This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: South American Fights and Fighters

And Other Tales of Adventure

Author: Cyrus Townsend Brady

Release Date: March 26, 2007 [eBook #20910]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AMERICAN FIGHTS AND FIGHTERS***

The first part of this new volume of the American Fights and Fighters Series needs no special introduction. Partly to make this the same size as the other books, but more particularly because I especially desired to give a permanent place to some of the most dramatic and interesting episodes in our history—especially as most of them related to the Pacific and the Far West—the series of papers in part second was included.

"The Yarn of the Essex, Whaler" is abridged from a quaint account written by the Mate and published in an old volume which is long since out of print and very scarce. The papers on the Tonquin, John Paul Jones, and "The Great American Duellists" speak for themselves. The account of the battle of the Pitt River has never been published in book form heretofore. The last paper "On Being a Boy Out West" I inserted because I enjoy it myself, and because I have found that others young and old who have read it generally like it also.

Thanks are due and are hereby extended to the following magazines for permission to republish various articles which originally appeared in their pages: Harper's, Munseys, The Cosmopolitan, Sunset and The New Era.

I project another volume of the Series supplementing the two Indian volumes immediately preceding this one, but the information is hard to get, and the work amid many other demands upon my time, proceeds slowly.

CYRUS TOWNSEND BRADY.

ST. GEORGE'S RECTORY,

Kansas City, Mo., February, 1910.

| PAGE | |

| PANAMA AND THE KNIGHTS-ERRANT OF COLONIZATION | |

| I. THE SPANISH MAIN | 3 |

| II. THE DON QUIXOTE OF DISCOVERERS AND HIS RIVAL | 5 |

| III. THE ADVENTURES OF OJEDA | 10 |

| IV. ENTER ONE VASCO NUÑEZ DE BALBOA | 17 |

| V. THE DESPERATE STRAITS OF NICUESA | 20 |

| PANAMA, BALBOA AND A FORGOTTEN ROMANCE | |

| I. THE COMING OF THE DEVASTATOR | 31 |

| II. THE GREATEST EXPLOIT SINCE COLUMBUS'S VOYAGE | 34 |

| III. "FUROR DOMINI" | 42 |

| IV. THE END OF BALBOA | 44 |

| PERU AND THE PIZARROS | |

| I. THE CHIEF SCION OF A FAMOUS FAMILY | 53 |

| II. THE TERRIBLE PERSISTENCE OF PIZARRO | 57 |

| III. "A COMMUNISTIC DESPOTISM" | 68 |

| IV. THE TREACHEROUS AND BLOODY MASSACRE OF CAXAMARCA | 73 |

| V. THE RANSOM AND MURDER OF THE INCA | 85 |

| VI. THE INCA AND THE PERUVIANS STRIKE VAINLY FOR FREEDOM | 93 |

| VII. "THE MEN OF CHILI" AND THE CIVIL WARS | 102 |

| VIII. THE MEAN END OF THE GREAT CONQUISTADOR | 105 |

| IX. THE LAST OF THE BRETHREN | 108 |

| THE GREATEST ADVENTURE IN HISTORY | |

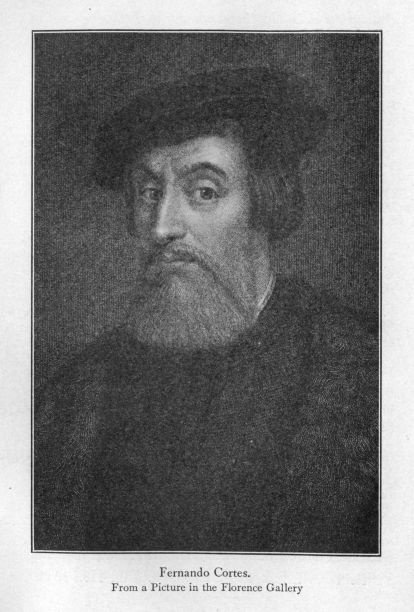

| I. THE CHIEF OF ALL THE SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE | 115 |

| II. THE EXPEDITION TO MEXICO | 120 |

| III. THE RELIGION OF THE AZTECS | 125 |

| IV. THE MARCH TO TENOCHTITLAN | 130 |

| V. THE REPUBLIC OF TLASCALA | 138 |

| VI. CORTES'S DESCRIPTION OF MEXICO | 147 |

| VII. THE MEETING WITH MONTEZUMA | 162 |

| VIII. THE SEIZURE OF THE EMPEROR | 171 |

| IX. THE REVOLT OF THE CAPITAL | 174 |

| X. IN GOD'S WAY | 177 |

| XI. THE MELANCHOLY NIGHT | 182 |

| XII. THE SIEGE AND DESTRUCTION OF MEXICO | 194 |

| XIII. A DAY OF DESPERATE FIGHTING | 198 |

| XIV. THE LAST MEXICAN | 215 |

| XV. THE END OF CORTES | 218 |

| THE YARN OF THE "ESSEX," WHALER | 231 |

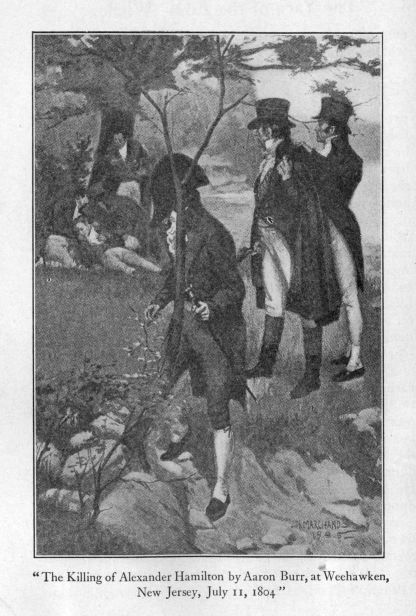

| SOME FAMOUS AMERICAN DUELS | 245 |

| I. A TRAGEDY OF OLD NEW YORK | 246 |

| II. ANDREW JACKSON AS A DUELLIST | 248 |

| III. THE KILLING OF STEPHEN DECATUR | 251 |

| IV. AN EPISODE IN THE LIFE OF JAMES BOWIE | 252 |

| V. A FAMOUS CONGRESSIONAL DUEL | 254 |

| VI. THE LAST NOTABLE DUEL IN AMERICA | 256 |

| THE CRUISE OF THE "TONQUIN" | 261 |

| JOHN PAUL JONES | 281 |

| I. THE BIRTH OF THE AMERICAN NAVY | 283 |

| II. JONES FIRST HOISTS THE STARS AND STRIPES | 284 |

| III. THE BATTLE WITH THE "SERAPIS" | 285 |

| IV. A HERO'S FAMOUS SAYINGS | 287 |

| V. WHAT JONES DID FOR HIS COUNTRY | 288 |

| VI. WHY DID HE TAKE THE NAME OF JONES | 289 |

| VII. A SEARCH FOR HISTORICAL EVIDENCE | 292 |

| VIII. THE JONESES OF NORTH CAROLINA | 296 |

| IX. PAUL JONES NEVER A MAN OF WEALTH | 297 |

| IN THE CAVERNS OF THE PITT | 301 |

| BEING A BOY OUT WEST | 315 |

| INDEX | 335 |

The publishers wish to acknowledge their indebtedness to The Cosmopolitan Magazine and Munsey's Magazine for permission to use several of the illustrations in this volume.

One of the commonly misunderstood phrases in the language is "the Spanish Main." To the ordinary individual it suggests the Caribbean Sea. Although Shakespeare in "Othello," makes one of the gentlemen of Cyprus say that he "cannot 'twixt heaven and main descry a sail," and, therefore, with other poets, gives warrant to the application of the word to the ocean, "main" really refers to the other element. The Spanish Main was that portion of South American territory distinguished from Cuba, Hispaniola and the other islands, because it was on the main land.

When the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea were a Spanish lake, the whole circle of territory, bordering thereon was the Spanish Main, but of late the title has been restricted to Central and South America. The buccaneers are those who made it famous. So the word brings up white-hot stories of battle, murder and sudden death.

The history of the Spanish Main begins in 1509, with the voyages of Ojeda and Nicuesa, which were the first definite and authorized attempts to colonize the mainland of South America.

The honor of being the first of the fifteenth-century {4} navigators to set foot upon either of the two American continents, indisputably belongs to John Cabot, on June 24, 1497. Who was next to make a continental landfall, and in the more southerly latitudes, is a question which lies between Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci.

