Project Gutenberg's American Eloquence, Volume IV. (of 4), by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: American Eloquence, Volume IV. (of 4)

Studies In American Political History (1897)

Author: Various

Release Date: March 17, 2005 [EBook #15394]

Last Updated: November 15, 2012

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN ELOQUENCE, IV. ***

Produced by David Widger

INTRODUCTION TO THE FOURTH VOLUME.

VII.—CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION.

JOHN C. BRECKENRIDGE, and EDWARD D. BAKER

VIII.—FREE TRADE AND PROTECTION.

GEORGE W. CURTIS From a painting by SAMUEL LAWRENCE.

JOHN C. BRECKENRIDGE From a photograph.

HENRY W. BEECHER Wood-engraving from photograph.

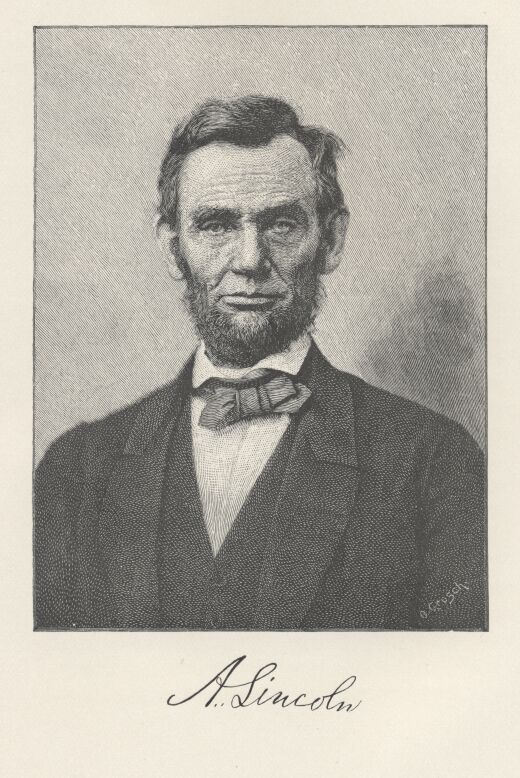

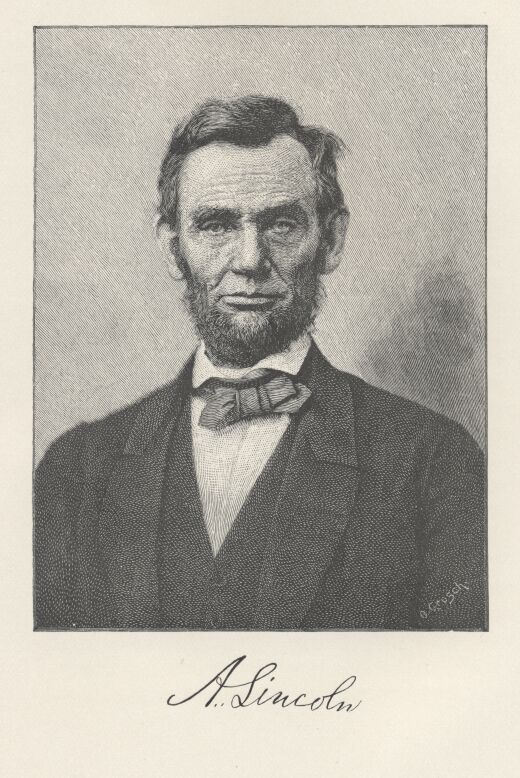

ABRAHAM LINCOLN Wood-engraving from photograph.

JAMES G. BLAINE Wood-engraving from photograph.

The fourth and last volume of the American Eloquent e deals with four great subjects of discussion in our history,—the Civil War and Reconstruction, Free Trade and Protection, Finance, and Civil Service Reform. In the division on the Civil War there has been substituted in the new edition, for Mr. Schurz's speech on the Democratic War Policy the spirited discussion between Breckenridge and Baker on the suppression of insurrection. The scene in which these two speeches were delivered in the United States Senate at the opening of the Civil war is full of historic and dramatic interest, while the speeches themselves are examples of superior oratory. Mr. Schurz appears to advantage in another part of the volume in his address on Civil Service Reform.

The speeches of Thaddeus Stevens and Henry J. Raymond, delivered at the opening of the Reconstruction struggle under President Johnson, are also new material in this edition. They are fairly representative of two distinct views in that period of the controversy. These two speeches are substituted for the Garfield-Blackburn discussion over a "rider" to an appropriation bill designed to forbid federal control of elections within the States. This discussion was only incidental to the problem of reconstruction, and may be said to have occurred at a time (1879) subsequent to the close of the Reconstruction period proper.

The material on Free Trade and Protection has been left unchanged for the reason that it appears to the present editor quite useless to attempt to secure better material on the tariff discussion. There might be added valuable similar material from later speeches on the tariff, but the two speeches of Clay and Hurd may be said to contain the essential merits of the long-standing tariff debate.

The section of the volume devoted to Finance and Civil Service Reform is entirely new. The two speeches of Curtis and Schurz are deemed sufficient to set forth the merits of the movement for the reform of the Civil Service. The magnitude of our financial controversies during a century of our history precludes the possibility of securing an adequate representation of them in speeches which might come within the scope of such a volume as this. It has, therefore, seemed best to the editor to confine the selections on Finance to the period since the Civil War, and to the subject of coinage, rather than to attempt to include also the kindred subjects of banking and paper currency. The four representative speeches on the coinage will, however, bring into view the various principles of finance which have determined the differences and divisions in party opinion on all phases of this great subject.

THE transformation of the original secession movement into a de facto nationality made war inevitable, but acts of war had already taken place, with or without State authority. Seizures of forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, and navy yards, and captures of Federal troops, had completely extinguished the authority of the United States in the secession area, except at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, and Fort Pickens and the forts at Key West in Florida; and active operations to reduce these had been begun. When an attempt was made, late in January, 1861, to provision Fort Sumter, the provision steamer, Star of the West, was fired on by the South Carolina batteries and driven back. Nevertheless, the Buchanan administration succeeded in keeping the peace until its constitutional expiration in March, 1861, although the rival and irreconcilable administration at Montgomery was busily engaged in securing its exclusive authority in the seceding States.

Neither of the two incompatible administrations was anxious to strike the first blow. Mr. Lincoln's administration began with the policy outlined in his inaugural address, that of insisting on collection of the duties on imports, and avoiding all other irritating measures. Mr. Seward, Secretary of State, even talked of compensating for the loss of the seceding States by admissions from Canada and elsewhere. The urgent needs of Fort Sumter, however, soon forced an attempt to provision it; and this brought on a general attack upon it by the Confederate batteries around it. After a bombardment of two days, and a vigorous defence by the fort, in which no one was killed on either side, the fort surrendered, April 14, 1861. It was now impossible for the United States to ignore the Confederate States any longer. President Lincoln issued a call for volunteers, and a proclamation announcing a blockade of the coast of the seceding States. A similar call on the other side and the issue of letters of marque and reprisal against the commerce of the United States were followed by an act of the Confederate Congress formally recognizing the existence of war with the United States. The two powers were thus locked in a struggle for life or death, the Confederate States fighting for existence and recognition, the United States for the maintenance of recognized boundaries and jurisdiction; the Confederate States claiming to be at war with a foreign power, the United States to be engaged in the suppression of individual resistance to the laws. The event was to decide between the opposing claims; and it was certain that the event must be the absolute extinction of either the Confederate States or the United States within the area of secession.

