THE PAPER SHORTAGE.

News Editor of "Daily Bugle Blast." "JUST TYPE A SHORT NOTICE THAT FINDERS OF FIRST SNOWDROP, CROCUS, PRIMROSE OR ANY EARLY SPRING PHENOMENA MUST APPRISE WORLD THROUGH OUR ADVERTISEMENT COLUMNS."

One of the latest peculiarities of the KAISER is an absolute horror at the thought of being prematurely buried. Several experts however say that this is impossible.

It appears that HINDENBURG accuses the CROWN PRINCE OF BAVARIA of having misunderstood an order, thus losing Grandcourt for the Germans. RUPPRECHT, we understand, retorted that the real culprits were the British.

In a character-sketch of VON BISSING, the Cologne Gazette says, "He is a fine musician and his execution is good." It would be.

News Editor of "Daily Bugle Blast." "JUST TYPE A SHORT NOTICE THAT FINDERS OF FIRST SNOWDROP, CROCUS, PRIMROSE OR ANY EARLY SPRING PHENOMENA MUST APPRISE WORLD THROUGH OUR ADVERTISEMENT COLUMNS."

No German submarine, says ADMIRAL VON CAPELLE, has been lost since the beginning of the submarine war. This assurance has been received with the liveliest satisfaction by several U-boat commanders who have been in the awkward predicament of not knowing whether they were officially missing.

Captain BOY ED is stated to have returned to the United States disguised. Not on this occasion, we may assume, as an officer and a gentleman.

According to the ex-Portuguese Consul at Hamburg bone tickets are issued for making soup, but the bone must be returned to the authorities. Possibly the hardship of the procedure would be mitigated if ticket-holders were permitted to growl.

A metallurgical engineer at the Surbiton Tribunal said he was forty-one years old, and only missed the age-limit by eighteen hours. It is not thought that he did it purposely.

At the Billericay Tribunal an applicant last week stated that he had nine children, but upon counting them again he discovered that he had ten. There seems to be no excuse for this sort of thing, for Adding machines are now fairly well advertised.

Discussing the latest dress fashion, a lady writer says, "It is a most ridiculous dress. Nothing worse could be conceived." This, of course, is foolish talk, for the lady has not seen next season's style.

Austrian tobacconists are now prohibited from selling more than one cigar a day to a customer. To conserve the supply still further it is proposed to compel the tobacconist to offer each customer the alternative of nuts.

"When I see a map of the British Empire," said Mr. PONSONBY, M.P., "I do not feel any pride whatsoever." People have been known to express similar sentiments upon sighting certain M.P.'s.

"The public must hold up the policeman's hands," said a London magistrate in a recent traffic case. It is astonishing how some policeman are able to hold them up without assistance for several seconds at a time.

The staff of the new Pensions Minister, it is announced, will be over two thousand. It is still hoped, however, that there may be a small surplus which can be devoted to the needs of disabled soldiers.

Several men have been arrested in Dresden for passing counterfeit food tickets. The defence will presumably be that it wasn't real food.

The Royal Engineers are advertising for seamen for the Inland Water Transport Section. The Chief Transport Officer, we understand, has already hoisted his bargee.

Eggs to the number of six million odd have just arrived from China, says a news item, and will be used for confectionery. Had they arrived three months ago nothing could have averted a General Election.

A hen while being sold at a Red Cross sale at Horsham laid an egg which fetched 35s. In the best hen circles, where steady silent work is being done, there is a growing tendency to frown upon these isolated acts of ostentatious patriotism.

The Times, it seems, has not published a complete list of its rivals in the desperate struggle for the smallest circulation. A Finchley Church magazine has increased its price to 1½d. a copy.

Paper bags are no longer being used by greengrocers in Bangor, and their customers are patriotically assisting this economy by unpodding their green peas and rolling them home.

"Bacon, as a breakfast food," says an evening paper, "is fast disappearing from the table." We have often noticed it do so.

"It is pitiful and disgraceful," says the Berliner Tageblatt, "to watch women-folk walking beside their half-starved dogs. There is no room in warfare for dogs." We have all along felt sorry for the poor animals at a time when one half the dachshund does not know how the other half lives.

"EGGS FOR LINCOLN HOSPITAL.

COL. —— LAYS A FALSE RUMOUR."—Lincoln Leader.

"PULLETS, laying 3s. 6d. each."—Provincial Paper.

Yet farmers persist in telling us there's no money in fowls.

"The first description of how the German Fleet reached Rome after the battle of Jutland is furnished by a neutral from Kiel."—Johannesburg Daily Mail.

Of all the roads that lead to Rome this is certainly the roughest.

The New Greeting: "Comment vous Devonportez-vous?"

Air—"To Althæa from Prison."

When Peace with wide and shining wings

Invades this warring isle,

And my beloved Germania brings

Wearing her largest smile;

When close about her waist I coil

And mouth to mouth apply,

Not SNOWDEN, patriot son of toil,

Will be more pleased than I.

When round the No-Conscription board

The wines of Rhineland flow,

And many a rousing Hoch! is roared

To toast the status quo;

When o'er the swiftly-circling bowl

Our happy tears run dry,

Not PONSONBY, that loyal soul,

Will be more pleased than I.

When sausages and sauerkraut

Fulfil the air with spice,

And loosened tongues the praise shall shout

Of Peace-at-any-price;

When German weeds our lips employ

And hearts are full and high,

Not CHARLES TREVELYAN, blind with joy,

Will be more pleased than I.

Stone walls do not my feet confine

Nor yet a barbed-wire cage;

I talk at large and claim as mine

The freeman's heritage;

And, if this wicked War but end

Ere German hopes can die,

Not WILLIAM'S self, my dearest friend,

Will be more pleased than I.

O.S.

"Now," I suggested as we left the drapery department, "you've got as much as you can carry." Unfortunately it was impossible to relieve her of the parcels as I had all my work cut out to manipulate those confounded crutches.

"There's only the toy department," returned Pamela, leading the way with her armful of packages. "I do hope you're not frightfully tired." Of course it seemed ridiculous, but I had not been out of hospital many days, and as yet I had not grown used to stumping about in this manner.

"Do you happen," asked Pamela at the counter, "to have such a thing as a box of broken soldiers?"

The young woman looked astonished and even a little hurt, but offered, with condescension, to inquire.

"Do you want them for Dick?" I asked, Dick being Pamela's youngest brother.

"For Dick and Alice," said Pamela. Alice was her sister, younger still.

"Why shouldn't I buy them a box of whole ones?"

"That wouldn't answer the purpose. They have three large boxes already," answered Pamela, as a young man appeared in a frock coat, with a silver badge on the right lapel, "For Services Rendered." In his hand was a dusty cardboard box, and in the box lay five damaged leaden soldiers, up-to-date soldiers in khaki; two without heads, two armless, one who had lost both legs.

"Those will do splendidly," said Pamela, and the young man with the silver badge obligingly put the soldiers into my tunic pocket. It seemed to be understood that they and I had been knocked out in the same campaign.

"Why," I asked on the way home in the taxi, "did you want the soldiers to be broken?"

"I—I didn't," murmured Pamela, with a sigh.

"Why did Dick?" I persisted.

"The children are so dreadfully realistic now-a-days. You see, Father objected to his breaking heads and arms off his new ones. Dick was quite rebellious. He wanted to know what he was to do for wounded; and Alice was more disappointed still."

