SECOND EDITION

Copyright 1921 by

Armstrong Cork Company

Linoleum Department

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

FOREWORD

Frank Alvah Parsons, President of the New York School of Fine and Applied Art, is a leading American authority on interior decoration. He long since has amply demonstrated his wonderful faculty for turning his knowledge to the common good. We know of no man who, with voice and pen, has fought harder or more unceasingly for better taste, for richer, fuller home life.

Mr. Parsons hardly can seem a stranger to the average reader of this book. Indeed, through his writings and lectures, he has become guide and counsellor and the personal friend of thousands of refined men and women, who have accepted the idea so well developed by Mr. Parsons in the following pages, that “Man is what he lives in;” that, generally speaking, man can be no greater or no less than the daily environment in which he works, thinks, and lives.

We take great satisfaction and pleasure in announcing Mr. Parsons as the author of that section of this book which is entitled “The Art of Home Furnishing and Decoration.” It is written in Mr. Parson’s typically intimate and forceful style, and every paragraph is replete with information and suggestions of great value. We are sure that this book will hold your interest from the first to the last word, and that in the end you will look on the possibilities of your home and your life within it in a fresh and considerably enlarged perspective.

After you have spent an hour with Mr. Parsons on the general theme of home furnishing and decoration, we believe that it will profit you to read what is written by ourselves in the latter part of the book on the specific subject of linoleum and its relation to the principles that Mr. Parsons has laid down.

Armstrong Cork Company

[Pg 5]

The Art of Home Furnishing and Decoration

FRANK ALVAH PARSONS

Man is exactly what he lives in, for environment is the strongest possible factor in man’s development. One may be so long among loud noises, bad odors, inharmonious colors and wrong arrangements of things that one doesn’t mind them, because one has let them become an integral part of one’s self. They are there, and they are as bad as they were at first, but one has become immune to them. This being admitted, it follows, of course, that concordant sounds, agreeable odors, harmonious colors and pleasing arrangements have their immediate effects, but their tendency is toward refinement, culture and artistic appreciation instead of toward brutality, ignorance and indifference. It is certainly not hard to see what effect is produced by living in any wrong environment. As a person accustoms himself to it, he becomes like it. When he is like it, he will admire only its kind, and whatever he does will be as nearly like his environment as he himself is.

The importance of thoroughly comprehending this truth cannot be overstated. The mental and artistic quality of the nation and even its physical comfort depend upon it. This viewpoint, being somewhat new to us, accounts for the upheaval in our ideas of what a home really is. Looking a little into this matter may perhaps stimulate us still further in our thinking, which will affect our way of doing whatever we attempt in the future.

In the first place the home is the center of all life’s activities. We are born there, and long before we have seen the shop, the office, the church or even the school, our first impressions of the fundamentals of life have become fixed. These are exceedingly hard to efface.

[Pg 6]

The school can hardly hope to counteract in the child’s mind the effect of hearing incorrect language spoken at home for six years; the church is greatly handicapped in its influence where wrong principles of life have determined habits during the first years; the artistic sense is practically dead and refinement of taste impossible in that child whose parents have given the usual wall papers, rugs, hangings, pictures and other objects of modern furnishing a chance to do their unrestricted work. Most of these have been made to sell, but not to people who use any judgment in buying. Occasionally we think of the durability or the comfort of an article, but how seldom of the colors, the patterns, the combinations of different periods with different meanings, all of which unite to make an unthinkable, inharmonious jumble which produces a reaction on an impressionable person little short of criminal. This being the case, is it any wonder that too frequently we are satisfied with inferior things or that we are not able to compete with other nations in creating better ones?

This view of the home as an educator places it above any other institution in life and makes it worthy of the most careful and scientific study from several points of view. It might be well to consider here four of the most important of these.

The first requisite of a house is physical comfort. Not only is this true of each article of furniture, but it is true also of the placing of each piece as it relates to the other pieces.

Take, for instance, a divan, a chair, a table, a lamp, some books and a footstool. It is not enough that the chair, the divan and the stool should each be comfortable to the body, but comfort demands that each be so placed that one can use the divan or chair with the stool, while the books on a table with a lamp are placed so that one may lounge or sit and read without effort and without expending energy to assemble what is required. The best possible arrangement, you see, demands more skill than at first appears.

[Pg 7]

Mental comfort is even more important to man in his home than physical comfort. He must, or should, find in his home an intellectual stimulus and a refining influence to complement the activities and struggles of his life outside, to calm and rest the tired nerves and to relieve the material or commercial stress which threatens entirely to destroy his power to see or know anything else. Unconsciously driven by this need he rushes from home to the club, to the theatre or elsewhere for diversion, amusement or rest. This is not as it should be, for in the right environment the home should furnish the rest and intellectual refreshment needed. Let us consider that there must be an expenditure of thought and skill in furnishing a home if it is to play its rightful part in the scheme of life.

Even then, there is another thing to consider. A man may succeed in accomplishing wonders in the realm of physical comfort, yet so completely ignore the question of sanitation as to menace the health of his family, if not to offend their sense of decent cleanliness. The horrors of Victorian plush upholstery, chenille portieres and nailed-down carpets are still fresh in the memory of some of us, and we have not yet been able to get a clear idea of a really clean thing because of the bad impression made on us by these conditions. Probably we never shall, until we succeed in effacing their memory by discarding the traditions they represent and adopting wholly different ideas in their places. Let us think of the question of sanitation as a second necessity in considering any household problem.

It is perhaps unnecessary to look at this matter from the viewpoint of economics, but to me it seems very important. We cannot all afford to buy everything we see, desire or even appreciate. Realizing this, we lose enthusiasm and take almost anything. This is not necessary, nor is it wise. Good things are not all costly, nor are all cheap things equally bad. One might also[Pg 8] add that frequently very costly things incline to be bad; at any rate, there is far greater danger of their being so because of the greater opportunity they afford for the expression of bad taste.

Knowledge furnishes the greatest defense against bad things in any form. The more one knows, the more capable he is of selecting the best for his money and of using his selections in such a way as to suggest that much more was paid for them than they really cost.

Intelligent selection—the art of buying the most appropriate furnishings and decorations for the home—leads logically to intelligent decoration, the art of arranging the furnishings and decorations so as to make possible a thoroughly attractive home and keenly enjoyable living for the family.

The introduction of the word “Art” always opens up a new field fraught with unpleasant possibilities. So many things masquerade under this name that we are almost deceived as to what it really is. Shall we not attack and dispose of some of these fallacies before attempting to see what it actually is?

Because it is an art to decorate we are apt to think that anything attached to or hung on to another thing is decoration, therefore artistic. Nothing could be further from the truth. Principles control decoration, and decoration is only possible when it conforms to these principles. In order to be decorative there must be something that requires decoration; that is, which is incomplete in itself. As soon as material of any kind is added after a thing is complete, the result becomes an aggregation, not a decoration.

Most houses belong to this class because the owner refuses to stop when he is done. He may also have erred through having no place to decorate, his background being of such a kind that, struggle as it might, nothing could compete for attention, therefore could not become decorative by contrast. Simplicity in backgrounds is the foundation of decorative possibility.

[Pg 9]

Oversentimentality is as bad as overdecoration. Sentiment is not only commendable but is an essential element that makes for human decency, but sentimentality, which by most people is thought to be the same thing, is unpleasant and unhealthy. Admiration, affection, veneration—each of these qualities has its place with all of us in its particular situation. This is well; but when, through association, we mistake an impersonal object for the real qualities of a person and begin to bestow adoration on it, then it is time to stop and think.

To be sure, one respects some things in his grandfather and his other forebears. He is not insensible to the excellent points in his friends and associates. But if he is a wise man, he does not apply all his grandfather’s good qualities to all the furniture he uses, nor the excellent points in his friends to all the objects they have felt impelled to give him at one time or another for some sort of reason. If half the rubbish in every house in America that exists for solely sentimental reasons or because of a fear of being detected in its destruction were to be burned now, the next generation would have a much clearer vision of what art is, unhampered by sentimental misconception.

A sentimental and an æsthetic feeling are quite distinct from each other. Who is there among us who does not love nature? The trees, the birds, the flowers—they seem to be a part of the great Divine scheme which calls for especial appreciation. This is also well; but nature is not art, neither is man’s imitation of it. Sometimes his interpretation of it is art, sometimes it is not. Not infrequently his conventionalization of nature and its adaptation to the material in which it is to be used become a decorative art; yet, even if this is accomplished, the thing may be spoiled in the use, and an inartistic whole may result. Just and reasonable homage to nature has impelled people to try in all sorts of ways to imitate it. This is not art. Art is creation, not imitation. One has but to reflect, and amazement must result when one realizes to what this impulse has led in every[Pg 10] field of expression. Flowers have been painted on everything known, from the kitchen floor to the plush sofa pillow. The more like nature these decorations have appeared, the more artistic they were thought to be, when the truth was actually the reverse. The more natural these are, the more inappropriate they are as seen from any viewpoint.

Who is there that would not hesitate to sit down on, or put his foot on, a perfectly natural rose or lily? Where is there a human being that would care to lie down on a pillow with the painted face, even of an Indian, in the center? Who can see nature insulted in various objects by the sticking-in of pins or the driving-in of nails? The whole thing is too simple. Nature has its place, but it is not art, nor is the imitation of it art.

This is so intimately associated with another fallacy that it should suggest it without comment. The appetites of man are ever insistent for attention. The desire for food, drink, shelter—these are physical appetites. They make their assertions naturally, and when normally treated bear their relation to the rest of life. But neither these nor the sensations attendant on them are art, nor should these senses be confounded with the artistic sense.

Apples and pears look well on trees, in suitable receptacles or on tables. They are to eat. Imitations of them painted on plates seem to win admiration at once for their likeness to the real thing. The saliva flows in the mouth, the digestive organs begin their natural functions, and, while our sensations are purely physical, strangely enough many think this artistic. It is the hunger appetite being appeased, not the æsthetic.

The atrocities committed in this field are innumerable. Exact copies of everything, from a bunch of grapes to an ostrich, may be found in one winter’s millinery display, while the real or copied forms of everything, from a dried fish to a gigantic moose head, may be seen in one dining-room at one time. This is not art. It is natural history and botany illustration in museum effect.

