DAVID IVES

A STORY OF ST. TIMOTHY’S

BY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

FRANKLIN WOOD

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1922

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY PERRY MASON COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1922, BY ARTHUR STANWOOD PIER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Riverside Press

CAMBRIDGE · MASSACHUSETTS

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

| I. | Farewell to Rosewood | 1 |

| II. | A Gentleman and a Scholar | 22 |

| III. | Hostilities | 36 |

| IV. | Friendships | 56 |

| V. | The Return | 73 |

| VI. | Probation | 91 |

| VII. | Blindness | 108 |

| VIII. | Wallace’s Examination | 123 |

| IX. | David’s Enlightenment | 137 |

| X. | Mr. Dean provides for the Future | 151 |

| XI. | The Family Migration | 169 |

| XII. | The New Neighbor | 183 |

| XIII. | Hero Worship | 196 |

| XIV. | Anti-Climax | 218 |

| XV. | The Torn Page | 231 |

| XVI. | Lester and David | 242 |

| XVII. | The First Marshal | 256 |

| XVIII. | Relinquishment | 278 |

| XIX. | Attainment | 294 |

The suburb in which David Ives lived and in which David’s father had most of his medical practice was by no means one of the wealthy and prosperous suburbs of the wealthy and prosperous city. It was a new and raw-looking region; many of the streets were unpaved, littered and weed-grown; and unfenced lots and two-family tenement houses were alike its characteristics; there were numerous billboards along the sidewalks; the trees were few in number and had grown half-heartedly.

But David, returning from the baseball field on a hot July afternoon, saw nothing depressing in the neighborhood. He walked with his coat flung over his shoulder and his cap in his hand. He had distinguished himself at the bat; he was thirsty and thinking of the cold ginger ale he would drink;[2] he was hungry and thinking of the raspberries he would eat; he was pleasantly tired and thinking of an evening to be passed in comfort and interest over “David Copperfield.” A gust of wind flung dirt and dust into his face and made him wonder why the watering-carts so seldom visited Rosewood,—for such was the misleading name of the suburb,—but the next moment he turned into a more shaded and attractive street and forgot his displeasure in the satisfaction of drawing near his home. He passed the Carters’ bungalow and the Porters’ Queen Anne cottage and the Jennisons’ mansard dwelling, and then he turned up the flagstone walk that led between two narrow bits of lawn to his father’s door.

The house was square and gray and shabby; there was a room thrown out at one end of the wide front porch, and over the door that admitted to this room hung a lantern bearing the words, “Dr. Ives.” The door and the window were both open, and just before passing into the front hall David had a glimpse of his father seated at his desk in a characteristic attitude, with his gray head resting on his hand while an invisible patient recited her symptoms. That the patient was a woman David knew, because he heard the querulous[3] drone of her voice—it was just the drone that he associated with his father’s numerous charity cases.

In the dining-room Maggie, the maid of all work, was setting the table for supper.

“Where’s mother, Maggie?” David asked.

“Search me!” replied Maggie, who looked red and hot and at war with the world.

As there was obviously nothing to be gained by complying with Maggie’s request, David passed on to the parlor and the library, and not finding his mother in either place, went upstairs three steps at a time. Then he saw her sitting in her room, looking disconsolately out of the window. So sad was the expression on her face that David forgot what had been in his mind and exclaimed:

“What’s the matter, mother?”

Mrs. Ives rose and came toward him, with her arms outstretched.

“Oh, David dear, I can’t bear to have you go, I can’t bear to have you go!” With her arms round his neck she was sobbing on his shoulder.

“Go where?” David was bewildered and distressed. “What are you talking about, mother?”

She did not immediately answer, but went on weeping quietly. Then she said: “I will let your father tell you about it. It is his decision.”

“Then it can’t be anything so very terrible, mother,” David said, and he stroked and patted her while she clung to him.

“Not for you, perhaps, David, but it seems very hard to me. It may all be for the best, but I don’t know—I don’t know—”

David could not help reflecting that his father was always the optimist of the family and his mother usually the pessimist, and that therefore it would be desirable to await his father’s unfolding of the mystery. So he set about getting his mother into better spirits, which he did by tweaking her ears, kissing her, and telling her that he did not know where he was going or for how long, but that, wherever it was, they could not keep him from coming back to home and mother. She was a pretty little woman who looked scarcely old enough to have such a tall and stalwart son, and as he held her in his arms she seemed to be a kind of child mother—an anxious, diffident, confiding, appealing little person, with sensitive lips and timorous, soft brown eyes. David looked like her and yet not like her; his eyes were brown and shone affectionately, but there was fearlessness rather than timorousness in their glance; his lips were sensitive, but their curve[5] showed a resolute rather than a vacillating character; he had his mother’s wavy brown hair. Soothing his mother, he smoothed her hair, he took her handkerchief and dried her eyes with it. “And now does this come next?” he asked, reaching for a powder-puff. So he got her to laugh, and her face had brightened when he led her downstairs.

“Found her, did you?” said Maggie as they passed the dining-room. Her tone was one of good-natured interest, but David did not feel it necessary to reply. He had reached an age when he was beginning to dislike Maggie’s familiar manners. Mrs. Ives admitted she was too much of a coward to try to correct them.

As David and his mother entered the library, his ten-year-old brother Ralph rushed in breathlessly, declaring his satisfaction at finding that he was not late for supper. “I guess you will be, if you try to get yourself properly ready for it,” remarked David, looking the unkempt and dirty-faced small boy over with disfavor. Ralph thrust out his tongue, but when David commanded him sternly to go upstairs and get clean, with some stamping and scuffing he obeyed.

Across the hall rose the violent clamor of the[6] supper bell, which Maggie always rang as if she were summoning the neighborhood to a fire. David and his mother had just seated themselves at the table when Ralph came crashing down the stairs, bounced into the room, and hurled himself into his chair, snorting and panting.

“Gee, you do make a noise!” David said.

“So do you—with your mouth,” Ralph rejoined promptly.

“Boys, boys!” sighed Mrs. Ives, and David turned red and restrained the ready retort. It was hard, because Ralph looked across the table at him jauntily, defiantly.

The entrance of Dr. Ives had a quieting effect on the provocative younger brother. David, glancing at his father, had the uneasy, vaguely apprehensive feeling that had frequently taken possession of him of late. He was always expecting, always hoping that his father would conform in appearance more nearly to the mental picture to which the boy constantly returned—the picture of a tall man, straight and ruddy and broad-shouldered, with laughing eyes and a collar that fitted his neck snugly. It was disappointing—it was worse than disappointing—to realize that his father’s shoulders looked thin and angular; that[7] his cheeks were pale, and his eyes, though kinder than ever, preoccupied and less sparkling; that his collars were looser about his neck than comfort required them to be. David often wondered whether his mother had noticed it, and if so what she thought about it. He did not wish to mention it first; if she was not worrying about it already, he was not going to put a new reason for anxiety into her head.

“Well, David,” said Dr. Ives in his usual cheerful voice, “have you had a talk with your mother?”

“I couldn’t tell him, Henry,” said Mrs. Ives plaintively. “I’ve left it for you to do.”

“Mother said something about my going away somewhere,” added David.

Ralph looked from one to another while his round eyes grew rounder in wonder and concern.

“Yes,” said Dr. Ives, evading his wife’s glance and speaking with great cheerfulness, “I’ve decided to send you away to boarding-school, David. To St. Timothy’s, in New Hampshire.”

“In six weeks,” added Mrs. Ives tearfully.

David felt a thrill of exultation and excitement, and then, because of his mother’s sadness and his father’s forced cheerfulness, he felt sorry. Ralph sat open-mouthed and subdued.

“Why am I going to St. Timothy’s, father?” David asked.