"I should have thought it was too painful a notion for her," I suggested.

"Oh!" cried Pamela, with a laugh, "Alice is a Red Cross nurse, you know. She's made a hospital out of a Noah's Ark. She only thinks of healing them."

"All the King's horses and all the King's men cannot put Humpty Dumpty together again," I said.

"Poor old boy!" whispered Pamela.

"I wonder whether broken soldiers have an interest for you as well," I remarked ... and Dick and Alice were completely forgotten until they met us clamorously in the hall.

"Did you get any, Pam?" cried Dick.

"Only five," was the answer, as I took the small paper parcel from my pocket and handed it over.

"Is that all?" demanded Alice.

"There's one more," I said.

"Is that for me?" cried Alice; but Pamela shook her head and smiled very nicely as she took my arm.

"No, that's for me," she said.

The night was a very dark one, for a cold damp fog hung over the Channel. The few lights we carried reflected in-board only, and, leaning over the rail, it was with difficulty that I could distinguish the dark waters washing below. Shore-ward I could see nothing, though I knew that a good-sized town lay there.

I had soon had enough of the inclement night. Keeping my feet with some difficulty upon the wet boards, I groped my way to a door and, pushing it open, entered.

A strange scene met my gaze. A spruce man in the uniform of a naval officer was seated at a table. Before him stood a tall well-set-up young seaman. His dishevelled head was hatless, but otherwise he looked trim, and his garments fitted him better than a seaman's garments generally do. On each side of him stood an armed guard.

"Have you anything to say for yourself?" asked the officer sternly.

"No, Sir, only that I am innocent," answered the man. He held his head high, almost defiantly. I could not but admire his courageous bearing, and yet there was an air of unreality about the whole thing. I felt almost as if I were dreaming it, but I knew that this was not a dream.

"The evidence against you is overwhelming," said the officer. "I have no alternative but to sentence you to death. The sentence will be carried out at dawn. Remove the prisoner."

The seaman took a step forward. For a moment he seemed to be struggling with himself, anxious to speak, yet forcing himself to silence. Then he bowed his head, and, turning, placed himself between the guards and was marched away.

The officer sighed. "It's a bad business," he said. "He's the best man I ever had on my ship."

He was speaking to himself, and again I had that strange sense of unreality, as indeed I well might, for this was the Third Act of True to the Death, a melodrama in the pavilion at the end of the pier.

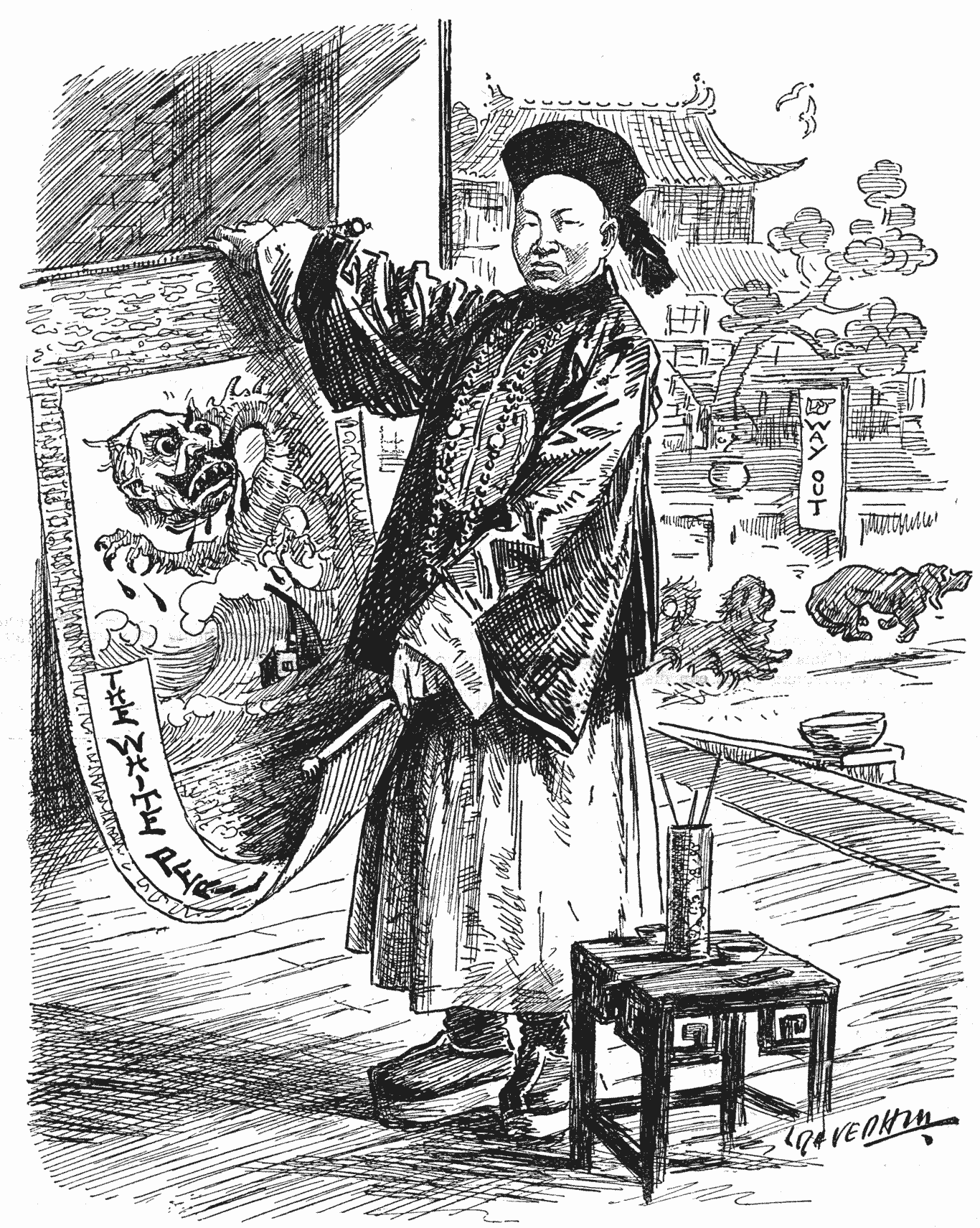

[China has threatened to break off relations with the German Government on account of its barbarity. It will be recalled that the KAISER once designed an allegorical picture entitled "The Yellow Peril."]

Grocer. "A LITTLE SUGAR WITH MY TART, PLEASE."

Waitress (late grocer's assistant). "CERTAINLY, SIR, IF YOU WILL ALSO TAKE MUSTARD, PEPPER, SALT, YORKSHIRE RELISH AND SALAD DRESSING."

It was 2 A.M. The mosquitoes were singing their nightly chorus, and the situation reports were coming in from the battalions in the line. With his hair sizzling in the flame of the candle, the Brigade Orderly Officer who was on duty for the night tried to decipher the feathery scrawl on the pink form.

"Situation normal A-A-A wind moderate N.E.," it read.

"Great Scott!" said the O.O. "North-East!" (Hun gas waits upon a wind with East in it). "Give me the message book."

Laboriously he wrote out warnings to the battalions and machine gun sections, etc., under the Brigade's control. Then he turned to the next message.

"Situation normal A-A-A wind light S.W."

"South-West?" said the O.O. blankly, viewing his now useless handiwork. "Which way is the wind then?"

