Project Gutenberg's From Powder Monkey to Admiral, by W.H.G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: From Powder Monkey to Admiral

A Story of Naval Adventure

Author: W.H.G. Kingston

Illustrator: Archibald Webb

Release Date: May 9, 2007 [EBook #21404]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FROM POWDER MONKEY TO ADMIRAL ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W.H.G. Kingston

"From Powder Monkey to Admiral"

Introduction.

A book for boys by W.H.G. Kingston needs no introduction. Yet a few things may be said about the origin and the purpose of this story.

When the Boys’ Own Paper was first started, Mr Kingston, who showed deep interest in the project, undertook to write a story of the sea, during the wars, under the title of “From Powder-monkey to Admiral.”

Talking the matter over, it was objected that such a story might offend peaceable folk, because it must deal too much with blood and gunpowder. Mr Kingston, although famed as a narrator of sea-fights, was a lover of peace, and he said that his story would not encourage the war spirit. Those who cared chiefly to read about battles might turn to the pages of “British Naval History.” He chose the period of the great war for his story, because it was a time of stirring events and adventures. The main part of the narrative belongs to the early years of life, in which boys would feel most interest and sympathy. And throughout the tale, not “glory” but “duty” is the object set before the youthful reader.

It was further objected that the title of the story set before boys an impossible object of ambition. The French have a saying, that “every soldier carries in his knapsack a marshal’s baton,” meaning that the way is open for rising to the very highest rank in their army. But who ever heard of a sailor lad rising to be an Admiral in the British Navy?

Let us see how history answers this question. There was a great sea captain of other days, whose fame is not eclipsed by the glorious reputations of later wars, Admiral Benbow. In the reign of Queen Anne, before the great Duke of Marlborough had begun his victorious career, Benbow had broken the power of France on the sea. Rank and routine were powerful in those days, as now; but when a time of peril comes, the best man is wanted, and Benbow was promoted out of turn, by royal command, to the rank of Vice-Admiral, and went after the fleet of Admiral Ducasse to the West Indies. In the little church of Saint Andrew’s, Kingston, Jamaica, his body lies, and the memorial stone speaks of him as “a true pattern of English courage, who lost his life in defence of queen and country.”

Like his illustrious French contemporary Jean Bart, John Benbow was of humble origin. He entered the merchant service when a boy. He was unknown till he had reached the age of thirty, when he had risen to the command of a merchant vessel. Attacked by a powerful Salee rover, he gallantly repulsed these Moorish pirates, and took his ship safe into Cadiz. The heads of thirteen of the pirates he preserved, and delivered them to the magistrates of the town, in presence of the custom-house officers. The tidings of this strange incident reached Madrid, and the King of Spain, Charles the Second, sent for the English captain, received him with great honour, and wrote a letter on his behalf to our King James the Second, who on his return to England gave him a ship. This was his introduction to the British Navy, in which he served with distinction in the reigns of William the Third and Queen Anne. But his obscure origin is the point here under notice, and the following traditional anecdote is preserved in Shropshire:—When a boy he was left in charge of the house by his mother, who went out marketing. The desire to go to sea, long cherished, was irresistible. He stole forth, locking the cottage door after him, and hung the key on a hook in a tree in the garden. Many years passed before he returned to the old place. Though now out of his reach, for the tree had grown faster than he, the key still hung on the hook. He left it there; and there it remained when he came back as Rear-Admiral of the White. He then pointed it out to his friends, and told the story. Once more his country required his services, but his fame and the echo of his victories alone came over the wave. The good town of Shrewsbury is proud to claim him as a son, and remembers the key, hung by the banks of the Severn, near Benbow House. Whatever basis of truth the story may have, its being told and believed attests the fact of the humble birth and origin of Admiral Benbow.

Another sailor boy, Hopson, in the early part of last century, rose to be Admiral in the British Navy. Born at Bonchurch in the Isle of Wight, of humblest parentage, he was left an orphan, and apprenticed by the parish to a tailor. While sitting one day alone on the shop-board, he was struck by the sight of the squadron coming round Dunnose. Instantly quitting his work, he ran to the shore, jumped into a boat, and rowed for the Admiral’s ship. Taken on board, he entered as a volunteer.

Next morning the English fleet fell in with a French squadron, and a warm action ensued. Young Hopson obeyed every order with the utmost alacrity; but after two or three hours’ fighting he became impatient, and asked what they were fighting for. The sailors explained to him that they must fire away, and the fight go on, till the white rag at the enemy’s mast-head was struck. Getting this information, his resolution was formed, and he exclaimed, “Oh, if that’s all, I’ll see what I can do.”

The two ships, with the flags of the commanders on each side, were now engaged at close quarters, yard-arm and yard-arm, and completely enveloped in smoke. This proved favourable to the purpose of the brave youth, who mounted the shrouds through the smoke unobserved, gained the French Admiral’s main-yard, ascended with agility to the main-topgallant mast-head, and carried off the French flag. It was soon seen that the enemy’s colours had disappeared, and the British sailors, thinking they had been hauled down, raised a shout of “Victory, victory!” The French were thrown into confusion by this, and first slackened fire, and then ran from their guns. At this juncture the ship was boarded by the English and taken. Hopson had by this time descended the shrouds with the French flag wrapped round his arm, which he triumphantly displayed.

The sailors received the prize with astonishment and cheers of approval. The Admiral being told of the exploit, sent for Hopson and thus addressed him, “My lad, I believe you to be a brave youth. From this day I order you to walk the quarter-deck, and if your future conduct is equally meritorious, you shall have my patronage and protection.” Hopson made every effort to maintain the good opinion of his patron, and by his conduct and attention to duty gained the respect of the officers of the ship. He afterwards went rapidly through the different ranks of the service, till at length he attained that of Admiral.

We might give not a few instances of more recent date, but the families and friends of those “who have risen” do not always feel the same honest pride as the great men themselves in the story of their life. While it is true that no sailor boy may now hope to become “Admiral of the Fleet,” yet there is room for advancement, in peace as in war, to what is better than mere rank or title or wealth,—a position of honour and usefulness. Good character and good conduct, pluck and patience, steadiness and application, will win their way, whether on sea or land, and in every calling.

The inventions of modern science and art are producing a great change in all that pertains to life at sea. The revolution is more apparent in war than in peace. There is, and always will be, a large proportion of merchant ships under sail, even in nations like our own where steam is in most general use. In war, a wooden ship without steam and without armour would be a mere floating coffin. The fighting Temeraire, and the saucy Arethusa, and Nelson’s Victory itself, would be nothing but targets for deadly fire from active and irresistible foes. The odds would be about the same as the odds of javelins and crossbows against modern fire-arms. Steam alone had made a revolution in naval warfare; but when we add to this the armour-plating of vessels, and the terrible artillery of modern times, “the wooden walls of old England” are only fit to be used as store-ships or hospitals for a few years, and then sent to the ship-yards to be broken up for firewood. But though material conditions have changed, the moral forces are the same as ever, and courage, daring, skill, and endurance are the same in ships of oak or of iron:—

“Yes, the days of our wooden walls are ended,

And the days of our iron ones begun;

But who cares by what our land’s defended,

While the hearts that fought and fight are one?

’Twas not the oak that fought each battle,

’Twas not the wood that victory won;

’Twas the hands that made our broadsides rattle,

’Twas the hearts of oak that served each gun.”

These are words from one of the “Songs for Sailors,” by W.C. Bennett, who has written better naval poems for popular use than any one since the days of Dibdin. The same idea concludes a rattling ballad on old Admiral Benbow:—

“Well, our walls of oak have become just a joke

And in tea-kettles we’re to fight;

It seems a queer dream, all this iron and steam,

But I daresay, my lads, it’s right.

But whether we float in ship or in boat,

In iron or oak, we know

For old England’s right we’ve hearts that will fight,

As of old did the brave Benbow.”

But, after all, even in war, fighting is only a small part of the sum of any sailor’s life, and the British flag floats over ships on every sea, whether under sail or steam, in the peaceful pursuits of commerce. The same qualities of heart and mind will have their play, which Mr Kingston has described in his stirring story,—a story which will be read with profit by the young, and with pleasure by both young and old.

