This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The True Story Book

Editor: Andrew Lang

Release Date: December 23, 2008 [eBook #27602]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TRUE STORY BOOK***

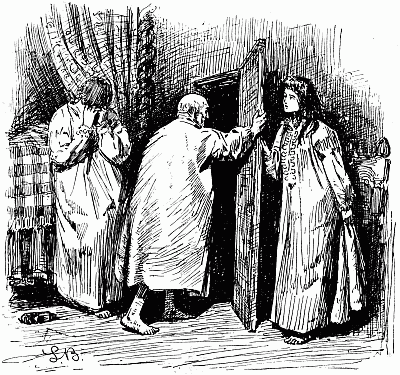

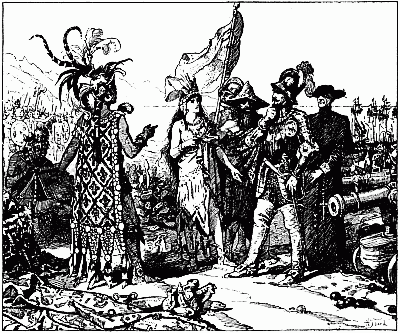

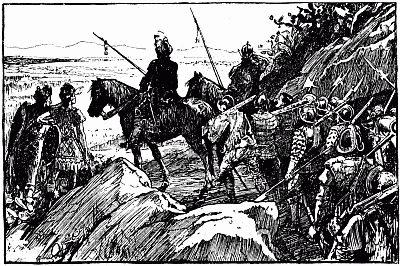

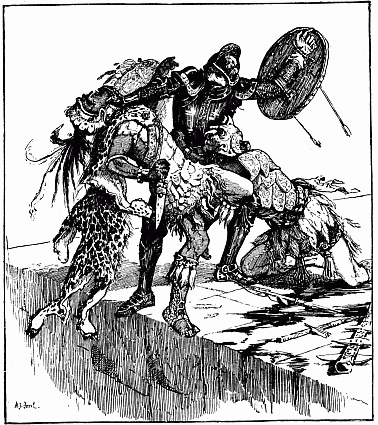

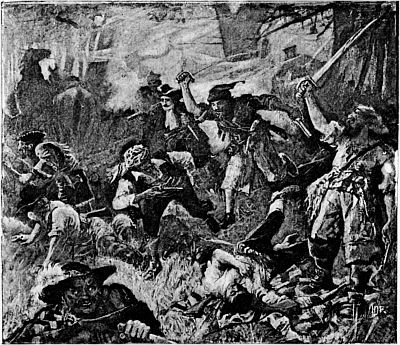

MONTEZUMA GREETS THE SPANIARDS

MONTEZUMA GREETS THE SPANIARDS

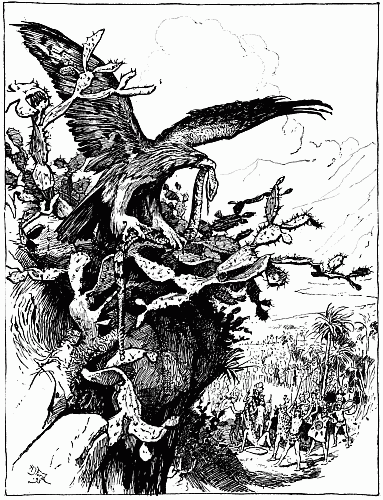

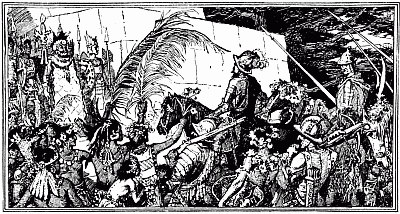

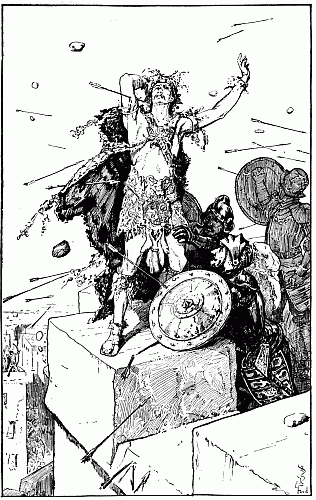

That is a very long story, but, to the editor's taste, it is simply the best true story in the world, the most unlikely, and the most romantic. For who could have supposed that the new-found world of the West held all that wealth of treasure, emeralds and gold, all those people, so beautiful and brave, so courteous and cruel, with their terrible gods, hideous human sacrifices, and almost Christian prayers? That a handful of Spaniards, themselves mistaken for children of a white god, should have crossed the sea, should have found a lovely lady, as in a fairy tale, ready to lead them to victory, should have planted the cross on the shambles of Huitzilopochtli, after that wild battle on the temple crest, should have been driven in rout from, and then recaptured, the Venice of the West, the lake city of Mexico—all this is as strange, as unlooked for, as any story of adventures in a new planet could be. No invention of fights and wanderings in Noman's land, no search for the mines of Solomon the king, can approach, for strangeness and romance, this tale, which is true, and vouched for by Spanish conquerors like Bernal Diaz, and by native historians like Ixtlilochitl, and by later missionaries like Sahagun. Cortés is the great original of all treasure-hunters and explorers in fiction, and here no feigned tale can be the equal of the real. As Mr. Prescott's admirable history is not a book much read by children (nor even by 'grown-ups' for that matter), the editor hopes children will be pleased to find the 'Adventures in Anahuac' in this collection. Miss Edgeworth tells us in Orlandino how much the tale delighted the young before Mr. Prescott wrote[xi] that excellent narrative of the world's chief adventure. May it please still, as it did when the century was young!

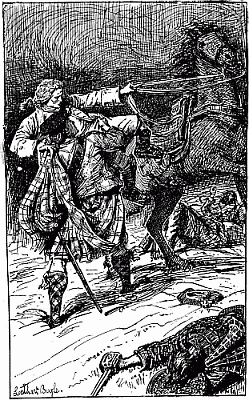

The adventures of Prince Charlie are already known, in part, to boys and girls who have read the Tales of a Grandfather, for pleasure and not as a school book. But here Mrs. McCunn has treated of them at greater length and more minutely. The source, here, is in these seven brown octavo volumes, all written in the closest hand, which are a treasure of the Advocates' Library in Edinburgh. The author is Mr. Forbes, a bishop of the persecuted Episcopalian Church in Scotland. Mr. Forbes collected his information very carefully, closely comparing the narratives of the various actors in the story. Into the boards of his volumes are fastened a scrap of the Prince's tartan waistcoat, a rag from his sprigged calico dress, a bit of his brogues—a twopenny treasure that has been wept and prayed over by the faithful. Nobody, in a book for children, would have the heart to tell the tale of the Prince's later years, of a moody, heart-broken, degraded exile. But, in the hills and the isles, bating a little wilfulness and foolhardiness, and the affair of the broken punch-bowl, Prince Charles is a model for princes and all men, brave, gay, much-enduring, good-humoured, kind, royally courteous, and considerate, even beyond what may be gathered from this part of the book, while the loyalty of the Highlanders (as in the case of Mackinnon, flogged nearly to death) was proof against torture as well as against gold. It is the Sobieski strain, not the Stuart, that we here admire in Prince Charles; it is a piety, a loyalty, a goodness like Gordon's that we revere in old Lord Pitsligo in another story.

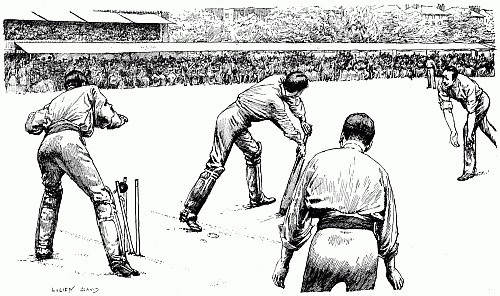

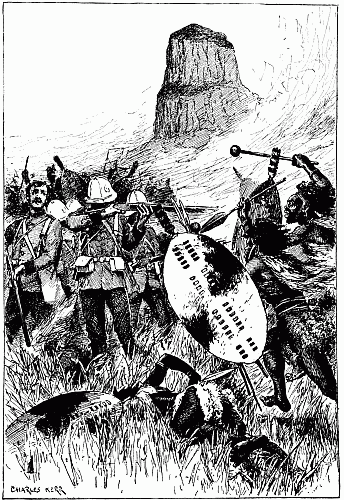

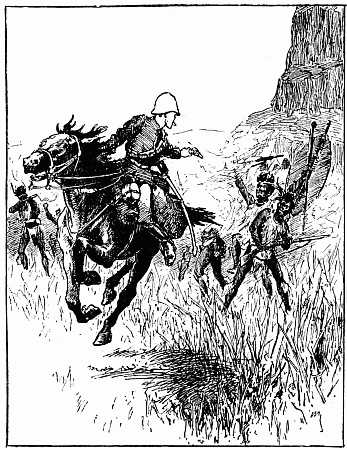

Many of the tales are concerned with fighting, for that is the most dramatic part of mortal business. These English captives who retake a ship from the Turks, these heroes of the Shannon and the Chesapeake, were doubtless good men and[xii] true in all their lives, but the light of history only falls on them in war. The immortal Three Hundred of Thermopylæ would also have been unknown, had they not died, to a man, for the sake of the honour of Lacedæmon. The editor conceives that it would have been easy to give more 'local colour' to the sketch of Thermopylæ: to have dealt in description of the Immortals, drawn from the friezes in Susa, lately discovered by French enterprise. But the story is Greek, and the Greeks did not tell their stories in that way, but with a simplicity almost bald. Yet who dare alter and 'improve' the narrative of Herodotus? In another most romantic event, the finding of Vineland the Good, by Leif the Lucky, our materials are vague with the vagueness of a dream. Later fancy has meddled with the truth of the saga. English readers, no doubt, best catch the charm of the adventure in Mr. Rudyard Kipling's astonishingly imaginative tale called 'The Best Story in the World.' For the account of Isandhlwana, and Rorke's Drift, 'an ower-true tale,' the editor has to thank his friend Mr. Rider Haggard, who was in South Africa at the time of the disaster, and who has generously given time and labour to the task of ascertaining, as far as it can be ascertained, the exact truth of the melancholy, but, finally, not inglorious, business. The legend of 'Two Great Cricket Matches' is taken, in part, from Lillywhite's scores, and Mr. Robert Lyttelton's spirited pages in the 'Badminton' book of Cricket. The second match the editor writes of 'as he who saw it,' to quote Caxton on Dares Phrygius. These legends prove that a match is never lost till it is won.

