The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, VOL. 103, November 26, 1892, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, Or The London Charivari, VOL. 103, November 26, 1892 Author: Various Editor: Francis Burnand Release Date: June 3, 2005 [EBook #15973] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

A Philosopher has deigned to address to me a letter. "Sir," writes my venerable correspondent, "I have been reading your open letters to Abstractions with some interest. You will, however, perhaps permit me to observe that amongst those to whom you have written are not a few who have no right whatever to be numbered amongst Abstractions. Laziness, for instance, and Crookedness, and Irritation—not to mention others—how is it possible to say that these are Abstractions? They are concrete qualities and nothing else. Forgive me for making this correction, and believe me yours, &c. A Platonist."—To which I merely reply, with all possible respect, "Stuff and nonsense!" I know my letters have reached those to whom they were addressed, no single one has come back through the Dead-letter Office, and that is enough for me. Besides, there are thousands of Abstractions that the mind of "A Platonist" has never conceived. Somewhere I know, there is an abstract Boot, a perfect and ideal combination of all the qualities that ever were or will be connected with boots, a grand exemplar to which all material boots, more or less, nearly approach; and by their likeness to which they are recognised as boots by all who in a previous existence have seen the ideal Boot. Sandals, mocassins, butcher-boots, jack-boots, these are but emanations from the great original. Similarly, there must be an abstract Dog, to the likeness of which, in one respect or another, both the Yorkshire Terrier and the St. Bernard conform. So much then for "A Platonist." And now to the matter in hand.

My dear Failure, there exists amongst us, as, indeed, there has always existed, an innumerable body of those upon whom you have cast your melancholy blight. Amongst their friends and acquaintances they are known by the name you yourself bear. They are the great army of failures. But there must be no mistake. Because a man has had high aspirations, has tried with all the energy of his body and soul to realise them, and has, in the end, fallen short of his exalted aim, he is not, therefore, to be called a failure. Moses, I may remind you, was suffered only to look upon the Promised Land from a mountain-top. Patriots without number—Kossuth shall be my example—have fought and bled, and have been thrust into exile, only to see their objects gained by others in the end. But the final triumph was theirs surely almost as much as if they themselves had gained it. On the other hand there are those who march from disappointment to disappointment, but remain serenely unconscious of it all the time. These are not genuine failures. There is Charsley, for instance, journalist, dramatist, novelist—Heaven knows what besides. His plays have run, on an average, about six nights; his books, published mostly at his own expense, are a drug in the market; but the little creature is as vain, as proud, and, it must be added, as contented, as though Fame had set him, with a blast of her golden trumpet, amongst the mighty Immortals. What lot can be happier than his? Secure in his impregnable egotism, ramparted about with mighty walls of conceit, he bids defiance to attack, and lives an enviable life of self-centred pleasure.

Then, again, there was Johnnie Truebridge. I do not mean to liken him to Charsley, for no more unselfish and kind-hearted being than Johnnie ever breathed. But was there ever a stone that rolled more constantly and gathered less moss? Yet no stroke could subdue his inconquerable cheerfulness. Time after time he got his head above the waters; time after time, some malignant emissary of fate sent him bubbling and gasping down into the depths. He was up again in a moment, striving, battling, buffeting. Nothing could make Johnnie despair, no disappointment could warp the simple straightforward sincerity, the loyal and almost childlike honesty of his nature. And if here and there, for a short time, fortune seemed to shine upon him, you may be sure that there was no single friend whom he did not call upon to bask with him in these fleeting rays. And what a glorious laugh he had; not a loud guffaw that splits your tympanum and crushes merriment flat, but an irrepressible, helpless, irresistible infectious laugh, in which his whole body became involved. I have seen a whole roomful of strangers rolling on their chairs without in the least knowing why, while Johnnie, with his head thrown back, his jolly face puckered into a thousand wrinkles of hearty delight, and his hands pressed to his sides, was shouting with laughter at some joke made, as most of his jokes were, at his own expense.