Fiske, in a very convincing argument awards the honor to Vespucci, whose first voyage (May 1497 to October 1498) carried him from the north coast of Honduras along the Gulf coast around Florida, and possibly as far north as the Chesapeake Bay, and to the Bahamas on his return.

Markham scouts this claim. Winsor neither agrees nor dissents. His verdict in the case is a Scottish one, "Not proven." Who shall decide when the doctors disagree? Let every one choose for himself. As for me, I am inclined to agree with Fiske.

If it were not Vespucci, it certainly was Columbus on his third voyage (1498-1500). On this voyage, the chief of the navigators struck the South American shore off the mouth of the Orinoco and sailed westward along it for a short distance before turning to the northward. There he found so many pearls that he called it the "Pearl Coast." It is interesting to note that, however the question may be decided, all the honors go to Italy. Columbus was a Genoese. Cabot, although born in Genoa, had lived many years in Venice and had been made a citizen there; while Vespucci was a Florentine.

The first important expedition along the northern coast of South America was that of Ojeda in 1499-1500, in company with Juan de la Cosa, next to Columbus the most expert navigator and pilot of the age, and Vespucci, perhaps his equal in nautical science as he {5} was his superior in other departments of polite learning. There were several other explorations of the Gulf coast, and its continuations on every side, during the same year, by one of the Pizons, who had accompanied Columbus on his first voyage; by Lepe; by Cabral, a Portuguese, and by Bastidas and La Cosa, who went for the first time as far to the westward as Porto Rico on the Isthmus of Darien.

On the fourth and last voyage of Columbus, he reached Honduras and thence sailed eastward and southward to the Gulf of Darien, having not the least idea that the shore line which he called Veragua was in fact the border of the famous Isthmus of Panama. There were a number of other voyages, including a further exploration by La Cosa and Vespucci, and a second by Ojeda in which an abortive attempt was made to found a colony; but most of the voyages were mere trading expeditions, slave-hunting enterprises or searches, generally fruitless, for gold and pearls. Ojeda reported after one of these voyages that the English were on the coast. Who these English were is unknown. The news, however, was sufficiently disquieting to Ferdinand, the Catholic—and also the Crafty!—who now ruled alone in Spain, and he determined to frustrate any possible English movement by planting colonies on the Spanish Main.

Instantly two claimants for the honor of leading such an expedition presented themselves. The first Alonzo de Ojeda, the other Diego de Nicuesa. Two more extraordinary characters never went knight-erranting upon the seas. Ojeda was one of the {6} prodigious men of a time which was fertile in notable characters. Although small in stature, he was a man of phenomenal strength and vigor. He could stand at the foot of the Giralda in Seville and throw an orange over it, a distance of two hundred and fifty feet from the earth![1]

Wishing to show his contempt for danger, on one occasion he ran out on a narrow beam projecting some twenty feet from the top of the same tower and there, in full view of Queen Isabella and her court, performed various gymnastic exercises, such as standing on one leg, et cetera, for the edification of the spectators, returning calmly and composedly to the tower when he had finished the exhibition.

He was a magnificent horseman, an accomplished knight and an able soldier. There was no limit to his daring. He went with Columbus on his second voyage, and, single-handed, effected the capture of a powerful Indian cacique named Caonabo, by a mixture of adroitness, audacity and courage.

Professing amity, he got access to the Indian, and, exhibiting some polished manacles, which he declared were badges of royalty, he offered to put them on the fierce but unsophisticated savage and then mount the chief on his own horse to show him off like a Spanish monarch to his subjects. The daring programme was carried out just exactly as it had been planned. When Ojeda had got the forest king safely fettered and mounted on his horse, he sprang up behind him, held him there firmly in spite of his efforts, and galloped off to Columbus with his astonished and disgusted captive.

Neither of the voyages was successful. With all of his personal prowess, he was an unsuccessful administrator. He was poor, not to say penniless. He had two powerful friends, however. One was Bishop Fonseca, who was charged with the administration of affairs in the Indies, and the other was stout old Juan de la Cosa. These two men made a very efficient combination at the Spanish court, especially as La Cosa had some money and was quite willing to put it up, a prime requisite for the mercenary and niggardly Ferdinand's favor.

The other claimant for the honor of leading the colony happened to be another man small in stature, but also of great bodily strength, although he scarcely equalled his rival in that particular. Nicuesa had made a successful voyage to the Indies with Ovando, and had ample command of means. He was a gentleman by birth and station—Ojeda was that also—and was grand carver-in-chief to the King's uncle! Among his other qualities for successful colonization were a beautiful voice, a masterly touch on the guitar and an exquisite skill in equitation. He had even taught his horse to keep time to music. Whether or not he played that music himself on the back of the performing steed is not recorded.

Ferdinand was unable to decide between the rival claimants. Finally he determined to send out two expeditions. The Gulf of Uraba, now called the Gulf of Darien, was to be the dividing line between the two allotments of territory. Ojeda was to have that portion extending from the Gulf to the Cape de la Vela, which is just west of the Gulf of Venezuela. This territory was named new Andalusia. Nicuesa was to take that between the Gulf and the Cape Gracias á Dios off {8} Honduras. This section was denominated Golden Castile. Each governor was to fit out his expedition at his own charges. Jamaica was given to both in common as a point of departure and a base of supplies.

The resources of Ojeda were small, but when he arrived at Santo Domingo with what he had been able to secure in the way of ships and men, he succeeded in inducing a lawyer named Encisco, commonly called the Bachelor[2] Encisco, to embark his fortune of several thousand gold castellanos, which he had gained in successful pleadings in the court in the litigious West Indies, in the enterprise. In it he was given a high position, something like that of District Judge.

With this reënforcement, Ojeda and La Cosa equipped two small ships and two brigantines containing three hundred men and twelve horses.[3]

They were greatly chagrined when the imposing armada of Nicuesa, comprising four ships of different sizes, but much larger than any of Ojeda's, and two brigantines carrying seven hundred and fifty men, sailed into the harbor of Santo Domingo.

The two governors immediately began to quarrel. Ojeda finally challenged Nicuesa to a duel which should determine the whole affair. Nicuesa, who had everything to lose and nothing to gain by fighting, but who could not well decline the challenge, said that he was willing to fight him if Ojeda would put up what would popularly be known to-day in the pugilistic {9} circles as "a side bet" of five thousand castellanos to make the fight worth while.[4]

Poor Ojeda could not raise another maravedi, and as nobody would stake him, the duel was off. Diego Columbus, governor of Hispaniola, also interfered in the game to a certain extent by declaring that the Island of Jamaica was his, and that he would not allow anybody to make use of it. He sent there one Juan de Esquivel, with a party of men to take possession of it. Whereupon Ojeda stoutly declared that when he had time he would stop at that island and if Esquivel were there, he would cut off his head.

Finally on the 10th of November, 1509, Ojeda set sail, leaving Encisco to bring after him another ship with needed supplies. With Ojeda was Francisco Pizarro, a middle-aged soldier of fortune, who had not hitherto distinguished himself in any way. Hernando Cortez was to have gone along also, but fortunately for him, an inflammation of the knee kept him at home. Ojeda was in such a hurry to get to El Dorado—for it was in the territory to the southward of his allotment, that the mysterious city was supposed to be located—that he did not stop at Jamaica to take off Esquivel's head—a good thing for him, as it subsequently turned out.

Nicuesa would have followed Ojeda immediately, but his prodigal generosity had exhausted even his large resources, and he was detained by clamorous creditors, the law of the island being that no one could leave it in debt. The gallant little meat-carver labored with success to settle various suits pending, and thought {10} he had everything compounded; but just as he was about to sail he was arrested for another debt of five hundred ducats. A friend at last advanced the money for him and he got away ten days after Ojeda. It would have been a good thing if no friend had ever interfered and he had been detained indefinitely at Hispaniola.

Ojeda made a landfall at what is known now as Cartagena. It was not a particularly good place for a settlement. There was no reason on earth why they should stay there at all. La Cosa, who had been along the coast several times and knew it thoroughly, warned his youthful captain—to whom he was blindly and devotedly attached, by the way—that the place was extremely dangerous; that the inhabitants were fierce, brave and warlike, and that they had a weapon almost as effectual as the Spanish guns. That was the poisoned arrow. Ojeda thought he knew everything and he turned a deaf ear to all remonstrances. He hoped he might chance upon an opportunity of surprising an Indian village and capturing a lot of inoffensive inhabitants for slaves, already a very profitable part of voyaging to the Indies.