[Pg 11]

The hardest thing in the world to combat is a universal belief in the infallibility of pictures. These are necessary to convey ideas and they have a function to perform. They are interesting, they may even be amusing, but they are by no means always artistic. So great has been the belief in and admiration for pictures, that we have, as a nation, pretty nearly surrendered to the idea that drawing and picture-making alone is art. No greater mistake than this has ever been made. There are a thousand more bad pictures than there are good ones and a hundred bad ones used in houses where one good one appears. This is because we seem to have a kind of fear that there may be a vacant place on the wall, and also because the picture idea has become a mania.

“Silence is golden,” but a blank space on a wall is often diamonds and emeralds compared to one filled with the average pictures that are hung, not to mention their frames. What shall we say of this phase of human dissipation, particularly when the frames are gilt ones? A person who allows himself to decorate his house with frames instead of pictures should be expected to hang his wardrobe in the front hall for the same purpose. The results of this mania should not be charged up to the credit side of art. Rather, the man afflicted with it is a slave to tradition.

For the most difficult thing in the world is for a person to change his established way of thinking or of doing anything. It is so much easier to think as one’s grandfather did and to do as one’s father did than it is to think and do for one’s self. For this reason we are somewhat handicapped in getting at the essence of art and its practical applications to ordinary life. If mahogany was the favored wood in the last half of the eighteenth century, of course it is a good idea to use it for anything, anywhere, forever afterward, even though a much better substitute is at hand. If floors were hardwood or soft wood or stone, or even plastered with Oriental rugs bearing no relation to the rest of the house, there seems to be no reason why people should change the rugs or have another kind of floor.

[Pg 12]

Examples of this adherence to tradition are so frequent and so deadly that to cite more would be a waste of time. Traditional belief that antiques are always good or that the work of some particular man is forever praiseworthy or that some particular article should always be used in some established way, has blinded us to the possibilities in the right use of new things in a progressive way. All this hinders a clear perception of what art really is.

If these things which have been misnamed art are carefully removed from consciousness permanently, it is easy enough to see what art is, and then it becomes almost an unconscious process to apply it, whether the application is made to the house, to clothes, or to other personal forms of expression.

In the first place, art is creation. It is the personal expression of the individual in any material or combination that completely conveys his conception of what he is trying to project.

This connection generally expresses a need which he himself feels. It may be for a house, a living-room, a divan, a hat, a footstool, a typewriter or an automobile. In any case, there is a need for something for a particular use. This need should be the reason for the art expression. Spurred on by the need, a man creates something which will fill the need.

This need is both functional or material and mental or artistic. One bar to seeing what art is rests in not recognizing this two-fold element in it. In so far as one is able to make a chair that fits the body, fulfils its special function as a dining-room chair, or a study chair, he has succeeded in creating the first artistic element. An object which does not do honestly and truthfully and sensibly what it purports to do cannot be artistic, no matter how it looks.

The second element that enters into art is appearance or beauty. This element or quality is a little more difficult to define because it is relative, just as heat is, or as goodness is. What seems warm to[Pg 13] one seems cold to another; what seems good to one may be bad to some one else; so, then, the standard of beauty depends entirely upon one’s own conception of it. This does not mean that anything that anybody considers beautiful is so, any more than it means that it is a warm day when the thermometer is at zero because somebody does not feel cold. It simply means that the person who judges may or may not have a right mental standard of what beauty really is. This standard may be acquired approximately by anyone, for it is determined by certain principles. If the principles of harmony are understood and applied, beauty will result.

