"For the Blast of Death is on the Heath,

and the

Grave yawns wide for the Child of Moy."ToList

Project Gutenberg's Strange Pages from Family Papers, by T. F. Thiselton Dyer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Strange Pages from Family Papers Author: T. F. Thiselton Dyer Release Date: November 11, 2005 [EBook #17050] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK STRANGE PAGES FROM FAMILY PAPERS *** Produced by Clare Boothby, Jeannie Howse and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note: Some very obvious typos

were corrected in this text.

For a list please

see the bottom of the document.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Fatal Curses | page 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Screaming Skull | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Eccentric Vows | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Strange Banquets | 69 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Mysterious Rooms | 88 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Indelible Bloodstains | 114 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Curious Secrets | 135 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Dead Hand | 154 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Devil Compacts | 162 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Family Death Omens | 180 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Weird Possessions | 198 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Romance of Disguise | 208 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Extraordinary Disappearances | 229 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Honoured Hearts | 253 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Romance of Wealth | 262 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Lucky Accidents | 279 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Fatal Passion | 289 |

| Index. | 309 |

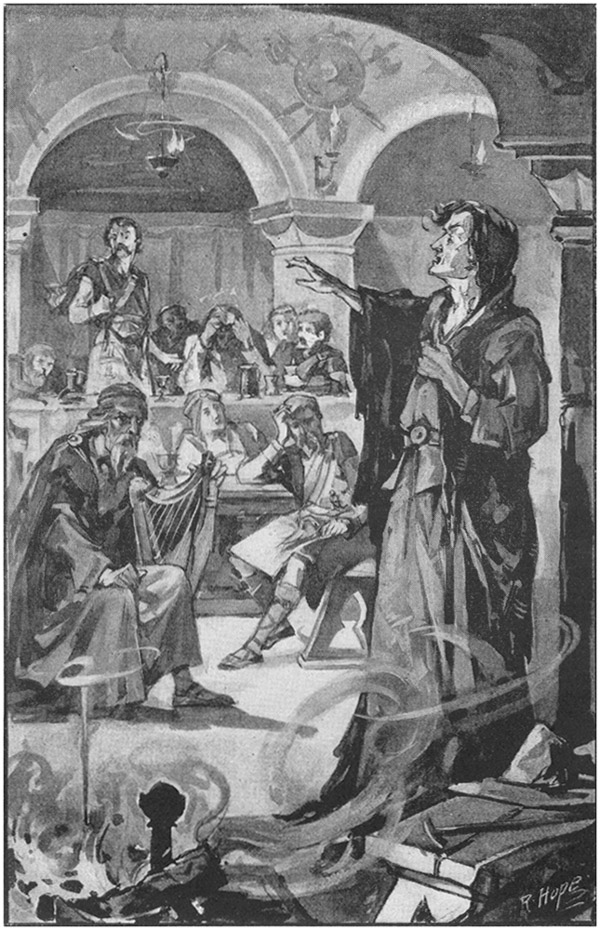

| 1. | "For the blast of Death is on the heath, And the grave yawns wide for the child of Moy." | Frontispiece. |

| 2. | She opened it in secret | page 38 |

| 3. | "Madam, you have attained your end. You and I shall meet no more in this world" | 72 |

| 4. | The figure stood motionless | 150 |

| 5. | Lady Sybil at the Eagle's Crag | 168 |

| 6. | Dorothy Vernon and the Woodman | 214 |

| 7. | Lady Mabel and the Palmer | 248 |

| 8. | There came an old Irish harper, and sang an ancient song | 272 |

|

May the grass wither from thy feet! the woods Deny thee shelter! Earth a home! the dust A grave! The sun his light! and heaven her God. |

| Byron, Cain. |

Many a strange and curious romance has been handed down in the history of our great families, relative to the terrible curses uttered in cases of dire extremity against persons considered guilty of injustice and wrong doing. It is to such fearful imprecations that the misfortune and downfall of certain houses have been attributed, although, it may be, centuries have elapsed before their final fulfilment. Such curses, too, unlike the fatal "Curse of Kehama," have rarely turned into blessings, nor have they been thought to be as harmless as the curse of the Cardinal-Archbishop of Rheims, who banned the thief—both body and soul, his life and for ever—who stole his ring. It was an awful curse, but none of the guests seemed the worse for it, except the poor jackdaw who had hidden the ring in some sly corner as a practical joke. But, if we are to believe traditionary and historical lore, only too many of the curses recorded in the chronicles of family history have been productive of the most disastrous results, reminding us of that dreadful malediction given by Byron in his "Curse of Minerva":

A popular form of curse seems to have been the gradual collapse of the family name from failure of male-issue; and although there is, perhaps, no more romantic chapter in the vicissitudes of many a great house than its final extinction from lack of an heir, such a disaster is all the more to be lamented when resulting from a curse. A catastrophe of this kind was that connected with the M'Alister family of Scotch notoriety. The story goes that many generations back, one of their chiefs, M'Alister Indre—an intrepid warrior who feared neither God nor man—in a skirmish with a neighbouring clan, captured a widow's two sons, and in a most heartless manner caused them to be hanged on a gibbet erected almost before her very door. It was in vain that, with well nigh heartbroken tears, she denounced his iniquitous act, for his comrades and himself only laughed and scoffed, and even threatened to burn her cottage to the ground. But as the crimson and setting rays of a summer sun fell on the lifeless bodies of her two sons, her eyes met those of him who had so basely and cruelly wronged her, and, after once more stigmatizing his barbarity, with deep measured voice she pronounced these ominous words, embodying a curse which M'Alister Indre little anticipated would so surely come to pass. "I suffer now," said the grief-stricken woman, "but you shall suffer always—you have made me childless, but you and yours shall be heirless for ever—never shall there be a son to the house of M'Alister."

These words were treated with contempt by M'Alister Indre, who mocked and laughed at the malicious prattle of a woman's tongue. But time proved only too truly how persistently the curse of the bereaved woman clung to the race of her oppressors, and, as Sir Bernard Burke remarks, it was in the reign of Queen Anne that the hopes of the house of M'Alister "flourished for the last time, they were blighted for ever." The closing scene of this prophetic curse was equally tragic and romantic; for, whilst espousing the cause of the Pretender, the young and promising heir of the M'Alisters was taken prisoner, and with many others put to death. Incensed at the wrongs of his exiled monarch, and full of fiery impulse, he had secretly left his youthful wife, and joined the army at Perth that was to restore the Pretender to his throne. For several months the deserted wife fretted under the terrible suspense, often silently wondering if, after all, her husband—the last hope of the House of M'Alister—was to fall under the ban of the widow's curse. She could not dispel from her mind the hitherto disastrous results of those ill-fated words, and would only too willingly have done anything in her power to make atonement for the wrong that had been committed in the past. It was whilst almost frenzied with thoughts of this distracting kind, that vague rumours reached her ears of a great battle which had been fought, and ere long this was followed by the news that the Pretender's forces had been successful, and that he was about to be crowned at Scone. The shades of evening were fast setting in as, overcome with the joyous prospect of seeing her husband home again, she withdrew to her chamber, and, flinging herself on her bed in a state of hysteric delight, fell asleep. But her slumbers were broken, for at every sound she started, mentally exclaiming "Can that be my husband?"

At last, the happy moment came when her poor overwrought brain made sure it heard his footsteps. She listened, yes! they were his! Full of feverish joy she was longing to see that long absent face, when, as the door opened, to her horror and dismay, there entered a figure in martial array without a head. It was enough—he was dead. And with an agonizing scream she fell down in a swoon; and on becoming conscious only lived to hear the true narrative of the battle of Sheriff-Muir, which had brought to pass the Widow's Curse that there should be no heir to the house of M'Alister.

This story reminds us of one told of Sir Richard Herbert, who, with his brother, the Earl of Pembroke, pursuing a robber band in Anglesea, had captured seven brothers, the ringleaders of "many mischiefs and murders." The Earl of Pembroke determined to make an example of these marauders, and, to root out so wretched a progeny, ordered them all to be hanged. Upon this, the mother of the felons came to the Earl of Pembroke, and upon her knees besought him to pardon two, or at least one, of her sons, a request which was seconded by the Earl's brother, Sir Richard. But the Earl, finding the condemned men all equally guilty, declared he could make no distinction, and ordered them to be hanged together.

