SOUTH AMERICA

[Pg v]

SOUTH AMERICA

INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL

SOUTH AMERICA

BY

ANNIE S. PECK, A.M., F.R.G.S.

AUTHOR OF

“A SEARCH FOR THE APEX OF AMERICA,” “THE SOUTH

AMERICAN TOUR, A DESCRIPTIVE GUIDE,” etc.

New York

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 Fifth Avenue

Copyright, 1922

By E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

“Industrial and Commercial South America” has been prepared, as was the descriptive guide, “The South American Tour,” with the desire to aid in promoting acquaintance with South America and, as a natural sequence, friendship and trade.

As far as possible the facts have been gleaned from publications of the various Governments, in a few cases from those of our own, from high officials of many large companies, and from a few authoritative works. While I can hardly hope that despite all care and effort I have made no slip anywhere, I devoutly trust that no errors will be discovered of such magnitude as I have often noted in my reading of important publications and that any here detected will receive lenient criticism.

The vast amount of labor involved in the collection of data and the effort made to attain accuracy has been such that no time remained for rhetorical embellishment unless with delayed publication.

Great pains have been taken with spelling and accents, the correct use of the latter discovered with difficulty, as they are altogether omitted in many works and in others by no means to be depended upon. Yet they are most important for correct pronunciation.

In this text the spelling of some names varies by intention because the two spellings are frequent and authorized, and should therefore be familiar. Thus Marowijne is the Dutch and Maroni the English name for the same river. So Suriname is spelled with and without the e.

South American names ending in either s or z are found, the z common in older publications. The s is a more recent[Pg vi] style, taking the place of z even in the middle of a word. Thus Huaráz is also written Huarás and even Cuzco, Cusco. But I drew the line there, as Cuzco is too well established in English to make the new and uglier form desirable.

My spelling of Chilian is consistent throughout. Formerly so spelled by all, Chile being earlier written Chili, when the Spanish form of the name was here adopted many imagined that the adjective should be changed also. For this no reason appears, but the contrary. The accepted ending for adjectives of this nature is ian, unless euphony demands a different, as Venezuelan. Where the ending ean is correctly employed as in Andean and European, also Caribbean, which unhappily is often mispronounced, the e is long and receives the accent. This would be proper in Chilean as the e in Chileno receives the accent; but as a change in our pronunciation is unlikely, it is better to drop the final vowel and add the suffix ian as is done in many other cases; thus Italy, Italian.

The frequent writing of maté in English is absolutely wrong. It is never so printed in Spanish, though naturally in French; but to copy their form for a Spanish word is absurd. The word of course has two syllables, but is accented on the first; not on the last as the written accent would imply.

Iguassú in Spanish is spelled Iguazú, but the Portuguese form has the right, because it is a Brazilian river, nowhere flowing in Argentina, and for a short distance only on the boundary. The Brazilian spelling should therefore be followed by us, and it has the advantage that it is more apt to be correctly pronounced.

Persons not undertaking the study of Spanish should at least learn the simple rules of pronunciation; the vowels having the ordinary continental sounds, the consonants in the main like our own, though in the middle of a word b is generally pronounced like v, d like th in this and ll like ly. The rules for accent are easily remembered, names ending in a vowel being accented on the penult, those in a consonant, except s, z, and n, on the ultima, unless otherwise indicated by an accent.

[Pg vii]

The heedlessness of many Americans on such matters is notorious and inexcusable. Knowing the correct pronunciation they continue to mispronounce even an easy word. A notable illustration is Panamá, which many former residents of the Canal Zone and others here persist in calling the ugly Pánama instead of the correct and agreeable Panamá. Although in English the accent is not generally used on this word or on Colón, Panamá is repeated throughout the book to emphasize the correct pronunciation.

It is hoped that other accents given will in general be found correct. It may however be said on Brazilian authority that the accents on Brazilian names are less important than in Spanish.

A considerable divergence in the date of statistics may be noted, for which there are several reasons. In some cases pre-war figures, in others figures for 1917 or 1918, seem to afford a fairer valuation; or they might be the only ones available. Some figures (often in the nearest round number) are given as late as 1921, but to bring all at the same time up to the moment was quite impossible. Great difficulty has been experienced in choosing between conflicting statements and figures. In one case three sets of figures of areas were presented by the same person, before I finally secured the most accurate.

My grateful appreciation is due and my hearty thanks are here expressed to all who in any degree have helped by supplying or verifying data of whatever nature. Officials of the various countries and of many large companies evinced kindly interest in the work and gave freely of their time, few being too busy to afford information. The names are too numerous to mention, but I trust that all will feel assured that their courtesy was recognized and that the remembrance will be cherished.

[Pg ix]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | xv | |

| I. | South America as a Whole | 1 |

| THE NORTH COAST | ||

| II. | Colombia: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 7 |

| III. | Colombia: Physical Characteristics | 14 |

| IV. | Colombia: The Capital, the States and Territories, Chief Cities | 20 |

| V. | Colombia: Ports and Transportation | 30 |

| VI. | Colombia: Resources and Industries | 40 |

| VII. | Venezuela: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 53 |

| VIII. | Venezuela: Physical Characteristics | 59 |

| IX. | Venezuela: Capital, States, Territories, Chief Cities | 63 |

| X. | Venezuela: Ports and Transportation | 77 |

| XI. | Venezuela: Resources and Industries | 86 |

| XII. | Guiana as a Whole: British Guiana | 100 |

| XIII. | Dutch and French Guiana | 109 |

| THE WEST COAST | ||

| XIV. | Ecuador: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 114 |

| XV. | Ecuador: Physical Characteristics | 121 |

| XVI. | Ecuador: Capital, Provinces, Chief Cities | 130 |

| XVII. | Ecuador: Ports and Interior Transportation | 135 |

| XVIII. | Ecuador: Resources and Industries | 141 |

| XIX. | Peru: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 148 |

| XX. | Peru: Physical Characteristics | 156[Pg x] |

| XXI. | Peru: Capital, Departments, Chief Cities | 162 |

| XXII. | Peru: Ports and Interior Transportation | 174 |

| XXIII. | Peru: Resources and Industries | 185 |

| XXIV. | Bolivia: Area, History, Government, Population, Physical Characteristics | 205 |

| XXV. | Bolivia: Capital, Departments, Chief Cities | 214 |

| XXVI. | Bolivia: Ports and Transportation | 221 |

| XXVII. | Bolivia: Resources and Industries | 229 |

| XXVIII. | Chile: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 245 |

| XXIX. | Chile: Physical Characteristics | 250 |

| XXX. | Chile: Capital, Individual Provinces, Cities | 254 |

| XXXI. | Chile: Ports and Transportation | 261 |

| XXXII. | Chile: Resources and Industries | 270 |

| THE EAST COAST | ||

| XXXIII. | Argentina: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 280 |

| XXXIV. | Argentina: Physical Characteristics | 287 |

| XXXV. | Argentina: The Capital, Individual Provinces and Territories | 291 |

| XXXVI. | Argentina: Seaports and Interior Transportation | 301 |

| XXXVII. | Argentina: Resources and Industries | 315 |

| XXXVIII. | Paraguay: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 332 |

| XXXIX. | Paraguay: Physical Characteristics | 338 |

| XL. | Paraguay: The Capital and Other Cities | 341 |

| XLI. | Paraguay: Resources and Industries | 345 |

| XLII. | Uruguay: Area, History, Government, Population, Physical Characteristics | 354 |

| XLIII. | Uruguay: Capital, Departments, Chief Cities, Ports | 360 |

| XLIV. | Uruguay: Transportation, Resources and Industries | 366 |

| XLV. | Brazil: Area, History, Government, Population, Etc. | 372 |

| XLVI. | Brazil: Physical Characteristics | 379 |

| XLVII. | Brazil: The Capital, Individual States, Cities | 390 |

| XLVIII. | Brazil: Transportation—Ocean, River and Railway | 406[Pg xi] |

| XLIX. | Brazil: Resources and Industries | 414 |

| L. | Brazil: Other Industries | 424 |

| LI. | South American Trade | 434 |

| LII. | Life in South America | 454 |

| Appendix I. Postal Regulations, etc. | 459 | |

| Appendix II. Leading Banks of South America | 462 | |

| Appendix III. Steamship Lines to South America | 467 | |

| Appendix IV. Publications | 477 | |

[Pg xiii]