“Just what I wanted to know!” said Mrs. Ives. “Hasn’t David been doing all right in high school?”

“Yes,” Dr. Ives admitted, “he has. But I think that now he is ready for a change; it will be broadening and instructive. I think, moreover, that both he and Ralph will be the better for being separated for a time from each other. It will do David good to get out into a world of his own, and it will do Ralph good to take over some of the responsibilities at home that David has had. Those are some of the reasons.”

Mrs. Ives shook her head forlornly. “I can’t see that they are sufficient.”

“Well,” said Dr. Ives, “I want my boys to have the best there is—and to be the best there are. From all that I can ascertain, St. Timothy’s is one of the best schools in the country. David already knows what he wants to be. He feels that he has a bent for surgery; he means to make that his profession. I should be glad to have him model his career on that of the best surgeon I know—Dr. Wallace. As far as I can I mean to give him every opportunity that Wallace had. Wallace went to[9] St. Timothy’s School, and to Harvard College, and to the Harvard Medical School. So shall David.”

“But Dr. Wallace’s father was rich, probably, and you are not,” said Mrs. Ives.

“I feel able to meet all the necessary expenses, and I can trust David not to be extravagant.”

“New Hampshire is so far away! And it will be so long before we see David again!”

“We shall hope to see him in the Christmas vacation.”

“Yes, of course. But I can’t help feeling that David will be leaving home for good; he will be coming back to us now only for visits! You don’t want to go, do you, David?”

“I don’t know, mother,” David said, torn by various impulses. “Yes, I think I do.” And then he jumped up and, going behind her chair, put his arm round her and his face down on hers and kissed her.

That evening Dr. Ives had to go out on some professional calls; he chugged away in the shabby little second-hand automobile that he had bought three years before. “Some day, when all my patients pay their bills, I’ll get a new machine,” he was accustomed to remark to the family. He also was accustomed to declare that he rather enjoyed tinkering the old rattletrap.

Now David, sitting in the library and perusing the catalogue of St. Timothy’s School, suspected that for some time he had been the object of his father’s many economies. Turning over the pages, he resolved that he would justify his father’s faith in him, that he would work hard and not be extravagant, and that he would come home showing that he had profited by the opportunities given him by the family’s sacrifice. And as he turned the pages the thrill of eager anticipation grew stronger in him. He glanced over the long list of names—boys from all quarters of the country, boys even from far corners of the earth. David, who had never traveled more than forty miles from the city in which he had been born and brought up, and who had never known any boys except those in the immediate neighborhood of his home, felt a tingling of romance as he read the names.

While he read Ralph sat quiet over a storybook, and Mrs. Ives, with a pile of mending in her lap, worked at intervals and at intervals gazed wistfully at her older boy. He was her favorite, though she felt guilty in admitting it even in her heart; Ralph had always been more thoughtless, more unmanageable, a more trying kind of boy. It made her feel quite helpless to think of dealing[11] with Ralph alone after David had gone. But that was not the worst to which she must look forward, that was not the saddening thought. What weighed her down was, as she had said, the premonition that when David went away it would be really for good and all. It would be years and years before home would be more than a place to which he made visits. Perhaps what was now, and always had been, his home would never really be his home again. And his father and his mother, who had always been so near to him, would never be so near to him again. Tears filled her eyes and fell unnoticed while David and Ralph read; she wiped them away furtively and determined to be brave. Perhaps it was all for the best, and she would not begrudge anything that was best for David. But it seemed such a doubtful venture,—and David’s father did not look well,—but she was not going to imagine that any more; it produced such a heaviness about the heart. She was going to try to be cheerful; she had never been cheerful enough.

She anticipated the usual rebelliousness and struggle when at nine o’clock she said, “Bed-time, Ralph.”

“All right, mother.” To her astonishment he[12] spoke with the utmost docility; he closed his book at once and came over and kissed her. With the same unusual docility he went across the room and kissed David. “I’m sorry you’re going away, Dave,” he whispered, and then he fled upstairs.

David looked at his mother.

“He’s a pretty good kid,” he said. “He won’t give you much trouble—not more than I’ve done.”

“You’ve never given any trouble, David.”

“Haven’t I?” He sprang up and went over to sit beside her. “Then don’t let me begin doing it now. Stop looking so troubled about me. That’s right, smile.”

She did her best, remembering that she had resolved to be cheerful.

Anyway, as the days passed and the time of David’s departure drew near there was one development on which his mother liked to dwell and from which she hoped and even dared to expect much. Dr. Ives had yielded to her persuasion and, as the first vacation that he had taken in years, was to accompany David on his journey. “A rest is all he needs,” his wife kept assuring herself. “A rest and a change—and when he comes back I won’t have to worry about him any more.” Dr. Ives had wanted her to take the trip, too, but she[13] had refused. She knew that he could ill afford such an additional expense, and besides there was Ralph to look after; no doubt Maggie was competent to care for him, and his Aunt Hattie would be willing to take him in, but Mrs. Ives felt that the absence of his father would give her the most favorable opportunity of getting on the right terms with her younger boy. His sense of chivalry would be more likely to awaken when he was not under the surveillance of a masculine disciplinary eye.

David’s mother went with him to the shops and helped him to purchase his slender wardrobe. A careful purchaser she was, leading him from shop to shop in search of bargains, feeling with distrustful fingers the material of the suit at last selected, insisting on underwear of the thickest woolens and on pyjamas of flannel, for doubtless New Hampshire winters were even colder than those at home. David felt that he was rather old for his mother to be buying his clothes for him,—he was sixteen,—but he had not the heart to assert any independence in the matter, to intimate that he had outgrown the need of her guidance.

Likewise he restrained the desire to intimate to Maggie that her criticism and comments were unwelcome. Maggie attacked him one day when he was alone in the library.

“What’s all this, David, about your goin’ away to boardin’-school?” she asked truculently, standing in the doorway with her hands on her hips.

“Well, it’s true,” David answered.

“Ain’t there no good schools near home?”

“Yes, but not so good.”

“Funny thing that nothing but the best is ever good enough for some folks.”

David, disdaining to reply, held his book up in front of his eyes and pretended to read.

“It’s none of my business,” continued Maggie in a somewhat more pacific tone, “but I think your pa and your ma both need looking after, and you’d ought to stay home to do it. Of course what it means is, it’ll all fall on me; things always does.”

“Nothing’s going to fall on you; what do you mean, Maggie?”

“Oh, it’s all very well to talk. But everybody can see your pa’s been failin’ of late and is in for a spell of sickness, and your ma gets upset so easy it’s always a matter of coaxin’ and urgin’ her along.”

“Father’s all right except that he’s been working too hard; a rest will fix him up,” David declared. “And mother’s all right, too, except that she worries.”

“Oh, yes, it’s all all right,” Maggie agreed with gloomy significance. “All I can say is, they’re lucky to have me to fall back on. I can deal with trouble when it comes.”

David disliked to admit to himself that this interview disturbed him. But there was no escape from the fact that it did have a depressing effect. He tried to assure himself that Maggie always delighted in forebodings of trouble, but in spite of that he was half the time wishing that he might withdraw from the adventure on which his father was launching him. Every day the expression in his mother’s eyes affected him as much as her tears could have done, every day he was troubled by his father’s haggard look. He had of course learned something about the burden in dollars and cents he was to be to the family, and he wondered if there could really be wisdom in his father’s decision. “It throws a big responsibility on me,” David thought gravely.

He suspected that in some ways his father was an impractical man and that he was often visionary in his enthusiasm. He had never forgotten how hurt he had felt once as a small boy when he had overheard his mother say to her sister, “It’s no use, Hattie; if Henry once has his mind set on a[16] thing, the only thing to do is to give him his head.” David did not know what had prompted the remark, but he had not liked hearing his father criticized even by his mother.

