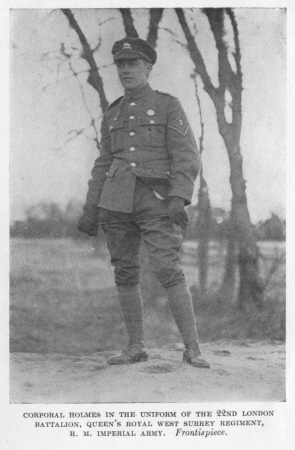

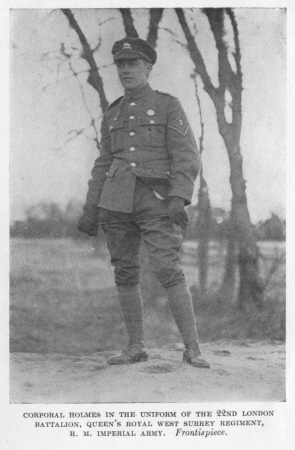

CORPORAL OF THE 22D LONDON BATTALION OF THE

QUEEN'S ROYAL WEST SURREY REGIMENT

ILLUSTRATED FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

TO MARION A. PUTTEE, SOUTHALL, MIDDLESEX, ENGLAND, I DEDICATE THIS BOOK AS A TOKEN OF APPRECIATION FOR ALL THE LOVING THOUGHTS AND DEEDS BESTOWED UPON ME WHEN I WAS A STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND

I have tried as an American in writing this book to give the public a complete view of the trenches and life on the Western Front as it appeared to me, and also my impression of conditions and men as I found them. It has been a pleasure to write it, and now that I have finished I am genuinely sorry that I cannot go further. On the lecture tour I find that people ask me questions, and I have tried in this book to give in detail many things about the quieter side of war that to an audience would seem too tame. I feel that the public want to know how the soldiers live when not in the trenches, for all the time out there is not spent in killing and carnage. As in the case of all men in the trenches, I heard things and stories that especially impressed me, so I have written them as hearsay, not taking to myself credit as their originator. I trust that the reader will find as much joy in the cockney character as I did and which I have tried to show the public; let me say now that no finer body of men than those Bermondsey boys of my battalion could be found.

I think it fair to say that in compiling the trench terms at the end of this book I have not copied any war book, but I have given in each case my own version of the words, though I will confess that the idea and necessity of having such a list sprang from reading Sergeant Empey's "Over the Top." It would be impossible to write a book that the people would understand without the aid of such a glossary.

It is my sincere wish that after reading this book the reader may have a clearer conception of what this great world war means and what our soldiers are contending with, and that it may awaken the American people to the danger of Prussianism so that when in the future there is a call for funds for Liberty Loans, Red Cross work, or Y.M.C.A., there will be no slacking, for they form the real triangular sign to a successful termination of this terrible conflict.

R. DERBY HOLMES.

I JOINING THE BRITISH ARMY

II GOING IN

III A TRENCH RAID

IV A FEW DAYS' REST IN BILLETS

V FEEDING THE TOMMIES

VI HIKING TO VIMY RIDGE

VII FASCINATION OF PATROL WORK

VIII ON THE GO

IX FIRST SIGHT OF THE TANKS

X FOLLOWING THE TANKS INTO BATTLE

XI PRISONERS

XII I BECOME A BOMBER

XIII BACK ON THE SOMME AGAIN

XIV THE LAST TIME OVER THE TOP

XV BITS OF BLIGHTY

XVI SUGGESTIONS FOR "SAMMY"

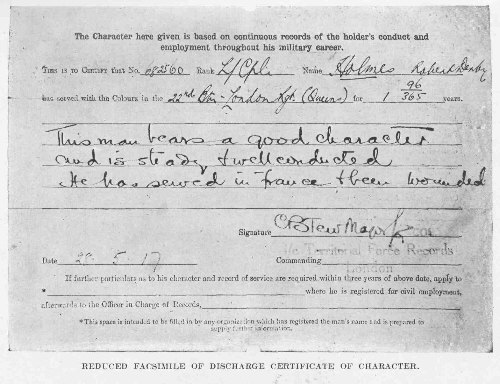

Reduced Facsimile of Discharge Certificate of Character

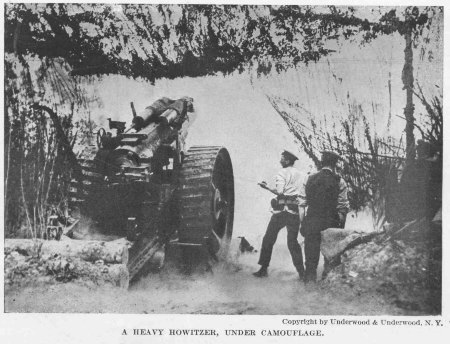

A Heavy Howitzer, Under Camouflage

Head-on View of a British Tank

Corporal Holmes with Staff Nurse and Another Patient, at Fulham Military Hospital, London, S.W.

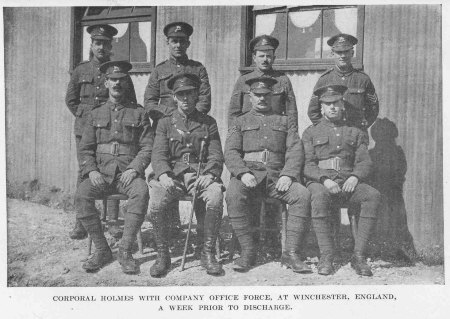

Corporal Holmes with Company Office Force, at Winchester, England, a Week Prior to Discharge

Once, on the Somme in the fall of 1916, when I had been over the top and was being carried back somewhat disfigured but still in the ring, a cockney stretcher bearer shot this question at me:

"Hi sye, Yank. Wot th' bloody 'ell are you in this bloomin' row for? Ayen't there no trouble t' 'ome?"

And for the life of me I couldn't answer. After more than a year in the British service I could not, on the spur of the moment, say exactly why I was there.

To be perfectly frank with myself and with the reader I had no very lofty motives when I took the King's shilling. When the great war broke out, I was mildly sympathetic with England, and mighty sorry in an indefinite way for France and Belgium; but my sympathies were not strong enough in any direction to get me into uniform with a chance of being killed. Nor, at first, was I able to work up any compelling hate for Germany. The abstract idea of democracy did not figure in my calculations at all.

However, as the war went on, it became apparent to me, as I suppose it must have to everybody, that the world was going through one of its epochal upheavals; and I figured that with so much history in the making, any unattached young man would be missing it if he did not take a part in the big game.

I had the fondness for adventure usual in young men. I liked to see the wheels go round. And so it happened that, when the war was about a year and a half old, I decided to get in before it was too late.

On second thought I won't say that it was purely love for adventure that took me across. There may have been in the back of my head a sneaking extra fondness for France, perhaps instinctive, for I was born in Paris, although my parents were American and I was brought to Boston as a baby and have lived here since.

Whatever my motives for joining the British army, they didn't have time to crystallize until I had been wounded and sent to Blighty, which is trench slang for England. While recuperating in one of the pleasant places of the English country-side, I had time to acquire a perspective and to discover that I had been fighting for democracy and the future safety of the world. I think that my experience in this respect is like that of most of the young Americans who have volunteered for service under a foreign flag.

I decided to get into the big war game early in 1916. My first thought was to go into the ambulance service, as I knew several men in that work. One of them described the driver's life about as follows. He said:

"The blessés curse you because you jolt them. The doctors curse you because you don't get the blessés in fast enough. The Transport Service curse you because you get in the way. You eat standing up and don't sleep at all. You're as likely as anybody to get killed, and all the glory you get is the War Cross, if you're lucky, and you don't get a single chance to kill a Hun."

That settled the ambulance for me. I hadn't wanted particularly to kill a Hun until it was suggested that I mightn't. Then I wanted to slaughter a whole division.

So I decided on something where there would be fighting. And having decided, I thought I would "go the whole hog" and work my way across to England on a horse transport.

One day in the first part of February I went, at what seemed an early hour, to an office on Commercial Street, Boston, where they were advertising for horse tenders for England. About three hundred men were earlier than I. It seemed as though every beach-comber and patriot in New England was trying to get across. I didn't get the job, but filed my application and was lucky enough to be signed on for a sailing on February 22 on the steam-ship Cambrian, bound for London.

