Half a loaf is better than none.

Or, to put it another way, how

many jelly beans can you get in ...

By FRANKLIN GREGORY

ILLUSTRATED by SUMMERS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories February 1960.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It seemed somehow appropriate to Justin that it was a little child who would finally save the world; since, broadly speaking, it was the little brats who caused the mess in the first place.

"Not," Justin hastened to assure Doris with a tenderly approving glance at her expanded umbilical region, "that it's all their fault. There's just so damn many of them."

Doris, supine like a pampered queen on the day bed, corrected him gently.

"Us," she said. "Really, Justin—"

"Yes, yes," Justin agreed. "With a name like mine. I ought to be more fair. Us, it is, of course, all ten damn billion of us. And it was really our Great Granddads to blame. If they'd listened to Huxley and the rest of the population-controllers, we'd not be in this box. We mightn't even be, period."

"What a frightening thing to think of!"

"I only meant," Justin pursued, "that since we were all kids, too, once, it does rather keep going back to that. The more kids, the more there are to grow up to beget more kids, ad infinitum till something gives. But with this lousy election coming on, maybe I'm not thinking so straight any more."

"You're a very straight thinker," Doris told him, and she smiled proudly at the Nobel scroll on the wall. "Everybody at N. Y. U. insists you're an absolute genius, one of the last."

Justin tried, and as usual failed, to contain his sarcasm.

"Everybody? You mean all twenty-six morons on the faculty, or that mob of half-literate bums they call a student body?"

"Now you're being difficult," Doris said. But Justin, genius-like, had stopped listening. Instead, he was thinking how silly his colleagues would look when he finally announced his answer. It was the obvious the clunkheads never saw; which, when you came down to it, was why clunkheads never won Nobel Prizes.

Nobody denied that in this year of Our Lord, 2060, a new frontier was needed to relieve the horrible overcrowding. So where else, they asked, would you find it except in Outer Space? You couldn't make the world stretch, could you? Of course not. But it was like saying a jar would hold only so many jelly beans. That was true, too, but only in a sense. It was the other sense the clunkheads didn't see.

Doris stirred and murmured. Justin stiffened with concern. Doris said: "It didn't really hurt. It was the surprise. I can't get used to the little monster bumping around inside me. You don't mind me calling it a little monster, do you?"

"Of course not."

"And it won't be, will it? You promised it wouldn't. Oh, Jus, I simply couldn't stand having an abnormal baby."

"No," he said, sticking to the truth as he saw it. "No, it won't be abnormal."

They had been through this before, ever since the first month when Doris agreed to the hormone injections and the special diet. He said suddenly:

"Did you ever hear of Count Borulwaski? He was a Pole. Handsome, witty, a scholar, and very healthy. He lived to be ninety-eight years old."

"Do you mean my baby will be like him? Oh, I'd love that!"

"I think he will be very much like Borulwaski," Justin said, again quite honestly. And he hoped to God Doris never took it into her pretty blonde head to look up the man in the encyclopedia. It wasn't likely. That was the nice thing about a girl with so few intellectual pretensions.

Justin himself—Dr. Justin Weatherby, biochemist, geneticist, endocrinologist, and politician perforce—got his belly full of intellect every day. Since he could abide neither brains nor absolute idiocy, he was often lonely. But President Austin told people:

"What I like about Weatherby, he's the only confounded scientist I can understand."

To a President of the United States in the hot spot of making unpopular decisions every day and simultaneously seeking reelection, this was important. And it was to have Justin's advice at hand that he had named him consultant to the National Demographic Authority, the agency which—in view of the galloping population crisis—had long since succeeded the Security Council as No. 1 pusher-around of people. Nobody envied Justin this position.

Nobody, either, gave Murray Austin a Chinaman's chance of whipping Senator Wheeler. In sixty years not one American President had won a second term; not one had made good his campaign promise to bring order out of chaos.

To this unavoidable handicap, President Austin had added one of his own: his deliberate by-passing of the powerful Strip City Bosses who had placed him in office.