Dr Macaulay, Founder of “Boy’s Own Paper.”

Chapter One.

Preparing to start.

No steamboats ploughed the ocean, nor were railroads thought of, when our young friends Jack, Tom, and Bill lived. They first met each other on board the Foxhound frigate, on the deck of which ship a score of other lads and some fifty or sixty men were mustered, who had just come up the side from the Viper tender; she having been on a cruise to collect such stray hands as could be found; and a curious lot they were to look at.

Among them were long-shore fellows in swallow-tails and round hats, fishermen in jerseys and fur-skin caps, smugglers in big boots and flushing coats; and not a few whose whitey-brown faces, and close-cropped hair, made it no difficult matter to guess that their last residence was within the walls of a gaol. There were seamen also, pressed most of them, just come in from a long voyage, many months or perhaps years having passed since they left their native land; that they did not look especially amiable was not to be wondered at, since they had been prevented from going, as they had intended, to visit their friends, or maybe, in the case of the careless ones, from enjoying a long-expected spree on shore. They were all now waiting to be inspected by the first lieutenant, before their names were entered on the ship’s books.

The rest of the crew were going about their various duties. Most of them were old hands, who had served a year or more on board the gallant frigate. During that time she had fought two fierce actions, which, though she had come off victorious, had greatly thinned her ship’s company, and the captain was therefore anxious to make up the complement as fast as possible by every means in his power.

The seamen took but little notice of the new hands, though some of them had been much of the same description themselves, but were not very fond of acknowledging this, or of talking of their previous histories; they had, however, got worked into shape by degrees: and the newcomers, even those with the “long togs,” by the time they had gone through the same process would not be distinguished from the older hands, except, maybe, when they came to splice an eye, or turn in a grummet, when their clumsy work would show what they were; few of them either were likely ever to be the outermost on the yard-arms when sail had suddenly to be shortened on a dark night, while it was blowing great guns and small arms.

The frigate lay at Spithead. She had been waiting for these hands to put to sea. Lighters were alongside, and whips were never-ceasingly hoisting in casks of rum, with bales and cases of all sorts, which it seemed impossible could ever be stowed away. From the first lieutenant to the youngest midshipman, all were bawling at the top of their voices, issuing and repeating orders; but there were two persons who out-roared all the rest, the boatswain and the boatswain’s mate. They were proud of those voices of theirs. Let the hardest gale be blowing, with the wind howling and whistling through the rigging, the canvas flapping like claps of thunder, and the seas roaring and dashing against the bows, they could make themselves heard above the loudest sounds of the storm.

At present the boatswain bawled, or rather roared, because he was so accustomed to roar that he could speak in no gentler voice while carrying on duty on deck; and the boatswain’s mate imitated him.

The first lieutenant had a good voice of his own, though it was not so rough as that of his inferiors. He made it come out with a quick, sharp sound, which could be heard from the poop to the forecastle, even with the wind ahead.

Jack, Tom, and Bill looked at each other, wondering what was next going to happen. They were all three of about the same age, and much of a height, and somehow, as I have said, they found themselves standing close together.

They were too much astonished, not to say frightened, to talk just then, though they all three had tongues in their heads, so they listened to the conversation going on around them.

“Why, mate, where do you come from?” asked a long-shore chap of one of the whitey-brown-faced gentlemen.

“Oh, I’ve jist dropped from the clouds; don’t know where else I’ve come from,” was the answer.

“I suppose you got your hair cropped off as you came down?” was the next query.

“Yes! it was the wind did it as I came scuttling down,” answered the other, who was evidently never at a loss what to say. “And now, mate, just tell me how did you get on board this craft?” he inquired.

“I swam off, of course, seized with a fit of patriotism, and determined to fight for the honour and glory of old England,” was the answer.

It cannot, however, be said that this is a fair specimen of the conversation; indeed, it would benefit no one were what was said to be repeated.

Jack, Tom, and Bill felt very much as a person might be supposed to do who had dropped from the moon. Everything around them was so strange and bewildering, for not one of them had ever before been on board a ship, and Bill had never even seen one. Having not been much accustomed to the appearance of trees, he had some idea that the masts grew out of the deck, that the yards were branches, and the blocks curious leaves; not that amid the fearful uproar, and what seemed to him the wildest confusion, he could think of anything clearly.

Bill Rayner had certainly not been born with a silver spoon in his mouth. His father he had never known. His mother lived in a garret and died in a garret, although not before, happily for him, he was able to do something for himself, and, still more happily, not before she had impressed right principles on his mind. As the poor woman lay on her deathbed, taking her boy’s hands and looking earnestly into his eyes, she said, “Be honest, Bill, in the sight of God. Never forget that He sees you, and do your best to please Him. No fear about the rest. I am not much of a scholar, but I know that’s right. If others try to persuade you to do what’s wrong, don’t listen to them. Promise me, Bill, that you will do as I tell you.”

“I promise, mother, that I will,” answered Bill; and, small lad as he was, meant what he said.

Poor as she was, being a woman of some education, his mother had taught him to read and write and cipher—not that he was a great adept at any of those arts, but he possessed the groundwork, which was an important matter; and he did his best to keep up his knowledge by reading sign-boards, looking into book-sellers’ windows, and studying any stray leaves he could obtain.

Bill’s mother was buried in a rough shell by the parish, and Bill went out into the world to seek his fortune. He took to curious ways,—hunting in dust-heaps for anything worth having; running errands when he could get any one to send him; holding horses for gentlemen, but that was not often; doing duty as a link-boy at houses when grand parties were going forward or during foggy weather; for Bill, though he often went supperless to his nest, either under a market-cart, or in a cask by the river side, or in some other out-of-the-way place, generally managed to have a little capital with which to buy a link; but the said capital did not grow much, for bad times coming swallowed it all up.

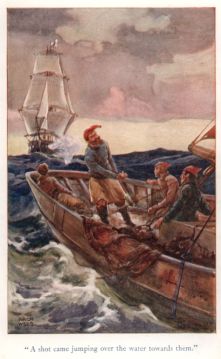

Bill, as are many other London boys, was exposed to temptations of all sorts; often when almost starving, without a roof to sleep under, or a friend to whom he could appeal for help, his shoes worn out, his clothing too scanty to keep him warm; but, ever recollecting his mother’s last words, he resisted them all. One day, having wandered farther east than he had ever been before, he found himself in the presence of a press-gang, who were carrying off a party of men and boys to the river’s edge. One of the man-of-war’s men seized upon him, and Bill, thinking that matters could not be much worse with him than they were at present, willingly accompanied the party, though he had very little notion where they were going. Reaching a boat, they were made to tumble in, some resisting and endeavouring to get away; but a gentle prick from the point of a cutlass, or a clout on the head, made them more reasonable, and most of them sat down resigned to their fate. One of them, however, a stout fellow, when the boat had got some distance from the shore, striking out right and left at the men nearest him, sprang overboard, and before the boat could be pulled round had already got back nearly half-way to the landing-place.

One or two of the press-gang, who had muskets, fired, but they were not good shots. The man looking back as he saw them lifting their weapons, by suddenly diving escaped the first volley, and by the time they had again loaded he had gained such a distance that the shot spattered into the water on either side of him. They were afraid of firing again for fear of hitting some of the people on shore, besides which, darkness coming on, the gloom concealed him from view.

They knew, however, that he must have landed in safety from the cheers which came from off the quay, uttered by the crowd who had followed the press-gang, hooting them as they embarked with their captives.

Bill began to think that he could not be going to a very pleasant place, since, in spite of the risk he ran, the man had been so eager to escape; but being himself unable to swim, he could not follow his example, even had he wished it. He judged it wiser, therefore, to stay still, and see what would next happen. The boat pulled down the river for some way, till she got alongside a large cutter, up the side of which Bill and his companions were made to climb.

From what he heard, he found that she was a man-of-war tender, her business being to collect men, by hook or by crook, for the Royal Navy.

