WESTY MARTIN IN THE ROCKIES

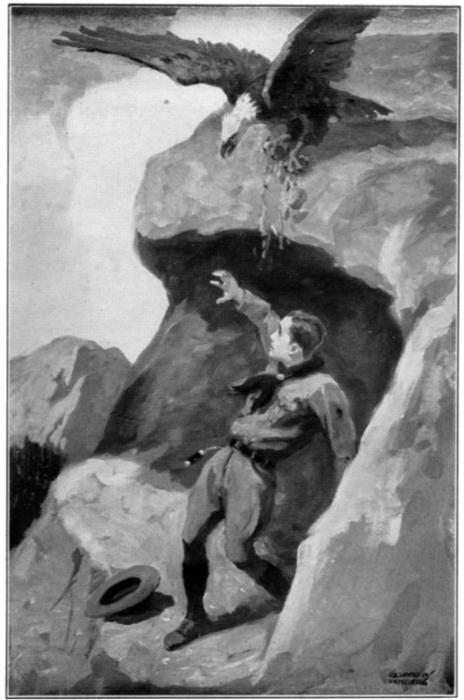

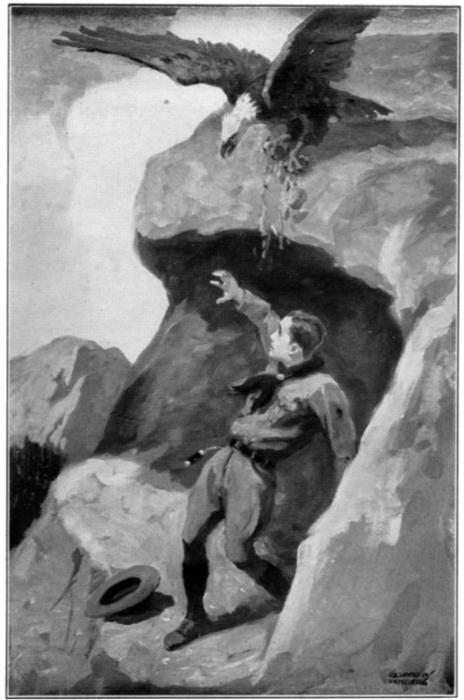

HIS WARM BLOOD SEEMED TO TURN INTO AN ICE-LIKE SUBSTANCE.

HIS WARM BLOOD SEEMED TO TURN INTO AN ICE-LIKE SUBSTANCE.

| CONTENTS | |

| I | A Sure Aim |

| II | The Spirit of the Camp |

| III | Good Man Friday |

| IV | The Captive |

| V | It Shall Not Pass |

| VI | The Rescuer |

| VII | Wicked Mr. Temple |

| VIII | What Might Have Been |

| IX | Friends |

| X | Out of the Past |

| XI | The Lost Agreement |

| XII | Mr. Martin’s Ultimatum |

| XIII | Westy Makes a Decision |

| XIV | Vindication |

| XV | A Life in the Balance |

| XVI | They’re Off |

| XVII | “Hills” |

| XVIII | “Silent” Ollie Baxter |

| XIX | Uncle Jeb Sounds a Warning |

| XX | Westy Makes a Discovery |

| XXI | The Mysterious Hollow |

| XXII | Something to Think About |

| XXIII | The Object on the Cliff |

| XXIV | Artie as a Modern Daniel |

| XXV | Taking Chances |

| XXVI | The Eagles’ Return |

| XXVII | Help |

| XXVIII | Between Two Fires |

| XXIX | Face to Face |

| XXX | Cries |

| XXXI | Westy Makes a Sacrifice |

| XXXII | The Bond Is Sealed |

| XXXIII | Uncle Jeb Faces a Crisis |

| XXXIV | Forgotten Footprints |

| XXXV | Ghosts |

| XXXVI | Westy Circumvents a Ghost? |

| XXXVII | Evidence |

| XXXVIII | Gone |

| XXXIX | The Man Without a Soul |

| XL | Ollie Makes His Exit |

| XLI | Skeletons |

| XLII | The Lost Is Found |

Westy Martin sat speechless in utter consternation. He glanced about him as if dazed. He seemed to be trying to make sure that he was awake, that the whole thing was not a dream. Then a sudden burst of shouting and applause recalled him to the reality of the clamorous scene.

The scene was very real. It was a familiar scene at Temple Camp and real with the savory realities of clam chowder and hunter’s stew and crullers piled high in tin dishpans. And waffles built into miniature skyscrapers and big glass pitchers full of sirup and honey. And Pee-wee Harris shouting, “I’ll go with you, I’ll go with you, I’ll be the one!” And Uncle Jeb Rushmore sitting at the head of the “eats board” with a smile of amusement hovering under his drooping white mustache.

Uncle Jeb Rushmore was one of those men who looked out of place at a dining table, even at a rustic “eats board.” By all the rules he should have eaten his meals squatting on the ground in proximity to a campfire, in the dense wilderness or on the prairie. He should never have eaten a meal without his trusty rifle by his side and without a keen eye on the lookout for stealthy Indians. He should certainly never have been waited on by a smiling negro connected with the cooking shack of a great modern camp. He should have dined in remote fastnesses, mountain passes, and in sound of the appalling voices of savage beasts. Everything about Uncle Jeb suggested not the covered table, but the covered wagon. He was an old western trapper and guide who had cooked bear’s meat with Buffalo Bill and fried his venison on silent trails while the caravan waited.

That this picturesque old member of a race that has all but passed away should be sitting at the head of a camp “eats board” was the fault of Mr. John Temple, the beneficent founder of Temple Camp in the Catskills. And so Westy Martin, scout, became identified with a series of adventures which I shall chronicle for you; adventures in the wildest region of the Wild West. Such adventures as boys do not even read of in these days of football and baseball and boarding schools and Saturday hikes. It is odd, when you come to think of it, how things happen. That Westy Martin should participate in adventures which in these days are commonly thought too extravagant even for boy’s stories! Yet this thing happened and it should be told. If the worst that can be said about it is that it is a wild-west story I will gladly bear the responsibility of telling it to my young friends.

To go back to where I started—they were having dinner at Temple Camp. It was Labor Day and soon the camp would close for the season. Mr. John Temple was its guest, as he usually was just before the season closed. He was standing at the head of the main “eats board” and it was something which he had just said in the course of his remarks that had set Westy Martin aghast. There were three of these “eats boards” in a vast open pavilion. The middle one was larger than the two that flanked it, and it was at the head of this large, rustic table that the guest of honor had been seated. At the head of Westy’s table sat Uncle Jeb in his accustomed place. And at the head of the other sat Mr. Bronson, resident trustee. Somewhat removed from these three enormous dining boards was another rough table for scoutmasters. In that great scout community some troops cooked their own meals near their cabins, but all were crowded in the “eats” pavilion on this memorable day in honor of the distinguished visitor.

“And now one word more,” said Mr. Temple. “It is both good news and bad news. Those of you who come next summer will not see Uncle Jeb.” Murmurs of surprise and apprehension greeted this announcement. “Uncle Jeb is going home, not to stay, but to visit for a season his beloved Montana and his old cabin, those scenes which I took him from to bring him here. I think you will all agree—our trustees have already agreed—that Uncle Jeb is entitled to visit his old home. He expects to return here next fall or, at the latest, early the following spring. He has said that he will do that, and as you know Uncle Jeb always hits the mark. He aims to be back with you after next summer and I never heard anybody ever say that he missed his aim.” This remark was greeted with laughter and applause.

“There is one thing more,” said Mr. Temple. “It has been thought that Uncle Jeb’s sojourn might afford a couple of our scouts an opportunity to visit the woolly West; I mean the regular West with all its wool on; the West that Uncle Jeb knows and which he once showed me. Uncle Jeb himself seems to like that idea. So I suggested that he be asked to choose one of the boys he knows best to go with him, and that this fortunate boy be permitted to choose a comrade in the great adventure. Uncle Jeb has named Westy Martin of the First Bridgeboro Troop of Bridgeboro, New Jersey. Westy Martin,” Mr. Temple added, glancing about, “wherever you are, I congratulate you.”

“There he is, third from the end, eating a waffle!” thundered the uproarious voice of Pee-wee Harris, “and I’ll be the one to go with him!”

So you see how it was. Uncle Jeb was seven years older than when he had come to cast the glow of pioneer and western romance over Temple Camp. But his eye was just as keen and his aim was just as true as in the days when he had hunted grizzlies and struck terror to Indians in his beloved Rockies. For those keen gray eyes had seen Westy Martin and picked him out and knocked him clean off his feet, in a way of speaking....

When Mr. John Temple conceived the big scout community which came to be known the country over as Temple Camp, he had an inspiration that showed his fine understanding of the scout idea.

He decided to introduce into the camp something which neither the solemn woods nor the tranquil lake could give it; something which all the projected rustic architecture could not supply. And that was an atmosphere.

He was resolved that the scouts who flocked to the sequestered lakeside resort should live in proximity to a real scout, one who had lived the sort of life that is commemorated by scouting.