By habit, Justin glanced at Doris and then at the calendar on his work table with its fatefully-ringed election date of two weeks hence—Tuesday, November 2. A bizarre race, he reflected, between the ballot and the stork. Mind-reading Doris teased:

"What if I had a miscarriage?"

"My God, don't even think it!"

Doris reached for her manicure set and began to do her nails. She'd really never understood why Justin thought her baby would be more important than anyone else's—except to themselves, of course. But if she were puzzled, and if she wished Justin were less secretive about the experiments that took him so often to his Rockland County laboratory camp, she did not actually worry. She said:

"You're rather fond of the old goat, aren't you?"

"Let us say, rather," said Justin stiffly, "I am fond of my country. Murray Austin is the first President I can remember who is really trying to do something."

"Meaning," smiled Doris, "that the old goat listens to you."

"Exactly. But I wish you would not call him an old goat. He's younger than I, a shade taller, and almost as handsome."

"Gee, we sure hate ourself."

Grinning, Justin stepped to the window, his usual method of closing a conversation. Three panes were cracked and he had patched them with tape. Just outside, the once-private terrace had been converted to a fire escape long ago when the apartments were sub-divided. Somebody had told him that Washington Square Village in the old days was a very nice place to live, with elevators even and private bathrooms. It would be pleasant to have your own bath. Still, they were darn lucky to have this single room to themselves, and that only because of his standing with the Government.

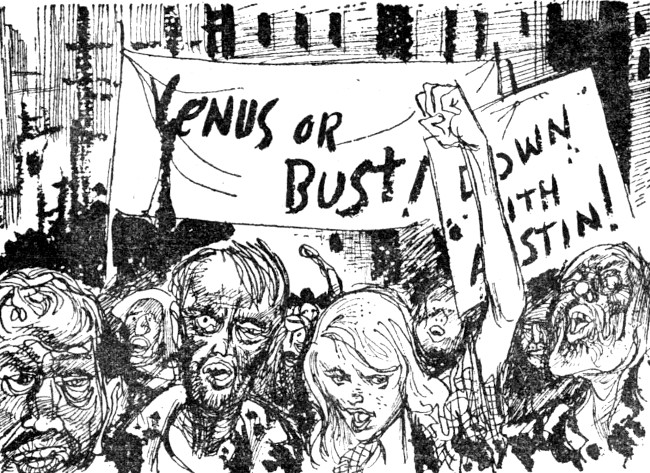

From his high vantage he could see into Washington Square where, under the autumnal nudity of the ancient trees, the students had their digs—old army tents mostly and packing-crate shanties. A snow threat hung in the bleak sky; a light breeze rippled the tent walls and churned the smoke from the community kitchen's licensed fire. Oblivious of the forming weather, a group of ragged students mustered near the ruined Arch. Some carried signs:

"Down with Austin! Vote for Wheeler!

"Venus or Bust!

"Damn the Budget, Try Again!"

In loose, unmilitary formation they filed past the Arch, perhaps to picket some visiting delegation; more likely to stage another hot-headed rally of their own Society for the Settlement of Space.

Exasperated at their persistence (and the persistence of all human hope) Justin watched as they lost themselves in the wretched pedestrian hordes of Fifth Avenue. A little uneasily, he wondered how they would take the President's announcement. Or, for that matter, his own.

"Hon, I'm gasping. Roll me one, huh?"

Justin returned to the table and lifted the porcelain top of the room's only antique, a 19th Century apothecary's jar deceptively labeled "Opium." There was but little tobacco left. Careful to spill not a single grain, he rolled a cigarette, inserted it between Doris' lips and held a match. When she'd inhaled, hungrily, she asked:

"Aren't you having one?"

"Joe's not sure when he can get some more," he said thoughtlessly, and at once regretted subtracting from her pleasure.

"I feel like a heel. Have a drag on this."

"No. No, thanks, I'm trying to quit," he lied lamely.

