Project Gutenberg's Footprints in the Forest, by Edward Sylvester Ellis This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Footprints in the Forest Author: Edward Sylvester Ellis Release Date: July 6, 2008 [EBook #25980] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FOOTPRINTS IN THE FOREST *** Produced by Taavi Kalju, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

CHAPTER I.—RETROSPECTIVE

CHAPTER II.—A VALUABLE ALLY

CHAPTER III.—THE CAMP OF THE STRANGERS

CHAPTER IV.—THE QUARREL

CHAPTER V.—SHAWANOE VS. PAWNEE

CHAPTER VI.—A DOUBLE FAILURE

CHAPTER VII.—A DISAPPOINTMENT

CHAPTER VIII.—THE FLIGHT OF DEERFOOT

CHAPTER IX.—THE PAWNEES ARE ASTONISHED

CHAPTER X.—SAUK AND PAWNEE

CHAPTER XI.—A REVERSAL OF SITUATION

CHAPTER XII.—INDIAN HONOR

CHAPTER XIII.—THE TWINKLE OF A CAMP-FIRE

CHAPTER XIV.—IN THE TREE-TOP

CHAPTER XV.—AN UNEXPECTED CALL

CHAPTER XVI.—A STARTLING CONCLUSION

CHAPTER XVII.—OTHER ARRIVALS

CHAPTER XVIII.—WITH THE RIVER BETWEEN

CHAPTER XIX.—JACK AND HAY-UTA

CHAPTER XX.—UNCONGENIAL NEIGHBORS

CHAPTER XXI.—JACK CARLETON MAKES A MOVE ON HIS OWN ACCOUNT

CHAPTER XXII.—A CLEW AT LAST

CHAPTER XXIII.—RECROSSING THE RIVER

CHAPTER XXIV.—A SUMMONS AND A SURRENDER

CHAPTER XXV.—LONE BEAR'S REVELATION

CHAPTER XXVI.—AN INTERESTING QUESTION

CHAPTER XXVII.—A STRANGE STORY

CHAPTER XXVIII.—A STARTLING INTERRUPTION

CHAPTER XXIX.—A FIGHT AND A RETREAT

CHAPTER XXX.—A SURPRISING DISCOVERY

CHAPTER XXXI.—A FATAL FAILURE

CHAPTER XXXII.—THE PRAYER OF HAY-UTA IS THE PRAYER OF DEERFOOT

CHAPTER XXXIII.—CONCLUSION

Famous Castlemon Books.

Alger's Renowned Books.

By C. A. Stephens.

By J. T. Trowbridge.

By Edward S. Ellis.

Those of my friends who have done me the honor of reading "Campfire and Wigwam," will need little help to recall the situation at the close of that narrative. The German lad Otto Relstaub, having lost his horse, while on the way from Kentucky to the territory of Louisiana (their destination being a part of the present State of Missouri), he and his young friend, Jack Carleton, set out to hunt for the missing animal. Naturally enough they failed: not only that, but the two fell into the hands of a band of wandering Sauk Indians, who held them prisoners.

Directly after the capture of the lads, their captors parted company, five going in one direction with Jack and the other five taking a different course with Otto. "Camp-Fire and Wigwam" gave the particulars of what befell Jack Carleton. In this story, I propose to tell all about the hunt that was made for the honest lad, who had few friends, and who had been driven from his own home by the cruelty of his parents to engage in a search which would have been laughable in its absurdity, but for the danger that marked it from the beginning.

The youth, however, had three devoted friends in Jack Carleton, his mother, and Deerfoot, the Shawanoe. But for the compassion which the good woman felt for the lad, she never would have consented that her beloved son should enter the wilderness for the purpose of bringing him home.

One fact must be borne in mind, however, in recalling the two expeditions. In the former Jack and Otto were the actors, but now the hunters were Jack and Deerfoot, and therein lay all the difference in the world. Well aware of the wonderful woodcraft of the young warrior, his courage and devotion to his friends, the parent had little if any misgivings, when she kissed her boy good-by, and saw him enter the wilderness in the company of the dusky Shawanoe.

Something like a fortnight had gone by, when Deerfoot and Jack Carleton sat near a camp-fire which had been kindled in the depths of the forest, well to the westward of the little frontier settlement of Martinsville. The air was crisp and cool, and two days had passed since any rain had fallen, so the climate could not have been more favorable.

The camp was similar to many that have been described before, and with which the reader has become familiar long ago. It was simply a small pile of blazing sticks, started close to a large tree, with a little stream of water winding just beyond. More wood was heaped near, and Jack was lolling lazily on the blanket which he had brought with him, while his friend sat on the pile of sticks opposite.

"Deerfoot, you remember I told you that while I was in the lodge of Ogallah, an Indian came in who was one of the five that had taken Otto away?"

The Shawanoe nodded his head to signify he recalled the incident.

"He made some of the queerest gestures to me, which I could no more understand than I could make out what his gibberish meant, but when I described his actions to you, you said they meant that Otto was still alive—that is, so far as the Indian knew?"

"My brother speaks the truth: such was the message of the Sauk warrior."

"They say all the red men can talk with each other by means of signs, but, without asking you to explain every word of the Sauk, I would like to hear again what it was he meant to tell me."

"He said that Otto had been given to a party of Indians, and they had started westward toward the setting sun with him."

"But why did they turn him over to the strangers?"

"Deerfoot was not there to ask the Sauk," was the reply of the young Shawanoe.

"That is true, for if you had been, you would have known all about it; but, old fellow, you can explain one thing: why do you not make your way to the Sauk village and get those warriors to give you the particulars?"

Such it would seem was the true course of the dusky youth, on whom it may be said the success or failure of the enterprise rested. He was silent a minute as though the question caused him some thought.

"It may be my brother is right, but it is a long ways to the lodges of the Sauks, and when they were reached it may be they could tell no more than Deerfoot knows."

Jack Carleton did not understand this remark.

He knew how little information he had given his friend, and it seemed idle to say that the real captors of Otto Relstaub could not tell more of him.

Strange things happen in this life. Several times during the afternoon Deerfoot stopped and glanced about him, just as Jack had seen him do when enemies were in the wood. He made no remark by way of explanation, and his friend asked him no question.

"It seems to me the Sauks can tell a good deal more than I; for instance—"

Deerfoot suddenly raised his forefinger and leaned his head forward and sideways. It was his attitude of intense attention, and he had signaled for Jack to hold his peace. The tableau lasted a full minute. Then Deerfoot looked toward his friend, and smiled and nodded, as if to say it had turned out just as he expected.

"What in the name of the mischief is the matter?" asked Jack, unable longer to repress his curiosity; "you've been acting queer all the afternoon."

"Deerfoot and his friend have been followed by some Indian warrior for many miles. He is not far away; he is now coming softly toward the camp; I have heard him often; he is near at hand."

"If he wants to make our acquaintance, there is no reason why he should feel so bashful," remarked Jack, glancing at different points in the darkening woods; "I don't see any reason why he should prowl around in that fashion."

The lad's uneasiness was increased by the fact that Deerfoot was manifestly looking over his head and into the forest behind Jack, as though the object which caused his remarks was coming from that direction.

"The Indian is not far off—he is coming this way—he will be in camp in a breath."

"And, if I stay here, he will stumble over me and perhaps break his neck," remarked Jack, who caught the rustle of leaves, and springing to his feet, faced toward the point whence the stranger was approaching.

It can not be said that the youth felt any special alarm, for he knew the sagacious Deerfoot would take care of him, but the knowledge that an armed stranger is stealing up behind a person, is calculated to make him nervous.

At the moment Jack faced about, he caught the outlines of a middle-aged warrior, who strode noiselessly from the wood and stepped into the full glare of the camp light. Without noticing Jack, he advanced to Deerfoot, who shook him by the hand, while the two spoke some words in a tongue which the lad did not understand.