President Lincoln called Congress together in special session, July 4, 1861; and Congress at once undertook to limit the scope of the war in regard to two most important points, slavery and State rights. Resolutions passed both Houses, by overwhelming majorities, that slavery in the seceding States was not to be interfered with, that the autonomy of the States themselves was to be strictly maintained, and that, when the Union was made secure, the war ought to cease. If the war had ended in that month, these resolutions would have been of some value; every month of the extension of the war made them of less value. They were repeatedly offered afterward from the Democratic side, but were as regularly laid on the table. Their theory, however, continued to control the Democratic policy to the end of the war.

For a time the original policy was to all appearance unaltered. The war was against individuals only; and peace was to be made with individuals only, the States remaining untouched, but the Confederate States being blotted out in the process. The only requisite to recognition of a seceding State was to be the discovery of enough loyal or pardoned citizens to set its machinery going again. Thus the delegates from the forty western counties of Virginia were recognized as competent to give the assent of Virginia to the erection of the new State of West Virginia; and the Senators and Representatives of the new State actually sat in judgment on the reconstruction of the parent State, although the legality of the parent government was the evident measure of the constitutional existence of the new State. Such inconsistencies were the natural results of the changes forced upon the Federal policy by the events of the war, as it grew wider and more desperate.

The first of these changes was the inevitable attack upon slavery. The labor system of the seceding States was a mark so tempting that no belligerent should have been seriously expected to have refrained from aiming at it. January 1, 1863, after one hundred days' notice, President Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves within the enemy's lines as rapidly as the Federal arms should advance. This one break in the original policy involved, as possible consequences, all the ultimate steps of reconstruction. Read-mission was no longer to be a simple restoration; abolition of slavery was to be a condition-precedent which the government could never abandon. If the President could impose such a condition, who was to put bounds to the power of Congress to impose limitations on its part? The President had practically declared, contrary to the original policy, that the war should continue until slavery was abolished; what was to hinder Congress from declaring that the war should continue until, in its judgment, the last remnants of the Confederate States were satisfactorily blotted out? This, in effect, was the basis of reconstruction, as finally carried out. The steady opposition of the Democrats only made the final terms the harder.

The principle urged consistently from the beginning of the war by Thaddeus Stevens, of Pennsylvania, was that serious resistance to the Constitution implied the suspension of the Constitution in the area of resistance. No one, he insisted, could truthfully assert that the Constitution of the United States was then in force in South Carolina; why should Congress be bound by the Constitution in matters connected with South Carolina? If the resistance should be successful, the suspension of the Constitution would evidently be perpetual; Congress alone could decide when the resistance had so far ceased that the operations of the Constitution could be resumed. The terms of readmission were thus to be laid down by Congress. To much the same effect was the different theory of Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts. While he held that the seceding States could not remove themselves from the national jurisdiction, except by successful war, he maintained that no Territory was obliged to become a State, and that no State was obliged to remain a State; that the seceding States had repudiated their State-hood, had committed suicide as States, and had become Territories; and that the powers of Congress to impose conditions on their readmission were as absolute as in the case of other Territories. Neither of these theories was finally followed out in reconstruction, but both had a strong influence on the final process.

President Lincoln followed the plan subsequently completed by Johnson. The original (Pierpont) government of Virginia was recognized and supported. Similar governments were established in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas, and an unsuccessful attempt was made to do so in Florida. The amnesty proclamation of December, 1863, offered to recognize any State government in the seceding States formed by one tenth of the former voters who should take the oath of loyalty and support of the emancipation measures. At the following session of Congress, the first bill providing for congressional supervision of the readmission of the seceding States was passed, but the President retained it without signing it until Congress had adjourned. At the time of President Lincoln's assassination Congress was not in session, and President Johnson had six months in which to complete the work. Provisional governors were appointed, conventions were called, the State constitutions were amended by the abolition of slavery and the repudiation of the war debt, and the ordinances of secession were either voided or repealed. When Congress met in December, 1865, the work had been completed, the new State governments were in operation, and the XIIIth Amendment, abolishing slavery, had been ratified by aid of their votes. Congress, however, still refused to admit their Senators or Representatives. The first action of many of the new governments had been to pass labor, contract, stay, and vagrant laws which looked much like a re-establishment of slavery, and the majority in Congress felt that further guarantees for the security of the freedmen were necessary before the war could be truly said to be over.

Early in 1866 President Johnson imprudently carried matters into an open quarrel with Congress, which united the two thirds Republican majority in both Houses against him. The elections of the autumn of 1866 showed that the two thirds majorities were to be continued through the next Congress; and in March, 1867, the first Reconstruction Act was passed over the veto. It declared the existing governments in the seceding States to be provisional only; put the States under military governors until State conventions, elected with negro suffrage and excluding the classes named in the proposed XIVth Amendment, should form a State government satisfactory to Congress, and the State government should ratify the XIVth Amendment; and made this rule of suffrage imperative in all elections under the provisional governments until they should be readmitted. This was a semi-voluntary reconstruction. In the same month the new Congress, which met immediately on the adjournment of its predecessor, passed a supplementary act. It directed the military governors to call the conventions before September 1st following, and thus enforced an involuntary reconstruction.

Tennessee had been readmitted in 1866. North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Arkansas were reconstructed under the acts, and were readmitted in 1868. Georgia was also readmitted, but was remanded again for expelling negro members of her Legislature, and came in under the secondary terms. Virginia, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas, which had refused or broken the first terms, were admitted in 1870, on the additional terms of ratifying the XVth Amendment, which forbade the exclusion of the negroes from the elective franchise.

In Georgia the white voters held control of their State from the beginning. In the other seceding States the government passed, at various times and by various methods during the next six years after 1871, under control of the whites, who still retain control. One of the avowed objects of reconstruction has thus failed; but, to one who does not presume that all things will be accomplished at a single leap, the scheme, in spite of its manifest blunders and crudities, must seem to have had a remarkable success. Whatever the political status of the negro may now be in the seceding States, it may be confidently affirmed that it is far better than it would have been in the same time under an unrestricted readmission. The whites, all whose energies have been strained to secure control of their States, have been glad, in return for this success to yield a measure of other civil rights to the freedmen, which is already fuller than ought to have been hoped for in 1867. And, as the general elective franchise is firmly imbedded in the organic law, its ultimate concession will come more easily and gently than if it were then an entirely new step.