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

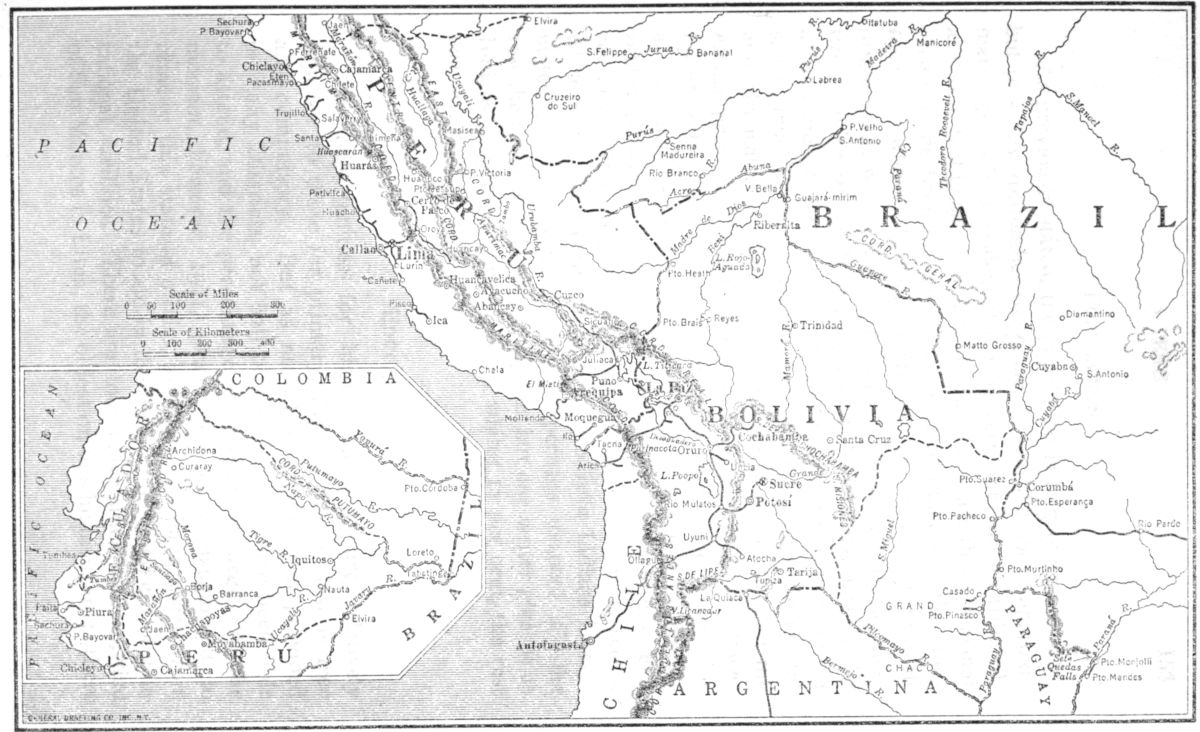

| South America | Frontispiece |

| Colombia | 10 |

| Colombia, Venezuela, Guiana, Ecuador, North Brazil | 64 |

| Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Southwest Brazil | 152 |

| Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay | 254 |

| Eastern Argentina, Uruguay | 308 |

| Eastern Brazil | 390 |

| Environs of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro | 408 |

[Pg xv]

Our recently awakened interest in foreign trade and in world affairs renders imperatively necessary a more accurate knowledge of other countries and a more intimate acquaintance with their peoples. Engaged in settling the various sections of our own country and in developing its manifold resources, we were too long self sufficient in thought and narrow in our activities. Yet years ago a few far-sighted statesmen like James G. Blaine realized that a broader field of action would soon become essential to our continued prosperity. A few manufacturers supplemented their domestic business with a modicum of foreign trade. A few men of affairs devoted their energies exclusively to the field of foreign commerce.

The Spanish War, first inspiring many with the idea that the United States had become a world power with interests beyond its boundaries, served to arouse in others a disposition to have a share in foreign trade. Following a gradual increase in the early years of this century, a sudden expansion of our commerce occurred a few months subsequent to the outbreak of the Great War. A scarcity of shipping prevented its attaining the proportions which might otherwise have been realized. Now that this obstacle is removed and the exactions of war service are over, adequate preparations should be made for the conduct of our developing commercial relations, especially with our Sister Continent at the south.

The supposition that those individuals who are directly engaged in foreign commerce are alone benefited thereby has unfortunately been widespread. Under our democratic form of government it is particularly essential that all should understand the advantages of foreign trade for the welfare of the[Pg xvi] entire nation, that this may not be hampered by the narrow views of local-thinking politicians, jealous of the prosperity of other individuals or sections, or by persons who concern themselves merely with the question of wages for a few or with other special matters; and thus that our commerce may be fostered by our Government according to the custom of other nations, with no purpose of bitter rivalry or unfriendly greed, but with the natural and proper desire of a great nation to share in the mutual benefits accruing to all countries where suitable and honorable foreign trade is developed, as in the case of individuals who buy and sell in the home market.

Some knowledge of other countries and peoples, of causes contributing to their present condition, and of their prospects for future development, while giving intelligent interest to trade and of service in making plans for permanent rather than transitory gain, is desirable for all who care to rise above ignorant narrow-minded provincialism, to be better prepared for civic and political duties, and to enjoy a broader outlook upon the entire world.

The most superficial observer cannot fail to perceive the enormous advantages which have arisen from division of labor among individuals and nations. The personal barter of primitive days was soon superseded by a medium of exchange, fixed locally though varying in different regions. There followed the transport from one city to another and from distant lands of the various products, natural or manufactured, of those cities and countries. As many things grow only in certain parts of the world, others we know are manufactured only in certain districts. That in the distant future the time may come when the entire habitable globe will be occupied, each portion produce what is best adapted to its environment, and the fruits of the whole earth be enjoyed by all its inhabitants, is from the physical point of view the ideal to which we may look[Pg xvii] forward, a goal for the attainment of which every nation may fittingly contribute.

Few are the portions of the earth where it is impossible for man to dwell, providing for his wants from his immediate surroundings. Each section not altogether barren produces such food and requisites for clothing as are essential to sustain life in that locality. The only considerable portion of the globe which is uninhabited, the Antarctic continent, seems likely so to continue, as it appears not merely the most unattractive spot in the world but devoid of the barest necessities for existence.

The North Polar regions, however, support a few people who live upon the products of the country and who probably would not survive if they adopted the customs of civilization as we regard them, though the use of a few articles which have been carried there may slightly ameliorate their hard existence.

The denizens of the tropical forest, who also have adapted themselves to their surroundings, being able to live with little labor, generally pursue an easy life, since necessity and ambition for improvement are lacking.

In other quarters of the globe where labor is necessary to sustain life but where its results may be a bare existence, comfort, or luxury, man has continually struggled for improvement, braving danger and suffering, and toiling long hours for the future good of himself or his children. Thus has the world made progress.

Here in the United States we might live in comfort with the products of our broad lands only; yet we do not desire to seclude ourselves within a Chinese Wall. We would enjoy the fruits of the whole earth, not by imperialistic conquest, but through friendly acquaintance, the sharing of ideas, and the exchange of products.

Some things we produce in such abundance that we have a superfluity to barter for others things which we produce not at all or not in sufficient quantities. In the past we have[Pg xviii] had more trade with Europe than with other continents. In various lines of manufactures and of artistic goods we are still unable to compete. While east and west trade will no doubt continue indefinitely, for natural products it would seem that the chief exchange should be north and south, a difference in latitude causing variety in climates, and a diversity in productions both animal and vegetable. With our expansion of shipping facilities following the conclusion of the War, we may hope for a continuing increase of movement from north to south on this hemisphere, making for friendship and political harmony as well as for material advantage.

In considering South America from a commercial and industrial point of view it is necessary to study the physical characteristics of the individual countries, their advantages and drawbacks; the climate and soil; the resources, including the animal, vegetable, and mineral products, and the water power; the character of the inhabitants including the quality and quantity of human labor; their present needs and wants; the future possibilities; the opportunity for investments of various kinds and political conditions affecting these; the instruments of exchange, banking and trade regulations; the means of communication and transport by land and water.

In addition we should know the difficulties which have retarded the development of countries settled earlier than our own, that instead of a supercilious mental attitude on account of real or fancied superiority in certain directions, we may have a sympathetic understanding of conditions, and of tremendous obstacles, some of which have been overcome in an extraordinary manner.

A general view of the continent as a whole may well precede a more detailed study of the several countries.

