A VISIT

TO

THE BAZAAR.

Bookseller

Published Feby. 20, 1818, by J. Harris,

corner of St. Pauls.

The Project Gutenberg eBook of A visit to the Bazaar, by Anonymous

Title: A visit to the Bazaar

Author: Anonymous

Release Date: April 19, 2023 [eBook #70595]

Language: English

Produced by: Charlene Taylor, Jwala Kumar Sista and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

1. Typographical errors were silently corrected.

2. Cover-page designed by the transcriber and placed in public domain.

3. Images are moved next to title-word headings which are appearing in original, before the title-word.

4. Table of Contents, not appearing in original, is added with hyperlinks.

5. Illustration "Book-seller" appearing as frontis and not appearing in the relevent title place, in the original, is aptly placed next to the title, in line with other title-wise illustrations.

6. UCLA catalog listing states: Local Notes Spec. Coll. copy: Contains duplicate plates of "Grocer," and is lacking the plate "Fancy Works."

[Pg 1-7]

| Chapter | Page | |

| THE BAZAAR | 08 | |

| THE JEWELLER | 20 | |

| LINEN DRAPER'S | 27 | |

| TOY SHOP | 33 | |

| PASTRY COOK'S | 36 | |

| MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS | 40 | |

| MUSIC SELLER | 46 | |

| HATTER | 49 | |

| LACE MAN | 53 | |

| OPTICIAN'S | 57 | |

| UMBRELLA | 63 | |

| WORK BASKETS | 66 | |

| WORK TRUNK MAKER | 71 | |

| ARTIFICIAL FLOWERS | 73 | |

| SWEET SINGING BIRDS | 77 | |

| ENGLISH CHINA | 83 | |

| HAIR MERCHANT | 87 | |

| SHOE MAKER | 89 | |

| GUN SMITH | 92 | |

| GREEN-HOUSES | 99 | |

| MILLINER | 103 | |

| CHEMIST AND DRUGGIST | 106 | |

| PRINTS | 113 | |

| FANCY WORKS | 117 | |

| GROCER'S | 120 | |

| FURRIER | 125 | |

| DRESS MAKER'S | 130 | |

| BRUSH MAKER'S | 133 | |

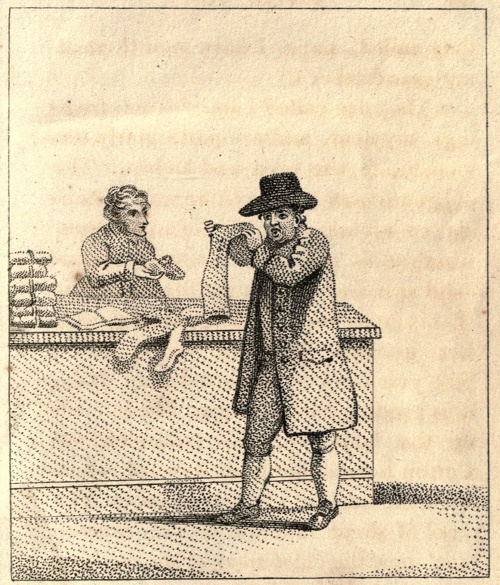

| BOOKSELLER | 135 | |

| WATCH MAKER | 140 | |

| FRUITERER'S | 146 | |

| THE HOSIER'S | 149 | |

| SCULPTOR | 155 | |

| FINIS | 160 | |

[Pg 2]

[Pg 3]

[Pg 4]

[Pg 5]

[Pg 6]

[Pg 7]

Bookseller

Published Feby. 20, 1818, by J. Harris,

corner of St. Pauls.

A VISIT

TO

THE BAZAAR:

BY THE AUTHOR OF

JULIET, OR THE REWARD OF FILIAL AFFECTION;

AND THE PORT FOLIO OF A SCHOOL GIRL.

THE THIRD EDITION.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR HARRIS AND SON,

CORNER OF ST. PAUL'S CHURCH YARD;

AND MAY ALSO BE HAD AT SEVERAL SHOPS IN

THE BAZAAR, SOHO SQUARE.

1820.

H. Bryer, Printer, Bridge-street, Blackfriars, London.

[Pg 8]

"My dear," said Mrs. Durnford to her husband on his return from a long walk, "I this morning received a letter from poor Susan Boscawen, full of the most lively expressions of her gratitude, for the kind assistance which you gave to her on the death of her father. She has established herself at the Bazaar, in Soho-square, which I understand is a most respectable institution, founded by a gentleman of considerable opulence residing in the place, and by this means, she is enabled to support her aged mother and her two helpless brothers. The one you know is a cripple, and the other was born blind. If you have no objection, I should like to take the children to town some morning, when it would be convenient to you to accompany us, and shew them the interior of our English Bazaar."

"Name your day and I will attend you," replied Mr. Durnford. "The sight will be both novel and pleasing to the children, and I shall feel myself particularly delighted in beholding the amiable Susan, placed in a situation of safety and emolument."

[Pg 9]

"Pray, papa," said Theodore, a fine boy about ten years of age, "what is the meaning of the word Bazaar?"

"My dear boy," replied Mr. Durnford, "the term Bazaar is given by the Turks and Persians to a kind of Market or Exchange, some of which are extremely magnificent; that of Ispahan, in Persia, surpasses all the other European exchanges, and yet that of Taurus exceeds it in size. There is the old and the new Bazaar at Constantinople, the former is chiefly for arms, and the latter for different articles belonging to goldsmiths, jewellers, furriers, and various other manufactures. [Pg 10] Our Bazaar in Soho-square, was founded by Mr. Trotter, on premises originally occupied by the store-keeper general, consisting of several rooms which are conveniently fitted up with handsome mahogany counters, extending not only round the sides, but in the lower and upper apartments, forming a parallelogram in the middle. These counters, having at proper distances flaps or falling doors, are in contiguity with each other, but are respectively distinguished by a small groove at a distance of every four feet of counter, the pannels of which are numbered with conspicuous figures, and these are let upon moderate terms to females who can bring forward sufficient testimonies of their moral respectability."

[Pg 11]

"It appears to me to be a most excellent establishment," said Mrs. Durnford, "as it enables many a worthy female to dispose of the produce of her labours, without incurring the risk of taking a shop which might prove unsuccessful, and thus she would not only be drained of every sixpence she possessed, but she might be reduced to actual beggary from the failure of her first attempt."

[Pg 12]

"True, my dear," replied Mr. Durnford, "such is too frequently the case. But in this institution no such danger can arise. The person who from strong recommendation obtains a counter in our Bazaar, pays daily, three-pence for every foot in length, and is not required to hold her situation more than from day to day. I have been told, that at present, there are upwards of a hundred females who are employed in these rooms, and a more pleasing and novel effect can hardly be imagined, than is here produced by the sight of these elegant little shops, filled with every species of light goods, works of art, and female ingenuity in general."

"Then you have seen the Bazaar, papa?" said Maria, the eldest daughter of Mr. Durnford.

[Pg 13]

"Yes, my love," replied her father, "I went over it about five weeks ago with Lady Bellenden, who has placed two very amiable young women there, both of whom are the orphan daughters of a country curate, one of them has a counter for all sorts of painted ornaments, the other for fine needle work. But you shall see the Bazaar yourself, Maria, and if your mother is disengaged, I think we will set out to-morrow morning, immediately after breakfast. We shall then have plenty of time to examine the contents of the Bazaar, and return in time to receive our guests for dinner."

To the inexpressible delight of all the children, Mrs. Durnford immediately assented to the proposal of her husband, and it was agreed, that as the young people had behaved themselves lately much to the satisfaction of their parents, they should all of them enjoy the pleasure of a "visit to the Bazaar," except the baby in arms, and the youngest boy.

[Pg 14]

Early the next morning Mr. and Mrs. Durnford, with Maria and Emily, who were twins, and just turned of twelve years of age, and Caroline, a sweet little girl about seven, accompanied by Theodore, proceeded with light hearts and buoyant spirits to town, which was only two miles from the residence of their father, a gentleman of large independent fortune. They had frequently visited the metropolis, had been once to a play, and had seen several other places worthy of their inspection, but they all felt their curiosity strongly excited to view the Bazaar, as well as to behold once more Susan Boscawen, who was a daughter of a deceased tradesman, long a resident in this village, and for whom they all entertained a sincere regard.