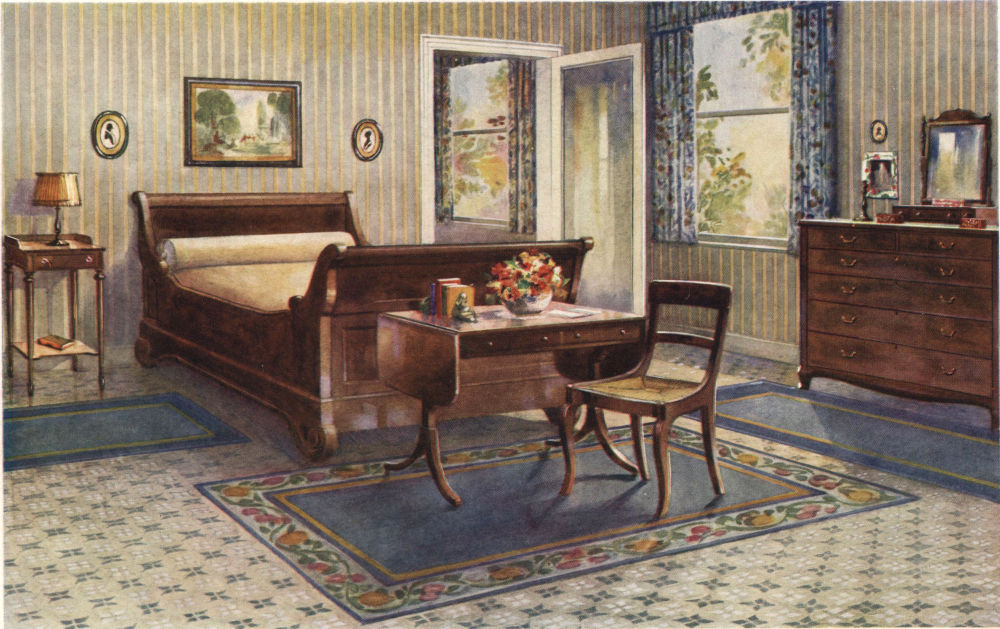

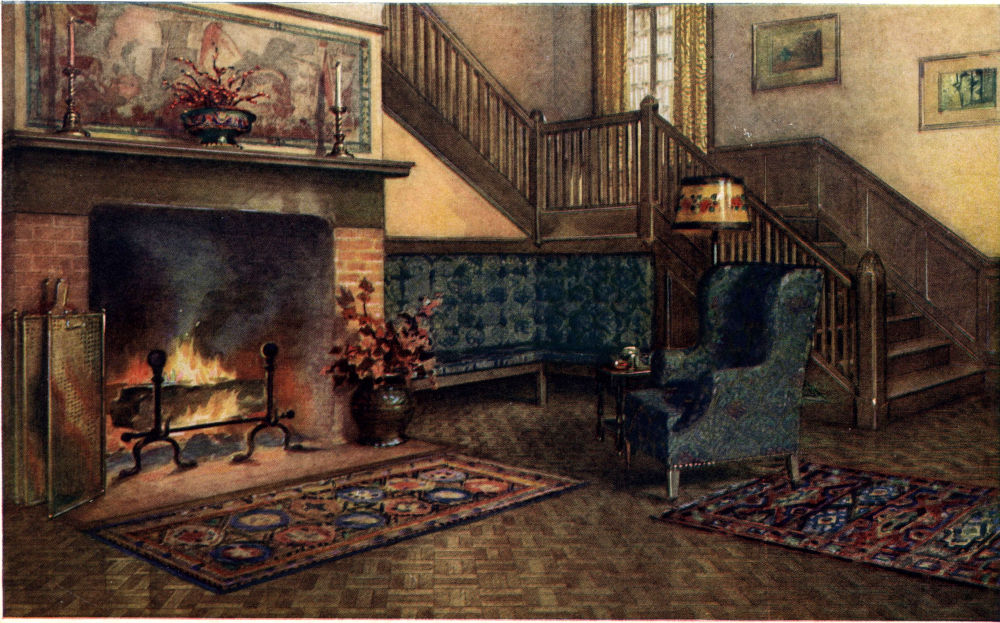

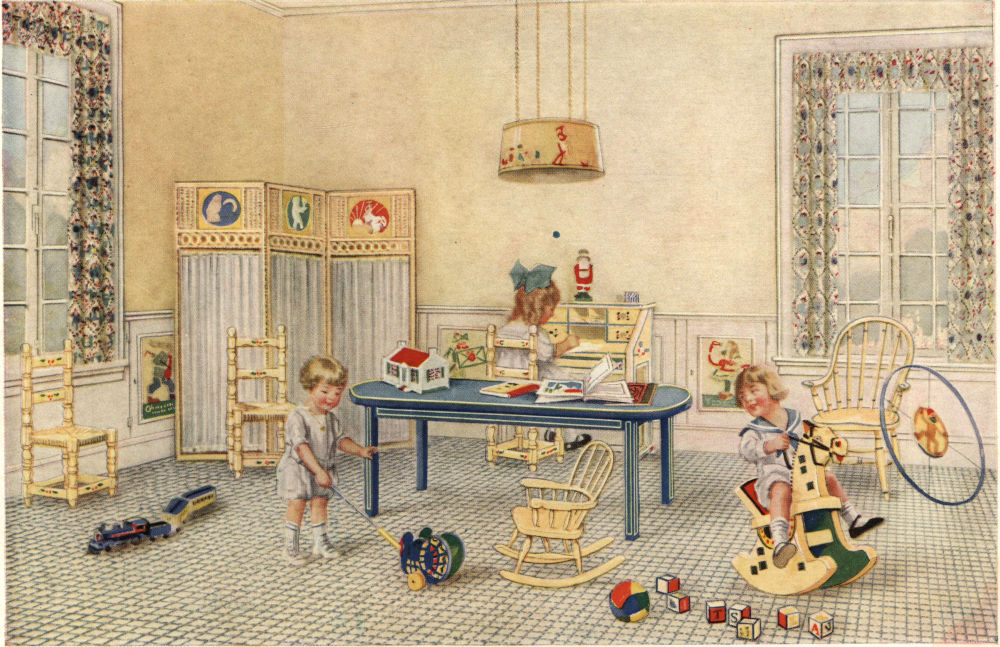

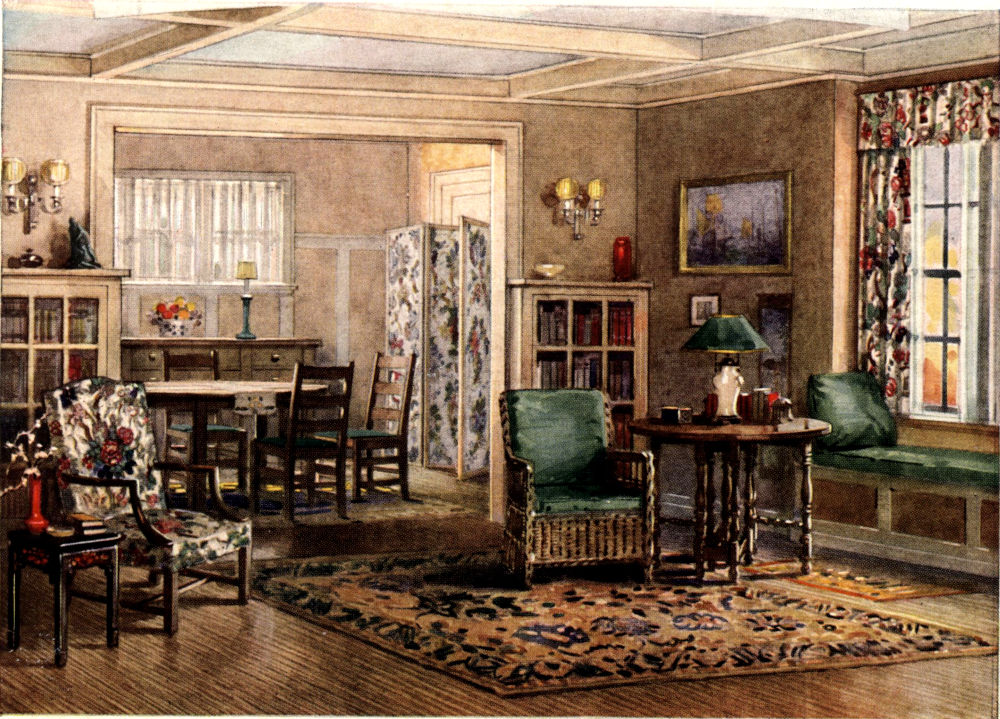

Take, for instance, the problem of a particular room. The first question to ask one’s self is: “What is this room for?” If it is a dining-room, it is a place in which to eat in peace. If it is a living-room, it is to live in and should have a quiet, restful, refined and otherwise pleasant atmosphere. If it is a bedroom, it is to rest and sleep in. From whatever standpoint the room is viewed, the question of use comes first. Anything in the dining-room that interferes with eating in peace is in bad taste. Whatever appears as decoration in the living-room that is unrestful, tawdry, common or unessential, is inartistic. If the bedroom contains anything that is out of tone with its general spirit, if it contains anything that makes for other than an atmosphere of calm contentment and deep, sound sleep, it should be removed at once. Let this point of view spur us on to make an investigation of our houses—room by room—and alter or remove everything that strikes a jarring note.

Let us start with the bedroom. Are there spotted fabrics or papers on the wall, the spots on which one involuntarily counts, even after going to sleep? Are there a half dozen small pictures in black frames against a white background, so hung that successive steps are formed which resemble the front hall stairs? Are there other diverting and disturbing arrangements in the room that seem to invite us to close our eyes to avoid further[Pg 14] annoyance? Much can be done in house decoration by elimination, and the strongest argument for this process will be found in submitting each room to the test as to the performance of its proper function.

These elements, fitness to use and beauty, which when combined make what is called the art of quality, must be made comprehensible by facts and truths which can be expressed in a language form that all may learn to understand. This art language is made up of color, form, line and texture, and depends for its efficiency on a knowledge of the principles which govern it and upon an appreciation for the niceties in its use. Anyone can learn the principles and will grow in appreciation as he makes a right use of what he knows. Of the qualities mentioned, color is the most interesting; at least, it is the easiest to see. At the same time it is the most misused. This is much too small a space in which to demonstrate with any thoroughness the color language idea, but two or three of the most important facts must be emphasized.

Nothing is more personal than color and nothing admits of expressing personality with clearer or more manifest charm. The normal colors—yellow, red, blue, green, orange and violet—may be used in illustration of this statement.

Color has its source in light, and natural light comes from the sun. Yellow looks most like the sun, as it expresses the quality that the sun seems to give out. From the sun we are cheered, made light-hearted and receive new life. Yellow in a room should, under normal conditions, produce the same feelings where it is the basis for the wall color or is used in curtains or in other spots. Red suggests blood and fire. It is associated with activity, aggression and passion. It heats and stimulates. One who fails to react to color is not normal or is immune from overcontact, while one who simply likes or dislikes a color and, therefore, uses it or never does, misses the real chance to express ideas. If one prefers red, there is no proof in the fact that[Pg 15] makes it incumbent on him to live surrounded by it. He may be erratic enough without it, or possibly he doesn’t need a stimulant. Need is the fundamental question rather than liking. It is a question of what one ought to have.

It is interesting to know that the aggressive quality of red makes a room in which it is used smaller in appearance, and there are times when this is not desirable. Its warming quality is not needed in hot climates or during a warm season.

Blue has an opposite effect from red. Its reactions are restraint, coolness, repose and distance. By association one thinks of a clear blue sky and the cool breezes from the blue waters of the ocean. This makes blue a suitable antidote for hot weather and a temperate force, useful in modifying some people’s dispositions. Green, which is a union of yellow and blue, expresses the qualities of both. Nothing could be more restful, soothing and agreeable than the cheering and cooling effects of a seat in the shade upon the green grass under luxuriant green trees, in the middle of a hot day. It is easy to see the practical application of this in decorative art.

Violet or purple has the qualities of red and blue, while orange has the qualities of yellow and red. It is interesting to study the natural reactions shown by people of all ages and conditions to these colors as environments under different mental conditions. Incomplete as these suggestions are, they are probably sufficient to establish the point that personal qualities or individual character traits can be definitely expressed in color terms and that antidotes for an excess of certain qualities are just as possible where a knowledge of color exists.

There is a second color quality that we must not ignore. If I think of one group of colors containing light pink, delicate blue, lavender, canary yellow and white as representing one idea, and dark crimson, heavy, dark green, blue with a rich dark purple and black as another group, I have a basis for comparison. If my problem of expression is the qualities that we generally attribute to youth, or the proper colors for a young girl’s[Pg 16] bedroom, or for the lighter and more delicate things in life, I have no hesitation in choosing the first group. If, on the other hand, the problem is one of clothes for a person of mature age, or a color scheme for a library in an old English house, or some other problem in which the qualities required are dignity, quietness and stability, there should be no question as to the preference for the second group.

This quality of light and darkness in color is called value and must not be forgotten in using color as a language.

There is no doubt that the third quality, called intensity, is the most important of all to a right understanding of interior decoration. This quality determines how brilliant or how forceful a color tone is. Softer and less aggressive tones are called neutral or neutralized colors. The most important question in using color decoratively is that which relates to the distribution and correct placing of neutralized colors in their relation to the more intense ones. The grossest errors in the whole realm of color used in decoration are committed in this field. One or two principles that relate to this matter must always be carefully observed: “Backgrounds should be less intense in color than objects that are to appear against them in any decorative way.” From this it obviously follows that walls, ceilings and floors of houses must be less intense in color than hangings, upholsteries, small rugs, pictures and other decorative material. This is one of the most important points to remember in every color problem.

There is a corollary to this which is equally important: “The larger the color area the less intense it should be, and the smaller the area, the more intense it may be.” According to this principle, hangings and large rugs must be less intense in color than sofa cushions, lamp shades and decorative bits of pottery and other materials. Keeping this relation of areas in mind is an aid in selecting any article for the house, as well as a help in choosing those things that are concerned with one’s personal appearance. A red necktie is more appealing than a red suit,[Pg 17] so is a red flower or ribbon more decorative on a black hat than a gray one would be on a red hat.

The slightest attempt at using color must disclose its power to express personality, its natural value feeling and its decorative dependence upon a proper distribution of intensities.

While the principles of form are a little less apparent in their illustration to most of us than color, yet they are no less important in producing a harmonious whole. One of the first premises of decoration is the assumption that there is a definite form or shape upon which a decoration is to be applied. The direction of the bounding lines of this form determines the direction of the principal lines of the decorative matter which is to be applied on it.

The bounding lines of a floor are generally straight and at right angles to each other. This fixes several important points regarding the disposition of rugs and furniture. Rugs that are placed at all sorts of angles on the floor and by their positions bid one go in any direction save the one he started to take are among the most disconcerting and distracting lines in a room arrangement. Place all rugs in accord with the bounding lines of a room and harmony is at once restored.

One must conform to this principle also in placing furniture. Most pieces should be parallel with the sides of the room, even though they are not against the walls. Curved line chairs or other small objects sometimes lend themselves naturally to a diagonal placement. Care should be taken in grouping furniture to give the appearance of harmony with the room structure. Let us look after the piano that is placed catacorner in the living-room, and the bed, in the same position, in the bedroom.

It is not unusual to see pictures strung over the walls in such a way that the line indicated from the top of one to another is a zigzag that illy suggests harmony with the structure of the wall. Triangular picture wires are ugly and distracting. Unless a picture is small enough to be hung with an invisible attachment[Pg 18] at the back, it should be hung with one long wire passed through two screw eyes, one at each top corner of the frame, with one wire paralleling each side of the frame and going over a hook above. This not only harmonizes the wire with the frame, but with the doors, windows and the room structure.

The choice and arrangement of essential materials in the room, so far as the aspect of beauty is concerned, will be treated in detail later on.

The principle of consistently related shapes and sizes finds scores of applications in the arrangement of a room. Who has not wondered what to do with a round clock, when everything else adjacent to it was either square or rectangular in form? Where is there a house in which there is not a round or oval picture to be placed, or a chair of wholly curved lines, where all others are straight? The attempt to place one isolated round object on a wall is generally a failure, because there is nothing to relate it to any other nearby lines. Oval and curved objects must be repeated by others similar in form in other positions in the room if they are to become in any sense a part of the design.

The second part of this principle—consistent sizes—is even more important and far-reaching than the first. To the architect, the decorator or the creator of any art object, this is a vital matter. Every interior, as well as exterior, architectural feature is thought of in relation to every other one in the matter of size.

