PORT SUNLIGHT

A RECORD OF

ITS ARTISTIC & PICTORIAL ASPECT

BY T·RAFFLES DAVISON Hon. A·R·I·B·A

LONDON

B·T·BATSFORD LTD 94 HIGH HOLBORN

[Pg vii]

Everyone has heard of Port Sunlight, but it is doubtful whether many have formed a definite or just estimate of this unique example of industrial housing. The following pages are an attempt to record its best features and to show how far the ideal which inspired it has succeeded. To those who have not seen it Port Sunlight is perhaps regarded as one of many other similar places. It is in reality something very different from all others, and especially does it stand by itself in the motive which founded it, which has carried it out, and which continues to administrate it. The breadth of vision which has made Port Sunlight possible is perhaps a greater matter than the village itself. This must inevitably have its effect, but the author ventures to predict that the artistic aspect of the place, which receives some permanent record herein, may also obtain full recognition and emulation as time goes on.

Those who look for finality in any human accomplishment are doomed to disappointment, but the measure of our success will surely be in proportion to the quality of our aims. The last and best word we can say about the village of Port Sunlight is that the aim of its founder has been based on the belief that sympathy for the wants and well-being of our fellow-men may find a large expression even in our business dealings.

It is very delightful to contemplate the results of an undertaking like Port Sunlight—a beneficent enterprise which no law could force from any public body or private employer, and which no mere compiler of accounts for capital and interest would dare to sanction. The ideal which prompted it is the real thing that matters, and though it may be maintained that the carrying out of it pays—and[Pg viii] pays well—we may still hold fast to the hope that both those who make such villages and those who live in them will ever cherish some beliefs which are above and beyond all that which is concerned with a mere monetary return. How fortunate the workpeople who are enabled to live under such ideal conditions!

This little book is entirely due to the desire of the author himself to illustrate the results of an enterprise which he has closely followed from its inception. The combination of the practical and the artistic has been achieved in Port Sunlight with outstanding success, and in these pages it is believed that this is fairly shown, though the building record is not yet by any means complete.

It would be the merest affectation to leave out of these pages any mention of the founder, Sir William Hesketh Lever, Bart., one of the leaders of industrial enterprise in this country. Amongst the many things he has done for the benefit of his fellow-countrymen there is surely nothing we have more to thank him for than the homes which are the subject of this book. To provide employment for thousands and then to give them such homes to live in must be a good reward for a life’s work to the man with an ideal.

My thanks are due to Mr. Herbert Batsford, the head of his firm, who has not only superintended every detail connected with the production but has added personal interest and advice due to his special sympathy with the subject. To Mr. Alex. Paul, of the Editorial and Social Department, Port Sunlight, I am indebted for much kind help.

The photographic views are largely from the studio of Mr. Geo. W. Davies, New Ferry.

T. Raffles Davison.

London,

August, 1916.

[Pg ix]

| PAGE | |

| Preface | vii |

| Contents | ix |

| List of Plates | xi |

| List of Text Illustrations | xiii |

| The Ideal | 1 |

| The Foundation | 5 |

| The Result | 8 |

| Characteristics | 10 |

| The Plan | 16 |

| General Scheme | 20 |

| Tree Planting | 23 |

| Cottage Plans | 25 |

| The Illustrations | 31 |

[Pg xi]

| Plate | Architects’ Names | |

| 1. | Birdseye View of Port Sunlight. | |

| 2. | The Diamond, looking towards Art Gallery. | |

| 3. | Greendale Road, looking towards Post Office. | |

| 4. | Westward View of Park Road, showing Kitchen Cottages | W. and S. Owen |

| 5. | View in Park Road towards the Lyceum | W. and S. Owen |

| 6. | South Side of Park Road. | |

| 7. | Greendale Road and Co-Partners’ Club Annexe | Grayson and Ould |

| 8. | New Chester Road | Huon A. Matear |

| 9. | Cottages in Bath Street | J. J. Talbot |

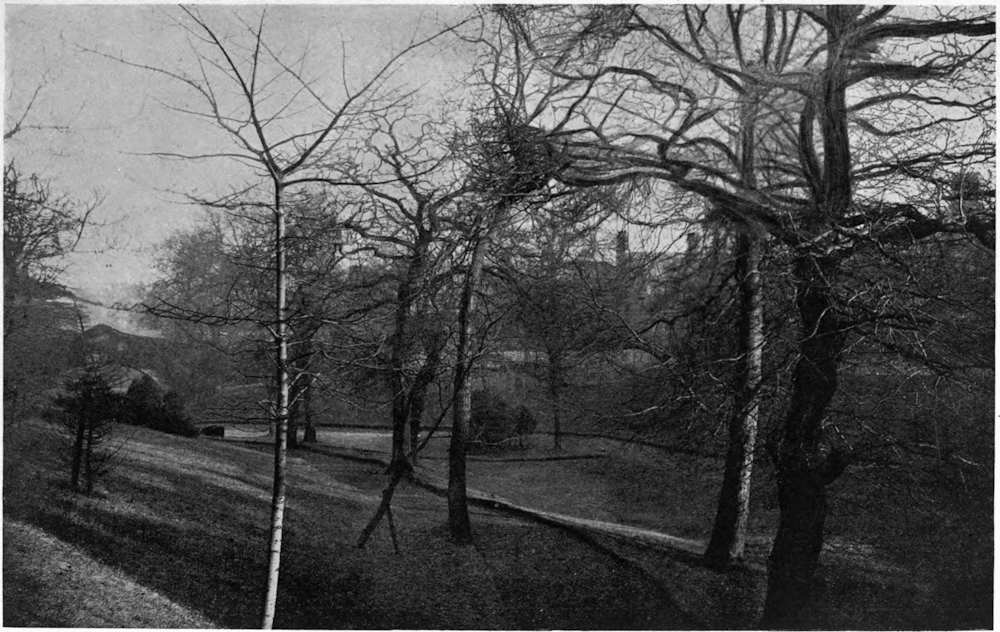

| 10. | The Dell. | |

| 11. | Semi-Quad of Cottages, Queen Mary’s Drive, The Diamond | J. L. Simpson |

| 12. | Park Road. Bridge Cottage in Foreground | Douglas and Fordham |

| 13. | The Causeway, looking towards Christ Church | Corner Cottage by Grayson and Ould |

| 14. | Park Road Cottages. Lyceum in distance | W. and S. Owen |

| 15. | Greendale Road. Cottage Group in foreground, reproducing Kenyon Old Hall | J. J. Talbot |

| 16. | Houses in Park Road. South Side | W. and S. Owen[Pg xii] |

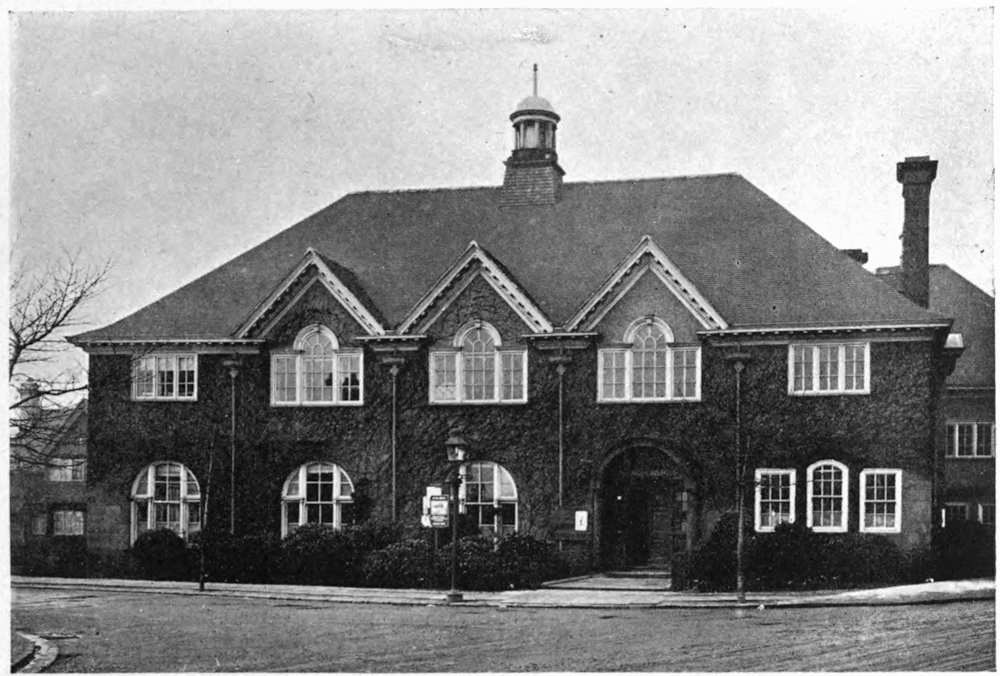

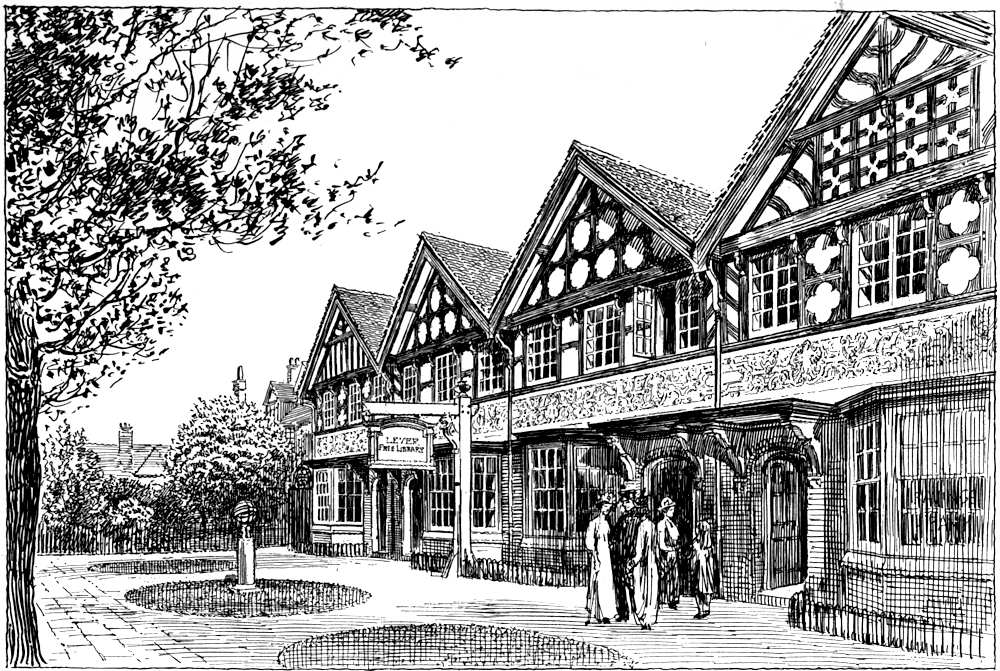

| 17. | Lever Free Library, Greendale Road | Maxwell and Tuke |

| 18. | A Bridge Street Group | Grayson and Ould |

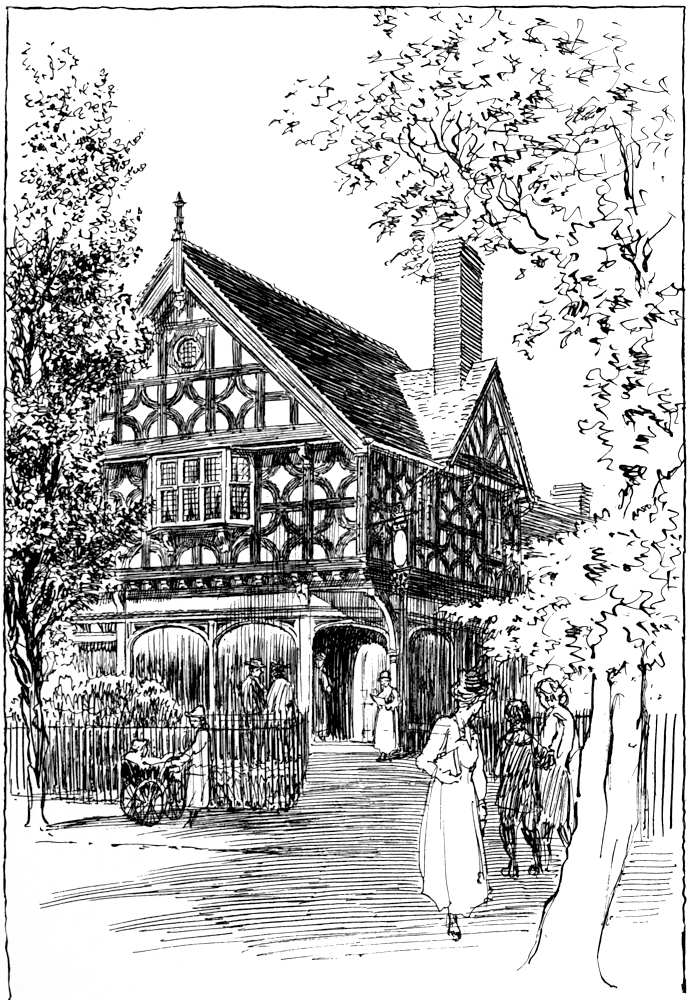

| 19. | Post Office | Grayson and Ould |

| 20. | Group of Cottages in Greendale Road, reproducing design of Kenyon Old Hall | J. J. Talbot |