[Pg 15]

On arriving at the place of their destination, the young people were surprized to see the square filled with elegant equipages, some of them belonging to our first nobility. "I believe, my dears," said Mr. Durnford, "that this is the first time any of you have seen Soho-square."

"Yes, papa, it is," cried Theodore, "pray whose statue is that which I see placed in the centre of that large area, and what are those figures at the feet of the statue."

[Pg 16]

"It is, as you may observe, a pedestrian statue of King Charles the Second," replied Mr. Durnford, "and those wretched mutilated figures are emblematical of the rivers, Thames, Trent, Severn, and the Humber. The Square was formerly called King-square, and I believe some efforts have been made to have that name revived. It has been greatly altered since the original disposition of the ground: then a fountain of four streams fell into a basin in the centre; where now stands the worn out statue of King Charles. It was once also called Monmouth-square, the Duke of Monmouth then residing in the second house; and tradition says, that on the death of the Duke, his admirers changed it to Soho, being the word of the day at the battle of Sedgemoor. [Pg 19] The name of the unfortunate Duke is, however, still preserved in that of Monmouth-street, long celebrated for old shops, old clothes, and shop cellars. That house, my dears, is celebrated as being the residence of the venerable and worthy Sir Joseph Banks, whose whole life has been devoted to science, and the diffusion of every branch of useful knowledge."

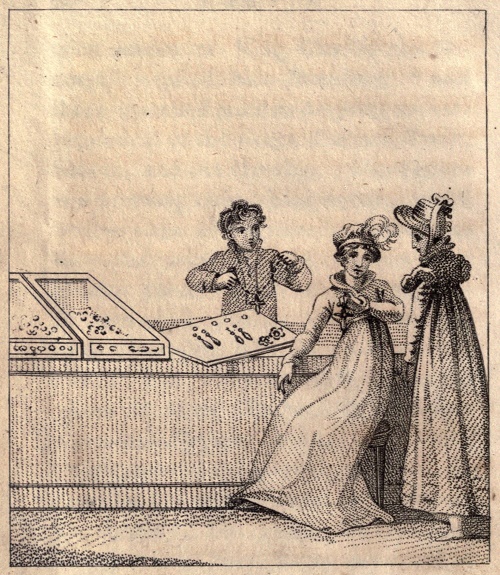

Jeweller

[Pg 20]

They now walked towards the Bazaar, and in a few minutes entered the first room, which is sixty-two feet long, and thirty-six broad. The walls were hung with red cloth, and at the ends were large mirrors which reflected the surrounding objects.

"Oh, dear mamma!" exclaimed Emily, "let us stop a moment to look at these beautiful ornaments, what a pretty gold cross and pearl chain; I should like to buy it for baby, only that it would come to more than all my pocket money."

"I think, papa," said Maria, "that I have read that pearls come chiefly from Ceylon, and are taken from a particular species of oyster."

[Pg 21]

"You are right, my love," replied Mr. Durnford, "there are too seasons for pearl fishing. The first is in March and April, and the last in August and September, and the more rain there falls in the year, the more plentiful are the fisheries. The method of procuring the pearls is rather singular. The diver binds a stone six inches thick, and a foot long under his body; which serves him as ballast, prevents his being driven away by the motion of the water, and enables him to walk steadily under the waves. They also tie a very heavy stone to one foot, by which they are speedily sent to the bottom of the sea; and as the oysters are firmly fastened to the rocks, they arm their hands with leather mittens, to prevent their being bruised in pulling the oysters violently off. Each diver carries down with him a large net, tied to his neck by a long cord, the other end of which is fastened to the side of his bark. The net is to hold the oysters, and the cord to pull up the diver when his bag is full. Thus equipped, he sometimes flings himself sixty feet under water, and when he arrives at the bottom, he runs from side to side, tearing up all the oysters he can meet with, and puts them into his net as expeditiously as possible."

[Pg 22]

"Oh, papa! how frightened I should be of the enormous great fishes," said Caroline.

"They are certainly to be dreaded, my love, but the diver no sooner perceives one of them approaching, than he pulls his cord, and the signal is attended to immediately by those above. Look, Emily, at this diamond, can you tell me from whence they come?"

[Pg 23]

"I believe from the East Indies, papa, and South America."

"Yes, my dear. This object of human vanity was formerly called Adamant, being the hardest body in nature. In the East Indies, there are also two rivers, in the sands of which are diamonds. The miners frequently dig through rocks, till they come to a sort of mineral earth, in which the diamonds are enclosed, and to prevent their concealing any of them they are obliged to go naked. The largest diamond ever known to have been found, was that in the possession of the Great Mogul, which weighed two hundred and seventy-nine carats, each carat being four grains."

[Pg 24]

"Diamonds are beautiful, and so are all the precious stones, but they are too dear for me at present," said Theodore; "but with your leave, papa, I should like to buy each of my sisters a little gold heart to wear with their gold chains."

The hearts and some other trifling ornaments were accordingly selected; and they next stopped to look at the contents of a

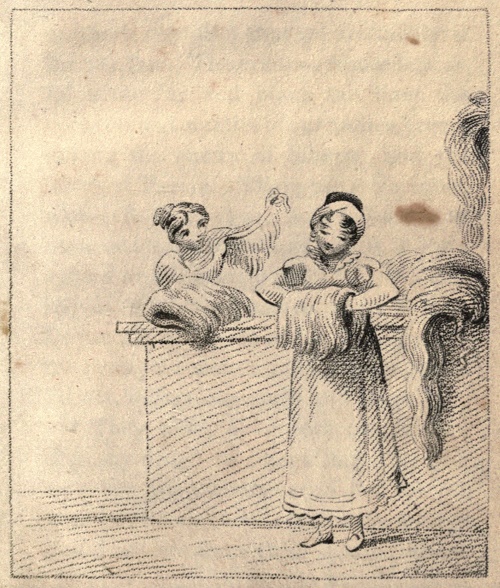

Linen Draper

[Pg 27]

counter. Maria called the attention of Emily to a short fat coarse looking woman, who was enquiring the price of some muslin which the owner was shewing her. "Five shillings a yard!" said she, in a shrill voice, at the same time enlarging her eyes and stretching out her hand, "Why, I can buy as good as this at any shop for three. Surely you must take me for a ninny, to ask so much money for your muslin." So saying, away she walked highly offended, although the article which she had rejected was offered to her at its fair price.

Mrs. Durnford desired to look at some Cambric, and while the man was searching for it, she asked Caroline if she remembered from what country the finest was imported. The little girl hesitated, and her mamma requested Maria to give her the necessary information. "Cambric is made in several parts of France and Flanders," said Miss Durnford. "That from Cambray is, however, esteemed the best. We imitate it in Scotland, but have not brought it to the perfection of the foreign Cambric."

[Pg 28]

"Very well! Maria," said her father, "I am pleased to find that you remember so well what you are told, and now Emily, can you inform me what that fine cloth is made of, which your mother has just bought for your brother's shirts?" "It is made of flax, papa, which in Latin is linum, from whence the word linen and linon is derived."

[Pg 29]

"You are a good girl," said Mr. Durnford, "and I mean to reward each of you according to the knowledge which you display during our visit to the Bazaar. Flax grows in many parts of England, and still more in Scotland and Ireland. When fit to gather, it is taken by the flax dressers, who pass it through water, strip the slender stalks of the rind; and then it becomes fit to split, and again undergoes a process to prepare it for the wheel. It is then spun into thread, more or less fine according to the purpose it is intended for. The very finest is as minute as the smallest hair, and is used by the lace makers. That is, of course, a very fine sort of which the Cambric is made. It is a singular thing that the Romans, who in consequence of their extensive conquests, became the most luxurious people on earth, never discovered the art of making linen from flax, or hemp, which is a coarser plant of the same kind. Their cloathing, though extremely magnificent, being embroidered [Pg 30] with purple, and often with gold, was woven only of wool, and Voltaire, a celebrated French writer, makes Tullia, the beautiful and accomplished daughter of Cicero, the greatest orator the world ever saw, admire the superior elegance of the toilet of an English lady. They had neither stockings nor linen, for which we should think the finery of their sandals attached with gold cords, or their embroidered vests fastened with diamond lockets, made but a poor compensation."

