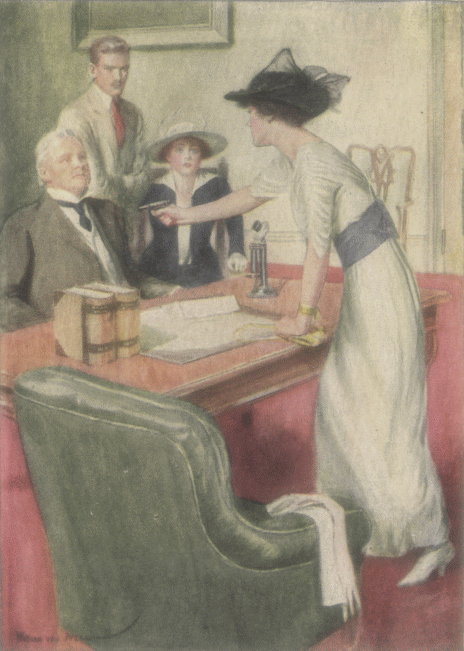

She Threw Up Her Hand, And A Nasty Little Automatic Was Covering The Secretary’s Heart. Drawn by William Van Dresser. (Chapter 24.)

AUTHOR OF

The Woman in Question, The Man In Evening Clothes, etc.

Frontispiece By William Van Dresser

She Threw Up Her Hand, And A Nasty Little Automatic Was Covering The Secretary’s Heart. Drawn by William Van Dresser. (Chapter 24.)

A.L. Burt Company

Publishers New York

Published by arrangement with G.P. Putnam’s Sons

1916

“A beautiful woman is never especially clever,” Rochester remarked.

Harleston blew a smoke ring at the big drop-light on the table and watched it swirl under the cardinal shade.

“The cleverest woman I know is also the most beautiful,” he replied. “Yes, I can name her offhand. She has all the finesse of her sex, together with the reasoning mind; she is surpassingly good to look at, and knows how to use her looks to obtain her end; as the occasion demands, she can be as cold as steel or warm as a summer’s night; she—”

“How are her morals?” Rochester interrupted.

“Morals or the want of them do not, I take it, enter into the question,” Harleston responded. “Cleverness is quite apart from morals.”

“You have not named the wonderful one,” Clarke reminded him.

“And I won’t now. Rochester’s impertinent question forbids introducing her to this company. Moreover,” as he drew out his watch, “it is half-after-twelve of a fine spring night, and, unless we wish to be turned out of the Club, we would better be going homeward or elsewhere. Who’s for a walk up the avenue?”

“I am—as far as Dupont Circle,” said Clarke.

“All hands?” Harleston inquired.

“It’s too late for exercise,” Rochester declined; “and our way lies athwart your path.”

“I don’t think you make good company, anyway, with your questions and your athwarts,” Harleston retorted amiably, as Clarke and he moved off.

“Who is your clever woman?” asked Clarke.

“Curious?” Harleston smiled.

“Naturally—it’s not in you to give praise undeserved.”

“I’m not sure it is praise, Clarke; it depends on one’s point of view. However, the lady in question bears several names which she uses as expediency or her notion suits her. Her maiden name was Madeline Cuthbert. She married a Colonel Spencer of Ours; he divorced her, after she had eloped with a rich young lieutenant of his regiment. She didn’t marry the lieutenant; she simply plucked him clean and he shot himself. I’ve never understood why he didn’t first shoot her.”

“Doubtless it shows her cleverness?” Clarke remarked.

“Doubtless it does,” replied Harleston, neatly spitting a leaf on the pavement with his stick. “Afterward she had various adventures with various wealthy men, and always won. Her particularly spectacular adventure was posing, at the instigation of the Duke of Lotzen, as the wife of the Archduke Armand of Valeria; and she stirred up a mess of turmoil until the matter was cleared up.”

“I remember something of it!” Clarke exclaimed.

“By that time she had so fascinated her employer, the Duke of Lotzen, that he actually married her—morganatically, of course.”

“Again showing her astonishing cleverness.”

“Just so—and, cleverer still, she held him until his death five years later. Which death, despite the authorized report, was not natural: the King of Valeria killed him in a sword duel in Ferida Palace on the principal street of Dornlitz. The lady then betook herself to Paris and took up her present life of extreme respectability—and political usefulness to our friends of Wilhelm-strasse. In fact, I understand that she has more than made good professionally, as well as fascinated at least half a dozen Cabinet Ministers besides.

“Wilhelm-strasse?” Clarke queried.

Harleston nodded. “She is in the German Secret Service.”

“They trust her?” Clarke marvelled.

“That is the most remarkable thing about her,” said Harleston, “so far as I know, she has never been false to the hand that paid her.”

“Which, in her position, is the cleverest thing of all!” Clarke remarked.

They passed the English Legation, a bulging, three-storied, red brick, dormer-roofed atrocity, standing a few feet in from the sidewalk; ugly as original sin, externally as repellent as the sidewalk and the narrow little drive under the porte-cochère are dirty.

“It’s a pity,” said Clarke, “that the British Legation cannot afford a man-servant to clean its front.”

“No one is presumed to arrive or leave except in carriages or motor cars,” Harleston explained. “They can push through the dirt to the entrance.”

“Why, would you believe it,” Clarke added, “the deep snow of last February lay on the walks untouched until well into the following day. The blooming Englishmen just then began to appreciate that it had snowed the previous night. Are they so slow on the secret-service end?”

“They have quite enough speed on that end,” Harleston responded. “They are on the job always and ever—also the Germans.”

“You’ve bumped into them?”

“Frequently.”

“Ever encounter the clever lady, with the assortment of husbands?”

“Once or twice. Moreover, having known her as a little girl, and her family before her, I’ve been interested to watch her travelling—her remarkable career. And it has been a career, Clarke; believe me, it’s been a career. For pure cleverness, and the appreciation of opportunities with the ability to grasp them, the devil himself can’t show anything more picturesque. My hat’s off to her!”

“I should like to meet her,” Clarke said.

“Come to Paris, sometime when I’m there, and I’ll be delighted to present you to her.”

“Doesn’t she ever come to America?”

“I think not. She says the Continent, and Paris in particular, is good enough for her.”

Harleston left Clarke at Dupont Circle and turned down Massachusetts Avenue.

The broad thoroughfare was deserted, yet at the intersection of Eighteenth Street he came upon a most singular sight.

A cab was by the curb, its horse lying prostrate on the asphalt, its box vacant of driver.

Harleston stopped. What had he here! Then he looked about for a policeman. Of course, none was in sight. Policemen never are in sight on Massachusetts Avenue.

As a general rule, Harleston was not inquisitive as to things that did not concern him—especially at one o’clock in the morning; but the waiting cab, the deserted box, the recumbent horse in the shafts excited his curiosity.

The cab, probably, was from the stand in Dupont Circle; and the cabby likely was asleep inside the cab, with a bit too much rum aboard. Nevertheless, the matter was worth a step into Eighteenth Street and a few seconds’ time. It might yield only a drunken driver’s mutterings at being disturbed; it might yield much of profit. And the longer Harleston looked the more he was impelled to investigate. Finally curiosity prevailed.

The door of the cab was closed and he looked inside.

The cab was empty.

As he opened the door, the sleeping horse came suddenly to life; with a snort it struggled to its feet, then looked around apologetically at Harleston, as though begging to be excused for having been caught in a most reprehensible act for a cab horse.

“That’s all right, old boy,” Harleston smiled. “You doubtless are in need of all the sleep you can get. Now, if you’ll be good enough to stand still, we’ll have a look at the interior of your appendix.”

The light from the street lamps penetrated but faintly inside the cab, so Harleston, being averse to lighting a match save for an instant at the end of the search, was forced to grope in semi-darkness.

On the cushion of the seat was a light lap spread, part of the equipment of the cab. The pockets on the doors yielded nothing. He turned up the cushion and felt under it: nothing. On the floor, however, was a woman’s handkerchief, filmy and small, and without the least odour clinging to it.

“Strange!” Harleston muttered. “They are always covered with perfume.”

Moreover, while a very expensive handkerchief, it was without initial—which also was most unusual.

He put the bit of lace into his coat and went on with the search:

Three American Beauty roses, somewhat crushed and broken, were in the far corner. From certain abrasions in the stems, he concluded that they had been torn, or loosed, from a woman’s corsage.

He felt again—then he struck a match, leaning well inside the cab so as to hide the light as much as possible.

