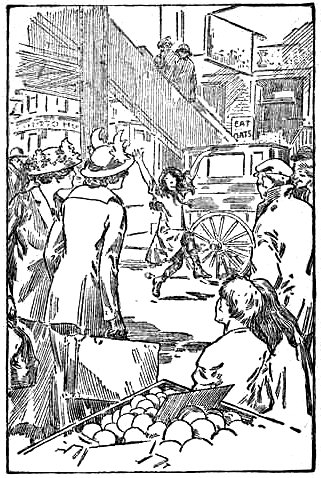

Before the Hand Organ Danced a Little Figure.

Frontispiece.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Madge Morton's Victory, by Amy D.V. Chalmers This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Madge Morton's Victory Author: Amy D.V. Chalmers Release Date: September 5, 2008 [EBook #26538] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MADGE MORTON'S VICTORY *** Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Before the Hand Organ Danced a Little Figure.

Frontispiece.

Madge Morton’s

Victory

By

AMY D. V. CHALMERS

Author of Madge Morton, Captain of the Merry Maid; Madge

Morton’s Secret, Madge Morton’s Trust.

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Akron, Ohio New York

Made in U. S. A.

Copyright MCMXIV

By THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Commencement Day at Miss Tolliver’s | 7 |

| II. | How it Was All Arranged | 16 |

| III. | Tania, a Princess | 24 |

| IV. | The Uninvited Guest | 37 |

| V. | Tania, a Problem | 51 |

| VI. | A Mischievous Mermaid | 58 |

| VII. | Captain Jules, Deep Sea Diver | 65 |

| VIII. | The Wreck of the “Water Witch” | 80 |

| IX. | The Owner of the Disagreeable Voice | 90 |

| X. | The Goody-Goody Young Man | 100 |

| XI. | The Beginning of Trouble | 112 |

| XII. | “The Anchorage” | 124 |

| XIII. | Tania’s Nemesis | 131 |

| XIV. | Captain Jules Makes a Promise | 141 |

| XV. | The Great Adventure | 150 |

| XVI. | A Strange Pearl | 161 |

| XVII. | The Fairy Godmother’s Wish Comes True | 172 |

| XVIII. | Missing, a Fairy Godmother | 180 |

| XIX. | The Wicked Genii | 198 |

| XX. | A Bow of Scarlet Ribbon | 206 |

| XXI. | The Race for Life | 215 |

| XXII. | Captain Jules Listens to a Story | 224 |

| XXIII. | The Victory Over Fate | 232 |

| XXIV. | The Little Captain Starts on a Journey | 243 |

Madge Morton’s Victory

“O Phil, dear! It is anything but fair. If you only knew how I hate to have to do it!” exclaimed Madge Morton impulsively, throwing her arms about her chum’s neck and burying her red-brown head in the soft, white folds of Phyllis Alden’s graduation gown. “No one in our class wishes me to be the valedictorian. You know you are the most popular girl in our school. Yet here I am the one chosen to stand up before everyone and read my stupid essay when your average was just exactly as high as mine.”

Madge Morton and Phyllis Alden were alone in their own room at the end of the dormitory of Miss Matilda Tolliver’s Select School for Girls, at Harborpoint, one morning late in May. Through the halls one could hear occasional bursts of girlish laughter, and the murmur of voices betokened unusual excitement. 8

It was the morning of the annual spring commencement.

Phyllis slowly unclasped Madge’s arms from about her neck and gazed at her companion steadfastly, a flush on her usually pale cheeks.

“If you say another word about that old valedictory, I shall never forgive you!” she declared vehemently. “You know that Miss Tolliver is going to announce to the audience that our averages were the same. You were chosen to deliver the valedictory because you can make a speech so much better than I. What is the use of bringing up this subject now, just a few minutes before our commencement begins? You know how often we have talked this over before, and that I told Miss Matilda that I wished you to be the valedictorian instead of me, even before she selected you.”

Phil’s earnest black eyes looked sternly into Madge’s troubled blue ones. “If you begin worrying about that now, you won’t be able to read your essay half as well,” declared Phil impatiently. “Please sit still for a minute and wait until Miss Jenny Ann calls us.”

Phil pushed Madge gently toward the big armchair. Then she walked over to stand by the window, in order to watch the carriages drive up to Miss Tolliver’s door and to keep her back turned directly upon her friend Madge. 9

The little captain sat very still for a few minutes. She had on an exquisite white organdie gown, a white sash, white slippers and white silk stockings. In the knot of sunny curled hair drawn high upon her head she wore a single white rose. A bunch of roses lay in her lap, also a manuscript in Madge’s slightly vertical handwriting, which she fingered restlessly.

The silence grew monotonous to Madge.

“Are you angry with me, Phil?” she asked forlornly.

Madge and Phyllis Alden had been best friends for four years, and had never had a real disagreement until this morning.

Phyllis was too honest to be deceitful. “I am a little cross,” she admitted without turning around. “I wish Lillian and Eleanor would come upstairs to tell us how many people have arrived for the commencement.”

Madge started across the room toward Phil. But Phyllis’s back was uncompromising. She pretended not to hear her friend’s light step. Suddenly Madge’s expression changed. The color rose to her face and her eyes flashed.

“I won’t apologize to you, Phil,” she said. “I had intended to, but I see no reason why I should not say it is unfair for me to be the valedictorian when you have the same claim to it that I have. It is hateful in you not to understand 10 how I feel about it. I am going to find Miss Jenny Ann.” Madge’s voice broke.

A knock on the door interrupted the two girls. Madge opened the door to a boy, who handed her a small parcel addressed in a curious handwriting to “Miss Madge Morton.” The letters were printed, but the writing did not look like a child’s. It was the fiftieth graduating gift that she had received. Phil’s number had already reached the half-hundred mark.

Madge dropped her newest package on the bed without opening it. She was half-way out in the hall when Phyllis pulled her back.

“Look me straight in the face,” ordered Phil. Madge obeyed, the flash in her eyes fading swiftly. “Now, see here, dear,” argued Phyllis, “suppose that Miss Matilda had chosen me to deliver the valedictory instead of you, wouldn’t you have been glad?”

Madge nodded happily. “I should say I would,” she murmured fervently.

Phyllis laughed, then leaned over and kissed her friend triumphantly.

“There, you have said just what I wanted to make you say,” went on Phil. “You say you would be glad if Miss Tolliver had chosen me for the valedictorian instead of you. Why can’t you let me have the same feeling about you? Please, please understand, Madge, dear”—the 11 tears started to Phil’s eyes—“that no one has been unfair to me because you were Miss Matilda’s choice.”

Madge glanced nervously at the little gold clock on their mantel shelf. “It is nearly time for the entertainment to begin, isn’t it?” she inquired. “I suppose Miss Jenny Ann will call us in time. What a lot of noise the girls are making in the hall!”

She idly untied her latest graduating gift. It was a small box, made after a fashion of long years ago, and its tops and sides were encrusted with tiny shells. On one side of the box the word “Madge” was worked out in tiny shells as clear and beautiful as jewels. Inside the box, on a piece of cotton, was a single, wonderful pearl. It was unset, but the two girls realized that it was rarely beautiful. There was no name in the box, no card to show from whom it came.

Madge turned the box upside down and peered inside of it. “I don’t know who could have sent this to me,” she declared, in a puzzled fashion. “Mrs. Curtis is the only rich person I know in the whole world, and she has already given us her presents. I must show this to Uncle and Aunt. I am afraid they won’t wish me to keep it. But I don’t know how we are ever going to return it to the giver when he or she is anonymous.” 12

“Isn’t that Miss Jenny Ann calling?” Madge turned pale with the excitement of the coming hour and thrust the gift under her pillow.

Phyllis picked up a great bunch of red roses. The eventful moment had arrived. The graduating exercises at Miss Matilda Tolliver’s were about to begin!

Neither of the two girls knew how they walked up on the stage. Before them swam “a sea of upturned faces.” It was impossible to tell one person from another. When Madge and Phil overcame their fright they discovered that they were among the twelve girl graduates, who formed a white semi-circle about the stage, and that Miss Matilda Tolliver was making an address of welcome to the audience.

Phyllis had no dreaded speech ahead of her. She looked out over the audience and saw her father and mother, Dr. and Mrs. Alden; and Madge’s uncle and aunt, Mr. and Mrs. Butler; but Madge could think of nothing save the terrifying fact that she must soon deliver her valedictory.

