BY

THIRTEEN PICTURES OF HAPPY THINGS

THAT WERE MADE BY THE CHILDREN IN

THE SHOP OF THE GOOD CROW CAW CAW,

DRAWN AND ARRANGED BY THE AUTHOR

WITH MARGINAL BY MR. ARTHUR HULL

Copyright 1917

By PATTEN BEARD

THE PILGRIM PRESS

BOSTON

THIS BOOK OF THE HAPPY SHOP

IS DEDICATED TO

HENRY JARRETT AND CAW CAW,

HIS GOOD PLAY

CROW

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Good Crow and Aunt Phoebe | 1 |

| II | The Happy Shop and the Magic Book | 13 |

| III | The Paper Dolls Jimsi Made | 27 |

| IV | The Toy Furniture | 39 |

| V | The Motion Picture Fun That the Crow Knew | 51 |

| VI | The Valentines of the Happy Shop | 69 |

| VII | The Embroidery Patterns in the Magic Book | 79 |

| VIII | The Scrapbooks Crow Told About | 95 |

| IX | The Pin-wheels, Birds, Butterflies | 107 |

| X | The May Baskets | 121 |

| XI | How the Magic Book Helped at School | 131 |

| XII | The Gifts That They Made in the Happy Shop | 141 |

| XIII | The Christmas-Tree That They Made in the Happy Shop | 153 |

The Good Crow and His Mail Box |

Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

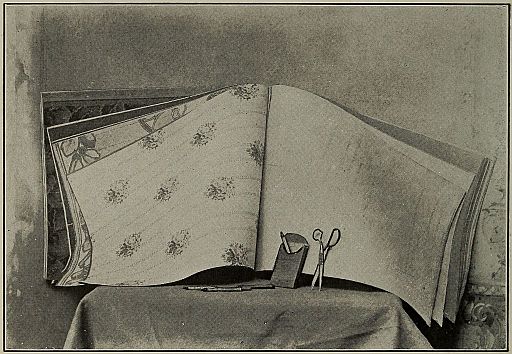

The Magic Book of the Good Crow’s Happy Shop Was a Big Sample Book of Wall Paper |

22 |

The Paper Dolls That Were Cut from Magazines and Whose Clothes Were Made from Wall Paper |

32 |

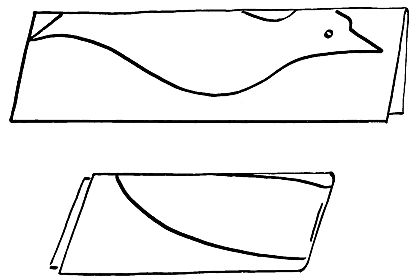

Paper Cutting Diagram I |

43 |

The Paper Doll Furniture That Was Cut From Cardboard and Upholstered with Wall Paper |

45 |

The Motion Pictures That Were Cut from Wall Paper |

57 |

The Valentines and Cards That Were Made Out of Wall Paper |

71 |

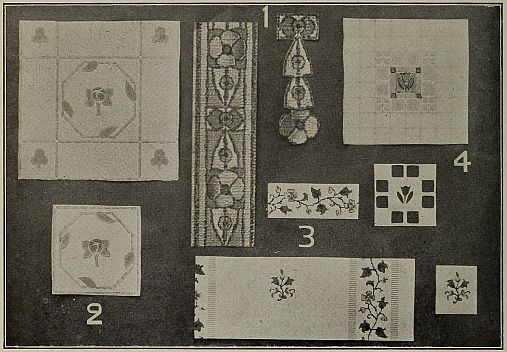

Embroidery Patterns and Stencil Designs That Were Found in Wall Paper |

84 |

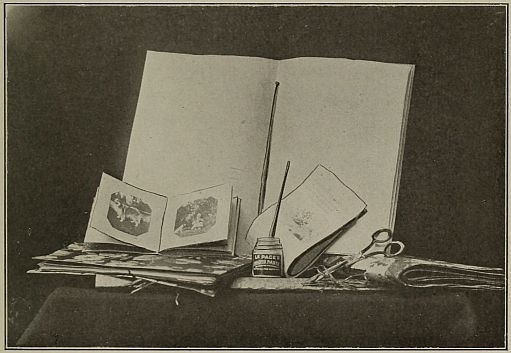

The Scrapbooks That the Children Made with Wall Paper Covers |

103 |

Paper Cutting Diagram II |

113 |

The Bird, the Butterflies and the Pin-wheels That Were Made Out of Wall Paper |

117 |

The May Baskets and the Flower-Pot Cover That Were Made of Wall Paper |

127 |

Here Are School Books with Pretty Covers Made to Keep Them Clean |

133 |

Some Desk Fittings That Were Made with Wall Paper |

147 |

The Christmas-Tree Decorations That Were Made of Wall Paper |

161 |

ONCE a year, Aunt Phoebe came to visit in the city at Jimsi’s house. Aunt Phoebe was Mother’s best friend. Jimsi and Henry and baby Katherine had known her ever so long. They could not remember the time when they did not know Aunt Phoebe. Probably the time dated back to the age of rattles and squeaky rubber dolls when the children were so small that they knew nothing at all about Aunt Phoebe’s Good Crow, Caw Caw.

You see, Aunt Phoebe was a “play aunt.” She did not really belong to the family as everyday aunts and uncles do. She began by playing she was an aunt and almost everything that she did was either make-believe or play or something equally jolly. And Aunt[2] Phoebe’s Good Crow Caw Caw was a play too. It was a happy make-believe that had grown up with Jimsi and Henry and Katherine.

Just how the play about the Good Crow started, nobody was ever able to tell. Even Aunt Phoebe herself could not say. But the make-believe was that Aunt Phoebe knew of a wonderfully delightful bird who was big and black and who liked nothing better than to do nice things for boys and girls.

Jimsi and Henry and Katherine knew well that all this was a lovely pretend. One might believe in it as one believed in fairies or fairy tales that one knows are not at all true—and yet fun to imagine. The Good Crow was a lovely pretend.

Everybody who knew Jimsi and Henry and Katherine, knew about Caw Caw. He appeared most frequently when the great visit of the year fell due and when the expressman had brought in Aunt Phoebe’s trunk and taken the strap off. Then Aunt Phoebe would say, “Oh, Jimsi, Caw Caw sent you a present. He sent one to Henry and Katherine too. I must get it out of my trunk! Come! Let’s see what it is[3]!”

Then Jimsi and Henry and Katherine would laugh and begin to play the play of Caw Caw Crow that would last as long as Aunt Phoebe stayed at their home—no, longer sometimes for the Good Crow often wrote little letters to the children, just for fun.

The presents that came from Caw Caw in Aunt Phoebe’s trunk were not very big presents; they were boxes of crayons or paints or things like scissors and tools to make things. Sometimes there would be a game or a ball or a very nice toy or transfer pictures. The things that Caw Caw Crow sent the children were mostly things to do. One can always find a use for scissors or paints or crayons and things to do, you know.

Maybe, when the children were little, he had begun with giving them boxes of blocks. Now that Jimsi was eleven and Henry nine and Katherine four, Aunt Phoebe’s crow sent them interesting things—not blocks or rubber dolls. He gave them each a plasticine outfit once. Another time he sent them all painting-books. He gave them something to do with their brains and their fingers. That is the best kind of play, don’t you think so?

Well, all the time Aunt Phoebe was at the[4] house in the city, her crow did jolly things for the children. He never really appeared. Jimsi and Henry and Katherine never saw him. He was a lovely pretend like Santa Claus. Aunt Phoebe, who knew more than anybody else did about Caw Caw, declared that he spent most of his time in the Santa Claus Land and that he flew only now and then to the home of Jimsi and Henry and Katherine when Aunt Phoebe was visiting there. He sometimes came at night when the children were sound asleep—exactly as Santa Claus comes. He flew in at the window and very, very often he left wee little letters under the children’s pillows. Maybe he left only a lollipop or a stick of peppermint candy. One never knew when one went to bed promptly and cheerfully what would be under one’s pillow! That was the fun of the play! There was mystery about it. It made fairyland a real everyday-come-true fun!

Some days, if Jimsi or Henry or Katherine had been naughty, there would be a little crow letter that would say:

“Dear Little Friend:

I was flying by the window when you were so horrid and spunky. I don’t like the[5] children who are horrid and spunky. I hope you’ll be different to-morrow.

Good-bye,

Crow.”

After this kind of letter one felt more than ever ashamed.

Maybe the Good Crow would put a different sort of letter under the pillow:

“Dear Little Friend:

It made me glad to see what you did to-day. I like children who eat what is set before them at the table. I send you a lollipop as a reward of merit. Happy dreams.

Good-bye,

Crow.”

One might come home from school and find that Aunt Phoebe’s crow had flown in at Aunt Phoebe’s window during school hours to leave tickets to go to a special children’s performance of Alice in Wonderland to be on Saturday afternoon. Oh, the crow was always doing things that were happy. And, you know, Aunt Phoebe kept him fully informed as to what the children liked best. She knew.