During this long period of almost continuous exertion of national power there were many subsidiary measures, such as the laws authorizing the appointment of supervisors for congressional elections, and the use of Federal troops as a posse comitatus by Federal supervisors, which were not at all in line with the earlier theory of the division between Federal and State powers. The Democratic party gradually abandoned its opposition to reconstruction, accepting it as a disagreeable but accomplished fact, but kept up and increased its opposition to the subsidiary measures. About 1876-7 a reaction became evident, and with President Hayes' withdrawal of troops from South Carolina, Federal control of affairs in the Southern States came to an end.

Foreign affairs are not strictly a part of our subject; but, as going to show one of the dangerous features of the Civil War, the possibility of the success of the secession sentiment in England in obtaining the intervention of that country, the speech of Mr. Beecher in Liver-pool, with the addenda of his audience, has been given.

FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MARCH 4, 1861. FELLOW CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES:

In compliance with a custom as old as the government itself, I appear before you to address you briefly, and to take in your presence the oath prescribed by the Constitution of the United States to be taken by the President "before he enters on the execution of his office."

I do not consider it necessary at present for me to discuss those matters of administration about which there is no special anxiety or excitement.

Apprehension seems to exist, among the people of the Southern States, that by the accession of a Republican administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There never has been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that "I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so." Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations, and had never recanted them. And more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read:

"Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its judgment exclusively, is essential to the balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend, and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter under what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes."

I now reiterate these sentiments; and, in doing so, I only press upon the public attention the most conclusive evidence of which the case is susceptible, that the property, peace, and security of no section are to be in any wise endangered by the now incoming administration. I add, too, that all the protection which, consistently with the Constitution and the laws, can be given, will be cheerfully given to all the States, when lawfully demanded, for whatever cause, as cheerfully to one section as to another.

There is much controversy about the delivering up of fugitives from service or labor. The clause I now read is as plainly written in the Constitution as any other of its provisions:

"No person held to service or labor in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due."

It is scarcely questioned that this provision was intended by those who made it for the re-claiming of what we call fugitive slaves; and the intention of the lawgiver is the law. All members of Congress swear their support to the whole Constitution—to this provision as much as any other. To the proposition, then, that slaves whose cases come within the terms of this clause, "shall be delivered up," their oaths are unanimous. Now, if they would make the effort in good temper, could they not, with nearly equal unanimity, frame and pass a law by means of which to keep good that unanimous oath?

There is some difference of opinion whether this clause should be enforced by National or by State authority; but surely that difference is not a very material one. If the slave is to be surrendered, it can be of but little consequence to him, or to others, by what authority it is done. And should any one, in any case, be content that his oath should go unkept, on a mere unsubstantial controversy as to how it shall be kept?

Again, in any law upon this subject, ought not all the safeguards of liberty known in civilized and humane jurisprudence to be introduced, so that a free man be not, in any case, surrendered as a slave? And might it not be well, at the same time, to provide by law for the enforcement of that clause of the Constitution which guarantees that "the citizens of each State shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several States"?

I take the official oath to-day with no mental reservation, and with no purpose to construe the Constitution or laws by any hypercritical rules. And while I do not choose now to specify particular acts of Congress as proper to be enforced, I do suggest that it will be much safer for all, both in official and private stations, to conform to and abide by all those acts which stand unrepealed, than to violate any of them, trusting to find impunity in having them held to be unconstitutional.

It is seventy-two years since the first inauguration of a President under our National Constitution. During that period, fifteen different and greatly distinguished citizens have, in succession, administered the Executive branch of the government. They have conducted it through many perils, and generally with great success. Yet, with all this scope for precedent, I now enter upon the same task for the brief constitutional term of four years, under great and peculiar difficulty. A disruption of the Federal Union, heretofore only menaced, is now formidably attempted.

I hold that in contemplation of universal law, and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments. It is safe to assert that no government proper ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination. Continue to execute all the express provisions of our National Government, and the Union will endure forever—it being impossible to destroy it, except by some action not provided for in the instrument itself.

Again, if the United States be not a government proper, but an association of States in the nature of contract merely, can it, as a contract, be peaceably unmade by less than all the parties who made it? One party to a contract may violate it—break it, so to speak; but does it not require all to lawfully rescind it?

Descending from these general principles, we find the proposition that, in legal contemplation, the Union is perpetual, confirmed by the history of the Union itself. The Union is much older than the Constitution. It was formed, in fact, by the Articles of Association in 1774.

It was matured and continued by the Declaration of Independence in 1776. It was further matured, and the faith of all the then thirteen States expressly plighted and engaged that it should be perpetual, by the Articles of Confederation in 1778. And, finally, in 1787, one of the declared objects for ordaining and establishing the Constitution was "to form a more perfect union."

But if destruction of the Union, by one, or by a part only, of the States, be lawfully possible, the Union is less perfect than before, the Constitution having lost the vital element of perpetuity.

It follows, from these views, that no State, upon its own mere motion, can lawfully get out of the Union; that resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void; and that acts of violence within any State or States, against the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.

I therefore consider that, in view of the Constitution and the laws, the Union is unbroken, and to the extent of my ability I shall take care, as the Constitution itself expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the States. Doing this I deem to be only a simple duty on my part; and I shall perform it, so far as practicable, unless my rightful masters, the American people, shall withhold the requisite means, or, in some authoritative manner, direct the contrary. I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union that it will constitutionally defend and maintain itself. In doing this there need be no blood-shed or violence; and there shall be none, unless it be forced upon the National authority. The power confided to me will be used to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the government, and to collect the duties and imposts; but beyond what may be necessary for these objects, there will be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere. Where hostility to the United States, in any interior locality, shall be so great and universal as to prevent competent resident citizens from holding the Federal offices, there will be no attempt to force obnoxious strangers among the people for that object. While the strict legal right may exist in the government to enforce the exercise of these offices, the attempt to do so would be so irritating, and so nearly impracticable withal, that I deem it better to forego, for the time, the uses of such offices.

The mails, unless repelled, will continue to be furnished in all parts of the Union. So far as possible, the people everywhere shall have that sense of perfect security which is most favorable to calm thought and reflection. The course here indicated will be followed, unless current events and experience shall show a modification or change to be proper, and in every case and exigency my best discretion will be exercised, according to circumstances actually existing, and with a view and a hope of a peaceful solution of the National troubles, and the restoration of fraternal sympathies and affections.

That there are persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union at all events, and are glad of any pretext to do it, I will neither affirm nor deny; but if there be such, I need address no word to them. To those, however, who really love the Union, may I not speak?

Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our National fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain why we do it? Will you hazard so desperate a step while there is any possibility that any portion of the certain ills you fly from have no real existence? Will you, while the certain ills you fly to are greater than all the real ones you fly from,—will you risk the omission of so fearful a mistake?

