This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Uncle Sam's Boys in the Ranks

or, Two Recruits in the United States Army

Author: H. Irving Hancock

Release Date: December 31, 2008 [eBook #27680]

Most recently updated: June 21, 2011

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK UNCLE SAM'S BOYS IN THE RANKS***

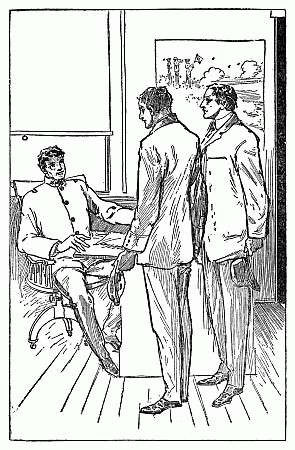

"And These Are Your Applications?"

"And These Are Your Applications?"

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"A soldier ain't a loafer, and it takes nerve to be a soldier. It's a job for the bravest kind of a man," retorted Jud Jeffers indignantly.

"Answer my c'nundrum," insisted Bunny.

"It ain't a decent conundrum," retorted Jud, with dignity, for his father had served as a volunteer soldier in the war with Spain.

"Go on, Bunny," broke in another boy in the group, laughing. "I'll be the goat. What is the difference between a soldier and a loafer?"

"A soldier gets paid and fed, and the other loafer doesn't," retorted Bunny, with a broadening grin. A moment later, when he realized that his "joke" had failed to raise a laugh, Bunny looked disappointed.

"Aw, go on," flared up Jud Jeffers. "You don't know anything about a soldier."[8]

"But my dad does," retorted Bunny positively. "Dad says soldiers don't produce anything for a living; that they take their pay out of the pockets of the public, and then laugh at the public for fools."

"And what does your father do for a living?" demanded Jud hotly.

"He's a man who knows a lot, and he lectures," declared Bunny, swelling with importance. "When my dad talks a whole lot of men get excited and cheer him."

"Yes, and they buy him beer, too," jeered Jud, hot with derision for the fellow who was running down the soldiers of the United States. "Your father does his lecturing in small, dirty halls, where there's always a beer saloon underneath. You talk about men being producers—and your father goes around making anarchistic speeches to a lot of workingmen who are down on everything because they aren't clever enough to earn as good wages as sober, industrious and capable workmen earn."

"Speech, Jud!" laughingly roared another boy in the crowd that now numbered a score of youngsters.

"Don't you dare talk against my dad!" sputtered Bunny, doubling his fists and trying to look fierce.

"Then don't say anything against soldiers,"[9] retorted Jud indignantly. "My father was one. I tell you, soldiers are the salt of the earth."

"Say, but they're a fine and dandy-looking lot, anyway," spoke up Tom Andrews, as he turned toward the post-office window in front of which the principal actors in this scene were standing. The place was one of the smaller cities in New Jersey.

In the post-office window hung a many-colored poster, headed "Recruits Wanted for the United States Army." Soldiers of the various arms of the service were shown, and in all the types of uniforms worn on the different occasions.

"Oh, yes, they're a fine and dandy lot of loafers—them soldiers!" declared Bunny Hepburn contemptuously.

This opinion might not have gotten him into trouble, but he emphasized his opinion by spitting straight at the glass over the center of the picture.

"You coward!" choked Jud.

Biff!

Jud Jeffer's fist shot out, with all the force there is in fourteen-year-old muscle. The fist caught Bunny Hepburn on the side of the face and sent him sprawling.

"Good for you, Jud!" roared several of the young boys together.[10]

"Go for him, Jud! He's mad, and wants it," called Tom Andrews.

Bunny was mad, all the way through, even before he leaped to his feet. Yet Bunny was not especially fond of fighting, and his anger was tempered with caution.

"You dassent do that again," he taunted, dancing about before Jud.

"I will, if you give me the same cause," replied Jud.

Bunny deliberately repeated his offensive act. Then he dodged, but not fast enough. Jud Jeffer's, his eyes ablaze with righteous indignation, sent the troublesome one to earth again.

This time Bunny got up really full of fight.

From the opposite side of the street two fine-looking young men of about eighteen had seen much of what had passed.

"Let's go over and separate them, Hal," proposed the quieter looking of the pair.

"If you like, Noll, though that young Hepburn rascal deserves about all that he seems likely to get."

"Jud Jeffers is too decent a young fellow to be allowed to soil his hands on the Hepburn kid," objected Oliver Terry quietly.

So he and Hal Overton hastened across the street.

Bunny Hepburn was now showing a faint[11] daub of crimson at the lower end of his nose. Bunny was the larger boy, but Jud by far the braver.

"Here, better stop all of this," broke in Hal good-naturedly, reaching out and grabbing angry Bunny by the coat collar.

Noll rested a rather friendly though detaining hand on Jud Jeffers's shoulder.

"Lemme at him!" roared Bunny.

"Yes! Let 'em finish it!" urged three or four of the younger boys.

"What's it all about, anyway?" demanded Hal Overton.

"That fellow insulted his country's uniform. It's as bad as insulting the Flag itself!" contended Jud hotly.

"That's right," nodded Hal Overton grimly. "I think I saw the whole thing. You're right to be mad about it, Jud, but this young what-is-it is too mean for you to soil your hands on him. Now, see here, Hepburn—right about face for you!"

Hal's grip on the boy's coat collar tightened as he swung Bunny about and headed him down the street.

"Forward, quick time, march! And don't stop, either, Hepburn, unless you want to hear Jud pattering down the street after you."

Hal's first shove sent Bunny darting along for[12] a few feet. Bunny discreetly went down the street several yards before he halted and lurched into a doorway, from which he peered out with a still hostile look on his face.

"Your view of the uniform, and of the old Flag, is all right, Jud, and I'm mighty glad to find that you have such views," Hal continued. "But you mustn't be too severe on a fellow like Bunny Hepburn. He simply can't rise above his surroundings, and you know what a miserable, egotistical, lying, slanderous fellow his father is. Bunny's father hates the country he lives in, and would set everybody to tearing down the government. That's the kind of a brainless anarchist Hepburn is, and you can't expect his dull-witted son to know any more than the father does. But you keep on, Jud, always respecting the soldier and his uniform, and the Flag that both stand behind."

"It gets on a good many of us," spoke up Tom Andrews, "to hear Bunny always running down the soldiers. He believes all his father says, so he keeps telling us that we're a nation of crooks and thieves, that the government is the rottenest ever, and that our soldiers and sailors are the biggest loafers of the whole American lot."

"It's enough to disgust anybody," spoke up Oliver Terry quietly. "But, boys, people who[13] talk the way the Hepburns do are never worth fighting with. And, unless they're stung hard, they won't fight, anyway."

"Oh, won't they?" growled Bunny, who, listening to all this talk with a flaming face, now retreated down the street. "Wait until I tell dad all about this nonsense about the Flag and the uniform!"

Hal and Noll stood for some moments gazing at the attractive recruiting poster in the post-office window. One by one the boys who had gathered went off in search of other interest or sport, until only Jud and Tom remained near the two older boys.

"I reckon you think I was foolish, don't you, Hal?" asked Jud, at last.

"No; not just that," replied Overton, turning, with a smile. "No American can ever be foolish to insist on respect for the country's Flag and uniform."

"I simply can't stand by and hear soldiers sneered at. My father was a soldier, you know, even if he was only a war-time volunteer, and didn't serve a whole year."

"When you get out of patience with fellows like Bunny Hepburn," suggested Noll Terry, "just you compare your father with a fellow like Bunny's father. You know, well enough, that your father, as a useful and valuable citizen,[14] is worth more than a thousand Hepburns can ever be."

"That's right," nodded Hal, with vigor. "And there's another man in this town that you can compare with Bunny's father. You know Mr. Wright? Sergeant Wright is his proper title. He's an old, retired sergeant from the Regular Army, who served his country fighting Indians and Spaniards, and now he has settled down here—a fine, upright, honest American, middle aged, and with retired pay and savings enough to support him as long as he lives. I haven't met many men as fine as Sergeant Wright."

"I know," nodded Jud, his eyes shining. "Sergeant Wright is a fine man. Sometimes he talks to Tom and me an hour at a time, telling us all about the campaigns he has served in. Say, Hal, you and Noll ought to call on him and ask him for some of his grand old Indian stories."

"We know some of them," laughed Hal. "Noll and I have been calling there often."