Mother and Daddy and Aunt Phoebe all liked the crow. Indeed, strange to relate, sometimes when Aunt Phoebe was visiting[6] and Mother happened to say that she had admired a certain kind of pretty plant that she had seen in a window down-town, the crow brought the plant and set it in the middle of the dining-room table next day! He left a card with it, of course. The card said, “With love from the children’s Crow.” (Of course, a real crow couldn’t have carried the things that Caw Caw did. Being a play crow and just pretend, he could bring almost anything.)

Oh, I tell you it was jolly! Everybody in the house crowed with laughter over Aunt Phoebe’s Caw Caw. He made jokes; he sent funny pictures cut from magazines; he wrote rhymes and verses that made Mother and Daddy and Jimsi and Henry and Katherine—and even Aunt Phoebe herself—just double up and laugh. One day he left each of the children a big black feather. The feathers were done up in reams and reams of tissue paper. You’d have thought there were BIG presents in the parcels that were waiting on the hall table till Jimsi and Henry came home from school! And then after unrolling and unrolling and unrolling and unrolling out dropped the black feathers. They looked as if somebody had found them in the feather[7] duster but they were labeled, “From Caw Caw’s wing, with love. Keep to remember me.”

Oh, Aunt Phoebe’s visits were such good fun and Caw Caw Crow was so jolly! It was always hard to say good-bye after the two weeks or the month had passed. Henry kept all his crow-treasures—except the eatable ones and those like Alice in Wonderland entertainment tickets. He put them in a drawer with his letters. Jimsi kept hers in a box. As for Katherine, she was still interested in blocks and squeaky dolls made of rubber. Mother kept Katherine’s crow letters till Katherine should grow up to enjoy them all over again some day.

Well, when Aunt Phoebe had gone, the Good Crow play usually stopped unless Mother kept it up or Jimsi or Henry or maybe Daddy tried it. But the crow was never as entertaining as when Aunt Phoebe was around.

Once upon a time, Jimsi got sick. She was really frightfully sick—sick for a long, long time. She had the doctor and then she began to get well slowly. At this time, almost every day in the mail would come a letter from Aunt[8] Phoebe’s Crow telling Jimsi something nice to play in bed. Some days a postal card would come. Some days a pretty book. Some days a bit of doll-sewing. But the very nicest thing of all came when Jimsi was well enough to go out-doors again and not well enough to go back to school. It was a crow letter and it came with a postmark of the town where Aunt Phoebe lived on it. This is what the letter said. (It was written on very wee blue notepaper and written in the tiny handwriting that Aunt Phoebe’s Good Crow usually liked.)

“Dearest Jimsi:

Do you think that your precious Mother would let you come to spend some time in the country with your Aunt Phoebe? She’d be very careful to see that you wore rubbers and didn’t take cold. She’ll see you take your bad medicine and have a peppermint afterwards to take the taste away.

I hope you can come because Aunt Phoebe wants to see you, and I want you to play in my Happy Shop.

Good-bye,

Caw Caw Crow.”

Oh, oh, oh! Hooray!

“Mumsey, I may go, mayn’t I?” pleaded Jimsi. “Oh, I never was at Aunt Phoebe’s! I’ll be good; I’ll go to bed early and I’ll try[9] not to read too much; I’ll take my horrid medicine and I’ll never, never forget to wear overshoes!”

“I want to go too,” urged Henry. “I want to go too!”

“Me too!” echoed baby Katherine. “Me too!”

“Hush!” cried Mother. “I’ll have to ask Daddy, Jimsi dear. We’ll see what the doctor thinks of it. Maybe Aunt Phoebe’s house is the best place a little girl could grow well and strong in. Maybe you can go—but I can’t promise; we’ll see.”

All day long Jimsi went about the house wondering whether she was going to be allowed to go to Aunt Phoebe’s. She and Henry talked about it. “What do you suppose the crow’s Happy Shop is?” they asked each other.

“It’s something ever so nice if it’s the crow,” declared Jimsi. “Maybe it’s a store where the crow buys things.”

“It might be the place where he makes things,” Henry suggested. “Shops are sometimes places where things are made.”

All day long they talked about it. After the doctor had come and gone and when[10] Daddy reached home after business, when the tea table things were cleared away and Jimsi and Henry and Mother and Daddy sat about the lamp in the living-room, they talked about the good crow and the Happy Shop some more. It was decided that day after to-morrow, Jimsi should really go to visit Aunt Phoebe and find out what a Happy Shop was!

Oh, oh, oh! Hooray! Three cheers for Aunt Phoebe and the Good Crow! Hip-hip-hoorah! Hip-hip-hoorah! Hip-hip-hoorah!

That night Jimsi was very happy. She fell asleep to dream of a big black crow who was sitting in a queer little store inside an odd house that was like the White Rabbit’s home in Alice in Wonderland. Of course Jimsi had never seen the crow face to face before but the dream seemed delightfully real and funny. She told Daddy and Mother about it in the morning, and Henry declared that dreams were never true and that, of course, Jimsi wouldn’t see the crow at Aunt Phoebe’s because the crow was all make-believe and there wasn’t any. “We just pretend there is a crow,” he said. “It’s a kind of game. The Happy Shop is prob-ab-ly—(the word is[11] quite a long one for nine years old)—prob-ab-ly another nice new play of Aunt Phoebe’s. There won’t be any real crow there, Jimsi!”

“Oh, I know,” smiled Jimsi. “But it will be a splendid fun of some kind. I can’t wait to find out what it is. When I find out, I’ll write home all about it.”

Really everybody was as interested to know what The Happy Shop really was as Jimsi. Poor Henry had to go off to school. Daddy went to his office downtown. Only Mother and Jimsi were left to speculate upon the subject that day. It was a busy day too for Jimsi had to get ready to go to Aunt Phoebe’s for weeks and weeks while she grew strong in the country. There had to be warm things in her trunk. Some of them had to be mended. It took time. But at last the trunk was packed. (Mother and Henry and Katherine wrote crow letters for Aunt Phoebe and tucked these away inside. Jimsi volunteered to see that they reached Aunt Phoebe’s pillow—somehow.)

And then the day came! Daddy took Jimsi’s bag. There was a big hugging for Mother and Katherine and Henry who couldn’t go to the train because he had to go to school—and then[12] Jimsi and Daddy walked down the street to take the car for the railway station. At the corner Jimsi turned for the forty-eleventh time: “Maybe you can come up for vacation, Henry,” she called back. “I’ll write you all about The Happy Shop.” Just at that moment the car came and they hopped aboard. Before she knew what was happening, Daddy and she were on the train and the train was leaving the city. Slowly the train came out of the dark tunnel that marked its departure from town. Out into open spaces of wide skies and fields it curved along the tracks. And as Jimsi gazed through the car window happily, watching the landscape bright in the sunlight, there flew from a thicket a single big black crow! “Caw-caw,” called the crow. “Caw-caw.” And Jimsi pulled Daddy’s arm—his head was deep in a newspaper—“Oh, look, look!” she cried. “Daddy, there’s the Good Crow!” Wasn’t it fun! Oh, wasn’t it fun! That big black crow had said caw-caw and he was flying in the same direction as Jimsi’s train! Already Aunt Phoebe’s play crow seemed more real than ever. And every moment the train was bringing Jimsi nearer and nearer to Aunt Phoebe and The Happy Shop.

THE first thing Jimsi said, when the train stopped at a little station where Aunt Phoebe was waiting to greet them on the platform, was, “Oh, Aunt Phoebe, I saw the Crow. He followed the train. I’m sure it must have been your crow because I heard him say caw-caw!”

Aunt Phoebe smiled. “Wasn’t that funny,” she laughed. “Wait, Jimsi, you’ll really see my crow soon. He’s in The Happy Shop now. But don’t expect too much, dear. You mustn’t be disappointed!”

They walked through the little country town together. Aunt Phoebe’s house, so she said, wasn’t far from the station. Everything seemed so quiet and there were so few people! Jimsi had only been in the country summers. Now that it was winter-time and the ground was bare and brown, the country didn’t seem like the same sort of a place. Jimsi began to[14] wonder what she would find to do all day long. True, Aunt Phoebe could always invent splendid things—and there was going to be a fine new play called The Happy Shop! Yes, there was The Happy Shop! “What is The Happy Shop?” she asked, looking up to Aunt Phoebe as she trotted along between Daddy and her. “I want to know all about The Happy Shop!”

“Oh, you’ll have to wait for that, Jimsi,” returned Aunt Phoebe. “Here we are”—and they turned in at a quaint green gate that led to a small bare garden that was shrouded in boughs of evergreen. The house was small like the garden. Aunt Phoebe lived here alone, though one never, never could imagine an aunt like Aunt Phoebe as being the least bit lonely. Why, she never could be lonely—there was too much for her to think about and do, don’t you know. It’s only the persons who sit still and think how miserable they are who are lonely!

Jimsi followed her into the hall. It was old-fashioned and quaint like the garden. Upstairs there was a wee little room that looked out into the boughs of the evergreens. It was papered in soft blue-green and it had a most inviting soft bed with a blue cover. Aunt[15] Phoebe took Jimsi’s cloak and hat and hung them in the closet. She put back the covers of the bed and made her lie down and rest. “You came here to grow well and strong,” she said. “We must do what Mother wants you to do. By and by I’ll call you and you can come down.” She covered Jimsi up with something downy. Then she kissed her. “Deary,” she smiled. “Look under the pillow—” and then she closed the door softly and left Jimsi lying there feeling under the pillow for—for—why a crow letter, of course!