Crazy, this young girl latching onto the habit forty-odd years after they'd switched the last Burley field to essential food grains. Only dimly could he himself remember when the Tobacco Prohibition Amendment was enacted. Could there be something in Doris' metabolism to demand nicotine? The thought startled him; would it make a difference in his calculations?

From behind her pillow Doris pulled out a fat, once-glossy magazine of a type not published for generations. It was dated January, 1959, and Justin had brought it home from the college library to amuse her. Turning to a splashy, full-page cigarette ad, she asked:

"Were they really manufactured a hundred years ago?"

"Oh, yes, they called them tailor-mades." He closed an eye to recall a specific fact. "Americans smoked nearly half a trillion a year. It was a tremendous industry."

Doris said slowly:

"You ought to have something relaxing to do."

"I could get drunk on lab alcohol, but that's illegal, too." He sat down beside her and stroked her neck. "Besides, I have you."

"You're leering! I'll see you after the baby is born."

She turned a page. It was hard to tell whether the slim girl stepping from the orchid-colored Cadillac in front of the theatre marquee was advertising the Cartier emerald necklace or the sable coat.

"You never see anything like this," Doris said.

"They're still around. In hiding, mostly. Once in a while, after a riot, and if you want to pay an outrageous price, you can get something like it under the counter."

"But you couldn't wear it!"

"Of course not. You'd be torn to pieces."

"And just anybody could fly to Europe or take cruises? And everyone had cars like this? Not just the Government?"

"Nearly," said Justin. "You could put all the people in all the autos and all the back seats would still be empty."

Doris sighed.

"It must have been a fabulous time to live."

Perhaps it was. Even history-minded Justin found it hard to believe the cold statistics of that storied era: a life expectancy at birth of sixty-eight years; a daily diet of three thousand calories; meat, eggs, milk whenever you wished (why, he himself could scarcely remember the taste of beef!); bountiful super-markets groaning with viands; choice liqueurs and wines; fresh fruit in winter; mountainous surpluses of wheat and corn; candy shops, jewelry shops, flower shops, book shops; opera, theatre, museums; a telephone for every three persons; half the population in steady jobs, another quarter in school ... and land, land, land for everyone!

Where had this great nation failed?

To the few who still troubled to study the past, there was no mystery. From the twelve billion a year spent during the infant age of Sputniks and Explorers, America had spilled her treasure like sand into the frantic race to conquer Space. Temporarily braked by the Wars, but with each Peace redoubling the effort, the nation in the decade after the Red collapse had poured half her national income into those innumerable stabs toward the stars.

Like the Mississippi Bubble, the madness mounted. With the first building of the Moon stations, with a lucky landing on Mars, hope in the great gamble rekindled and the world "ahh'd" like children watching fireworks.

No cost was counted. For, as the 20th Century turned into the 21st, the exploding population seemed to make success ever more urgent. Demagogues were swept into office on the mere promise of more Space spending. Their failure but paved the way for successor demagogues with still wilder plans.

Yet each new surge of the wasteful effort saw the economy erode, the dollar shrink, and private income shrivel and disappear. Markets for first the luxuries and then the staples contracted and vanished. Non-Space industries closed and scores of millions were thrown on the dole.

The simplest law of economics had asserted itself: the frantic expenditure of capital without return could only end in complete bankruptcy.

Corporate giants stopped their dividends and defaulted their bonds, trading ceased on the stock exchanges, insurance empires collapsed, banks failed and all the gold in Fort Knox could not make good on the insured deposits.

Newspapers folded for lack of advertising; television blacked out, and Government radio remained the sole means of mass communication.

Taxes soared—and went unpaid. Schools closed, colleges foundered. Skills, acquired in a thousand years of Western civilization, were lost to posterity. And the great medical discoveries of the 19th and 20th Centuries, so important a factor in the mushrooming population, were all but forgotten by the ever-diminishing ranks of doctors.

