Of all that were thy prisons--ah, untamed,

Ah, light and sacred soul!--none holds thee now;

No wall, no bar, no body of flesh, but thou

Art free and happy in the lands unnamed,

Within whose gates, on weary wings and maimed,

Thou still would'st bear that mystic golden bough

The Sybil doth to singing men allow,

Yet thy report folk heeded not, but blamed.

And they would smile and wonder, seeing where

Thou stood'st, to watch light leaves, or clouds, or wind,

Dreamily murmuring a ballad air,

Caught from the Valois peasants, dost thou find

A new life gladder than the old times were,

A love more fair than Sylvie, and as kind?

ANDREW LANG.

SYLVIE ET AURÉLIE.—ANDREW LANG

GÉRARD DE NERVAL

SYLVIE:

| I | A WASTED NIGHT | |

| II | ADRIENNE | |

| III | RESOLVE | |

| IV | A VOYAGE TO CYTHERA | |

| V | THE VILLAGE | |

| VI | OTHYS | |

| VII | CHAÂLIS | |

| VIII | THE BALL AT LOISY | |

| IX | HERMENONVILLE | |

| X | BIG CURLY-HEAD | |

| XI | RETURN | |

| XII | FATHER DODU | |

| XIII | AURÉLIE | |

| XIV | THE LAST LEAF |

Two loves there were, and one was born

Between the sunset and the rain;

Her singing voice went through the corn,

Her dance was woven 'neath the thorn,

On grass the fallen blossoms stain;

And suns may set and moons may wane,

But this love comes no more again.

There were two loves, and one made white

Thy singing lips and golden hair;

Born of the city's mire and light,

The shame and splendour of the night,

She trapped and fled thee unaware;

Not through the lamplight and the rain

Shalt thou behold this love again.

Go forth and seek, by wood and bill,

Thine ancient love of dawn and dew;

There comes no voice from mere or rill,

Her dance is over, fallen still

The ballad burdens that she knew:

And thou must wait for her in vain,

Till years bring back thy youth again.

That other love, afield, afar

Fled the light love, with lighter feet.

Nay, though thou seek where gravesteads are,

And flit in dreams from star to star,

That dead love thou shalt never meet,

Till through bleak dawn and blowing rain

Thy soul shall find her soul again.

ANDREW LANG.

Il a toujours cherché dans le monde

ce que le monde ne pouvait plus lui

donner.

LUDOVIC HALÉVY.

He has been a sick man all his life.

He was always a seeker after something

in the world that is there in no

satisfying measure, or not at all.

WALTER PATER.

Of Gérard de Nerval, whose true name was Gérard Labrunie, it has been finely said: "His was the most beautiful of all the lost souls of the French Romance."(*) Born in 1808, he came to his death by suicide one dark winter night towards the end of January.

The story of this life and its tragic finale was well known at the time to all men of letters,—Théophile Gautier, Paul de Saint-Victor, Arsène Houssaye,—friends who never forgot the young poet even after he went the way that madness lies. For it was insanity,—a nostalgia of the soul always imminent—that led him into the squalid Rue de la Vieille-Lanterne, in which long forgotten corner of old Paris his dead body was found one bleak belated dawn. And this was forty years ago.

In later days Maxime du Camp and Ludovic Halévy have retold with great feeling the history of Gérard, his early triumphs, his love for Jenny Colon,—the Aurélie of these Souvenirs du Valois,—and how at last life's scurrile play was ended.

(*) See A Century of French Verse, translated and edited by William John Robertson (4to, London, 1895).

One of Mr. Andrew Lang's most genuine appreciations occurs in an epistle addressed to Miss Girton, Cambridge; where, for the benefit of that mythical young person, he translates a few passages out of Sylvie, and favours us with a specimen of Gérard's verse.

"I translated these fragments," he tells her, "long ago in one of the first things I ever tried to write. The passages are as touching and fresh, the originals, I mean, as when first I read them, and one hears the voice of Sylvie singing:

'A Dammartin, l'y a trois belles filles,

L'y en a z'une plus belle que le jour.'

So Sylvie married a confectioner, and, like Marion in the 'Ballad of Forty Years,' 'Adrienne's dead' in a convent. That is all the story, all the idyl."

And just before this he has said of Gérard: "What he will live by, is his story of Sylvie; it is one of the little masterpieces of the world. It has a Greek perfection. One reads it, and however old one is, youth comes back, and April, and a thousand pleasant sounds of birds in hedges, of wind in the boughs, of brooks trotting merrily under the rustic bridges. And this fresh nature is peopled by girls eternally young, natural, gay, or pensive, standing with eager feet on the threshold of their life, innocent, expectant, with the old ballads of old France upon their lips. For the story is full of these artless, lisping numbers of the popular French muse, the ancient ballads that Gérard collected and put into the mouth of Sylvie, the pretty peasant-girl."

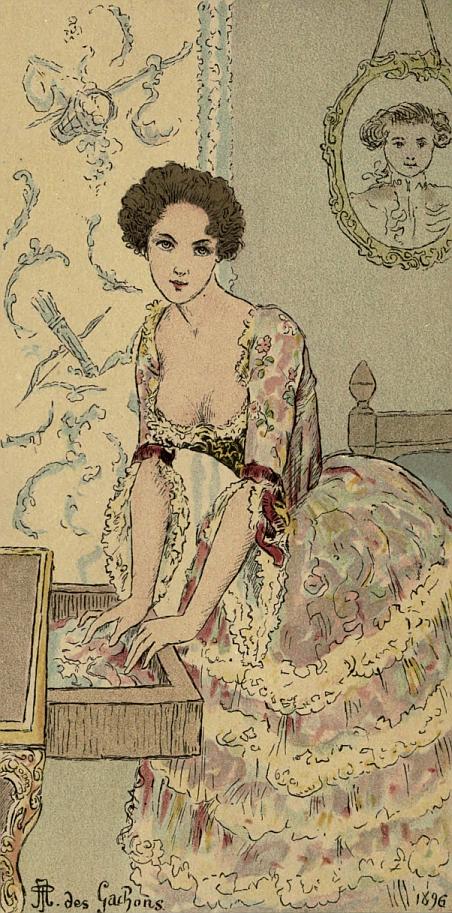

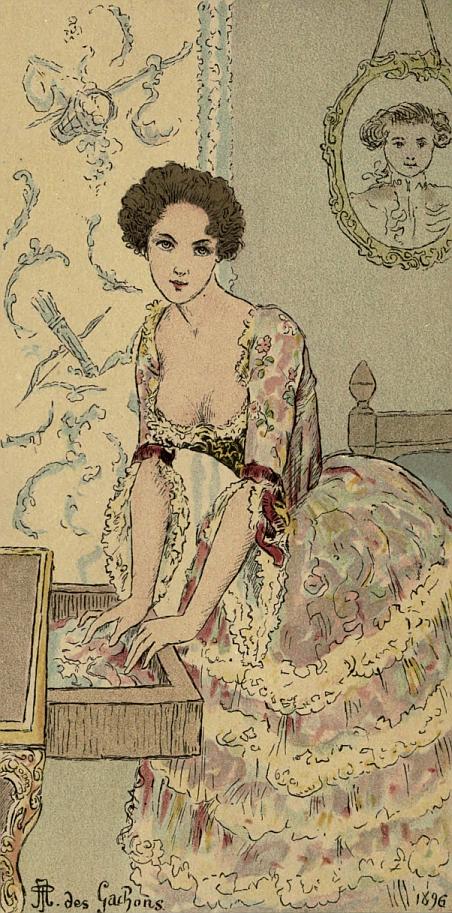

One more quotation from Mr. Lang, and we are done. Sylvie and Gérard have met, and they go on a visit to her aunt, who, while she prepares dinner, sends Gérard for her niece, who had "gone to ransack the peasant treasures in the garret." "Two portraits were hanging there—one, that of a young man of the good old times, smiling with red lips and brown eyes, a pastel in an oval frame. Another medallion held the portrait of his wife, gay, piquante, in a bodice with ribbons fluttering, and with a bird perched on her finger. It was the old aunt in her youth, and further search discovered her ancient festal-gown, of stiff brocade, Sylvie arrayed herself in this splendour; patches were found in a box of tarnished gold, a fan, a necklace of amber."

This is the charming moment chosen by M. Andhré des Gachons as the subject of his aquarelle, reproduced in colour as frontispiece to the present edition.

In thus bringing out a fresh version of Sylvie, not to include the all too few illusive lyrics "done into English" by Mr. Lang, his exquisite sonnet on Gérard, and the lovely lines upon "Sylvie et Aurélie," were a deplorable omission. The sonnet exists in an earlier form; preferably, the later version is here given.

