The Project Gutenberg EBook of On The Structure of Greek Tribal Society: An Essay by Hugh E. Seebohm

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: On The Structure of Greek Tribal Society: An Essay Author: Hugh E. Seebohm Release Date: August 18, 2008 [Ebook #26341] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ON THE STRUCTURE OF GREEK TRIBAL SOCIETY: AN ESSAY***

ON THE STRUCTURE

OF

GREEK TRIBAL SOCIETY

AN ESSAY

by

Hugh E. Seebohm

London

MacMillan And Co.

And New York

1895.

Contents

- Preface

- Chapter I. Introductory.

- Chapter II. The Meaning Of The Bond Of Kinship.

- § 1. The Duty Of Maintenance Of Parents During Life, And After Death At Their Tomb.

- § 2. The Duty Of Providing Male Succession.

- § 3. The Position Of The Widow Without Child And The Duties Of An Only Daughter.

- § 4. Succession Through A Married Daughter: Growth Of Adoption: Introduction Of New Member To Kinsmen.

- § 5. The Liability For Bloodshed.

- Chapter III. The Extent Of The Bond Of Kinship.

- § 1. Degrees Of Blood-Relationship; The Ἀγχιστεία.

- § 2. Limitations In Respect Of Succession Outside The Direct Line Of Descent.

- § 3. Division Amongst Heirs.

- § 4. Qualifications For The Recognition Of Tribal Blood.

- § 5. Limitations Of Liability For Bloodshed.

- Chapter IV. The Relation Of The Family To The Land.

- § 1. The Κλῆρος And Its Form.

- § 2. The Relation Of The Κλῆρος To The Οἶκος.

- § 3. The Householder In India: The Guest.

- § 4. Tenure Of Land In Homer: The Κλῆρος And The Τέμενος.

- § 5. Early Evidence continued: The Κλῆρος And The Maintenance Of The οἶκος.

- § 6. Early Evidence continued: The Τέμενος And The Maintenance Of The Chieftain.

- § 7. Summary Of The Early Evidence.

- § 8. Hesiod And His Κλήρος.

- § 9. Survivals Of Family Land In Later Times.

- § 10. The Idea Of Family Land Applied Also To Leasehold And Semi-Servile Tenure.

- Chapter V. Conclusion.

- Index.

- Footnotes

Preface

These notes, brief as they are, owe more than can be told to my father's researches into the structure and methods of the Tribal System. They owe their existence to his inspiration and encouragement. A suitable place for them might possibly be found in an Appendix to his recently published volume on the Structure of the Tribal System in Wales.

In ascribing to the structure of Athenian Society a direct parentage amongst tribal institutions, I am dealing with a subject which I feel to be open to considerable criticism. And I am anxious that the matters considered in this essay should be judged on their own merits, even though, in pursuing the method adopted herein, I may have quite inadequately laid the case before the reader.

My thanks are due, for their ready help, to Professor W. Ridgeway, Mr. James W. Headlam, and Mr. Henry Lee Warner, by means of whose kind suggestions the following pages have been weeded of several of their faults.

It is impossible to say how much I have consciously or unconsciously absorbed from the works [pg vi] of the late M. Fustel de Coulanges. His La Cité Antique and his Nouvelles Recherches sur quelques Problèmes d'Histoire (1891) are stores of suggestive material for the student of Greek and Roman customs. They are rendered all the more instructive by the charm of his style and method. I have merely dipped a bucket into his well.

In quoting from Homer, I have made free use of the translations of Messrs. Lang, Leaf, and Myers of the Iliad, and of Messrs. Butcher and Lang of the Odyssey; and I wish to make full acknowledgment here of the debt that I owe to them.

Some explanation seems to be needful of the method pursued in this essay with regard to the comparison of Greek customs with those of other countries. The selection for comparison has been entirely arbitrary.

Wales has been chosen to bear the brunt of illustration, partly, as I have said, because of my father's work on the Welsh Tribal System, partly because the Ancient Laws of Wales afford a peculiarly vivid glimpse into the inner organisation of a tribal people, such as cannot be obtained elsewhere.

The Ordinances of Manu, on the other hand, are constantly quoted by writers on Greek institutions; and, I suppose, in spite of the uncertainty of their date, they can be taken as affording a very fair account of the customs of a highly developed Eastern people. It would be hard, moreover, to [pg vii] say where the connection of the Greeks with the East began or ended.

The use made of the Old Testament in these notes hardly needs further remark. Of no people, in their true tribal condition before their settlement, have we a more graphic account than of the Israelites. Their proximity geographically to the Phœnicians, and the accounts of the widespread fame of Solomon and the range of his commerce, at once suggest comparison with the parallel and contemporaneous period of Achaian history, immediately preceding the Dorian invasion, when, if we may trust the accounts of Homer, the intercourse between the shores of the Mediterranean must have been considerable.

All reference to records of Roman customs has been omitted, not because they are not related or analogous to the Greek, but because they could not reasonably be brought within the scope of this essay. The ancestor-worship among the Romans was so complete, and the organisation of their kindreds so highly developed, that they deserve treatment on their own basis, and are sufficient to form the subject of a separate volume.

H. E. S.

The Hermitage, Hitchin.

July, 1895.

[Transcriber's Note: This e-book contains much Greek text which is often relevant to the point of the book. In the ASCII versions of the e-book, the Greek is transliterated into Roman letters, which do not perfectly represent the Greek original; especially, accent and breathing marks do not transliterate. The HTML and PDF versions contain the true Greek text of the original book. In the ASCII e-book, the markings such as (M1) indicate marginal notes, which were printed in the margins of the original book, but in the e-book are transcribed at the end with the footnotes.]

Chapter I. Introductory.

In trying to ascertain the course of social development among the Greeks, the inquirer is met by an initial difficulty. The Greeks were not one great people like the Israelites, migrating into and settling in a new country, flowing with milk and honey. Their movements were erratic and various, and took place at very different times. Several partial migrations are described in Homer, and others are referred to as having taken place only a few generations back. The continuation of unsettled life must have had the effect of giving cohesion to the individual sections into which the Greeks were divided, in proportion as the process of settlement was protracted and difficult.

But in spite of divergencies caused by natural surroundings, by the hostility or subservience of previous occupants of the soil, there are some features of the tribal system, wherever it is examined, so inherent in its structure as to seem almost indelible. A new civilisation was not formed to fit into the angles of city walls. Even modification could take place [pg 002] only of those customs whose roots did not strike too deeply into the essence of the composition of tribal society.

It is the object of these notes to try to put back in their true setting some of the conditions prevailing, sometimes incongruously with city life, among the Greeks in historical times, and by comparison with analogous survivals in known tribal communities, of whose condition we have fuller records, to establish their real historical continuity from an earlier stage of habit and belief.

There were three important public places necessary to every Greek community and symbolical to the Greek mind of the very foundations of their institutions. These were:—the Agora or place of assembly, the place of justice, and the place of religious sacrifice. From these three sacred precincts the man who stirred up civil strife, who was at war with his own people, cut himself off. Such an one is described in Homer as being, by his very act, “clanless” (ἀφρήτωρ), “out-law” (ἀθέμιστος), and “hearthless” (ἀνέστιος).1 In the camp of the Greeks before Troy the ships and huts of his followers were congregated by the hut of their chief or leader. Each sacrificed or poured libation to his favourite or familiar god at his own hut door.2 But in front of Odysseus' ships, which, we are told, were drawn up at the very centre of the camp, stood the great altar of Zeus Panomphaios—lord of all oracles—“exceeding fair.”3 “Here,” says the poet, “were Agora, Themis, and the altars of the gods.”

[pg 003]The Trojans held agora at Priam's doors,4 and it is noticeable that the space in front of the chief's hut or palace was generally considered available for such purposes as assembly, games, and so forth, just as it was with the ancient Irish.

