Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

THE LOST OASES

THE LOST OASES

BY

A. M. HASSANEIN BEY,

F.R.G.S.

BEING A NARRATIVE ACCOUNT OF THE AUTHOR’S

EXPLORATIONS INTO THE MORE REMOTE PARTS OF THE LIBYAN DESERT AND

HIS REDISCOVERY OF TWO LOST OASES

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY THE RIGHT HONORABLE SIR JAMES RENNELL RODD, G.C.B., G.C.M.G., G.C.V.O. ILLUSTRATED WITH AN ORIGINAL MAP, AND FROM MANY PHOTOGRAPHS MADE BY THE AUTHOR

![[Logo]](images/logo.png)

PUBLISHED BY THE CENTURY

CO.

NEW YORK AND LONDON

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

![[Symbol]](images/decor1.png)

Copyright, 1925, by

The Century Co.

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

IN HOMAGE AND

GRATITUDE

TO

HIS MAJESTY KING FOUAD I

WHO

BY HIS HELP AND ENCOURAGEMENT MADE

THIS JOURNEY POSSIBLE

[vii]INTRODUCTION

MY friend Ahmed Hassanein has asked me to write a few words of introduction to his record of a remarkable voyage of exploration. It was the more remarkable because the expedition, the results of which have enabled him to fill up an important gap in our knowledge of Africa and to determine with precision positions only approximately ascertained by that great pioneer in African research, Gerhardt Rohlfs, was conceived and led by him single-handed without other assistance or companionship than that of his guides and personal attendants.

A traveler whose work has been recognized by the award of the Founder’s Medal of the Royal Geographical Society should need no introduction to the British public. But I welcome the opportunity of drawing attention to his achievement in another field, in the production of a book which will, I feel sure, be acknowledged by all who read it to have exceptional interest, written in a language of which he has made himself a master, although it is not his own.

[viii]But first, disregarding any protests from his characteristic modesty, I have to present the author himself, who is only known to the majority of my countrymen as an intrepid traveler. I have had the pleasure of his acquaintance for a number of years, since he was the contemporary and friend of my son at Balliol. After considerable experience I have come to the conclusion that the experiment of sending students from the East to reside at a Western university is one which should only be tried in exceptional cases and with young men of exceptional character. In the case of Ahmed Hassanein I think all who know him will agree that it has been an unqualified success. He has retained all that is best of his own national and spiritual inheritance, while he has acquired a sympathetic understanding and appreciation of the mentality and feelings of men with very different social antecedents and training. It is possible that the blood of his Bedouin forefathers made intimacy with them easier for him, since the Briton and the Bedouin not infrequently find in one another a certain kinship of instinct which compels their mutual regard. Incidentally it may be mentioned that Ahmed Hassanein represented the University of Oxford as a fencer. In any case it is possible for him to be a sincere Egyptian patriot and none the less to entertain equally sincere friendship with members of the[ix] nation to which justice is not always done by the Younger Egypt.

He began his career at home in the Ministry of the Interior at Cairo. During the war when martial law was in force in Egypt he was attached to General Sir John Maxwell, a very old friend of his country. Now he has entered the diplomatic service, for which a wide experience of life, rare in so young a man, as well as his linguistic gifts, eminently qualifies him. He has occasionally consulted me as an elder friend and as the father of my son on certain matters of personal interest to himself. I may therefore claim to know him intimately, and I cannot refrain from recording my testimony that in all such questions, and especially in a very delicate matter which he submitted to me, I have always found him generous in his judgments and, for I know no other way of expressing what I mean, a great gentleman.

The story of his exploration of desert tracts unknown to geography and his discovery of two oases whose existence was only a vague tradition is the record of a great adventure of endurance. It is told so modestly and with such sober avoidance of overstatement that readers who have no experience of the vicissitudes of desert travel may perhaps hardly realize what courage and perseverance its successful accomplishment demanded. There is also another virtue[x] besides these which is indispensable for penetration into regions where the isolated inhabitants regard every intrusion with profound suspicion, and that is one which Hassanein appears to possess instinctively, the virtue of tact.

English readers are perhaps rather disposed to think of the desert in the terms with which romance has made them familiar, for which the grim reality offers little justification. There is indeed a romance of the desert, the romance of loyalties and sacrifices under the shadow of the inevitable, which is an element in the true romance. And that will not be found lacking in a book which bears upon it the impress of truth, interpreting the beauty which the desert can assume, the spiritual influence and inspiration of the great solitudes, the perpetual consciousness prevailing there of the narrowness of the border line between life and death.

Apart from its intrinsic interest as a record of discovery and the light which it throws on the origin, teaching, and influence of the Senussi fraternity, this volume will be welcome to many because its pages carry the reader away into the atmosphere of a great peace. He will be aware for a while of an ambience where the coarse and the trivial and the competitive do not exist. He will find himself in touch with men who, unconscious of the urge and tumult of a world[xi] for which they would have no use, lead strenuous but dignified contemplative lives. And as he perceives how for them privation and danger and even routine are illuminated by the conviction of unalterable faith in the guiding hand of Providence, he will probably formulate the silent hope that these dwellers in the lonely places may be left untouched by the invasion of the modern spirit. Their pleasures are as touchingly simple as their thoughts. These thoughts and these simple pleasures we may for a passing hour share as they are presented to us by a hand which seems to me to have an unerring touch in conveying fidelity of outline and color.

In conclusion it is a grateful duty to add that Hassanein Bey has more than once confirmed to me in conversation what is suggested in the dedication of his book, namely that he could not have undertaken his adventurous journey without the assistance and support which he received from his sovereign. The promotion of enterprise is no doubt an inherited impulse in King Fouad, and it is gratifying to feel that his encouragement may confidently be anticipated for that scientific and historical research for which Egypt still offers such an ample field.

The achievement of Hassanein Bey and the spirit in which his book is written cannot fail to appeal to the sympathies of my countrymen, and he has added[xii] another to his services by thus promoting the spirit of good feeling between the country of his education and the land of his birth which all are anxious to see restored.

Rennell Rodd.

October 19, 1924.

[xiii]ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I AM deeply indebted to Dr. John Ball, O.B.E., Director of Desert Surveys of Egypt, who has been good enough to summarize the scientific results of my expedition in the First Appendix to this volume. His advice and the instruction which he gave me in the use of scientific instruments were invaluable. I was indeed fortunate in being able to draw upon his great knowledge.

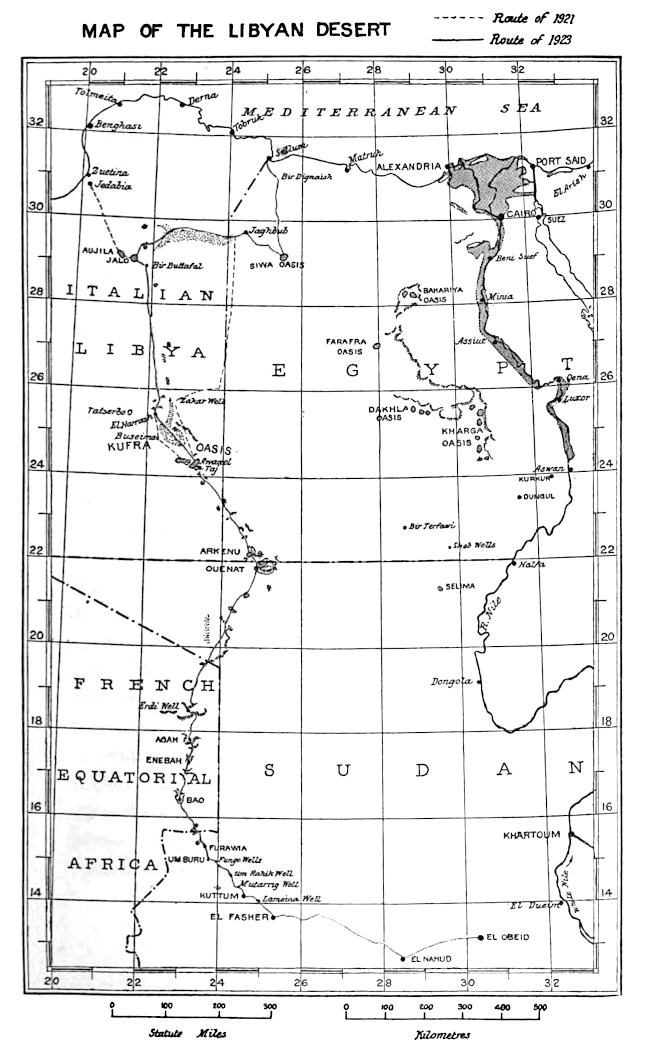

The maps of my journey, one of which accompanies this volume, were kindly prepared by Dr. Ball and Mr. Browne and other members of the Survey Department of Egypt.

Dr. Hume and Mr. Moon of the Geological Survey of Egypt classified the geological specimens which I brought back and prepared a report which is contained in the Second Appendix to this book. By this willing assistance they added much to the results of my expedition.

Lewa Spinks Pasha, D.S.O., and Meshalani Bey of the Ordnance Department of the Egyptian War[xiv] Office were responsible for the cases and containers and other camp equipment which I used. These proved to be satisfactory in every way, and I am grateful for the care and thought which were expended in their preparation.

My old friends Sayed El Sherif El Idrissi and his son Sayed Marghanny El Idrissi again gave me that good counsel and ready help which I had received from them in the course of my trip to Kufra in 1921.

Throughout my expedition I received the most friendly and effective assistance from Colonel Commandant Hunter Pasha, C.B., D.S.O., late Administrator of the Frontier Districts Administration; Colonel M. Macdonnell, late Governor of the Western Desert; Major de Halpert of the F.D.A.; Captain Hutton, O.C., Sollum; Captain Harrison, O.C. Armored Cars at Sollum; Abdel Aziz Fahmy Effendi and A. Kmel Effendi, Mamurs of Sollum and Siwa; Lieutenant Lawler, O.C., Siwa.

When I reached the Sudan my way was made easy and pleasant by the kindness of his Excellency Ferik Sir Lee Stack Pasha, G.B.E., C.M.G., Sirdar and Governor-General of the Sudan, and I cannot let this opportunity pass of expressing my cordial thanks to all the officials of the Sudan Government along my route, and especially to Lewa Midwinter Pasha, C.B., C.M.G., C.B.E., D.S.O., Acting Governor-General[xv] of the Sudan; Lewa Huddleston Pasha, C.M.G., D.S.O., M.C., Acting Sirdar; Kaimakam M. Hafiz Bey, O.C. Troops at Khartum; H. A. MacMichael, D.S.O., Assistant Civil Secretary; Captain J. E. Philips, M.C. Samuel Atiyah Bey, M.V.O., and Ahmed El Sayed Pifai of the Sudan Civil Service; Charles Dupuis, Acting Governor of Darfur; Sagh A. Hilym, S.O., El Fasher; J. D. Craig, O.B.E., Governor of Kordofan; Bimbashi A. Khalil, S.O., El Obeid; and the officers, officials, and notables of El Fasher and El Obeid.

To Bimbashi G. F. Foley, M.C., O.C. Artillery at El Fasher, I am grateful for the verse which adorns the last chapter of the book.

I am particularly indebted to Harold Howland and to W. H. L. Watson, an old Balliol friend, for their invaluable help and advice in the preparation of this book.

A. M. Hassanein.

[xvii]CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Desert | 3 |

| II. | The Planning of the Journey | 12 |

| III. | The Blessing of the Baggage | 16 |

| IV. | Supplies and Equipment | 19 |

| V. | Plots and Omens | 31 |

| VI. | The Senussis | 42 |

| VII. | The Peace of Jaghbub | 57 |

| VIII. | Meals and Medicine | 67 |

| IX. | Sand-Storms and the Road to Jalo | 76 |

| X. | At the Oasis of Jalo | 88 |

| XI. | On the Trek | 110 |

| XII. | The Road to Zieghen Well | 131 |

| XIII. | The Changing Desert and a Corrected Map | 156 |

| XIV. | Kufra: Old Friends and a Change of Plan | 170 |

| XV. | Kufra: Its Place on the Map | 185 |

| XVI. | The Lost Oases: Arkenu | 203 |

| XVII. | The Lost Oases: Ouenat | 219 |

| XVIII. | Night Marches to Erdi | 235 |

| [xviii]XIX. | Entering the Sudan | 257 |

| XX. | To Furawia on Short Rations | 277 |

| XXI. | Journey’s End | 293 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| I. | Note on the Cartographical Results of Hassanein Bey’s Journey | 309 |

| II. | Conclusions Derived from the Geological Data Collected by Hassanein Bey during His Kufra-Ouenat Expedition | 348 |

| III. | Notes on the Geology of Hassanein Bey’s Expedition, Sollum-Darfur, 1923 | 352 |

