A SKETCH OF THE LIFE AND TIMES OF

In the absence of any suitable biography of the author of “The Clockmaker,” his centenary may lend an interest to the following brief sketch of his life and times.

Thomas Chandler Haliburton was born at Windsor, in the Province of Nova Scotia, on the 17th day of December, 1796. He was descended from the Haliburtons of Mertoun and Newmains, a Border family, one of whom was Barbara Haliburton, only child of Thomas Haliburton, of Newmains, who married Robert Scott, and whose second son was Walter Scott, the father of the immortal Sir Walter. Her eldest son left numerous descendants. Sir Walter’s tomb is in the ancient burial place of the Haliburtons, St. Mary’s Aisle, in Dryburgh Abbey. About the beginning of the last century nearly all of her numerous uncles migrated to Jamaica, and the eldest of them, Andrew Haliburton, removed thence to Scituate, near Boston, Massachusetts, where he, and, subsequently, his son William, married members of the Otis family, to which the well-known James Otis belonged. William Haliburton (whose cousin, Major John Haliburton, Clive’s colleague, was, according to Mill’s History of India, “the Founder of the Sepoy force,”[3]) removed to Nova Scotia with many persons from Scituate, when the vacant lands of the Acadian French were offered to settlers. His son, the Hon. William Hersey Otis Haliburton, Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, in Nova Scotia, married Lucy Grant, a daughter of Major Alexander Grant, one of Wolfe’s Highland officers at the siege of Quebec, who, after the French war, settled in the colony of New York, where he married a Miss Kent, a near relative of the famous Chancellor Kent. He was killed in the Revolutionary War, at the storming of Fort Stanwix, while in command of the New York Volunteers.

Chief Justice William Hersey Otis Haliburton left an only child, the future author of “Sam Slick,” who was educated at the Grammar School, Windsor, and afterward, at the same place, at the University of King’s College, for Tory King’s College of the Colony of New York had migrated to Windsor, Nova Scotia, where, preserving the traditions of Oxford of olden times, it remained out and out Tory in its politics, and continued unchanged, even after Oxford itself had long felt the influence of modern ideas. In its collegiate school, as late at least as 1845, that venerable heirloom, “Lilly’s Latin Grammar,” which had not a word of English from cover to cover, and which was a familiar ordeal for boys long before Shakespeare was born (Cardinal Wolsey, it is said, assisted in its composition), was still employed. It even retained the quaint old frontispiece representing boys with knee-breeches and shoebuckles (probably a picture of the original “Blue-coat Boys”) climbing up the tree of knowledge, and throwing down the golden fruit. Daily, too, at the meals in the College Hall there was, and perhaps may be to this day, heard a quaint Latin grace, which was droned by the “senior scholar,” beginning, Oculi omnium ad te spectant, Domine; probably the same that was heard in some college halls in the days of the Crusades. It is to be hoped that the “spirit of the age” has not led it to discard this and other venerable heirlooms derived from an ancient ancestry. This truly conservative and orthodox institution, in which the future author was crammed with classics, and taught to “fear God and honour the King,” was then considered one of the most successful educational institutions in America, and it still ranks high in its reputation as a college. It is the oldest in the Colonies, and it is the only one that has a Royal Charter.

Mr. Haliburton used often to puzzle his friends by saying that he and his father were born twenty miles apart, and in the same house.

The enigma throws some light on the early history of Windsor. His father had extensive grants of land at Douglas, a place situated at the head waters of the St. Croix, a tributary of the Avon, as to which there is a gruesome tablet at St. Paul’s Church, Halifax, Nova Scotia, to the memory of a nobleman, who lost his life “from exposure during an inclement winter, while settling a band of brave Carolinians” at Douglas.

The famous Flora McDonald, whose husband was a captain in that regiment, spent a winter in Fort Edward, the old blockhouse of which still overlooks the village of Windsor.

The house at Douglas was built in the middle of the last century, like a Norwegian lodge, of solid timber covered with boards. When Mr. Haliburton’s father removed from Douglas it was floated down the river, and was placed on the bank of the Avon, where the town of Windsor now is, and in it Mr. Haliburton was born. The tide there is very remarkable, as it rises over thirty-six feet; and while at high tide hundreds of Great Easterns could float there, when the tide is out the river dwindles into a rivulet, lost in a vast expanse of square miles of chocolate. The village early in the century consisted of one straggling street along the river bank, under green arches formed by the meeting of the boughs of large elms, a pretty little Sleepy Hollow, the quiet of which was only at times disturbed by the arrival from Halifax of a six-horse stage-coach at full gallop, or by the melancholy whistle of a wheezy little steamer from St. John, New Brunswick. The limited society of the place, a bit of rural England which had migrated, was far more exclusive and aristocratic than that now found in Halifax, or any Canadian city (for a shop-keeper or retailer, however wealthy, could not get the entrée to it), and was composed mainly of families of retired naval and military officers, “U.E. Loyalists,” professional men, Church of England clergy, and professors at the College, and also one or two big provincial dignitaries, with still bigger salaries, who had country seats where they spent their summers. The officers, too, of a detachment of infantry stationed there largely contributed to break the monotony of the place.

