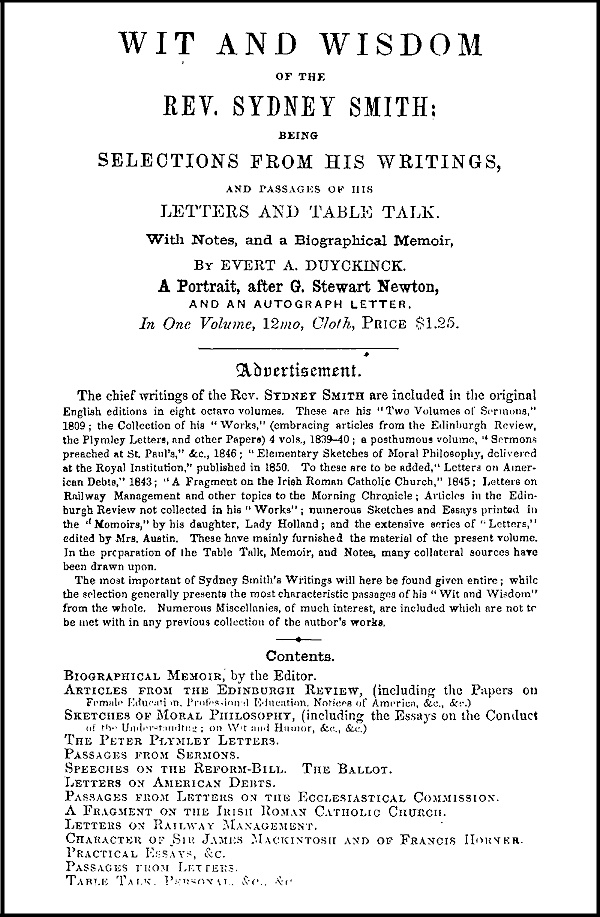

WIT AND WISDOM

OF THE

REV. SYDNEY SMITH:

BEING

SELECTIONS FROM HIS WRITINGS,

AND PASSAGES OF HIS

LETTERS AND TABLE TALK.

With Notes, and a Biographical Memoir,

By EVERT A. DUYCKINCK.

A Portrait, after G. Stewart Newton,

AND AN AUTOGRAPH LETTER.

In One Volume, 12mo, Cloth, Price $1.25.

Advertisement.

The chief writings of the Rev. Sydney Smith are included in the original English editions in eight octavo volumes. These are his “Two Volumes of Sermons,” 1809; the Collection of his “Works,” (embracing articles from the Edinburgh Review, the Plymley Letters, and other Papers) 4 vols., 1839-40; a posthumous volume, “Sermons preached at St. Paul’s,” &c., 1846; “Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy, delivered at the Royal Institution,” published in 1850. To these are to be added, “Letters on American Debts,” 1843; “A Fragment on the Irish Roman Catholic Church,” 1845; Letters on Railway Management and other topics to the Morning Chronicle; Articles in the Edinburgh Review not collected in his “Works”; numerous Sketches and Essays printed in the “Memoirs,” by his daughter, Lady Holland; and the extensive series of “Letters,” edited by Mrs. Austin. These have mainly furnished the material of the present volume. In the preparation of the Table Talk, Memoir, and Notes, many collateral sources have been drawn upon.

The most important of Sydney Smith’s Writings will here be found given entire; while the selection generally presents the most characteristic passages of his “Wit and Wisdom” from the whole. Numerous Miscellanies, of much interest, are included which are not to be met with in any previous collection of the author’s works.

Contents.

Biographical Memoir, by the Editor.

Articles from the Edinburgh Review, (including the Papers on Female Education, Professional Education, Notices of America, &c., &c.)

Sketches of Moral Philosophy, (including the Essays on the Conduct of the Understanding; on Wit and Humor, &c., &c.)

The Peter Plymley Letters.

Passages from Sermons.

Speeches on the Reform-Bill. The Ballot.

Letters on American Debts.

Passages from Letters on the Ecclesiastical Commission.

A Fragment on the Irish Roman Catholic Church.

Letters on Railway Management.

Character of Sir James Mackintosh and of Francis Horner.

Practical Essays, &c.

Passages from Letters.

Table Talk. Personal, &c., &c.

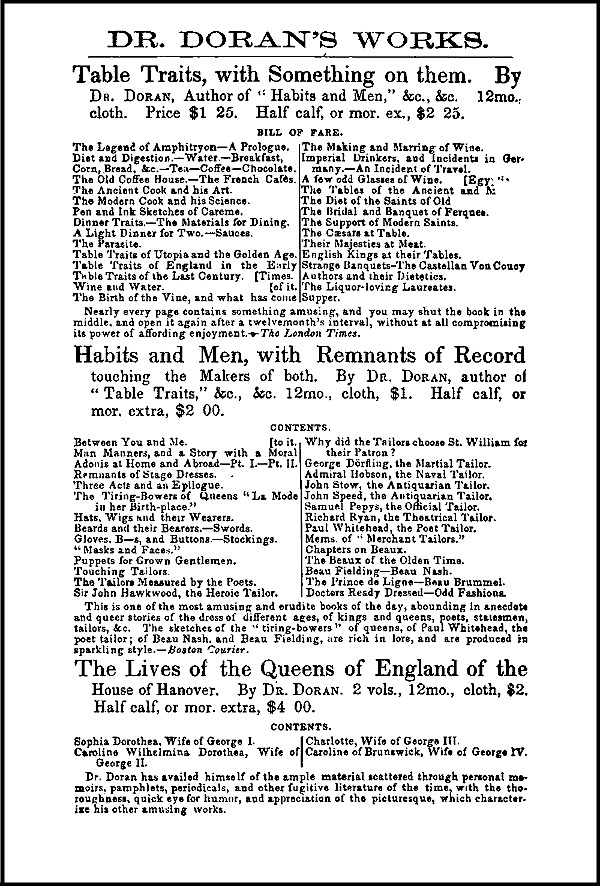

DR. DORAN’S WORKS.

Table Traits, with Something on them. By Dr. Doran, Author of “Habits and Men,” &c., &c. 12mo., cloth. Price $1 25. Half calf, or mor. ex., $2 25.

BILL OF FARE.

The Legend of Amphitryon—A Prologue.

Diet and Digestion.—Water—Breakfast,

Corn, Bread, &c.—Tea—Coffee—Chocolate.

The Old Coffee House.—The French Cafés.

The Ancient Cook and his Art.

The Modern Cook and his Science.

Pen and Ink Sketches of Careme.

Dinner Traits.—The Materials for Dining.

A Light Dinner for Two.—Sauces.

The Parasite.

Table Traits of Utopia and the Golden Age.

Table Traits of England in the Early Times.

Table Traits of the Last Century.

Wine and Water.

The Birth of the Vine, and what has come of it.

The Making and Marring of Wine.

Imperial Drinkers, and Incidents in Germany.—An

Incident of Travel.

A few odd Glasses of Wine. [Egyptian]

The Tables of the Ancient and Modern

The Diet of the Saints of Old.

The Bridal and Banquet of Ferques.

The Support of Modern Saints.

The Cæsars at Table.

Their Majesties at Meat.

English Kings at their Tables.

Strange Banquets—The Castellan Von Coucy.

Authors and their Dietetics.

The Liquor-loving Laureates.

Supper.

Nearly every page contains something amusing, and you may shut the book in the middle, and open it again after a twelvemonth’s interval, without at all compromising its power of affording enjoyment.—The London Times.

Habits and Men, with Remnants of Record touching the Makers of both. By Dr. Doran, author of “Table Traits,” &c., &c. 12mo., cloth, $1. Half calf, or mor. extra, $2 00.

CONTENTS.

Between You and Me.

Man Manners, and a Story with a Moral to it.

Adonis at Home and Abroad—Pt. I.—Pt. II.

Remnants of Stage Dresses.

Three Acts and an Epilogue.

The Tiring-Bowers of Queens “La Mode

in her Birth-place.”

Hats, Wigs and their Wearers.

Beards and their Bearers.—Swords.

Gloves, B—s, and Buttons.—Stockings.

“Masks and Faces.”

Puppets for Grown Gentlemen.

Touching Tailors.

The Tailors Measured by the Poets.

Sir John Hawkwood, the Heroic Tailor.

Why did the Tailors choose St. William for

their Patron?

George Dörfling, the Martial Tailor.

Admiral Hobson, the Naval Tailor.

John Stow, the Antiquarian Tailor.

John Speed, the Antiquarian Tailor.

Samuel Pepys, the Official Tailor.

Richard Ryan, the Theatrical Tailor.

Paul Whitehead, the Poet Tailor.

Mems. of “Merchant Tailors.”