Of De Nerval's prose little has yet found its way to us. His poetry is fully as inaccessible. Things of such iridescent hue are possibly beyond the art of translation. They are written in an unknown tongue; say, rather, in the language of Dreamland, "vaporous, unaccountable";—a world of crepuscular dawns, as of light irradiated from submerged sea caverns,—"the mermaid's haunt" beheld of him alone.

With what adieux shall we now take leave of our little pearl of a story? And of him who gave us this exquisite creation of heart and brain what words remain to say?

Thou, Sylvie, art an unfading flower of virginal, soft Spring, and faint, elusive skies. For thee Earth's old sweet nights have shed their tenderest dews, and in thy lovely Valois land thou canst not fade or die.

Thy lover, child, fared forth beneath an alien star. For him there was no true country, here;—no return to thy happy-hearted love: the desert sands long since effaced the valley track. Only the far distant lying,—the abyss that calls and is never dumb, urged his onward steps. And these things, and this divine homesickness led him, pale nympholept, beyond Earth's human shores. Thither to thee, rapt Soul, shall all bright dreams of day, all lonely visions of the night, converge at last.

There is an air for which I would disown

Mozart's, Rossini's, Weber's melodies,—

A sweet, sad air that languishes and sighs,

And keeps its secret charm for me alone.

Whene'er I hear that music vague and old,

Two hundred years are mist that rolls away;

The thirteenth Louis reigns, and I behold

A green land golden in the dying day.

An old red castle, strong with stony towers,

The windows gay with many coloured glass;

Wide plains, and rivers flowing among flowers,

That bathe the castle basement as they pass.

In antique weed, with dark eyes and gold hair,

A lady looks forth from her window high;

It may be that I knew and found her fair,

In some forgotten life, long time gone by.

(ANDREW LANG.)

I passed out of a theatre where I was wont to appear nightly, in the proscenium boxes, in the attitude of suitor. Sometimes it was full, sometimes nearly empty; it mattered little to me, whether a handful of listless spectators occupied the pit, while antiquated costumes formed a doubtful setting for the boxes, or whether I made one of an audience swayed by emotion, crowned at every tier with flower-decked robes, flashing gems and radiant faces. The spectacle of the house left me indifferent, that of the stage could not fix my attention until at the second or third scene of a dull masterpiece of the period, a familiar vision illumined the vacancy, and by a word and a breath, gave life to the shadowy forms around me.

I felt that my life was linked with hers; her smile filled me with immeasurable bliss; the tones of her voice, so sweet and sonorous, thrilled me with love and joy. My ardent fancy endowed her with every perfection until she seemed to respond to all my raptures—beautiful as day in the blaze of the footlights, pale as night when their glare was lowered and rays from the chandelier above revealed her, lighting up the gloom with the radiance of her beauty, like those divine Hours with starry brows, which stand out against the dark background of the frescoes of Herculaneum.

For a whole year I had not sought to know what she might be, in the world outside, fearing to dim the magic mirror which reflected to me her image. Some idle gossip, it is true, touching the woman, rather than the actress, had reached my ears, but I heeded it less than any floating rumours concerning the Princess of Elis or the Queen of Trebizonde, for I was on my guard. An uncle of mine whose manner of life during the period preceding the close of the eighteenth century, had given him occasion to know them well, had warned me that actresses were not women, since nature had forgotten to give them hearts. He referred, no doubt, to those of his own day, but he related so many stories of his illusions and disappointments, and displayed so many portraits upon ivory, charming medallions which he afterwards used to adorn his snuff-boxes, so many yellow love-letters and faded tokens, each with its peculiar history, that I had come to think ill of them as a class, without considering the march of time.

We were living then in a strange period, such as often follows a revolution, or the decline of a great reign. The heroic gallantry of the Fronde, the drawing-room vice of the Regency, the scepticism and mad orgies of the Directory, were no more. It was a time of mingled activity, indecision and idleness, bright utopian dreams, philosophic or religious aspirations, vague ardour, dim instincts of rebirth, weariness of past discords, uncertain hopes,—an age somewhat like that of Peregrinus and Apuleius. The material man yearned for the roses which should regenerate him, from the hands of the fair Isis; the goddess appeared to us by night, in her eternal youth and purity, inspiring in us remorse for the hours wasted by day; and yet, ambition suited not our years, while the greedy strife, the mad chase in pursuit of honour and position, held us aloof from every possible sphere of activity. Our only refuge was the ivory tower of the poets whither we climbed higher and higher to escape the crowd. Upon the heights to which our masters guided us, we breathed at last the pure air of solitude, we quaffed oblivion in the golden cup of fable, we were drunk with poetry and love. Love, alas! of airy forms, of rose and azure tints, of metaphysical phantoms. Seen nearer, the real woman repelled our ingenuous youth which required her to appear as a queen or a goddess, and above all, inapproachable.

Some of our number held these platonic paradoxes in light esteem, and athwart our mystic reveries brandished at times the torch of the deities of the underworld, that names through the darkness for an instant with its train of sparks. Thus it chanced that on quitting the theatre with the sense of bitter sadness left by a vanished dream, I turned with pleasure to a club where a party of us used to sup, and where all depression yielded to the inexhaustible vivacity of a few brilliant wits, whose stormy gaiety at times rose to sublimity. Periods of renewal or decadence always produce such natures, and our discussions often became so animated that timid ones in the company would glance from the window to see if the Huns, the Turkomans or the Cossacks were not coming to put an end to these disputations of sophists and rhetoricians. "Let us drink, let us love, this is wisdom!" was the code of the younger members. One of them said to me: "I have noticed for some time that I always meet you in the same theatre. For which one do you go?" Which! why, it seemed impossible to go there for another! However, I confessed the name. "Well," said my friend kindly, "yonder is the happy man who has just accompanied her home, and who, in accordance with the rules of our club, will not perhaps seek her again till night is over."

With slight emotion I turned toward the person designated, and perceived a young man, well dressed, with a pale, restless face, good manners, and eyes full of gentle melancholy. He flung a gold piece on the card-table and lost it with indifference. "What is it to me?" said I, "he or another?" There must be someone, and he seemed worthy of her choice. "And you?" "I? I chase a phantom, that is all."

On my way out, I passed through the reading-room and glanced carelessly at a newspaper, to learn, I believe, the state of the stock market. In the wreck of my fortunes, there chanced to be a large investment in foreign securities, and it was reported that, although long disowned, they were about to be acknowledged;—and, indeed, this had just happened in consequence of a change in the ministry. The bonds were quoted high, so I was rich again.

A single thought was occasioned by this sudden change of fortune, that the woman whom I had loved so long, was mine, if I wished. My ideal was within my grasp, or was it only one more disappointment, a mocking misprint? No, for the other papers gave the same figures, while the sum which I had gained rose before me like the golden statue of Moloch.

"What," thought I, "would that young man say, if I were to take his place by the woman whom he has left alone?"

I shrunk from the thought, and my pride revolted. Not thus, not at my age, dare I slay love with gold! I will not play the tempter! Besides, such an idea belongs to the past. Who can tell me that this woman may be bought? My eyes glanced idly over the journal in my hand, and I noticed two lines: "Provincial Bouquet Festival. To-morrow the archers of Senlis will present the bouquet to the archers of Loisy." These simple words aroused in me an entirely new train of thought, stirring long-forgotten memories of provincial days, faint echoes of the artless joys of youth.

The horn and the drum were resounding afar in hamlet and forest; the young maidens were twining garlands as they sang, and binding nosegays with ribbon. A heavy wagon, drawn by oxen, received their offerings as it passed, and we, the children of that region, formed the escort with our bows and arrows, assuming the proud title of knights,—we did not know that we were only preserving, from age to age, an ancient feast of the Druids that had survived later religions and monarchies.

I sought my bed, but not to sleep, and, lost in a half-conscious revery, all my youth passed before me. How often, in the border-land of dreams, while yet the mind repels their encroaching fancies, we are enabled to review in a few moments, the important events of a lifetime!

I saw a castle of the time of Henry IV., with its slate-covered turrets, its reddish front, jutting corners of yellow stone, and a stretch of green bordered by elms and lime-trees, through whose foliage, the setting sun shot its last fiery rays. Young girls were dancing in a ring on the lawn, singing quaint old tunes caught from their mothers, in a French whose native purity bespoke the old country of Valois, where for more than a thousand years had throbbed the heart of France. I was the only boy in the circle where I had led my young companion, Sylvie, a little maid from the neighboring hamlet, so fresh and animated, with her black eyes, regular features and slightly sun-burned skin. I loved but her, I had eyes but for her—till then! I had scarcely noticed in our round, a tall, beautiful blonde, called Adrienne, when suddenly, in following the figures of the dance, she was left alone with me, in the centre of the ring; we were of the same height, and they bade me kiss her, while the dance and song went whirling on, more merrily than before. When I kissed her, I could not forbear pressing her hand; her golden curls touched my cheek, and from that moment, a new feeling possessed me.