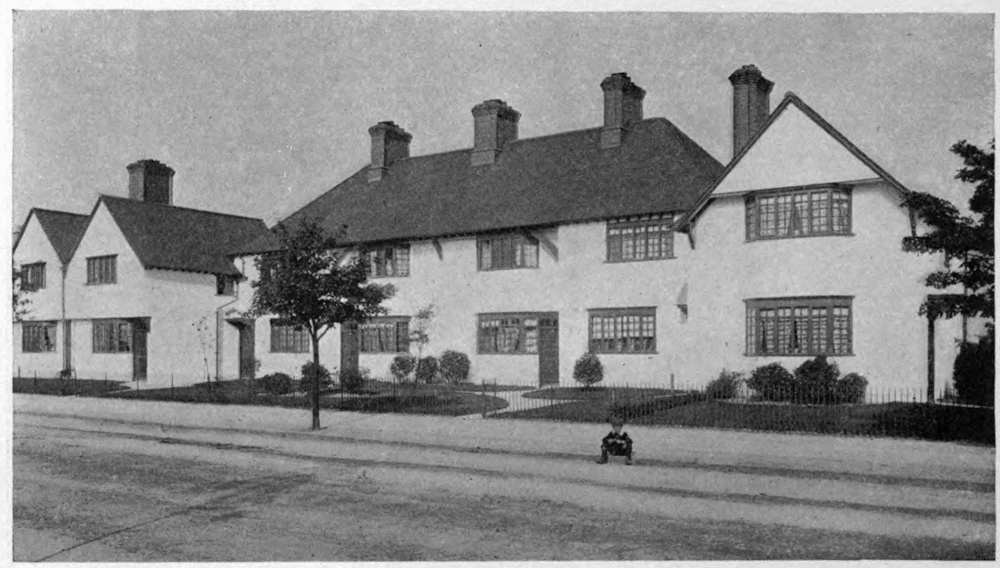

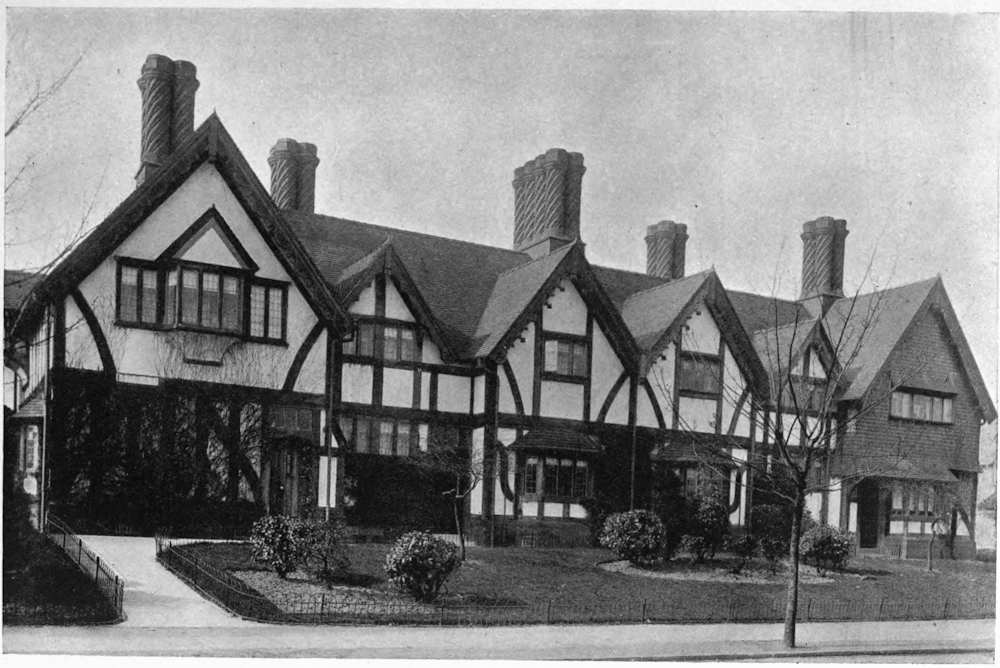

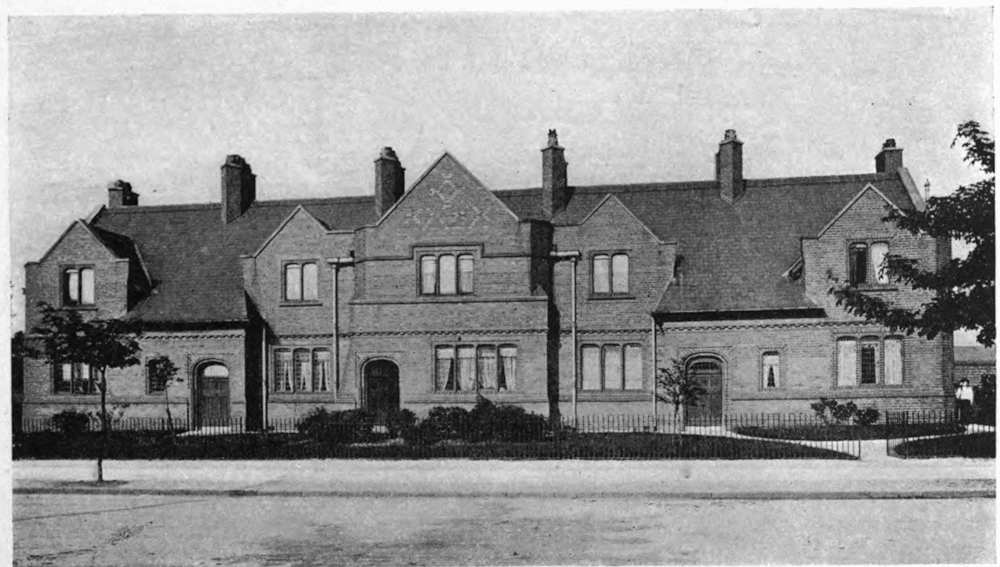

| 21. | Bolton Road Parlour Houses | W. and S. Owen |

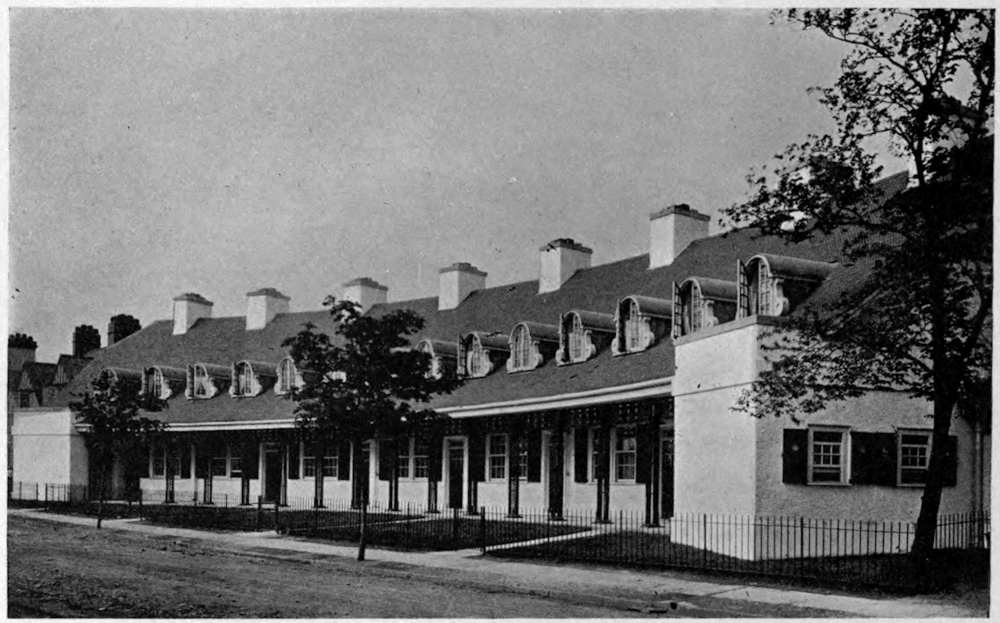

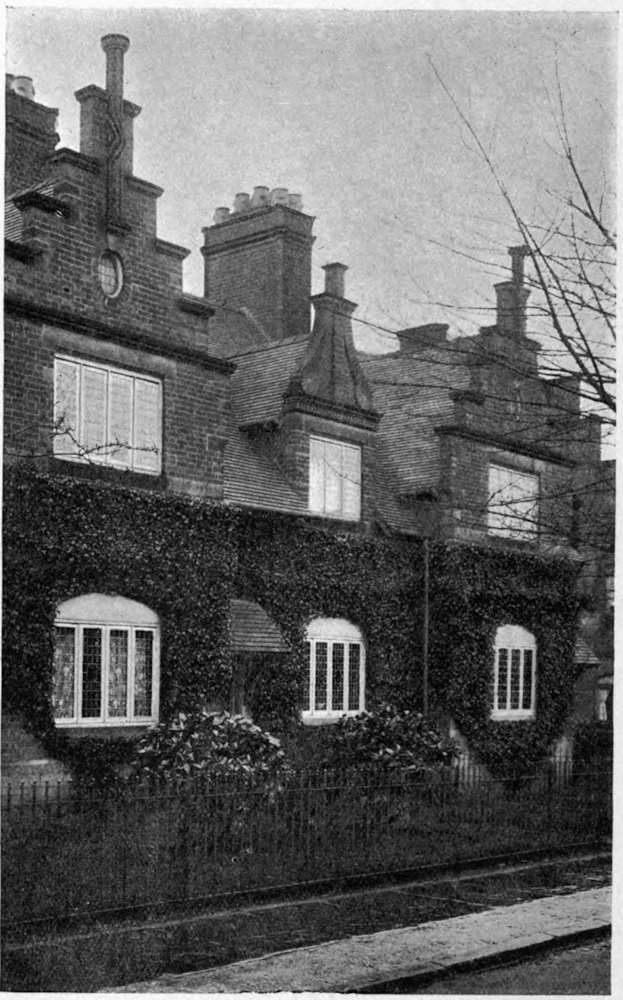

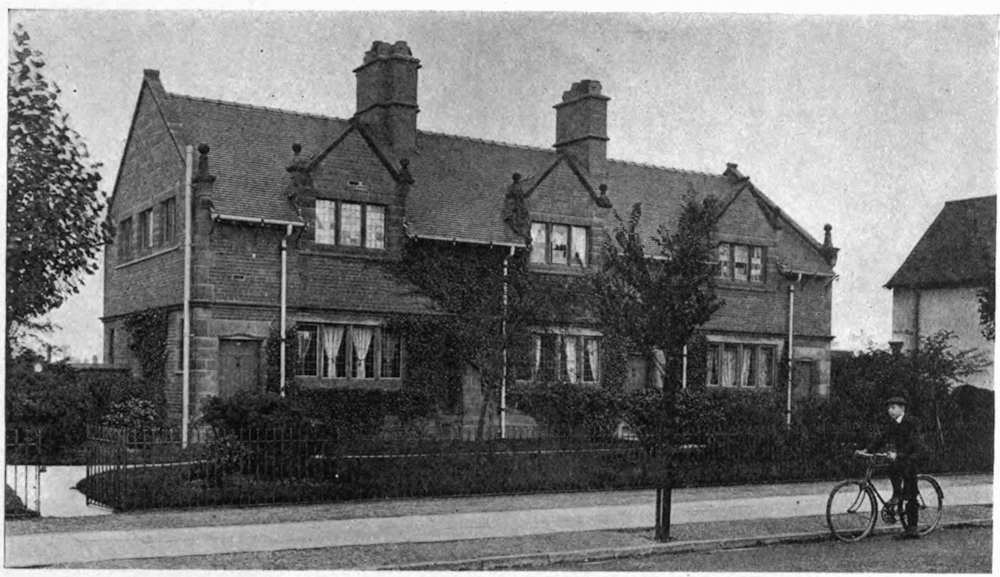

| 22. | Primrose Hill Cottages | Jonathan Simpson |

| Greendale Road Cottages | Pain and Blease | |

| 23. | Greendale Road Cottages | Grayson and Ould |

| Cottage Porch, Connolly Road | Huon A. Matear | |

| 24. | The Bridge Inn | Grayson and Ould |

| 25. | Co-Partners’ Club Hall | Grayson and Ould |

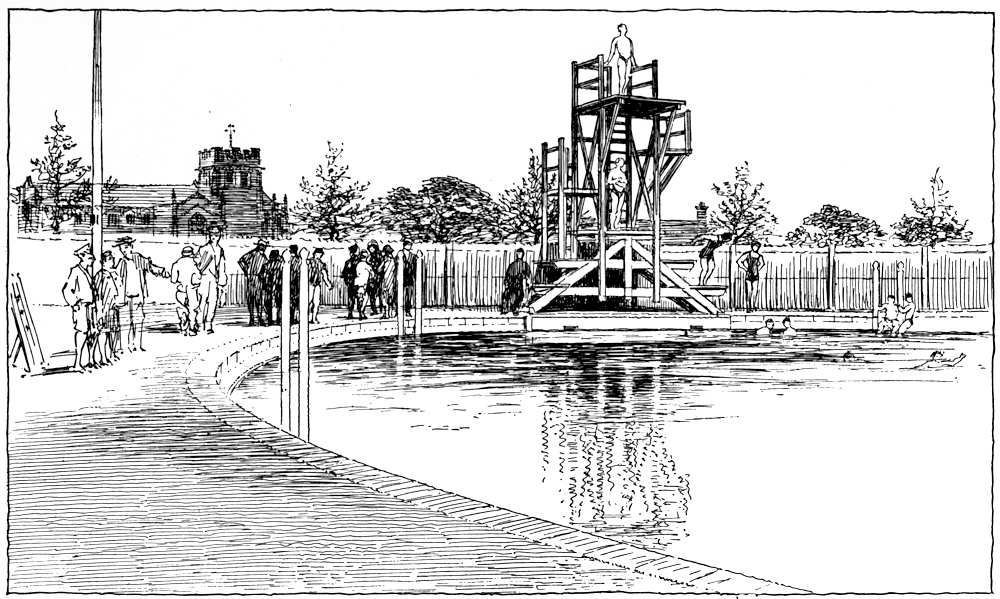

| 26. | Open Air Swimming Bath | W. and S. Owen |

| 27. | A Recessed Group in Cross Street | Grayson and Ould |

| 28. | Cottage in Wood Street | Douglas and Fordham |

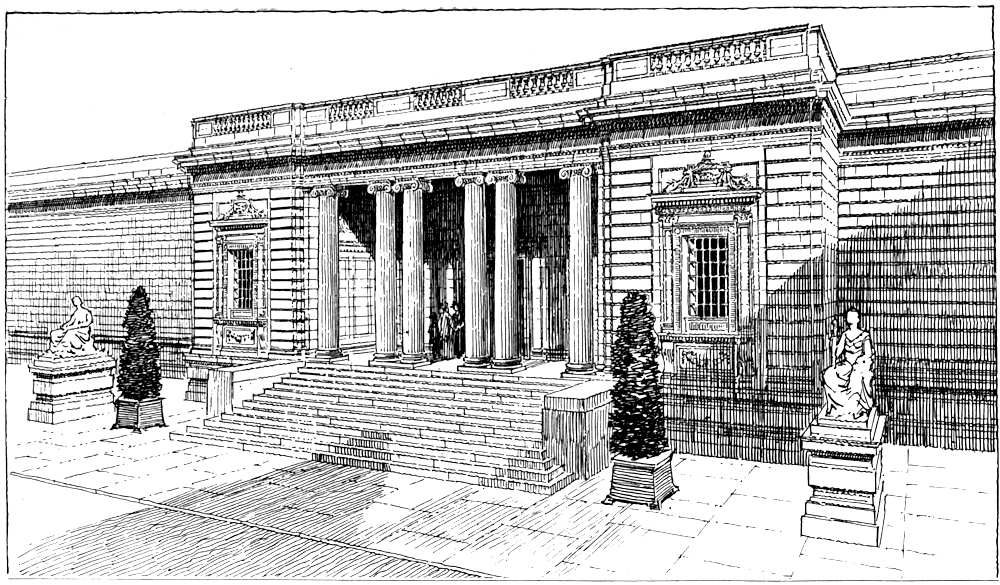

| 29. | The Library Entrance of the Art Gallery | W. and S. Owen |

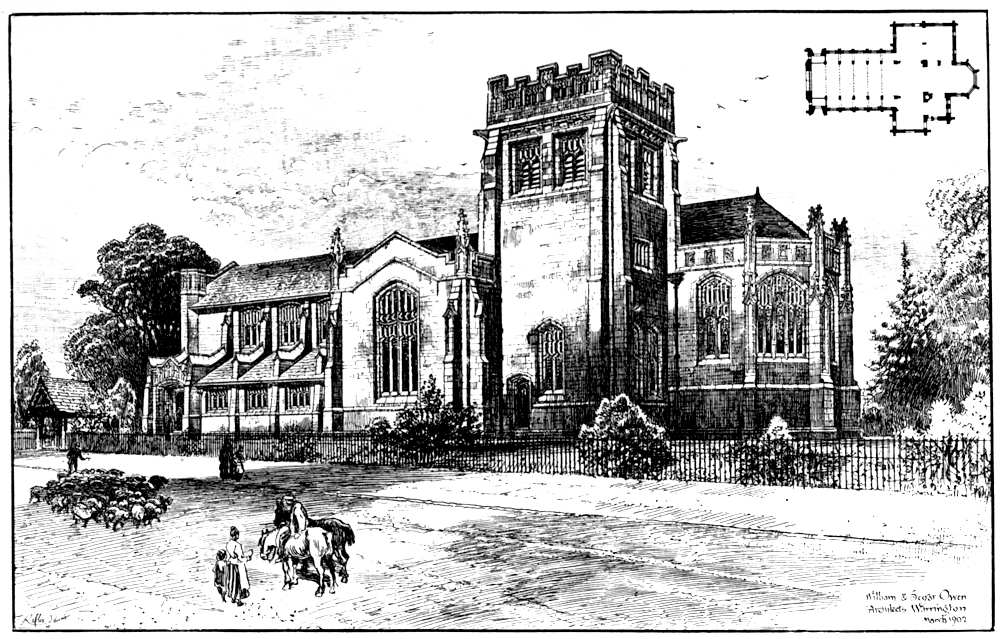

| 30. | S.E. View of Christ Church | W. and S. Owen |

| 31. | View under Tower, Christ Church | W. and S. Owen |

| 32. | Lady Lever Memorial Porch, Christ Church | W. and S. Owen |

| W. and S. Owen | ||

| 33. | The Lady Lever Memorial | Sir W. Goscombe John, |

| R.A., Sculptor |

[Pg xiii]

| Number | PAGE | |

| 1. | The Lyceum | 1 |

| 2. | The Dell Bridge | 2 |

| 3. | Corniche Road before Reclaiming of Ravine | 3 |

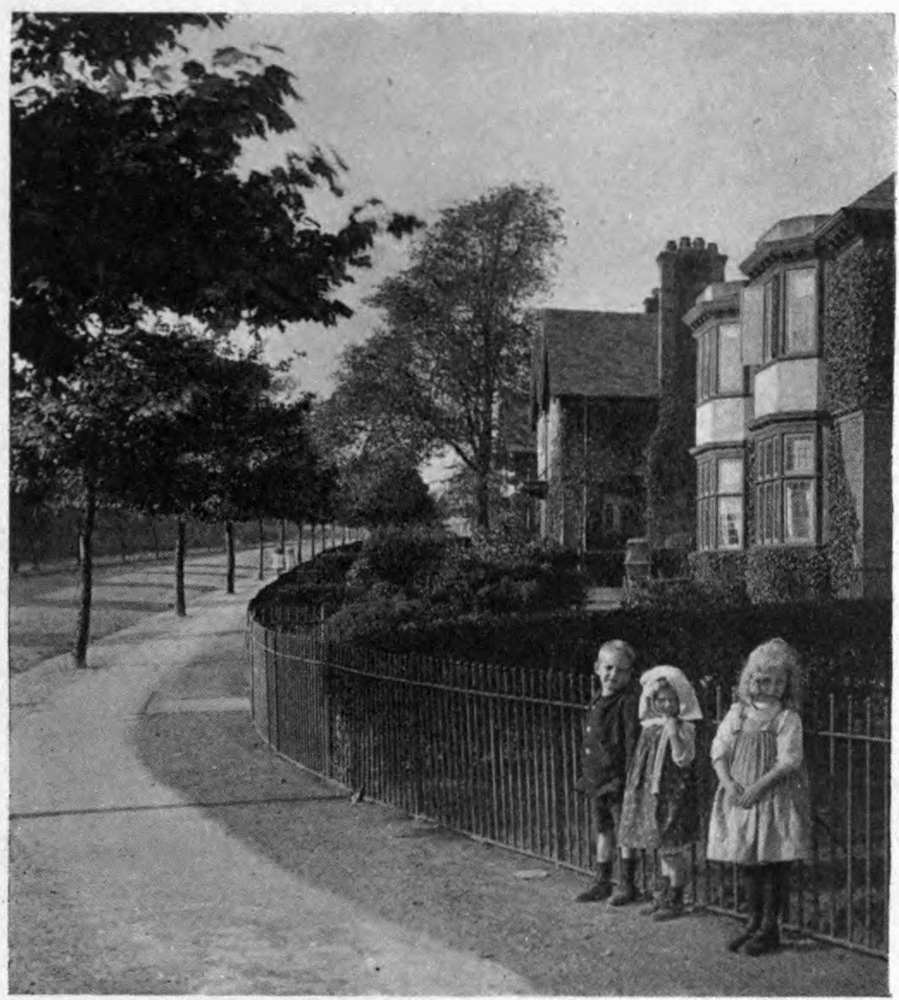

| 4. | Pool Bank | 3 |

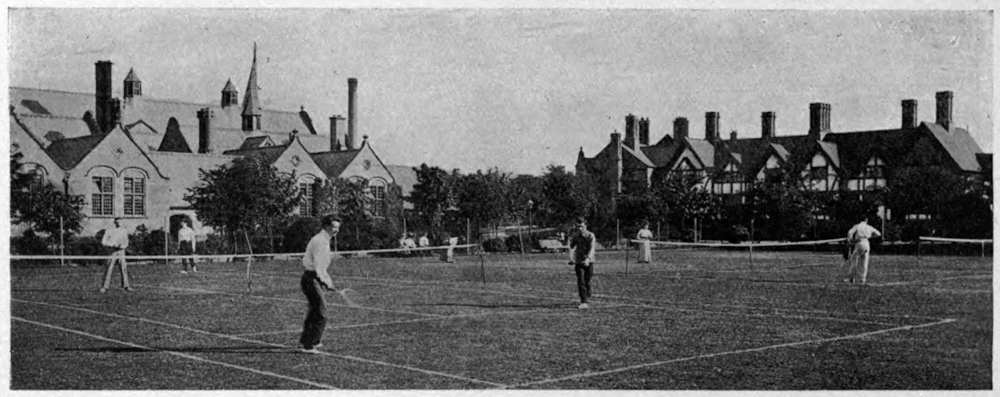

| 5. | Tennis Lawn | 4 |

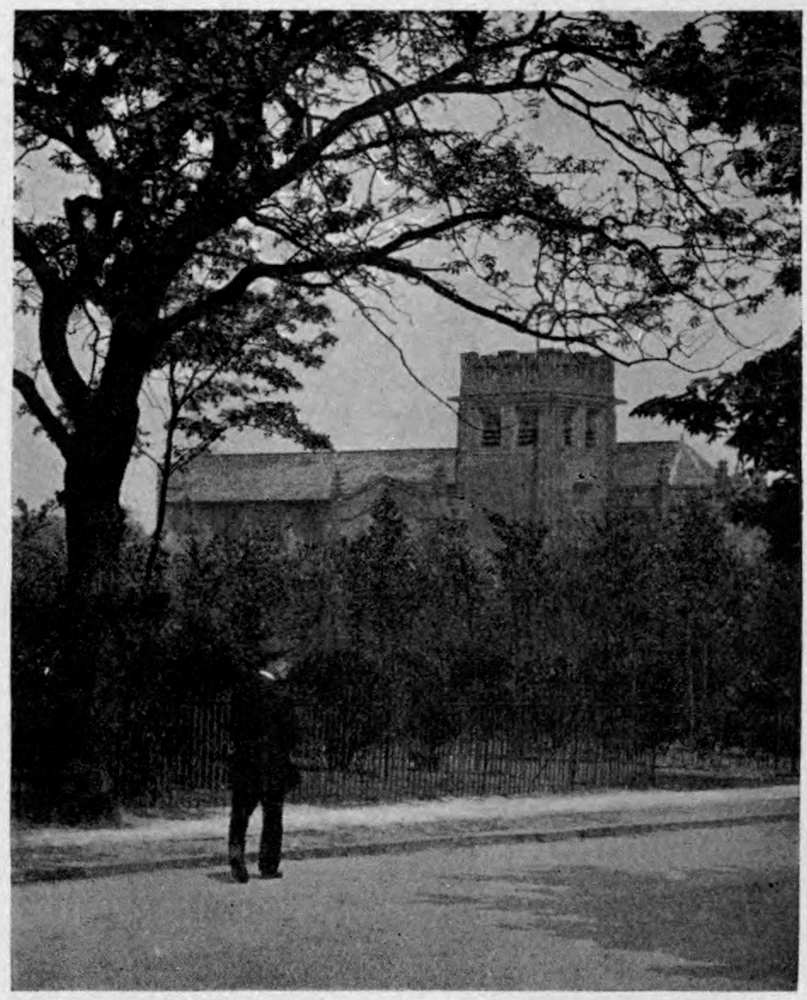

| 6. | Christ Church from Bolton Road | 4 |

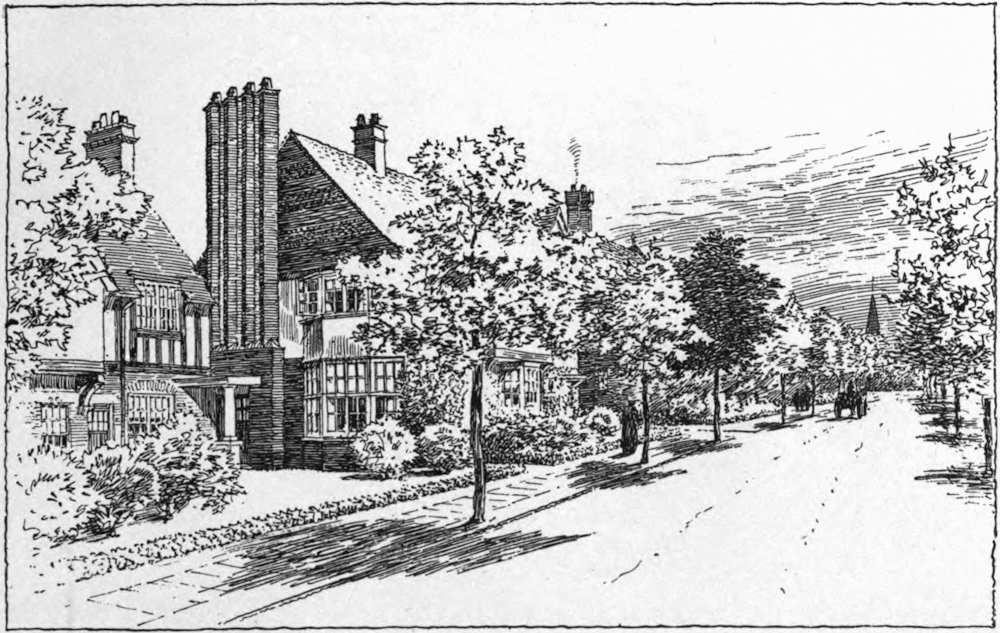

| 7. | Bolton Road, looking towards Bebington Church | 5 |

| 8. | Co-Partners’ Club and Bowling Green | 6 |

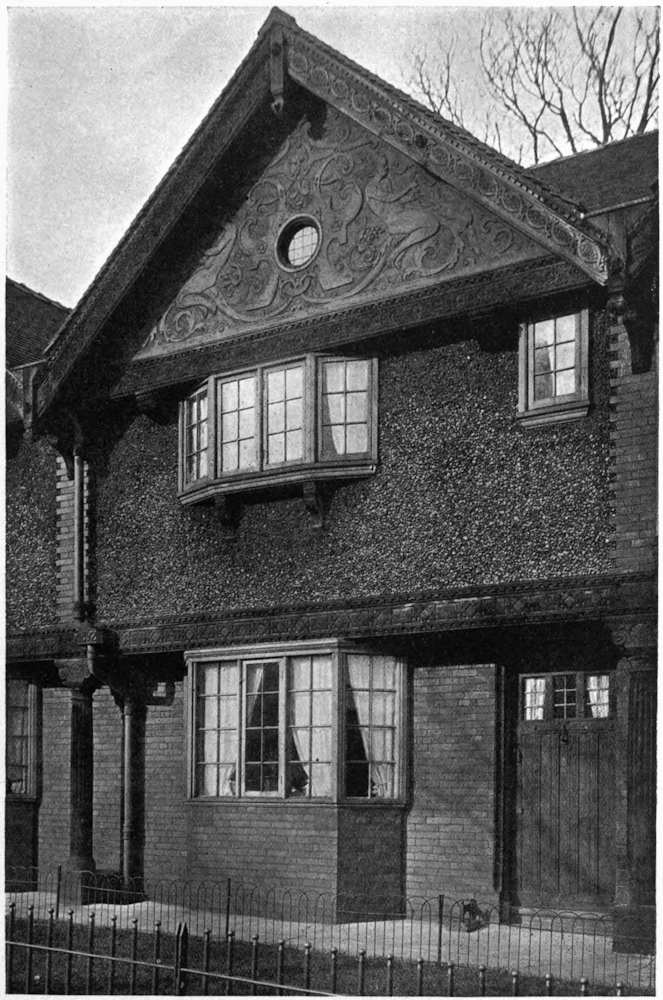

| 9. | Carved Oak and Decorative Plaster Work on Cottage in Park Road South | 7 |