In those days he noticed in his father a nervous exuberance over the prospect, which, if it failed to quiet David’s doubts, served to convince him of the futility of questioning. Dr. Ives talked gayly of the interest and happiness David would find in his new surroundings and of the increased pleasure they would all take in his vacations, told Ralph that he must so conduct himself as to qualify for St. Timothy’s when he grew older, and declared that for himself merely looking forward to the trip East with David was making a new man of him.

One morning Dr. Ives went downtown with David in the shabby little automobile to purchase the railway tickets. As they drew up to the curb a tall man in a gray suit came out of the ticket-office; he was about to step into a waiting limousine when Dr. Ives hailed him.

“O Dr. Wallace!”

“How are you, Dr. Ives?” Dr. Wallace nodded pleasantly and waited, for Dr. Ives clearly had something to say to him.

David, following his father, looked with interest[17] at the distinguished surgeon whose career was to be an example to him. Dr. Wallace was a younger and stronger man than Dr. Ives, and, so far as prosperity of appearance was concerned, there was the same contrast between the two men as between the shabby runabout and the shining limousine.

“Dr. Wallace,” said Dr. Ives, speaking eagerly, “I won’t detain you a moment, but I want to introduce my son David to you. David’s going to St. Timothy’s; I know you’re an old St. Timothy’s boy, and I thought you might be interested.”

“I am, indeed,” said Dr. Wallace, and he took David’s hand. “What form do you expect to enter?”

“Fifth, I hope,” said David.

“That will give him two years there before he goes to Harvard,” said Dr. Ives.

“Going to Harvard, too, is he?”

“Yes, and then to Harvard Medical School—following in your footsteps, you see, doctor.”

“That’s very interesting, very interesting,” said Dr. Wallace. “I must tell my boy to look you up; you know, I have a boy at St. Timothy’s; his second year; he’ll be in the fifth form, too.”

“And he’ll also be following in your footsteps, I suppose?” said Dr. Ives.

“Not too closely, I hope,” Dr. Wallace laughed. “I’m very glad to have met you; I wish you the best of success.” He shook hands again with David and again with David’s father, then stepped briskly into his limousine and was whirled away.

“That was a stroke of luck,” remarked Dr. Ives. “Now you won’t be going to St. Timothy’s as if you didn’t know anybody. Young Wallace will be friendly with you and help you to get started right.”

David accepted this as probable. He asked if Dr. Wallace was really so very remarkable as a surgeon.

“Oh, yes; he’s the ablest man we have,” replied Dr. Ives.

“I’m sure he’s not a bit better than you, father.”

“Oh, I’m a surgeon only under stress of emergency and as a last resort. The less surgery a family doctor practices on his patients the better for the patients.”

“Anyway, you could have been as good a surgeon as Dr. Wallace if you’d studied to be.”

“Oh, we don’t know what we might be, given certain opportunities. That’s why I want you to have those opportunities—the best. So that you can go far ahead of me.”

“I guess I never could catch up with you. And I don’t care what you say, I think you’re way ahead of Dr. Wallace or any other doctor. I’m sure you do more for people and think less about what you can get out of them.”

“I shall have to think more about that now, I shall for a fact,” said Dr. Ives, chuckling good-humoredly. “When you come home for the Christmas vacation, David, you’ll probably find me turned into a regular Shylock.”

“You couldn’t be that, and mother isn’t the kind that could turn you into one. If only you had Maggie to manage you and get after patients—”

They both laughed.

But in spite of all the brave little jokes, in spite of all the loving words and loving caresses, David’s last two days at home were painful to him and to the others of the family. He caught his mother shedding tears in secret; he felt her looking at him with a fondness that made him wretchedly uncomfortable; he received a mournful consideration from Ralph as disconcerting as it was novel; he could not help being depressed by the grim and relentless quality of Maggie’s disapproval. In such an atmosphere Dr. Ives desperately maintained cheerfulness, assumed gayety and light-heartedness,[20] and professed undoubting faith in David’s adventure and enthusiasm over his own share in it.

The bustle and confusion of packing lasted far into the evening; Mrs. Ives hurried now to the assistance of David, now of his father; Ralph prowled round in self-contained excitement until long after his bedtime. It was long after every one’s bedtime when David finally got into bed; and then his mother came and knelt beside him and besought him to think often of home and to do always as his father would have him do. Together they said their prayers as they had done every night when David was a little boy and as they had not done before for a long time; and it made David feel that he was a little boy again, and that he was glad to be so, this once, this last time in his life.

The next morning the expressman came for the trunks before breakfast; and before breakfast, too, Maggie showed her forgiving spirit by presenting David with a silk handkerchief bearing an ornate letter “D” embroidered in one corner. After breakfast while the family waited in the front hall, David bade Maggie good-bye, and for one who was usually so outspoken and fluent, Maggie was strangely inarticulate, saying merely, over and[21] over, “Well good-bye, David, I’m sure; good-bye, I’m sure.”

They took the trolley car to the station, and there after the trunks had been checked they all went aboard the train. Mrs. Ives and Ralph sat facing David and his father, and occasionally some one said something—just to show it was possible to speak. David said, “Ralph, you’re to take care of mother while father’s gone,” and Ralph said, “I guess I know that.” Dr. Ives looked at his watch and said, “Well, Helen, it’s time for you and Ralph to get off the train.”

That was the hardest moment of all—the last kisses, the last embraces, the last words.

Then, for just a few moments longer, David gazed through the window at Ralph and his mother on the platform—Ralph looking up solemn and round-eyed, his mother smiling bravely and winking her eyelids fast to stem back the tears. For a few moments only; then the train started, and the little woman and the little boy were left behind.

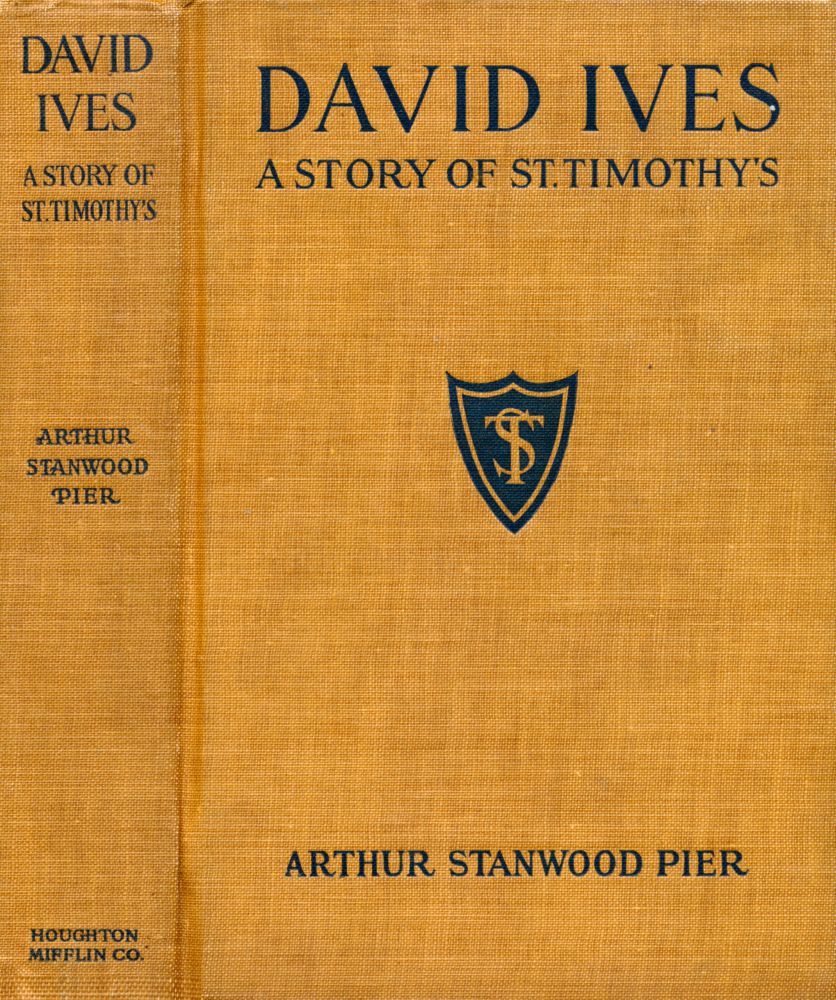

For an hour Dr. Ives had been pursuing his solitary explorations of the grounds and buildings of St. Timothy’s School. He and David had interviewed the rector, Dr. Davenport, had been shown the room in the middle school which David was to occupy and in which his trunk was already awaiting him, and had inquired the way to the auditorium, where David was now taking the examinations that were to determine his position.

