The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Sixth-Century Fragment of the Letters of

Pliny the Younger, by Elias Avery Lowe and Edward Kennard Rand

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Sixth-Century Fragment of the Letters of Pliny the Younger

A Study of Six Leaves of an Uncial Manuscript Preserved

in the Pierpont Morgan Library New York

Author: Elias Avery Lowe and Edward Kennard Rand

Release Date: September 17, 2005 [EBook #16706]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SIXTH-CENTURY FRAGMENT ***

Produced by Louise Hope, David Starner and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

|

I. Palaeography of Fragment Notes to Part I Fragment Transcription II. Text of Fragment Notes to Part II Plates |

T HE Pierpont Morgan Library, itself a work of art, contains masterpieces of painting and sculpture, rare books, and illuminated manuscripts. Scholars generally are perhaps not aware that it also possesses the oldest Latin manuscripts in America, including several that even the greatest European libraries would be proud to own. The collection is also admirably representative of the development of script throughout the Middle Ages. It comprises specimens of the uncial hand, the half-uncial, the Merovingian minuscule of the Luxeuil type, the script of the famous school of Tours, the St. Gall type, the Irish and Visigothic hands, and the Beneventan and Anglo-Saxon scripts.

Among the oldest manuscripts of the library, in fact the oldest, is a hitherto unnoticed fragment of great significance not only to palaeographers, but to all students of the classics. It consists of six leaves of an early sixth-century manuscript of the Letters of the younger Pliny. This new witness to the text, older by three centuries than the oldest codex heretofore used by any modern editor, has reappeared in this unexpected quarter, after centuries of wandering and hiding. The fragment was bought by the late J. Pierpont Morgan in Rome, in December 1910, from the art dealer Imbert; he had obtained it from De Marinis, of Florence, who had it from the heirs of the Marquis Taccone, of Naples. Nothing is known of the rest of the manuscript.

The present writers had the good fortune to visit the Pierpont Morgan Library in 1915. One of the first manuscripts put into their hands was this early sixth-century fragment of Pliny’s Letters, which forms the subject of the following pages. Having received permission to study the manuscript and publish results, they lost no time in acquainting classical scholars with this important find. In December of the same year, at the joint meeting of the American Archaeological and Philological Associations, held at Princeton University, two papers were read, one concerning the palaeographical, the other the textual, importance of the fragment. The two studies which follow, Part I by Doctor Lowe, Part II by Professor Rand, are an elaboration of the views presented at the meeting. Some months after the present volume was in the form of page-proof, Professor E. T. Merrill’s long-expected edition of Pliny’s Letters appeared (Teubner, Leipsic, 1922). We regret that we could not avail ourselves of it in time to introduce certain changes. The reader will still find Pliny cited by the pages of Keil, and in general he should regard the date of our production as 1921 rather than 1922.

iv The writers wish to express their gratitude for the privilege of visiting the Pierpont Morgan Library and making full use of its facilities. For permission to publish the manuscript they are indebted to the generous interest of Mr. J. Pierpont Morgan. They also desire to make cordial acknowledgment of the unfailing courtesy and helpfulness of the Librarian, Miss Belle da Costa Greene, and her assistant, Miss Ada Thurston. Lastly, the writers wish to thank the Carnegie Institution of Washington for accepting their joint study for publication and for their liberality in permitting them to give all the facsimiles necessary to illustrate the discussion.

E. K. RAND.

E. A. LOWE.

Contents

size

vellum

binding

T

HE Morgan fragment of Pliny the Younger contains the end of Book II and

the beginning of Book III of the Letters (II, xx. 13-III, v. 4).

The fragment consists of six vellum leaves, or twelve pages, which

apparently formed part of a gathering or quire of the original

volume.

The leaves measure 11-3/8 by 7 inches (286 x 180 millimeters); the written space measures 7-1/4 by 4-3/8 inches (175 x 114 millimeters); outer margin, 1-7/8 inches (50 millimeters); inner, 3/4 inch (18 millimeters); upper margin, 1-3/4 inches (45 millimeters); lower, 2-1/4 inches (60 millimeters).

The vellum is well prepared and of medium thickness. The leaves are bound in a modern pliable vellum binding with three blank vellum fly-leaves in front and seven in back, all modern. On the inside of the front cover is the book-plate of John Pierpont Morgan, showing the Morgan arms with the device: Onward and Upward. Under the book-plate is the press-mark M.462.

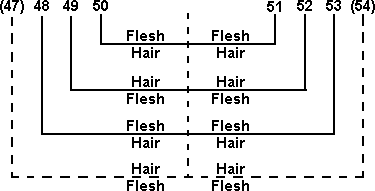

Ruling There are twenty-seven horizontal lines to a page and two vertical bounding lines. The lines were ruled with a hard point on the flesh side, each opened sheet being ruled separately: 48v and 53r, 49r and 52v, 50v and 51r. The horizontal lines were guided by knife-slits made in the outside margins quite close to the text space; the two vertical lines were guided by two slits in the upper margin and two in the lower. The horizontal lines were drawn across the open sheets and extended occasionally beyond the slits, more often just beyond the perpendicular bounding lines. The written space was kept inside the vertical bounding lines except for the initial letter of each epistle; the first letter of the address and the first letter of the epistle proper projected into the left margin. Here and there the scribe transgressed beyond the bounding line. On the whole, however, he observed the limits and seemed to prefer to leave a blank before the bounding line rather than to crowd the syllable into the space or go beyond the vertical line.

Relation of the six leaves to the rest of the manuscript One might suppose that the six leaves once formed a complete gathering of the original book, especially as the first and last pages, folios 48r and 53v have a darker appearance, as though they had been the outside leaves of a gathering that had been affected by exposure. But this darker appearance is sufficiently accounted for by the fact that both pages are on the hair side of the parchment, and the 4 hair side is always darker than the flesh side. Quires of six leaves or trinions are not unknown. Examples of them may be found in our oldest manuscripts. But they are the exception.1 The customary quire is a gathering of eight leaves, forming a quaternion proper. It would be natural, therefore, to suppose that our fragment did not constitute a complete gathering in itself but formed part of a quaternion. The supposition is confirmed by the following considerations:

In the first place, if our six leaves were once a part of a quaternion, the two leaves needed to complete them must have formed the outside sheet, since our fragment furnishes a continuous text without any lacuna whatever. Now, in the formation of quires, sheets were so arranged that hair side faced hair side, and flesh side flesh side. This arrangement is dictated by a sense of uniformity. As the hair side is usually much darker than the flesh side the juxtaposition of hair and flesh sides would offend the eye. So, in the case of our six leaves, folios 48v and 53r, presenting the flesh side, face folios 49r and 52v likewise on the flesh side; and folios 49v and 52r presenting the hair side, face folios 50r and 51v likewise on the hair side. The inside pages 50v and 51r which face each other, are both flesh side, and the outside pages 48r and 53v are both hair side, as may be seen from the accompanying diagram.

From this arrangement it is evident that if our fragment once formed part of a quaternion the missing sheet was so folded that its hair side faced the present outside sheet and its flesh side was on the outside of the whole gathering. Now, it was by far the more usual practice in our oldest uncial manuscripts to have the flesh side on the outside of the quire.2 And as our fragment belongs to the oldest 5 class of uncial manuscripts, the manner of arranging the sheets of quires seems to favor the supposition that two outside leaves are missing. The hypothesis is, moreover, strengthened by another consideration. According to the foliation supplied by the fifteenth-century Arabic numerals, the leaf which must have followed our fragment bore the number 54, the leaf preceding it having the number 47. If we assume that our fragment was a complete gathering, we are obliged to explain why the next gathering began on a leaf bearing an even number (54), which is abnormal. We do not have to contend with this difficulty if we assume that folios 47 and 54 formed the outside sheet of our fragment, for six quires of eight leaves and one of six would give precisely 54 leaves. It seems, therefore, reasonable to assume that our fragment is not a complete unit, but formed part of a quaternion, the outside sheet of which is missing.

Original size of the manuscript In the fifteenth century, as the previous demonstration has made clear, our fragment was preceded by 47 leaves that are missing to-day. With this clue in our possession it can be demonstrated that the manuscript began with the first book of the Letters. We start with the fact that not all the 47 folios (or 94 pages) which preceded our six leaves were devoted to the text of the Letters. For, from the contents of our six leaves we know that each book must have been preceded by an index of addresses and first lines. The indices for Books I and II, if arranged in general like that of Book III, must have occupied four pages.3 We also learn from our fragment that space must be allowed for a colophon at the end of each book. One page for the colophons of Books I and II is a reasonable allowance. Accordingly it follows that out of the 94 pages preceding our fragment 5 were not devoted to text, or in other words that only 89 pages were thus devoted.

Now, if we compare pages in our manuscript with pages of a printed text we find that the average page in our manuscript corresponds to about 19 lines of the Teubner edition of 1912. If we multiply 89 by 19 we get 1691. This number of lines of the size of the Teubner edition should, if our calculation be correct, contain the text of the Letters preceding our fragment. The average page of the Teubner edition of 1912 of the part which interests us contains a little over 29 lines. If we divide 1691 by 29 we get 58.3. Just 58 pages of Teubner text are occupied by the 47 leaves which preceded our fragment. So close a conformity is sufficient to prove our point. We have possibly allowed too much space for indices and colophons, especially if the former covered less ground for 6 Books I and II than for Book III. Further, owing to the abbreviation of que and bus, and particularly of official titles, we can not expect a closer agreement.