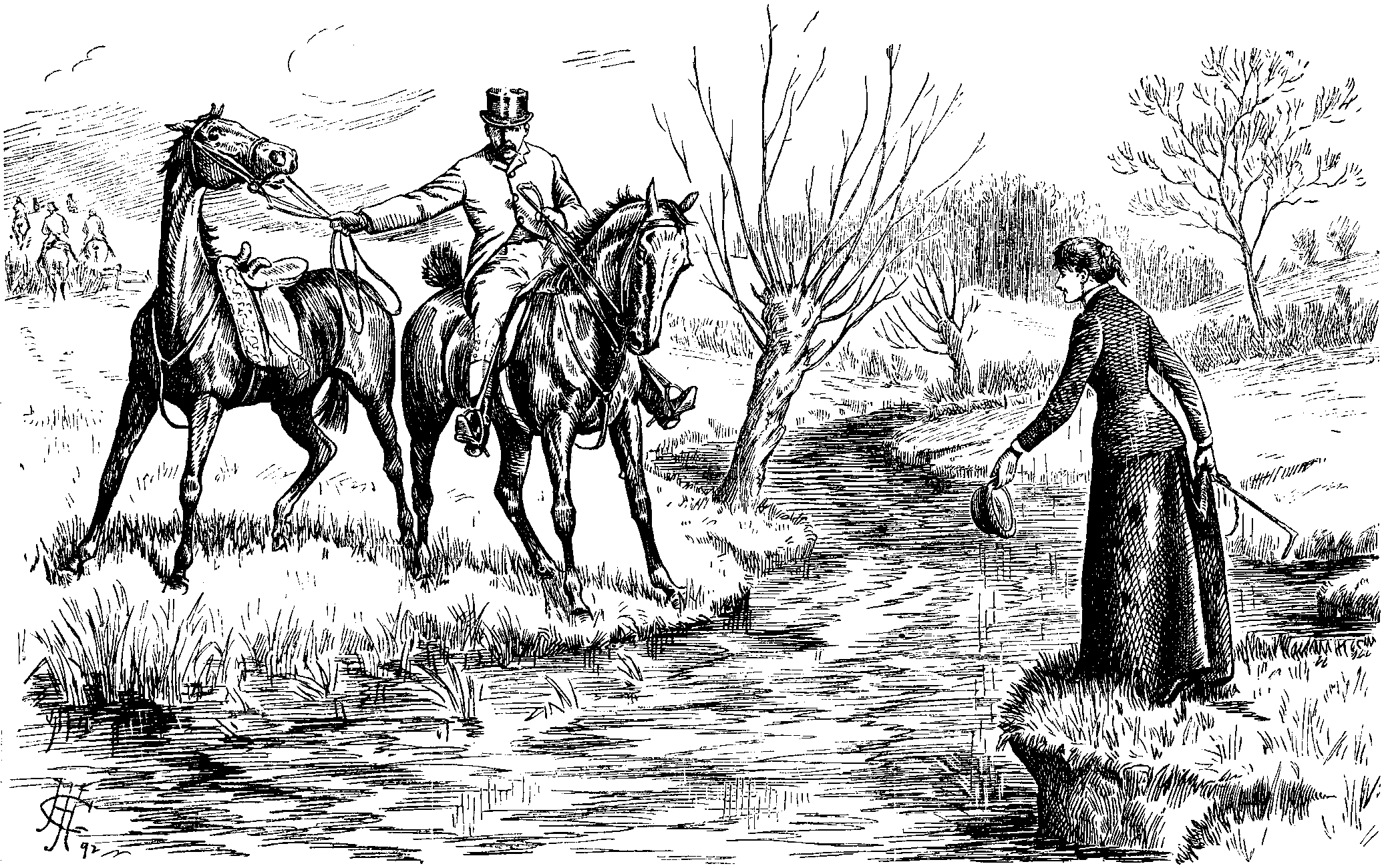

It was during one of his brief intervals of prosperity, at a meet of the Ditchington Stag-hounds that I first met Johnnie. He was beautifully got up. His top-hat shone scarcely less brilliantly than his rosy cheeks, his collar was of the stiffest, his white tie was folded and pinned with a beautiful accuracy, his black coat fitted him like a glove, his leather-breeches were smooth and speckless, and his champagne-coloured tops fitted his sturdy little legs as if they had been born with him. He was mounted on an enormous chestnut-horse, which Anak might have controlled, but which was far above the power and weight of Johnnie, plucky and determined though he was. Shortly after the beginning of the run, while the hounds were checked, I noticed a strange, hatless, dishevelled figure, riding furiously round and round a field. It was Johnnie, whose horse was bolting with him, but who was just able to guide it sufficiently to keep it going in a circle instead of taking him far over hill and dale. We managed to stop him, and I shall never forget how he laughed at his own disasters while he was picking up his crop and replacing his hat on his head. Not long afterwards, I saw our little Mazeppa crashing, horse and all, into the branches of a tree, but in spite of a black eye and a deep cut on his cheek, he finished the run—fortunately for him a very fast and long one—with imperturbable pluck and with no further misadventure. "Nasty cut that," I said to him as we trained back together, "you'd better get it properly looked to in town." "Pooh," said Johnnie, "it's a mere scratch. Did you see the brute take me into the tree? By Jove, it must have been a comic sight!" and with that he set off again on another burst of inextinguishable laughter.

About a week after this, the usual crash came. A relative of Johnnie was in difficulties. Johnnie, with his wonted chivalry, came to his help with the few thousands that he had lately put by, and, in a day or two, he was on his beam-ends once more. And so the story went on. Money slipped through his fingers like water—prosperity tweaked him by the nose, and fled from him, whilst friends, not a whit more deserving, amassed fortunes, and became sleek. But he was never daunted. With inexhaustible courage and resource, he set to work again to rebuild his shattered edifice, confident that luck would, some day, stay with him for good. But it never did. At last he threw in his lot with a band of adventurers, who proposed to plant the British flag in some hitherto unexplored regions of South or Central Africa. I dined with Johnnie the evening before he left England. He was in the highest spirits. His talk was of rich farms, of immense gold-mines. He was off to make his pile, and would then come home, buy an estate in the country—he had one in his eye—and live a life of sport, surrounded by all the comforts, and by all his friends. And so we parted, never to meet again. He was lost while making his way back to the coast with a small party, and no trace of him has ever since been discovered. But to his friends he has left a memory and an example of invincible courage, and unceasing cheerfulness in the face of misfortune, of constant helpfulness, and unflinching staunchness. Can it be said that such a man was a failure? I don't think so. I must write again. In the meantime I remain, as usual,

Signs of the Season.—"Beauty's Daughters!" These charming young ladies are to be obtained for the small sum of one penny! as for this trifling amount,—unless there is a seasonably extra charge,—you can purchase the Christmas Number of the Penny Illustrated, wherein Mr. Clement Scott "our dear departed" (on tour round the world—"globe-trotting"), leads off with some good verses. Will he be chosen Laureate? He is away; and it is characteristic of a truly great poet to be "absent." And the Editor, that undefeated story-teller, tells one of his best stories in his best style, and gives us a delightful picture of Miss Elsie Norman. "Alas! she is another's! she never can be mine!" as she is Somebody Elsie's. Success to your Beauties, Mr. Latey, or more correctly, Mr. Early-and-Latey, as you bring out your Christmas Number a good six weeks before Christmas Day.

Motto for the Labour Commission.—"The proper study of mankind is—Mann!"

The New Employment.—Being "Unemployed."

O Lud! O Lud! O Lud!

(As Tom Hood cried, apostrophising London),

November rules, a reign of rain, fog, mud,

And Summer's sun is fled, and Autumn's fun done.

Far are the fields M.P.'s have tramped and gunned on!

Malwood is far, and far is fair Dalmeny,

And Harwarden,

Like a garden

(To Caucus-mustered crowds) glowing and greeny

In soft September,

Is distant now, and dull; for 'tis November,

And we are in a Fog!

