Project Gutenberg's Troy and its Remains, by Henry (Heinrich) Schliemann

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license

Title: Troy and its Remains

Author: Henry (Heinrich) Schliemann

Editor: Philip Smith

Release Date: March 23, 2014 [EBook #45190]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TROY AND ITS REMAINS ***

Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

with special thanks to Stephen Rowland for help with the Greek.

|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed.

Illustrations

have been moved from mid-paragraph for ease of reading.

In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol  ,

or directly on the image,

will bring up a larger version of the image. ,

or directly on the image,

will bring up a larger version of the image.

Contents

Index

List of Illustrations

(etext transcriber's note) |

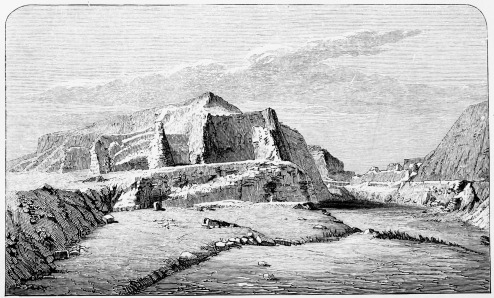

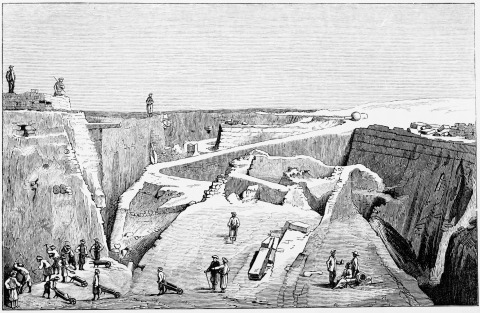

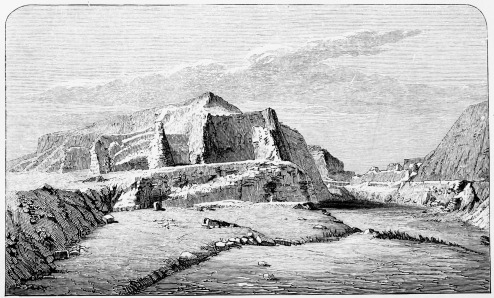

PLATE I.

VIEW OF HISSARLIK FROM THE NORTH. Frontispiece.

After the Excavations.

{i}

T R O Y

AND ITS REMAINS;

A NARRATIVE OF RESEARCHES AND DISCOVERIES

MADE ON THE SITE OF ILIUM,

AND IN THE TROJAN PLAIN.

BY DR. HENRY SCHLIEMANN.

Translated with the Author’s Sanction.

EDITED

BY PHILIP SMITH, B.A.,

AUTHOR OF THE ‘HISTORY OF THE ANCIENT WORLD,’ AND OF THE

‘STUDENT’S ANCIENT HISTORY OF THE EAST.’

WITH MAP, PLANS, VIEWS, AND CUTS,

REPRESENTING 500 OBJECTS OF ANTIQUITY DISCOVERED ON THE SITE.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

NEW YORK:

SCRIBNER, WELFORD, AND ARMSTRONG.

1875.

{ii}

{iii}

PREFACE BY THE EDITOR.

DR. SCHLIEMANN’S original narrative of his wonderful discoveries on the

spot marked as the site of Homer’s Ilium by an unbroken tradition, from

the earliest historic age of Greece, has a permanent value and interest

which can scarcely be affected by the final verdict of criticism on the

result of his discoveries. If he has indeed found the fire-scathed ruins

of the city whose fate inspired the immortal first-fruits of Greek

poetry, and brought to light many thousands of objects illustrating the

race, language, and religion of her inhabitants, their wealth and

civilization, their instruments and appliances for peaceful life and

war; and if, in digging out these remains, he has supplied the missing

link, long testified by tradition as well as poetry, between the famous

Greeks of history and their kindred in the East; no words can describe

the interest which must ever belong to the first birth of such a

contribution to the history of the world. Or should we, on the other

hand, in the face of all that has been revealed on the very spot of

which the Greeks themselves believed that Homer sang, lean to the

scepticism of the scholar who still says:—“I know as yet of one Ilion

only, that is, the Ilion as sung by Homer, which is not likely to be

found in the trenches of Hissarlik, but rather among the Muses who dwell

on Olympus;” even so a new interest of historic and antiquarian

curiosity would be excited by “the splendid ruins,” as the same high

authority rightly calls those “which{iv} Dr. Schliemann has brought to

light at Hissarlik.” For what, in that case, were the four cities,

whose successive layers of ruins, still marked by the fires that have

passed over them in turn, are piled to the height of fifty feet above

the old summit of the hill? If not even one of them is Troy, what is the

story, so like that of Troy, which belongs to them?

“Trojæ renascens alite lugubri

Fortuna tristi clade iterabitur.”

What is the light that is struggling to break forth from the varied mass

of evidence, and the half-deciphered inscriptions, that are still

exercising the ingenuity of the most able enquirers? Whatever may be the

true and final answer to these questions—and we have had to put on

record a signal proof that the most sanguine investigators will be

content with no answer short of the truth[1]—the vivid narrative

written by the discoverer on the spot can never lose that charm which

Renan has so happily described as “la charme des origines.”

The Editor may be permitted to add, what the Author might not say, that

the work derives another charm from the spirit that prompted the labours

which it records. It is the work of an enthusiast in a cause which, in

our “practical” age, needs all the zeal of its remaining devotees, the

cause of learning for its own sake. But, in this case, enthusiasm has

gone hand in hand with the practical spirit in its best form. Dr.

Schliemann judged rightly in prefixing to his first work the simple

unaffected record of that discipline in adversity and self-reliance,

amidst which he at once educated himself and obtained the means of

gratifying his ardent desire to throw new light on the{v} highest problems

of antiquity, at his own expense. His readers ought to know that,

besides other large contributions to the cause of learning, the cost of

his excavations at Hissarlik alone has amounted to 10,000l.; and this

is in no sense the speculative investment of an explorer, for he has

expressed the firm resolution to give away his collection, and not to

sell it.

Under this sense of the high and lasting value of Dr. Schliemann’s work,

the present translation has been undertaken, with the object of laying

the narrative before English readers in a form considerably improved

upon the original. For this object the Editor can safely say, on behalf

of the Publisher and himself, that no pains and cost have been spared;

and Dr. Schliemann has contributed new materials of great value.

