The front cover is the transcibers creation, not the original. It is in the public domain. More notes at the end of the book.

THE POPULAR SERIES

NEW YORK  CINCINNATI

CINCINNATI  CHICAGO

CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

1891

Copyright, 1891, by American Book Company.

To the American youth the history of our country is more important than any other branch of education. A fair degree of knowledge respecting the progress of the American people from the discovery of the New World to the present is almost essential to that citizenship into which our youth are soon expected to enter. In a government of the people, for the people and by the people, a familiar acquaintance with the course of events, with the movements of society in peace and war, is the great prerequisite to the exercise of those rights and duties which the American citizen must assume if he would hold his true place in the Nation.

Fortunately, the means for studying the history of our country are abundant and easy. American boys and girls have little cause any longer to complain that the writers and teachers have put beyond their reach the story of their native land. Great pains have been taken, on the contrary, to gather out of our annals as a people and nation the most important and romantic parts, and to recite in pleasing style, and with the aid of happy illustrations, the lessons of the past.

The author of the present volume has tried in every particular to put himself in the place of the student. He has endeavored to bring to the pupils of our great Common Schools a brief and easy narrative of all the better parts of our country's history. It has been his aim to tell the story as a lover of his native land should recite for others that which is dearest and best to memory and affection. He has sought to bring the careful results of historical research into the schoolroom without any of the superfluous rubbish and scaffolding of obtrusive scholarship and erudition.

Another aim in the present text-book for our youth has been to consider the events of our country's history somewhat from[Pg 4] our own point of view—not to despise the history of civilization in the Mississippi Valley, or to seek wholly for examples of heroism and greatness in the older States of the Union. Perhaps no part of our country is more favorably situated for taking such a view of our progress as a nation than is that magnificent region, constituting as it does the most fertile and populous portion of the continent. In the present History of the United States the author has not hesitated to make emphatic those paragraphs which relate to the development and progress of this region.

For the rest the author has followed the usual channel of narration from the aboriginal times to the colonization of our Atlantic coast by the peoples of Western Europe; from that event by way of the Old Thirteen Colonies to Independence; from Independence to regeneration by war; and from our second birth to the present epoch of greatness and promise. He cherishes the hope that his work in the hands of the boys and girls of our public schools may pass into their memories and hearts; that its lessons may enter into union with their lives, and conduce in some measure to their development into men and women worthy of their age and country.