Cabbin' it, Council? Ah! each absent Member

May be esteemed a vastly lucky dog!

The streets are up—of course! No Irish bog

Is darker, deeper, dirtier than that hole

Sp-nc-r is staring into. On my soul,

M-rl-y, we want that light you're seeking, swarming

Up that lank lamp-post in a style alarming!

Take care, my John, you don't come down a whopper!

And you, young R-s-b-ry, if you come a cropper

Over that dark, dim pile, where shall we be?

Pest! I can hardly see

An inch before my nose—not to say clearly.

Hold him up, H-rc-rt! He was down then, nearly,

Our crook-knee'd "crock." Seems going very queerly,

Although so short a time out of the stable.

Quiet him, William, quiet him!—if you're able.

This is no spot for him to fall. I dread

The need—just here—of "sitting on his head."

Cutting the traces

Will leave us dead-lock'd, here of all bad places!

Oh, do keep quiet, K-mb-rl-y! You're twitching

My cape again! Mind, Asq-th! You'll be pitching

Over that barrier, if you are not steady.

Fancy us getting in this fix—already!

Cabbin' it in a fog is awkward work,

Specially for the driver, who can't shirk,

When once his "fare" is taken.

I feel shaken.

'd rather drive the chariot of the Sun

(That's dangerous, but rare fun!)

Like Phaëthon,

Than play the Jehu in a fog so woful

To this confounded "Shoful"!

Dear Mr. Punch,

More than a fortnight ago I fled from the London fog, with the result that it got thicker than ever about me in the minds of your readers and yourself! I determined during my absence to do what many people in the world of Art and Letters have done before me, employ a "Ghost"—(my first dealings with the supernatural, and probably my last!). I wired to one of the leading Sporting Journals for their most reliable Racing Ghost—he was busy watching Nunthorpe—(who is only the Ghost of what he was!)—and the Bogie understudy sent to me was a Parliamentary Reporter!—(hence the stilted style of the letter signed "Pomperson." Heavens! what a name!)—I had five minutes to explain the situation to him before catching the train de luxe—(Lord Arthur had gone on with the luggage)—and I don't think he had the ghostliest idea of what I wanted!—the one point he grasped, was, that he was to use anonymous names—which he did with a vengeance!—My horror on reading his letter was such that I dropped all the money I had in my hand on the "red" instead of the "black"—and it won!—(I think I shall bring out a system based on "fright.")

Of course all my friends thought Lord Arthur and I had quarrelled, and I was "off" with someone else!—What a fog. This idea being confirmed by the following week's letter, which was the well-meant but misdirected effort of my friend Lady Harriett Entoucas, to whom I wired to "do something for me"—(she pretty nearly did for me altogether!)—there was nothing for it but to come home—where I am—Lord Arthur wanted to write you this week, but I thought one explanation at a time quite enough—so his shall follow—"if you want a thing done, do it yourself!"—so in future I will either be my own Ghost or have nothing to do with them! Yours apparitionally,

Inside the "Queen's Grand Collection of Moving Waxworks and Lions, and Museum Department of Foreign Wonders and Novelties."

The majority of the Public is still outside, listening open-mouthed to a comic dialogue between the Showman and a juvenile and irreverent Nigger. Those who have come in find that, with the exception of some particularly tame-looking murderers' heads in glazed pigeon-holes, a few limp effigies stuck up on rickety ledges, and an elderly Cart-horse in low spirits, there is little to see at present.

Melia (to Joe, as they inspect the Cart-horse.) This 'ere can't never be the live 'orse with five legs, as they said was to be seen inside!

Joe. Theer ain't no other 'orse in 'ere, and why shouldn't it be 'im, if that's all?

Melia. Well, I don't make out no more'n four legs to'un, nohow, myself.

Joe. Don't ye be in sech a 'urry, now—the Show ain't begun yet!

[The barrel-organ outside blares "God Save the Queen," and more Spectators come stumping down the wooden steps, followed by the Showman.

Showman. I shell commence this Exhibition by inviting your inspection of the wonderful live 'orse with five legs. (To the depressed Cart-horse.) 'Old up! (The poor beast lifts his off-fore-leg with obvious reluctance, and discloses a very small supernumerary hoof concealed behind the fetlock.) Examine it! for yourselves—two distinct 'oofs with shoes and nails complete—a great novelty!

Melia. I don't call that nothen of a leg, I don't—it ain't 'ardly a oof, even!

Joe (with phlegm). That's wheer th' old 'orse gits the larf on ye, that is!

Showman. We will now pass on to the Exhibition. 'Ere (indicating a pair of lop-sided Orientals in nondescript attire) we 'ave two life-sized models of the Japanese villagers who caused so much sensation in London on account o' their peculiar features—you will easily reckernise the female by her bein' the ugliest one o' the two. (Compassionate titters from the Spectators.) I will now call your attention to a splendid group, taken from English 'Istry, and set in motion by powerful machinery, repperesentin' the Parting Interview of Charles the First with his fam'ly. (Rolls up a painted canvas curtain, and reveals the Monarch seated, with the Duke of Gloucester on his knee, surrounded by Oliver Cromwell, and as many Courtiers, Guards, and Maids of Honour as can be accommodated in the limited space.) I will wind up the machinery and the unfortunate King will be seen in the act of bidding his fam'ly ajew for ever in this world.

[Charles begins to click solemnly and move his head by progressive jerks to the right, while the Little Duke moves his simultaneously to the left, and a Courtier in the background is so affected by the scene that he points with respectful sympathy at nothing; the Spectators do not commit themselves to any comments.