He landed without much difficulty, assembled the natives and read to them a perfectly absurd manifesto, which had been prepared in Spain for use in similar contingencies, summoning them to change their religion and to acknowledge the supremacy of Spain. Not one word of this did the natives understand and to it they responded with a volley of poisoned arrows. The Spanish considered this paper a most {11} valuable document, and always went through the formality of having the publication of it attested by a notary public.

Ojeda seized some seventy-five captives, male and female, as slaves. They were sent on board the ships. The Indian warriors, infuriated beyond measure, now attacked in earnest the shore party, comprising seventy men, among whom were Ojeda and La Cosa. The latter, unable to prevent him, had considered it proper to go ashore with the hot-headed governor to restrain him so far as was possible. Ojeda impetuously attacked the Indians and, with part of his men, pursued them several miles inland to their town, of which he took possession.

The savages, in constantly increasing numbers, clustered around the town and attacked the Spaniards with terrible persistence. Ojeda and his followers took refuge in huts and enclosures and fought valiantly. Finally all were killed, or fatally wounded by the envenomed darts except Ojeda himself and a few men, who retreated to a small palisaded enclosure. Into this improvised fort the Indians poured a rain of poisoned arrows which soon struck down every one but the governor himself. Being small of stature and extremely agile, and being provided with a large target or shield, he was able successfully to fend off the deadly arrows from his person. It was only a question of time before the Indians would get him and he would die in the frightful agony which his men experienced after being infected with the poison upon the arrow-points. In his extremity, he was rescued by La Cosa who had kept in hand a moiety of the shore party.

The advent of La Cosa saved Ojeda. Infuriated at the slaughter of his men, Ojeda rashly and {12} intemperately threw himself upon the savages, at once disappearing from the view of La Cosa and his men, who were soon surrounded and engaged in a desperate battle on their own account. They, too, took refuge in the building, from which they were forced to tear away the thatched roof that might have shielded them from the poisoned arrows, in fear lest the Indians might set it on fire. And they in turn were also reduced to the direst of straits. One after another was killed, and finally La Cosa himself, who had been desperately wounded before, received a mortal hurt; while but one man remained on his feet.

Possibly thinking that they had killed the whole party, and withdrawing to turn their attention to Ojeda, furiously ranging the forest alone, the Indians left the two surviving Spaniards unmolested, whereupon the dying La Cosa bade his comrade leave him, and if possible get word to Ojeda of the fate which had overtaken him. This man succeeded in getting back to the shore and apprised the men there of the frightful disaster.

The ships cruised along the shore, sending parties into the bay at different points looking for Ojeda and any others who might have survived. A day or two after the battle they came across their unfortunate commander. He was lying on his back in a grove of mangroves, upheld from the water by the gnarled and twisted roots of one of the huge trees. He had his naked sword in his hand and his target on his arm, but he was completely prostrated and speechless. The men took him to a fire, revived him and finally brought him back to the ship.

Marvelous to relate, he had not a single wound upon him!

Great was the grief of the little squadron at this dolorous state of affairs. In the middle of it, the ships of Nicuesa hove in sight. Mindful of their previous quarrels, Ojeda decided to stay ashore until he found out what were Nicuesa's intentions toward him. Cautiously his men broke the news to Nicuesa. With magnanimity and courtesy delightful to contemplate, he at once declared that he had forgotten the quarrel and offered every assistance to Ojeda to enable him to avenge himself. Ojeda thereupon rejoined the squadron, and the two rivals embraced with many protestations of friendship amid the acclaim of their followers.

The next night, four hundred men were secretly assembled. They landed and marched to the Indian town, surrounded it and put it to the flames. The defenders fought with their usual resolution, and many of the Spaniards were killed by the poisonous arrows, but to no avail. The Indians were doomed, and the whole village perished then and there.

Nicuesa had landed some of his horses, and such was the terror inspired by those remarkable and unknown animals that several of the women who had escaped from the fire, when they caught sight of the frightful monsters, rushed back into the flames, preferring this horrible death rather than to meet the horses. The value of the plunder amounted to eighteen thousand dollars in modern money, the most of which Nicuesa took.

The two adventurers separated, Nicuesa bidding Ojeda farewell and striking boldly across the Caribbean for Veragua, which was the name Columbus had given to the Isthmian coast below Honduras; while Ojeda crept along the shore seeking a convenient {14} spot to plant his colony. Finally he established himself at a place which he named San Sebastian. One of his ships was wrecked and many of his men were lost. Another was sent back to Santo Domingo with what little treasure they had gathered and with an appeal to Encisco to hurry up.

They made a rude fort on the shore, from which to prosecute their search for gold and slaves. The Indians, who also belonged to the poisoned-arrow fraternity, kept the fort in constant anxiety. Many were the conflicts between the Spaniards and the savages, and terrible were the losses inflicted by the invaders; but there seemed to be no limit to the number of Indians, while every Spaniard killed was a serious drain upon the little party. Man after man succumbed to the effects of the dreadful poison. Ojeda, who never spared himself in any way, never received a wound.

From their constant fighting, the savages got to recognize him as the leader and they used all their skill to compass destruction. Finally, they succeeded in decoying him into an ambush where four of their best men had been posted. Recklessly exposing themselves, the Indians at close range opened fire upon their prisoner with arrows. Three of the arrows he caught on his buckler, but the fourth pierced his thigh. It is surmised that Ojeda attended to the four Indians before taking cognizance of his wound. The arrow, of course, was poisoned, and unless something could be done, it meant death.

He resorted to a truly heroic expedient. He caused two iron plates to be heated white-hot and then directed the surgeon to apply the plates to the wound, one at the entrance and the other at the exit of the arrow. {15} The surgeon, appalled by the idea of such torture, refused to do so, and it was not until Ojeda threatened to hang him with his own hands that he consented. Ojeda bore the frightful agony without a murmur or a quiver, such was his extraordinary endurance. It was the custom in that day to bind patients who were operated upon surgically, that their involuntary movements might not disconcert the doctors and cause them to wound where they hoped to cure. Ojeda refused even to be bound. The remedy was efficacious, although the heat of the iron, in the language of the ancient chronicler, so entered his system that they used a barrel of vinegar to cool him off.

Ojeda was very much dejected by the fact that he had been wounded. It seemed to him that the Virgin, his patron, had deserted him. The little band, by this time reduced to less than one hundred people, was in desperate straits. Starvation stared it in the face when fortunately assistance came. One Bernardino de Talavera, with seventy congenial cut-throats, absconding debtors and escaped criminals, from Hispaniola, had seized a Genoese trading-ship loaded with provisions and had luckily reached San Sebastian in her. They sold these provisions to Ojeda and his men at exorbitant prices, for some of the hard-earned treasure which they had amassed with their great expenditure of life and health.

There was no place else for Talavera and his gang to go, so they stayed at San Sebastian. The supply of provisions was soon exhausted, and finally it was evident that, as Encisco had not appeared with any reënforcements or supplies, some one must go back to Hispaniola to bring rescue to the party. Ojeda offered to do this himself. Giving the charge of affairs at {16} San Sebastian to Francisco Pizarro, who promised to remain there for fifty days for the expected help, he embarked with Talavera.

Naturally Ojeda considered himself in charge of the ship; naturally Talavera did not. Ojeda, endeavoring to direct things, was seized and put in chains by the crew. He promptly challenged the whole crew to a duel, offering to fight them two at a time in succession until he had gone through the ship, of which he expected thereby to become the master; although what he would have done with seventy dead pirates on the ship is hard to see. The men refused this wager of battle, but fortune favored this doughty little cavalier, for presently a great storm arose. As neither Talavera nor any of the men were navigators or seamen, they had to release Ojeda. He took charge. Once he was in charge, they never succeeded in ousting him.

In spite of his seamanship, the caravel was wrecked on the island of Cuba. They were forced to make their way along the shore, which was then unsettled by Spain. Under the leadership of Ojeda the party struggled eastward under conditions of extreme hardship. When they were most desperate, Ojeda, who had appealed daily to his little picture of the Virgin, which he always carried with him, and had not ceased to urge the others to do likewise, made a vow to establish a shrine and leave the picture at the first Indian village they came to if they got succor there.

