-reading should be forbidden by the rules, and some codes even debar the offering of a Church Times to a suspected stranger. The Athenæum and Spectator may, however, be freely employed as bait. A simpler version of the same sport called "HOW MANY SCHOOLMASTERS?" is often indulged in between December 20th and January 15th, after which latter date it loses its point.

Other games, seldom chronicled but inquiring at least as much skill from their votaries as the better known varieties, are EARLY MORNING SKI-BAGGING—at which the Germans frequently carry all before them—and PRESSING THE PRESS-PHOTOGRAPHER, where the object of all the players is to appear recognizably in a snap-shot for the illustrated journals. At this the record score of three weekly and five daily papers has been held for two successive seasons by the same player, a gentleman whose dexterity is the subject of universal admiration.

SCENE—Interior of box at Fancy Dress Ball.

SCENE—Interior of box at Fancy Dress Ball.

Host of Party. "I SAY, BETTY, I WANT TO INTRODUCE YOU TO A CITY FRIEND OF MINE, MR. JONES."

Hostess (hospitably). "HOW D'YOU DO? OH, YOU'RE AWFULLY GOOD!"

Host (sotto voce). "TAKE CARE! HE'S NOT MADE UP AT ALL."

Canada has evolved a novelty described as a "new beef animal," which is a blend of the domestic cow and the North American bison. The resulting prodigy has the ferocious hump and shoulders of the bison, with the mildly benevolent face of the Herefordshire ox. It must not, however, be supposed that the old country is behind-hand in such experiments, as witness the following:—

Billingsgate salesmen have lately been supplied with advance copies of the new Codoyster fish. This epicurean triumph, which owes its existence to the research of several eminent specialists, is the result of a blend of the North Sea cod and the finest Whitstable native. The result is said to reproduce in a remarkable degree the succulent qualities of the original fish when eaten with oyster sauce, and caterers are sure to welcome the combination of these popular items in so handy a form.

Several fine examples of the Soho chicken have lately appeared upon the show benches at various important poultry contests. This ingenious creation, which has long been familiar to the patrons of our less expensive restaurants (hence the name), is said to possess qualities of endurance superior to anything previously on the market. Its muscular development is phenomenal, while the entire elimination of the liver, and the substitution of four extra drum-sticks for the ordinary wings and thighs, are noteworthy characteristics.

Success in another branch of the same endeavour is shown in the latest report of the Society for the Prolongation of Dachshunds. According to this the worm-ideal seems at last to be in sight, careful inter-breeding having now produced a variety called the Processional, selected specimens of which take from one to two minutes in passing any given spot. The almost entire disappearance of legs is another attractive feature.

Meanwhile Major-Gen. Threebottle writes from Oporto Lodge, Ealing, strongly protesting against any further complication of the fauna of these islands, and pointing out that the simple snakes and cats of our youth were already sufficiently formidable to a nervous invalid like himself without the addition of such objectionable novelties.

"Without warning, while the car was travelling at about fifteen miles per hour, the tyre of the front wheel burst."—Scotsman.

Our tyres are much better trained, and each of the four gives a distinctive cough before bursting.

"WAREHOUSEMAN (jun.), clothing dept., large corporation."—Advt. in "Glasgow Herald."

He should show off the new line in check waistcoats to the best advantage.

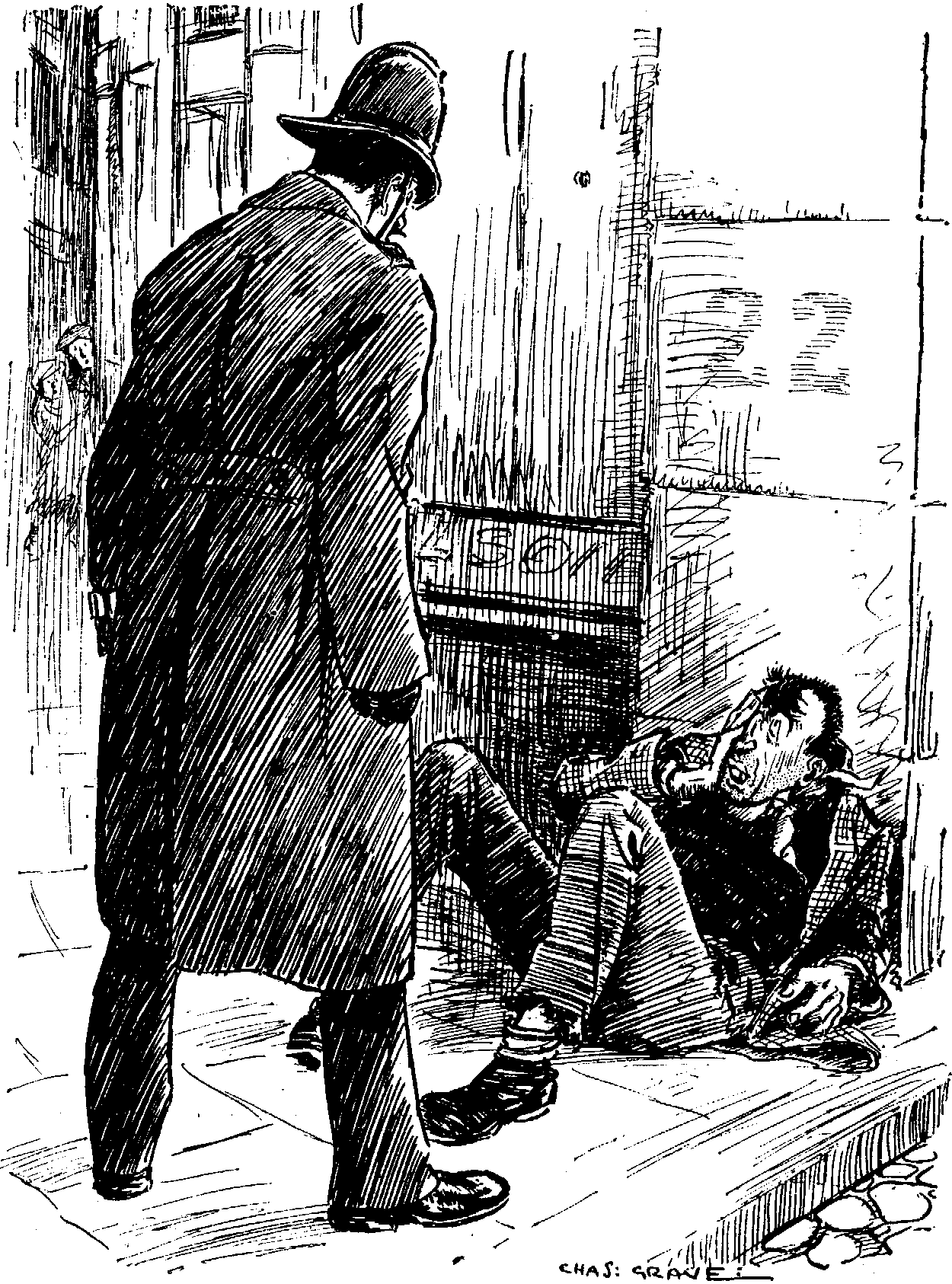

He had a coarse confident face, a red nose, a Cockney accent and a raucous voice. He was dressed as a sluttish woman.

Directly I saw him I was conscious of a feeling of repulsion, which I fear my expression must have indicated, for he looked surprised.

"Why aren't you laughing?" he asked.

"Why should I laugh?" I asked in return.

"Because you are looking at me," he said. "I am accustomed to laughter the instant I appear."

"Why?"

"Because I am a funny man," he said.

"How?"

"I look funny," he said; "I say funny things; I draw a good salary for it. If I wasn't funny I shouldn't draw a good salary, should I?"

"You do draw it," I said guardedly. "Be funny now."