Jimsi giggled softly to herself as she felt it under the pillow and drew it out.

“Dearest Jimsi:

Try to take a good nap like a good little girl. I am glad you are here and I hope you will do all you can to grow well and strong. To-morrow, maybe, Aunt Phoebe will show you The Happy Shop. I think you’ll like it. With love from your

Good Crow.”

It was such a darling little tiny letter! It had a wee stamp in one corner. The stamp was drawn with red ink. Oh, it was darling of thoughtful Aunt Phoebe to do that! Wasn’t it exactly like her too! Jimsi smiled as she folded the tiny sheet and put it back[16] in the envelope. Then, obediently, she curled down into the downy bed and shut her eyes tight, resolving to do all she could to help Aunt Phoebe keep the promise to Mother.

When she woke, it was growing dusk. Aunt Phoebe was at the door of the little blue room calling, “Up, Jimsi! What a fine nap you’ve had. It’s almost tea-time!” She lit a candle and helped Jimsi unpack her trunk a bit and dress. Then, hand in hand they went down to the hall where Daddy was consulting his watch. “I must be off,” he declared.

Well, for a few moments after he had gone, Jimsi thought she was going to cry—but she didn’t! Oh, no! Of course she didn’t! She knew that she was going to miss Daddy fearfully and Mother and Henry and Katherine too but Jimsi was a plucky girl. She swallowed the lump in her throat. “Can’t I help you get tea on the table, Aunt Phoebe?” she asked. (Mother told Jimsi once that the way to be happy was to forget oneself. “Think! See if you can’t help somebody, dear, when you feel like that. Try it and see!”)

So Jimsi tried to help. She set the table with the pretty blue plates. She found where knives and forks were in the sideboard. She[17] searched out the tumblers and by and by all was done.

“Shall we ask the crow in to tea?” demanded Aunt Phoebe, coming in from the kitchen with a dish steaming and good to sniff.

“Can we!” exclaimed Jimsi.

Aunt Phoebe smiled. “We might play it,” she suggested. “Lay another plate, just for fun. I’ll get the crow!”

Jimsi was mystified. Oh, dear! How jolly! How splendidly jolly! What was Aunt Phoebe up to now?

And then while she was still wondering and laughing softly, into the room stepped Aunt Phoebe and she had—she had a big black crow in her hand! He was a stuffed crow and very black and splendid. He was perched on a twig that was on a standard. Quite solemnly but with her eyes merry with a twinkle, Aunt Phoebe set the crow down in the chair that was to be his and introduced him.

“This is Jimsi, my play-niece,” said she, “Jimsi, this is my play-crow, Caw Caw.”

“I’m very happy to know you, Caw Caw,” said Jimsi, entering with spirit into the play. “You’ve always been a friend of mine but I never expected to see you really and truly. I[18] thought you were just pretend, you know—something like Cinderella’s lovely fairy godmother. And yet I always liked to play you were true. I’m glad now that I can play you’re true!”

The crow said nothing, of course. But Aunt Phoebe explained that he didn’t talk much, so the two of them ate supper and talked together, making conversation for the crow the way one plays dolls.

“Will you tell me about The Happy Shop, Mr. Crow?” inquired Jimsi politely of the funny stuffed crow. She could hardly keep her face straight but she hid a smile in her table napkin.

“I’ll have to talk for him,” Aunt Phoebe declared. “Yes, I’ll tell you about The Happy Shop. We’ll go there first thing in the morning. I think you’ll like it. There are ever so many nice things in it but the very nicest is the Magic Book, I think.”

“The Magic Book?” echoed Jimsi. “What’s the Magic Book?”

“I’ll show it to you after the Crow goes to roost,” answered Aunt Phoebe. “You mustn’t call him Mr. Crow! He doesn’t like it. His name is Caw Caw[19].”

Perhaps the Crow would have liked corn to eat. I’m afraid Aunt Phoebe’s crow, being just a stuffed play-crow, wouldn’t have eaten corn, though, if he had had it—no, not any more than a doll will eat cake at a party. You have to pretend that the doll eats. So Aunt Phoebe pretended most beautifully to pour out cocoa for the crow—a second cup, mind you! She gave him second helpings of nearly everything and Jimsi followed suit. Indeed, her appetite seemed really pretty good for a little girl who is getting well after a long sickness.

When tea was over, Aunt Phoebe said that they would go to see The Happy Shop, even though it was dark there now. She lit a dainty pink candle and with the Good Crow Caw Caw, they went into the hall.

Just off the hall at the side of the house was Aunt Phoebe’s study. She did ever so many wonderful things there. She wrote books. Maybe that was how Aunt Phoebe came to think up so many jolly things to play. She was almost always making up a story or writing an article for a magazine or something. She knew all manner of things and when she didn’t know about them, there were books in[20] the study that could tell—great big books all full of print, books that Aunt Phoebe did not write but books like those in the school library at home. Aunt Phoebe explained all about the books and showed Jimsi her desk and the big typewriter as they passed through into The Happy Shop that opened with glass doors into the study. It was—Oh, it was a little glass room. In the light of the candle, Jimsi could see blooming plants on shelves. There was also a couch and a big table and a chair. On the table, lay a big flat book—ever so big. It was a queer book. In the dark, Jimsi couldn’t see exactly what it was. Aunt Phoebe picked it up and said, “This is the Magic Book, Jimsi! You can’t see what it is like here but we’ll look it over in my study where there is a lamp. Now, we’ll leave Caw Caw here. It’s where he stays at night. In the morning when the plants are watered, I think he must fly off to the Santa Claus land but you’ll find his mail-box here and you can always look for letters in it.” She picked up a small white box that was very like a tiny mail-box. On it was written MAIL. (It looked as if Aunt Phoebe’s own fingers—that were very clever[21] fingers indeed—might have made the toy mail-box for the Good Crow.)

Oh, it was lovely—lovely! Jimsi squealed delightedly. The Happy Shop was splendid—of course, she didn’t understand all that it meant yet, but she knew it was going to be splendid, splendid!

Jimsi put the little mail-box back on the shelf beside the crow. She peered about in the candle-light to see more of The Happy Shop, but it was really too dark to see what else was there and she knew she would have to wait till morning. She followed Aunt Phoebe into the study to look at the Magic Book.

“I suppose,” said Aunt Phoebe, sitting down to her big study table and drawing Jimsi up on her lap quite as if she enjoyed having little girls muss up her pretty blue dress, “maybe you won’t think that this book is magic but I assure you that it IS! In it are ever so many, many, many different kinds of splendid things,—things to make, Jimsi.”

Jimsi looked at the big book spread out on the study table. On its cover was written the name of a wall paper firm. As she turned the leaves, there were papers of all kinds in it, blue and pink and yellow and green and red and[22] brown and violet and white and even purple. There were sheets of striped papers as well as plain papers. There were dotted papers, crossed papers, papers with big designs and papers with small designs. Some had flowers and some had none. Some were thin and some were heavy. Some had splendid dashing sprays of floral coloring. Others were inconspicuous and unassuming. There were all sorts of combinations[23] of color and pattern. Yes, there were even figures in some of the borders and there was paper meant for nursery walls. It had dogs and cats and little ducks in it. There was more of the nursery wall paper, they found. Why, there were fairies in one pattern! Jimsi was delighted! “They are beautiful! Look at this!” she kept exclaiming.

“All hidden in this book, Jimsi, are ever so many things. That’s why I called it the Magic Book. You can’t see half that is here. I don’t begin to know how many things are in these papers. We’ll have to ask Caw Caw to help us. You see, he knows much and he can tell you in his play letters, maybe. We call your sunny little room there The Happy Shop because you are going to learn how to make some of the things that are to be found in the Magic Book every day. In The Happy Shop is a work-table and some paste and a pair of scissors. To-morrow, the Good Crow will leave a letter in the mail-box, I think, and tell you what you can do to make your own fun all by yourself for play. What do you like best to play at home, Jimsi?”

“Dolls,” promptly sang out Jimsi. “I love to play dolls. But it isn’t much fun to[24] play dolls all alone and I left mine at home. I was afraid that my best doll would get hurt in packing and I didn’t want to break her—beside that, I thought you’d probably have The Happy Shop play to keep me busy.”

“Yes, you’re right, Jimsi! And it will keep you busy too!” smiled Aunt Phoebe. “Do you know, it was just luck that made me run across the Magic Book. You see I had the little room where you are repapered in blue. I’m so glad I did! And the paper hanger brought this sample book with him when he came. When I saw it and after I chose the blue paper in your room, I asked if I could buy it. He shook his head. ‘It’s just a sample book,’ he said, ‘We have ever so many of them. The dealers give them to us and we throw them away after we have no more use for them. The patterns are new every year and the fresh sample books come in in January. This happens to be a book of last year and if you want it, you are more than welcome to it, if it is of any use to you.’”

“Why, think of it!” Jimsi beamed, squeezing Aunt Phoebe’s hand. “Did you tell him?”