He would bring the prairies and the Rockies and the long, winding trails, and all the associations which cluster about Indians and grizzlies and buffaloes to Temple Camp in the romantic person of an old western scout and guide whom he had met while in the Far West on railroad business. Old Jeb Rushmore had guided Mr. Temple and a party of surveyors to a pass in the mountains following what he called a trail which was about as discernible to Mr. Temple as a trail left by an airplane. The founder of the camp had spent a night in Rushmore’s lonely cabin in Montana and had heard the voice of a grizzly in the distance.

A year later when land had been bought for the big camp in the Catskills, Mr. Temple recalled that his old guide had told him that he expected soon to give up his cabin in the Rockies and end his days at Fort Benton in his beloved Montana. “Reckon I’m gettin’ old,” he had told Mr. Temple. “That’s one thing yer can’t shoot,” he had added. Indeed old age was the only foe that had a ghost of a chance of stealing up on him.

So Mr. Temple invited Jeb Rushmore to come and live at Temple Camp and the old scout, after some hesitation, agreed to do so. He spent one night at the magnificent Temple residence in Bridgeboro where he seemed not the least bit embarrassed by the gorgeous surroundings. He smoked his pipe in Mr. Temple’s library and when that gentleman related how he had gone to Washington once to seek an audience with President Roosevelt, Jeb Rushmore casually remarked that he and Roosevelt had hunted together in the Rockies. It developed that Mr. Temple had tried to see Roosevelt and failed and that Roosevelt had gone a couple of hundred miles out of his way to get in touch with Jeb. It was not likely that Uncle Jeb would be dazzled by the formality of Mr. Temple’s household.

Uncle Jeb, as he came to be known at camp, was given the title of manager. But he had no executive duties. He was more than the camp’s manager, he was its spirit. I have seen a scout camp with a statue of an old pioneer on the camp grounds to convey the idea of scouting and outdoor life. But Uncle Jeb was the living embodiment of all these things; he wore a halo of tradition. It was a fine inspiration of Mr. Temple’s, bringing this old scout to camp.

Uncle Jeb built log cabins and made trails and instructed the scouts in pathfinding and stalking. He taught them the Indian trail marks. He would send a boy off to go where he would in the forest, give him half an hour’s head start, then take a party of boys and find him. He did this without the least trouble.

“Why didn’t yer double on yer trail?” he would demand of the astonished fugitive after running him down. “What’d I tell yer ’bout not steppin’ on no twigs ’n’ bustin’ ’em?”

“You can’t run without breaking twigs,” the embarrassed boy would protest. “And anyway, if I doubled on my trail you’d trace me anyway; so what’s the use?”

“Yer don’t hev ter tech no trees, do yer?” the old guide would say, “’n’ leave all yer duds hangin’ on ’em like a ole wash hangin’ out.”

“You can’t run in the woods without touching trees or even stepping on twigs,” the poor victim would protest. “Anyway, it’s no use trying to get away, not from you, Jiminy Christopher!”

What Uncle Jeb meant when he charged an unfortunate scout with leaving his duds hanging on trees “like a ole wash” was that the baffled youngster had left one strand of a fringe from his scout scarf on some obscure bramble bush.

“If yer decorate yer path like if a parade wuz comin’ ’tain’ no chore findin’ yer, now is it?” Uncle Jeb would ask. “Here yer scares away a turtle what was settin’ on a rock and I sees where the spot wuz he was a settin’ on. Yer ain’t reckonin’ I was blind, wuz yer?”

No, they didn’t think he was blind, they thought he had eyes all over him. It was disheartening trying to get away from Uncle Jeb.

“Now, youngster, you try agin,” the old man would say, “’n’ remember you ain’t diggin’ a cut fer a railroad ’n’ yer ain’t layin’ out no line o’ march ’s if yer wuz marchin’ through Georgie. ’N’ don’t make a noise like yer wuz shoutin’ the battle cry of freedom. ’Cause yer jes’ scare the birds ’n’ the turtles ’n’ they goes ’n’ tells on yer. Now you try once more.”

But it would be just the same thing over again.

The scouts liked to be with Uncle Jeb and help him, but they shared these enjoyments with other diversions, rowing, swimming, and visits to Leeds and Catskills where they conducted masterly assaults upon ice-cream parlors and frankfurter stands, and satiated themselves with movies.

But Westy Martin stuck and became Uncle Jeb’s right-hand man. A score of enthusiastic scouts would help in the starting of a new cabin. But only Westy would remain till it was finished. A clamorous throng would start blazing a trail back into the mountains and for the first mile or two there would be more scouts to do the blazing than there were trees to be blazed. But at the point of destination it often happened that Uncle Jeb and Westy were the only survivors.

During this very summer, of which we have witnessed almost the final scene, Uncle Jeb was engaged in making a continuous trail around the lake. This involved the building of log fords across inlets and a rough bridge at one point. The mountainside across the lake from camp was dense and precipitous and here the making of a real path was laborious. The gang of volunteer workers soon petered out, leaving only Westy and Uncle Jeb to fell the trees and pry up rocks. All the camp idolized Uncle Jeb, but Westy was his good man Friday.

So it was natural enough that Uncle Jeb should select Westy to accompany him on his visit to the old cabin in the Rockies, which had been his home, or rather headquarters, for so many years. And it was natural enough, too, that Westy (being the boy he was) had never dreamed of being chosen for this great adventure. Mr. Temple’s announcement struck him dumb.

It is significant, I think, that the first thought which entered Westy’s mind upon hearing Mr. Temple’s sensational announcement, was the thought of how his father would react to these tidings of great joy. He hoped that Mr. John Temple, who could do all things, would carry his interest to the point of interceding in the Martin stronghold in Bridgeboro. Sunshine had burst upon Westy and dazzled him. And then there was a shadow, a shadow of misgiving and apprehension.

But late as it was in the season something was yet to happen at Temple Camp destined to have an important bearing on Westy’s future adventures. There was one boy in his troop, who occasionally accompanied him and Uncle Jeb in their work of carving out this long-needed and circuitous trail. This was Artie Van Arlen, leader of the Raven Patrol in his own troop. He was tall and likable and intelligent, a real patrol leader. His patrol was more than a group, it was a well-conducted organization. And he had made it so.

Unlike many of the camp group, Artie had not set out to help and then grown tired of it and plunged into other diversions. Sometimes, when he felt like it, he would go across the lake and spend a day on the steep mountainside helping Uncle Jeb and Westy. He never said that he would surely be there the following day. He did not seem to consider his status as that of a helper, though he did help. He frequently rowed or paddled across at noontime with hot lunch for the two steady toilers, and often on such occasions he would remain, clearing away brush and prying rocks out of the projected path. Uncle Jeb liked him and found it pleasant when he took it into his head to hike around or row across.

Artie was rather amused at Westy’s constancy to this arduous labor. But that was the kind of boy Westy was. He worshiped at the shrine of Uncle Jeb and was a model of devotion to his hero. Dogs of certain breeds are said to recognize but one master and companion. Westy was of that exclusive and devoted type. He renounced the camp life to be with this keen-eyed old hickory nut of the plains and the Rockies. Uncle Jeb could hardly have thought of any one else to make the trip to Montana with him.

It was a day or two after Mr. Temple’s bombshell at the big “feed” in his honor that Artie rowed across the lake at noontime with some bean soup and hot muffins for the trail makers. They always took a snack with them and these luscious supplements to their cold lunch came as pleasant surprises.

If it was natural that Uncle Jeb should have selected Westy to accompany him to Montana, it seemed quite as natural that Westy should select Artie to be his companion on the big adventure. At camp it was taken for granted that he would do this, not only because Artie was in Westy’s troop and the two were pals, but because Artie was often with Uncle Jeb, and was serviceable to him in many ways. He was a frequent if not a steady helper.

Since work on the new trail had progressed to the opposite side of the lake from camp, the toilers saw much of him. They would hear the steady clink of oarlocks as the boat approached the shore and then Artie’s voice calling from below, “Are you hungry up there? Any big rocks that you can’t handle? If so, say the word; now’s your chance.” Then he would come scrambling up, all out of breath, to where the work was going on. They enjoyed his visits. Everybody liked Artie.

On this occasion he tied the boat (it was impossible to draw it up because the shore was so precipitous) and started scrambling up with the pail of soup to where the trail was being cut along the lower reaches of the mountain. A narrow and irregular shelf of land was being utilized to carry the trail through this precipitous area.

“How’s she coming?” Artie asked. “Here’s some soup; I nearly spilled it. There’s a boxful of muffins down in the boat—hot ones.”

“I’ll go down and get them,” Westy said; “you sit down and rest. What you been doing all morning? I thought we’d see you sooner.”

“Oh, swimming and playing basketball and reading,” said Artie. “Boy, but you’re getting along, hey?”

“I’ll say so,” said Westy. “What were you reading?”

“Oh, a book.”