All profess to be content in the Union, if all constitutional rights can be maintained. Is it true, then, that any right, plainly written in the Constitution, has been denied? I think not. Happily the human mind is so constituted that no party can reach to the audacity of doing this. Think, if you can, of a single instance in which a plainly written provision of the Constitution has ever been denied. If, by the mere force of numbers, a majority should deprive a minority of any clearly written constitutional right, it might, in a moral point of view, justify revolution—certainly would if such right were a vital one. But such is not our case. All the vital rights of minorities and of individuals are so plainly assured to them by affirmations and negations, guaranties and prohibitions in the Constitution, that controversies never arise concerning them. But no organic law can ever be framed with a provision specifically applicable to every question which may occur in practical administration. No foresight can anticipate, nor any document of reasonable length contain, express provisions for all possible questions. Shall fugitives from labor be surrendered by National or State authority? The Constitution does not expressly say. May Congress prohibit slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say. Must Congress protect slavery in the Territories? The Constitution does not expressly say.

From questions of this class spring all our constitutional controversies, and we divide upon them into majorities and minorities. If the minority will not acquiesce, the majority must, or the government must cease. There is no other alternative; for continuing the government is acquiescence on one side or the other. If a minority in such case will secede rather than acquiesce, they make a precedent which, in turn, will divide and ruin them; for a minority of their own will secede from them whenever a majority refuses to be controlled by such a minority. For instance, why may not any portion of a new confederacy, a year or two hence, arbitrarily secede again, precisely as portions of the present Union now claim to secede from it? All who cherish disunion sentiments are now being educated to the exact temper of doing this.

Is there such perfect identity of interests among the States to compose a new Union, as to produce harmony only, and prevent renewed secession?

Plainly, the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it, does, of necessity, fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible; the rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism, in some form, is all that is left. * * *

Physically speaking, we cannot separate. We cannot remove our respective sections from each other, nor build an impassable wall between them. A husband and wife may be divorced, and go out of the presence and beyond the reach of each other; but the different parts of our country cannot do this. They cannot but remain face to face, and intercourse, either amicable or hostile, must continue between them. It is impossible, then, to make that intercourse more advantageous or more satisfactory after separation than before. Can aliens make treaties easier than friends can make laws? Can treaties be more faithfully enforced between aliens than laws can among friends? Suppose you go to war, you cannot fight always, and when after much loss on both sides and no gain on either you cease fighting, the identical old questions as to terms of intercourse are again upon you.

This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing government they can exercise their constitutional right of amending it, or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it. I cannot be ignorant of the fact that many worthy and patriotic citizens are desirous of having the National Constitution amended. * * * I understand a proposed amendment to the Constitution—which amendment, however, I have not seen—has passed Congress, to the effect that the Federal Government shall never interfere with the domestic institutions of the States, including that of persons held to service. To avoid misconstruction of what I have said, I depart from my purpose not to speak of particular amendments, so far as to say that, holding such a provision now to be implied constitutional law, I have no objections to its being made express and irrevocable.'

The Chief Magistrate derives all his authority from the people, and they have conferred none upon him to fix terms for the separation of the States. The people themselves can do this also if they choose, but the Executive, as such, has nothing to do with it. His duty is to administer the present government as it came to his hands, and to transmit it, unimpaired by him, to his successor. Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better or equal hope in the world? In our present differences is either party without faith of being in the right? If the Almighty Ruler of Nations, with his eternal truth and justice, be on your side of the North, or yours of the South, that truth and that justice will surely prevail, by the judgment of this great tribunal of the American people. By the frame of the Government under which we live, the same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief, and have with equal wisdom provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals. While the people retain their virtue and vigilance, no administration, by any extreme of wickedness or folly, can very seriously injure the government in the short space of four years.

My countrymen, one and all, think calmly and well upon this whole subject. Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time. If there be an object to hurry any of you in hot haste to a step which you would never take deliberately, that object will be frustrated by taking time; but no good object can be frustrated by it. Such of you as are now dissatisfied still have the old Constitution unimpaired, and on the sensitive point, the laws of your own framing under it; while the new Administration will have no immediate power, if it would, to change either. If it were admitted that you who are dissatisfied hold the right side in this dispute there is still no single good reason for precipitate action. Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land are still competent to adjust in the best way all our present difficulty. In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen, and not in mine, are the momentous issues of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect, and defend" it.

I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break, our bonds of affection. The mystic cords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave to every living heart and hearth-stone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

INAUGURAL ADDRESS, MONTGOMERY, ALA., FEBRUARY 18, 1861.

GENTLEMEN OF THE CONGRESS OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA, FRIENDS, AND FELLOW-CITIZENS:

Our present condition, achieved in a manner unprecedented in the history of nations, illustrates the American idea that governments rest upon the consent of the governed, and that it is the right of the people to alter and abolish governments whenever they become destructive to the ends for which they were established. The declared compact of the Union from which we have withdrawn was to establish justice, ensure domestic tranquillity, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity; and when in the judgment of the sovereign States now composing this Confederacy it has been perverted from the purposes for which it was ordained, and ceased to answer the ends for which it was established, a peaceful appeal to the ballot-box declared that, so far as they were concerned, the government created by that compact should cease to exist. In this they merely asserted the right which the Declaration of Independence of 1776 defined to be inalienable. Of the time and occasion of this exercise they as sovereigns were the final judges, each for himself. The impartial, enlightened verdict of mankind will vindicate the rectitude of our conduct; and He who knows the hearts of men will judge of the sincerity with which we labored to preserve the government of our fathers in its spirit.

The right solemnly proclaimed at the birth of the States, and which has been affirmed and reaffirmed in the bills of rights of the States subsequently admitted into the Union of 1789, undeniably recognizes in the people the power to resume the authority delegated for the purposes of government. Thus the sovereign States here represented proceeded to form this Confederacy; and it is by the abuse of language that their act has been denominated revolution. They formed a new alliance, but within each State its government has remained. The rights of person and property have not been disturbed. The agent through whom they communicated with foreign nations is changed, but this does not necessarily interrupt their international relations. Sustained by the consciousness that the transition from the former Union to the present Confederacy has not proceeded from a disregard on our part of our just obligations or any failure to perform every constitutional duty, moved by no interest or passion to invade the rights of others, anxious to cultivate peace and commerce with all nations, if we may not hope to avoid war, we may at least expect that posterity will acquit us of having needlessly engaged in it. Doubly justified by the absence of wrong on our part, and by wanton aggression on the part of others, there can be no use to doubt the courage and patriotism of the people of the Confederate States will be found equal to any measure of defence which soon their security may require.

An agricultural people, whose chief interest is the export of a commodity required in every manufacturing country, our true policy is peace and the freest trade which our necessities will permit. It is alike our interest and that of all those to whom we would sell and from whom we would buy, that there should be the fewest practicable restrictions upon the interchange of commodities. There can be but little rivalry between ours and any manufacturing or navigating community, such as the northeastern States of the American Union. It must follow, therefore, that mutual interest would invite good-will and kind offices. If, however, passion or lust of dominion should cloud the judgment or inflame the ambition of those States, we must prepare to meet the emergency, and maintain by the final arbitrament of the sword the position which we have assumed among the nations of the earth.

