The Project Gutenberg EBook of Europa's Fairy Book, by Joseph Jacobs This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Europa's Fairy Book Author: Joseph Jacobs Illustrator: John D. Batten Release Date: July 10, 2008 [EBook #26019] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EUROPA'S FAIRY BOOK *** Produced by Sankar Viswanathan, David Edwards, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

"Do tell us a fairy tale, ganpa."

"Well, will you be good and quiet if I do?"

"Of course we will; we are always good when you are telling us fairy tales."

"Well, here goes.—Once upon a time, though it wasn't in my time, and it wasn't in your time, and it wasn't in anybody else's time, there was a——"

"But that would be no time at all."

"That's fairy tale time."

My Dear Little Peggy:—

Many, many, many years ago I wrote a book for your Mummey—when she was my little May—telling the fairy tales which the little boys and girls of England used to hear from their mummeys, who had heard them from their mummeys years and years and years before. My friend Mr. Batten made such pretty pictures for it—but of course you know the book—it has "Tom, Tit, Tot" and "The little old woman that went to market," and all those tales you like. Now I have been making a fairy-tale book for your own self, and here it is. This time I have told, again the fairy tales that all the mummeys of Europe have been telling their little Peggys, Oh for ever so many years! They must have liked them because they have spread from Germany to Russia, from Italy to France, from Holland to Scotland, and from England to Norway, and from every country in Europe that you will read about in your geography to every other one. Mr. Batten, who made the pictures for your mummey's book, has made some more for yours—isn't it good of him when he has never seen you?

Though this book is your very, very own, you will not mind if other little girls and boys also get copies of it from their mummeys and papas and ganmas and ganpas, for when you meet some of them you will, all of you, have a number of common friends like "The Cinder-Maid," or "The Earl of Cattenborough," or "The Master-Maid," and you can talk to one another about them so that you are old friends at once. Oh, won't that be nice? And when one of these days you go over the Great Sea, in whatever land you go, you will find girls and boys, as well as grown-ups, who will know all of these tales, even if they have different names. Won't that be nice too?

And when you tell your new friends here or abroad of these stories that you and they will know so well, do not forget to tell them that you have a book, all of your very own, which was made up specially for you of these old, old stories by your old, old

Ganpa.

P.S.—Do you hear me calling as I always do, "Peggy, Peggy"? Then you must answer as usual, "Ganpa, Ganpa."

Ever since—almost exactly a hundred years ago—the Grimms produced their Fairy Tale Book, folk-lorists have been engaged in making similar collections for all the other countries of Europe, outside Germany, till there is scarcely a nook or a corner in the whole continent that has not been ransacked for these products of the popular fancy. The Grimms themselves and most of their followers have pointed out the similarity or, one might even say, the identity of plot and incident of many of these tales throughout the European Folk-Lore field. Von Hahn, when collecting the Greek and Albanian Fairy Tales in 1864, brought together these common "formulæ" of the European Folk-Tale. These were supplemented by Mr. S. Baring-Gould in 1868, and I myself in 1892 contributed an even fuller list to the Hand Book of Folk-Lore. Most, if not all of these formulæ, have been found in all the countries of Europe where folk-tales have been collected. In 1893 Miss M. Roalfe Cox brought together, in a volume of the Folk-Lore Society, no less than 345 variants of "Cinderella" and kindred stories showing how widespread this particular formula was[vi] throughout Europe and how substantially identical the various incidents as reproduced in each particular country.

It has occurred to me that it would be of great interest and, for folk-lore purposes, of no little importance, to bring together these common Folk-Tales of Europe, retold in such a way as to bring out the original form from which all the variants were derived. I am, of course, aware of the difficulty and hazardous nature of such a proceeding; yet it is fundamentally the same as that by which scholars are accustomed to restore the Ur-text from the variants of different families of MSS. and still more similar to the process by which Higher Critics attempt to restore the original narratives of Holy Writ. Every one who has had to tell fairy tales to children will appreciate the conservative tendencies of the child mind; every time you vary an incident the children will cry out, "That was not the way you told us before." The Folk-Tale collections can therefore be assumed to retain the original readings with as much fidelity as most MSS. That there was such an original rendering eminating from a single folk artist no serious student of Miss Cox's volume can well doubt. When one finds practically the same "tags" of verse in such different dialects as Danish and Romaic, German and Italian, one cannot imagine that these sprang up independently in Denmark, Greece, Germany, and Florence. The same[vii] phenomenon is shown in another field of Folk-Lore where, as the late Mr. Newell showed, the same rhymes are used to brighten up the same children's games in Barcelona and in Boston; one cannot imagine them springing up independently in both places. So, too, when the same incidents of a fairy tale follow in the same artistic concatenation in Scotland, and in Sicily, in Brittany, and in Albania, one cannot but assume that the original form of the story was hit upon by one definite literary artist among the folk. What I have attempted to do in this book is to restore the original form, which by a sort of international selection has spread throughout all the European folks.

But while I have attempted thus to restore the original substance of the European Folk-Tales, I have ever had in mind that the particular form in which they are to appear is to attract English-speaking children. I have, therefore, utilized the experience I had some years ago in collecting and retelling the Fairy Tales of the English Folk-Lore field (English Fairy Tales, More English Fairy Tales), in order to tell these new tales in the way which English-speaking children have abundantly shown they enjoy. In other words, while the plot and incidents are "common form" throughout Europe, the manner in which I have told the stories is, so far as I have been able to imitate it, that of the English story-teller.

I have indeed been conscious throughout of my[viii] audience of little ones and of the reverence due to them. Whenever an original incident, so far as I could penetrate to it, seemed to me too crudely primitive for the children of the present day, I have had no scruples in modifying or mollifying it, drawing attention to such Bowdlerization in the somewhat elaborate notes at the end of the volume, which I trust will be found of interest and of use to the serious student of the Folk-Tale.

It must, of course, be understood that the tales I now give are only those found practically identical in all European countries. Besides these there are others which are peculiar to each of the countries or only found in areas covered by cognate languages like the Celtic or the Scandinavian. Of these I have already covered the English and the Celtic fields, and may, one of these days, extend my collections to the French and Scandinavian or the Slavonic fields. Meanwhile it may be assumed that the stories that have pleased all European children for so long a time are, by a sort of international selection, best fitted to survive, and that the Fairy Tales that follow are the choicest gems in the Fairy Tale field. I can only express the hope that I have succeeded in placing them in an appropriate setting.

It remains only to thank those of my colleagues and friends who have aided in various ways in the preparation of this volume, though of course their co-operation does not, in the slightest, imply responsibility for or approval of the method of[ix] treatment I have applied to the old, old stories. Miss Roalfe Cox was good enough to look over my reconstruction of "Cinderella" and suggest alterations in it. Prof. Crane gave me permission to utilize the version of the "Dancing Water," in his Italian Popular Tales. Sir James G. Frazer looked through my restoration of the "Language of Animals," which was suggested by him many years ago; and Mr. E. S. Hartland criticized the Swan-Maiden story. I have also to thank my old friend and publisher, Dr. G. H. Putnam, for the personal interest he has taken in the progress of the book.

J. J.

Yonkers, N. Y.

