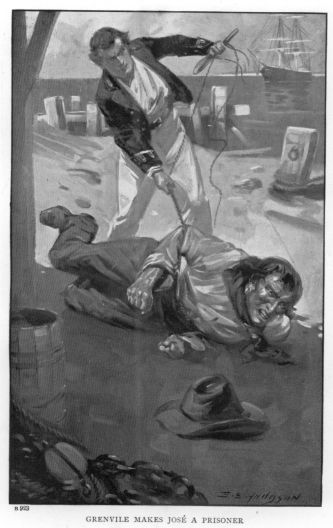

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Middy in Command, by Harry Collingwood

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: A Middy in Command

A Tale of the Slave Squadron

Author: Harry Collingwood

Illustrator: Edward S. Hodgson

Release Date: April 13, 2007 [EBook #21064]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A MIDDY IN COMMAND ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Harry Collingwood

"A Middy in Command"

Chapter One.

Our first prize.

The first faint pallor of the coming dawn was insidiously extending along the horizon ahead as H.M. gun-brig Shark—the latest addition to the slave-squadron—slowly surged ahead over the almost oil-smooth sea, under the influence of a languid air breathing out from the south-east. She was heading in for the mouth of the Congo, which was about forty miles distant, according to the master’s reckoning.

The night had been somewhat squally, and the royals and topgallant-sails were stowed; but the weather was now clearing, and as “three bells” chimed out musically upon the clammy morning air, Mr Seaton, the first lieutenant, who was the officer of the watch, having first scanned the heavens attentively, gave orders to loose and set again the light upper canvas.

By the time that the men aloft had cast off the gaskets that confined the topgallant-sails to the yards, the dawn—which comes with startling rapidity in those latitudes—had risen high into the sky ahead, and spread well along the horizon to north and south, causing the stars to fade and disappear, one after another, until only a few of the brightest remained twinkling low down in the west.

As I wheeled at the stern-grating in my monotonous promenade of the lee side of the quarter-deck, a hail came down from aloft—

“Sail ho! two of ’em, sir, broad on the lee beam. Look as if they were standin’ out from the land.”

“What are they like? Can you make out their rig?” demanded the first luff, as he halted and directed his gaze aloft at the man on the main-royal-yard, who, half-way out to the yard-arm, was balancing himself upon the foot-rope, and steadying himself with one hand upon the yard as he gazed away to leeward under the shade of the other.

“I can’t make out very much, sir,” replied the man. “They’re too far off; but one looks like a schooner, and t’other like a brig.”

“And they are heading out from the land, you say?” demanded the lieutenant.

“Looks like it, sir,” answered the man; “but, as I was sayin’, they’re a long way off; and it’s a bit thick down to leeward there, so—”

“All right, never mind; cast off those gaskets and come down,” interrupted Mr Seaton impatiently. Then, turning to me, he said:

“Mr Grenvile, take the glass and lay aloft, if you please, and see what you can make of those strangers. Mr Keene”—to the other midshipman of the watch—“slip down below and call the captain, if you please. Tell him that two strange sail have been sighted from aloft, apparently coming out from the Congo.”

By the time he had finished speaking I had snatched the glass from its beckets, and was half-way up the weather main rigging, while the watch was sheeting home and hoisting away the topgallant-sails and royals. When Keene reappeared on deck, after calling the skipper, I was comfortably astride the royal-yard, with my left arm round the spindle of the vane—the yard hoisting close up under the truck. With my right hand I manipulated the slide of the telescope and adjusted the focus of the instrument to suit my sight.

By this time the dawn had entirely overspread the firmament, and the sky had lost its pallor and was all aglow with richest amber, through which a long shaft of pale golden light, soaring straight up toward the zenith, heralded the rising of the sun. The thickness to leeward had by this time cleared away, and the two strange sail down there were now clearly visible, the one as a topsail schooner, and the other as a brig. They were a long way off, the topsails of the brig—which was leading—being just clear of the horizon from my elevated point of observation, while the head of the schooner’s topsail just showed clear of the sea. The brig I took to be a craft of about our own size, say some three hundred tons, while the schooner appeared to be about two hundred tons.

I had just ascertained these particulars when the voice of the skipper came pealing up to me from the stern-grating, near which he stood, with Mr Seaton alongside of him.

“Well, Mr Grenvile, what do you make of them?”

I replied, giving such information as I had been able to gather; and added: “They appear to be sailing in company, sir.”

“Thank you, that will do; you may come down,” answered the skipper. Then, as I swung myself off the yard, I heard the lieutenant give the order to bear up in chase, to rig out the port studding-sail booms, and to see all clear for setting the port studding-sails—or stu’n’sails, as they are more commonly called. I had reached the cross-trees, on my way down, when Captain Bentinck again hailed me.

“Aloft there! just stay where you are for a little while, Mr Grenvile, and keep your eye on those sail to leeward. And if you observe any alteration in the course that they are steering, report the fact to me at once.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” I answered, and settled myself down comfortably for what I anticipated might be a fairly long wait.

For a few minutes all was now bustle and confusion below and about me; the helm was put up and the ship wore short round, the yards were swung, and then several hands came aloft to reeve the gear, rig out the booms, and set the larboard studding-sails, from the royals down. We rather prided ourselves upon being a smart ship, and in less than five minutes from the moment the order was given we were sliding away upon our new course, at a speed of some five and a half knots, with all our studding-sails set on the port side, and all ropes neatly coiled down once more. But ere this had happened I had returned to my former post on the main-royal-yard, for I quickly discovered that the shift of helm had caused the head-sails to interpose themselves between me and the objects which it was my duty to watch, and this was to be remedied only by returning to the royal-mast-head.

The skipper, in setting the new course, had displayed what commended itself to me as sound judgment. We were at such a distance from the strangers of whom we were now in chase that even our most lofty canvas was—and would, for some little time longer, remain—invisible from their decks. This was highly desirable, since the nearer we could approach them without being discovered, the better would be our chance of ultimately getting alongside them. The only likelihood of a premature discovery of our proximity lay in the possible necessity, on the part of one or the other of them, to send a hand aloft; but this we could not guard against. Captain Bentinck, therefore, hoping that no such necessity would arise, had shaped a course not directly for them, but at an intercepting angle to their own course, by which means he hoped not only to hold way with them, but also to lessen very considerably the distance between them and ourselves before the sight of our canvas, rising above the horizon, would reveal our unwelcome presence to the two slavers, as we believed the strange craft to be. It was also of the utmost importance that we should have instant knowledge of their discovery of our presence in their neighbourhood, and of the action that they would thereupon take; hence the necessity for my remaining aloft to maintain a steady and careful watch upon their movements.

I had been anticipating—and, indeed, hoping—that my sojourn aloft would be a lengthy one, for I knew that, so long as the strangers continued to steer their original course, it would mean that they remained in ignorance of our proximity to them. But this was not to be, for I had but regained my original position on the royal-yard some ten minutes, when, as I kept the telescope steadily fixed upon them, I saw the brig bear up and run off square before the wind. The schooner promptly followed her example, and both of them immediately proceeded to rig out studding-sail booms on both sides.

“Deck ahoy!” hailed I. “The two strange sail to leeward have this instant put up their helms, and are running square off before the wind; they are also rigging out their studding-sail booms on both sides.”

“Thank you, Mr Grenvile,” replied the skipper. “How do they bear from us now?”

“About four points before the beam, sir,” answered I.

“Very good. Stay where you are a minute or two longer, for I am about to bear up in chase, and I want you to tell me when they are directly ahead of us,” ordered the skipper.

“Ay, ay, sir!” shouted I, giving the stereotyped answer to every order issued on board ship; and the next instant all was bustle and activity below me, as the helm was put up and preparations were made to set our studding-sails on the starboard side. As I glanced down on deck I saw the captain step to the binnacle, apparently watching the motion of the compass-card as the ship paid off, so I at once directed my gaze toward the strangers, and the moment they were brought in line with the fore-royal-mast-head I sang out:

“Steady as you go, sir; the strangers are now dead ahead of us!”

“Thank you, Mr Grenvile; you may come down now,” replied the captain. And as I swung off the yard I saw the skipper and the first lieutenant, with their heads together over the binnacle, talking earnestly.

Meanwhile the wind, scant as it was, seemed inclined to become more scanty still, until at length, by “six bells”—that is to say, seven o’clock—our courses were drooping motionless from the yards, the maintop-sail was wrinkling ominously, with an occasional flap to the mast as the brig hove lazily over the long low undulations of the swell—and only the light upper canvas continued to draw, the ship’s speed having declined to a bare two knots, which gave us little more than mere steerage way. And loud was the grumbling, fore and aft, when, a little later, as the hands were piped to breakfast, the breeze died away altogether, and the Shark, being no longer under the control of her helm, proceeded to “box the compass”—that is to say, to swing first this way and then that, with the send of the swell. Our only consolation was that the strangers to leeward were in the same awkward fix as ourselves; for if we had no wind wherewith to pursue them, they, in their turn, had none wherewith to run away from us.