We have entered upon a career of independence, and it must be inflexibly pursued through many years of controversy with our late associates of the Northern States. We have vainly endeavored to secure tranquillity and obtain respect for the rights to which we were entitled. As a necessity, not a choice, we have resorted to the remedy of separation, and henceforth our energies must be directed to the conduct of our own affairs, and the perpetuity of the Confederacy which we have formed. If a just perception of mutual interest shall permit us peaceably to pursue our separate political career, my most earnest desire will have been fulfilled. But if this be denied us, and the integrity of our territory and jurisdiction be assailed, it will but remain for us with firm resolve to appeal to arms and invoke the blessing of Providence on a just cause. * * *

Actuated solely by a desire to preserve our own rights, and to promote our own welfare, the separation of the Confederate States has been marked by no aggression upon others, and followed by no domestic convulsion. Our industrial pursuits have received no check, the cultivation of our fields progresses as heretofore, and even should we be involved in war, there would be no considerable diminution in the production of the staples which have constituted our exports, in which the commercial world has an interest scarcely less than our own. This common interest of producer and consumer can only be intercepted by an exterior force which should obstruct its transmission to foreign markets, a course of conduct which would be detrimental to manufacturing and commercial interests abroad.

Should reason guide the action of the government from which we have separated, a policy so detrimental to the civilized world, the Northern States included, could not be dictated by even a stronger desire to inflict injury upon us; but if it be otherwise, a terrible responsibility will rest upon it, and the suffering of millions will bear testimony to the folly and wickedness of our aggressors. In the meantime there will remain to us, besides the ordinary remedies before suggested, the well-known resources for retaliation upon the commerce of an enemy. * * * We have changed the constituent parts but not the system of our government. The Constitution formed by our fathers is that of these Confederate States. In their exposition of it, and in the judicial construction it has received, we have a light which reveals its true meaning. Thus instructed as to the just interpretation of that instrument, and ever remembering that all offices are but trusts held for the people, and that delegated powers are to be strictly construed, I will hope by due diligence in the performance of my duties, though I may disappoint your expectation, yet to retain, when retiring, something of the good-will and confidence which will welcome my entrance into office.

It is joyous in the midst of perilous times to look around upon a people united in heart, when one purpose of high resolve animates and actuates the whole, where the sacrifices to be made are not weighed in the balance, against honor, right, liberty, and equality. Obstacles may retard, but they cannot long prevent, the progress of a movement sanctioned by its justice and sustained by a virtuous people. Reverently let us invoke the God of our fathers to guide and protect us in our efforts to perpetuate the principles which by His blessing they were able to vindicate, establish, and transmit to their posterity; and with a continuance of His favor, ever gratefully acknowledged, we may hopefully look forward to success, to peace, to prosperity.

THE "CORNER-STONE" ADDRESS; ATHENAEUM, SAVANNAH, GA., MARCH 21, 1861 MR. MAYOR AND GENTLEMEN:

We are in the midst of one of the greatest epochs in our history. The last ninety days will mark one of the most interesting eras in the history of modern civilization. Seven States have in the last three months thrown off an old government and formed a new. This revolution has been signally marked, up to this time, by the fact of its having been accomplished without the loss of a single drop of blood. This new constitution, or form of government, constitutes the subject to which your attention will be partly invited.

In reference to it, I make this first general remark: it amply secures all our ancient rights, franchises, and liberties. All the great principles of Magna Charta are retained in it. No citizen is deprived of life, liberty, or property, but by the judgment of his peers under the laws of the land. The great principle of religious liberty, which was the honor and pride of the old Constitution, is still maintained and secured. All the essentials of the old Constitution, which have endeared it to the hearts of the American people, have been preserved and perpetuated. Some changes have been made. Some of these I should prefer not to have seen made; but other important changes do meet my cordial approbation. They form great improvements upon the old Constitution. So, taking the whole new constitution, I have no hesitancy in giving it as my judgment that it is decidedly better than the old.

Allow me briefly to allude to some of these improvements. The question of building up class interests, or fostering one branch of industry to the prejudice of another under the exercise of the revenue power, which gave us so much trouble under the old Constitution, is put at rest forever under the new. We allow the imposition of no duty with a view of giving advantage to one class of persons, in any trade or business, over those of another. All, under our system, stand upon the same broad principles of perfect equality. Honest labor and enterprise are left free and unrestricted in whatever pursuit they may be engaged. This old thorn of the tariff, which was the cause of so much irritation in the old body politic, is removed forever from the new.

Again, the subject of internal improvements, under the power of Congress to regulate commerce, is put at rest under our system. The power, claimed by construction under the old Constitution, was at least a doubtful one; it rested solely upon construction. We of the South, generally apart from considerations of constitutional principles, opposed its exercise upon grounds of its inexpediency and injustice. * * * Our opposition sprang from no hostility to commerce, or to all necessary aids for facilitating it. With us it was simply a question upon whom the burden should fall. In Georgia, for instance, we have done as much for the cause of internal improvements as any other portion of the country, according to population and means. We have stretched out lines of railroad from the seaboard to the mountains; dug down the hills, and filled up the valleys, at a cost of $25,000,000. * * * No State was in greater need of such facilities than Georgia, but we did not ask that these works should be made by appropriations out of the common treasury. The cost of the grading, the superstructure, and the equipment of our roads was borne by those who had entered into the enterprise. Nay, more, not only the cost of the iron—no small item in the general cost—was borne in the same way, but we were compelled to pay into the common treasury several millions of dollars for the privilege of importing the iron, after the price was paid for it abroad. What justice was there in taking this money, which our people paid into the common treasury on the importation of our iron, and applying it to the improvement of rivers and harbors elsewhere? The true principle is to subject the commerce of every locality to whatever burdens may be necessary to facilitate it. If Charleston harbor needs improvement, let the commerce of Charleston bear the burden. * * * This, again, is the broad principle of perfect equality and justice; and it is especially set forth and established in our new constitution.

Another feature to which I will allude is that the new constitution provides that cabinet ministers and heads of departments may have the privilege of seats upon the floor of the Senate and House of Representatives, may have the right to participate in the debates and discussions upon the various subjects of administration. I should have preferred that this provision should have gone further, and required the President to select his constitutional advisers from the Senate and House of Representatives. That would have conformed entirely to the practice in the British Parliament, which, in my judgment, is one of the wisest provisions in the British constitution. It is the only feature that saves that government. It is that which gives it stability in its facility to change its administration. Ours, as it is, is a great approximation to the right principle. * * *

Another change in the Constitution relates to the length of the tenure of the Presidential office. In the new constitution it is six years instead of four, and the President is rendered ineligible for a re-election. This is certainly a decidedly conservative change. It will remove from the incumbent all temptation to use his office or exert the powers confided to him for any objects of personal ambition. The only incentive to that higher ambition which should move and actuate one holding such high trusts in his hands will be the good of the people, the advancement, happiness, safety, honor, and true glory of the Confederacy.

But, not to be tedious in enumerating the numerous changes for the better, allow me to allude to one other—though last, not least. The new constitution has put at rest forever all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution, African slavery as it exists amongst us, the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson, in his forecast, had anticipated this as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old Constitution were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with; but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other, in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the Constitution, was the prevailing idea at that time. The Constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guaranties thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when "the storm came and the wind blew."

