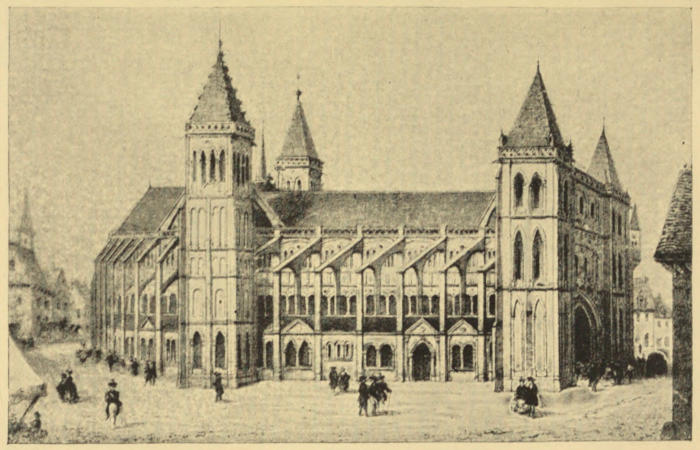

Plate I

The Abbey Church of St. Martin of Tours, before the pillage. To face p. 210.

ALCUIN OF YORK

LECTURES DELIVERED IN THE CATHEDRAL

CHURCH OF BRISTOL IN 1907 AND 1908

BY THE

RIGHT REV. G. F. BROWNE

D.D., D.C.L., F.S.A.

BISHOP OF BRISTOL

FORMERLY DISNEY PROFESSOR OF ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE TRACT COMMITTEE.

LONDON:

SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE.

NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.; 43, QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C.

BRIGHTON: 129, North Street.

New York: E. S. Gorham.

1908

No attempt has been made to correct the various forms of many of the proper names so as to make the spelling uniform. It is true to the period to leave the curious variations as Alcuin and others wrote them. In the case of Pope Hadrian, the name has been written Hadrian and Adrian indiscriminately in the text.

While Alcuin’s style is lucid, his habit of dictating letters hurriedly, and sending them off without revision if he had a headache, has left its mark on the letters as we have them. It has seemed better to leave the difficulties in the English as he left them in the Latin.

The edition used, and the numbering of the Epistles adopted, is that of Wattenbach and Dümmler, Monumenta Alcuiniana, Berlin 1873, being the sixth volume of the Bibliotheca Rerum Germanicarum.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| The authorship of the anonymous Life of Alcuin.—Alcuin’s Life of his relative Willibrord.—Willibrord at Ripon.—Alchfrith and Wilfrith.—Alcuin’s conversion.—His studies under Ecgbert and Albert at the Cathedral School of York.—Ecgbert’s method of teaching.—Alcuin becomes assistant master of the School.—Is ordained deacon.—Becomes head master.—Joins Karl | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Alcuin finally leaves England.—The Adoptionist heresy.—Alcuin’s retirement to Tours.—His knowledge of secrets.—Karl and the three kings his sons.—Fire at St. Martin’s, Tours.—References to the life of St. Martin.—Alcuin’s writings.—His interview with the devil.—His last days | 23 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The large bulk of Alcuin’s letters and other writings.—The main dates of his life.—Bede’s advice to Ecgbert.—Careless lives of bishops.—No parochial system.—Inadequacy of the bishops’ oversight.—Great monasteries to be used as sees for new bishoprics, and evil monasteries to be suppressed.—Election of abbats and hereditary descent.—Evils of pilgrimages.—Daily Eucharists | 51 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The school of York.—Alcuin’s poem on the Bishops and Saints of the Church of York.—The destruction of the Britons by the Saxons.—Description of Wilfrith II, Ecgbert, Albert, of York.—Balther and Eata.—Church building in York.—The Library of York | 68[v] |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The affairs of Mercia.—Tripartite division of England.—The creation of a third archbishopric, at Lichfield.—Offa and Karl.—Alcuin’s letter to Athelhard of Canterbury; to Beornwin of Mercia.—Karl’s letter to Offa, a commercial treaty.—Alcuin’s letter to Offa.—Offa’s death | 87 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Grant to Malmesbury by Ecgfrith of Mercia.—Alcuin’s letters to Mercia.—Kenulf and Leo III restore Canterbury to its primatial position.—Gifts of money to the Pope.—Alcuin’s letters to the restored archbishop.—His letter to Karl on the archbishop’s proposed visit.—Letters of Karl to Offa (on a question of discipline) and Athelhard (in favour of Mercian exiles) | 106 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| List of the ten kings of Northumbria of Alcuin’s time.—Destruction of Lindisfarne, Wearmouth, and Jarrow, by the Danes.—Letters of Alcuin on the subject to King Ethelred, the Bishop and monks of Lindisfarne, and the monks of Wearmouth and Jarrow.—His letter to the Bishop and monks of Hexham | 122 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Alcuin’s letters to King Eardulf and the banished intruder Osbald.—His letters to King Ethelred and Ethelred’s mother.—The Irish claim that Alcuin studied at Clonmacnoise.—Mayo of the Saxons | 140 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Alcuin’s letter to all the prelates of England.—To the Bishops of Elmham and Dunwich.—His letters on the election to the archbishopric of York.—To the new archbishop, and the monks whom he sent to advise him.—His urgency that bishops should read Pope Gregory’s Pastoral Care | 157[vi] |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Summary of Alcuin’s work in France.—Adoptionism, Alcuin’s seven books against Felix and three against Elipandus.—Alcuin’s advice that a treatise of Felix be sent to the Pope and three others.—Alcuin’s name dragged into the controversy on Transubstantiation.—Image-worship.—The four Libri Carolini and the Council of Frankfurt.—The bearing of the Libri Carolini on the doctrine of Transubstantiation | 172 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Karl and Rome.—His visits to that city.—The offences and troubles of Leo III.—The coronation of Charlemagne.—The Pope’s adoration of the Emperor.—Alcuin’s famous letter to Karl prior to his coronation.—Two great Roman forgeries, the Donation of Constantine and the Letter of St. Peter to the Franks | 186 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Alcuin retires to the Abbey and School of Tours.—Sends to York for more advanced books.—Begs for old wine from Orleans.—Karl calls Tours a smoky place.—Fees charged to the students.—History and remains of the Abbey Church of St. Martin.—The tombs of St. Martin and six other Saints.—The Public Library of Tours.—A famous Book of the Gospels.—St. Martin’s secularised.—Martinensian bishops | 202 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Further details of the Public Library of Tours.—Marmoutier.—The Royal Abbey of Cormery.—Licence of Hadrian I to St. Martin’s to elect bishops.—Details of the Chapter of the Cathedral Church of Tours | 219 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Great dispute on right of sanctuary.—Letters of Alcuin on the subject to his representatives at court and to a bishop.—The emperor’s severe letter to St. Martin’s.—Alcuin’s reply.—Verses of the bishop of Orleans on Charlemagne, Luitgard, and Alcuin | 231[vii] |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Alcuin’s letters to Charlemagne’s sons.—Recension of the Bible.—The “Alcuin Bible” at the British Museum.—Other supposed “Alcuin Bibles.”—Anglo-Saxon Forms of Coronation used at the coronations of French kings | 246 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| Examples of Alcuin’s style in his letters, allusive, jocose, playful.—The perils of the Alps.—The vision of Drithelme.—Letters to Arno.—Bacchus and Cupid | 264 |

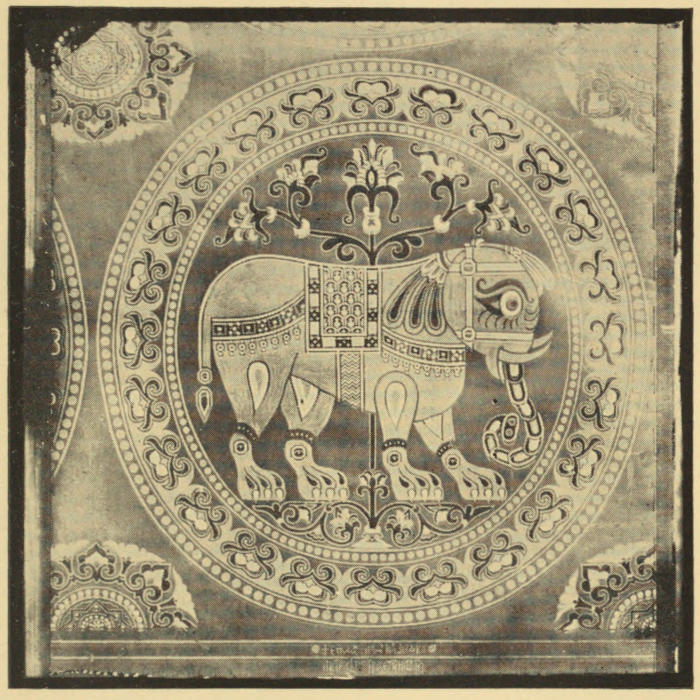

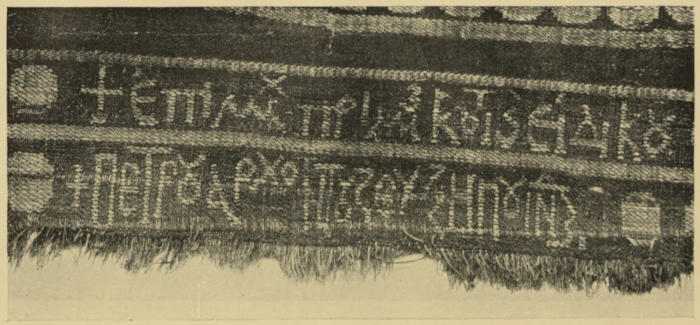

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| Grammatical questions submitted to Alcuin by Karl.—Alcuin and Eginhart.—Eginhart’s description of Charlemagne.—Alcuin’s interest in missions.—The premature exaction of tithes.—Charlemagne’s elephant Abulabaz.—Figures of elephants in silk stuffs.—Earliest examples of French and German.—Boniface’s Abrenuntiatio Diaboli.—Early Saxon.—The earliest examples of Anglo-Saxon prose and verse | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Alcuin’s latest days.—His letters mention his ill health.—His appeals for the prayers of friends, and of strangers.—An affectionate letter to Charlemagne.—The death scene | 298 |