Clifton, Windsor, N.S.

The migratory house was in time succeeded by a much more commodious one, built almost opposite to it; and this, in its turn, soon after Mr. Haliburton was made a Judge, was deserted for what was his home for a quarter of a century, Clifton, a picturesque property to the west of the village, consisting in all of over forty acres, bounding to the eastward on the village, to the north on the river, and to the south on the lands of King’s College. Underlaid by gypsum, it was much broken up and very uneven; and the enormous amount of earth excavated in opening up the gypsum quarries was all needed to make the property a comfortable and suitable place of residence. Lord Falkland, a Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia, used to say that he had never seen any place of its size that had such a variety of charming scenery. One precipitous, sunny bank, about one hundred and fifty feet long and thirty feet high, became a dense thicket of acacias, and when they were in bloom, was one mass of purple and white blossoms, while pathways wandered up and down through gleaming spruce copses and mossy glades.

One of its special points of interest was the “Piper’s Pond,” so named after a probably mythical piper of a Highland regiment, who, having dropped his watch into the water, dived after it, and never came up. It was one of the few “punch-bowls” in gypsum regions that are not found dry.

The Piper’s Pond.

As a landscape gardener, he was greatly aided by the thorough art training his assistant had obtained at the best ladies’ school of her day—one at Paris supported by the old Noblesse. Her history, from early childhood to the time when she arrived at Windsor, the youthful bride of Mr. Haliburton, who himself was still a minor, was a singular succession of romantic incidents. She was a daughter of Captain Laurence Neville, of the 19th Light Dragoons, and as she was very young when her mother died, her father, having made provision for her support and education before rejoining his regiment in India,[4] left her in charge of the widow of a brother officer, a sister of Sir Alexander Lockhart, who subsequently, unknown to him, married William Putnam McCabe, a man of means, who became the Secretary of “the United Irishmen” of ’98. When he escaped to France in an open smuggler’s boat, he took with him his wife and also her ward, Miss Neville; and in 1816, the year the latter was married, in spite of the ten thousand pounds placed on his head he secretly went to England to bid her good-bye.

Long before the thrilling tales of his escapes from the troops in pursuit of him, and other adventures, appeared in Madden’s “History of the United Irishmen,” they had been household words in the nursery at Clifton.

The story of her marriage was equally romantic. When her father, who was living at Henley-on-Thames in 1812, was on his death-bed, he heard that a very old military friend, named Captain Piercy, was living not far from that place, and he therefore wrote to him, asking him to call on Miss Neville, and to render her such services as she might need until the arrival of her only brother, who was then in India with his regiment, the 11th Hussars. He died in ignorance of the fact that he had written to a perfect stranger, an old retired naval officer of that name, who, with his wife, on receipt of the letter, called on Miss Neville, and invited her, as they had no children, to make their house her home. His step-nephew, Mr. Haliburton, while on a visit to England, met her at his house, and though still a minor, became engaged to and married her. The memory of these incidents was long preserved in the local traditions of Henley-on-Thames.

Mr. Haliburton, who had graduated with honors on leaving college, in time was called to the bar, and practised at Annapolis Royal, the former capital of Nova Scotia, where he acquired a large and lucrative practice; but a wider sphere of action was opened to him when he became the representative of the county of Annapolis, and, as such, by his power of debate and his ability, he speedily attained a leading position.[5]

He was the first public man who in a British Legislature successfully advocated the removal of Roman Catholic disabilities. Speaking of his speech on that occasion, Mr. Beamish Murdoch, in his “History of Nova Scotia,” says it was “the most splendid bit of declamation that it has ever been my fortune to listen to. He was then in the prime of life and vigor, both mental and physical. The healthy air of country life had given him a robust appearance, though his figure was yet slender and graceful. As an orator, his manner and attitude were extremely impressive, earnest and dignified; and, although the strong propensity of his mind to wit and humor was often apparent, they seldom detracted from the seriousness of his language, when the subject under discussion was important. Although he sometimes exhibited rather more hauteur than was agreeable, yet his wit was usually kind and playful. On this occasion he absolutely entranced his audience. He was not remarkable for readiness of reply in debate; but when he had time to prepare his ideas and language he was almost always sure to make an impression on his hearers.”

On this point Mr. Duncan Campbell, in his “History of Nova Scotia” (p. 334), says: “The late Mr. Howe spoke of him to the writer as a polished and effective speaker. On some passages of his more elaborate speeches he bestowed great pains, and in the delivery of them, Mr. Howe, who acted in the capacity of a reporter, was so captivated and entranced that he had to lay down his pen and listen to his sparkling oratory. It is doubtless to one of these passages that Mr. Beamish Murdoch refers.”