In the centre of most towns of Greece5 stood the Prytaneum or magistrates' hall, and in the Prytaneum was the sacred hearth to which attached such reverence that in the most solemn oaths the name of Hestia was invoked even before that of Zeus.6 Thucydides states that each κώμη or village of Attica had its hearth or Prytaneum of its own, but looked up to the Hestia and Prytaneum in the city of Athens as the great centre of their larger polity. In just the same way the lesser kindreds of a tribe would have their sacred hearths and rites, but would look to the hearth and person of their chief as symbolical of their tribal unity. Thucydides also mentions how great a wrench it seemed to the Athenians to be compelled to leave their “sacred” homes, to take refuge within the walls of Athens from the impending invasion by the Spartans.7

The word Prytanis means “chieftain.” It is probable that, as the duties sacred and magisterial of the chief became disseminated among the other officers of later civilisation, the chief's dwelling, called the [pg 004] Prytaneum, acquiring vitality from the indelible superstition attaching to the hearth within its precincts, maintained thereby its political importance, when nothing but certain religious functions remained to its lord and master in the office of Archon Basileus.

Mr. Frazer, in his article in the Journal of Philology8 upon the resemblance of the Prytaneum in Greece to the Temple of Vesta in Rome, shows that both had a direct connection with, if not an absolute origin in the domestic hearth of the chieftain. The Lares and Penates worshipped in the Temple of Vesta, he says, were originally the Lares and Penates of the king, and were worshipped at his hearth, the only difference between the hearth in the temple and the hearth in the king's house being the absence of the royal householder.9

Mr. Frazer also maintains that the reverence for the hearth and the concentration of such reverence on the hearth of the chieftain was the result of the difficulty of kindling a fire from rubbing sticks together, and of the responsibility thus devolving upon the chieftain unfailingly to provide fire for his people. Whether this was the origin or not, before the times that come within the scope of this inquiry, the hearth had acquired a real sanctity which had become involved in the larger idea of it as the centre of a kindred, including on occasion the mysterious presence also of long dead ancestors.

The basis of tribal coherence was community of blood, actual or supposed; the visible evidence of the [pg 005] possession of tribal blood was the undisputed participation, as one of a kindred, in the common religious ceremonies, from which the blood-polluted and the stranger-in-blood were so strictly shut out.10 It is therefore in the incidence of religious duties, and in the qualifications of the participants, that it is reasonable to seek survivals of true tribal sentiment.

Although the religious life of the Greeks was always complex, there is not to be found in Homer the broad distinction drawn afterwards between public and private gods. It is noticeable that the later Greeks sought to draw into their homes the beneficent influence of one or other of the greater gods, whose protection and guidance were claimed in times of need by all members of the household. Secondary influences, though none the less strongly felt, were those of the past heroes of the house, sometimes only just dead, to be propitiated at the family tombs or hearth. Anxiety on this head, and the deeply-rooted belief in the real need to the dead of attentions from the living, were, it will be seen, most powerful factors in the development of Greek society.

The worship of ancestors or household gods as such is not evident in the visible religious exercises of the Homeric poems. But this can hardly be a matter of surprise. The Greek chieftains mentioned in the poems are so nearly descended from the gods themselves, are in such immediate relation each with his guardian deity, and are so indefatigable in their attentions thereto, that it would surely be [pg 006] extremely irrelevant if any of the libations or hecatombs were perverted to any intermediate, however heroic, ancestor from the all-powerful and ever ready divinity who was so often also himself the boasted founder of the family.11

The libations and hecatombs themselves, however, seem to serve much the same purpose as the offerings to the manes or household gods, and relieved the luxurious craving for sustenance in the immortals, left unsatisfied by their ethereal diet of nectar and ambrosia.12

Yet it is strange that if libations and sacrifices were paid to the dead periodically at their tombs, no mention of the occurrence is to be found in Homer. That the dead were believed to appreciate such attentions may be gathered from the directions given by Circe to Odysseus.

This done, the ghosts flock up to drink of the blood of the victim. But the ghost of Elpenor, who met his death at the house of Circe by falling from the roof in his drunken haste to join his already departed [pg 007] comrades, and who had therefore received no burial at their hands, demands no libations or sacrifices for the refreshment of his thirsty soul, but merely burial with tears and a barrow upon the shore of the gray sea, that his name may be remembered by men to come.

Nestor's son elsewhere is made to remark that one must not grudge the dead their meed of tears; for the times are so out of joint, “this is now the only due we pay to miserable men, to cut the hair and let the tear fall from the cheek.”14

Is the right conclusion then that the Homeric Greeks did not sacrifice at the tombs of their fathers, and that the so-called ancestor-worship prevalent later was introduced or revived under their successors? Or is it that the aristocratic tone of the poet did not permit him to bear witness to the intercourse with any deity besides the one great family of Olympic gods, less venerable than a river or other personification of nature?15

There exists such close family relationship amongst Homer's gods, extended as it is also to most of his chieftains, that taking into account the conspicuous [pg 008] reverence displayed towards the hearth and the respect for seniority in age, it may perhaps be justifiable to suppose that domestic religious observances, other than those directed to the Olympic gods, were thought by the poet to be as much beneath his notice as the swarms of common tribesmen who shrink and shudder in the background of the poems.

Ancestor-worship would be as much out of place in the Old Testament; and yet there are references in the Bible to offerings to the dead which, unless they are held to refer only to importations from outside religions and not to relapses in the Israelites themselves to former superstitions of their own people, imply that the great tribal religion of the Israelites had superseded pre-existing ceremonies of ancestor-worship.

The transgressions of the Israelites in the wilderness are described in the Psalms:—“They joined themselves also unto Baalpeor and ate the sacrifices of the dead.”16

It was not necessary for an ancestor to become a god to be worthy of worship, or to need the attentions of the living. If he was thought to haunt tomb or hearth, and to keep his connection thus with his family in the upper world, he required nourishment on his visits. He was also considered [pg 009] to keep a jealous watch on the continuance of his fair fame among the living.

A close resemblance in this point lies between the Homeric poems and the Old Testament. Though actual food and drink is not provided for the dead, yet the stress laid on the permanence of the family, lest the name of the dead be cut off from his place, is quite in keeping with the request of Elpenor to Odysseus to insure the continuance of his name in the memory of living men.

It is quite possible that, as the story of the interview of Odysseus with the dead reveals that the idea of the dead enjoying sacrifices of food and drink was familiar at that time, even though the periodical supply of such is not mentioned, so the existence of Laban's household gods and the gathering of the kindred of Jesse to their family ceremony17 may bear witness to the presence of a survival of ancestor-worship in some equivalent form, underlying the all-absorbing religion of the Israelites. At this day the spirits of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are considered by the Mohammedans of Hebron actually to inhabit the cave of Machpelah, and, in the case of Isaac at any rate, to be extremely angered by any negligence shown to their altars, either by omission of the customary ceremonies or by admission within the sacred precinct of any stranger of alien faith.

It must not therefore be inferred altogether that the regular ancestor-worship so-called was of later origin amongst the Greeks, but rather that the constitution of society did not afford it the same [pg 010] prominence to the mind of Homer and perhaps his contemporaries, as it acquired later.

M. Fustel de Coulanges, in La Cité Antique, has so well established the prevalence of ancestor-worship among the Greeks, drawing illustration both from Indian and Roman sources, that no further instances of its existence are needed here.

The ceremonies however and offerings at the tombs of their fathers did not supersede, amongst the Athenians at any rate, their worship of the Olympic gods. The Olympic gods themselves moreover were clearly connected with their family life. The protection of Zeus was specially claimed under the title of γενέθλιος or even σύναιμος18 and as ἑρκεῖος he received worship upon the altar that stood in the court-yard of nearly every house in Attica.19 The permanent place of these gods in the homes of the people is further denoted by the use of such epithets as ἐγγενεῖς20 and πατρῷοι.21

The tombs, on the other hand, were not approached with the purpose of invoking powerful aid, but rather with the intent of soothing a troubled spirit with care and attention, and of providing it with such nourishing refreshment as could not be procured in the regions of the starving dead.