[Pg xix]

INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL

SOUTH AMERICA

[Pg 1]

In the study of South America one may observe certain points of resemblance with others of difference between that continent and North America. The outline of each, we perceive, is roughly triangular, broad at the north and tapering towards the south; but as the broad part of one is not far from the Arctic Circle while that of the other is near the equator, we find that the greater part of North America is in the temperate zone while most of South America is in the torrid; disparity in climate and productions follows.

The geological formation of the two continents is as similar as their outline. There is a correspondence on the northeast between what are called the Laurentian Highlands in Labrador and the uplands of Guiana; on the southeast between the Appalachian system of the North and the Serra do Mar of Brazil, each having a northeast to southwest trend and a fair similarity in height, though the tallest peak in either range is the Itatiaiá in Brazil, which by 3000 feet exceeds Mt. Mitchel, the highest of the Appalachians. A difference worth noting is that the Brazilian range is closer to the sea.

A similarity, perhaps greater, exists in the west where lie, close to the shore, the loftier ranges of the two continents, of much later origin than the eastern mountains, and containing many volcanic peaks. Each system includes several chains with valleys or plateaus between; but in the United States the system which includes the Rockies is wider than is that of the Andes at any point. The two systems are distinct, having[Pg 2] neither the same origin nor the same trend, while the altitude of the South American massif greatly exceeds that of the North American mountains.

Between the coastal regions both continents have great basins sloping to the north, east, and south with a large river draining each: the Mackenzie and the Orinoco flowing north, the St. Lawrence and the Amazon east, the Mississippi and the Paraná south. Were the two continents side by side there would be a great resemblance in production instead of the present considerable diversity.

While in area South America is ranked as smaller than North America, it may be a trifle larger in land surface, especially in habitable regions, if the opinion of Humboldt is correct that the Amazon Basin will one day support the densest population on the globe. The southern continent, comprising no large bodies of water like Hudson Bay and our Great Lakes, also has, save the slopes of the highest mountains, no regions like those near the Arctic Circle, incapable of supporting more than the scantiest population.

The outline of the continent is less irregular than that of North America, consequently there are fewer good harbors, especially on the west coast.

As three quarters of South America lie within the tropics, the entire north coast, and the wider part of the continent including most of Brazil with the countries on the west as far down as the northern part of Chile, a tropical climate and productions might here be expected. But happily within the torrid zone of both hemispheres are the loftiest mountain ranges of the world. These modify the climate of large sections to such a degree that in many places there is perpetual spring, a perennial May or June; in other districts one may in comparatively few hours go from regions of eternal summer to perpetual snow, finding on the way the products of every[Pg 3] clime. Thus the mountains and table-lands of South America are effective in causing moderate temperatures over extensive areas within the tropics, with accordant productions.

In comparing the climates of North and South America we must note that while the tropical region of the latter is much the larger, in corresponding latitudes it is in general cooler south of the equator than north. An examination of the isothermal lines, that is the lines of equal average heat around the globe, shows:

First, that the line of greatest heat, a mean temperature of 85°, is north of the equator most of the way. In the Western Hemisphere it runs well up into Central America; then it passes along the northeast coast of South America to a point just below the equator and the mouth of the Amazon, going far north again in Africa.

Second, that of the mean annual isotherms of 65°, which are regarded as the limits of the hot belt, the one in the Northern Hemisphere runs 30° or more from the equator, while that in South America hardly touches the 30th parallel, and on the west coast approaches the equator to within 12°: which means that the tropical region extends much farther north of the equator than it does south.

Third, that of the isotherms of 50° for the warmest month, which are considered as the polar limits of the temperate zones, the one is much nearer to the north pole than the other is to the south. Great masses of water, we know, have a tendency to equalize climate, as the water heats and cools more slowly than the land; but they do not make the average temperature higher. From the movement of the waters of the ocean their temperature over the globe is more nearly equal, while the stable land of broad continental masses has temperatures more nearly corresponding to the latitude, though with greater daily and annual extremes. But for practical purposes, that is for its effect on vegetation, the amount of heat received in summer is of more consequence than the extreme cold of winter. For this reason the temperature of[Pg 4] the warmest month instead of the annual mean is taken as the measure; for if that month’s mean temperature is below 50°, cereals and trees will not grow. The broad land masses in the Northern Hemisphere have a greater summer heat than the narrow stretch of land in extreme South America. The greater cold of winter in the north temperate zone does no harm.

We may observe further that in the Northern Hemisphere the west coasts of both continents are warmer in the same latitude than the east, at least in the temperate zone, while in South America a good part of the west coast within the tropics is much cooler than the east. In the temperate zone the variation is slight.

In the matter of rainfall, a most important factor of climate and production, South America is favored with a liberal supply, the arid portions being comparatively small in area, and many of these easily capable of irrigation and of resulting excellent crops.

Dividing the continent into tropical and temperate regions, the former includes (lowlands only) the entire north coast, the whole of Colombia with ports on the Pacific, and Ecuador beyond, the low interiors of Peru and Bolivia, and around on the east the greater part of Brazil, far beyond the mouth of the Amazon; these sections have much in common as to climate and productions. Below Ecuador on the west coast, though still in the torrid zone, we find cooler weather, practically no rain, and for 1600 miles a desert region; beyond this there is a temperate climate with gradually increasing rainfall, and at last in southern Chile too much. On the east coast tropical weather and products continue till we pass Santos and the Tropic of Capricorn, followed by sub-tropical and temperate climates and production. The mountainous regions even at the equator have cooler weather, the temperature ever lowering with increase of altitude.

[Pg 5]

In general we may say that the soil is extremely fertile and that the country contains wonderfully rich deposits of minerals of almost every kind. The immense store of precious metals found on this continent, some assert the greatest in any portion of the globe, was an important factor in its settlement; yet for true national prosperity the humbler coal and iron are of more value. Water power is also of material service. In these three important elements of wealth South America is not deficient, though her resources in these lines are but slightly developed.

Although many settlements were made in South America more than half a century earlier than our first at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, the population is much smaller than that of North America, the approximate number of inhabitants being 60,000,000 for South America and 150,000,000 for North; manifestly the development of her countries has been less rapid. For this there are obvious reasons.

The tropical climate of the north coast and of much of Brazil might seem less attractive to residents of temperate Europe and less conducive to strenuous labor on the part of those who came; the cooler regions of the south were more remote than the lands of North America. Moreover, the Spanish colony promising the greatest wealth, Peru, which at the same time was the seat of government, was indeed difficult of access, presenting besides, stupendous obstacles to interior travel. In view of these facts it seems wonderful that so many settlements were made on the west coast and that so great a degree of culture was there maintained.

Growth was further hampered by heavy taxes, merciless restrictions on trade, and other regulations by the home governments, almost until the countries achieved their independence. During the century of their freedom most of the Republics have suffered from revolutions and other troubles,[Pg 6] but in recent years several have enjoyed a rapid development with considerable immigration. All now present opportunities of various kinds for investment by capitalists, for general trade, and for other forms of business. Such opportunities, as well as the conditions of living, vary greatly in different countries and in localities of the same country.

It has long been a source of criticism on the part of the diplomats and residents of the various Republics that in our minds they have been lumped together; that we often refer to those portions of the New World which were settled by the Spanish and Portuguese as Latin America or to all save Brazil as Spanish America. Now that we are entering upon a period of closer relationship with our southern neighbors, it is obviously desirable that we should differentiate among them, learn of the diversity in productions and resources which characterize the various countries, and something of their social and political conditions, all of which have a bearing upon present and prospective possibilities for commercial relations. Therefore the countries must be studied carefully and individually.

So far as transportation and travel are concerned South America is often divided broadly into three sections: the East, the West, and the North Coasts, to which a fourth is sometimes added, the Amazon Basin. We may begin with the nearest, the countries on the North Coast, follow with those on the West, and coming up from the south conclude with Brazil. With the Republics of the North Coast we have the greatest percentage of trade, with those on the East the largest amount.

[Pg 7]

Colombia, nearest to the United States of the republics of South America, is recognized as one of the richest and most beautiful of the countries of that continent, containing magnificent scenery, with extraordinary variety and wealth of natural resources. Colombia is noted as the first producer in the world of platinum, emeralds, and mild coffee; the first in South America of gold.

Area. Colombia is fifth in size of the countries of South America, with an area variously given, but approximately of 464,000 square miles.

Population. She is probably third in population, official figures received March, 1921, of the 1918 census being 5,847,491. 6,000,000 may be credited to her in 1921.