| APPENDICES | |

| A. A letter of Alcuin to Fulda | 305 |

| B. The report of the papal legates, George and Theophylact, on their mission to England | 310 |

| C. The original Latin of Alcuin’s suggestion that a treatise by Felix should be sent to the Pope and three others | 319 |

| D. The Donation of Constantine | 320 |

| E. Harun Al Raschid and Charlemagne | 324 |

| Index | 325 |

| PAGE | |

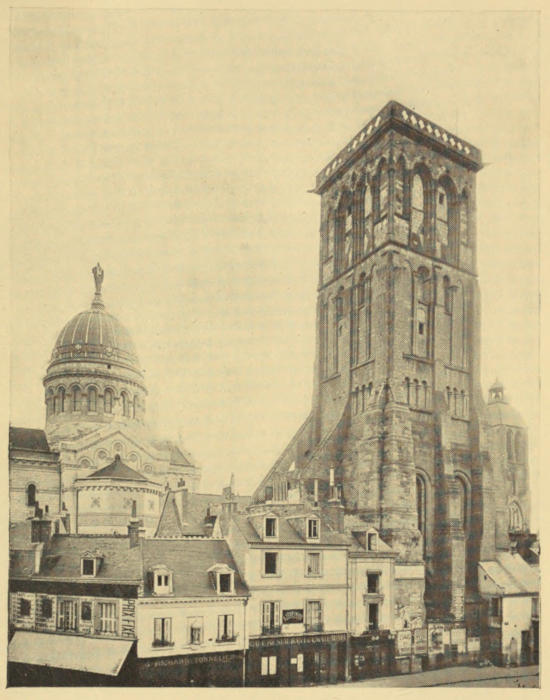

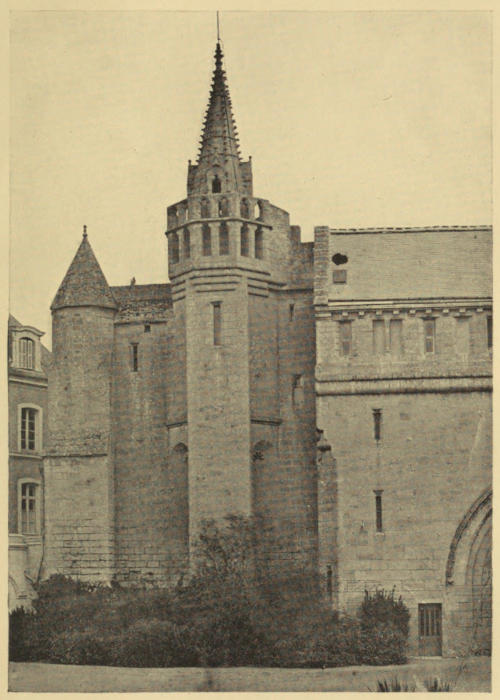

| Plate I. St. Martin’s, Tours, before the pillage | To face page 210 |

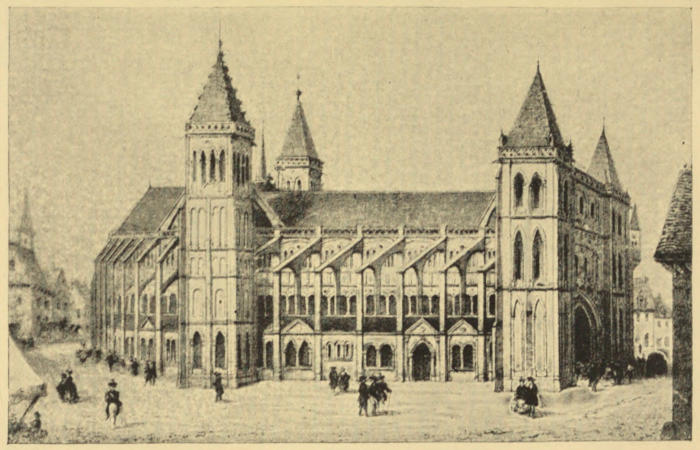

| Plate II. The Tour St. Martin | 211 |

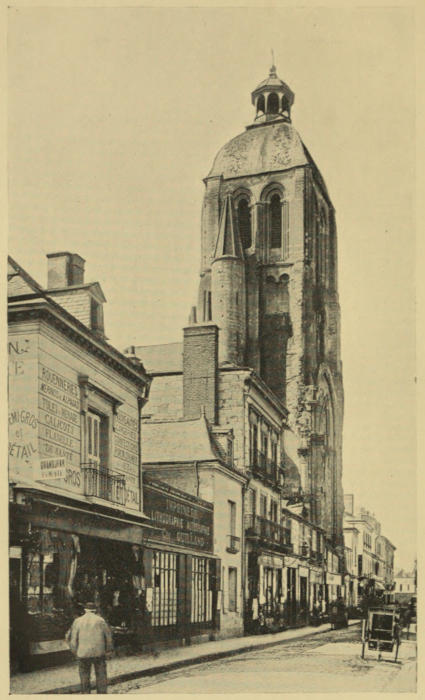

| Plate III. The Tour Charlemagne | 212 |

| Plate IV. The Tomb of St. Martin | 213 |

| Plate V. Some remains of Marmoutier | 222 |

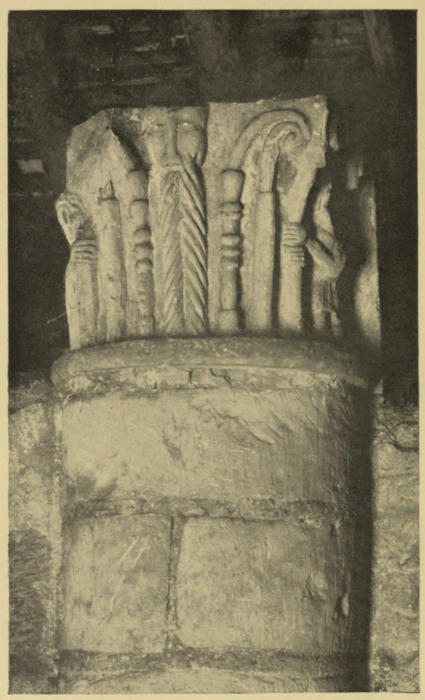

| Plate VI. Early capital at Cormery | 227 |

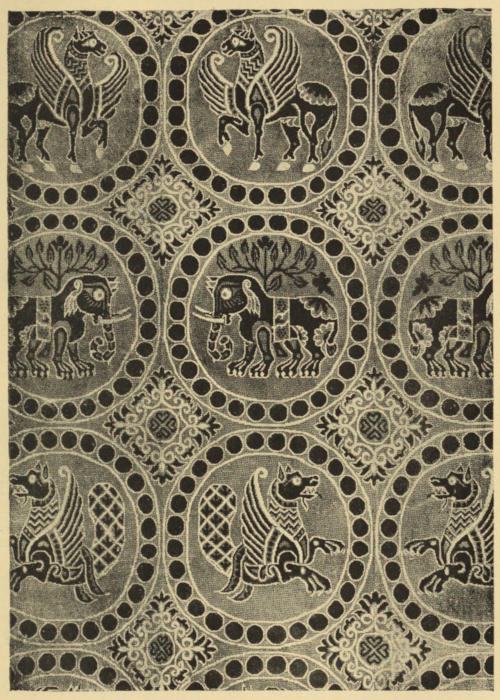

| Plate VII. Elephant from robes in the tomb of Charlemagne | 290 |

| Plate VIII. Inscription worked into the above robe | 291 |

| Plate IX. Silk stuff of the seventh or eighth century | 292 |

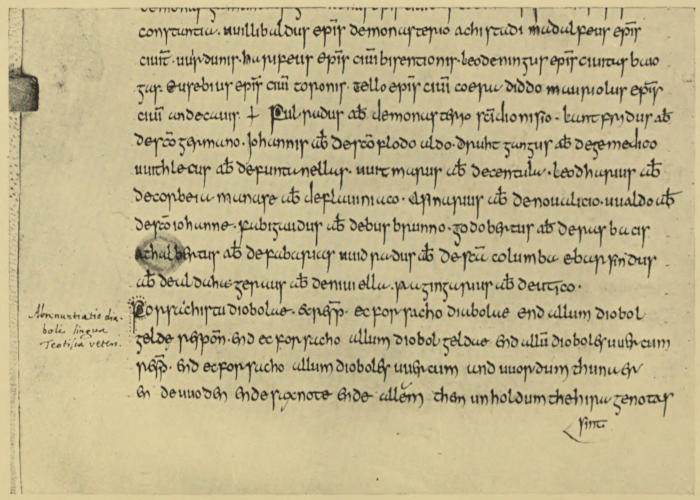

| Plate X. Archbishop Boniface’s form for renouncing the devil | 295 |

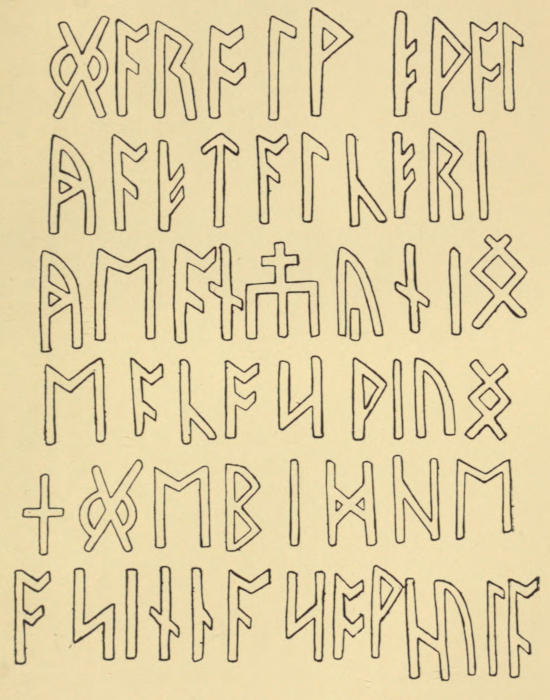

| Plate XI. The earliest piece of English prose | 296 |

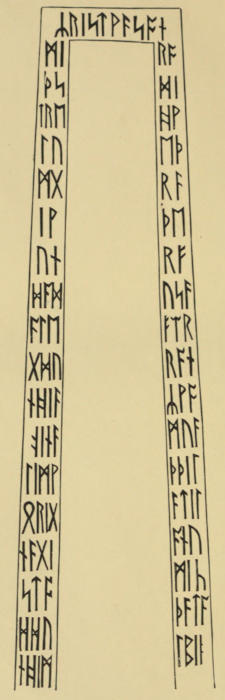

| Plate XII. The earliest piece of English verse | 297 |

The authorship of the anonymous Life of Alcuin.—Alcuin’s Life of his relative Willibrord.—Willibrord at Ripon.—Alchfrith and Wilfrith.—Alcuin’s conversion.—His studies under Ecgbert and Albert at the Cathedral School of York.—Ecgbert’s method of teaching.—Alcuin becomes assistant master of the School.—Is ordained deacon.—Becomes head master.—Joins Karl.