The momentary flare disclosed a square envelope standing on edge and close in against the seat. Extinguishing the match, he caught it up.

It was of white linen of superior quality, without superscription, and sealed; the contents were very light—a single sheet of paper, likely.

The handkerchief, the crushed roses, the unaddressed, sealed envelope—the horse, the empty and deserted cab, standing before a vacant lot, at one o’clock in the morning! Surely any one of them was enough to stir the imagination; together they were a tantalizing mystery, calling for solution and beckoning one on.

Harleston took another look around, saw no one, and calmly pocketed the envelope. Then, after noting the number of the cab, No. 333, he gathered up the lines, whipped the ends about the box, and chirped to the horse to proceed.

The horse promptly obeyed; turned west on Massachusetts Avenue, and backed up to his accustomed stand in Dupont Circle as neatly as though his driver were directing him.

Harleston watched the proceeding from the corner of Eighteenth Street: after which he resumed his way to his apartment in the Collingwood.

A sleepy elevator boy tried to put him off at the fourth floor, and he had some trouble in convincing the lad that the sixth was his floor. In fact, Harleston’s mind being occupied with the recent affair, he would have let himself be put off at the fourth floor, if he had not happened to notice the large gilt numbers on the glass panel of the door opposite the elevator. The bright light shining through this panel caught his eye, and he wondered indifferently that it should be burning at such an hour.

Subsequently he understood the light in No. 401; but then it was too late. Had he been delayed ten seconds, or had he gotten off at the fourth floor, he would have—. However, I anticipate; or rather I speculate on what would have happened under hypothetical conditions—which is fatuous in the extreme; hypothetical conditions never are existent facts.

Harleston, having gained his apartment, leisurely removed from his pockets the handkerchief, the roses, and the envelope, and placed them on the library table. With the same leisureliness, he removed his light top-coat and his hat and hung them in the closet. Returning to the library, he chose a cigarette, tapped it on the back of his hand, struck a match, and carefully passed the flame across the tip. After several puffs, taken with conscious deliberation, he sat down and took up the handkerchief.

This was Harleston’s way: to delay deliberately the gratification of his curiosity, so as to keep it always under control. An important letter—where haste was not an essential—was unopened for a while; his morning newspaper he would let lie untouched beside his plate for sufficiently long to check his natural inclination to glance hastily over the headlines of the first page. In everything he tried by self-imposed curbs to teach himself poise and patience and a quiet mind. He had been at it for years. By now he had himself well in hand; though, being exceedingly impetuous by nature, he occasionally broke over.

His course in this instance was typical—the more so, indeed, since he had broken over and lost his poise only that afternoon. He wanted to know what was inside that blank envelope. He was persuaded it contained that which would either solve the mystery of the cab, or would in itself lead on to a greater mystery. In either event, a most interesting document lay within his reach—and he took up the handkerchief. Discipline! The curb must be maintained.

And the handkerchief yielded nothing—not even when inspected under the drop-light and with the aid of a microscope. Not a mark to indicate who carried it nor whence it came.—Yet stay; in the closed room he detected what had been lost in the open: a faint, a very faint, odour as of azurea sachet. It was only a suggestion; vague and uncertain, and entirely absent at times. And Harleston shook his head. The very fact that there was nothing about it by which it might be identified indicated the deliberate purpose to avoid identification. He put it aside, and, taking up the roses, laid them under the light.

They were the usual American Beauties; only larger and more gorgeous than the general run—which might be taken as an indication of the wealth of the giver, or of the male desire to please the female; or of both. Of course, there was the possibility that the roses were of the woman’s own buying; but women rarely waste their own money on American Beauties—and Harleston knew it. A minute examination convinced him that they had been crushed while being worn and then trampled on. The stems, some of the green leaves, and the edges of one of the blooms were scarred as by a heel; the rest of the blooms were crushed but not scarred. Which indicated violence—first gentle, then somewhat drastic.

He put the flowers aside and picked up the envelope, looked it over carefully, then, with a peculiarly thin and very sharp knife, he cut the sealing of the flap so neatly that it could be resealed and no one suspect it had been opened. As he turned back the flap, a small unmounted photograph fell out and lay face upward on the table.

Harleston gave a low whistle of surprise.

It was Madeline Spencer.

“Good morning, madame!” said Harleston, bowing to the photograph. “This is quite a surprise. You’re taken very recently, and you’re worth looking at for divers aesthetic reasons—none of which, however, is the reason for your being in the envelope.”

He drew out the sheet of paper and opened it. On it were typewritten, without address nor signature, these letters:

DPNFNZQFEFBPOYVOAEELEHHEJYD

BIWFTCCFVDXNQYCECLUGSUGDZYJ

ENRYUIGYBSNRTDUHJWHGYZIPEPA

WPPOIMCHEIPRFBJXFVWWFTZNJPY

UFJDILDCEMBRVZDAYVAWALUMOFN

FCVDPGLPWFUUWVIEPTKVIPUMSFZ

NPSJJRFYASGZSDACSIGYUOFCEXA

AOIDJJFCJPSONPKUUYVCVCTIHDP

XMNOYKENHUSKHYMSFRRPCYWSLLW

SMVPPUNEIFIDJLZRWEHPQGODFUZ

TCEMQIQWNFYJTAALUMHJXILEEHY

ISOVOAZUCUDINBRLUZICUOTTUSV

LPNFFVQFANPVCYJHILTPFISGHCW

HYICPPNFDOUOCLDUWEIVIPJNQBV

ZLMIJRVKDSFRLWEGBKQYWSFFBEI

YORHMYSHTECPUTMPJXFNRNEEUME

ILJBWV.

“Cipher!” commented Harleston, looking at it with half-closed eyes.... “The Blocked-Out Square, I imagine. No earthly use in trying to dig it out without the key-word; and the key-word—” he gave a shrug. “I’ll let Carpenter try his hand on it; it’s too much for me.”

He knew from experience the futility of attempting the solution of a cipher by any but an expert; and even with an expert it was rarely successful.

As a general rule, the key to a secret cipher is discovered only by accident or by betrayal. There are hundreds of secret ciphers—any person can devise one—in everyday use by the various departments of the various governments; but, in the main, they are amplifications or variations of some half-dozen that have become generally accepted as susceptible of the quickest and simplest translation with the key, and the most puzzling without the key. Of these, the Blocked-Out Square, first used by Blaise de Vigenèrie in 1589, is probably still the most generally employed, and, because of its very simplicity, the most impossible of solution. Change the key-word and one has a new cipher. Any word will do; nor does it matter how often a letter is repeated; neither is one held to one word: it may be two or three or any reasonable number. Simply apply it to the alphabetic Blocked-Out Square and the message is evident; no books whatever are required. A slip of paper and a pencil are all that are necessary; any one can write the square; there is not any secret as to it. The secret is the key-word.

Harleston took a sheet of paper and wrote the square:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

BCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZA

CDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZAB

DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC

EFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCD

FGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDE

GHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEF

HIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFG

IJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGH

JKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHI

KLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJ

LMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJK

MNOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKL

NOPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLM

OPQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMN

PQRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNO

QRSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOP

RSTUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQ

STUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQR

TUVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRS

UVWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRST

VWXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTU

WXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUV

XYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVW

YZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWX

ZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXY

Assume that the message to be transmitted is: “To-morrow sure,” and that the key-word is: “In the inn.” Write the key-word and under it the message:

INTHEINNINTH

TOMORROWSURE

Then trace downward the I column of the top line of the square, and horizontally the T column at the side of the square until the two lines coincide in the letter B: the first letter of the cipher message. The N and the O yield B; the T and the M yield F; the H and the O yield V, and so on, until the completed message is:

BBFVVZBJAHKL

The translator of the cipher message simply reverses this proceeding. He knows the key-word, and he writes it above the cipher message:

INTHEINNINTH

BBFVVZBJAHKL

He traces the I column until B is reached; the first letter in that line, T, is the first letter of the message—and so on.

Simple! Yes, childishly simple with the key-word; and the key-word can be carried in one’s mind. Without the key-word, translation is impossible.

Harleston put down the paper and leaned back.