For an hour Dr. Ives had been alone, and he was beginning to realize what the loneliness of his journey home would be, what the gap in the family life would be. From the time when he and David had started East they had been together every moment; his happiness in the companionship of his son and the novelty of the vacation journeying had kept his spirits buoyant; but now the shadows had begun to come over his imagination. He had taken pleasure in viewing the wide playing fields and the circumambient cinder track and in[23] thinking of his boy happy and active there on sunny afternoons. He had taken pleasure in looking in upon the rows of desks in the great schoolroom, on the empty benches in the recitation rooms, on the quiet, booklined alcoves in the library, and in thinking of his boy passing in those places quiet, studious, faithful hours. He had enjoyed visiting the gymnasium and picturing his boy performing feats there on the flying rings and taking part with the others in brave and strengthening exercises. He had stood by the margin of the pond and in imagination had seen canoe races and boys splashing and swimming; even while he looked the season changed, and he had seen them speeding and skimming on the ice while their skates hummed and their hockey sticks rang, and always his boy had been foremost in his eye.

But now, though he had walked neither far nor fast, Dr. Ives found himself suddenly overcome with fatigue; he was near the study building and he sat down on the steps to rest. He grew tired so easily! He sat still for some time and was just rising to his feet when the door behind him opened and a tall man of about his own age, with a gray beard and heavily rimmed spectacles, came down the steps, glanced at him and said:

“You’re a stranger here, I think. Can I be of any assistance to you?”

“No, thank you,” said Dr. Ives. “I have a son in that building yonder, taking an examination. I’m just killing time till he comes out.”

“In that case wouldn’t you like me to show you round the place? I’ve been a master here for nearly forty years.”

“To tell you the truth,” Dr. Ives answered, “I’ve been wandering round till I’m played out. I was just on the point of going to the library in the hope of finding a chair.”

“I can offer you a more comfortable one; my rooms are in that yellow house—just beyond those trees. I’m at leisure for the rest of the day, and I shall be glad of your company. My name is Dean.”

In Mr. Dean’s pleasant rooms Dr. Ives was soon unburdening himself; the elderly master’s sympathy and friendliness invited confidences. So in a way did the character of the rooms, about which there was nothing formal or austere. They were the quarters of a scholar; although bookshelves crowded the walls, the library overflowed the space allotted; books were piled on the floor and on the table and on the chairs—books of all[25] descriptions and in all languages, books in workaday bindings and in no bindings at all, ponderous great volumes and learned little pamphlets, works of poets and novelists, historians and essayists, philosophers and naturalists, from the days of ancient Greece to the end of the nineteenth century. From the depth of the big leather chair in which Dr. Ives found himself he looked across a massive oak table covered with papers, books, and pamphlets in a bewildering confusion and saw the thoughtful, kindly face of his host; he felt that Mr. Dean was a man on whose courtesy, consideration, and wisdom any boy or parent might depend. It was the master’s eyes that were so assuring, so inspiring, so communicative—gray eyes that sparkled and twinkled and watched and seemed even to listen; the spectacles behind which they worked deprived them of no part of their expressiveness; the smile that hardly stirred in Mr. Dean’s beard sprang rollicking and frolicsome from his eyes. They were eyes that seemed to miss nothing and to interpret everything wisely, kindly, humorously. So in a little while Dr. Ives was confiding his hopes and dreams about his son, and some—not all—of the misgivings that he had never breathed to his wife.

“Of course,” he said, “I realize that probably most of the boys here are the sons of rich men—rich at least by comparison with me. And for some time I wondered if it were altogether wise or fair to David to put him into a school where, financially, anyway, he would be at a disadvantage.”

“It all depends upon the boy,” said Mr. Dean. “Not all our boys are rich—though most of them are. The spirit of the place is to take a fellow for what he is. If your boy is the sort who is simple and straightforward—as I have no doubt he is—he has nothing to fear from association with the sons of the rich. Is he an athlete?”

“He runs—he’s a pretty good quarter-miler. And he plays baseball. But he hasn’t any false notions of the importance of athletic success. You’ll find him a good student; he led his class at the high school.”

“We give a double welcome to every boy who comes with the reputation of being a good student; we have unfortunately a good many who have not been brought up to appreciate the importance of study.”

“David knows the importance of it. He knows that he’ll have to study in college and in the medical school, and the earlier he forms the habit[27] of work the better. Dr. Wallace, whom of course you know—I’ve said to David that Dr. Wallace couldn’t be what he is if he hadn’t early formed the habit of work.”

“I wish that his son would form it,” remarked Mr. Dean. “Lester Wallace is not one of our hard workers.”

“No doubt he will develop; otherwise he could hardly be his father’s son. Dr. Wallace is our most able and brilliant surgeon. Indeed, it’s largely because I should like to get my boy started on a career similar to his that I have brought David to St. Timothy’s.”

“Well,” said Mr. Dean, “I’ve had a good opportunity to note the careers of those who have passed through the school. And, generally speaking, those after lives have been most creditable have been the boys who while they were at school received from their fathers the most careful, sane, and intelligent interest—not those whose fathers felt that boarding-school had taken a problem off their hands. A good many fathers do feel that. It’s an extraordinary thing, the number of intelligent, successful, wide-awake Americans who do not seem to realize the importance of holding standards always before their sons.”

“I suppose,” Dr. Ives suggested, “that the very successful and active men are too busy.”

Mr. Dean shook his head. “I don’t think it’s that. A physician like yourself is probably much more busy and active than many of those eager, money-making men. No; the trouble with them is their egotism and ambition. They feel that their offspring derived importance and distinction from them, and they expect vaingloriously to shine in light reflected from their offspring. But there’s an interval when they regard their offspring as not much else than a nuisance, and for that interval they turn them over, body and soul, to a boarding-school to be developed into youths such as will shed luster on their parents. The school might possibly do it if there were no vacations, but three weeks at home at Christmas often undoes the good of the three preceding months at school.”

“You seem to be a pessimist about the value of home life for a boy.”

“No, not in the least. But I am a pessimist about the influences prevailing in the homes of some of our excessively solvent citizens. Boys of fifteen and sixteen go home and with other boys of the same age constitute a miniature aristocracy, a miniature society, that copies the vices and mannerisms[29] and foppishness of the grown-up social aristocracy, and that is encouraged and even educated in all the vulgar, useless, expensive, and demoralizing details by this purblind aristocracy. I tell you, Dr. Ives, there are boys in this school that the school is struggling to save from the pernicious influences to which they are exposed at home—but their fathers and mothers can’t be made to see it. Fortunately, there are not a great many of them. Our most common difficulty is with the boy whose father is too busy to give any thought to him, to stimulate him, or help him, or advise him. Well, it’s easy to see that your boy’s father is not that kind.”

“No,” said Dr. Ives. “David and I have always been too close to each other for that to happen.”

“You’re starting home to-day?”

“Yes, I’m just waiting round to see David again; my train leaves in a couple of hours.”