The only Life of Alcuin which we possess, coming from early times, was written by a monk who does not give his name, at the command of an abbat whose name, as also that of his abbey, is not mentioned by the writer. We have, however, this clue, that the writer learned his facts from a favourite disciple and priest of Alcuin himself, by name Sigulf. Sigulf received from Alcuin the pet name of Vetulus, “little old fellow,” in accordance with the custom of the literary and friendly circle of which Alcuin was the centre. Alcuin himself was Flaccus; Karl the King of the Franks, and afterwards Emperor, was David; and so on. We learn further that the abbat who assigned to the anonymous monk the task of writing the Life was himself a disciple of Sigulf. Sigulf succeeded Alcuin as Abbat of Ferrières; and when he retired on account of old age, he was in turn succeeded by two of his pupils[2] whom he had brought up as his sons, Adalbert and Aldric. The Life was written after the death of Benedict of Aniane, that is, after the year 823. Adalbert had before that date been succeeded by Aldric, and Aldric became Archbishop of Sens in the end of 829. The Life was probably written between 823 and 829 by a monk of Ferrières, by order of Aldric. Alcuin had died in 804. The writer of the Life had never even seen Alcuin; he was in all probability not a monk of Tours.

That is the view of the German editor Wattenbach as to the authorship and dedication of the Life. That learned man appears to have given inadequate weight to the writer’s manner of citing Aldric as a witness to the truth of a quaint story told in the Life. This is the story, as nearly as possible in the monk’s words:—

“The man of the Lord [Alcuin himself] had read in his youth the books of the ancient philosophers and the romances[1] of Vergil,[2] but he would not in his old age have them read to him or allow others to read them. The divine poets, he was wont to say, were sufficient for them, they did not need to be polluted with the luxurious flow of Vergil’s verse. Against this precept the little old fellow Sigulf tried to act secretly, and for this he was put to the blush publicly. Calling to him two youths whom he was bringing up as sons, Adalbert and Aldric, he bade them read Vergil with him in complete secrecy, ordering them by no means to let any one know, lest it come to the ears of Father Albinus [Alcuin]. But Albinus called him in an ordinary way to come to him,[3] and then said: ‘Where do you come from, you Vergilian? Why have you planned, contrary to my wish and advice, to read Vergil?’ Sigulf threw himself at his feet, confessed that he had acted most foolishly, and declared himself penitent. The pious father administered a scolding to him, and then accepted the amends he made, warning him never to do such a thing again. Abbat Aldric, a man worthy of God, who still survives, testifies that neither he nor Adalbert had told any one about it; they had been absolutely silent, as Sigulf had enjoined.”

It seems practically impossible to suppose that the monk would have put it in this way, if Aldric had been the abbat to whom he dedicated the Life, or indeed the abbat of his own monastery. It is clear that the Life was written while Aldric was still an abbat, that is between 823 and 829; and it seems most probable that it was written by a monk of some other monastery for his own abbat. Nothing of importance, however, turns upon this discussion. It is a rather curious fact, considering the severity of Alcuin’s objection to Vergil being read in his monastery, that the beautiful copy of Vergil at Berne, of very early ninth-century date, belonged to St. Martin of Tours from Carolingian times, and was written there.[3]

Not unnaturally, the Life, written in and for a French monastery, does not give details of the Northumbrian origin of Alcuin. It makes only the statement usual in such biographies, that he sprang from a noble Anglian family. Curiously enough, we get such further details as we have from a Life of St. Willibrord written by Alcuin himself at the request of Archbishop Beornrad of Sens, who was Abbat of Epternach, a monastery of Willibrord’s, from 777 to 797.

“There was,” he writes, “in the province of Northumbria, a father of a family, by race Saxon, by name Wilgils, who lived a religious life with his wife and all his house. He had given up the secular life and entered upon the life of a monk; and when spiritual fervour increased in him he lived solitary on the promontory which is girt by the ocean and the river Humber (Spurn Point)[4]. Here he lived long in fasting and prayer in a little oratory dedicated to St. Andrew[5] the Apostle; he worked miracles; his name became celebrated. Crowds of people consulted him; he comforted them with the most sweet admonitions of the[5] Word of God. His fame became known to the king and great men of the realm, and they conferred upon him some small neighbouring properties, so that he might build a church. There he collected a congregation of servants of God, moderate in size, but honourable. There, after long labours, he received his crown from God; and there his body lies buried. His descendants to this day hold the property by the title of his sanctity. Of them I am the least in merit and the last in order. I, who write this book of the history of the most holy father and greatest teacher Willibrord, succeeded to the government of that small cell by legitimate degrees of descent.”

Inasmuch as the book is dedicated to Beornrad by the humble Levite (that is, deacon) Alcuin, we learn the very interesting fact that Alcuin, born in 735, came by hereditary right into possession of the property got together by Wilgils, whose son Willibrord was born in 657. The dates make it practically almost certain that Wilgils was born a pagan. Alcuin informs us that he only entered upon marriage because it was fated that he should be the father of one who should be for the profit of many peoples. If Willibrord was, as Alcuin’s words mean, the only child of Wilgils, we must suppose that Alcuin was the great-great-great-nephew of Wilgils, allowing twenty-five years for a generation in those short-lived times.

Alcuin three times insists on the lawful hereditary descent of the ownership and government of a monastery. A second case is in his preface to this Life of Willibrord. The body of the saint, he says, “rests in a certain small maritime cell,[6] over which I, though unworthy, preside by God’s gift in lawful succession.” A third case occurs also in this Life. “There is,” he says, “in the city of Trèves a monastery[6] of nuns, which in the times of the blessed Willibrord was visited by a very severe plague. Many of the handmaids of the Lord were dying of it; others were lying on their beds enfeebled by a long attack; the rest were in a state of terror, as fearing the presence of death. Now there is near that same city the monastery of that holy man, which is called Aefternac,[7] in which up to this day the saint rests in the body, while his descendants are known to hold the monastery by legitimate paternal descent, and by the piety of most pious kings. When the women of the above-named monastery heard that he was coming to this monastery of his, they sent messengers begging him to hasten to them.” He went, as the blessed Peter went to raise Tabitha; celebrated a mass for the sick; blessed water, and had the houses sprinkled with it; and sent it to the sick sisters to drink. Needless to say, they all recovered.

In two of these cases, the two in which Alcuin speaks of his own property, he uses the word succession, “by legitimate succession” in the one case, legitima successione, “through legitimate successions” in the other case, per legitimas successiones, the former no doubt referring to the succession from his immediate predecessor, the latter referring to the four, or five, steps in the descent from Wilgils to Alcuin. In the case of the monastery[7] of Epternach he defines it from the other end, “from the legitimate handing-down,” traditione ex legitima, the piety of the most pious kings being called in to confirm the handing-down.

It is remarkable that Alcuin should thus go out of his way to insist upon the lawfulness of the hereditary descent of monasteries, when he knew well that his venerated predecessor Bede, following the positive principle of the founder of Anglian monasticism in Northumbria, Benedict Biscop, attributed great evils to such hereditary succession to the property and governance of monasteries. We shall see something of this when we come to the consideration of Bede’s famous letter to Ecgbert, written in or about the year of Alcuin’s birth.

It is probably not necessary to suppose that Alcuin intends to draw a distinction between the constitutional practice in Northumbria and that in the lands ruled by Karl, though it is a marked fact that he mentions the intervention of kings in the latter case and twice does not mention it in the former. Bede says so much about the bribes—or fees—paid to Northumbrian kings and bishops for ratification of first grants by their signatures, that we can hardly suppose there were no fees to pay on succession. We cannot press such a point as this in Alcuin’s Life of Willibrord, for he tells Beornrad in his Preface that he has been busy with other things all day long, and has only been able to dictate this book in the retirement of the night; and he urges that the work should be mercifully judged because he has not had leisure to polish it. The grammar of this dictated work needs a certain[8] amount of correction; Alcuin did not always remember with what construction he had begun a sentence. In these days of dictated letters he has the sympathy of many in this respect.

Alcuin’s young relative Willibrord was sent away to Ripon, as soon as he was weaned, to the charge of the brethren there. Alchfrith, the sub-King of Deira under his father Oswy, had driven out the Irish monks whom he had at one time patronised at Ripon, and had given their possessions to Wilfrith. Under the influence of that remarkable man the little child came, still, in Alcuin’s phrase, only an infantulus. His father’s purpose in sending him to Ripon was twofold. He was to be educated in religious study and sacred letters, in a place where his tender age might be strengthened by vigorous discipline, where he would see nothing that was not honourable, hear nothing that was not holy. At Ripon he remained till he was twenty years of age, and then he passed across to Ireland, to complete his studies under Ecgbert, the great creator of missionaries. With Ecgbert he spent twelve years.

