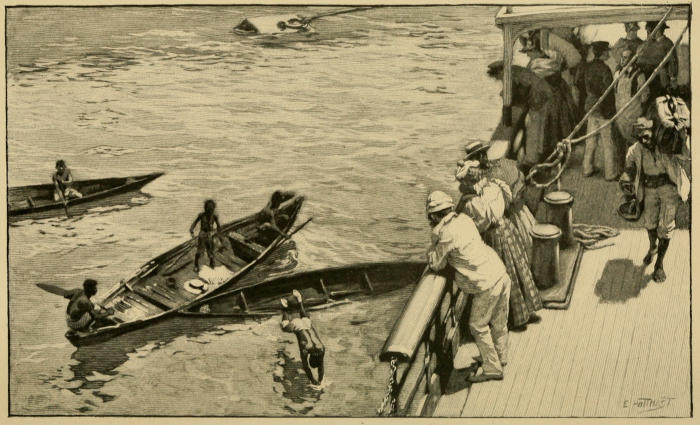

MALAYS DIVING FOR MONEY.

MALAYS DIVING FOR MONEY.

Java

The Garden of the East

By

Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore

Author of “Jinrikisha Days in Japan”

New York

The Century Co.

1898

Copyright, 1897,

By The Century Co.

The DeVinne Press

In presenting this account of a visit to one of the most beautiful countries of the world, I shall hope that many will be induced to follow there, and that my record may assist them to avoid certain things and to take advantage of others that will add to their enjoyment of the island where nature has been so prodigal with beauties and wonders.

After the body of this work had gone to press, the first copies of a small, compact, and most admirable “Guide to the Dutch East Indies,” written by Dr. J. F. Van Bemmelen and Colonel J. B. Hoover, by invitation of the Royal Steam Packet Company, Amsterdam, and translated into English by the Rev. B. J. Berrington, reached this country, and to this work I hasten to extend my salutations, since my own pages contain so many plaints for some such guide. It treats of all the islands under Dutch rule, turning especial light upon the so little-known Sumatra, where many[viii] attractions and possible resorts will invite pleasure-travel; and, leading one from end to end of Java, it more than supplements what Captain Schulze’s little guide had done for Batavia and the west end of the island. Translating so much of local and special lore hitherto locked away from the alien visitor in Dutch texts, it at last fairly opens Java to the tourist world, and excites my keen regret that its earlier publication had not lighted my way.

In preparing these pages every effort has been made to avoid errors, and I invite other corrections, and acknowledge here with great appreciation those suggested by Dutch readers, and at once made in certain chapters that originally appeared in the “Century Magazine.” In the varied English, French, and Dutch spelling of many words, in drawing statistics from works in as many languages, and in accepting as facts things verbally communicated to me by seemingly responsible people, there were chances of error; but one can only beg to be set right. In this connection I hasten to state that under the liberal policy of recent years the Dutch government has withdrawn its prohibition of the pilgrimage to Mecca, and more than six thousand of its Mohammedan subjects have availed themselves of the privilege in one year. It should also be noted that the Ashantee prince has not availed himself of the privilege of living and dying under the British flag in South Africa, and the pathetic tale of that exile, as told by Britons, lacks that completing touch of fact. For these suggestions in particular, others concerning Sumatra, and still others which had been anticipated, I thank Mr. R. A. Van Sandick[ix] of Amsterdam, with appreciation of the spirit and the loyalty to his own people which prompted his making them. Myths and legends and fairy tales grow with tropic rankness in those far ends of earth even to-day, and gravitate inevitably to the stranger’s ear.

E. R. S.

Washington, D. C., October 1, 1897.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Singapore and the Equator | 1 |