Boundary. Colombia has the good fortune to be the only South American country bordering upon two oceans. Having an irregular shape, with the Isthmus of Panamá dividing the two coasts nearly in the middle, Colombia has the Caribbean Sea on the north and northwest for a distance of 641 miles, and the Pacific Ocean, for a stretch of 468 miles, west of the main body of the country. Measuring the outline of all the indentations, the coast line would be two or three times as long. On the south are the Republics of Ecuador, Peru, and Brazil; on the east Brazil and Venezuela. The extreme length of the country, from 12° 24′[Pg 8] N. Lat. to 2° 17′ S., is a little over 1000 miles, as far as from New York to St. Louis; the greatest width, from 66° 7′ to 79° W. Long., is about 800 miles.

In 1502 Columbus sailed along the northern coast, a fact which may have prompted the inhabitants to give the country his name. As early as 1508 Alonzo de Ojeda, who in 1499 had first touched Colombian soil, made settlements on the coast; and in 1536 Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada explored the interior as far as the site of Bogotá, where he founded a city after establishing friendly relations with the aborigines.

The country was first named New Granada. By the middle of the century Spanish power was fairly established along the coast and in part of the interior. The territory was under the authority of the Viceroy at Lima, with a local presidency, until 1718, when a Viceroy, ruling Ecuador and Venezuela as well, was established at Bogotá. In 1810 an insurrection broke out against Spain, the war continuing at intervals until 1824. During those troublous years Simón Bolívar was the chief leader, both acting as commanding general and in 1821 becoming President. In 1819 Bolívar had inaugurated the Great Colombian Republic which united Venezuela and Ecuador with New Granada; but in 1829 Venezuela withdrew and in 1830, the year of Bolívar’s death, Ecuador also.

In 1831 the Republic of New Granada was established, but disorders followed. Many changes occurred in the form of government, which was at one time a confederation, then the United States and now the Republic of Colombia. There have been strife and insurrections: in 1903 that of Panamá made the United States and its people extremely unpopular in Colombia and for some time unfavorably affected our commercial dealings. The adoption by the Senate of the Treaty of Bogotá will doubtless increase the already more friendly feeling on the part of Colombians, which can but be of value for our investments and trade.

[Pg 9]

Since 1886 Colombia has been a unitary or centralized republic, the sovereignty of the States being abolished. The Departments, as they are called, have Governors appointed by the President, although each has an Assembly for the regulation of internal affairs. Besides the Departments, there are Territories of two varieties: Intendencias, directly connected with the Central Government and Comisarías, sparsely settled districts depending upon the nearest Department.

The President is elected for four years by direct vote of the people. He has a Cabinet of eight members, the heads of the various departments: the Ministers of the Interior (Gobierno), Foreign Affairs (Relaciones Exteriores), Finance (Hacienda), War (Guerra), Public Instruction (Instrucción Pública), Agriculture and Commerce (Agricultura y Comercio), Public Works (Obras Públicas), Treasury (Tesoro).

Instead of a Vice President two Designados, a first and a second, are elected annually by Congress to act as President in case of his death, absence from the country, or inability to serve.

The National Congress consists of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The 35 Senators are elected for four years by persons chosen for that purpose; the 92 Representatives, one for each 50,000 inhabitants, are elected for two years by direct vote. Two substitutes are chosen for each Member of Congress to replace them in case of inability to serve. Congress meets annually at the Capital, Bogotá, July 20, for 90 to 120 days. The President may call an extra session.

The Judicial Branch includes a Supreme Court of nine judges, a Superior Tribunal for each Department and a number of minor judges.

Colombia has 14 Departments: four bordering on the Caribbean, Magdalena, Atlántico, Bolívar, Antioquia; three on the Pacific, El Valle, Cauca, Nariño; seven in the interior, Huila, Tolima, Cundinamarca, Boyacá, Santander, Santander del[Pg 10] Norte, Caldas; Intendencias: Meta at the east; Chocó bordering on the Caribbean and the Pacific; the Islands, San Andrés and Providencia; six Comisarías: La Goajira, Arauca, Vichada, Vaupés, Caquetá, Putumayo.

The names of the Departments, their area, population, capitals and population follow:

| Departments | Area, in square miles | Population | Capitals | Population | Altitude, in feet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magdalena | 17,022 | 204,000 | Santa Marta | 18,000 | [2] |

| Atlántico | 1,200 | 135,000 | Barranquilla | 64,000 | [2] |

| Bolívar | 25,800 | 457,000 | Cartagena | 51,000 | [2] |

| Antioquia | 27,777 | 823,000 | Medellín | 80,000 | 4,860 |

| El Valle | 10,802 | 272,000 | Cali | 45,000 | 3,400 |

| Cauca | 9,625 | 240,000 | Popayán | 20,200 | 5,740 |

| Nariño | 11,574 | 340,000 | Pasto | 29,000 | 8,660 |

| Huila | 8,873 | 182,000 | Neiva | 25,000 | 1,515 |

| Tolima | 9,182 | 329,000 | Ibagué | 30,000 | 4,280 |

| Cundinamarca | 8,622 | 809,000 | Bogotá | 144,000 | 8,680 |

| Boyacá | 3,330 | 659,000 | Tunja | 10,000 | 9,200 |

| Santander | 11,819 | 439,000 | Bucaramanga | 25,000 | 3,150 |

| Santander del Norte | 7,716 | 239,000 | Cúcuta | 30,000 | 1,050 |

| Caldas | 3,300 | 428,000 | Manizales | 43,000 | 7,000 |

| Territories: | |||||

| Meta | 85,000 | 34,000 | Villavicencio | 4,700 | 1,500 |

| Chocó | 15,000 | 91,000 | Quibdó | 25,000 | 138 |

| San Andrés y Providencia | 6,000 | San Andrés | 3,000 | [2] | |

| La Goajira | 5,000 | 22,600 | San Antonio | 2,100 | [2] |

| Arauca | 5,000 | 7,500 | Arauca | 3,900 | 640 |

| Vichada | [1] | 5,540 | Vichada | 540 | [1] |

| Vaupés | [1] | 6,350 | Calamar | 750 | [1] |

| Caquetá | 187,000 | 74,000 | Florencia | 3,200 | [1] |

| Putumayo | [1] | 40,000 | Mocoa | 1,200 | 2,100 |

[1] No figures available.

[2] At or near sea level.

Note.—The figures for Meta doubtless include the area of the new Comisaría, Vichada, and those for Caquetá the areas of Vaupés and Putumayo.

COLOMBIA

[Pg 11]

Colombia, ranking third of the South American Republics in population, has about 6,000,000 inhabitants, very unevenly distributed, as is obvious from the figures of the Departments, already given. The average is 12 to a square mile, but in the Departments 26 to a square mile. The smallest Department, Atlántico, is the most densely populated, 114 to the square mile. The largest Department, Antioquia, more than three times the size of Massachusetts, has also the largest population, which is reputed to be the most enterprising.

The character of the population is varied. According to the Colombian statesman, Uribe, 66 per cent is composed of pure whites and of mestizos of white and Indian and white and negro origin, who through successive crossings during four centuries have acquired the traits of the Caucasian race, in some cases showing no traces of the extreme elements; the pure Indians are 14 per cent, pure black 4 per cent, and colored mixtures 16 per cent. The tendency is towards a closer fusion making a unique type which will give the desired national unification. There are about 600,000 Indians, the greater number more or less civilized; perhaps 150,000 wild Indians, some friendly, others hostile. How many there are in the forested Amazon region is uncertain; the recent census places the figure at a little over 100,000. Among all the Indians one hundred or more different languages are spoken.

A great diversity in social conditions is to be expected. A large proportion of the inhabitants dwell in the cities or smaller towns. In a number of these may be found the culture, dress, and refinements of European cities, splendid salons or modest drawing rooms with equal urbanity in each. The wants of the middle and lower classes and of the Indians would be quite different, and would depend further upon their place of residence; the requirements of dwellers in the tropical plains and valleys, and of those who live on or near the bleak paramos are obviously very diverse.

[Pg 12]

Considerable attention is paid to education, which in the primary grades is free but not compulsory. The percentage of illiteracy is about 70. Bogotá has a National University with Schools of Medicine, Law, Political Science, Engineering, and Natural Science. Connected with it is the National Library, an Astronomical Observatory, a School of Fine Arts, and an Academy of Music. A free institute of learning is the Universidad Republicana; there is also a School of Arts and Trades, giving both general and technical instruction, as in printing, carpentry, etc.; a colegio or school for secondary instruction, La Salle Institute, the largest in Colombia, which prepares for the University; and a Homœopathic Institute, from which at least one woman has been graduated.