Now in the thirty-two years covered by that short narration, from 657 to 689, events of the utmost moment had occurred in Northumbria, and had mainly centered round Ripon. At the most critical juncture of these events Bede becomes suddenly silent. Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon version of Bede goes further, and omits the bulk of what Bede does say. A few words from Alcuin would have been of priceless value, and he, writing in France to a Frank, could have no national or ecclesiastical reason for silence on points which Bede and Alfred let alone. The whole of the variance[9] between Oswy and his son and sub-King Alchfrith, on which Bede is determinedly silent, the only hint of which is preserved to us solely by the noble runes on the Bewcastle Cross, erected in 670 and still standing, which bid men pray for the “high sin” of Alchfrith’s soul[8]; the whole secret of the variance between Oswy and Wilfrith; of Oswy’s refusal to recognize Wilfrith’s consecration at Paris—with unrivalled magnificence of pomp—to the episcopal See of York; all this, and more, is included in the first thirteen years of Willibrord’s life at Ripon, and Ripon was the pivot of it all. Alcuin has no scintilla of a hint of anything unusual, not even when he mentions Ecgbert, the Northumbrian teacher, dwelling in Ireland, of whom we know from another source that he fled from Northumbria to safety in Ireland when Alchfrith and Wilfrith lost their power, and Alchfrith presumably lost his life. It is quite possible that if the head of the Bewcastle Cross were ever found[9] the runes on it might tell us just what we want to know. The illustration of this portion of the Cross given in Gough’s edition of Camden’s Britannia[10] was drawn in 1607, at which time English scholars could not read runic letters, and naturally could not copy them with perfect accuracy. Still, it is evident that the runes stand for rikaes dryhtnaes, apparently meaning ‘of the kingdom’s lord’, the copyist having failed to notice the mark of modification in the rune for u, which turned it into y.

Turning now to Alcuin himself, a remarkable story is told in the Life, evidently and avowedly on his authority. When he was still a small boy, parvulus, he was regular in attendance at church at the canonical hours of the day, but very seldom appeared there at night. What the monastery was in which he passed his earliest years we are not told; but inasmuch as no break or change is mentioned between the story to which we now turn and the description of his more advanced studies, which certainly indicates the Archiepiscopal School of York, we must understand that York was the scene of this occurrence.

“When he was eleven years of age, it happened one night that he and a tonsured rustic, one of the menial monks, that is, were sleeping on separate pallets in one cell. The rustic did not like being alone in the night, and as none of the rustics could accommodate him, he had begged that one of the young students might be sent to sleep in the cell. The boy Albinus was sent, who was fonder of Vergil than of Psalms. At cock-crow the warden struck the bell for nocturns, and the brethren got up for the appointed service. This rustic, however, only turned round onto his other side, as careless of such matters, and went on snoring. At the moment when the invitatory psalm was as usual being sung, with the antiphon, the rustic’s cell was suddenly filled with horrid spirits, who surrounded his bed, and said to him, ‘You sleep well, brother.’ That roused him, and they asked, ‘Why are you snoring here by yourself, while the brethren are keeping watch in the church?’ He then received a useful flogging, so that by his amendment a warning[11] might be given to all, and they might sing, ‘I will remember the years of the right hand of the Most Highest,’[11] while their eyes prevented the night watches. During the flogging of the rustic, the noble boy trembled lest the same should happen to him; and, as he related afterwards, cried from the very bottom of his heart, ‘O Lord Jesus, if Thou dost now deliver me from the cruel hands of these evil spirits, and I do not hereafter prove to be eager for the night watches of Thy Church and the ministry of praise, and if I any longer love Vergil more than the chanting of psalms, may I receive a flogging such as this. Only, I earnestly pray, deliver me, O Lord, now.’ That the lesson might be the more deeply impressed upon his mind, as soon as by the Lord’s command the flogging of the rustic ceased, the evil spirits cast their eyes about here and there, and saw the body and head of the boy most carefully wrapped up in the bedclothes, scarce taking breath. The leader of the spirits asked, ‘Who is this other asleep in the cell?’ ‘It is the boy Albinus,’ they told him, ‘hid away in his bed.’ When the boy found that he was discovered, he burst into showers of tears; and the more he had suppressed his cries before, the louder he cried now. They had all the will to deal unmercifully with him, but they had not the power. They discussed what they should do with him; but the sentence of the Lord compelled them to help him to keep the vow which he had made in his terror. Accordingly they said, imprudently for their purpose, but prudently for the purpose of the Lord, ‘We will[12] not chastise this one with severe blows, because he is young; we will only punish him by cutting with a knife the hard part of his feet.’ They took the covering off his feet. Albinus instantly protected himself with the sign of the Cross. Then he chanted with all intentness the twelfth psalm, ‘In the Lord put I my trust’; and then the rustic, half dead, the boy going before him with agile step, fled into the basilica to the protection of the saints.”

A cynical reader might suggest that the disciplinary officers of the School of York resorted in those early times to unusual methods of making an impression on a careless boy.

The Life proceeds to inform us that Alcuin was trained under the prelate Hechbert, whom we know as Ecgbert, Bishop and later Archbishop of York, 732 to 766. That learned man was a disciple of Bede. He had under his tuition a flock of the sons of nobles, some of whom studied grammar, others the liberal arts, others the divine scriptures.[12] They studied the doctrine set forth by “the holy apostle of the English, Gregory; by Augustine, his disciple; by holy Benedict[13]; also by Cuthbert and Theodore, who followed in all things [a word is omitted here, presumably the footsteps[14]] of their first father and apostle[15]; and by the man most[13] loved of the Lord, Bede the presbyter, Hechbert’s own preceptor.”

Then follows a very lifelike description of an ordinary day’s work, when no inevitable expedition came in the way, nor any high solemnity or great festival of the saints. “From dawn of day to the sixth hour, and very often to the ninth hour, Ecgbert lay on his couch and opened to his disciples such of the secrets of scripture as suited each. Then he rose, and betook himself to most secret prayer, offering first to the Lord fat burnt-offerings with the incense of rams, and afterward, following the example of the blessed Job, lest by chance his sons should slip into the pit of benediction,[16] offering the Body of Christ and the Blood for all. By this time the vesper hour was coming near, and, except in Lent, all through the year, winter and summer, he took with his disciples a meal, slight but fittingly prepared, not sparing the tongue of the reader, that both kinds of food might bring refreshment. Then you might see the youths piercing one another with shafts prepared, discussing in private what afterwards they are to shoot forth in proper order in public. Does it not seem to you that of this too it might be said,[17] “As an eagle provoketh her young ones to fly, fluttereth over them, spreadeth abroad her wings, taketh them, beareth them on her wings”?

“Twice in the day did this father of the poor, this great lover and helper of Christ, pour out most secret prayer, watered from the most pure fountain of tears, both knees bent on the ground,[14] hands long raised to heaven in the form of the Cross; once, namely, before taking food, and again before celebrating Compline with all his flock. Which ended, no one of his disciples ever dared commit his limbs to his bed without the master’s blessing laid upon his head.

“He loved all his disciples, but of all he loved Alcuin the most, for Alcuin more closely than any of them followed his example in act and deed. There were two special virtues in Alcuin—one, that he never did anything which he was not quite clear that his master’s approval covered; the other, that whatever devices and temptations the enemy brought to his mind, he told them all straight out to his master without any sense of shame. Thus it came to pass that any stimulus of lust which he ever felt was most gloriously conquered by this wonderful method, dashing the children of Babylon against the stones, bruising the head of the serpent with the heel. He was careful that against him the words of Christ should not be spoken—‘Every one that doeth evil hateth the light, neither cometh to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved’; but rather that his lot should be with them of whom it is added—‘But he that doeth truth cometh to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest that they are wrought in God.’ O true monk without the monk’s vow! how very seldom is thy example followed by one whose vow binds him to it[18].”

In the chapter from which these details are taken the author three times uses the name[15] “Albinus” for his hero, in place of “Alchuinus” with which he began the chapter. Throughout the Life he much more often calls him Albin than Alcuin. We must probably understand that he was known from his boyhood by both names; and it is evident that Albin would be more easy to pronounce than Alcuin, and would not unnaturally be more generally used. On the other hand, it is quite possible that he himself elected to call himself Albin.

If Alcuin took the name Albinus from any English source, the source is not far to seek. The English nation owes to the original Albinus the first suggestion to Bede that he should write the Church History of the English race. Bede tells us this in the Preface to his great work; and we have it still more directly expressed in a letter from him to Albinus in which he speaks of the History as ad quam me scribendam iamdudum instigaveras, and of Albinus as semper amantissimus in Christo pater optimus. He was Abbat of St. Peter and St. Paul, Canterbury, a pupil of Theodore and Hadrian, the latter of whom he succeeded. He greatly helped Bede by sending him full details of the conversion of Kent, “as he had learned the same from written records and from the oral tradition of his predecessors.” Bede sent to him the completed copy of the History, that he might have it transcribed, and informs us that Albinus had no small knowledge of Greek, and knew Latin as well as his native tongue, English. Alcuin may well have taken his name of Albinus from one with whom he had so much in common, who died only two or three years before Alcuin’s birth.

If, on the other hand, Alcuin took the name from some foreign source, again we have not far to seek. In Karl’s first year as King of the Franks he gave a confirmatory charter to “the Monastery of St. Albinus, which is built near to the walls of Angers”. The Tour St. Aubin and the Rue St. Aubin are still to be found at Angers, at the extreme south-east corner of the ancient city. Little is known of this martyr Albinus, and in consequence the Acts of our St. Alban have been transferred to him. At Angers, as at Alcuin’s own Tours, there are remains of a great church of St. Martin; and, as was in early times the case at Tours, the Cathedral is dedicated to St. Maurice. It is possible that Alcuin took his name of Albinus from this local source, but it does not seem at all probable.