Chapters on Beaux.

The Beaux of the Olden Time.

Beau Fielding—Beau Nash.

The Prince de Ligne—Beau Brummel.

Doctors Ready Dressed—Odd Fashions.

This is one of the most amusing and erudite books of the day, abounding in anecdote and queer stories of the dress of different ages, of kings and queens, poets, statesmen, tailors, &c. The sketches of the “tiring-bowers” of queens, of Paul Whitehead, the poet tailor; of Beau Nash, and Beau Fielding, are rich in lore, and are produced in sparkling style.—Boston Courier.

The Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover. By Dr. Doran. 2 vols., 12mo., cloth, $2. Half calf, or mor. extra, $4 00.

CONTENTS.

Sophia Dorothea, Wife of George I.

Caroline Wilhelmina Dorothea, Wife of George II.

Charlotte, Wife of George III.

Caroline of Brunswick, Wife of George IV.

Dr. Doran has availed himself of the ample material scattered through personal memoirs, pamphlets, periodicals, and other fugitive literature of the time, with the thoroughness, quick eye for humor, and appreciation of the picturesque, which characterize his other amusing works.

KNIGHTS

AND THEIR DAYS

BY DR. DORAN

AUTHOR OF “LIVES OF THE QUEENS OF ENGLAND OF THE HOUSE OF HANOVER,”

“TABLE TRAITS,” “HABITS AND MEN,” ETC.

REDFIELD

34 BEEKMAN STREET, NEW YORK

1856

TO

PHILIPPE WATIER, ESQ.

IN MEMORY OF MERRY NIGHTS AND DAYS NEAR METZ AND THE

MOSELLE,

THIS LITTLE VOLUME

Is inscribed

BY HIS VERY SINCERE FRIEND,

THE AUTHOR.

CONTENTS.

| A FRAGMENTARY PROLOGUE | PAGE 9 |

| THE TRAINING OF PAGES | 30 |

| KNIGHTS AT HOME | 36 |

| LOVE IN CHEVALIERS, AND CHEVALIERS IN LOVE | 51 |

| DUELLING, DEATH, AND BURIAL | 65 |

| THE KNIGHTS WHO “GREW TIRED OF IT” | 78 |

| FEMALE KNIGHTS AND JEANNE DARC | 104 |

| THE CHAMPIONS OF CHRISTENDOM | 113 |

| SIR GUY OF WARWICK, AND WHAT BEFELL HIM | 133 |

| GARTERIANA | 148 |

| FOREIGN KNIGHTS OF THE GARTER | 170 |

| THE POOR KNIGHTS OF WINDSOR, AND THEIR DOINGS | 184 |

| THE KNIGHTS OF THE SAINTE AMPOULE | 194 |

| THE ORDER OF THE HOLY GHOST | 200 |

| JACQUES DE LELAING | 208 |

| THE FORTUNES OF A KNIGHTLY FAMILY | 228 |

| THE RECORD OF RAMBOUILLET | 263 |

| SIR JOHN FALSTAFF | 276 |

| STAGE KNIGHTS | 295 |

| STAGE LADIES, AND THE ROMANCE OF HISTORY | 312 |

| THE KINGS OF ENGLAND AS KNIGHTS; FROM THE NORMANS TO THE STUARTS |

329 |

| “THE INSTITUTION OF A GENTLEMAN” | 351 |

| THE KINGS OF ENGLAND AS KNIGHTS; THE STUARTS | 358 |

| THE SPANISH MATCH | 364 |

| THE KINGS OF ENGLAND AS KNIGHTS; FROM STUART TO BRUNSWICK | 375 |

| RECIPIENTS OF KNIGHTHOOD | 388 |

| RICHARD CARR, PAGE, AND GUY FAUX, ESQUIRE | 410 |

| ULRICH VON HUTTEN | 420 |

| SHAM KNIGHTS | 439 |

| PIECES OF ARMOR | 455 |

[Pg 9]

THE

KNIGHTS AND THEIR DAYS.

Dr. Lingard, when adverting to the sons of Henry II., and their knightly practices, remarks that although chivalry was considered the school of honor and probity, there was not overmuch of those or of any other virtues to be found among the members of the chivalrous orders. He names the vices that were more common, as he thinks, and probably with some justice. Hallam, on the other hand, looks on the institution of chivalry as the best school of moral discipline in the Middle Ages: and as the great and influential source of human improvement. “It preserved,” he says, “an exquisite sense of honor, which in its results worked as great effects as either of the powerful spirits of liberty and religion, which have given a predominant impulse to the moral sentiments and energies of mankind.”

The custom of receiving arms at the age of manhood is supposed, by the same author, to have been established among the nations that overthrew the Roman Empire; and he cites the familiar passage from Tacitus, descriptive of this custom among the Germans. At first, little but bodily strength seems to have been required on the part of the candidate. The qualifications and the forms of investiture changed or improved with the times.

[Pg 10]

In a general sense, chivalry, according to Hallam, may be referred to the age of Charlemagne, when the Caballarii, or horsemen, became the distinctive appellation of those feudal tenants and allodial proprietors who were bound to serve on horseback. When these were equipped and formally appointed to their martial duties, they were, in point of fact, knights, with so far more incentives to distinction than modern soldiers, that each man depended on himself, and not on the general body. Except in certain cases, the individual has now but few chances of distinction; and knighthood, in its solitary aspect, may be said to have been blown up by gunpowder.

As examples of the true knightly spirit in ancient times, Mr. Hallam cites Achilles, who had a supreme indifference for the question of what side he fought upon, had a strong affection for a friend, and looked at death calmly. I think Mr. Hallam over-rates the bully Greek considerably. His instance of the Cid Ruy Diaz, as a perfect specimen of what the modern knight ought to have been, is less to be gainsaid.

In old times, as in later days, there were knights who acquired the appellation by favor rather than service; or by a compelled rather than a voluntary service. The old landholders, the Caballarii, or Milites, as they came to be called, were landholders who followed their lord to the field, by feudal obligation: paying their rent, or part of it, by such service. The voluntary knights were those “younger brothers,” perhaps, who sought to amend their indifferent fortunes by joining the banner of some lord. These were not legally knights, but they might win the honor by their prowess; and thus in arms, dress, and title, the younger brother became the equal of the wealthy landholders. He became even their superior, in one sense, for as Mr. Hallam adds:—“The territorial knights became by degrees ashamed of assuming a title which the others had won by merit, till they themselves could challenge it by real desert.”

The connection of knighthood with feudal tenure was much loosened, if it did not altogether disappear, by the Crusades. There the knights were chiefly volunteers who served for pay: all feudal service there was out of the question. Its connection with religion was, on the other hand, much increased, particularly[Pg 11] among the Norman knights who had not hitherto, like the Anglo-Saxons, looked upon chivalric investiture as necessarily a religious ceremony. The crusaders made religious professors, at least, of all knights, and never was one of these present at the reading of the gospel, without holding the point of his sword toward the book, in testimony of his desire to uphold what it taught by force of arms. From this time the passage into knighthood was a solemn ceremony; the candidate was belted, white-robed, and absolved after due confession, when his sword was blessed, and Heaven was supposed to be its director. With the love of God was combined love for the ladies. What was implied was that the knight should display courtesy, gallantry, and readiness to defend, wherever those services were required by defenceless women. Where such was bounden duty—but many knights did not so understand it—there was an increase of refinement in society; and probably there is nothing overcharged in the old ballad which tells us of a feast at Perceforest, where eight hundred knights sat at a feast, each of them with a lady at his side, eating off the same plate; the then fashionable sign of a refined friendship, mingled with a spirit of gallantry. That the husbands occasionally looked with uneasiness upon this arrangement, is illustrated in the unreasonably jealous husband in the romance of “Lancelot du Lac;” but, as the lady tells him, he had little right to cavil at all, for it was an age since any knight had eaten with her off the same plate.

Among the Romans the word virtue implied both virtue and valor—as if bravery in a man were the same thing as virtue in a woman. It certainly did not signify among Roman knights that a brave man was necessarily virtuous. In more recent times the word gallantry has been made also to take a double meaning, implying not only courage in man, but his courtesy toward woman. Both in ancient and modern times, however, the words, or their meanings, have been much abused. At a more recent period, perhaps, gallantry was never better illustrated than when in an encounter by hostile squadrons near Cherbourg, the adverse factions stood still, on a knight, wearing the colors of his mistress, advancing from the ranks of one party, and challenging to single combat the cavalier in the opposite ranks who was the most[Pg 12] deeply in love with his mistress. There was no lack of adversaries, and the amorous knights fell on one another with a fury little akin to love.