"'Wait till I catch you bending,'" he said with a violent grimace. "'What ho! 'Ave a drop of gin, ole dear?'"

"Be funny now," I repeated.

He looked bewildered. "I was being funny," he said. "I bring the house down with that, as a rule."

"Where?"

"In panto," he said.

"Oh!" I replied. "So you're the funny man of a pantomime, are you?"

"Yes," he said.

"Which one?"

"All of them," he said.

"Good," I replied. "I have long wanted a talk with you. There are things I want to ask you. Why, for instance, do you always pretend to be a grimy slum woman?"

"It seems to be expected," he said.

"Who expects it? The children?"

"What children?"

"The children who go to pantomimes," I said.

"Oh, those! Well, they laugh," he replied evasively.

"They like to see you quarrelling with your husband and getting drunk?"

"They laugh," he said.

"They like to hear you, as an Ugly Sister in Cinderella, singing 'Father's on the booze again; mother's off her chump'?"

"They laugh," he said.

"They like to see you as the wife of Ali Baba, finding pawntickets in your husband's pockets and charging him with spending his money on flappers?"

"They laugh," he said.

"They like to see you, as The Widow Twankay, visit a race meeting and get welshed and have your clothes torn off?"

"They laugh," he said.

"They like to see you, as Dick Whittington's mother, telling the cat that, if he must eat onions, at any rate he can refrain from kissing her?"

"They laugh," he said.

"They like to see you, as the dame in Goody Two Shoes, open a night club on the strict understanding that it is only for clergymen's daughters in need of recreation?"

"They laugh," he said again.

"But they don't know what you mean?"

"No. But I'm funny. That's what you don't seem to understand. I'm so funny that everything I say and do makes them laugh. It doesn't, in fact, matter what I say."

"Ah!" I replied, "I have you there! In that case why don't you say a few simpler and sweeter things?"

He seemed perplexed.

"Things," I explained, "that don't want quite so much knowledge of the seamy side of life?"

"Go on!" he said derisively. "I haven't got time to mug that up. I've got my living to get. You don't suppose I invent my jokes, do you? I collect them. I'm on the Halls the rest of the year, and I hear them there. There hasn't been a new joke in a pantomime these twenty years. But what you don't seem to get into your head, mister, is the fact that I make them laugh. Laugh. I'm a scream, I tell you."

"And laughter is all you want?" I asked.

"I must either make people laugh or get 'the bird.'"

"But hasn't it ever occurred to you," I said, "that children in a theatre at Christmas time are entitled to have a little fun that is not wholly connected with sordid domestic affairs and pothouse commonness?"

"Never," he said, and I believed him.

"Haven't you children of your own?"

"Several."

"And is that how you amuse them at home?"

"Of course not. They're too young."

"How old are they?"

"From six to thirteen."

"But that's the age of the children who go to pantomimes," I suggested.

"Well, it's different in your own home," he said. "Besides," he added, "it isn't children I aim at in my jokes. There's other things for them: the fairy ballets, the comic dog."

"And what is the audience you aim at?" I asked. "I suppose there is one definite figure you have in your mind's eye?"

"Yes," he said, "there is one. The person in the audience that I always aim at is the silly servant-girl in the front row of the gallery. That's why I so often say 'girls' before I make a joke. You've heard me, haven't you?"

"Haven't I?" I groaned.

It was yesterday afternoon, towards the close of the last beat of our annual cover shoot, that I perceived a fellow in a yellow waterproof popping up his head from time to time (at no little risk to his life) over a dyke some way behind the line of guns. As soon as the beaters came out he advanced and introduced himself as an Excise Officer, asking "if this would be a convenient moment to examine the game licences of the party."

It was not at all a convenient moment for Walter—who hadn't got one. My thoughts flew at once to Walter in this crisis, for I knew he was bound to be had. Walter never does have game licences, season tickets, adhesive labels, telegraph forms or things of that sort. And as he had only returned from Canada two days before and this was the first time that he had been out, and further as he immediately disappeared and hid behind the hedge, I knew that my worst suspicions must be confirmed. While the Excise Officer was taking down the names and addresses of the rest of the party I went after Walter. He was sitting in the ditch with his head in his hands.

"If this had happened a few years ago, old chap," he said, "when I was a younger man, I should have run for it. But to-day I believe that feller would overhaul me within half-a-mile. My wind's rotten. Do you think he'll find us here?"

"Yes," said I, "he is coming this way."

Walter got up. "There must be some way out of it," he said thoughtfully, "if one could only think of it." Then he boldly confronted his accuser.

"Since you put it to me," he said, "no, I have no game licence. But fortunately in my case it is not necessary. I am exempt."

The Officer stared at him a moment.

"Certainly it is necessary," he said.

"Kindly show me the form of this licence," said Walter in the most lordly, off-hand, de-haut-en-bas tone of voice, and the Officer handed him one belonging to the Major, which he had been scrutinizing. "This, I perceive," said Walter, when he had read it carefully, "is a licence or certificate to kill game. It doesn't apply to me."

"Why not?"

[pg 29]"Because I haven't killed any game."

"But you have your gun in your hand at this moment."

"That is so. This is my gun. But where, I ask you, is my dead game? The truth is, my dear fellow," he went on, dropping his voice to a more confidential level, "though it's pretty humiliating to have to admit it and all that, especially before the beaters—the truth is that I haven't hit a blamed thing to-day. Rotten, isn't it?"

Walter isn't much of a shot and there weren't many birds anyway, and he hadn't been very lucky in his stands—and when one came to think it over one couldn't just exactly remember anything at all having fallen to his gun.

"I call all these fellows to witness," said Walter most impressively, "that I have killed no game. If it pleases me to discharge my gun, at short intervals, for the sake of the bang—"

"You require a gun licence," said the Officer.

"That is not the point. I may or may not have a gun licence, but our present controversy relates to a certificate to kill game. Do not let us confuse the issue."

It now appeared, however, that the Officer had been waiting behind the dyke rather longer than we knew. "I myself," he said firmly, "saw you bring down a cock pheasant at the beginning of the last beat."

Walter consulted the paper in his hand. "I observe," he said, "that this licence (or certificate) relates to killing game. There is nothing said of bringing it down. I may, as you say, have induced a cock pheasant to descend. I certainly didn't kill him. As a matter of fact he was lightly touched on the wing, and he ran like a hare."

"He's in that patch of bracken there," said the Officer. "If you will send a keeper and a dog with me—"

"No, I can't do that," said Walter, "unless you can show me a written authority empowering you, in the KING's name, to borrow keepers and dogs."

It was then that the fun began. The Officer went off like a shot up the hillside, started the old cock, chased him up the ditch and through the hedge, and finally, to everyone's surprise and delight, collared him in a corner of the dyke. There were loud cheers from the enthusiastic crowd, but they were cut short by a sharp warning from Walter.

"Be careful how you handle that bird, Sir!" he cried. "If anything happens to him I shall hold you responsible. I have no reason to believe that you hold a licence (or certificate) to kill game. If he suffers a mortal injury I shall report you."

The Officer began to look rather bewildered and the old cock flapped his wings.

"I'll thank you for that bird," said Walter firmly, and he took it and tucked it comfortably under his arm.

"What are you going to do with it?" asked the Officer.

"I am going to nurse it back to health and strength," said Walter. "It only requires a little close attention. I shall be happy if you will call in about a week's time to enquire. Good afternoon. I am very pleased to have met you." And Walter held out his hand.

Well, that is where the matter rests. If Walter can keep the bird alive the case against him falls to the ground. If not, I suppose it means a three-pound licence and a ten-pound fine. He took him straight back to the Home Farm and secured for him dry and airy quarters in the poultry run, and did not leave him till he had seen to his comfort in every way and given minute directions as to his treatment....