As she was now full—indeed, so crowded that no more men could be stowed on board—she got under way with the first of the ebb, and dropped down the stream, bound for Spithead.

As Bill, with most of the pressed men, was kept below during this his first trip to sea, he gained but little nautical experience. He was, however, very sick, while he arrived at the conclusion that the tender’s hold, the dark prison in which he found himself, was a most horrible place.

Several of his more heartless companions jeered at him in his misery; and, indeed, poor Bill, thin and pale, shoeless and hatless, clad in patched garments, looked a truly miserable object.

As the wind was fair, the voyage did not last long, and glad enough he was when the cutter got alongside the big frigate, and he with the rest being ordered on board, he could breathe the fresh air which blew across her decks.

Tom Fletcher, who stood next to Bill, had considerably the advantage of him in outward appearance. Tom was dressed in somewhat nautical fashion, though any sailor would have seen with half an eye that his costume had been got up by a shore-going tailor.

Tom had a good-natured but not very sensible-looking countenance. He was strongly built, was in good health, and had the making of a sailor in him, though this was the first time that he had even been on board a ship.

He had a short time before come off with a party of men returning on the expiration of their leave. Telling them that he wished to go to sea, he had been allowed to enter the boat. From the questions some of them had put to him, and the answers he gave, they suspected that he was a runaway, and such in fact was the case. Tom was the son of a solicitor in a country town, who had several other boys, he being the fourth, in the family.

He had for some time taken to reading the voyages of Drake, Cavendish, and Dampier, and the adventures of celebrated pirates, such as those of Captains Kidd, Lowther, Davis, Teach, as also the lives of some of England’s naval commanders, Sir Cloudesley Shovell, Benbow, and Admirals Hawke, Keppel, Rodney, and others, whose gallant actions he fully intended some day to imitate.

He had made vain endeavours to induce his father to let him go to sea, but Mr Fletcher, knowing that he was utterly ignorant of a sea life, set his wish down as a mere fancy which it would be folly to indulge.

Tom, instead of trying to show that he really was in earnest, took French leave one fine morning, and found his way to Portsmouth, without being traced. Had he waited, he would probably have been sent to sea as a midshipman, and placed on the quarter-deck. He now entered as a ship-boy before the mast.

Tom, as he had made his bed, had to lie on it, as is the case with many other persons. Even now, had he written home, he might have had his position changed, but he thought himself very clever, and had no intention of letting his father know where he had gone. The last of the trio was far more accustomed to salt water than was either of his companions. Jack Peek was the son of a West country fisherman. He had come to sea because he saw that there was little chance of getting bread to put into his mouth if he remained on shore.

Jack’s father had lost his boats and nets the previous winter, and had shortly afterwards been pressed on board a man-of-war.

Jack had done his best to support himself without being a burden to his mother, who sold fish in the neighbouring town and country round, and could do very well for herself; so when he proposed going on board a man-of-war, she, having mended his shirts, bought him a new pair of shoes, and gave him her blessing. Accordingly, doing up his spare clothes in a bundle, which he carried at the end of a stick, he trudged off with a stout heart, resolved to serve His Majesty and fight the battles of Old England.

Jack went on board the first man-of-war tender picking up hands he could find, and had been transferred that day to the Foxhound.

He told Tom and Bill thus much of his history. The former, however, was not very ready to be communicative as to his; while Bill’s patched garments said as much about him as he was just then willing to narrate. A boy who had spent all his life in the streets of London was not likely to say more to strangers than was necessary.

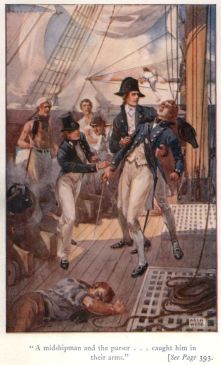

In the meantime the fresh hands had been called up before the first lieutenant, Mr Saltwell, and their names entered by the purser in the ship’s books, after the ordinary questions had been put to them to ascertain for what rating they were qualified.

Some few, including the smugglers, were entered as able seamen; others as ordinary seamen; and the larger number, who were unfit to go aloft, or indeed not likely to be of much use in any way for a long time to come, were rated as landsmen, and would have to do all the dirty work about the ship.

The boys were next called up, and each of them gave an account of himself.

Tom dreaded lest he should be asked any questions which he would be puzzled to answer.

The first lieutenant glanced at all three, and in spite of his old dress, entered Bill first, Jack next, and Tom, greatly to his surprise, the last. In those days no questions were asked where men or boys came from. At the present time, a boy who should thus appear on board a man-of-war would find himself in the wrong box, and be quickly sent on shore again, and home to his friends. None are allowed to enter the Navy until they have gone through a regular course of instruction in a training ship, and none are received on board her unless they can read and write well, and have a formally signed certificate that they have obtained permission from their parents or guardians.

Chapter Two.

Heaving up the anchor.

As soon as the boys’ names were entered, they were sent forward, under charge of the ship’s corporal, to obtain suits of sailor’s clothing from the purser’s steward, which clothing was charged to their respective accounts.

The ship’s corporal made them wash themselves before putting on their fresh gear; and when they appeared in it, with their hair nicely combed out, it was soon seen which of the three was likely to prove the smartest sea boy.

Bill, who had never had such neat clothing on before, felt himself a different being. Tom strutted about and tried to look big. Jack was not much changed, except that he had a round hat instead of a cap, clean clothes, and lighter shoes than the thick ones in which he had come on board.

As neither Tom nor Bill knew the stem from the stern of the ship, and even Jack felt very strange, they were handed over to the charge of Dick Brice, the biggest ship’s boy, with orders to him to instruct them in their respective duties.

Dick had great faith in a rope’s-end, having found it efficacious in his own case. He was fond of using it pretty frequently to enforce his instructions. Jack and Bill supposed that it was part of the regular discipline of the ship; but Tom had not bargained for such treatment, and informing Dick that he would not stand it, in consequence got a double allowance.

He dared not venture to complain to his superiors, for he saw the boatswain and the boatswain’s mate using their colts with similar freedom, and so he had just to grin and bear it.

At night, when the hammocks were piped down, the three went to theirs in the forepart of the ship. Bill thought he had never slept in a more comfortable bed in his life. Jack did not think much about the matter; but Tom, who had always been accustomed to a well-made bed at home, grumbled dreadfully when he tried to get into his, and tumbled out three or four times on the opposite side before he succeeded.

Had it not been for Dick Brice, who slung their hammocks for them, they would have had to sleep on the bare deck.

The next morning the gruff voice of the boatswain’s mate summoned all hands to turn out, and on going on deck they saw “Blue Peter” flying at the fore, while shortly afterwards the Jews and all other visitors were made to go down the side into the boats waiting for them. The captain came on board, the sails were loosed, and while the fife was setting up a merry tune, the seamen tramped round at the capstan bars, and the anchor was hove up.

The wind being from the eastward, in the course of a few minutes the gallant frigate, under all sail, was gliding down through the smooth waters of the Solent Sea towards the Needles.

Tom and Bill had something fresh to wonder at every minute. It dawned upon them by degrees that the forepart of the ship went first, and that the wheel, at which two hands were always stationed, had something to do with guiding her, and that the sails played an important part in driving her on.

Jack had a great advantage over them, as he knew all this, and many other things besides, and being a good-natured fellow, was always ready to impart his knowledge to them.

By the time they had been three or four weeks at sea, they had learned a great deal more, and were able to go aloft.

Bill had caught up to Jack, and had left Tom far behind. The same talent which had induced him to mend his ragged clothes, made him do, with rapidity and neatness, everything else he undertook, while he showed a peculiar knack of being quick at understanding and executing the orders he received.

Tom felt rather jealous that he should be surpassed by one he had at first looked down on as little better than a beggar boy.

It never entered into Jack’s head to trouble himself about the matter, and if Bill was his superior, that was no business of his.

There were a good many other people on board, who looked down on all three of them, considering that they were the youngest boys, and were at everybody’s beck and call.

As soon as the frigate got to sea the crew were exercised at their guns, and Jack, Tom, and Bill had to perform the duty of powder-monkeys. This consisted in bringing up the powder from the magazine in small tubs, on which they had to sit in a row on deck, to prevent the sparks getting in while the men were working the guns, and to hand out the powder as it was required.