It is not worth while to attempt a more elaborate calculation. With the edges matching so nearly, it is obvious that the original manuscript as known and used in the fifteenth century could not have contained some other work, however brief, before Book I of Pliny’s Letters. If the manuscript contained the entire ten books it consisted of about 260 leaves. This sum is obtained by counting the number of lines in the Teubner edition of 1912, dividing this sum by 19, and adding thereto pages for colophons and indices. It would be too bold to suppose that this calculation necessarily gives us the original size of the manuscript, since the manuscript may have had less than ten books, or it may, on the other hand, have had other works. But if it contained only the ten books of the Letters, then 260 folios is an approximately correct estimate of its size.

It is hard to believe that only six leaves of the original manuscript have escaped destruction. The fact that the outside sheet (foll. 48r and 53v) is not much worn nor badly soiled suggests that the gathering of six leaves must have been torn from the manuscript not so very long ago and that the remaining portions may some day be found.

Disposition The pages in our manuscript are written in long lines,4 in scriptura continua, with hardly any punctuation.

Each page begins with a large letter, even though that letter occur in the body of a word (cf. foll. 48r, 51v, 52r).5

Each epistle begins with a large letter. The line containing the address which precedes each epistle also begins with a large letter. In both cases the large letter projects into the left margin.

The running title at the top of each page is in small rustic capitals.6 On the verso of each folio stands the word EPISTVLARVM; on the recto of the following folio stands the number of the book, e.g., LIB. II, LIB. III.

To judge by our fragment, each book was preceded by an index of addresses 7 and initial lines written in alternating lines of black and red uncials. Alternating lines of black and red rustic capitals of a large size were used in the colophon.7

Ornamentation As in all our oldest Latin manuscripts, the ornamentation is of the simplest kind. Such as it is, it is mostly found at the end and beginning of books. In our case, the colophon is enclosed between two scrolls of vine-tendrils terminating in an ivy-leaf at both ends. The lettering in the colophon and in the running title is set off by means of ticking above and below the line.

Red is used for decorative purposes in the middle line of the colophon, in the scroll of vine-tendrils, in the ticking, and in the border at the end of the Index on fol. 49. Red was also used, to judge by our fragment, in the first three lines of a new book,8 in the addresses in the Index, and in the addresses preceding each letter.

Corrections The original scribe made a number of corrections. The omitted line of the Index on fol. 49 was added between the lines, probably by the scribe himself, using a finer pen; likewise the omitted line on fol. 52v, lines 7-8. A number of slight corrections come either from the scribe or from a contemporary reader; the others are by a somewhat later hand, which is probably not more recent than the seventh century.9 The method of correcting varies. As a rule, the correct letter is added above the line over the wrong letter; occasionally it is written over an erasure. An omitted letter is also added above the line over the space where it should be inserted. Deletion of single letters is indicated by a dot placed over the letter and a horizontal or an oblique line drawn through it. This double use of expunction and cancellation is not uncommon in our oldest manuscripts. For details on the subject of corrections, see the notes on pp. 23-34.

There is a ninth-century addition on fol. 53 and one of the fifteenth century on fol. 51. On fol. 49, in the upper margin, a fifteenth-century hand using a stilus or hard point scribbled a few words, now difficult to decipher.10 Presumably the same hand drew a bearded head with a halo. Another relatively recent hand, using lead, wrote in the left margin of fol. 53v the monogram QR11 and the roman numerals i, ii, iii under one another. These numerals, as Professor 8 Rand correctly saw, refer to the works of Pliny the Elder enumerated in the text. Further activity by this hand, the date of which it is impossible to determine, may be seen, for example, on fol. 49v, ll. 8, 10, 15; fol. 52, ll. 4, 10, 13, 21, 22; fol. 53, ll. 12, 15, 16, 17, 20, 27; fol. 53v, ll. 5, 10, 15.

Syllabification Syllables are divided after a vowel or diphthong except where such a division involves beginning the next syllable with a group of consonants.12 In that case the consonants are distributed between the two syllables, one consonant going with one syllable and the other with the following, except when the group contains more than two successive consonants, in which case the first consonant goes with the first syllable, the rest with the following syllable. That the scribe is controlled by this mechanical rule and not by considerations of pronunciation is obvious from the division san|ctissimum and other examples found below. The method followed by him is made amply clear by the examples which occur in our twelve pages:13

Orthography The spelling found in our six leaves is remarkably correct. It compares favorably with the best spelling encountered in our oldest Latin manuscripts of the fourth and fifth centuries. The diphthong ae is regularly distinguished from e. The interchange of b and u, d and t, o and u, so common in later manuscripts, is rare here: the confusion between b and u occurs once (comprouasse, fo. 52v, l. 1); the omission of h occurs once (pulcritudo, fo. 51v, l. 26); the use of k for c occurs twice (karet, fo. 51r, l. 14, and karitas, fo. 52r, l. 5). The scribe uses the correct forms in adolescet (fo. 51v, l. 14) and adulescenti (fo. 51v, l. 24); he writes auonculi (fo. 53v, l. 15), exsistat (fo. 51v, l. 9), and exsecutos (fo. 53r, l. 8). In the case of composite words he has the assimilated form in some, and in others the unassimilated form, as the following examples go to show:

10| fo. 48r, | line 3, | inpleturus | fo. 48r, | line 7, | improbissimum |

| 49r, | 13a, | adnotasse | 48v, | 23, | composuisse |

| 19, | adsumo | 50r, | 1, | ascendit | |

| 50r, | 1, | adsumit | 6, | imbuare | |

| 27, | adponitur | 22, | accubat | ||

| 50v, | 3, | adficitur | 51r, | 2, | optulissem |

| 51r, | 19, | adstruere | 3, | suppeteret | |

| 21, | adstruere | 16, | ascendere | ||

| 26, | adpetat | 51v, | 16, | accipiat | |

| 51v, | 9, | exsistat | 52v, | 1, | comprouasse |

| 12, | inlustri | 11, | collegae | ||

| 14, | inbutus | 17, | impetrassent | ||

| 52r, | 18, | admonebitur | 53r, | 8, | accusationibus |

| 52v, | 20, | inplorantes | 15, | comparatum | |

| 22, | adlegantes | 53v, | 1, | computabam | |

| 24, | adsensio | 5, | accusare | ||

| 27, | adtulisse | 11, | comprobantis | ||

| 53r, | 8, | exsecutos | 23, | composuit |

Abbreviations Very few abbreviated words occur in our twelve pages. Those that are found are subject to strict rules. What is true of the twelve pages was doubtless true of the entire manuscript, inasmuch as the sparing use of abbreviations in conformity with certain definite rules is a characteristic of all our oldest manuscripts.14 The abbreviations found in our fragment may conveniently be grouped as follows:

1. Suspensions which might occur in any ancient manuscript or inscription, e.g.:

| B· = | BUS |

| Q· = | QUE15 |

| ·C̅· = | GAIUS16 |

| P· C· = | PATRES CONSCRIPTI |

2. Technical or recurrent terms which occur in the colophons at the end of each book and at the end of letters, as:

| ·EXP· = | EXPLICIT |

| ·INC· = | INCIPIT |

| LIB· = | LIBER |

| VAL· = | VALE17 |

4. Omitted M at the end of a line, omitted N at the end of a line, the omission being indicated by means of a horizontal stroke, thickened at either end, which is placed over the space immediately following the final vowel.19 This omission may occur in the middle of a word but only at the end of a line.

Authenticity of the six leaves The sudden appearance in America of a portion of a very ancient classical manuscript unknown to modern editors may easily arouse suspicion in the minds of some scholars. Our experience with the “Anonymus Cortesianus” has taught us to be wary,20 and it is natural to demand proof establishing the genuineness of the new fragment.21 As to the six leaves of the Morgan Pliny, it may be said unhesitatingly that no one with experience of ancient Latin manuscripts could entertain any doubt as to their genuineness. The look and feel of the parchment, the ink, the script, the titles, colophons, ornamentation, corrections, and later additions, all bear the indisputable marks of genuine antiquity.

But it may be objected that a clever forger possessing a knowledge of palaeography would be able to reproduce all these features of ancient manuscripts. This objection can hardly be sustained. It is difficult to believe that any modern could reproduce faithfully all the characteristics of sixth-century uncials and fifteenth-century notarial writing without unconsciously falling into some error and betraying his modernity. Besides, there is one consideration which to my mind establishes the genuineness of our fragment beyond a peradventure. We have seen above that the leaves of our manuscript are so arranged that hair side faces hair side and flesh side faces flesh side. The visible effect of this arrangement is that two pages of clear writing alternate with two pages of faded writing, the faded appearance being caused by the ink scaling off from the less porous surface of the flesh side of the vellum.22 As a matter of fact, the flesh side of the vellum showed 12 faded writing long before modern time. To judge by the retouched characters on fol. 53r it would seem that the original writing had become illegible by the eighth or ninth century.23 Still, a considerable period of time would, so far as we know, be necessary for this process. It is highly improbable that a forger could devise this method of giving his forgery the appearance of antiquity, and even if he attempted it, it is safe to say that the present effect would not be produced in the time that elapsed before the book was sold to Mr. Morgan.

But let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the Morgan fragment is a modern forgery. We are then constrained to credit the forger not only with a knowledge of palaeography which is simply faultless, but, as will be shown in the second part, with a minute acquaintance with the criticism and the history of the text. And this forger did not try to attain fame or academic standing by his nefarious doings, as was the case with the Roman author of the forged “Anonymus Cortesianus,” for nothing was heard of this Morgan fragment till it had reached the library of the American collector. If his motive was monetary gain he chose a long and arduous path to attain it. It is hardly conceivable that he should take the trouble to make all the errors and omissions found in our twelve pages and all the additions and corrections representing different ages, different styles, when less than half the number would have served to give the forged document an air of verisimilitude. The assumption that the Morgan fragment is a forgery thus becomes highly unreasonable. When you add to this the fact that there is nothing in the twelve pages that in any way arouses suspicion, the conclusion is inevitable that the Morgan fragment is a genuine relic of antiquity.