We spent the morning of Washington's Birthday loading the horses. These government animals were selected stock and full of ginger. They seemed to know that they were going to France and resented it keenly. Those in my care seemed to regard my attentions as a personal affront.

We had a strenuous forenoon getting the horses aboard, and sailed at noon. After we had herded in the livestock, some of the officers herded up the herders. I drew a pink slip with two numbers on it, one showing the compartment where I was supposed to sleep, the other indicating my bunk.

That compartment certainly was a glory-hole. Most of the men had been drunk the night before, and the place had the rich, balmy fragrance of a water-front saloon. Incidentally there was a good deal of unauthorized and undomesticated livestock. I made a limited acquaintance with that pretty, playful little creature, the "cootie," who was to become so familiar in the trenches later on. He wasn't called a cootie aboard ship, but he was the same bird.

Perhaps the less said about that trip across the better. It lasted twenty-one days. We fed the animals three times a day and cleaned the stalls once on the trip. I got chewed up some and stepped on a few times. Altogether the experience was good intensive training for the trench life to come; especially the bunks. Those sleeping quarters sure were close and crawly.

We landed in London on Saturday night about nine-thirty. The immigration inspectors gave us a quick examination and we were turned back to the shipping people, who paid us off,—two pounds, equal to about ten dollars real change.

After that we rode on the train half an hour and then marched through the streets, darkened to fool the Zeps. Around one o'clock we brought up at Thrawl Street, at the lodgings where we were supposed to stop until we were started for home.

The place where we were quartered was a typical London doss house. There were forty beds in the room with mine, all of them occupied. All hands were snoring, and the fellow in the next cot was going it with the cut-out wide open, breaking all records. Most of the beds sagged like a hammock. Mine humped up in the middle like a pile of bricks.

I was up early and was directed to the place across the way where we were to eat. It was labeled "Mother Wolf's. The Universal Provider." She provided just one meal of weak tea, moldy bread, and rancid bacon for me. After that I went to a hotel. I may remark in passing that horse tenders, going or coming or in between whiles, do not live on the fat of the land.

I spent the day—it was Sunday—seeing the sights of Whitechapel, Middlesex Street or Petticoat Lane, and some of the slums. Next morning it was pretty clear to me that two pounds don't go far in the big town. I promptly boarded the first bus for Trafalgar Square. The recruiting office was just down the road in Whitehall at the old Scotland Yard office.

I had an idea when I entered that recruiting office that the sergeant would receive me with open arms. He didn't. Instead he looked me over with unqualified scorn and spat out, "Yank, ayen't ye?"

And I in my innocence briefly answered, "Yep."

"We ayen't tykin' no nootrals," he said, with a sneer. And then: "Better go back to Hamerika and 'elp Wilson write 'is blinkin' notes."

Well, I was mad enough to poke that sergeant in the eye. But I didn't. I retired gracefully and with dignity.

At the door another sergeant hailed me, whispering behind his hand, "Hi sye, mytie. Come around in the mornin'. Hi'll get ye in." And so it happened.

Next day my man was waiting and marched me boldly up to the same chap who had refused me the day before.

"'Ere's a recroot for ye, Jim," says my friend.

Jim never batted an eye. He began to "awsk" questions and to fill out a blank. When he got to the birthplace, my guide cut in and said, "Canada."

The only place I knew in Canada was Campobello Island, a place where we camped one summer, and I gave that. I don't think that anything but rabbits was ever born on Campobello, but it went. For that matter anything went. I discovered afterward that the sergeant who had captured me on the street got five bob (shillings) for me.

The physical examination upstairs was elaborate. They told me to strip, weighed me, and said I was fit. After that I was taken in to an officer—a real officer this time—who made me put my hand on a Bible and say yes to an oath he rattled off. Then he told me I was a member of the Royal Fusiliers, gave me two shillings, sixpence and ordered me to report at the Horse Guards Parade next day. I was in the British army,—just like that!

I spent the balance of the day seeing the sights of London, and incidentally spending my coin. When I went around to the Horse Guards next morning, two hundred others, new rookies like myself, were waiting. An officer gave me another two shillings, sixpence. I began to think that if the money kept coming along at that rate the British army might turn out a good investment. It didn't.

That morning I was sent out to Hounslow Barracks, and three days later was transferred to Dover with twenty others. I was at Dover a little more than two months and completed my training there.

Our barracks at Dover was on the heights of the cliffs, and on clear days we could look across the Channel and see the dim outlines of France. It was a fascination for all of us to look away over there and to wonder what fortunes were to come to us on the battle fields of Europe. It was perhaps as well that none of us had imagination enough to visualize the things that were ahead.

I found the rookies at Dover a jolly, companionable lot, and I never found the routine irksome. We were up at five-thirty, had cocoa and biscuits, and then an hour of physical drill or bayonet practice. At eight came breakfast of tea, bacon, and bread, and then we drilled until twelve. Dinner. Out again on the parade ground until three thirty. After that we were free.

Nights we would go into Dover and sit around the "pubs" drinking ale, or "ayle" as the cockney says it.

After a few weeks, when we were hardened somewhat, they began to inflict us with the torture known as "night ops." That means going out at ten o'clock under full pack, hiking several miles, and then "manning" the trenches around the town and returning to barracks at three A.M.

This wouldn't have been so bad if we had been excused parades the following day. But no. We had the same old drills except the early one, but were allowed to "kip" until seven.

In the two months I completed the musketry course, was a good bayonet man, and was well grounded in bombing practice. Besides that I was as hard as nails and had learned thoroughly the system of British discipline.

I had supposed that it took at least six months to make a soldier,—in fact had been told that one could not be turned out who would be ten per cent efficient in less than that time. That old theory is all wrong. Modern warfare changes so fast that the only thing that can be taught a man is the basic principles of discipline, bombing, trench warfare, and musketry. Give him those things, a well-conditioned body, and a baptism of fire, and he will be right there with the veterans, doing his bit.

Two months was all our crowd got at any rate, and they were as good as the best, if I do say it.

My training ended abruptly with a furlough of five days for Embarkation Leave, that is, leave before going to France. This is a sort of good-by vacation. Most fellows realize fully that it may be their last look at Blighty, and they take it rather solemnly. To a stranger without friends in England I can imagine that this Embarkation Leave would be either a mighty lonesome, dismal affair, or a stretch of desperate, homesick dissipation. A chap does want to say good-by to some one before he goes away, perhaps to die. He wants to be loved and to have some one sorry that he is going.

I was invited by one of my chums to spend the leave with him at his home in Southall, Middlesex. His father, mother and sister welcomed me in a way that made me know it was my home from the minute I entered the door. They took me into their hearts with a simple hospitality and whole-souled kindness that I can never forget. I was a stranger in a strange land and they made me one of their own. I shall never be able to repay all the loving thoughts and deeds of that family and shall remember them while I live. My chum's mother I call Mother too. It is to her that I have dedicated this book.

After my delightful few days of leave, things moved fast. I was back in Dover just two days when I, with two hundred other men, was sent to Winchester. Here we were notified that we were transferred to the Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment.

This news brought a wild howl from the men. They wanted to stop with the Fusiliers. It is part of the British system that every man is taught the traditions and history of his regiment and to know that his is absolutely the best in the whole army. In a surprisingly short time they get so they swear by their own regiment and by their officers, and they protest bitterly at a transfer.

Personally I didn't care a rap. I had early made up my mind that I was a very small pebble on the beach and that it was up to me to obey orders and keep my mouth shut.

On June 17, some eighteen hundred of us were moved down to Southampton and put aboard the transport for Havre. The next day we were in France, at Harfleur, the central training camp outside Havre.

We were supposed to undergo an intensive training at Harfleur in the various forms of gas and protection from it, barbed wire and methods of construction of entanglements, musketry, bombing, and bayonet fighting.

Harfleur was a miserable place. They refused to let us go in town after drill. Also I managed to let myself in for something that would have kept me in camp if town leave had been allowed.

The first day there was a call for a volunteer for musketry instructor. I had qualified and jumped at it. When I reported, an old Scotch sergeant told me to go to the quartermaster for equipment. I said I already had full equipment. Whereupon the sergeant laughed a rumbling Scotch laugh and told me I had to go into kilts, as I was assigned to a Highland contingent.

I protested with violence and enthusiasm, but it didn't do any good. They gave me a dinky little pleated petticoat, and when I demanded breeks to wear underneath, I got the merry ha ha. Breeks on a Scotchman? Never!