A knight thus slain for his love was duly honored by his lady and contemporaries. Thus we read in the history of Gyron le Courtois, that the chivalric king so named, with his royal cousin Melyadus, a knight, by way of equerry, and a maiden, went together in search of the body of a chevalier who had fallen pour les beaux yeux of that very lady. They found the body picturesquely disposed in a pool of blood, the unconscious hand still grasping the hilt of the sword that had been drawn in honor of the maiden. “Ah, beauteous friend!” exclaims the lady, “how dearly hast thou paid for my love! The good and the joy we have shared have only brought thee death. Beauteous friend, courteous and wise, valiant, heroic, good knight in every guise, since thou has lost thy youth for me in this manner, in this strait, and in this agony, as it clearly appears, what else remains for me to suffer for thy sake, unless that I should keep you company? Friend, friend, thy beauty has departed for the love of me, thy flesh lies here bloody. Friend, friend, we were both nourished together. I knew not what love was when I gave my heart to love thee,” &c., &c., &c. “Young friend,” continues the lady, “thou wert my joy and my consolation: for to see thee and to speak to thee alone were sufficient to inspire joy, &c., &c., &c. Friend, what I behold slays me, I feel that death is within my heart.” The lady then took up the bloody sword, and requested Melyadus to look after the honorable interment of the knight on that spot, and that he would see her own body deposited by her “friend’s” side, in the same grave. Melyadus expressed great astonishment at the latter part of the request, but as the lady insisted that her hour was at hand, he promised to fulfil all her wishes. Meanwhile the maiden knelt by the side of the dead knight, held his sword to her lips, and gently died upon his breast. Gyron said it was the wofullest sight that eye had ever beheld; but all courteous as Gyron was, and he was so to such a remarkable degree that he derived a surname from his courtesy, I say that in spite of his sympathy and gallantry, he appears to have had a quick eye toward making such profit as authors could make[Pg 13] in those days, from ready writing upon subjects of interest. Before another word was said touching the interment of the two lovers, Gyron intimated that he would write a ballad upon them that should have a universal circulation, and be sung in all lands where there were gentle hearts and sweet voices. Gyron performed what he promised, and the ballad of “Absdlon and Cesala,” serves to show what very rough rhymes the courteous poet could employ to illustrate a romantic incident. Let it be added that, however the knights may sometimes have failed in their truth, this was very rarely the case with the ladies. When Jordano Bruno was received in his exile by Sir Philip Sidney, he requited the hospitality by dedicating a poem to the latter. In this dedication, he says: “With one solitary exception, all misfortunes that flesh is heir to have been visited on me. I have tasted every kind of calamity but one, that of finding false a woman’s love.”

It was not every knight that could make such an exception. Certainly not that pearl of knights, King Arthur himself. What a wife had that knight in the person of Guinever? Nay, he is said to have had three wives of that name, and that all of them were as faithless as ladies well could be. Some assert that the described deeds of these three are in fact but the evil-doings of one. However this may be, I may observe summarily here what I have said in reference to Guinever in another place. With regard to this triple-lady, the very small virtue of one third of the whole will not salubriously leaven the entire lump. If romance be true, and there is more about the history of Guinever than any other lady—she was a delicious, audacious, winning, seductive, irresistible, and heartless hussy; and a shameless! and a barefaced! Only read “Sir Lancelot du Lac!” Yes, it can not be doubted but that in the voluminous romances of the old day, there was a sprinkling of historical facts. Now, if a thousandth part of what is recorded of this heart-bewitching Guinever be true, she must have been such a lady as we can not now conceive of. True daughter of her mother Venus, when a son of Mars was not at hand, she could stoop to Mulciber. If the king was not at home, she could listen to a knight. If both were away, esquire or page might speak boldly without fear of being unheeded; and if all were absent, in the chase, or at the fray, there was always a good-looking[Pg 14] groom in the saddle-room with whom Guinever could converse, without holding that so to do was anything derogatory. I know no more merry reading than that same ton-weight of romance which goes by the name of “Sir Lancelot du Lac.” But it is not of that sort which Mrs. Chapone would recommend to young ladies, or that Dr. Cumming would read aloud in the Duke of Argyll’s drawing-room. It is a book, however, which a grave man a little tired of his gravity, may look into between serious studies and solemn pursuits—a book for a lone winter evening by a library-fire, with wine and walnuts at hand; or for an old-fashioned summer’s evening, in a bower through whose foliage the sun pours his adieu, as gorgeously red as the Burgundy in your flask. Of a truth, a man must be “in a concatenation accordingly,” ere he may venture to address himself to the chronicle which tells of the “bamboches,” “fredaines,” and “bombances,” of Guinever the Frail, and of Lancelot du Lac.

We confess to having more regard for Arthur than for his triple-wife Guinever. As I have had occasion to say in other pages, “I do not like to give up Arthur!” I love the name, the hero, and his romantic deeds. I deem lightly of his light o’love bearing. Think of his provocation both ways! Whatever the privilege of chivalry may have been, it was the practice of too many knights to be faithless. They vowed fidelity, but they were a promise-breaking, word-despising crew. On this point I am more inclined to agree with Dr. Lingard than with Mr. Hallam. Honor was ever on their lips, but not always in their hearts, and it was little respected by them, when found in the possession of their neighbor’s wives. How does Scott consider them in this respect, when in describing a triad of knights, he says,

Yet how is it that knights are so invariably mentioned with long-winded laudation by Romish writers—always excepting Lingard—when they desire to illustrate the devoted spirit of olden times? Is it that the knights were truthful, devout, chaste, God-fearing? not a jot! Is it because the cavaliers cared but for one thing, in the sense of having fear but for one thing, and that the devil?[Pg 15] To escape from being finally triumphed over by the Father of Evil, they paid largely, reverenced outwardly, confessed unreservedly, and were absolved plenarily. That is the reason why chivalry was patted on the back by Rome. At the same time we must not condemn a system, the principles of which were calculated to work such extensive ameliorations in society as chivalry. Christianity itself might be condemned were we to judge of it by the shortcomings of its followers.

But even Mr. Hallam is compelled at last, reluctantly, to confess that the morals of chivalry were not pure. After all his praise of the system, he looks at its literature, and with his eye resting on the tales and romances written for the delight and instruction of chivalric ladies and gentlemen, he remarks that the “violation of marriage vows passes in them for an incontestable privilege of the brave and the fair; and an accomplished knight seems to have enjoyed as undoubted prerogatives, by general consent of opinion, as were claimed by the brilliant courtiers of Louis XV.” There was an especial reason for this, the courtiers of Louis XV. might be anything they chose, provided that with gallantry they were loyal, courteous, and munificent. Now loyalty, courtesy, and that prodigality which goes by the name of munificence, were exactly the virtues that were deemed most essential to chivalry. But these were construed by the old knights as they were by the more modern courtiers. The first took advantages in combat that would now be deemed disloyal by any but a Muscovite. The second would cheat at cards in the gaming saloons of Versailles, while they would run the men through who spoke lightly of their descent. So with regard to courtesy, the knight was full of honeyed phrases to his equals and superiors, but was as coarsely arrogant as Menschikoff to an inferior. In the same way, Louis XIV., who would never pass one of his own scullery-maids without raising his plumed beaver, could address terms to the ladies of his court, which, but for the sacred majesty which was supposed to environ his person, might have purchased for him a severe castigation. Then consider the case of that “first gentleman in Europe,” George, Prince of Wales: he really forfeited his right to the throne by marrying a Catholic lady, Mrs. Fitzherbert, and he freed himself unscrupulously from the scrape by uttering a lie.[Pg 16] And so again with munificence; the greater part of these knights and courtiers were entirely thoughtless of the value of money. At the Field of the Cloth of Gold, for instance, whole estates were mortgaged or sold, in order that the owners might outshine all competitors in the brilliancy and quality of their dress. This sort of extravagance makes one man look glad and all his relatives rueful. The fact is that when men thus erred, it was for want of observance of a Christian principle; and if men neglect that observance, it is as little in the power of chivalry as of masonry to mend him. There was “a perfect idea” of chivalry, indeed, but if any knight ever realized it in his own person, he was, simply, nearly a perfect Christian, and would have been still nearer to perfection in the latter character if he had studied the few simple rules of the system of religion rather than the stilted and unsteady ones of romance. The study of the latter, at all events, did not prevent, but in many instances caused a dissoluteness of manners, a fondness for war rather than peace, and a wide distinction between classes, making aristocrats of the few, and villains of the many.

