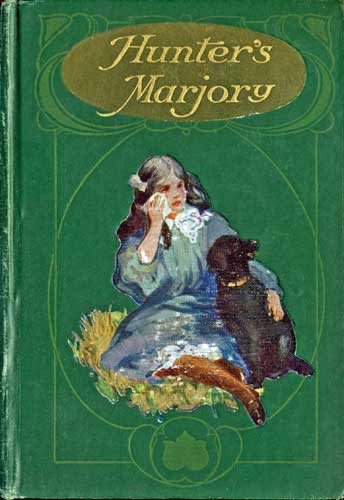

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Hunter's Marjory, by Margaret Bruce Clarke

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Hunter's Marjory

A Story for Girls

Author: Margaret Bruce Clarke

Release Date: January 3, 2007 [EBook #20258]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HUNTER'S MARJORY ***

Produced by Louise Pryor, Janet Blenkinship and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

TOMAS NELSON AND SONS

London, Edinburgh, Dublin, and New York

1907

Inconsistency in spelling and punctuation is as in the original.

| I. | TEARS. | 9 |

| II. | A FRIEND IN NEED. | 23 |

| III. | UNCLE AND NIECE. | 38 |

| IV. | TEA AT HUNTERS' BRAE. | 52 |

| V. | A VISIT TO THE LOW FARM. | 66 |

| VI. | CONFIDENCES. | 79 |

| VII. | MARJORY'S APOLOGY. | 94 |

| VIII. | THE SECRET CHAMBER. | 108 |

| IX. | PETER'S STORY. | 124 |

| X. | MARJORY'S BIRTHDAY. | 144 |

| XI. | THE MYSTERIOUS STRANGER. | 160 |

| XII. | MARJORY KEEPS A SECRET. | 175 |

| XIII. | THE OLD CHEST. | 188 |

| XIV. | THE PROPHECIES. | 202 |

| XV. | TWELFTH NIGHT. | 218 |

| XVI. | MISS WASPE GIVES GOOD ADVICE. | 232 |

| XVII. | ON THE LOCH. | 246 |

| XVIII. | THE STRANGER RETURNS. | 259 |

| XIX. | IMPORTANT LETTERS. | 274 |

| XX. | THE DOCTOR'S DISAPPOINTMENT. | 288 |

| XXI. | HOPES REALIZED. | 300 |

Marjory was lying under a tree in the wood beyond her uncle's garden; her head was hidden in the long, soft coat of a black retriever, and she was crying—sobbing bitterly as if her heart would break, and as if nothing could ever comfort her again.

"O Silky," she moaned, "if you only knew, you would be so sorry for me."

The faithful dog knew that something very serious was the matter with his young mistress, but he could only lick her hands and wag his tail as well as he was able with her weight upon his body.

A fresh burst of grief shook the girl; and Silky, puzzled by this unusual behaviour on Marjory's part,10 began to make little low whines himself. Suddenly the whines were changed to growls, the dog shook himself free from the girl's clasping arms and stood erect, staring into the wood beyond.

Marjory was too much overcome by her grief to notice Silky's doings, and it was not until she heard a voice quite close to her saying, "You poor little thing, what is the matter?" that she realized that she was not alone.

She looked up, startled, wondering who this stranger could be making free of her uncle's woods. She saw a lady, tall and fair, looking kindly at her, and a girl who might have stepped out of a picture, so sweet and fresh and pretty she looked in her white frock and shady hat.

For one minute Marjory gazed at her in admiration, and then, conscious of her tear-stained face and tumbled dress, let her head droop again and sobbed afresh.

The lady spoke again: "My dear child, what is wrong?"

"Nothing," sobbed Marjory—"nothing that I can tell you."

She felt ashamed of being seen in such a plight, and had an instinctive dislike of showing her feelings to a stranger, for Marjory was an extremely shy girl.

"But, my dear," remonstrated the lady, "I cannot leave you like this; besides," with a smile most winning, if only Marjory could have seen it, "I11 believe you are trespassing upon our newly-acquired property."

Marjory raised her head at this, and said quickly, and perhaps just a little proudly,—

"Oh no, I'm not; this is my uncle's ground."

"Oh dear; then Blanche and I are the trespassers, though quite innocent ones. And you must be Marjory Davidson, I think—Dr. Hunter's niece; and if so, I know a great deal about you, and we are going to be friends, and you must let me begin by helping you now."

So saying, the lady seated herself on the ground beside Marjory, her daughter looking on, at the same time stroking and patting Silky, who seemed much more disposed to be friendly than his mistress.

"Can't you tell me what the trouble is, Marjory? I am Mrs. Forester, and this is my daughter Blanche. We have just come to live at Braeside. Your uncle called on us to-day, and told us about you. Blanche and I have been looking forward to seeing you and making friends.—Haven't we, Blanche?"

"Yes, I've thought of nothing else since I heard about you," said the girl, rather shyly, the colour coming into her face as she spoke.

Marjory stole another glance at her, and she thought she had never seen or imagined any one so sweet and pretty as this girl.

"Blanche," she thought—"that means white; I know it from the names of roses and hyacinths.12 I've seen it on the labels. And she is just like her name—like a beautiful white rose with the tiniest bit of pink in it."

"Come now, Marjory dear," coaxed Mrs. Forester; "won't you take us for friends, and tell me a little about this trouble of yours? Won't you let me try to help you out of it?"

"No, you can't help me; nobody can. It's very kind of you," stammered Marjory, "but it's no use."

"Suppose you tell me, and let me judge whether I can help you or not." And Mrs. Forester took hold of one of Marjory's little brown hands and stroked it gently.

The soft touch and the gentle voice won Marjory's heart at last, and she said brokenly, between her sobs,—

"It's about—learning things—and going to school—and uncle—won't let me, and—and he won't tell me about my father, and I don't belong to anybody."

"Poor child, poor little one, don't cry so. Try to tell me all about it. I don't quite understand, but I am sure I shall be able to help you."

Bit by bit the story came out. The poor little heart unburdened itself to sympathetic ears, and the girl could hardly believe that it was she—Marjory Davidson—who was talking like this to a stranger. She felt for the first time in her life the relief of confiding in some one who really understands, and she experienced the comfort that sympathy can13 give. She felt as though she were dreaming, and that this gentle woman, whose touch was so loving and whose voice was so tender, might be the mother whom, alas! she had never seen but in her dreams.

Marjory's mother had died when her baby was only a few days old, and all that the child had ever been told about her father was that he was away in foreign parts at the time of her mother's death, and that he had never been seen or heard of since. Many and many a time did she think of this unknown father. Was he still alive? Did he never give a thought to his little girl? Would he ever come home to see her?

The true story was this: Dr. Hunter had been devotedly fond of his sister Marjory—the only one amongst several brothers and sisters who had lived to grow up. Many years younger than himself, she had been more like a daughter to him than a sister. On the death of their parents he had been left her sole guardian, and she had lived with him and been the light and joy of his home. The doctor might seem hard and cold to outsiders, wrapped up in his scientific studies and pursuits, giving little thought or care to any other affairs, but he had an intense capacity for loving, and he lavished his affection upon his young sister, leaving nothing undone that might increase her happiness or her comfort.

All went well until she married Hugh Davidson,14 handsome, careless, and of a roving disposition, as the doctor pronounced him to be. They loved each other, and the doctor had to take the second place.

Mr. and Mrs. Davidson made their home in England for a few months after their marriage; then he received an imperative summons from the other side of the world requiring his presence. He was needed to look after some mining property in the far away North-West in the interests of a company to which he belonged. He bade a hurried farewell to his wife, promising to be back in six months. She went home to her brother at Hunters' Brae, and lived with him until her death. She never recovered from the shock of the parting. Her husband's letters were of necessity few and far between. She had no idea of the difficulties and hardships of his life, and although she defended his long silences when the doctor made comment upon them, still she felt it was very hard that he should write so seldom, and when he did write that the letters should be so short. Could she have seen him struggling through an ice-bound country, enduring hardships and even privations such as are unknown to the traveller of to-day; could she have seen all this, she could never have blamed him, she could only have praised him for his faithful service to those who had sent him, and the cheerful tone of his letters to her, with no word of personal complaint.