I am afraid the old cock passed a rather restless night, but he was able to take part of a warm mash, with two drops of laudanum in it, at an early hour this morning. At this moment I hear Walter getting out his motor-bicycle. I fancy he is going for the vet.

Says Mr. CLEMENT SHORTER:—

"There is a journal in London which has the impertinence to call itself The Nation, but ... it does not represent the merest fraction of our countrymen."

Mr. SHORTER's own paper is called, more modestly, The Sphere.

I was in the train because I had to go to Birmingham; I was in the dining car because I had to dine. With all respect to the Company I cannot pretend that I regarded myself as doing anything remarkable or distinguished. The little man opposite me, however, felt differently. I have since been told that they of Birmingham are very proud of their non-stop train service by both routes.

"This, Sir," said the stranger, as I lowered my paper to help myself to a proffered roll—"this is one of the Two-Hour trains."

"You don't say," said I politely but not encouragingly.

"Two hours," he repeated impressively.

"Indeed? Two whole hours and not a moment less?" and I returned to my paper pending the soup's arrival.

"Is it not wonderful," he resumed when I was at his mercy again, "to be travelling at sixty miles an hour and eating soup at the same time?"

"Some people eat soup," said I, "and some drink it. For myself, I give it a miss;" and I returned to the news.

With the fish: "I came up by the breakfast train this morning," said he, "and I now return by the dining train." He meant by this to give credit to the Company rather than to himself, but even so it seemed to fall short of the complete ideal. There was something wanting. It was luncheon, of course.

"They run luncheon cars too," said he.

"Then there seems to be no reason why you should ever leave the train at all," I remarked, seeking refuge again in my paper. In spite, however, of my coldness, he continued to assail me with similar facts every time I emerged. Finally he took a sheet of slightly soiled paper and pencilled on it a schedule of our movements. It ran:—

| Mileage. | Place. | Time. | ||

| — | Euston | 6.55 | P.M. | |

| 5½ | Willesden | [7.4] | " | |

| 17½ | Watford | [7.18] | " | |

| 46¾ | Bletchley | [7.50] | " | |

| 82¼ | Rugby | [8.24] | " | |

| 94¼ | Coventry | [8.36] | " | |

| 113 | Birmingham | 8.55 | " |

"To give this the very careful consideration it deserves," said I, "I must be left absolutely to myself."

Later on, feeling that I had perhaps been rude, I offered the man a cigar by way of compensation. He accepted it as a mark of esteem and burst forth into more conversation. By now a little fed up with trains himself he suggested, for the sake of something new to say, that he had met me before somewhere. At first I had some idea of asking for my cigar to be returned, but instead I gave in to his persistence. More, I joined in the conversation with an energy which surprised him.

"Now I come to think of it we have seen each other before; but where?" I said.

He thought promiscuously, disconnectedly and aloud. I could accept none of his suggestions because all referred to commercial rooms in provincial hotels, places to which I have not the entrée. "But I know now," I declared brightly; "it was at a place just this side of London that I saw you first."

[pg 31]

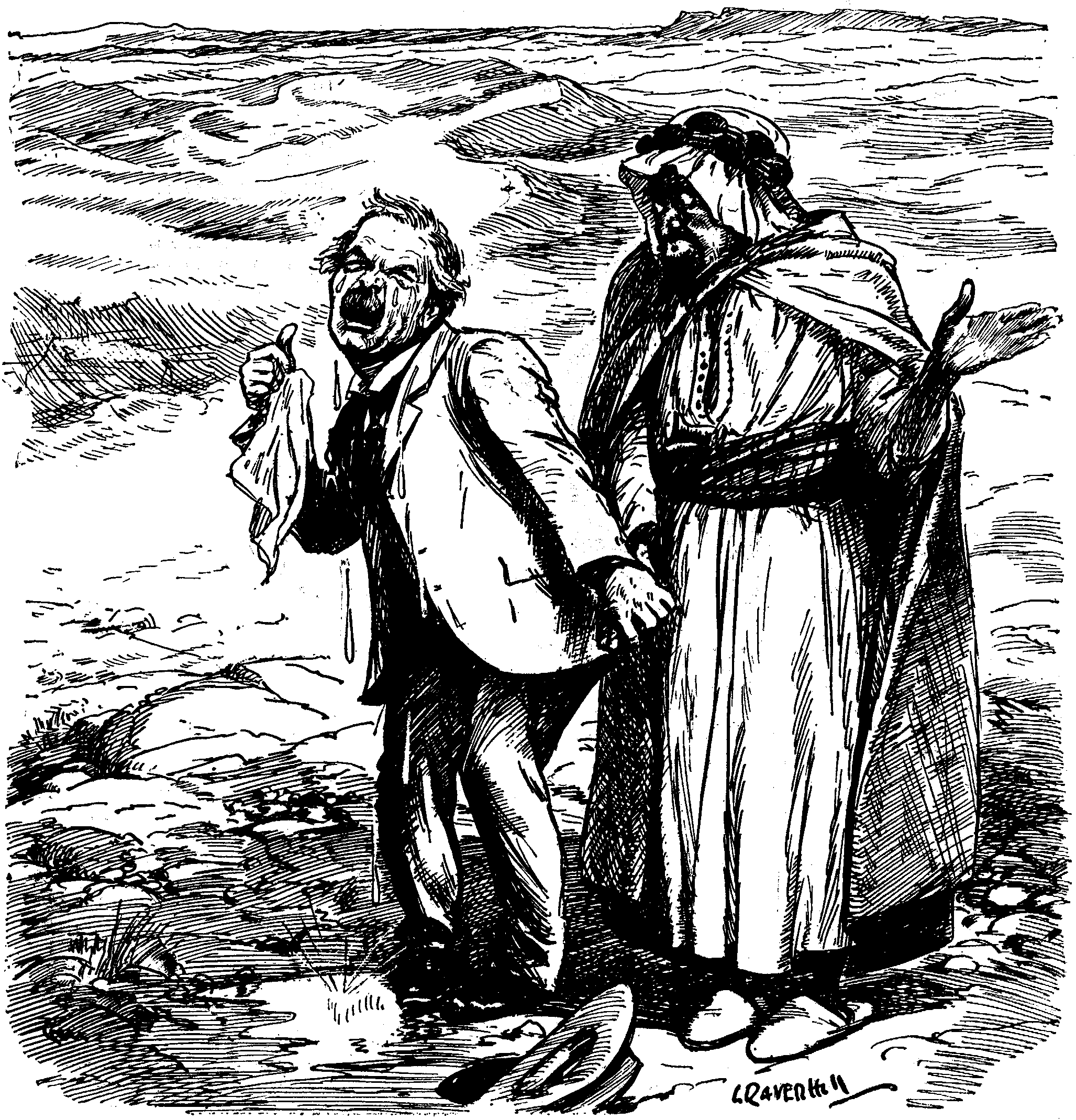

THE ARAB AND THE CHANCELLOR

WERE WALKING HAND-IN-HAND;

THE LATTER WEPT A LOT TO SEE

SUCH QUANTITIES OF SAND;

"WHY ARE YOU HOLDING UP," HE SAID,

"THIS VERY FERTILE LAND?"

"First?" he asked.

"Oh yes," said I. "I have seen you more than once. Surely you haven't forgotten that time at Watford?"

He felt that I had the advantage of him. "When was that?" he asked.

"Not very long after the first time; and the next occasion I remember seeing you was at a place called—called—something beginning with a B."

He was quite unable to cope with the situation.

"And the next time," I continued, "I happened to be passing through that town where the school is—you know, Rugby. I distinctly recollect noticing then that you hadn't changed in the least since I last saw you."

He couldn't decide whether to be more flattered at my remembering or more annoyed at his own forgetting.