July, 1915.

| PAGE | |||

| Preface | v | ||

| List of Illustrations | xiii | ||

| I. | —Cinder-Maid | 1 | |

| II. | —All Change | 13 | |

| III. | —The King of the Fishes | 19 | |

| IV. | —Scissors | 31 | |

| V. | —Beauty and the Beast | 34 | |

| VI. | —Reynard and Bruin | 42 | |

| VII. | —The Dancing Water, Singing Apple, and Speaking Bird | 51 | |

| VIII. | —The Language of Animals | 66 | |

| IX. | —The Three Soldiers | 72 | |

| X. | —A Dozen at a Blow | 81 | |

| XI. | —The Earl of Cattenborough | 90 | |

| XII. | —The Swan Maidens | 98 | |

| XIII. | —Androcles and the Lion | 107 | |

| XIV. | —Day Dreaming | 110 | |

| XV. | —Keep Cool | 115 | |

| XVI. | —The Master Thief | 121 | |

| XVII. | —The Unseen Bridegroom | 129 | |

| XVIII. | —The Master-Maid | 142 | |

| XIX. | —A Visitor from Paradise | 159 | |

| XX. | —Inside Again | 165 | |

| XXI. | —John the True | 170 | |

| XXII. | —Johnnie and Grizzle | 180 | |

| XXIII. | —The Clever Lass | 188 | |

| XXIV. | —Thumbkin | 194 | |

| XV. | —Snowwhite | 201 | |

| Notes | 215 | ||

| List of Incidents | 263 | ||

Once upon a time, though it was not in my time or in your time, or in anybody else's time, there was a great King who had an only son, the Prince and Heir who was about to come of age. So the King sent round a herald who should blow his trumpet at every four corners where two roads met. And when the people came together he would call out, "O yes, O yes, O yes, know ye that His Grace the King will give on Monday sennight"—that meant seven nights or a week after—"a Royal Ball to which all maidens of noble birth are hereby summoned; and be it furthermore known unto you that at this ball his[2] Highness the Prince will select unto himself a lady that shall be his bride and our future Queen. God save the King."

Now there was among the nobles of the King's Court one who had married twice, and by the first marriage he had but one daughter, and as she was growing up her father thought that she ought to have some one to look after her. So he married again, a lady with two daughters, and his new wife, instead of caring for his daughter, thought only of her own and favoured them in every way. She would give them beautiful dresses but none to her step-daughter who had only to wear the cast-off clothes of the other two. The noble's daughter was set to do all the drudgery of the house, to attend the kitchen fire, and had naught to sleep on but the heap of cinders raked out in the scullery; and that is why they called her Cinder-Maid. And no one took pity on her and she would go and weep at her mother's grave where she had planted a hazel tree, under which she sat.

You can imagine how excited they all were when they heard the King's proclamation called out by the herald. "What shall we wear, mother; what shall we wear?" cried out the two daughters, and they all began talking about which dress should suit the one and what dress should suit the other, but when the father suggested that Cinder-Maid should also have a dress they all cried out: "What, Cinder-Maid going to the King's Ball;[3] why, look at her, she would only disgrace us all." And so her father held his peace.

Now when the night came for the Royal Ball Cinder-Maid had to help the two sisters to dress in their fine dresses and saw them drive off in the carriage with her father and their mother. But she went to her own mother's grave and sat beneath the hazel tree and wept and cried out:

And with that the little bird on the tree called out to her,

So Cinder-Maid shook the tree and the first nut that fell she took up and opened, and what do you think she saw?—a beautiful silk dress blue as the heavens, all embroidered with stars, and two little lovely shoon made of shining copper. And when she had dressed herself the hazel tree opened and from it came a coach all made of copper with four milk-white horses, with coachman and footmen all complete. And as she drove away the little bird called out to her:[4]

When Cinder-Maid entered the ball-room she was the loveliest of all the ladies and the Prince, who had been dancing with her step-sisters, would only dance with her. But as it came towards midnight Cinder-Maid remembered what the little bird had told her and slipped away to her carriage. And when the Prince missed her he went to the guards at the Palace door and told them to follow the carriage. But Cinder-Maid when she saw this, called out:

And when the Prince's soldiers tried to follow her there came such a mist that they couldn't see their hands before their faces. So they couldn't find which way Cinder-Maid went.

When her father and step-mother and two sisters came home after the ball they could talk of nothing but the lovely lady: "Ah, would not you have liked to have been there?" said the sisters to Cinder-Maid as she helped them to take off their fine dresses. "There was a most lovely lady with a dress like the heavens and shoes of bright copper, and the Prince would dance with none but her; and when midnight came she disappeared and the Prince could not find her. He is going to give a[5] second ball in the hope that she will come again. Perhaps she will not, and then we will have our chance."

When the time of the second Royal Ball came round the same thing happened as before; the sisters teased Cinder-Maid saying, "Wouldn't you like to come with us?" and drove off again as before. And Cinder-Maid went again to the hazel tree over her mother's grave and cried:

And then the little bird on the tree called out:

But this time she found a dress all golden brown like the earth embroidered with flowers, and her shoon were made of silver; and when the carriage came from the tree, lo and behold, that was made of silver too, drawn by black horses with trappings all of silver, and the lace on the coachman's and footmen's liveries was also of silver; and when Cinder-Maid went to the ball the Prince would dance with none but her; and when midnight came round she fled as before. But the Prince, hoping[6] to prevent her running away, had ordered the soldiers at the foot of the stair-case to pour out honey on the stairs so that her shoes would stick in it. But Cinder-Maid leaped from stair to stair and got away just in time, calling out as the soldiers tried to follow her:

And when her sisters got home they told her once more of the beautiful lady that had come in a silver coach and silver shoon and in a dress all embroidered with flowers: "Ah, wouldn't you have liked to have been there?" said they.

Once again the Prince gave a great ball in the hope that his unknown beauty would come to it. All happened as before; as soon as the sisters had gone Cinder-Maid went to the hazel tree over her mother's grave and called out:

And then the little bird appeared and said:

And when she opened the nut in it was a dress of silk green as the sea with waves upon it, and her shoes this time were made of gold; and when the coach came out of the tree it was also made of gold, with gold trappings for the horses and for the retainers. And as she drove off the little bird from the tree called out:

Now this time, when Cinder-Maid came to the ball, she was as desirous to dance only with the Prince as he with her, and so, when midnight came round, she had forgotten to leave till the clock began to strike, one—two—three—four—five—six,—and then she began to run away down the stairs as the clock struck, eight—nine—ten. But the Prince had told his soldiers to put tar upon the lower steps of the stairs; and as the clock struck eleven her shoes stuck in the tar, and when she jumped to the foot of the stairs one of her golden shoes was left behind, and just then the clock struck TWELVE, and the golden coach, with its horses and footmen, disappeared, and the beautiful dress of Cinder-Maid changed again into her ragged clothes and she had to run home with only one golden shoe.

You can imagine how excited the sisters were when they came home and told Cinder-Maid all about it, how that the beautiful lady had come in a golden coach in a dress like the sea, with golden shoes, and how all had disappeared at midnight except the golden shoe. "Ah, wouldn't you have liked to have been there?" said they.

Now when the Prince found out that he could not keep his lady-love nor trace where she had gone he spoke to his father and showed him the golden shoe, and told him that he would never marry any one but the maiden who could wear that shoe. So the King, his father, ordered the herald[9] to take round the golden shoe upon a velvet cushion and to go to every four corners where two streets met and sound the trumpet and call out: "O yes, O yes, O yes, be it known unto you all that whatsoever lady of noble birth can fit this shoe upon her foot shall become the bride of his Highness[10] the Prince and our future Queen. God save the King."

And when the herald came to the house of Cinder-Maid's father the eldest of her two step-sisters tried on the golden shoe. But it was much too small for her, as it was for every other lady that had tried it up to that time; but she went up into her room and with a sharp knife cut off one of her toes and part of her heel, and then fitted her foot into the shoe, and when she came down she showed it to the herald, who sent a message to the Palace saying that the lady had been found who could wear the golden shoe. Thereupon the Prince jumped at once upon his horse and rode to the house of Cinder-Maid's father. But when he saw the step-sister with the golden shoe, "Ah," he said, "but this is not the lady." "But," she said, "you promised to marry the one that could wear the golden shoe." And the Prince could say nothing, but offered to take her on his horse to his father's Palace, for in those days ladies used to ride on a pillion at the back of the gentleman riding on horseback. Now as they were riding towards the Palace her foot began to drip with blood, and the little bird from the hazel tree that had followed them called out:

And the Prince looked down and saw the blood streaming from her shoe and then he knew that this was not his true bride, and he rode back to the house of Cinder-Maid's father; and then the second sister tried her chance; but when she found that her foot wouldn't fit the shoe she did the same as her sister, but all happened as before. The little bird called out:

And the Prince took her back to her mother's house, and then he asked, "Have you no other daughter?" and the sisters cried out, "No, sir." But the father said, "Yes, I have another daughter." And the sisters cried out, "Cinder-Maid, Cinder-Maid, she could not wear that shoe." But the Prince said, "As she is of noble birth she has a right to try the shoe." So the herald went down to the kitchen and found Cinder-Maid; and when she saw her golden shoe she took it from him and put it on her foot, which it fitted exactly; and then she took the other golden shoe from underneath the cinders where she had hidden it and put that on too. Then the herald knew that she was the true bride of his master; and he took her upstairs to where the Prince was; when he saw her face, he knew that she was the lady of his love. So[12] he took her behind him upon his horse; and as they rode to the Palace, the little bird from the hazel tree cried out:

And so they were married and lived happy ever afterwards.