Nobody dawdled very long over breakfast that morning; for, in the first place, the heat below was simply unbearable, and, in the next, we were all far too anxious to allow of our remaining in our berths while we knew that every conceivable expedient would be adopted by the captain to shorten the distance between us and the chase. It was my watch below from eight o’clock until noon, and I was consequently off duty; but although I had been on deck for eight hours of the twelve during the preceding night, I was much too fidgety to turn in and endeavour to get a little sleep; I therefore routed out a small pocket sextant that had been presented to me by a friend, and, making my way up into the fore-topmast cross-trees—from which the strangers could be seen—I very carefully measured with the instrument the angle subtended by the mast-head of the brig and the horizon, so that I might be able to ascertain from time to time whether or not that craft was increasing the distance between her and ourselves. I decided to measure this angle every half-hour; and, having made my first and second observations without discovering any appreciable difference between them, I employed the interval in looking about me, and watching the movements of two large sharks which were dodging off and on close alongside the ship, and which were clearly visible from my post of observation. At length, as “three bells”—half-past nine-o’clock—struck, I cast a glance all round the ship before again measuring my angle, when, away down in the south-eastern quarter, I caught a glimpse of very pale blue stretching along the horizon that elsewhere was indistinguishable owing to the glassy calm of the ocean’s surface.

“Deck ahoy!” shouted I; “there is a small air of wind creeping up out of the south-eastern quarter.”

“Thank you, Mr Grenvile,” replied the captain, who was engaged in conversation with Mr Fawcett, the officer of the watch. “Is it coming along pretty fast?” he continued.

I took another good long look.

“No, sir,” I answered; “it is little more than a cat’s-paw at present, but it has the appearance of being fairly steady.”

“How long do you think it will be before it reaches us?” asked the second luff.

“Probably half an hour, at the least, sir,” I answered.

I noticed Mr Fawcett say something to the skipper; and then they both looked up at the sails. The captain nodded, as though giving his assent to some proposal. The next moment the second lieutenant gave the order to range the wash-deck tubs along the deck, and to fill them. This was soon done; and while some of the hands were busy drawing water from over the side, and pouring it into the tubs, others came aloft and rigged whips at the yard-arms, by means of which water from the tubs was hoisted aloft in buckets and emptied over the sails until every inch of canvas that we could spread was thoroughly saturated with water. Thus the small interstices between the threads of the fabric were filled, and the sails enabled to retain every breath of air that might come along. By the time that this was done the first cat’s-paws of the approaching breeze were playing around us, distending our lighter sails for a moment or two, and then dying away again. But light and evanescent as these cat’s-paws were, they were sufficient to get the brig round with her jib-boom pointing straight for the chase once more; and a minute or two later the first of the true breeze reached us, and we began to glide slowly ahead before it, with squared yards. The men were still kept busy with the buckets, however, for, in order that the sails should be of any real service to us, it was necessary to keep them thoroughly wet, and this involved the continuous drawing and hoisting aloft of water, for the sun’s rays were so intensely ardent that the water evaporated almost as rapidly as it was thrown upon the canvas.

The breeze came down very slowly, and seemed very loath to freshen; but this, tantalising though it was to us, was all in our favour, for we thus practically carried the breeze down with us, while the two strange sail away in the western board remained completely becalmed. Of this latter fact I soon had most satisfactory evidence, for, without having recourse at all to my sextant, I was enabled, in that atmosphere of crystalline clearness, to see with the naked eye that we were steadily raising them, an hour’s sailing having brought the bulwark rail of both craft flush with the horizon at my point of observation. By this time, however, the breeze had slid some three miles ahead of us, its margin, where it met and overran the glassy surface of the becalmed sea ahead, being very distinctly visible. At last, too, the wind was manifesting some slight tendency to freshen, for, looking aft, I saw that all our after canvas, even to the heavy mainsail which was hanging in its brails, was swelling out and drawing bravely, while the little streak of froth and foam-bells that gathered under our sharp bows, and went sliding and softly seething aft into our wake, told me that we were slipping through the water at a good honest six-knot pace. With this most welcome freshening of the wind the necessity to keep the canvas continuously wet came to an end; and the men, glad of the relief, were called down on deck to clean up the mess made by the lavish use of the water.

Another half-hour passed, and the strange craft were hull-up, when the captain hailed me from the deck in the wake of the main rigging.

“What is the latest news of the strangers, Mr Grenvile?” he asked. “Has the breeze yet reached them?”

“No, sir; not yet,” I answered; “but I expect it will in the course of the next half-hour. They are hull-up from here, sir; and I should think that you ought to be able to see the mast-heads of the larger craft—the brig—from the deck, by this time.”

Hearing this, the skipper and Mr Fawcett walked forward to the forecastle, the former levelling the telescope that he carried in his hand, and pointing it straight ahead. Then, removing the tube from his eye, the captain handed over the instrument to the second luff, who, in his turn, took a good long look, and returned the telescope to the captain. They stood talking together for a minute or two; and then Captain Bentinck, glancing up at me, hailed.

“Mr Grenvile,” said he, “I am about to send this glass up to you by means of the signal halyards. I want you to keep an eye on those two craft down there, and report anything particular that you may see going on; and let me know when the breeze reaches them, and whether they keep together when it does so.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” I answered. And when the telescope came up I made myself comfortable, feeling quite prepared to remain in the cross-trees for the rest of the watch.

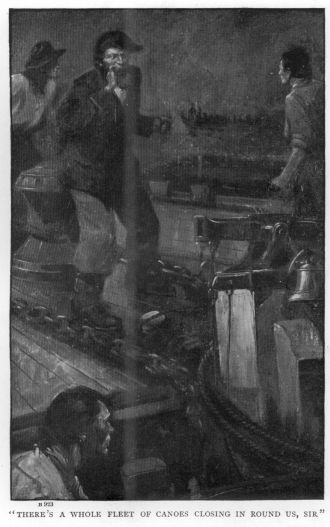

The breeze, meanwhile, continued steadily to freshen, and when at length it reached the two strange sail ahead of us we were buzzing along, with a long, easy, rolling motion over the low swell, at a speed of fully nine knots, with a school of porpoises gambolling under our bows—each of them apparently out-vying the others in the attempt to see which of them could shoot closest athwart our cut-water without being touched by it—and shoal after shoal of flying-fish sparking out from the bow surge and streaming away to port and starboard like so many handfuls of bright new silver coins flung hither and thither by Father Neptune.

As the strangers caught the first of the breeze they squared away before it; but I presently saw that, instead of steering precisely parallel courses, as though they intended to continue in each other’s company, they were diverging at an angle of about forty-five degrees, the brig bringing the wind about two points on her port quarter, while the schooner, steering a somewhat more northerly course, held it about two points on her starboard quarter. Thus, while they were running almost directly away from us, they were also rapidly widening the distance between each other, and it would therefore be very necessary for the skipper to make up his mind quickly which of the two craft he would pursue—for it was clear that, by this manoeuvre on their part, they had rendered it impossible for us to chase them both.

I was in the act of reporting this matter to the skipper and the second lieutenant, who were walking the quarter-deck together, when Mr Fawcett—who, with the captain, had come to a halt at my hail—suddenly reeled, staggered, and fell prone upon the deck with a crash. The skipper instantly sprang to his assistance, as did young Christy, a fellow mid of mine, who was pacing fore and aft on the opposite side of the deck, and three or four men who were at work about some job in the wake of the main rigging; and between them they raised the poor fellow up and carried him below. I subsequently learned—when I eventually descended from aloft—that the surgeon had reported him to be suffering from sunstroke, which was complicated by an injury to the skull sustained by his having struck his head upon a ring-bolt in the deck as he fell.

Meanwhile, during the temporary confusion that ensued on deck in consequence of this untoward incident, I employed myself in the careful measurement of the angle made by the mast-heads of the two strange sail with the now sharply defined horizon, and noting the result upon the back of an envelope which I happened to have in my jacket pocket. I had scarcely done this when the skipper hailed me, asking whether we seemed to be gaining anything upon the strangers, or whether I thought that they were running away from us. I replied that the breeze had reached them too recently to enable me to judge, but that I hoped to be in a position to let him know definitely in the course of the next half-hour. I then explained to him what I had done, and he was pleased to express his approval. Meanwhile we continued to steer a course about midway between that of the two strangers, by which means it was hoped that we should be able to keep both in sight, in readiness to haul up for that one upon which we seemed to be most decidedly gaining.