"Come, come," I exclaimed, "you surely cannot have forgotten that little chat we had at Coventry?"

"Coventry?" he asked. "But how long ago was that?"

"Quite recently," I asserted.

"But I haven't set foot in Coventry for years," said he.

"Nor have I, ever," said I.

I could understand his feelings thoroughly. It might be that I was a liar; it might be that I was a lunatic. In either case he did not wish to converse further with me. Happily, I had two newspapers available.

As the speed of our train, in which of old he had taken such a pride, began to slacken: "And I shouldn't be surprised," I said from behind my paper, "if you and I saw each other again quite soon. The world is a small place and these things soon develop into a habit."

He made no answer from behind his paper.

"If you ask me when and where" (as in fact he didn't), "I should say it is just as likely as not to happen at Birmingham at about 8.55 P.M.," I estimated, relying upon his own schedule.

Harold (who has just been kissed by his sister). "I SAY, I WONDER WHAT SHE'S UP TO?"

Friend. "SIGN OF AFFECTION, ISN'T IT?"

Harold. "AFFECTION, YOU GOAT! SHE NEVER DOES THAT TILL THE LAST DAY OF THE HOLS, AND THERE'S A WEEK TO GO YET."

"The play was preceded by 'The £12 Hook,' another Barrie comedy of more recent date."—Sydney Morning Herald.

We should prefer to call it "The £12 Eye."

"LABOUR IN SOUTH AFRICA.

BLACK OUTLOOK."

Morning Post.

Let us hear both sides. What is the White Outlook?

"The grievance of the men is in regard to the rate of pay. They are paid 5½d. per hair."—Glasgow News.

And then when they are old and bald they have to starve.

"TANGO RAPIDLY DYING.

DANCE UPHELD BY MR. MAX PEMBERTON."

Daily Chronicle.

This is the sort of thing that the Revue King has to put up with. Truly the lot of royalty is not an enviable one.

From an advertisement of Tango matinées in The Lyceum:—

| "RESERVED TAUTENILS (4 first rows) | 10/— |

| TAUTENILS (tea included) | 7/6 |

| TAUTENILS (tea not included) | 6/—" |

Gourmet (planking down his seven-and-six). "Tea and tautenils, please."

Seen on a Liverpool hoarding:—

"Quo Vadis: Whither goest thou in eight reels?"

Answer. "Anywhere in reason, but not home."

Weary of the struggle and the squalors

Which beset the politician's life—

Work that for a modicum of dollars

Brings a whole infinity of strife—

Three of England's most illustrious cronies

Started on a winter holiday,

With no thought of MURRAY or Marconis—

GEORGE and HENRY and the great TAY PAY.

Never since ÆNEAS and his raiders

Stayed with DIDO in the days of yore

Did such irresistible invaders

Land upon the Carthaginian shore.

GEORGE, of course, the largest crowds attended,

But I'm told the kind Algerians say

That ÆNEAS wasn't half so splendid

Or so pious as the good TAY PAY.

Noble sheikhs and black and bearded Bashas

Bowed, whene'er they met them, to the ground;

Festas and fantasias and tamashas

Followed in a never-ending round.

GEORGE no more on his detractors brooded;

HENRY simply sang the livelong day;

While unmixed benevolence exuded

From the loving heart of kind TAY PAY.

Side by side they read the works of HICHENS;

Hand in hand they sampled the bazaars;

Ate the sweetmeats cooked in native kitchens;

Flew about in sumptuous motor-cars;

Golfed where once great HANNIBAL was scheming;

Joked where luckless DIDO once held sway;

For the finest jokes were always streaming

From the lips of comical TAY PAY.

Other days they spent in caracoling,

Mounted each upon a mettled barb,

Or along the streets serenely strolling

Clad in semi-oriental garb;

HENRY with a cummerbund suburban;

GEORGE disguised to look like ENVER BEY;

While a kilt surmounted by a turban

Veiled the massive contours of TAY PAY.

Daily they partook of ripe and juicy

Fruit, and Mocha coffee and kibobs;

Daily they conversed with EL SENOUSSI

And a lot of other native nobs;

HENRY practised Algerine fandangos;

GEORGE upon the tom-tom learned to play;

And a dervish taught ten Arab tangos

To the light fantastical TAY PAY.

Whither will they wander next, I wonder?

Not, I hope and pray, within the reach

Of the tribes who live on loot and plunder,

Fanatics who practise what they preach.

Fancy if these horrible disturbers,

Swooping on our countrymen astray,

Touaregs and Bedouins and Berbers,

Carried off the succulent TAY PAY!

Hardly had this agonizing presage

Taken shape within my tortured brain,

When good REUTER flashed the welcome message,

"Chancellor Returns," across the main.

Neptune, be thy waters calm, not choppy,

As they speed them on their homeward way,

GEORGE and HENRY and, bowed down with "copy,"

Our unique arch-eulogist, TAY PAY.

Personally I think too much respect is paid to age. There is nothing clever in being old—nothing at all. On the other hand, youth has a charm of its own. Besides, twenty-two is not young; you wouldn't think me so if you really knew me. The doubt arises, I suppose, from a certain innate light-heartedness. It is really rather pathetic.

Daphne chooses to see humour in the situation, which is very absurd of her, and, as I point out, merely reflects on herself. Surely she doesn't wish to admit that it is foolish to love her.

And that, to make a clean breast of it, is exactly what I do, and do madly.

I follow her about, reverently watching her every movement, hanging on her every word—no light task. And my reward? A scant unceremonious "Hallo!" when we meet; a scanter "Night" or "Morning," according to the circumstances, when we part. A brave smile from me and she is gone, an unwitting spectator of a real tragedy.

Up to a few days ago I was content to bear with my lot, but last week I rebelled. It was at a dance, after supper. Daphne had certainly shown a sort of affection for me, motherly rather than otherwise, I think; nevertheless an affection. But then, and not for the first time, I had seen her flirting with another.

I decided to lose my temper. I went into the smoke-room and deliberated very close to the fire. In five minutes I left the room heated.

I found Daphne at once.

"Our dance," I said. "We will sit out."

My manner must have been rather terrifying. At any rate we sat out.

"Daphne," I began, "I am in a mood that brooks no trifling. For weeks I have loved you. You spurn me."

"Oh, Billy, do be sensible," Daphne murmured.

I moderated my tone. "Well, look here," I said, "why are you so cold to me and yet flirt with my cousin? I saw you putting his tie straight and patting his arm just now; and you won't let me even hold your hand. It's pretty hard, Daphne."

She laughed. "My dear Billy—"

"Many thanks for yours of yesterday. I am having a very good time and it is really kind of me to write."

"If you won't be sensible—"

"I am. It's just because I'm so serious that I jest. All the wittiest men are broken-hearted. Go on."

"Well, my dear Billy, you mustn't be foolish. I'm very fond of you, but you're so ridiculously young."

"You haven't a revolver about you?" I enquired.

Daphne sighed. "Billy, you're quite hopeless. Do let me try to explain. You see, I can't—well—flirt with you, because I don't really flirt, of course, and besides your cousin's different—he's married."

I got up quickly. "Good-bye," I said. "You must excuse my leaving you."

Daphne looked surprised. "Where are you going?" she enquired.

"To get married." I walked away with my head in the air.

A week later I wrote Daphne a letter. It ran as follows:—

"MY DEAR DAPHNE,—I am going to get married. Tina [pg 35] is nineteen, the same as you, and is in the chorus of a musical comedy. She has real jet black hair, so I am quite lucky. I hope you are fonder of me already.

Yours devotedly, BILLY."

In reply, and by return of post, I received an invitation to tea at Daphne's. Daphne, looking beautiful, was awaiting me.

