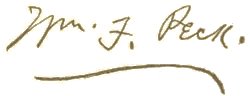

Mme. Roland in the Prison of Ste. Pélagie.

Project Gutenberg's Great Men and Famous Women. Vol. 6 of 8, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Great Men and Famous Women. Vol. 6 of 8

A series of pen and pencil sketches of the lives of more

than 200 of the most prominent personages in History

Author: Various

Editor: Charles F. Horne

Release Date: March 30, 2009 [EBook #28456]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GREAT MEN AND FAMOUS WOMEN. ***

Produced by Sigal Alon, Christine P. Travers and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Mme. Roland in the Prison of Ste. Pélagie.

A Series of Pen and Pencil Sketches of

THE LIVES OF MORE THAN 200 OF THE MOST PROMINENT PERSONAGES IN HISTORY.

VOL. VI.

Copyright, 1894, by SELMAR HESS

Edited By Charles F. Horne

New-York: Selmar Hess Publisher

Copyright, 1894, by Selmar Hess.

VOLUME VI.

PHOTOGRAVURES

| ILLUSTRATION | ARTIST | To face page |

| MME. ROLAND IN THE PRISON OF STE. PÉLAGIE, | Évariste Carpentier | Frontispiece |

| THE ARCH OF STEEL, | Jean Paul Laurens | 224 |

| CHARLOTTE CORDAY AND MARAT, | Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry | 230 |

| MARIE ANTOINETTE, | Théophile Gide | 244 |

| QUEEN LOUISE VISITING THE POOR, | Hugo Händler | 250 |

| THE FIRST VACCINATION—DR. JENNER, | Georges-Gaston Mélingue | 266 |

| VICTORIA GREETED AS QUEEN, | H. T. Wells | 362 |

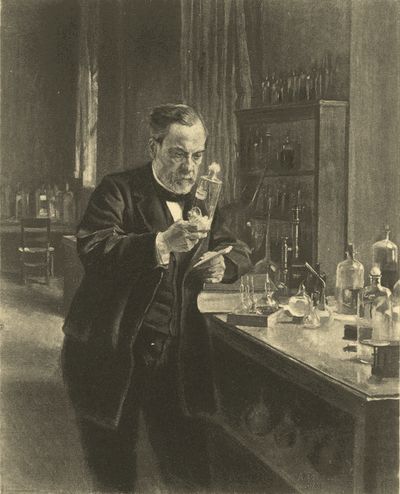

| PASTEUR IN HIS LABORATORY, | Albert Edelfelt | 380 |

WOOD-ENGRAVINGS AND TYPOGRAVURES

| ANDREAS HOFER LED TO EXECUTION, | Franz Defregger | 248 |

| WATT DISCOVERING THE CONDENSATION OF STEAM, | Marcus Stone | 256 |

| SAMUEL F. B. MORSE, INVENTOR OF THE TELEGRAPH, | From a photograph | 298 |

| CUTTING THE CANAL AT PANAMA, | Melton Prior | 338 |

| WINDSOR CASTLE, | G. Montbard | 364 |

| GORDON ATTACKED BY EL MAHDI'S ARABS, | W. H. Overend | 388 |

| CUSTER'S LAST FIGHT, | A. R. Ward | 394 |

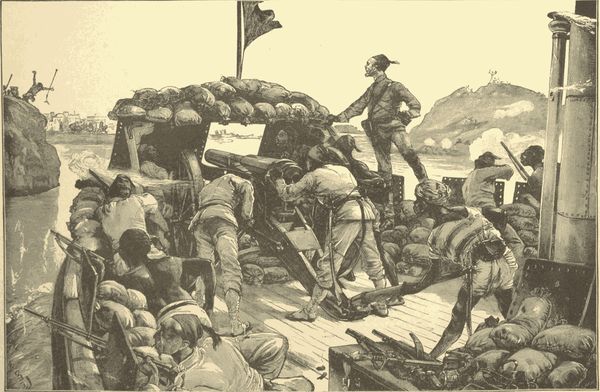

| STANLEY SHOOTING THE RAPIDS OF THE CONGO, | W. H. Overend | 400 |

| THOMAS A. EDISON—THE WIZARD OF MENLO PARK, | 406 |

Some of Arnold's biographers have declared that he was a very vicious boy, and have chiefly illustrated this fact by painting him as a ruthless robber of birds'-nests. But a great many boys who began life by robbing birds'-nests have ended it much more creditably. The astonishing and interesting element in Benedict Arnold's career was what one might term the anomaly and incongruity of his treason. Born at Norwich, Conn., in 1741, he was blessed from his earliest years by wholesome parental influences. The education which he received was an excellent one, considering his colonial environment. Tales of his boyish pluck and hardihood cannot be disputed, while others that record his youthful cruelty are doubtless the coinings of slander. It is certain that in 1755, when the conflict known as "the old French war" first broke out, he gave marked proof of patriotism, though as yet the merest lad. Later, at the very beginning of the Revolution, he left his thriving business as a West India merchant in New Haven and headed a company of volunteers. Before the end of 1775 he had been made a commissioned colonel by the authorities of Massachusetts, and had marched through a sally-port, capturing the fortress of Ticonderoga, with tough old Ethan Allen at his side and 83 "Green Mountain Boys" behind him. Later, at the siege of Quebec, he behaved with splendid courage. Through great difficulties and hardships he dauntlessly led his band to the high-perched and almost impregnable town. Pages might be filled in telling how toilsome was this campaign, now requiring canoes and bateaux, now taxing the strength of its resolute little horde with rough rocks, delusive bogs and all (p. 208) those fiercest terrors of famine which lurk in a virgin wilderness. Bitter cold, unmerciful snow-falls, drift-clogged streams, pelting storms, were constant features of Arnold's intrepid march. When we realize the purely unselfish and disinterested motive of this march, which has justly been compared to that of Xenophon with his 10,000, and to the retreat of Napoleon from Moscow as well, we stand aghast at the possibility of its having been planned and executed by one who afterward became the basest of traitors.

During the siege of Quebec Arnold was severely wounded, and yet he obstinately kept up the blockade even while he lay in the hospital, beset by obstacles, of which bodily pain was doubtless not the least. The arrival of General Wooster from Montreal with reinforcements rid Arnold, however, of all responsibility. Soon afterward the scheme of capturing Quebec and inducing the Canadas to join the cause of the United Colonies, came to an abrupt end. But in his desire to effect this purpose Arnold had identified himself with such lovers of their country as Washington, Schuyler, and Montgomery. And if the gallant Montgomery had then survived and Arnold had been killed, history could not sufficiently have eulogized him as a hero. Soon afterward he was promoted to the rank of brigadier-general, and on October 11, 1776, while commanding a flotilla of small vessels on Lake Champlain, he gained new celebrity for courage. The enemy was greatly superior in number to Arnold's forces. "They had," says Bancroft, "more than twice his weight of metal and twice as many fighting vessels, and skilled seamen and officers against landsmen." Arnold was not victorious in this naval fray, but again we find him full of lion-like valor. He was in the Congress galley, and there with his own hands often aimed the cannon on its bloody decks against the swarming masses of British gunboats. Arnold's popularity was very much augmented by his fine exploits on Lake Champlain. "With consummate address," says Sparks, "he penetrated the enemy's lines and brought off his whole fleet, shattered and disabled as it was, and succeeded in saving six of his vessels, and, it might be added, most of his men." Again, at the battle of Danbury he tempted death countless times; and at Loudon's Ferry and Bemis's Heights his prowess and nerve were the perfection of martial merit. It has been stated by one or two historians of good repute that Arnold was not present at all during the battle of Saratoga; but the latest and most trustworthy researches on this point would seem to indicate that he commanded there with discretion and skill. He was now a major-general, but his irascible spirit had previously been hurt by the tardiness with which this honor was conferred upon him, five of his juniors having received it before himself. He strongly disliked General Gates, too, and quarrelled with him because of what he held to be unfair behavior during the engagement at Bemis's Heights. At Stillwater, a month or so later in the same year (1777), he issued orders without Gates's permission, and conducted himself on the field with a kind of mad frenzy, riding hither and thither and seeking the most dangerous spots. All concur in stating, however, that his disregard of life was admirable, in spite of its foolish rashness. In this action he was also severely wounded.