The breeze still continued to freshen upon us, to such an extent that when my watch told me it was time to re-measure my angle, we were bowling along at the rate of nearly twelve knots, and the sea was beginning to rise, while our lighter studding-sail booms were buckling rather ominously. I took my angle again, and, rather to my surprise, found that we were slightly gaining upon the schooner, while the brig was fully holding her own with us, if indeed she was not doing something even better than that. I reported this to the skipper, who seemed to have made up his mind already as to his course of action; for upon hearing what I had to say he instantly gave orders for our helm to be shifted in pursuit of the schooner. Then, seeming suddenly to remember that it was my watch below, he hailed me, telling me that I might come down.

Having reached the deck, I at once trotted below to make my preparation for taking the sun’s meridian altitude, for it was now drawing on towards noon.

When, a little later, I again went on deck, I found that the wind had continued to freshen, and was now blowing a really strong breeze, while the sea had wrinkled under the scourging of it to a most beautiful deep dark-blue tint, liberally dashed with snow-white patches of froth as the surges curled over and broke in their chase after our flying hull. Our canvas was now dragging at the spars and sheets like so many teams of cart-horses, the delicate blue shadows coming and going upon the cream-white surfaces as the ship rolled with the regularity of a swinging pendulum. Every inch of our running gear was as taut as a harp-string, and through it the wind piped and sang as though the whole ship had been one gigantic musical instrument; while over all arched the blue dome of an absolutely cloudless sky, in the very zenith of which blazed the sun with a fierceness that made all of us eager to seek out such small patches of fugitive shadow as were cast by the straining canvas. The sun was so nearly vertical that our bulwarks, although they were high, afforded us no protection whatever from his scorching rays.

The two strange sail were by this time visible from our deck, and it was apparent that, in the strong breeze which was now blowing, we were rapidly overhauling the schooner, while the brig was not only holding her own with us, but had actually increased her distance, as she gradually hauled to the wind, so as to allow us to run away to leeward of her.

The pursuit of the schooner lasted all through the afternoon, and it was close upon sunset when we arrived within range of her, and plumped a couple of 24-pound shot clean through her mainsail, whereupon her skipper saw fit to round-to all standing, back his topsail, and hoist Spanish colours, only to haul them down again in token of surrender. Whereupon Mr Seaton, our first lieutenant, in charge of an armed boat’s crew, went away to take possession of the prize, and since I was the only person on board possessing even a passable acquaintance with the Spanish language, I was ordered to accompany him.

Our prize proved to be the Dolores, of two hundred tons measurement, with—as we had suspected—a cargo of slaves, numbering three hundred and fifty, which she had shipped in one of the numerous creeks at the mouth of the Congo on the previous day, and with which she was bound for Rio Grande. Her crew were transferred to the Shark; and then—the second lieutenant being ill and quite unfit for service—I was put in command of her, with a crew of fourteen men, and instructed to make the best of my way to Sierra Leone. My crew of fourteen included Gowland, our master’s mate, and young Sinclair, a first-class volunteer, as well as San Domingo, the servant of the midshipmen’s mess, to act as steward, and the cook’s mate. We therefore mustered only five forecastle hands to a watch, which I thought little enough for a schooner of the size of the Dolores; but as we hoped to reach Sierra Leone in a week at the outside, and as the schooner was unarmed, Captain Bentinck seemed to think that we ought to be able to manage fairly well. By the time that we had transferred ourselves and our traps to the prize it had fallen quite dark. The Shark therefore lost no time in hauling her wind in pursuit of the strange brig, which by this time had run out of sight, and of which the skipper of the Dolores professed to know nothing beyond the fact that she was French, was named the Suzanne, and was running a cargo of slaves across to Martinique.

Chapter Two.

Captured by a pirate.

When, in answer to the summons of our 24-pounders, the captain of the Dolores rounded-to and laid his topsail to the mast, he did not trouble his crew to haul down the studding-sails, for he knew that his ship was as good as lost to him, and the result was that the booms snapped short off at the irons, like carrots, leaving a raffle of slatting canvas, gear, and thrashing wreckage for the prize crew to clear away. Thus, although we at once hauled-up for our port upon parting company with the Shark, we had nearly an hour’s hard work before us in the dark ere the studding-sails were got in, the gear unrove and unbent, and the stumps of the booms cleared away, and I thought it hardly worth while to get a fresh set of booms fitted and sent aloft that night. We accordingly jogged along under plain sail until daylight, when we got the studding-sails once more upon the little hooker and tried her paces. She proved to be astonishingly fast in light, and even moderate, weather, and I felt convinced that had the wind not breezed up so strongly as it did on the previous day, the Shark would never have overtaken her.

During the following two days we made most excellent progress, the weather being everything that one could desire, and the water smooth enough to permit of the hatches being taken off and the unfortunate slaves brought on deck in batches of fifty at a time, for an hour each, to take air and exercise, while those remaining below were furnished with a copious supply of salt-water wherewith to wash down the slave-deck and clear away its accumulated filth. It proved to be a very fortunate circumstance that Captain Bentinck had permitted us to draw the negro San Domingo as one of our crew, for the fellow understood the language spoken by the slaves, and was able to assure them that in the course of a few days they would be restored to freedom, otherwise we should not have dared to give them access to the deck in such large parties, for they were nearly all men, and fine powerful fellows, who, unarmed as they were, could have easily taken the ship from us and heaved us all overboard.

The Dolores had been in our possession just forty-eight hours, and we were off Cape Three Points, though so far to the southward that no land was visible, when a sail was made out on our lee bow, close-hauled on the larboard tack, heading to the southward, the course of the Dolores at the time being about north-west by west. As we closed each other we made out the stranger to be a brig, and our first impression was that she was the Shark, which, having either captured or lost sight of the craft of which she had been in chase, was now returning, either to her station or to look for us and convoy us into Sierra Leone; and, under this impression, we kept away a couple of points with the object of getting a somewhat nearer view of her. By sunset we had raised her to half-way down her courses, by which time I had come to the conclusion that she was a stranger; but as Gowland, the master’s mate, persisted in his assertion that she was the Shark, we still held on as we were steering, feeling persuaded that, if she were indeed that vessel, she would be anxious to speak to us; while, if she should prove to be a stranger, no great harm would be done beyond the loss of a few hours on our part.

The night fell overcast and very dark, and we lost sight of the stranger altogether. Moreover the wind breezed up so strongly that we were obliged to hand our royal and topgallant-sail and haul down our gaff-topsail, main-topmast staysail, and flying-jib; the result of the freshening breeze being that a very nasty sea soon got up and we passed a most uncomfortable night, the schooner rolling heavily and yawing wildly as the seas took her on her weather quarter. We saw no more of the stranger that night, although some of us fancied that we occasionally caught a glimpse of something looming very faint and indefinite in the darkness away to windward.

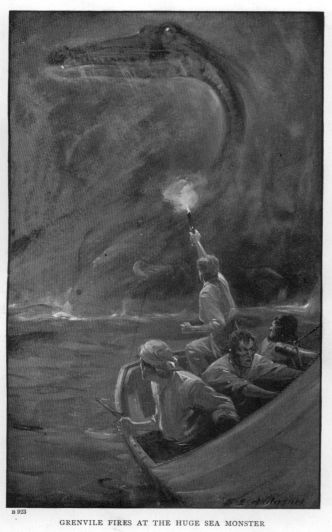

Toward the end of the middle watch the weather rapidly improved, the wind dropped, and the sea went down with it, although the sky continued very overcast and the night intensely dark. By four bells in the morning watch the wind had died away almost to a calm, and with the first pallor of the coming dawn the clouds broke away, and there, about a mile on our weather quarter—that is to say, dead to windward of us—lay the stranger of the preceding night, black and clean-cut as a paper silhouette against the cold whiteness of the eastern sky, rolling heavily, and with a number of hands aloft rigging out studding-sail booms. The brig, which was most certainly not the Shark, was heading directly for us, and I did not like the look of her at all, for she was as big as the sloop, if not a trifle bigger, showed nine guns of a side, and was obviously bent upon getting a nearer view of us. We lost no time in getting our studding-sails aloft on the starboard side, bracing the yards a trifle forward, and shaping a course that would give us a chance ultimately to claw out to windward of our suspicious-looking neighbour; but she would have none of it, for while we were still busy a ruddy flash leapt from her bow port, a cloud of smoke, blue in the early morning light, obscured the craft for a few seconds, and a round shot came skipping toward us across the black water, throwing up little jets of spray as it came, and finally sinking less than twenty yards away.