There was once a man who was the laziest man in all the world. He wouldn't take off his clothes when he went to bed because he didn't want to have to put them on again. He wouldn't raise his cup to his lips but went down and sucked up his tea without carrying the cup. He wouldn't play any sports because he said they made him sweat. And he wouldn't work with his hands for the same reason. But at last he found that he couldn't get anything to eat unless he did some work for it. So he hired himself out to a farmer for the season. But all through the harvest[14] he ate as much and he worked as little as he could; and when the fall came and he went to get his wages from his master all he got was a single pea. "What do you mean by giving me this?" he said to his master. "Why, that is all that your labor is worth," was the reply. "You have eaten as much as you have earned." "None of your lip," said the man; "give me my pea; at any rate I have earned that." So when he got it he went to an inn by the roadside and said to the landlady, "Can you give me lodging for the night, me and my pea?" "Well, no," said the landlady, "I haven't got a bed free, but I can take care of your pea for you." No sooner said than done. The pea was lodged with the landlady, and the laziest man went and lay in a barn near-by.

The landlady put the pea upon a dresser and left it there, and a chicken wandering by saw it and jumped up on the dresser and ate it. So when the laziest man called the next day and asked for his pea the landlady couldn't find it. She said, "The chicken must have swallowed it." "Well, I want my pea," said the man. "You had better give me the chicken." "Why, what—when—how?" stammered the landlady. "The chicken is worth thousands of your pea." "I don't care for that; it has got my pea inside it, and the only way I can get my pea is to have that which holds the pea." "What, give you my chicken for a single pea, nonsense!" "Well, if you don't I'll summon you[15] before the justice." "Ah, well, take the chicken and my bad wishes with it."

So off went the man and sauntered along all day, till that night he came to another inn, and asked the landlord if he and his chicken could stop there. He said, "No, no, we have no room for you, but we can put your chicken in the stable if you like." So the man said, "Yes," and went off for the night. But there was a savage sow in the stable, and during the night she ate up the poor chicken. And when the man came the next morning he said to the landlord, "Please give me my chicken." "I am awfully sorry, sir," said he, "but my sow has eaten it up." The laziest man said, "Then give me your sow." "What, a sow for your chicken, nonsense; go away, my man." "Then if you don't do that I'll have you before the justice." "Ah, well, take the sow and my curses with it," said the landlord.

And the man took the sow and followed it along the road till he came to another inn, and said to the landlady, "Have you room for me and my sow?" "I have not," said the landlady, "but I can put your sow up." So the sow was put in the stable, and the man went off to lie in the barn for the night. Now the sow went roaming about the stable, and coming too near the hoofs of the mare, was hit in the forehead and killed by the mare's hoofs. So when the man came in the morning and asked for his sow the landlady said, "I'm very[16] sorry, sir, but an accident has occurred; my mare has hit your sow in the skull and she is dead." "What, the mare?" "No, your sow." "Then give me the mare." "What, my mare for your sow, nonsense." "Well, if you don't I'll take you before the justice; you'll see if it's nonsense." So after some time the landlady agreed to give the man her mare in exchange for the dead sow.

Then the man followed on in the steps of the mare till he came to another inn, and asked the landlord if he could put him up for the night, him and his mare. The landlord said, "All our beds are full, but you can put the mare up in the stable if you will." "Very well," said the man, and tied the halter of the mare into the ring of the stable. Next morning early the landlord's daughter said to her father, "That poor mare has had nothing to drink; I'll go and lead it to the river." "That is none of your business," said the landlord; "let the man do it himself." "Ah, but the poor thing has had nothing to drink. I'll bring it back soon." So the girl took the mare to the river brink and let it drink the water; but, by chance, the mare slipped into the stream, which was so strong that it carried the mare away. And the young girl ran back to her mother and said, "Oh mother, the mare fell into the stream and it was carried quite away. What shall we do? What shall we do?"

When the man came round that morning he said, "Please give me my mare." "I'm very[17] sorry indeed, sir, but my daughter—that one there—wanted to give the poor thing a drink and took it down to the river and it fell in and was carried away by the stream; I'm very sorry indeed." "Your sorrow won't pay my loss," said the man; "the least you can do is to give me your daughter." "What, my daughter to you because of the mare!" "Well, if you don't I will take you before the justice." Now the landlord didn't like going before the justice.

So after much haggling he agreed to let his daughter go with the man. And they went along, and they went along, and they went along, till at last they came to another inn which was kept by the girl's aunt, though the man didn't know it. So he went in and said, "Can you give me beds for me and my girl here?" So the landlady looked at the girl who said nothing, and said, "Well, I haven't got a bed for you but I have got a bed for her; but perhaps she'll run away." "Oh, I will manage that," said the man. And he went and got a sack and put the girl in it and tied her up; and then he went off. As soon as he was gone the girl's aunt opened the bag and said, "What has happened, my dear?" And she told the whole story. So the aunt took a big dog and put it in the sack; and when the man came the next morning he said, "Where's my girl?" "There she is, so far as I know." So he took the sack and put it on his shoulder and went on his way for a time.[18] Then as the sun grew high he sat down under the shade of a tree and thought he would speak to the girl. And when he opened the sack the big dog flew out at him, and he fell back, and that's the last I heard of him.

Once upon a time there was a fisherman who was very poor and felt poorer still because he had no children. Now one day as he was fishing he caught in his net the finest fish he had ever seen, the scales all gold and eyes as bright as diamonds; and just as he was going to take it out of the net what do you think happened? The fish opened his jaws and said, "I am the King of the Fishes, and if you throw me back into the water you will never want a catch." The fisherman was so surprised that he let the fish slip into the water, and he flapped his big tail and dived under the waves. When he got home he told his wife[20] all about it, and she said, "Oh, what a pity, I have had such a longing to eat such a fish."

Well, next day the fisherman went again a-fishing and, sure enough, he caught the same fish again, and it said, "I am the King of the Fishes, if you let me go you shall always have your nets full." So the fisherman let him go again; and when he went back to his home he told his wife that he had done so. She began to cry and wail and said, "I told you I wanted such a fish, and yet you let him go; I am sure you do not love me." The fisherman felt quite ashamed of himself and promised that if he caught the King of the Fishes again he would bring him home to his wife for her to cook. So next day the fisherman went to the same place and caught the same fish the third time. But when the fish begged the fisherman to let him go he told the King of the Fishes what his wife had said and what he had promised her. "Well," said the King of the Fishes, "if you must kill me you must, but as you let me go twice I will do this for you. When the wife cuts me up throw some of my bones under the mare, and some of my bones under the bitch, and the rest of my bones bury beneath the rose-tree in the garden and then you will see what you will see."

So the fisherman took the King of the Fishes home to his wife, to whom he told what the fish had said; and when she cut up the fish for cooking they threw some of the bones under the mare, and[21] some under the bitch, and the rest they buried under the rose-tree in the garden.

Now after a time the fisherman's wife gave him two fine twin boys, whom they named George and Albert, each with a star on his forehead just under his hair, and at the same time the mare brought into the world two fine colts, and the bitch two puppies. And under the rose-tree grew up two rose bushes, each of which bore every year only one rose, but what a rose that was! It lasted through the summer and it lasted through the winter and, most curious of all, when George fell ill one of the roses began to wilt, and if Albert had an illness the same thing happened with the other rose.

