CARDINAL DE RICHELIEU

TRIPLE PORTRAIT BY PHILIPPE DE CHAMPAGNE

Title: Cardinal de Richelieu

Author: Eleanor Catherine Price

Release Date: September 10, 2023 [eBook #71607]

Language: English

Credits: Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CARDINAL DE RICHELIEU

TRIPLE PORTRAIT BY PHILIPPE DE CHAMPAGNE

BY

ELEANOR C. PRICE

AUTHOR OF “A PRINCESS OF THE OLD WORLD”

“Il est dans l’histoire de grandes et énigmatiques figures

sur lesquelles le ‘dernier mot’ ne sera peut-être jamais dit....

Telle est, assurément, celle du Cardinal de Richelieu.”

Baron A. de Maricourt.

WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS

SECOND EDITION

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

| First Published | September 19th 1912 |

| Second Edition | 1912 |

“Temerarious indeed must he appear who attempts to comprehend in so small a space the admirable actions of a Hero who filled the whole earth with the fame of his glory, and who, by the wonders he worked in our own days, effaced the most lofty and astounding deeds of Pagan demigods and illustrious Personages of Antiquity. But what encourages me to attempt a thing so daring is the preciousness of the material with which I have to deal; being such that it needs neither the workman nor his art for the heightening of its value. So that, however little I may say of the incomparable and inimitable actions of the great Armand de Richelieu, I shall yet say much; knowing also that if I were to fill large volumes, I should still say very little.”

Although the courtly language of the Sieur de la Colombière, Gentleman-in-Ordinary to Louis XIV., who wrote a Portrait of Cardinal de Richelieu some years after his death, may appear extravagant to modern minds, there is no denying that he is justified on one point—the marvellous interest of his subject.

Few harder tasks could be attempted than a complete biography of Richelieu. It would mean the history of France for more than fifty years, the history of Europe for more than twenty: even a fully equipped student[Pg v] might hesitate before undertaking it. At the same time, Richelieu’s personality and the times in which he lived are so rich in varied interest that even a passing glance at both may be found not unwelcome. If excuse is needed, there is that of Monsieur de la Colombière: “Pour peu que j’en parle, j’en dirai beaucoup.”

There are many good authorities for the life of Cardinal de Richelieu and for the details of his time, among which the well-known and invaluable works of M. Avenel and of the Vicomte G. d’Avenel should especially be mentioned. But any modern writer on the subject must, first and foremost, acknowledge a deep obligation to M. Hanotaux, concerning whose unfinished Histoire du Cardinal de Richelieu, extending down to the year 1624, one can only express the hope that its gifted author may some day find leisure and inclination to complete it.

E. C. P.

[Pg vi]

| List of Authorities | Pages xiii, xiv |

| PART I | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The birth of Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu—The position of his family—His great-uncles—His grandfather and grandmother—His father, François de Richelieu, Grand Provost of Henry III.—His mother and her family—His godfathers—The death of his father | Pages 1-9 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Friends and relations—The household at Richelieu—Country life in Poitou | Pages 10-15 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The University of Paris—The College of Navarre—The Marquis du Chillou—A change of prospect—A student of theology—The Abbé de Richelieu at Rome—His consecration | Pages 16-25 |

| PART II | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| A Bishop at the Sorbonne—State of France under Henry IV.—Henry IV., his Queen and his Court—The Nobles and Princes—The unhealthiness of Paris—The Bishop’s departure | Pages 26-37 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Richelieu arrives at Luçon—His palace and household—His work in the diocese—His friends and neighbours | Pages 38-47[Pg vii] |

| CHAPTER III | |

| “Instructions et Maximes”—The death of Henry IV.—The difficult road to favour—Père Joseph and the Abbey of Fontevrault | Pages 48-62 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Waiting for an opportunity—Political unrest—The States-General of 1614—The Bishop of Luçon speaks | Pages 63-71 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Richelieu appointed Chaplain to Queen Anne—Discontent of the Parliament and the Princes—The royal progress to the south—Treaty of Loudun—Return to Paris—Marie de Médicis and her favourites—The young King and Queen—The Duc de Luynes—Richelieu as negotiator and adviser—The death of Madame de Richelieu | Pages 72-87 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| A contemporary view of the state of France—Barbin, Mangot, and Richelieu—A new rebellion—Richelieu as Foreign Secretary—The Abbé de Marolles—Concini in danger—The death of Concini—The fall of the Ministry—Horrible scenes in Paris—Richelieu follows the Queen-mother into exile | Pages 88-100 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Richelieu at Blois—He is ordered back to his diocese—He writes a book in defence of the Faith—Marriage of Mademoiselle de Richelieu—The Bishop exiled to Avignon—Escape of the Queen-mother from Blois—Richelieu is recalled to her service | Pages 101-115 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Treaty of Angoulême—The death of Henry de Richelieu—The meeting at Couzières—The Queen-mother at Angers—Richelieu’s influence for peace—The battle of the Ponts-de-Cé—Intrigues of the Duc de Luynes—Marriage of Richelieu’s niece—The campaigns in Béarn and Languedoc—The death of Luynes—The Bishop of Luçon becomes a Cardinal | Pages 116-130[Pg viii] |

| PART III | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Cardinal de Richelieu—Personal descriptions—A patron of the arts—Court intrigues—Fancan and the pamphlets—The fall of the Ministers—Cardinal de Richelieu First Minister of France | Pages 131-142 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Richelieu’s aims—The English alliance—The affair of the Valtelline—The Huguenot revolt—The marriage of Madame Henriette—The Duke of Buckingham | Pages 143-157 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Peace with Spain—The making of the army and navy—The question of Monsieur’s marriage—The first great conspiracy—Triumph of Richelieu and death of Chalais | Pages 158-175 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Two famous edicts—The tragedy of Bouteville and Des Chapelles—The death of Madame and its consequences—War with England—The siege of La Rochelle | Pages 176-192 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Duc de Nevers and the war of the Mantuan succession—The rebellion in Languedoc—A new Italian campaign—Richelieu as Commander-in-Chief | Pages 193-206 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Illness of Louis XIII.—“Le Grand Orage de la Cour.”—The “Day of Dupes” | Pages 207-216 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Flight from France of the Queen-mother and Monsieur—New honours for Cardinal de Richelieu—The fall of the Marillac brothers—The Duc de Montmorency and Monsieur’s ride to Languedoc—Castelnaudary—The death of Montmorency—Illness and recovery of the Cardinal | Pages 217-233[Pg ix] |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Cardinal and his palaces—The château and town of Richelieu—The Palais-Cardinal—Richelieu’s household, daily life, and friends—The Hôtel de Rambouillet—Mademoiselle de Gournay—Boisrobert and the first Academicians—Entertainments at the Palais-Cardinal—Mirame | Pages 234-248 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Conquests in Lorraine—The return of Monsieur—The fate of Puylaurens—France involved in the Thirty Years’ War—Last adventures of the Duc de Rohan—Defeat, invasion, and panic—The turn of the tide—Narrow escape of the Cardinal—The flight of the Princes | Pages 249-262 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Palace intrigues—Mademoiselle de Hautefort—Mademoiselle de la Fayette—The affair of the Val-de-Grâce—The birth of the Dauphin—The death of Père Joseph—Difficulties in the Church | Pages 263-275 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Victories abroad—The death of the Comte de Soissons—Social triumphs—Marriage of the Duc d’Enghien—The revolt against the taxes—The conspiracy of Cinq-Mars—The Cardinal’s dangerous illness—He makes his will—The ruin of his enemies—His return to Paris | Pages 276-290 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| The Cardinal’s last days—Renewed illness—His death and funeral—His legacies—The feeling in France—The Church of the Sorbonne | Pages 291-298 |

| INDEX | Pages 299-306 |

[Pg x]