It is difficult to imagine a more uninviting arena than was presented at that time by Nova Scotian politics, or more undesirable associates in public life than the politicians of that day. The Province was ruled over by a Council consisting of a few officials living at Halifax, one of the leaders of which was the Church of England Bishop. In vain, therefore, year after year Mr. Haliburton got the House to vote a grant to a Presbyterian institution, the Pictou Academy. It was invariably rejected by the Council; while a small grant in aid of public schools was contemptuously rejected without any discussion as to it. His ridicule of the conduct of the Council in that matter gave them great offence, and they demanded an apology from the House, which, however, was refused, as the House resolved that there was nothing objectionable in his remarks, and also that they were privileged. The Council again more peremptorily demanded an apology, when the House, incredible as it may seem, unanimously stultified itself by resolving that Mr. Haliburton should be censured for his remarks. He accordingly attended in his place, and was censured by the Speaker! It must, therefore, have been an infinite relief, when an opportunity offered of escape from such an ordeal as public life was in those days.

He lived in the district embraced by the Middle Division of the Court of Common Pleas, of which his father was Chief Justice, while he himself was the leader on that circuit. When, therefore, his father died, the vacant post was, as a matter of course, offered to him, and was gladly accepted.

But in Pictou County, which was largely settled by “dour” Cameronians, and which gloried in those annual and ever-recurring battles against the Bishop and his followers, there are no doubt types of “Old Mortality” that will never cease to denounce his retirement from the perennial strife as a great sin, and an act of treason to his country, or (what is the same thing) to the Pictou Academy.

In 1828, when only thirty-two years of age, he received the appointment of Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas. In 1841 the Court of Common Pleas was abolished, and his services were transferred to the Supreme Court. In February, 1856, he resigned his office of a Judge of that Court, and soon afterwards removed to England, where he continued to reside till his death.

It was a curious instance of “the irony of fate,” when the successful advocate of the removal of the political disabilities of Roman Catholics was a quarter of a century afterwards called on as a Judge to rule that the rights of Roman Catholic laymen, as British subjects, could not be restricted by any ecclesiastical authority.

Carten, a very prominent and respected Irishman living in Halifax, having been excommunicated, was denied access to his pew in St. Mary’s Cathedral, of which he was the legal owner. Judge Haliburton’s ruling in favor of the plaintiff in Carten vs. Walsh et al. was a very able one. This was probably the only case in which a judge in Nova Scotia ever had to order a court room to be cleared in consequence of manifestations of public excitement and feeling.

About 1870 the same point was raised at Montreal in the famous “Guibord case.” The members of a French-Canadian literary society, which had refused to have standard scientific works weeded out of its library, were excommunicated. One of them, named Guibord, had bought and was the legal owner of a lot in the public cemetery at Montreal, and, when he died, his body was refused admission to it. Though this proceeding was justified by the Quebec courts, their judgments were reversed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council; and upon the defendants refusing to obey “the order of Her Majesty in Council in the matter,” some thousands of troops were called out, and the body, under military protection, was buried under several feet of Portland cement in the Guibord lot.

While the ruling in Carten vs. Walsh et al. created some bitter enemies that were powerful enough to make their hostility felt, some offence (perhaps not altogether without apparent cause) may also have been taken by them at a few incidental philosophical allusions in “Rule and Misrule of the English in America” to the important results that were likely to flow from the new rôle of the Roman Catholic Church as a political power in the New World, a subject that he would no doubt have prudently avoided could he have foreseen the bitter controversy as to that question that was about to be caused by the rise of the “Know-nothing Movement.”

Thanks to that wonder-worker, Time, the lapse of fifty years rarely fails to take all the caloric out of “burning questions,” and is able to convert the startling forecasts of thinkers into the trite truisms of practical politics.

The animus against him, however, was probably of a persistent type. “From the ills of life,” says Longinus, “there is for mortals a sure haven—death, while the woes of the gods are eternal.” But successful authors are not much better off than the unlucky gods, for their names and their works survive them and can be tabooed.

The generous tribute from the Archbishop of Halifax and Mr. Senator Power, at the Haliburton Centenary meeting at Halifax, to the important services he had rendered three-quarters of a century ago, is a pleasing proof that a public man may safely do his duty and leave his life to the impartial verdict of a later generation.

A few years after taking up his residence in England, he paid a visit to Ontario, Canada, where he negotiated the purchase by the Canadian Land and Immigration Company of an extensive tract of country near Peterborough. Most of it that is not now sold is included in the county of Haliburton, which returns a member to the Ontario Legislature, and the county town of Haliburton is the terminus of the Haliburton branch of the Grand Trunk Railway.

In 1816, as already stated, he married Louisa, only daughter of Captain Laurence Neville, of the 19th Light Dragoons (she died 1840), by whom he had a large family.[6] And secondly, in 1856, Sarah Harriet, widow of Edward Hosier Williams, of Eaton Mascott, Shrewsbury, by whom he had no issue, and who survived him several years.

That life-long exile, the poet Petrarch, says that men, like plants, are the better for transplanting, and that no man should die where he was born. For years Judge Haliburton stagnated and moped in utter solitude at Clifton, for his large family had grown up and were settled in life elsewhere, while death had removed the little band of intellectual companions whose society had been a great source of enjoyment to him. But he got a new lease of life by migrating to England. His second wife was a very intelligent and agreeable widow lady of a good social position, who even after having made a considerable sacrifice of her means in order to marry him, was comfortably off. It was a very happy match, and she proved to be a most devoted wife. Before they were married she had leased Gordon House, situated on the Thames, not far from Richmond (a house built by George I. for the Duchess of Kendal, who after his death believed that her royal lover used to visit her in the form of a crow in what is still known as “The haunted room”). In time the gardens and grounds there were referred to as showing what lady floriculturists can accomplish. His family, most of whom resided in England, were delighted at seeing him in his old age well cared for in a comfortable home.