Sure enough, they did reach a place called Cueyabos, where they were hospitably received by the Indians, and where Ojeda, fulfilling his vow, erected a log hut, or shrine, in the recess of which he left, with much regret, the picture of the Virgin which had accompanied {17} him on his wanderings and adventures. Means were found to send word to Jamaica, still under the governorship of Esquivel, whose head Ojeda had threatened to cut off when he met him. Magnanimously forgetting the purpose of the broken adventurer, Esquivel despatched a ship to bring him to Jamaica. We may be perfectly sure that Ojeda said nothing about the decapitation when the generous hearted Esquivel received him with open arms. Ojeda with Talavera and his comrades were sent back to Santo Domingo. There Talavera and the principal men of his crew were tried for piracy and executed.

Ojeda found that Encisco had gone. He was penniless, discredited and thoroughly downcast by his ill fortune. No one would advance him anything to send succor to San Sebastian. His indomitable spirit was at last broken by his misfortunes. He lingered for a short time in constantly increasing ill health, being taken care of by the good Franciscans, until he died in the monastery. Some authorities say he became a monk; others deny it; it certainly is quite possible. At any rate, before he died he put on the habit of the order, and after his death, by his own direction, his body was buried before the gate, so that those who passed through it would have to step over his remains. Such was the tardy humility with which he endeavoured to make up for the arrogance and pride of his exciting life.

Encisco, coasting along the shore with a large ship, carrying reënforcements and loaded with provisions for the party, easily followed the course of Ojeda's {18} wanderings, and finally ran across the final remnants of his expedition in the harbor of Cartagena. The remnant was crowded into a single small, unseaworthy brigantine under the command of Francisco Pizarro.

Pizarro had scrupulously kept faith with Ojeda. He had done more. He had waited fifty days, and then, finding that the two brigantines left to him were not large enough to contain his whole party, by mutual agreement of the survivors clung to the death-laden spot until a sufficient number had been killed or had died to enable them to get away in the two ships. They did not have to wait long, for death was busy, and a few weeks after the expiration of the appointed time they were all on board.

There is something terrific to the imagination in the thought of that body of men sitting down and grimly waiting until enough of them should die to enable the rest to get away! What must have been the emotions that filled their breasts as the days dragged on? No one knew whether the result of the delay would enable him to leave, or cause his bones to rot on the shore. Cruel, fierce, implacable as were these Spaniards, there is something Homeric about them in such crises as these.

That was not the end of their misfortunes, for one of the two brigantines was capsized. The old chroniclers say that the boat was struck by a great fish. That is a fish story, which, like most fish stories, it is difficult to credit. At any rate, sink it did, with all on board, and Pizarro and about thirty men were all that were left of the gallant three hundred who had followed the doughty Ojeda in the first attempt to colonize South America.

Encisco was for hanging them at once, believing that {19} they had murdered and deserted Ojeda, but they were able to convince him at last of the strict legality of their proceedings. Taking command of the expedition himself, as being next in rank to Ojeda, the Bachelor led them back to San Sebastian. Unfortunately, before the unloading of his ship could be begun, she struck a rock and was lost; and the last state of the men, therefore, was as bad as the first.

Among the men who had come with Encisco was a certain Vasco Nuñez, commonly called Balboa. He had been with Bastidas and La Cosa on their voyage to the Isthmus nine years before. The voyage had been a profitable one and Balboa had made money out of it. He had lost all his money, however, and had eked out a scanty living on a farm at Hispaniola, which he had been unable to leave because he was in debt to everybody. The authorities were very strict in searching every vessel that cleared from Santo Domingo, for absconders. The search was usually conducted after the vessel had got to sea, too!

Balboa caused himself to be conveyed aboard the ship in a provision cask. No one suspected anything, and when the officers of the boat had withdrawn from the ship and Hispaniola was well down astern, he came forth. Encisco, who was a pettifogger of the most pronounced type, would have dealt harshly with him, but there was nothing to do after all. Balboa could not be sent back, and besides, he was considered a very valuable reënforcement on account of his known experience and courage.

It was he who now came to the rescue of the wretched colonists at San Sebastian by telling them that across the Gulf of Darien there was an Indian tribe with many villages and much gold. Furthermore, these {20} Indians, unfortunately for them, were not acquainted with the use of poisoned arrows. Balboa urged them to go there. His suggestion was received with cheers. The brigantines, and such other vessels as they could construct quickly, were got ready and the whole party took advantage of the favorable season to cross the Gulf of Darien to the other side, to the present territory of Panama which has been so prominent in the public eye of late. This was Nicuesa's domain, but nobody considered that at the time.

They found the Indian villages which Balboa had mentioned, fought a desperate battle with Cacique Cemaco, captured the place, and discovered quantities of gold castellanos (upward of twenty-five thousand dollars). They built a fort, and laid out a town called Maria de la Antigua del Darien—the name being almost bigger than the town! Balboa was in high favor by this time, and when Encisco got into trouble by decreeing various oppressive regulations and vexatious restrictions, attending to things in general with a high hand, they calmly deposed him on the ground that he had no authority to act, since they were on the territory of Nicuesa. To this logic, which was irrefutable, poor Encisco could make no reply. Pending the arrival of Nicuesa they elected Balboa and one Zamudio, a Biscayan, to take charge of affairs.

The time passed in hunting and gathering treasure, not unprofitably and, as they had plenty to eat, not unpleasantly.

Now let us return to Nicuesa. Making a landfall, Nicuesa, with a small caravel, attended by the two {21} brigantines, coasted along the shore seeking a favorable point for settlement. The large ships, by his orders, kept well out to sea. During a storm, Nicuesa put out to sea himself, imagining that the brigantines under the charge of Lope de Olano, second in command would follow him. When morning broke and the storm disappeared there were no signs of the ships or brigantines.

Nicuesa ran along the shore to search for them, got himself embayed in the mouth of a small river, swollen by recent rains, and upon the sudden subsidence of the water coincident with the ebb of the tide, his ship took ground, fell over on her bilge and was completely wrecked. The men on board barely escaped with their lives to the shore. They had saved nothing except what they wore, the few arms they carried and one small boat.

Putting Diego de Ribero and three sailors in the boat and directing them to coast along the shore, Nicuesa with the rest struggled westward in search of the two brigantines and the other three ships. They toiled through interminable forests and morasses for several days, living on what they could pick up in the way of roots and grasses, without discovering any signs of the missing vessels. Coming to an arm of the sea, supposed to be Chiriqui Lagoon off Costa Rica, in the course of their journeyings, they decided to cross it in a small boat rather than make the long detour necessary to get to what they believed to be the other side. They were ferried over to the opposite shore in the boat, and to their dismay discovered that they were upon an almost desert island.

It was too late and they were too tired, to go farther that night, so they resolved to pass the night on the {22} island. In the morning they were appalled to find that the little boat, with Ribero and the three sailors, was gone. They were marooned on a desert island with practically nothing to eat and nothing but brackish swamp water to drink. The sailors they believed to have abandoned them. They gave way to transports of despair. Some in their grief threw themselves down and died forthwith. Others sought to prolong life by eating herbs, roots and the like.

They were reduced to the condition of wild animals, when a sail whitened the horizon, and presently the two brigantines dropped anchor near the island. Ribero was no recreant. He had been convinced that Nicuesa was going farther and farther from the ships with every step that he took, and, unable to persuade him of that fact, he deliberately took matters into his own hands and retraced his course. The event justified his decision, for he soon found the brigantines and the other ships. Olano does not seem to have bestirred himself very vigorously to seek for Nicuesa, perhaps because he hoped to command himself; but when Ribero made his report he at once made for the island, which he reached just in time to save the miserable remnant from dying of starvation.

As soon as he could command himself, Nicuesa, whose easy temper and generous disposition had left him under the hardships and misfortunes he had sustained, sentenced Olano to death. By the pleas of his comrades, the sentence was mitigated, and the wretched man was bound in chains and forced to grind corn for the rest of the party—when there was any to grind.

To follow Nicuesa's career further would be simply to chronicle the story of increasing disaster. He lost {23} ship after ship and man after man. Finally reduced in number to one hundred men, one of the sailors, which had been with Columbus remembered the location of Porto Rico as being a haven where they might establish themselves in a fertile and beautiful country, well-watered and healthy. Columbus had left an anchor under the tree to mark the place, and when they reached it they found that the anchor had remained undisturbed all the years. They were attacked by the Indians there, and after losing twenty killed, were forced to put to sea in two small brigantines and a caravel, which they had made from the wrecks of their ships. Coasting along the shore, they came at last to an open roadstead where they could debark.