“I don’t see any fun in firing away when there is no enemy in sight,” observed Tom, as he sat on his tub at a little distance from Bill.

“There may not be much fun in it, but it’s very necessary,” answered Bill. “If the men were not to practise at the guns, how could they fire away properly when we get alongside an enemy? See! some of the fresh hands don’t seem to know much what they are about, or the lieutenant would not be growling at them in the way he is doing. I am keeping my eye on the old hands to learn how they manage, and before long, I think, if I was big enough, I could stand to my gun as well as they do.”

Tom, who had not before thought of observing the crews of the guns, took the hint, and watched how each man was engaged.

By being constantly exercised, the crew in a few weeks were well able to work their guns; but hitherto they had fallen in with no enemy against whom to exhibit their prowess.

A bright look-out was kept from the mast-head from sunrise to sunset for a strange sail, and it was not probable that they would have to go long without falling in with one, for England had at that time pretty nearly all the world in arms against her. She had managed to quarrel with the Dutch, and was at war with the French and Spaniards, while she had lately been engaged in a vain attempt to overcome the American colonies, which had thrown off their allegiance to the British Crown.

Happily for the country, her navy was staunch, and many of the most gallant admirals whose names have been handed down to fame commanded her fleets; the captains, officers, and crews, down to the youngest ship-boys, tried to imitate their example, and enabled her in the unequal struggle to come off victorious.

The Foxhound had for some days been cruising in the Bay of Biscay, and was one morning about the latitude of Ferrol. The watch was employed in washing down decks, the men and boys paddling about with their trousers tucked up to their knees, some with buckets of water, which they were heaving about in every direction, now and then giving a shipmate, when the first lieutenant’s eye was off them, the benefit of a shower-bath: others were wielding huge swabs, slashing them down right and left, with loud thuds, and ill would it have fared with any incautious landsman who might have got within their reach. The men were laughing and joking with each other, and the occupation seemed to afford amusement to all employed.

Suddenly there came a shout from the look-out at the masthead of “Five sail in sight.”

“Where away?” asked Lieutenant Saltwell, who was on deck superintending the operations going forward.

“Dead to leeward, sir,” was the answer.

The wind was at the time blowing from the north-west, and the frigate was standing close hauled, on the starboard tack, to the westward.

The mate of the watch instantly went aloft, with his spy-glass hung at his back, to take a look at the strangers, while a midshipman was sent to inform Captain Waring, who, before many minutes had elapsed, made his appearance, having hurriedly slipped into his clothes.

On receiving the report of the young officer, who had returned on deck, he immediately ordered the helm to be put up, and the ship to be kept away in the direction of the strangers.

In a short time it was seen that most of them were large ships; one of them very considerably larger than the Foxhound.

The business of washing down the decks had been quickly concluded, and the crew were sent to their breakfasts.

Many remarks of various sorts were made by the men. Some thought that the captain would never dream of engaging so superior a force; while others, who knew him well, declared that whatever the odds, he would fight.

As yet no order had been received to beat to quarters, and many were of opinion that the captain would only stand on near enough to ascertain the character of the strangers, and then, should they prove enemies, make all sail away from them.

Still the frigate stood on, and Bill, who was near one of the officers who had a glass in his hand, heard him observe that one was a line-of-battle ship, two at least were frigates, while another was a corvette, and the fifth a large brig-of-war.

These were formidable odds, but still their plucky captain showed no inclination to escape from them, but, on the contrary, seemed as if he had made up his mind to bring them to action.

The question was ere long decided. The drum beat to quarters, the men went to their guns, powder and shot were handed up from below, giving ample occupation to the powder-monkeys, and the ship was headed towards the nearest of the strangers. She was still some distance off when the crew were summoned aft to hear what the captain had to say to them.

“My lads!” he said, “some of you have fought under me before now, and though the odds were against us, we licked the enemy. We have got somewhat greater odds, perhaps, at present, but I want to take two or three of those ships; they are not quite as powerful as they look, and if you will work your guns as I know you can work them, we’ll do it before many hours have passed. We have a fine breeze to help us, and will tackle one after the other. You’ll support me, I know.”

Three loud cheers were given as a response to this appeal, and the men went back to their guns, where they stood stripped to their waists, with handkerchiefs bound round their heads.

Notwithstanding the formidable array of the enemy, the frigate kept bearing down under plain sail towards them.

Our heroes, sitting on their tubs, could see but very little of what was going forward, though now and then they got a glimpse of the enemy through the ports; but they heard the remarks made by the men in their neighbourhood, who were allowed to talk till the time for action had arrived.

“Our skipper knows what he’s about, but that chap ahead of the rest is a monster, and looks big enough to tackle us without the help of the others,” observed one of the crew of the gun nearest to which Tom was seated.

“What’s the odds if she carries twice as many teeth as we have! we’ll work ours twice as fast, and beat her before the frigates can come up to grin at us,” answered Ned Green, the captain of the gun.

Tom did not quite like the remarks he heard. There was going to be a sharp fight, of that there could be no doubt, and round shot would soon be coming in through the sides, and taking off men’s heads and legs and arms. It struck him that he would have been safer at school. He thought of his father and mother, and brothers and sisters, who, if he was killed, would never know what had become of him; not that Tom was a coward, but it was somewhat trying to the courage even of older hands, thus standing on slowly towards the enemy. When the fighting had once begun, Tom was likely to prove as brave as anybody else; at all events, he would have no time for thinking, and it is that which tries most people.

The captain and most of the officers were on the quarter-deck, keeping their glasses on the enemy.

“The leading ship under French colours appears to me to carry sixty-four guns,” observed the first lieutenant to the captain; “and the next, also a Frenchmen, looks like a thirty-six gun frigate. The brig is American, and so is one of the sloops. The sternmost is French, and is a biggish ship.”

“Whatever they are, we’ll fight them, and, I hope, take one or two at least,” answered the captain.

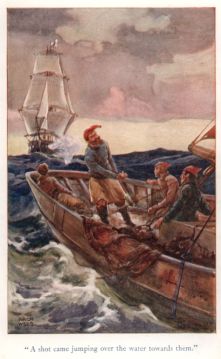

He looked at his watch. It was just ten o’clock. The next moment the headmost ship opened her fire, and the shot came whizzing between the ship’s masts.

Captain Waring watched them as they flew through the air.

“I thought so,” he observed. “There were not more than fifteen; she’s a store-ship, and will be our prize before the day is over. Fire, my lads!” he shouted; and the eager crew poured a broadside into the enemy, rapidly running in their guns, and reloading them to be ready for the next opponent.

The Foxhound was standing along the enemy’s line to windward, and as she came abreast of each ship she fired with well-directed aim; and though all the enemy’s ships in succession discharged their guns at her, not a shot struck her hull, though their object evidently was to cripple her, so that they might surround her and have her at their mercy.

Tom, who had read about sea-fights, and had expected to have the shot come rushing across the deck, felt much more comfortable on discovering this, and began to look upon the Frenchmen as very bad gunners.

The Foxhound’s guns were all this time thundering away as fast as the crews could run them in and load them, the men warming to their work as they saw the damage they were inflicting on the enemy.

Having passed the enemy’s line to windward, Captain Waring ordered the ship to be put about, and bore down on the sternmost French ship, which, with one of smaller size carrying the American pennant, was in a short time so severely treated that they both bore up out of the line. The Foxhound, however, followed, and the other French ships and the American brig coming to the assistance of their consorts, the Foxhound had them on both sides of her.

This was just what her now thoroughly excited crew desired most, as they could discharge their two broadsides at the same time; and right gallantly did she fight her way through her numerous foes till she got up with the American ship, which had been endeavouring to escape before the wind, and now, to avoid the broadside which the English ship was about to pour into her, she hauled down her colours.

On seeing this, the frigate’s crew gave three hearty cheers; and as soon as they had ceased, the captain’s voice was heard ordering two boats away under the command of the third lieutenant, who was directed to take charge of the prize, and to send her crew on board the ship.