| II. | In “Java Major” | 17 |

| III. | Batavia, Queen of the East | 25 |

| IV. | The Kampongs | 37 |

| V. | To the Hills | 49 |

| VI. | A Dutch Sans Souci | 62 |

| VII. | In a Tropical Garden | 79 |

| VIII. | The “Culture System” | 94 |

| IX. | The “Culture System” (Continued) | 109 |

| X. | Sinagar | 126 |

| XI. | Plantation Life | 136 |

| XII. | Across the Preanger Regencies | 147 |

| XIII. | “To Tissak Malaya!” | 156 |

| XIV. | Prisoners of State at Boro Boedor | 167 |

| XV. | Boro Boedor | 182 |

| XVI. | Boro Boedor and Mendoet | 203 |

| XVII. | Brambanam | 216 |

| XVIII. | Solo: the City of the Susunhan | 240 |

| XIX. | The Land of Kris and Sarong | 253 |

| XX. | Djokjakarta | 265 |

| XXI. | Pakoe Alam: the “Axis of the Universe” | 283 |

| XXII. | “Tjilatjap,” “Chalachap,” “Chelachap” | 301 |

| XXIII. | Garoet and Papandayang | 312 |

| XXIV. | “Salamat!” | 324 |

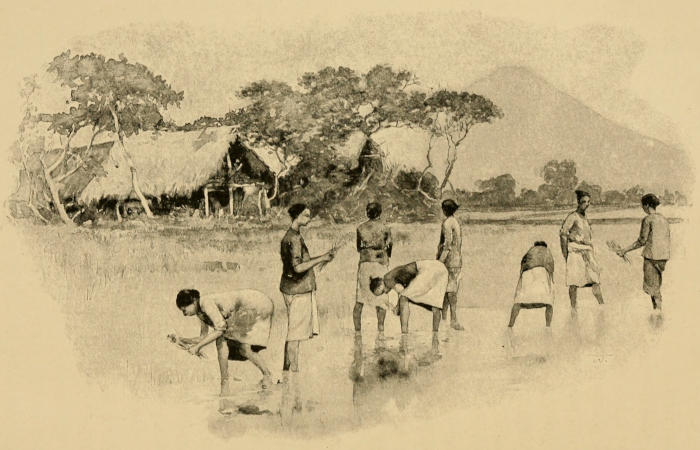

| Malays Diving for Money | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

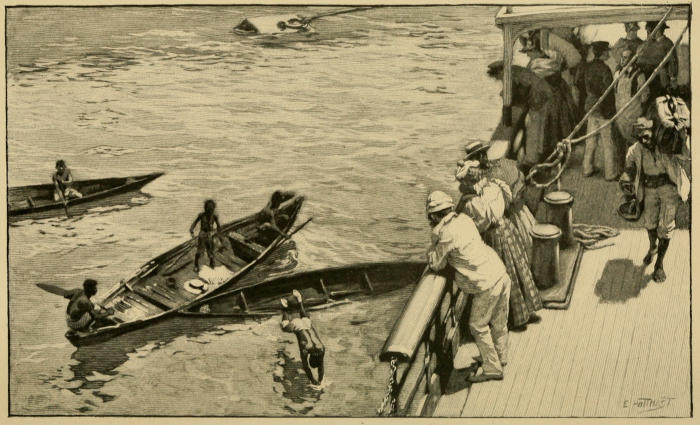

| A Street in Singapore | 5 |

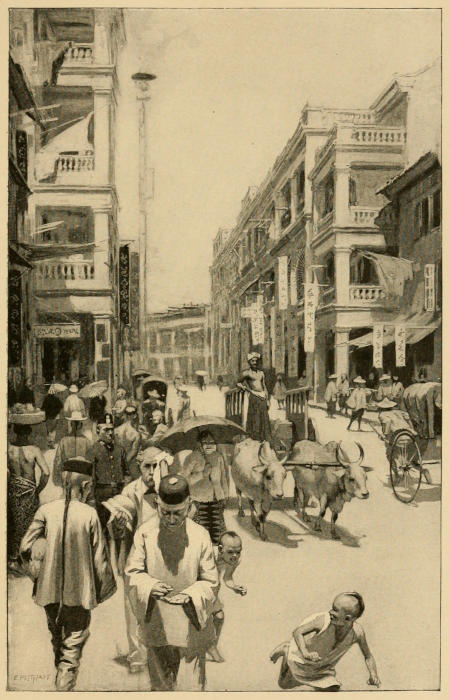

| Map of Java | 16 |

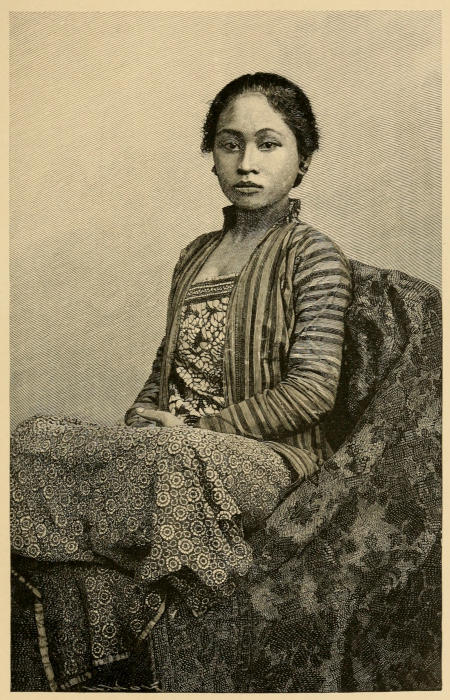

| A Javanese Young Woman | 27 |

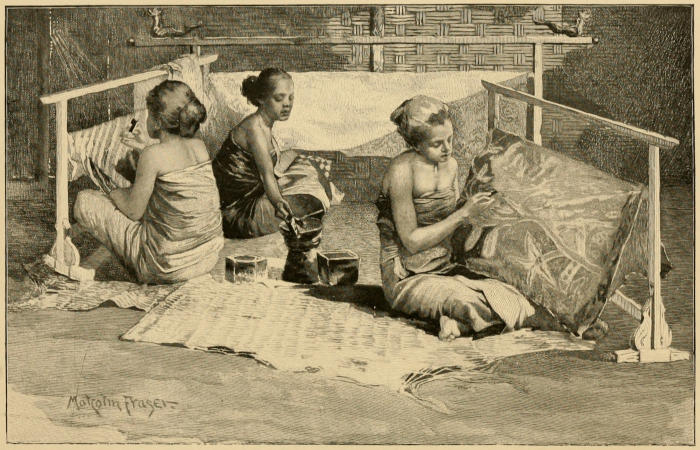

| Painting Sarongs | 43 |

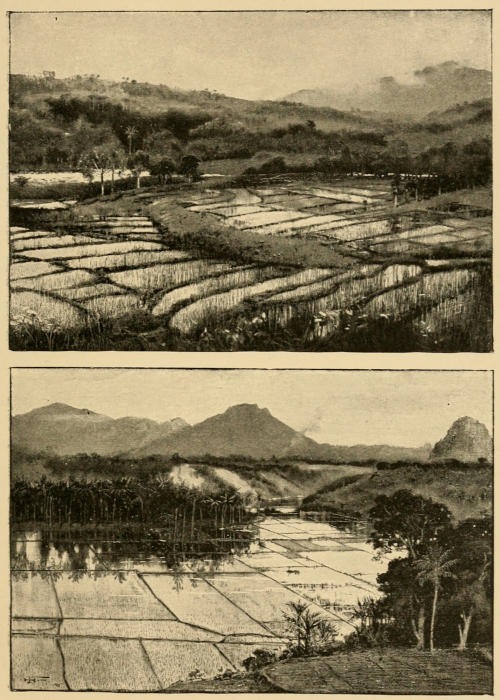

| Rice-fields | 53 |

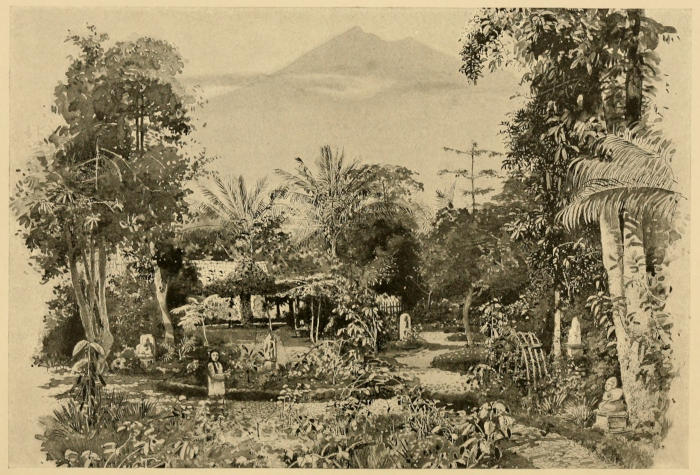

| Mount Salak, from the Resident’s Garden, Buitenzorg | 63 |

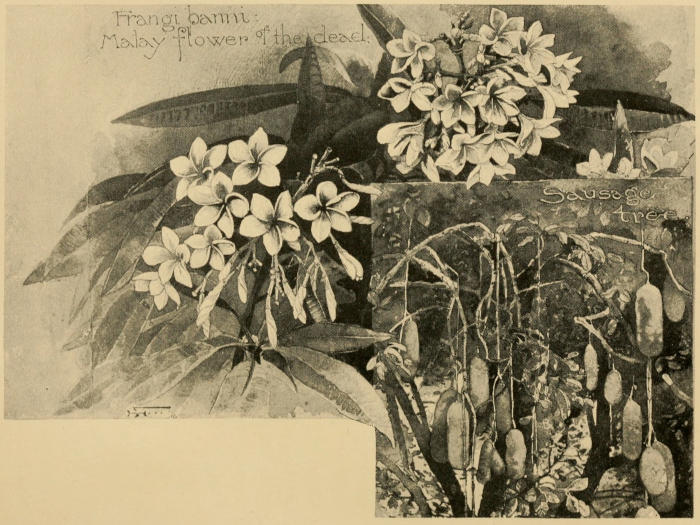

| Frangipani and Sausage-tree | 73 |

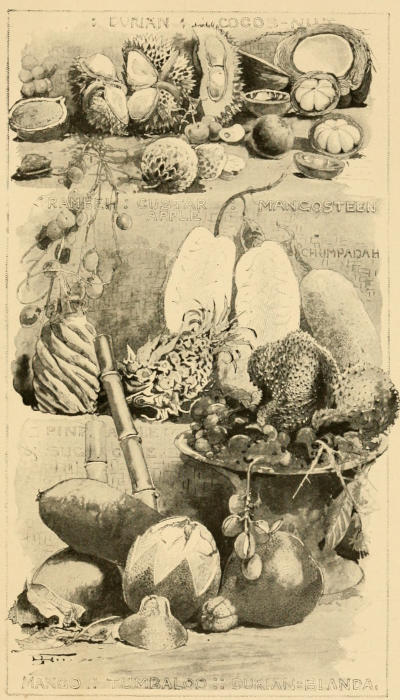

| Tropical Fruits | 81 |

| Tropical Fruits | 89 |

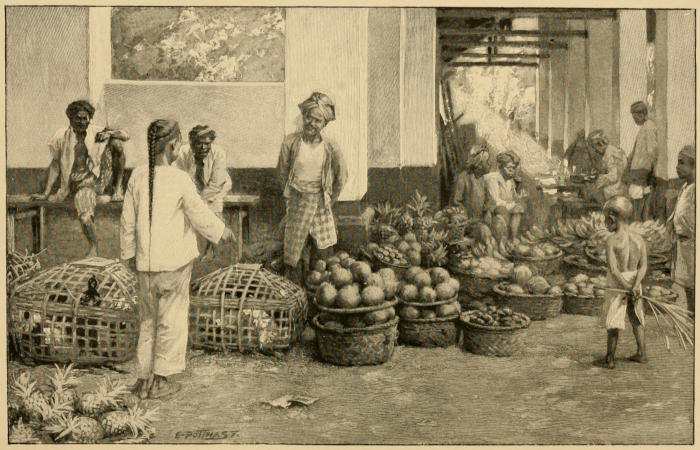

| A Market in Buitenzorg | 99 |

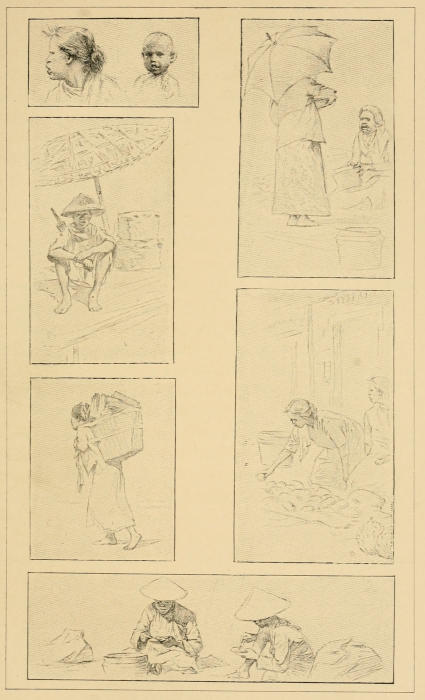

| Scenes around the Market | 105 |

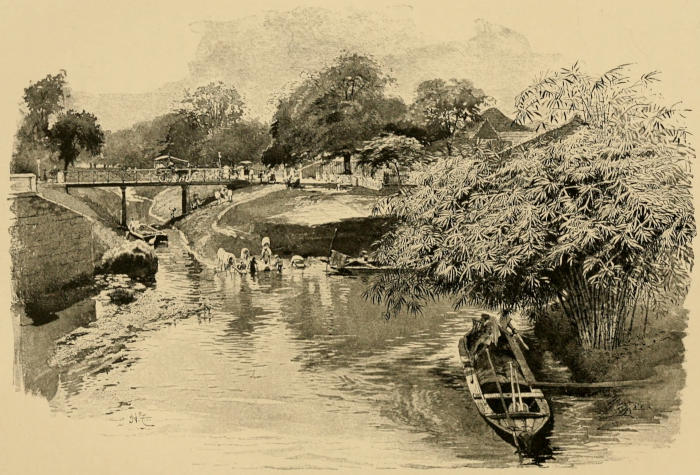

| A View in Buitenzorg | 111 |

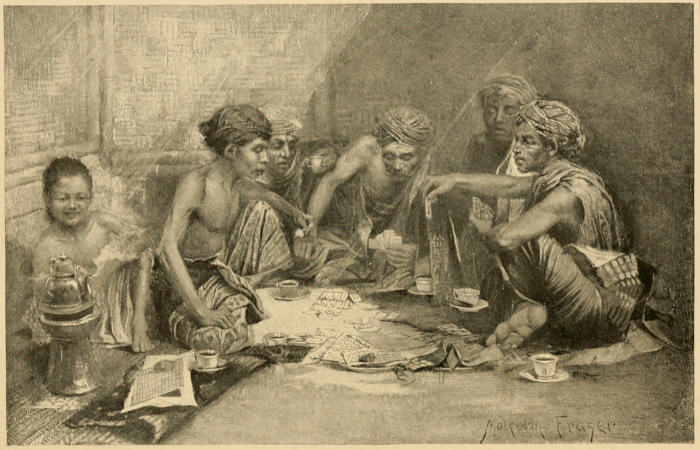

| Javanese Coolies Gambling | 123 |

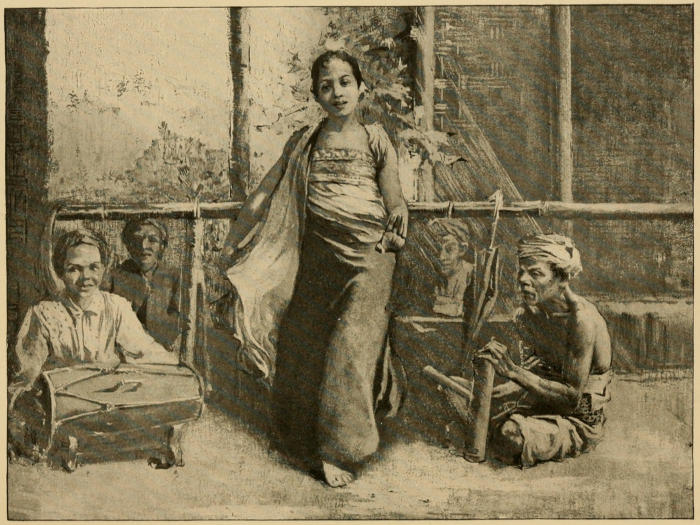

| Javanese Dancing-girl | 139 |

| A Mohammedan Mosque | 159 |

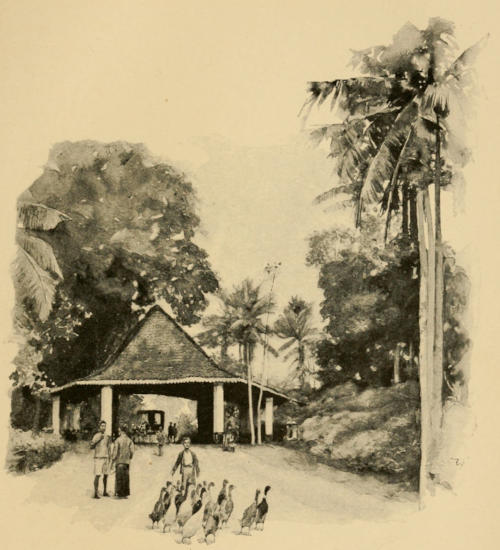

| Wayside Pavilion on Post-road | 177 |

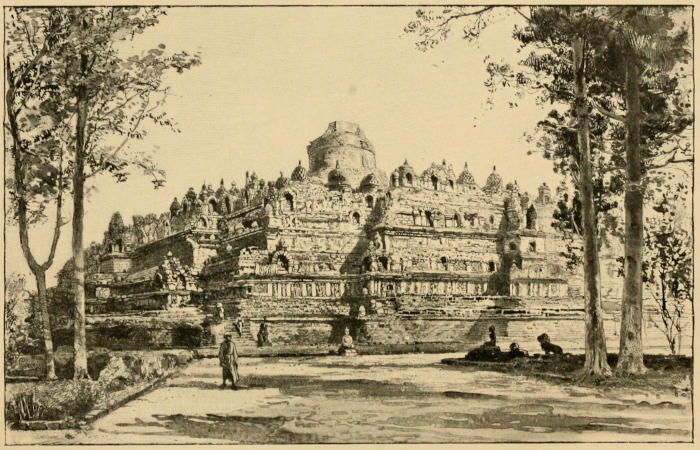

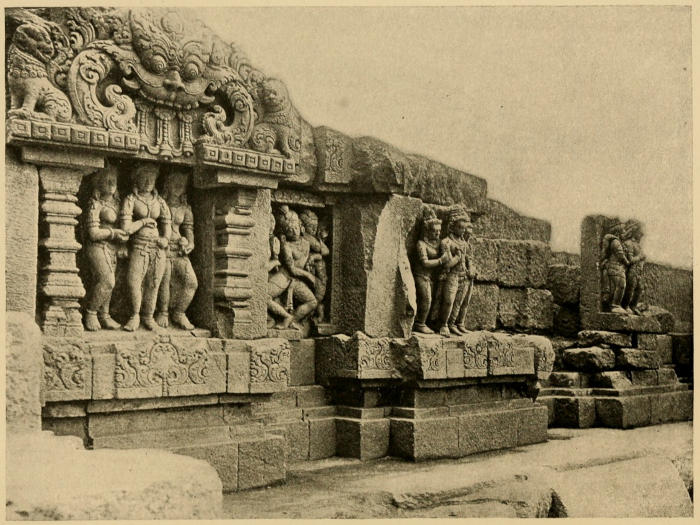

| Boro Boedor, from the Passagrahan | 183 |

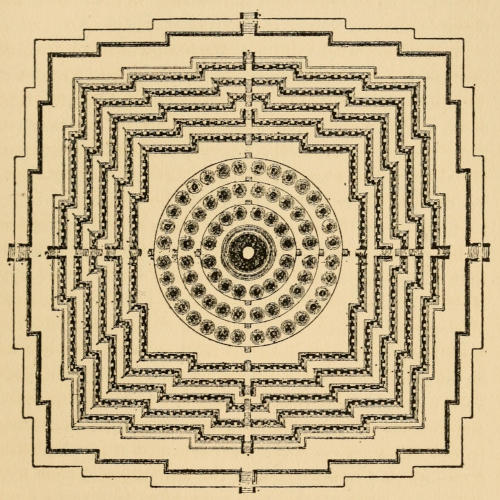

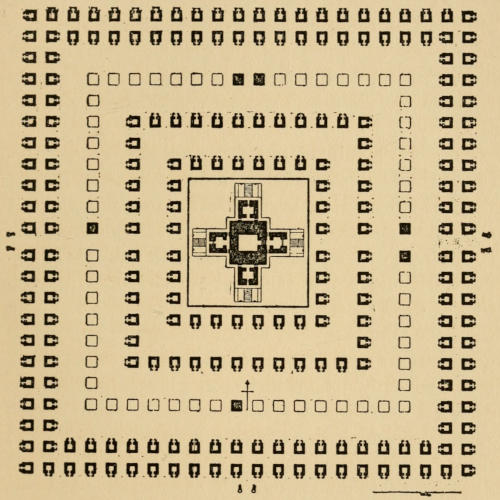

| Ground-plan of Boro Boedor | 187 |

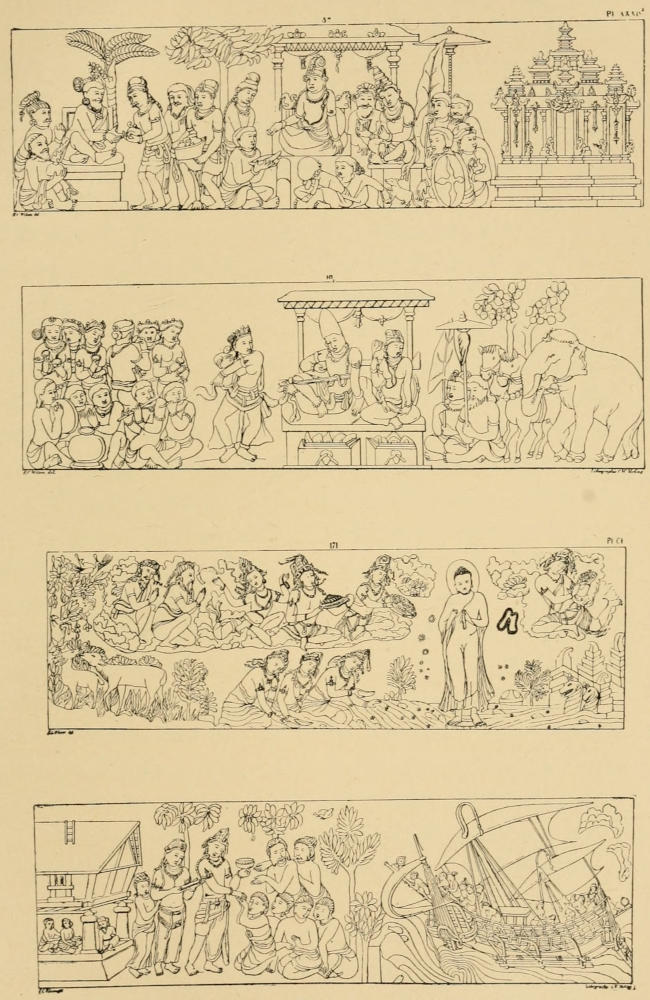

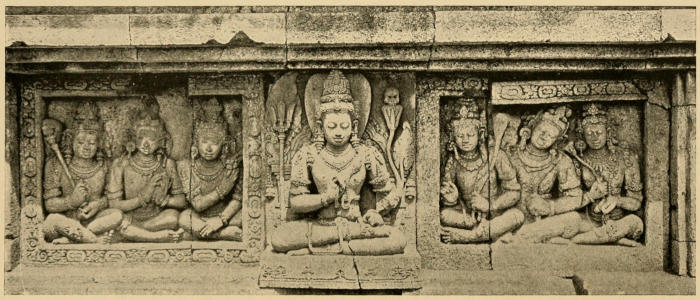

| Four Bas-reliefs from Boro Boedor | 191 |

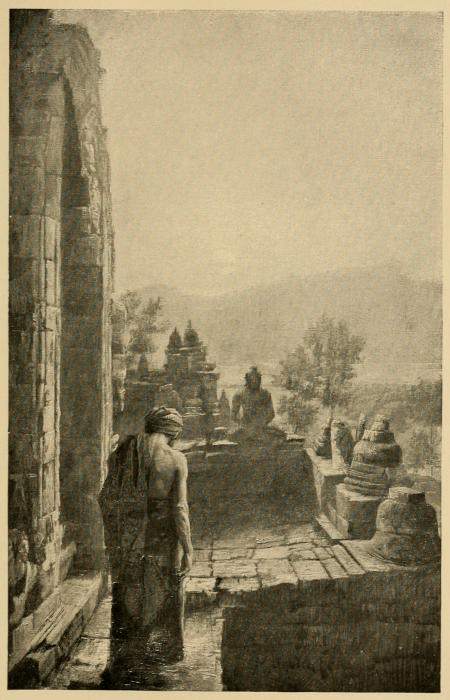

| On the Second Terrace | 195 |

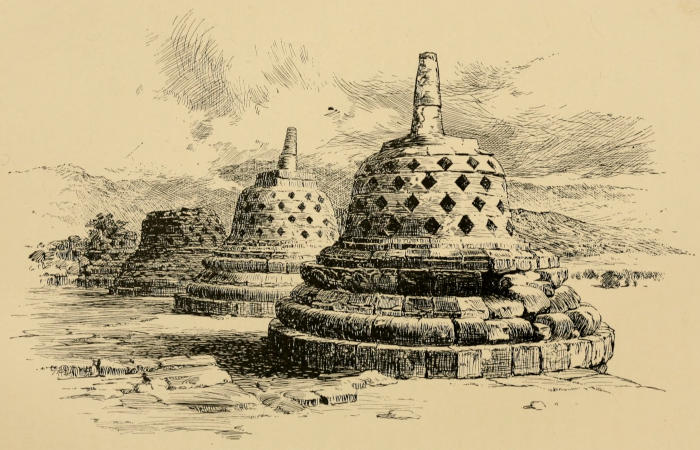

| The Latticed Dagobas on the Circular Terraces | 199[xiv] |

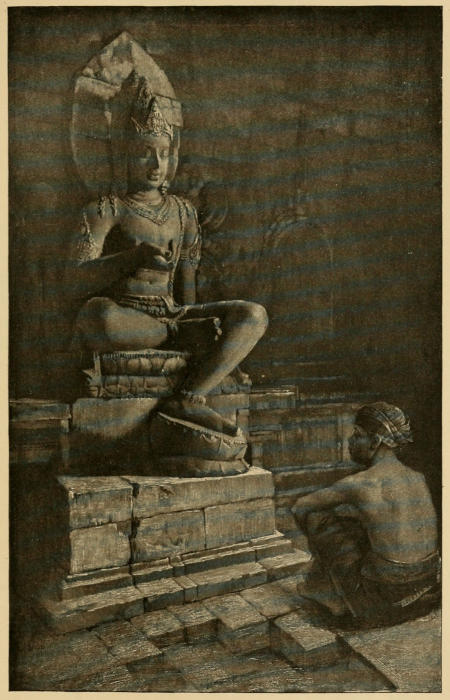

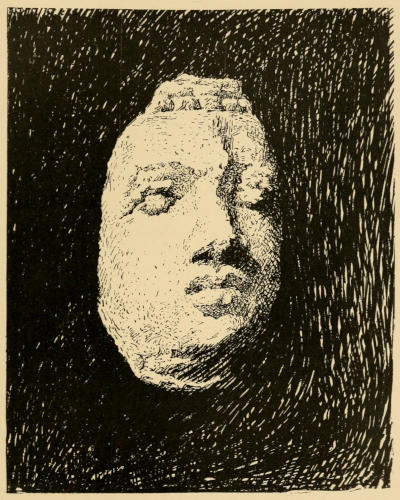

| The Right-hand Image at Mendoet | 207 |

| Temple of Loro Jonggran at Brambanam | 217 |

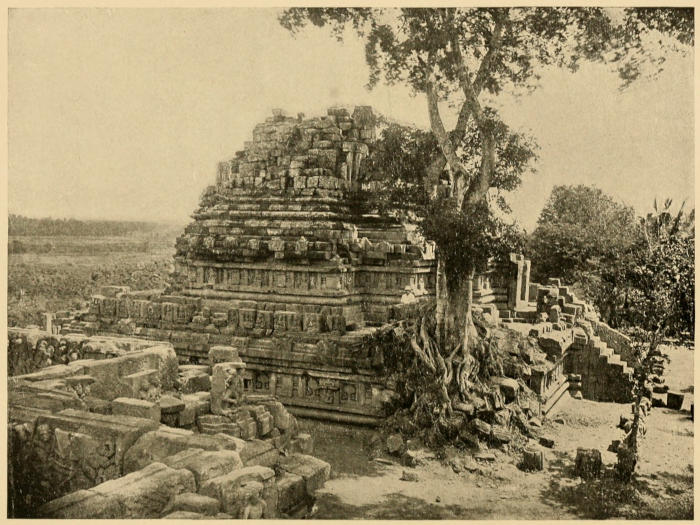

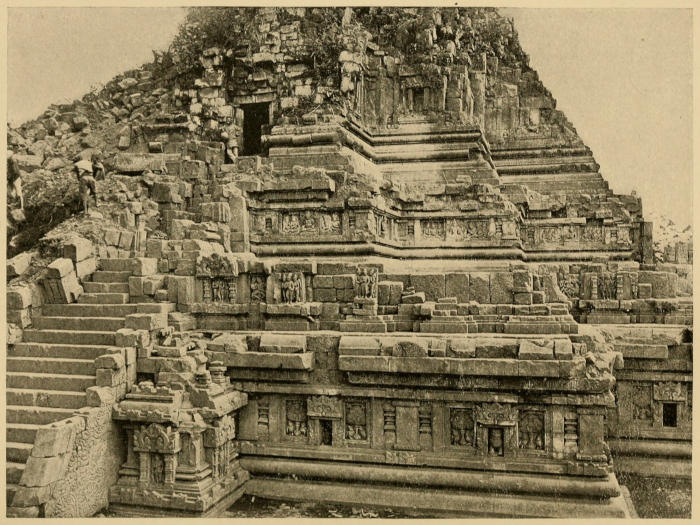

| Clearing Away Rubbish and Vegetation at Brambanam Temples | 221 |

| Krishna and the Three Graces | 225 |

| Loro Jonggran and her Attendants | 229 |

| Plan of Chandi Sewou (“Thousand Temples”) | 233 |

| Fragment from Loro Jonggran Temple | 235 |

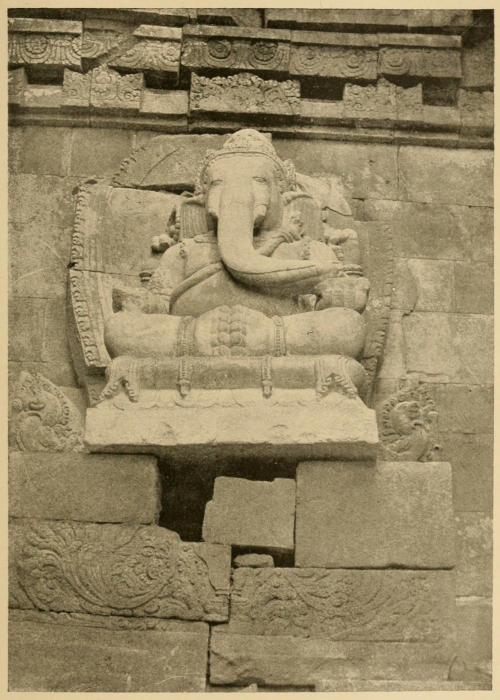

| Ganesha, the Elephant-headed God | 238 |

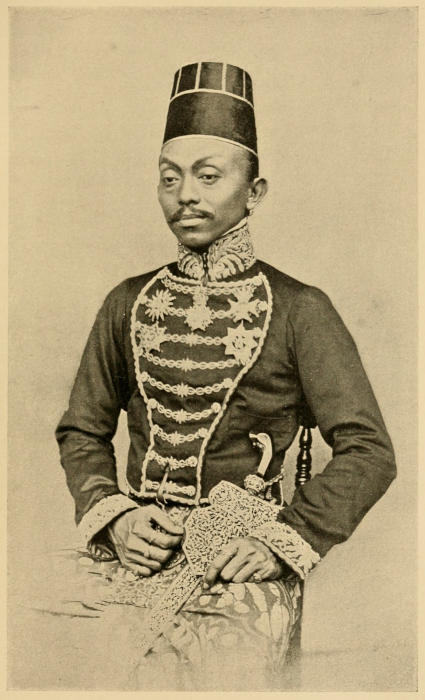

| The Susunhan | 243 |

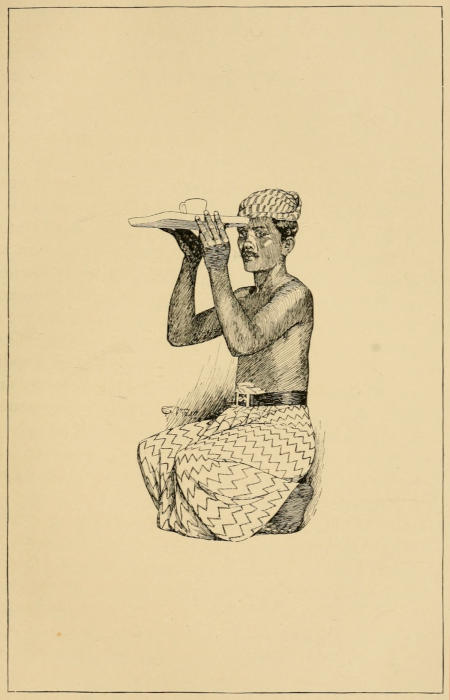

| The Dodok | 249 |

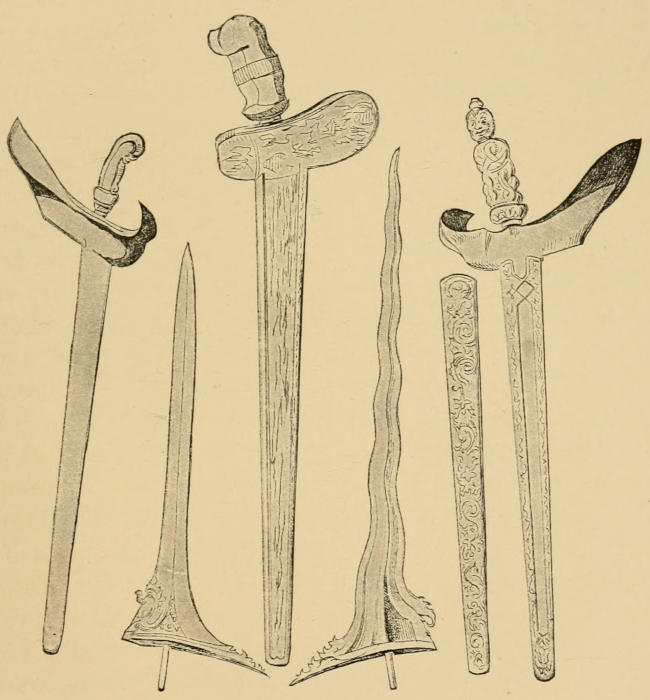

| Java, Bali, and Madura Krises | 255 |

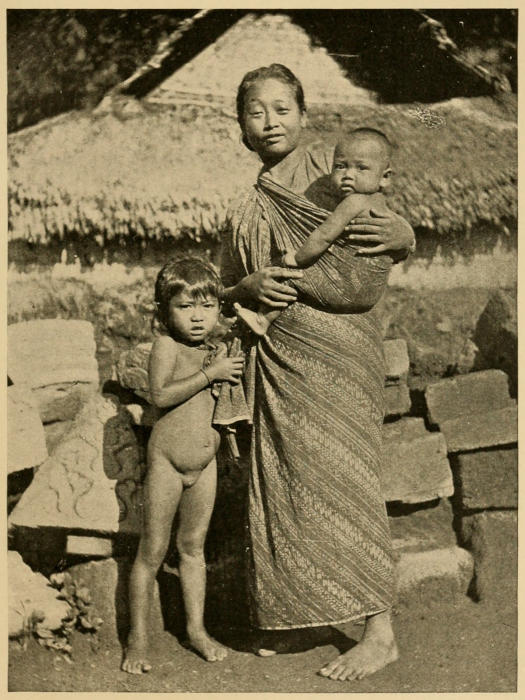

| The Brambanam Baby | 267 |

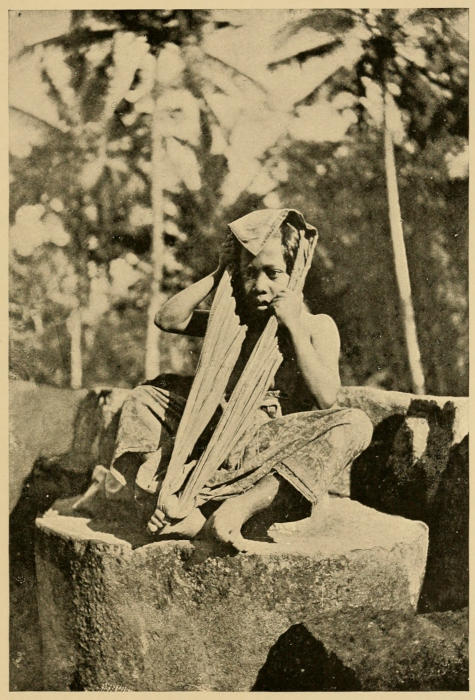

| Tying the Turban | 279 |

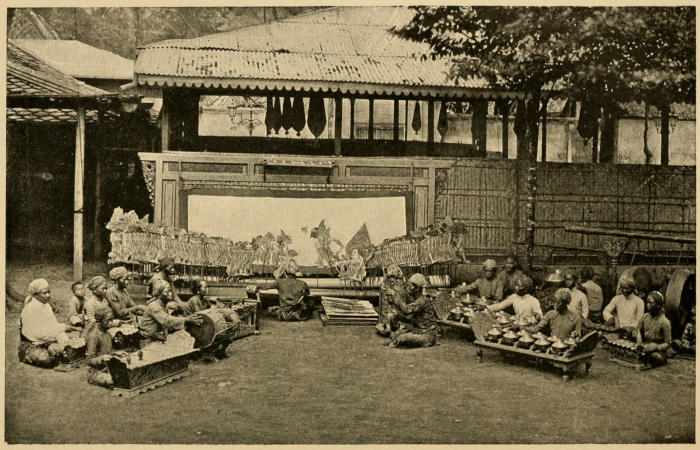

| Wayang-wayang | 285 |

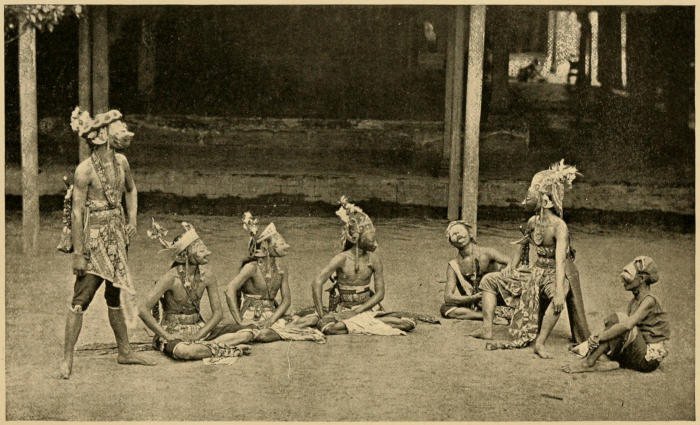

| Topeng Troupe with Masks | 291 |

| Transplanting Rice | 315 |