"In the name of God," said the disheartened Nicuesa, "let us stop here."

There they landed, called the place after their leader's exclamation, Nombre de Dios. The caravel, with a crew of the strongest, was despatched for succour, and was never heard of again.

One day, the colonists of Antigua were surprised by the sound of a cannon shot. They fired their own weapons in reply, and soon two ships carrying reënforcements for Nicuesa under Rodrigo de Colmenares, dropped anchor in front of the town.

By this time the colonists had divided into factions, some favoring the existing régime, others inclining toward the still busy Encisco, others desirous of putting themselves under the command of Nicuesa, whose generosity and sunny disposition were still affectionately remembered. The arrival of Colmenares and his party, gave the Nicuesa faction a decided preponderance; and, taking things in their own hands, they determined to despatch one of the ships, with two {24} representatives of the colony, up the coast in search of the governor. This expedition found Nicuesa without much difficulty. Again the rescuing ship arrived just in time. In a few days more, the miserable body of men, reduced now to less than sixty, would have perished of starvation.

Nicuesa's spirit had not been chastened by his unparalleled misfortunes. He not only accepted the proffered command of the colony—which was no more than his right, since it was established on his own territory—but he did more. When he heard that the colonists had amassed a great amount of gold by trading and thieving, he harshly declared that, as they had no legitimate right there, he would take their portion for himself; that he would stop further enterprises on their part—in short, he boastfully declared his intention of carrying things with a high hand in a way well calculated to infuriate his voluntary subjects. So arrogant was his bearing and so tactless and injudicious his talk, that the envoys from Antigua fled in the night with one of the ships and reported the situation to the colony. Olano, still in chains, found means to communicate with his friends in the other party. Naturally he painted the probable conduct of the governor in anything but flattering colors.

All this was most impolitic in Nicuesa. He seemed to have forgotten that profound political principle which suggests that a firm seat in the saddle should be acquired before any attempts should be made to lead the procession. The fable of "King Stork and the Frogs" was applicable to the situation of the colonists.

In this contingency they did not know quite what to do. It was Balboa who came to their rescue again. {25} He suggested that, although they had invited him, they need not permit Nicuesa to land. Accordingly, when Nicuesa hove in sight in the other ship, full of determination to carry things in his own way, they prevented him from coming ashore.

Greatly astonished, he modified his tone somewhat, but to no avail. It was finally decided among the colonists to allow him to land in order to seize his person. Arrangements were made accordingly, and the unsuspicious Nicuesa debarked from his ship the day after his arrival. He was immediately surrounded by a crowd of excited soldiers menacing and threatening him. It was impossible for him to make headway against them.

He turned and fled. Among his other gubernatorial accomplishments was a remarkable fleetness of foot. The poor little governor scampered over the sands at a great pace. He distanced his fierce pursuers at last and escaped to the temporary shelter of the woods.

Balboa, a gentleman by birth and by inclination as well—who had, according to some accounts, endeavored to compose the differences between Nicuesa and the colonists—was greatly touched and mortified at seeing so brave a cavalier reduced to such an undignified and desperate extremity. He secretly sought Nicuesa that night and profferred him his services. Then he strove valiantly to bring about an adjustment between the fugitive and the brutal soldiery, but in vain.

Nicuesa, abandoning all his pretensions, at last begged them to receive him, if not as a governor, at least as a companion-at-arms, a volunteer. But nothing, neither the influence of Balboa nor the entreaties {26} of Nicuesa, could mitigate the anger of the colonists. They would not have the little governor with them on any terms. They would have killed him then and there, but Balboa, by resorting to harsh measures, even causing one man to be flogged for his insolence, at last changed that purpose into another—which, to be sure, was scarcely less hazardous for Nicuesa.

He was to be given a ship and sent away forever from the Isthmus. Seventeen adherents offered manfully to share his fate. Protesting against the legality of the action, appealing to them to give him a chance for humanity's sake, poor Nicuesa was hurried aboard a small, crazy bark, the weakest of the wretched brigantines in the harbor. This was a boat so carelessly constructed that the calking of the seams had been done with a blunt iron. With little or no provisions, Nicuesa and his faithful seventeen were forced to put to sea amid the jeers and mockery of the men on shore. The date was March 1, 1511. According to the chroniclers, the last words that those left on the island heard Nicuesa say were, "Show thy face, O Lord, and we shall be saved." [5]

A pathetic and noble departure!

Into the misty deep then vanished poor Nicuesa and his faithful followers on that bright sunny spring morning. And none of them ever came back to tell the tale of what became of them. Did they die of starvation in their crazy brigantine, drifting on and on while they rotted in the blazing sun, until her seams opened and she sank? Did they founder in one of the sudden and fierce storms which sometimes swept {27} that coast? Did the deadly teredo bore the ship's timbers full of holes, until she went down with all on board? Were they cast on shore to become the prey of Indians whose enmity they had provoked by their own conduct? No one ever knew.

It was reported that years afterward on the coast of Veragua some wandering adventurers found this legend, almost undecipherable, cut in the bark of a tree, "Aqui anduvo el desdichado Diego de Nicuesa," which may be translated, "Here was lost the unfortunate Diego de Nicuesa." But the statement is not credited. The fate of the gallant little gentleman is one of the mysteries of the sea.

Of the original eleven hundred men who sailed with the two governors there remained perhaps thirty of Ojeda's and forty of Nicuesa's at Antigua with Encisco's command. This was the net result of the first two years of effort at the beginning of government in South America on the Isthmus of Panama, with its ocean on the other side still undreamed of. What these men did there, and how Balboa rose to further prominence, his great exploits, and finally how unkind Fate also overtook him, will form the subject of the next paper.

[1] At least, the assertion is gravely made by the ancient chroniclers. I wonder what kind of an outfielder he would have made today.

[2] From the Spanish word "bachiller," referring to an inferior degree in the legal profession.

[3] In the absence of particular information, I suppose the ships to be small caravels of between fifty and sixty tons, and the brigantines much smaller, open, flat-bottomed boats with but one mast—although a modern brigantine is a two-masted vessel.

[4] The castellano was valued at two dollars and fifty-six cents, but the purchasing power of that sum was much greater then than now. The maravedi was the equivalent of about one-third of a cent.

[5] Evidently he was quoting the exquisite measures of the Eightieth Psalm, one of the most touching appeals of David the Poet-King, in which he says over and over again, "Turn us again, O God, and cause Thy Face to shine, and we shall be saved."

This is the romantic history of Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, the most knightly and gentle of the Spanish discoverers, and one who would fain have been true to the humble Indian girl who had won his heart, even though his life and liberty were at stake. It is almost the only love story in early Spanish-American history, and the account of it, veracious though it is, reads like a novel or a play.

After Diego de Nicuesa had sailed away from Antigua on that enforced voyage from which he never returned, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa was supreme on the Isthmus. Encisco, however, remained to make trouble. In order to secure internal peace before prosecuting some further expeditions, Balboa determined to send him back to Spain, as the easiest way of getting rid of his importunities and complaints.

A more truculent commander would have no difficulty in inventing a pretext for taking off his head. A more prudent captain would have realized that Encisco with his trained mouth could do very much more harm to him in Spain than he could in Darien. Balboa thought to nullify that possibility, however, by sending Valdivia, with a present, to Hispaniola, and Zamudio {32} with the Bachelor to Spain to lay the state of affairs before the King. Encisco was a much better advocate than Balboa's friend Zamudio, and the King of Spain credited the one and disbelieved the other. He determined to appoint a new governor for the Isthmus, and decided that Balboa should be proceeded against rigorously for nearly all the crimes in the decalogue, the most serious accusation being that to him was due the death of poor Nicuesa. For by this time everybody was sure that the poor little meat-carver was no more.

An enterprise against the French which had been declared off filled Spain with needy cavaliers who had started out for an adventure and were greatly desirous of having one. Encisco and Zamudio had both enflamed the minds of the Spanish people with fabulous stories of the riches of Darien. It was curiously believed that gold was so plentiful that it could be fished up in nets from the rivers. Such a piscatorial prospect was enough to unlock the coffers of a prince as selfish as Ferdinand. He was willing to risk fifty thousand ducats in the adventure, which was to be conducted on a grand scale. No such expedition to America had ever been prepared before as that destined for Darien.

