The Project Gutenberg eBook of The presidental snapshot, by Bertram Lebhar

Title: The presidental snapshot

or, The all-seeing eye

Author: Bertram Lebhar

Release Date: March 30, 2023 [eBook #70413]

Language: English

Produced by: Demian Katz, Craig Kirkwood,and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University.)

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

Chapter I. A Cabinet Discussion.

Chapter II. A Matter in Confidence.

Chapter III. Paxton’s Warning.

Chapter VI. A Meeting After Dark.

Chapter VII. Discouraging News.

Chapter X. An Unpleasant Surprise.

Chapter XI. A Diplomat’s Daughter.

Chapter XII. On the Right Track.

Chapter XIV. A Mysterious Summons.

Chapter XVI. The Señora or the President.

Chapter XVII. A Serious Charge.

Chapter XX. What Gale Overheard.

Chapter XXIII. Under Sealed Orders.

Chapter XXV. Captain Cortrell’s Orders.

Chapter XXVI. The Plate Developed.

Chapter XXVII. A Serious Situation.

Chapter XXXI. Portiforo’s Way.

Chapter XXXIII. At the Palace.

Chapter XXXIV. Blue Spectacles.

Chapter XXXV. Wireless Warning.

Chapter XXXVI. A Welcome Intrusion.

Chapter XXXVIII. Like a Bad Penny.

Chapter XXXIX. Cause For Anxiety.

Chapter XL. An Interrupted Dinner.

Chapter XLII. Gale Turns a Trick.

Chapter XLIII. A Little Keepsake.

Chapter XLIV. The Developed Film.

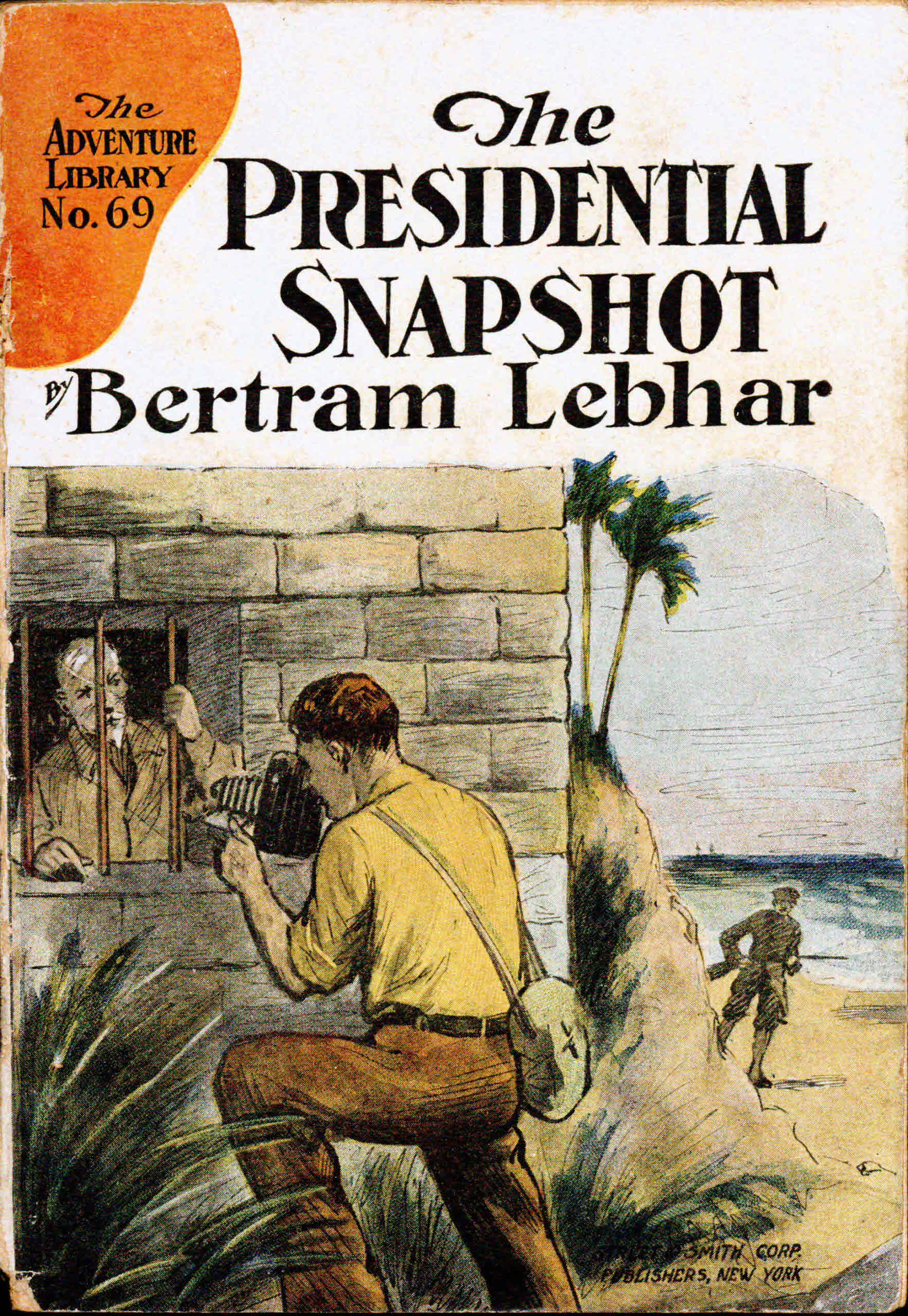

The Adventure Library No. 69

The

Presidential

Snapshot

By Bertram Lebhar

STREET & SMITH CORP. PUBLISHERS, NEW YORK

A CARNIVAL OF ACTION

ADVENTURE LIBRARY

Splendid, Interesting, Big Stories

This line is devoted exclusively to a splendid type of adventure story, in the big outdoors. There is really a breath of fresh air in each of them, and the reader who pays fifteen cents for a copy of this line feels that he has received his money’s worth and a little more.

The authors of these books are experienced in the art of writing, and know just what the up-to-date American reader wants.

ALL TITLES ALWAYS IN PRINT

By WILLIAM WALLACE COOK

| 1—The Desert Argonaut | |

| 2—A Quarter to Four | |

| 3—Thorndyke of the Bonita | |

| 4—A Round Trip to the Year 2000 | |

| 5—The Gold Gleaners | |

| 6—The Spur of Necessity | |

| 7—The Mysterious Mission | |

| 8—The Goal of a Million | |

| 9—Marooned in 1492 | |

| 10—Running the Signal | |

| 11—His Friend the Enemy | |

| 12—In the Web | |

| 13—A Deep Sea Game | |

| 14—The Paymaster’s Special | |

| 15—Adrift in the Unknown | |

| 16—Jim Dexter, Cattleman | |

| 17—Juggling with Liberty | |

| 18—Back from Bedlam | |

| 19—A River Tangle | |

| 20—Billionaire Pro Tem | |

| 21—In the Wake of the Scimitar | |

| 22—His Audacious Highness | |

| 23—At Daggers Drawn | |

| 24—The Eighth Wonder | |

| 25—The Cat’s-Paw | |

| 26—The Cotton Bag | |

| 27—Little Miss Vassar | |

| 28—Cast Away at the Pole | |

| 29—The Testing of Noyes | |

| 30—The Fateful Seventh | |

| 31—Montana | |

| 32—The Deserter | |

| 33—The Sheriff of Broken Bow | |

| 34—Wanted: A Highwayman | |

| 35—Frisbie of San Antone | |

| 36—His Last Dollar | |

| 37—Fools for Luck | |

| 38—Dare of Darling & Co. | |

| 39—Trailing “The Josephine” | |

| 40—The Snapshot Chap | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 41—Brothers of the Thin Wire | By Franklin Pitt |

| 42—Jungle Intrigue | By Edmond Lawrence |

| 43—His Snapshot Lordship | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 44—Folly Lode | By James F. Dorrance |

| 45—The Forest Rogue | By Julian G. Wharton |

| 46—Snapshot Artillery | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 47—Stanley Holt, Thoroughbred | By Ralph Boston |

| 48—The Riddle and the Ring | By Gordon McLaren |

| 49—The Black Eye Snapshot | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 50—Bainbridge of Bangor | By Julian G. Wharton |

| 51—Amid Crashing Hills | By Edmond Lawrence |

| 52—The Big Bet Snapshot | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 53—Boots and Saddles | By J. Aubrey Tyson |

| 54—Hazzard of West Point | By Edmond Lawrence |

| 55—Service Courageous | By Don Cameron Shafer |

| 56—On Post | By Bertram Lebhar |

| 57—Jack Cope, Trooper | By Roy Fessenden |

| 58—Service Audacious | By Don Cameron Shafer |

| 59—When Fortune Dares | By Emerson Baker |

| 60—In the Land of Treasure | By Barry Wolcott |

| 61—A Soul Laid Bare | By J. Kenilworth Egerton |

| 62—Wireless Sid | By Dana R. Preston |

| 63—Garrison’s Finish | By W. B. M. Ferguson |

| 64—Bob Storm of the Navy | By Ensign Lee Tempest, U. S. N. |

In order that there may be no confusion, we desire to say that the books listed below will be issued during the respective months in New York City and vicinity. They may not reach the readers at a distance promptly, on account of delays in transportation.