Not a moment was to be lost, as the rest of the enemy, under all sail, were endeavouring to make their escape.

The boats of the prize, which proved to be the Alexander, carrying twenty-four guns and upwards of a hundred men, were then lowered, and employed in conveying her crew to the ship.

The American captain and officers were inclined to grumble at first.

“Very sorry, gentlemen, to incommode you,” said the English lieutenant, as he hurried them down the side; “but necessity has no law; my orders are to send you all on board the frigate, as the captain is in a hurry to go in chase of your friends, of which we hope to have one or two more in our possession before long.”

The lieutenant altered his tone when the Americans began to grumble. “You must go at once, or take the consequences,” he exclaimed; and the prisoners saw that it would be wise to obey.

They were received very politely on board the ship, Captain Waring offering to accept their parole if they were ready to give it, and promise not to attempt to interfere with the discipline and regulations of the ship.

As soon as the prisoners were transferred to the Foxhound, she made all sail in chase of the large ship, which Captain Waring now heard was the sixty-four gun ship Mènager, laden with gunpowder, but now mounting on her maindeck twenty-six long twelve-pounders, and on her quarter-deck four long six-pounders, with a crew of two hundred and twenty men.

Her force was considerably greater than that of the English frigate, but Captain Waring did not for a moment hesitate to continue in pursuit of her. A stern chase, however, is a long chase. The day wore on, and still the French ship kept ahead of the Foxhound.

The crew were piped to dinner to obtain fresh strength for renewing the fight.

“Well, lads,” said Green, who was a bit of a wag in his way, as he looked at the powder-boys still seated on their tubs, “as you have still got your heads on your shoulders, you may put some food into your mouths. Maybe you won’t have another opportunity after we get up with the big ’un we are chasing. I told you, mates,” he added, turning to the crew of his gun, “the captain knew what he was about, and would make the Frenchmen haul down their flags before we hauled down ours. I should not be surprised if we got the whole lot of them.”

The boys, having returned their powder to the magazine till it was again wanted, were glad enough to stretch their legs, and still more to follow Green’s advice by swallowing the food which was served out to them.

The rest of the enemy’s squadron were still in sight, scattered here and there, and considerably ahead of the Mènager; the frigate was, however, gaining on the latter, and if the wind held, would certainly be up with her some time in the afternoon.

Every stitch of canvas she could carry was set on board the Foxhound.

It was already five o’clock. The crew had returned to their quarters, and the powder-monkeys were seated on their tubs. Both the pursuer and pursued were on the larboard tack, going free.

“We have her now within range of our guns,” cried Captain Waring. “Luff up, master, and we’ll give her a broadside.”

Just as he uttered the words a squall struck the frigate. Over she heeled, the water rushing in through her lower deck ports, which were unusually low, and washing over the deck.

The crews of the lee guns, as they stood up to their knees in water, fully believed that she was going over. In vain they endeavoured to run in their guns. More and more she heeled over, till the water was nearly up to their waists. None flinched, however. The guns must be got in, and the ports shut, or the ship would be lost.

“What’s going to happen?” cried Tom Fletcher. “We are going down! we are going down!”

Chapter Three.

Bill does good service.

The Foxhound appeared indeed to be in a perilous position. The water washed higher and higher over the deck. “We are going down! we are going down!” again cried Tom, wringing his hands.

“Not if we can help it,” said Jack. “We must get the ports closed, and stop the water from coming in.”

“It’s no use crying out till we are hurt. We can die but once,” said Bill. “Cheer up, Tom; if we do go to the bottom, it’s where many have gone before;” though Bill did not really think that the ship was sinking. Perhaps, had he done so, he would not have been so cool as he now appeared.

“That’s a very poor consolation,” answered Tom to his last remark. “Oh, dear! oh, dear! I wish that I had stayed on shore.”

Though there was some confusion among the landsmen, a few of whom began to look very white, if they did not actually wring their hands and cry out, the crews of the guns remained at their stations, and hauled away lustily at the tackles to run them in. The captain, though on the quarter-deck, was fully aware of the danger. There was no time to shorten sail.

“Port the helm!” he shouted; “hard a-port, square away the yards;” and in a few seconds the ship, put before the wind, rose to an even keel, the water, in a wave, rushing across the deck, some escaping through the opposite ports, though a considerable portion made its way below.

The starboard ports were now speedily closed, when once more the ship hauled up in chase.

The Foxhound, sailing well, soon got up again with the Mènager, and once more opened her fire, receiving that of the enemy in return.

The port of Ferrol could now be distinguished about six miles off, and it was thought probable that some Spanish men-of-war lying there might come out to the assistance of their friends. It was important to make the chase a prize before that should happen.

For some minutes Captain Waring reserved his fire, having set all the sail the Foxhound could carry.

“Don’t fire a shot till I tell you,” he shouted to his men.

The crews of the starboard guns stood ready for the order to discharge the whole broadside into the enemy. Captain Waring was on the point of issuing it, the word “Fire” was on his lips, when down came the Frenchman’s flag, and instead of the thunder of their guns the British seamen uttered three joyful cheers.

The Foxhound was hove-to to windward of the prize, while three of the boats were lowered and pulled towards her. The third lieutenant of the Foxhound was sent in command, and the Mènager’s boats being also lowered, her officers and crew were transferred as fast as possible on board their captor.

As the Mènager was a large ship, she required a good many people to man her, thus leaving the Foxhound with a greatly diminished crew.

It took upwards of an hour before the prisoners with their bags and other personal property were removed to the Foxhound. Captain Waring and Lieutenant Saltwell turned their eyes pretty often towards the harbour. No ships were seen coming out of it. The English frigate and her two prizes consequently steered in the direction the other vessels had gone, the captain hoping to pick up one or more of them during the following morning. Her diminished crew had enough to do in attending to their proper duties, and in looking after the prisoners.

The commanders of the two ships were received by the captain in his cabin, while the gun-room officers invited those of similar rank to mess with them, the men taking care of the French and American crews. The British seamen treated them rather as guests than prisoners, being ready to attend to their wants and to do them any service in their power. Their manner towards the Frenchmen showed the compassion they felt, mixed perhaps with a certain amount of contempt. They seemed to consider them indeed somewhat like big babes, and several might have been seen feeding the wounded and nursing them with tender care.

During the night neither the watch below nor any of the officers turned in, the greater number remaining on deck in the hopes that they might catch sight of one of the ships which had hitherto escaped them.

Note: This action and the subsequent events are described exactly as they occurred.

The American commander, Captain Gregory, sat in the cabin, looking somewhat sulky, presenting a great contrast to the behaviour of the Frenchman, Monsieur Saint Julien, who, being able to speak a little English, allowed his tongue to wag without cessation, laughing and joking, and trying to raise a smile on the countenance of his brother captive, the American skipper.

“Why! my friend, it is de fortune of war. Why you so sad?” exclaimed the volatile Frenchman. “Another day we take two English ship, and then make all right. Have you never been in England? Fine country, but not equal to ‘la belle France;’ too much fog and rain dere.”

“I don’t care for the rain, or the fog, Monsieur; but I don’t fancy losing my ship, when we five ought to have taken the Englishman,” replied the American.

“Ah! it was bad fortune, to be sure,” observed Monsieur Saint Julien. “Better luck next time, as you say; but what we cannot cure, dat we must endure; is not dat your proverb? Cheer up! cheer up! my friend.”

Nothing, however, the light-hearted Frenchman could say had the effect of raising the American’s spirits.

A handsome supper was placed on the table, to which Monsieur Saint Julien did ample justice, but Captain Gregory touched scarcely anything. At an early hour he excused himself, and retired to a berth which Captain Waring had courteously appropriated to his use.

During the night the wind shifted more to the westward, and then round to the south-west, blowing pretty strong. When morning broke, the look-outs discovered two sail to the south-east, which it was evident were some of the squadron that had escaped on the previous evening. They were, however, standing in towards the land.

