“Are you going to sit here all day, little girl?”

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Clematis, by Bertha B. Cobb and Ernest Cobb

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Clematis

Author: Bertha B. Cobb

Ernest Cobb

Illustrator: A. G. Cram

Willis Levis

Release Date: September 6, 2008 [EBook #26543]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CLEMATIS ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

|

OTHER BOOKS BY BERTHA B. AND ERNEST COBB ARLO CLEMATIS ANITA PATHWAYS ALLSPICE DAN’S BOY PENNIE ANDRÉ ONE FOOT ON THE GROUND ROBIN |

“Are you going to sit here all day, little girl?”

CLEMATIS

BY

BERTHA B. AND ERNEST COBB

Authors of Arlo, Busy Builder’s Book, Hand in Hand With Father Time, etc.

With illustrations by

A. G. CRAM

AND

WILLIS LEVIS

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

Copyright, 1917

By BERTHA B. and ERNEST COBB

Entered at Stationers’ Hall, London

for Foreign Countries

Twenty-second Impression

All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, must

not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Made in the United States of America

Somerset, Mass.

Dear Priscilla:

You have taken such a fancy to little Clematis that we hope other children may like her, too. We may not be able to buy you all the ponies, and goats, and dogs, and cats that you would like, but we will dedicate the book to you, and then you can play with all the animals Clematis has, any time you wish.

With much love, from

Bertha B. and Ernest Cobb.

To Miss Priscilla Cobb.

CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

| 1. | Lost in a Big City | 1 |

| 2. | The Children’s Home | 16 |

| 3. | The First Night | 28 |

| 4. | Who is Clematis? | 41 |

| 5. | Clematis Begins to Learn | 52 |

| 6. | Clematis Has a Hard Row to Hoe | 61 |

| 7. | What Clematis Found | 72 |

| 8. | A Visitor | 86 |

| 9. | The Secret | 97 |

| 10. | Two Doctors | 109 |

| 11. | A Long, Anxious Night | 121 |

| 12. | Getting Well | 134 |

| 13. | Off for Tilton | 145 |

| 14. | The Country | 160 |

| 15. | Clematis Tries to Help | 172 |

| 16. | Only a Few Days More | 186 |

| 17. | Where is Clematis? | 200 |

| 18. | Hunting for Clematis | 215 |

| 19. | New Plans | 230 |

| 20. | The True Fairy Story | 237 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

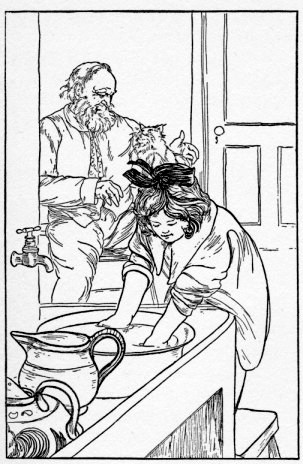

| 1. | “Are you going to sit here all day, little girl?” |

| 2. | “I don't want to stay here if you're going to throw my cat away.” |

| 3. | With Katie in the kitchen. |

| 4. | Thinking of the land of flowers. |

| 5. | Clematis held out her hand. |

| 6. | Clematis is better. |

| 7. | Off for Tilton. |

| 8. | In the country at last. |

| 9. | The little red hen. |

| 10. | Clematis watched the little fishes by the shore. |

| 11. | “I shan't be afraid.” |

| 12. | A little girl was coming up the path. |

| 13. | Deborah was very hungry. |

| 14. | “Didn't you ever peel potatoes?” |

| 15. | “What are you sewing?” |

| 16. | Clematis stuck one hand out. |

| 17. | She could see the little fish. |

| 18. | In Grandfather's house. |

CLEMATIS

It was early Spring. A warm sun shone down upon the city street. On the edge of the narrow brick sidewalk a little girl was sitting.

Her gingham dress was old and shabby. The short, brown coat had lost all its buttons, and a rusty pin held it together.

A faded blue cap partly covered her brown hair, which hung in short, loose curls around her face. 2

She had been sitting there almost an hour when a policeman came along.

“I wonder where that girl belongs,” he said, as he looked down at her. “She is a new one on Chambers Street.”

He walked on, but he looked back as he walked, to see if she went away.

The child slowly raised her big, brown eyes to look after him. She watched him till he reached the corner by the meat shop; then she looked down and began to kick at the stones with her thin boots.

At this moment a bell rang. A door opened in a building across the street, and many children came out.

As they passed the little girl, 3 some of them looked at her. One little boy bent down to see her face, but she hid it under her arm.

“What are you afraid of?” he asked. “Who’s going to hurt you?”

She did not answer.

Another boy opened his lunch box as he passed, and shook out the pieces of bread, left from his lunch.

Soon the children were gone, and the street was quiet again.

The little girl kicked at the stones a few minutes; then she looked up. No one was looking at her, so she reached out one little hand and picked up a crust of bread.

In a wink the bread was in her mouth. She reached out for 4 another, brushed off a little dirt, and ate that also.

Just then the policeman came down the street from the other corner. The child quickly bent her head and looked down.

This time he came to where she sat, and stopped.

“Are you going to sit here all day, little girl?” he asked.

She did not answer.

“Your mother will be looking for you. You’d better run home now, like a good girl. Where do you live, anyway?”

He bent down and lifted her chin, so she had to look up at him.

“Where do you live, miss? Tell us now, that’s a good girl.” 5

“I don’t know.” The child spoke slowly, half afraid.

“O come now, of course you know, a big girl like you ought to know. What’s the name of the street?”

“I don’t know.”

“Ah, you’re only afraid of me. Don’t be afraid of Jim Cunneen now. I’ve a little girl at home just about your age.”

He waited for her to answer, but she said nothing.

“Come miss, you must think. How can I take you home if you don’t tell me where you live?”

“I don’t know.”

“Oh, dear me! That is all I get for an answer. Well then, I’ll have to take you down to the 6 station. May be you will find a tongue down there.”

As he spoke, he took hold of her arm to help her up. Then he tried one more question.

“What is your name?”

“My name is Clematis.”

As she spoke she moved her arm, and out from the coat peeped a kitten. It was white, with a black spot over one eye.

“There, that is better,” answered the policeman. “Now tell me your last name.”

“That is all the name I have, just Clematis.”

“Well then, what is your father’s name?”

“I haven’t any father.”

“Ah, that is too bad, dear. 7 Then tell me your mother’s name.” He bent down lower to hear her reply.

“I haven’t any mother, either.”

“No father? No mother?” The policeman lifted her gently to her feet. “Well miss, we won’t stay here any longer. It is getting late.”

Just then the kitten stuck its head out from her coat and said, “Miew.”

It seemed very glad to move on.

“What’s that now, a cat? Where did you get that?”

“It is my kitty, my very own, so I kept it. I didn’t steal it. Its name is Deborah, and it is my very own.”

“Ah, now she is finding her 8 tongue,” said the policeman, smiling; while Clematis hugged the kitten.

But the little girl could tell him no more, so he led her along the street toward the police station.

Before they had gone very far, they passed a baker’s shop.

In the window were rolls, and cookies, and buns, and little cakes with jam and frosting on them.

The smell of fresh bread came through the door.

“What is the matter, miss?” The man looked down, as Clematis stood still before the window.

She was looking through the glass, at the rolls, and cakes, and cookies.

“I don’t want to stay here if you are going to throw my cat away”

The policeman smelled the fresh bread, and it made him hungry.

“Are you hungry, little girl?” he asked, looking down with a smile.

“Wouldn’t you be hungry if you hadn’t had anything to eat all day long?” Clematis looked up at him with tears in her big brown eyes.

“Nothing to eat all day? Why, you must be nearly starved!” As he spoke, the policeman started into the store, pulling Clematis after him.

She was so surprised that she almost dropped her kitten.

“Miew,” said poor Deborah, as if she knew they were going to 10 starve no longer. But it was really because she was squeezed so tight she couldn’t help it.

“Now, Miss Clematis, do you see anything there you like?”

Jim Cunneen smiled down at Clematis, as she peeped through the glass case at the things inside.

She stood silent, with her nose right against the glass.

There were so many things to eat it almost took her breath away.

“Well, what do you say, little girl? Don’t you see anything you like?”

“May I choose anything I want?”

“Yes, miss. Just pick out what you like best.” 11

The lady behind the counter smiled, as the policeman lifted Clematis a little, so she could see better. There were cakes, and cookies, and buns, and doughnuts.

“May I have a cream cake?” asked Clematis.