| Page | ||

| Preface | 3 | |

| Contents | 5 | |

| Introduction | 8 | |

| PART I. | ||

| PRIMITIVE AMERICA. | ||

| Chapter | ||

| I. | —The Aborigines | 11 |

| PART II. | ||

| VOYAGE AND DISCOVERY. | ||

| II. | —The Norsemen in America | 21 |

| III. | —Spanish Discoveries in America | 24 |

| IV. | —Spanish Discoveries in America.—Continued | 28 |

| V. | —The French in America | 35 |

| VI. | —English Discoveries and Settlements | 41 |

| VII. | —English Discoveries and Settlements.—Continued | 47 |

| VIII. | —Voyages and Settlements of the Dutch | 53 |

| PART III. | ||

| COLONIAL HISTORY. | ||

| IX. | —Virginia.—The First Charter | 57 |

| X. | —Charter Government.—Continued | 65 |

| XI. | —Virginia.—The Royal Government | 70 |

| XII. | —Massachusetts.—Settlement and Union | 76 |

| XIII. | —Massachusetts.—War and Witchcraft | 84 |

| XIV. | —New York.—Settlement and Administration of Stuyvesant | 94 |

| XV. | —New York under the English | 100 |

| XVI. | —Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire | 106 |

| XVII. | —New Jersey and Pennsylvania | 115 |

| XVIII. | —Maryland and North Carolina | 122 |

| XIX. | —South Carolina and Georgia | 128 |

| XX. | —French and Indian War | 135 |

| PART IV. | ||

| REVOLUTION AND CONFEDERATION. | ||

| XXI. | —Causes of the Revolution | 149 |

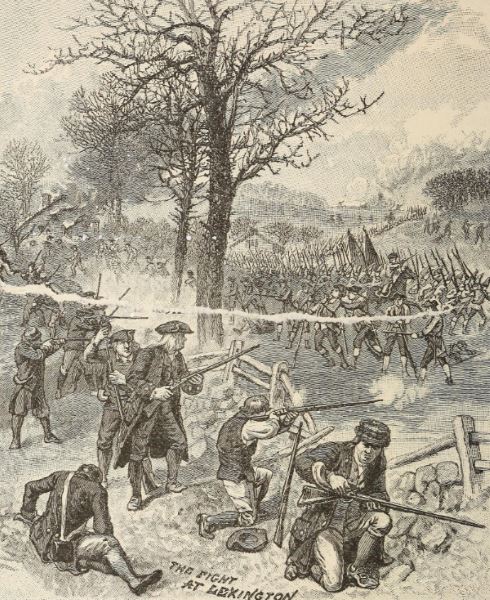

| XXII. | —The Beginning of the Revolution.—Events of 1775 | 157 |

| XXIII. | —The Events of 1776 | 163 |

| XXIV. | —Operations of 1777 | 171 |

| XXV. | —Events of 1778 and 1779 | 178 |

| XXVI. | —Reverses and Treason.—Events of 1780 | 187 |

| XXVII. | —Events of 1781 | 192 |

| XXVIII. | —Confederation and Union | 199 |

| PART V. | ||

| GROWTH OF THE UNION. | ||

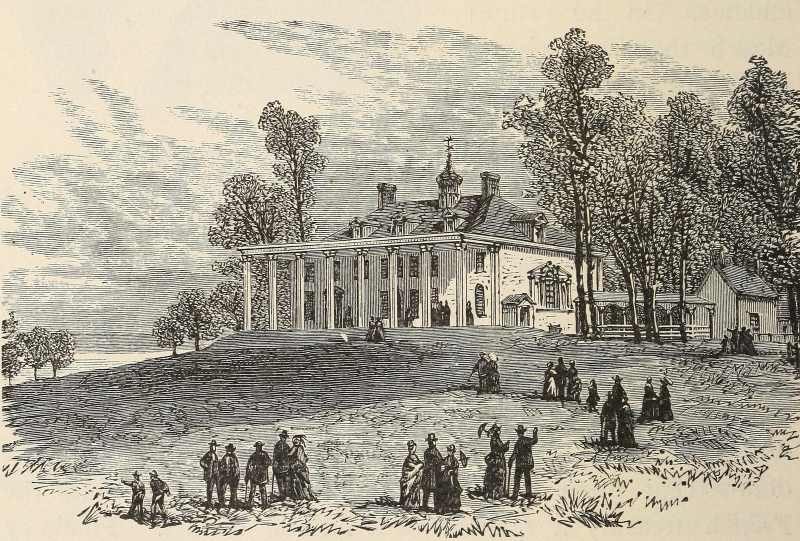

| XXIX. | —Washington's Administration | 205 |

| XXX. | —Adams's Administration | 211 |

| XXXI. | —Jefferson's Administration | 214 |

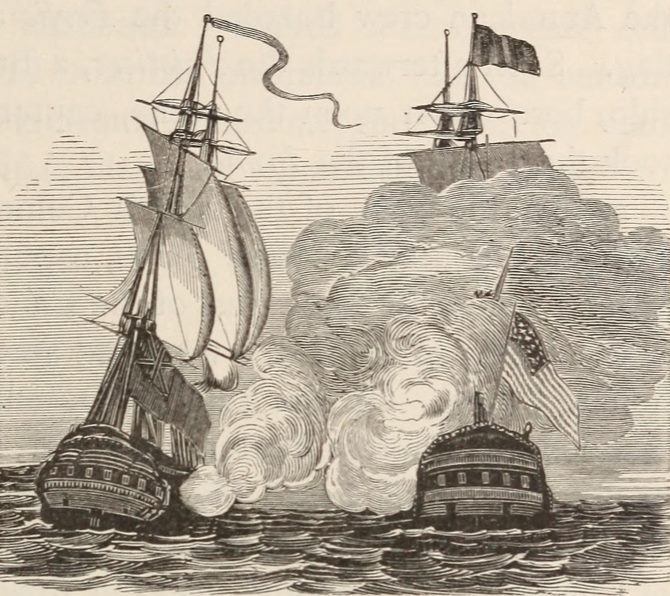

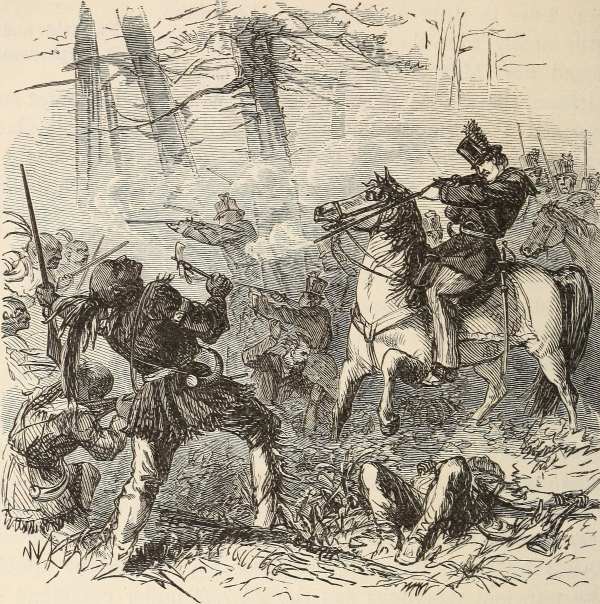

| XXXII. | —Madison's Administration.—War of 1812 | 221 |

| XXXIII. | —War of 1812.—Events of 1813 | 228 |

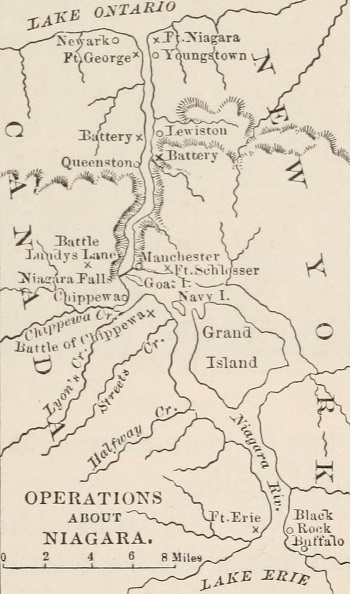

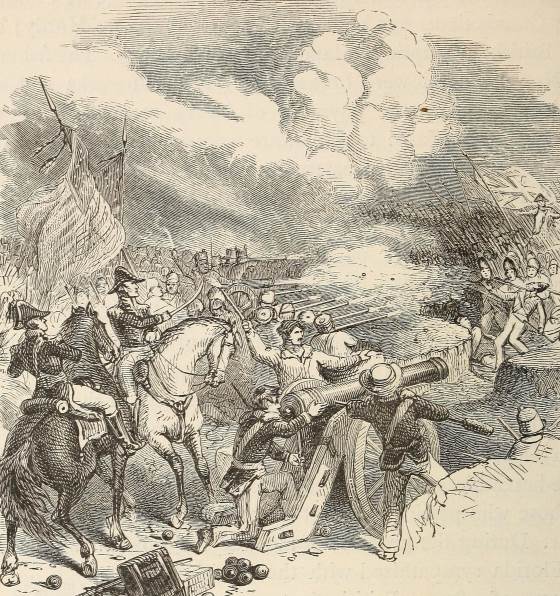

| XXXIV. | —The Campaigns of 1814 | 235 |

| XXXV. | —Monroe's Administration | 244 |

| XXXVI. | —Adams's Administration | 248 |

| XXXVII. | —Jackson's Administration | 250 |

| XXXVIII. | —Van Buren's Administration | 254 |

| XXXIX. | —Administrations of Harrison and Tyler | 257 |

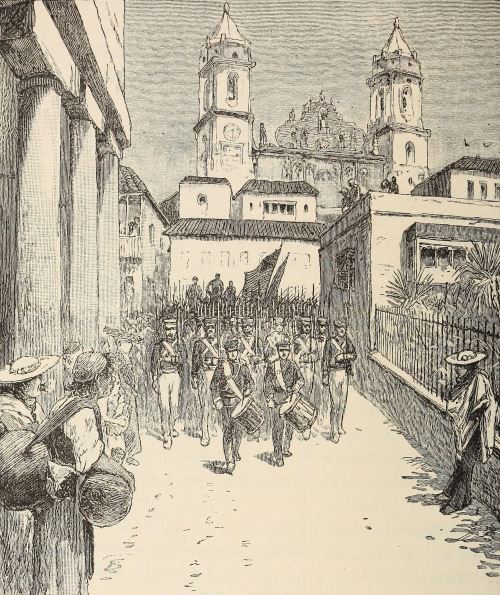

| XL. | —Polk's Administration and the Mexican War | 261 |

| XLI. | —Administrations of Taylor and Fillmore | 269 |

| XLII. | —Pierce's Administration | 273 |

| XLIII. | —Buchanan's Administration | 275 |

| PART VI. | ||

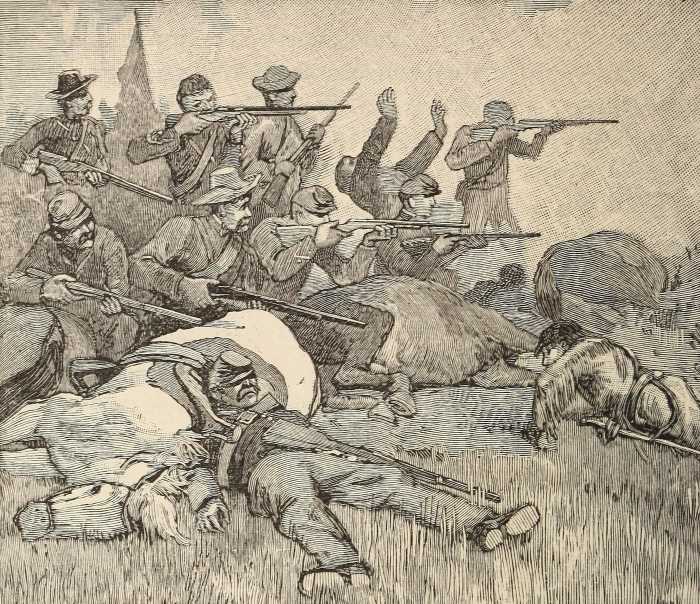

| THE CIVIL WAR. | ||

| XLIV. | —Lincoln's Administration and the Civil War | 281 |

| XLV. | —Causes of the Civil War | 284 |

| XLVI. | —Events of 1861 | 288 |

| XLVII. | —Campaigns of 1862 | 293 |

| XLVIII. | —The Events of 1863 | 302 |

| XLIX. | —The Closing Conflicts.—Events of 1864 and 1865 | 310 |

| PART VII. | ||

