FAIRFAX COUNTY

VIRGINIA

HUNTLEY

SITE LOCATION

By

Tony P. Wrenn

Published by the Fairfax County Division of Planning

under the direction of the County Board of Supervisors

in cooperation with the County History Commission

Fairfax, Virginia

November 1971

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 76-183058

Typography by ARVA Printers, Inc.

Printing by ARVA Printers, Inc.

Additional copies available for $1.50 from

Administrative Services, Massey Building

TABLE OF CONTENTS |

||

| Page | ||

| List of Illustrations | v | |

| Preface | vi | |

| Acknowledgments | vii | |

| Introduction | 1 | |

| Chapter I. | The Mason Family | 3 |

| Thomson Francis Mason | 3 | |

| Chapter II. | Huntley and Its Owners | 9 |

| Location and Site | 9 | |

| Origin of Name | 9 | |

| Owners and Occupants | 10 | |

| Mason ownership | 10 | |

| King ownership | 13 | |

| Harrison-Pierson ownership | 15 | |

| Harrison ownership | 17 | |

| Later owners | 23 | |

| Chapter III. | An Architectural Description | 27 |

| The Dwelling or Mansion House | 27 | |

| Room arrangement | 27 | |

| Windows and doors | 29 | |

| Interior features | 29 | |

| Exterior features | 31 | |

| The Tenant House | 31 | |

| The Storage House and Necessary | 33 | |

| The Icehouse | 35 | |

| The Root Cellar | 35 | |

| Dairy and Springs | 37 | |

| Early Structures No Longer Standing | 37 | |

| Chapter IV. | The Architect of Huntley | 41 |

| The Architectural Plan | 41 | |

| Area Architects, circa 1820 | 42 | |

| George Hadfield | 42 | |

| Similarities to the Work of Hadfield | 43 | |

| Summary | 47 | |

| Appendix A | Some Mason Houses in Northern Virginia | 50 |

| Appendix B | Chain of Title | 53 |

| List of Sources | 55 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Figure | Page | |

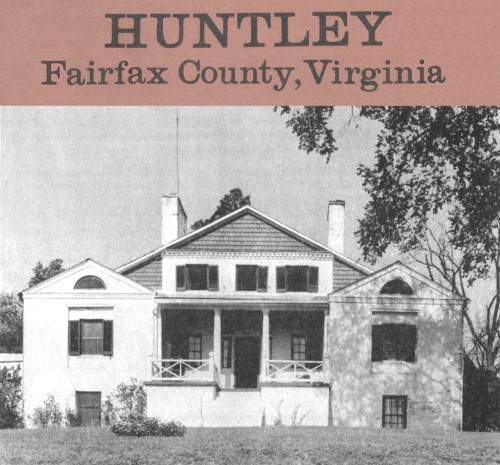

| 1. | Huntley, viewed from southwest, including root cellar and necessary, 1969 | viii |

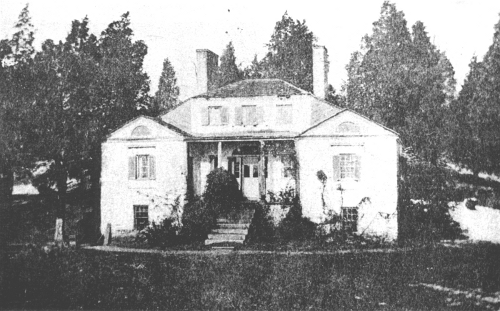

| 2. | Huntley house and barn complex, viewed from south, 1947 | 8 |

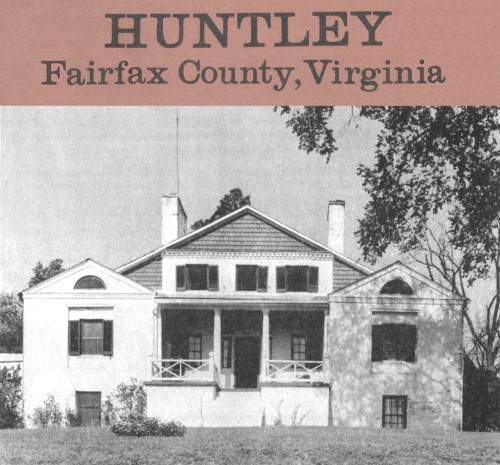

| 3. | Detail, Map of Eastern Virginia and Vicinity of Washington, 1862 | 12 |

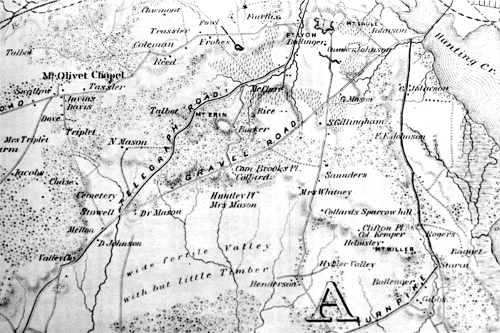

| 4. | Plat of Huntley division, 1868 | 14 |

| 5. | Detail, Hopkins, Atlas of Fifteen Miles around Washington, 1879 | 18 |

| 6. | Rear facade, c. 1890 | 19 |

| 7. | Rear facade, c. 1900 | 20 |

| 8. | Hindenburg disaster, Lakehurst, New Jersey | 22 |

| 9. | Front view, 1969 | 26 |

| 10. | Rear view, 1969 | 26 |

| 11. | Mantel, central first floor room, 1969 | 28 |

| 12. | Mantel, north room first floor, 1969 | 28 |

| 13. | Detail, exterior door, north facade, 1969 | 30 |

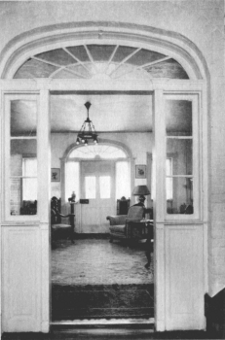

| 14. | Detail, interior of entrance door, south facade, 1969 | 30 |

| 15. | Detail, window and door, central first floor room, 1969 | 30 |

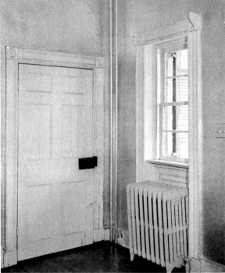

| 16. | Necessary and tenant house from the icehouse, 1969 | 32 |

| 17. | Necessary, rear or west facade, 1969 | 32 |

| 18. | Necessary, door detail, 1969 | 34 |

| 19. | Necessary, interior detail, 1969 | 34 |

| 20. | Icehouse, detail, dome and opening, 1969 | 36 |

| 21. | Icehouse door to root cellar, 1969 | 36 |

| 22. | Root cellar entrance to icehouse, 1969 | 36 |

| 23. | Dairy and spring house, viewed from southeast, 1969 | 38 |

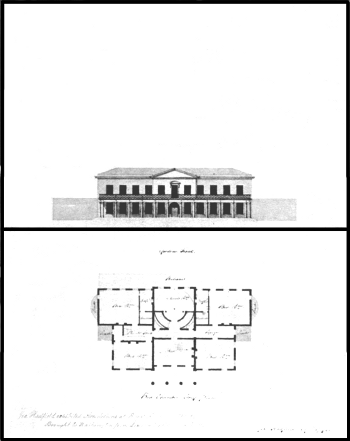

| 24. | Architect George Hadfield's ground plan exhibit at Royal Academy, 1780-82 | 40 |

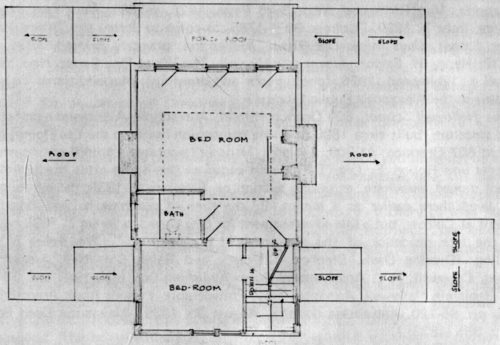

| 25. | Hadfield's design, bed chamber story plan | 40 |

| 26. | Arlington House (Custis-Lee Mansion) showing portico designed by Hadfield | 44 |