“Madge,” whispered Phil softly, “don’t look so frightened. You know you have made speeches before and have acted before people. I am not a bit afraid you will fail. See if you can find Mrs. Curtis and Tom. There they are, smiling at us from behind Eleanor and Lillian.” 13

Readers of “Madge Morton, Captain of the ‘Merry Maid’,” will remember the delightful fashion in which Madge Morton, Eleanor Butler, Lillian Seldon and Phyllis Alden spent a summer on a houseboat, which they evolved from an old canal boat and named the “Merry Maid.”

How they anchored at quiet spots along Chesapeake Bay, made the acquaintance of Mrs. Curtis, a wealthy widow, and what came of the friendship that sprang up between her and Madge Morton made a story well worth the telling.

In “Madge Morton’s Secret” the scene of their second houseboat adventure found them at Old Point Comfort, where, as Mrs. Curtis’s guests, they partook of the social side of the Army and Navy life to be found there. The origin of Captain Madge’s secret, and of how she kept it in spite of the humiliation and sorrow it entailed, the mysterious way in which the “Merry Maid” slipped her cable and drifted through heavy seas to a deserted island, where her crew lived the lives of girl Crusoes for many weeks, form a narrative of lively interest.

In “Madge Morton’s Trust” the further adventures of the “Merry Maid” were fully related. For the sake of the trip the happy houseboat girls saddled themselves with Miss Betsey 14 Taylor, a crotchety spinster, who was troubled with nerves, and who offered to pay liberally for her passage on their cosy “Ship of Dreams.”

Madge’s faith and unshakable trust in David Brewster, a poor young man who did the work on Tom Curtis’s yacht, which made the trip with the “Merry Maid,” her championing of David when suspicion pointed darkly toward him as a thief, and her unswerving loyalty to the unhappy youth until his innocence was established, revealed the little captain in the light of a staunch true comrade and doubly endeared her to all her companions.

Madge heard Miss Matilda Tolliver announce that the valedictory would be delivered by Miss Madge Morton. Phyllis gave her companion a little nudge, and somehow Madge arrived at the front of the stage and stood under a huge arch of flowers. Just above her head swung a great bell. Everyone was smiling at her. Madge was seized with a dreadful case of stage fright. Her tongue felt dry and parched. She tried to speak, but no sound came forth.

Mrs. Curtis’s lovely face, with its crown of soft, white hair, smiled encouragingly at her. Tom was crimson with embarrassment. Lillian and Eleanor held each other’s hands. Would Madge never begin her valedictory? 15

She tried again. No one heard her except her friends and teachers on the stage. Her voice was no louder than a faint whisper.

Miss Tolliver leaned over. “Madge, speak more distinctly,” she ordered.

Then the little captain realized that the most humiliating moment of her whole life had arrived. She had been selected as the valedictorian of her class, she had been chosen above her beloved Phil because of her gift as a speaker, yet she would be obliged to return to her seat without having delivered a line of her address. She would be disgraced forever!

Madge’s knees shook. Her lips trembled. Tears swam mistily in her eyes. She was a lovely picture despite her fright.

At eighteen she was in the first glory of her youth, a tall, slender girl, with a curious warmth and glow of life. Her lips were deeply crimson, her hair a soft brown, with red and gold lights in it, and her eyes were full of the eagerness that foreshadows both happiness and pain.

Phil and Miss Jenny Ann were exchanging glances of despair—Madge had broken down, there was no hope for her. Suddenly her face broke into one of its sunniest smiles. She lifted her head. Without glancing at the paper she held in her hand she began her address in a clear, penetrating voice.

Madge’s valedictory address was almost over. She had spoken of “Friendship,” what it meant to a girl at school and what it must mean to a woman when the larger and more important difficulties come into her life. “Schoolgirl friendships are of no small consequence,” declaimed Madge; “the friendships made in youth are the truest, after all!”

Phil listened to her chum’s voice, her eyes misty with tears. Only a half-hour before she and her beloved Madge had come very near to having the first real quarrel of their lives. Phil turned her gaze from Madge to glance idly at the arch of flowers above her friend’s head. Phil supposed that she must be dizzy from the heat of the room, or else that she could not see distinctly because of her tears; the arch seemed to be swaying lightly from side to side, as though it were blown by the wind. Yet the room was perfectly still. Phil looked again. She must be wrong. The arch was built of a framework of wood. It was heavy and she did not believe it would easily topple down. 17

Madge was happily unconscious of the wobbling arch. A few more lines and her speech would be ended! There was unbroken silence in the roomy chapel of the girls’ school, where the commencement exercises were being held. Suddenly some one in the back part of the room jumped to his feet. A hoarse voice shouted, “Madge!”

Madge started in amazement. Her manuscript dropped to the ground. Every face but hers blanched with terror. The swaying arch was now visible to other people besides Phil. Tom leaped to his feet, but he was tightly wedged in between rows of women. Phil Alden made a forward spring just as the arch tumbled. She was not in time to save Madge, but some one else had saved her; for, before Phil could reach the front of the stage, Madge’s name had been called again. Although the voice was an unknown one, Madge instinctively obeyed it. She made a little movement, leaning out to see who had summoned her, and the arch crashed down just at her back.

The quick cry from the audience frightened Madge, whose face was turned away from the wreck. She swung around without discovering her rescuer. Some one had fallen on the stage. Phyllis Alden had reached her friend’s side, not in time to save her, but to receive, herself, a 18 heavy blow from the great bell that was suspended from the arch.

Madge dropped on the stage at Phil’s side, forgetting her speech and the presence of strangers.

Miss Tolliver and Miss Jenny Ann lifted Phyllis before Dr. Alden had had time to reach the stage. There was a dark bruise over Phil’s forehead. In a moment she opened her eyes and smiled. “I am not a bit hurt, Miss Matilda; do let the exercises go on,” she begged faintly. “Let Madge and me go up to the front of the stage and bow, Miss Matilda. Then I can show people that I am all right. We must not spoil our commencement in this way.”

Miss Matilda agreed to this, and Madge and Phyllis went forward to the center of the stage. A storm of applause greeted them. Madge and Phil were a little overcome at the ovation. Madge supposed that they were being applauded because of Phil’s heroism, and Phil presumed that the demonstration was meant for Madge’s valedictory, therefore neither girl knew just what to do.

It was then that Miss Matilda Tolliver came forward. She was usually a very severe and imposing looking person. Most of her pupils were dreadfully afraid of her. But the accident that had so nearly injured her two favorite graduates 19 had completely upset her nerves. Instead of making a formal speech, as she had planned to do, she stepped between the two girls, taking a hand of each. “I had meant to introduce Miss Alden a little later on to our friends at the commencement exercises,” announced Miss Tolliver, “but I believe I would rather do it now. I wish to state that, although Miss Morton has delivered the valedictory, Miss Phyllis Alden’s average during the four years she has spent at my preparatory school has been equally high. It was her wish that Miss Morton should be chosen to deliver the valedictory. But Miss Alden’s friends have another honor which they wish to bestow upon her. She has been voted, without her knowledge, the most popular girl in my school. Her fellow students have asked me to present her with this pin as a mark of their affection.”

Miss Matilda leaned over, and before Phil could grasp what was happening had pinned in the soft folds of her organdie gown the class pin, which was usually an enameled shield with a crown of laurel above it; but the center of Phil’s shield was formed of small rubies and the crown of tiny diamonds.

Phyllis turned scarlet with embarrassment, but Madge’s eyes sparkled with delight. She was no longer ashamed of having been chosen 20 as valedictorian. In spite of herself, Phyllis Alden was the star of their commencement.

It was not until the four girls were seated with their dear ones about a round luncheon table in the largest hotel in Harborpoint that Madge suddenly recalled the stranger whose warning cry had probably saved her from a serious hurt.

Mrs. Curtis and Tom were entertaining in honor of Madge and Phyllis. There were no other guests except the two houseboat girls, Eleanor and Lillian, Dr. and Mrs. Alden, and Mr. and Mrs. Butler.

Madge sat next to Tom Curtis, and during the progress of the luncheon managed to say softly: “Did you see who it was that called my name so strangely this morning, Tom? I was so frightened at having to deliver my valedictory that when I heard that sudden shout, ‘Madge!’ I was too much confused to recognize the voice.”

Tom shook his head. “I don’t know who it was. I heard the voice but couldn’t discover its owner. It must have been some one at the very back of the room, for no one in the audience seems to know who called out to you.”

“I suppose I’ll never know,” sighed Madge. “It is a real commencement day mystery, isn’t it?”

Tom nodded smilingly. “By the way, Madge, 21 where are the houseboat girls going to spend the summer after you come to Madeleine’s wedding?” he asked. “You must be tired after your winter’s work.”

Madge shook her head soberly. “We are not going to be on the houseboat this year,” she whispered. “Going to New York to be bridesmaids is about as much as four girls can arrange. We haven’t even dared to think of the houseboat.”