(p. 209) One year later he was appointed to the command of Philadelphia, and here he married the daughter of a prominent citizen, Edward Shippen. This was his second marriage; he had been a widower for a number of years before its occurrence, and the father of three sons. Every chance was now afforded Arnold of wise and just rulership. In spite of past disputes and adventures not wholly creditable, he still presented before the world a fairly clean record, and whatever minor blemishes may have spotted his good name, these were obscured by the almost dazzling lustre of his soldierly career. But no sooner was he installed in his new position at Philadelphia than he began to show, with wilful perversity, those evil impulses which thus far had remained relatively latent. Almost as soon as he entered the town he disclosed to its citizens the most offensive traits of arrogance and tyranny. But this was not all. Not merely was he accused on every side of such faults as the improper issuing of passes, the closing of Philadelphia shops on his arrival, the imposition of menial offices upon the sons of freemen performing military duty, the use of wagons furnished by the State for transporting private property; but misdeeds of a far graver nature were traced to him, savoring of the criminality that prisons are built to punish. The scandalous gain with which he sought to fill a spendthrift purse caused wide and vehement rebuke. For a man of such high and peculiar place his commercial dabblings and speculative schemes argued most deplorably against him. There seems to be no doubt that he made personal use of the public moneys with which he was intrusted; that he secured by unworthy and illegal means a naval State prize, brought into port by a Pennsylvanian ship; and that he meditated the fitting up of a privateer, with intent to secure from the foe such loot on the high seas as piratical hazard would permit. His house in Philadelphia was one of the finest that the town possessed; he drove about in a carriage and four; he entertained with excessive luxury and a large retinue of servants; he revelled in all sorts of pompous parade. Such ostentation would have roused adverse comment amid the simple colonial surroundings of a century ago, even if he had merely been a citizen of extraordinary wealth. But being an officer intrusted with the most important dignities in a country both struggling for its freedom and impoverished as to funds, he now played a part of exceptional shame and folly.

Naturally his arraignment before the authorities of the State soon followed. The Council of Pennsylvania tried him, and though their final verdict was an extremely gentle one, its very mildness of condemnation proved poison to his truculent pride. Washington, the commander-in-chief, reprimanded him, but with language of exquisite lenity. Still, Arnold never forgave the stab that was then so deservingly yet so pityingly dealt him.

His colossal treason—one of the most monstrous in all the records of history, soon afterward began its wily work. Under the name of Gustavus he opened a correspondence with Sir Henry Clinton, an English officer in command at New York. Sir Henry at once scented the sort of villainy which would be of vast use to his cause, however he might loathe and contemn its designer. He instructed his aide-de-camp, Major John André, to send cautious and pseudonymic (p. 210) replies. In his letters Arnold showed the burning sense of wrong from which he believed himself (and with a certain amount of justice) to be suffering. He had, when all is told, received harsh treatment from his country, considering how well he had served it in the past. Even Irving, that most dispassionate of historians, has called the action of the court-martial just mentioned an "extraordinary measure to prepossess the public mind against him." Beyond doubt, too, he had been repeatedly assailed by slanders and misstatements. The animosity of party feeling had more than once wrongfully assailed him, and his second marriage to the daughter of a man whose Tory sympathies were widely known had roused political hatreds, unsparing and headstrong.

But these facts are merely touched upon to make more clear the motive of his infamous plot. Determined to give the enemy a great vantage in return for the pecuniary indemnity that he required of them, this unhappy man stooped low enough to ask and obtain from Washington, the command of West Point. André, who had for months written him letters in a disguised hand under the name of John Anderson, finally met him, one night, at the foot of a mountain about six miles below Stony Point, called the Long Clove. Arnold, with infinite cunning, had devised this meeting, and had tempted the adventurous spirit of André, who left a British man-of-war called the Vulture in order to hold converse with his fellow-conspirator. But before the unfortunate André could return to his ship (having completed his midnight confab and received from Arnold the most damning documentary evidence of treachery) the Vulture was fired upon from Teller's Point by a party of Americans, who had secretly carried cannon thither during the earlier night. André was thus deserted by his own countrymen, for the Vulture moved away and left him with a man named Joshua Smith, a minion in Arnold's employ. Of poor André's efforts to reach New York, of his capture and final pathetic execution, we need not speak. On his person, at the time of his arrest, was found a complete description of the West Point post and garrison—documentary evidence that scorched with indelible disgrace the name of the man who had supplied it.

On September 25, 1780, Arnold escaped to a British sloop-of-war anchored below West Point. He was made a colonel in the English army, and is said to have received the sum of £6,315 as the price of his treachery. The command of a body of troops in Connecticut was afterward given him, and he then showed a rapacity and intolerance that well consorted with the new position he had so basely purchased. The odium of his injured countrymen spoke loudly throughout the land he had betrayed. He was burned in effigy countless times, and a growing generation was told with wrath and scorn the abhorrent tale of his turpitude. Meanwhile, as if by defiant self-assurance to wipe away the perfidy of former acts, he issued a proclamation to "the inhabitants of America," in which he strove to cleanse himself from blame. This address, teeming with flimsy protestations of patriotism, reviling Congress, vituperating France as a worthless and sordid ally of the Crown's rebellious subjects, met on all sides the most contemptuous derision. Arnold passed nearly all the remainder of his life—eleven (p. 211) years or thereabouts—in England. He died in London, worn out with a nervous disease, on June 14, 1801. It is a remarkable fact that his second wife, who had till the last remained faithful to him, suffered acutely at his death, and both spoke and wrote of him in accents of strongest bereavement.

To the psychologic student of human character, Benedict Arnold presents a strangely fascinating picture. Elements of good were unquestionably factors of his mental being. But pride, revenge, jealousy, and an almost superhuman egotism fatally swayed him. He desired to lead in all things, and he had far too much vanity, far too little self-government, and not half enough true morality to lead with success and permanence in any. The wrongs which beyond doubt his country inflicted upon him he was incapable of bearing like a stoic. Virile and patriotic from one point of view, he was childish and weak-fibred from another. He has been likened to Marlborough, though by no means so great a soldier. Yet it is true that John Churchill won his dukedom by deserting his former benefactor, James II, and joining the Whig cause of William of Orange. If the Revolution had been crushed, we cannot blind our eyes to the fact that Arnold's treason would have received from history far milder dealing than is accorded it now. Even the radiant name of Washington would very probably have shone to us dimmed and blurred through a mist of calamity. Posterity may respect the patriot whose star sinks in unmerited failure, but it bows homage to him if he wages against despotism a victorious fight. Supposing that Arnold's surrender of West Point had extinguished that splendid spark of liberty which glowed primarily at Lexington and Bunker Hill, the chances are that he might have received an English peerage and died in all the odor of a distinction as brilliant as it would have been undeserved. The triumph of the American rebellion so soon after he had ignominiously washed his hands of it, sealed forever his own social doom. That, it is certain, was most severe and drastic. The money paid him by the British Government was accursed as were the thirty silver pieces of Iscariot; for his passion to speculate ruined him financially some time before the end of his life, and he breathed his last amid comparative poverty and the dread of still darker reverses.