“Of course you may. What else?” He lifted her a bit higher.

“Miew!” said Deborah, from under her coat.

“Oh, excuse me, cat,” he said, as he set Clematis down. “I forgot you were there too.”

The woman laughed, as she took out a cream cake, a cookie with nuts on it, and a doughnut.

“May I eat them now?” asked Clematis, as she took the bag. 12

“You start right in, and if that’s not enough, you can have more. But don’t forget the cat.”

Jim Cunneen laughed with the baker woman, while Clematis began to eat the doughnut, as they started out.

Before long they came to a brick building that had big doors.

“Here we are,” said the policeman. They turned, and went inside.

There another policeman was sitting at a desk behind a railing.

“Well, who comes here?” asked the policeman at the desk.

“That is more than I know,” replied Jim Cunneen. “I guess 13 she’s lost out of the flower show. She says her name is Clematis.”

Clematis said nothing. Her mouth was full of cream cake now, and a little cream was running over her fingers.

Deborah was silent also. She was eating the last crumbs of the doughnut.

“Is that all you could find out?” The other man looked at Clematis.

“She says she has no father and no mother. Her cat is named Deborah. That is all she told me.”

“Oh, well, I guess you scared her, Jim. Let me ask her. I’ll find out.”

The new policeman smiled at Clematis. “Come on now, sister,” 14 he said. “Tell us where you live. That’s a good girl.”

Clematis reached up one hand and took hold of her friend’s big finger. She looked at the new policeman a moment.

“If you didn’t know where you lived, how could you tell anyone?” she said.

Jim Cunneen laughed. He liked to feel her little hand.

“See how scared she is of me,” he said. “We are old friends now.”

Again they asked the little girl all the questions they could think of. But it was of no use. She could not tell them where she lived. She would not tell them very much about herself. 15

At last the Captain came in. They told him about this queer little girl.

He asked her questions also. Then he said:

“We shall have to send her to the Home. If anyone claims her he can find her there.”

So Clematis and Deborah were tucked into the big station wagon, and Jim Cunneen took her to the Home, where lost children are sheltered and fed.

As they climbed the steps leading to the Home, Clematis looked up at the policeman.

“What is this place?” she asked.

“This is the Children’s Home, miss. You will have a fine time here.”

A young woman with a kind face opened the door.

The policeman did not go in. “Here is a child I found on Chambers Street,” he said. “We can’t find out where she lives.”

“Oh, I see,” said the woman. 17

“Could you take her in for a while, till we can find her parents?”

“Yes, I guess we have room for her. Come in, little girl.”

At that moment there was a scratching sound, and Deborah stuck her head out.

“Miew,” said Deborah, who was still hungry. Perhaps she thought it was another bakery.

“Dear me!” cried the young woman, “we can’t have that cat in here.”

Clematis drew back, and reached for Jim Cunneen’s hand.

“It’s a very nice cat, I’m sure,” said the policeman.

He felt sorry for Clematis. He knew how she loved her kitten. 18

“But it’s against the rules. The children can never have cats or dogs in here.”

Clematis, with tears in her eyes, turned away.

“Come on,” she said to her big friend. “Let us go.”

But Jim Cunneen drew her back. He loved little girls, and was also fond of cats.

“Don’t you think the cook might need it for a day or two, to catch the rats?” he asked, with his best smile.

“Oh dear me, I don’t know. I don’t think so. It’s against the rules for children to bring in pets.”

“Ah then, just wait a minute. I’ll be right back.”

The policeman ran down the 19 steps and around the corner of the house, while the young woman asked Clematis questions.

“It’s all right then, I’m sure,” he called as he came back. “Katie says she would be very glad to have that cat to help her catch the rats.”

The young woman laughed; Clematis dried her tears, and Jim Cunneen waved his hand and said goodby.

In another moment the door opened, and Clematis, with Deborah still in her arms, was in her new home.

It was supper hour at the Children’s Home. In the big dining room three long tables were set. 20

At each place on the clean, bare table was a plate, a small yellow bowl, and a spoon.

Beside each plate was a blue gingham bib.

Jane, one of the girls in the Home, was filling the bowls on her table with milk from a big brown pitcher.

Two little girls worked at each of the tables. While one filled the bowls, the other brought the bread.

She put two thick slices of bread and a big cookie on each plate.

The young woman who had let Clematis in, came to the table near the door.

“There is a new girl at your table tonight, Jane,” she said. 21 “She will sit next to me.”

“All right, Miss Rose,” answered Jane, carefully filling the last yellow bowl.

“Please may I ring the bell tonight, Miss Rose?” asked Sally, who had been helping Jane.

Miss Rose looked at the table. Every slice of bread and every cookie was in place.

“Yes, dear; your work is well done. You may ring.”

At the sound of the supper bell, a tramping of many feet sounded in the long hall.

The doors of the dining room were opened, and Mrs. Snow came in, followed by a double line of little girls.

Each girl knew just where to 22 find her place, and stood waiting for the signal to sit.

A teacher stood at the head of each table, and beside Miss Rose was the little stranger.

Mrs. Snow was the housemother. She asked the blessing, while every little girl bowed her head.

Clematis stared about at the other children all this time, and wondered what they were doing.

Now they were seated, and each girl buttoned her bib in place before she tasted her supper.

Sally sat next to Clematis.

“They gave you a bath, didn’t they?” she said, as she put her bread into her bowl. 23

Clematis nodded.

“And you got a nice clean apron like ours, didn’t you?”

Clematis nodded again.

“Oh, see her hair, it’s lovely!” sighed a little girl across the table, who had short, straight hair.

Clematis’ soft brown curls were neatly brushed, and tied with a dark red ribbon.

She did not look much like the child who came in an hour before.

“What’s her name?” asked Jane, looking at Miss Rose.

“We’ll ask her tomorrow. Now stop talking please, so she can eat her supper.”

At that, the little girl looked up at Miss Rose and said: “My 24 name is Clematis, and my kitty’s name is Deborah.”

Just as she said this, a very strange noise was heard. Every child stopped eating. Miss Rose turned red, and Mrs. Snow looked up in surprise.

“Miew, miew, miew,” came from under the table. In another minute a little head peeped over the edge of the table where Clematis sat. It was a kitten, with a black spot over one eye.

“Miew, miew,” Deborah continued, and stuck her little red tongue right into the yellow bowl. She was very hungry, and could wait no longer.

Deborah was very hungry

Mrs. Snow rapped on the table, for every child laughed right out. What fun it was! No one had ever seen a cat in there before.

“Miss Rose, will you kindly put that cat out. Put her out the front door.” Mrs. Snow was very stern. She didn’t wish any cats in the Home.

Clematis looked at Mrs. Snow. Her eyes filled with tears, and she began to sob.

Miss Rose turned as red as Deborah’s tongue. She had not asked Mrs. Snow if she might let the cat in. She thought it would stay in the kitchen with Katie.

“Did you hear me, Miss Rose? I wish you would please put the cat out the door. We can’t have it here.” 26

Miss Rose started to get up, when Clematis slipped out of her chair, hugging Deborah tightly to her breast.

The tears were running down her cheeks, as she started for the door.

“Where are you going, little girl?” said Mrs. Snow.

Clematis did not answer, but kept right on.

“Stop her, Miss Rose. What is the matter, anyway? Dear me, what a fuss!”

Miss Rose caught Clematis by the arm.

“Wait, dear,” she said. “Don’t act like that. Answer Mrs. Snow.”

“I don’t care,” sobbed Clematis, looking back. “I don’t want 27 to stay here if you are going to throw my cat away.”

“I should have asked you, Mrs. Snow,” said Miss Rose. “She had the kitten with her. She cried to bring it in, and Katie said she would care for it in the kitchen.”

“Oh, so that is it. Well, don’t cry, child. Take it back to Katie, and tell her to keep the door shut.”

“She’s hungry,” said Clematis, drying her eyes on her sleeve.

“Well, ask Katie to feed her then, and come right back to the table.”

Supper was soon finished, with many giggles from the little girls, who hoped that Deborah would get in again.

Clematis ate every crumb of her bread and cookie. Her yellow bowl looked as if Deborah had lapped it dry.

“After supper, we play games. It’s great fun,” said Sally, as they were folding their bibs.

The bell rang, and the long line of children formed once more.

They marched out through the 29 long hall, up the broad stairs to the play room.

There were little tables, with low chairs to match. Some of the tables held games.

In one corner of the room was a great doll house, that a rich lady had given to the Home.

In another corner was a small wooden swing with two seats.