| 27. | Analostan, now demolished, possibly Hadfield designed | 44 |

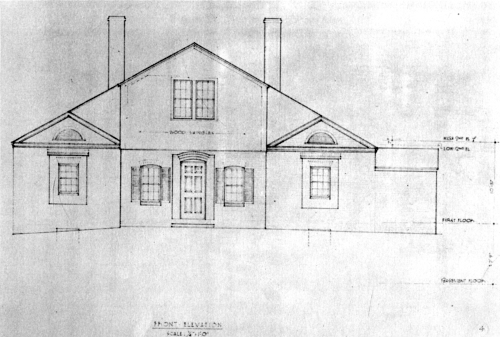

| 28. | Front elevation, Huntley, 1946 | 47 |

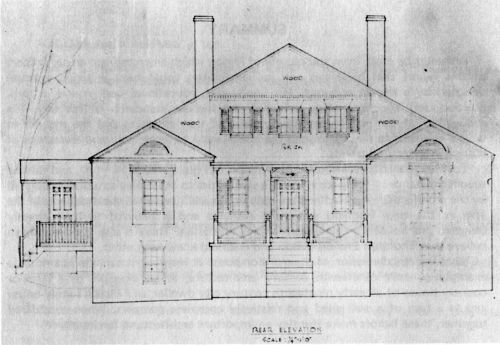

| 29. | Rear elevation, Huntley, 1946 | 48 |

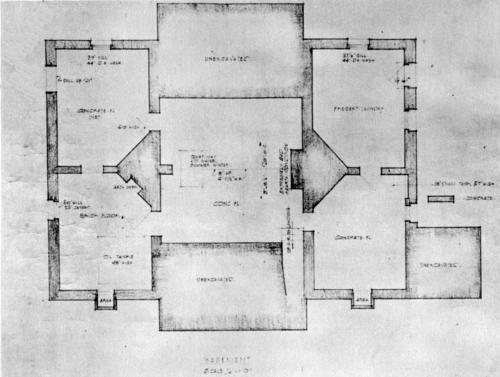

| 30. | Basement floor plan, 1946 | 48 |

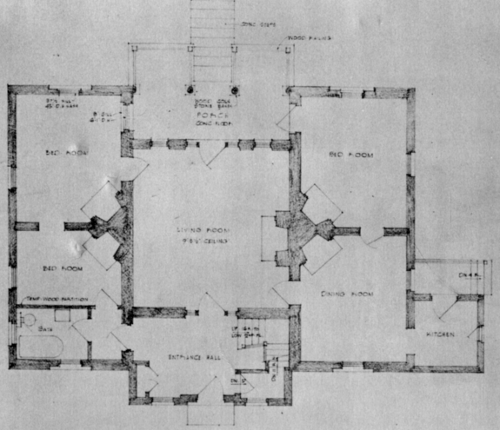

| 31. | First floor plan, 1946 | 49 |

| 32. | Second floor plan, 1946 | 49 |

I first visited Huntley in May, 1969 in the company of Edith Sprouse, Joyce Wilkinson, and Tony Wrenn. Neither I nor anyone else on the staff of the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission had ever seen or heard of the house, and my Fairfax guides were anxious that their "discovery" be brought to our attention. Having assumed that anything of interest in that section of Fairfax County had long been swept away for housing developments, I was in no way prepared when suddenly we rounded a corner and looked up to see a curious geometric structure sitting placidly among its outbuildings against a wooded hillside, aloof from its plebian neighbors. A quick scanning of composition and details dissipated any skepticism I may have had: here, on the outskirts of the capital city was a genuine Federal villa!

After being graciously escorted throughout the house by the owners, we all agreed that Huntley was, without question, one of Virginia's undiscovered architectural treasures. Since next to nothing was known either of its history or the development of its design, we concluded that the house deserved the most detailed study. All assumed that a house of such intriguing individuality had to have a story behind it.

Through the far-sighted patronage of the Fairfax County Government and the meticulous research of Tony Wrenn, this story has now been pieced together. The text which follows provides a history and descriptive analysis worthy of this distinguished Virginia landmark.

Calder Loth

Architectural Historian

Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission

This study was undertaken at the request of the Fairfax County History Commission in 1969, when Mrs. William E. Wilkinson was chairman, and in cooperation with the Fairfax County Division of Planning.

Colonel and Mrs. Ransom Amlong, owners of Huntley and their son Bill answered the author's numerous questions and gave him free rein to wander through the house and site. Edith Moore Sprouse provided frequent research leads and both E. Blaine Cliver, restoration architect, and Calder Loth, architectural historian with the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission, provided architectural analysis. William Edmund Barrett provided most of the architectural photography. A major source of material concerning Thomson F. Mason was a collection of his papers, lent to the Alexandria Library by William Francis Smith for our use. Other leads were provided by Mrs. Earl Alcorn, Mrs. Sherrard Elliot, Miss Patricia Carey of the Fairfax County Public Library and Miss Margaret Calhoun of the Alexandria Library. Mrs. Hugh Cox provided valuable material on T. F. Mason in Alexandria.

Acknowledgment is also due to those who read and made suggestions concerning the final draft of this report, among them Dr. John Porter Bloom, Patricia Williams, John Gott, Mrs. Ross Netherton, Julia Weston, and several others already named above.

T.P.W.

September, 1971

Figure 1. Huntley, viewed from the southwest, including root cellar and

necessary. November 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

It is difficult to understand how a house whose history is closely connected to the well-known Mason family has existed, practically without notice or mention, for one hundred and fifty years. This fact is all the more puzzling when the structure is as architecturally important as "Huntley."

Several possible explanations come to mind:

* Though near a major highway, the house is isolated on its hillside site.

* Because the structure has been somewhat altered, close inspection is necessary before its architectural merits can be fully recognized.

* The house was a country or secondary home for a member of the Mason family who, though important in his own right, was overshadowed by his more illustrious father, Thomson Mason of "Hollin Hall", and by his grandfather, George Mason IV of "Gunston Hall."

* No one has written in detail about the house before and there is little secondary material available concerning it.

Kate Mason Rowland's Life of George Mason, published in 1892,[1] gives one of the few references to Huntley found by the author in secondary sources. In an appendix titled "Land described in George Mason's will, and now owned by his descendent's," she notes:

It was incorrectly stated in one of the earlier volumes that "Lexington" was the only one of the Mason places in Virginia now in the family. The writer had overlooked "Okeley" in Fairfax County, about six miles from Alexandria. The farms of "Okeley" and "Huntley" were both parts of the estate bequeathed by George Mason to his son Thomson Mason of "Hollin Hall." A double ditch50 is still to be seen on the southern border of these two places, extending several miles from East to West, with a broad space about thirty feet wide separating the two ditches. These mark the line between the lands of George Mason and George Washington, as they were in the lives of those gentlemen. In General Washington's will he refers "to the back line or outer boundary of the tract between Thomson Mason and myself ... now double ditching with a post-and-rail fence thereon," etc. And he mentions in another place "the new double ditch" in connection with the boundary line between "Mt. Vernon" and the Mason property. In adding to his estate he had purchased land at one time from George Mason. And among the Washington papers preserved in the Lewis and Washington families, and recently sold to autograph collectors, are three letters of George Mason, on the subject of the bounds between the Washington and Mason plantations, one written in 1768, the others in 1769. Washington adds a memorandum to the former, saying that "the lines to which this letter has reference were settled by and between Colonel Mason and myself the 19th of April, 1769, as will appear ... by a survey thereof made on that day in his presence, and with his approbation." "Huntley" owned by Judge Thomson F. Mason of "Colross," son of Thomson Mason of "Hollin Hall," passed out of the family some years ago ...

Another mention is in Edith Moore Sprouse's Potomac Sampler, published in 1961.[2] She identifies Huntley as "a part of the estate of George Mason of Gunston Hall ... on a tract of land which bordered Washington's on the north and stretched from the Potomac to Kings Highway."

The following study of the Huntley complex combines the work of architects, architectural historians and historians in reading and interpreting the structures. At some future date, efforts of archaeologists will probably be rewarded with further information about the complex at various stages of development.

Introduction Notes

[1] Kate Mason Rowland, The Life of George Mason (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1892), p. 472

THE MASON FAMILY

The first George Mason came to Virginia during the middle of the seventeenth century.[3] Two other Georges followed before 1725, when the fourth George Mason, "The Pen of the Revolution," was born. Movement of the Mason family had been gradually northward, from Norfolk, then to Stafford and Prince William Counties in Virginia, across the Potomac River to Charles County, Maryland, and then back to Fairfax County in Virginia where, in 1758, George Mason IV built Gunston Hall.

The builder of Gunston Hall was later the author of the Fairfax Resolves, of the first Constitution of Virginia and of the Virginia Declaration of Rights. His Declaration of Rights, which was adopted by the Virginia House of Burgesses in Williamsburg on June 12, 1776, was the major source for the Federal Bill of Rights, adopted in 1791. Though a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Mason refused to sign the Constitution because it did not provide for the abolition of slavery, nor did it, in his views, sufficiently safeguard the rights of the individual.[4]

George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and other early American leaders were friends of George Mason and Mason's family surely met many of them at Gunston Hall. Jefferson, who called George Mason "the wisest man of his generation," was his last recorded visitor at Gunston Hall, on September 30, 1792.[5] On October 7, one week later, Mason died.

Nine of his children married. On December 17, 1788, George wrote to his son John that "Your brother Thomson and his family have just moved from Gunston to his own seat at Hollin Hall."

A tutor of General Thomson Mason's family, Elijah Fletcher, wrote in a letter from Alexandria, August 4, 1810:

[General Mason is] ... a man of note and respectability, his family very agreeable, social, affable and easy. I use as much freedom in the family as I did at my fathers house. I doubt not of their kindness to me in health or sickness. My employment is respectable and I consider my standing upon a par and equality with most of the people. Our living is rich and what in Vermont would be called extravagant. The family rise very late in the morning and consequently do not have breakfast till eight or nine. Our dinner at three and tea at eight in the evening.[6]

General Thomson Mason served as an officer of militia in the American Revolution, held numerous state and local offices and was active in organizing banks and transportation companies before his death in 1820.