“Well aimed, but not quite enough elevation,” exclaimed I to Gowland, who had charge of the deck, and who had called me a moment before. “Now, who is the fellow, and what does he mean by firing at us? Is he a Frenchman, think you, and does he take us for a slaver—which, by the way, is not a very extraordinary mistake to make? We had better show him our bunting, I think. Parsons,” to a man who was hovering close by, “bend on the ensign and run it up to the gaff-end.”

“There is no harm in doing that, of course,” remarked Gowland; “but he is no Frenchman—or at least he is not a French cruiser; I am sure of that by the cut of his canvas. Besides, we know every French craft on the station, and Johnny Crapaud has no such beauty as that brig among them. No; if you care for my opinion, Grenvile, it is that yonder fellow is a slaver that is not too tender of conscience to indulge in a little piracy at times, when the opportunity appears favourable, as it does at present. I have heard that, in contradiction of the adage that ‘there is honour among thieves’, there are occasionally to be found among the slavers a few that are not above attacking other slavers and stealing their slaves from them. It saves them the bother of a run in on the coast, with its attendant risk of losses by fever, and the delay, perhaps, of having to wait until a cargo comes down. Ah, I expected as much!” as another shot from the stranger pitched close to our taffrail and sent a cloud of spray flying over us. “So much for his respect for our bunting.”

“If the schooner were but armed I would make him respect it,” I exclaimed, greatly exasperated at being obliged to submit tamely to being fired at without the power to retaliate. “But,” I continued, “since we cannot fight we will run. The wind is light, and that brig must be a smart craft indeed if, in such weather as this, we cannot run away from her.”

The next quarter of an hour afforded us plenty of excitement, for while we were doing our best to claw out to windward of the brig she kept her jib-boom pointed straight at us, and thus, having a slight advantage of the wind, contrived to lessen the distance between us sufficiently to get us fairly within range, when she opened a brisk fire upon us from the 18-pounder on her forecastle. But, although the aim was fairly good, no very serious damage was done. A rope was cut here and there, but was immediately spliced by us; and when we had so far weathered upon our antagonist as to have brought her fairly into our wake, the advantage which we possessed in light winds over the heavier craft began to tell, and we soon drew away out of gunshot.

So far, so good; but I had been hoping that as soon as our superiority in speed became manifest the brig would bear up and resume her voyage to her destination—wherever that might be. But no; whether it was that he was piqued at being beaten, or whether it was a strong vein of pertinacity in his character that dominated him, I know not, but the skipper of the strange brig hung tenaciously in our wake, notwithstanding the fact that we were now steadily drawing away from him. Perhaps he was reckoning on the possibility that the breeze might freshen sufficiently to transfer the advantage from us to himself, and believing that this might be the case, I gave instructions to take in all our studding-sails, and to brace the schooner up sharp, hoping thus to shake him off. But even this did not discourage him; for he promptly imitated our manoeuvre, although we now increased our distance from him still more rapidly than before.

Meanwhile the wind was steadily growing more scant, and when I went on deck after breakfast I found that we were practically becalmed, although the small breathing, which was all that remained of the breeze, sufficed to keep the little hooker under command, and give her steerage way. The brig, however, I was glad to see, was boxing the compass some three miles astern of us, and about a point on our lee quarter.

It was now roasting hot, the sky was without a single shred of cloud to break its crystalline purity, and the sun poured down his beams upon us so ardently that the black-painted rail had become heated to a degree almost sufficient to blister the hand when inadvertently laid upon it, while the pitch was boiling and bubbling out of the deck seams. The surface of the sea was like a sheet of melted glass, save where, here and there, a transient cat’s-paw flecked it for a moment with small patches of delicate blue, that came and went as one looked at them. Even the flying-fish seemed to consider the weather too hot for indulgence in their usual gambols, for none of them were visible. I was therefore much surprised, upon taking a look at the brig through my glass, to see that she had lowered and was manning a couple of boats.

“Why, Pringle,” said I to the gunner, whose watch it was, “what does that mean? Surely they are not going to endeavour to tow the brig within gunshot of us, are they? They could never do it; for, although there is scarcely a breath of wind stirring, this little beauty is still moving through the water; and so long as she has steerage way on her we ought to be able—”

“No, sir, no; no such luck as that, I’m afraid,” answered the man. “May I have that glass for a moment? Thank you, sir!”

He placed the telescope to his eye, adjusted it to his focus, and looked through it long and intently.

“Just as I thought, Mr Grenvile,” he said, handing back the instrument. “If you’ll take another squint, sir, you’ll see that they’re getting up tackles on their yard-arms. That means—unless I’m greatly mistaken—that they’re about to hoist out their longboat; and that again means that they’ll stick a gun into the eyes of her, and attack us with the boats in regular man-o’-war fashion. But they ain’t alongside of us yet, and won’t be for another hour and a half if the wind don’t die away altogether—and, somehow, I don’t fancy it’s going to do that. No, what I’m most afraid of is”—and he took a long careful look round—“that in this flukey weather the brig may get a breeze first, and bring it down with her, when—ay, and there it is, sure enough! There’s blue water all round her, and I can see her canvas filling to it, even with my naked eye. And there she swings her yards to it. It’ll be ‘keep all fast with the boats’ now! If that little air o’ wind only sticks to her for half an hour she’ll have us under her guns, safe enough!”

It was as Pringle said. A light draught of air had suddenly sprung up exactly where the brig happened to lie; and by the time I had got my telescope once more focused upon her, she was again heading up for us, with her weather braces slightly checked, and quite a perceptible curl of white foam playing about her sharp bows. But it only helped her for about half a mile, and then left her completely becalmed, as before, while we were still stealing along at the rate of perhaps a knot and a quarter per hour. The skipper of the brig allowed some ten minutes or so to elapse, possibly waiting for another friendly puff of wind to come to his assistance, but, seeing no sign of any such thing, he hoisted out his longboat, lowered a small gun—to me it looked like a 6-pounder—into her, and dispatched her, with two other boats, in chase of us. The dogged determination which animated our pursuers was clearly exemplified by their behaviour; they made no attempt to cross with a rush the stretch of water intervening between us and them, but settled down steadily to accomplish the long pull before them as rapidly as possible consistent with the husbanding of their strength for the attack when they should arrive alongside. As they pushed off from the brig she fired a gun and hoisted Brazilian colours.

“The affair begins to look serious, Pringle,” I said, as I directed my telescope at the boats. “There must be close upon forty men in that attacking-party, and we do not mount so much as a single gun. Now, I wonder what their plan of attack will be? Will they dash alongside and attempt to carry us by boarding, think you; or will they lie off and pound us with their gun until we haul down our colours, or sink?”

“They may try both plans, sir,” answered Pringle. “That is to say, they may begin by trying a few shots at us with their gun, and if they find that no good I expect they’ll try what boarding will do for them. But they won’t sink us; that’s not their game. It’s the slaves they believe we’ve got in the hold that they’re after; so, if they bring their boat-gun into play you’ll find that it’ll be our top-hamper they’ll aim at, so as to cripple us. They’ll not hull us if they can help it.”

“Well, they shall not set foot upon this deck if I can help it,” said I. “Pass the word for the boatswain to come aft, Pringle, if you please. He will probably be able to tell us whether there are any boarding-nettings in the ship. If there are, we will reeve and bend the tricing lines at once, and see all clear for tricing up the nets.”

“Ay,” assented the gunner. “I think you’ll be wise in so doing, sir; there’s nothing like being prepared. Pass the word for the boatswain to come aft,” he added, to the little group of men constituting the watch, who were busy on the forecastle.

The word was passed, and presently the boatswain came along.

“Boatswain,” said I, “have you given the spare gear of this craft an overhaul as yet?”

“Well, sir, I have, and I haven’t, as you may say,” answered that functionary. “I knows, in a general sort of a way, what we’ve got aboard of us, but I haven’t examined anything in detail, so to speak. The fact is, seeing that the trip was likely to be only a short one, and we’ve been kept pretty busy since we joined the hooker, I’ve found plenty else to do.”

“Well, can you tell me whether there are any boarding-nettings in the ship?” I asked.

“Boarding-nettings!” answered the boatswain. “Oh yes, sir; I came across what I took to be a pile of ’em down below in the sail room, yesterday.”

“Good!” said I. “Then let them be brought on deck at once, and see that all is ready for tricing them up, should those boats succeed in getting dangerously near to us.”

“Ay, ay, sir!” answered the man. And away he hurried forward to attend to the matter.

Then I turned to the gunner.

“Mr Pringle,” said I, “have the goodness to get the arm-chest on deck, and see that the crew are armed in readiness to repel those attacking boats.”