Westy laughed. “That’s a wise crack. What kind of a book?”

“‘Winning of the West,’ by Roosevelt,” said Artie, with a slight suggestion of embarrassment. “It’s in the camp library. I just happened to pick one of the volumes up. That’s so, when you write to me from the Rockies, I’ll know what you’re writing about.”

“Maybe I won’t write you,” said Westy rather mysteriously.

Uncle Jeb winked at Artie and all three laughed; Artie’s laughter had that faint suggestion of embarrassment in it that had been discernible when he mentioned the subject of the book he had been reading. The fact is that Westy had every intention of asking Artie to share his great adventure with him, but he had said nothing about this. That was because the shadow of his father lay across the whole affair. He was a careful, thoughtful boy and he preferred not to say anything to his friend which he might have to unsay later. But just the same there was a tacit understanding (and Artie was a party to it) that these three would be the ones to visit the Far West. Perhaps Artie was a bit puzzled that Westy had not put his invitation into words. But he was just as sure of going as ever he had been sure of anything in his life.

To change the subject he laughed and said, “All right, go ahead down to the boat and get the muffins and look out you don’t drop them coming up; they’ll all roll back down into the lake if you do.... All right to sit down on this rock?” he asked Uncle Jeb as Westy departed.

Uncle Jeb sat down on a log and opened the dinner pail which he usually carried with him.

“Some trail, hey?” said Artie, glancing about.

“Good ’n’ plain so even boy scouts can foller it,” said Uncle Jeb. “Westy wants street lamps onto it, but I says no, you youngsters can shout across ter camp if yer get lost.”

“Oh, sure,” said Artie, taking the gibe in good part; “but maybe a sidewalk would be good, hey? You like bean soup, Uncle Jeb?”

“I reckon,” said the old scout.

Artie had leaned forward to pour some of the soup into the cover of Uncle Jeb’s pail when he felt a stirring of the rock on which he was seated. It was hardly more than a tremor, but it was followed almost immediately by a more pronounced jarring. He thought and acted quickly. Jumping up he hauled a small log around and got it under the rock, thus steadying it in its precarious position on the hillside. Uncle Jeb hauled the log on which he had seated himself over to the rock to reënforce the prop that Artie had jammed under it. The heavy rock stirred, then seemed to settle against this combined support and for a few seconds did not move.

“Guess she’s all right,” said Artie. “I prefer another seat though.”

He was looking about for a place to sit down when he happened to glance down to the lake. To his surprise Westy was sitting in the boat his body turning and wriggling; he seemed to be intent upon some physical effort.

“Are you eating all the muffins?” Artie called.

“No, but my foot’s caught under this plaguy stern seat,” Westy called; “it’s like a blamed old woodchuck trap.”

“Turn it sideways,” Artie laughed.

“I did, also endways and upside down,” Westy answered. “It’s a puzzle. I’ll manage it.”

As Artie moved his position for the better enjoyment of Westy’s predicament he saw that the rock which he and Uncle Jeb had wedged up was directly above the rowboat. He shuddered at this thought, but the rock seemed secure so he indulged himself in the pleasure of a few humorous taunts and bits of mirthful advice to the writhing captive. Then, suddenly, there was a crash, one of the logs went rolling down the hillside while the rock, still poised, trembled visibly. Then it moved ominously and some earth and small stones went out from beneath it, rolling away. It seemed to Artie that if he touched it or even breathed upon it, it would go crashing down to the lake. He held his breath, every nerve on edge....

“Loose the boat and push off if you can’t get your foot out,” Uncle Jeb called; “there’s a rock⸺”

“I can’t reach the rope,” Westy shouted, not knowing his danger.

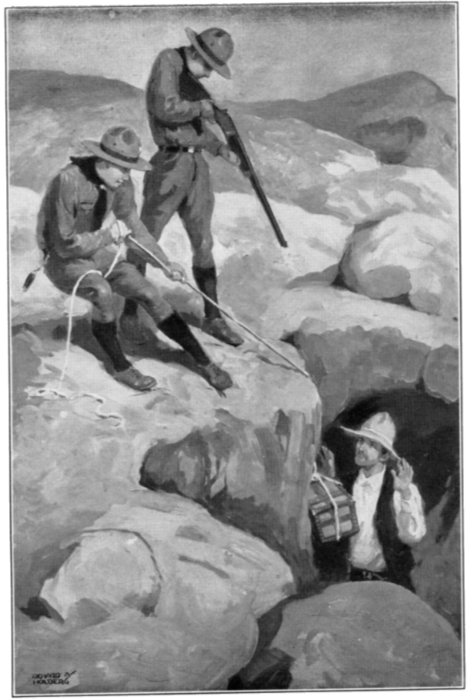

Artie did not pause to call to his friend. One fearful look at the big rock informed him that it was going down. It seemed pausing like a beast crouching, ready to spring. Frantically he ran down the hillside, stumbling, catching hold of trees, now on foot, now on hands and knees. He would do what he could do quickest, and that was to release the boat and get it out of the path of the threatening monster. So as not to lose a second’s time he carried his opened scout knife between his teeth.

He was about half-way down and going backwards so as not to stumble when he beheld something which caused him to act like lightning. Evidently Uncle Jeb had been putting another support under the rock. He saw the old man jump aside and heard him shout. He saw and heard in a panic of horror and did not know what Uncle Jeb said.

Artie was not conscious of thinking at all. He saw the bowlder rocking, then saw it move and roll down a few feet and stop against a big tree. There it paused, balanced for two or three seconds. Artie saw Uncle Jeb run toward it, doubtless to try and hold it poised behind the tree. In a kind of trance he saw the old man hauling a log down to where that tree had momentarily blocked it in its crashing descent.

But Artie did not wait upon the issue of this almost hopeless project. Like a panther he was up a sapling, looking hurriedly about as he ascended, taking note of its position in relation to neighboring trees. He was so frantic with haste that he had not time to close his scout knife; he dropped it from his mouth and forgot it. Near the top of the young tree he began swinging and swaying to make it bend under his weight, but he had to climb almost to the very end of it before it would do this. Then it only bent part way over. But it split somewhere below him and let him down almost to the ground where it lay against the trunk of a larger tree.

Thus in a few short seconds, fraught with peril, Artie had succeeded in doing just what he had hoped to do; he had laid a barrier, such as it was, across the path of the rock. Simultaneously with this lightning exploit the rock rolled aside the tree where it had caught and came crashing down against the fence which Artie had placed, as if by magic, in its path. Fortunately it had not gathered much momentum and the springy sapling bent to absorb the shock of impact, then held the bowlder fast.

The human machinery which had wrought this sudden miracle was not to be seen. Amid the sparse foliage of the prone sapling Artie writhed in agony, his right leg caught between the sapling and the trunk across which it lay. The whole weight of the nearby rock which made the sapling a sort of lever, held that torn and bleeding leg as in a vise. Beads of perspiration stood on Artie’s brow from the anguish he was suffering, and his hands were clammy. He saw Uncle Jeb hurrying past him down to the shore to rescue Westy and he said not a word. Then he saw the leaves near him change color, the whole world reeled, and oblivion came to relieve the torments he was suffering.

Released from the boat Westy looked up the hillside to where Uncle Jeb pointed. There was the bowlder held fast in almost a bee-line above the boat. Its weight strained the prone tree and it loomed conspicuously thus held behind this supple barrier. It looked out of place there, almost as if a human being held it. Westy shuddered as he looked. The lightning-moving human machinery which had interposed this obstacle to the rock’s descent was nowhere to be seen.

“She nigh on clipped yer,” drawled Uncle Jeb.

“Where’s Artie?” Westy asked.

For answer Uncle Jeb only started up the bank, Westy following silently. They found Artie lying where the prone sapling crossed the standing tree. His foot was caught as in a trap. He had brought the sapling down to this secure lodgment and it held him as securely as it held the menacing bowlder. His face was tense with pain, beads of perspiration stood upon his pale brow. He had regained consciousness and was aggravating the agony he suffered by raising his trapped body and trying to see the rock to assure himself that it was held fast.

“Oh,” he said weakly, “you here—you—all right, Wes⸺” Then he fell back again almost fainting.

They pried the sapling away from the tree-trunk, releasing Artie’s crushed foot, and as they did this the slight movement of the springy barrier gave the waiting rock the chance it wanted and it went crashing down to the shore and into the water.

That bowlder has never been seen since. Its murderous escapade ended, it became a submerged and lesser peril in the concealing waters of the lake. You had better not chug around there in the camp launch except in the company of a scout who knows where that rock lies hidden. Once it ripped open the bottom of the little sailboat. And when the wind sweeps the water you may see, even from the camp across the lake, a little spray which marks the grave of Artie’s rock, as they call it. They call that spray the dancing tenderfoot though some will point it out to you as the white devil. Anyway, keep away from it if you are in a boat, for it has a jagged edge sticking up.