Alcuin’s supremacy in wisdom and other virtues caused jealousy among his fellow disciples. This went so far that they could not look at him with unclouded eye or address him with pleasant words. He consulted his master, who by this time was Elcbert (Archbishop of York, 767-78), known to Alcuin as Aelbert, and to us as Albert. The master advised him to try the effect of heaping coals of fire on their heads. He followed this advice, taking care that they should never hear from him a contrary word, and very often yielding to them when their arguments were unsound. This course of conduct he pursued until a complete change took place, and they all rejoiced to acknowledge in him the second master of their studies, next under Albert.

The Life relates at this point an interesting episode, in the description of which we may seem to hear Alcuin himself speaking to us:—

“Alcuin was reading the Gospel of St. John before the master, in company of his fellow disciples. He came to a part of the Gospel which only the pure in heart can comprehend—that part, namely, from where John says that he lay on the Lord’s breast, down to the point at which he relates that Jesus went with His disciples across the brook Cedron.[19] Inebriated with the mystical reading of the Gospel, suddenly, as he sat before the master’s couch, his spirit was carried away in ecstasy, and by those same who once in a ray of sunlight showed before the eyes of the most holy father Benedict the whole world, collected as it were in an enclosure, the whole world was now set before the eyes of Alcuin. And as he looked intently at what he saw, he saw the whole of the enclosure surrounded by a circle of blood. While he was held by this marvellous vision, his fellow disciples gazed at him in wonder, for the blood seemed to have left his face. They tried to rouse him, as one asleep; the noise they made attracted the attention of Albert, who looked at him for some time in silence, and then said, ‘Go on reading, my sons, do not disturb him; if he rests awhile he will be able to follow me more effectively when I expound the passage.’ When the reading was completed, and Albin came to himself again, the father told them all to go except Alcuin. When they were gone, he said, ‘What hast thou seen? I beg thee, do not hide it.’ Alcuin wished to keep secret what he had seen, fearing to fall into the pitfall of elation; so he said, ‘Why, my lord[18] father?’ The blessed man said again, ‘Do not, my son, do not hide it from me. It is not from vain curiosity that I require this of you, but for your own good.’ Alcuin saw that he could not keep it secret, and he told, humbly, how he had seen the whole world. Then the father said to him, ‘See, my son, see that thou tellest not this vision to any but that one whom after my decease thou shalt hold to be the most faithful to thy person. And charge him to keep it secret up to the time of thy death.’ Acting on this counsel, he told it only to Sigulf[20] during his lifetime. If any one desires to know how the whole world could be seen in one enclosure, he may turn to the book of Dialogues of the holy Gregory[21]; and in the meantime he may know that it was not the heaven and the earth that were contracted into a small space, but the mind of the seer that was dilated, so that when rapt in the Lord he could without difficulty see everything that was under God. Perhaps some one inquiring further may ask why under this figure of an enclosure, or why surrounded by blood? He may know that the Blood of Christ surrounds the fold of the holy Church, so that from the rising of the sun to the setting thereof those who are redeemed by His Passion can say the words which, without doubt, dominated the mind of Albin when he read before the master: ‘O give thanks unto the Lord, for He is gracious,[19] and His mercy endureth for ever.’[22] The whole world, then, is seen in one enclosure surrounded by the Blood of Christ; for all that the holy fathers have done and have written figuratively since the beginning of the world is unlocked by the Passion of Christ alone, who is the lion of the tribe of Juda, the root of David. But if by the encircled enclosure any should wish to be understood the life of his own carnal crimes surrounded by blood, thus shown to him that it may be trodden under foot by him, let that interpretation be left to his own judgement.”

Alcuin had been tonsured in early years. He was ordained deacon at York on the day of the Purification of the holy Mary, in or about the year 768. Elcbert, who had been for some time in bad health, felt that his death was drawing nigh, and he gave to Alcuin a sketch of the course of life which he wished him to pursue. The writer gives us a report of his actual words, stating that “they are now known”; this means, presumably, that here also Alcuin had communicated them to Sigulf, to be made public only after his death. They run thus:—“My will is that you go to Rome, and on the way back visit France.[23] For I know that you will do much good there. Christ will be the leader of your journey, guiding you and controlling you on your arrival, that you may demolish that most nefarious heresy which will[20] attempt to set forth Christ as adoptive man, and that you may be the firmest defender and the clearest preacher of the faith in the Holy Trinity.[24] You will persevere in the land of your peregrination, illumining the souls of many.”

The holy father, Bishop Elcbert, after blessing him with the benedictions of his predecessor above named, migrated to God on the eighth day of November, 780. “The pious Albinus mourned with tears, as for his mother, and would not take comfort. Endowed in hereditary right with the holy benedictions of the fathers,[25] he took pains to multiply exceedingly the talent of his lord.[26] He taught many in Britain, and not few later in France. It was now that he associated with him a man dear to God, remarkable for the nobility of mind and of body, Sigulf, the presbyter, Warden of the Church of the City of York, to remain with him perpetually.[27] Sigulf had gone as a boy to France with his uncle Autbert the presbyter, and by him had been taken to Rome to learn the ecclesiastical order; he had then been sent to the city of Metz to learn chanting. There he worked hard for some time, in great poverty, but with much profit. After the holy man, his uncle,[21] migrated to the Lord, he came back to his own land.” We can almost see and hear Sigulf getting these little facts about himself and his uncle incorporated in the Life of Alcuin.

“When the Almighty God willed to glorify France with spiritual riches, as already with earthly riches, granting to the land a King after His own heart, a man of faith, fortitude, love of wisdom, and ineffable beauty of body, namely Karl, most illustrious in these respects, He put it into the mind of Albinus that he should fulfil the counsel and command of his father Albert, by going to Rome and then visiting France.

“By the command of Eanbald I, the Archbishop of York, the successor of Elcbert, he went to Rome to obtain the pallium for the archbishop from the Apostolic—that is, Hadrian I. On his way back with the pallium he met King Karl in the city of Parma.[28] The king addressed him with great persuasiveness and many prayers, begging that after completing his embassage he would come and join him in France. The king had become acquainted with him some years before, for Alcuin had been sent on a legation to him by the archbishop of the time.”

We may interrupt our author’s narrative at this point to state that the fact and the date of this former visit to Karl are recorded in the Life of Hadrian I, as also the further fact, not here hinted at, that Karl on that occasion sent Alcuin on to Rome. “In the year 773 Karl sent to Hadrian an embassy, consisting of the most holy bishop[22] George,[29] the religious abbat Uulfhard,[30] and the king’s favourite counsellor Albinus.”

We may now return to the author of the Life. He tells us, to quote his own words, that when Karl begged Alcuin to come to him, Alcuin desired to do what would be useful, and therefore asked permission of his own king, Alfwald, and of his archbishop, Eanbald I, to leave his mastership of the School of York. He obtained permission, but on condition that he should in time come back to them. Under Christ’s guidance he came to Karl. Karl embraced him as his father,[31] by whom he had been introduced to the liberal arts, in the study of which he could be somewhat cooled, but in his fervour he could never be too completely saturated with them. After Alcuin had spent some little time with him, he gave him two monasteries, that of Bethlehem, otherwise called Ferrières,[32] and that of St. Lupus[33] of Troyes.

Alcuin finally leaves England.—The Adoptionist heresy.—Alcuin’s retirement to Tours.—His knowledge of secrets.—Karl and the three kings his sons.—Fire at St. Martin’s, Tours.—References to the life of St. Martin.—Alcuin’s writings.—His interview with the devil.—His last days.

At length Alcuin felt that he ought not, without the authority of his own king and bishop, to desert the place in which he had been educated, tonsured, and ordained deacon. He asked leave of the great king to return to his fatherland. Karl received his request in a flattering manner. We may suppose that Alcuin retained an accurate recollection of the pleasant words and of his own answer, and reported them eventually to Sigulf, probably with a feeling that he had made a Yorkshire rejoinder to the king’s rather pointed balance-sheet. On a formal occasion such as this, they probably addressed each other as scholars, in the Latin tongue, so that in reading the Life we seem to hear them speaking the actual words reported. The manner of address we may take to be correctly represented.

“Karl. Illustrious master,—of earthly riches we have enough, wherewith it is our joy to honour thee. With thy riches, long desired by us and scarce anywhere found, we pray thee illumine us in the wealth of thy piety.

“Alcuin. My lord king,—I am not inclined to oppose thy will, when it shall have been confirmed[24] by the authority of the canons. Endowed in my paternal country with no small heritage, I am delighted to fling it away and stand here a pauper, so that I may be of use to thee. Thy part is only this,—to obtain for me the permission of my own king and bishop.”

Karl was at last persuaded to let him go; but he was not satisfied until it was settled that when Alcuin came back again he would stay with him always.

Some years after he came back to Karl a second time, he was placed at the head of the Monastery of St. Martin of Tours. In a godly manner he ruled this with his other monasteries. He corrected the lives of those under him as far as he could. Some were untamed when they came under his rule, but he so bestirred himself that they became reasonable, of honest morals, and seekers after truth. That is the author’s statement. We shall hear more on the subject in the course of our study.