But when the visitor stood revealed in the firelight, the boy looked him over and recognized him. He was the Indian who came into the hut of Ogallah, the Sauk chieftain, when Jack was a captive, and who went through the odd gesticulations, which the lad remembered well enough to repeat to Deerfoot, who, in turn, interpreted them to mean that Otto Relstaub had not been put to death, as the two youths had feared.

It was strange indeed that he should come to the camp of the lads, at the very time they were in need of such information as he could give.

While Jack identified the visitor as that personage, Deerfoot recognized him even sooner as Hay-uta, the Man-who-Runs-without-Falling. It was he who, while on a hunt for scalps, came upon the young Shawanoe and engaged him in a hand-to-hand encounter. You will recall how he was disarmed and vanquished by the younger warrior, and how the latter read to him from his Bible, and told him of the Great Spirit who dwelt beyond the stars, and whose will was contained in the little volume which was the companion of the Shawanoe. Hay-uta showed he was deeply impressed, and abruptly went away.

It will be remembered, therefore, that there were peculiar circumstances which caused the two red men to feel friendly toward each other and which led them to spend several minutes talking with such earnestness that neither seemed aware that another party was near. Jack did not object, but busied himself in studying the two aborigines.

Hay-uta has been already described as a middle-aged warrior. He was strong, iron-limbed and daring, but was not to be compared as respects grace, dignity and manly beauty to Deerfoot. What specially attracted Jack's attention was the rifle which he idly held with one hand while talking, the stock resting on the ground. It was the finest weapon the lad had ever seen—that is so far as appearance went. The stock was ornamented with silver, and the make and finish were as complete as was ever seen in those days. It was a rifle that would awaken admiration anywhere.

"I shouldn't wonder if he shot the owner so as to get it," thought the lad.

But therein he did the Sauk injustice. The savage gave all the furs and peltries that he was able to take during an entire winter to a white trader from St. Louis, who with a similar weapon bought enough more supplies to load him and his animal for their return trip to that frontier post.

While Hay-uta and Deerfoot talked, they smiled, nodded and gesticulated continually. Of course the watcher could not guess what they were talking about, until he noticed that Hay-uta was making the same motions that he saw him use in the lodge of Ogallah, adding, however, several variations which the youth was unable to recall.

"By George!" muttered Jack, "they're talking about Otto; now I shall learn something of him."

When the conversation had lasted some minutes, the talkers appeared to become aware that a third party was near. A remark of Deerfoot caused Hay-uta to turn and look at the young man, as though uncertain that he had ever met him before.

"Hay-uta has traveled a long ways since my brother saw him," said Deerfoot, who did not deem it worth while to explain why it was he had made such a journey: "he followed us a good while before he knew I was his friend; then he came to the camp that he might talk with me."

Hay-uta, though unable to understand these words, seemed to catch their meaning from the tone of Deerfoot, for they were scarcely spoken, when he extended his hand to Jack, who, of course, pressed it warmly and looked the welcome which he could not put into words that would be understood.

These ceremonies over, all three sat on the ground, Hay-uta lit his pipe and the singular conversation continued, Deerfoot interpreting to his friend, when he had any thing to tell that would interest him.

"What does he know about Otto?" asked Jack.

"He cannot tell much: the warriors who made him prisoner walked slowly till the next morning; they took another path to their lodges; on the road they met some strange Indians, and they sold our brother to them for two blankets, some wampum, a knife and three strings of beads."

"How many Indians were there in the party that bought Otto"

Deerfoot conferred with Hay-uta before answering.

"Four: they were large, strong and brave, and they wanted our brother; so he was sold, as the young man was sold by his brothers and taken into a far land, and afterward became the great chief of the country, and the friend of his brethren and aged father."

Astonished as was Jack Carleton to hear these tidings, he was more astonished to note that the young Shawanoe was comparing the experience of Otto Relstaub with that of the touching narrative told in the Old Testament of Joseph and his brethren.

"But who were the Indians?" asked Jack Carleton.

Deerfoot shook his head, smiled in his faint, shadowy way and pointed to the west.

"They came from the land of the setting sun; Hay-uta knows not their totem; he never saw any of their tribe before and knows not whither they went."

"I should, think that even an Indian would have enough curiosity to ask some questions."

"He did ask the questions," replied Deerfoot, "but the strange warriors did not give him answer."

"Then all that we know is that Otto was turned over to four red men who went westward with him."

Deerfoot nodded his head to signify that such was the fact, and then he continued his conversation with Hay-uta.

Jack Carleton recalled that when he and Deerfoot were guessing the fate of Otto, the suggestion was made that probably such had been the experience of the poor fellow. He had been bartered to a party of red men, who had gone westward with him, and beyond that important fact nothing whatever was known.

My reader will remember also that I spoke in "Campfire and Wigwam," of the strange Indians who were sometimes met by the hunters and trappers, and well as by the red men themselves. They were dusky explorers, as they may be termed, who like Columbus of the olden time, had the daring to pass beyond the boundaries of their own land, and grope through strange countries they had never seen.

The four warriors had come from some point to the west, and Hay-uta said they could not speak a word which the Sauks understood, nor could the Sauks utter any thing that was clear to them. But the sign-language never fails, and had the strangers chosen, they could have given a great deal of information to the Sauks.

A little reflection will show how limitless was the field of speculation that was opened by this news. Beyond the bare fact, as I have said, that the custodians of Otto Relstaub came from and went toward the west, little, if any thing, was known. Their hunting grounds may have been not far away on the confines of the present state of Kansas or the Indian Nation, or traversing those hundreds of miles of territory, they may have built their tepees around the headwaters of the Arkansas, in Colorado (as now called), New Mexico or the Llano Estacado of Texas. It was not to be supposed that they had come from any point beyond, since that would have required the passage of the Rocky Mountains—a feat doubtless often performed by red men, before the American Pathfinder led his little band across that formidable barrier, but the theory that Otto's new masters traveled from beyond, was too unreasonable to be accepted.

Yet from the little camp where the three persons were lounging, it was more than half a thousand miles to the Rocky Mountains, while the territory stretched far to the north and south, so that an army might lose itself beyond recovery in the vast wilderness.

The task, therefore, which faced them at the beginning was to learn whither the four warriors had gone with the hapless Otto.

It need not be said that none understood this necessity better than Deerfoot himself. Consequently he drew from Hay-uta, the Sauk, every particle of knowledge which he possessed; that, however, amounted to little more than has already been told. But that which the Shawanoe sought was a full account of their dress, their looks, arms and accouterments—such an account being more important to the young warrior than would be supposed.

The information he gained may be summed up: the strangers were taller, more powerful and better formed than Sauks. Each carried a rifle, tomahawk and knife as his weapons; they had blankets, and their clothing, while nearly the same as that of the Sauks, was of a darker and more sober color. They had no beads or ornaments; their leggings, moccasins, and the fringe of their hunting shirts, were less gaudy in color than those of the other party. Their moccasins were well worn, from which it was fair to infer they had traveled a long distance.

Hay-uta stated another fact which should be known: when the two parties discovered each other, the strangers showed a desire to engage in a fight, not that there was any special cause for so doing, but as may be said, on general principles. Though the Sauks were five to their four, they were afraid of the strangers, and they opened the negotiations for the transfer of Otto, with a view of diverting hostile intentions. The Sauks had the reputation of being brave and warlike, but they did not feel safe until many miles of trackless woods lay between them and the strangers.

So much, therefore, was known, and surely it was little enough. Hay-uta added the remark that as nearly as he could tell, Deerfoot and Jack were close to the very path which the strangers had taken on their way home. It might be they were on the trail itself, if such a thing be deemed possible, where no footprints in the forest existed, for since the passage of the four dusky aliens and their prisoner, the wilderness had been swept by storms which had not left the slightest trace on the leaves that could be followed, and, though our friends might be stepping in their very tracks, it was hardly possible that the lynx eyes of the young warrior could detect it.

When Deerfoot and Hay-uta had talked awhile longer, the former turned to Jack and amazed him by the remark:

"Hay-uta will go with us to give what help he can to find our brother who is lost."