The fair girl must sing a song to reclaim her place in the dance, and we seated ourselves about her. In a sweet, penetrating voice, somewhat husky, as is common in that country of mists and fogs, she sang one of those old ballads full of love and sorrow, which always carry the story of an imprisoned princess, shut in a tower by her father, as a punishment for loving. At the end of every stanza, the melody died away in those quavering trills which enable young voices to simulate so well the tremulous notes of old women.

While she sang, the shadows of the great trees lengthened and the light of the young moon fell full upon her, as she stood apart from the rapt circle. The lawn was covered with rising clouds of mist that trailed its white wreaths over every blade of grass. We thought ourselves in Paradise. The song ended and no one dared break the stillness—at last I rose and ran to the gardens where some laurels were growing in large porcelain vases painted in monochrome. I plucked two branches which were twined into a crown, bound with ribbon, and I placed it upon Adrienne's brow, where its glossy leaves gleamed above her fair locks in the pale moonlight. She looked liked Dante's Beatrice, smiling at the poet as he strayed on the confines of the Blest Abodes.

Adrienne rose and, drawing up her slender figure, bowed to us gracefully and ran back to the castle; they said she was the child of a race allied to the ancient kings of France, that the blood of the Valois princes flowed in her veins. Upon this festal day, she had been permitted to join in our sports, but we were not to see her again, for on the morrow she would return to the convent of which she was an inmate.

When I rejoined Sylvie, I found her weeping because of the crown I had given to the fair singer. I offered to make another for her, but she would not consent, saying she did not merit it. I vainly tried to vindicate myself, but she refused to speak as we went the homeward way.

Paris soon recalled me to resume my studies, and I bore with me the two-fold memory of a tender friendship sadly broken, and of a love uncertain and impossible, the source of painful musings which my college philosophy was powerless to dispel.

Adrienne's face alone haunted me, a vision of glory and beauty, sweetening and sharing the hours of arduous study.

In the vacation of the following year, I learned that this lovely girl, who had but flitted past me, was destined by her family to a religious life.

These memories, recalled in my dreamy revery, explained everything. This hopeless passion for an actress, which took possession of me nightly from the hour when the curtain rose until I fell asleep, was born of my remembrance of Adrienne, the pale moon-flower, as she glided over the green, a rose-tinted vision enveloped in a cloud of misty whiteness. The likeness of a face long years forgotten was now distinctly outlined; it was a pencil-sketch, which time had blurred, developed into a painting, like the first drafts of the old masters which delight us in a gallery, the completed masterpiece being found elsewhere.

To fall in love with a nun in the guise of an actress!... suppose they were one and the same!—it is enough to drive one mad, a fatal mystery, drawing me on like a will o' the wisp flitting over the rushes of a stagnant pool. Let us keep a firm foothold on reality.

Sylvie, too, whom I loved so dearly, why had I forgotten her for three long years? She was a charming girl, the prettiest maiden in Loisy; surely she still lives, pure and good. I can see her window, with the creeper twining around the rose-bush, and the cage of linnets hanging on the left; I can hear the click of her bobbins and her favourite song:

La belle était assise

Près du ruisseau coulant....

(The maiden was sitting

Beside the swift stream.)

She is still waiting for me. Who would wed her, so poor? The men of her native village are sturdy peasants with rough hands and gaunt, tanned faces. I, the "little Parisian," had won her heart in my frequent visits near Loisy, to my poor uncle, now dead. For the past three years I have been squandering like a lord the modest inheritance left by him, which might have sufficed for a lifetime, and Sylvie, I know, would have helped me save it. Chance returns me a portion, it is not too late.

What is she doing now? She must be asleep.... No, she is not asleep; to-day is the Feast of the Bow, the only one in the year when the dance goes on all night.... She is there. What time is it? I had no watch.

Amongst a profusion of ornaments, which it was then the fashion to collect, in order to restore the local colour of an old-time interior, there gleamed with freshly polished lustre, one of those tortoise-shell clocks of the Renaissance, whose gilded dome, surmounted by a figure of Time, was supported by caryatides in the style of the Medici, resting in their turn upon rearing steeds. The historic Diana, leaning upon her stag, was in bas-relief under the face, where, upon an inlaid background, enameled figures marked the hours. The works, no doubt excellent, had not been put in motion for two centuries. It was not to tell the hour that I bought this time-piece in Touraine.

I went down to the porter's lodge to find that his clock marked one in the morning. "In four hours I can be at Loisy," thought I.

Five or six cabs were still standing on the Place du Palais Royal, awaiting the gamblers and clubmen. "To Loisy," I said to the nearest driver. "Where is it?" "Near Senlis, eight leagues distant." "I will take you to the posting station," said the cabman, more alert than I.

How dreary the Flanders road is by night! It gains beauty only as it approaches the belt of the forest. Two monotonous rows of trees, taking on the semblance of distorted figures, rise ever before the eye; in the distance, patches of verdure and cultivated land, bounded on the left by the blue hills of Montmorency, Ecouen and Luzarches. Here is Gonesse, an ordinary little town, full of memories of the League and the Fronde.

Beyond Louvres is a road lined with apple-trees, whose white blossoms I have often seen unfolding in the night, like stars of the earth—it is the shortest way to the village. While the carriage climbs the slope, let me recall old memories of the days when I came here so often.

Several years had passed, and only a childish memory was left me of that meeting with Adrienne in front of the castle. I was again at Loisy on the annual feast, and again I mingled with the knights of the bow, taking my place in the same company as of old. The festival had been arranged by young people belonging to the old families, who still own the solitary castles, despoiled rather by time than revolution, hidden here and there in the forest. From Chantilly, Compiègne and Senlis, joyous companies hastened to join the rustic train of archers. After the long parade through hamlet and village, after mass in the church, contests of skill and awarding of prizes, the victors were invited to a feast prepared upon an island in the centre of one of the tiny lakes, fed by the Nonette and the Thève. Boats, gay with flags, conveyed us to this island, chosen on account of an old temple with pillars, destined to serve as a banquet hall. Here, as in Hermenonville, the country side is sown with these frail structures, designed by philosophical millionaires, in accordance with the prevailing taste of the close of the eighteenth century. Probably this temple was originally dedicated to Urania. Three pillars had fallen, bearing with them a portion of the architrave, but the space within had been cleared, and garlands hung between the columns, quite rejuvenated this modern ruin, belonging rather to the paganism of Boufflers and Chaulieu than of Horace. The sail on the lake was perhaps designed to recall Watteau's "Voyage to Cythera," the illusion being marred only by our modern dress. The immense bouquet was borne from its wagon and placed in a boat, accompanied by the usual escort of young girls dressed in white, and this graceful pageant, the survival of an ancient custom, was mirrored in the still waters that flowed around the island, gleaming in the red sunlight with its hawthorn thickets and colonnades.

All the boats soon arrived, and the basket of flowers borne in state, adorned the centre of the table, around which we took our places, the most fortunate beside a young girl; to win this favour it was enough to know her relatives, which explains why I found myself by Sylvie, whose brother had already joined me in the march, and reproached me for neglecting to visit them. I excused myself by the plea that my studies kept me in Paris, and averred that I had come with that intention.

"No," said Sylvie, "I am sure he has forgotten me. We are only village folk, and a Parisian is far above us." I tried to stop her mouth with a kiss, but she still pouted, and her brother had to intercede before she would offer me her cheek with an indifferent air. I took no pleasure in this salute, a favour accorded to plenty of others, for in that patriarchal country where a greeting is bestowed upon every passing stranger, a kiss means only an exchange of courtesies between honest people.