Upon this the mother, falling upon her knees, cursed the Earl, and prayed that God's mischief might fall upon him in the first battle in which he was engaged. Curious to relate, on the eve of the battle of Edgcot Field, having marshalled his men in order to fight, the Earl of Pembroke was surprised to find his brother, Sir Richard Herbert, standing in the front of his company, and leaning upon his pole-axe in a most dejected and pensive mood.

"What," cried the Earl, "doth thy great body" (for Sir Richard was taller than anyone in the army) "apprehend anything, that thou art so melancholy? or art thou weary with marching, that thou dost lean thus upon thy pole-axe?"

"I am not weary with marching," replied Sir Richard, "nor do I apprehend anything for myself; but I cannot but apprehend on your part lest the curse of the woman fall upon you."

And the curse of the frantic mother of seven convicts seemed, we are told, to have gained the authority of Heaven, for both the Earl and his brother Sir Richard, were defeated at the battle of Edgcot, were both taken prisoners and put to death.

Sir Walter Scott has made a similar legend the subject of one of his ballads in the "Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border," entitled "The Curse of Moy," a tale founded on an ancient Highland tradition that originated in a feud between the clans of Chattan and Grant. The Castle of Moy, the early residence of Mackintosh, the chief of the clan Chattan, is situated among the mountains of Inverness-shire, and stands on the edge of a small gloomy lake called Loch Moy, in which is still shown a rocky island as the spot where the dungeon stood in which prisoners were confined by the former chiefs of Moy. On a certain evening, in the annals of Moy, the scene is represented as having been one of extreme merriment, for

It is no ordinary occasion, for a wretched curse has long hung over the Castle of Moy, but at last the spell seems broken, and, as the well-spiced bowl goes round, shout after shout echoes and re-echoes through the castle, "An heir, an heir!" Many a year had passed without the prospect of such an event, and it had looked as if the ill-omened words uttered in the past were to be realised. It was no wonder then that "in the gloomy towers of Moy" there were feasting and revelry, for a child is born who is to perpetuate the clan which hitherto had seemed threatened with extinction. But, even on this festive night when every heart is tuned for song and mirth, there suddenly appears a mysterious figure, a pale and shivering form, by "age and frenzy haggard made," who defiantly exclaims "'Tis vain! 'Tis vain!"

At once all eyes are turned on this strange form, as she, in mocking gesture, casts a look of withering scorn on the scene around her, and startles the jovial vassals with the reproachful words "No heir! No heir!" The laughter is hushed, the pipes no longer sound, for the witch with uplifted hand beckons that she had a message to tell—a message from Death—she might truly say, "What means these bowls of wine—these festive songs?"

She then recounts the tale of treachery and cruelty committed by a chief of the House of Moy in the days of old, for which "his name shall perish for ever off the earth—a son may be born—but that son shall verily die." The witch brings tears into many an eye as she tells how this curse was uttered by one Margaret, a prominent figure in this sad feud, for it was when deceived in the most base manner, and when betrayed by a man who had violated his promise he had solemnly pledged, that she is moved to pronounce the fatal words of doom:

Such was the "Curse of Moy," uttered, it must be remembered, too, by a fair young girl, against the Chief of Moy for a blood-thirsty crime—the act of a traitor—in that, not content with slaying her father, and murdering her lover, he satiates his brutal passion by letting her eyes rest on their corpses.

Her tale ended, the witch departs, but now ceased the revels of the shuddering clan, for "despair had seized on every breast," and "in every vein chill terror ran." On the morrow, all is changed, no joyous sounds are heard, but silence reigns supreme—the silence of death. The curse has triumphed, the last hope of the house of Moy is gone, and—

But tyranny, or oppression, has always been supposed to bring its own punishment, as in the case of Barcroft Hall, Lancashire, where the "Idiot's Curse" is commonly said to have caused the downfall of the family. The tradition current in the neighbourhood states that one of the heirs to Barcroft was of weak intellect, and that he was fastened by a younger brother with a chain in one of the cellars, and there in a most cruel manner gradually starved to death. It appears that this unnatural conduct on the part of the younger brother was prompted by a desire to get possession of the property; and it is added that, long before the heir to Barcroft was released from his sufferings, he caused a report to be circulated that he was dead, and by this piece of deception made himself master of the Barcroft estate. It was in one of his lucid intervals that the poor injured brother pronounced a curse upon the family of the Barcrofts, to the effect that their name should perish for ever, and that the property should pass into other hands. But this malediction was only regarded as the ravings of an imbecile, unaccountable for his words, and little or no heed was paid to this death sentence on the Barcroft name. And yet, light as the family made of it, within a short time there were not wanting indications that their prosperity was on the wane, a fact which every year became more and more discernible until the curse was fulfilled in the person of Thomas Barcroft, who died in 1688 without male issue. After passing through the hands of the Bradshaws, the Pimlots, and the Isherwoods, the property was finally sold to Charles Towneley, the celebrated antiquarian, in the year 1795.[1] Whatever the truth of this family tradition, Barcroft is still a good specimen of the later Tudor style, and its ample cellarage gives an idea of the profuse hospitality of its former owners, some rude scribblings on one of the walls of which are still pointed out as the work of the captive.

In a still more striking way this spirit of persecution incurred its own condemnation. In the 17th century, Francis Howgill, a noted Quaker, travelled about the South of England preaching, which at Bristol was the cause of serious rioting. On returning to his own neighbourhood, he was summoned to appear before the justices who were holding a court in a tavern at Kendal, and, on his refusing to take the oath of allegiance, he was imprisoned in Appleby Gaol. In due time, the judges of assizes tendered the same oath, but with the like result, and evidently wishing to show him some consideration offered to release him from custody if he would give a bond for his good behaviour in the interim, which likewise declining to do, he was recommitted to prison. In the course of his imprisonment, however, a curious incident happened, which gave rise to the present narrative. Having been permitted by the magistrates to go home to Grayrigg for a few days on private affairs, he took the opportunity of calling on a justice of the name of Duckett, residing at Grayrigg Hall, who was not only a great persecutor of the Quakers but was one of the magistrates who had committed him to prison. As might be imagined, Justice Duckett was not a little surprised at seeing Howgill, and said to him, "What is your wish now, Francis? I thought you had been in Appleby Gaol."

Howgill, keenly resenting the magistrate's behaviour, promptly replied, "No, I am not, but I am come with a message from the Lord. Thou hast persecuted the Lord's people, but His hand is now against thee, and He will send a blast upon all that thou hast, and thy name shall rot out of the earth, and this thy dwelling shall become desolate, and a habitation for owls and jackdaws." When Howgill had delivered his message, the magistrate seems to have been somewhat disconcerted, and said, "Francis, are you in earnest?" But Howgill only added, "Yes, I am in earnest, it is the word of the Lord to thee, and there are many living now who will see it."

But the most remarkable part of the story remains to be told. By a strange coincidence the prophetic utterance of Howgill was fulfilled in a striking manner, for all the children of Justice Duckett died without leaving any issue, whilst some of them came to actual poverty, one begging her bread from door to door. Grayrigg Hall passed into the possession of the Lowther family, was dismantled, and fell into ruins, little more than its extensive foundations being visible in 1777, and, after having long been the habitation of "owls and jackdaws," the ruins were entirely removed and a farmhouse erected upon the site of the "old hall," in accordance with what was popularly known as "The Quaker's Curse, and its fulfilment." Cornish biography, however, tells how a magistrate of that county, Sir John Arundell, a man greatly esteemed amongst his neighbours for his honourable conduct—fell under an imprecation which he in no way deserved. In his official capacity, it seems, he had given offence to a shepherd who had by some means acquired considerable influence over the peasantry, under the impression that he possessed some supernatural powers. This man, for some offence, had been imprisoned by Sir John Arundell, and on his release would constantly waylay the magistrate, always looking at him with the same menacing eye, at the same time slowly muttering these words:

Notwithstanding Sir John Arundell's education and position, he was not wholly free from the superstition of the period, and might have thought, too, that this man intended to murder him. Hence he left his home at Efford and retired to the wood-clad hills of Trevice, where he lived for some years without the annoyance of meeting his old enemy. But in the tenth year of Edward IV., Richard de Vere, Earl of Oxford, seized St. Michael's Mount; on hearing of which news, Sir John Arundell, then Sheriff of Cornwall—led an attack on St. Michael's Mount, in the course of which he received his death wound in a skirmish on the sands near Marazion. Although he had broken up his home at Efford "to counteract the will of fate," the shepherd's prophecy was accomplished; and tradition even says that, in his dying moments, his old enemy appeared, singing in joyous tones:

The misappropriation of property, in addition to causing many a family complication, has occasionally been attended with a far more serious result. There is a strange curse, for instance, in the family of Mar, which can boast of great antiquity, there being, perhaps, no title in Europe so ancient as that of the Earl of Mar. This curse has been attributed by some to Thomas the Rhymer, by others to the Abbot of Cambuskenneth, and by others to the Bard of the House at that epoch. But, whoever its author, the curse was delivered prior to the elevation of the Earl, in the year 1571, to be the Regent of Scotland, and runs thus:

"Proud Chief of Mar, thou shalt be raised still higher, until thou sittest in the place of the King. Thou shalt rule and destroy, and thy work shall be after thy name, but thy work shall be the emblem of thy house, and shall teach mankind that he who cruelly and haughtily raiseth himself upon the ruins of the holy cannot prosper. Thy work shall be cursed, and shall never be finished. But thou shalt have riches and greatness, and shall be true to thy sovereign, and shalt raise his banner in the field of blood. Then, when thou seemest to be highest, when thy power is mightiest, then shall come thy fall; low shall be thy head amongst the nobles of the people. Deep shall be thy moan among the children of dool (sorrow). Thy lands shall be given to the stranger, and thy titles shall lie among the dead. The branch that springs from thee shall see his dwelling burnt, in which a King is nursed—his wife a sacrifice in that same flame; his children numerous, but of little honour; and three born and grown who shall never see the light. Yet shall thine ancient tower stand; for the brave and the true cannot be wholly forsaken. Thou, proud head and daggered hand, must dree thy weird, until horses shall be stabled in thy hall, and a weaver shall throw his shuttle in thy chamber of state. Thine ancient tower—a woman's dower—shall be a ruin and a beacon, until an ash sapling shall spring from its topmost stone. Then shall thy sorrows be ended, and the sunshine of royalty shall beam on thee once more. Thine honours shall be restored; the kiss of peace shall be given to thy Countess, though she seek it not, and the days of peace shall return to thee and thine. The line of Mar shall be broken; but not until its honours are doubled, and its doom is ended."

In support of this strange curse, it may be noted that the Earl of 1571 was raised to be Regent of Scotland, and guardian of James VI. As Regent, he commanded the destruction of Cambuskenneth Abbey, and took its stones to build himself a palace at Stirling, which never advanced farther than the façade, which has been popularly designated "Marr's Work."

In the year 1715, the Earl of Mar raised the banner of his Sovereign, the Chevalier James Stuart, son of James the Second, or Seventh. He was defeated at the battle of Sheriff-Muir, his title being forfeited, and his lands of Mar confiscated and sold by the Government to the Earl of Fife. His grandson and representative, John Francis, lived at Alloa Tower (which had been for some time the abode of James VI. as an infant) where, a fire breaking out in one of the rooms, Mrs. Erskine was burnt, and died, leaving, beside others, three children who were born blind, and who all lived to old age.

But this remarkable curse was to be further fulfilled, for at the commencement of the present century, upon the alarm of the French invasion, a troop of the cavalry and yeomen of the district took possession of the tower, and for a week fifty horses were stabled in its lordly hall; and in the year 1810, a party of visitors were surprised to find a weaver plying his loom in the grand old Chamber of State. Between the years 1815 and 1820, an ash sapling might be seen in the topmost stone, and many of those who "clasped it in their hands wondered if it really were the twig of destiny, and if they should ever live to see the prophecy fulfilled."

In the year 1822, George IV. visited Scotland and searched out the families who had suffered by supporting the Princes of the Stuart line. Foremost of them all was the Erskine of Mar, grandson of Mar who had raised the Chevalier's standard, and to him the King restored his earldom. John Francis, the grandson of the restored Earl, likewise came into favour, for when Queen Victoria accidentally met his Countess in a small room in Stirling Castle, and ascertained who she was, she detained her, and, after conversing with her, kissed her. Although the Countess had never been presented at St. James's, yet, in a marvellous way, "the kiss of peace was given to her, though she sought it not"; and then, after the curse had worked through 300 years, the "weird dreed out, and the doom of Mar was ended."[2]

Another instance which may be quoted relates to Sherborne Castle. According to the traditionary accounts handed down, it appears that Osmund, one of William the Conqueror's knights, who had been rewarded, among other possessions, with the castle and barony of Sherborne, in the decline of life determined to resign his temporal honours, and to devote himself exclusively to religion. In pursuance of this object, he obtained the Bishopric of Salisbury, to which he gave certain lands, but annexed to the gift the following conditional curse: "That whosoever should take those lands from the Bishopric, or diminish them in great or small, should be accursed, not only in this world, but in the world to come, unless in his lifetime he made restitution thereof." In a strange and wonderful manner this curse is said to have been more than once fulfilled. Upon Osmund's death, the castle and lands fell into the hands of the next bishop, Roger Niger, who was dispossessed of them by King Stephen, on whose death they were held by the Montagues, all of whom, it is affirmed, so long as they kept these lands, were subjected to grievous disasters, in so much that the male line became altogether extinct. About two hundred years from this time, the lands again reverted to the Church, but in the reign of Edward VI. the Castle of Sherborne was conveyed by the then Bishop of Sarum to the Duke of Somerset, who lost his head on Tower Hill. Sir Walter Raleigh, again, obtained the property from the crown, and it was to expiate this offence, it has been suggested, he ultimately lost his head. But in allusion to this reputed curse, Sir John Harrington gravely tells how it happened one day that Sir Walter riding post between Plymouth and the Court, "the castle being right in the way, he cast such an eye upon it as Ahab did upon Naboth's vineyard, and whilst talking of the commodiousness of the place, and of the great strength of the seat, and how easily it might be got from the Bishopric, suddenly over and over came his horse, and his very face—which was then thought a very good one—ploughed up the earth where he fell." Then again Prince Henry died shortly after he took possession, and Carr, Earl of Somerset, the next proprietor fell in disgrace. But the way the latter obtained Sherborne was far from creditable, for, having discovered a technical flaw in the deed in which Sir Walter Raleigh had settled the estate on his son, he solicited it of his royal master, and obtained it. It was in vain that Lady Raleigh on her knees appealed to James against this injustice, for he only answered, "I mun have the land, I mun have it for Carr." But Lady Raleigh was a woman of high spirit, and there on her knees, before King James, she prayed to God that He would punish those who had thus wrongfully exposed her, and her children, to ruin. She was, in fact, re-echoing the curse uttered centuries beforehand. And that prayer was not long unanswered, for Carr did not enjoy Sherborne for any length of time. Committed to the Tower for the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury, he was at last released and restricted to his house in the country, "where in constant companionship with the wife, for the guilty love of whom he had become the murderer of his friend, he passed the remainder of his life, loathing the partner of his crimes, and by her as cordially detested."

Spelman goes so far as to say that "all those families who took or had Church property presented to them, came, either in their own persons or those of their descendants, to sorrow and misfortune." One of the many strange occurrences relating to Sir Anthony Browne, standard-bearer to King Henry VIII., was communicated some years ago in connection with the famous Cowdray Castle, the principal seat of the Montagues. It is said that at the great festival given in the magnificent hall of the monks at Battle Abbey, on Sir Anthony Browne taking possession of his Sovereign's gift of that estate, a venerable monk stalked up the hall to the daïs, where Sir Anthony Browne sat, and, in prophetic language, denounced him and his posterity for usurping the possessions of the Church, predicting their destruction by fire and water—a fate which was eventually fulfilled.