| To be published in July, 1927. | |

| 65—Golden Bighorn | By William Wallace Cook |

| 66—The Square Deal Garage | By Burt L. Standish |

| To be published in August, 1927. | |

| 67—Ridgway of Montana | By Wm. MacLeod Raine |

| 68—The Motor Wizard’s Daring | By Burt L. Standish |

| 69—The Presidential Snapshot | By Bertram Lebhar |

| To be published in September, 1927. | |

| 70—The Sky Pilot | By Burt L. Standish |

| 71—An Innocent Outlaw | By William Wallace Cook |

| To be published in October, 1927. | |

| 72—The Motor Wizard’s Mystery | By Burt L. Standish |

| 73—From Copy Boy to Reporter | By W. Bert Foster |

| To be published in November, 1927. | |

| 74—The Motor Wizard’s Strange Adventure | By Burt L. Standish |

| 75—Lee Blake, Trolley Man | By Boland Ashford Phillips |

| To be published in December, 1927. | |

| 76—The Motor Wizard’s Clean-up | By Burt L. Standish |

| 77—Rogers of Butte | By William Wallace Cook |

When you get the

S & S Novels you

get the best!

OR

THE ALL-SEEING EYE

BY

BERTRAM LEBHAR

Author of “On Post,” “His Snapshot Lordship,”

“Snapshot Artillery,” etc.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1913-1914

By STREET & SMITH

The Presidential Snapshot

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign

languages, including the Scandinavian.

Printed in the U. S. A.

THE PRESIDENTIAL SNAPSHOT.

The President of the United States shook his head with an emphasis which caused the other men gathered around the massive mahogany table to realize that it would be almost a waste of time to pursue the discussion. “It is my opinion, gentlemen, that if there were the slightest basis for this rumor, Mr. Throgmorton’s report would not be couched in such positive terms!” he declared, pointing to a paper on the table before him. “There isn’t a man in the diplomatic service more alert or level-headed than he, so far as I know. I am confident that it would be impossible for Portiforo to pull the wool over his eyes.”

“Possibly Portiforo has not pulled the wool over Throgmorton’s eyes,” the little man who sat at the president’s right suggested quietly. “He may not have found it at all necessary to do that.” There was something about the speaker’s tone which caused the other members of the cabinet to look at him curiously, and prompted the president to ask, quite calmly: “Will you say what you mean to imply by that remark, Mr. Attorney General?”

The little man smiled—a peculiar form of smile which seemed to be done with his eye only. “The American minister to the Republic of Baracoa has[6] never given the impression of being exactly hostile to the Portiforo administration,” he remarked dryly.

The president frowned. “Are we to understand this as an insinuation against his good faith?”

“To be quite frank, Mr. President, I have never credited Mr. Throgmorton with a superabundance of good faith,” the attorney general replied. “I have known him for a long time—in fact, we were at college together, and—well, it would take more than his unsupported word to convince me that there is no truth in this startling story of Portiforo’s perfidy. He and the President of Baracoa are reputed to be close friends, and it is possible that his investigation might not be unbiased.”

“I protest against that remark,” the secretary of state exclaimed indignantly. “I, too, have known Mr. Throgmorton for a long time, and there isn’t a man living, Mr. President, in whose integrity I have greater confidence. If this hideous thing were true he would have told us so, no matter how amicably disposed he might be toward the Portiforo administration.”

The president nodded an acquiescence. “I have as much confidence in Throgmorton’s honesty as I have in his good judgment,” he declared. “As I said before, gentlemen, he is too conservative a man to have made such a positive denial unless he had good ground for doing so. I have felt all along that this rumor was nothing more than a concoction of Portiforo’s enemies; now I am sure of it.”

“And nothing would cause you to change your mind, Mr. President?” the attorney general inquired.

[7]

“I would not say that. I am always open to conviction. Of course, if you could bring me a photograph of Felix in a dungeon cell, I might be ready to believe that Portiforo has him in captivity. But even at that,” he added, a twinkle in his eyes, “I would have to be convinced that the snapshot was genuine.”

The attorney general smiled deprecatingly. “Then I’m afraid it will never be possible to convince you, Mr. President. I don’t imagine that there’s a photographer in all the world who could break into a South American dungeon, snapshot a prisoner, and get out again.”

“I’m not so sure of that,” put in the secretary of the interior. “I know of one man who might be able to accomplish even that remarkable feat. He’s a New York newspaper man named Hawley. He’s on the staff of the Sentinel. I met him some months ago, when I was in New York, and the experience I had with him then leads me to believe that there is scarcely any feat impossible of accomplishment where he is concerned.”

“Isn’t that the man they call ‘the Camera Chap’?” the president inquired, evincing keen interest.

“I believe they do call him that,” the secretary of the interior replied. “He is truly a wonderful photographer. I believe that if Portiforo really has Felix locked up in El Torro Fortress, Hawley could get a picture of him.”

The president made no comment on this, but, later that day, when the cabinet meeting was over, he said to his secretary: “I wish you would send word to[8] Mr. Bates, of the New York Sentinel, that I would like to see him at his earliest convenience.”

Bates, the Sentinel’s Washington correspondent, hurried over to the White House immediately upon receipt of this information, hoping that the head of the nation contemplated favoring his paper with some exclusive information. What the latter actually said to him caused him some mystification.

“Mr. Bates,” the president began, “I believe you have a photographer named Hawley employed on your paper?”

“You mean the Camera Chap, Mr. President?”

“Yes. I have heard a great deal about his exploits, and if what I have heard is true, he must be a very unusual fellow. Tell me more about him, if you don’t mind.”

The Sentinel’s star correspondent launched into the subject with enthusiasm. There was not a man on his paper, from the editor in chief down to the youngest office boy, who was not proud of the fact that Frank Hawley was connected with it. The Camera Chap occupied a position unique in the newspaper world. He commanded a large salary, and his extraordinary achievements had made him famous in every newspaper office in the country, and caused other managing editors to envy the Sentinel for having him under contract.

It took Bates more than half an hour to tell of some of Hawley’s most notable performances, and the president’s face lighted up as he listened. “Why,” he exclaimed[9] enthusiastically, “the Camera Chap must be a remarkable character! Does he ever come to Washington? I should very much like to meet him. You might make it a point to mention that to your managing editor the next time you communicate with your office, Mr. Bates.”

“I will be sure to do so, Mr. President,” said the Sentinel representative, who, being far from dull-witted, and well acquainted with the chief executive’s methods, surmised that there was behind this request some special motive.

As a result of the message which Bates sent over the wire which connected the Sentinel’s Washington bureau with the home office, a tall, slender young man, with a prepossessing countenance and a twinkle in his keen eyes, arrived at the capital the following afternoon.

Bates greeted him effusively. “Welcome to our city, Hawley, old man!” he exclaimed. “I don’t know whether the president contemplates offering you a position in his cabinet or whether he merely wants his picture taken, but, whatever the reason, he’s very keen to meet you. His secretary called me up this morning to make sure you were coming; and when I told him that you were on your way to Washington he sent over this note for you.”

Bates handed Hawley a square envelope, on which the address of the executive mansion was embossed. The Camera Chap opened it, and read its contents over twice, the expression of surprise on his face intensifying as he did so.

[10]

“Are you sure this isn’t a practical joke?” he inquired half incredulously, handing Bates the note.

An envious look came to the other’s face as he glanced at it. “That’s going some!” he exclaimed. “You certainly are lucky, old man. Some of us Washington correspondents pride ourselves on being pals with the president, but he’s never invited any of us to lunch at the White House.”

[11]

When the Camera Chap went to keep his luncheon appointment the following morning, Bates, who had some business to attend to at the treasury department, accompanied him as far as the White House grounds. As they were walking along Pennsylvania Avenue, a splendid touring car, with a silver crest on the door panels and a liveried footman on the box, passed them by. It contained two women, one of them a blonde, the other very dark. The former, recognizing Bates on the sidewalk, bowed graciously.

“That is Mrs. Fred V. Cooper, wife of the attorney general,” the correspondent explained to his companion, noting that the latter was staring at the automobile, as though fascinated. “She’s one of the beauties of Washington.”

“And the other woman—the dark one—who is she?” the Camera Chap demanded eagerly.