"Oh! what a beautiful shawl, papa," cried Caroline, "I wish my sisters had each one."

"That is very expensive, my sweet girl," said her father, "it is made of the fine wool of the Angora goat, a native of [Pg 33] the warm regions of the earth, and is manufactured in India. We vainly attempt to imitate them here, but cannot succeed. But come, let us turn to the

Toy Shop

as I perceive that your mamma has concluded her purchases."

They now advanced towards the counter, before which some children were standing. A fine little boy, the picture of health and happiness, was delighting himself with a cart, while his elder brother, with a less satisfied look, was listening to the advice of his sister. "I want that drum, and I will have it, Sophy, you know I may buy what I like."

[Pg 34]

"Yes, my dear Charles," replied his sister, mildly, "but pray do not buy the drum, as it will increase poor mamma's bad headache."

"Don't have it, Charles," cried a pretty rosy cheeked little girl, "don't have it, if Sophy says not. You know I mean to lay out my money just as she pleases."

"So you may," said Charles, grumblingly, "but I shall lay out mine as I please, and the drum I will have."

The drum was accordingly handed over to the young gentleman, and when his sisters had bought their toys, they gave them to a female attendant, and moved onward.

"What a disagreeable rude boy that was," remarked Caroline, "how unlike his sisters."

[Pg 35]

"Quite so, my dear," said Mrs. Durnford, "I am afraid he is badly managed at home, and that, joined to a bad disposition, will make him a very unamiable character as he grows up. He should have listened to the gentle advice of his eldest sister, who from her dutiful attention to the health and tranquillity of her mother, gave evident proofs of a kind and feeling heart."

Theodore and his sisters now selected a variety of toys as well for themselves as for their little brother, William. A composition doll was bought for the baby, and a very pretty white dog with a gilt collar round its neck. The young ladies had each a curious puzzle, and Caroline took a fancy to an ass with its panniers loaded [Pg 36] with vegetables. This toy her papa gave her, as well as a nice painted box full of sheep, trees, shepherd's hut, and a shepherd and his dog, telling her at the same time, that most of those kind of toys came from Holland, and that they were sold here much cheaper than we could make them.

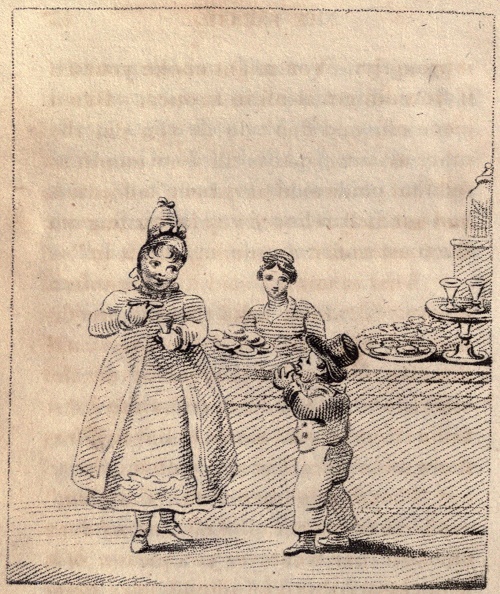

They next stopped at the

Pastry Cook

where a young lady was eating a jelly, and laughing archly at a little boy who greedily endeavoured to force a whole cake into his mouth at once.

[Pg 39]

"Why, you silly little fellow," said she, "what are you stretching your mouth so wide for? Why don't you eat it properly. You might choke yourself if you did get it all in at once. Bite a piece off, and don't do as you did the other evening at tea, fill your mouth so full that you would have been suffocated, had not Sally relieved you by turning out the toast as fast as you had put it in."

"Dear mamma," said Caroline in a low voice, "what a sad thing is greediness. I dare say that little boy would not give his sister a morsel for all the world, and I should not enjoy the finest thing that ever was made, unless my brothers and sisters shared it with me."

"That I will answer for, Caroline," replied her mother. "And now my dear children take whatever you please, as it is necessary that you should have some refreshment after your walk."

[Pg 40]

The attention of the young people was now drawn towards a counter of

Musical Instruments

at which a young lady was trying the tones of a Guitar, while her brother ran his lips over a Syrinx. Theodore told his father that he should like to have one. "Your wish shall be gratified," replied Mr. Durnford, "provided that you can tell me the origin of its being so called."

"I think," said Theodore, "that the god Pan fell in love with a nymph called Syrinx, in the train of Diana, who, when pursued by Pan fled for refuge to the river Ladon, her father, who changed her into a reed. Pan observing that the reeds, when agitated by the wind, produced [Pg 45] a pleasing sound, connected some of them together, and formed them into a rural pipe, and named it Syrinx."

"Have the goodness to hand me over that Syrinx," said Mr. Durnford, "this young gentleman has won it, by being able to account for the cause of its bearing that name." He now presented it to his delighted son, who received it with a double pleasure, as it was accompanied by the praise of his beloved father, and the smiles of his equally beloved mother. A couple of Tambourines were ordered to be sent home for Maria and Emily, and a triangle for Caroline, and they next proceeded to the

Music Seller

to examine the contents of his collection.

[Pg 46]

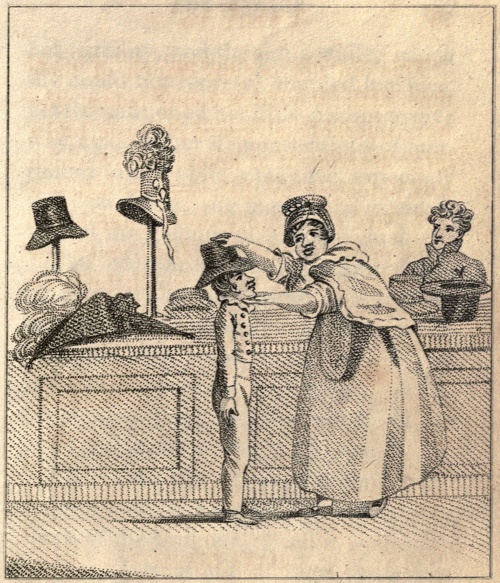

This did not occupy much of their time, as the two eldest young ladies, who were tolerably advanced in music, had a large assortment at home, part of which had belonged to their mother when a girl. Mrs. Durnford, however, purchased some pretty airs for the piano, and a few of Moore's sacred songs, which she knew were extremely beautiful; and which she wished Maria and Emily to learn, that they might sing them to their grandpapa, when he next paid them a visit. She was just quitting the counter, when Caroline burst into a loud laugh, pointing to the opposite counter, which was occupied by a

Hatter

[Pg 49]

Mrs. Durnford instantly saw the cause of her risibility, and though a smile, which she could not repress, dimpled her face, yet she cautioned her little girl not to give way again to her demonstrations of merriment in so public a manner, especially as by so doing, she might inadvertently wound the feelings of an individual.

The objects which had excited the laughter of Caroline, were a short thick made vulgar looking woman, and a tall thin boy who stood as stiff as a poker, with his hands fixed to his sides, while his mother tried to force a hat on his head, evidently too tight for him.

"It is too little for me, mother," cried the boy, pouting out his lips which were none of the thinnest, "and it won't do: besides, I want one of them there new fashioned caps, which all gentlemen's sons wear now."

[Pg 50]

"And what have you to do with gentlemen's sons," said his mother, trying to get the hat a little further on his head, "You know, Tommy, that your father is only a tailor. He only serves gentlemen, he is no gentleman himself. The hat is a nice hat, and a good one for the money, so you shall have it, Tommy. No new fangled frippery for my money."

"But it won't come on my head, mother," exclaimed the boy, half crying for vexation, because he was not to have a cap like a gentleman's son.

"I tell you what, Tommy, if you are not quiet, I'll trim your jacket for you, better than ever your father has done, as [Pg 51] soon as I gets you home. Not do, why it fits you delightfully, and you look quite spruce and handsome in it. I won't have it come any lower, spoiling the shape of your ears. You want them to be like Sam Wilson's ears, and they are just like the ears of an ass, because he always puts his hat behind them."

Poor Caroline now bit her lips, and turned another way, lest she should again offend her mamma by laughing.