Gordon House, Isleworth.

As an author, he first came before the public in 1829, as the historian of his native Province. His work, which was well received by both the public and the press, and was so highly thought of that the House of Assembly tendered him a vote of thanks, is to the present time regarded as a standard work in the Province.

Six years subsequently he became unconsciously the author of the inimitable “Sam Slick.” In a series of anonymous articles in the Nova Scotian newspaper, then edited by Mr. Joseph Howe, he made use of a Yankee peddler as his mouthpiece. The character proved to be “a hit,” and the articles greatly amused the readers of that paper, and were widely copied by the American press. They were collected together and published anonymously by Mr. Howe, of Halifax, and several editions were issued in the United States. A copy was taken thence to England by General Fox, who gave it to Mr. Richard Bentley, the publisher. To Judge Haliburton’s surprise, he found that an edition that had been very favorably received had been issued in England. For some time the authorship was assigned to an American gentleman in London, until Judge Haliburton visited England and became known as the real author.

For his “Sam Slick” he received nothing from the publisher, as the work had not been copyrighted, but Mr. Bentley presented him with a silver salver, on which was an inscription written by the Rev. Richard Barham, the author of the “Ingoldsby Legends.” Between Barham, Theodore Hook and Judge Haliburton an intimacy sprang up. They frequently dined together at the Athenæum Club, to which they belonged, and many good stories told by Hook and Barham were remembered by the Judge long after death had deprived him of their society.

As regards “Sam Slick,” he never expected that his name would be known in connection with it, or that his productions would escape the usual fate of colonial newspaper articles. On his arrival in London, the son of Lord Abinger (the famous Sir James Scarlett) who was confined to his bed, asked him to call on his father, as there was a question which he would like to put to him. When he called, his Lordship said, “I am convinced that there is a veritable Sam Slick in the flesh now selling clocks to the Bluenoses. Am I right?” “No,” replied the Judge, “there is no such person. He was a pure accident. I never intended to describe a Yankee clockmaker or Yankee dialect; but Sam Slick slipped into my book before I was aware of it, and once there he was there to stay.”

In some respects, perhaps, the prominence given to the Yankee dialect was a mistake, for, except in very isolated communities, dialect soon changes. A Harvard professor, nearly fifty years ago, indignantly protested against Sam Slick being accepted “as a typical American.” His indignation was a little out of place. It would be equally foolish in an Englishman should he protest against Sam Weller being regarded as a typical Englishman. Do typical Americans wander about in out-of-the-way regions selling wooden clocks? Sam Slick represented a very limited class that sixty years ago was seen oftener in the Provinces than in the United States, but we have the best proof that The Clockmaker suggested a true type of some “Downeasters” of that day in the fact that the people of many places in the North-eastern States were for many years convinced that they had among them the original character whom Judge Haliburton had met and described.

Sixty years ago the Southern States were familiar with the sight of Sam Slicks, who had always good horses, and whose Yankee clocks were everywhere to be seen in settlers’ log houses.

Since Sam Slick’s day the itinerant vendor of wooden clocks has moved far west, and when met with there, is a very different personage from Sam Slick. Within the past forty years, however, veritable Sam Slicks have occasionally paid a visit to Canada. One of them sold a large number of wooden clocks throughout Nova Scotia and Cape Breton. They were warranted to keep accurate time for a year, and hundreds of notes of hand were taken for the price. The notes passed by indorsement into third hands, but, unfortunately, the clocks would not go. Actions were brought in several counties by the indorsees, and the fact that Seth’s clocks had stopped caused as much lamentation and dismay as a money panic. The first case that came up was tried before Judge Haliburton, much to the amusement of the public and to the edification of the Yankee clockmaker, who had a long homily read to him on the impropriety of cheating Bluenoses with Yankee clocks that would do anything sooner than keep time.

But a man may be a Yankee clockmaker without having the “cuteness” and common sense of Sam Slick. In his Early Reminiscences, Sir Daniel Lysons describes such an one who, while selling clocks in Canada, was tempted to stake his money and clocks, etc., on games of billiards with a knowing young subaltern. “The clocks soon passed into British possession. They then played for the waggon and horse. Finally, Sam Slick, pluck to the backbone, and still confident, staked his broad-brimmed hat and his coat; Bob won them; and putting them on in place of his own, which he gave to his friend Sam, he mounted the waggon and drove into barracks in triumph, to the immense amusement of the whole garrison.”

An English Reader has for half a century been in use in French schools, which gives Sam Slick’s chapter on “Buying a Horse” as one of its samples of classical English literature.

Experience is proving that the value attached by Sam Slick to the geographical position and natural advantages of the Province of Nova Scotia was not a mistaken one. We are, however, apt to be more grateful to those that amuse than to those who instruct us. Many persons who laughed at Sam Slick’s jokes did not relish his truths, and his popularity as an author was far greater out of Nova Scotia than in it; but it had ceased to depend on the verdict of his countrymen.