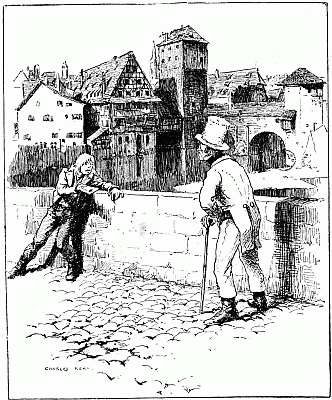

Some of the True Stories contain, we may surmise, traces of the imaginative faculty. The escapes of Benvenuto Cellini, of Trenck, and of Casanova must be taken as the heroes chose to report them; Benvenuto and Casanova have no firm reputation for veracity. Again, the escape of Cæsar[xii] Borgia is from a version handed down by the great Alexandre Dumas, and we may surmise that Alexandre allowed it to lose nothing in the telling; he may have 'given it a sword and a cocked hat,' as was Sir Walter's wont. About Kaspar Hauser's mystery we can hardly speak of 'the truth,' for the exact truth will never be known. The depositions of the earliest witnesses were not taken at once; some witnesses altered their evidence in later years; parts of the records of Nuremberg are lost in suspicious circumstances. The Duchess of Cleveland's book, Kaspar Hauser, is written in defence of her father, Lord Stanhope. The charges against Lord Stanhope, that he aided in, or connived at, the slaying of Kaspar, because Kaspar was the true heir of the House of Baden—are as childish as they are wicked. But the Duchess hardly allows for the difficulties in which we find ourselves if we regard Kaspar as absolutely and throughout an impostor. This, however, is not the place to discuss an historical mystery; this 'true story' is told as a romance founded on fact; the hypothesis that Kaspar was a son and heir of the house of Baden seems, to the editor, to be absolutely devoid of evidence.

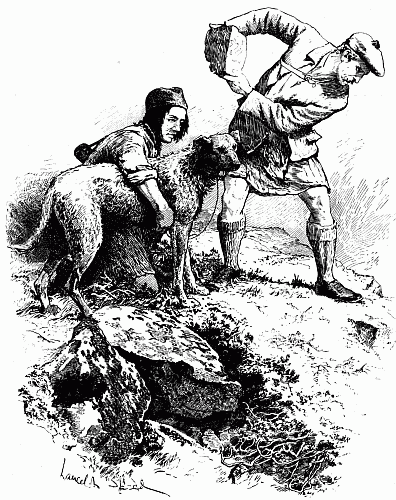

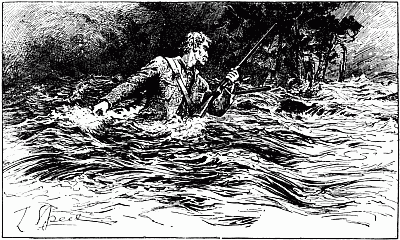

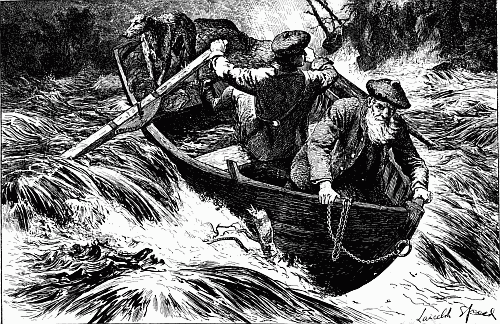

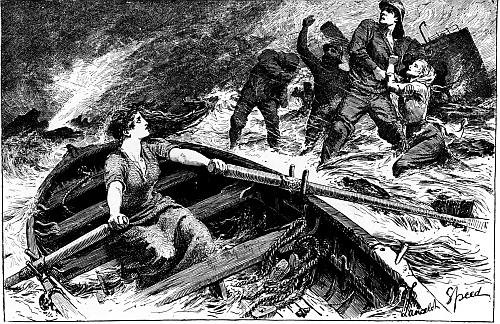

To Madame Von Platt Stuart the author owes permission to quote the striking adventures of her father, or of her uncle, on the flooded Findhorn. The Lays of the Deer Forest, which contain this tale in the volume of notes, were written by John Sobieski Stuart, and by Charles Edward Stuart, and the editor is uncertain as to which of those gentlemen was the hero of these perilous crossings of the Highland river. Many other good tales, legends, and studies of natural history and of Highland manners may be found in the Lays of the Deer Forest, apart from the curious interest of the poems. On the whole, with certain exceptions, the editor has tried to find true stories rather out of the beaten paths of history; the narrative of John Tanner, for instance,[xiv] is probably true, but the book in which his adventures were published is now rather difficult to procure. For 'A Boy among the Red Indians,' 'Two Cricket Matches,' 'The Spartan Three Hundred,' 'The Finding of Vineland the Good,' and 'The Escapes of Lord Pitsligo,' the editor is himself responsible, as far as they do not consist of extracts from the original sources. Miss May Kendall translated or adapted Casanova's escape and the piratical and Algerine tales. Mrs. Lang reduced the narrative of the Chevalier Johnstone, and did the escapes of Cæsar Borgia, of Trenck, and Cervantes, while Miss Blackley renders that of Benvenuto Cellini. Mrs. McCunn, as already said, compiled from the sources indicated the Adventures of Prince Charles, and she tells the story of Grace Darling; the contemporary account is, unluckily, rather meagre. Miss Alleyne did 'The Kidnapping of the Princes,' Mrs. Plowden the 'Story of Kaspar Hauser.' Miss Wright reduced the Adventures of Cortés from Prescott, and Mr. Rider Haggard has already been mentioned in connection with Isandhlwana.

Here the editor leaves The True Story Book to the indulgence of children, explaining, once more, that his respect for their judgment is very great, and that he would not dream of imposing lessons on them, in the shape of a Christmas book. No, lessons are one thing, and stories are another. But though fiction is undeniably stranger and more attractive than truth, yet true stories are also rather attractive and strange, now and then. And, after all, we may return once more to Fairyland, after this excursion into the actual workaday world.

|

|

| Montezuma greets the Spaniards | Frontispiece | |

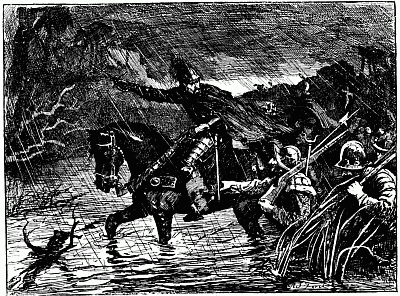

| The Findhorn | To face | 36 |

| Grace Darling | " | 44 |

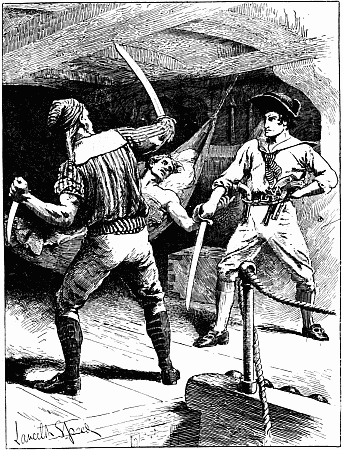

| 'Some of the Pirates . . . had thrown several Buckets of Claret upon him' | " | 60 |

| The Ball hit the Middle Stump | " | 108 |

| He prepared to attack the Sentry | " | 126 |

| Montezuma greets the Spaniards | " | 270 |

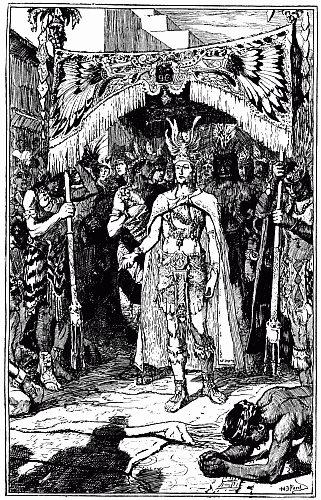

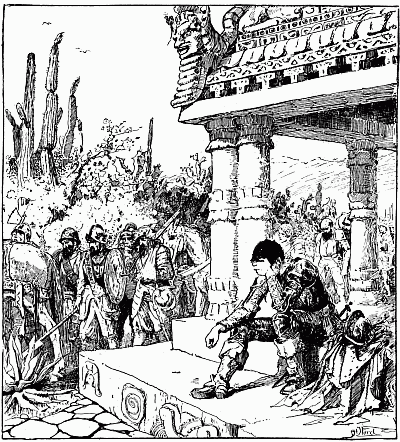

| Cortés in the Temple of Huitzilopochtli | " | 276 |

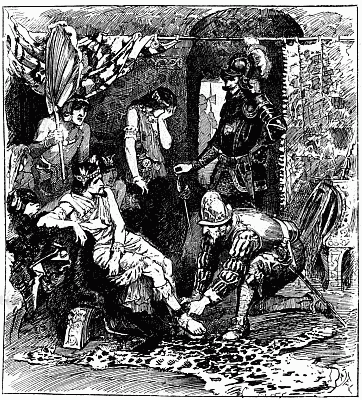

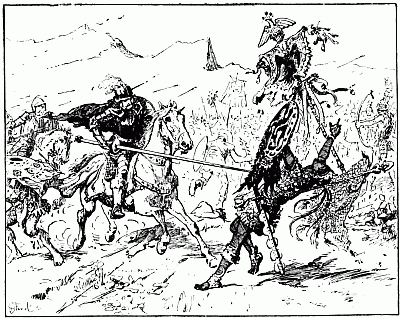

| Montezuma assailed by Missiles | " | 296 |

My father, whose name was John Tanner, was an emigrant from Virginia, and had been a clergyman.