"I think, papa," said Theodore, "that hats are made from the fur of different animals, are they not?"

"Yes, my dear. The best is the beaver, but many hats are now made of the fur of the rabbit. Emily, do you recollect to what bird we are indebted for those fine [Pg 52] long feathers which you see in the regimental hats of our officers; and which are now so universally worn by ladies in their bonnets?"

"They come from the ostrich, I believe," replied Emily.

"You are right, my love, but let us follow your mamma, who seems inclined to purchase that beautiful veil from the

Lace Shop

That truly elegant and costly article of a lady's dress, namely lace, is brought to the highest perfection in Brussels, which you know is in Flanders, and in the French provinces in general."

"But we have English lace, papa," said Miss Durnford.

[Pg 57]

"Certainly, but it is far inferior to the foreign. In Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire, great quantities are made annually by the poor people, who subsist by the sale of this article. I have seen British lace which has been very handsome, for instance, the black as well as the white lace gowns belonging to your mother. They will not, however, stand a comparison with the same article of foreign manufacture."

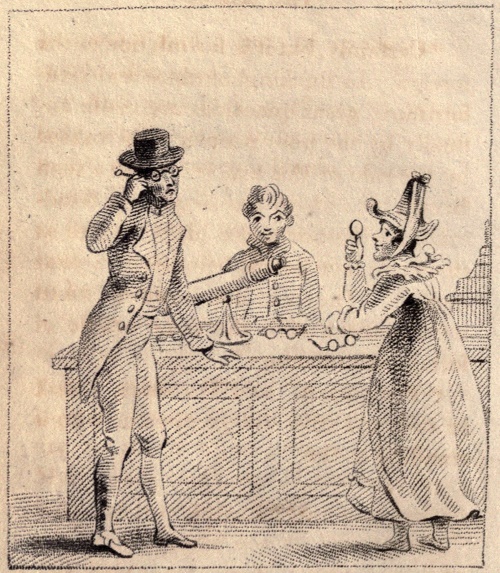

"Pray, papa," said Theodore, "look at that tall thin old gentleman who is standing at the

Optician

[Pg 58]

How woe begone he seems. I suppose he cannot find a pair of spectacles to suit his dim eyes."

"And pray look at that pert young lady, who appears to be making herself merry at the old gentleman's expence," cried Emily, "I hope she is not his granddaughter. See how cunningly she looks through the glass which she holds in her hand."

"She may not intend to make game of him," replied Mr. Durnford, "but young people cannot be too cautious how they take liberties with those who are so much their seniors. Perhaps, Maria, you can inform me, how telescopes were first invented. The optician has got a very good sized one on his counter."

[Pg 59]

"The invention is owing rather to chance than thought," said Miss Durnford, modestly, "for if I remember right, the children of a spectacle-maker at Middleburgh, in Zealand, playing in their father's shop, held two glasses between their fingers at some distance from each other, through which the weather-cock on the steeple appeared much larger than usual, and as if near to them, but inverted. They spoke of it to their father, who instantly thought of fixing two glasses in brass circles, and placing them so as to be drawn nearer or removed, by this means he found he could see objects more distinctly."

[Pg 60]

"That happened about the year 1590;" said Mr. Durnford, "but none of the telescopes there made were above eighteen inches long. The celebrated Galileo, astronomer to the Grand Duke of Tuscany, improved them; and the invention has often been ascribed to him. That was the refracting telescope, but the reflecting telescope is the invention of the great Sir Isaac Newton."

"I should like to have a microscope, papa," said Theodore.

"My telescope may be converted into a microscope, my dear," said his father, "by removing the object-glass to a greater distance from the eye-glass, as I will show you when we go home. It is generally supposed, that we owe the invention of them to the Hollanders, and that spectacles, so useful to the aged and the near-sighted, was first invented

[Pg 63]

by a monk of Pisa. The thermometer and barometer are both very useful instruments. The former ascertains the degrees of heat, and the latter the changes of the weather."

"Oh, mamma!" exclaimed Caroline, "only observe what an odd face that old woman has got, who is examining with such strict attention that nice large silk

Umbrella Maker

Does she not look as if she thought something might be the matter with it? I think she had better borrow a pair of spectacles of the optician. Let us go a little nearer, mamma, I wish I could hear her speak."

[Pg 64]

As Caroline promised to keep a guard over her risible muscles, her mamma granted her wish of being nearer to the little old woman, who was prying all over the nice new umbrella.

"Six and twenty shillings, Mr. Bates! why how could you think of asking a person like me, to give you six and twenty shillings! If you will take twenty, Mr. Bates, I will have it, though I think it looks a little soiled."

The man assured her that he could not take less than what he had asked, but that she might have a cotton one much cheaper.

[Pg 65]

"A cotton one, indeed! no, no, I am not so badly off, but what I can buy a silk umbrella if I like, but I won't give that money for one. So good morning, Mr. Bates."

"Umbrellas are a modern invention," said Mrs. Durnford, "at least within thirty or forty years, and in the country in particular they are very useful, but in London they are troublesome, from the number of passengers which we meet. I think, Caroline, that you must have a new parasol, for yours forms but a sad contrast to your sister's, though it was bought at the same time. I think the parasol equally as convenient, and as necessary to our comfort as the umbrella. It shades us from the burning rays of a summer sun, and enables us to take a long walk without being incommoded by its beams. We will now take a look at those

[Pg 66]

Work Baskets

Mark the different expression visible on the countenances of those two little girls. See, Maria, how happy and contented that dear fat cherub seems, with her newly purchased basket on her arm; while her sister, not yet suited, eagerly stretches forth her hand, anxious to examine more than she has already seen."

"Baskets are made from the osier and the willow, are they not, mamma?" said Maria.

"Yes, my dear girl, and extremely pretty they make them by colouring the wood, which has a pleasing effect. [Pg 71] They have brought the art of basket-making to great perfection. I think I must treat myself with one to hold fruit, and another for biscuits."

"When you are suited to your mind," said Mr. Durnford, "we will next examine the beauties of the

Work Trunk Maker

Come here, Emily, and tell me the name of this ware, as it is called."

"Tunbridge, I believe, papa," said Emily. "That is the principal place from whence all these beautiful boxes are brought to town," said Mr. Durnford. "Some are made of the lime-tree, and some of the box-tree. Here you see are work boxes, cotton and netting [Pg 72] boxes, writing boxes, all made at Tunbridge, besides a variety of smaller articles, all equally useful and ornamental. See, Maria, what an excellent imitation that trunk is of tortoise shell. Pray what is the price of it?"

"Eight shillings, Sir," replied a modest pretty looking young woman. Mr. Durnford paid the money, and ordered it to be sent home.

"Who do you intend it for, my dear?" enquired his wife.

"For those who shall best deserve it," said Mr. Durnford.

They now stopped at a maker of

Artificial Flowers

the sight of which gave great pleasure [Pg 75] to the young ladies. Here they perceived flowers of every description, some in wreaths for the ball-room, others for the head, and some in bunches, either for the bonnet or the bosom.

"What can be more beautiful than this bouquet of Rosebuds, Myrtle, and Geranium, how faithful a copy from nature!" exclaimed Mrs. Durnford, "at a little distance you would never suppose them to be artificial. Had it been my lot to have toiled for my daily support, I think I should have preferred this business to any other. It is a minor sort of painting, as the different teints must all be arranged by the hand of taste. I have seen flowers that were scented with the perfume belonging to them, but this made [Pg 76] them come expensive, and they now make them with the glowing colours of nature, but without the richness of her scent. I love to encourage humble merit, and will therefore order a few of its productions to be sent to Ivy Cottage."

"The flowers are beautiful, mamma, but how much more beautiful are those

Bird Seller

said Caroline. "What is the name of that large bird, papa? He will not hurt us, will he? I think he looks angry." "No, my darling! he will not hurt you," replied her father; "it is a blue Macaw, a larger species of Parrot. Like all foreign birds the plumage is more vivid [Pg 79] and brilliant than ours, but we have the advantage in song. The Humming-bird is the smallest bird in the world, being little more than three inches. The male is green and gold on the upper part, with a changeable copper gloss; the under parts are grey. The throat and fore part of the neck are a ruby colour, in some lights as bright as fire. When viewed sideways, the feathers appear mixed with gold, and beneath of a dull garnet colour. This beautiful little bird is as admirable for its vast swiftness in the air, and its manner of feeding, as for the elegance and brilliancy of its colours. Lightning is scarcely more transient than its flight, nor the glare more vivid than its colours. It never feeds but on the [Pg 80] wing, suspended over the flower from which it extracts its nourishment. If they find that any of their brethren have been before them, they will, in a rage, if possible, pluck it off and throw it on the ground, and sometimes even tear it to pieces.