Singapore (or S’pore, as the languid, perspiring, exhausted residents near the line most often write and pronounce the name of Sir Stamford Raffles’s colony in the Straits of Malacca) is a geographical and commercial center and cross-roads of the eastern hemisphere, like to no other port in the world. Singapore is an ethnological center, too, and that small island swinging off the tip of the Malay Peninsula holds a whole congress of nations, an exhibit of all the races and peoples and types of men in the world, compared to which the Midway Plaisance was a mere skeleton of a suggestion. The traveler, despite the overpowering, all-subduing influence of the heat, has some thrills of excitement at the tropical pictures of the shore, and the congregation of varicolored humanity grouped on the Singapore wharf; and there and in Java, where one least and last expects to find[2] such modern conveniences, his ship swings up to solid wharves, and he walks down a gang-plank in civilized fashion—something to be appreciated after the excitements and discomforts of landing in small boats among the screaming heathen of all other Asiatic ports.

On the Singapore wharf is a market of models and a life-class for a hundred painters; and sculptors, too, may study there all the tones of living bronze and the beauties of human patina, and more of repose than of muscular action, perhaps. Japanese, Chinese, Siamese, Malays, Javanese, Burmese, Cingalese, Tamils, Sikhs, Parsees, Lascars, Malabars, Malagasy, and sailor folk of all coasts, Hindus and heathens of every caste and persuasion, are grouped in a brilliant confusion of red, white, brown, and patterned drapery, of black, brown, and yellow skins; and behind them, in ghostly clothes, stand the pallid Europeans, who have brought the law, order, and system, the customs, habits, comforts, and luxuries of civilization to the tropics and the jungle. All these alien heathens and picturesque unbelievers, these pagans and idolaters, Buddhists, Brahmans, Jews, Turks, sun- and fire-worshipers, devil-dancers, and what not, have come with the white man to toil for him under the equatorial sun, since the Malays are the great leisure class of the world, and will not work. The Malays will hardly live on the land, much less cultivate it or pay taxes, while they can float about in strange little hen-coops of house-boats that fill the river and shores by thousands. Hence the Tamils have come from India to work, and the Chinese to do the small trading; and the Malay rests, or at most goes a-fishing, or sits by the canoe-loads[3] of coral and sponges, balloon-fish and strange sea treasures that are sold at the wharf.

A tribe of young Malays in dugout canoes meet every steamer and paddle in beside it, shrieking and gesticulating for the passengers to toss coins into the water. Their mops of black hair are bleached auburn by the action of sun and salt water, and the canoe and paddle fit as naturally to these amphibians as a turtle’s shell and flipper. They bail with an automatic sweep of the hollowed foot in regular time with the dip of the paddle; and when a coin drops, the Malay lets go the paddle and sheds his canoe without concern. There is a flash of brown heels, bubbles and commotion below, and the diver comes up, and chooses and rights his wooden shell and flipper as easily and naturally as a man picks out and assumes his coat and cane at a hall door. And in their hearts, the civilized folk on deck, hampered with their multiple garments and conventions, envy these happy-go-lucky, care-free amphibians in the land of the breadfruit, banana, and scant raiment, with dives into the cool, green water, teeming with fish and glittering with falling coins, as the only exertion required to earn a living. Cold and hunger are unknown; flannels and soup are no part of charity; and even that word, and the many organizations in its name, are hardly known in the lands low on the line.

S’pore is the great junction where travelers from the East or the West change ship for Java; a commercial cross-roads where all who travel must stop and see what a marvel of a place British energy has raised from the jungle in less than half a century. The Straits Settlements date from the time when Sir Stamford[4] Raffles, after Great Britain’s five years’ temporary occupancy of Java, returned that possession to the Dutch in 1816, the fall of Napoleon removing the fear that this possession of Holland would become a French colony and menace to British interests in Asia. It had been intended to establish such a British commercial entrepôt at Achin Head, the north end of Sumatra; but Sir Stamford Raffles’s better idea prevailed, and the free port of Singapore in the