When about to start one morning to a village at some distance, he gave, as it appeared, a strict charge to my sisters, Agatha and Lucy, to send me to school; but this they neglected to do until afternoon, and then, as the weather was rainy and unpleasant, I insisted on remaining at home. When my father returned at night, and found that I had been at home all day, he sent me for a parcel of small canes, and flogged me much more severely than I could suppose the offence merited. I was displeased with my sisters for attributing all the blame to me, when they had neglected even to tell me to go to school in the forenoon. From that time, my father's house was less like home to me, and I often thought and said, 'I wish I could go and live among the Indians.'

One day we went from Cincinnati to the mouth of the Big Miami, opposite which we were to settle. Here was some cleared land, and one or two log cabins, but they had been deserted on account of the Indians. My father rebuilt the cabins, and inclosed them with a strong picket. It was early in the spring when we arrived at the mouth of the Big Miami, and we were soon engaged in preparing a field to plant corn. I think it was not more than ten days after our arrival, when my father told us in the morning, that, from the actions of the horses, he perceived there were Indians lurking about in the woods, and he said to me, 'John, you[2] must not go out of the house to-day.' After giving strict charge to my stepmother to let none of the little children go out, he went to the field, with the negroes, and my elder brother, to drop corn.

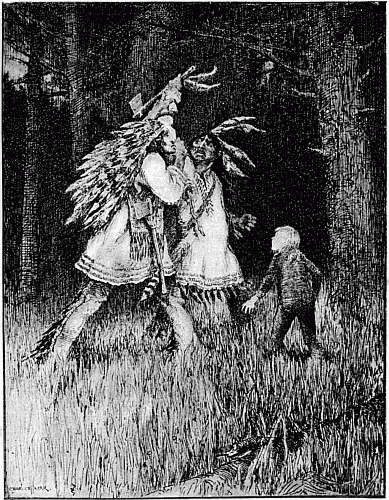

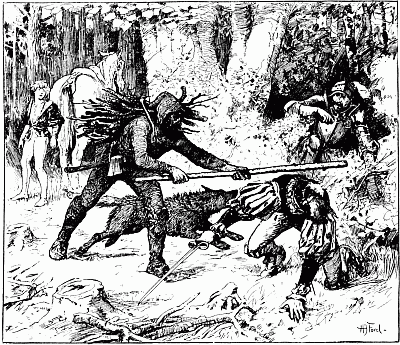

Three little children, besides myself, were left in the house with my stepmother. To prevent me from going out, my stepmother required me to take care of the little child, then not more than a few months old; but as I soon became impatient of confinement, I began to pinch my little brother, to make him cry. My mother, perceiving his uneasiness, told me to take him in my arms and walk about the house; I did so, but continued to pinch him. My mother at length took him from me to nurse him. I watched my opportunity, and escaped into the yard; thence through a small door in the large gate of the wall into the open field. There was a walnut-tree at some distance from the house, and near the side of the field where I had been in the habit of finding some of the last year's nuts. To gain this tree without being seen by my father and those in the field, I had to use some precaution. I remember perfectly well having seen my father, as I skulked towards the tree; he stood in the middle of the field, with his gun in his hand, to watch for Indians, while the others were dropping corn. As I came near the tree, I thought to myself, 'I wish I could see these Indians.' I had partly filled with nuts a straw hat which I wore, when I heard a crackling noise behind me; I looked round, and saw the Indians; almost at the same instant, I was seized by both hands, and dragged off betwixt two. One of them took my straw hat, emptied the nuts on the ground, and put it on my head. The Indians who seized me were an old man and a young one; these were, as I learned subsequently, Manito-o-geezhik, and his son Kish-kau-ko.

After I saw myself firmly seized by both wrists by the two Indians, I was not conscious of anything that passed for a considerable time. I must have fainted, as I did not cry out, and I can remember nothing that happened to me until they threw me over a large log, which must have been at a considerable distance from the house. The old man I did not now see; I was dragged along between Kish-kau-ko and a very short thick man. I had probably made some resistance, or done something to irritate this last, for he took me a little to one side, and drawing his tomahawk, motioned to me to look up. This I plainly understood, from the expression of his face, and his manner, to be a direction for me to look up for the last time, as he was about to kill me. I did as he[3] directed, but Kish-kau-ko caught his hand as the tomahawk was descending, and prevented him from burying it in my brains. Loud talking ensued between the two. Kish-kau-ko presently raised a yell: the old man and four others answered it by a similar yell, and came running up. I have since understood that Kish-kau-ko complained to his father that the short man had made an attempt[4] to kill his little brother, as he called me. The old chief, after reproving him, took me by one hand, and Kish-kau-ko by the other and dragged me betwixt them, the man who had threatened to kill me, and who was now an object of terror to me, being kept at some distance. I could perceive, as I retarded them somewhat in their retreat, that they were apprehensive of being overtaken; some of them were always at some distance from us.

It was about one mile from my father's house to the place where they threw me into a hickory-bark canoe, which was concealed under the bushes, on the bank of the river. Into this they all seven jumped, and immediately crossed the Ohio, landing at the mouth of the Big Miami, and on the south side of that river. Here they abandoned their canoe, and stuck their paddles in the ground, so that they could be seen from the river. At a little distance in the woods they had some blankets and provisions concealed; they offered me some dry venison and bear's grease, but I could not eat. My father's house was plainly to be seen from the place where we stood; they pointed at it, looked at me, and laughed, but I have never known what they said.

After they had eaten a little, they began to ascend the Miami, dragging me along as before.

It must have been early in the spring when we arrived at Sau-ge-nong, for I can remember that at this time the leaves were small, and the Indians were about planting their corn. They managed to make me assist at their labours, partly by signs, and partly by the few words of English old Manito-o-geezhik could speak. After planting, they all left the village, and went out to hunt and dry meat. When they came to their hunting-grounds, they chose a place where many deer resorted, and here they began to build a long screen like a fence; this they made of green boughs and small trees. When they had built a part of it, they showed me how to remove the leaves and dry brush from that side of it to which the Indians were to come to shoot the deer. In this labour I was sometimes assisted by the squaws and children, but at other times I was left alone. It now began to be warm weather, and it happened one day that, having been left alone, as I was tired and thirsty, I fell asleep. I cannot tell how long I slept, but when I began to awake, I thought I heard someone crying a great way off. Then I tried to raise up my head, but could not. Being now more awake, I saw my Indian mother and sister standing by me, and perceived that my face and head were wet. The old woman and her[5] daughter were crying bitterly, but it was some time before I perceived that my head was badly cut and bruised. It appears that, after I had fallen asleep, Manito-o-geezhik, passing that way, had perceived me, had tomahawked me, and thrown me in the bushes; and that when he came to his camp he had said to his wife, 'Old woman, the boy I brought you is good for nothing; I have killed him; you will find him in such a place.' The old woman and her daughter having found me, discovered still some signs of life, and had stood over me a long time, crying, and pouring cold water on my head, when I waked. In a few days I recovered in some measure from this hurt, and was again set to work at the screen, but I was more careful not to fall asleep; I endeavoured to assist them at their labours, and to comply in all instances with their directions, but I was notwithstanding treated with great harshness, particularly by the old man, and his two sons She-mung and Kwo-tash-e. While we remained at the hunting camp, one of them put a bridle in my hand, and pointing in a certain direction motioned me to go. I went accordingly, supposing he wished me to bring a horse: I went and caught the first I could find, and in this way I learned to discharge such services as they required of me.