The news was as pleasant as it was surprising. It did seem singular that the one who had helped take Otto Relstaub prisoner, and then sold him to strangers, should now offer to do what he could to bring back the lad to his friends. He could not fail to be a valuable ally, for, though vanquished by Deerfoot, he ranked among the best warriors of his people.

"I wonder what led him to volunteer?" said Jack.

"Deerfoot asked him, and he was kind enough to do so."

"That's because you overcame him."

The young Shawanoe had given a short account of his extraordinary meeting with Hay-uta, when the older warrior tried to take his life, but Jack knew nothing more than the main incident. He had not been told of the aboriginal sermon which Deerfoot delivered on that "auspicious occasion".

It was only natural that the Sauk should feel a strong admiration for the remarkable youth, but the Word which Deerfoot expounded to him had far more to do with his seeking the companionship of the Shawanoe.

The latter made no answer to the remark of Jack, but turning toward Hay-uta continued the conversation which had been broken several times. Young Carleton, believing there was nothing for him to do, spread his blanket near the fire, and, lying down, so as to infold himself from head to feet, was not long in sinking into slumber.

Ordinarily his rest would not have been broken, for his confidence in Deerfoot was so strong, that he felt fully as safe as if lying at home in his own bed, but, from some slight cause, he gradually regained his senses, until he recalled where he was. He was lying with his back to the blaze, but the reflection on the leaves in front, showed the fire was burning briskly. He heard too, the low murmur of a voice, which he knew belonged to Deerfoot.

"What mischief can be going on?" he asked himself, silently turning his head, so that he could look across to his friend.

The scene was one which could never be forgotten. Deerfoot was lying or rather reclining on one side, the upper part of his body resting on his elbow, so that his shoulders and head were several inches above the ground. In the hand of the arm which thus supported him, was held his little Bible, the light from the camp-fire falling on the page, from which he was reading in his low, musical voice that is he was translating the English into the Sauk tongue, seeking to put the words in such shape that the listener could understand them. It would be hard to imagine a more difficult task.

Between Deerfoot and Jack was stretched the Sauk, his posture such that his features were in sight. He lay on his face, his arms half folded under his chest, so that his shoulders were also held clear of the ground. His dark eyes were fixed upon the countenance of the Shawanoe youth, with a rapt expression that made him unconscious of every thing else. Into that heart was penetrating the partial light of a mystery which mortal man has never fully solved; he was learning the great lesson beside which all others sink into insignificance.

Jack Carleton moved as softly as he could, so as to view the picture without bodily discomfort. Deerfoot glanced at him, without checking himself, but Hay-uta heard him not. Watchful and vigilant as he was, an enemy might have stolen forward and driven his tomahawk through his brain, without any thought on his part of his peril.

"I wish I could understand what Deerfoot is saying," was the thought of Jack, whose eyes filled at the touching sight.

"A full-blooded Indian is urging the Christian religion on another Indian. Even I, who have a praying mother, have been reproved by him, and with good cause too."

By and by the senses of the young Kentuckian left him, and again he slept. This time he did not open his eyes until broad daylight.

The expedition on which Jack Carleton entered with his two companions promised to be similar in many respects to those which have been already described. It looked indeed as if it would be more dull, and, for a while, such was the fact, but it was not long before matters took a turn as extraordinary as unexpected, and which quickly led the Kentuckian to conclude that it was, after all, the most eventful enterprise of his life.

For nearly three days the westward journey was without incident which need be given in detail. They swam several streams of water, climbed and descended elevations and shot such game as they required. The weapon of Hay-uta proved to be fully as excellent as it looked. Though its flintlock and single muzzle-loading barrel would have made a sorry show in the presence of our improved modern weapons, yet it was capable of splendid execution. Jack Carleton was a fine marksman, but in a friendly contest in which the three engaged, the Sauk beat him almost every time. That this was due to the superiority of his gun was proven by the fact that when they exchanged rifles, the young Kentuckian never failed to beat the other, and the beauty of the whole proceeding was that when Deerfoot took the handsome weapon, he vanquished both; in fact he did it with the gun belonging to Jack Carleton.

Though the young Shawanoe clung to his bow, it was clear to his companions that he admired the new piece. He turned it over and examined every part, as though it possessed a special attraction.

"Deerfoot," said Jack, pinching his arm, "you could beat William Tell himself, if he were living, with the bow, but what's the use of talking? It can't compare with the rifle and you know it. Just because a gun of yours once flashed in the pan, you threw it away and took up the bow again, but it was a mistake, all the same."

"One of these days Deerfoot may use the rifle," he answered, as if talking to himself, "but not yet—not yet."

Little did he suspect how close he was to the crisis which would lead him to a decision on that question.

Toward the close of the three days referred to, the trio were in what is to-day the southwestern corner of Missouri. Had the time been a hundred years later, they would have had to go but a short distance to cross the border line into Kansas.

A remarkable feature of their journey to that point, was the fact that, while making the distance, they had not seen a single person besides themselves. Not once, when they climbed a tree or elevation and carefully scanned the country, did they catch sight of the smoke of a solitary camp-fire creeping upward toward the blue sky. They heard the crack of no gun beside their own, and the keen eyes which glanced to the right and left, as they trod the endless wilderness, failed to detect the figure of the stealthily moving warrior.

This was singular, for there were plenty of Indians at that day west of the Mississippi, and it would be hard to find a section through which such a long journey could be made without coming upon red men. But at the end of the three days, our friends could not complain that there was any lack of dusky strangers.

It was near the middle of the afternoon, when finding themselves in a dense portion of the wood, on a considerable elevation, they decided to "take another observation". To Jack Carleton it looked as if they were engaged on a hopeless errand, and, but for his unbounded faith in Deerfoot, he would have turned back long before in despair; it would be more proper indeed to say, that he never would have entered alone on such an enterprise.

There was no need for the three to climb a tree, so two stood on the ground while Deerfoot made his way among the limbs with the nimbleness of a monkey.

He went to the very top, and balancing himself on the swaying limb carefully parted the branches before his face. His penetrating glance was rewarded by a sight which caused an amazed "hooh!" to fall from his lips.

A little ways to the westward flowed a rapid stream, a hundred yards wide. The other shore, for a rod or two, was bare of trees and vegetation, except some stunted grass, and in this open space was encamped a party of Indians. The sentinel in the tree counted eleven, and suspected there were others who just then were not in sight. Though it lacked several hours of darkness and the air was pleasant, they had started a fire, big enough to warm a large space. Some of them seemed to have been fishing in the stream, for they had broiled a number of fish on the coals, and the nostrils of the young Shawanoe detected their appetizing odor.

Under ordinary circumstances there would have been nothing specially interesting in the group, but Deerfoot had studied them but a minute or two when he became convinced that they belonged to the same tribe which held Otto Relstaub a prisoner. Their dress, looks, and general appearance answered the description given by Hay-uta.

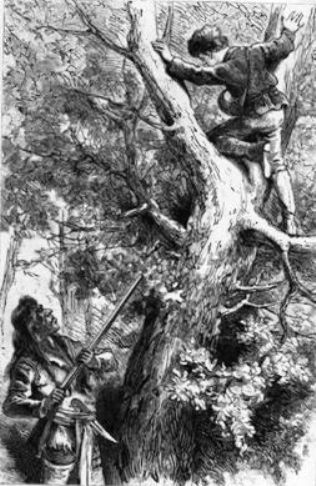

The heart of the youth beat faster over the thought that probably the four warriors whom he was seeking to follow were among them, and the fate of the German lad was about to be solved. He glanced down the trunk of the tree, and saw Jack Carleton and the Sauk standing on the ground and looking up at him, as though they suspected from his manner that some important discovery had been made. Without speaking, Deerfoot beckoned to the warrior to join him. The next instant the fellow was climbing among the limbs with such vigor that Deerfoot felt the jar at the very top.

Their combined weight was too great for such an elevation, and the younger perched himself somewhat lower, so as to give Hay-uta the advantage. A few words made known what Deerfoot had seen and that he wished the elder to answer the questions which the Shawanoe had asked himself.