Artemus Ward pronounced him to be the “father of the American school of humor.”

The illustrations of the Clockmaker by Hervieu, and of Wise Saws by Leech, supplied the conventional type of “Brother Jonathan,” or “Uncle Sam,” with his shrewd smile, his long hair, his goatee, his furry hat, and his short striped trousers held down by long straps, a precise contrast to the conventional testy, pompous, pot-bellied John Bull, with his knee-breeches and swallow-tail coat.

Among all the numerous notices of Sam Slick’s works that have appeared from time to time, that by the Illustrated London News, on July 15th, 1842, which was accompanied by an excellent portrait of Judge Haliburton, is the most discriminating and appreciative.

“Sam Slick’s entrée into the literary world would appear to have been in the columns of a weekly Nova Scotian journal, in which he wrote seven or eight years ago a series of sketches illustrative of homely American character. There was no name attached to them, but they soon became so popular that the editor of the Nova Scotian newspaper applied to the author for permission to reprint them entire; and this being granted, he brought them out in a small, unpretending duodecimo volume, the popularity of which, at first confined to our American colonies, soon spread over the United States, by all classes of whose inhabitants it was most cordially welcomed. At Boston, at New York, at Philadelphia, at Baltimore, in short, in all the leading cities and towns of the Union, this anonymous little volume was to be found on the drawing-room tables of the most influential members of the social community; while, even in the emigrant’s solitary farm house and the squatter’s log hut among the primeval forests of the Far West, it was read with the deepest interest, cheering the spirits of the backwoodsman by its wholesome, vigorous and lively pictures of every-day life. A recent traveller records his surprise and pleasure at meeting with a well-thumbed copy in a log hut in the woods of the Mississippi valley.

“The primary cause of its success, we conceive, may be found in its sound, sagacious, unexaggerated views of human nature—not of human nature as it is modified by artificial institutions and subjected to the despotic caprices of fashion, but as it exists in a free and comparatively unsophisticated state, full of faith in its own impulses and quick to sympathize with kindred humanity; adventurous, self-relying, untrammelled by social etiquette; giving full vent to the emotions that rise within its breast; regardless of the distinctions of caste, but ready to find friends and brethren among all of whom it may come in contact.

“Such is the human nature delineated in Sam Slick.

“Another reason for Sam Slick’s popularity is the humor with which the work is overflowing. Of its kind it is decidedly original. In describing it we must borrow a phrase from architecture, and say that it is of a ‘composite order;’ by which we mean that it combines the qualities of English and Scotch humor—the hearty, mellow spirit of the one, and the shrewd, caustic qualities of the other. It derives little help from the fancy, but has its ground-work in the understanding, and affects us by its quiet truth and force and the piquant satire with which it is flavored. In a word—it is the sunny side of common sense.”

A review of “Nature and Human Nature” drew attention to the fact that no writer has produced purer conceptions of the female character than are to be found in Sam Slick’s works. They show none of those morbid, sexualistic tendencies which are betrayed in some modern novels written by young ladies, or in semi-scientific papers on sexual subjects by “advanced females.” Tacitus praised the social purity of the Germans at the expense of his corrupt fellow-countrymen. “No one there makes a jest of vice,” which we may now read, “No one there writes novels about adultery.” Sam Slick tells us how he romped and flirted with country girls; but in all he has written there is not the slightest trace of impropriety, even by the most remote implication. There is no harm in Sam Slick’s jokes, which were originally intended for rough, plain-spoken backwoods Bluenoses of sixty years ago; for, while impurity corrupts, however refined it may be, coarseness does not. The Bible is often coarse, but never impure.

Some years before Sydney Smith made what is generally set down as his best joke, as to a day being so hot that it would be a comfort to “take off our flesh and sit in our bones,” it had made its appearance in “Sam Slick;” and the country girl who says, “I guess I wasn’t brought up at all, I growed up,” probably suggested Topsy’s, “spec I growed.”

After this sketch had been written, a somewhat startling suggestion, that the idea of The Clockmaker had been borrowed from Dickens, and that Sam Slick was merely a Yankee version of Sam Weller, led to an inquiry into the point. The coincidences were many, and could hardly be accidental. Dickens sends off Pickwick in his wanderings without any apparent object in view, accompanied by a shrewd and humorous Cockney valet, whose sayings and doings are the prominent feature of the book; while Judge Haliburton sends off the author on very similar travels, accompanied by a cute Yankee, for whose yarns and jokes the book is simply a peg on which they can be hung. In both cases there is the faintest apology for a connected story.

If any one had been guilty of plagiarism, it was Dickens, for the first number of the “Pickwick Papers” appeared in April, 1836, while the early chapters of “The Clockmaker” were published in 1835, and were at once widely copied by the American press, and may have been seen by Dickens.

The Cockney dialect was used as far back as 1811 in a farce by Samuel Beazley, architect; and no doubt the Yankee dialect in “The Clockmaker” was not its first appearance in literature.