Straits of Malacca has won the commercial supremacy of the East from Batavia, and has prospered beyond its founder’s dreams. It is a well-built and a beautifully ordered city, and the municipal housekeeping is an example to many cities of the temperate zone. Even the untidy Malay and the dirt-loving Chinese, who swarm to this profitable trading-center, and have absorbed all the small business and retail trade of the place, are held to outer cleanliness and strict sanitary laws in their allotted quarters. The stately business houses, the marble palace of a bank, the long iron pavilions shading the daily markets, the splendid Raffles Museum and Library, are all regular and satisfactory sights; but the street life is the fascination and distraction of the traveler before everything else. The array of turbans and sarongs gives color to every thoroughfare; but the striking and most unique pictures in Singapore streets are the Tamil bullock-drivers, who, sooty and statuesque, stand in splendid contrast between their humped white oxen and the mounds of white flour-bags they draw in primitive carts. Tiny Tamil children, shades blacker, if that could really be, than their ebon- and charcoal-skinned parents, are seen on suburban roads, clothed only in silver chains,[5] bracelets, and medals; and these lithe, lean people from the south end of India are first in the picturesque elements of the great city of the Straits. The Botanical Garden, although so recently established, promises to become famous; and one arriving from the farther East meets there for the first time the beautiful red-stemmed Banka palm, and the symmetrical traveler’s palm of Madagascar, the latter all conventionalized ready for sculptors’ use. Scores of other splendid palms, giant creepers, gorgeous blossoms and fantastic orchids, known to us only by puny examples in great conservatories at home, equally delight one—all the wealth of jungle and swamp growing beside the smooth, hard roads of an English park, over which one may drive for hours in the suburbs of Singapore.

A STREET IN SINGAPORE.

After photograph by E. S. Platt.

The Dutch mail-steamers to and from Batavia connect with the English mail-steamers at Singapore; a French line connects with the Messagerie’s ships running between Marseilles and Japan; an Australian line of steamers gives regular communication; and independent steamers, offering as much comfort, leave Singapore almost daily for Batavia. The five hundred miles’ distance is covered in forty-eight or sixty hours, for a uniform fare of fifty Mexican dollars or ninety Dutch gulden—an excessive and unusual charge for a voyage of such length in that or any other region. The traveler is usually warned long beforehand that living and travel in the Netherlands Indies is the most expensive in the world; and the change from the depreciated Mexican silver-dollar standard and the profitable exchange of the far East to the gold standard of Holland dismays one at the start. The[8] completion of railways across and to all parts of the island of Java, however, has greatly reduced tourist expenses, so that they are not now two or three times the average of similar expenses in India, China, and Japan.

At Singapore, only two degrees above the equator, the sun pursues a monotony of rising and setting that ranges only from six minutes before to six minutes after six o’clock, morning and evening, the year round. Breakfasting by candle-light and leaving the hotel in darkness, there was all the beauty of the gray-and-rose dawn and the pale-yellow rays of the early sun to be seen from the wet deck when our ship let go from the wharf and sailed out over a sea of gold. For the two days and two nights of the voyage, with but six passengers on the large blue-funnel steamer, we had the deck and the cabins, and indeed the equator and the Java Sea, to ourselves. The deck was furnished with the long chairs and hammocks of tropical life, but more tropical yet were the bunches of bananas hanging from the awning-rail, that all might pick and eat at will; for this is the true region of plenty, where selected bananas cost one Mexican cent the dozen, and a whole bunch but five cents, and where actual living is far too cheap and simple to be called a science.