It was his son, Thomson Francis Mason, born in 1785 at Gunston Hall, who built "Huntley."

Thomson Francis Mason

Thomson Francis Mason was heir to a family tradition of important friendships, public service and good taste, and he carried on this tradition. Educated at Princeton, Class of 1807,[7] he chose to return to the Fairfax County area to practice law and enter public service.

His life story is difficult to trace. No biography exists, nor is he mentioned in most works concerning Alexandria, even though he later attained significant recognition there.

On November 24, 1817, the Alexandria Gazette announced the marriage, on Wednesday evening, November 19th of:

Thomson F. Mason, Esq., of this place, to Miss Elizabeth C. Price of Leesburg, Loudoun County, Virginia....

The young Mrs. Mason was familiarly known as Eliza Clapham Price, not as Elizabeth C., but Thomson F. called her Betsey.

The use of the phrase "of this place" is of interest here, and open to several interpretations. It could mean that he was living in Alexandria at the time or only that he had an office there. He could have been living in Alexandria and building a home in Fairfax County at the same time.

Mason was probably already a practicing lawyer at the time of his marriage and was by 1824 a man of consequence in Alexandria.

The fight to get out of the District began in 1824, while it was not settled by Congress until 1846. The citizens of Alexandria, becoming tired of being in the District of Columbia, made an attempt to have Alexandria receded to Virginia. A meeting was held March 9, 1824, for the purpose of preparing a memorial to Congress on the subject. S. Thompson Mason was Chairman of the meeting....[8]

The memorial sent to Congress was couched in legal enough terms to have been drafted by Mason, who later became a judge. His political activities gave him enough local standing to insure his election as Mayor of Alexandria in 1827 and again in 1836.[9]

A glimpse of Mason as a family man can be seen in a reply to a letter from his wife in which she complained of an exchange of words with Huntley's overseer (in 1828), Slighter Smith. Mason, who must have been in court at Leesburg, wrote:

I have been indeed a little surprised at hearing the conduct of Mr. Smith. Altho' I knew about the general unkind and bad temper which he possessed, I had no idea that he would have ventured to exhibit it in your presence—or have him guilty of the insolence of threatening violence in your presence and to one under your protection.... I still cannot believe that he would seriously attempt it....

In that same letter Mason noted:

... the great pleasure and pride I have ever felt in seeing you placed above the flame, and having you so looked up to by others.[10]

As a good plantation manager, he also included a note to Smith informing him of his surprise and displeasure at the outbreak and suggesting:

I feel it is proper to inform you that I shall feel it my duty to inquire strictly into this subject—And with regard to the threatened violence I beg leave ... to put you on your guard and to inform you that any new attempt will be followed by the most serious consequences.

Mason lived in several houses in Alexandria (see Appendix A), but it was the time he spent at Colross which seems to have received the most notice. Mrs. Marian Gouverneur wrote in her book, As I Remember:

Another Virginia family of social prominence, whose members mingled much in Washington Society, while I was still visiting the Winfield [5]Scotts, was that of the Masons of "Colross," the name of their old homestead near Alexandria in Virginia. Mrs. Thomson F. Mason was usually called Mrs. "Colross" Mason to distinguish her from another family by the same name, that of James M. Mason, United States Senator from Virginia. The family thought nothing of the drive to Washington and no entertainment was quite complete without the "Mason girls," who were especially bright and attractive young women. Open house was kept at this delightful country seat, and many were the pleasant parties given there....[11]

Indeed the Mason occupancy of Colross made such an impression, that for years afterward the house was known as "The Mason Mansion." During the Civil War, on October 12, 1864, the Alexandria Gazette, in reporting the military occupation of the town, carried the following item on Colross:

... The fine old Mason mansion, in the suburbs of the town, was hired by an army officer.... The Mason mansion ... is a fair type of the residence of a wealthy Virginian. A wide hall in the centre opens into various rooms, while the front entrance is approached through a pleasant courtyard. At the rear of the house is a spacious area, paved with marble in diamond shaped blocks, looking out upon a large garden, well shaded with fruit trees and surrounded by a heavy brick wall. At one corner of this garden is the family tomb, in which are the remains of old Judge Mason, the former owner of the estate, who died just before the war broke out. He was a near relative of the present Confederate Commissioner to England, and his widow now resides at Point of Rocks....

Colross remained in the Mason family until the 1880's, Mrs. Betty Carter Smoot, Alexandria historian, who lived at Colross, wrote in 1934, of the house and family:

Jonathan Swift and his wife, and the Masons, who for many years resided at Colross, are said to have lived in great style and elegance. As regarded the Masons, there were still some evidences of this when we went there. Although pretty well denuded of its furnishings, there were one or two fine old mahogany pieces which had not been removed, and some handsome mirrors, with gilded frames, of a size appropriate to the surroundings. In the garret was stored quantities of china, remains of dinner sets, some in white and gold and others in blue willow pattern. There were some beautiful old cut glass decanters, wine glasses, and goblets. I remember also some vases and other bric-a-brac. Much of this was mutilated, but it furnished a fair sample of the style of living maintained in palmy days of the past. These belongings of the Masons were all packed, under the supervision of a daughter of the family, Miss Caroline Mason, and disposed of by her.[12]

When Thomson F. Mason died on December 21, 1838, his obituary in the Alexandria Gazette ran two full columns.[13] It was noted that Mason, who was a Judge of the Criminal Court of the District of Columbia at the time of his death, had:

... graduated at Princeton with the highest honors of that institution ... studied law and practiced with much success and celebrity, until he was elevated by the Executive of the United States to [6]that Station on the Bench, which he filled with such ability at the time of his decease ... his services were eminently valuable not only in the character of Chief Magistrate of their City (Alexandria), the duties of which he discharged for many years, but in all their public undertakings....

That same issue of the Gazette carried resolutions of the Common Council of Alexandria decreeing that they would:

... attend his funeral, and will wear crape on the left arm for one month.... That, as a further mark of respect, and to evince the sense of his community of their loss, the great bell in the public building be tolled on Sunday next, from 1 o'clock P.M., till half past 4 P.M....

Members of the Bar and Officers of the Courts of Alexandria County voted to:

... attend his funeral ... and wear the usual badge of mourning for thirty days ... that a committee of three be appointed respectively to tender them [family] our condolence ... that the proceeding of the meeting be published in the Alexandria Gazette....

The Bar and Officers of the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia voted to:

... attend his funeral, and, during the residue of the term, wear the usual badges of mourning ... that the Chairman [Francis Scott Key] with Richard Coxe and Alexander Hunter, Esqrs., be a Committee to tender to the family of the deceased the sympathy of this meeting at the death of one endeared to us by long acquaintance, which has made known the character of the deceased as one deserving of our warmest personal regard and highest respect, and which rendered this event a great public loss, as well as a private affliction....

T. F. Mason had been appointed to the newly organized Criminal Court of the District of Columbia less than six months before his death. He was the first judge appointed to that court, and its only judge during its formative period. As a Justice of Peace he had received his first appointment in February 1828, and was reappointed in 1833, and 1838.[14]

The story of Mason's life presented here is only a partial one but it is included to show something of the type of man who built Huntley.[15]

Chapter 1 Notes

[3] Stevens Thompson Mason, Mason Family Chart (Baltimore: privately printed, 1907). All genealogical material is taken either from this chart or from Kate Mason Rowland, The Life of George Mason.

[4] Rowland, George Mason, p. 365.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid., p. 307; The Letters of Elijah Fletcher, ed. by Martha von Briesen, (University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, 1965), p. 8.

[7] Princeton Alumni Association, Princeton University

[8] Mary G. Powell, The History of Old Alexandria Virginia, (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1928), p. 324. In her list of the Mayors of Alexandria Mrs. Powell also lists T.F. Mason incorrectly as S. Thomson (sic) Mason, although she spells the name without a "p" there.

[10] Thomson Francis Mason Papers, 1820-38, Collection of William Francis Smith, Alexandria, Virginia.

[11] Marian Gouverneur, As I Remember (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1911), p. 212.

[12] Mrs. Betty Carter Smoot, Days in an Old Town (Alexandria: privately printed, 1934), p. 127. Colross was moved to Princeton, N.J., in 1929. According to a clipping in the Gunston Hall archives, which is undated and unidentified, it moved in "... a grand total of 16 carloads of brick, wood, marble, etc...."

[13] Alexandria Gazette. December 27, 1838.

[14] Noel F. Regis, "Some Notable Suits in Early District Courts," Records of the Columbia Historical Society. Volume 24 (1922), 68, and Charles S. Bundy, "History of the Office of Justice of the Peace," Volume 5 (1902), 278.

[15] Additional information may be found in the Thomson Francis Mason Papers, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, Accession #1146. Also Gunston Hall Library, Gunston Hall, Lorton, Virginia.

Figure 2. Huntley house and barn complex, viewed from the south. 1947. Photo by Bill Amlong, copy by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

HUNTLEY AND ITS OWNERS

Location and Site

Huntley, 6918 Harrison Lane, near Woodlawn Plantation, Fairfax County, Virginia, is currently owned by Colonel and Mrs. Ransom G. Amlong. It is located off the Jefferson Davis Highway (U.S. Route 1), in the Groveton community, on Harrison Lane, between Lockheed Boulevard and Kings Highway (Route 633).