But Mrs. Davidson slowly lost her strength. She15 faded away as a beautiful fragile lily might, and Hunters' Brae was once more left desolate—yet not quite desolate, for there was the baby girl; and, thinking of her, the doctor resolved that she should take her mother's place with him. He would devote himself to her, he would try to avoid all the mistakes he had made with his sister, and, above all, her father should not even know of her existence. He would keep her all to himself, she should know no other care but his, and thus her whole affection should be his alone.

It must be owned that jealousy had blinded Dr. Hunter to his brother-in-law's good qualities. He had never troubled to inquire into the circumstances of his going abroad. Enough for him that the man had left his wife alone only a few months after their marriage, and he obstinately refused to hear one word in his defence, and would believe no good of him. He was quite honest in his desire to do the best that was possible for the child, and in the feeling that it would be better to keep all knowledge of her father from her. He looked upon Hugh Davidson as a black sheep. A black sheep could do no good to any one; therefore, he argued, he should not come near this precious child.

Acting upon this determination, he wrote a very curt note to Mr. Davidson, acquainting him with the fact of his wife's death, and telling him that it was entirely his fault—that he had practically16 killed her by leaving her alone—but making no mention of the child.

Poor Mr. Davidson received this letter just at a time when he dared to hope that his work was nearly done and he could allow himself to think of going home, and his grief was pitiable. He had no near relatives, having been the only child of his parents, who had been dead many years. His wandering life had cut him adrift from the acquaintances and surroundings of his youth. He and his wife had lived in a world of their own during those few short months, and she had been his only correspondent in the old country when he left it. Thus it came about that there was no one to give him the information which Dr. Hunter withheld; and the poor man, thinking himself alone in the world, with no ties, no friends, never had the heart to return home to the scenes of his former happiness; and thus it was that he never knew, never thought of his little girl growing up in that remote Scottish home, lonely like himself, longing for and dreaming of things that seemed beyond her reach.

In the first weeks after his sister's death Dr. Hunter derived much consolation from the thought of the child. He had named her Marjory after her mother, and took it for granted that she would be just such another Marjory—fair-haired and blue-eyed—and he pictured her growing up gentle and17 quiet, as her mother had been. Certainly the infant's eyes were blue at first, and there was no hair to be seen on her head to trouble the doctor's visions by its unexpected colour; but slowly and surely it showed itself dark—black as night—crisp, and curly like her father's. The eyes deepened and deepened till they too were dark, liquid, and shining, with a look of appeal in them, even in those early days.

To say that Dr. Hunter was disappointed would be a most inadequate description of his feelings. He was dismayed at first when he realized the total reversal of his expectations, and finally enraged to think that this living image of the man he disliked, and whom his conscience at times would insist he had wronged, would be constantly before him to remind him of things he would prefer to forget.

But these feelings passed, and the child soon found her way into her uncle's heart—the heart that was really so big and so loving, though the way to it might be hard and rough. The little toddling child knew no fear of her stern old uncle; it was only as she grew up that shyness, restraint, and awkwardness in his presence took possession of Marjory.

Dr. Hunter had looked after her education himself. She had been a delicate little child, and he had not troubled about any lessons in the ordinary sense of the word for some years. He wished her18 body to grow strong first, so she had spent her days in the garden, on the hills, or on the lake with him; she had learned the ways of birds and flowers and animals, and meanwhile had grown sturdy and healthy. Her uncle had not allowed her to make friends with any of the children in the neighbourhood; he himself was intimate with none of his neighbours except the minister, Mr. Mackenzie, and the doctor, Dr. Morison. The minister had no children, and the doctor's two boys were at school, so that Marjory only saw them occasionally in the holidays. She had no playmates of her own age, and the children of the village looked upon her as an alien amongst them, regarding her almost with dislike, although it was not her fault that she was obliged to hold aloof from them.

Dr. Hunter had a theory that his sister had been too dreamy and romantic; that he had petted her and given in to her too much, instead of insisting upon her learning to be more practical. He blamed the fairy tales of her childhood, the influence of her school companions, the poetry and novels of later years as the chief causes of what he called her dreamy ways and romantic nonsense, and he determined that Marjory should be very differently brought up. She must learn to cook and to sew and to be useful in the house. She should not be allowed to read fairy tales or poetry, nor should she be sent to school; he himself would teach19 her what it was necessary for her to learn; he would be very careful before allowing her to make any friendships; and with all these precautionary measures he felt that she must grow into a good, strong, sensible, capable girl.

So Lisbeth the housekeeper was ordered to teach the child to dust and to sew and other useful things; and Peter, her husband, must teach her to hoe and to rake, to sow seeds in her little garden and keep it tidy. The doctor's own part in the programme was to teach her to read and write and cast up figures. That would be enough, he considered, for the present. Music, languages, and poetry were to be left out as being likely to lead to romantic ideas and dreams and unrealities. "Time enough for them when she is older," he decided. "When the foundation of common-sense has been laid, there will be no danger. Till then I shall keep her to facts and nothing else."

The doctor did his best to carry out these plans, which he honestly believed to be for the child's good in every possible way. Lisbeth and Peter, grown old in service at Hunters' Brae, were warned on no account to talk to Marjory about her father or old times, or to encourage her in doing so; and they tried hard to do as their master bade them, though it was difficult sometimes to resist those pleading eyes when the child would say, "Won't you tell me about my father, Lisbeth dear?"20 or "Peter darling," as the case might be. Peter was a gardener and man-of-all-work, and his hands were sometimes very dirty, but he was a darling all the same to Marjory, and indeed he was a good old man. If he and his wife had known the truth, that Mr. Davidson had never been told about his child, it is likely that Peter's strict sense of justice would have prompted him to right that wrong. But, like every one else, he took it for granted that the news had gone to Mr. Davidson, and in his kind old heart was often tempted to blame the seemingly careless father.

"Could he but see the bonnie lamb," he would say sometimes to his wife, "the vera picter o' himsel', he wouldna hae the heart to leave her. I've wondered whiles if the doctor wouldna send him a bit photograph, just to show him what like she is."

Lisbeth would reply, "Peter, it's just nae manner o' use thinkin' o' ony sic a thing. The doctor he's that set against Mr. Davidson that ye micht as weel try to move Ben Lomond itsel' as to move him."

These conversations usually ended in an admonition from Lisbeth to Peter to eat his meat and no blether. The suggestion was never made to the doctor, no word ever reached Mr. Davidson, and things went on much in the same way year after year; and although at times the doctor would question the21 efficacy of his plans for Marjory's education, on the whole he was fairly satisfied with them.

The day on which this story opens had seen the doctor take a most unusual step. Hearing from an old acquaintance in London—a scientific man and student like himself whose opinion he considered worth something—that some friends of his had bought Braeside, the property adjoining Hunters' Brae, he determined to do his duty as a neighbour, and go to welcome the newcomers as soon as they arrived. His friend had written, "Mrs. Forester is a most charming woman, Forester himself a thoroughly good fellow, and their little girl Blanche one of the sweetest children I have ever seen. She will make a good companion for your niece, poor little thing."

This letter had set the doctor thinking. First, he was nettled by his friend's use of the words "poor little thing." Why should Marjory be pitied as a poor little thing? Had he not done everything he possibly could for her? Then came one of those painful stabs of conscience which insisted now and then on being felt. What about her father? Have you done right in that matter?

He salved his conscience for the time being by making up his mind to go and see the Foresters, and if they were indeed all that his friend had said, there could be no reason why he should not encourage a friendship between the two girls. Marjory certainly had been very quiet and inclined22 to mope of late, and it would be a good thing for her to be roused by this new interest. The child was seldom out of his thoughts for long together; he loved her as his own; and yet Marjory was not happy—she was lonely, she did not understand her uncle and misjudged him, and he found her cold and unresponsive. There was something wanting between them; both were conscious of this want, yet neither knew how to supply it and so mend matters.