One of the last viscounts was, in 1793, drowned when trying to pass the Falls of Schaffhausen on the Rhine, accompanied by Mr. Sedley Burdett, the elder brother of the distinguished Sir Francis. They had engaged an open boat to take them through the rapids; but it seems the authorities tried to prevent so dangerous an enterprise. In order, however, to carry out their project, they started two hours earlier than the time previously fixed—four o'clock in the morning—and successfully passed the first or upper fall. But, unhappily, the same good fortune failed them in their next descent, for "the boat was swamped and sunk in passing the lower fall, and was supposed to have been jammed in a cleft of the submerged rock, as neither boat nor adventurers ever appeared again. In the same week, the ancient seat of the family, Cowdray Castle, was destroyed by fire, and its venerable ruins are the significant monument at once of the fulfilment of the old monk's prophecy, and of the extinction of the race of the great and powerful noble."

It is further added that the last inheritor of the title—the immediate successor and cousin of the ill-fated young nobleman of Schaffhausen, Anthony Browne, the last Montague, who died at the opening of this century—left no male issue, and his estates devolved on his only daughter, who married Mr. Stephen Poyntz, a great Buckinghamshire landlord. Some years after their marriage Mr. Poyntz was desirous of obtaining a grant of the dormant title "Viscount Montague" in favour of the elder of his two sons, issue of this marriage; but his hopes were suddenly destroyed by the death of the two boys, who were drowned while bathing at Bognor, the "fatal water" thus becoming the means, in fulfilment of the monk's terrible denunciation on the family in his fearful curse.

In a similar manner the great Tichborne trial followed, it is said, upon the fulfilment, in a manner, of a prophecy, respecting that ancient family, made more than seven hundred years before. When the Lady Mabelle Tichborne, wife of the Sir Roger who flourished in the reign of Henry II., was lying on her death-bed, she besought her husband to grant her the means of leaving behind her a charitable bequest in the form of an annual dole of bread. To gratify her whim, he accordingly promised her the produce of as much land in the vicinity of the park as she could walk over while a certain brand was burning; for, as she had been bedridden for many years, he supposed that she would be able to go round only a small portion of the property. But when the venerable dame was carried out upon the ground, she seemed to regain her strength, and, greatly to the surprise of her husband, crawled round several rich and goodly acres, which, to this day, retain the name of "The Crawls." On being reconveyed to her chamber, Lady Mabelle summoned her family to her bedside and predicted its prosperity so long as the annual dole was observed, but she left her solemn curse on any of her descendants who should discontinue it, prophesying that when such should happen, the old house would fall, and the family name "become extinct from failure" of male issue. And she further added, that this would be foretold by a generation of seven sons being followed immediately after by a generation of seven daughters and no son.

The custom of the annual doles was observed for six hundred years on every 25th of March, until—owing to the complaints of the magistrates and local gentry that vagabonds, gipsies, and idlers of every description swarmed into the neighbourhood, under the pretence of receiving the dole—it was discontinued in the year 1796. Strangely enough, Sir Henry Tichborne, the baronet of that day, had issue seven sons, and his eldest son, who succeeded him, had seven daughters and no son. The prophecy was apparently completed by the change of name of the possessors of the estate to Doughty, in the person of Sir Edward Doughty, who had assumed the name under the will of a relative from whom he inherited certain property. Finally, it may be added, "the Claimant" appeared, and instituted one of the most costly lawsuits ever tried, in which the Tichborne estate was put to an expense of close upon one hundred thousand pounds!

But, occasionally, the effect of a family curse, through the misappropriation of property, has been more sweeping and speedy in its retribution, as in the case of Furvie or Forvie, which now forms part of the parish of Slains, Scotland—much, if not most of it, being covered with sand. The popular account of the downfall of this parish tells how, in times gone by, the proprietor to whom it belonged left three daughters as heirs of his fair lands; who were, however, most unjustly bereft of their property, and thrown homeless on the world. On quitting their home—their legal heritage—they uttered a terrible curse, which was quickly accomplished, and was considered an unmistakable sign of Divine displeasure at the wrong they had received. Before many days had elapsed, a storm of almost unparalleled violence—lasting nine days—burst over the district, and transformed the parish of Forvie into a desert of sand;—a calamity which is said to have befallen the district about the close of the 17th century. In this way, many local traditions account for the ruined and desolate condition of certain wild and uninhabited spots. Ettrick Hall, for instance, near the head of Ettrick Water, had such a history. On and around its site in former days there was a considerable village, and "as late as the Revolution, it contained no fewer than fifty-three fine houses." But about the year 1700, when the numbers in this little village were still very considerable, James Anderson, a member of the Tushielaw family, pulled down a number of small cottages, leaving many of the tenants—some of whom were aged and infirm—homeless. It was in vain that these poor people appealed to him for a little merciful consideration, for he refused to lend an ear to their complaints, and in a short time a splendid house was built on the property, known as Ettrick Hall. What was considered by the inhabitants far and wide as an act of cruel injustice incurred its own punishment, for a prophetic rhyme was about the same period made on it, by whom nobody could tell, and which, says James Hogg, writing in the year 1826, has been most wonderfully verified:

The curse that alighted on this fair mansion at length accomplished its destructive work, because nowadays there is not a vestige of it remaining, nor has there been for these many years; indeed, so complete was the collapse of this ill-fated house, that its site could only be identified by the avenue and lanes of trees; while many clay cottages, on the other hand, which were built previously, long remained intact. Equally fatal, also, was the curse uttered against the old persecuting family of Home of Cowdenknowes—a place in the immediate neighbourhood of St. Thomas's Castle.

This anathema, awful as the cry of blood, is generally said to have been realised in the extinction of the family and the transference of their property to other hands. But some doubt, writes Mr. Robert Chambers,[3] seems to hang on the matter, "as the Earl of Home—a prosperous gentleman—is the lineal descendant of the Cowdenknowes branch of the family which acceded to the title in the reign of Charles I., though, it must be admitted, the estate has long been alienated."

Love and marriage, again, have been associated with many imprecations, one of which dates as far back as the time of Edmund, King of the East Angles, in connection with his defeat and capture at Hoxne, in Suffolk, on the banks of the Waveney not far from Eye. The story, as told by Sir Francis Palgrave in his Anglo-Saxon History, is this: "Being hotly pursued by his foes, the King fled to Hoxne, and attempted to conceal himself by crouching beneath a bridge, now called Goldbridge. The glittering of his golden spurs discovered him to a newly-married couple, who were returning home by moonlight, and they betrayed him to the Danes. Edmund, as he was dragged from his hiding place, pronounced a malediction upon all who should afterwards pass this bridge on their way to be married. So much regard was paid to this tradition by the good folks of Hoxne that no bride or bridegroom would venture along the forbidden path."

That inconstancy has not always escaped with impunity may be gathered from the following painful story, one which, if it had not been fully attested, would seem to belong to the domain of fiction rather than truth: On April 28, 1795, a naval court-martial, which had lasted for sixteen days, and created considerable excitement, was terminated. The officer tried was Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy, of H.M. Ship Cæsar and the charge brought against him was that, in the memorable battle of June 1, 1794, he did not bring his ship into action, and exert himself to the utmost of his power. The decision of the court was adverse to the Captain, but, "having found that on many previous occasions Captain Molloy's courage had been unimpeachable," he was sentenced to be dismissed his ship, instead of the penalty of death.

It is said that Captain Molloy had behaved dishonourably to a young lady to whom he was betrothed. The friends of the lady wished to bring an action for breach of promise against the Captain, but the lady declined doing so, only remarking that God would punish him. Some time afterwards the two accidentally met at Bath, when the lady confronted her inconstant lover by saying: "Capt. Molloy, you are a bad man. I wish you the greatest curse that can befall a British officer. When the day of battle comes, may your false heart fail you!"

Her words were fully realised, his subsequent conduct and irremediable disgrace forming the fulfilment of her wish.[4]

Another curse, which may be said to have a historic interest, has been popularly designated the "Midwife's Curse." It appears that Colonel Stephen Payne, who took a foremost part in striving to uphold the tottering fortunes of the Stuarts, had wooed and won a fair wife amid the battles of the Rebellion. The Duke of York promised to stand as godfather to the first child if it should prove a boy; but when a daughter was born, the Colonel in his mortification, it is said, "formally devoted, in succession, his hapless wife, his infant daughter, himself and his belongings, to the infernal deities."