A rocking horse stood near the window, and a box of bean bags lay on a low shelf near by.

Soon all were playing happily, except Clematis, who stood near the window.

She was looking at the trees, which were sending out red buds. The sun had set, and the sky was rosy with the last light of day. 30

“Don’t you want to play?” asked Miss Rose, coming across the room.

Clematis shook her head.

“What would you like to do, dear?”

Clematis thought a moment.

“I should like to help Katie in the kitchen. She must need some little girl.”

Miss Rose smiled. “If Clematis can get down into the kitchen, she can see her kitten,” she thought. “She is a sly little puss herself.”

“I don’t think you could go down tonight, but if you are a good girl I am sure Katie will want you to help her before long.” 31

Clematis smiled.

“Come now, and I will ask Jane to show you the doll house.”

So the little girls took Clematis over to the doll house that stood in the corner.

Jane opened the front door, so they could look in and see four pretty rooms.

Lace curtains hung at the tiny windows. New rugs were on the floors.

There was a tiny kitchen, with a tiny stove and tiny kettles, all just like your own house. It was enough to make any girl happy.

It was so much fun that Clematis forgot to be sad, and was not ready to leave the doll house 32 when the bell rang once more. It was bedtime.

“That is the sleepy bell,” said Jane, closing the door to the doll house, and running toward the stairs.

Clematis was at the end of the row, as the girls went out of the playroom, and Miss Rose spoke as she passed through the door.

“I will show you where you are to sleep, my dear. You go with the other children, and I’ll come in a few minutes.”

Clematis followed the other children up the stairs to the sleeping rooms.

Miss Rose soon came, and together they went to the room at the end of the hall. 33

How sweet that room looked to the tired little stranger!

A white iron bed stood against the wall, near the window. A small table held a wash basin and pitcher. There was a cup and soap dish, too.

Two clean towels hung near by.

Best of all was the little white bureau, with a mirror. The mirror had a white frame.

There was a pink rug before the bureau, and beside the bureau was a white chair.

“Oh, my!” cried Clematis, “see the flowers on the wall!” The pink wall paper was covered with white roses and their green leaves.

Miss Rose took a white nightdress 34 from the bureau, and laid it on the bed.

“Now, Clematis, I shall give you just ten minutes to undress. When I come back I want you to be all ready for me.”

Miss Rose went out, and Clematis started on her shoes.

“I guess she don’t know how fast I can undress,” she said to herself.

When Miss Rose came back, in ten minutes, she found Clematis already in bed, and half asleep.

“Why Clematis, this will never do!” Miss Rose pulled back the sheet and made Clematis sit up.

There, beside the bed, was a pile of clothes. There were the stockings, just as she had pulled them off. 35

The boots were thrown down on the clean gingham dress, and the fresh apron was sadly crushed.

“I am sorry, little girl,” said Miss Rose, “but you will have to get right up.”

“Why?” asked Clematis.

“No little girl can go to bed without washing her face and hands. No little girl can leave her clothes like this.”

“Isn’t this my room?” said Clematis, slowly getting out of bed.

“It is for tonight. We always let a new child sleep alone the first night.”

“Wasn’t I quick in getting into bed? Why must I get up?”

“Look, dear. Look at that pile of clothes.” 36

“Oh, I always leave them there,” replied Clematis. “Then I know just where to find them in the morning.”

“We don’t do so here, Clematis. Now please pick up the clothes, fold them, and put them on the chair.

“Then put your boots under the chair, and take off your pretty hair ribbon.”

Clematis gathered the clothes together, but she was not happy.

“I know you are tired, dear, but I am tired too, and we must do things right, even if we are tired.

“Now I must show you how to wash, and brush your teeth, and then have you say your prayers, before I can leave you.” 37

“Oh bother!” sighed Clematis.

“No, we mustn’t say words like that. Come now, we will get washed.”

Miss Rose poured some water from the pitcher, and made Clematis wash her hands, and arms, and face, carefully. Then she took a toothbrush from a box and gave it to her.

“What is this for?” asked Clematis.

“Why dear,” answered Miss Rose in surprise, “that is a tooth brush.”

“A tooth brush! Why, there is no hair on my teeth.”

Miss Rose laughed. “No dear, perhaps not, but we must brush them carefully each night with 38 water, or they will soon be aching.”

“Will that stop teeth from aching?”

“Yes indeed, it will help very much to keep them from aching.”

“All right, then.” Clematis began to brush her teeth. “My teeth ached last week. I nearly died,” she answered.

The teeth were cleaned, and Clematis was ready for bed.

“Now dear, let us say our prayers.”

“I don’t know any prayers.”

Miss Rose looked at Clematis in pity. “Don’t you really know any prayers at all?”

“Would you know any prayers if you had never learned any?” 39

Miss Rose smiled sadly.

“Well, then,” she said, “we will learn the Lord’s Prayer, and then you will know the most beautiful prayer of all.”

They knelt down together, and Clematis said over the words after Miss Rose.

“Now good night, dear, and pleasant dreams,” said Miss Rose, as she tucked her in.

“Good night,” said Clematis.

The door closed, and all was dark.

The maple trees swayed gently outside the window.

They nodded to Clematis, as she watched them with sleepy eyes.

One little star peeped in at her through the maple tree.

The bright sun was shining on the red buds of the maple tree when Clematis woke the next morning.

It was early. The rising bell had not rung. Clematis got up and looked out of the open window.

She could see nothing but houses across the street, but the buds of the maple were beautiful in the sun.

“I wish I had some of those buds to put in my room,” said Clematis to herself.

She took her clothes, and began 42 to dress. While she was dressing, she looked again at the maple buds, and wanted them more than ever.

“If I reached out a little way, I could get some of those, I just know I could,” she thought.

As soon as she got her shoes on she pushed the window wide open.

She leaned out. Some beautiful buds were very near, but she could not quite reach them.

She leaned out a little farther. Then she climbed upon the window sill.

They were still out of her reach.

For a minute she stopped. Then she put one foot out in the gutter. With one hand she held the blind, and reached out to the nearest branch. 43

At last she had it. She drew it nearer, and broke off a piece with many buds.

As the piece broke off, the branch flew back again to its place, and Clematis almost fell back through the window to the floor.

She patted the red buds and made a little bunch of them. She filled her cup with water and put the buds in it; then she put it on the bureau.

Clematis was looking proudly at them, when the door opened, and Miss Rose came in.

She looked at Clematis, and then at the buds.

“Why, Clematis!” she said.

Then she looked out the window. There, several feet beyond 44 the window, was the broken end. Drops of sap were running from the white wood.

“How did you get those buds?” asked Miss Rose.

“I reached out of the window,” said Clematis, “why, was that stealing?”

Miss Rose gasped.

“Clematis, do you mean to tell me that you climbed out of the window and reached for that branch?”

Clematis nodded. Tears came into her eyes. She must have done something very wrong, but she did not know just what was so wicked about taking a small branch from a maple tree.

“I didn’t know it was stealing,” she sobbed. 45

“It isn’t that, Clematis. It is not wrong to take a twig, but think of the danger. Don’t you know you might have fallen and killed yourself?”

Clematis wiped her eyes on her sleeve.

“Oh, that’s nothing,” she said, “I had hold of the blind all the time. I couldn’t fall.”

“Now, Clematis, no child ever did such a thing before, and you must never, never, do it again. Do you understand?”

“Yes’m.”

“Do you promise?”

“Yes’m.”

“Well then, let’s get ready for breakfast.”

Clematis washed her face and 46 hands, brushed her hair, and cleaned her teeth carefully.

Soon she was ready to go down stairs, and took one of the maple buds to put in her dress.

As they went out, Miss Rose saw that she wanted to say something.

“Do you want something?” she said.

“Can I help Katie this morning?”

“After breakfast I will ask Mrs. Snow, but breakfast is almost ready now.”

Just then the breakfast bell rang, and Clematis marched in with the other children. She was thinking about Deborah, and wondering if she had caught any rats. 47

For breakfast they had baked apples, oatmeal with milk, and rye gems.

It did not take them long to eat this. Soon they were through, and ready for the morning work.

As they were getting up, Mrs. Snow came to speak to Miss Rose.

Clematis held her breath when she heard what was said.

“Perhaps this little girl would like to go down and play with her kitten a while. We can find some work for her by and by.”

“Oh yes,” said Clematis, “I would.”

“Well, you can tell Katie I said you might. Be sure not to get in her way.” 48

Off ran Clematis to the kitchen, to find her dear Deborah.

There she was, curled up like a little ball under the stove.