Showman (concluding a quotation from Markham). "And the little Dook, with the tears a-standin' in 'is heyes, replies, 'I will be tore in pieces fust!'" Other side, please! No, Mum, the lady in mournin' ain't the beautiful but ill-fated Mary, Queen o' Scots—it's Mrs. Maybrick, now in confinement for poisonin' her 'usban', and the figger close to her is the Mahdi, or False Prophet. In the next case we 'ave a subject selected from Ancient Roman 'Istry, bein' the story of Androcles, the Roman Slave, as he appeared when, escaping from his crule owners, he entered a cave and found a lion which persented 'im with 'is bleedin' paw. After some 'esitation, Androcles examined the paw, as repperesented before you. (Winds the machinery up, whereupon the lion opens his lower jaw and emits a mild bleat, while Androcles turns his head from side to side in bland surprise.) This lion is the largest forestbred and blackmaned specimen ever imported into this country—the other lion standing beyind (disparagingly), has nothing whatever to do with the tableau, 'aving been shot recently in Africa by Mr. Stanley, the two figgers at the side repperesent the Boy Murderers who killed their own father at Crewe with a 'atchet and other 'orrible barbarities. I shall conclude the Collection by showing you the magnificent group repperesentin' Her Gracious Majisty the Queen, as she appeared in 'er 'appier and younger days, surrounded by the late Mr. Spurgeon, the 'Eroes of the Soudan, and other Members of the Royal Fam'ly.

After some tight-rope, juggling, and boneless performances have been given in the very limited arena, the Clown has introduced the Learned Pony.

Clown. Now, little Pony, go round the Company and pick me out the little boy as robs the Farmer's orchard.

[The Pony trots round, and thrusts his nose confidently into a Small Boy's face.

Small Boy (indignantly). Ye're a liar, Powney; so theer!

Clown. Now, see if you can find me the little gal as steals her mother's jam and sugar. Look sharp now, don't stand there playin' with yer bit!

A Little Girl (penitently, as the Accusing Quadruped halts in front of her). Oh, please, Pony, I won't never do it no more!

Clown. Now go round and pick me out the Young Man as is fond o' kissin' the girls and married ladies when their 'usbands is out o' the way. (The Pony stops before an Infant in Arms.) 'Ere, think what yer doin' now. You don't mean 'im, do you? (The Pony shakes his head.) Is it the Young Man standin' just beyind as is fond o' kissin the girls? (The Pony nods.) Ah, I thought so!

The Rustic Lothario (with a broad grin). It's quoite tri-ew!

Clown. Now I want you, little Pony, to go round and tell me who's the biggest rogue in the company. (Reassuringly, as the Pony goes round, and a certain uneasiness is perceptible among some of the spectators). I 'ope no Gentleman 'ere will be offended by bein' singled out, for no offence is intended,—it is merely a 'armless—(Finds the Pony at his elbow.) Why, you rascal! do you mean to say I'm the biggest rogue 'ere? (The Pony nods.) You've been round, and can't find a bigger rogue than me in all this company? (Emphatic shake of the head from Pony; secret relief of inner circle of Spectators.) You and me'll settle this later!

First Spectator (as audience disperses). That war a clever Pony, sart'nly!

Second Spect. Ah, he wur that. (Reflectively.) I dunno as I shud keer partickler 'bout 'avin of 'im, though!

A small canvas booth with a raised platform, on which a Young Woman in short skirts has just performed a few elementary conjuring tricks before an audience of gaping Rustics.

The Showman. The Second Part of our Entertainment will consist of the performances of a Real Live Zulu from the Westminster Royal Aquarium. Mr. Farini, in the course of 'is travels, discovered both men and women—and this is one of them. (Here a tall Zulu, simply attired in a leopard's-skin apron, a bead necklace, and an old busby, creeps through the hangings at the back.) He will give you a specimen of the strange and remarkable dances in his country, showin' you the funny way in which they git married—for they don't git married over there the same as we do 'ere—cert'n'ly not! (The Spectators form a close ring round the Zulu.) Give him a little more room, or else you won't notice the funny way he moves his legs while dancin'.

[The ring widens a very little, and contracts again, while the Zulu performs a perfunctory prance to the monotonous jingle of his brass anklets.

Melia (critically). Well, that's the silliest sort of a weddin' as iver I see!

Joe. He do seem to be 'avin' it a good deal to 'isself, don't 'e?

Showman. He will now conclude 'is entertainment by porsin round, and those who would like to shake 'ands with 'im are welcome to do so, while at the same time, those among you who would like to give 'im a extry copper for 'isself you will 'ave an opportunity of noticin' the funny way in which he takes it.

Spectators (as the Zulu begins to slink round the tent, extending a huge and tawny paw). 'Ere, come arn!

[The booth is precipitately cleared.

"Write Letter Days" should be the companion volume to Red Letter Days, published by Bentley.

Boy. "Second-Class, Sir?"

Captain. "I nevah travel Second-Class!"

Boy. "This way Third, Sir!"

The subject of the Smoking-room would seem to be intimately and necessarily connected with the subject of smoke, which was dealt with in our last Chapter. A very good friend of mine, Captain Shabrack of the 55th (Queen Elizabeth's Own) Hussars, was good enough to favour me with his views the other day. I met the gallant officer, who is, as all the world knows, one of the safest and best shots of the day, in Pall Mall. He had just stepped out of his Club—the luxurious and splendid Tatterdemalion, or, as it is familiarly called, "the Tat"—where, to use his own graphic language, he had been "killing the worm with a nip of Scotch."

"Early Scotch woodcock, I suppose," says I, sportively alluding to the proverb.

"Scotch woodcock be blowed," says the Captain, who, it must be confessed, does not include an appreciation of delicate humour amongst his numerous merits; "Scotch, real Scotch, a noggin of it, my boy, with soda in a long glass; glug, glug, down it goes, hissin' over the hot coppers. You know the trick, my son, it's no use pretendin' you don't"—and thereupon the high-spirited warrior dug me good-humouredly in the ribs, and winked at me with an eye which, if the truth must be told, was bloodshot to the very verge of ferocity.