The ship slipped out from the harbor through the glassy river of the Straits of Malacca, and on past points and shores that to me had never been anything but geographic names. There was some little thrill of excitement in being “on the line” in the heart of the tropics, the half-way house of all the world, and one expected strange aspects and effects. There was[9] a magic stillness of air and sea; the calm was as of enchantment, and one felt as if in some hypnotic trance, with all nature chained in the same spell. The pale, pearly sky was reflected in smooth stretches of liquid, pearly sea, with vaporous hills, soft green visions of land beyond. Everywhere in these regions the shallow water shows pale green above the sandy bottom, and the anchor can be dropped at will. All through the breathless day the ship coursed over this shimmering yellow and gray-green sea, with faint pictures of land, the very landscapes of mirage, drawn in vaporous tints on every side. We were threading a way through the thousand islands, the archipelago lying below the point of the Malay Peninsula, a region of unnamed, uncounted “summer isles of Eden,” chiefly known to history as the home of pirates.

The high mountain-ridges of Sumatra barred the west for all the first equatorial day, the land of this “Java Minor” sloping down and spreading out in great green plains and swamps on the fertile but unhealthy eastern coast. The large settlements and most attractive districts are on the west coast, where the hills rise steeply from the ocean, and coffee-trees thrive luxuriantly. Benkoelen, the old English town, and Padang, the great coffee-mart, are on that coast, and from the latter a railway leads to high mountain districts of great picturesqueness. There are few government plantations on Sumatra, where land-tenures and leases are the same as in Java. Immense areas have been devoted to tobacco-culture near Deli, on the north or Straits coast, planters employing there and on lower east-coast estates more than forty-three[10] thousand Chinese coolies—the Chinese, the one Asiatic who toils with ardor and regularity, whom the tropics cannot debilitate, and to whom malaria and all germs, microbes, and bacilli seem but tonic agents.

When the British returned Java, after the Napoleon scare was over, they retained Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope, and sovereign rights over Sumatra, relinquishing this latter suzerainty in 1872, in exchange for Holland’s imaginary rights in Ashantee and the Gold Coast of Africa. The Dutch then attempted to reduce the native population of Sumatra to the same estate as the more pliant people of Java; but the wild mountaineers and bucaneers, of the north, or Achin, end of the island in particular, warned by the sad fate of the Javanese, had no intention of being conquered and enslaved, of giving their labor and the fruit of their lands to the strangers from Europe’s cold swamps. The Achin war has continued since 1872, with little result save a general loss of Dutch prestige in the East, an immense expenditure of Dutch gulden, causing a deficit in the colonial budget every year, a fearful mortality among Dutch troops, and the final abandonment, in this decade of trade depression, of the aggressive policy. Dutch commanders are well satisfied to hold their chain of forts along the western hills, and to punish the Achinese in a small way by blockading them from their supplies of opium, tobacco, and spirits. In one four years of active campaigning the Achin war cost seventy million gulden, and seventy out of every hundred Dutch soldiers succumbed to the climate before going into an encounter. The Achinese merely retired to their swamps and jungles and waited, and[11] the climate did the rest, their confidence in themselves only shaken during the command of General Van der Heyden, who for a time actually crushed the rebellion. This picturesque fighter, a half-brother of Baron de Stuers, inherited Malay instincts from a native mother, and carried on such a warfare as the Achinese understood. He lost an eye in one encounter, and the natives, then remembering an old tradition that their country would be conquered by a one-eyed man, practically gave up the struggle—to resume it, however, as soon as General Van der Heyden retired and sailed for Holland, and military vigilance was relaxed in consequence of Dutch economy. The Achinese leader, Toekoe Oemar, has several times apparently yielded to the Dutch, only to perpetrate some greater injury; and his treachery and crimes have given him repute as the very prince of evil ones.

One’s sympathy goes naturally with the brave, liberty-loving Achinese; and in view of their indomitable spirit, Great Britain did not lose so much when she let go unconquerable Sumatra. British tourists are saddened, however, when they see what their ministers let slip with Java, for with that island and Sumatra, all Asia’s southern shore-line, and virtually the far East, would have been England’s own.

Geologically this whole Malay Archipelago was one with the Malay Peninsula, and although so recently made, is still subject to earthquake change, as shown in the terrible eruption of the island of Krakatau in the narrow Sunda Strait, west of Java, in August, 1883. Native traditions tell that anciently Sumatra, Java, Bali, and Sumbawa were one island, and “when three[12] thousand rainy seasons shall have passed away they will be reunited”; but Alfred Russel Wallace denies it, and proves that Java was the first to drop away from the Asiatic mainland and become an island.

While the sun rode high in the cloudless white zenith above our ship the whole world seemed aswoon. Hills and islands swam and wavered in the heat and mists, and the glare and silence were terrible and oppressive. One could not shake off the sensation of mystery and unreality, of sailing into some unknown, eerie, other world. Every voice was subdued, the beat of the engines was scarcely felt in that glassy calm, and the stillness of the ship gave a strange sensation, as of a magic spell. It was not so very hot,—only 86° by the thermometer,—but the least exertion, to cross the deck, to lift a book, to pull a banana, left one limp and exhausted, with cheeks burning and the breath coming faster, that insidious, deceptive heat of the tropics declaring itself—that steaming, wilting quality in the sun of Asia that so soon makes jelly of the white man’s brain, and that in no way compares with the scorching, dry 96° in the shade of a North American, hot-wave summer day.

At five o’clock, while afternoon tea and bananas were being served on deck, we crossed the line—that imaginary parting of the world, the invisible thread of the universe, the beginning and the end of all latitude—latitude 0°, longitude 103° east, the sextant told. The position was geographically exciting. We were literally “down South,” and might now speak disrespectfully of the equator if we wished. A breeze sprang up as soon as we crossed the line, and all that evening[13] and through the night the air of the southern hemisphere was appreciably cooler. The ship went slowly, and loitered along in order to enter the Banka Straits by daylight; and at sunrise we were in a smooth river of pearl, with the green Sumatra shores close on one hand, and the heights of Banka’s island of tin on the other. A ship in full sail swept out to meet us, and four more barks under swelling canvas passed by in that narrow strait, whose rocks and reefs are fully attested by the line of wrecks and sunken masts down its length. The harbor of Muntuk, whence there is a direct railway to the tin-mines, was busy with shipping, and the white walls and red roofs of the town showed prettily against the green.

The open Java Sea was as still and glassy as the straits had been, and for another breathless, cloudless day the ship’s engines beat almost inaudibly as we went southward through an enchanted silence. When the heat and glare of light from the midday sun so directly overhead drove us to the cabin, where swinging punkas gave air, we had additional suggestion of the tropics; for a passenger for Macassar, just down from Penang and Malacca, showed us fifty freshly cured specimens of birds, whose gorgeous plumage repeated the most brilliant and dazzling tints of the rainbow, the flower-garden, and the jewel-case, and left us bereft of adjectives and exclamations. Here we found another passenger, who spoke Dutch and looked the Hollander by every sign, but quickly claimed citizenship with us as a naturalized voter of the great republic. He asked if we lived in Java, and when we had answered that we were going to Java en touriste,[14] “merely travelers,” he established comradeship by saying, “I am a traveling man myself—New York Life.” This naturalized American citizen said quite naturally, “We Dutchmen” and “our queen”—Americanisms with a loyal Holland ring.

After the gold, rose, gray, and purple sunset had shown us such a sky of splendor and sea of glory as we had but dreamed of above the equator, banks of dark vapor defined themselves in the south. A thin young moon hung among the huge yellow stars, that glowed steadily, with no cold twinkling, in that intense night sky; but before the Southern Cross could rise, dense clouds rolled up, and flashes, chains, and forks of angry lightning made a double spectacular play against the inky-black sky and the mirror-black sea. The captain promised us a tropical thunder-storm from those black clouds in the south, and went forward to give ship’s orders, advising us to make all haste below when the first drop should fall, as in an instant a sheet of blinding rain would surround the decks, against which the double awnings would be no more protection than so much gauze, and through which one could not see the ship’s length. The clouds remained stationary, however, and we missed the promised sensation, although we waited for hours on deck, the ship moving quietly through the soft, velvety air of the tropic’s blackest midnight, and the lightning-flashes becoming fainter and fainter.

MAP OF JAVA.

In the earliest morning a clean white lighthouse on an islet was seen ahead, and as the sun rose, bluish mountains came up from the sea, grew in height, outlined themselves, and then stood out, detached volcanic peaks of most lovely lines, against the purest, pale-blue sky; soft clouds floated up and clung to the summits; the blue and green at the water’s edge resolved itself into groves and lines of palms; and over sea and sky and the wonderland before us was all the dewy freshness of dawn in Eden. It looked very truly the “gem” and the “pearl of the East,” this “Java Major” of the ancients, and the Djawa of the native people, which has called forth more extravagant praise and had more adjectives expended on it than any other one island in the world. Yet this little continent is only 666 miles long and from 56 to 135 miles wide, and on an area of 49,197 square miles (nearly the same as that of the State of New York) supports a population of 24,000,000, greater than that of all the other islands of the Indian Ocean put together. With 1600 miles[18] of coast-line, it has few harbors, the north shore being swampy and flat, with shallows extending far out, while the southern coast is steep and bold, and the one harbor of Tjilatjap breaks the long line of surf where the Indian Ocean beats against the southern cliffs. Fortunately, hurricanes and typhoons are unknown in the waters around this “summer land of the world,” and the seasons have but an even, regular change from wet to dry in Java. From April to October the dry monsoon blows from the southeast, and brings the best weather of the year—dry, hot days and the coolest nights. From October to April the southwest or wet monsoon blows. Then every day has its afternoon shower, the air is heavy and stifling, all the tropic world is asteam and astew and afloat, vegetation is magnificent, insect life triumphant, and the mountains are hidden in nearly perpetual mist. There are heavy thunderstorms at the turn of the monsoon, and the one we had watched from the sea the Hallowe’en night before our arrival had washed earth and air until the foliage glistened, the air fairly sparkled, nature wore her most radiant smiles, and the tropics were ideal.

It was more workaday and prosaic when the ship, steaming in between long breakwaters, made fast to the stone quays of Tandjon Priok, facing a long line of corrugated-iron warehouses, behind which was the railway connecting the port with the city of Batavia. The gradual silting up of Batavia harbor after an eruption of Mount Salak in 1699, which first dammed and then sent torrents of mud and sand down the Tjiliwong River, finally obliged commerce to remove to this deep bay six miles farther east, where the[19] colonials have made a model modern harbor, at a cost of twenty-six and a half million gulden, all paid from current revenues, without the island’s ceasing to pay its regular tribute to the crown of Holland. The customs officers at Tandjon Priok were courteous and lenient, passing our tourist luggage with the briefest formality, and kindly explaining how our steamer-chairs could be stored in the railway rooms until our return to port. It is but nine miles from the Tandjon Priok wharf to the main station in the heart of the original city of Batavia—a stretch of swampy ground dotted and lined with palm-groves and banana-patches, with tiny woven baskets of houses perched on stilts clustered at the foot of tall cocoa-trees that are the staff and source of life and of every economical blessing of native existence. We leaped excitedly from one side of the little car to the other, to see each more and more tropical picture; groups of bare brown children frolicking in the road, and mothers with babies astride of their hips, or swinging comfortably in a scarf knotted across one shoulder, and every-day life going on under the palms most naturally, although to our eyes it was so strange and theatrical.

At the railway-station we met the sadoe (dos-à-dos), a two-wheeled cart, which is the common vehicle of hire of the country, and is drawn by a tiny Timor or Sandalwood pony, with sometimes a second pony attached outside of the shafts. The broad cushioned seat over the axles will accommodate four persons, two sitting each way. The driver faces front comfortably; but the passenger, with no back to lean against but[20] the driver’s, must hold to the canopy-frame while he is switched about town backward in the footman’s place, for one gulden or forty cents the hour.

Whether one comes to Java from India or China, there is hasty change from the depreciated silver currency of all Asia to the unaltered gold standard of Holland, and the sudden expensiveness of the world is a sad surprise. The Netherlands unit of value, the gulden (value, forty cents United States gold), is as often called a florin, a rupee, or a dollar—the “Mexican dollar” or the equivalent “British dollar” of the Straits Settlements, a coin which trade necessities drove British conservatism to minting, which act robs the Briton of the privilege of making further remarks upon “the almighty dollar” of the United States, with its unchanging value of one hundred cents gold. This confusion of coins, with prices quoted indifferently in guldens, florins, rupees, and dollars, is further increased by dividing the gulden into one hundred cents, like the Ceylon rupee, so that, between these Dutch fractions, the true cents of the United States dollar that one instinctively thinks of, and the depreciated cents of the British or the battered Mexican dollar, one’s brain begins to whirl when prices are quoted, or any evil day of reckoning comes.