Altogether it was a most interesting collection, these four articles on the table. It was a pity that the cab and the sleeping horse were not among the exhibits. Number one: a lady’s lace handkerchief. Number two: three American Beauty roses, somewhat the worse for wear and violent usage. Number three: a cipher message. Number four: photograph of Madame—or Mademoiselle—de Cuthbert, de Spencer, de Lotzen. There was a pretty plot behind these exhibits; a pretty plot, or he missed his guess. It might concern the United States—and it might not. It would be his duty to find out. Meanwhile, the picture stirred memories that he had thought long dead. Also it suggested possibilities. It was some years since they had matched their wits against each other, and the last time she rather won out—because all the cards were hers, as well as the mise en scène. And she had left—

His thought trailed off into silence; and the silence lasted so long, and he sat so still, that the ash fell unnoticed from his cigarette; and presently the cigarette burned itself into the tip, and to his fingers.

He tossed it into the tray and laughed quietly.

Rare days—those days of the vanished protocol and its finding! He could almost wish that they might be again; with a different mise en scène, and a different ending—and a different client for his. He was becoming almost sentimental—and he was too old a bird for sentiment, and quite too old at this game; which had not any sentiment about it that was not pretence and sham. Yet it was a good game—a mighty entertaining game; where one measured wits with the best, and took long chances, and played for high stakes; men’s lives and a nation’s honour.

He picked up the photograph and regarded it thoughtfully.

“And what are to be the stakes now, I wonder,” he mused. “It’s another deal of the same old cards, but who are players? If America is one, then, my lady, we shall see who will win this time—if you’re in it; and I take it you are, else why this picture. Yet to induce you to break your rule and cross the Atlantic, the moving consideration must be of the utmost weight, or else it’s purely a personal matter. H-u-m! Under all the circumstances, I should say the latter is the more likely. In which event, I may not be concerned further than to return these—” with a wave of his hand toward the exhibits.

For a while longer he sat in silence, eyes half closed, lips a bit compressed; a certain sternness, that was always in his countenance, showing plainest when in reflective thought. At last, he smiled. Then he lit another cigarette, took up the letter and the photograph, and put them in the small safe standing behind an ornate screen in the corner—not, however, without another look at the calmly beautiful face.

The roses he left lie on the table; the steel safe would not preserve them in statu quo; moreover, he knew, or thought he knew, all that they could convey. He swung the door shut; then swung it open, and looked again at the picture—and for sometime—before he put it up and gave the knob a twirl.

“I’m sure bewitched!” he remarked, going on to his bedroom. “It’s not difficult for me to understand the Duke of Lotzen. He was simply a man—and men, at the best, are queer beggars. No woman ever understands us—and no more do we understand women. So we’re both quits on that score, if we’re not quite on some others.” Then he raised his hands helplessly, “Oh, Lord, the petticoats, the petticoats!”

Just then the telephone rang—noisily as befits two o’clock in the morning.

“Who the devil wants me at such an hour?” he muttered.

The clang was repeated almost instantly and continued until he unhooked the receiver.

“Well!” he said sharply.

“Is that Mr. Harleston?” asked a woman’s voice. A particularly soft and sweet and smiling voice, it was.

“I am Mr. Harleston,” he replied courteously—the voice had done it.

“Oh, how do you do, Mr. Harleston!” the voice rippled. “I suppose you are rather astonished at being called up at such an unseemly hour—”

“Not at all—I’m quite used to it, mademoiselle,” Harleston assured her.

“Now you’re sarcastic,” the voice replied again; “and, somehow, I don’t like sarcasm when I’m the cause of it.”

“You’re the cause of it but not the object of it,” he assured her. “I’m quite sure I’ve never met you, and just as sure that I hope to meet you today.”

“Your hope, Mr. Harleston, is also mine. But why, may I ask, do you call me mademoiselle? I’m not French.”

“It’s the pleasantest way to address you until I know your name.”

“You might call me madame!”

“Perish the thought! I refuse to imagine you married.”

“I might be a widow.”

“No.”

“Or even a divorcée.”

“And you might be a grandmother,” he added.

“Yes.”

“And doing the Maxixe at the Willard, this minute.”

“Yes!” she laughed.

“But you aren’t; and no more are you a widow or a divorcée.”

“All of which is charming of you, Mr. Harleston but it’s not exactly the business I have in hand.”

“Business at two o’clock in the morning!” he exclaimed.

He had tried to place the voice, and had failed; he was becoming convinced that he had not heard it before.

“What else would justify me in disturbing you?” she asked.

“Yourself, mademoiselle. Let us continue the pleasant conversation and forget business until business hours.”

“When are your business hours, Mr. Harleston—and where’s your office?”

“I have no office—and my business hours depend on the business in hand.”

“And the business in hand depends primarily on whether you are interested in the subject matter of the business, n’est-ce pas?”

“I am profoundly interested, mademoiselle, in any matter that concerns you—as well as in yourself. Who would not be interested in one so impulsive—and anything so important—as to call him on the telephone at two in the morning.”

“And who on his part is so gracious—and wasn’t asleep,” she answered.

Harleston slowly winked at the transmitter and smiled.

He thought so. What puzzled him, however, was her idea in prolonging the talk. Maybe there was not any idea in it, just a feminine notion; yet something in the very alluring softness of her voice told him otherwise.

“You guessed it,” he replied. “I was not asleep. Also I might guess something in regard to your business.”

“What?”

“No, no, mademoiselle! It’s impertinent to guess about what does not concern me—yet.”

“Delete the word ‘yet,’ Mr. Harleston, and substitute the idea that it was—pardon me—rather gratuitous in you to meddle in the first place.”

“I don’t understand,” said Harleston.

“Oh, yes you do!” she trilled. “However, I’ll be specific—it’s time to be specific, you would say; though I might respond that you’ve known all along what my business is with you.”

“The name of an individual is a prerequisite to the transaction of business,” he interposed.

“You do not know me, Mr. Harleston.”

“Hence, your name?”

“When we meet, you’ll know me by my voice.”

“True, mademoiselle, for it’s one in a million; but as yet we are not met, and you desire to talk business.”

“And I’m going to talk business!” she laughed. “And I shall not give you my name—or, if you must, know me as Madame X. Are you satisfied?”

“If you are willing to be known as Madame X,” he laughed back, “I haven’t a word to say. Pray begin.”

“Being assured now that you have never before heard my voice, and that you have it fixed sufficiently in your memory—all of which, Mr. Harleston, wasn’t in the least necessary, for we shall meet today—we will proceed. Ready?”

“Ready, mademoiselle—I mean Madame X.”

“What do you intend to do, sir, in regard to the incident of the deserted cab with the sleeping horse?” she asked.

“I have not determined. It depends on developments.”

“You see, Mr. Harleston, you were not in the least surprised at my question.”

“For a moment, a mere man may have had a clever woman’s intuition,” he replied.

“And, I suppose, the woman will be expected to aid developments.”

“Isn’t that her present intention?”

“Not at all! Her present intention is to avoid developments so far as you are concerned, and to have matters take their intended course. It’s to that end that I have ventured to call you.”

“What do you wish me to do, Madame X?”

“As if you did not know!” she mocked.

“I’m very dense at times,” he assured her.

“Dense!” she laughed. “Shades of Talleyrand, hear the man! However, as you desire to be told, I’ll tell you. I wish you to forget that you saw anything unusual on your way home this morning, and to return the articles you took from the cab.”

“To the cab?” Harleston inquired.

“No, to me.”

“What were the articles?”

“A sealed envelope containing a message in cipher.”

“Haven’t you forgotten something?”

“Oh, you may keep the roses, Mr. Harleston, for your reward!” she laughed.

She had not missed the handkerchief, or else she thought it of no consequence.

“Assuming, for the moment, that I have the articles in question, how are they to be gotten to you?”

“By the messenger, I shall send.”

“Will you send yourself?”

“What is that to you, sir?” she trilled.

“Simply that I shall not even consider surrendering the articles, assuming that I have them, to any one but you.”

“You will surrender them to me?” she whispered.

“I won’t surrender them to any one else.”

“In other words, I have a chance to get them. No one else has a chance?”

“Precisely.”

“Very well, I accept. Make the appointment, Mr. Harleston.”

“Will five o’clock this afternoon be convenient?”

“Perfectly—if it can’t be sooner,” she replied, after a momentary pause. “And the place?”

“Where you will,” he answered. He wanted her to fix it so that he could judge of her good faith.

And she understood.

“I’m not arranging to have you throttled!” she laughed. “Let us say the corridor of the Chateau—that is safe enough, isn’t it?”

“Don’t you know, Madame X, that Peacock Alley is one of the most dangerous places in town?”