Extreme sensitiveness is apt to accompany a spirit of just his high-strung, petulant, and spleenful sort. Beyond doubt he must have suffered keen torments at the disdain with which he was everywhere met in English society, and chiefly among the military officers whom his very conduct, renegade though it was, had in a measure forced to recognize him. When Lord Cornwallis gave his sword to Washington, its point pierced Arnold's breast with a wound rankling and incurable. He had played for high stakes with savage and devilish desperation. Our national independence meant his future slavery; our priceless gain became his irretrievable loss. It is stated that as death approached him he grew excessively anxious about the risky and shattered state of his affairs. His mind wandered, as Mrs. Arnold writes, and he fancied himself once more fighting those battles which had brought him honor and fame. It was then that he would call for his old insignia of an American soldier and would desire to be again clothed in them. (p. 212) "Bring me, I beg of you," he is reported to have said, "the epaulettes and sword-knots which Washington gave me. Let me die in my old American uniform, the uniform in which I fought my battles!" And once, it is declared, he gave vent to these most significant and terrible words: "God forgive me for ever putting on any other!" That country which he forswore in the hour of its direst need can surely afford to forgive Benedict Arnold as well. Grown the greatest republic of which history keeps any record, America need not find it difficult both to forget the wretched frailties of this, her grossly misguided son, and at the same time to remember what services he performed for her while as yet his baleful qualities had not swept beyond all bounds of restraint.[Back to Contents]

Nathan Hale, a martyr soldier of the American Revolution, was born in Coventry, Conn., on June 6, 1755. When but little more than twenty-one years old he was hanged, by order of General William Howe, as a spy, in the city of New York, on September 22, 1776.

At the great centennial celebration of the Revolution, and the part which the State of Connecticut bore in it, an immense assembly of the people of Connecticut, on the heights of Groton, took measures for the erection of a statue in Hale's honor. Their wish has been carried out by their agents in the government of the State. A bronze statue of Hale is in the State Capitol. Another bronze statue of him has been erected in the front of the Wadsworth Athenæum in Hartford. Another is in the city of New York.

Nathan Hale's father was Richard Hale, who had emigrated to Coventry, from Newbury, Mass., in 1746, and had married Elizabeth, the daughter of Joseph Strong. By her he had twelve children, of whom Nathan was the sixth.

Richard Hale was a prosperous and successful farmer. He sent to Yale College at one time his two sons, Enoch and Nathan, who had been born within two years of each other. This college was then under the direction of Dr. Daggett. Both the young men enjoyed study, and Nathan Hale, at the exercises of (p. 213) Commencement Day took what is called a part, which shows that he was among the thirteen scholars of highest rank in his class.

From the record of the college society to which he belonged, it appears that he was interested in their theatrical performances. These were not discouraged by the college government, and made a recognized part of the amusements of the college and the town. Many of the lighter plays brought forward on the English stage were thus produced by the pupils of Yale College for the entertainment of the people of New Haven.

When he graduated, at the age of eighteen, he probably intended at some time to become a Christian minister, as his brother Enoch did. But, as was almost a custom of the time, he began his active life as a teacher in the public schools, and early in 1774 accepted an appointment as the teacher of the Union Grammar School, a school maintained by the gentlemen of New London, Conn., for the higher education of their children. Of thirty-two pupils, he says, "ten are Latiners and all but one of the rest are writers."

In his commencement address Hale had considered the question whether the higher education of women were not neglected. And, in the arrangement of the Union School at New London, it was determined that between the hours of five and seven in the morning, he should teach a class of "twenty young ladies" in the studies which occupied their brothers at a later hour.

He was thus engaged in the year 1774. The whole country was alive with the movements and discussions which came to a crisis in the battle of Lexington the next year. Hale, though not of age, was enrolled in the militia and was active in the military organization of the town.

So soon as the news of Lexington and Concord reached New London, a town-meeting was called. At this meeting, this young man, not yet of age, was one of the speakers. "Let us march immediately," he said, "and never lay down our arms until we obtain our independence." He assembled his school as usual the next day, but only to take leave of his scholars. "He gave them earnest counsel, prayed with them, shook each by the hand," and bade them farewell.

It is said that there is no other record so early as this in which the word "independence" was publicly spoken. It would seem as if the uncalculating courage of a boy of twenty were needed to break the spell which still gave dignity to colonial submission.

He was commissioned as First Lieutenant in the Seventh Connecticut regiment, and resigned his place as teacher. The first duty assigned to the regiment was in the neighborhood of New London, where, probably, they were perfecting their discipline. On September 14, 1775, they were ordered by Washington to Cambridge. There they were placed on the left wing of his army, and made their camp at the foot of Winter Hill. This was the post which commanded the passage from Charlestown, one of the only two roads by which the English could march out from Boston. Here they remained until the next spring. Hale himself gives the most interesting details of that great victory by which Washington and his officers changed that force of minute-men, by which they had overawed (p. 214) Boston in 1775, into a regular army. Hale re-enlisted as many of the old men as possible, and then went back to Coventry to engage, from his old school companions, soldiers for the war. After a month of such effort at home, he came back with a body of recruits to Roxbury.

On January 30th his regiment was removed to the right wing in Roxbury. Here they joined in the successful night enterprise of March 4th and 5th, by which the English troops were driven from Boston.

So soon as the English army had left the country, Washington knew that their next point of attack would be New York. Most of his army was, therefore, sent there, and Webb's regiment among the rest. They were at first assigned to the Canada army, but because they had a good many seafaring men, were reserved for service near New York, where their "web-footed" character served them well more than once that summer. Hale marched with the regiment to New London, whence they all went by water to New York. On that critical night, when the whole army was moved across to New York after the defeat at Brooklyn, the regiment rendered effective service.

It was at this period that Hale planned an attack, made by members of his own company, to set fire to the frigate Phœnix. The frigate was saved, but one of her tenders and four cannons and six swivels were taken. The men received the thanks, praises, and rewards of Washington, and the frigate, with her companions, not caring to risk such attacks again, retired to the Narrows. Soon after this little brush with the enemy, Colonel Knowlton, of one of the Connecticut regiments, organized a special corps, which was known as Knowlton's Rangers. On the rolls of their own regiments the officers and men are spoken of as "detached on command." They received their orders direct from Washington and Putnam, and were kept close in front of the enemy, watching his movements from the American line in Harlem. It was in this service, on September 15th, that Knowlton's Rangers, with three Virginia companies, drove the English troops from their position in an open fight. It was a spirited action, which was a real victory for the attacking force. Knowlton and Leitch, the leaders, were both killed. In his general orders Washington spoke of Knowlton as a gallant and brave officer who would have been an honor to any country.

But Hale, alas! was not fighting at Knowlton's side. He was indeed "detached for special service." Washington had been driven up the island of New York, and was holding his place with the utmost difficulty. On September 6th he wrote, "We have not been able to obtain the least information as to the enemy's plans." In sheer despair at the need of better information than the Tories of New York City would give him, the great commander consulted his council, and at their direction summoned Knowlton to ask for some volunteer of intelligence, who would find his way into the English lines, and bring back some tidings that could be relied upon. Knowlton summoned a number of officers, and stated to them the wishes of their great chief. The appeal was received with dead silence. It is said that Knowlton personally addressed a non-commissioned officer, a Frenchman, who was an old soldier. He did so only to receive the natural (p. 215) reply, "I am willing to be shot, but not to be hung." Knowlton felt that he must report his failure to Washington. But Nathan Hale, his youngest captain, broke the silence. "I will undertake it," he said. He had come late to the meeting. He was pale from recent sickness. But he saw an opportunity to serve, and he did the duty which came next his hand.

William Hull, afterward the major-general who commanded at Detroit, had been Hale's college classmate. He remonstrated with his friend on the danger of the task, and the ignominy which would attend its failure. "He said to him that it was not in the line of his duty, and that he was of too frank and open a temper to act successfully the part of a spy, or to face its dangers, which would probably lead to a disgraceful death." Hale replied, "I wish to be useful, and every kind of service necessary to the public good becomes honorable by being necessary. If the exigencies of my country demand a peculiar service, its claims to perform that service are imperious." These are the last words of his which can be cited until those which he spoke at the moment of his death. He promised Hull to take his arguments into consideration, but Hull never heard from him again.