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Cardinal de Richelieu. Triple Portrait by Philippe de Champagne (National Gallery) | Frontispiece |

| Henry IV. From an engraving after the picture by François Porbus | 26 |

| Cloister at Champigny | 34 |

| From a photo by A. Pascal, Thouars. | |

| The Majority of Louis XIII. (Louis XIII. and Marie de Médicis). From the picture by Rubens in the Louvre | 68 |

| From a photo by Neurdein, Paris. | |

| Cardinal de Richelieu. Portrait by Philippe de Champagne | 132 |

| From a photo by A. Giraudon, Paris. | |

| Gaston de France, Duc d’Orléans. From a contemporary portrait | 162 |

| From a photo by Neurdein, Paris. | |

| Louis XIII. From a contemporary portrait | 188 |

| From a photo by Neurdein, Paris. | |

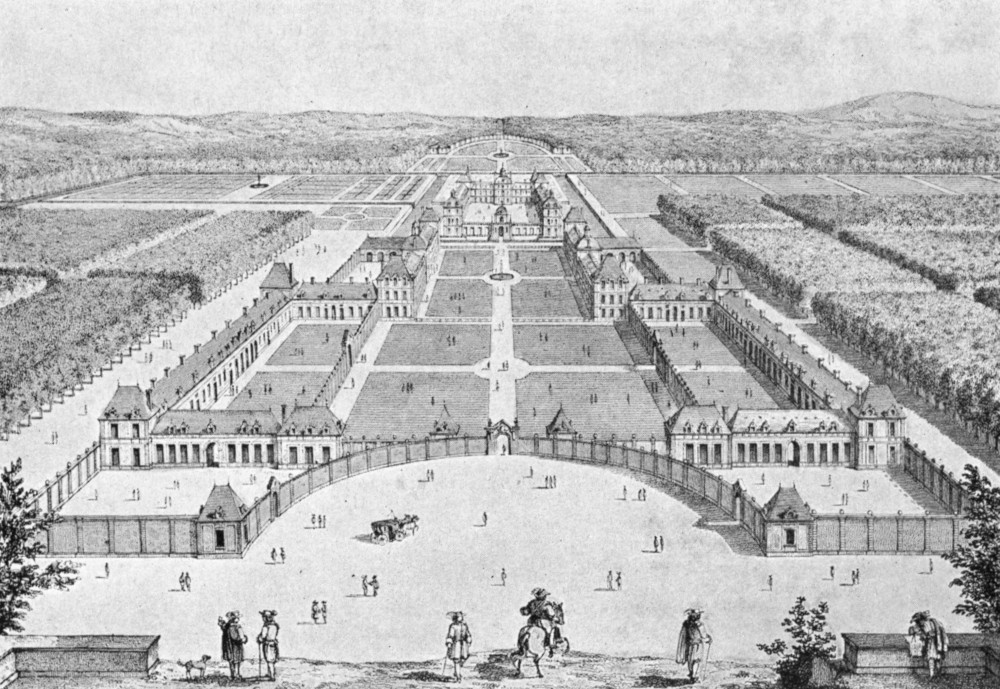

| The Château de Richelieu. From an old print | 234 |

| The Town of Richelieu. From an old print | 238 |

| Anne of Austria. From a miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum | 268 |

| Porte de Châtellerault, Richelieu | 280 |

| From a photo by Imprimerie Photo-Mécanique, Paris. | |

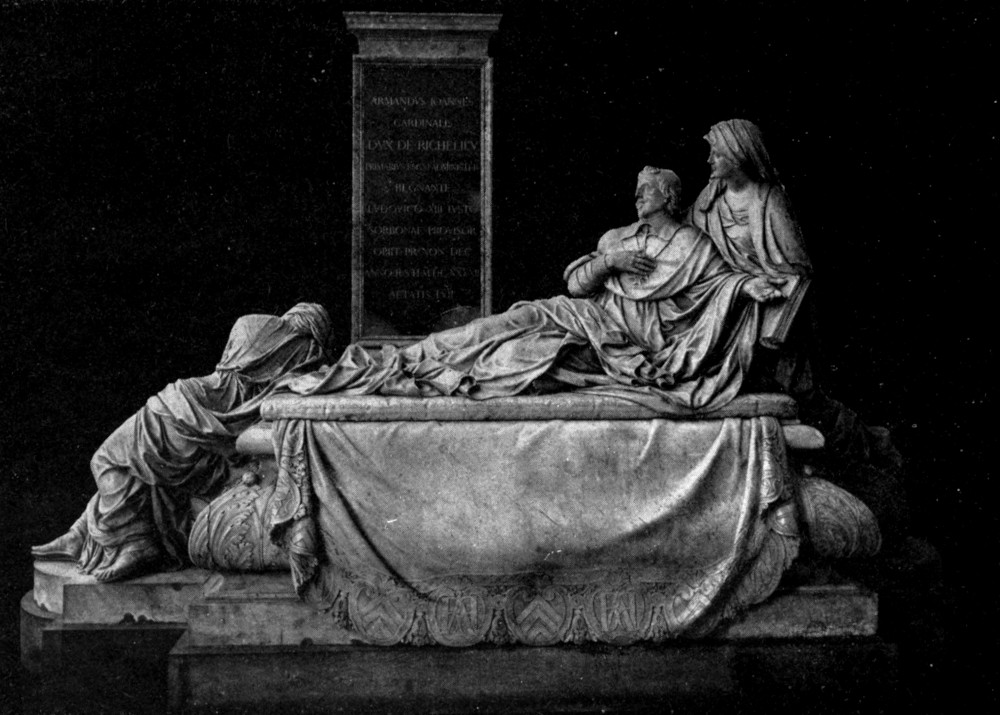

| Tomb of Cardinal de Richelieu, by Girardon, in the Church of the Sorbonne | 294 |

| From a photo by Neurdein, Paris. |

[Pg xii]

Lettres, Instructions Diplomatiques et Papiers d’État du Cardinal de Richelieu. Recueillis et publiés par M. Avenel.

Mémoires du Cardinal de Richelieu. Édition Petitot et Monmerqué.

Mémoires du Cardinal de Richelieu. New Edition. With Notes, etc. (Société de l’Histoire de France.) Not completed.

Mémoires sur la Régence de Marie de Médicis, par Pontchartrain. Édition Petitot et Monmerqué.

Mémoires de Bassompierre. Édition Petitot et Monmerqué.

Journal de Pierre de l’Estoile. Édition Petitot et Monmerqué.

Mémoires du Marquis de Montglat. Édition Petitot et Monmerqué.

Mémoires de Madame de Motteville. Édition Riaux.

L’Histoire du Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu. L. Aubery.

Testament Politique du Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu.

Journal de M. le Cardinal-Duc de Richelieu. 1630, 1631.

Portraits des Hommes Illustres François. M. de Vulson, Sieur de la Colombière.

Le Véritable Père Joseph, Capucin. 1704.

Histoire du Roy Henry le Grand. Hardouin de Péréfixe.

Mémoire d’Armand du Plessis de Richelieu, Evêque de Luçon, 1607 ou 1610. Édition Armand Baschet.

Description de la Ville de Paris. Germain Brice.

Les Historiettes de Tallemant des Réaux.

Etc., etc.

[Pg xiii]

Histoire du Cardinal de Richelieu. G. Hanotaux.

Histoire de France. H. Martin. Vol. xi.

Histoire de France. Michelet. Vols. xiii. and xiv.

Vie Intime d’une Reine de France, Marie de Médicis. L. Batiffol.

Le Roi Louis XIII. à Vingt Ans. L. Batiffol.

Louis XIII. et Richelieu. Marius Topin.

Richelieu et les Ministres de Louis XIII. B. Zeller.

La Noblesse Française sous Richelieu. Vicomte G. d’Avenel.

Prêtres, Soldats et Juges sous Richelieu. Vicomte G. d’Avenel.

Le Cardinal de Bérulle et le Cardinal de Richelieu. M. l’Abbé M. Houssaye.

Gentilshommes Campagnards de l’Ancienne France. Pierre de Vaissière.

Le Père Joseph et Richelieu. G. Fagniez.

Madame de Hautefort. Victor Cousin.

Madame de Chevreuse. Victor Cousin.

Le Règne de Richelieu. Émile Roca.

Le Cardinal de Richelieu: Étude Biographique. L. Dussieux.

Le Plaisant Abbé de Boisrobert. Émile Magne.

Etc., etc.

[Pg xiv]

[Pg 1]

CARDINAL DE RICHELIEU

The birth of Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu—The position of his family—His great-uncles—His grandfather and grandmother—His father, François de Richelieu, Grand Provost of Henry III.—His mother and her family—His godfathers—The death of his father.

In the year 1585, when Elizabeth of England was at the height of her power, when Mary of Scotland lay in prison within two years of her death, when Philip of Spain was beginning to dream of the Invincible Armada, when Henry of Guise and the League were triumphing in France, the future dominator of European politics was born.

Armand Jean du Plessis, third and youngest son of François du Plessis, Seigneur de Richelieu, was an infant of no great importance. Even his birthplace, for a long time, was not known with any certainty.

His family was noble, but not of the higher nobility which governed provinces, commanded armies, and glittered at Court. He belonged to that race of French country gentlemen which led a strenuous life in the sixteenth century, either for good or evil—perhaps mostly for evil. They were generally poor, proud, and greedy. If, by fair[Pg 2] means or foul, they could capture a rich wife of their own station, so much the better; if not, they readily sacrificed birth for money, and bestowed an old name, coat and sword, rough manners and ruinous walls, on some heiress of the bourgeoisie. When the resource of marriage failed, such a gentleman would turn himself into a mercenary soldier, Catholic or Huguenot, or creep into Court employment in the shadow of some great noble of his province; or failing such honest means, he might clap on a mask and take to highway robbery, rich travellers being better worth pillaging than the peasants who hid in their hovels as his horse’s heavy hoofs clanked by. Sometimes Religion herself, or the false Duessa who personified her in those days, might help a needy gentleman to a livelihood. There was many an abbot who had never been a monk; and there were lucky families—that of Du Plessis, for instance—who possessed a bishopric as provision for a younger son.