"You have?" said Jud gleefully. "Say, ain't Sergeant Wright one of the finest men ever? I'll bet he's been a regular up-and-down hero himself, though he never tells us anything about his own big deeds."

"He wears the medal of Congress," replied[15] Hal warmly. "A soldier who wears that doesn't need to brag."

"Say," remarked Jud thoughtfully, "I guess you two fellows are about as much struck with the soldiers as I am."

"I'll tell you and Tom something—if you can keep a secret," replied Hal Overton, after a side glance at his chum.

"Oh, we can keep secrets all right!" protested Tom Andrews.

"Well, then, fellows, Noll and I are going to New York to-morrow, to try to enlist in the Regular Army."

"You are?" gasped Jud, staring at Hal and Noll in round-eyed delight. "Oh, say, but you two ought to make dandy soldiers!"

"If the recruiting officer accepts us we'll do the best that's in us," smiled Hal.

"You'll be regular heroes!" predicted Jud, gazing at these two fortunate youngsters with eyes wide open with approval.

"Oh, no, we can't be heroes," grimaced Noll. "We're going to be regulars, and it's only the volunteers who are allowed to be heroes, you know," added Noll jocosely. "There's nothing heroic about a regular fighting bravely. That's his trade and his training."

"Don't you youngsters tell anyone," Hal insisted. "Or we shall be sorry that we told you."[16]

"What do you take us for?" demanded Jud scornfully.

Hal and Noll had had it in mind to stroll off by themselves, for this was likely to be their last day in the home town for many a day to come. But Jud and Tom were full of hero worship of the two budding soldier boys, and walked along with them.

"There's Tip Branders," muttered Tom suddenly.

"I don't care," retorted Jud. "He won't dare try anything on us; and, if he does, we can take care of him."

"What has Tip against you?" asked Hal Overton.

"He tried to thrash me, yesterday."

"Why?"

"I guess it was because I told him what I thought of him," admitted Jud, with a grin.

"How did that happen?"

"Well, Tom and I were down in City Hall Park, sitting on one of the benches. Tip came along and ordered us off the bench; said he wanted to sit there himself. I told him he was a loafer and told him we wouldn't get off the bench for anybody like him."

"And then?" asked Hal.

"Why, Tip just made a dive for me, and there was trouble in his eyes; so I reconsidered, and[17] made a quick get-away. So did Tom. Tip chased us a little way, but we went so fast that we made it too much work for him. So he halted, but yelled after us that he'd tan us the next time he got close enough."

Tip Branders surely deserved the epithet of "loafer." Though only nineteen he had the look of being past twenty-one. He was a big, powerful fellow. Though he had not been at school since he was fifteen, Tip had not worked three months in the last four years. His mother, who kept a large and prosperous boarding-house, regarded Tip as being one of the manliest fellows in the world. She abetted his idleness by supplying him with too much money. Tip dressed well, though a bit loudly, and walked with a swagger. He was in a fair way to go through life without becoming anything more than a bully.

Hal Overton, on the other hand, was a quiet though merry young man, just above medium height, slim, though well built, brown-haired, blue-eyed, and a capable, industrious young fellow. The elder Overton was a clerk in a local store. Ill-health through many years had kept the father from prospering, and Hal, after two years in High School, had gone to work in the same store with his father at the age of sixteen.

Oliver Terry, too, had been at work since the[18] age of sixteen. Noll's father was engineer at one of the local machine shops, so Noll had gone into one of the lathe rooms, and was already accounted a very fair young mechanic.

Both were only sons; and, in the case of each, the fathers and mothers had felt sorry, indeed, to see the young men go to work before they had at least completed their High School courses.

By this time the fathers of both Hal and Noll had found themselves in somewhat better circumstances. Hal and Noll, being ambitious, had both felt dissatisfied, of late, with their surroundings and prospects, and both had received parental permission to better themselves if they could. So our two young friends, after many talks, and especially with Sergeant Wright, had decided to serve at least three years in the regular army by way of preliminary training.

Unfortunately, few American youths, comparatively speaking, are aware of the splendid training that the United States Army offers to a young American. The Army offers splendid grounding for the young man who prefers to serve but a single enlistment and then return to civil life. But it also offers a solidly good career to the young man who enlists and remains with the colors until he is retired after thirty years of continuous service.[19]

Both Hal and Noll had looked thoroughly into the question, and each was now convinced that the Army offered him the best place in life. Both boys had very definite ideas of what they expected to accomplish by entering the Army, as will appear presently.

Tip—even Tip Branders—had something of an ambition in life. So far as he had done anything, Tip had "trained" with a gang of young hoodlums who were "useful" to the political machine in one of the tough wards of the little city. Tip's ultimate idea was to "get a city job," at good pay, and do little or nothing for the pay.

But Tip dreaded a civil service examination—knew, in fact, that he could not pass one. In most American cities, to-day, an honorably discharged enlisted man from the Army or Navy is allowed to take an appointment to a city position without civil service examination, or else to do so on a lower marking than would be accepted from any other candidate for a city job.

So, curiously enough, Tip had decided to serve in the United States Army. One term would be enough to serve his purpose.

Tip, too, had kept his resolve a secret—even from his mother.

As Hal and Noll, Jud and Tom strolled along they came up with Tip Branders.[20]

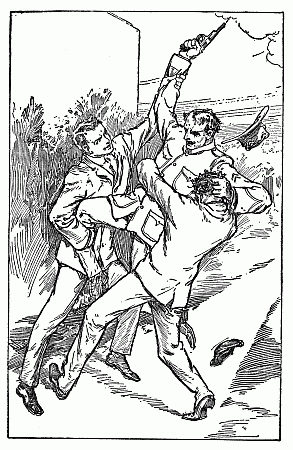

"So this is you, you little freshy!" growled Tip, halting suddenly, and close to Jud. "Now I'll give ye the thrashing I promised yesterday."

His big fist shot out, making a grab for young Jeffers.

But Hal Overton caught the wrist of that hand, and shoved it back.

"That doesn't look exactly manly in you, Branders," remarked Hal quietly.

"Oh, it doesn't, hey?" roared Tip. "What have you got to say about it?"

"Nothing in particular," admitted Hal pleasantly. "Nothing, except that I'd rather see you tackle some one nearer your own size."

"Would, hey?" roared Tip. "O. K!"

With that he swung suddenly, and so unexpectedly that the blow caught Hal Overton unawares, sending him to the sidewalk.

"I believe I'll take a small hand in this," murmured Noll Terry, starting to take off his coat.

But Hal was up in a twinkling.

"Leave this to me, please, Noll," he begged, and sailed in.

Tip Branders was waiting, with an ugly grin on his face. He was far bigger than Hal, and stronger, too. Yet, for the first few moments, Tip had all he could do to ward off Hal's swift, clever blows.[21]

Then Tip swung around swiftly, taking the aggressive.

It seemed like a bad mistake, for now Hal suddenly drove in a blow that landed on Brander's nose, drawing the blood.

"Now, I'll fix ye for that!" roared Tip, after backing off for an instant.

Just as he was about to charge again the big bully felt a strong grip on his collar, while a deep, firm voice warned him:

"Don't do anything of the sort, Branders, or I'll have to summon an officer to take you in."

Tip wheeled, to find himself looking into the grizzled face of Chief of Police Blake. Tip often bragged of his political "pull," but he knew he had none with this chief.

"I got a right to smash this fellow," blustered Tip. "He hit me."

"I'll wager you hit him first, though, or else gave young Overton good cause for hitting you," smiled the chief. "I know Overton, and he's the kind of boy his neighbors can vouch for. I don't know as much good of you. But I'll tell you, Tip, how you can best win my good opinion. Take a walk—a good, brisk walk—straight down the street. And start now!"

Something in the police chief's voice told Tip that it would be well to obey. He did so.

"Too many young fellows like him on the[22] street," observed Chief Blake, with a quiet smile. "Good morning, boys."

At the next corner Hal and Noll turned.

"Oh, you're going to see Sergeant Wright?" asked Jud.

"Yes," nodded Hal. "Our last visit to him."

"Then you won't want us along," said Jud sensibly. "But say, we wish you barrels of luck—honest—in the new life you're going into."

"Thank you," laughed Hal good-humoredly, holding out his hand.

"Send me a brass button soon, one that you've worn on your uniform blouse, will you?" begged Jud.

"Yes," agreed Hal, "if there's nothing in the regulations against it."

"And you, Noll? Will you do as much for me?" begged Tom.

"Surely, on the same conditions," promised Noll Terry.

"But we haven't succeeded in getting into the service yet, you must remember," Hal warned them.