“The examinations close very soon. I will walk over to the building with you; I should like to meet your boy.”

So it happened that on emerging from the test David found himself shaking hands with an elderly gentleman whose kindly eyes and pleasant voice won his liking.

“He looks like the right sort,” said Mr. Dean, turning to Dr. Ives with a smile. “How did you find the examinations?”

“Not very hard,” replied David.

“Good; then you’ll be in the fifth form without a doubt; the Latin class will assist us to a better acquaintance. Good-bye, Dr. Ives; we’ll take good care of your son.”

Dr. Ives looked after the tall figure of the master as he swung away, gripping his stout cane by the middle, and said:

“David, my boy, there’s a gentleman and a scholar. Be his friend, and let him be yours.”

“Yes, father,” David said obediently.

They walked slowly to the building in which David had his room, climbed the stairs, and sat down by the window. Dr. Ives looked out in silence for a time, wishing to fix in his mind the view that was to become so familiar to his son—the grassplots bounded by stone posts and white rail fences, the roadways, lined with maple trees, the clustered red-brick buildings above which rose the lofty chapel tower in the sunlight of the warm September day.

“This should be a good place to study in, David,” he said. “It’s in the quiet places that a man can prepare himself best.”

“I don’t know how quiet it will be to-morrow,” said David, “when about two hundred and fifty old boys arrive.”

“Oh, yes, it will be lively enough at times, and I’m glad of that, too. And you’ll go in for all the activities there are; I needn’t urge that. The thing I do want to emphasize, David, is the importance of making full use of all the quiet hours.”

“I will do my best, father.”

“And you will remember, of course, that it’s more necessary for you than for most of the fellows you will associate with to practice economy.”

“Yes, father, I shall be careful.”

There was silence, and during it they saw a motor-car turn in at the gateway and a moment later draw up before the steps of the building. They both knew what it meant, yet each shrank from declaring it to the other.

“Write to us often, David,” said Dr. Ives. “You will be always in our hearts; we shall be thinking and talking of you every day. Don’t forget us.”

David found himself unable to speak. He shook his head and squeezed his father’s hand. They sat again in silence for a little while.

“Well, my boy—” said Dr. Ives.

Hand in hand they went along the corridor and down the stairs. Outside the building the father turned and took his son into his arms. That last kiss became one of David’s sweetest and saddest memories.

It was surprising even to himself how soon he fitted into place. His seat in chapel, his desk in the schoolroom, his locker in the gymnasium, his place in the dining-hall—at the end of a week he thought of them as if they had always been his. In the same short time he was recognized as the fellow who was likely to lead his division of the fifth form in scholarship. His uncomfortable zeal for study and his tendency to forge instantly to the head of his class, regardless of being a “new kid,” were not conducive to the attainment of popularity. So, although in superficial ways the school soon became a second home to him, he felt that in the things that counted he remained a stranger.

He was disappointed in his expectation that Lester Wallace would come forward and welcome him. When in Mr. Dean’s Latin class he first heard Wallace called on to recite, he glanced round in eager interest. A stocky, smiling, good-natured-looking youth was slowly rising to his feet; his voice, as he began to translate, was lazy,[33] yet had a pleasant tone; his manner when he came to a full stop in the middle of an involved sentence that had entangled him suggested that he was humorously amused by a puzzle rather than concentrating his mind on the solution. He acquiesced without rancor in Mr. Dean’s suggestion that he had better sit down. Later when David was called on to recite, he wondered whether Wallace was looking at him with any interest; he wondered whether the name of Ives had any significance for Wallace. Apparently it had not, for after the hour Wallace passed David on the stairs without pausing to speak.

When the noon recess came some of the fellows, instead of dispersing to the dormitories, lingered in groups outside the study building. Among them was Wallace, and with the faint hope that Wallace might now come up to him, David lingered, too. He was too shy to make any advances to one who was an “old” boy, too proud to court the friendship of one who was obviously well known and popular; yet Wallace, with his pleasant, lazy voice, twinkling eyes, and leisurely air of good nature, attracted him. While he stood looking on, a girl, perhaps fifteen years old, came through the rectory gate just across the road; she was tossing a baseball[34] up and catching it and now and then thumping it into the baseball glove that she wore on her left hand. She was slender and graceful, and the smile with which she responded to the general snatching off of caps seemed to David sweet and fascinating; her large straw hat prevented him from determining how pretty she was, but he was sure about her smile and her rosy cheeks and her merry eyes.

“Here you are, Ruth!” Lester Wallace held up his hands.

She threw the ball to him, straight and swift, with a motion very like a boy’s, and yet oddly, indescribably feminine. He returned it, and she caught it competently.

“Isn’t any one going to play scrub?” she asked. At once Wallace cried, “Yes; one!” She cried, “Two!”—and they danced about while the others shouted for places. When they had all moved off toward the upper school with the girl and Wallace in the lead, David followed, partly out of curiosity and partly also out of reluctance to dismiss quickly such a pleasant person from his sight.

He watched the game of scrub behind the upper school and was struck by the girl’s skill, her freedom and grace of action, her fearlessness in facing and catching hard-hit balls, and also by the rather[35] more than brotherly courtesy of all the fellows; they seemed to try to give her the best chances and yet never to condescend too much. Apparently she and Wallace were especially good friends; she reproached him slangily, “O Lester, you lobster!” and he was often comforting or encouraging—“Take another crack at it, Ruth!” “Beat it, Ruth, beat it!” and once in rapture at a stop that she had made, “Oh, puella pulchrissima!”

Looking on, David felt there was another person in the school besides Wallace that he would very much like to know. He ventured to ask a boy standing by who the girl was.

“The rector’s daughter—Ruth Davenport. Peach, isn’t she?”

“Yes, peach,” said David.

He continued to look on until the ringing of the quarter bell for luncheon put an end to the game.

Afterwards, looking back upon those early days at St. Timothy’s, David sometimes wondered whether he had possessed any individuality whatever. It seemed to him that he had been merely a submerged unit that had brief periods of consciousness,—of homesickness, of pleasure, of suffering,—but that for the most part was swept along on its curiously insensate way. He remembered the sharpness of contrast between the day when he first saw St. Timothy’s and the day when the school formally opened—the quiet, depopulated aspect of one and the bustling and populous activity of the other. From that opening day life seemed to flow in currents all about him and to drag him on with it, passive, bewildered sometimes, sometimes struggling, sometimes swimming blithely, but always in a current that bore him on and on. Each morning it began, with the streams of boys flowing at the same hour toward the same spot, from the dormitories to the chapel; then from the[37] chapel to the schoolroom; finally from the schoolroom back to the dormitories again; afterwards to the playgrounds, where they trickled off into a lot of separate bubbling little springs, only to be sluiced together again at the distant ringing of a bell and sent streaming back to the school.

Gradually David made friends; gradually, too, he came into hostile relations with certain fellows. Chief among his friends was another new boy and fifth-former, Clarence Monroe, whom he sat next to at table. They were, as it happened, the only new boys at that table, and their newness might of itself have bound them together. But they quickly discovered sympathetic qualities—love of reading and of the same authors, keenness for baseball and for track athletics, and, in the circumstances most uniting of all, kindred antipathies. For the sixth-formers at the table, of whom there were several, seemed to feel that their sanctity was invaded by the two “new kids” and were disposed to be offish and censorious. One of them in particular, Hubert Henshaw, who sat opposite David, made himself disagreeable. He was apparently a leader in certain ways.

“The glass of fashion and the mould of form,” commented Monroe satirically to David. They[38] were reading Shakespeare in the English class, and David replied:

“Yes, perfumed like a milliner. I think it’s all right for a fellow to keep anything up his sleeve except his handkerchief.”

“I always feel there’s something wrong with a fellow that always has his socks match his necktie,” said Monroe.