Hay-uta was as guarded in his actions as Deerfoot could have been. He spent several minutes in a study of the group on the other side of the stream. Had he and the Shawanoe suspected they were so close to a camp of red men, neither would have climbed the tree, for little, if any thing, was to be gained by doing so; the strangers could have been scrutinized from the ground as well as from the elevation. It was a noteworthy fact that two such skillful woodmen as Hay-uta and Deerfoot should approach so close to another party without discovering it.

While Hay-uta was inspecting the warriors, Deerfoot quietly awaited him on a limb some ten feet below, and Jack Carleton, peering aloft from the ground until his neck ached, wondered what it all meant.

The Sauk softly withdrew the hand extended in front of his face, and the leaves came together with scarcely a rustle. With several long reaches of his arms and legs, he placed himself beside his friend below and told what he had learned. The two of course talked in the Indian tongue and I give a liberal translation:

"What does my brother know?" asked Deerfoot.

"They belong to the tribe who took the pale-face; Hay-uta knows not their name, but their looks show it."

"Then their village can not be far away."

"We must learn that of a surety for ourselves; two warriors among them are the same that gave us the wampum and blankets for the pale-face boy."

"Does my brother make no error?" asked Deerfoot, surprised to be told they were so close upon the heels of a couple of the very red men whom they scarcely hoped to find.

But the suspicion that such was the fact caused the Sauk to keep up his scrutiny until no doubt was left. He assured Deerfoot of the truth, adding that the taller was the one who handed over the wampum, and who showed such a willingness to draw the Sauks into a fight without waiting for provocation.

This was news of moment and raised several questions which the friends discussed while perched in the tree. If two of the original warriors were present, where were the others? Was it not likely they were out of sight only for the time being? It seemed probable that the four while journeying toward their own hunting grounds, had joined a company of friends, with whom they were making the rest of the trip.

Then followed the question, What of Otto Relstaub? Varied as might be the answers to the question, all the probabilities pointed to his death, and that, too, in the most painful manner; but it was idle to grope in the field of conjecture. It was for the friends to decide on the means of learning the truth.

In the hope of getting more knowledge, Deerfoot again climbed to the highest point, and studied the group on the other side of the stream; but was disappointed, and he and Hay-uta made their way to the ground, where Jack Carleton was told all.

The eyes of the young Kentuckian expanded, and, when the story was finished, he exclaimed in a guarded voice:

"They've got Otto—of course they have."

The expression of the Shawanoe's face showed he was not sure of the meaning of his friend, who added:

"The whole four that had charge of him are with those fellows, and, if Otto isn't there also we may as well give up and go back, for he is no longer alive."

Deerfoot made no answer, but Jack was sure he shared the fear with him.

A discussion of the situation and the difficulties before them, led the two warriors to decide on a curious line of action.

It was agreed that one should cross boldly over and mingle with the strangers, while the other should reconnoiter the camp and learn what he could, without allowing himself to be seen.

It would be supposed that, inasmuch as Hay-uta was acquainted with two of the Indians, and had parted from them on friendly terms, he would be selected to enter camp, while Deerfoot's matchless woodcraft would lead to his selection to work outside; but these situations were reversed.

Since the strangers had journeyed far to the eastward into the hunting grounds of the Sauks and Osages (probably to the very shore of the great Mississippi), it followed that no surprise should be felt by them to find that some equally inquiring red man had traveled toward the Rocky Mountains, with a view of seeing the strange land and its people. It was the intention of the young Shawanoe to assume such a part. Should any mishap befall Hay-uta, he would give out that he was engaged on a similar mission, and not knowing he was near friends, he was reconnoitring the party from a safer distance.

There were several reasons for this reversal of duties, as they may be called, but it is necessary to give only one or two. The appearance of Hay-uta among them most likely would raise suspicion that it bore some relation to the captive Otto. The red men, therefore, would be put upon their guard and the difficulty of securing him—if alive—greatly increased.

But the strongest reason was that Deerfoot would be sure to do better when brought in contact with the Indians. He was greatly the superior of the Sauk in mental gifts, and, with his remarkable power of reading sign language, would be sure to extract knowledge that was beyond the reach of Hay-uta.

Having decided on the course they were to follow, no time was lost in talking over the plan agreed upon. Jack Carleton was informed of the particulars by Deerfoot.

"I suppose it's the best thing to be done, though my opinion don't amount to much in this crowd. What am I to do?"

"My brother may sleep," said the Shawanoe, with that slight approach to humor which he sometimes showed.

"Yes; I would do a great deal of sleeping; but go ahead and I'll be on the lookout for you. I don't suppose you can tell when you are likely to get back?"

Deerfoot shook his head, but intimated that he hoped to learn all that he sought to know before the coming night should end.

A few minutes previous to this, Hay-uta had walked down the stream, keeping so far back that he could not be seen by any one on the other side. The Shawanoe took the opposite direction, the purpose of each being to act independently, and, in case circumstances brought them together in the presence of the aliens, the agreement was that Sauk and Shawanoe should comport themselves as though they had never met before.

When the time should come for the scouts, as they may be called, to return to the shore from which they started, they would have no trouble in finding Jack Carleton, with whom it was easy to communicate by means of signals. The most trying task was that of the young Kentuckian himself, who was left without any employment for mind or body.

Deerfoot walked several hundred yards up stream until he had passed a bend, where he swam across. He kept his bow so far above surface that the string was not wetted.

When he had surveyed himself, as best he could, he walked in the direction of the camp of the hostiles, as he more than suspected they should be classed. Had any one noticed him just then, he would have observed that the Shawanoe walked with a limp, as though suffering from some injury.

The readers of "Ned in the Block House," will recall that Deerfoot once saved his life by feigning lameness, and the youth saw nothing to lose and possibly much to gain by such strategy in the enterprise on which he was engaged.

Deerfoot was by no means free from misgivings when he limped from the woods, and, crossing the narrow space that lined the stream, advanced to the camp-fire around which the warriors were lounging.

Their appearance showed they were doughty fighters, and what Hay-uta had told proved the same thing. But the Shawanoe had no fear that they would rush upon and overwhelm him, and he had been in too many perilous situations to hesitate before any duty.

The Indians turned their heads and surveyed him as he walked unevenly forward, holding his bow in one hand, and making signs of comity with the other. They showed no surprise, for such was not their custom; but stoical and guarded as they were, Deerfoot could see they felt considerable curiosity, and the fact that he carried a bow instead of a gun must have struck them as singular, for he came from the East, where the white men had their settlements, and such weapons were easily obtained. These strange Indians had firearms, though beyond them in the far West were thousands who had never seen a pale-face.

Deerfoot's friendly salutations were answered in the same spirit, and he shook hands with each of the eleven warriors, who seemed accustomed to the civilized fashion. He seated himself a short distance from the fire, so as to form one of the dozen which encircled it. No food was offered the visitor, but when one of the strangers handed him his long-stemmed pipe, Deerfoot accepted and indulged in several whiffs from the red clay bowl.

The two warriors whom Hay-uta had pointed out as members of the party that had bought Otto Relstaub from the Sauks, were objects of much interest to the youth. They could not have observed it, but he scanned them closely, and when he sat down, managed to place himself between them—one being on the right, and the other on the left.

Thus far, hosts and guest had spoken only by signs, but a surprise came to Deerfoot when the warrior on his right addressed him in language which he understood.

"My brother has journeyed far to visit the hunting grounds of his brothers, the Pawnees."

The words of the warrior made known the fact that the party belonged to the Pawnee tribe, but the amazing feature of his remark was that it was made in Deerfoot's own tongue—the Shawanoe. The youth turned like a flash the instant the first word fell upon his ear. He knew well enough that no one around him belonged to that tribe, but well might he wonder where this savage had gained his knowledge of the language of the warlike people on the other side of the Mississippi.

"My brother speaks with the Shawanoe tongue," said Deerfoot, with no effort to hide his astonishment.