No Europeans live at Tandjon Priok, nor in the old city of Batavia, which from the frightful mortality during two centuries was known as “the graveyard of Europeans.” The banks and business houses, the Chinese and Arab towns, are in the “old town”; but Europeans desert that quarter before sundown, and betake themselves to the “new town” suburbs, where[21] every house is in a park of its own, and the avenues are broad and straight, and all the distances are magnificent. The city of Batavia, literally “fair meadows,” grandiloquently “the queen of the East,” and without exaggeration “the gridiron of the East,” dates from 1621, when the Dutch removed from Bantam, where quarrels between Portuguese, Javanese, and the East India Company had been disturbing trade for fifteen years, and built Fort Jacatra at the mouth of a river off which a cluster of islands sheltered a fine harbor. Its position in the midst of swamps was unhealthy, and the mortality was so appalling as to seem incredible. Dutch records tell of 87,000 soldiers and sailors dying in the government hospital between 1714 and 1776, and of 1,119,375 dying at Batavia between 1730 and August, 1752—a period of twenty-two years and eight months.[1] The deadly Java fever occasioning this seemingly incredible mortality was worst between the years 1733 and 1738, during which time 2000 of the Dutch East India Company’s servants and free Christians died annually. Staunton, who visited Batavia with Lord Macartney’s embassy in 1793, called it the “most unwholesome place in the universe,” and “the pestilential climate” was considered a sufficient defense against attack from any European power.

The people were long in learning that those who went to the higher suburbs to sleep, and built houses of the most open construction to admit of the fullest sweep of air, were free from the fever of the walled town, surrounded by swamps, cut by stagnant canals, and facing a harbor whose mud-banks were exposed at[22] low tide. The city walls were destroyed at the beginning of this century by the energetic Marshal Daendels, who began building the new town. The quaint old air-tight Dutch buildings were torn down, and streets were widened; and there is now a great outspread town of red-roofed, whitewashed houses, with no special features or picturesqueness to make its street-scenes either distinctively Dutch or tropical. Modern Batavia had 111,763 inhabitants on December 31, 1894, less than a tenth of whom are Europeans, with 26,776 Chinese and 72,934 natives. While the eighteenth-century Stadhuis might have been brought from Holland entire, a steam tramway starts from its door and thence shrieks its way to the farthest suburb, the telephone “hellos” from center to suburb, and modern inventions make tropical living possible.

The Dutch do not welcome tourists, nor encourage one to visit their paradise of the Indies. Too many travelers have come, seen, and gone away to tell disagreeable truths about Dutch methods and rule; to expose the source and means of the profitable returns of twenty million dollars and more for each of so many years of the last and the preceding century—all from islands whose whole area only equals that of the State of New York. Although the tyrannic rule and the “culture system,” or forced labor, are things of the dark past, the Dutch brain is slow and suspicious, and the idea being fixed fast that no stranger comes to Java on kindly or hospitable errands, the colonial authorities must know within twenty-four hours why one visits the Indies. They demand one’s name, age, religion, nationality, place of nativity, and occupation,[23] the name of the ship that brought the suspect to Java, and the name of its captain—a dim threat lurking in this latter query of holding the unlucky mariner responsible should his importation prove an expense or embarrassment to the island. Still another permit—a toelatings-kaart, or “admission ticket”—must be obtained if one wishes to travel farther than Buitenzorg, the cooler capital, forty miles away in the hills. The tourist pure and simple, the sight-seer and pleasure traveler, is not yet quite comprehended, and his passports usually accredit him as traveling in the interior for “scientific purposes.” Guides or efficient couriers in the real sense do not exist yet. The English-speaking servant is rare and delusive, yet a necessity unless one speaks Dutch or Low Malay. Of all the countries one may ever travel in, none equals Java in the difficulty of being understood; and it is a question, too, whether the Malays who do not know any English are harder to get along with than the Dutch who know a little.

Thirty years ago Alfred Russel Wallace inveighed against the unnecessary discomforts, annoyances, and expense of travel in Java, and every tourist since has repeated his plaint. The philippics of returned travelers furnish steady amusement for Singapore residents; and no one brings back the same enthusiasm that embarked with him. It is not the Java of the Javanese that these returned ones berate so vehemently, but the Netherlands India, and the state created and brought about by the merciless, cold-blooded, rapacious Hollanders who came half-way round the world and down to the equator, nine thousand[24] miles away from their homes, to acquire an empire and enslave a race, and who impose their hampering customs and restrictions upon even alien visitors. Java undoubtedly is “the very finest and most interesting tropical island in the world,” and the Javanese the most gentle, attractive, and innately refined people of the East, after the Japanese; but the Dutch in Java “beat the Dutch” in Europe ten points to one, and there is nothing so surprising and amazing, in all man’s proper study of mankind, as this equatorial Hollander transplanted from the cold fens of Europe; nor is anything so strange as the effect of a high temperature on Low-Country temperament. The most rigid, conventional, narrow, thrifty, prudish, and Protestant people in Europe bloom out in the forcing-house of the tropics into strange laxity, and one does not know the Hollanders until one sees them in this “summer land of the world,” whither they threatened to emigrate in a body during the time of the Spanish Inquisition.

When one has driven through the old town of Batavia and seen its crowded bazaars and streets, and has followed the lines of bricked canals, where small natives splash and swim, women beat the family linen, and men go to and fro in tiny boats, all in strange travesty of the solemn canals of the old country, he comes to the broader avenues of the new town, lined with tall tamarind- and waringen-trees, with plumes of palms, and pyramids of blazing Madagascar flame-trees in blossom. He is driven into the long garden court of the Hotel Nederlanden, and there beholds a spectacle of social life and customs that nothing in all travel can equal for distinct shock and sensation. We had seen some queer things in the streets,—women lolling barefooted and in startling dishabille in splendid equipages,—but concluded them to be servants or half-castes; but there in the hotel was an undress parade that beggars description, and was as astounding on the last as on the first day in the country. Woman’s vanity and man’s conventional ideas evidently[26] wilt at the line, and no formalities pass the equator, when distinguished citizens and officials can roam and lounge about hotel courts in pajamas and bath slippers, and bare-ankled women, clad only in the native sarong, or skirt, and a white dressing-jacket, go unconcernedly about their affairs in streets and public places until afternoon. It is a dishabille beyond all burlesque pantomime, and only shipwreck on a desert island would seem sufficient excuse for women being seen in such an ungraceful, unbecoming attire—an undress that reveals every defect while concealing beauty, that no loveliness can overcome, and that has neither color nor grace nor picturesqueness to recommend it.

The hotel is a series of one-storied buildings surrounding the four sides of a garden court, the projecting eaves giving a continuous covered gallery that is the general corridor. The bedrooms open directly upon this broad gallery, and the space in front of each room, furnished with lounging-chairs, table, and reading-lamp, is the sitting-room of each occupant by day. There is never any jealous hiding behind curtains or screens. The whole hotel register is in evidence, sitting or spread in reclining-chairs. Men in pajamas thrust their bare feet out bravely, puffing clouds of rank Sumatra tobacco smoke as they stared at the new arrivals; women rocked and stared as if we were the unusual spectacle, and not they; and children sprawled on the cement flooring, in only the most intimate undergarments of civilized children. One turned his eyes from one undressed family group only to encounter some more surprising dishabille; and meanwhile servants were hanging whole mildewed wardrobes on[27] clothes-lines along this open hotel corridor, while others were ironing their employers’ garments on this communal porch.

A JAVANESE YOUNG WOMAN.

We were sure we had gone to the wrong hotel; but the Nederlanden was vouched for as the best, and when the bell sounded, over one hundred guests came into the vaulted dining-room and were seated at the one long table. The men wore proper coats and clothes at this midday riz tavel (rice table), but the women and children came as they were—sans gêne.

The Batavian day begins with coffee and toast, eggs and fruit, at any time between six and nine o’clock; and the affairs of the day are despatched before noon, when that sacred, solemn, solid feeding function, the riz tavel, assembles all in shady, spacious dining-rooms, free from the creaking and flapping of the punka, so prominent everywhere else in the East. Rice is the staple of the midday meal, and one is expected to fill the soup-plate before him with boiled rice, and on that heap as much as he may select from eight or ten dishes, a tray of curry condiments being also passed with this great first course. Bits of fish, duck, chicken, beef, bird, omelet, and onions rose upon my neighbors’ plates, and spoonfuls of a thin curried mixture were poured over the rice, before the conventional chutneys, spices, cocoanut, peppers, and almond went to the conglomerate mountain resting upon the “rice table” below. Beefsteak, a salad, and then fruit and coffee brought the midday meal to a close. Squeamish folk, unseasoned tourists, and well-starched Britons with small sense of humor complain of loss of appetite at these hotel riz tavels; and those Britons further[30] criticize the way in which the Dutch fork, or most often the Dutch knife-blade, is loaded, aimed, and shoveled with a long, straight stroke to the Dutch interior; and they also criticize the way in which portions of bird or chicken are managed, necessitating and explaining the presence of the finger-bowl from the beginning of each meal. But we forgot all that had gone before when the feast was closed with the mangosteen—nature’s final and most perfect effort in fruit creation.

After the riz tavel every one slumbers—as one naturally must after such a very “square” meal—until four o’clock, when a bath and tea refresh the tropic soul, the world dresses in the full costume of civilization, and the slatternly women of the earlier hours go forth in the latest finery of good fortune, twenty-six days from Amsterdam, for the afternoon driving and visiting, that continue to the nine-o’clock dinner-hour. Batavian fashion does not take its airing in the jerky sadoe, but in roomy “vis-à-vis” or barouches, comfortable “milords” or giant victorias, that, being built to Dutch measures, would comfortably accommodate three ordinary people to each seat, and are drawn by gigantic Australian horses, or “Walers” (horses from New South Wales), to match these turnouts of Brobdingnag.

Society is naturally narrow, provincial, colonial, conservative, and insular, even to a degree beyond that known in Holland. The governor-general, whose salary is twice that of the President of the United States, lives in a palace at Buitenzorg, forty miles away in the hills, with a second palace still higher up in the[31] mountains, and comes to the Batavia palace only on state occasions. This ruler of twenty-four million souls, who rules as a viceroy instructed from The Hague, with the aid of a secretary-general and a Council of the Indies, has, in addition to his salary of a hundred thousand dollars, an allowance of sixty thousand dollars a year for entertaining, and it is expected that he will maintain a considerable state and splendor. He has a standing army of thirty thousand, one third Europeans, of various nationalities, raised by volunteer enlistment in Holland, who are well paid, carefully looked after, and recruited by long stays at Buitenzorg after short terms of service at the sea-ports. After the Indian mutiny the Dutch were in great fear of an uprising of the natives of Java, and placed less confidence in native troops. Only Europeans can hold officers’ commissions; and while the native soldiers are all Mohammedans, and great consideration is paid their religious scruples, care is taken not to let the natives of any one province or district compose a majority in any one regiment, and these regiments frequently change posts. The colonial navy has done great service to the world in suppressing piracy in the Java Sea and around the archipelago, although steam navigation inevitably brought an end to piracy and picturesque adventure. The little navy helps maintain an admirable lighthouse service, and with such convulsions as that of Krakatau always possible, and changes often occurring in the bed of the shallow seas, its surveyors are continually busied with making new charts.

The islands of Amboyna, Borneo, Celebes, and Sumatra are also ruled by this one governor-general of the Netherlands Indies, through residents; and the island of Java is divided into twenty-two residencies or provinces, a resident, or local governor, ruling—or, as “elder brother,” effectually advising—in the few provinces ostensibly ruled by native princes. A resident receives ten thousand dollars a year, with house provided and a liberal allowance made for the extra incidental expenses of the position—for traveling, entertaining, and acknowledging in degree the gifts of native princes. University graduates are chosen for this colonial service, and take a further course in the colonial institute at Haarlem, which includes, besides the study of the Malay language, the economic botany of the Indies, Dutch law, and Mohammedan justice, since, in their capacity as local magistrates, they must make their decisions conform with the tenets of the Koran, which is the general moral law, together with the unwritten Javanese code. They are entitled to retire upon a pension after twenty years of service—half the time demanded of those in the civil service in Holland. All these residents are answerable to the secretary of the colony, appointed by the crown, and much of executive detail has to be submitted to the home government’s approval. Naturally there is much friction between all these functionaries, and etiquette is punctilious to a degree. A formal court surrounds the governor-general, and is repeated in miniature at every residency. The pensioned native sovereigns, princes, and regents maintain all the forms, etiquette, and barbaric splendor of their old court life, elaborated[33] by European customs. The three hundred Dutch officials condescend equally to the rich planters and to the native princes; the planters hate and deride the officials; the natives hate the Dutch of either class, and despise their own princes who are subservient to the Dutch; and the wars and jealousies of rank and race and caste, of white and brown, of native and imported folk, flourish with tropical luxuriance.

