The Project Gutenberg EBook of Companion to the Bible, by E. P. Barrows This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Companion to the Bible Author: E. P. Barrows Release Date: December 9, 2005 [EBook #17265] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK COMPANION TO THE BIBLE *** Produced by John Hagerson, Juliet Sutherland, David King, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

The design of the present work, as its title indicates, is to assist in the study of God's word. The author has had special reference to teachers of Bible classes and Sabbath-schools; ministers of the gospel who wish to have ready at hand the results of biblical investigation in a convenient and condensed form; and, in general, the large body of intelligent laymen and women in our land who desire to pursue the study of Scripture in a thorough and systematic way.

The First Part contains a concise view of the Evidences of Revealed Religion. Here, since Christianity rests on a basis of historic facts, special prominence has been given to the historic side of these evidences; those, namely, which relate to the genuineness, integrity, authenticity, and inspiration of the several books of the Bible. A brief view is added of the evidences which are of an internal and experimental character.

In the Introductions to the Old and New Testament which follow in the Second and Third Parts, the general facts are first given; then an account of the several divisions of each, with their office and mutual relations, and such a notice of each particular book as will prepare the reader to study it intelligently and profitably.

The Fourth Part is devoted to the Principles of Biblical Interpretation. Here the plan is to consider the Scriptures, first, on the human side, as addressed to men in human language and according to human modes of thinking and speaking; then, on the divine side, as containing a true revelation from God, and differing in this respect from all other writings. To this twofold view the author attaches great importance. To the human side belong the ordinary principles of interpretation, {4} which apply alike to all writings; to the divine side, the question of the unity of revelation, and the interpretation of types and prophecies.

In each of the abovenamed divisions the author has endeavored to keep prominently in view the unity of revelation and the inseparable connection of all its parts. It is only when we thus contemplate it as a glorious whole, having beginning, progress, and consummation, that we can truly understand it. Most of the popular objections to the Old Testament have their foundation in an isolated and fragmentary way of viewing its facts and doctrines; and they can be fairly met only by showing the relation which these hold to the entire plan of redemption.

The plan of the present work required brevity and condensation. The constant endeavor has been to state the several facts and principles as concisely as could be done consistently with a true presentation of them in an intelligible form. It may be objected that some topics, those particularly which relate to the Pentateuch, are handled in too cursory a way. The author feels the difficulty; but to go into details on this subject would require a volume. He has endeavored to do the best that was consistent with the general plan of the work. The point of primary importance to be maintained is the divine authority and inspiration of the Pentateuch—the whole Pentateuch as it existed in our Saviour's day and exists now. There are difficult questions connected with both its form and the interpretation of certain parts of it in respect to which devout believers may honestly differ. For the discussion of these the reader must be referred to the works professedly devoted to the subject.

The present volume is complete in itself; yet it does not exhaust the circle of topics immediately connected with the study of the Bible. It is the author's purpose to add another volume on Biblical Geography and Antiquities, with a brief survey of the historic relations of the covenant people to the Gentile world.

{5}CHAPTER I.

Introductory Remarks. 1. Christianity rests on a Basis of Historic Facts inseparably connected from First to Last—2. This Basis to be maintained against Unbelievers—3. General Plan of Inquiry—Christ's Advent the Central Point—From this We look forward and backward to the Beginning—4. Importance of viewing Revelation as a Whole—5. Fragmentary Method of Objectors—Particular Order of the Parts in this Investigation

CHAPTER II.

Genuineness of the Gospel Narratives. 1. Terms defined—Necessity of knowing the Authors of the Gospels—2. Remarks on their Origin—They were not written immediately, but successively at Intervals—Earlier Documents noticed by Luke—3. Manner of Quotation by the Early Church Fathers—4. External Evidences traced upward from the Close of the Second Century—Testimony of Irenæus—Of Tertullian—Of Clement of Alexandria—Letter of the Churches of Lyons and Vienne—5. Comprehensiveness and Force of these Testimonies—Freedom of Judgment in the Primitive Churches—This shown by the History of the Disputed Books—6. Public Character and Use of the Gospels—7. Earlier Testimonies—Justin Martyr—His Designation of the Gospels—They are Our Canonical Gospels—Explanation of his Variations and Additions—His References to the Gospel of John—8. Testimony of Papias—9. Epistle to Diognetus—10. The Apostolic Fathers—Clement of Rome—Ignatius Polycarp—The So-called Epistle of Barnabas—11. The Ancient Versions and Muratorian Canon—Syriac Peshito—Old Latin—12. Testimony of the Heretical Sects—Marcion—Valentinus—Tatian—13. Conclusiveness of the above External Testimony—14. Internal Evidences—Relation of the First Three Gospels to the Last—They differ in Time—The First Three written before the Destruction of Jerusalem; the Fourth after that Event—They differ in Character and Contents—Yet were all alike received by the Churches—15. Relation of the First Three Gospels to Each Other—They have Remarkable Agreements and Differences—These and their General Reception explained by their Genuineness—16. The Gospels contain no Trace of Later Events—17. Or Later Modes of Thought. 18. From the Character of the Language

{6}CHAPTER III.

Uncorrupt Preservation of the Gospel Narratives. 1. What is meant by an Uncorrupt Text—2. Ancient Materials for Writing—Palimpsests—Uncial and Cursive Manuscripts—3. The Apostolic Autographs have perished, but We have their Contents—This shown from the Agreement of Manuscripts—From the Quotations of the Fathers—From Ancient Versions—Character of the "Various Readings"—They do not affect the Substance of the Gospel—4. The Ancient Versions made from a Pure Text—This shown from the Public Reading of the Gospels from the Beginning—From the Multiplication of Copies—From the High Value attached to the Gospels—From the Want of Time for Essential Corruptions—From the Absence of all Proof of such Corruptions—5. The Above Remarks apply essentially to the other New Testament Books

CHAPTER IV.

Authenticity and Credibility of the Gospel Narratives. 1. General Remarks—2. Their Authors Sincere and Truthful—3. Competent as Men—4. And as Witnesses—5. Character of the Works which they record—Supernatural Character of our Lord's Miracles—They were very Numerous and Diversified, and performed openly—6. And in the Presence of His Enemies—7. The Resurrection of Jesus—Its Vital Importance—8. The Character of Jesus proves the Truth of the Record—Its Originality and Symmetry—It unites Tranquillity with Fervor—Wisdom with Freedom from Guile—Prudence with Boldness—Tenderness with Severity—Humility with the Loftiest Claims—He is Heavenly-minded without Asceticism—His Perfect Purity—His Virtues Imitable for All alike—Our Lord's Character as a Teacher—His Freedom from the Errors of His Age and Nation—His Religion One for All Men and Ages—This explained by its Divine Origin—Our Lord's Manner of Teaching—His Divine Mission—Divinity of His Person—Originality of its Manifestations—God His Father in a Peculiar Sense—He is the Source of Light and Life—He has Inward Dominion over the Soul—He dwells in Believers, and they in Him—The Inference—His Power over the Human Heart—Supernatural Character of the Gospel—A Word on Objections

CHAPTER V.

The Acts of the Apostles and the Acknowledged Epistles. 1. These Books a Natural Sequel to the Gospels—2. The Acts of the Apostles—External Testimonies—3. Internal Evidence—4. Credibility—5. Date of Composition—6. The Acknowledged Epistles—Distinction of Acknowledged and Disputed Books—7. First Group of Pauline Epistles—Second Group, or the Pastoral Epistles—Their Date—Their Peculiar Character—8. First Epistles of Peter and First of John—9. Mutual Relation between the Gospels and Later Books—10. Argument from Undesigned Coincidences

CHAPTER VI.

The Disputed Books. 1. The Question here simply concerning the Extent of the Canon—2. The Primitive Age One of Free Inquiry—3. Its Diversity of {7} Judgment no Decisive Argument against a Given Book—4. The Caution of the Early Churches gives Weight to their Judgment—This Judgment Negative as well as Positive

CHAPTER VII.

Inspiration and the Canon. General Remarks—1. Rule of Judgment determined—It is the Writer's Relation to Christ—2. Christ Himself Infallible—3. The Apostles—They held the nearest Relation to Him—Their Infallibility as Teachers shown—From the Necessity of the Case—From Christ's Express Promises—From their Own Declarations—Summary of the Argument in Respect to the Apostles—4. Inspiration of the Apostolic Men—5. Argument from the Character of the Books of the New Testament—6. The Inspiration of the Sacred Writers Plenary—7. Principles on which the Canon is formed

CHAPTER VIII.

Inseparable Connection Between the Old and the New Testament. General Remarks—1. Previous Revelations implied in Christ's Advent—2. In the Character of the Jewish People—3. Proved from the New Testament—Christ's Explicit Declarations—4. The New Testament based on the Facts of the Old—The Fall of Man—The Abrahamic Covenant, which was conditioned on Faith alone, and fulfilled in Christ—Christ the End of the Mosaic Economy—In its Prophetical Order—In its Kingly Office—In its Priestly Office—5. The New Testament Writers the Interpreters of the Old

CHAPTER IX.

Authorship of the Pentateuch. Meaning of the Term—1. It existed in its Present Form from Ezra's Day—2. "The Law" ascribed to Moses in the New Testament—How Much is included in this Term—3. Force of the New Testament Testimony—4. The Law of Moses at the Restoration—5. Jewish Tradition that Ezra settled the Canon of the Old Testament—He left the Pentateuch essentially as he found it—References to the Law in the Books of Kings and Chronicles—6. The Book of Deuteronomy—Its Mosaic Authorship Certain—7. The Inference Certain that he wrote the Preceding Laws—8. This corroborated by their Form—9. By References in the New Testament—And the Old also—10. Relation of Deuteronomy to the Earlier Precepts—In Respect to Time—And Design—Change in Moses' Personal Relation to the People—Peculiarities of Deuteronomy explained from the Above Considerations—Meaning of "the Words of this Law" in Deuteronomy—11. Mosaic Authorship of Genesis shown—From Antecedent Probability—From its Connection with the Following Books—Objections considered—Supposed Marks of a Later Age—And of Different Authors—12. Unity of the Pentateuch

CHAPTER X.

Authenticity and Credibility of the Pentateuch. 1. Its Historic Truth assumed in the New Testament—This shown by Examples—2. It was the Foundation of the Whole Jewish Polity—And could not have been imposed {8} upon the People by Fraud—Contrast between Mohammed and Moses—3. Scientific Difficulties connected with the Pentateuch—4. Alleged Moral Difficulties—Exclusiveness of the Mosaic Economy—Its Restrictions on Intercourse with Other Nations—5. Its Numerous Ordinances—The Mosaic Laws required Spiritual Obedience—6. Objections from the Toleration of Certain Usages—7. Extirpation of the Canaanites—8. The Mosaic Economy a Blessing to the Whole World

CHAPTER XI.