There are universities also at Cartagena, Popayán, Pasto, and Medellín; in the last named city, a School of Mines, which is a part of the National University. Elementary instruction is the most zealously promoted in Antioquia, Caldas, Boyacá, and Cauca; in the other Departments the school attendance is poor. In Colombia, Spanish is spoken with greater purity than in most of the other Republics.

Institutions giving instruction in agriculture, in arts and trades, and in general science are greatly needed, as also the teaching of sanitation and hygiene.

Press. The Press is free, and bold in discussion.

Religion. The Constitution recognizes the Roman Catholic Religion as that of the country but permits other forms of worship.

Telegraph. The 700 telegraph offices are connected by 13,750 miles of line. Colombia has cable connection at Buenaventura, San Andrés, and Barranquilla; wireless stations at Santa Marta, Puerto Colombia, and Cartagena. An[Pg 13] international wireless station is expected at Bogotá in 1921. Other stations will be at Barranquilla, Arauca, Cúcuta, Cali, Medellín. There are 13,000 miles of telephone wire.[3]

Money. The money of Colombia approximates our own: that is, a gold peso is worth 97.3 cents. Five pesos equal an English sovereign. A condor is 10 pesos; a medio condor, 5 pesos, an English pound. Silver coins are 50, 40, and 10 centavos or cents; nickel coins are 1, 2, and 5 cents.

The Metric System of weights and measures is legal and official as in all the other Republics, although to some extent in domestic business the old Spanish measures are used; as libra, 1.10 pound, arroba, 25 libras, quintal, 100 libras, cargo, 250 libras. The vara, 80 centimeters, and the fanega, about a bushel are other measures. The litre is of course the standard of liquid measure.

[Pg 14]

Colombia is called a very mountainous country, and the most casual visitor would not dispute the statement. Mountains are in evidence along both shores and on the way to interior cities; but the unseen part, the hinterland, is of a different character. Only two fifths of the country is mountainous, but this part extremely so. In this section, very sensibly, most of the people live, as in the neighboring countries; for as the mountains are near the sea the majority of the early settlers soon found their way up into the more healthful and agreeable highlands. The chief drawback to these is the difficulty of access; and we can not but admire the courage and endurance of those stout-hearted people who settled in remote places among the mountains of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and amid untold hardships there preserved for centuries civilization and a high degree of culture.

The great mountain chains of Colombia constitute the northern terminal of the great Andean system. In northern Ecuador the Andes has become a single massive chain; but beginning in Colombia with an irregular mass of peaks, the mountains soon divide into three distinct ranges, the East, West, and Central Cordilleras.

The Central Cordillera may be considered the main range, having the highest peaks: three above 18,000 feet,[Pg 15] and a number nearly 16,000. Many of the summits are crowned with eternal snow, and many are volcanoes, as are peaks in the southern group and in the other two chains.

The West Cordillera, branching from the Central, follows the coast line to 4° N. Lat. where it leaves a space on the west for another coast ridge, the Serranía de Baudó, which has come down from the north as the conclusion of the low Panamá range and terminates the North American system. Between this and the West Cordillera are the valleys of the Atrato and the San Juan Rivers; the former flowing north into the Caribbean Sea, the other south, turning into the Pacific where the low Baudó ends. On the other (east) side of the West Cordillera is the Cauca Valley with the Central Cordillera beyond. These two Cordilleras end in low hills some distance from the Caribbean coast.

The East Cordillera, with the Magdalena Valley between that and the Central, divides into two branches: one running far north dying out at the extremity of the Goajira Peninsula, the other more to the east, extending into Venezuela.

Curiously, along the coast of the Caribbean, northeast of the mouth of the Magdalena, is another seemingly independent range of mountains, detached from the East Cordillera and quite in line with the Central: the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, which has snow crowned summits rising 16,000-17,000 feet above the sea. The entire mountainous region of Colombia is subject to earthquakes, which, however, are less severe than those in Ecuador and Venezuela; in some sections there are volcanic disturbances.

Between the mountain chains, besides the narrow valleys are limited plateau regions, the latter occupying about 900 square miles; while more than half of the country, an immense tract east of the Andes, broadening towards the[Pg 16] southern boundary, is a great plain slightly inclining towards the east and south: the northern part belonging to the Orinoco Basin, the larger section at the south to that of the Amazon. This Amazon region has an area equal to that of the entire State of California. Its higher portion, as well as most of the Orinoco Basin in Colombia, where there are wet and dry seasons, is composed chiefly of grassy plains called llanos. Nearer the Amazon, where it rains a good part of the year, the country is heavily forested.

Rivers entering the Caribbean Sea. Most important at present as also best known are the rivers which flow into the Caribbean Sea. Chief of these is the Magdalena, 1020 miles long, the principal route to the interior. The most important affluent of the Magdalena is the Cauca, which enters it about 200 miles from the sea, after descending nearly 15,000 feet in a distance of 810 miles. The Magdalena has many other tributaries, 500 or more, a few of which, entering from the east, are navigable for small steamers. The Atrato River, 340 miles long, flows north between the highlands of the West Cordillera and the Coast Range, later turning east into the Gulf of Urabá. Of smaller streams flowing into the Caribbean, the Sinú bears considerable traffic. Besides these, there are the navigable Zulia, 120 miles, and the Catatumbo, 108 miles, which by way of Lake Marcaibo in Venezuela also enter the Caribbean.

Rivers entering the Pacific. Into the Pacific flow many streams carrying much water, as the rainfall of the region is excessive; but the courses are mostly so short and the fall is so steep that few are navigable for any considerable distance. The longest of them, the Patía, 270 miles, is the only one which rises on the east side of the West Cordillera. Worth noting is the fact that this river[Pg 17] and four others, the five belonging to three different basins, rise very near together in the highlands of southern Colombia; the Cauca and Magdalena going north to the Caribbean, the Putumayo and Caquetá southeast to the Amazon. The Patía penetrates the West Cordillera by a remarkable gorge with perpendicular walls several hundred feet in height. On the swampy lowlands the river channels are navigable. The San Juan River, 180 miles long, is navigable for 140 miles, as it, like the Atrato, flows a long distance parallel with the coast between the Baudó Range and the Cordillera, until it turns west into the Pacific.

Amazon Tributaries. The Amazon receives two large tributaries from the southern part of Colombia: the Putumayo, 840 miles; and farther east the Caquetá, 1320 miles, the last also called the Yapurá, especially in Brazil. These rivers are navigable by canoe and by steamers of shallow draft for hundreds of miles, though with interruptions in places from difficult rapids. The Putumayo is the better, having been ascended a distance of 800 miles from the Amazon in a steamer drawing six feet. (The entire length of the Hudson is 350 miles.) Smaller rivers, the Guainía and the Vaupés, unite with the Casiquiare from Venezuela to form the Rio Negro, another important affluent of the Amazon. These rivers have many smaller tributaries, but the section has been little explored save for going up or down the main stream.

The Orinoco River, which part of the way forms the boundary between Colombia and Venezuela, receives several important tributaries from the former country: the Guaviare, 810 miles long, the Vichada, 312 miles, the Meta, 660 miles, and the Arauca, 480 miles. Though all are more or less navigable the Meta is the most important. Joining the Orinoco below the Maipures cataract and the Atures rapids, which higher up obstruct the greater river, it permits continuous navigation to the Atlantic Ocean. Where joined by the Meta the Orinoco is a mile wide. The Meta[Pg 18] is navigable for 150 miles above the junction, in the rainy season 500 miles, to a point but 100 miles from Bogotá.

It has already been noted that the altitude of a district as well as its latitude affects the climate, which may be modified further by the direction of prevailing winds and by ocean currents. The extensive and lofty mountain ranges of Colombia therefore give the country a greater variety of climate than it would otherwise enjoy, with temperatures agreeable to every taste and suited to products of almost every character. The configuration of the mountain ranges and valleys causes a further difference in temperature and in rainfall among points at the same altitude; the elevations being responsible not only for their own lower temperatures, but for the greater heat of secluded valleys, and for other variations.