Batavian life differs considerably from life in British India and all the rest of Asia, where the British-built and conventionally ordered places support the same formal social order of England unchanged, save for a few luxuries and concessions incident to the climate. The Dutchman does not waste his perspiration on tennis or golf or cricket, or on any outdoor pastime more exciting than horse-racing. He does not make well-ordered and expensive dinners his one chosen form of hospitality. He dines late and dines elaborately, but the more usual form of entertainment in Batavia is in evening receptions or musicales, for which the spacious houses, with their great white porticos, are well adapted. Batavian residents have each a paradise park around their dwellings, and the white houses of classic architecture, bowered in magnificent trees and palms, shrubs and vines and blooming plants, are most attractive by day. At night, when the great portico, which is drawing-room and living-room and as often dining-room, is illuminated by many lamps, each lovely villa glows like a fairyland in its dark setting. If the portico lamps are not lighted, it is a sign of “not at home,” and mynheer and his family may sit in undress at their ease. There are weekly concerts[34] at the Harmonie and Concordia clubs, where the groups around iron tables might have been summoned by a magician from some continental garden. There are such clubs in every town on the island, the government subsidizing the opera and supporting military bands of the first order; and they furnish society its center and common meeting-place. One sees fine gowns and magnificent jewels; ladies wear the heavy silks and velvets of an Amsterdam winter in these tropical gardens, and men dance in black coats and broadcloth uniforms. Society is brilliant, formal, and by lamplight impressive; but when by daylight one meets the same fair beauties and bejeweled matrons sockless, in sarongs and flapping slippers, the disillusionment is complete.

The show-places of Batavia are easily seen in a day: the old town hall, the Stadkirche, the lighthouse, the old warehouse, and the walled gate of Peter Elberfeld’s house, with the spiked skull of that half-caste rebel against Dutch rule pointing a more awful reminder than the inscription in several languages to his “horrid memory.” The pride of the city, and the most creditable thing on the island, is the Museum of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences (“Bataviaasch Genootschap von Kunsten en Wepenschappen”), known sufficiently to the world of science and letters as “the Batavian Society,” of which Sir Stamford Raffles was the first great inspirer and exploiter, after it had dreamed along quietly in colonial isolation for a few years of the last century. In his time were begun the excavations of the Hindu temples and the archæological work which the Dutch government and the Batavian[35] Society have since carried on, and which have helped place that association among the foremost learned societies of the world. The museum is housed in a beautiful Greek temple of a building whose white walls are shaded by magnificent trees, and faces the broad Koenig’s Plein, the largest parade-ground in the world, the Batavians say. The halls, surrounding a central court, shelter a complete and wonderful exhibit of Javanese antiquities and art works, of arms, weapons, implements, ornaments, costumes, masks, basketry, textiles, musical instruments, models of boats and houses, examples of fine old metal-work, and of all the industries of these gifted people. It is a place of absorbing interest; but with no labels and no key except the native janitor’s pantomime, one’s visit is often filled with exasperation.

There is a treasure-chamber heaped with gold shields, helmets, thrones, state umbrellas, boxes, salvers, betel and tobacco sets of gold, with jeweled daggers and krises of finest blades, patterned with curious veinings. Tributes and gifts from native sultans and princes display the precious metals in other curious forms, and a fine large coco-de-mer, the fabled twin nut of the Seychelles palm, that was long supposed to grow in some unknown, mysterious isle of the sea-gods, is throned on a golden base with all the honors due such a talisman. The ruined temples and sites of abandoned cities in Middle Java have yielded rich ornaments, necklaces, ear-rings, head-dresses, seals, plates, and statuettes of gold and silver. A room is filled with bronze weapons, bells, tripods, censers, images, and all the appurtenances of Buddhist worship, characteristic examples of[36] the Greco-Buddhist art of India, which even more surprisingly confronts one in these treasures from the jungles of the far-away tropical island. A central hall is filled with bas-reliefs and statues from these ruins of Buddhist and Brahmanic temples, in which the Greek influence is quite as marked, and Egyptian and Assyrian suggestions in the sculptures give one other ideas to puzzle over.

The society’s library is rich in exchanges, scientific and art publications of all countries; and the row of reports of the Smithsonian Institution, the Geological Survey and Bureau of Ethnology, are as much a matter of pride to the American visitor as the framed diplomas of institutes and international expositions are to the Batavian curator. The council-room contains the state chairs of native sovereigns, and portraits and souvenirs of the great explorers and navigators who passed this way in the last century and in the early years of this cycle. Captain Cook left stores of South Sea curios on his way to and fro, and during this century the museum has been the pet and pride of Dutch residents and officials, and the subject of praise by all visitors.

The palace of the governor-general on this vast Koenig’s Plein is a beautiful modern structure, but more interest attaches to the old palace of the Waterloo Plein, the palys built by the great Marshal Daendels, who, supplanted by the British after but three years’ energetic rule, withdrew to Europe.

The Tjina, or China, and the Arab kampongs, are show-places to the stranger in the curious features of life and civic government they present. Each of these foreign kampongs, or villages, is under the charge of a captain or commander, whom the Dutch authorities hold responsible for the order and peace of their compatriots, since they do not allow to these yellow colonials so-called “European freedom”—an expression which constitutes a sufficient admission of the existence of “Asiatic restraint.” Great wealth abides in both these alien quarters, whose leading families have been there for generations, and have absorbed all retail trade, and as commission merchants, money-lenders, and middlemen have garnered great profits and earned the hatred of Dutch and Javanese alike. The lean and hooked-nosed followers of the prophet conquered the island in the fifteenth century, and have built their messigits, or mosques, in every province. The Batavian messigit is a cool little[38] blue-and-white-tiled building, with a row of inlaid wooden clogs and loose leather shoes at the door; and turbaned heads within bow before the mihrab that points northwestward to Mecca. Since the Mohammedan conquest of 1475, the Javanese are Mohammedan if anything; but they take their religion easily, and are so lukewarm in the faith of the fire and sword that they would easily relapse to their former mild Brahmanism if Islam’s power were released. The Dutch have always prohibited the pilgrimages to Mecca, since those returning with the green turban were viewed with reverence and accredited with supernatural powers that made their influence a menace to Dutch rule. Arab priests have always been enemies of the government and foremost in inciting the people to rebellion against Dutch and native rulers; but little active evangelical work seems to have been done by Christian missionaries to counteract Mohammedanism, save at the town of Depok, near Batavia.

In all the banks and business houses is found the lean-fingered Chinese comprador, or accountant, and the rattling buttons of his abacus, or counting-board, play the inevitable accompaniment to financial transactions, as everywhere else east of Colombo. The 251,325 Chinese in Netherlands India present a curious study in the possibilities of their race. Under the strong, tyrannical rule of the Dutch they thrive, show ambition to adopt Western ways, and approach more nearly to European standards than one could believe possible. Chinese conservatism yields first in costume and social manners; the pigtail shrinks to a mere symbolic wisp, and the well-to-do Batavian Chinese[39] dresses faultlessly after the London model, wears spotless duck coat and trousers, patent-leather shoes, and, in top or derby hat, sits complacent in a handsome victoria drawn by imported horses, with liveried Javanese on the box. One meets correctly gotten-up Celestial equestrians trotting around Waterloo Plein or the alleys of Buitenzorg, each followed by an obsequious groom, the thin remnant of the Manchu queue slipped inside the coat being the only thing to suggest Chinese origin. The rich Chinese live in beautiful villas, in gorgeously decorated houses built on ideal tropical lines; and although having no political or social recognition in the land, entertain no intention of returning to China. They load their Malay wives with diamonds and jewels, and spend liberally for the education of their children. The Dutch tax, judge, punish, and hold them in the same regard as the natives, with whom they have intermarried for three centuries, until there is a large mixed class of these Paranaks in every part of the island. The native hatred of the Chinese is an inheritance of those past centuries when the Dutch farmed out the revenue to Chinese, who, being assigned so many thousand acres of rice-land, and the forced labor of the people on them, gradually extended their boundaries, and by increasing exactions and secret levies oppressed the people with a tyranny and rapacity the Dutch could not approach. In time the Chinese fomented insurrection against the Dutch, and in 1740, joining with disaffected natives, entrenched themselves in a suburban fort. The Dutch in alarm gave the order, and over 20,000 Chinese then within the walls were put[40] to death, not an infant, a woman, nor an aged person being spared. In fear of the wrath of the Emperor of China, elaborate excuses were framed and sent to Peking. Sage old Keen-Lung responded only by saying that the Dutch had served them right, that any death was too good for Chinese who would desert the graves of their ancestors.

After that incident they were restrained from all monopolies and revenue farming, and restricted to their present humble political state. An absolute exclusion act was passed in 1837, but was soon revoked, and the Chinese hold financial supremacy over both Dutch and natives, trade and commerce being hopelessly in the hands of the skilful Chinese comprador. The Dutch vent their dislike by an unmerciful taxation. They formerly assessed them according to the length of their queues and for each long finger-nail. The Chinese are mulcted on landing and leaving, for birth and death, for every business venture and privilege; yet they prosper and remain, and these Paranaks in a few more generations may attain the social and political equality they seek. It all proves that under a strong, tyrannical government the Chinese make good citizens, and can easily put away the notions and superstitions that in China itself hold countless millions in the bondage of a long-dead past. The recent exposure of Chinese forgeries of Java bank-notes to the value of three million pounds sterling has put the captains of Batavia and Samarang kampongs in prison, and has led to wholesale arrests of rich Chinese throughout the island.

Native life swarms in this land of the betel and[41] banana, where there seems to be more of inherent dream and calm than in other lands of the lotus. The Javanese are the finer flowers of the Malay race—a people possessed of a civilization, arts, and literature in that golden period before the Mohammedan and European conquests. They have gentle voices, gentle manners, fine and expressive features, and are the one people of Asia besides the Japanese who have real charm and attraction for the alien. They are more winning, too, by contrast, after one has met the harsh, unlovely, and unwashed people of China, or the equally unwashed, cringing Hindu. They are a little people, and one feels the same indulgent, protective sense as toward the Japanese. Their language is soft and musical—“the Italian of the tropics”; their ideas are poetic; and their love of flowers and perfumes, of music and the dance, of heroic plays and of every emotional form of art, proves them as innately esthetic as their distant cousins, the Japanese, in whom there is so large an admixture of Malay stock. Their reverence for rank and age, and their elaborate etiquette and punctilious courtesy to one another, are as marked even in the common people as among the Japanese; but their abject, crouching humility before their Dutch employers, and the brutality of the latter to them, are a theme for sadder thinking, and calculated to make the blood boil. When one actually sees the quiet, inoffensive peddlers, who chiefly beseech with their eyes, furiously kicked out of the hotel courtyard when mynheer does not choose to buy, and native children actually lifted by an ear and hurled away from the vantage-point on the curbstone which a pajamaed Dutchman wishes for[42] himself while some troops march by, one is content not to see or know any more.

These friendly little barefoot people are of endless interest, and their daily markets, or passers, are panoramas of life and color that one longs to transplant entire. Life is so simple and primitive, too, in the sunshine and warmth of the tropics. A bunch of bananas, a basket of steamed rice, and a leaf full of betel preparations comprise the necessaries and luxuries of daily living. With the rice may go many peppers and curried messes of ground cocoanut, which one sees made and offered for sale in small dabs laid on bits of banana-leaf, the wrapping-paper of the tropics. Pinned with a cactus-thorn, a bit of leaf makes a primitive bag, bowl, or cup, and a slip of it serves as a sylvan spoon. All classes chew the betel- or areca-nut, bits of which, wrapped in betel-leaf with lime, furnish cheer and stimulant, dye the mouth, and keep the lips streaming with crimson juice. In Canton and in all Cochin China, across the peninsula, and throughout island and continental India, men and women have equal delight in this peppery stimulant. The Javanese lays his quid of betel tobacco between the lower lip and teeth, and so great seem to be the solace and comfort of it that dozing venders and peddlers will barely turn an eye and grunt responses to one’s eager “Brapa?” (“How much?”)

PAINTING SARONGS.