Remaining Books of the Old Testament. 1. General Remarks—2. The New Testament assumes their Divine Authority—Historical Books—3. Books not strictly Historical or Prophetical—4. Prophetical Books—Argument from Prophecy for the Divine Origin of the Old Testament—5. Christ the Fulfilment of Prophecy—In his Office as a Prophet—as a King—as a Priest—6. The Jewish Institutions and History a Perpetual Adumbration of Christ preparatory to His Advent—7. Remarks on the Canon of the Old Testament—8. Principle of its Formation—9. Inspiration of the Old Testament

CHAPTER XII.

Evidences Internal and Experimental. 1. External Evidences Important, but not Indispensable to True Faith—2. Internal Evidences—View which the Bible gives of God's Character—3. Code of Morals in the Bible—It is Spiritual, Reasonable, and Comprehensive—Obedience to It the Sum of all Goodness—4. All Parts of the Bible in Harmony with Each Other—5. Power of the Bible over the Conscience—6. Argument from Personal Experience—7. From the Character of Jesus—8. From General Experience—The Love of Jesus the Mightiest Principle of Action—Persecution first winnows, then strengthens the Church—The Church corrupted and weakened by Worldly Alliances—9. The Gospel gives an Inward Victory over Sin—It purifies and elevates Society—10. Its Self-purifying Power—11. The Argument summed up

FIRST DIVISION—GENERAL INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER XIII.

Names and External Form of the Old Testament. 1. Origin and Meaning of the Word Bible—Jewish Designations of the Old Testament—2. Origin of the Terms Old and New Testament—Earlier Latin Term—2. The Unity—Scripture has its Ground in Divine Inspiration—Its Great Diversity in Respect to Human Composition—4. Classification and Arrangement of the Old {9} Testament Books—Classification of the Hebrew: of the Greek Version of the Seventy; of the Latin Vulgate—No One of these follows entirely the Order of Time—5. Original Mode of Writing called Continuous—6. Ancient Sections—Open and Closed; Larger Sections called Parshiyoth and Haphtaroth—7. Chapters and Verses—Caution in Respect to our Modern Chapters

CHAPTER XIV.

The Original Text and its History. 1. Chaldee Passages in the Hebrew Scriptures—Divisions of the Hebrew and Cognate Languages—2. The Assyrian or Square Character not Primitive—Jewish Tradition respecting its Origin—3. The Hebrew Alphabet and its Character—4. Change in the Language of the Hebrew Nation—5. Introduction of the Vowel-Points and Accents—The Question of their Antiquity—6. Jewish Rules for the Guidance of Copyists—Their Deep Reverence for the Sacred Text—Its Uncorrupt Transmission to Us—7. Age and Character of Hebrew Manuscripts—8. Form of Hebrew Manuscripts—the Public in Rolls, the Private in the Book Form, Poetical Passages, Columns, Pen and Ink Accompaniments—9. The Samaritan Pentateuch

CHAPTER XV.

Formation and History of the Hebrew Canon. I. Meaning of the Word "Canon"—Gradual Formation of the Hebrew Canon—Its Main Divisions—1. The Pentateuch—2. General Remark on its Hebrew Name—3. The Pentateuch forms the Nucleus of the Old Testament Canon—It was given by Divine Authority, committed to the Charge of the Priests, kept by the Side of the Ark, and to be publicly read at Stated Times—II. The Historical Books—4. The Authors and Exact Date of Many of them Unknown—Important Historical Documents were deposited in the Sanctuary—5. The Authors of the Books of Joshua and Judges made Use of such Documents—6. The Author of the Books of Samuel also—7. Original Sources for the Books of Kings and Chronicles—8. These Two Works refer not to Each Other, but to a Larger Collection of Original Documents—9. Character of these Documents—They were written, in Part at Least, by Prophets, and they all come to us with the Stamp of Prophetic Authority.—10. The Books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther—III. The Prophetical Books—11. The Books enumerated—Paucity of Prophets before Samuel—Schools of the Prophets established by him—The Prophets a Distinct Order of Men in the Theocracy from his Day onward—12. The Era of Written Prophecy—IV. The Poetical Books—13. Their General Character—The Book of Job—14. The Book of Psalms—15. Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Canticles—Completion of the Canon—16. Preservation of the Sacred Books to the Time of Ezra—The Law; the Prophetical Books; the Psalms and other Canonical Writings—17. The Completion of the Canon ascribed by the Jews to Ezra and his Coadjutors—This Tradition True for Substance.—No Psalms written in the Maccabean Age—18. Contents of the Hebrew Canon—as given by Jesus the Son of Sirach, by Josephus, by Origen and Eusebius, by Jerome—19. The Apocryphal Books

{10}CHAPTER XVI.

Ancient Versions of the Old Testament. I. The Greek Version called the Septuagint—1. Its Antiquity; its Great Influence on the Language of the New Testament—2. Jewish Account of its Origin—3. Judgment of Biblical Scholars on this Account—4. Time occupied in the Completion of the Work—5. Inequalities of this Version—Its Importance to the Biblical Student—6. Its Close Connection with the New Testament—Quotations from it by New Testament Writers—Their Manner and Spirit—7. Hebrew Text from which this Version was made—II. Other Greek Versions—8. The Septuagint originally in High Esteem among the Jews—Change in their Feelings in Regard to it, and Rise of New Versions—9. Aquila's Version—10. Theodotion—11. Symniachus—12. Origen's Labors on the Text of the Septuagint—the Tetrapla and Hexapla—III. The Chaldee Targums—13. General Remarks on these—14. The Targum of Onkelos—Its General Fidelity and Excellence—Its Peculiarities—Jewish Tradition respecting Onkelos—15. The Targum of Jonathan Ben Uzziel—16. Of Pseudo-Jonathan and Jerusalem—17. Other Targums—The Samaritan Version of the Samaritan Pentateuch—IV. 18. The Syriac Peshito—Its Age and Character

CHAPTER XVII.

Criticism of the Sacred Text. 1. The Object to ascertain its Primitive Form—2. Means at Our Disposal—Ancient Hebrew Manuscripts—Remarks on their Quality and Age—3. Ancient Versions—4. Primary Printed Editions—5. Parallel Passages—6. Quotations from the Old Testament in the New—7. Quotations in the Talmud and by Rabbinical Writers—8. Critical Conjecture

SECOND DIVISION—PARTICULAR INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER XVIII.

The Books of the Old Testament as a Whole. 1. Province of Particular Introduction—The Necessity of Understanding the Unity of Divine Revelation—2. Relation of the Old Testament as a Whole to the System of Revelation—It is a Preparatory, Introductory to a Final Revelation, of which the Gospel everywhere avails itself—the Unity of God; Vicarious Sacrifice; General Principles; Well-developed State of Civilization—Connection of the Hebrews with the Great World Powers—Their Dispersion through the Nations at our Lord's Advent—Relation of the Gospel to Civilization—3. A Knowledge of the Preparatory Character of the Old Testament Revelations enables us to judge correctly concerning them—Severity of the Mosaic Laws; Their Burdensome Multiplicity; Objection from their Exclusive Character answered—4. Office of each Division of the Old Testament Revelations—the Pentateuch; the Historical Books; the Prophetical Books—Character and Officers of the Hebrew Prophets—Era of Written Prophecy—The Poetical Books—5. Each Particular Book has its Office—6. The Old Testament was a Revelation for the Men of its Own Age, as well as for those of Future Ages—the Promise {11} made to Abraham; the Deliverance from Egypt; the Mosaic Law; the Words of the Prophets; the Psalms of David: the Wisdom of Solomon—7. Value of the Old Testament Revelations to us—the System of Divine Revelation can be understood only as a Whole; Constant Reference of the New Testament to the Old; the Old Testament a Record of God's Dealings with Men; the Principles embodied in the Theocracy Eternal; the Manifold Wisdom of God seen only when the Whole System of Revelation is studied

CHAPTER XIX.

The Pentateuch. I. Its Unity—Its Fivefold Division—1. Genesis—2. Its Hebrew Name—Its Greek Name—3. Its Office—It is the Introductory Book of the Pentateuch—Its Connection with the Following Books—4. Divisions of the Book of Genesis—First Part and its Contents; Second Part and its Contents—5. Its Mosaic Authorship—Supposed Traces of a Later Hand—6. Difficulties connected with the Pentateuch—Scientific Difficulties: the Six Days of Creation; the Age of the Antediluvian Patriarchs; the Unity of the Human Race; the Deluge—Historical Difficulties: the Two Accounts of the Creation; Cain's Wife—Chronological Difficulties: Discrepancies between the Masoretic Hebrew, the Samaritan Hebrew, and the Septuagint, in Respect to (1) the Antediluvian Genealogy; (2) the Genealogy from Noah to Abraham—Remarks on these Discrepancies—II. Exodus—7. Hebrew Name of this Book—Its Unity—Its Two Chief Divisions—Contents of the First Division; of the Second Division—8. Time of the Sojourn in Egypt—Sojourn in the Wilderness—III. Leviticus—9. Its Character and Contents—10. The Priestly Office and Sacrifices the Central Part of the Mosaic Law—IV. Numbers—11. Office and Contents of this Book—The Three Epochs of its History: the Departure from Sinai, the Rebellion of the People upon the Report of the Twelve Spies, the Second Arrival of Israel at Kadesh with the Events that followed—V. Deuteronomy—12. Its Peculiar Character, Divisions, and Contents—13. It brings the Whole Pentateuch to a Suitable Close

CHAPTER XX.