In the forest region of the Amazon there is much precipitation. The open plains of the Orinoco section have less rain, with a dry season when the rivers, which overflow in the wet season, return to their channels and the vegetation withers. Farther north, the Sierra de Perija of the East Cordillera condenses the moisture of the northeast trade winds, causing heavy rainfall on the eastern slope, but having a dry section on the west. The Caribbean coast near Panamá has plenty of rain, which diminishes towards the north, Goajira being quite arid. Excessive precipitation occurs on the West Cordillera, on the Baudó Range, and on the southern part of the Pacific Coast, where the plains are heavily forested and unhealthful like the valleys of the San Juan and Atrato farther north. The lower valleys of the Magdalena and Cauca, shut off from the prevailing winds, are decidedly hot. These and other lowland plains have the tropical climate, in general great humidity, and many dense forests, except for the open drier llanos.

[Pg 19]

Above this region are enjoyable climates, the sub-tropical ranging from 1500 to 7500 feet; still higher to 10,000 feet the seasons are agreeably temperate in character. Beyond this altitude it becomes quite cold, with bleak plains and passes, here called paramos, mostly from 12,000 to 15,000 feet above the sea. Higher yet are regions of perpetual snow.

The Santa Marta Plateau, the upper section of the Cauca Valley, the greater part of the country traversed by the East Cordillera, and the northern end of the Central enjoy the subtropical or the temperate climate. Here is a large proportion of the white population, and here the chief industries are located. In the tropical forests and in the lower plains and valleys the annual mean temperature is from 82° to over 90°; at Medellín with an altitude of 5000 feet it is 70°, and at Bogotá, altitude 8600 feet, it is 57°.

In the north there are two seasons a year, a wet and a dry, though not everywhere well defined; nearer the equator there are four, two wet and two drier, as the sun passes overhead twice a year. On the damp paramos the moist wintry seasons are long and cold, so these parts are unfrequented save by shepherds in the warmer periods. It is estimated that a section of 150,000 square miles, twice the size of England, has an elevation of 7000 feet or more, and there are few points on the coast from which an agreeable climate could not be reached in a few hours by automobile or train if roads were provided.

[Pg 20]

Bogotá, the Capital of Colombia, is situated on a plateau or savanna, a sort of shelf over 8000 feet above the sea, on the west side of the East Cordillera. The shelf, overlooked by fine snowclad volcanoes, has a low rim on the west and a high ridge on the east. About 70 miles long and 30 wide, it is entirely covered with towns and farms. The city is the largest in Colombia (population probably 150,000), on account of its being the capital and having a good climate; the mean temperature ranges from 54° to 64°. 600 miles from the north coast and 210 from the Pacific, Bogotá is the most difficult of access of any of the South American capitals. Nevertheless, the city has always been noted as the home of culture and of intellectual tastes. It is well laid out and covers a large area, as the houses are of only one or two stories with interior patios or courts, as in most South American cities. Many streets have asphalt pavements; there are hundreds of carriages and automobiles, also 23 miles of electric tramways. Like all South American cities, it has large plazas, open squares usually with trees and other green in the centre, and public gardens. The Capitol is an imposing building covering two and a half acres. Other good public buildings include the Presidential Palace, a public library, a museum, etc. Of course there is a cathedral and many churches, two theatres of the first rank, several fair hotels, a large bull ring, a hippodrome, polo grounds, etc. Here are telephones and electric lights as in[Pg 21] all other considerable cities. The people are industrious, intelligent, and fond of amusement.

A more precise idea of the geography of Colombia and of the commercial possibilities of the different sections will be gained by reviewing them in order, beginning with the north coast, going around the outside, and concluding with the interior.

The Goajira Peninsula, a Comisaría at the northeast, is inhabited chiefly by Indians who are practically independent. They gather forest products such as tagua nuts (vegetable ivory), breed useful horses, and do some trading at the port of Riohacha in Magdalena. A few savage tribes make travel in some sections dangerous. The peninsula contains much wet lowlands, as well as mountains, extensive forests, and fine fertile country, with considerable mineral wealth yet unexploited: gold, and probably extensive veins of coal. Large sections covered with guinea grass are capable of supporting great herds of cattle.

Magdalena, adjoining the Peninsula, is a Department a great part of which is low and hot. The inhabitants include many Indians, a friendly tribe on the Sierra Nevada. Back of these mountains are rich valleys, where white settlers have been disturbed by savage Indians who live on the lower slopes of the East Cordillera. Among the products of the region are coffee, cocoa, sugar, and bananas. The upper valleys are the better settled and cultivated; mineral wealth including petroleum is evident.

Santa Marta, the capital, an ancient city and port, founded 1525, has recently entered upon an era of prosperity, largely due to the enterprise of the United Fruit Company. Finely located on a good harbor west of the Nevada of Santa Marta, some distance east of the mouth of the Magdalena, the city is an important centre of the banana industry, to which it owes its present development;[Pg 22] other agricultural products are for local consumption. The climate is hot but healthful, though the banana zone is malarial. An excellent hospital is maintained by the United Fruit Company. Within a few miles are regions with a delightful temperature. A Marconi wireless, one of the most powerful in South America, is of general service, though the property of the Fruit Company. Their enormous banana trade is served by a 100 mile network of railways into sections favorable to this fruit.

Atlántico is a small Department occupying the flat hot delta of the Magdalena River.

Barranquilla, the capital, is a busy place with many resident foreigners. It has quays, a large new warehouse, hotels, one of which is said to have all conveniences, theatres, two clubs, electric lights, trams, and telephones. In spite of the heat, which averages 82° for the year, the deaths are less than 25 per 1000, a percentage better than in some other tropical cities.

Bolívar follows, a very large Department, with the Magdalena River for its eastern boundary. Bolívar like Atlántico has vast plains suited to tropical agriculture and to cattle raising, now a growing industry. The great natural resources of forest, agriculture, and mineral products are but moderately developed. The breeding of horses, donkeys, and mules is a profitable business followed by many. Ten gold mines are worked.

Cartagena, the capital, is considered the most interesting city on the Caribbean coast and one of the most picturesque in South America. Its massive walls and fortifications were erected at great expense nearly four centuries ago—1535. It has fine buildings both ancient and modern, and comfortable hotels. Montería and Lorica are busy commercial cities on the Sinú River, each with a population of 20,000 or more.

Antioquia, the next and largest department, has a smaller coast line. The coast section has Bolívar on the east and the[Pg 23] Gulf of Urabá on the west; but the larger part is south of Bolívar, bordering at the east on the Magdalena River, with the Departments of Santander and Boyacá opposite. At the west is the Atrato River and through the centre the Cauca River. All these rivers are more or less navigable by steamboats as are some of their affluents; others at least by rafts and canoes. Traversed also by the West and Central Cordillera Antioquia has great diversity of character. It is the leading Department in mining, in education, and as centre of industries; it is among the foremost in agriculture, has the largest, most enterprising, and prosperous population. Nearly one-fourth of the coffee exported from Colombia comes from Antioquia, that from Medellín bringing the highest price. The forests contain hard wood and rubber. The Department has five cities besides the capital with a population of 20,000 or above, and 30 more with a population over 10,000.

Medellín, the capital, the second largest city of the Republic, is said to be the wealthiest for its size of any city in South America. It has wide streets, well built houses, many factories, and many educational institutions. The climate is excellent, the altitude being 4600 feet. Here is the National Mint.

Caldas, south of Antioquia and formerly a part of it, is a small Department, very mountainous, with Cundinamarca east and Chocó west. The population, mostly white, possessing sturdy qualities, is devoted to mining, stock raising, and to agriculture of various zones. The rivers have rich alluvium inciting to 2600 mining claims. In the valleys the mean temperature ranges from 77° to 86°. Palm straw and fibres are employed in making hats, cordage, and sacking.

Manizales, the capital, is an important, comparatively new city, founded in 1846. Although distant from any river or railway at an altitude above 7000 feet, it is growing rapidly as a distributing centre. Sulphur and salt mines are near and thermal and saline springs; large herds of cattle graze on the plains.

Chocó, the next coast region to Antioquia, is in striking[Pg 24] contrast to Caldas. An Intendencia bordering on Panamá and the Pacific as well as on the Caribbean, it is rich in possibilities for mining, and for agricultural and forest products; but the excessive rainfall and great heat, unpleasant throughout the district, make the lowlands swampy and unhealthful, and the whole region unattractive to settlement. Less than one-tenth of the population is white; negroes form the great majority of the rest, and there are some Indians. Of the latter, there are three principal tribes in the Atrato Basin and four near the rest of the Caribbean Coast. The Atrato Basin with that of the San Juan forms one of the richest mining sections in Colombia, important for the rare platinum, most of the tributaries carrying this metal with gold. The San Juan Basin is probably the richer in platinum. Rubber, cacao, hides, and timber are other exports. The region will be developed some time.