"Oh, shucks!" retorted Jud. "I wish I were as sure of anything that I want. The recruiting officer'll be tickled to death when he sees you two walking in on him."

"I hope you're a real, true prophet, Jud," replied Hal, with a wistful smile.[23]

Neither of these two younger boys had any idea how utterly Hal Overton had set his heart on entering the service, nor why. The reader will presently discover more about the surging "why."

On one of the side streets the boys paused before the door of a cozy, little cottage in which lived Sergeant Wright and the wife who had been with him nearly the whole of his time in the service.

Ere they could ring the bell the door opened, and Sergeant Wright, U. S. Army, retired, stood before them, holding out his hand.

"Well, boys," was the kindly greeting of this fine-looking, middle-aged man, "have you settled the whole matter at home?"

"Yes," nodded Hal happily. "We go to New York, to-morrow, to try our luck with the recruiting officer."

"Come right in, boys, and we'll have our final talk about the good old Army," cried the retired sergeant heartily.

It was that same afternoon that Tip Branders next espied Jud and Tom coming down a street. Tip darted into a doorway, intent on lying in wait for the pair.

As they neared his place of hiding, however, Tip heard Jud and Tom talking of something that changed his plan.[24]

"What's that?" echoed Tip to himself, straining his hearing.

"Say," breathed Tom Andrews fervently, "wouldn't it be fine if we could go to New York to-morrow morning, too, and see Hal and Noll sworn into the United States Army?"

Tip held his breath, listening for more. He heard enough to put him in possession of practically all of the plans of Hal and Noll.

"Oho!" chuckled Tip, as he strode away from the place later. "So that pair of boobs are going to try for the Army. Oh, I daresay they'll get in. But so will I—and in the same company with them. I wouldn't have missed this for anything. I'll be the thorn in Hal Overton's side the little while that he'll be in the service! I've more than to-day's business to settle with that stuck-up dude!"

All of which will soon appear and be made plain.

Both Hal and Noll were "only children," or, at least, so thought their mothers.

Messrs. Overton and Terry, the elders, gave their sons' hands a last strong grip. No good advice was offered by either father at parting. That had already been attended to.

Naturally the boys' mothers cried a good bit over them. Both mothers, in fact, had wanted to go over to New York with their sons. But the fathers had objected that this would only prolong the pain of parting, and that soldiers in the bud should not be unfitted for their beginnings by tears.

So Hal and Noll met at the station, to take an early morning train. There were no relatives to see them off. Early as the hour was, though, Jud Jeffers and Tom Andrews had made a point of being on hand.

"We wanted to see you start," explained Jud, his face beaming and eyes wistful with longing. "We didn't know what train you'd take, so we've been here since half-past six."[26]

"We may be back by early afternoon," laughed Hal.

"Not you two!" declared Jud positively. "The recruiting officer will jump right up, shake hands with you, and drag you over to where you sign the Army rolls."

The train came along in time to put a stop to a long conversation.

As the two would-be soldiers stepped up to the train platform Jud and Tom did their best to volley them with cheers.

Noll blushed, darting into a car as quickly as he could, and sitting on the opposite side of the train from these noisy young admirers.

Hal, however, good-humoredly waved his hand from a window as the train pulled out. Then, with a very solemn face, all of a sudden, young Overton crossed and seated himself beside his chum.

Neither boy carried any baggage whatever. If they failed to get into the Army they would soon be home again. If they succeeded in enlisting, then the Army authorities would furnish all the baggage to be needed.

"Take your last look at the old town, Hal," Noll urged gravely, as the train began to move faster. "It may be years before we see the good old place again."

"Oh, keep a stiff upper lip, Noll," smiled Hal,[27] though he, also, felt rather blue for the moment. "Our folks will be down to the recruit drilling place to see us, soon, if we succeed in getting enrolled."

It hurt both boys a bit, as long as any part of their home city remained in sight. Each tried bravely, however, to look as though going away from home had been a frequent occurrence in their lives.

By the time that they were ten miles on their way both youngsters had recovered their spirits. Indeed, now they were looking forward with almost feverish eagerness to their meeting the recruiting officer.

"I hope the Army surgeon doesn't find anything wrong with our physical condition," said Hal, at last.

"Dr. Brooks didn't," replied Noll, as confidently as though that settled it.

"But Dr. Brooks has never been an Army surgeon," returned Hal. "He may not know all the fine points that Army surgeons know."

"Well we'll know before the day is over," replied Noll, with a catching of his breath. "Then, of course, we don't know whether the Army is at present taking boys under twenty-one."

"The law allows it," declared Hal stoutly.

"Yes; but you remember Sergeant Wright[28] told us, fairly, that sometimes, when the right sort of recruits are coming along fast, the recruiting officers shut down on taking any minors."

"I imagine," predicted Hal, "that much more will depend upon how we happen, individually, to impress the recruiting officer."

In this Hal Overton was very close to being right.

The ride of more than two hours ended at last, bringing the young would-be soldiers to the ferry on the Jersey side. As they crossed the North River both boys admitted to themselves that they were becoming a good deal more nervous.

"We'll get a Broadway surface car, and that will take us right up to Madison Square," proposed Noll.

"It would take us too long," negatived Hal. "We can save a lot of time by taking the Sixth Avenue "L" uptown and walking across to Madison Square."

"You're in a hurry to have it over with?" laughed Noll, but there was a slight tremor in his voice.

"I'm in a hurry to know my fate," admitted Hal.

Oliver Terry had been in New York but once before. Hal, by virtue of his superiority in[29] having made four visits to New York, led the way straight to the elevated railroad. They climbed the stairs, and were just in time to board a train.

A few minutes later they got out at Twenty-third Street, crossed to Fifth Avenue and Broadway, then made their way swiftly over to Madison Square.

"There's the place, over there!" cried Noll, suddenly seizing Hal's arm and dragging him along. "There's an officer and a man, and the soldier is holding a banner. It has something on it that says something about recruits for the Army."

"The man you call an officer is a non-commissioned officer—a sergeant, in fact," Hal replied. "Don't you see the chevrons on his sleeve?"

"That's so," Noll admitted slowly. "Cavalry, at that. His chevrons and facings are yellow. It was his fine uniform that made me take him for an officer."

"We'll go up to the sergeant and ask him where the recruiting office is," Hal continued.

Certainly the sergeant looked "fine" enough to be an officer. His uniform was immaculate, rich-looking and faultless. Both sergeant and private wore the olive khaki, with handsome visored caps of the same material.[30]

The early April forenoon was somewhat chilly, yet the benches in the center of the square were more than half-filled by men plainly "down on their luck." Some of these men, of course, were hopelessly besotted or vicious, and Uncle Sam had no use for any of these in his Army uniform. There were other men, however, on the seats, who looked like good and useful men who had met with hard times. Most of these men on the benches had not breakfasted, and had no assurance that they would lunch or dine on that day.

It was to the better elements among these men that the sergeant and the private soldier were intended to appeal. Yet the sergeant was not seeking unwilling recruits; he addressed no man who did not first speak to him.

In the tidy, striking uniforms, their well-built bodies, their well-fed appearance and their whole air of well-being, these two enlisted men of the regular army must have presented a powerful, if mute, appeal to the hungry unfortunate ones on the benches.

"Good morning, Sergeant," spoke Hal, as soon as the two chums had reached the Army pair.

"Good morning, sir," replied the sergeant.

"You're in the recruiting service?" Hal continued.[31]

"Yes, sir."

Always the invariable "sir" with which the careful soldier answers citizens. In the Army men are taught the use of that "sir," and to look upon all citizens as their employers.

"Then no doubt you will direct us to the recruiting office in this neighborhood?" Hal went on.

"Certainly, sir," answered the sergeant, and wheeling still further around he pointed north across the square to where the office was situated.

"You can hardly miss it, sir, with the orderly standing outside," said the sergeant, smiling.

"No, indeed," Hal agreed. "Thank you very much, Sergeant."

"You're welcome, sir. May I inquire if you are considering enlisting?"

"Both of us are," Hal nodded.

"Glad to hear it, sir," the sergeant continued, looking both boys over with evident approval. "You look like the clean, solid, sensible, right sort that we're looking for in the Army. I wish you both the best of good luck."

"Thank you," Hal acknowledged. "Good morning, Sergeant."

"Good morning, sir."

Still that "sir" to the citizen. The sergeant would drop it, as far as these two boys were[32] concerned, if they entered the service and became his subordinates.