The orderly went out to see, and returned presently with a moistened forefinger and the information that it was "blowing acrossways, leastways it seemed like it." The O.O. got out of his little wire bed, searched in his pyjamas for the North Star, and, finally deciding that if there was any wind at all (which was doubtful) it was due South, reported it as such. The responsibility incurred kept him awake for some time, but when the Brigade on the right flank reported a totally different wind he concluded there must be a whirlwind in the line, and, putting up a barrage of bad language, went to sleep.

In due course the matter came to the ears of the Staff Captain, who broached the subject at breakfast as the General was probing his second poached egg.

"This," said the General, who is rather given to the vernacular, "is the limit. A North-South-East-West report is preposterous. Something must be done. Haven't we got a weather-vane of our own? Pass the marmalade, will you?"

Four people reached hastily for the delicacy, and the O.O. feeling out of it passed the milk for no reason. (Generals really get a very good time. People have been known to pass things to them unasked.)

"What about those two vanes in our last headquarters, Sir?" said the Staff Captain brightly—he is very bright and bird-like in the mornings—"the ones the padre thought were Russian fire-guards. Can't we get them? They aren't ours, but then they aren't anybody's—they've been there a year, the old woman told me."

"Where's the Orderly Officer?" (He was there with a mouthful of toast.) "Take the mess limber and fetch 'em back if the Heavy Group Artillery will let you—they're in there now, aren't they?"

"And if you're g-going into the town g-get some fish for dinner," said the Brigade Major; "everlasting ration beef makes my s-stammer worse."

"Why?" said the General.

"Indigestion—nerves, Sir; I can hardly talk over the telephone at all after dinner."

"Good heavens!" said the General; "bring a turbot."

"Fish!" said the B.M. at dinner. "Bong!"

"I brought the vanes, Sir."

"Have any trouble?"

[pg 137]"No, Sir. I saw the A.D.C., and said we had 'left them behind,' which was true, you know, Sir." (The O.O. for once felt himself the centre of interest and desired to improve the occasion). "We did 'leave them behind,' so it wasn't a lie exactly ..."

"I don't care if it was," said the General; "you've got 'em, that's the main thing."

"Where will you have one put, Sir?"

"In the fields," said the B.M.

"Not too low," said the Captain.

"Or too high," said Signals.

"Or too far away," said the attached officer.

"Well, now you know," said the General, "pass the chutney."

They all passed it as well as several other things until he was thoroughly dug-in.

"Another N.S.E.W. report, Sir," said the Staff Captain next morning.

"——!" said the General. (I think I mentioned his partiality for the vernacular). "Where's our vane?"

"It's up, Sir," said the O.O., shining proudly again, "and I—"

"We'll have' a look at it," and out they all went—General, Brigade Major (enunciating pedantically after a fish breakfast), Staff Captain (bright and birdlike), and the O.O. It was a brilliant spectacle.

"North is—there!" said the General in his best field-day manner, "and this is pointing—due East!" He touched the vane gently. It did not budge. He touched it again. A cold sweat broke out on the forehead of the O.O.

"Paralysed," said the B.M.

"Give it a 'stand-east,' Sir," said the Staff Captain.

"It's stiff!" said the General; "wants-oil" (pause); "wants oil!" and the O.O. slid away, returning at once with oil (salad, bottle, one).

"Now pour it over the top—top, boy, top!"

A flood sprayed over the top flange, and the B.M. searched hastily for a handkerchief.

"Making a salad of you?" said the General. "Ha! ha!"

The B.M. smiled a smile (sickly, one).

"That's better!" The General spun it round. "What's it say now? East!"

"Better wait," said the B.M., "it'll change its mind in a minute."

"It's going!" cried the General excitedly. "There! Well, I'm—West!"

"The padre was right—it must be a fireguard, after all," said the Staff Captain.

"Or a s-sundial," muttered the B.M.

I believe the meteorological report was finally entered as: "Wind light to moderate (to strong), varying from East to West (via North and South)."

"Of course," said the General kindly to the O.O., "it's not quite perpendicular, it's a bit too low; wants a stronger prop, wires are a bit slack, the vane itself wants looking to, and the whole thing is in rather a bad position, but otherwise it's all right—quite all right."

"Yes, Sir," said the O.O.

"And there's too much oil," added the General, as he moved off.

"There is," said the B.M., discovering [pg 138] another blob on his shiny boots, "and on m-me!"

The Staff were unaccountably late. The O.O. breakfasted alone. For three days he had been the despair of the small and perspiring body of pioneers, who towards the end had fled at the mere sight of him. But at last the vane was working.

"Well," said the General when he came in, "how's the wind, expert?"

"N.N.E.," said the O.O. proudly. (It was the first thing he had done since he came on the Brigade three weeks before, and he was pleased at the interest the Staff had taken in his little achievement.) "I've had the pioneers working on it, and we've got it up another four feet, Sir, tightened the pole, and wired it on to the supports on every side. It's quite perpendicular now. I've marked out the points of the compass on it, and fixed up a little arrangement for gauging the strength of the wind—that flap thing, you know, Sir—"

"Yes, yes," said the General, who seemed to have lost his first keenness, "I'm glad it's working all right. By the way, we shall be moving from here to-morrow; the division's going back."

The O.O. drained the teapot in silence, and was glad it was strong and bitter.

The Major (sings). "AND WE DIDN'T CARE A BUTTON IF THE ODDS WERE ON THE FOE TEN—TWENTY—THIRTY—FORTY—"

Colonel (roused from surreptitious snooze). "AS YOU WERE!—NUMBER!"

Notice on a railway bookstall:—

"MEN AROUND THE KAISER.

MUCH REDUCED."

"On the pier a man was arrested who declared excitedly that he was Frederick Hohenzollern, the Kaiser's nephew, but he appeared quite harmless."—Daily News.

Obviously an impostor.

"The khaki-clad boys were as merry as a party of undergraduates celebrating some joyous event at the college tuck-shop."—Yorkshire Herald.

What memories of the Junior Common Room are recalled by this artless phrase.

"The Lyman M. Law was stopped by a gunshot fired by a submarine, which boarded the American boat, took the names of all on board, and then authorised the continuation of the voyage."—Evening News.

Experiences of Mr. GERARD'S party:—

"Our first surprise on reaching Paris was to find taxi-cabs, and taxi-cubs with pneumatic tyres."—Scots Paper.

We suggest that our M.F.H.'s should import a few of these in time for next season's cubbing. They give an excellent run for the money—a mile for eightpence or so.

What is Master WINSTON doing?

What new paths is he pursuing?

What strange broth can he be brewing?

Is he painting, by commission,

Portraits of the Coalition

For the R.A. exhibition?

Is he Jacky-obin or anti?

Is he likely to "go Fanti,"

Or becoming shrewd and canty?

Is he in disguise at Kovel,

Living in a moujik's hovel,

Making a tremendous novel?

Does he run a photo-play show?

Or in sæva indignatio

Is he writing for HORATIO?

Fired by the divine afflatus

Does he weekly lacerate us,

Like a Juvenal renatus?

As the great financial purist,

Will he smite the sinecurist

Or emerge as a Futurist?

Is he regularly sending

HAIG and BEATTY screeds unending,

Good advice with censure blending?

Is he ploughing, is he hoeing?