“Not for you, Mr. Harleston,” she replied. “However—”

“Oh, I’ll chance it; though it’s a perilous setting with one of your adorable voice—and the other things that simply must go with it.”

“And lest the other things should not go with it,” she added, “I’ll wear three American Beauties on a black gown so that you may know me.”

“Good! Peacock Alley at five,” he replied and snapped up the receiver.

“The affair promises to be quite interesting,” he confided to the paper-knife, with which he was spearing tiny holes in the blotter of the pad. “Peacock Alley at five—but there are a few matters that come first.”

He went straight to the safe, unlocked it, took out the photograph, the cipher message, and the handkerchief, carried these to the table and placed them in a large envelope, which he sealed and addressed to himself. Then with it, and the three American Beauties, he passed quickly into the corridor and to an adjoining apartment. There he rang the bell vigorously and long.

He was still ringing when a dishevelled figure, in blue pajamas and a scowl, opened the door.

“What the devil do you—” the disturbed one growled.

“S-h-h!” said Harleston, his finger on his lips. “Keep these for me until tomorrow, Stuart.”

And crowding the roses and the envelope in the astonished man’s hands, he hurried away.

The pajamaed one glared at the flowers and the envelope; then he turned and flung them into a corner of the living-room.

“Hell!” he said in disgust. “Harleston’s either crazy or in love: it’s the same thing anyway.”

He slammed the door and went back to bed.

Harleston, chuckling, returned to his quarters; retrieved from the floor a leaf and a petal and tossed them out of the window. Then, being assured by a careful inspection of the room that there were no further traces of the roses remaining, he went to bed.

Two minutes after his head touched the pillow, he was asleep.

Presently he awoke—listening!

Some one was on the fire-escape. The passage leading to it was just at the end of his suite; more than that, one could climb over the railing, and, by a little care, reach the sill of his bedroom window. This sill was wide and offered an easy footing. If the window were up, one could easily step inside; or, even if it were not, the catch could be slipped in a moment.

Harleston’s window, however, was up—invitingly up; also the window on the passage; it was a warm night and any air was grateful.

He lay quite still and waited developments. They came from another quarter: the corridor on which his apartment opened. Someone was there.

Then the knob of his door turned; he could not distinguish it in the uncertain light, yet he knew it was turning by a peculiarly faint screech—almost so faint as to be indistinguishable. One would not notice it except at the dead of night.

The door hung a moment; then cautiously it swung back a little way, and two men entered. The moon, though now low, was sufficient to light the place faintly and to enable them to see and be seen.

For a brief interval they stood motionless. They came to life when Harleston, reaching up, pushed the electric button.

“What can I do for you, gentlemen?” he asked, blinking into their levelled revolvers.

They were medium-sized men and wore evening clothes; one was about forty-five and rather inclined to stoutness, the other was under forty and rather slender. They were not masked, and their faces, which were strange to Harleston, were the faces of men of breeding, accustomed to affairs.

“You startled us, Mr. Harleston,” the elder replied; “and you blinded us momentarily by the rush of light.”

“It was thoughtless of me,” Harleston returned. He waved his hand toward the chairs. “Won’t you be seated, messieurs—and pardon my not arising; I’m hardly in receiving costume. May I ask whom I am entertaining.”

“Certainly, sir,” the elder smiled. “This is Mr. Sparrow; I am Mr. Marston. We would not have you put yourself to the inconvenience, not to mention the hazard from drafts. You’re much more comfortable in bed—and we can transact our business with you quite as well so; moreover if you will give us your word to lie quiet and not call or shoot, we shall not offer you the slightest violence.”

“I’ll do anything,” Harleston smiled, “to be relieved of looking down those unattractive muzzles. Ah! thank you!—The chairs, gentlemen!” with a fine gesture of welcome.

“We haven’t time to sit down, thank you,” said Sparrow. “Time presses and we must away as quickly as possible. We shall, we sincerely hope, inconvenience you but a moment, Mr. Harleston.”

“Pray take all the time you need,” Harleston responded. “I’ve nothing to do until nine o’clock—except to sleep; and sleep is a mere incidental to me. I would much rather chat with visitors, especially those who pay me such a delightfully early morning call.”

“Do you know what we came for?” Marston asked.

“I haven’t the slightest idea. In fact, I don’t seem to recall ever having met either of you. However—you’ll find cigars and cigarettes on the table in the other room. I’ll be greatly obliged, if one of you will pass me a cigarette and a match.”

Both men laughed; Sparrow produced his case and offered it to Harleston, together with a match.

“Thank you, very much,” said Harleston, as he struck the match and carefully passed the flame across the tip. “Now, sirs, I’m at your service. To what, or to whom, do I owe the honour of this visit?”

“We have ventured to intrude on you, Mr. Harleston,” said Marston, “in regard to a little matter that happened on Eighteenth Street near Massachusetts Avenue shortly before one o’clock this morning.”

Harleston looked his surprise.

“Yes!” he inflected. “How very interesting.”

“I’m delighted that you find it so,” was the answer. “It encourages me to go deeper into that matter.”

“By all means!” said Harleston, pushing the pillow aside and sitting up. “Pray, proceed. I’m all attention.”

“Then we’ll go straight to the point. You found certain articles in the cab, Mr. Harleston—we have come for those articles.”

“I am quite at a loss to understand,” Harleston replied. “Cab—articles! Have they to do with your little matter of Eighteenth and Massachusetts Avenue several hours ago?”

“They are the crux of the matter,” Marston said shortly. “And you will confer a great favour upon persons high in authority of a friendly power if you will return the articles in question.”

“My dear sir,” Harleston exclaimed, “I haven’t the articles, whatever they may be; and pardon me, even if I had, I should not deliver them to you; I’ve never, to the best of my recollection, seen either of you gentlemen before this pleasant occasion.”

“My dear Mr. Harleston,” remarked Sparrow, “all your actions at the cab of the sleeping horse were observed and noted, so why protest?”

“I’m not protesting; I’m simply stating two pertinent facts!” Harleston laughed.

“We will grant the fact that you’ve never seen us,” said Marston, “but that you have not got the articles in question, we,” with apologizing gesture, “beg leave to doubt.”

“You’re at full liberty to search my apartment,” Harleston answered. “I’m not sensitive early in the morning, whatever I may be at night.”

“The letter is easy to conceal,” was the reply, “and the safe yonder is an impasse without your assistance.”

“The safe is not locked,” Harleston remarked. “I think I neglected to turn the knob. If you will—”

“Don’t disturb yourself, I pray,” was the quick reply, the revolver glinting in his hand; “we will gladly relieve you of the trouble.”

“I was only about to say that if you try the door it will open for you,” Harleston chuckled. “Go through it, sir,” he remarked to the younger, “and don’t, I beg of you, disturb the papers more than necessary. The key to the locked drawer is in the lower compartment on the right. Proceed, my elderly friend, to search the apartment; I’ll not balk you. The thing’s rather amusing—and entirely absurd. If it were not—if it didn’t strike my funny-bone—I should probably put up some sort of a fight; as it is, you see I’m entirely acquiescent. Your tiny automatics didn’t in the least intimidate me. I could have landed you both as you entered. I’ve got a gun of a much larger calibre right to my hand. See!” and he lifted the pillow and exposed a 38. “Want to borrow it?”

“Why didn’t you land us?” Marston asked, as he took the 38.

“It wouldn’t have been kind!” Harleston smiled. “When visitors come at such an hour, they deserve to be received with every attention and courtesy—particularly when they come on a mistaken impression and a fruitless quest.”

The man looked at Harleston doubtfully. Just how much of this was bluff, he could not decide. Harleston’s whole conduct was rather unusual—the open door, the open safe, the unemployed revolver, were not in accordance with the game they were playing. He should have made a fight, some sort of a fight, and not—

“The letter’s not in the safe,” Sparrow reported.

“I didn’t think it was,” said the other, “but we had to make search.”

“You’re very welcome to look elsewhere and anywhere,” Harleston interjected. “I’ll trust you not to pry into matters other than the letter. By the way, whose was the letter?”

“His Majesty of Abyssinia!” was the answer.

“Taken by wireless, I presume.”

“Exactly!”

“Then, why so much bother, my friend?” Harleston asked. “If you do not find it, you can get others by the same quick route.”

“The King of Abyssinia never duplicates a letter.”

“When,” supplemented Harleston, “it has been carelessly lost in a cab.”