“Oh, I told him that I’d like to have the book very much and that I thought there were[25] ever so many children who would like his old sample books of wall paper,” returned Aunt Phoebe. “He just gives them away. Paper-hangers, it seems, always throw them out or sell them to the junkmen and they never give them to children because, Jimsi dear, the children don’t know anything at all about them. Nobody but the Good Crow and I know about Magic that is in old sample books of wall paper! But, Jimsi, it’s time for bed and you know we both made Mother a promise. Kiss me good-night, dear. Here’s the candle. I’ll come up for a hug later as Mother does.”

And then Jimsi went up to the little blue room with her candle. She turned down the covers and slipped her hand under the pillow but the crow had not put any other letter there. Not again that day!

THE sun woke Jimsi in the morning. It was peeping into the little blue room from between the evergreen trees outside. For a moment, Jimsi wondered where she was and then she remembered, of course! She hopped into her red woolly wrapper and slipped on the slippers that had Peter Rabbit’s picture on their toes. The door was open into Aunt Phoebe’s room and in she ran to say good-morning. “I just can’t wait to see The Happy Shop, Auntie,” she chirped. “Please, might I go and look at it right away now!

“Well—yes,” Aunt Phoebe deliberated, “only come right back after you’ve peeked into the mail-box. I dare say the crow has left something there.”

So off sped Jimsi in the little red shoes that had Peter Rabbit’s picture on them, through the study where pages of white paper on the big desk showed that Aunt Phoebe had worked[28] writing a story late last night. Jimsi opened the glass door that led into The Happy Shop. It opened with a wee brass doorknob and the doors swung open into the study. Beyond there was a kind of enclosed porch—only it was not a porch. It was more like a conservatory or a room with glass sides and top. There were blue curtains that could be drawn to keep out the sunlight and windows that opened wide to let in the fresh air. Plants bloomed all about on shelves. Right beside the shelf where Aunt Phoebe had put the crow last night there was a beautiful green vine that had blue-petaled buds and star-shaped flowers. Could anybody imagine a more lovely place in which to play than this Happy Shop!

Jimsi sighed happily. It was all so perfect! How she wished Mother could see it! Wouldn’t Henry and Katherine like to play there! Then Jimsi remembered that she had promised not to stay long and she reached for the Crow Mail-Box. Surely! there was a tiny envelope in the box! What fun!

Upstairs, seated on the bed in the little blue room with Aunt Phoebe hovering about to watch her read it, Jimsi chuckled over the Good Crow Caw Caw’s letter.

“Dear Jimsi:

To-day I’ve gone off to a crow convention, so I leave this letter to tell you something you will find in the Magic Book to-day. You’ll find paper doll dresses! You’ll have to hunt for them, but you’ll find them—whole wardrobes of them: blue, pink, green, red, yellow, flowered, striped. Look for them.

In the drawer of the big table there are pencils and some sheets of cardboard.

My friend Jim Crow is calling, so I must close this letter now.

I send you a crow kiss—a peck of love.

Caw Caw.

P. S.

You’ll find paper dolls enough for days and days of play, if you look in the big fashion papers that are in the magazine rack beside the couch in The Happy Shop. Cut the stylish ladies out. Mount them on the cardboard with your paste. I must fly!

Crow.”

Jimsi could hardly wait to finish breakfast and then, afterwards, she and Aunt Phoebe took a brisk walk to market and back. All of it delayed the crow play but all the time Jimsi was talking about it. “Oh, I never knew there were such splendid papers to make paper doll clothes anywhere, Aunt Phoebe! I didn’t think of it at all last night when you showed me the Magic Book! It will be the most jolly[30] kind of fun! Think of the dresses that the flowered papers will make!”

“Yes,” smiled Aunt Phoebe, “and jackets and cloaks and hats and muffs and scarfs and kimonos—oh, my! I can’t begin to name all the clothes you can make.”

“Are there little girl dolls in the fashion magazines? There are, aren’t there?”

Aunt Phoebe nodded.

“Then I’ll make little girl dresses for them—O-oo! Party dresses!”

“Maybe there are babies and little boys and men in the colored picture pages of the fashion books too!”

“Oh, I’ll make a whole family! I think it will be simply dandy! Maybe I can copy the styles in the magazine. That would be nice! Oh, Aunt Phoebe, aren’t we about ready to go home?” But though Jimsi wanted to get to The Happy Shop, she waited patiently while Aunt Phoebe did errands. It was about half past ten before Jimsi was able to throw off her coat and rush for The Happy Shop.

“I’m going to be very busy,” Aunt Phoebe warned. “You’ll hear the typewriter click-click-click. The crow has put all kinds of little things in the drawer of the table, I think. You[31] won’t have to disturb me, Jimsi. I’m ever so particular about not being spoken to when I’m busy, Jimsi. But you’ll be busy yourself. When I finish, I want to see all the splendid paper dolls you have made and you must show me every one of their dresses and hats!”

With that, Aunt Phoebe pulled out her desk chair and became suddenly absorbed in her morning’s work. Jimsi, in the sunny Happy Shop, slowly turned to close the glass doors after her. The windows were open a bit and, the softest of fresh breezes fluttered the leaves of the blue vine that crept past the crow’s mail-box. The little girl could not decide what to do first! The Magic Book was so wonderfully interesting; the patterns of paper so wonderfully pretty. Which should she choose for the first paper doll dress? Jimsi decided on one that had pink sprigs of daisies in it. Then, suddenly, she saw another that was covered with yellow flowers. And, beside these, there were numbers and numbers more! Jimsi turned the leaves of the Magic Book on and on. Each new pattern seemed the prettiest one yet. And how many leaves there were in that sample book! Why, the leaves were so very large and long that each[32] would make hundreds of dresses all alike, if one wished.

At last Jimsi decided to leave the Magic Book and make at least one paper doll that could be dressed. She settled herself cosily on the wicker couch with a pile of the fashion books beside her. Of course, she found a pretty lady right away. The lady had dark hair done up in a very modern and stylish way. Jimsi cut her out.[33]

But the paper doll had a dress on! Oh dear! How can you put another dress on a doll that already has a costume on her? Jimsi thought: she decided to take the lady’s outline as a guide and make a new body using the head as it was printed. So she placed the paper doll on the sheet of cardboard and traced around her to get the outline. Then she pasted the head on the cardboard and drew stockings and slippers. She colored the arms on the cardboard flesh-tint and the stockings and slippers black. Then she cut out the cardboard outline that had the paper head and there, if you please, was a real paper doll, as splendid as any you ever saw anywhere!

Of course one paper doll is lonely by herself and Jimsi had to make the lady doll a sister. This time, she chose a fashion print that had light hair. But she made the paper doll as she had made the other. It was terribly exciting now! Jimsi had to make up her mind what kind of a dress to make for the first paper doll. She named her Mrs. Sweet. The sister was Miss Pretty.

At last, Jimsi thought Mrs. Sweet ought to have the dress with pink flowers and Miss[34] Pretty the one with yellow buds. She placed the doll—Mrs. Sweet—on the sheet of wall paper and outlined all around her with a pencil, making the skirt of the frock just a stylish ankle length. At the top where the shoulders were, Jimsi drew tabs to bend and hold the dress on the doll. Then she cut the dress out, making it have a V neck. The pink flowers were in a long stripe right down the front of the dress. They looked like a dainty trimming. But the dress still needed to be finished, so Jimsi found the box of crayons that thoughtful crow had left on the table and she made jiggles to represent lace, straight parallel lines to represent tucks, little dots to represent smocking. Black dots that were larger were buttons, of course. One could make almost any sort of trimming in this simple way. The black crayon could be very black indeed. One could make black velvet trimming? Oh, it was splendid fun! Jimsi was so occupied that she never even heard Aunt Phoebe open the glass doors of The Happy Shop and it was not till Aunt Phoebe stood right beside her that she was aware. Aunt Phoebe laughed. “Well, Jimsi, you found some of the magic, didn’t you? It’s exactly[35] ten minutes past twelve. Did you know it was so late?”

Jimsi held up the beautiful Mrs. Sweet in one hand and the handsome Miss Pretty in the other. “Oh, I’ve just begun,” she protested. “I haven’t done anything but start. See!——”

“Well, I’ve finished,” declared Aunt Phoebe. “I’ll help. Suppose I make some hats!”

So Aunt Phoebe made the hats. She made them by cutting big and little ovals out of the wall paper. Cutting a strip horizontally across the center, one could slip the doll’s head up through this and put the hat right on. Aunt Phoebe trimmed the hats she made with wall paper flowers or bows cut from paper or by drawing on them with crayon. There were big and little hats—some plain walking hats and others evidently meant for dressy occasions.

While Aunt Phoebe was helping with the hats, Jimsi cut a cloak for Miss Pretty. It must have been an opera cloak for it was loose and flowing and made of something quite silky. (For the wall paper had a satin stripe in it, you know.) It was an exceptional success.[36] Jimsi surveyed it happily. It was splendid. Such a cloak ought to cost at least—but how much do cloaks cost? It must be nice to be a paper doll and be able to dress so well in “just paper”!