The Du Plessis were an old family of Poitou. In that ancient and famous province they had held several fiefs so far back as the early thirteenth century; but they were a wandering, fighting race, without strong attachment, it seems, to their native soil. One of them is said to have gone to England in the suite of Guy de Lusignan, and to have married a noble English wife. Another journeyed to Cyprus with the same distinguished patron. In the Hundred Years War, two Du Plessis brothers were found fighting on opposite sides, French and English. Pierre, the elder, head of the less distinguished branch of the family, was a robber of Church property as well as a traitor to the national cause; but in the way of morals there was not much to choose between him and his brother Sauvage, the patriot, in favour of whom their father threatened to disinherit him.

Sauvage was a man of strong, acquisitive character, and everything prospered in his hands, though he began his career by carrying off a younger brother’s wife. It was his son, Geoffroy, who laid the real foundation of future greatness by his marriage with Perrine Clérembault,[Pg 3] of a good old family, whose brother was Seigneur of Richelieu. Louis de Clérembault, who held a post in the Court of Charles VII, left his fortune and estates to François du Plessis, his sister’s son. The young man not only succeeded to the fortified château of Richelieu and a good position in his native province, but also to a connexion with the Court which lasted into the reign of Louis XI, and which helped him to lift his family a step higher by marrying his own son, François, to the daughter of Guyon Le Roy, of Chavigny, in the Forest of Fontevrault, a distinguished courtier, and Vice-Admiral of France under François I. This François du Plessis de Richelieu was great-grandfather to the famous Cardinal.

An ecclesiastical turn—for the sake of gain rather than of godliness—was given to the family by its relationship with that “true prelate of the Renaissance,” Jacques Le Roy, uncle of Madame de Richelieu. He was successively Abbot of Villeloing, Cluny, and St. Florent-de-Saumur, and Archbishop of Bourges, and in him the bad sixteenth-century alliance between the Church and the world, the consequence of royal nomination to benefices, might be seen at its most flourishing point.

He chose three out of his five Richelieu great-nephews to follow in his footsteps. Two of them rose to be abbot and bishop; the other, Antoine, took the vows as a monk at Saumur against his will, and after a short religious life varied by floggings and other punishments for rebellion, unfrocked himself and ran away to the wars. Known throughout his military life as “the Monk,” he was a cruel and ferocious soldier. With his brother François, a man of very different type, he first saw service in the Italian campaigns under the Maréchal de Montluc. Both brothers returned to Poitou towards 1560, and both took the Catholic side in the religious civil war which raged for years in the miserable western provinces of France, where Protestantism, from various causes, had taken a firm hold. Attached to the Guise faction, the brothers became special partisans of the Duc de Montpensier, the King’s lieutenant in Poitou and their own near neighbour at the Château de[Pg 4] Champigny. His army swept the province with fire and sword, and among his many fierce and adventurous followers François and Antoine du Plessis-Richelieu led the way.

The former, however, seems to have been an honest soldier rather than a bloodthirsty demon. He, nicknamed “le Sage” and regretted as “un fort brave gentilhomme,” lost his life in an expedition against the English, who had occupied Le Havre. Le Moine survived his brother some years, and his fame as a fighter became worth a post at Court and a knightly order. With an ever-growing reputation for vice and violence, he was killed in a street brawl in Paris—“mort symbolisante à sa vie,” says the chronicler l’Estoile. His most characteristic exploit, and the most startling among many, was the single-handed massacre of a hundred Huguenots who had taken refuge in a church near Poitiers. Antoine de Richelieu “amused himself” by shooting down these poor defenceless creatures in cold blood.

So much for the Cardinal’s great-uncles. His grandfather, Louis du Plessis, Seigneur de Richelieu, the eldest of the family, died a young man, but not before he had helped on its fortunes by a marriage profitable in dignity, if not in coin. The heir of Richelieu was of a quieter spirit than his brothers. He entered the household of a fine old noble—Antoine de Rochechouart, seneschal of Toulouse, distinguished for valour in the reigns of Louis XII and François I—as lieutenant of his bodyguard; and very shortly married his master’s daughter, thus distantly connecting his famous grandson with one of the noblest old ducal families in France, from which sprang Madame de Montespan and her brilliant brothers and sisters, the Duc de Vivonne, Madame de Thianges, and the learned Abbess of Fontevrault. His Rochechouart grandmother was the one precious link between Cardinal de Richelieu and the higher nobility.

M. de Rochechouart was poor, probably extravagant, and his daughter Françoise, whom tradition makes neither young, pretty, nor amiable, seems to have lived in a sort[Pg 5] of dependence on the great Dame Anne de Polignac, dowager of La Rochefoucauld, at Verteuil, where Charles V was royally entertained in 1539. These circumstances may account for the mésalliance which Mademoiselle de Rochechouart certainly made in marrying Louis du Plessis. Her interest gained him the Court appointment of échanson, or chief butler, to Henry II. But he was neither clever nor prudent, and his widow was left with five young children, very little money, a sharp, proud temper, and a deep discontent with her lot in life.

She settled herself at Richelieu, then only a small castle on an island in the river Mable, in the heart of a country terribly disturbed by civil war, and commanded, from the neighbouring hills, by the strongholds of unfriendly neighbours. Here she brought up her children, of whom the second son, François, was the father of Cardinal de Richelieu.

The story goes that a tragic event made François lord of Richelieu. There was a feud, centuries old, between the Du Plessis in their moated castle and the family of Mausson, perched upon the hill. The quarrel had been in abeyance during the peaceable, absentee life of Louis du Plessis, but when his proud widow, with her haughty, passionate boys, took up her abode at Richelieu, it broke out again furiously. Louis, the eldest son, was just growing into manhood, an officer in the Duc de Montpensier’s guards, when he fell out with the Sieur de Mausson over that ancient bone of contention, a seat in church.

Both families attended the village church of Braye, on the forest slope close by. In those days, and long afterwards, the chief gentleman in the parish had rights over the church quite as jealously guarded as any other of his feudal privileges. He sat with his family high up in the choir. He ordered the hour of mass, and the curé did not venture to begin before he arrived. The congregation followed his lead throughout. When he was absent, his servants sat in his place and insolently demanded the honours due to him. His coat of arms was hung up for[Pg 6] all to see. If he died, the bells chimed unceasingly for forty days, and the church was hung with black velvet for a year and a day.

It appears that the Sieur de Mausson and the young Seigneur de Richelieu both demanded honours which could not be paid to both. The young man, pushed on by his mother, made an angry resistance to the Mausson claims. His neighbour, by way of settling the question, lay in wait for Louis and murdered him.

Madame de Richelieu thought of nothing but revenge. Her younger son, François, was page to King Charles IX.: she sent for him, and he lived at Richelieu, mother and son with one object, one intention, till the watched-for time came. Then one day, when Mausson was fording the river, François and his men rushed out from the shadow of the willows. They had set a cunning trap for the enemy, a cart-wheel hidden under water, and while his restive horse was plunging, they fell upon him and killed him. So ended the feud between Mausson and Richelieu, still a lingering tradition in the valley of the Mable.

There was not much justice in those days, but it appears that François was obliged to fly the country. He wandered as far as Poland, where Henry of Anjou was playing at being King, and shared in the adventures of that most worthless of the Valois when he ran away with the Polish crown jewels and travelled round by Austria and Venice to succeed Charles IX on the throne of France.

François de Richelieu became Henry’s trusted servant. Certainly there was nothing of the mignon about him. Very tall, thin, solemn and dismal, his looks were suitable to his dreary but necessary office—first Provost of the King’s house, then Grand Provost of France, charged with arresting malefactors and presiding over their punishment. He was known at Court as “Tristan l’Hermite,” so that he must have struck his contemporaries as resembling, not in his office alone, the famous Provost of Louis XI.

[Pg 7]

François de Richelieu was affianced in early youth, before the Mausson affair drove him abroad, to Suzanne de la Porte, who belonged by birth to the higher bourgeoisie of his native province. Circumstances brought about this marriage, to which one cannot imagine that the proud Françoise de Rochechouart gave a very willing consent.

The family of La Porte, highly respectable, and clever with all the Poitevin shrewdness, possessed estates in Poitou and elsewhere. François de la Porte, the Cardinal’s maternal grandfather, was a brilliant scholar at the University of Poitiers, only second in fame to that of Paris, and first in Europe for the study of Roman law in the original spirit; keen, solid, logical, practical.

François de la Porte became a learned and distinguished advocate in the law-courts of Paris, but did not lose interest in his own province and his neighbours there. He appears to have been specially concerned with the affairs of Louis de Richelieu, who, according to Tallemant, was not only very poor, but “embrouilla furieusement sa maison,” and left his family in real distress. M. de la Porte made himself very useful to Dame Françoise de Richelieu, no doubt partly as to the management of her more distant property, difficult enough in those desperate times, and satisfied the vanity with which his contemporaries credit him by marrying his daughter to her son. The exact date of the marriage does not seem to be known.

As Grand Provost, François de Richelieu had a house in Paris, in the Rue du Bouloy, and all probabilities point to the fact of his son Armand having been born there. He was certainly baptized in Paris, though not till eight months after his birth, the delay being caused partly by his extreme delicacy, partly by the long and dangerous journey from Poitou which had to be made by his grandmother, who was present at the church of Saint-Eustache as one of his sponsors.