But the story goes that the midwife, Douce Vardon, was commissioned by the shade of Normandy's first duke to announce to her master that not only would his daughter die in infancy, but that neither he nor anyone descended from him would ever again be blessed with a daughter's love. Not many days afterwards the child died, "whose involuntary coming had been the cause of the Payne curse." Time passed on, and that "Heaven is merciful," writes Sir Bernard Burke,[5] Stephen Payne experienced in his own person, for his wife subsequently presented him with a son, who was sponsored by the Duke of York by proxy. "But six generations of the descendants of Colonel Stephen Payne," it is added, "have come and gone since the utterance of the midwife's curse, but they never yet have had a daughter born to them." Such is the immutability of the decrees of Fate.

[1] Harland's "Lancashire Legends" (1882), 4, 5.

[2] See Sir J. Bernard Burke's "Family Romance," 1853.

[3] "Popular Rhymes of Scotland" (1870), 217-18.

[4] See "Book of Days," I., 559.

[5] "The Rise of Great Families," 191-202.

|

"Look on its broken arch, its ruined wall, Its chambers desolate, its portals foul; Yes, this was once Ambition's airy hall— The dome of thought, the palace of the soul." |

| Byron. |

There are told of certain houses, in different parts of the country, many weird skull stories, the popular idea being that if any profane hand should be bold enough to remove, or in any way tamper with, such gruesome relics of the dead, misfortune will inevitably overtake the family. Hence, for years past, there have been carefully preserved in some of our country homes numerous skulls, all kinds of romantic traditions accounting for their present isolated and unburied condition.

An old farmstead known as Bettiscombe, near Bridport, Dorsetshire, has long been famous for its so-called "screaming skull," generally supposed to be that of a negro servant who declared before his death that his spirit would not rest until his body was buried in his native land. But, contrary to his dying wish, he was interred in the churchyard of Bettiscombe, and hence the trouble which this skull has ever since occasioned. In the August of 1883, Dr. Richard Garnett, his daughter, and a friend, while staying in the neighbourhood determined to pay this eccentric skull a visit, the result of which is thus amusingly told by Miss Garnett:

"One fine afternoon a party of three adventurous spirits started off, hoping to discover the skull and investigate its history. This much we knew, that the skull would only scream when it was buried, and so we hoped to get leave to inter it in the churchyard. The village of Bettiscombe was at length reached, and we found our way to the old farmhouse, which stood at the end of the village by itself. It had evidently been a manor house, and a very handsome one, too. We were admitted into a fine paved hall, and attempted to break the ice by asking for milk. We then endeavoured to draw the good woman of the house into conversation by admiring the place, and asking in a guarded manner respecting the famous skull. On this subject she was most reserved. She had only lately had the farmhouse, and had been obliged to take possession of the skull also; but she did not wish us to suppose that she knew much about it; it was a veritable 'skeleton in the closet' to her. After exercising great diplomacy, we persuaded her to allow us a sight of it. We tramped up the fine old staircase till we reached the top of the house, when, opening a cupboard door, she showed us a steep, winding staircase, leading to the roof, and from one of the steps the skull sat grinning at us. We took it in our hands and examined it carefully; it was very old and weather-beaten, and certainly human. The lower jaw was missing, the forehead very low and badly proportioned. One of our party, who was a medical student, examined it long and gravely, and then, after first telling the good woman that he was a doctor, pronounced it to be, in his opinion, the skull of a negro. After this oracular utterance, she resolved to make a clean breast of all she knew, which, however, did not amount to much. The skull, we were informed, was that of a negro servant, who had lived in the service of a Roman Catholic priest. Some difference arose between them; but whether the priest murdered the servant, in order to conceal some crimes known to the negro, or whether the negro, in a fit of passion, killed his master, did not clearly appear.

However, the negro had declared before his death that his spirit would not rest unless his body was taken to his native land and buried there. This was not done, he being buried in the churchyard of Bettiscombe. Then the haunting began; fearful screams proceeded from the grave, the doors and windows of the house rattled and creaked, strange sounds were heard all over the house; in short, there was no rest for the inmates until the body was dug up. At different periods attempts were made to bury the body, but similar disturbances always recurred. In process of time the skeleton disappeared, 'all save the skull,' and its reputation as 'the screaming skull' remains unimpaired."

In a farm-house in Sussex are preserved two skulls from Hastings Priory, about which many gruesome stories are current in the neighbourhood. One of these skulls, it appears, has been in the house many years; the other was placed there by a former tenant of the farm. It is the prevalent impression in the locality, that, if by any chance the former skull were to be removed, the cattle in the farm would die, and unearthly sounds be heard in and about the house at night time. According to a local tradition, the skull belonged to a man who murdered the owner of the house, and marks of blood are pointed out on the floor of the adjoining room, where the murder is said to have been committed, and which no washing will remove. But, on more than one occasion, the skull has been taken away without any ill-effects, and, one year, was placed by a profane hand in a branch of a neighbouring tree, where it remained a whole summer, during which time a bird's nest was constructed within it, and a young brood successfully reared. And yet the old superstition still survives, and the prejudice against tampering with this peculiar skull has in no way diminished.[6]

There are the remains of a skull, in three parts, at Tunstead, a farmhouse about a mile and a half from Chapel-en-le-Frith, which, although popularly known by the male cognomen "Dickie," has always been said to be that of a woman. How long it has been located in its present home is not known, but tradition tells how one of two co-heiresses residing here was murdered, who solemnly affirmed that her bones should remain in the place for ever. In days past, this skull has been guilty of all sorts of eccentric pranks, many of which are still told by the credulous peasantry with respectful awe. It is added,[7] also, that if "Dickie" should accidentally be removed, everything in the farm will go wrong. The cows will be dry and barren, the sheep have the rot, and horses fall down, breaking their knees and otherwise injuring themselves. The story goes, too, that when the London and North-Western Railway to Manchester was being made, the foundations of a bridge gave way in the yielding sands and bog, and, after several attempts to build the bridge had failed, it was found necessary to divert the highway, and pass it under the railway on higher ground. These engineering failures were attributed to the malevolent influence of "Dickie," but as soon as the road was diverted it was bridged successfully, because no longer in Dickie's territory.

A similar superstition attaches to a skull kept in a farmhouse at Chilton Cantelo, in Somersetshire. From the date on the tombstone of the former owner of the skull—1670—it has been conjectured that he came to the retired village, in which he was buried, after taking an active part, on the Republican side, in the Civil War; and that seeing the way in which the bodies of some of them who had acted with him were treated after the Restoration, he wished to provide against this in his own case. But, whatever the previous history of this curious skull, it has at times caused a good deal of trouble, resenting any proposal to consign it to the earth, for buried it will not be, no matter how many attempts are made to do so. Strange to say, most of this class of skulls behave in the same extraordinary fashion. At a short distance from Turton Tower—one of the most interesting structures in the neighbourhood of Bolton—is a farmhouse locally designated Timberbottom, or the Skull House, so called from the circumstance that two skulls are or were kept there, one of which was much decayed, whereas the other appeared to have been cut through by a blow from some sharp instrument. These skulls, it is said, have been buried many times in the graveyard at Bradshaw Chapel, but they have always had to be exhumed, and brought back to the farm-house. On one occasion, they were thrown into the adjacent river, but to no purpose; for they had to be fished up and restored to their old quarters before the ghosts of their owners could once more rest in peace.

A popular cause assigned for this strange behaviour on the part of certain skulls is that their owners met with a violent death, and that the avenging spirit in this manner annoys the living, reminding us of Macbeth's words:

Hence, a romantic and tragic story is told of two skulls which have long haunted an old house near Ambleside. It appears that a small piece of ground, known as Calgrath, was owned by a humble farmer, named Kraster Cook, and his wife Dorothy. But their little inheritance was coveted by a wealthy magistrate, Myles Phillipson, who, unable to induce them to part with it, swore "he'd have that ground, be they 'live or dead." As time wore on, however, he appeared more gracious to Kraster and Dorothy, and actually invited them to a great Christmas banquet given to the neighbours. It was a dear feast for them, for Myles Phillipson pretended they had stolen a silver cup, and, sure enough, it was found in Kraster's house—a "plant," of course. Such an offence was then capital, and, as Phillipson was the magistrate, Kraster and Dorothy were sentenced to death. Thereupon, Dorothy arose in the court-room and addressed Phillipson in words that rang through the building and impressed all for their awful earnestness:

"Guard thyself, Myles Phillipson! Thou thinkest thou hast managed grandly, but that tiny lump of land is the dearest a Phillipson has ever bought or stolen, for you will never prosper, neither your breed. Whatever scheme you undertake will wither in your hand; the side you take will always lose; the time shall come when no Phillipson shall own an inch of land; and while Calgarth walls shall stand we'll haunt it night and day. Never will ye be rid of us!"