The Historical Books. 1 and 2. Their Office to Unfold the History of God's Dealings with the Covenant People—General Remarks on the Character of this History—I. Joshua—3. Contents of this Book. Its Immediate Connection with the Pentateuch—Its Two Divisions with their Contents—4. Its Authorship—5. Its Authenticity and Credibility—The Miracle of the Arrest of the Sun and Moon in their Course—II. Judges and Ruth—6. Name of this Book—Office of the Judges whose History it records—Condition of the Hebrew Nation during the Administration of the Judges—Office of this Book in the General Plan of Redemption—7. Arrangement of its Materials—its Twofold Introduction; the Body of its History; its Two Appendixes—8. Its Date and Authorship—9. Uncertainty of its Chronology—10. The Book of Ruth. Its Place in the History of Redemption—III. The Books of Samuel—11. The Two Books of Samuel originally One Work—Their Name—12. Their Office in the History of Redemption—Eventful Character of the Period whose History they record—Change to the Kingly Form of Government—God's {12} Design in this—The Kingly Office Typical of Christ—13. Contents of the Books of Samuel—Introductory Division; Second Division; Third Division—14. Authorship and Date of their Composition—IV. The Books of Kings—15. They Originally constituted a Single Book—Their Names and Office—Their Manner of Execution—Their Main Divisions—16. The First Period—17. The Second Period—18. The Third Period—19. Chronology of the Books of Kings. Their Date and Authorship—V. The Books of Chronicles—20. They originally constituted One Work—Their Various Names—They constitute an Independent Work—Their Office different from that of the Books of Kings—Peculiarities which distinguish them from these Books—Particular Attention to the Matter of Genealogy; Fullness of Detail in Respect to the Temple Service; Omission of the History of the Kingdom of Israel; other Omissions—21. Position of the Chronicles in the Hebrew Canon—Their Authorship and Date—Their Relation to the Books of Kings—22. Difficulties connected with these Books—VI. Ezra and Nehemiah—23. General Remarks on these Books—Change in the Relation of the Hebrews to the Gentile Nations—Gradual Withdrawal of Supernatural Manifestations—24. While the Theocracy went steadily forward to the Accomplishment of its End—The Jews reclaimed from Idolatry in Connection with the Captivity—Establishment of the Synagogue Service and its Great Influence—25. The Book of Ezra—Its Authorship—Parts written in Chaldee—Persian Monarchs mentioned by Ezra and Nehemiah—26. The Book of Nehemiah—Its Contents and Divisions—First Division; Second Division; Third Division—27. Authorship and Date of the Book—VII. Esther—28. Contents of this Book—Feast of Purim—29. The Ahasuerus of this Book—Remarks on its History

CHAPTER XXI.

The Poetical Books (Including Also Ecclesiastes and Canticles). 1. Books reckoned as Poetical by the Hebrews—Hebrew System of Accentuation—A. Characteristics of Hebrew Poetry—Its Spirit—Harmony with the Spirit of the Theocracy; Vivid Consciousness of God's Presence; Originality; Freshness and Simplicity of Thought; Variety—Job and Isaiah. David, Solomon; Diversity of Themes; Oriental Imagery; Theocratic Imagery—Form of Hebrew Poetry—3. Its Rhythm that of Clauses—Antithetic Parallelism; Synonymous Parallelism; Synthetic Parallelism—Combinations of the above Forms—Freedom of Hebrew Poetry—Peculiarities of Diction—Office of Hebrew Poetry—4. The Celebration of God's Interpositions in Behalf of the Covenant People; Song for the Sanctuary Service; Didactic Poetry; Prophetic Poetry—B. The Several Poetical Books—I. Job—1. Survey of its Plan—6. Its Design to Show the Nature of God's Providential Government over Men—7. Age to which Job belonged—Age and Authorship of the Book—8. Its Historic Character—II. The Book of Psalms—9. Its Office—Authors of the Psalms—Date of their Composition—10. External Division of the Psalms into five Books—First Book; Second Book; Third Book; Fourth Book; Fifth Book—Subscription appended to the Second Book—Principle of Arrangement—Attempted Classification of the Psalms—Frequent Quotation of the Psalms in the New Testament—11. Titles of the Psalms—the Dedicatory Title; Titles relating to the Character of the Composition to the Musical {13} Instruments, or the Mode of Musical Performance—These Titles very Ancient, but not in all Cases Original—III. The Proverbs of Solomon—12. Place of this Book in the System of Divine Revelation—13. Its Outward Form—First Part; Second Part; Third Part; Fourth Part—14. Arrangement of the Book in its Present Form—IV. Ecclesiastes—15. Authorship of this Book and its View of Life—16. Summary of its Contents—V. The Song of Solomon—17. Meaning of the Title. Ancient Jewish and Christian View of this Song—18. It is not a Drama, but a Series of Descripture Pictures—Its Great Theme—Caution in Respect to the Spiritual Interpretation of it

CHAPTER XXII.

The Greater Prophets. 1. General Remarks on the Prophetical Writings—2. Different Offices of the Prophets under the Theocracy—Their Office as Reprovers—3. As Expounders of the Mosaic Law in its Spirituality—4. And of its End, which was Salvation through the Future Redeemer—They wrote in the Decline of the Theocracy—Their Promises fulfilled only in Christ—I. Isaiah—5. He is the First in Order, but not the Earliest of the Prophets—His Private History almost wholly Unknown—Jewish Tradition Concerning him—Period of his Prophetic Activity—6. Two Great Divisions of his Prophecies—Plans for Classifying the Contents of the First Part—Analysis of these Contents—General Character of the Second Part, and View of its Contents—7. Objections to the Genuineness of the Last Part of Isaiah and Certain Other Parts—General Principle on which these Objections are to be met—Previous Preparation for the Revelations contained in this Part—True Significance of the Promises which it contains—Form of these Promises—Mention of Cyrus by Name—Objection from the Character of the Style considered—8. Direct Arguments for the Genuineness of this Part—External Testimony; Internal Evidences—9. Genuineness of the Disputed Passages of the First Part—II. Jeremiah—10. Contrast between Isaiah and Jeremiah in Personal Character and Circumstances—Our Full Knowledge of his Outward Personal History and Inward Conflicts—11. His Priestly Descent—His Native Place—Period of his Prophetic Activity—Degeneracy of the Age—Persecutions to which his Fidelity subjected him—He is more occupied than Isaiah with the Present—His Mission is emphatically to unfold the Connection between National Profligacy and National Ruin; yet he sometimes describes the Glory of the Latter Days—12. The Chronological Order not always followed in his Prophecies—General Divisions of them—First Division; Second Division; Appendix—Attempts to disprove the Genuineness of Certain Parts of Jeremiah—The Book of Lamentations—13. Its Hebrew Name—Its Authorship and the Time of its Composition—14. Structure of its Poetry—III. Ezekiel—15. His Priestly Descent and Residence—Notices of his Personal History—Period of his Prophetic Activity—16. Peculiarities of his Style—17. His Allegoric and Symbolic Representations—General Remarks on the Nature of Allegories and Symbols—18. The Two Divisions of the Book—Contents of the First Part; of the Second Part—Prophecies against Foreign Nations—Promises relating to the Glory of the Latter Days—Ezekiel's Vision of a New Jerusalem with its Temple—Meaning of this Vision and Principles according to which it is to be interpreted—IV. Daniel—19. Its Place in the Hebrew Canon—Notices of Daniel's Personal History—20. Arrangement and Contents of the Book—First {14} Series of Prophecies; Second Series—Intimate Connection between the Book of Daniel and the Apocalypse—21. Assaults made upon the Book of Daniel in Respect to its Genuineness and Credibility—Grounds on which it is received as a Part of the Sacred Canon—Its Unity; Uniform Tradition of the Jews and its Reliability; Testimony of Josephus; of the Saviour; Language and Style; Intimate Acquaintance with the Historical Relations and Manners and Customs of the Age—22. Insufficiency of the Various Objections urged against the Book—Chronological and Historical Difficulties; Difficulties connected with the Identification of Belshazzar and Darius the Mede; Silence of Jesus the Son of Sirach respecting Daniel; Alleged Linguistic Difficulties; Commendations bestowed upon Daniel—The Real Objection to the Book on the Part of its Opponents lies in the Supernatural Character of the Events which it records—Remarks on this Objection

CHAPTER XXIII.

The Twelve Minor Prophets.—1. Jewish Arrangement of these Books—Their Order in the Masoretic Text and in the Alexandrine Version—2. General Remarks on their Character I. Hosea—3. Period of his Prophecying and its Character—4. Peculiarly of his Style—Contents of the Book II. Joel—5. Place and Date of his Prophecies—6. Character and Contents of his Book—III. Amos—7. Date of his Prophecies—Notices of his Person—He was a Jew, not trained in any Prophetical School, and sent to prophesy against Israel—Character and Contents of his Writings—IV. Obadiah—8. Date and Contents of his Prophecy—V. Jonah—9. His Age—10. Remarks on the History of the Book—11. Authorship and Historic Truth of the Book—VI. Micah—12. His Residence and the Time of his Prophetic Activity—His Prophecies directed against both Israel and Judah—13. Divisions of the Book with the Contents of Each—Passages Common to Micah and Isaiah—General Agreement between the Two Prophets—VII. Nahum—14. His Prophecy directed against Nineveh—Its Probable Date—15. Contents of the Book—VIII. Habakkuk—16. Date of the Book and its Contents—Remarks on the Ode contained in the Third Chapter—IX. Zephaniah—17. Date and Contents of his Book—X. Haggai—18. Date and Scope of the Book—19. Its Different Messages—XI. Zechariah—20. His Priestly Descent—Date of his Prophecies—21. The Three Divisions of the Book—First Division; Second Division; Third Division—22. Remarks on the Character of Zechariah's Prophecies—XII. Malachi—23. Name of this Prophet—Date of his Prophecies, and Condition of the Jewish People—24 Contents of the Book

APPENDIX TO PART II.

The Apocryphal Books of the Old Testament—1. The Term Apocrypha and its Origin—2. Remarks on the Date of the Apocryphal Books—Their Reception by the Alexandrine Jews—3. History of these Books in the Christian Church—4. Their Uses—I. The Two Books of Esdras—5. Name of this Book—Its Contents—Its Date—6. The Second Book of Esdras found only in Versions—Remarks on these Versions—7. Its Contents and Date—II. Tobit—8. Accounts of the Contents of this Book—9. Various Texts in which this Book {15} is Extant—Its General Scope—III. Judith—10. Contents of the Book—11. Remarks on its Character, Date, and Design—IV. Additions to the Book of Esther—12. Account of these—V. The Wisdom of Solomon—13. Its Divisions and their Contents—14. Authorship of the Book—Its Merits and Defects—VI. Ecclesiasticus—15. Its Titles and Contents—16. Date of the Book and of its Translation—VII. Baruch and the Epistle of Jeremiah—17. Character and Contents of the Book of Baruch—18. Second, or Syriac Book of Baruch—19. So-called Epistle of Jeremiah—VIII. Additions to the Book of Daniel—20. Enumeration of these—Their Authorship and Date—IX. The Prayer of Manasses—21. Remarks on this Composition—X. The Books of the Maccabees—22. Number of these Books—Remarks on their Historic Order—Origin of the Name Maccabee—23. First Book—Its Genuineness and Credibility—Its Authorship and Date—Original Language—24. Second Book—Its Character and Contents—25. Third Book—Its Contents and Character—Fourth Book—Its Stoical Character—Its Contents—Fifth Book—Its Original Language and Contents

FIRST DIVISION—GENERAL INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER XXIV.