Among the many claimants for its command, he picked out an old cavalier named Pedro Arias de Avila, called by the Spaniards Pedrarias.[1]

This Pedrarias was seventy-two years old. He was of good birth and rich, and was the father of a large and interesting family, which he prudently left behind him in Spain. His wife, however, insisted on going {33} with him to the New World. Whether or not this was a proof of wifely devotion—and if it was, it is the only thing in history to his credit—or of an unwillingness to trust Pedrarias out of her sight, which is more likely, is not known. At any rate, she went along.

Pedrarias, up to the time of his departure from Spain, had enjoyed two nick-names, El Galan and El Justador. He had been a bold and dashing cavalier in his youth, a famous tilter in tournaments in his middle age, and a hard-fighting soldier all his life. His patron was Bishop Fonseca. Whatever qualities he might possess for the important work about to be devolved upon him would be developed later.

His expedition included from fifteen hundred to two thousand souls, and there were at least as many more who wanted to go and could not for lack of accommodations. The number of ships varies in different accounts from nineteen to twenty-five. The appointments both of the general expedition and the cavaliers themselves were magnificent in the extreme. Many afterward distinguished in America went in Pedrarias's command, chief among them being De Soto. Among others were Quevedo, the newly appointed Bishop of Darien, and Espinosa, the judge.

The first fleet set sail on the 11th of April, 1514, and arrived at Antigua without mishap on the 29th of June in the same year. The colony at that place, which had been regularly laid out as a town with fortifications and with some degree at least of European comfort, numbered some three hundred hard-bitten soldiers. The principle of the survival of the fittest had resulted in the selection of the best men from all the previous expeditions. They would have been a {34} dangerous body to antagonize. Pedrarias was in some doubt as to how Balboa would receive him. He dissembled his intentions toward him, therefore, and sent an officer ashore to announce the meaning of the flotilla which whitened the waters of the bay.

The officer found Balboa, dressed in a suit of pajamas engaged in superintending the roofing of a house. The officer, brilliant in silk and satin and polished armour, was astonished at the simplicity of Vasco Nuñez's appearance. He courteously delivered his message, however, to the effect that yonder was the fleet of Don Pedro Arias de Avila, the new Governor of Darien.

Balboa calmly bade the messenger tell Pedrarias that he could come ashore in safety and that he was very welcome. Balboa was something of a dissembler himself on occasion, as you will see. Pedrarias thereupon debarked in great state with his men, and, as soon as he firmly got himself established on shore, arrested Balboa and presented him for trial before Espinosa for the death of Nicuesa.

During all this long interval, Balboa had not been idle. A singular change had taken place in his character. He had entered upon the adventure in his famous barrel on Encisco's ship as a reckless, improvident, roisterous, careless, hare-brained scapegrace. Responsibility and opportunity had sobered and elevated him. While he had lost none of his dash and daring and brilliancy, yet he had become a wise, a prudent and a most successful captain. Judged by the high standard of the modern times, Balboa was {35} cruel and ruthless enough to merit our severe condemnation. Judged by his environments and contrasted with any other of the Spanish conquistadores he was an angel of light.

He seems to have remained always a generous, affectionate, open-hearted soldier. He had conducted a number of expeditions after the departure of Nicuesa to different parts of the Isthmus, and he amassed much treasure thereby, but he always so managed affairs that he left the Indian chiefs in possession of their territory and firmly attached to him personally. There was no indiscriminate murder, outrage or plunder in his train, and the Isthmus was fairly peaceable. Balboa had tamed the tempers of the fierce soldiery under him to a remarkable degree, and they had actually descended to cultivating the soil between periods of gold-hunting and pearl-fishing. The men under him were devotedly attached to him as a rule, although here and there a malcontent, unruly soldier, restless under the iron discipline, hated his captain.

Fortunately he had been warned by a letter from Zamudio, who had found means to send it via Hispaniola, of the threatening purpose of Pedrarias and the great expedition. Balboa stood well with the authorities in Hispaniola. Diego Columbus had given him a commission as Vice-Governor of Darien, so that as Darien was clearly within Diego Columbus's jurisdiction, Balboa was strictly under authority. The news in Zamudio's letter was very disconcerting. Like every Spaniard, Vasco Nuñez knew that he could expect little mercy and scant justice from a trial conducted under such auspices as Pedrarias's. He determined, therefore, to secure himself in his position by some splendid achievement, which would so work upon the {36} feelings of the King that he would be unable, for very gratitude, to press hard upon him.

The exploit that he meditated and proposed to accomplish was the discovery of the ocean upon the other side of the Isthmus. When Nicuesa came down from Nombre de Dios, he left there a little handful of men. Balboa sent an expedition to rescue them and brought them down to Antigua. Either on that expedition or on another shortly afterward, two white men painted as Indians discovered themselves to Balboa in the forest. They proved to be Spaniards who had fled from Nicuesa to escape punishment for some fault they had committed and had sought safety in the territory of an Indian chief named Careta, the Cacique of Cueva. They had been hospitably received and adopted into the tribe. In requital for their entertainment, they offered to betray the Indians if Vasco Nuñez, the new governor, would condone their past offenses. They filled the minds of the Spaniards, alike covetous and hungry, with stories of great treasures and what was equally valuable, abundant provisions, in Coreta's village.

Balboa immediately consented. The act of treachery was consummated and the chief captured. All that, of course, was very bad, but the difference between Balboa and the men of his time is seen in his after conduct. Instead of putting the unfortunate chieftain to death and taking his people for slaves, Balboa released him. The reason he released him was because of a woman—a woman who enters vitally into the subsequent history of Vasco Nuñez, and indeed of the whole of South America. This was the beautiful daughter of the chief. Anxious to propitiate his captor, Careta offered Balboa this flower of the family {37} to wife. Balboa saw her, loved her and took her to himself. They were married in accordance with the Indian custom; which, of course, was not considered in the least degree binding by the Spaniards of that time. But it is to Balboa's credit that he remained faithful to this Indian girl. Indeed, if he had not been so much attached to her it is probable that he might have lived to do even greater things than he did.

In his excursions throughout the Isthmus, Balboa had met a chief called Comagre. As everywhere, the first desire of the Spanish was gold. The metal had no commercial value to the Indians. They used it simply to make ornaments, and when it was not taken from them by force, they were cheerfully willing to exchange it for beads, trinkets, hawks' bells, and any other petty trifles. Comagre was the father of a numerous family of stalwart sons. The oldest, observing the Spaniards brawling and fighting—"brabbling," Peter Martyr calls it—about the division of gold, with an astonishing degree of intrepidity knocked over the scales at last and dashed the stuff on the ground in contempt. He made amends for his action by telling them of a country where gold, like Falstaff's reasons, was as plenty as blackberries. Incidentally he gave them the news that Darien was an isthmus, and that the other side was swept by a vaster sea than that which washed its eastern shore.

These tidings inspired Balboa and his men. They talked long and earnestly with the Indians and fully satisfied themselves of the existence of a great sea and of a far-off country abounding in treasure on the other side. Could it be that mysterious Cipango of Marco Polo, search for which had been the object of Columbus's voyage? The way there was discussed and the {38} difficulties of the journey estimated, and it was finally decided that at least one thousand Spaniards would be required safely to cross the Isthmus.

Balboa had sent an account of this conversation to Spain, asking for the one thousand men. The account reached there long before Pedrarias sailed, and to it, in fact, was largely due the extensive expedition. Now when Balboa learned from Zamudio of what was intended toward him in Spain, he determined to undertake the discovery himself. He set forth from Antigua the 1st of September, 1513, with a hundred and ninety chosen men, accompanied by a pack of bloodhounds, very useful in fighting savages, and a train of Indian slaves. Francisco Pizarro was his second in command. All this in lieu of the one thousand Spaniards for which he had asked, which was not thought to be too great a number.

The difficulties to be overcome were almost incredible. The expedition had to fight its way through tribes of warlike and ferocious mountaineers. If it was not to be dogged by a trail of pestilent hatreds, the antagonisms evoked by its advance must be composed in every Indian village or tribe before it progressed farther. Aside from these things, the topographical difficulties were immense. The Spaniards were armour-clad, as usual, and heavily burdened. Their way led through thick and overgrown and pathless jungles or across lofty and broken mountain-ranges, which could be surmounted only after the most exhausting labor. The distance as the crow flies, was short, less than fifty miles, but nearly a month elapsed before they approached the end of their journey.