Things had come to a climax that afternoon. Marjory had driven by herself to the village to get some things that Lisbeth wanted, and also to buy some stamps for her uncle. Peter usually accompanied her on these expeditions, but to-day he was busy in the vine-house, and excused himself from attending upon his little mistress. She was quite accustomed to driving, however, and Brownie, the pony, was a very steady, well-behaved little animal, and a great pet of Marjory's; so she started off in good spirits, Silky running beside the cart as usual. She did her errands in the village, finishing up at the post office, which was also the bakery and the most important building in the place. Mrs. Smylie, the baker's wife and postmistress, served her with the stamps, and Marjory was about to say24 good-afternoon and leave the shop, when Mrs. Smylie opened a door and called out,—

"Mary Ann, here's Hunter's Marjory; maybe ye'd like to see her." And turning to Marjory, she explained, "Mary Ann's just hame frae the schule for a wee bit."

The Smylies were the most important people in the village of Heathermuir. Their mills supplied the countryside with flour, and their bakery was the only one of any size in the district. They had built their own house; it had a garden attached to it and a greenhouse; and, to crown all, their only child Mary Ann was to be brought up as a lady. With this object in view, the ambitious parents had sent the girl to a "Seminary for Young Ladies" at Morristown, some twenty miles away, and were greatly pleased with the result, feeling that Mary Ann was really quite a lady. That young person was delighted to come home and be worshipped by her admiring parents; and their idea that a real lady should never soil her fingers by household work, or indeed by work of any kind, suited her very well.

Mrs. Smylie, bursting with pride as her daughter appeared, watched the meeting between the two girls. Mary Ann's dress was very much overtrimmed, her hair was frizzed into a spiky bush across her forehead, and her somewhat freckled face was composed into an expression of serene self-complacency. She was the only girl in the village who was at a board25ing-school; not even Hunter's Marjory, with all her airs, could boast this advantage, she thought; and Mary Ann felt her superiority, and gloried in it.

Mrs. Smylie noted with great pride that the hand her daughter held out to Marjory was white and delicate—in great contrast to Marjory's brown one. "But then," she reflected, "the puir bairn hasna got her mither to watch her like oor Mary Ann has. Bless me! how the lassie glowers! Mary Ann has the biggest share o' manners onyways."

It must be confessed that Marjory was "glowering." She regarded the overdressed girl with aversion, answered her mincingly-spoken "How do you do, Marjory?" very curtly, and continued to "glower," as Mrs. Smylie described it, without saying another word.

"Won't you come into the house?" asked Mary Ann, and Marjory went.

She did not care about these people; she had never liked Mary Ann, and could hardly bear to look at her now, or listen to her affected way of talking. Still, she did not wish to be rude, so she followed Mary Ann through the shop into the house, and was ushered into the sitting-room, or parlour as it was called. The room was like Mary Ann's dress—full of all sorts of bright colours and gaudy ornaments of poor quality.

There was one thing about Mary Ann which interested Marjory profoundly, and that was her school26 experience. She felt that she would like to question the girl about it, and yet was too proud to betray her curiosity by bringing up the subject. Mary Ann, however, saved her the trouble, for as soon as they were seated she began at once,—

"Why don't your uncle send you to school? Any one would think a great girl like you ought to be sent to school. Why don't he send you?"

"Uncle doesn't wish me to go to school."

"Maybe he don't want to pay the fees," said Mary Ann.

Marjory said nothing.

"I learn French and German and music. I'm getting on fine with the piano, and papa's going to buy me one of my own soon. You haven't got a piano at Hunters' Brae, have you?"

"No," said Marjory shortly.

As a matter of fact there was a piano at Hunters' Brae, but it was kept in the room that had been her mother's—a room that Marjory was not allowed to enter. For reasons of his own the doctor had forbidden Marjory to go into it. She should do so on her fifteenth birthday, but not before. Lisbeth went in once a week with pail, broom, and duster, but she always carefully locked the door behind her, and Marjory knew nothing of the room or its contents. "Some bonnie day," was all that the old woman would say when she questioned her.

Mary Ann continued,27—

"It seems a shame you can't be made a lady of too."

"I can be a lady without going to school," said Marjory sulkily.

The other looked at her in surprise.

"Oh no, you can't. Who is there to teach you? You have to learn manners and deportment and accomplishments and all that sort of thing first. I don't see that you've got any chance here, you poor little thing," patronizingly.

"I don't care," said Marjory, knowing in her heart that she did care beyond everything, and that her greatest desire was to learn all sorts of things. "I don't care a pin," she repeated.

"Yes, you do, or you wouldn't get so red," said Mary Ann provokingly. Then she continued, "Your uncle's queer, isn't he?"

"What do you mean by 'queer'?"

"Well—queer—in his head, you know. People say he is, and, anyhow, he does queer things—keeping that room shut up, and all that. I should say he must be a little bit mad."

"He isn't," indignantly. "He's a very clever, celebrated man."

Mary Ann went off into peals of laughter.

"Oh dear! who told you that?" she cried at last.

"Lisbeth," defiantly.

Another peal of laughter greeted this statement.

"It really is too funny; you little simpleton, to believe such a thing. Why, if he was celebrated,28 he would be rich enough to send you to school, and he wouldn't let you sew and dust the way you do, just like any village girl. I never dust; mamma doesn't wish me to." And Mary Ann looked at her white hands admiringly, and shot a glance, which Marjory felt rather than saw, at the brown ones nervously clasping and unclasping themselves.

"I wonder," continued her tormentor, "that you don't insist on being sent to school, so that you could learn to earn your own living. I've heard mamma say your uncle gets no money for your keep; no letters ever come from foreign parts from your father. It must be strange to have a father you've never seen. It must be horrid to be like you, because, really, when you come to think of it, you are no better off than a charity child, are you?"

But Mary Ann had gone too far. A tempest was raging in Marjory's heart, and as soon as she could find her voice, which seemed suddenly to have deserted her, she cried,—

"You are a beast, Mary Ann Smylie, and I hate you; and although I haven't been to school, I don't say 'if he was,' and 'don't' instead of doesn't." And with this parting shot Marjory rushed through the shop and jumped into the cart; and Brownie, infected by his mistress's excitement, galloped nearly all the way home, his unusual haste and Silky's sympathetic barking causing quite a commotion in the sleepy, quiet village.29

Arrived home, Marjory ran to her uncle's study, knocked loudly at the door, and hardly waiting for permission, went in, leaving Silky, breathless and panting, outside.

The doctor was sitting in his armchair in his favourite attitude—his legs crossed, the tips of his fingers meeting, his eyes fixed upon them, but his thoughts far away. As a matter of fact he was thinking of Marjory at this very moment, of his visit to the Foresters, and the plans they had been making for the two girls.

"Well, Marjory, what is it?" he asked kindly, as the excited girl stood before him. She was trembling with agitation, her cheeks were scarlet, and her dark eyes flashed upon her uncle as she replied,—

"I want you to send me to school. I don't want to live on your charity any longer. I never knew I was till to-day," with a sob; then, piteously, "Won't you send me to school, Uncle George?"

"My dear child!" exclaimed the doctor, "what is all this? Who has been talking to you and putting such nonsense into your head?" looking at his niece in astonishment.

The quiet, usually almost sullen girl was transformed into a passionate little fury for the time being, and her uncle hardly recognized her. She burst out again,—

"Mary Ann Smylie looks down on me because I don't go to school. She says I can't ever be a lady;30 and she says that you get no money for my keep, and that I am no better than a charity child. I want to learn what other girls learn. I want you to send me to school, and I want you to tell me about my father, and to let me go into my mother's room!"

The child almost screamed these last words, and stamped upon the floor to emphasize them.

The doctor, now thoroughly aroused, rose from his chair, saying very sternly,—

"Marjory, I cannot alter my decision upon these matters. I do not wish you to go to school. I refuse to tell you any more than you have already been told about your father. I have promised that you shall go into your mother's room and take possession of it on your fifteenth birthday. That is enough. I am grieved that you should have listened to vulgar gossip about our affairs; but I may tell you that your mother left money to provide for you ten times over, if need be."

"Then you are unkind and cruel not to use it to send me to school and let me have what other girls have," cried Marjory passionately.

"Marjory," said her uncle quietly, "I cannot listen to you while you are in this mood. You had better go, and come back again when you can talk more reasonably."