[xix]ILLUSTRATIONS

| FACING PAGE | |

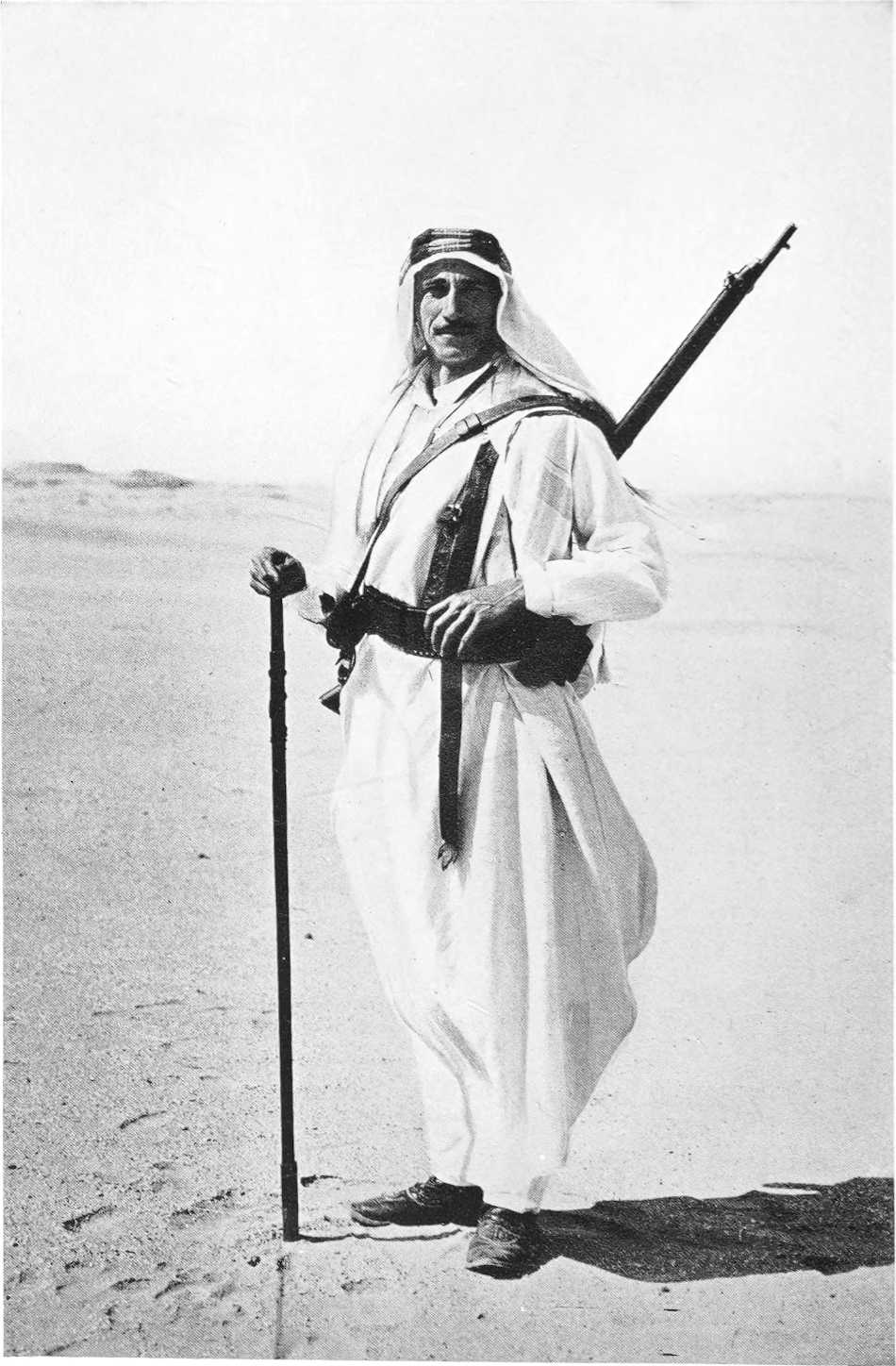

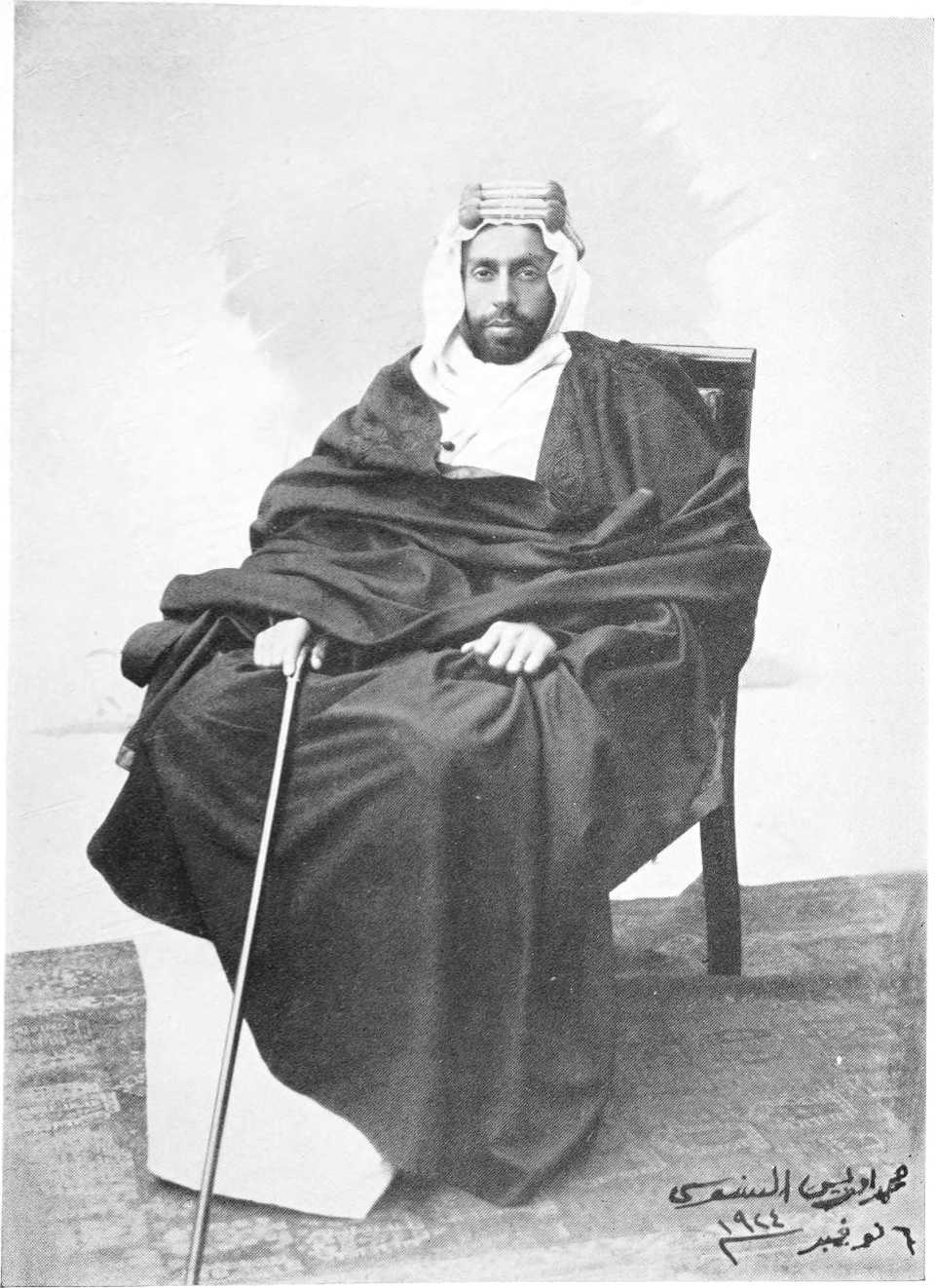

| Hassanein Bey | Frontispiece |

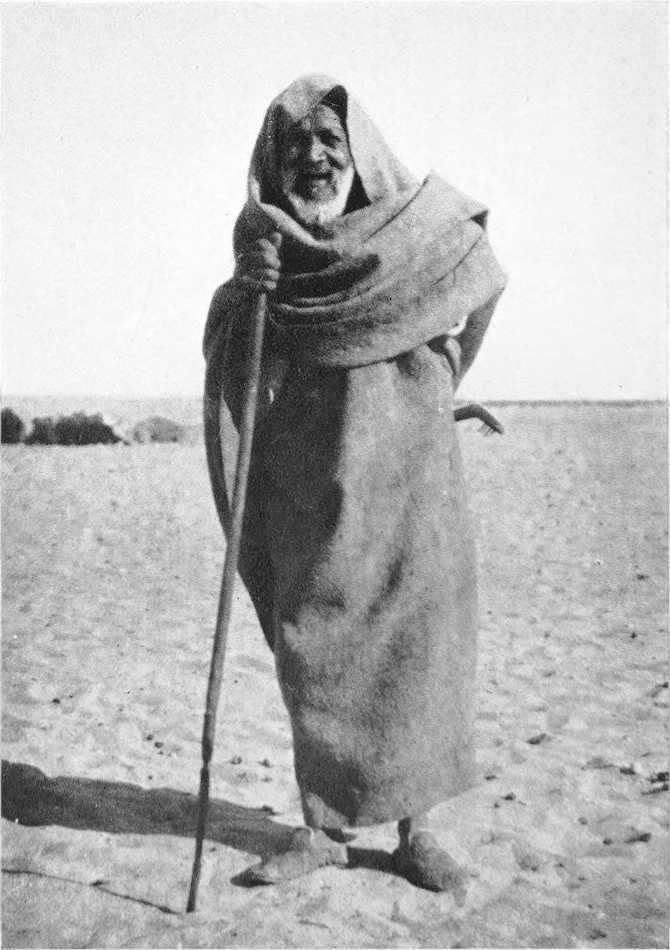

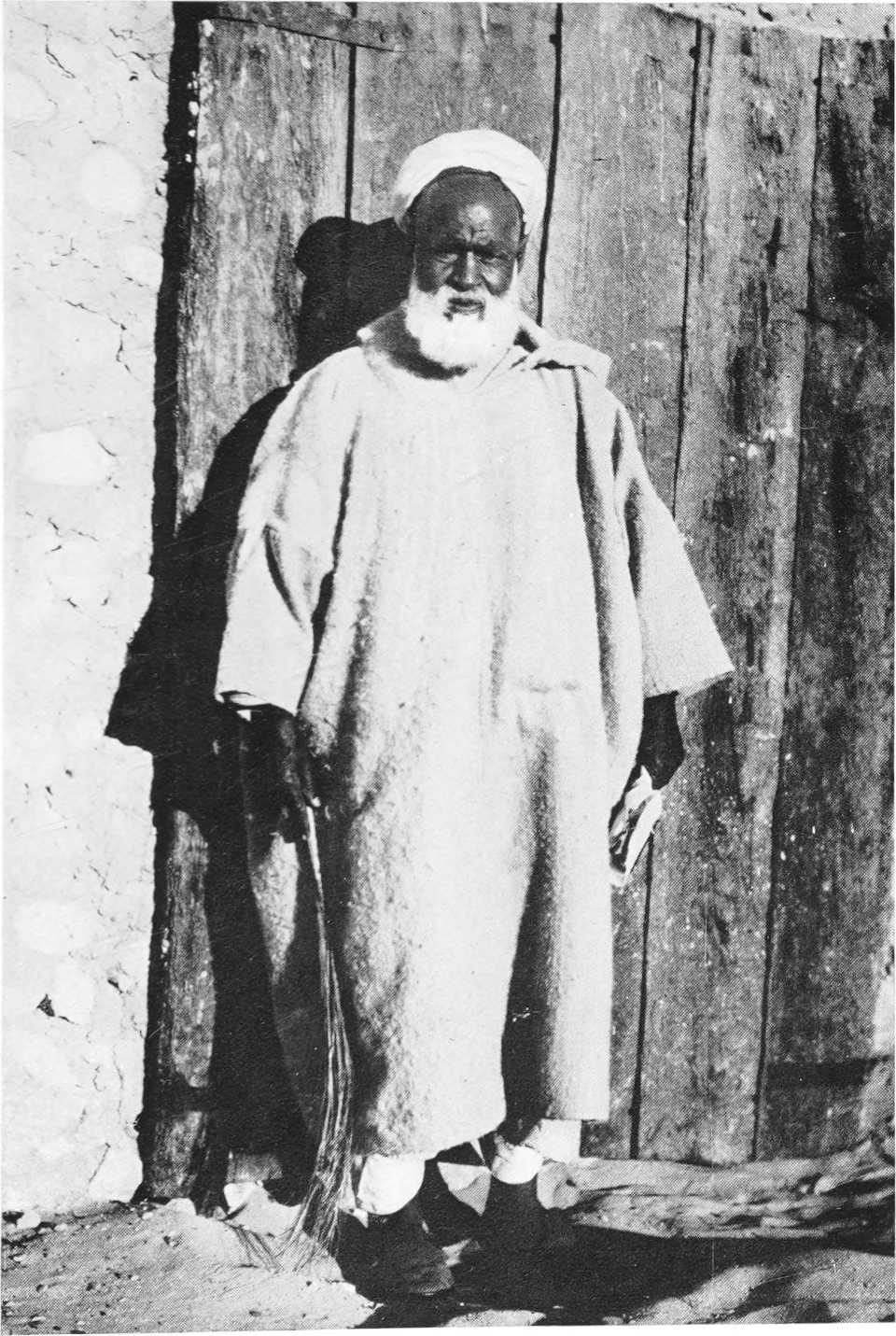

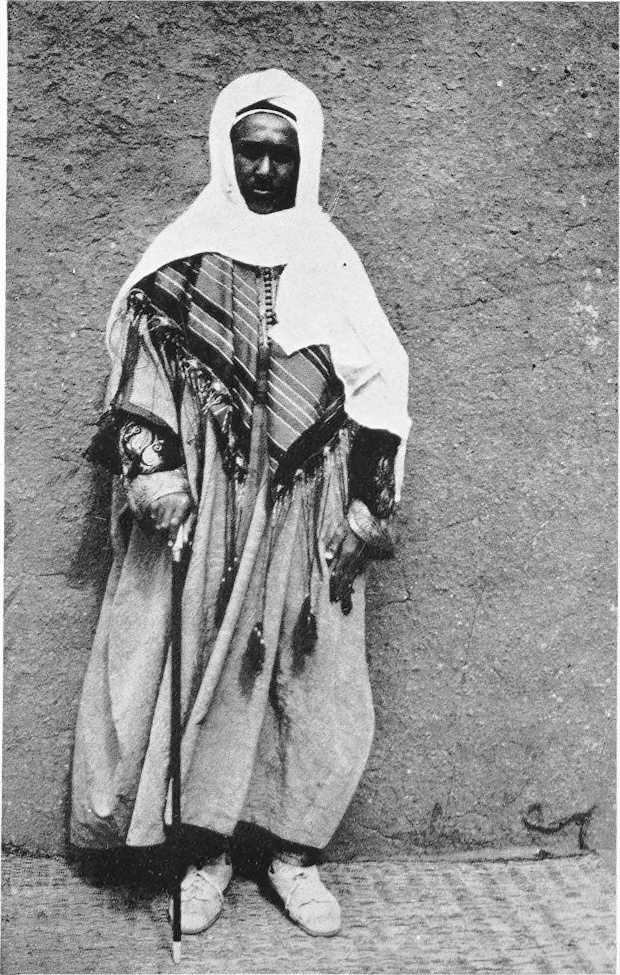

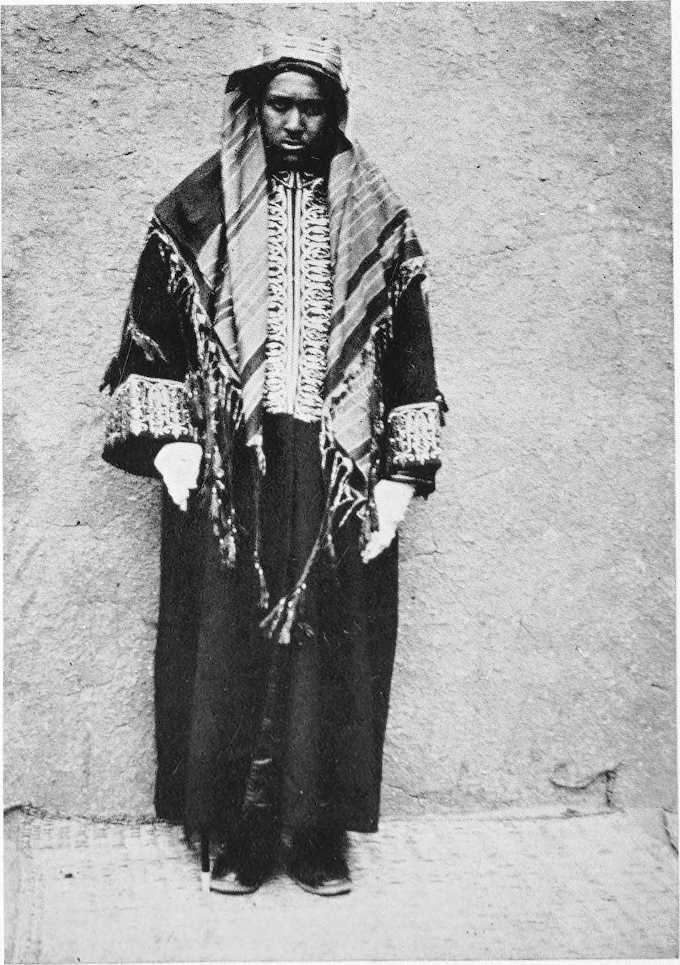

| The Oldest Man at Jalo | 17 |

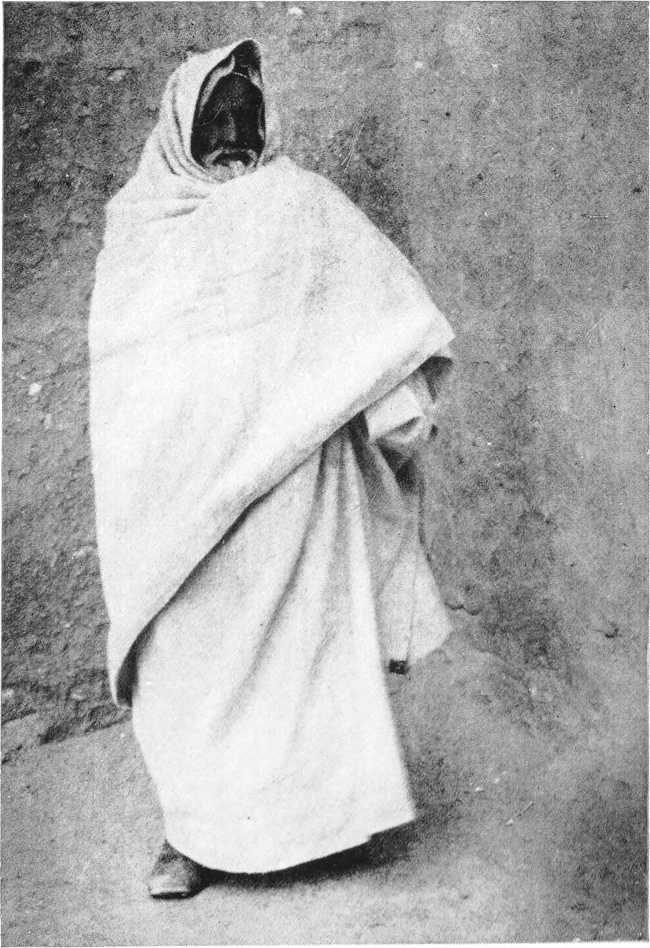

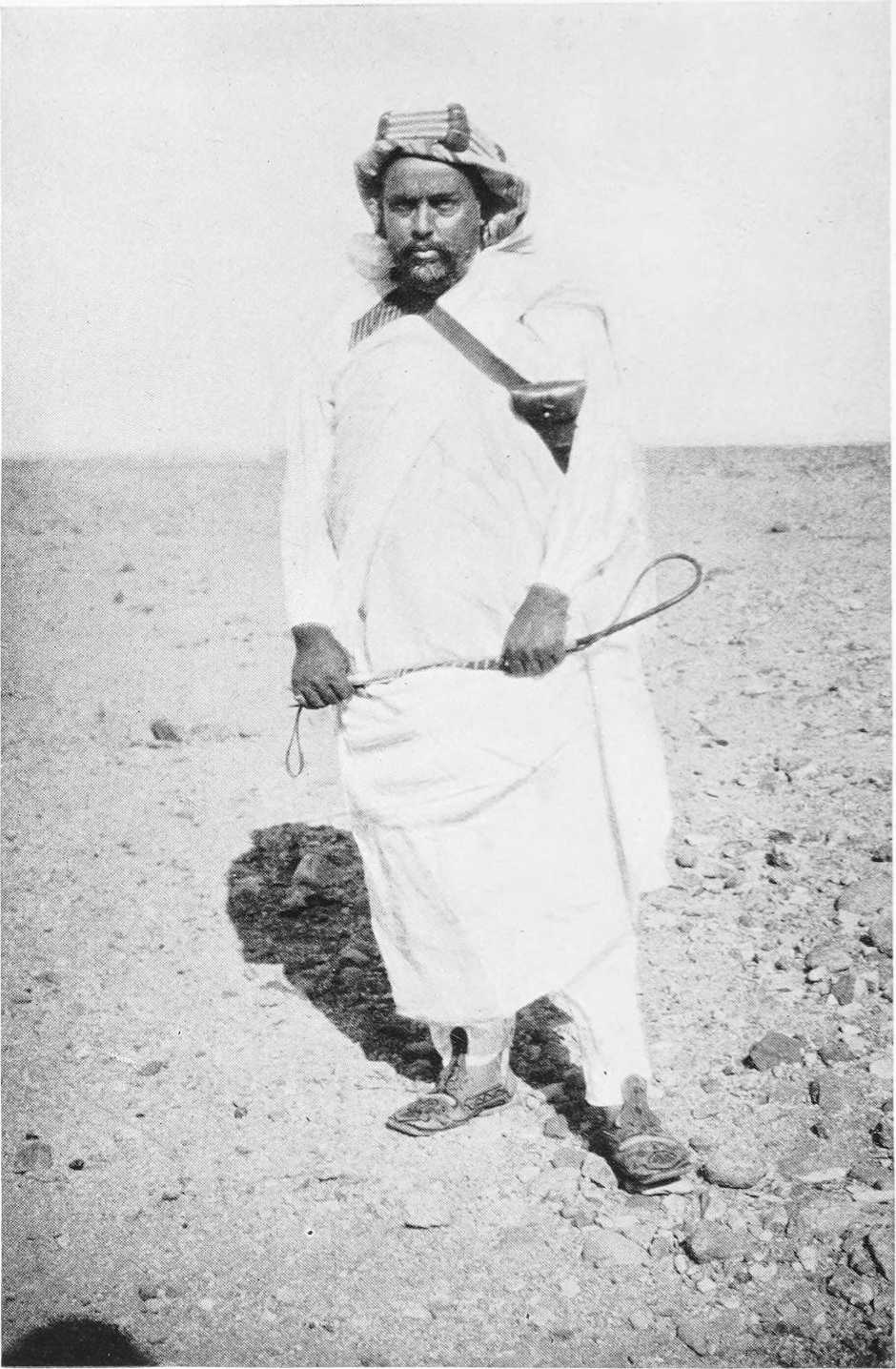

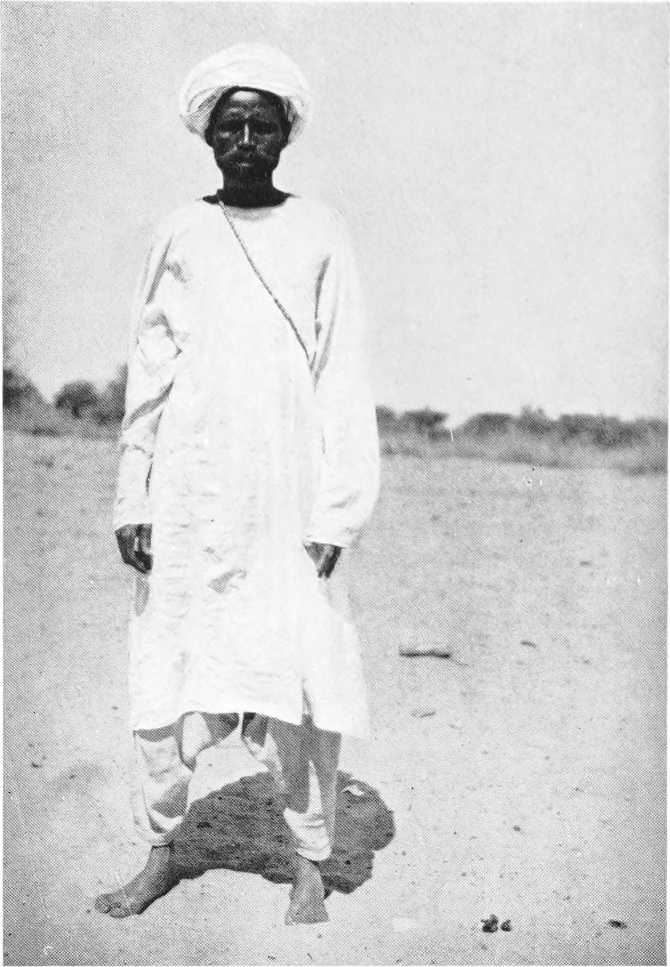

| Sidi Hussein Weikil | 17 |

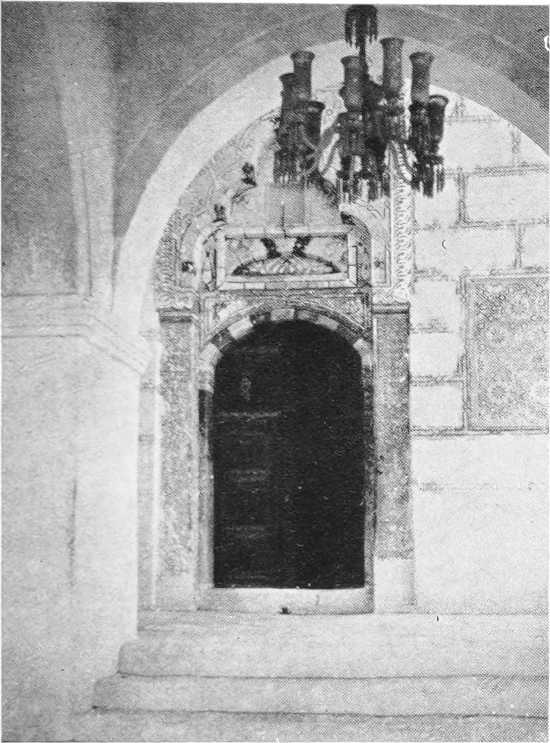

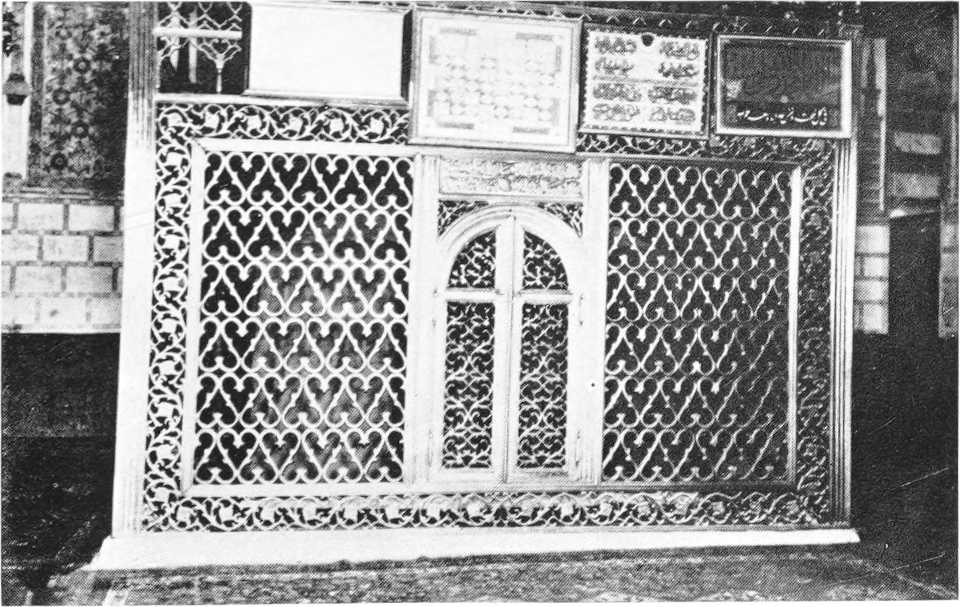

| Door to the Grand Senussi’s Tomb | 20 |

| The Tomb of the Founder of the Senussi | 20 |

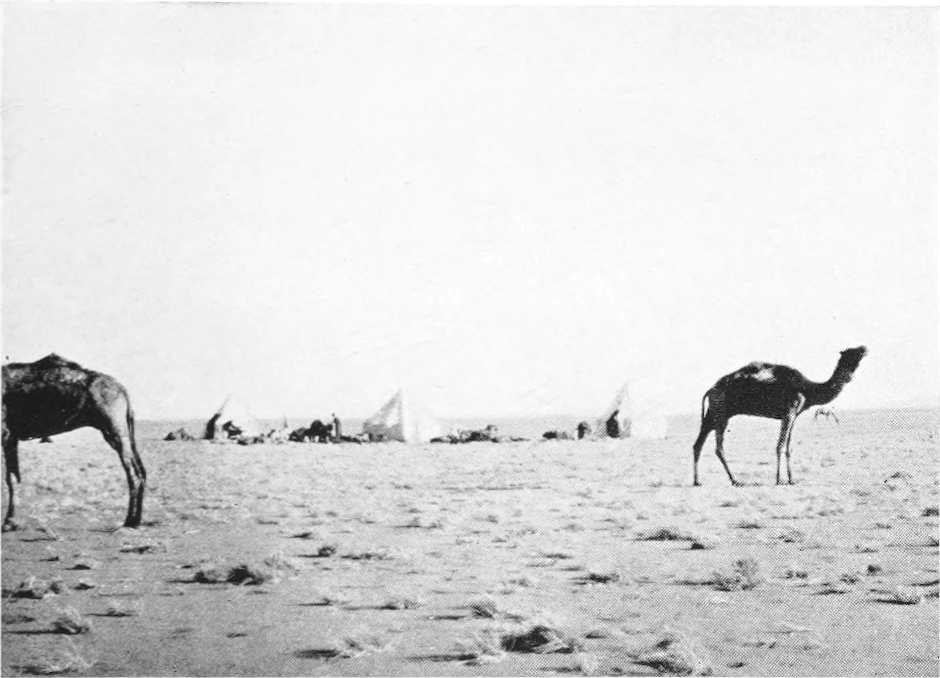

| Camel Serenading the Camp at Ouenat | 24 |

| A Dying Camel | 24 |

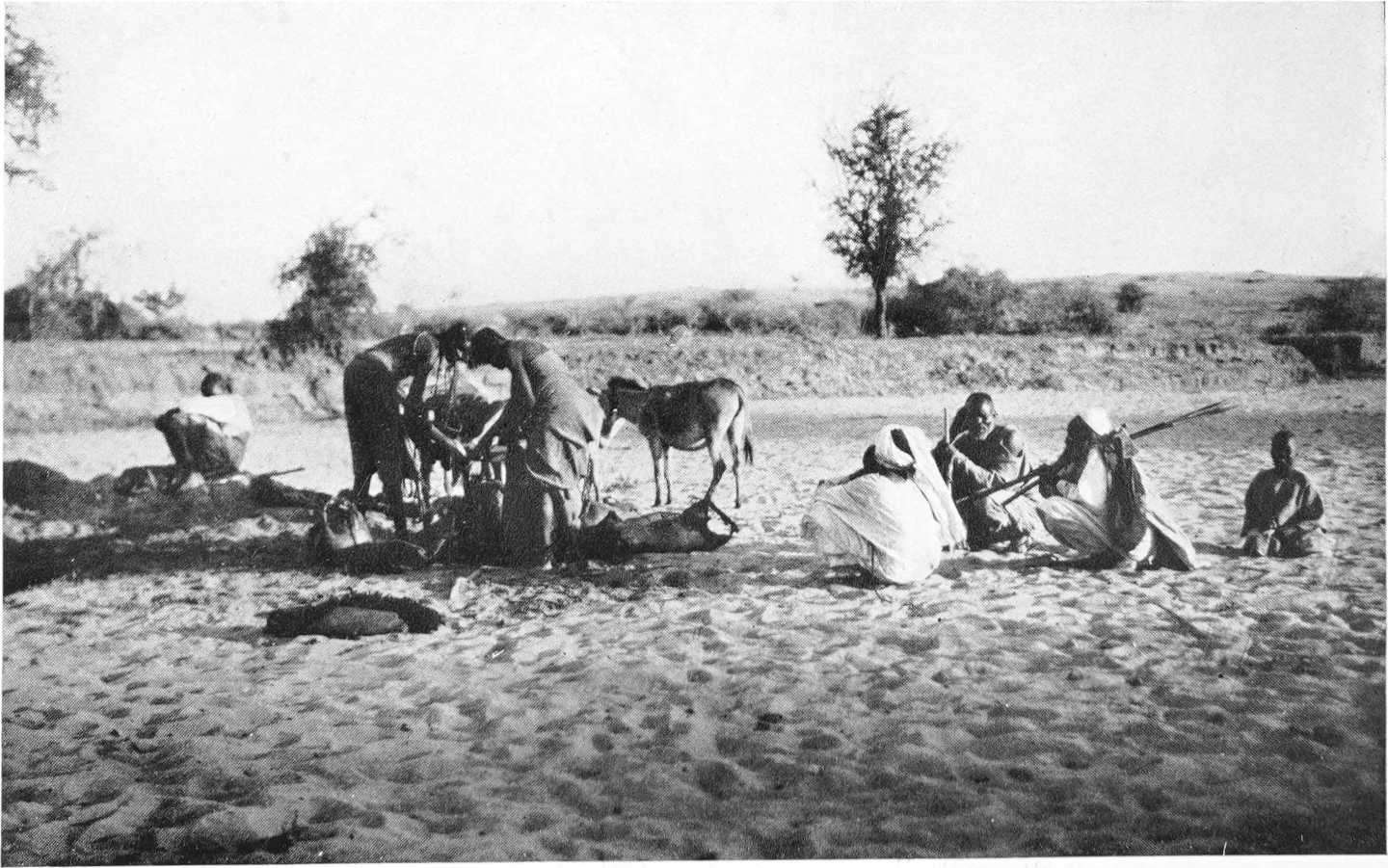

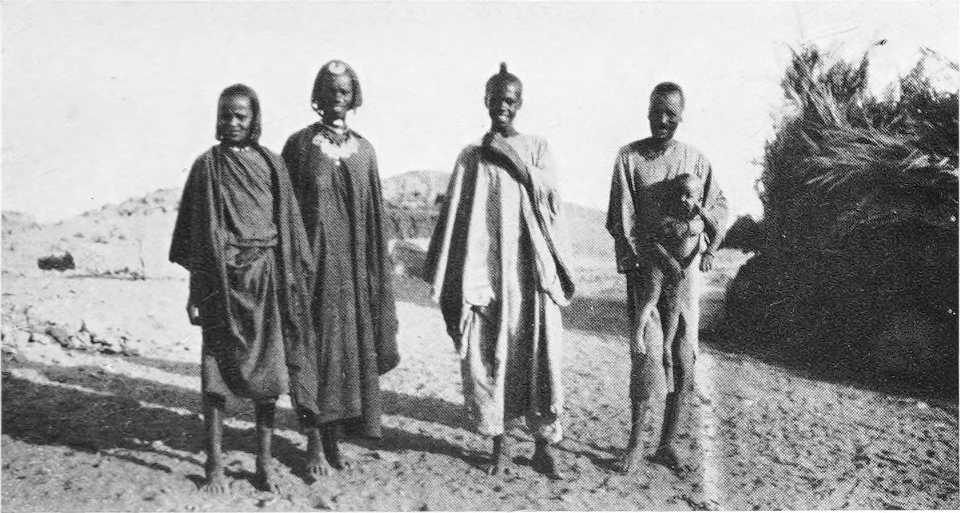

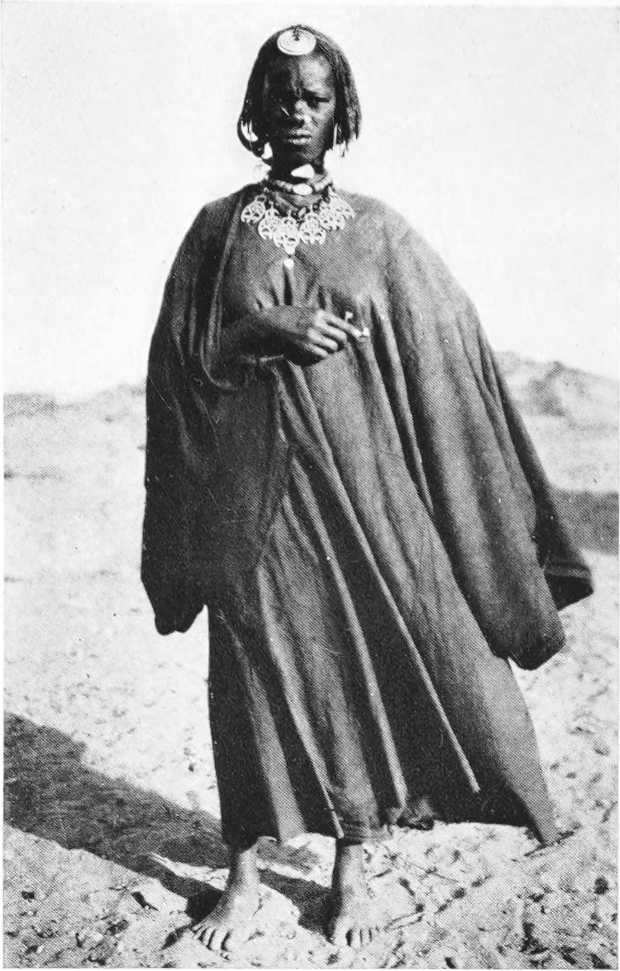

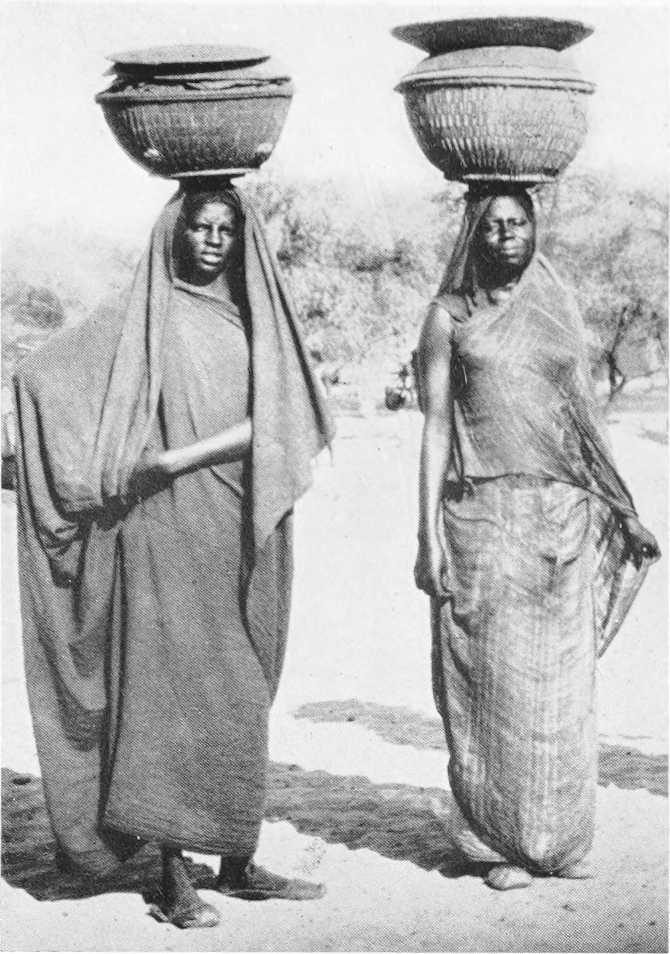

| Women of the Zaghawa Tribe | 29 |

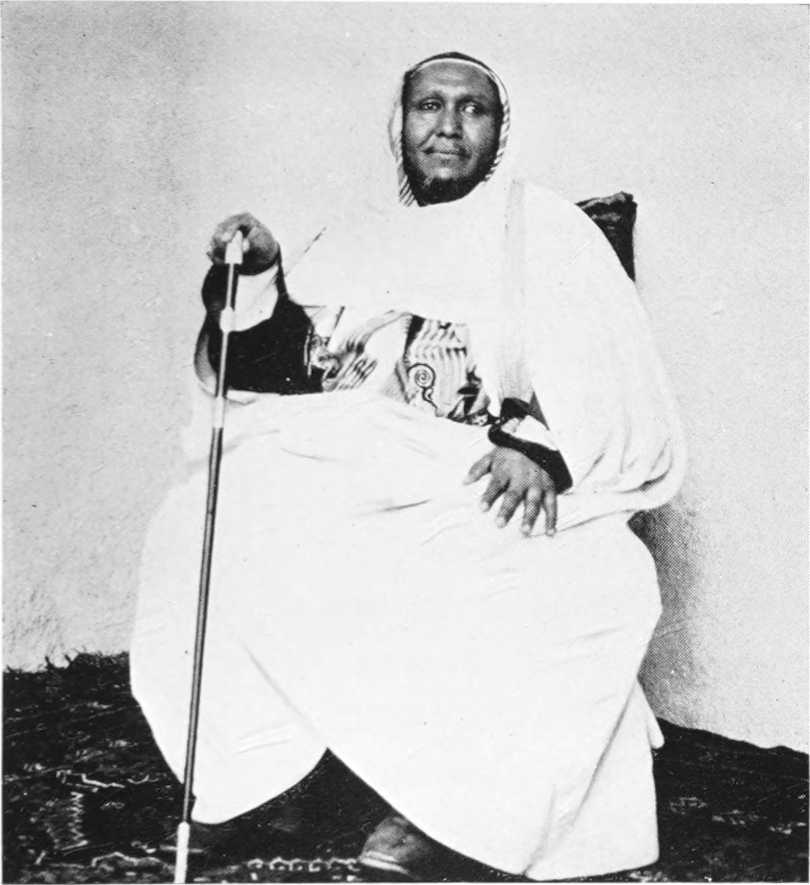

| Sayed Idris El Senussi | 32 |

| The Judge of Jalo | 36 |

| Zerwali | 45 |

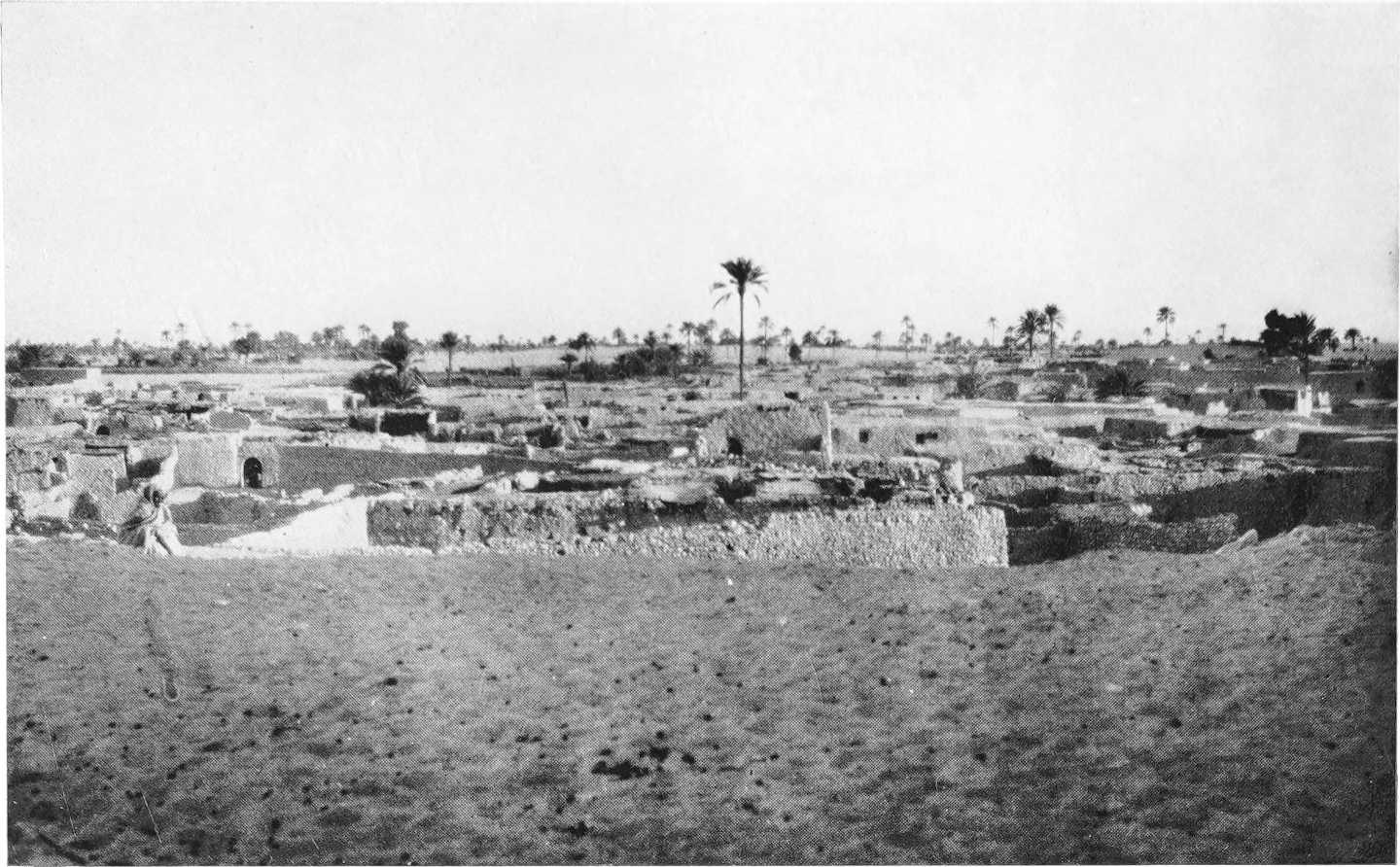

| Siwa | 48 |

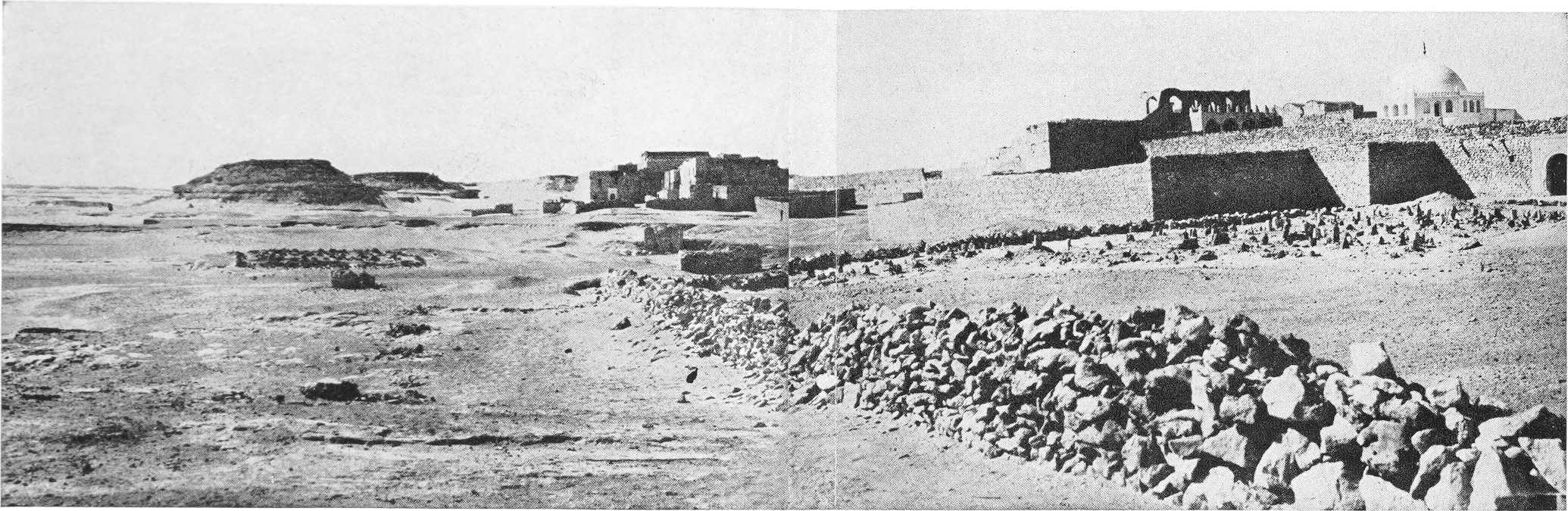

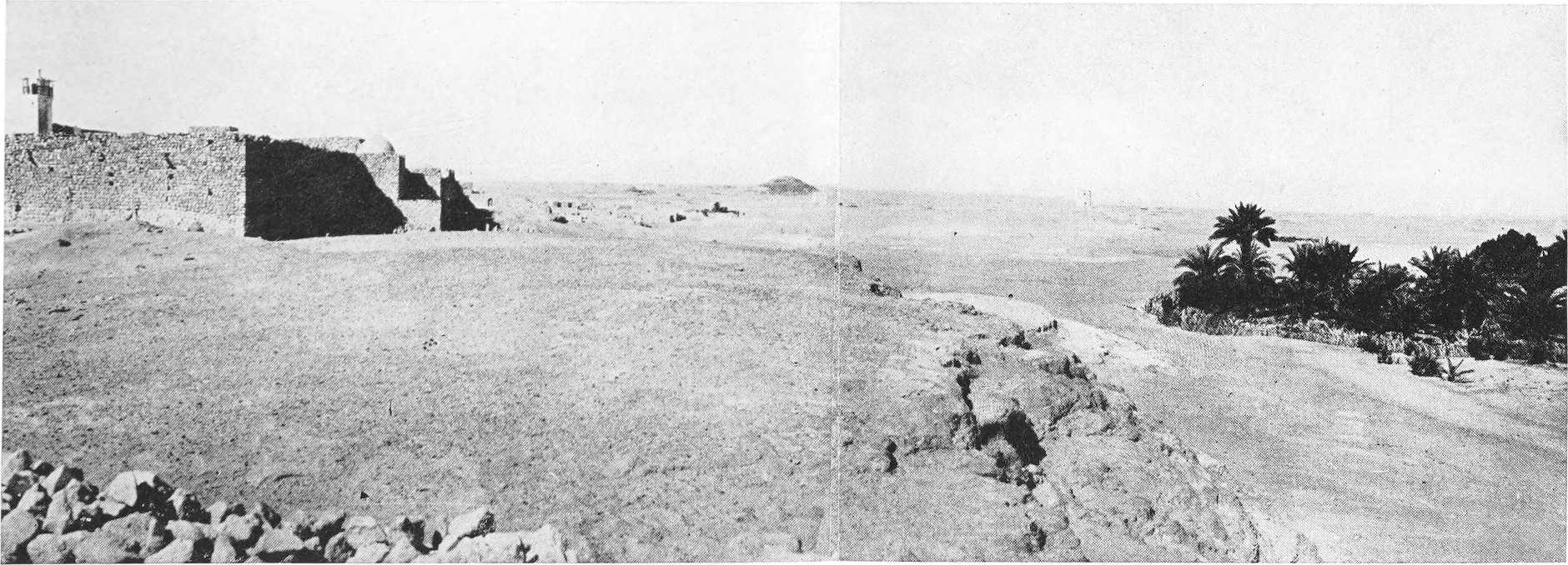

| Panorama of Jaghbub | 52 |

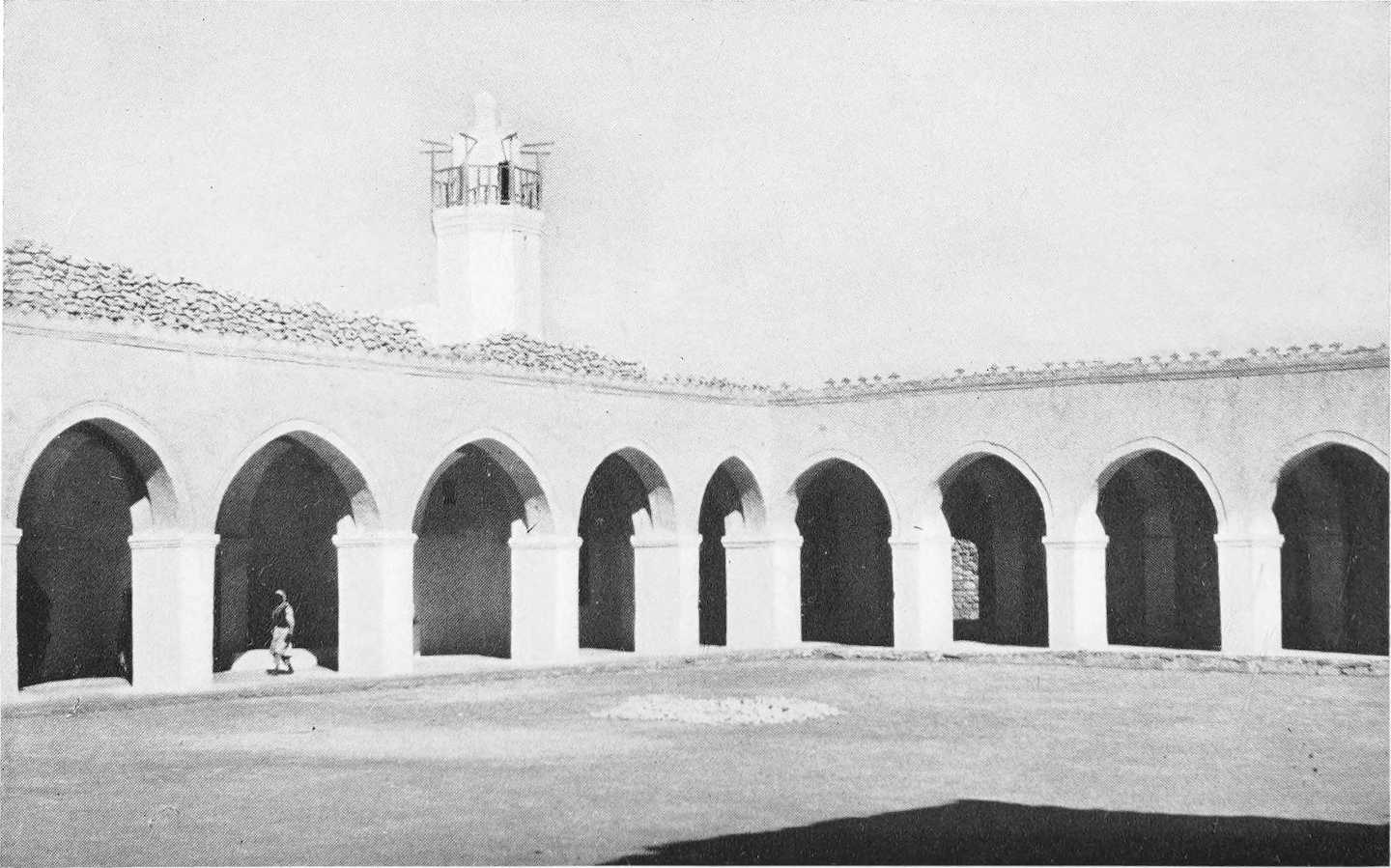

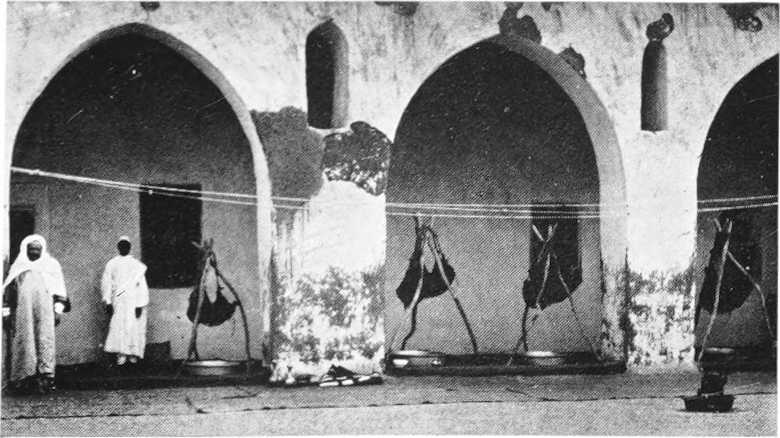

| The Courtyard of the Mosque at Jaghbub | 61 |

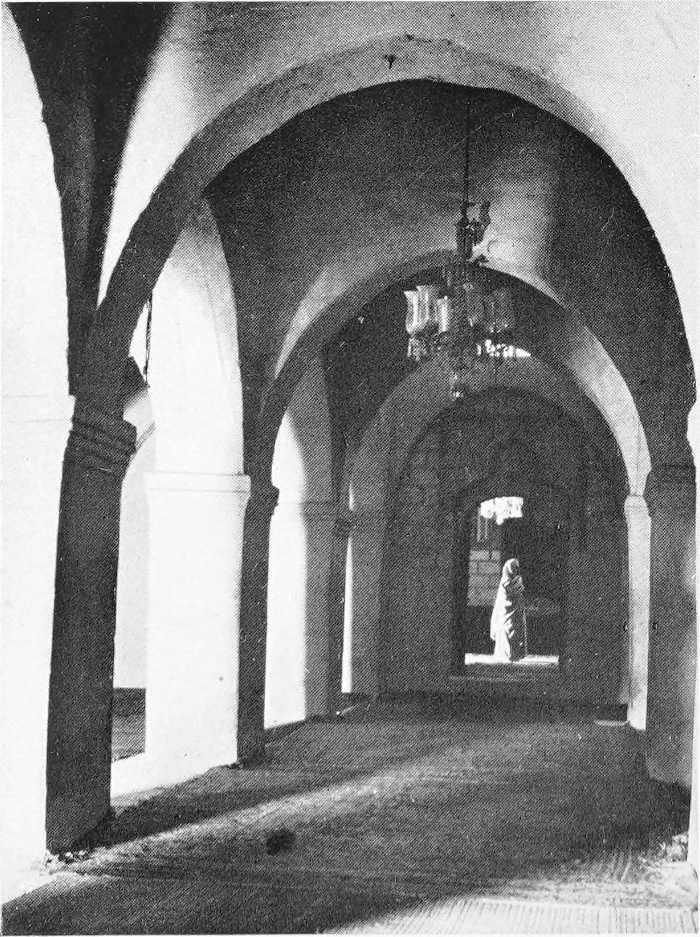

| A Cloister at the Mosque of Jaghbub | 65 |

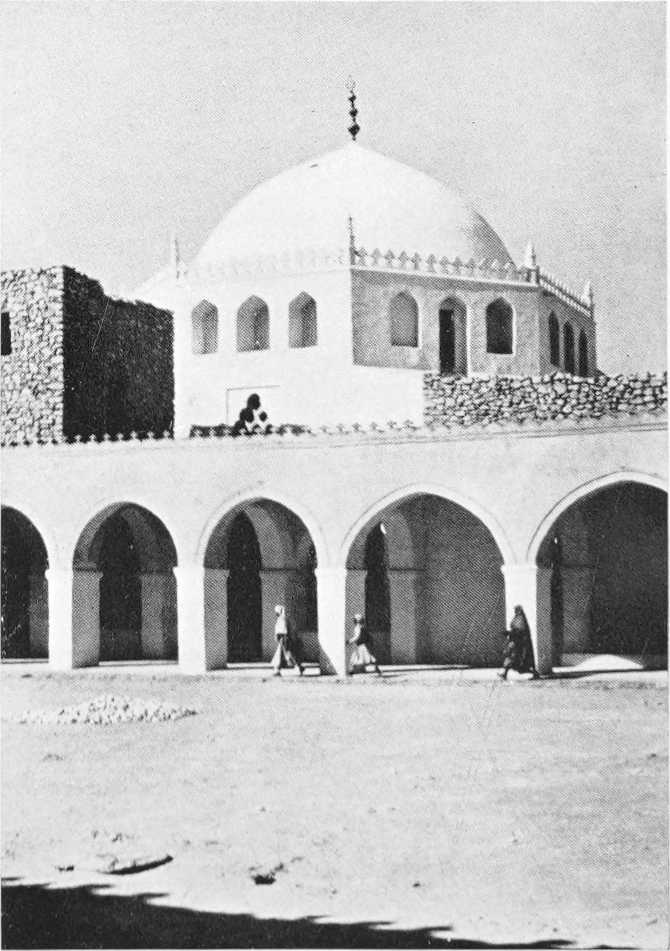

| The Dome of the Mosque at Jaghbub | 65 |

| The Explorer’s Caravan in a Sand-Storm | 69 |

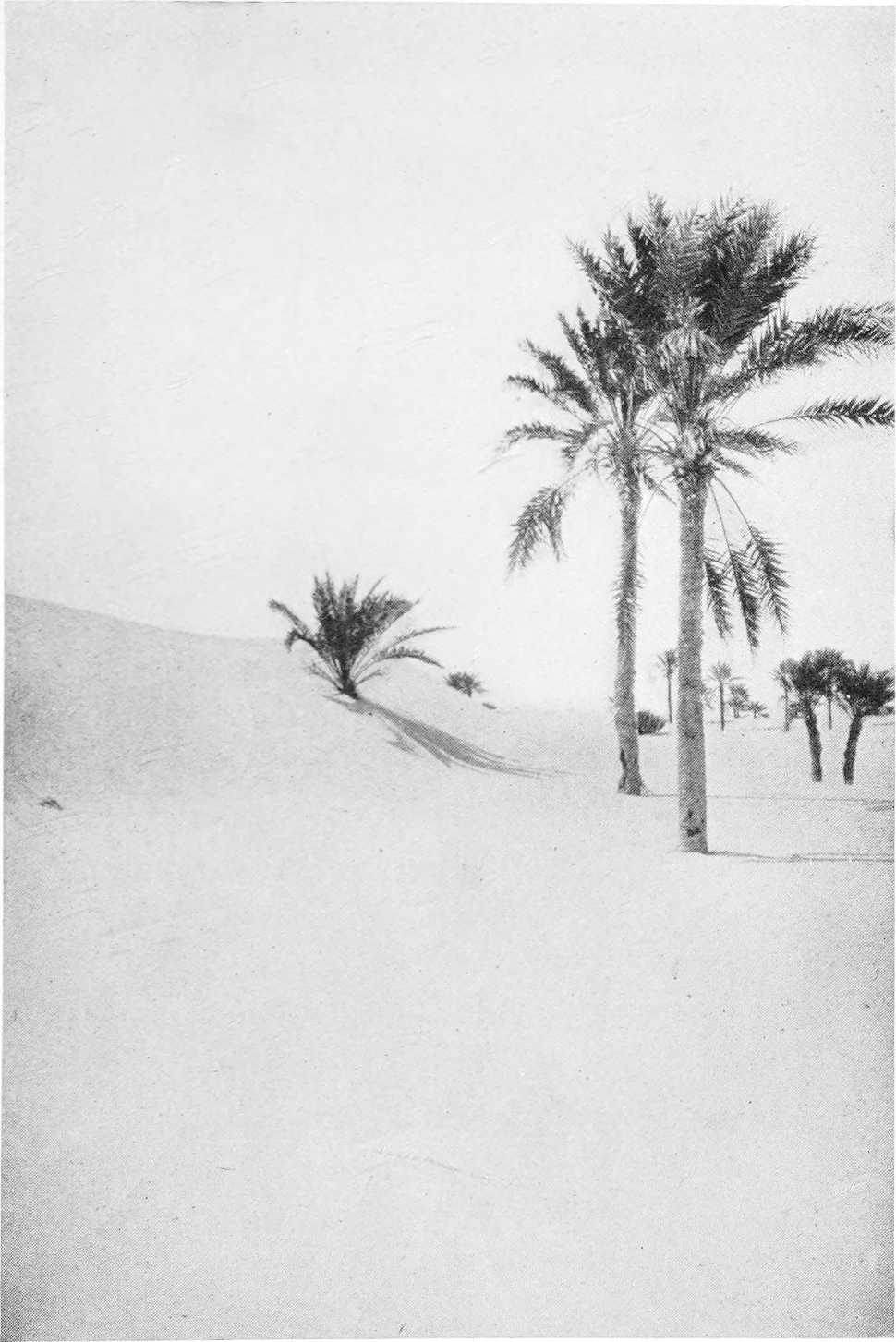

| Desert Sands Covering Date-Trees | 72 |

| [xx]The Zieghen Well | 76 |

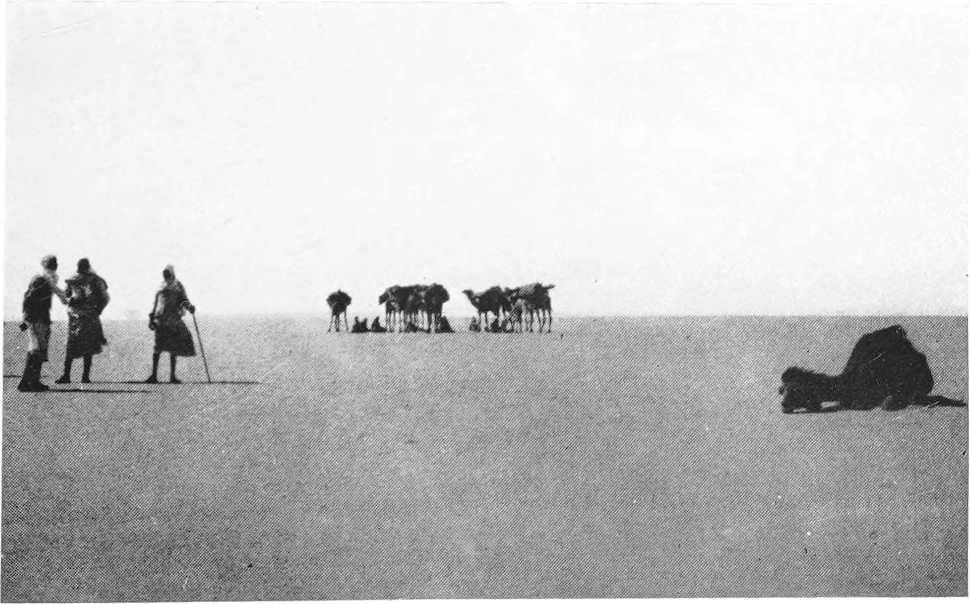

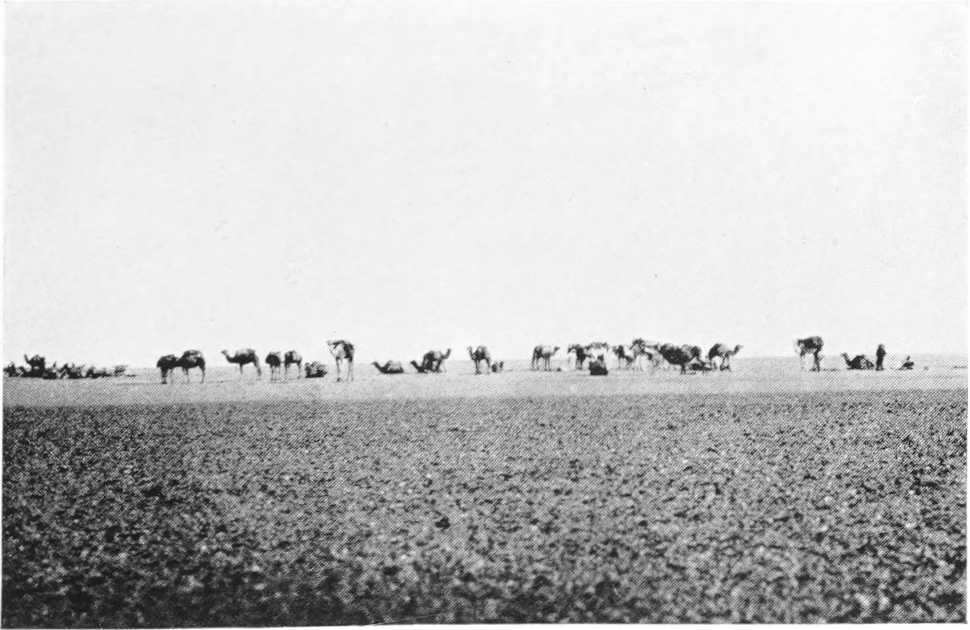

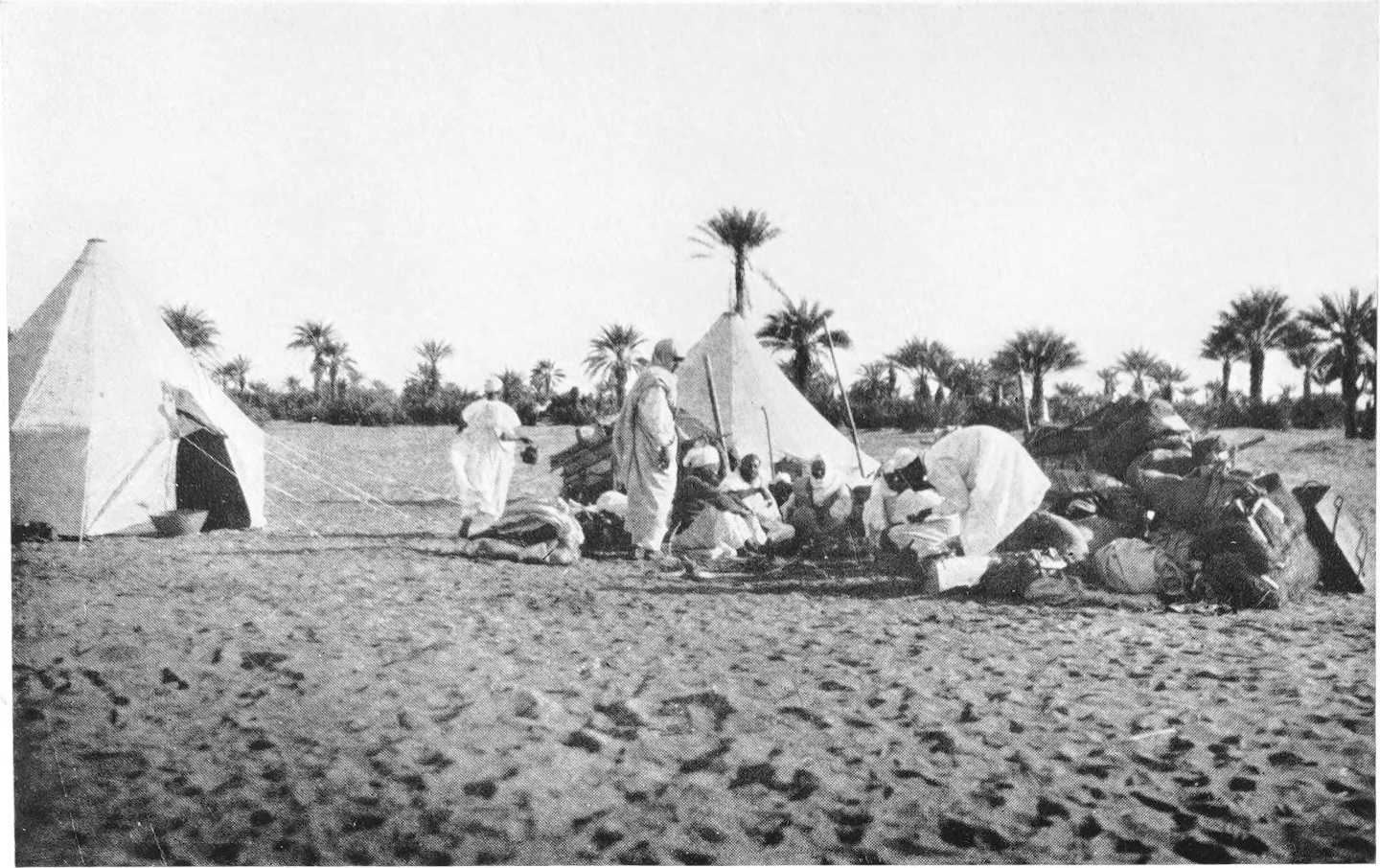

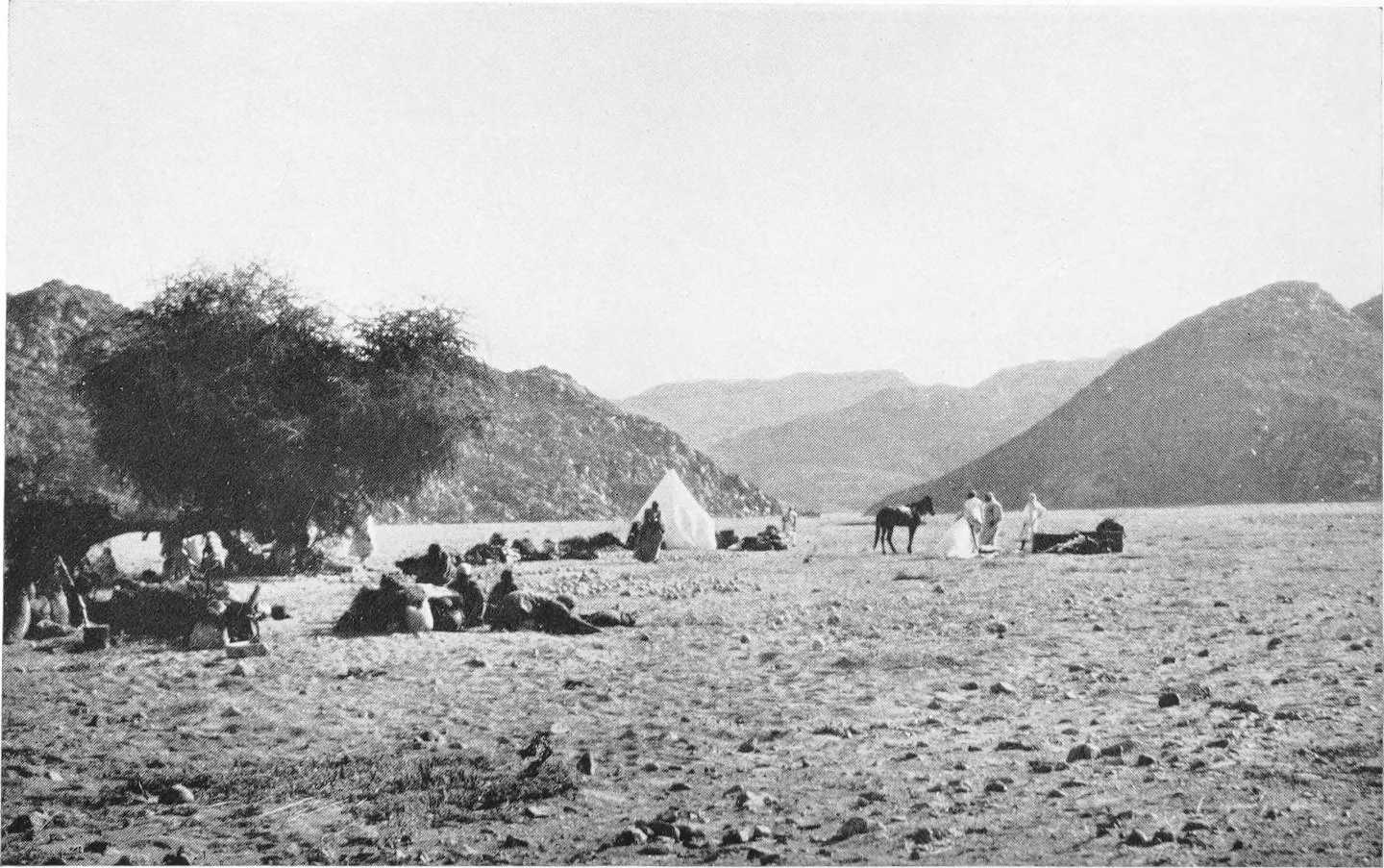

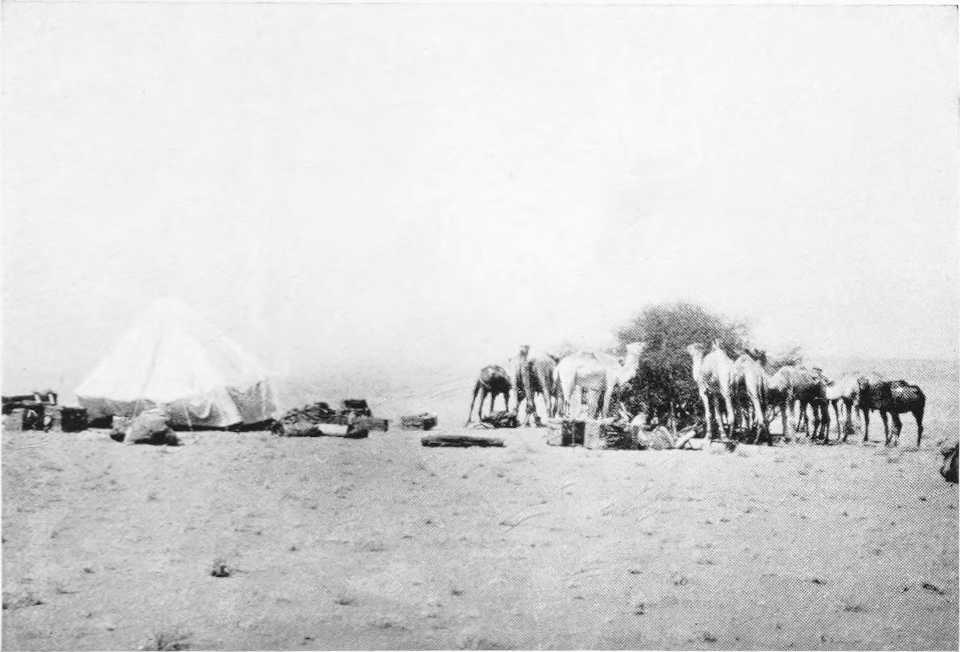

| A Halt in the Desert | 76 |

| The Armed Men of the Caravan | 81 |

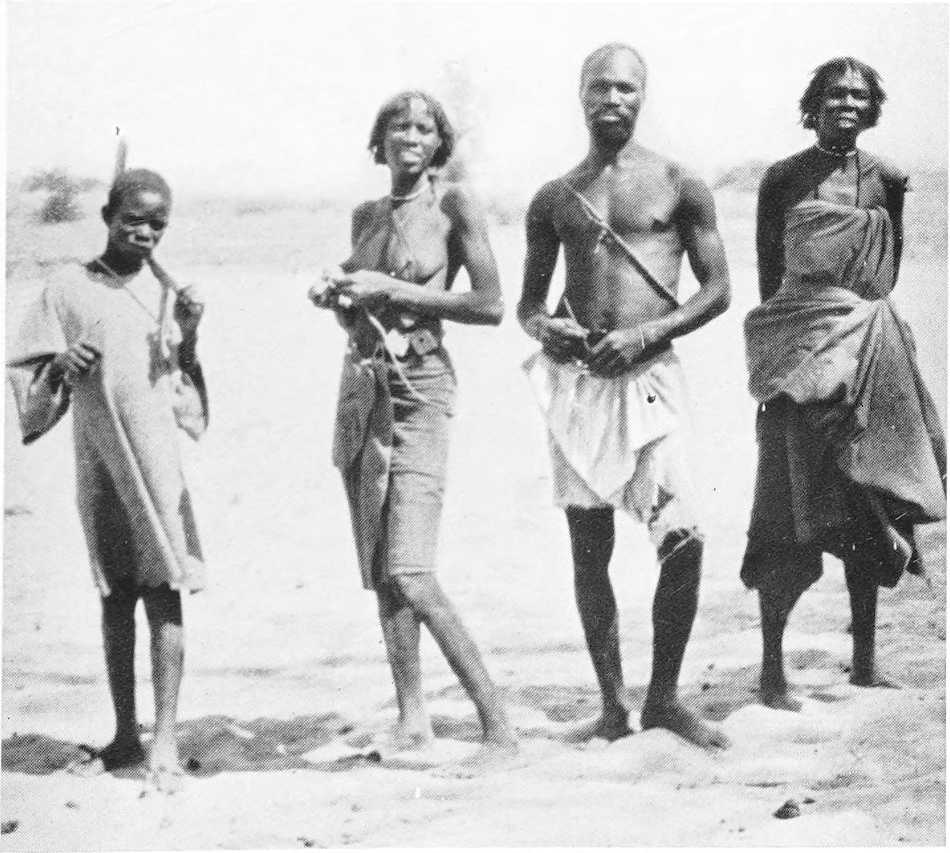

| Happy Tebus at Kufra | 84 |

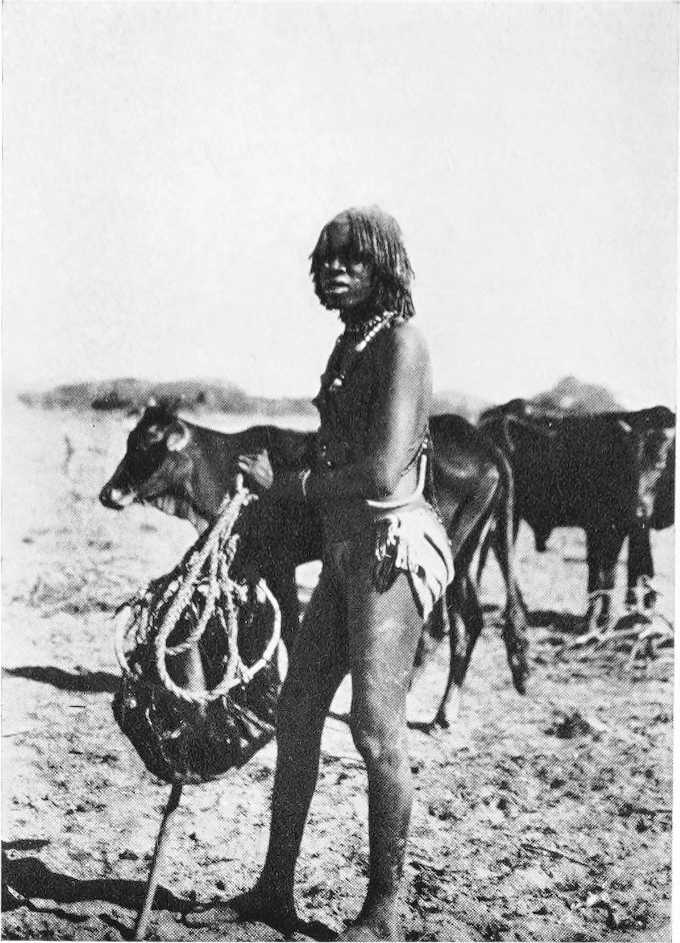

| A Bidiyat Family | 84 |

| Hawaria, a Landmark of Kufra | 88 |

| Camels Crossing the Sand-Dunes | 93 |

| Sayed Mohammed El Abid | 96 |

| The House of Sayed El Abid | 96 |

| Tebu Girl Wearing Bedouin Clothes | 100 |

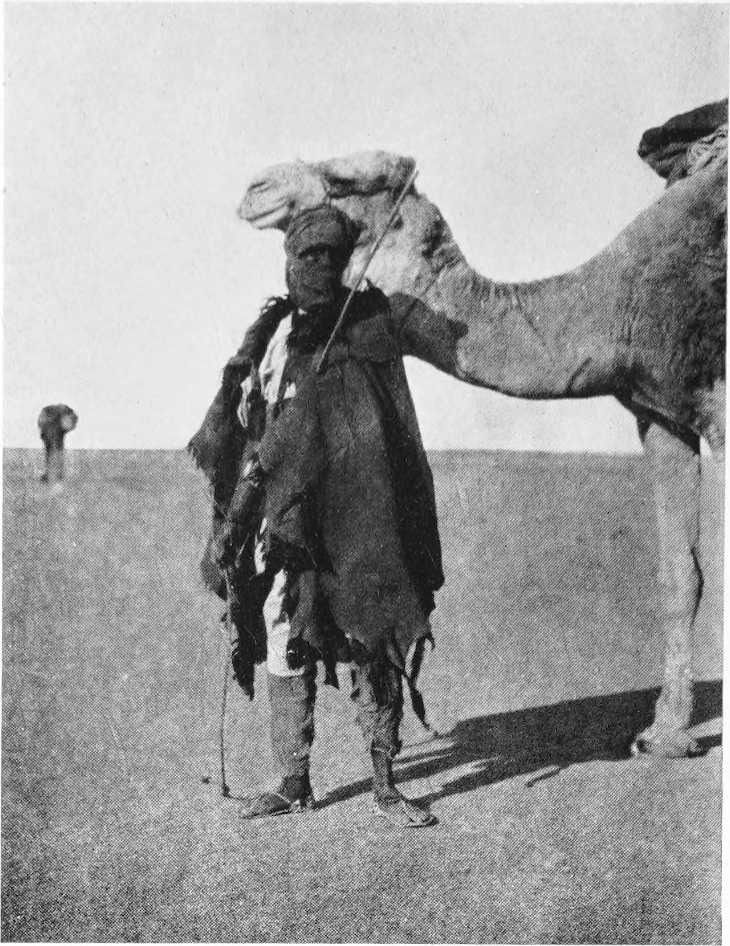

| A Tebu with his Camel | 100 |

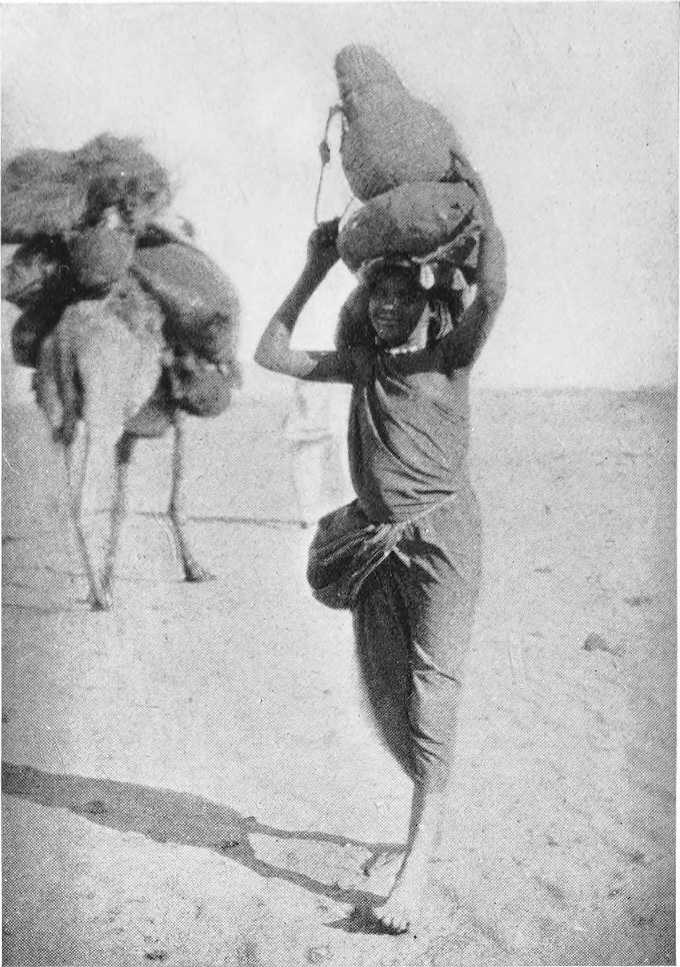

| Slave at Kufra | 104 |

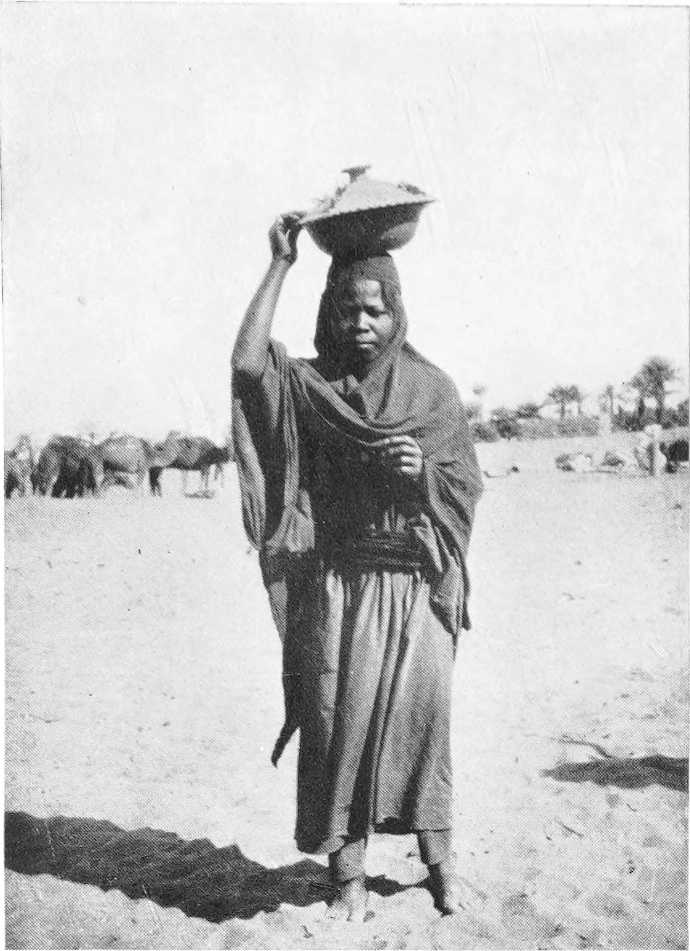

| Tebu Girl Carrying Burden on her Head | 104 |

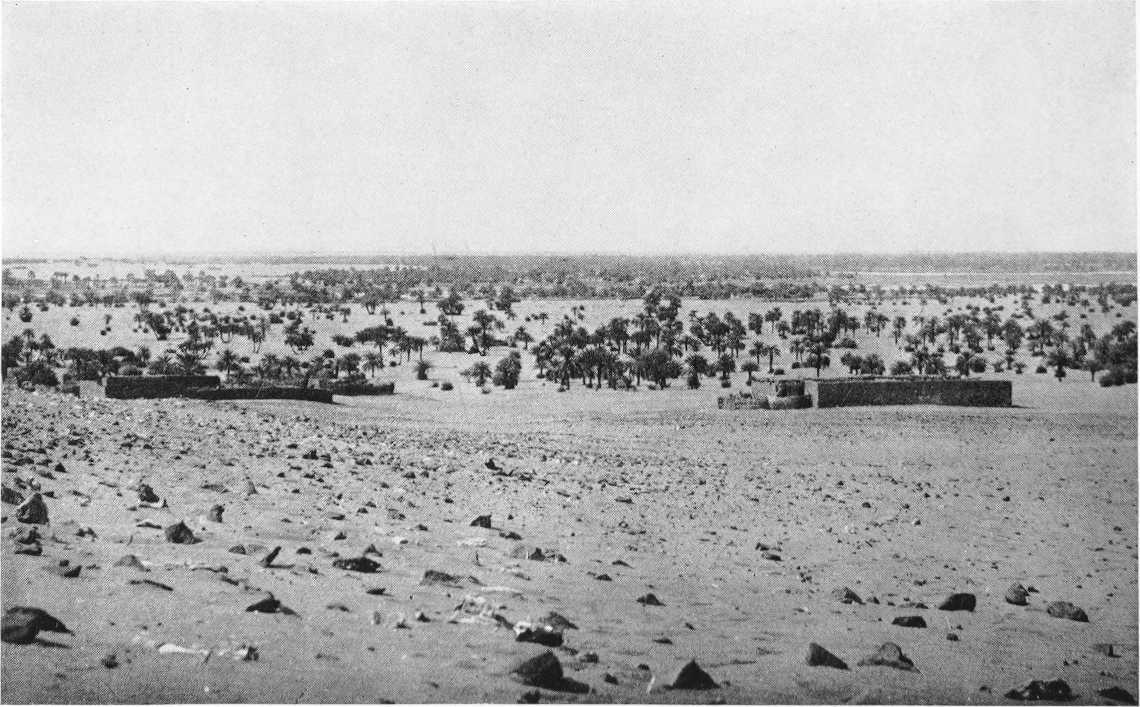

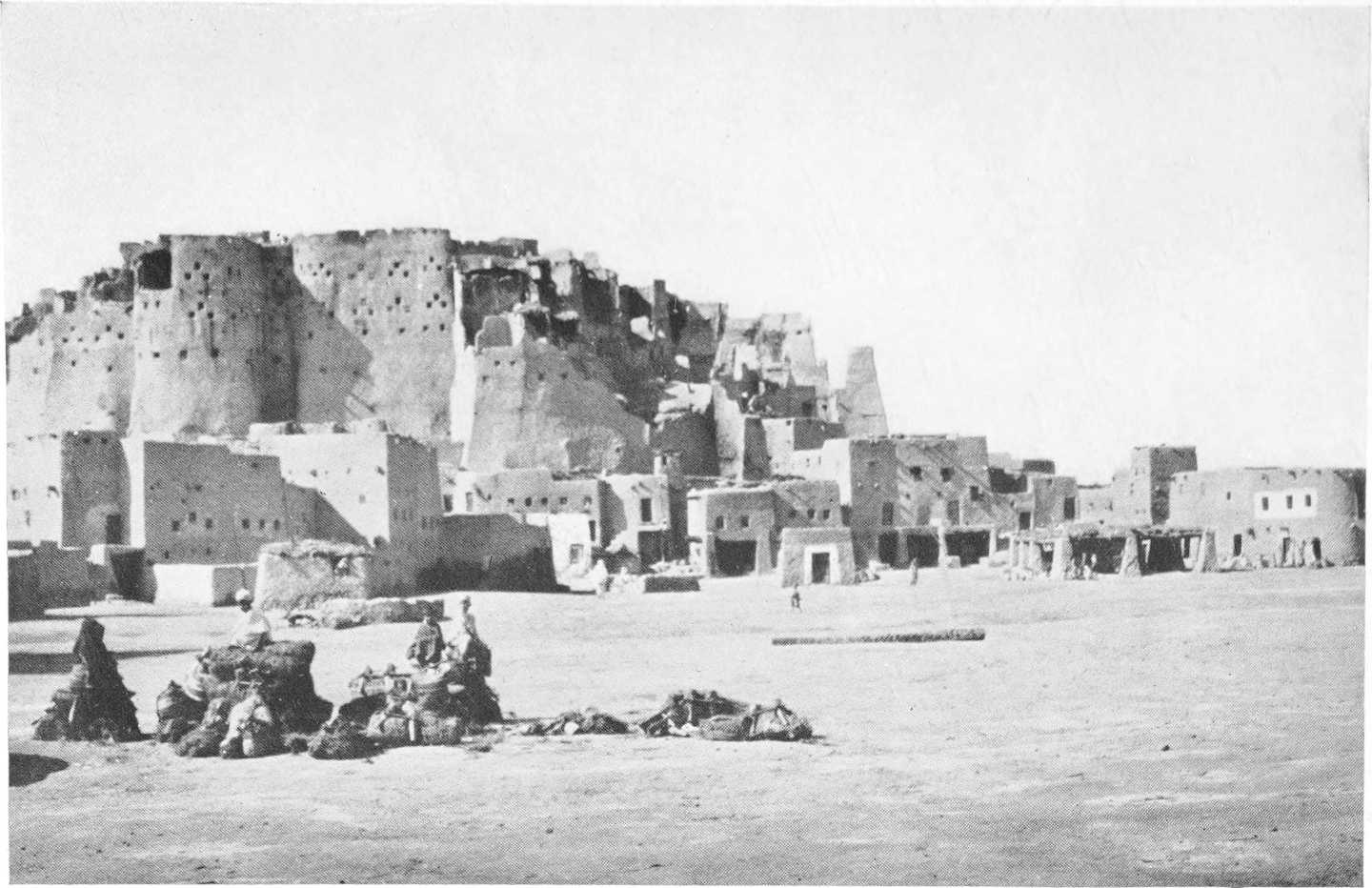

| Kufra | 109 |

| The Oasis of Hawari | 112 |

| South of Kufra | 116 |

| Ruins of Kufra | 120 |

| A Senussi Prince at Kufra | 125 |

| Governor of Kufra | 125 |

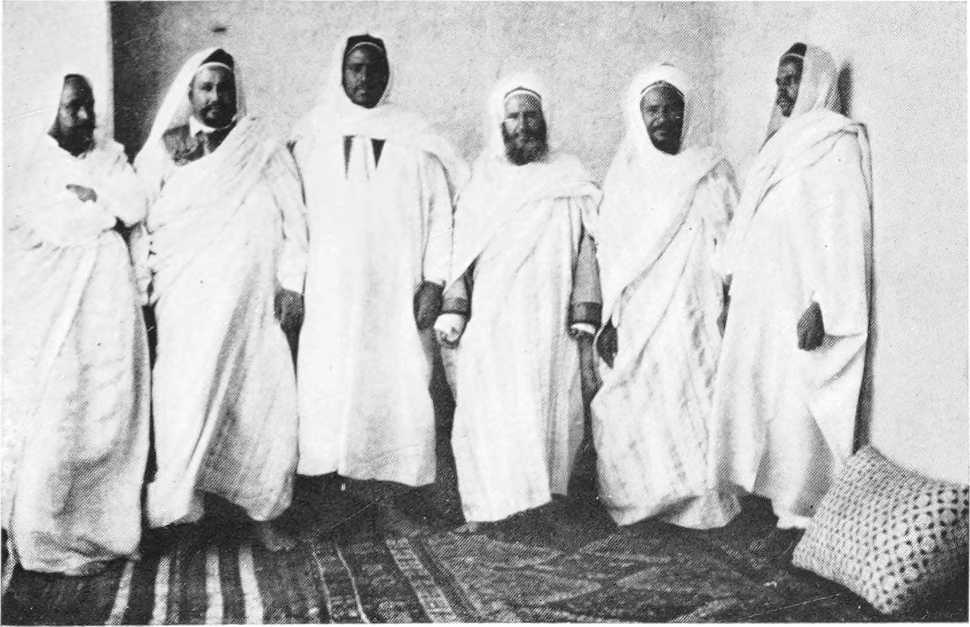

| Zwaya Chiefs at Kufra | 129 |

| The Lake at Kufra | 132 |

| El Taj | 136 |

| The Council of Kufra | 136 |

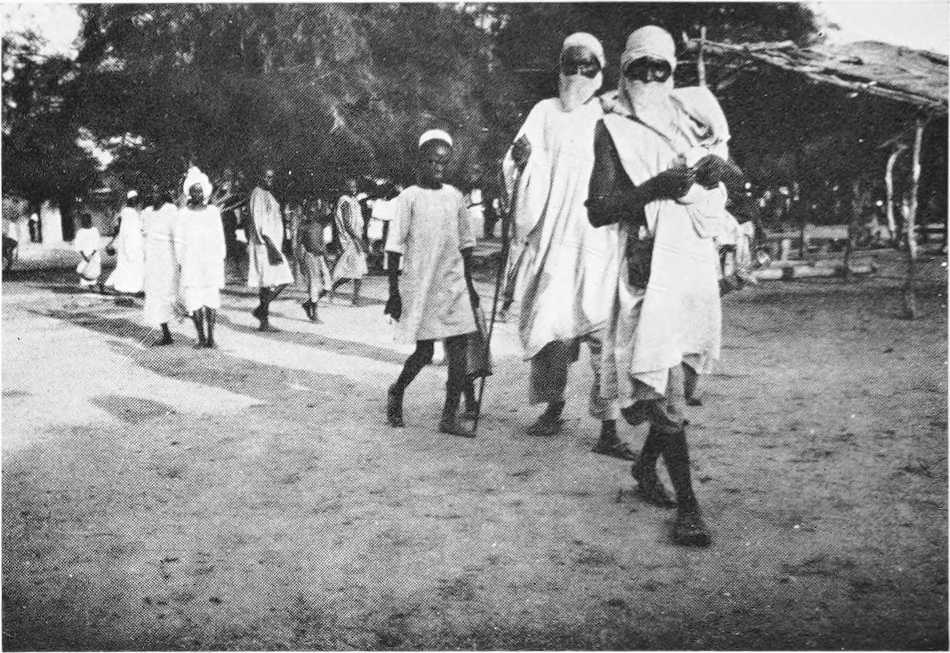

| Tuaregs in Kufra | 141 |

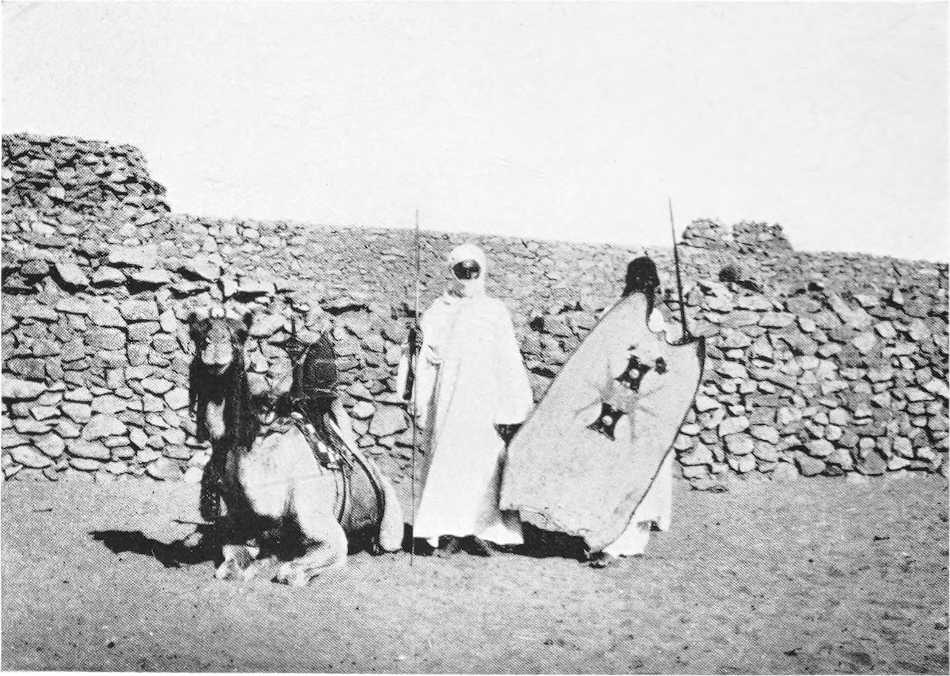

| [xxi]Two Tuaregs in Warrior Attire | 141 |

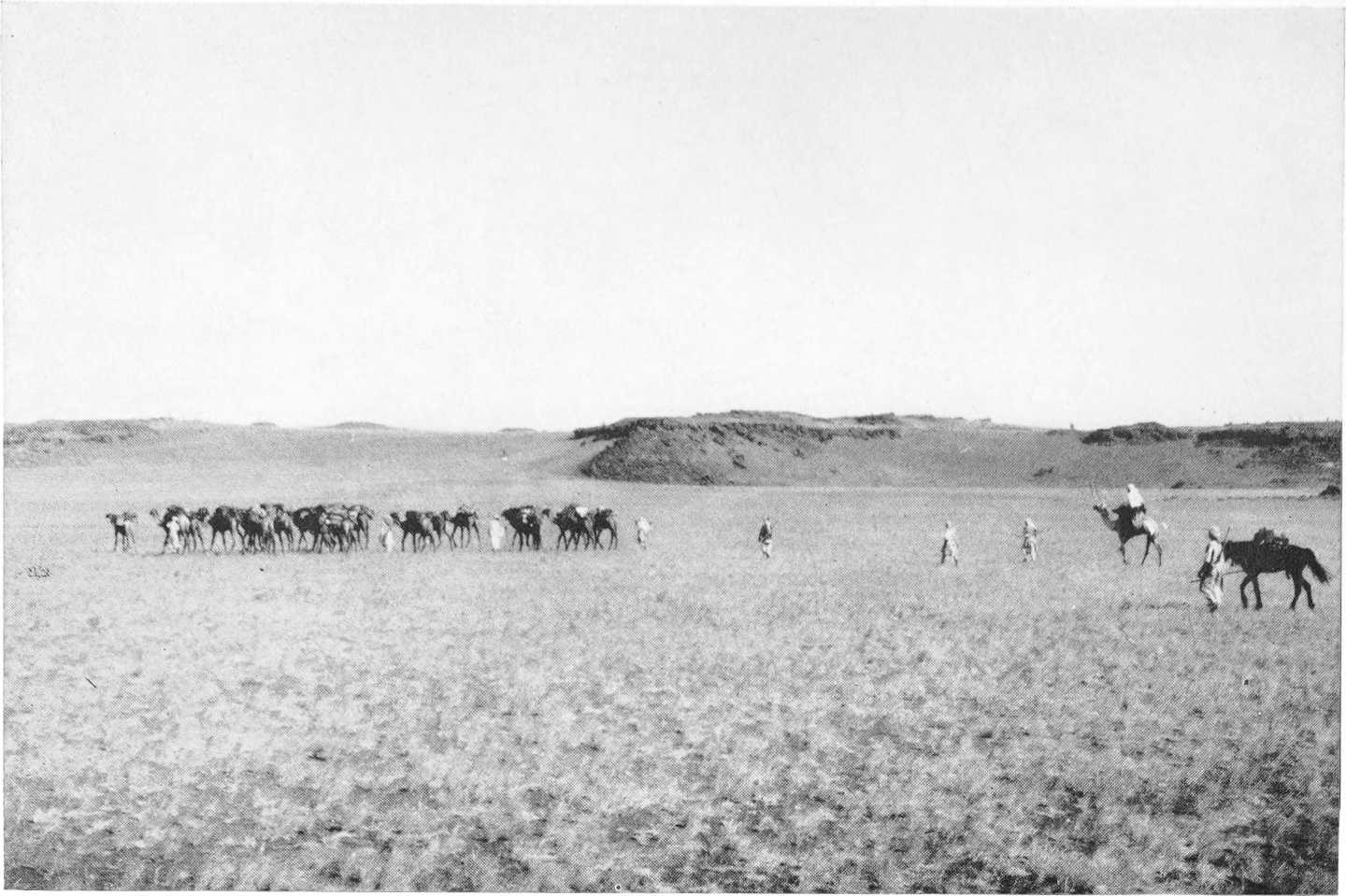

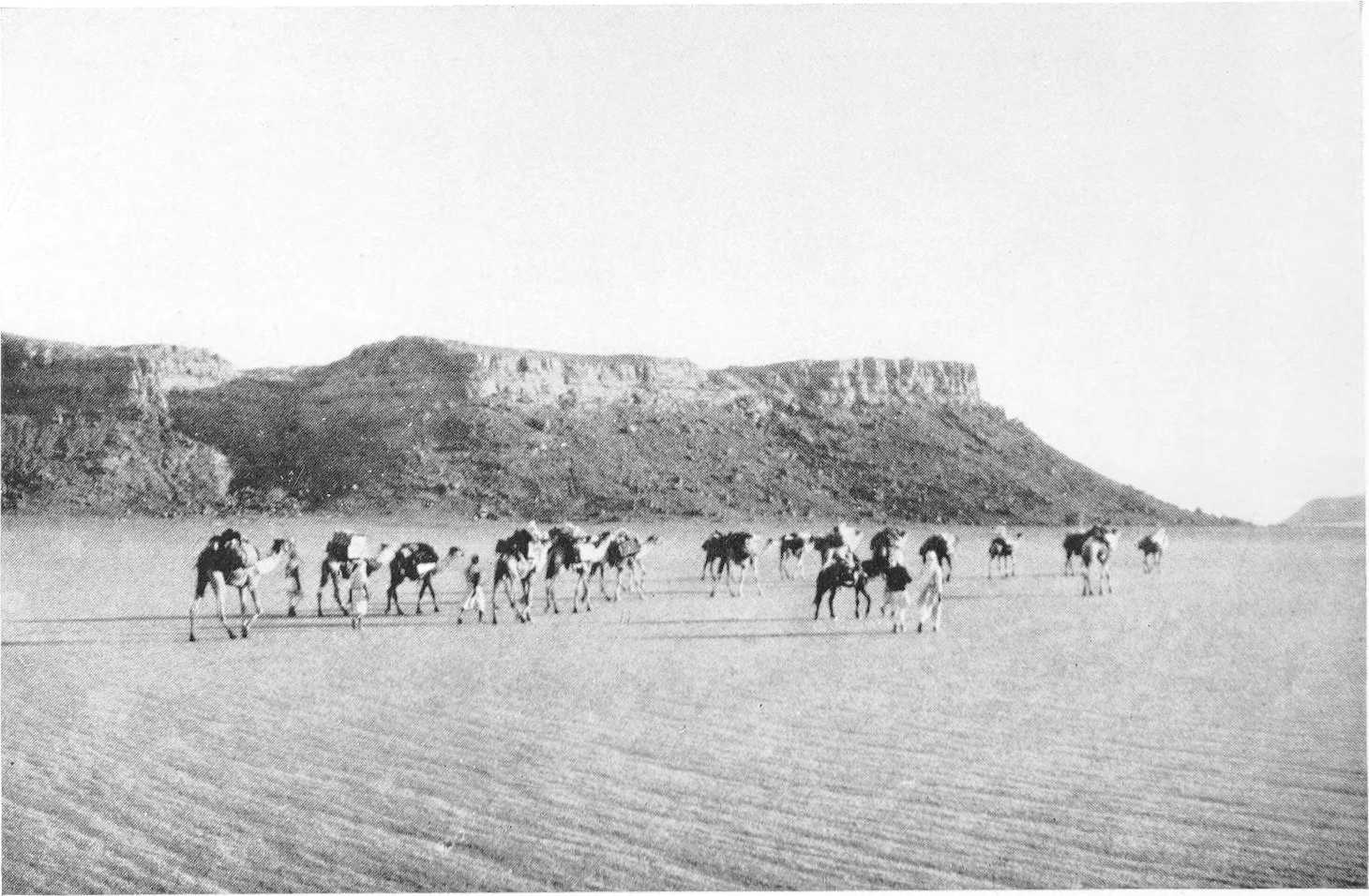

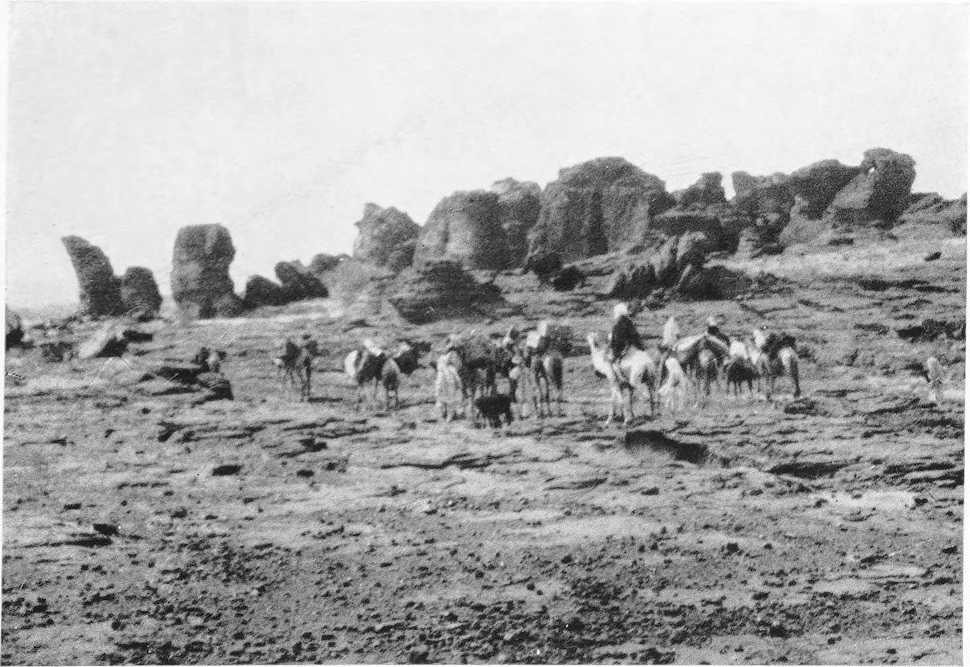

| The Caravan on the Move in the Desert to Agah | 144 |

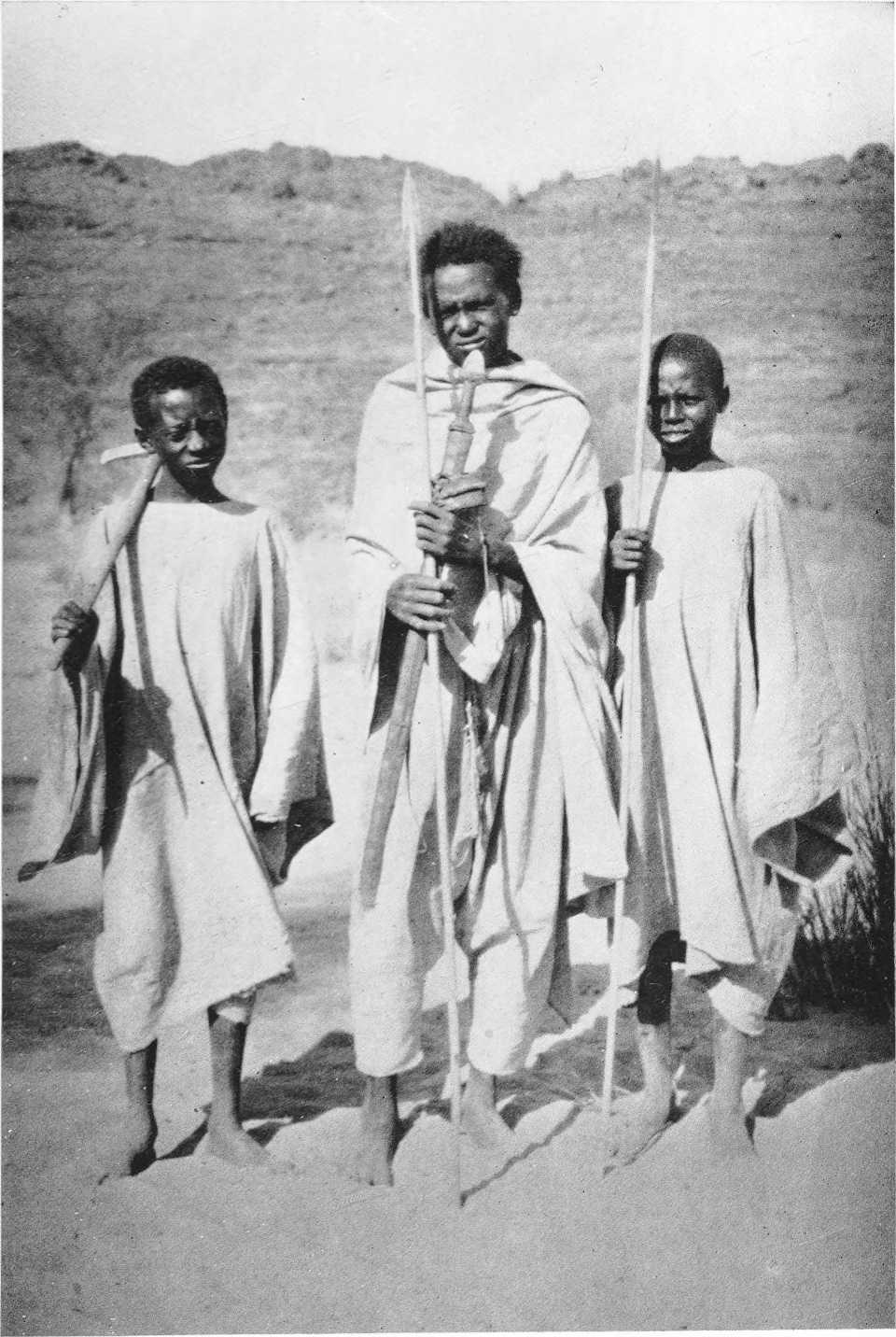

| Sons of Sheikh Herri | 148 |

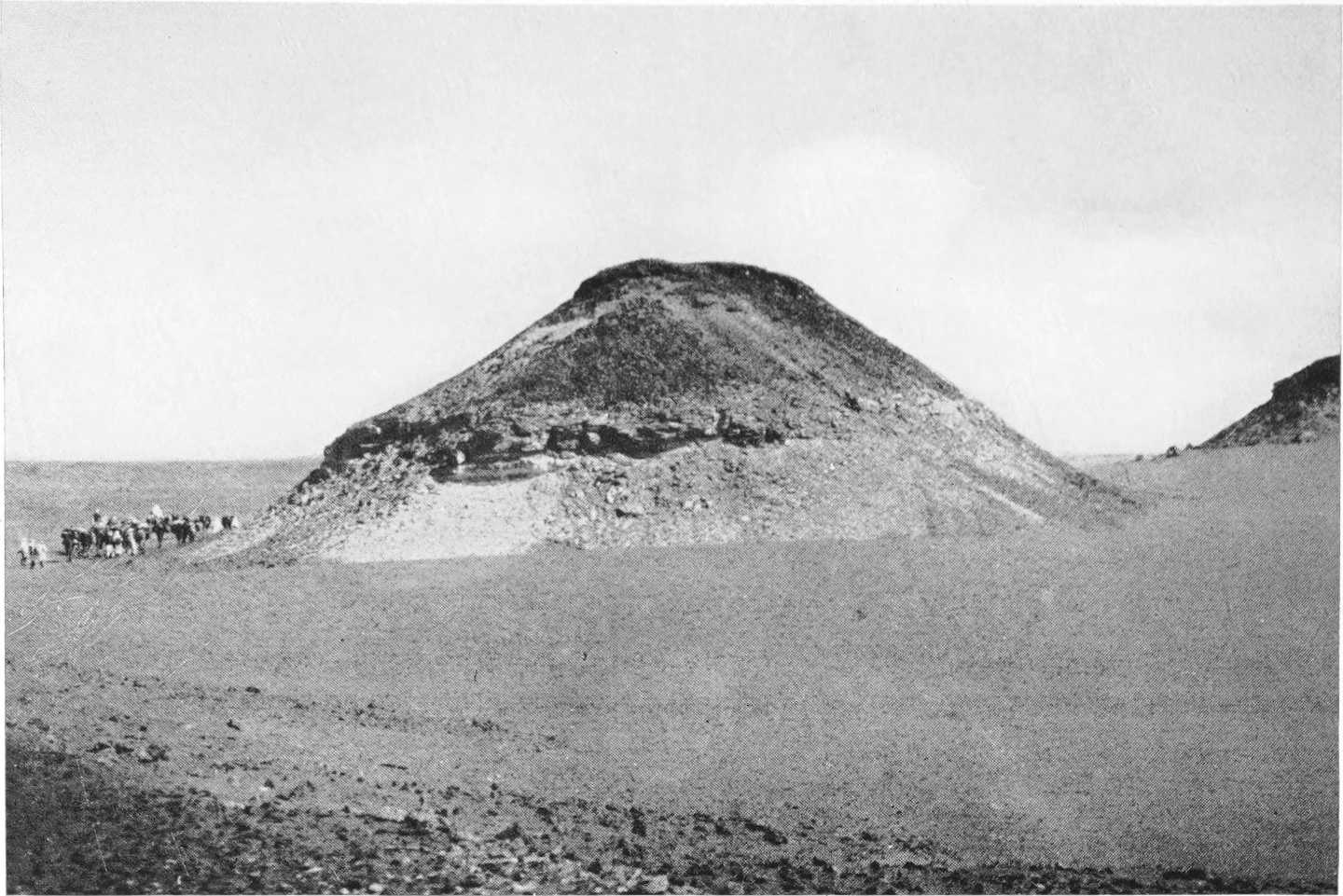

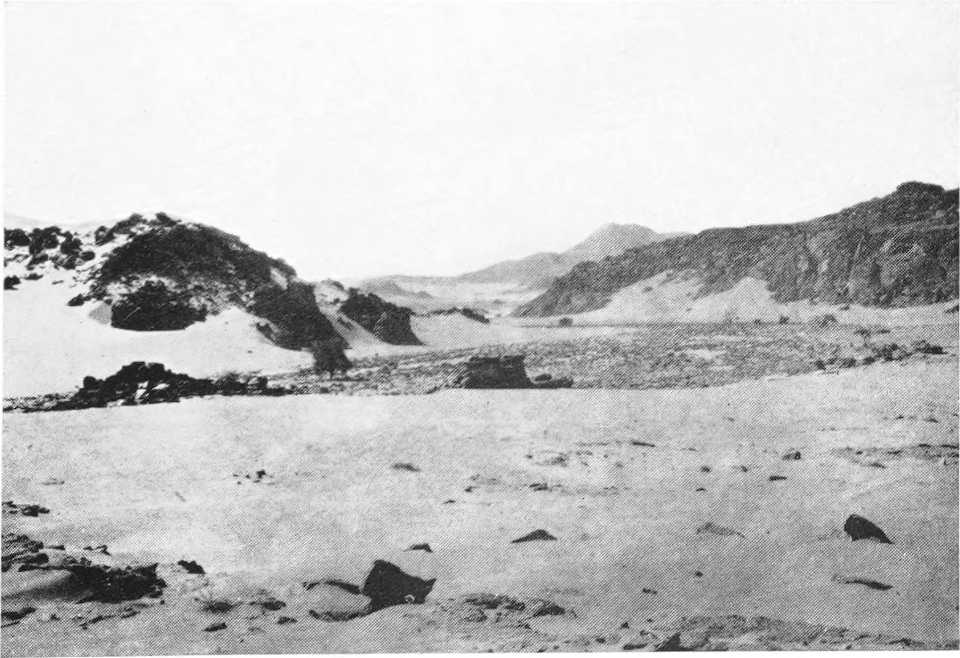

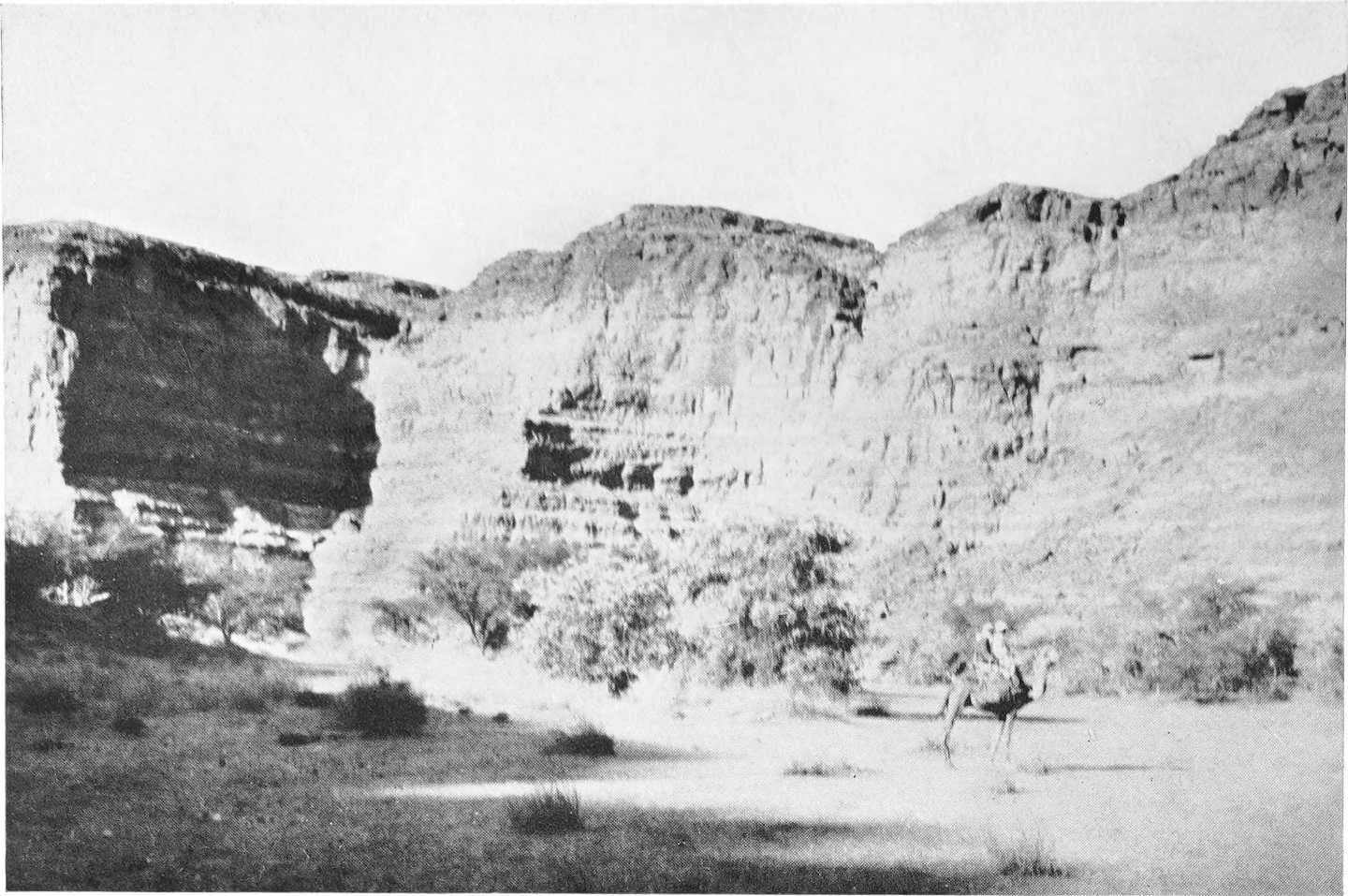

| Approaching the Hills of Arkenu | 152 |

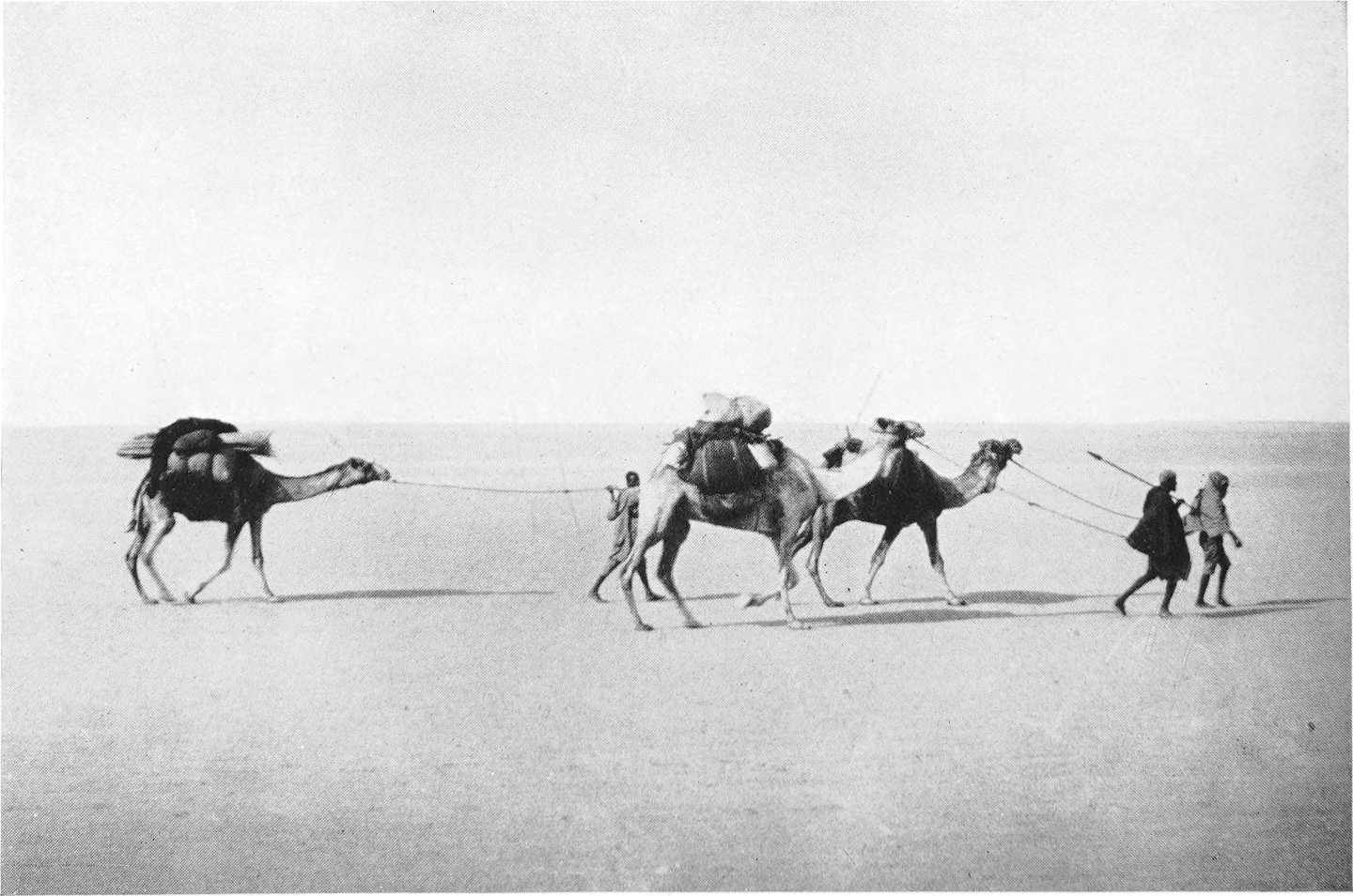

| In the Open Desert | 157 |

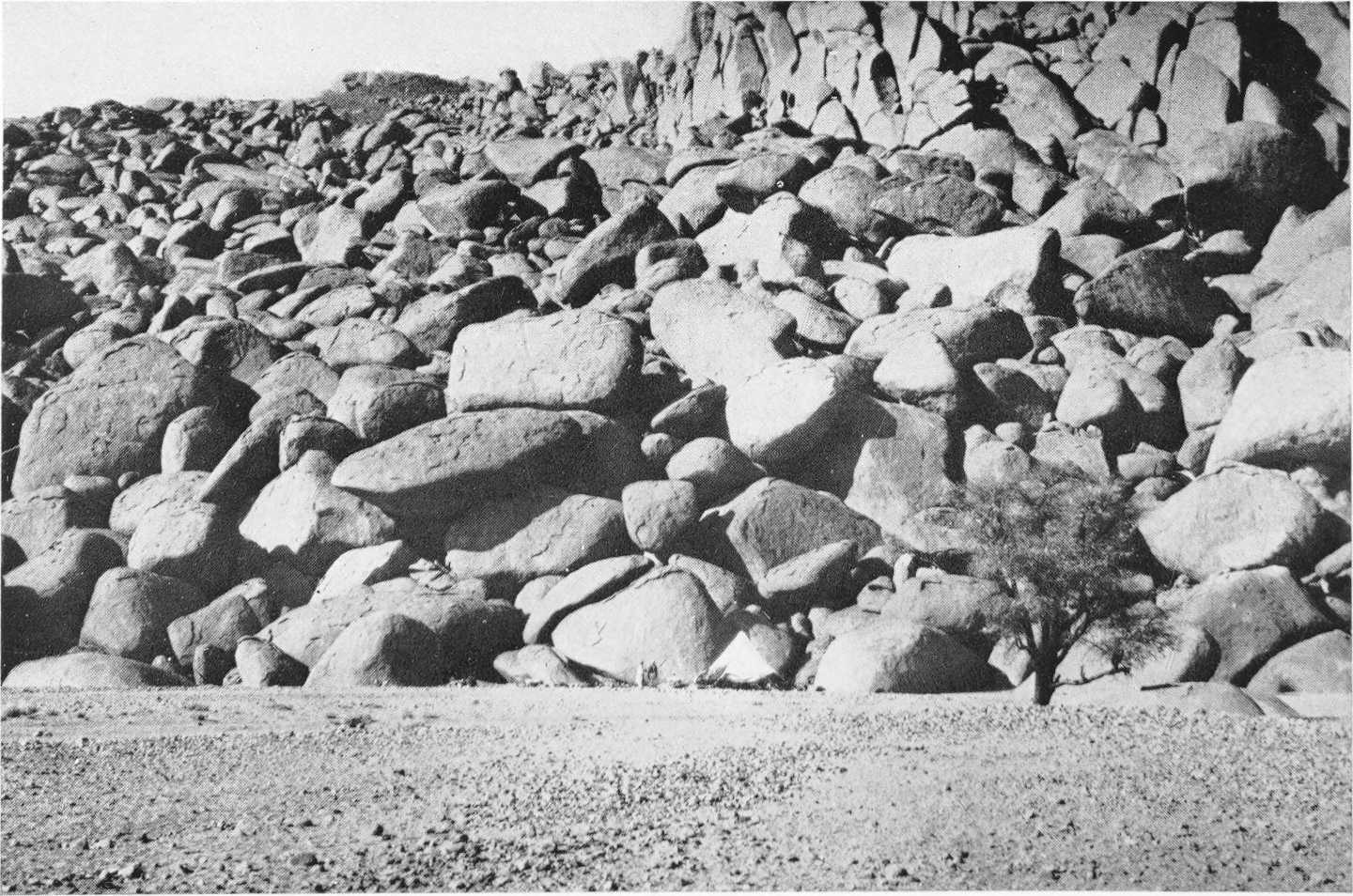

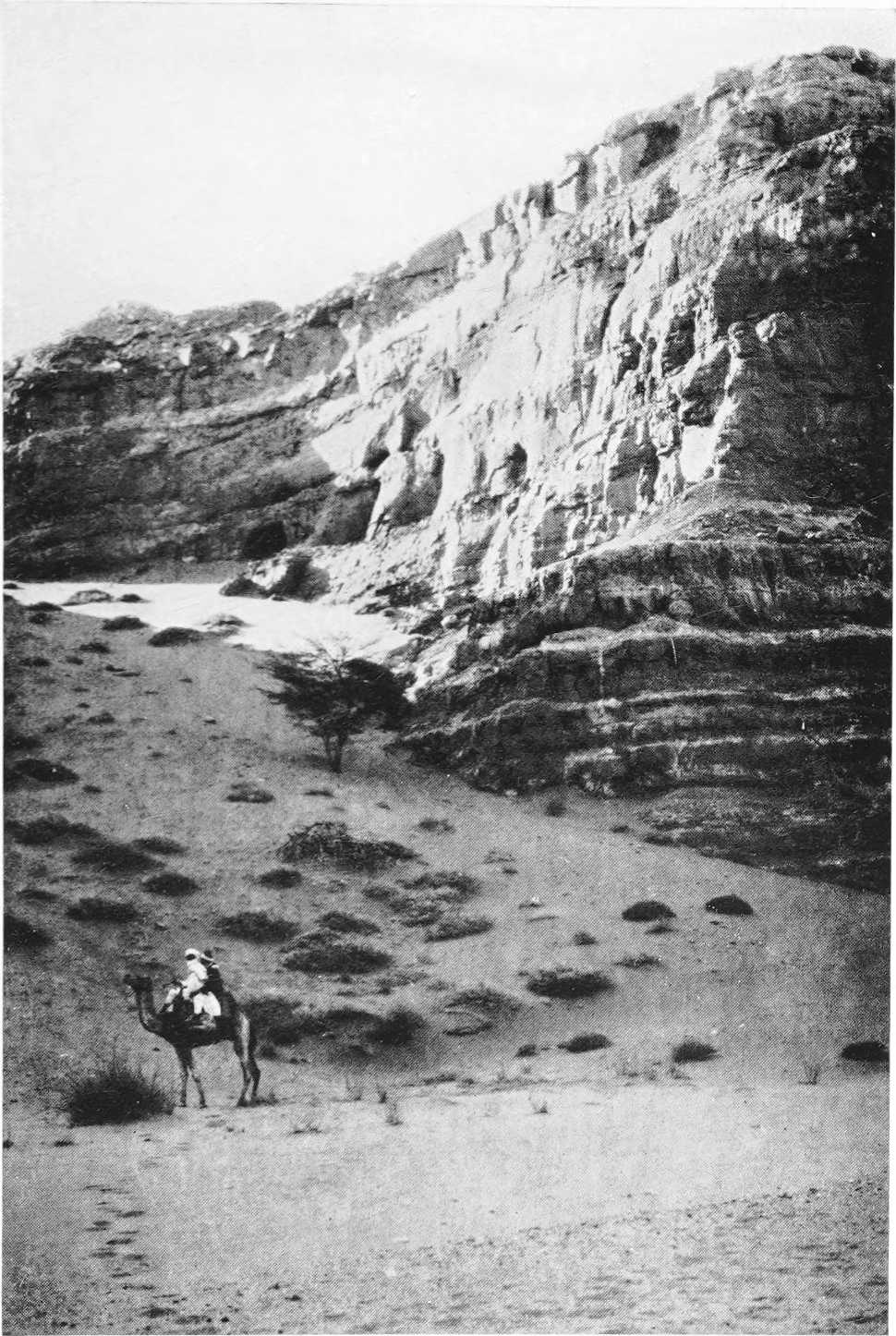

| The Hills of Arkenu | 161 |

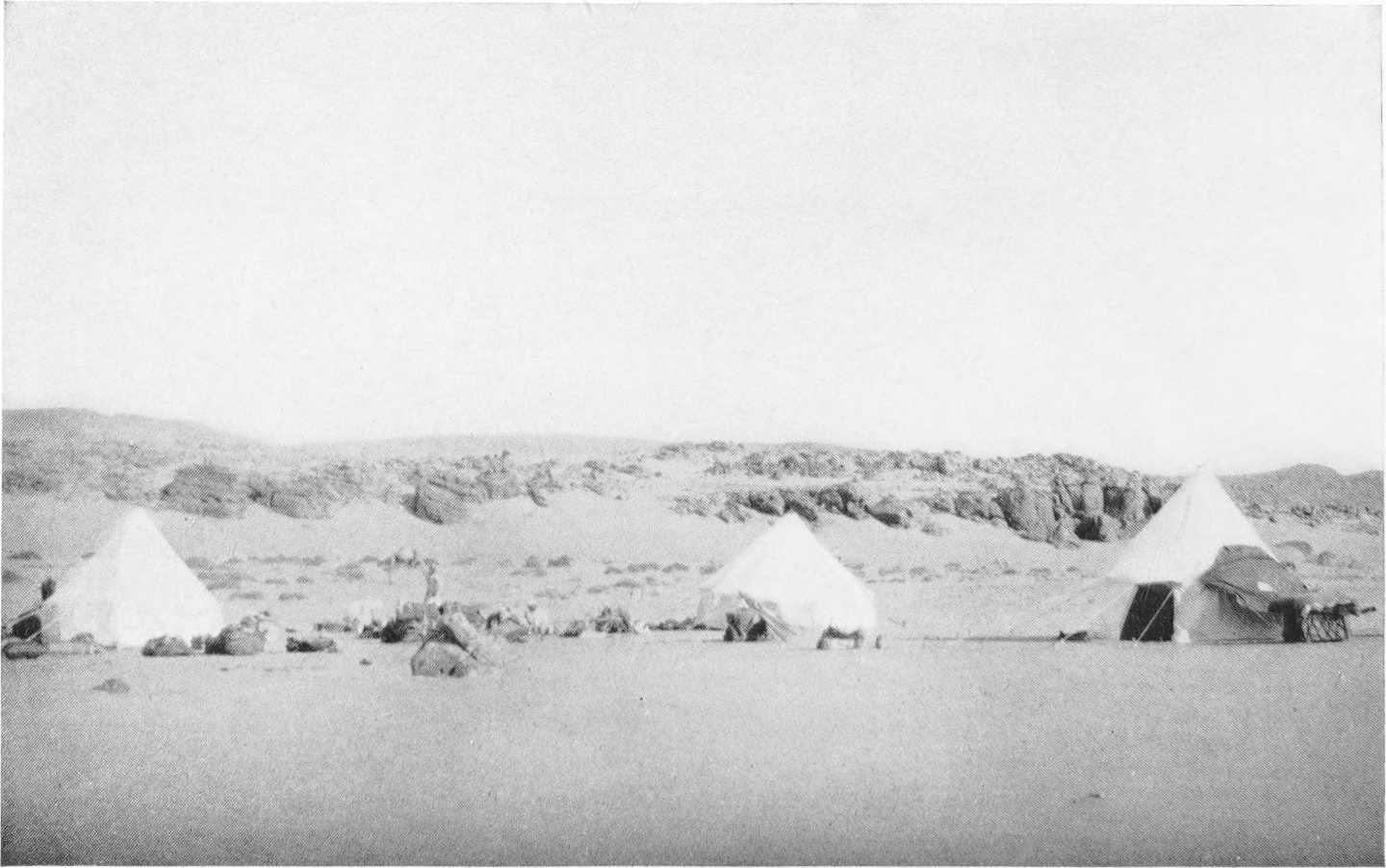

| The Explorer’s Camp at Ouenat | 164 |

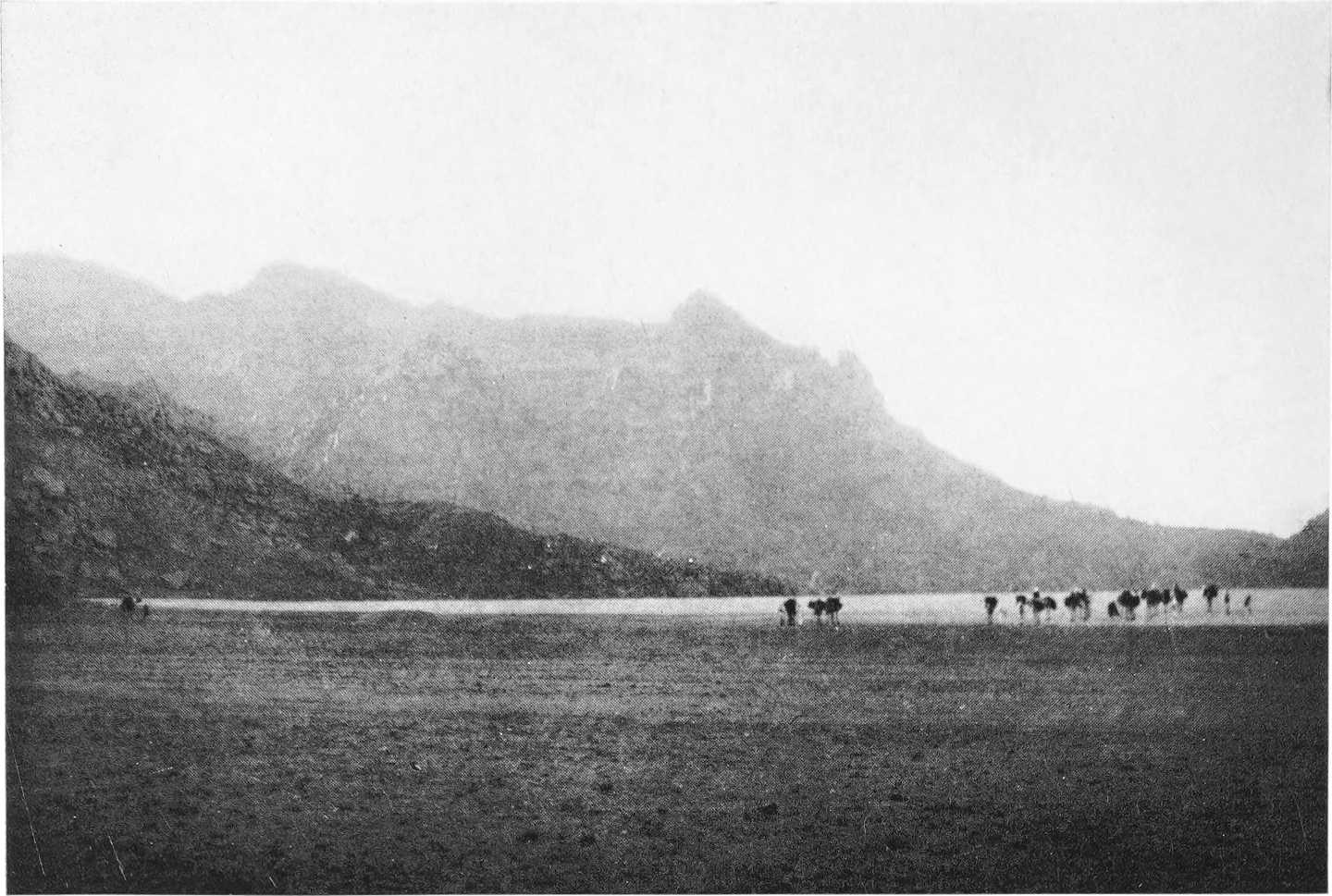

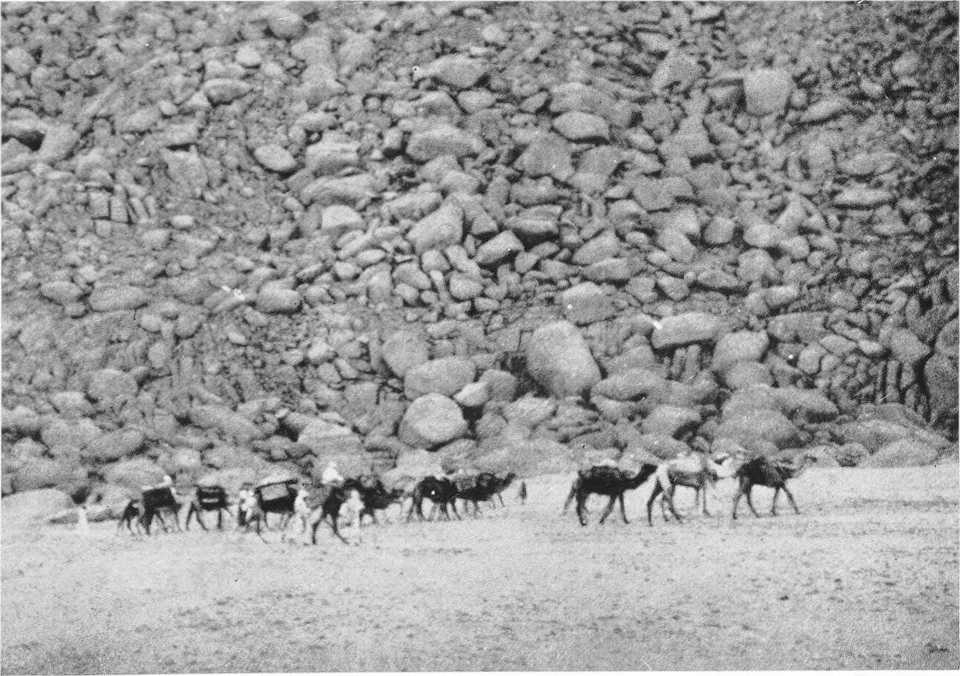

| The Caravan Approaching the Granite Hills of Ouenat | 164 |

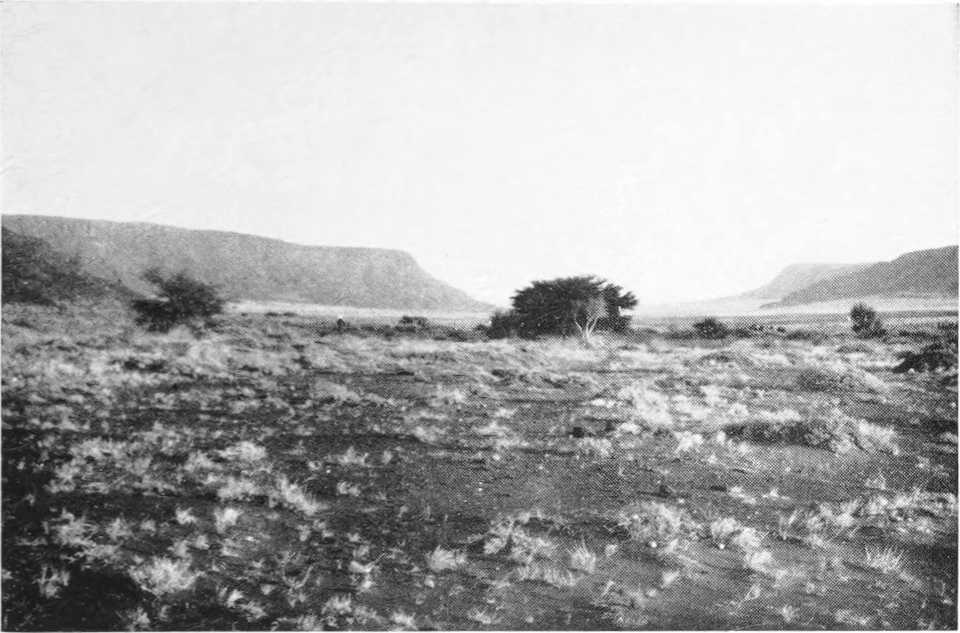

| Valley of Erdi | 168 |

| Desert Breaking into Rock Country South of Ouenat | 168 |

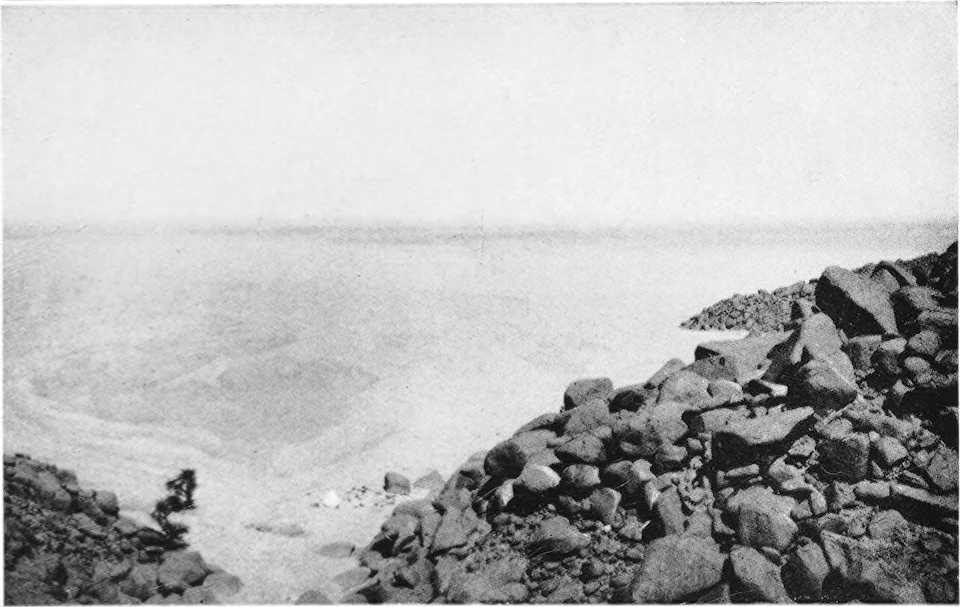

| The Desert from the Hills of Ouenat | 173 |

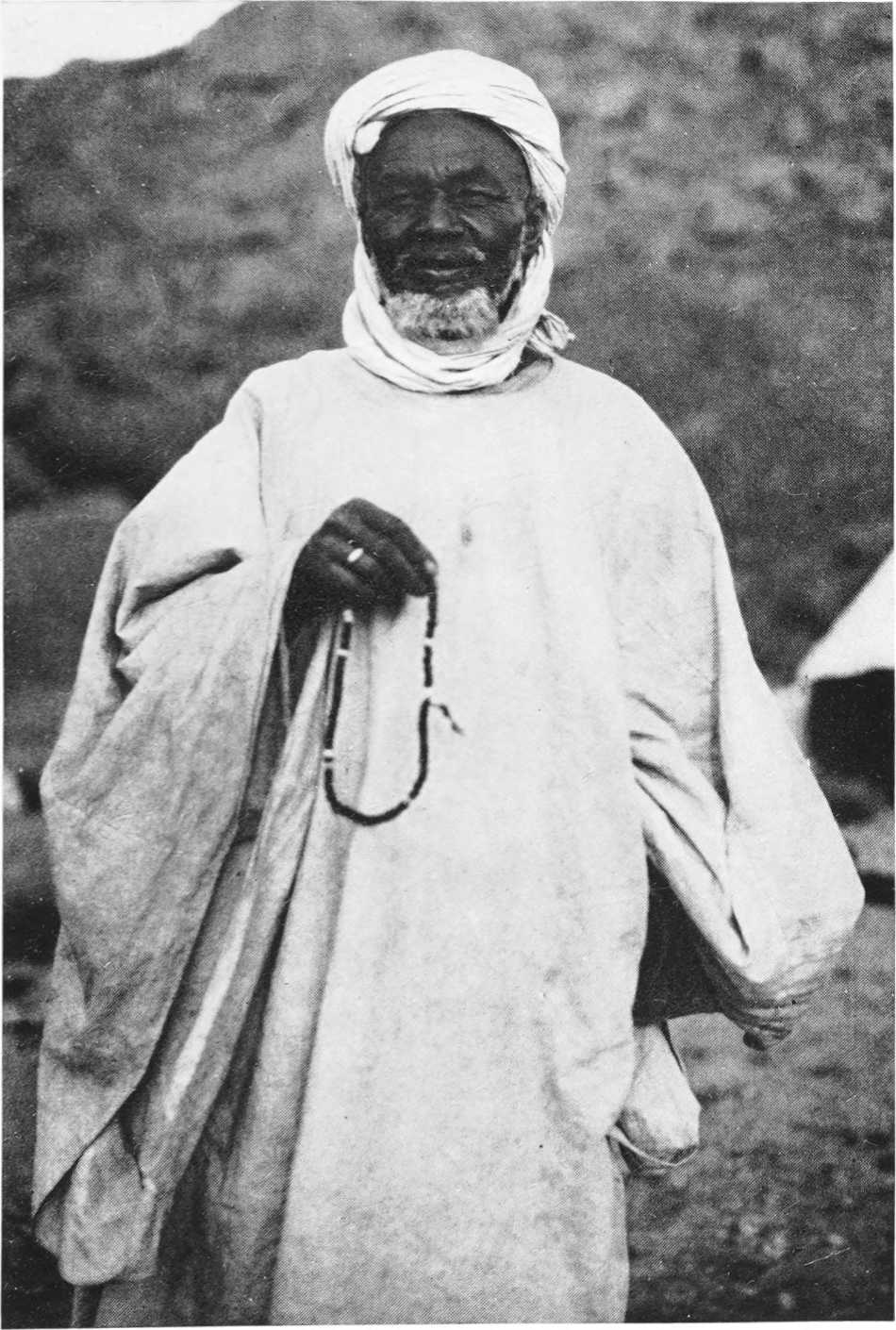

| The King of Ouenat | 176 |

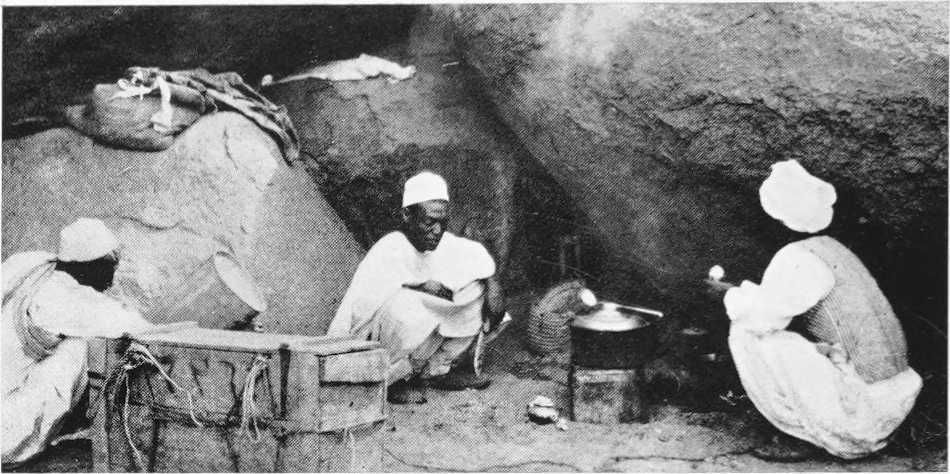

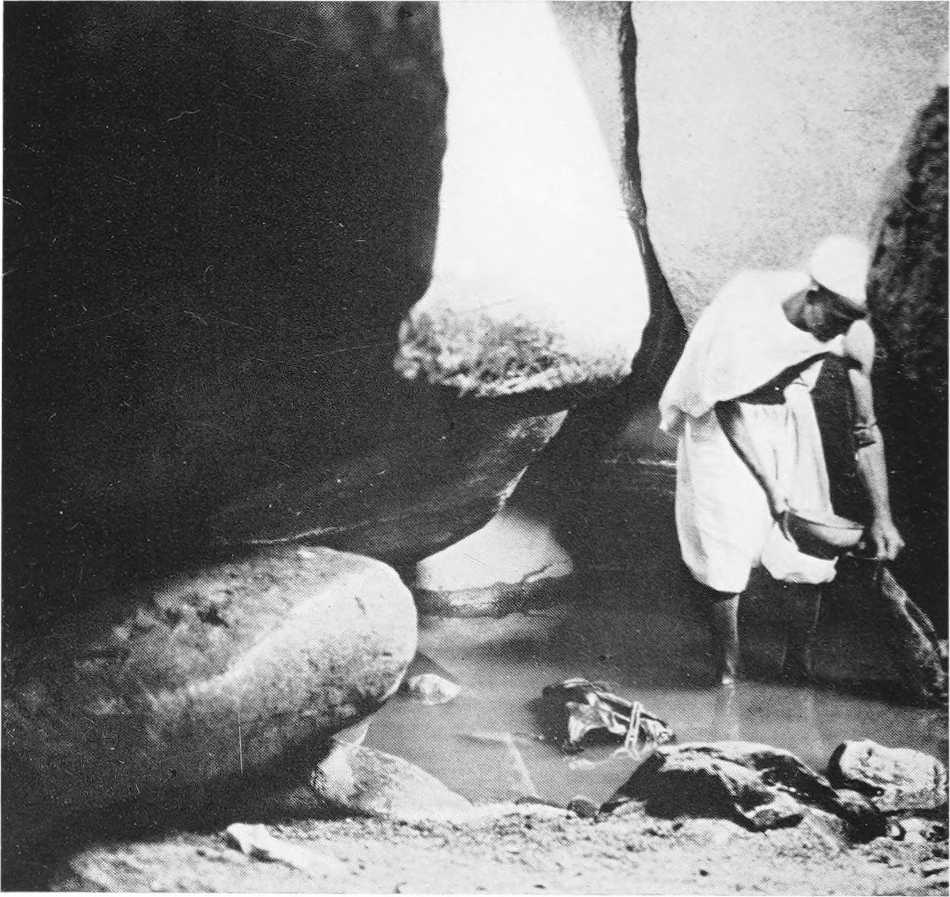

| The Explorer’s Kitchen in a Cave | 181 |