Archetype As to the original from which our manuscript was copied, very little can be said. The six leaves before us furnish scanty material on which to build any theory. The errors which occur are not sufficient to warrant any conclusion as to the script of the archetype. One item of information, however, we do get: an omission on fol. 52v goes to show that the manuscript from which our scribe copied was written in lines of 25 letters or thereabout.24 The scribe first wrote excucuris|sem commeatu. Discovering his error of omission, he erased sem at the beginning of line 8 and added it at the end of line 7 (intruding upon margin-space in order to do so), and then supplied, in somewhat smaller letters, the omitted words accepto ut praefectus aerari. As there are no homoioteleuta to 13 account for the omission, it is almost certain that it was caused by the inadvertent skipping of a line.25 The omitted letters number 25.

A glance at the abbreviations used in the index of addresses on foll. 48v-49r teaches that the original from which our manuscript was copied must have had its names abbreviated in exactly the same form. There is no other way of explaining why the scribe first wrote ad iulium seruianum (fol. 49, l. 12), and then erased the final um and put a point after seruian.

Our manuscript was written in Italy at the end of the fifth or more probably at the beginning of the sixth century.

The manuscripts with which we can compare it come, with scarcely an exception, from Italy; for it is only of more recent uncial manuscripts (those of the seventh and eighth centuries) that we can say with certainty that they originate in other than Italian centres. The only exception which occurs to one is the Codex Bobiensis (k) of the Gospels of the fifth century, which may actually have been written in Africa, though this is far from certain. As for our fragment, the details of its script, as well as the ornamentation, disposition of the page, the ink, the parchment, all find their parallels in authenticated Italian products; and this similarity in details is borne out by the general impression of the whole.

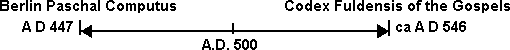

The manuscript may be dated at about the year A.D. 500, for the reason that the script is not quite so old as that of our oldest fifth-century uncial manuscripts, and yet decidedly older than that of the Codex Fuldensis of the Gospels (F) written in or before A.D. 546.

On the dating of uncial manuscripts In dating uncial manuscripts we must proceed warily, since the data on which our judgments are based are meagre in the extreme and rather difficult to formulate.

The history of uncial writing still remains to be written. The chief value of excellent works like Chatelain’s Uncialis Scriptura or Zangemeister and Wattenbach’s Exempla Codicum Latinorum Litteris Maiusculis Scriptorum lies in the mass of material they offer to the student. This could not well be otherwise, since clear-cut, objective criteria for dating uncial manuscripts have not yet been formulated; and that is due to the fact that of our four hundred or more uncial manuscripts, ranging from the fourth to the eighth century, very few, indeed, can be dated with 14 precision, and of these virtually none is in the oldest class. Yet a few guide-posts there are. By means of those it ought to be possible not only to throw light on the development of this script, but also to determine the features peculiar to the different periods of its history. This task, of course, can not be attempted here; it may, however, not be out of place to call attention to certain salient facts.

The student of manuscripts knows that a law of evolution is observable in writing as in other aspects of human endeavor. The process of evolution is from the less to the more complex, from the less to the more differentiated, from the simple to the more ornate form. Guided by these general considerations, he would find that his uncial manuscripts naturally fall into two groups. One group is manifestly the older: in orthography, punctuation, and abbreviation it bears close resemblance to inscriptions of the classical or Roman period. The other group is as manifestly composed of the more recent manuscripts: this may be inferred from the corrupt or barbarous spelling, from the use of abbreviations unfamiliar in the classical period but very common in the Middle Ages, or from the presence of punctuation, which the oldest manuscripts invariably lack. The manuscripts of the first group show letters that are simple and unadorned and words unseparated from each other. Those of the second group show a type of ornate writing, the letters having serifs or hair-lines and flourishes, and the words being well separated. There can be no reasonable doubt that this rough classification is correct as far as it goes; but it must remain rough and permit large play for subjective judgement.

A scientific classification, however, can rest only on objective criteria—criteria which, once recognized, are acceptable to all. Such criteria are made possible by the presence of dated manuscripts. Now, if by a dated manuscript we mean a manuscript of which we know, through a subscription or some other entry, that it was written in a certain year, there is not a single dated manuscript in uncial writing which is older than the seventh century—the oldest manuscript with a precise date known to me being the manuscript of St. Augustine written in the Abbey of Luxeuil in A.D. 669.26 But there are a few manuscripts of which we can say with certainty that they were written either before or after some given date. And these manuscripts which furnish us with a terminus ante quem or post quem, as the case may be, are extremely important to us as being the only relatively safe landmarks for following development in a field that is both remote and shadowy.

The Codex Fuldensis of the Gospels, mentioned above, is our first landmark of importance.27 It was read by Bishop Victor of Capua in the years A.D. 546 and 547, as is testified by two entries, probably autograph. From this it follows that 15 the manuscript was written before A.D. 546. We may surmise—and I think correctly—that it was shortly before 546, if not in that very year. In any case the Codex Fuldensis furnishes a precise terminus ante quem.

The other landmark of importance is furnished by a Berlin fragment containing a computation for finding the correct date for Easter Sunday.28 Internal evidence makes it clear that this Computus Paschalis first saw light shortly after A.D. 447. The presumption is that the Berlin leaves represent a very early copy, if not the original, of this composition. In no case can these leaves be regarded as a much later copy of the original, as the following purely palaeographical considerations, that is, considerations of style and form of letters, will go to show.

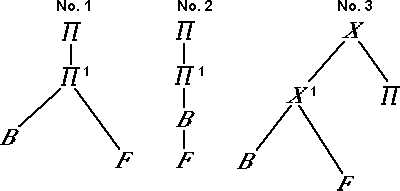

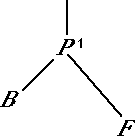

Let us assume, as we do in geometry, for the sake of argument, that the Fulda manuscript and the Berlin fragment were both written about the year 500—a date representing, roughly speaking, the middle point in the period of about one hundred years which separates the extreme limits of the dates possible for either of these two manuscripts, as the following diagram illustrates:

If our hypothesis be correct, then the script of these two manuscripts, as well as other palaeographical features, would offer striking similarities if not close resemblance. As a matter of fact, a careful comparison of the two manuscripts discloses differences so marked as to render our assumption absurd. The Berlin fragment is obviously much older than the Fulda manuscript. It would be rash to specify the exact interval of time that separates these two manuscripts, yet if we remember the slow development of types of writing the conclusion seems justified that at least several generations of evolution lie between the two manuscripts. If this be correct, we are forced to push the date of each as far back as the ascertained limit will permit, namely, the Fulda manuscript to the year 546 and the Berlin fragment to the year 447. Thus, apparently, considerations of form and style (purely palaeographical considerations) confirm the dates derived from examination of the internal evidence, and the Berlin and Fulda manuscripts may, in effect, be considered two dated manuscripts, two definite guide-posts.

If the preceding conclusion accords with fact, then we may accept the traditional date (circa A.D. 371) of the Codex Vercellensis of the Gospels. The famous Vatican palimpsest of Cicero’s De Re Publica seems more properly placed in the fourth than in the fifth century; and the older portion of the Bodleian manuscript of Jerome’s translation of the Chronicle of Eusebius, dated after the year A.D. 442, becomes another guide-post in the history of uncial writing, since a comparison with the Berlin fragment of about A.D. 447 convinces 16 one that the Bodleian manuscript can not have been written much after the date of its archetype, which is A.D. 442.

Dated uncial manuscripts Asked to enumerate the landmarks which may serve as helpful guides in uncial writing prior to the year 800, we should hardly go far wrong if we tabulate them in the following order:29

ca. a. 371 1. Codex Vercellensis of the Gospels (a).

post a. 442 2. Bodleian Manuscript (Auct. T. 2. 26) of Jerome’s translation of the Chronicle of Eusebius (older portion).

ca. a. 447 3. Berlin Computus Paschalis (MS. lat. 4º. 298).

ante a. 546 4. Codex Fuldensis of the Gospels (F), Fulda MS. Bonifat. 1, read by Bishop Victor of Capua.

a. 438-ca. 550 5. Codex Theodosianus (Turin, MS. A. II. 2).

Manuscripts containing the Theodosian Code can not be earlier than A.D. 438, when this body of law was promulgated, nor much later than the middle of sixth century, when the Justinian Code supplanted the Theodosian and made it useless to copy it.

a. 600-666 6. The Toulouse Manuscript (No. 364) and Paris MS. lat. 8901, containing Canons, written at Albi.

a. 669 7. The Morgan Manuscript of St. Augustine’s Homilies, written in the Abbey of Luxeuil. Later at Beauvais and Chateau de Troussures.

a. 699 8. The Berne Manuscript (No. 219B) of Jerome’s translation of the Chronicle of Eusebius, written in France, possibly at Fleury.

a. 695-711 9. Brussels Fragment of a Psalter and Varia Patristica (MS. 1221 = 9850-52) written for St. Medardus in Soissons in the time of Childebert III.

ante a. 716 10. Codex Amiatinus of the Bible (Florence Laur. Am. 1) written in England.

a. 719 11. The Treves Prosper (MS. 36, olim S. Matthaei).

ca. a. 750 12. The Milan Manuscript (Ambros. B. 159 sup.) of Gregory’s Moralia, written at Bobbio in the abbacy of Anastasius.

ante a. 752 13. The Bodleian Acts of the Apostles (MS. Selden supra 30) written in the Isle of Thanet.

a. 754 14. The Autun Manuscript (No. 3) of the Gospels, written at Vosevium.

a. 739-760 15. Codex Beneventanus of the Gospels (London Brit. Mus. Add. MS. 5463) written at Benevento.

post a. 787 16. The Lucca Manuscript (No. 490) of the Liber Pontificalis.