"Yes, I will go, and I wish I need never come back. I hate everything, and I wish I were dead."31

With these words she flung out of the room, rushed blindly through the house into the garden and on into the wood, where she threw herself down under a tree, and sobbed out her grief to the faithful Silky until Mrs. Forester found her.

Dr. Hunter was very much troubled and puzzled by his niece's behaviour. Never before had she given way to such an outburst. He had not believed her capable of such a storm of passion, and felt himself quite at a loss. He was grieved and shocked beyond measure by Marjory's words. "Unkind, cruel," he muttered to himself. "Surely not. I love the little thing as though she were my own." And while Marjory was weeping bitterly under the tree in the wood, her uncle, very sorrowful and thoughtful, was pacing up and down his study wondering what he could do for the best. It seemed all the more grievous as, only that afternoon, he had been making plans for Marjory with Mrs. Forester—that she should share Blanche's lessons and enjoy her companionship.

Mrs. Forester had heard much of the doctor and his niece from the mutual friend in London who had written to the doctor, and she knew exactly how to manage things, so that in the course of one short hour plans were made which were to alter Marjory's whole existence.

But she, poor child, knew nothing of this, and her grief was bitter—the more so as she slowly realized that she had been wrong to give way to her passion.32 First, she had called Mary Ann Smylie a beast. Well, she had been very much shocked once to hear a child in the street use that word to another, but she herself had used it quite easily, and still felt as if she would like to use it again; but, worst of all, she had called her uncle unkind and cruel. Thinking over the scene in the study, she remembered the look on his face as she said these words. "It was as if I had struck him," she thought; and then came more tears and sobs.

Mrs. Forester's motherly heart yearned over the girl as she made her confession. Brokenly and with many tears the story was told, and relief came to Marjory in the telling of it. Blanche, with instinctive tact, had walked away a little distance with Silky, so that Marjory should feel free to talk to her mother. When the recital was over, Mrs. Forester said cheerfully, "I told you I thought I should be able to help you. First of all, I have got some delightful news for you. Only to-day your uncle and I have been making plans for you to share in Blanche's lessons. You are to learn everything that she does, including French and music," with a smile at the recollection of her battle against the doctor's prejudices.

A breathless "oh" was all that Marjory could say.

Mrs. Forester continued,—

"Blanche has a very good, kind governess. Unfortunately, she has rather an ugly name, and it may33 make you smile. It is Waspe—W, a, s, p, e—not pretty, is it? But she is as sweet as she can be, and very accomplished, and Blanche gets on nicely with her. It will be much more interesting for Blanche to have some one to share her lessons with, and good for you too, won't it?"

"Oh, indeed it will!" replied Marjory, bewildered by this wonderful piece of news.

"And in return for this I want you to teach Blanche all you can."

"I?" asked Marjory in surprise.

"Yes, you," with a smile at the girl's puzzled expression. "Blanche is a little too much like her name at present; she isn't very strong. Living in London didn't suit her, and it is for her sake that we have come to live here. I want you to show her all your favourite nooks and corners, to teach her all you know about the birds and flowers, and to let her help you in your garden. Will you do this, and keep her out of doors as much as you can?"

"I shall love it!" cried Marjory emphatically. "It's like a dream, and seems too good to be true."

"Now, my child," continued Mrs. Forester seriously, "listen to me. I think you have been doing your uncle a great injustice. You say you called him unkind and cruel; he is neither the one nor the other."

"I know," replied Marjory in a low voice.

"He is very fond of you," said Mrs. Forester.34

Marjory looked up quickly.

"He never says so," she objected.

"Ah!" said Mrs. Forester, "now we have got to the root of the whole matter. So, then, just because her uncle doesn't say, 'Marjory, I am very fond of you,' therefore Marjory thinks that he doesn't care for her very much."

Marjory nodded.

"My dear child, you never made a greater mistake. It is not in your uncle's nature to say much; he is content with doing things for you. This afternoon he talked of nothing but his plans for you, his ideas for your education—how his first care has been that you should grow strong and healthy amongst those outdoor things that you love. For your sake he has been content to stay in this obscure place, when he would receive the recognition he is entitled to if he went more into the world. His very meals he takes at times which he considers best for you. Look at your frock. Perhaps you don't think much of it, but let me tell you it is made of the very best tweed that Scotland can produce. Your boots are strong and sensible-looking, but they are of the finest quality of leather; your stockings are the best that money can buy. Let me see your handkerchief. Ah! I thought so," as Marjory obediently produced from her pocket the little hard, wet ball her tears had made. "This is a plain handkerchief, but so fine that it is fit for a princess to use. I don't suppose you ever thought35 about these things; but it must mean a great deal of trouble and care to your uncle to get them for you. He told me he looks after your wardrobe himself. Now, haven't I proved that he thinks about you a great deal?"

Marjory nodded.

"Don't you believe that, even if your mother had not left you provided for, your uncle would have been glad to keep you—that he would never have felt you a burden?"

"I don't know," said Marjory slowly. She was beginning to see her uncle in a new light, but she could not see him as he really was just yet.

"Well, you will know some day. There are many things which you are too young to understand, and you must try to trust in your uncle's knowing what is best for you in the matter of your father, who will return to you some day, I hope."

"Oh! do you really think that is possible?" cried Marjory. "Could it ever happen?"

"Certainly it might. I don't see any reason at all why you shouldn't hope for his coming. And if you will promise to be very patient, and to hope for the best, I will tell you something very nice that I heard said about your father a little while ago."

Marjory's eyes grew big with wonder. "Oh, do tell me. Indeed I will try to be patient."

"Well, an old friend of mine in London, who knows your uncle, and met your father long ago,36 said to me, 'A fine fellow was Hugh Davidson. I always feel that he may turn up again some day.'"

Mrs. Forester did not repeat other words said at the same time—namely, that "Hunter was always jealous, and would see no good in him;" but she felt justified in telling Marjory what she did, for she well knew how the girl would treasure the words, and how they might often comfort and encourage her.

"Oh! that is good," said Marjory. "I do thank you for telling me." And she squeezed her friend's hand.

"Now you must try to be very patient and hopeful. If God sees fit, be sure that He will give your father to you for your very own some day. In the meantime you must do all you can to be the sort of girl that a father would be proud of; and, Marjory, I have been thinking that your uncle might say the same of you as you do of him. You are fond of him, really, aren't you?"

"Yes, of course," assented Marjory.

"Well, do you ever tell him so?"

"No."

"Why not?"

"Oh, I shouldn't dare to."

"Nonsense! I suppose you would quite like it if he were to put his arms round you and call you his dear little Marjory?"

"Yes." Marjory was quite sure that she would like it very much, but she could hardly imagine such a thing happening.37

"Well, do you ever go near enough to him to let him do it if he wanted to, or do you simply give him your cheek to kiss, morning and evening, and nothing more?"

"Yes, that's just what I do," confessed Marjory, laughing.

"Then perhaps your poor uncle thinks that you consider yourself too big to be kissed and hugged, and so he doesn't do it. You can't blame him, you know; if you just give him a little peck, and run away, you don't give him a chance. You take my advice: try to be a little more loving in your manner towards him, and it will soon make a difference. Perhaps you don't like a stranger to speak so plainly to you, but I have heard so much about you that I don't feel like a stranger at all. But I must be going now. Dr. Hunter has invited Blanche to come to tea with you to-morrow, and I hope this will be the beginning of a brighter life for you, my child. Good-bye, dear," kissing her.—"Come, Blanche; we must be going now."

The girls bade each other good-bye somewhat shyly, while Silky looked on approvingly, wagging his tail, as if he knew that in some way these strangers had been good to his mistress; and when they were gone he turned to Marjory and rubbed his soft, wet nose against her hand as if to say, "It's all right now, isn't it?" Marjory returned the dog's caress, and walked slowly and thoughtfully towards the house.