The same idea of nourishment of the dead, though shared with the other gods, determines the offerings in the Egyptian Book of the Dead.23

There is one passage that almost implies that the dead retained in idea a claim upon the produce of the land which nourished them whilst alive, or that they had a special allotment even in the other world:—

Chapter cxliv. of the Book of the Dead is to be said,

Chapter cxlviii. ordains that there

In the next chapters frequent reference will be made to the offerings to ancestors, or manes, among the ancient Hindoos. With them the cake-offering to the dead became a most important symbol, uniting in a common duty all descendants from certain ancestors within fixed degrees, and marking them off in the matter of responsibility thereto from more distant relations, who owed similar duty elsewhere.

Being thus surrounded by nations that believed intensely in the need in the dead of nourishment at the hands of their relatives on earth, it would indeed be surprising if the Greeks were found not to share in the belief. But the fact remains that in the earliest Greek literature it is least conspicuous, and the gulf seems widest between the living and the dead. Can this be laid to the charge of the artificial superstitions of a philosophical class of poets? Or is it due to the true evolution of such beliefs, that as long as our search touches upon the unsettled periods of semi-migratory life, the tombs of individual members of a family being scattered here or there wherever they meet their deaths, the offering to the dead takes a special form, inasmuch as the solidarity of the tribe eclipses the importance of the family as a unit, and the religious ceremonies of the chieftain absorb the attention of the lesser members of the tribe?

M. de Coulanges points out that the meaning of the Latin word Lar is lord, prince or master, and [pg 013] that Hestia was sometimes designated by the Greeks with the similar title of mistress of the house, or princess.27

If, as long as the tribe was felt to be a real unit, the religious instincts of the tribesmen were concentrated upon the worship of their tribal deities—the great ancestors of the tribe, and more emphatically and directly the ancestors of their chieftain—it would be quite natural, in the weakening of the central worship, for the titles of honour and respect to be used equally towards those meaner ancestors who henceforth occupied the religious energies of the head of each family or household. In fulfilment of a similar sentiment, the later Greeks commonly used the word ἥρως in speaking of a dead friend, deeming that any one who departed this life passed to the ranks of those princes of the community from whom all were proud to trace descent.

M. de Coulanges considers that the sacred rites of the family at the hearth formed a more real tie than the belief in a common blood; and that upon this religious basis was built up the greater hearth of the Prytaneum as the centre of city life, to bind together the several families composing the community. But without pretending to come to a final decision on this the main tendency of social development, surely something may yet be said in favour of the contrary theory; that the reverence that centred in the hearth was in effect the expression of the sanctity of the tie of blood, as felt by all members of the house, and that this feeling drew its real importance for the community, [pg 014] not from the founding of the city by the amalgamation of several families, but as a survival from an earlier stage of life, when society circled round what was then in more than name the Prytaneum of the tribal chieftain.

Facts are wanting to justify a conclusion as to which of these theories bears the closest resemblance to the truth, but it is easy to imagine what might be the line of development if the latter hypothesis be maintained.

During the wanderings and migrations of peoples in the search for greener pastures or broader lands, each community or tribe would be constantly under arms and subject to attack from the enemies they were passing through or subjugating. This constant sojourning in a strange land, surrounded by foes, would be a source of much solidarity to the tribe itself, drawing its members closely together for mutual defence and subsistence.

But when once the tribe had found a country to its taste, and had made a settlement with borders comparatively permanently established, emphasis would be transferred to the petty quarrels and internal dissensions arising between different sections within the community itself. The tie of common blood, uniting all members of the tribe, would be gradually disregarded and displaced by the less homely and more political relation of fellow-citizenship, which, though retaining many of the characteristics of the tribal bond, would necessarily be felt in a very different manner.

In this disintegration of the larger unit, the existence of kinship by blood would be acknowledged [pg 015] only where the relationship was obvious and well known. And it would no longer be sufficient merely to prove membership of a kindred; as those outside certain limits would claim exemption from the responsibilities entailed by closer relationship.

So, too, in the matter of religious observance: the reverence of the individual for the Prytaneum and common hearth of the state would undergo a change into a less personal sentiment; the rites connected therewith would be delegated to an official priest; and it is with the head of each family, surrounded by those who are really conscious of their connection by blood in common descent from much more immediate ancestors, that the true tribal feeling would longest survive, though, of course, on much narrower lines.

The privileges of citizenship were, it will be seen, as carefully guarded as those of the tribe, but in a more perfunctory and arbitrary manner; whilst the intimate connection of the members of the family with the hearth and the graves of their ancestors stands out in strong relief.

By the time of Hesiod, besides the violation of the universal sanctity of a guest or suppliant, the chief sins are against members of the same household, defrauding orphans, or insulting an aged parent.28 Behaviour to other than blood-relations is regulated by expediency, by what you may expect in return from your neighbours.29

Whether the family is to be regarded as the chief factor in the composition of the city, or how much of [pg 016] its composition the city owes to direct inheritance from the tribal system, must, as has been said, be left unsolved. Some small light may perhaps be shed upon the problem as this inquiry proceeds.

At any rate, if the true basis of the organisation of the family and the kindred, as found in historic times in Greece, could once be established, material assistance ought to have been gained for rightly understanding the structure of that earlier society, whatever it was, from which the rules, that govern those within the bond of kinship, were survivals.

Chapter II. The Meaning Of The Bond Of Kinship.

§ 1. The Duty Of Maintenance Of Parents During Life, And After Death At Their Tomb.

As the hearth was the centre of the sanctity and reverence of the family, so the word οἶκος was the customary term to signify the smaller group of the composite γένος, consisting of a man and his immediate descendants. In the first place, the individual was absolutely committed to sacrifice all his personal feelings for the sake of the continuity of his οἶκος, and this was his supreme duty. But whereas several οἶκοι traced their descent from a common ancestor, a group of gradually diverging lines of descent were formed, sharing mutually the responsibility of the maintenance of continuity, and the privilege of inheritance and protection.

Before examining how far these parallel lines remained within the reach of claims of kinship, or how soon the reverence for the more immediate predecessors [pg 018] absorbed the memory of the more remote ancestor, it will be well to have a clear understanding of what the claims of kindred were, and how they affected the member of the οἶκος, in respect of his duties thereto.

Plato30 declares that honour should be given to:—

1. Olympian Gods.

2. Gods of the State.

3. Gods below.

4. Demons and Spirits.

5. Heroes.

6. Ancestral Gods.

7. Living Parents, “to whom we have to pay the greatest and oldest of all debts: in property, in person, in soul; paying the debts due to them for the care and travail which they bestowed on us of old in the days of our infancy, and which we are now to pay back to them when they are old and in the extremity of their need.”

The candidates for the archonship were asked, among other things, whether they treated their parents properly.31 It was only in case of some indelible stain, such as wife-murder, that the debt of maintenance of the parent was cancelled.32 Yet even when the father had lost his right of maintenance by crime or foul treatment, the son was still bound to bury him when he died and to perform all the customary rites at his tomb.33

[pg 019]“Is it not,” says Isaeus, “a most unholy thing, if a man, without having done any of the customary rites due to the dead, yet expects to take the inheritance of the dead man's property?”34

The duty of maintenance of the parent thus extended even beyond the tomb, and this retrospective attitude of the individual gives us the clue to his position of responsibility also with regard to posterity.

The strongest representation possible of this attitude is given in the Ordinances of Manu, where it is stated that a man “goes to hell” who has no son to offer at his death the funeral cake.

“No world of heaven exists for one not possessed of a son.” The debt, owed by the living member of a family to his manes, was to provide a successor to perform the rites necessary to them after his own death.

i.e. one representative was sufficient as regards the duties to the manes in the house of the grandfather.

Plato expresses the same feeling in the Laws:36

The functions and duties of the individual towards his family and relations thus find their explanation in his position as link, between the past and the future, in the transmission to eternity of his family blood.