Is he planting beet, or going

In for early 'tato-growing?

Is he writing verse or prosing,

Or intent upon disclosing

Gifts for musical composing?

Is he lecturing to flappers?

Is he tunnelling with sappers?

Has he joined the U-boat trappers?

Or, to petrify recorders

Of events within our borders,

Has he taken Holy Orders?

Is he well or ill or middling?

Is he fighting, is he fiddling?—

He can't only be thumb-twiddling.

These are merely dim surmises,

But experience advises

Us to look for weird surprises,

Somersaults, and strange disguises.

Thus we summed the situation

When Sir HEDWORTH MEUX' oration

Brought about a transformation.

Lo! the Blenheim Boanerges

On a sudden re-emerges

And, to calm the naval gurges,

FISHER'S restoration urges.

"At an interval in the evening some carols were sung by members of our G.F.S., and a collection was taken on behalf of a fund for providing Huns for our soldiers."—Parish Magazine.

No one can answer the question, and I have not the pluck—being a law-abiding citizen—to try for myself. But I do so want to know. I ask everyone. I ask my partners at dinner (when any dinner comes my way). I ask casual acquaintances. I would ask the officials themselves, only they are so preoccupied. But the words certainly set up a very engrossing problem, and upon this problem many minor problems depend, clustering round it like chickens round the maternal hen. But I should be quite content with an answer only to the hen; the rest could wait. Yet there is an inter-dependence between them that cannot be overlooked. For example, did someone once do it and meet with such a calamity that everyone else had to be warned? Or is it merely that the authorities dislike us to be comfy? Or is it thought that the public might get so much attracted by the habit as to convert the place into a house where a dance is in progress? I wish I knew these things.

Will not some Member ask for information in the House, and then—arising out of this question—get all the other subsidiary facts? We are told so many things that don't matter, such as the enormous number of Ministers in the new Government, which was formed, if I remember rightly, as a protest against too large a Cabinet; such as the colossal genius of each and every performer in Mr. COCHRANE'S theatrical companies; such as the best place in Oxford Street to contract the shopping habit; such as the breaks made day by day all through the War by billiard champions; such as the departure of Mr. G.B. SHAW on his bewildering and, one would think, totally unnecessary visit to the Front and his return from that experience; such as—but enough. I am told by the informative Press all these and more things, but no one tells me the one thing I want to know.

Perhaps YOU can.

I want to know why we may not sit on the Tube moving staircases, and I want to know what would happen if we did.

"FOR SALE.—Pure Bred Irish Terrier Dog, right thing to wear now. Seamless, comfortable. All Wool."—Bedford Daily Circular.

"Bread embroideries encircle the figure."—Glasgow Citizen.

An appropriate adornment for the bread basket, no doubt, but too extravagant in these times.

This scheme of keeping rabbits

To fatten them as food

Breaks up the kindly habits

Acquired in babyhood;

For we, as youthful scions,

Were taught to love the dears

And bring them dandelions

And lift them by the ears.

We learned how each new litter

That came to Flip or Fan

Grew finer and grew fitter

With tea-leaves in the bran;

We learned which stalks were milky

And which were merely tough,

What grass was good for Silky

And what was good for Fluff.

Such moral mild up-bringing

Now makes me much distressed

When little necks need wringing

And little paws protest,

Lest wraiths from empty hutches

Should haunt me, hung in pairs,

And ghosts—'tis here it touches—

Of happy Belgian hares.

However, with my morals

I manfully shall cope,

And back my country's quarrels,

But none the less I hope

Before poor Bunny's taken

As stuff for knife and fork

The hedge-hog will be bacon,

The guinea-pig be pork.

W.H.O.

The Metropolitan Commissioner of Police having decided to sanction women taxicab drivers, we understand that all applicants for licences will be required to pass a severe examination in "knowledge of London." As, however, this will be concerned mainly with localities and quickest routes, we venture to suggest to the examiners a few supplementary questions of a more general character:—

(I.) How far should a cab-wheel revolving at fifteen miles an hour, be able to fling a pint of London mud?

(II.) Has a pedestrian any right to cross a road? and, if so, how much?

(III.) With three toots of an ordinary motor-horn indicate the following:—(a) contempt, (b) rage, (c) homicidal mania.

(IV.) Under what circumstances, if any, should the words "Thank you" be employed?

(V.) Having been engaged at 11.35 P.M. to drive an elderly gentleman, wearing a fur-coat, to Golder's Green, you are tendered the legal fare plus twopence. Express, within ladylike limits, your appreciation of this generosity.

(VI.) On subsequently discovering the same gentleman to be a member of the Petrol Control Committee, revise your answer accordingly.

(VII.) Sketch, within ten sheets of MS., your idea of a becoming and serviceable uniform for a lady-driver.

(VIII.) Who said, and in what connection—

"The hand that stops the traffic rules the world"?

"This flag shall not be lowered at the bidding of an alien"?

(IX.) At the top of St. James's Street you are hailed simultaneously by two spinster ladies with hand luggage, wishing to be driven to Euston, and by a single unencumbered gentleman whose destination is the Savoy Grill. Well?

(X.) At what hour do performances at the London theatres end, and which do you consider the best places of concealment in which to secrete yourself at that time?

(XI.) What would be your correct procedure on receiving a simple direction to "The Palace" from—

(a) The PRIME MINISTER?

(b) The Bishop of LONDON?

(c) Any Second-Lieutenant?

Old Lady (buying records to send to France—to assistant in Gramophone Department).

"IF THAT ONE IS THE SONG CALLED, 'THERE'S A SHIP THAT'S BOUND FOR BLIGHTY,' I'LL TAKE IT. BUT WILL YOU FIRST LET ME KNOW IF IT CONTAINS ANY INFORMATION WHICH COULD BE OF ADVANTAGE TO THE ENEMY?"

"SIR EDWARD CARSON ON THE ADMIRALTY'S NEW FIGHTING POLICY.

'IT CAN AND WILL BE DEFEATED.'"—Headlines in "The Daily Chronicle."

From an official circular relating to the British Industries Fair:—

"Information regarding the best means of reaching the Fair from all parts of London will be obtainable at the Fair, but will not be available before the opening day."

You must get there first, if you want to be told how to get there.

The Vicar (to Mrs. Bloggs, who has been describing the insulting behaviour of the lady next door). "WELL, WELL, IT MUST BE MOST UNPLEASANT BEING SHOUTED AT OVER THE WALL, BUT I SUPPOSE THE BEST THING IS TO TAKE NO NOTICE."

Mrs. Bloggs. "THAT'S WHAT I SHOULD LIKE TO DO, SIR. BUT O' COURSE I 'AS TO GIVE 'ER A ANSWER BACK NOW AND AGAIN—JUST TO KEEP THE PEACE, LIKE."

When JOOLIUS CÆSAR took 'is guns along the pavvy road

An' strafed the bloomin' 'eathens on the Rhine,

The men 'oo did 'is dirty work an' bore the 'eavy load

Was the men 'ose job did correspond to mine.

When NAP. dug in 'is swossung-kangs be'ind the ugly Fosse

And made the Prooshians sweat their souls with fear,

The men 'oo 'elped 'im most of all to slip it well across

Was the men with actin' rank o' bombardier.