One thing showed itself very clearly to Marjory's mind—she must tell her uncle at once that she was sorry for what she had said, though how she was to bring herself to do so she did not know. She had never had to do such a thing before, and now that she was calm again it seemed impossible that she could have spoken those wild words. She realized how these feelings against her uncle had been gathering force for a long time. Very slowly, very gradually they had grown, to arrive at their full strength as she listened to Mary Ann Smylie's tormenting suggestions. She had grown to hate even the name by which she was known in and about Heathermuir. Why did people call her "Hunter's Marjory"? Why couldn't they give her39 her own name—her father's name? Some of these feelings still rankled in her heart; but she was truly sorry for her outburst, and made up her mind to tell her uncle so. She determined to go at once to his study; and, once inside it and in his presence, perhaps she would know what to say and do. So accordingly she went and knocked at the study door. There was no answer. She knocked again louder, and still there was no answer. Then she opened the door cautiously and looked in, thinking her uncle might be asleep; but no—the room was empty. Disappointed, she turned away, and going towards the kitchen, called,—

"Lisbeth, where's Uncle George?"

The reply came in shouts from the distant kitchen,—

"He's awa to the doctor's. He winna be in to supper the nicht, and ye're to gang awa early to yer bed."

The shouts came nearer as Lisbeth, wiping her floury hands on the large apron she always wore when cooking, came bustling along the passage.

"Gude save us!" she cried, when she saw Marjory's face; "what's wrang wi' the bairn—eyes red and face peekit like a wet hen? Come yer ways in, lambie, an' Lisbeth'll gie ye some nice supper, for nae tea ye've had. But I've got scones just newly bakit, an' I'll mak ye a cup o' fine coffee. Come awa."

"Dear old Lisbeth," cried Marjory, "I would kiss40 you if you weren't so floury. But I'm really quite happy, except that I wanted to see Uncle George to tell him something."

"Weel, if yon's the way ye look when ye're quite happy, I wunner how ye'll look when ye're quite meeserable. Havers," said the old woman contemptuously, "somebuddy's been tormentin' ye. Come awa."

The good cheer which Lisbeth provided was much appreciated by Marjory, who did ample justice to the scones and cookies. She had been without food for several hours, and was really quite hungry now that she had got over the worst of her trouble. She listened to Lisbeth's cheerful chatter as she bustled about the room, encouraging her "bairn" to try a piece of this, a "wee bit scrappie" of that, till Marjory told her that she simply couldn't eat any more.

"I'm going out to say good-night to Peter, and to give Silky his supper, and then I'm going to bed," she announced.

"Peter, indeed!" said the old woman wrathfully. "It's little I've seen o' him the day. Mony's the wee bit job I've wanted him to dae; but na, na, no the day, he must be lookin' after the vine, he says." And Lisbeth tossed her head.

"Well, you know, Peter isn't as young as he once was, and when he has to climb up the steps to reach the top bits of the vine, it takes him a long time,"41 said Marjory, with a view to calming the old woman's wrath.

Lisbeth flounced round. "Don't you go for to say my Peter's slow at his work. It's little ye ken how hard he's at it, nicht an' day, slavin' for you an' the doctor, miss; and he's nane sae auld neither, an' ye needna be ca'in' him an auld rheumaticky body that canna climb a lether."

"O Lisbeth, I didn't," reproachfully.

"You did so."

"I did nothing of the kind; I tried to make excuses for him because you were so cross with him."

"Me cross! Me cross wi' Peter!" ejaculated Lisbeth. "Me that's never been cross wi' my man in a lifetime o' years! What next?"

"Just that you're a dear, funny old thing, and I'm going to bed."

"Ye're a peart-mouthed lassie, that's what ye are. Ye'd best get awa to yer bed."

It was always thus with Lisbeth and Peter. Did any one cast the slightest shadow of blame on either, the other was up in arms at once; and though each might blame the other for some omission or commission, as soon as any third person agreed in laying blame, that person found himself in very hot water indeed.

Marjory went out to give Silky his supper. He always had his food in the stable, but his bed was42 on a mat outside Marjory's bedroom door. Then she went down the garden to find Peter.

She found him just putting away his tools for the night.

"Good-night, Peter," she said. "I just came to tell you I've got a friend, and also that Lisbeth's cross."

"She cross! Na, na; that canna be, Miss Marjory. Weary maybe wi' her cookin' an' siclike for you an' the doctor, but no cross; na, na."

"Well, but, Peter, didn't you hear me say I've found a friend? Aren't you glad?"

"Glad indeed I am. That's a bonnie bit news. An' what like is she?"

"She's the sweetest, prettiest girl you ever saw," said Marjory enthusiastically.

"Ay, maybe she's that," replied the old man doubtfully, looking significantly at Marjory.

"But I tell you she is, Peter, and her mother is so kind and gentle. Their name is Forester, and they've just come to live at Braeside."

"Oh, they," said the old man.

The Foresters, being newcomers, did not hold a very high place in Peter's estimation as yet.

"That's quick wark, Miss Marjory," he continued; and then, as if to atone for his want of enthusiasm, "I'm glad to hear it, for whiles it must be a bit lonesome here for a lassie the likes o' you."

"And, Peter darling, you'll be good to her, like43 you are to me, won't you? And you'll show her the birds' eggs, and where to look for nests; and you'll tell us stories on wet days, won't you?"

Peter looked guilty. He knew his master disapproved of fairy stories; and his tales, although he would declare they were true ones and was always careful to point them with an excellent moral, dealt largely with the old Scottish fairy folk, and with the many superstitions handed down from generation to generation amongst the peasantry.

"Na, na, Miss Marjory; ye're gettin' ower auld for Peter's stories; they are but bairnie's tales."

"Now, Peter, you mustn't be obstinate. You must try to remember some nice new ones."

"Aweel, gin I must, I must," said the old man, with a twinkle in his eye, for if there was one thing he enjoyed above another, it was to see Marjory sitting wide-eyed and open-mouthed drinking in some tale of olden times.

"That's a good Peter. Now, remember, the first wet day that comes you're engaged to us in the wood-shed. Good-night."

It was a beautiful still evening. July was not yet ended, and roses, lilies, and mignonette breathed their fragrance upon the air. Overhead one clear star was shining; like the star of promise that shone of old, it seemed to Marjory an omen of a new life for her. Peace entered into her soul as she gazed upwards. Away to the west the last44 lingering tints of a late sunset were still to be seen; the whole world seemed at rest. She, too, would lie down and sleep, calm after the storm, and to-morrow she would begin a new day. She would tell her uncle she was sorry, and would try to follow Mrs. Forester's advice. Loving words that she would say to the doctor came into her mind, and she fell asleep thinking of him with tenderness and gratitude.

When the morrow came, Marjory awoke with a confused sense that something unusual was to happen that day. She gradually remembered her resolution of the night before; but the loving words she had planned to say seemed frozen inside her, and she felt as if she did not dare to speak to her uncle.

She went down to breakfast dreading the meeting with him; but Dr. Hunter said good-morning as usual, just as if nothing had happened. Marjory noticed, with a pang of self-reproach, that he looked tired, and that his eyes had a weary expression that was not usually there. He ate his breakfast in silence, but that was nothing out of the common, for they often sat through a meal with little or no conversation. Marjory hated this state of things, and yet she had never had the courage to try to alter it. She would sit and rack her brains for something to say, and then decide that it was impossible that anything she could say would interest a grown-up man, and a man so stern and silent as Uncle45 George. Lately she had actually come to dreading meal-times, and would be thankful when they were over and she could escape. All this was very foolish on her part, no doubt, but it arose entirely from her misunderstanding of her uncle.

Contrary to her usual custom, she hovered about the dining-room after breakfast was over that morning, trying to make up her mind to speak. She watched her uncle wind the clock on the mantelpiece, saying to herself that she would speak when he left off turning the key, but she let the opportunity slip by. Then the doctor gathered up his letters and papers and went to his study without a word or a look in her direction. In fact, he was quite unconscious of her presence for the time being; he was thinking deeply over a scientific problem which absorbed his whole attention.

Marjory despised herself for being so weak and timid, and at last scolded herself into a determination to go and knock boldly at the study door. She would be obliged to go in then; there could be no turning back or putting off.

Her heart beating very quickly, she went and knocked at the door; and in response to her uncle's "Come in," she opened it and walked across to the table at which the doctor was sitting.

Interested as he was in his work, when he saw who was the cause of this unusual disturbance, he smiled at her, asking,46—

"Well, Marjory, what is it?"

The girl turned white to the lips and said, her voice low and trembling,—

"I am very sorry about yesterday; will you forgive me?"