That rock did not terminate its brief mad career on earth without leaving a memorial of its murderous power. It crushed the rowboat into splinters as it struck the water and one of those bits of wood which drifted near to the launch that took the stricken hero and his friend across to camp, was picked up by Westy and kept as a souvenir of the near tragedy.

For a day or two it seemed that this bit of wood on which Westy carved the date of the affair might be a sad keepsake. Artie Van Arlen lay with a raging fever in the little camp hospital while the doctors considered whether the amputation of his foot would be necessary, and whether even that would save his life. But the danger which they feared as the sequel of his accident passed and in a week or two his parents, who had waited anxiously, took him home to Bridgeboro. Westy saw him lifted into Mr. John Temple’s big car and saw the white face smiling wanly down at him, humorously, ruefully, as they lifted the bandaged foot up onto one of the small folding seats.

“Wonder how I’d look going scout pace now,” Artie said.

Westy said nothing. He wished he was going back to Bridgeboro too. But that could not be for he was to help Uncle Jeb board up the cabins after the noisy throng had departed. He was looking forward to being alone for a few days with the old scout. They would talk about their big sojourn in the spring and he would ask for the hundredth time, “Are you sure there are still grizzlies there? And do you think we can start just as soon as my school closes?”

Yes, he wanted to stay for those few delightful post-season days in the deserted camp. It would be almost like the lonely life he was going to have a glimpse of in the far Rockies. The far Rockies! How that phrase lingered in Westy’s mind! But he wanted to get in that big car and go back to Bridgeboro with his friend, his rescuer. And when the car had rolled away he felt lonesome and a little guilty, he hardly knew why. That was Westy Martin all over.

When Westy departed from Temple Camp leaving Uncle Jeb alone in his glory for the long winter, he was filled with thoughts of the far-off springtime which loomed up beyond the long, cheerless, intervening season of cold and waiting. He would have liked remaining in the deserted camp all winter with old Uncle Jeb and helping him with the winter “chorin’” with which the solitary old occupant always busied himself.

He burst elatedly into his home in Bridgeboro, New Jersey, on the evening before the day on which school opened, his duffel bag over his back, his face wreathed in smiles. His mother and his sister Doris had only that day returned from the mountains and their trunks cluttered the living room. There was a riot of embracing incidental to this family reunion. Ghostly sheets which had protected the upholstered furniture during the season of Mr. Martin’s lonely occupancy were still in evidence and the paintings on the wall were concealed behind these uncompanionable hangings. One of the trunks stood open with part of its contents pulled out and Westy sniffed the pleasing odor of apples, those souvenirs of vacation time which nestle coyly in the corners of homecoming trunks. The disused living room, bereft of all its familiar bric-a-brac, had a musty odor.

Westy sat down on an unopened trunk and poured out his tidings of great joy. “You’re a nice lot, you are, never writing me anything about my big award. You didn’t say anything about it in your last letter, Mom; I guess you were too busy playing tennis, Dorrie. I should worry. Some work I’ve done this last week, believe me! I suppose you know I’m going to Montana next summer with Uncle Jeb and I’m going to live in his cabin in the Rocky Mountains and you can hear eagles screeching where that cabin is; you can hear grizzlies, too. And I can choose a fellow to go with me; that’s what I get for helping Uncle Jeb all summer. Have you seen Mr. Temple, Dad? He can tell you all about it. Gee williger, I told in letters and you didn’t even say anything about it. Didn’t you get the letter I sent you up to Mountainvale, Dorrie? Talk about mountains! Why Mountainvale is—it’s—it’s only⸺”

“I did and I think it’s perfectly glorious,” said Doris, aged nineteen. “You know how it is, Wes, when you’re up in the country, you just never write letters.”

“She has a new beau,” explained Mrs. Martin.

“Oh, what I know about you, Dorrie!” Westy teased in the overflow of his joy. “I should worry about letters. Anyway, I won’t be here to kid you next summer. I bet you’ll be glad of that. Did you can that Arnold fellow?”

“You shouldn’t talk that way,” said Mrs. Martin in mild reproof. “Mr. Captroop is a very nice young man and your father likes him. He’s in the brokerage business in Wall Street and he’s doing very well indeed.”

“He’s a right sort of a young fellow,” said Mr. Martin, “steady and sane.”

It was evident that these remarks of Mr. and Mrs. Martin were intended rather for Doris than for Westy.

“It’s nice to think he’s not insane,” said Doris.

“What’s his name—Claptrap?” said Westy.

“You haven’t asked about your friend, Artie Van Arlen,” said Mr. Martin. “He had a very narrow escape from death up at Temple Camp. And so did you, from all I hear. You didn’t write us a great deal about that, Wes.”

“I didn’t want you to worry,” said Westy, a trifle embarrassed.

The fact was that Westy had not in his letters depicted the affair of the rock in all its seriousness. Every opportunity for adventure that he had ever had had been wrenched from his father after a struggle in which Doris had boldly championed her brother and poor Mrs. Martin had been his gentler ally.

Mr. Martin believed in people, even young people, being “steady and sane” and he seemed forever haunted by the thought that scouting was something in which boys broke their necks and that camps were places where they contracted typhoid fever. You could not pry those ideas out of Mr. Martin’s head with a crowbar. It was for this reason that poor Westy always skimmed lightly over his adventures and related the doings at Temple Camp with cautious reticence. But he might have known that the news of Artie’s mishap would reach Bridgeboro before him.

“Well, my boy,” said Mr. Martin, sensing the cause of his son’s reticence and speaking mildly in consideration of the boy’s homecoming, “I think you should have told us the whole story.”

“I don’t see what Artie’s accident has to do with Wes’s going out to Montana,” said Doris. “It wasn’t a case of telling the whole story at all; they are two different stories.”

“Well, then, I don’t see why he didn’t tell both of them,” said Mr. Martin. “The Van Arlen boy had a close call from death while in company of this old man. From all I can gather Wes had a pretty narrow escape too—helping this old man. And this is the very same old man that Mr. Temple wants Wes to go off to the four corners of the earth with and risk his neck. It’s very easy for Mr. John Temple to arrange for other people’s sons’ fighting Indians and all such nonsense and breaking their necks into the bargain. Mr. John Temple has no son of his own. Why, I thought all this dime novel hocus-pocus was put on the shelf long ago. Now here is Mr. John Temple filling boys’ minds with all such nonsense and sending them off with some old fire-eater to the frontier of nowhere. The man’s philanthropy has gone to his head. Here you are all home again, not three hours in the house, and Wes talking about going to some cabin or other out West next summer when he ought to be thinking about school to-morrow morning. What boy is he going to take with him, I’d like to know?”

“I made up my mind. It’s Artie,” said Westy timidly.

“Oh, I’m so glad,” said Doris; “he deserves it, for his heroism.”

“Well, that isn’t the way to reward him,” said Mr. Martin.

“You might give him a lollypop,” said Doris, winking at Westy.

“Well,” said Mrs. Martin, putting her arm about poor Westy and speaking in her gentle way, “we’re not going to quarrel about next summer the very first evening we’re all together and have so much to tell each other; we’re just going to forget all about it, dearie.”

“I’ll tell you one thing,” exploded Mr. Martin, speaking to Westy, but at his daughter. “If Archie Captroop had gone shooting buffaloes when he was sixteen and got his head filled up with all this wild-west business he wouldn’t be drawing forty dollars a week at Ketchem and Skinners in Wall Street now. There was none of this falderal when he was sixteen, and look at him now.”

“Picture him hunting buffaloes,” Doris exploded mirthfully.

“Do you mean I can’t go then?” said Westy.

“I mean you should settle down to school now,” said his father not unkindly, “and forget everything else.”

Mr. Martin was not as good a scout as his son. Westy was steeled then and there to hear the worst. But Mr. Martin had not the courage to tell him the worst. He would hem and haw and bluster all winter. But he had no intention of letting Westy go. He would talk about boys breaking their necks until the household would be weary of hearing him. By such talk he would take all the pleasure of going from Westy. Westy’s hope and spirit would be broken instead of his neck. That was the way Mr. Martin worked.

The Martins, notwithstanding their moderate prosperity, kept no car. Because people broke their necks with cars. Likewise, notwithstanding their moderate prosperity, Westy was not going to go to college. Because he wanted to go in for football and in that way boys broke their necks. Mr. Martin was not a bad sort of man, he was just (as Doris said) impossible.

The first summer that Westy went to Temple Camp a solemn promise had been extorted from him that he would not go on the water. Adventure, particularly big adventure with moderate risks, did not fit into Mr. Martin’s scheme of life. He called Tom Slade a daredevil. He was certainly not opposed to the moral side of scouting, he subscribed to all the scout virtues. But the adventurous side he could not contemplate calmly. He did not believe in boys going away from home. His idea of young manhood was embodied in the person of Mr. Archibald Captroop.