Well, I got into the fool things, and I felt as though I was naked from ankle to wishbone. I couldn't get used to the outfit. I am naturally a modest man. Besides, my architecture was never intended for bare-leg effects. I have no dimples in my knees.

So I began an immediate campaign for transfer back to the Surreys. I got it at the end of ten days, and with it came a hurry call from somewhere at the front for more troops.

The excitement of getting away from camp and the knowledge that we were soon to get into the thick of the big game pleased most of us. We were glad to go. At least we thought so.

Two hundred of us were loaded into side-door Pullmans, forty to the car. It was a kind of sardine or Boston Elevated effect, and by the time we reached Rouen, twenty-four hours later, we had kinks in our legs and corns on our elbows. Also we were hungry, having had nothing but bully beef and biscuits. We made "char", which is trench slang for tea, in the station, and after two hours moved up the line again, this time in real coaches.

Next night we were billeted at Barlin—don't get that mixed up with Berlin, it's not the same—in an abandoned convent within range of the German guns. The roar of artillery was continuous and sounded pretty close.

Now and again a shell would burst near by with a kind of hollow "spung", but for some reason we didn't seem to mind. I had expected to get the shivers at the first sound of the guns and was surprised when I woke up in the morning after a solid night's sleep.

A message came down from the front trenches at daybreak that we were wanted and wanted quick. We slung together a dixie of char and some bacon and bread for breakfast, and marched around to the "quarters", where they issued "tin hats", extra "ammo", and a second gas helmet. A good many of the men had been out before, and they did the customary "grousing" over the added load.

The British Tommy growls or grouses over anything and everything. He's never happy unless he's unhappy. He resents especially having anything officially added to his pack, and you can't blame him, for in full equipment he certainly is all dressed up like a pack horse.

After the issue we were split up into four lots for the four companies of the battalion, and after some "wangling" I got into Company C, where I stopped all the time I was in France. I was glad, because most of my chums were in that unit.

We got into our packs and started up the line immediately. As we neared the lines we were extended into artillery formation, that is, spread out so that a shell bursting in the road would inflict fewer casualties.

At Bully-Grenay, the point where we entered the communication trenches, guides met us and looked us over, commenting most frankly and freely on our appearance. They didn't seem to think we would amount to much, and said so. They agreed that the "bloomin' Yank" must be a "bloody fool" to come out there. There were times later when I agreed with them.

It began to rain as we entered the communication trench, and I had my first taste of mud. That is literal, for with mud knee-deep in a trench just wide enough for two men to pass you get smeared from head to foot.

Incidentally, as we approached nearer the front, I got my first smell of the dead. It is something you never get away from in the trenches. So many dead have been buried so hastily and so lightly that they are constantly being uncovered by shell bursts. The acrid stench pervades everything, and is so thick you can fairly taste it. It makes nearly everybody deathly sick at first, but one becomes used to it as to anything else.

This communication trench was over two miles long, and it seemed like twenty. We finally landed in a support trench called "Mechanics" (every trench has a name, like a street), and from there into the first-line trench.

I have to admit a feeling of disappointment in that first trench. I don't know what I expected to see, but what I did see was just a long, crooked ditch with a low step running along one side, and with sandbags on top. Here and there was a muddy, bedraggled Tommy half asleep, nursing a dirty and muddy rifle on "sentry go." Everything was very quiet at the moment—no rifles popping, as I had expected, no bullets flying, and, as it happened, absolutely no shelling in the whole sector.

I forgot to say that we had come up by daylight. Ordinarily troops are moved at night, but the communication trench from Bully-Grenay was very deep and was protected at points by little hills, and it was possible to move men in the daytime.

Arrived in the front trench, the sergeant-major appeared, crawling out of his dug-out—the usual place for a sergeant-major—and greeted us with,

"Keep your nappers down, you rooks. Don't look over the top. It ayen't 'ealthy."

It is the regular warning to new men. For some reason the first emotion of the rookie is an overpowering curiosity. He wants to take a peep into No Man's Land. It feels safe enough when things are quiet. But there's always a Fritzie over yonder with a telescope-sighted rifle, and it's about ten to one he'll get you if you stick the old "napper" up in daylight.

The Germans, by the way, have had the "edge" on the Allies in the matter of sniping, as in almost all lines of artillery and musketry practice. The Boche sniper is nearly always armed with a periscope-telescope rifle. This is a specially built super-accurate rifle mounted on a periscope frame. It is thrust up over the parapet and the image of the opposing parapet is cast on a little ground-glass screen on which are two crossed lines. At one hundred fifty yards or less the image is brought up to touching distance seemingly. Fritz simply trains his piece on some low place or anywhere that a head may be expected. When one appears on the screen, he pulls the trigger,—and you "click it" if you happen to be on the other or receiving end. The shooter never shows himself.

I remember the first time I looked through a periscope I had no sooner thrust the thing up than a bullet crashed into the upper mirror, splintering it. Many times I have stuck up a cap on a stick and had it pierced.

The British sniper, on the other hand—at least in my time—had a plain telescope rifle and had to hide himself behind old masonry, tree trunks, or anything convenient, and camouflaged himself in all sorts of ways. At that he was constantly in danger.

I was assigned to Platoon 10 and found they were a good live bunch. Corporal Wells was the best of the lot, and we became fast friends. He helped me learn a lot of my new duties and the trench "lingo", which is like a new language, especially to a Yank.

Wells started right in to make me feel at home and took me along with two others of the new men down to our "apartments", a dug-out built for about four, and housing ten.

My previous idea of a dug-out had been a fairly roomy sort of cave, somewhat damp, but comparatively comfortable. Well, this hole was about four and a half feet high—you had to get in doubled up on your hands and knees—about five by six feet on the sides, and there was no floor, just muck. There was some sodden, dirty straw and a lot of old moldy sandbags. Seven men and their equipment were packed in here, and we made ten.

There was a charcoal brazier going in the middle with two or three mess tins of char boiling away. Everybody was smoking, and the place stunk to high heaven, or it would have if there hadn't been a bit of burlap over the door.

I crowded up into a corner with my back against the mud wall and my knees under my chin. The men didn't seem overglad to see us, and groused a good deal about the extra crowding. They regarded me with extra disfavor because I was a lance corporal, and they disapproved of any young whipper-snapper just out from Blighty with no trench experience pitchforked in with even a slight superior rank. I had thought up to then that a lance corporal was pretty near as important as a brigadier.

"We'll soon tyke that stripe off ye, me bold lad," said one big cockney.

They were a decent lot after all. Since we were just out from Blighty, they showered us with questions as to how things looked "t' 'ome." And then somebody asked what was the latest song. Right here was where I made my hit and got in right. I sing a bit, and I piped up with the newest thing from the music halls, "Tyke Me Back to Blighty." Here it is:

Tyke me back to dear old Blighty,

Put me on the tryne for London town,

Just tyke me over there

And drop me anywhere,

Manchester, Leeds, or Birmingham,

I don't care.

I want to go see me best gal;

Cuddlin' up soon we'll be,

Hytey iddle de eyety.

Tyke me back to Blighty,

That's the plyce for me.

It doesn't look like much and I'm afraid my rendition of cockney dialect into print isn't quite up to Kipling's. But the song had a pretty little lilting melody, and it went big. They made me sing it about a dozen times and were all joining in at the end.

Then they got sentimental—and gloomy.

"Gawd lumme!" says the big fellow who had threatened my beloved stripes. "Wot a life. Squattin' 'ere in the bloody mud like a blinkin' frog. Fightin' fer wot? Wot, I arsks yer? Gawd lumme! I'd give me bloomin' napper to stroll down the Strand agyne wif me swagger stick an' drop in a private bar an' 'ave me go of 'Aig an' 'Aig."

"Garn," cuts in another Tommy. "Yer blinkin' 'igh wif yer wants, ayen't ye? An' yer 'Aig an' 'Aig. Drop me down in Great Lime Street (Liverpool) an' it's me fer the Golden Sheaf, and a pint of bitter, an' me a 'oldin' 'Arriet's 'and over th' bar. I'm a courtin' 'er when," etc., etc.

And then a fresh-faced lad chirps up: "T' 'ell wif yer Lonnon an' yer whuskey. Gimme a jug o' cider on the sunny side of a 'ay rick in old Surrey. Gimme a happle tart to go wif it. Gawd, I'm fed up on bully beef."