"Of course I will, and gladly," said the doctor heartily. "My dear child, you didn't understand; you don't know that I only wish to do what is for your good. I may have made mistakes. I was told yesterday that I have made some big ones," sadly, "but I intend to try to rectify them now. Things are going to be different, little one. You are to have a companion, and you are to learn some of the things you are so anxious about. Will that please you?"

"Oh yes," eagerly.

"And you take back those words, 'unkind and cruel'? I never thought to hear my dear sister's child use such words to me."

Marjory's answer was a storm of tears.

"There, there, my child; don't cry. You won't think so hardly of me again. Come, let us forget all our troubles." And the doctor took out his handkerchief, and began to dry Marjory's tears, clumsily, it must be owned, but with the kindest intention.

"See, Marjory, the sun is shining, and everything out of doors looks bright and happy; you must be happy too. Follow the example of the flowers. They droop under a storm of rain, but when the47 rain leaves off and the sun begins to shine, they hold up their heads as straight as ever."

"Yes; but they aren't wicked like people are; they haven't got things to be sorry for."

"Tut, tut, child; now you want to argue. That opens up a very large field for discussion, and little girls have no business arguing. Run away into the garden and play with Peter or Silky, or both, for both dearly love an excuse for a game."

Marjory obeyed, saying to herself as she went, "Why will he always treat me as such a child? I'm nearly thirteen, and I want to know about things. I should like to know why people were made so that they can so easily be naughty, and so suddenly too, without really wanting to." And she thought of yesterday. "I suppose Uncle George knows everything; but grown-up people always say that you wouldn't understand, and they won't tell you anything. I wonder if trees and flowers are really as good as they look. I know birds and insects, and even little tiny ants, are naughty, because I've seen them quarrelling. I do wonder about the flowers, because they are just as much alive as people or animals."

Turning over this problem in her mind, she went slowly down the garden to Peter, who was at work again in his beloved vinery.

"Peter," she said, "do you think that flowers and trees and vegetables are ever naughty?"48

The old man paused in his work and scratched his head thoughtfully.

"Aweel, Miss Marjory," he said, "I'm thinkin' not. Seems to me that the bonnie flowers hae been gien us for a gude example. They aye bloom as best they can. Sunshine an' shade, rain an' wind, they tak them a' as God Almichty sends them, an' are aye sweet, an' aye content just to dae their best. I dinna ken for certain, Miss Marjory, but that's what I'm thinkin'."

"I think so too, Peter. They certainly don't look as if they were ever naughty. My new friend is just like a lovely white rose, and she doesn't look as if she could ever be naughty either."

"H'm," remarked Peter, "she's no mortal, lassie, then."

"Peter, you're not a bit nice about the Foresters. I tell you they are just as sweet as they can be, both Blanche and her mother."

"It's just this," replied Peter, thus admonished. "I'm no a man that can gae heid ower ears a' in a meenit; I must prove folks first. These Foresters, they're English for ae thing, an' maybe they'll bring new fangles to Braeside, which, bein' a Scotsman, I canna gie my approbation to. I'm no sayin' they wull, but they micht. Na, na, Miss Marjory; I maun prove them first."

"You're an obstinate old thing; but you can begin proving, as you call it, this very afternoon,49 for Blanche is coming to tea; and I say, Peter, will you spare time to take us down to the Low Farm after tea? Blanche comes from London, and I'm sure she would love to see over it."

"London," muttered Peter in a voice that meant volumes of disapproval.

"Now, do be nice, and promise," coaxed Marjory. "I'm going to ask Lisbeth a favour too, and I'm sure she'll say yes."

Not to be outdone in good nature by his wife, the old man at last gave his promise.

"Gin the doctor can spare me," he said.

Marjory smiled, for she well knew that Peter had had his own way at Hunters' Brae for many a long year, and the doctor had very little to do with the disposal of his time; but Peter was faithful to the smallest detail, his duty was his life, and the doctor could trust him.

Marjory then betook herself to the kitchen to try her powers of persuasion upon Lisbeth.

The kitchen at Hunters' Brae was a picture to see. A large room, bright and airy, plates in orderly rows upon the dresser, copper pans that shone like mirrors, spotless table and spotless floor, a big open fire throwing out a cheerful glow—such was Lisbeth's domain. To complete the picture, there was Lisbeth herself, a most wholesome hearty-looking old lady, with rosy cheeks and kindly eyes. Her dress was made of lilac-coloured print, and her apron was50 an immense size. She wore a round cap with a goffered frill and strings which tied under her chin. She was firmly convinced that no finer family than the Hunters of Hunters' Brae ever existed, and that the world did not contain such another man as her Peter—two beliefs which went a long way towards maintaining that domestic peace which was the rule at Hunters' Brae.

"Weel, Marjory, what is't?" she asked, as Marjory entered the kitchen. Lisbeth had never adopted the formal "Miss" in her mode of addressing Marjory, the baby she had seen grow up. She had determined that when the "bairn" should reach the age of fifteen, then would be time enough to begin it.

"I want to ask you a favour," said Marjory.

"Ask awa," replied Lisbeth, her arms akimbo.

"Will you do it?"

"No till I hear what it is."

"Well, I want you to make some shortbread for tea."

"Shortbread the day?" asked the old woman in surprise; "the morn's no the Sawbath."

"I know; but Blanche Forester, my new friend, is coming to tea, and I want her to taste it. You know very well that you make the best shortbread and wear the biggest aprons in Heathermuir. You will make us some, won't you? Peter has promised to do what I asked him," added naughty Marjory.51

"I suppose I micht just as weel, though there's scones and cookies enough for a regiment only bakit yesterday."

"That's a good Lisbeth," said Marjory, delighted with the result of her mission, and feeling that the success of the afternoon's entertainment was assured.

The day passed very slowly for Marjory until four o'clock, which was the time appointed for the arrival of her visitor. She wondered whether Uncle George would have tea with them, and, it must be confessed, she secretly hoped that he would not, telling herself that it would be much nicer without him, because Blanche and she would then feel free to talk to each other. It must not be supposed that a better understanding of her uncle could be reached by leaps and bounds. The change from the confidence of the baby child to the constraint and awkwardness of the older girl had been gradual, and the return to that fearless confidence must be gradual too; but Marjory had taken a step in the right direction that morning, and she really meant to try hard.53

The girl had never had a friend of her own age to tea in her life, and she felt how delightful it would be if they could be alone together.

There were occasional tea-parties at Hunters' Brae, but they were dreaded rather than looked forward to by Marjory. The company usually consisted of the minister and his wife and the doctor and his wife, and it seemed to Marjory that these parties had been exactly the same in every detail for years. The guests made the same flattering remarks about Lisbeth's scones, cookies, and shortbread; they told the same tales, and they put Marjory through the same catechism. How old was she now? How was she getting on with her lessons? Could she sew her seam nicely? Could she turn the heel of a sock? When these questions were asked and answered, there would be long silences, broken only by the crunching of shortbread and the swallowing of tea. To Marjory these silences caused the most acute pain. She felt helpless and inclined to run away, or scream, or do something to create a diversion. She would watch the hands of the clock, hoping that each minute might bring a remark from somebody. But the other people did not seem to mind the lack of conversation; and once she counted ten whole minutes during which no one said anything except what was necessary in passing and handing eatables! How different her tea-party might be, she thought, if only—But then she stopped, thinking of her new54 resolves. Still, it was a great relief when the doctor said,—

"I'm going to Morristown this afternoon, Marjory, so you must entertain your visitor yourself. Do you think you can manage it?"

There was a twinkle of mischief in the doctor's eyes as he asked the question, but Marjory did not see it. She was looking at the ground, blushing rather guiltily as she realized how pleased she was to hear of this plan.

"Oh yes," she replied, "I shall manage quite well, Uncle George."

"Then just go and tell Peter I want him at once to drive me to the station."

"Oh, mayn't I drive you?" asked Marjory eagerly.

"Of course you may," replied the doctor, looking at his niece in some surprise. This was the first time she had ever suggested such a thing, and he was more pleased than he cared to own even to himself. As for Marjory, the words had slipped out almost before she knew what she was saying; and when she had spoken them she felt half afraid of their effect, and wholly surprised at herself.