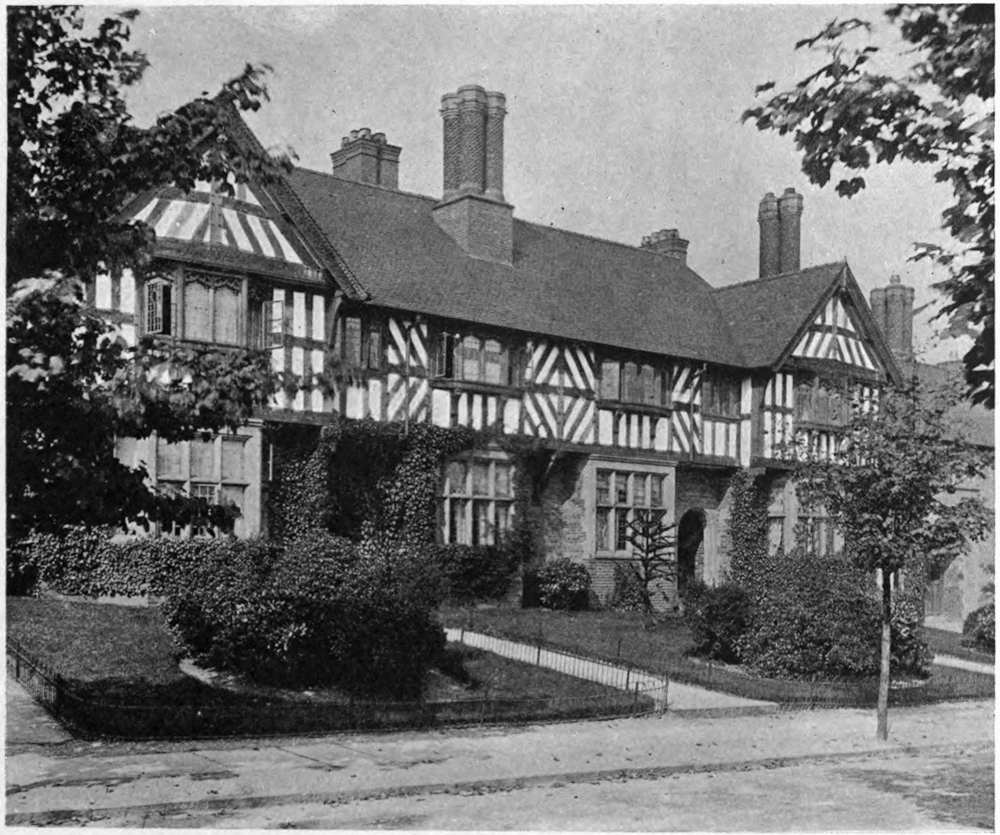

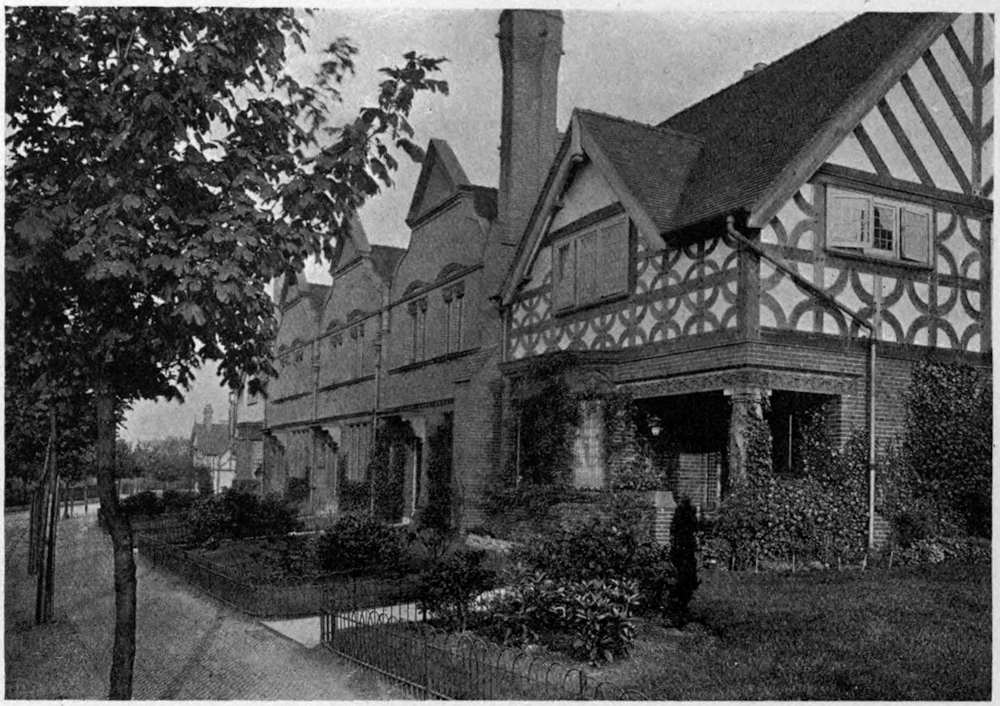

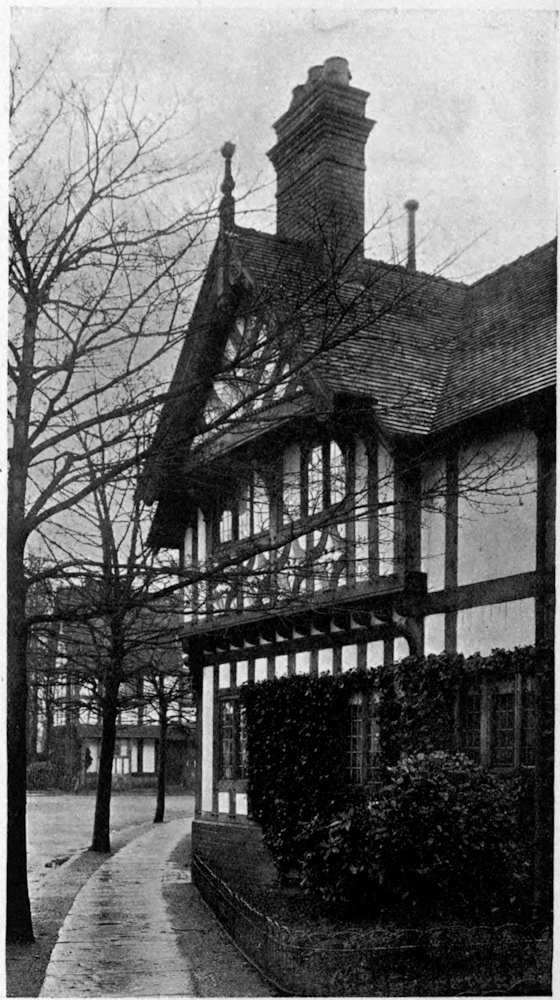

| 10. | Half-timber Cottages in Park Road | 8 |

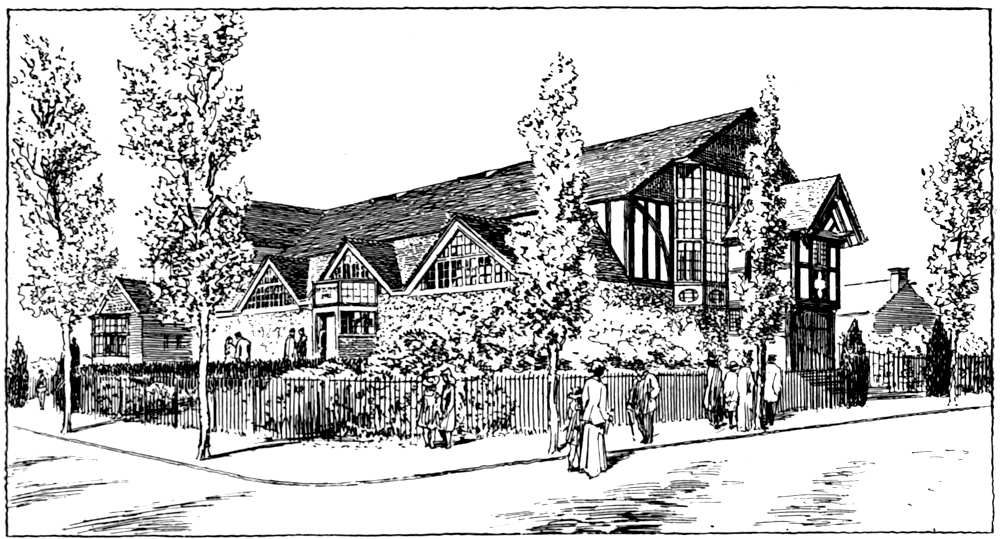

| 11. | Employees’ Provident Stores and Collegium | 9 |

| 12. | Cottages in Corniche Road | 10 |

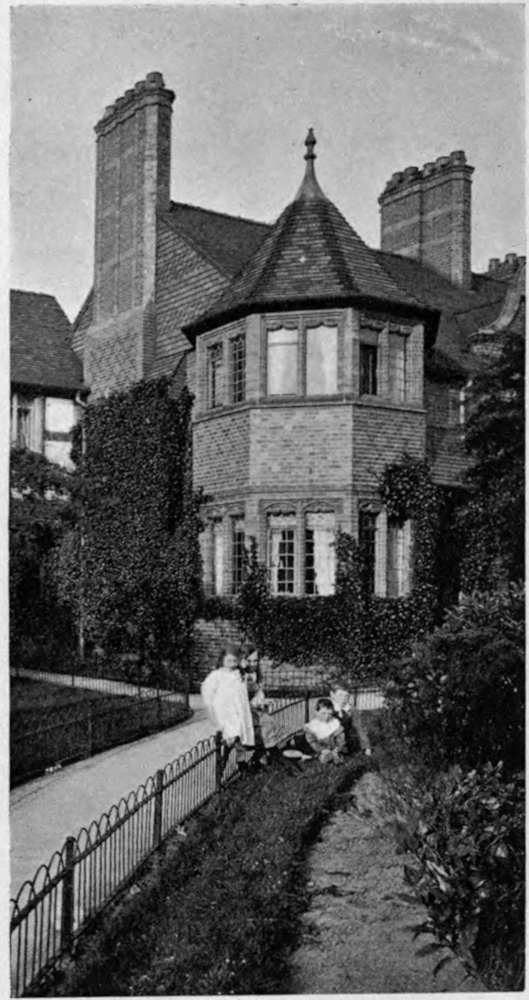

| 13. | An Angle Bay in Bridge Street | 10 |

| 14. | Some Park Road Houses | 11 |

| 15. | Cottages in New Chester Road | 12 |

| 16. | Group at angle of Lower Road and Central Road | 13 |

| 17. | A Recessed Group in Greendale Road | 14 |

| 18. | Cottages on semi-circular plan in Lower Road | 14 |

| 19. | First Cottages built at Port Sunlight | 15 |

| 20. | A Three-gabled Group in New Chester Road | 15[Pg xiv] |

| 21. | A Picturesque Corner in Park Road South | 16 |

| 22. | Bebington Road Cottages | 17 |

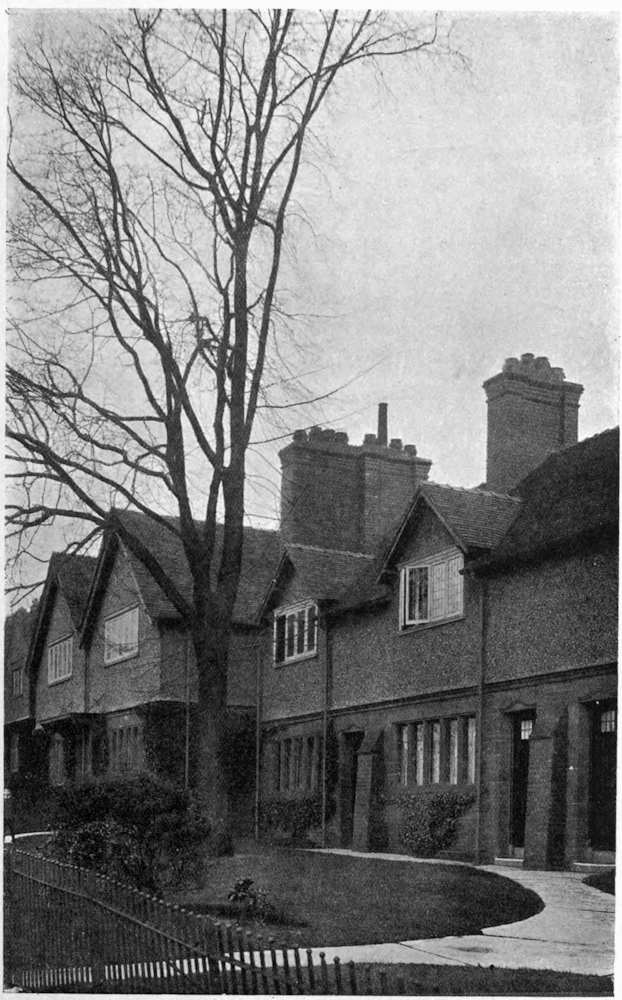

| 23. | Cottages, Pool Bank | 18 |

| 24. | Cottages, Pool Bank | 19 |

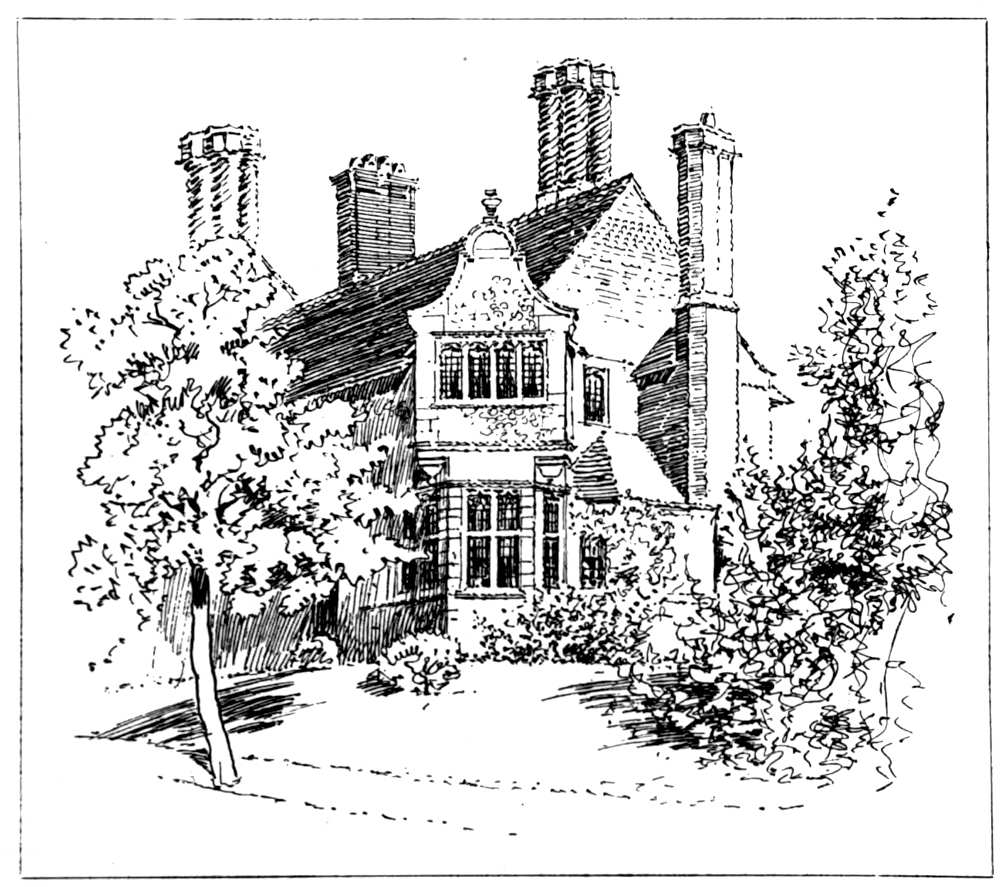

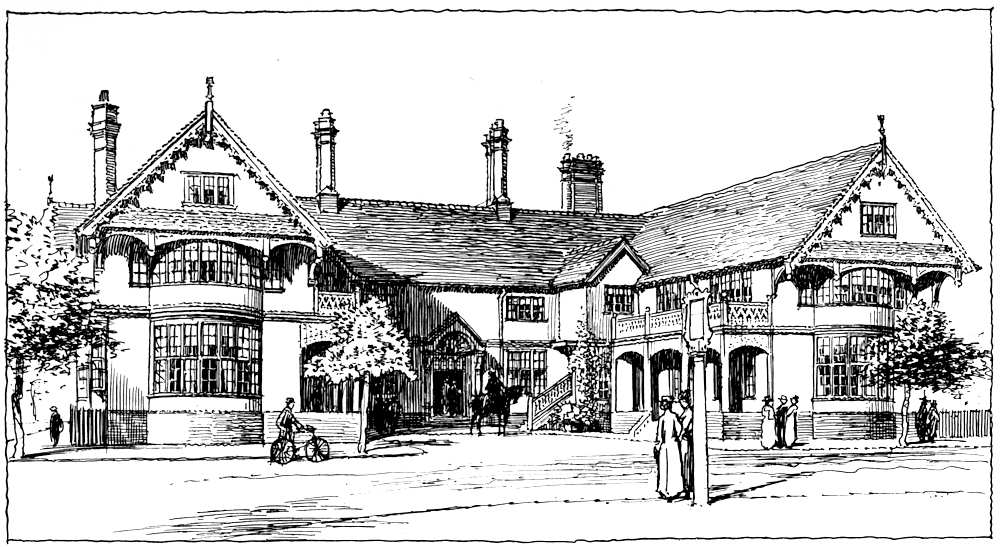

| 25. | Hulme Hall | 20 |

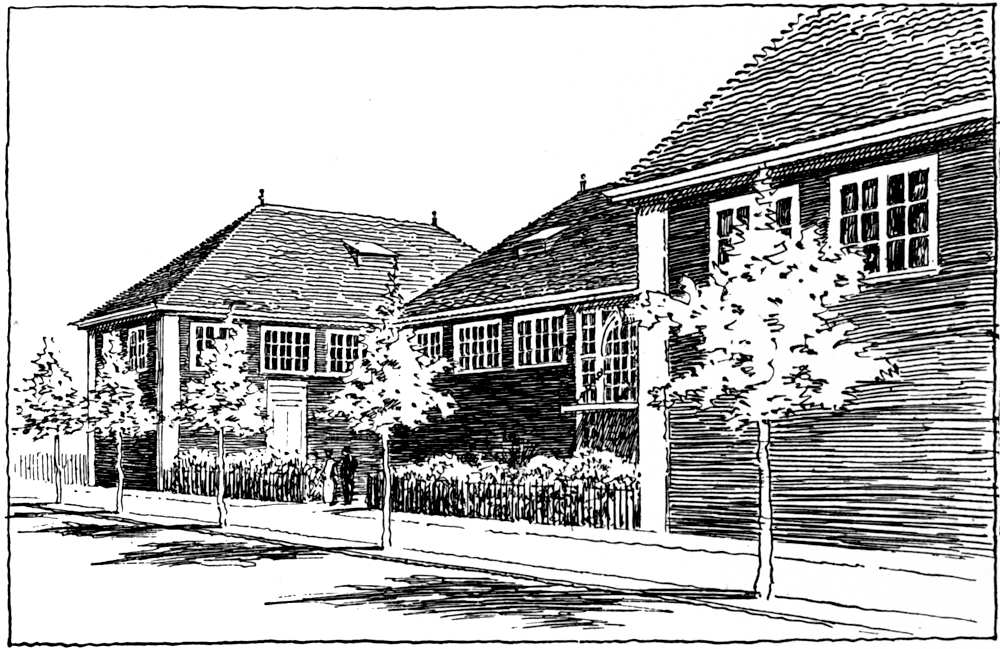

| 26. | Gladstone Hall | 21 |

| 27. | Park Road by Poets’ Corner | 22 |

| 28. | Bridge Cottage | 23 |

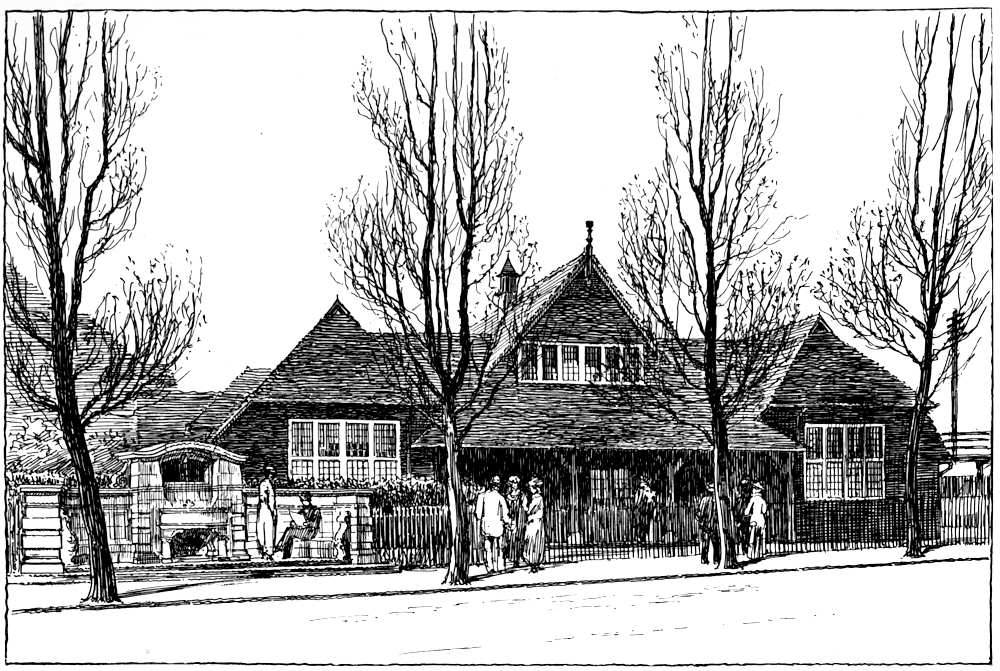

| 29. | The Gymnasium | 24 |

| 30. | The Technical Institute | 25 |

| 31. | Wood Street Cottages | 26 |

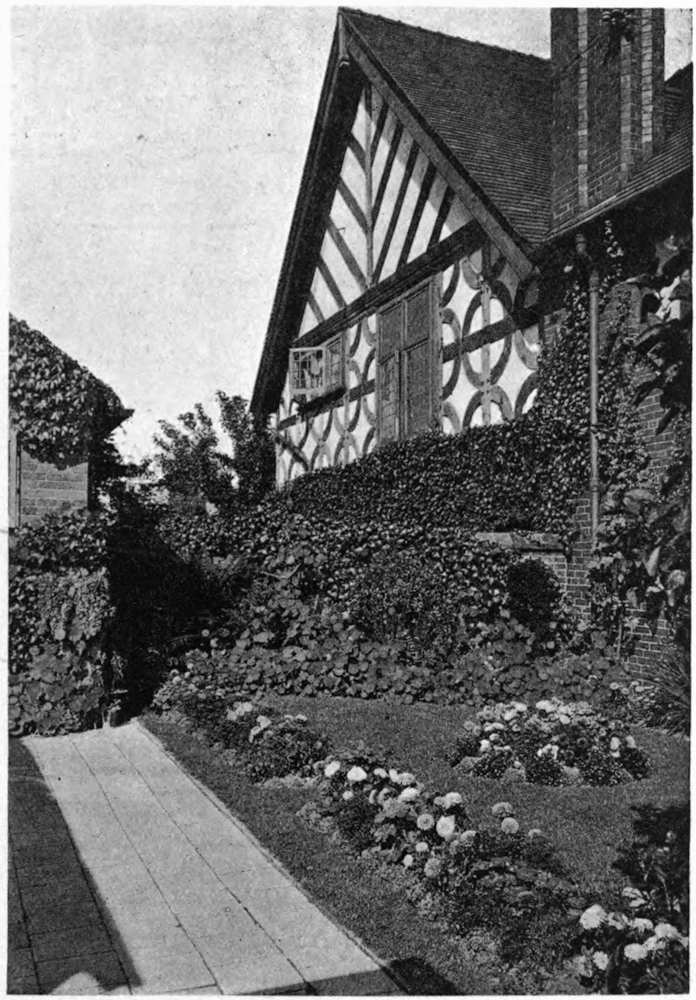

| 32. | A Garden Corner | 27 |

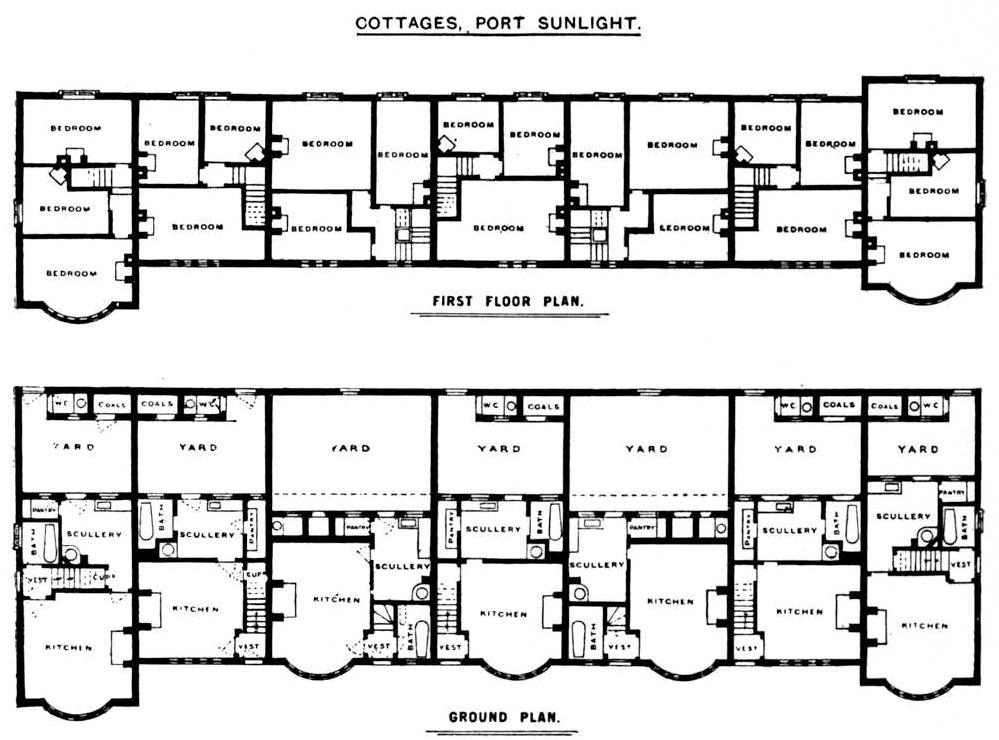

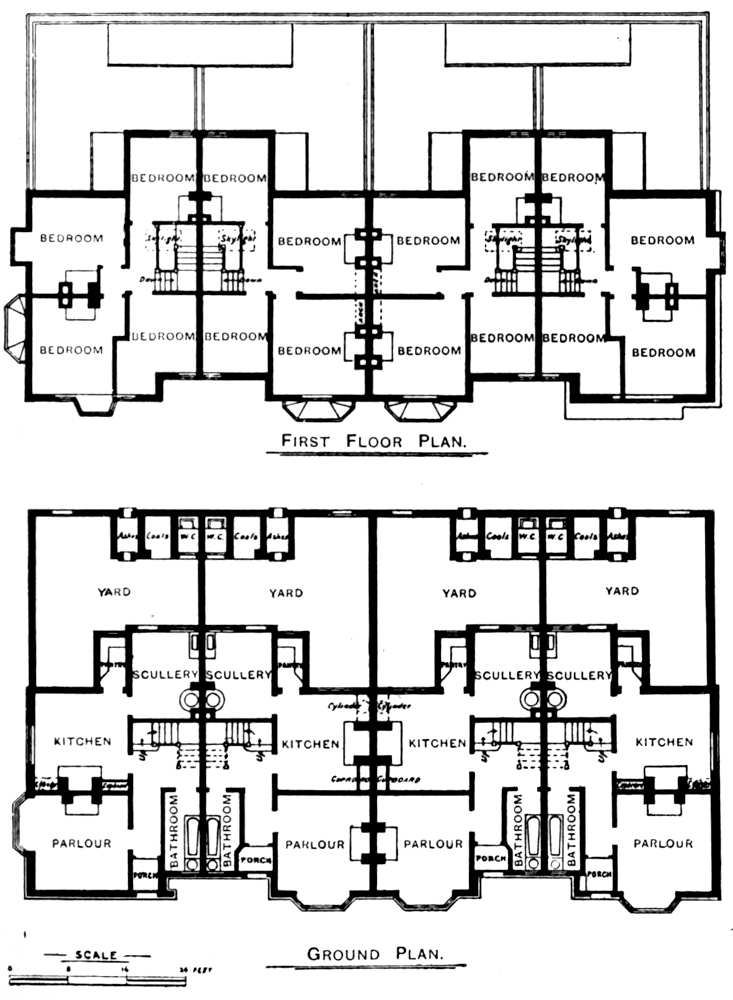

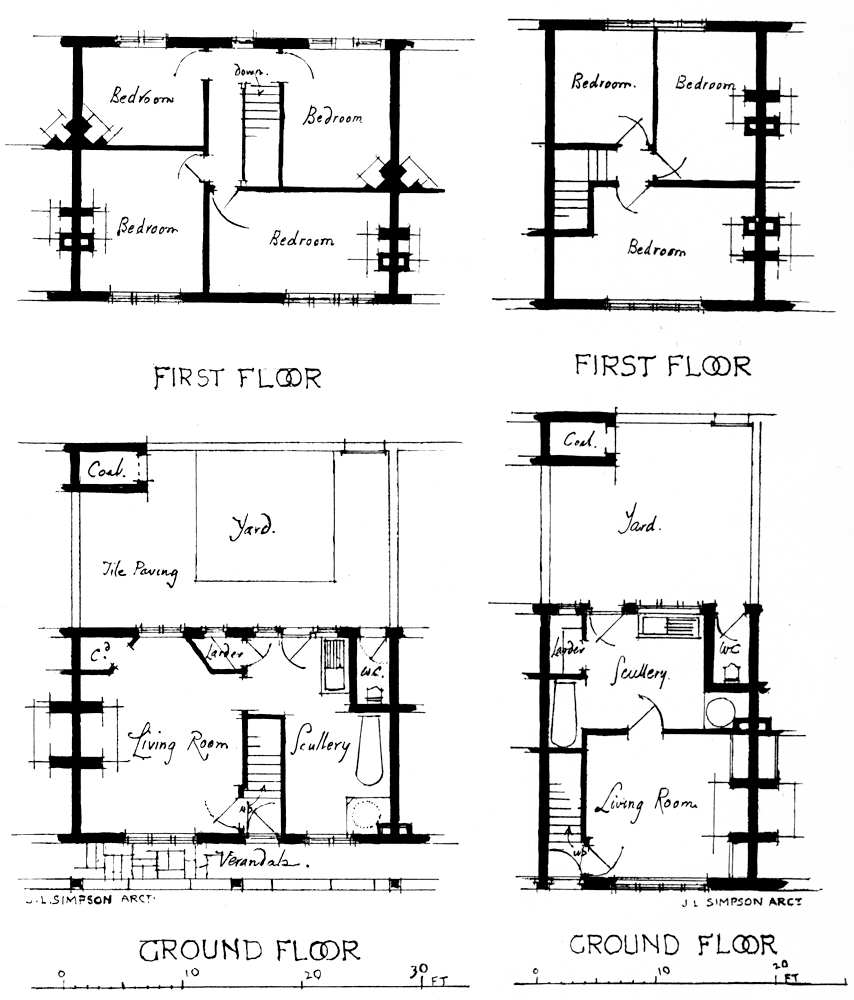

| 33. | Plans of Kitchen Cottages | 28 |

| 34. | Plans of Parlour Cottages | 29 |

| 35. | Plans of Kitchen Cottages | 30 |

| 36. | The Bridge Inn | 31 |

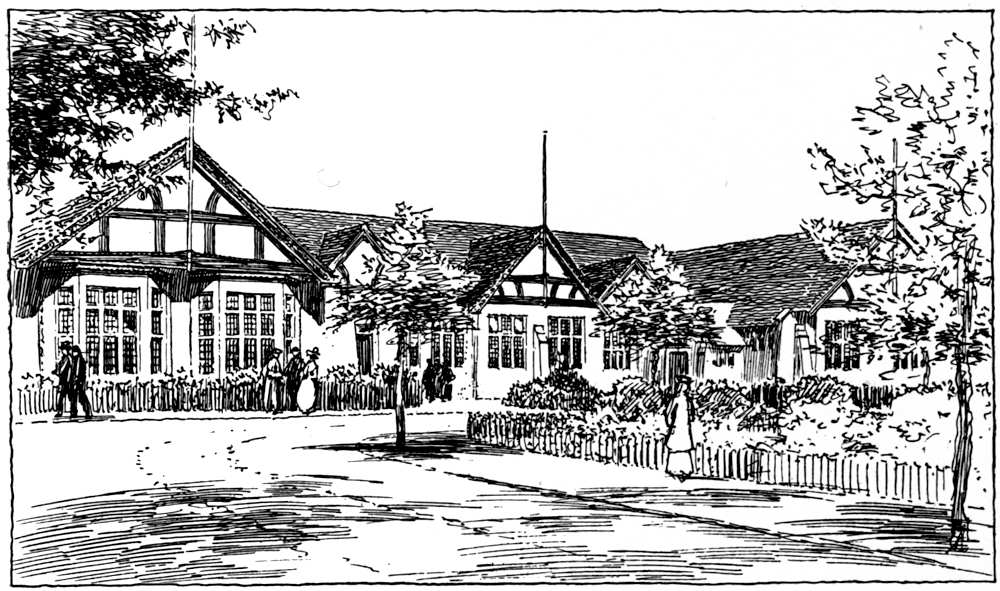

| 37. | The Girls’ Club | 32 |

| 38. | An Example of Simple Treatment | 35 |

| 39. | A General Plan of the Village | 36 |

[Pg xv]

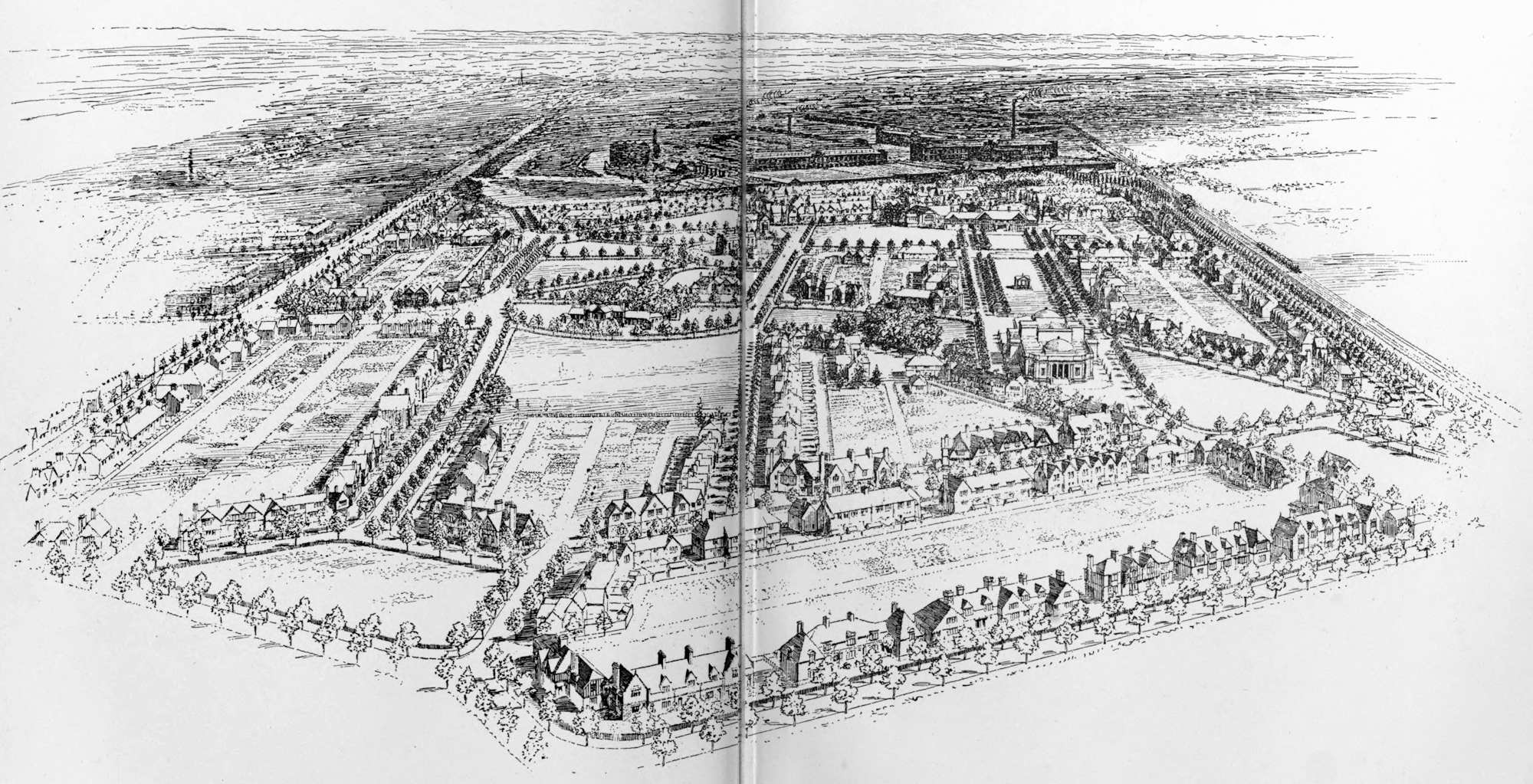

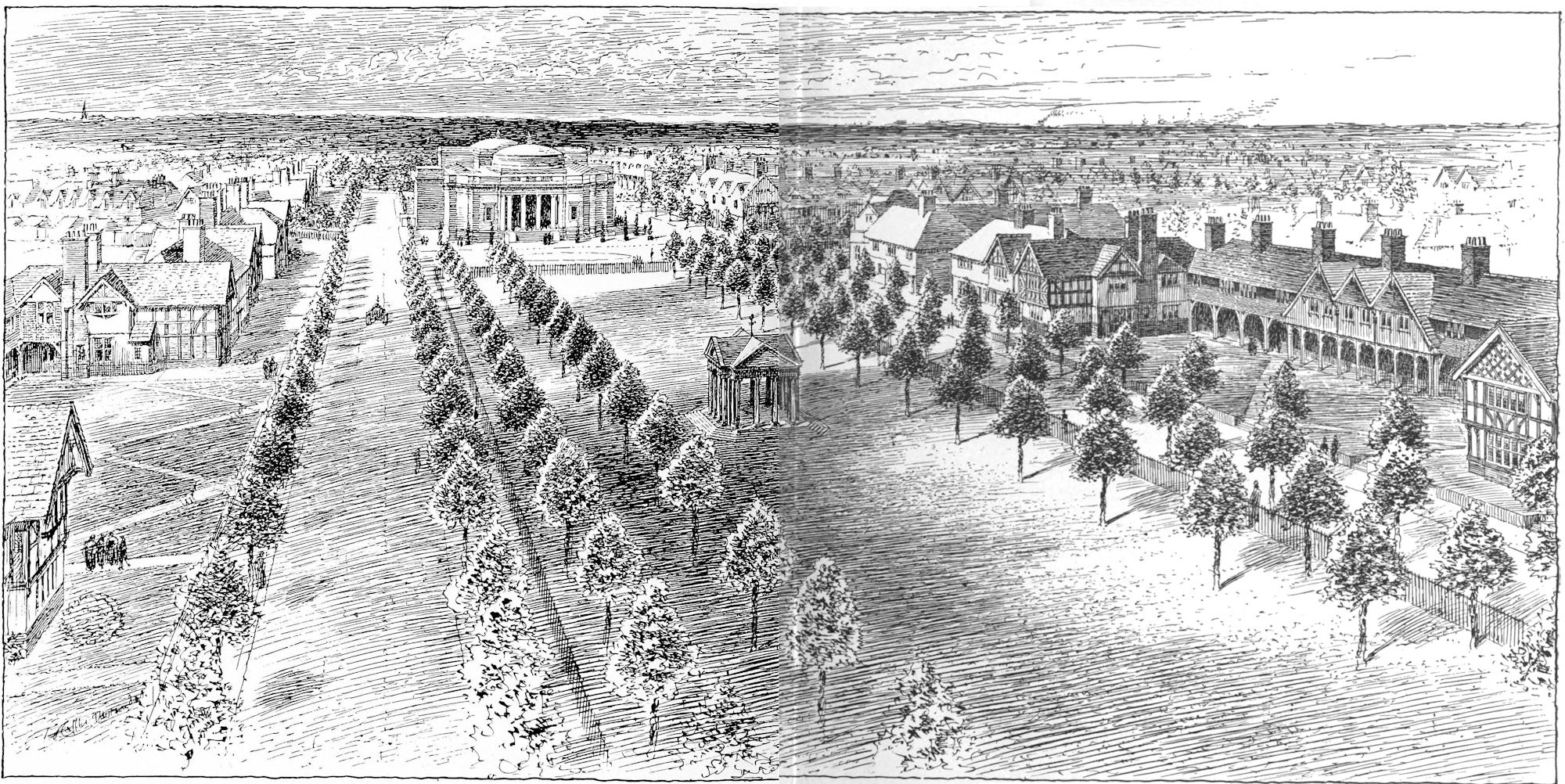

PLATE 1.

BIRDSEYE VIEW OF PORT SUNLIGHT.

[Pg 1]

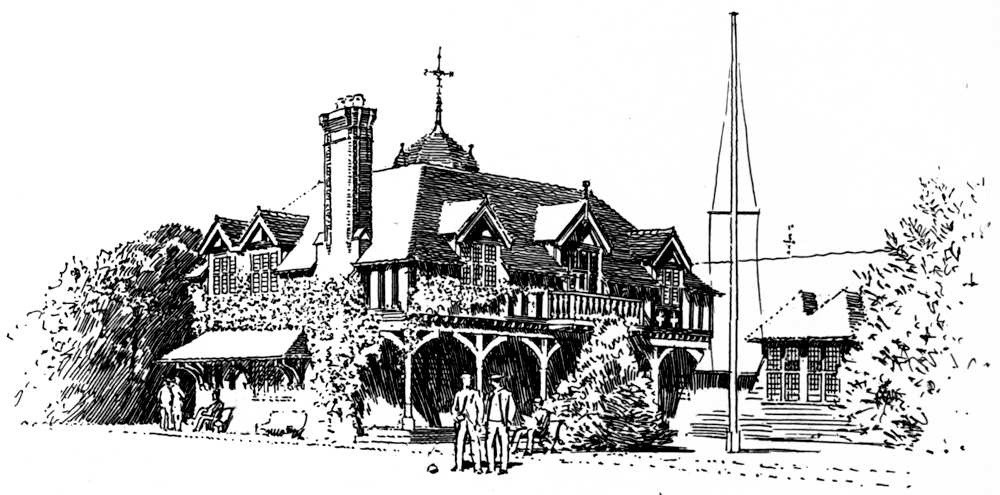

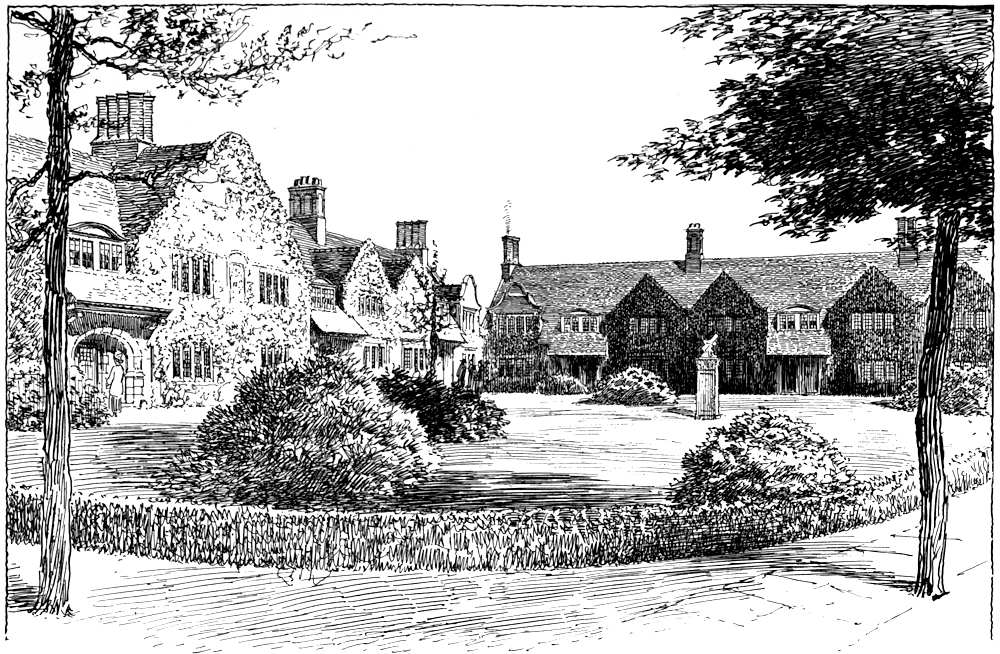

DOUGLAS AND FORDHAM,

Architects.

1. THE LYCEUM.

The individual or community which has no ideal is to be pitied. For, whatever may happen, there is always a better chance for those who maintain a high ideal than for those who, without one, adventure themselves against the chances and difficulties that surround us. Nothing is more disheartening to the idealist and reformer than to find not only thousands of individuals but whole communities without a guiding star of faith and hope.