I had been about two years at Sau-ge-nong, when a great council was called by the British agents at Mackinac. This council was attended by the Sioux, the Winnebagoes, the Menomonees, and many remote tribes, as well as by the Ojibbeways, Ottawwaws, &c. When old Manito-o-geezhik returned from this council, I soon learned that he had met there his kinswoman, Net-no-kwa, who, notwithstanding her sex, was then regarded as principal chief of the Ottawwaws. This woman had lost her son, of about my age, by death; and, having heard of me, she wished to purchase me to supply his place. My old Indian mother, the Otter woman, when she heard of this, protested vehemently against it. I heard her say, 'My son has been dead once, and has been restored to me; I cannot lose him again.' But these remonstrances had little influence when Net-no-kwa arrived with plenty of whisky and other presents. She brought to the lodge first a ten-gallon keg of whisky, blankets, tobacco, and other articles of great value. She was perfectly acquainted with the dispositions of those with whom she had to negotiate. Objections were made to the exchange until the contents of the keg had circulated for some time; then an additional keg, and a few more presents, completed the bargain, and I was transferred to Net-no-kwa. This woman, who was then advanced[6] in years, was of a more pleasing aspect than my former mother. She took me by the hand, after she had completed the negotiation with my former possessors, and led me to her own lodge, which stood near. Here I soon found I was to be treated more indulgently than I had been. She gave me plenty of food, put good clothes upon me, and told me to go and play with her own sons. We remained but a short time at Sau-ge-nong. She would not stop with me at Mackinac, which we passed in the night, but ran along to Point St. Ignace, where she hired some Indians to take care of me, while she returned to Mackinac by herself, or with one or two of her young men. After finishing her business at Mackinac, she returned, and, continuing on our journey, we arrived in a few days at Shab-a-wy-wy-a-gun.

The husband of Net-no-kwa was an Ojibbeway of Red River, called Taw-ga-we-ninne, the hunter. He was seventeen years younger than Net-no-kwa, and had turned off a former wife on being married to her. Taw-ga-we-ninne was always indulgent and kind to me, treating me like an equal, rather than as a dependent. When speaking to me, he always called me his son. Indeed, he himself was but of secondary importance in the family, as everything belonged to Net-no-kwa, and she had the direction in all affairs of any moment. She imposed on me, for the first year, some tasks. She made me cut wood, bring home game, bring water, and perform other services not commonly required of the boys of my age; but she treated me invariably with so much kindness that I was far more happy and content than I had been in the family of Manito-o-geezhik. She sometimes whipped me, as she did her own children: but I was not so severely and frequently beaten as I had been before.

Early in the spring, Net-no-kwa and her husband, with their family, started to go to Mackinac. They left me, as they had done before, at Point St. Ignace, as they would not run the risk of losing me by suffering me to be seen at Mackinac. On our return, after we had gone twenty-five or thirty miles from Point St. Ignace, we were detained by contrary winds at a place called Me-nau-ko-king, a point running out into the lake. Here we encamped with some other Indians, and a party of traders. Pigeons were very numerous in the woods, and the boys of my age, and the traders, were busy shooting them. I had never killed any game, and, indeed, had never in my life discharged a gun. My mother had purchased at Mackinac a keg of powder, which, as they thought[7] it a little damp, was here spread out to dry. Taw-ga-we-ninne had a large horseman's pistol; and, finding myself somewhat emboldened by his indulgent manner toward me, I requested permission to go and try to kill some pigeons with the pistol. My request was seconded by Net-no-kwa, who said, 'It is time for our son to begin to learn to be a hunter.' Accordingly, my father, as I called Taw-ga-we-ninne, loaded the pistol and gave it to me, saying, 'Go, my son, and if you kill anything with this, you shall immediately have a gun and learn to hunt.' Since I have been a man, I have been placed in difficult situations; but my anxiety for success was never greater than in this, my first essay as a hunter. I had not gone far from the camp before I met with pigeons, and some of them alighted in the bushes very near me. I cocked my pistol, and raised it to my face, bringing the breech almost in contact with my nose. Having brought the sight to bear upon the pigeon, I pulled trigger, and was in the next instant sensible of a humming noise, like that of a stone sent swiftly through the air. I found the pistol at the distance of some paces behind me, and the pigeon under the tree on which he had been sitting. My face was much bruised, and covered with blood. I ran home, carrying my pigeon in triumph. My face was speedily bound up; my pistol exchanged for a fowling-piece; I was accoutred with a powder-horn, and furnished with shot, and allowed to go out after birds. One of the young Indians went with me, to observe my manner of shooting. I killed three more pigeons in the course of the afternoon, and did not discharge my gun once without killing. Henceforth I began to be treated with more consideration, and was allowed to hunt often, that I might become expert.

Game began to be scarce, and we all suffered from hunger. The chief man of our band was called As-sin-ne-boi-nainse (the Little Assinneboin), and he now proposed to us all to move, as the country where we were was exhausted. The day on which we were to commence our removal was fixed upon, but before it arrived our necessities became extreme. The evening before the day on which we intended to move my mother talked much of all our misfortunes and losses, as well as of the urgent distress under which we were then labouring. At the usual hour I went to sleep, as did all the younger part of the family; but I was wakened again by the loud praying and singing of the old woman, who continued her devotions through great part of the night. Very early on the following morning she called us all to get up, and put on[8] our moccasins, and be ready to move. She then called Wa-me-gon-a-biew to her, and said to him, in rather a low voice, 'My son, last night I sung and prayed to the Great Spirit, and when I slept, there came to me one like a man, and said to me, "Net-no-kwa, to-morrow you shall eat a bear. There is, at a distance from the path you are to travel to-morrow, and in such a direction" (which she described to him), "a small round meadow, with something like a path leading from it; in that path there is a bear." Now, my son, I wish you to go to that place, without mentioning to anyone what I have said, and you will certainly find the bear, as I have described to you.' But the young man, who was not particularly dutiful, or apt to regard what his mother said, going out of the lodge, spoke sneeringly to the other Indians of the dream. 'The old woman,' said he, 'tells me we are to eat a bear to-day; but I do not know who is to kill it.' The old woman, hearing him, called him in, and reproved him; but she could not prevail upon him to go to hunt.

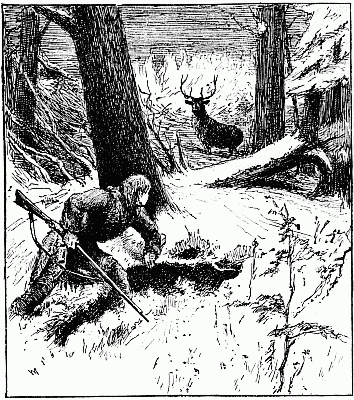

I had my gun with me, and I continued to think of the conversation I had heard between my mother and Wa-me-gon-a-biew respecting her dream. At length I resolved to go in search of the place she had spoken of, and without mentioning to anyone my design, I loaded my gun as for a bear, and set off on our back track. I soon met a woman belonging to one of the brothers of Taw-ga-we-ninne, and of course my aunt. This woman had shown little friendship for us, considering us as a burthen upon her husband, who sometimes gave something for our support; she had also often ridiculed me. She asked me immediately what I was doing on the path, and whether I expected to kill Indians, that I came there with my gun. I made her no answer; and thinking I must be not far from the place where my mother had told Wa-me-gon-a-biew to leave the path, I turned off, continuing carefully to regard all the directions she had given. At length I found what appeared at some former time to have been a pond. It was a small, round, open place in the woods, now grown up with grass and small bushes. This I thought must be the meadow my mother had spoken of; and examining around it, I came to an open space in the bushes, where, it is probable, a small brook ran from the meadow; but the snow was now so deep that I could see nothing of it. My mother had mentioned that, when she saw the bear in her dream, she had, at the same time, seen a smoke rising from the ground. I was confident this was the place she had indicated, and I watched[9] long, expecting to see the smoke; but, wearied at length with waiting, I walked a few paces into the open place, resembling a path, when I unexpectedly fell up to my middle in the snow. I extricated myself without difficulty, and walked on; but, remembering that I had heard the Indians speak of killing bears in their holes, it occurred to me that it might be a bear's hole into which I had fallen, and, looking down into it, I saw the head of a bear lying close to the bottom of the hole. I placed the muzzle of my gun nearly between his eyes and discharged it. As soon as the smoke cleared away, I took a piece of stick and thrust it into the eyes and into the wound in the head of the bear, and, being satisfied that he was dead, I endeavoured to lift him out of the hole; but being unable to do this, I returned home, following the track I had made in coming out. As I came near the camp, where the squaws had by this time set up the lodges, I met the same woman I had seen in going out, and she immediately began again to ridicule me. 'Have you killed a bear, that you come back so soon, and walk so fast?' I thought to myself, 'How does she know that I have killed a bear?' But I passed by her without saying anything, and went into my mother's lodge. After a few minutes, the old woman said, 'My son, look in that kettle, and you will find a mouthful of beaver meat, which a man gave me since you left us in the morning. You must leave half of it for Wa-me-gon-a-biew, who has not yet returned from hunting, and has eaten nothing to-day.' I accordingly ate the beaver meat, and when I had finished it, observing an opportunity when she stood by herself, I stepped up to her, and whispered in her ear, 'My mother, I have killed a bear.' 'What do you say, my son?' said she. 'I have killed a bear.' 'Are you sure you have killed him?' 'Yes.' 'Is he quite dead?' 'Yes.' She watched my face for a moment, and then caught me in her arms, hugging and kissing me with great earnestness, and for a long time. I then told her what my aunt had said to me, both going and returning, and this being told to her husband when he returned, he not only reproved her for it, but gave her a severe flogging. The bear was sent for, and, as being the first I had killed, was cooked all together, and the hunters of the whole band invited to feast with us, according to the custom of the Indians. The same day one of the Crees killed a bear and a moose, and gave a large share of the meat to my mother.