Mr. Archibald Captroop was twenty-four and he never went without his rubbers when it rained. There was a young man for you! He did not sport negligee khaki and go without a hat as Tom did. He worked in Wall Street and commuted and earned forty dollars a week. He lived in Raleigh Park about five miles from Bridgeboro so it was something of a coincidence that Doris and her mother had met him at Mountainvale during the summer. Doris had played tennis with him. After the return of the Martins to Bridgeboro, Archibald proved a frequent caller, making the journey to and from Raleigh Park by the trolley. That was one thing Mr. Martin liked about him, he had no automobile.

Archibald had no attraction for Westy. He was pleasant enough and not unmanly, but he was a smug little business man before his time. Mr. Martin approved of his saving his money instead of buying a Ford and he liked him immensely. He thought that Tom Slade, assistant at Temple Camp, might take a lesson from this steady young commuter. Mr. Martin could not believe that helping to manage a camp was really a business. The idea that a man could be a scout and guide in the silent places and call it a business was preposterous. To him old Uncle Jeb was a dubious character who had carried a gun, but never really had a business.

On his way home from school the next day Westy stopped up at the Van Arlen place. Artie was limping about, but getting better, though he was not to return to school for a week or so.

“I came to see you the first thing,” Westy said; “I’m on my way home from school.”

“I don’t have to go, thanks to you,” Artie said with his pleasant smile.

“Yes, I hear you say so,” Westy answered. “A lot you have to thank me for. It looks even as if I can’t pay you back like I meant to do.”

“Pay me back? Did you have a good time up there alone with Uncle Jeb? I was thinking about you alone up there. I bet it was nice just the pair of you. Two’s a company, hey? I couldn’t do much else beside sit and read, so I was thinking of you.”

“What were you reading?” Westy asked.

“Oh, wild-west stuff.”

“Listen, Artie,” Westy said. “I’ll tell you now that you were the one I was going to ask to go out West with me. I guess you know that, don’t you?”

“How should I know it?”

“Well, you just didn’t let yourself think of it, but anyway, you were the one. The only reason why I didn’t say anything about it up at camp was because—well, you know how my father is. I was kind of afraid all the time that maybe he’d say nix and I wanted for you not to be disappointed. I kind of didn’t let myself think of it till I got back, but all the while I was a little sort of shaky about what he’d say.”

“What did he say?” Artie asked.

“Oh, he’s just sort of begun to say I can’t go; I know how it’ll be. It’s all off and I suppose I have to write to Uncle Jeb. Dad says your folks wouldn’t let you go either after what happened to you.”

“Oh, yes, they would,” Artie laughed; “they’d be glad to get rid of me, I guess. My father said when I⸺ He said how a soldier⸺”

“Yes, what did he say when you⸺ You asked him if you could go in case I asked you, now didn’t you?”

“Well, yes, I did,” Artie said, embarrassed, but still amused at himself.

“So you wanted me to ask you, you old⸺”

“Don’t hit me on the foot,” Artie laughed, as Westy’s arm was raised in good-humored menace; “any place except on the foot.”

“Yes, and what about the soldier?”

“The soldier? Oh, yes, my father said there was a soldier who got wounded in eleven places and he was in six hospitals in France and he was gassed besides, and he got over all that and when he got home he slipped on the back steps and broke his neck. My father said it’s just as bad to break your neck in one part of the country as another. That’s what Pee-wee calls logic, hey? No, gee whiz, my father would be glad to see me go, my mother too. I know the cook would.”

“That’s what my father’s always saying about breaking my neck,” Westy said. “He let me go to Yellowstone that time because it was the Rotary Club and they’re all business men. But he thinks Uncle Jeb is some old bandit, I guess. Anyway, it’s all off, Art; he didn’t exactly say so, but I can see it coming. Only I just wanted to tell you that you were going to be the one to go with me. Now that I know what’s what I can tell you.”

“That’s all right, Wes,” Artie said. “As long as you tell me that I’ll admit I wanted to go. But I wouldn’t go unless you did, that’s sure. We should worry, hey? Gee, it’ll seem funny up at Temple Camp next summer without Uncle Jeb there. How’s school anyway? Is Grouchy Gordon teaching the fourth grade yet?”

“Sure, and Four-eyes is teaching drawing yet, too.”

“I thought she was going to get married,” said Artie, carefully changing his position on the porch swing seat so as not to hurt his foot. “False alarm, I guess, hey? Don’t move, there’s plenty of room, only I have to be careful of my plaguy foot.”

“Seen any of the fellows in the troop yet?” said Wes.

Westy drew his legs up onto the seat, careful not to touch Artie’s bandaged foot. And so these two friends sat one at either end of the seat facing each other and chatting. Artie was the one boy in all the troop whom it was impossible to quarrel with. He had almost a girl’s delicacy and an amiability that made him likeable to every one.

“Yes, but you wanted to go all right,” said Westy.

“What you don’t get you don’t miss,” Artie said.

“Well, I’m going to miss it,” said Westy sullenly.

“Well, what do you say we both miss it together?” said Artie. “Then we’ll have some fun missing it. I dare say my mother will be disappointed; she’s getting postcards from me out there already. Well, let’s see. You were asking if I’ve seen any of the troop. Elsie Harris sent me up some jelly; the chauffeur brought it; I guess she wouldn’t trust Pee-wee. Safety first, hey? Sure, all the troop have been up. Mary Temple was here yesterday; she’s in Barnard now. Say, Wes, do you know how Mr. Temple first got hold of Uncle Jeb.”

“Sure, he was out in Montana.”

“Yes, but do you know how he got in with him? Mary was telling me about it.”

“They were surveying or something, weren’t they?”

“Sure, they were surveying for a branch of a railroad through a pass in the mountains. Mr. Temple himself went out there when they got to the pass because he wanted to see that place with his own eyes. Boy, but it must be lonely out there!” Artie burst out laughing at the solemn stare of interest and disappointment on Westy’s face. “Wait till you hear what I’m going to tell you,” Artie added.

“You only make it worse,” Westy said.

“I had to laugh at the way Mary Temple shuddered when she told me about it,” said Artie, still laughing.

“Yes, and you wanted to go out there just as much as I did,” Westy said. “Go on, what did Mary tell you?”

“I’ve got you interested, hey?”

“Will you go on and tell me?”

“Sure, but I can’t tell you the whole thing, because it’s a mystery.”

“Yes, go on.”

“All right,” said Artie, “one, two, three, go. Mr. Temple went out to Montana to see the pass; it was all like a deep ravine through the mountains. That’s the Continental Divide out there. From there if you don’t look out you go rolling down into the Pacific Ocean, kersplash.”

“Will you talk sense and go on?” Westy fairly pleaded.

Artie craned his neck under the swing seat and glanced inquiringly here and there. “Your father isn’t anywhere around, is he? Because there’s a peach of a place for breaking your neck out there. Well, Mr. Temple went out there⸺”

“You said that four times.”

Artie continued, “He went to a large city with a population of thirty-two people in it—and two dogs. I think there was a cat too⸺”

“Will you please⸺”

“The name of it is Eagle City; I guess it’s named after the Eagle Scout Award, hey? All right, I’ll go on. Mr. Temple went there, there’s a train stops there every Tuesday and a week from Friday⸺”

“You’re worse than Roy Blakeley,” said Westy.

“All right, he went to Eagle City,” said Artie, pursuing his narrative more seriously. “That was as near as he could get to the pass by railroad. That’s where he first met Uncle Jeb. Uncle Jeb was buying tobacco at the village store and Mr. Temple wanted somebody to guide him up to the pass; I guess it was about fifty miles. They told Mr. Temple that Uncle Jeb was an old trapper and a guide and a lot of things like that. That’s how Mr. Temple got in with Uncle Jeb. Uncle Jeb said his cabin was up toward the pass, somewhere up that way, so anyway it wouldn’t be out of his way if he guided Mr. Temple to where he wanted to go.”

“Did Mary tell you that?”

“Sure she did,” said Artie, “and there must be some reason why nobody at Temple Camp knows anything about it. Anyway, I never heard Mr. Temple or Uncle Jeb say anything, did you? So then Uncle Jeb guided Mr. Temple up into the mountains—oh, but it was wild and lonely! They stopped at Uncle Jeb’s cabin, just where you and I were going to go⸺”

“Yes, go on,” urged Westy.

“Then they went on up to the pass, but they couldn’t find the surveyors anywhere. Uncle Jeb found marks that showed they had been there and he showed them to Mr. Temple. He found little holes in the ground that showed where one of those surveyors’ instruments had stood, and they found footprints, and a place where a campfire had been, and a place where a tent rope had been around a tree—gee, I guess Uncle Jeb didn’t miss anything. They kept following the pass where it led through the mountains and they found more signs, remains of fires and all like that, but they never found the surveyors and those surveyors were never heard of again—not to this day. Tell your father that!”

Westy stared. “You mean they never got any news about them at all, ever?”

“And there’s something else too,” said Artie.

But Mary Temple did not reveal to Artie the full details of this tragic story. There was something about the expression on her father’s face that had always lingered in her memory; an expression so fraught with anxiety and keen disappointment, that a lapse of ten years had not obliterated the impression one bit.