It is not uncommon to enter a room and find a chimney large enough for an Elizabethan banquet hall, while the room itself, in size, suggests a city flat. Nor is it less common to find a table or divan of gigantic proportions being required to live in harmony with chairs or other articles of various pigmy types. These unusual and unhappy relationships cannot conform to the principle of consistent sizes.

In our use of hangings, upholstery, rugs, etc., the lack of feeling for consistent sizes is still more often apparent. Before[Pg 19] discussing this, let us look for a moment at patterns and motifs as they are used in textiles, wall papers and rugs.

For some unknown reason we have come to believe that there is no beauty in anything in which there is not a pattern plainly visible, forgetting that three-fourths of all wall and floor spaces are backgrounds on which to show other more important things, including people, who have some right to be exploited even against wall paper. There are some phases of the motif running through a design, that may be considered here in some detail.

There are three distinct varieties of motif. First, the motif which aims to reproduce identically a natural object. Such things are rarely successful. The second is known as the abstract type, where the motif is of a form and color not derived from a natural source, being a matter of space and line arrangement, often resulting in geometric forms. The third, known as the conventional motif, takes a natural thing and attempts to translate it into form and color suited by its appearance and feeling to some particular material in which the design is developed. In the conventional design, beauty is attained by harmonizing the motif with the material on which the design is made, while the naturalistic motif strives to represent some natural thing and takes a chance on its being appropriate in the material in which it is to be rendered. Harmony in motifs means, first, a relation in this particular, from which it follows that a rug or floor which is entirely geometric in pattern cannot be used successfully with hangings which show a purely naturalistic design.

Another opportunity for harmony is found in consistently related motifs as to size and shape. It frequently happens that the floor motif, for example, is small and delicate in size and refined in line treatment. If a person is naturally sensitive to color rather than form and he finds a rug or hangings pleasing in color, he is often satisfied. For harmony in relationship, however, he must ask if the motif in the rug and that in the hangings are consistent in size and shape with the floor and wall motifs.

[Pg 20]

A third principle of form is known as balance. This is the principle of arrangement whereby attractions are equalized and through this equalization a restful feeling is obtained; that is, a feeling of equilibrium or safety. It is somewhat disconcerting to enter a small room and find a black piano across one corner and a delicate Hepplewhite chair in the opposite corner. One instinctively rushes to the aid of the chair. Attraction may be of color, size, shape or texture, and one learns only by constant practice to see and feel the attraction forces in different objects used.

There are two types of balance to consider. The first one, known as bi-symmetric balance, is the equalization of attractions on either side of a vertical center by using objects the same size, shape, color and texture. This is formal, dignified and safe, but lacks in some ways the delicacy and subtlety resulting from an attempt to get a less formal placing. Consider a vertical line drawn through the center of a chimney-piece placed in the middle of a wall space. On either side of the chimney-piece and equally distant from it may be placed two pictures similar in size, form and color, and the result is bi-symmetrical. If two similar candlesticks are placed one at either end of the chimney-piece and equidistant from the end, with a portrait in the center, there is still bi-symmetric arrangement. So long as this arrangement is maintained, bi-symmetry results.

A second kind of balance is known as occult balance. This term is used to signify that the balance is rather felt or sensed than exactly determined. If the same vertical line is drawn through the same chimney-piece, one picture is placed a certain distance from the left and two smaller pictures of unequal size are used on the right to balance this. The two pictures must be so placed that their attraction equals that of the larger one at the left. Similarly, if one large porcelain jar and two or three other articles are to be used, there must be a feeling of equal attraction on either side of the vertical line.

[Pg 21]

To explain briefly the primary laws of balance we may give the rules: “Equal attractions balance each other at equal distances from the center.” And, conversely: “Unequal attractions balance each other at unequal distances from the center.”

A third and a little more complicated law is stated as follows: “Unequal attractions balance each other at distances from the center which are in inverse ratio to their powers of attraction.” Translated, this means that objects with the strongest attractions tend to gravitate toward the central line, while less attractive ones tend to draw from this line.

The application of the rules of balance not only to objects on the wall, but to the furniture when seen against the wall or against the floor, is essential to room composition. It is also essential that the floor, in its general appearance, should bear a balanced relation to the walls and to the hangings.

There is no better place, perhaps, than at this point to make clear the relations of these three bounding surfaces. The ceiling should be unobtrusive, but keyed in color to the rest of the room. A perfectly white ceiling, except in a white room, or an over-ornamented ceiling anywhere is an annoyance to him who would see his friends or furnishings. A too-aggressive wall paper or other wall covering makes a bid for attention quite out of proportion to its rights as a background, while aggressive and over-assertive floors or rugs are in bad taste, particularly when they assume the prerogatives of the hostess in their attempt at attraction.

The ceiling should be about as much lighter and less attractive than the walls, as the walls are lighter and less attractive than the floor. This is a balanced arrangement of ceilings, walls and floors. Operating exactly opposite to the principle of balance is one known as movement. This is calculated to cause unrest, excitement and similar sensations, by creating an interest which causes the eye to move from one thing to another. It is very desirable in many cases that movement, particularly of[Pg 22] a violent type, should not occur. Allusion to stair arrangements in picture hangings has already been made. This is not conducive to sleep. Erratic crawling vine patterns, creeping up the curtains or the wall paper, are a little suggestive in the early morning hours if one chances to awake. Violent contrasting lines, created by bad furniture placing or by spotted wall papers or floor covering, also become tiresome and disturbing, except to those who by long contact with such things have become immune to their influence. Even such may suffer a subconscious disturbance, though they do not realize it.

There is a certain monotony attendant on the continual presentation of one sound, one color or one form, for mental consideration. On the other hand, there is a complete disorganization of the powers of the human mind if a host of colors, forms or sounds are presented at one time. If one is poverty, the other is certainly gluttony, and neither should be accepted. It is through a judicious selection and arrangement that sufficient variety is obtained to give pleasure, while restraint results in making life humanly possible. It is very rarely that we err on the side of simplicity, but it is not at all unlikely that we may become flagrantly sumptuous, with an uncomfortable, tawdry result.

The principle known as emphasis is one which we must regard as important. In a bedroom one ought to see a bed; it is vastly more important than the picture exhibition hung about it. In a dining-room a well-set table is the emphatic note, not the chenille curtains nor the products of the chase hung upon the wall. In the living-room the easy-chair, the divan, the bookcase, the beautiful portrait, lamp or picture—all these things should be emphasized by color, form or line, that their importance as related to other things in the room may be apparent at sight.

Knowing this to be true, is it not strange that we still find people who are willing to emphasize the wall paper or the floor or the unpleasant ceiling decorations, to the absolute exclusion[Pg 23] of anything else that may have to be used in the room? The relation of background to decorative objects cannot be insisted upon too much.

The final principle of form is known as unity. In this limited discussion only a word can be said of it. A room is a unit, so should a house be. It is impossible to look with equanimity from an Old English dining-room into a Louis XVI sitting-room. These styles are very far apart in their meaning and can only be harmonized by those who know how, when, where and how much of each element to use.

It is just as impossible to make a unit out of a mixture of Fifteenth, Seventeenth and Nineteenth Century furniture, unless one knows how. Every article used in furnishing a house not only has its conventional value, but its design also. If one knows thoroughly the exact meaning and power of a Louis XVI chair, an Elizabethan table, an Italian console or a William and Mary bookcase, there is no doubt that these may be used successfully in one room.

There are so many considerations in such a problem that it is insufficient to choose single objects for their value alone. Each thing must be chosen with a clear understanding of what room it is to go in and with what other things it is in the future to be associated. A failure to do this will certainly result in pandemonium.

What shall we do with the things we have? Use them if we have to, destroy them if we are willing to—at least eliminate everything that is nonessential. The pernicious practice of giving everything one learns to dislike or that has become worn out, to the poor, does more to prevent them from enjoying a personal growth than any other one thing.

Perhaps no better way to think of the principle of unity can be suggested than to quote the definition of an eminent Nineteenth Century historian: “A unit is that to which nothing can be added and from which nothing can be taken without interfering materially with the idea itself.”

[Pg 24]

The question of texture as a form of expression must not be omitted. Texture is that quality of an object which seems to convey the idea of how it feels. It is a combination of a degree of solidity, strength, roughness, coarseness, etc. One finds this quality in the grained effects of wood, in the weaves of different textiles, in the appearance of braided straws, and even in feathers and other materials.

It is this sense of fitness in textural feeling that forbids the use of hard, harsh-grained oaks with the finer textures of mahogany and satin-wood. Disregarding this quality, people often combined the coarser, heavier and more-resisting woolens or linens with soft, impressionable and destructible silks or fine cottons. Harmony in the texture quality cannot fail to contribute to harmony in the finished unit.

Such is the language of art expression in color, form, line and texture. The principles which govern the right selection and combination of all materials that go to make a house are the real guides to growth in artistic appreciation.

Good taste, which is the final criterion in all art, is cultivated or improved in most people by a constant study and application of the principles which control artistic expression.

Should we not, all of us, do well often to take time to remind ourselves of certain great established principles and to endeavor constantly to see more clearly and completely the principles that govern the expression of these truths? Thereby we may unconsciously form habits of thinking and of doing things that will not only make for broader and better personal growth, but will contribute to a higher type of national civilization. We have not to worry if all the powers of science are not directed to the development of so-called efficient service, in lines that are wholly material and commercial.

We are extraordinarily committed to this propaganda, as a people, and we might ask ourselves whether we may not be[Pg 25] developing this idea at the expense of mental and spiritual ideals that, after all, are the real things that not only determine what we actually are, but are the only things that are truly permanent. Life is certainly something beside machinery, raw materials and money, even granting these to be essentials.

Perceiving the desirability of the art quality results generally in an effort to possess it, and that entails immediate action in two distinct ways. First, go out to find the simple, fundamental principles that control the language of color, form, line and texture; second, apply these principles at once in the home, in the shop, in clothes, in printed paper or in any concrete thing where interest and possibility are found. Through every application growth is assured.