His duties to his ancestors began with the death of his father. He had at Athens to carry out the corpse, provide for the cremation, gather the remains of the burnt bones, with the assistance of the rest of the kindred,37 and show respect to the dead by the usual form of shaving the head, wearing mourning clothes, and so on. Nine days after the funeral he must perform certain sacrifices and periodically after that visit the tombs and altars of his family in the family burying-place.38 If he had occasion to perform military service, he must serve in the tribe and the deme of his parent (στρατεύειν ἐν τῇ φυλῇ καὶ ἐν τῷ δήμῳ).39 Before he can enter into his inheritance he must fulfil all the ordinances incumbent on one in his position, and in the Gortyn Laws it is [pg 021] stated that an adopted heir cannot partake of the property of his adoptive father unless he undertakes the sacred duties of the house of the deceased.40 Thus the right of ownership of the family estate rested always with the possession of the blood of the former owners; and such a representative demonstrated his right by stepping into his predecessor's shoes and by taking upon himself all responsibility for the fulfilment of the rites, thereafter to be performed to him also when he shall have been gathered to the majority of his family.

§ 2. The Duty Of Providing Male Succession.

But however piously and carefully he performed his many duties to his ancestors, his work was only transitory and incomplete, unless he provided a successor to continue them after him into further generations.

The procreation of children was held to be of such importance at Sparta41 that if a wife had no children, with the full knowledge of her husband she admitted some other citizen to her, and children born from such a union were reckoned as born to the continuation of her husband's family, without breach of the former relations of husband and wife.42 This is the exact custom stated in the Ordinances of Manu [pg 022] (ix. 59), where it is laid down that a wife can be “commissioned” by her husband to bear him a son, but she must only take a kinsman within certain degrees, whose connection with her ceases on the birth of one son.43 Otherwise it was a man's duty to divorce a barren wife and take another. But he must divorce the first, and could not have two hearths or two wives.44

A curious instance of how this sentiment worked in practice in directly the opposite direction to our modern ideas, is mentioned in Herodotus. Leaders of forlorn hopes nowadays would be inclined to pick out as comrades the unmarried men, as having least to sacrifice and fewest duties to forego. Whereas Leonidas, in choosing the 300 men to make their famous and fatal stand at Thermopylae, is stated to have selected all fathers with sons living.45

Hector is made to use this idea in somewhat similar manner. He encourages his soldiers with:—

If the enemy are driven out, though he be killed himself, yet if he leave children behind, his household and their property will remain unharmed.

All about to die, says Isaeus, take thought not to leave their οἶκος desolate (ἔρημος),47 but that there shall be some one to carry the name of their house [pg 023] down to posterity, who shall perform all the customary rites at the tomb due to them also when they shall have joined the ranks of ancestors.48

Where children were reckoned of the tribe of their father and not of their mother, and where a woman was incapable of performing sacred rites, a male heir was necessary for the direct transmission of blood and property. Sons entered upon their inheritance immediately on the death of their father, nor had he the power to dispossess them in favour of others, whilst brothers, cousins, legatees, had always to prove their title and procure judgment from the court in their favour.49

Failing sons however, the next descent lay through a daughter. Nor were her qualifications in herself complete or sufficient in theory to form the necessary link in the chain of succession. The next of kin male had to marry her with the property of which she was ἐπίκληρος;50 but neither she nor he really possessed the property, and the sons born from the marriage succeeded thereto directly on attaining a certain age. The next of kin had in the meantime of course to represent his wife's father in all the religious observances, and was said to have power to live with the woman (κύριος συνοικῆσαι τῇ γυναικί), but not to dispose of the property (κύριος τῶν χρημάτων);51 the sons becoming κύριοι τῶν χρημάτων at sixteen years old, and owing thence only maintenance (τρέφειν) to their mother from [pg 024] the property.52 The heiress was compelled to marry at a certain age and was adjudicated by law to the proper kinsman.53

Again an exact parallel is to be found in the Ordinances of Manu:—

The whole property of a man is taken by this daughter's son,54 and, by her bearing a son, her father “becomes possessed of a son, who should give the funeral cake and take the property.”55

If she die without a son, her husband would take (presumably by a sort of adoption).56 But this would be perfectly natural, if, as in Greece, her husband was bound to be the next of kin and therefore heir failing issue from her.

At Athens it was part of the office of the archon to see that no οἶκος failed for want of representatives, to constrain a reluctant heiress to marry or to compel the next of kin to perform his duty. Plato57 asks pardon for his imaginary legislator, if he shall be found to give the daughter of a man in marriage having regard only to the two conditions—nearness of kin, and the preservation of the property; disregarding, in his zeal for these, the further considerations, which the father himself might be expected [pg 025] to have had, with regard to the suitability of the match.58

A certain leniency was however allowed to the heiress who was unwilling to marry an obnoxious kinsman, and to the kinsman who had counterclaims upon him in his own house. Nevertheless the rules remained very strict. Isaeus states emphatically,59 “Often have men been compelled by law to give up their properly wedded wives, owing to their becoming ἐπίκληροι through the death of their brother to their father's property and having to marry the next of kin (τοῖς ἐγγυτάτα γένους),” to prevent the extinction of their father's house.

Manu warns those about to marry to be careful that their children shall not be required to continue their wives' father's family, to the desolation of their own.

Again Isaeus:—

In the laws of Gortyn very clear rules are laid [pg 026] down to be followed where there were difficulties in the way of the heiress marrying the next of kin.

There is also a statement made by Demosthenes63 that sounds as if it might have come from the Ordinances of Manu. It is there stated that if there were more than one heiress, only one need be dealt with in respect to providing succession, though all shared in the property.

The law of Gortyn goes on:—

Such pains were taken to find a representative [pg 027] for the deceased in his family, or at any rate in his tribe.64

The same questions seem to have arisen amongst the Israelites in the time of Moses.

§ 3. The Position Of The Widow Without Child And The Duties Of An Only Daughter.

The levirate, or marriage with deceased husband's brother, seems to have had no place in Greek family law. The wife was of no kin necessarily to the husband; and so it would not tend to strengthen the transmission of blood if the next of kin married the widow on taking the inheritance of his relative deceased without issue. The wife in Greek law could not inherit from her husband, whose property went to his father's or mother's relations; and only when it became a question of finding an heir to her son, and failing all near paternal kinsmen, could the [pg 028] inheritance pass through her, and then as the mother of her dead son, not as widow of her dead husband. Even then, being a woman, she had no right of enjoyment, only of transmission. She could only inherit on behalf of her issue by a second husband, and failing her issue the inheritance would pass to her brothers and so on. In Greece the claim upon the δαήρ (Latin levir) for marriage seems to have begun with his brother's daughter, not his brother's widow.

The childless widow on the death of her husband had to return to her own family or whoever of her kindred was guardian (κύριος) of her, and if she wished, be given again in marriage by him.65

The woman at Athens even after marriage always retained her κύριος or guardian,66 who was at once her protector and trustee. He was probably the head of the οἶκος to which she originally belonged—her next of kin—and had great power over her.67

A case there is68 where the heir to the property also takes the wife of the previous owner; but in this case the husband may have been κύριος of his own [pg 029] wife, and so could bequeath, or give her away to whomever he liked.69

In the Ordinances of Manu, the limitations of the levirate are very strictly defined.70 In the case of a man leaving a widow, she must not marry again, or she lost her place in heaven by his side.

But if she was childless, the next of kin of her husband must beget one son by her; he did not marry her, and his connection with her ceased on the birth of a son.

The laws of Manu otherwise are strict against the marriage of close relations; a restriction not found in Greece.

Isaeus71 mentions that it was thought quite natural for a man to marry his first cousin in order to concentrate the family blood, and prevent her dowry or whatever property might come to her from going outside his οἶκος, and we know that even marriage with a half-sister (not born of the same mother) was not forbidden.

There are more instances than one in Homer of a man marrying his aunt, or niece.

The nearest resemblance to the levirate in Greece is the occasional custom at Sparta, mentioned already, of a wife being “commissioned” to bear children by another man into the family of her husband. But this exists in Manu, side by side with the above-mentioned custom of levirate proper.