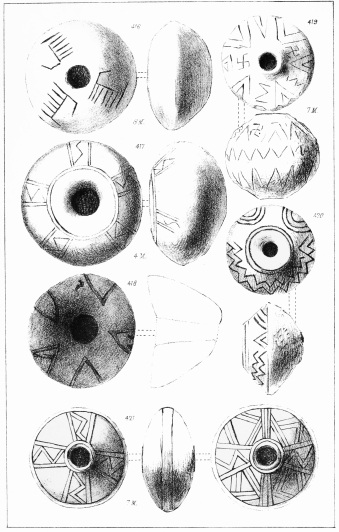

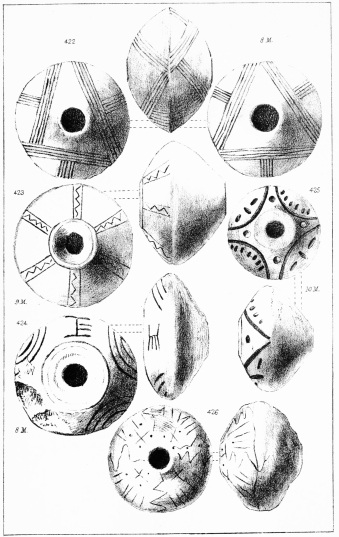

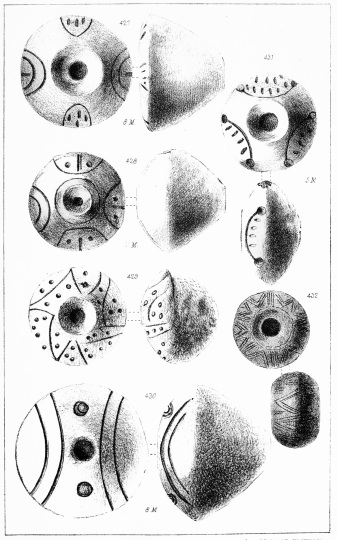

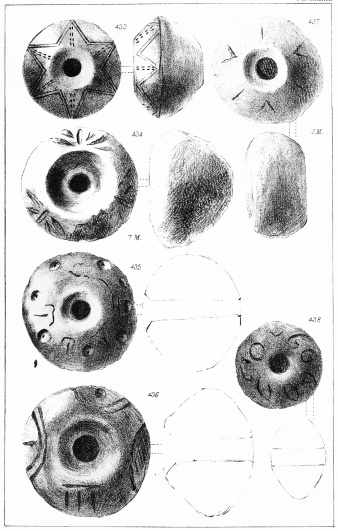

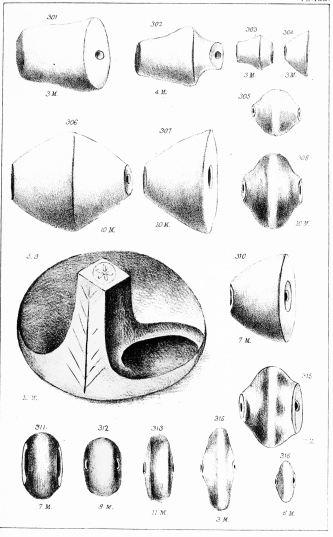

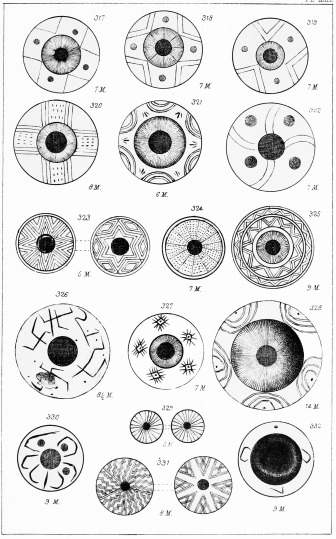

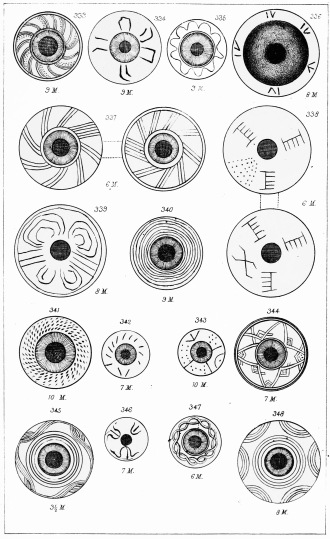

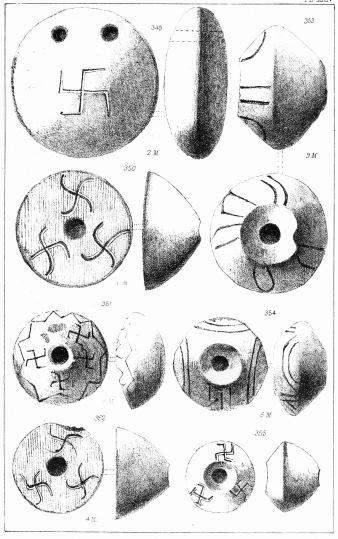

The original work[2] was published, at the beginning of this year, as an

octavo volume, accompanied by a large quarto “Atlas” of 217 photographic

plates, containing a Map, Plans, and Views of the Plain of Troy, the

Hill of Hissarlik, and the excavations, with representations of upwards

of 4000 objects selected from the 100,000 and more brought to light by

Dr. Schliemann, which were elaborately described in the letter-press

pages of the Atlas. The photographs were taken for the most part from

drawings; and Dr. Schliemann is the first to acknowledge that their{vi}

execution left much to be desired. Many of his original plans and

drawings have been placed at our disposal; and an especial

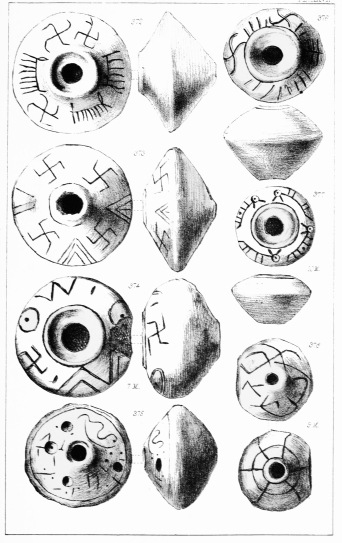

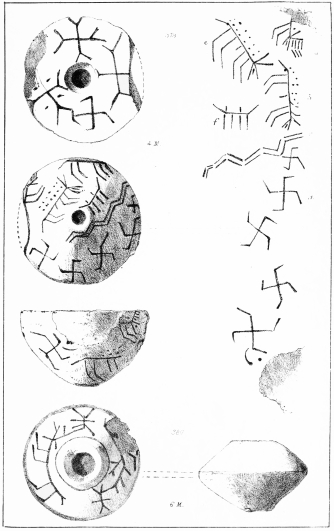

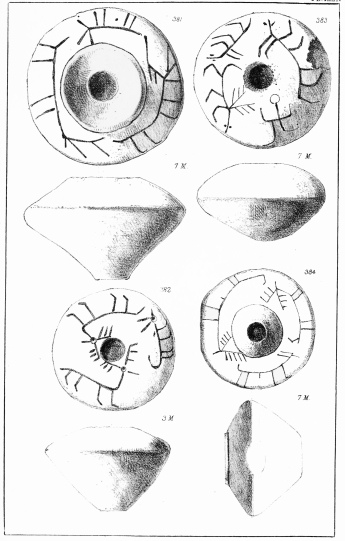

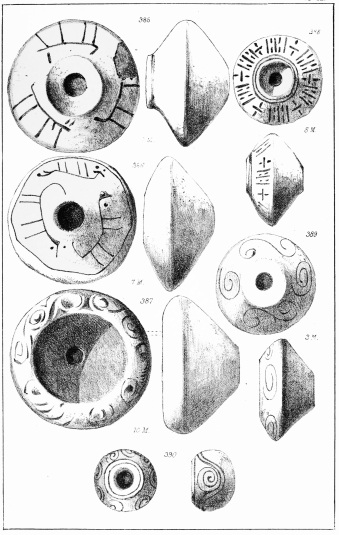

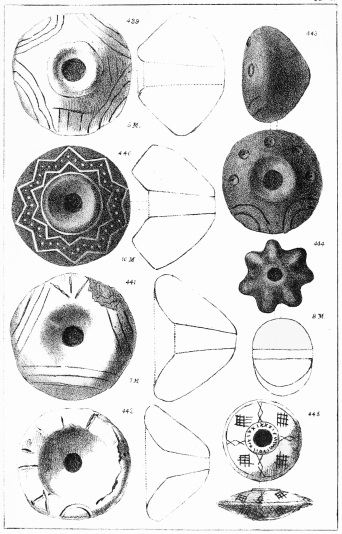

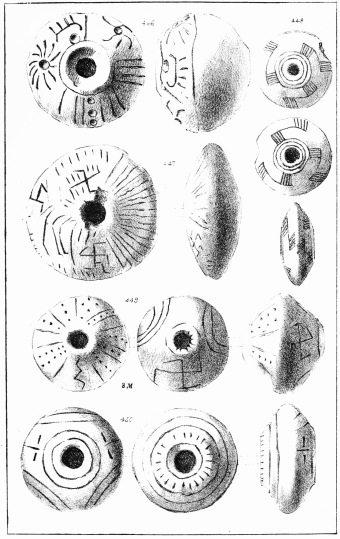

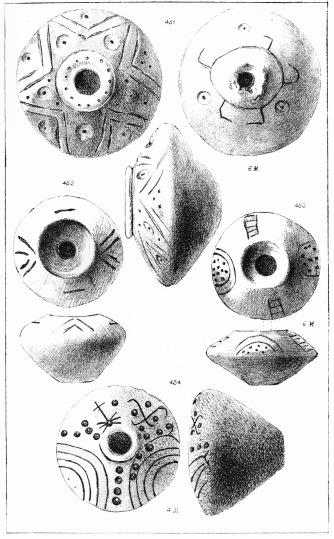

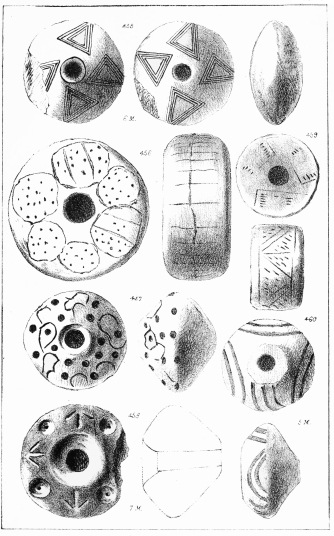

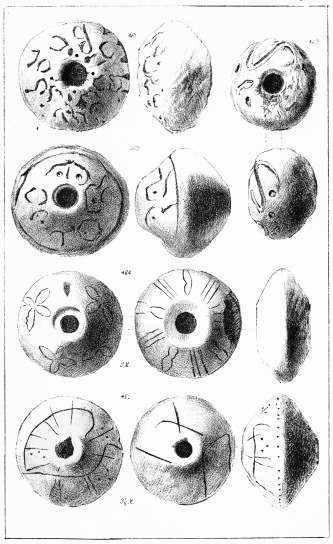

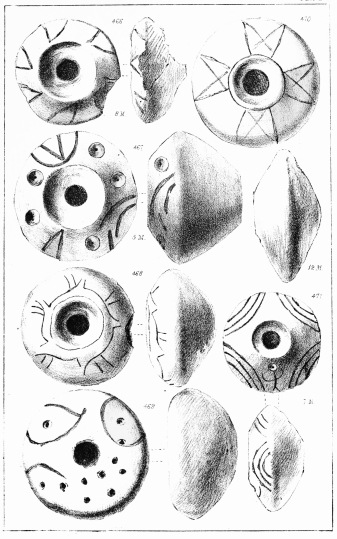

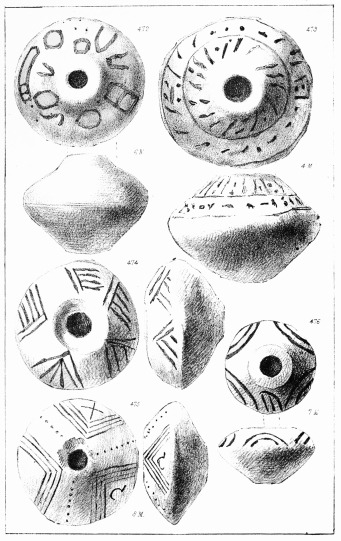

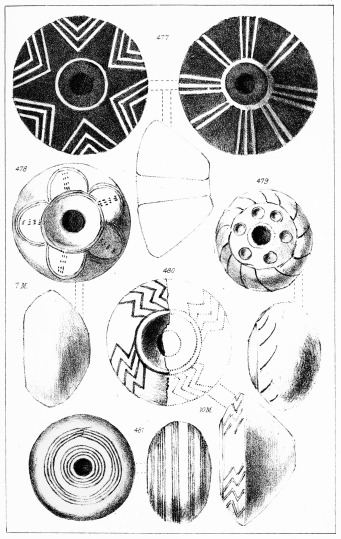

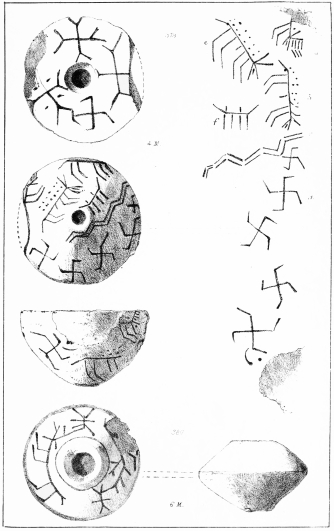

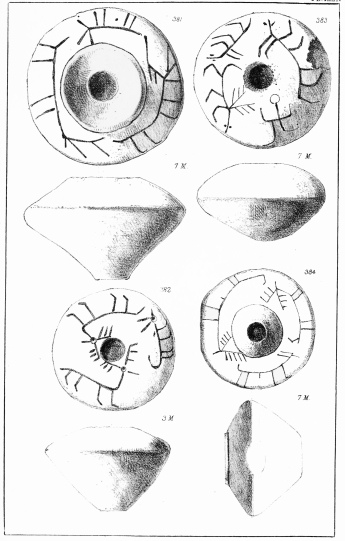

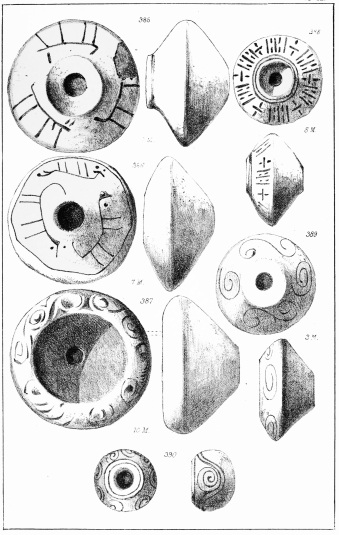

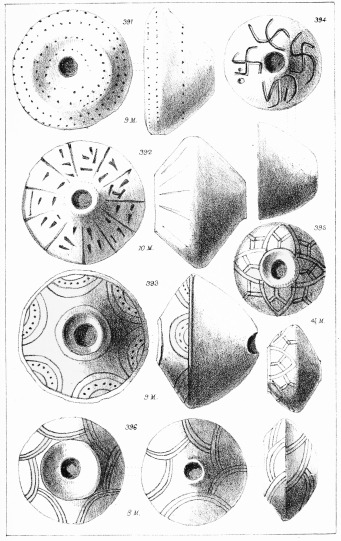

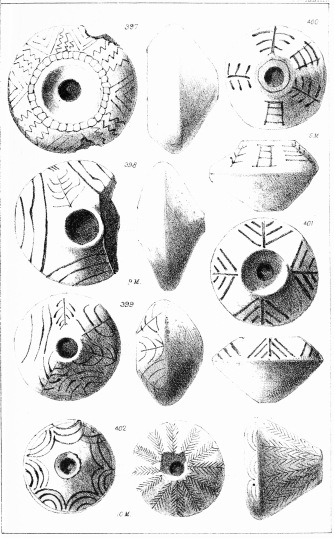

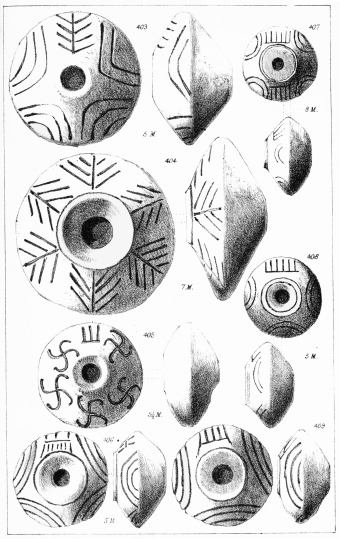

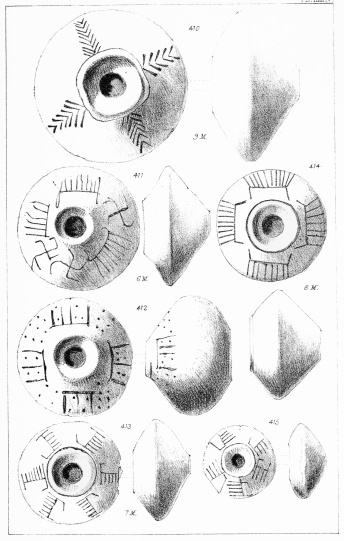

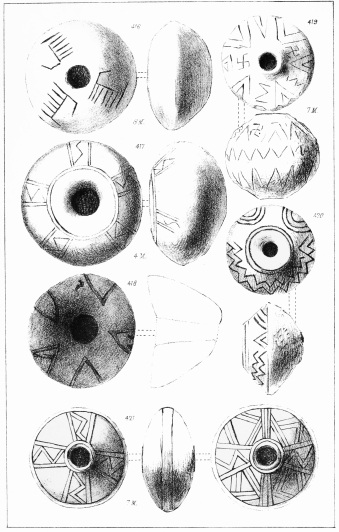

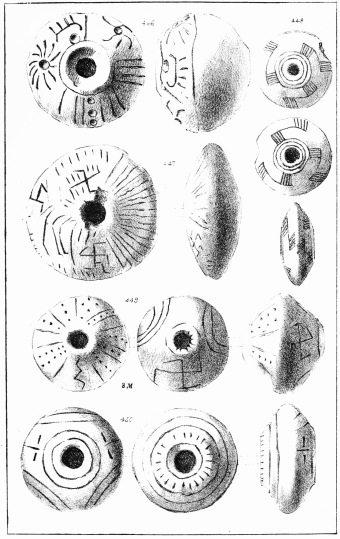

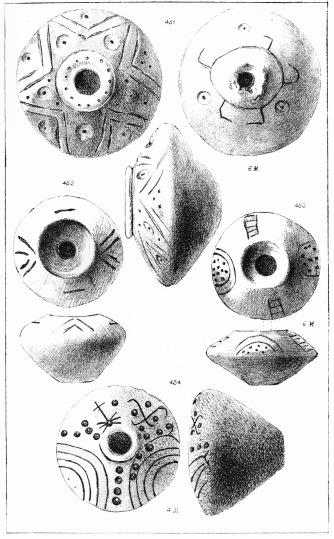

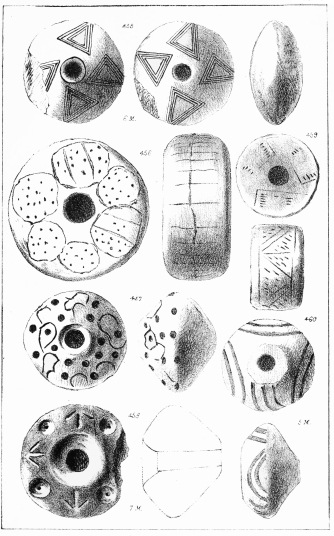

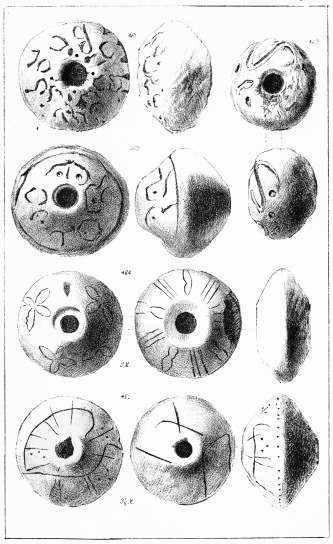

acknowledgment is due both to Dr. Schliemann and Monsieur Émile Burnouf,

the Director of the French School at Athens, for the use of the

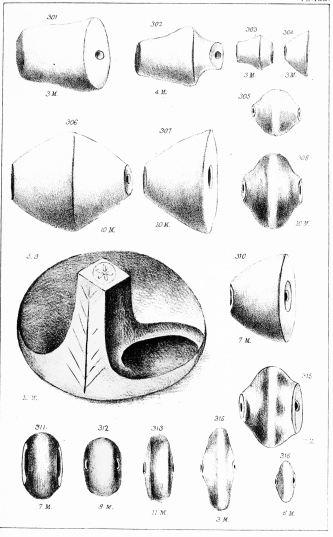

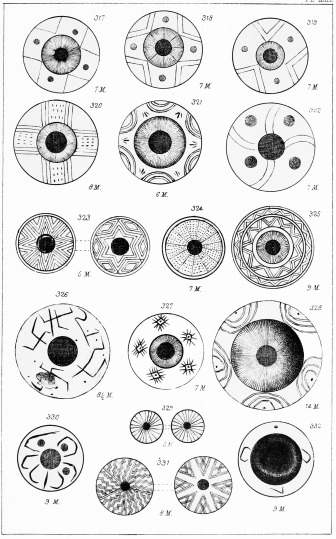

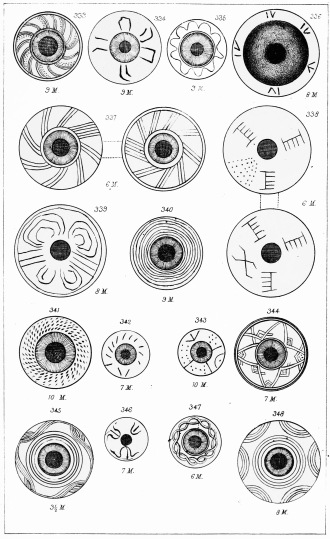

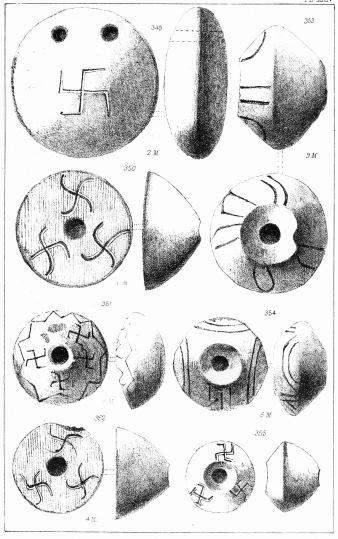

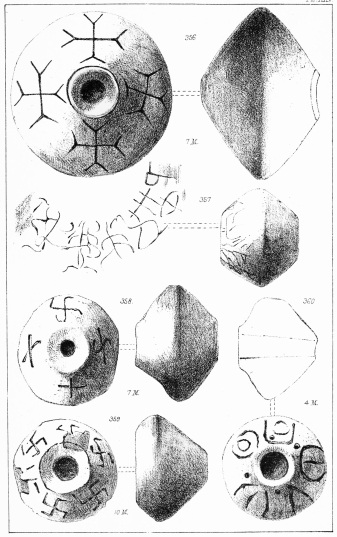

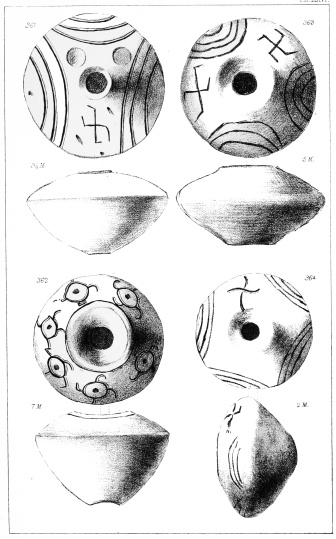

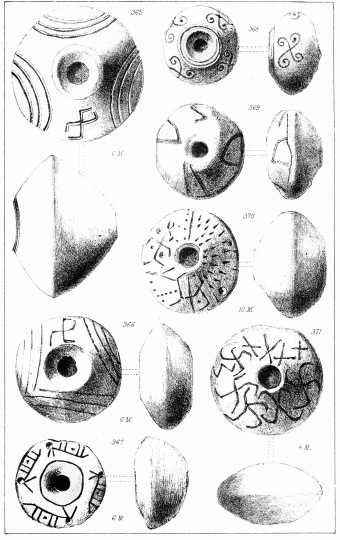

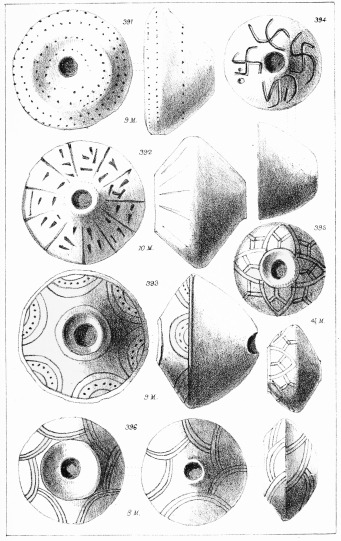

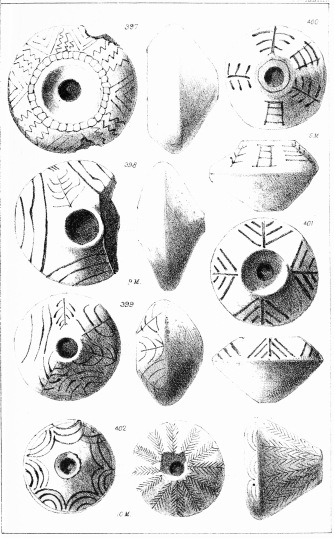

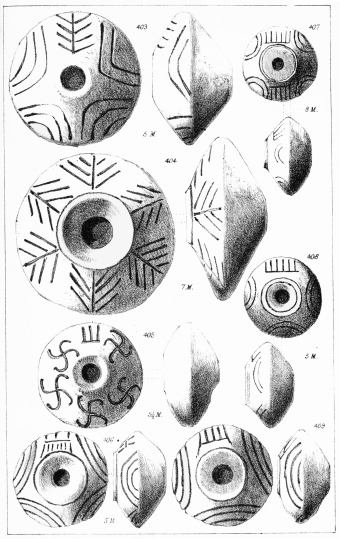

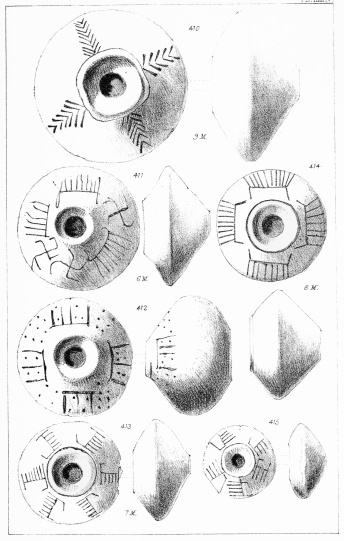

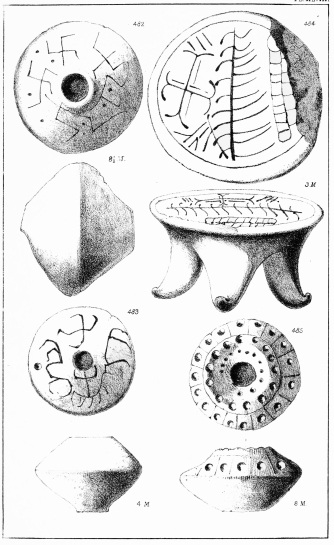

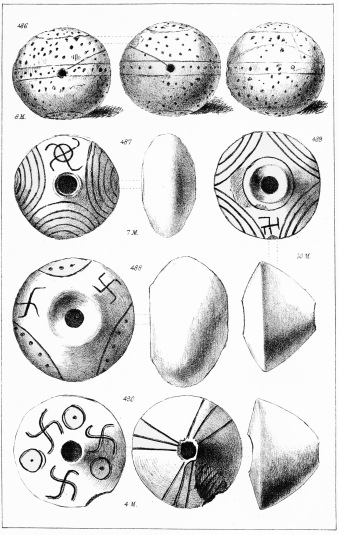

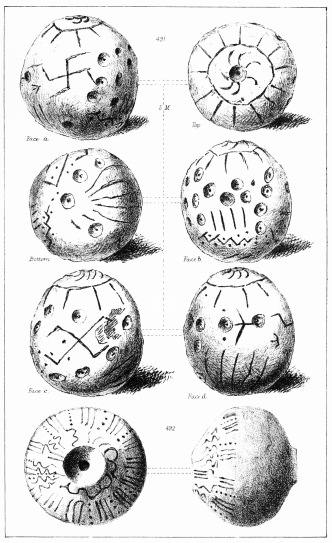

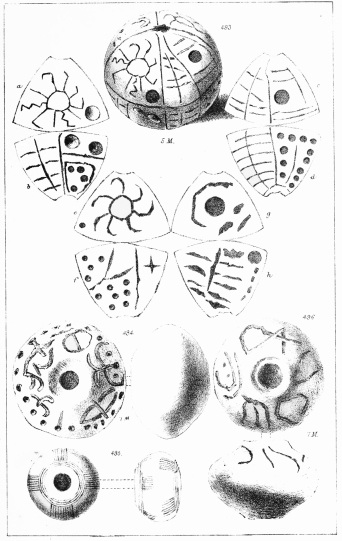

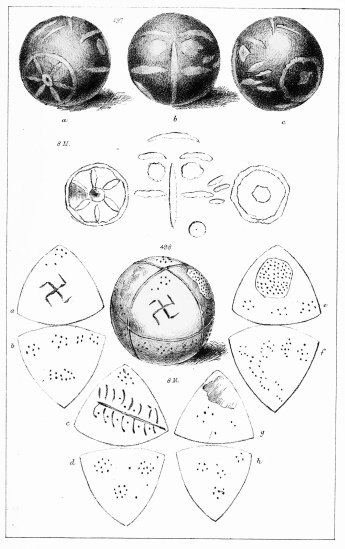

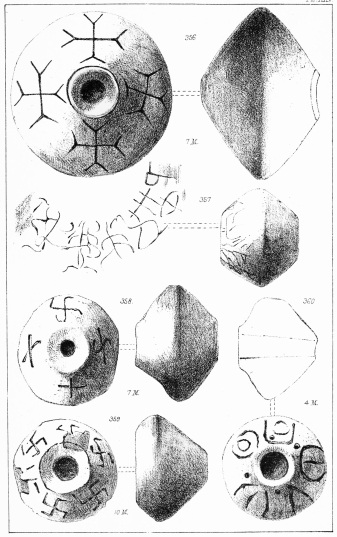

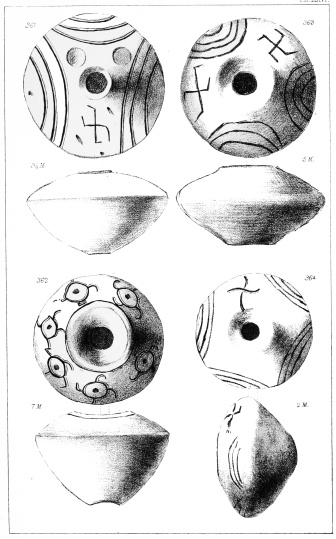

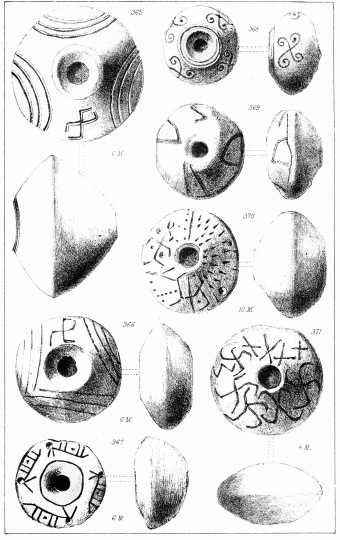

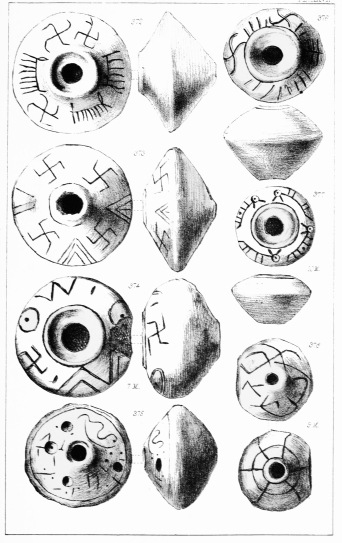

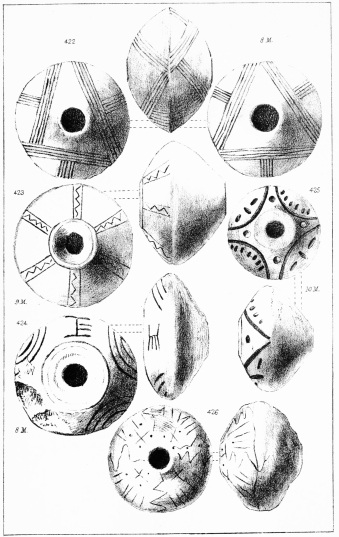

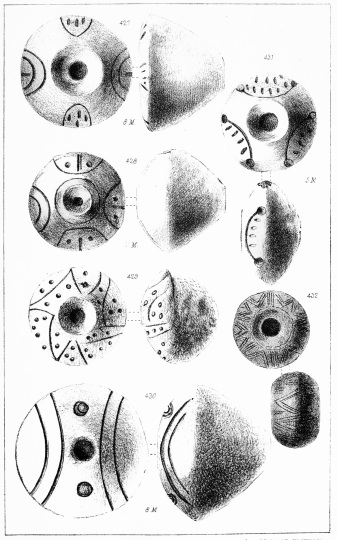

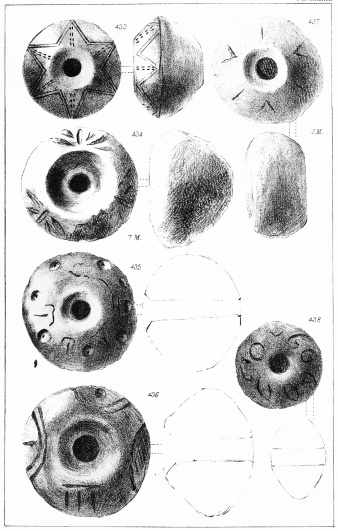

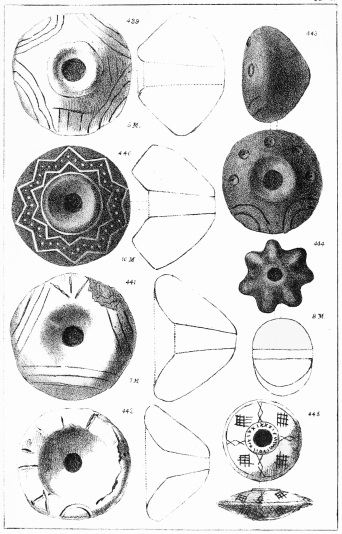

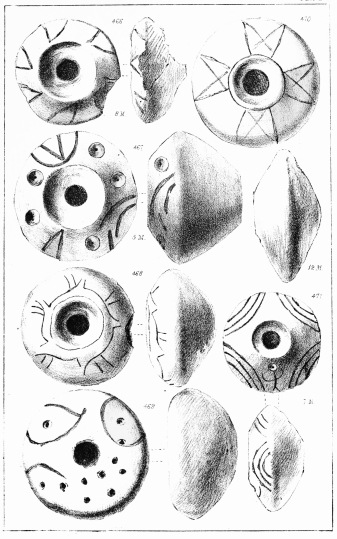

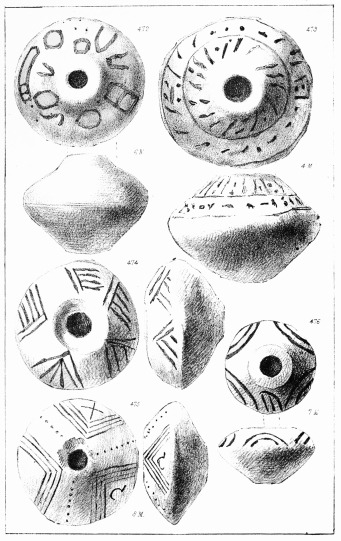

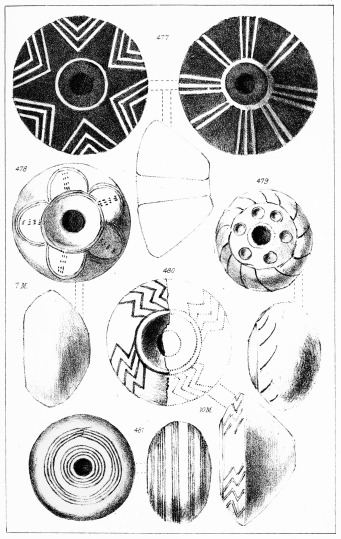

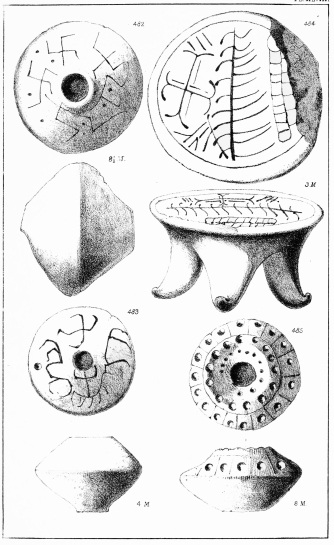

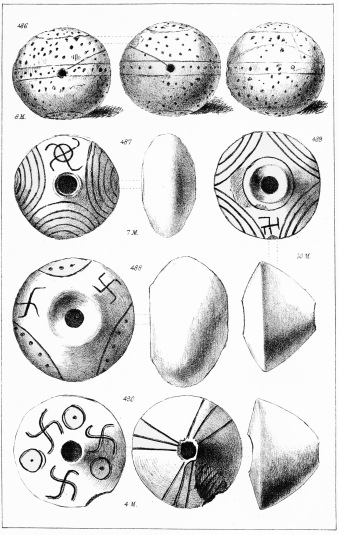

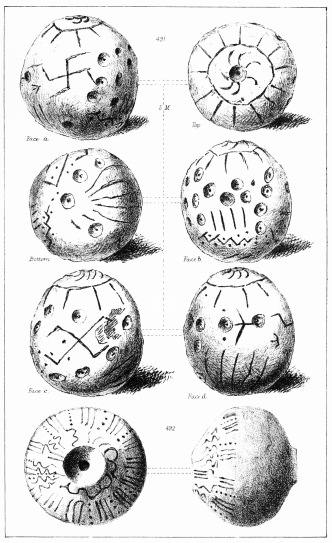

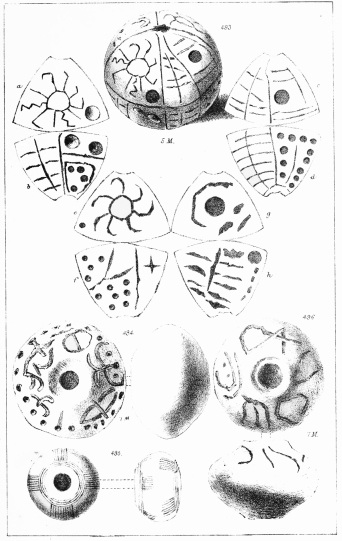

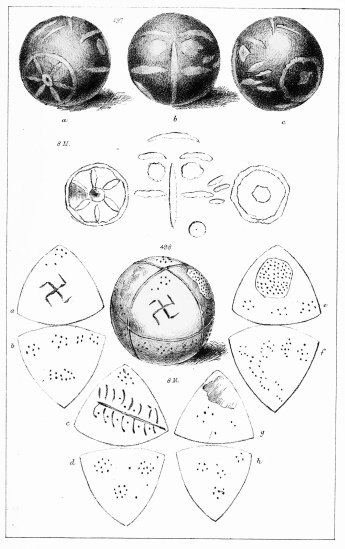

admirable drawings of the terra-cotta whorls and balls made by M.

Burnouf and his accomplished daughter. A selection of about 200 of these

objects, which are among the most interesting of Dr. Schliemann’s

discoveries, occupies the 32 lithographic plates at the end of this

volume. With the exception of the first three Plates (XXI.-XXIII.),

which are copied from the Atlas, in order to give a general view of the

sections of the whorls and the chief types of the patterns upon

them, all the rest are engraved from M. Burnouf’s drawings. They are

given in the natural size, and each whorl is accompanied by its

section. The depth at which each object was found among the layers of

débris is a matter of such moment (as will be seen from Dr.

Schliemann’s work) that the Editor felt bound to undertake the great

labour of identifying each with the representation of the same object in

the Atlas, where the depth is marked, to which, unfortunately, the

drawings gave no reference. The few whorls that remain unmarked with

their depth have either escaped this repeated search, or are not

represented in the Atlas. The elaborate descriptions of the material,

style of workmanship, and supposed meanings of the patterns, which M.

Burnouf has inscribed on most of his drawings, are given in the “List of

Illustrations.” The explanations of the patterns are, of course, offered

only as conjectures, possessing the value which they derive from M.

Burnouf’s profound knowledge of Aryan antiquities. Some of the

explanations of the patterns are Dr. Schliemann’s; and the Editor has

added a few descriptions, based on a careful attempt to analyze and

arrange the patterns according to{vii} distinct types. Most of these types

are exhibited on Plates XXII. and XXIII.

The selection of the 300 illustrations inserted in the body of the work

has been a matter of no ordinary labour. One chief point, in which the

present work claims to be an improvement on the original, is the

exhibition of the most interesting objects in Dr. Schliemann’s

collection in their proper relation to the descriptions in his text. The

work of selection from 4000 objects, great as was the care it required,

was the smallest part of the difficulty. It is no disparagement to Dr.

Schliemann to recognize the fact that, amidst his occupations at the

work through the long days of spring and summer, and with little

competent help save from Madame Schliemann’s enthusiasm in the cause,

the objects thrown on his hands from day to day could only be arranged

and depicted very imperfectly. The difficulty was greatly enhanced by a

circumstance which should be noticed in following the order of Dr.

Schliemann’s work. It differed greatly from that of his forerunners in

the modern enterprise of penetrating into the mounds that cover the

primeval cities of the world. When, for example, we follow Layard into

the mound of Nimrud, and see how the rooms of the Assyrian palaces

suddenly burst upon him, with their walls lined with sculptured and

inscribed slabs, we seem almost to be reading of Aladdin’s descent into

the treasure-house of jewels. But Schliemann’s work consisted in a

series of transverse cuttings, which laid open sections of the various

strata, from the present surface of the hill to the virgin soil. The

work of one day would often yield objects from almost all the strata;

and each successive trench repeated the old order, more or less, from

the remains of Greek Ilium to those of the first settlers on the hill.

The marvel is that Dr. Schliemann should have been able to preserve any

order at all, rather than that he was{viii} obliged to abandon the attempt in

the later Plates of his Atlas (see p. 225); and special thanks are due

for his care in continuing to note the depths of all the objects found.

This has often given the clue to our search, amidst the mixed objects of

a similar nature on the photographic Plates, for those which he

describes in his text, where the figures referred to by Plate and Number

form the exception rather than the rule. We believe that the cases in

which we have failed to find objects really worth representing, or in

which an object named in the text may have been wrongly identified in

the Plates, are so few as in no way to affect the value of the work. How