Bates smiled. “There’s a woman with a history,” he said. “She is Señora Francisco Felix, wife of the former president of the Republic of Baracoa. You remember reading about him, of course?”

“Oh, yes. He’s the chap who disappeared a couple of years ago.”

“Disappeared is a gentle way of putting it,” returned the other, grinning. “He sneaked away in his private yacht, one memorable night, and the good people of Baracoa awoke next morning to find that they[12] were minus a president, and incidentally the greater part of the national treasury. The scamp took away with him every bolivar he could lay hands on. The little republic would have gone bankrupt if General Portiforo hadn’t stepped in and saved the situation.”

Hawley nodded. “Yes, I remember. What is his wife doing in Washington?”

“She’s been living here ever since her husband absconded. I guess she didn’t find it exactly comfortable in Baracoa after the scandal. She and Mrs. Cooper are great friends; they’ve known each other since they were girls. The señora was educated in the United States; I believe she and the attorney general’s wife were in the same class at Vassar. She—why, what’s the matter, old man?”

Hawley had given vent to a sharp exclamation, at the same time gripping his companion’s arm excitedly. “Did you notice that swarthy chap in the taxicab which just passed?” he asked.

“The fellow with a beard? Yes. What about him?”

“Don’t happen to know who he is, do you?”

Bates shook his head. “I suppose he’s connected with one of the Spanish-American embassies. There are so many of those fellows running around Washington that it isn’t possible for us to know them all. Why the interest in him?”

“This isn’t the first time I have seen him. I saw him in New York a couple of weeks ago. He was shadowing Señora Felix.”

“Señora Felix!”

[13]

“Yes; this is not the first time I’ve seen her, either, although I did not know who she was until now. The other day, Bates, I witnessed a queer incident outside the Hotel Mammoth. I was passing there just as that woman came out of the Thirty-fourth Street entrance and entered a taxicab. My attention was attracted to her not only because of her striking beauty, but because of the nervousness she displayed. As she stepped into the cab she kept glancing about her in all directions, as though aware that she was being watched. As she drove off I noticed a man skulking in the doorway of a store on the opposite side of the street. It was that same dark-skinned, bearded chap who just passed us. I saw him hurry across the street and rush up to another taxi that was waiting at the cab stand. I heard him instruct the driver to follow the woman’s cab, no matter where it went. He spoke in English, but with a decidedly foreign accent. My curiosity was aroused, and I decided to see the thing out. I, too, jumped into a taxi and joined in the procession.

“Straight down Fifth Avenue we went, as far as Washington Square. Then the three of us turned into a side street, and came to a stop. The woman’s cab had halted outside the door of a dingy-looking house in a neighborhood which had seen better days, but which now consists mostly of cheap rooming houses. The bearded man’s cab had drawn up about fifty yards away. He jumped out quickly, and I alighted, too, as inconspicuously as possible. A surprise awaited us both. The first cab was empty. The woman had disappeared.”

[14]

Bates laughed knowingly. “She must have been wise to the fact that she was being shadowed, and took advantage of a chance to drop out somewhere along the trail.”

“Of course. It’s an old trick. You ought to have seen our bearded friend’s face when he found that he had been fooled. He said a lot of things to himself in Spanish. I have enough knowledge of that language to know that his utterances weren’t fit for publication. Wonder if he’s shadowing her again now.”

“Most likely,” said Bates. “I suppose he’s one of Portiforo’s spies. Naturally, the present government of Baracoa would be interested in the movements of Señora Felix. I presume they hope, by watching her, to get a line on where her husband is.”

“You think she knows that?”

“It is more than a bare possibility. Felix hasn’t been heard of since he landed from his yacht on the south coast of France two years ago, but it is exceedingly likely that he has been in communication with his wife. I understand they were a very devoted couple. In fact, it was a surprise to everybody that when he skipped he didn’t take her along. Well, here we are at the White House grounds. See you later, old man. I am burning up with curiosity to know what the president wants of you.”

Bates’ curiosity in that respect was not destined to be gratified that day, nor for many days after. When the Camera Chap returned from his interview with the president, and dropped in at the Sentinel bureau, he was provokingly uncommunicative.

[15]

“It was a fine lunch,” he said. “The White House chef certainly knows his business; and the president is a genial host. He is one of the most democratic men I have ever met.”

“But what did you talk about?” Bates asked impatiently. “I know very well that he didn’t send for you merely to make your acquaintance. What did he want, old man? You can trust me, you know.”

“Of course I can,” the Camera Chap agreed cheerfully. “We discussed many things—ranging all the way from Park Row to South America.”

“South America!” the correspondent exclaimed eagerly. “What did he have to say about that?”

Hawley’s eyes twinkled. “He asked me whether I’d ever been out there, and when I told him no he expressed great surprise, saying that I certainly ought to make it a point to go; that he felt sure I would find many interesting things to photograph in that part of the world.”

Hearing which Bates had a shrewd suspicion that the president had suggested some particularly interesting thing to photograph in some part of South America; but, although he was a past master in the art of extracting information from unwilling lips, his efforts failed to draw out the Camera Chap further along this line.

It was the president’s closing remark to Hawley which had compelled the latter to adopt this sphinx-like attitude.

“I will not pledge you to secrecy,” the chief executive had said. “I will merely urge you to be discreet,[16] Mr. Hawley. I think I am able to estimate a man at first sight, and if I did not feel that you could be relied upon I would not have asked you to undertake this mission. You realize, of course, that in addition to the risk you will be running, a human life may depend upon your discretion.”

[17]

Inasmuch as the president had not pledged him to secrecy, the Camera Chap decided to take one person into his confidence regarding his visit to the White House. He knew that Tom Paxton, managing editor of the Sentinel, could be trusted, and there were reasons why Hawley felt that it was necessary to have him know the purpose of the undertaking on which he was about to embark. So he returned to New York that night, and arrived at the Sentinel office just as Paxton was closing down his desk with the intention of going home.

“Back so soon!” The boyish-looking managing editor greeted him, grinning. “I supposed it would take you at least a couple of weeks to tell the president all you know about how to run the ship of state. Seriously speaking, though, old man, I’m glad you’ve returned. I’ve got a little job for you up in Canada that needs your immediate attention. It——”

“I’m sorry, Tom,” the Camera Chap interrupted, “but I’m afraid I’ll have to ask you to hand that assignment to somebody else. I can’t touch it. I’ve got to have a couple of months’ leave of absence—to begin at once.”

Paxton looked his astonishment. “What are you going to do with it?”

“I am going to South America,” Hawley announced.[18] “To Baracoa, to be precise. I suppose you recall, Tom, the sensational disappearance of President Felix, a couple of years ago?”

“Of course,” Paxton replied. He had a phenomenal memory for contemporaneous history. It was the boast of the Sentinel staff that he could give, offhand, facts and figures of any event of importance in any part of the world within the past ten years.

“Francisco Felix,” he went on, as though reading from a book, “the poor Baracoa laborer who became president. They called him ‘the South American Abraham Lincoln.’ He was the idol of the people—the most beloved and respected executive Baracoa has ever had—until he proved himself to be a crook by absconding with the contents of the national treasury.”

The Camera Chap smiled. “That is the story which is generally accepted,” he said quietly. “But there is a possibility that the world may have done President Felix a great injustice.”

“What do you mean?” Paxton asked, looking searchingly in the other’s face.

“It now appears,” said the Camera Chap, “that instead of being a fugitive and an absconder, Felix may really have been the victim of a daring conspiracy; that instead of being free in some part of Europe at this moment, living in luxury on his loot, the unhappy man is in reality eating out his heart in a South American dungeon—where he has been ever since that fatal night that he is supposed to have skipped from Baracoa in his private yacht. In other words, Tom, it was all[19] a frame-up. According to this story, Felix was kidnaped by the Portiforo party, who, realizing that he was too strong with the people to be deposed by an ordinary revolution, took this means of discrediting him and seizing the reins of government.”

Editor Paxton smiled incredulously. “Sounds pretty far-fetched. Yet I don’t know,” he added musingly. “Almost anything is possible down in that part of the continent; and I recall that there were some circumstances about Felix’s disappearance which struck me at the time as queer. There is the fact, for instance, that he has never been seen since the day his yacht reached the south coast of France.”

“He wasn’t seen even then,” Hawley reminded him. “At least, there is no proof that the man who came ashore was really Felix. The only persons who saw him were some French peasants, and, of course, they wouldn’t know Felix by sight.”

“There was the crew of the yacht,” Paxton suggested. “You are forgetting, perhaps, that later on they were caught and they admitted the whole business.”

“It is possible that they were in the conspiracy,” Hawley argued. “Every member of the crew could have been a Portiforo agent, carefully instructed as to the story he was to tell.”