To crown the enjoyment of the day, a surprise had been contrived, and, at the close of the repast, a wild swan, hitherto imprisoned beneath the flowers, soared into the air, bearing aloft on his powerful wings, a tangle of wreaths and garlands, which were scattered in every direction. While he darted joyously toward the last bright gleams of the sun, we tried to seize the falling chaplets, to crown our fair neighbours. I was so fortunate as to secure one of the finest, and Sylvie smilingly granted me a kiss more tender than the last, by which I perceived that I had now redeemed the memory of a former occasion. She had grown so beautiful that my present admiration was without reserve, and I no longer recognised in her the little village maid, whom I had slighted for one more skilled in the graces of the world. Sylvie had gained in every respect; her black eyes, seductive from childhood, had become irresistibly fascinating, and there was something Athenian in her arching brows, together with the sudden smile lighting up her quiet, regular features. I admired this classic profile contrasting with the mere prettiness of her companions. Her taper fingers, round, white arms and slender waist changed her completely, and I could not refrain from telling her of the transformation, hoping thus to hide my long unfaithfulness. Everything favoured me, the delightful influences of the feast, her brother's regard, the evening hour, and even the spot chosen by a tasteful fancy to celebrate the stately rites of ancient gallantry. We escaped from the dance as soon as possible, to compare recollections of our childhood and to gaze, side by side, with dreamy pleasure, upon the sunset sky reflected in the calm waters. Sylvie's brother had to tear us from the contemplation of this peaceful scene by the unwelcome summons that it was time to start for the distant village where she dwelt.

They lived at Loisy, in the old keeper's lodge, whither I accompanied them, and then turned back toward Montagny, where I was staying with my uncle. Leaving the highway to cross a little wood that divides Loisy from Saint S——, I plunged into a deep track skirting the forest of Hermenonville. I thought it would lead me to the walls of a convent, which I had to follow for a quarter of a league. The moon, from time to time, concealed by clouds, shed a dim light upon the grey rocks, and the heath which lay thick upon the ground as I advanced. Right and left stretched a pathless forest, and before me rose the Druid altars guarding the memory of the sons of Armen, slain by the Romans. From these ancient piles I discerned the distant lakelets glistening like mirrors in the misty plain, but I could not distinguish the one where the feast was held.

The air was so balmy, that I determined to lie down upon the heath and wait for the dawn. When I awoke, I recognized, one by one, the neighbouring landmarks. On the left stretched the long line of the convent of Saint S——, then, on the opposite side of the valley, La Butte aux Gens d'Armes, with the shattered ruins of the ancient Carlovingian palace. Close by, beyond the tree-tops, the crumbling walls of the lofty Abbey of Thiers, stood out against the horizon. Further on, the manor of Pontarmé, surrounded as in olden times, by a moat, began to reflect the first fires of dawn, while on the south appeared the tall keep of La Tournelle and the four towers of Bertrand Fosse, on the slopes of Montméliant.

The night had passed pleasantly, and I was thinking only of Sylvie, but the sight of the convent suggested the idea that it might be the one where Adrienne lived. The sound of the morning bell was still ringing in my ears and had probably awakened me. The thought came to me, for a moment, that by climbing to the top of the cliff, I might take a peep over the walls, but on reflection, I dismissed it as profane. The sun with its rising beams, put to flight this idle memory, leaving only the rosy features of Sylvie. "I will go and awaken her," I said to myself, and again I started in the direction of Loisy.

Ah, here at the end of the forest track, is the village, twenty cottages whose walls are festooned with creepers and climbing roses. A group of women, with red kerchiefs on their heads, are spinning in the early light, in front of a farmhouse, but Sylvie is not among them. She is almost a young lady, now she makes dainty lace, but her family remain simple villagers. I ran up to her room without exciting surprise, to find that she had been up for a long time, and was busily plying her bobbins, which clicked cheerfully against the square green cushion on her knees. "So, it is you, lazybones," she said with her divine smile; "I am sure you are just out of bed."

I told her how I had lost my way in the woods and had passed the night in the open air, and for a moment she seemed inclined to pity me.

"If you are not too tired, I will take you for another ramble. We will go to see my grand-aunt at Othys."

Before I had time to reply, she ran joyously to smooth her hair before the mirror, and put on her rustic straw hat, her eyes sparkling with innocent gaiety.

Our way, at first, lay along the banks of the Thève, through meadows sprinkled with daisies and buttercups; then we skirted the woods of Saint Lawrence, sometimes crossing streams and thickets to shorten the road. Blackbirds were whistling in the trees, and tomtits, startled at our approach, flew joyously from the bushes.

Now and then we spied beneath our feet the periwinkles which Rousseau loved, putting forth their blue crowns amid long sprays of twin leaves, a network of tendrils which arrested the light steps of my companion. Indifferent to the memory of the philosopher of Geneva, she sought here and there for fragrant strawberries, while I talked of the New Heloise, and repeated passages from it, which I knew by heart.

"Is it pretty?" she asked.

"It is sublime."

"Is it better than Auguste Lafontaine?"

"It is more tender."

"Well, then," said she, "I must read it. I will tell my brother to bring it to me the next time he goes to Senlis."

I went on reciting portions of the Heloise, while Sylvie picked strawberries.

When we had left the forest, we found great tufts of purple foxglove, and Sylvie gathered an armful, saying it was for her aunt who loved to have flowers in her room.

Only a stretch of level country now lay between us and Othys. The village church-spire pointed heavenward against the blue hills that extend from Montméliant to Dammartin. The Thève again rippled over the stones, narrowing towards its source, where it forms a tiny lake which slumbers in the meadows, fringed with gladiolus and iris. We soon reached the first houses where Sylvie's aunt lived in a little cottage of rough stone, adorned with a trellis of hop-vine and Virginia creeper. Her only support came from a few acres of land which the village folk cultivated for her, now her husband was dead. The coming of her niece set the house astir.

"Good morning, aunt; here are your children!" cried Sylvie; "and we are very hungry." She kissed her aunt tenderly, gave her the flowers, and then turned to present me, saying, "He is my sweetheart."

I, in turn, kissed the good aunt, who exclaimed, "He is a fine lad! why, he has light hair!" "He has very pretty hair," said Sylvie. "That does not last," returned her aunt; "but you have time enough before you, and you are dark, so you are well matched."

"You must give him some breakfast," said Sylvie, and she went peeping into cupboards and pantry, finding milk, brown bread and sugar which she hastily set upon the table, together with the plates and dishes of crockery adorned with staring flowers and birds of brilliant plumage. A large bowl of Creil china, filled with strawberries swimming in milk, formed the centrepiece, and after she had raided the garden for cherries and goose-berries, she arranged two vases of flowers, placing one at each end of the white cloth. Just then, her aunt made a sensible speech: "All this is only for dessert. Now, you must let me set to work." She took down the frying-pan and threw a fagot upon the hearth. "No, no; I shall not let you touch it," she said decidedly to Sylvie, who was trying to help her. "Spoiling your pretty fingers that make finer lace than Chantilly! You gave me some, and I know what lace is."

"Oh, yes, aunt, and if you have some left, I can use it for a pattern."

"Well, go look upstairs; there may be some in my chest of drawers."

"Give me the keys," returned Sylvie.

"Nonsense," cried her aunt; "the drawers are open." "No; there is one always locked." While the good woman was cleaning the frying-pan, after having passed it over the fire to warm it, Sylvie unfastened from her belt a little key of wrought steel and showed it to me in triumph.

I followed her swiftly up the wooden staircase that led to the room above. Oh youth, and holy age! Who could sully by an evil thought the purity of first love in this shrine of hallowed memories? The portrait of a young man of the good old times, with laughing black eyes and rosy lips, hung in an oval gilt frame at the head of the rustic bed. He wore the uniform of a gamekeeper of the house of Condé; his somewhat martial bearing, ruddy, good-humoured face, and powdered hair drawn back from the clear brow, gave the charm of youth and simplicity to this pastel, destitute, perhaps, of any artistic merit Some obscure artist, bidden to the hunting parties of the prince, had done his best to portray the keeper and his bride who appeared in another medallion, arch and winning, in her open bodice laced with ribbons, teasing with piquant frown, a bird perched upon her finger. It was, however, the same good old dame, at that moment bending over the hearth-fire to cook. It reminded me of the fairies in a spectacle who hide under wrinkled masks, their real beauty revealed in the closing scene when the Temple of Love appears with its whirling sun darting magic fires.

"Oh, dear old aunt!" I exclaimed, "how pretty you were!"

"And I?" asked Sylvie, who had succeeded in opening the famous drawer which contained an old-fashioned dress of taffeta, so stiff that the heavy folds creaked under her touch. "I will see if it fits me," she said; "I shall look like an old fairy!" "Like the fairy of the legends, ever young," thought I.

Sylvie had already unfastened her muslin gown and let it fall to her feet. She bade me hook the rich robe which clung tightly to her slender figure.

"Oh, what ridiculous sleeves!" she cried; and yet, the lace frills displayed to advantage her bare arms, and her bust was outlined by the corsage of yellow tulle and faded ribbon which had concealed but little the vanished charms of her aunt.