much, on the other hand, its value is increased by the style in which

our illustrations have been engraved, will be best seen by a comparison

with the photographic Plates. It should be added that the present work

contains all the illustrations that are now generally accessible, as the

Atlas is out of print, and the negatives are understood to be past

further use.

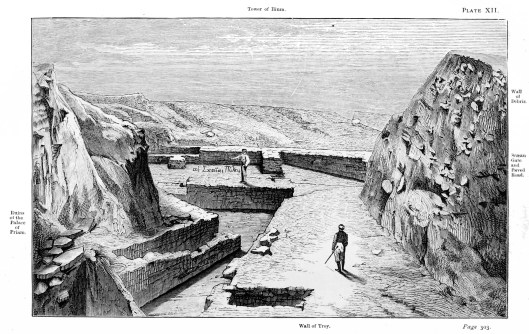

Twelve of the views (Plates II., III.,

IV., V., VI., VII. A and B, IX.,

X., XI. A and B, and XII., besides the Great Altar, No. 188) were

engraved by Mr. Whymper; all the other views and cuts by Mr. James D.

Cooper; and the lithographed map, plans, and plates of whorls and balls

by Messrs. Cooper and Hodson. In the description appended to each

engraving all that is valuable in the letter-press to the Atlas has been

incorporated, and the depth at which the object was found is added. Some

further descriptions of the Plates are given in the “List of

Illustrations.”

The text of Dr. Schliemann’s work has been translated by Miss L. Dora

Schmitz, and revised throughout by the Editor. The object kept in view

has been a faithful rendering of the Memoirs, in all the freshness due

to their composition on the spot during the progress of the work. That

mode of composition, it is true, involved not a few of{ix} those mistakes

and contradictions on matters of opinion, due to the novelty and the

rapid progress of the discoveries, which Dr. Schliemann has confessed

and explained at the opening of his work (see p. 12). To have attempted

a systematic correction and harmonizing of such discrepancies would have

deprived the work of all its freshness, and of much of its value as a

series of landmarks in the history of Dr. Schliemann’s researches, from

his first firm conviction that Troy was to be sought in the Hill of

Hissarlik, to his discovery of the “Scæan Gate” and the “Treasure of

Priam.” The Author’s final conclusions are summed up by himself in the

“Introduction;” and the Editor has thought it enough to add to those

statements, which seemed likely to mislead the reader for a time,

references to the places where the correction may be found. On one point

he has ventured a little further. All the earlier chapters are affected

by the opinion, that the lowest remains on the native rock were those of

the Homeric Troy, which Dr. Schliemann afterwards recognized in the

stratum next above. To avoid perpetual reference to this change of

opinion, the Editor has sometimes omitted or toned down the words “Troy”

and “Trojan” as applied to the lowest stratum, and, both in the

“Contents” and running titles, and in the descriptions of the

Illustrations, he has throughout applied those terms to the discoveries

in the second stratum, in accordance with Dr. Schliemann’s ultimate

conclusion.

In a very few cases the Editor has ventured to correct what seemed to

him positive errors.[3] He has not deemed it any part of his duty to

discuss the Author’s opinions or to review his conclusions. He has,

however, taken such{x} opportunities as suggested themselves, to set Dr.

Schliemann’s statements in a clearer light by a few illustrative

annotations. Among the rest, the chief passages cited from Homer are

quoted in full, with Lord Derby’s translation, and others have been

added (out of many more which have been noted), as suggesting remarkable

coincidences with the objects found by Dr. Schliemann.

From the manner in which the work was composed, and the great importance

attached by Dr. Schliemann to some leading points of his argument, it

was inevitable that there should be some repetitions, both in the

Memoirs themselves, and between them and the Introduction. These the

Editor has rather endeavoured to abridge than completely to remove. To

have expunged them from the Memoirs would have deprived these of much of

the interest resulting from the discussions which arose out of the

discoveries in their first freshness; to have omitted them from the

Introduction would have marred the completeness of the Author’s summary

of his results. The few repetitions left standing are a fair measure of

the importance which the Author assigns to the points thus insisted on.

A very few passages have been omitted for reasons that would be evident

on a reference to the original; but none of these omissions affect a

single point in Dr. Schliemann’s discoveries.

The measures, which Dr. Schliemann gives with the minutest care

throughout his work, have been preserved and converted from the French

metric standard into English measures. This has been done with great

care, though in such constant conversion some errors must of course have

crept in; and approximate numbers have often been given to avoid the

awkwardness of fractions, where minute accuracy seemed needless. In

many cases both the French and English measures are given, not only{xi}

because Dr. Schliemann gives both (as he often does), but for another

sufficient reason. A chief key to the significance of the discoveries is

found in the depths of the successive strata of remains, which are

exhibited in the form of a diagram on page 10. The numbers which express

these in Meters[4] are so constantly used by Dr. Schliemann, and are

so much simpler than the English equivalents, that they have been kept

as a sort of “memory key” to the strata of remains. For the like reason,

and for simplicity-sake, the depths appended to the Illustrations are

given in meters only. The Table of French and English Measures on page

56 will enable the reader to check our conversions and to make his own.

The Editor has added an Appendix, explaining briefly the present state

of the deeply interesting question concerning the Inscriptions which

have been traced on some of the objects found by Dr. Schliemann.

With these explanations the Editor might be content to leave the work to

the judgment of scholars and of the great body of educated persons, who

have happily been brought up in the knowledge and love of Homer’s

glorious poetry, “the tale of Troy divine,” and of

“Immortal Greece, dear land of glorious lays.”

Long may it be before such training is denied to the imagination of the

young, whether on the low utilitarian ground, or on the more specious

and dangerous plea of making it the select possession of the few who can

acquire it “thoroughly":

Νήπιοι, οὐκ ἴσασιν ὅσῳ πλέον ἥμισυ παντός.

To attempt a discussion of the results of Dr. Schliemann’s{xii} discoveries

would be alike beyond the province of an Editor, and premature in the

present state of the investigation. The criticisms called forth both in

England and on the Continent, during the one year that has elapsed since

the publication of the work, are an earnest of the more than ten years’

duration of that new War of Troy for which it has given the signal. The

English reader may obtain some idea of the points that have been brought

under discussion by turning over the file of the “Academy” for the

year, not to speak of many reviews of Schliemann’s work in other

periodicals and papers. Without plunging into these varied discussions,

it may be well to indicate briefly certain points that have been

established, some lines of research that have been opened, and some

false issues that need to be avoided.

First of all, the integrity of Dr. Schliemann in the whole matter—of

which his self-sacrificing spirit might surely have been a sufficient

pledge—and the genuineness of his discoveries, are beyond all

suspicion. We have, indeed, never seen them called in question, except

in what appears to be an effusion of spite from a Greek, who seems to

envy a German his discoveries on the Greek ground which Greeks have

neglected for fifteen centuries.[5] In addition to the consent of

scholars, the genuineness and high antiquity of the objects in Dr.