“I have,” interposed Phyllis, who had heard the remark and the reply, “but we don’t wish our families to know. You see, Madge and I are hoping and planning to go to college next winter, so, of course, we can’t afford another summer holiday,” she ended under her breath.

“What’s that, Phil?” inquired Dr. Alden from the other end of the table.

Phil blushed. “Nothing important, Father,” she answered.

“Oh, then I must have been mistaken,” replied Dr. Alden, “for I thought I caught the magic word, ‘houseboat.’ No one of you girls has ever spoken of the ‘Merry Maid’ as unimportant.”

A cloud instantaneously overspread five faces about the luncheon table. Neither Mrs. Curtis nor Dr. Alden realized that in mentioning the houseboat they had forced the houseboat passengers 22 to break a vow of silence. Only the day before the five of them had met in Miss Jenny Ann Jones’s room. There they had solemnly pledged themselves that, since it was impossible for them to have this year’s vacation aboard the “Merry Maid,” they would bear the sorrow in silence. This time there was no “Miss Betsey” to pay the expenses of the trip. The girls and Miss Jenny Ann hadn’t a dollar to spare. The cost of going to Madeleine Curtis’s New York wedding was appalling to all of the girls except Lillian, whose parents were in affluent circumstances. But, of course, Madeleine was almost a houseboat girl herself. Readers of the first houseboat story will recall how Madeleine’s fiancé, Judge Hilliard, rescued Madge and Phyllis from a serious situation and saved Madeleine from a far worse plight than that in which he found the two girls.

“Mrs. Curtis,” remarked Dr. Alden in the midst of the mournful silence, “Mr. and Mrs. Butler, my wife and I have just been talking things over. We have decided that it would be a good thing for our girls to spend several weeks on board their houseboat. But, of course, if they have decided differently——”

It was a good thing that Mrs. Curtis was not giving a formal luncheon. A united shriek of delight suddenly arose from four throats. 23 Madge sprang from the table to hug her uncle, Eleanor blew kisses to her mother from across the room, Lillian clapped both hands, and Miss Jenny Ann smiled rapturously.

Phil’s face was the only serious one. “Are you sure we can afford it, Father?” she queried.

Dr. Alden nodded convincingly. “For a few weeks, certainly,” he returned.

“Then we don’t need to worry about afterward,” rejoined Madge. “And don’t you think, girls, it will be perfectly great, so long as we are going to Madeleine’s wedding in New York, for us to spend this holiday at the seashore?”

“Where, Madge?” asked Lillian.

“I’ll tell you,” answered Mrs. Curtis, “only, not to-day. It is a secret. Here is our pineapple lemonade. Let’s hope for the happiest of holidays for the little captain and her crew aboard the good ship ‘Merry Maid’.”

“Madge, do you think there is any chance that Tom won’t meet us?” inquired Eleanor Butler nervously. “I do wish we could have come on to New York with Lillian, Phil, and Miss Jenny Ann instead of making that visit to Baltimore. It seems so funny that they have been in New York two whole days before us. I suppose they have seen Madeleine’s presents, and our bridesmaids’ dresses—and everything!”

Eleanor sighed as she leaned back luxuriously in the chair of the Pullman coach, gazing down the aisle at her fellow passengers.

Madge was occupied in staring very hard at her reflection in the small mirror between her seat and Eleanor’s. She had wrinkled her small nose and was surreptitiously applying powder to the tip end of it.

“Of course Tom and the girls will meet us, Eleanor,” she replied emphatically. “Tom would expect us to be lost forever if we were to be turned loose in New York by ourselves. Oh, dear me, isn’t it too splendid that we are going to be Madeleine’s bridesmaids? I wonder if 25 we shall look very ‘country’ before so many society people?”

“Of course we shall,” returned Eleanor calmly. “You need not look at yourself again in that mirror. You are very well satisfied with yourself, aren’t you?” teased Eleanor.

Madge blushed and laughed. “I do like our clothes, Nellie,” she admitted candidly. “You know perfectly well that we have never had tailored suits before in our lives. You do look too sweet in that pale gray, like a little nun. That pink rose in your hat gives just the touch of color you need. I am sure I don’t see why you are so sure we shall seem countrified,” ended Madge. She had liked her reflection in the glass. She wore a light-weight blue serge traveling suit without a wrinkle in it, a spotless white linen waist, and her new hat was particularly attractive. Her cheeks were becomingly flushed and her eyes glowed with the excitement of arriving for the first time in New York City.

“We are almost in Jersey City now, aren’t we, Madge?” exclaimed Eleanor, making a leap for her bag, which promptly tumbled out of the rack above and fell directly on the head of a young man who was walking down the aisle of the car.

Madge giggled. Eleanor, however, was crimson with mortification. The young man did not 26 appear to be pleased. The girls had a brief glimpse of him. He had blue eyes and sandy hair and was exceedingly tall. Eleanor’s bag had knocked his glasses off and he was obliged to stoop in search of them in the aisle.

“Oh, I am so sorry,” apologized Eleanor in her soft, Southern voice, as she picked up the glasses and restored them to their owner. “I am glad they were not broken.”

The young man paid not the slightest attention to her apology.

“Hurry, Nellie,” advised Madge, “it is nearly time for us to get off the train and your hat is on crooked. Don’t be such a timid little goose! You are actually trembling. Of course Tom or some one will meet us, and if they don’t I shall not be in the least frightened.” Madge announced this grandly. “That whistle means we are entering Jersey City. We will find Tom waiting for us at the gate.”

Eleanor obediently followed Madge out of their coach. The little captain seemed older and more self-confident since she had been graduated at Miss Tolliver’s, but Nellie hoped devoutly that her cousin would not become imbued with the impression that she was really grown-up. It would spoil their good times.

The two girls had never seen such a headlong rush of people in their lives. They clung 27 desperately to their bags when a porter attempted to carry them. A man bumped violently against Madge, but he made no effort to apologize as he rushed on through the crowd.

“I never saw so many people in such a hurry in my life,” declared Nellie pettishly. “They behave as though they thought New York City were on fire and they were all rushing to put the fire out. I shall be glad when Tom takes charge of us.”

Once through the great iron gates the girls looked anxiously about for Tom, but saw no trace of him.

“I suppose Tom must have missed the ferry,” declared Madge with pretended cheerfulness. “We shall have to wait here for only about ten minutes until the next ferry boat comes across from New York.”

When fifteen minutes had passed and there was still no sign of Tom, Madge began to feel worried.

“Madge, I am sure you have made some kind of mistake,” argued Eleanor plaintively. “I know Mrs. Curtis would not fail to have some one here on time to meet us for anything in the world. Perhaps Tom wrote for us to come across the ferry, and that he would meet us on the New York side. Where is his letter?”

“It is in my trunk, Nellie,” replied Madge 28 in a crestfallen manner. She was not nearly so grown-up or so sure of herself as she had been half an hour before. “I know it was silly in me not to have brought Tom’s letter with me, but I was so sure that I knew just what it said. Perhaps we had better go on over to New York. Let’s hurry. Perhaps that boat is just about to start.”

The two young women hurried aboard the boat, which left the dock a moment later, just as a tall, fair-haired young man, accompanied by two girls, hurried upon the scene. The young man was Tom Curtis and the young women were Phyllis Alden and Lillian Seldon.

In the meantime Madge and her cousin had crossed the river and had landed on the New York side. What was the dreadful roar and rumble that met their ears? It sounded like an earthquake, with the noise of frightened people shrieking above it. After a horrified moment it dawned on the two little strangers that this was only the usual roar of New York, which Tom Curtis had so often described to them.

“There isn’t any use of our staying here very long, Eleanor,” declared Madge, feeling a great wave of loneliness and fear sweep over her. “An accident must have happened to Tom’s automobile on his way to the train to meet us. I am afraid we were foolish not to 29 have stayed at the Jersey City station. I am sure Tom wrote he would meet us there. I have behaved like a perfect goose. It is because I boasted so much about not being frightened and knowing what to do. But I do know Mrs. Curtis’s address. We can take a cab and drive up there.”

Eleanor would fall in with Madge’s plans to a certain point; then she would strike. Now she positively refused to get into a cab. Her mother and father and Miss Jenny Ann had warned her never to trust herself in a cab in a strange city. New York was too terrifying! Eleanor would search for Mrs. Curtis’s home on foot, in a car, or a bus, but in a cab she would not ride.

Madge was obliged to give in gracefully. A policeman showed the girls to a Twenty-third Street car. He explained that when they came to the Third Avenue L they must get out of the car and take the elevated train uptown, since Madge had explained to him that Mrs. Curtis lived on Seventieth Street between Madison and Fifth Avenues.