How fortunate is a place like Port Sunlight, when we compare its history and possibilities with those of London! It is pleasant to realise that what has become a problem of such a very serious kind in London after so many years of haphazard and chance, is happily barred out of the horizon in the definitely schemed plan of the garden city or the model village. But it is one thing to have a[Pg 2] scheme or an ideal and another to have a good one. Moreover, as to whether it is good or bad, or wholly or only partially good or bad, the scheme does not always show until it has been some time in operation. In time the awkward corners may be rounded off, or they may become more acute, but the actual life of the community in any so-called model village or town soon proves the value or the unimportance of those features which have been part of the design.

DOUGLAS AND FORDHAM,

Architects.

2. THE DELL BRIDGE.

What most impresses itself on those who study the industrial village of Port Sunlight is the fact that it is the definite outcome of a genuine ideal. Whether its present state has surpassed the hopes of its founder or has failed to realise them, we can at any rate see that this was meant to be something better than what had been before, and that no effort was to be wanting to secure this. We are sure that the inconsequent charm and the haphazard picturesqueness of an old English village were not the main objects in view, but that the aim was a conveniently planned and healthy settlement laid out with all possible artistic thought on sound business lines. Garden grounds, roads, and open spaces were to be ample without being wasteful, houses[Pg 3] were to be picturesque but sensibly planned. Avenues were to be planted and gardens laid out with needful limitations as to size and direction. The individuality of separate gardens was to be subordinated to a definite idea of communal amenity. Variety of plan was to be obtained only within a certain economic range.

3. CORNICHE ROAD BEFORE RECLAIMING OF RAVINE.

4. POOL BANK.

It is surely often realised that many of our beautiful gardens could not have been laid out in a complete and detailed scheme from the beginning, but that a good deal of their success has been evolved from a[Pg 4] gradual development of possibilities. So also whilst the picturesque charm of an old town or village may result from the chances and changes of many years, we cannot expect that fully developed schemes for new settlements can attain perfection at the outset. The constant maintenance of an ideal in the life of a town or village is, therefore, of the greatest import, and no niggardly spirit should stand in the way of changes for which time alone may prove the need.