Schliemann’s collection have been specially attested by so competent a

judge as Mr. Charles Newton, of the British Museum, who went to Athens

for the express purpose of examining them.[6]{xiii} A letter by Mr. Frank

Calvert, who is so honourably mentioned in the work, deserves special

notice for the implied testimony which it bears to Dr. Schliemann’s good

faith, while strongly criticising some of his statements.[7]

Among the false issues raised in the discussion, one most to be avoided

is the making the value of Dr. Schliemann’s discoveries dependent on the

question of the site of Troy as determined by the data furnished by

the Iliad. The position is common to Schliemann and his adverse critics,

that Homer never saw the city of whose fate he sang;—because, says

Schliemann, it had long been buried beneath its own ashes and the

cities, or the ruins of the cities, built above it;—because, say the

objectors, Homer created a Troy of his own imagination. The former

existence and site of Troy were known to Homer—says Schliemann—by the

unbroken tradition belonging to the spot where the Greek colonists

founded the city which they called by the same name as, and believed to

be the true successor of, the Homeric Ilium. Of this, it is replied, we

know nothing, and we have no other guide to Homer’s Troy save the data

of the Iliad. Be it so; and if those data really point to Hissarlik—as

was the universal opinion of antiquity, till a sceptical grammarian

invented another site, which all scholars now reject—as was also the

opinion of modern scholars, till the new site of Bunarbashi was invented

by Lechevalier to suit the Iliad, and accepted by many critics, but

rejected by others, including the high authority of Grote—then the

conclusion is irresistible, that Schliemann has found the Troy of which

Homer had heard through the lasting report of poetic fame: Ἡμεῖς δὲ

κλέος οἶον ἀκούομεν{xiv}.[8] But the corresponding negative does not

follow; for, if Homer’s Troy was but a city built in the ethereal region

of his fancy, his placing it at Bunarbashi, or on any other spot, could

not affect the lost site of the true Troy, if such a city ever

existed, and therefore can be no objection to the argument, that the

discovery of an ancient city on the traditional site of the heroic Troy

confirms the truth of the tradition on both points—the real existence

of the city, as well as its existence on this site. The paradox—that

Troy never existed and that Bunarbashi was its site—was so far

confirmed by Schliemann that he dug at Bunarbashi, and found clear

evidence that the idea of a great city having ever stood there is a mere

imagination. The few remains of walls, that were found there, confirm

instead of weakening the negative conclusion; for they are as utterly

inadequate to be the remains of the “great, sacred, wealthy Ilium,” as

they are suitable to the little town of Gergis, with which they are now

identified by an inscription. In short, that the real city of Troy could

not have stood at Bunarbashi, is one of the most certain results of

Schliemann’s researches.

The same sure test of downright digging has finally disposed of all the

other suggested sites, leaving by the “method of exhaustion” the

inevitable conclusion, that the only great city (or succession of

cities), that we know to have existed in the Troad before the historic

Grecian colony of Ilium, rose and perished—as the Greeks of Ilium

always said it did—on the ground beneath their feet, upon{xv} the Hill of

Hissarlik. And that Homer, or—if you please—the so-called Homeric

bards, familiar with the Troad, and avowedly following tradition, should

have imagined a different site, would be, at the least, very surprising.

This is not the place for an analysis of the Homeric local evidence;

but, coming fresh from a renewed perusal of the Iliad with a view to

this very question, the Editor feels bound to express the conviction

that its indications, while in themselves consistent with the site of

Hissarlik, can be interpreted in no other way, now that we know what

that site contains.[9]

Standing, as it does, at the very point of junction between the East and

West, and in the region where we find the connecting link between the

primitive Greeks of Asia and Europe,[10] the Hill of Hissarlik answers

at once to the primitive type of a Greek city, and to the present

condition of the primeval capitals of the East. Like so many of the

first, in Greece, Asia Minor, and Italy, the old city was a hill-fort,

an Acropolis built near but not close upon the sea, in a situation

suited at once for defence against the neighbouring barbarians, and for

the prosecution of that commerce, whether by its own maritime

enterprise, or by intercourse with foreign voyagers, of which the

copper, ivory, and other objects from the ruins furnish decisive{xvi}

proofs.[11] This type is as conspicuously wanting at Bunarbashi, as it

is well marked by the site of Hissarlik.

Like the other great oriental capitals of the Old World, the present

condition of Troy is that of a mound, such as those in the plain of the

Tigris and Euphrates, offering for ages the invitation to research,

which has only been accepted and rewarded in our own day. The

resemblance is so striking, as to raise a strong presumption that, as

the mounds of Nimrud and Kouyunjik, of Khorsabad and Hillah, have been

found to contain the palaces of the Assyrian and Babylonian kings, so we

may accept the ruins found in the mound of Hissarlik as those of the

capital of that primeval empire in Asia Minor, which is indicated by the

Homeric tradition, and proved to have been a reality by the Egyptian

monuments.[12]

This parallel seems to throw some light on a question, concerning which

Dr. Schliemann is forced to a result which disappointed himself, and

does not appear satisfactory to us—that of the magnitude of Troy. As

the mounds opened by Layard and his fellow labourers contained only the

“royal quarters,” which towered above the rude buildings of cities the

magnitude of which is attested by abundant proofs, so it is reasonable

to believe that the ruins at Hissarlik are those of the royal quarter,

the only{xvii} really permanent part of the city, built on the hill capping

the lower plateau which lifted the huts of the common people above the

marshes and inundations of the Scamander and the Simoïs. In both cases

the fragile dwellings of the multitude have perished; and the pottery

and other remains, which were left on the surface of the plateau of

Ilium, would naturally be cleared away by the succeeding settlers.

Instead, therefore, of supposing with Schliemann, that Homer’s poetical

exaggeration invented the “Pergamus,” we would rather say that he

exalted the mean dwellings that clustered about the Pergamus into the

“well-built city” with her “wide streets.”

We cannot sympathize with the sentimental objection that, in proportion

as the conviction grows that the Troy of Homer has been found, his

poetry is brought down from the heights of pure imagination. Epic

Poetry, the very essence of which is narrative, has always achieved its

noblest triumphs in celebrating events which were at least believed to

be real, not in the invention of incidents and deeds purely imaginary.

The most resolute deniers of any historic basis for the story of Troy

will admit that neither the scene nor the chief actors were invented by

Homer, or, if you please, the Homeric poets, who assuredly believed the

truth of the traditions to which the Iliad gave an immortal form. Any

discovery which verifies that belief strengthens the foundation without

impairing the superstructure, and adds the interest of truthfulness to

those poetic beauties which remain the pure creation of Homer.

Leaving the Homeric bearings of the question to the discussion of which

no speedy end can be anticipated, all are agreed that Dr. Schliemann’s

discoveries have added immensely to that growing mass of evidence which

is tending to solve one of the most interesting problems in the history

of the world, the connection between the East and{xviii} West, especially with

regard to the spread of Aryan civilization.[13] Two points are becoming

clearer every day, the early existence of members of the Greek race on

the shores of Asia, and the essential truth of those traditions about

the Oriental influence on Greek civilization, which, within our own

remembrance, have passed through the stages of uncritical acceptance,

hypercritical rejection, and discriminating belief founded on sure

evidence.

It would seem as if Troy, familiar to our childhood as the point of

contact in poetry between the East and West, were reappearing in the

science of archæology as a link between the eastern and western branches

of the antiquities of the great Aryan family, extending its influence to

our own island in another sense than the legend of Brute the Trojan. How

great an increase of light may soon be expected from the deciphering of

the Inscriptions found at Hissarlik may be inferred, in part, from the

brief account, in the Appendix, of the progress thus far made. In fine,

few dissentients will be found from the judgment of a not too favourable

critic, that “Dr. Schliemann, in spite of his over-great enthusiasm, ...

has done the world an incalculable service.”[14]

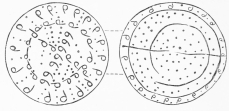

The decipherment of the inscriptions will probably go far to determine

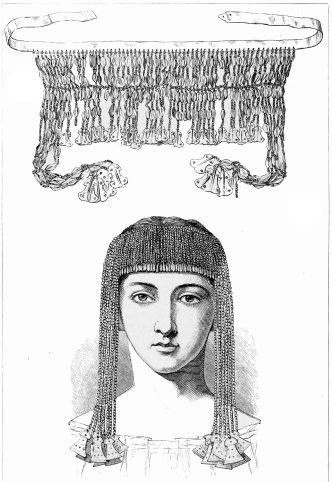

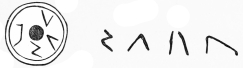

the curious question of the use of the terra-cotta whorls, found in

such numbers in all the four pre-Hellenic strata of remains at

Hissarlik. That they had{xix} some practical purpose may be inferred both

from this very abundance, and from the occurrence of similar objects

among the remains of various early races. Besides the examples given by

Dr. Schliemann, they have been found in various parts of our own island,

and especially in Scotland, but always (we believe) without decorations.

On the other hand, the Aryan emblems and the inscriptions[15] marked

upon them would seem to show that they were applied to, if not

originally designed for, some higher use. It seems quite natural for a

simple and religious race, such as the early Aryans certainly were, to

stamp religious emblems and sentences on objects in daily use, and then

to consecrate them as ex voto offerings, according to Dr. Schliemann’s

suggestion. The astronomical significance, which Schliemann finds in

many of the whorls, is unmistakeable in most of the terra-cotta balls;

and this seems to furnish evidence that the people who made them had

some acquaintance, at least, with the astronomical science of Babylonia.

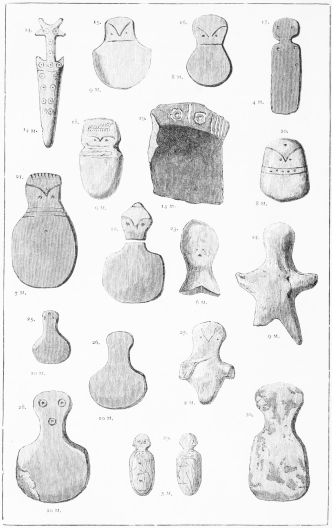

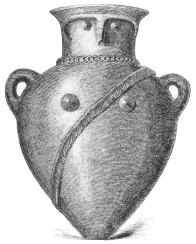

The keen discussion provoked by Dr. Schliemann’s novel explanation of

the θεὰ γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη might be left “a pretty quarrel as it

stands,”[16] did there not appear to be a key of which neither party has

made sufficient use. The symbolism, which embodied divine attributes in

animal forms, belonged unquestionably to an early form of the Greek

religion, as well as to the Egyptian and Assyrian.[17]{xx} The ram-headed

Ammon, the hawk-headed Ra, the eagle-headed Nisroch, form exact

precedents for an owl-headed Athena, a personation which may very well

have passed into the slighter forms of owl-faced, owl-eyed, bright-eyed.

Indeed, we see no other explanation of the constant connection of the

owl with the goddess, which survived to the most perfect age of Greek

sculpture. The question is not to be decided by an etymological analysis

of the sense of γλαυκῶπις in the Greek writers, long after the old

symbolism had been forgotten, nor even by the sense which Homer may have

attached to the word in his own mind. One of the most striking

characters of his language is his use of fixed epithets; and he might

very well have inherited the title of the tutelar goddess of the Ionian

race with the rest of his stock of traditions. If γλαυκῶπις were merely

a common attributive, signifying “bright-eyed,” it is very remarkable

that Homer should never apply it to mortal women, or to any goddess save

Athena. We are expressing no opinion upon the accuracy of Schliemann’s

identification in every case; but the rudeness of many of his

“owl-faced idols” is no stumbling-block, for the oldest and rudest

sacred images were held in lasting and peculiar reverence. The Ephesian

image of Artemis, “which fell down from Jove,” is a case parallel to

what the “Palladium” of Ilium may have been.

The ethnological interpretation of the four strata of remains at

Hissarlik is another of the questions which it would be premature to

discuss; but a passing reference{xxi} may be allowed to their very

remarkable correspondence with the traditions relating to the site.

First, Homer recognizes a city which preceded the Ilium of Priam, and

which had been destroyed by Hercules; and Schliemann found a primeval

city, of considerable civilization, on the native rock, below the ruins

which he regards as the Homeric Troy. Tradition speaks of a Phrygian

population, of which the Trojans were a branch, as having apparently

displaced, and driven over into Europe, the kindred Pelasgians. Above

the second stratum are the remains of a third city, which, in the type

and patterns of its terra-cottas, instruments, and ornaments, shows a

close resemblance to the second; and the link of connection is rivetted

by the inscriptions in the same character in both strata. And so, in the

Homeric poems, every reader is struck with the common bonds of genealogy

and language, traditions and mutual intercourse, religion and manners,

between the Greeks who assail Troy and the Trojans who defend it. If the

legend of the Trojan War preserves the tradition of a real conquest of

the city by a kindred race, the very nature of the case forbids us to

accept literally the story, that the conquerors simply sailed away

again.[18] It is far more reasonable to regard the ten years of the

War, and the ten years of the Return of the Chiefs (Νόστοι) as

cycles of ethnic struggles, the details of which had been sublimed into

poetical traditions. The fact, that Schliemann traces in the third

stratum a civilization lower than in the second, is an objection only

from the point of view of our classical prepossessions. There are not

wanting indications in{xxii} Homer (as Curtius, among others, has pointed

out) that the Trojans were more civilized and wealthy than the Greeks;

and in the much earlier age, to which the conflict—if real at all—must

have belonged, we may be sure that the Asiatic people had over their

European kindred an advantage which we may venture to symbolize by the

golden arms of Glaucus and the brazen arms of Diomed (Homer, Iliad,

VI. 235, 236). Xanthus, the old historian of Lydia, preserves the

tradition of a reflux migration of Phrygians from Europe into Asia,

after the Trojan War, and says that they conquered Troy and settled in

its territory. This migration is ascribed to the pressure of the

barbarian Thracians; and the fourth stratum, with its traces of merely

wooden buildings, and other marks of a lower stage of civilization,

corresponds to that conquest of the Troad by those same barbarian

Thracians, the tradition of which is preserved by Herodotus and other

writers. The primitive dwellings of those races in Thrace still furnish

the flint implements, which are most abundant in the fourth stratum at

Hissarlik.

The extremely interesting concurrence of instruments of stone with those

of copper (or bronze, see p. 361) in all the four strata at Hissarlik,

may be illustrated by a case which has fallen under our notice while

dismissing this sheet for press. A mound recently opened at the Bocenos,

near Carnac (in the Morbihan), has disclosed the remains of a Gallic

house, of the second century of our era, in which flint implements

were found, intermixed with pottery of various styles, from the most

primitive to the finest examples of native Gallic art, and among all

these objects was a terra-cotta head of the Venus Anadyomene.[19] Such

facts as{xxiii} these furnish a caution against the too hasty application of

the theory of the Ages of Stone, Bronze, and Iron.

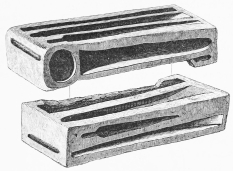

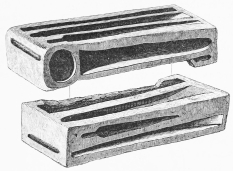

Another illustration is worth adding of the persistence of the forms of

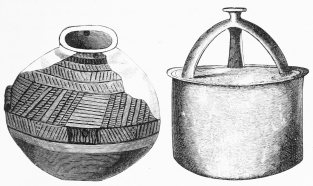

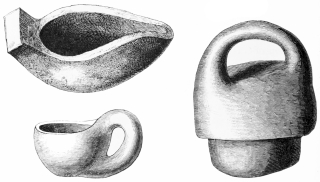

objects in common use in the same region. (See p. 47.) Mr. Davis, in his

recently published travels in Asia Minor,[20] describes a wooden vessel

for carrying water, which he saw at Hierapolis, in Phrygia, of the very

same form as the crown-handled vase-covers of terra-cotta found in such

numbers by Schliemann (see p. 25, 48, 86, 95, &c.). “They are made of a

section of the pine: the inside is hollowed from below, and the bottom

is closed by another piece of wood exactly fitted into it.” The two

drawings given by Mr. Davis closely resemble our cut, No. 51, p. 86.

Our last letter from Dr. Schliemann announced the approaching

termination of his lawsuit with the Turkish Government, arising out of

the dispute referred to in the ‘Introduction’ (p. 52). The collection

has been valued by two experts; and Dr. Schliemann satisfies the demand

of the Turkish Government by a payment in cash, and an engagement to

continue the excavations in Troy for three or four months for the

benefit of the Imperial Museum at Constantinople. We rejoice that he has

not “closed the excavations at Hissarlik for ever” (see p. 356), and

wait to see what new discoveries may equal or surpass those of the

“Scæan Gates,” the “Palace,” and the “Treasure of Priam.”

Meanwhile, as the use of so mythical a name as that of Troy’s last king

has furnished a special butt for critical scorn, it seems due to Dr.

Schliemann to quote his reason for retaining it:—[21]

{xxiv}

“I identify with the Homeric Ilion the city second in succession from

the virgin soil, because only in that city were used the Great Tower,

the great Circuit Wall, the great Double Gate, and the ancient palace of

the chief or king, whom I call Priam, because he is called so by the

tradition of which Homer is the echo; but as soon as it is proved that

Homer and the tradition were wrong, and that Troy’s last king was called

‘Smith,’ I shall at once call him so.” Those who believe Troy to be a

myth and Priam a shadow as unsubstantial as the shape, whose head

“The likeness of a kingly crown had on,”

need not grudge Schliemann the satisfaction of giving the unappropriated

nominis umbra to the owner of his very substantial Treasure. The name

of Priam may possibly even yet be read on the inscriptions, as the names

of the Assyrian kings have been read on theirs, or it may be an

invention of the bard’s; but the name of Troy can no longer be withheld

from the “splendid ruins” of the great and wealthy city which stood upon

its traditional site—a city which has been sacked by enemies and burnt

with fire.

PHILIP SMITH.

HAMPSTEAD,

Christmas Eve, 1874.

{xxv}

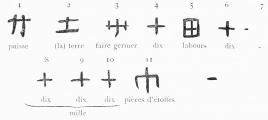

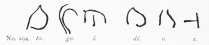

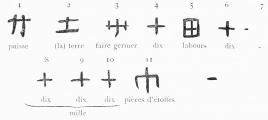

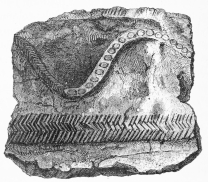

Terra-cotta Tablets from the Greek Stratum (1-2 M.).