She was quite young then but she had not forgotten her father’s evident apprehension for those lost men.

Her mother then told her in full how it had all happened and what a financial loss it had been to the railroad with which Mr. Temple was connected. It meant a terrific loss to him at the time, being one of the largest stockholders, but being the man he was he took his loss cheerfully, seeming to be more concerned with the surveyors’ disappearance, than with his own losses.

So it happened that no one but the Temple family and Uncle Jeb Rushmore knew the true details of this unsolved mystery.

It seems that Mr. Temple undertook this trip to Eagle City for the sole purpose of looking over this mountain pass, that was to give way to modern engineering and serve its end as a branch line for the railroad.

The surveyors had secured a sort of agreement from one Ezra Knapp, a farmer, whose property ran parallel to Mr. Temple’s and which he wanted to procure so that the thing could be accomplished by extending the branch line through the distant pass and so on down the ravine.

After the agreement had entered their possession the surveyors wired Mr. Temple for one of his representatives to come without delay and close the contract.

He decided then to go himself, not only for the benefit of his fellow-stockholders but for his own personal satisfaction.

Arriving at Eagle City, he found to his dismay that there wasn’t any hotel in the immediate vicinity.

The station agent directed him to the general store about procuring some conveyance to ride in to the Inn, which was about fifteen miles distant and on the way to Eagle Pass, which was Mr. Temple’s destination.

As he was strolling over leisurely, amusedly observing the quaint hitching posts outside, his attention was arrested by a picturesque figure emerging from the store.

Mr. Temple stood contemplating this young-old man, who was in the act of lighting a pipe as unusual looking as himself.

He judged him to be about sixty years of age, as his face was deeply lined, although he realized one could not tell definitely about that either, as the carriage and raiment of this strange figure bespoke the fact that he was ostensibly a trapper or guide and the outdoor life would in itself line his face indelibly, as a sequence of his continuous battle with the elements.

His hair was snowy white and two shrewd eyes of deep blue twinkled out from under heavy brows and lashes. A drooping mustache of pure white also marked a vivid contrast to his brown, leather-like skin. Withal there was a vivacity and good-humor about him that was undeniably contagious.

Looking up he saw Mr. Temple standing there watching him and with a genial smile of welcome on his face walked over.

“I take it yure a stranger in these parts!” he said, cordially shaking Mr. Temple’s hand.

“Yes, I am indeed,” Mr. Temple returned. “And with whom, may I ask, is it my good fortune to speak?”

“Me?” he asked, his face wreathed with the light of the noonday sun. “Why, I’m probably what you Easterners call Old Timer.” He chuckled softly to himself.

“Well, well,” Mr. Temple said laughingly. “Surely such an individual as you, should bear a name more in keeping with yourself.”

“Yes, yes,” he laughed heartily this time. “I wuz born to the name of Jeremiah Rushmore and they call me Jeb for short. All the folks hereabouts has allus called me Uncle. I’m Uncle to everybody and yit I hev’n’t one relative in the world,” he concluded.

“That, I should think,” Mr. Temple remarked, “is rather a mark of respect.”

“I s’pose so, stranger,” he said more soberly, and then: “Who may you be, sir?” he asked respectfully.

Mr. Temple then proceeded to tell him, and of the nature of his visit and how he wanted a guide to take him through the pass. He also told him that he wanted to get the agreement from his surveyors so that he could close the deal with Ezra Knapp.

“Wa-al,” drawled Uncle Jeb, “I can guide yuh to whar yuh want ter go, fer I wuz jest on my way up to the Inn to take a look-in on my ol’ pardner afore goin’ home. So, you might jes as well come along with me, Mr. Temple.”

And that was the way that Mr. Temple met Uncle Jeb Rushmore.

Mr. Temple jogged along with Uncle Jeb in a dilapidated buckboard, oblivious of any discomfort, for he was fascinated with this old scout’s quaint views of life, and listened attentively to the reminiscences of his trapping days.

“Don’t do much else now but chore aroun’,” he said rather sadly. “Guess I’m a-gittin’ too old!”

“Not at all,” Mr. Temple reassured him.

“Wa-al, anyway I’m a figgerin’ on givin’ up my cabin one of these days,” he said. “’Tain’t jest the thing when a man gits so old ter live by himself, and my cabin’s pretty fur frum the Inn.”

“I’d very much like to see it,” Mr. Temple remarked.

“Wa-al, sir, yure shure are welcome ter come and stay a piece with me.”

“That’s very kind, but I couldn’t stay but one night with you.”

“I’m right glad to hev yuh and I’ll take yuh up and bring yer back so yer kin git to Ezry’s place after.”

By that time they had arrived at the Inn.

The next morning they started before sun-up, just Mr. Temple and Uncle Jeb, on foot, of course. The trail began at the foot of the mountain just back of the Inn. Along toward ten o’clock they came in sight of Eagle Pass, where the surveyors had met Uncle Jeb the week previous when he was on his way down to Eagle City.

“Said they’d be here when I come back this way,” he remarked, “but I guess they hevn’t been able to git as fur as this yit.”

“I suppose not,” Mr. Temple said. “You don’t think by any chance we have missed them?”

“No, indeed,” replied Uncle Jeb. “Thar’s not a track o’ them anywheres!”

They finally came to a spot where a lake could be seen in the distance lying right in the center of the mountains.

Looking up, Mr. Temple noted two cliffs identical in appearance on either side of the lake.

“Twin Cliffs, I calls ’em,” explained Uncle Jeb. “Jes’ like twins excep’ thet the one has a hollow underneath. Regular nestin’ place fer eagles in the winter and sometimes in the summer. Durn good place to keep away frum.”

“I suppose so,” Mr. Temple agreed.

Suddenly Uncle Jeb’s eyes were fixed intently on the ground.

Then he pointed.

There was nothing so startling that Mr. Temple could see but a few small holes and some footprints here and there. Also, some blackened embers, evidently the remnants of campfires long since dead, that had been blown hither and thither by the mischievous summer breezes.

“What,” Mr. Temple asked, “would that signify?”

“Them surveyors,” Uncle Jeb replied with a rueful shake of his head. “They come as fur as here and they didn’t go back and they didn’t go on.”

He was now gazing significantly up a trail that led up to the hollow that he had previously pointed out.

“Do you think by any chance they were up there?” Mr. Temple asked anxiously.

“Dunno,” he replied, “I warned them not ter go, I know that! Thar’s been a little landslide here since I passed and thet would cover up the tracks—if thar wuz any.”

Mr. Temple looked and found that parts of the trail were indeed covered with sand and rock. Becoming alarmed he turned to Uncle Jeb searchingly.

“I’m sorry, Mr. Temple,” he said. “Yuh kin go up if yer want to, but I’m a-thinkin’ yuh won’t find nuthin.”

However, Uncle Jeb led the way up the trail and, needless to say, they searched, they shouted and in a frenzy Mr. Temple rushed to a trail that ran back of the cliff, but to his distraction soon realized that it became impassable after a few feet and finally obliterated itself in the impenetrable fastnesses of the deep mountain forest.

“And so your father went on to Mr. Rushmore’s cabin,” said Mrs. Temple.

“Didn’t he look in the hollow?” Mary breathlessly asked.

“Oh, yes, my dear.”

“Did he succeed with Mr. Ezra Knapp then?”

“No, it was all futile.”

“Why so, Mother?”

“He said he had changed his mind and refused to honor the agreement.”

“How perfectly mean!” Mary exclaimed. “But couldn’t Father hold him to it after making such a contract?”

“Assuredly in any other case, but you see this was different.”

“How so?”

“The agreement disappeared along with the surveyors!”

After leaving Artie, Westy strolled home thoughtfully in the haze of an early fall afternoon. He was thrilled beyond measure and equally despondent at the same time, over the knowledge that he would never be able to see those mountain passes where the surveyors had met their doom.

He was sorry, of course, that such a calamity had befallen those poor fellows, but there was no denying, he secretly admitted, that it added still more zest and charm than before to that haven of Paradise in the far-off Rockies.

It was certainly an Eden-like temptation to poor Westy to have heard that story, for the more he thought about it, the greater his desire became to participate in the wild life for one whole glorious summer.

Still, he realized that some great good fortune would have to wave its fairy wand over the Martin household to convince his respected father that he was able to take care of himself and come back safe from that hazardous wilderness.

“I want to go so much,” Westy said half-aloud, as he was mounting the steps of the house. “Gee whiz, I’d do almost anything to go.”

“What were you saying?” asked Mr. Martin who had previously come home from business and was divesting himself of his topcoat and hat in the front hall. “Were you speaking to me, son?”

“No, Father,” Westy respectfully answered. “I was just thinking of something.”

“Well, my boy,” he said firmly, “you must always do your thinking in the proper places. I noticed as I came along in the bus from the station that you barely escaped being run over. One of those foolhardy speeders came rushing along without any regard to the privacy of your thoughts. There isn’t any room in the world for dreamers, especially the business world. You must quit dreaming if you ever expect to make a mark for yourself in business when you get there.”