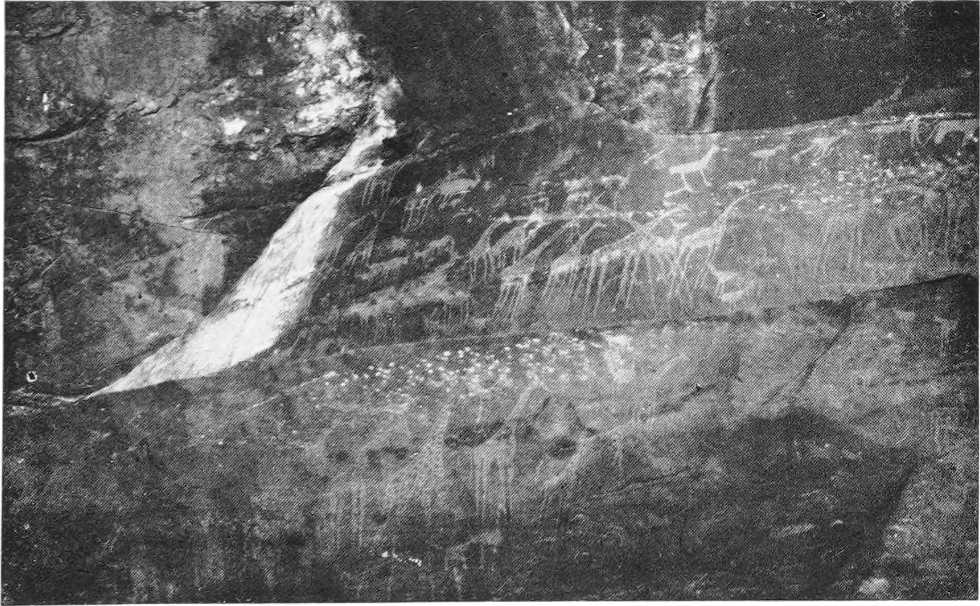

| The Rock Valley Wells Found at Ouenat | 181 |

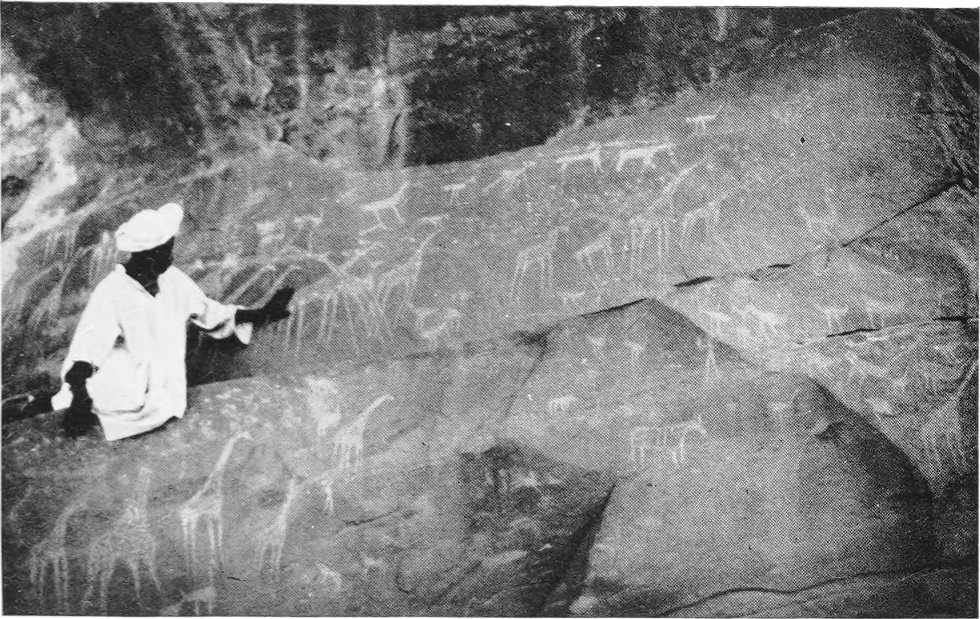

| At Arkenu | 188 |

| The Most Important Discovery Made at Ouenat | 188 |

| White Sand Valley and Explorer’s Camp | 193 |

| The Caravan Arriving at Ouenat | 197 |

| The Valley of Erdi | 200 |

| The First Tree Seen Approaching Erdi | 204 |

| The Explorer’s Camp in the Valley of Erdi | 208 |

| South of Erdi | 208 |

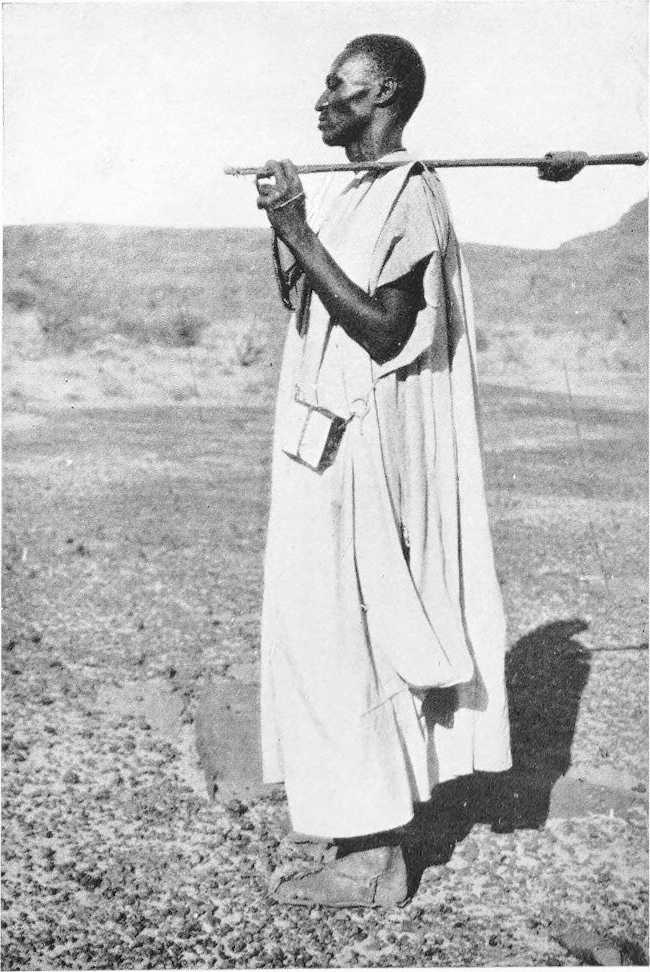

| The Chieftain of the Bidiyat Tribe | 213 |

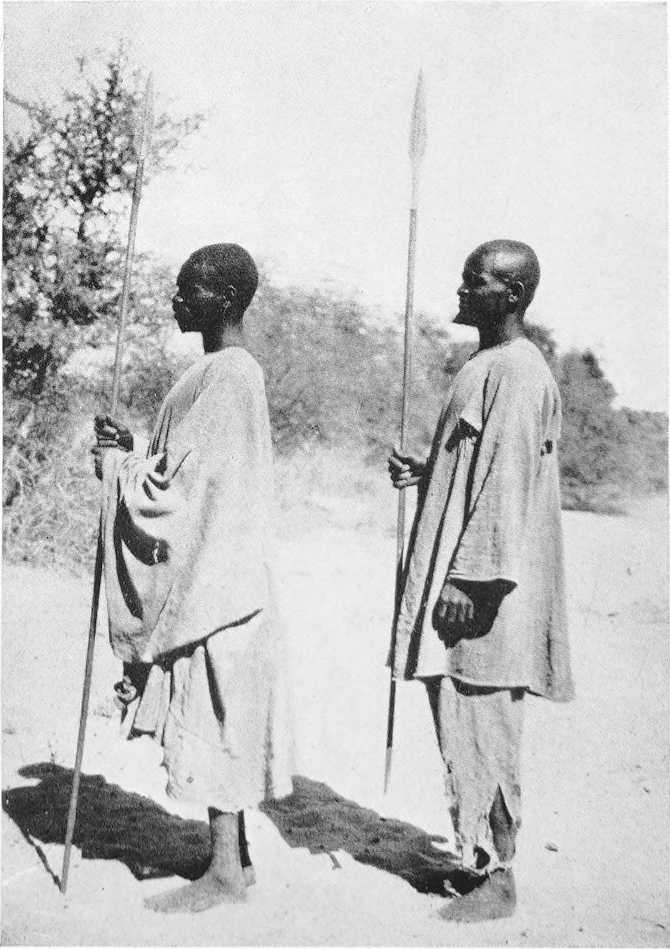

| [xxii]Two Bidiyat Men | 213 |

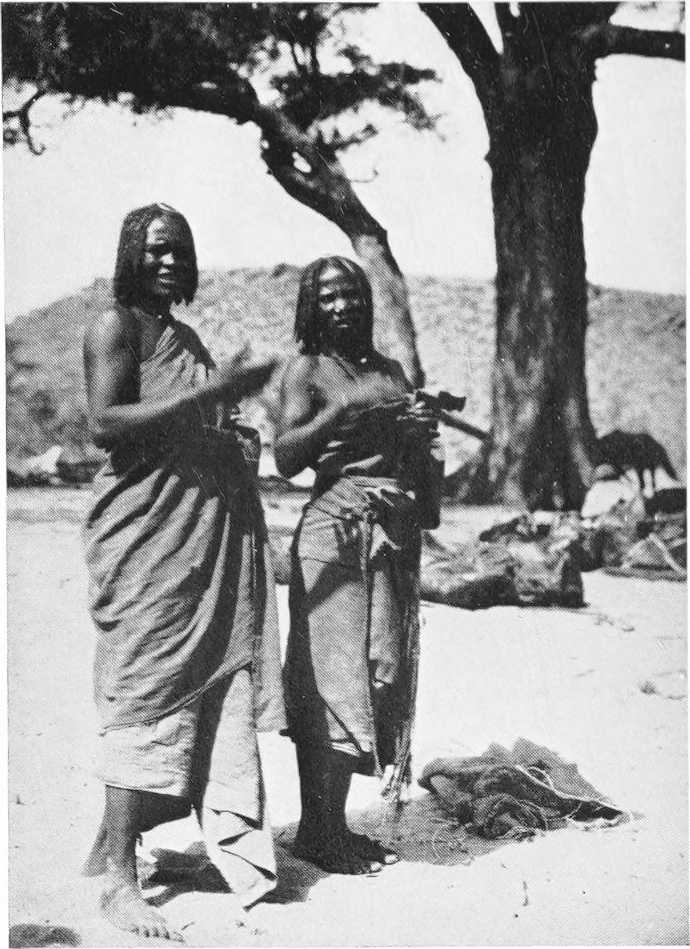

| Bidiyat Belles | 216 |

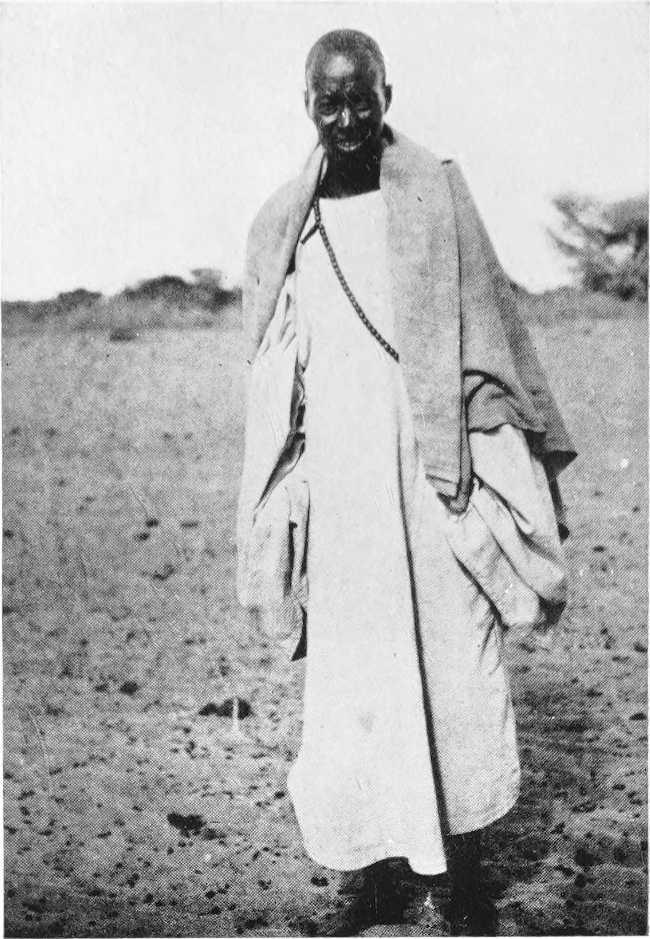

| Bidiyat Priest | 216 |

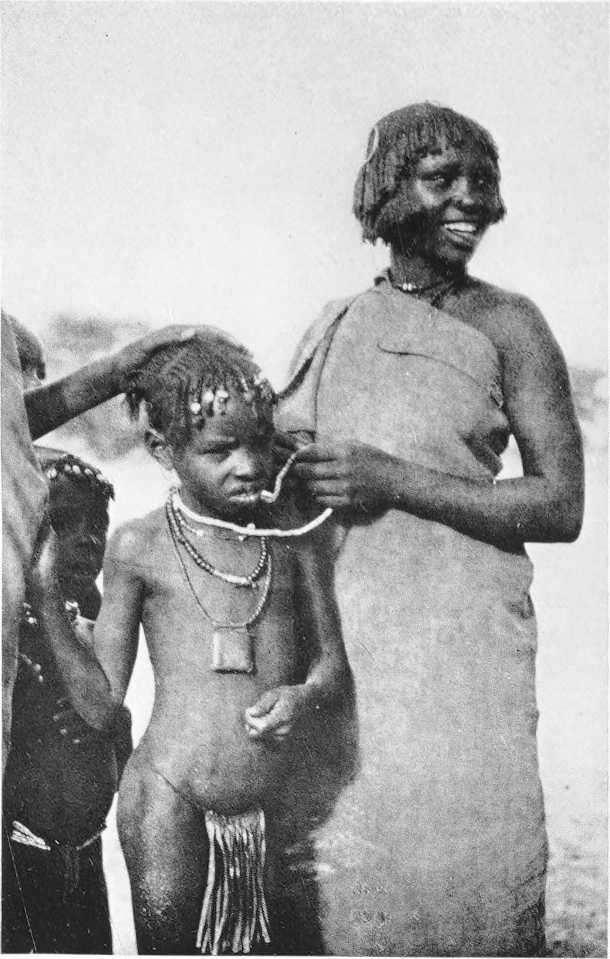

| A Bidiyat Girl, with Her Sister | 220 |

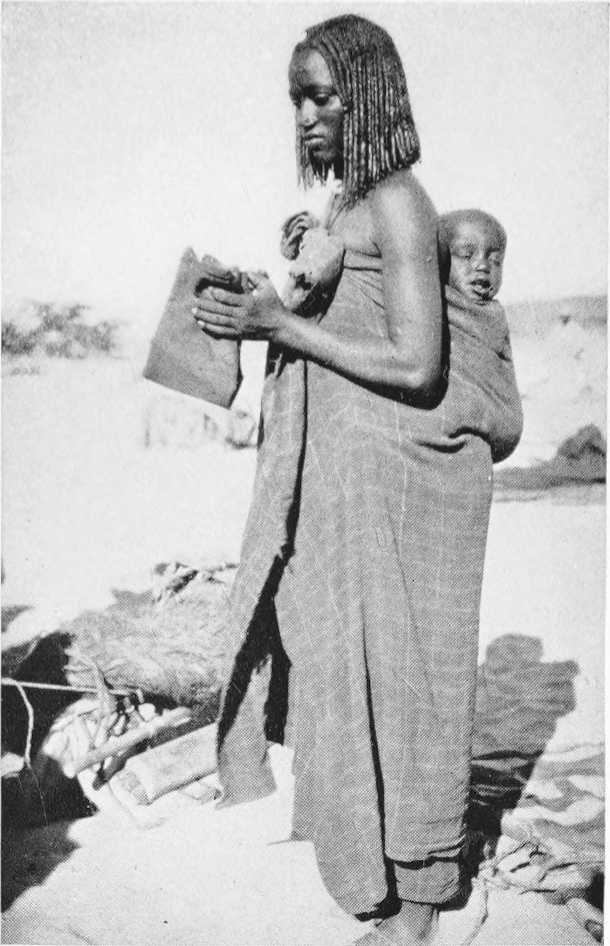

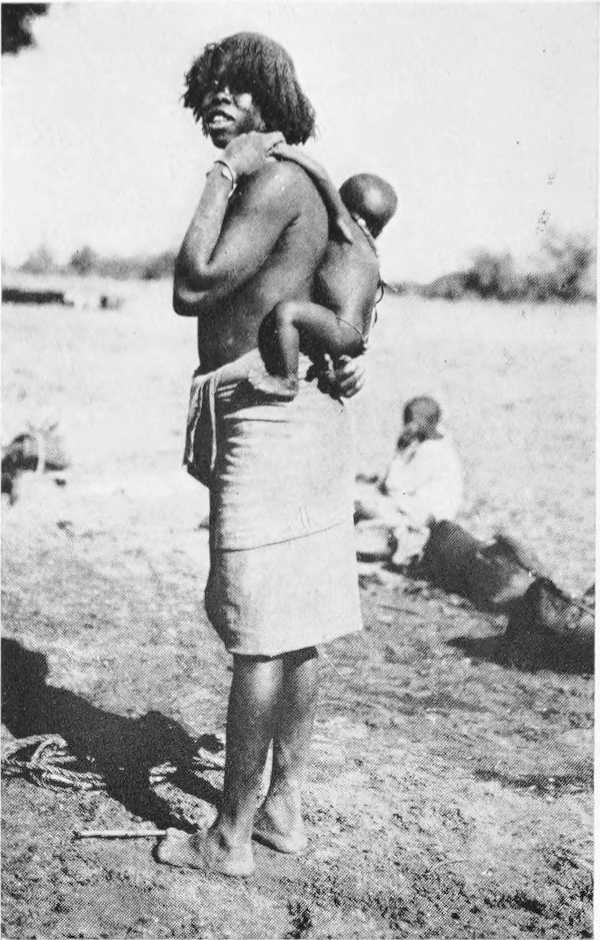

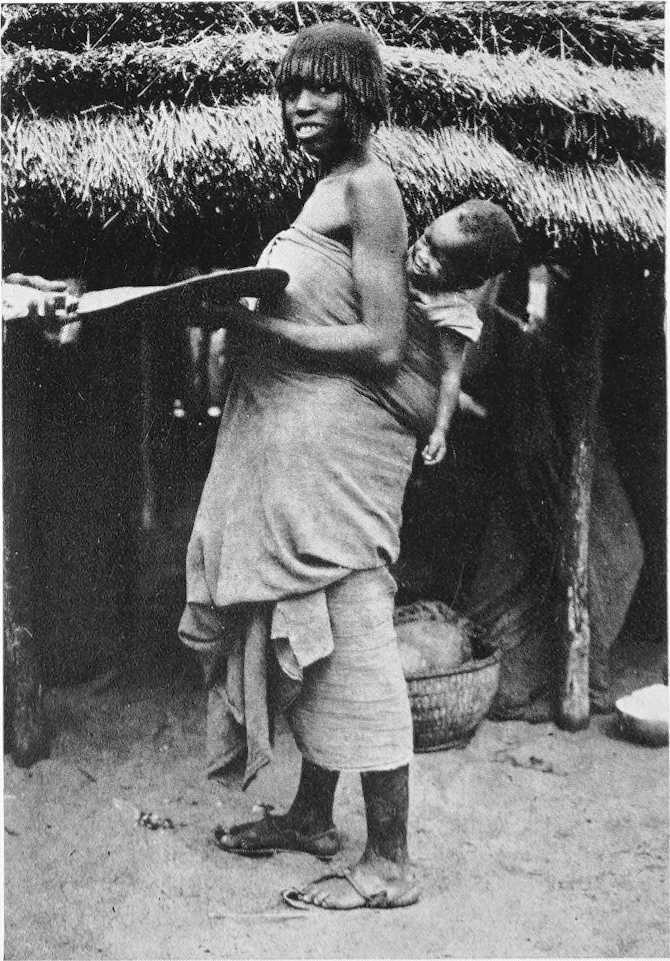

| A Bidiyat Girl, with Her Child | 220 |

| A Bidiyat Party | 225 |

| Girls at El Fasher Going to Market | 225 |

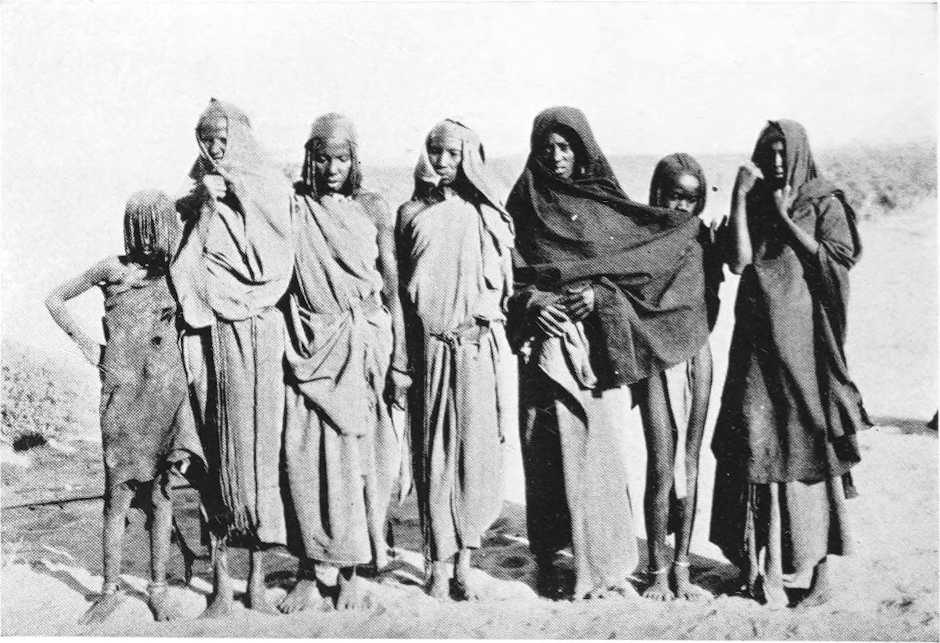

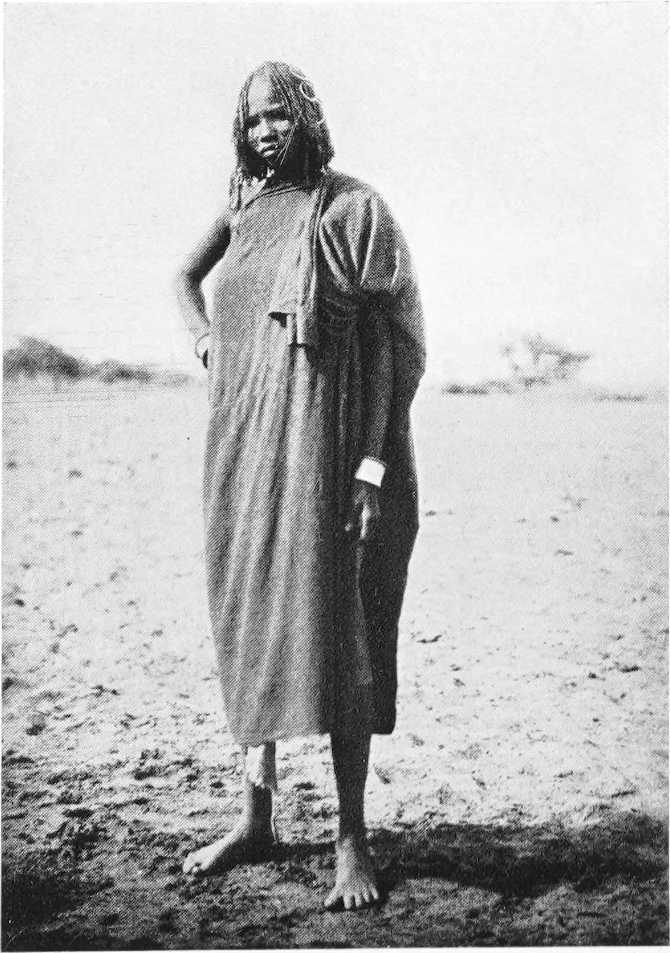

| Bidiyat Women | 228 |

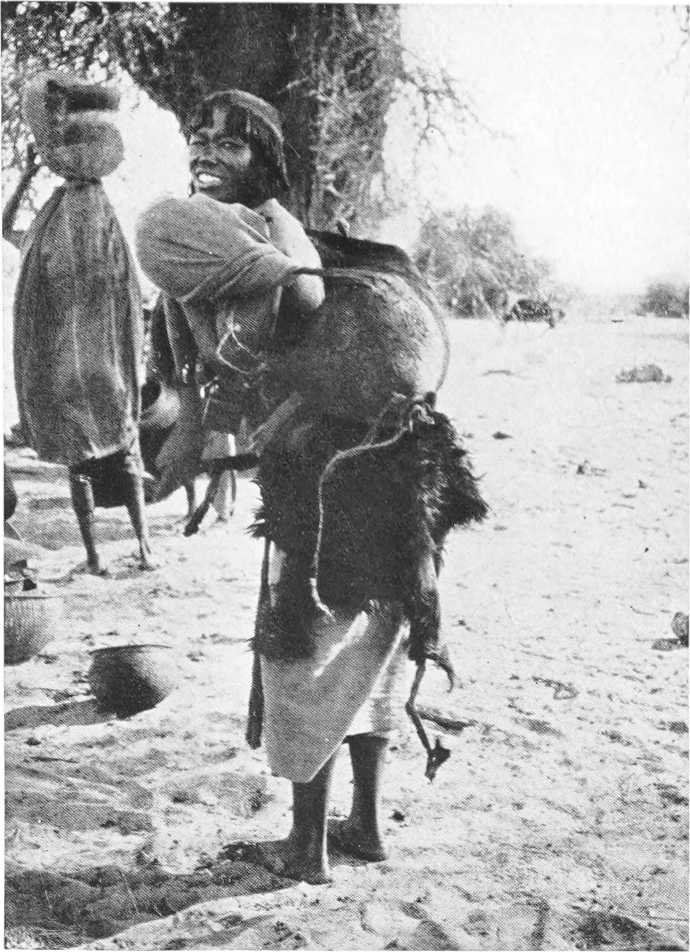

| Zaghawa Girl and Her Infant | 228 |

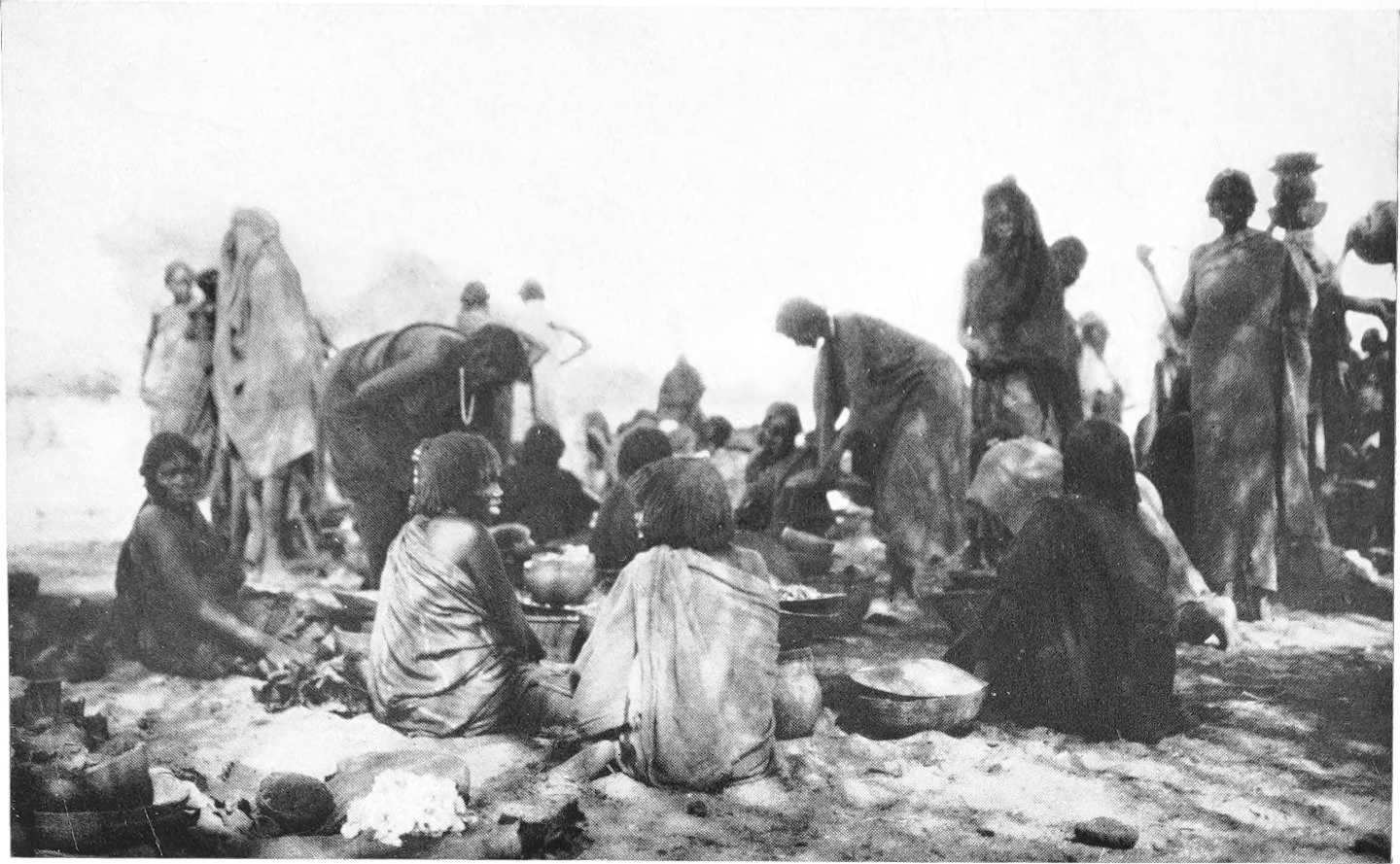

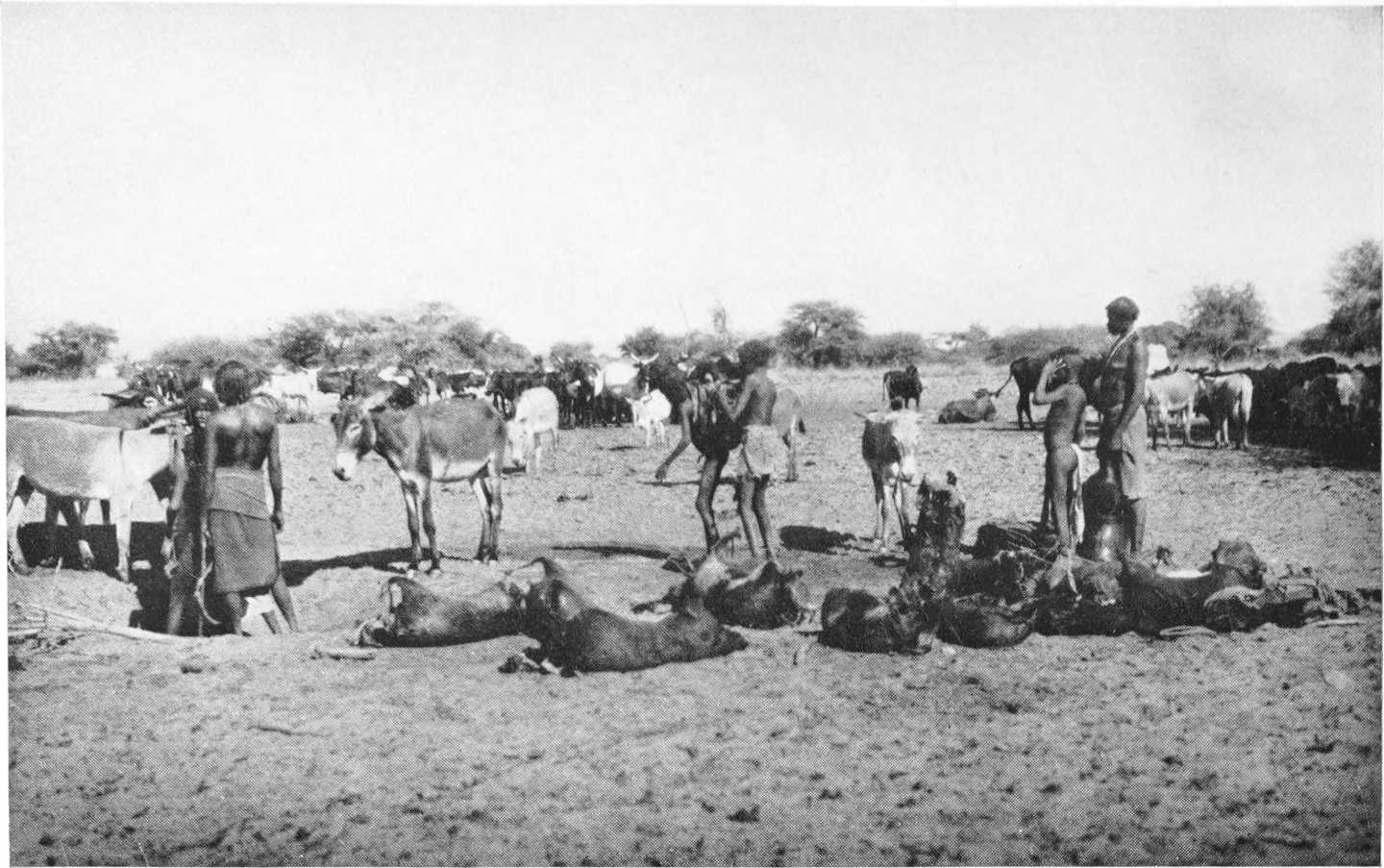

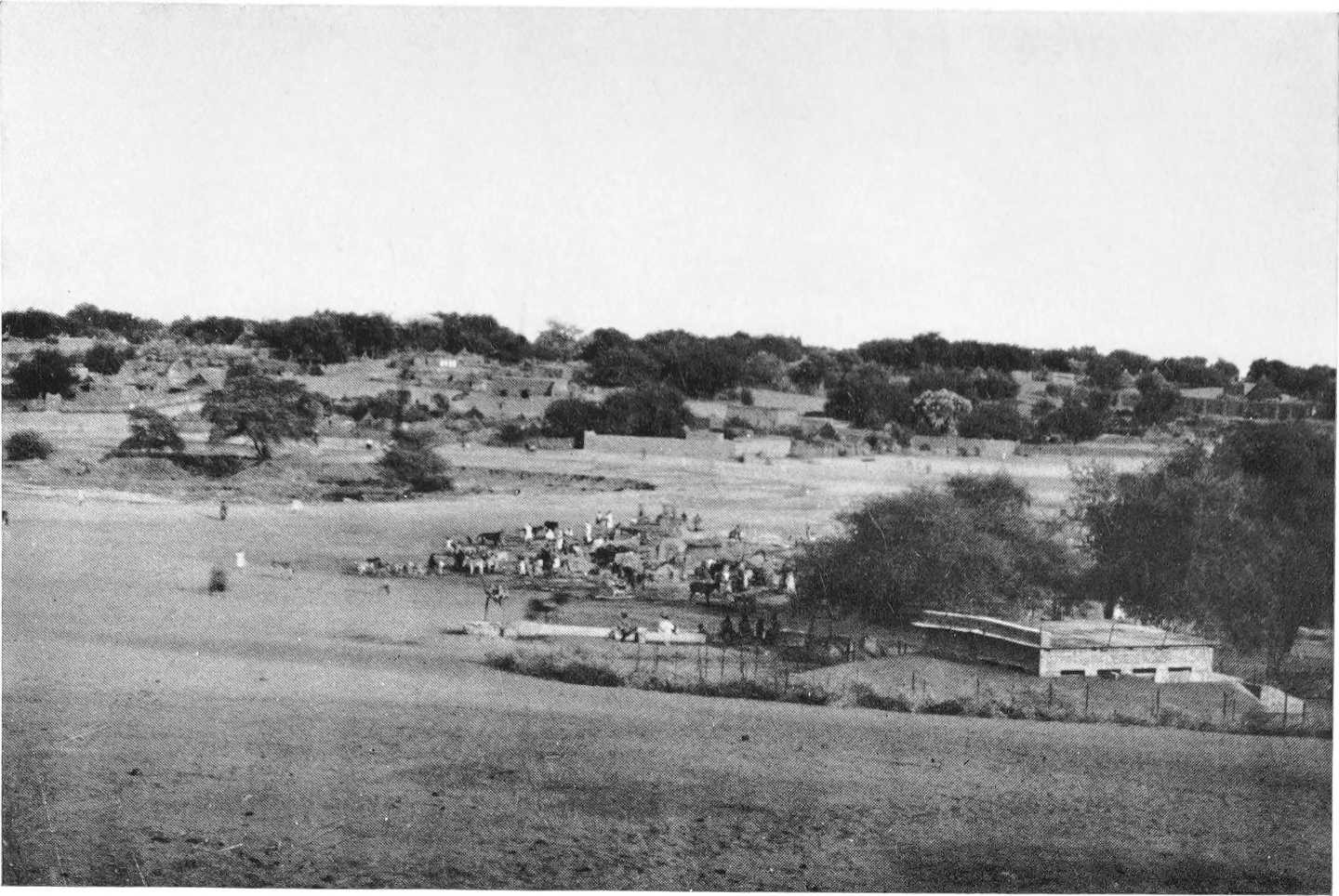

| Market at Um Buru | 232 |

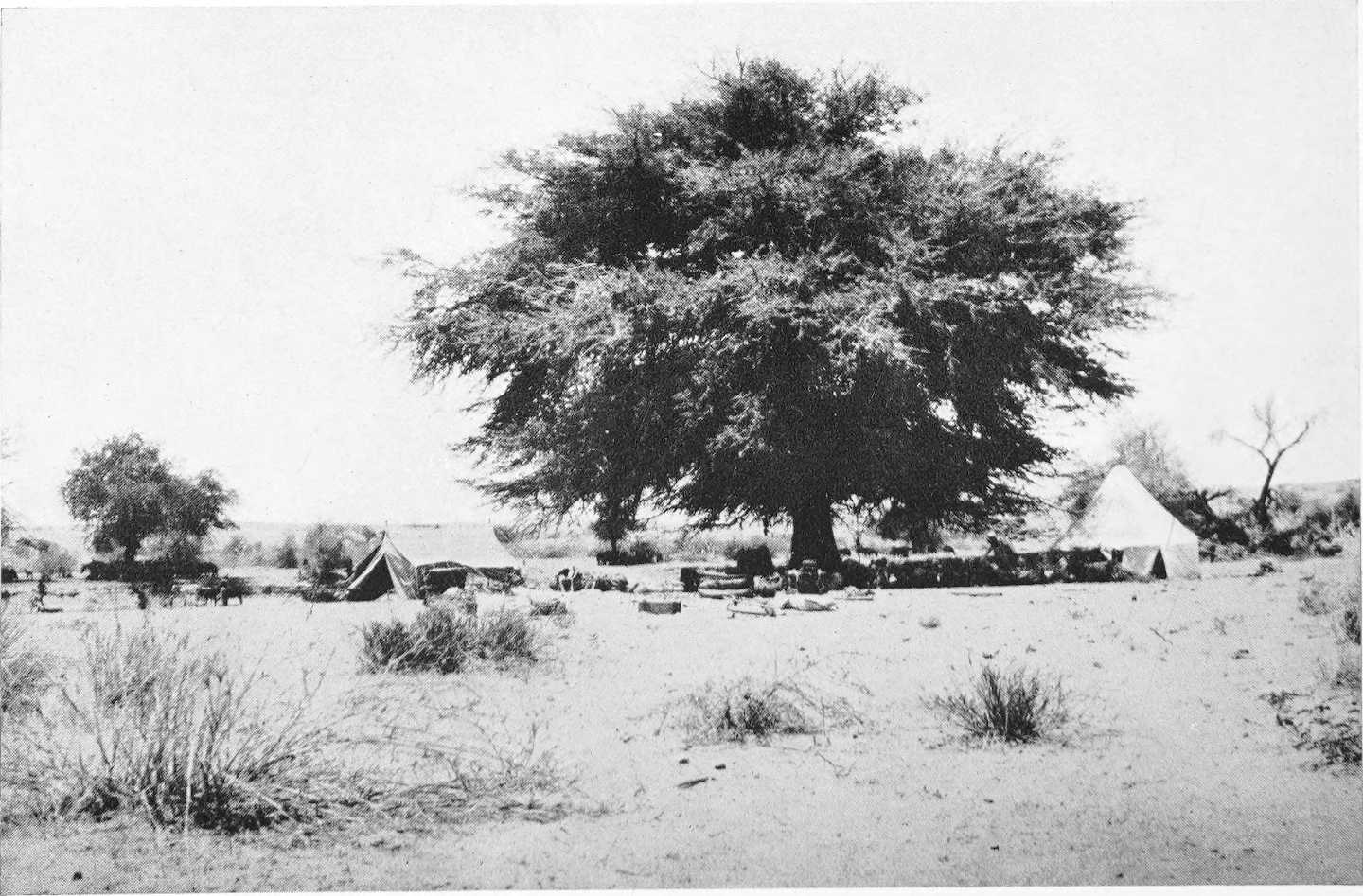

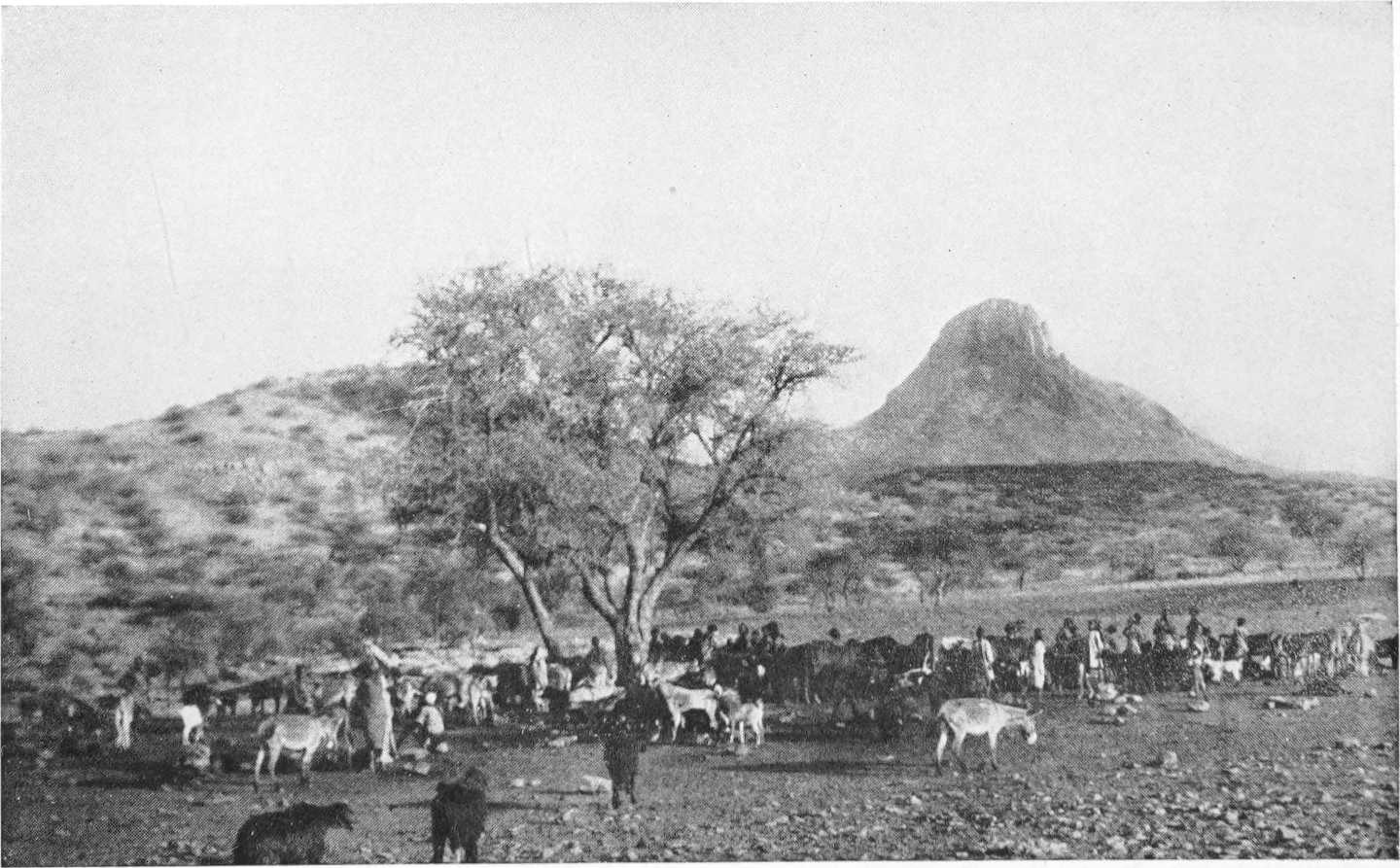

| Explorer’s Camp at Um Buru | 237 |

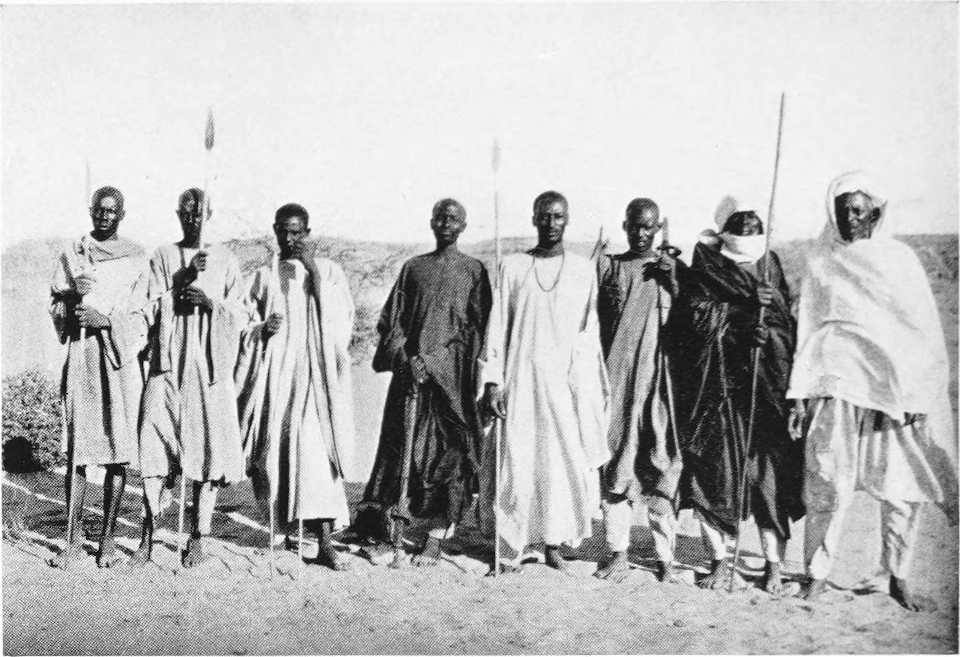

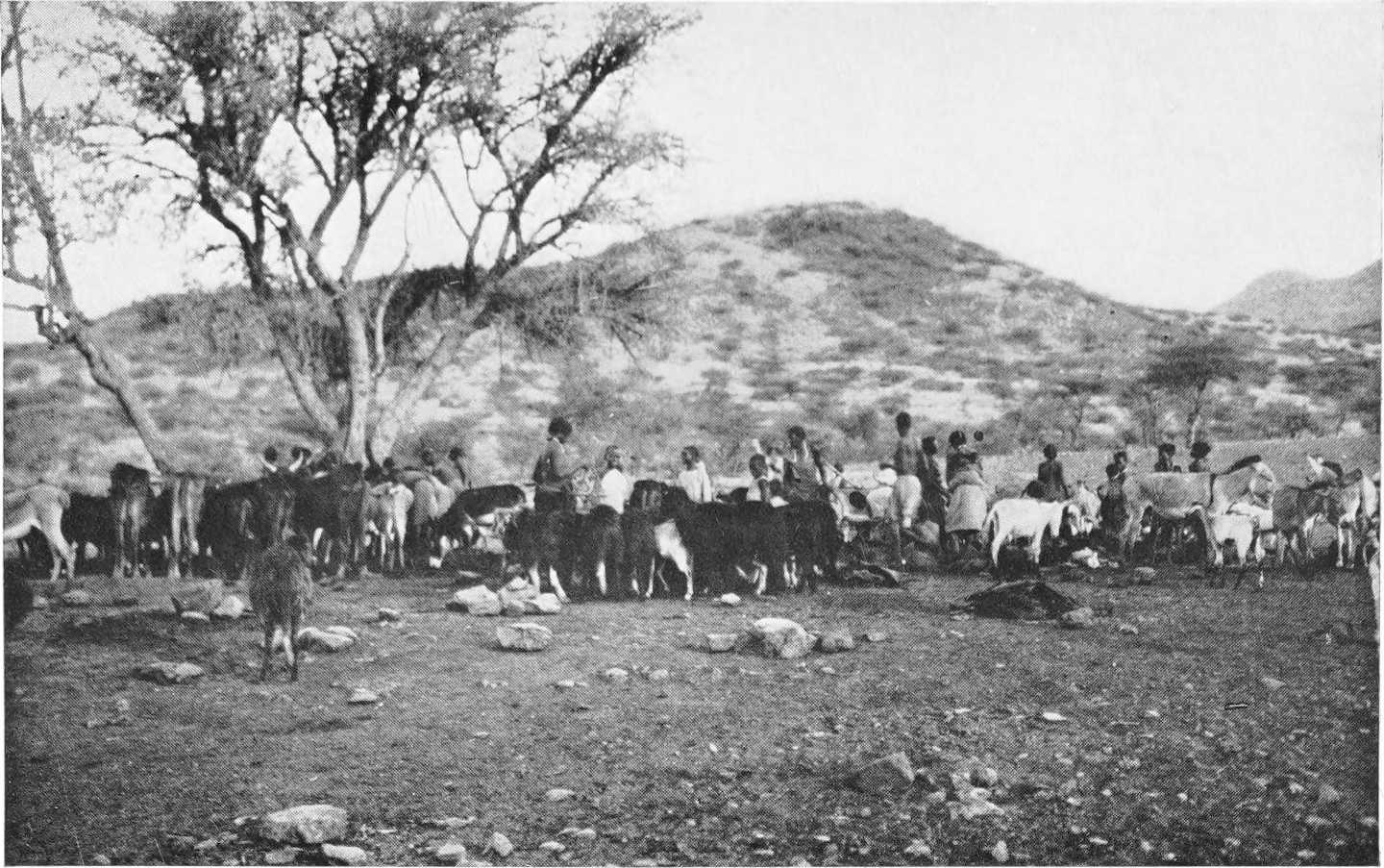

| Zaghawa Chiefs Coming Out to Welcome the Party at Um Buru | 241 |

| A Zaghawa Sheikh | 244 |

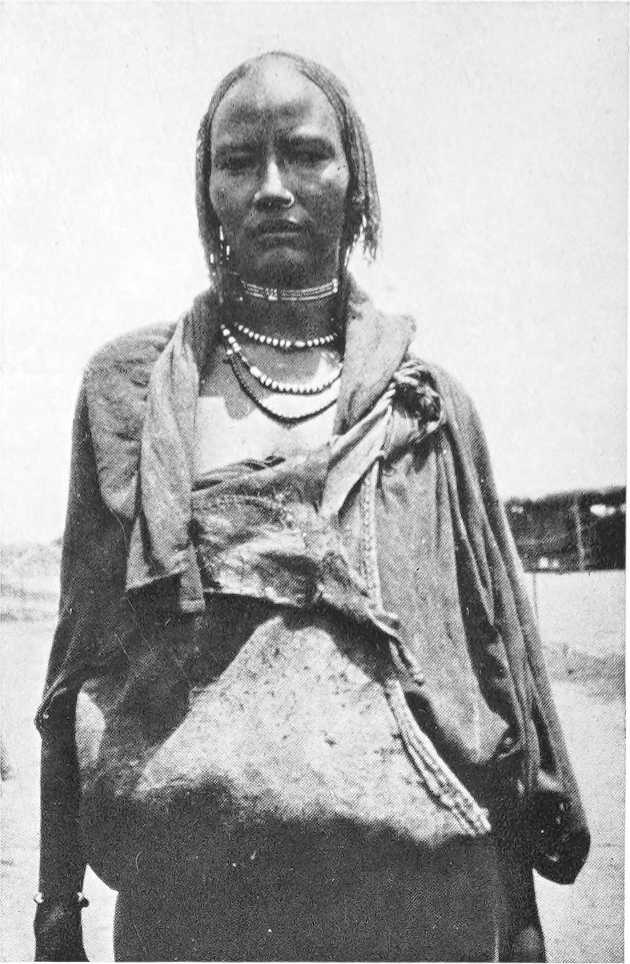

| A Zaghawa Woman | 244 |

| A Belle of the Zaghawa Tribe | 253 |

| Zaghawa Girl | 253 |

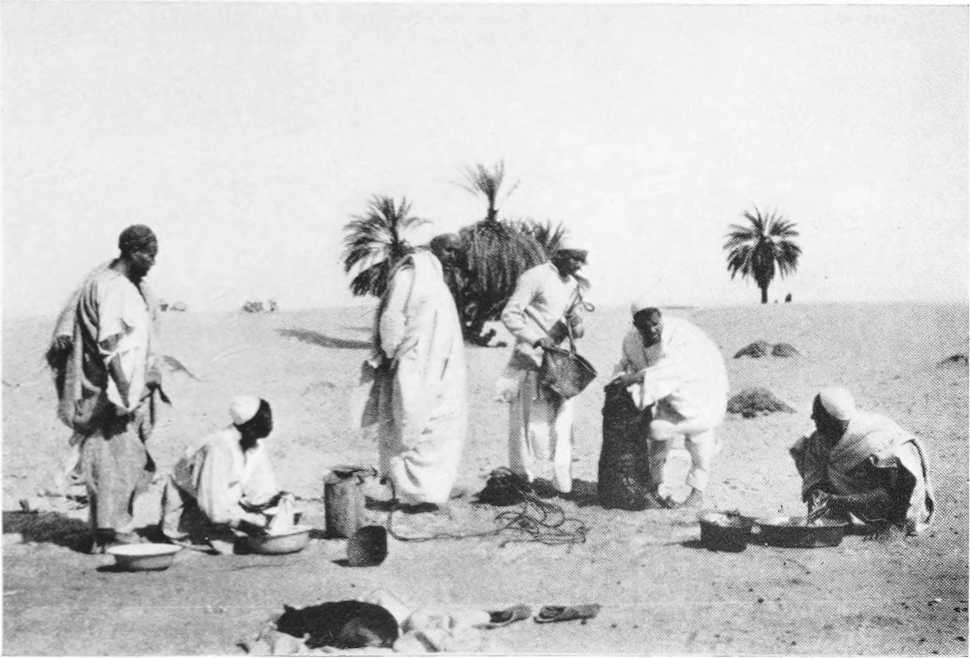

| Well on the Frontier of Darfur | 256 |

| A Water-Carrier in the Desert | 260 |

| A Woman of the Fallata Tribe | 260 |

| A Well near Kuttum in Darfur. Women Working | 269 |

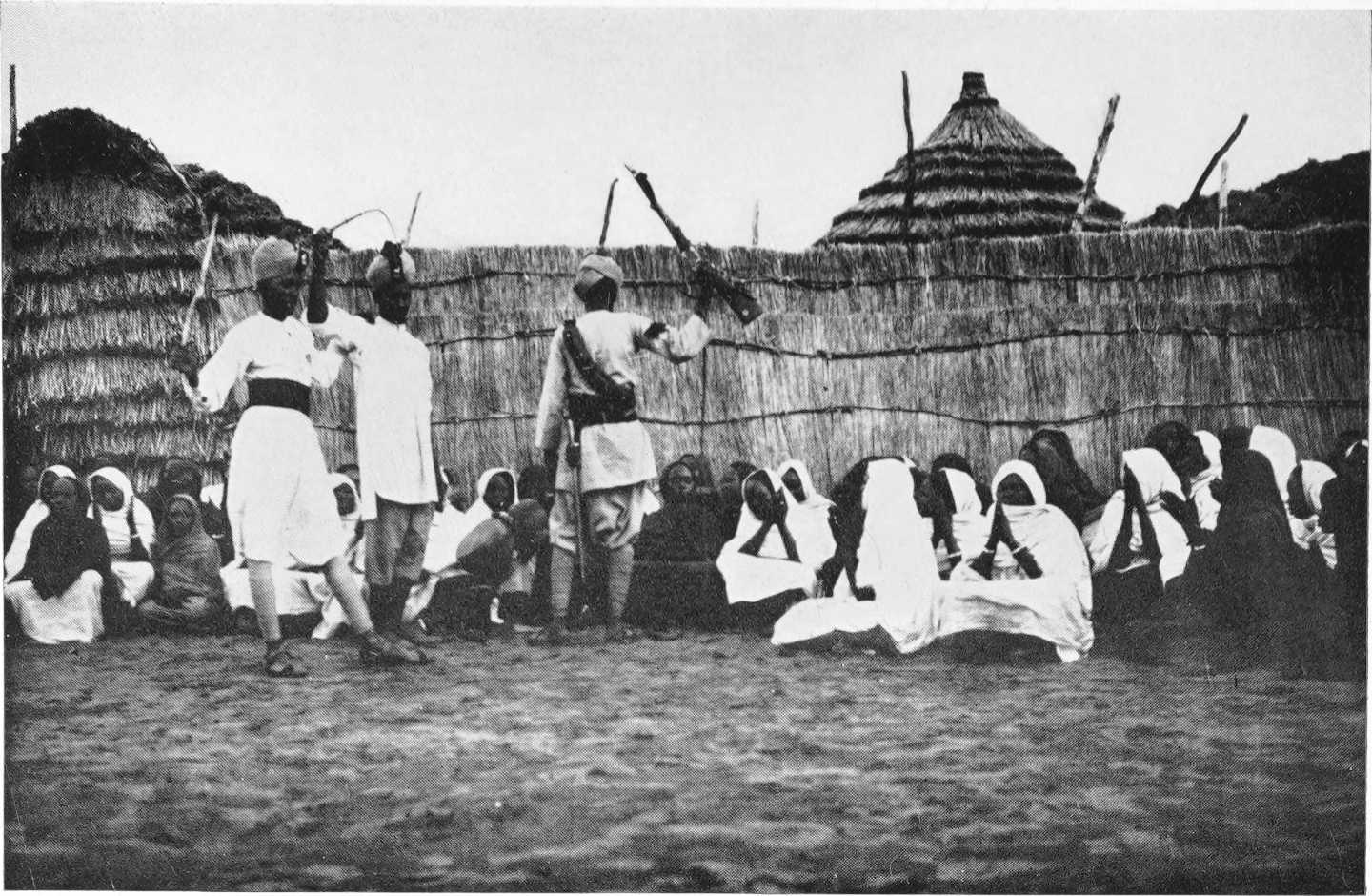

| Sudanese Troops and Girls | 272 |

| Well on the Frontier of Darfur | 280 |

| A Chief of the Zaghawa Tribe of Darfur | 289 |

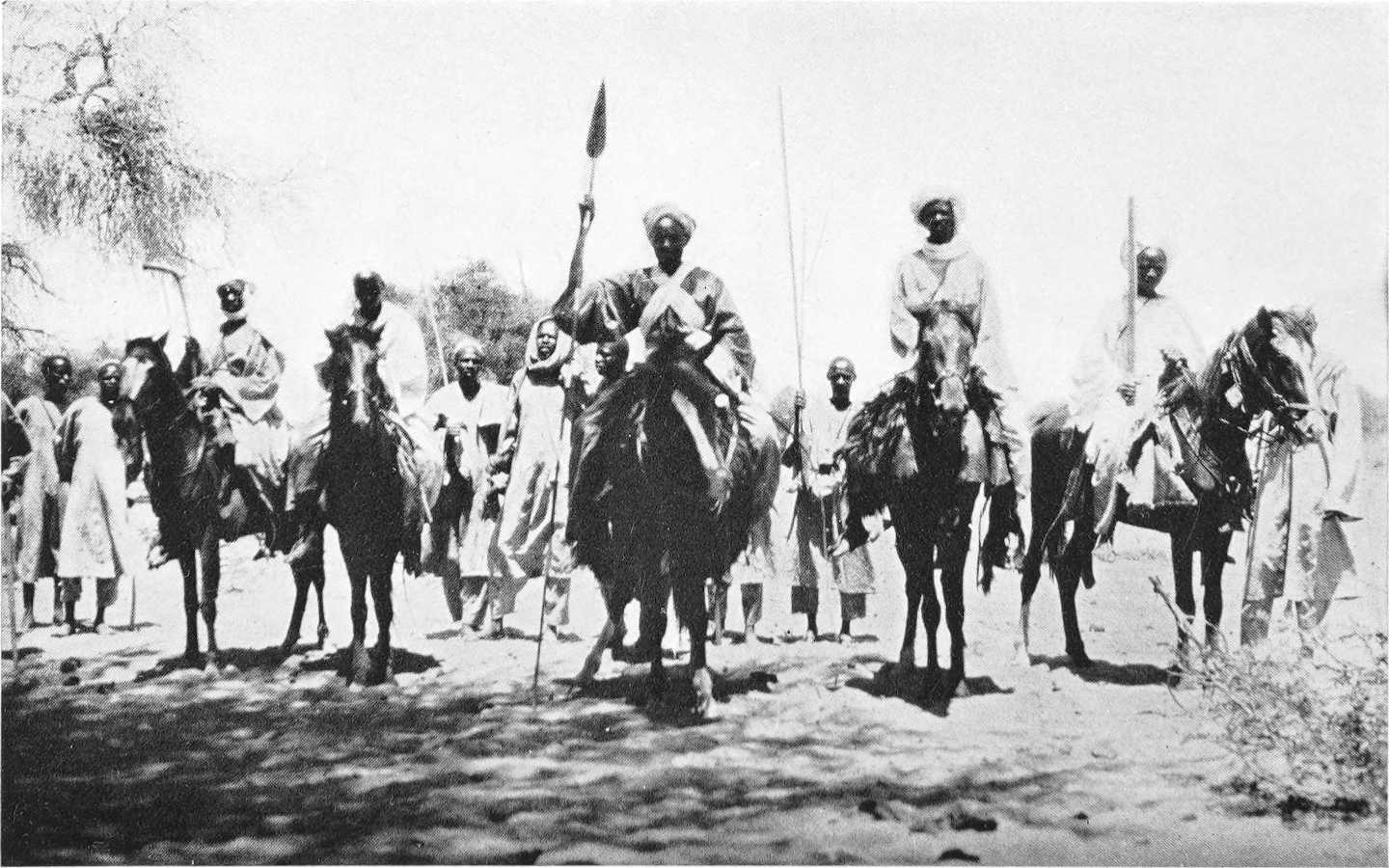

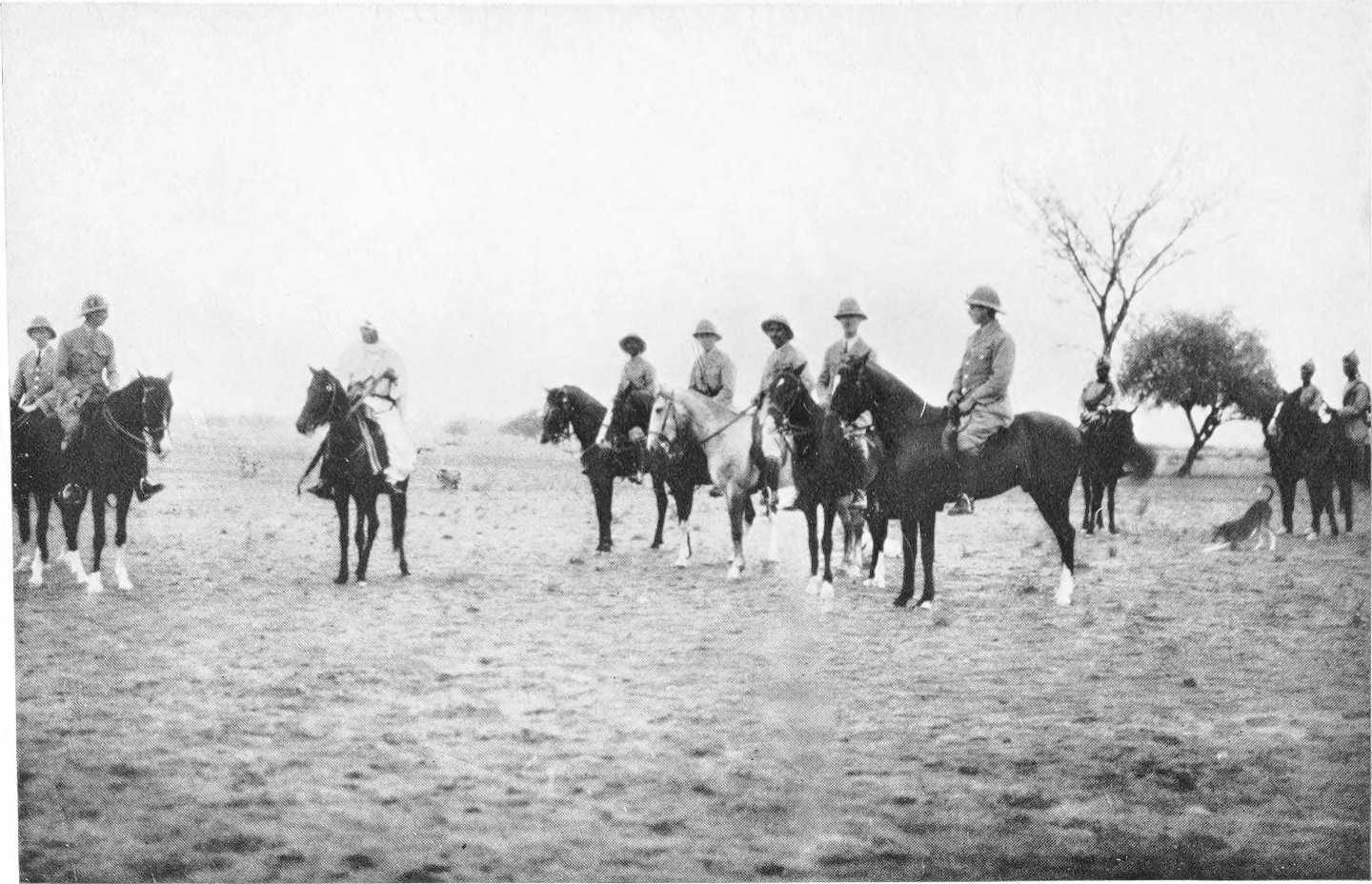

| [xxiii]The Reception of the Explorer at El Fasher | 296 |

| El Fasher | 304 |

| MAP | |

| The Libyan Desert Showing the Author’s Route | 8 |

THE LOST OASES

[3]The Lost Oases

CHAPTER I

THE DESERT

ON my first trip through the Libyan Desert I took a vow.

We had lost our way, and we had lost all hope. There was no sign of the oasis we sought, no sign of any well near-by. The desert seemed cruel and merciless, and I vowed that if ever we came through alive I would not return again.

Two years later I was back in the same desert, at the same spot where we had lost our way, and landed at the same well that had saved our lives on the previous occasion.

The desert calls, but it is not easy to analyze its attraction and its charm. Perhaps the most wonderful part of desert life is the desert night. You have walked the whole day on blistered feet, because even walking was less painful than riding on a camel; you[4] have kept up with the caravan with eyes half shut; you follow mechanically the rhythm of the camels’ steps. Your throat is parched, and there is no well in sight. The men are no more in the humor to sing. Their faces are drawn with exhaustion, and with eyes bloodshot they keep a vague, hopeless look on the ever faint line between the blue of the sky and the dull yellow of the sand. The sheepskin water-vessels dangle limply on either side of the camels.

We do not talk very much in the desert. The desert breeds silence. And when we are in trouble we avoid one another’s eyes. There is no need for speech. Everybody knows what is happening, and everybody bears it with fortitude and dignity, for to grumble is to throw blame on the Almighty, a thing that no Bedouin will do. To the Bedouin, this is the life that was intended for him; it is the route that God decreed him to take; maybe it leads to the death that the Almighty has chosen for him. Therefore he must accept it. No man can run away from that which God has decreed, says the Bedouin. “Wherever you may be, Death will reach you . . . even though you take your refuge in fortified towers.”