"Come, make haste!" said Sylvie. "Do you not know how to hook a dress?" She looked like the village bride of Greuze. "You ought to have some powder," said I. "We will find some," and she turned to search the drawers anew. Oh! what treasures, what sweet odours, what gleams of light from brilliant hues and modest ornaments! Two mother-of-pearl fans slightly broken, some pomade boxes covered with Chinese designs, an amber necklace and a thousand trifles, among them two little white slippers with sparkling buckles of Irish diamonds. "Oh! I will put them on," cried Sylvie, "if I find the embroidered stockings."

A moment more, and we were unrolling a pair of pink silk stockings with green clocks; but the voice of the old aunt, accompanied by the hiss of the frying-pan, suddenly recalled us to reality. "Go down quickly," said Sylvie, who refused to let me help her finish dressing. Her aunt was just turning into a platter the contents of the frying-pan, a slice of bacon and some eggs. Presently, I heard Sylvie calling me from the staircase. "Dress yourself as soon as possible," and, completely attired herself, she pointed to the wedding clothes of the gamekeeper, spread out upon the chest. In an instant I was transformed into a bridegroom of the last century. Sylvie waited for me on the stairs, and we went down, arm in arm. Her aunt gave a cry when she saw us. "Oh, my children!" she exclaimed, beginning to weep and then smiling through her tears. It was the image of her own youth, a cruel, yet charming vision. We sat beside her, touched, almost saddened, but soon our mirth came back, for after the first surprise, the thoughts of the good old dame reverted to the stately festivities of her wedding day. She even recalled the old-fashioned songs chanted responsively from one end of the festal board to the other, and the quaint nuptial hymn whose strains attended the wedded pair when they withdrew after the dance. We repeated these couplets with their simple rhymes, flowery and passionate as the Song of Solomon. We were bride and bridegroom the space of one fair summer morn.

It is four o'clock in the morning; the road winds through a hollow and comes out on high ground; the carriage passes Orry, then La Chapelle. On the left is a road that skirts the forest of Hallate. Sylvie's brother took me through there one evening in his covered cart, to attend some local gathering on the Eve of Saint Bartholomew, I believe. Through the woods, along unfrequented ways, the little horse sped as if hastening to a witches' sabbath. We struck the highway again at Mont-l'Évêque, and a few moments later pulled up at the keeper's lodge of the old abbey of Chaâlis—Chaâlis, another memory!

This ancient retreat of the emperors offers nothing worthy of admiration, save its ruined cloisters with their Byzantine arcades, the last of which are still mirrored in the lake—crumbling fragments of the abodes of piety, formerly attached to this demesne, known in olden times as "Charlemagne's farms." In this quiet spot, far from the stir of highways and cities, religion has retained distinctive traces of the prolonged sojourn of the Cardinals of the House of Este during the time of the Medici; a shade of poetic gallantry still lingers about its ceremonial, a perfume of the Renaissance breathing beneath the delicately moulded arches of the chapels decorated by Italian artists. The faces of saints and angels outlined in rose tints upon a vaulted roof of pale blue produce an effect of pagan allegory, which recalls the sentimentality of Petrarch and the weird mysticism of Francesco Colonna. Sylvie's brother and I were intruders in the festivities of the evening. A person of noble birth, at that time proprietor of the demesne, had invited the neighbouring families to witness a kind of allegorical spectacle in which some of the inmates of the convent close by were to take part. It was not intended to recall the tragedies of Saint Cyr, but went back to the first lyric contests, introduced into France by the Valois princes. What I saw enacted resembled an ancient mystery. The costumes, consisting of long robes, presented no variety save in colour, blue, hyacinth or gold. The scene lay between angels on the ruins of the world. Each voice chanted one of the glories of the now extinct globe, and the Angel of Death set forth the causes of its destruction. A spirit rose from the abyss, holding a flaming sword, and convoked the others to glorify the power of Christ, the conqueror of bell. This spirit was Adrienne, transfigured by her costume as she was already by her vocation. The nimbus of gilded cardboard encircling her angelic head seemed to us a circle of light; her voice had gained in power and compass, and an infinite variety of Italian trills relieved with their bird-like warbling the stately severity of the recitative.

In recalling these details, I come to the point of asking myself, "Are they real or have I dreamed them?" Sylvie's brother was not quite sober that evening. We spent a few minutes in the keeper's house, where I was much impressed by a cygnet displayed above the door, and within there were tall chests of carved walnut, a large clock in its case and some archery prizes, bows and arrows, above a red and green target. A droll-looking dwarf in a Chinese cap, holding a bottle in one hand and a ring in the other, seemed to warn the marksmen to take good aim. I think the dwarf was cut out of sheet-iron. Did I really see Adrienne as surely as I marked these details? I am, however, certain that it was the son of the keeper who conducted us to the hall where the representation took place; we were seated near the door behind a numerous company who seemed deeply moved. It was the feast of Saint Bartholomew—a day strangely linked with memories of the Medici, whose arms, impaled with those of the House of Este, adorned these old walls. Is it an obsession, the way these memories haunt me? Fortunately the carriage stops here on the road to Plessis; I leave the world of dreams and find myself with only a fifteen-minutes walk to reach Loisy by forest paths.

I entered the ball of Loisy at that sad yet pleasing hour when the lights flicker and grow dim at the approach of dawn. A faint bluish tinge crept over the tops of the lime-trees, sunk in shadow below. The rustic flute no longer contended so gayly with the trills of the nightingale. The dancers all looked pale, and among the dishevelled groups I distinguished with difficulty any familiar faces. Finally, I recognized a tall girl, Sylvie's friend Lise.

"We have not seen you for a long time, Parisian," said she.

"Yes; a long time."

"And you come so late?"

"By coach."

"And you traveled slowly!"

"I came to see Sylvie; is she still here?"

"She will stay till morning; she loves to dance."

In a moment I was beside her; she looked tired, but her black eyes sparkled with the same Athenian smile as of old. A young man stood near her, but she refused by a gesture to join the next country-dance, and he bowed to her and withdrew.

It began to grow light, and we left the ball hand in hand. The flowers hung lifeless and faded in Sylvie's loosened tresses, and the nosegay at her bosom dropped its petals on the crumpled lace made by her skilful hands. I offered to walk home with her; it was broad day, but the sky was cloudy. The Thève murmured on our left, leaving at every curve a little pool of still water where yellow and white pond-lilies blossomed, and lake star-worts, like Easter daisies, spread their delicate broidery. The plain was covered with hay-ricks whose fragrance seemed wafted to my brain, affecting me as the fresh scent of the woods and hawthorn thickets had done in the past. This time neither of us thought of crossing the meadows.

"Sylvie," said I, "you no longer love me."

She sighed. "My friend," she continued, "you must console yourself, since things do not happen as we wish in this world. You once mentioned the New Heloise; I read it, and shuddered when I found these words, at the beginning: 'Any young girl who reads this book is lost.' However, I kept on, trusting in my discretion. Do you remember the day we put on the wedding clothes, at my aunt's house? The engravings in the book also represented lovers dressed in olden costumes, so that to me you were Saint-Preux and I was Julie. Ah! why did you not come back then? But they said you were in Italy. You must have seen there far prettier girls than I!"

"Not one, Sylvie, with your expression or the pure lines of your profile. You do not know it, but you are a nymph of antiquity. Besides, the woods here are as beautiful as those about Rome. There are granite masses yonder, not less sublime, and a cascade which falls from the rocks like that of Terni. I saw nothing there to regret here."

"And in Paris?" she asked.

"In Paris—" I shook my head, but did not answer. Suddenly I remembered the vain shadow which I had pursued so long. "Sylvie," cried I, "let us stop here, will you?"

I threw myself at her feet, and with hot tears I confessed my irresolution and fickleness; I evoked the fatal spectre that haunted my days.

"Save me!" I implored, "I come back to you forever."

She turned toward me with emotion, but at this moment our conversation was interrupted by a loud burst of laughter, and Sylvie's brother rejoined us with the boisterous mirth always attending a rustic festival, and which the abundant refreshments of the evening had stimulated beyond measure. He called to the gallant of the ball, who was concealed in a thicket, but hastened to us. This youth was little firmer on his feet than his companion, and appeared more embarrassed by the presence of a Parisian than by Sylvie. His candid look and awkward deference prevented any dislike on my part, on account of his dancing so late with Sylvie at the ball; I did not consider him a dangerous rival.

"We must go in," said Sylvie to her brother. "We shall meet again soon," she said, as she offered me her cheek to kiss, at which the lover was not offended.

Not feeling inclined to sleep, I walked to Montagny to revisit my uncle's house. Sadness fell upon me at the first glimpse of its yellow front and green shutters. Everything looked as before, but I was obliged to go to the farmer's to obtain the key. The shutters once open, I surveyed with emotion the old furniture, polished from time to time, to preserve its lustre, the tall cupboard of walnut, two Flemish paintings said to be the work of an ancient artist, our ancestor, some large prints after Boucher, and a whole series of framed engravings representing scenes from "Emile" and the "New Heloise" by Moreau; on the table was the dog, now stuffed and mounted, that I remembered alive, as the companion of my forest rambles, perhaps the last "Carlin," for it had belonged to that breed now extinct.