And so it went. All about pubs and bar-maids and the things they'd eat and drink, and all of it Blighty.

They were in the midst of a discussion of what part of the body was most desirable to part with for a permanent Blighty wound when a young officer pushed aside the burlap and wedged in. He was a lieutenant and was in command of our platoon. His name was Blofeld.

Blofeld was most democratic. He shook hands with the new men and said he hoped we'd be live wires, and then he told us what he wanted. There was to be a raid the next night and he was looking for volunteers.

Nobody spoke for a long minute, and then I offered.

I think I spoke more to break the embarrassing silence than anything else. I think, too, that I was led a little by a kind of youthful curiosity, and it may be that I wanted to appear brave in the eyes of these men who so evidently held me more or less in contempt as a newcomer.

Blofeld accepted me, and one of the other new men offered. He was taken too.

It turned out that all the older men were married and that they were not expected to volunteer. At least there was no disgrace attaching to a refusal.

After Blofeld left, Sergeant Page told us we'd better get down to "kip" while we could. "Kip" in this case meant closing our eyes and dozing. I sat humped up in my original position through the night. There wasn't room to stretch out.

Along toward morning I began to itch, and found I had made the acquaintance of that gay and festive little soldier's enemy, the "cootie." The cootie, or the "chat" as he is called by the officers, is the common body louse. Common is right. I never got rid of mine until I left the service. Sometimes when I get to thinking about it, I believe I haven't yet.

In the morning the members of the raiding party were taken back a mile or so to the rear and were given instruction and rehearsal. This was the first raid that "Batt" had ever tried, and the staff was anxious to have it a success. There were fifty in the party, and Blofeld, who had organized the raid, beat our instructions into us until we knew them by heart.

The object of a raid is to get into the enemy's trenches by stealth if possible, kill as many as possible, take prisoners if practicable, do a lot of damage, and get away with a whole hide.

We got back to the front trenches just before dark. I noticed a lot of metal cylinders arranged along the parapet. They were about as big as a stovepipe and four feet long, painted brown. They were the gas containers. They were arranged about four or five to a traverse, and were connected up by tubes and were covered with sandbags. This was the poison gas ready for release over the top through tubes.

The time set for our stunt was eleven P.M. Eleven o'clock was "zero." The system on the Western Front, and, in fact, all fronts, is to indicate the time fixed for any event as zero. Anything before or after is spoken of as plus or minus zero.

Around five o'clock we were taken back to Mechanics trench and fed—a regular meal with plenty of everything, and all good. It looked rather like giving a condemned man a hearty meal, but grub is always acceptable to a soldier.

After that we blacked our faces. This is always done to prevent the whiteness of the skin from showing under the flare lights. Also to distinguish your own men when you get to the Boche trench.

Then we wrote letters and gave up our identification discs and were served with persuader sticks or knuckle knives, and with "Mills" bombs.

The persuader is a short, heavy bludgeon with a nail-studded head. You thump Fritz on the head with it. Very handy at close quarters. The knuckle knife is a short dagger with a heavy brass hilt that covers the hand. Also very good for close work, as you can either strike or stab with it.

We moved up to the front trenches at about half-past ten. At zero minus ten, that is, ten minutes of eleven, our artillery opened up. It was the first bombardment I had ever been under, and it seemed as though all the guns in the world were banging away. Afterwards I found that it was comparatively light, but it didn't seem so then.

The guns were hardly started when there was a sound like escaping steam. Jerry leaned over and shouted in my ear: "There goes the gas. May it finish the blighters."

Blofeld came dashing up just then, very much excited because he found we had not put on our masks, through some slip-up in the orders. We got into them quick. But as it turned out there was no need. There was a fifteen-mile wind blowing, which carried the gas away from us very rapidly. In fact it blew it across the Boche trenches so fast that it didn't bother them either.

The barrage fire kept up right up to zero, as per schedule. At thirty seconds of eleven I looked at my watch and the din was at its height. At exactly eleven it stopped short. Fritz was still sending some over, but comparatively there was silence. After the ear-splitting racket it was almost still enough to hurt.

And in that silence over the top we went.

Lanes had been cut through our wire, and we got through them quickly. The trenches were about one hundred twenty yards apart and we still had nearly one hundred to go. We dropped and started to crawl. I skinned both my knees on something, probably old wire, and both hands. I could feel the blood running into my puttees, and my rifle bothered me as I was afraid of jabbing Jerry, who was just ahead of me as first bayonet man.

They say a drowning man or a man in great danger reviews his past. I didn't. I spent those few minutes wondering when the machine-gun fire would come.

I had the same "gone" feeling in the pit of the stomach that you have when you drop fast in an elevator. The skin on my face felt tight, and I remember that I wanted to pucker my nose and pull my upper lip down over my teeth.

We got clean up to their wire before they spotted us. Their entanglements had been flattened by our barrage fire, but we had to get up to pick our way through, and they saw us.

Instantly the "Very" lights began to go up in scores, and hell broke loose. They must have turned twenty machine guns on us, or at us, but their aim evidently was high, for they only "clicked" two out of our immediate party. We had started with ten men, the other fifty being divided into three more parties farther down the line.

When the machine guns started, we charged. Jerry and I were ahead as bayonet men, with the rest of the party following with buckets of "Mills" bombs and "Stokeses."

It was pretty light, there were so many flares going up from both sides. When I jumped on the parapet, there was a whaling big Boche looking up at me with his rifle resting on the sandbags. I was almost on the point of his bayonet.

For an instant I stood with a kind of paralyzed sensation, and there flashed through my mind the instructions of the manual for such a situation, only I didn't apply those instructions to this emergency.

Instead I thought—if such a flash could be called thinking—how I, as an instructor, would have told a rookie to act, working on a dummy. I had a sort of detached feeling as though this was a silly dream.

Probably this hesitation didn't last more than a second.

Then, out of the corner of my eye, I saw Jerry lunge, and I lunged too. Why that Boche did not fire I don't know. Perhaps he did and missed. Anyhow I went down and in on him, and the bayonet went through his throat.

Jerry had done his man in and all hands piled into the trench.

Then we started to race along the traverses. We found a machine gun and put an eleven-pound high-explosive "Stokes" under it. Three or four Germans appeared, running down communication trenches, and the bombers sent a few Millses after them. Then we came to a dug-out door—in fact, several, as Fritz, like a woodchuck, always has more than one entrance to his burrow. We broke these in in jig time and looked down a thirty-foot hole on a dug-out full of graybacks. There must have been a lot of them. I could plainly see four or five faces looking up with surprised expressions.

Blofeld chucked in two or three Millses and away we went.

A little farther along we came to the entrance of a mine shaft, a kind of incline running toward our lines. Blofeld went in it a little way and flashed his light. He thought it was about forty yards long. We put several of our remaining Stokeses in that and wrecked it.

Turning the corner of the next traverse, I saw Jerry drop his rifle and unlimber his persuader on a huge German who had just rounded the corner of the "bay." He made a good job of it, getting him in the face, and must have simply caved him in, but not before he had thrown a bomb. I had broken my bayonet prying the dug-out door off and had my gun up-ended—clubbed.

When I saw that bomb coming, I bunted at it like Ty Cobb trying to sacrifice. It was the only thing to do. I choked my bat and poked at the bomb instinctively, and by sheer good luck fouled the thing over the parapet. It exploded on the other side.

"Blimme eyes," says Jerry, "that's cool work. You saved us the wooden cross that time."

We had found two more machine guns and were planting Stokeses under them when we heard the Lewises giving the recall signal. A good gunner gets so he can play a tune on a Lewis, and the device is frequently used for signals. This time he thumped out the old one—"All policemen have big feet." Rat-a-tat-tat—tat, tat.

It didn't come any too soon.

As we scrambled over the parapet we saw a big party of Germans coming up from the second trenches. They were out of the communication trenches and were coming across lots. There must have been fifty of them, outnumbering us five or six to one.

We were out of bombs, Jerry had lost his rifle, and mine had no "ammo." Blofeld fired the last shot from his revolver and, believe me, we hooked it for home.

We had been in their trenches just three and a half minutes.

Just as we were going through their wire a bomb exploded near and got Jerry in the head. We dragged him in and also the two men that had been clicked on the first fire. Jerry got Blighty on his wound, but was back in two months. The second time he wasn't so lucky. He lies now somewhere in France with a wooden cross over his head.