| THE NATION REUNITED. | ||

| L. | —Johnson's Administration | 323 |

| LI. | —Grant's Administration | 328 |

| LII. | —Hayes's Administration | 337 |

| LIII. | —Administrations of Garfield and Arthur | 344 |

| LIV. | —Cleveland's Administration | 350 |

| LV. | —Harrison's Administration | 361 |

| Appendix. | —Constitution of the United States | 371 |

| Index | 387 |

| PAGE | |

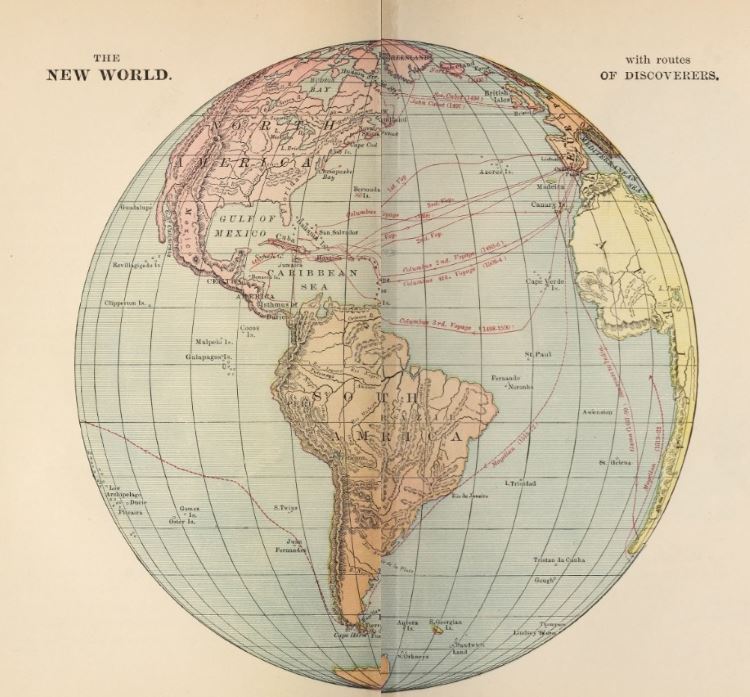

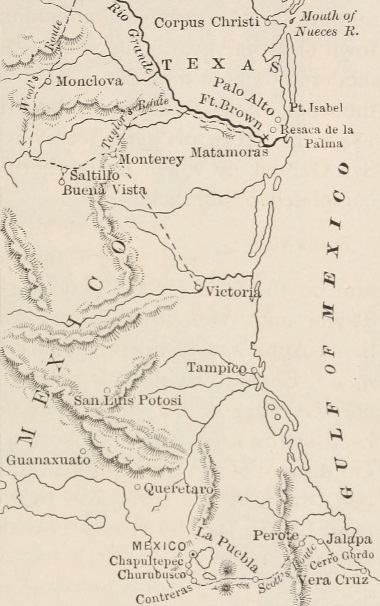

| The New World, with Routes of Discoveries | 24 |

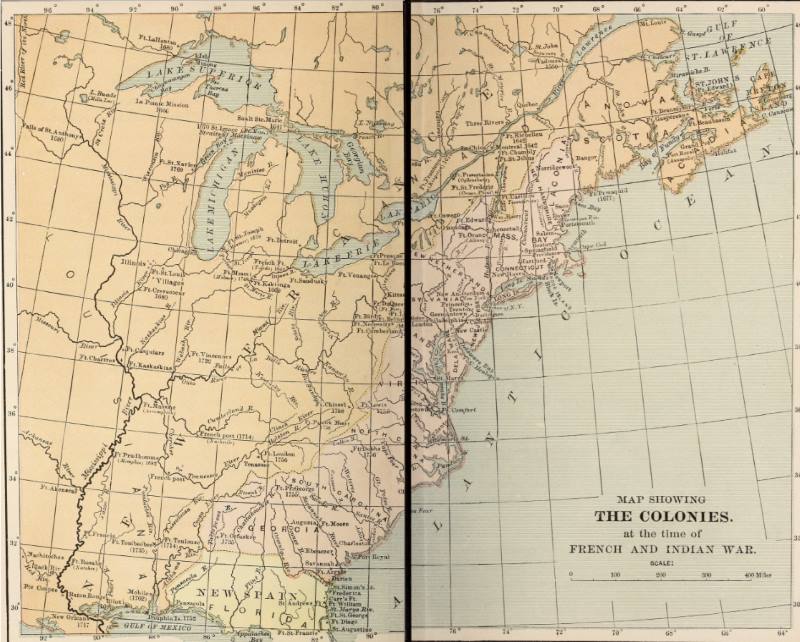

| The Colonies at the time of the French and Indian War | 144 |

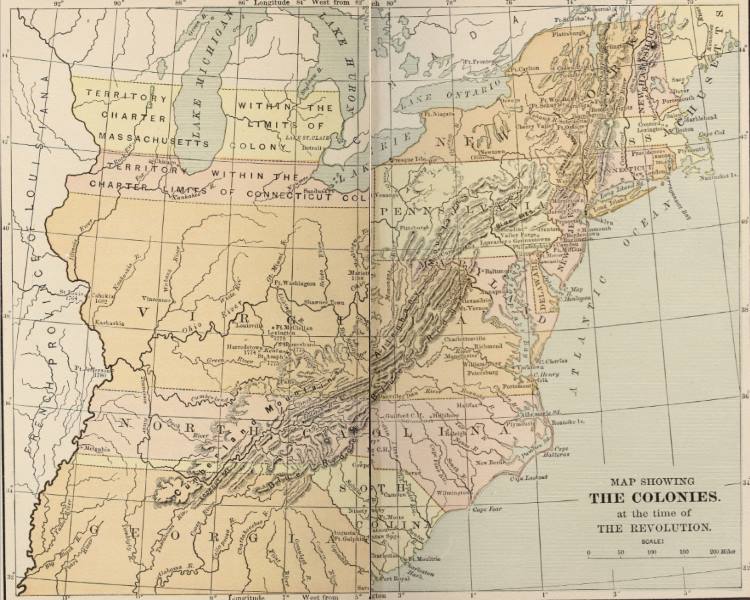

| The Colonies at the time of the Revolution | 192 |

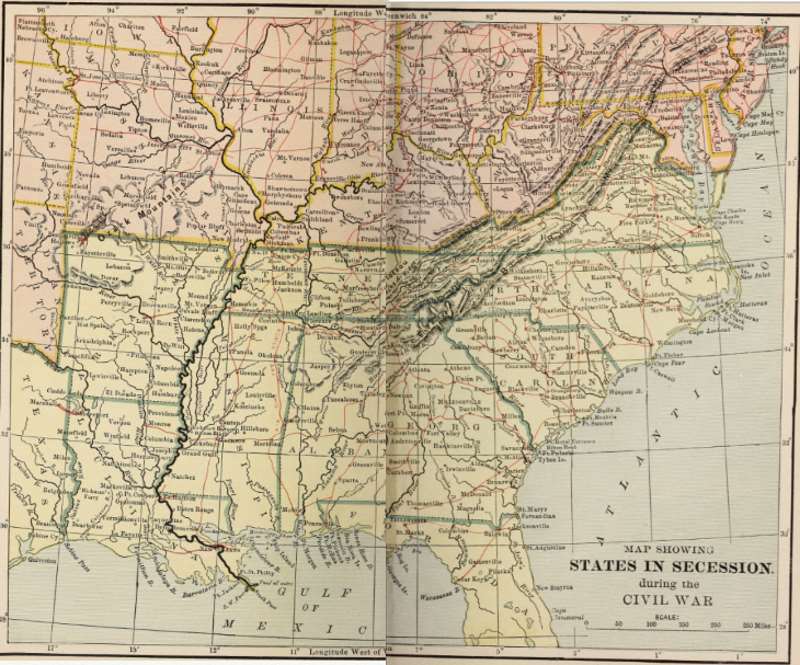

| The States in America during the Civil War | 304 |

| The States in America during the Civil War | 304 |

| PAGE | |

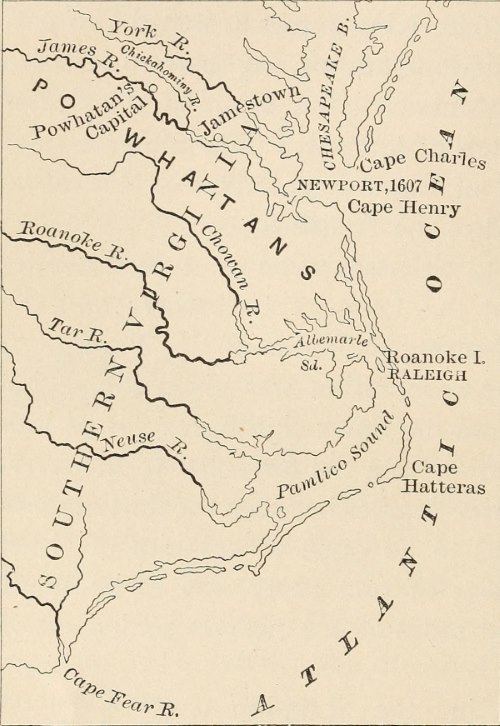

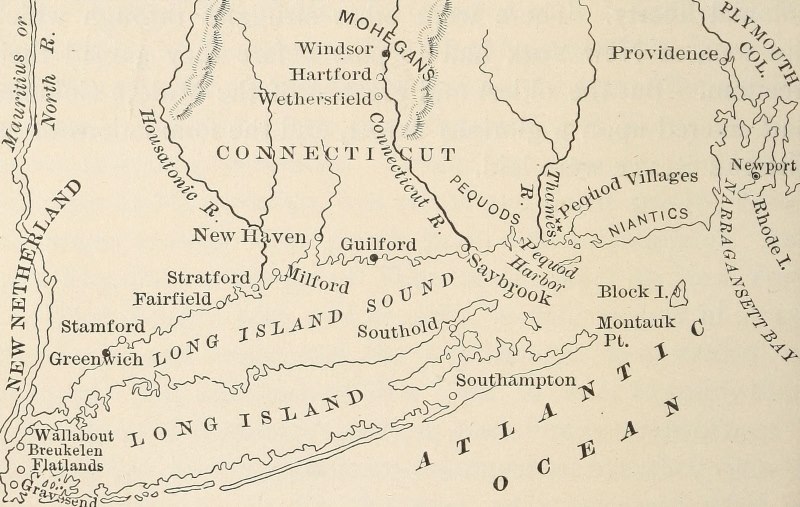

| The First English Settlements | 48 |

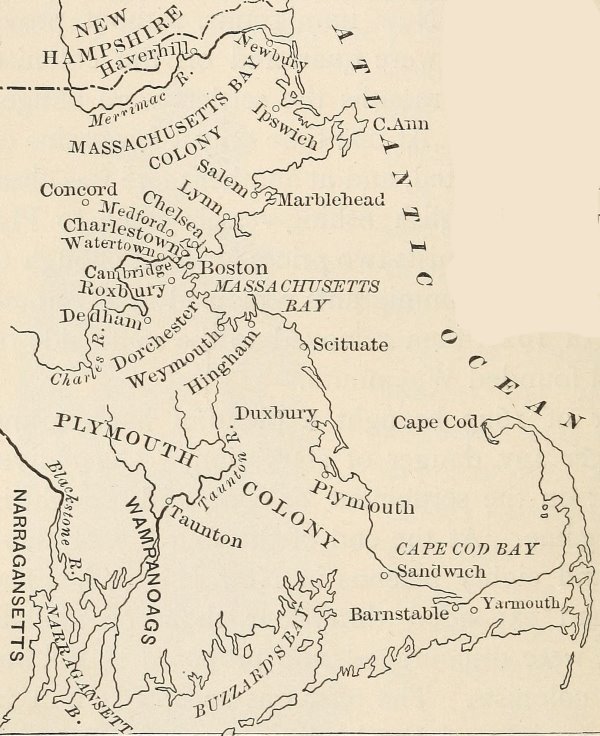

| Early Settlements in East Mass. | 78 |

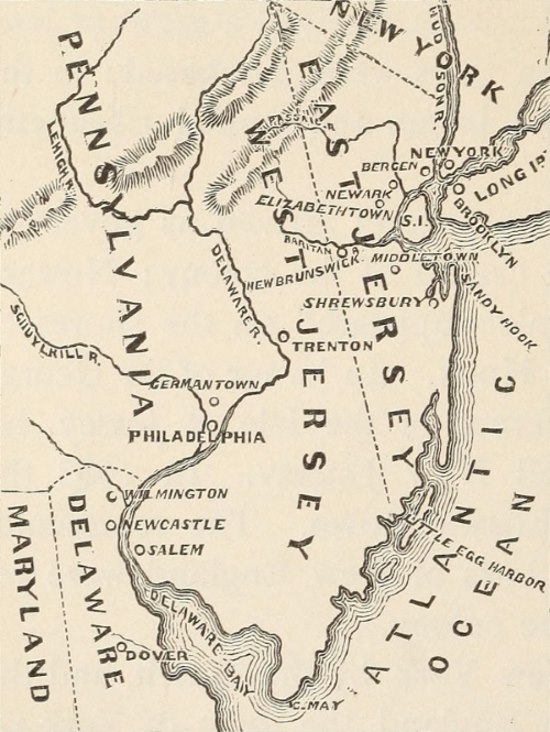

| Middle Colonies | 116 |

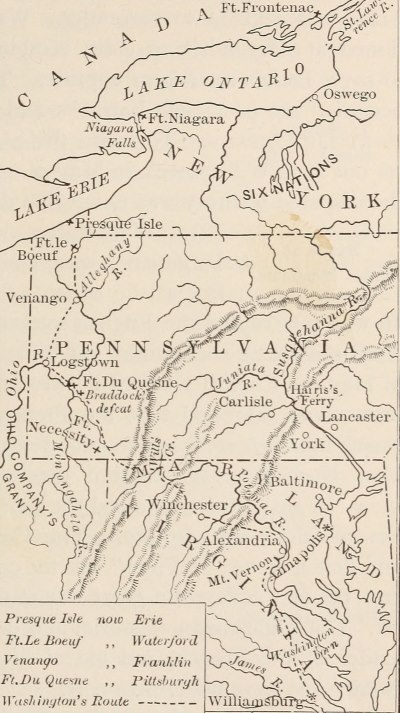

| Washington's Route to Fort LeBœuf | 139 |

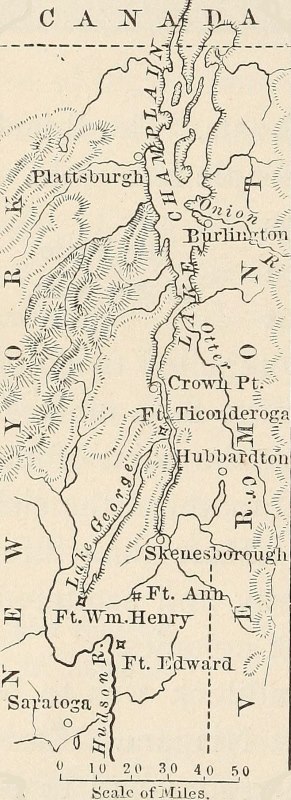

| Lake Champlain | 142 |

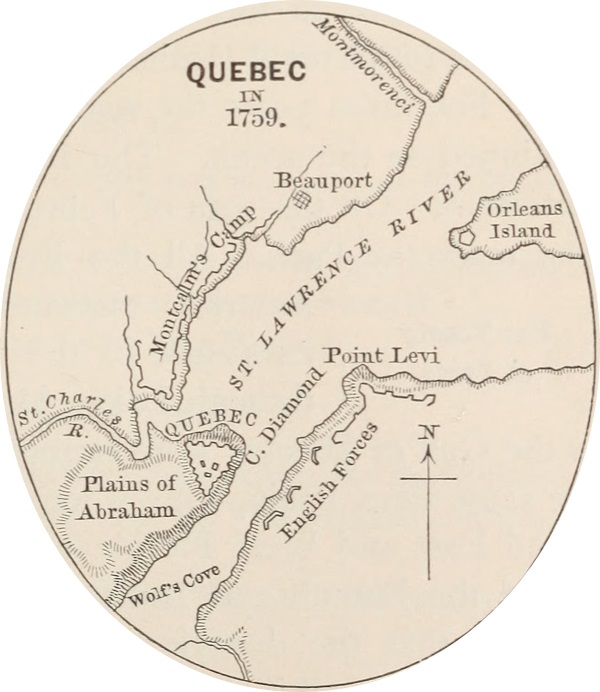

| Quebec in 1759 | 145 |

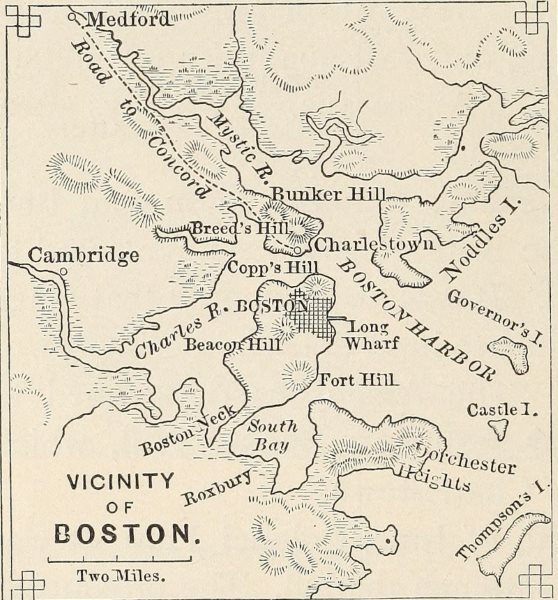

| Vicinity of Boston | 160 |

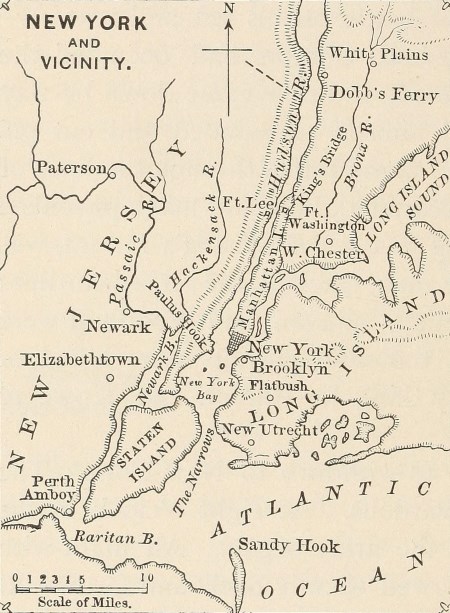

| New York and Vicinity | 168 |

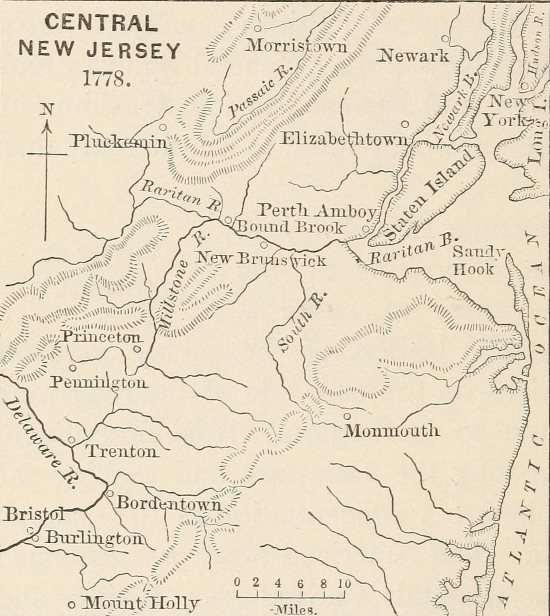

| Central New Jersey | 170 |

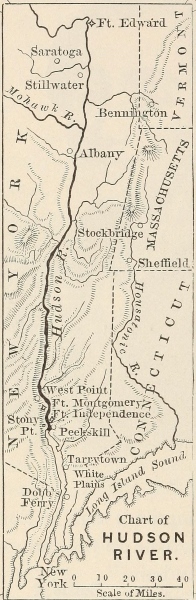

| Hudson River | 174 |

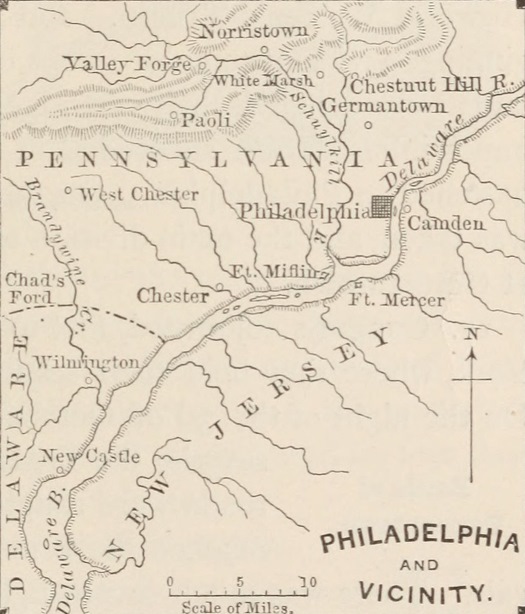

| Philadelphia and Vicinity | 176 |

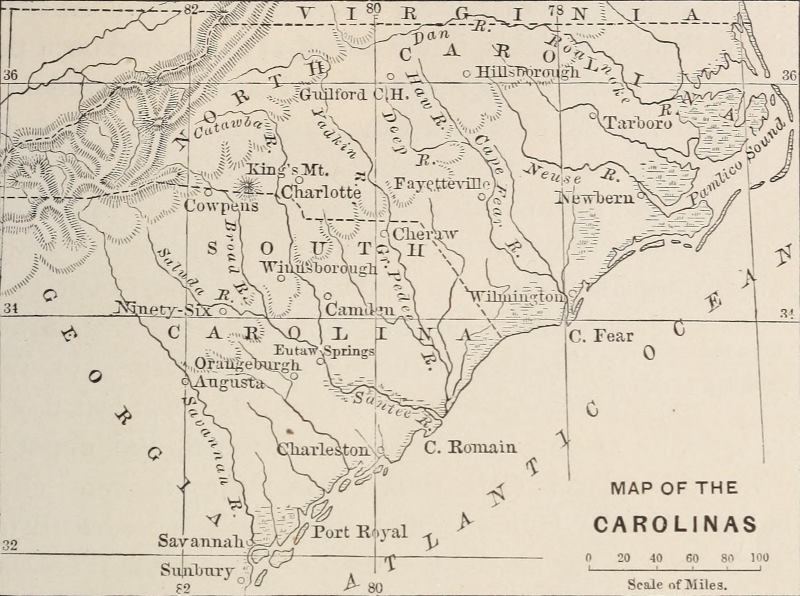

| The Carolinas | 186 |

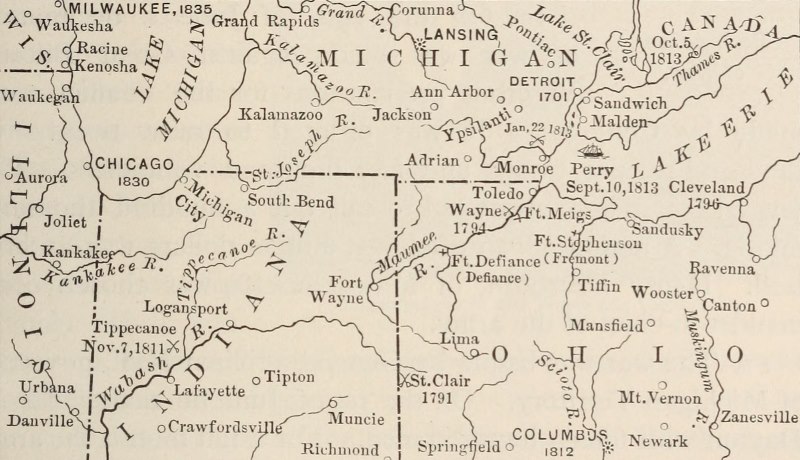

| Western Battlefields of the War of 1812 | 223 |

| Operations about Niagara | 235 |

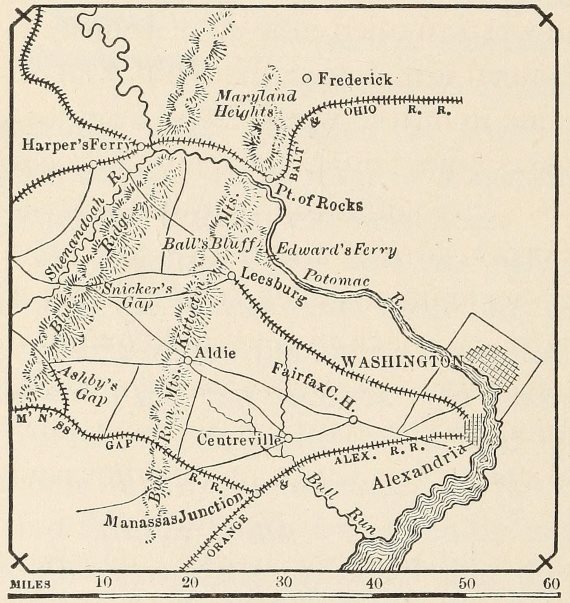

| Vicinity of Manassas Junction | 288 |

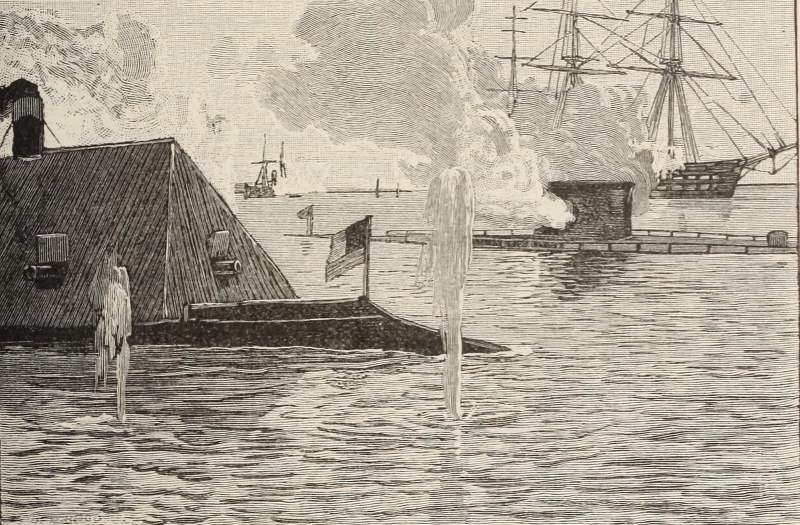

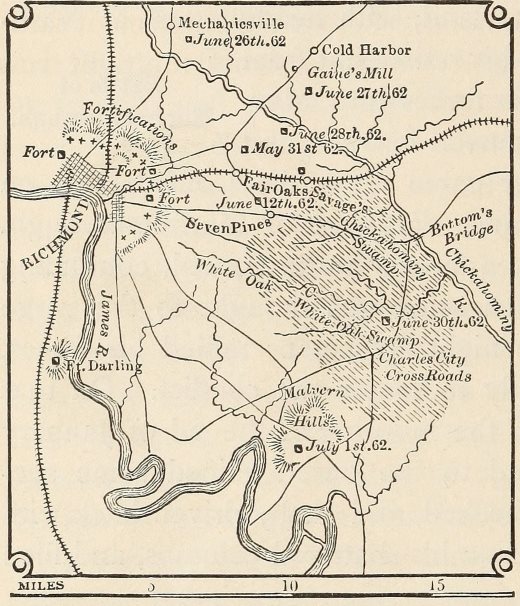

| Vicinity of Richmond, 1862 | 298 |

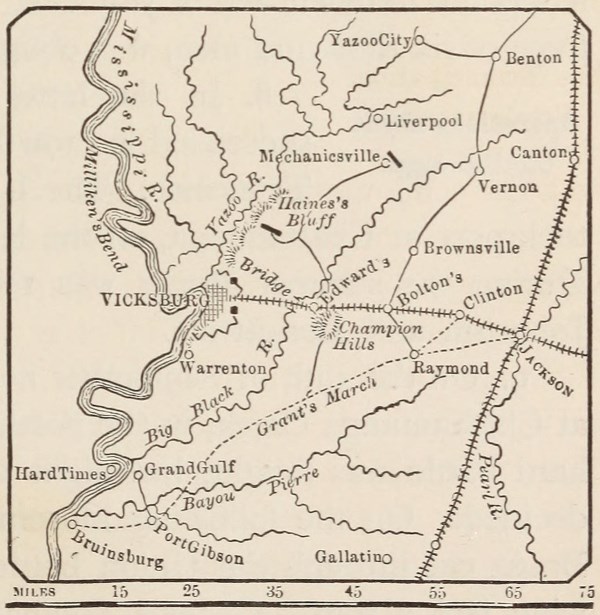

| Vicksburg and Vicinity, 1863 | 303 |

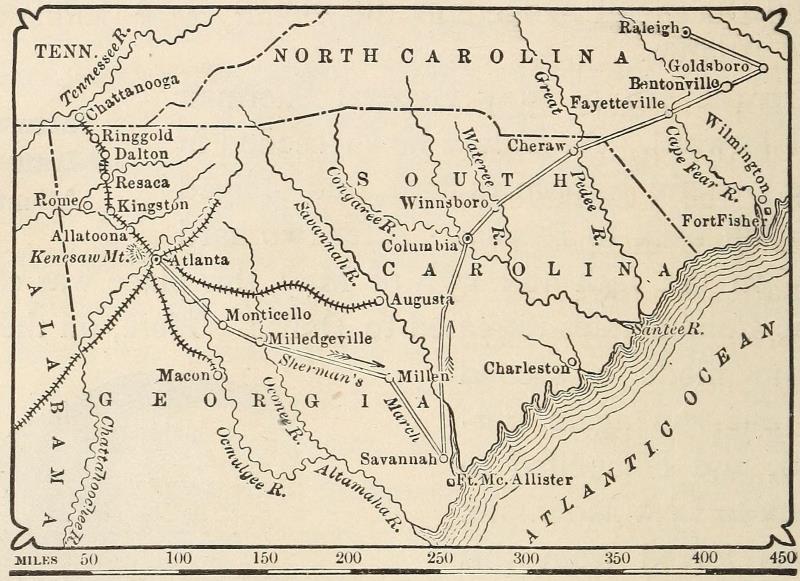

| Sherman's Atlanta Campaign | 312 |

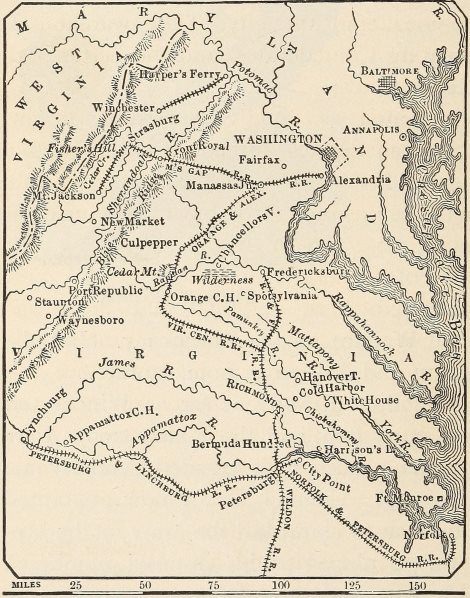

| Operations in Virginia, 1864 and 1865 | 318 |

| PAGE | |

| George Washington | 10 |

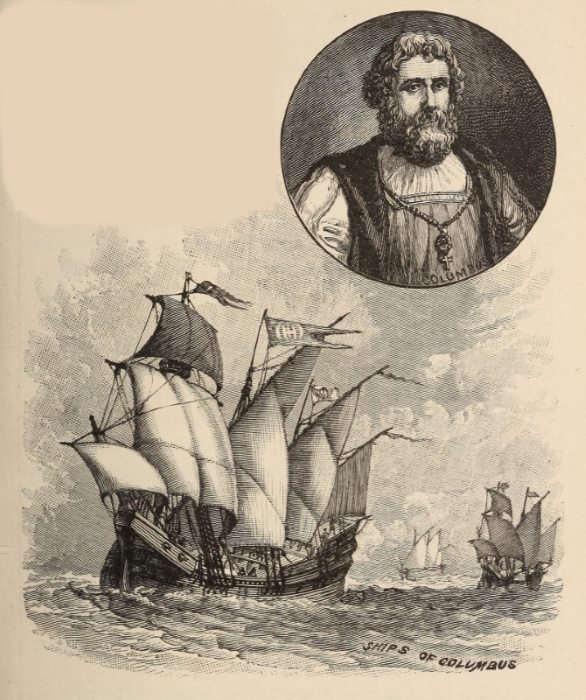

| Christopher Columbus | 25 |

| Pedro Menendez | 33 |

| Samuel Champlain | 39 |

| Sebastian Cabot | 42 |

| Sir Walter Raleigh | 44 |

| Captain John Smith | 60 |

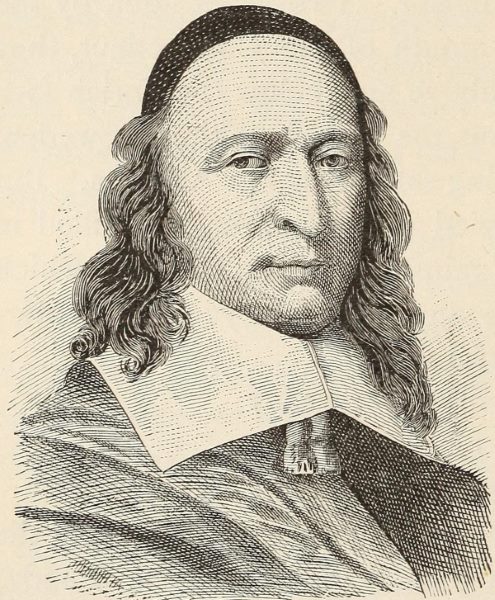

| Peter Stuyvesant | 96 |

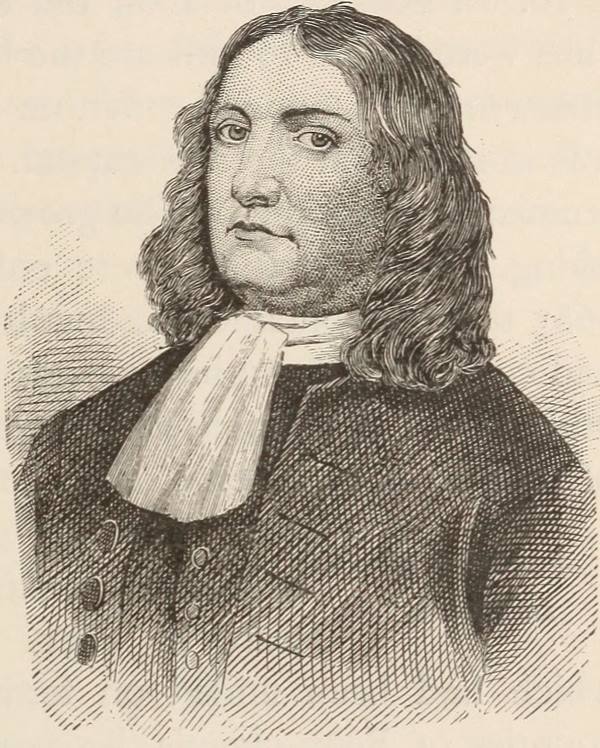

| William Penn | 119 |

| Cecil Calvert, Lord Baltimore | 123 |

| James Oglethorpe | 131 |

| Patrick Henry | 152 |

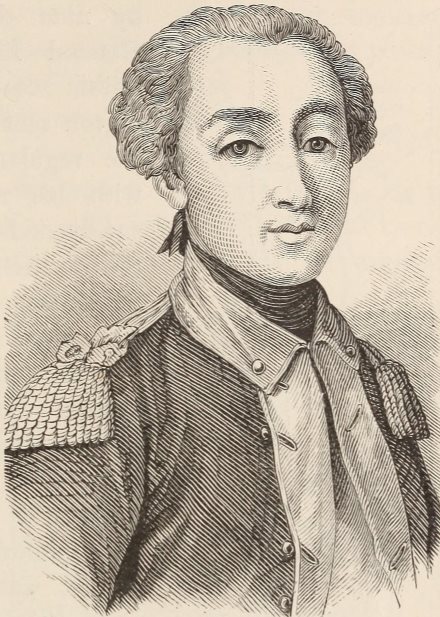

| Marquis de La Fayette | 173 |

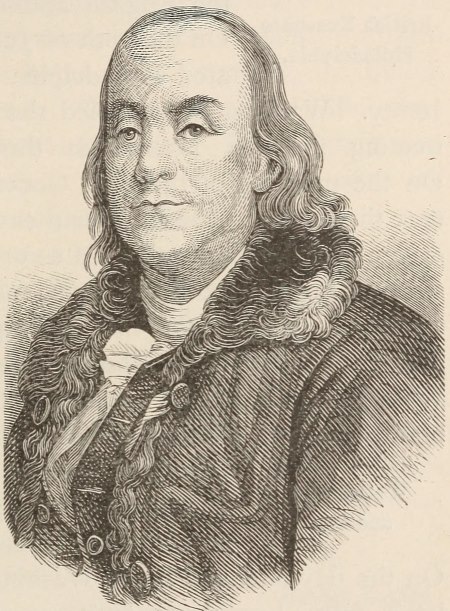

| Benjamin Franklin | 179 |

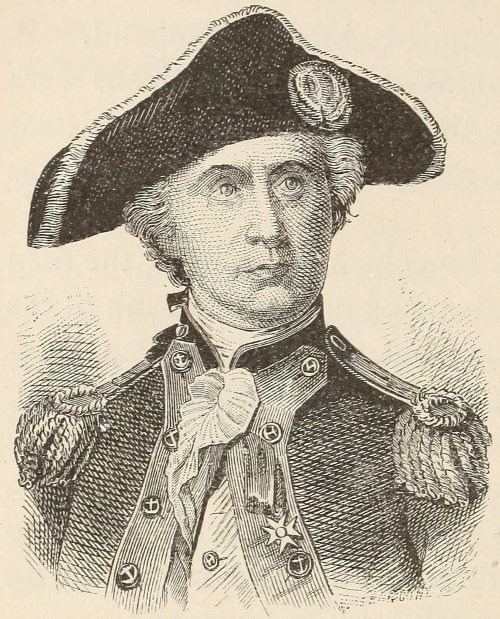

| Paul Jones | 186 |

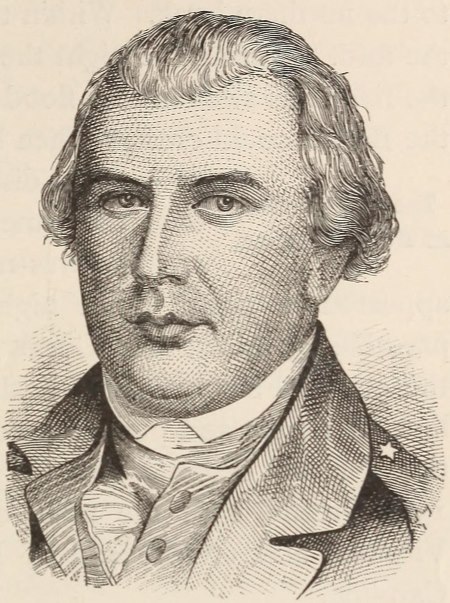