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man, that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.

This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. This truth has been slow in the process of its development, like all other truths in the various departments of science. It has been so even amongst us. Many who hear me, perhaps, can recollect well that this truth was not generally admitted, even within their day. The errors of the past generation still clung to many as late as twenty years ago. Those at the North who still cling to these errors, with a zeal above knowledge, we justly denominate fanatics. All fanaticism springs from an aberration of the mind, from a defect in reasoning. It is a species of insanity. One of the most striking characteristics of insanity, in many instances, is forming correct conclusions from fancied or erroneous premises. So with the antislavery fanatics; their conclusions are right, if their premises were. They assume that the negro is equal, and hence conclude that he is entitled to equal rights and privileges with the white man. If their premises were correct, their conclusions would be logical and just; but, their premise being wrong, their whole argument fails. I recollect once hearing a gentleman from one of the Northern States, of great power and ability, announce in the House of Representatives, with imposing effect, that we of the South would be compelled ultimately to yield upon this subject of slavery, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics as it was in physics or mechanics; that the principle would ultimately prevail; that we, in maintaining slavery as it exists with us, were warring against a principle, founded in nature, the principle of the equality of men. The reply I made to him was that upon his own grounds we should ultimately succeed, and that he and his associates in this crusade against our institutions would ultimately fail. The truth announced, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics as it was in physics and mechanics, I admitted; but told him that it was he, and those acting with him, who were warring against a principle. They were attempting to make things equal which the Creator had made unequal.

In the conflict, thus far, success has been on our side, complete throughout the length and breadth of the Confederate States. It is upon this, as I have stated, our social fabric is firmly planted; and I cannot permit myself to doubt the ultimate success of a full recognition of this principle throughout the civilized and enlightened world.

As I have stated, the truth of this principle may be slow in development, as all truths are and ever have been, in the various branches of science. It was so with the principles announced by Galileo. It was so with Adam Smith and his principles of political economy. It was so with Harvey and his theory of the circulation of the blood; it is stated that not a single one of the medical profession, living at the time of the announcement of the truths made by him, admitted them. Now they are universally acknowledged. May we not, therefore, look with confidence to the ultimate universal acknowledgment of the truths upon which our system rests? It is the first government ever instituted upon the principles in strict conformity to nature and the ordination of Providence in furnishing the materials of human society. Many governments have been founded upon the principle of the subordination and serfdom of certain classes of the same race; such were and are in violation of the laws of nature. Our system commits no such violation of nature's laws. With us, all the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro; subordination is his place. He, by nature or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material—the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it; and by experience we know that it is best not only for the superior race, but for the inferior race, that it should be so. It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator. It is not for us to inquire into the wisdom of His ordinances, or to question them. For His own purposes He has made one race to differ from another, as He has made "one star to differ from another star in glory." The great objects of humanity are best attained when there is conformity to His laws and decrees, in the formation of governments as well as in all things else. Our Confederacy is founded upon principles in strict conformity with these views. This stone, which was rejected by the first builders, "is become the chief of the corner," the real "corner-stone" in our new edifice. * * *

Mr. Jefferson said in his inaugural, in 1801, after the heated contest preceding his election, that there might be differences of opinion without differences of principle, and that all, to some extent, had been Federalists, and all Republicans. So it may now be said of us that, whatever differences of opinion as to the best policy in having a cooperation with our border sister slave States, if the worst came to the worst, as we were all cooperationists, we are all now for independence, whether they come or not. * * *

We are a young republic, just entering upon the arena of nations; we will be the architects of our own fortunes. Our destiny, under Providence, is in our own hands. With wisdom, prudence, and statesmanship on the part of our public men, and intelligence, virtue, and patriotism on the part of the people, success to the full measure of our most sanguine hopes may be looked for. But, if unwise counsels prevail, if we become divided, if schisms arise, if dissensions spring up, if factions are engendered, if party spirit, nourished by unholy personal ambition, shall rear its hydra head, I have no good to prophesy for you. Without intelligence, virtue, integrity, and patriotism on the part of the people, no republic or representative government can be durable or stable.

JOHN C. BRECKENRIDGE, OF KENTUCKY, (BORN 1825, DIED 1875), EDWARD D. BAKER, OF OREGON, (BORN 1811, DIED 1861) ON SUPPRESSION OF INSURRECTION, UNITED STATES SENATE, AUGUST I, 1861.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. I do not know how the Senate may vote upon this question; and I have heard some remarks which have dropped from certain Senators which have struck me with so much surprise, that I desire to say a few words in reply to them now.

This drama, sir, is beginning to open before us, and we begin to catch some idea of its magnitude. Appalled by the extent of it, and embarrassed by what they see before them and around them, the Senators who are themselves the most vehement in urging on this course of events, are beginning to quarrel among themselves as to the precise way in which to regulate it.

The Senator from Vermont objects to this bill because it puts a limitation on what he considers already existing powers on the part of the President. I wish to say a few words presently in regard to some provisions of this bill, and then the Senate and the country may judge of the extent of those powers of which this bill is a limitation.

I endeavored, Mr. President, to demonstrate a short time ago, that the whole tendency of our proceedings was to trample the Constitution under our feet, and to conduct this contest without the slightest regard to its provisions. Everything that has occurred since, demonstrates that the view I took of the conduct and tendency of public affairs was correct. Already both Houses of Congress have passed a bill virtually to confiscate all the property in the States that have withdrawn, declaring in the bill to which I refer that all property of every description employed in any way to promote or aid in the insurrection, as it is denominated, shall be forfeited and confiscated. I need not say to you, sir, that all property of every kind is employed in those States, directly or indirectly, in aid of the contest they are waging, and consequently that bill is a general confiscation of all property there.

As if afraid, however, that this general term might not apply to slave property, it adds an additional section. Although they were covered by the first section of the bill, to make sure of that, however, it adds another section, declaring that all persons held to service or labor; who shall be employed in any way to aid or promote the contest now waging, shall be discharged from such service and become free: Nothing can be more apparent than that that is a general act of emancipation; because all the slaves in that country are employed in furnishing the means of subsistence and life to those who are prosecuting the contest; and it is an indirect, but perfectly certain mode of carrying out the purposes contained in the bill introduced by the Senator from Kansas (Mr. Pomeroy). It is doing under cover and by indirection, but certainly, what he proposes shall be done by direct proclamation of the President.

Again, sir: to show that all these proceedings are characterized by an utter disregard of the Federal Constitution, what is happening around us every day? In the State of New York, some young man has been imprisoned by executive authority upon no distinct charge, and the military officer having him in charge refused to obey the writ of habeas corpus issued by a judge. What is the color of excuse for that action in the State of New York? As a Senator said, is New York in resistance to the Government? Is there any danger to the stability of the Government there? Then, sir, what reason will any Senator rise and give on this floor for the refusal to give to the civil authorities the body of a man taken by a military commander in the State of New York?