Peddlers bring to one’s doorway fine Bantam basketry and bales of the native cotton cloth, or battek, patterned in curious designs that have been in use from time out of mind. These native art fabrics are sold at the passers also, and one soon recognizes the conventional[45] designs, and distinguishes the qualities and merits of these hand-patterned cottons that constitute the native dress. The sarong, or skirt, worn by men and women alike, is a strip of cotton two yards long and one yard deep, which is drawn tightly around the hips, the fullness gathered in front, and by an adroit twist made so firm that a belt is not necessary to native wearers. The sarong has always one formal panel design, which is worn at the front or side, and the rest of the surface is covered with the intricate ornaments in which native fancy runs riot. There are geometrical and line combinations, in which appear the swastika and the curious latticings of central Asia; others are as bold and natural as anything Japanese; and in others still, the palm-leaves and quaint animal forms of India and Persia attest the rival art influences that have swept over these refined, adaptive, assimilative people. One favorite serpentine pattern running in diagonal lines does not need explanation in this land of gigantic worms and writhing crawlers; nor that other pattern where centipedes and insect forms cover the ground; nor that where the fronds of cocoa-palm wave, and the strange shapes of mangos, jacks, and breadfruit are interwoven. The deer and tapir, and the “hunting-scene” patterns are reserved for native royalty’s exclusive wear. In village and wayside cottages up-country we afterward watched men and women painting these cloths, tracing a first outline in a rich brown waxy dye, which is the foundation and dominant color in all these batteks. The parts which are to be left white are covered with wax, and the cloth is dipped in or brushed over with the[46] dye. This resist, or mordant, must be applied for each color, and the wax afterwards steamed out in hot water, so that a sarong goes through many processes and handlings, and is often the work of weeks. The dyes are applied hot through a little tin funnel of an implement tapering down to a thin point, which is used like a painter’s brush, but will give the fine line- and dot-work of a pen-and-ink drawing. The sarong’s value depends upon the fineness of the drawing, the elaborateness of the design, and the number of colors employed; and beginning as low as one dollar, these brilliant cottons, or hand-painted calico sarongs, increase in price to even twenty or thirty dollars. The Dutch ladies vie with one another in their sarongs as much as native women, and their dishabille dress of the early hours has not always economy to recommend it. The battek also appears in the slandang, or long shoulder-scarf, which used to match the sarong and complete the native costume when passed under the arms and crossed at the back, thus covering the body from the armpits to the waist. It is still worn knotted over the mother’s shoulder as a sling or hammock for a child; but Dutch fashion has imposed the same narrow, tight-sleeved kabaia, the baju, or jacket, that Dutch women wear with the sarong. The kam kapala, a square handkerchief tied around men’s heads as a variant of the turban, is of the same figured battek, and, with the slandang, often exhibits charming color combinations and intricate Persian designs. When one conquers his prejudices and associated ideas enough to pay seemingly fancy prices for these examples of free-hand calico printing, the taste grows, and he soon shares[47] the native longing for a sarong of every standard and novel design.

The native silversmiths hammer out good designs in silver relief for betel- and tobacco-boxes, and exhibit great taste and invention in belt- and jacket-clasps, and in heavy knobs of hairpins and ear-rings, that are often made of gold and incrusted over with gems for richer folk.

There are no historic spots nor show-places of native creation in Batavia; no kratons, or aloon-aloons, as their palaces and courtyards are called; and only a sentimental interest for a virtual exile pining in his own country is attached to the villa of Raden Saleh. This son of the regent of Samarang was educated in Europe, and lived there for twenty-three years, developing decided talents as an artist, and enjoying the friendship of many men of rank and genius on the Continent, among the latter being Eugène Sue, who is said to have taken Raden Saleh as model for the Eastern Prince in “The Wandering Jew.” In Java he found himself sadly isolated from his own people by his European tastes and habits; and he had little in common with the coarse, rapacious mynheers whose sole thoughts were of crops and gulden. “Coffee and sugar, sugar and coffee, are all that is talked here. It is a dreary atmosphere for an artist,” said Raden Saleh to D’Almeida, who visited him at Batavia sixty odd years ago. He has left a monument of his taste in this charming villa, in a park whose land is now a vegetable-patch, its shady pleasance a beer-garden and exposition-ground, and the sign “Tu Huur” (“To Hire”) hung from the royal entrance. The exposition of arts and[48] industries in these grounds in 1893 was a great event in Java, the governor-general Van der Wyk opening and closing the fair by electric signal, and the natives making a particularly interesting display of their products and crafts.

One’s most earnest desire, in the scorch of Batavian noondays and stifling Batavian nights, is to seek refuge in “the hills”—in the dark-green groves and forests of the Blue Mountains, that are ranged with such admirable effect as background when one steams in from the Java Sea. At Buitenzorg, only forty miles away and seven hundred and fifty feet above the sea, heat-worn people find refuge in an entirely different climate, an atmosphere of bracing clearness tempered to moderate summer’s warmth. Buitenzorg (“without care”), the Dutch Sans Souci, has been a general refuge and sanitarium for Europeans, the real seat of government, and the home of the governor-general for more than a century. It is the pride and show-place of Java, the great center of its social life, leisure interests, and attractions. The higher officials and many Batavian merchants and bankers have homes at Buitenzorg, and residents from other parts of the island make it their place of recreation and goal of holiday trips.

Undressed Batavia was just rousing from its afternoon nap, and the hotel court was surrounded with barefoot guests in battek pajamas and scant sarongs, a sockless, collarless, unblushing company, that yawned and stared as we drove away, rejoicing to leave this Sans Gêne for Sans Souci. The Weltevreden Station, on the vast Koenig’s Plein, a spacious, stone-floored building, whose airy halls and waiting- and refreshment-rooms are repeated on almost as splendid scale at all the large towns of the island, was enlivened with groups of military officers, whose heavy broadcloth uniforms, trailing sabers, and clanking spurs transported us back from the tropics to some chilly European railway-station, and presented the extreme contrast of colonial life. The train that came panting from Tandjon Priok was made up of first-, second-, and third-class cars, all built on the American plan, in that they were long cars and not carriages, and we entered through doors at the end platforms. The first-class cars swung on easy springs; there were modern car-windows in tight frames, also window-frames of wire netting; while thick wooden venetians outside of all, and a double roof, protected as much as possible from the sun’s heat. The deep arm-chair seats were upholstered with thick leather cushions, the walls were set with blue-and-white tiles repeating Mauve’s and Mesdag’s pictures, and adjustable tables, overhead racks, and a dressing-room furnished all the railroad comforts possible. The railway service of Netherlands India is a vast improvement on, and its cars are in striking contrast to, the loose-windowed, springless, dusty, hard-benched carriages in which first-class passengers are jolted across British[51] India. The second-class cars in Java rest on springs also, but more passengers are put in a compartment, and the fittings are simpler; while the open third-class cars, where native passengers are crowded together, have a continuous window along each side, and the benches are often without backs. The fares average 2.2 United States cents a kilometer (about five eighths of a mile) for first class, 1.6 cents second class, and 6 mills third class. The first-class fare from Batavia to Sourabaya, at the east end of the island, is but 50 gulden ($20) for the 940-kilometer journey, accomplished in two days’ train-travel of twelve and fourteen hours each, so that the former heavy expense (over a dollar a mile for post-horses, after one had bought or rented a traveling-carriage) and the delays of travel in Java are done away with.

The railways have been built by both the government and private corporations, connecting and working together, the first line dating from 1875. The continuous railway line across the island was completed and opened with official ceremonies in November, 1894. The gap of one hundred miles or more across the “terra ingrata,” the low-lying swamp and fever regions either side of Tjilatjap, had existed for years after the track was completed to the east and west of it. Dutch engineers built and manage the road, but the staff, the working force of the line, are natives, or Chinese of the more or less mixed but educated class filling the middle ground between Europeans and natives, between the upper and lower ranks. Wonderful skill was shown in leading the road over the mountains, and in building a firm track and bridges through the[52] reeking swamps, where no white man could labor, even if he could live. The trains do not run at night, which would be a great advantage in a hot country, for the reason that the train crews are composed entirely of natives (since such work is considered beneath the grade of any European), and the cautious Dutch will not trust native engineers after dark. Through trains start from either end of the line and from the half-way stations at five and six o’clock each morning, and run until the short twilight and pitch-darkness that so quickly succeed the unchanging six-o’clock tropical sunset. These early morning starts, and the eight- and nine-o’clock dinner of the Java hotels, make travel most wearisome. One may buy fruit at every station platform, and always tea, coffee, chocolate, wine and schnapps, bread and biscuits at the station buffets. At the larger stations there are dining-rooms, or a service of lunch-baskets, in which the Gargantuan riz tavel, or luncheon, is served hot in one’s compartment as the train moves on.

The hour-and-a-half’s ride from Batavia to Buitenzorg gave us an epitome of tropical landscapes as the train ran between a double panorama of beauty. The soil was a deep, intense red, as if the heat of the sun and the internal fires of this volcanic belt had warmed the fruitful earth to this glowing color, which contrasted so strongly with the complemental green of grain and the groves of palms and cacao-trees. The level rice-fields were being plowed, worked, flooded, planted, weeded, and harvested side by side, the several crops of the year going on continuously, with seemingly no regard to seasons. Nude little boys, astride[53] of smooth gray water-buffaloes, posed statuesquely while those leisurely animals browsed afield; and no pastoral pictures of Java remain clearer in memory than those of patient little brown children sitting half days and whole days on buffalo-back, to brush flies and guide the stupid-looking creatures to greener and more luscious bits of herbage. Many stories are told of the affection the water-ox often manifests for his boy keeper, killing tigers and snakes in his defense, and performing prodigies of valor and intelligence; but one doubts the tales the more he sees of this hideous beast of Asia. Men and women were wading knee-deep in paddy-field muck, transplanting the green rice-shoots from the seed-beds, and picturesque harvest groups posed in tableaux, as the train shrieked by. Children rolled at play before the gabled baskets of houses clustered in toy villages beneath the inevitable cocoa-palms and bananas, the combination of those two useful trees being the certain sign of a kampong, or village, when the braided-bamboo houses are invisible.

RICE-FIELDS.

At Depok there was a halt to pass the down-train, and the natives of this one Christian village and mission-station, the headquarters of evangelical work in Java, flocked to the platform with a prize horticultural display of all the fruits of the season for sale. The record of mission work in Java is a short one, as, after casting out the Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, the Dutch forbade any others to enter, and Spanish rule in Holland had perhaps taught them not to try to impose a strange religion on a people. During Sir Stamford Raffles’s rule, English evangelists began work among the natives, but were summarily interrupted and obliged to[56] withdraw when Java was returned to Holland. All missionaries were strictly excluded until the humanitarian agitation in Europe, which resulted in the formal abolition of slavery and the gradual abandonment of the culture system, led the government to do a little for the Christianization and education of the people. The government supports twenty-nine Protestant pastors and ten Roman Catholic priests, primarily for the spiritual benefit of the European residents, and their spheres are exactly defined—proselytizing and mutual rivalries being forbidden. Missionaries from other countries are not allowed to settle and work among the people, and whatever may be said against this on higher moral grounds, the colonial government has escaped endless friction with the consuls and governments of other countries. The authorities have been quite willing to let the natives enjoy their mild Mohammedanism, and our Moslem servant spoke indifferently of mission efforts at Depok, with no scorn, no contempt, and apparently no hostility to the European faith.

Until recently, no steps were taken to educate the Javanese, and previous to 1864 they were not allowed to study the Dutch language. All colonial officers are obliged to learn Low Malay, that being the recognized language of administration and justice, instead of the many Javanese and Sundanese dialects, with their two forms of polite and common speech. These officials receive promotion and preferment as they make progress in the spoken and written language. Low Malay is the most readily acquired of all languages, as there are no harsh gutturals or difficult[57] consonants, and the construction is very simple. Children who learn the soft, musical Malay first have difficulty with the harsh Dutch sounds, while the Dutch who learn Malay after their youth never pronounce it as well or as easily as they pronounce French. The few Javanese, even those of highest rank, who acquired the Dutch language and attempted to use it in conversation with officials, used to be bruskly answered in Malay, an implication that the superior language was reserved for Europeans only. This helped the conquerors to keep the distinctions sharply drawn between them and their subject people, and while they could always understand what the natives were saying, the Dutch were free to talk together without reserve in the presence of servants or princes. Dutch is now taught in the schools for natives maintained by the colonial government, 201 primary schools having been opened in 1887, with an attendance of 39,707 pupils. The higher schools at Batavia have been opened to the sons of native officials and such rich Javanese as can afford them, and conservatives lament the “spoiling” of the natives with all that the government now does for them. They complain that the Javanese are becoming too “independent” since schoolmasters, independent planters, and tourists came, just as the old-style foreign residents of India, the Straits, China, and Japan bemoan the progressive tendencies and upheavals of this era of Asiatic awakening and enlightenment; and tourist travel is always harped upon as the most offending and corrupting cause of the changes in the native spirit.

Once above the general level of low-lying rice-lands, cacao-plantations succeeded one another for miles[58] beyond Depok; the small trees hung full of fat pods just ripening into reddish brown and crimson. The air was noticeably cooler in the hills, and as the shadows lengthened the near green mountains began to tower in shapes of lazuli mist, and a sky of soft, surpassing splendor made ready for its sunset pageant. When we left the train we were whirled through the twilight of great avenues of trees to the hotel, and given rooms whose veranda overhung a strangely rustling, shadowy abyss, where we could just discern a dark silver line of river leading to the pale-yellow west, with the mountain mass of Salak cut in gigantic purple silhouette.