| General Greene | 193 |

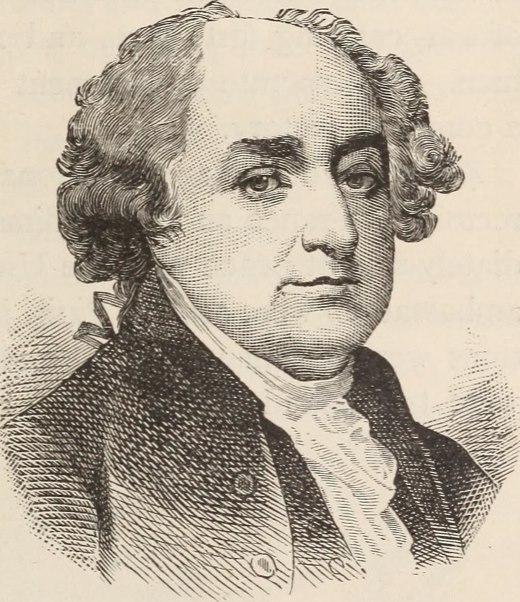

| John Adams | 211 |

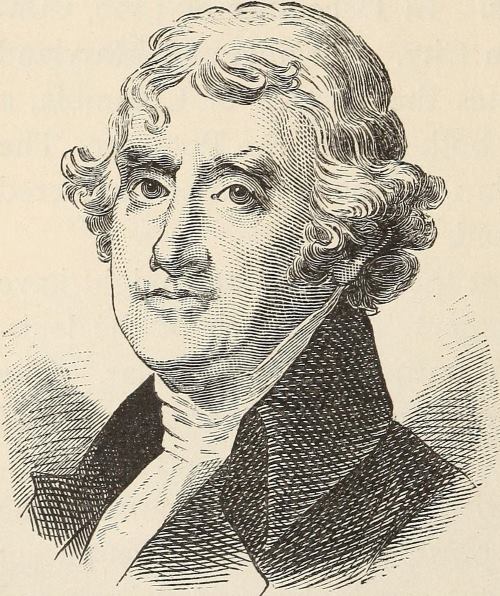

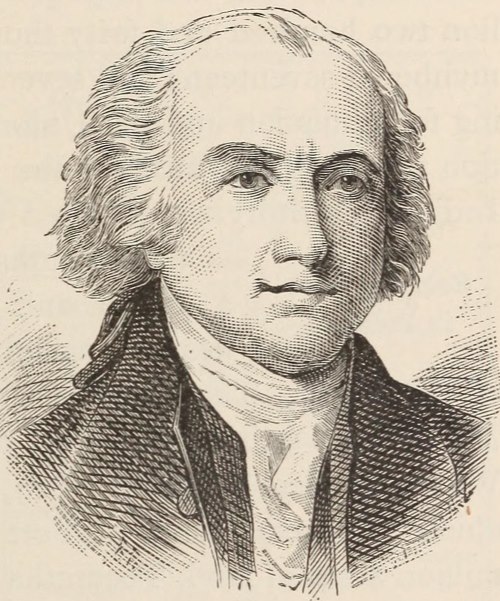

| Thomas Jefferson | 214 |

| James Madison | 221 |

| James Monroe | 244 |

| Henry Clay | 247 |

| John Quincy Adams | 248 |

| Andrew Jackson | 250 |

| Daniel Webster | 251 |

| Martin Van Buren | 254 |

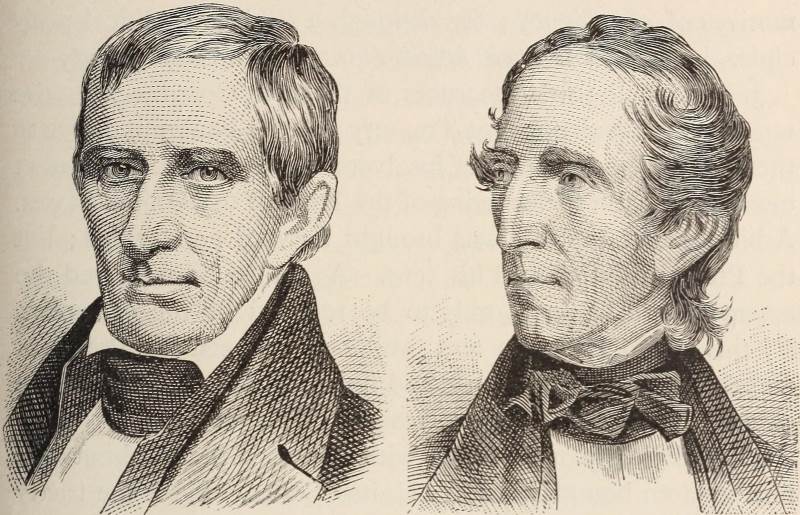

| William Henry Harrison | 257 |

| John Tyler | 257 |

| James K. Polk | 261 |

| John Charles Fremont | 263 |

| Zachary Taylor | 269 |

| Millard Fillmore | 270 |

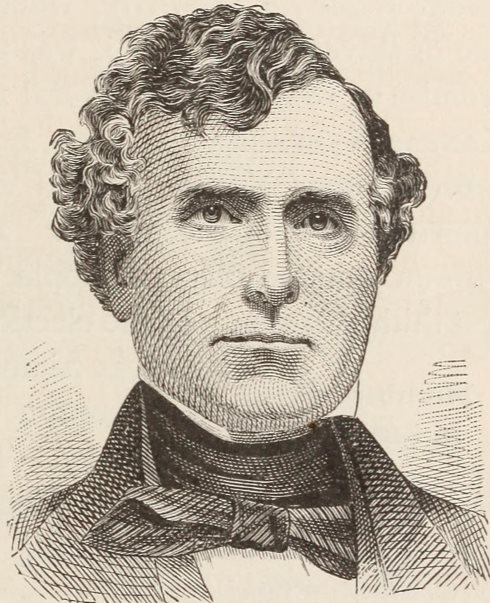

| Franklin Pierce | 273 |

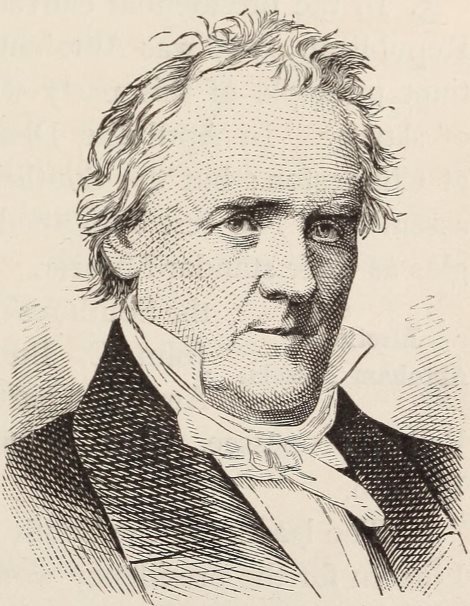

| James Buchanan | 275 |

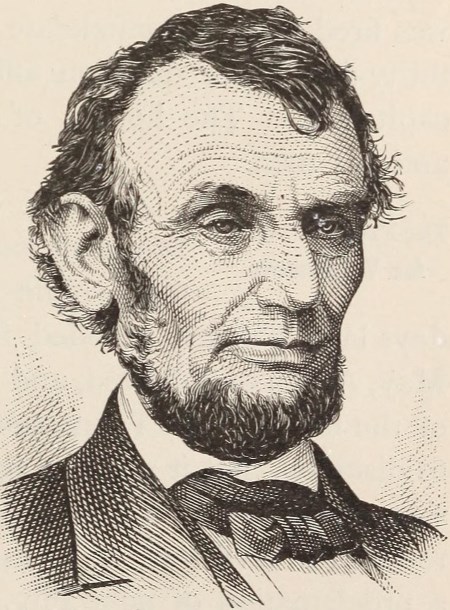

| Abraham Lincoln | 281 |

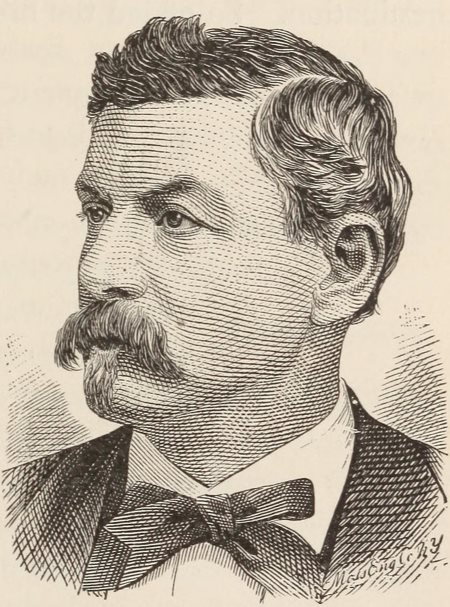

| George B. McClellan | 291 |

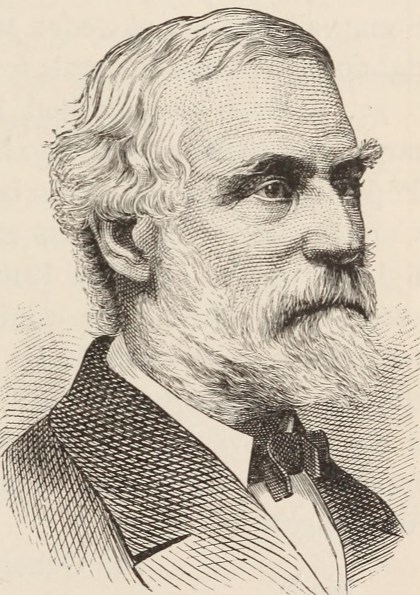

| Robert E. Lee | 299 |

| Stonewall Jackson | 307 |

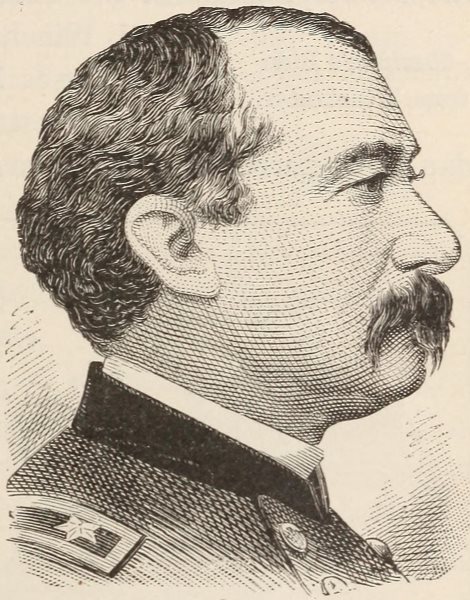

| William T. Sherman | 311 |

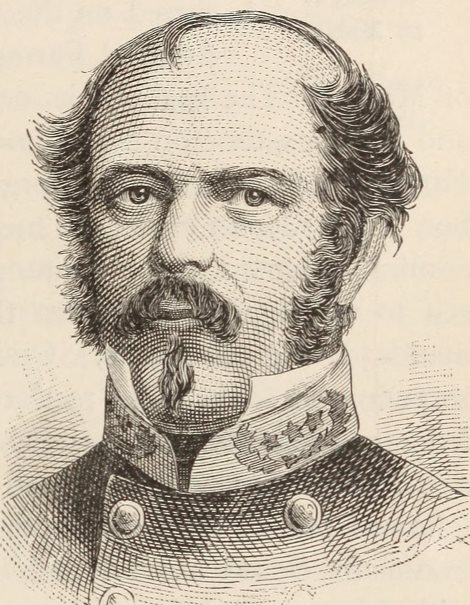

| Joseph E. Johnston | 313 |

| Philip H. Sheridan | 317 |

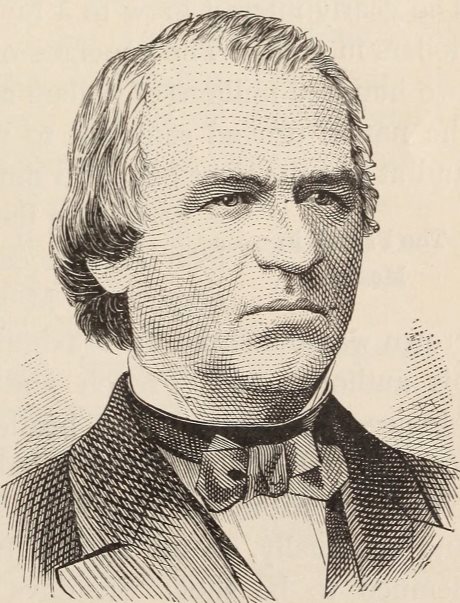

| Andrew Johnson | 323 |

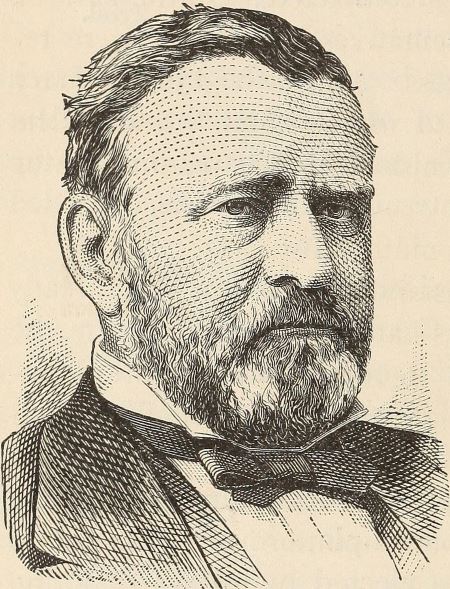

| Ulysses S. Grant | 328 |

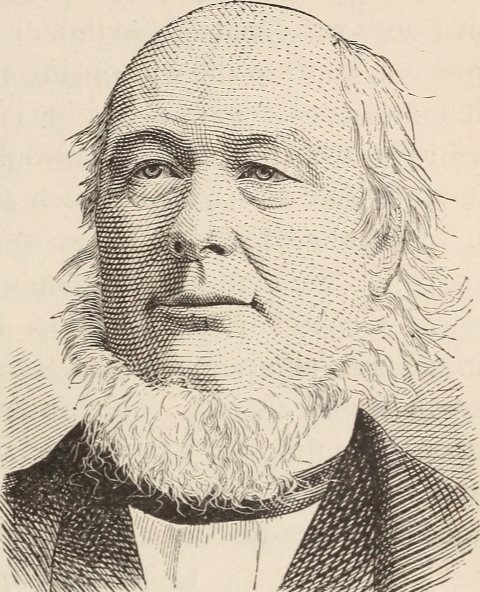

| Horace Greeley | 331 |

| Rutherford B. Hayes | 337 |

| Oliver P. Morton | 342 |

| James A. Garfield | 344 |

| Chester A. Arthur | 346 |

| Grover Cleveland | 350 |

| Thomas A. Hendricks | 356 |

| Benjamin Harrison | 361 |

THERE are several Periods in the history of the United States. It is important for the student to understand these at the beginning. Without such an understanding his notion of our country's history will be confused and his study rendered difficult.

2. First of all, there was a time when the Western continent was under the dominion of the Red men. The savage races possessed the soil, hunted in the forests, roamed over the prairies. This is the Primitive Period in American history.

3. After the discovery of America, the people of Europe were for a long time engaged in exploring the New World and in becoming familiar with its shape and character. For more than a hundred years, curiosity was the leading passion with the adventurers who came to our shores. Their disposition was to go everywhere and settle nowhere. These early times may be called the Period of Voyage and Discovery.

4. Next came the time of planting colonies. The adventurers, tired of wandering about, became anxious to found new States in the wilderness. Kings and queens turned their attention to the work of colonizing the New World. Thus arose a third period—the Period of Colonial History.

5. The colonies grew strong and multiplied. There were thirteen little seashore republics. The rulers of the mother-country began a system of oppression and tyranny. The colonies revolted, fought side by side, and won their freedom.[Pg 9] Not satisfied with mere independence, they formed a Union destined to become strong and great. This is the Period of Revolution and Confederation.