"As for the parrot," said the farmer, "he is still alive, and I took him home with me."

The garden offered a magnificent picture of the growth of wild vegetation, and there in a corner was the plot I had tended as a child. A shudder came over me as I entered the study, which still contained the little library of choice books, familiar friends of him who was no more, and where upon his desk lay antique relics, vases and Roman medals found in the garden,—a local collection, the source of much pleasure to him.

"Let us go to see the parrot," I said to the farmer. The parrot clamoured for his breakfast, as in his best days, and gave me a knowing look from his round eye peering out from the wrinkled skin, like the wise glances of the old.

Full of sad thoughts awakened by my return to this cherished spot, I felt that I must again see Sylvie, the only living tie which bound me to that region, and once more I took the road to Loisy. It was the middle of the day, and I found them all asleep, worn out by the night of merry-making. It occurred to me that it might divert my thoughts to stroll to Hermenonville, a league distant, by the forest road. It was fine summer weather, and on setting out I was delighted by the freshness and verdure of the path which seemed like the avenue of a park. The green branches of the great oaks were relieved by the white trunks and rustling leaves of the birches. The birds were silent, and I heard no sound but the woodpecker tapping the trees to find a hollow for her nest. At one time I was in danger of losing my way, the characters being wholly effaced on the guide-posts which served to distinguish the roads. Passing the Desert on the left, I came to the dancing-ring where I found the benches of the old men still in place. All the associations of ancient philosophy, revived by the former owner of the demesne, crowded upon me, at the sight of this picturesque realisation of "Anacharsis" and "Emile."

When I caught sight of the waters of the lake sparkling through the branches of willows and hazels, I recognised a spot which I had often visited with my uncle. Here stands to this day, sheltered by a group of pines, the Temple of Philosophy which its founder had not the good fortune to complete. It is built in the form of the temple of the Tiburtine Sibyl, and displays with pride the names of all the great thinkers from Montaigne and Descartes to Rousseau. This unfinished structure is now but a ruin around which the ivy twines its graceful tendrils, while brambles force their way between its disjointed steps. When but a child, I witnessed the celebrations here, where young girls, dressed in white, came to receive prizes for scholarship and good conduct. Where are the roses that girdled the hillside? Hidden by brier and eglantine, they are fast losing all traces of cultivation. As for the laurels, have they been cut down, according to the old song of the maidens who no longer care to roam the forest? No! these shrubs from sweet Italy have withered beneath our unfriendly skies. Happily, the privet of Virgil still thrives as if to emphasize the words of the Master, inscribed above the door, Rerum cognoscere causas. Yes! like so many others, this temple crumbles, and man, weary or thoughtless, passes it by, while indifferent nature reclaims the soil for which art contended, but the thirst for knowledge is eternal, the mainspring of all power and activity.

Here are the poplars of the island and the empty tomb of Rousseau. O Sage! thou gavest us the milk of the strong and we were too weak to receive it! We have forgotten thy lessons which our fathers knew, and we have lost the meaning of thy words, the last faint echoes of ancient wisdom! Still, let us not despair, and like thee, in thy last moments, let us turn our eyes to the sun!

I revisited the castle, the quiet waters about it, the cascade which complains among the rocks, the causeway that unites the two parts of the village with the four dove-cotes that mark the corners, and the green that stretches beyond like a prairie, above which rise wooded slopes; the tower of Gabrielle is reflected from afar in the waters of an artificial lake studded with ephemeral blossoms; the scum is seething, the insects hum. It is best to escape the noxious vapours and seek the rocks and sand of the desert and the waste lands where the pink heath blooms beside green ferns. How sad and lonely it all seems! In by-gone days, Sylvie's enchanting smile, her merry pranks and glad cries enlivened every spot! She was then a wild little creature with bare feet and sun-burned skin, in spite of the straw hat whose long strings floated loosely amid her dark locks. We used to go to the Swiss farm to drink milk, and they said: "How pretty your sweetheart is, little Parisian!" Ah! no peasant lad could have danced with her in those days! She would have none but me for her partner, at the yearly Feast of the Bow.

I went back to Loisy and they were all awake. Sylvie was dressed like a young lady, almost in the fashion of the city. She led me up to her room with all her old simplicity. Her bright eyes smiled as charmingly as ever, but the decided arch of her brows made her at times look serious. The room was simply decorated, but the furniture was modern: a mirror in a gilt frame had replaced the old-fashioned looking-glass where an idyllic shepherd was depicted offering a nest to a blue and pink shepherdess; the four-post bed, modestly hung with flowered chintz, was succeeded by a little walnut couch with net curtains; canaries occupied the cage at the window where once there were linnets. I was impatient to leave this room, where nothing spoke to me of the past. "Shall you make lace to-day?" I asked Sylvie. "Oh, I do not make lace now; there is no demand for it here, and even at Chantilly the factory is closed." "What is your work then?" She brought forward, from the corner of the room, an iron tool which resembled a long pair of pincers.

"What is that?"

"It is called the machine and is used to hold the leather in place while the gloves are sewed."

"Then you are a glove-maker, Sylvie?"

"Yes, we work here for Dammartin; it pays well now, but I shall not work to-day; let us go wherever you like." I glanced towards Othys, but she shook her head, and I understood that the old aunt was no more. Sylvie called a little boy and bade him saddle an ass. "I am still tired from yesterday," she said, "but the ride will do me good; let us go to Chaâlis."

We set out through the forest, followed by the boy armed with a branch. Sylvie soon wished to stop, and I kissed her as I led her to a seat. Our conversation could no longer be very intimate. I had to talk of my life in Paris, my travels.... "How can anyone go so far?" she demanded. "It seems strange to me, when I look at you."

"Oh! of course,"

"Well, admit that you were not so pretty in the old days."

"I cannot tell."

"Do you remember when we were children and you the tallest?"

"And you the wisest?"

"Oh! Sylvie!"

"They put us on an ass, one in each pannier."

"And we said thee and thou to each other? Do you remember how you taught me to catch crawfish under the bridges over the Nonette and the Thève?"

"Do you remember your foster-brother who pulled you out of the water one day?"

"Big Curly-head? It was he who told me to go in."

I made haste to change the subject, because this recollection had brought vividly to mind the time when I used to go into the country, wearing a little English coat which made the peasants laugh. Sylvie was the only one who liked it, but I did not venture to remind her of such a juvenile opinion. For some reason, my mind turned to the old aunt's wedding clothes in which we had arrayed ourselves, and I asked what had become of them.

"Oh! poor aunt," cried Sylvie; "she lent me her gown to wear to the carnival at Dammartin, two years ago, and the next year she died, dear, old aunt!" She sighed and the tears came, so I could not inquire how it chanced that she went to a masquerade, but I perceived that, thanks to her skill, Sylvie was no longer a peasant girl. Her parents had not risen above their former station, and she lived with them, scattering plenty around her like an industrious fairy.

The outlook widened when we left the forest and we found ourselves near the lake of Chaâlis. The galleries of the cloister, the chapel with its pointed arches, the feudal tower and the little castle which had sheltered the loves of Henry IV. and Gabrielle, were bathed in the crimson glow of evening against the dark background of the forest.

"Like one of Walter Scott's landscapes, is it not?" said Sylvie. "And who has told you of Walter Scott?" I inquired. "You must have read much in the past three years! As for me, I try to forget books, and what delights me, is to revisit with you this old abbey where, as little children, we played hide and seek among the ruins. Do you remember, Sylvie, how afraid you were when the keeper told us the story of the Red Monks?"

"Oh, do not speak of it!"

"Well then, sing me the song of the fair maid under the white rose-bush, who was stolen from her father's garden."

"Nobody sings that now."

"Is it possible that you have become a musician?"

"Perhaps."

"Sylvie, Sylvie, I am positive that you sing airs from operas!"

"Why should you complain?"

"Because I loved the old songs and you have forgotten them."

Sylvie warbled a few notes of a grand air from a modern opera.... She phrased!

We turned away from the lakeside and approached the green bordered with lime-trees and elms, where we had so often danced. I had the conceit to describe the old Carlovingian walls and to decipher the armorial bearings of the House of Este.