The doctor, who did nothing by halves, had planned this trip to Morristown for himself, so as to leave the coast quite clear for the two girls to enjoy themselves in their own way. It was a most considerate action on his part, for he disliked railway travelling, and at that time was much engrossed in the study55 of the scientific problem before mentioned. He told himself that if he were to stay anywhere in the neighbourhood of Heathermuir he would not be able to keep away from his study for long, so he decided to banish himself to Morristown.

Marjory drove her uncle to the station, and was back in plenty of time to prepare for the reception of her guest. She could see the house at Braeside very well from her bedroom, and, perched on the window-sill, she watched for Blanche's coming. At last she saw two figures—a small one and a tall one—coming out of the house. The tall one was a man, and must be Mr. Forester she decided; and in that case she would not go to meet them—she felt too shy. She watched them coming across the park which surrounded their house; then they were lost to sight in the wood which was at the end of the Hunters' Brae garden. The doctor must have told them to come this way, as it was much nearer than coming by the road.

Marjory was rather relieved to see that when at last the garden gate opened Blanche was alone. She rushed downstairs and through the garden, eager to welcome her visitor; but when she reached Blanche she felt almost tongue-tied, and all she could say was, "How do you do?" which sounded very stiff and formal, compared with what she felt.

But Blanche was equal to the occasion.

"How nice of you to come and meet me!" she said.56 "Dr. Hunter told us we might come this way, as it is so much nearer. But how did you know just when to come?"

"I was watching from my bedroom window."

"Then I believe we can see each other's bedroom windows, because mine looks to the front of the house. How lovely! We shall be able to signal to each other. Won't that be fun?"

"Yes, indeed it will. We shall be able to say 'good-night' and 'good-morning' to each other, and all sorts of things." And Marjory's busy brain at once began to devise methods of signalling.

"What a lovely garden!" exclaimed Blanche as they walked towards the house. "Ours is all weeds and rubbish, it has been left alone so long. Nobody seems to have bothered about the garden while the house was empty."

"It will soon begin to look nice, now you've come," said Marjory consolingly; and, indeed, it seemed to her as if the very flowers in the garden must grow to greet the coming of her friend.

"What a lot there is to see here!" said Blanche enthusiastically. "Where shall we begin?"

"Well, let's have tea first," suggested Marjory. "Then we can go over the house, then the garden; and then Peter has promised to take us to the Low Farm—that is, if you would like it," she added, looking shyly at her companion.

"I shall simply love it all," Blanche replied em57phatically; and then, in a burst of confidence, "I say, I'm awfully glad you haven't got on your best frock—at least," quickly, "it's the same one you had on yesterday. Mother said she didn't think I need put mine on; that we might be in the garden, perhaps, and I should enjoy it better if I didn't have to think about my frock."

"I never put my best one on unless I'm obliged to," said Marjory. "I always feel so boxed up in it, and it always reminds me of sermons and tea-parties."

Blanche laughed merrily. "Oh!" she cried, "are the sermons very long here?"

"Well," laughing too, "they are not very short; but that's not why I dislike them. It's because uncle likes me to write them down afterwards."

"Oh, how dreadful! And do you manage to do it?"

"I try to. Sometimes it's easier than others; but sometimes there are so many firstlies and secondlies divided into other firstlies and secondlies that I get into a regular muddle. Uncle always says that it's a very good exercise for the memory, as well as teaching me about Church things. Sometimes Mr. Mackenzie preaches a sermon for children in the afternoon, and then it's quite different; I could remember every word. But the funny thing is that uncle never wants me to write them!"

"Too easy, I suppose!"58

Blanche laughed again, such a joyous laugh that Marjory was infected by it and laughed too. Blanche was a child of most unusual beauty, though she herself seemed quite unconscious of it. Her face in repose wore an expression of innocent loveliness which went straight to the heart. Her skin was fair and soft, her eyes large and dark and of an indescribable colour, neither brown nor gray, and her hair was like burnished copper, with pretty waves in it, and the dearest little fine tendrils curling about her neck and ears. Her childhood had been very happy. Surrounded and protected by the loving care of devoted parents, she had grown to look out upon the world with happy eyes, and her sunshiny disposition made pleasure for herself and for others. Marjory had fallen in love with her at first sight, and felt that she could never tire of looking at her friend's sweet face.

They found tea laid for them in the dining-room. It was a pleasant room, long and low-ceilinged, with oak beams and high panelled doors. At one end of it stood an old-fashioned dresser, its shelves decorated with precious china and silver. On the walls were pictures of bygone Hunters in various costumes, Marjory's favourite being a dashing young cavalier, with hat and feather, collar and frills of costly lace, and all the other appointments of the period. Marjory used to amuse herself trying to imagine her Uncle George dressed in such a style. There was the59 admiral in cocked hat and gold lace; the minister in black gown and orthodox white bands; there was the brave young soldier who had died for Prince Charlie; and there were many others, most of them celebrated in some way, for the Hunters had been a race of strong men.

Lisbeth, resplendent in a black silk dress, with muslin apron and cap in honour of the occasion, stood at the door to meet the girls. On such a day as this, Jean, the young maid, gave place to her superior.

"This is Blanche Forester," said Marjory by way of introduction; and turning to Blanche, "This is dear old Lisbeth."

"I'm pleased to see ye," said the old lady graciously, nodding with satisfaction, her eyes fixed upon Blanche's flower-like face. "Ye're a bit ower white like for health," she remarked.

Shyness was not a failing that afflicted either Lisbeth or Peter: they were both apt to say exactly what they thought, regardless of time, place, or person.

Marjory was delighted by Lisbeth's evident approval of her friend, and felt very grateful to the old woman for putting on her "silk," which only came out on great occasions; and when she saw the table daintily spread with all sorts of good things, her satisfaction was complete.

"If ye want onything, just ring the bell and I'll come," said Lisbeth, and she rustled slowly out of60 the room. That was what Marjory called Lisbeth's "silk walk." Dressed in her ordinary gown she bustled and clattered about, but in the silk she was as stately and dignified as a duchess.

"I am glad it isn't a ladies' tea," said Blanche as they took their seats, Marjory at the head of the table to "pour out."

Marjory looked at her questioningly.

"I mean where there's nothing to sit up to—no place to put your cup and plate except your own knee; and if you want to blow your nose or cough, you're sure to spill your tea; and the bread and butter is always so thin that it drops to pieces before you can fold it up. But this is lovely; and it is so nice to have it all to ourselves!" And she settled herself comfortably in her chair.

Marjory felt quite at her ease by this time, and the two girls chattered gaily while they disposed of Lisbeth's good things.

Tea over, they started on a tour of inspection round the house. It had been built by a Hunter long ago, and Hunters had lived in it ever since, and had added to it in many ways; but there was still part of the original building left—an old wing which was now unused. There were various stories told in the village about this old part of the house. Footsteps were heard sometimes, it was said, and lights had been seen in the night by belated passers-by. Lisbeth and Peter knew of the tales and wild61 rumours that were current in the neighbourhood, but they were careful to say nothing to Marjory or the doctor, and also very careful to lock themselves in at night, as they were by no means free from foolish fears and superstitions.

First of all, the girls examined the portraits in the dining-room. Blanche inquired why there were no ladies amongst them.

"Don't they count as ancestors?" she asked.

"Oh yes," replied Marjory, laughing, "but they are all in the drawing-room. I've often thought it would be much nicer to hang them up in pairs, but Uncle George won't hear of it. He says they always have been kept separate, and he doesn't like to have anything altered. Come and see the ladies."

To the drawing-room accordingly they went. It was a large room, and contained many treasures in the way of beautiful and valuable old furniture and china. As a rule it was kept shrouded in dust-sheets, but to-day Lisbeth had uncovered everything in preparation for the visitor. There was a faint, delicious scent of potpourri about the room, the recipe of which had been handed down from one generation of Hunter ladies to the next, and was a speciality of the house. On the walls hung the portraits of these same ladies, smiling serenely down upon the room they had known so well. On the rare occasions when Marjory spent any time in this room, she used to study the faces of these dames,62 and try to trace some likeness to herself amongst them; but not one of them had the curly hair and dark eyes that were her portion, and the child sometimes felt sad to think that she was so unlike all the rest of her family.