Now when George and Albert grew up they heard that a Seven-Headed Dragon was ravaging the neighbouring kingdom, and that the king had promised his daughter's hand to anyone that would free the land from this scourge. They both wanted to go and fight the dragon, but at last the twins agreed that George go and Albert stop at home and look after their father and mother, who had now grown old. So George took his horse and his dog and rode off where the dragon had last been seen. And when he came to Middlegard, the capital of the kingdom, he rode with his horse and his dog to the chief inn of the town and asked the landlady why everything looked so gloomy and why the houses were draped in black. "Have you not heard, sir," asked the landlady, "that the Dragon[22] with the Seven Heads has been eating up a pure maiden every month? And now he demands that the princess herself shall be delivered up to him this day. That is why the town is draped in black and we are all so gloomy." Thereupon George took his horse and his dog and rode out to where the princess was exposed to the coming of the Dragon with Seven Heads. And when the princess saw George with his horse and his sword and his dog she asked him, "Why come you here, sir? Soon the Dragon with Seven Heads, whom none can withstand, will be here to claim me. Flee before it is too late." But George said, "Princess, a man can die once, and I will willingly try to save you from the dragon." Now as they were talking a horrible roar rent the air and the Dragon with the Seven Heads came towards the princess. But when it saw George it called out, "Can'st fight?" and George said, "If I can't I can learn." "I'll learn thee," said the dragon. And thereupon began a mighty combat between George and the dragon; and whenever the dragon came near to George his dog would spring at one of his paws, and when one of the heads reared back to deal with it George's horse would spring to that side, and George's sword would sweep that head away. And so at last all the seven heads of the dragon were shorn off by George's sword, and the princess was saved. And George opened the mouths of seven of the dragon's heads and cut out the tongues,[23] and the princess gave him her handkerchief, and he wrapt all the seven tongues in it and put them away next his heart. But George was so tired out by the fight that he laid down to sleep with his head in the princess's lap, and she parted his hair with her hands and saw the star on his brow.

Meanwhile the king's marshal, who was to have married the princess if he would slay the dragon, had been watching the fight from afar off; and when he saw that the dragon had been slain and that George was lying asleep after the fight, he crept up behind the princess and, drawing his dagger, said, "Put his head on the ground or else I will slay thee." And when she had done that he bade her rise and come with him after he had collected the seven heads of the dragon and strung them on the leash of his whip. The princess would have wakened George but the marshal threatened to kill her if she did. "If I cannot wed thee he shall not." And then he made her swear that she would say that the marshal had slain the Dragon with the Seven Heads. And when the princess and the marshal came near the city the king and his courtiers and all his people came out to meet them with great rejoicing, and the king said to his daughter, "Who saved thee?" and she said, "this man." "Then he shall marry thee," said the king. "No, no, father," said the princess, "I am not old enough to marry yet; give me, at any rate, a year and a day before the wedding takes place," for[24] she hoped that George would come and save her from the wicked marshal. The king himself, who loved his daughter greatly, gave way at last and promised that she should not be married for a year and a day.

When George awoke and saw the dead body and found the princess there no longer he did not know what to make of it but thought that she did not wish to marry a fisherman's son. So he mounted his horse, and with his faithful hound went on seeking further adventures through the world, and did not come that way again till a year had passed, when he rode into Middlegard again and alighted at the same inn where he had stopped before. "How now, hostess," he cried, "last time I was here the city was all in mourning but now everything is agog with glee; trumpets are blaring, lads and lasses are dancing round the trees, and every house has flags and banners flowing from its windows. What is happening?" "Know you not, sir," said the hostess, "that our princess marries to-morrow?" "Why, last time," he said, "she was going to be devoured by the Dragon with Seven Heads." "Nay, but he was slain by the king's marshal who weds the princess to-morrow as a reward for his bravery, and every one that wishes may join the wedding feast to-night in the king's castle."

That night George went up to the king's castle and took his place at the table not far off from where sat the king with the princess on one side of him and the marshal on the other; and after the banquet the king called upon the marshal once more to tell how he had slain the Dragon with the Seven Heads. And the marshal told a long tale of how he had cut off the seven heads of the dragon, and at the finish he ordered his squire to bring in a platter on which were the seven heads. Then up rose George and spoke to the king and said, "And pray, my lord, how does it happen that the dragon's heads had no tongues?" And the king said, "That I know not; let us look and see." And the jaws of the dragon's heads were opened, and behold there were no tongues in them. Then the king asked the marshal, "Know you aught of this?" And the marshal had nothing to say. And the princess looked up and saw her champion again. Then George took out from his doublet the seven tongues of the dragon, and it was found that they fitted. "What is the meaning of this, sir," said the king. Then George told the story of how he had slain the dragon and fallen asleep in the princess's lap and had awoke and found her gone. And the princess, when asked by her father, could not but tell of the treachery of the marshal. "Away with him," cried out the king, "let his head be taken off and his tongue be taken out, and let his place be taken by this young stranger."

So George and the princess were married and[28] lived happily, till one night, looking out of the window of the castle where they lived, George saw in the distance another castle with windows all lit up and shining like fire. And he asked the princess, his wife, what that castle might be. "Go not near that, George," said the princess, "for I have always heard that none who enters that castle ever comes out again." The next morning George went with horse and hound to seek the castle; and when he got near it he found at the gate an old dame with but one eye; and he asked her to open the gate, and she said she would but that it was a custom of the castle that who ever entered had to drink a glass of wine before doing so; and she offered him a goblet full of wine; but when he had drunk it he and his horse and his dog were all turned into stone.

Just at the very moment when George was turned to stone Albert, who had heard nothing of him, saw George's rose in the garden close up and turn the colour of marble; then he knew that something had happened to his brother, and he had out his horse and his dog and rode off to find out what had been George's fate. And he rode, and he rode, till he came to Middlegard, and as soon as he reached the gate the guard of the gate said, "Your highness, the princess has been in great anxiety about you; she will be so happy to know that you have returned safe." Albert said nothing, but followed the guard until he came to the princess's[29] chamber, and she ran to him and embraced him and cried out, "Oh, George, I am so delighted that you have come back safe." "Why should I not," said Albert. "Because I feared that you had gone to that castle with flaming windows, from which nobody ever returns alive," said the princess.

Then Albert guessed what had happened to George, and he soon made an excuse and went off again to seek the castle which the princess had pointed out from the window. When Albert got there he found the same old dame sitting by the gate, and asked if he might go in and see the castle. She said again that none might enter the castle unless they had taken a glass of wine and brought out the goblet of wine once more. Albert was about to drink it up when his faithful dog jumped up and spilt the wine, which he began to lap up, and as soon as he had drunk a little of it his body turned to marble, just by the side of another stone which looked exactly the same. Then Albert guessed what had happened, and descending from his horse he took out his sword and threatened the old witch that he would kill her unless she restored his brother to his proper shape. In fear and trembling the old dame muttered something over the four stones in front of the castle, and George and his horse and his hound and Albert's dog became alive again as they were before. Then George and Albert rode back to the princess who, when she saw them both so much alike, could not[30] tell which was which; then she remembered and went up to Albert and parted his hair on his forehead and saw there the star, and said, "This is my George"; but then George parted his own hair, and she saw the same star there. At last Albert told her all that had happened, and she knew her own husband again. And soon after the king died, and George ruled in his place, and Albert married one of the neighbouring princesses.

Once upon a time, though it was not in my time nor in your time nor in anybody else's time, there lived a cobbler named Tom and his wife named Joan. And they lived fairly happily together, except that whatever Tom did Joan did the opposite, and whatever Joan thought Tom thought quite contrary-wise. When Tom wanted beef for dinner Joan liked pork, and if Joan wanted to have chicken Tom would like to have duck. And so it went on all the time.