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| EDITOR’S PREFACE | Page | iii |

| Autobiographical Notice Of Dr. Henry Schliemann | ” | 1 |

| Diagram showing the successive Strata of Remains on the Hill of Hissarlik | ” | 10 |

| Introduction | ” | 11 |

| Comparative Table of French Meters and English Measures | ” | 56 |

| WORK AT HISSARLIK IN 1871. |

CHAPTER I.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, October 18th, 1871. |

The site of Ilium described—Excavations in 1870: the City Wall of

Lysimachus—Purchase of the site and grant of a firman—Arrival

of Dr. and Madame Schliemann in 1871, and beginning of the

Excavations—The Hill of HISSARLIK, the Acropolis of the Greek

Ilium—Search for its limits—Difficulties of the work—The great

cutting on the North side—Greek coins found—Dangers from fever | 57 |

CHAPTER II.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, October 26th, 1871. |

Number of workmen—Discoveries at 2 to 4 meters deep—Greek

coins—Remarkable terra-cottas with small stamps, probably Ex

votos—These cease, and are succeeded by the whorls—Bones of

sharks, shells of mussels and oysters, and pottery—Three Greek

Inscriptions—The splendid panoramic view from Hissarlik—The Plain

of Troy and the heroic tumuli—Thymbria: Mr. Frank Calvert’s

Museum—The mound of Chanaï Tépé—The Scamander and its ancient

bed—Valley of the Simoïs, and Ruins of Ophrynium | 64 |

CHAPTER III.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, November 3rd, 1871. |

Puzzling transitions from the “Stone Age” to a higher

civilization—The stone age reappears in force, mixed with pottery

of fine workmanship, and{xxvi} the whorls in great number—Conjectures

as to their uses: probably Ex votos—Priapi of stone and

terra-cotta: their worship brought by the primitive Aryans from

Bactria—Vessels with the owl’s face—Boars’ tusks—Various

implements and weapons of stone—Hand mill-stones—Models of canoes

in terra-cotta—Whetstones—The one object of the excavations, to

find TROY | 75 |

CHAPTER IV.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, November 18th, 1871. |

Another passage from the Stone Age to copper implements mixed with

stone—The signs of a higher civilization increase with the depth

reached—All the implements are of better workmanship—Discovery of

supposed inscriptions—Further discussion of the use of the

whorls—Troy still to be reached—Fine terra-cotta vessels of

remarkable forms—Great numbers of stone weights and hand

mill-stones—Numerous house-walls—Construction of the great

cutting—Fever and quinine—Wounds and arnica | 81 |

CHAPTER V.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, November 24th, 1871. |

Interruptions from Rain—Last works of the season, 1871—The

supposed ruins of Troy reached—Great blocks of stone—Engineering

contrivances—Excavations at the “Village of the Ilians:” no traces

of habitation, and none of hot springs—Results of the excavations

thus far—Review of the objects found at various depths—Structure

of the lowest houses yet reached—Difficulties of the

excavations—The object aimed at—Growth of the Hill of Hissarlik | 90 |

| WORK AT HISSARLIK IN 1872. |

CHAPTER VI.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, April 5th, 1872. |

New assistants for 1872—Cost of the excavations—Digging of the

great platform on the North—Venomous snakes—A supporting buttress

on the North side of the hill—Objects discovered: little idols of

fine marble—Whorls engraved with the suastika

and 卐—Significance of these emblems in the old

Aryan religion—Their occurrence among other Aryan

nations—Mentioned in old Indian literature—Illustrative quotation

from Émile Burnouf

and 卐—Significance of these emblems in the old

Aryan religion—Their occurrence among other Aryan

nations—Mentioned in old Indian literature—Illustrative quotation

from Émile Burnouf | 98 |

CHAPTER VII.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, April 25th, 1872. |

Smoking at work forbidden, and a mutiny suppressed—Progress of the

great platform—Traces of sacrifices—Colossal blocks of stone

belonging to great buildings—Funereal and other huge

urns—Supposed traces of Assyrian art—Ancient undisturbed

remains—Further discoveries of stone implements and owl-faced

idols—Meaning of the epithet “γλαυκῶπις”—Parallel of Ἥρα βοῶπις,

and expected discovery of ox-headed idols at Mycenæ—Vases of

remarkable forms—Dangers and engineering{xxvii} expedients—Georgios

Photidas—Extent of the Pergamus of Troy—Poisonous snakes, and the

snake-weed—The whorls with the central sun, stars, the suastika,

the Sôma, or Tree of Life, and sacrificial altars—The name of

Mount Ida, probably brought from Bactria | 107 |

CHAPTER VIII.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, May 11th, 1872. |

Hindrances through Greek festivals—Thickness of the layers of

débris above the native rock—Date of the foundation of

Troy—Impossibility of the Bunarbashi theory—Homeric epithets

suitable to Hissarlik—Etymology of Ἴλιος, signifying probably the

“fortress of the Sun”—The Aruna of the Egyptian

records—Progress of the platform, and corresponding excavation on

the south—The bulwark of Lysimachus—Ruins of great

buildings—Marks of civilization increasing with the depth—Vases,

and fragments of great urns—A remarkable terra-cotta—A whorl with

the appearance of an inscription | 122 |

CHAPTER IX.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, May 23rd, 1872. |

Superstition of the Greeks about saints’ days—Further engineering

works—Narrow escape of six men—Ancient building on the western

terrace—The ruins under this house—Old Trojan mode of

building—Continued marks of higher civilization—Terra-cottas

engraved with Aryan symbols: antelopes, a man in the attitude of

prayer, flaming altars, hares—The symbol of the moon—Solar

emblems, and rotating wheels—Remarks on former supposed

inscriptions—Stone moulds for casting weapons and

implements—Absence of cellars, and use of colossal jars in their

stead—The quarry used for the Trojan buildings—“Un Médecin malgré

lui.”—Blood-letting priest-doctors—Efficacy of

sea-baths—Ingratitude of the peasants cured—Increasing heat | 131 |

CHAPTER X.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, June 18th, 1872. |

A third platform dug—Traces of former excavations by the

Turks—Block of triglyphs, with bas-relief of Apollo—Fall of an

earth-wall—Plan of a trench through the whole hill—Admirable

remains in the lowest stratum but one—The plain and engraved

whorls—Objects of gold, silver, copper, and ivory—Remarkable

terra-cottas—The pottery of the lowest stratum quite distinct

from that of the next above—Its resemblance to the Etruscan, in

quality only—Curious funereal urns—Skeleton of a six months’

embryo—Other remains in the lowest stratum—Idols of fine marble,

the sole exception to the superior workmanship of this stratum—The

houses and palaces of the lowest stratum, of large stones joined

with earth—Disappearance of the first people with the destruction

of their town.

The second settlers, of a different civilization—Their buildings

of unburnt brick on stone foundations—These bricks burnt by the

great conflagration—Destruction of the walls of the former

settlers—Live toads{xxviii} coëval with Troy!—Long duration of the

second settlers—Their Aryan descent proved by Aryan

symbols—Various forms of their pottery—Vases in the form of

animals—The whorls of this stratum—Their interesting

devices—Copper weapons and implements, and moulds for casting

them—Terra-cotta seals—Bracelets and ear-rings, of silver, gold,

and electrum—Pins, &c., of ivory and bone—Fragments of a

lyre—Various objects.

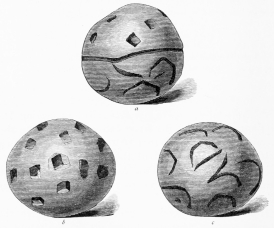

The third stratum: the remains of an Aryan race—Hardly a trace

of metal—Structure of their houses—Their stone implements and

terra-cottas coarser—Various forms of pottery—Remarkable

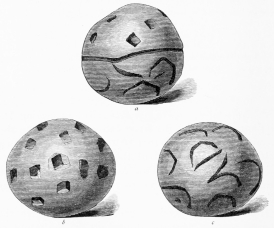

terra-cotta balls with astronomical and religious

symbols—Whorls—Stone weapons—Whetstones—Hammers and instruments

of diorite—A well belonging to this people—This third town

destroyed with its people.

The fourth settlers: comparatively savage, but still of Aryan

race—Whorls with like emblems, but of a degenerate form—Their

pottery inferior, but with some curious forms—Idols of

Athena—Articles of copper—Few stones—Charred remains, indicating

wooden buildings—Stone weights, handmills, and knives and saws of

flint—With this people the pre-Hellenic ages end—The stone

buildings and painted and plain terra-cottas of Greek Ilium—Date

of the Greek colony—Signs that the old inhabitants were not

extirpated—The whorls of very coarse clay and patterns—Well, and

jars for water and wine—Proofs of the regular succession of

nations on the hill—Reply to the arguments of M. Nikolaïdes for

the site at Bunarbashi—The Simoïs, Thymbrius, and Scamander—The

tomb of Ajax at In-Tépé—Remains in it—Temple of Ajax and town of

Aianteum—Tomb of Achilles and town of Achilleum—Tombs of

Patroclus and Antilochus—The Greek camp—The tomb of Batiea or

Myrina—Further discussion of the site | 143 |

CHAPTER XI.

On the Hill of Hissarlik, July 13th, 1872. |

Increase of men and machinery and cost on the works: but slow

progress—Continued hurricane on “the windy Ilium” (Ἴλιος

ἠνεμόεσσα)—The great platform proves too high—New

cutting—Excavation of the temple—Objects found—Greek statuettes

in terra-cotta—Many whorls with 卐 and suns—Wheel-shaped whorls

with simple patterns in the lowest strata—Terra-cotta balls with

suns and stars—Use of the whorls as amulets or coins

discussed—Little bowls, probably lamps—Other articles of

pottery—Funnels—A terra-cotta bell—Various beautiful

terra-cottas—Attempts at forgery by the workmen—Mode of naming

the men—The springs in front of Ilium—Question of Homer’s hot and

cold spring—Course of the Simoïs—The tomb of Batiea or Myrina

identified with the Pacha Tépé—Theatre of Lysimachus—Heat and

wind—Plague of insects and scorpions—Konstantinos Kolobos, a

native genius without feet | 184 |

CHAPTER XII.

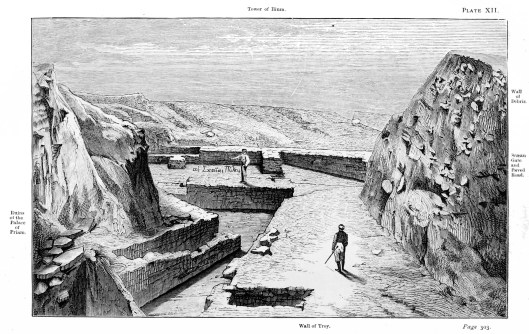

Pergamus of Troy, August 4th, 1872. |

Discovery of an ancient wall on the northern slope—Discovery of a

Tower on the south side—Its position and construction—It is

Homer’s Great{xxix} Tower of Ilium—Manner of building with stones and

earth—A Greek inscription—Remarkable medal of the age of

Commodus—Whorls found just below the surface—Terra-cottas found

at small depths—Various objects found at the various depths—A

skeleton, with ornaments of gold, which have been exposed to a

great heat—Paucity of human remains, as the Trojans burnt their

dead—No trace of pillars—Naming of the site as “Ilium” and the

“Pergamus of Troy” | 200 |

CHAPTER XIII.

Pergamus of Troy, August 14th, 1872. |

Intended cessation of the work—Further excavation of the

Tower—Layers of red ashes and calcined stones—Objects found on

the Tower—Weapons, implements, and ornaments of stone, copper, and

silver—Bones—Pottery and vases of remarkable forms—Objects found

on each side of the Tower—First rain for four months—Thanks for

escape from the constant dangers—Results of the excavations—The

site of Homer’s Troy identified with that of Greek Ilium—Error of

the Bunarbashi theory—Area of the Greek city—Depth of the

accumulated débris unexampled in the world—Multitude of

interesting objects brought to light—Care in making drawings of

them all | 212 |

CHAPTER XIV.

Athens, September 28th, 1872. |

Return to Troy to take plans and photographs—Damage to retaining

walls—The unfaithfulness of the watchman—Stones carried off for a

neighbouring church and houses—Injury by rain—Works for security

during the winter—Opening up of a retaining wall on the side of

the hill, probably built to support the temple of Athena—Supposed

débris of that temple—Drain belonging to it—Doric style of the

temple proved by the block of Triglyphs—Temple of Apollo also on

the Pergamus | 220 |

| WORK AT HISSARLIK IN 1873. |

CHAPTER XV.

Pergamus of Troy, February 22nd, 1873. |

Return to Hissarlik in 1873—Interruptions by holydays and

weather—Strong cold north winds—Importance of good overseers—An

artist taken to draw the objects found—Want of

workmen—Excavations on the site of the Temple—Blocks of Greek

sculptured marble—Great increase of the hill to the east—Further

portions of the great Trojan wall—Traces of fire—A terra-cotta

hippopotamus, a sign of intercourse with Egypt—Idols and owl-faced

vases—Vases of very curious forms—Whorls—Sling-bullets of copper

and stone—Piece of ornamented ivory belonging to a musical

instrument—New cutting from S.E to N.W.—Walls close below the

surface—Wall of Lysimachus—Monograms on the stones—An

inscription in honour of Caius Cæsar—Patronage of Ilium by the

Julii as the descendants of Æneas—Good wine of the Troad{xxx} | 224 |

CHAPTER XVI.

Pergamus of Troy, March 1st, 1873. |

Increased number of workmen—Further uncovering of the great

buttress—Traces of a supposed small temple—Objects found on its

site—Terra-cotta serpents’ heads: great importance attached to the

serpent—Stone implements: hammers of a peculiar form—Copper

implements: a sickle—Progress of the works at the south-east

corner—Remains of an aqueduct from the Thymbrius—Large jars, used

for cellars—Ruins of the Greek temple of Athena—Two important

inscriptions discussed—Relations of the Greek Syrian Kings

Antiochus I. and III. to Ilium | 233 |

CHAPTER XVII.

Pergamus of Troy, March 15th, 1873. |

Spring weather in the Plain of Troy—The Greek temple of

Athena—Numerous fragments of sculpture—Reservoir of the

temple—Excavation of the Tower—Difficulties of the work—Further

discoveries of walls—Stone implements at small depths—Important

distinction between the plain and decorated whorls—Greek and Roman

coins—Absence of iron—Copper nails: their peculiar forms:

probably dress and hair pins: some with heads and beads of gold and

electrum—Original height of the Tower—Discovery of a Greek

house—Various types of whorls—Further remarks on the Greek

bas-relief—It belonged to the temple of Apollo—Stones from the

excavations used for building in the villages around—Fever | 248 |

CHAPTER XVIII.

Pergamus of Troy, March 22nd, 1873. |

Weather and progress of the work—The lion-headed handle of a

sceptre—Lions formerly in the Troad—Various objects

found—Pottery—Implements of stone and copper—Whorls—Balls

curiously decorated—Fragments of musical instruments—Remains of

house walls—The storks of the Troad | 259 |

CHAPTER XIX.

Pergamus of Troy, March 29th, 1873. |

Splendid vases found on the Tower—Other articles—Human skull,

bones, and ashes, found in an urn—New types of whorls—Greek

votive discs of diorite—Moulds of mica-schist—The smaller

quantity of copper than of stone implements explained—Discussion

of the objection, that stone implements are not mentioned by

Homer—Reply to Mr. Calvert’s article—Flint knives found in the

Acropolis of Athens—A narrow escape from fire | 266 |

CHAPTER XX.

Pergamus of Troy, April 5th, 1873. |

Discovery of a large house upon the Tower—Marks of a great

conflagration—Primitive Altar: its very remarkable position—Ruins

of the temple{xxxi} of Athena—A small cellar—Skeletons of warriors

with copper helmets and a lance—Structure of the

helmet-crests—Terra-cottas—A crucible with copper still in

it—Other objects—Extreme fineness of the engravings on the

whorls—Pottery—Stone implements—Copper pins and other objects | 276 |

CHAPTER XXI.

Pergamus of Troy, April 16th, 1873. |

Discovery of a street in the Pergamus—Three curious stone walls of

different periods—Successive fortifications of the hill—Remains

of ancient houses under the temple of Athena, that have suffered a

great conflagration—Older house-walls below these, and a wall of

fortification—Store, with the nine colossal jars—The great

Altar—Objects found east of the Tower—Pottery with Egyptian

hieroglyphics—Greek and other terra-cottas, &c.—Remarkable

owl-vase—Handle, with an ox-head—Various very curious objects—A

statue of one Metrodorus by Pytheas of Argos, with an

inscription—Another Greek inscription, in honour of C. Claudius

Nero | 287 |

CHAPTER XXII.

Pergamus of Troy, May 10th, 1873. |

Interruptions through festivals—Opening of the tumulus of

Batiea—Pottery like that of the Trojan stratum at Hissarlik, and

nothing else—No trace of burial—Its age—Further discoveries of

burnt Trojan houses—Proof of their successive ages—Their

construction—Discovery of a double gateway, with the copper bolts

of the gates—The “Scæan Gate” of Homer—Tests of the extent of

ancient Troy—The place where Priam sat to view the Greek

forces—Homer’s knowledge of the Heroic Troy only

traditional—Description of the gates, the walls, and the “PALACE

OF PRIAM”—Vases, &c., found in Priam’s house—Copper, ivory, and

other implements—The δέπα ἀμφικύπελλα—Houses discovered on the

north platform—Further excavations of the city walls—Statuettes

and vessels of the Greek period—Top of the Tower of Ilium

uncovered, and its height determined—A curious trench in it,

probably for the archers—Further excavations at Bunarbashi: only a

few fragments of Greek pottery—The site of Ilium uninhabited since

the end of the fourth century—The place confused with Alexandria

Troas—No Byzantine remains at Hissarlik—Freshness of the Greek

sculptures | 300 |

CHAPTER XXIII.

Troy, June 17th, 1873. |

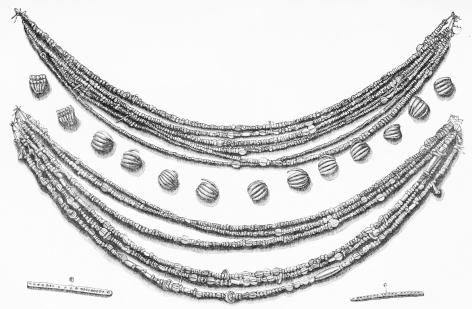

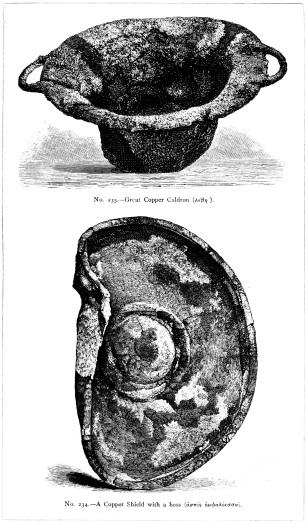

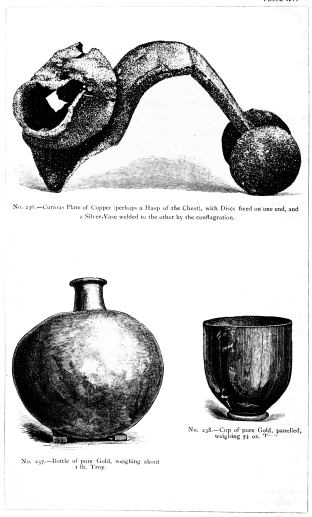

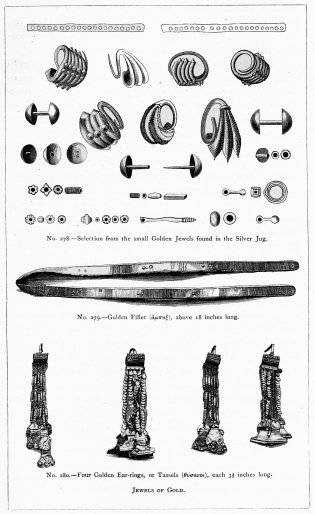

Further discoveries of fortifications—The great discovery of the

TREASURE on the city wall—Expedient for its preservation—The

articles of the Treasure described—The Shield—The Caldron—Bottle

and Vases of Gold—The golden δέπας ἀμφικύπελλον—Modes of working

the gold—A cup of electrum—Silver plates, probably the talents

of Homer—Vessels of Silver—Copper lance-heads: their peculiar

form—Copper battle-axes—Copper daggers—Metal articles fused

together{xxxii} by the conflagration—A knife and a piece of a

sword—Signs of the Treasure having been packed in a wooden

chest—The key found—The Treasure probably left behind in an

effort to escape—Other articles found near the Treasure—The

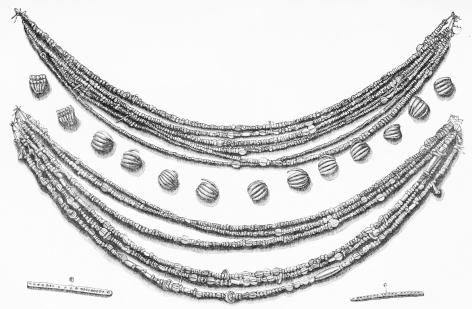

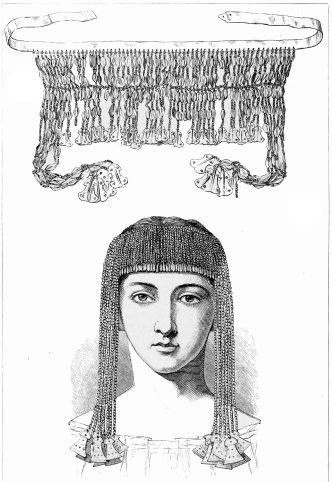

thousands of gold jewels found in a silver vase—The two golden

diadems—The ear-rings, bracelets, and finger-rings—The smaller

jewels of gold—Analysis of the copper articles by M.