But it is at such times as these that you vow, if your life is spared, that you will never come back to the desert again.

Then the day’s work is at an end. Camp is[5] pitched. No tents are erected, for the men are too exhausted, too careless to mind what happens to their bodies. And night falls. It may be a starlit night, or there may be a moon. Gradually a serenity gets hold of you. Gradually, after a day of silence, conversation starts. Feeble jokes are cracked. One of the men, probably the youngest of the caravan, ventures a joke with more cheerfulness than the rest, and his voice is pitched in a higher key. Unconsciously the Bedouins attune their voices to that higher, louder pitch, and the volume of sound increases. The desert is working her charm.

The gentle night breeze revives the spirits of the caravan. In a few minutes the empty fantasses are used as drums, and there is song and dance. At the first sound of music men may have been tending the camels, repairing the luggage or the camels’ saddles, but that first note brings all the caravan round the embers of the dying fire. Every one looks at his comrades to make sure that all are alive and happy; and every one tries to be a little more cheerful than his neighbor, to give him more confidence. There is a game of make-believe, a little ghastly in its beginnings. We force ourselves to be cheerful, to make light of our troubles. “The camels are all right; I saw to that wound, and it is not so bad as I thought,” says one. “Bu Hassan says he has sighted the landmark[6] of the well not far to our right,” says another. We work ourselves up by degrees to a belief that everything is really all right. It is bluff, maybe, from beginning to end, but the charm of the desert has prevailed.

It is as though a man were deeply in love with a very fascinating but cruel woman. She treats him badly, and the world crumples in his hand; at night she smiles on him, and the whole world is a paradise. The desert smiles, and there is no place on earth worth living in but the desert.

Song and dance take out from the men of the caravan the little vitality that is left after the ravages of the day. Their spirit is exhausted, and they fall asleep. They sleep beneath the beautiful dome of the sky and the stars. Few people in civilization know the pleasure of just sitting down and looking at the stars. No wonder the Arabs were masters of the science of astronomy! When the day’s work is done the solitary Bedouin has nothing left but to sit down and watch the movements of the stars and absorb the uplifting sense of comfort that they give to the spirit. These stars become like friends that one meets every day. And when they go, it is not abruptly as when men say farewell at a parting, but it is like watching a friend fade gradually from view, with the hope of seeing him again the following night.

[7]“To prayers, O ye believers; prayers are better than sleep!” The cry comes from the first man of the caravan to awake. A few stars are still scattered in the sky. The men get up, and there is nothing better illustrates the phrase “collect their bodies.” Every limb is aching, and again their throats are parched. Yet what changed men they are! There is hope in them, confidence, perhaps an inward belief that all will come well.

The world then is a gray void, and only the morning fire breaks the cold north breeze. Our eyes instinctively turn to the east where the sun is rising. If there are no clouds, there comes a yellowish tinge in the sky that throws a curious elusive, elongated shadow behind camels and men, so faint that you can scarcely call it a shadow at all. Then comes a reddish tinge that gives warmth. It is just between dawn-break and sunrise that there is color in the desert. Once the sun is risen there is nothing but the endless stretch of blue and yellow, and the blue fades and fades until by midday the sky is almost wrung dry of color.

Morning brings new vitality; night brings peace and serenity. These are the hours wherein one learns the desert’s charm.