Duncan Campbell says in his “History of Nova Scotia” (p. 335), “Sam Slick, the Clockmaker, immediately attracted attention. The character proved to be as original and amusing as Sam Weller. Samuel amuses us only. Slick both amuses and instructs. Rarely do we find in any character, not excepting the best of Scott’s, the same degree of originality and force, combined with humor, sagacity, and sound sense, as we find in the Clockmaker. Industry and perseverance are effectively inculcated in comic story and racy narrative. In the department of instructive humor Haliburton stands, perhaps, unrivalled in English literature.”

The Spectator (London) calls him “One of the shrewdest of humorists;” and his biographer in Chambers’ Encyclopedia says, “he attained a place and fame difficult to acquire at all times—that of a man whose humor was a native of one country and became naturalized in another, for humor is the least exotic of the gifts of Genius.”

Philarète Chasles in the Revue des Deux Mondes,[7] in a long and favorable notice of Judge Haliburton’s works, pronounced them to be unequalled by anything that had been written in England since the days of Sir Walter Scott.

Long after “Sam Slick, the Clockmaker,” first appeared, it was by many persons referred to as a store-house of practical wisdom and common sense, and a vade mecum as to the affairs of every-day life. Forty years ago an able but very eccentric Danish Governor at St. Thomas, in the West Indies, was noted far and wide for his excessive admiration for Sam Slick’s works. Whenever a very knotty point arose before him and his Council, which consisted of three persons, he used to say “We must adjourn till to-morrow. I should like to look into this point. I must see what Sam Slick has to say about it.”

A traveller on reaching the most northern town in the world, Hammerfest, found that Sam Slick had been there before him, for the “Clockmaker” was a hobby and a textbook of a humorous Scotchman, who was the British consul there at that time.

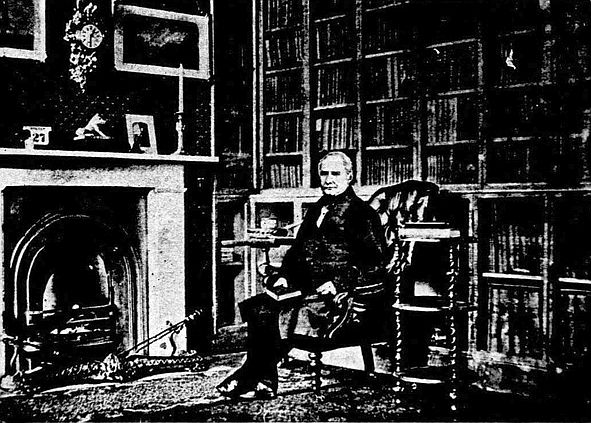

Judge Haliburton was very fond of youthful society; old men were too old for him, for he used to say that a large majority of men when they begin to grow old become very prosy. On the other hand, his humor and conversational powers were very attractive to young men. In illustration of this, the late Sir Fitzroy Kelly, who considered him the most agreeable talker he had ever met, used to tell of meeting him once during the shooting season, at a country house. Next morning, to his surprise, he found all the young men gathered around the Judge in the smoking room, instead of their being among the turnips. They preferred hearing Sam Slick talk to the delights of shooting.

Library, Gordon House, Isleworth.

In 1859, he consented to run for Launceston, where his friend, the Duke of Northumberland, had great influence. On his election he thanked his constituents, “in behalf of four million of British subjects on the other side of the water, who, up to the present time, had not one individual in the House of Commons through whom they might be heard.”

It seems almost providential that when an advocate of the Unity of the Empire was most sorely needed, he had for a quarter of a century been writing in favor of the colonies. But for the strong public opinion as to their value among the masses, whom the popularity of his works had enabled him to reach, fanatical free-traders, in order to prevent the possibility of a return to “the Colonial System,” might have persuaded the nation to burn its ships by getting rid of its colonies.

A solitary colonist at that period in the House of Commons soon found that he had fallen on evil times, and that among all classes above the mass of the people, but especially among politicians, Conservative as well as Liberal, there was a growing hostility to the colonies.

“Oh! was it wise, when, for the love of gain,

England forgot her sons beyond the main;

Held foes as friends, and friends as foes, for they

To her are dearest, who most dearly pay?”

Though no one in Parliament dared to openly advocate disintegration, there was a settled policy on the part of a secret clique, whose headquarters were in the Colonial Office, to drive the colonies out of the Empire by systematic snubbing, injustice and neglect.

This infamous state of things, of which all classes of Englishmen profess now to be ashamed, was made apparent when Judge Haliburton moved in the House of Commons that some months’ notice should be given of the Act to throw open British markets to Baltic timber, a measure which, if suddenly put in operation, would seriously injure New Brunswick merchants; and he urged as a reason for due consideration for that interest, that it was not represented in Parliament. Mr. Gladstone did not condescend to give any explanation or reply, but led his willing majority to the vote, and the Bill was passed.

People sometimes cite what occurred at this debate as a proof that “Judge Haliburton was not a success in the House of Commons;” but it is difficult to imagine a more uncongenial audience for an advocate of Imperial Unity.