Balboa's enthusiasm and courage had surmounted every obstacle. He made friends with the chiefs {39} through whose territories he passed, if they were willing to be friends. If they chose to be enemies, he fought them, he conquered them and then made friends with them then. Such a singular mixture of courage, adroitness and statesmanship was he that everywhere he prevailed by one method or another. Finally, in the territory of a chief named Quarequa, he reached the foot of the mountain range from the summit of which his guides advised him that he could see the object of his expedition.

There were but sixty-seven men capable of ascending that mountain. The toil and hardship of the journey had incapacitated the others. Next to Balboa, among the sixty-seven, was Francisco Pizarro. Early on the morning of the 25th of September, 1513, the little company began the ascent of the Sierra. It was still morning when they surmounted it and reached the top. Before them rose a little cone, or crest, which hid the view toward the south. "There," said the guides, "from the top of yon rock, you can see the ocean." Bidding his men halt where they were, Vasco Nuñez went forward alone and surmounted the little elevation.

A magnificent prospect was embraced in his view. The tree-clad mountains sloped gently away from his feet, and on the far horizon glittered a line of silver which attested the accuracy of the claim of the Indians as to the existence of a great sea on the other side of what he knew now to be an isthmus. Balboa named the body of water that he could see far away, flashing in the sunlight of that bright morning, "the Sea of the South," or "the South Sea." [2]

Drawing his sword, he took possession of it in the {40} name of Castile and Leon. Then he summoned his soldiers. Pizarro in the lead they were soon assembled at his side. In silent awe they gazed, as if they were looking upon a vision. Finally some one broke into the words of a chant, and on that peak in Darien those men sang the "Te Deum Laudamus."

Somehow the dramatic quality of that supreme moment in the life of Balboa has impressed itself upon the minds of the successive generations that have read of it since that day. It stands as one of the great episodes of history. That little band of ragged, weather-beaten, hard-bitten soldiers, under the leadership of the most lovable and gallant of the Spaniards of his time, on that lonely mountain peak rising above the almost limitless sea of trackless verdure, gazing upon the great ocean whose waters extended before them for thousands and thousands of miles, attracts the attention and fires the imagination.

Your truly great man may disguise his imaginative qualities from the unthinking public eye, but his greatness is in proportion to his imagination. Balboa, with the centuries behind him, shading his eye and staring at the water:

——Dipt into the future far as human eye could see,

Saw the visions of the world, and all the wonder that would be.

He saw Peru with its riches; he saw fabled Cathay; he saw the uttermost isles of the distant sea. His imagination took the wings of the morning and soared over worlds and countries that no one but he had ever dreamed of, all to be the fiefs of the King of Castile. It is interesting to note that it must have been to Balboa, of all men, that some adequate idea of the real size of the earth first came.

Well, they gazed their fill; then, with much toil, they cut down trees, dragged them to the top of the mountain and erected a huge cross which they stayed by piles of stones. Then they went down the mountain-side and sought the beach. It was no easy task to find it, either. It was not until some days had passed that one of the several parties broke through the jungle and stood upon the shore. When they were all assembled, the tide was at low ebb. A long space of muddy beach lay between them and the water. They sat down under the trees and waited until the tide was at flood, and then, on the 29th of September, with a banner displaying the Virgin and Child above the arms of Spain in one hand and with drawn sword in the other, Balboa marched solemnly into the rolling surf that broke about his waist and took formal possession of the ocean, and all the shores, wheresoever they might be, which were washed by its waters, for Ferdinand of Aragon, and his daughter Joanna of Castile, and their successors in Spain. Truly a prodigious claim, but one which for a time Spain came perilously near establishing and maintaining.[3]

Before they left the shore they found some canoes and voyaged over to a little island in the bay, which they called San Miguel, since it was that saint's day, and where they were nearly all swept away by the rising tide. They went back to Antigua by another route, somewhat less difficult, fighting and making peace as before, and amassing treasure the while. Great was the joy of the colonists who had been left behind, when Balboa and his men rejoined them. {42} Those who had stayed behind shared equally with those who had gone. The King's royal fifth was scrupulously set aside and Balboa at once dispatched a ship, under a trusted adherent named Arbolancha, to acquaint the King with his marvelous discovery, and to bring back reënforcements and permission to venture upon the great sea in quest of the fabled golden land toward the south.

Unfortunately for Vasco Nuñez, Arbolancha arrived just two months after Pedrarias had sailed. The discovery of the Pacific was the greatest single exploit since the voyage of Columbus. It was impossible for the King to proceed further against Balboa under such circumstances. Arbolancha was graciously received, therefore, and after his story had been heard a ship was sent back to Darien instructing Pedrarias to let Balboa alone, appointing him an adelantado, or governor of the islands he had discovered in the South Sea, and all such countries as he might discover beyond.

All this, however took time, and Balboa was having a hard time with Pedrarias. In spite of all the skill of the envenomed Encisco, who had been appointed the public prosecutor in Pedrarias's administration, Balboa was at last acquitted of having been concerned in the death of Nicuesa. Pedrarias, furious at the verdict, made living a burden to poor Vasco Nuñez by civil suits which ate up all his property.

It had not fared well with the expedition of Pedrarias, either, for in six weeks after they landed, over seven hundred of his unacclimated men were dead of fever and other diseases, incident to their lack of {43} precaution and the unhealthy climate of the Isthmus. They had been buried in their brocades, as has been pithily remarked, and forgotten. The condition of the survivors was also precarious. They were starving in their silks and satins.

Pedrarias, however, did not lack courage. He sent the survivors hunting for treasures. Under different captains he dispatched them far and wide through the Isthmus to gather gold, pearls, and food. They turned its pleasant valleys and its noble hills into earthly hells. Murder, outrage and rapine flourished unchecked, even encouraged and rewarded. All the good work of Balboa in pacifying the natives and laying the foundation for a wise and kindly rule was undone in a few months.

Such cruelties had never before been practised in any part of the New World settled by the Spaniards. I do not suppose the men under Pedrarias were any worse than others. Indeed, they were better than some of them, but they took their cue from their terrible commander. Fiske calls him "a two-legged tiger." That he was an old man seems to add to the horror which the story of his course inspires. The recklessness of an unthinking young man may be better understood than the cold, calculating fury and ferocity of threescore and ten. To his previous appellations, a third was added. Men called him, "Furor Domini"—"The Scourge of God." Not Attila himself, to whom the title was originally applied, was more ruthless and more terrible.

Balboa remonstrated, but to no avail. He wrote letter after letter to the king, depicting the results of Pedrarias' actions, and some tidings of his successive communications, came trickling back to the {44} governor, who had been especially cautioned by the King to deal mercifully with the inhabitants and set them an example of Christian kindness and gentleness that they might be won to the religion of Jesus thereby! Pedrarias was furious against Balboa, and would have withheld the King's dispatches acknowledging the discovery of the South Sea by appointing him adelantado; but the Bishop of Darien, whose friendship Balboa had gained, protested and the dispatches were finally delivered. The good Bishop did more. He brought about a composition of the bitter quarrel between Balboa and Pedrarias. A marriage was arranged between the eldest daughter of Pedrarias and Balboa. Balboa still loved his Indian wife; it is evident that he never intended to marry the daughter of Pedrarias, and that he entered upon the engagement simply to quiet the old man and secure his countenance and assistance for the undertaking he projected to the mysterious golden land toward the south. There was a public betrothal which effected the reconciliation. And now Pedrarias could not do enough for Balboa, whom he called his "dear son."

Balboa, therefore, proposed to Pedrarias that he should immediately set forth upon the South Sea voyage. Inasmuch as Pedrarias was to be supreme in the New World and as Balboa was only a provincial governor under him, the old reprobate at last consented.

Balboa decided that four ships, brigantines, would be needed for his expedition. The only timber fit for shipping, of which the Spaniards were aware, {45} grew on the eastern side of the Isthmus. It would be necessary, therefore, to cut and work up the frames and timbers of the ships on the eastern side, then carry the material across the Isthmus, and there put it together. Vasco Nuñez reconnoitered the ground and decided to start his ship-building operations at a new settlement called Ada. The timber when cut and worked had to be carried sixteen miles away to the top of the mountain, then down the other slope, to a convenient spot on the river Valsa, where the keels were to be laid, the frames put together, the shipbuilding completed, and the boats launched on the river, which was navigable to the sea.