Now it happened that one day Joan was cleaning up the kitchen and, turning suddenly, she knocked two or three pots and pans together and broke them all. So Tom, who was working in the[32] front room, came and asked Joan, "What's all this? What have you been doing?" Now Joan had got the pair of scissors in her hand, and sooner than tell him what had really happened she said, "I cut these pots and pans into pieces with my scissors."

"What," said Tom, "cut pottery with your scissors, you nonsensical woman; you can't do it!"

"I tell you I did with my scissors!"

"You couldn't."

"I did."

"You couldn't."

"I did."

"Couldn't."

"Did."

"Couldn't."

"Did."

"Couldn't."

"Did."

At last Tom got so angry that he seized Joan by the shoulders and shoved her out of the house and said, "If you don't tell me how you broke those pots and pans I'll throw you into the river." But Joan kept on saying, "It was with the scissors"; and Tom got so enraged that at last he took her to the bank of the river and said, "Now for the last time, will you tell me the truth; how did you break those pots and pans?"

"With the scissors."

And with that he threw her into the river, and[33] she sank once, and she sank twice, and just before she was about to sink for the third time she put her hand up into the air, out of the water, and made a motion with her first and middle finger as if she were moving the scissors. So Tom saw it was no use to try to persuade her to do anything but what she wanted. So he rushed up the stream and met a neighbour who said, "Tom, Tom, what are you running for?"

"Oh, I want to find Joan; she fell into the river just in front of our house, and I am afraid she is going to be drowned."

"But," said the neighbour, "you're running up stream."

"Well," said Tom, "Joan always went contrary-wise whatever happened." And so he never found her in time to save her.

There was once a merchant that had three daughters, and he loved them better than himself. Now it happened that he had to go a long journey to buy some goods, and when he was just starting he said to them, "What shall I bring you back, my dears?" And the eldest daughter asked to have a necklace; and the second daughter wished to have a gold chain; but the youngest daughter said, "Bring back yourself, Papa, and that is what I want the most." "Nonsense, child," said her father, "you must say something that I may remember to bring back for you." "So," she said, "then bring me back a rose, father."

Well, the merchant went on his journey and did his business and bought a pearl necklace for his eldest daughter, and a gold chain for his second daughter; but he knew it was no use getting a rose for the youngest while he was so far away because it would fade before he got home. So he made up his mind he would get a rose for her the day he got near his house.

When all his merchanting was done he rode off[35] home and forgot all about the rose till he was near his house; then he suddenly remembered what he had promised his youngest daughter, and looked about to see if he could find a rose. Near where he had stopped he saw a great garden, and getting off his horse he wandered about in it till he found a lovely rose-bush; and he plucked the most beautiful rose he could see on it. At that moment he heard a crash like thunder, and looking around he saw a huge monster—two tusks in his mouth and fiery eyes surrounded by bristles, and horns coming out of its head and spreading over its back.

"Mortal," said the Beast, "who told thee thou mightest pluck my roses?"

"Please, sir," said the merchant in fear and terror for his life, "I promised my daughter to bring her home a rose and forgot about it till the last moment, and then I saw your beautiful garden and thought you would not miss a single rose, or else I would have asked your permission."

"Thieving is thieving," said the Beast, "whether it be a rose or a diamond; thy life is forfeit."

The merchant fell on his knees and begged for his life for the sake of his three daughters who had none but him to support them.

"Well, mortal, well," said the Beast, "I grant thy life on one condition: Seven days from now thou must bring this youngest daughter of thine, for whose sake thou hast broken into my garden, and leave her here in thy stead. Otherwise swear[36] that thou wilt return and place thyself at my disposal."

So the merchant swore, and taking his rose mounted his horse and rode home.

As soon as he got into his house his daughters came rushing round him, clapping their hands and showing their joy in every way, and soon he gave the necklace to his eldest daughter, the chain to his second daughter, and then he gave the rose to his youngest, and as he gave it he sighed. "Oh, thank you, Father," they all cried. But the youngest said, "Why did you sigh so deeply when you gave me my rose?"

"Later on I will tell you," said the merchant.

So for several days they lived happily together, though the merchant wandered about gloomy and sad, and nothing his daughters could do would cheer him up till at last he took his youngest daughter aside and said to her, "Bella, do you love your father?"

"Of course I do, Father, of course I do."

"Well, now you have a chance of showing it"; and then he told her of all that had occurred with the Beast when he got the rose for her. Bella was very sad, as you can well think, and then she said, "Oh, Father, it was all on account of me that you fell into the power of this Beast; so I will go with you to him; perhaps he will do me no harm; but even if he does better harm to me than evil to my dear father."[37]

So next day the merchant took Bella behind him on his horse, as was the custom in those days, and rode off to the dwelling of the Beast. And when he got there and they alighted from his horse the doors of the house opened, and what do you think they saw there! Nothing. So they went up the steps and went through the hall, and went into the dining-room and there they saw a table spread with all manner of beautiful glasses and plates and dishes and napery, with plenty to eat upon it. So they waited and they waited, thinking that the owner of the house would appear, till at last the merchant said, "Let's sit down and see what will happen then." And when they sat down invisible hands passed them things to eat and to drink, and they ate and drank to their heart's content. And when they arose from the table it arose too and disappeared through the door as if it were being carried by invisible servants.

Suddenly there appeared before them the Beast who said to the merchant, "Is this thy youngest daughter?" And when he had said that it was, he said, "Is she willing to stop here with me?" And then he looked at Bella who said, in a trembling voice, "Yes, sir."

"Well, no harm shall befall thee." With that he led the merchant down to his horse and told him he might come that day week to visit his daughter. Then the Beast returned to Bella and said to her, "This house with all that therein is[38] thine; if thou desirest aught clap thine hands and say the word and it shall be brought unto thee." And with that he made a sort of bow and went away.

So Bella lived on in the home with the Beast and was waited on by invisible servants and had whatever she liked to eat and to drink; but she soon got tired of the solitude and, next day, when the Beast came to her, though he looked so terrible, she had been so well treated that she had lost a great deal of her terror of him. So they spoke together about the garden and about the house and about her father's business and about all manner of things, so that Bella lost altogether her fear of the Beast. Shortly afterwards her father came to see her and found her quite happy, and he felt much less dread of her fate at the hands of the Beast. So it went on for many days, Bella seeing and talking to the Beast every day, till she got quite to like him, until one day the Beast did not come at his usual time, just after the midday meal, and Bella quite missed him. So she wandered about the garden trying to find him, calling out his name, but received no reply. At last she came to the rose-bush from which her father had plucked the rose, and there, under it, what do you think she saw! There was the Beast lying huddled up without any life or motion. Then Bella was sorry indeed and remembered all the kindness that the Beast had shown her; and she threw herself down by it and said, "Oh, Beast, Beast, why did you die? I was getting to love you so much."

No sooner had she said this than the hide of the Beast split in two and out came the most handsome young prince who told her that he had been enchanted by a magician and that he could not recover his natural form unless a maiden should, of her own accord, declare that she loved him.

Thereupon the prince sent for the merchant and his daughters, and he was married to Bella, and they all lived happy together ever afterwards.

You must know that once upon a time Reynard the Fox and Bruin the Bear went into partnership and kept house together. Would you like to know the reason? Well, Reynard knew that Bruin had a beehive full of honeycomb, and that was what he wanted; but Bruin kept so close a guard upon his honey that Master Reynard didn't know how to get away from him and get hold of the honey. So one day he said to Bruin, "Pardner, I have to go and be gossip—that means god-father, you know—to one of my old friends." "Why, certainly," said Bruin. So off Reynard goes into the woods, and after a time he crept back and uncovered the beehive and had such a feast of honey. Then he went back to Bruin, who asked him what name had been given to the child. Reynard had forgotten all about the christening and could only say, "Just-begun." "What a funny name," said Master Bruin.