Did that muddy old trench look good when we tumbled in? Oh, Boy! The staff was tickled to pieces and complimented us all. We were sent out of the lines that night and in billets got hot food, high-grade "fags", a real bath, a good stiff rum ration, and letters from home.

Next morning we heard the results of the raid. One party of twelve never returned. Besides that we lost seven men killed. The German loss was estimated at about one hundred casualties, six machine guns and several dug-outs destroyed, and one mine shaft put out of business. We also brought back documents of value found by one party in an officer's dug-out.

Blofeld got the military cross for the night's work, and several of the enlisted men got the D.C.M.

Altogether it was a successful raid. The best part of it was getting back.

After the strafing we had given Fritz on the raid, he behaved himself reasonably well for quite a while. It was the first raid that had been made on that sector for a long time, and we had no doubt caught the Germans off their guard.

Anyhow for quite a spell afterwards they were very "windy" and would send up the "Very" lights on the slightest provocation and start the "typewriters" a-rattling. Fritz was right on the job with his eye peeled all the time.

In fact he was so keen that another raid that was attempted ten days later failed completely because of a rapidly concentrated and heavy machine-gun fire, and in another, a day or two later, our men never got beyond our own wire and had thirty-eight casualties out of fifty men engaged.

But so far as anything but defensive work was concerned, Fritz was very meek. He sent over very few "minnies" or rifle grenades, and there was hardly any shelling of the sector.

Directly after the raid, we who were in the party had a couple of days "on our own" at the little village of Bully-Grenay, less than three miles behind the lines. This is directly opposite Lens, the better known town which figures so often in the dispatches.

Bully-Grenay had been a place of perhaps one thousand people. It had been fought over and through and around early in the war, and was pretty well battered up. There were a few houses left unhit and the town hall and several shops. The rest of the place was ruins, but about two hundred of the inhabitants still stuck to their old homes. For some reason the Germans did not shell Bully-Grenay, that is, not often. Once in a while they would lob one in just to let the people know they were not forgotten.

There was a suspicion that there were spies in the town and that that accounted for the Germans laying off, but whatever was the cause the place was safer than most villages so near the lines.

Those two days in repose at Bully-Grenay were a good deal of a farce. We were entirely "on our own", it is true, no parade, no duty of any kind—but the quarters—oof! We were billeted in the cellars of the battered-down houses. They weren't shell-proof. That didn't matter much, as there wasn't any shelling, but there might have been. The cellars were dangerous enough without, what with tottering walls and overhanging chunks of masonry.

Moreover they were a long way from waterproof. Imagine trying to find a place to sleep in an old ruin half full of rainwater. The dry places were piled up with brick and mortar, but we managed to clean up some half-sheltered spots for "kip" and we lived through it.

The worst feature of these billets was the rats. They were the biggest I ever saw, great, filthy, evil-smelling, grayish-red fellows, as big as a good-sized cat. They would hop out of the walls and scuttle across your face with their wet, cold feet, and it was enough to drive you insane. One chap in our party had a natural horror of rats, and he nearly went crazy. We had to "kip" with our greatcoats pulled up over our heads, and then the beggars would go down and nibble at our boots.

The first day somebody found a fox terrier, evidently lost and probably the pet of some officer. We weren't allowed to carry mascots, although we had a kitten that we smuggled along for a long time. This terrier was a well-bred little fellow, and we grabbed him. We spent a good part of both mornings digging out rats for him and staged some of the grandest fights ever.

Most of the day we spent at a little estaminet across the way from our so-called billets. There was a pretty mademoiselle there who served the rotten French beer and vin blanc, and the Tommies tried their French on her. They might as well have talked Choctaw. I speak the language a little and tried to monopolize the lady, and did, which didn't increase my popularity any.

"I say, Yank," some one would call, "don't be a blinkin' 'og. Give somebody else a chawnce."

Whereupon I would pursue my conquest all the more ardently. I was making a large hit, as I thought, when in came an officer. After that I was ignored, to the huge delight of the Tommies, who joshed me unmercifully. They discovered that my middle name was Derby, and they christened me "Darby the Yank." Darby I remained as long as I was with them.

Some of the questions the men asked about the States were certainly funny. One chap asked what language we spoke over here. I thought he was spoofing, but he actually meant it. He thought we spoke something like Italian, he said. I couldn't resist the temptation, and filled him up with a line of ghost stories about wild Indians just outside Boston. I told him I left because of a raid in which the redskins scalped people on Boston Common. After that he used to pester the life out of me for Wild West yarns with the scenes laid in New England.

One chap was amazed and, I think, a little incredulous because I didn't know a man named Fisk in Des Moines.

We went back to the trenches again and were there five days. I was out one night on barbed wire work, which is dangerous at any time, and was especially so with Fritz in his condition of jumpy nerves. You have to do most of the work lying on your back in the mud, and if you jingle the wire, Fritz traverses No Man's Land with his rapid-firers with a fair chance of bagging something.

I also had one night on patrol, which later became my favorite game. I will tell more about it in another chapter.

At the end of the five days the whole battalion was pulled out for rest. We marched a few miles to the rear and came to the village of Petite-Saens. This town had been fought through, but for some reason had suffered little. Few of the houses had been damaged, and we had real billets.

My section, ten men besides myself, drew a big attic in a clean house. There was loads of room and the roof was tight and there were no rats. It was oriental luxury after Bully-Grenay and the trenches, and for a wonder nobody had a word of "grousing" over "kipping" on the bare floor.

The house was occupied by a very old peasant woman and a very little girl, three years old, and as pretty as a picture. The old woman looked ill and sad and very lonesome. One night as we sat in her kitchen drinking black coffee and cognac, I persuaded her to tell her story. It was, on the whole, rather a cruel thing to ask, I am afraid. It is only one of many such that I heard over there. France has, indeed, suffered. I set down here, as nearly as I can translate, what the old woman said:

"Monsieur, I am very, very old now, almost eighty, but I am a patriot and I love my France. I do not complain that I have lost everything in this war. I do not care now, for I am old and it is for my country; but there is much sadness for me to remember, and it is with great bitterness that I think of the pig Allemand—beast that he is.

"Two years ago I lived in this house, happy with my daughter and her husband and the little baby, and my husband, who worked in the mines. He was too old to fight, but when the great war came he tried to enlist, but they would not listen to him, and he returned to work, that the country should not be without coal.

"The beau-fils (son-in-law), he enlisted and said good-by and went to the service.

"By and by the Boche come and in a great battle not far from this very house the beau-fils is wounded very badly and is brought to the house by comrades to die.

"The Boche come into the village, but the beau-fils is too weak to go. The Boche come into the house, seize my daughter, and there—they—oh, monsieur—the things one may not say—and we so helpless.

"Her father tries to protect her, but he is knocked down. I try, but they hold my feet over the fire until the very flesh cooks. See for yourselves the burns on my feet still.

"My husband dies from the blow he gets, for he is very old, over ninety. Just then mon beau-fils sees a revolver that hangs by the side of the German officer, and putting all his strength together he leaps forward and grabs the revolver. And there he shoots the officer—and my poor little daughter—and then he says good-by and through the head sends a bullet.

"The Germans did not touch me but once after that, and then they knocked me to the floor when they came after the pig officer. By and by come you English, and all is well for dear France once more; but I am very desolate now. I am alone but for the petite-fille (granddaughter), but I love the English, for they save my home and my dear country."

I heard a good many stories of this kind off and on, but this particular one, I think, brought home, to me at least, the general beastliness of the Hun closer than ever before. We all loved our little kiddie very much, and when we saw the evidence of the terrible cruelties the poor old woman had suffered we saw red. Most of us cried a little. I think that that one story made each of us that heard it a mean, vicious fighter for the rest of our service. I know it did me.

One of the first things a British soldier learns is to keep himself clean. He can't do it, and he's as filthy as a pig all the time he is in the trenches, but he tries. He is always shaving, even under fire, and show him running water and he goes to it like a duck.

More than once I have shaved in a periscope mirror pegged into the side of a trench, with the bullets snapping overhead, and rubbed my face with wet tea leaves afterward to freshen up.