“Just so. Therefore—”

“I repeat that I have not got the articles,” said Harleston, a bit wearily, “nor are they in my apartment. You have been misinformed. I find I am getting drowsy—this thing is not as absorbing as I had thought it would be. With your permission I’ll drop off to sleep; you’re welcome to continue the search. Make yourselves perfectly at home, sirs.” He lay back and drew up the sheet. “Just pull the door shut when you depart, please,” he said, and closed his eyes.

“You’re a queer chap,” remarked Sparrow, pausing in his search and surveying Harleston with a puzzled smile. “One would suppose you’re used to receiving interruptions at such hours for such purposes.”

“I try never to be surprised at anything however outré,” Harleston explained. “Good-night.”

The two men looked at the recumbent figure and then at each other and laughed.

“He acts the part,” said the elder. “Have you found anything?”

“Nothing! It’s not in the safe nor the writing-table—nor anywhere else that is reasonable. I’ve been through everything and there’s nothing doing.”

“You’re not going?” Harleston remarked.

“You’re asleep, Mr. Harleston!” Marston reminded. “The letter is here: we’ve simply got to find it.”

“A letter is easy to conceal,” the younger replied. “There’s nothing but to overturn everything in the place—and so on; and that will require a day.”

“So that you replace things, I’ve not the slightest objection,” Harleston interjected. “Bang away, sirs, bang away! Anything to relieve me from suspicion.”

“It prevents him from sleeping!” Sparrow laughed.

“Also yourselves,” Harleston supplemented. “However, you for it, remembering that cock-crow comes earlier now than in December, and the people too are up betimes. You risk interruption, I fear, from my solicitous friends.”

And even as he spoke the corridor door opened and a man stepped in.

From where he lay, Harleston could see him; the others could not.

“’Pon my soul, I’m popular this morning!” Harleston remarked, sitting up.

Instantly the new-comer covered him with his revolver.

“What did you say?” Sparrow inquired from the sitting-room, just as the stranger appeared around the corner.

Like a flash, the latter’s revolver shifted to him.

“Easy there!” said he.

Sparrow sprang up—then he laughed.

“Easy yourself!” said he. “Marston, let this gentleman see your hand.”

Marston came slowly forward until he stood a little behind but sufficiently in view to enable the stranger to see that he himself was covered by an automatic.

“For heaven’s sake, Crenshaw,” said Sparrow, “don’t let us get to shooting here! If you wing me, Marston will wing you, and we’ll only stir up a mess for ourselves.”

“Then hand over the letter,” said Crenshaw

“Do you fancy we would be hunting it if we had it?”

“I don’t fancy—produce the goods!”

“We haven’t the goods,” Marston shrugged. “We can’t find it.”

Sparrow shook his head curtly.

“It’s the truth,” Harleston interjected. “They haven’t found the goods for the very good reason that the goods are not here. Plunge in and aid in the search; I wish you would; it will relieve me of your triple intrusion in one third less time. I’m becoming very tired of it all; it has lost its novelty. I prefer to sleep.”

“I want the letter!” Crenshaw exclaimed.

“I assumed as much from the vigour of your quest,” Harleston shrugged. “The difficulty is that I haven’t the letter. Neither is it in my apartment. But you’ll facilitate the search if you’ll depress your respective cannon from the angle of each other’s anatomy and get to work. As I remarked before, I’m anxious to compose myself for sleep. You can hold your little dispute later on the sidewalk, or in jail, or wherever is most convenient.”

“Mr. Harleston,” said Marston, “do you give us your word that the letter is not in your apartment?”

“You already have it,” Harleston replied wearily.

“Then, sir, we’ll take your word and withdraw.”

“Thank you,” said Harleston.

“He has it somewhere!” Crenshaw declared, fingering his revolver.

“My dear fellow,” Marston returned, “we are willing to accept Mr. Harleston’s averment.”

“He knows where it is—he took it—let him tell where it is hidden.”

“What good will that subserve? We can’t get it tonight, and tomorrow will be too late.”

“And all because of you two meddlers.”

“Three meddlers, Crenshaw!” Marston laughed. “You must not forget your sweet self. We’ve bungled the affair, I admit. We can’t improve it now by murdering each other—”

“We can make it very uncomfortable for the fourth meddler,” Crenshaw threatened, eyeing the figure on the bed.

“Haven’t you made me uncomfortable enough by this untimely intrusion?” Harleston muttered sleepily.

“What is your idea in not offering any opposition?” Crenshaw demanded. “Is it a plant?”

“It was courtesy at first, and the novelty of the experience; but it’s ceased to be novel, and courtesy is a bit supererogatory. By the way, which of you came up the fire-escape?”

The three shook their heads.

“I’m not a burglar,” Crenshaw snapped.

“The burden is on you to prove it, my friend!” Harleston smiled. “However, it’s no matter. Just drop cards before you leave so that I can return your call. Once more, good-night!”

“I’m off,” said Marston. “Come along, Crenshaw, you can’t do anything more here, and we’ll all forget and forgive and start fresh in the morning.”

“Start?” cried Crenshaw? “what for—home? I tell you the letter is here—he took it, didn’t he? He was at the cab.”

“Will you also give your word that you didn’t take a letter from the cab?” Crenshaw demanded, turning upon Harleston.

“I’ll give you nothing since you’ve asked me in that manner,” Harleston replied sharply; “unless you want this.” His hand came from under the sheet, and Crenshaw was looking into a levelled 38. Harleston had a pair of them.

“Beat it, my man!” Harleston snapped. “None of you are of much success as burglars; you’re not familiar with the trade. You’re novices, rank novices. Also myself. I’ll give you until I count five, Crenshaw, to make your adieux. One ... two ... No need for you two to hurry away—the time limit applies only to Mr. Crenshaw.”

“It’s quite time we were going, Mr. Harleston,” Marston answered. “Good-night, sir—and pleasant dreams. Come on, Crenshaw.”

“Three ... four ...”

Crenshaw made a gesture of final threat.

“Meddler!” he exclaimed. Then he followed the other two.

Harleston lay for a few minutes, brows drawn in thought; then he arose, crossed to the telephone, and took down the receiver.

“Good-morning, Miss Williams,” he said. “Has it been a long night?”

“Pretty long, Mr. Harleston,” the girl answered. “There hasn’t been a thing doing for two hours.”

“Haven’t three gentlemen just left the building?”

“No one has passed in or out since you came in, Mr. Harleston.”

“Then I must be mistaken.”

“You certainly are. It’s so lonely down here, Mr. Harleston, you can pick up chunks of it and carry off.”

“Been asleep?”

“I don’t think!” she laughed. “I’m not minded to lose my job. Suppose some peevish woman wanted a doctor and she couldn’t raise me; do you think I’d last longer than the morning and the manager’s arrival? Nay! Nay!”

“It’s an unsympathetic world, isn’t it, Miss Williams?”

“Only when you’re down—otherwise it’s not half bad. Say, maybe here’s one of your men now; he’s walking down. Shall I stop him?”

“No, no, let him go. When he’s gone, tell me if he’s slender, or stout, or has a moustache and imperial.”

“Sure, I will.”

Through the telephone Harleston could hear someone descend the stairs, cross the lobby, and the revolving doors swing around.

The next moment, the operator’s voice came with a bit of laugh.

“Are you there, Mr. Harleston?”

“I’m here.”

“Well, your man was a woman—and she was accidentally deliberately careful that I shouldn’t see her face.”

“H-u-m!” said Harleston. “Young or old?”

“She’s got ripples enough on her gown to be sixty, and figure enough to be twenty.”

“Slender?”

“Yes; a perfect peach!”

“How’s her walk?”

“As if the ground was all hers.”

“I see!” Harleston replied. “What would you, as a woman, make her age—being indifferent and strictly truthful?”

“Not over twenty-eight—probably less!” she laughed. “And I’ve a notion she’s some to look at, Mr. Harleston.”

“You mean she’s a beauty?”

“Sure.”

“Call me if she comes back; also if any of the men go out. They are strangers to the Collingwood so you will know them.”

“Very good, Mr. Harleston.”

He hung up the receiver and went back to bed.

If no one had come in and no one had left the Collingwood since his return, the men must have been in the building—unless they had come by another way than the main entrance; which was the only entrance open after midnight. If the former was the case, then someone on the outside must have communicated to them as to him.

With a muttered curse on his stupidity, he returned to the telephone.