Captain Waring, after consultation with his first lieutenant and master, determined to let them escape. He had already three hundred and forty prisoners on board, while his own crew amounted to only one hundred and ninety. Should he take another prize, he would have still further to diminish the number of the ship’s company, while that of the prisoners would be greatly increased. The French and American captains had come on deck, and were standing apart, watching the distant vessels.

“I hope these Englishmen will take one of those fellows,” observed Captain Gregory to Monsieur Saint Julien.

“Why so, my friend?” asked the latter.

“They deserve it, in the first place, and then it would be a question who gets command of this ship. We are pretty strong already, and if your people would prove staunch, we might turn the tables on our captors,” said the American.

“Comment!” exclaimed Captain Saint Julien, starting back. “You forget dat we did pledge our honour to behave peaceably, and not to interfere with the discipline of the ship. French officers are not accustomed to break their parole. You insult me by making the proposal, and I hope dat you are not in earnest.”

“Oh, no, my friend, I was only joking,” answered the American skipper, perceiving that he had gone too far.

Officers of the U.S. Navy, we may here remark, have as high a sense of honour as any English or French officer, but this ship was only a privateer, with a scratch crew, some of them renegade Englishmen, and the Captain was on a level with the lot.

The Frenchman looked at him sternly. “I will be no party to such a proceeding,” he observed.

“Oh, of course not, of course not, my friend,” said Captain Gregory, walking aside.

It being finally decided to allow the other French vessels to escape, the Foxhound’s yards were squared away, and a course shaped for Plymouth, with the two prizes in company.

Soon after noon the wind fell, and the ships made but little progress. The British crew had but a short time to sleep or rest, it being necessary to keep a number of men under arms to watch the prisoners.

The Frenchmen were placed on the lower deck, where they sat down by themselves; but the Americans mixed more freely with the English. As evening approached, however, they also drew off and congregated together. Two or three of their officers came among them.

Just before dusk Captain Gregory made his appearance, and was seen talking in low whispers to several of the men.

Among those who observed him was Bill Rayner. Bill’s wits were always sharp, and they had been still more sharpened since he came to sea by the new life he was leading. He had his eyes always about him to take in what he saw, and his ears open whenever there was anything worth hearing. It had struck him as a strange thing that so many prisoners should submit quietly to be kept in subjection by a mere handful of Englishmen. On seeing the American skipper talking to his men, he crept in unobserved among them. His ears being wide open, he overheard several words which dropped from their lips.

“Oh, oh!” he thought. “Is that the trick you’re after? You intend to take our ship, do you? You’ll not succeed if I have the power to prevent you.”

But how young Bill was to do that was the question. He had never even spoken to the boatswain or the boatswain’s mate. It seemed scarcely possible for him to venture to tell the first lieutenant or the captain; still, if the prisoners’ plot was to be defeated, he must inform them of what he had heard, and that without delay.

His first difficulty was how to get away from among the prisoners. Should they suspect him they would probably knock him on the head or strangle him, and trust to the chance of shoving him through one of the ports unobserved. This was possible in the crowded state of the ship, desperate as the act might seem.

Bill therefore had to wait till he could make his way on deck without being remarked. Pretending to drop asleep, he lay perfectly quiet for some time; then sitting up and rubbing his eyes, he staggered away forward, as if still drowsy, to make it be supposed that he was about to turn into his hammock. Finding that he was unobserved, he crept up by the fore-hatchway, where he found Dick, who was in the watch off deck.

At first he thought of consulting Dick, in whom he knew he could trust; but second thoughts, which are generally the best, made him resolve not to say anything to him, but to go at once to either the first lieutenant or the captain.

“If I go to Mr Saltwell, perhaps he will think I was dreaming, and tell me to ‘turn into my hammock and finish my dreams,’” he thought to himself. “No! I’ll go to the captain at once; perhaps the sentry will let me pass, or if not, I’ll get him to ask the captain to see me. He cannot eat me, that’s one comfort; if he thinks that I am bringing him a cock-and-bull story, he won’t punish me; and I shall at all events have done my duty.”

Bill thought this, and a good deal besides, as he made his way aft till he arrived at the door of the captain’s cabin, where the sentry was posted.

“Where are you going, boy?” asked the sentry, as Bill in his eagerness was trying to pass him.

“I want to see the captain,” said Bill.

“But does the captain want to see you?” asked the sentry.

“He has not sent for me; but he will when he hears what I have got to tell him,” replied Bill.

“You must speak to one of the lieutenants, or get the midshipman of the watch to take in your message, if he will do it,” said the sentry.

“But they may laugh at me, and not believe what I have got to say,” urged Bill. “Do let me pass,—the captain won’t blame you, I am sure of that.”

The sentry declared that it was his duty not to allow any one to pass.

While Bill was still pleading with him, the door of the inner cabin was opened, and the captain himself came out, prepared to go on deck.

“What do you want, boy?” he asked, seeing Bill.

“Please, sir, I have got something to tell you which you ought to know,” said Bill, pulling off his hat.

“Let me hear it then,” said the captain.

“Please, sir, it will take some time. You may have some questions to ask,” answered Bill.

On this the captain stepped back a few paces, out of earshot of the sentry.

“What is it, boy?” he asked; “you seem to have some matter of importance to communicate.”

Bill then told him how he came to be among the prisoners, and had heard the American captain and his men talking together, and proposing to get the Frenchmen to rise with them to overpower the British crew.

Captain Waring’s countenance showed that he felt very much disposed to disbelieve what Bill had told him, or rather, to fancy that Bill was mistaken.

“Stay there;” he said, and he went to the door of the cabin which he had allowed the American skipper to occupy.

The berth was empty! He came back and cross-questioned Bill further. Re-entering the inner cabin, he found the French captain seated at the table.

“Monsieur Saint Julien,” he said; “are you cognisant of the intention of the American captain to try and overpower my crew?”

“The proposal was made to me, I confess, but I refused to accede to it with indignation; and I did not suppose that Captain Gregory would make the attempt, or I should have informed you at once,” answered Saint Julien.

“He does intend to make it, though,” said Captain Waring, “and I depend on you and your officers to prevent your men from joining him.”

“I fear that we shall have lost our influence over our men, but we will stand by you should there be any outbreak,” said the French captain.

“I will trust you,” observed Captain Waring. “Go and speak to your officers while I take the steps necessary for our preservation.”

Captain Waring on this left the cabin, and going on deck, spoke to the first lieutenant and the midshipmen of the watch, who very speedily communicated the orders they had received to the other officers.

The lieutenant of marines quickly turned out his men, while the boatswain roused up the most trustworthy of the seamen. So quickly and silently all was done, that a strong body of officers and men well armed were collected on the quarter-deck before any of the prisoners were aware of what was going forward. They were awaiting the captain’s orders, when a loud report was heard. A thick volume of smoke ascended from below, and the next instant, with loud cries and shouts, a number of the prisoners were seen springing up the hatchway ladders.

Chapter Four.

The frigate blown up.

The Americans had been joined by a number of the Frenchmen, and some few of the worst characters of the English crew—the jail-birds chiefly, who had been won over with the idea that they would sail away to some beautiful island, of which they might take possession; and live in independence, or else rove over the ocean with freedom from all discipline.

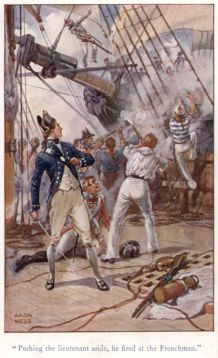

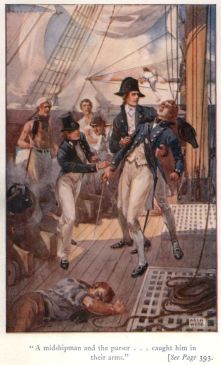

They had armed themselves with billets of wood and handspikes; and some had got hold of knives and axes, which they had secreted. They rushed on deck expecting quickly to overpower the watch.

Great was their dismay to find themselves encountered by a strong body of armed men, who seized them, or knocked them down directly they appeared.

So quickly were the first overpowered that they had no time to give the alarm to their confederates below, and thus, as fresh numbers came up, they were treated like the first. In a couple of minutes the whole of the mutineers were overpowered.