"Beautiful as is the plumage of the foreign birds, I give the preference to our own. Who that ever heard the exquisite note of the plain brown Nightingale would regret its want of brilliant plumage? What can equal the melodious tones of the Robin, the mellow note of the Linnet, the sweet call of the Blackbird, and numerous others whose daily song seems to arise in grateful thankfulness to the throne of the Creator. We [Pg 83] have some birds, however, which may almost vie with the beautiful plumage of the foreign species. The Goldfinch, King's Fisher, Bullfinch, and various others, many of which you have seen at your grandpapa's. The Pigeon and Dove, the Peacock and Pheasant are extremely beautiful. Indeed, nothing in my opinion can equal the splendour of the Peacock."

"From nature we will once more turn to art," said Mrs. Durnford, "surely nothing of foreign manufacture can exceed the elegance and design of that

China Seller

[Pg 84]

Look at these flowers, how admirably they are formed, designed and painted: where will you find a landscape more correctly executed, more beautifully shaded than is to be seen on that flower vase."

"We have certainly arrived to great perfection, my dear," said Mr. Durnford, "both in the manufacture of our China, and in the art of painting it, but you must allow me to give the preference to that which is imported from foreign states. Their earth is far superior to ours, so are their colours. Shew me any of our own that can boast the vivid glow of theirs. However we are greatly indebted to Mr. Wedgewood, who was the first to introduce that superior sort of ware, which for neatness and elegance is [Pg 87] certainly unrivalled. Painting upon China is become one of the fashionable amusements, like painting upon velvet, but I trust that it will never become so common, as to injure those who get their living by the produce of their industrious exertions."

"Mamma," cried Theodore, "look at that lady who is bargaining for a flaxen wig. How anxious she seems to have the opinion of the

which will best suit her complexion. Where does all that hair come from which is to be seen in the shops of the metropolis?"

Hair Merchant

[Pg 88]

"The dark hair is imported from Germany and France, while the beautiful flaxen ringlets of various shades is brought over from the North. We import a vast quantity, as our own country would afford us but little. The hair of horses, besides many other purposes that it is applied to, such as stuffing furniture and saddles, is woven into those coverings for chairs and sofas, that are so durable and look like black satin. Nay, I have seen very lately, the hair of a horse adorn the helmets of our gallant warriors."

The next counter was occupied by a

where a genteel looking woman was trying on a pair of shoes for her little baby.

Shoe Maker

Published Feby 1, 1815, by J. Harris, corner of St. Pauls.

[Pg 91]

"Shoes," said Mr. Durnford, "are made of various materials, such as satin, silk, stuff, kid, Spanish leather, seal skin, and morocco. The latter comes from a place in Africa of that name, but we imitate it ourselves, and not badly. The hide of cattle serves for the soles. The silk you know is the produce of the Southern climates, and comes from the silk worm. Vast quantities of raw silk are imported here from Italy and different parts, as well as velvet, of which again we have an imitation. You understand, my children, that our imitations of foreign manufactures come considerably lower than those which we import. Shoe making has also become one of the amusements of the [Pg 92] fashionable world, but it gives me infinite pleasure to know that your mother has never adopted this fashion, which, like many others must tend to injure the interests of the industrious tradesman."

Their attention was now awakened by a violent scream, which proceeded from a young lady, who, with her brother, was standing at the counter of a

Gun Smith

The boy had thoughtlessly taken up a pistol and presented it at his sister, who, terrified by the sight of so deadly a weapon aimed against her breast, had uttered the piercing scream, which immediately brought Mrs. Durnford and her [Pg 95] family to her assistance. By degrees they tranquillized the poor girl's mind, while Mr. Durnford strongly reprobated the wanton levity of her brother.

"Surely, Sir," said the youth, "she must be extremely foolish not to know that these things are never loaded when exposed to sale."

"That may be very true," said Mr. Durnford, "but so many accidents occur hourly by the same thoughtless conduct as your own, that I am surprised that any humane person can ever run the risk of wounding either the feelings or the body of a fellow creature."

The young lady was now sufficiently recovered to thank Mrs. Durnford for her kind attentions, and taking the arm of [Pg 96] her thoughtless brother, she quitted the Bazaar.

"Theodore," said Mr. Durnford, "can you remember when muskets were first invented?"

"I think, papa, in the time of Henry the Eighth, when brass cannon were first cast in England, as well as mortars. The finest steel is that of Damascus in Asiatic Turkey."

"We import a vast quantity of swords and dirks from Germany likewise," said Mr. Durnford, "but as the implements of war are unpleasing objects to the female mind, we will turn to a more agreeable subject, and take a survey of those beautiful plants which are the pride of our

[Pg 99]

Green House Plants

Published Feby 1 1818, by J. Harris, corner of St. Pauls.

"How lovely is the Illicium Floridanum with its large red flower!" said Mrs. Durnford; "only smell how delicious is the perfume of its leaves."

"Delicious, indeed!" said Mr. Durnford, "I must purchase one on purpose that I may enjoy the scent. It comes from Florida. I must also treat myself with one of those Camellia Japonica, or Japan roses. The blossom is uncommonly fine. Pray what is the name of this tall flower?"

"The Lobelia Fulgens," replied the proprietor. "It is a native of North America, and is a hardy plant."

[Pg 100]

"I should like that pot of China roses, mamma," said Emily; "they came originally, I believe, from China, and are called Rosasinensis."

"That mignonette is very luxuriant," said Maria, "pray have some, mamma, the smell is so fragrant. Do they not call it Resecla Odorata."

"Yes, my love, and it came first from Egypt."

"Oh, mamma; do buy that sweet myrtle," cried Caroline, "I am so fond of myrtles and geraniums. What is the Latin term for myrtle?"

"There are eleven different sorts, my dear;" said her mother, "the common myrtle is a native of the South of Europe, and is called Myrtus Communis. Many [Pg 103] come from the West India Islands, and some from Asia. In the Isle of Wight we have hedges of them, and in the South of England they will grow in the open air, as well as some of the geraniums, of which latter there are too many for me to enumerate. How lovely is the Convallaria Majalis, or lilly of the valley. It is a simple flower, a native of Britain, but the perfume is delightful."

From the Florist, they now turned towards the

Milliner

where little Caroline again saw something to excite her laughter, and to call forth the smile of her father. A lady, long past the prime of life, but dressed [Pg 104] in a style of girlish fashion, with short sleeves which shewed her shrivelled arms, and still shorter petticoats, was viewing herself with much complacency, as she placed on her head, the grey hairs of which were concealed by the flowing tresses of an auburn wig, a large straw hat, loaded with flowers and feathers, and only fit for a young woman under thirty.

"Surely, mamma," cried Emily, "that old lady can never intend to buy that hat? It is too gay for one of her years."

"She certainly does," said Maria, "and I dare say believes that it will make her look twenty years younger than she is."

"She thinks wrong then, sister," exclaimed Theodore. "For, unless she [Pg 105] can hide the wrinkles in her face and neck, and the loss of her teeth, and the leanness of her body, she will only the more expose her age, by dressing so ridiculously."

"Your remark is a just one, my boy," said his father. "Old age of itself is respectable, and calls for the attention and veneration of youth, but when it apes the dress and follies of the latter, it only excites the sneer of contempt, and the laugh of ridicule."

"From contemplating the weakness of the human mind," said Mrs. Durnford, "let us now turn towards that which has the power of strengthening and invigorating the human body. What would [Pg 106] our physicians and other medical gentlemen do, without the aid of the

Chemist & Druggist

The physician writes his prescription, and it is then sent to the shop of the druggist, who makes it up according to the order. Several of their medicines are rendered expensive, by having musk, camphire, and other dear articles introduced in them. Apothecaries Hall is the best place to buy drugs, for they never vend any that are not genuine."