“Miss Williams,” said he, “there has been a queer occurrence in the building since two A.M., and I should like to know confidentially whether any one has communicated with an apartment since one thirty.”

The girl knew that Harleston was on intimate terms with the State Department, and with the police, and she answered at once.

“Save only yours, not a single in or out call has been registered since twelve fifty-two when apartment No. 401 was connected for a short while.”

“Who has No. 401?”

“A Mr. and Mrs. Chartrand. It’s one of the transient apartments; and they have occupied it only a few days.”

“You didn’t by any chance overhear—”

“The conversation?” she laughed. “Sure, I heard it; anything to put in the time during the night. It was very brief, however; something about him being here, and to meet him at ten in the morning.”

“Who were talking?”

“Mrs. Chartrand and a man—at least I took it to be Mrs. Chartrand; it was a woman’s voice.”

“Did they mention where they were to meet, or the name of the man?”

“No. The very vagueness of the talk made its impression on me at that time of night. In the daytime, I would not have even listened.”

“I understand,” said Harleston. “Call me up, will you, if there are any developments as to the men I’ve described—or the conversation. Meanwhile, Miss Williams, not a word.”

“Not a word, Mr. Harleston—and thank you.”

“What for?”

“For treating me as a human being. Most persons treat me like an automaton or a bit of dirt. You’re different; most of the men are not so bad; it’s the women, Mr. Harleston, the women! Good-night, sir. I’ll call you if anything turns up.”

“All of which shows,” reflected Harleston, as he returned to bed, “that the telephone people are right in asking you to smile when you say ‘hello.’”

It was a very interesting condition of affairs that confronted him.

The episode of the cab of the sleeping horse was leading on to—what?

Three men in the Collingwood knew of the occurrence, yet no one had come in or gone out, and no one had telephoned. Moreover, they also knew of Harleston’s part in the matter. The girl had not lied, he was sure; therefore they must have gained entrance from the outside; and, possibly, were now hiding in the Chartrand apartment—if the telephone message to No. 401 had to do with the occupant of the deserted cab and the lost letter. Yet how to connect things? And why bother to connect them?

He did not care for the vanished lady of the cab—he had the letter and the photograph; and because of them he was to have a talk with an interesting young woman at five o’clock that afternoon. The cipher letter, which was the much desired quantity, was safely across the hall, waiting to be turned over to Carpenter, the expert of the State Department, for translation. Meanwhile, what concerned Harleston was the photograph of Madeline Spencer and her connection with the case—and to know if the United States was concerned in the affair.

At this point he turned over and calmly went to sleep. Tomorrow was another day.

He was aroused by a vigorous pounding on the corridor door. It was seven-thirty o’clock. He yawned and responded to the summons—which grew more insistent with every pound.

It was Stuart—the envelope and the flowers in his hand.

“Scarcely heard your gentle tap,” Harleston remarked. “Why don’t you knock like a man?”

“Here’s your damn bouquet, also your envelope,” said Stuart, “You probably don’t recall that you left them with me about two this morning. I do.”

“I’m mighty much obliged, old man,” Harleston responded. “You did me a great service by taking them—I’ll tell you about it later.”

“Hump!” grunted Stuart. “I hope you’ll come around to tell me at a more seasonable hour. So long!”

Harleston closed the door, and was half-way across the living-room when there came another knock.

Tossing the envelope and the faded roses on a nearby table, he stepped back and swung open the door.

Instantly, a revolver was shoved into his face, and Crenshaw sprang into the hall and closed the door.

“I thought as much!” he exclaimed. “I’ll take that envelope, my friend, and be quick about it.”

“What envelope?” Harleston inquired pleasantly, never seeming to notice the menacing automatic.

“Come, no trifling!” Crenshaw snapped. “The envelope that the man from the apartment across the corridor just handed you.”

Harleston laughed. “You are obsessed with the notion that I have something of yours, Mr. Crenshaw.”

“The letter!” exclaimed Crenshaw.

“That envelope is addressed to me, sir; it’s not the one you seem to want.”

“I suppose the flowers are also addressed to you,” Crenshaw derided, advancing. “Get back, sir,—I’ll get the envelope myself.”

“My dear man,” Harleston expostulated, retreating slowly toward the door of the living-room, “I’ll let you see the envelope; I’ve not the slightest objection. Put up your gun, man; I’m not dangerous.”

“You’re not so long as I’ve got the drop on you!” Crenshaw laughed sneeringly. “Get back, man, get back; to the far side of the table—the far side, do you hear—while I examine the envelope yonder beside the roses. The roses are very familiar, Mr. Harleston. I’ve seen them before.”

Harleston, retreating hastily, backed into a chair and fell over it.

“All right, stay there, then!” said Crenshaw, and reached for the letter.

As he did so, Harleston’s slippered foot shot out and drove hard into the other’s stomach. With a grunt Crenshaw doubled up from pain. The next instant, Harleston caught his wrist and the struggle was on.

It was not for long, however. Crenshaw was outweighed and outstrengthed; and Harleston quickly bore him to the floor, where a sharp blow on the fingers sent the automatic flying.

“If it were not for spoiling the devil’s handiwork, my fine friend, I’d smash your face,” Harleston remarked.

“Smash it!” the other panted. “I’ll promise—to smash yours—at the first opportunity.”

“Which latter smashing won’t be until some years later,” Harleston retorted, as he turned Crenshaw over. Bearing on him with all his weight, he loosed his own pajama-cord and tied the man’s hands behind him. Next he kicked off his pajama trousers, and with them bound Crenshaw’s ankles. Then he dragged him to a chair and plunked him into it, securing him there by a strap.

“It’s scarcely necessary to gag you,” he remarked pleasantly. “In your case, an outcry would be embarrassing only to yourself.”

“What do you intend to do with me?” Crenshaw demanded.

“Ultimately, you mean. I have not decided. It may depend on what I find.”

“Find?”

Harleston nodded. “In your pockets.”

“You dog!” Crenshaw burst out, straining at his bonds. “You miserable whelp! What do you think to find?”

“I’m not thinking,” Harleston smiled; “it isn’t necessary to speculate when one has all the stock, you know.” Then his face hardened.

“One who comes into another’s residence in the dead of night, revolver in hand and violence in his intention, can expect no mercy and should receive none. You’re an ordinary burglar, Crenshaw and as such the law will view you if I turn you over to the police. You think I found a letter in an abandoned cab at 18th and Massachusetts Avenue early this morning, and instead of coming like a respectable man and asking if I have it and proving your property—do you hear, proving your property—you play the burglar and highwayman. Evidently the letter isn’t yours, and you haven’t any right or claim to it. I have been injected into this matter; and having been injected I intend to ascertain what can be found from your papers. Who you are; what your object; who are concerned beside yourself; and anything else I can discover. You see, you have the advantage of me; you know who I am, and, I presume, my business; I know nothing of you, nor of your business, nor what this all means; though I might guess some things. It’s to obviate guessing, as far as possible, that I am about to examine such evidence as you may have with you.”

Crenshaw was so choked with his anger that for a moment he merely sputtered—then he relapsed into furious silence, his dark eyes glowing with such hate that Harleston paused and asked a bit curiously:

“Why do you take it so hard? It’s all in the game—and you’ve lost. You’re a poor sort of sport, Crenshaw. You’d be better at ping-pong or croquet. This matter of—letters, and cabs, is far beyond your calibre; it’s not in your class.”

“We haven’t reached the end of the matter, my adroit friend,” gritted Crenshaw. “My turn will come, never fear.”

“A far day, monsieur, a far day!” said Harleston lightly. “Meanwhile, with your permission, we will have a look at the contents of your pockets. First, your pocketbook.”

He unbuttoned the other’s coat, put in his hand, and drew out the book.

“Attend, please,” said he, “so you can see that I replace every article.”

Crenshaw’s only answer was a contemptuous shrug.

A goodly wad of yellow backs of large denominations, and some visiting cards, no two of which bore the same name, were the contents of the pocketbook.

“You must have had some difficulty in keeping track of yourself,” Harleston remarked, as he made a note of the names.

Then he returned the bills and the cards to the book, and put it back in Crenshaw’s pocket.

“It’s unwise to carry so much money about you,” he remarked; “it induces spending, as well as provokes attack.”

“What’s that to you?” replied Crenshaw angrily.

“Nothing whatever—it’s merely a word of advice to one who seems to need it. Now for the other pockets.”