She looked with sleepy eyes at Clematis, and crawled down into her lap.

Then Clematis smoothed her and patted her, till she purred her very sweetest purr.

“Ah,” said Katie. “It’s a fine cat. It caught a big rat in the night, and brought it in, as proud as pie.”

“Do you think they will let me keep her?” asked Clematis.

“Oh, I guess so. If she catches the rats, she will be welcome here. You can be sure of that. I hate rats.” 49

While Clematis and Deborah were having such a good time in the kitchen, Mrs. Snow took Miss Rose to her room.

“Well, Miss Rose, have you found out anything about that strange little child?”

“Not very much yet. She talks very little, and has had very little care.”

“What makes you think so?”

“Why, the poor child didn’t know what a tooth brush was for. She said she always left her clothes in a pile by the bed, because she could find them all in the morning.”

Mrs. Snow sighed.

“Dear me, she will need much care, to teach her how to do things 50 well. But I guess her folks will come for her before long.”

“I don’t know who her folks can be. She has never learned any prayers.”

“Poor child, she must be a sad case.” Mrs. Snow sighed again.

“But she is very fearless. This morning, before I went to her room, she had climbed out of the window and broken off a piece of the maple tree with buds on it.”

“What, way up there at the roof?”

“Yes, she said that was nothing, for she had hold of the blind.”

“What did she want the branch for?”

“She wanted it for the red 51 buds. She broke them off and put them in her cup, like flowers.”

“Well, Miss Rose, take her out to walk this afternoon, and ask her some questions. Perhaps you can find out where she lives.”

Clematis played with Deborah all the morning. She forgot about helping Katie, and when Katie asked her if she wanted to help her peel some potatoes, she said:

“I don’t know how.”

“Didn’t you ever peel potatoes?”

“Didn’t you ever peel potatoes?” asked Katie.

“No, I never had to do any work.”

“Well, you will have to be doing some work round here. It’s lucky for you that Mrs. Snow is good to little girls. You would 53 have a hard row to hoe in some homes, believe me.”

Clematis was busy tying her hair ribbon round Deborah’s neck, and did not answer.

The morning went fast, and the dinner was ready before Clematis was ready to leave her kitten.

For dinner they had soup, in the little yellow bowls, with a big piece of Johnny cake, and some ginger bread.

As soon as dinner was over, Miss Rose brought Clematis a brown coat.

It was not new, but it was neat and warm, much better than the one she had worn the day before.

“Come, Clematis,” she said, 54 “I am going out to walk. Don’t you want to go with me?”

“Where are you going?” asked Clematis, shrinking back.

“Oh, out in the park, and down by the river. I think you will like it.”

Clematis put on the coat as quickly as she could. Then she took Miss Rose by the hand.

“Come on, let’s go,” she said.

“You might wait till I get my coat and hat on.” Miss Rose was laughing at her.

Soon they were down by the river. Miss Rose sat on the gravel, while Clematis ran along the edge of the water.

She sailed bits of wood for boats, and threw little stones in, to see the rings they made. She was very, very happy.

“Clematis,” said Miss Rose, “don’t you remember the street you lived on?”

Clematis thought a minute.

“How would you know the street you lived on if nobody ever told you?”

Miss Rose thought a moment.

“Don’t you remember your mother’s name?”

Clematis shook her head.

“I don’t remember. It was a long time ago.”

“Do you mean she died a long time ago?”

Miss Rose asked her some other questions. At last she said: 56

“Well, tell me the name of the man you lived with.”

“His name was Smith.”

“Oh dear, there are so many Smiths, we shall never guess the right one. Dear me, Clematis. I don’t know how we shall ever find your home.”

Clematis threw a big stone into the water, which made a big splash.

“I hope you never will,” she said.

“Why, Clematis! Do you mean that you wish never to go back where you came from?”

“Well, how would you like to live in a place where you had to stay in an old brick yard all day, and never saw even grass?”

Thinking of the land of flowers

Miss Rose thought a while. Then she got up and started back to the Home.

Clematis followed her slowly. She was sorry to go.

That night Mrs. Snow talked with Miss Rose again.

“She must have lived in the city,” said Miss Rose. “She had to stay in a yard paved with bricks all day. She doesn’t remember her parents at all. She ran away, that is sure.”

“I hardly know what to do,” said Mrs. Snow, at last. “She can stay here for a while, and perhaps the people she lived with will find her here.”

So Mrs. Snow told the policeman what they had found out, 58 and he said they would do the best they could to find her people.

That night Clematis did not go to the little room near the maple tree to sleep. She went into the big room.

Jane slept in the bed next to hers. Miss Rose told her to see that Clematis had what help she needed in going to bed.

The day had been a busy one for Clematis. She was very sleepy.

“I guess I won’t bother with teeth and things tonight,” she said to herself.

So she pulled off her clothes, and got into bed.

“Oh Clematis, you can’t do that. You’ve got to pick up your 59 clothes, and clean your teeth, and do lots of things.”

Jane came and shook her, as she snuggled under the clothes.

“Oh, I’m too tired tonight. I’ll do it tomorrow night.”

Clematis did not stir.

Just then Miss Rose came into the sleeping room.

She saw Jane trying to get Clematis out of bed. She also saw the pile of clothes.

“Clematis, I can’t have this. Get right out of bed, and do as I told you last night.”

She wanted children to obey her, and she had tried to be very kind to Clematis.

The other children giggled, as Clematis got slowly out of bed. 60

But Miss Rose frowned at them.

“You see that she does every single thing she ought,” said Miss Rose to Jane, “and if she doesn’t, you tell me.”

Then Miss Rose went away, and left the girls to get ready for bed.

Poor Clematis had a hard time of it. The other girls made fun of her, because she was so clumsy and slow. At last she got her clothes folded up, and went to wash.

“She isn’t washing her neck and ears,” said Jane to herself, “but I guess I won’t tell.”

So at last Clematis got into bed again, and went to sleep.

It was all Jane could do the next morning to make Clematis get up when the rising bell rang.

“I don’t want to get up yet,” grumbled Clematis. “I will get up pretty soon.”

“No you won’t either. You’ll get up right off now. We have to be ready for breakfast in fifteen minutes.”

Jane pulled down the clothes, while the other girls laughed. Poor Clematis had to get up.

At first she was cross, but when 62 she looked out of the window, she smiled.

From this window she could see way off to a beautiful hill, golden brown in the morning sun.

Part way to the hill was a river. Its little waves shimmered and danced. Its shores were quite green already.

Now Clematis was wide awake and happy. She started to dress.

“Wash first,” said Jane.

Clematis started to grumble again, but when she looked into the mirror above the wash stand, there was the river, smiling at her in the mirror.

She knew this river. She had been there. Perhaps she would go again some day. 63

For breakfast they had a bowl of oatmeal and milk, with two slices of bread.

Clematis looked around while they were eating.

“Don’t you ever get a cup of coffee for breakfast?” she asked of Sally, who sat next to her.

“Oh, no, never, but sometimes we have cocoa, on real cold mornings.”

Clematis turned up her nose a little. She did not care much for oatmeal.

“I like doughnuts and coffee a great deal better,” she said.

“Huh, you won’t have any doughnuts and coffee round here,” said Jane. “You’d better eat what you have.” 64

Clematis took her advice, and had just finished her bread, when the bell sounded.

“Now, Clematis,” said Miss Rose, “you are going to stay here for a while anyway, so you must take your part in the daily work.”

“Yes’m.”

“I think you said yesterday you would like to help Katie in the kitchen.”

“Oh, yes’m,” said Clematis. She had been thinking of Deborah and longing to see her.

“Well, let’s go down and see what Katie can find for you to do.”

There was Deborah, sleeping under the edge of the stove. 65 Clematis took her while Miss Rose was asking Katie.

“This little girl thinks she would like to have some work down here in the kitchen, Katie. Is there anything you would like her to do?”

“Ah, no thank you, Miss Rose, she wouldn’t be any use at all.”

Clematis looked up. She did not feel very happy.

“Why, don’t you think she could help you?” Miss Rose looked surprised.

“No miss, she is no use at all. Yesterday I asked her to peel some potatoes, but she never lifted a finger. She said she didn’t know how.” 66

“Why, Clematis, I am surprised.”

“Well,” said Clematis, “if you never learned to peel potatoes, would you know how to do it?”

“Yes, I think I should. Katie would have shown you, if you had been willing to try.”

Clematis hung her head, and buried her face in Deborah’s soft fur.