Diseases, once thought banished forever, reappeared. Ignorance spread. Tensions gripped the nation. The hospitals, prisons and madhouses spilled over, and each night brought new terror from marauding gangs. Life became a nightmare.

By 2030 the last foundations for any industrial nation collapsed as increasing man—cancer on his own planet, spendthrift and wastrel—exhausted his oil and coal and gas and minerals. By that year the subways had stopped in New York; trains braked to a halt from Coast to Coast; great liners rusted at their docks; planes grounded, and the lights went out in street and home.

Nor did power from atom or wind or sun or tide begin to fill the breach. Research, so long channeled into the single paramount objective of celestial pyrotechnics, had neglected to find replacement fuels.

This was the chaotic age in which Justin Weatherby reached manhood and Doris was born.

Charlie Hackett paid one of his rare calls next morning, flushed from climbing the seven backstairs flights. He was Doris' uncle, a former Mayor of New York and still the undisputed political boss with sixty million votes in his pocket if you counted the Upstate graveyards. He was past middle age, plumper than the austere times permitted, and it took him a moment to sit and recover his breath.

"Lord!" he exclaimed, blinking. "It's good to get out of that mob, and the smallpox out of hand again. Why d'you know, when I was Mayor twenty years ago, this town had only twenty-eight million people. It must be twice that now."

Justin, wondering what prompted the visit, said:

"And it was built for only eight."

"Really? Hmm. You ever been to India?"

"Oh, yes."

"Worse'n here?"

"Much worse," said Justin. "Though I judge we're about where they were eighty or ninety years ago."

"I was in London last week, gov'ment trip. This Hindu diplomat was blamin' us for their troubles."

Justin guessed what was coming and smiled. Hackett went on:

"He said we went over there a century or so ago with our bloody doctors and our bloody anti-biotics and our bloody surplus food and cured their diseases and filled their tummies. We cut down their death rate and now, where they'd had at least a place to lie down, there's hardly room to stand. He claimed it wasn't moral."

"I suppose," murmured Justin, "we should have let them keep on dying like flies."

"That's what I told him, but he said we coulda educated 'em first and maybe they'da turned to family planning."

Justin was grinning.

"Education on an empty stomach? Like which comes first, the chick or the egg? Rats! Education wasn't the answer. We had more schools than anywhere, but it happened here. We had two hundred million people back in 1975 and today we've got a billion. Which just proves that old Tom Malthus was right: the population outruns the food supply every time if you don't keep it down with war, famine, disease or sexual discipline."

"And I guess," grunted Hackett, "we can't put a cop in every bedroom." He colored. "Sorry, Doris."

"It's perfectly all right," Doris said. "It might be a very good idea."

Her uncle slapped his knee with delight and Justin chuckled.

"Y'know," said Hackett, "there's people in Europe still think we shoulda used our nuclear bombs those last two wars. Maybe they're right, it woulda cut down the population."

"No," said Justin, "but say we had. There were four billion in the world in 1980. How many could the bombs kill before knocking both sides out? A billion? All Europe, Russia and North America? So you'd put the clock back only twenty years to 1960 when there were only three billion, and delayed the crisis by only that much. But you'd still have it. No, it was better not and we hadn't the blood on our hands."

He winked.

"Besides, it saved our nuclear power for the Great Adventure."

Hackett missed the malicious irony.

"But you can't tell 'em that. They blame us for everything. They're poor. God, they're poor. And because we're a mite better off, and by some miracle still have free elections, they hate our guts."

"They always did," said Justin. "The legend of Uncle Shylock dies hard."

"They hate us," Hackett repeated. "And yet, it's just pitiful the way they look to us for the answer."

And now Justin suspected why Hackett had called.

"Space?"

"Space," affirmed Hackett. "They're waitin', like we all are, for the time we can start movin' people upstairs."

Justin said nothing, and Hackett stared out the window. Then, a bit too casually:

"I hear Austin's goin' before Congress with some fool announcement?"

Justin thought: Damn Austin! If ever he needed grass roots support which only the Bosses could give, it was now. Yet the idiot had failed even to consult the most powerful man in the East!