5. TENNIS LAWN.

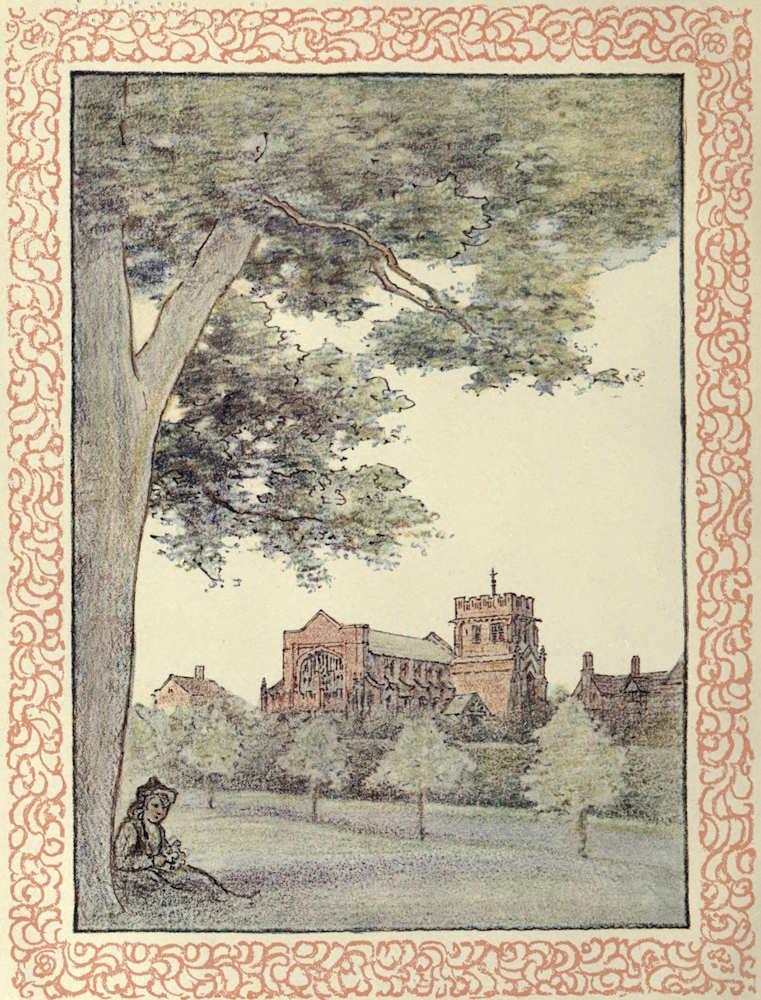

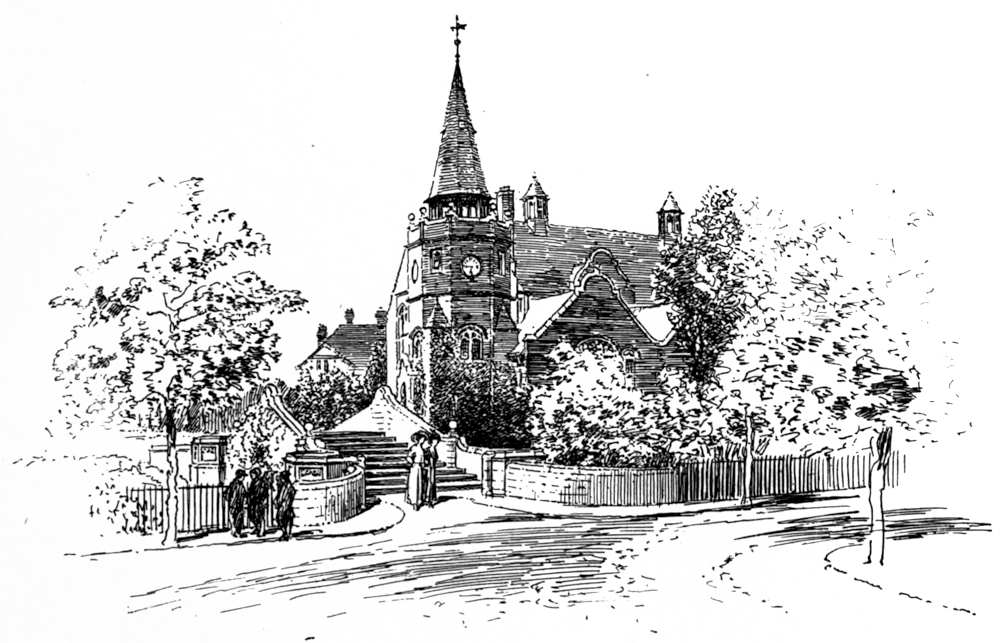

6. CHRIST CHURCH FROM BOLTON ROAD.

The best conceived plans for the present time are not necessarily the best for the future, and an insistent look out for possible improvements is the only safeguard for the future even where the most careful design and thought have been devoted to the beginnings of such a successful enterprise as that which is here recorded.

[Pg 5]

7. BOLTON ROAD LOOKING TOWARDS BEBINGTON CHURCH.

The life of a village or town must be created of enduring materials and based on some sort of sound business principles. It is the very essence of the village of Port Sunlight that it is claimed to be a sound business enterprise. Though much more than half a million pounds of capital spent on land and buildings has been left out of count for interest, it is still maintained that all outlays have in the main been justified by sound business principles. That the well-being and comfort of their workpeople is a valuable business asset is no new belief with employers of labour. The belief has been acted upon for many years past, but its application has made rapid strides in more recent times. It is probable, however, that there is not another place where this belief has been so very completely demonstrated as at Port Sunlight. The inhabitants of this fortunate village appear to have been saved every needless risk, and have even escaped the snare of mere profit-sharing, in favour of[Pg 6] prosperity-sharing and copartnership. It will be of interest here to quote from a Paper by the founder, Sir W. H. Lever, on prosperity-sharing, in November, 1900. “The truest and highest form of enlightened self-interest requires that we pay the fullest regard to the interest and welfare of those around us, whose well-being we must bind up with our own, and with whom we must share our prosperity. We cannot live in comfort with others if we do not share our comforts with them. If we wish men to be honest towards ourselves, we must be honest with them. If we wish men to help us to achieve prosperity, they must feel assured that we will share that prosperity with them. If capital and management think of nothing but their own narrowest, selfish self-interest, without a thought for labour, care nothing for the comfort or welfare of labour, care nothing whether labour is well or ill-housed, whether labour is provided with opportunity for reasonable and proper recreation and relief from toil or not, then capital and management are blind to their own highest interest.... Also the converse of the above is equally true.... If labour adopts the spirit of enlightened and intelligent self-interest, and if capital and management do the same, if each recognise the principle that by looking after the interests of the other they are taking the surest means to achieve[Pg 7] their own self-interest, business will be healthier, happiness in business will be greater, the prosperity of the business of the whole country will be assured, and the bogey of foreign competition will be laid once and for all. I venture to submit that prosperity-sharing on the basis of enlightened self-interest will secure this.”

GRAYSON AND OULD,

Architects.

8. CO-PARTNERS’ CLUB AND BOWLING GREEN.

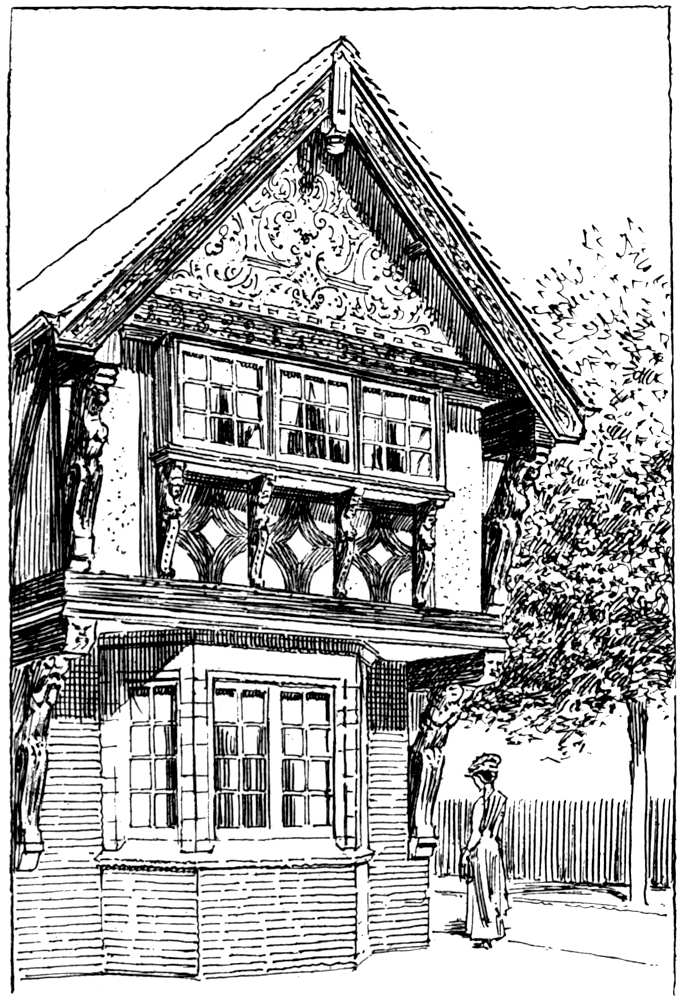

9. CARVED OAK AND DECORATIVE PLASTER WORK ON COTTAGE IN PARK ROAD SOUTH.

W. OWEN, Architect.

It is the aim which lies behind such words as these which is of real importance, and makes possible the creation of beautiful homes and pleasant surroundings. We may be quite sure that this is the one vital factor in all our efforts, and no excuse need be offered for the reiteration of this point in the pages of this book. We should all live for some sort of ideals, and in proportion as these are right and good, so shall we find the measure of our success.

[Pg 8]

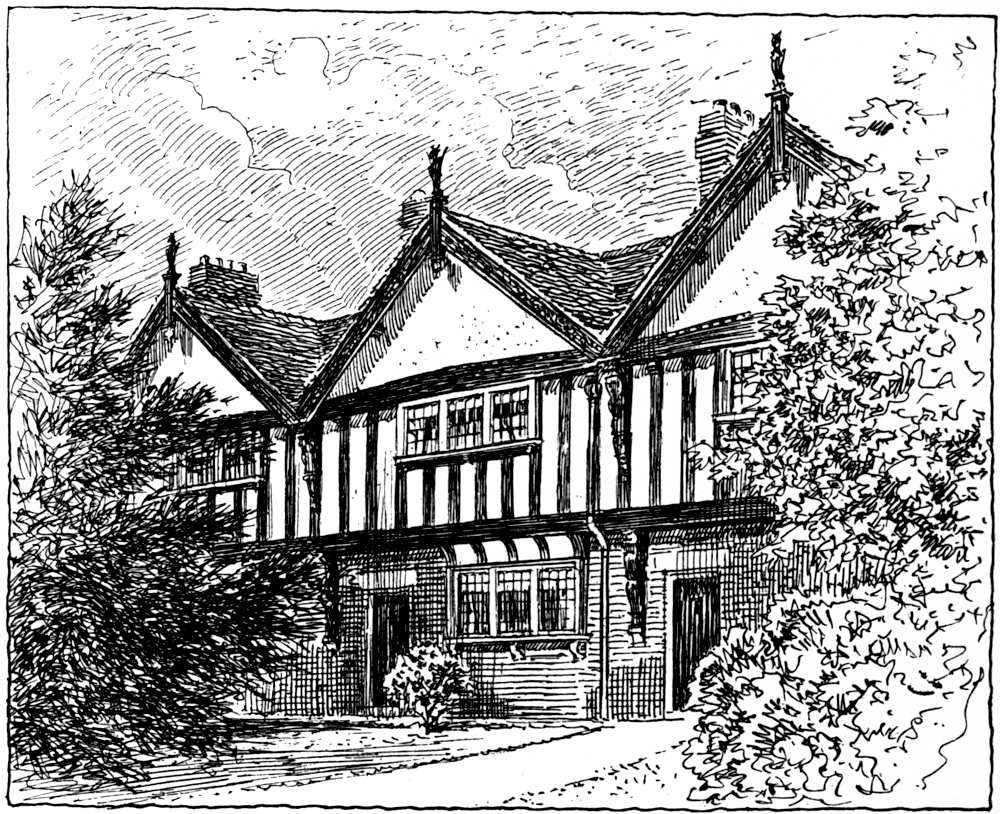

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

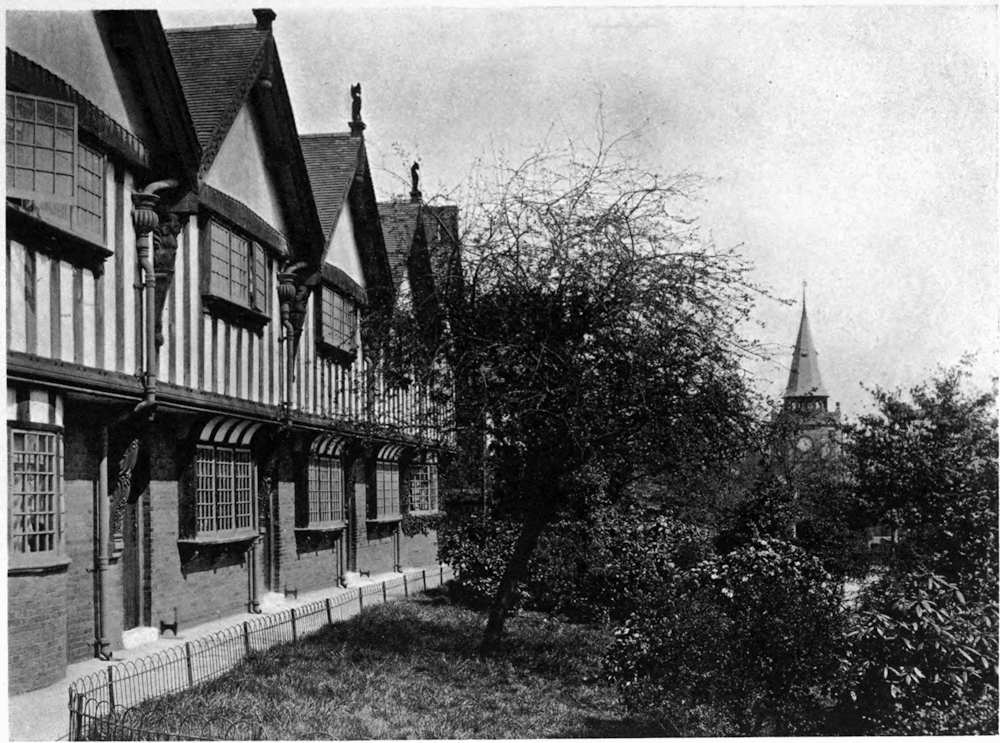

10. HALF-TIMBER COTTAGES IN PARK ROAD.

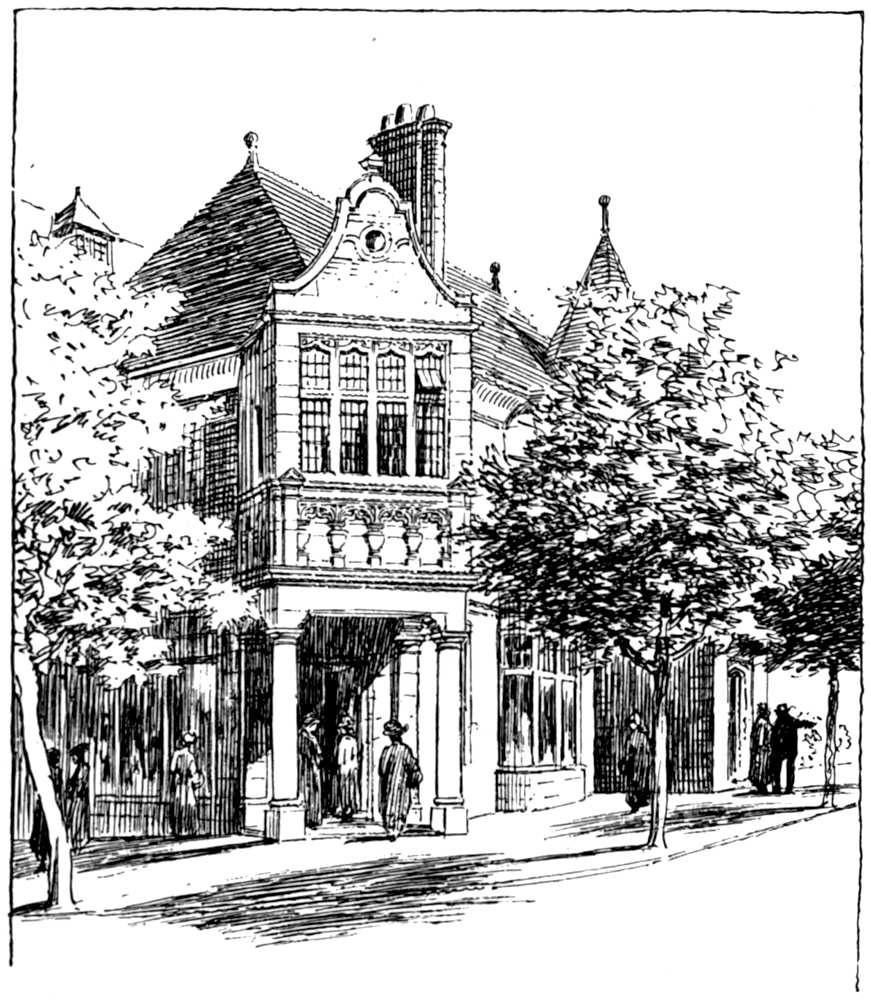

11. EMPLOYEES’ PROVIDENT STORES AND COLLEGIUM.

DOUGLAS AND FORDHAM, Architects.

It is only by comparing the conditions at Port Sunlight with those of other residential areas that the full measure of their value can be ascertained. In some respects the outsider is perhaps a better judge of the success of such a village than are the residents, who come to take a good deal for granted. Thus the visitor who now for the first time goes to Port Sunlight and realises the extent and quality of the work done is naturally much impressed by the variety and interest which the whole village affords, whilst those who are in constant residence may not realise it so keenly. It is hardly possible that those who live in the many charming cottages which have sprung up in this country in recent years, or who have lived a long[Pg 9] time in some of the best of our old English cottages, can take that delight in their appearance which the detached observer feels. It is quite possible that wide staring panes of glass and sash windows and treeless streets have as many admirers amongst the average public as are found for the quaint latticed windows and leafy avenues of Port Sunlight. But the air of detachment which inevitably goes with the outside observer of new places is an element of some moment in arriving at an estimate of results. It is obvious that the estimation of a place like this may be based upon practical issues chiefly, or from the purely artistic standpoint, or again, from a point of view which includes both. The main concern of this book is to emphasise the artistic and picturesque qualities of the village whilst not overlooking the fact that artistic values should not be obtained by the sacrifice of practical needs. This could be the only possible point of view which would give final satisfaction to the business man. It is maintained that no undertaking in the world which has been based on purely artistic desires and which has had no basis of practical value has been of any lasting value. The whole foundation of Port Sunlight is believed to consist of[Pg 10] practical values and sound business principles.

12. COTTAGES IN CORNICHE ROAD.

GRAYSON AND OULD,

Architects.

13. AN ANGLE BAY IN BRIDGE STREET.

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

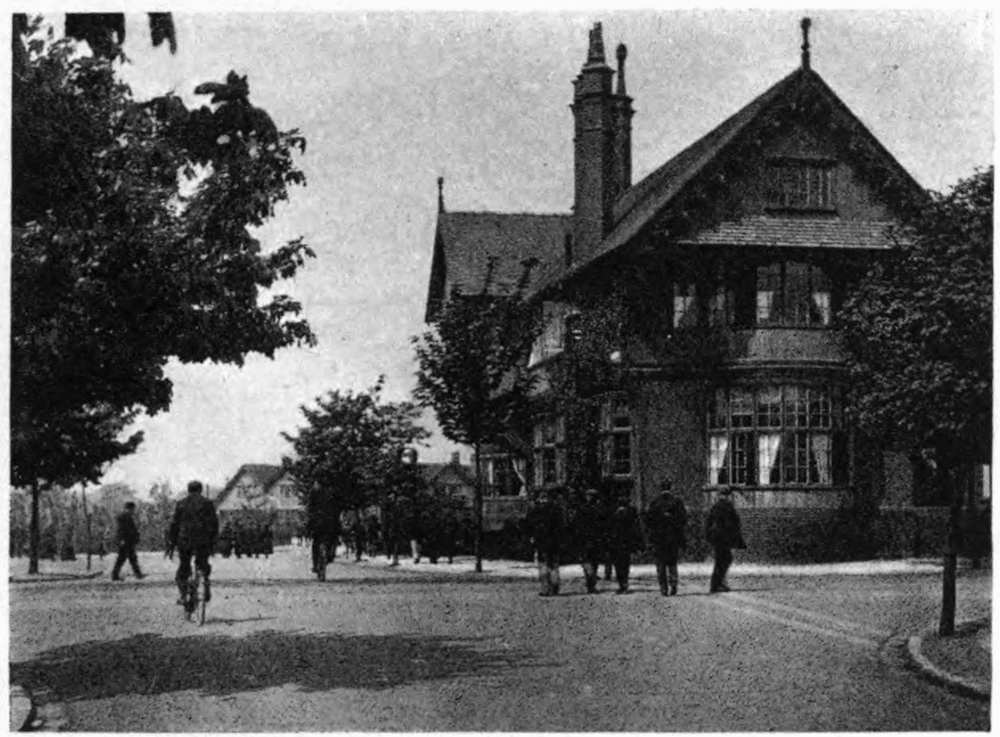

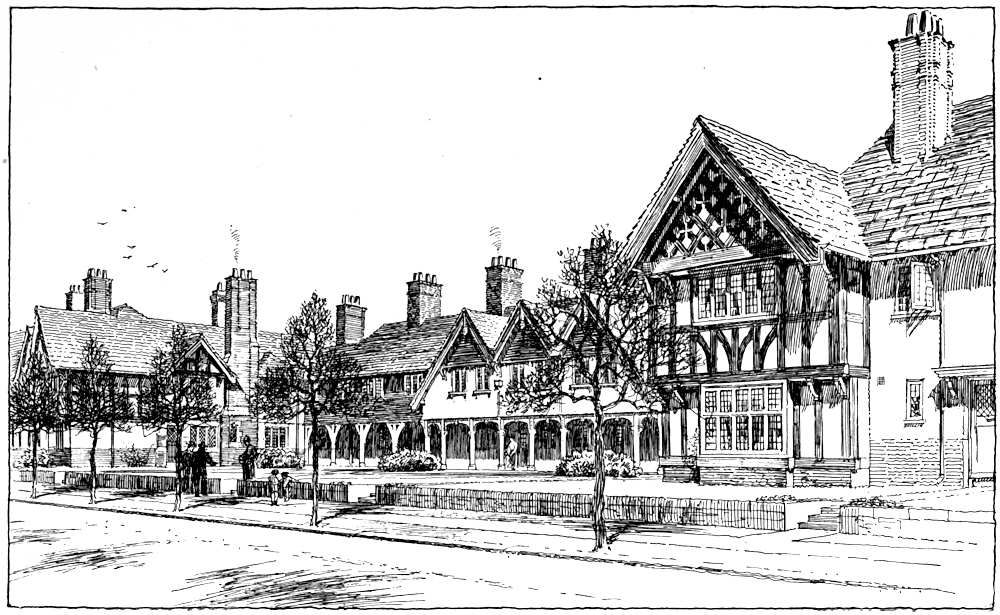

One thing which is at once obvious from the general scheme is the adoption of open spaces, communal gardens, and allotments in preference to the spaces which are devoted to individual gardens surrounding each cottage in so many other places. There is something to be said for and against this. The general amenity of the village gains by the Port Sunlight method, whilst the special charm of individual gardens which enthusiastic efforts produce is naturally lacking. In this way we get less value of contrasts, and lose something of that spirit of emulation which spurs the individual to special effort. Of one thing, however, there can be no doubt. The absence of the many dividing lines of fences between each cottage frontage produces a breadth of effect along the lines of[Pg 11] roadways which is in itself very pleasing. From the point of view of the town-planner who looks for the collective result this is, of course, very satisfactory.