Gladstone, as if to remove any doubt as to his animus in these proceedings, sent a singularly insolent reply to a letter written to him by a New Brunswick timber merchant protesting against this unexpected measure. “You protest, as well as remonstrate. Were I to critically examine your language, I could not admit your right, even individually, to protest against any legislation which Parliament may think fit to adopt on this matter.” Had the protest only been in the form of dynamite he would have submissively bowed down at the sound of that “chapel bell” which has since then from time to time called him and his cabinets to repentance. His two attempts to destroy the Empire, first by attacking its extremities through Imperial disintegration, and, next, its heart by Home Rule, alike failed; and he has retired from public life, leaving behind him the fragments, not of a great Empire, but of a shattered party.

Though a majority of both parties, Conservatives as well as Liberals, agreed with their two leaders in their wish to get rid of the Colonies, (for Disraeli, as far back as 1852, wrote, “These wretched Colonies will all be independent in a few years, and are a millstone around our neck”), the people were wiser and more patriotic than their politicians; and in 1869 (only four years after Judge Haliburton’s death) over one hundred and four thousand workingmen of London signed an address to the Queen protesting against any attempt to get rid of that heritage of the people of England—the Colonial Empire. This memorial was not considered worthy of any reply or acknowledgment.[8] At that time, when the fate of England as a first-class power was in the balance, there was no need for the masses to be “educated up” to the subject; it was rather their statesmen and politicians that required to be educated down—down to the common sense of the common people.

The next move against the Disintegrationists was made four years later, in 1872, when “The United Empire Review” revived the now familiar watchword of the old “U. E. Loyalists” of 1776 (those Abe Lincolns, who fought for the Union a hundred years ago), “a United Empire;” and in 1873 an agitation was begun in the Premier’s own constituency (Greenwich) against the dismemberment policy of the Government, that six months later drove them out of power at the general election.

While Gladstone was deliberately striving to breed disunion between the people of England, Scotland, Ireland and “gallant little Wales,” and to get rid of our Colonial Empire, his exact antipodes in everything, Bismarck, that Colossus of the Nineteenth Century, was devoting his giant energies to his life-work,—the unity of Germany, and the creation of a German Colonial Empire. It is possible that, as Sam Slick’s works are among his favorite books, he may have imbibed to some extent Sam Slick’s ideas as to the value of our colonies, and the incredible folly of those that wished to get rid of them; and that we may here find a clue to the unmeasured contempt which the Prince used so often to openly express for English politicians. But he must have been most interested in Rule and Misrule of the English in America, one of the most profoundly philosophical and prophetic works to be found in the literature of any country. Published in England, and by Harper Brothers, New York, in 1851, a troubled time all over Europe, and even in America, which had its Tammany Hall rule, and, later on, its “Know-nothing Movement,” it pointed out that American republican institutions, which dated back to the old Puritans, were of slow growth, and could not be acquired or preserved in European countries by revolutions and universal suffrage; and he foretold the collapse of the French Republic, the rise of Communism, the stern rule of self-imposed Imperialism, and nearly all the leading features of the political history of Europe and America since that date.

Time, however, had a marvel in store, the fruit of half a century of social and political development, which even he did not foresee—a French-Canadian Roman Catholic, supported by a Liberal majority from Quebec, ruling from ocean to ocean over a new Dominion!

Some of his views, visionary as they may have appeared fifty years ago, seem to have taken a practical shape at the Queen’s Jubilee.

“The organization is all wrong. They are two people, but not one. It shouldn’t be England and her colonies, but they should be integral parts of one great whole—all counties of Great Britain. There should be no tax on colonial produce, and the colonies should not be allowed to tax British manufactures. All should pass free, as from one town to another in England; the whole of it one vast home market from Hong-Kong to Labrador. . . . They should be represented in Parliament, help to pass English laws, and show them what laws they want themselves. It should no more be a bar to a man’s promotion, as it is now, that he lived beyond the sea, than being on the other side of the channel. It should be our navy, our army, our nation. That’s a great word, but the English keep it to themselves, and colonists have no nationality. They have no place, no station, no rank. Honors don’t reach them; coronations are blank days to them; no brevets go across the water except to the English officers, who are ‘on foreign service in the colonies.’ No knighthood is known there—no stars—no aristocracy—no nobility. They are a mixed race; they have no blood. They are like our free niggers. They are emancipated, but they haven’t the same social position as the whites. The fetters are off, but the caste, as they call it in India, remains. Colonists are the Pariahs of the Empire.”

Many persons have been surprised that the ablest colonial statesman and journalist since the days of Franklin, the Hon. Joseph Howe, “the father of Responsible Government,” and an advocate of the Unity of the Empire, died without having received any mark of Imperial recognition, while a motley crowd of Maltese, Levantines and stray Englishmen in the colonies were able to add a handle to their unknown names. That this was the case need not surprise us, for the dispensing of such favors was (and we must trust no longer is) in the hands of those who were able, from behind the scenes, to pull the strings of the Dismemberment movement.

The Rev. George Grant, D.D., in a very able address at Halifax, on the life and times of Joseph Howe, said:

“We are, all of us, pupils of Haliburton and Howe. Is not this a proof that, if you would know those secrets of the future which slumber in the recesses of a nation’s thought, unawakened as yet into consciousness, you must look for them in the utterances of the nation’s greatest sons?”