“Meantime the heresy hateful to God, which flourished in the parts of Spain, asserting that the Son of God is adoptive according to the flesh, is brought to the ears of Karl. The great king, in all things catholic, looked into this, and strove with all his might that the seed of the devil should be destroyed, and the tares completely eradicated from the wheat of God. Summoning to him Albinus his instructor from Tours, and the wretched Felix the constructor of this heresy from the parts of Spain, he collected a great synod of bishops in the imperial palace of Aix. Seated himself in the midst, he ordered Felix, who was[25] most unwilling, to dispute in argument with the most learned Albinus on the nature of the Son of God according to the flesh. What silence reigned among the bishops! How clear and unanswerable, with the authority of Karl, was the master’s confession and defence of the faith! Felix tried to hide himself in all sorts of obscurities; Albinus pierced him with more and more darts, at such length that he ‘went through almost all the cities of Israel[34] till the Son of Man should come’. Little else was done from the second to the seventh day of the week. At length his stupidity was laid bare to all. The heresy was confuted by the whole of the bishops with apostolic authority. To himself alone his folly was foully hidden, up to the point when he read with lamentable voice the words of Cyril the martyr, turned against him by Albinus: That nature which was corrupted by the devil is exalted above the angels by the triumph of Christ, and is set down at the right hand of the Father. When he read this sentence, he at last testified by voice and by excessive weeping that he had found himself out, that he had acted impiously. Any one who thirsts to know this more perfectly should read the master’s letters to Felix and Elipantus, and theirs to him. He will then at once learn what he desires to know.

“By permission of Christ,” the biographer continues, “I have up to this point written a little about the early part of the Life of Albinus, facts that I have supposed to be not known to all.[26] I have not thought of inserting in this little work facts about him which all know. From this point I shall attempt to trace to his last days my shaken reed of a pen, though it be with contemptible roughness.

“When he felt himself affected by old age, and increasingly by one infirmity,[35] he informed King Karl that he wished to retire from the world, as he had long had it in mind to do. He asked leave to live the monastic life, in accordance with the Rule of St. Benedict, at St. Boniface of Fulda,[36] and to distribute among his disciples the monasteries which had been granted to him, if that might be done. But the king, terrible and pious, with all regard for Alcuin’s request, denied the one part, while he received the other gladly. He begged that he would reside at Tours, in perfect quiet and in the greatest honour, and would not refuse to continue the spiritual care of Karl himself and of all the holy Church committed to him; the secular burdens which he had borne, the king, at his request, most willingly portioned out among his disciples. Albinus acted as the most wise king had asked, seeking what would be useful, not to himself but to many; and at Tours he awaited his last day. His manner of life was not inferior to the monastic life which he had desired. He abounded in fastings, in prayers, in mortification of the flesh, in almsgivings, in much celebration of psalms and masses,[37] and in the other virtues[27] with which it is possible for human nature to be adorned. When he had fasted till evening, there very frequently was sent from heaven to his mouth such sweetness as no human speech could utter; whatever he then willed, he could dictate most rapidly without any effort, so that he could say,—I have loved, Lord, Thy commandments above gold and precious stone; how sweet are thy words unto my mouth, yea, sweeter than honey and the honeycomb. In his youth he had not loved the study of the Psalms so much as another kind of reading; in his old age he could never have too much of them. As has been described in the case of his master,[38] he poured forth most secret prayer during the day, with long extension of his hands in the form of a cross, and with much groaning, for he very rarely found tears. This practice he passed on to his disciples, of whom the most noble was Sigulf, ‘the little old fellow,’ and the magnanimous Withso[39]; after them, Fredegisus[40] and his companions. In his latest days there clung to him assiduously Raganard and Waldramn, who still survive; Adalbert of blessed memory, who was with him as much as he could, being at that[28] time the son of Sigulf, afterwards a venerated father as Abbat of Ferrières; and many others, the names of all of whom I trust that Christ knows. These with all circumspection earnestly studied to do nothing in his presence with which he could find fault, and very often in his absence too. For they knew that he was in close communion with God, and was enlightened by His Spirit; and though with his bodily eyes he could no longer see clearly, from old age and infirmity, they feared that nothing which they did escaped his knowledge.

“Filled as he was with the Spirit, he foretold to some their future, as he did to Raganard about Osulf.[41] This Raganard had in his sleep a horrible vision, which it is better not to describe. He told it the next day to the father, in fear lest it referred to himself. The father knew that it referred not to Raganard but to Osulf. With great grief he spoke thus: ‘O Osulf, thou wretched one, how oft have I warned thee, how oft corrected! Much labour did I devote to thine uncle, that he should reform and begin to walk in the way of the commandments of God; and I told him that if he did not he would be smitten with the plague of leprosy; which thing happened to him. And to thee, my son, I predict of Osulf, of whom is this vision, that neither in this land, nor in the land of his birth, shall he die.’ The prediction was true; he died in Lombardy.

“This same Raganard, unknown to everybody, tried himself by vigils of too long duration and by an excess of abstinence; by this intemperance he fell into a most dangerous fever. Father Albinus came to visit him, and sent out of the house all except Sigulf. Then he rebuked Raganard thus: ‘Why hast thou tried to act so intemperately, without advice of any? I knew that thou didst wish to act thus, and therefore it was that I ordered thee to sleep in the dwelling in which I sleep. But thou didst immediately, when all were asleep, secretly light a candle, conceal it in a lantern, and going to that place didst watch through the whole night.’ And then all that he did there secretly, known to God alone, he told him of, and added:—‘When thou didst go with me to the refectory, and I bade thee drink wine, in the most crafty way thou didst say—I have drunk sufficiently, my lord father, with my uncle. But when thou didst come to thy uncle, and he too bade thee drink wine, thou didst say thou hadst drunk with me. Thy will was to delude us, and thou art deceived. When thou hast risen up from the fever, take thou care never to attempt anything of this kind again.’

“When Raganard heard this, he turned red, and was in great fear, knowing that he was caught. In wonder that his secret deeds could not escape the knowledge of Albinus, he asked how was this made known. To this day he bears witness that no man knew it before it was revealed; God alone. He repented, and for the rest of Alcuin’s life he never attempted anything of the kind without his advice and command.

“It very often happened that when messengers[30] were coming to Alcuin from the king and other friends, while they were yet a long way off, he would tell of their coming and of the cause of their coming, what they brought with them, what they wished to take back. Certain disciples, when they heard him speak thus, set it down to the folly of an old man, till it was proved to be true. Benedict[42], the man of the Lord, who beyond all monks was bound in intimacy with Alcuin, used often to come to him from the parts of Gothia, to obtain advice for himself and his monks. On one occasion Benedict wished to come secretly, unknown to any one at Tours, so that Alcuin should not know till he stood in the doorway. When he was by no means near Tours, Albinus summoned an attendant, and said to him, ‘Hasten to meet Benedict in such and such a place, and tell him to come to me quickly.’ The messenger did as he was told, and on the third day arrived at the place, found Benedict there, and delivered his message. Astonished that his plan was discovered, Benedict went with all haste to Tours. When they had joyously kissed one another, Benedict, the reverend father, began suppliantly, ‘Lord father, who foretold to thee my arrival?’ He answered, ‘No man told me by word of mouth.’ Benedict asked again, ‘Who then, my lord? Perhaps thou hast heard in a letter from some one?’ He replied, ‘Of a truth, not in a letter.’ Again[31] Benedict asked, ‘If neither from the words of any man, nor from any man’s letter, thou knewest this beforehand, pray, my father, in what way didst thou know it?—tell me.’ Albinus said, ‘Do not interrogate me further on this.’ There the matter ended. When the venerable man Benedict was minded to return, he asked Albinus to tell him in what special words he prayed, when he prayed for himself. Albinus said, ‘This is what I ask of Christ:—Lord, grant me to understand my sins, and to make true confession, and to do fitting penance; and grant unto me remission of my sins.’ The godly man Benedict said, ‘Let us add, my father, to this thy prayer, one word, namely this, after remission, save me.’ Albinus rejoiced, and said, ‘Let it be so, most reverent son, let it be so.’ Benedict then asked another question, would he tell him what were the words that silently moved his lips when he saw the Cross and bent before it? Albinus answered, ‘Thy Cross we adore, O Lord; Thy glorious Passion we recall. Have mercy on us, Thou Who didst die for us.’ Albinus then saw him on his way for a short distance, and sent him back rejoicing to his own place and people.”

The biographer next sets before us a remarkable picture of the four most important personages of the time.

“The great king and powerful emperor Karl, wishing to offer prayer and to have some mutually desired conversation with Alcuin, paid a visit to the tomb of the holy Martin at Tours, with his sons Charles, Pepin, and Louis. The emperor took Alcuin by the hand, and said to him privately, ‘My lord master, which of these sons of mine does[32] it seem to thee that I shall have as my successor in this honour to which God has raised me, all unworthy?’ Alcuin turned his face towards Louis, the youngest of the three, and the most remarkable for his humility, on account of which he was regarded by many as of little account, and said, ‘In the humble Louis thou shalt have an illustrious successor.’ The emperor alone heard what he said. But when, later on, sitting on the spot where he wished to be buried, Alcuin saw these same three kings[43] enter the Church of St. Stephen for prayer, with head erect, and Louis with head bent, he said to those who stood by—‘Do you see that Louis is more humble than his brothers? You will most certainly see him the most exalted successor of his father.’ When with his own hand he administered to them the Communion of the Body of Christ and the Blood, the same Louis, most noted above all for humility, bent before the holy father and kissed his hand.[44] The man of the Lord said to Sigulf who stood by, ‘Whosoever exalteth himself shall be abased, and he that humbleth himself shall be exalted. Certainly the Frankish land shall rejoice to have this man emperor after his father.’ That this has taken place, the biographer adds, we both see and rejoice.[45] They who seemed to be cedars are[33] cast down, and the fruitful olive tree in the house of God is exalted.[46]

“The father Alcuin had with great care instructed Karl in liberal arts and in divine scripture, so that he became the most learned of all kings of the Franks who have been since the coming of Christ. He taught him, also, which of the Psalms he should sing throughout his whole life for various occasions; for times of penitence, with litany and entreaties and prayers; for times of special prayer; of praising God; of any tribulation; and for his being moved to exercise himself in divine praise. Any one who wishes to know all this may read it in the little book which he wrote to Karl on the principles of prayer.”[47]

At this point in his narrative the biographer relates the scrape into which “the little old fellow” got in connexion with his secret study of Vergil, already described on page 2. As a further instance of Alcuin’s remarkable knowledge of what was going on, he adds the interesting little story about a present of wine to Cormery which will be found on p. 223. Then comes the following amusing account, with its revelation of a dislike of Karl’s favourites the foreigners, a dislike which Eginhard thus frankly reports in his vivid picture of the great King,[48] “He loved foreigners, and took great pains to attract them to him and to maintain them, so much so that the multitude of them not unreasonably[34] seemed a heavy burden, not to the palace only but to the kingdom. His greatness of mind, however, was such, that he was not troubled by a burden of this kind; indeed even great inconveniences he regarded as compensated by the praise won by liberality and by the reward of good report.”