Landerer—Discovery of another room in the palace containing an

inscribed stone, and curious terra-cottas—Silver dishes—Greek

terra-cotta figures—Great abundance of the owl-faced

vases—Limited extent of Troy—Its walls traced—Poetic

exaggerations of Homer—The one great point of Troy’S reality

established—It was as large as the primitive Athens and

Mycenæ—The wealth and power of Troy—Great height of its

houses—Probable population—Troy known to Homer only by

tradition—Question of a temple in Homer’s time—Characteristics of

the Trojan stratum of remains, and their difference from those of

the lowest stratum—The former opinion on this point

recalled—Layer of metallic scoriæ through the whole hill—Error

of Strabo about the utter destruction of Troy—Part of the real

Troy unfortunately destroyed in the earlier excavations; but many

Trojan houses brought to light since—The stones of Troy not used

in building other cities—Trojan houses of sun-dried bricks, except

the most important buildings, which are of stones and earth—Extent

and results of the excavations—Advice to future explorers—Further

excavations on the north side—Very curious terra-cotta

vessels—Perforated vases—A terra-cotta with hieroglyphics—Heads

of oxen and horses; their probable significance—Idols of the Ilian

Athena—Greek and Roman medals—Greek inscriptions—Final close of

the excavations; thanksgiving for freedom from serious

accidents—Commendations of Nicolaus Saphyros Jannakis, and other

assistants, and of the artist Polychronios Tempesis, and of the

engineer Adolphe Laurent | 321 |

NOTE A. The river Dumbrek is not the Thymbrius, but the Simoïs | 358 |

NOTE B. Table of terra-cotta weights found at Hissarlik | 359 |

NOTE C. Analysis by M. Damour of some of the metallic objects

found | 361 |

Appendix on the Inscriptions Found at Hissarlik | 363 |

INDEX: A,

B,

C,

D,

E,

F,

G,

H,

I,

J,

K,

L,

M,

N,

O,

P,

Q,

R,

S,

T,

U,

V,

W,

X. | 375 |

Comparative Table of the Illustrations in Dr. Schliemann’s

Atlas and the Translation | 386 |

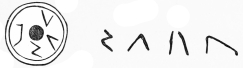

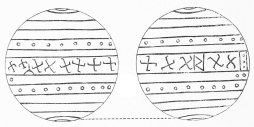

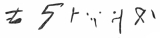

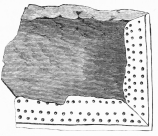

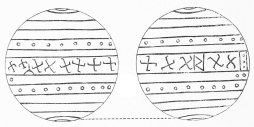

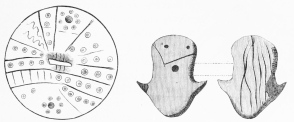

Two Inscribed Whorls (5 M. and 7 M.).

{xxxiii}

Terra-cotta Tablets from the Greek Stratum (2 M.).

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

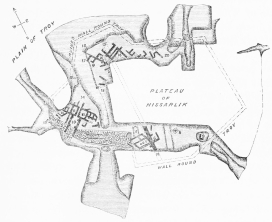

| MAPS AND PLANS. |

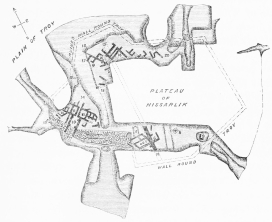

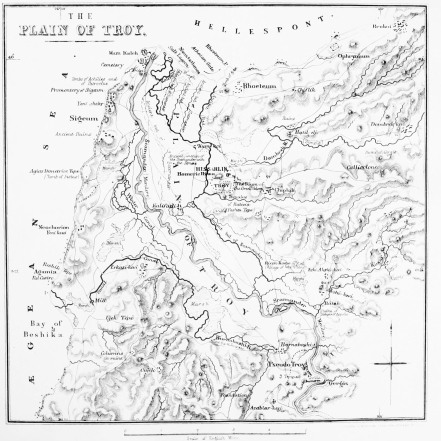

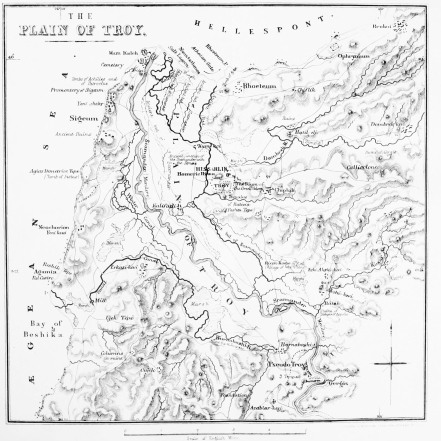

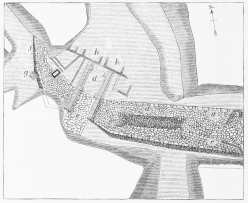

| Map of The Plain of Troy | End of Volume |

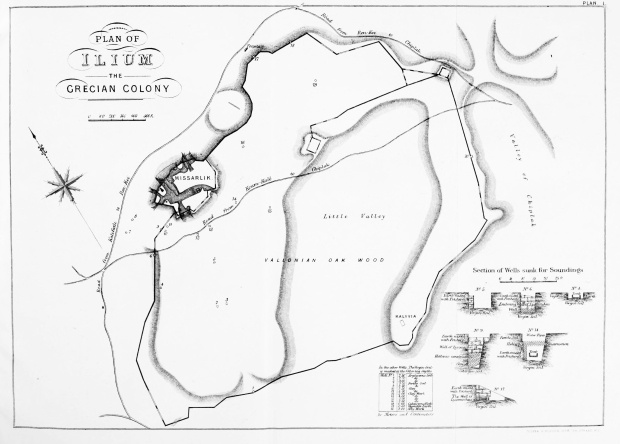

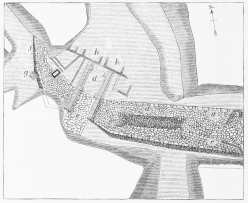

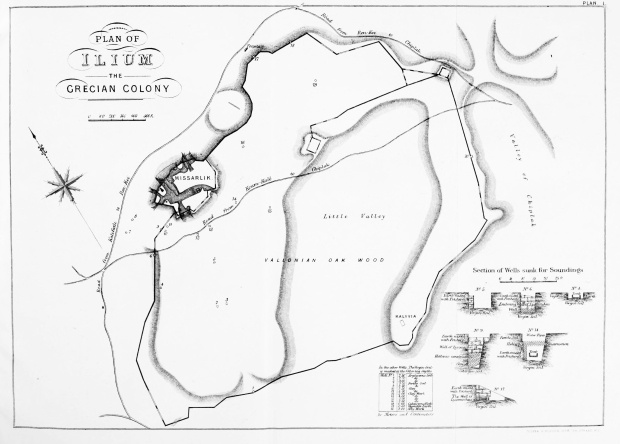

| Plan I. Ilium, the Grecian Colony | “ |

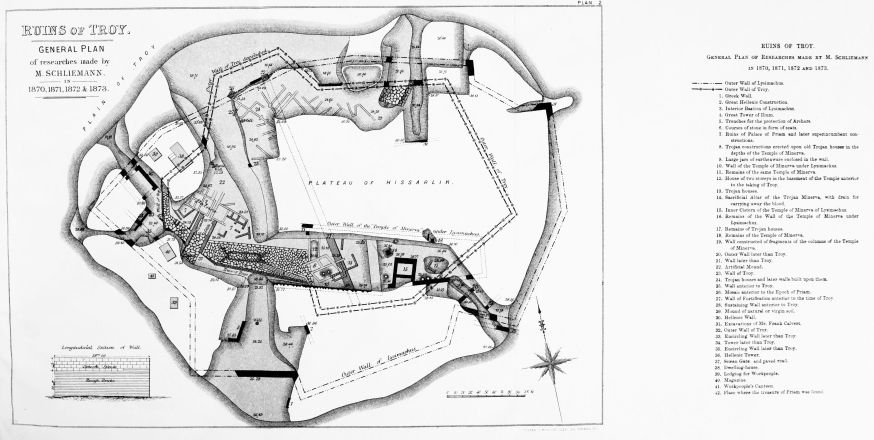

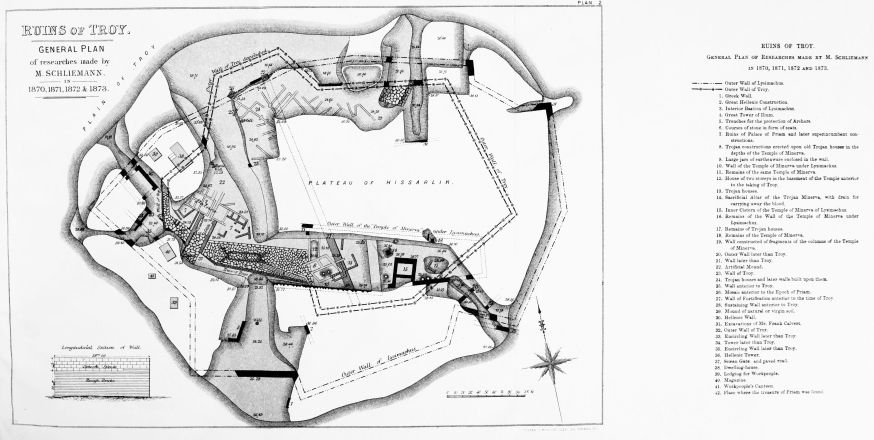

| Plan II. Ruins of Troy—General Plan of Researches made by Dr. Schliemann in 1870, 1871, 1872, and 1873 | “ |

| Plan III. The Tower of Ilium and the Scæan Gate | Page 306 |

| Plan IV. Troy at the Epoch of Priam, according to Dr. Schliemann’s Excavations | 347 |

| PLATES AND CUTS. |

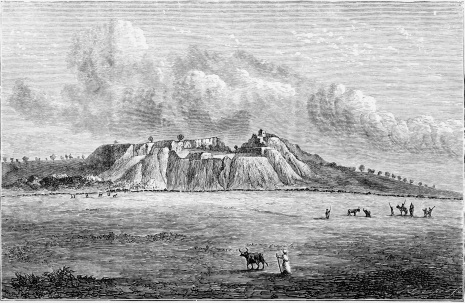

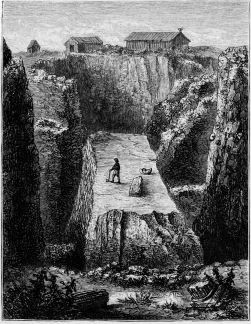

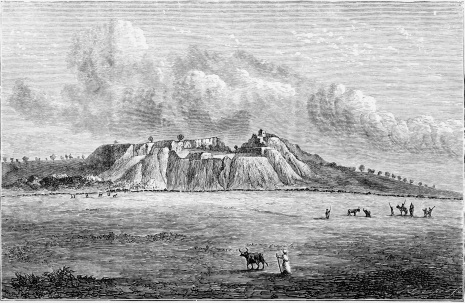

| PLATE I. |

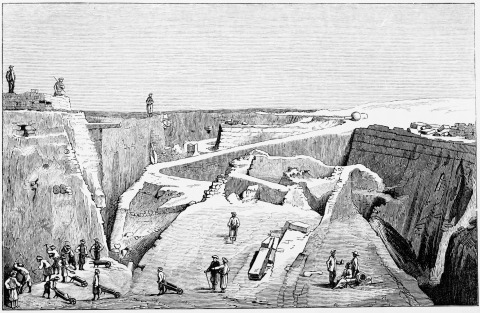

View of The Hill of Hissarlik, Containing the Ruins of Troy,

from the North, after Dr. Schliemann’s Excavations In 1870, 1871, 1872, 1873

| Frontispiece |

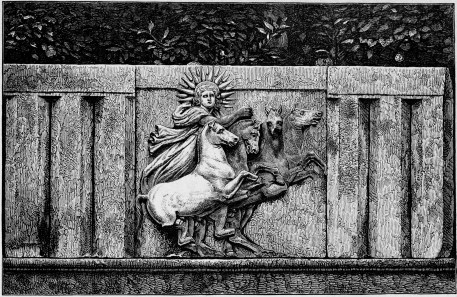

| The excavation to the left is on the site of the Greek Temple of

Apollo, where the splendid metopé of the Sun-God was found. Then

follows the great platform and the great trench cut through the

whole hill. Still further to the right is the cutting of April,

1870, in continuing which, in June, 1873, the Treasure was

discovered. |

| Three Tablets of Terra-cotta, from the Ruins of Greek Ilium (1-2 M.){xxxiv}

| xv |

| Two inscribed Whorls |

xxxii |

| Three Tablets of Terra-cotta (2 M.) |

xxxiii |

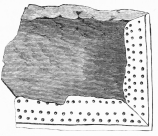

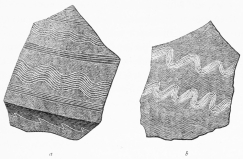

| | No. 1 Fragment of painted Pottery, from the lowest stratum | 15 |

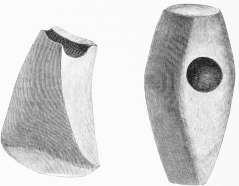

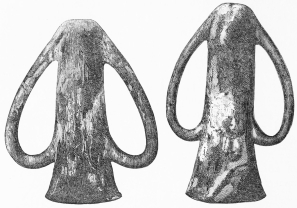

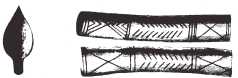

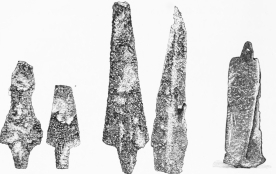

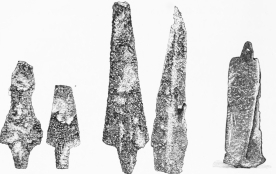

| | No. 2 Small Trojan Axes of Diorite (8 M.) | 21 |

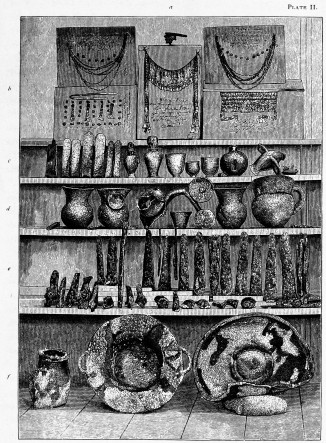

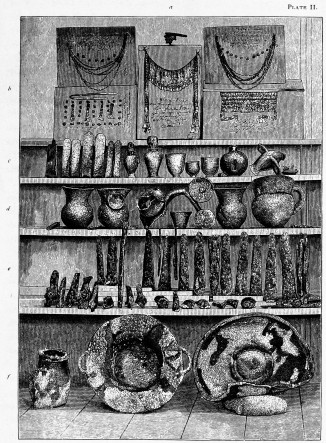

| PLATE II. | General View of The Treasure of Priam | To face 22 |

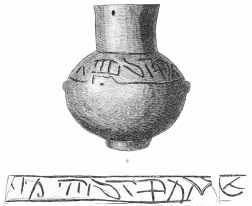

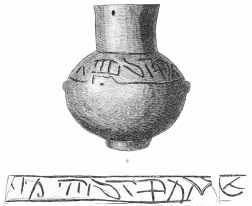

| | No. 3 inscribed Terra-cotta Vase from the Palace (8 M.) | 23 |

| | No. 4 inscribed Terra-cotta Seal (7 M.) | 24 |

| | No. 5 Piece of Red Slate, perhaps a Whetstone, with an inscription (7 M.) | 24 |

| | No. 6 Terra-cotta Vase Cover (8 M.) | 25 |

| | No. 7 Ornamented Ivory Tube, probably a Trojan Flute (8 M.) | 25 |

| | No. 8 Piece of Ivory, belonging to a Trojan Lyre with Four Strings (about 8 M.) | 25 |

| | No. 9 Ornamented Piece of Ivory belonging to a Trojan Seven-stringed Lyre (7 M.) | 27 |

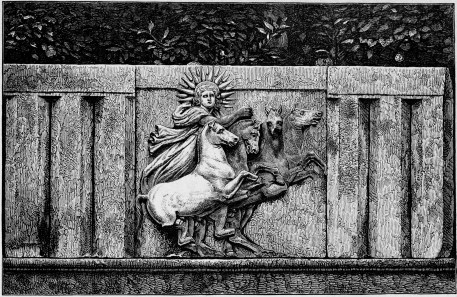

| PLATE III. | Block of Triglyphs, With Metopé of The Sun-god. From The Temple of Apollo in The Ruins of Greek Ilium | To face 32 |

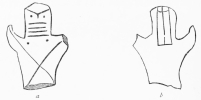

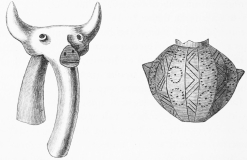

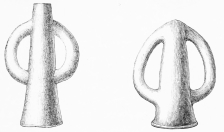

| | Nos. 10, Nos. 11, Nos. 12. Terra-cotta Covers of Vases, with the Owl’s Face (2, 3, and 7 M.) | 34 |

| | No. 13 Terra-cotta Vase, marked with an Aryan symbol (6 M.) | 35 |

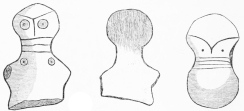

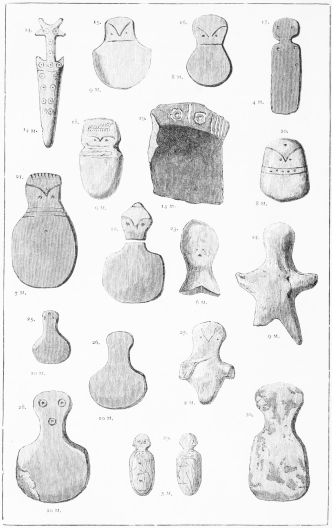

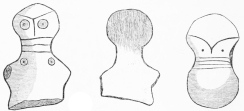

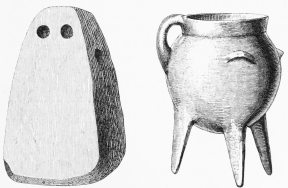

| | Nos. 14-30-30 Rude Idols found in the various Strata (2 to 14 M.) | 36 |

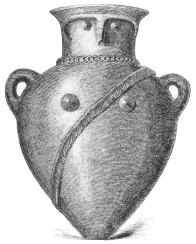

| | No. 31 Remarkable Trojan Terra-cotta Vase, representing the Ilian Athena (9 M.) | 37 |

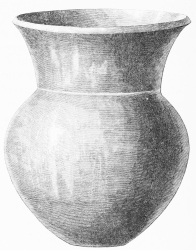

| | No. 32 The largest of the Terra-cotta Vases found in the Royal Palace of Troy. Height 20 inches | 48 |

| | No. 33 inscribed Trojan Vase of Terra-cotta (8½ M.) | 50 |

| | No. 34 inscription on the Vase No. 33 | 50 |

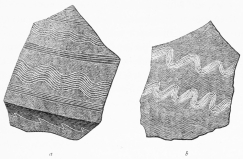

| | No. 35 Fragment of a second painted Vase, from the Trojan Stratum. (From a new Drawing.) | 55 |

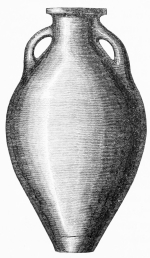

| | No. 36 A large Trojan Amphora of Terra-cotta (8 M.) | 63 |

| | Nos. 37-39. Stamped Terra-cottas (1½-2 M.) | 65 |

| | No. 40 Stamped Terra-cotta (2 M.) | 65 |

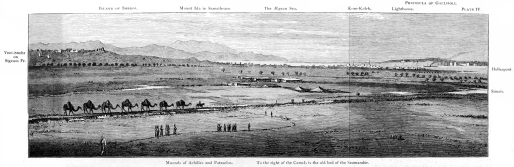

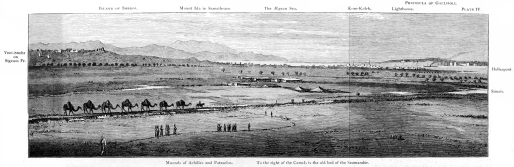

| PLATE IV. | View of The Northern Part of The Plain of Troy, From The Hill of Hissarlik | To face 70 |

| With the ancient bed of the Scamander, the Tombs of Achilles

and Patroclus, Cape Sigeum, the villages of Yeni-Shehr and

Kum-Kaleh, the Hellespont and Ægean Sea, the peninsula of

Gallipoli and the islands of Imbrus and Samothrace. The

Tumulus of Æsyetes is in the central foreground, in front of the

wretched little village of Kum-koï.