6. Then the United States of America entered upon its career as a nation. Emigrants flocked to the Land of the Free. New States were formed and added to the Union in rapid succession. To protect itself from jealous neighbors, the nation pushed her boundaries across the continent. This Period may be called the Growth of the Union.

7. But the nation was not truly free. Human slavery existed in the South. This institution engendered sectional hatred and desires for disunion which finally developed into the dark and bloody Period of the Civil War.

8. Then the reunited nation laid aside its arms and entered upon a period of prosperity and material development which has not yet reached its culmination and with which History affords no parallel.

9. We thus find seven periods in the history of our country:

In this order the History of the United States will be presented in the following pages.

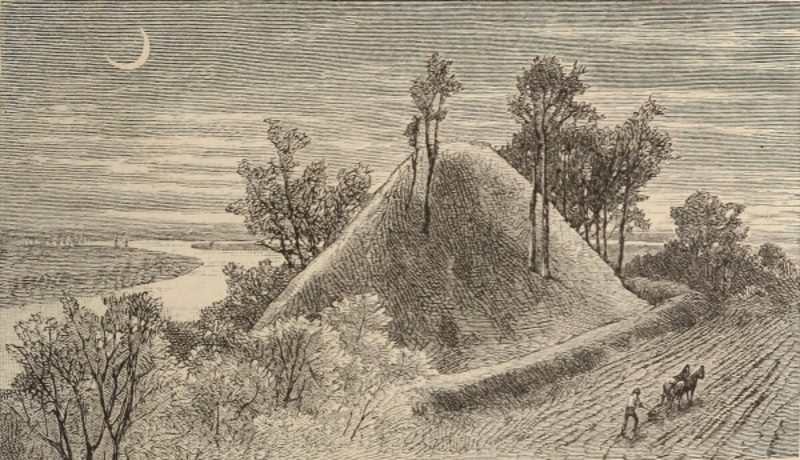

An Ancient Mound

BEFORE the times of the Red men, North America was inhabited by other races, of whom we know but little. Of these primitive peoples the Indians preserved many traditions. Vague stories of the wars, migrations, and cities of the nations that preceded them were recited by the red hunters at their camp-fires, and were repeated from generation to generation.

2. Other evidences, more trustworthy than legend and story, exist of the presence of aboriginal peoples in our country. The traces of a rude civilization are found in almost every part of the present United States. It is certain that the relics left behind by the prehistoric peoples are not the work of the Indian races, but of peoples who preceded them in the occupation of this continent. That class of scholars called antiquarians, or archæologists, have taken great pains to restore for us an outline of the life and character of the nations who first dwelt in the great countries between the Atlantic and the Pacific.

3. These primitive peoples are known to us by the name of Mound-builders. The building of mounds seems to have been one of their chief forms of activity. The traveler of to-day, in passing across our country, will ever and anon discover one of those primitive works of a race which has left to us no other monuments. As the ancient people of Egypt built pyramids of stone for their memorials, so the unknown peoples of the New World raised huge mounds of earth as the tokens of their presence, the evidences of their work in ancient America.

4. The mounds referred to are found in many parts of the United States, but are most abundant in the Mississippi Valley. Here also they are of greatest extent and variety. Some of them are as much as ninety feet in height, and one has been estimated to contain twenty million cubic feet of earth. It is evident that they were formed before the present forest growth of the United States sprang into existence. The mounds are covered with trees, some of them several feet in diameter; and the surface has the same appearance as that of the surrounding country.

5. As we have said, we know but little of the people by whom the mounds and earthworks of primitive America were constructed. Some of the works in question are of a military character. One of these, called Fort Hill, near the mouth of the Little Miami River, has a circumference of nearly four[Pg 13] miles. It is certain that great nations, frequently at war with each other, dwelt in our country between the Northern Lakes and the Southern Gulf; but who those peoples were we have no method of ascertaining. Their language has perished with the people who spoke it. Only a few of the relics and implements of the primitive races remain to inform us of the men by whom they were made.

6. In many parts of the Mississippi Valley, particularly in the States of Ohio and Indiana, the ancient mounds may be seen as they were at the time of the discovery of America. One of the greatest is situated in Illinois, opposite the city of St. Louis. It is elliptical in form, being about seven hundred feet in length by five hundred feet in breadth. It rises to a height of ninety feet. Another of much interest is at Grave Creek, near Wheeling, in West Virginia. A mound at Miamisburg, Ohio, is nearly seventy feet in height. One of the finest of all is the conical mound at Marietta, Ohio. Some of the mounds, as those of Wisconsin, are shaped like animals. One of the most peculiar and interesting is the great serpent mound in Adams County, Ohio. The work has the shape of a serpent more than a thousand feet in length, the body being about thirty feet broad at the surface. The mouth of the serpent is opened wide, and an object resembling a great egg lies partly within the jaws.

7. The use of the mounds has not been ascertained. Some have supposed that they were tombs in which the slain of great armies were buried, but on opening them, human remains are rarely found. Others have believed that the mounds were true memorials, intended by their magnitude to impress the beholder and transmit a memory. Still others have thought the elevations were intended for watch-towers from which the movements of the enemy might be watched and thwarted.

8. What we know of the prehistoric races has been mostly gained from an examination of their implements and utensils.

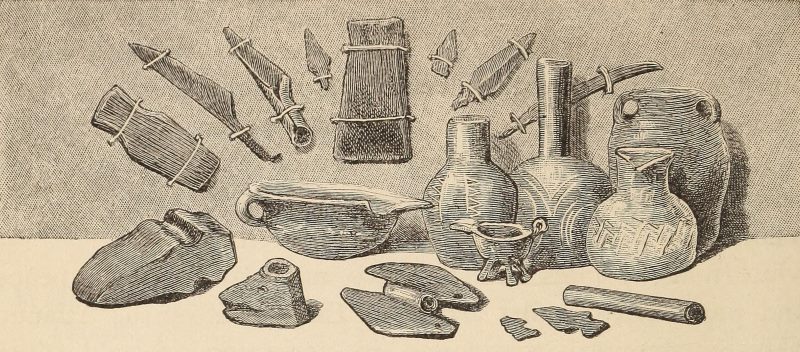

Relics from the Mounds.

These were of either stone or copper. It appears that the more advanced of the peoples, especially the nations living on the borders of the Great Lakes, were able to manufacture utensils of copper. In other parts of the country, the weapons and implements were made of flint and other varieties of stone, by chipping or polishing. The range of tools and implements was extensive, including axes, spear-heads, arrow-points, knives, chisels, hammers, rude millstones, and many varieties of earthen ware. Besides these, there were articles of ornamentation and personal use, such as pipes, bracelets, ear-rings, and beads. The common belief that the articles here referred to were the product of Indian workmanship is held by many antiquarians to be wholly erroneous. These antiquarians think that the Indians knew nothing more of the origin and production of such implements as the arrow-points, spear-heads, and stone axes than we know ourselves.

9. In many parts of Indiana the mounds of the ancient races are plentifully distributed. Almost every county has some relics of this kind within its borders. But the most interesting remains of the primitive races are those discovered in the ancient cemeteries scattered between Lake Michigan and the Tennessee River. In many places the aboriginal tombs still yield the relics of this people of whom we know so little.[Pg 15] In recent years a burial ground near Bedford, Indiana, has been opened, from which have been taken primitive skulls and other parts of human skeletons, belonging possibly to some unknown race long preceding the Indians in our country.

10. With the Mound-builders, history can be but little concerned; but with the Red men, or Indians, who succeeded them, the white race was destined to have many relations of peace and war. On the first arrival of Europeans on the Atlantic coast, the country was found in possession of wild tribes living in the woods and on the river banks, in rude villages from which they went forth to hunt or to make war on other tribes. Their manners and customs were fixed by usage and law, and there was at least the beginning of civil government among them.

11. To these tribes the name Indian was given from their supposed identity with the people of India. Columbus and his followers believed that they had reached the islands of the far East, and that the natives were of the same race as the inhabitants of the Indies. The mistake of the Spaniards was soon discovered; but the name Indian has ever since remained to designate the native tribes of the Western continent.

12. The origin of the Indians is involved in obscurity. At what date or by what route they came to the New World is unknown. The notion that the Red men are the descendants of the Israelites is absurd. That Europeans or Africans, at some early period, crossed the Atlantic by sailing from island to island, seems improbable. That the people of Kamchatka came by way of Bering Strait into the northwestern parts of America, has little evidence to support it. Perhaps a more thorough knowledge of the Indian languages may yet throw some light on the origin of the race.

13. The Indians belong to the Bow-and-Arrow family of men. To the Red man the chase was everything. Without the chase he languished and died. To smite the deer and the[Pg 16] bear was his chief delight and profit. Such a race could live only in a country of woods and wild animals.

14. The northern parts of America were inhabited by the Esquimos. The name means the eaters of raw meat. They lived in snow huts or hovels. Their manner of life was that of fishermen and hunters. They clad themselves in winter with the skins of seals, and in summer with those of reindeer.

15. The greater portion of the United States east of the Mississippi was peopled by the family of the Algonquins. They were divided into many tribes, each having its local name and tradition. Agriculture was but little practiced by them. They roamed about from one hunting-ground and river to another. When the White men came, the Algonquin nations were already declining in numbers and influence. Only a few thousands now remain.

16. Around the shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario lived the Huron-Iroquois. At the time of their greatest power, they embraced no fewer than nine nations. The warriors of this confederacy presented the Indian character in its best aspect. They were brave, patriotic, and eloquent; faithful as friends, but terrible as enemies.

17. South of the Algonquins were the Cherokees and the Mobilian Nations. The former were highly civilized for a primitive people. The principal tribes of the Mobilians were the Yamassees and Creeks of Georgia, the Seminoles of Florida, and the Choctaws and Chickasaws of Mississippi. These displayed the usual disposition and habits of the Red men.

18. West of the Mississippi was the family of the Dakotas. South of these, in a district nearly corresponding with the State of Texas, lived the wild Comanches. Beyond the Rocky Mountains were the Indian nations of the Plains; the great families of the Shoshones, the Selish, the Klamaths, and the Californians. On the Pacific slope, farther southward, dwelt in former times the civilized but feeble race of Aztecs.

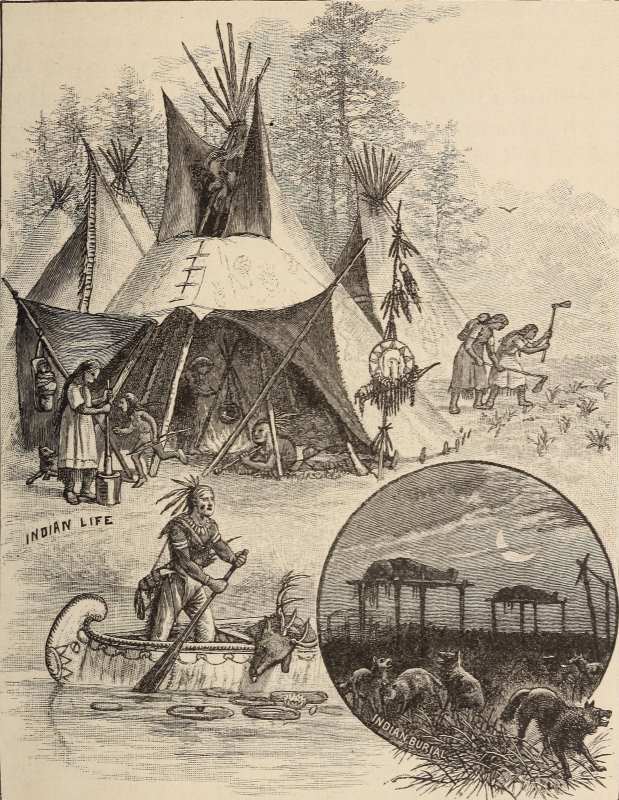

INDIAN LIFE

19. The Red men had a great passion for war. Their wars were undertaken for revenge rather than conquest. To forgive an injury was considered a shame. Revenge was the noblest of the virtues. The open battle of the field was unknown in Indian warfare. Fighting was limited to the ambuscade and the massacre. Quarter was rarely asked, and never granted.

20. In times of peace the Indian character appeared to a better advantage. But the Red man was always unsocial and solitary. He sat by himself in the woods. The forest was better than a wigwam, and a wigwam better than a village. The Indian woman was a degraded creature—a mere drudge and beast of burden.

21. In the matter of the arts the Indian was a barbarian. His house was a hovel, built of poles set up in a circle, and covered with skins and the branches of trees. Household utensils were few and rude. Earthen pots, bags, and pouches for carrying provisions, and stone hammers for pounding corn, were the stock and store. His weapons of offense and defense were the hatchet and the bow and arrow. In times of war the Red man painted his face and body with all manner of glaring colors. The fine arts were wanting. Indian writing consisted of half-intelligible hieroglyphics scratched on the face of rocks or cut in the bark of trees.

22. The Indian languages bear little resemblance to those of other races. The Red man's vocabulary was very limited. The principal objects of nature had special names, but abstract ideas could hardly be expressed. Indian words had a very intense meaning. There was, for instance, no word signifying to hunt or to fish; but one word signified "to-kill-a-deer-with-an-arrow"; another, "to-take-fish-by-striking-the-ice." Among some of the tribes, the meaning of words was so restricted that the warrior would use one term and the squaw another to express the same idea.

23. The Indians were generally serious in manners and behavior. Sometimes, however, they gave themselves up to merry-making and hilarity. The dance was universal—not the social dance of civilized nations, but the solemn dance of religion and of war. Gaming was much practiced among all the tribes. Other amusements were common, such as running, wrestling, shooting at a mark, and racing in canoes.

24. In personal appearance the Indians were strongly marked. In stature they were below the average of Europeans. The Esquimos are rarely five feet high. The Algonquins are taller and lighter in build; straight and agile; lean and swift of foot. The eyes are jet-black and sunken; hair black and straight; skin copper-colored or brown; hands and feet small; body lithe, but not strong; expression sinister, or sometimes dignified and noble.

25. The best hopes of the Indian race seem now to center in the Choctaws, Cherokees, Creeks, and Chickasaws of the Indian Territory. These nations have attained a considerable degree of civilization. Most of the other tribes are declining in numbers and influence. Whether the Indians have been justly deprived of the New World will remain a subject of debate. That they have been deprived of it can not be questioned. The white races have taken possession of the vast domain. To the prairies and forests, the hunting-grounds of his fathers, the Red man says farewell.

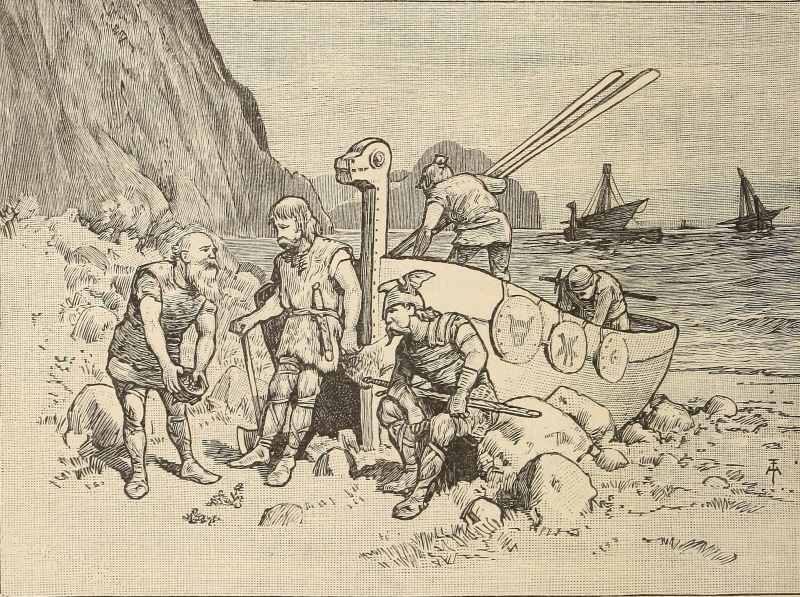

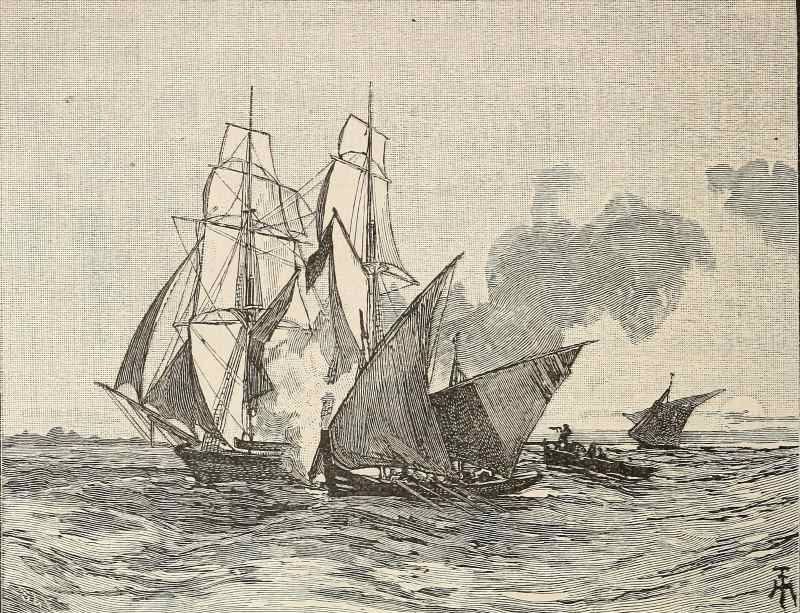

THE western continent was first seen by white men in A. D. 986. A Norse navigator by the name of Herjulfson, sailing from Iceland to Greenland, was caught in a storm and driven westward to Newfoundland or Labrador. Two or three times the shores were seen, but no landing was attempted. The coast was so different from the well-known cliffs of Greenland as to make it certain that another shore, hitherto unknown, was in sight. On reaching Greenland, Herjulfson and his companions told wonderful stories of the new land seen in the west.