"How d'you do?" I said gravely.

"Billy," Daphne began, "will you be really serious with me?"

I immediately assumed a business manner and coughed.

"Well?" I said.

The word was sharp and incisive, a regular lawyer's question.

"Of course, you're joking about this chorus girl?"

"Joking! Daphne, you know I'd do anything for you."

Daphne smiled. "But, Billy, I shan't like you any better if you marry her."

I bit a piece of cake coldly. "I don't understand you, Daphne," I said. "When I ask you to show me a little affection, only just what you show others, you tell me I'm young and married men are different. I arrange to be different at considerable personal sacrifice, and you tell me you won't like me any better." I swallowed convulsively.

"But, Billy—dear—you're not actually engaged?"

"I'm not so sure," I replied. "These girls are wonderfully sharp; and then, of course, I'm so young." (A good touch.)

There was a silence.

"I shall hate you if you marry a chorus girl," said Daphne.

"Then why did you tell me married men were different?"

"Because most of them are." Daphne smiled slowly. "I think I might like you better if you were married to some really nice girl."

I laughed bitterly. "To you, for instance?"

"Yes, to me," said Daphne very sweetly.

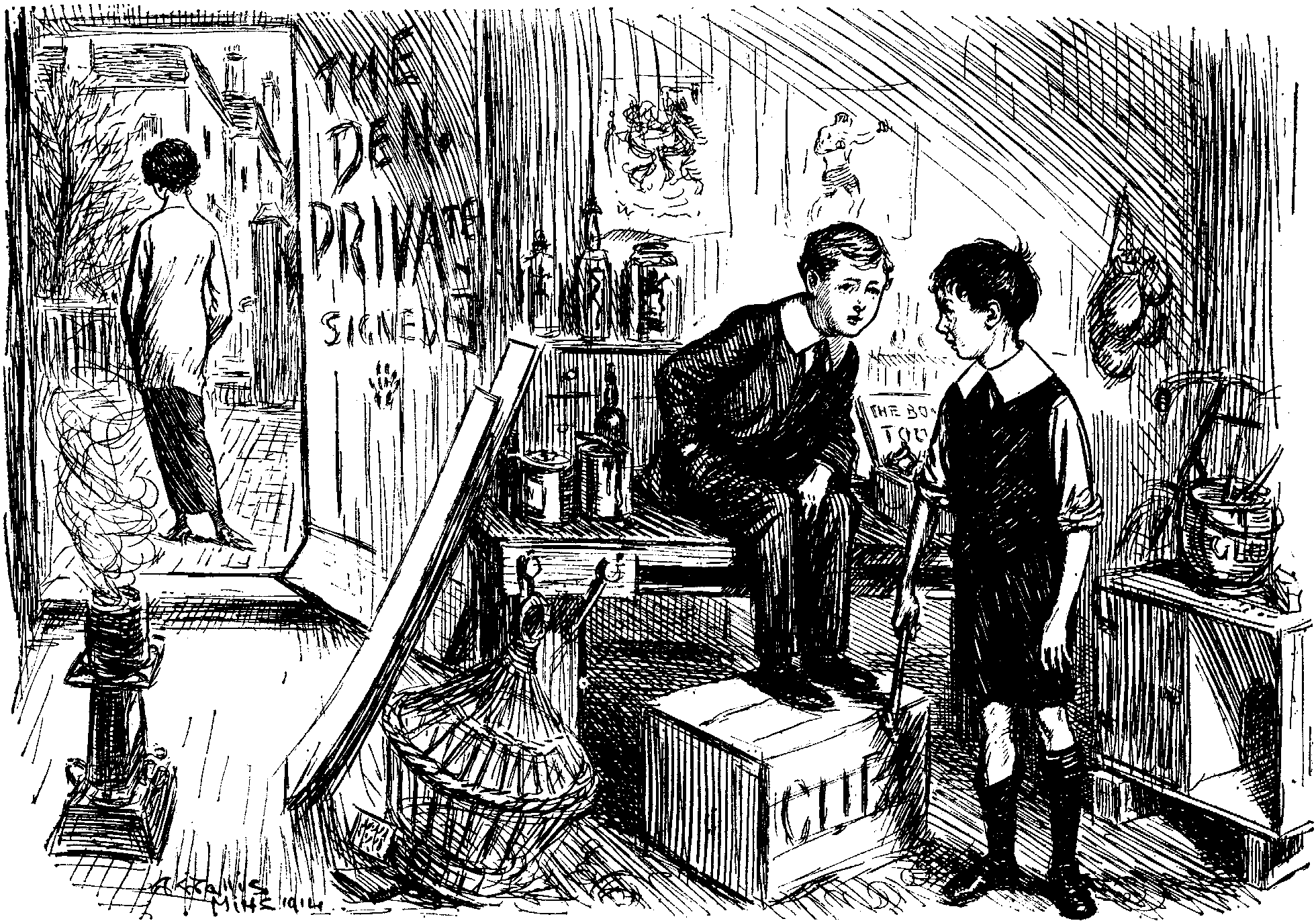

IN VIEW OF THE EXAGGERATED AND MISLEADING

REPORTS OF WHAT OCCURS AT THE CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN

MR. ASQUITH AND MR. BONAR LAW ON THE ULSTER QUESTION

WE VENTURE TO THINK THAT A LITTLE MAKE-UP AND CAREFUL

CHOICE OF RENDEZVOUS WOULD ENABLE THE LEADERS TO HAVE

MANY A LONG CHAT ON THE SUBJECT WITHOUT ANYONE BEING

AWARE OF THEIR HAVING MET.