"When Lone Bear was a child," said the other, as if willing to clear up the mystery, "he was taken across the great river into the hunting grounds of the Shawanoes; he went with a party of Pawnee hunters, but the Shawanoes killed them and took young Lone Bear to their lodges."

"The Shawanoes are brave," remarked Deerfoot, his eyes kindling with natural pride.

"Lone Bear staid many moons in the lodges of the Shawanoes, but one night he rose from his sleep, slew the warrior and his squaw, and made haste toward the great river; he swam across and hunted for many suns till he found his people."

If this statement was fact, it told a striking story, but Deerfoot doubted its truth. The reason was that, judging from the age of the warrior, the exploit must have taken place when Deerfoot was very young, if not before he was born. The capture of a Pawnee youth and his escape in the manner named, formed an episode so interesting that it would have been spoken of many times during the early boyhood of Deerfoot, who ought to have heard of it, but he was sure that this was the first time the story had fallen on his ears. Deerfoot's sagacity told him that Lone Bear, as he called himself, was the only Pawnee who understood a word of their conversation; that much was evident to the eye. It might be, too, that there was a good deal of truth in the words of the warrior. At any rate, it was easy to test him.

"Did Lone Bear dwell with Allomaug?"

"Allomaug was a brave chief; he was the father of my brother Deerfoot, who is fleeter of foot than the wild buck."

That settled it. The reader will remember that Allomaug was the parent of the youth, and that he was a noted sachem among the Shawanoes. Lone Bear had told such a straight story that Deerfoot was convinced that he must have dwelt at one time among his people.

All this was supplemented by the fact that Deerfoot himself was recognized and addressed by the name he had received from the white people. The young Shawanoe half expected the other to make some reference to the youth's escape from Waughtauk and his revengeful warriors, but Lone Bear had no knowledge of that episode, which took place long after his flight from the tribe. Deerfoot was puzzled to know by what means the warrior identified him, when he was certain he had never seen Lone Bear until he surveyed him a short time before from the tree-top.

Deerfoot noticed that during their conversation, the others seemed to listen with as much interest as the American Indians ever allow themselves to show, and Lone Bear, now and then, turned and addressed them in their own tongue. When he did so, he spoke to the whole group and every word was strange to Deerfoot. While the latter could understand a number of dialects used by the tribes west as well as east of the Mississippi, he knew nothing of that of the Pawnees.

"Why does Deerfoot wander so far from his hunting grounds?" asked Lone Bear.

"Deerfoot has not wandered as far as the Pawnees," was the truthful reply of the Shawanoe. "He once lived beyond the great river, but he lives not there now."

The Pawnee looked as though he suspected Deerfoot was telling him fiction, but he was too shrewd to express any such thought.

"Where are the companions of my brother?" was the pointed question of Lone Bear.

"Deerfoot is alone and his companion is the Great Spirit."

The reader will observe that the reply of the Shawanoe partook of the nature of a falsehood, inasmuch as it was accepted by Lone Bear (and such was Deerfoot's purpose), as a declaration that he had traveled the whole distance alone. Enough has been told to show the extreme conscientiousness of the young Shawanoe, and no danger could lead him to recoil from duty. He had imperiled himself many a time from that very motive, but he believed it right to do his best to deceive Lone Bear. In fact, his visit was of itself a piece of deception.

"Why does Deerfoot come to the camp of the Pawnees?" continued Lone Bear, as though his guest was on the witness stand.

"Not many suns ago the Sauk warriors made captives of two pale-faced youths; one of them has come back to his people, but the other has not. He was a friend of Deerfoot; he went among the Sauks, but his friend was not there; he was told that he had been bartered for wampum and blankets and beads to the Pawnees. Can Lone Bear tell Deerfoot of his friend?"

This was coming to the point at once, but it was the wiser course. Deerfoot saw that any other statement he might make would be doubted, as most probably was the explanation itself. He looked into the face of Lone Bear, so as to study his expression, while answering the question.

"The words of my brother sound strange to the ears of Lone Bear; he has not seen his pale-faced friend."

"Has not he seen him?" immediately asked Deerfoot, pointing to the Pawnee on the other side.

Lone Bear exchanged words for two or three minutes with the latter, and then replied to the visitor.

"Eagle-of-the-Rocks has not seen the pale-face friend of my brother; he and Lone Bear have staid with their Pawnee brothers; they have met no pale-faces in many moons."

Here was a direct contradiction of what Hay-uta had told. It might seem that the Sauk had mistaken the identity of Lone Bear and Eagle-of-the-Rocks, and had there been but one of them in question, it was possible; but Deerfoot was satisfied that no such error had been made. Hay-uta was positive respecting both, and he could not have committed a double error.

Furthermore, the study of the Pawnee's face convinced Deerfoot that Lone Bear was lying to him, though to ordinary eyes the expression of the warrior's face was like that of stone.

Why this falsehood should have been used was beyond the power of the Shawanoe to guess. The band was so far from the settlements that they could feel no fear from white men. Nevertheless, Deerfoot was sure that, had Lone Bear chosen, he could have told every thing necessary to know about Otto Relstaub.

Two answers to the query presented themselves: the poor lad had either been slain or he had been turned over to the custody of still another party of Indians. As for escape, that was out of the question.

The probability that the Pawnees had put Otto to death occurred to Deerfoot more than once, and while seated on the ground, he had looked for signs that might show what had been done. There were several scalps dangling at the girdles of the warriors, but the hair of each was long, black and wiry, showing that it had been torn from the crown of one of their own race. The yellow tresses of the German lad would have been noticed at once by Deerfoot.

The latter was angered by the course of Lone Bear, who had told an untruth, without, so far as Deerfoot could see, any proper motive. So sure was the youth on this point, that he did not hesitate to tell the Indian his belief.

"My brother, Lone Bear, has spoken, but with a double tongue. He and Eagle-of-the-Rocks have seen my pale-faced friend; they gave the beads and wampum for him; Deerfoot knows it; Deerfoot has spoken."

Lone Bear, like all his race and the most of ours, was one of those who looked upon the charge of falsehood (especially if true) as a deadly insult. His dull, broad face seemed to crimson beneath its paint, and turning partly toward the daring youth, he grasped the handle of his knife.

"Dog of a Shawanoe! Who bade you come to the camp of the Pawnees? Do you think we are squaws who are ill, that we will let a dog bark at our heels without kicking him from our path?"

Lone Bear talked louder and faster with each word, until when the last passed his lips, he was in a passion. He had faced clear round, so that he glowered upon the youth. He now rose to his feet and Deerfoot, seeing that trouble was at hand, did the same. As he came up, he took care to limp painfully and to stand as though unable to bear any part of his body's weight on the injured leg.

"Lone Bear is as brave as the fawn that runs to its mother, when it hears the cry of the hound; he is in the camp of his friends and it makes him brave; but if he stood alone before Deerfoot, then would his heart tremble and he would ask Deerfoot to spare him!"

No more exasperating language could be framed than that which was uttered by the young Shawanoe. He meant that it should fire Lone Bear and he succeeded.

Why it was Deerfoot sought a quarrel with the Pawnee can not be made fully clear. I incline to believe that his quick penetration detected signs among the warriors that they did not mean to let him withdraw, when he should seek to do so, and his plan was to use the quarrel as a shield to thwart their purpose. This may seem a strained explanation but let us see how it worked.

It is not impossible that the wonderful young warrior brought about the disturbance in what may be called pure wantonness; that is, his confidence in his own prowess led him to invite a contest, which scarcely any other person would dare seek.

His last words were the spark to the magazine. The knife griped by Lone Bear was snatched from his girdle, and he sprang forward, striking with lightning-like viciousness at the chest of the Shawanoe, who avoided him with half an effort.

In dodging the blow, the youth moved backward and to one side, so as to bring all the warriors in front, and to leave open his line of retreat. He had been as quick as Lone Bear to draw his weapon, but he did not counter the blow—that is to an effective extent. He struck his antagonist in the face, but only with the handle of the weapon. Perhaps a pugilist would have said that the younger "heeled" the other.