Again: the police commissioners of Baltimore were arrested by military authority without any charges whatever. In vain they have asked for a specification. In vain they have sent a respectful protest to the Congress of the United States. In vain the House of Representatives, by resolution, requested the President to furnish the representatives of the people with the grounds of their arrest. He answers the House of Representatives that, in his judgment, the public interest does not permit him to say why they were arrested, on what charges, or what he has done with them—and you call this liberty and law and proceedings for the preservation of the Constitution! They have been spirited off from one fortress to another, their locality unknown, and the President of the United States refuses, upon the application of the most numerous branch of the national Legislature, to furnish them with the grounds of their arrest, or to inform them what he has done with them.

Sir, it was said the other day by the Senator from Illinois (Mr. Browning) that I had assailed the conduct of the Executive with vehemence, if not with malignity. I am not aware that I have done so. I criticised, with the freedom that belongs to the representative of a sovereign State and the people, the conduct of the Executive. I shall continue to do so as long as I hold a seat upon this floor, when, in my opinion, that conduct deserves criticism. Sir, I need not say that, in the midst of such events as surround us, I could not cherish personal animosity towards any human being. Towards that distinguished officer, I never did cherish it. Upon the contrary, I think more highly of him, as a man and an officer, than I do of many who are around him and who, perhaps guide his counsels. I deem him to be personally an honest man, and I believe that he is trampling upon the Constitution of his country every day, with probably good motives, under the counsels of those who influence him. But, sir, I have nothing now to say about the President. The proceedings of Congress have eclipsed the actions of the Executive; and if this bill shall become a law, the proceedings of the President will sink into absolute nothingness in the presence of the outrages upon personal and public liberty which have been perpetrated by the Congress of the United States.

Mr. President, gentlemen talk about the Union as if it was an end instead of a means. They talk about it as if it was the Union of these States which alone had brought into life the principles of public and of personal liberty. Sir, they existed before, and they may survive it. Take care that in pursuing one idea you you do not destroy not only the Constitution of your country, but sever what remains of the Federal Union. These eternal and sacred principles of public men and of personal liberty, which lived before the Union and will live forever and ever somewhere, must be respected; they cannot with impunity be overthrown; and if you force the people to the issue between any form of government and these priceless principles, that form of government will perish; they will tear it asunder as the irrepressible forces of nature rend whatever opposes them.

Mr. President, I shall not long detain the Senate. I shall not enter now upon an elaborate discussion of all the principles involved in this bill, and all the consequences which, in my opinion, flow from it. A word in regard to what fell from the Senator from Vermont, the substance of which has been uttered by a great many Senators on this floor. What I tried to show some time ago has been substantially admitted. One Senator says that the Constitution is put aside in a struggle like this. Another Senator says that the condition of affairs is altogether abnormal, and that you cannot deal with them on constitutional principles, any more than you can deal, by any of the regular operations of the laws of nature, with an earthquake. The Senator from Vermont says that all these proceedings are to be conducted according to the laws of war; and he adds that the laws of war require many things to be done which are absolutely forbidden in the Constitution; which Congress is prohibited from doing, and all other departments of the Government are forbidden from doing by the Constitution; but that they are proper under the laws of war, which must alone be the measure of our action now. I desire the country, then, to know this fact; that it is openly avowed upon this floor that constitutional limitations are no longer to be regarded; but that you are acting just as if there were two nations upon this continent, one arrayed against the other; some eighteen or twenty million on one side, and some ten or twelve million on the other, as to whom the Constitution is nought, and the laws of war alone apply.

Sir, let the people, already beginning to pause and reflect upon the origin and nature and the probable consequences of this unhappy strife, get this idea fairly lodged in their minds—and it is a true one—and I will venture to say that the brave words which we now hear every day about crushing, subjugating, treason, and traitors, will not be so uttered the next time the Representatives of the people and States assemble beneath the dome of this Capitol.

Mr. President, we are on the wrong tack; we have been from the beginning. The people begin to see it. Here we have been hurling gallant fellows on to death, and the blood of Americans has been shed—for what? They have shown their prowess, respectively—that which belongs to the race—and shown it like men. But for what have the United States soldiers, according to the exposition we have heard here to-day, been shedding their blood, and displaying their dauntless courage? It has been to carry out principles that three fourths of them abhor; for the principles contained in this bill, and continually avowed on the floor of the Senate, are not shared, I venture to say, by one fourth of the army.

I have said, sir, that we are on the wrong tack. Nothing but ruin, utter ruin, to the North, to the South, to the East, to the West, will follow the prosecution of this contest. You may look forward to countless treasures all spent for the purpose of desolating and ravaging this continent; at the end leaving us just where we are now; or if the forces of the United States are successful in ravaging the whole South, what on earth will be done with it after that is accomplished? Are not gentlemen now perfectly satisfied that they have mistaken a people for a faction? Are they not perfectly satisfied that, to accomplish their object, it is necessary to subjugate, to conquer—aye, to exterminate—nearly ten millions of people? Do you not know it? Does not everybody know it? Does not the world know it? Let us pause, and let the Congress of the United States respond to the rising feeling all over this land in favor of peace. War is separation; in the language of an eminent gentleman now no more, it is disunion, eternal and final disunion. We have separation now; it is only made worse by war, and an utter extinction of all those sentiments of common interest and feeling which might lead to a political reunion founded upon consent and upon a conviction of its advantages. Let the war go on, however, and soon, in addition to the moans of widows and orphans all over this land, you will hear the cry of distress from those who want food and the comforts of life. The people will be unable to pay the grinding taxes which a fanatical spirit will attempt to impose upon them. Nay, more, sir; you will see further separation. I hope it is not "the sunset of life gives me mystical lore," but in my mind's eye I plainly see "coming events cast their shadows before." The Pacific slope now, doubtless, is devoted to the union of States. Let this war go on till they find the burdens of taxation greater than the burdens of a separate condition, and they will assert it. Let the war go on until they see the beautiful features of the old Confederacy beaten out of shape and comeliness by the brutalizing hand of war, and they will turn aside in disgust from the sickening spectacle, and become a separate nation. Fight twelve months longer, and the already opening differences that you see between New England and the great Northwest will develop themselves. You have two confederacies now. Fight twelve months, and you will have three; twelve months longer, and you will have four.

I will not enlarge upon it, sir. I am quite aware that all I say is received with a sneer of incredulity by the gentlemen who represent the far Northeast; but let the future determine who was right and who was wrong. We are making our record here; I, my humble one, amid the sneers and aversion of nearly all who surround me, giving my votes, and uttering my utterances according to my convictions, with but few approving voices, and surrounded by scowls. The time will soon come, Senators, when history will put her final seal upon these proceedings, and if my name shall be recorded there, going along with yours as an actor in these scenes, I am willing to abide, fearlessly, her final judgment.

MR. BAKER.