The others were two Marshals of France, Armand de Gontaut-Biron and Jean d’Aumont; each of whom gave[Pg 8] the child a name. Both these gallant soldiers are celebrated by Voltaire in the Henriade:

Both were intimate friends of the Grand Provost, and joined him later in placing their swords at the command of Henry IV.

The name of François de Richelieu is frequently to be met with in the documents of Henry III.’s reign. He received the highest honour Royalty could bestow, the Order of the Holy Spirit. The King’s personal safety depended largely on him, and allowing for the general corruption of the time, he seems to have performed his duties, often secret and mysterious, with honesty, loyalty, and courage. On that wild day in 1588, when the Duc de Guise had been welcomed by Paris with mad enthusiasm, when the streets were chained and barricaded against the King’s troops, and Henry was escaping from his “ungrateful city,” it was the Grand Provost who checked the pursuers at the Porte de la Conférence. Old writers say that the gate took its name from that circumstance, and tell how “François de Richelieu, Grand Prévôt de France, père du Cardinal de même nom, arrêta les Parisiens qui vouloient suivre le Roi, pour tâcher de le surprendre.”

Luckily for his own fame, this “wise officer” was not an active agent in the murder of the Duc de Guise at Blois, a few months later. But he was sent to the Hôtel de Ville to arrest those dignified citizens whom the King suspected of being concerned in the Guise conspiracy. And in the following summer he performed his last duty towards Henry III. by arresting the miserable monk, Jacques Clément, whom the Duchesse de Montpensier, sister of Guise, had persuaded to earn his salvation by murdering the King, “enemy of the Catholic religion.”

In the confusion that followed Henry’s death, the wise “Tristan” did not trust himself to the faction of the Guises. With other Catholic nobles, and in spite of family traditions, he turned to the one man in whose[Pg 9] hands he saw safety for France and himself, the Protestant Henry of Navarre. That clever Prince received him cordially and confirmed him in his appointments. So it came to pass that the nephew of “the Monk” reddened his sword with Catholic blood at Arques and at Ivry, and followed his new King, still as Grand Provost of France, to the camp before Paris. There his career was cut short by a fever in the summer of 1590, at the age of forty-two.

[Pg 10]

Friends and relations—The household at Richelieu—Country life in Poitou.

Whether the widow of François de Richelieu was in famine-stricken Paris during the siege—one of those afflicted ladies to whom the good-natured and politic Henry sent provisions first, passports later, that they might escape from the city—or whether she had already, her husband being so strongly in opposition to the ruling powers there, removed herself and her five children into the country it seems impossible to know.

She was not without influential friends in Paris; the more useful, perhaps, because they were not in the fighting line. Her father lived in the Rue Hautefeuille, near the Church of St. André-des-Arcs, in the heart of the Latin quarter; the old turrets of his house still remain. He was divided from the Rue du Bouloy, on the north side of the river beyond the Louvre, by two bridges, the Island, and a labyrinth of dirty, narrow, dangerous streets. There may well have been a gulf fixed, during those horrible months of the siege, between the old advocate and his daughter.

But Amador de la Porte, his younger son, and Denys Bouthillier, his head clerk and future successor, were not likely to let Suzanne and her children suffer any unnecessary privation. Both were strong and brilliant men, worthy members of that bourgeoisie which was the pride and life of Paris. Amador, some years younger than his[Pg 11] sister, was apparently too restless to settle down in his father’s profession. But François de la Porte had been very useful, as advocate, to the Order of Malta. They rewarded him by receiving Amador as a Knight of the Order, without a too close inquiry into his proofs of nobility. His foot once on the ladder, Amador rose to be Commander, then Grand Prior of France, and by his nephew’s favour held several important governments.

These two men, Amador de la Porte and Denys Bouthillier, were constant friends and guardians of the Richelieu children. Bouthillier and his sons were devoted to the Cardinal throughout his career, to their very great advantage. Claude, the eldest, made an enormous fortune as surintendant des finances under Louis XIII., and his son Léon, Comte de Chavigny, was a minister under both Richelieu and Mazarin. Sébastien and Victor rose high in the Church. Denys became private secretary to Queen Marie de Médicis, and was created Baron de Rancé; he was the father of Armand Jean de Rancé, the famous Abbot of La Trappe.

Through the Cardinal’s other La Porte uncle, of whom, personally, not much is known, the old advocate’s family stepped up into something like equality with the highest in the kingdom. His son, Charles, a bold, eccentric creature, attached himself from the first to the fortunes of his cousin, Armand de Richelieu, and by this means became a Marshal of France and Duc de la Meilleraye. He was one of the Cardinal’s most trusted aides-de-camp, and later on, a conspicuous figure in Paris during the troubles of the Fronde.

In the autumn of 1590, if not sooner, a family of women and children was established at the Château de Richelieu. There were Dame Françoise de Rochechouart, widow of the Seigneur Louis, and her daughter, also a widow, Françoise du Plessis, Madame de Marconnay. There were Suzanne de la Porte, widow of the Grand Provost, and her five children; Françoise, a girl of twelve—who married first the Seigneur de Beauvau, secondly, René de Vignerot, Seigneur du Pont-de-Courlay, and was the mother of the[Pg 12] Cardinal’s favourite niece, Madame de Combalet, afterwards created Duchesse d’Aiguillon; Henry, a well-known courtier of Louis XIII.’s young days; Alphonse, at this time intended for the Bishopric of Luçon; Armand Jean, the political genius, now a delicate, feverish atom of five years old; Nicole, who married the Marquis de Maillé-Brézé, and whose daughter, Claire Clémence, became the wife of the great Condé.

The head of this household, according to immemorial French custom, was the grandmother, Françoise de Rochechouart. Her rule, no doubt, was severe, and there are evidences that her daughter-in-law, a woman of gentler type, suffered under it. The hard old aristocrat who had condescended in her marriage with Louis du Plessis was scornful of the bourgeoise mother of her grandchildren. She was soured too by the losses and troubles of her life. Probably Suzanne brought from Paris the habits of a civilisation that did not suit that rough old home, that “ancient house of stone, roofed with slates,” strongly fortified with walls and moats as useful now as in the time of the English wars, when they were new. In 1590, the civil wars were by no means at an end. The province, devastated for years by Catholics and Huguenots flying at each other’s throats, now suffered equally in the struggle between Henry IV. and the League. Poitiers took the latter side, and for three years, from 1591 to 1594, the King’s army besieged it in vain. All the neighbouring country, including the valley of the Mable, was ruined and unsafe. A band of ruffian soldiers sacked the small town of Faye-la-Vineuse, on the hills overlooking Richelieu. No wonder if the gentle Suzanne, “loyal lady” and tender mother, was kept sleepless by burning horizons as often as by her little Armand, shivering with fever in the unwholesome mists of that river valley.

Her anxieties indeed were many; for though Dame Françoise might be mistress of the house, all the business connected with her children and her inheritance devolved on her. And the Richelieu affairs were in an embarrassed state. The Grand Provost had left heavy debts behind[Pg 13] him. There was the management of various small estates and châteaux in Poitou, which by some means or other had become possessions of the family: one of these was Mausson, name of ill-omen, which had been taken in exchange for an estate in Picardy, part of the dowry of Suzanne de la Porte.

She was an excellent woman of business, with hereditary instincts of law and order. All her tact and capacity, directed by strong affection, were devoted to the interests of her children. The words she wrote to Armand, years later, when he was Bishop of Luçon, seem to have been the key-note of her life:

“L’inquiétude que j’ai me tue et je vois bien que je n’aurai jamais de joie que lorsque, vous sachant tous heureux, je serai en paradis.”

With such a mother, and with an indulgent aunt in Madame de Marconnay—in spite of a fierce grandmother, barred gates and alarms of war—the children’s life at Richelieu need not have been unhappy. Indeed it was not so, if one may judge by the Cardinal’s recollections of it, and his constant devotion to the old place where most of his childhood was spent. After all, the family was on the winning side. France was growing tired of the League, attracted by the sunny, accommodating patriotism of Henry IV. If the harvests of Poitou were destroyed, woods cut down, villages burnt and pillaged, it was often, odd as this may sound, the work of friends, and in the intervals of these stormy visits of robber bands, country life went on cheerfully.

The strong old manor nestled snugly on the islet in the river-bed, something after the fashion of Chenonceaux in Touraine or Bazouges in Anjou. On the border of these two provinces and of Poitou, the country round Richelieu had something of the character of all three. The rich fertility of Touraine, the vineyards and gardens, though not unknown here, soon gave way to the forests and marshes of the wilder provinces. But Richelieu had its park and its avenues, leading from the high road which ran south from Chinon and Champigny into Poitou. By[Pg 14] this road came all the travellers, all the visitors: Amador de la Porte, the beloved uncle, with news from Paris; Jacques du Plessis, the great-uncle, the non-resident Bishop of Luçon, with his eye on a young successor; or, less welcome to the heads of the family, the Duc de Montpensier, the feudal neighbour, with his pack of wolf-hounds and swaggering troop of guards and followers. One may fancy, even then, that the dark eyes of Armand watched the owner of Champigny, scarred from the wars, without much friendliness.