In the silence of these vast open spaces human sensitiveness becomes so sharpened that eventually[8] the desert traveler feels the nearness of some inhabited oasis. Likewise his instinct tells him of the few hundred miles that separate him from any breathing thing. In the silent infinity of the desert, body, mind, and soul are cleansed. Man feels nearer to God, feels the presence of a mighty Power from which nothing any longer diverts his attention. Little by little an inevitable fatalism and an unshakable belief in the wisdom of God’s decree bring resignation even to the extent of offering his life to the desert without grudge. There are times when he feels that it really does not matter. . . .

The desert brings out the best that is in every man. Civilization confronts the crowd with danger, and each one fights for himself and his own safety. In the desert self becomes less and less important. Each tries to do the best he can for his comrades. Let disaster threaten a caravan, there may be one man who can see a chance to save himself, but I do not believe there is a Bedouin who would desert his comrades and so save his own life. One of the most appalling things that can happen in the desert is a shortage of water, and you would think that in such a case you would try to keep what water you have for yourself. Instead of that, you find yourself with your favorite water-bottle, taking it in your arms, going round the men asking would any of them like[9] a drink, as nonchalantly as though there were plenty of it and to spare. The question of personal safety is eliminated. Whatever happens, let it happen to the whole caravan; you do not want to escape alone. That is the feeling that gets hold of you.

I never cease to marvel at the Bedouin serenity and courage, which nothing disturbs. In desert travel there are three elements: camels, water-supply, the guide. Camels, the best of them, and for no apparent reason, give in, as it happened when I left Kufra and one of my best camels died on the second night, while, on the other hand, the weakest camel of the caravan, which left Kufra tottering under its load, went through the whole trip, about 950 miles, and arrived tottering at El Fasher. “God will protect it,” said its Bedouin owner when rebuked for bringing such a sorry animal, and in truth God did protect it. The death of a camel is a serious matter, for it means throwing away most, perhaps the whole, of its load. Water is carried chiefly in sheepskins, and the best of sheepskins, tested for days and weeks beforehand, have suddenly started to leak or the water to evaporate from them; or in night trekking two camels may bump together and cause one or two sheepskins to burst. And then the guide, for various reasons, may say that his head has gone round and round, which means he has lost his head; if there are[10] clouds that hide the sun for a few hours, or one mistake in a landmark, it may cause the guide to lose his way. But there is one thing still more necessary than these three items: camels, water, guide. It is Faith, profound and illimitable Faith.

The desert can be beautiful and kindly, and the caravan fresh and cheerful, but it can also be cruel and overwhelming, and the wretched caravan, beaten down by misfortune, staggers desperately along. It is when your camels droop their heads from thirst and exhaustion; when your water-supply has run short and there is no sign of the next well; when your men are listless and without hope; when the map you carry is a blank, because the desert is uncharted; when your guide, asked about the route, answers with a shrug of the shoulders that God knows best; when you scan the horizon, and all around, wherever you look, it is always the same hazy line between the pale blue of the sky and the yellow of the sand; when there is no landmark, no sign to give the slightest excuse for hope; when that immense expanse looks like, feels like a circle drawing tighter and tighter round your parched throat—it is then that the Bedouin feels the need of a Power bigger even than that ruthless desert. It is then that the Bedouin, when he has offered his prayers to this Almighty Power for deliverance, when he has offered up his prayers and they have not[11] been granted, it is then that he draws his jerd around him, and, sinking down upon the sands, awaits with astounding equanimity the decreed death. This is the faith in which the journey across the desert must be made.

The desert is terrible, and it is merciless, but to the desert all those who once have known it must return.

[12]CHAPTER II

THE PLANNING OF THE JOURNEY