It seemed to Hal and Noll as if they could not get over the ground fast enough until they reached that doorway where the orderly stood. The orderly directed them how to reach the office upstairs, and both boys, after thanking him, proceeded rapidly to higher regions.

They soon found themselves before the door. It stood ajar. Inside sat a sergeant at a flat-top desk. He, too, was of the cavalry. There were also two privates in the room.

Doffing their hats Hal and Noll entered the room. Overton led the way straight to the sergeant's desk.

"Good morning, Sergeant. We have come to see whether we can enlist."

"How old were you on your last birthday?" inquired the sergeant, eyeing Hal keenly.

"Eighteen, Sergeant."

"And you?" turning to Noll.

"Seventeen," Noll replied.

"You are too young, I'm sorry to say," replied the sergeant to Noll.

Then, turning to Hal, he added:

"You may be accepted."

"But I've got another birthday coming very soon," interjected Noll.

"How soon?"[33]

"To-morrow."

"You'll be eighteen to-morrow?" questioned the sergeant.

"Yes, sir."

"That will be all right, then," nodded the sergeant. "You won't need to be sworn in before to-morrow. You have both of you parents living?"

"Yes, sir," Hal answered, this time.

"It is not necessary, or usual, to say 'sir,' when answering a non-commissioned officer," the sergeant informed them. "Say 'sir,' always, when addressing a commissioned officer or a citizen."

"Thank you," Hal acknowledged.

"Now, you have the consent of your parents to enlist?"

"Yes, Sergeant."

"Both of you?"

"Yes."

"Aldridge!"

One of the pair of very spruce-looking privates in the room wheeled about.

"Furnish these young men with application blanks, and take them over to the high desk."

Having said this the sergeant turned back to some papers that he had been examining.

"You will fill out these papers," Private Aldridge explained to the boys, after he had led[34] them to the high desk. "I think all the questions are plain enough. If there are any you don't understand then ask me."

It was a race between Hal and Noll to see which could get a pen in his hand first. Then they began to write.

The first question, naturally, was as to the full name of the applicant; then followed his present age and other questions of personal history.

For some time both pens flew over the paper or paused as a new question was being considered.

When he came to the question as to which arm of the service was preferred by the applicant Noll turned to Hal to whisper:

"Is it still the infantry?" young Terry asked.

"Still and always the infantry," Hal nodded.

"All right," half sighed Noll. "I'm almost wishing for the cavalry, though, so I could ride a horse."

"The infantry is best for our plans," Hal replied.

When they had finished making out their papers Hal and Noll went back to the sergeant's desk.

"Do we hand these to you?" Hal asked.

"Yes," said the sergeant, taking both papers. He ran his eyes over them hurriedly, then rose[35] and passed into an inner office. When he came out all he said was:

"Take seats over there until you're wanted."

Two or three minutes later a buzzer sounded over the sergeant's head. Rising, he entered the inner room.

"Our time's come, now, I guess," whispered Noll.

"Or else something else is going to happen," replied Hal, smiling. "You and I are not the only two problems with which the Army concerns itself."

Noll's guess was right, however. The sergeant speedily returned to the outer office and crossed over to the boys, who rose.

"Lieutenant Shackleton will see you," announced the sergeant. "Step right into his office. Stand erect and facing him. Use the word, 'sir,' when answering him, and be very respectful in all your replies. Let him do all the talking."

"We understand, thank you," nodded Hal.

The sergeant, who had his cap in his hand, turned to leave the office for a few moments on other business. As he was going out he nearly bumped into a heavily-built young fellow who was entering.

Hal Overton had reached the door leading into the lieutenant's office and pulled it open.[36]

Just as he did so he heard a rather familiar voice behind him demand:

"Where's the officer in charge?"

"In that office," replied one of the soldiers, pointing.

The newcomer did not stop to thank the soldier, but sprang toward the door that Hal had just opened.

"Here, you kids can stand aside until a man gets through with his business in there," exclaimed Tip Branders, gripping Hal by the shoulders and swinging him aside.

Instead, Hal and Noll paused by the door, while Tip, with a confident leer on his face, strode into the inner office.

Lieutenant Shackleton, a man of twenty-eight, in blue fatigue uniform, with the single bar of the first lieutenant on his shoulder-straps, looked up quickly and in some amazement.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"I've come to see you about enlisting in the Army," continued Tip, who, with his hat still on, was marching up to the desk.

"Take off your hat."

"Eh? Huh?"

"Take off your hat!" came the repeated order, with a good deal more of emphasis.

"Hey? Oh, cert. Anything to oblige," assented Tip, with a sheepish grin, as he removed his hat.

"Is your name Overton?" asked the recruiting officer, glancing at the papers before him.

"Naw, nothing like it," returned Tip easily.[38]

"Or, Terry?"

"Them two boobs is outside," returned Tip, with evident scorn. "I told 'em to stand aside until I went in and had my rag-chew out with you."

Lieutenant Shackleton flashed an angry look at Branders, though a keen reader of faces would have known that this experienced recruiting officer was trying hard to conceal a smile. The lieutenant had dealt with many of these "tough" applicants.

"Orderly!" rasped out the lieutenant.

Private Aldridge appeared in the doorway, standing at attention.

"Orderly, I understand that this man wishes to enlist——"

"That's dead right," nodded Tip encouragingly.

"But his application has not been received by me," continued the lieutenant, ignoring the interruption. "Take him outside and let Sergeant Wayburn look him over first. Also ask the sergeant to inform this man as to the proper way to approach and address an officer."

"Very good, sir," replied Private Aldridge. He tried to catch Tip's eye, but Branders was not looking at him, so the soldier crossed over to Branders, resting a hand on his arm.

"Come with me," requested the soldier.[39]

"Hey?" asked Tip.

"My man, go with that orderly," cried Lieutenant Shackleton, in an annoyed tone.

"Me? Oh, all right," nodded Tip, and went out with the soldier.

"Overton! Terry!" called the recruiting officer.

"Here, sir," answered Hal, as both boys entered the room.

"One of you close the door then come here," directed Lieutenant Shackleton.

Noll closed the door, after which both boys advanced to the roll-top desk behind which the lieutenant sat.

"You are Henry Overton and Oliver Terry?" asked the officer.

"Yes, sir," Hal answered.

"And these are your applications?"

"Yes, sir."

"You have filled them out truthfully, in every detail?"

"Yes, sir."

"You, Overton, are already eighteen?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you, Terry, will be eighteen years old to-morrow?"

"Yes, sir——" from Noll.

The lieutenant looked them both over keenly, as if to make up his own mind about their ages.[40]

"May I speak, sir?" queried Hal.

"Yes."

"To satisfy any doubt about our ages, sir, we have brought with us copies of our birth certificates, both certified to by the city clerk at home."

"You're intelligent lads," exclaimed the officer, with a gratified smile. "You go at things in the right way. Be good enough to turn over the certificates to me."

Hal took some papers from his pocket, passing two of them over to the recruiting officer, who examined the certificates swiftly.

"All regular," he declared. "Terry, of course, if he passes, cannot be sworn in until to-morrow. You have other papers there?"

"Yes, sir," Hal admitted. "The consent for our joining, signed by both our fathers and mothers, since we are under twenty-one."

"But I cannot know, until I have ascertained, that these are the genuine signatures of your parents. That investigation will take a little time."

"Pardon me, sir," Hal answered, laying the two remaining papers before the officer, "but you will find both papers witnessed under the seal of a notary public, who states that our parents are personally known to him."

"Well, well, you are bright lads—good enough[41] to make soldiers of," laughed Lieutenant Shackleton almost gleefully, as he scanned the added papers.

"May I speak, sir?"

"Yes."

"We can't claim credit for bringing these papers. We are well acquainted with a retired sergeant of the Army, who suggested that these papers, in their present form, would save us a lot of bother."

"Then you don't deserve any of the credit?"

"No, sir."

"You deserve a higher credit, then, for you are both honest lads."

Again the lieutenant turned to look them over keenly, sizing them up, as it were. Both were plainly more than five-feet-four, and so would not be rejected on account of height. They seemed like good, solid youngsters, too.

"Smoke cigarettes?" suddenly shot out the lieutenant.

"No, sir!"

"Smoke anything else, or chew tobacco? Or drink alcoholic beverages?"

"We have never done any of these things, sir," Hal replied.

"I see that you express a preference for the infantry," continued the recruiting officer.

"Yes, sir," Hal replied.[42]

"I am almost sorry for that," continued the officer. "I would like to see two lads of your evident caliber going into my own arm of the service—the cavalry."