“Well, I don’t expect to get there,” Westy whispered to himself.

“What was that you said?” Mr. Martin asked.

“Oh, I said I don’t suppose I get enough air,” Westy replied, feeling absolved from his white lie immediately, when his mother came forward to greet him. She smiled knowingly at her son, thankful that he had evaded any unnecessary argument.

“Well, if you have been in school studying all afternoon it won’t hurt you any. The more you study the quicker you’ll get through and get to business like Mr. Captroop,” Mr. Martin reminded him.

“Come now,” Mrs. Martin interposed, “dinner is about ready.”

Westy looked upon his mother at that moment as one might look on an angel of mercy, for she had saved him from listening to a prolonged discourse on the safe and sane business career for all young men and the many admirable qualities of the Hon. Archie Captroop.

But to Westy’s dismay, the estimable Mr. Martin took up the conversation at the dinner table, where he had left off.

“As I was going to say before dinner,” he began, “I think it would be a very wise plan for Westy to make the most of his next summer’s vacation.”

“How?” Westy hopefully asked.

“By getting something to do like most energetic boys would do, instead of running around wild the whole summer with some unknown Wild Westerner.”

“But, Father,” Westy, crestfallen, despairingly pleaded, “I was speaking to Art to-day and it seems that he was planning on me asking him to go. His mother and father had already given their consent.”

“Really, my boy, that was quite a presumptuous thing for him to do considering that he had not yet been asked. Perhaps though, you had given him encouragement!”

“No, that’s just it. I knew I wouldn’t be able to go and that’s why I didn’t ask him.”

“Then he was presuming,” his father said. “Talking about the Rocky Mountains it reminds me that I was talking with Archie on my way home on the train and I was telling him about this idiotic thing that Mr. Temple had planned for you and this Rushmore man, and he thought, as I do, that it’s a perfectly ridiculous idea for two such young boys as you and Artie Van Arlen to go in that wild country, accompanied only by this perfect stranger whom even Mr. Temple knows little about. Archie remarked that he thought perhaps he might take a longer vacation next summer and visit the Rockies himself. A nice, steady young man like that is well deserving of some recreation when he works as faithfully as he does the year round.

“Now,” Mr. Martin continued, “if a sensible person like Captroop was to accompany you, why I might make allowances!”

“That would be better than missing it altogether, Wes,” his sister Doris remarked.

“It wouldn’t be fair to Artie though, after him saving my life like he did,” Westy chokingly remarked.

“It would be more fair to the boy not to ask him, after what has just happened, and allow him to take any more risks in your interests. You can go if you decide wisely and ask Archie; he can look out for you best. Think it over!”

That night as Westy lay in his bed the thoughts flashed like code messages in his brain and he wondered....

Two weeks had passed by and still Artie was unable to return to school. His foot was slow in mending and he still limped about painfully.

“I ought to be able to get out by spring at least,” he called cheerfully to Westy, who was on his way home from school.

“Aw, don’t get discouraged, Art,” Westy returned feelingly, as he walked up to the Van Arlen residence and seated himself alongside of Artie in the porch swing. “You’ll be out before Thanksgiving, I bet.”

“Gee, I hope so anyway!” Artie doubtfully exclaimed. “Still, I’d be worse off if I was dead.”

“Now you’re saying something!” Westy put in, feeling a pang of conscience, for before he had reached Artie’s home he was wondering how he would tell him of the proposition his father had put up to him. It wouldn’t be sporting to tell him now, he thought. It would be better not to tell him at all—that is not until his foot was entirely better and by that time perhaps he would have considered the matter thoroughly and decide to the contrary.

Not that Westy had contemplated anything definite as yet. Oh, no! But he had pondered it over until he couldn’t think of anything else and was at his wit’s end between wanting to go and the debt he owed to Artie.

He thought as he neared home that it was a bit of luck that Artie had not brought up the subject.

That night, Mr. Martin again broached the conversation along those lines.

“Son,” he said, looking straight at Westy and with decision, “you have until the end of this week to make up your mind as to whether you prefer going with Archie or staying home this summer.”

“Yes, sir,” replied Westy sadly.

“Archie has told me,” Mr. Martin resumed, “that he will decide Sunday as to where in the West he wants to go. He’s going to get some booklets from the different railroads and then he will start next week to make reservations.”

“Why next week, when summer is such a long way off?” Westy queried.

“Why? Because, my dear boy, Mr. Captroop is a very unusual young man and thoroughly conservative in everything he does. Consequently, he’s not putting off until the last minute what can be done next week and, furthermore, he always makes sure of where and what he’s going to do before he starts out.”

“Quite a remarkable person,” Mrs. Martin remarked with a hint of sarcasm in her voice.

Mother-like, Mrs. Martin resented Archie Captroop being held up as an example to her son, for his lovable romantic and non-conservative traits were the very things that endeared him to her most.

Doris Martin, who was expecting the cause of the discussion to call on her that certain Wednesday evening, entered the room.

“Well,” she said, “I hope Mr. Captroop takes me somewhere this evening instead of sitting around buzzing like a stock ticker!”

“You ought to be thankful,” said Mr. Martin, “that he saves his money instead of throwing it away on some senseless movie that doesn’t teach you anything. My motto is never to spend your money on something that doesn’t bring you a full return.”

“Horrors, Father!” exclaimed Doris. “You talk like a confirmed moralist.”

The door bell rang its warning of Archie’s arrival, so she hurried to the door.

“Do not speak about it to-night,” Mr. Martin warned Westy. “It would be more proper for you to go to his house and extend the invitation—that is, if you have decided,” he added meaningly.

The strains of some popular waltz were drifting in from the living room, so Westy knew it meant that Archie Captroop would add one more dollar to his savings account that evening.

He decided to go up to his room, as his mother was busily sewing and non-committal. She was heartily in sympathy with her son, but she dared not show it.

The first book Westy picked up in his room was the one Artie had been telling about and loaned to him two weeks ago. He had not read it before, for he thought it would only be adding insult to injury and also too tempting.

But he could not resist it this particular evening with the fate of this promised adventure lying in the hollow of his hand.

In the dark silence of his room some hours later he argued the point with himself, that he couldn’t have much fun with that “Claptrap” guy if he did go, for he’d probably want to sit around like some old lady and not want to do anything but read the whole time.

“Still,” a little voice inside him whispered, “it’s far better than staying home, isn’t it?”

“I suppose that’s right,” Westy declared, weakening. Then feeling a little mean for giving voice to the thought he added: “I could ask Archie Saturday afternoon and I wouldn’t have to say anything to Artie about it, for a while, anyway!”

So Westy made his decision.

The days succeeding were difficult ones for Westy’s peace of mind. He even avoided passing Artie’s house in the event that he would see him, and so be thwarted from his set purpose.

But Friday night came quickly and he went to bed feeling as though he was facing some terrible catastrophe on the morrow. His slumber was restless and broken throughout the night.

His mother allowing him the luxury of sleeping late on Saturday morning proved a boon to Westy on this particular day, as it prevented any meeting with his father at the breakfast table. That, he was thankful for.

Lunch time came and he ate in ominous silence. Then, as the clock ticked its way around to one o’clock and finally one thirty, he left the house with unwilling steps.

“I think you’re just in time to catch the bus Father’s due on,” his mother called after him, coming out on the porch.

“Archie may be on it too!” his sister Doris added, joining her mother.

“Uh huh!” muttered Westy.

“What a funereal expression, when he ought to be tickled that he got Father to relent this far,” Doris remarked to her mother.

“I know, my dear, but your brother feels that it is a breach of honor to slight Artie and I’m rather in sympathy with him. Still, I suppose, one must be optimistic and think it is all for the best.”

Westy had reached the corner by this time and looked down the street before turning. The bus that he was to take stopped directly opposite Artie’s house, but as there was still ten minutes to the good he decided he would wait where he was until he saw the bus coming.

He kept consoling himself that it was the better way not to have to face Artie just now. Leaning against a telegraph pole, he tried to whistle softly, but the notes sounded hollow and false. Now and then he would step out into the street looking for the bus, although he knew it wasn’t yet due.

At this one instance, while he was gazing down the long, paved roadway, a figure emerged from one of the houses and limped painfully down the stone walk. Westy dared not draw back or run, as much as he would have liked to, for he knew that it was Artie, and he also knew that Artie had recognized him. There was a lump in his throat as he saw with what effort Artie was hobbling along to meet him half way. He felt despicable as he smiled to this brave pal of his, by way of greeting.

“’Lo, Wes, old top,” Artie said cheerily. “I was just going to try and make it to your house when I saw you. Wondered what happened you haven’t been around. Been sick?”

“Well, y-y-yes!” Westy lied, flushing with embarrassment for doing so.

“Oh, I say, but I’m sorry! Feel better now, huh? Were you coming to see me too?”

“Yes—that is—first I was, but I didn’t think I’d have time. Going to take the bus to Archie’s. Invited there this afternoon,” Westy said, and then to relieve the pounding around his heart: “Don’t feel keen about going, though.”