This amazing undertaking was carried out as planned. There were two setbacks before the work was completed. In one case, after the frames had been made and carried with prodigious toil to the other side of the mountain, they were discovered to be full of worms and had to be thrown away. After they had been replaced, and while the men were building the brigantines, a flood washed every vestige of their labor into the river. But, as before, nothing could daunt Balboa. Finally, after labors and disappointments enough to crush the heart of an ordinary man, two of the brigantines were launched in the river. Most of the carrying had been done by Indians, over two thousand of whom died under the tremendous exactions of the work.

Embarking upon the two brigantines, Balboa soon reached the Pacific, where he was presently joined by the two remaining boats as they were completed. He had now four fairly serviceable ships and three hundred of the best men of the New World under his command. He was well equipped and well provisioned {46} for the voyage and lacked only a little iron and a little pitch, which, of course, would have to be brought to him from Ada on the other side of the Isthmus. The lack of that little iron and that little pitch proved the undoing of Vasco Nuñez. If he had been able to obtain them or if he had sailed away without them, he might have been the conqueror of Peru; in which case that unhappy country would have been spared the hideous excesses and the frightful internal brawls and revolutions which afterward almost ruined it under the long rule of the ferocious Pizarros. Balboa would have done better from a military standpoint than his successors, and as a statesman as well as a soldier the results of his policy would have been felt for generations.

History goes on to state that while he was waiting for the pitch and iron, word was brought to him that Pedrarias was to be superseded in his government. This would have been delightful tidings under any other circumstances, but now that a reconciliation had been patched up between him and the governor, he rightly felt that the arrival of a new governor might materially alter the existing state of affairs. Therefore, he determined to send a party of four adherents across the mountains to Ada to find out if the rumours were true.

If Pedrarias was supplanted the messengers were to return immediately, and without further delay they would at once set sail. If Pedrarias was still there, well and good. There would be no occasion for such precipitate action and they could wait for the pitch and iron. He was discussing this matter with some friends on a rainy day in 1517—the month and the date not being determinable now. The sentry attached to the governor's quarters, driven to the shelter of the {47} house by the storm, overheard a part of this harmless conversation. There is nothing so dangerous as a half-truth; it is worse than a whole lie. The soldier who had aforetime felt the weight of Balboa's heavy hand for some dereliction of duty, catching sentences here and there, fancied he detected treachery to Pedrarias and thought he saw an opportunity of revenging himself, and of currying favor with the governor, by reporting it at the first convenient opportunity.

Now, there lived at Ada at the time one Andres Garavito. This man was Balboa's bitter enemy. He had presumed to make dishonorable overtures to Balboa's Indian wife. The woman had indignantly repulsed his advances and had made them known to her husband. Balboa had sternly reproved Garavito and threatened him with death. Garavito had nourished his hatred, and had sought opportunity to injure his former captain. The men sent by Balboa to Ada to find out the state of affairs were very maladroit in their manoeuvres, and their peculiar actions awakened the suspicions of Pedrarias. The first one who entered the town was seized and cast into prison. The others thereupon came openly to Ada and declared their purposes. This seems to have quieted, temporarily, the suspicions of Pedrarias; but the implacable Garavito, taking opportunity, when the governor's mind was unsettled and hesitant, assured him that Balboa had not the slightest intention whatever of marrying Pedrarias's daughter; that he was devoted to his Indian wife, and intended to remain true to her; that it was his purpose to sail to the South Sea, establish a kingdom and make himself independent of Pedrarias.

{48} The old animosity and anger of the governor awoke on the instant. There was no truth in the accusations except in so far as it regarded Vasco Nuñez's attachment to his Indian wife, and indeed Balboa had never given any public refusal to abide by the marital engagement which he had entered into; but there was just enough probability in Garavito's tale to carry conviction to the ferocious tyrant. He instantly determined upon Balboa's death. Detaining his envoys, he sent him a very courteous and affectionate letter, entreating him to come to Ada to receive some further instructions before he set forth on the South Sea.

Among the many friends of Balboa was the notary Arguello who had embarked his fortune in the projected expedition. He prepared a warning to Vasco Nuñez, which unfortunately fell into the hands of Pedrarias and resulted in his being clapped into prison with the rest. Balboa unsuspiciously complied with the governor's request, and, attended by a small escort, immediately set forth for Ada.

He was arrested on the way by a company of soldiers headed by Francisco Pizarro, who had nothing to do with the subsequent transactions, and simply acted under orders, as any other soldier would have done. Balboa was thrown into prison and heavily ironed; he was tried for treason against the King and Pedrarias. The testimony of the soldier who had listened in the rainstorm was brought forward, and, in spite of a noble defense, Balboa was declared guilty.

Espinosa, who was his judge, was so dissatisfied with the verdict, however, that he personally besought Pedrarias to mitigate the sentence. The stern old tyrant refused to interfere, nor would he entertain {49} Balboa's appeal to Spain. "He has sinned," he said tersely; "death to him!" Four of his companions—three of them men who had been imprisoned at Ada, and the notary who had endeavored to warn him—were sentenced to death.

It was evening before the preparations for the execution were completed. Balboa faced death as dauntlessly as he had faced life. Pedrarias was hated in Ada and Darien; Balboa was loved. If the veterans of Antigua had not been on the other side of the Isthmus, Balboa would have been rescued. As it was, the troops of Pedrarias awed the people of Ada and the judicial murder went forward.

Balboa was as composed when he mounted the scaffold as he had been when he welcomed Pedrarias. A proclamation was made that he was a traitor, and with his last breath he denied this and asserted his innocence. When the axe fell that severed his head, the noblest Spaniard of the time, and one who ranks with those of any time, was judicially murdered. One after the other, the three companions, equally as dauntless, suffered the unjust penalty. The fourth execution had taken place in the swift twilight of the tropical latitude and the darkness was already closing down upon the town when the last man mounted the scaffold. This was the notary, Arguello, who had interfered to save Balboa. He seems to have been beloved by the inhabitants of the town, for they awakened from their horror, and some of consideration among them appealed personally to Pedrarias, who had watched the execution from a latticed window, to reprieve the last victim. "He shall die," said the governor sternly, "if I have to kill him with my own hand."

So, to the future sorrow of America, and to the {50} great diminution of the glory and peace of Spain, and the world, passed to his death the gallant, the dauntless, the noble-hearted Balboa. Pedrarias lived until his eighty-ninth year, and died in his bed at Panama; which town had been first visited by one of his captains, Tello de Guzman, founded by Espinosa and upbuilt by himself.

There are times when a belief in an old-fashioned Calvinistic hell of fire and brimstone is an extremely comforting doctrine, irrespective of theological bias. Else how should we dispose of Nero, Tiberius, Torquemada, and gentlemen of their stripe? Wherever such a company may be congregated, Pedro Arias de Avila is entitled to a high and exclusive place.

[1] In the English chronicles he is often spoken of as Davila, which is near enough to Diabolo to make one wish that the latter sobriquet had been his own. It would have been much more apposite.

[2] It was Magellan who gave it the inappropriate name of "Pacific."

[3] To-day not one foot of territory bordering on that sea belongs to Spain. The American flag flies over the Philippines—shall I say forever?

The reader will look in vain on the map of modern Spain for the ancient province of Estremadura, yet it is a spot which, in that it was the birthplace of the conquerors of Peru and Mexico—to say nothing of the discoverer of the Mississippi—contributed more to the glory of Spain than any other province in the Iberian peninsula. In 1883, the ancient territory was divided into the two present existing states of Badajoz and Caceres. In the latter of these lies the important mountain town of Trujillo.

Living there in the last half of the fifteenth century was an obscure personage named Gonzalo Pizarro. He was a gentleman whose lineage was ancient, whose circumstances were narrow and whose morals were loose. By profession he was a soldier who had gained some experience in the wars under the "Great Captain," Gonsalvo de Cordova. History would take no note of this vagrom and obscure cavalier had it not been for his children. Four sons there were whose qualities and opportunities were such as to have enabled them to play a somewhat large part in the world's affairs {54} in their day. How many unconsidered other progeny, male or female, there may have been, God alone knows—possibly, nay probably, a goodly number.