The stroke was a smart one, and delivered as it was on the nose, intensified, by its indignity, the fury of Lone Bear. He lost all self-control, as Deerfoot meant he should do.

This flurry, as may be supposed, centred the interest of the others upon the two. The quarrel started as suddenly as it sometimes does among a group of fowl, and, before it was understood, the combatants, with drawn knives were facing each other. Few sights are more entertaining to men than that of a fight. The Pawnees in an instant were on their feet, with eyes fixed on the scene.

It must be believed that every one of the eleven Pawnees was sure it was out of Deerfoot's power to elude the vengeance of Lone Bear. The only fear of the ten was that he would dispatch the youth so quickly that much of their enjoyment would be lost. When they saw him strike Lone Bear in the face, a general shout of derision went up at the elder antagonist, for permitting such an outrage. This did not add to the good temper of Lone Bear, who compressed his lips, while his eyes seemed to shoot lightning, as he bounded at Deerfoot, intending to crush him to the earth and to stamp life from him.

But even though the youth seemed to be lame, he leaped backward and again escaped him. Lone Bear dashed forward, to force him down, but Deerfoot kept limping away just fast enough to continue beyond the reach of his enemy.

"Lone Bear runs like the fowl that has but one leg," was the odd remark of Deerfoot, who pointed the finger of his left hand at the other's face by way of tantalizing him.

But the fierce Pawnee was now pursuing so swiftly that Deerfoot had to whirl about and run with his face from him. He still limped, though had any one studied his gait, the trick would have been detected; but the sight of Lone Bear chasing a lame youth and failing to overtake him, did not calm his rage.

The warrior, however, was fleet, and marvellous as was the speed of the young Shawanoe, he was compelled to put forth considerable exertion to keep beyond his reach. His course took him quite close to the edge of the wood, along which he ran, so that, should it become necessary, he could leap among the trees. He watched his pursuer over his shoulder, to prevent his coming too close. His plan was to keep just beyond his reach and tempt him to the utmost effort.

Faster and faster went the fugitive, while the pursuer desperately put forth every effort, maddened beyond expression that the outstretched hand failed only by a few inches to grasp the flying Deerfoot. The spectators were amused to the last degree. Expecting quite a chase, they ran forward, as persons along shore follow a boat race, so as not to lose a phase of the struggle.

In the depths of his wrath, Lone Bear regained something of his self-command, and called to mind the stories he had heard of the fleetness of the young Shawanoe. That, with the fact that there was no longer the least halt in his gait, told the disadvantage in which the pursuer was placed.

If he could not reach the Shawanoe with his knife, he could with his tomahawk or his rifle. Hastily thrusting back the knife, he whipped out his tomahawk and raising it over his shoulder, hurled it with might and main at the crown surmounted by the stained eagle feathers and streaming black hair. At that moment, pursuer and fugitive were scarcely ten feet apart.

But Deerfoot knew what was coming, and the instant the missile left the hand of Lone Bear, he dropped flat on his side, as if smitten by a thunderbolt. The shouting Pawnees, who were some distance behind, supposed his skull had been cloven by the fiercely-driven tomahawk, but it was not so.

Lone Bear did not see the trick of Deerfoot in time to escape its purpose. The fall was so sudden, that before he could check himself, his moccasin struck the prostrate figure, and he sprawled headlong over him, heels in the air, and with a momentum almost violent enough to cause him to overtake the tomahawk that had sped end over end several rods in advance.

Before the Pawnee could rise, Deerfoot bounded up, sprang forward, and, placing one foot on the head of Lone Bear, leaped high in the air and spun around so as to face the party. Brandishing his bow aloft, he emitted a shout of defiance and called out:

"Why do not the Pawnees run? Is none of their warriors fleet enough to seize Deerfoot when he is lame?"

The only one of the company who could understand these questions was the slightly stunned Lone Bear, who just then was climbing to his feet; but the gestures and manner of the fugitive told the meaning of the performance.

The young Shawanoe stood still on the edge of the wood, as if to show his contempt for the Pawnees, who before Lone Bear could recover from his discomfiture, sped forward in pursuit. One of them emitted several whoops, which Deerfoot half suspected were meant as a signal, though of course he could not be sure of their meaning.

It seemed like tempting fate to stand motionless, when only a few seconds were required to bring his enemies to the spot, but Deerfoot waited till Lone Bear was erect again, when he called to him,

"The heart of Deerfoot is sad because Lone Bear can not run without falling; let him go to the lodges of the Pawnees and ask the squaws to teach him how to run."

Lone Bear made no reply, for it is safe to say he could not "do justice to his feelings". Few Indian tongues contain words that answer for expletives, which in one sense was fortunate and in another unfortunate for Lone Bear.

When several of the pursuers brought their guns to their shoulders, Deerfoot shot like an arrow among the trees and vanished. It was time to do so, for his enemies were close upon him.

Though the Pawnees had learned of the swiftness of the young Shawanoe, they had no thought of abandoning the attempt to capture him. The flying tresses would make the most tempting of scalps to dangle from the ridge-pole of the wigwam, and because he could outrun all their warriors was no proof that he could not be overcome by strategy.

When the fugitive disappeared, the same signal of which I have spoken was repeated, and the Pawnees scattered—that is to say they plunged into the wood at different points: they did not try to overhaul him by direct pursuit.

Two of the Indians declined to join in the chase, but walked toward Lone Bear, who having assumed the perpendicular again, was looking around, as if uncertain of the best course to pursue.

The American Indian, as a rule, is melancholy and doesn't enjoy innocent fun as much as he ought, but, as I have shown, there are few or none in which the element of humor is altogether wanting. The two of whom I am just now speaking, shook with laughter, as they saw Lone Bear sprawl over Deerfoot, his heels flying in air, and their mirth became so great when the young Shawanoe used his crown as a stepping stone, that they paused from weakness.

Lone Bear knew nothing of this, and when he saw them approaching, their faces were as long and grave as if on the way to attend the funeral of their dearest friend. Perhaps he expected to receive a little sympathy, but he must have felt some misgiving.

"Lone Bear runs like the wild buck," was the remark of one of the warriors, though the observation itself did not amount to much, nor could the one to whom it was addressed see why it should be made at all. He, therefore, remained silent, feeling as though he would like to rub some of the bruised portions of his body, but too dignified to do so.

"If the wolf or buffalo crosses the path of Lone Bear, he does not turn aside."

"No; he runs over him."

"Even though he be a warrior, Lone Bear goes over him, as though he were not there."

The party of the third part began to see the drift of these comments, and he glared as though debating which one to slay first.

"Lone Bear has a kind heart; it is like that of the squaw that presses her pappoose to her heart."

"He is kinder than the squaw, for he lies still and lets the Shawanoe rest his weary foot on his head."

Lone Bear glowered from one to the other, as they spoke in turn, and kept his hand on his knife at his girdle, as if to warn them they were going too far. They seemed to hold him in little fear, however, and continued their mock sympathy. One walked to where the tomahawk had lain untouched since it left the hand of the Pawnee, and, picking it up, examined it with much care.

"There is no blood on it," he remarked, as if talking to himself, but making sure he spoke loud enough for the other to hear; "we were mistaken when we thought it went through the body of the Shawanoe; the hand of Lone Bear trembles like that of an old man, and he can not drive his tomahawk into the tree which he reaches with his hand."

The black eyes of the Pawnees sparkled, and they seemed on the point several times of breaking into laughter, but managed to restrain themselves.

Still resting his hand on his knife, Lone Bear directed his first remark to the last speaker.

"Let Red Wolf keep his tongue; he talks like the pappoose."

Red Wolf, however, did not seem to be alarmed. He glanced into the face of his companion and added:

"Though Red Wolf talks like the pappoose, his heart is not so faint that he lies on the ground, that his enemy may have a soft place where he may rest his moccasin."

This, beyond question, was a severe remark, and, as the two broke again into laughter, Lone Bear was almost as angry as when he took a header over the body of the Shawanoe; but the warriors were as brave as he; without reply, he turned sullenly away, and walked toward the camp fire which he had left a short time before.