This is the story. The presbyter Aigulf[49], an Anglo-Saxon[50] himself too, came to Tours to visit the father. When he was standing at the door of Alcuin’s dwelling, there happened to be four of the brethren of Tours talking together. When they saw him, they said one to another, not imagining that he knew anything of their language, “Here’s a Briton, or a Scot[51], come to see that other Briton inside. O God, deliver this monastery from these Britons! Like bees coming back to the mother-bee, these all come to this man of ours!” What would we not give to have this in the words in which they spoke it, instead of in the author’s Latin. The presbyter went into Alcuin’s dwelling, and, after other matters, told him what he had heard. “Do you know which they are?” Alcuin asked. “Indeed I do not. I could not for shame[35] look at them when they said that.” Alcuin said, “I am sure I know who they are.” He called in some of the brethren by name, and said, “These are they.” Greatly grieved by their folly, Alcuin yet spared them, saying, “May Christ, the Son of God, spare them.” Then he gave them each a cup of wine to drink, and without severity sent them away. Aigulf afterwards made diligent inquiry, and found that they were the right men. We of to-day may remark that Alcuin evidently knew the characters of his pupils; but his ideas of discipline differed from ours. We should not have let them know that we had heard personal remarks of that kind; and we should not have given them glasses of wine. We may remember the words of Archbishop Temple to Bishop Creighton, when the Bishop had received the late Mr. John Kensit for an interview at Fulham, and had given him tea. “It was all right to receive the man; but you shouldn’t ha’ given him tea.”

As we have seen, the biographer on the whole confines himself to those parts of Alcuin’s Life which were not of common knowledge. But there was one story of sufficient importance in his judgement to be related at length, although it was well known. We may well take the same view, and be grateful to our author for having departed from his self-imposed limitations.

“I ought not”, he writes, “to pass over in silence one fact which many know. The Keeper of the Sepulchre of St. Martin, who provided the wax and all the vestments which pertained to the basilica itself, entering with a lighted candle the sacristy where they were kept, fixed the candle on a[36] spike, and when he left he forgot to take it with him. He locked the door and went away. The burning candle fell upon some wax and sent a great flame which set fire to the vestments hanging on the pegs; and the vestments sent the flame up to the roof.[52] When the warden saw this, he fled with the key to another monastery.[53] People rushed from all sides; they beat at the door, but all their efforts failed to burst it open. The clerks threw out of the windows any valuables they had in their abode. The Church of St. Martin was denuded of some vestments, and no one expected anything but the burning of the whole monastery. The roof was all stripped of lead. Albinus came; he was now blind. He asked what was being done. One of his disciples, his ‘little old fellow’, said, ‘Come away, father, or you will be killed by the lead they are throwing down or burned to death.’ When Albinus was willing to go, Vetulus said to[37] him, ‘My lord father, go to the sepulchre of the lord Martin, and intercede for us.’ Albinus did as was suggested, and when he got to the place, he stretched himself on the ground in the form of a cross, and uttered groans heavenward. As soon as Albinus cast himself on the ground, in some wonderful and incredible way the whole fire was put out, as completely as if extinguished by a great river. When the clerks saw this, they rushed in joyous stupefaction to the spot where Albinus lay prostrate before the sepulchre of St. Martin, in the form of a cross, praying to God for them. They raised him from the ground, blessing God who through the prayers of Albinus had saved the whole monastery of Saint Martin from being consumed by fire. These be thy worthy examples, holy Martin, who once when thou wouldest escape the fire couldest not; turned to God in prayer thou hast extinguished this fire that threatened us. Lofty of a truth is the faith that by its ardour can extinguish globes of fire. Nor is it a matter of wonder that the elements leave their proper force at the prayers and commands of Albinus, since he rests in the heart of Him who loves them that love Him, and permits them not to be singed by the flame when they walk in fire. Thee in these we adore, Thee we glorify, Thee we laud, who, as Thou hast deigned to make promises to Thy servants who keep Thy commandments, hast shown them forth most clearly by Thy works in Thine own Albinus. Thou hast said, O Christ Jesus, whatsoever ye shall ask of Me in My name, that will I do, that the Father may be glorified in the Son.”

It will have been noticed that this passage from the Life attributes to St. Martin a failure to prevent the progress of a fire. The reference appears at first sight to be to the eleventh chapter of the Life of St. Martin by Sulpicius Severus[54], written some four hundred years before the fire here described, and published in the lifetime of St. Martin, whom Severus had visited at Tours for the special purpose of learning the facts of his life.

“In a certain town, Martin set fire to a very ancient and famous pagan shrine. A house was attached to the walls of the temple, and the wind blew the globes of fire on to this house. When Martin saw this, he climbed rapidly to the roof of the house, and faced the flames. Then you would see the flame turn back in a marvellous manner against the force of the wind, the two elements fighting the one against the other. Thus by the virtue of Martin the fire operated only where it was bidden.”

This is the only account in the Life of St. Martin to which the remark in the text could apply. But, as a matter of fact, the occasion referred to was quite different from this. The little story is an interesting example of the keenness of criticism in those very early times, and of the need of immediate corrections.

The contemporary readers of the Life were well aware of the fact that Martin himself was[39] once half-burned. Knowing this, they fastened on the passage quoted, and spoke in a depreciatory way of Martin. They asked how could he be so great as to prevent houses being burned, if he was not great enough to prevent himself from being set on fire and nearly burned to death. These depreciatory remarks came to the ears of Sulpicius, and the very next day[55], he sat down and wrote a letter to the presbyter Eusebius, to tell the actual facts of the other story with which unfavourable comparison has been made. The facts were as follows:—

The saint was visiting his diocese in midwinter. A bed had been prepared for him in a vestry, which was warmed by a fire below the floor. The pavement was rough and dilapidated. They had made for the saint a specially soft and comfortable bed of straw, but his practice was to sleep on the bare ground. Not being able to endure the blandient comfort of the straw, he threw it away and slept on the ground. By midnight the fire below had got at the straw through the crevices in the pavement, and Martin awoke to find the vestry full of fire. Then came, as he told Sulpicius, the temptation of the devil. Martin tried to escape, instead of turning to prayer. He rushed to the door and struggled with the bolt, in vain. The flames caught his dress and set it on fire. He fell down, and then remembered to pray. The flames felt the change and spared him. The monks, who had heard the fire crackling and roaring,[40] burst open the door and looked for his dead body; they found him safe and sound. He confessed to Sulpicius, not without groaning, that the devil had for the time overcome him. In these modern times, to lie down on the floor is a common precaution against being smothered by the smoke in a burning room.

This Life of St. Martin is very interesting reading. It is too tempting to give the substance of the chapter previous to the one given above. The saint was at his usual work of destroying a very ancient temple. When he had accomplished this, he set to work to fell a pine-tree which stood near. The chief priest and the pagan crowd drew the line at that, and would not allow it. Martin told them there was nothing worthy of worship in a piece of wood; it was dedicated to a demon and it must come down. Thereupon a crafty pagan, seeing his way to getting rid of this objectionable destroyer of temples, and regarding the sacred tree as well lost for such a gain, proposed a bargain. “If you have sufficient confidence in your God whom you say you serve, we will ourselves cut down the tree, and it shall fall upon you; if your Lord is with you, as you say, you will escape with your life.” The bargain was struck on both sides. The tree leaned in a certain direction, so that there was no doubt where it would fall. Martin was tied by the rustics in the right place, and they began to cut with their axes. The tree began to nod, leaned more and more to the precise spot they had selected. At last they had cut deep enough; the crash of the rending trunk was heard; the monks turned pale; the saint raised[41] his hand and made the sign of the cross; at the moment a whirlwind came and blew the tree far to one side.

We must now return to the life of St. Martin’s faithful follower, Alcuin.

“This also must be mentioned to the praise of the Lord, that very frequently many infirm people, when they came to Albinus and received his benediction with faith, recovered bodily health. On a certain occasion, as is reported by some of the chief authorities, a poor man came, having his eyesight obstructed by a grievous dimness. He reached the door of the outer dwelling of Albinus, and begged that water be given him with which his eyes might be bathed; for he said it had been revealed to him that if he could wash his eyes with some of it he would recover his sight.[56] Unknown to Albinus, some of the water in which he had washed his own face and eyes was secretly given to the poor man who begged for water. The poor man bathed his eyes with the water, in full faith; the dimness disappeared, and he recovered his clearness of sight. We, too, are enlightened by thy sweat, father, and the sins of our souls are washed by thy pious doctrine. Thou, too, didst scarce see anything with thy bodily sight, but wast always engaged in lightening the eyes of others; and those whom thou couldest not enlighten in bodily presence thou didst in absence instruct by letters, writing many things profitable to the whole church.