Oh, the Colonel strafes the Old Man, an' 'e strafes the Capting too,

Then to the subs the 'eavy language flows;

They comes an' calls their Numbers One an inefficient crew

An' down it comes to junior N.C.O.'s;

An' then the B.S.M. chips in an' gives 'em 'oly 'ell,

An' the full edition's poured into the ear

Of the man that's got to be ubeek (an' you be—blest as well),

The man with actin' rank o' bombardier.

Or, if there's nothin' doin' of a winter afternoon,

The Old Man's at 'eadquarters 'avin' tea,

The section subs is feedin' up with oysters in Bethoon,

The Capting's snorin' out at the O.P.;

The Sergeant-Major's cleaned 'is teeth an' gone a prommynard,

The N.C.O.s is somewhere drinkin' beer,

An' the man they've left to work an' drill an' grouse an' mount the guard

Is of course your 'umble actin' bombardier.

Oh, I'm the man that takes fatigues for bringin' stores at night,

Conductin' G.S. wagons in the snow,

An' I'm the man that scrounges round to keep the 'ome fires bright

("An' don't you bloomin' well be pinched, you know");

An' I'm the man that lashes F.P.1.'s up to the gun,

An' acts the nursemaid 'alf the ruddy day;

An' fifty other little jobs that ain't exactly fun

Accompany one stripe (without the pay).

But no, we never grouses in the Roy'l Artillerie,

Of cheerful things to think there's quite a lot;

Old Sergeant Blobbs is goin' 'ome the end of Februree

To do instructin' stunts at Aldershot;

The S.M.'s recommended ('Eavens!) for commissioned rank,

An' little changes means a step up 'ere,

So if I keep me temper an' go easy with vang blank,

I'll soon drop "actin'" off the "bombardier."

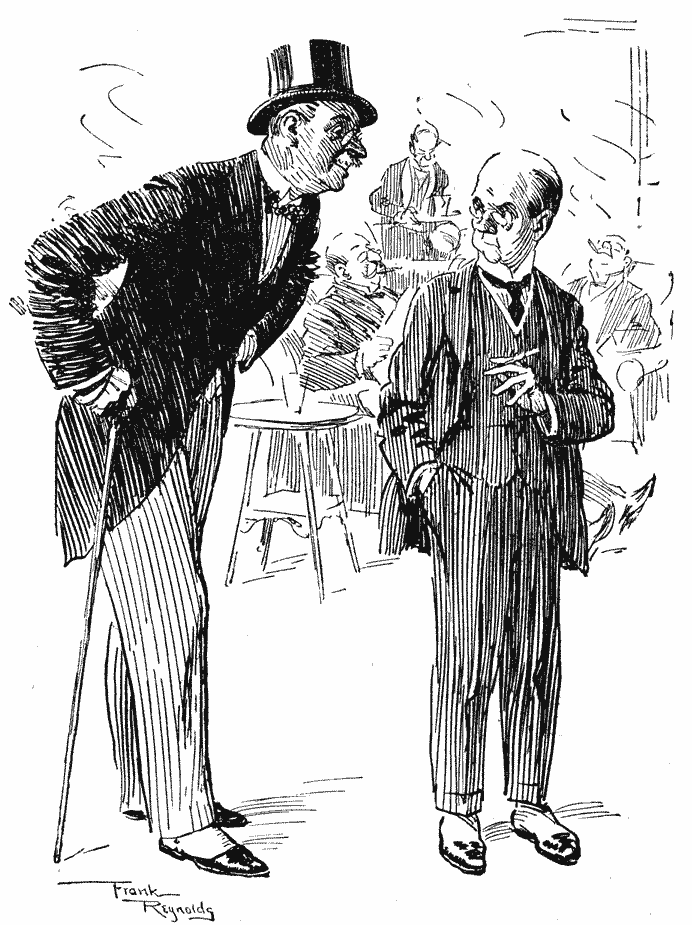

| MR. WINSTON CHURCHILL (patting Sir EDWARD CARSON on the back) | } "HE'S BEEN TALKING SENSE." |

| MR. HERBERT SAMUEL (patting Mr. BONAR LAW on the back) |

Monday, February 19th.—The CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER announced that the "new money" subscribed for the War Loan amounted to at least seven hundred millions. Being a modest man he refrained from saying, "A loan, I did it," though it was largely due to his faith in the generosity and good sense of his fellow-citizens that the rate of interest was not more onerous to the State.

Mr. LYNCH thinks it would be a good idea if Ireland were specially represented at the Peace Conference, in order that her delegates might assert her right to self-government. I dare say, if pressed, he would be prepared to nominate at least one of her representatives. Having regard to the Nationalist attitude towards military service Mr. BALFOUR might have retorted that only belligerents would be represented at the Peace Conference, but he contented himself with a simple negative.

There is an erroneous impression that Mr. LLOYD GEORGE sits in his private room scheming out new Departments and murmuring like the gentleman in the advertisement of the elastic bookcase, "How beautifully it grows!" Up to the present, however, there are only thirty-three actual Ministers of the Crown, not counting such small fry as Under-Secretaries, and their salaries merely amount to the trifle of £133,500. It is pleasant to learn that a branch of the Shipping Controller's department is appropriately housed in the Lake Dwellings in St. James's Park; and, in view of Mr. KING'S objection that the members of the Secret Service with whom he has come into contact make no sort of secret about their business (one pictures them confiding in this gentleman), it is expected that the Board of Works will shortly commandeer a strip of Tube Railway to conceal them in.

Tuesday, February 20th.—In one respect the two representatives of the War Office in the House of Commons are singularly alike. When answering their daily catechism both wear spectacles—Mr. FORSTER an ordinary gold-rimmed pair, Mr. MACPHERSON the fearsome tortoise-shell variety which gives an air of antiquity to the most youthful countenance; and each, when he has to answer an awkward "supplementary," begins by carefully taking off his glasses and so giving himself an extra moment or two to frame a telling reply.

This afternoon Mr. MACPHERSON'S spectacles were on and off half-a-dozen times as he withstood an assault directed from various quarters against the refusal of the War Office to admit the profession of "manipulative surgery" to the Army Medical Service. In vain he was informed of wonderful cures effected by this means on generals and admirals, and even members of the Government; in vain Mr. LYNCH sought from him an admission that the life of one private soldier was more valuable than that of the two Front Benches put together. All these attempts at manipulative surgery quite failed to reduce Mr. MACPHERSON'S obstinate stiff neck; and at last the SPEAKER had to intervene to stop the treatment.

The persistence with which a little knot of Members below the Gangway advances the proposition that all Germany is longing to make an honourable peace, and that it is only the insatiate ambition of the Allies which stands in the way, would be pathetic if it were not mischievous. Mr. PONSONBY, [pg 143] Mr. TREVELYAN, and Mr. SNOWDEN once more argued this hopeless case with a good deal of varied ability. A small house listened politely, but was more impressed by a masterly exposé of the facts by Mr. RONALD M'NEILL, and an Imperialist slogan by Sir HAMAR GREENWOOD; while later in the debate Mr. BONAR LAW restated the national aims in the War with a cogency that drew from Mr. SAMUEL a generous pledge "on behalf of those who sit opposite the Government" to give Ministers their whole-hearted support.

Wednesday, February 21st.—The House learned with satisfaction that crews of our river gun-boats in Mesopotamia are to get their hard-lying money; and when the authors of the Turkish communiqués hear of it they are expected to put in a similar claim.