Mr. President, it has not been my fortune to participate in at any length, indeed, not to hear very much of, the discussion which has been going on—more, I think, in the hands of the Senator from Kentucky than anybody else—upon all the propositions connected with this war; and, as I really feel as sincerely as he can an earnest desire to preserve the Constitution of the United States for everybody, South as well as North, I have listened for some little time past to what he has said with an earnest desire to apprehend the point of his objection to this particular bill. And now—waiving what I think is the elegant but loose declamation in which he chooses to indulge—I would propose, with my habitual respect for him, (for nobody is more courteous and more gentlemanly,) to ask him if he will be kind enough to tell me what single particular provision there is in this bill which is in violation of the Constitution of the United States, which I have sworn to support—one distinct, single proposition in the bill.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. I will state, in general terms, that every one of them is, in my opinion, flagrantly so, unless it may be the last. I will send the Senator the bill, and he may comment on the sections.

MR. BAKER. Pick out that one which is in your judgment most clearly so.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. They are all, in my opinion, so equally atrocious that I dislike to discriminate. I will send the Senator the bill, and I tell him that every section, except the last, in my opinion, violates the Constitution of the United States; and of that last section, I express no opinion.

MR. BAKER. I had hoped that that respectful suggestion to the Senator would enable him to point out to me one, in his judgment, most clearly so, for they are not all alike—they are not equally atrocious.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. Very nearly. There are ten of them. The Senator can select which he pleases.

MR. BAKER. Let me try then, if I must generalize as the Senator does, to see if I can get the scope and meaning of this bill. It is a bill providing that the President of the United States may declare, by proclamation, in a certain given state of fact, certain territory within the United States to be in a condition of insurrection and war; which proclamation shall be extensively published within the district to which it relates. That is the first proposition. I ask him if that is unconstitutional? That is a plain question. Is it unconstitutional to give power to the President to declare a portion of the territory of the United States in a state of insurrection or rebellion? He will not dare to say it is.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. Mr. President, the Senator from Oregon is a very adroit debater, and he discovers, of course, the great advantage he would have if I were to allow him, occupying the floor, to ask me a series of questions, and then have his own criticisms made on them. When he has closed his speech, if I deem it necessary, I will make some reply. At present, however, I will answer that question. The State of Illinois, I believe, is a military district; the State of Kentucky is a military district. In my judgment, the President has no authority, and, in my judgment, Congress has no right to confer upon the President authority, to declare a State in a condition of insurrection or rebellion.

MR. BAKER. In the first place, the bill does not say a word about States. That is the first answer.

MR. BRECKENRIDGE. Does not the Senator know, in fact, that those States compose military districts? It might as well have said "States" as to describe what is a State.

MR. BAKER. I do; and that is the reason why I suggest to the honorable Senator that this criticism about States does not mean anything at all. That is the very point. The objection certainly ought not to be that he can declare a part of a State in insurrection and not the whole of it. In point of fact, the Constitution of the United States, and the Congress of the United States acting upon it, are not treating of States, but of the territory comprising the United States; and I submit once more to his better judgment that it cannot be unconstitutional to allow the President to declare a county or a part of a county, or a town or a part of a town, or part of a State, or the whole of a State, or two States, or five States, in a condition of insurrection, if in his judgment that be the fact. That is not wrong.

In the next place, it provides that that being so, the military commander in that district may make and publish such police rules and regulations as he may deem necessary to suppress the rebellion and restore order and preserve the lives and property of citizens. I submit to him, if the President of the United States has power, or ought to have power, to suppress insurrection and rebellion, is there any better way to do it, or is there any other? The gentleman says, do it by the civil power. Look at the fact. The civil power is utterly overwhelmed; the courts are closed; the judges banished. Is the President not to execute the law? Is he to do it in person, or by his military commanders? Are they to do it with regulation, or without it? That is the only question.

Mr. President, the honorable Senator says there is a state of war. The Senator from Vermont agrees with him; or rather, he agrees with the Senator from Vermont in that. What then? There is a state of public war; none the less war because it is urged from the other side; not the less war because it is unjust; not the less war because it is a war of insurrection and rebellion. It is still war; and I am willing to say it is public war,—public as contra-distinguished from private war. What then? Shall we carry that war on? Is it his duty as a Senator to carry it on? If so, how? By armies under command; by military organization and authority, advancing to suppress insurrection and rebellion. Is that wrong? Is that unconstitutional? Are we not bound to do, with whomever levies war against us, as we would do if he were a foreigner? There is no distinction as to the mode of carrying on war; we carry on war against an advancing army just the same, whether it be from Russia or from South Carolina. Will the honorable Senator tell me it is our duty to stay here, within fifteen miles of the enemy seeking to advance upon us every hour, and talk about nice questions of constitutional construction as to whether it is war or merely insurrection? No, sir. It is our duty to advance, if we can; to suppress insurrection; to put down rebellion; to dissipate the rising; to scatter the enemy; and when we have done so, to preserve, in the terms of the bill, the liberty, lives, and property of the people of the country, by just and fair police regulations. I ask the Senator from Indiana, (Mr. Lane,) when we took Monterey, did we not do it there?

When we took Mexico, did we not do it there? Is it not a part, a necessary, an indispensable part of war itself, that there shall be military regulations over the country conquered and held? Is that unconstitutional?

I think it was a mere play of words that the Senator indulged in when he attempted to answer the Senator from New York. I did not understand the Senator from New York to mean anything else substantially but this, that the Constitution deals generally with a state of peace, and that when war is declared it leaves the condition of public affairs to be determined by the law of war, in the country where the war exists. It is true that the Constitution of the United States does adopt the laws of war as a part of the instrument itself, during the continuance of war. The Constitution does not provide that spies shall be hung. Is it unconstitutional to hang a spy? There is no provision for it in terms in the Constitution; but nobody denies the right, the power, the justice. Why? Because it is part of the law of war. The Constitution does not provide for the exchange of prisoners; yet it may be done under the law of war. Indeed the Constitution does not provide that a prisoner may be taken at all; yet his captivity is perfectly just and constitutional. It seems to me that the Senator does not, will not take that view of the subject.

Again, sir, when a military commander advances, as I trust, if there are no more unexpected great reverses, he will advance, through Virginia and occupies the country, there, perhaps, as here, the civil law may be silent; there perhaps the civil officers may flee as ours have been compelled to flee. What then? If the civil law is silent, who shall control and regulate the conquered district, who but the military commander? As the Senator from Illinois has well said, shall it be done by regulation or without regulation? Shall the general, or the colonel, or the captain, be supreme, or shall he be regulated and ordered by the President of the United States? That is the sole question. The Senator has put it well.

I agree that we ought to do all we can to limit, to restrain, to fetter the abuse of military power. Bayonets are at best illogical arguments. I am not willing, except as a case of sheerest necessity, ever to permit a military commander to exercise authority over life, liberty, and property. But, sir, it is part of the law of war; you cannot carry in the rear of your army your courts; you cannot organize juries; you cannot have trials according to the forms and ceremonial of the common law amid the clangor of arms, and somebody must enforce police regulations in a conquered or occupied district. I ask the Senator from Kentucky again respectfully, is that unconstitutional; or if in the nature of war it must exist, even if there be no law passed by us to allow it, is it unconstitutional to regulate it? That is the question, to which I do not think he will make a clear and distinct reply.