Let us again remember that man is exactly what he lives in, for environment is the strongest possible factor in man’s development. Let us not forget that what man really is, is what his mind is, and this he must express in all he does.

This places the importance of the home where it deserves to be and makes its furnishing one of the most serious and at the same time one of the most delightful things in life, never for an instant minimizing what has always been desirable, but vastly enlarging and ennobling the idea for which it stood.

In recognizing anew the part art is to play in this matter, let us not forget that it in no way interferes with the three essential qualities that are inevitably factors in every home problem simple or elaborate, as the case may be.

Perfect physical comfort is necessary, if only from the standpoint of more efficient service on our part and the relief it brings us, not to be constantly thinking how hard the bed is, how uncomfortable the chair seems, or how rough and uneven the floor feels. Art in no way interferes with physical comfort; in fact, it demands it, as an element of the eternal fitness of things.

The nation is awake to the power of cleanliness as a factor in making an efficient physical, and thereby, indirectly, a finer[Pg 26] mental being, as a contribution to modern civilization. Every article selected for the home should have this requirement considered. Including this in the art idea will remove the misapprehension under which some people labor, that art implies disorder at home, a dowdy or unkempt person and a disregard of nature’s most obvious laws. The first law of Heaven is order; it is no less so of art.

Expense is the constant excuse of those who want better things but cannot afford them. There are as many bad expensive things as there are cheap ones. No home is too poor to have much better things, much better arranged, than it has, and no home is so rich that much of the furnishing might not well be publicly burned and the rest rearranged.

From any standpoint, comfort, sanitation, economics or art, the home is to become the greatest moulding influence in human life. Shall we remain apathetic and indifferent to this most vital problem, satisfied to increase our bank account only, or shall we awaken now and contribute our mite to a fuller national life and a higher and happier existence? This certainly will not decrease our power to increase the bank account, but will enable us to do it with far less physical effort.

Traditions have generally obtained in each generation and fashion as to what materials should be used in various parts of the house and how to use them. The original ideas which went to establish these traditions or manners differed in their origins, but were always the logical outcomes of times in which they were developed. For instance, the walls of the house in the Italian Renaissance were of stone. Steel was not thought of and wood unsuited, while in American Colonial days wood was the most plentiful material and the quickest and easiest to handle in building in the manner in which the people lived.

At various times climate, geography, religious and social customs and the developments of science or art have changed[Pg 27] conditions, and with this, methods and materials have undergone similar changes.

Floors, for example, have mostly been of clay, stone, tile or wood, dictated by one or more of the modifying influences of which we have spoken. Wood cannot take the place of stone, neither should it try to pretend to do so, but there is no denying that one is better than the other under certain conditions and that neither is the only good floor under all conditions.

Linoleum as a floor is not a substitute for stone, wood, tile or clay. It is another material, recent in conception and suited to particular conditions, because of properties that neither stone, clay nor wood have in exactly the same proportions.

Like other floors in modern houses, linoleum ought to combine the qualities of sanitation, comfort, durability to fulfil completely its functions. When made to conform to these ends—as it does if properly designed, and then selected and arranged so as to harmonize perfectly with its surroundings—it is not only suitable but desirable. Linoleum is sanitary, because the most obvious thing about it is the ease with which it can be cleaned and kept clean.

Linoleum is comfortable, because it is soft, quiet and resilient underfoot. It is economical, because it is durable.

In parts of Europe, the artistic possibilities of linoleum have been developed to such a degree that many fine homes are furnished throughout with floors of that material. There is no reason why, in this country, the development of the art side of linoleum should not follow the general development of interior decoration. For patterns and colors, suitable for any scheme of house furnishing and decoration, seemingly, can be produced.

[Pg 28]

How To Select Linoleum Floors

KATHLEEN CLINCH CALKINS[1]

While the principles and suggestions on home furnishing and decoration set forth by Mr. Parsons on the preceding pages are fresh in our minds, let us see how they may be applied specifically to the selection of floors in the modern home. According to Mr. Parsons, if properly designed and selected to harmonize with its surroundings, modern linoleum is not only suitable but desirable as a floor for every room in the house. Let us first define the various types of linoleum, and then, going from one room to another, learn how to use linoleum floors effectively and artistically, keeping in mind the fundamental principles that Mr. Parsons has explained to us.

Linoleum was invented in England in 1863. The name comes from two Latin words, linum (flax) and oleum (oil). Thus linoleum takes its name from its principal ingredient, linseed oil. Before it can be used in making linoleum, however, the linseed oil must be oxidized by exposing it to the air until it hardens into a tough, rubber-like substance. The oxidized oil is then mixed with powdered cork, wood flour, various gums, and color pigments; and the resulting plastic mass is pressed on burlap by means of great rollers that exert a pressure of hundreds of pounds to the square inch. The “green linoleum” then passes into huge drying ovens, where it is hung up in festoons to cure and season. This curing process takes from one to six weeks, depending on the thickness of the material.

There are several varieties of linoleum, designated as follows:

(a) Plain linoleum—of solid color, without pattern—the heavier grades of which are used for covering the decks of battleships and hence are known as “battleship linoleum.”

(b) Jaspe linoleum, which is like inlaid linoleum in that the[Pg 29] colors run clear through the fabric. It is made in plain colorings, with a pleasing graining in two tones of the same color.

(c) Inlaid linoleum, in which the colors of the pattern go through to the burlap back.

(d) Granite linoleum, which is also a variety of inlaid. It has a mottled appearance, resembling terrazzo.

(e) Printed linoleum, which is simply plain linoleum with a design printed on the surface with oil paint.

Turn for a moment to the colorplates at the back of this book, and note the illustrations of various types of linoleum floors. Your local merchant has actual samples of linoleum, and will be glad to show you the different grades.

As Mr. Parsons has suggested, the use of linoleum floors all over the house is not new; it is one of the excellent ideas in home building that has come to us from Europe. There the designing of linoleum, for many years, has been given particular attention; and linoleum floors have found ready acceptance in bedrooms, living-rooms, dining-rooms, etc., not alone in homes of persons of moderate means, but just as frequently in those of the rich and well-to-do. European architects are accustomed to specify linoleum floors in new buildings instead of other materials less desirable.

The European housewife takes particular pride in keeping her linoleum floors in spick-and-span condition by waxing and polishing them. And, as the years pass, linoleum floors soften in color and deepen in tone, taking on a finish not unlike that of wood which has been mellowed by age.

In America, the makers of Armstrong’s Linoleum were the first to give attention to the designing of linoleum patterns that would lend themselves to acceptable use in the modern American home. Skilled designers were brought from the best European establishments and given carte blanche in the development of designs particularly appropriate to American ideas of home decoration[Pg 30] and conditions of living. As a result, we can state with confidence that for beauty, attractiveness, and general utility the Armstrong floor designs now available are not excelled either in Europe or America.

Miss Rene Stillman, a writer on interior decoration, in discussing recently in the Philadelphia Public Ledger the change from unsanitary carpets to the use of fabric rugs speaks also of the change in linoleums and their relation to modern interior decoration. She says, ... “and then the new linoleums, not the old kitchen kind, but modern floors which have become works of art, some of which are not unlike the floors in old palaces. Not long ago I went to an exhibit given by a number of prominent interior decorators. There I went through one of the most charmingly decorated houses you ever saw, and every floor had linoleum upon it. It was a house of Spanish architecture, and there was a central court, with fountains and foliage—an unpretentious, but very beautiful, little court. And, would you believe it? it was paved—I use the word advisedly—with linoleum of the large black-and-white blocks, for all the world like large black-and-white marble tiles. The other rooms were also covered with linoleum, which toned with the woodwork or the walls or the general scheme of the furnishings. But these rooms were also covered with fabric rugs, some of them large central rugs, allowing the linoleum floor to show about the edges. In other rooms, the rugs were smaller and scattered over a larger surface of the linoleum. Of course, it was very good linoleum, mostly cork I think, and the pattern went all the way through. I was charmed with the subtle colors, the often exquisite designs.”

As a matter of fact, in the last few years many leading architects and interior decorators have used linoleum floors in homes they have planned, particularly because of the decorative effects it is possible to achieve with linoleum floors, as contrasted with other materials. Where the problem is to redecorate a house, linoleum is being more and more widely used to resurface[Pg 31] worn wood floors. And, in many new homes, owners and architects have specified linoleum floors instead of wood; they have used linoleum not alone because of the economy in dollars and cents but because linoleum floors are so very much easier to take care of. Especially where the housewife has to do her own work, or good help is difficult to obtain, linoleum aids materially in solving this almost universal household problem.

The portfolio of colorplates and black-and-white reproductions included with this book will give you an excellent idea of just how linoleum floors look in modern homes. If you are planning to build a new house, you owe it to yourself to investigate the possibilities that linoleum floors offer you in making the home unusually interesting and attractive.

The hall is the first place in your home that visitors see. It must be kept speckless and spotless. A linoleum hall floor proclaims the neatness of the housewife to all visitors the moment they cross the threshold because it is so easy to keep such a floor fresh and inviting.

And no matter what the decorative treatment of your hall, there are patterns in Armstrong’s Linoleum that will harmonize perfectly with rugs, walls, and furniture. For a formal vestibule, there are exclusive designs that will appeal to all tastes. For instance, Pattern 350, which is a six-inch block design of alternate black and white squares, suggests marble tile. Or there is an interesting Persian tile, Pattern No. 232, in cream, red, and black. The newer designs in marble and tile inlaids permit many interesting combinations. In an entrance hall proper, you may prefer wood effects. There are several linoleum parquetries which, waxed and polished, make splendid floors for halls and reception rooms, as well as living- and dining-rooms.

The durability of good linoleum should always be kept in mind. The number of footsteps it would take to wear it out cannot be estimated, and dripping umbrellas and wet rubbers do not damage it.