Among the Israelites, the levirate was in full force; the craving for continuance was the same as among the followers of Manu and the Greeks; and [pg 030] the custom with regard to heiresses is so vividly told that it is worth quoting at some length.

Such was the scorn felt for the man who refused to perform the duties of nearest kinsman. In the thirty-eighth chapter of Genesis is told the story of Tamar, the wife of Judah's eldest son who died childless. The second son's refusal to raise up seed to his brother because he knows that his own name will not be perpetuated thereby, but his brother's, meets with summary punishment. “And the thing that he did was evil in the sight of the Lord, and He slew him also.”72 Afterwards, when it was reported to her father-in-law that Tamar had a child by some one not of his family, he was exceedingly wroth, and said, “Bring her forth and let her be burnt.” Accordingly, after he had received his own “tokens” from her hand, [pg 031] his approval of her action, in her desire to perpetuate the name of her dead husband, is all the more striking, and shows how real such a claim as Tamar's was in the practice of those days, extreme though her action was felt to be. And Judah acknowledged his tokens and said, “She hath been more righteous than I: because that I gave her not to Shelah my [youngest] son.”

The statement of the customary procedure in Deuteronomy is very picturesquely illustrated and fulfilled in detail in the story of Ruth, who though only a daughter-in-law takes the position of heiress through a sort of adoption by her mother-in-law Naomi, on her refusal to go back to her own people. “Where thou goest, I will go: where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God, my God. Where thou diest will I die, and there will I be buried.” She accepts Naomi's hearth her kin, her religion, and finally her tomb.

Elimelech and his two sons dying in Moab, Naomi and both her daughters-in-law are left widows in a strange land. If Naomi had other sons, upon them would have devolved the duty of taking Orpah and Ruth to wife. But Naomi declares herself73 too old to marry again and be the mother of sons, and implores her daughters-in-law to return to their own people in Moab, where she hopes they will start afresh with new husbands, a course which seems always to have been open to wives in tribal communities. Orpah does so, but Ruth elects to remain with Naomi, and returning with her to Bethlehem takes her chance [pg 032] among the kindred of Elimelech. Happening to arrive at Bethlehem at the beginning of the barley harvest, it so chances that Ruth goes forth to glean upon that part of the open field which belonged to Boaz—a rich man of the συγγενία of Elimelech, who, having heard of her devotion to Naomi and the house of his late kinsmen, protects her from possible insult from strangers and treats her richly. On her return home Naomi informs her that Boaz is of their next of kin (τῶν ἀγχιστευόντων)74 whose place it was to redeem property sold or lost by a kinsman. This duty is thus set forth in Leviticus:—

An instance of it in practice is given in Jeremiah.

But on Ruth's applying to Boaz, he informs her that though he is ἀγχιστεύς, i.e. within the reach of the claim on the next of kin, yet is there one ἀγχιστεύς who is nearer than he, and who must first be asked.

The rendering of the Vulgate of the kinsman's reply is more easily understood:—“I yield up my right of near kinship: for neither ought I to blot out the continuance (posteritas) of my family: do thou use my privilege, which I declare that I freely renounce.”

Now Boaz was sixth in descent from this Perez whose mother Tamar, as quoted above, had been in much the same position as Ruth.

It is interesting to read further that the son born of this marriage of Ruth and Boaz is taken by the women of Bethlehem to Naomi, saying, “There is a son born to Naomi,” emphasising the duty of the heiress to bear a son, not into her husband's family, but to that of her father.

[pg 034]The story of Ruth is not, therefore, an exact example of the custom of levirate. But it illustrates incidentally the unity of the family. The sons of Elimelech died before the family division had taken place, and the house of Elimelech their father was thus in jeopardy of extinction. If Naomi had come within the proper operation of the levirate, the next of kin ought to have married her, but by her adoption of Ruth as her daughter, she gave Ruth the position of heiress or ἐπίκληρος, whilst the heir born to Ruth was called son, not of Ruth's former or present husband, but of Elimelech and (by courtesy) of Naomi, Elimelech's widow, through whom the issue ought otherwise to have been found.

§ 4. Succession Through A Married Daughter: Growth Of Adoption: Introduction Of New Member To Kinsmen.

But if the heiress was already married and had sons, she need not be divorced and marry the next of kin, though that still lay in her power. It was considered sufficient if she set apart one of her sons to be heir to her father's house. But she must do this absolutely: her son must entirely leave her husband's house and be enfranchised into the house of her father. If she did not do this with all the necessary ceremonies, the house of her father would become extinct, which would be a lasting shame upon her.

Isaeus75 mentions a case where a wife inherits from her deceased brother a farm and persuades her [pg 035] husband to emancipate their second son in order that he may carry on the family of her brother and take the property.

In another passage76 the conduct of married sisters in not appointing one of their own sons to take his place as son in the house of their deceased brother, and in absorbing the property into that of their husbands, whereby the οἶκος of their brother became ἔρημος, is described as shameful (αἰσχρῶς).

In Demosthenes77 a man behaving in similar wise is stigmatised as ὑβριστής.

Herein lay the reason that adoption became so favourite a means in classical times of securing an heir. It became almost a habit among the Athenians who had no sons, to adopt an heir—often even the next of kin who would naturally have succeeded to the inheritance.78

The transfer of the adopted son from the οἶκος of his father to the οἶκος he was chosen to represent was so real that he lost all claim to inheritance in his original family, and henceforth based his relationship and rights of kinship from his new position as son of his adoptive father. This absolutely insured the childless man that his successor would not merge the inheritance in that of another οἶκος, and made it extremely unlikely that he would neglect his religious duties as they would be henceforth his own ancestral rites.

Sometimes, it seems,79 sons of an unfortunate [pg 036] father were adopted into another οἶκος so as not to share in the disgrace brought upon their family. In such a case presumably their father's house would be allowed to become extinct.

The inheritance of property being only an accessory to the heirship,80 the ceremony of adoption consisted of an introduction to the kindred and to the ancestral altars, and an assumption of the responsibilities connected therewith.

The process was the same as for the proclamation of the true blood of a son, and was exactly in accordance with tribal instincts.

Whatever the history of the φρατρία at Athens, in it seems to have been accumulated a great number of the survivals of tribal sentiment.

The adoption at Athens took place at the gathering of the phratores in order that all the kin might be present (παρόντων τῶν συγγενῶν).81 The adopter must lead his son to the sacrifices on the altars82 and must show him to the kinsmen (συγγενεῖς or γεννῆται) and phratores: he must give assurance on the sacrifices that the young man was born in lawful wedlock from free citizens. This done, and no one questioning his rights, the assembly proceeded to vote83 and if the vote was in his favour, then and not till then he was enrolled in the common register (εἰς τὸ κοινὸν γραμματεῖον) of the phratria in the name of son of his adopted father. As a father could not without reason disinherit his true-born sons, so the phratores could not without reason refuse to accept them to the kinship.84

[pg 037]If any of the phratores objected to the admission of the new kinsman, he must stop the sacrifices and remove the victim from the altar.85 He would have to state the grounds of his objection, and if he could not produce good reasons, he incurred a fine. If there was no objection, the unsacrificial parts of the victim were divided up and each member took home with him his share,86 or joined in a feast provided by the father of the admitted son.87

The ceremonial given in the Gortyn laws is similar:—

The adopted son gets all the property and shall fulfil the divine and human duties of his adoptive father88 and shall inherit as in the law for true-born sons. But if he does not fulfil them according to law, the next of kin shall take the property. He can only renounce his adoption by paying a fine.