One winter I hunted for a trader called by the Indians Aneeb, which means an elm-tree. As the winter advanced, and the[10] weather became more and more cold, I found it difficult to procure as much game as I had been in the habit of supplying, and as was wanted by the trader. Early one morning, about mid-winter, I started an elk. I pursued until night, and had almost overtaken him; but hope and strength failed me at the same time. What clothing I had on me, notwithstanding the extreme coldness of the weather, was drenched with sweat. It was not long after I turned towards home that I felt it stiffening about me. My leggings were of cloth, and were torn in pieces in running through the bush. I was conscious I was somewhat frozen before I arrived at the place where I had left our lodge standing in the morning, and it was now[11] midnight. I knew it had been the old woman's intention to move, and I knew where she would go; but I had not been informed she would go on that day. As I followed on their path, I soon ceased to suffer from cold, and felt that sleepy sensation which I knew preceded the last stage of weakness in such as die of cold. I redoubled my efforts, but with an entire consciousness of the danger of my situation; it was with no small difficulty that I could prevent myself from lying down. At length I lost all consciousness for some time, how long I cannot tell, and, awaking as from a dream, I found I had been walking round and round in a small circle not more than twenty or twenty-five yards over. After the return of my senses, I looked about to try to discover my path, as I had missed it; but, while I was looking, I discovered a light at a distance, by which I directed my course. Once more, before I reached the lodge, I lost my senses; but I did not fall down; if I had, I should never have got up again; but I ran round and round in a circle as before. When I at last came into the lodge, I immediately fell down, but I did not lose myself as before. I can remember seeing the thick and sparkling coat of frost on the inside of the pukkwi lodge, and hearing my mother say that she had kept a large fire in expectation of my arrival; and that she had not thought I should have been so long gone in the morning, but that I should have known long before night of her having moved. It was a month before I was able to go out again, my face, hands, and legs having been much frozen.

There is, on the bank of the Little Saskawjewun, a place which looks like one the Indians would always choose to encamp at. In a bend of the river is a beautiful landing-place, behind it a little plain, a thick wood, and a small hill rising abruptly in the rear. But with that spot is connected a story of fratricide, a crime so uncommon that the spot where it happened is held in detestation, and regarded with terror. No Indian will land his canoe, much less encamp, at 'the place of the two dead men.' They relate that many years ago the Indians were encamped here, when a quarrel arose between two brothers, having she-she-gwi for totems.[1] One drew his knife and slew the other; but those of the band who were present, looked upon the crime as so horrid that, without hesitation or delay, they killed the murderer, and buried them together.

As I approached this spot, I thought much of the story of the two brothers, who bore the same totem with myself, and were, as I[12] supposed, related to my Indian mother. I had heard it said that, if any man encamped near their graves, as some had done soon after they were buried, they would be seen to come out of the ground, and either re-act the quarrel and the murder, or in some other manner so annoy and disturb their visitors that they could not sleep. Curiosity was in part my motive, and I wished to be able to tell the Indians that I not only stopped, but slept quietly at a place which they shunned with so much fear and caution. The sun was going down as I arrived; and I pushed my little canoe in to the shore, kindled a fire, and, after eating my supper, lay down and slept. Very soon I saw the two dead men come and sit down by my fire, opposite me. Their eyes were intently fixed upon me, but they neither smiled nor said anything. I got up and sat opposite them by the fire, and in this situation I awoke. The night was dark and gusty, but I saw no men, or heard any other sound than that of the wind in the trees. It is likely I fell asleep again, for I soon saw the same two men standing below the bank of the river, their heads just rising to the level of the ground I had made my fire on, and looking at me as before. After a few minutes, they rose one after the other, and sat down opposite me; but now they were laughing, and pushing at me with sticks, and using various methods of annoyance. I endeavoured to speak to them, but my voice failed me; I tried to fly, but my feet refused to do their office. Throughout the whole night I was in a state of agitation and alarm. Among other things which they said to me, one of them told me to look at the top of the little hill which stood near. I did so, and saw a horse fettered, and standing looking at me. 'There, my brother,' said the ghost, 'is a horse which I give you to ride on your journey to-morrow; and as you pass here on your way home, you can call and leave the horse, and spend another night with us.'

At last came the morning, and I was in no small degree pleased to find that with the darkness of the night these terrifying visions vanished. But my long residence among the Indians, and the frequent instances in which I had known the intimations of dreams verified, occasioned me to think seriously of the horse the ghost had given me. Accordingly I went to the top of the hill, where I discovered tracks and other signs, and, following a little distance, found a horse, which I knew belonged to the trader I was going to see. As several miles travel might be saved by crossing from this point on the Little Saskawjewun to the Assinneboin, I left the[13] canoe, and, having caught the horse, and put my load upon him, led him towards the trading-house, where I arrived next day. In all subsequent journeys through this country, I carefully shunned 'the place of the two dead'; and the account I gave of what I had seen and suffered there confirmed the superstitious terrors of the Indians.

I was standing by our lodge one evening, when I saw a good-looking young woman walking about and smoking. She noticed me from time to time, and at last came up and asked me to smoke with her. I answered that I never smoked. 'You do not wish to touch my pipe; for that reason you will not smoke with me.' I took her pipe and smoked a little, though I had not been in the habit of smoking before. She remained some time, and talked with me, and I began to be pleased with her. After this we saw each other often, and I became gradually attached to her.

I mention this because it was to this woman that I was afterwards married, and because the commencement of our acquaintance was not after the usual manner of the Indians. Among them it most commonly happens, even when a young man marries a woman of his own band, he has previously had no personal acquaintance with her. They have seen each other in the village; he has perhaps looked at her in passing, but it is probable they have never spoken together. The match is agreed on by the old people, and when their intention is made known to the young couple, they commonly find, in themselves, no objection to the arrangement, as they know, should it prove disagreeable mutually, or to either party, it can at any time be broken off.

I now redoubled my diligence in hunting, and commonly came home with meat in the early part of the day, at least before night. I then dressed myself as handsomely as I could, and walked about the village, sometimes blowing the Pe-be-gwun, or flute. For some time Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa pretended she was not willing to marry me, and it was not, perhaps, until she perceived some abatement of ardour on my part that she laid this affected coyness entirely aside. For my own part, I found that my anxiety to take a wife home to my lodge was rapidly becoming less and less. I made several efforts to break off the intercourse, and visit her no more; but a lingering inclination was too strong for me. When she perceived my growing indifference, she sometimes reproached me, and sometimes sought to move me by tears and entreaties; but I said nothing to the old woman about bringing her home, and[14] became daily more and more unwilling to acknowledge her publicly as my wife.

About this time I had occasion to go to the trading-house on Red River, and I started in company with a half-breed belonging to that establishment, who was mounted on a fleet horse. The distance we had to travel has since been called by the English settlers seventy miles. We rode and went on foot by turns, and the one who was on foot kept hold of the horse's tail, and ran. We passed over the whole distance in one day. In returning, I was by myself, and without a horse, and I made an effort, intending, if possible, to accomplish the same journey in one day; but darkness, and excessive fatigue, compelled me to stop when I was within about ten miles of home.

When I arrived at our lodge, on the following day, I saw Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa sitting in my place. As I stopped at the door of the lodge, and hesitated to enter, she hung down her head; but Net-no-kwa greeted me in a tone somewhat harsher than was common for her to use to me. 'Will you turn back from the door of the lodge, and put this young woman to shame, who is in all respects better than you are? This affair has been of your seeking, and not of mine or hers. You have followed her about the village heretofore; now you would turn from her, and make her appear like one who has attempted to thrust herself in your way.' I was, in part, conscious of the justness of Net-no-kwa's reproaches, and in part prompted by inclination; I went in and sat down by the side of Mis-kwa-bun-o-kwa, and thus we became man and wife. Old Net-no-kwa had, while I was absent at Red River, without my knowledge or consent, made her bargain with the parents of the young woman, and brought her home, rightly supposing that it would be no difficult matter to reconcile me to the measure. In most of the marriages which happen between young persons, the parties most interested have less to do than in this case. The amount of presents which the parents of a woman expect to receive in exchange for her diminishes in proportion to the number of husbands she may have had.

I now began to attend to some of the ceremonies of what may be called the initiation of warriors, this being the first time I had been on a war-party. For the first three times that a man accompanies a war-party, the customs of the Indians require some peculiar and painful observances, from which old warriors may, if they choose, be exempted. The young warrior must constantly paint[15] his face black; must wear a cap, or head-dress of some kind; must never precede the old warriors, but follow them, stepping in their tracks. He must never scratch his head, or any other part of his body, with his fingers, but if he is compelled to scratch he must use a small stick; the vessel he eats or drinks out of, or the knife he uses, must be touched by no other person.

The young warrior, however long and fatiguing the march, must neither eat, nor drink, nor sit down by day; if he halts for a moment, he must turn his face towards his own country, that the Great Spirit may see that it is his wish to return home again.

It was Tanner's wish to return home again, and after many dangerous and disagreeable adventures he did at last, when almost an old man, come back to the Whites and tell his history, which, as he could not write, was taken down at his dictation.[2]

The cell in which he was imprisoned was one of seven called 'The Leads,' because they were under the palace roof, which was covered neither by slates nor bricks, but great heavy sheets of lead. They were guarded by archers, and could only be reached by passing through the hall of council. The secretary of the Inquisition had charge of their key, which the gaoler, after going the round of the prisoners, restored to him every morning. Four of the cells faced eastward over the palace canal, the other three westward over the court. Casanova's was one of the three, and he calculated that it was exactly above the private room of the inquisitors.