{xxxv} |

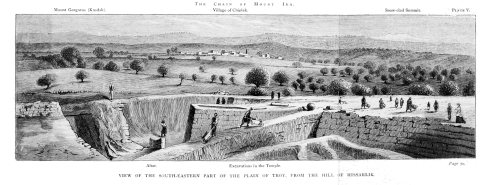

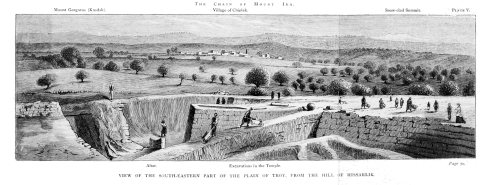

| PLATE V. | View of The South-eastern Part of

the Plain of

Troy, from the Hill of Hissarlik

| To face 70 |

| The foreground shows the excavations in the eastern part of Troy,

the foundations of the Temple, and the Altar of Athena; beyond

is the village of Chiplak; in the distance the chain of Mount

Ida, capped with snow, except in July and August. |

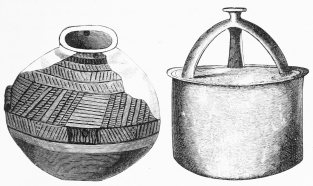

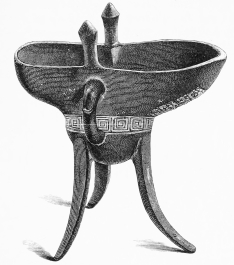

| | No. 41 A great mixing Vessel (κρατήρ) of Terra-cotta (7 M.) | 74 |

| | Nos. 42-44. Terra-cotta Whorls (7-14 M.) | 80 |

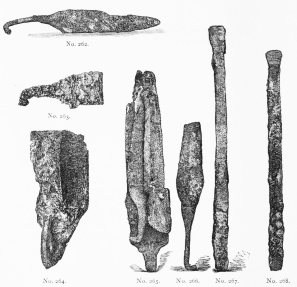

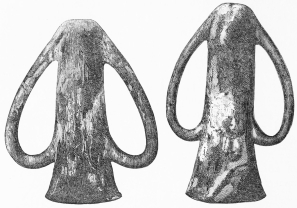

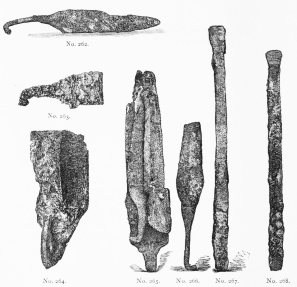

| | No. 45 Copper Implements and Weapons from the Trojan stratum (8 M.) | 82 |

| | No. 46 A Mould of Mica-schist for casting Copper Implements (8 M.) | 82 |

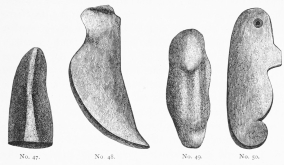

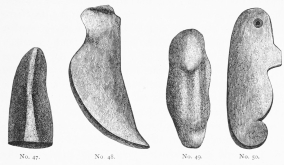

| | Nos. 47, 48, 49, 50. Stone instruments from the Trojan stratum (8 M.) | 83 |

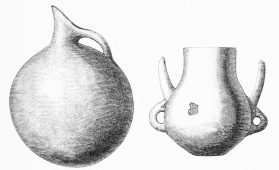

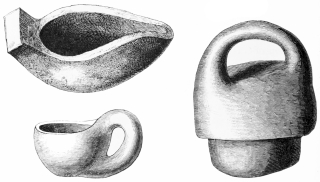

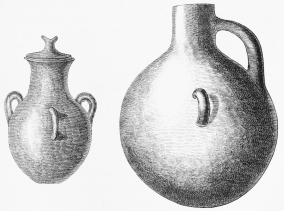

| | Nos. 51, 52. Trojan Terra-cottas (8 M.) | 86 |

| | No. 53 Small Trojan Vase (9 M.) | 87 |

| | Nos. 54, 55. Trojan Terra-cotta Vases (8 M.) | 87 |

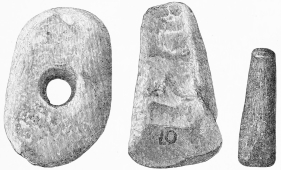

| | Nos. 56-61. Stone Implements of the earliest Settlers | 94 |

| | No. 62 Small Trojan Vase of Terra-cotta, with Decorations | 95 |

| | No. 63 A Trojan Vase-cover of red Terra-cotta (7 M.) | 95 |

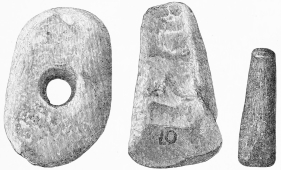

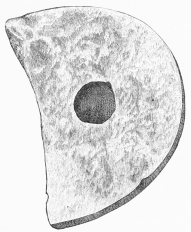

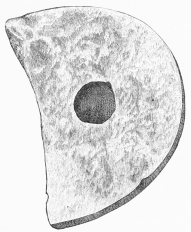

| | No. 64 A stone Implement of unknown use (2 M.) | 97 |

| | No. 65 A strange Vessel of Terra-cotta (15 M.) | 97 |

| | Nos. 66, 67, 68. Trojan Sling-bullets of Loadstone (9 and 10 M.) | 101 |

| | No. 69 The Foot-print of Buddha | 103 |

| | No. 70 Large Terra-cotta Vase, with the Symbols of the Ilian Goddess (4 M.) | 106 |

| | No. 71 A Mould of Mica-schist for casting Ornaments (14 M.) | 110 |

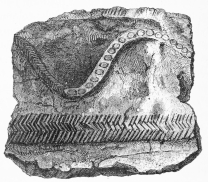

| | No. 72 Fragment of a large Urn of Terra-cotta with Assyrian (?) Decorations, from the Lowest Stratum (14 M.) | 110 |

| | No. 73 Trojan Plates found on the Tower (8 M.) | 114 |

| | No. 74 Vase Cover with a human face (8 M.) | 115 |

| | No. 75 A Whorl, with three animals (3 M.) | 121 |

| | No. 76 Fragment of a Vase of polished black Earthenware, with Pattern inlaid in White (14 M.) | 129 |

| | No. 77 Fragment of Terra-cotta, perhaps part of a box (16 M.) | 129 |

| | No. 78 A Trojan Terra-cotta Seal (8 M.) | 130 |

| | No. 78ª. Terra-cottas with Aryan Emblems (4 M.; 3 M.; 5 M.){xxxvi} | 130 |

| | No. 79 Fragment of a brilliant dark-grey Vessel (13 M.) | 135 |

| | No. 80 Whorl with pattern of a moving Wheel (16 M.) | 137 |

| | No. 81 Whorl with Symbols of Lightning (7 M.) | 138 |

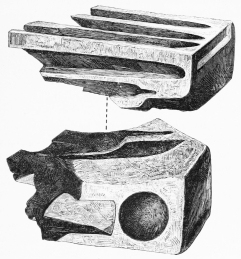

| | No. 82 Two fragments of a great Mould of Mica-schist for casting Copper Weapons and Ornaments (14 M.) | 139 |

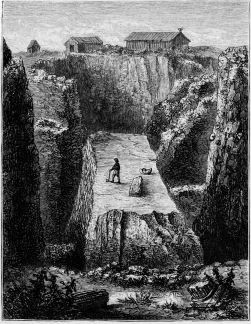

| PLATE VI. | Trojan Buildings On The North Side, And in The Great Trench Cut Through The Whole Hill | To face 143 |

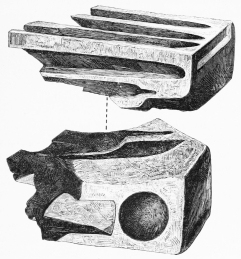

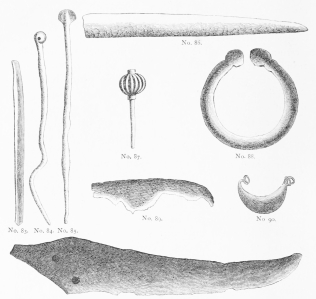

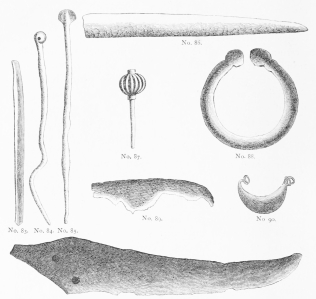

| | Nos. 83-91. Objects of Metal from the Lowest Stratum | 150 |

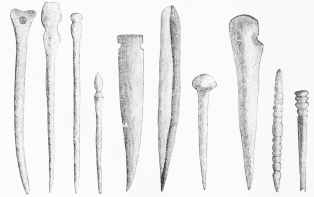

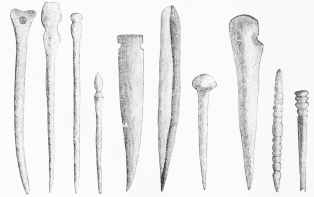

| | Nos. 92-101. Ivory Pins, Needles, &c. (11-15 M.) | 150 |

| | Nos. 102, 103. Hand Millstones of Lava (14-16 M.) | 151 |

| | No. 104 A splendid Vase with Suspension-rings (15 M.) | 151 |

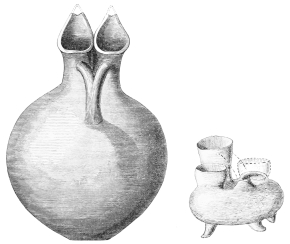

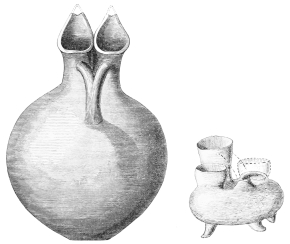

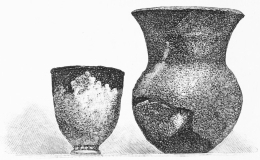

| | No. 105 Singular Double Vase (13-14 M.) | 152 |

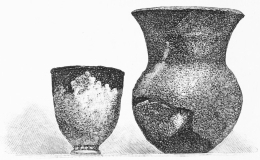

| | No. 106 Black Vase of Terra-cotta (14 or 15 M.) | 152 |

| | No. 107 Funereal Urn of Stone, found on the Primary Rock, with Human Ashes in it (15½ M.) | 153 |

| | No. 108 a, Hand Millstone of Lava (15 M.). b, Brilliant black Dish with side Rings for hanging it up (14 M.). c, c, c, c, Small decorated Rings of Terra-cotta (10-14 M.) | 155 |

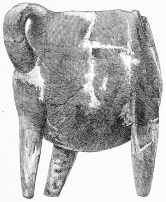

| | No. 109 Rude Terra-cotta Idol (14 M.) | 155 |

| | No. 110 Fragment of Pottery, with the Suastika (14 M.) | 157 |

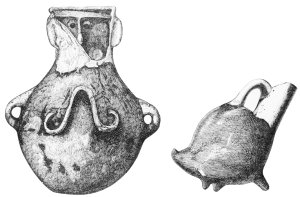

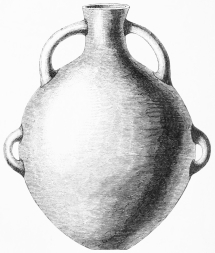

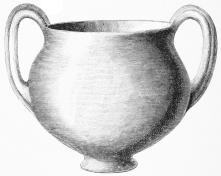

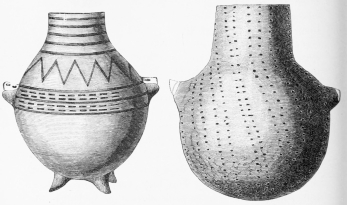

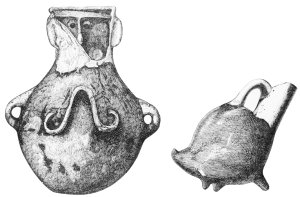

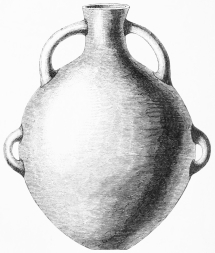

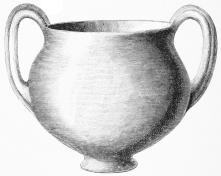

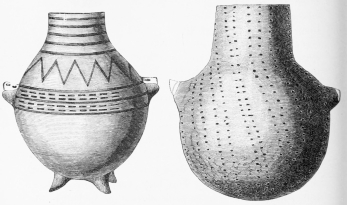

| | Nos. 111, 112. Double-handled Vases of Terra-cotta, from the Trojan Stratum (9 M.) | 158 |

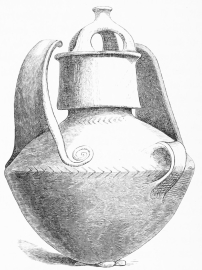

| | No. 113 A Trojan Vase in Terra-cotta of a very remarkable form (8 M.) | 159 |

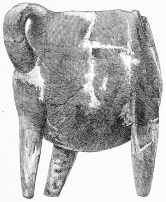

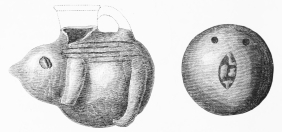

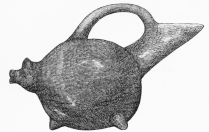

| | No. 114 Engraved Terra-cotta Vessel in the form of a Pig (or Hedgehog?). 7 M. | 160 |

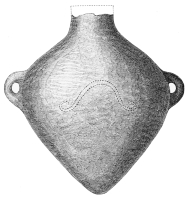

| | No. 115 inscribed Whorl (7 M.) | 161 |

| | No. 116 Terra-cotta Seal (1 M.) | 162 |

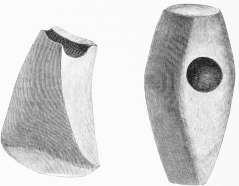

| | No. 117 A Trojan Hand Millstone of Lava (10 M.) | 163 |

| | No. 118 A piece of Granite, perhaps used, by means of a wooden Handle, as an upper Millstone (10 M.) | 163 |

| | No. 119 A massive Hammer of Diorite (10 M.) | 163 |

| | No. 120 Piece of Granite, probably used as a Pestle. From the Lowest Stratum (11-16 M.) | 163 |

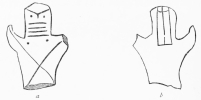

| | No. 121 Idol of Athena (8 M.) a. Front; b. Back | 164 |

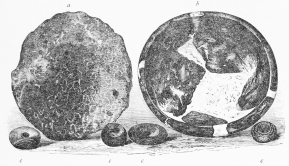

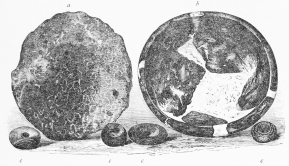

| | Nos. 122-124. Balls of fine red Agate (9 M.) | 165 |

| | No. 125 A curious Terra-cotta Cup (4 M.) | 166 |

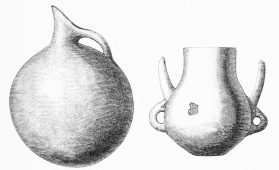

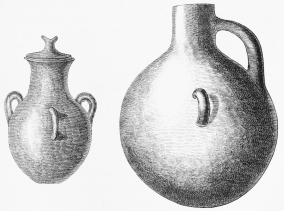

| | No. 126 Terra-cotta Pitcher of a frequent form (6 M.) | 166 |

| | No. 127 A small Terra-cotta Vase, with two Handles and three feet (6 M.){xxxvii} | 167 |

| | No. 128 Terra-cotta Vase of a frequent form (6 M.) | 167 |

| | No. 129 Terra-cotta Vase of a form frequent at the depth of 3-5 M. | 169 |

| | No. 130 Terra-cotta Vessel (4 M.) | 170 |

| | No. 131 A small Terra-cotta Vase with two Rings for suspension (2 M.) | 170 |

| | Nos. 132, 133. Owl-faced Vase-covers (3 M.) | 171 |

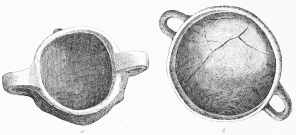

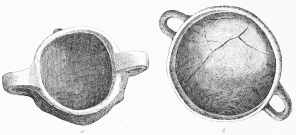

| | Nos. 134, 135. Two-handled Cups from the upper Stratum (2 M.) | 171 |

| | No. 136 Terra-cotta Vase (2 M.) | 171 |

| | No. 137 Perforated Terra-cotta (2 M.) | 171 |

| | Nos. 138, 139. Deep Plates (pateræ) with Rings for suspension, placed (a) vertically or (b) horizontally (1 and 2 M.) | 172 |

| | Nos. 140, 141. Idols of the Ilian Athena (3 M.) | 172 |

| | No. 142 Mould in Mica-schist (2½ M.) | 173 |

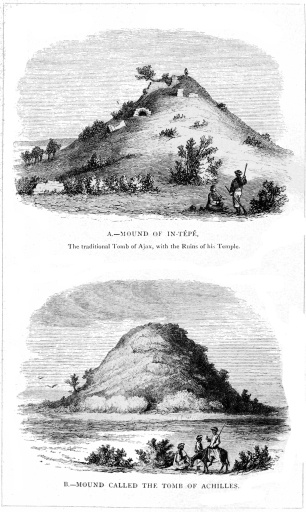

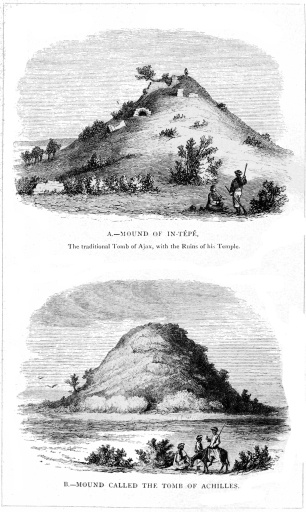

| PLATE VII. | A.—Mound of in-tépé, The Traditional Tomb of Ajax | To face 178 |

| Upon the mound, which stands about one-third of a mile from the

Hellespont, are seen the remains of a little temple, which was

restored by Hadrian. Beneath the ruins is seen a vaulted passage,

built of bricks, nearly 4 feet in height and width. |

| B.—Mound called the Tomb of Achilles. |

| Formerly on the sea-shore, from which it is now divided by a low

strip of sand. |

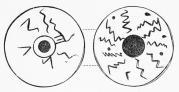

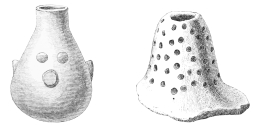

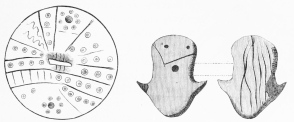

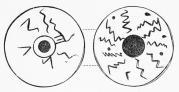

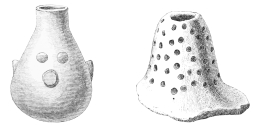

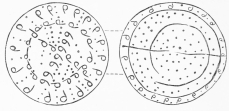

| | No. 143 Terra-cotta Ball, representing apparently the climates of the globe (8 M.) | 188 |

| | No. 144 Small Terra-cotta Vessel from the Lowest Stratum, with four perforated feet, and one foot in the middle (14 M.) | 190 |

| | Nos. 145, 146. Two little Funnels of Terra-cotta, inscribed with Cyprian Letters (3 M.) | 191 |