Henceforth, the Phillipsons had for their guests two skulls. They were found at Christmas at the head of a staircase. They were buried in a distant region, but they turned up in the old house again. Again and again were the two skulls burned; they were brazed to dust and cast to the winds, and for several years they were cast in the lake, but the Phillipsons could never get rid of them. In the meantime, Dorothy's weird went steadily on to its fulfilment, until the family sank into poverty, and at length disappeared.[8]

As a more rational explanation of the matter, it is told by some local historians "that there formerly lived in the house a famous doctress, who had two skeletons by her for the usual purposes of her profession, and these skulls, happening to meet with better preservation than the rest of the bones, they were accidentally honoured" with this singular tradition.[9]

Wardley Hall, Lancashire, has its skull, which is supposed to be the witness of some tragedy committed in the past, and to have belonged to Roger Downes, the last male representative of his family, and who was one of the most abandoned courtiers of Charles II. Roby, in one of his "Traditions," entitled "The Skull House," has represented him as rushing forth "hot from the stews," drawing his sword as he staggered along, and swearing that he would kill the first man he met. Terrible to say, that fearful oath was fulfilled, for his victim was a poor tailor, whom he ran through with his weapon and killed on the spot. He was apprehended for the crime, but his interest at Court quickly procured him a free pardon, and he soon continued his reckless course. But one evening, as his sister and cousin Eleanor were chatting together at Wardley, the carrier from Manchester brought a wooden box, "which had come all the way from London by Antony's waggon." Suspecting that there was something mysterious connected with this package, for the direction was "a quaint, crabbed hand," she opened it in secret, when, to her amazement and horror, this writing attracted her notice:

"Thy brother has at length paid the forfeit of his crimes. The wages of sin is death! And his head is before thee. Heaven hath avenged the innocent blood he hath shed. Last night, in the lusty vigour of a drunken debauch, passing over London Bridge, he encounters another brawl, wherein, having run at the watchmen with his rapier, one blow of the bill which they carried severed thy brother's head from his trunk. The latter was cast over the parapet into the river. The head only remained, which an eye witness, if not a friend, hath sent to thee!" His sister tried at first to keep the story of her brother's death a secret, and hid with all speed this ghastly memorial for ever, as she hoped, from the gaze and knowledge of the world. It was her desire to conceal this foul stain upon the family name, but "the grave gives back its dead. The charnel gapes. The ghastly head hath burst its cold tabernacle, and risen from the dust." No human power could drive it away. It hath "been torn in pieces, burnt, and otherwise destroyed, but even on the subsequent day it is seen filling its wonted place. Yet it was always observed that sore vengeance lighted on its persecutors. One who hacked it in pieces was seized with such horrible torments in his limbs that it seemed as though he might be undergoing the same process. Sometimes, if only displaced, a fearful storm would arise, so loud and terrible that the very elements themselves seemed to become the ministers of its wrath." Nor will this eccentric piece of mortality allow the little aperture in which it rests to be walled up, for it remains there still, whitened and bleached by the weather, "looking forth from those rayless sockets upon the scenes which, when living, they had once beheld." Towards the close of the last century, Thomas Barritt, the Manchester antiquary, visited this skull—"this surprising piece of household furniture," as he calls it, and adds that "one of us who was last in company with it, removed it from its place into a dark part of the room, and there left it, and returned home." But on the following night a violent storm arose in the neighbourhood, causing an immense deal of damage—trees being blown down and roofs unthatched—and the cause, as it was supposed, being ascertained, the skull was replaced, when these terrific disturbances ceased. And yet, as Thomas Barritt sensibly remarks, "All this might have happened had the skull never been removed; but withal it keeps alive the credibility of the tradition." Formerly two keys were provided for this "place of a skull," one being kept by the tenant of the Hall, and the other by the Countess of Ellesmere, the owner of the property. The Countess occasionally accompanied visitors from the neighbouring Worsley Hall, and herself unlocked the door, and revealed to her friends the grinning skull of Wardley Hall.[10]

Another romantic story is associated with Burton Agnes Hall, between Bridlington and Driffield, Yorkshire, which is haunted by the spirit of a lady a former co-heiress of the estate—who is popularly known as "Awd Nance." The skull of this lady is carefully preserved in the Hall, and so long as it is left undisturbed all goes well, but whenever any attempt is made to remove it, the most unearthly noises are heard in the house, and last until it is restored. According to a local tradition, many years ago the three co-heiresses of the estate of Burton Agnes were possessed of considerable wealth, and finding the ancient mansion, in which they resided, not in harmony with their ideas of what a home should be suited to their position, determined to erect a house in such a style as should eclipse all others in the neighbourhood. The most prominent organiser of the scheme was the younger sister, Anne, who could talk or think of nothing but the magnificent home about to be built, which in due time, it is said, "emerged from the hands of artists and workmen, like a palace erected by the genii of the Arabian Nights, a palace encrusted throughout on walls, roof, and furniture with the most exquisite carvings and sculptures of the most skilled masters of the age, and radiant with the most glowing tints of the pencil of Peter Paul."

But soon after its completion and occupation by its three co-heiresses, Anne, the enthusiast, paid an afternoon visit to the St. Quentins, at Harpham. On starting to return home about nightfall with her dog, she had gone no great distance when she was confronted by two ruffianly-looking beggars, who asked alms. She readily gave them a few coins, and in doing so the glitter of her finger-ring accidentally attracted their notice, which they at once demanded should be given up to them. This she refused to do, as it had been her mother's ring, and was one which she valued above all price.

"Mother or no mother," gruffly replied one of the rogues, "we mean to have it, and if you do not part with it freely, we must take it," whereupon he seized her hand and attempted to drag off the ring.

Frightened at this act of violence, Anne screamed for help, at which the other ruffian, exclaiming, "Stop that noise!" struck her a blow, and she fell senseless to the earth. But her screams had attracted attention, and the approach of some villagers caused the villains to make a hasty retreat, without being able to get the ring from her finger. In a dying condition, as it was supposed, Anne was carried back to Harpham Hall, where, under the care of Lady St. Quentin, she made sufficient recovery to be removed the following day to her own home. The brutal treatment she had received from the highwaymen, however, had done its fatal work, and after a few days, during which she was alternately sensible and delirious, she succumbed to the effects. Her one thought previous to death was her devotion to her home, which had latterly been the ruling passion of her life; and bidding her sisters farewell, she addressed them thus:—

"Sisters, never shall I sleep peacefully in my grave in the churchyard unless I, or a part of me at least, remain here in our beautiful home as long as it lasts. Promise me this, dear sisters, that when I am dead my head shall be taken from my body and preserved within these walls. Here let it for ever remain, and on no account be removed. And understand and make it known to those who in future shall become possessors of the house, that if they disobey this my last injunction, my spirit shall, if so able and so permitted, make such a disturbance within its walls as to render it uninhabitable for others so long as my head is divorced from its home."

Her sisters promised to accede to her dying request, but failed to do so, and her body was laid entire under the pavement of the church. Within a few days Burton Agnes Hall was disturbed by the most alarming noises, and no servant could be induced to remain in the house. In this dilemma, the two sisters remembered that they had not carried out Anne's last wish, and, at the suggestion of the clergyman, the coffin was opened, when a strange sight was seen. The "body lay without any marks of corruption or decay; but the head was disengaged from the trunk, and appeared to be rapidly assuming the semblance of a fleshless skull." This was reported to the two sisters, and on the vicar's advice the skull of Anne was taken to Burton Agnes Hall, where, so long as it remained undisturbed, no ghostly noises were heard. It may be added that numerous attempts have from time to time been made to rid the hall of this skull, but without success.