In the second week of September he left the camp for Stamford with Stephen Hempstead, a sergeant in Webb's regiment, from whom we have the last direct account of his journey. With Hempstead and Asher Wright, who was his servant in camp, he left his uniform and some other articles of property. He crossed to Long Island in citizen's dress, and, as Hempstead thought, took with him his college diploma, meaning to assume the aspect of a Connecticut schoolmaster visiting New York in the hope to establish himself. He landed near Huntington, or Oyster Bay, and directed the boatman to return at a time fixed by him, the 20th of September. He made his way into New York, and there, for a week or more apparently, prosecuted his inquiries. He returned on the day fixed, and awaited his boat. It appeared, as he thought; and he made a signal from the shore. Alas! he had mistaken the boat. She was from an English frigate, which lay screened by a point of woods, and had come in for water. Hale attempted to retrace his steps, but was too late. He was seized and examined. Hidden in the soles of his shoes were his memoranda, in the Latin language. They compromised him at once. He was carried on board the frigate, and sent to New York the same day, well guarded.

It was at an unfortunate moment, if anyone expected tenderness from General Howe. Hale landed while the city was in the tenor of the great conflagration of September 21st. In that fire nearly a quarter of the town was burned down. The English supposed, rightly or not, that the fire had been begun by the Americans. The bells had been taken from the churches by order of the Provincial Congress. The fire-engines were out of order, and for a time it seemed impossible to check the flames. Two hundred persons were sent to jail upon the supposition that they were incendiaries. It is in the midst of such confusion that Hale is taken to General Howe's head-quarters, and there he meets his doom.

(p. 216) No testimony could be stronger against him than the papers on his person. He was not there to prevaricate, and he told them his rank and name. There was no trial, and Howe at once ordered that he should be hanged the next morning. Worse than this, had he known it, he was to be hanged by William Cunningham, the Provost-Major, a man whose brutality, through the war disgraced the British army. It is a satisfaction to know that Cunningham was hanged for his deserts in England, not many years after.[3]

Hale was confined for the night of September 21st in the greenhouse of the garden of Howe's head-quarters. This place was known as the Beckman Mansion, at Turtle Bay. This house was standing until within a few years.

Early the next day he was led to his death. "On the morning of the execution," said Captain Montresor, an English officer, "my station being near the fatal spot, I requested the Provost-Marshal to permit the prisoner to sit in my marquee while he was making the necessary preparations. Captain Hale entered. He asked for writing materials, which I furnished him. He wrote two letters; one to his mother and one to a brother officer. The Provost-Marshal destroyed the letters, and assigned as a reason that the rebels should not know that they had a man in their army who could die with so much firmness."

Hale asked for a Bible, but his request was refused. He was marched out by a guard and hanged upon an apple-tree in Rutgers's orchard. The place was near the present intersection of East Broadway and Market Streets. Cunningham asked him to make his dying "speech and confession." "I only regret," he said, "that I have but one life to lose for my country."[Back to Contents]

Among the remarkable men of modern times there is perhaps none whose fame is purer from reproach than that of Thaddeus Kosciusko. His name is enshrined in the ruins of his unhappy country, which, with heroic bravery and devotion, he sought to defend against foreign oppression and foreign domination. Kosciusko was born at Warsaw about the year 1746. He was educated at the School of Cadets, in that city, where he distinguished himself so much in scientific studies as well as in drawing, that he was selected as one of four students of that institution (p. 217) who were sent to travel at the expense of the state, with a view of perfecting their talents. In this capacity he visited France, where he remained for several years, devoting himself to studies of various kinds. On his return to his own country he entered the army, and obtained the command of a company. But he was soon obliged to expatriate himself again, in order to fly from a violent but unrequited passion for the daughter of the Marshal of Lithuania, one of the first officers of state of the Polish court.

He bent his steps to that part of North America which was then waging its war of independence against England. Here he entered the army, and served with distinction as one of the adjutants of General Washington. While thus employed, he became acquainted with Lafayette, Lameth, and other distinguished Frenchmen serving in the same cause, and was honored by receiving the most flattering praises from Franklin, as well as the public thanks of the Congress of the United Provinces. He was also decorated with the new American order of Cincinnatus, being the only European, except Lafayette, to whom it was given.

At the termination of the war he returned to his own country, where he lived in retirement till the year 1789, at which period he was promoted by the Diet to the rank of major-general. That body was at this time endeavoring to place its military force upon a respectable footing, in the vain hope of restraining and diminishing the domineering influence of foreign powers in what still remained of Poland. It also occupied itself in changing the vicious constitution of that unfortunate and ill-governed country—in rendering the monarchy hereditary, in declaring universal toleration, and in preserving the privileges of the nobility, while at the same time it ameliorated the condition of the lower orders. In all these improvements Stanislas Poniatowski, the reigning king, readily concurred; though the avowed intention of the Diet was to render the crown hereditary in the Saxon family. The King of Prussia (Frederick William II.), who, from the time of the treaty of Cherson, in 1787, between Russia and Austria, had become hostile to the former power, also encouraged the Poles in their proceedings; and even gave them the most positive assurances of assisting them, in case the changes they were effecting occasioned any attacks from other sovereigns.

Russia at length, having made peace with the Turks, prepared to throw her sword into the scale. A formidable opposition to the measures of the Diet had arisen, even among the Poles themselves, and occasioned what was called the confederation of Targowicz, to which the Empress of Russia promised her assistance. The feeble Stanislas, who had proclaimed the new constitution in 1791, (p. 218) bound himself in 1792 to sanction the Diet of Grodno, which restored the ancient constitution, with all its vices and all its abuses. In the meanwhile Frederick William, King of Prussia, who had so mainly contributed to excite the Poles to their enterprises, basely deserted them, and refused to give them any assistance. On the contrary, he stood aloof from the contest, waiting for that share of the spoil which the haughty empress of the north might think proper to allot to him, as a reward of his non-interference.

But though thus betrayed on all sides, the Poles were not disposed to submit without a struggle. They flew to arms, and found in the nephew of their king, the Prince Joseph Poniatowski, a general worthy to conduct so glorious a cause. Under his command Kosciusko first became known in European warfare. He distinguished himself in the battle of Zielenec, and still more in that of Dubienska, which took place on June 18, 1792. Upon this latter occasion he defended for six hours, with only 4,000 men, against 15,000 Russians, a post which had been slightly fortified in twenty-four hours, and at last retired with inconsiderable loss.

But the contest was too unequal to last; the patriots were overwhelmed by enemies from without, and betrayed by traitors within, at the head of whom was their own sovereign. The Russians took possession of the country, and proceeded to appropriate those portions of Lithuania and Volhynia which suited their convenience; while Prussia, the friendly Prussia, invaded another part of the kingdom.

Under these circumstances the most distinguished officers in the Polish army retired from the service, and of this number was Kosciusko. Miserable at the fate of his unhappy country, and at the same time an object of suspicion to the ruling powers, he left his native land and retired to Leipsic, where he received intelligence of the honor which had been conferred upon him by the Legislative Assembly of France, who had invested him with the quality of a French citizen.

But his fellow-countrymen were still anxious to make another struggle for independence, and they unanimously selected Kosciusko as their chief and generalissimo. He obeyed the call, and found the patriots eager to combat under his orders. Even the noble Joseph Poniatowski, who had previously commanded in chief, returned from France, whither he had retired, and received from the hands of Kosciusko the charge of a portion of his army.

The patriots had risen in the north of Poland, to which part Kosciusko first directed his steps. Anxious to begin his campaign with an action of vigor, he marched rapidly toward Cracow, which town he entered triumphantly on March 24, 1794. He forthwith published a manifesto against the Russians; and then, at the head of only 5,000 men, he marched to meet their army. He encountered, on April 4th, 10,000 Russians at a place called Wraclawic, and entirely defeated them after a combat of four hours. He returned in triumph to Cracow, and shortly afterward marched along the left bank of the Vistula to Polaniec, where he established his head-quarters.

Meanwhile the inhabitants of Warsaw, animated by the recital of the heroic (p. 219) deeds of their countrymen, had also raised the standard of independence, and were successful in driving the Russians from the city, after a murderous conflict of three days. In Lithuania and Samogitia an equally successful revolution was effected before the end of April, while the Polish troops stationed in Volhynia and Podolia marched to the reinforcement of Kosciusko.