THIS is the story of a journey which I made in 1923 from Sollum on the Mediterranean to El Obeid in the Sudan, some two thousand two hundred miles. In the course of it I was fortunate enough to discover two “lost” oases, Arkenu and Ouenat, which previously had not been known to geographers. My journey was primarily a scientific expedition, but I have tried in this book to avoid wearying the reader with technical matter and to write a straightforward narrative which may be of some interest even to those who are not acquainted with Egypt, the Sudan, or the Libyan Desert.

It had always been my greatest ambition to penetrate to Kufra, a group of oases in the Libyan Desert, which had only once been visited by an explorer. In 1879 the intrepid German, Rohlfs, had succeeded, but he had barely escaped with his life, and all his note-books and the results of his scientific observations were destroyed.

[13]In 1915 I had been fortunate enough to meet in Cairo Sayed Idris El Senussi, the famous head of the Senussi brotherhood, when he was returning from a pilgrimage to Mecca. The capital of the Senussi is Kufra, and when in 1917 I went on a mission to Sayed Idris with Colonel the Honorable Milo Talbot, C.B., R.E., a distinguished officer, who had retired from the Egyptian Army but had returned to the service during the Great War, and renewed my acquaintance with that notable man at Zuetina, a little port near Jedabia in Cyrenaica, I seized the opportunity and told him of my ambition.

Sayed Idris was most sympathetic and asked me to let him know when I proposed to make the expedition, so that he might give me the help and countenance without which a journey to Kufra could not be undertaken. I met him again at Akrama near Tobruk and told him then that I would set out as soon as I was free from my war duties. At Tobruk, Francis Rodd, an old Balliol friend, was with me, and we decided that we would go together.

When the war was over Mrs. Rosita Forbes (now Mrs. A. McGrath) brought me a letter of introduction from Mr. Rodd and asked that she might join us. We proceeded to plan an expedition à trois, but, when the time came, Mr. Rodd was prevented from making one of the party. Finally in 1920 Mrs.[14] Forbes and I set out by ourselves, and with the friendly cooperation of the Italian authorities and the promised countenance and assistance of Sayed Idris—he provided us with our caravan—we reached Kufra in January, 1921.

But this trip to Kufra, interesting as it was, only tempted me to explore the vast unknown desert which lay beyond. There were rumors, too, of “lost” oases which even the people of Kufra knew only by hearsay and tradition, and I returned to Cairo resolved to make another expedition and instead of coming straight back from Kufra, as Mrs. Forbes and I had done, to strike south across the unknown desert until I came to Wadai and the Sudan.

Again on the first trip our only scientific instruments were an aneroid barometer and a prismatic compass. It was not, therefore, possible for me to make exact scientific observations, and all that I brought back was notes for a simple compass traverse of the route based on the meager material I had obtained. I was eager to check Rohlfs’s observations and to determine once and for all the place of Kufra on the map.

In 1922, then, I submitted my plan for a journey across the desert from the Mediterranean to the Sudan to his Majesty King Fouad I, who had been gracious enough to display his interest in my first trip[15] by decorating me with the Medal of Merit. He sympathized warmly with my project, directed that I should be given long leave of absence from my official duties, and later caused the expenses of the expedition to be defrayed by the Egyptian Treasury. Indeed, my expedition could not possibly have met with the success that it did, had it not been for his Majesty’s invaluable support.

I completed my preparations, and in December, 1922, I had collected my baggage in the house of my father so that in accordance with the ancient practice of my race it might be blessed before I set out on my expedition across the Libyan Desert.

[16]CHAPTER III

THE BLESSING OF THE BAGGAGE