The adopted son thus introduced was considered to have become of the blood of his adoptive father, and was unable to leave his new family and return to his original home unless he left in the adoptive house a son to carry on the name to posterity. As long as he remained in the other οἶκος, i.e. had not provided for his succession and by certain legal ceremonies been readmitted to his former family, he [pg 038] was considered of no relationship to them and had no right of inheritance in their goods.89

An adopted son could not adopt or devise by will, and if he did not provide for the succession by leaving a son to follow him, the property went back into the family and to the next of kin of his adopted father.90

If he did return to his former οἶκος, leaving a son in his place and that son died, he could not return and take the property thus left without heir direct.91

Adoption amongst the Hindoos took place in like manner before the convened kindred. The adopting father offered a burnt-offering, and with recitation of holy words in the middle of his dwelling completed the adoption with these words:—

The adopted son should be as near a relation as possible, and when once the ceremony had taken place, was considered to have as completely lost his position in his former family as if he had never been born therein.93

The introduction into the deme which took place at the age of eighteen at Athens, including the enrolment in the ληξιαρχικόν γραμματεῖον, seems to have been a registration of rights of property and an assumption of the full status of citizen. The word ληξιαρχικός is [pg 039] defined by Harpocration as meaning “capable of managing the ancestral estate (τὰ πατρῷα οἰκονομεῖν).” The word λῆξις is used by Isaeus for the application, by others than direct descendants, to the Archon for the necessary powers to take their property.

It appears to have been at this period that the young man left the ranks of boyhood and dedicated himself to the responsibilities of his life.

Plutarch94 states that it was the custom at coming of age to tonsure the head and offer the hair to some god, and describes the young Theseus as adopting what we know as the Celtic tonsure, thenceforth called after his name.

This cutting the hair as token of dedication to any particular object or deity was of common occurrence. Achilles' hair was dedicated as an offering to the river Spercheios in case of his safe return.98 Knowing that this is impossible, in his grief at the death of Patroklos, with apologies to the god he cuts his [pg 040] flowing locks and lays them in the hand of his dead friend.

Pausanias declares that it was the custom with all the Greeks to dedicate their hair to rivers.99

Theophrastus100 mentions as a characteristic of the man of Petty Ambition that he will “take his son away to Delphi to have his hair cut (ἀποκεῖραι),” showing that this venerable custom had by that time become pedantic and an object of ridicule.

According to Athenaeus,101 when the young men cut their hair they brought a large cup of wine to Herakles and, pouring a libation, offered it to the assembled people to drink.

The age at which the hair was cut seems to have varied. The Ordinances of Manu102 give the following instructions:—

But whenever the actual tonsure was performed, it seems to have been a very widely spread custom, symbolical in some way of devotion to a deity or kindred, or to some particular course of life.

Its importance in this place, however, lies in its being one of the special acts relating to the admission to tribal status, and to the devotion, so to speak, of the services of the individual to the corporate needs of his tribe or kindred.

The public introduction to the kindred, combined [pg 041] with publicity of marriage and of the birth of children would, it is obvious, be a very important protection for the preservation of the jealously guarded purity of the tribal blood. Isaeus104 says that all relations (προσήκοντες), all the phratores, and most (οἱ πολλοί) of the demesmen would know whom a man married, and what children he had. This, in addition to the oath (πίστις) of the father or of the mother105 of the legitimacy of the son introduced to his kin, would seem a very sufficient safeguard.106

If a child was not introduced to the phratores, it was considered illegitimate,107 and could have no share in the rites of kindred and property.108

§ 5. The Liability For Bloodshed.

A notable feature of the tribal system all over the world was the blood-feud, wiped out only by the death of the manslayer or by the payment of a sufficient recompense. The incidence of the responsibility for murder and for payment of the recompense upon a group instead of only on the guilty individual was of remarkable tenacity, and survived to comparatively late days.

In Arabia the whole tribe of the murderer subscribed to the blood-money, which went to all the males in the tribe of the murdered man.109

[pg 042]But in Greece the responsibility fell upon the next of kin, with the help and under the supervision of the rest of the immediate kindred. He had to see that a spear was carried in front of the funeral of the slain man and planted in his grave, which must be watched for three days.110 He must make proclamation of the foul deed at the tomb, and must undergo purificatory rites, himself and his whole house (οἰκία). If the dead body be found in the country and no cause of death known, the demarch must compel the relatives to bury the corpse and to purify the deme on the same day.111

The subject is a familiar one in Homer. The wanderer (μετανάστης) is said to have no value (he is ἀτίμητος), no fine is exacted for his death.

There are many men told of in the Iliad and Odyssey who were in the position of refugees at the court of some chief. As many of them were wealthy—chiefs' sons or even chiefs—and well able to pay large recompenses, it seems probable that (as is definitely stated in some instances), if the murder was committed on a member of the same family or tribe as the murderer, [pg 043] the only way to wipe out the stain was by death or perpetual exile, as in the case of the typical fratricide Cain. The blood-price was then only between tribe and tribe or city and city. Within the kindred there would be no ransom allowed.113

Medon had slain the brother of his step-mother and was a fugitive from his country.114

Epeigeus ruled (ἤνασσε) fairest Boudeion of old, but having slain a good man of his kin (ανεψιόν), to Peleus fled, a suppliant.115

Tlepolemos slew his own father's maternal uncle, gathered much folk together and fled across the sea, because the other sons and grandsons of his father threatened him.116

If ransom there was none for the murderer within the tribe, there was equally none for murders between citizen and citizen,—in this point also the inheritors of the sentiments of tribesmen. In the law of Solon118 it [pg 044] was forbidden to take payment in compensation from the murderer:—

Plato119 describes the soul of the deceased as troubled with a great anger against the murderer, so that even the innocent and unintentional homicide must needs flee at any rate for a year. The presence too of a man thus denied with bloodshed at the sacred altars was held to be a gross impiety and source of divine anger. Plato120 says:—

In the case of a suicide, the hand that committed the crime was to be cut off and buried separately.

In Isacus122 it is related how Euthukrates in a quarrel over a boundary-stone was so flogged by his brother Thoudippos that, dying some days after, he charged his friends (οἱκεῖοι) not to allow any of Thoudippos' people (τῶν Θουδίππου) to approach his tomb. But if the murdered man before his death forgave his murderer, the relatives could not proceed against him.

If the murderer escaped fleeing he must go forever: if he returned he could be killed at sight by any one and with impunity.123 The pollution rested on the whole kindred of the murdered man.

The pollution cannot be washed out until the homicidal soul has given life for life and has laid to sleep the wrath of the whole family (ξυγγένια).125

If it is a beast that has killed the man, it shall be slain to propitiate the kin and atone for the blood shed.

If it is a lifeless thing that has caused death, it shall solemnly be cast out before witnesses to acquit the whole family from guilt.126

Amongst the Israelites, treating of homicides amongst themselves, compensation was forbidden in like manner.

Let us complete this subject with the following story told by Herodotus:127—Adrastus, having slain his brother, flees to the court of Croesus. There he becomes as a son to Croesus and a brother to Atys, Croesus' son. This Atys Adrastus has the terrible misfortune to slay, thereby incurring a three-fold pollution. He has brought down upon himself the triple wrath of Zeus Katharsios, Ephestios, and Hetaireios: he has violated his own innocence, his protector's hearth, and the comradeship of his friend.

In despair he commits suicide.

Chapter III. The Extent Of The Bond Of Kinship.

§ 1. Degrees Of Blood-Relationship; The Ἀγχιστεία.

Such being the character of the burden of mutual responsibility borne by members of kindred blood, it remains, if possible, to obtain some idea of how this responsibility became narrowed and limited to the nearest relations, and what was the meaning underlying the distinction drawn between certain degrees of relationship.

When examining the more detailed structure of the organisation of the kindred, considerable light seems to be thrown upon survivals in Athens by comparison with the customs of other communities, which were undergoing earlier stages of the same process of crystallisation from the condition of semi-nomadic tribes into that of settled provinces or kingdoms.