The managing editor nodded. “Yes; that’s possible. By George!” he added, a glint in his eyes, “what a wonderful story—if it should be true. Where on earth did you get hold of it?”

[20]

“At the White House,” the Camera Chap replied, sinking his voice almost to a whisper.

“What! You don’t mean to say the president believes it?”

“Not exactly. In fact, he is strongly inclined to think that it is a preposterous theory concocted by Portiforo’s enemies. Still, there is a doubt in his mind. That is why I am going to Baracoa.”

“He is sending you there to investigate this yarn?”

“To find Felix, if he is really in Baracoa, and to bring back a snapshot of him,” Hawley said simply.

“Good stuff!” Paxton approved. “If we had photographic evidence the United States would be in a position to intervene, and demand Felix’s immediate release. That, of course, would mean the finish of Portiforo, and I happen to know that there are reasons why Washington wouldn’t be exactly sorry to see a change in the government of Baracoa. But I say, old man,” he added anxiously, “do you appreciate the magnitude of the job you’re tackling? Do you realize the danger?”

“Surely I do,” Hawley answered. “The president warned me that I would have to be very careful—that if the story happened to be true, and Portiforo should find out the object of my trip to Baracoa, the consequences would be serious. They would probably seek to remove the evidence—by murdering poor Felix before I had a chance to get to him.”

Paxton frowned. “Yes, I have no doubt they would do that. They would make short work of Felix. But I wasn’t referring to him; I was thinking of what[21] might happen to you if they were to nab you in the act of trying to get that snapshot.” His tone was very grave. “I am afraid, old man, that they would stand you up against a stone wall, with a handkerchief around your eyes and spray you with lead from their guns.”

The Camera Chap laughed. “Not as bad as that, I guess. A dungeon cell and a ball and chain would be about the limit.”

“I’m not so sure,” Paxton muttered. “What protection does the president promise you in case you are caught?”

“He didn’t promise me any protection,” the Camera Chap replied cheerfully. “On the contrary, he gave me clearly to understand that I am going into this thing at my own risk. He explained that if I am apprehended in the act of violating any of the laws of a friendly nation, the United States government wouldn’t have any right to intervene.”

“I thought so,” growled Paxton. “Why the deuce couldn’t he have given this job to a secret-service man instead of you?”

“I didn’t ask him that,” Hawley answered, smiling. “But don’t worry, Tom. I’m going to get along all right. They’re not going to catch me, you know.”

The managing editor shook his head forebodingly. “I’ve a good mind to refuse you that leave of absence,” he said. “I’d do it, too, if I didn’t know that you’d go, anyway—and if you were working for anybody else but the President of the United States. When do you expect to start?”

[22]

“To-morrow. The Colombia, of the Andean line, sails for South American waters at two p. m. I’ve engaged passage on her.”

“You’re certainly not losing any time,” Paxton chuckled. “Would you like me to send somebody along to help you, old man? You can have the pick of our staff.”

The Camera Chap declined this offer. “I’m ever so much obliged,” he said, “but I have decided that I had better work alone. It seems to me that this is one of those cases where one head will be better than two.” He extended his hand. “Good-by, Tom. I’ll trot along. I’ve got to go home and pack my trunk.”

“Good-by, old man,” said the managing editor, gripping the outstretched hand with a fervor he rarely displayed. “Good-by, and good-luck to you! You’ll need all the luck you can command; for this is by far the most dangerous job you’ve ever tackled. By the way, let me give you a little tip that may prove valuable. If you should happen to get into trouble, and have to appeal to the American minister to save you, you’d better not let him know, if you can help it, that you are a member of the Sentinel staff.”

“Why not? I should think——”

“Minister Throgmorton doesn’t like the Sentinel,” Paxton interrupted dryly. “He has good reason for his prejudice. We have been roasting him editorially ever since he was appointed. So, under the circumstances, I scarcely think he would move heaven and earth to help a Sentinel man.”

[23]

The Andean line steamship Colombia was about to weigh anchor when the Camera Chap came aboard. He was not the only passenger who narrowly missed being left behind. As his taxicab drew up at the wharf two women were just alighting from an electric brougham. One of them was a blonde, and the other a pronounced brunette. Hawley gave a start of surprise at sight of them.

“Bon voyage, dear,” the blond woman was saying. “I trust that everything will come out all right, and that you will soon be back in Washington. After all, your father’s condition may not be as serious as the telegram makes out. You know how doctors sometimes exaggerate.”

The dark woman smiled faintly. “I pray that it may be so,” she said; “but I am greatly worried. They would not have sent for me unless it was very serious. Au revoir, and thank you a thousand times for all your kindnesses.”

“All aboard, ladies!” the officer at the gangplank cried. “Please hurry.”

The women embraced, and the blonde, whom Hawley had recognized as the wife of the United States attorney general, reëntered the brougham. The other hurried up the gangplank, the Camera Chap following close behind her.

[24]

“Señora Felix!” he said to himself. “I didn’t expect to have her for a fellow passenger. Lucky, I guess, that I decided to take this boat.”

On board the señora was greeted by a younger woman, whom she addressed as Celeste, and who, Hawley learned later, was her maid. They went immediately to her stateroom.

Hawley soon learned that Señora Felix’s departure from the United States was no secret. He had brought an evening newspaper on board, and on an inside page he came across the following heading, so inconspicuously displayed that it had first escaped his notice:

“Fugitive President’s Wife Goes Back.—Victoria Felix, ‘Grass Widow’ of Baracoa’s Missing Chief Executive, Sails To-day for Her Native Land After Two Years’ Exile in Washington.—Serious Illness of Her Father Given as Cause of Trip.”

From the quarter of a column of smaller type which appeared beneath this heading he learned that Señora Felix’s father was Doctor Emilio Hernandez, a prominent physician of San Cristobal, the capital of Baracoa. He had been seized with a paralytic stroke, and his daughter had been hurriedly summoned.

It was not until the vessel was well out at sea that the Camera Chap saw the señora again. She did not appear in the dining saloon for the evening meal, nor did she show herself on deck during the first day of the voyage. He inquired of one of the stewards, and learned that she was indisposed. But on the second day he saw her reclining in a steamer chair on the[25] promenade deck, apparently absorbed in the pages of a French novel. He stood with his back against the starboard rail at a sufficient distance from her chair to avoid making his attention too marked, and covertly studied her.

She was slender, dark-eyed, about forty, and of aristocratic bearing. She was still beautiful, although suffering had imprinted deep lines on her olive skin. The set of her chin and the shape of her delicate mouth denoted character; in that respect the young man who was so intently watching her felt that he had never seen a face which impressed him more favorably. He recalled what Bates had said about the probability of her knowing the whereabouts of her fugitive husband, and he decided that the Washington correspondent must be wrong about that.

“If Felix isn’t the martyr I believe him to be—if his disappearance was voluntary, that woman was not a party to it, either before or afterward,” he told himself confidently. “A woman with a face like hers wouldn’t shield a crook, even if he was her husband. I take her to be the kind that would go through fire for a man worthy of her love, but a woman who wouldn’t have a particle of use for a moral weakling.”

As he was thus soliloquizing, the subject of his thoughts looked up from her book, and their eyes met. A faint tinge of pink made itself visible beneath her dark skin, as though she were embarrassed by his scrutiny. She frowned slightly; then resumed her reading.

Feeling that he owed her an apology for his seeming[26] rudeness, Hawley was debating in his mind whether it would be discreet to take her into his confidence as to his mission to Baracoa, when an incident occurred which diverted his attention. Two men strolling along the promenade deck suddenly halted a short distance from where the señora was sitting, and stood leaning with their elbows resting on the rail. Hawley recognized both of these men. One of them, in fact, occupied the stateroom opposite his own. He was a clean-shaven, swarthy man of middle age, who was down on the passenger list as Señor José Lopez. The first time he had seen him on the boat it had struck Hawley that there was something familiar about the fellow’s face, but so far he had cudgeled his brain in an effort to recall when and where he had seen him before.

The other man was of striking appearance. He was tall, and of soldierly carriage. His dark, curly hair was gray at the temples, but, apart from this evidence of years, his handsome face was so youthful looking that he could easily have passed for a man in the early thirties. His complexion was ruddy, his dark eyes were sparkling. His well-waxed mustache, the ends of which were as sharp as stiletto points, gave his countenance a decidedly foreign aspect, otherwise he might have been taken for an American. The Camera Chap had learned that his name was Juan Cipriani, that he was a native of Argentine, and on his way back to that country.

The pair had been engaged in conversation as they approached, and now, as they leaned against the rail,[27] they continued talking. They spoke in Spanish, and it seemed to Hawley that their voices were pitched above their normal register.