"And you! How much more you have read than I, and how learned you have become!" said Sylvie. I was vexed by her tone of reproach, as I had all the way been seeking a favourable opportunity to resume the tender confidences of the morning, but what could I say, accompanied by a donkey and a very wide-awake lad who pressed nearer and nearer for the pleasure of hearing a Parisian talk? Then I displayed my lack of tact, by relating the vision of Chaâlis which I recalled so vividly. I led Sylvie into the very hall of the castle where I had heard Adrienne sing. "Oh, let me hear you!" I besought her; "let your loved voice ring out beneath these arches and put to flight the spirit that torments me, be it angel or demon!" She repeated the words and sang after me:

"Anges, descendez promptement

au fond du purgatoire...."

(Angels descend without delay

To dread abyss of purgatory.)

"It is very sad!" she cried.

"It is sublime! An air from Porpora, I think, with words translated in the present century."

"I do not know," she replied.

We came home through the valley, following the Charlepont road which the peasants, without regard to etymology, persistently called Châllepont. The way was deserted, and Sylvie, weary of riding, leaned upon my arm, while I tried to speak of what was in my heart, but, I know not why, could find only trivial words or stilted phrases from some romance that Sylvie might have read. I stopped suddenly then, in true classic style, and she was occasionally amazed by these disjointed rhapsodies. Having reached the walls of Saint S—— we had to look well to our steps, on account of the numerous stream-lets winding through the damp marshes.

"What has become of the nun?" I asked suddenly.

"You give me no peace with your nun! Ah, well! it is a sad story!" Not a word more would Sylvie say.

Do women really feel that certain words come from the lips rather than the heart? It does not seem probable, to see how readily they are deceived, and what an inexplicable choice they usually make—there are men who play the comedy of love so well! I never could accustom myself to it, although I know some women lend themselves wittingly to the deception. A love that dates from childhood is, however, sacred, and Sylvie, whom I had seen grow up, was like a sister to me; I could not betray her. Suddenly, a new thought came to me. "At this very hour, I might be at the theatre. What is Aurélie (that was the name of the actress) playing to-night? No doubt the part of the Princess in the new play. How touching she is in the third act! And in the love scene of the second with that wrinkled actor who plays the lover!"

"Lost in thought?" said Sylvie; and she began to sing:

"A Dammartin l'y a trots belles filles:

L'y en a z'une plus belle que le jour...."

(At Dammartin there are three fair maids,

And one of them is fairer than day.)

"Little tease!" I cried, "you know you remember the old songs."

"If you would come here oftener, I would try to remember more of them," she said; "but we must think of realities; you have your affairs at Paris, I have my work here; let us go in early, for I must rise with the sun to-morrow."

I was about to reply, to fall at her feet and offer her my uncle's house which I could purchase, as the little estate had not been apportioned among the numerous heirs, but just then we reached Loisy, where supper awaited us and the onion-soup was diffusing its patriarchal odour. Neighbours had been invited to celebrate the day after the feast, and I recognised at a glance Father Dodu, an old wood-cutter who used to amuse or frighten us, in the evenings by his stories. Shepherd, carrier, gamekeeper, fisherman and even poacher, by turns, Father Dodu made clocks and turnspits in his leisure moments. For a long time he acted as guide to the English tourists at Hermenonville, and while he recounted the last moments of the philosopher, would lead them to Rousseau's favourite spots for meditation. He was the little boy employed to classify the herbs and gather the hemlock twigs from which the sage pressed the juice into his cup of coffee. The landlord of the Golden Cross contested this point and a lasting feud resulted. Father Dodu had once borne the reproach of possessing some very innocent secrets, such as how to cure cows by saying a rhyme backwards and making the sign of the cross with the left foot, but he had renounced these superstitions—thanks, he declared, to his conversations with Jean Jacques.

"That you, little Parisian?" said Father Dodu; "have you come to carry off our pretty girls?"

"I, Father Dodu?"

"You take them into the woods when the wolf is away!"

"Father Dodu, you are the wolf."

"I was as long as I could find sheep, but at present I meet only goats, and they know how to take care of themselves! As for you, why, you are all rascals in Paris. Jean Jacques was right when he said, 'Man grows corrupt in the poisonous air of cities.'"

"Father Dodu, you know very well that men become corrupt everywhere."

"Father Dodu began to roar out a drinking song, and it was impossible to stop him at a questionable couplet that everyone knew by heart. Sylvie would not sing, in spite of our entreaties, on the plea that it was no longer customary to sing at table. I bad already noticed the lover of the ball, seated at her left, and his round face and tumbled hair seemed familiar. He rose and stood behind me, saying, "Have you forgotten me, Parisian?" A good woman who came back to dessert after serving us, whispered in my ear: "Do you not recognize your foster-brother?" Without this warning, I should have made myself ridiculous. "Ah, it is Big Curly-head!" I cried; "the very same who pulled me out of the water." Sylvie burst out laughing at the recollection.

"Without considering," said the youth em-bracing me, "that you had a fine silver watch and on the way home you were more concerned about it than yourself, because it had stopped. You said, 'the creature is drowned does not go tick-tack; what will Uncle say?'" "A watch is a creature," said Father Dodu; "that is what they tell children in Paris!"

Sylvie was sleepy, and I fancied there was no hope for me. She went upstairs, and as I kissed her, said: "Come again to-morrow." Father Dodu remained at table with Sylvain and my foster-brother, and we talked a long time over a bottle of Louvres ratafia.

"All men are equal," said Father Dodu between glasses; "I drink with a pastry-cook as readily as with a prince."

"Where is the pastry-cook?" I asked.

"By your side! There you see a young man who is ambitious to get on in life."

My foster-brother appeared embarrassed and I understood the situation. Fate had reserved for me a foster-brother in the very country made famous by Rousseau, who opposed putting children out to nurse! I learned from Father Dodu that there was much talk of a marriage between Sylvie and Big Curly-head, who wished to open a pastry-shop at Dammartin. I asked no more. Next morning the coach from Nanteuil-le-Haudouin took me back to Paris.

To Paris, a journey of five hours! I was impatient for evening, and eight o'clock found me in my accustomed seat Aurélie infused her own spirit and grace into the lines of the play, the work of a contemporary author evidently inspired by Schiller. In the garden scene she was sublime. During the fourth act, when she did not appear, I went out to purchase a bouquet of Madame Prevost, slipping into it a tender effusion signed An Unknown, "There," thought I, "is something definite for the future," but on the morrow I was on my way to Germany.

Why did I go there? In the hope of com-posing my disordered fancy. If I were to write a book, I could never gain credence for the story of a heart torn by these two conflicting loves. I had lost Sylvie through my own fault, but to see her for a day, sufficed to restore my soul. A glance from her had arrested me on the verge of the abyss, and henceforth I enshrined her as a smiling goddess in the Temple of Wisdom. I felt more than ever reluctant to present myself before Aurélie among the throng of vulgar suitors who shone in the light of her favour for an instant only to fall blinded.

"Some day," said I, "we shall see whether this woman has a heart."

One morning I learned from a newspaper that Aurélie was ill, and I wrote to her from the mountains of Salzburg, a letter so filled with German mysticism that I could hardly hope for a reply, indeed I expected none. I left it to chance or ... the unknown.

Months passed, and in the leisure intervals of travel I undertook to embody in poetic action the life-long devotion of the painter Colonna to the fair Laura who was constrained by her relatives to take the veil. Something in the subject lent itself to my habitual train of thought, and as soon as the last verse of the drama was written, I hastened back to France.

Can I avoid repeating in my own history, that of many others? I passed through all the ordeals of the theatre. I "ate the drum and drank the cymbal," according to the apparently meaningless phrase of the initiates at Eleusis, which probably signifies that upon occasion we must stand ready to pass the bounds of reason and absurdity; for me it meant to win and possess my ideal.

Aurélie accepted the leading part in the play which I brought back from Germany. I shall never forget the day she allowed me to read it to her. The love scenes had been arranged expressly for her, and I am positive that I rendered them with feeling. In the conversation that followed I revealed myself as the "Unknown" of the two letters. She said: "You are mad, but come again; I have never found anyone who knew how to love me."

Oh, woman! you seek for love ... but what of me?

In the days which followed I wrote probably the most eloquent and touching letters that she ever received. Her answers were full of good sense. Once she was moved, sent for me and confessed that it was hard for her to break an attachment of long standing. "If you love me for myself alone, then you will understand that I can belong to but one."

Two months later, I received an effusive letter which brought me to her feet—in the meantime, someone volunteered an important piece of information. The handsome young man whom I had met one night at the club had just enlisted in the Turkish cavalry.