“I hope it may not come to that, Mr Grenvile,” said the gunner; “if it does, I’m afraid it’ll be a pretty bad look-out for some of us, considerin’ our numbers. But, of course, it’s the only thing to do.” He took a look round the horizon, directed his gaze first aloft, then over the side, and shook his head. “The sun’s eating up what little air there is,” he remarked gloomily, “and I reckon that another ten minutes ’ll see us without steerage way.” And he, too, departed to carry out his instructions.

There seemed only too much reason to fear that the gunner’s anticipations with regard to the wind would prove true; but while I stood near the transom, watching the steady relentless approach of the boats—which were by now almost within gunshot of us—I suddenly became aware of a gentle breeze fanning my sun-scorched features, and the slight but distinct responsive heel of the schooner to it; and in another minute we were skimming merrily away at a speed of quite five knots under the benign influence of one of those partial breezes which, on a calm day at sea, seem to spring up from nowhere in particular, last for half an hour or so, and then die away again. In the present case, however, the breeze lasted nearly two hours before it failed us, by which time we had left the brig hull-down astern of us, and had enjoyed the satisfaction of seeing the boats abandon the chase and return to their parent ship.

These partial breezes are among the most exasperating phenomena which tax a sailor’s patience. They are, of course, only met with on exceptionally calm days, and not always then. They consist simply of little eddies in the otherwise motionless atmosphere, and are so strictly local in their character that it is by no means uncommon to see a ship sailing briskly along under one of them, while another ship, perhaps less than a mile away, is lying helpless in the midst of a stark, breathless calm. Or two ships, a mile or two apart, may be seen sailing in diametrically opposite directions, each of them with squared yards and a fair wind. Under ordinary circumstances the fickle and evanescent character of these atmospheric eddies is of little moment; they involve a considerable amount of box-hauling of the yards, and cause a great deal of annoyance to the exasperated and perspiring seamen, very inadequately compensated by the paltry mile or so which the ship has been driven toward her destination; and their aggravating character begins and ends there.

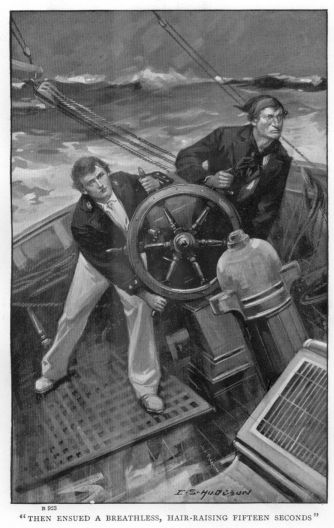

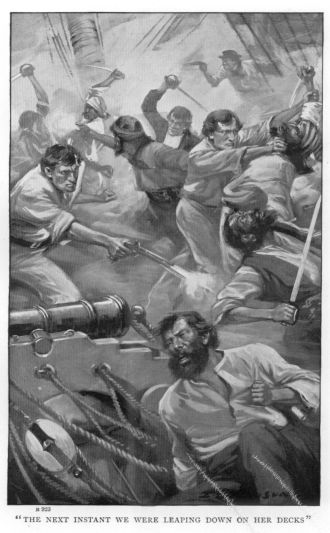

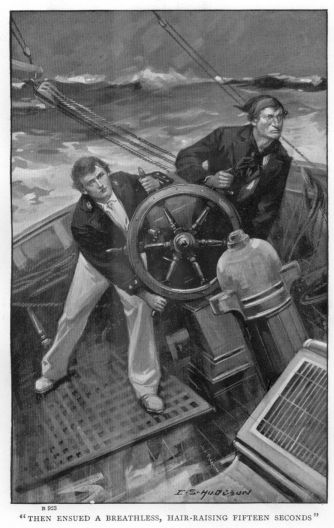

But when one ship is chasing, or being chased by, another, it is quite a different matter; for the eccentric behaviour of these same partial breezes may make all the difference between capturing a prize, and helplessly watching the chase sail away and make good her escape. Or, as was the case with ourselves, it may make precisely the difference between losing a prize and retaining possession of her. Thus we felt supremely grateful to the erratic little draught of air that swept us beyond the reach of the pursuing boats; but we piped a very different tune when, some two hours later, we beheld the brig come bowling along after us under the influence of a slashing breeze, while we lay becalmed in the midst of a sea of glass and an atmosphere so stagnant that even the vane at our mast-head drooped motionless save for the oscillation imparted to it by the heave of the schooner over the swell. We had, of course, long ere this, got the boarding-nettings up and stretched along in stops, with the tricing lines bent on, and everything ready for tricing up at a moment’s notice; but, remembering the number of men that I had seen in the boats, I felt that, should the brig succeed in getting alongside, there was a tough fight before us, in which some at least of our brave fellows would lose the number of their mess; and I could not help reflecting, rather bitterly, that if the breeze were to favour us instead of the brig, a considerable loss of life would be avoided. But that the brig would get alongside us soon became perfectly evident, for she was already within a mile of us, coming along with a spanking breeze, on the starboard tack, with her yards braced slightly forward, all plain sail set, to her royals, the sheets of her jibs and stay-sails trimmed to a hair, and every thread drawing perfectly, while around us the atmosphere remained absolutely stagnant.

I looked for her to open fire upon us as soon as she drew up within range; but although her guns were run out—and were doubtless loaded—she came foaming along in grim silence; doubtless her skipper saw, as clearly as we did, that he had us now, and did not think it necessary to waste powder and shot to secure what was already within his power. His aim was, apparently, to range up alongside us on our port quarter, and when at length he had arrived within a short half-mile of us, with no sign of the smallest puff of wind coming to help us, I gave orders to trice up and secure the nettings, and then for all hands to range themselves along the port bulwarks in readiness to repel the boarders. It was now too late for us to dream of escape, for even should the breeze, that the brig was bringing down with her, reach us, we were by this time so completely under her guns that she could have unrigged us with a single well-directed broadside.

Anxious though I was as to the issue of the coming tussle, I could not help admiring that brig. She was a truly beautiful craft; distinctly a bigger vessel than the Shark, longer, more beamy, with sides as round as an apple, and with the most perfectly moulded bows that it was possible to conceive. She was coming very nearly stem-on to us, and I could not therefore see her run, but I had no doubt that it was as perfectly shaped as were her bows, for I estimated her speed at fully eight knots, and for a vessel to travel at that rate in such a breeze she must of necessity have possessed absolute perfection of form. She was as heavily rigged as a man-o’-war, and her canvas—which was so white that it must have been woven of cotton—had evidently been cut by a master hand, for the set of it was perfect and flatter than any I had ever seen before. She was coppered to the bends, was painted black to her rails, with the exception of a broad red ribbon round her, and was pierced for eighteen guns.

When she had arrived within about half a cable’s-length of us she suddenly ran out of the breeze that had helped her so well, and instantly floated upright, with all her square canvas aback in the draught caused by her own speed through the stagnant atmosphere; and now we were afforded a fresh opportunity to gauge the strength of her crew, for no sooner did this happen than all her sheets and halyards were let go, and the whole of her canvas was clewed up and hauled down together, man-o’-war fashion. And thus, with her jibs and stay-sails hauled down, and her square canvas gathered close up to her yards by the buntlines and leech-lines, she swerved slightly from her previous course and headed straight for us, still sliding fast through the water with the “way” or momentum remaining to her, and just sufficient to bring her handsomely alongside.

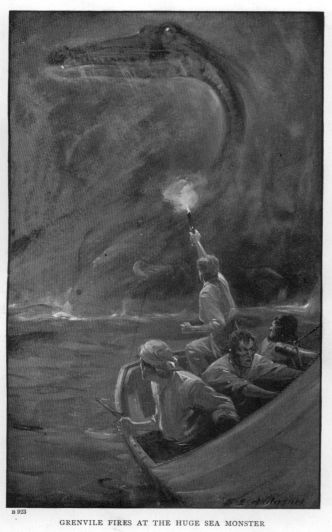

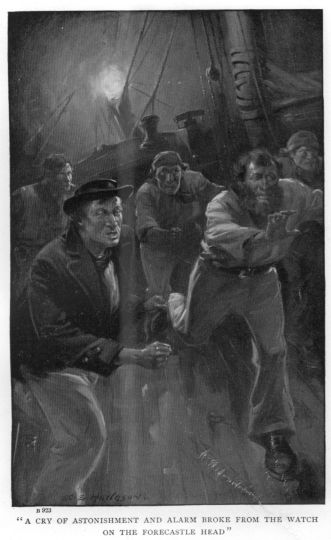

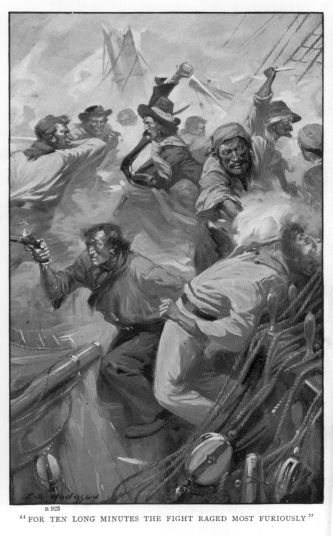

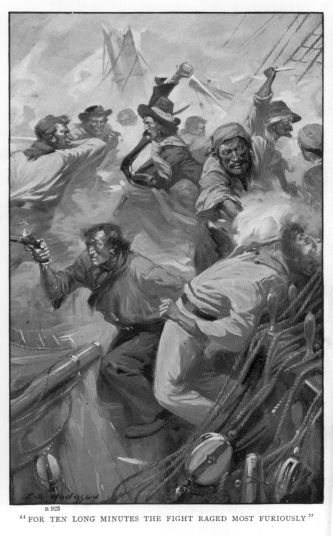

“Now stand by, lads!” I cried. “We must not only beat those fellows off, but must follow them up when they retreat to their own ship. She will be a noble prize, well worth the taking!”