Back in billets the very first thing that comes off is the big clean-up. Uniforms are brushed up, and equipment put in order. Then comes the bath, the most thorough possible under the conditions. After that comes the "cootie carnival", better known as the "shirt hunt." The cootie is the soldier's worst enemy. He's worse than the Hun. You can't get rid of him wherever you are, in the trenches or in billets, and he sticks closer than a brother. The cootie is a good deal of an acrobat. His policy of attack is to hang on to the shirt and to nibble at the occupant. Pull off the shirt and he comes with it. Hence the shirt hunt. Tommy gets out in the open somewhere so as not to shed his little companions indoors—there's always enough there anyhow—and he peels. Then he systematically runs down each seam—the cootie's favorite hiding place—catches the game, and ends his career by cracking him between the thumb nails.

For some obscure psychological reason, Tommy seems to like company on one of these hunts. Perhaps it is because misery loves company, or it may be that he likes to compare notes on the catch. Anyhow, it is a common thing to see from a dozen to twenty soldiers with their shirts off, hunting cooties.

"Hi sye, 'Arry," you'll hear some one sing out. "Look 'ere. Strike me bloomin' well pink but this one 'ere's got a black stripe along 'is back."

Or, "If this don't look like the one I showed ye 'fore we went into the blinkin' line. 'Ow'd 'e git loose?"

And then, as likely as not, a little farther away, behind the officers' quarters, you'll hear one say:

"I say, old chap, it's deucedly peculiar I should have so many of the beastly things after putting on the Harrisons mothaw sent in the lawst parcel."

The cootie isn't at all fastidious. He will bite the British aristocrat as soon as anybody else. He finds his way into all branches of the service, and I have even seen a dignified colonel wiggle his shoulders anxiously.

Some of the cootie stories have become classical, like this one which was told from the North Sea to the Swiss border. It might have happened at that.

A soldier was going over the top when one of his cootie friends bit him on the calf. The soldier reached down and captured the biter. Just as he stooped, a shell whizzed over where his head would have been if he had not gone after the cootie. Holding the captive between thumb and finger, he said:

"Old feller, I cawn't give yer the Victoria Cross—but I can put yer back."

And he did.

The worst thing about the cootie is that there is no remedy for him. The shirt hunt is the only effective way for the soldier to get rid of his bosom friends. The various dopes and patent preparations guaranteed as "good for cooties" are just that. They give 'em an appetite.

Food is a burning issue in the lives of all of us. It is the main consideration with the soldier. His life is simplified to two principal motives, i.e., keeping alive himself and killing the other fellow. The question uppermost in his mind every time and all of the time, is, "When do we eat?"

In the trenches the backbone of Tommy's diet is bully beef, "Maconochie's Ration", cheese, bread or biscuit, jam, and tea. He may get some of this hot or he may eat it from the tin, all depending upon how badly Fritz is behaving.

In billets the diet is more varied. Here he gets some fresh meat, lots of bacon, and the bully and the Maconochie's come along in the form of stew. Also there is fresh bread and some dried fruit and a certain amount of sweet stuff.

It was this matter of grub that made my life a burden in the billets at Petite-Saens. I had been rather proud of being lance corporal. It was, to me, the first step along the road to being field marshal. I found, however, that a corporal is high enough to take responsibility and to get bawled out for anything that goes wrong. He's not high enough to command any consideration from those higher up, and he is so close to the men that they take out their grievances on him as a matter of course. He is neither fish, flesh, nor fowl, and his life is a burden.

I had the job of issuing the rations of our platoon, and it nearly drove me mad. Every morning I would detail a couple of men from our platoon to be standing mess orderlies for the day. They would fetch the char and bacon from the field kitchen in the morning and clean up the "dixies" after breakfast. The "dixie", by the way, is an iron box or pot, oblong in shape, capacity about four or five gallons. It fits into the field kitchen and is used for roasts, stews, char, or anything else. The cover serves to cook bacon in.

Field kitchens are drawn by horses and follow the battalion everywhere that it is safe to go, and to some places where it isn't. Two men are detailed from each company to cook, and there is usually another man who gets the sergeants' mess, besides the officers' cook, who does not as a rule use the field kitchen, but prepares the food in the house taken as the officers' mess.

As far as possible, the company cooks are men who were cooks in civil life, but not always. We drew a plumber and a navvy (road builder)—and the grub tasted of both trades. The way our company worked the kitchen problem was to have stew for two platoons one day and roast dinner for the others, and then reverse the order next day, so that we didn't have stew all the time. There were not enough "dixies" for us all to have stew the same day.

Every afternoon I would take my mess orderlies and go to the quartermaster's stores and get our allowance and carry it back to the billets in waterproof sheets. Then the stuff that was to be cooked in the kitchen went there, and the bread and that sort of material was issued direct to the men. That was where my trouble started.

The powers that were had an uncanny knack of issuing an odd number of articles to go among an even number of men, and vice versa. There would be eleven loaves of bread to go to a platoon of fifty men divided into four sections. Some of the sections would have ten men and some twelve or thirteen.

The British Tommy is a scrapper when it comes to his rations. He reminds me of an English sparrow. He's always right in there wangling for his own. He will bully and browbeat if he can, and he will coax and cajole if he can't. It would be "Hi sye, corporal. They's ten men in Number 2 section and fourteen in ourn. An' blimme if you hain't guv 'em four loaves, same as ourn. Is it right, I arsks yer? Is it?" Or,

"Lookee! Do yer call that a loaf o' bread? Looks like the A.S.C. (Army Service Corps) been using it fer a piller. Gimme another, will yer, corporal?"

When it comes to splitting seven onions nine ways, I defy any one to keep peace in the family, and every doggoned Tommy would hold out for his onion whether he liked 'em or not. Same way with a bottle of pickles to go among eleven men or a handful of raisins or apricots. Or jam or butter or anything, except bully beef or Maconochie. I never heard any one "argue the toss" on either of those commodities.

Bully is high-grade corned beef in cans and is O.K. if you like it, but it does get tiresome.

Maconochie ration is put up a pound to the can and bears a label which assures the consumer that it is a scientifically prepared, well-balanced ration. Maybe so. It is my personal opinion that the inventor brought to his task an imperfect knowledge of cookery and a perverted imagination. Open a can of Maconochie and you find a gooey gob of grease, like rancid lard. Investigate and you find chunks of carrot and other unidentifiable material, and now and then a bit of mysterious meat. The first man who ate an oyster had courage, but the last man who ate Maconochie's unheated had more. Tommy regards it as a very inferior grade of garbage. The label notwithstanding, he's right.

Many people have asked me what to send our soldiers in the line of food. I'd say stick to sweets. Cookies of any durable kind—I mean that will stand chance moisture—the sweeter the better, and if possible those containing raisins or dried fruit. Figs, dates, etc., are good. And, of course, chocolate. Personally, I never did have enough chocolate. Candy is acceptable, if it is of the sort to stand more or less rough usage which it may get before it reaches the soldier. Chewing gum is always received gladly. The army issue of sweets is limited pretty much to jam, which gets to taste all alike.

It is pathetic to see some of the messes Tommy gets together to fill his craving for dessert. The favorite is a slum composed of biscuit, water, condensed milk, raisins, and chocolate. If some of you folks at home would get one look at that concoction, let alone tasting it, you would dash out and spend your last dollar for a package to send to some lad "over there."

After the excitement of dodging shells and bullets in the front trenches, life in billets seems dull. Tommy has too much time to get into mischief. It was at Petite-Saens that I first saw the Divisional Folies. This was a vaudeville show by ten men who had been actors in civil life, and who were detailed to amuse the soldiers. They charged a small admission fee and the profit went to the Red Cross.

There ought to be more recreation for the soldiers of all armies. The Y.M.C.A. is to take care of that with our boys.

By the way, we had a Y.M.C.A. hut at Petite-Saens, and I cannot say enough for this great work. No one who has not been there can know what a blessing it is to be able to go into a clean, warm, dry place and sit down to reading or games and to hear good music. Personally I am a little bit sorry that the secretaries are to be in khaki. They weren't when I left. And it sure did seem good to see a man in civilian's clothes. You get after a while so you hate the sight of a uniform.

Another thing about the Y.M.C.A. I could wish that they would have more women in the huts. Not frilly, frivolous society girls, but women from thirty-five to fifty. A soldier likes kisses as well as the next. And he takes them when he finds them. And he finds too many. But what he really wants, though, is the chance to sit down and tell his troubles to some nice, sympathetic woman who is old enough to be level-headed.