A little while after Reynard thought he would[43] like another feast of honey. So he told Bruin that he had to go to another christening; and off he went. And when he came back and Bruin asked him what was the name given to the child Reynard said, "Half-eaten." The third time the same thing occurred, and this time the name given by Reynard to the child that didn't exist was "All-gone,"—you can guess why.

A short time afterwards Master Bruin thought he would like to eat up some of his honey and asked Reynard to come and join him in the feast. When they got to the beehive Bruin was so surprised to find that there was no honey left; and he turned round to Reynard and said, "Just-begun, Half-eaten, All-gone—so that is what you meant; you have eaten my honey." "Why no," said Reynard, "how could that be? I have never stirred from your side except when I went a-gossiping, and then I was far away from here. You must have eaten the honey yourself, perhaps when you were asleep; at any rate we can easily tell; let us lie down here in the sunshine, and if either of us has eaten the honey, the sun will soon sweat it out of us." No sooner said than done, and the two lay side by side in the sunshine. Soon Master Bruin commenced to doze, and Mr. Reynard took some honey from the hive and smeared it round Bruin's snout; then he woke him up and said, "See, the honey is oozing out of your snout; you must have eaten it when you were asleep."[44]

Some time after this Reynard saw a man driving a cart full of fish, which made his mouth water. So he ran and he ran and he ran till he got far away in front of the cart and lay down in the road as still as if he were dead. When the man came up to him and saw him lying there dead, as he thought, he said to himself, "Why, that will make a beautiful red fox scarf and muff for my wife Ann." And he got down and seized hold of Reynard and threw him into the cart all along with the fish, and then he went driving on as before. Reynard began to throw the fish out till there were none left, and then he jumped out himself without the man noticing it, who drove up to his door and called out, "Ann, Ann, see what I have brought you." And when his wife came to the door she looked into the cart and said, "Why, there is nothing there."

Reynard in the meantime had brought all his fish together and began eating some when up comes Bruin and asked for a share. "No, no," said Reynard, "we only share food when we have shared work. I fished for these, you go and fish for others."

"Why, how could you fish for these? the water is all frozen over," said Bruin.

"I'll soon show you," said Reynard, and brought him down to the bank of the river, and pointed to a hole in the ice and said, "I put my tail in that, and the fish were so hungry I couldn't draw[45] them up quick enough. Why do you not do the same?"

So Bruin put his tail down and waited and waited but no fish came. "Have patience, man," said Reynard; "as soon as one fish comes the rest will follow."

"Ah, I feel a bite," said Bruin, as the water commenced to freeze round his tail and caught it in the ice.

"Better wait till two or three have been caught and then you can catch three at a time. I'll go back and finish my lunch."

And with that Master Reynard trotted up to the man's wife and said to her, "Ma'am, there's a big black bear caught by the tail in the ice; you can do what you like with him." So the woman called her husband and they took big sticks and went down to the river and commenced whacking Bruin who, by this time, was fast in the ice. He pulled and he pulled and he pulled, till at last he[46] got away leaving three quarters of his tail in the ice, and that is why bears have such short tails up to the present day.

Meanwhile Master Reynard was having a great time in the man's house, golloping everything he could find till the man and his wife came back and found him with his nose in the cream jug. As soon as he heard them come in he tried to get away, but not before the man had seized hold of the cream jug and thrown it at him, just catching him on the tail, and that is the reason why the tips of foxes' tails are cream white to this very day.

Well, Reynard crept home and found Bruin in such a state, who commenced to grumble and complain that it was all Reynard's fault that he had lost his tail. So Reynard pointed to his own tail and said, "Why, that's nothing; see my tail; they hit me so hard upon the head my brains[47] fell out upon my tail. Oh, how bad I feel; won't you carry me to my little bed." So Bruin, who was a good-hearted soul, took him upon his back and rolled with him towards the house. And as he went on Reynard kept saying, "The sick carries the sound, the sick carries the sound."

"What's that you are saying?" asked Bruin.

"Oh, I have no brains left, I do not know what I am saying," said Reynard but kept on singing, "The sick carries the sound, ha, ha, the sick carries the sound."

Then Bruin knew that he had been done and threw Reynard down upon the ground, and would have eaten him up but that the fox slunk away and rushed into a briar bush. Bruin followed him closely into the briar bush and caught Reynard's hind leg in his mouth. Then Reynard called out, "That's right, you fool, bite the briar root, bite the briar root."

Bruin thinking that he was biting the briar root, let go Reynard's foot and snapped at the nearest briar root. "That's right, now you've got me,

called out Reynard, and slunk away.

When Bruin heard Reynard's voice dying away in the distance he knew that he had been done[48] again, and that was the end of their partnership.

Some time after this a man was plowing in the field with his two oxen, who were very lazy that day. So the man called out at them, "Get a move on or I'll give you to the Bear"; and when they didn't quicken their pace he tried to frighten them by calling out, "Bear, Bear, come and take these lazy oxen." Sure enough, Bruin heard him and came out of the woods and said, "Here I am, give me the oxen, or else it'll be worse for you." The man was in despair but said, "Yes, yes, of course they are yours, but please let me finish my morning's plowing so I may finish this acre." Bruin could not say "No" to that, and sat down licking his chops and waiting for the oxen. The man went on plowing, thinking what he should do, when just at the corner of the field Reynard came up to him and said, "If you will give me two geese, I'll help you out of this fix and deliver the Bear into your hands." The man agreed and he told him what to do and went away into the woods. Soon after, the Bear and the man heard a noise like "Bow-wow, Bow-wow"; and the Bear came to the man and said, "What's that?" "Oh, that must be the lord's hounds out hunting for bears." "Hide me, hide me," said Bruin, "and I will let you off the oxen." Then Reynard called out from the wood, "What's that black thing you've got there?" And the Bear said, "Say it's the stump of a tree." So when the man had called this out[49] to the Fox, Reynard called out, "Put it in the cart; fix it with the chain; cut off the boughs, and drive your axe into the stump." Then the Bear said to the man, "Pretend to do what he bids you; heave me into the cart; bind me with the chain; pretend to cut off the boughs, and drive the axe into the stump." So the man lifted Bruin into the cart, bound him with the chain, then cut off his limbs and buried the axe in his head.

Then Reynard came forward and asked for his reward, and the man went back to his house to get the pair of geese that he had promised.

"Wife, wife," he called out, as he neared the house, "get me a pair of geese, which I have promised the Fox for ridding me of the Bear."

"I can do better than that," said his wife Ann, and brought him out a bag with two struggling animals in it.

"Give these to Master Reynard," said she; "they will be geese enough for him." So the man took the bag and went down to the field and gave the bag to Reynard; but when he opened it out sprang two hounds, and he had great trouble in running away from them to his den.

When he got to his den the Fox asked each of his limbs, how they had helped him in his flight. His nose said, "I smelt the hounds"; his eyes said, "We looked for the shortest way"; his ears said, "We listened for the breathing of the hounds"; and his legs said, "We ran away with you."[50] Then he asked his tail what it had done, and it said, "Why, I got caught in the bushes or made your leg stumble; that is all I could do." So, as a punishment, the Fox stuck his tail out of his den, and the hounds saw it and caught hold of it, and dragged the Fox out of his den by it and ate him all up. So that was the end of Master Reynard, and well he deserved it. Don't you think so?

There was once an herb-gatherer who had three daughters who earned their living by spinning. One day their father died and left them all alone in the world. Now the king had a habit of going about the streets at night, and listening at the doors to hear what the people said of him. So one night he listened at the door of the house where the three sisters lived, and heard them[52] disputing. The oldest said: "If I were the wife of the royal butler, I could give the whole court to drink out of one glass of water, and there would be some left."

The second said: "If I were the wife of the keeper of the royal wardrobe, with one piece of cloth I could clothe all the attendants, and have some left."

But the youngest daughter said: "Were I the king's wife, I would bear him two children: a son with a sun on his forehead, and a daughter with a moon on her brow."

The king went back to his palace, and the next morning sent for the sisters, and said to them: "Do not be frightened, but tell me what you said last night." The oldest told him what she had said, and the king had a glass of water brought, and commanded her to prove her words. She took the glass, and gave all the attendants some water to drink, and still there was some water left.