The house is on a plateau, overlooking Hybla Valley, at 150 feet above sea level. To the south, or in front of the house, the ground level drops in three terraces to 130 feet above sea level. To the north or rear there is a sharp rise to 200 feet.

A church and several houses are located directly in front of Huntley, but the vista from the house toward the Potomac River, especially in summer, is relatively undisturbed. The general area is one of intense commercial and residential development. Hybla Valley, through which Barnyard Creek flows from Huntley, constitutes the major part of the view from the house, and much of this land is owned by the U.S. Government.

The Huntley complex consists of:

1. The mansion house.

2. Necessary with flanking storage rooms.

3. Root cellar.

4. Ice house.

5. Spring house.

6. Tenant house.

All the buildings are brick. The house itself is a significant Federal period structure, built during the ownership of Thomson F. Mason, c. 1820, and believed to have been influenced by George Hadfield, architect of Washington's first City Hall and first superintendent of the Capitol's construction.

Origin of the Name

The first known use of "Huntley" as a place name for the Harrison Lane house appears in an 1859 deed of the property by Betsey C. Mason, widow of T.F. Mason, to her sons John Francis and A. Pendleton Mason. The property is described as:

... all that certain tract of land in the County of Fairfax and state of Virginia called "Huntley" and containing about one thousand acres....[16]

It is probable that the plantation was named Huntley before Thomson F. Mason died in 1838, although his will of that year mentions no real estate, or personal property specifically.

If he followed the Mason tradition, the house may have been named after an ancestral home in England, and probably after the home of a maternal ancestor. In writing of Gunston Hall, Helen Hill Miller says:

They called their home "Gunston Hall." The name had come down through several generations of Mason's maternal ancestry: his grandmother was Mary Fowke of Gunston Hall in Charles County, Maryland, and her grandfather was the Gerald Fowke of Gunston Hall in Staffordshire who emigrated to Virginia at the same time as the first George Mason. The habit of naming new homes in America after the [10]old ones in England was general among the planters of the Virginia Tidewater. Mason conformed to this tradition for a second time when he made a gift of a nearby plantation to his son Thomson and called it "Hollin Hall," after the home of his mother's people near Ripon....[17]

If Thomson F. Mason had followed the same procedure he could have used the name "Huntley," which might at any point have had an "e" added. His father was General Thomson Mason of Hollin Hall, who was married to Sarah McCarty Chichester.[18] Sarah was the daughter of Richard McCarty Chichester, whose first wife had been Ann Gordon.[19] The ancestral Gordon home in Scotland was called "Huntley."

In these lands of Strathbogie Sir Adam (Adam the V) fixed his residence, and was the first of the Gordons who removed from the south of Scotland to the North. He obtained from the parliament holden at Perth anno 1311, that his new estate should be called Huntley, as it is still called in writings and public instruments, altho' amongst the vulgar it retains the old name of Strathbogie.[20]

OWNERS AND OCCUPANTS

Mason Ownership

The will of General Thomson Mason of Hollin Hall was written on April 15, 1797, and probated, after his death, on November 21, 1820.[21] That will does not specifically mention real estate, but does:

... give and devise unto my Son Thomason Mason my gold watch and I confirm unto him his right and title to a mulatto boy named Bill, given him by his Grandfather Mr. Richard Chichester and I also give and devise unto him my interest in the Potomack Company....

One reason no real estate is specifically mentioned may be cleared up by a later deed (1823)[22] in which other heirs of General Mason deed to:

Thomson F. Mason of the Town of Alexandria in the District of Columbia, ... a certain tract of land situate in the County of Fairfax and State of Virginia known and called by the name of Hunting Creek Farm....

This deed reaffirms settlements made by General Mason during his lifetime on January 1, 1817, and includes the land on which Huntley is located.

Thomson F. could have begun Huntley at any time after January 1, 1817. On the 29th of January 1818, he paid Alexander Baggett $37.79-1/2 for, among other things:

40 Ft. Double Architrave

18 Ft. Jamb lining

1 Carpet strip

2 pr hinges put on

1 mortice lock put on

2 Flush Bolts

135 Ft 4/4 clear boards

locks, hinges, bolts, nails, and Springs....[23]

Also included is one item labeled "folding doors" (double doors). No double doors have been located at Huntley, although Mason is not known to have been[11] building elsewhere at this period. During the latter part of 1819 he was still building and paid $28.00 for:

Sept 20—20 bushels plaster

Sept 22—20 bushels plaster

Oct 10—10 bushels plaster....[24]

There was probably a structure at Huntley by 1823, for in February of that year Mason sent "to his farm by surry ten bushels shoots and six bran...."[25]

By 1826 the house must have been substantially finished, for in that year Mason's Grandmother Chichester wanted:

to spend a few days at Mr. T.F. Mason's farm, but was deterred from doing so by the apprehension that, as Mr. Mason resided in Town, and there was no other white person on the farm but the overseer ... she would not be secure.[26]

By implication there was a dwelling at Huntley ready for her occupancy.

Another letter written to Mason on August 18, 1827, now incomplete and in poor condition, suggests finishing some construction work and notes that the writer, whose name is missing:

... had understood you had only rented the place by the month, tho the man has a little crop on the land growing and if the season proves good at the end of the year may be worth ... [the rest is missing][27]

Almost a year later the Alexandria Gazette, on Thursday morning August 5, 1828, had an advertisement offering:

$25 Reward/ran away from the farm of Thompson F. Mason/Fairfax County on the night of 2d instant negro/BOB. He is about 6 feet high, stout made, very black/and about 45 years of age; has a stammering in his/speech; his right leg sore. Had on when he eloped,/brown linen shirt and trowsers and took with him/blue coat, white linsey trowsers, and black fur hat-/I will give $10 for taking him so I get him again if in the County. If taken out of the County/or District of Columbia, $25./Slighter Smith, Agent for Thompson F. Mason/Fairfax County, State of Virginia/August 5.

Mr. Smith had been replaced as Overseer at Huntley by 1832 for in that year Price Skinner wrote:

... being moved to your house last friday—we are in a bad fix—I want you if you please to ride out to see what you will have don—if I was you I wood have the floor layed down with the plank not used—the whole of the cappenders work may be made in less than one day—and I ast John Parsons what the cappenders work wood be worth—he said about fourty dollars—and forty cents I believe wood be anough there is but three suns [?] worth—to lay the floor and weather bord the shed Sir you will please to ride out....[28]

Mason had already acquired Colross, in Alexandria (see Appendix A.), by 1833, for in March of that year an estimate was submitted by Thos. Beale for:

Labour and Materials, for repairs on the large Building North of the Town of Alexandria....

The estimate included plastering, painting, brickwork, erection of porches and porticos, and fencing of the property.[29] It is Colross with which Thomson F. Mason's name is normally linked. He died December 21, 1838, and was buried there.

Figure 3. Detail from Map of Eastern Virginia and Vicinity of Washington, Arlington, January 1, 1862, Bureau of Topographic Engineers,

Record Group 77, National Archives. Copy by Stuart C. Schwartz.

His will was probated on February 4, 1839,[30] with Mrs. Mason as executrix, though it was not recorded until February 18, 1839.[31] Seven days before his death Mason had written in his will:

... I devise all my estate real and personal in possession remainder or reversion or in expectancy to my beloved wife B.C.M. for her maintenance and support of our children during her life and widowhood.... For any aid or assistance which my wife may require in the management of my estate, I recommend her to my brother Richard C. Mason, and my most excellent friends Benjamin King and Bernard Hooe....

Though Thomson F. Mason had built Huntley, it never served as his permanent residence. It was occupied by a succession of renters, overseers and farmers. Mason's "excellent friend Benjamin King," a doctor, was to have a more personal connection with Huntley, however.

King Ownership

In November of 1859, Betsey C. Mason, having been authorized:

... by deed or will, to dispose of all or any part of his estate to their children or any of them, at such times and in such proportions as she may think just and prudent, and whereas, the said Betsey C. Mason deems if just and prudent to dispose of a portion of said estate to her said sons [John Francis and A. Pendleton] ... all that certain tract of land in the County of Fairfax and state of Virginia called "Huntley" and containing about one thousand acres....[32]

At the same time Mrs. Mason transferred to her two sons:

... eighty five negroes, slaves for life, which said negroes are particularly mentioned and set forth in the scheduled annexes to this deed ... Daniel Humphreys and his wife Rachel and their son Daniel, now living at Huntley ... and Priscilla, their daughter and her child named Thomas, the last two being at Huntley ... Sandy living at Huntley....[33]

Of the 85 more than six may have lived at Huntley, but only these six are specified.