“I can imagine,” Artie said with feeling, “but it’ll do you good if you’ve been sick to be quiet for a while. You better cross now, Wes, I think I hear your bus coming now. See you later. Wait! Look! Whassa matter with it?”

The bus came lumbering down the street pell-mell and careened from one side to the other like a drunken man.

The two boys could see, even from a distance, that something had evidently happened to the driver, as he had slunk down in his seat and his head hung over the wheel.

The huge car was running wild!

“My Father!” Westy cried. “He’s in it!”

“Maybe you can⸺” Artie yelled as Westy ran toward the center of the road.

“Yes, maybe I can!” Westy’s voice could hardly be heard above the cries of the few pedestrians in the street and the frenzied shouts of the passengers within the bus.

Westy then gauged the distance from where he stood and then backed over to the curb. With a rush it came directly toward him, heading straight for the large elm tree at his back. He must avoid that at all costs, he thought.

The door of the bus was open, the weather still being mild; so Westy jumped blindly! Just making the step he reached across the inert form of the driver, whom he could tell at one glance was dead, grasped the emergency brake, and jamming his feet down taut and firm, stopped the car with a grinding shriek just at the edge of the curb.

There were only two faces that Westy could ever remember afterward in that near-fateful bus. One was the white and trembling face of Archie Captroop, whose quivering lips revealed the fact that not only had he lost his head in that near-tragedy but also his nerve. The other face was that of his father, lying prone upon the floor, the blood streaming out of a deep gash in his scalp and entirely covering his head.

With a cry of distress Westy knelt beside him and spoke to him tenderly, but there came no answer to his earnest pleadings.

He lifted his father’s head up gently and with a sob that bespoke his anguish realized at once that his father was unconscious, probably dying.

The House of Martin during the next few hours was the scene of much anxiety and despair.

A white-capped nurse was passing in and out of the sick-room, while Westy and his sister sat on the stairway, apprehensive each time that she had come to tell them the worst.

Mrs. Martin, sitting faithfully by her husband’s side, dry-eyed, seemed shaken with grief inwardly and her white face looked haunted with lost hope.

Four hours had passed and still he had not regained consciousness. The doctor was standing, silently gazing down into the darkened street. He turned back toward the bedside and Mrs. Martin, watching his mobile face intently, thought she detected the faintest glimmer of hope pass across his features.

“Another half hour will tell,” he told her, “and if he lives he’ll have his son to thank not only for his life, but for the half-dozen others he saved from being dashed to pieces.”

The doctor, it seems, had witnessed the accident, and sang Westy’s praises for many a long day after.

Archie had left to go home two hours before, saying he was too upset from the ordeal to stand the suspense of waiting. They couldn’t seem to get a coherent account from him as to how Mr. Martin injured his head. He said he couldn’t seem to remember, he was so excited, except that he saw him fall just as Westy jumped on the steps of the runaway bus.

So Archie went and no one cared to detain him.

Twenty minutes, then a half hour, went by that seemed to the waiting trio like years.

The nurse, reëntering the room, took the sick man’s pulse and nodded to the doctor who was standing close by.

Slowly but surely Mr. Martin opened his eyes, smiling rather wanly at his wife, who was now bending eagerly over him. She was afraid to speak lest he should fall back again into that coma.

The doctor, suspecting her fear, spoke softly. “He’ll be all right now, providing he has nothing to excite him. Perfect quiet and rest will do the trick. I’ll be back in a few hours!”

The nurse went out of the room with him and Mrs. Martin clasped her husband’s hand in hers, fighting back the fears of joy that were continually overflowing. The door opened once again, but this time it was Doris and Westy whose youthful figures were framed in the doorway.

Mrs. Martin put her finger to her lips and motioned for them to come.

“That’s all right,” Mr. Martin spoke weakly. “I want to talk to that boy of mine!”

“Not now, dear,” Mrs. Martin said almost pleadingly. “I’m afraid you’re not quite up to it just yet.”

“Rats!” he replied firmly this time. “Takes a whole lot to kill me, I guess. Westy, come here!”

“Yes, Father,” said Westy, with tears brimming in his large eyes as he knelt once more by his father’s side.

“My boy, you’re a real he-man, do you know that?” he said, raising his hand from under the coverlet and placing it on Westy’s bowed head. “I’m no end proud of you, lad!”

“M-mm,” was all Westy could say.

“After what I witnessed to-day—is it still to-day?” he asked, turning his head toward the window where the shades were now drawn.

His wife nodded.

“After what I witnessed to-day,” he continued, sheer gratitude inflecting his voice, “I’m quite sure that there isn’t a boy alive who is any better able to take care of himself than our boy. Isn’t that right, Mother?”

Mrs. Martin smiled her assent.

“And so,” he went on, “the only way I can repay this modern hero of ours is to grant him the wish of his heart’s desire.”

“I don’t wish to be repaid, Father. It was no more than I should have done,” Westy said, vainly trying to conceal his embarrassment.

“Oh, no, son, that wasn’t any mere duty you performed on my behalf and also the others; it was true courage, the stuff that one rarely sees displayed so splendidly. I wouldn’t have believed it was in you really!”

“I’ve always tried to tell you that!” Mrs. Martin exclaimed with a touch of maternal pride.

“But, Father,” chimed in Doris, clasping her father’s other hand, “just what was it that happened to you?”

“It’s not much to tell, Dorrie, it all happened so quick. Archie and I were sitting together in the back seat of the bus chatting, after we left the station. We had gone but a few blocks when I happened to notice that the driver didn’t stop as we passed by River Street, and I thought it was strange, as a lady waiting there had hailed to him, but he seemed to take no notice of her. Suddenly, as I was just about to mention it to Archie, the poor fellow collapsed, and of course we were all thrown into a panic. No one seemed to know what to do to stop it, and by that time we were running wild. Then, I chanced to look ahead and there was Westy standing in the middle of the street waving his arms frantically. Naturally I forgot all else and got up out of the seat intending to start for the front of the bus. Previously we had all been seated, as the car, swerving from one side of the street to the other, prevented us from keeping on our feet. Archie, meanwhile, had been quaking with fear and I did my best to calm him, but, as I was saying, when I saw Westy I got up and Archie evidently misinterpreted my intention for he arose also. I suppose he didn’t know what he was doing—panic-stricken, I guess, but he pushed me aside to try and get to the front of the bus first and in doing so knocked me backwards, throwing me against the rear window. My head must have gone clear through it, for I could hear the crash of glass and then I seemed to strike something sharp. I don’t remember anything after that.”

“Miss Doris Martin, a Mr. Captroop is downstairs and wishes to see you!” the nurse said, entering the room.

“If you’ll be so kind, Miss Treat, will you tell him I’m not at home and that my father is doing nicely?”

“Surely, I’m only too glad to,” the nurse replied, “and now if you will let Mr. Martin rest for a while, you can see him again in the morning.”

“Before you go,” Mr. Martin said, “I want to tell Westy that he can do as he wants to, providing he comes back next fall determined to get through school as quick as he can and get to business instead of wasting his summers hereafter.”

“Do you mean, Father,” Westy asked breathlessly, “that I can ask Artie? Do you mean that?”

“Something like that,” Mr. Martin answered.

Westy grasped his father’s hand and impetuously stooped and kissed him. Rushing out of the room and down the stairs he flung his coat and hat on in the hall and hurried to tell the news to Artie!

There wasn’t a pair of feet on the paved sidewalks of Bridgeboro that night that stepped any lighter than Westy’s. He seemed to be nearing Artie’s house on air and there were a thousand tiny voices all singing inside him at once.

The night felt frosty and damp after the rather warm afternoon, but as far as Westy was concerned summer dwelt within his heart eternal.

Ringing the bell he waited, excitement and joy kindling his cheeks with radiance. Mr. Van Arlen opened the door.

“Where’s Art?” he asked, stepping inside quickly.

“How is your father?” Mrs. Van Arlen called, hearing Westy’s voice.

“Getting on fine,” Westy answered with gladness in his voice. “Where’s Art?”

“You’re a fine boy, Westy,” Mr. Van Arlen now remarked, as though he hadn’t heard Westy’s question. “I hear the bus company are going to reward you for your bravery and no doubt you’ll get a medal from your troop for such heroism.”

“Yeh? Has Art gone to bed?” he queried, indifferent as to what rewards or medals he might get and intent only on bearing the glad tidings to his friend.

“Here I am, Wes,” Artie shouted from the living-room. “What’s all the excitement?”

“Gee whiz, Art, gee whiz! Bet you can’t guess?”

“Quit keeping me suspended!” Artie laughed. “What is it?”

“We’re going!”

“Where?”

“Why, you dumb-bell! Where would we be going?”

“Wes! You don’t mean⸺”

“Sure.”

“Honest and truly?”

“Cross my heart’n hope to die if we’re not. Father just gave his consent.”

“Oh, boy, but we’re two lucky guys!”