[pg 047]

In the Gortyn Laws we read:—

The headship of the οἶκος and the ownership of the property vested in the parent as long as he lived and wished to maintain his power. Even after his death, unless they wished it, the sons need not divide up amongst themselves, but could live on with joint ownership in the one οἶκος of their deceased father. The eldest son would probably take the house itself, i.e. the hearth, with the duties to the family altars which devolved upon him as head of the family.128

An example of this joint ownership occurs in the speech of Demosthenes against Leochares.129 The two sons of Euthumachos after his death gave their sister in marriage (no doubt with her proper portion), and lived separately but without dividing their inheritance (τὴν οὐσίαν ἀνέμητον). Even after the marriage of one brother, they still left the property undivided, each living on his share of the income, one in Athens, the other in Salamis.

The possibility of thus living in one οἶκος and on an undivided patrimony is implied in another passage in Demosthenes, where, however, the exact opposite is described as actually having taken place.130

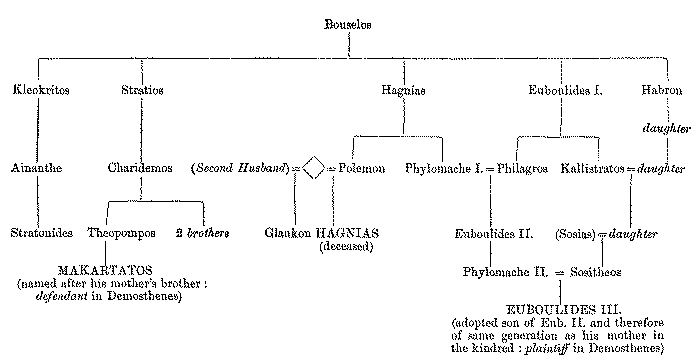

Bouselos had five sons. He divided (διένειμεν τὴν οὐσίαν) his substance amongst them all as was fair and right, and they married wives and begat children and [pg 048] children's children. Thus five οἶκοι sprang up out of the one of Bouselos, and each brother dwelt apart, having his own οἶκος and bringing up his own offspring (ἔκγονοι) himself (χωρὶς ἕκαστος ᾤκει).

Whilst the parents were alive the family naturally held very closely together, and often probably lived in one patriarchal household like Priam's at Troy.

Isaeus declares:—The law commands that we maintain (τρέφειν) our parents (γονεῖς): these are—parents, grandparents and their parents, if they are still alive:

The duty of maintenance (τρέφειν) owed to the ancestor would follow the same relationship as the right of inheritance from him, and this common debt towards their living forebears could not help further consolidating the group of descendants already bound together by common rites at the tombs of the dead.

But granted this community of rights and debts, is it possible to formulate for the Greeks anything of the same limitations in the incidence of responsibility amongst blood-relations that is to be found elsewhere?

In western Europe, owing perhaps to the influence of Christianity, the rites of ancestor-worship have no prominence. Ecclesiastical influence however was unable to prevent an exceedingly complex subdivision of the kindred existing in Wales and elsewhere. Whether this subdivision finds its raison d'être in the worship of ancestors or not, the groups [pg 049] thus formed serve as units for sustaining the responsibilities incident to tribal life, and being, as will be seen, governed by similar considerations to those existing among the Greeks, they afford very suitable material for comparison, and throw considerable light upon one another.

As the various departments affected by blood-relationship or purity of descent come under notice, it will be seen that the position of great-grandson as at once limiting the immediate family of his parents and heading a new family of descendants is marked with peculiar emphasis.

In the ancient laws of Wales it rests with great-grandsons to make the final division of their inheritance and start new households.

Second cousins may demand redivision of the heritage descending (and perhaps already divided up in each generation between) from their great-grandfather. After second cousins no redivision or co-equation can be claimed.132

In the meanwhile the oldest living parents maintained their influence in family matters. In the story of Kilhwch and Olwen, in the Mabinogion, the father of Olwen, before betrothing her to Kilhwch, declares that “her four great-grandmothers and her four great-grandsires are yet alive; it is needful that I take counsel of them.”133

Even when feudalism refused to acknowledge other than an individual responsibility for a fief, it was unable to overcome the tribal theory of the [pg 050] indivisibility of the family, which maintained its unity in some places even under a feudal exterior. But as generations proceeded, and the relationships within the family diverged beyond the degree of second cousin, a natural breaking up seems to have taken place, though in the direction of subinfeudation under the feudal enforcement of the rule of primogeniture, instead of the practice, more in accordance with tribal instincts, of equal division and enfranchisement. It may however be surmised that the subdivision and subinfeudation of a holding in the occupation of such a group of kinsmen would be carried out by the formation of further similar groups.

In the Coustumes du Pais de Normandie mention is made of such a method of land-holding, called parage. It consists of an undivided tenure of brothers and relations within the degree of second cousins.

The eldest does homage to the capital lord for all the paragers. The younger and their descendants hold of the eldest without homage, until the relationship comes to the sixth degree inclusive (i.e. second cousins). When the lineage is beyond the sixth degree, the heirs of the cadets have to do homage to the heirs of the eldest or to whomsoever has acquired the fief. Then parage ceases.134

The tenure then becomes one of subinfeudation. As long as the parage continued, the share of a deceased parager would be dealt with by redivision of rights, and no question would arise of finding heirs. But when it became a question of [pg 051] finding an heir to the group, failing heirs in the seventh degree inclusive, that is, son of second cousins—looked upon as son to the group—failing such an heir, the estate escheated to the lord.

There is an interesting passage in the Ancient Laws of Wales ordaining that the next-of-kin shall not inherit as heir to his deceased kinsman, but as heir to the ancestor, who, apart from himself, would be without direct heir, i.e. presumably their common ancestor.

This of course refers to inheritance within the group of co-heirs, the members of which held their position by virtue of their common relationship within certain degrees to the founder. And we may infer that emphasis was thus laid on the proof of relationship by direct descent, in order to prevent shares in the inheritance passing from hand to hand unnoticed, beyond the strict limit where subdivision could be claimed per capita by the individual representatives of the diverging stirpes.

The kindred in the Ordinances of Manu is divided into two groups:—

1. Sapindas, who owe the funeral cake at the tomb.

[pg 052]2. Samānodakas, who pour the water libation at the tomb.

This may be put in tabular form:—

Receivers of water.

1. Great-grandfather's great-grandfather.

2. Great-grandfather's grandfather.

3. Great-grandfather's father.

Receivers of cake.

1. Great-grandfather.

2. Grandfather.

3. Father.

4. Giver of cake and water

5. Excluded

Or inversely:—

Givers of cake or Sapindas.

Householder

Brothers

1st cousins

2nd cousins

Pourers of water or Samānodakas.

3rd cousins

4th cousins

5th cousins

Within the Sapinda-ship of his mother, a “twice-born” man may not marry.137 Outside the Sapinda-ship, a wife or widow, “commissioned” to bear children to the name of her husband, must not go.

All are Sapindas who offer the cake to the same ancestors.

The head of the family would himself offer or share with all his descendants in the offering of the one cake to his great-grandfather, his grandfather, and his father. And if this passage is taken in conjunction with the one quoted just above, the number sharing in the cake-offering, limited as in the text at the seventh person from the first ancestor who receives the cake, is just sufficient to include the great-grandson of the head of the family, supposed to be making the offering.

The group, thus sharing the same cake-offering, would in the natural course be moving continually downwards, generation by generation as the head of the family died, thereby causing the great-grandfather to pass from the receivers of the cake-offering to the receivers of the water libation, and admitting the great-grandson's son into the number of Sapindas who shared the cake-offering. And at no time would more than four generations have a share in the same cake offered to the three nearest ancestors of the head of the family.

The Samānodakas, or pourers of the water libation appear to have been similarly grouped.

“Ignorance of birth and name” was in Wales considered to be equivalent to beyond fifth cousins. According to the Gwentian Code, “there is no proper name in kin further than that”—i.e. fifth cousins.139 And this tallies exactly with the previous quotation from Manu limiting the water libation to [pg 054] three generations of ancestors beyond those to whom the cake is due, which, as has been seen, includes fifth cousins.

And it must be borne in mind that fifth cousins are great-grandsons of the great-grandsons of their common ancestor, or two generations of groups of second cousins.