Thus far fortune seemed to smile upon the cause of Polish freedom—the scene was, however, about to change. The undaunted Kosciusko, having first organized a national council to conduct the affairs of government, once more advanced against the Russians. On his march he met a new enemy in the person of the faithless Frederick William, of Prussia, who, without having even gone through the preliminary of declaring war, had advanced into Poland at the head of 40,000 men.

Kosciusko, with but 13,000 men, attacked the Prussian army on June 8th, at Szcekociny. The battle was long and bloody; at length, overwhelmed by numbers, he was obliged to retreat toward Warsaw. This he effected in so able a manner that his enemies did not dare to harass him in his march; and he effectually covered the capital and maintained his position for two months against vigorous and continued attacks. Immediately after this reverse the Polish general, Zaionczeck, lost the battle of Chelm, and the Governor of Cracow had the baseness to deliver the town to the Prussians without attempting a defence.

These disasters occasioned disturbances among the disaffected at Warsaw, which, however, were put down by the vigor and firmness of Kosciusko. On July 13th the forces of the Prussians and Russians, amounting to 50,000 men, assembled under the walls of Warsaw, and commenced the siege of that city. After six weeks spent before the place, and a succession of bloody conflicts, the confederates were obliged to raise the siege; but this respite to the Poles was but of short duration.

Their enemies increased fearfully in number, while their own resources diminished. Austria now determined to assist in the annihilation of Poland, and caused a body of her troops to enter that kingdom. Nearly at the same moment the Russians ravaged Lithuania; and the two corps of the Russian army commanded by Suwarof and Fersen, effected their junction in spite of the battle of Krupezyce, which the Poles had ventured upon, with doubtful issue, against the first of these commanders, on September 16th.

Upon receiving intelligence of these events Kosciusko left Warsaw, and placed himself at the head of the Polish army. He was attacked by the very superior forces of the confederates on October 10, 1794, at a place called Macieiowice, and for many hours supported the combat against overwhelming odds. At length he was severely wounded, and as he fell, he uttered the prophetic words "Finis Poloniæ." It is asserted that he had exacted from his followers an oath, not to suffer him to fall alive into the hands of the Russians, and that in consequence the Polish cavalry, being unable to carry him off, inflicted some severe sabre wounds on him and left him for dead on the field; a savage fidelity, which we half admire even in condemning it. Be this as it may, he was recognized and (p. 220) delivered from the plunderers by some Cossack chiefs; and thus was saved from death to meet a scarcely less harsh fate—imprisonment in a Russian dungeon.

Thomas Wawrzecki became the successor of Kosciusko in the command of the army; but with the loss of their heroic leader all hope had deserted the breasts of the Poles. They still, however, fought with all the obstinacy of despair, and defended the suburb of Warsaw, called Praga, with great gallantry. At length this post was wrested from them. Warsaw itself capitulated on November 9, 1794; and this calamity was followed by the entire dissolution of the Polish army on the 18th of the same month.

During this time, Kosciusko remained in prison at St. Petersburg; but, at the end of two years, the death of his persecutress, the Empress Catharine, released him. One of the first acts of the Emperor Paul was to restore him to liberty, and to load him with various marks of his favor. Among other gifts of the autocrat was a pension, by which, however, the high-spirited patriot would never consent to profit. No sooner was he beyond the reach of Russian influence than he returned to the donor the instrument by which this humiliating favor was conferred. From this period the life of Kosciusko was passed in retirement. He went first to England, and then to the United States of America. He returned to the Old World in 1798, and took up his abode in France, where he divided his time between Paris and a country-house he had bought near Fontainebleau. While here he received the appropriate present of the sword of John Sobieski, which was sent to him by some of his countrymen serving in the French armies in Italy, who had found it in the shrine at Loretto.

Napoleon, when about to invade Poland in 1807, wished to use the name of Kosciusko in order to rally the people of the country round his standard. The patriot, aware that no real freedom was to be hoped for under such auspices, at once refused to lend himself to his wishes. Upon this the emperor forged Kosciusko's signature to an address to the Poles, which was distributed throughout the country. Nor would he permit the injured person to deny the authenticity of this act in any public manner. The real state of the case was, however, made known to many through the private representations of Kosciusko; but he was never able to publish a formal denial of the transaction till after the fall of Napoleon.

When the Russians, in 1814, had penetrated into Champagne, and were advancing toward Paris, they were astonished to hear that their former adversary was living in retirement in that part of the country. The circumstances of this discovery were striking. The commune in which Kosciusko lived was subjected to plunder, and among the troops thus engaged he observed a Polish regiment. Transported with anger, he rushed among them, and thus addressed the officers: "When I commanded brave soldiers they never pillaged; and I should have punished severely subalterns who allowed of disorders such as those which we see around. Still more severely should I have punished older officers, who authorized such conduct by their culpable neglect." "And who are you," was the general cry, "that you dare to speak with such boldness to us?" "I am Kosciusko." The effect was electric: the soldiery cast down their arms, prostrated (p. 221) themselves at his feet, and cast dust upon their heads according to a national usage, supplicating his forgiveness for the fault which they had committed. For twenty years the name of Kosciusko had not been heard in Poland save as that of an exile; yet it still retained its ancient power over Polish hearts; a power never used but for some good and generous end.

The Emperor Alexander honored him with a long interview, and offered him an asylum in his own country. But nothing could induce Kosciusko again to see his unfortunate native land. In 1815 he retired to Soleure, in Switzerland; where he died, October 16, 1817, in consequence of an injury received by a fall from his horse. Not long before he had abolished slavery upon his Polish estate, and declared all his serfs entirely free, by a deed registered and executed with every formality that could insure the full performance of his intention. The mortal remains of Kosciusko were removed to Poland at the expense of Alexander, and have found a fitting place of rest in the cathedral of Cracow, between those of his companions in arms, Joseph Poniatowski, and the greatest of Polish warriors, John Sobieski.[Back to Contents]

Marie Jean Paul Roch Yves Gilbert Motier, Marquis de la Fayette,[5] one of the most celebrated men that France ever produced, was born at Chavaignac, in Auvergne, on September 6, 1757, of a noble family, with a long line of illustrious ancestors. Left an orphan at the age of thirteen, he married, three years later, his cousin Anastasie, Countess de Noailles. Inspired from the earliest age with a love of freedom and aversion to constraint, the impulses of childhood became the daydreams of youth and the realities of maturer life. Filled with enthusiastic sympathy for the struggling colonies of America in their contest with Great Britain, he offered his services to the United States, and, though his enterprise was forbidden by the French Government, hired a vessel, sailed for this country, landed at Charleston in April, (p. 222) 1777, and proceeded to Philadelphia. His advances having been treated by Congress with some coldness, by reason of the incessant application of other foreigners for commissions, he offered to serve as a volunteer and at his own expense. Congress may be excused for having taken him at his word; on July 31st it appointed him major-general, without pay the titular honor, which carried with it no command, being, perhaps, the highest ever given in America to a young man of nineteen years. Having accepted the cordial invitation of General Washington, the commander-in-chief, to live at his head-quarters and to serve on his staff, Lafayette was severely wounded in the leg at the battle of the Brandywine, on September 11th, and the intrepidity he displayed in that engagement was equalled by the fortitude that he evinced during the following winter, in which he shared the privations of the American army in the wretched camp at Valley Forge. His fidelity to Washington at this time, when the latter was maligned by secret foes and conspired against by Conway's cabal, cemented the friendship between those great men. Lafayette was soon afterward detached to take command of an expedition that was to set out from Albany, cross Lake Champlain on the ice, and invade Canada; but, on arriving at the intended starting-point, and finding that no adequate preparations had been made, he refused to repeat the unfortunate experiment of Montgomery and Arnold of two years before, and waited for suitable supplies to be sent to him before setting out. These came not, the ice melted in March, and he returned to Valley Forge, with the thanks of Congress for his forbearance in abstaining from risking the loss of an army in order to acquire personal glory. France having declared war against England, May 2, 1778, and at the same time effected an alliance with the colonies, Lafayette returned home in January, 1779; on his arrival at Paris he was lionized and fêted, and during his stay there he received from the United States Congress a sword with massive gold handle and mounting, presented to him in appreciation of his services and particularly of his gallantry at the battle of Monmouth, on June 28th, in the preceding year. The high reputation that he had acquired in America increased his influence at home to such a degree that he was able to accomplish the object of his mission and procure money and troops from the ministry of war. These followed him to this country in the following year, but little was accomplished thereby, D'Estaing, the commander of the fleet, being blockaded in the harbor of Newport, and Washington being unwilling to undertake the contemplated attack on New York, even with the assistance of the French military force, without naval co-operation. In February, 1781, Lafayette was sent with a division into Virginia, where he soon found himself arrayed against the British general, Lord Cornwallis. That distinguished officer, the best, perhaps, of all on that side of the conflict, expected to make short work of his youthful antagonist, but Lafayette, who had learned from Washington the art of skilful retreat combined with cautious advance, succeeded, after a long series of skirmishes, in shutting Cornwallis up in Yorktown. In September, the French fleet, under the Count de Grasse, appeared and landed a force of 3,000 men under the Marquis de St. Simon. Lafayette was urged to (p. 223) make the assault at once and gain the glory of an important capture, but a feeling of honor, combined possibly with prudential considerations, impelled him to wait for the arrival of the main allied army under Washington and Rochambeau. They came a fortnight later, the investment was regularly made, and on October 14th Lafayette successfully led the Americans to the assault of one of the redoubts, while another was taken by the French under the Baron de Viomesnil. The surrender of Cornwallis, with his army of 7,000, took place on the 19th, which ended, practically, the American war of independence, though the final treaty of peace was not signed till January 20, 1783, the first knowledge of which came to Congress by a letter from Lafayette, who had returned to Europe in the meantime. Revisiting the United States in 1784, he was treated with great consideration by his old comrades in arms, and the next year he travelled through Russia, Austria, and Prussia, in the last of which he attended the military reviews of Frederick the Great in company with that renowned soldier.