There are signs that the family at Richelieu was on kindly terms with its neighbours of lower estate. The curé of Braye, M. Yver, who said mass often in the chapel of the château, was an intimate friend. There was no oppression of the peasants, who lived round about in their low, mud-floored, one-roomed cottages, and eked out their poor harvest by catching game in the forest or fishing in the river. All through the western provinces, indeed, then and for long afterwards, seigneur and peasant lived well together; the contrary was the exception. And the contrary came to pass, in great measure, through the action of the founder of absolute monarchy, the boy who ran about hand in hand with his mother at Richelieu.

In the meanwhile, Dame Suzanne befriended and doctored the people, knew them all by name, visited them, gossiped with them. She and her children witnessed their marriages, were sponsors at the baptism of their babes; a few years later, in 1618, the old registers of Braye bear witness that the infant son of young Henry du Plessis was named at the font, in the chapel at Richelieu, by two “poor orphans,” assisted by “ten other poor persons.” The gates of the château were open to any humble neighbours who suffered in the wars; the kitchen supplied them with food, sometimes not too plentiful even there; and holy-days found the courtyard full of peasants playing their bagpipes, dancing their quaint provincial dances, singing the songs of Poitou. Thus masters and servants alike managed to forget the hardships and terrors of the time.

Among scenes like these the Cardinal’s early childhood[Pg 15] was spent, and to his dying day, with all France at his feet, he loved that corner of Poitou. It must be added that the traditions of Richelieu itself, supported by many writers of the seventeenth century, declare that he was born there. When Mademoiselle de Montpensier, in 1637, paid her visit to Madame d’Aiguillon at the magnificent palace into which the Cardinal had transformed the little stronghold of his fathers, and found some of the rooms inconceivably small and mean, compared with the stately exterior, it was explained to her that the Cardinal had ordered Le Mercier, his architect, to preserve unaltered that part of the old building where his parents had lived and where he was born. The witnesses on the same side are too many to quote. On the other hand, Richelieu himself declared on more than one occasion that he was born in Paris, a Parisian, a native of the city which always had his heart; and his enemies dwelt strongly on the same fact, treating the Poitevin theory as an outcome of that immense pride and vanity which encouraged the Cardinal’s worshippers to represent his family and their possessions as older and greater than they really were; feudal magnates of centuries, instead of country gentlemen with their fortune to seek.

[Pg 16]

The University of Paris—The College of Navarre—The Marquis du Chillou—A change of prospect—A student of theology—The Abbé de Richelieu at Rome—His consecration

Before Armand de Richelieu was eleven years old, his uncle Amador, who was among the first to recognize the boy’s brilliant gifts, carried him off to Paris and placed him at the University. It was the family intention that Armand should carve out his living in a career of arms. The eldest brother, Henry, the seigneur of Richelieu, was to marry, and to cut a figure at Court. Being a charming and agreeable young fellow, he was likely to succeed in this line. Alphonse was a saint, and a born ecclesiastic; his future needed no arrangement; the see of Luçon was waiting for him. After the death of the great-uncle, Jacques du Plessis, in 1592, the revenues of the diocese were taken over by a titular bishop—no other than M. Yver, curé of Braye and chaplain at Richelieu—a worthy warming-pan who paid the largest portion to Madame de Richelieu, and wasted as little as possible on the cathedral and the diocese. The canons rebelled and complained most unreasonably, we are told; but Henry IV. had confirmed Henry III.’s grant of the bishopric to the Richelieu family, and the Chapter could obtain no redress. They had to wait till Alphonse was of age to be consecrated.

It was the right thing for every young Frenchman, of every rank, whatever his future walk in life might be, to go through his course at one of the universities. A king’s[Pg 17] son might be found on the Paris benches, listening to the same lecture with the clever son of a tradesman or even a peasant from a remote province. The poor students were quite as numerous as the rich; they filled the high houses and crowded the narrow streets of the famous Pays Latin; they “lived as they could,” and their character as a community did not alter much in the course of centuries.

When Armand de Richelieu was first entered at the College of Navarre, where “the great Henry” had studied before him, the University was at a low ebb, both as to professors and students. The wars of the League, the fighting in the streets, the horrors of the siege, had driven most decent people away from Paris, while armies of vagabonds and fugitives took possession of the city, even of that “city within a city,” which the University had been ever since the time when Philippe Auguste built its enclosing wall.

That wall still existed long after the young days of Richelieu. Its broad ditches, its battlements and frequent towers, its seven or eight formidable gateways, two of which defended a bridge and a ferry over the Seine, while the Tour de Nesle, at the western corner, frowned across at the Louvre—all enclosed with mediæval strength that Latin quarter, a half-moon in shape, which sloped up, a mass of lanes, colleges, convents, churches, to the old royal abbey and Church of Ste. Geneviève, where her shrine, the chief religious treasure of Paris, was kept; destroyed in the eighteenth century and replaced by the Pantheon with Voltaire’s bones and Soufflot’s ugly dome.

The University existed before the colleges. They were founded, one by one, by charitable men and women, mostly for the benefit of the poor scholars of different special towns or countries. Often their names told their story; but sometimes they were called by the name of the founder, such as the “Collège du Cardinal Lemoine.”

The College of Navarre was one of the best known and highest in reputation. It was founded in 1304 by Jeanne, wife of Philippe le Bel and Queen of Navarre in[Pg 18] her own right, in memory of the victory of Mons-en-Puelle in Flanders. It was thus nearly three hundred years old when Armand de Richelieu entered it, and had already that royal and military reputation which lasted through three or four centuries more. An old writer on Paris says that the sons of the greatest nobles in the kingdom boarded in this college, and in order that they might not be distracted by intercourse with outside students—a real danger, one would think, and of worse things than distraction—no other scholars were received. “Navarre” did not always remain so exclusive. But this was probably its character in Richelieu’s time, though we do not positively know whether the young gentleman, with his private tutor and his footmen—all of whom remained many years in his service—lodged in the college or at his grandfather’s house in the Rue Hautefeuille.

The College of Navarre had had famous men among its tutors and professors. Nicolas Oresme, one of its early head masters, was tutor to King Charles V., who owed to him his surname of “The Wise.” He was a translator of Aristotle, and is supposed to have made the first French version of the Bible. Somewhat later, the celebrated mystic, Jean Gerson, believed by many to be the real author of the Imitatio Christi, was a teacher in the college and became Chancellor of the University. A famous Principal, also Chancellor, was Cardinal d’Ailly, Archbishop of Cambray, a theologian of tremendous strength, known at the Council of Constance as the “Eagle of France,” and “the Hammer of the Heretics.”

The traditions of “Navarre” were inspiring and severe. At the end of the sixteenth century, when young Richelieu was going through its courses of “grammar” and “philosophy,” the college was ruled by Jean Yon, a lover of Cicero, of discipline, and of Church ceremonies. Long after the days of dry study and compulsory Latin were over, the Cardinal kept a friendly recollection of his old master, and declared that he could never see him without “a feeling of respect and fear.” Probably, therefore, Jean Yon was wisely careful to hide his admiration of the boy,[Pg 19] who, according to one of his biographers, “avala comme d’un trait toute la grammaire,” knew by instinct how to baffle his examiners by puzzling counter-questions, and dazzled both teachers and comrades by the bold and sparkling flashes of his genius.

But Master Yon was not always the stern pedagogue. The Cardinal ever remembered with peculiar pleasure taking part, as a singing boy, in the great procession which marched from Ste. Geneviève on her hill, right across Paris, to visit the tomb of St. Denis. The whole University joined in the procession, and on this occasion it was led by Jean Yon and a chanting choir from the College of Navarre.

Once upon a time, they say, that procession was so long that when the head was entering the Church of St. Denis, far away in the northern outskirts of the city, the tail, of great dignity, had not yet come forth from the Church of the Mathurins, where the general rendezvous had been fixed. This was in the time of Charles VI., when all Paris was praying and making processions that his lost senses might be restored to him. In those days, we are told, the University of Paris was the centre of learning for all the nations of Europe and the mother of all their universities, including “Oxfort en Angleterre.” Her European fame and the number of her students had dwindled a good deal before the day when Armand de Richelieu, the slim, keen, black-haired boy of twelve, marched in her procession as an enfant de chœur.