"Yes," Justin said, "and after that, I'm to make an announcement, too."

Hackett asked with blunt anger:

"You tellin'? Or is it too top-drawer for the likes of me?"

"No, no. Listen! He should have told you. I don't blame you for being sore, or McPhail or Harvey and the rest of your bunch. But this is once you've got to forgive him. You know the strain he's been under and it's too important for the country—"

He glanced at Doris, not wishing to shock her, wondering how much she had guessed.

"He's going to announce," Justin said slowly, "that the Space Program has failed."

For an utterly disbelieving moment, Boss Hackett sat very still. Only his hands moved, to clench and unclench.

"The blasted fool!"

Justin waited.

"And I'm supposed to forgive that? Why, he'll lose the election for sure now—not that he had much chance!"

Justin said quietly:

"Isn't it about time we quit kidding ourselves?"

Hackett glared.

"My God, man! To destroy in a single stroke everything we've looked forward to for Heaven knows how many years! It's our only hope!"

Justin shook his head.

"Not our only hope." Again he glanced at Doris, disliking to leave her alone now that it might happen at any hour. Still, there were the women next door. He said: "If you could spare a few hours, I want you to see what I've done up at my lab at Camp Jukes."

As the charcoal-burning Government car inched on through the miserable, sluggish throngs of mid-Manhattan, Justin closed his eyes. It was all there, every evil man had prophesied for multiplying man: the skin lesions of pellagra, the deformities left by infantile rickets, the starvation of face and body and mind. Silent expressionless sheep, they moved slowly out of the way; and only a few of the more alert turned to curse or spit.

At 42nd and Fifth, long lines queued patiently up worn stone steps to secure their meager daily rations in what had once been the great Public Library.

The driver was new, and new to New York.

"Jeez! Where do they live, sir?"

Justin nodded toward the soaring skyscrapers, weather-blackened monuments to a commercial past.

"As far up," he said wearily, "as they care to climb."

Hackett emerged from his moody silence.

"Where you from, boy?"

"Iowa, sir."

"It's better out there?"

"Well, sir, really not. They're hungry, too. But there does seem a bit more room."

"Like for some of our people?"

"I didn't mean that, sir. They're moving folks out in fact. That's why I'm here. Grandpa had this farm, but they took it. They took 'em all and threw 'em together with automation. For better production, they claimed. Nobody's allowed back but the damned button-pushers." He spoke bitterly. "They said the rest of us would get in the way of the machines."

"In the towns where do they live?"

"Well, the empty factories mostly. Like here, they're all closed down, you know, except the ones on the Space Program."

He did not speak again until they had crossed the sagging, rust-coated George Washington Bridge. Looming out of a great signboard high on the Palisades a space-helmeted Uncle Sam pointed an imperative finger at their approach:

"For the American Dream, Buy Space Bonds!"

There was eager conviction in the lad's voice:

"Gosh, when will we make it, sir?"

Even Boss Hackett, viewing Camp Jukes in its isolated fold of the Rockland County Ramapos, marveled at the political strings Justin must have pulled to create it. Its spacious gardens studded with miniature rustic cabins stood like a last remnant of heaven in a world gone to hell. But as they watched from a rise of ground the group's calisthenics on the playing field below, Hackett burst out:

"Dammit, man! You bring me clear up here to see a couple dozen children?"

"You'd better look again," Justin said quietly. "They are not children."

Hackett glared—and gasped.

"But I can well remember when they were," Justin went on. "When I took them from various welfare bureaus, their average age was eighteen months. The girls' average height was thirty-one inches, the boys a trifle more. Well, that's still their height, but they are now twenty years old. Their bodies are of perfect proportion, and their health and I.Q. are far above the national average.

"Are you trying to tell me—" Hackett began in horror.