There was only one point that the policeman failed to make clear to Eleanor and Madge. He neglected to tell them that elevated trains, as well as other cars, travel both up and down New York City, and the way to discover which way 30 the “L” train is moving is to consult the signs on the steps that lead up to the elevated road. The policeman supposed that the two young women would make this observation for themselves. Of course, under ordinary circumstances, Madge and Nellie would have been more sensible, but they were frightened and confused at the bare idea of being alone in New York and consequently lost their heads, and they dashed up the Third Avenue elevated steps without looking for signs, settled themselves in the train and were off, as they supposed, for Seventieth Street.

They were too much interested in gazing into upstairs windows, where hundreds of people were at work in tiny, dark rooms, to pay much attention to the first stops at stations that their train made. They knew they were still some distance from Mrs. Curtis’s. Madge was completely fascinated at the spectacle of a fat, frowsy woman holding a baby by its skirt on the sill of a six-story tenement house. Just as the car went by the baby made a leap toward the train. Madge smothered her scream as the woman jerked the child out of danger just in time. Then it suddenly occurred to her that this was hardly the kind of neighborhood in which to find Mrs. Curtis’s house. The sign at the next stop was a name and not a street number. It 31 could not be possible that she and Eleanor had made another mistake!

Madge hurried back to the end of the car to find the conductor.

“We wish to get out at the nearest station to Seventieth Street and Lexington Avenue,” she declared timidly.

The man paid not the slightest attention to her. Madge repeated her question in a somewhat bolder tone.

“You ain’t going to get off near Seventieth Street for some time if you keep a-traveling away from it,” retorted the conductor crossly. “You’ve got on a downtown ‘L’ ’stead of an up. Better change at the next station. You’ll find an uptown train across the street,” the man ended more kindly, seeing the look of consternation on Madge’s white face.

The girls walked sadly down the elevated steps, dragging their bags, which seemed to grow heavier with every moment. They found themselves in one of the downtown foreign slums of New York City. It was a bright, early summer afternoon. The streets were swarming with grown people and children. Pushcarts lined the sidewalks. On an opposite corner a hand organ played an Italian song. In front of it was a small open space, encircled by a group of idle men and women. Before the organ 32 danced a little figure that Madge and Eleanor stopped to watch. They forgot their own bewilderment in gazing at the strange sight. The dancer was a little girl about twelve years old, as thin as a wraith. Her hair was black and hung in straight, short locks to her shoulders. Her eyes were so big and burned so brightly that it was difficult to notice any other feature of her face. The child looked like a tropical flower. Her face was white, but her cheeks glowed with two scarlet patches. She flung her little arms over her head, pirouetted and stood on her tip toes. She did not seem to see the curious crowd about her, but kept her eyes turned toward the sky. Her dancing was as much a part of nature as the summer sunshine, and Madge and Eleanor were bewitched.

A rough woman came out of a nearby doorway. She stood with her hands on her hips looking in the direction of the music. “Tania!” she called angrily. Elbowing her way through the crowd, she jostled Madge as she passed by her. “Tania!” she cried again. The men and women spectators let the woman make her way through them as though they knew her and were afraid of her heavy fist. Only the child appeared to be unconscious of the woman’s approach. Suddenly a big, red arm was thrust out. It caught the little girl by the skirt. With the 33 other hand she rained down blows on the child’s upturned face. One blow followed the other in swift succession. The little dancer made no outcry. She simply put one thin arm over her head for protection.

The music went on gayly. No one of the watching men and women tried to stop the woman’s brutality. But Madge was not used to the indifference of the New York crowd. Like a flash of lightning she darted away from Eleanor and rushed over to the woman, who was dragging the child along and cuffing her at each step.

“Stop striking that child!” she ordered sharply. “How can you be so cruel? You are a wicked, heartless woman!”

The woman paid no attention to Madge. She did not seem even to have heard her, but lifted her big, coarse arm for another blow.

Madge’s breath came in swift gasps. “Don’t strike that child again,” she repeated. “I don’t know who she is, nor what she has done, but she is too little for you to beat her like that. I won’t endure it,” the little captain ended in sudden passion.

The woman turned her cruel, bloodshot eyes slowly toward Madge. She was one of the strongest and most brutal characters in the slums of New York, and few dared to oppose 34 her. She was even a terror to the policemen in the neighborhood.

“Git out!” she said briefly.

Her arm descended. It did not strike the child. Quick as a flash, Madge Morton had flung herself between the woman and the child. For a moment the blow almost stunned the girl. The East Side crowd closed in on the girl and the woman. If there was going to be a fight, the spectators did not intend to miss it. Eleanor was numb with fear and sympathy. She did not know whether to be more frightened for Madge than sorry for the child.

The woman’s face was mottled and crimson with anger. Madge’s face was very white. She held her head high and looked her enemy full in the face.

“Git out of this and stop your interferin’!” shouted the virago. “This here child belongs to me and I’ll do what I like with her. If you are one of them social settlers coming around into poor people’s places and meddlin’ with their business, you’d better git back where you belong or I’ll social-settle you.”

At this moment a thin, hot hand caught hold of Madge’s and pulled it gently. Madge gazed down into a little face, whose expression she never forgot. It was whiter than it had been before. The scarlet color had gone out of the 35 cheeks and the big, black eyes burned brighter. But there was not the slightest trace of fear in the look. Instead, the child’s lips were curved into an elf-like smile.

“Don’t stay here, lady, please,” she begged. “The ogress will be horrid to you. She can’t hurt me. You see, I am an enchanted Princess.”

An instant later the child received a savage blow from the woman’s hard hand full in the face without shrinking. It was Madge who winced. Tears rose to her eyes. She put her arms about the child and tried to shelter her.

“Don’t be calling me no names, Tania,” the woman cried, dragging at the child’s thin skirts. “Jest you come along home with me and you’ll git what is comin’ to you, you good-for-nothin’ little imp.”

“Is she your mother?” asked Madge doubtfully, gazing at the brutal woman and the strange child.

Tania shook her black head scornfully. “Oh, dear, no,” she answered. “It is only that I have to live with her now, while I am under the enchantment. Some day, when the wicked spell is broken, I shall go away, perhaps to a wonderful castle. My name is Titania. I think it means that I am the Queen of the Fairies.”

The woman laughed brutishly. “Queen of gutter, you are, Miss Tania. I’ll tan you,” 36 she jeered, as she dragged the little girl from Madge’s arms.

The little captain looked despairingly about her. There, a calm witness of the entire scene, was a big New York policeman. “Officer,” commanded Madge indignantly, “make that woman leave that child alone.”

The big policeman looked sheepish. “I can’t do nothing with Sal,” he protested. “If I make her stop beating Tania now, she’ll only be meaner to her when she gets her indoors. Best leave ’em alone, I think. I have interfered, but the child says she don’t mind. I don’t think she does, somehow; she’s such a queer young ’un’.”

Sal was now engaged in shaking Tania as she pushed her along in front of her. Madge and Eleanor were in despair.

Suddenly a well-dressed young man appeared in the crowd. There was something oddly familiar in his appearance to Eleanor, but she failed to remember where she had seen him before. “Sal!” he called out sharply, “leave Tania alone!”

Instantly the woman obeyed him. She slunk back into her open doorway. The crowd melted as though by magic; they also recognized the young man’s authority. A moment later he was gone. Madge, Eleanor, and the strange little girl stood on the street corner almost alone.

“Are you good fairies who have strayed away from home?” inquired Tania, calmly gazing first at Madge and then at Eleanor. She was perfectly self-possessed and asked her question as though it were the most natural one in the world.

The two girls stared hard at the child. Was her mind affected, or was she playing a game with them? Tania seemed not in the least disturbed. “Do go away now,” she urged. “I am all right, but something may happen to you.”

“You odd little thing!” laughed Madge. “We are not fairies. We are girls and we are lost. We are on our way to visit a friend, Mrs. Curtis, who lives on Seventieth Street near Fifth Avenue. She will be dreadfully worried about us if we don’t hurry on. But what can we do for you? We can’t take you with us, yet you must not go back to that wicked woman.”

“Oh, yes, I must,” returned Tania cheerfully. “I am not afraid of her. When the time comes I shall go away.”

“But who will take care of you, baby?” asked 38 Eleanor. “Fairies don’t live in big cities like New York. They live only in beautiful green woods and fields.”

The black head nodded wisely. “Good fairies are everywhere,” she declared. “But I can make handfuls of pennies when I like,” she continued boastfully. “Let me show you how you must go on your way.”

“You can’t possibly know, little girl,” replied Madge gently. “It is so far from here.”