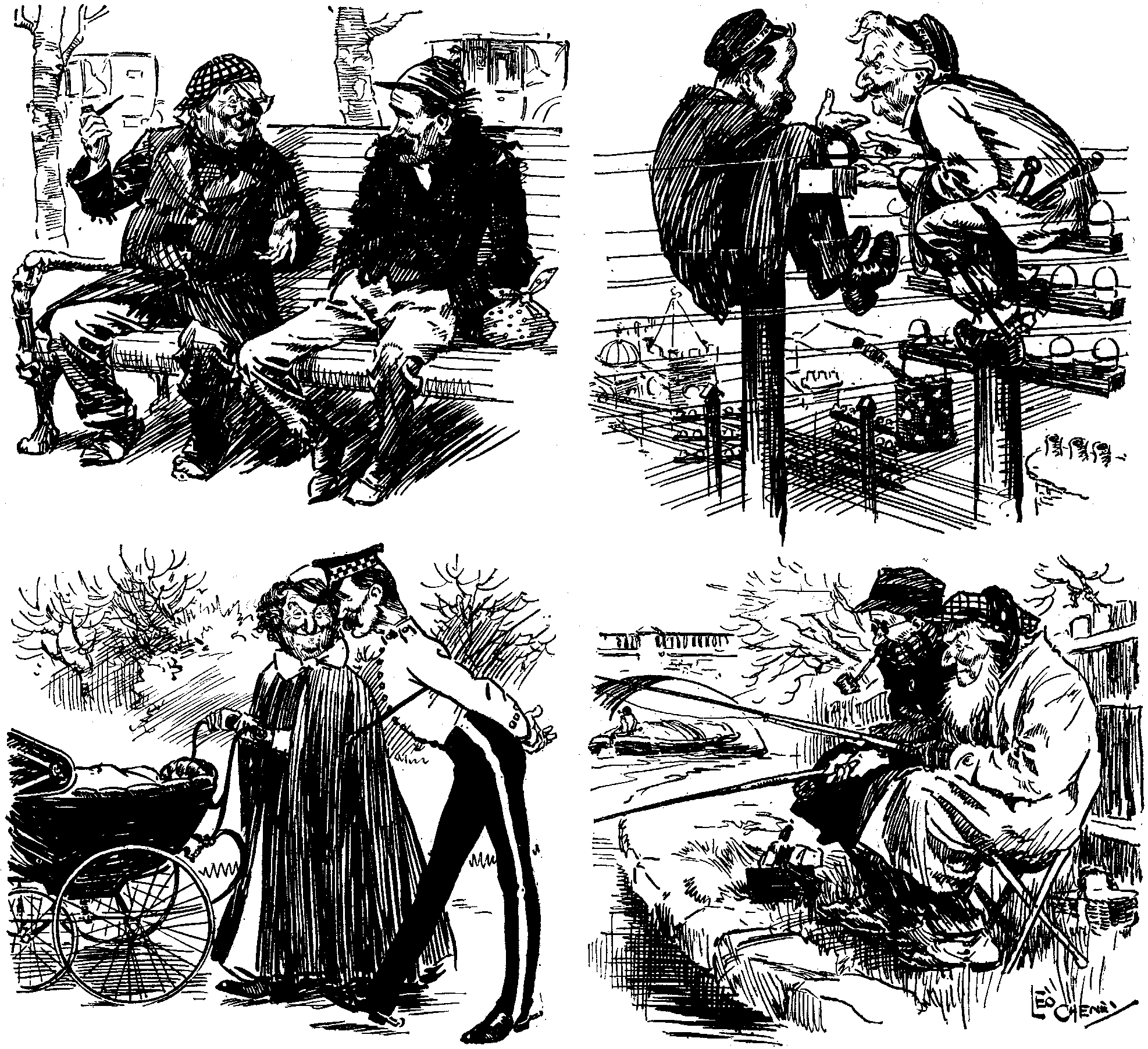

IN VIEW OF THE EXAGGERATED AND MISLEADING

REPORTS OF WHAT OCCURS AT THE CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN

MR. ASQUITH AND MR. BONAR LAW ON THE ULSTER QUESTION

WE VENTURE TO THINK THAT A LITTLE MAKE-UP AND CAREFUL

CHOICE OF RENDEZVOUS WOULD ENABLE THE LEADERS TO HAVE

MANY A LONG CHAT ON THE SUBJECT WITHOUT ANYONE BEING

AWARE OF THEIR HAVING MET.

8th December, 1913.

Mr. and Mrs. Melbrook request the pleasure of Mr. Hugh Melbrook's company at the marriage of their daughter Muriel Irene with Mr. Adolphus Smith, at St. Peter's, Hashton, on Wednesday, December 31st, 1913, at 1.30 o'clock, and afterwards at Westlands, Hashton.

R.S.V.P.

9th December, 1913.

Mr. Hugh Melbrook thanks Mr. and Mrs. Melbrook for the opportunity of being present at the wedding of their daughter Muriel Irene, but much regrets that, owing to great pressure of work, he cannot be there. He desires that Mr. and Mrs. Melbrook should not feel constrained to alter their present arrangements on that account.

26th December, 1913.

MESSRS. HALL, MARK & Co., Silversmiths.

SIRS,—Kindly despatch at once to the address given below a seasonable wedding gift, costing no more than the amount of the enclosed postal order. I send my card for inclusion. Whatever change there may be please return it to me, and oblige

Yours faithfully,

H. MELBROOK.

27th December, 1913.

H. MELBROOK, ESQ.

DEAR SIR,—We are in receipt of your esteemed favour of yesterday's date and beg to advise you that we have this day forwarded to the address you gave a handsome cut-glass anchovy dish with a finely-chased silver lid and tray. We enclose the receipted bill for the dish, which stands in our list at exactly the amount remitted by you.

We are, dear Sir,

Yours faithfully,

HALL, MARK & Co.

29th December, 1913.

MY DEAR HUGH.—Thank you very, very much for the sweet little butterdish. It's ripping. Do try to get down, Hugh, there's a good boy! If you can find time to choose me such a nice present—I know what you are, it must have taken you hours—surely you could take the day off for once. Say yes.

In tremendous haste, and thanking you again and again,

Your affectionate cousin,

MURIEL.

P.S.—I've just heard that Mr. Parsley, who is to marry us, is very strict about obedient weddings, and I promised Geraldine I wouldn't "obey" if she didn't. Now it's my turn. Tell me something to do.

30th December, 1913.

MY GOOD MURIEL,—That's a caviare dish! Caviare dishes, I understood, were all the rage just now, and here am I slaving away to be in the fashion, and you calmly write back and say, "Thank you very much for the butt—" My good Muriel!

I really wanted to send you something quite different, something equally novel but more seasonable; no less, in fact, than a nose-muff or nose-warmer. It is a little idea of my own, the Melbrook "Rhinotherm." Briefly, the mechanism consists of pieces of heated charcoal, potato or what-not, encased in some non-conducting material, the whole being then unostentatiously affixed to the frigid end of the nose. Stupidly, I forgot to take a plaster cast of your nose. You'll forgive me, won't you?

And now about coming down on the happy day. I feel very hurt about it. You know perfectly well that I wanted you to be married on a Saturday, but you wouldn't. It isn't as though you get married every day, and I do think you might have considered me a little more. But, even if I did come, even if by working all night Monday and Tuesday I could scrape together a few hours of freedom, I know what it would be. I should never be allowed in the vestry afterwards, while all the fun was going on. And yet you have the effrontery to sit there and ask my help in evading your, responsibilities as a married woman. Still, if you promise to breathe not a word of this to any woman I may marry hereafter, here's a dead snip for you. Listen! When you come to the words "to love, cherish and to obey," you simply drop the second "to" (nobody will miss it) and run the "d" of the "and" into the "obey," and lo! we have a French word, to wit, dauber, meaning to cuff, drub or belabour. What say you to that, my bonny bride? I think that deserves an extra large slice of cake, to put under my pillow. And I say, Muriel, I do hope there won't be any of those rotten cassowary seeds in it. If there are, for pity's sake rake them out and give them to someone who likes them. And I'll have his share of the marzipan.

Your affectionate cousin,

HUGH.

... During the service an amusing incident occurred. It was noticed that the, bride, who is rumoured to have feminist leanings, betrayed some difficulty in pronouncing the vow of obedience. The Rev. Thos. Parsley considerately paused and helped her to repeat the words after him in a clear and audible manner. In an interview with our representative, Mr. Parsley smilingly explained that he was determined, in his parish at any rate, to discourage any possible evasion of the matrimonial vows. He considered that a great deal of post-nuptial unhappiness was attributable to the lamentable laxity of the clergy in joining young people in matrimony without requiring their future relations to be clearly defined at the outset. The young bride refused to make any comment, but seemed highly amused at the incident....

"Hashton Weekly Hash."

"A gem ring lost last summer by Franz Schroder while travelling in a steamer on the Danube, near Prague, was found inside a carp caught at Mayence by his nephew."—Manchester Evening News.

The fact that Mayence is not on the Danube need not bother you. Only last week our uncle lost a white elephant while travelling in a barge on the Regent's Park Canal, near Maida Vale, and it was found inside the hat-box of the Editor of The Manchester Evening News by FRANZ SCHRODER. Bless you, these things are always happening.

Irate Cottager. "Hi! YOU'RE BREAKIN' MY 'EDGE!"

Mild Sportsman. "OH, NO; YOUR HEDGE IS BREAKING MY FALL, AND IF YOU WILL KINDLY PUSH ME BACK AGAIN I SHALL TRY TO REJOIN MY HORSE."

It is impossible to describe to you exactly how Herbert looked. But shame, defiance and unconcern were the principal ingredients in his expression as he stood on the kerb and stared across the road.

He started guiltily as I approached.

"Hallo, Herbert!" I began with my customary bonhomie.

"Hallo!" he said dismally.

"What are you doing here?" I asked sternly.