Exactly one month later, the two Mason boys, being:

... justly indebted to the said Benjamin King the just sum of thirteen thousand dollars, lawful money of the United States, to be paid to the said Benjamin King on the first day of January one thousand eight hundred and sixty two....

transferred as security for a debt to John A. Smith:

... that certain tract or parcel of land ... known and commonly called Huntley ... containing one thousand acres, more or less ... together with all and singular its appurtenances ... for the following purposes and none other, that is to say to permit the said John Francis Mason and Arthur Pendleton Mason, their heirs or assigns to retain possession of the said tract or land, without account of rents or profits, until a sale become necessary under this deed and if the said John Francis and Arthur Pendleton Mason, shall fail to pay the sum of thirteen thousand dollars, as the same shall become due according to the conditions of the [14]

[15]said bond ... the said John A. Smith shall upon the request of the said parties entitled to said payment proceed to sell at public auction, to the highest bidder for cash, the said tract or parcel of land or as much thereof as may be necessary ... after having given at least 30 days notice of the time and place of sale in some newspaper printed in the town of Alexandria....[34]

Figure 4. Survey, Huntley, prior to May 15, 1868. Fairfax County Deed Book

1-4, p. 240. Copy by Stuart C. Schwartz.

There the ownership remained until the Civil War. A map of that era (1862) shows "Huntley Pl—Mrs. Mason's". The overview is labelled "Wide fertile Valley with but little Timber."[35] This map also labels Kings Highway the "Gravel Road," a term used in many of the Huntley deeds.

Why the Masons became indebted to Benjamin King is not known, but on June 12, 1862, the property was transferred from Smith to King. According to the deed they did:

... advertise the said property in the Alexandria News, a paper published in the City of Alexandria, for upwards of thirty days for sale at public auction and wheras pursuant to said advertisement the said John A. Smith did on Thursday, the 12th day of June, 1862, at 12 o'clock a.m. in front of the Mayor's office in the City of Alexandria, offer at public sale to the highest bidder ... several bids having been made therefor, the said property was struck off to Benjamin King at and for the sum of thirteen thousand dollars ... that certain tract of land known as "Huntley" ... together with all and singular the appurtenances thereto....[36]

As nearly as can be determined no Alexandria News was being published at the time, and the property was not advertised in the Gazette. The transaction was noted in its "Local News";

... the property known as "Huntley" in Fairfax County, containing about 1,000 acres, was sold today at public auction by John A. Smith, esq., Trustee. It was subject to a lien of about $10,000, and was purchased by Dr. Benjamin King, subject to said lien, for $13,000 cash.[37]

Evidently King either already had moved to Huntley, or did at that time. He next appeared in the Gazette when he was leaving the property in 1868.

For sale on Tuesday the 19th instant at 10 o'clock a.m. at "Huntley" the residence of Doctor B. King, all his HOUSEHOLD and KITCHEN FURNITURE consisting of sideboard, chairs, tables, bedsteads, bureaus and glasses, wash stands, toilet sets, and c. Also stock and farming utensils, horses, cows, plows, harrows, corn cob and crushers, horse power and threshers, cauldron, kettles, and c. with all articles usually found on a farm. Terms at sale, my 11—1 w.[38]

Harrison-Pierson Ownership

Dr. King sold Huntley to Albert W. Harrison and Nathan W. Pierson of New Jersey. The instrument of sale provided:

... the tract hereby conveyed containing eight hundred and ninety and one half acres, more or less, known as and commonly called "Huntley"....[39]

The deed more specifically noted that the courses in this deed had been so changed as:

... to make them conform to the ancient surveys of the land, and being the same land which was surveyed by George and others to Thomson F. Mason, by deed dated October 1st, eighteen hundred and twenty three ...

Accompanying the deed was a survey which was accomplished for Dr. King by Thomas W. Carter, "formerly surveyor, Prince William County." The survey was received by the County Clerk on May 15, 1868. The "Gravel Road" was shown as running north of the "Mansion House," and the "South Branch Little Hunting Creek" east of the house. The Huntley part of the purchase was shown as a plot of land with 682 acres, 0 rods and 30 poles, containing the "Mansion House."

The "Journal of Records of Huntley Farm," covering the period between 1868-89, is currently in the possession of Mrs. Earl Alcorn of Alexandria. It details the purchase, subsequent division between Pierson and Harrison, payment of liens, etc., on Huntley. The Journal indicates that the farm was actually purchased on March 1, 1868. Dr. King was probably given time to settle his affairs, as the transfer was not recorded until November of that year. At any rate, the Journal entry for March 1, 1868, reads:

956 acres at $32.50 per acre31,070.00

Paid down each $5,00010,000.00

————

21,070.00

The Harrisons obviously entered into community affairs, for by May 1870:

The regular monthly meeting of the Woodlawn Farmers' Club was held on Saturday last pursuant to adjournment at Huntley, the residence of A.W. Harrison. The President being absent, Courtland Lukens was appointed Chairman pro tem. Twenty four members were present. Theron Thompson was admitted as a member. The report of the committee on vegetables and a supplement for March last was called for, again read, and discussed at some length. The committee on cereals presented their report on the condition of things about the farm and premises of Huntley, which was a good one and rather commendatory of Mr. Harrison as a practical farmer, and elicited several pertinent questions and answers. Some discussion ensued as to the best method of ridding farms of garlic. E. E. Mason produced several "pips" taken dexterously with the thumb nail from under the tongue of young chickens. The "pip" is a little boney substance similar to a fish scale, a negative of the tongue, and prevents the chick from eating unless it is removed. A conversational style of discussion ensured on the subject of poultry. An invitation to supper, as usual, was unanimously accepted without debate. The club then adjourned to meet one month hence at Edward Daniels' [Gunston Hall].[40]

In the 1870 census Harrison was recorded as being 36 years old, having four daughters, real estate worth $28,000 and personal property worth $8,000.[41]

Harrison became a well known citizen. The Alexandria Gazette reported on March 3, 1870, that "Mr. Harrison's horses ran away," causing great excitement in the city.

Harrison Ownership

Pierson and Harrison divided the Huntley tract on March 11, 1871,[42] and by the time the Hopkins Atlas was published in 1879, the house was listed clearly as "A.W. Harrison, 'Huntley'."[43]

In 1875 "A.F.B.", evidently a correspondent for the Syracuse (N.Y.) Journal, visited Huntley, and on July 25th filed a dispatch to the Journal. The story indicated much about life at Huntley during the era, including the marks left by the Civil War and the life of the Northerners who had moved to the South:

To come to Huntley you take the steamer from Washington to Alexandria. The cars run hourly or nearly so, but the river ride is more pleasant. If you have been to Alexandria at any time since the century opened, you will recognize the place. Many things change in three score years and fifteen, but Alexandria is not one of them. It is the same yesterday and today. Your hospitable friends at Huntley will meet you on the wharf, and you shall have a charming ride through the Fairfax fair fields for four miles, until you reach the Old Dominion plantation of Judge Mason. It joins on the south Mt. Vernon, which is plainly visible from the ancient family residence of the Masons, now the home of an enterprising eastern gentleman, who has a fondness for agriculture on a grand scale. The house stands boldly on a hill spur, looking over broad acres of corn, rye, wheat, oats, and fertile meadows—a sight to see. Beyond, in plain vision, rolls the Potomac. Vessels of many kinds—by sail and by steam—are going to and from the city of Washington.... We took a walk today over the great farm. I dare not say how many were the acres of corn standing eleven and twelve feet high, with tasseled ears. Our host had us through the meadows, going like Boaz of old among his men. He speaks well of the ex-slaves, and of their service. Among them I met a Washington and an Andrew Jackson....

As we walked on into shady woods we came upon an old encampment of our Union Forces in the war. If fruit and berries were as abundant then as now, the boys in blue had a good time in their season. Nor could the weather have been peculiarly trying. At night we get the west winds from off the Alleghanies, and at times the delicious coolness of the sea-side is rivaled. I counted as many as thirty open graves here from which the forms of those who had been buried had been taken away. Trees are growing in the places of the tents, and time is fast sweeping away the marks of war.

The Southern people are not considered by these northern farmers especially unfriendly. There is little social intercourse, however, because the women got so thoroughly mad, that they will never get over it in this world.... Nevertheless, there is such a sprinkling of Yankees in these parts that life here has its social attractions.

The farmers' clubs meet statedly to picnic, to discuss, and to prove that the lines have fallen to them in pleasant places. And a better home for a farmer can scarcely be imagined. The winter is short; the spring early; the summer not oppressive, and the autumn continuous, rich and glorious. The people catch the inspiration and are "given to hospitality." One could do much worse than to live at Huntley. As for us, we are coming again.

Figure 5. Detail, G.M. Hopkins, Atlas of Fifteen Miles Around Washington,

Philadelphia, 1879. p. 71.

Figure 6. Rear facade, c. 1890. Courtesy Mrs. Ransom Amlong. Copy by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Figure 7. Rear facade, c. 1900; Courtesy Mrs. Earl Alcorn. Copy by Stuart C. Schwartz.

In May, 1892, the Gazette reported another meeting of the Woodlawn Farmers' Club at Huntley, though the column was a little garble, noting that the Club:

... met at Huntley, the residence of Mrs. Pierson.... The farm of our hostess consists of about 300 acres and is part of the estate formerly owned by Mrs. Thomson Mason. A new cottage has been built overlooking a fertile valley, and giving a fine prospect including the Potomac River, Mt. Vernon, Woodlawn and Belvoir estates and is carried on by Harry Pierson, son of our former President.[44]

The Pierson House may be the structure directly across Harrison Lane from Huntley. It has the same outlook and general location as Huntley, and is located on part of the original Huntley tract.