"We have chosen the infantry, sir," Hal explained, "because we will have more leisure time there than in the cavalry or artillery."

"Looking for easy berths?" asked Lieutenant Shackleton, with a suddenly suspicious ring to his voice.

"No, sir," Hal rejoined. "May I explain, sir?"

"Yes; go ahead."

"We both of us have hopes, sir, if we can get into the Army, that we may be able to rise to be commissioned officers. We have learned that there is less to do in the infantry, ordinarily, and that we would therefore have more time in the infantry for study to fit ourselves to take examinations for officer's commissions."

"Then, to save you from possible future disappointment, I had better be very frank with you about the chances of winning commissions from the ranks," said the lieutenant. "In the Army we have some excellent officers who have risen from the ranks. Each year a few enlisted men are promoted to be commissioned officers. The examination, however, is a very stiff one. Out of the applicants each year more enlisted[43] men are rejected than are promoted. The difficulty of the examination causes most enlisted men to fail."

"Thank you, sir. We have thought of all that, and have looked over the nature of the examinations given enlisted men who seek to be officers," Hal replied. "We know the examinations are very hard, but we have twelve years if need be in which to prepare ourselves for the examination. Enlisted men, so I am told, may apply for commissions up to the age of thirty."

"Yes; that is right," nodded the lieutenant. "But how much schooling have you behind you?"

"We have each had two years in High School, sir."

"On that basis you will both have hard times to prepare yourselves for officers' examinations. However, with great application, you may make it—if you achieve also sufficiently good records as enlisted men."

This explanation being sufficient, Lieutenant Shackleton paused, then went on:

"As you are unusually in earnest about enlisting I fancy that you want to hear the surgeon's verdict as soon as possible."

"Yes, sir, if you please," replied Hal.

"Orderly!"

One of the two soldiers entered. Lieutenant[44] Shackleton made some entries on the application papers, then handed them to the soldier.

"Orderly, take these young men to the surgeon at once."

"Yes, sir. Come this way, please."

Hal and Noll were again conducted into the outer office. The sergeant had returned by this time and was at his desk. Over at the high desk stood Tip Branders, making out his application.

"Oh, we're it, aren't we?" demanded Tip, looking around with a scowl at the chums. "You freshies!"

"Be silent," ordered the sergeant looking up briskly.

"Well, those two kids——" began Tip. But the sergeant, though a middle-aged man, showed himself agile enough to reach Tip Branders' side in three swift, long bounds.

"Young man, either conduct yourself properly, or get out of here," ordered the sergeant point-blank.

Muttering something under his breath, Tip turned back to his writing, at which he was making poor headway, while the orderly led Hal and Noll down the corridor, halting and knocking at another door.

"Come in!" called a voice.

"Lieutenant Shackleton's compliments, sir, and two applicants to be examined, sir."[45]

"Very good, Orderly," replied Captain Wayburn, assistant surgeon, Army Medical Corps, as he received the papers from the orderly. The latter then left the room, closing the door behind him.

"You are Overton and Terry?" questioned Captain Wayburn, eyeing the papers, then turning to the chums, who answered in the affirmative.

Captain Wayburn, being a medical officer of the Army, wore shoulder straps with a green ground. At the ends of each strap rested the two bars that proclaimed his rank of captain. Being a staff officer, Captain Wayburn wore black trousers, instead of blue, beneath his blue fatigue blouse. Moreover, the black trousers of the staff carried no broad side stripe along the leg. The side stripe is always in evidence along the outer leg side of the blue trousers of the line officer, and the color of the stripe denotes to which arm of the service the officer belongs—a white stripe denotes the infantry officer, while a yellow stripe distinguishes the cavalry and a red stripe the artillery officer.

Captain Wayburn now laid out two other sets of papers on his desk. These were the blanks for the surgeon's report on an applicant for enlistment.

At first this examination didn't seem to[46] amount to much. The surgeon began by looking Hal Overton's scalp over, next examining his face, neck and back of head. Then he took a look at Hal's teeth, which he found to be perfect.

"Stand where you are. Read this line of letters to me," ordered the surgeon, stepping across the room to a card on which were ranged several rows of printed letters of different sizes.

Hal read the line off perfectly.

"Read the line above."

Hal did so. He read all of the lines, to the smallest, in fact, without an error.

"There's nothing the matter with your vision," remarked Captain Wayburn, in a pleased tone. "Now tell me—promptly—what color is this?"

The surgeon held up a skein of yarn.

"Red," announced Hal, without an instant's hesitation.

"This one?"

"Green."

"And this?"

"Blue."

And so on. Hal missed with none of the colors.

"Go to that chair in the corner, Overton, and strip yourself, piling your clothing neatly on the chair. Terry, come here."[47]

Noll went through similar tests with equal success. By the time he had finished Hal was stripped. Now came the real examination. Hal's heart and other organs were examined; his skin and body were searched for blemishes. He was made to run and do various other exercises. After this the surgeon again listened to his heart from various points of examination. Finally Hal was told to lie down on a cot. Now, the examination of the heart was made over again in this position. It was mostly Greek to the boy. When the examination was nearly over Noll was ordered to strip and take his turn.

When it was over Captain Wayburn turned to them to say:

"If I pronounced you young men absolutely flawless in a physical sense, it wouldn't be much of an exaggeration. You are just barely over the one hundred and twenty pound weight, but that is all that can be expected at your age."

"You pass us, sir," asked Hal eagerly.

"Most decidedly. As soon as Terry is dressed I'll hand you each your papers to take back to the recruiting officer."

Five minutes later Hal and Noll returned to the main waiting room.

"Pass?" inquired the sergeant, with friendly interest.

"Yes," nodded Hal.[48]

Tip Branders was sitting in a chair, a dark scowl on his face.

"Orderly, take Branders to the surgeon, now," continued the sergeant, and Tip disappeared. Then the sergeant knocked at the door of the lieutenant's office and entered after receiving the officer's permission. He came out in a moment, holding the door open.

"Overton and Terry, the lieutenant will see you now."

Hal and Noll entered, handing their papers back to Lieutenant Shackleton, who glanced briefly at the surgeon's reports.

"I don't see much difficulty about your enlisting," smiled the officer. "I congratulate you both."

"We're delighted, sir," said Noll simply.

"Now, Overton, I can let you sign, provisionally, to-day but I can't accept your friend, Terry, until to-morrow, when he will have reached the proper age for enlisting. This may seem like a trivial thing to you, but Terry is just one day short of the age, and the regulations provide that an officer who knowingly enlists a recruit below the proper age is to be dismissed from the service. Now, if you prefer, Overton, you can delay enlisting until to-morrow, so as to enter on the same date with your friend."

"I'd prefer that, sir," admitted Hal[49].

"You are both in earnest about enlisting?"

"Indeed we are, sir," breathed Noll fervently.

"I believe you," nodded the officer. "Now, have you money enough for a hotel bed and meals until to-morrow forenoon?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then be here at nine o'clock to-morrow morning, sharp, and I'll sign you both on the rolls of the Army. Now, furnish me with home references, and, especially, the name of your last employer. These will be investigated by telegraph. Also, are you acquainted with the chief of police in your home city?"

Hal and Noll answered these questions.

Then, having nothing pressing on his hands for the moment, Lieutenant Shackleton offered the boys much sound and wholesome advice as to the way to conduct themselves in the Army. He laid especial stress upon truthfulness, which is the keystone of the service. He warned them against bad habits of all kinds, and told them to pick their friends with care, both in and out of the service.

"In particular," continued the lieutenant, "I want to warn you against contracting the 'guard-house habit.' That is what we call it when a soldier gets in the habit of committing petty breaches of discipline such as will land him in the guard-house for a term of confinement[50] for twenty-four hours or more. The 'guard-house habit' has spoiled hundreds of men, who, but for that first confinement, would have made admirable soldiers. The enlisted man with the 'guard-house habit' is as useless and hopeless as the tramp or the petty thief in civil life."

It was an excellent talk all the way through. Both boys listened respectfully and appreciatively. It struck them that Lieutenant Shackleton was giving them a large amount of his time. They learned, later, that a competent officer is always willing and anxious to talk with his men upon questions of discipline, duty and efficiency. It is one of the things that the officer is expected and paid to do.

By the time they came out Tip was just returning from the surgeon's examination.

"You freshies needn't think ye're the only ones that passed," growled Tip in a low voice, as he passed.