Let me add here, as I have been speaking of the romance of “Lancelot du Lac,” that I quite agree with Montluc, who after completing his chronicle of the History of France, observed that it would be found more profitable reading than either Lancelot or Amadis. La Noue especially condemns the latter as corrupting the manners of the age. Southey, again, observes that these chivalric romances acquired their poison in France or in Italy. The Spanish and Portuguese romances he describes as free from all taint. In the Amadis the very well-being of the world is made to rest upon chivalry. “What would become of the world,” it is asked in the twenty-second book of the Amadis, “if God did not provide for the defence of the weak and helpless against unjust usurpers? And how could provision be made, if good knights were satisfied to do nothing else but sit in chamber with the ladies? What would then the world become, but a vast community of brigands?”

Lamotte Levayer was of a different opinion. “Les armes,” he says, when commenting upon chivalry and arms generally; “Les armes detruisent tous les arts excepté ceux qui favorisent la gloire.”[Pg 17] In Germany, too, where chivalry was often turned to the oppression of the weak rather than employed for their protection, the popular contempt and dread of “knightly principles” were early illustrated in the proverb, “Er will Ritter an mir werden,” He wants to play the knight over me. In which proverb, knight stands for oppressor or insulter. In our own country the order came to be little cared for, but on different grounds.

Dr. Nares in his “Heraldic Anomalies,” deplores the fact that mere knighthood has fallen into contempt. He dates this from the period when James I. placed baronets above knights. The hereditary title became a thing to be coveted, but knights who were always held to be knights bachelors, could not of course bequeath a title to child or children who were not supposed in heraldry to exist. The Doctor quotes Sir John Ferne, to show that Olibion, the son of Asteriel, of the line of Japhet, was the first knight ever created. The personage in question was sent forth to battle, after his sire had smitten him lightly nine times with Japhet’s falchion, forged before the flood. There is little doubt but that originally a knight was simply Knecht, servant of the king. Dr. Nares says that the Thanes were so in the north, and that these, although of gentle blood, exercised the offices even of cooks and barbers to the royal person. But may not these offices have been performed by the “unter Thans,” or deputies? I shall have occasion to observe, subsequently, on the law which deprived a knight’s descendants of his arms, if they turned merchants; but in Saxon times it is worthy of observation, that if a merchant made three voyages in one of his own ships, he was thenceforward the Thane’s right-worthy, or equal.

Among the Romans a blow on the ear gave the slave freedom. Did the blow on the shoulder given to a knight make a free-servant of him? Something of the sort seems to have been intended. The title was doubtless mainly but not exclusively military. To dub, from the Saxon word dubban, was either to gird or put on, “don,” or was to strike, and perhaps both may be meant, for the knight was girt with spurs, as well as stricken, or geschlagen as the German term has it.

There was striking, too, at the unmaking of a knight. His heels were then degraded of their spurs, the latter being beaten[Pg 18] or chopped away. “His heels deserved it,” says Bertram of the cowardly Parolles, “his heels deserved it for usurping of his spurs so long.” The sword, too, on such occasions, was broken.

Fuller justly says that “the plainer the coat is, the more ancient and honorable.” He adds, that “two colors are necessary and most highly honorable: three are very highly honorable; four commendable; five excusable; more disgraceful.” He must have been a gastronomic King-at-Arms, who so loaded a “coat” with fish, flesh, and fowl, that an observer remarked, “it was well victualled enough to stand a siege.” Or is the richest coloring, but, as Fuller again says, “Herbs vert, being natural, are better than Or.” He describes a “Bend as the best ordinary, being a belt athwart,” but a coat bruised with a bar sinister is hardly a distinction to be proud of. If the heralds of George the Second’s time looked upon that monarch as the son of Count Königsmark, as Jacobite-minded heralds may have been malignant enough to do, they no doubt mentally drew the degrading bar across the royal arms, and tacitly denied the knighthood conferred by what they, in such foolish case, would have deemed an illegitimate hand.

Alluding to reasons for some bearings, Fuller tells us that, “whereas the Earls of Oxford anciently gave their ‘coats’ plain, quarterly gules and or, they took afterward in the first a mullet or star-argent, because the chief of the house had a falling-star, as it was said, alighting on his shield as he was fighting in the Holy Land.”

It is to be observed that when treating of precedency, Fuller places knights, or “soldiers” with seamen, civilians, and physicians, and after saints, confessors, prelates, statesmen, and judges. Knights and physicians he seems to have considered as equally terrible to life; but in his order of placing he was led by no particular principle, for among the lowest he places “learned writers,” and “benefactors to the public.” He has, indeed, one principle, as may be seen, wherein he says, “I place first princes, good manners obliging all other persons to follow them, as religion obliges me to follow God’s example by a royal recognition of that original precedency, which he has granted to his vicegerents.”

The Romans are said to have established the earliest known order of knighthood; and the members at one time wore rings, as[Pg 19] a mark of distinction, as in later times knights wore spurs. The knights of the Holy Roman Empire were members of a modern order, whose sovereigns are not, what they would have themselves considered, descendants of the Cæsars. If we only knew what our own Round Table was, and where it stood, we should be enabled to speak more decisively upon the question of the chevaliers who sat around it. But it is undecided whether the table was not really a house. At it, or in it, the knights met during the season of Pentecost, but whether the assembly was collected at Winchester or Windsor no one seems able to determine; and he would impart no particularly valuable knowledge even if he could.

Knighthood was a sort of nobility worth having, for it testified to the merit of the wearer. An inherited title should, indeed, compel him who succeeds to it, to do nothing to disgrace it: but preserving the lustre is not half so meritorious as creating it. Knights bachelors were so called because the distinction was conferred for some act of personal courage, to reward for which the offspring of the knight could make no claim. He was, in this respect, to them as though he had been never married. The knight bachelor was a truly proud man. The word knecht simply implied a servant, sworn to continue good service in honor of the sovereign, and of God and St. George. “I remain your sworn servant” is a form of epistolary valediction which crept into the letters of other orders in later times. The manner of making was more theatrical than at the present time; and we should now smile if we were to see, on a lofty scaffold in St. Paul’s, a city gentleman seated in a chair of silver adorned with green silk, undergoing exhortation from the bishop, and carried up between two lords, to be dubbed under the sovereign’s hand, a good knight, by the help of Heaven and his patron saint.

In old days belted earls could create knights. In modern times, the only subject who is legally entitled to confer the honor of chivalry is the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland; and some of his “subjects” consider it the most terrible of his privileges. The attempt to dispute the right arose, perhaps, from those who dreaded the exercise of it on themselves. However this may be, it is certain that the vexata questio was finally set at rest in 1823, when the judges declared that the power in question undoubtedly resided[Pg 20] in the Lords Lieutenant, since the Union, as it did in the viceroys who reigned vicariously previous to that period. According to the etiquette of heraldry, the distinctive appellation “Sir” should never be omitted even when the knight is a noble of the first hereditary rank. “The Right Honorable Sir Hugh Percy, Duke of Northumberland,” would have been the proper heraldic defining of his grace when he became Knight of the Garter, for it is a rule that “the greater dignity doth never drown the lesser, but both stand together in one person.”

A knight never surrendered his sword but to a knight. “Are you knight and gentleman?” asked Suffolk, when, four hundred years ago, he yielded to Regnault: “I am a gentleman,” said Regnault, “but I am not yet a knight.” Whereupon Suffolk bade him kneel, dubbed him knight, received the accustomed oaths, and then gave up his old sword to the new chevalier.

Clark considered that the order was degraded from its exclusively military character, when membership was conferred upon gownsmen, physician, burghers, and artists. He considered that civil merit, so distinguished, was a loss of reputation to military knights. The logic by which he arrives at such a conclusion is rather of the loosest. It may be admitted, however, that the matter has been specially abused in Germany. Monsieur About, that clever gentleman, who wrote “Tolla” out of somebody else’s book, very pertinently remarks in his review of the fine-art department of the Paris Exhibition, that the difference between English and German artists is, that the former are well-paid, but that very few of them are knights, while the latter are ill-paid and consequently ill-clothed; but, for lack of clothes, have abundance of ribands.

Dr. Nares himself is of something of the opinion of Clark, and he ridicules the idea of a chivalric and martial title being given to brewers, silversmiths, attorneys, apothecaries, upholsterers, hosiers, tailors. &c. He asserts that knighthood should belong only to military members: but of these no inconsiderable number would have to be unknighted, or would have to wait an indefinite time for the honor were the old rule strictly observed, whereby no man was entitled to the rank and degree of knighthood, who had not actually been in battle and captured a prisoner with his own hands. With respect to the obligation on knights to defend and[Pg 21] maintain all ladies, gentlewomen, widows, and orphans; the one class of men may be said to be just as likely to fulfil this obligation, as the other class.

France, Italy, and Germany, long had their forensic knights, certain titles at the bar giving equal privileges; and the obligations above alluded to were supposed to be observed by these knights—who found esquires in their clerks, in the forensic war which they were for ever waging in defence of right. Unhappily these forensic chevaliers so often fought in defence of wrong and called it right, that the actual duty was indiscriminately performed or neglected.