However, it was Tania who finally saw the two lost houseboat girls on board the elevated train that would take them to within a few blocks of their destination. Tania explained that she knew almost all of New York, and particularly she liked to wander up and down Fifth Avenue to gaze at the beautiful palaces. She was not young, she was really dreadfully old—almost thirteen!

The last look Madge and Eleanor had of Tania the child had apparently forgotten all about them. She was gazing up in the air, above all the traffic and roar of New York, with a happy smile on her elfish face.

“My dear children, I wouldn’t have had it happen for worlds!” was Mrs. Curtis’s first 39 greeting as she came out from behind the rose-colored curtains of her drawing room. “Tom has been telephoning me frantically for the past hour. How did he and the girls miss you? You poor dears, you must be nearly tired to death after your unpleasant experience.”

While Mrs. Curtis was talking she was leading her visitors up a beautiful carved oak staircase to the floor above. Her house was so handsomely furnished that Madge and Eleanor were startled at its luxurious appointments.

Mrs. Curtis brought her guests into a large sleeping room which opened into another bedroom which was for the use of Phil and Lillian.

Madeleine was to be married the next afternoon at four o ’clock. The girls had not brought their bridesmaids’ dresses along with them, as Mrs. Curtis had asked to be allowed to present them with their gowns.

It was all that Madge could do not to beg Mrs. Curtis to show them their frocks. She hoped that their hostess would offer to do so, but during the rest of the day their time was occupied in seeing Madeleine, her hundreds of beautiful wedding gifts, meeting Judge Hilliard all over again, and being introduced to Mrs. Curtis’s other guests. The four girls went to bed at midnight, thinking of their bridesmaids’ gowns, 40 but without having had the chance even to inquire about them.

Mrs. Curtis belonged to the old and infinitely more aristocratic portion of New York society. She did not belong to the new smart set, which numbers nearer four thousand, and does so much to make society ridiculous. Madeleine had asked that she might be married very quietly. She had never become used to the gay world of fashion after her strange and unhappy youth. It made the girls and their teacher smile to see what Mrs. Curtis considered a quiet wedding.

Miss Jenny Ann and her four charges had their coffee and rolls in Madge’s room the next morning at about nine o’clock. Madge peeped out of the doorway, there were so many odd noises in the hall. The upstairs hall was a mass of beautiful evergreens. Men were hanging garlands of smilax on the balusters. The house was heavy with the scent of American Beauty roses. But there was no sign of Mrs. Curtis or of Madeleine or Tom, and still no mention of the bridesmaids’ costumes for the girls.

Lillian Seldon was looking extremely forlorn. “Suppose Mrs. Curtis has forgotten our frocks!” she suggested tragically, as Madge came back with her report of the house’s decorations. “She has had such an awful lot to attend 41 to that she may not have remembered that she offered to give us our frocks. Won’t it be dreadful if Madeleine has to be married without our being bridesmaids after all?”

“O Lillian! what a dreadful idea!” exclaimed Eleanor.

Even Phyllis looked sober and Miss Jenny Ann looked exceedingly uncomfortable.

“O, you geese! cheer up!” laughed Madge. “I know Mrs. Curtis would not disappoint us for worlds. Why, she has all our measures. She couldn’t forget. Oh, dear, does my breakfast gown look all right? There is some one knocking at our door. It may be that Mrs. Curtis has sent up our frocks.”

“Then open the door, for goodness’ sake,” begged Eleanor. “Your breakfast gown is lovely; only at home we called it a wrapper, but then you were not visiting on Fifth Avenue.”

Madge made a saucy little face at Eleanor. Then she saw a group of persons standing just outside their bedroom door. A man-servant held four enormous white boxes in his arms; a maid was almost obscured by four other boxes equally large. Behind her servants stood Mrs. Curtis, smiling radiantly, while Tom was peeping over his mother’s shoulder.

Madge clasped her hands fervently, breathing 42 a quick sigh of relief. “Our bridesmaids’ dresses! I’m too delighted for words.”

“Were you thinking about them, dear?” apologized Mrs. Curtis. “I ought to have sent the frocks to you sooner, but I wanted to bring them myself, and this is the first moment I have had. You’ll let Tom come in to see them, too, won’t you?”

The man-servant departed, but Mrs. Curtis kept the maid to help her lift out the gowns from the billows of white tissue paper that enfolded them. She lifted out one dress, Miss Jenny Ann another, and the maid the other two.

The girls were speechless with pleasure.

Mrs. Curtis, however, was disappointed. Perhaps the girls did not like the costumes. She had used her own taste without consulting them. Then she glanced at the little group and was reassured by their radiant faces.

“O you wonderful fairy godmother!” exclaimed Madge. “Cinderella’s dress at the ball couldn’t have been half so lovely!”

Madeleine’s wedding was to be in white and green. The bridesmaids’ frocks were of the palest green silk, covered with clouds of white chiffon. About the bottom of the skirts were bands of pale green satin and the chiffon was caught here and there with embroidered wreaths of lilies of the valley. The hats were of 43 white chip, ornamented with white and pale green plumes.

It was small wonder that four young girls, three of them poor, should have been awestruck at the thought of appearing in such gowns.

“I shall save mine for my own wedding dress!” exclaimed Eleanor.

“I shall make my début in mine,” insisted Lillian.

“We can’t thank you enough,” declared Phyllis, a little overcome by so much grandeur.

Tom was standing in a far corner of the room.

“I would like to suggest that I be allowed to come into this,” he demanded firmly.

“You, Tom?” teased Madge. “You’re merely the audience.”

Tom took four small square boxes out of his pocket. “Don’t you be too sure, Miss Madge Morton. My future brother-in-law, Judge Robert Hilliard, has commissioned me to present his gifts to his bridesmaids. Madge shall be the last person to see in these boxes, just for her unkind treatment of me.”

“All right, Tom,” agreed Madge; “I don’t think I could stand anything more just at this instant.”

Nevertheless Madge peeped over Phil’s 44 shoulder. Judge Hilliard had presented each one of the houseboat girls with an exquisite little pin, an enameled model of their houseboat, done in white and blue, the colors of the “Merry Maid.”

The wedding was over. There were still a few guests in the dining room saying good-bye to Mrs. Curtis and Tom; but Madeleine and Judge Hilliard had gone. The four girls and Miss Jenny Ann found a resting place in the beautiful French music room.

Madeleine’s wedding presents were in the library, just behind the music room.

“It was simply perfect, wasn’t it, Miss Jenny Ann?” breathed Lillian, as they drew their chairs together for a talk.

“Madeleine must be perfectly happy,” sighed Eleanor sentimentally. “Judge Hilliard is so good-looking.”

“Oh, dear me!” broke in Madge, coming out of a brown study. She was sitting in a big carved French chair. “I don’t see how Madeleine Curtis could have left her mother and this beautiful home for any man in the world. I am sure if I had such an own mother I should never leave her,” finished the little captain. 45

“Until some one came along whom you loved better,” interposed Miss Jenny Ann.

“That could never be, Miss Jenny Ann,” declared Madge stoutly, her blue eyes wistful. “Why, if my father is alive and I find him, I shall never leave him for anybody else.”

“What’s that noise?” demanded Phyllis sharply.

It was after six o’clock and the Curtis home was brilliantly lighted. The window blinds were all closed. But there was a curious rapping and scratching at one of the windows that opened into a small side yard.

“It may be one of the servants,” suggested Miss Jenny Ann, listening intently.

“It can’t be,” rejoined Madge. “No one of them would make such a strange noise.”

“I think I had better call Tom,” breathed Eleanor faintly. “It must be a burglar trying to steal Madeleine’s wedding gifts.”

Madge shook her head. “Wait, please,” she whispered. She ran to the window. There was the faint scratching noise again! Madge lifted the shade quickly. Perched on the window sill was the oddest figure that ever stepped out of the pages of a fairy book. It was impossible to see just what it was, yet it looked like a little girl. One hand clung to the window facing, a small nose pressed against the pane. 46

“Why, it’s a child!” exclaimed Miss Jenny Ann in tones of relief. “Open the window and let her come in.”

Madge flung open the window. Light as a thistledown, the unexpected little visitor landed in the center of the room.

Madge and Eleanor had completely forgotten the elfin child they had met in the slums of New York City; but now she appeared among them just as mysteriously as though she were the fairy she pretended to be.

She wore a small red coat that was half a dozen sizes too tiny for her. Her skirt was patched with odds and ends of bright flowered materials. On her head perched a cap, a scarlet flower, cut from an odd scrap of old wall paper. In her hands Tania clasped a ridiculous bundle, done up in a dirty handkerchief.