Neither chum paid any heed to Branders. Somehow, as long as he kept his hands at his sides, Branders didn't seem worth noticing.

"Make it?" asked the sergeant at the street door.

"Yes; we sign to-morrow, if our references are all right," Hal nodded happily.

With a sudden recollection that soldiers must[51] hold themselves erect, Hal and Noll braced their shoulders until they thought they looked and carried themselves very much as the sergeant did. They kept this pose until they had turned the corner into Broadway.

"Whoop!" exploded the usually quiet Noll Terry unexpectedly.

"What's wrong, old fellow?" asked Hal quickly.

"Nothing! Everything's right, and we're soldiers at last!" cried Noll, his eyes shining.

"At least, we shall be to-morrow, if all goes well," rejoined Hal.

"Oh, nonsense! Everything is going to go right, now. It can't go any other way."

As he spoke, Noll turned to cross Broadway at the next corner.

Hal made a pounce forward, seizing his comrade by an arm. Then he backed like a flash, dragging Noll back to the sidewalk with him. Even at that a moving automobile brushed Noll's clothes, leaving a layer of dirt on them.

"Things will go wrong, if you don't watch where you're going," cried Hal rather excitedly. "Noll, Noll, don't try to walk on clouds, but remember you're on Broadway."

"Let's get off of Broadway, then," begged young Terry. "I'm so tickled that I want a chance to enjoy my thoughts."[52]

"We'll cross and go down Broadway, then," Hal proposed. "I have the address of a hotel with rates low enough to suit our treasury, and it's some blocks below here."

"Say," muttered Noll, "of all the things I ever heard of! Think of Tip Branders wanting to serve the Flag!"

The boys talked of this puzzle, mainly, until they reached their street and crossed once more to go to the hotel. They registered, went to their room, and here Noll put in the next twenty minutes in making his clothes look presentable again.

"If you've got that done, let's go downstairs," proposed happy Hal. "I'm hungry enough to scare the bill of fare clear off the table."

As they descended into the lobby Hal suddenly touched Noll's arm and stood still.

"I guess Tip is going to stay right with us," whispered Overton in his chum's ear. "That's Tip's mother over there in the chair. She and her son must be stopping at this hotel."

"They surely are," nodded Noll, "for there's Tip himself just coming in."

Neither mother nor son noted the presence of the chums near by.

Tip hurried up to his mother, a grin on his not very handsome face.[53]

"Well, old lady," was that son's greeting, "I've gone and done it."

"You don't mean that you've gotten into any trouble, do you, Tip?" asked his mother apprehensively.

"Trouble—nothing!" retorted Tip eloquently. "Naw! I've been around to the rookie shed and got passed as a soldier in the Regular Army."

"What?" gasped his mother paling.

"Now, that ain't nothing so fierce," almost growled Tip. "But there is a fool rule—me being under twenty-one—that you've got to go and give your consent. So that's the cloth that's cut for you this afternoon, old lady."

"Oh, oh, oh!" cried Mrs. Branders, sinking back in her chair and covering her face with her hands. "What have I ever done that I should be disgraced by having a son of mine going to—enlist in the Army!"

Hal's eyes were flashing with indignation over Mrs. Brander's remark.

Noll, on the other hand, was smiling quietly.

"That must be a severe blow to Mrs. Branders," murmured Noll aloud, as the boys slipped into their chairs at table. "To think of gentle Tip going off into anything as rough and brutal as the Army! And poor little Tip raised so tenderly as a pet!"

As it afterwards turned out, however, Mrs. Branders, after offering her son a present of a hundred dollars to stay out of the Army, had at last tearfully given her consent to his becoming a soldier.

She even went to the recruiting office that afternoon with Tip, and gave a reluctant consent to her son's enlistment.

"Be here at nine o'clock, sharp, to-morrow morning," directed Lieutenant Shackleton.

It was doubtful if either youngster slept very well that night. Both were too full of thoughts[55] of the Army and of the service. When Hal did dream it was of Indians and Filipinos.

Both were up early, and had breakfast out of the way in record time—and then they hurried to Madison Square. They reached there ten minutes ahead of time.

The sergeant, however, came along five minutes later, and admitted them to the recruiting office.

Hardly had they stepped inside when Tip and his mother also appeared. Then came the other enlisted men stationed at this office. Punctually at the stroke of nine Lieutenant Shackleton entered, lifted his uniform cap to Mrs. Branders and entered his own inner office.

"Now you kids will get orders to skin back home," jeered Tip, in a low tone, as he glanced over at Hal and Noll.

"No pleasantries of that sort here," directed the sergeant, glancing up from his desk.

The door of the inner office opened, and Lieutenant Shackleton stepped out.

"Overton and Terry, your references prove to be absolutely good. I will enlist you presently."

Then the officer moved over to where Tip Branders and his mother sat. Tip rose awkwardly.

"Branders, I'm sorry to say we must decline[56] your enlistment," announced the recruiting officer, in a low tone.

"Wot's that?" demanded Tip unbelievingly.

"I find myself unable to accept you as a recruit in the Army," replied the lieutenant.

"Why, wot's the matter?" demanded Tip, thunderstruck. "Didn't I get by the sawbones all right?"

"If you mean the surgeon, yes," replied the recruiting officer. "But I regret to say that we do not receive satisfactory accounts of you from the home town."

"Wot's the matter? Somebody out home trying to give me the crisscross?" demanded Tip indignantly.

"We do not receive a satisfactory account of your character, Branders, and therefore you are not eligible for enlistment," went on Shackleton. "Madam, I am extremely sorry, but the regulations allow me to pursue no other course in the matter. I cannot enlist your son."

"See here, officer——" began Mrs. Branders hoarsely, as she got upon her feet.

"When addressing Mr. Shackleton, call him 'lieutenant,' not 'officer,'" murmured one of the orderlies in her ear.

"You mind your own business," flashed Mrs. Branders, turning her face briefly to the orderly.[57] Then she wheeled, giving her whole attention to the lieutenant.

"See here, officer, do you mean to say that my boy ain't good enough to get into the Army?"

"I am sorry, madam, but the report we receive of his character isn't satisfactory," answered Shackleton quietly.

"What? My boy ain't good enough to go with the loafers and roughs in the Army?" cried Mrs. Branders angrily. "He's too good for 'em—a heap sight too good for any such low company! But s'posing Tip has been just a little frisky sometimes, what has that got to do with his being a soldier? I thought you wanted young fellows to fight—not pray!"

"The soldier who can do both makes the better soldier, madam," replied the lieutenant, feeling sorry for the mother's humiliation. "And now I will say good morning to you and your son, madam, for I am very busy to-day. Overton and Terry, come into my office."

Before turning, Lieutenant Shackleton bowed to Mrs. Branders as gracefully and courteously as he could have done to the President's wife. Then he started for his office, leaving Mrs. Branders and Tip to depart in bewilderment and anger.

Hal and Noll followed the lieutenant, trying[58] not to let their faces betray any feeling over Tip's troubles.

"You still wish to enlist?" asked Shackleton, turning to the waiting lads, after he had seated himself.

"Yes, sir," answered both.

"Then you will sign the rolls," directed the recruiting officer, passing papers forward, dipping a pen in ink and passing it to Hal.

Hal signed, slowly, with a solemn feeling. It was Noll's turn next.

"I will now administer the oath," continued Lieutenant Shackleton gravely, as he rose at his desk. "Raise your right hand, Overton, and repeat after me."

This was the oath of service that Hal repeated:

"'I Henry Overton, do solemnly swear that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the United States of America; that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies whomsoever; and that I will obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and articles of war.'"

Then Noll took the same oath.

"You have already signed the same oath as a part of your enlistment contract," continued Lieutenant Shackleton. "I have now to certify[59] that you have taken the oath and signed before me."

Seating himself once more the recruiting officer certified in the following form on each set of papers:

"Subscribed and duly sworn to before me this — day of —— , A. D. ——

"That is all," finished the recruiting officer. "You are now recruits in the United States Army. I wish you both all happiness and success. You will take your further orders from my sergeant, or from the corporal to whom he turns you over. You will probably find yourself at the recruit rendezvous at Bedloe's Island in time for dinner to-day."

Touching a button on his desk the lieutenant waited until the sergeant entered.

"Sergeant, turn these men over to Corporal Dodds. Come back in ten minutes for the papers."

"Very good, sir."

The sergeant led them down the corridor, opening a door and leading the way inside.

"Corporal Dodds, here are two recruits. Take care of them until I bring the papers."[60]

"Very good, Sergeant."