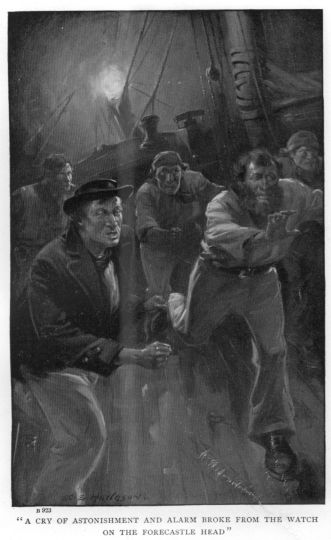

The men responded to my invocation with a cheer—it is one of the most difficult things in the world to restrain a British sailor’s propensity to cheer when there is fighting in prospect—and as they did so the brig yawed suddenly and poured her whole starboard broadside of grape slap into us. I saw the bright flashes of the guns, and the spouting wreaths of smoke, snow-white in the dazzling sunshine, and the next instant felt a crashing blow upon my right temple that sent me reeling backward into somebody’s arms, stunned into complete insensibility.

My first sensation, upon the return of consciousness, was that of a splitting, sickening headache, accompanied by a most painful smarting on the right side of my forehead. I was lying prone upon the deck, and when I attempted to raise my head I found that it was in some way glued to the planking—with my own blood, as I soon afterwards discovered—so effectually that it was impossible for me to move without inflicting upon myself excruciating pain.

My feeble movements, however, had evidently attracted the notice of somebody, for as I raised my hands toward my head, with some vague idea of releasing myself, I heard a voice, which I identified as that of the carpenter, murmur, in a low, cautious tone.

“Don’t move, Mr Grenvile; don’t move, sir, for all our sakes. Hold on as you are, sir, a bit longer; for if them murderin’ pirates sees that you’re alive they’ll either finish you off altogether or lash you up as they’ve done the rest of us; and then our last chance ’ll be gone.”

“What has happened, then, Simpson?” murmured I, relaxing my efforts, as I endeavoured to collect my scattered wits.

“Why,” answered Chips, “that brig that chased us—you remember, Mr Grenvile?—turns out to be a regular pirate. As they ranged up alongside of us they poured in a whole broadside of grape that knocked you over, and killed five outright, woundin’ six more, includin’ yourself, after which of course they had no difficulty in takin’ the schooner. Then they clapped lashin’s on those of us that I s’pose they thought well enough to give ’em any trouble; and now they’re transferrin’ the poor unfortunate slaves, with the water and provisions for ’em, from our ship to their own. What they’ll do after that the Lord only knows, but I expect it’ll be some murderin’ trick or another; they’re a cut-throat-lookin’ lot enough in all conscience!”

Yes; I remembered everything now; the carpenter’s statement aided my struggling memory and enabled me to recall all that had happened up to the moment of my being struck down by a grape-shot. But what a terrible disaster was this that had befallen us—five killed and six wounded out of our little party of fifteen! And, in addition to that, we were in the power of a band of ruthless ruffians who were quite capable of throwing the quick and the dead alike over the side when they could find time to attend to us!

“Who are killed, Simpson?” I asked.

“Hush, sir! better not talk any more just now,” murmured the carpenter. “If these chaps got the notion into their heads that you was alive, as like as not they’d put a bullet through your skull. They’ll soon be finished with their job now, and then we shall see what sort of fate they’re going to serve out to us.”

I dared not look up nor move my head in any way, to see what was going on, but by listening I presently became aware that the last of the slaves had passed over the side, and that the pirates were now transferring the casks of water and the sacks of meal from our ship to their own, which—the water being perfectly smooth—they had lashed alongside the schooner, with a few fenders between the two hulls to prevent damage by the grinding of them together as they rose and fell upon the long scarcely perceptible undulations of the swell. About a quarter of an hour later the rumbling of the rolling water-casks and the loud scraping sound of the meal-sacks on the deck ceased; there was a pause of a minute or so, and then I heard a voice say in Spanish:

“The last of the meal and the water has gone over the rail, señor capitan. Is there anything else?”

“No,” was the answer, in the same language; “you may all go back to the brig. And, Dominique, see all ready for sheeting home and hoisting away the moment that I join you. There is a little breeze coming, and it is high time that we were off. Now, Juan, are you ready with the auger?”

“Quite ready, señor,” answered another voice.

“Then come below with me, and let us get this job over,” said the first voice, and immediately upon this I heard the footsteps of two people descending the schooner’s companion ladder. Some ten minutes later I heard the footsteps returning, and presently the two Spaniards were on deck. Then there came a slight pause, as though the pirate captain had halted to take a last look round.

“Are you quite sure, Juan, that the prisoners are all securely lashed?” asked he.

“Absolutely, señor,” answered Juan. “I lashed them myself, and, as you are aware, I am not in the habit of bungling the job. They will all go to the bottom together, the living as well as the dead!”

“Bueno!” commented the captain. “Ah, here comes the breeze! Aboard you go, Juan, amigo. Cast off, fore and aft, Dominique, and hoist away your fore-topmast staysail.”

Another moment and the two miscreants had gone.

Chapter Three.

The sinking of the “Dolores.”

As the sound of the hanks travelling up the brig’s fore-topmast stay reached my ear I murmured cautiously to the carpenter.

“Is it safe for me to move now, Chips?”

“No, sir, no,” he replied, in a low, strained whisper; “don’t move a muscle for your life, Mr Grenvile, until I tell you, sir. The brig’s still alongside, and that unhung villain of a skipper’s standin’ on the rail, holdin’ on to a swifter, and lookin’ down on our decks as though, even now, he ain’t quite satisfied that his work is properly finished.”

At this moment I felt a faint breath of air stirring about me, and heard the small, musical lap of the tiny wavelets alongside as the new breeze arrived. The brig’s canvas and our own rustled softly aloft; and the cheeping of sheaves and parrals, the rasping of hanks, the flapping of canvas, and the sound of voices aboard the pirate craft gradually receded, showing that she was drawing away from us.

When, as I supposed, the brig had receded from us a distance of fully a hundred feet, the carpenter said, this time in his natural voice:

“Now, Mr Grenvile, you may safely move, sir, and the sooner you do so the better, for them villains have scuttled us, and I don’t doubt but what the water’s pourin’ into us like a sluice at this very moment. So please crawl over to me, keepin’ yourself well out of sight below the rail, for I’ll bet anything that there’s eyes aboard that brig still watchin’ of us, and cast me loose, so that I can make my way down below and plug them auger-holes without any loss of time.”

I at once made a move, with the intention of getting upon my hands and knees, but instantly experienced the most acute pain in my temple, due to the fact, which I now discovered, that the shot which had struck me down had torn loose a large piece of the skin of my forehead, which had become stuck fast to the deck planking by the blood which had flowed from the wound and had by this time dried. To loosen this flap of skin cost me the most exquisite pain, and when at length I had succeeded in freeing myself, and rose to my hands and knees, so violent a sensation of giddiness and nausea suddenly swept over me that I again collapsed, remaining insensible for quite ten minutes according to the carpenter’s account.

But even during my unconsciousness I was vaguely aware of some urgent, even vital, necessity for me to be up and doing, and this it was, I doubt not, that helped me to recover consciousness much sooner than I should have done but for the feeling to which I have alluded. Once more I rose to my hands and knees, half-blinded by the blood that started afresh from my wound, and crawled over to where the carpenter lay on the deck, in what must have been a most uncomfortable attitude, hunched up against the port bulwarks, with his wrists lashed tightly together behind his back and his heels triced up to them, so that it was absolutely impossible for him to move or help himself in the slightest degree.

As I approached him the poor fellow groaned rather than spoke.