Oh, yes, Jimsi made Mrs. Sweet a tailor suit all of plain brown wall paper and both of the dolls had separate skirts for shirt waists, kimonos, dressing-jackets and muffs. (The muffs were made of dark wall paper and were fat ovals with slits cut at either end so the doll’s hand could be slipped in.)

Aunt Phoebe and Jimsi were so very, very busy that they were both ever so surprised when suddenly the little white-aproned maid who worked by the day for Aunt Phoebe appeared at the door of The Happy Shop. “Lunch is served,” said she. And there was nothing but to leave the play and run as fast as possible to wash the paste off hands and give one’s hair a smart pat with a hurried hair-brush.

At lunch Jimsi announced that she was going to make little girl dolls next. She thought she would have three little girl dolls in her family: a baby, a middling-sized girl of ten or eleven, and an older girl of High School[37] age. “I’m going to have one boy,” she said. “Boys won’t be so much fun because their clothes are so plain. But I’ll make a waterproof coat for this one, an overcoat, and one or two plain suits. The papa doll can have the same kind.”

But Aunt Phoebe decided that Jimsi must run out-doors in the garden after lunch and then come in and take a nap. After that, of course, she could do anything she wished in The Happy Shop. Aunt Phoebe thought it might be pleasant to write Mother a letter. So the afternoon passed with the out-doors and the nap and the letter. Jimsi found the little girl dolls in the fashion papers and had them all ready to cut and paste next day, but by that time had flown by so fast that the evening had come and with it there were new interests to draw her away from paper dolls. There was the crow who came back mysteriously and whom Jimsi discovered sitting up high on one of Aunt Phoebe’s bookshelves; there was the going for stamps to mail the letter home. It was quite chilly and the stars in the night sky were bright like diamonds when the two came back and opened the front door at Aunt Phoebe’s. Jimsi hadn’t been[38] lonely at all—why the whole day had passed and she had been almost all the time alone. Only the time before lunch and just before dinner at night, had Aunt Phoebe been with her; yet Jimsi had been happy. The secret, Aunt Phoebe said, was that she had been busy with happy play and work. “That, as everybody knows, is the one way to keep glad—but there’s another, Jimsi. Maybe the crow’ll tell you what that is some day.”

The next day Jimsi dashed down to the Good Crow’s letter-box hoping for a letter. But there was none. Aunt Phoebe said that she thought the crow meant that there was no need for him to write till Jimsi needed a new kind of magic play. It was a bit disappointing not to find a letter in the mail-box, but Jimsi consoled herself. Aunt Phoebe was going to let her water the plants every morning. There was a cunning little watering-pot painted red. It stood in a corner of The Happy Shop. It was really fun to water the thirsty plants and watch to see that dead leaves were kept from them. After having done this little duty to help, Jimsi went to market again with Aunt Phoebe and then, afterwards, she was again in The Happy Shop to play at cutting doll dresses. Oh, she made the little girl dolls this time. They were made in the same way as the lady dolls. And she also made the gentleman doll[40] and the little boy. By that time it was lunch again. Oh, dear! There had been not a second yet to dress the boy doll!

And then came the out-door and the—yes, the horrid old nap! (Don’t you hate to take naps! I hope you don’t have to—but if you do, I do hope you’re good about it and that you don’t pout and act disagreeable. I do! The nap has to come, so you might much better be pleasant and happy about it and have nothing to be ashamed of.)

Jimsi believed in doing what she was told to do and, beside, that nap had been one of the conditions that governed the visit to Aunt Phoebe’s and The Happy Shop—and both Aunt Phoebe and Jimsi had promised.

When she woke up, Aunt Phoebe told her she could play in the shop till dinner-time, if she chose. It was rather damp and chilly out-doors. So Jimsi made the boy doll’s clothes and cut out the daddy of the family. That was a good afternoon’s work!

At bed-time, Jimsi was about to hop into the cosy white four-poster when, somehow, her hand began to feel under the pillow and there, my dear, there—there was a letter![41] How like the crow to make it a surprise and not put it in the letter-box downstairs!

By the light of the pink candle, Jimsi tore open the wee envelope and read:

“Dearest Little Girl:

When I came to perch on my shelf last night, I saw the lovely dolls you made and the wonderfully beautiful dresses and hats and cloaks and muffs and evening wraps and things. When you have finished the family, I’ll tell you something nice: make a doll house for them. I can tell you how to make furniture to fit your dolls. You’ll find ever so many things for the furnishing of a doll house right in your Magic Book.

Lovingly,

Crow.

P. S.

You were good to take that nap without pouting. I wish Mother had seen you start right on the dot. I like children who keep their promises. Look for a letter to-morrow.”

Jimsi woke quite early the next morning, even before the sun began to shine through the boughs of the evergreens outside the window. It was first dusk and then soft pink and then came faint sunbeams that grew brighter and brighter. But the clock on the bureau was pointing to an early hour and Jimsi waited for Aunt Phoebe to move. She did not want to wake her, for she was a thoughtful[42] little girl—but she did want the crow letter that she knew must be in the mail-box in The Happy Shop!

Aunt Phoebe was so late in waking that Jimsi had to scurry to get dressed and couldn’t go downstairs at all after that letter. And then there was breakfast immediately. But afterwards—afterwards, she and Aunt Phoebe dashed to the mail-box that stood on the crow’s shelf in The Happy Shop. Sure enough, there was the letter!

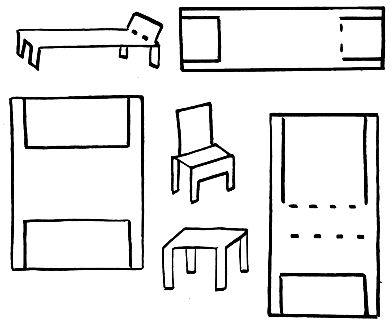

Jimsi tore open the envelope—why, there was nothing written in it. It was just some diagrams of the promised furniture for the paper dolls—but wasn’t that worth getting! All the time, Jimsi had been wondering how to cut furniture. She hadn’t known at all. She had hoped the crow would send her the directions but here were just diagrams, the very things to puzzle over and use! Under each diagram was written what it would make and the diagrams were like this.

Of course, the Good Crow couldn’t draw

very well but he did wonderfully considering

that he had to write and draw with a claw instead

of a hand, Jimsi thought. The idea of

the crow’s drawing made her laugh. “Aunt[43]

[44]

Phoebe,” she giggled, “that crow of yours is

ever so funny! Imagine a crow’s drawing

pictures! But I’m going to make the furniture

and start right away!”

So Aunt Phoebe shut the doors of The Happy Shop and went to her work while Jimsi began to puzzle over the crow’s diagrams. First there was the bed. That was to be cut from a long piece of paper about as long as a paper doll—the longest doll, of course. Jimsi decided that the very, very heavy wall paper might be used to make the toy furniture and she found some that was wood-color in the Magic Book.

She cut the bed’s legs about an inch and a quarter long and parallel with the length of the oblong piece of cardboard. Then, she bent the legs down and the rest of the ends upward to make baseboards. That made a paper bed.

But, somehow, when the bed was placed on its legs it sank under the weight of the paper dolls, so Jimsi made another bed out of cardboard and pasted the wall paper bed over it. That did splendidly!

She made a pillow of white wall paper and added a coverlet. (There might have been a[45] fancy blanket under the coverlet, of course. This would have been cut from some other paper with a pattern design upon it.)

Jimsi made a table next. It was cut like the bed, but in finishing it, the footboard parts were entirely cut off. And then, too, the table had longer legs than the bed. It was made to fit the size of the dolls by measuring. It was necessary to cut the legs the length of the paper dolls from feet up to waist. The[46] table was measured to fit the big lady doll and the gentleman.

The chairs were a bit different: to make a chair one had to cut a piece of cardboard the least little bit smaller than a table—and not half so wide. One cut the front legs to fit below the table and cut off the bit of cardboard there as the table end was cut. The rear of the chair oblong was straight then. The next step was to cut legs of the same length as the front legs. These were bent down like the first and the part that remained was the back of the chair! Jimsi upholstered the chairs with fancy designs cut from other colored sheets of wall paper. It was jolly! Jimsi made enough chairs for all the doll family. Indeed, the dolls seemed most sociable as they sat in a row on The Happy Shop’s table!

A sofa could be made on lines like the chair, only making the cutting of the cardboard oblong wide and giving it the depth of the chair also. The sofa was likewise upholstered. Oh, the toy furniture was great! Jimsi longed to start a doll house and looked about The Happy Shop to see if she could find a place to lay it out. At last she did discover a place,[47] on the floor at one end of the shop. She fixed it up beautifully. Bits of wall paper design cut out in ovals and oblongs, fringed by snipping with the scissors, made rugs for the house. If Jimsi had only had a box of some kind—if she could have interrupted Aunt Phoebe to ask for it, she could have made carpets of wall paper and had wall paper curtains too.

When the house was done, Jimsi made believe that Mr. and Mrs. Sweet went to walk in the park. The park was all of the greenery of The Happy Shop. The ferns made a wonderful grove. All the Sweet children wanted to have a picnic there. So Jimsi made a white table cloth from the Magic Book’s paper and cut rounds for plates and funny snips of three cornered wall paper bits for sandwiches. And there was a big round cake too! Oh, yes-and some pies that were colored with crayons.