But though they indulged themselves thus freely in shrewd comment when they were alone together and revenged themselves in imagination by such criticism for the slights and indignities put upon them, they could not resent effectively the treatment that Henshaw and, under his leadership, the others administered to them. There were frequent comments on the ignoble character of the fifth form and the scrubby quality of its new kids. Henshaw occasionally expressed the opinion that the school was deteriorating: “There was no such rabble of new kids when we were young.” He went on one day to say, looking meanwhile over David’s head: “Many of them even seem not to have decent clothes. Has any one seen more than two or three new kids with the slightest pretense to gentility?”

David recognized the thrust at him and his clothes and said, “I’ve seen one sixth-former with plenty of pretense.”

It was not a smart retort, but it caused the blood to gather in Henshaw’s forehead, and for the time being it silenced him. But the episode rankled in David’s mind. It was the first intimation he had received that the discrepancies of which he himself had been aware between his dress and that of most of the fellows had been noticed by the others. No one but Henshaw had been unkind enough to comment; even Henshaw’s friends at the table had looked uncomfortable when he made the remark; but David, thinking of the pains and the careful thought and the enforced economy of expenditure with which his mother had assisted him to purchase his clothes, and of the satisfaction that she had taken in their appearance, was wounded not merely in his pride but in his affection. From that moment he hated Henshaw.

It disappointed him to learn, as by observation he soon did learn, that Henshaw, though a sixth-former, was a friend of Wallace’s. They were often together, walking from the dormitory to the chapel or lounging in the dormitory hall. Their intimacy was explained to David when one evening while he was sitting in the hall waiting for the dinner bell Wallace came up and said:

“Hello, Ives; my cousin, Huby Henshaw, tells[40] me that you come from my town. I wish I’d known it earlier.”

He seated himself beside David and continued with cheerful geniality:

“How are you getting on? I know you are a shark in lessons, of course; all right otherwise?”

“Pretty fair, thanks.”

“Funny I didn’t know about you till Huby happened to mention it. Whereabouts do you live—what part of the town? How did you happen to come here?”

“In a way, because of your father,” David answered. “My father is a doctor in Rosewood, and he wants me to be a surgeon like yours. He thought that, since your father came here to school, I had better come here, too.”

“I must write and tell dad about it: he’ll be awfully pleased. I guess he’ll think you’re more of a credit to him than I am.”

“Oh, I guess not,” said David. Then, prompted by Wallace’s friendliness, he went on to tell of his meeting with Dr. Wallace and of hoping that Wallace would come up to him—just as he had done.

“Dad forgot all about it,” said Wallace. “I’m glad you told me. You room in the north wing, don’t you?”

“Yes.”

“I’m in the south. Come and see me sometime.”

Apparently Henshaw had not poisoned Wallace’s mind, whether he had tried to do so or not, and for his cousin’s sake David was for a little while more kindly disposed toward Henshaw.

But the era of good feeling could not last. Two days later, as David and Monroe were passing after breakfast from the dining-room into the outer hall, Henshaw thrust his way up to them.

“Ives,” he said, “we’ve all got mighty sick of that necktie. Is it the only one you have?”

“Oh, shut up, Hube!” It was Wallace, at Henshaw’s side, who spoke; even in the stupefaction of his anger David saw that on Wallace’s face a look of concern was overspreading its habitual good nature; Wallace was plucking at his cousin’s sleeve. “Shut up, Hube; you make me tired!”

“If you sat at our table, that necktie would make you tired. What’s the reason that you never make a change, Ives? Is it your only one?”

David’s eyes were hard and glittering. With a suddenness that startled every one he gave Henshaw a resounding slap on the cheek with his open hand. Henshaw staggered from the blow and stood for an instant, blinking, gathering pugnacity, while his[42] cheek showed the livid marks of David’s fingers. Before he could retaliate, Mr. Dean was sweeping the crowd aside and exclaiming in a stern voice, “Henshaw, Ives, what’s this?”

They both looked at him, silent, equally defiant. David felt that he could justify himself and that he must not—a feeling that intensified his bitterness. Why should an act prompted by righteous indignation disgrace and discredit him before the man who had been ready to befriend him?

“You may go now.” Mr. Dean’s eyes were as stern as his voice.

The two principals in the row were escorted by a crowd out of the door and down the steps. At the bottom Henshaw turned and said to David, “You’ve got to fight me for this.”

“It will be a pleasure,” David answered bitterly.

Meanwhile Wallace and Monroe had remained behind, close to Mr. Dean. Wallace was the first to speak.

“Mr. Dean,” he said, “I hope you won’t report Ives. He simply had to slap Huby’s face.”

“Why?”

“Huby insulted him.”

“Henshaw’s always insulting him,” broke in[43] Monroe. “At the table he’s always saying nasty things. Ives couldn’t stand it any longer, Mr. Dean.”

“What was the remark that provoked the blow?”

Wallace repeated it as he remembered it; Monroe’s version was essentially the same.

“I am glad to have your evidence,” said Mr. Dean. “However, there is no question that Ives infringed the rules, and for that he will have to be punished.”

“It isn’t fair!” protested Monroe.

“Possibly not. Sometimes it is necessary to be unfair in the interests of discipline. At any rate, you both may feel that you have done Ives and me a service by telling me the facts in the case.”

Wallace and Monroe alike wondered what the service had been when after chapel they heard David’s name read out on the list of moral delinquents for the day: “Ives, disorder in dormitory, one sheet.” That meant an hour of work that afternoon on Latin lines.

David, hearing it, flushed with mortification. So Mr. Dean had chosen to judge him harshly. It was natural enough; so far as Mr. Dean had been aware, there were no mitigating circumstances.

His thoughts wandered from his books that morning. He continued to make creditable recitations when called on, but at other times he did his work listlessly and with many pauses. He was not afraid to fight Henshaw; he wanted to fight him; he wanted to administer a punishment more severe than that one resounding slap on the face. And yet he hated fighting; he had never engaged in a fight at the high school; he remembered the most savage fight there that he had ever seen, how he had stood by, fascinated and yet disgusted, too, by the blazing fury in the combatants’ eyes, their dishevelment, their blood-marked faces, the animal wrath with which they mauled and grunted and battered. He had been disgusted by it all, by his own interest in the spectacle, by the gloating eyes of the other bystanders. It revolted him now to think of presenting such a spectacle himself; and yet he knew that unless Henshaw came to him and apologized he would fight him as long as either of them could stand.

In the five minutes’ intermission before the Latin class Wallace and Monroe came and told him of their interview with Mr. Dean. That cheered him; so did Wallace’s remark: “Henshaw’s my cousin, but he makes me awfully tired at times. I’m with you and not with him in this.”

At the end of the Latin recitation when David was going out Mr. Dean said, “Ives, one moment, please.” David stopped while the master gathered up books and exercises. “If you’re going up to the dormitory, I’ll walk along with you,” said Mr. Dean. And as they walked along the corridor he asked, “Where did you get your feeling for the language?”

“For Latin? I didn’t know I had it.”

“Oh, yes, you have, to quite a marked degree. I hope that you’ll continue to cultivate the language—not, like so many, abandon it at the first opportunity. There are very few persons nowadays who read Latin for pleasure—with pleasure. You will be able to do it if you keep on, for you have the feeling for the language. It will help you in acquiring other languages.”

They passed out of the door, and then Mr. Dean said abruptly:

“No doubt it seems harsh to you that I should be punishing you alone for the disorder this morning. Well, discipline often must stand on technicalities. Yours was the only visible breach; so you have to suffer. I want to say, however, that I realize there are occasions when self-respect, to vindicate itself, must defy rules—and[46] this appears to have been one of those occasions. If Henshaw affords you the opportunity, I trust you will complete his punishment. Make it substantial.”