[Pg 32]

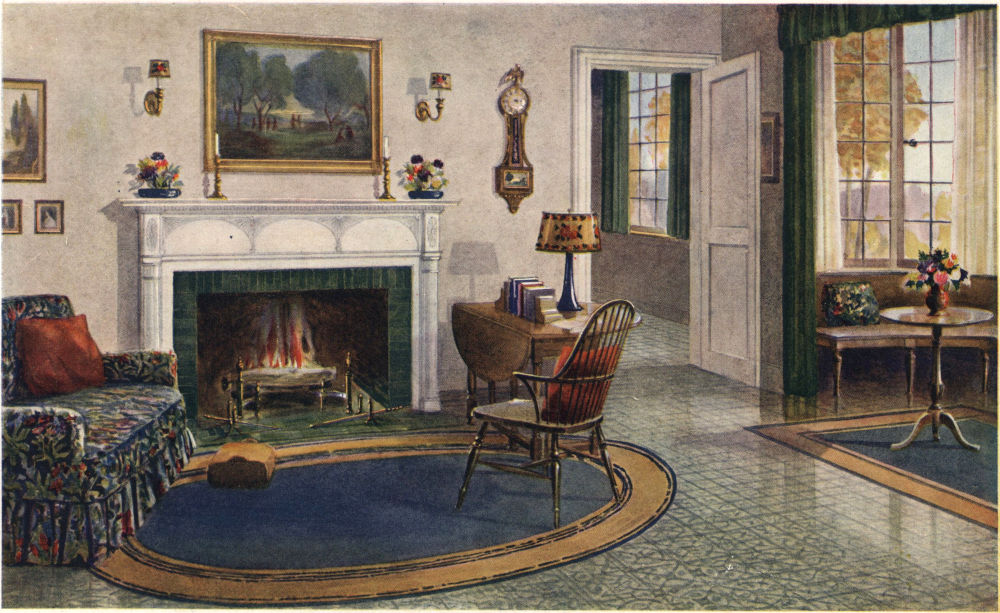

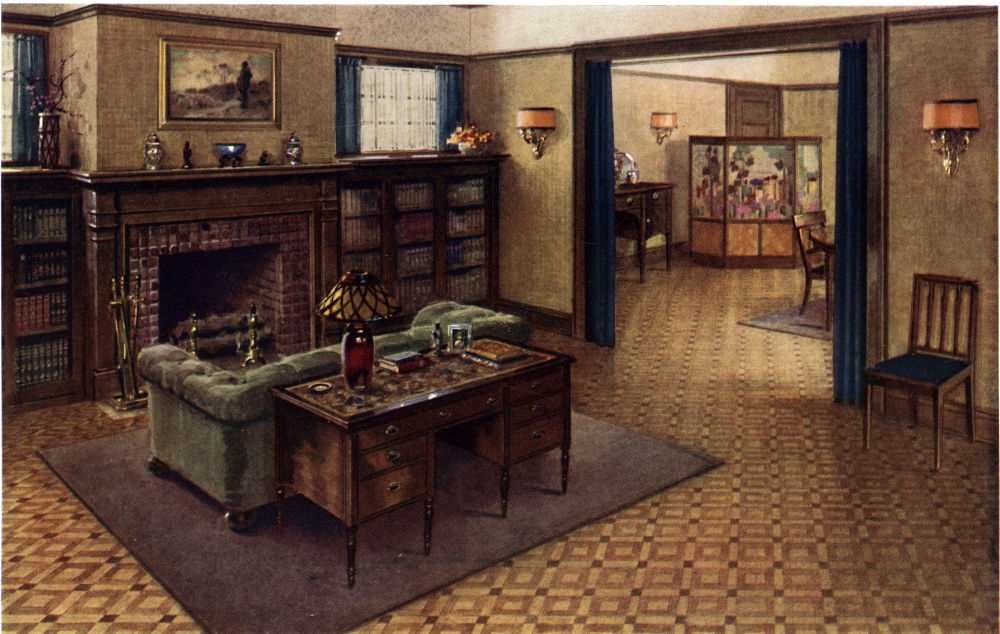

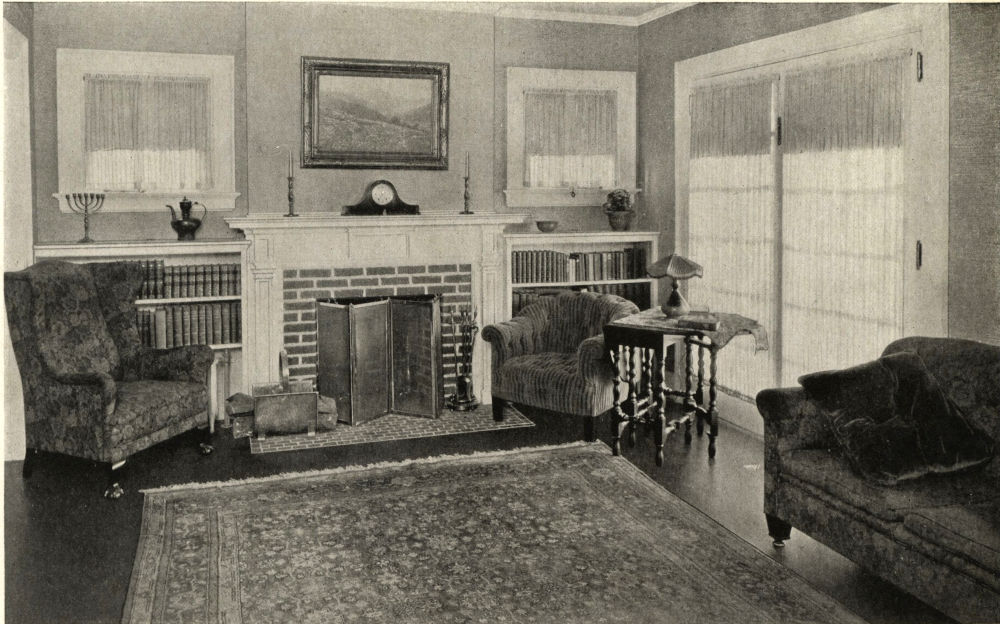

Linoleum for the living-room? Remember, we are now speaking of linoleum as a floor and not as a covering. There is a vital distinction. Over linoleum installed as a permanent floor, naturally, you will lay your fabric rugs, whether they are domestic or Oriental. And you will select your linoleum floor carefully, because it must serve as a background not only for the rugs placed upon it, but for all the furnishings of the room, just as the wall-covering is a background for the pictures or draperies hung against it. The general rule is that the linoleum floor should be darker in tone than the walls and woodwork. It is the foundation upon which the whole plan of furnishing is based. Thus you will select your linoleum floors, keeping in mind the type of furniture, the woodwork, and the general effect you wish to produce.

For example, if the woodwork is dark and the furniture tends toward the massive in style, one of the darker tones of plain brown, the brown jaspe, or a parquetry linoleum floor is appropriate. If the woodwork is white or ivory, the floors may be selected in softer tones of gray, green, and light brown, depending on the character of the furnishings.

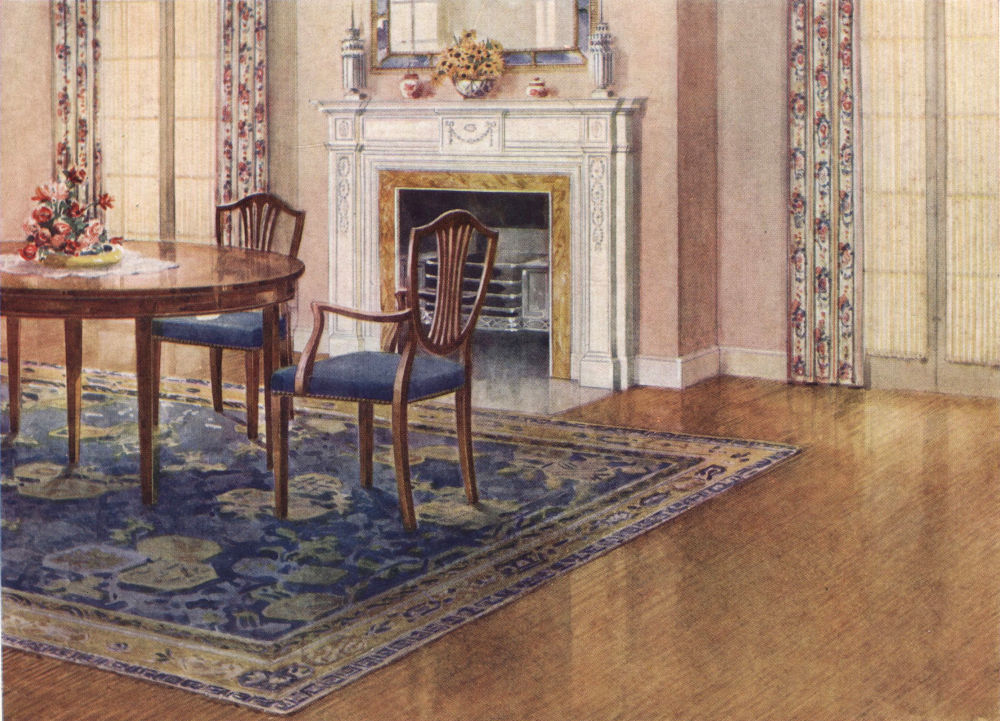

Linoleum is truly the logical floor for the dining-room. Every practical consideration persuades its use. In the dining-room, cheerfulness and individuality are the prime requisites. A thoughtful selection of the floor in relation to the furnishings may be made to contribute not a little to the charm of a room. The newer linoleum designs offer many interesting suggestions; for instance, a marble tile, with contrasting interliners, or one of the carpet inlaids of all-over pattern, permits out-of-the-ordinary floor treatment. Pattern No. 201, a little three-inch tile of alternating black and gray blocks, is reminiscent of Italian influence. In the woods, Parquetry No. 600 is particularly good. Or, for the average home, nothing is better than the jaspes in browns and grays, or a plain linoleum in appropriate coloring.

[Pg 33]

In any room, a nice balance in the use of figured and plain surfaces is always desirable. For instance, if a plain coloring or a jaspe linoleum is used for the floor, figured rugs and wall coverings may well be chosen. If, however, a patterned linoleum floor is employed, the fabric rugs and wall coverings should be plainer, or of small all-over pattern. Avoid overemphasis of pattern or, conversely, too much monotony of plain surfaces.