Albert W. Harrison, to whom Huntley had passed in 1868, died in 1911. The Gazette noted that:

Mr. Albert W. Harrison, an old, well known and esteemed resident of Fairfax County, died at his home "Huntley" in the Woodlawn neighborhood at 7:30 o'clock last night. The deceased was 80 years old. He leaves four children, a son and three daughters. Mr. Harrison was a native of Montclair, New Jersey, but moved to Fairfax County in 1869. His frequent visits to this city for more than forty years made him as well known in Alexandria as any resident of the City. Mr. Harrison was a member of the Second Presbyterian Church. His funeral will take place Saturday afternoon at the residence. The interment will be in Alexandria.[45]

On April 5, 1911 the married daughter, Margaret N. Harrison Gibbs, and her husband J. Norman Gibbs, deeded:

... all of their right, title and interest, legal and equitable in and to the personal estate of said Albert W. Harrison, deceased, except his watch, and also to hold as tenants in common, the following described tract of land containing three hundred fifty eight and three quarters (358 3/4) being part of "Huntley" so called and known ...[46]

to Clara B. Harrison, unmarried; Mary C. Harrison, unmarried, and Albert R. Harrison, unmarried. The part of the Huntley tract transferred contained the house.

For the next 19 years neither the Harrisons nor Huntley seem to have made the news. Then in 1930, a full page Alexandria Gazette article appeared entitled "Nation's Greatest Air Center."[47] The rest of the headline read:

George Washington Air Junction Tract Found Ideal for Trans-Atlantic Terminal for Airships of Zeppelin and R-101 types without Interfering with Thousand-Acre Airport for Planes—Admiral Chester Shows That Historic Ancestral Lands of George Washington and George Mason, First Selected by War Department 12 Years Ago for Army Aviation Field, Afford Only Tract Ideal for Great National Air Center.

The "only ideal tract" was the valley in front of Huntley. Admiral Chester was reported as saying that the War Department in 1916-17, made an investigation:

... of all possible sites for an Army Aviation field near Washington, and found that the Air Junction site was the only ideal site for a large air center.

Figure 8. Hindenburg disaster, Lakehurst, New Jersey, May 6, 1937. Photo

published in New York Times, National Archives print.

Public Relations men for the Air Junction certainly used local history as a promotional gimmick:

It will be a twentieth century aeronautic, scientific and historic center, but retaining the gorgeous 18th Century pastoral setting, including beautiful groves that teem with birdlife ... a dozen bubbling springs that have been making for centuries the sparkling Little Hunting Creek and Dogue Creek.... There are many other alluring surprises that one would not dream of finding within only nine miles from the Capital, such as Mason's poetic "Huntley," a gem of colonial architecture, surrounded by stately trees. George Mason's "Huntley" and "Okeley" are both part of the George Washington Air Junction. These estates ... had been forgotten, due to the lack of signs on the Washington-Richmond Highway to make known that a modest lane led to them. The lane has now been widened into a 50 foot gravel road and has become the entrance to the Air Junction.

As the visitors drive into the Junction, past the historic Little Hunting Creek, about 3,000 feet westward, they behold "Huntley," a gem of colonial architecture, which graces one of the hills on the north side of the Washington Air Junction Drive and overlooks the Thousand Acres Airport. It is surrounded by stately trees, and its sides are screened by vines and picturesque thick bushes of lilacs, roses and other flowers.

"May I carry it away?" is the usual query from visitors, as from the distance "Huntley" looks small enough to carry away. Failing to obtain permission to remove this colonial gem, the visitors feel happy in being photographed on the quaint porch and steps....

The writer had apparently convinced himself of at least one thing, for under the photograph of Huntley, which accompanies the article, the house is again called "a gem of colonial architecture."

Air Junction promoters invited the Graf Zeppelin and subsequent airships to make their base here rather than at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The same invitation went to the British and to others, but the accidental burning of the Hindenburg at Lakehurst on May 6, 1937, seems to have put an end to dreams of a great airship junction at Huntley, though there was an operative airport there. Such names as Lockheed Boulevard, Fairchild Drive, Piper Lane, Beechcraft Drive and Fordson Road still survive.

Later Owners

Albert R. Harrison, still unmarried and last of the Harrison children, died on March 24, 1946, and in September his executors sold Huntley to August W. and Eleanor S. Nagel.[48] For some reason the Nagels had Edward M. Pitt, an Arlington architect, do seven sheets of drawings of Huntley that same year.[49]

Less than three years later the Nagels sold the house to the present owners, Colonel and Mrs. Ransom G. Amlong.[50]

Chapter 2 Notes

[16] Deed Book B., No. 4, p. 448, November 7, 1859 Fairfax County, Virginia. T.F. Mason's first name is spelled "Thomason," "Thompson" and "Thomson."

[17] Helen Hill Miller, George Mason Constitutionalist (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938), p. 18.

[18] Stevens Thompson Mason, Mason Family Chart.

[19] Ann was not Mason's grandmother, but the first wife of his grandfather. Thomson was a favorite of Grandfather Chichester and he would have known of Ann Gordon. Mr. Chichester had, as a matter of fact, spent his first married years with the Gordon family.

[20] C.A. Gordon, History of the House of Gordon (Aberdeen: D. Wyllie & Son, 1890), p. 11.

[21] Will Book M, No. 1, p. 130, November 21, 1820, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[22] Deed Book W, No. 2, p. 199, October 1, 1823, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[23] January 29, 1818, Letter to Alexandria Baggett from Thomson F. Mason, Alexandria, William Francis Smith Collection, Thomson F. Mason Papers.

[24] Ibid., A.P. Glover [?] to T.F. Mason, October 18, 1819.

[25] Ibid., P. Taylor "sent T.F. Mason, esq...." February 5, 1823. Mason either was not at Huntley at the time, or the items were for his tenant. The bill notes specifically that the delivery was for "W.T.R.".

[26] Lee vs. Chichester, #60, Fairfax County Court House. From a deposition of Bernard Hooe.

[27] Letter, William Francis Smith Collection.

[28] Ibid., Price Skinner to T.F. Mason, December 7, 1832.

[29] At least 10 documents concerning the work which Mason did at Colross are in the William Francis Smith Collection.

[30] Will Book T, No. 1, p. 3, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[31] Will Book T, No. 1, pps. 1-4, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[32] Deed Book B, No. 4, p. 448, November 7, 1859, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[33] Deed Book B, No. 4, pps. 449-50, November 7, 1859, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[34] Deed Book B, No. 4, p. 451, December 7, 1859, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[35] United States, National Archives, Record Group 77, Map of Eastern Virginia and Vicinity of Washington, Arlington, January 1, 1862, Bureau of Topographical Engineers.

[36] Deed Book E, No. 4, p. 195, June 12, 1862, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[37] Alexandria Gazette, June 12, 1862.

[38] Alexandria Gazette, May 13, 1868. King, then in the U.S. Army, married on May 18, 1827, according to the Christ Church Register. On May 14, 1879, when he sold Lloyd's Lot, which is adjacent to the Huntley property, to Pierson and Harrison, he is listed as "Benjamin King of Anne Arundel County." King, John Mason, and T.F. Mason, all married girls named Price and may have been relatives. It is possible therefore that King was the brother-in-law of T.F.

[39] Deed Book I, No. 4, p. 236, November 21, 1868, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[40] Alexandria Gazette, May 16, 1870.

[41] 1870 Census, Reel 108, Frame Number 197, National Archives. In earlier censuses neither Mason nor King appeared. The actual occupant at Huntley prior to this time was usually an overseer or tenant. Not knowing who most of these were and having no maps coded to the census, the author was unable to gather any earlier information from the census.

[42] Deed Book O, No. 4, p. 338, March 11, 1871, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[43] G.M. Hopkins, Atlas of Fifteen Miles Around Washington. (Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins, 1879), p. 71.

[44] Alexandria Gazette, May 14, 1892. A Pierson property is shown adjacent to "Huntley" on the 1879 Hopkins map.

[45] Alexandria Gazette, March 3, 1911. The Fairfax Herald, March 10, 1911, also carried an obituary. The March 4, 1911, Alexandria Gazette, noted that the funeral took place "from the residence this afternoon ... conducted by Rev. J.M. Nourse. The remains were interred in Presbyterian Cemetery in this City." The Harrison plot is in the third section to the left from the entrance. Stones bear no epitaphs, only names and dates of birth and death.

[46] Deed Book J, No. 7, p. 22, April 5, 1911, Fairfax County, Virginia.

[47] Alexandria Gazette, "Northern Virginia Industrial Edition," January 1, 1930, Section C, p. 8.

[48] Deed Book 515, p. 60, September 1, 1946, Fairfax County, Virginia. See also Deed Book 515, p. 64, August 21, 1953. A survey of the area is shown on pps. 62-63. The plat is marked "Farm and Mansion House Area," and shows the "House," "Tenant House," and "Barn."

[49] According to the records of the American Institute of Architects, Mr. Pitt died January 18, 1969.