After Jimsi had played all this, it was lunch time and again the hours had flown by fast.

In the afternoon, when Jimsi went upstairs, right on top of her pillow there was another crow letter!

“Dear Jimsi:

I have told you about two new plays that I think ever so many little girls would like to know about. I hope you will tell other children about them when you go home. I don’t think Henry would care much but Katherine will when she grows older.

There is a little lame girl next door. I know her, just as I know you. Don’t you want to tell her about your Magic Book and show her the plays you have found out about?

It would be ever so nice to have somebody to play paper dolls with and I’m sure she’d like to know you.

Some day, I’ll write you where she lives more exactly and I’ll send you word when you can go to see her.

Your

Caw Caw.

P. S.

If I were you I’d keep my paper dolls nicely and put them in envelopes. In the drawer of the table in The Happy Shop, there is a package of big Manilla envelopes you can use. Write the name of each doll on the envelope you use for it and its dresses.

P. S. P. S.

If I were you, Jimsi, I’d pick up The Happy Shop this afternoon. The bits of paper on the floor look untidy and I think when one is cutting, it is a good plan to put a newspaper over the floor to catch scraps. I like neat children and my Happy Shop should be very well kept.

Thank you for watering the flowers.

C. C.”

[49]A wave of shame came to Jimsi sitting there on the bed—Oh, dear! She wanted to run right down and clean up the shop. She remembered that those bits of paper did look untidy. Oh, dear! But the nap came first. Soon she was sound asleep.

Nothing of great importance happened the rest of that day, for Jimsi spent a large part of time in tidying The Happy Shop when she woke. Then she fixed up the paper dolls in the envelopes. And it was bed-time. That night, however, the paper dolls slept in beds all arranged on Jimsi’s dresser at bed-time.

When she went to sleep, she dreamed that she and the Good Crow were making toy furniture and that the crow was really using scissors with his claw. She woke up in the middle of the night laughing and Aunt Phoebe heard her and asked if anything was the matter. “It was just the crow,” chirped Jimsi. “I was dreaming of The Happy Shop and he was there cutting toy furniture for paper dolls.”

“I think,” Aunt Phoebe’s voice answered, “that maybe a real little girl playmate would appreciate paper dolls more, wouldn’t she[50]?” Jimsi said, “Yes,” and then drowsed off to sleep again, hoping that the Good Crow would tell her soon that she could go and amuse the little lame girl who lived somewhere nearby.

SURE enough, there was a crow letter in the mail-box next morning! It was written on the same wee note paper with a real crow stamp that was drawn in pencil in the upper right-hand corner. Jimsi brought it to breakfast with her and read it aloud—exactly as if Aunt Phoebe didn’t know what was in it already! You know, that was the crow play always!

This was the letter:

“Dear Jimsi:

To-day, I want you to do something for me. You see I do quite a bit for you. I like to make you happy, you know, and tell you of jolly things to play. What I want you to do for me is to tell a little lame girl about your paper doll play and the toy furniture that my Magic Book made.

The little lame girl cannot go out-doors as you can. She has to stay in a wheel-chair and the hours are very long for her. I would like to have you help her. You can help her[52] much better than I can because you are a little girl and I am only a play crow.

Good-bye,

Caw Caw.

P. S.

Her name is Joyce. She lives in the third house from the corner.”

“Oh, I’d love to go!” declared Jimsi. “When can I go?”

“As soon as we’ve had our walk,” Aunt Phoebe answered. “Maybe you’d like to do something else for Joyce and the Good Crow—would you?”

Jimsi nodded. “I’d love to!”

“Well, when we go to town, we’ll buy Joyce some crayons like yours and a bottle of five-cent library paste. You shall take them to her to work with and you can tell her the crow sent them.”

“Splendid!”

So they went to market and Jimsi bought the crayons in the ten cent store. She insisted on paying for them herself because she said that this time it was going to be her crow. Then, when they reached home, Jimsi wrote a crow letter to the little lame girl, Joyce, and did the crayons up with the five cent bottle[53] of paste that Aunt Phoebe insisted was her crow.

With a box full of paper doll envelopes and toy furniture, and Jimsi’s own crayons and scissors from The Happy Shop, the Magic Book rolled up to make a big package to carry under one arm, Jimsi ran over to the third brown house from the corner and rang the bell. It was rather a dingy little house. It did not look pretty. It looked poor and sad.

But when the door opened, it opened on the most cheerful room you can imagine. It was Joyce’s mother who opened it. She wore a big white apron as if she were busy working and she beamed down at Jimsi standing on the steps with her arms so full of the Magic Book and the box of paper dolls that she could hardly hold them.

“I came because the Good Crow wrote me a letter about Joyce,” stated Jimsi. “The Good Crow said she’d like to know about my paper dolls so she could play at making dresses too. So I came.”

“Oh, come right in, little girl,” invited Joyce’s mother. “Yes. The crow sent Joyce a letter yesterday to say that his friend, Jimsi,[54] was coming over with a magic book. We’re very glad you came, aren’t we, Joyce?”

Jimsi hadn’t seen Joyce but now she looked toward the window and saw a wheel-chair with a beautiful dark-haired girl of twelve propped up in it and holding out a welcoming hand. “I’m ever so glad you came,” she laughed. “Don’t you love the Good Crow? I do. Miss Phoebe’s ever so lovely, I think. She’s every day thinking up something nice for me to do, almost. There’s sure to be a crow letter full of fun whenever I need it most.”

“Yes,” declared Joyce’s mother. “I don’t know what I’d do, if it weren’t for the Good Crow who belongs to Miss Phoebe. There’s only one thing Joyce wants do do when she isn’t reading. It’s checkers! I’ve played more games of checkers than you can shake a stick at, Jimsi! But when the crow letters come with new suggestions for things to do—why, you know, Joyce doesn’t want to read or even play checkers! The Good Crow’s play is best of all. Tell Jimsi about the motion picture play, darling!”

Motion picture play! Why the very idea of it! Goodness, how interesting! Do you know[55] anything that is nicer than motion pictures! At once Jimsi was wide awake and eager. “Oh, I want to know about the motion picture play!” she exclaimed. “Oh, please do tell me! Was it really true moving pictures?”

“Yes,” asserted Joyce, “they were real, weren’t they, Mother? But the pictures weren’t photographs at all. You wait and I’ll show you my motion picture screen and my whole outfit! Mother, will you get them for me, please?—You see, Jimsi, it was in the fall when the crow told me about these pictures. In summer I can go outdoors and once Daddy wheeled me into town and they let me see the motion pictures. (I can’t go often because it is such a long ride for me.) Well, I could think of nothing else afterwards but how much I wanted to go again! You know how it is.”

Jimsi wagged her head hard, “yes.” She didn’t want to interrupt the story.

“One day when Miss Phoebe was over here, I told her about how I wanted to go to motion pictures again and Miss Phoebe said she’d see what the crow could do about it— You know how Miss Phoebe makes believe always[56]!”

Again Jimsi nodded. “I love to make believe the way auntie does,” she beamed. “Please tell me what happened next.”

“Well, next, of course, came a crow letter. I found it in a bunch of flowers Miss Phoebe sent over.” (Joyce was trying to cover up the things that her mother had laid in her lap. Jimsi’s eyes had been busy with the details. There looked as if paper dolls were there.)

“You mustn’t peep,” admonished Joyce. “It won’t be a surprise if you see. It was a surprise for me! I didn’t know that one could really make motion picture fun right at home—not till Miss Phoebe’s crow wrote me a play letter about it.”

“Well, I can’t see how you do it!”

“You can do it with the papers in the Magic Book,” declared Joyce.

“Oh, have you a magic book too!”

They both laughed. What fun!

“I wonder if yours is like mine?” questioned Jimsi. “I didn’t know you had a Magic Book too, so I brought mine along with me! I was going to tell you about how to make paper dolls and toy furniture from the papers in my Magic Book!”

“Oh, I’d love to know how,” beamed Joyce.[57] “I think paper dolls are just the nicest play—almost. You must show me about them. I don’t know how to make them. The crow never told me. But he did tell me about the motion pictures and I made this—” she held up for Jimsi’s examination now a picture frame that was about twelve inches long and eight inches wide. At the back of the frame where the glass had been, there was stretched some heavy white cloth-cotton cloth. Back of this,[58] where one would place the picture, if one were framing one, was the glass that fitted the picture frame.

Joyce turned the frame over. “You see,” she explained, “when I hold it front-face, it looks exactly as a motion picture screen does, doesn’t it?—That’s before the picture play begins!”

Yes, it was true. The frame looked like the frame of a motion picture screen.

“The difference is,” went on Joyce, “that the crow’s motion pictures aren’t photographs. They’re really shadow pictures. One cuts silhouettes out of heavy wall paper that is in the Magic Book—oh, everything—and then one puts the chairs or tables, or cupboards next to the glass to make the screen. (I always have a little paper curtain that I put before my frame while I arrange this. It is like the big curtain in the theatre because it shuts off the picture screen.) When I have arranged the furniture and am ready to make the actors walk about in the room, I take the paper away so the audience can see.”