"Bravo!" cried the king, and summoned the butler. "This is your husband. Now it is your turn," said the king to the next sister, and commanded a piece of cloth to be brought, and the young girl at once cut out garments for all the attendants, and had some cloth left.

"Bravo!" cried the king again, and gave her the keeper of the wardrobe for her husband. "Now it is your turn," said the king to the youngest.[53]

"Please your Majesty, I said that if I were the king's wife, I would bear him two children: a son with a sun on his forehead, and a daughter with a moon on her brow."

"If that is true," replied the king, "you shall be my queen; if not, you shall die," and straightway he married her.

Very soon the two older sisters began to be envious of the youngest. "Look," said they; "she is going to be queen, and we must be servants!" and they began to hate her. A few months before the queen's children were to be born, the king declared war, and was obliged to go with his army, but he left word that if the queen had two children: a son with a sun on his forehead, and a girl with a moon on her brow, the mother was to be respected as queen; if not, he was to be informed of it, and would tell his servants what to do. Then he departed for the war.

When the queen's children were born, a son with a sun on his forehead and a daughter with a moon on her brow, as she had promised, the envious sisters bribed the nurse to put little dogs in the place of the queen's children, and sent word to the king that his wife had given birth to two puppies. He wrote back that she should be taken care of for two weeks, and then put into a tread-mill.

Meanwhile the nurse took the little babies, and carried them out of doors, saying: "I will make[54] the dogs eat them up," and she left them alone. While they were thus exposed, three fairies passed by and exclaimed: "Oh how beautiful these children are!" and one of the fairies said: "What present shall we make these children?" One answered: "I will give them a deer to nurse them." "And I a purse always full of money." "And I," said the third fairy, "will give them a ring which will change colour when any misfortune happens to one of them."

The deer nursed and took care of the children until they grew up. Then the fairy who had given them the deer came and said: "Now that you have grown up, how can you stay here any longer?" "Very well," said the brother, "I will go to the city and hire a house." "Take care," said the deer, "that you hire one opposite the royal palace." So they went to the city and hired a palace as directed, and furnished it as if they had been princes. When the aunts saw the brother and sister, imagine their terror! "They are alive!" they said. They could not be mistaken for there was the sun on the forehead of the son, and the moon on the girl's brow. They called the nurse and said to her: "Nurse, what does this mean? are our nephew and niece alive?" The nurse watched at the window until she saw the brother go out, and then she went over as if to make a visit to the new house. She entered and said: "What is the matter, my daughter; how do you do? Are you perfectly happy? You lack nothing. But do you know what is necessary to make you really happy? It is the Dancing Water. If your brother loves you, he will get it for you!" She remained a moment longer and then departed.

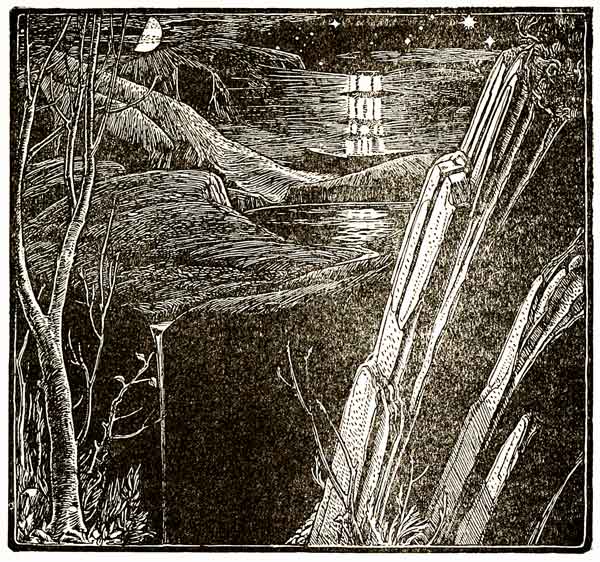

When the brother returned, his sister said to him; "Ah! my brother, if you love me go and get me the Dancing Water." He consented, and next morning saddled a fine horse, and departed. On his way he met a hermit, who asked him, "Where are you going, cavalier?"

"I am going for the Dancing Water." "You are going to your death, my son; but keep on until you find a hermit older than I." He continued his journey until he met another hermit, who asked him the same question, and gave him the same direction. Finally he met a third hermit, older than the other two, with a white beard that came down to his feet, who gave him the following directions: "You must climb yonder mountain. On top of it you will find a great plain and a house with a beautiful gate. Before the gate you will see four giants with swords in their hands. Take heed; do not make a mistake; for if you do, that is the end of you! When the giants have their eyes closed, do not enter; when they have their eyes open, enter. Then you will come to a door. If you find it open, do not enter; if you find it shut, push it open and enter. Then you will find four lions. When they have their eyes[58] shut, do not enter; when their eyes are open, enter, and you will see the Dancing Water." The youth took leave of the hermit, and hastened on his way.

Meanwhile the sister kept looking at the ring constantly, to see whether the stone in it changed colour; but as it did not, she remained undisturbed.

A few days after leaving the hermit the youth arrived at the top of the mountain, and saw the palace with the four giants before it. They had their eyes shut, and the door was open. "No," said the youth, "that won't do." And so he remained on the lookout a while. When the giants opened their eyes, and the door closed, he entered, waited until the lions opened their eyes, and passed in. There he found the Dancing Water, and filled his bottles with it, and escaped when the lions again opened their eyes.

The aunts, meanwhile, were delighted because their nephew did not return; but in a few days he appeared and embraced his sister. Then they had two golden basins made, and put into them the Dancing Water, which leaped from one basin to the other. When the aunts saw it they exclaimed: "Ah! how did he manage to get that water?" and called the nurse, who again waited until the sister was alone, and then visited her. "You see," said she, "how beautiful the Dancing Water is! But do you know what you want now? The Singing Apple." Then she departed. When the brother who had brought the Dancing Water[59] returned, his sister said to him: "If you love me you must get for me the Singing Apple." "Yes, my sister, I will go and get it."

Next morning he mounted his horse, and set out. After a time he met the first hermit, who sent him to an older one. He asked the youth where he was going, and said: "It is a difficult task to get the Singing Apple, but hear what you must do: Climb the mountain; beware of the giants, the door, and the lions; then you will find a little door and a pair of shears in it. If the shears are open, enter; if closed, do not risk it." The youth continued his way, found the palace, entered, and found everything favourable. When he saw the shears open, he went in a room and saw a wonderful tree, on top of which was an apple. He climbed up and tried to pick the apple, but the top of the tree swayed now this way, now that. He waited until it was still a moment, seized the branch, and picked the apple. He succeeded in getting safely out of the palace, mounted his horse, and rode home, and all the time he was carrying the apple it kept on singing.

The aunts were again delighted because their nephew was so long absent; but when they saw him return, they felt as though the house had fallen on them. Again they summoned the nurse, and again she visited the young girl, and said: "See how beautiful they are, the Dancing Water and the Singing Apple! But should you see the Speaking[60] Bird, there would be nothing left for you to see." "Very well," said the young girl; "we will see whether my brother will get it for me."

When her brother came she asked him for the Speaking Bird, and he promised to get it for her. He met, as usual on his journey, the first hermit, who sent him to the second, who sent him on to a third one, who said to him: "Climb the mountain and enter the palace. You will find many statues. Then you will come to a garden, in the midst of which is a fountain, and on the basin is the Speaking Bird. If it should say anything to you, do not answer. Pick a feather from the bird's wing, dip it into a jar you will find there, and anoint all the statues. Keep your eyes open, and all will go well."

The youth already knew well the way, and soon was in the palace. He found the garden and the bird, which, as soon as it saw him, exclaimed: "What is the matter, noble sir; have you come for me? You have missed it. Your aunts have sent you to your death, and you must remain here. Your mother has been sent to the tread-mill." "My mother in the tread-mill?" cried the youth, and scarcely were the words out of his mouth when he became a statue like all the others.