Language of the New Testament—1. God's Providence as seen in the Languages of the Old and New Testaments—Fitness of the Hebrew for its Office in History, Poetry, and Prophecy—2. Adaptation of the Greek to the Wants of the New Testament Writers—3. Providential Preparation for a Change in the Language of the Inspired Writings—Cessation of the Hebrew as the Vernacular of the Jews, and Withdrawal of the Spirit of Prophecy Contemporaneous—4. Introduction of the Greek Language into Asia and Egypt—Its Use among the Jews, especially in Egypt—Its General Use in our Lord's Day—5. Character of the New Testament Greek—Its Basis the Common Hellenic Dialect, with an Hebraic Coloring received from the Septuagint, and an Aramaic Tinge also—The Writers of the New Testament Jews using the Language of Greece for the Expression of Christian Ideas—Technical Terms in the New Testament—6. Adaptation of the New Testament Greek to its Office

CHAPTER XXV.

External Form of the New Testament—1. The Three Main Divisions of the New Testament Writings: Historical, Epistolary, Prophetical—2. Natural Order of these Divisions—3. Subdivisions—In the Historic Part—In the Epistolary Part—Diversity of Arrangement in Manuscripts—4. Arrangement of the New Testament Writings not Chronological—Importance of Knowing {16} this—5. Continuous Writing of the Ancient Uncial Manuscripts—Stichometrical Mode of Writing—This led gradually to the Present System of Interpunction Cursive Manuscripts—7. Ancient Divisions in the Contents of the Sacred Text—Ammonian Sections and Eusebian Canons—8. Divisions called Titles—9. Divisions of the Other New Testament Books—10. Chapters and Verses—Church Lessons—11. Remarks on the above Divisions—Paragraph Bibles—12. Titles and Subscriptions

CHAPTER XXVI.