Down the hill they wound, threading the dark labyrinth of high college walls, then perhaps following the Rue St. Jacques, the old Roman road, down to the Petit Châtelet, guarding with its tunnelled gateway the entrance to the Petit Pont; or, more likely, keeping to their own Latin-speaking quarter as far west as the Pont St. Michel—the Pont Neuf was not yet finished—and there crossing to the Island and passing in front of the Palais de Justice, through crowds of men of law, red-robed councillors, officials and hangers-on of the Parliament, quite as busy and as noisy as the ecclesiastical throng they had left[Pg 20] behind them. The Pont-au-Change, haunt of money-changers and bird-catchers, carried them on to the farther shore; one of those steep and ancient bridges, chiefly built of wood and blocked with houses, shops and stalls, which were difficult to cross at all times and were constantly in danger from flood or fire. Then the procession’s way was almost blocked by the great round towers and frowning prison walls of the Grand Châtelet. Then through dark and narrow ways it passed out into the wider spaces, the gayer air, of the Paris of the north bank, of kings and their palaces, and leaving the Louvre to the left, the Hôtel de Ville, Bastille, and Temple far to the right, went on by the Rue St. Denis towards the gate of that name, and so out into the frequented road leading to the old towers that sheltered the shrine of the Saint.

All the way there was a constant carillon of bells from a hundred steeples; the red and gold of vestments and banners glowed in the sunshine; trumpets brayed; and with loud chanting the procession paced along. To a boy fresh from his lessons, who was to live on into more colourless times, such a holiday glimpse of the Middle Ages may very well have been a pleasant recollection.

At this time young Richelieu was looking forward to nothing but the life of a soldier, and of course a mercenary one, for his family was likely to endow him with little means of living. The world was his oyster, which he with sword must open. It was nothing new: he would walk in the footsteps of his father and his great-uncles, with the advantage of serving a King whom he heartily admired; of this his Memoirs give proof enough.

When the usual University course was over, M. de la Porte proceeded to make a man and a soldier of his nephew. He placed him at the famous Academy of M. de Pluvinel, a former companion-in-arms of the Grand Provost, who had made a career for himself as a trainer of young gentlemen. He taught them fencing, riding, dancing, music, mathematics, various manly games. He was an authority on fashion and style, wit and manners,[Pg 21] the ways of foreign nations; in short, he turned boys fresh from college into men of the world, courtiers, soldiers, diplomatists. There was scarcely a leading man in France in the early seventeenth century who had not passed through the “manège royal” of M. de Pluvinel.

A title was necessary, in order to swagger successfully among the gay cadets of the Academy. Armand became Marquis du Chillou, taking the name from a small estate in Poitou brought into the family by his great-grandmother.

His years of study at the Academy seem to have been among the happiest of his life. Made mentally of steel and flame as he was, ancestral hardness and strength of will joined with a passionate ambition all his own, the fighting career of a successful soldier was likely to attract him irresistibly. When he was young, it seemed indeed the one chance of shining in the world, of commanding men. And he never lost his love for the profession he had to renounce, though it became clear that for a daring spirit such as his, the red robe was as practical a garment as the buff coat. “Sous le prêtre, on retrouve toujours en lui le soldat,” says M. Hanotaux.

There was one drawback to the military prospects of Armand de Richelieu. The delicate, aguish boy had not grown into a strong youth. His keen spirit was now, as ever, a sword too sharp for its frail sheath. Hard study and lack of fresh air during his college days had had their likely effect on his weak constitution and slight frame. For his sake, his mother did not mourn over the family circumstances that forbade him, after all, to be a soldier. “Mon malade,” as she called him, was not of those who could sleep on open field or fell, in mud or mire, as soundly as within stone walls with curtains round his bed.

For the family, it was a question of losing the revenues of the see of Luçon. Alphonse de Richelieu, its intended Bishop, at the age of nineteen or twenty, turned away in disgust from the worldly-wise arrangement, and decided to become a Carthusian monk. It may not be unfair to[Pg 22] describe him as “dévot et bizarre”; but one seems to see in this singular resolution an outcome of the reaction against the dead and conscienceless state into which the sixteenth century had brought the French Church; the reaction which was already living and moving in such men as François de Sales, Vincent de Paul, Pierre de Bérulle, though leading them, as to their religious life, into reforming action rather than lonely contemplation.

Armand’s choice was soon made. No doubt the change was to him inevitable. There could not be two young men more different than himself and Alphonse; yet he too had a conscience of his own, of the truly Latin kind which demands any and every sacrifice for the sake of the family. He is said to have written to his uncle, who, one may well believe, was sincerely sorry for him: “The will of God be done: I accept all, for the good of the Church and the glory of our name.” The latter aspiration, at least, was fulfilled.

At seventeen, in the year 1602, the Marquis du Chillou laid down his sword and his title, left M. de Pluvinel’s Academy and returned to the University. A year or two later, there was no more eager student of philosophy and theology than the Abbé de Richelieu. There are merry stories of the time which suggest that he and his private tutor M. Mulot, afterwards his chaplain, were concerned in wild pranks, such as robbing gardens and orchards, which would have been impossible under the strict discipline of old Master Yon. There is a pretty legend which tells that the Cardinal, in his last days, sent for an old college gardener whose peaches he had stolen—the good man’s name was Rabelais, and he came from Chinon—and paid him a large sum of money as compensation for being both robbed and frightened: at that time, an unlucky wretch who was summoned before the Eminentissime went in very reasonable fear of his life.

The sober University, in its clock-work course, hardly knew what to make of Armand de Richelieu. He swallowed theology as he had swallowed grammar, and the ordinary progress of learning was far too slow for him. After[Pg 23] studying independently with several learned masters, especially with Richard Smith, an Englishman, of the University of Louvain, afterwards Vicar Apostolic in England, he was ambitious to hold a public disputation at the Sorbonne.

The doctors of that reverend foundation refused the unusual request; but Richelieu, who ardently desired to become an adept in controversy, persuaded his old College of Navarre to be less timidly narrow and conservative. Here the lad of nineteen, worn to a shadow by studying hard eight hours a day, set forth his thesis and defended it against all comers. The listeners were slightly uneasy, for his argument was based rather on philosophy than on strictly theological grounds, and was indeed flavoured by the influence of Jansenius, who came to Paris about this time. But the long struggle between Gallicans and Ultramontanes, Bishops and Jesuits, was only at its beginning, and Jansenism proper was not born; the sixteenth century had known little more than the fiercer, simpler quarrel between Catholics and Protestants, the heretic and the faithful. As a fact, in his own original way, Richelieu held all the doctrines approved and taught by the Sorbonne.

There was every reason why the future Bishop should hurry on his theological studies. The Chapter of Luçon had completely lost its patience; and this is not surprising, for both the cathedral and the episcopal palace were falling into ruins, while no money could be extracted from M. Yver and Madame de Richelieu, until, at last, a decree of the Parliament forced them to provide for the necessary repairs. If the bishopric was to remain in the Richelieu family, Armand must be consecrated with as little delay as possible.

He was not yet near the canonical age of a bishop. He had, however, been ordained deacon in 1606, and early in that year, while he was still hurrying through his last examinations, King Henry wrote to his Ambassador at Rome, recommending the Abbé Armand Jean du Plessis, royally nominated to the bishopric of Luçon, to the favour of His Holiness Paul V., and praying for an early consecration[Pg 24] on the ground of the young man’s “mérite et suffisance,” which were such as to make the legal delays morally quite unnecessary.

Such dispensations were common enough, but this one was slow in coming. Paul V., the Borghese Pope, had not long been elected, but was already known for his determined will and strong sense of duty. He was not a man who would lightly break through any laws or customs of the Church, and certainly not to please King Henry IV., whose conversion he distrusted and whose way of life he condemned. The Abbé de Richelieu, hearing nothing from Rome, resolved to wait no longer. In the autumn of 1606 he left Paris and travelled hard to Rome, very impatient, and quite sure that if he could once gain the Pope’s ear and plead his own cause, it would speedily be won.

He was not mistaken, though Paul V. received him coldly on his first introduction by the Ambassador: a self-confident, presumptuous boy who expected to be ordained priest and consecrated bishop at twenty-one, was not likely to meet with instant favour from an elderly, legal-minded martinet. Various tales are told, by friends and enemies, as to the means by which Richelieu quickly gained his ends at the Papal Court. Some say that he added a year to his age, or falsified the date of his baptism, and that the Pope, hearing too late of the trick, observed, “This young man will be a great knave.” On the other hand, it is said that, struck with admiration of Richelieu’s genius, the Pope made no difficulty, saying, “It is just that one whose wisdom is above his age should be ordained under age.” On the whole, the latter story seems the more probable; but neither has any real foundation.

It is certain, at any rate, that the Abbé de Richelieu made the best use of the months he spent at Rome, and convinced Paul V., himself a clever man, that King Henry’s praise was not undeserved. He preached before the Pope, and his ready learning and splendour of diction were considered miraculous. He carried on arguments with His[Pg 25] Holiness on the morals of Henry and other subjects, so firmly yet so respectfully that Paul was altogether charmed. He studied the spirit of Rome, that mysterious city which was at once “the capital of the Catholic world and the centre of the civilized, world.” As the centre of an older world still, of ancient history and pagan art, Rome had not the same attraction for him. All that was to come later, when the Cardinal attempted, without great success, to pose as one of the chief art patrons in Europe.