Deerfoot the Shawanoe darted among the trees and ran a hundred yards with great swiftness. He seemed to avoid the trunks and limbs with the ease of a bird when sailing through the tree tops.

Coming to a halt, he looked around. He had not followed a direct course into the woods, but turning to the right, ran parallel to the open space which bordered the stream. He knew the Pawnees would do their best, either to capture or kill him. So long as there was a chance of making him prisoner, they would do him no harm, for the pleasure of acting as they chose with such a captive was a hundred fold greater than that which could be caused by his mere death. The American Indian is as fond of enjoying the suffering of another as is his civilized brother.

The burst of speed in which the youth indulged gave him a position where it would require some searching on the part of the Pawnees to discover him; but they were at work, as speedily became evident.

A few seconds only had passed, when he caught sight of several forms flitting among the trees. While they were separated from each other by two or three rods, they were not far off, and their actions showed they had observed him at the same moment he detected them. They made no outcry, but, spreading still further apart, acted as if carrying out a plan for surrounding him.

Deerfoot was too wise to presume on his fleetness of foot, and he now broke into a loping trot which was meant to be neither greater nor less than the gait of his pursuers. Glancing back he saw they were running faster than he, whereupon he increased his speed.

Suddenly one of them discharged his gun, and a moment later another shot was heard. The first bullet sped wide, but the second clipped off a dead branch just above the head of the fugitive. There was no mistake, therefore, as to the purpose of those who fired.

It was not the first time that Deerfoot had served as a target for the rifle of an enemy, and though never wounded, his sensations were any thing but pleasant. Where a good marksman failed, a poor one was liable to succeed: for the most wonderful shots are those made by chance.

Deerfoot now ran as fast as he dared, where branches and tree trunks were so numerous. Glancing to the rear, as he continually did, he noticed that two of the Pawnees were leading in the pursuit. The thought came to him that no better time could be selected for teaching them the superiority of the bow over the rifle.

As he ran, he drew an arrow from the quiver over his shoulder and fitted it to the string. This was difficult, for the long bow caught in the obstructions around him and compelled him to slacken his pace. Then, like a flash, he leaped partly behind a tree and drew the arrow to a head.

The Pawnees must have been amazed to discover, while in full pursuit of an enemy, that he had vanished as though swallowed by some opening in the earth; for the action of the fugitive was so sudden that it was not observed. They ran several rods further, during which Deerfoot made his aim sure. As they had discharged their guns, and had not yet slackened their pace to reload them, he had no fear of being hurt.

All at once the foremost Pawnee saw the long bow, with the gleaming eyes behind the arrow, whose head was supported by the right hand which grasped the middle of the bow.

"Whoof!" he gasped, dropping to the earth as if pierced through the heart. His action saved his life, for a second sooner would have enabled the matchless archer to withhold the shot, which was as unerring as human skill could make it. Though the flight of the feather-tipped missile could be traced when the spectator stood on one side of the line, yet the individual who was unfortunate enough to serve as a target, could not detect its approach.

Just as the leader went down, a quick whiz was heard, and the arrow clove the space over him. Had his companion been in line he would have been pierced, but he was just far enough to one side, to be taught a lesson.

The strongly-driven missile went through the fleshy part of his arm, and sped twenty feet beyond, nipping several branches and twigs before its force was spent. No doubt the American race as a rule is hardy and stoical, but the stricken Pawnee acted like a schoolboy. Dropping his gun, he clasped his hand over the wound, and emitted a yell which surpassed everything in that line that had been heard during the day.

Even the warrior on the ground called to him to hold his peace, and the wounded Pawnee, awaking perhaps to a sense of the unbecoming figure he was cutting, compressed his thin lips and became silent.

But the other took good care to reload and prime his rifle before rising, and even then he came up with the utmost slowness, peering toward the tree from which had come the missile. He was not surprised because he saw nothing of the Shawanoe. Having discharged the weapon, it was natural that the latter should shelter himself from the bullet that was to be expected in return. Deerfoot (so reasoned the Pawnee), would not dare show himself again; but therein the warrior made a mistake.

The latter slowly came up, his form in a crouching position, his head about four feet above ground, while his eyes were fixed on the tree from behind which had sped the well nigh fatal missile.

"He will soon show himself," must have been the thought of the Indian, "the bullet can travel faster than the arrow."

At that moment his companion, who was still clasping his wounded arm, uttered a warning cry. He had discovered the Shawanoe behind another tree, aiming a second arrow at the breast of the leader.

With incredible dexterity, Deerfoot had run to a trunk fully twenty yards from the one which first sheltered him. He crouched so low and passed so swiftly that he reached the shelter before there was a possibility of discovery. It was accident which led the second warrior to detect the long bow, bending almost like a horseshoe, with the arrow aimed at the other.

The latter could not grasp in an instant the full nature of the peril which impended, though, as a matter of course, he knew it must be at the hands of the Shawanoe. He cast one glance around him, and again dropped on his face, but this time the arrow was quicker than he.

Zip came the missile straight for the brawny chest which never could have dodged from its path in time to escape; but, as if fate had determined to interfere, the pointed flint impinged against a tiny branch protruding from the tree nearest the Pawnee, clipping off enough of the tender bark to leave a gleaming white spot, and glanced harmlessly beyond.

Deerfoot was astonished beyond measure. He had discharged two arrows at the foremost foe, and had failed to harm a hair of him. Such a double failure had never before taken place in his history.

But the cause was self-manifest. The Indian dodged the first, and the twig turned the second aside. All this was natural enough, but the fact which impressed the young Shawanoe was that it would have taken place in neither case had he used a rifle. Was it a wise thing, therefore, when months before, he had flung aside his gun and taken up his bow again?

Deerfoot had asked himself the same question more than once since that time, and the doubt had deepened until he could no longer believe he was wise in clinging to his bow and arrow, great as was his skill in their use.

But a third arrow was quickly drawn, and stepping from behind the tree, so that he stood in full sight, he swung his hand aloft with a defiant shout, and coolly walked away, as though the warriors were too insignificant to be noticed further.

The wounded Pawnee was so much occupied with his hurt that he was willing the youth should leave the neighborhood without further molestation from him. Taking care to keep an oak fully a foot in diameter between them, he was content to let him depart in peace.

Not so with the other, who, waiting only long enough to make sure the back of the youth was toward him, straightened up and brought his rifle to his shoulder. The distance was considerable, but he ought to have reached the mark, and probably would have done so, had not a disturbing cause prevented.

While sighting along the barrel, the startling fact broke upon him that the face of Deerfoot was toward him, and he was in the act of drawing a third arrow to the head: He had whirled about almost at the same instant that the Pawnee leveled his gun. To say the least, it was very disconcerting, and, anxious to anticipate the Shawanoe, the other fired before he could be certain of his aim. The bullet went so wide that Deerfoot heard nothing of its passage among the branches around him.

Although it looked as if the Shawanoe had the other at his mercy, yet he refrained from discharging the arrow. In fact, his whole action was designed rather to disconcert the Pawnee than to injure him. Not only had Deerfoot's confidence in his bow and arrow weakened, but the two escapes of the Pawnee gave him a half-superstitious belief that it was intended the latter should not be injured. He, therefore, relaxed the string of the bow, but, without replacing the arrow in the quiver, he strode off, continually glancing back to make sure the Pawnee did not use the advantage thus given him.

You will understand that the pursuit of Deerfoot the Shawanoe was not confined to the two Pawnees, whom he thwarted in the manner described. Their superior activity simply brought them to the front and hastened the collision.

It will be seen, therefore, that the incidents must have taken place in a brief space of time: had it been otherwise, Deerfoot would have been engaged with the entire party. No one could have known that better than he. The whoops, signals and reports of the guns could not fail to tell the whole story, and to cause the Pawnees to converge toward the spot. In fact, when Deerfoot lowered his bow and turned his back for the second time on the warrior, he caught more than one glimpse of other red men hastening thither.