"Talkin' of woodcock," he continued—we were now walking along Pall Mall together—"they tell me you're writin' some gas or other about shootin'. Well, if you want a tip from me, just you let into the smokin' room shots a bit; you know the sort I mean, fellows who are reg'lar devils at killin' birds when they haven't got a gun in their hands. Why, there's that little son of a corn-crake, Flickers—when once he gets talkin' in a smokin' room nothing can hold him. He'd talk the hind leg off a donkey. I know he jolly nearly laid me out the last time I met him with all his talk—No, you don't," continued the Captain, imagining, perhaps, that I was going to rally him on his implied connection of himself with the three-legged animal he had mentioned, "no you don't—it wouldn't be funny; and besides, I'm not donkey enough to stand much of that ass Flickers. So just you pitch into him, and the rest of 'em, my bonny boy, next time you put pen to paper." At this moment my cheerful friend observed a hansom that took his fancy. "Gad!" he said, "I never can resist one of those india-rubber tires. Ta, ta, old cock—keep your pecker up. Never forget your goloshes when it rains, and always wear flannel next your skin," and, with that, he sprang into his hansom, ordered the cabman to drive him round the town as long as a florin would last, and was gone.

Had the Captain only stayed with me a little longer, I should have thanked him for his hint, which set me thinking. I know Flickers well. Many a time have I heard that notorious romancer holding forth on his achievements in sport, and love, and society. I have caught him tripping, convicted him of imagination on a score of occasions; dozens of his acquaintances must have found him out over and over again; but the fellow sails on, unconscious of a reverse, with a sort of smiling persistence, down the stream of modified untruthfulness, of which nobody ought to know better than Flickers the rapids, and shallows, and rocks on which the mariner's bark is apt to go to wreck. What is there in the pursuit of sport, I ask myself, that brings on this strange tendency to exaggeration? How few escape it. The excellent, the prosaic Dubson, that broad-shouldered, whiskered, and eminently snub-nosed Nimrod, he too, gives way occasionally. Flickers's, I own, is an extreme case. He has indulged himself in fibs to such an extent, that fibs are now as necessary to him as drams to the drunkard. But Dubson the respectable, Dubson the dull, Dubson the unromantic—why does the gadfly sting him too, and impel him now and then to wonderful antics. For was it not Dubson who told me, only a week ago, that he had shot three partridges stone dead with one shot, and in measuring the distance, had found it to be 100 yards less two inches? Candidly, I do not believe him; but naturally enough I was not going to be outdone, and I promptly returned on him with my well-known anecdote about the shot which ricocheted from a driven bird in front of me and pierced my host's youngest brother—a plump, short-coated Eton boy, who was for some reason standing with his back to me ten yards in my rear—in a part of his person sacred as a rule plagoso Orbilio. The shrieks of the stricken youth, I told Dubson, still sounded horribly in my ears. It took the country doctor an hour to extract the pellets—an operation which the boy endured, with great fortitude, merely observing that he hoped his rowing would not be spoiled for good, as he should bar awfully having to turn himself into a dry-bob. This story, with all its harrowing details, did I duly hammer into the open-mouthed Dubson, who merely remarked that "it was a rum go, but you can never tell where a ricochet will go," and was beginning upon me with a brand-new ricochet anecdote of his own, when I hurriedly departed.

Wherefore, my gay young shooters, you who week by week suck wisdom and conversational ability from these columns, it is borne in upon me that for your benefit I must treat of the Smoking-room in its connection with shooting-parties. Thus, perhaps, you may learn not so much what you ought to say, as what you ought not to say, and your discretion shall be the admiration of a whole country-side. "The Smoking-room: with which is incorporated 'Anecdotes.'" What a rollicking, cheerful, after-dinner sound there is about it. Shabrack might say it was like the title of a cheap weekly, which as a matter of fact, it does resemble. But what of that? Next week we will begin upon it in good earnest.

From Smith and Mitchell to a Kangaroo!!!

The "noble art" is going up! Whilloo!

Stay, though! Since pugilist-man seems coward-clown,

Perhaps 'tis the Marsupial coming down!

"I've brought you some Lace for your Stall at the Bazaar, Lizzie. I'm afraid it's not quite Old enough to be really valuable. I had it when I was a little Girl."

"Oh, that's Old enough for Anything, dearest! How lovely! Thanks so very much!"

["With all his faults, M. de Lesseps is perhaps the most remarkable—we may even say the most illustrious—of living Frenchmen."—The Times.]

Jacques Bonhomme loquitur:—

Someone should suffer—yes, of course—

For the depletion of my stocking;

But Le Grand Français? Bah! Remorse

Moves me to tears. It seems too shocking.

Get back my money? Pas de chance!

And then he is the pride of France!

I raged, I know, four years ago,

Against those Panama projectors.

The law seemed slack, inquiry slow;

How I denounced them, the Directors,

Including him—in some vague fashion;

But then—Bonhomme was in a passion!

And now to see the gendarme's hand—

Half-shrinkingly—upon his shoulder,

Our Grand Français—so old, so grand!

Ma foi, it palsies the beholder.

And will it lessen my large loss

To fix a stain on the Grand Cross?

Too sanguine? Too seductive? Yes!

But was it not such hopeful charming

That led him to his old success?

The thought is softening, and disarming;

O'er Suez and the Red Sea glance,

And see what he has done for France!

Peste on this Panama affair!

Egyptian sands sucked not our savings

As did those swamps. Still I can't bear

To see him suffer. 'Midst my cravings

For la revanche, I'd fain not touch

Our Greatest Frenchman—'tis too much!

["The Young Ladies of Nottingham have formed a Short-skirt League."—Daily Graphic.]

Ye pretty girls of England,

So famous for your looks,

Whose sense has braved a thousand fads

Of foolish fashion-books,

Your glorious standard launch again

To match another foe,

And refrain

From the train

While the stormy tempests blow,

While the sodden streets are thick with mud,

And the stormy tempests blow!