“You see, miss, she’s of no use to me. She don’t want to work at all. Her cat, now, is a worker. She caught a big rat in the night.”

“Well then, Clematis, we shall have to ask Mrs. Snow to find you something else to do.”

Clematis dropped her kitten, 67 and the tears ran down her cheeks, as she followed Miss Rose upstairs.

Katie looked after her with a sad smile.

“She’ll have a hard row to hoe round here, believe me,” she said to herself.

Mrs. Snow frowned when Miss Rose told her.

“I am very sorry,” she said. “She may work with Jane, then, in the dormitory. Jane is a good worker and can teach her.”

Poor Clematis was rather frightened when she heard that she was to work in the dormitory. She was afraid a dormitory was some dark place like a prison. She did not know that the dormitory 68 was the big room where she had slept.

Soon Clematis was back in the big room again. There she took the place of another little girl, who was making up the beds with Jane.

“Hurry up now,” said Jane. “We have got to get these beds all made up before nine o’clock. School begins then.”

She showed Clematis how to tuck the sheet in, down at the foot, and pull it up smooth at the head of the bed.

Clematis was looking out of the window, way over the river, to the sunny brown hill.

“There now. Why don’t you look out?” said Jane. For Clematis had given such a pull that 69 she pulled all the clothes out at the foot of the bed.

“I was looking out, so there,” said Clematis.

“Yes, looking out of the window, that’s all.” Jane was vexed.

“Now hurry up and get them tucked in again.”

But Clematis was very clumsy, and not very willing. She had never had to make beds before. She didn’t see any need of it.

“Why can’t you leave the blankets till you go to bed, and then just pull them up?” she said, pouting.

“Because you can’t, that’s why. And you’d better try, or you’ll never get a chance to go to the country.” 70

“What do you mean? Who goes to the country?”

Clematis came round the bed and took Jane by the arm.

“Why, most of the children who do well, or try hard to do well, go to the country for two weeks in the summer.”

“To the country where the flowers grow, and where there is grass all around?”

“Sure, and where they give you milk and apple pie. Oh, apple pie even for breakfast, and doughnuts between meals. I had doughnuts every day.”

“Crickety!” said Clematis.

“You’d better not let Miss Rose hear you say that, and you needn’t worry. You won’t go to any 71 country, when you can’t even make beds.”

Clematis gave Jane a frightened look, and started to work the best she knew how.

But the best Clematis knew how was very poor work, and by the time the bell rang for school, one bed still had to be done.

“Let it alone,” said Jane. “I can make it up faster myself.”

Her hands and feet moved fast enough to surprise little Clematis, who followed her friend down to the school room, wondering how long it would take her to learn to make beds.

School began with music, and Miss Rose went to the piano. The minute she began to play, Clematis stood up, and stared at her.

“Sit down. Don’t stand up now.” Jane pulled her sleeve.

But Clematis paid no attention. She kept her eyes on the piano, and seemed to hear nothing else.

The song was of Spring; of birds, and brooks, and flowers. Clematis listened to every word, and when it was finished she sat down with a sigh. 73

After the singing, they had a class in reading.

Clematis stared at the words on the blackboard, but could not tell any of them.

“Have you learned any of your letters?” asked Miss Rose.

“No’m,” said Clematis.

The other children giggled, for Clematis was as large as Jane. Jane was eight, and could read very well.

“Tomorrow you must go into the special class, and you must work hard, and catch up as fast as you can.”

“Yes’m.”

Clematis was angry. She didn’t like to be laughed at.

At recess, all the children ran 74 out into the yard to play. It was a large yard, with a high wooden fence around it.

Glad to be free, Jane ran off to find some chums, and left Clematis to play by herself.

So Clematis wandered round by the fence till she came to a sunny spot, near the big maple tree with the red buds.

Here she picked up a dead twig and sat down, turning over the dried leaves with the twig, and throwing them in the air.

As she picked up the leaves, she saw some blades of grass beneath them.

Then she picked up more leaves, and found many blades of grass growing beneath their warm shelter. 75

Clematis got up and walked near the fence, where the leaves were thicker. There she poked them away, and found longer blades of grass, and new leaves, green and shiny.

“Oh,” she said to herself, “I hope I can come out here every day.”

Then she stopped. She pushed away some more leaves. She looked around at the other children.

None of them were looking at her.

She stooped, and took something from under the pile of leaves.

Again she looked about, but nobody was paying attention to her. All the children were playing games. 76

Then a sound made her look up. It was the bell. Recess was over, and all the children were going in.

Clematis put her hand into her apron pocket quickly, and followed the other children back to school.

“How has the new girl done today?” asked Mrs. Snow, just before they sat down to dinner.

“She seems to feel more at home,” replied Miss Rose. “She doesn’t know her letters yet. I guess she has grown up all by herself.”

“That is too bad. I will give her a test this afternoon, about three. If she would like to play with her kitten in the playroom for an 77 hour, after dinner, she may do so.”

“Oh, I am sure she would be glad to see her kitten. She is a queer child. At recess she stole away all by herself, to play by the fence.”

The children were coming in now, and Mrs. Snow nodded to Miss Rose, as she went to her chair.

Little Sally had been just behind Miss Rose as she said the last words to Mrs. Snow. She heard part of the words she said, and began to whisper to her neighbor.

“She said somebody stole something. It must be that new girl. See how queer she looks.” 78

Then of course the neighbor had to whisper to the girl next to her.

“Do you know what it was the new girl stole? See how funny she looks. She’d better not steal anything of mine.”

In a minute Clematis knew they were talking about her. She didn’t know what it was, but she knew it was unkind.

They were looking at her, and talking to each other. Her face turned red. She could not eat. One hand went deep into her apron pocket.

Miss Rose quickly saw that something was wrong. She knew that little girls often made fun of the strangers, and it vexed her.

“Any little girl who is not 79 polite,” she said, “may leave the table at once.”

The girls stopped talking, but they poked each other with their feet under the table. They were sure Clematis had stolen something, for she looked just as if she had.

“Come, Clematis, eat your dinner now.”

“Yes’m,” said Clematis. But it was hard to swallow the bread.

She drank the soup, and left most of the bread by her bowl.

As soon as the bell rang, Miss Rose beckoned to her.

“Would you like to take Deborah to the playroom for a while, and play with her there?”

Clematis looked very much surprised. 80 She had expected some new trouble.

“Oh, yes’m,” she gasped, and started down to the kitchen, glad to get away from the other girls, who had been watching.

Then Miss Rose beckoned to Jane.

“Jane, what were the girls saying about Clematis at the table?”

Jane hung her head. She did not like to repeat such awful things about Clematis, for she really liked her, though it was hard to teach her to work.

“Tell me, Jane. Miss Rose wants to know.”

“The girls were saying she stole something.” 81

“Stole something? Why, what did she steal, Jane?”

“I don’t know. I just heard them saying she had stolen something. She looked just as if she had.”

“Very well. Thank you, Jane.”

Jane went down to the school room, where all the girls were eager to know what Clematis had stolen. But Jane could tell them nothing.

“She just asked me what you said,” Jane declared.

“That’s just like Jane,” cried Sally. “She knows all the time, only she won’t tell.”

While they were talking, Clematis was finding a cosy corner in the playroom, and smoothing out 82 every hair on Deborah’s smooth back.

Deborah seemed very happy, and purred all the time.

“I don’t care if they do say mean things, and make noses at me. You won’t ever, will you, Debby?”

“Purr, purr, purr,” said Deborah. No indeed, she never would.

Time went fast, and it was three o’clock before Clematis had got Deborah settled down for sleep in a little bed she made for her beneath the window.

“Take her downstairs now, Clematis,” said Miss Rose, coming in. “Then come up to Mrs. Snow’s room. We want to ask you some questions.” 83

Again Clematis turned red. She went slowly downstairs, with Deborah under one arm. The other hand deep in her apron pocket.

“She surely looks as if something were wrong,” thought Miss Rose, as Clematis disappeared.

Clematis looked very unhappy when she went to Mrs. Snow’s room.

“Come in, little girl,” said Mrs. Snow, kindly. “There are some things I want to ask you about.”

“Yes’m,” replied Clematis, her lips quivering.

“First, I want to know what all this talk is about. Some of the girls were saying that you 84 took something which did not belong to you. Can that be true?”

Clematis hung her head. The tears came into her eyes.

“Don’t cry, Clematis,” said Miss Rose. “Just tell Mrs. Snow what it is, and perhaps we can make it all right again.”

“What was it, little girl?” asked Mrs. Snow, as she drew her nearer.