“Thank God that you’re able to move at last, Mr Grenvile! I was mortal afraid that ’twas all up with you when you toppled over just now. For pity’s sake, sir, cut me loose as soon as you can, for these here lashin’s have been drawed so tight that I’ve lost all feelin’ in my hands and feet, while my arms and legs seems as though they was goin’ to burst. What! haven’t you got a knife about you, sir? I don’t know what’s become of mine, but some of the men’ll be sure to have one, if you enquire among ’em.”

Hurried enquiry soon revealed the disconcerting fact that we could not muster a solitary knife among us; we had all either lost them, or had had them taken from us; there was therefore nothing for it but to heave poor Chips over on his face, and cast him adrift with my hands, which proved to be a longer and much more difficult job than I could have believed, owing, of course, to the giddiness arising from my wound, which made both my sight and my touch uncertain. But at length the last knot was loosed, the last turn of the rope cast off, and Chips was once more a free man.

But when he essayed to stand, the poor fellow soon discovered that his troubles were not yet over. For his feet were so completely benumbed that he had no feeling in them, and when he attempted to rise his ankles gave way under him and let him down again upon the deck. Then, as the blood once more began to circulate through his benumbed extremities, the pricking and tingling that followed soon grew so excruciatingly painful that he fairly groaned and ground his teeth in agony. To allay the pain I chafed his arms and legs vigorously, and in the course of a few minutes he was able to crawl along the deck to the companion, and then make his way below.

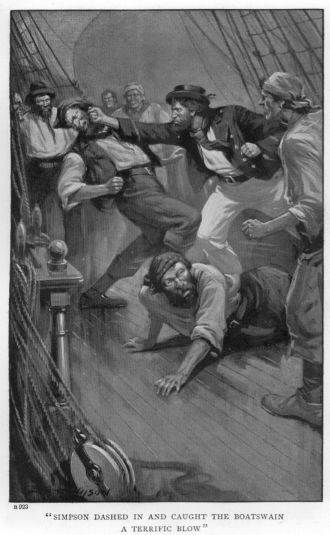

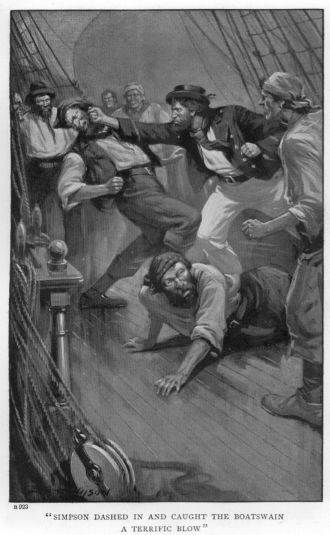

Meanwhile, taking the utmost care to keep my head below the level of the bulwarks, in order that my movements might not be detected by any chance watcher aboard the pirate craft, I cast loose the three unwounded men—the carpenter being the fourth of our little band who had escaped the destructive broadside of the pirates—and bade them assist me to cast off the lashings which confined the wounded. We were still thus engaged when Simpson came up through the companion, dripping wet, glowering savagely, and muttering to himself.

“Well, Chips,” said I, “what is the best news from below?”

“Bad, sir; pretty nigh as bad as can be,” answered the carpenter. “They’ve scuttled us most effectually, bored eight holes through her skin, close up alongside the kelson, three of which I’ve managed to plug after a fashion, but by the time I had done them the water had risen so high that I found it impossible to get at t’others. I reckon that sundown will about see the last of this hooker; but by that time yonder brig ’ll be pretty nigh out of sight, and we shall have a chance to get away in the boats, which, for a wonder, them murderin’ thieves forgot to damage.”

“There is no hope, you think, of saving the schooner, if all of us who are able were to go below and lend you a hand?” said I.

“No, sir; not the slightest,” answered Simpson. “If I could have got below ten minutes earlier, something might have been done; but now we can do nothing.”

“Very well, then,” said I; “let San Domingo take two of the uninjured men to assist him in getting up provisions and water, while you and the other overhaul the boats, muster their gear, and get everything ready for putting them into the water as soon as we may venture to do so without attracting the attention of the brig and tempting her to return and make an end of us.”

While these things were being done, the wounded men assisted each other down into the little cabin of the schooner, where I dressed their injuries and coopered them up to the best of my ability with such means as were to hand; after which, young Sinclair, whose wound was but a slight one, bathed my forehead, adjusted the strip of displaced skin where it had been torn away, and strapped it firmly in position with sticking-plaster.

Meanwhile, the breeze which had sprung up so opportunely to take the brig out of our immediate neighbourhood not only lasted, but continued to freshen steadily, with the result that by the time that we had patched each other up, and were ready to undertake the mournful task of burying our slain, the wicked but beautiful craft that had inflicted such grievous injury and loss upon us had slid away over the ocean’s rim, and was hull-down. By this time also the water had risen in the schooner to such a height that it was knee-deep in the cabin. We lost no time, therefore, in committing our dead comrades to their last resting-place in the deep, and then proceeded to get the boats into the water, and stock them with provisions for our voyage.

Now, with regard to this same voyage, I had thus far been much too busy to give the matter more than the most cursory consideration, but the time had now arrived when it became necessary for me to decide for what point we should steer when the moment arrived for us to take to the boats. Poor Gowland was, unfortunately, one of the five who had been killed by the brig’s murderous broadside of grape, and I was therefore deprived of the benefit of his advice and assistance in the choice of a port for which to steer; but I was by this time a fairly expert navigator myself, quite capable of doing without assistance if necessary. I therefore spread out a chart on the top of the skylight, and, with the help of the log-book, pricked off the position of the schooner at noon that day, from which I discovered that Cape Coast Castle was our nearest port. But to reach it with the wind in the quarter from which it was then blowing it would be necessary to put the boats on a taut bowline, with the possibility that, even then, we might fall to leeward of our port, whereas it was a fair wind for Sierra Leone. I therefore arrived at the conclusion that, taking everything into consideration, it would be my wisest plan to make for the latter port, and I accordingly determined there and then the proper course to be steered upon leaving the schooner.

The Dolores had by this time settled so deeply in the water that it was necessary to complete our preparations for leaving her without further delay. San Domingo had contrived to get together and bring on deck a stock of provisions and fresh water that I considered would be ample for all our needs, and Simpson had routed out and stowed in the boats their masts, sails, oars, rowlocks, and, in short, everything necessary for their navigation. It now remained, therefore, only to get the craft themselves in the water, stow the provisions and our kits in them, and be off as quickly as possible.

The boats of the Dolores were three in number, namely, a longboat in chocks on the main hatch, a jolly-boat stowed bottom-upward in the longboat, and a very smart gig hung from davits over the stern. The longboat was a very fine, roomy, and wholesome-looking boat, big enough to accommodate all that were left of us, as well as our kits and a very fair stock of provisions; but in order to afford a little more room and comfort for the wounded men I decided to take the gig also, putting into her a sufficient quantity of provisions and water to ballast her, and placing Simpson in charge of her, with one of the unwounded and two of the most slightly-wounded men as companions, leaving six of us to man the longboat.

Simpson’s estimate of the time at our disposal proved to be a very close one, for the sun was within ten minutes of setting when, all our preparations having been completed, I followed the rest of our little party over the side, and, entering the longboat, gave the order to shove off and steer north-west in company. There was at this time a very pleasant little breeze blowing, of a strength just sufficient to permit the boats to carry whole canvas comfortably; the water was smooth, and the western sky was all ablaze with the red and golden glories of a glowing tropical sunset.

We pulled off to a distance of about a hundred yards from the schooner; and then, as with one consent, the men laid in their oars and waited to see the last of the little hooker. Her end was manifestly very near, for she had settled to the level of her waterways, and was rolling occasionally on the long, level swell with a slow, languid movement that dipped her rail amidships almost to the point of submergence ere she righted herself with a stagger and hove her streaming wet side up toward us, all a-glitter in the ruddy light of the sunset, as she took a corresponding roll in the opposite direction; and we could hear the rush and swish of water athwart her deck as she rolled. She remained thus for some three or four minutes, each roll being heavier than the one that had preceded it, when, quite suddenly, she seemed to steady herself; then, as we watched, she slowly settled down out of sight, on a perfectly even keel, the last ray of the setting sun gleaming in fire upon her gilded main truck a moment ere the waters closed over it.—“Sic transit!” muttered I, as I turned my gaze away from the small patch of whirling eddies that marked the spot where the little beauty had disappeared, following up the reflection with the order: “Hoist away the canvas, lads, and shape for Sierra Leone!”