See how the girls of Nottingham

Inaugurate a League

For skirts five inches from the ground;

They'll walk without fatigue,

No longer plagued with trains to lift

Above the slush or snow;

They'll not sweep

Mud that's deep

While the stormy tempests blow;

Long dresses do the Vestry's work,

While stormy tempests blow.

O pretty girls of Nottingham,

If you could save us men

From our frightful clothing,

How we should love you then!

We'd shorten turned-up trouser,

And widen pointed toe,

Leave off that

Vile silk hat,

When the stormy tempests blow—

Wretched hat that stands not wind or rain

When the stormy tempests blow.

We're fools. Yet, girls of England,

We might inquire of you,

Why wear those capes and sleeves that seem

Quite wide enough for two?

And why revive the chignons—

Huge lumps pinned on? You know

You would cry

Should they fly

Where the stormy tempests blow;

For they catch the wind just like balloons,

Where the stormy tempests blow.

Faults o' Both Sides.—Ardent Radicals grumbled at the Government for not holding an Autumn Session. That was a fault of omission. Now touchy Tories are angry with it for showing too strong a tendency to what Mr. Gladstone once sarcastically called "a policy of examination and inquiry"—into the case of Evicted Tenants, Poor-Law Relief, &c. This is a fault of (Royal) Commission. Luckless Government! The verdict upon it seems to be that it

"Does nothing in particular,

And does it very—ill."

Notice.—The Twin Fountains of Trafalgar Square regret to inform the British Public that, although they have performed gratuitously and continuously for a number of years, they are compelled to retire from business, as they cannot compete with the State-aided spouting which takes place in their Square.

A Great "Treat."—Public-house Politics at Election time.

Jacques Bonhomme (regarding M. de Lesseps, apart). "BAH! I HAVE LOST MY MONEY! (Pause.) ALL THE SAME, I CANNOT DESIRE THAT HE, SO OLD AND SO DISTINGUISHED, SHOULD SUFFER!!"

Lady (having had a fall at a Brook, and come out the wrong side,—to Stranger, who has caught her Horse). "Oh, I'm so much obliged to you! Now, do you mind just bringing him over?"

Books from the publishing house of Fisher Unwin are always goodly to look upon, the public having to thank him for something new in form, binding, and colour, in other series than the Pseudonym Library. In a new edition of The Sinner's Comedy, just issued at the modest price of Eighteenpence, he has solved a problem that has long baffled the publisher, and bothered the public. Few like the appearance of a book with the pages machine-cut; fewer still can spare the time to cut a book. Mr. Fisher Unwin compromises by presenting this dainty little volume with the top pages ready cut, the reader having nothing to do but to slice the side-pages, a labour which no book-lover would grudge, seeing that it leaves the volume with the uncut appearance dear to his heart. The story, told in 146 pages, is, my Baronite says, worthy the distinction of its appearance. The characters are clearly drawn, the plot is interesting, the conversation crisp, and the style throughout pleasantly cynical. The author, John Oliver Hobbes, has a pretty turn of aphorism. "A man's way of loving is so different from a woman's"; and again, "Genius is so rare, and ambition is so common." Here be truths, old enough perhaps, but cleverly re-set.

Some people complain that politics are dull. They should read the parliamentary and extra-parliamentary utterances of the Member for Wrottenborough. They appear weekly in that rising young paper, the Sunday Times, and an extremely readable selection of them has lately been published "in book form," for the enlivening of the Recess. Adapting the Laureate's lines, the Baron would say,—

"They who would vote for an M.P. whose sense with humour chimes,

Will read the Member for Wrottenborough, all in the Sunday Times—

A paper our sires paid Sevenpence for, along of its grit and go,

Seventy years ago, my Public, seventy years ago!"

For whimsical audacity, and quaint unexpectedness. Mr. Pain, in his latest book, Playthings and Parodies, would be hard to beat. In this there is a good back-ground of shrewd observation. He does not propose to make your flesh creep, or your eyes run torrents. He simply succeeds in making you laugh. In "The Processional Instinct," Mr. Pain informs us that he has discovered that our private life is circular, and our public life is rectilineal. Shakspeare, who, being for all time, and not merely for an age, recommends this author to the general public when he says that everybody "should be so conversant with Pain."

The Memories of Dean Hole is rather a misleading title; "but," says the Baron, "I suppose the term 'Reminiscences' is played out. The word 'Memories' seems to suggest that someone, whether Dean Hole, or Dean Corner, or any other Dean, had more than one memory, as indeed those persons appear to possess who mention their 'good memory for names,' and their 'bad memory for dates,' and vice versâ. Soit!" quoth the Baron, in excellent French, "you may take it from me (if I'll part with it) that the Hole book is by no means a half-and-half sort of book, but is vastly entertaining." The stories of "The Cloth" form the most entertaining part of the work. The Baron wishes success to this work of the Dean in Holey Orders, and suggests that the volume should be re-entitled Gathered Leaves from Dean Hole's Rose Garden, a better title than "Reminiscences."

Marion Crawford's Don Orsino (published by Macmillan & Co.) would be worth reading were it only for the colour of its word-painting, and for its high-comedy dialogue. Yet is Mr. Crawford rather given to pause in his story, for the sake of moralising on the tendencies of the age; and the reader, patient though he may be, when he has become interested in the personages of the novel, does not care to be button-holed by a digression. Marion Crawford's recipe for commencing an amorous duologue (early in Vol. III.), which is to lead up to a declaration of love, is deliciously ingenious. It begins with the gentleman taking a seat, and his first remark is upon the chair. Mr. Crawford evidently remembers the old story of how the tenor who knew but one song, "In my Cottage near a Wood," used to introduce it into any scene of any Opera by the simple process of making his entrance alone and finding a chair on the stage. "Aha!" quoth he. "What's this? A chair? and made of wood! Ah! that word! how it reminds me of my 'umble home, 'my cottage near a wood.'" Cue for band; chord; song. In this instance, the love-scene, admirably led up to on the above plan, is strikingly powerful; it is the work of a master-hand. The dénoûment is both artistically original and, at the same time, ordinarily probable. May all readers enjoy this excellent novel as much as has the sympathetic

Classical Question.—If some schoolboys, home for Christmas holidays, wanted Sir Augustus Druriolanus to give them a Christmas Box (not a private one at the Pantomime), what Ancient Philosopher would they mention? Why—of course—"Aristippus."