The coat yielded nothing additional; the waist-coat, only a few matches and an open-faced gold watch, which Harleston inspected rather carefully both inside and out; the trousers, a couple of handkerchiefs with the initial C in the corner, some silver, and a small bunch of keys—and in the fob pocket a crumpled note, with the odour of carnations clinging to it.

Harleston glanced at Crenshaw as he opened the note—and caught a sly look in his eyes.

“Something doing, Crenshaw?” he queried.

Another shrug was Crenshaw’s answer—and the sly look grew into a sly smile.

The note, apparently in a woman’s handwriting, was in French, and contained five words and an initial:

À l’aube du jour.

M.

Harleston looked at it long enough to fix in his mind the penmanship and to mark the little eccentricities of style. Then he folded it and put it in Crenshaw’s outside pocket.

“Thank you!” said he, with an amused smile.

“You forgot to look in the soles of my shoes?” Crenshaw jeered.

“Someone else will do that,” Harleston replied.

“Someone else?” Crenshaw inflected.

“The police always search prisoners, I believe.”

“My God, you don’t intend to turn me over to the police?” Crenshaw exclaimed.

“Why not?” And when Crenshaw did not reply: “Wherein are you different from any other felon taken red-handed—except that you were taken twice in the same night, indeed?”

“Think of the scandal that will ensue!” Crenshaw cried.

“It won’t affect me!” Harleston laughed.

“Won’t affect you?” the other retorted. “Maybe it won’t—and maybe it will!”

“We shall try it,” Harleston remarked, and picked up the telephone.

Crenshaw watched him with a snarling sneer on his lips.

Harleston gave the private number of the police superintendent. He himself answered.

“Major Ranleigh, this is Harleston. I’d like to have a man report to me at the Collingwood at once.—No; one will be enough, thank you. Have him come right up to my apartment. Good-bye!—Now if you’ll excuse me for a brief time, Mr. Crenshaw, I’ll get into some clothes—while you think over the question whether you will explain or go to prison.”

“You will not dare!” Crenshaw laughed mockingly. “Your State Department won’t stand for it a moment when they hear of it—which they’ll do at ten o’clock, if I’m missing.”

“Let me felicitate you on your forehandedness,” Harleston called from the next room. “It’s admirably planned, but not effective for your release.”

“Hell!” snorted Crenshaw, and relapsed into silence.

Presently Harleston appeared, dressed for the morning.

“Why not spread your cards on the table, Crenshaw?” he asked. “I did stumble on the deserted cab this morning, wholly by accident; I was on my way here. I did find in it a letter and these roses, and I brought them here. I don’t know if you know what that letter contained—I do. It’s in cipher—and will be turned over to the State Department for translation. What I want to know is: first—what is the message of the letter, if you know; second—who was the woman in the cab, and the facts of the episode; third—what governments, if any, are concerned.”

“You’re amazingly moderate in your demands,” Crenshaw sarcasmed; “so moderate, indeed, that I would acquiesce at once but for the fact that I’m wholly ignorant of the contents of the letter. The name of the woman, and the episode of the cab are none of your affair; nor do the names of parties, whether personal or government, concern you in the least.”

“Very well. We’ll close up the cards and play the game. The first thing in the game, as I said a moment ago, Crenshaw, is not to squeal when you are in a hole and losing.”

A knock came at the door. Harleston crossed and swung it open.

A young man—presumably a business man, quietly-dressed—stood at attention and saluted. If he saw the bound man in the chair, his eyes never showed it.

“Ah, Whiteside,” Harleston remarked. “I’m glad it is you who was sent. Come in.... You will remain here and guard this man; you will prevent any attempt at escape or rescue, even though you are obliged to use the utmost force. I’m for down-town now; and I will communicate with you at the earliest moment. Meanwhile, the man is in your charge.”

“Yes, Mr. Harleston!” Whiteside answered.

“I want some breakfast!” snapped Crenshaw.

“The officer will order from the cafe whatever you wish,” Harleston replied; and picking up his stick he departed, the letter and the photograph in the sealed envelope in his inside pocket.

As he went out, he smiled pleasantly at Crenshaw.

Harleston walked down Sixteenth Street—the Avenue of the Presidents, if you have time either to say it or write it. The Secretary of State resided on it, and, as chance had it, he was descending the front steps as Harleston came along.

Now the Secretary was duly impressed with all the dignity of his official position, and he rarely failed to pull it on the ordinary individual—cockey would be about the proper term. In Harleston, however, he recognized an unusual personage; one to whom the Department was wont to turn when all others had failed in its diplomatic problems; who had some wealth and an absolutely secure social position; who accepted no pecuniary recompense for his service, doing it all for pure amusement, and because his government requested it.

“It’s too fine a day to ride to the Department,” said the Secretary. “It’s much too fine, really, to go anywhere except to the Rataplan and play golf.”

Harleston agreed.

“I’ll take you on at four o’clock,” the Secretary suggested.

“If that is not a command,” said Harleston, “I should like first to consult you about a matter which arose last night, or rather early this morning. I was bound for your office now. I can, however, give you the main facts as we go along.”

“Proceed!” said the Secretary. “I’m all attention.”

“It may be of grave importance and it may be of very little—”

“What do you think it is?”

“I think it is of first importance, judging from known facts. If Carpenter can translate the cipher message, it will—”

“The Department has full faith in your diagnosis, Harleston. You’re the surgeon; you prescribe the treatment and I’ll see that it is followed. Now drive on with the story.”

“It begins with a letter, a photograph, a handkerchief, three American Beauty roses—all in the cab of the sleeping horse—”

“God bless my soul!” exclaimed the Secretary.

“—at one o’clock on Massachusetts Avenue and Eighteenth Street.”

“Is the horse still asleep, Harleston?”

“The horse awoke, and straightway went to his stand in Dupont Circle!” Harleston laughed and related the incidents of the night and early morning, finishing his account in the Secretary’s private office.

“Most amazing!” the latter reflected, eyes half-closed as though seeing a mental picture of it all.

Then he picked up the photograph and studied it awhile.

“So this is the wonderful Madeline Spencer—who came so near to throwing our friend, the King of Valeria, out of his Archdukeship, and later from his throne. I remember the matter most distinctly. I was a friend of the Dalberg family of the Eastern Shore, and of Armand Dalberg himself.” He paused, and looked again at the picture. “H-u-m! She is a very beautiful woman, Harleston, a very beautiful woman! I think I have never seen her equal; certainly never her superior. These dark-haired, classic featured ones for me, Harleston; the pale blonde type does not appeal. The peroxides come of that class.” Again the photograph did duty. “I could almost wish that she were the lost lady of the cab of the sleeping horse—so that I might see her in the flesh. I’ve never seen her, you know.”

Harleston smoothed back a smile. The Secretary too was getting sentimental over the lady, and he had never seen her; though he had known of her rare doings; and those doings had, it appeared, had their natural effect of enveloping her in a glamour of fascination because of what she had done.

“You’ve seen her?” the Secretary asked.

“I’ve known her since she was Madeline Cuthbert. Since then she’s had a history. Possibly, taken altogether she’s a pretty bad lot. And she is not only beautiful; she’s fascinating, simply fascinating; it’s a rare man, a very rare man, who can be with her ten minutes and not succumb to her manifold attractions of mind and body.”

“You have succumbed?” the Secretary smiled.

“I have—twenty times at least. You’ll join the throng, if she has occasion to need you, and gives you half a chance.”

“I’m married!” said the Secretary.

“I’m quite aware of it!”

“I’m immune!”

“And yet you’re wishing to see her in the flesh!” Harleston smiled.

“I think I can safely take the risk!” smoothing his chin complacently.

“Other men have thought the same, I believe, and been burned. However, if the lady is in Washington I’ll engage that you meet her. Also, I’ll acquaint her of your boasted immunity from her beaux yeux.”

“The latter isn’t within the scope of your duty, sir,” the Secretary smiled. “Now we’ll have Carpenter.”

He touched a button.

A moment later Carpenter entered; a scholarly-looking man in the fifties; bald as an egg, with the quiet dignity of bearing which goes with a student, who at the same time is an expert in his particular line—and knows it. He was the Fifth Assistant Secretary, had been the Fifth Assistant and Chief of the Cipher Division for years. His superior was not to be found in any capital in Europe. His business with the secret service of the Department was to pull the strings and obtain results; and he got results, else he would not have been continued in office. His specialty, however, was ciphers; and his chief joy was in a case that had a cipher at the bottom. Ciphers were his recreation, as well as his business.