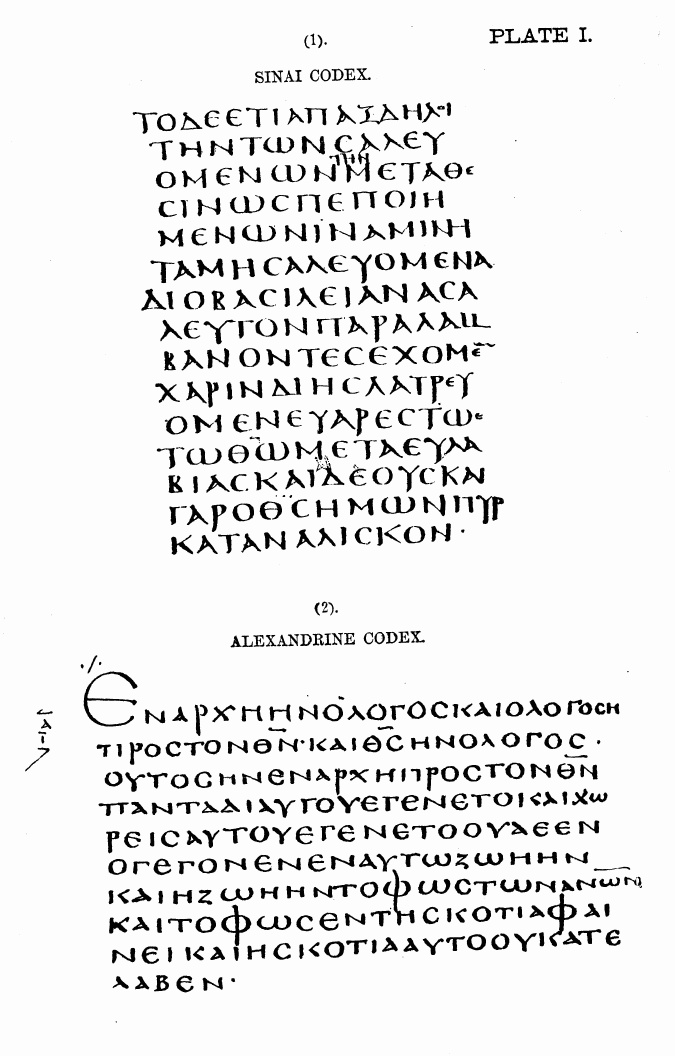

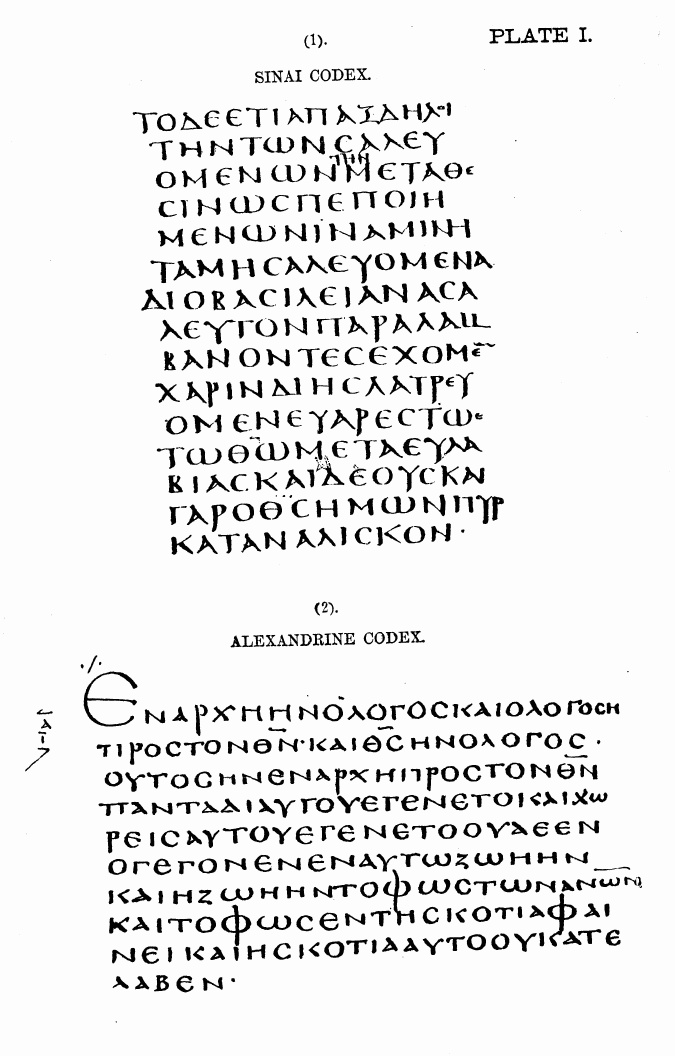

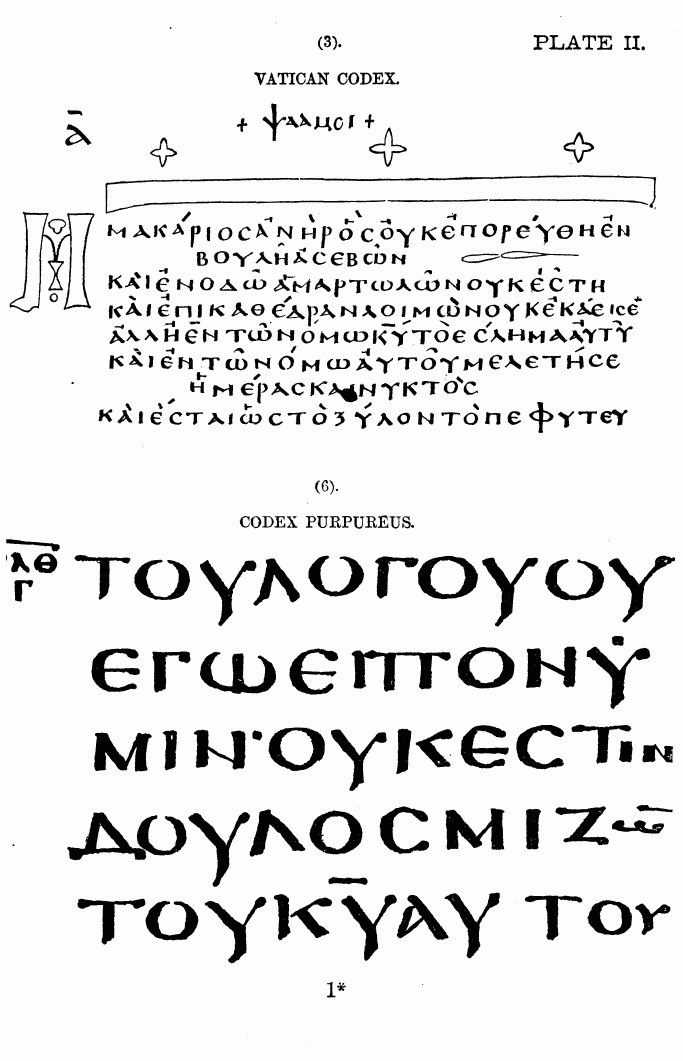

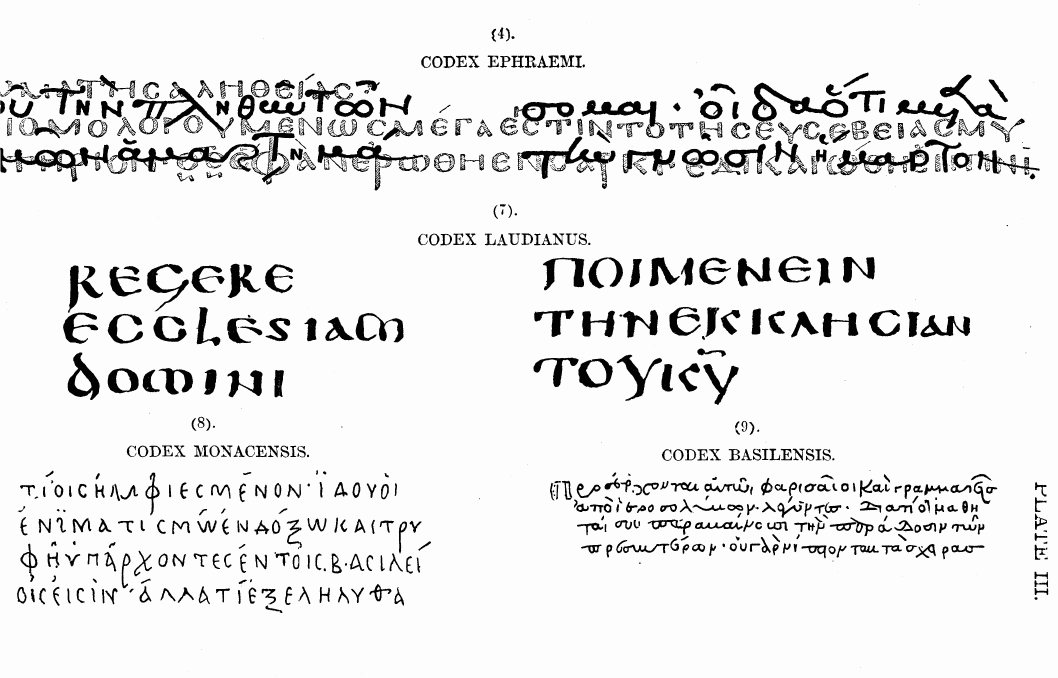

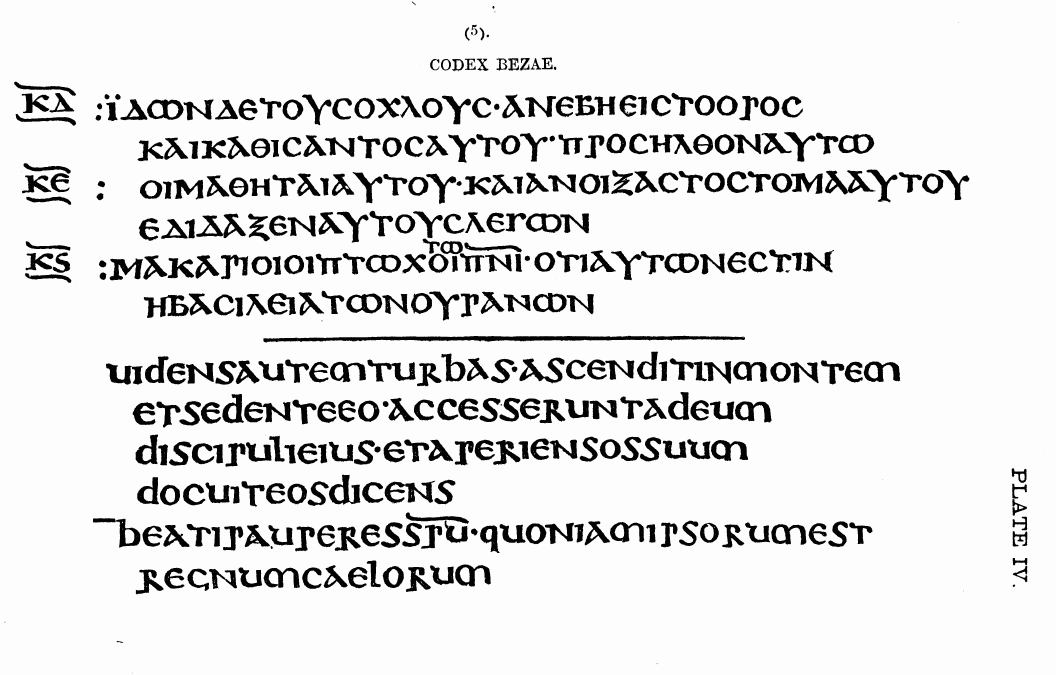

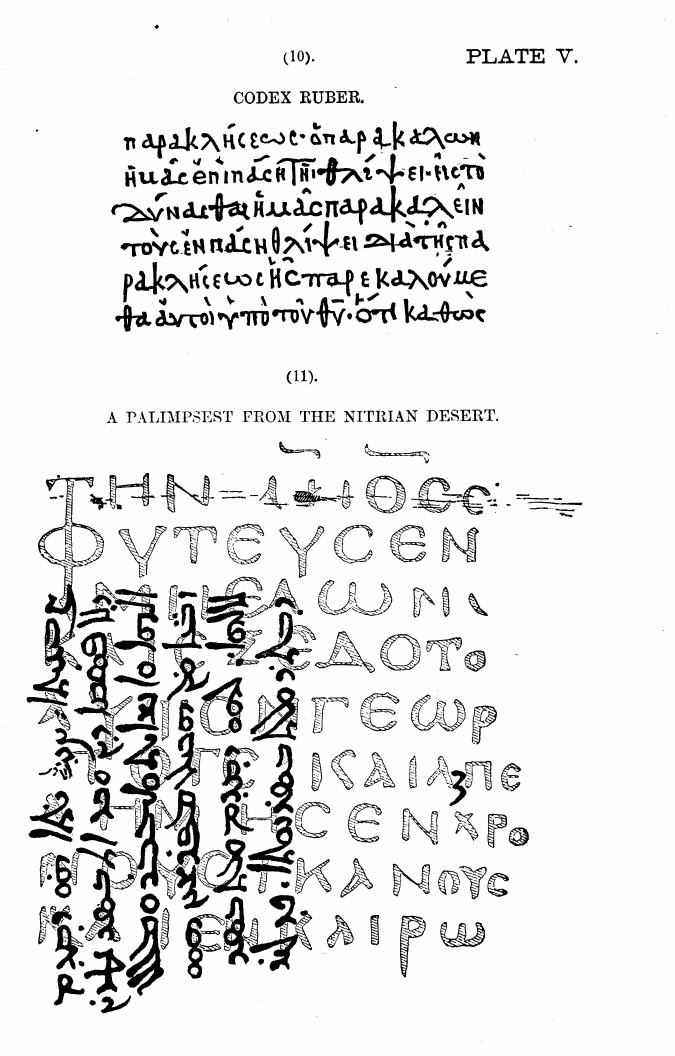

The New Testament Text and its History—I. The Manuscript Text—1 and 2. General Remarks—3. Origin of Various Readings and their Classification—Substitutions, Insertions, Omissions—Arising from Inadvertence, or Unskilful Criticism—Wilful Falsifications cannot be imputed to the Copyists—4. Materials for Textual Criticism—General Results—5. Notice of some Manuscripts—The Vatican, Sinai, Alexandrine, Ephraem, Palimpsest, Dublin Palimpsest, Beza or Cambridge (Bilingual), Purple. Cursive Manuscripts—II. The Printed Text—6. Primary Editions and their Sources—Complutensian Polyglott, Erasmian, Stephens', Beza's, Elzevir Editions—7. Remarks on the Received Text—III. Principles of Textual Criticism—8. Its End—Sources of Evidence—Greek Manuscripts—Their varying Value—9. Ancient Versions and their Value—10. Citations of the Church Fathers—11. Canons of Criticism

CHAPTER XXVII.

Formation and History of the New Testament Canon—1. General Remarks—2. Different Periods to be noticed—3. Apostolic Age—4. Age of the Apostolic Fathers—Remarks on their Quotations—5. Age of Transition—Events of this Age which awakened the Christian Church to a Full Consciousness of the Divine Authority of the Apostolic Writings—Execution of Versions—6. Age of the Early Church Fathers—They recognized a Canon, though not yet Complete—Canon of the Syriac Peshito, Muratorian Canon—Canon of the Councils of Laodicea and Carthage—7. Closing Remarks

CHAPTER XXVIII.

Ancient Versions of the New Testament—I. Latin Versions—1. Interest attaching to these Versions—2. The Ante-Hieronymian or Old Latin Version—3. Its Canon—Remarks on its Text—Manuscripts containing it—4. Jerome's Revision of the Old Latin Version—5. Jerome's New Version of the Old Testament—Books left untranslated—The Vulgate and its Diversified Character—Remarks on the History of the Vulgate—II. Syriac Versions—6. The Peshito—It comprises the Old and New Testaments—Its Date—Its Name—7. Character of the Peshito—The Curetonian Syriac—Its Relation to the Peshito—Its high Critical Value—8. The Philoxenian Syriac—Its extremely Literal Character—Hexaplar Syriac—Remarks on these Versions—Jerusalem Syriac Lectionary—III. Egyptian and Ethiopic Versions—Memphitic Version, Thebaic, Bashmuric—10. Ethiopic Version—IV. Gothic and other Versions—11. Gothic Version of Ulphilas—12. Palimpsest Manuscripts of this Version—13. Ancient Armenian Version

{17}SECOND DIVISION—PARTICULAR INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER XXIX.

The Historical Books—1. The New Testament a Necessary Sequel to the Old—The Two Testaments interpret Each Other, and can be truly understood only as an Organic Whole—2. Remarks on the Use Made of the Old Testament by the Writers of the New—Fundamental Character of the Gospel Narratives—I. The Gospel as a Whole—3. Signification of the Word "Gospel"—Its Primary and Secondary Application—4. General Remarks on the Relation of the Gospels to Each Other—5. Agreements of the Synoptic Gospels—6. Differences—7. Theories of the Origin of these Three Gospels: That of Mutual Dependence; That of Original Documents; That of Oral Apostolic Tradition—Remarks on this Tradition—Its Distinction from Tradition in the Modern Sense—8. No One of the Gospels gives the Entire History of our Lord, nor always observes the Strict Chronological Order of Events—Remarks on our Lord's Life before his Baptism—9. Remarks on the Peculiar Character of the Fourth Gospel—This and the other Three mutually Supplementary to Each Other—10. Harmonies of the Gospels—Relative Size of the Gospels—II. Matthew—11. Personal Notices of Matthew—12. Original Language of his Gospel—The Problem stated—13. Testimony of the Ancients on this Point—14. Various Hypotheses considered—15. Primary Design of this Gospel to show that Jesus of Nazareth was the Promised Messiah—16. He is also exhibited as the Saviour of the World—17. Fulness of Matthew's Record in Respect to our Lord's Discourses—18. He does not always follow the Exact Order of Time—19. Place and Date—20. Integrity—Genuineness of the First Two Chapters—III. Mark—21. Personal Notices of Mark—Intimate Relation of Mark to Peter and Paul—22. Place—Date—Language—23. Design of this Gospel to exhibit Jesus as the Son of God—He makes the Works of Jesus more Prominent than his Discourses—24. Characteristics of Mark as a Historian—25. Closing Passage in Mark's Gospel—IV. Luke—26. Notices of Luke in the New Testament—27. Sources of his Gospel—His Relation to Paul—28. Date and Place of Writing—29. Universal Aspect of Luke's Gospel—30. Its Character and Plan—Comparison of the Gospels in Respect to Peculiar Matter and Concordances—31. Integrity of Luke's Gospel—The Two Genealogies of Matthew and Luke—V. John—32. John's Manner of indicating himself—33. Personal Notices of him—34. Late Composition of his Gospel and Place of Writing—35. Peculiarity of this Gospel in Respect to Subject-Matter—Its Relation to the First Three Gospels—36. General Design of this Gospel—It is peculiarly the Gospel of Christ's Person—VI. Acts of the Apostles—37. Author of this Book—38. Plan of the Book—Its First Division; Second Division—Notices of Antioch—39. Office of this Book—Portraiture of the Apostolic Age of Christianity; Cursory View of the Inauguration of the Christian Church; Various Steps by which the Abolition of the Middle Wall of Partition between Jews and Gentiles was effected—40. Concluding Remarks

{18}CHAPTER XXX.