The cheerful tile designs in Armstrong’s Linoleum are particularly appropriate for the breakfast alcove or sun porch now found in many homes. In a recent issue of The Delineator, Martha Hill Cutler, writing on “Linoleum Floors—Durable, Smart,” after saying that “linoleum has now ‘arrived’ as an artistic as well as a practical possibility for every room in the house,” speaks particularly of the use of linoleum in the breakfast-room.

She says, “In a breakfast-room or sun-parlor one can do daring things. There are fascinating possibilities in a linoleum design of brilliant colorings, the black-and-orange, for instance, the green-and-white, green-and-black, or blue-and-green.

“Breakfast-rooms are almost always so small that rugs are not absolutely essential, but plain rugs against these brilliant tiles as backgrounds are very effective. Brilliantly colored curtains to harmonize, an unusual chintz or cretonne, and painted furniture can be combined with them with colorful results.”

By using the same linoleum floor through a series of rooms, it is possible to gain unity and a feeling of spaciousness. On the second floor, not infrequently the rooms open from a central hall or top stair landing. There are a number of colors and designs in Armstrong’s Linoleum that are specially suitable for groups of rooms because they lend themselves as a background for the draperies in each room, and yet bind all the rooms together as a unit. The gray jaspe, plain dark gray, and light gray linoleums are particularly appropriate with old Colonial painted woodwork in white, ivory, or soft gray; the brown jaspe, plain dark brown[Pg 34] or tan, the parquetries, and certain carpet patterns are equally appropriate with oak, cypress, gum, or chestnut woodwork in the natural finish or painted woodwork in buff and tan.

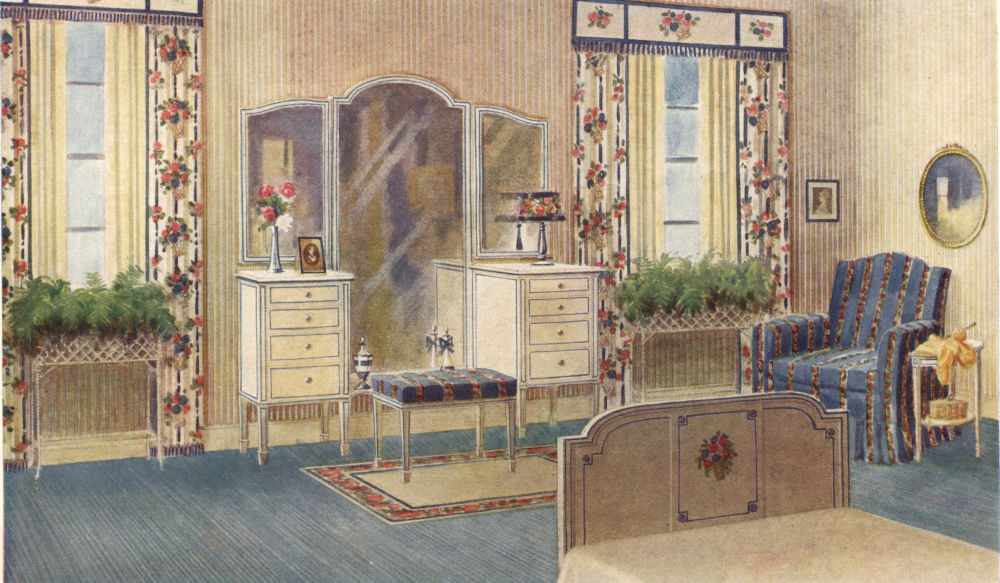

For the bedroom, no floor is so sanitary and so easily cared for as linoleum. It appeals to the most fastidious. And linoleum is not a cold floor—in fact, it is as warm as any wood surface. We have said that linoleum is made largely of cork and linseed oil. Cork is widely used for heat insulating purposes. Engineers regard it as good, if not a better heat retainer than wood. And a linoleum floor has certain advantages over wood floors. There are no cracks or crevices to catch dust or harbor germs. The oxidized linseed oil, moreover, has known germicidal powers that actually tend to destroy bacteria.

There are some very dainty small designs in delicate colors in Armstrong’s Printed Linoleum that are particularly suitable for bedrooms—blue-and-white, pink-and-white, green-and-blue, and green-and-white. Bedroom floors like these, or of plain light blue, rose, or light gray are very charming.

Over the bedroom linoleum floor you will, of course, use small fabric rugs beside the bed, in front of the dressing table, or before the easy chair. You would not leave a wood floor bare. Let us emphasize again that linoleum is a floor—and not merely a floor-covering.

Perhaps in your home bedroom floors have been a problem because they are of soft wood, which must be repainted frequently and which are always hard to keep looking well. Linoleum offers you new floors for old—and at relatively slight expense, far less than the cost of putting in new wood floors. Remember that linoleum floors do not need periodical refinishing, as does hardwood. This is an additional saving.

Many people do not consider a house complete nowadays unless it has a sleeping-porch. Here, again, to secure a thoroughly satisfactory floor is a problem. But linoleum solves it nicely and[Pg 35] economically. Granite linoleums, which resemble terrazzo, or a neat tile effect will be especially pleasing.

Water is always being spilled upon the bathroom floor. It rots wood; it gets into the cracks of tiling and, in time, may cause the tiles to come up. What is needed in a bathroom, therefore, is a floor that is proof against moisture, easy to clean, sanitary, comfortable, and exceptionally durable. If laid properly—that is, cemented down with waterproof cement—a linoleum floor in a bathroom will last for years. The designs of Armstrong’s Linoleum which are offered for the bathroom combine cleanable, sanitary, comfortable, durable, and beautiful qualities in the highest degree.

In decorating the children’s playroom, a linoleum floor, chosen in pattern to harmonize with the color scheme, gives one an opportunity to work out a charming relationship between the floor, the furniture, and the draperies, to suit the playroom idea. In Armstrong’s Linoleum, there are a score of designs in pleasing matting and wood effects and carpet patterns especially appropriate for such a room. And the floor need not be expensive—Armstrong’s Printed Linoleum will last through childhood’s romp and play. And, when the toys and games are put away for more mature interests, the room may be refurnished at slight expense.

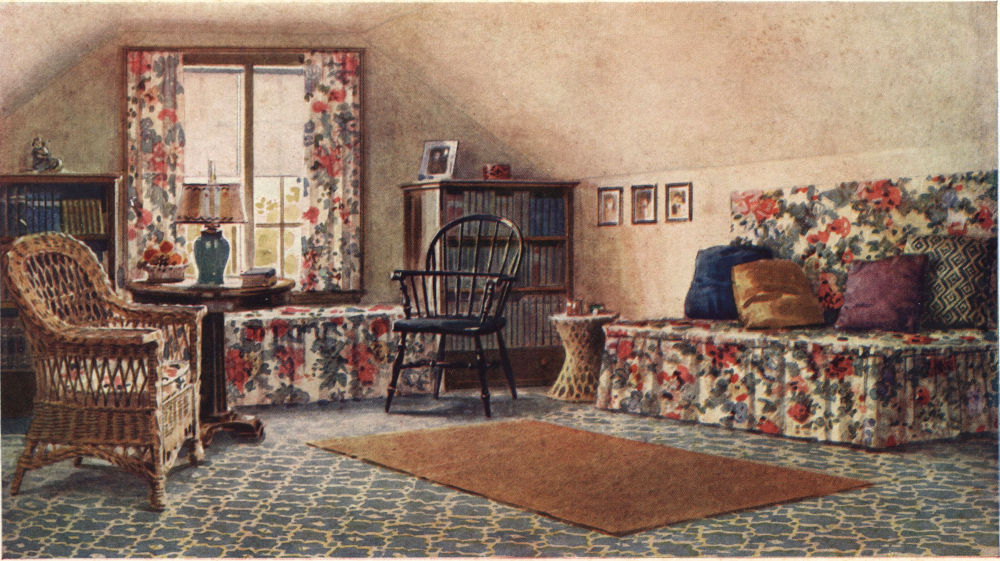

In many homes, the attic is being changed from a store-room into an attractive, comfortable spare room at little expense. The skillful use of odd pieces of furniture, the pleasing blending of draperies, and the covering of the floor with an attractive linoleum pattern will easily make this room one of the most interesting in the home. Whether the room is used as an extra sleeping-room or for sewing, the advantages of a linoleum floor are obvious. It is so easy to clean; cuttings and threads are easily swept up; they do not stick to the smooth-surfaced[Pg 36] linoleum. For a very small outlay, you can transform the attic in your home into a usable, attractive room.

If your kitchen or pantry floor is the kind that requires you to spend hours with water pail and scrubbing brush and back-breaking labor to keep it clean, it is time you change to a linoleum floor. And, even with linoleum floors, many women find it hard to get away from the scrubbing habit. Most people scrub linoleum entirely too frequently. A plain or inlaid linoleum floor should be thoroughly waxed with liquid floor wax. The wax provides a coating which prevents the dirt from being ground into the surface. Such a floor needs only to be swept and then wiped with a damp cloth, and the wax renewed every five to six weeks. Varnishing a printed linoleum floor will add to the life of the linoleum and make it easier to keep clean. All these considerations hold equally true for vestibule, laundry, and closets. There are many bright patterns in Armstrong’s Linoleum for the kitchen or pantry from which you can make a selection that will exactly fit into your idea of what these rooms should look like.

By way of summing up, consider for just a moment what the qualities are that you really need and demand in the floors in your home. Certainly, you want your floors to be durable. And is there any floor you can think of—cost considered—that can approach a good linoleum in wearing quality? Next, you demand sanitation. Do you know of any floor that excels linoleum in that respect? Most assuredly, you want floors that are easy to keep clean. Have you not found linoleum easy to clean? And you must have comfort. Is not linoleum easy underfoot?

But, you say, we must have warmth, too. Certainly, you must. But you would hardly think of leaving the wood floor in your bedroom and living-room bare, would you? No, you use rugs. Follow the same course, then, with your linoleum floors; and you will find them equally as comfortable as hardwood. In[Pg 37] fact, thickness for thickness, linoleum is a better non-conductor of heat than wood is.