For many hours after the gaoler first turned the key upon Casanova he was left alone in the gloomy cell, not high enough for him to stand upright in, and destitute even of a couch. He laid aside his silk mantle, his hat adorned with Spanish lace and a white plume—for, when roused from sleep and arrested by the Inquisition, he had put on the suit lying ready, in which he intended to have gone to a gay entertainment. The heat of the cell was extreme: the prisoner leaned his elbows on the ledge of the grating which admitted to the cell what light there was, and fell into a deep and bitter reverie. Eight hours passed, and then the complete solitude in which he was left began to trouble him. Another hour, another, and another; but when night really fell, to take Casanova's own account,

'I became like a raging madman, stamping, cursing, and uttering wild cries. After more than an hour of this furious exercise, seeing no one, not hearing the least sign which could have made me imagine that anyone was aware of my fury, I stretched myself[17] on the ground. . . . But my bitter grief and anger, and the hard floor on which I lay, did not prevent me from sleeping.

'The midnight bell woke me: I could not believe that I had really passed three hours without consciousness of pain. Without moving, lying as I was on my left side, I stretched out my right hand for my handkerchief, which I remembered was there. Groping with my hand—heavens! suddenly it rested upon another hand, icy cold! Terror thrilled me from head to foot, and my hair rose: I had never in all my life known such an agony of fear, and would never have thought myself capable of it.

'Three or four minutes I passed, not only motionless, but bereft of thought; then, recovering my senses, I began to think that the hand I touched was imaginary. In that conviction I stretched out my arm once more, only to encounter the same hand, which, with a cry of horror, I seized, and let go again, drawing back my own. I shuddered, but being able to reason by this time, I decided that while I slept a corpse had been laid near me—for I was sure there was nothing when I lay down on the floor. But whose was the dead body? Some innocent sufferer, perhaps one of my own friends, whom they had strangled, and laid there that I might find before my eyes when I woke the example of what my own fate was to be? That thought made me furious: for the third time I approached the hand with my own: I clasped it, and at the same instant I tried to rise, to draw this dead body towards me, and be certain of the hideous crime. But, as I strove to prop myself on my left elbow, the cold hand I was clasping became alive, and was withdrawn—and I knew that instant, to my utter astonishment, that I held none other than my own left hand, which, lying stiffened on the hard floor, had lost heat and sensation entirely.'

That incident, though comic, did not cheer Casanova, but gave him matter for the darkest reflections—since he saw himself in a place where, if the unreal seemed so true, reality might one day become a dream. In other words, he feared approaching madness.

But at last came daybreak, and by-and-by the gaoler returned, asking the prisoner if he had had time to find out what he would like to eat. Casanova was allowed to send for all he needed from his own apartments in Venice, but writing-implements, any metal instruments whatever, even knife and fork, and the books he mentioned, were struck from his list. The inquisitors sent him books which they themselves thought suitable, and which drove him, he said, to the verge of madness.[18]

He was not ill-treated—having a daily allowance given him to buy what food he liked, which was more than he could spend. But the loss of liberty soon became insupportable. For months he believed that his deliverance was close at hand; but when November came, and he saw no prospect of release, he began to form projects of escape. And soon the idea of freeing himself, however wild and impossible it seemed, took complete possession of him.

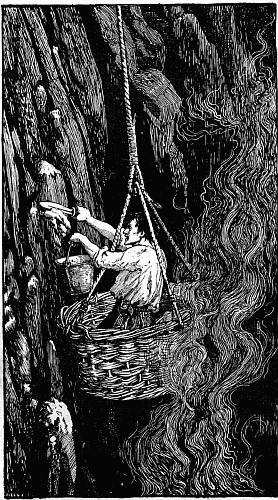

By-and-by he was allowed half an hour's daily promenade in the corridor (galetas) outside his cell—a dingy, rat-infested place, into which old rubbish was apt to drift. One day Casanova noticed a piece of black marble on the floor—polished, an inch thick and[19] six inches long. He picked it up stealthily, and without any definite intention, managed to hide it away in his cell.

Another morning his eyes fell upon a long iron bolt, lying on the floor with other old odds and ends, and that also, concealed in his dress, he bore into his cell. When left alone, he examined it carefully, and realised that if pointed, it would make an excellent spontoon. He took the black marble, and after grinding one end of the bolt against it for a long while, he saw that he had really succeeded in wearing the iron down. For fifteen days he worked, till he could hardly stir his right arm, and his shoulder felt almost dislocated. But he had made the bolt into a real tool; or, if necessary, a weapon, with an excellent point. He hid it in the straw of his armchair so carefully that, to find it, one must have known that it was there; and then he began to consider what use he should make of it.

He was certain that the room underneath was the one in which on entering he had seen the secretary of the Inquisition, and which was probably opened every morning. A hole once made in the floor, he could easily lower himself by a rope made of the sheets of his bed, and fastened to one of the bed-posts. He might hide under the great table of the tribunal till the door was opened, and then make good his escape. It was probable, indeed, that one of the archers would mount guard in this room at night; but him Casanova resolved to kill with his pointed iron. The great difficulty really was that the hole in the floor was not to be made in a day, but might be a work of months. And therefore some pretext must be found to prevent the archers from sweeping out the cell, as they were accustomed to do every morning.

Some days after, alleging no reason, he ordered the archers not to sweep. This omission was allowed to pass for several mornings, and then the gaoler demanded Casanova's reason. He answered, that the dust settled on his lungs, and made him cough, and might give him a mortal disease. Laurent, the gaoler, offered to throw water on the floor before sweeping it; but Casanova's arguments against the dampness of the atmosphere that would result were equally ingenious. Laurent's suspicions, however, were roused, and one day he ordered the room to be swept most carefully, and even lit a candle, and on the pretence of cleanliness, searched the cell thoroughly. Casanova seemed indifferent, but the next day, having pricked his finger, he showed his handkerchief stained with blood, and said that the gaoler's cruelty had brought on so severe a[20] cough that he had actually broken a small blood-vessel. A doctor was sent for, who took the prisoner's part, and forbade sweeping out the cell in future. One great point was gained; but the work could not begin yet, owing to the fearful cold. The prisoner would have been forced to wear gloves, and the sight of a worn glove might have excited suspicion. So he occupied himself with another stratagem—the creation, little by little, of a lamp, for the solace of the endless winter nights. One by one, the gaoler himself, unsuspectingly, brought the different ingredients: oil was imported in salads, wick the prisoner himself made from threads pulled from the quilt, and in time the lamp was complete.

The very unwelcome sojourn of a Jewish usurer, like himself captive of the Inquisition, in his cell, forced Casanova to delay his projects of escape till after Easter, when the Jew was imprisoned elsewhere.

No sooner had he left than Casanova, by the light of the lamp constructed with so much difficulty, began his task. Drawing his bed away, he set to work to bore through the plank underneath, gathering the fragments of wood in a napkin—which the next morning he contrived to empty out behind a heap of old cahier books in the corridor—and after six hours' labour, pulling back his bed, which concealed all trace of it from the gaoler's eyes.

The first plank was two inches thick; the next day he found another plank beneath it, and he pierced this only to find a third plank. It was three weeks before he dug out a cavity large enough for his purpose in this depth of wood, and his disappointment was great when, underneath the planks, he came to a marble pavement which resisted his one tool. But he remembered having read of a general who had broken with an axe hard stones, which he first made brittle by vinegar, and this Casanova possessed. He poured a bottle of strong vinegar into the hole, and the next day, whether it was the effect of the vinegar or of his stronger resolution, he managed to loosen the cement which bound the pieces of marble together, and in four hours had destroyed the pavement, and found another plank, which, however, he believed to be the last.

At this point his work was once more interrupted by the arrival of a fellow prisoner, who only stayed, however, for eight days. A more serious delay was caused by the fact that unwittingly a part of his work had been just above one of the great beams that supported the ceiling, and he was forced to enlarge the hole by one-fourth. But at last all was done. Through a hole so thin as to be[21] quite imperceptible from below he saw the room underneath. There was only a thin film of wood to be broken through on the night of his escape. For various reasons, he had fixed on the night of August 27. But hear his own words:

'On the 25th,' writes Casanova, 'there happened what makes me shudder even as I write. Precisely at noon I heard the rattling of bolts, a fearful beating of my heart made me think that my last moment had come, and I flung myself on my armchair, stupefied. Laurent entered, and said gaily:

'"Sir, I have come to bring you good news, on which I congratulate you!"

'At first I thought my liberty was to be restored—I knew no other news which could be good; and I saw that I was lost, for the discovery of the hole would have undone me. But Laurent told me to follow him. I asked him to wait till I got ready.

'"No matter," he said, "you are only going to leave this dismal cell for a light one, quite new, where you can see half Venice through the two windows; where you can stand upright; where——"

'But I cannot bear to write of it—I seemed to be dying. I implored Laurent to tell the secretary that I thanked the tribunal for its mercy, but begged it in Heaven's name to leave me where I was. Laurent told me, with a burst of laughter, that I was mad, that my present cell was execrable, and that I was to be transferred to a delightful one.

'"Come, come, you must obey orders," he exclaimed.

'He led me away. I felt a momentary solace in hearing him order one of his men to follow with the armchair, where my spontoon was still concealed. That was always something! If my beautiful hole in the floor, that I had made with such infinite pains, could have followed me too—but that was impossible! My body went; my soul stayed behind.

'As soon as Laurent saw me in the fresh cell, he had the armchair set down. I flung myself upon it, and he went away, telling me that my bed and all my other belongings should be brought to me at once.'

For two hours Casanova was left alone in his new cell, utterly hopeless, and expecting to be consigned for the rest of his life to one of the palace dungeons, from which no escape could be possible. Then the gaoler returned, almost mad with rage, and demanded the axe and all the instruments which the prisoner must have employed in penetrating the marble pavement. Calmly, without[22] stirring, Casanova told him that he did not know what he was talking about, but that, if he had procured tools, it could only have been from Laurent himself, who alone had entrance to the cell.