DOUGLAS AND FORDHAM,

Architects.

14. SOME PARK ROAD HOUSES.

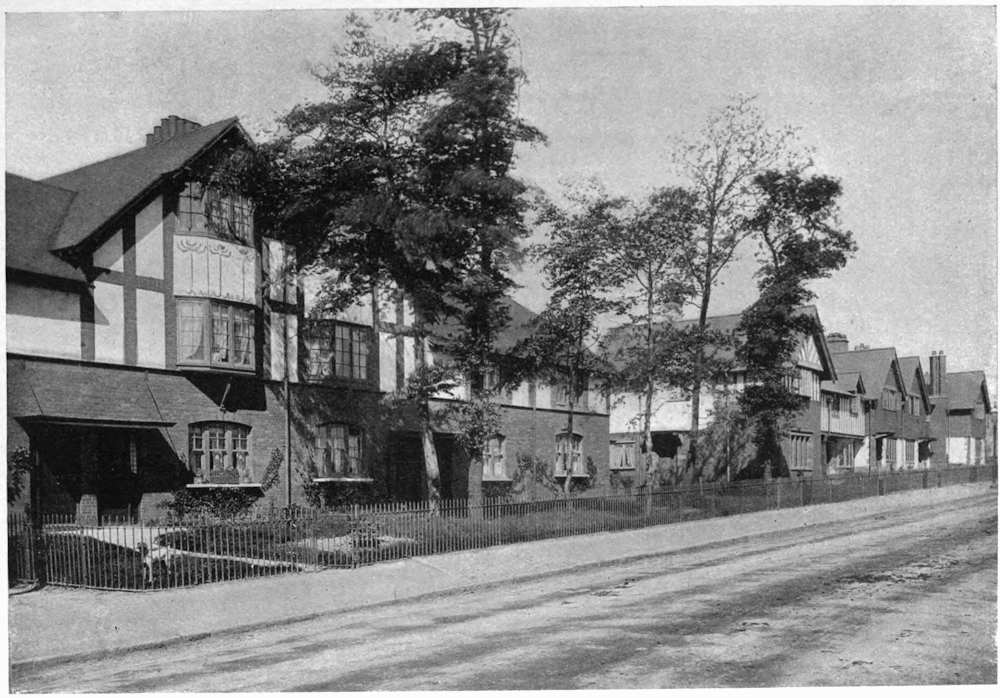

15. COTTAGES IN NEW CHESTER ROAD.

W. OWEN, Architect.

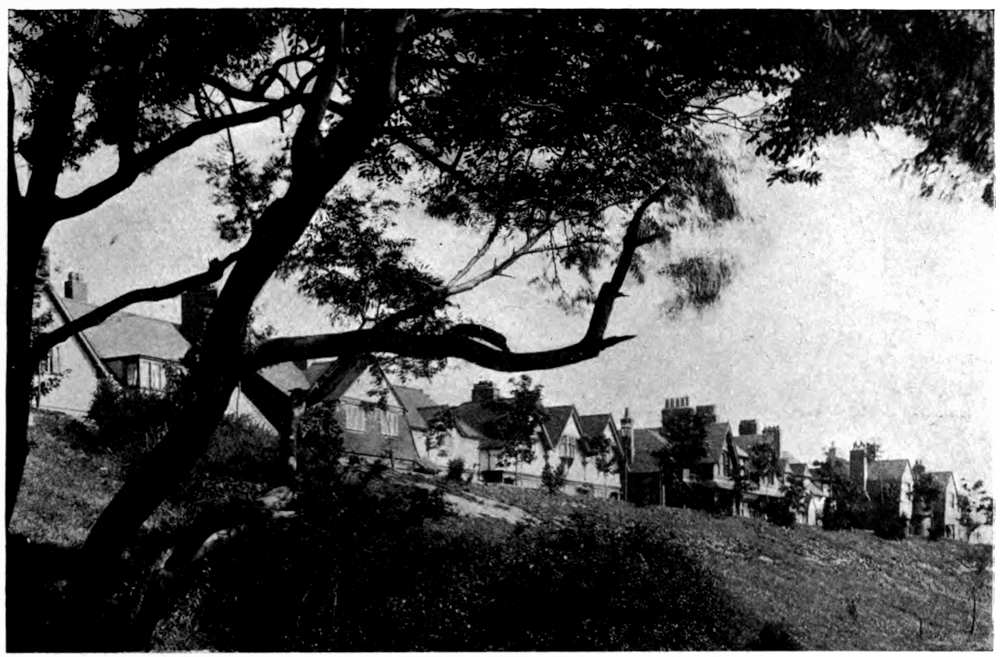

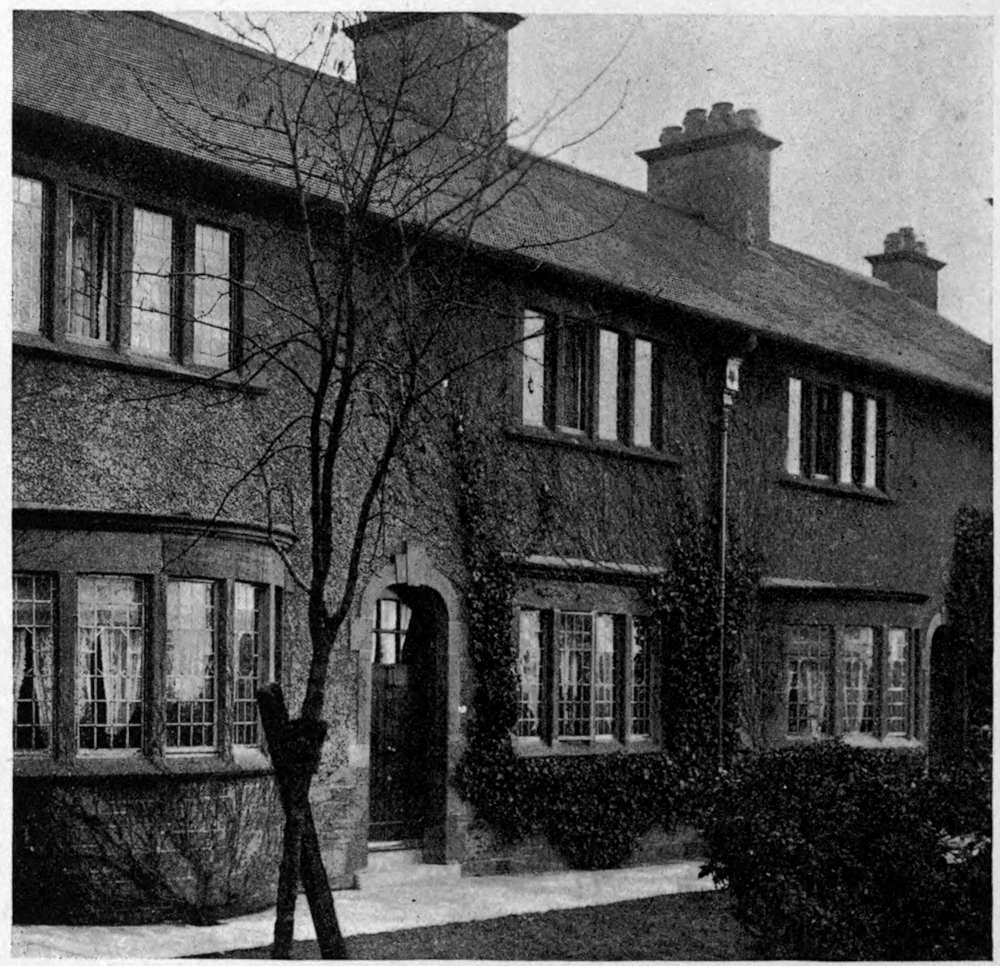

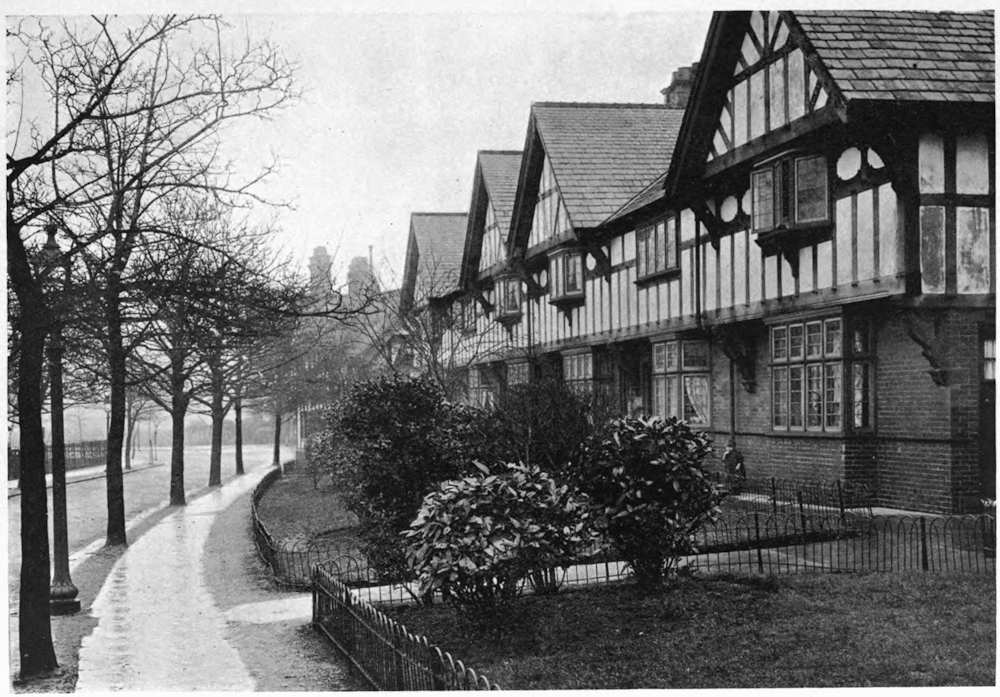

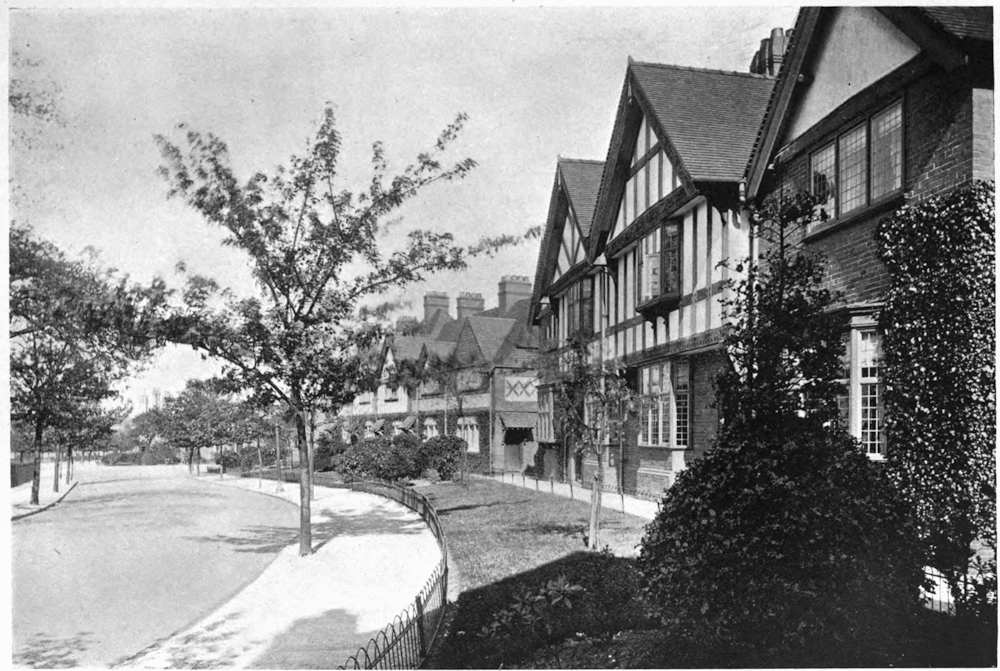

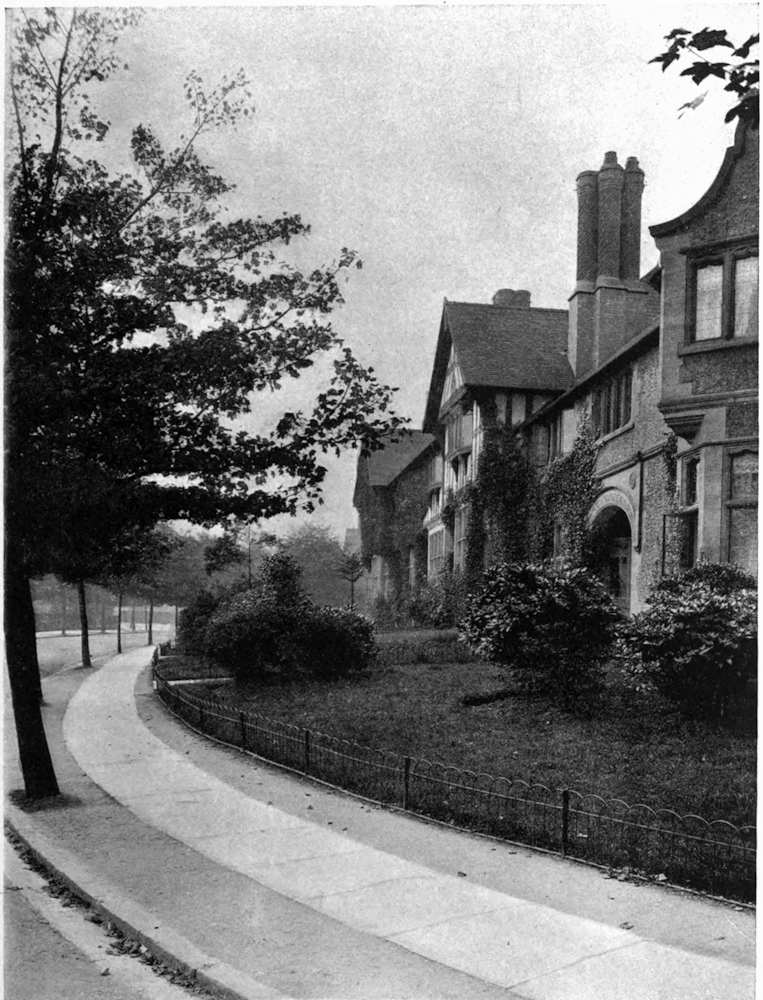

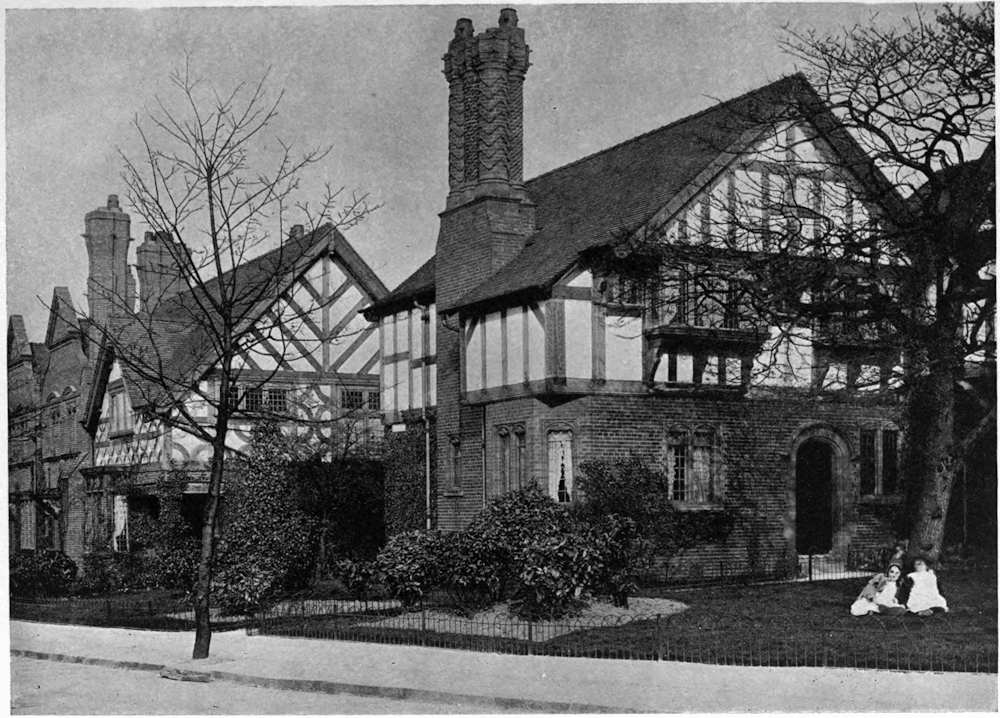

Another thing which will be noticed in the illustrations is the elevation of many of the houses above the level of the roadway. This gives a much wider and pleasanter outlook from the windows of the cottages, besides producing a much better effect in the buildings from the roadway than when they are placed on the same level. The sloping green banks leading up to terraced paths in front of the cottages are a distinctive feature of the village. (See Pl. 4.)

It has been maintained that without a good deal of monotony you cannot get very fine architectural results, and it must be admitted that many examples go to prove it. There is a large surface of[Pg 12] monotony in the Pyramids; there is a marvellous monotony of detail in the Houses of Parliament; there is a boundless monotony in the house fronts in Gower Street, yet all these have been admired. So this line of argument might have suggested the continued employment of only one architect, or at least only one type of design, for the cottages at Port Sunlight. The great variety of designs in the cottages, which has proved one of the attractions of the place, has, however, in some sense at least, justified itself. Even the flamboyant Gothic dormers and the stepped Belgian gables have a reacting influence on some of their neighbours, though we might consider the latter rather unpractical on the one hand, or the former too pretentious on the other. Moreover, whilst we wonder at the generosity of view which could bestow some of these solid oak-framed structures with their wealth of carving and enriched plaster panellings on the working classes of an industrial village, we cannot but feel grateful to the hand that gave them, though we ourselves may never be able to afford such luxuries of the building art for ourselves. May we not accept these as symbols of some kindly gratitude with which a profitable company decorates the homes of its industrial population? Honestly, we cannot regret these bonnes bouches in the building scheme, though they bravely put out of sight the counting-house and the rates of interest! These are really very welcome ebullitions from that solid undercurrent of practical economy which has placed the whole concern on a sound business footing.

[Pg 13]

16. GROUP AT ANGLE OF LOWER ROAD AND CENTRAL ROAD.

J. L. SIMPSON, Architect.

ERNEST GEORGE AND YEATES,

Architects.

17. A RECESSED GROUP IN GREENDALE ROAD.

C. H. REILLY,

Architect.

18. COTTAGES ON SEMI-CIRCULAR PLAN IN LOWER ROAD.

W. OWEN, Architect.

19. FIRST COTTAGES BUILT AT PORT SUNLIGHT.

Awarded Grand Prix, Brussels Exhibition, 1910, for their reproduction there.

GRAYSON AND OULD,

Architects.

20. A THREE-GABLED GROUP IN NEW CHESTER ROAD.

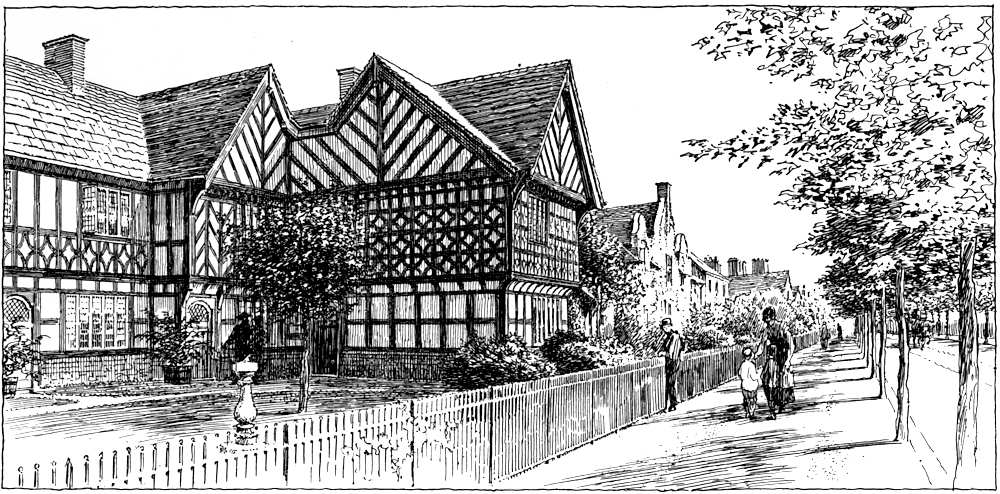

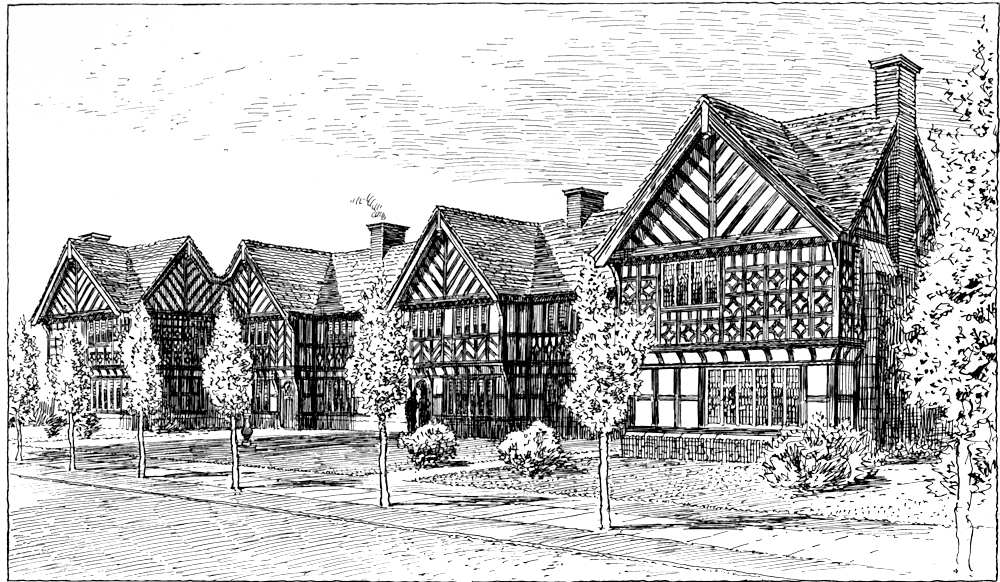

This element of variety which is so marked in the design of the cottages at Port Sunlight has been obtained without much departure from the genuine English type. Even where a Dutch or Belgian character appears it is carried out with something of the breadth and simplicity which one associates with purely English work. There is very little, if anything, that could be called freakish or odd. The stepped gables or the flamboyant dormers which vary the treatment are not unacceptable as variants. As to the use of oak framing with plaster panels—the familiar Old English style—no one can deny its charm or fail to wish there were even more of it. Nothing is so picturesque and nothing so cheerful of aspect as the black and white work which forms so frequent a feature in the earlier buildings erected. One only regrets that it is difficult to justify it from a strictly commercial point of view, especially if it is executed in a sound and substantial manner. Whether the half-timber work is used for the whole building, or only partially in connection with the fine red sandstone of the district, or with bricks or flint-work, it has an undeniable and enduring charm, and we owe much of our [Pg 16]pleasure in the whole appearance of Port Sunlight to the liberal views of the founder, who did not permit his vision of a beautiful village to be obscured by the clouds of philistinism! You cannot, of course, pretend that such gables as those shown in our illustrations are necessary to cottage building. Nor is it surely possible for even a Port Sunlight to be entirely built in such a way; but the pleasure produced by such character of work is, after all, common property, and is a valuable item in regard to the whole scheme.