It has often been said of “orders” that they are indelible. However this may be with the clergy, it is especially the case with knights. To whatever title a knight might attain, duke, earl, or baron, he never ceased to be a knight. In proof too that the latter title was considered one of augmentation, is cited the case of Louis XI., who, at his coronation, was knighted by Philip, Duke of Burgundy. “If Louis,” says an eminent writer (thus cited by Dr. Nares), “had been made duke, marquis, or earl, it would have detracted from him, all those titles being in himself.”

The crown, when it stood in need of the chivalrous arms of its knights, called for the required feudal service, not from its earls as such, but from its barons. To every earldom was annexed a barony, whereby their feudal service with its several dependent duties was alone ascertained. “That is,” says Berington, in his Henry II., “the tenure of barony and not of earldom constituted the legal vassal of the crown. Each earl was at the same time a baron, as were the bishops and some abbots and priors of orders.”

Some of these barons were the founders of parish churches, but the terms on which priest and patron occasionally lived may be seen in the law, whereby patrons or feudatarii killing the rector, vicar, or clerk of their church, or mutilating him, were condemned to lose their rights; and their posterity, to the fourth generation, was made incapable of benefice or prelacy in religious houses. The knightly patron was bound to be of the same religious opinions, of course, as his priest, or his soul had little chance of being prayed for. In later times we have had instances of patrons determining the opinions of the minister. Thus as a parallel, or[Pg 22] rather in contrast with measures as they stood between Sir Knight and Sir Priest, may be taken a passage inserted in the old deeds of the Baptist chapel at Oulney. In this deed the managers or trustees injoined that “no person shall ever be chosen pastor of this church, who shall differ in his religious sentiments from the Rev. John Gibbs of Newcastle.” It is rather a leap to pass thus from the baronial knights to the Baptist chapels, but the matter has to do with my subject at both extremities. Before leaving it I will notice the intimation proudly made on the tombstone in Bunhill Fields Cemetery, of Dame Mary Page, relict of Sir George Page. The lady died more than a century and a quarter ago, and although the stone bears no record of any virtue save that she was patient and fearless under suffering, it takes care to inform all passers-by, that this knight’s lady, “in sixty-seven months was tapped sixty-six times, and had taken away two hundred and forty gallons of water, without ever repining at her case, or ever fearing its operation.” I prefer the mementoes of knight’s ladies in olden times which recorded their deeds rather than their diseases, and which told of them, as White said of Queen Mary, that their “knees were hard with kneeling.”

I will add one more incident, before changing the topic, having reference as it has to knights, maladies, and baptism. In 1660, Sir John Floyer was the most celebrated knight-physician of his day. He chiefly tilted against the disuse of baptismal immersion. He did not treat the subject theologically, but in a sanitary point of view. He prophesied that England would return to the practice as soon as people were convinced that cold baths were safe and useful. He denounced the first innovators who departed from immersion, as the destroyers of the health of their children and of posterity. Degeneracy of race, he said, had followed, hereditary diseases increased, and men were mere carpet-knights unable to perform such lusty deeds as their duly-immersed forefathers.

There are few volumes which so admirably illustrate what knights should be, and what they sometimes were not, as De Joinville’s Chronicle of the Crusades of St. Louis—that St. Louis, who was himself the patron-saint of an order, the cross of which was at first conferred on princes, and at last on perruquiers. The faithful chronicler rather profanely, indeed, compares the royal[Pg 23] knight with God himself. “As God died for his people, so did St. Louis often peril his life, and incurred the greatest dangers, for the people of his kingdom.” After all, this simile is as lame as it is profane. The truth, nevertheless, as it concerns St. Louis, is creditable to the illustrious king, saint, and chevalier. “In his conversation he was remarkably chaste, for I never heard him, at any time, utter an indecent word, nor make use of the devil’s name; which, however, now is very commonly uttered by every one, but which I firmly believe, is so far from being agreeable to God, that it is highly displeasing to him.” The King St. Louis, mixed water with his wine, and tried to force his knights to follow his example, adding, that “it was a beastly thing for an honorable man to make himself drunk.” This was a wise maxim, and one naturally held by a son, whose mother had often declared to him, that “she would rather he was in his grave, than that he should commit a mortal sin.” And yet wise as his mother, and wise as her son was, the one could not give wise religious instructors to the latter, nor the latter perceive where their instruction was illogical. That it was so, may be discerned in the praise given by De Joinville, to the fact, that the knightly king in his dying moments “called upon God and his saints, and especially upon St. James, and St. Genevieve, as his intercessors.”

It is interesting to learn from such good authority as De Joinville, the manner in which the knights who followed St. Louis prepared themselves for their crusading mission. “When I was ready to set out, I sent for the Abbot of Cheminon, who was at that time considered as the most discreet man of all the White Monks, to reconcile myself with him. He gave me my scarf, and bound it on me, and likewise put the pilgrim’s staff in my hand. Instantly after I quitted the castle of Joinville, without even re-entering it until my return from beyond sea. I made pilgrimages to all the holy places in the neighborhood, such as Bliecourt, St. Urban, and others near to Joinville. I dared never turn my eyes that way, for fear of feeling too great regret, and lest my courage should fail on leaving my two fine children, and my fair castle of Joinville, which I loved in my heart.” “One touch of nature makes the whole world kin,” and here we have the touch the poet speaks of. Down the Saône and subsequently down the Rhone,[Pg 24] the crusaders flock in ample vessels, but not large enough to contain their steeds, which were led by grooms along the banks. When all had re-embarked at Marseilles and were fairly out at sea, “the captain made the priests and clerks mount to the castle of the ship, and chant psalms in praise of God, that he might be pleased to grant us a prosperous voyage.” While they were singing the Veni Creator in full chorus, the mariners set the sails “in the name of God,” and forthwith a favorable breeze sprang up in answer to the appeal, and knights and holy men were speedily careering over the billows of the open sea very hopeful and exceedingly sick. “I must say here,” says De Joinville, who was frequently so disturbed by the motion of the vessel, so little of a knight, and so timid on the water as to require a couple of men to hold him as he leant over the side in the helpless and unchivalrous attitude of a cockney landsman on board a Boulogne steamer—“I must say,” he exclaims—sick at the very reminiscence, “that he is a great fool who shall put himself in such dangers, having wronged any one, or having any mortal sins on his conscience; for when he goes to sleep in the evening, he knows not if in the morning he may not find himself under the sea.”

This was a pious reflection, and it was such as many a knight, doubtless, made on board a vessel, on the castle of which priests and clerks sang Veni Creator and the mariners bent the sail “in the name of God.” But whether the holy men did not act up to their profession, or the secular knights cared not to profit by their example, certain it is that in spite of the saintly services and formalities on board ship, the chevaliers were no sooner on shore, than they fell into the very worst of practices. De Joinville, speaking of them at Damietta, remarks that the barons, knights, and others, who ought to have practised self-denial and economy, were wasteful of their means, prodigal of their supplies, and addicted to banquetings, and to the vices which attend on over-luxuriant living. There was a general waste of everything, health included. The example set by the knights was adopted by the men-at-arms, and the debauchery which ensued was terrific. The men were reduced to the level of beasts, and wo to the women or girls who fell into their power when out marauding. It is singular to find De Joinville remarking that the holy king was obliged “to[Pg 25] wink at the greatest liberties of his officers and men.” The picture of a royal saint winking at lust, rapine, and murder, is not an agreeable one. “The good king was told,” says the faithful chronicler, “that at a stone’s throw round his own pavilion, were several tents whose owners made profit by letting them out for infamous purposes.” These tents and tabernacles of iniquity were kept by the king’s own personal attendants, and yet the royal saint winked at them! The licentiousness was astounding, the more so as it was practised by Christian knights, who were abroad on a holy purpose, but who went with bloody hands, unclean thoughts, and spiritual songs to rescue the Sepulchre of Christ from the unworthy keeping of the infidel. Is it wonderful that the enterprise was ultimately a failure?

De Joinville himself, albeit purer of life than many of his comrades, was not above taking unmanly advantage of a foe. The rule of chivalry, which directed that all should be fair in fight, was never regarded by those chivalrous gentlemen when victory was to be obtained by violating the law. Thus, of an affair on the plains before Babylon, we find the literary swordsman complacently recording that he “perceived a sturdy Saracen mounting his horse, which was held by one of his esquires by the bridle, and while he was putting his hand on his saddle to mount, I gave him,” says De Joinville, “such a thrust with my spear, which I pushed as far as I was able, that he fell down dead.” This was a base and cowardly action. There was more of the chivalrous in what followed: “The esquire, seeing his lord dead, abandoned master and horse; but, watching my motions, on my return struck me with his lance such a blow between my shoulders as drove me on my horse’s neck, and held me there so tightly that I could not draw my sword, which was girthed round me. I was forced to draw another sword which was at the pommel of my saddle, and it was high time; but when he saw I had my sword in my hand, he withdrew his lance, which I had seized, and ran from me.”