"Drugs are composed of minerals as well as vegetables, are they not, papa?" said Theodore.

[Pg 109]

"Yes, my dear boy. But do you perfectly comprehend what is a mineral?"

"A mineral, papa, is a semi-metal, as they are called by the chemists, such as antimony, zinc, bismuth, and others. They are not inflammable, but are hard and brittle, and may be reduced into powder. Mercury or quicksilver has been classed with semi-metals. Shall I tell you how many metals there are, papa?"

"If you please Theodore."

"There are six, papa. Gold, silver, copper, tin, lead, and iron. The most precious metals, such as gold and silver, do not form the most splendid ones. The pyrites, which are a mixture of iron and sulphur, are more beautiful to the eye."

[Pg 110]

"Very well remembered, Theodore. But you forget to class the magnet as a mineral."

"I do not perfectly understand the nature of the magnet, papa."

"It is a species of Iron found in iron mines," said Mr. Durnford, "which has the singular property of attracting metal. The ancients knew no means of finding their way at sea, but by the stars; of course when those celestial bodies were not visible, the sailor was frequently at a loss how to steer. A piece of steel is now procured, made something like a needle, but flat, about four inches long; this is rubbed with the loadstone, and then balanced exactly on two points or pivots, so that it may turn round freely. [Pg 113] This needle when fixed in a box, is called the mariner's compass, and as it invariably turns toward the North, the sailors can now steer to any part of the world, which they could not do without the help of this piece of iron. The first knowledge of this useful application of the magnet is supposed to come from Marco Polo, a Venetian, in the thirteenth century; but it is said to have been known to the Chinese."

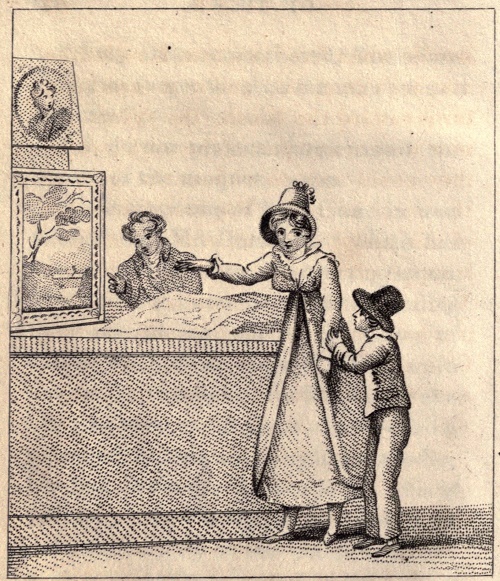

"We will now take a view of those

Print-seller

said Mrs. Durnford, "I am as fond of the sight as any of my children."

[Pg 114]

"A fine engraving is very valuable," replied Mr. Durnford, "and I have lately seen some on wood, which pleased me extremely. Albert Durer, was I believe the first inventor of engraving on wood. Etching on copper was not known until Henry the Sixth's time."

"What is that picture, papa, which that lady has just turned aside?" enquired Miss Durnford.

"It is the representation of one of the most important events in English history, my love. Namely, the signing of a deed called Magna Charta, by the weak-minded and worthless King John. The place is called Runnymead, near Windsor; where the barons compelled John to sign that famous deed, which laid the foundation of that freedom, [Pg 115] which for centuries has been the glory, boast, and security, of the English people. I will buy the print, that I may have the pleasure of placing underneath it, those fine lines by Dr. Akenside, which were intended for a pillar or monument of that transaction at Runnymead."

After they were written, Mr. Durnford desired Theodore to read them, which he did in a voice and manner so truly admirable, that several present stood listening with delight, while their bosoms proudly swelled at the recollection of those blessings, which as Englishmen they were privileged to enjoy.

[Pg 116]

"Thou who the verdant plain dost traverse here,

"While Thames among his willows from thy view

"Retires, O stranger! stay thee, and the scene

"Around contemplate well.—This is the place

"Where England's ancient Barons, clad in arms

"And stern with conquest, from their tyrant king

"(Then rendered tame) did challenge and secure

"The charter of their freedom.—Pass not on

"Till thou hast bless'd their memory, and paid

"Those thanks which God appointed the reward

"Of public virtue.—And if chance thy home

"Salute thee with a father's honoured name,

"Go call thy sons, instruct them what a debt

"They owe their ancestors; and make them swear

"To pay it, by transmitting down entire

"Those sacred rights to which themselves were born."

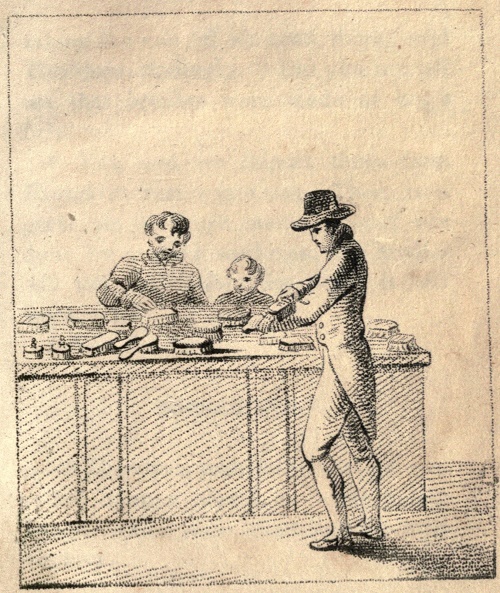

The young people now stopped to admire a collection of

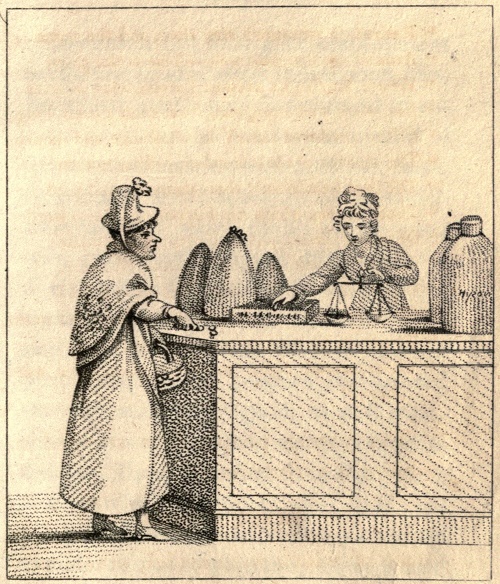

Grocer

[Pg 119]

some of which were useful, others only ornamental, but as it gave employment to the young and to the industrious, Mrs. Durnford generously determined to encourage the art by purchasing several of the prettiest articles, such as flower cases, card racks, hand screens, all of which were made of paper, highly ornamented with gold, and elegant little painted devices. Her daughters had been taught a variety of fancy works by their governess, but their mamma felt a pleasure in purchasing these, because she trusted that she was doing good, as well as assisting to support some worthy object in distress. Upon learning from the young person who sold them, that this was really the case, she ordered her children to make choice of what they pleased, and then hastened forward to avoid the warm effusions of gratitude, which her liberality had called forth.

[Pg 120]

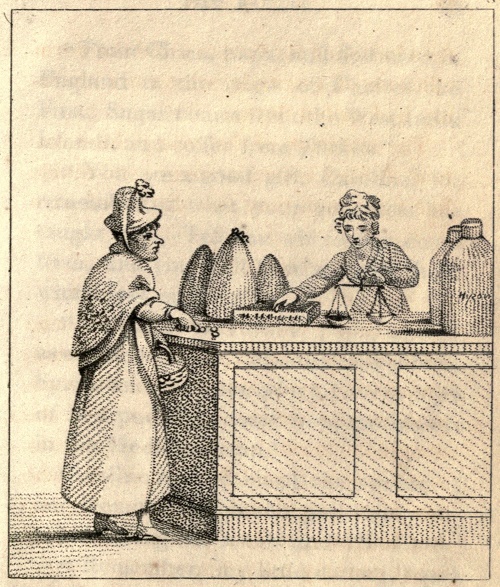

The attention of the young ladies was now divided between some remarkable fine figs which they saw displayed at a

Grocer

and a short vulgar looking female, who with a sharp turned up nose, pointed chin, and staring eyes, was watching the woman as she weighed the tea, lest she should fail to give her the turn of the scale.