Dangerous as was the situation of the youth, he did not forget another incident which was liable to add to the difficulty of extricating himself. From the moment he began his flight several of the Pawnees gave utterance to shouts which were clearly meant as signals. These had been repeated several times, and Deerfoot could form no suspicion of their full meaning. Had the red men been Shawanoes, Wyandots or almost any tribe whose hunting grounds were east of the Mississippi, he would have read their purpose as readily as could those for whose ears they were intended.

The interpretation, however, came sooner than was expected.

Deerfoot ran a little ways with such swiftness that he left every one out of sight. Then he slackened his gait, and was going in a leisurely fashion, when he came upon a narrow creek which ran at right angles to the course he was following. The current was swift and deep, and the breadth too great for him to leap over.

He saw that if he ran up or down the bank too far, he was likely to place himself in peril again. He could have readily swam to the other side, but preferred some other means, and concluded to take a minute or two in looking for it.

A whoop to the left and the rear made known that no time was to be lost. He was about to run in the opposite direction, when he caught sight of the bridge for which he was hunting. A tree growing on the opposite side had fallen directly across, so that the top extended several yards from the shore. The trunk was long, thin, covered with smooth bark, and with only a few branches near the top, but it was the very thing the fugitive wanted, and, scarcely checking his gait, he dashed toward it, heedless of the Pawnees, a number of whom were in sight.

He slowed his pace when about to step on the support, and placing one foot on the thin bridge, tested it. So far as he could judge it was satisfactory, and, balancing himself, he began walking toward the other shore. Only four steps were taken, when a Pawnee stepped upon the opposite end, and advanced directly toward the Shawanoe.

It began to look, after all, as though Deerfoot had presumed too far on his own prowess, for his enemies were coming fast after him, and now, while treading the delicate structure, he was brought face to face with a warrior as formidable as Lone Bear or Eagle-of-the-Rocks.

But there was no time to hesitate. The Pawnee had caught the signals from the other side of the stream, and hurried forward to intercept the enemy making his way in that direction. He advanced far enough from the spreading base of the tree to render his foothold firm, when he braced himself with drawn knife, to receive the youth. He had flung his blanket and rifle aside, before stepping on the trunk, so as not to be hindered in his movements.

His painted face seemed to gleam with exultation, for, if ever a man was justified in believing he had a sure thing it was that Pawnee warrior, and if ever a person made a mistake that Pawnee warrior was the individual.

Instead of turning back Deerfoot drew his knife, and grasped it with his right hand, as though he meant to engage the other in conflict where both had such unsteady footing. Had the young Shawanoe held such a purpose, his left hand, but the Pawnee, having never seen him before, could not know that, and he was confident that the slaying of the youth was the easiest task he could undertake.

Deerfoot not only continued his advance, but broke into a trot composed of short, quick steps, such as a leaper takes when gathering on the edge of a cliff for his final effort. He still held his bow in his left and his knife in his right hand, and tightly closing his lips, looked into the eyes of the Pawnee.

Just as the latter drew back his weapon with the intention of making the decisive blow, and when two paces only separated the enemies, the Shawanoe dropped his head and drove it with terrific force against the chest of the Pawnee. The latter was carried off the log as completely as if he had been smitten with a battering ram.

He went over with feet pointing upward, and dropped with a splash into the stream. The blow was so violent indeed that the breath was knocked from him, and he emitted a grunt as he toppled off the support. As he disappeared, Deerfoot, too, lost his balance, but he was so close to land, that he leaped clear of the water. Then, as if he thought the Pawnee might need his blanket and rifle, he picked them up and tossed them into the stream after him.

Incidents followed each other with a rush, and the report of two guns in quick succession reminded the youth that it would not do to linger any longer in the vicinity; but assured now of the meaning of the signals which he had heard, he scanned the woods in front, as much as he did those in the rear. It was well he did so.

By calling into play his magnificent fleetness, he rapidly increased the distance between him and his enemies, but was scarcely able to pass beyond their sight, before, to his astonishment, he found he was confronted by two other warriors, coming from the opposite direction. They were doubtless on a hunt when signaled by the large party to intercept an enemy fleeing from them.

It began to look to Deerfoot as though he had struck either a settlement of Pawnees, or a very large war party, for, beyond question, the "woods were full of them". To have continued straight on would have brought about an encounter with the two, and there was too much risk in that, though from what the reader learned long ago of Deerfoot, it is unnecessary to say that he would not have hesitated to make such a fight, had there been a call to do so.

Truth to tell, the red men were firing off their guns too rapidly to allow the fugitive to feel comfortable. Thus far, although he had swept his foes from his path, as may be said, he had refrained from slaying any one. He would not take life unless necessary, but he began to doubt whether he had acted wisely in showing mercy. Had he pierced two or three of his foes through and through, the others would not have been so enthusiastic in pursuing him across stream and through wood.

At any rate, he decided to be more resolute, and when necessary, drive a shaft "home".

The moment he observed the two Pawnees advancing from a point in front, he made another change in his course. This time it was to the right, and again he put forth a burst of speed the like of which his enemies had never seen. He passed in and out among the trees, and through the undergrowth, with such bewildering swiftness, that, though he was within gunshot, neither would risk firing, where it was more difficult to take aim than at the bird darting through the tree tops.

The last act of the fugitive had, as he believed, thrown all his pursuers well to the rear. When he made the turn, the two whom he last encountered tried to head him off by cutting across, as it may be called, but they relinquished the effort when they saw how useless it was.

Thus far, though Deerfoot had been placed in situations of great danger, he had managed to free himself without any effort that could be deemed unusual for him, though it would have been remarkable had it been performed by any one else. But now, when it began to look as if the worst were over, he was made aware that the most serious crisis of all had come.

At the moment when he began to lessen his speed, simply because the intervening limbs annoyed him, he made the discovery that still more of the Pawnees were in front. He caught the glimmer of their dress between the trees scarcely, more than a hundred yards in advance, and, instead of one or two, there were at least five who were drawing near.

These were what may be called strangers, since they and Deerfoot now saw each other for the first time. Had they known the exact circumstances, they would have kept out of sight until the fugitive had run, as may be said, into their arms; but, like the rest, they were moving toward the camp, in obedience to the signals, keeping a lookout at the same time for the enemy that they knew was somewhere in the neighborhood. The reason they had not put in an earlier appearance was because they were further off than the rest.

At the moment Deerfoot observed them, he was not far off from the winding stream over which he had passed on the fallen tree. Like a flash, he turned about and ran with his own extraordinary fleetness, directly over his own trail.

It will be seen that the peril of this course reached almost a fatal degree, for the other Pawnees could not be far off, and a very brief run would take him in full sight of them.

The last comers showed more vigor than the others. The glimpse they caught of the strange warrior dashing toward them, told the whole truth. The sight of a man running at full speed with a whooping mob a short distance behind, is all the evidence needed to prove he is a fugitive. Besides, when the Pawnees bore down on Deerfoot they knew far more of the neighborhood than he, and were sure he was entrapped.

The purpose of the Shawanoe was to put forth his utmost swiftness, hoping to place himself, if only for part of a minute, beyond sight of his enemies. Though he made the closest kind of calculation, circumstances were against him, and he not only failed to disappear from the last two, but, short as was the distance he doubled on his own trail, it took him into the field of vision of the parties whom he had eluded but a few minutes before. So it came about that he was in full view of a number of enemies, rapidly converging toward him, while a deep, swift stream was flowing across his line of flight.

The success of the pursuers now looked so certain that their leader emitted several whoops, a couple of which were meant as a command for none to fire: the Shawanoe was cornered and they meant to make him prisoner.

It need not be said that under the worst conditions the capture of the young warrior would have been no easy matter. He could fight like a tiger when driven into corner, and his great quickness availed him against superior strength. He had bounded out of more desperate situations than any person of double his years, and, knowing that no mercy was to be expected from the warlike Pawnees, it must have been a strange conjunction of disasters that could compel him to throw up his hands and yield.