I have said that this knight who took such unfair advantage of a foe, was more of a Christian nevertheless than many of his fellows. This is illustrated by another trait highly illustrative of the principles which influenced those brave and pious warriors. De Joinville remarks that on the eve of Shrove-tide, 1249, he saw a thing[Pg 26] which he “must relate.” On the vigil of that day, he tells us, there died a very valiant and prudent knight, Sir Hugh de Landricourt, a follower of De Joinville’s own banner. The burial service was celebrated; but half-a-dozen of De Joinville’s knights, who were present as mourners, talked so irreverently loud that the priest was disturbed as he was saying mass. Our good chronicler went over to them, reproved them, and informed them that “it was unbecoming gentlemen thus to talk while the mass was celebrating.” The ungodly half-dozen, thereupon, burst into a roar of laughter, and informed De Joinville, in their turn, that they were discussing as to which of the six should marry the widow of the defunct Sir Hugh, then lying before them on his bier! De Joinville, with decency and common sense “rebuked them sharply, and said such conversation was indecent and improper, for that they had too soon forgotten their companion.” From this circumstance De Joinville tries to draw a logical inference, if not conclusion. He makes a sad confusion of causes and effects, rewards and punishments, practice and principle, human accidents and especial interferences on the part of Heaven. For instance, after narrating the mirth of the knights at the funeral of Sir Hugh, and their disputing as to which of them should woo the widow, he adds: “Now it happened on the morrow, when the first grand battle took place, although we may laugh at their follies, that of all the six not one escaped death, and they remained unburied. The wives of the whole six re-married! This makes it credible that God leaves no such conduct unpunished. With regard to myself I fared little better, for I was grievously wounded in the battle of Shrove Tuesday. I had besides the disorder in my legs and mouth before spoken of, and such a rheum in my head it ran through my mouth and nostrils. In addition I had a double fever called a quartan, from which God defend us! And with these illnesses was I confined to my bed for half of Lent.” And thus, if the married knights were retributively slain for talking about the wooing of a comrade’s widow, so De Joinville himself was somewhat heavily afflicted for having undertaken to reprove them! I must add one more incident, however, to show how in the battle-field the human and Christian principle was not altogether lost.

The poor priest, whom the wicked and wedded knights had[Pg 27] interrupted in the service of the mass by follies, at which De Joinville himself seems to think that men may, perhaps, be inclined to laugh, became as grievously ill as De Joinville himself. “And one day,” says the latter, “when he was singing mass before me as I lay in my bed, at the moment of the elevation of the host I saw him so exceedingly weak that he was near fainting; but when I perceived he was on the point of falling to the ground, I flung myself out of bed, sick as I was, and taking my coat, embraced him, and bade him be at his ease, and take courage from Him whom he held in his hand. He recovered some little; but I never quitted him till he had finished the mass, which he completed, and this was the last, for he never celebrated another, but died; God receive his soul!” This is a pleasanter picture of Christian chivalry than any other that is given by this picturesque chronicler.

Chivalry, generally, has been more satirized and sneered at by the philosophers than by any other class of men. The sages stigmatize the knights as mere boasters of bravery, and in some such terms as those used by Dussaute, they assert that the boasters of their valor are as little to be trusted as those who boast of their probity. “Defiez vous de quiconque parle toujours de sa probité comme de quiconque parle toujours de bravoure.”

It will not, however, do for the philosophers to sneer at their martial brethren. Now that Professor Jacobi has turned from grave studies for the benefit of mankind, to the making of infernal machines for the destruction of brave and helpless men, at a distance, that very unsuccessful but would-be homicide has, as far as he himself is concerned, reduced science to a lower level than that occupied by men whose trade is arms. But this is not the first time that philosophers have mingled in martial matters. The very war which has been begun by the bad ambition of Russia, may be traced to the evil officiousness of no less a philosopher than Leibnitz. It was this celebrated man who first instigated a European monarch to seize upon a certain portion of the Turkish dominion, whereby to secure an all but universal supremacy.

The monarch was Louis XIV., to whom Leibnitz addressed himself, in a memorial, as to the wisest of sovereigns, most worthy to have imparted to him a project at once the most holy, the most just, and the most easy of accomplishment. Success, adds the[Pg 28] philosopher, would secure to France the empire of the seas and of commerce, and make the French king the supreme arbiter of Christendom. Leibnitz at once names Egypt as the place to be seized upon; and after hinting what was necessary, by calling his majesty a “miracle of secresy,” he alludes to further achievements by stating of the one in question, that it would cover his name with an immortal glory, for having cleared, whether for himself or his descendants, “the route for exploits similar to those of Alexander.”

There is no country in the memorialist’s opinion the conquest of which deserves so much to be attempted. As to any provocation on the part of the Turkish sovereign of Egypt, he does not pause to advise the king even to feign having received cause of offence. The philosopher goes through a resumé of the history of Egypt, and the successive conquests that had been made of, as well as attempts against it, to prove that its possession was accounted of importance in all times; and he adds that its Turkish master was just then in such debility that France could not desire a more propitious opportunity for invasion. This argument shows that when the Czar Nicholas touched upon this nefarious subject, he not only was ready to rob this same “sick man,” the Turk, but he stole his arguments whereby to illustrate his opinions, and to prove that his sentiments were well-founded.

“By a single fortunate blow,” says Leibnitz, “empires may be in an instant overthrown and founded. In such wars are found the elements of high power and of an exalted glory.” It is unnecessary to repeat all the seductive terms which Leibnitz employs to induce Louis XIV. to set his chivalry in motion against the Turkish power. Egypt he calls “the eye of countries, the mother of grain, the seat of commerce.” He hints that Muscovy was even then ready to take advantage of any circumstance that might facilitate her way to the conquest of Turkey. The conquest of Egypt then was of double importance to France. Possessing that, France would be mistress of the Mediterranean, of a great part of Africa and Asia, and “the king of France could then, by incontestable right, and with the consent of the Pope, assume the title of Emperor of the East.” A further bait held out is, that in such a position he could “hold the pontiffs much more in his power[Pg 29] than if they resided at Avignon.” He sums up by saying that there would be on the part of the human race, “an everlasting reverence for the memory of the great king to whom so many miracles were due!” “With the exception of the philosopher’s stone,” finally remarks the philosopher, “I know nothing that can be imagined of more importance than the conquest of Egypt.”

Leibnitz enters largely into the means to be employed, in order to insure success; among them is a good share of mendacity; and it must be acknowledged that the spirit of the memorial and its objects, touching not Egypt alone, but the Turkish empire generally, had been well pondered over by the Czar before he made that felonious attempt in which he failed to find a confederate.

The original of the memorial, which is supposed to have been presented to Louis XIV. just previous to his invasion of Holland—and, as some say, more with the intention of diverting the king from his attack on that country, than with any more definite object—was preserved in the archives of Versailles till the period of the great revolution. A copy in the handwriting of Leibnitz was, however, preserved in the Library at Hanover. Its contents were without doubt known to Napoleon when he was meditating that Egyptian conquest which Leibnitz pronounced to be so easy of accomplishment; a copy, made at the instance of Marshal Mortier for the Royal Library in Paris, is now in that collection.

The suggestion of Leibnitz, that the seat, if not of universal monarchy, at least of the mastership of Christendom, was in the Turkish dominions, has never been forgotten by Russia; and it is very possible that some of its seductive argument may have influenced the Czar before he impelled his troops into that war, which showed that Russia, with all its boasted power, could neither take Silistria nor keep Sebastopol.

But in this fragmentary prologue, which began with Lingard and ends with Leibnitz, we have rambled over wide ground. Let us become more orderly, and look at those who were to be made knights.

[Pg 30]

I have in another chapter noticed the circumstance of knighthood conferred on an Irish prince, at so early an age as seven years. This was the age at which, in less precocious England, noble youths entered wealthy knights’ families as pages, to learn obedience, to be instructed in the use of weapons, and to acquire a graceful habit of tending on ladies. The poor nobility, especially, found their account in this system, which gave a gratuitous education to their sons, in return for services which were not considered humiliating or dishonorable. These boys served seven years as pages, or varlets—sometimes very impudent varlets—and at fourteen might be regular esquires, and tend their masters where hard blows were dealt and taken—for which encounters they “riveted with a sigh the armor they were forbidden to wear.”