"Nothing," said Herbert. "Have you ever noticed what a fine building that post-office is?"

"No," I said; "neither have you. Herbert, you are concealing something from me. What have I done to deserve it? Have I not enjoyed your confidence these many years, and have you ever known me betray it? Is it marriage that has changed you thus? Is it—"

"Shut up," said Herbert. "I'll tell you, if you stop talking."

I stopped talking.

"It's this way. My wife and I have had a little discussion. And I stated my belief that there was nothing in an ordinary way that a woman could do that a man couldn't. Whereupon she defied me to go out and—er—buy a bloater. As you see, I have gone out, and—er—"

"Yes," I said, "you have gone out. Splendid of you! And all that remains to be done is to buy a bloater. Why not? Yonder, if I mistake not, is the shop of a bloaterer."

"But a bloater!" said Herbert. "It isn't fair. If she'd said some salmon, or a lobster, or even a pound of sausages; or if she'd allowed me to 'phone for it. It's not as if I'd ever had any practice. It's not decent to start a beginner on a hand-bought bloater."

"Tush!" I said. "This is not manly. Remember, our sex is at stake. Come!"

I took him by the arm. He advanced under protest.

Four paces from the shop he stopped abruptly and laughed—a horrible laugh.

"Do you know," he said, "I do believe I've come out without a cent on me."

"I don't believe it for a moment," I said, "but as it happens I can lend you pounds and pounds—almost enough for two bloaters."

Herbert reluctantly found some money in one of the seven pockets he had not felt in. Then we advanced once more.

This time there was no going back. Right into the body of the fishmonger's we strode and stood firmly opposite the salesman.

"Now," I whispered tensely.

But Herbert hesitated, and even as he wobbled the salesman began his suggestions.

"Yes, Sir? Lobsters or prawns, Sir? Some very good salmon this morning—very fine fish indeed, Sir."

"Er, as a matter of fact," said Herbert, "we just wanted to know if you would be so kind as to direct us to the nearest post-office?—the one just across the road, you know," he added nervously.

"Herbert," I said in his private ear, "be a man."

Herbert pulled himself together. "Would you," he said to the salesman, "would you please let me look at some b-b-blobsters?"

Sunday.—Great news! The plan suggested by the Anglo-German Alliance Committee is at last to be carried out. There is to be an exchange of garrisons, that is to say, certain English towns are to be garrisoned by German regiments, while certain German towns are to have English garrisons. Our own town, though a small one, is to have the distinguished honour of being the first to give this mark of friendship to the world. All the arrangements have been made, and to-morrow the 901st Prussian regiment of infantry is to march in. It will be a great day for Dartlebury, and we shall all do our best, though the public notice has been short, to give our gallant visitors a warm and truly British reception.

Monday.—Our German friends have arrived. At 11 o'clock this morning it was announced that they were approaching, headed by their band. The Mayor, Alderman Farthingale, and the whole Corporation, including the three Labour members recently elected, immediately proceeded to the old city wall to meet them. They were accompanied by the municipal band in full uniform, playing "Die Wacht am Rhein," which they had been assiduously practising. Unfortunately this led to what might have been a somewhat painful contretemps. On meeting the municipal band the Prussian commander, Colonel von Brausebrum, halted his soldiers and in a loud voice declared that our men were playing out of tune. Perhaps this was true, but the offence was involuntary and in any case it was hardly serious enough to call for the arrest of the whole band. Arrested, however, they were, and it was a melancholy sight to see them marched off by a corporal's guard. Mr. Zundnadel, the chief of the band, is himself of German origin, and his feelings can be better imagined than described. The Mayor saved the situation by making an extremely cordial speech, in which he spoke of the English and the Germans as ancient brothers-in-arms. The Colonel in his reply said his mission was a glorious one, and everything would depend on the way we conducted ourselves. What can he have meant? The march was then resumed, but another halt was made in the High Street to remove the French flag which Mucklow, the linen-draper, had very tactlessly stuck up over his shop. He too was arrested, with wife and family, and was lodged in jail. Luckily no further incident disturbed the harmony of the proceedings.

Tuesday.—This morning Lieutenant von Schornstein, while walking in Brewer's Alley, trod on a piece of banana-skin and fell heavily on the pavement. As he rose he observed that two small boys were, so he alleged, laughing at him. He immediately ran after the two urchins, and was proceeding to put them to the sword when the Brewery men interfered and disarmed him. He pleaded that his uniform had been insulted and that it was necessary for him to punish them. "Ich muss sie durch den Leib rennen" were his words. The men, however, were not inclined to admit the force of this plea, especially as they understood no German, and they sent him back to barracks in a taxi-cab. The Mayor at once wired his apologies to the Colonel, and it is hoped that nothing further will be heard of the incident. I ought to add that the boys deny that they laughed, but the lieutenant is certain that they wore a smiling expression.

The "Friendship Banquet" was held this evening in the Town Hall, with the Mayor in the chair. No very great enthusiasm was shown, and when the Mayor, in proposing the health of our visitors, alluded to the friendly rivalry of the two nations in commerce and the arts of peace, the Colonel pulled him back into his seat and begged him not to proceed. "Maul halten," he said. The three Labour members of the Council were afterwards arrested for not having joined with sufficient heartiness in the singing of "Deutschland über Alles."

Wednesday.—A state of siege has been declared in Dartlebury, and we are all living under martial law. Lord Gruffen was arrested for having knocked up against a soldier. The magistrates, on leaving the police-court, were handcuffed and removed to barracks. A crisis is evidently approaching.

Thursday.—An insurrection started this morning. A huge crowd attacked the barracks and overpowered all resistance. Blood flowed like water, but in an hour all was over. There is a strong feeling that the experiment of the Alliance Committee was a rash one, though no doubt it was well meant. We live and learn.

They said, "He goes a-tumbling through the hollow

And trackless empyrean like a clown,

Head pointed to the earth where weaklings wallow,

Feet up toward the stars; not such renown

Even our lord himself, the bright Apollo,

Gets in his gilded car. For one bob down

You shall behold the thing." "Right-o," I said,

Clapping the old brown bay leaves on my head.

So to the hangars. Time, about eleven,

The air full chill, the ground a mess of muck,

And long time gazed I on the wintry heaven

And thought of many a deed of Saxon pluck;

How DRAKE, for instance, good old DRAKE of Devon,

Played bowls at Plymouth Hoe. Twelve-thirty struck.

No one had vaulted through the air's abyss;

DRAKE would have plunged tail up an hour ere this.

Brief interval for lunch, and then a drizzle

Fell on the dreary field. Like some dead moth

The thing remained. Chagrin commenced to sizzle,

And certain people cried, "A thillingth loth."

Others, "Hey, Mister Airman, it's a swizzle!"

Then a stern man came out, and with a cloth

Lightly, as one well used to such a feat,

Swaddled the brute's propeller and its seat.

The skies grew darkling, and there went a rumour,

"The thing is off; he will not fly to-day;"

And forth we wandered, some in rare ill-humour,

But not, oh, not the bard. Yet this I say—

There are two kinds of courage: one's a boomer

Avid of gold and glory; this is A,

Crowned with a palm, and in her hands I see

Sheaves of press cuttings. There is also B.

Not venturesome, this last, to brave the billows,

To beard the panther in his hidden lair,

To probe the epiderms of armadillos,

Nor execute wild cart-wheels in the air;

But who shall say how much Britannia still owes

To B, the kind of courage that can bear

Dauntless to wait, whate'er the skies portend,

(Having paid entrance) to the bitter end?

The heavenly hero in his suit of leather

Soars through Olympus with the world beneath

Sometimes, and sometimes, owing to the weather,

Scratches his fixtures in the tempest's teeth.