Guided by the above manuscripts, we may proceed to determine the place which the Morgan Pliny occupies in the series of uncial manuscripts. The student of manuscripts recognizes at a glance that the Morgan fragment is, as has been said, distinctly older than the Codex Fuldensis of about the year 546. But how much older? Is it to be compared in antiquity with such venerable monuments as the palimpsest of Cicero’s De Re Publica, with products like the Berlin Computus Paschalis or the Bodleian Chronicle of Eusebius? If we examine carefully the characteristics of our oldest group of fourth- and fifth-century manuscripts and compare them with those of the Morgan manuscript we shall see that the latter, though sharing some of the features found in manuscripts of the oldest group, lacks others and in turn shows features peculiar to manuscripts of a later group.

Oldest group of uncial manuscripts Our oldest group would naturally be composed of those uncial manuscripts which bear the closest resemblance to the above-mentioned manuscripts of the fourth and fifth centuries, and I should include in that group such manuscripts as these:

181. Rome, Vatic. lat. 5757.—Cicero, De Re Publica, palimpsest.

2. Rome, Vatic. lat. 5750 + Milan, Ambros. E. 147 sup.—Scholia Bobiensia in Ciceronem, palimpsest.

3. Vienna, 15.—Livy, fifth decade (five books).

4. Paris, lat. 5730.—Livy, third decade.

5. Verona, XL (38).—Livy, first decade, 6 palimpsest leaves.

6. Rome, Vatic. lat. 10696.—Livy, fourth decade, Lateran fragments.

7. Bamberg, Class. 35a.—Livy, fourth decade, fragments.

8. Vienna, lat. 1a.—Pliny, Historia Naturalis, fragments.

9. St. Paul in Carinthia, XXV a 3.—Pliny, Historia Naturalis, palimpsest.

10. Turin, A. II. 2.—Theodosian Codex, fragments, palimpsest.

1. Vercelli, Cathedral Library.—Gospels (a) ascribed to Bishop Eusebius (†371).

2. Paris, lat. 17225.—Corbie Gospels (ff2).

3. Constance-Weingarten Biblical fragments.—Prophets, fragments scattered in the libraries of Stuttgart, Darmstadt, Fulda, and St. Paul in Carinthia.

4. Berlin, lat. 4º. 298.—Computus Paschalis of ca. a. 447.

5. Turin, G. VII. 15.—Bobbio Gospels (k).

6. Turin, F. IV. 27 + Milan, D. 519. inf. + Rome, Vatic. lat. 10959.—Cyprian, Epistolae, fragments.

7. Turin, G. V. 37.—Cyprian, de opere et eleemosynis.

8. Oxford, Bodleian Auct. T. 2. 26.—Eusebius-Hieronymus, Chronicle, post a. 442.

9. Petrograd Q. v. I. 3 (Corbie).—Varia of St. Augustine.

10. St. Gall, 1394.—Gospels (n).

Characteristics of the oldest uncial manuscripts The main characteristics of the manuscripts included in the above list, which is by no means complete, may briefly be described thus:

1. General effect of compactness. This is the result of scriptura continua, which knows no separation of words and no punctuation. See the facsimiles cited above.

2. Precision in the mode of shading. The alternation of stressed and

unstressed strokes is very regular. The two arcs of ![]() are

shaded not in the middle, as in Greek uncials, but in the lower left and

upper right parts of the letter, so that the space enclosed by the two

arcs resembles an ellipse leaning to the left at an angle of about 45°,

thus

are

shaded not in the middle, as in Greek uncials, but in the lower left and

upper right parts of the letter, so that the space enclosed by the two

arcs resembles an ellipse leaning to the left at an angle of about 45°,

thus ![]() . What is true of the

. What is true of the

![]() is true of other curved strokes.

The strokes are often very short, mere touches of pen to parchment, like

brush work. Often they are unconnected, thus giving a mere suggestion of

the form. The attack or fore-stroke as well as the finishing stroke is a

very fine, oblique hair-line.30

is true of other curved strokes.

The strokes are often very short, mere touches of pen to parchment, like

brush work. Often they are unconnected, thus giving a mere suggestion of

the form. The attack or fore-stroke as well as the finishing stroke is a

very fine, oblique hair-line.30

3. Absence of long ascending or descending strokes. The letters lie

virtually between two lines (instead of between four as in later

uncials), the upper and lower shafts of letters like ![]() projecting but slightly beyond the head and base lines.

projecting but slightly beyond the head and base lines.

4. The broadness of the letters ![]()

5. The relative narrowness of the letters ![]()

6. The manner of forming ![]()

B with the lower bow considerably larger than the upper, which often has the form of a mere comma.

E with the tongue or horizontal stroke placed not in the middle, as in later uncial manuscripts, but high above it, and extending beyond the upper curve. The loop is often left open.

L with very small base.

M with the initial stroke tending to be a straight line instead of the well-rounded bow of later uncials.

N with the oblique connecting stroke shaded.

P with the loop very small and often open.

S with a rather longish form and shallow curves, as compared with the broad form and ample curves of later uncials.

T with a very small, sinuous horizontal top stroke (except at the beginning of a line when it often has an exaggerated extension to the left).

7. Extreme fineness of parchment, at least in parts of the manuscript.

20 8. Perforation of parchment along furrows made by the pen.

9. Quires signed by means of roman numerals often preceded by the letter Q· (= Quaternio) in the lower right corner of the last page of each gathering.

10. Running titles, in abbreviated form, usually in smaller uncials than the text.

11. Colophons, in which red and black ink alternate, usually in large-sized uncials.

12. Use of a capital, i.e., a larger-sized letter at the beginning of each page or of each column in the page, even if the beginning falls in the middle of a word.

13. Lack of all but the simplest ornamentation, e.g., scroll or ivy-leaf.

14. The restricted use of abbreviations. Besides B· and Q· and such suspensions as occur in classical inscriptions only the contracted forms of the Nomina Sacra are found.

15. Omission of M and N allowed only at the end of a line, the omission being marked by means of a simple horizontal line (somewhat hooked at each end) placed above the line after the final vowel and not directly over it as in later uncial manuscripts.

16. Absence of nearly all punctuation.

17. The use of ![]() in the text where an

omission has occurred, and

in the text where an

omission has occurred, and ![]() after the supplied omission in the lower margin, or the same

symbols reversed if the supplement is entered in the upper margin.

after the supplied omission in the lower margin, or the same

symbols reversed if the supplement is entered in the upper margin.

If we now turn to the Morgan Pliny we observe that it lacks a number

of the characteristics enumerated above as belonging to the oldest type

of uncial manuscripts. The parchment is not of the very thin sort. There

has been no corrosion along the furrows made by the pen. The running

title and colophons are in rustic capitals, not in uncials. The manner

of forming such letters as ![]() differs from that employed in the oldest group.

differs from that employed in the oldest group.

B with the lower bow not so markedly larger than the upper.

E with the horizontal stroke placed nearer the middle.

M with the left bow tending to become a distinct curve.

R S T have gained in breadth and proportionately lost in height.

Date of the Morgan manuscript Inasmuch as these palaeographical differences mark a tendency which reaches fuller development in later uncial manuscripts, it is clear that their presence in our manuscript is a sign of its more recent character as compared with manuscripts of the oldest type. Just as our manuscript is clearly older than the Codex Fuldensis of about the year 546, so it is clearly more recent than the Berlin Computus Paschalis of about the year 447. Its proper place is at the end of the oldest series of uncial manuscripts, which begins with the Cicero palimpsest. Its closest neighbors are, I believe, the Pliny palimpsest of St. Paul in Carinthia and the Codex Theodosianus of Turin. If we conclude by saying that the Morgan manuscript was written about the year 500 we shall probably not be far from the truth.

21Later history of the Morgan manuscript The vicissitudes of a manuscript often throw light upon the history of the text contained in the manuscript. And the palaeographer knows that any scratch or scribbling, any probatio pennae or casual entry, may become important in tracing the wanderings of a manuscript.

In the six leaves that have been saved of our Morgan manuscript we have two entries. One is of a neutral character and does not take us further, but the other is very clear and tells an unequivocal story.

The unimportant entry occurs in the lower margin of folio 53r. The words “uir erat in terra,” which are apparently the beginning of the book of Job, are written in Carolingian characters of the ninth century. As these characters were used during the ninth century in northern Italy as well as in France, it is impossible to say where this entry was made. If in France, then the manuscript of Pliny must have left its Italian home before the ninth century.31

That it had crossed the Alps by the beginning of the fifteenth century we know from the second entry. Nay, we learn more precise details. We learn that our manuscript had found a home in France, in the town of Meaux or its vicinity. The entry is found in the upper margin of fol. 51r and doubtless represents a probatio pennae on the part of a notary. It runs thus:

“A tous ceulz qui ces presentes lettres verront et

orront

Jehan de Sannemeres garde du scel de la provoste de

Meaulx & Francois Beloy clerc Jure de par le Roy

nostre sire a ce faire Salut sachient tuit que par.”

The above note is made in the regular French notarial hand of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.32 The formula of greeting with which the document opens is in the precise form in which it occurs in numberless charters of the period. All efforts to identify Jehan de Sannemeres, keeper of the seal of the provosté of Meaux, and François Beloy, sworn clerk in behalf of the King, have so far proved fruitless.33

Conclusion Our manuscript, then, was written in Italy about the year 500. It is quite possible that it had crossed the Alps by the ninth century or even before. It is certain that by the fifteenth century it had found asylum in France. When and under what circumstances it got back to Italy will be shown by Professor Rand in the pages that follow.