“It was mine, I found it first,” sobbed Clematis.

“Yes, but you must remember that if we find a thing, that does not make it ours. We must find the true owner, and give it back. That is the only honest thing to do.” 85

“What was it you found?” asked Miss Rose.

“I don’t kn-ow.”

“Where did you find it?”

“Do-wn by the fe-ence.”

“Where is it now, Clematis?” Mrs. Snow spoke kindly, as she wiped the child’s face with her handkerchief.

“It’s in my pocket,” answered Clematis.

She drew out her closed hand, held it before the two ladies, and slowly opened it.

Within lay a limp, withered dandelion blossom.

Mrs. Snow still tells the story of how Clematis stole the first dandelion of the springtime, out under the leaves.

People laugh when they hear the story. You see, it all came about because the children told tales on each other, and it was a good joke on them.

But as Clematis stood there, before Mrs. Snow and Miss Rose, she didn’t see the joke at all. She cried, and hid her face in her arms.

“Come here, dear,” said Mrs. Snow. “It is all right, and you 87 shall have every dandelion you find in the yard.”

“Wasn’t it stealing?” sobbed Clematis.

“No, it was all right, if you found it first.”

“And can I have all I find first?”

“Yes, indeed you can.”

Clematis lifted her head, and wiped the tears from her eyes.

“Oh,” she said, and seemed happy once more. She smoothed the limp little flower in her hot hand.

“And now,” said Mrs. Snow, “I wonder if you can tell us some more about yourself.”

“Yes’m, I’ll tell you all you ask, and I won’t tell any lies.” 88

“I’m sure you won’t. Perhaps you can remember, now, where you lived before you came here.”

Clematis shook her head. “I told Miss Rose every single thing,” she said, “except—”

“Except what?”

“Except that I ran away.”

Clematis hung her head again.

“Why did you run away?”

“Well, wouldn’t you run away, if you had to stay in a yard all day that was nothing but bricks?”

Mrs. Snow smiled. “Perhaps I would,” she replied.

“Didn’t you ever go out at all?” asked Miss Rose, who had been listening.

“Just sometimes, to go over to the store. Just across the street and back, and that was all bricks, too.”

Clematis held out her hand

“Do you think you could find your way home again, if Miss Rose went with you?”

Clematis shook her head. “Oh, no. It was a long, long way. I was most dead from walking.”

Mrs. Snow thought a moment. Then she said, “Miss Rose tells me that you have not learned to read. Is that true?”

“Yes’m, I never learned to do anything except count the change I got. But I can learn to read, and do numbers, too.”

Clematis spoke without sobbing now. She was thinking of the country, where girls went who did well. 90

“Do you think you could take her in a class by herself for a short time?” Mrs. Snow asked, turning to Miss Rose.

Miss Rose was about to answer, when one of the older girls came to the door.

“What is it, Ruth?”

“Please, Mrs. Snow, a man wants to see you.”

“What is his name?”

“His name is Smith. He wants to see you about a little girl.”

As she said this, Miss Rose looked up quickly.

Clematis also looked up. Her face turned red, and she put a finger in her mouth.

“Tell him to come in here.” 91

In another minute a small, thin man walked in.

He was poorly dressed, and looked as if he had been ill.

“Did you wish to see me about one of the children?” asked Mrs. Snow.

“Yes, marm, about this little girl right here.”

The man turned and smiled at Clematis, who was standing close by Miss Rose.

“Hello, Clematis, I thought I should find you somewhere.”

Clematis smiled too, but she did not speak.

“Oh,” said Mrs. Snow, “are you the one who took care of this little girl?”

“Yes, marm. I’ve had her 92 ever since she was a little baby.”

Mrs. Snow thought a minute.

“I suppose you want to take her home with you.”

“I don’t know about that. I have no home to keep a child in, and do right by her. You see, my wife is sick most of the time.”

“Don’t you know any of her folks who could care for her?”

“No, marm. Her mother came to our house when Clematis was a tiny baby. She said the father was dead. Then she died too, and we could never find out who she was.”

“Do you know her last name?” asked Miss Rose.

“No, miss. We never knew 93 her last name. She said it was Jones, but we never believed that was the truth. This little girl we just called Clematis.”

“Didn’t she have anything to help you find out who she was?” asked Mrs. Snow in surprise.

“Not a single thing, except this picture.”

The man took out a small photograph.

It showed three girls standing together in front of a brick building.

“That is her mother on the left, marm, but I don’t see how the picture helps very much.”

“That is true. Still, the picture is better than nothing.”

“That is just what we thought, 94 marm,” Mr. Smith replied. “We kept her along, hoping we should find some one to claim her, but no one came. She is too big for us to care for now.”

“Then you are ready to give her up?”

“Yes, marm, if you will care for her. She is very restless, and always wanting to run off.”

Mrs. Snow turned to Clematis.

“Do you think you would rather stay here, than go back with Mr. Smith?”

“Yes’m,” said Clematis, quickly. She had been thinking of the visits to the country. If she went back to the yard, all made of bricks, how would she ever see the grass and flowers? 95

“Very well, Mr. Smith. I think you have done a good deal to keep her as long as you have. She was well fed, even if she didn’t learn much.”

“Thank you, marm.”

Then Miss Rose took Clematis out of the office, while Mrs. Snow talked with Mr. Smith.

All the afternoon Clematis wondered what they were going to do with her.

After supper Miss Rose called to her, as the children were going to the playroom.

“Clematis,” she said, “do you think that if you stayed here you could work real hard, and learn to do as the other children do?”

“Very well. Mrs. Snow finds that we can keep you here. I will try to teach you myself, so you can catch up with the other children.”

“Yes’m,” said Clematis.

That is all she said, but she was so glad, that she could not sleep for a long time after she went to bed.

She lay awake thinking, and thinking, of the things she would learn to do, so she might go at last to the country, the land of flowers, and grass, and birds; the land where white clouds floated always in a blue, blue sky.

The next morning Clematis did better in helping Jane with the beds, and before many mornings had passed she learned so well that Miss Rose praised her for her work.

When she wanted to stop trying, and wanted to get up without washing her face and hands, and cleaning her teeth, she would look out the window at the hill beyond the river.

It seemed to smile at her and say:

“Don’t forget the beautiful 98 country, little girl. Remember the birds and the flowers. Do the best you can.”

But there were so many things to do that it seemed to poor Clematis as if she would never learn half of them.

When she tried to help in setting the table, she dropped some plates.

She said things that made the other girls cross, for she had never learned to play with other girls, and she forgot that she could no longer do just as she pleased.

Worst of all, she did not always pay attention to study, and when Miss Rose left her to do some numbers, would be looking out of 99 the window, instead of working on her paper.

So the days went on, and spring was almost over.

The dandelions had all blossomed and grown up tall, with white caps on their heads, and there were no other flowers in the yard.

One day Clematis found something which made her almost as happy as if she had found some flowers.

At first she thought she would keep it a secret, and tell no one about it. Then she thought how good Jane had been to her, so she went up to her when she was standing alone.

“Say, Jane, if I tell you a 100 secret will you promise not to tell anybody else?”

“Sure, I’ll promise,” said Jane. “What is it?”

Clematis looked around. The other children were playing games.

“Come over here,” she said.

She led Jane to the big board fence which stood at the back of the yard.

Then she got down on her knees and took hold of one of the boards. It was loose, and she could pull it out.

“See, look through there,” said Clematis, in a low voice.

Her face shone with pleasure as she peeped through.

Jane knelt down, and peeped through too. Beyond the fence 101 she could see into another yard.

In this yard there was grass growing, and flower-beds, where the flowers were beginning to grow up in green shoots.

But this was not all. Not far from the fence, by a corner of the garden, stood a low bush. She could smell its sweet fragrance from where she knelt.

“Do you see it?” whispered Clematis.

“Of course I see it. I can smell it too. It’s great.”

Jane took in a long breath of the fragrance, and smiled at Clematis.

“Oh, I wish I had some of those blossoms.” Clematis looked 102 eagerly at the blossoms. “Do you know what they are, Jane?”

“Oh, yes; those are lilacs.”

The two girls had just time to take one more deep breath, full of the fragrance from the lilac blossoms, before the bell rang.

Jane kept her promise, and while the lilacs lasted, they used to go often to their secret place and smell the fragrance of the blossoms.

The first of July, some of the girls began to start for their vacations in the country.

Now it was harder than ever for Clematis to stick to her work. She kept thinking of the beautiful fields, when she should have been thinking of numbers. 103

“I don’t know what we are going to do with you, Clematis,” said Miss Rose one day.