He shook hands with David quite solemnly and then turned aside up the path leading to his house.

The talk put new cheerfulness into David’s heart. Mr. Dean understood and sympathized and was still his friend. And fighting was just one of those unpleasant things that you had to do now and then in life, and there was no use in letting yourself get disgusted at the thought of it.

He felt so much better in his mind that at the luncheon table he turned back Henshaw’s scowl with a cheerfully ignoring glance and devoted himself with unconcern to his friend Monroe until Truesdale, the sixth-former who sat on his left, said:

“Henshaw wants me to tell you he’ll meet you this afternoon back of the sawmill at three o’clock.”

“He’ll have to make it half-past three,” David replied. “I have lines until then.”

Truesdale glanced across the table at Henshaw, who nodded.

“All right; half-past three,” Truesdale said. “Don’t bring a crowd.”

“I shan’t bring anybody but Monroe here,” David answered.

“You fellows will probably collect the whole sixth form,” said Monroe, whose pugnacity was roused even more than David’s.

“Don’t get excited, little one,” replied Truesdale. “All we care about is to see fair play.”

After luncheon Monroe walked with David to the study building, where David for an hour was to perform his task of penmanship.

“Are you pretty good with your fists?” Monroe asked.

“I have no special reason to think so,” David answered. “But I guess I can hit as hard as he can.”

“If you’re not much on boxing, you’ll have to stand up to him and take what you get until you can put in enough good cracks to finish him.” Monroe spoke with a certain satisfaction in the prospect of a sanguinary encounter. He was a freckled-faced, red-haired, snub-nosed boy; his blue eyes were sparkling and snapping with expectancy.

“I’m not worrying much,” David answered. “He may lick me or I may lick him, but either way I guess he will regret having brought it on himself. And that’s the main thing.”

“Sure,” said Monroe. “But lick him.”

They parted at the door of the study. Monroe assured David that he would meet him there at a little before half-past three o’clock.

When David finally emerged, he found Monroe waiting outside and Wallace again passing a ball with the rector’s daughter.

“I’ve got to stop now, Ruth; I have a date,” Wallace said.

She put the ball into the pocket of her leather coat and drew off her glove. Then she greeted David with a nod and a smile.

“You know Ives, don’t you, Ruth? And Monroe?” Wallace performed the belated introduction.

“Oh, yes, I know everybody.” She shook hands with each of them. “Your name’s Clarence, and yours is David. Oh, don’t you want to have a game of scrub?”

She looked from one to another with hopeful, boyish eyes. Wallace was the ready-tongued one of the three. “Sorry, Ruth, but we have a date to go for a walk—going to meet some fellows in the woods.”

“Oh!” Her voice was regretful. “Well, good-bye.”

The boys touched their caps to her as she turned away; David glanced back at her remorsefully.

“She’s a pretty good kid,” Wallace remarked. “Sort of hard luck on her; there are no other girls of her age round here for her to play with. She’s very decent about not butting in; fellows can’t always be having a girl round.”

“No, you bet not,” agreed Monroe, though like David he had cast sheepish backward glances.

As for David, the sight of the girl had revived the sense of loathing for the brutalities of battle that Mr. Dean’s cheerful words of encouragement had aided him temporarily to suppress. He walked on silently, thinking how that girl would hate him if she knew what he was about to do. His mood again became one of sullen revengefulness against Henshaw, whose behavior had forced the situation upon him.

He and his friends entered the pine woods that bordered the pond behind the gymnasium. Soon they passed beyond sight of the school buildings; they walked on until they emerged from the quiet woods upon a hillside crowned with a decrepit apple orchard; they climbed a hill and followed a path that led them into a thicket of birch and oak; and at last they came out into an open space behind a disused sawmill. There seven or eight fellows, among them Henshaw, were waiting.

One of the sixth-formers, Fred Bartlett, who had played end on the school football team the preceding year, stepped forward.

“I’ve been asked to referee this scrap,” he said. “Any objection, Ives?”

David shook his head.

“Two-minute rounds. Get ready now, both of you; strip.”

Ruth had stood with a puzzled look in her eyes gazing after David and Wallace and Monroe as they entered the path into the woods. A few minutes before, a group of her sixth-form friends had passed that way and to her friendly inquiry whither they were bound had, like Wallace and Monroe, returned vague, evasive answers. On an afternoon ideal for games it seemed to Ruth incomprehensible that so many fellows should be going for a walk. She had not been brought up in a boarding-school without acquiring wisdom in the ways of boys, and when another group of fifth-formers slipped by and entered the path into the woods her suspicions were aroused.

Harry Carson, captain of the school eleven and the most influential and popular fellow in St. Timothy’s, came sauntering down from the upper[51] school with his roommate, John Porter. They took off their caps as they passed Ruth and then turned into the path that all the others had followed.

Ruth formed a sudden, courageous resolve.

“O Harry!” she called. “Won’t you wait a moment, please?”

Carson turned and came back toward her, and she advanced to meet him.

“Why is everybody going into the woods this afternoon?”

“Is every one?” said Carson.

“Yes, I think it must be that there’s going to be a fight. Isn’t that it, Harry?”

“What put such an idea as that into your head?”

“I just feel it, and I know it from the way you ask that question. I think a fight is perfectly horrid. Won’t you stop it?”

“Sometimes when there’s bad blood between two fellows the best thing is to let them fight it out.”

“Who are the fellows?”

“It would hardly be fair for me to tell.”

“I suppose it wouldn’t. But fighting seems such a stupid and senseless way of settling a difference. And it’s just as likely to settle it the wrong way as the right way. I wish you’d stop this fight, Harry.”

“I haven’t any authority to stop it.”

“They wouldn’t fight if you told them they weren’t to do it. Why, they wouldn’t fight if even I told them they weren’t to do it!” cried Ruth with sudden conviction. Her eyes flashed as she added: “If you won’t give me your word that you’ll stop it, I’ll go into the woods myself and find those boys and stop them.”

“No, that wouldn’t do at all, Ruth,” said Carson anxiously.

“I will, unless you promise.”

“I’ll do what I can.”

“Good for you! And do hurry!”

Carson turned away and rejoined his companion, to whom he reported the conversation.

“The girl’s more or less right,” said Porter. “Henshaw ought to be made by the crowd to apologize to Ives; it oughtn’t to be necessary for Ives to fight him. I’m with you in what ever you do.”

Carson and Porter came into the open space behind the sawmill just as the two combatants, stripped to the waist, stood up to face each other. Carson broke rudely through the circle of eager onlookers and shoved his heavy bulk between the two gladiators.

“It’s all off,” he said, addressing Henshaw rather more than David. “If you fellows have so much energy and fight to get rid of get out and play football. One of you owes the other an apology, and he knows mighty well that he does. When he makes it there will be no occasion for anything further.”

“Oh, let them go to it, Harry!” cried a disappointed spectator. “It’ll do them good.”

“I’ll fight anybody that tries to make them fight,” replied Carson belligerently, and the crowd laughed. “I’ll fight them if they try to fight,” he added. “And I’ll say that one of these two fellows, if he doesn’t apologize to the other for his insulting remarks, deserves a licking—whether he gets it or not.”

David spoke up crisply, “I have nothing to apologize for.”

There was a moment’s silence, and then Henshaw said in a rather subdued voice: “I have. I beg your pardon, Ives. I was insulting, and you had a right to resent it.”

David put out his hand, Henshaw took it, and Carson administered to each of them a loud and stinging clap on the bare back, which drew an[54] “Ow!” from Henshaw and a delighted guffaw from the crowd.

The two participants in the bloodless encounter put on their clothes, the meeting broke up, and in groups of twos and threes the fellows took their way back to the school.

Ruth came out of the rectory as David and Monroe and Wallace were going by.