At this time, his whole mind was given to present advancement, and his intuition as to his own interest was faultless. He learned Italian and Spanish, he courted the Cardinals and other dignitaries, and while dazzling his company with all the light French brilliancy of his young wit, he pleased them by the gentleness and modesty he knew well how to assume. Thus he saved himself from much envy and jealousy which might have nipped his career at the outset.

On April 17, 1607, Armand Jean du Plessis de Richelieu, aged twenty-two years and seven months, was ordained priest and consecrated bishop by the Cardinal de Givry, who had always been his friend. The suffering diocese of Luçon was no longer without a head, and the Roman Easter bells rang in one of the greatest figures in French history.

[Pg 26]

A Bishop at the Sorbonne—State of France under Henry IV.—Henry IV., his Queen and his Court—The Nobles and Princes—The unhealthiness of Paris—The Bishop’s departure.

The diocese of Luçon—in itself one of the least desirable in France—had to endure some months more of neglect before its new Bishop came into residence.

Richelieu’s return to France, in the early summer of 1607, was a return to Paris and the University, which now saw the unusual sight of a bishop among its students. There were still examinations to pass and distinctions to gain: the theological honours of the Sorbonne were not lightly bestowed, even on a dignitary of the Church. But Richelieu, once more, triumphantly satisfied his examiners, and in the autumn of 1607 he was admitted to the degree of Doctor of the Sorbonne. One may say that the old institution was his mother and his child. She trained the brain that transformed France and directed Europe; she was made illustrious by his munificent care, and his feverish life at last found rest in the shadow of her walls.

FROM AN ENGRAVING AFTER THE PICTURE BY FRANÇOIS PORBUS

In the winter of 1607-8, Henry IV. was at the height of his power and popularity, although certain dreamers, prophets of evil, necromancers, and such-like creatures of the darkness, suggested that his useful reign was near[Pg 27] its end. For whatever the immoralities of his life may have been—and they had a fatal influence on society—his political ends and means were excellent. His favourite dream was of a general European peace with religious toleration: and one need only realize the state of France a hundred years later—populations crushed by cruel taxation and dying of famine by thousands—to see what the difference might have been if Henry and Sully could have worked their will for twenty years more, keeping the nobles in check, insisting on justice, studying and carrying into practical effect the means of making the country prosperous by useful public works, by careful training in agriculture and other industries. Under Henry and his minister—who did not, however, share his master’s popularity—farming was encouraged, rivers were made navigable, bridges were built, waste lands were reclaimed, new roads were made, new crops, such as potato and beet-root, were introduced, a labourer’s tools were safe from seizure for debt. France was beginning to breathe after long horrors of civil war: feudal oppression was passing away, and the country generally was on the eve of better things, under the eye of a King who, absolute as he certainly meant to be, loved his people and wished them well. All was doomed to fall to pieces with the death of Henry, followed by the regency of a stupid woman and the new policy of Richelieu.

Henry was himself the centre point of Paris, the beloved city, which he made his home, only leaving the Louvre for visits to Saint-Germain and Fontainebleau, or for hunting excursions in the country. Small, active, carelessly dressed, ever on the move, the Parisians saw their King among them at all seasons, all hours, riding or driving in the streets, equally eager after business and amusement; gambling at the famous Fair of Saint-Germain—held during the early months of the year on the left bank of the Seine—or planning with Sully, within the walls of the Arsenal, those economies and financial rearrangements which gained him the reputation of being a miser. Henry was a curious character, half a hero, made of gold and of[Pg 28] clay; but his Parisians, as a rule, saw little but the gold. He was a familiar sight among them, the frank, good-natured man, with his rosy cheeks, long nose, and whitening beard and hair. They loved him because he was affable, kind, easy-going, polite, and yet could be stern and royal enough when any one displeased him. They loved his keen interest in the city, shown by plans for rebuilding and improving, some of which were already carried out when he died, while some lingered on into the days of Richelieu. His favourite works were the Grande Galerie of the Louvre, the Pont Neuf, the Hôtel de Ville, burnt by the Commune, and the Place Royale, now known as Place des Vosges.

The Court at the Louvre, under a King impatient of etiquette—except when Parliament or Protestants had to be awed, or foreign ambassadors received—seems to have been lacking in dignity. It had not the splendour, the mystery, the romance and cultivation, however evil, of the Valois; nor had it the stiff magnificence of an absolute Louis XIV. The tone of the Court, in fact, was bourgeois; and it is curious enough that the early seventeenth century in England, as well as in France, had this intimate flavour of something like vulgarity. James I. cracked coarse jokes with his courtiers and slapped them on the back. Henry IV., though a far more intelligent man, encouraged the same kind of manners among his jovial companions at the Louvre.

The King and Queen quarrelled perpetually, and in public. The young Bishop of Luçon, admitted at Court not only by the means of his elder brother, a popular courtier, but through the King’s personal liking for him, saw with his own eyes scenes to which the Cardinal de Richelieu alluded in his Memoirs, dictated many years later. With all his enmity towards Marie de Médicis, he had to acknowledge that the King’s love-affairs, result of the besetting weakness of a great prince, might justly have irritated a woman less naturally jealous, proud and unforgiving. As one intrigue succeeded another during the whole of Henry’s later life, and as the Queen could never be brought to take these things meekly, it follows that peace seldom reigned at the Louvre. Henry, on his[Pg 29] side, turned the tables on his wife by injurious suspicions almost certainly without foundation, and the Duc de Sully himself told Richelieu that he had never known a week pass without a quarrel. On one occasion, in passionate anger, Marie raised her hand to box Henry’s ears! “M. de Sully stopped her so roughly that her arm was bruised, crying out with an oath: ‘Are you mad, Madame? He could have your head off in half an hour. Have you lost your senses, not to remember what the King can do?’ The King went out; and after much coming and going he (Sully) appeased them both. Afterwards, the Queen complained that the Duc de Sully had struck her.”

Sometimes these quarrels had a comic side. The Queen would refuse to dine as usual with the King, and would order a small table to be brought into her cabinet. On these occasions the good-tempered Henry, who never could be angry long, and who preferred living at peace with a wife he did not really dislike, would send her choice morsels from his table, even from his plate. If Marie’s temper had not reached the level of accepting a peace-offering, she would coldly return the dainties. Court gossip declared that she was afraid of poison.

In his book on Marie de Médicis, M. Batiffol gives a curious description, drawn from old records, of the royal dinner at the Louvre when the King and Queen dined together.

No one sat at the table with them, but a privileged public, including the whole Court, crowded the room. The Swiss guards stood round the table, bearded, fierce, German-speaking warriors, “old servants of the Crown,” leaning on their halberds, dressed in velvet, white, blue, and red. Six gentlemen served their Majesties, taking the dishes from the “officers of the kitchen,” who brought them into the room. The menu, a very considerable one, was drawn up by the Queen’s maître d’hôtel and counter-signed by herself. Sometimes, generally on Sundays only, the King’s musicians gave a concert during dinner. As a rule, there was a good deal of conversation. The King and Queen talked to the courtiers who stood in ranks[Pg 30] behind the Swiss Guard; not of “affairs,” but of any light and interesting subject that might occur.

On such an occasion the King may well have shown special favour to a young man in episcopal purple, of middle height, very thin, with black hair, a delicate, pointed face, keen dark eyes, under a broad brow full of intelligence, quick to catch and respond to every slightest glance from Royalty. Young Richelieu—“My Bishop,” Henry called him—may have had stories to tell of his Roman experiences, stories pleasing to the King, who had taken the trouble to push his fortunes; and the wit, the memory, the reasoning power, which amazed the Sorbonne, may also have been noticeable at the Louvre.

Sometimes the talk led on to thin ice, and Richelieu knew it: for instance, when the King reminded him of certain things he had written about the Maréchal de Biron, his godfather’s son, beheaded for conspiracy in 1602. It was a lesson as to giving a handle to jealous enemies, which Richelieu did not soon forget.

Dinner over, the Queen returned to her dogs and monkeys and parrots, her gaming, card-tricks and music, or walked in the garden, or drove in the city, perhaps visiting her divorced predecessor, Queen Marguerite de Valois—large, self-indulgent, with a flaxen wig—who led an extravagantly immoral but literary and charitable life in Paris, the adopted sister and aunt of the Royal family; perhaps driving out to Saint-Germain to see the children, who lived there, a large household, legitimate and otherwise, under the care of the Baronne—afterwards Marquise—de Montglat.

The King too, though never forgetful of public business, had his amusements of many kinds—gambling, hunting, building, making love. Sometimes he and the Queen dined out together in Paris, frequently with M. Zamet, banker and money-lender and Henry’s very faithful servant, at his palatial hôtel in the Marais. Sometimes they delighted the Parisians by sharing their amusements in the streets and on the bridges—jousts, sham fights in masquerade, running at the ring. Then were to be seen[Pg 31] the young nobles of France, infected with Henry’s own dash and daring recklessness, flinging themselves so desperately into these mock battles that real wounds were given and lives were lost. The famous Baron de Bassompierre, chief of the “dix-sept seigneurs,” leaders of fashion, to whose exclusive ranks Henry de Richelieu also belonged, was nearly killed in one of these encounters in the paved court of the Louvre.