“How splendid!” sighed Jimsi, delightedly. “I think Henry’d be quite crazy about this sort of thing. He’s my brother, you know.[59] He’s a boy, so he thinks paper dolls are girls’ things and he won’t play with them. Do you use paper dolls? I should think that it would be hard to make them move about behind the furniture. I should think it would show that somebody was moving them.”

“It doesn’t though— You’ll see!” Here the little lame girl took the frame. “Don’t look,” she admonished with a raised forefinger. “Pretend you’re interested in the cat!”

Indeed, Jimsi hadn’t noticed the cat before. But now she ran over to the big open fireplace where pussy was purring before the wood fire. Joyce’s mother was sewing on a machine. She seemed very busy indeed. Jimsi waited for her new friend to give the word. She stroked the comfortable tabby and thought how wonderful it was that a sick girl who couldn’t go about except in a wheel-chair could be so cheerful and so happy. “I hope if I’m ever sick like that that I won’t be a whiney person,” she thought. “It’s splendid to be happy and glad when things are like that and you know you aren’t going to be able to run about and play—ever. Oh, I like the crow’s little lame girl wonderfully!” And it did seem strange that the little lame girl[60] was telling Jimsi about her play even before Jimsi had told the little lame girl about hers!

But right here, Joyce sang out, “Ready!” so Jimsi forgot the pussy cat instantly and sprang to her feet.

“I put the frame on a table when I have a real motion picture performance,” Joyce explained. “But you can see in the daylight better if I hold the frame in the sunlight. Look!”

Sure enough! There was the furniture in a small room: table, chair, cupboard! They were outlined in shadow.

“One ought to have motion pictures in the dark,” Joyce laughed. “I used to play that way last fall. I lit a candle in the dark and placed the candle behind my frame on the table. Then I moved the actors about so—”

Jimsi watched. Joyce had a paper doll-like actor cut in outline. To the back of this was pasted a strip of heavy paper. As she moved the doll across the back of the motion picture screen, holding it by the long strip of cardboard, one could only see the figure move across the little room. One did not see the hand that moved it or the strip of cardboard by which it was held.

Jolly! I should say so! Why, that was exactly the best fun Jimsi had ever seen!

“Hurrah for the crow!” she chuckled. “Why, I think that’s better than paper dolls—almost!”

“I’ll show you some more,” the little lame girl volunteered. “You just wait.”

Again she changed the things that lay beside the white cloth and the glass. When Jimsi looked, she saw that now there was out-door scenery: bushes, trees, a fence. Why, it might have been a street in a little town!

“I’ll show you something else!”

This time, the “something” was an automobile.

As Joyce held the frame in the clear sunlight, its shadow on the screen was plain. As Jimsi watched, the automobile rushed rapidly across the screen from one end of the frame to the other! Oh, what fun! And the shadow people in it seemed evidently out for a joy ride. One wondered that the automobile didn’t spill them out till Joyce turned the frame around and showed Jimsi that the automobile was cut out of heavy paper and that it and the people were all one piece!

“I’d like to see one of your motion picture[62] plays,” declared Jimsi. “Can’t you start one and make it go right through from beginning to end?”

“If it were only dark, I could,” said the little lame girl. “But you see Mother needs the light for her sewing just now. So we can’t draw the curtains. I’ll show you my scenery instead. Some other time we’ll make the whole motion picture play— Wouldn’t it be fun for the paper dolls, when I have made mine! Your paper dolls and mine can go to see the pictures: we’ll have a big time! Maybe, we can make up a new play and I can show you how to cut the scenery for it—shall I?”

“What plays have you made?”

“Well,” said the little lame girl, “you know I read a great deal. I make the plays of the stories that I read. I made Alice in Wonderland for one. I traced the pictures from the illustrations in my book and cut them out of heavy wall paper. (One can use cardboard for furniture and scenery and actors, only it’s more expensive, you know.) I traced most of my actors but not all. Some I had to draw—I’m not very good at drawing because I never had lessons. Mother says, she thinks[63] I could draw if I did have lessons but I just do the best I can without.”

“I think,” Jimsi insisted, “I think that you must know how to draw pretty well to cut out outlines of people from paper.”

“Oh, no,” contradicted Joyce. “Sometimes I can’t think the way things ought to look. Then I go through some pictures in a book and when I find an outline that will be good to use, I copy it. Or else, sometimes, I just double a piece of thin paper and cut out the way little children do to make paper dolls when they make both sides exactly alike. Mother used to make dolls in strings that way when I was small.”

“I saw Alice in Wonderland in moving pictures,” said Jimsi. “It was the crow who gave us all tickets once when Aunt Phoebe was visiting us. And I saw Cinderella with Mary Pickford. Did you?”

The little lame girl smiled. “Yes, the Good Crow gave me a ticket for it, and Mrs. Smith who has an automobile carried me up there. Wasn’t it lovely!”

The two little girls gazed into each other’s eyes, beaming. “After that, I made a play of Cinderella,” said Joyce. “Mine was just[64] a kind of paper doll play, but I had ever so much fun doing it. Sometime, I’ll show it all to you when it is dark and we can use a candle. Here’s the fairy godmother!”

She held up a silhouette doll cut with a long cloak and a pointed hat. The godmother had a wand in her hand. One would have known anywhere that it was Cinderella’s fairy!

“Here’s the pumpkin,” Joyce explained. “See! And here’s the coach! And here’s Cinderella before the fairy transformed her! (I had to make a second Cinderella figure for the play after the fairy touched her with the wand.) The way I do this is to change the figures very quickly. It takes a good deal of skill to act it out right. I had long times when I practiced with the figures last autumn. Then, when I thought I could do it perfectly, I’d give a motion picture play for Mother and Daddy in the evening. Often Miss Phoebe would come in to see my plays. She liked them. She used to help me sometimes. She thinks it’s fun!”

“We could make Red Riding Hood into a motion picture play,” suggested Jimsi. “We could make the bushes for the woods by cutting the paper out irregularly like the outline[65] of bushes if one saw them in shadow. You cut trees, didn’t you?”

The little lame girl assented. “I’ve cut trees and fences and little hills and the outlines of houses and—oh, ever so many things more than I can think of. In Alice in Wonderland, I really made a rabbit hole and when Alice was in the field, I made the funny rabbit go walking by and go down it and I made Alice follow him and—”

“How did you ever do it!” exclaimed Jimsi. “I don’t see how you did that!”

“You see how I made the field by putting bushes and a fence in the frame, don’t you?”

Jimsi nodded.

“The rabbit hole was a kind of oval with the middle part cut out,” went on the little lame girl. “All I had to do to make the rabbit go down was to pass the rabbit figure right into the centre of that and then draw him quickly away out of sight. It was the same with Alice. And oh, I did have such a splendid Pool of Tears with the mouse swimming in it! I made the Walrus and the Carpenter and Humpty Dumpty and everything!”

“What play could we give?”

“We might make one up[66]!”

“What would it be about?”

They wondered.

“It would be harder to make one up than to copy a story,” thought Jimsi.

“I tell you what we could do,” suddenly flashed Joyce. “It isn’t exactly a play, but it would be fun even if it wasn’t a real story. We could make Mother Goose motion pictures!”

“That sounds nice,” agreed Jimsi. She waited for the little lame girl to explain.

“We’d cut out a scene for Mother Hubbard’s house, you know,” pursued the little lame girl. “Then when we’d made the cupboard and the chairs and things, we could cut out Mother Hubbard and the dog and make a motion picture of it—just a short one.”

“And Jack and Jill Went Down the Hill!”

“And The Lion and the Unicorn!”

“And Little Bo-Peep and Little Boy Blue, too.”

“And—and—”

But right here, just exactly as Cinderella’s clock had struck twelve strokes, so the clock on the mantel of the little lame girl’s fireplace struck, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding—DING![67]

Oh, dear! There it was exactly the time when Jimsi had promised Aunt Phoebe to come home!

She jumped from her chair. “Oh, I was having such a good time,” she declared. “I didn’t know that it was anywhere near twelve. Oh, dear! I hate to say good-bye. I’ve had a perfectly splendid time—but I haven’t shown you my paper dolls at all! And the crow told me to show you my crow play and here I’ve just been listening to yours! But I’ll leave my paper dolls for you to look at and the toy furniture too. You’ll see how it is done. Then, some time when I come over, I’ll take them back. I’ll take my Magic Book home with me. Good-bye and thank you!”

“Come back soon,” sang the little lame girl as Jimsi turned to wave from the street. “Come soon!”

Then Jimsi waved a frantic and happy “Yes,” and sped back to Aunt Phoebe’s. She burst into the study where Aunt Phoebe was putting away her papers and clearing her desk. “Oh, oh,” she laughed, “do you know what I think, Aunt Phoebe?”

She waited.

“I think,” she beamed, “that your crow is[68] about the nicest crow ever! The little lame girl told me all about the motion picture play he gave her and I didn’t even have a chance to tell her about the paper dolls! We hadn’t half begun to play when the clock struck twelve! Oh, dear! I didn’t want to come right away—but I tell you what I’m going to do: I’m going to write to Henry and tell him about the crow’s motion pictures. He’d love to make them. He could act out Robinson Crusoe and Treasure Island.”