Lord FISHER was in his customary place over the Clock—his friends all tell us that he is superior to Time; Lord BERESFORD was at a suitable—I had almost said respectful—distance from him in the Peers' Gallery; and conspicuous among the Distinguished Strangers was Sir JOHN JELLICOE. They and all of us listened intently while for over an hour Sir EDWARD CARSON, now as much at home on the quarter-deck as ever he was at quarter sessions, discoursed eloquently and frankly on the wonderful and never-ending work of the Senior Service.

He did not underestimate the danger of the submarines, or pretend that the Admiralty had yet discovered any sovran remedy for their attacks. Nor could he say—for reasons which seemed to satisfy the House—how many of them had already been captured or sunk. But he told us enough to convict Admiral VON CAPELLE, who was at that moment declaring that not a single U-boat had been lost since the opening of the new campaign, of being either singularly misinformed or highly imaginative.

Thursday, February 22nd.—A strange sympathy seems to exist between the SPEAKER and Mr. GINNELL. Each, I fancy, has a soft spot somewhere. Mr. LOWTHER'S is in his heart, and makes him go out of his way to help the wayward Member for North Westmeath. Mr. GINNELL, whose soft spot seems to be higher up, wanted to show that he did not approve of Mr. MACPHERSON, and called him an impertinent Minister. Ordered to withdraw the expression, he substituted "impudent." That would not do either, and there seemed danger of a deadlock and another expulsion until Mr. LOWTHER suggested that "incorrect" was a Parliamentary epithet which might suit the hon. Member's purpose. Mr. GINNELL handsomely accepted this variation in the spirit in which it was offered.

Sir GEORGE CAVE is the Ministerial maid-of-all-work. Whenever there is a disagreeable or awkward measure to introduce it falls to the Quite-at-Home Secretary, if I may borrow an expression coined by my friend, TOBY, M.P., for one of Sir GEORGE'S predecessors. So judiciously did he accentuate the good points and soften the possible asperities of the National Service Bill that even Sir CHARLES HOBHOUSE, who had come to condemn, remained to bless.

Friday, February 23rd.—Owing to a variety of causes, we are short of tonnage, and unless we manage to grow more and consume less we shall before very long be within reach of the gaunt finger of Famine. That was the burden of the PRIME MINISTER'S appeal to the Nation. The farmer is to have a guaranteed minimum price for his produce, the agricultural labourer is to be raised to comparative affluence by a minimum wage of 25s. a week, and the rest of us are to go without most of our imported luxuries and a good many necessities. So impressed were Members by the gloominess of the prospect that the moment the speech was over they rushed out to secure what they felt might be their last really substantial luncheon, and Mr. DAVID MASON, who had nobly essayed to fill the breach caused by Mr. ASQUITH'S absence, was soon talking to empty benches.

The Big 'Un. "MY DEAR FELLOW! IS IT REALLY TRUE THAT YOU HAVE TO JOIN UP?"

The Little 'Un. "YES; BUT DON'T LET IT GET ABOUT. YOU SEE, THE IDEA IS TO SPRING IT ON THE GERMANS, AS IT WERE, IN MARCH."

ACROBAT, HAVING BEEN OFFICIALLY INFORMED THAT HE BELONGS TO ONE OF THE NON-ESSENTIAL PROFESSIONS, DETERMINES NEVERTHELESS TO DEVOTE HIS TALENT TO THE CAUSE OF HIS SUFFERING FELLOW-COUNTRYMEN.

We all know the man with a grievance and avoid him. But there is another man with a grievance whom I rather like, and this is his story. I must, of course, let him tell it in the first-person-singular, because otherwise what is the use of having a grievance at all? The first-person-singular narrative form is the grievance's compensation. Listen.

"I am an old Oxonian who joined the Royal Naval Division as an ordinary seaman not long after the outbreak of the War, and being perhaps not too physically vigorous and having a certain rhetorical gift, developed at the Union, I was told off, after some months' training, to take part in a recruiting campaign. We pursued the usual tactics. First a trumpeter awakened the neighbourhood, very much as Mr. HAWTREY is aroused from his coma in his delightful new play, and then the people drew round. One by one we mounted whatever rostrum there was—a drinking fountain, say—and spoke our little piece, urging the claims of country.

"As a rule the audience was either errand-boys, girls or old men; but we did our best.

"Sometimes, however, there would be an evening meeting in a public building, and then the proceedings were more formal and pretentious. The trumpeter disappeared and a chairman would open the ball. The occasion of which I am thinking was one of these meetings in the East End, where the Chairman was a local tradesman. He said that this was a war for liberty and that England could never sheathe the sword until Belgium was free; he told the audience how many of his relations were fighting; and then he made way for our gallant boys in blue who were to address the company.

"Well, we addressed the company, I by no means the least of the orators, and then the Chairman wound up the meeting. He said how much he had enjoyed the speeches and how much he hoped that they would bear good fruit; and indeed he felt confident of that, because 'we 'ere in the East End are plain straight-forward folk, who like plain straight-forward talk, and we would rather listen to the honest 'omely sailors who 'ave been talking to us this evening, than any fine Oxford gentleman.'"

That is the story of my friend with a grievance. And yet, now I come to think about it again, and his manner of telling it, I'm not sure I ought not rather to call him a man with a triumph.

"Farmer's Daughter wanted, to learn daughter Cheddar cheesemaking for 1 month, from March 25th; 25 cows; treated as family."—Bristol Times and Mirror.

A little less than kin and more than kine.

The representatives of thirty leading American railways have agreed virtually to an embargo on eastern shipments of freight for export until the present congestion on the eastern sideboard is relieved."—Evening Standard.

This is all very well for the Americans, but what we are concerned about is the depletion of our own sideboard.

From an official advertisement in favour of tillage:—

"An acre of Oats will

feed for a week . . 100 people.

An acre of Potatoes . . 200 "

" " of Beef . . 8 " "— Irish Times.

We understand that Lord DEVONPORT accepts no responsibility for the last statement.

Father. "YOU'RE VERY BACKWARD. THERE'S NORMAN SMITHERS, THE SAME AGE AS YOU, AND HE'S TWO FORMS HIGHER. AREN'T YOU ASHAMED?"

Hopeful. "NO. HE CAN'T HELP IT—IT'S HEREDITARY."

A PARABLE OF GERMANY'S COLONIES.

Long ages ere the Age of Man,

While yet this earthly crust was thinnish,

The War of Might and Right began,

Proceeding swiftly to a finish;

And this provides in many ways

An object-lesson nowadays.

The Saurians, clad in coats of mail,

Shone with a most attractive lustre;

Strong claws, long limbs, a longer tail—

They pinned their faith to bulk and bluster;

They laid their eggs in every land

And hid them deftly in the sand.

The Mammals, small as yet and few,

Relying less on scales and muscles,

Developed diaphragms, and grew

Non-nucleated red corpuscles;

They walked more nimbly on their legs

And learnt the art of sucking eggs.

The Saurians, spoiling for a fight,

Went off in high explosive fashion;

They lashed themselves to left and right

Into a pre-historic passion;

The Mammals, on the other hand,

Ate all their eggs up in the sand.

Those precious eggs, a source of pride

On which the Saurian hopes depended,

Kept all their enemies supplied

With life by which their own was ended;

And where they fondly hoped to spread

The Mammals lived and throve instead.