“In my opinion, it is a piece of impertinence for her to return to Baracoa,” the one known as Cipriani said emphatically. “If she has any delicacy she must realize how unwelcome she will be to the people whom her rascally husband robbed and betrayed.”

“But if her father is dying,” the other argued tolerantly.

“Bah!” retorted Cipriani, with a contemptuous gesture. “Who would believe that story? You can depend upon it, my friend, her sole purpose in going back there is to make trouble. If your President Portiforo were wise he would instruct his port officers to refuse to permit her to leave the ship. That is the only way to deal with a woman of her stripe.”

“But, after all, it is scarcely fair to blame her for her husband’s sins,” Lopez suggested mildly. “We must admit that the abominable Felix treated her as shabbily as he did my unfortunate country. I understand that she has not once heard from him since he fled.”

The other laughed ironically. “Are you so ingenuous, my friend, as to believe that? You can be sure that he has been in constant communication with her, and that she is only waiting for a chance to join him and help him spend his stolen fortune. No doubt, she would have done so before now if she had not feared that she was too closely watched to—— I beg your pardon, sir—what did you say?”

[28]

This last remark was addressed to the Camera Chap, who, unable to contain himself any longer, had stepped up, frowning angrily, a menacing glint in his eyes. He knew Spanish well enough to make out most of their conversation, and although he had stood some distance away, every word that they had uttered had reached his ears. He knew, too, that the señora had heard. She was making a brave pretense of being absorbed in her novel, but the book trembled perceptibly in her hand. Up to this point Hawley had hesitated to interfere, feeling that such a course might only add to her embarrassment; but now he decided that this cruelty must be stopped. If these men were permitted to go on there was no telling what they might say next.

“I say that your conversation is offensive,” he repeated quietly, but with emphasis. “I ask you to stop it immediately.”

He spoke in English, and Cipriani answered him in that language, which he spoke fluently, although with a marked accent. “It seems to me that you are impertinent, sir,” the latter said, his dark eyes flashing. “Might I inquire in what way our conversation could possibly be offensive to you?”

The Camera Chap lowered his voice. “Don’t you realize that every word you are saying is being heard by Señora Felix? What kind of men are you, any way, to insult a woman like this? I thought you South Americans boasted of your chivalry.”

Señor Cipriani glanced toward the woman in the steamer chair. Suddenly she rose and walked away[29] with dignity. A look of astonishment came in Cipriani’s face. “Señora Felix!” he repeated. “My dear sir, you don’t mean to tell me that is she?”

“Of course. Didn’t you know it?”

Cipriani shook his head. “How unfortunate!” he murmured, and if the regret in his tone was feigned, it was skillfully done. “I assure you, sir, that I would rather have had my tongue cut out than intentionally make such remarks in the presence of the lady. I would apologize to her most abjectly, but I fear that would only be making matters worse. You see, I’ve never met the señora—this is the first time I have seen her since she came aboard.” Then, seized with a sudden thought, he turned upon Lopez, his face flaming with rage. “But you must have known her!” he declared hotly. “It is not possible that you did not recognize the wife of your former president. Why did you let me go ahead? Why did you not warn me of what I was doing?”

The clean-shaven, swarthy man shrugged his shoulders. “I did not notice that the señora was sitting there,” he said deprecatingly. “I was so engrossed in your interesting remarks that I did not observe our surroundings.” As he spoke he smiled—an expansive grin which bared his large, exceedingly white teeth, which somehow reminded the Camera Chap of the fangs of a wolf.

“Now, where the deuce have I seen that man?” Hawley asked himself. “The more I see of him, the more I feel that we met before we came aboard, but to save my life I can’t place him.”

[30]

Muttering an apology, Lopez walked away, and as he strode rapidly across the deck toward the companionway, the Camera Chap noted curiously that his footsteps were uncannily noiseless. Cipriani, too, seemed to observe that fact, for he remarked, with a smile: “Our friend certainly is most appropriately named. Does not his walk suggest to you the lope of a wolf?”

“Exactly what I was thinking,” said the Camera Chap. “Who is he?”

“His name is José Lopez, and he hails from Baracoa. That is all I can tell you about him. I have just made his acquaintance. We got to talking about his country, and that is how we came to discuss Señora Felix. I wish I could express to you how deeply I regret that I so cruelly hurt her feelings. If you are acquainted with the lady and——”

“I am not,” Hawley hastily interrupted. “I merely know her by sight. She was pointed out to me the other day in Washington.”

“Ah! You are from Washington?” It seemed to the Camera Chap that the other looked at him very keenly.

“Not guilty,” he said, with a laugh. “New York is my stamping ground. I merely happened to be in Washington for a couple of days.”

[31]

“I see. And you are now bound for——” Cipriani paused interrogatively.

“I am going as far as Puerto Cabero.”

Once more the other looked at him searchingly. “Might I inquire the object of your visit to Baracoa, if the question is not too personal?”

Hawley smiled. “I haven’t any great objection to answering it,” he said. “I am an artist, and I am going to make some pictures. I understand that the landscapes there are very fine.”

“An artist,” the other exclaimed. “That is interesting. I should very much like to see some of your work.”

“Perhaps some day I will show you,” said the Camera Chap, his eyes twinkling. “And now, having answered your question, may I ask you one in return?”

“I am at your service, señor.”

“I would like to know why you are so bitterly prejudiced against Señora Felix. She doesn’t strike me as being the sort of woman who deserves the unkind things you said about her.”

Cipriani shrugged his shoulders. “You are young, my friend. When you have lived as long as I you will not judge by appearances,” he said gravely.

“But that isn’t answering my question,” Hawley insisted. “Have you any special reason for believing that the señora knows where her husband is?”

“Only my knowledge of human nature,” Cipriani replied. “As I said before, it is only logical to suppose that Felix has communicated with his wife since[32] he ran away. I understand that they were a most devoted couple. I presume that when he fled they had an understanding that she was to join him later on; probably she has found it impossible to do so because of the close watch that Portiforo has kept on her.”

“How do you know that Portiforo has been keeping a close watch on her?” Hawley asked quickly.

Cipriani seemed discomfited by the question. He winced, and his ruddy face changed color; but his confusion quickly passed. “Of course, I do not know it,” he said suavely. “I only assume it. Is it not logical to suppose that the government of Baracoa would keep the wife of an absconding president under close surveillance? If you had ever lived in South America you would not have asked that question. There are more spies down there than there are people to spy on.”

He threw the stub of his cigarette into the sea, and took a gold case from his pocket to supply himself with another. “May I offer you one of these?” he said. “They are of my own manufacture. I am in the cigarette business in Buenos Aires.”

“No, thank you,” said Hawley. “I prefer a pipe.” He felt in his pocket. “That reminds me; I left my brier in my stateroom. I’ll go and get it. See you again, sir.”

The South American smiled and bowed, but as the Camera Chap walked away the smile abruptly left his face, and was replaced by an anxious expression. “We must find out more about that interesting young[33] man,” he mused. “I don’t think he is going to Baracoa to paint landscapes.”

When Hawley reached his stateroom he made a disconcerting discovery. The room had been entered since he was there last, and somebody had been through his baggage. He knew that such was the case because certain articles were not as he had left them. Nothing was missing—a close inventory of his effects satisfied him as to that; but the contents of his trunk and his suit case were slightly disarranged.

With a frown he stepped out into the corridor, and went in search of the steward. “Didn’t happen to see anybody go in or out of my room during the last two hours, did you?” he inquired.

The man looked worried. “No, sir; I—I didn’t actually see anybody—go in or out,” he stammered. “But, now that you speak of it, I saw something that was rather queer.”

“What was that?”

“As I was passing your door, ten minutes ago, I saw a man fumbling with the lock. It looked to me as if he was just locking the door; but when I stepped up to him he explained that he had made a mistake, and was trying to get in, thinking it was his own room.”

“Ah!” Hawley exclaimed. “Do you know who he was?”

“Yes, sir; it was the gentleman who occupies the room across the hall from yours—Señor José Lopez.”

“The deuce!” muttered Hawley. “No wonder he[34] has such a catlike tread. Evidently he needs it in his business. Begins to look as if he might be one of Portiforo’s spies sent—— By Jove! I’ve got the answer, now, as to where I’ve seen his face. What a chump I am not to have remembered before. It was the absence of his whiskers that fooled me. His appearance is considerably changed without them, but I’m quite sure, now, that he’s the same busybody who was trailing Señora Felix in a taxicab.”

[35]

If the Camera Chap had witnessed a meeting which took place that night between Señora Felix and a certain tall, soldierly-looking male passenger, and if he could have overheard their conversation, he would have been greatly amazed and perplexed.