The Secretary with a gesture turned him over to Harleston—and Harleston handed him the letter.

“What do you make out of it, Mr. Carpenter?” he asked.

Carpenter took the letter and examined it for a moment, holding it to the light, and carefully feeling its texture.

“Not a great deal cursorily,” he answered. “It’s a French paper—the sort, I think, used at the Quay d’Orsay. Have you the envelope accompanying it?”

“Here it is!” said Harleston.

“This envelope, however, is not French; it’s English,” Carpenter said instantly. “See! a saltire within an orle is the private water-mark of Sergeant & Co. I likely can tell you more after careful examination in my workshop.”

“How about the message itself?” Harleston asked.

“It is the Vigenèrie cipher, that’s reasonably certain; and, as you are aware, Mr. Harleston, the Vigenèrie is practically impossible of solution without the key-word. It is the one cipher that needs no code-book, nor anything else that can be lost or stolen—the code-word can be carried in one’s mind. We used it in the De la Porte affair, you will remember. Indeed, just because of its simplicity it is used more generally by every nation than any other cipher.”

“I thought that you might be able to work it out,” said Harleston. “You can do it if any one on earth can.”

“I can do some things, Mr. Harleston,” smiled Carpenter deprecatingly, “but I’m not omniscient. For instance: What language is the key-word—French, Italian, Spanish, English? The message is written on French paper, enclosed in an English envelope.—However, the facts you have may clear up that phase of the matter.”

“Here are the facts, as I know them,” said Harleston. Carpenter leaned back in his chair, closed his eyes, and listened.

“The message is, I should confidently say, written in English or French, with the chances much in favour of the latter,” he said, when Harleston had concluded. “Everyone concerned is English or American; the men who descended upon you so peculiarly and foolishly, and who showed their inexperience in every move, were Americans, I take it, as was also the woman who telephoned you. Moreover, she is fighting them.”

“Then your idea is that the United States is not concerned in the matter?” the Secretary asked.

“Not directly, yet it may be very much concerned in the result. We will know more about it after Mr. Harleston has had his interview with the lady.”

“That’s so!” the Secretary reflected. “We shall trust you, Harleston, to find out something definite from her. Keep me advised if anything turns up. It seems peculiar, and it may be only a personal matter and not an affaire d’état. At all events, you’ve a pleasant interview before you.”

“Maybe I have—and maybe I haven’t!” Harleston laughed—and he and Carpenter went out, passing the French Ambassador in the anteroom.

Harleston went straight to Police Headquarters. The Chief was waiting for him.

“I had Thompson, your cab driver, here,” said Ranleigh, “and he tells a somewhat unusual but apparently straight tale; moreover, he is a very respectable negro, well known to the guards and the officers on duty around Dupont Circle, and they regard him as entirely trustworthy. He says that last evening about nine o’clock, when he was jogging down Connecticut Avenue on his way home—he owns his rig—he was hailed by a fare in evening dress, top coat, and hat, who directed him to drive west on Massachusetts Avenue. In the neighbourhood of Twenty-second Street, the fare signalled to stop and ordered him to come to the door. There he asked him to hire the horse and cab until this morning, when they would be returned to him at that point. Thompson naturally demurred; whereupon the man offered to deposit with him in cash the value of the horse and cab, to be refunded upon their return in the morning less fifty dollars for their hire. This was too good to let slip and Thompson acquiesced, fixing the value at three hundred and fifty dollars, which sum the man skinned off a roll of yellow-backs. Then the fare buttoned his coat around him, jumped on the box, and drove east on Massachusetts Avenue. This morning the horse and cab were backed up to the curb at their customary stand in Dupont Circle, where they were found by officer Murphy shortly after daybreak; before he could report the absence of the driver, Thompson came up and explained.”

“Can Thompson describe the man?” Harleston asked.

“Merely that he was clean-shaved, medium-sized, somewhat stout, wore evening clothes, and was, apparently, a gentleman. Thompson thinks however, that he could readily recognize the man, so we should let him have a look at the fellow that’s under guard in your apartment.”

“It isn’t he,” Harleston explained. “He’s slender, with a mustache and imperial. It was Marston, likely. Did any of your officers see cab No. 333 between nine P.M. and this morning?”

“The reports are clean of No. 333, but we are investigating now. It’s not likely, however. Meanwhile, if there is anything else I can do, Mr. Harleston—”

“You can listen to the balance of the episode—beginning at half-past one this morning, when I found the cab deserted at Eighteenth Street and Massachusetts Avenue, with the horse lying in the roadway, asleep in the shafts....”

“What do you wish the police to do, Mr. Harleston?” the Superintendent asked at the end.

“Nothing, until I’ve seen the Lady of Peacock Alley. Then I’ll likely know something definite—whether to keep hands off or to get busy.”

“Shan’t we even try to locate the two men, in preparation for your getting busy?”

“H’m!” reflected Harleston. “Do it very quietly then. You see, I don’t know whom you’re likely to locate, nor whether we want to locate them.”

“The men who visited your apartment are not of the profession, Mr. Harleston.”

“It’s their profession that’s bothering me!” Harleston laughed. “Why are three Americans engaged in what bears every appearance of being a diplomatic matter, and of which our State Department knows nothing?”

“There’s a woman in it, I believe; likely two, possibly three!” was the smiling reply.

“Hump!” said Harleston. “A woman is at the bottom of most things, that’s a fact; she’s about the only thing for which a man will betray his country. However, as they’re three men there should be three women—”

“One woman is enough—if she is sufficiently fascinating and plays the men off against one another. Though you’ve plenty of women in the case, Mr. Harleston, if you’re looking for the three:—the one whom you’re to meet this afternoon; the unknown who left the Collingwood so mysteriously; and the one of the photograph. If the other two are as lovely as she of the photograph they are some trio. I shouldn’t care for the latter lady to tempt me overlong.”

“Wise man!” Harleston remarked, as he arose to go. “I’ll advise you after the interview. Meanwhile you might have the cabby look at the fellow in durance at the Collingwood. Possibly he has seen him before; which may give us a lead—if we find we want a lead.”

The telephone buzzed; Ranleigh answered it—then raised his hand to Harleston to remain. After a moment, he motioned for Harleston to come closer and held the receiver so that both could hear.

“I can see you at three o’clock,” Ranleigh said.

“Three o’clock will be very nice,” came a feminine voice—soft, with a bit of a drawl.

“Very well,” Ranleigh replied. “If you will give me your name—I missed it. Whom am I to expect at three?”

“Mrs. Winton, of the Burlingame apartments. I’ll be punctual—and thank you so much. Good-bye!”

“Anything familiar about the voice?” Ranleigh asked, pushing back the instrument.

Harleston shook his head in negation.

“I thought it might be your Lady of Peacock Alley, for it’s about the cab matter. She says that she has something to tell me regarding a mysterious cab on Eighteenth Street last night sometime about one o’clock.”

“There are quite too many women in this affair,” Harleston commented. “However, the Burlingame is almost directly across the street from where I found the cab, so her story will be interesting—if it’s not a plant.”

“And it may be even more interesting if it is a plant,” Ranleigh added. “If you will come in a bit before three, I’ll put you where you can see and hear everything that takes place.”

“I’ll do it!” said Harleston.

Harleston returned at a quarter to three, and Ranleigh showed him into the small room at the rear, provided with every facility for seeing what went on and overhearing and reducing what was said in the Superintendent’s private office.

Promptly at three, Mrs. Winton was announced by appointment, and was instantly admitted.

She was about thirty years of age, slender, with dark hair and a face just missing beauty. She was gowned in black, with a bunch of violets at her waist, and she wore a large mesh veil, through which her particularly fine dark eyes sparkled discriminatingly.

The Superintendent arose and bowed graciously. Ranleigh was a gentleman by birth and by breeding.

“What can I do for you, Mrs. Winton?” he asked, placing a chair for her—where her face would be in full view from the cabinet.

“You can do nothing for me, sir,” she replied, with a charming smile. “I came to you as head of the Police Department for the purpose of detailing what I saw in connection with the matter I mentioned to you over the telephone. It may be of no value to you—I even may do wrong in volunteering my information, but—”

“On the contrary,” the Superintendent interjected, “you confer a great favour on this Department by reporting to it any suspicious circumstances. It is for it to investigate and determine whether they call for action. Pray proceed, my dear Mrs. Winton.”

She gave him another charming smile and went on.