“You do try hard sometimes. You have learned to make beds well. You are a good girl about your clothes, morning and night. But you are dreaming of other things, I fear. What is it you dream about so much?”

Clematis thought a moment.

“Do you think I will have a chance to go to the country?”

She looked up at Miss Rose. Her face was white and anxious.

“Why Clematis. I don’t know. You wouldn’t be very much help I am afraid. You quarrel with the other children, and you are very slow to learn.” 104

“Yes’m,” said Clematis, and hung her head.

“Still,” said Miss Rose, “you might have a chance later. If you try hard I will not forget you.”

Clematis tried to feel happier then, but there were so many things to learn, and so few days to learn them in, that she hardly dared to hope very much.

She found it very hard to learn to play happily with the other children, and liked it much better just to get Deborah all by herself and play with her.

July went by, and the children began to come back again. They told stories of the wonderful things they had seen, and now Clematis was only too glad to sit near them and listen.

Clematis is better

“Oh,” said Sally, who had been to Maine, “Mr. Lane had a field almost as big as a whole city, full of long grass and daisies.”

“Would he let you pick the daisies?” asked Clematis.

“Of course he would; all you wanted.”

“Where is Maine?” asked Clematis, eagerly.

“Hear her talk,” said another girl, named Betty, with a sniff. “She needn’t worry, she’ll never get a chance to pick any.”

Betty was not very kind, and did not like Clematis. She often made fun of the younger children.

Clematis turned red. Her eyes 106 flashed, and she was about to answer, when the supper bell rang.

They had just sat down at the table, when Betty said to a girl near by:

“You ought to hear Clematis. She thinks she is going to the country. Just as if anybody would have her around.”

Betty sat next to Clematis, who heard every word.

She had tried to be a good girl and learn, just as Miss Rose asked her to.

Her face burned, and her eyes flashed more than ever.

Before she stopped to think, she turned and waved her spoon before Betty’s face, saying: 107

“You can’t stop me. You’d better keep quiet, you old pig!”

Betty was so startled that she moved back. Her arm struck her bowl of milk, and the milk spilled out, all over the table.

Part of it spilled down into her lap.

Then Clematis began to cry. When Miss Rose sent her away from the table, and up to her bed, she went willingly.

She was glad to get away from the other children.

Miss Rose saw how sad she was, and knew how naughty Betty had been, so she did not punish her.

“I am very sorry you have not learned to behave more 108 politely, Clematis. Perhaps this will be a lesson to you.”

That was all she said before Clematis went to bed, but Clematis cried quietly a long, long time.

She felt that she had made every one look at her, right in front of Mrs. Snow. What would Mrs. Snow think of her now?

It was very late before Clematis fell asleep that night, and in the morning she had a headache.

When she got up she had to sit on the bed, she felt so dizzy.

Miss Rose found her sitting there.

“Why, Clematis,” she said. “Are you sick?”

“Yes’m, I guess so,” whispered the poor little girl.

“Lie right down again, dear, and perhaps you will feel better.”

They brought her a cup of 110 cocoa, and some toast, for breakfast, but she could not eat.

All day she lay there, pale and sick.

In the afternoon old Doctor Field came in to see her. He sat down by the bed and asked her some questions.

He looked at her tongue, and felt her pulse. Then he took out some little pills and gave them to Miss Rose.

“I guess you had better put her in a single room,” he said. “Give her some of these in water, every two hours during the day.”

He smiled at Clematis before he went out. “I guess she will feel better in the morning, when I come again.” 111

But in the morning Clematis was not better. She was worse.

“How did she pass the night?” asked Doctor Field, as he felt her pulse.

“Not very well,” said Miss Rose. “She did not sleep much, and had a good deal of pain.”

Doctor Field looked at her chest and arms.

“It might be chicken pox, or measles,” he said, “but I don’t see any of the usual signs.”

Little Clematis lay and looked at him steadily.

“Did you want something, dear?” he asked.

“I want a drink,” she said. “I want a drink of cold, cold water.” 112

“Yes, dear, you shall have a drink, of course you shall.”

The old doctor went into the hall with Miss Rose.

“She may have a drink, but only a little at a time. And I wouldn’t let it be too cold. She really gets enough water with her medicine.”

Soon they brought Clematis a little water in a cup. She raised her head and drank it, but then made a face and turned her head away.

“It isn’t any good,” she said.

That evening old Doctor Field came again. He looked carefully at Clematis, and shook his head.

“I guess it’s only a slow fever. It’s nothing catching,” he 113 said. “She’ll be better in a few days.”

The few days passed, but Clematis was not better.

At night she was restless, and slept little. Even when she did sleep, her slumber was disturbed by bad dreams.

She talked to herself during these dreams, though people couldn’t understand what she said.

Doctor Field came to see her every day or two, but he could not tell what her sickness was. He always said:

“Just give her the medicine as directed, and she will be better soon.”

Miss Rose had asked Mrs. Snow if she might take care of her, for 114 she had come to love little Clematis, and Clematis loved her in return.

The school work did not take her time very much now, so Mrs. Snow was glad to let Miss Rose care for Clematis.

If she stayed away very long, Clematis would call for her. She wanted her in the room.

“Mrs. Snow,” said Miss Rose, one day, after Clematis had been ill more than two weeks, “I am very anxious about Clematis.”

“Is she no better?”

“No, I feel she is worse. She keeps asking for a cold drink of water, and says she is burning up. I wish I dared give her some, and keep her cooler.” 115

“Well, I think I should follow the doctor’s directions. It wouldn’t be wise to do anything that is not directed by him.”

“Don’t you suppose we could have another doctor to look at her, Mrs. Snow?”

“No, I fear not; not just now, anyway.”

Miss Rose went back to the little room upstairs with a sad heart. She knew Clematis was very ill.

That night she prayed that something might be done for the little sick girl, and the next morning she felt as if her prayers had been answered, when Doctor Field came.

“I shall have to be away for a 116 short time, Miss Rose,” he said, after he looked at Clematis, and felt her pulse.

“A young man, Doctor Wyatt, will take my place, and I am sure he will do all that can be done.”

“Can he come today?” asked Miss Rose. “I wish he could see her soon.”

“I will ask him. I think he will be much interested in Clematis. I should like to see her well again myself, but I must be out of town a few weeks.”

“Oh, I hope he will come today, and I hope he will take an interest in my little girl,” said Miss Rose to herself.

“I know she can be cured, if we only know what is the matter.” 117

That afternoon Doctor Wyatt came. Miss Rose was glad when she saw him, for he was so kind, and so wise, that she knew he would do the best he could.

The afternoon was hot, and Clematis was covered with hot blankets, as directed by Doctor Field.

Dr. Wyatt took the blankets, and threw them off.

“The poor child will roast under those,” he said.

Then he sat beside her, and watched her.

“Is there anything you would like?” he said at last, in a pleasant voice.

“Yes, I want a cold drink of 118 water.” Her voice sounded faint and feeble now.

“What does she have to drink?” asked Doctor Wyatt.

“We give her water now and then, as directed by Dr. Field. But we do not give her very much, and not very cold.”

“Have you any oranges in the house?”

“I could get some.”

“Then take the white of an egg, and put with it the juice of a whole orange. Add half a glass of water, with pieces of ice.

“Have good big pieces of ice,” Doctor Wyatt called after her, as he saw that Clematis had fixed her eye on him.

Clematis smiled when he said 119 that, and turned toward him with a sigh.

Soon Miss Rose came back with the glass. Dr. Wyatt held it to the lips of the little sick girl. She drank slowly.

“Oh thanks,” she whispered, when he took the glass away.

“Give her some of that whenever she asks for it,” he said.

“Now tell me about the nights,” the doctor went on.

“She is restless, and sleeps very little. She has bad dreams when she does sleep, and talks to herself.”

“What does she talk about?”

“I don’t know. We can’t make out.” 120

“Do you keep the room lighted at night?”

“Oh, no, it is kept dark.”

“Well, tonight keep it lighted. People who have bad dreams are often frightened by the dark.”

“Shall I give her the medicine as directed?”

“No, don’t give her any more medicine at present. Give her all she wants of the orange and egg. I’ll be back in the morning.”

And Dr. Wyatt was gone.

“He’s a good doctor,” said Clematis, licking her dry lips. “I want a drink.”

Miss Rose smiled, and put the glass to her lips.

Off for Tilton

“Well,” said Doctor Wyatt, the next morning, “how is Clematis today?”