From this time Lafayette's history is bound up with that of his country. Beginning by formulating plans for meliorating the condition of the slaves on his plantation in French Guiana, his philanthropic thoughts soon turned homeward. He saw France groaning under oppression and the people suffering from a thousand antiquated abuses. Some of these he succeeded in mitigating, in his capacity of member of the Assembly of the Notables, in 1787, but, as nothing of permanent value was accomplished by that body, he urged the convocation of the States General. In this assemblage, which met at Versailles, on May 4, 1789, he sat at first among the nobility, but when the deputies of the people declared themselves to be the National Assembly—afterward called the Constituent Assembly—he was one of the earliest of his order to join them and was elected one of the vice-presidents. On July 14th the Bastille was taken by the mob, and on the following day Lafayette was chosen commandant of the National Guard of Paris; an irregular body, partly military, partly police, having no connection with the royal army and in full sympathy with the people, from which its ranks were filled. On the 17th King Louis XVI. came into the city, where he was received by the populace with the liveliest expressions of attachment and escorted to the Hôtel de Ville, where Lafayette and Mayor Bailly awaited him at the foot of the staircase, up which he passed under an arch of steel formed by the uplifted swords of the members of the Municipal Council. Bailly offered to the king a tricolor cockade, which had been recently adopted as the national emblem, Lafayette, in devising it, having added white, the Bourbon color, to the red and blue that were the colors of Paris, to show the fidelity of the people to the institution of royalty. The king accepted the badge, pinned it to his breast, appeared with it on the balcony before the vast throng, and returned to Versailles with the feeling, on his part and that of others, that the reconciliation between all parties was complete and that the era of popular government had begun. Instead of that, the troubles continually increased, and Lafayette was placed in a most trying position, equally opposed to the encroachments of the destructionists and to the intrigues of the court, and longing as eagerly for the retention of the monarchy as for the establishment (p. 224) of the constitution. The brutal murder of Foulon, the superintendent of the revenue, and of his son-in-law Berthier, who were torn in pieces by the enraged populace on the 22d, in spite of the commands, entreaties, and even tears of Lafayette, so disgusted him that he resigned his command, and resumed it only when the sixty districts of Paris agreed to support him in his efforts to maintain order. On October 5th a mob of several thousand women set out from Paris to march to Versailles, with vague ideas of extorting from the National Assembly the passage of laws that should remove all distresses, of obtaining in some way a supply of food that should relieve the immediate needs of the capital, and of bringing back with them the royal family. The National Guard were urgent to accompany the women, partly from a desire to protect them in case of a possible collision with the royal troops, but still more to bring on a conflict with a regiment lately brought from the frontier, and to exterminate the body-guard of the king, the members of which had, at a supper given a few nights before, been so indiscreet as to trample the tricolor under their feet and pin the white cockade to their lapels. Lafayette did all in his power to prevent the march of the National Guard, sitting on his horse for eight hours in their midst, and refusing all their entreaties to give the word of command, till the Municipal Council finally issued the order and the troops set forth. Arrived at Versailles he posted one of his regiments in different parts of the palace, to protect it in case it were really attacked by rioters, and then, in the early morning, repairing to his head-quarters in an adjoining street, he threw himself on a bed, for a short season of necessary repose. Monarchical writers generally have reproached him for this act, calling it his "fatal sleep," the source of unnumbered woes, the beginning of the downfall; but it is difficult to see wherein he can justly be blamed for yielding, wearied out with fatigue, to the imperative demand of nature, after providing as far as possible for the preservation of order. Awakened in a few minutes by the report that the worst had happened, he hurried to the scene and found that the mob, having broken down the iron railings of the courtyard, had invaded the palace and massacred two of the body-guard, and that the lives of the king and queen were in instant peril. With characteristic courage, activity, and address he prevented the further effusion of blood, and the entire royal family, together with the Assembly, migrated to Paris the same day, escorted by the citizen soldiers and a turbulent mob both male and female. July 14, 1790, was memorable for the Oath of Federation, taken in the Champ de Mars, with imposing ceremonies, upon a platform of earth raised by the voluntary labors of all the citizens. Lafayette, as representative of the nation, and particularly of the militia, was the first to take the oath to be faithful to the law and the king and to support the constitution then under consideration by the Assembly. With a shout of affirmation from all of the National Guard, the taking of the entire oath by the president of the Assembly and the king, followed by a roar of assent from nearly half a million of spectators, and the joyful spreading of the news throughout the country by prearranged signals, the dream of peace and harmony came back again, as bright and as fleeting as the year before. Three days later the National Guard of (p. 225) France, outside of the city, united in an address to Lafayette, expressive of their confidence in his ability and his patriotism, and regretting their inability to serve under him, for, by the terms of a law proposed by himself, the commander of the militia of Paris was to have no authority over other troops. In September the municipality made a strong appeal to him to revoke his declaration that he would accept no pay or salary or indemnity of any kind, but he refused fixedly, saying that his fortune was considerable, that it had sufficed for two revolutions and that it would be devoted to a third, if one should arise, for the benefit of the people. By the death of Mirabeau, April 2, 1791, the last chance of a compromise between the court party and the radicals was taken away. Two weeks later the royal family attempted to leave the Tuileries for St. Cloud, in order to pass the Easter holidays there and to hear mass in the royal chapel; but the populace blocked the way, and even a portion of the National Guard, in a state of semi-mutiny, threatened to interfere if the other battalions fired on the people. This, nevertheless, Lafayette offered to do, and to force a passage at all hazards, but the king positively forbade the shedding of blood on his account, and resumed his virtual imprisonment in the palace. Lafayette was so chagrined by the seditious behavior of his troops that he again threw down his commission, whereupon an extraordinary revulsion of feeling took place; the municipality and the citizens were terror-stricken lest universal anarchy should ensue, and even the National Guard, repentant of their disgraceful conduct, cast themselves at the feet of their general, joining their voices to those of others in entreating him to resume his office, which, after three days, he consented to do, upon promise of obedience in the future.

The Arch of Steel.