"No, let me finish. Really, there isn't much new. The old Romans practiced a crude form of artificial dwarfing, but for their own sadistic amusement. And we've always had natural midgets and some very famous ones. Philetas, the tutor of Ptolemy; Richard Gibson, the painter; Count Borulwaski of Poland. They were all tiny, extremely intelligent, and lived good long lives.

"What the early endocrinologists found was that a deficiency of growth hormone in the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland caused the condition. They corrected it by injecting the right pituitary extracts so the midgets grew normally.

"Charlie, what I've done is merely reverse the process by a proper manipulation of glandular balance. It's nothing they couldn't have done a century ago. And there's your result: a new and better breed of human in which nothing is omitted but size."

Hackett sat heavily down on a rock and stared at the group.

"Good Lord, man, why did you do it?"

Justin replied with another question.

"Honestly now, Charlie, how long since we first suspected the Space Program would fail?"

"I don't know, twenty years maybe."

"Yes, which was when I began work on the problem. The goal, of course, was to regain our high standard of living. And we thought there were only two answers: move half the population off the planet, or—kill 'em. Those were the only alternatives.

"But here I've come up with a third way: reduction in size. Can't you see what it means? As workers, these little people can produce as much as normal adults. Yet they need only half the food and yardage in clothes, smaller houses, smaller everything. Think of the tremendous savings in natural resources!"

He paused.

"I know you are terribly shocked," he resumed earnestly. "I was startled myself when the idea occurred. We've always thought progress meant bigness. The ideal man was six feet tall and all that. But it's bunk. Even when our standard of living was at record high, that ideal was still the exception. And since our time of trouble began, the average height has actually decreased by three inches."

Hackett was shaking his head.

"But dammit, you can't make 'em small all at once."

"No, it's a long haul and it will take all kinds of courage for Congress to pass the laws. But if we don't start now, soon it will be too late. Here is my plan:

"Some of us think the malnutrition and spreading disease are starting to stabilize the population at about one billion, which is still way too high. About fourteen million die each year; at present some fifteen million babies survive birth.

"I can't work it on children over two years old. By then they're too tall. But if we stop the growth, right now, of the thirty million in that age group, allowing for natural mortality, in twenty years we'll have over two hundred million small people—a fifth of our number. At least it will give us some elbow room to attack our miserable standard of living."

Still Hackett protested:

"It would be rough. Nobody wants to be peewees."

"I know, and there's another problem. At about age twenty, they'll be having their own kids. And midgets don't give birth to midgets. So we'd have to keep on with artificial dwarfing in perpetuity, except—"

Justin had reached the most delicate point.

"Well, I tackled it from another angle. What science has known for years is that it's the condition of the child in the womb during the first three months of pregnancy that regulates size. I developed a simple injection and diet, and I think the baby Doris delivers will be the answer."

Hackett sprang to his feet.

"You practiced on my niece? You cold-blooded louse!"

Justin held out a pleading hand.

"Please. I said it would take courage, more guts than the human race has ever known. But if my procedure succeeds with Doris, we'd adopt it as part of the normal pre-natal care for all prospective mothers. And in two generations anyone over three feet tall would be the exception."

Hackett was sneering.

"Has it occurred to the Great Nobel Mind that when we have finally be-littled ourselves, the foreign giants will move in and knock us off?"

"Yes, and it's also occurred to Austin. The obvious answer is that sheer size hasn't counted since the invention of firearms. My guess is when they see our returning health and prosperity, they'll be only too glad to join us."

Hackett gazed down toward the field. The girls, apple-cheeked and hair in disarray, had teamed against the muscular boys in a softball game. It had been a long time since he had seen such spirit and laughter. Heavily he asked:

"What d'ya want from me?"

Justin chose his words carefully:

"When Austin admits the Space failure, there will be a great wave of despondency. Then, when all hope seems lost, I am to go before Congress with this—new hope. Now I'd be damned naive to think Austin's strong enough to push it through by himself. But Congress would do it for you, and McPhail in Chicago and Harvey out on the Coast, and the rest of your crowd."