Quibdó, the capital, is a busy trading centre, which within the last ten years has increased in population fourfold in spite of the disagreeable climate.

El Valle, the Department on the south, again is a striking contrast. Although including a strip of coast with the chief Pacific port, Buenaventura, the name of the Department indicates the part deemed of the greatest importance; and the one that is The Valley among so many we must expect to have especial merits. With an altitude of 3000 feet and upwards, it is a beautiful garden spot between the West and Central Cordilleras, where plantains grow two feet long, a bunch of bananas weighs 200 pounds, the cacao without cultivation commands a higher price than that of Ecuador, where its culture is a specialty; and sugar plantations are said to yield for several generations without replanting or fertilizing. At greater altitudes grow the products of temperate climes. Such a region must some day receive intensive culture, although now the leading industry is cattle raising; since the upper classes are indolent, it is said, the negro laborers also. Yet a brilliant future is sure to come. The mining outlook is good.[Pg 25] Many claims for gold mines have been filed, some for platinum and for silver, one each for emery, talc, copper, iron. There is a large deposit of coal and of rich crystal. The rivers possess auriferous alluvium.

Cali, the capital, is an old, but progressive and important commercial city, with a fine climate, altitude 4000 feet, mean temperature 77°. It has fine old buildings and new ones, poor hotels, banks, automobiles, etc. Other busy cities farther north, are Palmira, 27,000 population, and Cartago, 21,000.

Cauca follows, five times the size of El Valle but with no larger population, of which 25 per cent is white. It extends back from the ocean south of El Valle and of the Department Huila as well. The region has many undeveloped coal mines, and other minerals, with vegetation tropical and temperate in abundance. In some parts there are dense forests. Over 4000 mining claims have been filed, and gold and platinum are exported, but agriculture is the chief industry.

Popayán, the capital, was founded in 1536 at an altitude of nearly 6000 feet. At the foot of an extinct volcano and 17 miles from an active one, with a good climate it has violent electric storms and earthquakes. It has some fine old buildings, a university, and some say that here the best Spanish in the New World is spoken.

Nariño, the last Department at the south, has a large settled Indian population, with some Indians uncivilized. It contains a number of volcanoes a few of which are active; several rivers flow into the Pacific, the Patía the most important. Gold mines have been worked from colonial times and gold is one of the chief exports. Other mines exist and 2500 claims have been denounced. Rich copper has been noted; corundum and sapphires have been found. Besides gold the chief exports are Panamá hats, hides, rubber, coffee, tobacco, and anise.

Pasto, the capital, at an elevation of 8650 feet, at the base of the volcano Galera, has a beautiful location, a fine climate, and a hardy industrious people. There are 21 Indian settlements[Pg 26] near. Barbacoas, 100 miles from the coast, is a considerable city of over 12,000 population where the making of Panamá hats is a leading industry. Tumaco, population 15,000, is a picturesque island port with a better climate than Buenaventura.

Putumayo, a Comisaría east and extending far to the southeast of Nariño, is on the northeast boundary of Ecuador, from which it is separated by the watershed between the river Napo and the Putumayo, which latter separates it from Caquetá, both rivers affluents of the Amazon. The northern part with an elevation of 3000 feet or more has a comfortable climate.

Mocoa, the capital, is in this section, and a few small towns, several entirely Indian.

Caquetá, the adjoining Comisaría, is similar in character, the higher portion a good cattle country. The animals with other products could easily be shipped down stream to Manaos, where they would command high prices. The lower section is a good rubber district; cinnamon, cacao, tagua, hides, oils, balsams, sarsaparilla, varnishes, and feathers are other products of the region.

Vaupés, the next Comisaría shares the characteristics of the low, untrodden, rainy, forest region and of the more open and agreeable lands higher up, a promising territory for the rather distant future. In the Vaupés section the rivers are of black water, near which are no mosquitoes, therefore a more healthful region. Along the rivers of white water, which are in the majority, mosquitoes are a terrible pest. The distinction generally prevails in the countries of the north coast.

North of the Amazon region is that of the llanos belonging to the Orinoco Basin. There is hardly a real watershed between the two; in a number of places channels, especially in the rainy season, connect different tributaries, besides the well known Casiquiare connection between the Orinoco and, by way of the Rio Negro, the Amazon.

The Meta Intendencia, formerly separated from Vaupés[Pg 27] by the Guaviare, the most southern tributary of the Orinoco in Colombia, extends to the Meta River on the north. This section with some country farther north is similar to the llanos of Venezuela, chiefly grass lands of inferior quality, with patches of forest. It supports some cattle and might a great many more, although much of the pasture land is very wet in the long rainy season, and so dry in the short dry season that in many districts the grass practically disappears. The Meta River in its lower part has Venezuela on the north; higher at the northwest is the Casanare region (similar) of the Department of Boyacá. Near the Meta River are more towns, a few cattle centres, richer soil, with easier outlet to Venezuela, to which the few exports chiefly go. The forests of the section teem with deer and other animals, the rivers are full of alligators; the only entrance to Casanare safe from tribes of wild Indians is the Cravo highway from Sogamoso, an ancient town in Boyacá, where Chibcha priests once dwelt in palaces roofed with gold.

The Vichada Comisaría, so recently organized as not to appear on any map (1921), is along the Vichada River between Vaupés and Meta.

Arauca, a small Comisaría, is a part of the region north of the Meta River between Boyacá and Venezuela.

Arauca, the capital, on the river Arauca is called but three days by water (generally seven) from Ciudad Bolívar, the eastern port of Venezuela on the Orinoco.

Boyacá, west and north, except for the Casanare Province, is a Department chiefly in the tierra fria of the East Cordillera. The population is mostly Indian and mestizo, the agriculture is mainly of temperate character: wheat, barley, maize, alfalfa, potatoes. Mining is actively carried on: gold, silver, copper, iron, quicksilver, marble, have been denounced, and 157 emerald claims. Asphalt is worked; there are salt works at Chita, an old Indian town, population 11,000.

Tunja, the capital, is called a fine old city with three public libraries.

[Pg 28]

Santander del Norte, north of Santander, is also traversed by the East Cordillera. The mean temperatures vary greatly: 46° on several paramos, and 81° in the valleys of the Catatumbo and Zulia. Gold, silver, copper, lead, coal are mined. Rio de Oro, tributary to the Catatumbo, has rich auriferous deposits, and what is now of greater importance, it passes through a district rich in petroleum. The varied crops are the chief source of wealth: wheat and potatoes, coffee and cacao.

Cúcuta, the capital, altitude 1000 feet, with a temperature of 84°, is an important commercial city.

Santander, written also with Sur, south of Santander del Norte and of Magdalena, has Boyacá on the east and south; Antioquia and Bolívar are across the Magdalena River on the west. Similar to Santander del Norte, it has more low plains. Gold, silver, copper, talc, asphalt are found.

Bucaramanga, the capital, has a mean temperature ranging from 64° to 84°.

Cundinamarca, south of Boyacá, has Meta on the east, Tolima and Huila south, and Tolima west. Less than one-half of the population is white; about one-third is on the high plateau, the rest on the slopes or in the Magdalena Valley, or on the Orinoco watershed. The scattered population is in 110 municipalities. Agriculture is most important, the land near Bogotá being especially well cultivated. In the city many factories are operated and a variety of trades followed. Mines are widely distributed: iron, gold, silver, copper, lead, coal, jasper, etc.

Bogotá is the capital of the Department as well as of the country.

Huila, south of Cundinamarca and Tolima, has Meta and Caquetá east, Cauca south, and Cauca and Tolima west. Half of Huila is Government land, forest and mountain. Cattle raising is well developed. Wheat, maize, rice, coffee, sugar, tobacco, are cultivated on a large scale. There are four quartz mines, and gold placers receive attention.

Neiva, the capital, is practically at the head of steam navigation[Pg 29] on the Magdalena River. With an altitude of about 1500 feet it has an even temperature approximating 80°.

Tolima, west of Huila and Cundinamarca, is a long Department with the Magdalena River on the east and the Central Cordillera west. Cacao and coffee are raised on the warm lowlands. Twenty-six million coffee trees have been producing; perhaps 4,000,000 more are now in bearing. Over 2,000,000 tobacco plants grow on the foothills, other crops higher, also cattle. Of the last there are 580,000, also 140,000 horses, 100,000 hogs, with fewer sheep and goats. The rivers are auriferous and 60 properties are worked for gold and silver.