Many other similar skulls are still existing in various places, and, in addition to their antiquarian interest, have attracted the sightseer, connected as they mostly are with tales of legendary romance. An amusing anecdote of a skull is told by the late Mr. Wirt Sikes.[11] It seems that on a certain day some men were drinking at an inn when one of them, to show his courage and want of superstition, affirmed that he was "afraid of no ghosts," and dared to go to the church and fetch a skull. This he did, and after an hour or so of merrymaking over the skull, he carried it back to where he had found it; but, as he was leaving the church, "suddenly a tremendous blast like a whirlwind seized him, and so mauled him that he ever after maintained that nothing should induce him to do such a thing again." The man was still more convinced that the ghost of the original owner of the skull had been after him, when his wife informed him that the cane which hung in his room had been beating against the wall in a dreadful manner.

Byron had his skull romance at Newstead, but in this case the skull was more orderly, and not given to those unpleasant pranks of which other skulls have seemingly been guilty. Whilst living at Newstead, a skull was one day found of large dimensions and peculiar whiteness. Concluding that it belonged to some friar who had been domesticated at Newstead—prior to the confiscation of the monasteries by Henry VIII.—Byron determined to convert it into a drinking vessel, and for this purpose dispatched it to London, where it was elegantly mounted. On its return to Newstead, he instituted a new order at the Abbey, constituting himself grand master, or abbot, of the skull. The members, twelve in number, were provided with black gowns—that of Byron, as head of the fraternity, being distinguished from the rest. A chapter was held at certain times, when the skull drinking goblet was filled with claret, and handed about amongst the gods of this consistory, whilst many a grim joke was cracked at the expense of this relic of the dead. The following lines were inscribed upon it by Byron:

The skull, it is said, is buried beneath the floor of the chapel at Newstead Abbey.

[6] Sussex Archæological Collections xiii. 162-3.

[7] See Notes and Queries, 4th S., XI. 64.

[8] Told by Mr. Moncure Conway in Harper's Magazine.

[9] "Tales and Legends of the English Lakes," 96-7.

[10] "Harland's Lancashire Legends," 1882, 65-70.

[11] "British Goblins," 1880, p. 146.

|

No man takes or keeps a vow, But just as he sees others do; Nor are they 'bliged to be so brittle As not to yield and bow a little: For as best tempered blades are found Before they break, to bend quite round, So truest oaths are still more tough, And, tho' they bow, are breaking-proof. |

| Butler's "Hudibras," Ep. to his Lady, 75. |

Some two hundred and fifty years ago, the prevailing colour in all dresses was that shade of brown known as the "couleur Isabelle," and this was its origin:—A short time after the siege of Ostend commenced, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, Isabella Eugenia, Gouvernante of the Netherlands, incensed at the obstinate bravery of the defenders, is reported to have made a vow that she would not change her chemise till the town surrendered. It was a marvellously inconvenient vow, for the siege, according to the precise historians thereof, lasted three years, three months, three weeks, three days, and three hours; and her highness's garment had wonderfully changed its colour before twelve months of the time had expired. But the ladies and gentlemen of the Court, in no way dismayed, resolved to keep their mistress in countenance, and, after a struggle between their loyalty and their cleanliness, they hit upon the compromising expedient of wearing dresses of the presumed colour, finally attained by the garment which clung to the Imperial Archduchess by force of religious obstinacy. But, foolish and eccentric as was the conduct of Isabella Eugenia, there have been persons gifted, like herself, with sufficient mental power and strength of character to keep the vows they have sworn.

Thus, at a tournament held on the 17th November, 1559—the first anniversary of Queen Elizabeth's accession—Sir Henry Lee, of Quarendon, made a vow that every year on the return of that auspicious day, he would present himself in the tilt yard, in honour of the Queen, to maintain her beauty, worth, and dignity, against all comers, unless prevented by infirmity, accident, or age. Elizabeth accepted Sir Henry as her knight and champion; and the nobility and gentry of the Court formed themselves into an Honourable Society of Knights Tilters, which held a grand tourney every 17th November. But in the year 1590, Sir Henry, on account of age, resigned his office, having previously, by Her Majesty's permission, appointed the famous Earl of Cumberland as his successor. On this occasion, the royal choir sang the following verses as Sir Henry Lee's farewell to the Court:

But not long after Sir Henry Lee had resigned his office of especial champion of the beauty of the sovereign, he fell in love with the new maid of honour—the fair Mrs. Anne Vavasour—who, though in the morning flower of her charms, and esteemed the loveliest girl in the whole court, drove a whole bevy of youthful lovers to despair by accepting this ancient relic of the age of chivalry.[12]

Queen Isabella vowed to make a pilgrimage to Barcelona, and return thanks at the tomb of that City's patron Saint, if the Infanta Eulalie recovered from an apparently mortal illness, and Queen Joan of Naples honoured the knight Galeazzo of Mantua by opening the ball with him at a grand feast at her castle of Gaita. At the conclusion of the dance, Galeazzo, kneeling down before his royal partner, vowed, as an acknowledgment of the honour he had received, to visit every country where feats of arms were performed, and not to rest until he had subdued two valiant knights, and presented them as prisoners to the queen, to be disposed of at her royal pleasure. After an absence of twelve months, Galeazzo, true to his vow, appeared at Naples, and laid his two prisoners at the feet of Queen Joan, but who, it is said, displayed commendable wisdom on the occasion, and "declined her right to impose rigorous conditions on her captives, and gave them liberty without ransom."

Such cases, it is true, have been somewhat rare, for made oftentimes on the impulse of the moment, "unheedful vows," as Shakespeare says, "may heedfully be broken." But, scarce as the records of unbroken vows may be, they are deserving of a permanent record, more especially as the direction of their eccentricity is, for the most part, in itself curious and uncommon. Love, for instance, has been responsible for many strange and curious vows in the past, and some years ago it was stated that the original of Charles Dickens's Miss Havisham was living in the flesh not far from Ventnor in the person of an old maiden lady, who, because of the maternal objection to some love affair in her early life, made and kept a vow that she would retire to her bed, and there spend the remainder of her days. It was a stern vow but she kept her word, "and the years have come and gone, and the house has never been swept or garnished, the garden is an overgrown tangle, and the eccentric lady has spent twenty years between the sheets." But whether this piece of romance is to be accepted or not, love has been the cause of many foolish acts, and many a disappointed damsel, has acted in no less eccentric a fashion than Miss Havisham, who was so completely overcome by the failure of Compeyson to appear on the wedding morning that she became fossilised, and gave orders that everything was to be kept unchanged, but to remain as it had been on that hapless day. Henceforth she was always attired in her bridal dress with lace veil from head to foot, white shoes, bridal flowers in her white hair, and jewels on her hands and neck. Years went on, the wedding breakfast remained set on the table, while the poor half demented lady flitted from one room to another like a restless ghost; and the case is recorded of another lady whose lover was arrested for forgery on the day before their marriage was to have taken place. Her vow took the form of keeping to her room, sitting winter and summer alike at her casement and waiting for him who was turning the treadmill, and who was never to come again.

On the other hand, vows have been made, but persons have contrived to rid themselves of the inconveniences without breaking them, reminding us of Benedick, who finding the charms of his "Dear Lady Disdain" too much for his celibate resolves, gets out of his difficulty by declaring that "When I said I would die a bachelor, I did not think I should live till I were married." Equally ludicrous, also, is the story told of a certain man, who, greatly terrified in a storm, vowed he would eat no haberdine, but, just as the danger was over, he qualified his promise with "Not without mustard, O Lord." And Voltaire, in one of his romances, represents a disconsolate widow vowing that she will never marry again, "so long as the river flows by the side of the hill." But a few months afterwards the widow recovers from her grief, and, contemplating matrimony, takes counsel with a clever engineer. He sets to work, the river is deviated from its course, and, in a short time, it no longer flows by the side of the hill. The lady, released from her vow, does not allow many days to elapse before she exchanges her weeds for a bridal veil. However far fetched this little romance may be, a veritable instance of thus keeping the letter of the vow and neglecting the spirit, was recorded not so very long ago: A Salopian parish clerk seeing a woman crossing the churchyard with a bundle and a watering can, followed her, curious to know what intentions might be, and discovered that she was a widow of a few months' standing. Inquiring what she was going to do with the watering pot, she informed him that she had been obtaining some grass seed to sow on her husband's grave, and had brought a little water to make it spring up quickly. The clerk told her there was no occasion to trouble, the grave would be green in good time. "Ah! that may be," she replied, "but my poor husband made me take a vow not to marry again until the grass had grown over his grave, and, having a good offer, I do not wish to break my vow, or keep as I am longer than I can help."