Blanche was delighted, and studied all the portraits to the last one—that of Marjory's grandmother.

"But isn't there one of your mother?" she asked.

Marjory blushed. "Yes, there is one," she replied, "but it's in another room."

Somehow she felt ashamed of that shut-up, silent room with its hidden treasures that she had never seen.

"But," she continued, "I've got a picture of her when she was a girl, inside this locket." And she unfastened a small, old-fashioned trinket which she wore on a fine gold chain round her neck.

"Oh, how pretty!" cried Blanche; "but not a bit like you, is she?" And then, somewhat confused lest Marjory should misunderstand her, she continued, "I don't mean that you're not pretty, because you are; only it's so funny that you are so dark and your mother was so fair."

"I often and often wish I were fair," said Marjory wistfully. "I should love to be."

"Oh, but your hair is so curly and nice, it's just as good as fair hair. Mother always says that all young girls are pretty so long as they keep themselves tidy and fresh and try to be good. I used to63 be very cross with my hair, especially when boys in London would call 'carrots' after me, until at last mother made me understand that it is really quite wrong not to be pleased with whatever hair or eyes God has given us, and now I'm more content with it."

"It is lovely hair, and I would kick any boy that called it carrots," cried Marjory stoutly; and she took hold of a strand of it and kissed it impulsively. "Oh, I do think you're such a darling!" she said. "I'm going to be so happy now I've got you!"

This from quiet, self-contained Marjory! Here indeed was a revelation.

Marjory was just putting her locket back inside the neck of her dress, where she always kept it hidden, when Blanche's attention was attracted by something else which hung on the chain.

"What's this silver thing?" she asked; and Marjory explained that it was the half of a sixpence with a hole in it. "Lisbeth says my mother wore it for luck, so I always wear it too."

"How interesting! I wonder where the other half is."

"Lisbeth doesn't know; she says she never saw or heard of the other half."

"If you were in a fairy tale, you'd make all the knights that wanted to marry you go all over the world to find the other half; and then most likely the person that had it would turn out to be a king's64 son, and he would marry you, and you would be a queen, and be happy ever after."

Marjory laughed. "You shall make a story of it and tell it to me some day; but come now and see my bedroom."

On the way to Marjory's bedroom they had to pass the locked chamber, and of course Blanche had to inquire what it was, and Marjory had to explain, which she did in an apologetic, shamefaced way.

"But how romantic—much better than a fairy tale! How you must long to be fifteen and go in and see it!"

"Yes, I do. I wish it every day. But it takes such a lot of days to make a year, and there are still two more years to come." And Marjory sighed.

"Oh, they'll soon go," said Blanche cheerfully, "now that you've got to have lessons and be so busy."

When they reached the bedroom the girls went straight to the window, and were delighted to find that Blanche's room could be seen from it, so that the proposed signalling could easily be managed. They arranged that it should be done by waving white handkerchiefs. Four waves were to mean "Can you come out?" One wave in reply was to mean "No," and a lot of little waves "Yes." If either had to go out elsewhere, or should be prevented in any way from waiting till the other appeared at her window, the handkerchief was to be hung on a65 nail outside. They agreed that they would always go to signal directly after breakfast every morning.

All this took some time to plan, and Marjory said that if they were to see the garden and the farm they must leave the old part of the house till another day. Blanche agreed, and they went out into the garden.

The garden at Hunters' Brae was a charming place. Like the house, it had been the care and pleasure of generations of the Hunters. Its lawns were soft and velvety. The impertinent daisy and the pushing dandelion had never been allowed their way amongst the tender grass, and it was smooth and springy to walk on. It was Peter's pride that no such lawns could be shown anywhere in or around Heathermuir. There was nothing stiff or formal in this garden, no chessboard patterns or stripes of colour round the borders, but there were lovely masses of luxuriant blooms, radiant colourings, delicious scents, and all in such harmony that the result was a charm which no more regular arrangement could have produced.

One of Marjory's favourite walks was a narrow67 grass path bordered on each side by stately hollyhocks. When she was a little girl she used to wonder how long it would be before she grew as tall as they were. This walk led to the rose garden, which had always had a great attraction for the lonely child. A real rose garden it was, with low stone walls, gold and green with the mossy growth of many years. There was a sundial in the centre of it, which had seen many a sunny day since it had been set up to mark the passing of time for the visitors to the rose garden. Here were roses of many sorts and colours, some rare, some common, but all sweet, as only roses can be. Peter knew their secrets—knew just how to treat these lovely queens among flowers—knew, too, that, above all, they like to have undisputed possession of the ground, for they are exclusive these royal ladies, and do not care to share with all and sundry; and they rewarded the old man's care and consideration by blooming early and late and in the most wonderful profusion.

It would take many pages to tell of all the delights of the Hunters' Brae garden, with its unexpected turns and nooks and corners, its rustic seats in shady places for hot days, in sunny places for cold ones, and even in many pages it would be impossible to convey the old-world charm pervading it, its stately dignity and the aspect of long-established well-being over all. Peter seemed68 to know every inch of it, every plant in it was as a child to him, and not the tiniest seedling was overlooked, for—

Dr. Hunter was often quite astonished at the amount of work the old man would get through. Certainly he had two or three assistants, but they were young and raw and had to be watched and told what to do; but Peter always said he preferred them young, because "They didna hae quite sic a gude conceit o' theirsels," and any young man who could get his training under Peter thought himself very fortunate. Everything with him was done in due season and for love of his work; there was no rushing or hurrying—it was indeed a garden of peace.

Marjory loved the garden. It was here that the happiest hours of her life had been spent; here that she had watched the ways of birds and flowers and insects; here that she had listened to Peter's tales of olden times; and here that she had dreamed dreams of her father, and built many a castle in the air. She was glad when she saw that this beloved garden was casting its charm upon her friend. It was looking very lovely in the afternoon sunshine. Butterflies were69 flitting amongst the flowers, and the hum of bees and many insects made the air musical with sound of happy life. A gorgeous dragon-fly sailed past them, wheeling round as if to show its wonderful glittering colours to the best advantage in the sunshine. Blanche had never seen such a thing in her life, and after it had gone she lingered many minutes hoping that it might pass back again. But it did not come, and the time was slipping away. Marjory spied the bent back of Peter in the distance, and the two girls went towards him, Marjory calling to him to come and take them to the farm.

Peter was not to be hurried; he was tying up a carnation plant, and he continued his job with only a nod at the girls. He finished the last knot just as they reached him, and straightening himself and raising his hat, he said, "I'm ready noo."

Marjory said to Blanche, "This is Peter;" and then turning to Peter, "This is Miss Forester. Aren't you pleased to see her?"

"I am that," replied the old man, looking at Blanche for the first time; and then, as if satisfied with what he saw, he repeated much more enthusiastically, "'Deed an' I am that," with a nod and a smile at Blanche.

Marjory felt great satisfaction in the assurance that her friend had found favour in the eyes of the two very important personages in the Brae household—Lisbeth and Peter.70

The girls chatted gaily to the old man as they went down the hill on the other side of the wood to Low Farm.

Marjory never liked to go to the farm without Peter or Lisbeth or her uncle, for she was a little afraid of the woman who managed it. Mrs. Shaw was very tall and strongly built, with black hair turning gray about the temples, and dark, deep-set, piercing eyes, and eyebrows which Marjory always thought looked long enough to comb. This gave Mrs. Shaw, as she was called, a somewhat forbidding look, and, added to her quick, decided, almost rough way of speaking, made her more feared than loved. No one knew anything of her life before she came to Heathermuir; but the story went that her husband had gone away to foreign parts and never come back again, and that her temper was soured in consequence. Be that as it might, she was an excellent manager; everything at the Low Farm was in spick-and-span order, and fit for inspection at any time of the day. Maids and men alike knew that they must do their work, or Alison Shaw would demand the reason of any neglect or unpunctuality; and with those black eyes fixed upon them it was impossible to prevaricate or offer excuses.

The young ladies' visit must have been expected, for when they were ushered by Mrs. Shaw into the little parlour, there was a tray on the table71 with glasses on it, and a bottle of gooseberry wine and a cake of shortbread.