Neither pages, varlets, nor household, could be said to have been always as roystering as modern romancers have depicted them. There was at least exceptions to the rule—if there was a rule of roystering. Occasionally, the lads were not indifferently taught before they left their own homes. That is, not indifferently taught for the peculiar life they were about to lead. Even the Borgias, infamous as the name has become through inexorable historians and popular operas, were at one time eminently respectable and exemplarily religious. Thus in the household of the Duke of Gandia, young Francis Borgia, his son, passed his time “among[Pg 31] the domestics in wonderful innocence and piety.” It was the only season of his life, however, so passed. Marchangy asserts that the pages of the middle ages were often little saints; but this could hardly have been the case since “espiègle comme un page,” “hardi comme un page,” and other illustrative sayings have survived even the era of pagedom. Indeed, if we may believe the minstrels, and they were often as truth-telling as the annalist, the pages were now and then even more knowing and audacious than their masters. When the Count Ory was in love with the young Abbess of Farmoutier, he had recourse to his page for counsel.

How ready was the ecstatic young scamp with his reply:—

What came of this advice, the song tells in very joyous terms, for which the reader may be referred to that grand collection the “Chants et Chansons de la France.”

On the other hand, Mr. Kenelm Digby, who is, be it said in passing, a painter of pages, looking at his object through pink-colored glasses, thus writes of these young gentlemen, in his “Mores Catholici.”

“Truly beautiful does the fidelity of chivalrous youth appear in the page of history or romance. Every master of a family in the middle ages had some young man in his service who would have rejoiced to shed the last drop of his blood to save him, and who, like Jonathan’s armor-bearer, would have replied to his summons: ‘Fac omnia quæ placent animo tuo; perge quo cupis; et ero tecum ubicumque volueris.’ When Gyron le Courtois resolved to proceed on the adventure of the Passage perilleux, we read that the valet, on hearing the frankness and courtesy with which his lord spoke to him, began to weep abundantly, and said, all in tears, ‘Sire, know that my heart tells me that sooth, if you proceed further, you will never return; that you will either perish there, or you will remain in prison; but, nevertheless, nothing[Pg 32] shall prevent me going with you. Better die with you, if it be God’s will, than leave you in such guise to save my own life;’ and so saying, he stepped forward and said, ‘Sire, since you will not return according to my advice, I will not leave you this time, come to me what may.’ Authority in the houses of the middle ages,” adds Mr. Digby, “was always venerable. The very term seneschal is supposed to have implied ‘old knight,’ so that, as with the Greeks, the word signifying ‘to honor,’ and to ‘pay respect,’ was derived immediately from that which denoted old age, πρεσβευω being thus used in the first line of the Eumenides. Even to those who were merely attached by the bonds of friendship or hospitality, the same lessons and admonitions were considered due. John Francis Picus of Mirandola mentions his uncle’s custom of frequently admonishing his friends, and exhorting them to a holy life. ‘I knew a man,’ he says, ‘who once spoke with him on the subject of manners, and who was so much moved by only two words from him, which alluded to the death of Christ, as the motive for avoiding sin, that from that hour, he renounced the ways of vice, and reformed his whole life and manner.’”

We smile to find Mr. Digby mentioning the carving of angels in stone over the castle-gates, as at Vincennes, as a proof that the pages who loitered about there were little saints. But we read with more interest, that “the Sieur de Ligny led Bayard home with him, and in the evening preached to him as if he had been his own son, recommending him to have heaven always before his eyes.” This is good, and that it had its effect on Bayard, we all know; nevertheless that chevalier himself was far from perfect.

With regard to the derivation of Seneschal as noticed above, we may observe that it implies “old man of skill.” Another word connected with arms is “Marshal,” which is derived from Mar, “a horse,” and Schalk, “skilful,” one knowing in horses; hence “Maréchal ferrant,” as assumed by French farriers. Schalk, however, I have seen interpreted as meaning “servant.” Earl Marshal was, originally, the knight who looked after the royal horses and stables, and all thereto belonging.

But to return to the subject of education. If all the sons of noblemen, in former days, were as well off for gentle teachers as[Pg 33] old historians and authors describe them to have been, they undoubtedly had a great advantage over some of their descendants of the present day. In illustration of this fact it is only necessary to point to the sermons recently delivered by a reverend pedagogue to the boys who have the affliction of possessing him as headmaster. It is impossible to read some of these whipping sermons, without a feeling of intense disgust. Flagellation is there hinted at, mentioned, menaced, caressed as it were, as if in the very idea there was a sort of delight. The worst passage of all is where the amiable master tells his youthful hearers that they are noble by birth, that the greatest humiliation to a noble person is the infliction of a blow, and that nevertheless, he, the absolute master, may have to flog many of them. How the young people over whom he rules, must love such an instructor! The circumstance reminds me of the late Mr. Ducrow, who was once teaching a boy to go through a difficult act of horsemanship, in the character of a page. The boy was timid, and his great master applied the whip to him unmercifully. Mr. Joseph Grimaldi was standing by, and looked very serious, considering his vocation. “You see,” remarked Ducrow to Joey, “that it is quite necessary to make an impression on these young fellows.”—“Very likely,” answered Grimaldi, dryly, “but it can hardly be necessary to make the whacks so hard!”

The discipline to which pages were subjected in the houses of knights and noblemen, does not appear to have been at all of a severe character. Beyond listening to precept from the chaplain, heeding the behests of their master, and performing pleasant duties about their mistress, they seem to have been left pretty much to themselves, and to have had, altogether, a pleasant time of it. The poor scholars had by far a harder life than your “Sir page.” And this stern discipline held over the pale student continued down to a very recent, that is, a comparatively recent period. In Neville’s play of “The Poor Scholar,” written in 1662, but never acted, the character of student-life at college is well illustrated. The scene lies at the university, where Eugenes, jun., albeit he is called “the poor scholar,” is nephew of Eugenes, sen., who is president of a college. Nephew and uncle are at feud, and the man in authority imprisons his young kinsman, who contrives to escape from durance[Pg 34] vile, and to marry a maiden called Morphe. The fun of the marriage is, that the young couple disguise themselves as country lad and lass, and the reverend Eugenes, sen., unconsciously couples a pair whom he would fain have kept apart. There are two other university marriages as waggishly contrived; and when the ceremonies are concluded, one of the newly-married students, bold as any page, impudently remarks to the duped president, “Our names are out of the butteries, and our persons out of your dominions.” The phrase shows that, in the olden time, an “ingenuus puer” at Oxford, if he were desirous of escaping censure, had only to take his name off the books. But there were worse penalties than mere censure. The author of “The Poor Scholar” makes frequent allusion to the whipping of undergraduates, stretched on a barrel, in the buttery. There was long an accredited tradition that Milton had been thus degraded. In Neville’s play, one of the young Benedicks, prematurely married, remarks, “Had I been once in the butteries, they’d have their rods about me.” To this remark Eugenes, jun., adds another in reference to his uncle the president, “He would have made thee ride on a barrel, and made you show your fat cheeks.” But it is clear that even this terrible penalty could be avoided by young gentlemen, if they had their wits about them; for the fearless Aphobos makes boast, “My name is cut out of the college butteries, and I have now no title to the mounting a barrel.”

Young scions of noble houses, in the present time, have to endure more harsh discipline than is commonly imagined. They are treated rather like the buttery undergraduates of former days, than the pages who, in ancient castles, learned the use of arms, served the Chatellaine, and invariably fell in love with the daughters. They who doubt this fact have only to read those Whipping Sermons to which I have referred. Such discourses, in days of old, to a body of young pages, would probably have cost the preacher more than he cared to lose. In these days, such sermons can hardly have won affection for their author. The latter, no doubt, honestly thought he was in possession of a vigorously salubrious principle; but there is something ignoble both in the discipline boasted of, and especially in the laying down the irresistible fact to young gentlemen that a blow was the worst offence that[Pg 35] could be inflicted on persons of their class, but that he could and would commit such assault upon them, and that gentle and noble as they were, they dared not resent it!