But vows have not always been broken with impunity. Janet Dalrymple, daughter of the first Lord Stair, secretly engaged herself to Lord Rutherford, who was not acceptable to her parents, either on account of his political principles, or his want of fortune. The young couple broke a piece of gold together, and pledged their troth in the most solemn manner, the young lady, it is said, imprecating dreadful evils on herself should she break her plighted faith. But shortly afterwards another suitor sought the hand of Janet Dalrymple, and, when she showed a cold indifference to his overtures, her mother, Lady Stair, insisted upon her consenting to marry the new suitor, David Dunbar, son and heir of David Dunbar of Baldoon, in Wigtonshire. It was in vain that Janet Dalrymple confessed her secret engagement, for Lady Stair treated this objection as a mere trifle.

Lord Rutherford, apprised of what had happened, interfered by letter, and insisted on the right he had acquired by his troth plighted with Janet Dalrymple. But Lady Stair answered in reply that "her daughter, sensible of her undutiful behaviour in entering into a contract unsanctioned by her parents, had retracted her unlawful vow, and now refused to fulfil her engagement with him." Lord Rutherford wrote again to Lady Stair, and briefly informed her that "he declined positively to receive such an answer from anyone but Janet Dalrymple," and, accordingly, an interview was arranged between them, at which Lady Stair took good care to be present, with pertinacity insisting on the Levitical law, which declares that a woman shall be free of a vow which her parents dissent from.

While Lady Stair insisted on her right to break the engagement, Lord Rutherford in vain entreated Janet Dalrymple to declare her feelings; but she remained "mute, pale, and motionless as a statue," and it was only at her mother's command, sternly uttered, she summoned strength enough to restore the broken piece of gold—the emblem of her troth. At this unexpected act Lord Rutherford burst into a tremendous passion, took leave of Lady Stair with maledictions, and, as he left the room, gave one angry glance at Janet Dalrymple, remarking, "For you, madam, you will be a world's wonder"—a phrase denoting some remarkable degree of calamity.

In due time, the marriage between Janet Dalrymple and David Dunbar of Baldoon, took place, the bride showing no repugnance, but being absolutely impassive in everything Lady Stair commanded or advised, always maintaining the same sad, silent, and resigned look.

The bridal feast was followed by dancing, and the bride and bridegroom retired as usual, when suddenly the most wild and piercing cries were heard from the nuptial chamber, which at length became so hideous that a general rush was made to learn the cause. On opening the door a ghastly scene presented itself, for the bridegroom was discovered lying on the floor, dreadfully wounded, and streaming with blood. The bride was seen sitting in the corner of the large chimney, dabbled in gore—grinning—in short, absolutely insane, and the only words she uttered were; "Take up your bonny bridegroom." She survived this tragic event little over a fortnight, having been married on the 24th August, and dying on the 12th September.

The unfortunate bridegroom recovered from his wounds, but, strange to say, he never permitted anyone to ask him respecting the manner in which he had received them; but he did not long survive this dreadful catastrophe, meeting with a fatal injury by a fall from a horse as he was one day riding between Leith and Holyrood House. As might be expected, various reports went abroad respecting this mysterious affair, most of them being inaccurate.[13] But the story has gained a lasting notoriety from Sir Walter Scott having founded his "Bride of Lammermoor" upon it; who, in his introductory notes to that novel, has given some curious facts concerning this tragic occurrence, quoting an elegy of Andrew Symson, which takes the form of a dialogue between a passenger and a domestic servant. The first recollecting that he had passed Lord Stair's house lately, and seen all around enlivened by mirth and festivity, is desirous of knowing what has changed so gay a scene into mourning, whereupon the servant replies:—

Many a vow too rashly made has been followed by an equally tragic result, instances of which are to be met with in the legendary lore of our county families. A somewhat curious legend is connected with a monument in the church of Stoke d'Abernon, Surrey. The story goes that two young brothers of the family of Vincent, the elder of whom had just come into his estate, were out shooting on Fairmile Common, about two miles from the village. They had put up several birds, but had not been able to get a single shot, when the elder swore with an oath that he would fire at whatever they next met with. They had not gone far before a neighbouring miller passed them, whereupon the younger brother reminded the elder of his oath, who immediately fired at the miller, and killed him on the spot. Through the influence of his family, backed by large sums of money, no effective steps were taken to apprehend young Vincent, but, after leading a life of complete seclusion for some years, death finally put an end to the insupportable anguish of his mind.

A pretty romance is told of Furness Abbey, locally known as "The Abbey Vows." Many years ago, Matilda, the pretty and much-admired daughter of a squire residing near Stainton, had been wooed and won by James, a neighbouring farmer's son. But as Matilda was the only child, her father fondly imagined that her rare beauty and fortune combined would procure her a good match, little thinking that her heart was already given to one whose position he would never recognise. It so happened, however, that the young people, through force of circumstances, were separated, neither seeing nor hearing of each other for some years.

At last, by chance, they were thrown together, when the active service in which James was employed had given his fine manly form an appearance which was at once imposing and captivating. Matilda, too, was improved in every eye, and never had James seen so lovely a maid as his former playmate. Their youthful hearts were disengaged, and they soon resolved to render their attachment as binding and as permanent as it was pure and undivided. The period had arrived, also, when James must again go to sea, and leave Matilda to have her fidelity tried by other suitors. Both, therefore, were willing to bind themselves by some solemn pledge to live but for each other. For this purpose they repaired, on the evening before James's departure, to the ruins of Furness Abbey. It was a fine autumnal evening; the sun had set in the greatest beauty, and the moon was hastening up the eastern sky; and in the roofless choir they knelt, near where the altar formerly stood, and repeated, in the presence of Heaven, their vows of deathless love.

They parted. But the fate of the betrothed lovers was a melancholy one. James returned to his ship for foreign service, and was killed by the first broadside of a French privateer, with which the captain had injudiciously ventured to engage. As for Matilda, she regularly went to the abbey to visit the spot where she had knelt with her lover; and there, it is said, "she would stand for hours, with clasped hands, gazing on that heaven which alone had been witness to their mutual vows."

Another momentous vow, but one of a terribly tragic nature, relates to Samlesbury Hall, which stands about midway between Preston and Blackburn, and has long been famous for its apparition of "The Lady in White." The story generally told is that one of the daughters of Sir John Southworth, a former owner, formed an attachment with the heir of a neighbouring house, and nothing was wanting to complete their happiness except the consent of the lady's father. Sir John was accordingly consulted by the youthful couple, but the tale of their love for each other only increased his rage, and he dismissed them with the most bitter denunciations.

"No daughter of his should ever be united to the son of a family which had deserted its ancestral faith," he solemnly vowed, and to intensify his disapproval of the whole affair, he forbade the young man his presence for ever. Difficulty, however, only served to increase the ardour of the lovers, and, after many secret interviews among the wooded slopes of the Ribble, an elopement was arranged, in the hope that time would eventually bring her father's forgiveness. But the day and place were unfortunately overheard by the lady's brother, who had hidden himself in a thicket close by, determined, if possible, to prevent what he considered to be his sister's disgrace. On the evening agreed upon both parties met at the appointed hour, and, as the young knight moved away with his betrothed, her brother rushed from his hiding-place, and, in pursuance of a vow he had made, slew him. After this tragic occurrence, Lady Dorothy was sent abroad to a convent, where she was kept under strict surveillance; but her mind at last gave way—the name of her murdered sweetheart was ever on her lips—and she died a raving maniac. It is said that on certain clear, still evenings, a lady in white can be seen passing along the gallery and the corridors, and then from the hall into the grounds, where she meets a handsome knight, who receives her on his bended knees, and he then accompanies her along the walks. On arriving at a certain spot, in all probability the lover's grave, both the phantoms stand still, and as they seem to utter soft wailings of despair, they embrace each other, and then their forms rise slowly from the earth and melt away into the clear blue of the surrounding sky.[14]