Hardouin de Péréfixe, tutor to Louis XIV. and afterwards Archbishop of Paris, wrote for his pupil’s instruction a history of his royal grandfather, Henry the Great. Drawing on his own memory, or something very near it, he sketched the state of society at the beginning of the century. While the King and his ministers were working hard in lifting their country out of the slough of war and abject misery, most of the nobles were finding mischief for their idle hands to do. The Memoirs of Bassompierre and others prove that Péréfixe told less than the truth: he was too courtier-like, too careful of offending young royal ears, to give much idea of the brutality of manners which existed in the society of Henry IV. and Marie de Médicis; but he describes vividly the temper of the men among whom Armand de Richelieu, clever, poor, observant, shielded by his elder brother’s popularity, was growing into manhood.

“The French noblesse,” says Péréfixe, “being at peace, could not be doing nothing; some spent their time in hunting; some in the company of ladies; some studied belles lettres and mathematics; others travelled in foreign lands; others kept up the exercise of war under Prince Maurice in Holland. But many, with itching hands, eager to show off their courage without leaving home, became punctilious, and at the least word, or at crossing glances, had their swords in their hands. Thus a mania for duels seized on the minds of gentlemen. And these encounters were so frequent that the nobles shed nearly as much blood between themselves as their enemies had made them lose in battle.”

Royal edicts, one after another, had little effect in[Pg 32] cooling these hot spirits; especially as Henry usually forgave a crime which his laws threatened with forfeiture of life and goods. In the following reign such laws were less of a mockery, as the nobles found to their cost. Louis XIII. was made of harder stuff; and Richelieu had learnt by personal experience—his brother’s death in a duel with the Marquis de Thémines—the need of a strong hand.

There was not much personal distinction, at this time, among the grandees of France. Henry de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, nearest in blood to the throne, was a shy, gloomy youth, mean in looks and character, and though really clever and ambitious, eccentric to the verge of madness. “Monsieur le Prince,” says Brunet, “père du grand Condé, s’imaginoit être quelque fois oiseau et d’autres fois sanglier, et se cachoit sous les lits et sous les tables comme s’il avoit été dans les forêts.” It was not till 1609, after Richelieu had retired to his diocese, that King Henry, for his own ends, married this young man to the marvellously beautiful Mademoiselle de Montmorency. Then, to the King’s rage and disgust, Condé proved that he had some individuality, and ran away with his wife to Flanders. But for the dagger of Ravaillac, a European war might have followed on this elopement.

François de Bourbon, Prince de Conti, the King’s first cousin, uncle of Condé, brother of Henry’s old companion-in-arms and once himself a fighter, was elderly, deaf, and incapable. He appeared little at Court, but lived in Paris on the revenues of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. His wife, Louise Marguerite de Lorraine, a brilliant mischief-maker, with her mother, the lively old Duchesse de Guise, widow of Henry le Balafré, was among the few really intimate friends of Queen Marie de Médicis. Henry IV., who had once thought of marrying her, ended by disliking her, resenting her influence over his wife. But she kept her place at Court, and after the Prince de Conti’s death she is said to have secretly married Bassompierre, first of courtiers and her lover of many years.

Charles de Bourbon, Comte de Soissons, usually known[Pg 33] as Monsieur le Comte, was the Prince de Conti’s half-brother, his mother, Françoise d’Orléans-Longueville, having been the second wife of Louis I., Prince de Condé. Though outwardly loyal to Henry IV., he was perhaps the most dangerous enemy the King had in his own immediate circle. Ambitious, proud and violent, he never forgave Henry for breaking an early promise of marrying him to his sister, Catherine of Navarre. Jealous of his own position, he resented every mark of favour shown by the King, especially the honours showered on the young Duc de Vendôme, Henry’s eldest legitimised son. If a fit of the sulks had not kept Monsieur le Comte out of Paris at the time of Henry’s death, he would have disputed the regency with the Queen. Not being on the spot, he was neither clever, strong, nor popular enough to disturb the appointed order of things.

Henry de Bourbon, Duc de Montpensier—familiar to the Richelieu family as lord of Champigny—was of no account at all, in court or camp, during his later years. But he had been an heroic soldier. Son of that Montpensier, the leader and patron of “the Monk” Richelieu and his brother, who swept Poitou with fire and sword in the religious wars, and of his furious Duchess, the soul of the League, the sister of Henry le Balafré, who brought about the murder of Henry III., he, with so many other Catholic princes and nobles, fought his uncles and the League under the banner of Henry of Navarre. A terrible wound in the face received at Dreux, where he commanded a regiment of cavalry, brought Henry de Montpensier’s public career to an end at twenty-seven. His life, after this, was one of more or less suffering. He fell out of favour for some time with the King, being suspected of sympathy with the Biron conspiracy. He married, in middle life, his cousin Henriette Catherine de Joyeuse, another of the Queen’s intimate friends, and they had one daughter, born in 1605, the heiress of all the immense Montpensier possessions; by her marriage with Gaston of France the mother of the famous Anne Marie d’Orléans, Duchesse de Montpensier, commonly known as La Grande Mademoiselle.

[Pg 34]

M. de Montpensier appears to have lived a great deal at Champigny, a favourite among his many châteaux. Thirty years after his death, on her way to visit the new splendours of Richelieu, his granddaughter found that he was still beloved there, although the almighty Cardinal, levelling his house with the ground, would gladly have destroyed his memory.

The Duke died at his hôtel in Paris on the last day of February 1608, wasted by a long decline, and devotedly nursed to the end by his eccentric Capuchin father-in-law, Père Ange, in the world Duc de Joyeuse. “Bon prince,” l’Estoile says of Montpensier, “and as such regretted and mourned by the King, the nobility and all the people.” The usual amusements of the Carnival were stopped; even the little Dauphin was not allowed to dance his ballet before the King. Three weeks later a funeral service was held at Notre Dame, with an oration by the popular preacher M. Fenouillet, Bishop of Montpellier. The ceremony, which was simple, derived dignity from the presence of one hundred and twenty poor men in long robes, carrying torches. Another and grander service was held in April. Between these two occasions, the last male descendant of Robert, son of Saint Louis, was conveyed with an escort of three hundred horse to Champigny, and was buried in the chapel which still exists there.

The Duc de Montpensier’s widow married Charles, Duc de Guise, who, with his brothers, represented the princely House of Lorraine at the French Court. By birth and position, of course, he was one of the first men in France; personally he was of little account, and hardly a worthy descendant of the great Dukes of the sixteenth century. He had not even their looks, being short and snub-nosed. He was witty, agreeable and generous, very frivolous and a great flirt. Richelieu, in the first volume of his Memoirs, gives Henry IV.’s own estimate of this head of the Guise family: “Plus de montre que d’effet”; rather brilliant in company, and judged capable of great things by those who did not know him; but so slothful and lazy that he cared for nothing but[Pg 35] pleasure, “et qu’en effet son esprit n’était pas plus grand que son nez.”

CLOISTER AT CHAMPIGNY

Among the more conspicuous nobles, the Duc de Bouillon, the malcontent leader of the Protestants, was a constant thorn in the King’s side. The Duc d’Épernon, an ambitious, adventurous courtier of Gascon origin, had been a favourite of Henry III., and was not much loved by Henry IV., who did not trust him. His son, Bernard, married Gabrielle-Angélique de Bourbon, the King’s daughter by the Marquise de Verneuil. This alliance was roughly declined by the old Duc de Montmorency, Constable of France, to whom Henry proposed it for his splendid young son, that Henry de Montmorency, last of the direct line, whose high head was among those to be mown down, at a future day, by the implacable Cardinal.

Among left-hand Royalties, the oldest was Charles de Valois, Comte d’Auvergne, afterwards Duc d’Angoulême, a man of a certain courage and humorous charm, but foolish, dishonest, and unlucky. He was the son of Charles IX. and Marie Touchet, who married the Comte d’Entraigues after the King’s death, and became the mother of Henriette d’Entraigues, Marquise de Verneuil, Henry IV.’s passion and the special abhorrence of Marie de Médicis. In a fit of jealous fury, and in the supposed interest of her children, Madame de Verneuil intrigued with Spain against Henry. It was only the King’s enduring infatuation which saved her half-brother, the Comte d’Auvergne, from losing his head. As it was, he spent ten of his best years, from 1606 to 1616, shut up in the Bastille.

Henry’s own son by Gabrielle d’Estrées, Duchesse de Beaufort, the legitimised prince who was first known as César-Monsieur, then created Duc de Vendôme, was the spoilt favourite among his children. No more odious young fellow was to be found in France. Spiteful, of vicious tendencies, “c’est un mauvais drôle, violent, moqueur, brutal.” There was every probability that César, whom the King openly preferred to his little lawful son, the future Louis XIII., would one day be the most powerful[Pg 36] of all the princes. Henry had already arranged a marriage for him with a rich heiress of royal blood, Françoise de Lorraine, only daughter of the Duc de Mercœur.