2. Fourteen years later, the actual discovery of America was made by Leif, a son of Eric. Resolving to know the truth about the country which Herjulfson had seen, he sailed westward from Greenland, and in the spring of the year 1001 reached Labrador. Landing with his companions, he made explorations for a considerable distance along the coast. The country was milder and more attractive than his own, and he was in no haste to return. Southward he went as far as Massachusetts, where the company remained for more than a year. Rhode Island was also visited; and it is alleged that the adventurers found their way into New York harbor.

3. In the years that followed Leif's discovery, other bands of Norsemen came to the shores of America. Thorwald, Leif's brother, made a voyage to Maine and Massachusetts in 1002, and is said to have died at Fall River in the latter State. Then another brother, Thorstein by name, arrived with a band of followers in 1005; and in the year 1007, Thorfinn Karlsefne, the most distinguished mariner of his day, came with a crew of a hundred and fifty men, and made explorations along the coast of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and perhaps as far south as the capes of Virginia.

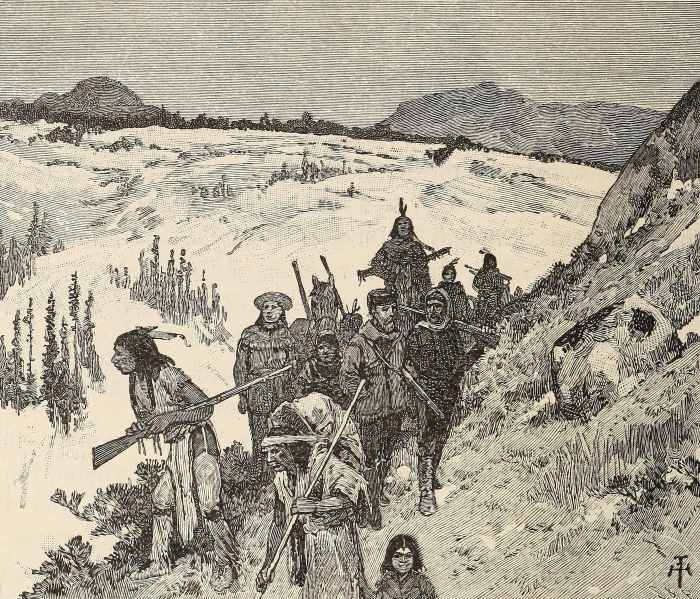

Norsemen in America.

4. Other companies of Icelanders and Norwegians visited the countries farther north, and planted colonies in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Little, however, was known or imagined by these rude sailors of the extent of the country which they had discovered. They[Pg 23] supposed that it was only a portion of Western Greenland, which, bending to the north around an arm of the ocean, had reappeared in the west. Their settlements were feeble and were soon broken up. Commerce was an impossibility in a country where there were only a few wretched savages with no disposition to buy and nothing at all to sell. The spirit of adventure was soon appeased, and the restless Norsemen returned to their own country. To this undefined line of coast, now vaguely known to them, the Norse sailors gave the name of Vinland.

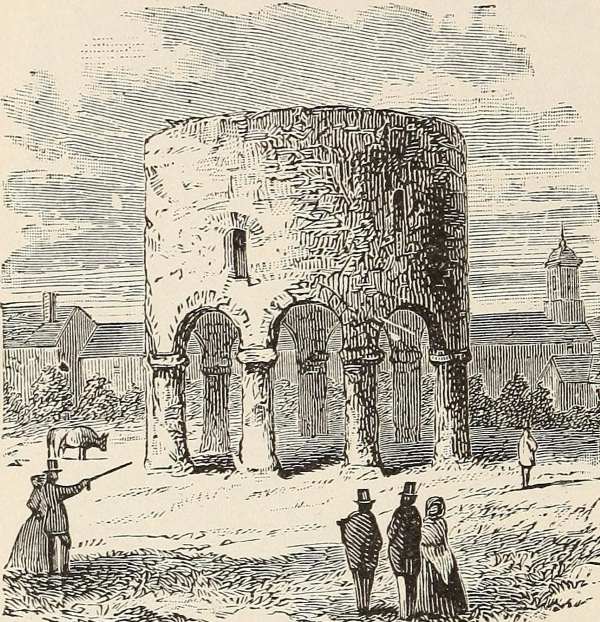

5. During the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries occasional voyages were made; and as late as A. D. 1347, a Norwegian ship visited Labrador and the northeastern parts of the United States. In 1350 Greenland and Vinland were depopulated by a great plague which had spread thither from Norway. From that time forth communication with the New World ceased, and the history of the Northmen in America was at an end. The Norse remains, which have been found at Newport, at Fall River, and several other places, point clearly to the events here narrated; and the Icelandic historians give a consistent account of these early exploits of their countrymen. When the word America is mentioned in the hearing of the schoolboys of Iceland, they will at once answer, with enthusiasm, "Oh, yes; Leif Ericsson discovered that country in the year 1001."

6. An event is to be weighed by its consequences. From the discovery of America by the Norsemen, nothing whatever resulted. The world was neither wiser nor better. Among the Icelanders themselves the place and the very name of Vinland were forgotten. Europe never heard of such a country or such a discovery. Historians have until late years been incredulous on the subject, and the fact is as though it had never been. The curtain which had been lifted for a moment was stretched again from sky to sea, and the New World still lay hidden in the shadows.

The New World, with Routes of Discoveries

IT was reserved for the people of a sunnier clime than Iceland first to make known to the European nations the existence of a Western continent. Spain was the happy country under whose patronage a new world was to be added to the old; but the man who was destined to make the revelation was not himself a Spaniard: he was to come from Italy, the land of valor and the home of greatness. Christopher Columbus was the name of that man whom after ages have rewarded with imperishable fame.

2. The idea that the world is round was not original with Columbus. The English traveler, Sir John Mandeville, had declared in the first English book ever written (A. D. 1356) that the world is a sphere, and that it was practicable for a man to sail around the world and return to the place of starting. But Columbus was the first practical believer in the theory of circumnavigation.

3. The great mistake with Columbus was not concerning the figure of the earth, but in regard to its size. He believed the world to be no more than ten thousand or twelve thousand miles in circumference. He therefore confidently expected that, after sailing about three thousand miles to the westward, he should arrive at the East Indies.

4. Christopher Columbus was born at Genoa, Italy, in A. D. 1435. He was carefully educated, and then devoted himself to the sea. For twenty years he traversed the parts of the Atlantic adjacent to Europe; he visited Iceland; then went to Portugal, and finally to Spain. He spent ten years in trying [Pg 25]to explain to dull monarchs the figure of the earth and the ease with which the rich islands of the East might be reached by sailing westward. He found one appreciative listener, the noble and sympathetic Isabella, Queen of Castile. To the faith, insight, and decision of a woman the final success of Columbus must be attributed.

SHIPS OF COLUMBUS

5. On the morning of the 3d day of August, 1492, Columbus, with three ships, left the harbor of Palos. After seventy-one days of sailing, in the early dawn of October 12, Rodrigo Triana, a sailor on the Pinta, set up a shout of "Land!" A gun was[Pg 26] fired as the signal. The ships lay to. Just at sunrise Columbus stepped ashore, set up the banner of Castile in the presence of the natives, and named the island San Salvador. During the three remaining months of this first voyage, the islands of Concepcion, Cuba, and San Domingo were added to the list of discoveries; and in the last-named island was erected a fort, the first structure built by Europeans in the New World. In January, 1493, Columbus sailed for Spain, where he arrived in March, and was greeted with rejoicings and applause.

6. In the following autumn, Columbus sailed on his second voyage, which resulted in the discovery of the Windward group and the islands of Jamaica and Porto Rico. It was at this time, and in San Domingo, that the first colony was established. Columbus's brother was appointed governor. After an absence of nearly three years, Columbus returned to Spain. The rest of his life was clouded with persecutions and misfortunes.

7. In 1498, during a third voyage, Columbus discovered the island of Trinidad and the mainland of South America. Thence he sailed back to San Domingo, where he found his colony disorganized; and here, while attempting to restore order, he was seized by an agent of the Spanish government, put in chains, and carried to Spain. After much disgraceful treatment, he was sent out on a fourth and last voyage, in search of the Indies; but the expedition accomplished little, and Columbus returned to his ungrateful country. The good Isabella was dead, and the great discoverer, a friendless and neglected old man, sank into the grave.

8. Columbus was even robbed of the name of the new continent. In the year 1499, Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine navigator, reached the eastern coast of South America. Two years later he made a second voyage, and then gave to Europe the first published account of the Western World. In his narrative all reference to Columbus was omitted; and thus the name of Vespucci, rather than that of the true discoverer, was given to the New World.

9. The discovery of America produced great excitement in Europe. Within ten years after the death of Columbus, the principal islands of the West Indies were explored and colonized. In the year 1510 the Spaniards planted on the Isthmus of Darien their first continental colony. Three years later, De Balboa, the governor of the colony, crossed the isthmus, and from an eminence looked down upon the Pacific. Not satisfied with merely seeing the great water, he waded in a short distance, and, drawing his sword, took possession of the ocean in the name of the king of Spain.

10. Meanwhile, Ponce de Leon, who had been a companion of Columbus, fitted out an expedition of discovery. He had grown rich as governor of Porto Rico, and had also grown old. But there was a Fountain of Perpetual Youth somewhere in the Bahamas—so said a tradition in Spain—and in that fountain the old soldier would bathe and be young again. So in the year 1512 he set sail from Porto Rico; and on Easter Sunday came in sight of an unknown shore. There were waving forests, green leaves, and birds of song. In honor of the day, called Pascua Florida, he named the new shore Florida—the Land of Flowers.

11. A landing was made near where St. Augustine was afterwards founded. The country was claimed for the king of Spain, and the search was continued for the Fountain of Youth. The adventurer turned southward, discovered the Tortugas, and then sailed back to Porto Rico, no younger than when he started.

12. The king of Spain gave Ponce the governorship of his Land of Flowers, and sent him thither to establish a colony. He reached his province in the year 1521, and found the Indians hostile. Scarcely had he landed when they fell upon him in battle; many of the Spaniards were killed, and the rest had to fly to the ships for safety. Ponce de Leon himself was wounded, and carried back to Cuba to die.

THE year 1517 was marked by the discovery of Yucatan by Fernandez de Cordova. While exploring the northern coast of the country, he was attacked by the natives, and mortally wounded. During the next year the coast of Mexico was explored for a great distance by Grijalva, assisted by Cordova's pilot. In the year 1519 Fernando Cortez landed with his fleet at Tabasco, and, in two years, conquered the Aztec empire of Mexico.

2. Among the daring enterprises at the beginning of the sixteenth century was that of Ferdinand Magellan. A Portuguese by birth, this bold man determined to discover a southwest passage to Asia. He appealed to the king of Portugal for ships and men; but the monarch gave no encouragement. Magellan then went to Spain, and laid his plans before Charles V., who ordered a fleet of five ships to be fitted out at the public expense.

3. The voyage was begun from Seville in August of 1519. Magellan soon reached the shores of South America, and passed the winter on the coast of Brazil. Renewing his voyage southward, he came to that strait which still bears his name, and passing through, found himself in the open and boundless ocean which he called the Pacific.

4. Magellan held on his course for nearly four months, suffering much for water and provisions. In March of 1520 he came to the islands called the Ladrones. Afterwards he reached the Philippine group, where he was killed in battle with the natives. But a new captain was chosen, and the voyage was[Pg 29] continued to the Moluccas. Only a single ship remained; but in this vessel the crews embarked, and, returning by way of the Cape of Good Hope, arrived in Spain in September, 1522. The first circumnavigation of the globe had been accomplished.

5. The next important voyage to America was in the year 1520. De Ayllon, a judge in St. Domingo, and six other wealthy men, determined to stock their plantations with slaves, by kidnapping natives from the Bahamas. Two vessels reached the coast of South Carolina. The name of Chicora was given to the country, and the River Combahee was called the Jordan. The natives made presents to the strangers and treated them with great cordiality. They flocked on board the ships; and when the decks were crowded De Ayllon weighed anchor and sailed away. A few days afterwards a storm wrecked one of the ships; while most of the poor wretches who were in the other ship died of suffocation.

6. In 1526 Charles V. appointed De Narvaez governor of Florida. His territory extended from Cape Sable three fifths of the way around the Gulf of Mexico. De Narvaez arrived at Tampa Bay with two hundred and sixty soldiers and forty horsemen. The natives treated them with suspicion, and holding up their gold trinkets, pointed to the north. The Spaniards, whose imaginations were fired with the sight of the precious metal, struck into the forests, expecting to find cities and empires, and found instead swamps and savages. They finally came to Appalachee, a squalid village of forty cabins.

7. Oppressed with fatigue and hunger, they wandered on, until they reached the harbor of St. Mark's. Here they constructed some brigantines, and put to sea in hope of reaching Mexico. After shipwrecks and almost endless wanderings, four men only of all the company, under the leadership of the heroic De Vaca, reached the village of San Miguel, on the Pacific coast, and were conducted to the city of Mexico.

8. In the year 1537 Ferdinand de Soto was appointed governor of Cuba and Florida, with the privilege of exploring and conquering the latter country. He selected six hundred of the most gallant and daring young Spaniards, and great preparations were made for the conquest. Arms and stores were provided; shackles were wrought for the slaves; tools for the forge and workshop were supplied; twelve priests were chosen to conduct religious ceremonies; and a herd of swine was driven on board to fatten on the maize and mast of the country.

9. The fleet first touched at Havana, where De Soto left his wife to govern Cuba during his absence. After a voyage of two weeks, the ships cast anchor in Tampa Bay. Some of the Cubans who had joined the expedition were terrified and sailed back to the security of home; but De Soto and his cavaliers began their march into the interior. In October of 1539 they arrived at the country of the Appalachians, where they spent the winter. For four months they remained in this locality, sending out exploring parties in various directions. One of these companies reached Pensacola, and made arrangements that supplies should be sent out from Cuba to that place in the following summer.

10. In the early spring the Spaniards continued their march to the north and east. An Indian guide told them of a populous empire in that direction; a woman was empress, and the land was full of gold. De Soto and the freebooters pressed on through the swamps and woods, and in April, 1540, came upon the Ogeechee River. Here the Indian guide went mad, and lost the whole company in the forest. By the 1st of May they reached South Carolina, near where De Ayllon had lost his ships.

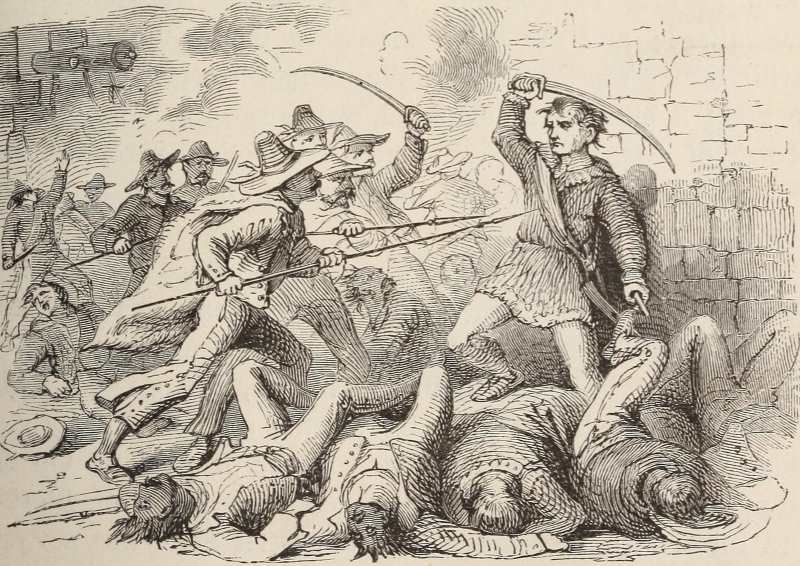

11. From this place the wanderers passed across Northern Georgia from the Chattahoochee to the Coosa; thence down that river to Lower Alabama. Here they came upon the[Pg 31] Indian town of Mauville, or Mobile, where a battle was fought with the natives. The town was set on fire, and two thousand five hundred of the Indians were killed or burned to death. Eighteen of De Soto's men were killed and a hundred and fifty wounded. The Spaniards also lost most of their horses and baggage.

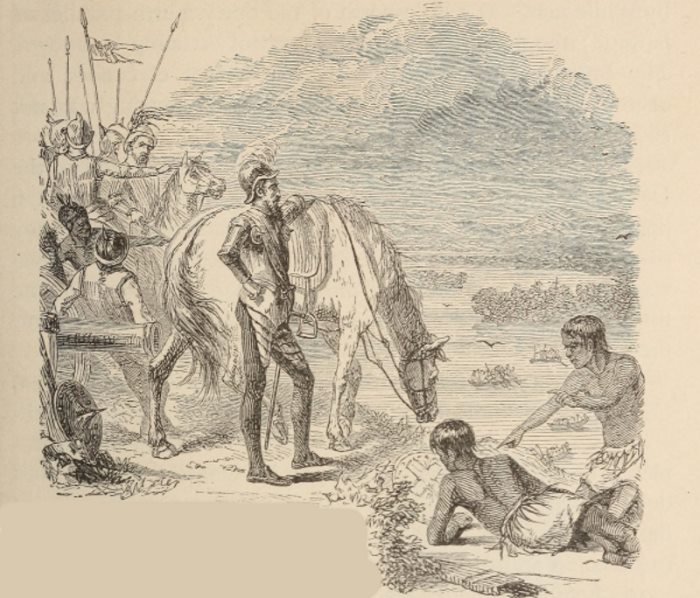

De Soto Reaches the Mississippi.