So it is France that has saved this, the oldest extant witness of Pliny’s Letters, 22 for modern times. To mediaeval France we are, in fact, indebted for the preservation of more than one ancient classical manuscript. The oldest manuscript of the third decade of Livy was at Corbie in Charlemagne’s time, when it was loaned to Tours and a copy of it made there. Both copy and original have come down to us. Sallust’s Histories were saved (though not in complete form) for our generation by the Abbey of Fleury. The famous Schedae Vergilianae, in square capitals, as well as the Codex Romanus of Virgil, in rustic capitals, belonged to the monastery of St. Denis. Lyons preserved the Codex Theodosianus. It was again some French centre that rescued Pomponius Mela from destruction. The oldest fragments of Ovid’s Pontica, the oldest fragments of the first decade of Livy, the oldest manuscript of Pliny’s Natural History—all palimpsests—were in some French centre in the Middle Ages, as may be seen from the indisputably eighth-century French writing which covers the ancient texts. The student of Latin literature knows that the manuscript tradition of Lucretius, Suetonius, Cæsar, Catullus, Tibullus, and Propertius—to mention only the greatest names—shows that we are indebted primarily to Gallia Christiana for the preservation of these authors.

|

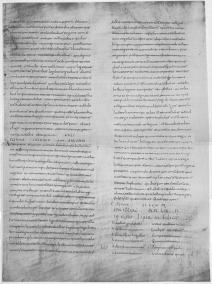

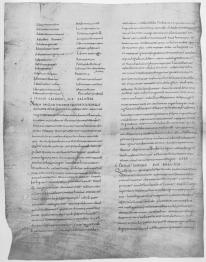

folio 48r folio 49r folio 50r folio 51r folio 52r folio 53r |

folio 48v folio 49v folio 50v folio 51v folio 52v folio 53v |

LIBER·II· |

|

|

CESSIT UT IPSE MIHI DIXERIT CUM

CON SULERET QUAM CITO SESTERTIUM SESCEN TIES INPLETURUS ESSET INUENISSE SE EX | |

|

TA DUPLICATA QUIBUS PORTENDI MILLIES1

ET DUCENTIES HABITURUM ET HABEBIT SI MODO UT COEPIT ALIENA TESTAMENTA QUOD EST IMPROBISSIMUM GENUS FAL SI IPSIS QUORUM SUNT ILLA DICTAUERIT UALE |

1. L added by a hand which seems contemporary, if not the scribe’s own. If the scribe’s, he used a finer pen for corrections. |

| 2· C · PLINI · SECUNDI | |

| EPISTULARUM · EXPLICIT · LIBER · II. | 2-2 The colophon is written in rustic capitals, the middle line being in red. |

| · INCIPIT · LIBER · III · FELICITER2 |

|

AD CALUISIUM RUFUM1

5

NESCIO AN ULLUM

AD UIBIUM · MAXIMUM

QUOD · IPSE AMICIS TUIS

|

1. On this and the following page lines in red alternate with lines in black. The first line is in red. |

|

AD CAERELLIAE HISPULLAE2

CUM PATREM TUUM

|

2. The h seems written over an erasure. |

|

10

AD CAECILIUM3

MACRINUM

QUAMUIS ET AMICI

AD BAEBIUM MACRUM

PERGRATUM EST MIHI

|

3. ci above the line by first hand. |

|

4AD ANNIUM4 SEUERUM

15

4EX HEREDITATE4 QUAE

AD CANINIUM RUFUM

MODO NUNTIATUS EST

|

4-4 Over an erasure apparently. |

|

AD SUETON5 TRANQUE

FACIS AD PRO CETERA

|

5. t over an erasure. |

|

20

AD CORNELIUM6

MINICIANUM

POSSUM IAM PERSCRIB

AD UESTRIC SPURINN ·

COMPOSUISSE ME QUAED

|

6. c over an erasure. |

|

AD IULIUM GENITOR ·

5

EST OMNINO ARTEMIDORI

AD CATILINUM SEUER ·

UENIAM AD CENAM

AD UOCONIUM ROMANUM

LIBRUM QUO NUPER

10

AD PATILIUM

REM ATROCEM

AD SILIUM PROCUL ·

PETIS UT LIBELLOS TUOS

| |

|

ad nepotem adnotasse uideor fata

dictaque·1

AD IULIUM SERUIAN ·2

15

RECTE OMNIA

AD UIRIUM SEUERUM

OFFICIU CONSULATUS

AD CALUISIUM RUFUM ·

ADSUMO TE IN CONSILIUM

20

AD MAESIUM MAXIMUM

MEMINISTINE TE

AD CORNELIUM PRISCUM

AUDIO UALERIUM MARTIAL ·

|

1. Added interlineally, in black, by first hand using a finer pen.

2. This is followed by an erasure of the letters um in red. |

· EPISTULARUM · | |

|

·C·PLINIUS · CALUISIO SUO SALUTEM NESCIO AN ULLUM IUCUNDIUS TEMPUS EXEGERIM QUAM QUO NUPER APUD SPU RINNAM FUI ADEO QUIDEM UT NEMINEM 5 MAGIS IN SENECTUTE SI MODO SENESCE RE DATUM EST AEMULARI UELIM NIHIL EST ENIM ILLO UITAE GENERE DISTIN CTIUS ME AUTEM UT CERTUS SIDERUM CURSUS ITA UITA HOMINUM DISPOSITA 10 DELECTAT SENUM PRAESERTIM NAM IUUENES ADHUC CONFUSA QUAEDAM ET QUASI TURBATA NON INDECENT SE NIBUS PLACIDA OMNIA ET ORDINATA1 CON | |

|

UENIUNT QUIBUS INDUSTRIA SERUA1TURPIS 15 AMBITIO EST HANC REGULAM SPURIN NA CONSTANTISSIME SERUAT · QUIN ETIAM PARUA HAEC PARUA · SI NON COTIDIE FIANT ORDINE QUODAM ET UELUT ORBE CIRCUM |

1. Letters above the line were added by first or contemporary hand. |

|

AGIT MANE LECTULO2 CONTINETUR HORA 20 SECUNDA CALCEOS POSCIT AMBULAT MI LIA PASSUUM TRIA NEC MINUS ANIMUM QUAM CORPUS EXERCET SI ADSUNT AMICI HONESTISSIMI SERMONES EXPLICANTUR SI NON LIBER LEGITUR INTERDUM ETIAM PRAE 25 SENTIBUS AMICIS SI TAMEN ILLI NON GRAUAN |

2. u corrected to e. |

|

TUR DEINDE CONSIDIT3 ET LIBER RURSUS AUT SERMO LIBRO POTIOR · MOX UEHICULUM |

3. Second i corrected to e (not the regular uncial form) apparently by the first or contemporary hand. |

· LIBER · III · | |

|

ASCENDIT ADSUMIT UXOREM SINGU LARIS EXEMPLI UEL ALIQUEM AMICORUM UT ME PROXIME QUAM PULCHRUM ILLUD QUAM DULCE SECRETUM QUANTUM IBI AN 5 TIQUITATIS QUAE FACTA QUOS UIROS AU DIAS QUIBUS PRAECEPTIS IMBUARE QUAMUIS ILLE HOC TEMPERAMENTUM MODESTIAE SUAE INDIXERIT NE PRAECIPE REUIDEATUR PERACTIS SEPTEM MILIBUS PASSUUM ITE 10 RUM AMBULAT MILLE ITERUM RESIDIT UEL SE CUBICULO AC STILO REDDIT SCRI BIT ENIM ET QUIDEM UTRAQUE LINGUA LY RICA DOCTISSIMA MIRA ILLIS DULCEDO | |

|

MIRA SUAUITAS MIRA HILARITAṪİS1 CUIUS 15 GRATIAM CUMULAT SANCTITAṪİS2 SCRI BENTIS UBI HORA BALNEI NUNTIATA EST EST AUTEM HIEME NONA · AESTATE OCTA UA IN SOLE SI CARET UENTO AMBULAT NUDUS DEINDE MOUETUR PILA UEHE 20 MENTER ET DIU NAM HOC QUOQUE EXER CITATIONIS GENERE PUGNAT CUM SE NECTUTE LOTUS ACCUBAT ET PAULIS PER CIBUM DIFFERT INTERIM AUDIT LE GENTEM REMISSIUS ALIQUID ET DULCIUS 25 PER HOC OMNE TEMPUS LIBERUM EST AMICIS UEL EADEM FACERE UEL ALIA |

1. The scribe first wrote hilaritatis. To correct the error he or

a contemporary hand placed dots above the t and i and drew

a horizontal line through them to indicate that they should be omitted.

This is the usual method in very old manuscripts.