Five minutes later we were speeding gaily away, with the wind over our starboard quarter and the sheets eased well off, the gig, with her finer lines and lighter freight, revealing so marked a superiority in speed over the longboat, in the light weather and smooth water with which we were just then favoured, that she was compelled to luff and shake the wind out of her sails at frequent intervals to enable us to keep pace with her. Meanwhile, the pirate brig, which, like ourselves, had gone off before the wind, had sunk below the horizon to the level of her lower yards. I had, between whiles, been keeping the craft under fairly steady observation, for what Simpson had said relative to the behaviour of her captain, and the attitude of doubt and suspicion which the latter had exhibited when leaving the Dolores, had impressed me with the belief that he would possibly cause a watch to be maintained upon the schooner until she should sink, with the object of assuring himself that none of us had escaped to tell the tale of his atrocious conduct. As I have already mentioned, the Dolores happened to founder at the precise moment of sunset, and in those latitudes the duration of twilight is exceedingly brief. Still, following upon sunset there were a few minutes during which the light would be strong enough to enable a sharp eye on board the distant brig, especially if aided by a good glass, to detect the presence of the two boats under sail; and I was curious to see whether anything would occur on board the brig to suggest that such a discovery had been made. For a few minutes nothing happened; the brig’s canvas, showing up clear-cut and purple almost to blackness against the gold and crimson western sky, revealed no variation in the direction in which she was steering; but presently, as I watched the quick fading of the glowing sunset tints, and noted how the sharp silhouette of the brig’s canvas momentarily grew more hazy and indistinct, I suddenly became aware of a lengthening out of the fast-fading image, and I had just time to note, ere they merged into the quick-growing gloom, that the two masts had separated, showing that the brig had shifted her course and was now presenting a broadside view to us. That I was not alone in marking this change was evidenced a moment later when, as we drew up alongside the gig, which had been waiting for us, Simpson hailed me with the question:

“Did ye notice, sir, just afore we lost sight of the brig, that he’d hauled his wind?”

“Yes,” said I, “I did. And I have a suspicion that he has done so because he had a hand aloft to watch for and report the sinking of the schooner; and that hand has caught sight of the boats. If my suspicion is correct, he has waited until he believed we could no longer see him, and has then hauled his wind in the hope that by making a series of short stretches to windward he will fall in with us in the course of an hour or two and be able to make an end of us. He probably waited until we had been lost sight of in the gathering darkness, and then shifted his helm, forgetful of the fact that his canvas would show up against the western sky for some few minutes after ours had vanished.”

“That’s just my own notion, sir,” answered Simpson, “I mean about his wishin’ to fall in with and make an end of us. And he’ll do it, too, unless we can hit upon some plan to circumvent him.”

“Quite so,” said I. “But we must see to it that we do not again fall into his hands. And to avoid doing so I can think of nothing better than to shift our own helm and shape a course either to the northward or the southward, with the wind about two points abaft the beam; by doing which we may hope to get to leeward of the brig in about two hours from now, when we can resume our course for Sierra Leone with a reasonable prospect of running the brig out of sight before morning. And, as she was heading to the northward when we last saw her, our best plan will be to steer a southerly course. So, up helm, Simpson, and we will steer west-south-west for the next two hours, keeping a sharp look-out for the brig, meanwhile, that we may not run foul of her unawares.”

We had been steering our new course about an hour when it became apparent that a change of weather was brewing, though what the nature of the impending change might be it was, for the moment, somewhat difficult to guess. The appearance of the sky seemed to portend a thunderstorm, for it had rapidly become overcast with dense masses of heavy, lowering cloud, which appeared to have quite suddenly gathered from nowhere in particular, obscuring the stars, yet not wholly shutting out their light, for the forms of the cloud-masses could be made out with a very fair degree of distinctness, and it would probably also have been possible to distinguish a ship at the distance of a mile. It was the presence of this light in the atmosphere, emanating apparently from the clouds themselves, that caused me rather to doubt the correctness of the opinion, pretty freely expressed by the men, that what was brewing was nothing more serious than an ordinary thunderstorm, for I had witnessed something of the same kind before, on the coast, but in a much more marked degree, it is true; and in that case the appearance had been followed by a tornado, brief in duration, but of great violence while it lasted. I therefore felt distinctly anxious, the more so as it was evident that the wind was dropping, and this I regarded as a somewhat unfavourable sign. I hailed Simpson, and asked him what he thought of the weather.

“Why, sir,” replied he, “the wind’s droppin’, worse luck; and if it should happen to die away altogether, or even to soften down much more, we shall have to out oars and pull; for we must get out of sight of that brig somehow, between this and to-morrow morning.”

“Undoubtedly,” said I. “But that is not precisely what I mean. What is worrying me just now is the question whether there is anything worse than thunder behind the rather peculiar appearance of the sky.”

He directed his glance aloft, attentively studying the aspect of the heavens for a few moments.

“It’s a bit difficult to say, sir,” he replied at last. “Up to now I’ve been thinkin’ that it only meant thunder and, perhaps, heavy rain; but, now that you comes to mention it, I don’t feel so very sure that there ain’t wind along with it, too—perhaps one of these here tornaders. And if that’s what’s brewin’ we shall have to stand by, and keep our weather eye liftin’; for a tornader’d be an uncommon awk’ard customer to meet with in these here open boats.”

“You are right there,” said I, “and for that reason it is especially desirable that the boats should keep together for mutual support and assistance, if need be. You have the heels of us in such light weather as the present, and might very easily slip away from and lose sight of us in the darkness; therefore I think that, for the present at all events, in order to avoid any such possibility, you had better take the end of our painter and make it fast to your stern ring-bolt. Then you can go ahead as fast as you please, without any risk of the boats losing sight of each other.”

This was done, and for the next two hours the boats slid along in company, the gig leading and towing the longboat, although of course the towing did not amount to much, since we in the longboat kept our sails set to help as much as possible.

It was by this time close upon three bells in the first watch, and notwithstanding the softening of the wind I came to the conclusion that we must have slipped past the brig, assuming our suspicion, that she had hauled her wind in chase of us, to be correct. I therefore ordered our helm to be shifted once more, and our course to be resumed in a north-westerly direction.

Half an hour later the wind had dropped to a flat calm, and Simpson suggested that, as a measure of precaution, in view of the possibility that the brig might still be to the westward of us, we should get out the oars and endeavour to slip past her. But I had for some time past been very anxiously watching the weather, and had at length arrived at the conclusion that, if not an actual tornado, there was at least a very heavy and dangerous squall brewing away down there in the eastern quarter, before which, when it burst, not only we, but also the brig, would be obliged to run; and, since she would run faster than the boats, it was no longer desirable, but very much the reverse, that we should lie to the westward of her. I therefore decided to keep all fast with the oars for the present, and employ such time as might be left to us upon the task of preparing the boats, as far as possible, for the ordeal to which it seemed probable that they were about to be subjected.

I was far less anxious about the safety of the longboat than I was about that of the gig, which, being a more lightly built and much smaller craft, and excellent in every way for service in fine weather and smooth water, yet was not adapted for work at sea except under favourable conditions; and in the event of it coming on to blow hard I feared that in the resulting heavy sea she would almost inevitably be swamped. I therefore turned my attention to her in the first instance, causing her to be brought alongside the longboat and her painter to be made fast to the ring-bolt in the stern of the latter, thus reversing the original arrangement; my intention being that, in the event of bad weather, the longboat should tow the gig. This done, I caused Simpson to unstep the gig’s single mast and lay it fore and aft in the boat, with the heel resting upon and firmly lashed to the small grating which covered the after end of the boat between the backboard of the stern-sheets and the stern-post, while the head was supported by a crutch formed of two stretchers lashed together and placed upright upon the bow thwart, the whole being firmly secured in place by the two shrouds attached to the mast-head. Thus arranged, the mast formed a sort of ridge pole which sloped slightly upward from the boat’s stern toward the bow. The lugsail was then unbent from the yard, stretched across the mast, fore and aft—thus forming a sort of tent over the open boat for about two-thirds of her length from the stern-post,—and the luff and after-leach of the sail were then strained tightly down to the planking of the boat outside, by short lengths of ratline led underneath the gig’s keel. The result was that, when the job was finished, the gig was almost completely covered in by the tautly stretched sail, which I hoped would not only afford a considerable amount of protection to her crew, but would also keep out the breaking seas that would otherwise be almost certain to swamp her.

So pleased was I with the job, when it was finished, that I determined to attempt something similar in the case of the longboat. This craft was rigged with two masts, carrying upon the foremast a large standing lug and a jib, and a small lug upon the jigger-mast. These latter, that is to say the jigger-mast and the small lug, we stretched over the stern-sheets of the longboat in the same way as we had dealt with the gig, leading the yoke lines forward on top of the sail, so that the steering arrangements might not be interfered with. And finally, we close-reefed the big lug and took in the jib, when we were as ready for the expected outfly as it was possible for people in such circumstances to be.