It was well on toward midnight. The musicians had long ago ceased playing, and most of the passengers had turned in. The promenade deck was as deserted as Broadway after four a. m. The señora, as she stood at the rail, pensively watching the moonbeams playing upon the waves, was as motionless as a wax figure. She was wrapped in a long, black silk shawl so arranged about her head that most of her face was hidden, but the tall, soldierly-looking man who stepped up to her had no difficulty in recognizing her.

She turned swiftly at the sound of his footfall behind her, and an exclamation of pleasure escaped her lips. “So you managed it all right!” she whispered in Spanish.

“Yes, señora; but it is very unwise. I got your message, and I felt that I had to obey this time—but it must not occur again. The risk is too great.”

“I know,” she acquiesced. “As you say, it must not occur again. From now on we must be as strangers; but I felt that I must have this one talk with you. I am so very anxious.”

[36]

A frown darkened his handsome features. “It is exceedingly unfortunate, señora, that you should have sailed on this boat,” he said ungraciously. “Your presence here is likely to prove disastrous. If only you had waited for another week.”

“I couldn’t,” she answered deprecatingly. “They sent me word that my father’s condition was most serious, and I felt it my duty to go to him at once. But I had no idea that you would be here. I understood that you were to sail next Tuesday on the Panama.”

“Such was my original intention,” he answered; “but there were good reasons why I had to alter my plans. I certainly would have delayed my sailing, however, if I had suspected that there was the slightest chance of your being here. I greatly fear the fact that we are traveling on the same boat is regarded as more than a mere coincidence by our friend who calls himself José Lopez.”

A worried expression came to the señora’s face. “How much does he know?” she inquired.

“I would give much to be able to answer that question,” her companion replied, with a grim smile. “Of this much I am sure, however: He already has a strong suspicion that my name is not Juan Cipriani, and that my destination is not Buenos Aires. He forced his acquaintanceship upon me in the smoking room to-day, and began straightway to cross-examine me in a manner which, no doubt, he considered adroit, but which I saw through immediately. In an attempt to lull his suspicion I went through that painful little[37] scene in front of you. I need scarcely assure you, señora, of my profound regret at being obliged to hurt your feelings so cruelly.”

“That is all right,” she answered. “I realized the necessity. You managed it very skillfully. I feel sure that he must have been convinced that you were unacquainted with me, and that we have no interest in common.”

“I am not so certain of that,” the man answered, shaking his head. “The best that we can hope is that I succeeded in establishing a doubt in his mind; but I fear that he guessed it was all a trick contrived to deceive him. For the rest of this voyage, I am afraid, he will be watching us closely—on the alert for the slightest glance that passes between us. You must be very careful, señora.”

“I will,” she promised. “Where is he now?”

“Asleep in his stateroom. I made sure of that before I came here to keep this appointment.” The man paused. “But it is not him alone we have cause to fear,” he exclaimed suddenly. “There is somebody else on board whose presence is a grave menace to us. That good-looking young American who so impulsively came to your rescue this afternoon—do you know who he is?”

The señora shook her head. “That was one of the reasons I felt it necessary to have this talk with you. I, too, am uneasy about that young man. In spite of his interference in my behalf this afternoon, I have reason to suspect that he belongs to our enemies.”

Her companion frowned. “Would you mind telling[38] me your reasons for thinking that, señora?” he asked.

“The first time I noticed him was in New York, several days ago,” the woman explained. “It was that day I visited your headquarters. You remember my telling you that I had been followed?”

The man nodded. “That was the time you worked that clever trick with the taxicab,” he said, with a smile. “But I understood you to say that it was Lopez who was shadowing you?”

“There were two of them. Lopez was in one cab, but there was another taxi behind his. It contained that young American. I had previously noticed him watching me as I came out of the Mammoth.”

Her companion uttered a sharp exclamation.

“And that wasn’t the only time,” the señora went on. “I saw him in Washington, the day before he sailed. I was driving in Pennsylvania Avenue, and I noticed him on the sidewalk. That may have been a coincidence, of course, but I am afraid not. I noticed that he was observing me very closely. And then, again, he came on board this ship at exactly the same time I did. He was close behind me as I walked up the gangplank. All of which leads me to believe that he is on this vessel for the purpose of spying upon us. I have had Celeste make inquiries about him, and she has learned that he is a New Yorker named Hawley. He claims to be an artist on his way to Baracoa to paint some landscapes, but I am sure that that is only a bluff. The man is one of Portiforo’s spies.”

[39]

Her companion smiled. “You are mistaken about that, señora. I, too, have been making inquiries about this young man. I was fortunate enough to get hold of a fellow passenger, an American, who could tell me all about him. He is not connected with Portiforo—but he is just as dangerous to us as if such were the case.”

“Who is he?” the señora asked quickly.

“Hawley is his right name, and, as he has said, he is an artist. But he does not wield a brush. He makes his pictures with a camera. He is a newspaper photographer—on the staff of the New York Sentinel.”

The señora gave vent to a faint cry. “Hawley, of the New York Sentinel!” she exclaimed agitatedly. “I have heard of him. He is that wonderful photographer they call the Camera Chap.”

Her companion nodded. “I see that you realize, señora, how careful we must be of him. The press is as much to be feared by us as our enemies in Baracoa. If a Yankee newspaper were to get hold of our secret we should be lost. I don’t know what he is after, but I shall——”

“I do,” the señora interrupted tensely. “Now that I know who that young man is, I understand fully why he is going to Baracoa. And he must be stopped,” she added, her voice vibrant with emotion. “He must not be permitted to go ahead. We must find some way of preventing it.”

[40]

It was not until the Colombia was approaching Puerto Guerra, the first port of call in Baracoa, that the Camera Chap exchanged a single word with Señora Felix. Possibly he could have conversed with her before that had he desired to do so, for she spent much time on deck, and on several occasions, as he passed her steamer chair, he caught her dark eyes regarding him with keen interest. Several incidents arose, too, which seemed to offer him an opportunity to make her acquaintance, and, modest young man though he was, he could not help suspecting that these incidents were arranged by her in an effort to bring about that result.

Once, for instance, as he walked past where she sat, she dropped the magazine she was reading, and it seemed to Hawley that it was done somewhat ostentatiously, as though she fully expected him to pick it up. On another occasion her shawl fell from her shoulders to the deck as she was promenading, when Hawley was standing near by, and once more it seemed to him that the act was done deliberately.

But even at the sacrifice of having to appear boorish, he ignored these and other advances—if they were advances—for although, under other circumstances, he would have been delighted to make the fair señora’s acquaintance, he had decided that it[41] would be most indiscreet to do so now. He had made up his mind to keep away from her throughout the entire trip.

It was the mysterious, soft-treading passenger known as Señor José Lopez who was responsible for this decision on his part. There was no doubt now in Hawley’s mind that the fellow was a spy, a secret agent of the Portiforo government, and such being the case he deemed it highly necessary to keep Lopez from guessing that there was aught in common between himself and the wife of the missing president of Baracoa. The slightest evidence of friendship between himself and the woman, he surmised, might give the spy cause to suspect the real object of his mission to South America.

But one evening, as the vessel was approaching the hilly coast line of Baracoa, a steward handed him a note. The missive was in a woman’s handwriting, and although it bore no signature he guessed at once from whom it had come. It was short—merely a couple of lines stating that the writer would appreciate it very much if Mr. Hawley would make it a point to be on the promenade deck after eleven o’clock that night.

Guessing whom he would meet there if he kept this appointment, the Camera Chap’s first thought was to ignore the summons. But upon reflection, he changed his mind. “It would be a pretty shabby way to act,” he told himself. “Besides, I’m too curious to know what she wants of me to be able to resist the temptation. I’ll take a chance—provided I can dodge that[42] infernal busybody with the gumshoes. I’m afraid I can’t afford to keep the appointment if he’s going to be there. However, I think I’ll be able to get rid of him.”

That evening most of the passengers retired unusually early. The Colombia was to dock at sunrise the following morning, and everybody, even those who were not going ashore, desired to be awake early to get the first sight of land. At nine-thirty, as the orchestra finished its final selections, Hawley exchanged “Good night” with several of his acquaintances, and went to his stateroom. A few minutes later, Señor José Lopez came down the corridor with his noiseless, catlike tread, and stood listening intently outside the Camera Chap’s door.

The latter grinned as he heard the eavesdropper’s soft breathing. He was aware of the fact that his neighbor across the hall paid him this attention each night, never going to bed until he had made sure that Hawley had retired. That cautious young man now went through the formality of disrobing. Señor Lopez heard the thud of his shoes as he allowed them to drop noisily to the floor. Shortly afterward there was the click of the electric light being switched off, and soon after that a sound like a buzz saw in action satisfied the eavesdropper that the occupant of the room was well settled in the land of dreams. Then Lopez stole across the corridor to his own stateroom, and turned in with an easy mind.