Nearly every soldier reverts more or less to a boyish point of view. He hankers for somebody to mother him. I should be glad to see many women of that type in the Y.M.C.A. work. It is one of the great needs of our army that the boys should be amused and kept clean mentally and morally. I don't believe there is any organization better qualified to do this than the Y.M.C.A.

Most of our chaps spent their time "on their own" either in the Y.M.C.A. hut or in the estaminets while we were in Petite-Saens. Our stop there was hardly typical of the rest in billets. Usually "rest" means that you are set to mending roads or some such fatigue duty. At Petite-Saens, however, we had it "cushy."

The routine was about like this: Up at 6:30, we fell in for three-quarters of an hour physical drill or bayonet practice. Breakfast. Inspection of ammo and gas masks. One hour drill. After that, "on our own", with nothing to do but smoke, read, and gamble.

Tommy is a great smoker. He gets a fag issue from the government, if he is lucky, of two packets or twenty a week. This lasts him with care about two days. After that he goes smokeless unless he has friends at home to send him a supply. I had friends in London who sent me about five hundred fags a week, and I was consequently popular while they lasted. This took off some of the curse of being a lance corporal.

Tommy has his favorite in "fags" like anybody else. He likes above all Wild Woodbines. This cigarette is composed of glue, cheap paper, and a poor quality of hay. Next in his affection comes Goldflakes—pretty near as bad.

People over here who have boys at the front mustn't forget the cigarette supply. Send them along early and often. There'll never be too many. Smoking is one of the soldier's few comforts. Two bits' worth of makin's a week will help one lad make life endurable. It's cheap at the price. Come through for the smoke fund whenever you get the chance.

Café life among us at Petite-Saens was mostly drinking and gambling. That is not half as bad as it sounds. The drinking was mostly confined to the slushy French beer and vin blanc and citron. Whiskey and absinthe were barred.

The gambling was on a small scale, necessarily, the British soldier not being at any time a bloated plutocrat. At the same time the games were continuous. "House" was the most popular. This is a game similar to the "lotto" we used to play as children. The backers distribute cards having fifteen numbers, forming what they call a school. Then numbered cardboard squares are drawn from a bag, the numbers being called out. When a number comes out which appears on your card, you cover it with a bit of match. If you get all your numbers covered, you call out "house", winning the pot. If there are ten people in at a franc a head, the banker holds out two francs, and the winner gets eight.

It is really quite exciting, as you may get all but one number covered and be rooting for a certain number to come. Usually when you get as close as that and sweat over a number for ten minutes, somebody else gets his first. Corporal Wells described the game as one where the winner "'ollers 'ouse and the rest 'ollers 'ell!"

Some of the nicknames for the different numbers remind one of the slang of the crap shooter. For instance, "Kelly's eye" means one. "Clickety click" is sixty-six. "Top of the house" is ninety. Other games are "crown and anchor", which is a dice game, and "pontoon", which is a card game similar to "twenty-one" or "seven and a half." Most of these are mildly discouraged by the authorities, "house" being the exception. But in any estaminet in a billet town you'll find one or all of them in progress all the time. The winner usually spends his winnings for beer, so the money all goes the same way, game or no game.

When there are no games on, there is usually a sing-song going. We had a merry young nuisance in our platoon named Rolfe, who had a voice like a frog and who used to insist upon singing on all occasions. Rolfie would climb on the table in the estaminet and sing numerous unprintable verses of his own, entitled "Oh, What a Merry Plyce is Hengland." The only redeeming feature of this song was the chorus, which everybody would roar out and which went like this:

Cheer, ye beggars, cheer!

Britannia rules the wave!

'Ard times, short times

Never'll come agyne.

Shoutin' out at th' top o' yer lungs:

Damn the German army!

Oh, wot a lovely plyce is Hengland!

Our ten days en repos at Petite-Saens came to an end all too soon.

On the last day we lined up for our official "bawth."

Petite-Saens was a coal-mining town. The mines were still operated, but only at night—this to avoid shelling from the Boche long-distance artillery, which are fully capable of sending shells and hitting the mark at eighteen miles. The water system of the town depended upon the pumping apparatus of the mines. Every morning early, before the pressure was off, all hands would turn out for a general "sluicing" under the hydrants. We were as clean as could be and fairly free of "cooties" at the end of a week, but official red tape demanded that we go through an authorized scouring.

On the last day we lined up for this at dawn before an old warehouse which had been fitted with crude showers. We were turned in twenty in a batch and were given four minutes to soap ourselves all over and rinse off. I was in the last lot and had just lathered up good and plenty when the water went dead. If you want to reach the acme of stickiness, try this stunt. I felt like the inside of a mucilage bottle for a week.

After the official purification we were given clean underwear. And then there was a howl. The fresh underthings had been boiled and sterilized, but the immortal cootie had come through unscathed and in all its vigor. Corporal Wells raised a pathetic wail:

"Blimme eyes, mytie! I got more'n two 'undred now an' this supposed to be a bloomin' clean shirt! Why, the blinkin' thing's as lousy as a cookoo now, an me just a-gittin' rid o' the bloomin' chats on me old un. Strike me pink if it hain't a bleedin' crime! Some one ought to write to John Bull abaht it!"

John Bull is the English paper of that name published by Horatio Bottomley, which makes a specialty of publishing complaints from soldiers and generally criticising the conduct of army affairs.

Well, we got through the bath and the next day were on our way. This time it was up the line to another sector. My one taste of trench action had made me keen for more excitement, and in spite of the comfortable time at Petite-Saens, I was glad to go. I was yet to know the real horrors and hardships of modern warfare. There were many days in those to come when I looked back upon Petite-Saens as a sort of heaven.

We left Petite-Saens about nine o'clock Friday night and commenced our march for what we were told would be a short hike. It was pretty warm and muggy. There was a thin, low-lying mist over everything, but clear enough above, and there was a kind of poor moonlight. There was a good deal of delay in getting away, and we had begun to sweat before we started, as we were equipped as usual with about eighty pounds' weight on the back and shoulders. That eighty pounds is theoretical weight.

As a matter of practice the pack nearly always runs ten and even twenty pounds over the official equipment, as Tommy is a great little accumulator of junk. I had acquired the souvenir craze early in the game, and was toting excess baggage in the form of a Boche helmet, a mess of shell noses, and a smashed German automatic. All this ran to weight.

I carried a lot of this kind of stuff all the time I was in the service, and was constantly thinning out my collection or adding to it.

When you consider that a soldier has to carry everything he owns on his person, you'd say that he would want to fly light; but he doesn't. And that reminds me, before I forget it, I want to say something about sending boxes over there.

It is the policy of the British, and, I suppose, will be of the Americans, to move the troops about a good deal. This is done so that no one unit will become too much at home in any one line of trenches and so get careless. This moving about involves a good deal of hiking.

Now if some chap happens to get a twenty-pound box of good things just before he is shifted, he's going to be in an embarrassing position. He'll have to give it away or leave it. So—send the boxes two or three pounds at a time, and often.

But to get back to Petite-Saens. We commenced our hike as it is was getting dark. As we swung out along the once good but now badly furrowed French road, we could see the Very lights beginning to go up far off to the left, showing where the lines were. We could distinguish between our own star lights and the German by the intensity of the flare, theirs being much superior to ours, so much so that they send them up from the second-line trenches.

The sound of the guns became more distant as we swung away to the south and louder again as the road twisted back toward the front.

We began to sing the usual songs of the march and I noticed that the American ragtime was more popular among the boys than their own music. "Dixie" frequently figured in these songs.

It is always a good deal easier to march when the men sing, as it helps to keep time and puts pep into a column and makes the packs seem lighter. The officers see to it that the mouth organs get tuned up the minute a hike begins.

At the end of each hour we came to a halt for the regulation ten minutes' rest. Troops in heavy marching order move very slowly, even with the music—and the hours drag. The ten minutes' rest though goes like a flash. The men keep an eye on the watches and "wangle" for the last second.

We passed through two ruined villages with the battered walls sticking up like broken teeth and the gray moonlight shining through empty holes that had been windows. The people were gone from these places, but a dog howled over yonder. Several times we passed batteries of French artillery, and jokes and laughter came out of the half darkness.

Topping a little rise, the moon came out bright, and away ahead the silver ribbon of the Souchez gleamed for an instant; the bare poles that once had been Bouvigny Wood were behind us, and to the right, to the left, a pulverized ruin where houses had stood. Blofeld told me this was what was left of the village of Abalaine, which had been demolished some time before when the French held the sector.