Ibagué, the capital, is a pleasant and important city, an active commercial town with mines and thermal springs in the neighborhood, exporting a variety of articles, and with a considerable cattle trade.

[Pg 30]

Foreign commerce is carried on chiefly through five ports, Buenaventura on the Pacific; on the Caribbean, Cartagena, Puerto Colombia, Santa Marta, and Riohacha. Besides these are Tumaco far south on the Pacific, and Villamizar in Santander on the river Zulia, near the boundary of Venezuela, well situated for trade with that neighboring country.

Puerto Colombia, the chief seaport of the country, is situated a little west of the mouth of the Magdalena River. Although with a notable pier a mile in length, the place is small, merely a landing port for the greater city on the Magdalena, to which leads a railway 17¹⁄₂ miles long.

Barranquilla is frequently mentioned as the port instead of Puerto Colombia, since it contains the national custom house through which at least 60 per cent of the commerce of the country passes. Yet it is not a real seaport, being 15 miles up the river, which is inaccessible to ocean steamers. When a channel is dredged through the Boca de Ceniza so that such steamers can reach Barranquilla, it will be of great advantage to commerce. This work, previously arranged for, but blocked by the outbreak of the European War, may soon be accomplished.

It might have been better to make use of the “Dique,” a natural river channel 60 miles long extending from Calamar to the sea 15 miles south of Cartagena. This is now used in the rainy season by river steamers, though swamps near Cartagena[Pg 31] present difficulties. Intended improvements in the channel from Sincerín, where there is a large sugar plantation and refinery, will make it navigable for boats of a few hundred tons. Beginning at the “Dique” rich agricultural land extends south.

Cartagena, the port second in importance, has a fine natural harbor and excellent wharfage facilities; the custom house depots alongside are among the best in South America. It is less than 2000 miles to New York (4500 to Liverpool) and 266 from Colón.

Santa Marta, northeast, is finely located on a good harbor. Like the ports already mentioned, it has weekly steamers to New York, New Orleans, and also to England.

Riohacha, population 10,000, still farther east, is a poor port of much less importance. Merely an open roadstead, it is seldom visited by steamers but is frequented by sailing vessels from Curaçao and other points.

Buenaventura, the chief Colombian port on the Pacific, with a population of 9000, is situated on an island in the Bay of the same name, which can accommodate vessels of 24 foot draft. A new pier, 679 feet long, just completed, has twin docks and two railway approaches; on one side water is 28-44 feet deep. The place is regularly visited by steamers and is an important port of entry for the rich Cauca Valley.

Tumaco, farther south, a town of 15,000, is a port of some importance for southern Colombia, the bay receiving ships of 21 foot draft, which are served by lighters.

Villamizar on the River Zulia through that and the Catatumbo is connected with Lake Maracaibo and the Caribbean.

Orocué, population 2500, on the Meta, and Arauca on the Arauca River, may be reached by steamer from Ciudad Bolívar on the Orinoco and so communicate with the sea.

[Pg 32]

It is evident that the physical conformation of Colombia is such as to render extremely difficult the construction of railways or indeed roads of any kind. Lack of capital, and internal disturbances have contributed to retard development in this direction. The rivers therefore have been of prime importance for inland travel and transport. While these are supplemented by local railways and cart roads, the greater part of transportation over this extensive territory is, aside from the waterways, accomplished by means of pack and saddle animals over caminos or bridle paths of varying degrees of excellence.

The Magdalena River is the main artery of traffic, its normal transportation being more than doubled because of the important railways leading to or branching from the River. As its mouth is navigable only for light launches, nearly all freight and travel comes by rail either from Puerto Colombia to Barranquilla, 17 miles, or from Cartagena to Calamar, 65 miles. However, Barranquilla has some traffic with Santa Marta by means of steam launches of light draft through channels of the delta. By the Cartagena railway freight is shipped without cartage to Calamar within five days. At this town of 10,000, there is a good pier, but poor hotel accommodations for the traveler, who may be compelled to wait some time for a steamer. The river has a width of from half a mile to a mile, and an average depth of 30 feet, but in the dry season shoals sometimes prevent for a month the ascent of the river by steamer. Much time is consumed in loading wood for fuel, as well as in other calls, and part of the way is unsafe for navigation at night. This at least has been the case, but recent and prospective dredging both on the Magdalena and the Cauca promise much better conditions in the future.

The Magdalena, the regular route of travel for Bogotá,[Pg 33] is navigable about 600 miles, to La Dorada on the west bank, for steamers of 500 tons. The facilities for comfort for the six to nine days’ journey (which has been prolonged to three weeks in periods of low water) include staterooms with electric lights; but passengers must now carry their sheets, pillows, and mosquito netting; and some take food to supplement the table fare, or make purchases en route. It is reported that 100 eggs were bought for $2.00 in February, 1919. If the five gliders drawing but a few inches, which have been ordered in France for the Magdalena, prove a success, facilities for travel will be immensely improved. A hydroplane service for passengers and mail, Barranquilla to Girardot, is now in regular operation. Other service elsewhere is proposed.

At La Dorada, the terminus of the sail on the lower river, a change is made to the railway 70 miles long, which was built to Ambalema, population 7000, to avoid the Honda Rapids. Overlooking these is the busy town of Honda, population 10,000, in the Department of Tolima, for 300 years an important centre of trade. A suspension bridge crosses the river from which, by a rough bridle path, until 1908 most of the traffic went to Bogotá 67 miles distant. Some freight still goes over this trail to Bogotá, or to Facatativá, 45 miles, a two days’ ride, as well as a few tourists, better to enjoy the scenery, to escape the heat of the valley, or more likely, when compelled by the upper river being too shallow for steamer traffic.

Usually the railway is left at Puerto Beltrán, altitude 755 feet, population 2000 (just below Ambalema), where a 100 ton steamer is taken for the 100 miles on the shallower stream above to Girardot, a new town, population 13,000, on the east bank, with ten hotels, and rapidly growing in commercial importance.

From Girardot, altitude 1000 feet, to Facatativá, population 11,000, the Colombia National Railway climbs the East Cordillera about 8000 feet in a distance of 82 miles[Pg 34] on the way to Bogotá. Twenty-five miles more on the Sabana Railway, a road of a different gauge, brings one to the capital, having made six changes from the ocean steamer: first to the railway at the port; next to a steamer on the lower river; third to the railway at La Dorada; at Puerto Beltrán to a smaller steamer for Giradot; fifth to the railway to Facatativá; thence to the one to Bogotá.

Aside from the traffic to the capital, the Magdalena with its 500 tributaries is of enormous service. The boats call at many small places (sometimes a single house) along the river, from which mule trails (or a stream) lead to interior towns in the various Departments. The first river port of importance, about 70 miles from Barranquilla, is Calamar, where travelers and freight from Cartagena are taken on board. Magangué, population about 15,000, is the next considerable town. Between Magangué and Banco the Cauca enters the river.

Up the Cauca steamboats run 170 miles to Caceres; also on one of its branches, the Nechi. Through most of its length the Cauca is nearly parallel to the Magdalena, but confined in a narrow valley its course is far less smooth. Above Valdivia navigation is prevented by a stretch of 250 miles of narrow cañon and rapids; in the upper valley is another navigable section of 200 miles, from Cali to a little below Cartago. Being disconnected from the Caribbean this section must seek an outlet on the Pacific.

The San Jorge River, nearly parallel with the lower Cauca and entering the Magdalena a little farther down, is navigable for 112 miles.

At Banco, a town of 7700 on the Magdalena, a smaller boat may be taken up the Cesar River coming from the northeast; at Bodega Central, population 4000, one up the Lebrija towards Bucaramanga, to which there is another route by way of Puerto Wilches beyond. From the latter a railway, long ago planned and in operation for 12 miles, is now in construction, imperatively necessary for the development[Pg 35] of this part of the country. The distance is 90 miles. From La Ceiba, 70 miles up the Lebrija, a mule trail leads to Ocaña, population 20,000, as well as one to Bucaramanga, which is also reached by a shorter route from a point 22 miles up the shallower Sogamoso when that is practicable.

The first railway above Calamar, found at Puerto Berrío, population 1000, nearly 500 miles south of Barranquilla, leads to the important city of Medellín. This, the oldest road in Colombia, has a break where a 15 mile ride is necessary across the mountains. When the tunnel contracted for is completed the entire length of the road will be 120 miles. Its prospects are excellent. A second railroad has Medellín, the Amagá, running 23 miles south towards the rich Cauca valley, which it will soon reach. These two roads are said to carry more freight than any others in the country.