The Epistles of Paul—1. General Remarks on the Epistles—2. Paul's Epistles all written in the Prosecution of his Work as the Apostle to the Gentiles—Nature of this Work—3. Paul's Peculiar Qualifications for this Work—His Mode of Procedure—Union in him of Firmness and Flexibility—4. Character of the Apostle's Style—5. Points to be noticed in the Separate Epistles—Notices of Paul's Labors in the Acts of the Apostles—6. Present Arrangement of Paul's Epistles and of the Epistles generally—Chronological Order of Paul's Epistles—Four Groups of these Epistles—I. Epistle to the Romans—7. Date and Place of this Epistle—8. Composition of the Roman Church—9. Occasion and Design of the Epistle—Its General Outlines—10. Special Office of this Epistle—II. Epistles to the Corinthians—First Epistle—11. Place and Time of its Composition—12. Notices of the Corinthian Church—Occasion of the Apostle's Writing—13. General Tone of the Epistle as contrasted with that to the Galatians—Second Epistle—14. Place and Time of its Composition—15. Its Occasion—Prominence of the Apostle's Personality in this Epistle and its Ground—Peculiarities of its Diction—Its Office in the Economy of Revelation—III. Epistle to the Galatians—16. Historical Notice of Galatia—Missionary Visits of the Apostle to that Province—Date of the Present Epistle and Place of Composition—17. Occasion and Design—18. Outlines of the Epistle—The Historic Part, the Argumentative, the Practical—IV. Epistles to the Ephesians, Colossians, and Philemon—19. Contemporaneousness of these Epistles—20. Place and Date—21. Chronological Order of the First Two—Epistle to the Colossians—22. Notices of Colosse and the Church there—Occasion of this Epistle—Character of the False Teachers at Colosse—23. Outlines of the Epistle—Its Argumentative Part, its Practical—The Epistle from Laodicca—Epistle to the Ephesians—24. Notices of Ephesus—Labors of Paul at Ephesus—Occasion of the Present Epistle—Its General Character—Various Hypotheses respecting it—25. Its Outlines—Its Argumentative Part, its Practical—Epistle to Philemon—26. Its Occasion and Design—V. Epistle to the Philippians—27. Notices of Philippi and the Formation of the Church there—28. Occasion of this Epistle—Place and Date of its Composition—29. Its Character—General View of its Contents—VI. Epistles to the Thessalonians—30. Notices of Thessalonica and the Apostle's Labors there—First Epistle to the Thessalonians—31. Date and Place of its Composition—32. Its Occasion and Design—Outlines of the Epistle—Second Epistle—33. Place of Writing and Date—Its Design—Its General Outlines—34. Comparison between the Epistles to the Thessalonians and that to the Philippians—VII. The Pastoral Epistles—35. The Date of these Epistles and Related Questions—36. Character of the False Teachers referred to in these Epistles—37. Genuineness of the Pastoral Epistles—38. Their Office—First Epistle to Timothy—39. Its Date and Place of Composition—Its Occasion and Design—Its Contents—Scriptural Notices of Timothy—Epistle to Titus—40. Its Agreement with the Preceding Epistle—The Cretan Church and Titus—Second Epistle, to Timothy—41. Its Occasion and Character in Contrast with the Two Preceding Epistles—Its Office—Epistle to the Hebrews—42. Question of its Authorship—How it was regarded in the Eastern Church—How in the Western—General Remark—43. Persons addressed {19} in this Epistle—Time and Place of its Composition—Manner of Reference to the Levitical Priesthood and Temple Services—44. Central Theme of this Epistle—Dignity of Christ's Person in Contrast with the Ancient Prophets, with Angels, and with Moses—Divine Efficacy of his Priesthood in Contrast with that of the Sons of Aaron—Design of the Epistle—Its Office in the System of Revelation

CHAPTER XXXI.

The Catholic Epistles—1. Origin of the Name "Catholic"—1. Epistle of James—2. Question respecting the Person of James—3. Place of Writing this Epistle—Persons addressed—4. Question of its Date—5. Its Genuineness and Canonical Authority—6. Its Practical Character—Alleged Disagreement between Paul and James without Foundation—II. Epistles of Peter—First Epistle—7. Its Canonical Authority always acknowledged—8. Persons addressed—9. Place of its Composition—Its Occasion and Date—Traditions respecting Peter—10. Outline of the Epistle—Second Epistle—11. Persons addressed—Time of Writing—12. Question respecting the Genuineness of this Epistle—External Testimonies—Internal Evidence—General Result—13. Object of the Present Epistle—Peculiar Character of the Second Chapter—Its Agreement with the Epistle of Jude—III. Epistles of John—First Epistle of John—14. Its Acknowledged Canonicity—Time and Place of its Composition—Persons addressed—15. General View of its Contents—Second and Third Epistles—16. Their Common Authorship—Their Genuineness—17. The Occasion and Office of Each—IV. Epistle of Jude—18. Question respecting Jude's Person—Time of the Epistle, and Persons addressed—19. Its Canonical Authority—Its Design

CHAPTER XXXII.

The Apocalypse—1. Meaning of the Word "Apocalypse"—Abundance of External Testimonies to this Book—2. Internal Arguments considered—Use of the Apostle's Name, Devotional Views, Spirit of the Writer, Style and Diction—Here must be taken into Account the Difference between this Book and John's other Writings in Subject-Matter, in the Mode of Divine Revelation, in the Writer's Mental State and Circumstances; also its Poetic Diction—General Results—3. Date of the Apocalypse and Place of Writing—4. Different Schemes of Interpretation—The Generic—The Historic—5. Symbolic Import of the Numbers in this Book—The number Seven, Half of Seven, Six; The Number Four, a Third and Fourth Part; the Number Twelve; the Number Ten—6. Office of the Apocalypse in the System of Revelation

APPENDIX TO PART III.

Writings of the Apostolic Fathers, With Some Notices of the Apocryphal New Testament Writings—1. The Writings of the Apostolic Fathers distinguished from the Proper New Testament Apocrypha—Some Remarks on the Character of these Writings

{20}I. Writings of Clement of Rome—2. His Epistle to the Romans—Its Genuineness Character, and Age—3. Its Occasion, with a Notice of its Contents—4. The so-called Second Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians—Its Genuineness not admitted—Vague and General Character of its Contents—5. Notice of some Other Writings falsely ascribed to Clement—Recognitions of Clement, and the Clementines, with their Plan and Contents; Constitutions of Clement, and their Contents; Apostolic Canons

II. Epistles of Ignatius—6. Notices of Ignatius—The Seven Genuine Epistles that bear his Name—Unsatisfactory State of the Text—Syriac and Armenian Versions—Enumeration of these Epistles—Their Character—Strong Ecclesiastical Spirit that pervades them—His Letter to the Romans—The Undue Desire of Martyrdom which it manifests—His Letter to Polycarp—7. Spurious Epistles ascribed to Ignatius, and their Character

III. Epistle of Polycarp—8. Notices of Polycarp—His Epistle to the Philippians—Its Character and Contents—Time and Occasion of its Composition

IV. Writings of Barnabas and Hermas—9. Their Doubtful Authority—10. The So-called Epistle of Barnabas—Tischendorf's Discovery of the Original Greek Text—The Author and Date of the Work—Notice of its Contents—Its Fanciful Method of Interpretation—11. The Shepherd of Hernias—Outward Form of the Work—Its Internal Character—Its Author and Age

V. The Apostle's Creed—12. In what Sense it belongs to the Apostolic Fathers—Apostolic Character of its Contents

VI. Apocryphal Gospels and Acts—13. Their Number—Their Worthless Character in Contrast with that of the Canonical Gospels and Acts

CHAPTER XXXIII.

Introductory Remarks—1. Definition of Certain Terms—Hermeneutics, Exegesis, Epexegesis—2. The Expositor's Office—Parallel between his Work and that of the Textual Critic—3. Qualifications of the Biblical Interpreter—A Supreme Regard for Truth—4. A Sound Judgment with the Power of Vivid Conception—Office of Each of these Qualities and their Relation to Each Other—5. Sympathy with Divine Truth—6. Extensive and Varied Acquirements—The Original Languages of the Bible; Sacred Geography and Natural History; Biblical Antiquities; Ancient History and Chronology—7. General Remarks on the above Qualifications—8. The Human and Divine Side to Biblical Interpretation—The Importance of observing Both

{21}FIRST DIVISION—INTERPRETATION VIEWED ON THE HUMAN SIDE.

CHAPTER XXXIV.

General Principles of Interpretation—1. Signification of the Terms employed how ascertained, with some Superadded Remarks—2. On Ascertaining the Sense of Scripture—3. The Scope General and Special—Its Supreme Importance illustrated—How the Scope is to be ascertained—The Author's Statements; Inferential Remarks; Historical Circumstances—Important Help derived from the Repeated and Careful Perusal of a Work—4. The Context defined and distinguished from the Scope—Indispensable Necessity of attending to it—This illustrated by Examples—Question respecting the Limits of the Context—In some Cases no Context exists—On the Use of Biblical Texts as Mottoes—Various Applications of the Principle contained in a Given Passage a Legitimate Mode of Exposition—5. Parallelisms Verbal and Real—Help derived from the Former—Subdivision of Real Parallelisms into Doctrinal and Historic—Importance of Doctrinal Parallelisms with Illustrations—Value of Historic Parallelisms illustrated—Difficulties arising from them, and the Principle of their Adjustment—Illustration—6. External Acquirements—Various Illustrations of the Importance of these—7. Sound Judgment—Office of this Quality illustrated—Inept Interpretations: Interpretations Contrary to the Nature of the Subject; Necessary Limitations of an Author's Meaning; Reconciliation of Apparent Contradictions; Forced and Unnatural Explanations and the Rejection of Well-established Facts—8. Remarks on the Proper Office of Reason in Interpretation

CHAPTER XXXV.