A little more than an hour later the Camera Chap arose, dressed himself in the dark, and, with his feet[43] incased in a pair of tennis shoes, emerged from his stateroom, and moved along the corridor with a secrecy which would have done credit to Lopez himself.

When he reached the promenade deck and strode past the long row of empty chairs, there was not a person to be seen. He was beginning to wonder if he were not the victim of a practical joke, when suddenly he espied a shrouded figure, which looked almost ghostly in the moonlight, coming toward him. With a cautious glance behind him, he stepped forward to meet her.

“It was very good of you to come,” the woman said softly. “But I knew that you would—just as I feel confident that you will grant me the favor that I am going to ask of you.” As she spoke she drew aside the silken, fringed mantilla which concealed all of her face except her eyes, but even before she did this the Camera Chap knew with whom he was talking.

“If there is any service I can render you, señora, you have only to name it,” he avowed impulsively. And he meant it, for as he gazed into her dark, sad eyes all the chivalry in him was stirred, and he thrilled with pity for this frail, unhappy woman. At that moment he would have been prepared to go to the rescue of her husband with a sword instead of a camera if more could have been gained that way.

“I am glad to hear you say that,” Señora Felix said gratefully. “I trust that you will not change your mind, Mr. Hawley, when I tell you that the[44] favor I am going to ask of you concerns the errand which has brought you to Baracoa.”

The Camera Chap gave a start of surprise. “Then you know——” he began excitedly, but suddenly on his guard, abruptly checked himself. “The errand which has brought me to Baracoa!” he exclaimed, with well-feigned bewilderment. “I beg your pardon, señora; I’m afraid I don’t quite understand.”

The woman laughed softly. “You can be quite frank with me,” she said. “I know who has sent you to Baracoa, and what you expect to find—in the fortress of El Torro.” She paused, and an anxious expression flitted across her face. “And the favor I’m going to ask of you, Mr. Hawley, is—to give up this undertaking.”

The Camera Chap stared at her in astonishment. “To give it up!” he exclaimed incredulously. “Surely you can’t mean that, señora! If you really know who sent me and what I hope to accomplish, it seems to me you are the last person in the world who should make such a request of me.”

The woman sighed. “There is a good reason for what I ask. You would be running a great risk, and——”

“Don’t worry about the risk, señora,” the Camera Chap interrupted cheerfully. “If that’s your only reason for asking me to quit, I’m afraid I’ll have to refuse to listen to you.”

“It isn’t the only reason,” she rejoined. “If there was anything to be gained by it, I’m afraid I would[45] be selfish enough to let you go ahead in spite of the danger you would incur; but when I know that you have come on a wild-goose chase, I feel it my duty to prevent you from sacrificing yourself.”

“A wild-goose chase!” the Camera Chap repeated.

“Yes; for your president is misinformed,” the señora declared tensely. “My husband is not confined in El Torro. He is not in Baracoa. There is no truth in the rumor which has brought you here.”

It was almost as if she had struck Hawley a physical blow. Although, of course, he had realized all along that there was a possibility of the story turning out to be baseless, and although the president had intimated that he himself placed no stock in the sensational rumor, and was merely sending Hawley to Baracoa in order to remove the last possible doubt from his mind, somehow the Camera Chap had been confident until that moment that he was embarked on no fruitless mission. Instinctively he had felt that Felix was a martyr instead of the rogue which the world believed him. But now this statement, coming from the missing man’s wife, seemed to dispel all hope that such was the case.

“Do you know where he is, señora?” he inquired, his disappointment evident in his voice.

The woman hesitated, and he caught the shade which flitted across her face. “I do,” she said at length, almost in a whisper. “He is—in Europe.”

“You are quite sure, señora? Is it not possible that you, too, have been deceived?”

[46]

She shook her head. “No; that is not possible—for I have been in constant communication with him. I received a letter from him only last week.” She smiled sadly. “So you see, Mr. Hawley, there is nothing for you to do.”

[47]

The Camera Chap was noted on Park Row, among other things, for the buoyancy of his nature and his refusal to permit disappointments and setbacks to ruffle him. But he was scarcely in a cheerful frame of mind as he took his leave of Señora Felix and went back to his stateroom. To have traveled several thousand miles only to discover that he had come on a fool’s errand, and, what was worse, to have had all his dreams shattered, was a severe strain even for his abundant stock of philosophy.

For a long time he sat on the edge of his berth, meditating on his conversation with the wife of the missing president. One thing puzzled him exceedingly: Why had the woman taken him into her confidence to the extent of telling him that she knew the whereabouts of her husband? Why was she so keen to dissuade him from persisting in his undertaking? He took no stock in her assertion that solicitude for his welfare had caused her to take this step. Surely, he told himself, she would not have jeopardized her husband’s safety and confessed herself an accessory to a crime merely to save a stranger from getting into trouble. There must be some more weighty reason which had prompted her to intrust him with her secret.

Suddenly his face lighted up, and he gave vent to[48] a joyous ejaculation. “Of course, that must be it,” he muttered. “The poor little señora! I hate to doubt the word of a lady, but I’m afraid I’ll have to take your statements with a grain of salt.”

His mind more at ease now, he climbed into his berth, and was soon in a sound sleep. He was awakened early in the morning by the voice of the steward in the corridor notifying those passengers whose destination was Puerto Guerra that their port had been sighted.

Hawley hurried into his clothes and went on deck. He was not going to disembark at that point; he had decided to land at Puerto Cabero, farther on along the coast of Baracoa, and only a few miles from the capital. Yet he was anxious to get his first sight of the land which was to be the scene of his activities.

The ship was picking her way through the coral reefs as he walked to the bow, and stood gazing with interest at the palm-fringed harbor. There he was soon joined by other passengers, among them Señora Felix. She was not going ashore at this port; like Hawley, she was booked to land at Puerto Cabero, but she had left instructions to be awakened as soon as land was sighted, and she now stood against the rail, a pathetically wistful expression on her sad countenance as she stared at the blue-black mountains which formed a background to the quiet little village of thatched houses.

There was only one pier in the harbor. It projected from a low stone structure which, the Camera Chap overheard somebody say, was the custom house.[49] A handful of swarthy-faced men in blue uniforms stood on the pier, languidly watching the approach of the steamship. When the Colombia had docked and began to unload freight, these men gathered around six huge packing cases which were carried ashore, and studied them with great interest.

A fat official whose blue uniform was decorated with much gold lace gave some orders to two of the men, who grinned and began to pry off the lid of one of these packing cases. As she watched this act from the deck of the ship an involuntary exclamation escaped Señora Felix. It was only a slight murmur, but it reached the ears of the Camera Chap, who was standing near by. He glanced at her, and observed that her hands were gripping the top of the rail so hard that the knuckles showed white through the nut-brown skin. Evidently she was under a great nervous strain.

Abruptly his attention was drawn from the woman at his side to what was taking place on shore. A force of men on horseback, fifty strong, had galloped up to the group of soldiers gathered around the packing cases. The newcomers were wild-looking fellows, raggedly dressed, and all of them armed. They uttered loud cries as they surrounded the handful of soldiers, who promptly threw up their hands in surrender.

Astonished as the Camera Chap was by this spectacle, he presently witnessed something which amazed him still more. A man rushed from the ship to the pier, and as he went down the gangplank he was greeted by cheers from the wild-looking horsemen.[50] The man was the tall, handsome passenger whom Hawley had known at Señor Juan Cipriani, of Buenos Aires. He was clad now in a gorgeous uniform of blue and gold, and he brandished a sword which flashed in the sunlight. As he joined the group on the pier they gathered around him, and welcomed him with shouts of “Viva Rodriguez! Viva el general!” He acknowledged this ovation with a graceful sweep of his sombrero, and as he happened to turn toward the ship, Hawley saw that his face was aglow with enthusiasm.

Something caused the Camera Chap to glance, just then, at Señora Felix. A great change had come over her. Her face, too, was radiant with happiness, and she was sobbing softly.

But suddenly she uttered a cry of mingled horror and dismay; she clutched the rail in front of her, as though to save herself from falling. The Camera Chap had only to glance toward the dock to realize the cause of her agitation. With the swiftness of a moving-picture drama, the scene there had changed. A regiment of infantry, springing up apparently from nowhere, had surrounded the group of horsemen. The latter were now surrendering as meekly as the handful of soldiers had previously surrendered to them. The only man making the slightest attempt to fight was Cipriani. He was struggling frantically in the grasp of two burly infantrymen.

These two successive bloodless victories struck Hawley as so ludicrous that he would have laughed but for the evident grief of the woman beside him.[51] There was not the slightest doubt that this latest development meant tragedy to her, however amusing it might appear to a disinterested spectator. Making a valiant effort to regain her calm, she hurried below to her stateroom.