"Caroline," said Mr. Durnford, who saw his little girl endeavouring to repress her laughter, "can you tell me from what country tea is imported?"

[Pg 123]

"From China, papa, and first used in England in the reign of Charles the First. Sugar comes from the West India Islands, and coffee from Turkey."

"You are a good girl, Caroline, for remembering what your governess has taught you. Tell me where figs come from, and you shall have some of those which look so fine."

"I think it is Turkey, papa, as well as our best raisins. Malaga raisins from Spain, and currants, which I am so fond of in a pudding, come from the islands in the Mediterranean."

Caroline now received the reward of her memory which she generously divided among her sisters and Theodore.

[Pg 124]

"Remember, my little darling," said Mrs. Durnford, "that rice, of which you are also very fond, comes from Asia. Tamarinds and other preserved fruits from the West Indies, and spices from the Molucca or Spice Islands. Almonds and dates are imported from Africa, as well as a variety of other commodities not sold by the grocer."

"Now, Maria," said Mr. Durnford, "I must tax your memory a little. Let us take a look at those comfortable articles of winter clothing which are exposed for sale by the

Furrier

[Pg 127]

"I understand you, papa, and will try to recollect. I know that it is to the northern countries that we are indebted for our furs. The ermine, whose beautiful white fur and black tail lines the coronets and mantles of our nobles, creeps among the snows of Siberia, and the north of Russia. There too is the sable, whose fur is so dear, that I think you once told me, a robe lined with it, is often valued at a thousand pounds. We also import furs from America, and I believe frequently make use of that belonging to the pretty innocent rabbit, and the graceful cat, to line our muffs and shoes."

"They suffer alike with the faithful dog, my dear," said her father, "as well as other animals who are killed for our use. In the northern regions the natives could not stir from their homes, unless [Pg 128] they were shielded from the severity of the weather, by lining their clothes with fur. Even in England, the gentlemen feel the comforts of fur on their great coats, and the ladies enjoy the benefit of their muffs and tippets, although our winter is not to be compared with that of other countries."

"Mamma! mamma!" cried Caroline, "there is the very same old lady looking at that beautiful crape dress, at the

Dress Maker

who was trying on the large straw hat with such a profusion of feathers and flowers."

[Pg 131]

"Hush! my lovely girl," said her mamma, "if you are not more silent I must take you home."

"It is just the thing, Mrs. Tasteful," screamed out the old lady. "It will suit my figure exactly. Square bosom, and off the shoulders, why with a lace frill I shall look delightful. A saucy fellow had the impudence to tell me, as I was getting out of my carriage, that I had better wear my petticoat a little longer to hide my legs, and put a shawl on to conceal my neck. The fool had no more taste than a Hottentot. Well, my dear woman, you will let me have this dress immediately. I am going out to a ball this evening, and shall want to put it on. Primrose coloured crape over white sarsenet. Charming, I declare!"

[Pg 132]

"Come on, my dears," said Mr. Durnford, hastily, "I have no inclination to listen any longer to such disgusting vanity and folly. The age of that lady ought to have enabled her to set good examples to the younger and inexperienced part of her sex, instead of which she is only a disgrace to it. Come on, my dears, I will not stay a moment longer, lest another burst of weakness should offend my ear. You all know what is the province of a dress maker, therefore it requires no explanation."

"I am in want of some hair-brushes," said Mrs. Durnford, "therefore if you please we must stop a few minutes at the

Brush Maker

[Pg 135]

"That gentleman seems afraid of taking the nap off his coat, papa," said Theodore, smilingly. "Did you not tell me that brushes were made of hog's bristles?"

"Yes, and we import them from Russia in vast quantities. There is a great art in brush making, for if not done by a good workman, the bristles will fall out, before the brush is half worn out."

"Now for the

Bookseller

Published Feby. 20, 1818, by J. Harris,

corner of St. Pauls.

cried Theodore, with delight, as his eyes rested upon a parcel of books neatly bound, which were placed on the next counter.

[Pg 136]

"I have no objection to your selecting one book a-piece," said his father, "but you remember, Theodore, that I always make a point of buying all your books at the corner of St. Paul's Church-yard. You may, however, purchase a few of this person, who appears to have got a very good selection."

"I had them, Sir, of Mr. Harris, in St. Paul's Church-yard," said the woman. "He was so good as to choose for me what he thought would sell best."

"Then you may look over them, my dears," said Mr. Durnford. "I suppose, Caroline, that you know what paper is made from?"

"Of linen rags, papa, but I do not know how it is made."

[Pg 137]

"No, my love, neither can I explain it to you now, as the process is too long. Theodore, can you inform me of the origin of printing."

"Coining, and taking impressions in wax, are of great antiquity," said Theodore, "and the principle is precisely the same as that of printing. The application of this principle to the multiplication of books, constituted the discovery of the art of printing. The Chinese have for many ages printed with blocks, or whole pages engraved on wood; but the application of single letters or moveable types, forms the merit and the superiority of the European art. The honour of giving rise to this method, has been claimed by the cities of Harlem, Mentz, and Strasburg; and to each of these it may be ascribed in some degree, as printers resident in each, made improvements in the art."

[Pg 138]

"So far you are right, my dear boy," said his father, "it is recorded, that one Laurentius, of Harlem, was the first inventor of the leaden letters, which he afterwards changed for a mixture of tin and lead, as a more solid and durable substance. We may suppose this to have been about 1430. From this period, printing made a rapid progress in most of the chief towns of Europe. In 1490 it reached Constantinople, and was extended by the middle of the following century, to Africa and America. It was for a long time believed that printing was introduced into England, by one William Caxton, a mercer, and citizen [Pg 139] of London, who having resided many years in Holland, Flanders, and Germany, had made himself master of the whole art, and set up a press in Westminster, in 1471. But a book has since been found, with a date of its impression at Oxford, in 1468, and is considered as a proof that printing began in that University before Caxton practised it in London. Emily, what have you got there bound so handsomely in morocco?"

"Mrs. Chapone's Letters, papa, it is a present from mamma. And Maria has got European Scenes, for Tarry at Home Travellers, a very pretty book, full of engravings. And Caroline has chosen Keeper's Travels in Search of his Master."

[Pg 140]

"Very well, my dear, and here is Sandford and Merton for our Theodore, half-bound in Russia. This leather is now made use of in libraries, because it preserves the books from the moth, the smell, perhaps, is not so agreeable. Other books are bound in calves' skin, which is a very pretty binding, and others are only half-bound, as it is called, or in boards. Now, if you are suited, we will pass on to the

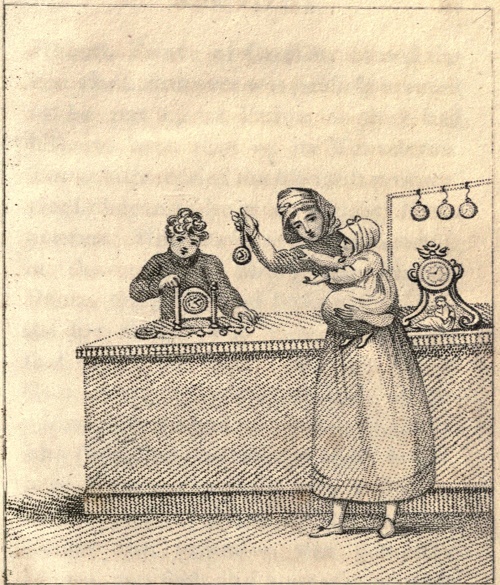

Watch Maker

"The invention of clocks," said Mr. Durnford, "is to be ascribed to the Saracens, to whom we are indebted for most of our mathematical sciences. [Pg 143] Hubert, Prince of Carrara, caused the first clock that ever was publicly erected to be put up at Padua, as they had hitherto been shut up in Monasteries. Towards the end of the fifteenth century, clocks began to be in use among private persons. Watches were used in London, in the reign of Henry the Eighth. Dante, the celebrated Italian poet, was the first Author who mentions a clock that struck the hour. But the use of clocks was not confined to Italy at this period; for we had an artist in England, who furnished the famous clock house, near Westminster Hall, with a clock to be heard by the courts of law, in 1288. Before this invention was generally known, sun dials and hour glasses were [Pg 144] used. The Elector of Saxony had a clock set in the pummel of his saddle, and the Emperor Charles the Fifth, had a watch set as a jewel, in a ring. Nothing can equal the perfection to which this species of mechanism is now carried. I have half a mind, Theodore, to treat you to a watch, for you have deserved one by your attention to your studies, and our poor watch-maker looks so woe begone, that I fear he has not sold one to-day. Examine this plain gold hunting watch, and tell me if you like it."