Then, finally, you demand beauty and economy in your floors—and justly so. As for color harmony, hardwood has distinct limitations. Shades of brown and tan are about the only colors that are available. But, with linoleum, the range of colors and patterns is well-nigh unlimited, and your floors can thus be made an integral part of your general color scheme. On this point, the colorplates that accompany this book speak for themselves.

As to economy, linoleum floors of good quality are less expensive today than the cheapest hardwood. And they cost less to maintain, too. Given reasonable care and proper treatment, linoleum floors will last indefinitely, without the periodic refinishing that all hardwood requires.

So you can see for yourself, once you analyze the subject, how remarkably linoleum does combine each and every one of the qualities you want the floors in your home to possess.

Naturally, we want you to be thoroughly satisfied with your floors of Armstrong’s Linoleum—not only as to wearing quality but in respect to pattern and color as well. And, since the selection of suitable linoleum floors to harmonize with the different types of furnishings and color schemes involves the application of the principles of interior decoration, we have organized a Bureau of Interior Decoration to answer any questions you may care to ask about the use of Armstrong’s Linoleum in your home.

If you are planning to refurnish or redecorate your home, write our Bureau of Interior Decoration, describing your furniture, wallpaper, rugs, and the color scheme you have in mind. Our Interior Decorator will be glad to make suggestions that may be helpful to you, and will send you lithographs of linoleum patterns that will make suitable floors for your home. There is no charge or implied obligation for this service.

[Pg 38]

First, get in touch with the merchant in home furnishings with whom you are accustomed to trade. If he does not have on hand an adequate assortment of Armstrong patterns to suit your taste, ask him to show you his copy of the Armstrong Pattern Book, which contains colorplates of all of the two hundred and fifty designs and colorings in the Armstrong line. From this book, you can select your first, second, and third choice; and doubtless he will be glad to place an order for the pattern you desire.

Certain patterns, including plain colorings, jaspes, and carpet inlaids, are carried in the factory in our Cut-Order Department; and the merchant can order exact room sizes for you.

If, however, you have difficulty in getting just what you want, please write us, not forgetting to include the merchant’s name and address. Then we shall do all in our power to see that you can secure what you require through some good store near you.

As manufacturers, we sell only through the regular trade channels, and, therefore, we cannot quote you prices. In fact, it is really to your advantage to buy through your dealer, as he purchases Armstrong’s Linoleum in large quantities, and thus the transportation charges are much less than if a small quantity of linoleum were shipped direct from the factory.

Every yard of Armstrong’s Linoleum is fully guaranteed to give satisfactory service. Your merchant will be authorized to make good to you any defect in manufacture, either by replacing the linoleum or by making an adjustment satisfactory to you.

[Pg 39]

[1] Armstrong Bureau of Interior Decoration.

How To Care for Linoleum Floors

A linoleum floor, properly cared for, is easier to clean and will retain its new and attractive appearance longer than any other kind of floor. Linoleum has a smooth, unbroken surface, without cracks and crevices to catch dirt and germs. In Armstrong’s Linoleum, the colors used are bright and clear and will retain their luster and brilliancy for years.

As every housewife knows, linoleum floors require less attention than wood floors; but it is possible to lessen materially the work of caring for linoleum floors by observing the simple rules set forth in the paragraphs following.

When you install a new inlaid, jaspe, or plain linoleum floor, it should first be washed carefully with tepid water and pure soap and then, before it is tracked up, waxed with a liquid floor wax, rubbing the wax in very thoroughly.

After that, you will care for your linoleum floor just as you would for a waxed floor. A weighted brush, such as is used for wood floors, is convenient for polishing; or a heavy brick, wrapped in a soft cloth, will serve.

The daily care of a waxed linoleum floor is simple. Ordinarily, all that is needed is to go over the floor around the fabric rugs with a dry mop. At doorways, or where the traffic is greatest, the wax coating will wear away, and should be renewed at those points as often as appearance demands. Given this sort of care, it is not necessary to scrub or wash linoleum floors, except at rare intervals. Muddy footprints may be wiped up with a damp cloth, as occasion requires.

Any good floor wax, such as Johnson’s Liquid Wax or Old English Brightener, is suitable for use on linoleum floors. Most people prefer to use liquid wax because it is easier to apply than paste wax and permits evener distribution on the linoleum. Whether you use liquid or paste wax, apply it very sparingly and be sure to rub it in thoroughly. If you put the wax coating on too thick, it will not harden properly. As a result, the excess wax will absorb and hold the dirt. It will look greasy and unsightly, and the floor will remain in a slippery condition.

Many people find that printed linoleum wears better and retains its original freshness of coloring longer if given a coating of varnish or clear white shellac. It is economical to use only a high-grade waterproof varnish or a clear white shellac, as the cheaper grades are likely to scratch or turn white under water. Such varnishes as Valspar or “61” Floor Varnish are recommended.

Before varnishing or shellacking, the linoleum must be cleaned carefully and should be thoroughly dried. The varnish should be applied as evenly as possible and allowed to dry twelve hours before the floor is used. At least two coats should be applied over new linoleum; thereafter, the varnish need be renewed but once or twice a year, according to the wear on the floor. Care should be used in revarnishing to avoid streaked and spotty effects.

[Pg 40]

In the kitchen, pantry, or bathroom, where water is spilled and there is naturally more dirt, owing to the ordinary household activities, than on other floors of the house, washing linoleum will, at times, become necessary. However, going over the waxed linoleum floor with a dry or waxed mop will usually keep it clean. As previously stated, scrubbing linoleum should rarely be necessary. In washing the linoleum, warm, sudsy water, made with a mild soap, such as Ivory, will clean a linoleum floor thoroughly. It is best to wash and dry only about a square yard at a time, rinsing the linoleum with clear water and wiping it up thoroughly. Never flood the surface of the linoleum with water, nor allow the water to stand around the edges or seams.

Contrary to the idea held by a good many housewives, certain advertised cleaning soaps and washing powders are not good to use on linoleum. Practically all of these cleansers contain strong alkali or caustics which are positively injurious. More harm is done to linoleum by the use of such agents than in any other way. The chemical action of these substances disintegrates the oxidized linseed oil and cork in linoleum just as it destroys the varnish on hardwood. A good rule is to avoid the use of soda, lye, or potash cleansing powders and strong scouring soaps altogether. A good mild soap is all that is necessary.

After washing with soap and water, inlaid linoleum, particularly, should be polished with a soft cloth or brush. The wax finish may be dulled somewhat by the washing, but is quickly restored by a brisk rubbing. Where the wax has been removed by washing, it should be renewed at once.

The casters ordinarily used are apt to cut into linoleum if the furniture is heavy, therefore it is best to use glass or metal sliding shoes which have a wide bearing surface and no rough edges. They are made in several sizes, have a shank similar to that on a regular caster, and will fit the same sockets. Heavy felt casters may be purchased at the furniture stores which are also recommended for use on linoleum floors.

Always lay a piece of carpet on the floor, or a board, just as over a hardwood floor, when moving very heavy furniture, to prevent marring the surface of the linoleum.

[Pg 41]

How To Lay Linoleum Floors

In the past, linoleum has been regarded by many as a temporary floor-covering. Not much care has been used in laying it. But you want well-finished floors in your home that will need a minimum amount of attention as the years go by. For this reason, we strongly recommend that you have your linoleum floors installed by the merchant from whom you buy the goods. Experience has taught their layers how to cut the linoleum so as to avoid waste and how to lay it to prevent buckling and cracking, conditions which result from faulty workmanship.

Insist that your linoleum be laid right. If the merchant does not employ skilled mechanics to do this work, go to a merchant who has a staff of layers and who will guarantee his laying. He will make a charge for the cost of labor and materials; but, in the long run, it will prove greater economy for you to pay well to have your linoleum laid properly than to have the laying done in a makeshift manner in order to save a few cents per yard.

LAY LINOLEUM AS A PERMANENT FLOOR

When you purchase a good grade of linoleum to be installed as a floor in your living-room, dining-room, or even in the kitchen or bathroom, naturally you desire to have it put down as a permanent floor. The most satisfactory way to install linoleum is to cement it down solidly over a lining of builders’ deadening felt paper. This will give you a permanent floor, smooth, firm, without cracks or crevices. Owing to the variations in moisture conditions, any wood underflooring will expand in summer and dry out in winter, leaving cracks. Linoleum cannot be cemented directly to such a wood underflooring without possibility of damage. One of the chief advantages of the felt lining is that it tends to take up this expansion and contraction, thus saving the linoleum floor from breaking or cracking. In addition, the felt acts as a cushion, deadening sound and adding to the warmth and comfort of the floor, making it delightful to walk or stand on.

Should it become necessary, in time, to remove such a linoleum floor, this can be done easily, without damage to the linoleum.

Leading contract linoleum layers and good stores have adopted the felt paper method of laying linoleum and recommend its use to their customers. A brief description is given here of this method in order that you may understand how the work should be done. If your merchant is not yet equipped to lay linoleum by this method, ask him to write for a copy of our linoleum layers’ handbook, “Detailed Directions for Laying and Caring for Linoleum,” which lists all of the materials and equipment needed, and includes illustrations showing the several steps in laying linoleum by this improved method. A copy of this handbook will also be sent to you, without charge, upon request.

[Pg 42]

In cementing linoleum down over felt paper, the felt is first cut into lengths to go across the short way of the room. The quarter-round floor molding is removed, and the felt fitted snugly at each end. A linoleum paste is then applied to the undersurface of the felt, which is then rolled or pressed down until it adheres firmly to the floor.

The lengths of the linoleum are next pressed in position crosswise to the direction of the felt strips, or the long way of the room. One piece is laid at a time. The surface of the felt under each strip of linoleum is well coated with paste, except for four to six inches along each end and side and along the seams, which spaces are left bare. The linoleum is put down and rolled. After the paste has begun to dry, the free edges of the linoleum are trimmed to fit neatly at all points. Then waterproof linoleum cement (a kind of glue) is applied to the felt along all edges and seams back under the linoleum for a distance of four to six inches. This cement makes the floor perfectly water-tight. Finally, the linoleum is well rolled with a heavy roller to insure perfect adhesion at all points.