Figurative Language of Scripture—1. Figurative Language defined and illustrated—General Remarks respecting it—2. Rules for the Ascertaining of Figurative Language—Nature of the Subject; Scope, Context, and Analogy of Scripture—Error of understanding Literal Language figuratively—Remark on the Interpretation of Prophecy—3. Different Kinds of Figures—The Trope in its Varieties of Metonymy, Synecdoche, and Metaphor—Remarks on Comparisons—The Allegory—Its Definition and Distinction from the Metaphor—Distinction between True Allegory and the Allegorical Interpretation of History—The Parable—How distinguished from the Allegory—The Fable—The Symbol—Its Various Forms—The Proverb—It always embodies a General Truth—Its Various Forms—Signification of the Word "Myth"—It does not come within the Sphere of Scriptural Interpretation—4. General Remarks on the Interpretation of the Figurative Language of Scripture—5. Its Certainty and Truthfulness—6. Key to the Interpretation of the Allegory—Examples: The Vine Transplanted from Egypt, Psa. 80; the two Eagles and the Cedar Bough, Ezek. 17:3-10; The Song of Solomon; the Two Allegories of Ezekiel, chaps., 16 and 23-7. The Interpretation of the Parable—How it differs from that of the Allegory—Point of Primary Importance—How far the Details are significant—Examples: The Sower, Matt. 13:3-8, 19-23; the Tares in the Field {22} Matt. 13:24-30, 37-43; the Ten Virgins, Matt, 25:1-13—Remark respecting the Personages introduced in Parables with Illustrations—The Unforgiving Servant, Matt. 18: 23-35; the Importunate Friend, Luke 11:5-8; the Unjust Judge, Luke 18:1-8; the Unfaithful Steward, Luke 16:1-9—8. Scriptural Symbols-How to determine whether they are Real or Seen in Prophetic Vision—Principles on which they are to be interpreted—Examples—9. Remarks on the Interpretation of Numerical Symbols

SECOND DIVISION—INTERPRETATION VIEWED ON THE DIVINE SIDE.

CHAPTER XXXVI.

Unity of Revelation—1. Essential Unity between the Old and the New Testament—2. This Unity one that coexists with Great Diversity—Illustrations from the Analogy of God's Works—3. Unity in Diversity in Respect to the Form of God's Kingdom—4. The Forms of Public Worship—5. Forms of Religious Labor—6. Spirit of Revelation—7. Way of Salvation—8. Sternness of the Mosaic Dispensation explained from its Preparatory Character—9. Inferences from the Unity of Revelation—9. Each Particular Revelation Perfect in its Measure—10. The Later Revelations the Exponents of the Earlier; Christ and his Apostles in a Special Sense the Expositors of the New Testament—11. The Extent of Meaning in a Given Revelation that which the Holy Spirit intended—12. The Obscure Declarations of Scripture to be interpreted from the Clear, with Illustrations—13. Remarks on the Analogy of Faith—The Term Defined—Rules for its Use

CHAPTER XXXVII.

Scriptural Types—1. Types distinguished from Analogy—2. And from the Foreshadowing of Future Events by the Present—3. The Type defined in its Three Essential Characters

I. Historical Types—4. In Respect to these Two Extremes to be avoided—Typical History has a Proper Significance of its Own—This illustrated by Examples: The Kingly Office; the Prophetical Office; Typical Transactions—Remarks on the Inadequacy of All Types

II. Ritual Types—5. The Sacrifices the Essential Part of the Mosaic Ritual—What is implied in them—The Sanctuary God's Visible Dwelling-place where alone they could be offered—6. The Mosaic Tabernacle described—7. Its General Typical Import—8. Significance of its Different Parts and Appointments—Preciousness of the Materials; Gradation in this Respect—9. The Inner Sanctuary with its Appointments—10. The Outer Sanctuary with its Appointments—11. The Brazen Altar with its Laver—The Levitical Priests typified Christ—12. The Levitical Sacrifices typified Christ's Offering of Himself for the Sins of the World—This shown from Scripture—General Remark respecting Christ's Propitiatory Sacrifice—13. Characteristics of the Types {23} Themselves—The Levitical Priests had a Common Human Nature with those for whom they officiated; were appointed to their Office by God; were Mediators between God and the People; and Mediators through Propitiatory Sacrifices—Points of Dissimilarity between the Type and the Antitype—Remarks on the Central Idea of Priesthood—14. Scriptural Idea of Sacrifice the Offering of One Life in Behalf of Another—Classification of the Levitical Sacrifices with the Ideas belonging to Each: Sin and Trespass Offerings; Burnt Offerings; Peace-Offerings—Sacrificial Nature of the Passover—Other Sacrifices of a Special Character—All Sacrificial Victims to be without Blemish—The Unbloody Offerings and their Signification—15. Typical Transactions connected with the Sacrifices and Oblations: The Laying of the Offerer's Hands on the Head of the Victim; the Waving and Heaving of Offerings; the Sprinkling of the Victim's Blood; the Burning of the Offering—16. Typical Meaning of the Tabernacle as a Whole—The Several Points of Adumbration considered: Adumbration of God's Presence with Men; Impossibility of approaching God without a Mediator; Adumbration of Christ's Expiatory Sacrifice and Heavenly Intercession on the Great Day of Atonement; Burning of the Victim without the Camp—17. Distinctions between Clean and Unclean—Levitical View of Bodily Infirmities

CHAPTER XXXVIII.

Interpretation of Prophecy—1. General Remarks

I. Prophecies relating to the Near Future—2. Their Specific Character—Examples

II. Prophecies relating to the Last Days—3. Meaning of the Term "Last Days," and its Equivalents—General Character of this Class of Prophecies—4. Prophecies in which the Order of Events is indicated—Daniel's Fourth Monarchy; the Great Red Dragon of Revelation, the Two Beasts that succeeded to his Power, and the Woman riding a Scarlet-Colored Beast—5. Prophecies which give General Views of the Future—Examples—6. The Prophets give an Inward View of the Vital Forces which sustain and extend God's Kingdom—Unity of the Plan of Redemption; its Continual Progress; Indications of the End towards which it is tending; the End Itself the Chief Object of Interest—Great Crisis in the Church's History—Spirit that should actuate the Interpreter of Prophecy

III. Question of Double Sense—7. The Term defined—8. Examples of Literal and Typical Sense—Melchizedek's Priesthood; the Rest of Canaan—9. The Messianic Psalms—Different Principles on which they are interpreted: Exclusive Application to Christ; Reference to an Ideal Personage; Christ the Head and his Body the Church; Typical View—10. The Principle of Progressive Fulfilment

IV. Question of Literal and Figurative Meaning—11. General Remarks—12. Representative Use in Prophecy of Past Events—13. Of the Institutions of the Mosaic Economy—14. The Principle of Figurative Interpretation not to be pressed as Exclusive—15. Question of the Literal Restoration of the Jews to the Land of Canaan—16. Question of our Lord's Personal Reign on Earth during the Millennium

{24}CHAPTER XXXIX.

Quotations From The Old Testament in the New—1. General Remarks on the Authority of the New Testament Writers—2. Outward Form of their Quotations—Its very Free Spirit—This illustrated by Example—3. Contents of the New Testament Quotations—The So-called Principle of Accommodation; in what Sense True, and in what Sense to be rejected—4. Quotations by Way of Argument—5. Quotations as Prophecies of Christ and his Kingdom—Remarks on the Formula: "That it might be fulfilled"—6. Prophecies referring immediately to Christ—7. Prophecies referring to Christ under a Type—Closing Remark

{26}Many thousands of persons have a full and joyous conviction of the truth of Christianity from their own experience, who yet feel a reasonable desire to examine the historic evidence by which it is confirmed, if not for the strengthening of their own faith, yet for the purpose of silencing gainsayers, and guarding the young against the cavils of infidelity. It is our duty to give to those who ask us a reason of the hope that is in us; and although our own personal experience may be to ourselves a satisfactory ground of assurance, we cannot ask others to take the gospel on our testimony alone. It is highly desirable that we understand and be able to set forth with clearness and convincing power the proofs that this plan of salvation has God for its author.

Then there is a class of earnest inquirers who find themselves perplexed with the difficulties which they hear urged against the gospel, and which they find themselves unable to solve in a satisfactory way. It is of the highest importance that such persons be met in a candid spirit; that the immense mass of evidence by which the Christian religion is sustained be clearly set before them; and that they understand that a religion thus supported is not to be rejected on the ground that there are difficulties connected with it which have not yet been solved—perhaps never can be solved here below.

Are you, reader, such an earnest inquirer after truth? We {28} present to you in the following pages a brief summary of the historic evidence by which the Bible, with the plan of salvation which it reveals, is shown to be the word of God; and we wish, here at the outset, to suggest to you some cautions respecting the state of mind with which this great inquiry is to be pursued.

First of all, we remind you that, whatever else may be uncertain, you know that you must soon die, and try for yourself the realities of the unseen world. The question now before you is, Whether God has spoken from heaven, and made any revelations concerning that world. If so, they are more precious than gold; for in the decisive hour of death you will wish to know not what man, the sinner, has reasoned and conjectured concerning a future judgment, forgiveness of sin, and the life to come; but what God, the Judge, has declared. Now the Bible claims to contain such a message from God. If its claims are valid, it will not flatter you and speak to you smooth things, but will tell you the truth. And you must be prepared to receive the truth, though it condemn you. Sooner or later you must meet the truth face to face: be ready to do so now; you have no interest in error; falsehood and delusion cannot help you, but will destroy you.

Do not come to the examination of this great question with the idea that you must clear away all mysteries connected with the gospel before you believe it. The world in which you live is full of mysteries. One would think that if any thing could be fully comprehended, it must be the acts of which we are ourselves the authors. By a volition you raise your hand to your head; but how is the act performed? True, there is in your body an apparatus of nerves, muscles, joints, and the like; but in what way does the human will have power over this apparatus? No man can answer this question: it is wrapped {29} in deep mystery. Why be offended, then, because the way of salvation revealed in the Bible has like mysteries—mysteries concerning not your duty, but God's secret and inscrutable methods of acting?

And since the question now before you is not one of mere speculation, but one that concerns your immediate duty, be on your guard against the seductive influence of sinful passion and sinful habit. There is a deep and solemn meaning in the words of Jesus: "Every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved." Corrupt feeling in the heart and corrupt practice in the life have a terrible power to blind the mind. The man who comes to the examination of the Bible with a determination to persist in doing what he knows to be wrong, or in omitting what he knows to be right, will certainly err from the truth; for he is not in a proper state of mind to love it and welcome it to his soul.

Remember also that it is not the grosser passions and forms of vice alone that darken the understanding and alienate the heart from the truth. Pride, vanity, ambition, avarice—in a word, the spirit of self-seeking and self-exaltation in every form—will effectually hinder the man in whose bosom they bear sway from coming to the knowledge of the truth; for they will incline him to seek a religion which flatters him and promises him impunity in sin, and will fatally prejudice him against a system of doctrines and duties so holy and humbling as that contained in the Bible. Take, as a comprehensive rule for the investigation of this weighty question, the words of the Saviour: "If any man will do his will"—the will of God—"he shall know of the doctrine, whether it be of God, or whether I speak of myself." So far as you already know the will of God, do it; do it sincerely, earnestly, and prayerfully, and God will give {30} you more light. He loves the truth, and sympathizes with all earnest and sincere inquirers after it. He never leaves to fatal error and delusion any but those who love falsehood rather than truth, because they have pleasure in unrighteousness. Open your heart to the light of heaven, and God will shine into it from above; so that, in the beautiful words of our Saviour, "the whole shall be full of light, as when the bright shining of a candle doth give thee light."