At this point guides came out and met us to conduct us to the trenches. The order went down the line to fall in, single file, keeping touch, no smoking and no talking, and I supposed we were about to enter a communication trench. But no. We swung on to a "duck walk." This is a slatted wooden walk built to prevent as much as possible sinking into the mud. The ground was very soft here.

I never did know why there was no communication trench unless it was because the ground was so full of moisture. But whatever the reason, there was none, and we were right out in the open on the duck walk. The order for no talk seemed silly as we clattered along the boards, making a noise like a four-horse team on a covered bridge.

I immediately wondered whether we were near enough for the Boches to hear. I wasn't in doubt long, for they began to send over the "Berthas" in flocks. The "Bertha" is an uncommonly ugly breed of nine-inch shell loaded with H.E. It comes sailing over with a querulous "squeeeeeee", and explodes with an ear-splitting crash and a burst of murky, dull-red flame.

If it hits you fair, you disappear. At a little distance you are ripped to fragments, and a little farther off you get a case of shell-shock. Just at the edge of the destructive area the wind of the explosion whistles by your ears, and then sucks back more slowly.

The Boches had the range of that duck walk, and we began to run. Every now and then they would drop one near the walk, and from four to ten casualties would go down. There was no stopping for the wounded. They lay where they fell. We kept on the run, sometimes on the duck walk, sometimes in the mud, for three miles. I had reached the limit of my endurance when we came to a halt and rested for a little while at the foot of a slight incline. This was the "Pimple", so called on account of its rounded crest.

The Pimple forms a part of the well-known Vimy Ridge—is a semi-detached extension of it—and lies between it and the Souchez sector. After a rest here we got into the trenches skirting the Pimple and soon came out on the Quarries. This was a bowl-like depression formed by an old quarry. The place gave a natural protection and all around the edge were dug-outs which had been built by the French, running back into the hill, some of them more than a hundred feet.

In the darkness we could see braziers glowing softly red at the mouth of each burrow. There was a cheerful, mouth-watering smell of cookery on the air, a garlicky smell, with now and then a whiff of spicy wood smoke.

We were hungry and thirsty, as well as tired, and shed our packs at the dug-outs assigned us and went at the grub and the char offered us by the men we were relieving, the Northumberland Fusiliers.

The dug-outs here in the Quarries were the worst I saw in France. They were reasonably dry and roomy, but they had no ventilation except the tunnel entrance, and going back so far the air inside became simply stifling in a very short time.

I took one inhale of the interior atmosphere and decided right there that I would bivouac in the open. It was just getting down to "kip" when a sentry came up and said I would have to get inside. It seemed that Fritz had the range of the Quarries to an inch and was in the habit of sending over "minnies" at intervals just to let us know he wasn't asleep.

I had got settled down comfortably and was dozing off when there came a call for C company. I got the men from my platoon out as quickly as possible, and in half an hour we were in the trenches.

Number 10 platoon was assigned to the center sector, Number 11 to the left sector, and Number 12 to the right sector. Number 9 remained behind in supports in the Quarries.

Now when I speak of these various sectors, I mean that at this point there was no continuous line of front trenches, only isolated stretches of trench separated by intervals of from two hundred to three hundred yards of open ground. There were no dug-outs. It was impossible to leave these trenches except under cover of darkness—or to get to them or to get up rations. They were awful holes. Any raid by the Germans in large numbers at this time would have wiped us out, as there was no means of retreating or getting up reinforcements.

The Tommies called the trenches Grouse Spots. It was a good name. We got into them in the dense darkness of just before dawn. The division we relieved gave us hardly any instruction, but beat it on the hot foot, glad to get away and anxious to go before sun-up. As we settled down in our cosey danger spots I heard Rolfie, the frog-voiced baritone, humming one of his favorite coster songs:

Oh, why did I leave my little back room in old Bloomsbury?

Where I could live for a pound a week in luxury.

I wanted to live higher

So I married Marier,

Out of the frying pan into the bloomin' fire.

And he meant every word of it.

In our new positions in the Grouse Spots the orders were to patrol the open ground between at least four times a night. That first night there was one more patrol necessary before daylight. Tired as I was, I volunteered for it. I had had one patrol before, opposite Bully-Grenay, and thought I liked the game.

I went over with one man, a fellow named Bellinger. We got out and started to crawl. All we knew was that the left sector was two hundred yards away. Machine-gun bullets were squealing and snapping overhead pretty continuously, and we had to hug the dirt. It is surprising to see how flat a man can keep and still get along at a good rate of speed. We kept straight away to the left and presently got into wire. And then we heard German voices. Ow! I went cold all over.

Then some "Very" lights went up and I saw the Boche parapet not twenty feet away. Worst of all there was a little lane through their wire at that point, and there would be, no doubt, a sap head or a listening post near. I tried to lie still and burrow into the dirt at the same time. Nothing happened. Presently the lights died, and Bellinger gave me a poke in the ribs. We started to crawfish. Why we weren't seen I don't know, but we had gone all of one hundred feet before they spotted us. Fortunately we were on the edge of a shallow shell hole when the sentry caught our movements and Fritz cut loose with the "typewriters." We rolled in. A perfect torrent of bullets ripped up the dirt and cascaded us with gravel and mud. The noise of the bullets "crackling" a yard above us was deafening.

The fusillade stopped after a bit. I was all for getting out and away immediately. Bellinger wanted to wait a while. We argued for as much as five minutes, I should think, and then the lights having gone out, I took matters in my own hands and we went away from there. Another piece of luck!

We weren't more than a minute on our way when a pair of bombs went off about over the shell hole. Evidently some bold Heinie had chucked them over to make sure of the job in case the machines hadn't. It was a close pinch—two close pinches. I was in places afterwards where there was more action and more danger, but, looking back, I don't think I was ever sicker or scareder. I would have been easy meat if they had rushed us.

We made our way back slowly, and eventually caught the gleam of steel helmets. They were British. We had stumbled upon our left sector. We found out then that the line curved and that instead of the left sector being directly to the left of ours—the center—it was to the left and to the rear. Also there was a telephone wire running from one to the other. We reported and made our way back to the center in about five minutes by feeling along the wire. That was our method afterwards, and the patrol was cushy for us.

I want to say a word right here about patrol work in general, because for some reason it fascinated me and was my favorite game.

If you should be fortunate—or unfortunate enough, as the case might be—to be squatting in a front-line trench this fine morning and looking through a periscope, you wouldn't see much. Just over the top, not more than twenty feet away, would be your barbed-wire entanglements, a thick network of wire stretched on iron posts nearly waist high, and perhaps twelve or fifteen feet across. Then there would be an intervening stretch of from fifty to one hundred fifty yards of No Man's Land, a tortured, torn expanse of muddy soil, pitted with shell craters, and, over beyond, the German wire and his parapet.

There would be nothing alive visible. There would probably be a few corpses lying about or hanging in the wire. Everything would be still except for the flutter of some rag of a dead man's uniform. Perhaps not that. Daylight movements in No Man's Land are somehow disconcerting. Once I was in a trench where a leg—a booted German leg, stuck up stark and stiff out of the mud not twenty yards in front. Some idiotic joker on patrol hung a helmet on the foot, and all the next day that helmet dangled and swung in the breeze. It irritated the periscope watchers, and the next night it was taken down.

Ordinarily, however, there is little movement between the wires, nor behind them. And yet you know that over yonder there are thousands of men lurking in the trenches and shelters.

After dark these men, or some of them, crawl out like hunted animals and prowl in the black mystery of No Man's Land. They are the patrol.

The patrol goes out armed and equipped lightly. He has to move softly and at times very quickly. It is his duty to get as close to the enemy lines as possible and find out if they are repairing their wire or if any of their parties are out, and to get back word to the machine gunners, who immediately cut loose on the indicated spot.

Sometimes he lies with his head to the ground over some suspected area, straining his ears for the faint "scrape, scrape" that means a German mining party is down there, getting ready to plant a ton or so of high explosive, or, it may be, is preparing to touch it off at that very moment.

Always the patrol is supposed to avoid encounter with enemy patrols. He carries two or three Mills bombs and a pistol, but not for use except in extreme emergency. Also a persuader stick or a trench knife, which he may use if he is near enough to do it silently.