The pages of old time occasionally met with dreadful harsh treatment from their chivalrous master. The most chivalrous of these Christian knights could often act cowardly and unchristian-like. I may cite, as an instance, the case of the great and warlike Duke of Burgundy, on his defeat at Muret. He was hemmed in between ferocious enemies and the deep lake. As the lesser of two evils, he plunged into the latter, and his young page leaped upon the crupper as the Duke’s horse took the water. The stout steed bore his double burden across, a breadth of two miles, not without difficulty, yet safely. The Duke was, perhaps, too alarmed himself, at first, to know that the page was hanging on behind; but when the panting horse reached the opposite shore, sovereign Burgundy was so wroth at the idea that the boy, by clinging to his steed, had put the life of the Duke in peril, that he turned upon him and poignarded the poor lad upon the beach. Lassels, who tells the story, very aptly concludes it with the scornful yet serious ejaculation, “Poor Prince! thou mightest have given another offering of thanksgiving to God for thy escape, than this!” But “Burgundy” was rarely gracious or humane. “Carolus Pugnax,” says Burton, in his Anatomy of Melancholy, “made Henry Holland, late Duke of Exeter, exiled, run after his horse, like a lackey, and would take no notice of him.” This was the English peer who was reduced to beg his way in the cities of Flanders.

Of pages generally, we shall have yet to speak incidentally—meanwhile, let us glance at their masters at home.

[Pg 36]

“Entrez Messìeurs; jouissez-vous de mon coin-de-feu. Me voilà, chez moi!”— Arlequin à St. Germains.

Ritter Eric, of Lansfeldt, remarked, that next to a battle he dearly loved a banquet. We will, therefore, commence the “Knight at Home,” by showing him at table. Therewith, we may observe, that the Knights of the Round Table appear generally to have had very solid fare before them. King Arthur—who is the reputed founder of this society, and who invented the table in order that when all his knights were seated none could claim precedency over the others—is traditionally declared to have been the first man who ever sat down to a whole roasted ox. Mr. Bickerstaff, in the “Tatler,” says that “this was certainly the best way to preserve the gravy;” and it is further added, that “he and his knights set about the ox at his round table, and usually consumed it to the very bones before they would enter upon any debate of moment.”

They had better fare than the knights-errant, who

This, however, is only one poet’s view of the dietary of the errant gentlemen of old. Pope is much nearer truth when he says, that—

[Pg 37]

—that basket-hilt of which it is so well said in Hudibras, that—

The lords and chivalric gentlemen who fared so well and fought so stoutly, were not always of the gentlest humor at home. It has been observed that Piedmontese society long bore traces of the chivalric age. An exemplification is afforded us in Gallenga’s History of Piedmont. It will serve to show how absolute a master a powerful knight and noble was in his own house. Thus, from Gallenga we learn that Antonio Grimaldi, a nobleman of Chieri, had become convinced of the faithlessness of his wife. He compelled her to hang up with her own hand her paramour to the ceiling of her chamber; then he had the chamber walled up, doors and windows, and only allowed the wretched woman as much air and light, and administered with his own hand as much food and drink, as would indefinitely prolong her agony. And so he watched her, and tended her with all that solicitude which hatred can suggest as well as love, and left her to grope alone in that blind solitude, with the mute testimony of her guilt—a ghastly object on which her aching eyes were riveted, day by day, night after night, till it had passed through every loathsome stage of decomposition. This man was surely worse in his vengeance than that Sir Giles de Laval, who has come down to us under the name of Blue-Beard.

This celebrated personage, famous by his pseudonym, was not less so in his own proper person. There was not a braver knight in France, during the reigns of Charles VI. and VII., than this Marquis de Laval, Marshal of France. The English feared him almost as much as they did the Pucelle. The household of this brave gentleman was, however, a hell upon earth; and licentiousness, blasphemy, attempts at sorcery, and, more than attempts at, very successful realizations of, murder were the little foibles of this man of many wives. He excelled the most extravagant monarchs[Pg 38] in his boundless profusion, and in the barbaric splendor of his court or house: the latter was thronged with ladies of very light manners, players, mountebanks, pretended magicians, and as many cooks as Julian found in the palace of his predecessor at Constantinople. There were two hundred saddle-horses in his stable, and he had a greater variety of dogs than could now be found at any score of “fanciers” of that article. He employed the magicians for a double purpose. They undertook to discover treasures for his use, and pretty handmaids to tend on his illustrious person, or otherwise amuse him by the display of their accomplishments. Common report said that these young persons were slain after a while, their blood being of much profit in making incantations, the object of which was the discovery of gold. Much exaggeration magnified his misdeeds, which were atrocious enough in their plain, unvarnished infamy. At length justice overtook this monster. She did not lay hold of him for his crimes against society, but for a peccadillo which offended the Duke of Brittany. Giles de Laval, for this offence, was burnt at Nantes, after being strangled—such mercy having been vouchsafed to him, because he was a gallant knight and gentleman, and of course was not to be burnt alive like any petty villain of peasant degree. He had a moment of weakness at last, and just previous to the rope being tightened round his neck, he publicly declared that he should never have come to that pass, nor have committed so many excesses, had it not been for his wretched education. Thus are men, shrewd enough to drive bargains, and able to discern between virtue and vice, ever ready, when retribution falls on them at the scaffold, to accuse their father, mother, schoolmaster, or spiritual pastor. Few are like the knight of the road, who, previous to the cart sliding from under him, at Tyburn, remarked that he had the satisfaction, at least, of knowing that the position he had attained in society was owing entirely to himself. “May I be hanged,” said he, “if that isn’t the fact.” The finisher of the law did not stop to argue the question with him, but, on cutting him down, remarked, with the gravity of a cardinal before breakfast, that the gentleman had wronged the devil and the ladies, in attributing his greatness so exclusively to his own exertions.

I have said that perhaps Blue-Beard’s little foibles have been[Pg 39] exaggerated; but, on reflection, I am not sure that this pleasant hypothesis can be sustained. De Laval, of whom more than I have told may be found in Mezeray, was not worse than the Landvogt Hugenbach, who makes so terrible a figure in Barante’s “Dukes of Burgundy.” The Landvogt, we are told by the last-named historian, cared no more for heaven than he did for anybody on earth. He was accustomed to say that being perfectly sure of going to the devil, he would take especial care to deny himself no gratification that he could possibly desire. There was, accordingly, no sort of wild fancy to which he did not surrender himself. He was a fiendish corruptor of virtue, employing money, menaces, or brutal violence, to accomplish his ends. Neither cottage nor convent, citizen’s hearth nor noble’s château, was secure from his invasion and atrocity. He was terribly hated, terribly feared—but then Sir Landvogt Hugenbach gave splendid dinners, and every family round went to them, while they detested the giver.

He was remarkably facetious on these occasions, sometimes ferociously so. For instance, Barante records of him, that at one of his pleasant soirées he sent away the husbands into a room apart, and kept the wives together in his grand saloon. These, he and his myrmidons despoiled entirely of their dresses; after which, having flung a covering over the head of each lady, who dared not, for her life, resist, the amiable host called in the husbands one by one, and bade each select his own wife. If the husband made a mistake, he was immediately seized and flung headlong down the staircase. The Landvogt made no more scruple about it than Lord Ernest Vane when he served the Windsor manager after something of the same fashion. The husbands who guessed rightly were conducted to the sideboard to receive congratulations, and drink various flasks of wine thereupon. But the amount of wine forced upon each unhappy wretch was so immense, that in a short time he was as near death as the mangled husbands, who were lying in a senseless heap at the foot of the staircase.

They who would like to learn further of this respectable individual, are referred to the pages of Barante. They will find there that this knight and servant of the Duke of Burgundy was more[Pg 40] like an incarnation of the devil than aught besides. His career was frightful for its stupendous cruelty and crime; but it ended on the scaffold, nevertheless. His behavior there was like that of a saint who felt a little of the human infirmity of irritability at being treated as a very wicked personage by the extremely blind justice of men. So edifying was this chivalrous scoundrel, that the populace fairly took him for the saint he figured to be; and long after his death, crowds flocked to his tomb to pray for his mediation between them and God.

The rough jokes of the Landvogt remind me of a much greater man than he—Gaston de Foix, in whose earlier times there was no lack of rough jokes, too. The portrait of Gaston, with his page helping to buckle on his armor, by Giorgione da Castel Franco, is doubtless known to most of my readers—through the engraving, if not the original. It was formerly the property of the Duke of Orleans; but came, many years ago, into the possession, by purchase, of Lord Carlisle. The expression of the page or young squire who is helping to adjust Gaston’s armor is admirably rendered. That of the hero gives, perhaps, too old a look to a knight who is known to have died young.

This Gaston was a nephew of Louis XII. His titles were Duke of Nemours and Count d’Etampes. He was educated by his mother, the sister of King Louis. She exulted in Gaston as one who was peculiarly her own work. “Considering,” she says, “how honor became her son, she was pleased to let him seek danger where he was likely to find fame.” His career was splendid, but proportionally brief. He purchased imperishable renown, and a glorious death, in Italy. He gained the victory of Ravenna, at the cost of his life; after which event, fortune abandoned the standard of Louis; and Maximilian Sforza recovered the Milanese territories of his father, Ludovic. This was early in the sixteenth century.