The Vicar. "And were you at the Ball last Night, Mrs. Ramsbottom?"

Mrs. R. "Oh, yes; I was Shampooing Eight Young Ladies there!"

Mr. Alfred Austin, in his new poem, Fortunatus, the Pessimist, has hit upon a new notion, to say nothing of a novel rhyme. Sings he:—

"When the foal and brood-mare hinny,

And in every cut-down spinney

Lady's-Smocks grow mauve and mauver,

Then the Winter days are over."

This opens a polychromatic vista to the New Poetry. Technical Art comes to the aid of the elder Muses. The products of gas-tar alone should greatly regenerate a something time-worn poetic phraseology. As thus:—

When the poet, Mr. Pennyline,

Is inspired by beauteous Aniline,

Products chemical and gas-tarry

Give the modern Muse new mastery.

Mauve may chime with love, and mauver

Form a decent rhyme to lover;

While (and if not, why not?) mauvest

Antiphonetic proves to lovest.

(Verse erotic always sports

Tricksily with longs and shorts.

Verbal votaries of Venus

Are an arbitrary genus,

And as arrogant as Howells

In their dealings with the vowels.

Love, move, rove, linked in a sonnet,

Pass for rhymes; the best have done it!)

Then again there is Magenta!

Surely science never sent a

Handier rhyme to—well, polenta,

Or (for Cockney Muses) Mentor!

The poetic sense auricular

Can't afford to be particular.

Rags of rhymes, mere assonances,

Now must serve. Pegasus prances,

Like a Buffalo Bill buck-jumper,

When you have a "regular stumper"

(Such as "silver") do not care about

Perfect rhyming; "there or thereabout"

Is the Muse's maxim now.

You may get (bards have, I trow)

Rhyme's last minimum irreducible,

From dye-vat, retort, or crucible.

Verily (as Touchstone says), "I'll rhyme you so, eight years together, dinners and suppers, and sleeping hours excepted." And if it is "the right butterwoman's rate to market," or "the very false gallop of verses," it is at any rate good enough for a long-eared public or a postulant for the Laureateship.

Monday.—Extremely awkward—the entire British Fleet have come ashore; and, as it is impossible to move them on account of their enormous tonnage, this will entail a loss of £24,000,000,000!

Tuesday.—Troubles never come singly! The French, taking advantage of the temporary suspension of our naval operations, have declared war. This means the utter ruin of the bathing season, not only at Herne Bay, but Southend, and the Isle of Thanet.

Wednesday.—As I expected! The French Fleet are coming up towards London. They are sure to pepper us as they pass. As every gun carries several hundred miles, I do not see how books can be uninterruptedly issued from and returned to the Circulating Library.

Thursday.—Our first slice of luck! The entire French Fleet during the mist last night came into collision with the Nore Light, and sank immediately. I was surprised at their sparing the Reculvers and the local bathing-machines, but now the mystery is explained.

Friday.—Just learned that the great gun of Paris, which carries forty-four thousand miles, is to be tried for the first time to-morrow. It would have been used earlier, had it not been necessary to raise a foreign loan to supply funds to load it. Trust it won't be laid in our direction. This war has already caused the Insurance Companies to double their charges! Too bad!

Saturday.—All's well that ends well. Hostilities are at an end. This morning all the glass in the windows were broken at 8 o'clock. Ten minutes later the Champs Elysées was deposited half a mile from Birchington. We now know that the great Paris gun burst on its first discharge, and France exists no longer as a country, but as a "geographical expression" is deposited in various parts of Europe.

REAL AND IDEAL.—"A Really Hard-Headed Man"—the Iron-skulled individual now exhibiting at the Aquarium. If his will is as iron as his head, what a despot he would be! If France is tired of her Republic, she might try the Iron-Headed Man as a ruler. There is the chance, of course, that he might turn out a numskull, and be only King Log, after all.

["Do the poor make the slums, or the slums make the poor?"—Henry Lazarus, in "Landlordism."]

Is it the poor wot makes the Slums, or the Slums wot makes the poor?

Well, that's the question, Guv'nor, and I've 'eared it arsked afore,

And the arnser ain't so easy, if you wants to be O.K.

Don't suppose as I can settle it, but I'll have my little say.

My old friend Mister Lazarus, now, he ups and sez, sez he,

The great Ground Landlord is the great prime cause. "Yah! fiddlededee!"

Cries the House-Farmer; "Slums is Slums, acos the Poor is Pigs!"

"You try 'em, friend philanthropist! They'll play you proper rigs."

Yus, there's two sides to heverythink, wus luck! That's where we're fogged.

Passiges like foul pigstyes, gents, and backyards like black bogs,

Banisters broke for firewood, and smashed winders stuffed with rags,

These make the sniffers slate the poor, Perticular if they're wags.

Well, gents, you know, it's this way. Just you fancy yerselves born

In a back-slum like Ragman's Rents. 'Old 'ard, don't larf with scorn!

Some on us is born there, yer know; it might ha' bin your luck,

If yer mother'd bin a boozer, and yer father'd got the chuck.

Of course yourn was respectable; mine wosn't; there's the diff.!

Ah! things like this ain't settled by a snort or by a sniff.

Jest fancy hopening yer eyes fust time in a dark dive,

Or a sky-parlour where a plarnt o' musk won't keep alive.

Emagine, if yer washups can, some ten foot square o' room,

With a stror-heap in one corner, and a "dip" to light the gloom;

With the walls dirt-streaked with damp-lines, outside, a drunken din,

And hinside, a whiff of sewer-gas in a hatmosphere of gin.