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

21. A PICTURESQUE CORNER IN PARK ROAD SOUTH.

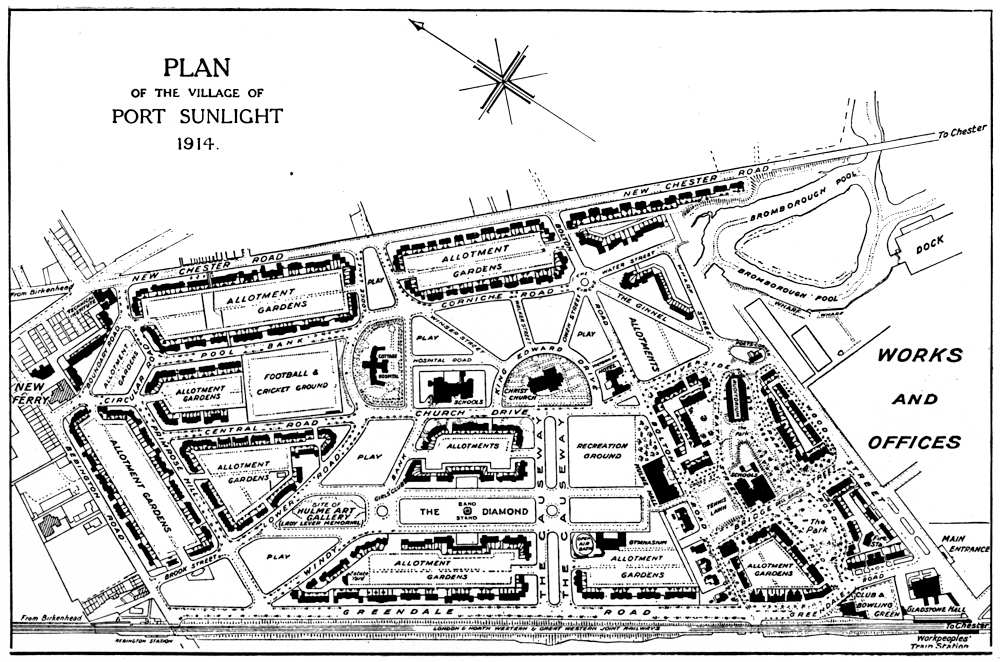

The general plan of Port Sunlight shows now an inhabited area nearly a mile long by nearly half that wide, bounded on the longer sides by the new Chester Road (on the east) and the main railway lines to London, and Greendale Road (on the west). (See No. 39.)[Pg 17] There is enough variety of level to avoid the monotony of an entirely flat area, and one piece of natural dell, well grown over with trees and shrubs, forms a delightful feature near the Works end of the village. Goods from the Works are loaded, on the one side, into railway wagons, and on the other into barges on the Bromborough Pool, from which they emerge into the River Mersey. From this pool there used to be gutters or ravines, up which the muddy tidal water flowed right up into where the village now stands, but these have all been cut off from the tide and, with the exception of the dell above referred to, filled up.

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

22. BEBINGTON ROAD COTTAGES.

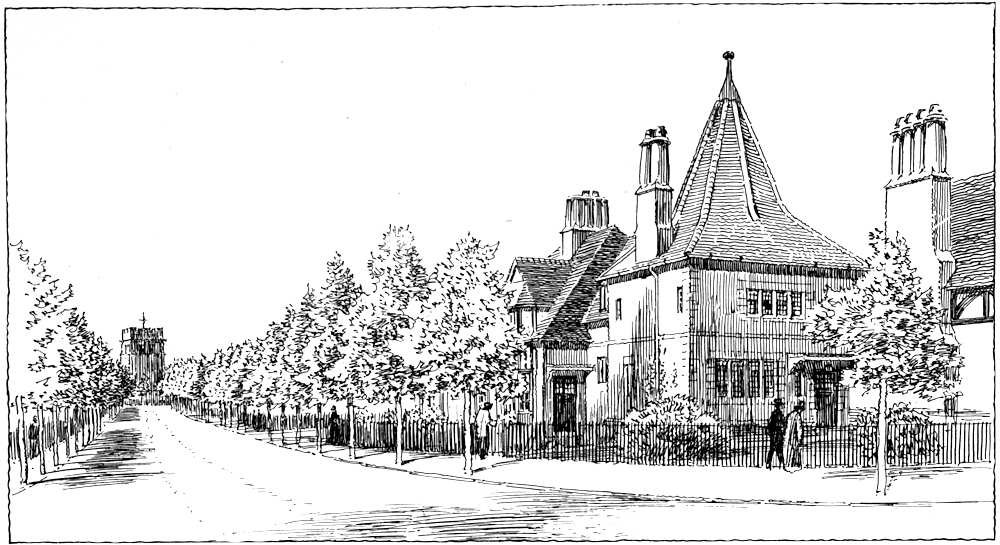

One very notable innovation on the common practice of estate development is the fronting of houses towards the railway instead of the long lines of unlovely backs which usually exhibit all their unhappy privacies to the railway passengers. Though one long thoroughfare—the Greendale Road—runs alongside the railway embankment for the greater part of a mile, one cannot feel it to be other than one of the pleasantest roads on the estate. One of the illustrations indicates the excellent result here obtained.

[Pg 18]

WILSON AND TALBOT,

Architects.

23. COTTAGES, POOL BANK.

Every intelligent student of town-planning knows that you cannot rule out a number of rectangular plots arranged on axial lines without due consideration of varying levels and a proper expression of local features. Moreover, the planning of many right-angled plots is not in itself a very desirable aim. But at Port Sunlight it was possible to create some rectangular spaces with the Art Gallery and the Church on their axial lines in such a way as to make a striking and orderly scheme as a central feature in the estate. There are numbers of winding or diagonal roads which give variety and interest and afford pleasant lines of perspective to the groups of houses.

DOUGLAS AND MINSHALL,

Architects.

24. COTTAGES, POOL BANK.

In an especial way one might claim that the best results in the planning of a new village will be obtained through bearing in mind [Pg 20]the classical saying, “Ars est celare artem.” In such a scheme we do not wish to be confronted with buildings of ponderous dignity or a big display of formal lines and places. Anything approaching ostentation or display is surely out of place, and what we want is something expressing the simplicity and unobtrusiveness which is the tradition handed down to us through the charm of the old English village. This is best attained by variety in direction of roads and shapes of houses by forming unexpected corners, recessed spaces, and winding vistas.

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

25. HULME HALL.

Port Sunlight village (founded in 1888), apart from the Works, covers 222 acres, on which the houses may approach 2,000 for a population of 10,000. The tenancies of the houses are limited to employés of the Works. Already over 1,000 houses have been built or are in process of building, and the length of broad roadways exceeds five miles. The first block of cottages built in 1888-1889[Pg 21] was reproduced at the Brussels Exhibition of 1910, and was awarded the Grand Prix. It is intended to limit the number of cottages to ten per acre, and it is hoped to keep below that maximum.

W. & S. OWEN,

Architects.

26. GLADSTONE HALL.

The general width of the roadways is 40 feet, giving 24 feet to the road, and 8 feet for each footpath; but there are roads 48 feet wide, including footpaths. The paths are flagged along the central portion only.

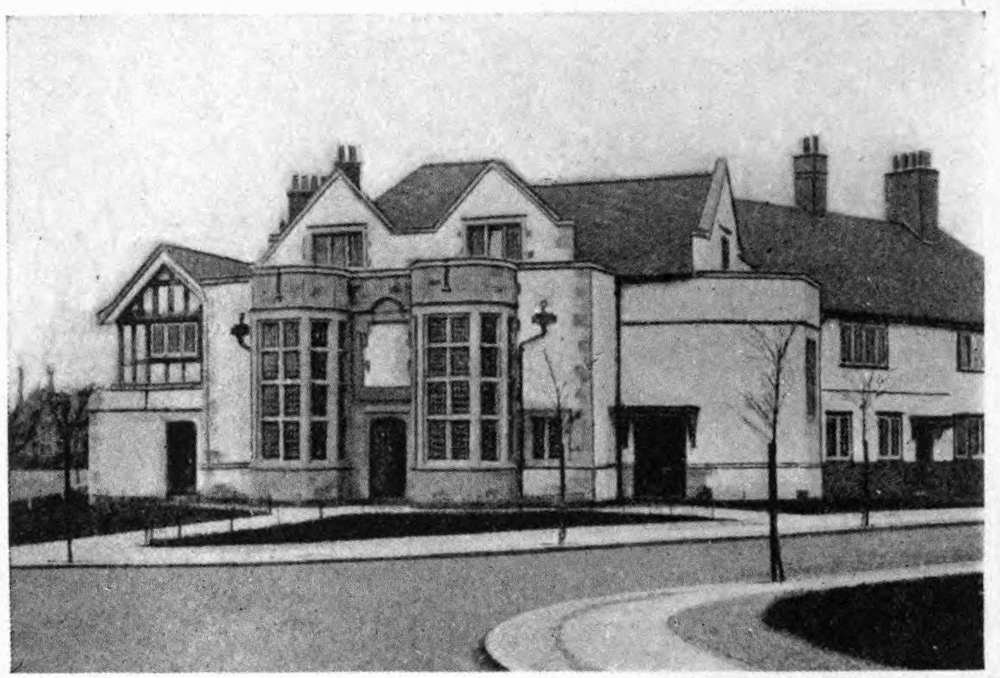

In a progressive world, and especially in such a progressive part of it as Port Sunlight, one cannot hope to give a record which will for long represent existing facts. The arrangements which have been made for the benefit of the inhabitants of this village have necessarily been altered or modified. At the present time the buildings for general use include Christ Church (No. 6 and Pls. 31-33), an admirable Late Gothic building in a central position, the Schools, which accommodate about 1,600 children, a Lyceum, a Cottage Hospital, a Gymnasium (No. 29), an open-air Swimming Bath (Pl. 26), Post Office (Pl. 19), a Village Inn (No. 36 and Pl. 24), Village Stores, a Fire Station, the Auditorium, to seat 3,000, the Collegium (No. 11), the Gladstone Hall (No. 26), the[Pg 22] Hulme Hall (No. 25), Co-Partners’ Club with billiard rooms and bowling green (No. 8), a Village Fountain, and, finally, the Hulme Art Gallery (Pl. 29), which is destined to hold the Public Library as well as fine collections of Pictures, Pottery, and Furniture.

27. PARK ROAD BY POETS’ CORNER.

Port Sunlight has been an object of attraction to visitors for years, and this is not only due to the interest and variety of its cottage houses, and as a model for town planners the world over, but to the whole-hearted endeavour to meet all the practical and social needs of everyday life which is expressed in its various public buildings. But another source of great and enduring attraction lies in its Art Gallery. Here it outdistances every other village of the kind, for this Art Gallery holds no fortuitous collection of odd things, but carefully chosen examples of fine art got together by expert[Pg 23] knowledge. The pictures, china, furniture, etc., would alone bring many visitors to study such a superb and finely-housed collection of works of art.

DOUGLAS AND FORDHAM,

Architects.

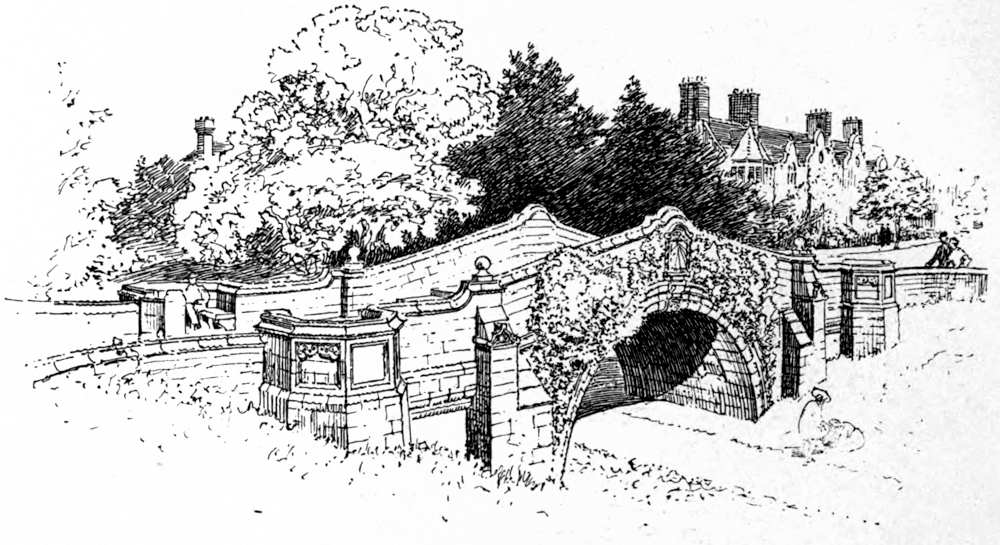

28. BRIDGE COTTAGE.

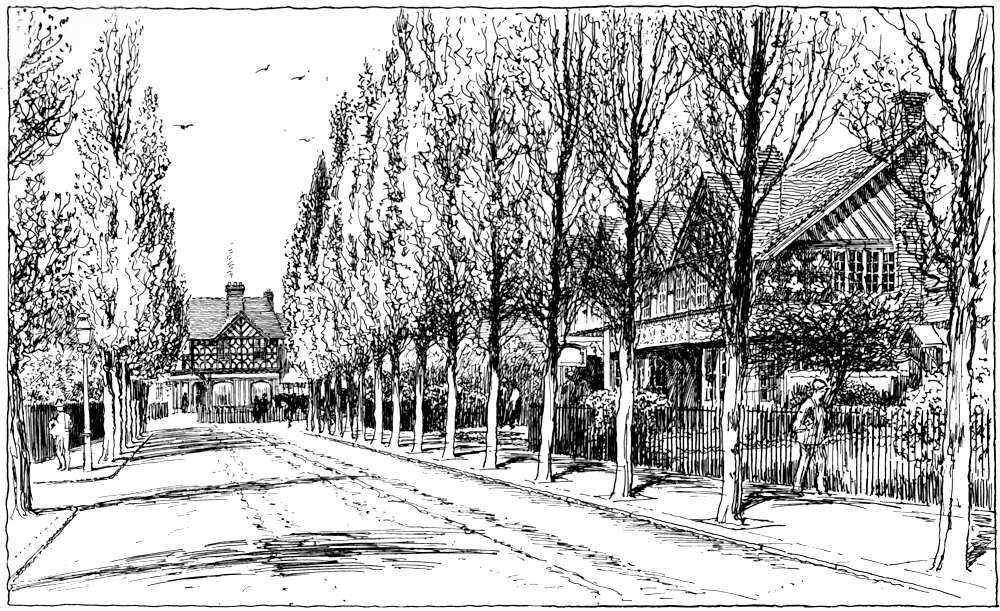

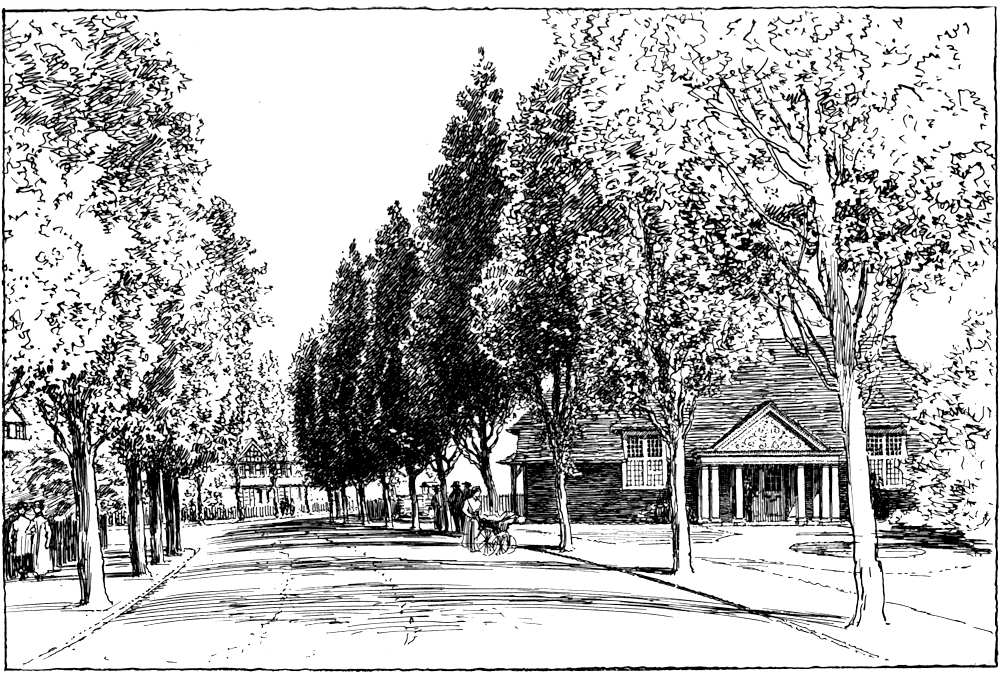

We are apt to forget that a newly created village or town does not reap all its benefits at once. Not only as regards the results of growth in trees and shrubs, the development of gardens, and the mellowing influences of time and tone, but also in relation to all the amenities of social life, we must wait for those influences which can only come in a gradual process. The subject of trees alone, of the best method to deal with living growth, is not finished with for some time, if ever. Some of the avenues at Port Sunlight are charming now, and show an admirable balance of effect between trees and buildings. Down the avenue of poplars one of our sketches (Pl. 3) shows how delightfully the Club and the Library peep out, and how well the vista leads up to the Post Office beyond—so in some of the winding roads the effect even in summer is just right. But trees keep growing, and unless the houses are to suffer they will have to be cut down and some removed entirely. Then, again, the Diamond (Pl. 2) (which in spite of its name is a great oblong open space), bordered by groups of cottages and bounded at one[Pg 24] end by the new Art Gallery, will very well bear all the height the trees will ever reach. This is a very fine open space, and borders of big trees will help, and never belittle it. Possibly the secret of successful planting amongst cottage houses is to have plenty of slow-growing evergreens, and forest trees only at intervals. It is quite certain that if the garden spaces at Port Sunlight were punctuated with decoratively placed evergreens, and inclosed by living borders of box or yew, the result would be both pleasing and long-lasting. The open spaces now secured should make for ever pleasant oases amongst the long lines of houses, and even if all the tree avenues had to go, there would still be left much to excite the envy of those who have to live in our dirty old towns.

W. & S. OWEN, Architects.

29. THE GYMNASIUM.

One of our sketches shows the avenue which leads to Christ Church from Greendale Road (Pl. 13). It is obvious that the sturdy breadth and dignity of the church will never lose anything, however lofty the avenue becomes. Unfortunately we cannot afford the space in the thoroughfares for the trees so that they[Pg 25] will not be a trouble to the buildings some day. The only possible way would be to plant them down the centre of the roads, so keeping the traffic in the two opposite directions in its right place. This is a counsel of perfection, but it has been done where wide road spaces were practicable.

J. J. TALBOT, Architect.

30. THE TECHNICAL INSTITUTE.

It will be noted that at either side of the Diamond the land round and between the houses is bordered by a low wall through which steps lead up to the pathways. The effect is very pleasing and might be repeated in other cases with advantage.

31. WOOD STREET COTTAGES.

An evidence of the careful economic spirit which has guided the whole enterprise may be found in the plans of the buildings at Port Sunlight. There are here no freaks or features created simply for picturesque effect, nor any serious attempt to give the[Pg 26] occupants something they do not want. It will probably be a long time before any great reform in cottage planning can be maintained in face of the varying views of the tenants. Thus the rooms must be big enough, but they must not be so large as to cause needless work. The better class cottages must have parlours, and only those who cannot afford them will go without. Plaster walls seem to be almost always preferred to those lined with boarding, white-washed bricks, or any other healthy or artistic departure from the modern British type. Thus we find that the compact and economic plans in the village are what give the most universal satisfaction. But in the scheme of the planning the juxtaposition of the cottages has been dealt with in a free and varied manner, so that we find rows of houses, or L-shaped blocks, or semi-quads, or curved frontages, or semi-splayed quads. A census of opinion would probably be all in favour of straight rows, and have been dead against the judicious variety which gives so much interest to[Pg 27] the place. Theoretically, one would perhaps like those who live in cottages to give up the fetish of the parlour and have one really ample living-room instead. But the inherent yearning for privacy is an English characteristic which closes the door of domestic affairs from the casual visitor. Moreover, the sin of affectation creeps into all our buildings, and thus the cottage apes the little villa, the little villa apes the large one, the large one apes the mansion, and the mansion apes the palace.