The Frenchmen who had not actually joined them cried out for mercy, declaring that they had no intention of doing so.

What might have been the case had the Americans been successful was another matter.

All those who had taken part in the outbreak having been secured, Captain Waring sent a party of marines to search for the American captain. He was quickly found, and brought on the quarter-deck.

“You have broken your word of honour; you have instigated the crew to mutiny, and I should be justified were I to run you up to the yard-arm!” said Captain Waring, sternly.

“You would have done the same,” answered the American captain, boldly. “Such acts when successful have always been applauded.”

“Not, sir, if I had given my word of honour, as you did, not to interfere with the discipline of the ship,” said Captain Waring. “You are now under arrest, and, with those who supported you, will remain in irons till we reach England.”

Captain Gregory had not a word to say for himself. The French captain, far from pleading for him, expressed his satisfaction that he had been so treated.

He and the officers who had joined him were marched off under a guard to have their irons fixed on by the armourer.

After this it became necessary to keep a strict watch on all the prisoners, and especially on the Americans, a large proportion of whom were found to be English seamen, and some of the Foxhound’s crew recognised old shipmates among them.

Captain Waring, believing that he could trust to the French captain and his officers, allowed them to remain on their parole, a circumstance which greatly aggravated the feelings of Captain Gregory.

The captain had not forgotten Bill, who, by the timely information he had given, had materially contributed to preserve the ship from capture. Bill himself did not think that he had done anything wonderful; his chief anxiety was lest the fact of his having given the information should become known. The sentinel might guess at it, but otherwise the captain alone could know anything about it. Bill, as soon as he had told his story to the captain, and found that it was credited, stole away forward among the rest of the crew on deck, where he took very good care not to say a word of what had happened; so that not till the trustworthy men received orders to be prepared for an outbreak were they aware of what was likely to occur.

He therefore fancied that his secret had been kept, and that it would never be known; he was, consequently, surprised when the following morning the ship’s corporal, touching his shoulder, told him that the captain wanted to speak to him.

Bill went aft, feeling somewhat alarmed at the thoughts of being spoken to by the captain.

On the previous evening he had been excited by being impressed with the importance of the matter he was about to communicate, but now he had time to wonder what the captain would say to him.

He met Tom and Jack by the way.

“Where are you going?” asked Tom.

Bill told him.

“I shouldn’t wish to be in your shoes,” remarked Tom. “What have you been about?”

Bill could not stop to answer, but followed his conductor to the cabin door.

The sentry, without inquiry, admitted him.

The captain, who was seated at a table in the cabin, near which the first lieutenant was standing, received him with a kind look.

“What is your name, boy?” he asked.

“William Rayner, sir,” said Bill.

“Can you read and write pretty well?”

“No great hand at either, sir,” answered Bill. “Mother taught me when I was a little chap, but I have not had much chance of learning since then.”

“Should you like to improve yourself?” asked the captain.

“Yes, sir; but I have not books, or paper, or pens.”

“We’ll see about that,” said the captain. “The information you gave me last night was of the greatest importance, and I wish to find some means of rewarding you. When we reach England, I will make known your conduct to the proper authorities, and I should like to communicate with your parents.”

“Please, sir, I have no parents; they are both dead, and I have no relations that I know of; but I am much obliged to you, sir,” answered Bill, who kept wondering what the captain was driving at.

“Well, my boy, I will keep an eye on you,” said the captain. “Mr Saltwell, you will see what is best to be done with William Rayner,” he added, turning to the first lieutenant. “If you wish to learn to read and write, you can come and get instruction every day from my clerk, Mr Finch. I will give him directions to teach you; but remember you are not forced to do it.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Bill. “I should like to learn very much.”

After a few more words, the captain dismissed Bill, who felt greatly relieved when the formidable interview was over.

As he wisely kept secret the fact of his having given information of the mutiny, his messmates wondered what could have induced the captain so suddenly to take an interest in him.

Every day he went aft for his lesson, and Mr Finch, who was a good-natured young man, was very kind. Bill, who was remarkably quick, made great progress, and his instructor was much pleased with him.

He could soon read easily, and Mr Finch, by the captain’s orders, lent him several books.

The master’s assistant, calling him one day, told him that he had received orders from the captain to teach him navigation, and, greatly to his surprise, put a quadrant into his hands, and showed him how to use it.

Bill all this time had not an inkling of what the captain intended for him. It never occurred to him that the captain could have perceived any merits or qualifications sufficient to raise him out of his present position, but he was content to do his duty where he was.

Tom felt somewhat jealous of the favour Bill was receiving, though he pretended to pity him for having to go and learn lessons every day. Tom, indeed, knew a good deal more than Bill, as he had been at school, and could read very well, though he could not boast much of his writing.

Jack could neither read nor write, and had no great ambition to learn; but he was glad, as Bill seemed to like it, that he had the chance of picking up knowledge.

“Perhaps the captain intends to make you his clerk, or maybe some day you will become his coxswain,” observed Jack, whose ambition soared no higher. “I should like to be that, but I suppose that it is not necessary to be able to read, or write, or sum. I never could make any hand at those things, but you seem up to them, and so it’s all right that you should learn.”

Notwithstanding the mark of distinction Bill was receiving, the three young messmates remained very good friends.

Bill, however, found himself much better off than he had before been. That the captain patronised him was soon known to all, and few ventured to lay a rope’s-end on his back, as formerly, while he was well treated in other respects.

Bill kept his eyes open and his wits awake on all occasions, and thus rapidly picked up a good knowledge of seamanship, such as few boys of his age who had been so short a time at sea possessed.

The Foxhound and her prizes were slowly making their way to England. No enemy appeared to rob her of them, though they were detained by contrary winds for some time in the chops of the Channel.

At length the wind shifted a point or two, and they were able to get some way up it. The weather, however, became cloudy and dark, and no observation could be taken.

It was a trying time, for the provisions and water, in consequence of the number of souls on board, had run short.

The captain was doubly anxious to get into port; still, do all he could, but little progress was made, till one night the wind again shifted and the sky cleared. The master was aware that the ship was farther over to the French coast than was desirable, but her exact position it was difficult to determine.

The first streaks of sunlight had appeared in the eastern sky, when the look-out shouted—

“A ship to the southward, under all sail.”

As the sun rose, his rays fell on the white canvas of the stranger, which was now seen clearly, standing towards the Foxhound.

Captain Waring made a signal to the two prizes, which were somewhat to the northward, to make all sail for Plymouth, while the Foxhound, under more moderate canvas, stood off shore.

Should the stranger prove an enemy, of which there was little doubt, Captain Waring determined to try and draw her away from the French coast, which could be dimly seen in the distance. He, at the same time, did not wish to make an enemy suppose that he was flying. Though ready enough to fight, he would rather first have got rid of his prisoners, but that could not now be done.

It was necessary, therefore, to double the sentries over them, and to make them clearly understand that, should any of them attempt in any way to interfere, they would immediately be shot.

Jack, Tom, and Bill had seen the stranger in the distance, and they guessed that they should before long be engaged in a fierce fight with her. There was no doubt that she was French. She was coming up rapidly.

The captain now ordered the ship to be cleared for action. The men went readily to their guns. They did not ask whether a big or small ship was to be their opponent, but stood prepared to fight as long as the captain and officers ordered them, hoping, at all events, to beat the enemy.

The powder-monkeys, as before, having been sent down to bring up the ammunition, took their places on their tubs. Of course they could see but little of what was going forward, but through one of the ports they at last caught sight of the enemy, which appeared to be considerably larger than the Foxhound.

“We have been and caught a Tartar,” Bill heard one of the seamen observe.

“Maybe. But whether Turk or Tartar, we’ll beat him,” answered another.

An order was passed along the decks that not a gun should be fired till the captain gave the word. The boys had not forgotten their fight a few weeks before, and had an idea that this was to turn out something like that. Then the shot of the enemy had passed between the masts and the rigging; but scarcely one had struck the hull, nor had a man been hurt, so they had begun to fancy that fighting was a very bloodless affair.