“ALLAH yesadded khatak—may God guide your steps.” The Arabic words fell reverently on the air of the great bare room, where candlelight and clouds of drifting incense contended for supremacy. Along the walls bulked a strange collection of baggage: big boxes, little boxes, sheepskin water-bags, tin fantasses for carrying water, stuffed food-sacks, bales of tents, carrying-cases of leather and metal containing scientific instruments, and my own personal kit. After the bustle of getting everything corded and tied and strapped and arranged in order, a hush had come as we took our stand in the middle of the room. Outside, the Egyptian night had fallen, and across the garden the faint hum of the evening life of Cairo entered our windows.

We were three: myself; Abdullahi, a Nubian from Asswan, who was to be one of my most trusted men; and Ahmed, also from Asswan, looking half a wreck after a spell of city life as he stood beside us, but[17] later to prove himself an excellent cook and on the trek “the life of the party.”

Before us stood a tall old man with white flowing beard dressed in a deep orange-colored silk kuftan. His delicately wrinkled features spoke of the peace that comes with saintliness. His long slim fingers clicked softly against each other the amber beads of a rosary. The white smoke from the incense in the wrought-silver censer, held by a servant beside him, mounted in a delicate spiral. The saintly man put aside his rosary and lifted his hands, palms upward, toward heaven. His voice, thin with age but clear with conviction, sounded the prayer for those about to go upon a journey.

“May God guide your steps, may He crown your efforts with success, and may He return you to us safe and victorious.”

He went round the room, swinging the censer rhythmically before each pile of baggage and uttering little prayers. This was the traditional ceremony of the blessing of the baggage, made sacred by ages of Arab usage at the setting out of a caravan. It has largely fallen into disuse in these latter days, but in the house of my father, who walks through life deeply absorbed in scholarship and the faith of the Prophet, it was the most natural thing in the world, when the only son was going forth into the desert.

[18]As I stood before the saintly man to receive his blessing, I was no longer an Egyptian of to-day but a Bedouin going back to the desert where his father’s fathers had pitched their tents.

Then I turned and went to my father.

For fifteen years, since I had been sent to Europe for my education, our ways had rarely met. Sometimes I wished that I had studied the subjects in which he was interested so that I might profit by his profound learning.

“He is going to live in another generation; let him get the education he will need for it,” my father had said once of a fellow-scholar of mine. But now when I was returning to the desert from which our forefathers had come we knew what was in each other’s minds and understood.

After a moment’s silence, he put his hands on my shoulders and prayed, “May safety be your companion, may God guide your steps, may He give you fortitude, and may He give success to your undertakings.”

The baggage blessed, Abdullahi and Ahmed took the heavy stuff and set out for Sollum, leaving with me the scientific instruments and the cameras for more careful handling. On December 19 I left Alexandria by boat for Sollum.

[19]CHAPTER IV

SUPPLIES AND EQUIPMENT

THE twenty-first found me disembarking at Sollum, which is a tiny seaport close to the western frontier of Egypt. There we were to take camel and go by way of Jaghbub to Jalo, the important center of desert trade where our own caravan would be organized and the great trek southward begun. A journey like this of mine always has several starting-points, each with its own variety of emotions and experiences. In the dimly lighted, incense-scented room in my father’s house the enterprise was a kind of dream, fascinating in its possibilities but hardly yet real. At Sollum came the practical reality of assembling stores and equipment, packing and repacking to get everything into the smallest compass and most convenient shape for handling, checking it all over to make sure that nothing had been forgotten, and arranging with camel-owners for the first stage of the trip. At Jalo would came the third start, with[20] my own caravan at my back, and the road to Kufra, already traversed but still by no means familiar, before me. Then the last setting out of all, as I rode out of Kufra with my face toward the unknown and the unexplored.

Abdullahi and Ahmed were already at Sollum, with the heavy baggage, and the camels were arranged for, the agreement only awaiting my approval. We proceeded to get our outfit and supplies in order.