Such a reply did not soften the gaoler's anger, and for some time Casanova was very badly treated. Everything was searched; but his tool had been so cleverly concealed that Laurent never found it. Fortunately it was the gaoler's interest not to let the tribunal know of the discovery he had made. He had the floor of the cell mended without the knowledge of the secretary of the Inquisition, and when this was done, and he found himself secure from blame, Casanova had little difficulty in making peace with him, and even told him the secret of the lamp's construction.

Fortunately, out of the tribunal's allowance to the prisoner enough was always left, after he had provided for his own needs, for a gift—or bribe, to the gaoler. But Laurent did not relax his vigilance, and every morning one of the archers went round the cell with an iron bar, giving blows to walls and floor, to assure himself that there was nothing broken. But he never struck the ceiling, a fact which Casanova resolved to turn to account at the first opportunity.

One day the prisoner ordered his gaoler to buy him a particular book, and Laurent, objecting to an expense which seemed to him quite needless, offered to borrow him a book of one of the other prisoners, in exchange for one of his own. Here at last was an opportunity. Casanova chose a volume out of his small library, and gave it to the gaoler, who returned in a few minutes with a Latin book belonging to one of the other prisoners.

Pen and ink were forbidden, but in this book Casanova found a fragment of paper; and he contrived, with the nail of his little finger, dipped in mulberry juice, to write on it a list of his library—and returned the volume, asking for a second. The second came, and in it a short letter in Latin. The correspondence between the prisoners had really begun.

The writer of the Latin letter was the monk Balbi, imprisoned in the Leads with a companion, Count André Asquin. He followed it by a much longer one, giving the history of his own life, and all that he knew of his fellow-prisoners. Casanova formed a very poor opinion of Father Balbi's character from his letters; but assistance of some kind he must have, since the gaoler must needs discover any attempt to break through the ceiling, unless that attempt was made from above. But Casanova soon thought of[23] a plan by which Balbi could break through his ceiling, undiscovered.

'I wrote to him,' he relates, 'that I would find some means of sending him an instrument with which he could break through the roof of his cell, and having climbed upon it, go to the wall separating his roof from mine. Breaking through that, he would find himself on my roof, which also must be broken through. That done, I would leave my cell, and he, the Count, and I together, would manage to raise one of the great leaden squares that formed the highest palace roof. Once outside that, I would be answerable for the rest.

'But first he must tell the gaoler to buy him forty or fifty pictures of saints, and by way of proving his piety, he must cover his walls and ceiling with these, putting the largest on the ceiling. When he had done this, I would tell him more.

'I next ordered Laurent to buy me the new folio Bible that was just printed; for I fancied its great size might enable me to conceal my tool there, and so send it to the monk. But when I saw it, I became gloomy—the bolt was two inches longer than the Bible. The monk wrote to me that the cell was already covered according to my direction, and hoped I would lend him the great Bible which Laurent told him I had bought. But I replied that for three or four days I needed it myself.

'At last I hit upon a device. I told Laurent that on Michaelmas Day I wanted two dishes of macaroni, and one of these must be the largest dish he had, for I meant to season it, and send it, with my compliments, to the worthy gentleman who had lent me books. Laurent would bring me the butter and the Parmesan cheese, but I myself should add them to the boiling macaroni.

'I wrote to the monk preparing him for what was to happen, and on St. Michael's Day all came about as I expected. I had hidden the bolt in the great Bible, wrapped in paper, one inch of it showing on each side. I prepared the cheese and butter; and in due time Laurent brought me in the boiling macaroni and the great dish. Mixing my ingredients, I filled the dish so full that the butter nearly ran over the edge, and then I placed it carefully on the Bible, and put that, with the dish resting on it, into Laurent's hand, warning him not to spill a drop. All his caution was necessary: he went away with his eyes fixed on his burden, lest the butter should run over; and the Bible, with the bolt projecting from it, were covered, and more than covered, by the huge dish.[24] His one care was to hold that steady, and I saw that I had succeeded. Presently he came back to tell me that not a drop of butter had been spilt.'

Father Balbi next began his work, detaching from the roof one large picture, which he regularly put back in the same place to conceal the hole. In eight days he had made his way through the roof, and attacked the wall. This was harder work, but at last he had removed six and twenty bricks, and could pass through to Casanova's roof. This he was obliged to work at very carefully, lest any fracture should appear visible below.

One Monday, as Father Balbi was busy at the roof, Casanova suddenly heard the sound of opening doors. It was a terrible moment, but he had time to give the alarm signal, two quick blows on the ceiling. Then Laurent entered, bringing another prisoner, an ugly, ill-dressed little man of fifty, in a black wig, who looked like what he was, a spy of the Inquisition.

Casanova soon learned the history of Soradici—for this was the spy's name—and when his new companion was asleep he wrote to Balbi the account of what had happened. For the present, evidently the work must be given up, no confidence whatever could be placed in Soradici. Yet soon Casanova thought of a plan of making use even of this traitor.

First he ordered Laurent to buy him an image of the Virgin Mary, holy water, and a crucifix. Next he wrote two letters, addressed to friends in Venice—letters in which he made no complaint, but spoke of the benevolence of the Inquisition, and the blessing that his trials had been to him. These letters, which, even if they reached the hands of the secretary, could do him no possible harm, he entrusted to Soradici, in case he should soon be set free; exacting the spy's solemn oath, on the crucifix and the image of the Virgin, not to betray him, but to give the letters to his friends.

Soradici took the oath required of him, and sewed the letters into his vest. None the less, Casanova felt confident that he would be betrayed, and this was exactly what happened. Two days after the spy was sent for to the secretary, and when he returned to the cell, his companion soon discovered that he had given up the letters.

Casanova affected the utmost anguish and despair. He flung himself down before the image of the Virgin, and demanded vengeance on the monster who had ruined him by breaking so solemn a pledge. Then he lay down with his face to the wall, and for the whole day uttered no single word to the spy, who, terrified at his[25] companion's prayer for vengeance, entreated his forgiveness. But when the spy slept he wrote to Father Balbi and told him to go on with his work the next day, beginning at exactly three o'clock, and working four hours.

The next day, after the gaoler had left them, bearing with him the book of Father Balbi in which the prisoner's letter was concealed, Casanova called his companion. The spy, by this time, was really ill with terror; for he believed that he had provoked the wrath of the Virgin Mary by breaking his oath. He was ready to do anything his companion told him to do, and weak enough to credit any falsehood.

Casanova put on a look of inspiration, and said:

'Learn that at break of day the Holy Virgin appeared to me, and commanded me to forgive you. You shall not die. The grief that your treachery caused me made me pass all the night sleepless, since I knew that the letters you had given to the secretary would prove my ruin—and my one consolation was to believe that in three days I should see you die in this very cell. But though my mind was full of my revenge—unworthy of a Christian—at break of day the image of the Blessed Virgin that you see moved, opened her lips, and said: "Soradici is under my protection: I would have you pardon him. In reward of your generosity I will send one of my angels in figure of a man, who shall descend from heaven to break the roof of the cell, and in five or six days to release you. To-day this angel will begin his work at three o'clock, and will work till half an hour before the sun sets, for he must return to me by daylight. When you escape you will take Soradici with you, and you will take care of him all his life, on condition that he quits the profession of a spy for ever." With these words the Blessed Virgin disappeared.'

At first even the spy's credulity would hardly be persuaded that Casanova had not dreamed; but when at the appointed hour the sound of the angel working in the roof was really to be heard, when it lasted four hours, and ceased again as foretold, all his doubt vanished, and he was ready to follow Casanova blindly. The thought of once more betraying him never entered his mind; he believed that the Blessed Virgin herself was on the side of his companion.

The angel would appear, Casanova told him, on the evening of October 31. And at the hour appointed Father Balbi, not looking in the least like an angel, came feet foremost through the ceiling. Casanova embraced him, left him to guard the spy, and himself[26] ascending through the roof, crossed over into the other cell and greeted the monk's fellow-prisoner, Count André, who had all this time kept their secret, but, being old and infirm, had no desire to fly with them.

The next thing was to return into the garret above the two cells, and set to work to break through the palace roof itself. Most of this task fell to Casanova, till he reached the great sheet of lead surmounting the planks, and there the monk's help was necessary. Uniting their strength, they raised it till an opening was made wide enough to pass through. But outside the moonlight was too strong, and they would have been seen from below had they ventured on the roof. They returned into the cell and waited. Casanova had made strong ropes by tying together sheets, towels, and whatever else would serve. Now, since there was nothing to be done till the moon sank, he sat down and wrote a courteous letter to the Inquisition, explaining his reasons for attempting to escape.

The spy, too cowardly to risk his life in so daring a venture, and beginning to see that he had been imposed upon, begged Casanova on his knees to leave him behind, praying for the fugitives—and this Casanova was thankful to do, for Soradici could only have encumbered him. Father Balbi, though for the last hour he had been heaping reproaches on his friend's rashness, was less of a coward than the spy, and as the time had come to start he followed Casanova. They crept out on the roof, and began cautiously to ascend it. Half-way up the monk begged his companion to stop, saying that he had lost one of the packages tied round his neck.

'Was it the package of cord?' asked Casanova.

'No,' replied the monk, 'but a black coat, and a very precious manuscript.'

'Then,' said Casanova, resisting a sudden temptation to throw Balbi after his packet, 'you must be patient, and come along.'