And so the Saurians passed from view,

Leaving behind the faintest traces,

No longer bent on hacking through,

Though looking still for sunny places;

Dwarfed to a more convenient size

They spend their time in catching flies.

"To O.C. . . . From . . . Brigade. —— Corps requires services of an officer who can speak Italian fluently for four or five days."

"Under the auspices of the Women's Reform Club, a Ladies' Fancy Dress Ball will be held at the Residential Club, Main Street. No Gentlemen. No Wallflowers. Ladies may appear in mail attire."—Bulawayo Chronicle.

In their "knighties," so to speak?

"Bosley and district churchmen have thus a gaol set before them which it should be and, no doubt, will be their aim to reach as soon as possible."—Congleton Chronicle.

"A few minutes later, with his suit-case in one hand and his type-writer in the other, he let himself out at the front-door,"—Munsey's Magazine.

Another case of the Hidden Hand.

"Horse (vanner), thick set, 16 hands, 7 years, master 2 tons, reason sale, requires care when taken out of harness."—Birmingham Daily Mail.

Any horse might be excused for kicking up his heels on getting rid of a master of that weight.

"Furnished room wanted; preferable where chicken run."—Enfield Gazette.

Our landlady won't let us keep even a canary in ours.

"BARONY UNITED FREE CHURCH.—Special Lecture—'The Great War Novel, Mr. Bristling Sees it Through.'"—Glasgow Evening News.

Mr. WELLS ought to have thought of this.

"Francesca," I said, "what are you doing to help Lord DEVONPORT?"

"Lots of things," she said. "For one thing, we're living under his ration-scheme, and we're doing it pretty well, thank you."

"Yes, I know," I said; "I've heard you mention it once or twice. It seems to consist very largely of rissoles and that kind of food."

"Well," she said, "we must use up everything; and, besides, you'd soon get tired of beefsteak if I gave it to you every day."

"Tired of beefsteak?" I said. "Never. The toughest steak would always be a joy to me."

"I've come to the conclusion," she said, "that men really like their eatables tough."

"Yes, they want something they can bite into, you know."

"But you can't bite into our beefsteak, now can you?"

"Perhaps not," I said, "but you can't help feeling it's there, which is a great help when you're being rationed."

"That," she said, "may be all very well for a man, but women don't care for that feeling. They like their food light but stimulating."

"They do," I said, "and they prefer it all brought in on one tray and at irregular hours. Lord DEVONPORT'S scheme is to them a sort of wicked abundance. To a man it is—"

"Plenty and to spare," she said. "Why, you won't have to tighten your belt even by one hole. Now admit, if you hadn't known you were being rationed you'd never have found it out."

"I will admit," I said, "that if the privations we have suffered this last week in the matter of beefsteaks and that kind of food are the worst that can happen to us we shan't have much to complain of—but I should like a chop to-night instead of a rissole."

"You can call it a chop if you like, but it's going to be a cutlet."

"Well, anyhow," I said, "we don't seem to be doing as much as we might for Lord DEVONPORT."

"You're wrong," she said; "I'm keeping hens in the stable-yard."

"Hens? What do you know about hens?"

"For the matter of that, what do you?"

"That's not the question," I said, "but I'll answer it all the same. I know that most hens are called Buff Orpingtons, and that they never lay any eggs unless you put a china egg in their nest just to coax them along and rouse their ambition. Francesca, have you put a china egg where our Buff Orpingtons can see it?"

"Frederick is looking after these domestic details. He seems to think that if he goes to the hen-house every ten minutes or so the laying of eggs will be promoted. Won't you go round with him next time?"

"No," I said, "I've never seen a hen lay an egg yet, and I'm not going to begin at my time of life. Besides, I've already said they never lay eggs even when you don't watch them."

"Wrong again," she said. "We got one egg this morning."

"Francesca," I said, "this is exciting. Did the happy mother announce the event to the world in the usual way?"

"Yes, she screamed and cackled for about a quarter-of-an-hour, and Frederick came along and seized the subject of her rejoicing. You're going to have it to-night, boiled, instead of soup and fish."

"Isn't that splendid?" I said. "At this rate we shall soon be self-supporting, and then we can snap our fingers at Lord DEVONPORT."

"I never snap my fingers," she said. "No well-brought-up hen-keeper ever does. Besides, it's our duty to help the Government all we can, so that Lord DEVONPORT may have so much more to play with."

"Why should he want to play with it?" I said. "He doesn't strike me as being that kind of man at all."

"I daresay he plays in his off-hours."

"A man like that," I said, "hasn't any off-hours. He's chin-deep in his work."

"Anyhow," she said, "I should like him to know that we're pulling up the herbaceous border and planting it with potatoes, and that we've started keeping hens, and that we've already got one egg, and that when the time comes we shall not lack for chicken, roast or boiled."

"Francesca," I said, "how can you allude so flippantly to the tragedies which are inseparable from the possession of Buff Orpingtons? In the morning a young bird struts about in his pride, resolved to live his life fearlessly and to salute the dawn at any and every hour before the break of day. Then something happens: a gardener, a family man not naturally ruthless, comes upon the scene; there is a short but terrible struggle; a neck (not the gardener's) is wrung, and there is chicken for dinner."

"Don't move me," she said, "to tears, or I shall have to countermand your egg. Besides, I don't think I could ever make a real friend of a fowl. They've got such silly ways and their eyes are so beady."

"Their ways are not sillier nor are their eyes beadier than our Mrs. Burwell's, yet she is honoured as a pillar of propriety, while they—no matter; I hope the chicken when its moment comes will be tender and succulent."

"Hark!" said Francesca.

"Yes," I said, "another egg has come into the world, and there's Frederick rushing round like a mad thing with a basket, to find himself once more too late. Never mind," I said, "I can have two boiled eggs to-night with my chop,—I mean cutlet."

"No," she said.

"Yes," I said, "and you can have all the rissoles."

I remember a day when I felt quite tall

Because of a gift of five whole shillings;

I was Johnson major then, I recall,

And didn't I swank and put on frillings!

Well, we know that children are parents of men;

And, now that I'm getting an ancient stager,

Here am I pleased with a crown again,

And signing myself as Johnson, Major.

"Experienced General disengaged 1st March, one lady; no washing; would take England."—Irish Times.

The advertiser should wire to KAISER, Potsdam.

"During the night an enemy raiding party in the neighbourhood of Gueudecourt was driven off by our baggage before reaching our line."—Continental Daily Mail.

There is no end to our warlike inventions. First the Tanks, and now the Trunks.

"The Tigris, immediately above Kut, runs South-East for about four miles. Then there is a sharp bend, and its course is almost due South for about the same distance. Then against the stream it goes due North for about the same distance."—Glasgow Citizen.

With the river behaving in this unnatural fashion General MAUDE deserves all the greater credit for his success.

She (referring to host). "YOU KNOW, THERE'S SOMETHING RATHER NICE ABOUT MR. THOMKINS-SMITH."

He. "YES—I THINK IT MUST BE HIS WIFE."

(By Mr. Punch's Staff of Learned Clerks.)