12. De Soto and his men next turned to the north, and by the middle of December reached the country of the Chickasaws. They crossed the Yazoo, and found an Indian village, which promised them shelter for the winter. Here, in February, 1541, they were attacked by the Indians, who set the town on fire, but Spanish weapons and discipline again saved De Soto and his men.

13. The Spaniards next set out to journey farther westward, and the guides brought them to the Mississippi. The point where the Father of Waters was first seen[Pg 32] by White men was a little north of the thirty-fourth parallel of latitude; the day of the discovery can not certainly be known. The Indians came down the river in a fleet of canoes, and offered to carry the Spaniards over; but a crossing was not effected until the latter part of May.

14. De Soto's men now found themselves in the land of the Dakotas. The natives at one place were going to worship the Spaniards, but De Soto would not permit such idolatry. They continued their march to the St. Francis River; thence westward for about two hundred miles; thence southward to the tributaries of the Washita River. On the banks of this stream they passed the winter of 1541-42.

15. De Soto now turned toward the sea, and came upon the Mississippi in the neighborhood of Natchez. His spirit was completely broken. A fever seized upon his emaciated frame, and death shortly ensued. The priests chanted a requiem, and in the middle of the night his companions put his body into a rustic coffin and sunk it in the Mississippi.

16. Before his death, De Soto had named Moscoso as his successor. Under his leadership, the half-starved adventurers next crossed the country to the upper waters of the Red River, and then ranged the hunting-grounds of the Pawnees and the Comanches. In December of 1542 they came again to the Mississippi, where they built seven boats, and on the 2d of July, 1543, set sail for the sea. The distance was almost five hundred miles, and seventeen days were required to make the descent. On reaching the Gulf of Mexico, they steered to the southwest, and finally reached the settlement at the mouth of the River of Palms.

17. The next attempt to colonize Florida was in the year 1565. The enterprise was intrusted to Pedro Menendez, a Spanish soldier. He was commissioned by Philip II. to plant in some favorable district of Florida a colony of not less than five hundred persons, and was to receive two hundred and[Pg 33] twenty-five square miles of land adjacent to the settlement. Twenty-five hundred persons joined the expedition.

Pedro Menendez.

18. The real object of Menendez was to destroy a colony of French Protestants, called Huguenots, who had made a settlement near the mouth of the St. John's River. This was within the limits of the territory claimed by Spain. The Catholic party of the French court had communicated with the Spanish court as to the whereabouts and intentions of the Huguenots, so that Menendez knew where to find and how to destroy them.

19. It was St. Augustine's day when the Spaniards came in sight of the shore, and the harbor and river which enters it were named in honor of the saint. On the 8th day of September, Philip II. was proclaimed monarch of North America; a solemn mass was said by the priests; and the foundations of the oldest town in the United States were laid. This was seventeen years before the founding of Santa Fé, and forty-two years before the settlement at Jamestown.

20. Menendez soon turned his attention to the Huguenots. He collected his forces at St. Augustine, stole through the woods, and falling on the defenseless colony, utterly destroyed it. Men, women, and children were alike given up to butchery. Two hundred were massacred. A few escaped into the forest, Laudonniere, the Huguenot leader, among the number, and were picked up by two French ships.

21. The crews of the vessels were the next object of vengeance. Menendez discovered them, and deceiving them with treacherous promises, induced them to surrender. As they approached the Spanish fort a signal was given, and seven hundred defenceless victims were slain. Only a few mechanics and Catholic servants were left alive.

22. The Spaniards had now explored the coast from the Isthmus of Darien to Port Royal in South Carolina. They were acquainted with the country west of the Mississippi as far north as New Mexico and Missouri, and east of that river they had traversed the Gulf States as far as the mountain ranges of Tennessee and North Carolina. With the establishment of their first permanent colony on the coast of Florida, the period of Spanish voyage and discovery may be said to end.

23. A brief account of the only important voyages of the Portuguese to America will here be given. In 1495, John II., king of Portugal, was succeeded by his cousin Manuel, who, in order to secure some of the benefits which yet remained to discoverers, fitted out two vessels, and in the summer of 1501 sent Gaspar Cortereal to make a voyage to America.

24. The Portuguese ships reached Maine in July, and explored the coast for nearly seven hundred miles. Little attention was paid by Cortereal to the great forests of pine which stood along the shore, promising ship-yards and cities. He satisfied his rapacity by kidnapping fifty Indians, whom, on his return to Portugal, he sold as slaves. A new voyage was then undertaken, with the purpose of capturing another cargo of natives; but a year went by, and no tidings arrived from the fleet. The brother of the Portuguese captain sailed in hope of finding the missing vessels. He also was lost, but in what manner is not known. The fate of the Cortereals and their slave-ships has remained a mystery of the sea.

FRANCE was not slow to profit by the discoveries of Columbus. As early as 1504 the fishermen of Normandy and Brittany reached the banks of Newfoundland. A map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence was drawn by a Frenchman in the year 1506. Two years later some Indians were taken to France; and in 1518 the attention of Francis I. was turned to the New World. In 1523 John Verrazano, of Florence, was commissioned to conduct an expedition for the discovery of a northwest passage to the East Indies.

2. In January, 1524, Verrazano left the shores of Europe, with a single ship, called the Dolphin. After fifty days he discovered the mainland in the latitude of Wilmington. He sailed southward and northward along the coast and began a traffic with the natives. The Indians were found to be a timid race, unsuspicious and confiding. A half-drowned sailor, washed ashore by the surf, was treated with kindness, and permitted to return to the ship.

3. The voyage was continued toward the north. The coast of New Jersey was explored, and the hills marked as containing minerals. The harbor of New York was entered, and at Newport Verrazano anchored for fifteen days. Here the French sailors repaid the confidence of the natives by kidnapping a child and attempting to steal an Indian girl.

4. From Newport, Verrazano continued his explorations northward. The long line of the New England coast was traced with care. The Indians of the north would buy no toys, but were eager to purchase knives and weapons of iron. In the[Pg 36] latter part of May, Verrazano reached Newfoundland. In July he returned to France and published an account of his great discoveries. The name of New France was given to the country.

5. In 1534, James Cartier, a seaman of St. Malo, made a voyage to America. His two ships, after twenty days of sailing, anchored on the 10th day of May off the coast of Newfoundland. Cartier circumnavigated the island, crossed the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and ascended the estuary until the narrowing banks made him aware that he was in the mouth of a river. Cartier, thinking it impracticable to pass the winter in the New World, set sail for France, and in thirty days reached St. Malo.

6. Another voyage was planned immediately. Three ships were provided; a number of young noblemen joined the expedition, and on the 19th of May the voyage was begun. The passage to Newfoundland was made by the 10th of August. It was the day of St. Lawrence, and the name of that martyr was given to the gulf and to the stream which enters it from the west. The expedition proceeded to the island of Orleans, where the ships were moored. Two Indians, whom Cartier had taken with him to France, gave information that there was an important town higher up the river. Proceeding thither, the French captain found a village at the foot of a high hill in the middle of an island. Cartier named the island and town Mont Real, and the country was declared to belong to the king of France. During this winter twenty-five of Cartier's men were swept off by the scurvy.

7. With the opening of spring, a cross was planted on the shore, and the homeward voyage began. The good king of the Hurons was decoyed on board and carried off to die. On the 6th of July the fleet reached St. Malo; but the accounts which Cartier published greatly discouraged the[Pg 37] French; for neither silver nor gold had been found in New France.

8. Francis of Roberval was next commissioned by the court of France to plant a colony on the St. Lawrence. The man who was chiefly relied on to give character to the proposed colony was James Cartier. His name was accordingly added to the list, and he was honored with the office of chief pilot and captain-general.

9. It was difficult to find material for the colony. The French peasants were not eager to embark, and the work of enlisting volunteers went on slowly, until the government opened the prisons of the kingdom, giving freedom to whoever would join the expedition. There was a rush of robbers and swindlers, and the lists were immediately filled. Only counterfeiters and traitors were denied the privilege of gaining their liberty in the New World.

10. In May of 1541, five ships, under command of Cartier, left France, reached the St. Lawrence, and ascended the river to the site of Quebec, where a fort was erected and named Charlesbourg. Here the colonists passed the winter. Cartier soon sailed away with his part of the squadron, and returned to Europe. Roberval was left in New France with three shiploads of criminals who could be restrained only by whipping and hanging. The winter was long and severe, and spring was welcomed for the opportunity which it gave of returning to France.

11. About the middle of the sixteenth century Admiral Coligny, of France, formed the design of establishing in America a refuge for the Huguenots of his own country. In 1562 John Ribault, of Dieppe, was selected to lead the Huguenots to the land of promise. In February the colony reached the coast of Florida near the site of St. Augustine. The River St. John's was entered and named the River of May. The vessel then sailed to the entrance of Port Royal; here it was deter[Pg 38]mined to make the settlement. The colonists were landed on an island, and a stone was set up to mark the place. A fort was erected and named Carolina. In this fort Ribault left twenty-six men, and then sailed back to France. In the following spring the men in the fort mutinied and killed their leader. Then they built a rude brig and put to sea. They were at last picked up by an English ship and carried to France.

12. Two years later another colony was planned, and Laudonniere chosen leader. The character, however, of this second Protestant company was very bad. A point on the River St. John's was selected for the settlement. A fort was built here, but a part of the colonists contrived to get away with two of the ships. The rest of the settlers were on the eve of departure when Ribault arrived with supplies and restored order. It was at this time that Menendez discovered the Huguenots and murdered them.

13. But Dominic de Gourgues, of Gascony, visited the Spaniards with signal vengeance. This man fitted out three ships, and with only fifty seamen arrived on the coast of Florida. He surprised three Spanish forts on the St. John's, and made prisoners of the inmates. Unable to hold his position, he hanged the leading captives to the trees, and put up this inscription to explain what he had done: "Not as Spaniards, but as murderers."

14. In the year 1598 the Marquis of La Roche was commissioned to found a colony in the New World. The prisons of France were again opened to furnish the emigrants. The vessels reached Sable Island, a dismal place off Nova Scotia, where forty men were left to form a settlement. La Roche returned to France and died, and for seven years the forty criminals languished on Sable Island. Then they were picked up and carried back to France, but were never remanded to prison.

15. In the year 1603 the country, from the latitude of Philadelphia to that of Quebec, was granted to De Monts. The[Pg 39] chief provisions of his patent were a monopoly of the fur-trade, and religious freedom for the Huguenots. With two shiploads of colonists De Monts left France in March of 1604, and reached the Bay of Fundy. Poutrincourt, the captain of one of the ships, asked and obtained a grant of some beautiful lands in Nova Scotia, and with a part of the crew went on shore. De Monts began to build a fort at the mouth of the St. Croix. But in the following spring they abandoned this place and joined Poutrincourt. Here, on the 14th of November, 1605, the foundations of the first permanent French settlement in America were laid. The name of Port Royal was given to the fort, and the country was called Acadia.

Samuel Champlain.

16. In 1603 Samuel Champlain, the most soldierly man of his times, was commissioned by Rouen merchants to establish a trading-post on the St. Lawrence. The traders saw that a traffic in furs was a surer road to riches than the search for gold and diamonds. Champlain crossed the ocean, sailed up the river, and selected the spot on which Quebec now stands as the site for a fort. In the autumn he returned to France.

17. In 1608 Champlain again visited America, and on the 3d of July in that year the foundations of Quebec were laid. The next year he and two other Frenchmen joined a company of Huron and Algonquin Indians who were at war with[Pg 40] the Iroquois of New York. With this band he ascended the Sorel River until he came to the long, narrow lake, which has ever since borne the name of its discoverer.

18. In 1612 Champlain came to New France for the third time, and the success of the colony at Quebec was assured. Franciscan monks came over and began to preach among the Indians. Champlain again went with a war-party against the Iroquois. His company was defeated, he himself wounded and obliged to remain all winter among the Hurons. In 1617 he returned to the colony, and in 1620 began to build the fortress of St. Louis. Champlain became governor of New France, and died in 1635. To him, more than to any other man, the success of the French colonies in North America must be attributed.

ON the 5th of May, 1496, Henry VII., king of England, commissioned John Cabot, of Venice, to make discoveries in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and to take possession of all countries which he might discover. Cabot was a brave, adventurous man, who had been a sailor from his boyhood, and was now a wealthy merchant of Bristol. Five ships were fitted out, and in April, 1497, the fleet left Bristol. On the morning of the 24th of June, the gloomy shore of Labrador was seen. This was the real discovery of the American continent. Fourteen months elapsed before Columbus reached the coast of Guiana, and more than two years before Vespucci saw the main land of South America.

2. Cabot explored the coast of the country for several hundred miles. He supposed that the land was a part of the dominions of the Khan of Tartary; but finding no inhabitants, he went on shore and took possession in the name of the English king. No man forgets his native land; by the side of the flag of his adopted country Cabot set up the banner of the republic of Venice—emblem of another republic which should one day rule from sea to sea.

3. As soon as he had satisfied himself of the extent of the country, Cabot sailed for England. On the voyage he twice saw the coast of Newfoundland. After an absence of three months he reached Bristol, and was greeted with enthusiasm. The town had holiday, and the people were wild about the great discovery. The king gave him money; new ships were fitted out, and a new commission was signed in February,[Pg 42] 1498. But after the date of this patent the name of John Cabot disappears from history.

Sebastian Cabot.

4. Sebastian, son of John Cabot, inherited his father's genius. He had already been to the New World on the first voyage, and now he took up his father's work with all the fervor of youth. The very fleet which had been equipped for John Cabot was intrusted to Sebastian. The object in view was the discovery of a northwest passage to the Indies.

5. The voyage was made in the spring of 1498. Far to the north the icebergs compelled Sebastian to change his course. It was July, and the sun scarcely set at midnight. Seals were seen, and the ships plowed through such shoals of codfish as had never before been heard of. Labrador was again seen. New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Maine were next explored. The whole coast of New England and of the Middle States was now, for the first time since the days of the Norsemen, traced by Europeans. Nor did Cabot desist from this work, which was bestowing the title of discovery on the crown of England, until he reached Cape Hatteras.

6. The future career of Cabot was a strange one. Henry VII. was slow to reward the discoverer. When that monarch died, the king of Spain enticed Cabot away from England and made him pilot-major of the Spanish navy. He lived to be very old, but the place and circumstances of his death are unknown.

7. The year 1498 is the most marked in the whole history of discovery. In the month of May, Vasco da Gama, of Portugal, doubled the Cape of Good Hope and succeeded in reaching Hindostan. During the summer, the younger Cabot traced the eastern coast of North America through more than twenty[Pg 43] degrees of latitude. In August, Columbus himself reached the mouth of the Orinoco. Of the three great discoveries, that of Cabot has proved to be by far the most important.

8. In 1493 Pope Alexander drew an imaginary line three hundred miles west of the Azores, and gave all countries west of that line to Spain. Henry VII. was a Catholic and did not care to have a conflict with his Church by claiming the New World. Henry VIII. adopted the same policy, and it was not until after the Reformation in England that the decision of the pope was disregarded.

9. During the reign of Edward VI. the spirit of adventure was again aroused. In 1548 the old admiral Sebastian Cabot quitted Seville and once more sailed under the English flag. In the reign of Queen Mary the power of England on the sea was not materially extended, but with the accession of Elizabeth a new impulse was given to voyage and adventure.

10. Martin Frobisher began anew the work of discovery. Three small vessels were fitted out to sail in search of a northwest passage to Asia. One ship was lost on the voyage, another returned to England, but the third sailed on as far north as Hudson Strait. A large island lying northward was named Meta Incognita. Frobisher entered the strait which has ever since borne his name, and then sailed for England, carrying with him an Esquimo and a stone said to contain gold.

11. London was greatly excited. In May, 1577, a new fleet departed for Meta Incognita to gather the precious metal. But the vessels did not sail as far as Frobisher had done on a previous voyage. The mariners sought the first opportunity to get out of these dangerous seas and return to England.

12. The English gold-hunters were not yet satisfied. Fifteen new vessels were fitted out, and in 1578 a third voyage was begun. Three of the ships, loaded with emigrants, were to remain in the promised land. The vessels, struggling through the icebergs, finally reached Meta Incognita and took on[Pg 44] cargoes of dirt. With several tons of the supposed ore under the hatches, the ships set sail for home. The El Dorado of the Esquimos had proved a failure.

13. In 1577 Sir Francis Drake, following Magellan, became a terror to the Spanish vessels in the Pacific. He hoped to find a northwest passage, and thence sail eastward around the continent. He proceeded northward as far as Oregon, when his sailors began to shiver with the cold, and the enterprise was given up. Drake passed the winter of 1579-80 in a harbor on the coast of Mexico.

Sir Walter Raleigh.

14. Sir Humphrey Gilbert was perhaps the first to form a rational plan of colonization in America. His idea was to plant an agricultural and commercial state. Assisted by his illustrious half-brother, Walter Raleigh, Gilbert prepared five vessels, and in June of 1583 sailed for the west. In August Gilbert reached Newfoundland, and took possession of the country. Soon the sailors discovered some scales of mica, and went to digging the supposed silver, while others attacked the Spanish fishing-ships in the neighboring harbors.