Some on you carn't emagine there's sech 'orrors on the earth;

But there are, you bet your buttons. Who'd select 'em for their birth?

Not you, not me, not no one, if you asked 'em, I expect;

But yer place o' birth yer see, gents' jest the thing yer carn't select.

If you're born where streets is narrer, and where rooms is werry small,

Where you've damp sludge for a ceiling, rotting plarster for a wall;

Where yer carn't eat, sleep, wash yerselves, or lay up when you're sick,

Without tumbling one o'er tother, wy, yer sinks, gents, pooty quick.

Sinks! Yes, when wot yer lives in is a sink, or somethink wus;

With a drunkard for a mother, and some neighbour for a nuss;

With the gutter for yer playground, and a 'ome from which yer shrink,

Can you wonder that poor Slum-birds is give o'er to Dirt and Drink.

Ah! them two D's goes together. Just you plant some orty Queen

In a rookery, in her kidhood, and then tell her to keep clean,

Wash 'er face, and mend 'er garments,—wich they're mostly sewed-up rags,—

In six months she'd be a scare-crow, 'ands like sut, and 'air all jags.

Wot yer washups don't quite tumble to's the fack as like breeds like.

If you would himprove Slum-dwellers, at the Slum you fust must strike.

Give us small dark 'oles to dwell in, and you must be jolly green

If you think folks bred in dirt like, are a-going to keep 'em clean.

When the sewer-rats take to sweetening and lime-washing their foul 'oles,

And bright light and disinfectants are the fads of skunks and moles,

Then poor souls in cellar-dwellings and in jerry-builders' dens,

Will be smart as young canaries and as clean as clucking hens.

Nocky Spriggings guyed me proper, in his chuckly sorter style,

With his thumb 'ooked orful hartful, and his chickaleary smile.

"Jim," sez he, "wot price your jabber? Do yer think the blooming blokes

Cares a cuss for me and you, Jim, any more than for our mokes?

"Shut yer face, you pattering josser! Dirt and Drink is good for Rents!

If the Poor wos clean and sober, where 'ud be their cent-per-cents?

If it's Public 'Ouse 'gainst Wash 'Ouse, if it's Slumland wersus Swipes,

I am on for booze and backy 'stead o' drains and water-pipes.

"You may be too jolly clean, Jim, and a precious sight too light,

Were's the good to scrub yer skin orf! And if when a cove gits tight,

Or would give his donah wot-for on the Q.T. wot a lark

If there weren't no 'andy alleys, nor no corners snug and dark.

"If the Public—and the Slops—wos always fly to wot we done,

'Long o' widened streets and gas-light, wy we'd 'ave no blooming fun.

Lagged for larrupping yer missus, nailed for boozing till yer nod?

Wy, you jabbering young Juggins, we should always be in quod!"

'Ard nut is Nocky Spriggings—of the sort as make the slums,

'Cos there ain't much chance for cleanness, or for comfort, when he comes.

He's as 'appy in the dirt, gents, as a blowfly or a 'og;

Or poor Paddy in his tater-patch alongside of a bog;

He'd chop up 'is doors and winders for a fire to 'ot his lush,

Don't care a 'ang for decency, and never raised a blush.

But, arter my hexperience—and I've 'ad some down our court—

I believe that—fair at bottom—it's the Slum as makes his sort.

Anyways I'm pooty certain, if we'd got more light and space,

And were not jammed up together in a filthy, ill-drained place;

If the sunlight could but see us, and the public and the cops,

There would be less booze and bashing, fewer drabs and drinking-shops.

Aye, and fewer Nocky Spriggingses! I don't go for to say

As it's all along o' Landlords, who'd rent 'ell, if 'twould but pay;

But I've noticed you find fewest mice where there are lots of cats,

And where there ain't no rat-holes, well—yer won't spot many rats!

The enormous crowd cheered again and again. It was furious. The enthusiasm spread from throng to throng, until a mighty chorus filled every portion of the land. And there was indeed reason for the rejoicing. Had not the great Arctic Explorer come home? Had he not been to the North Pole and back? At that very moment were not a couple of steam-tugs drawing his wooden vessel towards his native shore? It was indeed a moment for congratulation—not only personal but national, nay cosmopolitan. The victory of art over nature belonged to more than a country, it belonged to the world!

And the tugs came closer and closer, and the cheers grew louder and louder. Then the vessel bearing the Explorer was near at hand. The crowd joyously jumped into the water, and raising him on their shoulders, bore him triumphantly to land.

How they welcomed him! How they seized his hands and kissed them! How they cried and called him "Master," and "Victor," and "Hero!" It was a scene never to be forgotten!

When the excitement had somewhat subsided, they began to ask him questions. At last one of them wished to know how he contrived to find the North Pole and get back in safety?

"You intended to drift?" said they. "Great and glorious hero, victorious victor, triumphant explorer, did you do this?"

"I did," was the reply.

"And tell us what was your method of obtaining the knowledge you now possess? Oh, great chief, how did you manage it?"

Then came the answer—

"By sitting still, and doing nothing!"

And now it being dark, they separated to illuminate their homes in honour of the fresh industry—an industry admirably adapted to that great and contented class of the community, the Unemployed!

☞ NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, Or The London Charivari, VOL.

103, November 26, 1892, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 15973-h.htm or 15973-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

https://www.gutenberg.org/1/5/9/7/15973/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, William Flis, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

https://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH F3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS' WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTIBILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need, is critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation web page at https://www.pglaf.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Its 501(c)(3) letter is posted at

https://pglaf.org/fundraising. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at

809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887, email

business@pglaf.org. Email contact links and up to date contact

information can be found at the Foundation's web site and official

page at https://pglaf.org

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit https://pglaf.org

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including including checks, online payments and credit card

donations. To donate, please visit: https://pglaf.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared

with anyone. For thirty years, he produced and distributed Project

Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as Public Domain in the U.S.

unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not necessarily

keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search facility:

https://www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.