Shall the high gods, who gaze on both together,

Count him the nobler, or confer their wreath

On the brave bull-dog bard, who risks his thews

Standing about all day in thin-soled shoes?

EVOE.

Just as one may say of certain novelists that they write at the top of their voices, so, I think, one might describe Miss VIOLA MEYNELL as writing in a whisper. This certainly is the effect that Modern Lovers (SECKER) produced upon me. The gentle method of it invested the story—which of itself is a very slight thing—with an odd significance almost impossible to communicate in criticism; but the reading of a few pages will show you what I mean. The title is apt enough, for the tale is about nothing but love, as it affects a group of five young people, three men and two girls. Of the girls, who are sisters, Effie Rutherglen is the more important and detailed figure. Effie, in the time before the story opens, had an affair with Oliver Bligh; then, summoned North to live with her futile and uncomprehending parents, she fell (as did her sister Milly and most of the local spinsters) under the fascination of one Clive Maxwell, who was an author and had appealing eyes and obviously a way with him. Then Oliver turned up again, and poor Effie didn't know which of them she wanted. I speak lightly, but, if you think all this made for comedy, your conception of Miss MEYNELL's methods is very much at fault. Love to her is very much what it was to Patience in the opera—by no means a wholly enviable boon. I can hardly praise too much the exquisite refinement and restraint of her treatment of commonplace things. But one small point baffled me: Oliver appears to have been a professional diver and bath-keeper—we are told, indeed, that he had occupied that position at Rugby (a statement that I have private and personal reasons for discrediting)—yet we find him staying as a welcome and honoured guest in the house of the Rutherglens, whom I take to be more or less "county." Surely this, though of no real importance, is at least remarkable?

"What," I asked myself, "is just the matter with this apparently quite nice book?" (It was Joan's Green Year, and written by E.L. DOON and published by MACMILLAN.) It is the kind of book that grows out of a romantic disposition and an assiduously stuffed commonplace book. It consists of letters from Joan, a paying guest in the Manor House Farm at Pelton, to her brother Keith, a soldier in India, telling him all about her year of holiday and "soul discipline" in the country, the village gossip, her proposals and her one acceptance, and giving a sort of farmer's calendar of the seasons as interpreted by the guileless amateur. Joan has what is known as a nice mind. But to tell truth she has chosen a difficult and dangerous if alluring art form. Of course letters enable you to evade some of the difficulties of the novelist's task, to be discursive, allusive and incomplete. But you can't be let off anything of the precision and subtlety of your characterisation. On the contrary. And Joan makes everyone in Pelton (except the rustics, whose authenticity I gravely suspect) talk as Joan writes. They have nearly all seen her commonplace book, I judge. Then, again, you must not have (like Joan) a large list of acquaintances, or you breed confusion and dissipate interest accordingly. Joan is very young in many ways. She is extravagant in the matter of the equipment of her heroes. Bob Ingleby, the farmer (a gentleman, because he had been at Winchester), is a "great comely giant," yet wins events one and three of the Hunt Steeplechase, though thrown badly in number two. I have a suspicion that this work is really Joan's tee shot, and that after a notable recovery, which on the best of her present form I can safely prophesy, she will reach her green year next time.

Mrs. T.P. O'CONNOR has written a fascinating book. My Beloved South she calls it, and PUTNAMS publish it. There is not a lifeless page in the 427 that make up a bountiful feast. Every one contains vivid reproductions of incidents in social life in the South "befo' de wa'" and after. At the outset we make the acquaintance of a typical Southron, Mrs. O'CONNOR's grandfather, Governor of Florida when it was still a Territory, with native Indians fighting fiercely for their land and homes. Mrs. O'CONNOR was, of course, not to the fore in those early days. But so steeped is she in lore of the South, much of it gained from the lips of nurses and out-door servants, so keen is her sympathy, so quick and true her instinct that she is able to revivify the old scenes and reproduce the atmosphere of the time. The darkey nurse of earliest childhood lives again, sometimes bringing with her plantation songs like "Voodoo-Bogey-Boo," quaintly musical. Many passages of the grandfather's conversations are preserved, in which we may detect the voice of the gifted granddaughter. But the influence of heredity is strong, more especially "down South." Also there are many charming stories redolent of the South. I was about to mention the page on which will be found the thrilling history of a mule aptly named "Satan." On reflection I won't spoil the reader's pleasure in unexpectedly coming upon it somewhere about the middle of the book. Nobody—man or woman, girl or boy—who begins to read My Beloved South will skip a page. So the story cannot be overlooked.

In Lost Diaries (DUCKWORTH) Mr. MAURICE BARING travels by an easy road to humour, and he does not pound it with too laborious feet. This is perhaps a fortunate thing, for a farcical reconstruction of history in the light of modern sentiment and circumstances might easily tire; a Comic History of England, for instance, is stiffer reading to-day than GARDNER or GREEN. Sometimes, however, Mr. BARING seems to carry to extreme lengths his conscientious avoidance of efforts to be funny; and in the imaginary records of one or two of his subjects there is little more to laugh at than the unaided fancy of the student has long ago perceived. Tristram loved two Iseults, and JOHN MILTON was an exasperating husband; but these things I knew, and the author of Lost Diaries has made no more capital out of the situations than the eternal merriment which the bare statement of the facts inspires. But where Mr. BARING, pleasantly disdainful alike of consistency and taste, examines the pocket-book of the "Man in the Iron Mask," and finds him complaining of the noise and disturbance in dungeon after dungeon until he is removed at last to the lotus island of the Bastille; or records the blameless botanical pursuits of TIBERIUS in seclusion; or the first consumption of the Colla di Gallo by COLUMBUS in the newly discovered West, he is, for all the simplicity of his methods, amusing enough. Yet even so I am inclined to think that the first of his essays, which reads like an actual transcript from the jottings of a nineteenth-century private-school boy, is the diary which I most heartily congratulate Mr. BARING on having rediscovered, and which I should be least willing for him to lose again.

With the Land Question staring us in the face, Folk of the Furrow (SMITH ELDER) should attract the attention of those who wish thoroughly to understand what the agricultural labourer wants and why he wants it. Mr. CHRISTOPHER HOLDENBY is no amateur, for as Mr. STEPHEN REYNOLDS has lived with fishermen and shared their daily lives so he has lodged in labourers' cottages and hoed and dug with the best (and worst) of them. The result is a book that is stamped with the hall-mark of a great sincerity; and three facts at least can be gathered from it by the very dullest of gleaners. First, and I think foremost, that the decencies of life cannot be observed if children of very various ages are to be crowded into cottages too small to hold them; secondly, that it is useless to expect morality from youths who have few or no amusements provided for them; thirdly, that the passing of the old families and the advent of the week-end "merchant princes" do not make a change for the better. All which may be stale news, but after reading this book I think that you will admit that Mr. HOLDENBY has contrived to make an old tale very impressive. In some instances it is true that I could bring evidence directly in opposition to his, but on the whole he deserves well for the way in which he has won the confidence of a class naturally suspicious and silent, and for his manner of stating his case. Had I for my sins to cram our M.P.'s for the debates that lie before them, I should feed them liberally upon Folk of the Furrow.

Not yet the end; only the end of strife.

But now—while still the brave unwearied heart,

Fixed upon England, fain to keep its part

In her Imperial life,

Beats with the old unconquerable pride—

Now leave to younger limbs the dust and palm,

And let the weary body seek the calm

That comes with eventide.

There take your rest within the sunset glow,

All feuds forgotten of your fighting days,

Circled with love and laurelled with the praise

Of friend and ancient foe.

O.S.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, Vol.

146., January 14, 1914, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH, JANUARY 14, 1914 ***

***** This file should be named 12536-h.htm or 12536-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/2/5/3/12536/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team.

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few