{31}I. The Christian religion is not a mere system of ideas, like the philosophy of Plato or Aristotle. It rests on a basis of historic facts. The great central fact of the gospel is thus expressed by Jesus himself: "God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life," John 3:16; and by the apostle Paul thus: "This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptation, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners." 1 Tim. 1:15. With the appearance of God's Son in human nature were connected a series of mighty works, a body of divine teachings, the appointment of apostles and the establishment of the visible Christian church; all which are matters of historic record.

Nor is this all. It is the constant doctrine of Christ and his apostles that he came in accordance with the scriptures of the Old Testament, and that his religion is the fulfilment of the types and prophecies therein contained: "Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil." Matt. 5:17. "All things must be fulfilled which were written in the law of Moses, and in the prophets, {32} and in the psalms concerning me." Luke 24:44. The facts of the New Testament connect themselves, therefore, immediately with those of the Old, so that the whole series constitutes an indivisible whole. The Bible is, from beginning to end, the record of a supernatural revelation made by God to men. As such, it embraces not only supernatural teachings, but supernatural facts also; and the teachings rest on the facts in such a way that both must stand or fall together.

II. This basis of supernatural facts, then, must be firmly maintained against unbelievers whose grand aim is to destroy the historic foundation of the gospel, at least so far as it contains supernatural manifestations of God to men. Thus they would rob it of its divine authority, and reduce it to a mere system of human doctrines, like the teachings of Socrates or Confucius, which men are at liberty to receive or reject as they think best. Could they accomplish this, they would be very willing to eulogize the character of Jesus, and extol the purity and excellence of his precepts. Indeed, it is the fashion of modern unbelievers, after doing what lies in their power to make the gospel a mass of "cunningly-devised fables" of human origin, to expatiate on the majesty and beauty of the Saviour's character, the excellence of his moral precepts, and the benign influence of his religion. But the transcendent glory of our Lord's character is inseparable from his being what he claimed to be—the Son of God, coming from God to men with supreme authority; and all the power of his gospel lies in its being received as a message from God. To make the gospel human, is to annihilate it, and with it the hope of the world.

III. When the inquiry is concerning a long series of events intimately connected together so as to constitute one inseparable whole, two methods of investigation are open to us. We may look at the train of events in the order of time from beginning to end; or we may select some one great event of especial prominence and importance as the central point of inquiry, and from that position look forward and backward. The latter of {33} these two methods has some peculiar advantages, and will be followed in the present brief treatise. We begin with the great central fact of revelation already referred to, that "the Father sent the Son to be the Saviour of the world." 1 John 4:14. When this is shown to rest on a foundation that cannot be shaken, the remainder of the work is comparatively easy. From the supernatural appearance and works of the Son of God, as recorded in the four gospels, the supernatural endowment and works of his apostles, as recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, and their authoritative teachings, as contained in their epistles, follow as a natural and even necessary sequel. Since, moreover, the universal rule of God's government and works is, "first the blade, then the ear, after that the full corn in the ear," (Mark 4:28,) it is most reasonable to suppose that such a full and perfect revelation as that which God has made to us by his Son, which is certainly "the full corn in the ear," must have been preceded by exactly such preparatory revelations as we find recorded in the Old Testament. Now Jesus of Nazareth appeared among the Jews, the very people that had the scriptures of the Old Testament, and had been prepared for his advent by the events recorded in them as no other nation was prepared. He came, too, as he and his apostles ever taught, to carry out the plan of redemption begun in them. From the position, then, of Christ's advent, as the grand central fact of redemption, we look backward and forward with great advantage upon the whole line of revelation.

IV. We cannot too earnestly inculcate upon the youthful inquirer the necessity of thus looking at revelation as a whole. Strong as are the evidences for the truth of the gospel narratives considered separately, they gain new strength, on the one side, from the mighty revelations that preceded them and prepared the way for the advent of the Son of God; and on the other, from the mighty events that followed his advent in the apostolic age, and have been following ever since in the history of the Christian church. The divine origin of the Mosaic institutions can be shown on solid grounds, independently of the {34} New Testament; but on how much broader and deeper a foundation are they seen to rest, when we find (as will be shown hereafter, chap. 8) that they were preparatory to the incarnation of Jesus Christ. As in a burning mass, the heat and flame of each separate piece of fuel are increased by the surrounding fire, so in the plan of redemption, each separate revelation receives new light and glory from the revelations which precede and follow it. It is only when we view the revelations of the Bible as thus progressing "from glory to glory," that we can estimate aright the proofs of their divine origin. If it were even possible to impose upon men as miraculous a particular event, as, for example, the giving of the Mosaic law on Sinai, or the stones of the day of Pentecost, the idea that there could have been imposed on the world a series of such events, extending through many ages, and yet so connected together as to constitute a harmonious and consistent whole, is a simple absurdity. There is no explanation of the unity that pervades the supernatural facts of revelation, but that of their divine origin.

V. In strong contrast with this rational way of viewing the facts of revelation as a grand whole, is the fragmentary method of objectors. A doubt here, a cavil there, an insinuation yonder; a difficulty with this statement, an objection to that, a discrepancy here—this is their favorite way of assailing the gospel. If one chooses to treat the Bible in this narrow and uncandid way, he will soon plunge himself into the mire of unbelief. Difficulties and objections should be candidly considered, and allowed their due weight; but they must not be suffered to override irrefragable proof, else we shall soon land in universal skepticism: for difficulties, and some of them too insoluble, can be urged against the great facts of nature and natural religion, as well as of revelation. To reject a series of events supported by an overwhelming weight of evidence, on the ground of unexplained difficulties connected with them, involves the absurdity of running into a hundred difficulties for the sake of avoiding five. If we are willing to examine the {35} claims of revelation as a whole, its divine origin will shine forth upon us like the sun in the firmament. Our difficulties we can then calmly reserve for further investigation here, or for solution in the world to come.

VI. When we institute an examination concerning the facts of revelation, the first question is that of the genuineness and uncorrupt preservation of the books in which they are recorded; the next, that of their authenticity and credibility. We may then conveniently consider the question of their inspiration. In accordance with the plan marked out above, (No. III.,) the gospel narratives will be considered first of all; then the remaining books of the New Testament. After this will be shown the inseparable connection between the facts of revelation recorded in the Old Testament and those of the New; and finally, the genuineness of the books which constitute the canon of the Old Testament, with their authenticity and inspiration. The whole treatise will be closed by a brief view of the internal and experimental evidences which commend the Bible to the human understanding and conscience as the word of God.

{36}I. Preliminary Remarks. 1. A book is genuine if written by the man whose name it bears, or to whom it is ascribed; or when, as in the case of several books of the Old Testament, the author is unknown, it is genuine if written in the age and country to which it is ascribed. A book is authentic which is a record of facts as opposed to what is false or fictitious; and we call it credible when the record of facts which it professes to give is worthy of belief. Authenticity and credibility are, therefore, only different views of the same quality.

In the case of a book that deals mainly with principles, the question of authorship is of subordinate importance. Thus the book of Job, with the exception of the brief narratives with which it opens and closes, and which may belong to any one of several centuries, is occupied with the question of Divine providence. It is not necessary that we know what particular man was its author, or at what precise period he wrote. We only need reasonable evidence (as will be shown hereafter) that he was a prophetical man, writing under the guidance of the Holy Spirit. But the case of the gospel narratives is wholly different. They contain a record of the supernatural appearance and works of the Son of God, on the truth of which rests our faith in the gospel. So the apostle Paul reasons: "If Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain." 1 Cor. 15:14. It is, then, of vital importance that we know the relation which the authors of these narratives held to Christ. If they were not apostles or apostolic men, that is, associates of the apostles, laboring with them, enjoying their full confidence, and in circumstances to obtain their information directly from them—but, instead of this, wrote after the apostolic age—their testimony is not worthy of the unlimited faith which the church in all ages has reposed in it. The question, then, of the genuineness of the gospel narratives and that of their authenticity and credibility must stand or fall together.

2. In respect to the origin of the gospels, as also of the other books of the New Testament, the following things should be carefully remembered:

{37}First. There was a period, extending, perhaps, through some years from the day of Pentecost, when there were no written gospels, their place being supplied by the living presence and teachings of the apostles and other disciples of our Lord.

Secondly. When the need of written documents began to be felt, they were produced, one after another, as occasion suggested them. Thus the composition of the books of the New Testament extended through a considerable period of years.

Thirdly. Besides the gospels universally received by the churches, other narratives of our Lord's life were attempted, as we learn from the evangelist Luke (1:1); but those never obtained general currency. The churches everywhere received the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, because of the clear evidence which they had of their apostolic origin and trustworthiness; and because, also, these gospels, though not professing to give a complete account of our Lord's life and teachings, were nevertheless sufficiently full to answer the end for which they were composed, being not fragmentary sketches, but orderly narratives, each of them extending over the whole course of our Lord's ministry. The other narratives meanwhile gradually passed into oblivion. The general reception of these four gospels did not, however, come from any formal concert of action on the part of the churches, (as, for example, from the authoritative decision of a general council, since no such thing as a general council of the churches was known till long after this period;) but simply from the common perception everywhere of the unimpeachable evidence by which their apostolic authority was sustained.

The narratives referred to by Luke were earlier than his gospel. They were not spurious, nor, so far as we know, unauthentic; but rather imperfect. They must not be confounded with the apocryphal gospels of a later age.

3. In respect to the quotations of Scripture by the early fathers of the church, it is important to notice their habit of {38} quoting anonymously, and often in a loose and general way. They frequently cite from memory, blending together the words of different authors, and sometimes intermingling with them their own words. In citing the prophecies of the Old Testament in an argumentative way, they are, as might have been expected, more exact, particularly when addressing Jews; yet even here they often content themselves with the scope of the passages referred to, without being particular as to the exact words.

With the above preliminary remarks, we proceed to consider the evidences, external and internal, for the genuineness of the gospel narratives.

II. External Evidences. 4. Here we need not begin at a later date than the last quarter of the second century. This is the age of Irenæus in Gaul, of Tertullian in North Africa, of Clement of Alexandria in Egypt, and of some other writers. Their testimony to the apostolic origin and universal reception of our four canonical gospels is as full as can be desired. They give the names of the authors, two of them—Matthew and John—apostles, and the other two—Mark and Luke—companions of apostles and fellow-laborers with them, always associating Mark with Peter, and Luke with Paul; they affirm the universal and undisputed reception of these four gospels from the beginning by all the churches; and deny the apostolic authority of other pretended gospels. In all this, they give not their individual opinions, but the common belief of the churches. It is conceded on all hands that in their day these four gospels were universally received by the churches as genuine and authoritative records of our Lord's life and works, to the exclusion of all others.