[50] Deed Book 694, p. 400, June 11, 1949, Fairfax County, Virginia. Col. Amlong is a retired U.S. Army officer.

Figure 9. Huntley, front view. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Figure 10. Huntley, rear view. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

AN ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION[51]

The buildings currently comprising the Huntley complex include the mansion house, the tenant house, the storage and necessary house, the ice house, the root cellar and the spring house.

The Dwelling or Mansion House

Huntley, the mansion house, is of brick construction. The brick is laid in common, or American, bond, with five courses of stretchers to one of headers. Average brick size is eight and three-eights inches by four inches by two and one-quarter inches thick.[52] "The brickwork does not seem to have been laid ornamentally, but this is not strange for a building of the early part of the nineteenth century, where the emphasis was taken away from brick and it was often either stuccoed or painted."[53]

Room Arrangement

Originally the house was "H" shaped. The center portion is three stories at the front (south), two at the rear, and only one room deep. The wings on either side are two stories at the front, one at the rear and two rooms deep. Construction of the house on the slope of the hill accounts for the difference in height. Major entrances are on the first floor, although a ground floor is located beneath it. The wings project about half their width front and rear from the center section. This arrangement provides a large center room at the first floor level, with two rooms on each side. On the second floor level there is only one large center room, while on the ground floor level there is a large center room with two flanking rooms on each side. Here were the kitchen, various storage rooms, and possibly quarters for the household staff.

Every room on the first floor and almost every room on the ground floor had an exterior entrance. There is no obvious physical evidence to indicate the means of access to the second story room. Evidence of a dumbwaiter from the ground floor kitchen area to the floor above still exists in the rear ground floor room of the west wing.

A wing has been added to the rear portion of the west side of the house. This is partly brick and partly frame and is of relatively recent construction. The rear of the H-shaped building has been filled in to create a hall space, bath and an enclosed stair to the second floor room. At the second floor level it provides an extra room and a bath. This work is probably nineteenth century, but the exact date is unknown.

In front, at the first floor level is a porch addition. This is built around earlier steps which are of quarried stone supported by a brick wall on each side. The present porch roof covers and obscures the brick arch and top of the fanlight over the entrance. There was probably no covered porch on the house originally.

Figure 11. Mantel, central first floor room. 1969. Photo by Wm.

Edmund Barrett.

Figure 11. Mantel, central first floor room. 1969. Photo by Wm.

Edmund Barrett. |

Figure 12. Mantel, north room first floor. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund

Barrett.

Figure 12. Mantel, north room first floor. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund

Barrett. |

Windows and Doors

Windows in the facade are unique in that they are set into recessed brick frames. While the frames in the root cellar are arched, those in the residence are square panels, with the window set into the center of the frame. According to architectural historian E. Blaine Cliver, the exterior window construction is quite simple with a double beaded frame set into the brick two to three inches from the front surface. The simplicity of the window framing, which is Federal in style, would place the house somewhat after the late Colonial period, in the early nineteenth century. Windows on the ground and first floor are six-over-six, double-hung sash, except adjacent to the entrance on the first floor porch where they are four-over-four. Windows on the second floor consist of a single, nine-pane sash, which opens to the side on hinges. The pane size is eight and a half inches by ten inches and a large portion of the glass is early. The exterior shutters consist of a single panel of fixed louvers and much shutter hardware survives. This includes several types of shutter stops, which are generally wrought rather than stamped. A fine boot scraper also exists at the rear first floor entrance.

The door entrance in the south front has framing sidelights and an elliptical fanlight with wood tracery. In general, the oval fanlight came into use in the 1790's and went out of common use around 1825; although according to Mr. Cliver it probably was not common in this area until after 1800. The stiles of the entrance are basically the pilaster type although the reeding within the pilaster is rounded rather than flat. An opposing door at the north or rear of the center room was also originally exterior. The keystone over the fanlight has a beaded center portion which is similar to those found in the work of nineteenth century architect Asher Benjamin.

Interior Features

The center first floor room has a fine mantel which is also similar in proportion to the Federal styles of Benjamin. The mantel is somewhat busy, and a little heavy, yet it has delicate detail and reeding on the sides. The mantels in the side rooms are much simpler, as might be expected in ancillary rooms. Basically, however, their proportions are the same, dateable to the early nineteenth century but with much less style involved. All four of the side mantels are of the same basic design, but each has been given an individual detail or refinement.

The second floor room has a simple mantel and moldings. It has the ovolo curve in the molding around the architraves which was common in the eighteenth century and persisted into the nineteenth.[54] This room would have been less used than downstairs rooms and the moldings are bound to be simpler, as is often found in the nineteenth century, when the upstairs was no longer as much used as in the eighteenth century. This room has a tray ceiling of the type one would expect to find beneath a hip roof, such as Huntley had in the nineteenth century.

Much of the flooring in the house is early, consisting of wide random width pine boards. The saw marks in the subflooring above the ground floor center room are vertical, but apparently from a mechanical saw. Beams under this portion of the house are hand-sawn on one side and broad-axed on the other.

Figure 13. Detail, exterior door, north facade. 1969. |

Figure 14. Detail, interior of entrance door, south facade, 1969. |

Figure 15. Detail, window and door, central first floor room. 1969. Photos by Wm. Edmund Barrett |

On the ground floor only the kitchen fireplace in the west side is open. There is evidence of a possible oven in the west chimney in the center room. In the east wing the front fireplace has been closed, though a balancing structural arch in the adjacent room is still open. The floor on the ground level was brick but floors in all rooms except the rear room in the east wing have been covered with concrete.

Much early hardware remains at Huntley, some of which fits stylistically into the period of construction. Most of it cannot be positively dated. The front door latch, for example, is an old Carpenter-type lock, generally common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but having no visible manufacturers mark, it cannot be positively dated.

Door and window architraves in the center first floor room, and in rooms in the east wing have corner blocks, while those in the west wing do not. Detail of the architraves throughout is early, and those with corner blocks are probably contemporary with the rest of the house. In the center room, first floor, the mantel, door and window architraves, and panelling beneath windows, all have the same molding details, indicating that all woodwork is of the same age.

Exterior Features

On the two wings the wooden cornice is fairly deep, approximately eight inches, providing a slight projection. This may be indicative of a somewhat later date—moving toward the cornices of the Greek Revival period. They are probably of a later date, but if so, certainly within thirty to forty years after the house was constructed, or no later than the mid-nineteenth century. The saw-tooth cornice line does not run behind the present wooden cornice, indicating, along with the fact that brick bonding continues into the gable end, that the roof configuration on the wings is probably original. The only probable differences between the original roof and that now in place is that the gable ends over the center section were clipped, giving the appearance of a hip roof when seen from the front. This roof continued, shed style, over the wings. There probably were no covered porches and the front porch at the first floor level may have been open above and below.

The Tenant House

The tenant house is a brick two-story structure with a ridge roof, a slightly off-center interior chimney and a three bay front. The building is approximately thirty-two feet long and twenty-two feet wide. A seven foot projection on the right end, added in this century, houses bath and kitchen facilities. It is approximately two hundred seventy feet west of the mansion house.

The brick is laid in common bond, with five courses of stretchers to one of headers. The average brick size is eight and one-half inches by four inches by two and one-eighth inches. The cornice line is composed of three rows of bricks stepped outward. The first and third courses are stretchers and the middle course is composed of headers laid to form a dentil course.

This structure burned in 1947; now only the exterior walls are original. All windows, doors and interiors date from remodelling after the fire. As part of the Huntley complex, it is still a visually important building.

Figure 16. Necessary and tenant house from the icehouse, 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Figure 17. Necessary, rear or west elevation. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

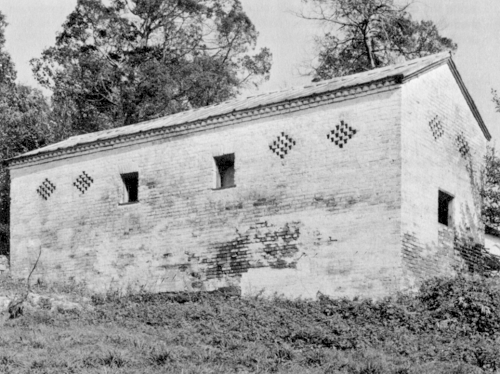

The Storage House and Necessary

The building referred to by the present owners as the slave quarters does not seem to have been suitable for the housing of human beings, and may actually not have been used for that purpose. It is a one-story brick structure with a ridge roof over three rooms. Neither of the end rooms has a finished floor or ceiling nor do they appear ever to have had finished walls; the windows are wall openings protected by iron bars; each room has four brick diamond-shaped ventilators and neither seems to have been heated—in addition to being open, there are no chimneys or flues. It is likely that both rooms were used for storage spaces and, from the evidence in existing doors and windows, secure ones. The overall measurements of the building are approximately thirty-four feet eight inches by ten feet ten inches, each end room measuring approximately eleven feet eleven inches by ten feet ten inches.

The necessary, a privy or outdoor toilet, occupies the central recessed portion between the two end storage rooms. It measures approximately ten feet ten inches by five feet five inches, and includes separate men's and women's sections.