2. sanctitatis is corrected to sanctitas in the manner described in the preceding note. |

| SI MALINT ADPONITUR3 CENA NON MINUS | 3. i added above the line, apparently by first hand. |

· EPISTULARUM ·NITIDA QUAM FRUGI IN ARGENTO PURO ET | |

|

ANTIQUO SUNT IN USU ET CHORINTHIA1 QUIBUS

DE LECTATUR ET ADFICITUR FREQUENTER CO MOEDIS CENA DISTINGUITUR UT UOLUPTA 5 TES QUOQUE STUDIIS CONDIANTUR SUMIT ALI QUID DE NOCTE ET AESTATE NEMINI1 HOC LON GUM EST TANTA COMITATE CONUIUIUM TRAHITUR INDE ILLI POST SEPTIMUM ET SEPTUAGENSIMUM ANNUM AURIUM 10 OCULORUM UIGOR INTEGER INDE AGILE ET UIUIDUM CORPUS SOLAQUE EX SENEC TUTE PRUDENTIA HANC EGO UITAM UO TO ET COGITATIONE PRAESUMO INGRES SURUS AUIDISSIME UT PRIMUM RATIO AE |

1. The letters above the line are additions by the first, or by another contemporary, hand. |

|

15

TATIS RECEPTUI CANERE PERMISERIT2 IN TERIM MILLE LABORIBUS CONTEROR QUI HO RUM MIHI ET SOLACIUM ET EXEMPLUM EST IDEM SPURINNA NAM ILLE QUOQUE QUOAD HONESTUM FUIT OBIIT1 OFFICIA 20 GESSIT MAGISTRATUS PROVINCIAS RE XIT MULTOQUE LABORE HOC OTIUM ME RUIT IGITUR EUNDEM MIHI CURSUM EUN DEM TERMINUM STATUO IDQUE IAM NUNC APUD TE SUBSIGNO UT SI ME LONGIUS SE |

2. permiserit: t stands over an erasure, and original it seems to be corrected to et, with e having the rustic form. |

|

25

EUEHI3 UIDERIS IN IUS UOCES AD HANC EPIS TULAM MEAM ET QUIESCERE IUBEAS CUM INERTIAE CRIMEN EFFUGERO UALE·4 |

3. The scribe first wrote longius se uehi. The e which

precedes uehi was added by him when he later corrected the page

and deleted se.

4. uale: The abbreviation is marked by a stroke above as well as by a dot after the word. |

· LIBER · III · | |

|

A tout ceulz qui ces presentes lettres verront et orront

Jehan de sannemeres garde du scel de la provoste de

Meaulx & francois Beloy clerc Jure de par le Roy

nostre sire a ce faire Salut sachient tuit que par.1

|

|

|

·C̅·PLINIUS · MAXIMO SUO

SALUTEM QUOD IPSE AMICIS TUIS OPTULISSEM · SI MI HI EADEM MATERIA SUPPETERET ID NUNC IURE UIDEOR A TE MEIS PETITURUS ARRIA 5 NUS MATURUS ALTINATIUM EST PRINCEPS CUM DICO PRINCEPS NON DE FACULTATI BUS LOQUOR QUAE ILLI LARGE SUPER SUNT SED DE CASTITATE IUSTITIA GRA UITATE PRUDENTIA HUIOS EGO CONSI 10 LIO IN NEGOTIIS IUDICIO IN STUDIIS UT OR NAM PLURIMUM FIDE PLURIMUM VERITATE PLURIMUM INTELLEGENTIA PRAESTAT AMAT ME NIHIL POSSUM AR |

1. A fifteenth-century addition, see above, p. 21. |

|

DENTIUS DICERE UT TU KARET AMBITUI2 15 IDEO SE IN EQUESTRI GRADU TENUIT CUM FACILE POSSIT3 ASCENDERE ALTISSIMUM MIHI TAMEN ORNANDUS EXCOLENDUS QUE EST ITAQUE MAGNI AESTIMO DIGNITATI EIUS ALIQUID ADSTRUERE INOPINANTIS 20 NESCIENTIS IMMO ETIAM FORTASSE NOLENTIS ADSTRUERE AUTEM QUOD SIT SPLENDIDUM NEC MOLESTUM CUIUS GENERIS QUAE PRIMA OCCASIO TIBI CON FERAS IN EUM ROGO HABEBIS ME HABE 25 BIS IPSUM GRATISSIMUM DEBITOREM QUAMUIS ENIM ISTA NON ADPETAT TAM GRATE TAMEN EXCIPIT QUAM SI CONCU |

2. The scribe originally divided i-deo between two lines. On

correcting the page he (or a contemporary corrector) cancelled the

i at the end of the line and added it before the next.

3. i changed to e (not the uncial form) possibly by the original hand in correcting. |

· EPISTULARUM ·PISCAT · UALE ·C̅·PLINIUS · CORELLIAE · SALUTEM · CUM PATREM TUUM GRAUISSIMUM ET SAN CTISSIMUM UIRUM SUSPEXERIM MAGIS 5 AN AMAUERIM DUBITEM TEQUE IN MEMO | |

|

RIAM EIUS ET IN HONOREM TUUM IUNUIICE1

DILIGAM CUPIAM NECESSE EST ATQUE ETIAM QUANTUM IN ME FUERIT ENITAR UT FILIUS TUUS AUO SIMILIS EXSISTAT EQUIDEM 10 MALO MATERNO QUAMQUAM2 ILLI PATER NUS ETIAM CLARUS SPECTATUSQUE3 CONTIGE RIT PATER QUOQUE ET PATRUUS INLUSTRI LAU DE CONSPICUI QUIBUS OMNIBUS ITA DEMUM SIMILIS ADOLESCET SIBI INBUTUS HONES |

1. inuice: corrected to unice by cancelling i and

ui (the cancellation stroke is barely visible) and writing

u and i above the line. The correction is by a somewhat

later hand.

2. u above the line is by the first hand. 3. q· above the line is added by a somewhat later hand. |

|

15

TIS ARTIBUS FUERIT QUAS PLURIMUM REFER4 ṘȦT5 A QUO POTISSIMUM ACCIPIAT ADHUC ILLUM PUERITIAE RATIO INTRA CONTUBER NIUM TUUM TENUIT PRAECEPTORES DOMI |

4. Final r is added by a somewhat later hand.

5. The dots above ra indicate deletion. The cancellation stroke is oblique. |

|

HABUIT UBI EST ERRORIBUS MODICA

UELST6 ETIAM 20 NULLA MATERIA IAM STUDIA EIUS EXTRA LIMEN CONFERANDA SUNT IAM CIRCUMSPI CIENDUS RHETOR LATINUS CUIUS SCHO LAE SEUERITAS PUDOR INPRIMIS CASTITAS CONSTET ADEST ENIM ADULESCENTI NOS 25 TRO CUM CETERIS NATURAE FORTUNAEQUE |

6. A somewhat later corrector, possibly contemporary, changed est to uel by adding u before e and l above s and cancelling both s and t. |

| DOTIBUS EXIMIA CORPORIS PULCHRITUDO7 CUI IN HOC LUBRICO AETATIS NON PRAECEP | 7. h added above the line by a hand which may be contemporary. |

· LIBER · III ·TOR MODO SED CUSTOS ETIAM RECTORQUE QUAERENDUS EST UIDEOR ERGO DEMON | |

|

STRARE TIBI POSSE IULIUM GENITIOREM1

AMNATUR2 A ME IUDICIO3 TAMEN

MEO NON 5 OBSTAT KARITAS HOMINIS QUAE EX4IUDI CIO NATA EST UIR EST EMENDATUS ET GRA UIS PAULO ETIAM HORRIDIOR ET DURIOR UT IN HAC LICENTIA TEMPORUM QUAN TUM ELOQUENTIA UALEAT PLURIBUS CRE 10 DERE POTES NAM DICENDI FACULTAS APERTA ET EXPOSITA · STATIM CERNITUR UITA HOMINUM ALTOS RECESSUS MAG NASQUE LATEBRAS HABET CUIUS PRO GE NITORE ME SPONSOREM ACCIPE NIHIL 15 EX HOC UIRO FILIUS TUUS AUDIET NISI |

1. The scribe wrote gentiorem: a somewhat later corrector changed

it to genitorem by adding an i above the line between

n and t and cancelled the i after t.

2. Above the m a somewhat later hand wrote n. It was cancelled by a crude modern hand using lead. 3. u added above the line by the later hand. 4. ex added above the line by the later corrector. |

|

PROFUTURUM NIHIL DISCET QUOD NESCIS5

SE RECTIUS FUERIT NEC6 MINUS SAEPE AB ILLO QUAM A TE MEQUE ADMONEBITUR QUIBUS IMAGINIBUS ONERETUR QUAE NOMI 20 NA ET QUANTA SUSTINEAT PROINDE FAUEN |

5. cis is added in the margin by the later hand. The original

scribe wrote nes | se.

6. c is added above the line by the later hand. |

|

TIBUS DIIS TRADE EUM7 PRAECEPTORI A QUO MORES PRIMUM MOX ELOQUENTIAM DISCAT QUAE MALE SINE MORIBUS DIS CITUR UALE 25 ·C· PLINIUS MACRINO SALUTEM QUAMUIS ET AMICI QUOS PRAESENTES HABEBAM ET SERMONES HOMINUM |

7. e added above the line. |

· EPISTULARUM · | |

|

FACTUM MEUM COMPROUASSE UIDEAN TUR MAGNI TAMEN AESTIMO SCIRE QUID SENTIAS TU NAM CUIUS INTEGRA RE CON SILIUM EXQUIRERE OPTASSEM1 HUIUS ETIAM 5 PERACTA IUDICIȦUM2 NOSSE MIRE CONCU PISCO CUM PUBLICUM OPUS MEA PECU |

1. p added above the line by the scribe.

2. The superfluous a is cancelled by means of a dot above the letter. |

|

NIA INCHOATURUS IN TUSCOS EXCUCURISsem

ac

aefectus aerari

cepto ut pr COMMEATU3 LEGATI

PROVINCIAE

|

|

|

BAETICAE QUESTURI DE PROCONSULATUṠ4 10 CAECILII CLASSICI ADVOCATUM ME A SE NATU PETIERUNT COLLEGAE OPTIMI MEIQUE AMANTISSIMI DE COMMUNIS OFFICII NE CESSITATIBUS PRAELOCUTI EXCUSARE ME ET EXIMERE TEMPTARUNT FACTUM 15 ṪU̇Ṁ5 EST SENATUS CONSULTUM PERQUAM HONORIFICUM UT DARER6 PROVINCIALIBUS PATRONUS SI AB IPSO ME IMPETRASSENT LEGATI RURSUS INDUCTI ITERUM ME IAM |

3. The scribe originally wrote excucuris | sem commeatu, omitting

accepto ut praefectus aerari. Noticing his error, he erased

sem and wrote it at the end of the preceding line, and added the

omitted words over the erasure and the word commeatu.