Before closing this sketch it is but right to mention an instance (the only one) in which the British Government seemed disposed to pay a tribute to the ablest author and the most profound thinker that the Colonial Empire has yet produced. As Judge Haliburton’s unrivalled mastery of colonial questions eminently fitted him to be the Governor of an important dependency, the Colonial Office offered to appoint him President of Montserrat, a wretched little West Indian Island, inhabited by a few white families and a thousand or two of blacks. As the manufacture of Montserrat lime-juice had not then been commenced the island must have been even more desolate and woe-begone than it now is.

“Judge Haliburton died at his residence at Isleworth, on the banks of the Thames, where he had greatly endeared himself to the people of the place during the few years which he had spent among them, and was buried in the Isleworth churchyard; and, in accordance with one of his last wishes, his funeral was plain and unostentatious.”

“In the words of a local chronicler:—‘The village of Isleworth will henceforth be associated with the most pleasing reminiscences of Mr. Justice Haliburton; and the names of Cowley, Thompson, Pope, and Walpole will find a kindred spirit in the world-wide reputation of the author of Sam Slick, who, like them, died on the banks of the Thames.’”[9]

In the same graveyard rests the immortal Vancouver. Judge Haliburton, several years before his death, was told by the sexton that a famous navigator was buried there, but he did not remember the name, as it had become illegible on the tombstone. It was found, on making enquiries, that the person in question must have been Vancouver. A new tombstone, with a suitable inscription, was placed over Vancouver’s grave; and several years subsequently a tablet to his memory was erected in the church. It is to be hoped that the day will come when a suitable monument will be raised to the great explorer; and that Westminster Abbey and St. Paul’s may yet become the Valhalla, not only of the Mother Country, but also of her Colonial Empire.

It matters not that there is no public memorial to an author whose writings created among the masses a public opinion in favor of the colonies that baffled the dismemberment craze of English statesmen and theorists. He will have a monument as long as the British Empire lasts.

|

The anonymous form seemed to me the most convenient to adopt in writing the above sketch, and it was understood that, while I should be generally known as the author, my name should not be published as such. As, however, since the above was written, the circulars announcing the forthcoming volume have mentioned my name in connection with it, I have thought it best to append this note.—R. G. Haliburton. |

|

(Publisher’s Note: Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year one thousand eight hundred and ninety-seven, by Robert Grant Haliburton, at the Department of Agriculture.) |

|

The only references to him in Scott’s “Memorials of the Haliburtons” (printed privately in 1820 to show that that family had become extinct in the male line) are, “killed on parade at Madras by a fanatical Sepoy,” and “he was the last survivor in the male line of the Haliburtons of Newmains and Mertoun.” Mill speaks of his death, and says that “the name of Haliburton was long remembered by the Madras Sepoys.” There is no tablet to his memory in the burial place of his family. |

|

The sword of Tippoo Sahib, taken from his dead body by Capt. Neville, after the famous charge of his regiment at Seringapatam, which earned for them the name of “the Terror of India,” is now in the possession of Sir Arthur Haliburton, G.C.B. |

|

With the permission of Mr. Henry J. Morgan, portions of this paper are reproduced, in an abridged form, from his “Bibliotheca Canadensis,” published in 1887. |

|

He left two sons and five daughters. |

|

Tome XXVI, 307 (1841). |

|

It could not have been conveniently pigeon-holed, for it required six men to carry it; but we may assume that it never got farther than the Home Office, and that Her Majesty never heard of it, and therefore never replied to it. The petition was written by the truest friend the colonies have ever had—one who died in harness while working in their cause—the late C. W. Eddy, who informed the writer that the Disintegration party had for a time so effectually “captured” the Royal Colonial Institute, of which he was Secretary, that the Council refused to allow the petition to lie on the table of the reading-room on the ground that it was “revolutionary!” So unsatisfactory was their conduct as late as 1872, that another colonial society would have been founded, had not the colonial element gained the day in the Institute. How far the petition was “revolutionary” may be seen from the following extracts: “We beg to represent to your Majesty that we have heard with regret and alarm that your Majesty has been advised to consent to give up the colonies, containing millions of acres of unoccupied land, which might be employed profitably both to the colonies and to ourselves as a field for emigration. We respectfully submit that your Majesty’s colonial possessions were won for your Majesty, and settled by the valor and enterprise and the treasure of the English people; and that, having thus become part of the national freehold and inheritance of your Majesty’s subjects, they are held in trust by your Majesty, and ought not to be surrendered, but transmitted to your Majesty’s successors, as they were received by your Majesty.” The petition, after urging that by proclamation the mother country and the colonies should be declared to be one Empire, adds, “we would also submit that your Majesty might call to your Privy Council representatives from the colonies for the purpose of consultation on the affairs of the more distant parts of your Majesty’s dominion.” |

|

Morgan’s Bibliotheca Canadensis, p. 169. |

Obvious printer errors have been corrected.

Some illustrations have been moved to coincide with the text.

A cover was created for this ebook.

[The end of A Sketch of the Life and Times of Judge Haliburton, by Robert Grant Haliburton]