This was the meridian of Lafayette's career, when his popularity and his influence were at their height. Power we can hardly call it, for that implies some voluntary deed of assumption, and he always acted in obedience to others, to some authority constituted at least under the forms of law, or, in the absence of that, to the sovereign people. From this time difficulties thickened around him and he was constantly environed by suspicion and by intrigues of all kinds against his character and his life, but he never swerved from the line of his duty. Not one of the political parties gave him its entire confidence, and each in turn conspired against him, only to be baffled by the underlying conviction, on the part of the masses, of his supreme patriotism and integrity. After the flight of the king and his family, on June 20th, Lafayette was violently denounced in the Jacobin club as a friend to royalty, and accused of having assisted in the evasion; but the attempt to proscribe him in the Assembly failed utterly, and that body appointed six commissioners to protect him from the sudden fury of the people. The royal fugitives having been stopped at Varennes and brought back to the Tuileries on the 25th, he saved them, by his personal efforts, from being torn in pieces by the mob, but was compelled to guard them much more strictly than before. On July 17th a disorderly assemblage gathered in the Champ de Mars to petition for the overthrow of the monarchy, and, in the tumult that ensued on the appearance of the troops, Lafayette ordered a volley of musketry, whereby (p. 226) the rioters were dispersed with a loss of several killed and wounded, but whereby, also, while that act of firmness elicited commendation from all lovers of order, occasion was given for further intrigues on the part of his enemies and the shattering of his influence among the lower classes. A momentary gleam of sunshine broke forth in September, when, the king having accepted the new constitution, Lafayette took advantage of the general state of good feeling thereby produced to propose a comprehensive act of amnesty for all offences committed on either side during the revolution, which was passed by the Constituent Assembly just before its final adjournment on the 30th. On that day he resigned, permanently, the command of the National Guard, and retired to his estate at Chavaignac, being followed by the most gratifying testimonials of public regard, among them a sword and a marble statue of Washington, presented by the city of Paris, and a sword cast from one of the bolts of the Bastille, given by his old soldiers. Contrary to his personal wishes, his friends and his patriotism persuaded him, in November, to stand as a candidate for the mayoralty of Paris, with the result that might have been foreseen, for Pétion, being supported both by the Jacobins and by the court party, was elected by a large majority. This defeat did not prevent Lafayette's appointment, a month later, to the command of one of the three armies formed to defend the frontier against an expected invasion of the Austrians, the rank of lieutenant-general being given to him, with the exalted honor of marshal of France. War was declared against Austria, April 20, 1792, and hostilities began, but even the active service in which he was engaged could not keep his thoughts from the political condition of the country, and on June 16th he wrote to the Legislative Assembly, which had succeeded the Constituent in the previous autumn, a letter in which he pointed out the dangers that menaced the nation and denounced the Jacobins as the faction whose growing power was full of peril to the state. Four days later the mob invaded the Tuileries and passed riotously through all the rooms, insulting in the grossest manner the royal family, who were compelled to stand before them and undergo this humiliation for three hours. On hearing of this event Lafayette hurried from his camp and appeared before the Assembly, entreating the punishment of the instigators of the outrage. His sublime audacity in thus opposing his own personality to the machinations of his enemies, and that, too, before a body already irritated by his unasked advice, paralyzed the fury of his adversaries, while his eloquence charmed the hearts of his hearers; but all was in vain, and the only result of this heroic action was that a decree of accusation was brought in against him, which was rejected by a vote of 406 to 224. Upon the massacre of the Swiss Guards, on August 10th, followed by the actual deposition and imprisonment of the king, Lafayette sounded his army to ascertain if they would march to Paris in defence of constitutional government, but he found them vacillating and untrustworthy. His own dismissal from command came soon after: orders were sent for his arrest, and nothing remained for him but flight.

On August 19th he left the army and attempted to pass through Belgium on (p. 227) his way to England, but he was captured by Austrian soldiers near the frontier. He protested that he no longer held rank as an officer in the army and should be considered as a private citizen; but his rights were not respected in either capacity, for he was not treated as a prisoner of war neither was he arraigned as a criminal. On the contrary, without any charges being preferred against him, and without the formality of a trial of any kind, he was immediately thrown into prison and was detained in various Belgian, Prussian, and Austrian jails and fortresses for more than five years, the last three being passed in close confinement at Olmutz. An unsuccessful attempt at escape increased the severity of his detention, and he nearly lost his life through the hardships and privations that he endured, till his wife and daughters came, in 1795, and voluntarily shared his incarceration. The only reason for the savage treatment that he received, unjustified by any forms of international, of military, or of criminal law, seems to have lain in the fact that he had been a member of the National Assembly and prominent in the constitutional struggle for liberty. A feeling of revenge, as mean as it was groundless—for he had done everything in his power to protect the dignity as well as the life of Marie Antoinette, the sister of the Austrian emperor—joined with a fear that other peoples might follow the lead of the French and overthrow monarchical institutions unless deterred by some world-shocking example, formed the mainspring of this atrocious procedure. Efforts were made in this country and in England to procure the release of the prisoner, but no governmental action was taken in that direction, the United States Congress declining to pass a resolution to that effect, so that President Washington was left alone in his unceasing attempts, by instructions to our ministers abroad and by a personal letter to the emperor, to repay some of the debt that he and the whole country owed to our adopted citizen. It was not till the successes of the French republican armies enabled General Bonaparte, at the instance of the Directory, to insist upon the liberation of Lafayette as one of the conditions of the treaty of Campo Formio, that he was discharged on September 19, 1797, the Austrian Government pretending that this was done out of regard for the United States of America. Passing into Denmark and Holland he resided in those countries for two years, when he returned to France only to receive from Bonaparte a significant message recommending to him a very quiet life, a piece of advice which, as it accorded with his own desires, he followed, settling down at Lagrange, an estate inherited by his wife, as his own property had been confiscated by the National Convention, which had succeeded the Legislative Assembly. True to the principles that he had always entertained, he cast his vote, in 1802, with less than nine thousand others, and in opposition to the suffrages of more than three-and-a-half millions, against the decree to make Bonaparte consul for life, writing after his name on the polling register the statement that he could not vote for such a measure till public freedom was sufficiently guaranteed. This insured the continued displeasure of the military despot, who revenged himself by refusing to Lafayette's only son, George Washington, the promotion that he had earned by his brilliant exploits in the army. President Jefferson's offer (p. 228) in 1803, of the governorship of the province of Louisiana, just after its purchase from France, was rejected by Lafayette, who continued in his retirement through the time of the empire and after the first restoration of the Bourbons, till the return from Elba, in March, 1815, of Napoleon, who used every exertion to conciliate him and win his support. All these overtures he declined, but, on the other hand, accepted an election to the popular branch of the Legislature, of which he was chosen vice-president. After the battle of Waterloo, on June 18th, Napoleon returned to Paris and proposed to his council the dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies and the assumption of absolutely dictatorial power; a desperate project which was frustrated only by the alertness, vigor, and energy of Lafayette, whose eloquent appeals induced the Legislature to compel the final abdication of the emperor, under the alternative threat of forfeiture and expulsion. Five commissioners, with Lafayette at the head, appointed by the chambers, proceeded to the head-quarters of the allied sovereigns, at Haguenau, to treat for peace; but, while negotiations were pending, the foreign armies pushed on toward the capital, and he returned on July 3d, to find that Paris had capitulated and was at the mercy of the conquerors, who dictated their own terms, forcibly dissolved the Corps Législatif, and replaced Louis XVIII. on the throne. Lafayette retired to Lagrange, but was again elected, in 1817, a deputy, in spite of the strenuous opposition of the Government, and exerted his influence in favor of liberal measures, though with indifferent success. In 1824, on the invitation of President Monroe, he revisited this country, travelled through every State, was received with the highest honors by Congress (which voted him $200,000 and a township of land for his services), by legislatures, by colleges, by corporations of cities, by societies of all kinds by his surviving comrades of the revolution, and by the whole nation; took part in the laying of the corner-stone of the Bunker Hill Monument June 17, 1825, and sailed for home in September, on the United States frigate Brandywine, which had been put at his disposal by the Government. Soon after his return to France he was re-elected to the Corps Législatif, and served as a member for most of the remainder of his life. The stupid tyranny of King Charles X. having caused an outbreak of the Parisians in July, 1830, Lafayette unhesitatingly espoused the popular cause, and, though nearly seventy-three years old, accepted the command of the National Guard; after a conflict of three days the royal troops gave way, the king abdicated, to be succeeded by the Duke of Orleans as King Louis Philippe, and Lafayette had the satisfaction of contributing largely to the establishment of what he had advocated so strongly forty years before—a constitutional monarchy. He died at his home, in the country, on May 20, 1834, but his remains were taken to Paris for interment, and as the funeral train passed through the streets the lamentations on every hand attested the affection and the sorrow of the people. Few men have lived who present a figure so attractive to the eye of the student; fewer still, so prominent on the theatre of history, who will bear, with so little possibility of censure, the closest scrutiny, the severest judgment. His actions were visible to all the world, his motives were transparent, his sentiments were unconcealed, his (p. 229) life was blameless. To the physical endowments of dignity of person and resistless charm of manner he added all desirable qualities of head and heart, a dauntless courage, an enthusiasm beautiful and yet consistent, a sublime patriotism, a disinterested generosity. If, with all these, he seems to have failed of achieving the highest success, it was because not of what he lacked but of what he possessed in the fullest degree, a lofty integrity that forbade him to pander to the passions of the mob, a supreme regard for the rights of the community and of the individual. He might have snatched the sovereign power, but in doing it he would have lost his self-respect. In place, then, of glittering success, he obtained the quiet admiration of mankind and the loving gratitude of two nations.[Back to Contents]