Theodore was in raptures with it, as he had long sighed to possess a watch. "Tell me in what country the gold which composes the case of this watch is to be found," said his father.

[Pg 145]

"The Mines of Chili and Peru, in America, are the richest, papa," replied Theodore, "but very fine gold is found in some parts of the East Indies. Gold dust is found on the coast of Guinea, in Africa, and hence the name of our largest gold coin. Silver Mines are in all parts of the world, but those of Potosi in Peru, and some others in America, are the most productive. All the precious stones, which so frequently enrich the backs and fronts of our watches, come also from America, and Cornelian stones, of which seals are made."

Mr. Durnford, highly delighted with his son, now made him a present of a gold watch and seals, one of which he ordered to be engraved with his name. They next proceeded to the

[Pg 146]

Fruiterer

where the children were desired to take what they liked best.

"All our fruits originally came from abroad," said Mr. Durnford, "but we have improved upon them, although our climate is not sufficiently warm to bring them to that perfection, which is the boast of the Southern nations. The pineapple, which you know is a most delicious fruit, comes from the West Indies, but we have excellent pineries in England, as well as fine melons. They also are natives of both the Indies. Our finest pears are from France, oranges, nuts, almonds, [Pg 149] olives, grapes, chestnuts, pomegranates, lemons, and prunes, all come from the South of Europe. Oranges originally came from China. We do not know the real flavour of an orange in this country, as they are pulled long before they are ripe, and sent over here to be purchased by the fruit merchants. Some of these look very good, therefore we will buy some. Caroline, open your basket, and take some of these grapes, and a few pears."

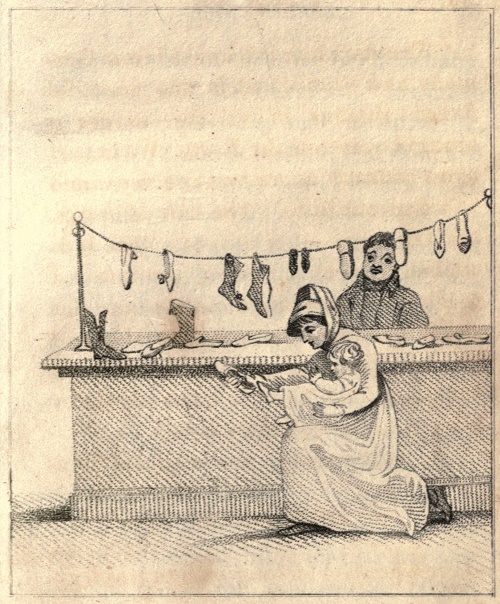

"Yes, dear papa," cried the little girl, "only pray let me look at that old gouty farmer, who is buying at

Hosier

those nice warm stockings. What are they called, papa, I have seen them at my grandfather's."

[Pg 150]

"They are called Lambs'-wool stockings, my dear, and are particularly serviceable to the aged and infirm. The old gentleman looks as if he was reckoning up his money, that he may know whether his purse will allow of his indulging himself with more than one pair of his favourite Lambs'-wool stockings. Let us look at some white silk.—Silk you know is imported from Italy, it is produced by a worm which feeds on the leaves of the mulberry-tree. Cotton is imported from Asia, of which we make our fine cotton stockings. The wool of sheep supplies us with worsted stockings, the chief wear of the working classes of men, and the skins of animals give us that necessary finish to our dress, gloves. The best and handsomest of this latter article are made in France, but are prohibited from being sold in England, that they may not injure our own manufactures."

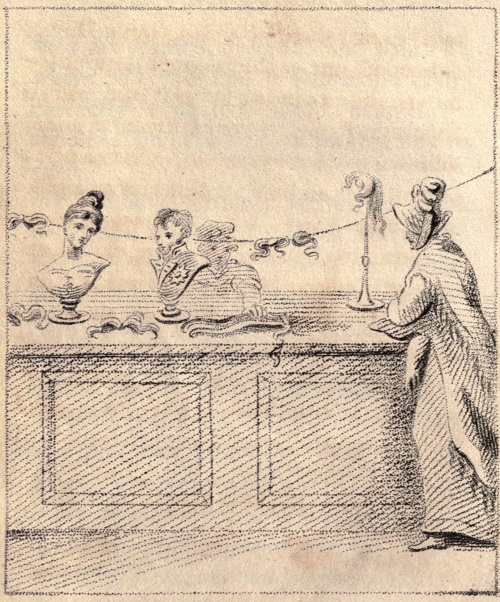

"Let us now examine the beauties of the

[Pg 155]

Sculptor

said Mrs. Durnford, "the imitative arts of sculpture and painting, made an early appearance in Greece. Statuary, a more simple imitation than painting, was soonest brought to perfection: the statues of Jupiter by Phidias, and of Juno by Polycletes, were executed long before the art of light and shade was known. [Pg 156] Another cause likewise concurred to advance statuary before painting, namely, the great demand for statues of the gods. In all countries where the people are barbarous and illiterate, the progress of the arts is extremely slow. Fine arts are also precarious; they are not relished but by persons of taste, who are comparatively very few; for which reason, they will never flourish in any country, unless patronized by the Sovereign, or by men of power and opulence. Our own cathedrals can boast some beautiful specimens of this art, among which the works of Bacon and of Flaxman stand conspicuous. Look, Caroline, at this figure, can you tell me who it is meant to represent?"

[Pg 157]

Caroline thought it was Mercury, "but what does he hold in his hand, mamma?"

"A caduceus, or wand, my dear, round which are entwined two serpents. Mercury is the god of eloquence, of arts and sciences, and the messenger of Jupiter. When you are a little older, you must learn the history of the Heathen gods and goddesses, else you will remain ignorant of many beautiful allusions in poetry. They are introduced likewise into painting, of which I shall be happy, my Theodore, if you can give me some account."

"It is said to have had its rise among the Egyptians," said Theodore, "but the Greeks, who learned it of them, carried it to the summit of perfection, if we may [Pg 158] believe the stories related of their Apelles and Zeuxis. The Romans, in the latter times of the Republic, and under the first emperors, were not without considerable masters in the art; but the inundation of barbarians which deluged Italy, proved fatal to the arts, and almost reduced painting to its first elements. It was in Italy, however, that painting returned to its ancient honour, when Cimaluce, born at Florence, transferred the poor remains of the art from a Greek painter into his own country."

"You are right, my dear boy," said his father, "he was seconded in his attempts by other Florentines. The first who gained any reputation, were Ghirlaudias, Michael Angelo's master; Pietro Perugino, the master of Raphael Urbino; [Pg 159] and Andrea Verocchio, the teacher of Leonardo da Vinci. Michael Angelo founded the School of Florence; Raphael that of Rome, and Leonardo da Vinci, the School of Milan; to which I may add, the Lombard School under Georgione and Titian. France also has given birth to some eminent painters, as Poussin, Lebrun, David, and others, and our own country, during the last century, has been distinguished by artists, such as Reynolds, Hogarth, West, Barry, Wilson, Morland, Gainsborough, and many others. At the exhibition at Somerset House, you will see a fine collection of paintings, and models of Sculpture, besides a variety of miniature pictures, which are very beautiful. And now, my dear children, I think we have seen all the contents of the Bazaar, which I hope has amused as well as instructed you."

[Pg 160]

The young people all expressed their thanks to their kind parents for the entertainment they had received, as well from the curious characters which they had seen drawn together by the same motives, as from the inspection of the various articles which the neat and elegant little shops contained.

"I think we could not have spent a morning better," said Mrs. Durnford, "and since we are all of the same opinion we will now return home to dinner, perfectly well satisfied with The Visit to the Bazaar."

H. Bryer, Printer, Bridge-Street, Blackfriars, London.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.