“You strange little witch!” exclaimed Madge. “However did you find your way here? Be very still and good until the lovely lady who owns this house sees you, then I wouldn’t be at all surprised if she gave you some cake and ice cream before she sends you away.”

Tania sat down in the corner still as a mouse. Her thin knees were hunched close together. She held her poor bundle tightly. Her big black eyes grew larger and darker with wonder as she had her first glimpse of a fairyland, outside her 47 own imagination, in the beautiful room and the group of lovely girls who occupied it.

Mrs. Curtis came in a minute later, followed by a man who had been one of the guests at the wedding. Madge, Eleanor, and Tania recognized him instantly. He was the young man who had protected Tania from the blows of the brutal woman the afternoon before, but Tania did not seem pleased to see him. Her face flushed hotly, her lips quivered, though she made no sound.

Mrs. Curtis smiled quizzically. Madge could see that there were tears behind her smiles. “Who is our latest guest, Madge?” she asked, gazing kindly at the odd little person.

Tania rose gravely from her place on the floor. “I am a fairy who has been under the spell of a wicked witch,” she asserted with solemnity, “but now the spell is broken and I’ve run away from her. I shan’t go back ever any more.”

Mrs. Curtis’s young man guest took the child firmly by the shoulders.

“What do you mean by coming here to trouble these young ladies?” he demanded sternly. “I thought I recognized your friends, Mrs. Curtis. They saved this child yesterday from a punishment she probably well deserved. She is one of the children in our slum neighborhood that we 48 have not been able to reach. I will take her back to her home with me at once.”

The child’s head was high in the air. She caught her breath. Her eyes had a queer, eerie look in them. “You can’t take me back now,” she insisted. “The spell is broken. I shall never see old Sal again.”

Madge put her arm about the small witch girl. “Let her stay here just to-night, Mrs. Curtis, please,” begged Madge earnestly. “I wish to find out something about her. I will look after her and see that she does not do any harm.”

Quite seriously and gently Tania knelt on one knee and kissed Mrs. Curtis’s hand. “Let me stay. I shall be on my way again in the morning,” she pleaded, “but I am a little afraid of the night.”

“My dear child,” said Mrs. Curtis, gently drawing the waif to her side, “you are far too little to be running away from home. You may stay here to-night, then to-morrow we will see what we can do for you. I won’t trouble you with her to-night, Philip,” she added, turning to her guest.

“It will be no trouble,” returned Philip Holt blandly. “She lives less than an hour’s ride from here. Her foster mother will be greatly worried at her absence.”

Mrs. Curtis looked hesitatingly at Tania, who 49 had been listening with alert ears. The child’s black eyes took on a look of lively terror. “Please, please let me stay,” she begged, clasping her thin little hands in anxious appeal.

“Won’t you let Tania stay here to-night, Mrs. Curtis?” asked Madge for the second time. “I am sorry to disagree with Mr. Holt, but I do not believe that poor little Tania is either lawless or incorrigible. The woman who claims her is the most cruel, brutal-looking person I ever saw. I am sure she is not Tania’s mother. Let me keep her here to-night, and to-morrow I will inquire into her case.”

“Very well, Madge,” said Mrs. Curtis reluctantly. She glanced toward Philip Holt. His eyes, however, were fixed upon Madge with an expression of disapproval and dislike. For the first time it occurred to Mrs. Curtis that Philip Holt might be very disagreeable if thwarted. She immediately dismissed the thought as unworthy when the young man said smoothly: “I shall be only too glad to have Miss Morton investigate the child’s record. I am sorry that my word has not been sufficient to convince her.”

Madge made no reply to this thrust. Then an awkward silence ensued. Mrs. Curtis looked annoyed, Tania triumphant, Madge belligerent, and the other girls sympathetic. Making a 50 strong effort, Philip Holt controlled his anger and, extending his hand to Mrs. Curtis, said: “Pray, pardon my interference. I was prompted to speak merely in your interest. I trust I shall see you again in the near future. Good night.” He bowed coldly to the young women and took his departure.

“What a disagreeable——” Madge stopped abruptly. Her face flushed. “I beg your pardon, Mrs. Curtis,” she said contritely. “I shouldn’t have spoken my mind aloud.”

“I forgive you, my dear,” there was a slight tone of constraint in Mrs. Curtis’s voice, “but I am sure if you knew Mr. Holt as I do you would have an entirely different opinion of him.”

“Perhaps I should,” returned Madge politely, but in her heart she knew that she and Philip Holt were destined not to be friends, but bitter enemies.

“Don’t you think it would be a splendid plan for Tania?” asked Madge eagerly. “Miss Jenny Ann and the girls are willing she should come to us. Tania is such a fascinating little person, with her dreams and her pretences, that she is the best kind of company. Besides, I am awfully sorry for her.”

Mrs. Curtis and Madge were seated in the latter’s bedroom indulging in one of their old-time confidential talks.

“Tania would be a great deal of care for you, Madge,” argued Mrs. Curtis. “She is worrying my maids almost distracted with her foolishness. Last night she wrapped herself in a sheet and frightened poor Norah almost to death by dancing in the moonlight. She explained to Norah that she was pretending that she was a moonflower swaying in the wind. I wonder where the child got such odd fancies and bits of information? She has never seen a moonflower in her life.” Mrs. Curtis laughed and frowned at the same time. “Poor little daughter of the tenements! She is indeed a problem.” 52

“Shall I tell you all I have been able to find out about Tania?” asked Madge. “Her history is quite like a story-book tale. I think her father and mother were actors, but the father died when Tania was only a little baby. That is why, I suppose, they called the child by such an absurd name as ‘Titania.’ I looked it up and it comes from Shakespeare’s play of ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream.’ I think perhaps her mother was just a dancer, or had only a small part in the plays in which she appeared, for they never had any money. Tania has lived in a tenement always. The mother used to take care of her baby when she could, and then leave her to the neighbors. But the mother must have been unusual, too, for she taught Tania all sorts of poetry and music when Tania was only a tiny child. Indeed, Tania knows a great deal more about literature than I do now,” confessed Madge honestly. “It isn’t so strange, after all, that Tania pretends. Why, she and her mother used to play at pretending together. When they sat down to their dinner they used to rub their old lamp and play that it was Aladdin’s wonderful lamp, and that their poor table was spread with a wonderful feast, instead of just bread and cheese. They tried to make light of their poverty.”

Mrs. Curtis’s eyes were full of tears. She 53 could understand better than Madge the scene the young girl pictured.

“Tania was eight years old when her mother died,” finished Madge pensively. “Since then poor Tania has had such a dreadful time, living with that wretched old Sal, who has made a regular slavey of her, and she just had to go on with her pretending in order to be able to bear her life at all.”

Madge and Mrs. Curtis were both silent for a moment. The bright June sunshine flooded the room, offering a sharp contrast to Tania’s sad little story.

“You see why I wish to take her on the houseboat,” pleaded Madge. “It seems so wonderful that we are going to Cape May and will be on the really seashore, near you and Tom, that each one of us feels the desire to do something for somebody just to show how happy we are. Miss Jenny Ann says we may take Tania, if you think it wouldn’t be unwise.”

“She ought to go to school, Madge,” argued Mrs. Curtis half-heartedly. “Tania does not know any of the things she should. Philip Holt, who does so much good work among the poor in Tania’s tenement district, says that the child is most unreliable and does not tell the truth.”

Madge wrinkled her nose with the familiar expression she wore when annoyed. Her investigations 54 had proved Philip Holt a liar, but she refrained from saying so.

“You don’t like Philip, do you?” continued Mrs. Curtis. “It isn’t fair to have prejudices without reason. Mr. Holt is a fine young man and does splendid work among the poor. Madeleine and I have entrusted him with the most of the money we have given to charity. I am sorry that you girls don’t like him, because he is coming to visit me at Cape May this summer.”

Madge dutifully stifled her vague feeling of regret. “Of course, we will try to like him, if he is your friend,” she replied loyally. “It was only that we thought Mr. Holt had a terribly superior manner for such a young man, and looked too ‘goody-goody’! But you have not answered me yet about Tania. Do let us have Tania. I’ll teach her lots of things this summer, and it won’t be so hard for her when she goes to school in the fall. She is pretty good with me.”

“Very well,” consented Mrs. Curtis reluctantly, “for this summer only. The child will get you into difficulties, but I suppose they won’t be serious. What is Madge Morton going to do next fall? Is she going to college with Phil, or is she coming to be my daughter?”

Madge lowered her red-brown head. “I don’t know, dear,” she faltered. “You know I have 55 said all along to Uncle and Aunt that, just as soon as I was grown up, I was going to start out to find my father. I shall be nineteen next winter. It surely is time for me to begin.”