The monk sighed, and followed. Soon they had reached the highest point of the roof, and here Balbi contrived to lose his hat, which rolled down the roof, failed to lodge in the gutter, and fell into the canal below. The poor fellow grew desperate, and said it was a bad omen. Casanova soothed him, and left him seated where he was, while he himself went to investigate, his faithful tool in his hand.

Now fresh difficulties began. For a long time Casanova could find no way of re-entering the palace, except into the cell they had quitted. He was growing hopeless, when he saw a skylight, that he was sure was too far away from their starting point to belong to[27] any of the cells. He made his way to it; it was barred with a fine iron grating that needed a file. And Casanova only had one tool!

Sitting on the roof of the skylight, he nearly abandoned himself to despair, till the bell striking midnight suddenly roused him. It was the first of November: All Saint's Day—the day on which he had long had a curious foreboding that he should recover his liberty. Fired with hope, he set his tool to work at the grating, and in a quarter of an hour he had wrenched it away entire. He set it down by the skylight, and went back for the monk. They regained the skylight together.

Casanova let down his companion through the skylight by the cord, and found that the floor was so far away that he himself dared not risk the leap. And though the cord was still in his hands, he had nowhere to fasten it. The monk, inside, could give him no help—and, not knowing what to do, he set out on another voyage of discovery.

It was successful, for in a part of the roof which he had not yet visited he found a ladder left by some workmen, and long enough for his purpose. Indeed, it seemed likely to be too long, for when he tried to introduce it into the skylight, it only entered as far as the sixth round, and then was stopped by the roof. However, with a superhuman effort Casanova, hanging to the roof, below the skylight, managed to lift the other end of the ladder, nearly, in the action, flinging himself down into the canal. But he had succeeded in forcing the ladder farther in, and the rest was comparatively easy. He climbed up again to the skylight, lowered the ladder, and in another moment was standing by his companion's side.

They found themselves in a garret opening into another room, well barred and bolted. But just then Casanova was past all exertion. He flung himself on the ground, the packet of cord under his head, and fell into a sleep of utter exhaustion. It was dawn when he was roused at last by the monk's despairing efforts. For two hours the latter had been shaking him, and even shouting in his ears, without the slightest effect!

Casanova rose, saying:

'This place must have a way out. Let us break everything—there is no time to lose!'

They found, at last, a door, of which Casanova's tool forced the lock, and which led them into the room containing the archives or records of the Venetian Republic. From this they descended a staircase, then another, and so made their way into the[28] chancellor's office. Here Casanova found a tool which secretaries used to pierce parchment, and which was some little help to them—for he found it impossible to force the lock of the door through which they had next to part, and the only way was to break a hole in it. Casanova set to work at the part of the door that looked most likely to yield, while his companion did what he could with the secretary's instrument—they pushed, rent, tore the wood; the noise that they made was alarming, but they were compelled to risk it. In half an hour they had made a hole large enough to get through. The monk went first, being the thinner; he pulled Casanova after him—dusty, torn, and bleeding, for he had worked harder than Father Balbi, who still looked respectable.

They were now in a part of the palace guarded by doors against which no possible effort of theirs could have availed. The only way was to wait till they were opened, and then take flight. Casanova tranquilly changed his tattered garments for a suit which he had brought with him, arranged his hair, and made himself look—except for the bandages he had tied round his wounds—much more like a strayed reveller than an escaped prisoner. All this time the monk was upbraiding him bitterly, and at last, tired of listening, Casanova opened a window, and put out his head, adorned with a gay plumed hat. The window looked out upon the palace court, and Casanova was seen at once by people walking there. He drew back his head, thinking that he had brought destruction upon himself; but after all the accident proved fortunate. Those who had seen him went immediately to tell the authority who kept the key of the hall at the top of the grand staircase, at whose window Casanova's head had appeared, that he must unwittingly have shut someone in the night before. Such a thing might easily have happened, and the keeper of the keys came immediately to see if the news were true.

Presently the door opened, and quite at his ease, the keeper appeared, key in hand. He looked startled at Casanova's strange figure, but the latter, without stopping or uttering a word, passed him, and descended the stairs, followed by the frightened monk. They did not run, nor did they loiter; Casanova was already, in spirit, beyond the confines of the Venetian Republic. Still followed by the monk, he reached the water-side, stepped into a gondola, and flinging himself down carelessly, promised the rowers more than their fare if they would reach Fusina quickly. Soon they had left Venice behind them; and a few days after his wonderful escape Casanova was in perfect safety beyond Italy.

I had lost my boat in the last speat; it was the third which had been taken away in that year, and, until I obtained another, I was obliged to ford the river. I went one day as usual; there was a dark bank of cloud lying in the west upon Beann-Drineachain, but all the sky above was blue and clear, and the water moderate, as I crossed into the forest. I merely wanted a buck, and, therefore, only made a short circuit to the edge of Dun-Fhearn, and rolled a stone down the steep into the deep, wooded den. As it plunged into the burn below, I heard the bound of feet coming up; but they were only two small does, and I did not 'speak' to them, but amused myself with watching their uneasiness and surprise as they perked into the bosky gorge, down which the stone had crashed like a nine-pounder; and, as their white targets jinked over the brae, I went on to try the western terraces.

There is a smooth dry brae opposite to Logie Cumming, called 'Braigh Choilich-Choille,'[3] great part of the slope of which is covered with a growth of brackens from five to six feet high, mixed with large masses of foxgloves, of such luxuriance that the stems sometimes rise five from a single root, and more than seven feet in height, of which there is often an extent of five feet of blossoms, loaded with a succession of magnificent bells. As we crossed below this beautiful covert, I observed Dreadnought suddenly turn up the wind towards it. I immediately made for the crest beyond where the bank rises smooth and open, and whence I had a free sweep of the summit and of both sides. I had just reached the top when the dog entered the thicket of the ferns, and I saw their tall heads stir about twenty yards before him,[30] followed by a roar from his deep tongue, and a fine buck bolted up the brae. I gave a short whistle to stop him, and immediately he stood to listen, but behind a great spruce fir, which then, with many others, formed a noble group upon the summit of the terrace. The sound of the dog dislodged him in an instant, and he shot out through the open glade, when I followed him with the rifle, and sent him over on his horns like a wheel down the steep, and splash,[31] like a round shot, into the little rill at its foot. We brittled him on the knog of an old pine, and rewarded the dog, and drank the Dochfalla; when, having occasion to send the piper to the other side of the wood, and being so near home, I shouldered the roe, and took the way for the ford of Craig-Darach, a strong wide broken stream with a very bad bottom, but the nearest then passable.

As I descended the Bruach-gharbh, Dreadnought stopped and looked up into a pine, then approaching the tree, searched it all round with his nose. I scanned the branches, but could see nothing except an old hawk's nest, which had been disused long ago; and if it had not, I do not understand how it should be interesting to a hound. The dog, however, continued to investigate the stump and stem of the fir, gaze into the branches, turning his head from side to side, and setting up his ears like a cocked-hat. I laid down the buck, and unslung my double gun, and threw a stick at the nest, when out shot a large pine-martin, and, like a squirrel, sprung along the branches from tree to tree, till I brought him to the ground. Dreadnought examined him with a sort of wrinkle in his whiskers, and turned away, and sat down in dignified abstraction; while I remounted the buck, and braced the martin to his feet with the little 'ial-chas,' or foot-straps used for trussing the legs of the roe. We then resumed our path for the ford.

As I descended through the Boat-Shaw, I heard a heavy sound from the water, but when I came out from the birches upon the green bank on its brink, I saw that the river had come down, and was just lipping with the top of the stone, the sight of whose head was the mark for the last possibility of crossing. As I looked upon its contracting ring, I perceived that the stream was still growing; there was no time to be lost, for the alternative now was to go round by the bridge of Daltulich, a circuit of four miles; and I knew that, before I reached the next good ford, the water would be a continuous rapid, probably six feet deep: I decided, therefore, upon trying the chance where I was. Dreadnought, who had gone about thirty yards up the stream to take the deep water in the pool of Craig-Darach, had observed my hesitation with one leg out and one in the water, and was standing on the point of the rock waiting the result. As soon as I made another step he plunged into the river, and in a few moments was rolling on the bank of silver sand thrown up by the back-water upon the opposite side of the river. As I advanced through the stream, he looked at me occasionally,[32] and I at him, and the beautiful smooth sand and green bank upon his side—for by that time I began to wish I was there too. I was then in pretty deep water for a ford, but still some distance from the deepest part; my kilt was floating round me in the boiling water, and the strong eddy, formed by the stream running against my legs, gulped and gushed with increasing weight. I moved slowly and carefully, for the whole ford was filled with large round slippery stones from the size of a sixty-pound shot to a two-hundredweight shell. I stopped to rest, and looked back to the ford mark: it was wholly gone, and I saw only the broad smooth wave of water which slipped over its head. Ten paces more, and I should be through the deepest part. I stepped steadily and rigidly, but I wanted the use of my balancing limbs and the freedom of my breath; for the barrels of the double gun and rifle, which were slung at my back, were passed under my arms to keep them out of the water; and I was also obliged to hold the legs of the buck, which, loaded with the 'wood-cat,' were crossed upon my breast. At every step the round and slidering stones endangered my footing, rendered still more unsteady by the upward pressure of the water. In this struggle the current gave a great gulp, and a wave splashed up over my guns. I staggered downwards with the stream, and could not recover a sure footing for several yards. At last I secured my hold against a large fixed stone, and paused to rest. After a little I made another effort to proceed.