The despotism of Louis XIV. and the exhaustion of the finances by his wars and his reckless extravagance had reduced France to a very unhappy condition. His son, the Grand-Dauphin, died four years before his father, and his grandson, the Duke of Burgundy, a year later. Louis the Great was therefore succeeded by his great-grandson, Louis XV. During this reign the nation continued on the decline. He was followed by his grandson, Louis XVI., a better man than his immediate predecessor, but too weak to carry out the reforms necessary to restore the prosperity of the nation. Voltaire, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and many other writers, as well as the influence of the American Revolution, had fostered democratic ideas among the people, for the government was reeking with abuses.

The parliament had not assembled for three-quarters of a century; but representatives of the people met in 1789, in spite of the opposition of the king. The extreme of license followed the extreme of absolutism. The king opposed the Constituent Assembly, for this body changed its name several times, till the political conflict ended in the death by the guillotine of Louis XVI., and later by the execution of his queen, Marie Antoinette. For every two hundred and fifty of the gross population there was a member of the nobility who was exempted from the payment of any land tax, though this kind of property was almost exclusively in their possession, and from many other taxes and burdens, (p. 230) which all the more heavily weighed down the great body of the people. The latter had a long list of genuine grievances which the king and his advisers refused to remedy.

The revolution became an accomplished fact in the capture and destruction of the Bastille, on July 14, 1789, which day is still celebrated as a national holiday in France. It had been for hundreds of years a prison for political offenders, and was regarded by the people as the principal emblem and instrument of tyranny. The population became as intemperate as their rulers had been, thousands perished by the guillotine, and the reign of terror was established. The National Convention proclaimed a republic; but this body was divided by conflicting opinions, and had not the power to inaugurate their ideal government. Blood flowed in rivers, and the reaction was infinitely more terrible than the tyranny which had produced it.

The Convention was divided into at least four parties, though the lines which separated them were not very clearly defined. The Jacobins were the most prominent, and the most radical. It had its origin in the Jacobin Club, formed in Versailles, taking its name from a convent in which it met. This organization soon spread through its branches all over France, and its party was the most violent and blood-thirsty in the convention. Danton, Robespierre, Marat, Desmoulins, and other desperate leaders were of this faction.

The Girondists were next in numbers and influence. They were the moderate republicans of the time, though at first they were inclined to accept the constitution, and favor a limited monarchy. Its name came from the earliest leaders of the party who were representatives from the department of the Gironde. Its members labored to check the violence and bloodshed of the times, and might be called the respectable party of the period. Unfortunately they were in the minority, and all the members of the party in the Convention who did not escape, were arrested, convicted, and guillotined.

The Montagnards (mountaineers) or Montagne (Mountain) was the term applied to the Democrats holding the most extreme views, though its members were also Jacobins and Cordeliers. Among them were the most blood-thirsty, unreasonable, and intolerant men of the time, for Danton, Robespierre, Marat, St. Just, and others of that stamp, affiliated with them. They took their name from the fact that they were grouped together in the uppermost seats of the chamber of the Convention. The Cordeliers was hardly more than another name for a club of the same men, so called from the chapel of a Franciscan monastery where they held their meetings.

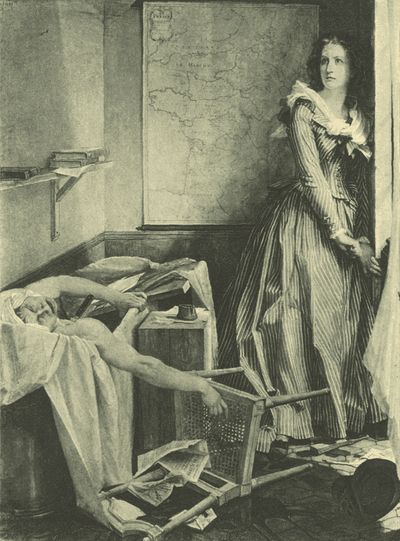

Charlotte Corday and Marat.

Jean Paul Marat was one of the most prominent personages of the Revolution, whose infamy will continue to be perpetuated down to generations yet to come, with other of his red-handed associates. He was a Frenchman, though he spent considerable time in Holland and Great Britain, where he practised medicine, having studied the profession at Bordeaux. He made some reputation as a political writer, and in Edinburgh obtained a degree. It is believed that he was convicted for stealing, and sentenced to five years imprisonment at Oxford under (p. 231) several aliases. Perhaps he was sincere in his opinions, and he threw himself vigorously into the work of the Revolution in Paris, issuing inflammatory pamphlets, which he caused to be printed and circulated secretly. He established an infamous journal, attacking the king and all his supporters, and especially the Girondists, whose moderation disgusted him. His virulence caused him to be intensely hated, and twice he was compelled to flee to London, and once to hide in the sewers. In the latter he contracted a loathsome disease of the skin which soon began to eat away his life; and his sufferings from it intensified his zeal and his hatred.

Marat was elected to the Convention as a delegate from Paris. Perhaps he was to a greater degree responsible for the September massacre than any other man. While he was dying of his malady he was urging on his fanatical measures, and declared that most of the members of the Convention, Mirabeau first, ought to be executed. His most virulent hatred was directed against the Girondists, whose execution he advocated with all the venom of his nature. Though he could write only when seated in a bath, he continued to hurl his invectives against them, impatient for the guillotine to do its gory work upon them.

The avenger was at hand. Charlotte Corday d'Armont was the granddaughter of Corneille, the great tragic poet of France. Though of noble descent, she was born in a cottage, for her father was a country gentleman so poor that he could not support his family. His daughters worked in the fields like the peasants, till he was compelled to abandon them. Then they obtained admission to a convent in Caen, where they were received on account of their birth and their poverty. The library furnished Charlotte abundant reading matter, and she read works on philosophy, though she also rather inflated her imagination by the perusal of romances, which had some influence on her after life.

When monasteries and convents were abolished, she was turned loose upon the world; but her aunt, as poor almost as her father, took the young woman, now nineteen years old, to her home in Caen. Charlotte had developed into a beautiful girl, rather tall, honest, and innocent. She had imbibed republican sentiments from her father in spite of his nobility, and Caen was the head-quarters of the Girondists. She was familiar with the details of the struggle between the Jacobins and the Girondists, and they inspired her with an intense feeling against the persecutors of her people, as she regarded the latter. The members of that party who had been driven from Paris instructed her. She was a woman; but if she had been a queen she had the nerve to rule a nation and fight its battles.