“But, Madge, dear, you can’t find your father unless you know where to look for him. The world is a very large place! I am sorry”—Mrs. Curtis smoothed Madge’s soft hair tenderly—“but I agree with your uncle and aunt; your father must be dead. Were he alive he would surely have tried to find his little daughter long before this. Your uncle and aunt have never heard from or of him during all these years.”

“I don’t feel sure that he is dead,” returned Madge thoughtfully. “You see, my father disappeared after his court-martial in the Navy. He never dreamed that some day his superior officer would confess his own guilt and declare Father innocent. I can’t, I won’t, believe he is dead. Somewhere in this world he lives and some day I shall find him, I am sure of it. Phil, Lillian and Eleanor have all pledged themselves to my cause, too,” she added, smiling faintly.

“I’ll do all that I can to help you, Madge. Just have a good time this summer, and in the autumn, perhaps, there may be some information for you to work on. What is that dreadful noise? I never heard anything like it in my house before!” exclaimed Mrs. Curtis. 56

Madge sprang to her feet. There was the sound of a heavy fall in the next room, a scream, then a discreet knock on Madge’s door.

“Come!” commanded Mrs. Curtis.

The door opened and the butler appeared in the doorway, his solemn, red face redder and more solemn than usual.

“Please, it’s that child again,” he said. “While the young ladies was out in the automobile with Mr. Tom, she went in their room, emptied out one of their trunks and shut herself inside. She said she was ‘Hope’ and the trunk was ‘Pandory’s Box,’ or some such crazy foolishness. She meant to jump out when the young ladies came back, but Norah went into the room with some clean towels, and when the little one bobs her head out of that box, just like a black witch, poor Norah is scared out of her wits and drops on the floor all of a heap. If that child doesn’t go away from here soon, Ma’am, I don’t know how we can ever bear it.”

“That will do, Richards,” answered Mrs. Curtis coldly. But Madge could see that she was dreadfully vexed at Tania’s latest naughtiness.

The little captain gave Mrs. Curtis a penitent hug. “It is all my fault, dear. I should never have brought the little witch here,” she murmured. “I’ll go and make it all right with Norah 57 and see that Tania does no more mischief—for a while, at least.”

Mrs. Curtis looked somewhat mollified, nevertheless, she was far from pleased, and Madge’s championship of little Tania was to cause the little captain more than one unhappy hour.

There was a splash over the side of a boat, then another, one more, and a fourth. The water rippled and broke away into smooth curves. Down a long streak of moonlight four dark objects floated above the surface of the waves. For a few seconds there was not a sound, not even a shout, to show that the mermaids were at play.

Two dark heads kept in advance of the others.

“Madge,” warned a voice, “we must not go too far out. Remember, we promised Jenny Ann. My, but isn’t this water glorious! I feel as though I could swim on forever.”

A graceful figure turned over and the moonlight shone full on a happy face. The two swimmers moved along more slowly.

“Nellie, Lillian!” Madge called back, “are you all right? Do you wish to go on farther?”

Phil and Madge floated quietly until their two friends caught up with them.

“I feel as though I could go on all night at this rate,” declared Lillian Seldon. Eleanor put her hand out. “May I float along with you a little, Madge?” she asked. “I am tired. How 59 wide and empty the ocean looks to-night! We must not get out of sight of the lights of the ‘Merry Maid’.”

“There is no danger!” scoffed Madge.

“Look out!” cried Phil Alden sharply. She was swimming ahead. She saw first the sails of a small yacht making across the bay with all speed to the line of the shore that the girls had just quitted.

“Let’s follow the boat back home,” suggested Madge. “We can keep far enough away for them not to see us. It will be rather good fun if they take us for porpoises or mermaids, or any other queer sea creature.”

“Don’t run into that Noah’s ark that we saw anchored in the creek this morning, Roy,” came a shrill voice from the deck of the yacht. “I saw half a dozen women going aboard her this afternoon laden with boxes and trunks—everything but the parrot and the monkey. It looked as though they meant to spend the summer aboard her.”

“Perhaps they do, Mabel,” a man’s voice answered. “The ‘Noah’s Ark’ is a houseboat. It looked very tiny for so many people, but I thought it was rather pretty.”

“Well, we have girls enough at Cape May this summer—about six to every man,” argued Mabel crossly. “I vote that we give these new 60 persons the cold shoulder. Nobody knows who they are, nor where they come from. It is bad enough to have to associate with tiresome hotel visitors, but I shall draw the line at these water-rats, and I hope you will do the same.”

“She means us,” gasped Eleanor. “What a perfectly horrid girl!”

The high, sharp voice on the yacht was distinctly audible over the water. The boat had slowed down as it drew nearer to the shore.

“Swim along with Phil, Nellie,” proposed Madge. “I am going to have some fun with those young persons. I don’t care if I am nearly grown-up; I am not going to miss a lark when there’s a chance. I have that rubber ball that Phil and I brought out to play with in the water. Watch me throw it on their yacht. They’ll think it’s a bomb, or a meteor, if I can throw straight enough. I am going to settle with them this very minute for the disagreeable things they just said about us and our pretty ‘Merry Maid.’”

“Don’t do it, Madge!” expostulated Phil; but she was too late; Madge had dived and was swimming along almost completely under the water. She swam in the darkness cast by the shadow of the boat as it passed within a few yards of them.

Like a flash she lifted her great rubber ball. 61 She had better luck than she deserved. The ball came out of nowhere and landed in the center of the group of three young people on the yacht. It fell first on the deck, and then bounced into the lap of the offending Mabel.

It was hard work for the waiting girls not to laugh aloud as naughty Madge came slowly back to them.

A wild shriek went up from on board the yacht. “Oh, dear, what was that?” one girl asked faintly, when the first cries of alarm had died away.

“Where is it? What was it?” growled a masculine voice. “Are you really hurt, Mabel? You are making so much fuss that I can’t tell.”

Mabel had dropped back in a chair. She was white with fear and trembling violently.

“It is in my lap,” she moaned. “It may explode any moment—do take it away!”

The owner of the yacht, Roy Dennis, turned a small electric flashlight full on his two girl guests. There, in Mabel’s lap, was surely a round, globular-shaped object that had either dropped from the sky or had been thrown at them by an unknown hand. Roy had really no desire to pick it up without seeing it more clearly.

The other girl was less timid. She reached over and took hold of Madge’s ball. Then she 62 laughed aloud. Oddly enough, her laugh was repeated out on the water.

“Why, it’s only a rubber ball!” she asserted. Ethel Swann, who was one of the old-time cottagers at Cape May, ran to the side of the boat. “See!” she exclaimed, “over there are some boys swimming. I suppose they threw the ball on board just to frighten us. They certainly were successful.” She hurled Madge’s ball back over the water, but Roy Dennis’s small yacht had gone some distance from the group of mischievous mermaids and he did not turn back. “If I find out who did that trick, I surely will get even with them,” muttered Roy. “I don’t like to be made a fool of.”

“Don’t tell Jenny Ann, please, girls,” begged Madge, as the four girls clambered aboard the “Merry Maid.” “It was a very silly trick that I played. I should hate to have the cottagers at the Cape hear of it. I don’t suppose I shall ever grow up.”

“Girls, whatever made you stay in the water so long?” demanded Miss Jenny Ann, coming into the girls’ stateroom with a big pitcher of hot chocolate and a plate of cakes. “I have been uneasy about you. You have been in the water for half an hour. That’s too long for a first swim. Poor Tania is fast asleep. The child is utterly worn out with so much excitement. Think 63 of never having been out of a crowded city in her life, and then seeing this wonderful Cape May! Tania wanted to stay up to wish you good night. I left her staring out of the cabin window at the stars when I went into our kitchen to make the chocolate. When I came back she was asleep.”

“Dear Jenny Ann,” said Madge penitently, pulling their chaperon down on the berth beside her, while Lillian poured the chocolate, “it was my fault we were late. The bad things are always my fault. But we are going to have a perfectly glorious time this summer, aren’t we? Just think, next year Phil and I shall be nineteen and nearly old ladies.”

“I wonder if anything special is going to happen to us this holiday?” pondered Phil, crunching away on her third cake.

“Something special always does happen to us,” declared Lillian. “Let’s go to bed now, because, if we are going to row up the bay in the morning to explore the shore, we shall have to get up early to put the ‘Merry Maid’ in order. We must be regular old Cape May inhabitants by the time that Mrs. Curtis and Tom arrive.”

Next morning bad news came to the crew of the little houseboat. Mrs. Curtis had been called to Chicago by the illness of her brother, and Tom had gone with her. They did not know how soon they would be able to come on to 64 Cape May; but within a very few days Philip Holt, the goody-goody young man who was one of Mrs. Curtis’s special favorites, would come on to Cape May, and Mrs. Curtis hoped that the girls would see that he had a good time.