Some description of the two Egyptians who accompanied me throughout the expedition may be of interest. Abdullahi was a Nubian from Asswan, heavily built, well set up and strong, with a pair of small eyes, deeply set, that could mask a malicious sense of humor with great indifference or dignity. A man of about forty, he was well educated and knew his Koran well. I met him first in 1914, when he was attached to the Idrissi family in Egypt, and I took an enormous liking to him because of his deeply rooted sense of humor and his loyalty. He was honest, too, extremely honest, and therefore I put him in charge of the commissariat. In Abdullahi’s kit one could always find anything that was needed from strips of leather with primitive Bedouin needles for mending shoes to elaborate contrivances for propping up a broken tent-pole. He was ready, moreover, with[21] “inaccuracies” to suit every situation, whether he wanted me to appear to be a wandering Bedouin from Egypt, or a merchant, or an important government official when we landed in the midst of officialdom in the Sudan. Abdullahi had one peculiarity: between sunset and an hour or two later it was apparently a most difficult task to keep him awake; though he might be sitting down holding a discussion, he would go on dozing as he sat. On one occasion we had just finished dinner, and, it being about the hour, Zerwali, my Bedouin loyal companion, who joined our caravan at Jalo, as a joke took a lot of zatar (a strong scent used for flavoring tea) and put it in Abdullahi’s tea. In between dozes, the latter woke up, tasted his tea, knew what had happened, said nothing, but simply put back his glass. After a while, however, Abdullahi turned round and said to Zerwali, “I believe you are expecting a man to see you; I think I hear him coming.” As Zerwali got up to look, Abdullahi quietly changed round the glasses, so that Zerwali drank the highly “flavored” tea while Abdullahi dozed off peacefully once more.

THE TOMB OF THE FOUNDER OF THE SENUSSI

The tomb, which is covered with an embroidered green silk cloth, is inclosed in a heavy brass cage. From the ceiling of the great tomb hang many crystal candelabra, the gifts of the sultans of Turkey and the khedives of Egypt. The floor is strewn with very valuable Persian rugs.

Abdullahi’s business instinct came out at its best when we arrived at inhabited country toward the end of the journey and were short of food. He collected all the odds and ends of the caravan, including empty tins and bottles of medicine, even the few used Gillette[22] blades, and bartered them with the natives for butter, milk, spices, and leather.

It was Abdullahi also who was greatly upset when I showed my film of the expedition at a lecture given before H. M. King Fouad at the Royal Opera House in Cairo. When Abdullahi found that he appeared in many of the pictures with a tattered shirt, he resented being shown to his king in such an unsuitable garment and asked if something could not be done so that he should appear in a shirt that was cleaner and less well worn.

Ahmed too was a Nubian from Asswan, a slight, wiry fellow who never gave in. He was my valet and cook. Although very well educated, he became a cook because he liked to live a free life; had he become a religious man, as his father wished, he would have been obliged to lead a model life, and that apparently did not appeal to him. He was always cheerful, and though no one in the caravan did so much cursing, the Bedouins did not mind him. At a word that Ahmed said, had it come from any other, there would have been bloodshed, but the Bedouins got accustomed to him, and there was only one row. After his cooking was over Ahmed used to sit down with the Bedouins and scorn their knowledge of religion; he would prove his superiority by reciting from memory bits of poetry about religion and the Arabic[23] language and some of the Prophet’s sayings. Never once did Ahmed fail to make me a glass of tea even in circumstances of the greatest difficulty. On one occasion after a whole night’s trek he was suffering badly from a hurt foot, and as we were pitching camp I told him casually that I did not want any breakfast or tea until I had slept and ordered him to go to bed at once. Nevertheless, just as I was getting my shelter ready, Ahmed arrived with a steaming glass of tea. He cursed all the Bedouins, but there was no Bedouin in the caravan for whom, if he felt ill, Ahmed would not do everything in his power to give him relief. He had learned gradually the use of such medicines as I had, and frequently when in doubt would bring me a little bottle to ask whether it was quinine or aspirin.

The requirements for a desert trek are simple, and the list of what one takes with one is almost stereotyped. For food there are, first of all, flour, rice, sugar, and tea. All the people of the desert are very fond of meat, but it naturally cannot be carried. One must either shoot it by the way or go without. Tea is the drink in the Libyan Desert, rather than coffee, and for that there are two reasons. The first is religious; the second is practical. Sayed Ibn Ali El Senussi, the founder of that interesting brotherhood that controls the destinies of the country through[24] which I was to travel, forbade his followers all luxuries. His prohibition included tobacco and coffee but, for some reason, did not extend to tea. His followers, therefore, are tea-drinkers, if you can call by the same name the delicate, aromatic, pale fluid that graces the tea-tables of Europe and America and the murky, bitter liquid which sustains the Bedouin on his marches and revives him at the day’s end. The second reason is that tea is a stimulant to work on, while coffee is not. Tea is the thing with which to finish off each meal of the desert day and to refresh the weary traveler at the end of a hard day’s trek, leaving coffee for the less strenuous life of the oasis and the home.

After these staples come dates; or perhaps they ought to be put first. The camels live on dates, as does the whole caravan when other foods are exhausted or there is no time to halt and cook a meal. But the dates are not the rich, sweet, sugary things one is accustomed to for dessert or a picnic delicacy in western lands. The date which one must use for desert travel has little sugar about it. Sugar breeds thirst, and where wells are days apart the water-supply is not to be prodigally spent.

I took some tinned things with me, bully beef, vegetables and fruits; but tins are heavy, and to carry enough food in tins for a long trek would demand a score of extra camels or more. There was a little[25] coffee in our stores, but we seldom drank it. I used most of it for presents to the friends we made along the way. A few bottles of malted milk tablets proved useful for emergency lunches when food ran low. The Bedouins, however, were not keen on them. “They fill us up,” they said, “without the pleasure of the taste.”

That was our commissary list, except for salt and some spices, especially pepper for the asida, a pudding of boiled flour and oil, made pepper hot. There was little variety; but variety is the one thing one has to give up when one’s supplies are to be carried by animals who must themselves live chiefly on what they can carry. There were no luxuries, no matter how pleasant they might have been to relieve the monotony of rice, unleavened bread, dates, and tea. If one has experience in desert travel and the wisdom to learn by it, one takes no foods of which there is not enough to feed every one in the caravan. On the trek in the desert there is no distinction of rank or class, high or low.

The sole exception to the rule of no luxuries was tobacco. Since only one of the men who were with me at any time on the trip smoked, however, this was no real violation of the rule. A stock of Egyptian cigarettes and tobacco afforded me constant pleasure and comfort throughout the journey.

[26]Next comes water, the one great and unceasing problem of desert travel. Men have lived for an unbelievable number of days without food, whether from necessity or from curiosity. But the man who could go for four days without water would be a miracle. A desert is a desert just because it lacks water. The desert traveler must think first of his drinking supply.

We carried water in two ways. The regular supply was held in twenty-five girbas, the traditional sheepskin water-carrier of the desert. Each holds from four to six gallons—and is easily burst if two camels carrying girbas bump together in the dark on a rocky road! So the reserve water-supply for emergencies is carried in fantasses. They are long tin containers, oblong or oval shaped in cross-section to hang easily along the camel’s side. We had four fantasses holding four gallons each and four others holding twelve gallons each. Our full supply, therefore, was something like two hundred gallons, enough to last our caravan, when it was finally organized, on the longest trek from well to well that we were likely to encounter. We carried only our reserve supply in fantasses, although they were less liable to injury, because the girbas, when empty, took up so little space. All twenty-five of them could be carried on one camel, while only two fantasses went[27] to a camel, full or empty. We had no camels to spare.

There were also some individual water-bottles, but most of them were soon discarded because the men hated the nuisance of carrying them. A few were kept for cooling water later on in the journey when the weather became hot. The evaporation of the moisture through the canvas sides of the bottles or bags kept the water within at a pleasant temperature.

Four tents, two bell-shaped and two rectangular, and numerous cooking-utensils, of which the chief was a huge brass halla or bowl for boiling rice, made up the tale of our equipment. For emergencies there was a medicine-chest, with quinine, iodine, cotton and bandages, bismuth salicylate for dysentery, morphine tablets and a hypodermic syringe, anti-scorpion serum—which was to plunge me into an apparently serious predicament and rescue me from it—zinc ointment for eczema, indigestion tablets, and Epsom salts. I had a primitive surgical kit and a few dental instruments and remedies which a dentist friend had given me. I was equipped to take care of the simple every-day ills; if anything more serious befell, I should have to say, “Recovery comes from God.”

For hunting and possible defense I took three rifles, three automatic pistols, and a shot-gun. By[28] the time of our return the shot-gun had been given as a present, and the rest of the arsenal had been increased by six rifles and one pistol. When the rifles arrived at Sollum in their characteristically shaped boxes, it was immediately rumored through the town that I was carrying a machine-gun, for some mysterious purpose which gossip elaborated to suit itself.

In order to make the report of what I found and saw as vivid and truthful as possible I took five cameras. Three of them were Kodaks, which functioned perfectly to the end; one a more elaborate instrument with a focal-plane shutter, which was ruined by the penetrating sand; and the last a cinema machine. For all the cameras I carried Eastman Kodak films, which were packed with elaborate care, first in air-tight tins, then in tin cases, sawdust filled, and finally in wooden boxes. These precautions in packing proved to be none too great, in view of the intense heat of the first part of the route and the rain and dampness which we encountered later on in the Sudan. For the cinema camera I took nine thousand feet of film. Fortune was with me in all the photographic work. The films were not developed until my return eight months later to Egypt, but the percentage of failures was gratifyingly low. For clothing I took the usual Bedouin garb of white shirts and[29] long drawers, both made of calico, and a woolen jerd, the voluminous Bedouin wrap; also silk jackets and waistcoats and cloth drawers like riding-breeches, but reaching to the ankles; the latter were used only on ceremonious occasions, such as entering or leaving an oasis; there were naturally a few changes of each. I did not wish to put on the desert dress until the end of the first stage of the journey, so I left Sollum in old khaki coat and riding-breeches, which had already seen their best days. With yellow Bedouin slippers on my feet, the only possible wear in desert travel, and a Jaeger woolen night-cap on my head, for the weather was keenly cold, I must have been an amusing figure when we made our start.

When traveling into unknown lands, especially in the East, it is important to be able to make presents to those of prominence whom you meet. I had what seemed to me an enormous supply of silks, copper bowls, and censers inlaid with silver, bottles of scent, silk handkerchiefs, silver tea-pots and tea-glasses, silver call-bells—which the Bedouin is delighted to be able to use for summoning his slaves instead of the usual clapping of the hands. When I saw all this array being packed, I felt sure that we should bring half of it back with us. But by the time we had reached Kufra, I discovered that not only those who were of use to me this time but every one who had[30] rendered the slightest service on my previous trip was expectant of reward for services rendered. What with postponed expectations and the opportunities which the present trip afforded for making presents, we had none too many of the goods I have mentioned. In making these gifts, however, I did not feel that it was so much an endeavor to smooth the way of my expedition as a courtesy from a Bedouin of the town to his brother Bedouin of the desert.

Most important of all for the ultimate value of the expedition, if it was to have any, was the scientific apparatus, which is detailed in Dr. Ball’s report in the appendix.

The fortnight at Sollum was filled with busy days. Simple as our equipment was, everything had to be as nearly right as thought and care could achieve. Things carried on camel-back, put on each morning and taken off each night and built into barricades against weather and possible attacks, must be snugly and securely packed. At the end of a day’s trek, careless or tired camelmen often find it easier to let boxes and bundles drop without ceremony from the camels’ sides than to handle them with proper care.

[31]CHAPTER V

PLOTS AND OMENS

MY plans were all made for a trek straight south to Jaghbub when, two days before the date determined upon for the start, an incident happened which disquieted me.

I was sitting one evening in my room in the little government rest-house, busy with the figures of my scientific observations. There came a knock at the door. I could not imagine who could want me at that hour, but I went to the door and opened it a little way. A Bedouin whom I did not know was standing there, muffled Bedouin fashion in his jerd. I shut the door quickly and demanded, “Who are you?”

“A friend,” was the answer, which somehow did not convince me.

“What is your name and your business?” I asked.

“I am a friend, and I have something to tell you[32] which you ought to know,” explained my visitor through the closed door.

I opened the door and demanded what he had to tell. He came in.

“You are going by the straight road to Jaghbub?” he half queried.

I nodded assent.

“Don’t go,” he continued with vigor.

“Why not?” I asked.

“The bey is a rich man,” he said. “He carries with him great stores of the bounty of God, and the Bedouins are greedy. The rumor is that you have many boxes of gold.”

I could see that he half believed it, though he was pretending not to.

“The camelmen have agreed with friends on the road that you shall be waylaid and robbed. You will lose your money and probably your life.”

“One can always fight,” I suggested.

“Perhaps,” he agreed, “if you had plenty of men of your own.”

I hadn’t, so I proceeded to question him further about his information. The story seemed straight enough, and when I learned that my visitor was a relative of a man to whom I had done a good turn when on the last mission to the Senussis, I felt that it would be wise to believe him. I thanked him for his[33] warning, and he went away into the night. I sat down to consider the unpleasantly melodramatic situation.

The desert people are quick to ferret out your purpose if they can, and, if they cannot, to build up imaginary stories to account for what you are and have and intend to do. Much of our paraphernalia was in boxes. Boxes, to the Bedouin mind, mean treasure. If three rifles in a case could be translated into a machine-gun, why should not cameras and instruments in boxes be translated into gold and bank-notes? It was no wonder that the men whose camels we had hired were convinced that I was going into the desert with vast wealth for some unknown purpose. It was quite possible that they planned to rob me. It was a cheerful outlook for the very beginning of our journey. A fight, no matter how successful, would be a poor start for our undertaking. I decided that it would be better to avoid this first obstacle in our path rather than to encounter it.

Promptly the next day the camel-owners whose pleasant little plan had been revealed to me found themselves discharged. Others with their camels were forthwith hired to take me to Siwa. Instead of the straight line to Jaghbub we would go along the two other sides of the triangle whose apices were Sollum, Siwa, and Jaghbub. It would materially[34] lengthen this first part of our journey, but, after all, time and distance were less important than safe arrival. The road by way of Siwa had several advantages. It lay in Egyptian territory and not in the country inhabited by the tribes to which the first set of camelmen belonged. In the second place, it ran through more frequented territory, where a treacherous waylaying of our caravan would have been more perilous to the waylayers. Lastly, our quick departure after the change of plan gave the conspirators no time to develop any new plot if they had wanted to. It looked safe, and it proved to be as safe as it looked.

On January 1 the caravan started, and three days later Lieutenant Bather very kindly took me in a motor-car to catch up with it. We found the caravan at Dignaish, thirty-six miles out; and, saying good-by to the lieutenant, I took up the journey.

It was then a six days’ trek to Siwa. Our spare time was profitably spent in camouflaging the boxes and cases in our luggage to look like the usual Bedouin impedimenta. The only event of interest during the six days was the first of three good omens that foretold success to the trip. On the fifth day in the late afternoon I saw a gazelle feeding a little distance off our track. Without other thought than the pleasant anticipation of fresh meat, I set out after[35] it. As I went I heard discouraging shouts and howls from the men behind me. I could not understand their reluctance to have me go after the game, in view of the Bedouin’s love of meat. I imagined that they were afraid I would be led away some distance from them and thus hold up the progress of the caravan. The reason did not seem sufficient, and so I pursued my quest. After some chase I got a shot at the gazelle and brought it down.

As I approached the caravan with my game, I was surprised again. The men came running toward me with waving arms and shouts of joyful congratulation. I understood their present state of mind no more than I had their former one, until the explanation was forthcoming.

Then I learned that among the Bedouins the first shot fired at game after a caravan sets out is the critical one. If it is a miss, disaster is certain to overtake the caravan before the journey’s end. If it is a hit, fortune will smile upon the whole undertaking. The men of the caravan had been reluctant to see me put our luck to the test so soon. If I had remembered the Bedouin travel lore, I should have saved my first shot at game until we reached El Fasher, six months later.

We were three days in Siwa, hiring other camels for the trek to Jaghbub and making a few final[36] preparations. Siwa was the last outpost of the world I was leaving behind. There the postal service and the telegraph end. Beyond that point there is nothing to be bought except the products of the desert, or occasionally a little rice or cloth, perhaps at exorbitant prices. In my three days I enjoyed the hospitality and valuable assistance of the Frontier Districts Administration, in the persons of the mamur and town officials and of Lieutenant Lawler, in command of the troops there.

Siwa is the biggest and most charming of oases; springs of wonderful water, excellent fruit, the best dates in the world, picturesque scenery, and the quaintest and most interesting of customs. For example, if a woman loses her husband she is kept forty days without washing, and nobody sees her. Her food is passed through a crack in the door. When the forty days have expired, she goes to bathe in one of the wells, and everybody tries to avoid crossing her path, for she is then called ghoula and is supposed to bring very bad luck to anybody who sees her on that day of the first bath.

In the date market, called the mistah, all the dates are piled together, the best quality and the most inferior. No one thinks of touching one date that does not belong to him or mixing the dates together with a view to gaining an advantage thereby. On the other[37] hand, anybody can go into a mistah and eat as much as he likes from the best quality without paying a millième, but he must not take any away with him.

In Siwa there is a shrine of a saint where people may deposit their belongings for safety. If a man is going away he can take his bags with the most valuable things and put them near this shrine, and nobody would dream of touching them. Literally, if any one left a bundle of gold there, no one would touch it, because of the very simple but unshakable belief in them that if you touch anything near that shrine and it does not belong to you, you would have bad luck for the rest of your life.

When I was ready to leave Siwa, my little group of personal retainers had doubled in number. At Sollum I had added to Abdullahi and Ahmed a man of the Monafa tribe named Hamad. He was the hardest-working individual in the entire caravan. I never saw him tired. He took charge of my camel and later of the horse which I secured at Kufra. The fourth member of the group was Ismail, a Siwi. He looked like a weakling, but on the trek he was always the last man to give in and ride a camel. Ismail was the one whom I used to take with me when prospecting for geological specimens or making elaborate scientific observations. Coming from an oasis in Egyptian territory where the post and the telegraph made connection[38] with the outside world, he had less of the wild Bedouin’s suspicion that interprets every simple action of the stranger into something with an ulterior motive. Why should the bey be chipping off bits of rock, the Bedouin might say to himself, unless there were gold in it, or he intended to come and conquer the country? Not so Ismail. If the bey wanted a bit of rock, that was for the bey to say.

We left Siwa on the fourteenth with our new caravan. Our last link with the outside world was broken. At the first stop I took off my faded khaki and put on the Bedouin costume and felt myself now a part of the desert life. The effect upon the men was immediate. Till now they had approached me with embarrassment and awkwardness. Now they came up naturally, kissed my hand in Bedouin fashion, and said, “Now you are one of us.”

Our second good omen befell us a few miles out of Siwa. We found dates in our path, where some unfortunate date merchant taking his cargo to market had had an accident. Dates in the way are a promise of good fortune for the journey. Often, when a Bedouin is setting out with his caravan, friends will go secretly ahead and drop dates where he will be sure to pass them. With my first shot and the gazelle and the dates in the path, we had every reason to be cheerful. But the best omen of all was to come.

[39]I had sent two men ahead with a letter to Sayed Idris at Jaghbub, to inform him of my approach. In the desert one does not rush upon a friend or a dignitary headlong and unannounced. There should be time for both to put on fresh clothing and go with dignity to the meeting as becomes gentlemen of breeding.

Two days out from Siwa I was riding some distance behind the caravan and presently came upon it halted. I asked the reason for the unusual stop and received the reply, “Messengers have come to say that Sayed Idris will be here within an hour.” The men could scarcely conceal their excitement. To be met by the great head of the Senussis himself at the beginning of our journey was the most auspicious of omens. The rest of the message was indicative of the etiquette of the desert. “He asks the bey to camp so that he may come to him.”

We immediately made camp, and before long the vanguard of Sayed Idris’s caravan appeared and made camp in their turn a short distance away. A half-hour later Sayed Idris himself, with his retinue, advanced toward my camp, and I went to meet him.

Sayed Idris met me with warm cordiality, and we renewed the acquaintance made on our previous meetings with deep gratification on my part and apparent pleasure on his. The former trip could never[40] have been successful without the countenance he gave to it and the assistance he rendered; how much more the present one, which was to take me three times as far and into more completely unknown regions.

In his tent we lunched on rice, stuffed chicken, and sweet Bedouin cakes, followed by glasses of tea delicately scented with mint and rose-water. I told him of my plans and gave him news of the outside world. He was interested to know the final issue of the Peace Conference at Versailles.

At his suggestion, I brought all the men of my caravan to his tent to receive his blessing. As I stood with them and heard the familiar words fall from his lips, there came irresistibly to my mind that moment in the incense-shrouded room in Cairo and my father’s blessing upon my undertaking. Then my imagination had leaped out to meet the vision of the desert, the camels, the Bedouin life. Now the need for imagination was gone. I was in Bedouin kit, with the camels of my caravan behind me, and the road to the goal I sought stretching ahead.

To my men the experience of being blessed by Sayed Idris himself was the greatest augury of success that we could have had. Nothing could harm us now.

In the afternoon we said farewell, both camps were broken, and both caravans took up the march,[41] Sayed Idris going east into Egypt and I west to Jaghbub and the long trail into the desert. As we marched my men insisted on following the track made by the caravan of Sayed Idris, to prolong the great good fortune that had befallen us.

[42]CHAPTER VI

THE SENUSSIS

ANY story of the Libyan Desert would not be complete without some consideration of the Senussis, the most important influence in that region. The subject is a complicated one. Justice might be done to it if an entire volume were available, but within the limits of a chapter only the important points of Senussi history can be touched.

The Senussis are not a race nor a country nor a political entity nor a religion. They have, however, some of the characteristics of all four. In fact they are almost exclusively Bedouins; they inhabit, for the most part, the Libyan Desert; they exert a controlling influence over considerable areas of that region and are recognized by the governments of surrounding territory as a real power in the affairs of northeastern Africa; and they are Moslems. Perhaps the best short description of the Senussis would be as a religious order whose leadership is hereditary and[43] which exerts a predominating influence in the lives of the people of the Libyan Desert.

The history of the brotherhood may be roughly divided into four periods. In each it took its color from the personality of the leader. These were respectively Sayed Ibn Ali El Senussi, the founder; Sayed El Mahdi, his son; Sayed Ahmed, the nephew of the latter; and Sayed Idris, the son of El Mahdi, the present head of the brotherhood.

Sayed Mohammed Ibn Ali El Senussi, known as the Grand Senussi, was born in Algeria in the year 1202 after the Hegira, which corresponds to 1787 in the Christian calendar. He was a descendant of the Prophet Mohammed and had received an unusually scholarly education in the Kairwan University, in Fez, and at Mecca, where he became the pupil of the famous theologian Sidi Ahmed Ibn Idris El Fazi. He developed an inclination to asceticism and a conviction that what his religion needed was a return to a pure form of Islam as exemplified in the teachings of the Prophet.

At the age of fifty-one he was compelled to leave Mecca by the opposition of the older sheikhs, who challenged his orthodoxy. He returned through Egypt to Cyrenaica and began to establish centers for teaching his doctrines among the Bedouins.

At this point an explanation of the meaning of[44] three Arabic words will elucidate the text. They are zawia, ikhwan, and wakil.

A zawia is a building of three rooms, its size depending on the importance of the place in which it is situated. One room is a school-room in which the Bedouin children are taught by the ikhwan; the second serves as the guest-house in which travelers receive the usual three days’ hospitality of Bedouin custom; in the third the ikhwan lives. The zawia is generally built near a well where travelers naturally stop. Attached to the zawia is often a bit of land which is cultivated by the ikhwan. The ikhwan are the active members of the brotherhood, who teach its principles and precepts. Ikhwan in Arabic is really a plural form, which means “brothers.” But the singular of the word is never used, ikhwan having come to be used for one or more. A wakil is the personal representative or deputy of the head of the Senussis.

The Grand Senussi found the Moslems of Cyrenaica fallen into heresies and in danger of rapid degeneration, not only from a religious but from a moral point of view. Some small examples may serve to illustrate this point.

At Jebel Akhdar, in the north of Cyrenaica, certain influential Bedouin chiefs had established a sort of Kaaba, an imitation of the true one at Mecca to[45] which every believer who could possibly do so should make his pilgrimage. These founders of a false Kaaba tried to establish the theory that a pilgrimage thither was a worthy substitute for the haj, the authentic pilgrimage to the central shrine of Islam.

The keeping of the month of Ramadan as a time of abstinence and religious contemplation is an important tenet of the Moslem faith. The Bedouins used to go before the beginning of Ramadan to a certain valley called Wadi Zaza, noted for the multiple echo given back by its walls. In chorus they would shout a question, “Wadi Zaza, Wadi Zaza, shall we keep Ramadan or no?” The echo of course threw back the last word of the question, “No—no—no!” Those who had appealed thus to the oracle would then go home justified in their own minds in their desire to forego the keeping of the fast.

There were also prevalent among the Bedouins remnants of old barbaric customs—such as the killing of female children “to save them from the evils which life might bring”—which stood between them and their development into worthy exponents of Islam.

In such circumstances what the founder of the Senussi brotherhood had to give, in his teaching and preaching of a return to the pure tenets of Islam, met a poignant need.

Sayed Ibn Ali El Senussi founded his first zawia[46] on African soil at Siwa, which is in Egypt close to the western frontier. From that point he moved westward into Cyrenaica, establishing zawias at Jalo and Aujila. He traveled westward through Tripoli and Tunis, gradually spreading his teachings among the Bedouins. His reputation as a saintly man and a scholar had preceded him, and he was much sought after by the Bedouin chiefs, who vied with one another to give him hospitality.

On his return to Cyrenaica in the year 1843 he established at Jebel Akhdar near Derna a large zawia called El Zawia El Beda, the White Zawia. Until this time he had no headquarters but led the life of a wandering teacher. He settled down at El Zawia El Beda and received visits from the leading Bedouin dignitaries of Cyrenaica.

The Grand Senussi preached a pure form of Islam and strict adherence to the laws of God and his Prophet Mohammed.

His teachings may perhaps be best illustrated by a passage from a letter to the people of Wajanga, in Wadai, the original of which I saw at Kufra and translated. The passage reads as follows:

We wish to ask you in the name of Islam to obey God and His Prophet. In his dear Book he says, praise be to him, “O ye, who are believers, obey God and obey the Prophet!” He also says, “He who obeys the Prophet has also[47] obeyed God.” He also says, “He who obeys God and His Prophet has won a great victory.” He also says, “Those who obey God and the Prophet, they are with the prophets whom God has rewarded.”

We wish to ask you to obey what God and His Prophet have ordered; making the five prayers every day, keeping the month of Ramadan, giving tithes, making the haj to the sacred home of God [the pilgrimage to Mecca], and avoiding what God has forbidden—telling lies, slandering people behind their backs, taking unlawfully other people’s money, drinking wine, killing men unlawfully, bearing false witness, and the other crimes before God.

In following these you will gain everlasting good and endless benefits which can never be taken from you.

The principal concern of the founder of the Senussis was with the religious aspect of life. He did not set out to be a political leader or to grasp temporal power. He counseled austerity of life with the same enthusiasm with which he practised it. He taught no special theological doctrines and demanded acceptance of no particular dogmas. He cared much more for what his followers did than for any technicalities of belief. His only addition to the Moslem ritual was a single prayer, which he wrote and which the Senussis use, called the hezb. It is not opposed to anything taught by the older theologians, nor does it add anything to what is found in the Koran. It is simply expressed in different language. In the letter to the people of Wajanga, which I have[48] quoted, another passage described his mission, which God had laid upon him, as that of “reminding the negligent, teaching the ignorant, and guiding him who has gone astray.”

He forbade all kinds of luxurious living to those who allied themselves with his brotherhood. The possession of gold and jewels was prohibited—except for the adornment of women—and the use of tobacco and coffee. He imposed no ritual and only demanded a return to the simplest form of Islam as it was found in the teaching of the Prophet. He was intolerant of any intercourse, not only with Christians and Jews, but with that part of the Moslem world which, in his conviction, had digressed from the original meaning of Islam.

In the year 1856 Sayed Ibn Ali founded at Jaghbub the zawia which eventually developed into the center of education and learning of the Senussi brotherhood. His choice of Jaghbub was not haphazard or accidental but a demonstration of his wisdom and practical sagacity. He conceived it to be of the first importance to reconcile the different tribes of the desert to each other and to bring peace among them. One more quotation from his letter illustrates this point:

We intend to make peace between you and the Arabs [the people of Wajanga to whom this letter is addressed[49] are of the black race] who invade your territory and take your sons as slaves and your money. In so doing we shall be carrying out the injunction of God, who has said, “If two parties of believers come into conflict, make peace between them.” Also we shall be following his direction, “Fear God, make peace among those about you, and obey God and his Prophet if you are believers.”

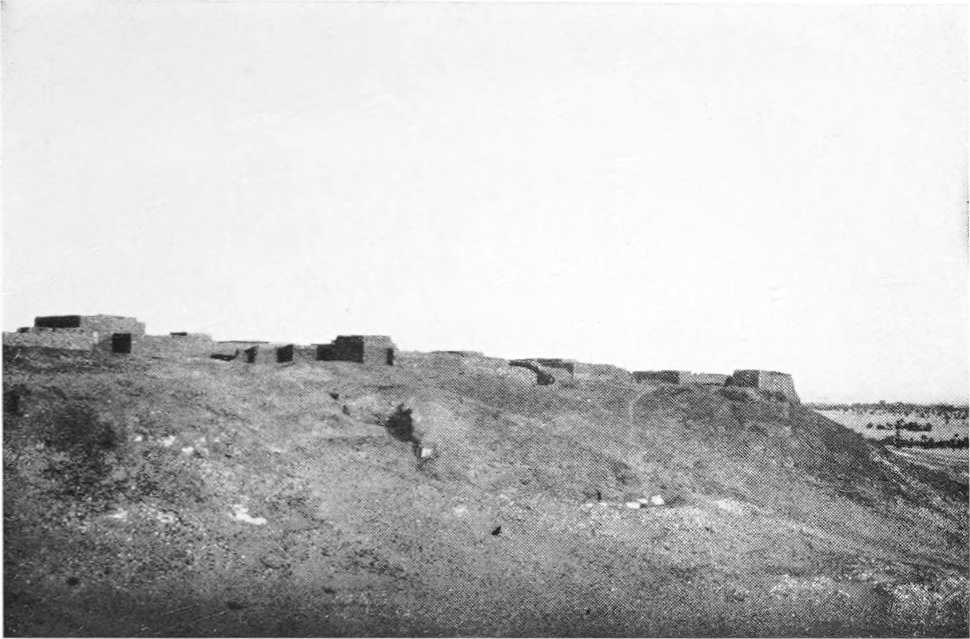

SIWA

One of the most historic oases of northern Africa. It was noted for its temple of Amon even before the time of Herodotus, and Alexander the Great came here to consult the oracle. In the middle distance, slightly to the right, is the covered market-place. Lofty structures indicate that Siwa was at one time a point of defense from desert tribes.

Jaghbub was a strategic point for his purpose. It stood midway between tribes on the east and on the west who had been in constantly recurring conflict. With his headquarters there the Grand Senussi could bring his influence to bear on the warring rivals and carry out the command of the Prophet to “make peace among those about you.” From a practical standpoint Jaghbub was an unpromising place in which to set up such a center of educational and religious activity as the Grand Senussi had in contemplation. It is not much of an oasis, if indeed it can be called an oasis at all. Date-trees are scarce there, the water is brackish, and the soil very difficult to cultivate. Its strategic importance, however, was clear, and without hesitation he selected it as the site of his headquarters. The raids made upon each other by the tribes to the east and the west were brought to an end through his influence. He settled many old feuds not only between those tribes but among the other tribes in Cyrenaica.

[50]Sayed Ibn Ali lived for six years after establishing himself at Jaghbub and extended his influence far and wide. The Zwaya tribe, who had been known as the brigands of Cyrenaica, “fearing neither God nor man,” invited him to come to Kufra, the chief community of their people, and establish a zawia there. They agreed to give up raiding and thieving and attacking other tribes and offered him one third of all their property in Kufra if he would come to them. He could not go in person but sent a famous ikhwan, Sidi Omar Bu Hawa, who established the first Senussi zawia at Jof in Kufra, and began the dissemination of the teachings of the Grand Senussi among the Zwayas. Sayed Ibn Ali also commissioned ikhwan to go into many other parts of the Libyan Desert, and before his death all the Bedouins on the western frontier of Egypt and all over Cyrenaica had become his disciples.

He died in the year 1859, and was buried in the tomb over which rises the kubba of Jaghbub.

The Grand Senussi was succeeded by his son Sidi Mohammed El Mahdi, who was sixteen years old when his father died. In spite of his youth his succession as head of the order was strengthened by two circumstances. It was remembered that on one occasion, at the end of an interview with his father, El Mahdi was about to leave the room, when the[51] Grand Senussi rose and performed for him the menial service of arranging his slippers, which had been taken off on entering. The founder of the order then addressed those present in these words: “Witness, O ye men here present, how Ibn Ali El Senussi arranges the slippers of his son, El Mahdi.” It was realized that he meant to indicate that the son not only would succeed the father but would surpass him in holiness and sanctity.

Then too there was an ancient prophecy that the Mahdi who would reconquer the world for Islam would attain his majority on the first day of Moharram in the year 1300 after the Hegira, having been born of parents named Mohammed and Fatma and having spent several years in seclusion. Each part of this prophecy was fulfilled in the person of El Mahdi. The choice as successor to the Grand Senussi fell upon him.

When Sayed El Mahdi reached his majority there were thirty-eight zawias in Cyrenaica and eighteen in Tripolitania. Others were scattered over other parts of North Africa; and there were nearly a score in Egypt. It has been estimated that between a million and a half and three million people owed spiritual allegiance to the head of the brotherhood when El Mahdi became its active head. He was the most illustrious of the Senussi family.

[52]He saw from the first that there was more scope for the influence of the brotherhood in the direction of Kufra and the regions to the southward than in the north. In the year 1894 he removed his headquarters from Jaghbub to Kufra. Before his departure he freed all his slaves, and some of them and their children are still to be found living at Jaghbub.

His going to Kufra marked the beginning of an important era in the history of the Senussis and also in the development of trade between the Sudan and the Mediterranean coast by way of Kufra. The difficult and waterless trek between Buttafal Well near Jalo and Zieghen Well just north of Kufra became in El Mahdi’s time a beaten route continually frequented by trade caravans and by travelers going to visit the center of the Senussi brotherhood. “A man could walk for half a day from one end of the caravan to the other,” a Bedouin told me.

The route from Kufra south to Wadai was also a hard and dangerous journey in those days, and El Mahdi caused the two wells of Bishra and Sara to be dug on the road from Kufra to Tekro.

Under the rule of the Zwaya tribe of Bedouins, who had conquered Kufra from the black Tebus, that group of oases was the chief center of brigandage in the Libyan Desert. The Zwayas are a warlike tribe, and in the days before the coming of the Senussis they[53] were a law unto themselves and a menace to all those who passed through their territory. Each caravan going through Kufra north or south was either pillaged or, if lucky, was compelled to pay a route tax to the Zwayas. These masters of Kufra were induced by El Mahdi to give up this exacting of tribute. He realized the importance of developing the trade of the oases and of the routes across the Libyan Desert from the north to the south. He strove to make desert travel safe, and in his day, Bu Matari, a Zwaya chieftain, told me at Kufra, a woman might travel from Barka (Cyrenaica) to Wadai unmolested.

El Mahdi also extended the circle of influence of the Senussis in many directions. Ikhwan were sent out to establish zawias from Morocco as far east as Persia. But his greatest work was in the desert, among the Bedouins and the black tribes south of Kufra. He made the Senussis not only a spiritual power in those regions, and a powerful influence for peace and amity among the tribes, but a strong mercantile organization under whose stimulus trade developed and flourished. In the last years of his life he undertook to extend the influence of the brotherhood to the southward in person. He had gone to Geru south of Kufra when his death came suddenly in the year 1900.

[54]The sons of El Mahdi were then minors, and his nephew Sayed Ahmed was made the head of the brotherhood. He was the guardian of Sayed Idris, who, as the eldest son of El Mahdi, was his legitimate successor.