It was extremely improbable that a man would see further than his great-grandchildren born to him before his death. And it might also occasionally occur in times of war or invasion that a man's sons and grandsons might go out to serve as soldiers, leaving the old man and his young great-grandchildren at home.

If the fighting members of the family were killed, the great-grandsons (who would be second cousins or nearer to each other) would have to inherit directly from their great-grandfather: and thus, especially in cases where the property was held undivided after the father's death, we can easily see that second cousins (i.e. all who traced back to the common great-grandfather) might be looked upon as forming a natural limit to the immediate descendants in any one οἶκος, and as the furthest removed who could claim shares of the ancestral inheritance.

After the death of the great-grandfather or head of the house, his descendants would probably wish to divide up the estate and start new houses of their own. The eldest son was generally named after his father's father,140 and would carry on the name of the [pg 055] eldest branch of his great-grandfather's house, and would be responsible for the proper maintenance of the rites on that ancestor's tomb. He would also be guardian of any brotherless woman or minor amongst his cousins, each of whom would be equally responsible to him and to each other for all the duties and privileges entailed upon blood-relationship.

Thus seems naturally to spring up an inner group of blood-relations closely drawn together by ties which only indirectly reached other and outside members of the γένος.

In the fourth century B.C. this compact group limited to second cousins still survived at Athens, responsible to each other for succession, by inheritance or by marriage of a daughter; for vengeance and purification after injury received by any member, and for all duties shared by kindred blood.

This close relation was called ἀγχιστεία, and all its members were called ἀγχιστεῖς i.e. any one upon whom the claim upon the next-of-kin might at any time fall.

The speech of Demosthenes against Makartatos affords considerable information as to the constitution of the family-group or οἶκος. The five sons of Bouselos,141 we are told, on his death divided his substance amongst them, and each started a new οἶκος and begat children and children's children.142 The action, which was the occasion of the speech, lay between the great-grandsons of two of these five founders of οἶκοι, Stratios and Hagnias, and had reference to the disposal of the estate of the grandson [pg 056] of the latter, which had come into the hands of the great-grandson of Stratios.

One might have supposed that the descendants of Bouselos, with their common burial ground143 and so forth, would have ranked as all in the same οἶκος under their title of Bouselidai. But it is clear from this speech of Demosthenes, that too many generations had already passed to admit of Bouselos being considered as still head of an unbroken οἶκος, and that his great-great-grandsons were subdivided into separate οἶκοι under the names of their respective great-grandfathers, Stratios, Hagnias, &c. (οἵ εἰσιν ἐκ τοῦ Στρατίου οἴκου, ἐκ δὲ τοῦ Ἁγνίου οὐδεπώποτ᾽ ἐγένοντο).144

§ 2. Limitations In Respect Of Succession Outside The Direct Line Of Descent.

The Gortyn law quoted above in the previous section goes on:—

This clause takes the evidence one step further, and it is noticeable how the right of inheritance is determined by the great-grandchild of the common ancestor. In the direct line, a man's descendants [pg 057] down to his great-grandchildren inherited his estate. In dealing with inheritance through a brother of the deceased the heirship terminates with the grandchild of the brother, who would be great-grandchild of the nearest common ancestor with the previous owner of the estate. If there is no brother, the child of the cousin limits the next branch, as will be seen.

Isaeus145 describes the working of the then-existing (c. 350 B.C.) law of inheritance at Athens as follows:—

The law gives “brothers' property” (i.e. property without lineal succession) to

That is to say, failing first cousins once removed, the inheritance goes back and begins again at the mother of the deceased, who however, being a woman, can only inherit on behalf of her issue, present or prospective.146 If she has married again and has a son (half-brother to her deceased son) he would inherit. Failing her issue, her brother and so on to first cousin's children [pg 058] of the deceased, through his mother, would have the inheritance.

Failing these, the nearest kinsman to be found on the father's side, of whatsoever degree, is to inherit.

The law as stated by Demosthenes147 coincides with this:—

Whenever this law is quoted the limit of relationship laid down therein for the immediate ἀγχιστεία is always that of ἀνεψιῶν παῖδες, or sons of first cousins, who inherit from their first cousins once removed (oncle à la Brétagne, or Welsh uncle as this relation has been called). Occasionally the patronymic form ἀνεψιαδοῖ is used, apparently with the same signification, though properly ἀνεψιαδοῖ would mean sons of two first cousins, i.e. second cousins.148

It appears from the evidence reviewed hitherto, that any great-grandson could inherit from any grandson of a common ancestor, and the conclusion [pg 059] also seems to be justified, that the group of great-grandsons were considered to divide up their right to inherit once for all, and that having done so, with respect to that inheritance they were considered to have begun a new succession. To put it differently, in case of the death of one of these second cousins, after the final division of their inheritance had taken place, the rest of the second cousins would have no right to a share in his portion; an heir would have to be found within his nearer relations. Thus, they share responsibilities towards any of their relations within the group and higher up in their families, and also stand shoulder to shoulder in sharing such burdens as pollution and so on, but are outside the immediate ἀγχιστεία with respect to each other's succession. The reason for this will perhaps be more apparent as the argument proceeds.

That the grandson of a first cousin was outside the ἀγχιστεία is clear from the speech of Demosthenes already mentioned,149 where the plaintiff, who originally stands in that relationship to the deceased whose inheritance is in dispute, is adopted as son of his grandfather (first cousin of the deceased), in order to come within the legal definition of ἀνεψιοῦ παῖς.

That the son of a second cousin was also without the pale is directly stated in several passages in Isaeus.

It must be remembered that by “inheritance” is meant the assumption of all the duties incumbent on the ἀγχιστεύς, and that the man who “inherited” took [pg 060] his place for the future as son of the deceased in the family pedigree, and reckoned his relationship to the rest of the γένος thenceforth from his new position, in the house into which he had come.150

Now if it is true that to the great-grandson was the lowest in degree to which property could directly descend without entering a new οἶκος, and if that great-grandson was also looked upon as beginning with his acquired property a new portion of the continuous line of descent; any one, who “inherited” from him and ranked in the scale of relationship as HIS SON, would necessarily fall outside the former group and would be considered as forming the nearest relative in the next succeeding group. This, it seems, is the meaning of the language of the law which limits the ἀγχιστεία to the children of first cousins who could inherit from their parent's first cousins, and still retain their relationship as great-grandsons of the same ancestor. Whereas any one taking the place of son to his second cousin would be one degree lower down in descent, and pass outside the limit of the four generations. The law makes the kinsmen therefore exhaust all possible relationships within the group by reverting to the mother's kindred with the same limitation before allowing the inheritance to pass outside or lower down.

In confirmation of this view the following passage may be quoted from Plato's Laws:—

Before dishonouring one of the family and so bereaving it of a member owing duties which, by his disinheritance, may fall into abeyance or be neglected, the parent calls together all to whom his son might perhaps ultimately become the only living representative and heir, and who might at some future time be dependent on him for the performance of ancestral rites. That this was in Plato's mind when he wrote is shown by the next sentence, in which he provides for the possibility of some relation already having need of the young man and being desirous to adopt him as his son, in which case he shall by no means be prevented. The concurrence of all relations in such a position was therefore necessary.

In other cases where Plato mentions similar gatherings of the kin but for different purposes, he extends the summons to cousin's children. But here it can be seen they would have no place. They would be second cousins to the disgraced youth; they might have to share privilege or pollution with him, but had no claim on him for duties towards themselves. He would be “cousin's son” to his father's first cousins—the limit of such a claim in the ἀγχιστεία.

In the speech of Isaeus concerning the estate of Hagnias, a real second cousin is in possession of the estate. He won the case at the time and died in [pg 062] possession, and an action against his son Makartatos for the same property is the occasion of one of the speeches of Demosthenes. To fully understand the relationships referred to in these cases, the accompanying genealogical tree of the descendants of Bouselos may be of assistance. It will also serve as an example of how a kindred hung together, and how by intermarriage and adoption the name of the head of an οἶκος was carried on down a long line of male descendants.