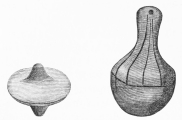

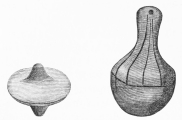

| | No. 147 A Trojan Humming-top (7 M.) | 192 |

| | No. 148 Terra-cotta Bell, or Clapper, or Rattle (5 M.) | 192 |

| | No. 149 A Trojan decorated Vase of Terra-cotta (7 M.) | 199 |

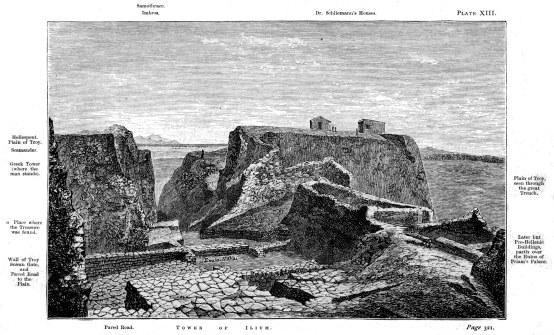

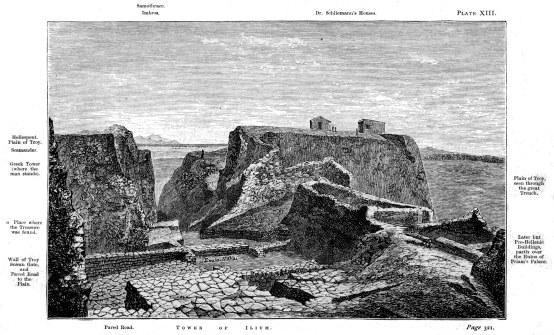

| PLATE VIII. | The Great Tower of Ilium, From The S.e. | To face 200 |

| | No. 150 Terra-cotta Vase (7 M.) | 208 |

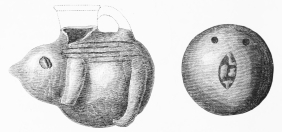

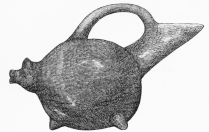

| | No. 151 Terra-cotta Vase in the form of an Animal (10 M.) | 208 |

| | No. 152 Terra-cotta Vessel in the shape of a Pig (14 M.) | 209 |

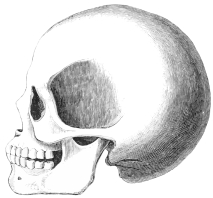

| | No. 153 Skull of a Woman, found near some gold ornaments in the Lowest Stratum (13 M.){xxxviii} | 209 |

| | No. 154 Block of Limestone, with a socket, in which the pivot of a door may have turned (12 M.) | 211 |

| | No. 155 A Trojan Terra-cotta Vase, with an Ornament like the Greek Lambda (8 M.) | 214 |

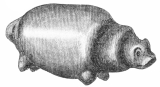

| | No. 156 Curious Terra-cotta Vessel in the shape of a Mole (Tower: 7 or 8 M.) | 214 |

| | No. 157 A Trojan Dish with side Rings, and Plates turned by the Potter (Tower: 7 M.) | 215 |

| | No. 158 A curious Trojan Jug of Terra-cotta (8 M.) | 219 |

| | No. 159 Terra-cotta Image of a Hippopotamus (7 M.) | 228 |

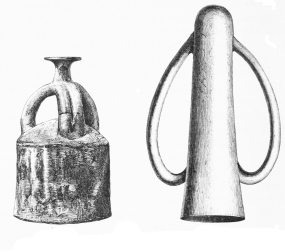

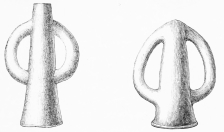

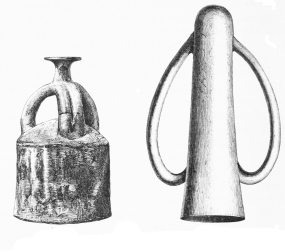

| | No. 160 Remarkable Terra-cotta Vessel in the shape of a Bugle, with three feet (3 M.) | 229 |

| | No. 161 Terra-cotta Vessel with three feet, a handle, and two ears (5 M.) | 229 |

| | No. 162 Terra-cotta Image of a Pig, curiously marked with Stars (4 M.) | 232 |

| | No. 163 One of the largest marble Idols, found in the Trojan Stratum (8 M.) | 234 |

| | No. 164 Terra-cotta Pot-lid, with symbolical marks (6 M.) | 235 |

| | No. 165 A curious Terra-cotta Idol of the Ilian Athena (7 M.) | 235 |

| | No. 166 Pretty Terra-cotta Jug, with the neck bent back (7 M.) | 236 |

| | No. 167 Remarkable Trojan Idol of Black Stone (7 M.) | 236 |

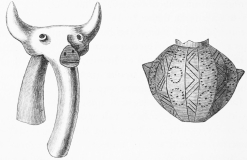

| | Nos. 168, 169. Heads of Horned Serpents (4 M.) | 237 |

| | No. 170 A Serpent’s Head, with horns on both sides, and very large eyes (6 M.) | 237 |

| | No. 171 Head of an Asp in Terra-cotta (both sides) (4 M.) | 238 |

| | No. 172 A Whorl, with rude Symbols of the Owl’s Face, Suastika, and lightning (3 M.) | 255 |

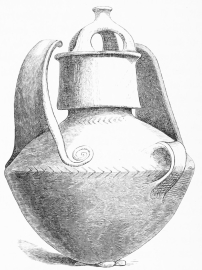

| | No. 173 Splendid Trojan Vase of Terra-cotta, representing the tutelary Goddess of Ilium, θεὰ γλαυκῶπις Ἀθήνη. The cover forms the helmet (8 M.) | 258 |

| PLATE IX. | Upper Part of The Buildings Discovered in The Depths of The Temple of Athena. in The Background Are Seen The Altar And The Reservoir | To face 259 |

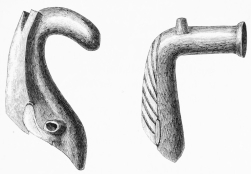

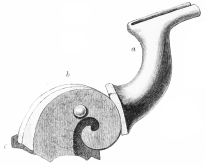

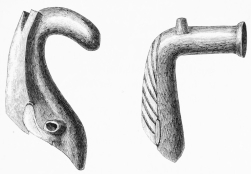

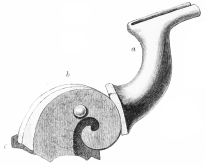

| | No. 174 A Lion-headed Sceptre-handle of the finest crystal; found on the Tower (8 M.) | 260 |

| | No. 175 A mould of Mica-schist, for casting various metal instruments (Tower: 8 M.) | 261 |

| | No. 176 A curious instrument of Copper (3 M.) | 261 |

| | No. 177 A perforated and grooved piece of Mica-schist, probably for supporting a Spit. Found on the Tower (8 M.){xxxix} | 261 |

| | No. 178 A large Terra-cotta Vase, with two large Handles and two small Handles or Rings (5 M.) | 262 |

| | No. 179 A remarkable Terra-cotta Ball (6 M.) | 264 |

| | No. 180 A finely engraved Ivory Tube, probably part of a Flute. Found on the Tower (8 M.) | 264 |

| | No. 181 Knob for a Stick, of fine marble (3 M.) | 265 |

| | No. 182 Bone handle of a Trojan Staff or Sceptre (7 M.) | 265 |

| | No. 183 A brilliant Black Vase, with the Symbols of the Ilian Athena, from the Tower (8 M.) | 267 |

| | No. 184 Vase-cover with Handle in shape of a Coronet (8 M.) | 268 |

| | No. 185 Vase-cover with a Human Face (Tower, 8 M.) | 268 |

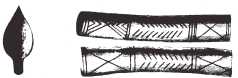

| | No. 186 Flat piece of Gold, in the form of an Arrow-head: from the Tower (8 M.) | 268 |

| | No. 187 Prettily decorated Tube of Ivory (Tower, 8 M.) | 268 |

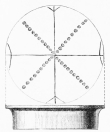

| | No. 188 Great Altar for Sacrifices, found in the depths of the Temple of Athena (1-25th of the real size) | 278 |

| | No. 189 Copper Lance of a Trojan Warrior, found beside his Skeleton (7 M.) | 279 |

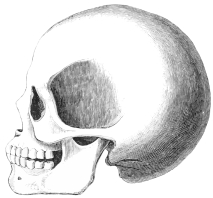

| | No. 190 Skull of a Trojan Warrior, belonging to one of the two Skeletons found in the House on the Tower (7 M.) | 280 |

| | No. 191 The upper and lower pieces of a Trojan Helmet-crest φάλος placed together (7 M.) | 280 |

| | No. 192 Great Copper Ring, found near the Helmet-crest (7 M.) | 281 |

| | No. 193 An elegant bright-red Vase of Terra-cotta, decorated with branches and signs of lightning, with holes in the handles and lips, for cords to hang it up by (Tower, 8 M.) | 282 |

| | No. 194 Terra-cotta Vase. Found on the Tower (8 M.) | 282 |

| | No. 195 Profile of a Vase-cover, with the Owl’s Face and Helmet of Athena, in brilliant red Terra-cotta. Found in an urn on the Tower (8 M.) | 283 |

| | No. 196 An Earthenware Crucible on four feet, still containing some Copper. Found on the Tower (7 M.) | 283 |

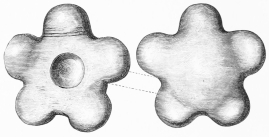

| | No. 197 Flower Saucer: the flat bottom ornamented. Found on the Tower (8 M.) | 284 |

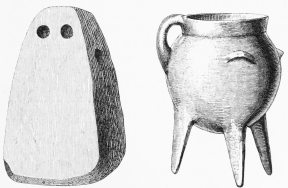

| | No. 198 A piece of Terra-cotta, with two holes slightly sunk in front like eyes, and a hole perforated from side to side (8 M.) | 285 |

| | No. 199 A remarkable Terra-cotta Vessel on three long feet, with a handle and two small ears (7 M.) | 285 |

| | No. 200 A beautiful bright-red Terra-cotta Box, decorated with a + and four 卐, and a halo of solar rays (3 M.) | 286 |

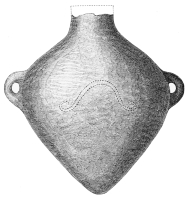

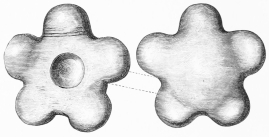

| | Nos. 201, 202. Little Decorated Whorls, of a remarkable shape{xl} | 286 |

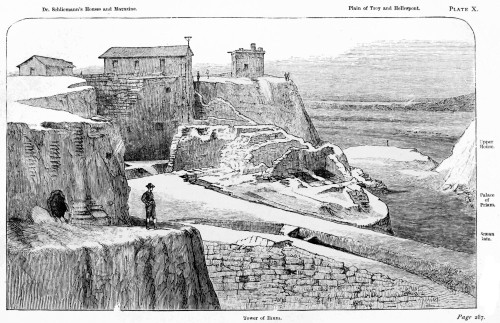

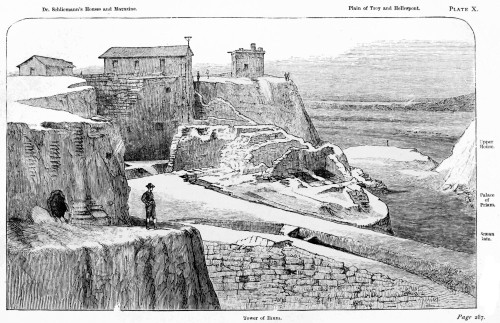

| PLATE X. | The Tower of Ilium, Scæan Gate, And Palace of Priam. Looking North Along The Cutting Through The Whole Hill | To face 287 |

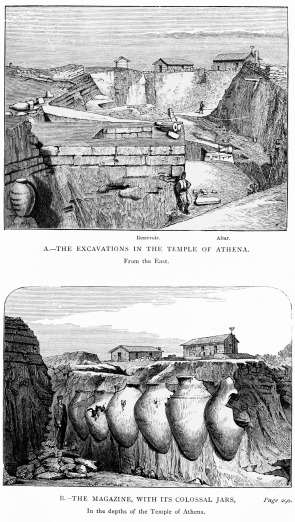

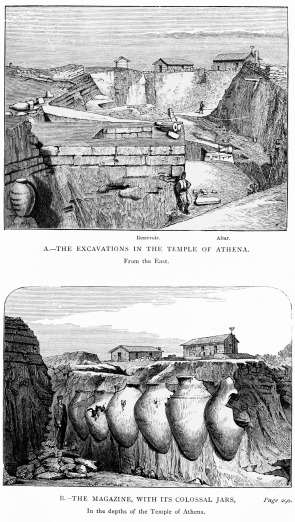

| PLATE XI. | A.—the Excavations in The Temple of Athena. From The East | To face 290 |

| In front is seen the great Reservoir of the Temple, then the

sacrificial Altar. On the right, a stone block of the foundations

of the Temple is seen projecting out of the wall of earth. in the

background, underneath where the man stands, is the position of the

double Scæan Gate, of which, however, nothing is here visible. in

the left-hand corner is one of the colossal jars, not visible in

the next Plate. |

| B.—THE MAGAZINE, WITH ITS COLOSSAL JARS, in the depths of the

Temple of Athena. |

| Of the nine Jars, six are visible; a seventh (to the right,

out of view) is broken. The two largest are beyond the wall of the

Magazine, and one of these is seen in the preceding Plate. |

| | No. 203 Fragment of a Terra-cotta Vase, with Egyptian hieroglyphics, from the bottom of the Greek Stratum (2 M.) | 291 |

| | No. 204 A Greek Lamp on a tall foot (2 M.) | 292 |

| | No. 205 Fragment of a two-horned Serpent (κεράστης), in Terra-cotta (3 M.) | 292 |

| | No. 206 Terra-cotta Cylinder, 1¼ in. long, with Symbolical Signs (5 M.) | 293 |

| | No. 207 Terra-cotta Vase with helmeted image of the Ilian Athena (6 M.) | 294 |

| | No. 208 Fragment of a large Cup-handle in black Terra-cotta: with the head of an Ox (6 M.) | 294 |

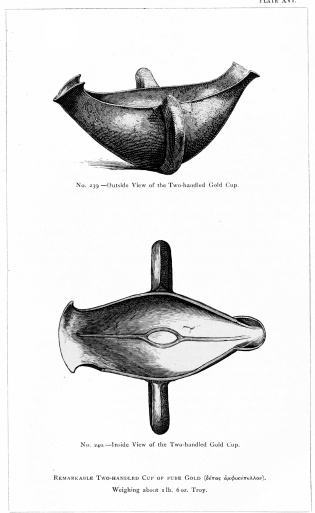

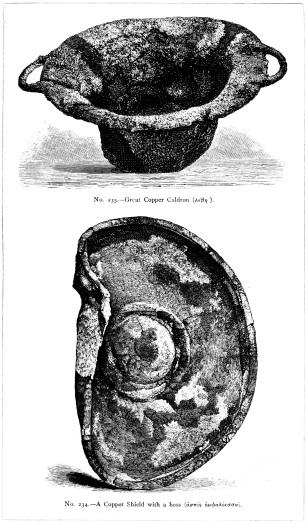

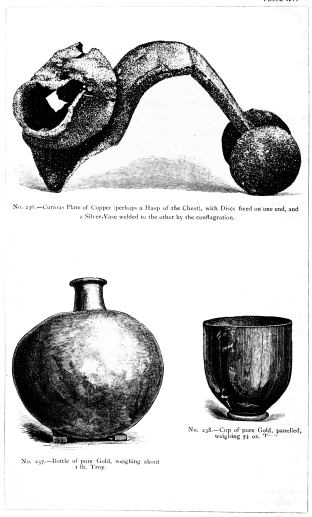

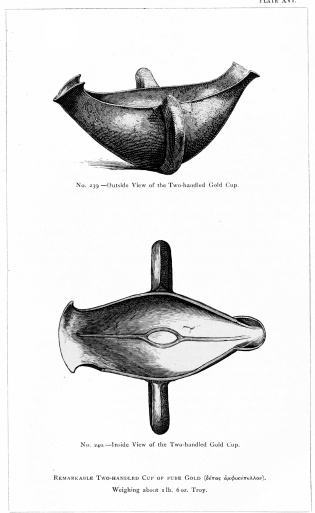

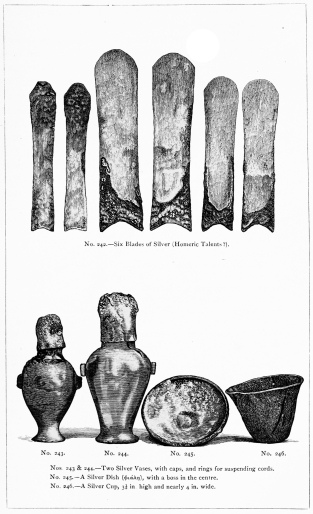

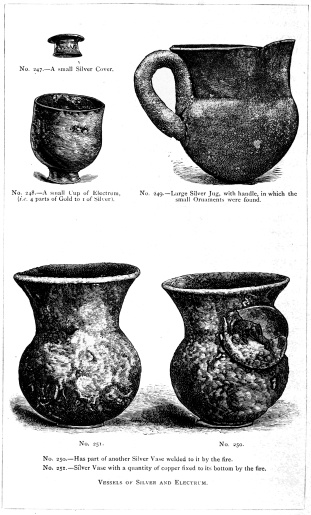

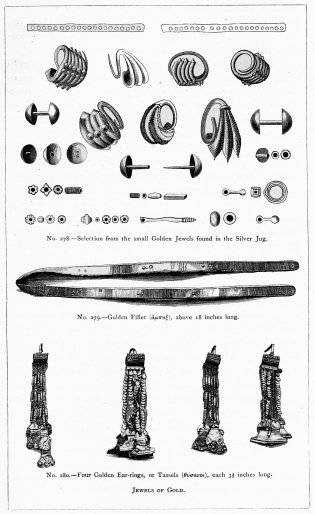

| | No. 209 A finely decorated little Vase of Terra-cotta (6 M.) | 294 |