War and the Future (CASSELL), by Mr. H.G. WELLS, is not a sustained thesis but just jets of comment and flashes of epigram about the War as he has seen it on the French, Italian and British fronts, and has thought about it in peaceful Essex. A characteristic opening chapter, "The Passing of the Effigy," suggests that "the Kaiser is perhaps the last of that long series of crowned and cloaked and semi-divine personages which has included Caesar and Alexander and Napoleon the First—and Third. In the light of the new time we see the emperor-god for the guy he is." Generalissimo JOFFRE, on the other hand, he found to be a decent most capable man, without fuss and flummery, doing a distasteful job of work singularly well. There is some particularly interesting matter about aeroplane work, and the writer betrays a keen distress lest the cavalry notions of the soldiers of the old school should make them put their trust in the horsemen rather than the airmen in the break-through. As for "tanks," he offers the alternative of organised world control or a new warfare of mammoth landships, to which the devastation of this War will be merely sketchy; but I doubt if he quite makes his point here. And finally this swift-dreaming thinker proclaims a vision which he has seen of a new world-wide interrelated republicanism founded on a recognition of the over-lordship of God.... You put the book down feeling you have had a long, desultory and intimate conversation with a very interesting fellow-traveller.

Really, if Mr. ROBERT HICHENS continues his present spendthrift course, whatever Board controls the consumption of paper will have to put him on half rations. I believe that his literary health would benefit enormously by such a régime. This was my first thought in contemplating the almost six hundred pages of In the Wilderness (METHUEN), and it persists, strengthened now that I have turned the last, of them. Here is a direct and moving tragedy of three lives, much of the appeal of which is lost in a fog of superfluous words. Of its theme I will tell you only this, that it shows the contrasting loves, material and physical, of two widely divergent types of womanhood. Probably human nature, rather than Mr. HICHENS, should be blamed for the fact that the unmoral Cynthia is many times more interesting than the virtuous but slightly fatiguing Rosamund. The former is indeed far the most vital character in the tale, a figure none the less sinister for its clever touch of austerity. Possibly, however, her success is to some extent due to contrast; for certainly both Rosamund and Dion, the husband whom she alienated by her unforgiving nature, embody all the worst characteristics of Mr. HICHEN'S creations. Perhaps you know what I mean. Chiefly it is a matter of super-sensibility to surroundings, which renders them so fluid that often the scenery seems to push them about. It is this, coupled with the author's own lingering pleasure in a romantic setting, that delays the conflict, which is the real motive of the book, over long. But once this has come to grips the interest and the skill of it will hold you a willing captive to Mr. HICHENS at his best.

Much as I have enjoyed some previous work by Baroness VON HUTTEN I am glad to say that I consider Magpie (HUTCHINSON) her best yet. It is indeed a long time since I read a happier or more holding story. The title is a punning one, as the heroine's name is really Margaret Pye, but I am more than willing to overlook this for the sake of the pleasantly-drawn young woman to whom it refers and the general interest of the tale. Briefly, this has two movements, one forward, which deals with the evolution of Mag from a fat, rather down-at-heel little carrier of washing into the charming young lady of the cover; the other retrospective, and concerned with the mystery of a wonderful artist who has disappeared before the story opens. I have no idea of clearing up, or even further indicating, this problem to you. But I will say that the secret is so adroitly kept that the perfect orgy of elucidation in the final chapter left me a little breathless. Of course the whole thing is a fairy tale, with a baker's dozen of glaring improbabilities; but I am much mistaken if you will enjoy it the less for that. A quaint personal touch, which (to anyone who does not recall the cast of Pinkie and the Fairies on its revival) might well seem an impertinence, produced in me the comfortable glow of superiority that rewards the well-informed. But I can assure Baroness VON HUTTEN that she is all wrong about the acting of that particular part.

As it is not Mr. Punch's habit to admit reviews of periodical publications, I ought to say that the case of The New Europe (CONSTABLE), whose first completed volume lies before me, is exceptional. In thirty years' experience of journalism I never remember a paper containing so much "meat"—some of it pretty strong meat, too—in proportion to its size. In hardly a single week since its first issue in October last have I failed to find between its tangerine-coloured covers some article giving me information that I did not know before, or furnishing a fresh view of something with which I thought myself familiar. And I take it there are many other writers—and even, perhaps, some statesmen—who have enjoyed the same experience. Dr. SETON-WATSON and the accomplished collaborators who march under his orange oriflamme may not always convince us (I am not sure, for example, that Austria est delenda may prove the only or the best prescription for bringing freedom to the Jugo-Slavs of South-Eastern Europe), but they always furnish the reader with the facts enabling him to test their conclusions; and that in these times is a great merit. My own feeling is that if they had begun their concerted labours a few years earlier the War might never have happened; or at least we should have gone into it with a much more accurate notion of the real aims of the Central Powers, and a much better chance of quickly defeating them. The tragedies of Serbia and Roumania would almost certainly have been averted.

I am unable to hold out much prospect that you will find Frailty (CASSELL) a specially enlivening book. The scope of Miss OLIVE WADSLEY'S story, sufficiently indicated by its title, does not admit of humorous relief. But it is both vigorous and vital. Certainly it seemed hard luck on Charles Ley that, after heroically curing himself of the drug habit, he should marry the girl of his choice only to find her a victim to strong drink. But of course, had this not happened, the "punch" of Miss WADSLEY'S tale would have been weakened by half. Do not, however, be alarmed; the author knows when to stop, and confines her awful examples to these two, thereby avoiding the error of Mrs. HENRY WOOD, who (you may recall) plunged the entire cast of Danesbury House into a flood of alcohol. Not that Miss WADSLEY herself lacks for courage; she can rise unusually to the demands of a situation, and I have seldom read chapters more moving of their kind than those that depict the gradual conquest of Charles by the cocaine fiend, and his subsequent struggle back to freedom. Here the "strong" writing seemed to me both natural and in place; ever so much more convincing therefore than when employed upon the love scenes. I have my doubts whether, even in this age of what I might call the trampling suitor, anyone was over quite so heavy-booted over the affair as was Charles when he carried off his chosen mate from a small-and-early in Grosvenor Square. Fortunately the other parts of the story are less melodramatic, and make it emphatically a book not to be missed.

Happy is the reviewer with a book which gives him so much delightful information that he tries to ration himself to so many pages per day. This is what I resolved to do with In the Northern Mists (HODDER AND STOUGHTON); but I could not keep to my resolution, so attractive was the fare. These sketches are the work of a Grand Fleet Chaplain, and are packed with wisdom from all the ages. If you haven't the luck to be a sailor you will learn a lot from this admirable theologian about the men and methods and the spirit of the Grand Fleet. His book fills me with pride; yet I dare not express it for fear of offending the notorious modesty of the senior service. So shy indeed is our Fleet of praise that I feel my apologies are due to their Chaplain for my perfectly honest commendation of his book. But he seems human enough to pardon the more venial sins.

"YOUR LITTLE DOG DOESN'T SEEM TO MIND THE WEATHER. I SUPPOSE HIS COAT KEEPS HIM WARM."

"I DON'T THINK IT'S THAT ALTOGETHER. YOU SEE, HE HAS RUM-AND-MILK WITH HIS CUTLET EVERY MORNING BEFORE HE GOES OUT."

"Peterborough's youngest investor was Herbert Trollope Gill, barely three months old, who subscribed the whole of his life's savings. He arrived at the bank with his mother, and there was poured out before the astonished gaze of the officials four hundred threepenny pieces."—Weekly Dispatch.

We congratulate HERBERT on his patriotism and regret that it should have compelled him to go into liquidation.