Mentally he ticked them off: Blake in Atlanta and Lipsky up in Alaska and Cabot in Boston ... the all-powerful clique of Strip City Bosses who actually ran the country.

"Of course," he pressed, "you'd have to reelect Austin as the only man who has the nerve to see the thing through."

Hackett grunted.

"That's just the trouble," he said.

Darkness had fallen when they started back. There was still no telling what Hackett was thinking. He sat stonily alone in the rear seat, a man in deep thought.

A bit before six, Justin switched on the radio. For a few moments an uninspired concert filled the car. Then:

"We again interrupt to repeat an important warning. Attention all personnel using Government vehicles! If you are in normal riot zones, abandon cars at once and proceed on foot. We repeat—"

Hackett stirred.

"Blast it, now what's up?"

Already the driver was slowing down. Hackett pressed his nose to the window.

"We're in Fort Lee. We're okay here, but we sure can't make it across the bridge. Dammit, we'll have to walk into town, but first let's hear the news."

Tires crunched on gravel as the car, lights dimmed, swung into a by-street and stopped in the shadow of a high wall.

"And now for our news report!

"Riots, the worst in thirty years, swept the nation late today in the wake of President Austin's stunning message to Congress. The Federal Building in St. Louis is burning. In the San Francisco Embarcadero thousands of rock-throwing hoodlums are fighting Federal troops. In Manhattan, mobs raided food depots.

"From Japan and India comes word that the President's message touched off a new wave of suicides....

"The message was brief and, in the view of his party's leaders, courageous. He told Congress he has ordered abandonment of the Moon stations. He also has ordered immediate dismantlement of all rocket-launching installations, the closing of rocket-building yards, and the complete cessation of all Space research. He has turned back to the General Treasury the last nineteen billion dollars earmarked for the Space Program. We give you this recording—"

President Austin's voice came on, precise, cool:

"My decision, believe me, was most difficult. The destruction of a long-cherished dream can never be easy. But within recent years, it has become increasingly clear to our leading scientists that man can never reach the stars.

"For better or worse, the ten billion of us humans who had hoped to find a solution for our population problems in Outer Space must remain chained to this old and tired planet.

"I say, it is old and tired. But let us remember, too, that for six thousand years of recorded history this Earth of ours has made a pretty good home. With Thomas Jefferson, I believe that our world belongs to the living and not to the dead. I do not, I will not, give up hope.

"Thank you and God bless you."

For a moment the silence in the car was insufferable. Then Hackett said gruffly:

"We'd best get out now."

Justin heard Doris' tortured sobbing long before he reached the top flight. Trying to hurry, his legs buckled. The long tramp across George Washington Bridge, the nine miles down the west face of Manhattan; the skirting of hysterical, shouting mobs; the senseless crushing to death of women under their feet ... no wonder he was exhausted.

And there was Austin's speech. At Times Square, the mob had hanged him in effigy and wrecked his campaign headquarters. It was there, in the red glare of a burning building, that Hackett reached his decision.

"Okay," he'd said. "I'm still sore as hell with Austin, but we'll go along. I'll call McPhail and the boys tomorrow. This is only providing, of course, that Doris turns out all right."

Justin reached his landing and swung into the corridor. Ahead, a door opened and the midwife flitted out.

Doris was shrieking now. It tore at his heart. As he reached his door, the shrieking stopped. Doris whimpered:

"It's a dwarf, I tell you! Oh Justin, how could you?"

Justin nodded at the midwife. Her answering nod was assuring.

"Rotten I'm late." He crossed to his table. From a drawer he procured a bottle, poured green fluid into a glass, stepped to the bed, held it to Doris' lips. Her eyes were wide and frightened.

"Drink," ordered Justin. "Drink, damn it, I love you."

Only when the sedative calmed her did he step to the basket and peer in. Slowly, and with pride and great tenderness, he smiled.

"He's perfect."

"But so tiny," whispered the midwife in awe. "It can't weigh a pound. Can it live?" Justin was grinning.

"It's a new creation," he said.

THE END