15. One of Gilbert's vessels became worthless, and was abandoned. With the rest he sailed toward the south. Off the coast of Massachusetts the largest of the ships was wrecked, and a hundred sailors were drowned. Gilbert determined to return to England. The weather was stormy, and the two ships now remaining were unfit for the sea. The captain[Pg 45] remained in the weaker vessel, called the Squirrel. As the ships were struggling through the sea at midnight, the Squirrel was suddenly engulfed; not a man of the crew was saved. The other vessel finally reached Falmouth in safety.

16. The project of colonization was renewed by Raleigh. In the spring of 1584 he obtained a new patent for a tract in America extending from the thirty-third to the fortieth parallel of latitude. This territory was to be peopled and organized into a state. Two ships were fitted out, and the command given to Philip Amidas and Arthur Barlow.

17. In July the vessels reached Carolina. The woods were full of beauty and song. The natives were generous and hospitable. The shores of Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds were explored, and a landing effected on Roanoke Island, where the English were entertained by the Indian queen. But after a stay of two months Amidas and Barlow returned to England, praising the beauties of the new land. Queen Elizabeth gave to her delightful country in the New World the name of Virginia, for she was called the Virgin Queen.

18. In December, 1584, Sir Walter fitted out a second expedition, and appointed Ralph Lane governor of the colony. Sir Richard Grenville commanded the fleet, and a company, partly composed of young nobles, made up the crew. The fleet of seven vessels reached Roanoke on the 26th of June.

Here Lane was left with a hundred and ten of the immigrants to form a settlement. But hostilities soon broke out between the English and the Indians; and when Sir Francis Drake came with a fleet, the colonists prevailed on him to carry them back to England.

19. Soon Sir Richard Grenville came to Roanoke with three well-laden ships, and made a fruitless search for the colonists. Not to lose possession of the country, he left fifteen men on the[Pg 46] island, and set sail for home. Another colony was easily made up, and in July the emigrants arrived in Carolina. A search for the fifteen men who had been left on Roanoke revealed the fact, that the natives had murdered them. Nevertheless, the northern extremity of the island was chosen as the site for a city.

20. Disaster attended the enterprise. The Indians were hostile, and the fear of starvation soon compelled Governor White to return to England for supplies. The 18th of August was the birthday of Virginia Dare, the first-born of English children in the New World. Raleigh returned in 1590 to search for the unfortunate colonists. No soul remained to tell their story. Sir Walter, after spending two hundred thousand dollars, gave up the enterprise, and assigned his rights to an association of London merchants.

21. The next English expedition was that of Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602. Thus far all the voyages to America had been by way of the Canary Islands and the West Indies. Abandoning this path, Gosnold, in a small vessel called the Concord, sailed directly across the Atlantic, and in seven weeks reached Maine. He explored the coast and went on shore at Cape Cod. It was the first landing of Englishmen within the limits of New England. He loaded the Concord with sassafras root, and reached home in safety.

22. Another expedition to America was soon planned, with Martin Pring for commander. In April, 1603, his vessels came safely to Penobscot Bay, and spent some time in exploring the harbors of Maine. He loaded his vessels with sassafras at Martha's Vineyard, and returned to England, after an absence of six months.

23. Two years later, George Waymouth made a voyage to America. He reached the coast of Maine, and explored a harbor. Trade was opened with the Indians, some of whom returned with Waymouth to England. This was the last English expedition before the actual establishment of a colony in America.

ON the 10th of April, 1606, King James I. issued two patents to men of his kingdom, authorizing them to colonize all that portion of North America lying between the thirty-fourth and forty-fifth parallels of latitude. The immense tract extended from the mouth of Cape Fear River to Passamaquoddy Bay, and westward to the Pacific Ocean.

2. The first patent was to an association of nobles, gentlemen and merchants called the London Company; and the second to a similar body bearing the name of the Plymouth Company. To the former corporation was given the region between the thirty-fourth and the thirty-eighth degrees of latitude, and to the latter the tract from the forty-first to the forty-fifth degree. The belt of three degrees between the thirty-eighth and forty-first parallels was to be open to colonies of either company, but no settlement of one party was to be made within less than a hundred miles of the nearest settlement of the other.

3. The leading man in the London Company was Bartholomew Gosnold. His principal associates were Edward Wingfield, a rich merchant, Robert Hunt, a clergyman, and John Smith, an adventurer. The affairs of the company were to be administered by a Superior Council in England, and an Inferior Council in the colony. All legislative authority was vested in the king. A provision in the patent required the colony to hold all property in common for five years. The best law of the charter allowed the emigrants to retain in the New World all the rights of Englishmen.

4. In 1606 the Plymouth Company sent two ships to America, and in the summer of 1607 dispatched a colony of one hundred persons. A settlement was begun at the mouth of the Kennebec. The ships returned to England, leaving a colony of forty-five persons; but in the winter of 1607-8, some of the settlers were starved and some frozen; the storehouse was burned, and the remnant escaped to England.

The First English Settlements.

5. The London Company had better fortune. A fleet of three vessels was fitted out under command of Christopher Newport. In December the ships, having on board a hundred and five colonists, among whom were Wingfield and Smith, left England. Entering Chesapeake Bay, the vessels came to the mouth of a beautiful river, which was named in honor of King James. Proceeding up stream about fifty miles, Newport found on the northern bank a peninsula noted for its beauty; the ships were moored and the emigrants went on shore. Here, on the 13th of May (Old Style), 1607, were laid the foundations of Jamestown, the oldest English settlement in America.

6. Meanwhile Captain John Smith, in 1609, left Jamestown and returned to England. There he formed a partnership with[Pg 49] four wealthy merchants of London to trade in furs and establish a colony within the limits of the Plymouth grant. Two ships were freighted with goods and put under Smith's command. The summer of 1614 was spent on the coast of Maine, where a traffic was carried on with the Indians. But Smith himself explored the country, and drew a map of the whole coast from the Penobscot to Cape Cod. In this map, the country was called New England.

7. In 1615 a small colony of sixteen persons, led by Smith, was sent out in a single ship. When nearing the American coast, they encountered a storm and were obliged to return to England. The leader renewed the enterprise, and raised another company. Part of his crew mutinied in mid-ocean. His own ship was captured by a band of French pirates, and himself imprisoned. But he escaped and made his way to London. The years 1617-18 were spent in making plans of colonization, until finally the Plymouth Company was superseded by a new corporation called the Council of Plymouth. On this body were conferred almost unlimited powers and privileges. All that part of America lying between the fortieth and the forty-eighth parallels of north latitude, and extending from ocean to ocean, was given to forty men.

8. John Smith was now appointed admiral of New England. The king issued a proclamation enforcing the charter, and everything gave promise of the early settlement of America. Meanwhile the time had come when, without the knowledge or consent of James I. or the Council of Plymouth, a permanent settlement should be made on the shores of New England.

9. About the close of the sixteenth century, a number of poor Puritans in the north of England joined together for free religious worship. They believed that every man has a right to know the truth of the Scriptures for himself. Such a doctrine was repugnant to the Church of England. Queen Eliza[Pg 50]beth declared such teaching to be subversive of the monarchy. King James was also intolerant; and violent persecutions broke out against the sect.

10. Many of the Puritans went into exile in Holland. They took the name of Pilgrims, and grew content to have no home or resting-place. But they did not forget their native land. They pined with unrest, and were anxious to do something to convince King James of their patriotism.

11. In 1617 the Puritans began to meditate a removal to the New World. John Carver and Robert Cushman were dispatched to England to ask permission to settle in America. The agents of the Council of Plymouth favored the request, but the king refused. The most that he would do was to make a promise to let the Pilgrims alone in America.

12. The Puritans were not discouraged. The Speedwell, a small vessel, was purchased at Amsterdam, and the Mayflower, a larger ship, was hired for the voyage. The former was to carry the emigrants to Southampton, where they were to be joined by the Mayflower from London. Assembling at the harbor of Delft, as many of the Pilgrims as could be accommodated went on board the Speedwell. The whole congregation accompanied them to the shore, where their pastor gave them a farewell address, and the prayers of those who were left behind followed the vessel out of sight.

13. On the 5th of August, 1620, the vessels left Southampton; but the Speedwell was unable to breast the ocean, and put back to Plymouth. The Pilgrims were encouraged by the citizens, and the more zealous went on board the Mayflower for a final effort. On the 6th of September the first colony of New England, numbering one hundred and two souls, saw the shores of Old England sink behind the sea.

14. For sixty-three days the ship was buffeted by storms. On the 9th of November the vessel was anchored in the bay off Cape Cod; a meeting was held and the colony organized under a solemn compact. In the charter which they made for[Pg 51] themselves the emigrants declared their loyalty to the English king, and agreed to live in peace and harmony. Such was the simple constitution of the oldest New England State. To this instrument all the heads of families, forty-one in number, set their names. An election was held, and John Carver was chosen governor.

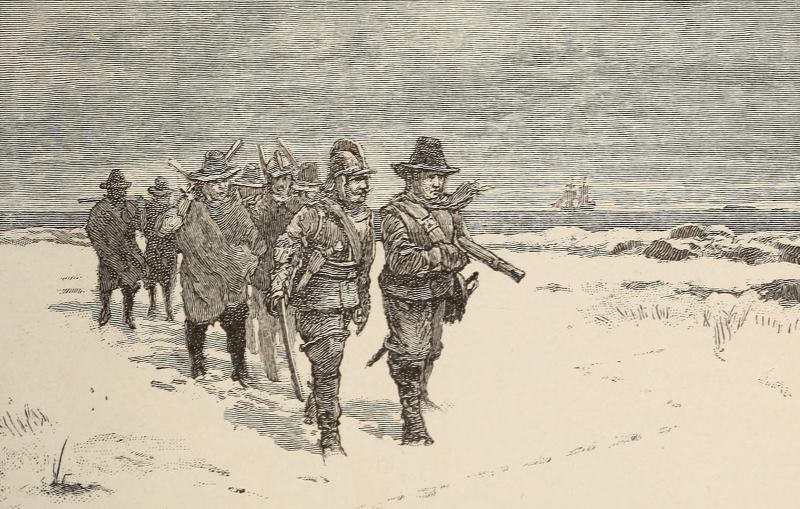

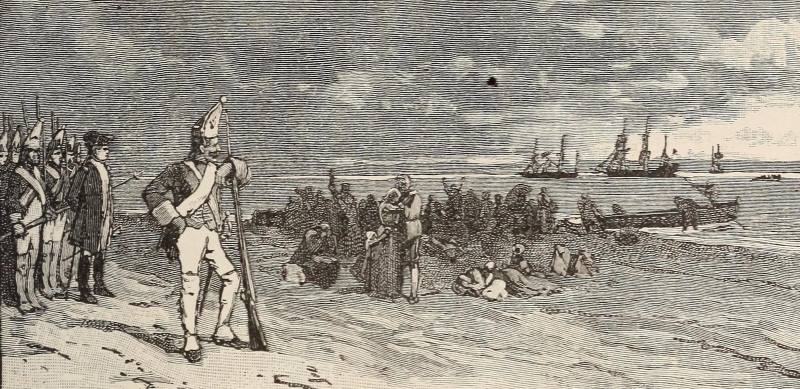

The Landing of the Pilgrims.

15. Miles Standish, John Bradford, and a few others, went on shore and explored the country; nothing was found but a heap of Indian corn under the snow. On the 6th of December the governor landed with fifteen companions. The weather was dreadful. Snow-storms covered the clothes of the Pilgrims with ice. They were attacked by the Indians, but escaped to the ship with their lives. The vessel was at last driven by accident into a haven on the west side of the bay. The next day, being the Sabbath, was spent in religious services, and on Monday, the 11th of December (Old Style), 1620, the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock.

16. It was the dead of winter. The houseless immigrants fell a-dying of hunger and cold. But a site was selected near[Pg 52] the first landing, and, on the 9th of January, the toilers began to build New Plymouth. Every man took on himself the work of making his own house; but the ravages of disease grew daily worse. At one time only seven men were able to work on the sheds which were built for protection. If an early spring had not brought relief, the colony must have perished. Such were the sufferings of the winter when New England began its being.

The Half Moon on Hudson River.

THE first Dutch settlement in America was made on Manhattan Island. The colony resulted from the voyages of Sir Henry Hudson. In the year 1607 this great sailor was employed by a company of London merchants to discover a new route to the Indies. He first made two unsuccessful voyages into the North Atlantic, and his employers gave up the enterprise. In 1609 the Dutch East India Company furnished him with a ship called the Half Moon, and in April he set out for the Indies. Again he ran among the icebergs, and further sailing was impossible. But not discouraged, he immediately set sail for America.

2. In July Hudson reached the coast of Maine; and in August, the Chesapeake. On the 28th of the month he an[Pg 54]chored in Delaware Bay, and on the 3d of September the Half Moon came to Sandy Hook. Two days later a landing was effected. The natives came with gifts of corn, wild fruit, and oysters. On the 10th the vessel passed the Narrows, and entered the noble river which bears the name of Hudson.

3. For eight days the Half Moon sailed up the river. Such beautiful forests and valleys, the Dutch had never seen before. On the 19th of September the vessel was moored at Kinderhook; but an exploring party rowed up stream beyond the site of Albany. The vessel then dropped down the river, and on the 4th of October the sails were spread for Holland. But the Half Moon was detained in England.

4. In the summer of 1610 a ship, called the Discovery, was given to Hudson, who sailed in the track which Frobisher had taken, and on the 2d day of August entered the strait which bears the name of its discoverer. The great captain believed that the route to China was at last discovered; but he soon found himself environed in the frozen gulf of the North. With great courage he bore up until his provisions were almost exhausted. Then the crew broke out in mutiny. They seized Hudson and his only son, with seven other faithful sailors, and cast them off among the icebergs. The fate of the illustrious mariner has never been ascertained.

5. In 1610 the Half Moon was liberated and returned to Amsterdam. In the same year several ships owned by Dutch merchants sailed to the banks of the Hudson and engaged in the fur-trade. In 1614 an act was passed by the States-General of Holland, giving to merchants of Amsterdam the right to trade and establish settlements in the country explored by Hudson. A fleet of five trading-vessels arrived in the summer of the same year at Manhattan Island. Here some rude huts had already been built by former traders, and the settlement was named New Amsterdam.

6. In the fall of 1614 Adrian Block sailed into Long Island Sound, and made explorations as far as Cape Cod. Christianson, another Dutch commander, sailed up the river from Manhattan to Castle Island, and erected a block-house, which was named Fort Nassau. Cornelius May, the captain of a small vessel called the Fortune, sailed from New Amsterdam and explored the Jersey coast as far as the Bay of Delaware. Upon these two voyages Holland set up a claim to the country, which was now named New Netherlands, extending from Cape Henlopen to Cape Cod. Such were the feeble beginnings of the Dutch colonies in New York and Jersey.

THE first settlers at Jamestown were idle and improvident. Only twelve of those who came in 1607 were common laborers. There were four carpenters in the company, six or eight masons and blacksmiths, and a long list of gentlemen. The few married men had left their families in England.

2. The affairs of the colony were badly managed. Captain John Smith, the best man in the colony, was suspected of making a plot to murder the council and to make himself king of Virginia. He was arrested and confined until the end of the voyage. When the colonists reached their destination, the king's instructions were unsealed and the names of the Inferior Council made known. A meeting was held and Edward Wingfield elected first governor.

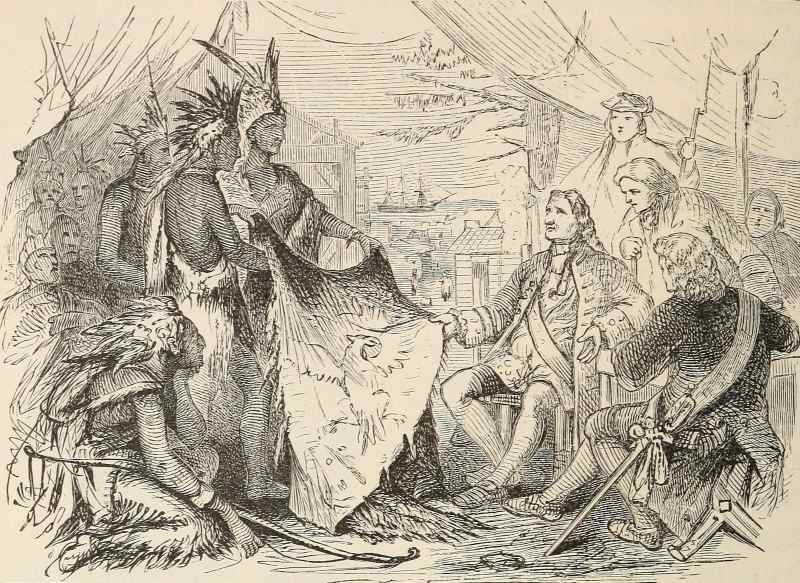

3. As soon as the settlement was well begun, Smith and Newport, with twenty others, explored James River for forty-five miles. Just below the falls, the explorers found the capital of Powhatan, the Indian king. But the "city" was only a squalid village of twelve wigwams. The monarch received the foreigners with courtesy and showed no dislike at the intrusion.

4. The colonists now began to realize their situation. They were alone in the New World. Winter was approaching. Dreadful diseases broke out, and the colony was brought almost to ruin. At one time only five men were able to go on duty as sentinels, and before the middle of September one half of the colonists died. But the frosts came, and disease was checked.