The door closed.

"Help yourselves to chairs, or stand and look out of the window, if you'd rather," invited Corporal Dodds, who, himself, was seated at a small desk.

Hal and Noll tried sitting down at first. This soon became so irksome that they rose and went to one of the windows.

Corporal Dodds said nothing until the door opened once more, and the sergeant entered with an envelope.

"Here are the papers for Privates Overton and Terry. You are directed to see that the young men go with you on the eleven o'clock ferry to Bedloe's Island. You will report with these recruits to the post adjutant as usual."

"Very good, Sergeant," replied Corporal Dodds, and again the boys were alone with their present guide.

To the raw young recruits it was a tremendously solemn day, but to the corporal, it was simply a matter of dry routine.

"Ten-fifteen," yawned the corporal, at last. "Come along, rookies; nothing like being on time—in the Army, especially."

"Rookie" is the term by which a new recruit is designated in Army slang. It is a term of mild derision.[61]

Corporal Dodds paused long enough at the recruiting office to turn over his key to the sergeant; then he led the way to the street, across to the Sixth Avenue Elevated road, and thence they embarked on a train bound down town.

All the way to the Battery Corporal Dodds did not furnish his pair of recruits with more than a dozen words by way of conversation.

But neither Hal nor Noll felt much like talking. Though either would have died sooner than admit it, each was suffering, just then from acute homesickness, and also from a secret dread that the Army might not turn out to be as rosy as they had painted it in their imagination.

"This way to the Army ferry," directed Corporal Dodds, leading them across the Battery.

Once aboard a small steamer that flew the flag of the Quartermaster's Department, United States Army, Corporal Dodds watched his two young rookies as though he suspected they would desert if they got a chance.

After the ferry had left the slip, however, Dodds paid no more heed to them. He at least left them free to end it all by jumping over into the bay, if they wished to do so.

Finding that he was under no restrictions, Private Hal Overton, United States Army, sauntered forward to the bow. Private Noll[62] Terry, feeling, if anything a bit more forlorn, followed him.

Just as they were nearing the dock at Bedloe's Island, Noll ventured:

"I wonder how Tip Branders feels about now."

"I wonder," muttered Hal.

It was, in fact, a long walk from the dock to the adjutant's office at headquarters.

"Hit up the stride, rookies," ordered Corporal Dodds. "Double-time march—hike. Don't keep the post adjutant from his luncheon."

Corporal Dodds' real reason for haste was that he had a crony in one of the squad rooms at barracks whom he wanted to see as early as possible.

Shortly the rookies and their guide entered the adjutant's office. The adjutant proved to be a captain of infantry with a corporal and two privates on duty in his office as clerks.

"Sir, I report with two recruits," announced Corporal Dodds, coming to a salute, which the adjutant returned.

"Their papers?" asked the adjutant.

"Here, sir."

"Very good, Corporal. You may go."[64]

Turning to the chums Captain Anderson asked:

"You are Overton?"

"Yes, sir," Hal replied, doing his best to salute as neatly as Corporal Dodds had. Again the adjutant returned the salute in kind. "Then you are Terry?" he asked, turning.

"Yes, sir," Noll returned, not omitting to salute.

The adjutant called to his principal clerk.

"Corporal, make the proper entries for these men. Then take them over to Sergeant Brimmer's squad room."

With that the adjutant picked up his uniform cap and left the office, all the enlisted men present rising and standing at attention until he had closed the door after him.

The corporal made the necessary entries, then rose and picked up his own uniform cap.

"Come with me, rookies," he directed briefly.

So Hal and Noll followed, feeling within them another surge of that curiously lonely and depressed feeling.

This corporal led them into the barracks building, and down a corridor on the ground floor. He paused, at last, before a door that he flung open. Striding into the room, the corporal looked about him.

"Where is Sergeant Brimmer?" he asked.[65]

"Not here now," replied another corporal, coming forward.

"Two rookies. Hand 'em over to Brimmer when he comes in," replied the conductor from the adjutant's office.

With that he strode out again, shutting the door after him.

The last corporal of all proved to be an older man than any of his predecessors. He appeared to be about thirty-five years old; he was tall, dark-featured and rather sullen-looking.

In this room there were twenty cot beds, arranged in two opposite rows, with their heads to the walls. On each cot the bedding had been rolled back in a peculiarly exact fashion.

At the further end of the squad room was a table and several chairs.

The occupants of the room, at this moment, were a dozen men, besides the corporal. Three of the men, like our young rookies, were still wearing the clothes in which they had enlisted. The others wore light blue uniform trousers and fatigue blouses of dark blue. Some of these men in uniform looked almost indescribably "slouchy." They were men who had received their uniforms, but who had not yet had enough of the setting-up drills to know how to wear their uniforms.

"What are you looking about you for?" demanded[66] the corporal. "Wondering why dinner ain't spread on that table yonder?"

"No," replied Hal quietly. "We're just waiting to be told what to do with ourselves."

"What do I care what you do with yourselves?" demanded the corporal, turning on his heel and walking away.

So Hal and Noll remained where they were, the feeling of loneliness growing all the time.

"Don't mind Corporal Shrimp any more than you have to," advised one of the uniformed rookies, coming over to them after a few moments. "Shrimp is a terror and a grouch all the time. Sergeant Brimmer you'll find a real old soldier, and a gentleman all the time."

"Then it's just our luck to find Sergeant Brimmer out," smiled Hal.

"Here he comes now," murmured the uniformed rookie, as the door of the squad room opened.

At the first glimpse of the newcomer Hal made up his mind that he was going to like Sergeant Brimmer. He was a man of about thirty, tall, rather slender, erect, thoroughly well built, with light, almost golden hair and mustache, and a keen but kindly blue eye.

"Recruits?" he asked, as he approached the boys.

Both answered in the affirmative.[67]

"Corporal Shrimp," called Brimmer, "have you no report to make to me about these new men?"

"Why, yes," answered Shrimp, coming from the further end of the room. "These men have just been brought here from the adjutant. They're assigned to your squad room."

"Very good, Corporal. Men, what are your names?"

Hal and Noll both answered.

"Friends?" asked Sergeant Brimmer.

"Chums," Hal stated.

"Then you'll be bunkies, too, of course. You want beds together, don't you?"

"If we may have them," Noll answered.

"Follow me, then. Here you are. Eight and nine will be your beds until further orders. Later, when you have your clothing issued, Corporal Shrimp or I will show you how and where to take care of it. Now, men, you'll likely find it a bit dull here for a day or two. Recruits generally do. Then that will all wear off, and you'll be glad you're in the Army. If there's anything you need to know, ask Corporal Shrimp"—Hal winced inwardly—"or me. The mess call will soon go for dinner. When it does, follow me outside, but take your places in the rear of A Company, which is the recruit company that you now belong to. I'll[68] show you where to stand. New recruits don't march with the battalion—not until they've been drilled enough to know how to march."

"Is there a battalion here, Sergeant?"

"Two recruit companies, at present. The non-commissioned officers, of course, are trained soldiers. Then there are a few old-time privates in each company—just enough to give the recruits some steadiness. The trained privates also act as instructors sometimes."

With this remark Sergeant Brimmer moved away.

"He's all right," murmured Noll Terry. "If all were like Sergeant Brimmer we wouldn't feel so lonely and blue."

Noll had let that last word escape him without thinking. But Hal, who felt just as blue, pretended not to have heard.

"It'll all look different to us, just as soon as we get into uniform, and get past the first breaking-in," predicted young Overton.

Ta-ra-ra-ra-ta! sounded a bugle, out in the corridor.

"That must be the call to dinner," muttered Hal.

But a uniformed recruit, passing them, stopped to say, pleasantly:

"No; that's first call to mess. Every call by the bugler has a 'first call,' sounded just a little[69] while before. That 'first call' is always just the same strain. But the real call differs, according to what is meant. The mess call itself, which is the one you'll hear next, sounds like this."

The recruit hummed mess call for them.

"Thank you," acknowledged Hal gratefully.

"Feeling lonesome?" asked the uniformed rookie.

"J-j-just a bit," assented Hal.

"I'm getting almost over it," smiled the uniformed one, "The older men, those who have seen service with a regiment, tell me that a man soon gets to find delight in being in the Army. But that's after he has gotten away from the recruit rendezvous."

"Oh, we'll get over it before then," promised Hal. "We'll be all over it by to-morrow."

"Look out for that Shrimp," whispered the uniformed rookie.