“She seems a little more comfortable,” said Miss Rose.

The doctor sat by her for half an hour. He felt her pulse, and looked her all over. Then he shook his head.

That day he spent a long time studying his books.

In the evening he came again, and sat by Clematis. He shook his head, sadly.

“I must tell you, Miss Rose, 122 that Clematis is a very sick little girl,” he said, as they stood in the hall.

“Can’t you do anything for her?” The tears sprang to her eyes.

“Perhaps I can. If she is no better tomorrow, I shall feel very anxious.”

Again that night the doctor spent a long time over his big books. Then he went and talked with doctors in the hospital.

“I shall be here most of the time tonight,” he said the next morning. “Keep her cool, and as comfortable as you can.”

Miss Rose went back to the bed with aching heart.

“Oh, if we only knew what 123 was the matter with you, Clematis,” she thought, as she looked at the little white face.

In the evening Doctor Wyatt came back once more.

“Now, Miss Rose,” he said, “you are very tired. You must go away for a walk, or a visit, or a rest. I will take care of her tonight.”

“Don’t you think I had better stay, too?”

“No, you must rest. Please have a cup of coffee sent to me about ten. I shall stay right here. You will be needed tomorrow.”

Doctor Wyatt sat down to watch by Clematis.

It was a warm evening, so he 124 gave her a drink, and fanned her, to cool her hot face.

As it grew late, she fell into a light sleep. As she slept, she began to talk in low tones.

The doctor bent his head down very near her lips, and listened carefully to everything she said.

Hour after hour he watched and listened, until he, too, fell asleep, just as the sun was coming up.

Miss Rose found him there in the morning, sleeping in his chair, close by the bed.

“Miss Rose,” he asked, as he started up, “did this little girl want anything very much indeed?”

“Yes, she did. She wanted to go to the country, as the other 125 children did, but it did not seem quite possible.”

“That’s it! That’s just it!” exclaimed Doctor Wyatt. “She spoke of flowers, of lilacs and daisies. I couldn’t tell much what she said, but I could hear those words.”

At that moment, Clematis opened her eyes and stared about her.

Doctor Wyatt took one thin, frail hand in his big brown ones.

“Clematis,” he said in a loud, firm tone, “I know a lovely place in the country. If you will get well, you can go there for two whole weeks.”

Clematis stared at him, but did not seem to hear him. 126

“I want a drink,” she said feebly.

He put the glass to her lips.

“You can pick daisies, and goldenrod, and all sorts of flowers in the country, if you’ll just get well, can’t she, Miss Rose?”

“Yes, Clematis, you can.” Miss Rose tried to speak cheerfully, but it was hard. She wanted to cry.

Clematis stared at her also for a minute, and then turned away.

“I’ll go get some sleep now. Keep her cool and comfortable, till I come back again this evening.”

The day passed slowly. Mrs. Snow came in two or three times 127 to look at Clematis, and feel her pulse.

Some of the other teachers came to peep in also. They went away softly, wiping their eyes.

“She is a queer little girl,” said one, “but I do love her.”

That is what they all felt.

At evening Doctor Wyatt returned. He looked anxious, as he took his seat beside the bed.

“I shall stay till about ten, Miss Rose, so you must rest now.”

“I don’t want to go,” said Miss Rose.

“You must, you will be needed later. She will need great care tonight, I think.”

At ten, Miss Rose returned. 128 She had not rested much, and was glad to get back to the bedside.

“Here is my telephone number, Miss Rose. You can get me very soon by calling me up. Watch her carefully, and if you see any change at all, send for me at once.”

“Do you think there may be a change tonight?” Miss Rose looked straight into his face to see just what he meant.

“Yes, Miss Rose, there may be, and I hope it will be for the better.”

“You hope?” Miss Rose held her breath a minute.

“Yes, let us hope. Hope does more than all the medicine in the world.” 129

The minutes crept along into hours, and midnight passed, while Miss Rose watched.

Clematis seemed restless, but she did not talk to herself any more.

Miss Rose held the glass to her lips now and then, but she did not drink.

When Miss Rose wiped her face with a cold, wet cloth, she smiled a faint little smile, as if she liked it. Then the look of pain would come again, as she turned restlessly.

The clock outside struck one. How slowly the minutes went.

At last it struck two, and a breeze stirred the leaves outside.

They were the leaves of the 130 maple Clematis had broken in the early Spring. Now they seemed to whisper softly to each other.

All else was silent.

Miss Rose had watched a long time. Many days she had been by the bed. Her eyes began to droop.

“I’ll rest my head just a minute,” she thought, and leaned back upon the chair.

Slowly the clock struck three. As the last stroke came, Miss Rose stirred, and opened her eyes.

Then she started up.

“I must have been asleep,” she said aloud. “Oh, shame on me for sleeping, when I promised to watch.”

She looked down at the bed. 131

Clematis lay there, peaceful and quiet. Her little hand was white and still as marble. Her face seemed very happy. All pain was gone, and a smile lay upon the pale lips.

“Oh, little Clematis. To think I should have been asleep!”

Miss Rose took out her handkerchief, and bent her head down on the bed, weeping.

A slight sound seemed to come from the pillow. Miss Rose looked up.

The child’s eyes were open wide. She was looking at her in wonder.

“He said I could go, didn’t he?” said Clematis in a faint voice. 132

Miss Rose choked down her sobs.

“Yes, yes, Clematis, he did, he did.”

“Well, then, what are you crying about?”

Clematis closed her eyes again and lay, still as before, with a little smile on her lips.

Miss Rose was so astonished that she sat staring at her for some minutes, until she heard a step in the hall.

It was Doctor Wyatt.

He came in softly and looked at the little figure on the bed.

He felt her pulse, and listened to her heart. Then he smiled, and led Miss Rose from the room. 133

“She is all right now,” he whispered. “Let her sleep as long as she can.”

Clematis slept all night, and all the next day. It was evening when she woke.

Miss Rose was beside the bed, and heard her as she moved.

“Do you feel better now, dear little girl?” asked Miss Rose.

Clematis looked at her a moment with eyes wide open.

“He said I could go, didn’t he?” she asked.

“Yes, surely he did, and you can go; you shall go just as soon as you are well.”

Clematis smiled a happy smile. 135

“I want a drink of that orange juice.”

Miss Rose brought a glass with ice in it, and held it, while Clematis sipped it slowly. Then she washed her face and hands in cold water.

“Thanks,” the little girl whispered, as she turned on the pillow, and went off to sleep again.

There was great joy all through the Home, for every one knew that Clematis was getting well.

Doctor Wyatt came every day to look at his little sick girl, and laugh, and pat her cheeks.

“You just wait till you see the apple pies my aunt can make,” he would say.

Then Clematis would smile. 136

“Tell me about the garden. Are there any lilacs?”

“No lilac blossoms now, little sister, but asters, and hollyhocks, and goldenrod. You just wait till you see them.”

Then the doctor would go out, with another laugh.

Soon Clematis got so well that she could sit up in bed.

Miss Rose would sit by the window, sewing, and sometimes she would read a story.

One afternoon she saw that Clematis was anxious about something. She had a little wrinkle in her forehead.

“What is it you are thinking about? Is there something you want?”

In the country at last

Miss Rose went and stood by the bed, smoothing her forehead with her soft hand.

“I was thinking,” said Clematis. “I was thinking that—that perhaps I could have Deborah come to see me, just for a minute.”

“Well, you wait a minute, and I’ll see.”

Miss Rose went out, and Clematis waited to hear her steps again. She had not seen Deborah for a long time.

Soon she heard Miss Rose coming back. She shut her eyes till the footsteps came up to the bed, and before she opened them, there was a little pounce beside her.

Her dear Deborah was rubbing a cold nose against her cheek, and 138 purring how glad she was to see her.

Clematis smoothed and patted her a long time, as she lay purring close by her side.

After that, Deborah came up often, and lay there on the bed, while Miss Rose sewed by the window.

“What are you sewing?” asked Clematis one day, when she was well enough to sit up.

“What do you suppose?”

“It looks like a dress.”

“That’s just what it is. It’s a new dress for a little girl to wear to the country.”

“Oh, who is going to have it? Let me see it. Please hold it up.” 139

Miss Rose held the dress before her. It was nearly done.

The skirt was of serge, navy blue, with two pockets. With it went a middy blouse, with white lacings at the neck, and white stars on the sleeves.

“Oh, please tell me. Who is going to have it?” The child’s eyes danced as she saw the pretty dress.

“I’ll give you just one guess,” said Miss Rose, smiling.