4. The dot over s indicates deletion. 5. tum: error due to diplography. The correction is made by means of dots and crossing out. 6. r added by the scribe. |

|

PRAESENTEM ADUOCATUM POSTULAUE7

20

RUNT INPLORANTES FIDEM MEAM QUAM ESSENT CONTRA MASSAM BAE |

7. u added apparently by a contemporary hand. |

|

BIUM EXPERTI ADLEGANTES PATROCINII8

FOEDUS SECUTA EST SENATUS CLARIS SIMA ADSENSIO QUAE SOLET DECRETA 25 PRAECURRERE TUM EGO DESINO IN QUAM P. C. PUTARE ME IUSTAS EXCUSA TIONIS CAUSAS ADTULISSE PLACUIT ET |

8. c added above the line, apparently by a contemporary hand. |

· LIBER · III ·MODESTIA SERMONIS ET RATIO COM PULIT AUTEM ME AD HOC CONSILIUM NON SOLUM CONSENSUS SENATUS QUAMQUAM HIC MAXIME UERUM ET ALII QUIDEM 5 MINORIS SED TAMEN NUMERI UENI EBAT IN MENTEM PRIORES NOSTROS | |

|

ETIAM SINGULORUM HOSPİTIUM1 INIU RIAS ACCUSATIONIBUS UOLUNTARIIS EX SECUTOS QUO DEFORMIUS ARBITRABAR |

1. Deletion of i before u is marked by a dot above the letter and a slanting stroke through it. |

|

10

PUBLICI HOSPITII IURA2 NEGLEGERE

PRAE TEREA CUM RECORDARER QUANTA PRO IISDEM BAETICIS PRIORE ADUOCA TIONE ETIAM PERICULA SUBISSEM CON SERVANDUM UETERIS OFFICII MERITUM 15 NOVO VIDEBATUR EST ENIM ITA COM PARATUM UT ANTIQUIORA BENEFICIA SUB UERTAS NISI ILLA POSTERIORIBUS CUMU |

2. h and i above the line are apparently by the first hand. |

|

LES NAM QUAMLIBET SAEPE OBLIGA(N)3

TI SIQUID4 UNUM NEGES HOC SOLUM 20 MEMINERUNT QUOD NEGATUM EST DUCEBAR ETIAM QUOD DECESSERAT CLASSICUS AMOTUMQUE ERAT QUOD I5N EIUSMODI CAUSIS SOLET ESSE TRIS |

3. n (in brackets) is a later addition.

4. The letters uid are plainly retraced by a later hand. The same hand retouched neges h in the same line. 5. i before n added by a later corrector who erased the i which the scribe wrote after quod, in the line above. |

|

ṪİTISSIMUM6 PERICULUM SENATORIS 25 UIDEBAM ERGO ADUOCATIONI MEAE NON MINOREM GRATIAM QUAM SI UIUERET ILLE PROPOSITAM INUIDIAM |

6. Superfluous ti cancelled by means of dots and oblique stroke. |

| Uir erat in terra7 | 7. Added by a Caroline hand of the ninth century. |

· EPISTULARUM ·NULLAM IN SUMMA COMPUTABAM | |

|

SI MUNERE HOC TERTIO FUNGERER1 FACILI OREM MIHI EXCUSATIONEM FORE SI QUIS INCIDISSET QUEM NON DEBEREM 5 ACCUSARE NAM CUM EST OMNIUM OFFI CIORUM FINIS ALIQUIS TUM OPTIME LIBERTATI UENIA OBSEQUIO PRAEPARA TUR AUDISTI CONSILII MEI MOTUS SUPER EST ALTERUTRA EX PARTE IUDICIUM TUUM |

1. r added above the line by the scribe or by a contemporary hand. |

|

10

IN QUO MIHI AEQUE IUCUINDA2 ERIT SIM PLICITAS DISSINTIENTIS3 QUAM COMPRO BANTIS AUCTORITAS UALE ·C̅·PLINIUS MACRO · SUO · SALUTEM PERGRATUM EST MIHI QUOD TAM DILIGEN 15 TER LIBROS AUONCULI MEI LECTITAS UT HABERE OMNES UELIS QUAERASQUE QUI SINT OMNES ḊĖFUNGAR4 INDICIS PARTIBUS ATQUE ETIAM QUO SINT ORDINE SCRIPTI NOTUM TIBI FACIAM EST ENIM HAEC 20 QUOQUE STUDIOSIS NON INIUCUNDA COG NITIO DE IACULATIONE EQUESTRI UNUS · HUNC CUM PRAEFECTUS ALAE MILITA |

2. i added above the second u by the scribe or by a

contemporary hand.

3. The scribe wrote dissitientis. A contemporary hand changed the second i to e and wrote an n above the t. 4. de is cancelled by means of dots above the d and e and oblique strokes drawn through them. |

|

RET· PARI5 INGENIO CURAQUE COMPOSUIT· DE UITA POMPONI SECUNDI DUO A QUO 25 SINGULARITER AMATUS HOC MEMORIAE AMICI QUASI DEBITUM MUNUS EXSOL UIT · BELLORUM GERMANIAE UIGINTI QUIBUS |

5. The strokes over the i at the end of this word and at the beginning of the next were added by a corrector who can not be much older than the thirteenth century. |

The Codex Parisinus A LDUS MANUTIUS, in the preface to his edition of Pliny’s Letters, printed at Venice in 1508, expresses his gratitude to Aloisio Mocenigo, Venetian ambassador in Paris, for bringing to Italy an exceptionally fine manuscript of the Letters; the book had been found not long before at or near Paris by the architect Fra Giocondo of Verona. The editio princeps, 1471, was based on a family of manuscripts that omitted Book VIII, called Book IX Book VIII, and did not contain Book X, the correspondence between Pliny and Trajan. Subsequent editions had only in part made good these deficiencies. More than a half of Book X, containing the letters numbered 41-121 in editions of our day, was published by Avantius in 1502 from a copy of the Paris manuscript made by Petrus Leander.2 Aldus himself, two years before printing his edition, had received from Fra Giocondo a copy of the entire manuscript, with six other volumes, some of them printed editions which Giocondo had collated with manuscripts. Aldus, addressing Mocenigo, thus describes his acquisition:

“Deinde Iucundo Veronensi Viro singulari ingenio, ac bonarum literarum studiosissimo, quod et easdem Secundi epistolas ab eo ipso exemplari a se descriptas in Gallia diligenter ut facit omnia, et sex alia uolumina epistolarum partim manu scripta, partim impressa quidem, sed cum antiquis collata exemplaribus, ad me ipse sua sponte, quae ipsius est ergo studiosos omneis beneuolentia, adportauerit, idque biennio ante, quam tu ipsum mihi exemplar publicandum tradidisses.”

So now the ancient manuscript itself had come. Aldus emphasizes its value in supplying the defects of previous editions. The Letters will now include, he declares:

“multae non ante impressae. Tum Graeca correcta, et suis locis restituta, atque retectis adulterinis, uera reposita. Item fragmentatae epistolae, integrae factae. In medio etiam epistolae libri octaui de Clitumno fonte non solum uertici calx additus, et calci uertex, sed decem quoque epistolae interpositae, ac ex Nono libro Octauus factus, et ex Octauo Nonus, Idque beneficio exemplaris correctissimi, & mirae, ac uenerandae Vetustatis.”

38The presence of such a manuscript, “most correct, and of a marvellous and venerable antiquity,” stimulates the imagination: Aldus thinks that now even the lost Decades of Livy may appear again:

“Solebam superioribus Annis Aloisi Vir Clariss. cum aut T. Liuii Decades, quae non extare creduntur, aut Sallustii, aut Trogi historiae, aut quemuis alium ex antiquis autoribus inuentum esse audiebam, nugas dicere, ac fabulas. Sed ex quo tu ex Gallia has Plinii epistolas in Italia reportasti, in membrana scriptas, atque adeo diuersis a nostris characteribus, ut nisi quis diu assuerit, non queat legere, coepi sperare mirum in modum, fore aetate nostra, ut plurimi ex bonis autoribus, quos non extare credimus, inueniantur.”

There was something unusual in the character of the script that made it hard to read; its ancient appearance even suggested to Aldus a date as early as that of Pliny himself.

“Est enim uolumen ipsum non solum correctissimum, sed etiam ita antiquum, ut putem scriptum Plinii temporibus.”

This is enthusiastic language. In the days of Italian humanism, a scholar might call almost any book a codex pervetustus if it supplied new readings for his edition and its script seemed unusual. As Professor Merrill remarks:3

“The extreme age that Aldus was disposed to attribute to the manuscript will, of course, occasion no wonder in the minds of those who are familiar with the vague notions on such matters that prevailed among scholars before the study of palaeography had been developed into somewhat of a science. The manuscript may have been written in one of the so-called ‘national’ hands, Lombardic, Visigothic, or Merovingian. But if it were in a ‘Gothic’ hand of the twelfth or thirteenth centuries, it might have appeared sufficiently grotesque and illegible to a reader accustomed for the most part to the exceedingly clear Italian book hands of the fifteenth century.”