Now when her brother did not come back the third time the sister looked at her ring, and it had become black, and she knew that something had befallen him. Poor child! not having anything[61] else to do, she dressed herself like a page and set out.

Like her brother, she met the three hermits, and received their instructions. The third concluded thus: "Beware, for if you answer when the bird speaks you will lose your life, but if you speak not, it will come to you; take one of its feathers and dip it in the jar you will see there and anoint your brother's nostril with it." She continued her way, followed exactly the hermit's directions, and reached the garden in safety. When the bird saw her it exclaimed: "Ah! you here, too? Now you will meet the same fate as your brother. Do you see him lying there? Your father is at the war. Your mother is in the tread-mill. Your aunts are rejoicing."

But the sister made no reply, but let the bird sing on. When it had nothing more to say it flew down, and the young girl caught it, pulled a feather from its wing, dipped it into the jar, and anointed her brother's nostrils, and he at once came to life again. Then she did the same with all the other statues, with the lions and the giants, until all became alive again. Then she departed with her brother, and all the noblemen, princes, barons, and kings' sons rejoiced greatly. Now when they had all come to life again the palace disappeared, and the hermits disappeared, for they were the three fairies.

The day after the brother and sister reached the[62] city where they lived, they summoned a goldsmith, and had him make a gold chain, and fasten the bird with it. The next time the aunts looked out they saw in the window of the palace opposite the Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird. "Well," said they, "the real trouble is coming now!"

The bird directed the brother and sister to procure a carriage finer than the king's, with twenty-four attendants, and to have the service of their palace, cooks, and servants, more numerous and better than the king's. All of which the brother and sister did at once. And when the aunts saw these things they were ready to die of rage.

At last the king returned from the war, and his subjects told him all the news of the kingdom, and the thing they talked about the least was his wife and children. One day the king looked out of the window and saw the palace opposite furnished in a magnificent manner. "Who lives there?" he asked, but no one could answer him. He looked again and saw the brother and sister, the former with the sun on his forehead, and the latter with the moon on her brow. "Gracious! if I did not know that my wife had given birth to puppies, I should say that those were my children," exclaimed the king. Another day he stood by the window and enjoyed the Dancing Water and the Singing Apple, but the bird was silent.

After the king had heard all the music, the bird[63] said: "What does your Majesty think of it?" The king was astonished at hearing the Speaking Bird, and answered: "What should I think? It is marvellous."

"There is something more marvellous," said the bird; "just wait."

Then the bird told his mistress to call her brother, and said: "There is the king; let us invite him to dinner on Sunday. Shall we not?"

"Yes, yes," they said. So the king was invited and accepted, and on Sunday the bird had a grand dinner prepared and the king came. When he saw the young people near, he clapped his hands and said: "They must be my children."

He went over the palace and was astonished at its richness. Then they went to dinner, and while they were eating the king said: "Bird, every one is talking; you alone are silent."

"Ah! your Majesty, I am ill; but next Sunday I shall be well and able to talk, and will come and dine at your palace with this lady and this gentleman."

The next Sunday the bird directed his mistress and her brother to put on their finest clothes; so they dressed in royal style and took the bird with them. The king showed them through his palace and treated them with the greatest ceremony; the aunts were nearly dead with fear. When they had seated themselves at the table, the king said: "Come, bird, you promised me you would speak;[64] have you nothing to say?" Then the bird began and related all that had happened from the time the king had listened at the door until his poor wife had been sent to the tread-mill; then the bird added: "These are your children, and your wife was sent to the tread-mill, and is dying."

When the king heard all this, he hastened to embrace his children, and then went to find his poor wife, who was reduced to skin and bones and was at the point of death. He knelt before her and begged her pardon, and then summoned her sisters and the nurse, and when they were in his presence he said to the bird: "Bird, you who have[65] told me everything, now pronounce their sentence." Then the bird sentenced the nurse to be thrown out of the window, and the sisters to be cast into a cauldron of boiling oil. This was at once done. The king was never tired of embracing his wife. Then the bird departed and the king and his wife and children lived together in peace.

There was once a man who had a son named Jack, who was very simple in mind and backward in his thought. So his father sent him away to school so that he might learn something; and after a year he came back from school.

"Well, Jack," said his father, "what have you learnt at school?"

And Jack said, "I know what dogs mean when they bark."[67]

"That's not much," said his father. "You must go to school again."

So he sent him to school for another year, and when he came back he asked him what he had learnt.

"Well, father," said the boy, "when frogs croak I know what they mean."

"You must learn more than that," said the father, and sent him once more to school.

And when he returned, after another year, he asked him once more what he had learnt.

"I know all the birds say when they twitter and chirp, caw and coo, gobble and cluck."

"Well I must say," said the father, "that does not seem much for three years' schooling. But let us see if you have learnt your lessons properly. What does that bird say just above our heads in the tree there?"

Jack listened for some time but did not say anything.

"Well, Jack, what is it?" asked his father.

"I don't like to say, father."

"I don't believe you know or else you would say. Whatever it is I shall not mind."

Then the boy said, "The bird kept on saying as clear as could be, 'the time is not so far away when Jack's father will offer him water on bended knees for him to wash his hands; and his mother shall offer him a towel to wipe them with.'"[68]

Thereupon the father grew very angry at Jack and his love for him changed to hatred, and one day he spoke to a robber and promised him much money if he would take Jack away into the forest and kill him there and bring back his heart to show that he had done what he had promised. But instead of doing this the robber told Jack all about it and advised him to flee away, while the robber took back to Jack's father the heart of a deer saying that it was Jack's. Then Jack travelled on and on till one night he stopped at a castle on the way; and while they were all supping together in the castle hall the dogs in the court-yard began barking and baying. And Jack went up to the lord of the castle and said, "There will be an attack upon the castle to-night."

"How do you know that?" asked the lord.

"The dogs say so," said Jack.

At that the lord and his men laughed, but never-the-less put an extra guard around the castle that night, and, sure enough, the attack was made, which was easily beaten off because the men were prepared. So the lord gave Jack a great reward for warning him, and he went on his way with a fellow traveller who had heard him warn the lord.

Soon afterwards they arrived at another castle in which the lord's daughter was lying sick unto death; and a great reward had been offered to him that should cure her. Now Jack had been listening to the frogs as they were croaking in the moat[69] which surrounded the castle. So Jack went to the lord of the castle and said, "I know what ails your daughter."

"What is it," asked the lord.

"She has dropped the holy wafer from her mouth and it has been swallowed by one of the frogs in the moat."

"How do you know that?" said the lord.

"I heard the frogs say so."

At first the lord would not believe it; but in order to save his daughter's life he got Jack to point out the frog who was boasting of what he had swallowed, and, catching it, found what Jack had said was true. The frog was caught and killed, the wafer got back, and the girl recovered. So the lord gave Jack the reward which was promised, and he went on further with his companion and with another guest of the castle who had heard what Jack had said and done.

So Jack, with his two companions, travelled on towards Rome, the city of cities where dwelt the Pope, in those days the head of all Christendom. And as they were resting by the roadside Jack said to his companions, "Who would have thought it? One of us is going to be the Pope of Rome."

And his comrades asked him how he knew.

And he said, "The birds above in the tree have said so."

And his comrades at first laughed at him, but then remembered that what he had said before of[70] the barking of dogs and of the croaking of frogs had turned out to be true.

Now when they arrived at Rome they found that the Pope had just died and that they were about to select his successor. And it was decided that all the people should pass under an arch whereon was a bell and two doves, and he upon whose shoulders the doves should alight, and for whom the bell should ring as he passed under the arch was to be the next Pope. And when Jack and his companions came near the arch they all remembered his prophecy and wondered which of the three should receive the signs. And his first comrade passed under the arch and nothing happened, and then the second and nothing happened,[71] but when Jack went through the doves descended and alighted upon his shoulder and the bell began to toll. So Jack was made Pope of all Christendom, and he took the name of Pope Sylvester.