32. A GARDEN CORNER.

The cottage reformer would of course say that the cottage tenant would be far happier and healthier as a rule without a parlour, for then he would have a fine living-room which might be free of all incumbrances and free of draughts. But it has to be taken for granted that most who can afford parlours prefer to have them; therefore the plans are of two types, the kitchen cottage and the parlour cottage. Our illustrations show how these are planned, and it is not of little interest to see how varied may be the exterior treatment as developed from these plans.

[Pg 28]

J. J. Talbot Architect

33. KITCHEN COTTAGES.

Some of the plans which have been found successful we give illustrations of. These (Nos. 33-35) are carefully schemed. There is a bath in each and three bedrooms, each with a fireplace. The W.C.’s are entered from outside. The parlour cottage plan is also given. It shows what a fine living-room might be obtained in a scheme which eliminated the parlour. It is obvious that the question of cost is more or less elusive. The original cost of the smaller cottages was £200, and of the parlour cottages £330 to £350, but this has risen now to £330 for cottages and £550 for parlour houses. At the present time the gross rentals of the kitchen cottages average now 6s. 3d. each, whilst for the parlour cottages the rent would be 7s. 6d., excluding rates and taxes.[1]

34. PARLOUR COTTAGES.

In any estimate of the value of Port Sunlight as a housing scheme it must always be remembered, as Mr. W. L. George has pointed out, that it is an experiment rather in ideal than in cheap[Pg 29] housing. This question of ideal was the first point referred to in this record. That it has been largely realised and entirely justified is something for which its founder must feel profoundly glad. All sorts of economies and precautions might have been adopted which have been boldly and generously set aside. The ideal was always kept in view, and if it ever disappears it will be only after the disappearance of the original founder himself! It is a pleasant task to gather together in this little book the evidence of belief that a more real partnership between capitalist and workpeople would work a lasting good. That good is not to be measured in a notation of gold, nor even amongst those who live and thrive under the immediate benefits of Port Sunlight. Its influence goes round the world like the beneficent rays which are symbolised in its own expressive title.

35. KITCHEN COTTAGES.

GRAYSON AND OULD,

Architects.

36. THE BRIDGE INN.

Many of those who scan these pages will never see Port Sunlight itself, and so will not realise how much better is the reality than the printed page. In judging the results it must never be forgotten that the saving grace of common sense has been a constant guide in its ultimate development and expression. No one [Pg 31]could pretend that these thousand cottages form the finest possible aggregate of architectural skill in individual design or co-ordinated effect. Here and there one finds perhaps an exaggeration of simplicity on the one hand or of richness on the other; in some cases the restraint may be a little obvious or the picturesqueness a little overstrained, but the balance of effect is that of a well-ordered and varied interest. To realise the value of Port Sunlight as an industrial village one has only to compare it with other enterprises. The architect can read clearly enough from it many lessons in design, a few of what to avoid perhaps, but many that he may emulate. The social reformer sees an object lesson in the value of a pleasant and well-planned community of houses in which individuality is left ample freedom of expression. The projector of industrial enterprise realises the mutual benefits of good and attractive housing. Little, if anything, in this country can be compared to it in its general measure of success. This success should act as a stimulus to an ever-widening effort to make the improved conditions of daily life one of the definite aims of industrial enterprise generally.

J. L. SIMPSON,

Architect.

37. THE GIRLS’ CLUB.

The full-page Plates 3 to 27 give an idea of the road views and the relation of the houses to them, with their perspective[Pg 32] effects in straight or winding lines of frontage, with quadrangular recesses as in Pls. 11 and 20, or where the L-shaped blocks of cottages leave a good open space as in Pl. 9. The sturdy tower of Christ Church is a telling feature at the end of the Causeway (see Pl. 13), and the picturesque pavilion roof with its clever tiling makes a telling feature at the junction of the Causeway with Greendale Road. It is hard to imagine anything more delightful in the early spring or autumn than the Greendale Road where it approaches the post office, with the peeps of the buildings through the tall poplars. The view towards the post office in both directions (Pls. 3 and 7) are equally pleasing. Nothing shows better the good qualities of an Old English half-timber building than such a setting. There is hardly anything in the village which comes back on one with such recurring charm as the row of five gables in the Park Road cottages shown in Pls. 5 and 14. In Pl. 5 we see something of the delightful result of the continuous sloping banks from the road up to the cottage, and a certain picturesque irregularity where the old hawthorn bushes which formerly existed have been left at intervals. This vertical timber framing has a simple breadth of effect which is well shown in Pls. 4, 5, and 14. It would be difficult to do justice to Greendale Road with its continuous line of 97 cottages, which form a picture of great variety and interest as viewed from the passing trains, and give us a long perspective of trees and houses, broken at the point of view of our sketch (Pl. 15) by the half-timber group of cottages which is an exact replica of the design of Kenyon Old Hall. This delightful[Pg 33] group is also shown in Pl. 20. There is nothing more satisfactory in proportion and colour than the recessed group of cottages which fronts the Diamond in the Queen Mary’s Drive. The yellow-grey stone slates, the red brick chimneys, the white rough cast, dark boarding, and robust half-timber work in the flanking gables, make up a picture of colour and texture which is most satisfactory (Pl. 2). The cottages here have the advantage of a raised terrace bounded by a stone wall. One of the nearest approaches to the charm of an old English village is probably the L-shaped group of cottages in Bath Street (see Pl. 9). A photograph of the Dell has been taken to show one of the natural features which has been turned to so good an account in the village (see Pl. 10). The cottages looking over the roadways surrounding the Dell have delightful outlooks over here. Our view was taken in the winter, so as to show something of the bridge and houses. The stone bridge at the end of the Dell is an excellent architectural feature (see Nos. 1 and 2), and groups with remarkably good result below the Lyceum buildings.

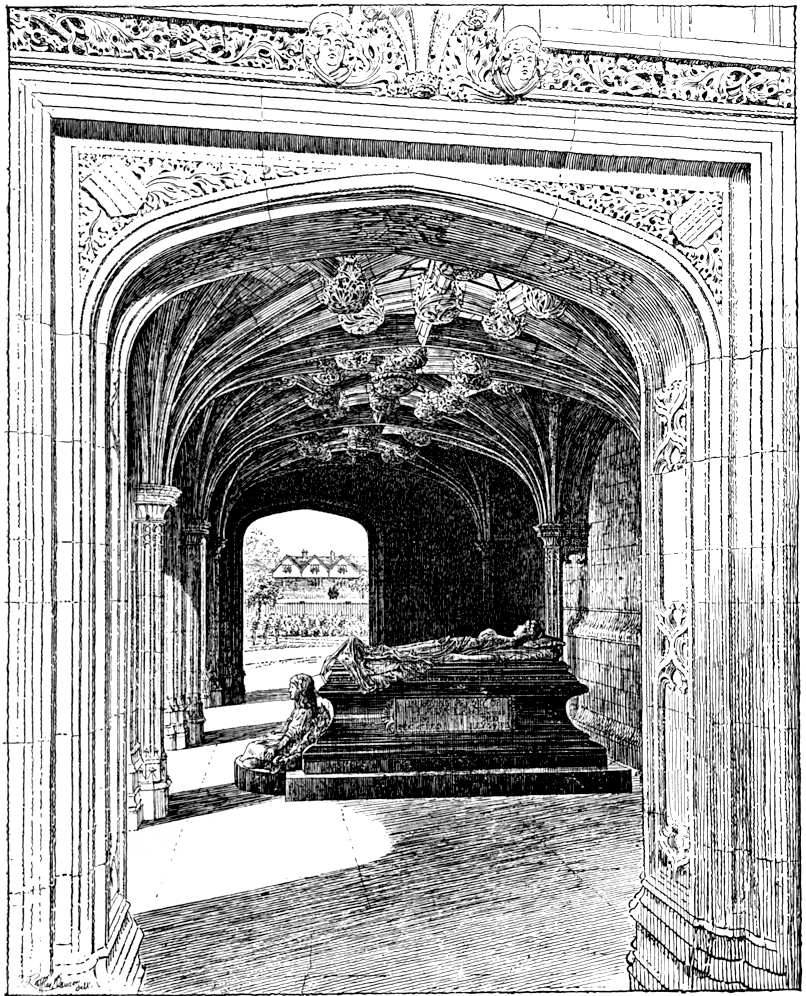

No illustrative account of Port Sunlight could be considered complete without some reference to Christ Church, which is a central and interesting feature. Its solidly built red stone walls and stone slated roof, and its finely appointed interior with a wealth of enriched oak timber work, commands one’s attention whether as architect or layman. It speaks of strength and endurance and a sincere love and study of our traditional English Gothic. Its value is sufficiently apparent both from the social and the artistic point of view. In one respect, however, this church may claim a special distinction, for at its western end has been erected a richly detailed narthex, with a vaulted roof, forming a shrine for a beautiful sculptured memorial to the late Lady Lever. Both in idea and execution, this forms a striking and touching memorial to a gracious lady whose kindliness of heart endeared her to all. Children were her special friends, and this is reflected in the two charming figures of children at one end of the sarcophagus. Sir Goscombe John, the sculptor, has never been more successful than in this tenderly and gracefully modelled reclining figure of Lady Lever. This vaulted porch, with its richly[Pg 34] carved bosses (on one of which are painted the arms of Sir William), largely enhances the value of the memorial sarcophagus itself, which is one of the most satisfactory of recent years. The illustration of the interior (see Pl. 33) is from a large drawing exhibited by the architect at the Royal Academy in 1916.

Our illustrations, in a general way, represent what may be taken to be the best examples of design in the village. They do not, of course, show all the best. In Pl. 28 we have a very good example of the quality of detail which lifts the work at Port Sunlight so far above the level of the ordinary speculative cottage building. Here we find carved oak beams and posts and brackets and barges, and an excellent piece of modelled plaster work in the gable. When it is remembered that this is no isolated example, we see how unusually liberal has been the hand that directed the outlay. Corners like the picturesque grouping of chimneys in No. 28, or the carved oak and modelled plaster in the corner gable (No. 9), would not have existed in an industrial village had not the founder been imbued with a keen appreciation of architectural values. One would present a sketch proposal for such a type of cottages with some trepidation to the average building owner! One of the noticeable bits of rich detail is to be found in the Flamboyant and Gothic dormers in Pl. 27. We have in No. 32 a delightful corner of half-timber building with a sweet little garden foreground. The old Cheshire type of half-timber work is tellingly expressed in the corner houses in Park Road (Pl. 16). Other especially effective corners are seen in Nos. 11 and 27. A contrast between Queen Anne brick gables and the half-timber house is effectively shown in No. 21. Contrasting again with the richness of carved oak and modelled plaster in the more elaborate buildings, we come across delightfully simple designs, such as Nos. 15 and 17, which may some day very well pass for ancient buildings.

Amongst the conspicuously successful of recent groups is that of the parlour houses in Bolton Road (Pl. 21), which has the advantage of a good setting on the front of a circular place. This only needs a terrace wall and some formal planting to make it one of the[Pg 35] pictures of the village. What an enticing prospect opens up in the possibilities of formal evergreen planting amongst all these cottage homes!

It is with some feeling of regret that more sketches have not been given showing examples of interesting ornamental detail which lift the quality of these cottage homes so much above the ordinary level of industrial homes. But the limits of the volume place an inevitable check on one’s desires. If the author has been able to convey to his readers a tithe of the pleasure he has felt in the subject of this little book he will be amply rewarded.

38. AN EXAMPLE OF SIMPLE TREATMENT.

Enough has perhaps been said in appreciation of some points which mark out the qualities of Port Sunlight. Much more might be written, but for the rest we leave the illustrations to tell their own tale. We have shown nothing of the great auditorium which seats 3,000 people, or of the detailed appointments of the new Art Gallery, but we have a sketch of the splendid open air swimming pool and our birds-eye view of the Diamond gives some notion of the pleasant grouping of the homes amongst pleasant open spaces and tree-lined avenues. A great deal of what we do not show is left in reserve for those who can find opportunity to go and see for themselves what this wonderful scheme of industrial housing can teach.

[Pg 36]

PLAN OF THE VILLAGE OF PORT SUNLIGHT 1914.

39. A GENERAL PLAN OF THE VILLAGE.

[Pg 37]

PLATE 2.

THE DIAMOND, LOOKING TOWARDS ART GALLERY.

[Pg 38]

PLATE 3.

GREENDALE ROAD, LOOKING TOWARDS POST OFFICE.

POST OFFICE.

LEVER FREE LIBRARY.

[Pg 39]

PLATE 4.

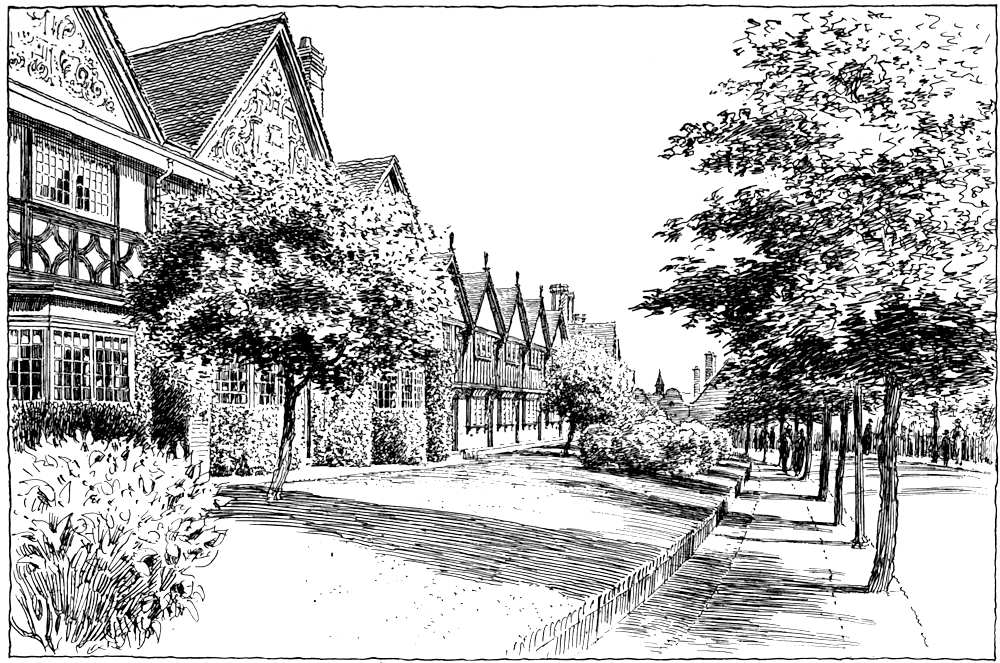

WESTWARD VIEW OF PARK ROAD, SHOWING KITCHEN COTTAGES.

[Pg 40]

PLATE 5.

VIEW IN PARK ROAD TOWARDS THE LYCEUM.

[Pg 41]

PLATE 6.

SOUTH SIDE OF PARK ROAD.

[Pg 42]

PLATE 7.

GREENDALE ROAD AND CO-PARTNERS’ CLUB ANNEXE.

[Pg 43]

PLATE 8.

NEW CHESTER ROAD.

[Pg 44]

PLATE 9.

COTTAGES IN BATH STREET.

[Pg 45]

PLATE 10.

THE DELL.

[Pg 46]

PLATE 11.

SEMI-QUAD OF COTTAGES, QUEEN MARY’S DRIVE, THE DIAMOND.

[Pg 47]

PLATE 12.

PARK ROAD. BRIDGE COTTAGE IN FOREGROUND.

[Pg 48]

PLATE 13.

THE CAUSEWAY, LOOKING TOWARDS CHRIST CHURCH.

[Pg 49]

PLATE 14.

PARK ROAD COTTAGES. LYCEUM IN DISTANCE.

[Pg 50]

PLATE 15.

GREENDALE ROAD. COTTAGE GROUP IN FOREGROUND, REPRODUCING KENYON OLD HALL.

[Pg 51]

PLATE 16.

HOUSES IN PARK ROAD. SOUTH SIDE.

[Pg 52]

PLATE 17.

LEVER FREE LIBRARY, GREENDALE ROAD.

[Pg 53]

PLATE 18.

A BRIDGE STREET GROUP.

[Pg 54]

PLATE 19.

POST OFFICE.

[Pg 55]

PLATE 20.

GROUP OF COTTAGES IN GREENDALE ROAD, REPRODUCING DESIGN OF KENYON OLD HALL.

[Pg 56]

PLATE 21.

BOLTON ROAD PARLOUR HOUSES.

[Pg 57]

PLATE 22.

PRIMROSE HILL COTTAGES.

GREENDALE ROAD COTTAGES.

[Pg 58]

PLATE 23.

GREENDALE ROAD COTTAGES.

COTTAGE PORCH, CONNOLLY ROAD.

[Pg 59]

PLATE 24.

THE BRIDGE INN.

[Pg 60]

PLATE 25.

CO-PARTNERS’ CLUB HALL.

[Pg 61]

PLATE 26.

OPEN AIR SWIMMING BATH.

[Pg 62]

PLATE 27.

A RECESSED GROUP IN CROSS STREET.

[Pg 63]

PLATE 28.

COTTAGE IN WOOD STREET.

[Pg 64]

PLATE 29.

THE LIBRARY ENTRANCE OF THE ART GALLERY.

[Pg 65]

PLATE 30.

S.E. VIEW OF CHRIST CHURCH.

[Pg 66]

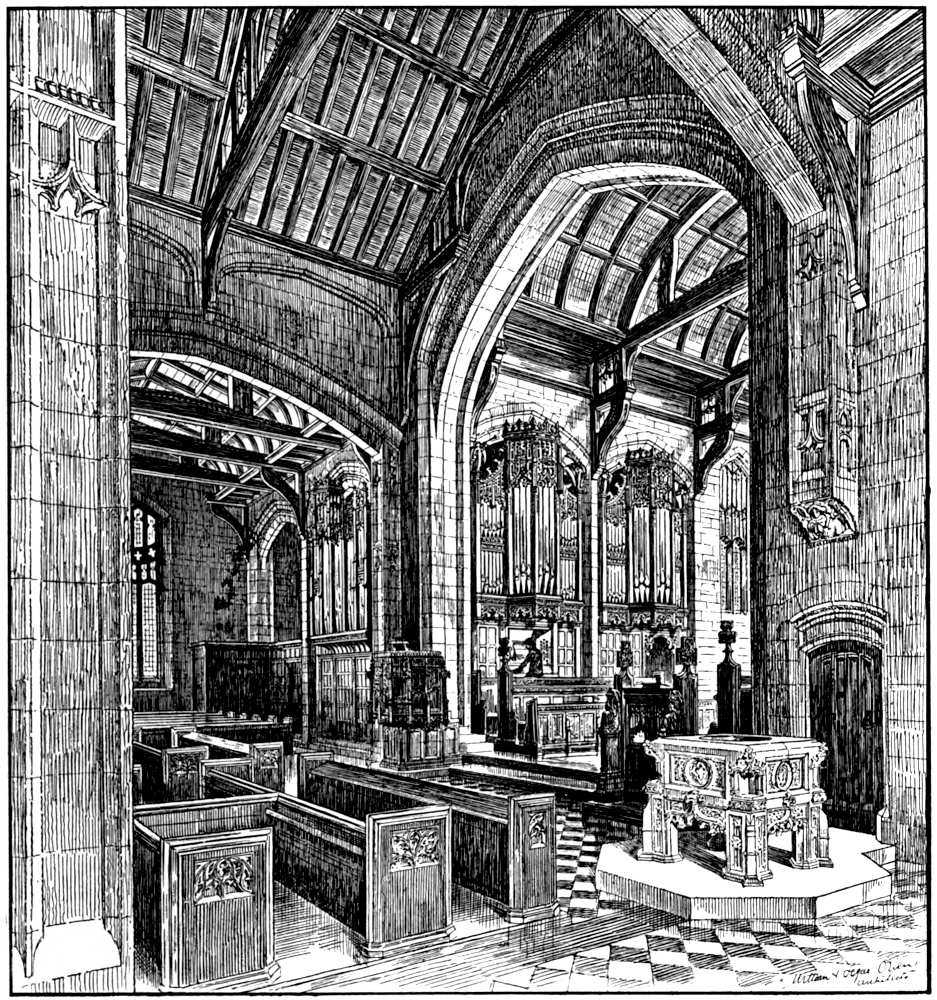

PLATE 31.

VIEW UNDER TOWER, CHRIST CHURCH.

[Pg 67]

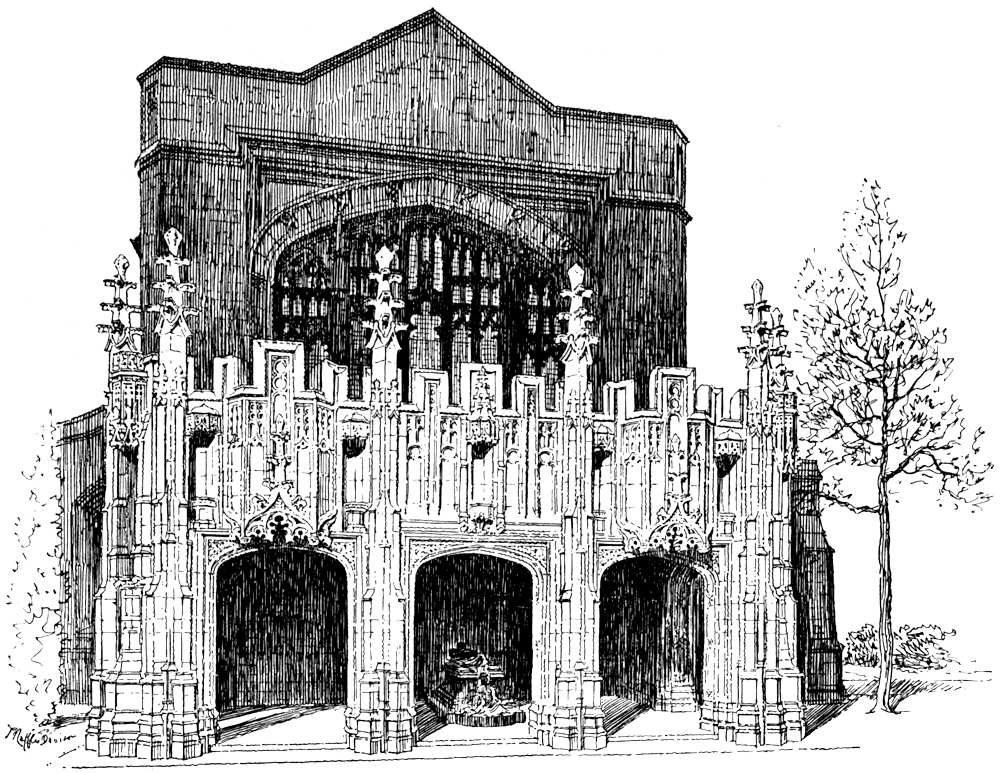

PLATE 32.

LADY LEVER MEMORIAL PORCH, CHRIST CHURCH.

[Pg 68]

PLATE 33.

THE LADY LEVER MEMORIAL.