"Does anyone ever need that warning, after seeing the corporal and hearing him talk?" laughed Hal, in an undertone.

"Don't you rookies go to take this squad-room for a vawdy-vill show," growled Corporal Shrimp, from the near distance, as he heard the three laughing. Sergeant Brimmer had just stepped outside.

Ta-ra-ta-ra-ta! sounded a bugle again in the corridor.[70]

"A little time to ourselves now," whispered the uniformed recruit. "That's mess call."

The men in the room were quickly filing out. Outside of barracks A Company was falling in, with B Company to the left of it.

"You un-uniformed recruits take your position at the rear, without forming," ordered Sergeant Brimmer coming up. "As your company starts Corporal Shrimp will instruct you how to form at the rear of the company."

What followed was little understood by the two recruits. But presently the two first sergeants gave their commands, and marched their companies into the mess hall.

"Fall in lively, there, by twos!" growled Shrimp roughly. "Hurry up! Don't get in the way of the head of B Company!"

To give emphasis to his orders Shrimp seized Hal and Noll each by an arm and swung them into place.

Both recruits went in with flushed faces. Shrimp's treatment had been such as to make them feel uncomfortably "raw." But as the men marched to their seats at the long tables in the mess hall this feeling of humiliation left both boys.

Hal's new friend occupied a seat at their right.

"All the corporals ain't Shrimps," he whispered.[71] "We've probably got one of the meanest corporals in the Army."

"He knows how to make everyone else feel as mean as himself," Hal whispered back.

Then all hands fell to at the meal, which tasted uncommonly good. It consisted of a stew, with plenty of meat and potatoes, and other vegetables in it. There was also bread and butter. Pie and coffee followed. Then the recruit companies were marched out again and were dismissed.

"We have twenty minutes for relaxation now," laughed Hal's new friend, who had introduced himself as Private Stanley. "After that I suppose Shrimp will get you for the setting-up drills. He always has the new men in our squad room. He——"

At this moment Sergeant Brimmer stepped up to the trio as they stood in the open air chatting.

"Overton and Terry, you'll be under Corporal Shrimp's orders after the recreation period. He'll instruct you in some of the first work of the recruit. Go with him when he orders you to turn out."

"Very good, Sergeant."

No sooner had a bugle sounded than Corporal Shrimp appeared, followed by two other un-uniformed rookies walking behind him.[72]

"You, Overton, and you, Terry, fall in by twos behind these two raw rookies," ordered Shrimp. "Try to act a bit as though you were marching, at that. Don't be too dumb! Forward!"

Conscious that they were not cutting much of a figure, Hal and Noll followed the pair ahead of them.

Shrimp led them to a bit of green some distance away from any of the larger drill grounds.

"Squad halt!" he rumbled. "Now, rookies, you'll fall in in single rank, facing the front and about four inches apart. No, no, ye idiots!" as the four rookies started confusedly to obey. "You'll wait until I give the order 'fall in.' When I do, Overton, being the tallest, will take his place at the right, Terry next him, then Strawbridge, and then Healy. Now, rookies, d'ye think ye understand? And you'll take your places about four inches apart—just enough distance to allow each man the free use of his body. Fall in!"

So confused were the poor rookies under the scowling glances of Shrimp that, in their haste to obey, they nearly upset each other.

"Ye're a bad lot," commented the corporal, eyeing them with extreme disfavor. "You don't even know how to judge the interval between each man. Now, let every man except[73] the man at the left rest his left hand on his hip, just below where his belt would be if he wore one. Let the right arm hang flat at the side. Now, each man move up so that his right arm just touches his neighbor's left elbow. Careful, there! Don't crowd. Now, let your left arms fall flat. There, you ostriches, you have the interval from man to man as well as rookies can get it inside of a week. Now, each one of you note his interval from the man at his right. So. Fall out!"

Without moving the rookies stood looking uncertainly at Corporal Shrimp.

"Fall out, I say!" roared the corporal.

"Do we go back to the squad room?" asked one of the rookies.

"Listen to the man, now!" growled Shrimp. "Do you go back to the squad room! You'll be lucky if ye ever live to see the squad room again. Fall out—fall out of ranks, ye idiots!"

"Oh," answered the same rookie. "Why didn't you say so?"

"Why didn't I say so?" roared Shrimp. "Why didn't I say so, indeed! Ye'll take the order the way I give it—not the way ye want it. When I tell ye to fall in, that means to get into line, with the proper interval from man to man. When I say fall out, ye're to get out of ranks again. Now, then—fall in!"[74]

In a twinkling the recruits jumped to obey. Shrimp surveyed their alignment with a scowl. Nothing that a recruit could do would satisfy him.

"Left hand on the hips, again. Now, get the interval—get it!" roared Shrimp. "Dress up there, ye rookie idiots!"

Shrimp would have made an excellent drillmaster had he possessed the patience and the human decency of Sergeant Brimmer. But this corporal made his work doubly hard, and hindered the rookies from learning, by his persistent nagging and bad temper.

"Now, we'll see whether ye can do as well at learning the position of the soldier," he snapped out nastily, after a while. "Whenever, in barracks, or elsewhere, in ranks or out, if you hear the command, 'Attention,' ye'll come to the position of the soldier. Now, watch me, ye thick-pated rookies, and, as I describe it, bit by bit, I'll come to the position of the soldier."

After lounging for an instant Corporal Shrimp continued:

"Heels on the same line, and as near together as possible. Turn your feet out equally so that they form an angle of sixty degrees."

Then, straightening up, this irate drillmaster went on:

"Hold your knees straight, but don't have[75] 'em stiff. Keep your body erect on the hips, but inclined ever so little forward; keep your shoulders squared, and let 'em fall equally. Let your arms and hands hang naturally, with the backs of the hands outward and the little fingers almost touching the seams of your trousers legs. Keep your elbows near the body. Head erect and square to the front. Draw yer chin in slightly, but don't hold it as if it was glued there, and keep yer eyes straight to the front."

Corporal Shrimp illustrated excellently in his own person. But then he glared at the rookies and shouted, "Attention!"

Of course none of the rookies did it just right.

"Fall out! Overton, ye lobster, come on the carpet before me, and I'll teach ye or make ye crazy!"

"The—the carpet?" asked Hal, staring dubiously. His head was tired from the corporal's badgering, or he would have been brighter.

"On that spot!" glared Shrimp, pointing at the grass about six feet in front of him, and adding an oath that made Hal's face flush. But young Overton obeyed, nevertheless. Shrimp scolded and hounded, but Hal did his best to keep his patience and really learn. Then it was Noll's turn. Terry came in for a worse badgering than ever.[76]

"Ye bandy-legged griddle-greaser!" snarled Shrimp, beside himself. "Is that what ye call letting yer arms hang naturally. Where did ye get yer ideas of nature, anyway, ye spindle-shanked carpenter's apprentice?"

Sergeant Brimmer had stepped within view, though behind the corporal's back, and stood looking quietly on.

"Ye wart on an Army buzzard!" howled Shrimp. "Ye——"

"That will do, Corporal," broke in Sergeant Brimmer quietly. "You're relieved, Corporal. I have time to take over the squad myself. You may go to the squad room."

Shrimp turned with a glare, but with the snarl somehow dying on his lips. He gasped with anger and humiliation, then turned about and stalked away toward barracks.

During the next hour things went along very differently. Sergeant Brimmer was an alert drillmaster, and he permitted no lagging or indifference on the part of the recruits. Neither did he hesitate to single out any rookie who did a thing improperly. But the sergeant's method of drilling was wholly manly. He was patient, even if firm, and he called no rookie uncomplimentary names.

"Fall out," ordered the sergeant presently. "Sit down if you want to, men, or walk about.[77] And I'll answer any questions that you may want to ask me out of ranks."

"What a difference between non-coms," uttered Hal to Noll, as the two chums stepped away a few yards. "Sergeant Brimmer is a man, first of all. I'd cheerfully drill under him until I dropped."

"Non-com" is the abbreviation used in the Army for non-commissioned officer—a corporal or sergeant.

"I hope we don't have to have much to do with Shrimp," muttered Noll Terry. "And I hope we don't find many Shrimps in the Army."

"Fall in!" sounded Sergeant Brimmer's voice, at last. How the young rookies sprang to obey, their eyes shining with interest!

Sergeant Brimmer now began to explain the "rests." Next he came to the salute. For some minutes he drilled them in the first principles of marching. But brief rests were frequent, and during these rests he answered all questions put to him.