The Camera Chap did not see her again until the Colombia arrived at Puerto Cabero. But before they arrived at the latter port a steward stealthily handed him at note. The missive was unsigned, but he recognized the handwriting, and although to anybody else its wording might have been vague, he had no difficulty in grasping its meaning. The note ran:

“Pay no attention to what was said to you last night. What you have witnessed has changed the situation. Now, our only hope lies in your discretion and your ability to carry out the mission intrusted to you.”

[52]

As the Colombia steamed into the harbor of Puerto Cabero the following day, the Camera Chap caught sight of a turreted, forbidding-looking gray edifice on the east shore, and he did not have to make inquiries in order to know what this building was. Although he had never seen it before, he knew that he was gazing on the fortress of El Torro, which, in addition to being the main defense of Baracoa’s chief seaport, was also internationally famous as the living tomb of several ill-starred wretches whose political activities had earned for them the grim decoration of the ball and chain.

According to the rumor which had brought Hawley to South America, it was within this building that Portiforo had the unhappy Felix locked up; therefore the Camera Chap viewed it with more than idle interest. As he noted the sentries marching to and fro in front of the gray walls it impressed him as being “a pretty formidable sort of a joint,” and he didn’t imagine that it was going to be exactly a picnic to get inside of it.

“I observe that the señor is interested in El Torro,” exclaimed a voice close behind him. “It is a place much easier to enter than it is to leave.”

Coming as though in response to his unspoken thought, the words startled Hawley. He wheeled[53] swiftly, and found himself gazing into the swarthy countenance of Señor José Lopez.

“What do you mean by that remark?” he demanded sharply. Then, suddenly on his guard, he added more mildly: “What makes you think that I am particularly interested in El Torro?”

The other bared his large teeth in a wolflike grin. “I judged that such was the case from the manner in which the señor was staring at it,” he replied quietly.

The Camera Chap laughed. “It is a picturesque pile,” he declared. “From an artistic standpoint it appeals to me greatly. I certainly will have to make a picture of it before I return to the United States. That is, of course, if it isn’t against the rules.”

Lopez shrugged his shoulders. “I dare say there will be no objection to Señor Hawley making as many pictures as he desires—of the outside of El Torro,” he remarked.

“Now, I wonder what the deuce he meant by that!” Hawley reflected, as the other walked away. “I’d give a lot to know whether that confounded spy suspects anything.”

Until that moment he had felt confident that he had his inquisitive fellow passenger guessing as to the object of his visit to Baracoa, but the significant remark which the latter had just let drop made him exceedingly uneasy. There being no doubt in his mind that Lopez was a secret agent of the Portiforo government, he feared that he was going to have a hard time losing him when they got ashore; in fact, he[54] was now even prepared to be challenged by the immigration authorities, and told that his presence in Baracoa was not desired. But, greatly to his relief, both these fears proved unfounded. When the vessel docked, the pier authorities manifested no more interest in him than in any of the other passengers; on the contrary, the customs officers were so careless in their examination of his baggage that they did not even discover the big camera in his trunk. And when he went ashore, Lopez made no attempt to shadow him; in fact, he saw the latter board a train without even a glance in his direction.

Another circumstance which surprised him somewhat was that Señora Felix was also permitted to land without undue attention from the authorities. In view of what had happened at Puerto Guerra, and her obvious interest therein, he had been wondering ever since whether she would not be placed under arrest as soon as she attempted to land, on a charge of being in some way connected with the affair, and he was very glad to find that such was not the case.

Hawley watched the landing of the señora with great interest. He observed that as she and her maid stepped from the pier, many people stared at her, recognizing her as the wife of their missing president; but nobody spoke to her, with the exception of a blond-haired, blue-eyed girl in a pink dress, who stepped up and greeted her effusively.

This young woman aroused the Camera Chap’s curiosity. It was quite evident that she was not a native of Baracoa; at first sight he would have been[55] willing to bet all the money he had in his pocket that she was of his own people. She appeared to be still in her “teens,” and was of such an attractive personality that almost any one would have bestowed more than one glance upon her, even if his interest had not been intensified by the fact that she was there to welcome Señora Felix.

For a few minutes the two women stood chatting together in the plaza in front of the steamship pier, Celeste, the señora’s maid, hanging respectfully in the background. Then, followed by the latter, they made their way toward a touring car standing near by, which they entered. The girl in pink gave some instructions to the liveried negro at the wheel, and the car dashed up one of the steep roads which led to the capital.

Not once since she had come ashore had the señora appeared to notice the Camera Chap—he suspected that she studiously refrained from doing so for reasons which he fully appreciated—but just before the automobile started she whispered something to her fair companion, and the latter turned in her seat and looked deliberately toward where he was standing. There were several other persons in his vicinity, and it might have been any of these at whom her glance was directed, but Hawley, modest man though he was, felt positive that he was the object of her scrutiny, and somehow the thought afforded him much satisfaction.

He was not left long in ignorance as to the identity of this prepossessing young woman, for, as the car[56] started off, the conversation of two natives standing near him supplied him with that information.

“Is it not somewhat surprising that the daughter of the American minister should be on such friendly terms with the wife of the abominable Felix?” Hawley overheard one of them remark in Spanish. To which the other responded, with a shrug: “Nothing is surprising about those Yankees.”

The Camera Chap was too much absorbed in the information he had gleaned even to feel like resenting the slur upon his countrymen. So the girl in pink was Miss Throgmorton, the daughter of the American minister to Baracoa! And she was on such intimate terms with Señora Felix that she alone had come to welcome the latter back to her native land! Here was an interesting discovery, indeed.

At that moment there flashed through his mind what his friend and managing editor, Tom Paxton, had said about the sentiments of the United States minister to Baracoa toward the Sentinel, and all men connected with it. He devoutly hoped that the daughter did not share her father’s prejudices in that respect, for he had already fully decided that if it were possible he was going to make Miss Throgmorton’s acquaintance before he had been many days in Baracoa.

[57]

The Camera Chap did not linger long at Puerto Cabero. He had decided to make Santa Barbara, the capital, his headquarters, that city being only ten miles away from the seaport. It is situated on a highland three thousand feet above the sea level, and, as Hawley traveled on the antiquated railroad, he marveled at the manner in which the line twisted and turned like a huge corkscrew.

When he arrived at his journey’s end he found the city in gala attire. The streets and shops were decorated with flags and bunting, and a band was playing in the plaza. At the Hotel Nacional, where he registered, he inquired whether he had struck town on a national holiday, and was informed that the festivities were the result of the extraordinary scene he had witnessed at Puerto Guerra the previous day.

“You see, señor,” explained the hotel clerk, who spoke very good English, “President Portiforo has ordered a day of public rejoicing because of the defeat of General Rodriguez.”

“Rodriguez!” exclaimed Hawley, who recalled that he had heard the man whom he had known as Juan Cipriani hailed by that name by the group of wild-looking horsemen on the pier. “What was he trying to do? Was he starting a revolution?”

The clerk nodded, and proceeded to tell Hawley a[58] story which fully enlightened him as to the significance of the drama he had seen enacted at the customhouse at Puerto Guerra. The Camera Chap learned that the big packing cases which the steamship Colombia had brought, and which were invoiced as containing farming implements, had in reality contained machine guns intended for the use of the new revolutionary party which General Emilio Rodriguez, alias Juan Cipriani, had come to Baracoa to lead.

Rodriguez, Hawley was informed, was a native of Baracoa, but had been in Europe for the past ten years. He had held a commission in the French army, which he had resigned in order to come back and attempt to overthrow the Portiforo government; which attempt, however, had been rendered futile by the alertness of President Portiforo.

“But you don’t mean to tell me that that chap was going to have the nerve to buck against the government forces with that handful of men I saw at the pier?” the Camera Chap exclaimed in astonishment. “Why, there couldn’t have been more than fifty of them in all.”

The clerk smiled deprecatingly. “That was only the beginning, señor. If Rodriguez’s plans had not miscarried, he was to have taken to the hills with that escort, and there proclaimed the revolution. He had been assured that the people would flock by thousands to his banner, and that as soon as he gave the word the army was prepared to revolt and go over to him. But things didn’t go just as he expected. President Portiforo learned of the plot in time to[59] nip the revolution in the bud. A few days ago he raised the pay of everybody in the federal army, from the commander in chief down to the newest recruit, and thereby kept the troops loyal to him. He set a trap for Rodriguez, and when that unhappy man stepped off the boat at Puerto Guerra yesterday, expecting the whole country to be ready to respond to his call to arms, he was seized and thrown into jail.” The clerk grinned. “One has to get up very early in the morning in order to catch our President Portiforo napping, señor,” he said.