In a later article Professor Merrill well adds that even the uncial script would have seemed difficult and alien to one accustomed to the current fifteenth-century style.4 A contemporary and rival editor, Catanaeus, disputed Aldus’s claims. In his second edition of the Letters (1518), he professed to have used a very ancient book that came down from Germany and declared that the Paris manuscript had no right to the antiquity which Aldus had imputed to it. But Catanaeus has been proved a liar.5 He had no ancient manuscript from Germany, and abused Aldus mainly to conceal his cribbings from that scholar’s edition; we may discount his opinion of the age of the Parisinus. Until Aldus, an eminent scholar and honest publisher,6 is proved guilty, we should assume him innocent of mendacity or naïve ignorance. He speaks in earnest; his words ring true. We must be prepared for the possibility that his ancient manuscript was really ancient.

39 Since Aldus’s time the Parisinus has disappeared. To quote Merrill again:7

“This wonderful manuscript, like so many others, appears to have vanished from earth. Early editors saw no especial reason for preserving what was to them but copy for their own better printed texts. Possibly some leaves of it may be lying hid in old bindings; possibly they went to cover preserve-jars, or tennis-racquets; possibly into some final dust-heap. At any rate the manuscript is gone; the copy by Iucundus is gone; the copy of the correspondence with Trajan that Avantius owed to Petrus Leander is gone; if others had any other copies of Book X, in whole or in part, they are gone too.”

The Bodleian volume In 1708 Thomas Hearne, the antiquary, bought at auction a peculiar volume of Pliny’s Letters. It consisted of Beroaldus’s edition of the nine books (1498), the portions of Book X published by Avantius in 1502, and, on inserted leaves, the missing letters of Books VIII and X.8 The printed portions, moreover, were provided with over five hundred variant readings and lemmata in a different hand from that which appeared on the inserted leaves; the hand that added the variants also wrote in the margin the sixteenth letter of Book IX, which is not in the edition of Beroaldus. Hearne recognized the importance of this supplementary matter, for he copied the variants into his own edition of the Letters (1703), intending, apparently, to use them in a larger edition which he is said to have published in 1709; he also lent the book to Jean Masson, who refers to it in his Plinii Vita. Upon Hearne’s death, this valuable volume was acquired by the Bodleian Library in Oxford, but lay unnoticed until Mr. E. G. Hardy, in 1888,9 examined it and, after a comparison of the readings, pronounced it the very copy from which Aldus had printed his edition in 1508. External proof of this highly exciting surmise seemed to appear in a manuscript note on the last page of the edition of Avantius, written in the hand that had inserted the variants and supplements throughout the volume:10

“hae plinii iunioris epistolae ex uetustissimo exemplari parisiensi et restitutae et emendatae sunt opera et industria ioannis iucundi prestantissimi architecti hominis imprimis antiquarii.”

What more natural to conclude than that here is the very copy that Aldus prepared from the ancient manuscript and the collations and transcripts sent him by Fra Giocondo? One fact blocks this attractive conjecture: though there are many agreements between the readings of the emended Bodleian book and those of Aldus, there are also many disagreements. Mr. Hardy removed the obstacle by assuming that Aldus made changes in the proof; but the changes are numerous; they are not too numerous for a scholar who can mark up his galleys free of cost, but they are decidedly too numerous if the scholar is also his own printer.

40 Merrill, in a brilliant and searching article,11 entirely demolishes Hardy’s argument. Unlike most destructive critics, he replaces the exploded theory by still more interesting fact. For the rediscovery of the Bodleian book and a proper appreciation of its value, students of Pliny’s text must always be grateful to Hardy; we now know, however, that the volume was never owned by Aldus. The scholar who put its parts together and added the variants with his own hand was the famous Hellenist Guillaume Budé (Budaeus). The parts on the supplementary leaves were done by some copyist who imitated the general effect of the type used in the book itself; Budaeus added his notes on these inserted leaves in the same way as elsewhere. It had been shown before by Keil12 that Budaeus must have used the readings of the Parisinus; indeed, it is from his own statement in Annotationes in Pandectas that we learn of the discovery of the ancient manuscript by Giocondo:13

“Verum haec epistola et aliae non paucae in codicibus impressis non leguntur: nos integrum ferme Plinium habemus: primum apud parrhisios repertum opera Iucundi sacerdotis: hominis antiquarii Architectique famigerati.”

The wording here is much like that in the note at the end of the Bodleian book. After establishing his case convincingly from the readings followed by Budaeus in his quotations from the Letters, Merrill eventually was able to compare the handwriting with the acknowledged script of Budaeus and to find that the two are identical.14 The Bodleian book, then, is not Aldus’s copy for the printer. It is Budaeus’s own collation from the Parisinus. Whether he examined the manuscript directly or used a copy made by Giocondo is doubtful; the note at the end of the Bodleian volume seems to favor the latter possibility. Budaeus does not by any means give a complete collation, but what he does give constitutes, in Merrill’s opinion, our best authority for any part of the lost Parisinus.15

The Morgan fragment possibly a part of the lost

Parisinus

The script

Perhaps we may now say the Bodleian volume has been hitherto our

best authority. For a fragment of the ancient book, if my conjecture is

right, is now, after various journeys, reposing in the Pierpont Morgan

Library in New York City.

First of all, we are impressed with the script. It is an uncial of about the year 500 A.D.—certainly venerandae vetustatis. If Aldus had this same uncial codex at his disposal, we can understand his delight and pardon his slight exaggeration, for it is only slight. The essential truth of his statement remains: he had found a book of a different class from that of the ordinary manuscript—indeed diversis a nostris characteribus. Instead of thinking him arrant knave or fool enough to 41 bring down “antiquity” to the thirteenth century, we might charitably push back his definition of “nostri characteres” to include anything in minuscules; script “not our own” would be the majuscule hands in vogue before the Middle Ages. That is a position palaeographically defensible, seeing that the humanistic script is a lineal descendant of the Caroline variety. Furthermore, an uncial hand, though clear and regular as in our fragment, is harder to read than a glance at a page of it promises. This is due to the writing of words continuously. It takes practice, as Aldus says, to decipher such a script quickly and accurately. Moreover, the flesh sides of the leaves are faded.

Provenience and contents We next note that the fragment came to the Pierpont Morgan Library from Aldus’s country, where, as Dr. Lowe has amply shown, it was written; how it came into the possession of the Marquis Taccone would be interesting to know. But, like the Parisinus, the book to which our fragment belonged had not stayed in Italy always. It had made a trip to France—and was resting there in the fifteenth century, as is proved by the French note of that period on fol. 51r. We may say “the book” and not merely “the present six leaves,” for the fragment begins with fol. 48, and the foliation is of the fifteenth century. The last page of our fragment is bright and clear, showing no signs of wear, as it would if no more had followed it;16 I will postpone the question of what probably did follow. Moreover, if the probatio pennae on fol.53r is Carolingian,17 it would appear that the book had been in France at the beginning as well as at the end of the Middle Ages. Thus our manuscript may well have been one of those brought up from Italy by the emissaries of Charlemagne or their successors during the revival of learning in the eighth and ninth centuries. The outer history of our book, then, and the character of its script, comport with what we know of Aldus’s Parisinus.

The text closely related to that of Aldus But we must now subject our fragment to internal tests. If Aldus used the entire manuscript of which this is a part, his text must show a general conformity to that of the fragment. An examination of the appended collation will establish this fact beyond a doubt. The references are to Keil’s critical edition of 1870, but the readings are verified from Merrill’s apparatus. I will designate the fragment as Π, using P for Aldus’s Parisinus and a for his edition.

We may begin by excluding two probable misprints in Aldus, 64, 1 conturbernium and 65, 17 subeuertas. Then there are various spellings in which Aldus adheres to the fashion of his day, as sexcenties, millies, millia, tentarunt, caussas, autoritas, quanquam, syderum, hyeme, coena, ocium, hospicii, negociis, solatium, adulescet, 42 exoluit, Thuscos; there are other spellings which modern editors might not disdain, i.e., aerarii and illustri, and some that they have accepted, namely apponitur, existat, impleturus, implorantes, obtulissem, balinei, caret (not karet), caritas (not karitas).18

A study of our collation will also show some forty cases of correction in Π by either the scribe himself or a second and possibly a third ancient hand. Here Aldus, if he read the pages of our fragment and read them with care, might have seen warrant for following either the original text or the emended form, as he preferred. The most important cases are:61, 14 sera] Πa serua Π2 61, 21 considit] Π considet Π2a. The original reading of Π is clearly considit. The second i has been altered to a capital e, which of course is not the proper form for uncial. 62, 5 residit] Π residet a. Here Π is not corrected, but Aldus may have thought that the preceding case of considet (m. 2) supported what he supposed the better form residet. 63, 11 posset] a possit (in posset m. 1?) Π. Again the corrected e is capital, not uncial, but Aldus would have had no hesitation in adopting the reading of the second hand. 64, 2 modica vel etiam] a modica est etiam (corr. m. 2) Π. 64, 28 excurrissem accepto, ut praefectus aerari, commeatu] a. Here Π omitted accepto ut praefectus aerari,—evidently a line of the manuscript that he was copying, for there are no similar endings to account otherwise for the omission. 66, 2 dissentientis] a ex dissitientis m. 1 (?) Π.

There are also a few careless errors of the first hand, uncorrected, in Π, which Aldus himself might easily have corrected or have found the right reading already in the early editions. 62, 23 conteror quorum] a conteror qui horum Π B F 63, 28 si] a sibi Π 64, 24 conprobasse] comprouasse Π.

In view of these certain errors of the first hand of Π, most of them corrected but a few not, Aldus may have felt justified in abiding by one of the early editions in the following three cases, where Π might well have seemed to him wrong; in 43 one of them (64,3) modern editors agree with him: 62, 20 aurium oculorum vigor] Π aurium oculorumque uigor a 64, 3 proferenda] a conferanda Π 65, 11 et alii] Π etiam alii a.