“What shall we do with the prisoners, if we take her, I wonder?” asked Tom. “We’ve got Monsieurs enough on board already.”

“I daresay the captain will know what to do with them,” responded Bill.

“We must not count our chickens before they’re hatched,” said Jack. “Howsumdever, we’ll do our best.” Jack’s remark, which was heard by some of the crew of the gun near which he was seated, caused a laugh.

“What do you call your best, Jack?” asked Ned Green.

“Sitting on my tub, and handing out the powder as you want it,” answered Jack. “What more would you have me do, I should like to know?”

“Well said, Jack,” observed Green. “We’ll work our guns as fast as we can, and you’ll hand out the powder as we want it.”

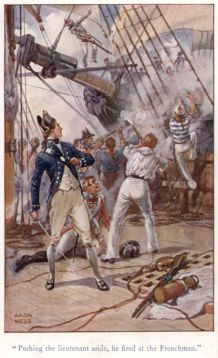

The talking was cut short by the voices of the officers ordering the men to be ready for action.

The crews of the guns laid hold of the tackles, while the captains stood with the lanyards in their hands, waiting for the word of command, and ready at a moment’s notice to fire.

The big ship got nearer and nearer. She could now be seen through the ports on the starboard side.

“Well, but she’s a whopper!” exclaimed Ned Green, “though I hope we’ll whop her, notwithstanding. Now, boys, we’ll show the Monsieurs what we can do.”

Just then came the word along the decks—

“Fire!”

And the guns on the starboard side, with a loud roar, sent forth their missiles of death.

While the crew were running them in to re-load, the enemy fired in return; their shot came crashing against the sides, some sweeping the upper deck, others making their way through the ports.

The smoke from the guns curled round in thick eddies, through which objects could be but dimly seen.

The boys looked at each other. All of them were seated on their tubs, but they could see several forms stretched on the deck, some convulsively moving their limbs, others stilled in death.

This was likely to be a very different affair from the former action.

Having handed out the powder, Jack, Tom, and Bill returned to their places once more.

The Foxhound’s guns again thundered forth, and directly after there came the crashing sound of shot, rending the stout sides of the ship.

For several minutes the roar was incessant. Presently a cheer was heard from the deck.

One of the Frenchman’s masts had gone over the side; but before many minutes had elapsed, a crashing sound overhead showed that the Foxhound had been equally unfortunate.

Her foremast had been shot away by the board, carrying with it the bowsprit and maintopmast.

She was thus rendered almost unmanageable, but still her brave captain maintained the unequal contest.

The guns, as they could be brought to bear, were fired at the enemy with such effect that she was compelled to sheer off to repair damages.

On seeing this, the crew of the Foxhound gave another hearty cheer; but ere the sound had died away, down came the mainmast, followed by the mizenmast, and the frigate lay an almost helpless hulk on the water.

Captain Waring at once gave the order to clear the wreck, intending to get up jury-masts, so as to be in a condition to renew the combat should the French ship again attack them.

All hands were thus busily employed. The powder in the meantime was returned to the magazine, and the guns run in and secured.

The ship was in a critical condition.

The carpenters, before anything else could be done, had to stop the shot-holes between wind and water, through which the sea was pouring in several places.

It was possible that the prisoners might not resist the temptation, while the crew were engaged, to attempt retaking the ship.

The captain and officers redoubled their watchfulness. The crew went steadily about their work, as men who knew that their lives depended on their exertions. Even the stoutest-hearted, however, looked grave.

The weather was changing for the worse, and should the wind come from the northward, they would have a hard matter to escape being wrecked, even could they keep the ship afloat.

The enemy, too, was near at hand, and might at any moment bear down upon them, and recommence the action.

The first lieutenant, as he was coming along the deck, met Bill, who was trying to make himself useful in helping where he was wanted.

“Rayner,” said Mr Saltwell, “I want you to keep an eye on the prisoners, and report to the captain or me, should you see anything suspicious in their conduct—if they are talking together, or look as if they were waiting for a signal. I know I can trust you, my boy.”

Bill touched his hat.

“I will do my best, sir,” he answered; and he slipped down to where the prisoners were congregated.

They did not suspect that he had before informed the captain of their intended outbreak, or it would have fared but ill with him.

Whatever might have been their intentions, they seemed aware that they were carefully watched, and showed no inclination to create a disturbance.

The greatest efforts were now made to set up the jury-masts. The wind was increasing, and the sea rising every minute. The day also was drawing on, and matters were getting worse and worse; still Captain Waring and his staunch crew worked away undaunted. If they could once get up the jury-masts, a course might be steered either for the Isle of Wight or Plymouth. Sails had been got up from below; the masts were ready to raise, when there came a cry of, “The enemy is standing towards us!”

“We must beat her off, and then go to work again,” cried the captain.

A cheer was the response. The powder-magazine was again opened. The men flew to their guns, and prepared for the expected conflict.

The French ship soon began to fire, the English returning their salute with interest. The round shot, as before, whistled across the deck, killing and wounding several of the crew.

The sky became still more overcast; the lightning darted from the clouds; the thunder rattled, mocked by the roaring of the guns.

Bill saw his shipmates knocked over on every side; but, as soon as one of the crew of a gun was killed, another took his place, or the remainder worked the gun with as much rapidity as before.

The cockpit was soon full of wounded men. Though things were as bad as they could be, the captain had resolved not to yield.

The officers went about the decks encouraging the crew, assuring them that they would speedily beat off the enemy.

Every man, even the idlest, was doing his duty.

Jack, Tom, and Bill were doing theirs.

Suddenly a cry arose from below of “Fire! fire!” and the next moment thick wreaths of smoke ascended through the hatchways, increasing every instant in density.

The firemen were called away. Even at that awful moment the captain and officers maintained their calmness.

Now was the time to try what the men were made of. The greater number obeyed the orders they received. Buckets were handed up and filled with water to dash over the seat of the fire. Blankets were saturated and sent down below.

The enemy ceased firing, and endeavoured to haul off from the neighbourhood of the ill-fated ship. In spite of all the efforts made, the smoke increased, and flames came rushing up from below. Still, the crew laboured on; hope had not entirely abandoned them, when suddenly a loud roar was heard, the decks were torn up, and hundreds of men in one moment were launched into eternity.

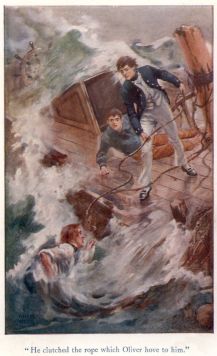

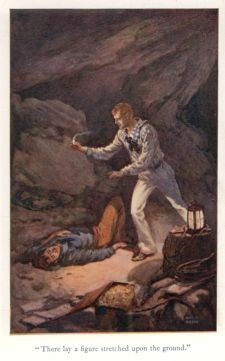

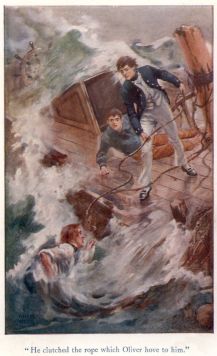

Jack, Tom, and Bill had before this made their escape to the upper deck. They had been talking together, wondering what was next to happen, when Bill lost all consciousness; but in a few moments recovering his senses, found himself in the sea, clinging to a piece of wreck.

He heard voices, but could see no one. He called to Tom and Jack, fancying that they must be near him, but no answer came.

He must have been thrown, he knew, to some distance from the ship, for he could see the burning wreck, and the wind appeared to be driving him farther and farther away from it.

The guns as they became heated went off, and he could hear the shot splashing in the water around him.

“And Jack and Tom have been lost, poor fellows!” he thought to himself. “I wish they had been sent here. There’s room enough for them on this piece of wreck.

“We might have held out till to-morrow morning, when some vessel might have seen us and picked us up.”

Curiously enough, he did not think much about himself. Though he was thankful to have been saved, he guessed truly that the greater number of his shipmates, and the unfortunate prisoners on board, must have been lost; yet he regretted Jack and Tom more than all the rest.

The flames from the burning ship cast a bright glare far and wide over the ocean, tinging the foam-topped seas.