Races were held at Chantilly the next season, and the theatre troupe to which Aurélie belonged gave a performance. Once in the country, the company was for three days subject to the orders of the director. I had made friends with this worthy man, formerly the Dorante of the comedies of Marivaux and for a long time successful in lovers' parts. His latest triumph was achieved in the play imitated from Schiller, when my opera-glass had discovered all his wrinkles. He had fire, however, and being thin, produced a good effect in the provinces. I accompanied the troupe in the quality of poet, and persuaded the manager to give performances at Senlis and Dammartin. He inclined to Compiègne at first, but Aurélie was of my opinion. Next day, while arrangements with the local authorities were in progress, I ordered horses and we set out on the road to Commelle to breakfast at the castle of Queen Blanche. Aurélie, on horseback, with her blonde hair floating in the wind, rode through the forest like some queen of olden times, and the peasants were dazzled by her appearance. Madame de F—— was the only woman they had ever seen so imposing and so graceful. After breakfast we rode down to the villages like Swiss hamlets where the waters of the Nonette turn the busy saw-mills. These scenes, which my remembrance cherished, interested Aurélie, but did not move her to delay. I had planned to conduct her to the castle near Orry, where I had first seen Adrienne on the green. She manifested no emotion. Then I told her all; I revealed the hidden spring of that love which haunted my dreams by night and was realized in her. She listened with attention and said: "You do not love me! You expect me to say 'the actress and the nun are the same'; you are merely arranging a drama and the issue of the plot is lacking. Go! I no longer believe in you."

Her words were an illumination. The unnatural enthusiasm which had possessed me for so long, my dreams, my tears, my despair and my tenderness,—could they mean aught but love? What then is love?

Aurélie played that night at Senlis, and I thought she displayed a weakness for the director, the wrinkled "young lover" of the stage. His character was exemplary, and he had already shown her much kindness.

One day, Aurélie said to me: "There is the man who loves me!"

Such are the fancies that charm and beguile us in the morning of life! I have tried to set them down here, in a disconnected fashion, but many hearts will understand me. One by one our illusions fall like husks, and the kernel thus laid bare is experience. Its taste is bitter, but it yields an acrid flavour that invigorates,—to use an old-fashioned simile. Rousseau says that the aspect of nature is a universal consolation. Sometimes I seek again my groves of Clarens lost in the fog to the north of Paris, but now, all is changed! Hermenonville, the spot where the ancient idyl blossomed again, transplanted by Gessner, thy star has set, the star that glowed for me with two-fold lustre. Blue and rose by turns, like the changeful Aldebaran, it was formed by Adrienne and Sylvie, the two halves of my love. One was the sublime ideal, the other, the sweet reality. What are thy groves and lakes and thy desert to me now? Othys, Montagny, Loiseaux, poor neighbouring hamlets, and Chaâlis now to be restored, you guard for me no treasures of the past. Occasionally, I feel a desire to return to those scenes of lonely musing, where I sadly mark the fleeting traces of a period when affectation invaded nature; sometimes I smile as I read upon the granite rocks certain lines from Boucher, which I once thought sublime, or virtuous maxims inscribed above a fountain or a grotto dedicated to Pan. The swans disdain the stagnant waters of the little lakes excavated at such an expense. The time is no more when the hunt of Condé swept by with its proud riders, and the forest-echoes rang with answering horns! There is to-day no direct route to Hermenonville, and sometimes I go by Creil and Senlis, sometimes by Dammartin.

It is impossible to reach Dammartin before night, so I lodge at the Image of Saint John. They usually give me a neat room hung with old tapestry, with a glass between the windows. This room shows a return to the fashion for bric-à-brac which I renounced long ago. I sleep comfortably under the eider-down covering used there. In the morning, when I throw open the casement wreathed with vines and roses, I gaze with rapture upon a wide green landscape stretching away to the horizon, where a line of poplars stand like sentinels. Here and there the villages nestle guarded by their protecting church-spires. First Othys, then Eve and Ver; Hermenonville would be visible beyond the wood, if it had a belfry, but in that philosophic spot the church has been neglected. Having filled my lungs with the pure air of these uplands, I go down stairs in good humour and start for the pastry-cook's. "Helloa, big Curly-head!" "Helloa, little Parisian!" We greet each other with sly punches in the ribs as we did in childhood, then I climb a certain stair where two children welcome my coming. Sylvie's Athenian smile lights up her classic features, and I say to myself: "Here, perhaps, is the happiness I have missed, and yet...."

Sometimes I call her Lotty, and she sees in me some resemblance to Werther without the pistols, which are out of fashion now. While Big Curly-head is busy with the breakfast, we take the children for a walk through the avenues of limes that border the ruins of the old brick towers of the castle. While the little ones practise with their bows and arrows, we read some poem or a few pages from one of those old books all too short, and long forgotten by the world.

I forgot to say that when Aurélie's troupe gave a performance at Dammartin, I took Sylvie to the play and asked her if she did not think the actress resembled someone she knew.

"Whom, pray?"

"Do you remember Adrienne?"

She laughed merrily, in reply. "What an idea!"

Then, as if in self-reproach, she added with a sigh: "Poor Adrienne! she died at the convent of Saint S—— about 1832."

I am that dark, that disinherited.

That all dishonoured Prince of Aquitaine,

The Star upon my scutcheon long hath fled;

A black sun on my lute doth yet remain!

Oh, thou that didst console me not in vain,

Within the tomb, among the midnight dead,

Show me Italian seas, and blossoms wed,

The rose, the vine-leaf, and the golden grain.

Say, am I Love or Phoebus? have I been

Or Lusignan or Biron? By a Queen

Caressed within the Mermaid's haunt I lay,

And twice I crossed the unpermitted stream,

And touched on Orpheus' lute as in a dream,

Sighs of a Saint, and laughter of a Fay!

(ANDREW LANG.)

When it was currently reported that Gérard de Nerval had become insane, Alexander Dumas, who was then publishing that amusing journal Le Mousquetaire, endeavored to explain and interpret the poet's peculiar form of mental alienation. Gérard, who presently came to himself, as was his wont, took note of the study, and in return dedicated to Dumas his Filles du Feu, thus acknowledging the obligation conferred by the great novelist in inditing the epitaph of the poet's "lost wits."

This dedication, now done into English for the first time, is interesting and important, as embodying the author's own interpretation of his singular mental constitution. He confesses that he is unable to compose without incarnating himself in his creations so thoroughly as to lose his own identity. In illustration, he throws into the text the tragic history of a mythical hero. It is easy to trace in this story of a nameless prince, unable to prove his lofty origin, involved in a network of misfortunes through the crafty machinations of the arch plotter La Rancune (malice) and abandoned by his mistress, the beautiful guiding Star of his destiny, allegorical allusions to the poet, the heir of genius and of glory, unable to prove or justify his noble birthright, his highest impulses misunderstood and trampled upon by a heartless and vulgar world.

LUCIE PAGE.

I dedicate this book to you, my dear Master, as I dedicated Lorely to Jules Janin. I was indebted to him for the same service that I owe to you. A few years ago, it was reported that I was dead, and he wrote my biography. A few days ago, I was thought to have lost my reason, and you honoured me by devoting some of your most graceful lines to the epitaph of my intelligence. Such an inheritance of glory has fallen to me before my time. How shall I venture, yet living, to deck my forehead with these shining crowns? It becomes me to assume an air of modesty and beg the public to accept, with suitable deductions, the eulogy bestowed upon my ashes, or rather upon the lost wits contained in the bottle which, like Astolpho, I have been to seek in the moon, and which, I trust, I have now restored to their normal place in the seat of thought.

Being, therefore, no longer mounted upon the hippogriff, and having, in the popular conception, recovered what is vulgarly termed reason,—let us proceed to the exercise of that faculty.

Here is a fragment of what you wrote concerning me, the tenth of last December:

"As you can readily perceive, he possesses a subtle and highly cultivated intellect, in which is manifested from time to time a singular phenomenon which, fortunately, let us hope, has no serious import to himself or his friends. At intervals, when preoccupied by literary toil, imagination goaded to frenzy masters reason and drives it from the brain; then, like an opium-smoker of Cairo, or a hashish-eater of Algiers, Gérard finds again the talismans that evoke spirits. Now he is King Solomon waiting for the Queen of Sheba; then by turns Sultan of the Crimea, Count of Abyssinia, Duke of Egypt, or Baron of Smyrna. Next day, he declares himself mad and relates the whole series of events from which his madness sprung, with such a joyous abandon, such an ingenious fertility of resource that one is ready to part with his wits in order to follow such a fascinating guide through the desert of dreams and hallucinations, sprinkled with oases fresher and greener than any which dot the route from Alexandria to Ammon. Finally, melancholy becomes his muse of inspiration, and now, restrain your tears if you can, for never did Werther, René, or Antony pour forth sobs and complaints more tender and pathetic!"