OF course after the first visit to the little lame girl’s home, Jimsi made ever and ever so many others. They not only made paper dolls and paper dolls’ furniture and paper dolls’ dresses and furnished paper dolls’ houses and had paper doll motion pictures but they did other things with their Magic Books, too.

Once, they tried kindergarten weaving with strips that they cut out of colored papers. Another time, they twisted long strips of the wall paper to make old-fashioned “lamp-lighters” for Joyce’s mother to use in lighting the fire in the fireplace. It was when they were doing this one day that, suddenly, Jimsi gave a big bounce out of her chair. She jumped up and down and up and down in the funniest excited manner, and she kept squealing delightedly, “Oh, I’ve got an idea! I’ve got an i-dea[70]!”

“What!” exclaimed Joyce. “WHAT IS IT?”

“Um-m! Um-m!” came from the happy Jimsi. “Oh, you guess!”

“I can’t guess!”

“Oh—no, you can’t guess! You wouldn’t think of it! Oh, it’s lovely—splendid—scrum-ti-fer-ous!”

“Well, what is it?” The little lame girl was almost impatient but she was as glad as Jimsi to prolong the suspense. She knew that Jimsi was making the most of her discovery.

“It couldn’t be better if the crow had written about it,” she asserted, stopping to sit down beside the little lame girl’s table. “I’ll tell you what it is: It’s VALENTINES! It’s VALENTINES! All the beautiful fancy papers are just the thing to make valentines! Think how beautiful valentines will be when they’re made out of the flowered papers! Let’s try it! We can save the valentines till we need them—put them away in a box or, I’ll tell you what!—Why couldn’t we send them up to The Children’s Home for a valentine party? Once I went with Daddy to an entertainment at The Children’s Home.[71] I felt as if I’d love to do something for the children there. It’s so—so very unhomelike!”

The Valentines and Cards That Were Made out of Wall Paper

“It would be splendid to do that,” agreed Joyce. “Let’s begin right away. You take your Magic Book and I’ll take mine. You can spread newspapers on the floor so we won’t make a clutter and let’s see who can make the prettiest. We’ll have a valentine exhibition afterwards and invite Miss Phoebe and the crow.”

“All right[72]!”

The leaves of the magic wall paper sample books turned and turned. There were squeals of delight from Joyce and chuckles from Jimsi. “Oh, I’ve found something that will be lovely!” one would cry. “Oh, look at this!” the other exclaimed. And the little lame girl’s mother who was called to admire couldn’t tell which was the prettiest paper—you see both were lovely!

First the little lame girl found some paper that had sprays of yellow roses on it. She cut out a big heart that was figured all over with them. It really was a beautiful, beautiful valentine.

Jimsi suggested that if one were to color the edge all around with green crayon, that would give the valentine a good finish. One could use the crayon to print on the valentine too.

Then, Jimsi improved on Joyce. She folded her paper double and cut her heart out double, making the top of her valentine heart touch the crease of the paper. Her heart opened with two sides. Inside, she wrote a verse. At the top she tied ribbon bows, using some very narrow baby ribbon that she had in the paper doll box.

Joyce made valentines like it only she put pictures as well as verses inside the double heart. Some of the verses she made up. Others, she copied from old valentines that were in her scrapbook.

After they had tried all manner of heart valentines, made of plain papers, flowered papers, papers with designs, papers with figures, striped papers, cross-barred papers, they decided to try something different. Jimsi cut out a diamond-shaped figure from her paper. It was really lovely. It was a basket of daisies. The diamond was bordered with blue and Jimsi cut diamond-shaped pieces of white paper and put them at the back of the picture with a verse—the old, old verse that everybody changes. It begins:

Jimsi changed it to:

It wasn’t a very wonderful verse but it was a real valentine verse and it fitted the picture of the valentine perfectly.

After Jimsi made her diamond-shaped valentine,[74] Joyce tried to make one. She found a cross-pattern of little rosebuds in her Magic Book. She cut the valentine out like a diamond-shaped book and put leaves in it. The leaves were tied in with ribbon. From the centre of the front of her valentine, she cut out a wee diamond in the paper and it made a most fascinating opening into which one could peep and see a picture that was pasted inside. Of course, she used the crayons to finish the edge in color. Jimsi and she discovered that the crayoning of all rims gave finish to the cards.

And so the play went on and on. They made valentines that opened square like books. They cut bunches of flowers from the wall papers that had large floral patterns and then, too, they cut out bits of wall paper shaped like baskets. These they filled with wall paper flowers and tied at the top of the basket sometimes bits of narrow baby ribbon that they had treasured for doll-play. Oh, they made a fine lot of valentines—almost fifty! It didn’t take long to make a valentine, once one had chosen a paper to use for it.

“Oh, we can make Easter cards too,” suggested Joyce, when the valentine pile was[75] grown quite large. She started out to see what she could do. Oh, yes! One could easily cut out pretty colored Easter eggs and paste them on heavy white paper to make clusters of dyed eggs. One could cut Easter eggs that had flowers on them as one had made hearts with flowers in pattern. One could cut colored bunnies out of the paper too. To do this, Joyce used the brown and yellow and the white wall papers in her Magic Book. It was fun!

“We could make birthday cards too,” said Jimsi. “Only I won’t try it because they’d be the same as the Easter cards that just have flower patterns and open like a book.”

“We could make Hallowe’en favor cards,” Joyce cried, suddenly. And then, they began to cut out witches and cats and jack-o’lanterns. Why, one never knew what would come next! The two little girls worked away. “Just for fun, let’s see what we can do,” they agreed. So they cut hatchets for Washington’s Birthday greetings; they cut New Year’s cards and flowered Christmas cards. They cut holly leaves from green wall paper and made red berries for wreathes from the red wall paper; they cut Thanksgiving favors too!

It really isn’t possible to tell all that the two very busy little girls did do that morning. At noon when the clock struck twelve, the jolliest thing happened. The door-bell rang and when Joyce’s mother went to answer it, there on the door-step was a big market basket with a cover on it! When Joyce saw it she declared, “Well, I know that’s from Miss Phoebe’s crow!” Anybody would have known it for on top of the basket was a wee letter. The letter was addressed to Jimsi and Joyce. It read:

“Dear Friends of the Magic Book and The Happy Shop:

Picnics don’t come in winter usually but I am sending you an in-door picnic to-day. If you open the big basket you’ll find that there are some nice picnic-y things inside. This is so that Jimsi can stay with Joyce a little longer, and also so Joyce can have Jimsi a little longer.

Good-bye,

Crow.

P. S.

In the little bottle is Jimsi’s bad medicine. She doesn’t like to take it but Joyce will please see her swallow it after the picnic is over. Please ask Jimsi to bring the picnic basket home to The Happy Shop with her when it is nap-time.

C. C.”

[77]The two little girls cleared the table of the valentines and cards. Jimsi ran about picking up stray bits of paper that had flown to remote places beyond the newspapers. Joyce arranged the things on the table. It was moved close to her chair.

My, my! Such tempting sandwiches! And such dainty paper table-cloth and napkins, and paper plates! “There’s only one thing lacking,” declared Joyce, as she laid an extra plate at one end of the table for her mother. “Miss Phoebe ought to be here too!”

“Yes, she ought,” assented Jimsi. “Aunt Phoebe and the Good Crow!”

IN the days that passed after Joyce and Jimsi made the valentines and cards, ever so many things happened. They played other things beside crow plays—checkers and dominoes and Messenger Boy games. But, after all, the Magic Book with the fun in it was best of all. Crow had written them both letters and in his last letter he had said:

“Dear Jimsi:

Find your own something to do in the Magic Book I gave you. If you think, you’ll find something more that is as jolly as valentine-making.”

Jimsi went over and over the Magic Book in The Happy Shop wondering what she could find to do with the papers. It seemed as if almost everything must have been done when paper doll dresses, paper doll furniture, cards, and motion picture play had been done!

Aunt Phoebe wouldn’t even give her a[80] hint. “Do as the crow says, dear,” she urged. “Put on your thinking-cap!”

“But I can’t think!” declared Jimsi. “I did make up the valentines!”

“Try to find something else. The crow and I might help but we want you to have the fun of discovering all for yourself!”

But Jimsi couldn’t find anything more to do. She spent the morning looking over the papers and then she wrote a letter to the crow and put it in the mail-box.

“Dear Crow:

Your Magic Book is like a puzzle and I am not a bit good at puzzles. Please tell me something nice to do with the colored papers of the magic wall paper sample book.

Lovingly,

Jimsi.

P. S.

I enclose a pretty flower that I cut out for you from the Magic Book. I think if I had my scrapbook from home I could use these flowers for scrap-pictures to paste in it. I can’t think of anything else.”

To this letter the crow replied the next day in a little letter that Jimsi found in the mail-box. The crow’s letter said:

“Dear Jimsi:

Your suggestion about using the flower-patterns for scrapbook decorations is good.[81] But you must puzzle longer and find still other jolly plays in your Magic Book.

Playfully,

Crow.

P. S.