Neither Madge, Phil, Lillian nor Eleanor felt particularly pleased at this information. But Tania, who was the only one of the party that knew the young man well, burst unexpectedly into a flood of tears, the cause of which she obstinately refused to explain.

The “Water Witch” rocked lazily on the breast of the waves, awaiting the coming of the four girls, who had planned to row up the bay on a voyage of discovery. They were not much interested in staying about among the Cape May cottagers, after the conversation which they had innocently overheard from the deck of the launch the night before. Of course, if Mrs. Curtis and Tom had come on to Cape May at once to occupy their cottage, as they had expected to do, all would have been well. The four young women and their chaperon would have been immediately introduced to the society of the Cape. However, the girls were not repining at their lack of society. They had each other; there was the old town of Cape May to be explored with the great ocean on one side and Delaware Bay on the other.

“Do be careful, children,” called Miss Jenny Ann warningly as the girls arranged themselves for a row in their skiff. “In all our experience on the water I never saw so many yachts and pleasure boats as there are on these waters. If you don’t keep a sharp lookout one of the larger 66 boats may run into you. Don’t get into trouble.”

“We are going away from trouble, Miss Jenny Ann,” protested Phil. “There is a yacht club on the sound, but we are going to row up the bay past the shoals and get as far from civilization as possible.”

Madge stood up in the skiff and waved her hand to their chaperon. The girls looked like a small detachment of feminine naval cadets in their nautical uniforms. Each one of them wore a dark blue serge skirt of ankle length and a middy blouse with a blue sailor collar. They were without hats, as they hoped to get a coating of seashore tan without wasting any time.

“I shall expect you home by noon,” were Miss Jenny Ann’s final words as the “Water Witch” danced away from the houseboat.

“Aye, aye, Skipper!” the girls called back in chorus. “Shall we bring back lobsters or clams for luncheon, if we can find them?”

“Clams!” hallooed Miss Jenny Ann through her hands. “I am dreadfully afraid of live lobsters.” Then the houseboat chaperon retired to write a letter to an artist, a Mr. Theodore Brown, whose acquaintance she had made during the first of the houseboat holidays. He had suggested that he would like to come to Cape May some time later in the summer if any of his houseboat friends would be pleased to see him, 67 and she was writing to tell him just how greatly pleased they would be.

The “Merry Maid” had found a quiet anchorage in one of the smaller inlets of the Delaware Bay, not far from the town of Cape May. The larger number of the summer cottages were farther away on the tiny islands near the sound and along the ocean front.

The “Water Witch” sped gayly over the blue waters of the bay in the brilliant late June sunshine. Madge and Phil, as usual, were at the oars. Tania crouched quietly at Lillian’s feet in the stern of the skiff. Eleanor sat in the prow.

“What do you think of it all, Tania?” Madge asked the little adopted houseboat daughter. Tania had been very silent since their arrival at the seashore. If she were impressed at the wonderful and beautiful things she had seen since she left New York City, she had, so far, said nothing.

Her large black eyes blinked in the dazzling light. She was looking straight up toward the sky in a curious, absorbed fashion. “I was trying to make up my mind, Madge, if this place was as beautiful as my kingdom in Fairyland,” answered Tania seriously, “and I believe it is.”

“Have you a kingdom in Fairyland, little Tania?” inquired Phil gently. She did not understand 68 the child’s odd fancies, as Madge did.

Tania nodded her head quietly. “Of course I have,” she returned simply. “Hasn’t every one a Fairyland, where things are just as they should be, beautiful and good and kind? I am the queen of my kingdom.”

Phil looked puzzled, but Madge only laughed. “Don’t mind Tania, Phil. She is going to be a very sensible little houseboat girl before our holiday is over. Besides, I understand her. She only says some of the things I used to think when I was a tiny child. But I do wish the people on the boats would not stare at us so; there is nothing very wonderful in our appearance.”

The girls were trying to guide their rowboat among the other larger craft that were afloat on the bay. They wished to get into the more remote waters. In the meantime it was embarrassing to have smartly dressed women and girls put up their lorgnettes and opera glasses to gaze at the girls as the latter rowed by.

“Can there be anything the matter with us?” asked Phil solicitously. “I never saw anything like this fire of inquisitive stares.”

“Of course not, Phil,” answered Lillian sensibly. “It is only because we are strangers at Cape May, and most of the people whom we see about come here each year. Then we are the only persons who live in a Noah’s ark, as those 69 pleasant people on the yacht called our pretty ‘Merry Maid’ last night. Don’t worry. Have you thought how odd it is that we won’t even know them if we should be introduced to them later? We did not see either them or their boat very plainly last night; we only overheard them talking.”

“But I’ll know the voice of that woman who screamed,” replied Madge rather grimly. “I just dare her to shriek again without my recognizing her dulcet tones.”

The girls were now drawing away from the crowded end of the bay. They kept along fairly close to the shore. There was an occasional house near the water, but these dwellings were farther and farther apart. Finally the girls rowed for half a mile without seeing any residence save an occasional fisherman’s hut. They hoped to reach some place where they could catch at least a glimpse of the wonderful cedar woods that flourish farther up the coast of the bay.

Suddenly Lillian sang out: “Look, girls, there is the dearest little house! It is almost in the water. It rivals our houseboat, it is so like a ship. Isn’t it too cunning for anything!”

Madge and Phyllis rested on their oars. The girls stared curiously.

They saw a house built of shingles that had 70 turned a soft gray which exactly resembled an old three-masted schooner. It had a tiny porch in front, but the first roof ended in a point, the second rose higher, like a larger sail, and the third, which must have covered the kitchen, was about the height of the first.

“See, Tania, I can make the funny house by putting my fingers together,” laughed Lillian. “My thumbs are the first roof, my three fingers the second, and my little fingers the last.”

The girls rowed nearer the odd cottage. The place was deserted; at least they saw no one about. Over the front door of the house hung a trim little sign inscribed, “The Anchorage.”

“Dear me, here is a boathouse, and we’ve a houseboat!” exclaimed Eleanor. “I wish we dared go ashore and knock at the door, to ask some one to show us over it.”

“I don’t think we had better try it, Eleanor,” remonstrated Phil. “The house probably belongs to some grouchy old sea captain who has built it to get away from people.”

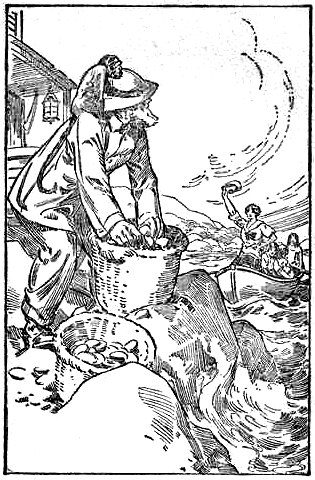

At this moment a man at least six feet tall, wearing old yellow tarpaulins, came around the side of the house of the three sails with a large basket on each arm. He sat down on a rock in front of the house and began lifting mussel and oyster shells out of one of his baskets. He would peer at them earnestly before throwing them over to one side. He was a giant of a man, past middle age. His face was so weather-beaten that his skin was like leather. His eyes were blue as only a sailor’s eyes can be. On one of the man’s shoulders perched a wizened little monkey that every now and then tugged at its master’s grizzled hair or chattered in his ear.

“Good Morning” Shouted Madge.

The man did not observe the girls in the rowboat, although they were only a few yards away.

“Good morning,” sang out Madge cheerfully, forgetting the vow of silence which the girls had made that morning against the Cape Mayites. But then, the girls had never dreamed of seeing such a fascinating seafaring old mariner. Their vow had been taken against the society people.

The sailor, however, did not return Madge’s friendly salutation; he went on examining his oyster and mussel shells.

Madge looked crestfallen. The old sailor had such a splendid, strong face. He did not seem to be the kind of man who would fail to return a friendly good morning greeting.

“I don’t think he heard you, Madge. Let’s all halloo together,” proposed Lillian.

“Good morning!” shouted five young voices in a mischievous chorus.

The seaman lifted his big head. His smile came slowly, wrinkling his face into heavy 74 creases. “Good morning, mates,” he called heartily. “Coming ashore?”

“Oh, may we?” cried Madge in return. “We should dearly love to!”

The five girls needed no further invitation. They piled out of the “Water Witch” before their host could come near enough to assist them.

The seaman did not invite them into the house. The girls took their seats on the big rock near the water. Madge was farthest away, but promptly the monkey leaped from its master’s shoulder and planted itself in Madge’s hair, pulling the strands violently while he chattered angrily.