Brick in the structure has an average size of nine inches by four and one-quarter inches by two and one-quarter inches. The bond is common, varying from three courses of stretchers to one of headers at the foundations, to five to one at the gable end. Queen closers are used at the corners of the structure. The cornice line is three bricks deep, stepped outward. The bottom and top course are stretchers, while the middle course is set at an angle in a saw-tooth pattern,[55] the same cornice as is used on the house.

The structure is symmetrical. Brick ventilators, two in each gable end and two to the rear of each end section, are worked into the brick wall. They are in the shape of a flattened diamond, with sixteen headers eliminated to form the pattern.[56]

To the rear of the structure the roof has been replaced, though the front part of the ridge is old. This may be accounted for by the fact that the rear wall is bowed back two or three inches out of plumb. This may be immediately seen in the joint of the wall dividing the storage room on the left from the necessary. This shift could have necessitated the replacement of the roof to the rear.

Hand wrought, rose head nails were used in the construction of the doors to the necessary; they may have been used for their clenching properties. The latches are hand wrought, or at least one of the early fabrications. The left door consists of three vertical boards, from left to right; nine, ten and eleven inches in width. The center board is beaded on each side, while the outer boards are undecorated.

Hand wrought rose head nails are also used in the construction of the barred windows in the front of the storage rooms. Here they are used structurally, tho the effect is decorative. The bars are iron, and the original frame and bars remain in the left storage unit window.

The storage rooms have dirt floors and unfinished ceilings. Bars at the windows, strong doors and the open ventilators would indicate storage areas needing light, ventilation and security. Such an area might be required for any number of farm produced commodities.

Both necessaries, in the center portion, are completely finished, with plaster walls, well shaped seats, windows with sash and glass, and brick floors, now covered with concrete. The necessary for men to the right has one seat, while that for women, to the left, has three. Two of these are at ordinary height, while the third is[34] at a child's height. The necessary was cleaned from the rear. A tray, inserted beneath a log sill at the foundation line, could be removed, cleaned and reinserted daily.

Figure 18. Necessary, door detail. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Figure 19. Detail, interior, women's necessary, 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Part of the lath in the ceiling of the necessary is split; there has been some replacement with sawn lath. Lath nails in a piece of split lath removed from the ceiling probably postdate 1830, while nails used in the seats are cut and probably postdate 1840. The significance of dating these nails is minimal as the interiors could have been finished at any time after the construction of the building.

The ceiling and columns of the recessed entrance to the necessaries were recently replaced by the present owners, the Amlongs. They replaced the round columns with square posts. The brick floor laid in a herringbone pattern, if not original, is certainly early.

In the absence of documentary material it is difficult to date this structure. It would probably be safe to say that it was built as early as the house, c. 1820, and possibly before.

The Icehouse

The icehouse, located sixty-six feet northwest of the mansion, is one of the most striking structures at Huntley, and one that differs from most other Virginia icehouses known to the author. It exhibits quality of design and workmanship seldom seen in a utilitarian structure. Most icehouses are square, a simple form which would offer easier construction than the round structure at Huntley. Not only is this structure round, but the roof is hemispherical, forming a complete circular dome. Construction of the dome is all headers. Some of the bricks are fired to a dark color but there is no discernible pattern in the brick work.

All of the structure is below ground. At the top of the dome is a square opening of quarried stone which is at ground level. The stone here shows the wear of ropes which were used to lower and raise ice. Most other ice houses are at least partially above ground, with some type of superstructure, or reveted into a bank or side of a hill.[57] They require some depth, and insulation, so that they are usually finished in brick or stone. Sawdust was an ingredient commonly used for storing ice, used in alternating layers of block ice and sawdust. Sawdust was certainly used in the icehouse at Huntley, and has covered the floor to such an extent that it is not possible to determine the original depth of the structure. Walking on the present "floor" gives one somewhat the same feeling as walking on a peat bog. The distance is at least twelve feet from the present floor level to the entrance at the top of the dome, and approximately fifteen and one-half feet in diameter.

The dome is strong enough to support the Amlong automobile, which is parked above it in a recently constructed carport. Access to the icehouse may be had directly from the adjacent root cellar. One stone step exists, in the root cellar wall. There may have been a ladder or wooden steps at one time. The walls between the root cellar and icehouse are separate, indicating that the two structures were constructed at different dates.

The Root Cellar

This building, located fifty feet northwest of the mansion and adjacent to the icehouse, consists of a one story brick structure above ground, approximately[36] fifteen feet two inches square, with a full cellar below ground level. Access to the cellar is through steep steps of rough cut stone, located on the right side of the structure. Access to the icehouse is directly opposite.

Figure 20. Detail, dome and ground level opening, icehouse. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

Figure 21. Detail, icehouse door to root cellar. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett. |

Figure 22. Detail, root cellar entrance to icehouse. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett. |

Evidence of ventilators can be seen on both front and rear. These were barred openings approximately six inches deep with vents to the surface, which were finished with brick and faced with quarried stone at ground level. The bars are now gone, but they were horizontal, instead of vertical as are those in the storage rooms adjacent to the necessary and of approximately the same size. There is no shelving or other built-in furniture to indicate the use of the cellar. Since the room above and the roof are replacements, there is little indication of actual use, and the name "root cellar" has been used only for convenience.

The cellar walls are brick, laid in common bond, with three courses of stretchers to one of headers. This bond is uniform for the structure, above and below ground. The average size of bricks is eight and three-eighths by four by two and one-half inches. The plain cornice is uniform, probably indicating that the roof was originally hipped.

With the exception of the brick walls, which stand substantially as constructed, the structure has been entirely rebuilt. Windows in these walls are set into brick arches which are decorative rather than structural. The recessed windows of the building like those in the mansion house are of particular interest.

Dairy and Springs

A dairy or springhouse is located at the base of the hill, some one hundred fifty-six feet southeast of the mansion house, near the point where the south driveway to Huntley meets Harrison Lane. This spring, and the one immediately across the road, form the source of the south branch of Little Hunting Creek, from which derived the early name of Huntley, "Hunting Creek Farm." The springhouse is brick, now overgrown and filled almost completely so that there is no flow of water and original use is difficult to ascertain. The structure may have had a door and shelves in the brick wall. The roof is arched, one brick course deep, and the structure is reveted into the hillside.

There is another spring on the hill to the northwest above the mansion house. This, too, is encased with bricks, all below ground, and could have furnished water to the house through gravity flow. Since both this cistern type spring and the springhouse below the mansion house are probably contemporary, the lower one may have served exclusively as a dairy.

At least two other springs or shallow wells also exist on the property, providing the headwaters for Barnyard Creek, and for part of Dogue Creek.

Early Structures No Longer Standing

Though barns existed until the 1950's, none of these, as evidenced by photographs, would seem to date from the period of construction of the house. Some one hundred seventy-one feet west of the tenant house, and in a straight line with the main house, are the remains of a large brick foundation. This foundation supported a sizeable structure in the Huntley complex, which may have been a barn. The ruins are rectangular, and approximately thirty-three by sixty feet.

Figure 23. Dairy and springhouse, viewed from the southeast. 1969. Photo by Wm. Edmund Barrett.

None of the storage rooms in the outbuildings show any evidence of ever having been used as a smoke house, though the structure over the root cellar may have been used for that purpose. It has been completely remodeled inside, including a floor and roof, and any evidence of smoke house use has been eradicated. Though one would expect to find, in a complete southern plantation complex, barns, slave quarters, and a smoke house, none of these now exist at Huntley, as is the case with most surviving eighteenth and nineteenth century mansions.

Chapter 3 Notes

[51] All quotes in this section unless otherwise credited are from E. Blaine Cliver who visited the site with the author on November 11, 1969, and taped his comments. Mr. Cliver is with the firm of Geoffrey W. Fairfax, AIA, Honolulu, Hawaii, where he is working as restoration architect for Iolani Palace. Calder Loth, architectural historian with the Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission visited the site with the author on May 12, 1969. Their comments were of immeasurable value in the investigation.

[52] All measurements are approximate, and are only used to suggest scale and distance.

[53] In this area examples include Arlington House, 1802-17; Tudor Place, about 1815; and Oatlands, Loudoun County, 1800-27.

[54] Similar moldings may be found at Sully, 1794, Fairfax County, and at Monticello, about 1770-1808.

[55] This was a relatively common cornice line in the Washington area. It appears on, among others, Earps Ordinary in Fairfax, last half of the eighteenth century; Millers House, Colvin Run, about 1825; servants wing of Decatur House, 1818, Washington.

[56] This design is used, among other places, in the outbuildings at Bremo, about 1820, Fluvanna County, and the jail, about 1848, Palmyra. In the immediate area the use is known to the author only in the barn at the Oxon Hill Childrens Museum, Prince Georges County, Maryland, early nineteenth century.

[57] The icehouse at Belle Grove, Middletown, late eighteenth century, is the former type, while Woodlawn, Fairfax County, 1805, is believed to have been the latter type.

Figure 24. Architect George Hadfield's exhibit at the Royal Academy, 1780-82. |

Figure 25. Hadfield's design, bed chamber story plan. Courtesy, Avery Library, Columbia University |

THE ARCHITECT OF HUNTLEY