“For at the request of Karl he wrote a most useful book on the Holy Trinity; also on rhetoric, dialectic, and music. He wrote to Gundrad on the nature of the soul. At the most honourable request of the ladies Gisla and Rotruda, he composed a remarkable book on the Gospel of St. John, partly his own and partly taken from the holy Augustine. He wrote also on four Epistles of Paul, to the Ephesians, to Titus, to Philemon, and to the Hebrews;[57] to Fredegisus on the Psalms;[58] to Count Wido[59] homilies on the principal vices and virtues; to his own Sigulf very useful notes on Genesis; on the Proverbs of Solomon, on Ecclesiastes, on the Song of Songs clearly, briefly, indescribably. Under the names Frank and Saxon[60] he wrote a most able book on grammar in the form of question and answer. He collected two volumes of homilies from many works of the Fathers. He wrote on orthography. On the 118th Psalm (our 119th) he wrote with a pen of gold. There are many other writings in which any one who reads and studies them attentively will find no small edification, as in the letters which he wrote to[43] many persons. In these and like works he spent the remainder of his days, living on earth the life of heaven. Preparing himself in his latest days for the coming of the Son of Man, that he might go in with Him to the wedding, he washed every night his couch with tears,[61] always fortifying himself with the intercessions of the saints, whose solemnities he regularly celebrated, lest he should be pierced by any darts of the ancient enemy, who never could steal into his dwelling so secretly as not to be at once detected by him and driven out by the sign of the Cross.

“On a certain night, when he desired to pour forth prayer in secret after his wont, with chanting of Psalms, he was oppressed by very heavy sleep. But he rose from his couch, and put on his cape; and when again he was oppressed with sleep, he took off all his clothes except his shirt and drawers. The sleepiness continuing, he took a censer, and going to the place where fire was kept burning, he filled it with live coal and put incense on it, and a sweet odour filled the chamber. In that hour the devil presented himself to him in bodily form, as it were a large man, very black and misshapen and bearded, hurling at him darts of blasphemy. ‘Why dost thou act the hypocrite, Alcuin?’[62] he asked. ‘Why dost thou attempt to appear just before men, when thou art a deceiver and a great dissimulator? Dost thou suppose that for these feignings of thine Christ can hold thee[44] to be acceptable?’ But the soldier of Christ, invincible, standing with David in the tower[63] builded for an armoury, wherein there hang a thousand bucklers, all shields of mighty men, said with a heavenly voice, ‘The Lord is my light and my salvation; whom then shall I fear? He is the strength of my life; of whom then shall I be afraid? Hear my crying, O Lord; incline thine ear to my calling, my King and my God, for unto Thee do I make my prayer.’ With these and other verses of the Psalms the enemy was at length put to flight; Albinus completed his prayer and went to rest.[64] At that time only one of his disciples, Waltdramn by name, who is still alive, was watching with him; he saw all this from a place of concealment, a witness of this thing that took place.”

St. Martin himself once had a meeting with the devil[65]. There came into his cell a purple light, and one stood in the midst thereof clad in a royal robe, having on his head a diadem of gold and precious stones, his shoes overlaid with gold, his countenance serene, his face full of joy, looking like anything but the devil. The devil spoke first. “Know, Martin, whom you behold. I am Christ. I am about to descend from heaven to the world. I willed first to manifest myself to thee.” Martin held his tongue. “Why dost thou doubt, Martin, whom thou seest? I am Christ.” Then the Spirit[45] revealed that this was the devil, not God, and he answered, “The Lord Jesus did not predict that He would come again resplendent with purple and diadem. I will not believe that Christ has come, except in the form in which He suffered, bearing the stigmata of the Cross.” Thereupon the apparition vanished like smoke, leaving so very bad a smell that there was no doubt it was the devil. “This account I had from the mouth of Martin himself,” Sulpicius adds.

“The father used a little wine, in accordance with the apostle’s precept, not for the pleasure of the palate, but by reason of his bodily weakness.[66] In every kind of way he avoided idleness; either he read, or he wrote, or he taught his disciples, or he gave himself to prayer and the chanting of Psalms, yielding only to unavoidable necessities of the body. He was a father to the poor, more humble than the humble, an inviter to piety of the rich, lofty to the proud, a discerner of all, and a marvellous comforter. He celebrated every day many solemnities of masses[67] with honourable diligence, having proper masses deputed for each day of the week. Moreover, on the Lord’s day, never at any time after the light of dawn began to[46] appear did he allow himself to slumber, but swiftly preparing himself as deacon with his own priest Sigulf he performed the solemnities of special masses till the third hour, and then with very great reverence he went to the public mass. His disciples, when they were in other places, especially when they assisted ad opus Dei, carefully studied that no cause of blame be seen in them by him.

“The time had come when Albinus had a desire to depart and be with Christ. He prayed with all his will that if it might be, he should pass from the world on the day on which the Holy Spirit was seen to come upon the apostles in tongues of fire, and filled their hearts. Saying for himself the vesper office, in the place which he had chosen as his resting-place after death, namely, near the Church of St. Martin, he sang through the evangelic hymn of the holy Mary with this antiphon[68], ‘O Key of David, and sceptre of the house of Israel, who openest and none shutteth, shuttest and none openeth, come and lead forth from the house of his prison this fettered one, sitting in darkness and the shadow of death.’ Then he said the Lord’s Prayer. Then several Psalms—Like as the hart desireth the water-brooks. O how amiable are Thy dwellings, Thou Lord of hosts. Blessed are they that dwell in Thy house. Unto Thee lift I up mine eyes. One thing I have desired of the Lord. Unto Thee, O Lord, will I lift up my soul.

“He spent the season of Lent, according to his custom, in the most worthy manner, with all[47] contrition of flesh and spirit and purifying of habit. Every night he visited the basilicas of the saints which are within the monastery of St. Martin,[69] washing himself clean of his sins with heavy groans. When the solemnity of the Resurrection of the Lord was accomplished, on the night of the Ascension he fell on his bed, oppressed with languor even unto death, and could not speak. On the third day before his departure he sang with exultant voice his favourite antiphon, ‘O key of David,’ and recited the verses mentioned above. On the day of Pentecost, the matin office having been performed, at the very hour at which he had been accustomed to attend masses, at opening dawn, the holy soul of Albinus is[70] released from the body, and by the ministry of the celestial deacons, having with them the first martyr Stephen and the archdeacon Laurence, with an army of angels, he is led to Christ, whom he loved, whom he sought; and in the bliss of heaven he has for ever the fruition of the glory of Him whom in this world he so faithfully served.”

The Annals of Pettau enable us to fill in some details of Alcuin’s death. Pettau was not far from Salzburg, and therefore the monastery was likely to be well informed. Arno of Salzburg, Alcuin’s great admiration and his devoted personal friend, would see to it that in his neighbourhood all ecclesiastics knew the details. The seizure on the occasion of his falling on his bed was a paralytic stroke. It occurred, according to the Annals[48] from which we are quoting, on the fifth day of the week on the eighth of the Ides of May, that is, on May 8; but in that year, 804, Ascension Day fell on May 9, so that for the eighth of the Ides we must read the seventh of the Ides. The seizure took place at vesper tide, after sunset. He lived on till May 19, Whitsunday, on which day he died, just as the day broke.

“On that night,” to return to the Life, “above the church of the holy Martin there was seen an inestimable clearness of splendour, so that to persons at a distance it seemed that the whole was on fire. By some, that splendour was seen through the whole night, to others it appeared three times in the night. Joseph the Archbishop of Tours testified that he and his companions saw this throughout the night. Many that are still sound in body testify the same. To more persons, however, this brightness appeared in the same manner, not on that but on a former night, namely, on the night of the first Sunday after the Ascension.

“At that same hour there was displayed to a certain hermit in Italy the army of the heavenly deacons, sounding forth the ineffable praises of Christ in the air; in the midst of whom Alchuin[71] stood, clothed with a most splendid dalmatic, entering with them into heaven to minister with perennial joy to the Eternal Pontiff. This hermit on that same day of Pentecost told what he had seen to one of the brethren of Tours, who was making his accustomed way to visit the thresholds[49] of the Apostles.[72] The hermit asked him these questions,—‘Who is that Abbat that lives at Tours, in the monastery of the holy Martin? By what name is he called? And was he well in body when you left?’ The brother replied, ‘He is called Alchuin, and he is the best teacher in all France. When I started on my way hither, I left him well.’ The solitary made rejoinder, with tears, that he was indeed enjoying the very happiest health; and he told him what he had seen at day-break that day. When the brother got back to Tours, he related what he had heard.

“Father Sigulf, with certain others, washed the body of the father with all honour, and placed it on a bier. Now Sigulf had at the time a great pain in the head, but being by faith sound in mind, he found a ready cure for his head. Raising his eyes above the couch of the master, he saw the comb[73] with which he was wont to comb his head. Taking it in his hands he said, ‘I believe, Lord Jesus, that if I combed my head with this my master’s comb, my head would at once be cured by his merits.’ The moment he drew the comb across his head, that part of the head which it touched was immediately cured, and thus by combing his head all round he lost the pain completely. Another of his disciples, Eangist by name, was grievously afflicted with immense pain in his teeth. By Sigulf’s advice he touched his[50] teeth with the comb, and forthwith, because he did it in faith, he received a cure by the merits of Alchuin.

“When Joseph, the bishop of the city of Tours, a man good and beloved of God, heard that the blessed Alchuin was dead, he came to the spot immediately with his clerks, and washing Alchuin’s eyes with his tears, he kissed him frequently. He advised, moreover, using wise counsel, that he should not be buried outside, in the place where the father himself had willed, but with all possible honour within the basilica of the holy Martin, that the bodies of those whose souls are united in heaven should on earth lie in one home. And thus it was done. Above his tomb was placed, as he had directed, a title which he had dictated in his lifetime, engraved on a plate of bronze let into the wall.”[74]

The simple epitaph, apart from the title, ran thus:—

“Here doth rest the lord Alchuuin the Abbat, who died in peace on the fourteenth of the Kalends of June. When you read, O all ye who pass by, pray for him and say, The Lord grant unto him eternal rest.”

The large bulk of Alcuin’s letters and other writings.—The main dates of his life.—Bede’s advice to Ecgbert.—Careless lives of bishops.—No parochial system.—Inadequacy of the bishops’ oversight.—Great monasteries to be used as sees for new bishoprics, and evil monasteries to be suppressed.—Election of abbats and hereditary descent.—Evils of pilgrimages.—Daily Eucharists.