“Why, you weren’t gone very long on your walk, were you?” she said.

“Well, no,” Wallace answered. “We decided we’d do something else, after all.”

At that moment Carson and a group of sixth-form friends, among them Henshaw, came up.

“I have the honor to report, Ruth,” said Carson, “that I fulfilled orders. I am the great pacificator.” He suddenly grabbed Henshaw by the collar with his right hand and David by the collar with his left. “I have the honor to restore to you one Huby Henshaw of the sixth form and one David Ives of the fifth, unscathed, unscratched, unharmed.”

“Good boy!” exclaimed Ruth. Her eyes sparkled with amusement, laughter rose from the crowd, and David and Henshaw stood blushing and grinning foolishly.

“You certainly do look like a pair of sillies,” said Ruth. “But you might be looking even worse—and you’ve got me as well as Harry Carson to thank that you aren’t. Come in now, and I’ll give you all some tea.”

David learned that the handicap track meet held every autumn by the Pythians and Corinthians would take place in the latter part of October. He entered his name for the quarter-mile as a representative of the Pythians.

He found that he had outgrown the running shoes that he had worn in the spring when he had been the “crack” quarter-miler of the high school. So he put on his tennis “sneakers” and practiced daily on the track in those. Most of the candidates for the track meet proved to be very casual in their training; they were nearly all out trying for a place on one of the Pythian or Corinthian football elevens, and that meant that they had to do their track work in the half-hour recess before luncheon or on occasions when they were excused from football. There was no regular coaching for them; Bartlett, the Pythian captain, and Carson, the Corinthian, were alike devoting their chief energies to football, but occasionally found time to[57] supervise the work of their candidates, and more often Mr. Dean, though superannuated so far as active participation in athletics was concerned, gave hints and advice out of a historic past.

Among those who were playing football on the Corinthian eleven was Wallace. He told David, however, that he meant to enter the quarter-mile, too, and that he was coming out a couple of days before the meet to see if he could get back his speed; he had finished third in the championship meet of the preceding spring. When he made his appearance in running clothes two days before the race he asked David to time him and was much pleased because he ran the distance in only one second more than at the spring meet. “And if I’d had to, I could have pushed myself a little. Now I’ll time you, Ives. You haven’t got on your running shoes—spikes hurt your feet?”

“Yes, the old shoes are too small. But these will do.”

David started off, and while he was circling the track Bartlett came over from the football practice and watched him.

“Look here!” exclaimed Wallace in excitement when David stopped, panting, in front of him. “As nearly as I can make it your time is the same as mine to a fraction!”

“Then I guess I shall have to push myself a little, too,” David said.

“Both Johnson and Adams, who licked me last year, have left the school, and I thought I had a cinch,” Wallace complained. “And now you turn up, running like a deer!”

Bartlett put in a word of praise. “You’re going pretty well, Ives. To-morrow be sure to come out in running shoes.”

“I haven’t any,” David replied.

“You can get them at the store in the basement of the study.” [see Tr. Notes]

“I’m sorry, but I can’t afford to buy them.”

“You needn’t pay cash. You can have them charged on your term bill.”

“I can’t afford it, anyway.”

Bartlett looked at him perplexed, unable to see why a fellow could not afford to have a thing charged on his term bill—for his father to pay.

Wallace spoke up. “Maybe you could wear an old pair of mine,” he said. “What’s your size?”

“Eight, I think.”

“So is mine. I’ll see if I can’t fit you out.”

“Thanks. I guess, though, I can run in these.”

“No, you can’t,” Bartlett said. “It will be[59] mighty decent of you to lend him your extra pair, Wallace.”

Half an hour later David entered the basement of the study and went to the locker room to hang up his sweater. Returning, he passed the open door of the room in which athletic supplies were kept for sale and saw Wallace trying on a pair of shoes; a second glance showed David that they were running shoes. He flushed with instant understanding, and without letting Wallace know of his presence he went upstairs.

Before dinner that evening Wallace came to his room, bearing a pair of spiked shoes.

“Yes, I found I had an extra pair,” he said carelessly. “Here you are. I hope they fit.”

David gravely tried them on. “Yes they’re a perfect fit,” he said. “I hope your new ones fit you as well.”

“My new ones?”

“Yes. You’ve been running in these right along, and you’ve just bought yourself a new pair in order to give these to me.”

“Oh, you’re dreaming.”

“It was no dream when I saw you trying them on in the store. You oughtn’t to have done it, Wallace. It was awfully good of you.”

“Oh,” Wallace said, trying to conceal his embarrassment, “I didn’t want to have you run in sneakers and lick me. That would be too much. Besides, old top, we’ve got to stand by each other; we come from the same town.”

If David could not express his appreciation fully to Wallace, he could at least tell some one who would appreciate Wallace’s act, and it came into his mind to tell Mr. Dean. Not only would Mr. Dean, who had followed his practice, be interested, but he might be moved to look more leniently on Wallace, who was giving very casual attention to his Latin.

A good opportunity presented itself the next afternoon. Mr. Dean watched him while he made his trial and after it congratulated him on his speed and commented on the improvement produced by the aid of the running shoes.

“I owe them to Wallace,” David said, and then he described the manner in which Wallace had relieved his need.

“Very thoughtful and tactful as well as very sportsmanlike,” commented Mr. Dean. “That’s the kind of thing I like to hear of a fellow’s doing. I’m almost tempted to raise his Latin marks.”

“I hoped you might be.”

“Even if I were, it wouldn’t help his prospects for passing his college entrance examinations. The trouble with Wallace is he has never yet learned how to study.” Mr. Dean paused for a moment; then he said, “Come up to my rooms after you’ve dressed, and we’ll talk over Wallace’s case.”

So in half an hour they were holding a conference.

“I suppose that you’d like to help Wallace if you could,” Mr. Dean began, and David assented earnestly.

“It may be possible—just a moment till I change my seat; my eyes are bothering me; the light troubles them. Now! As I said, Wallace hasn’t learned how to study. Would you be willing to teach him?”

“Of course, if I could.”

“Now suppose that you and Wallace were excused from the schoolroom for an hour each day and given a room to yourselves in which to work out the Latin together, without interference or supervision from anybody—just put on your honor to study Latin every minute of that hour—couldn’t you be of some use to Wallace?”

“I might be,” said David thoughtfully. “I should try.”

“The trouble with him is, sitting at his desk in the schoolroom he doesn’t concentrate his thoughts. He studies, or thinks he studies, for a few minutes; then he changes to another book, then his eyes wander and with them his thoughts, then he takes up a pen and begins to practice writing his signature; it’s really wonderful, the variety of flourishes and the decorative illegibility that he has managed to impart to it through such frequent idle practice. Of course when he’s detected wasting time he’s brought to book for it, but the master in charge of the schoolroom can’t ever compel him to give more than the appearance of studiousness. And that, I am afraid, is the most that he ever does give. But he’s an honorable fellow; and I believe that, put on his honor to study where there was no watchful eye to challenge his sporting spirit and with you to guide him, he might achieve results. On the other hand, for a while, anyway, such an arrangement would probably slow you up.”

“I should try not to let it. Even if it did, it wouldn’t be a serious matter.”

“No more serious probably than slipping from first place to second or third.”

“That wouldn’t be important.”

“If it happened as a consequence, I should write[63] to your father and explain. I hope, by the way, that you have good news of him?”

David’s face clouded. “Not very. He doesn’t say anything himself, but mother writes that his vacation seems to have done him no good. She says he looks bad and seems played out. But he goes on working.”

“That’s a habit of good doctors. Remember me to him when you write. I will have a talk with the rector and see what arrangements we can make for you and Wallace. Good luck to you in your race to-morrow. The handicapping committee are putting you and Wallace together at scratch.”

David expressed his satisfaction at that news.

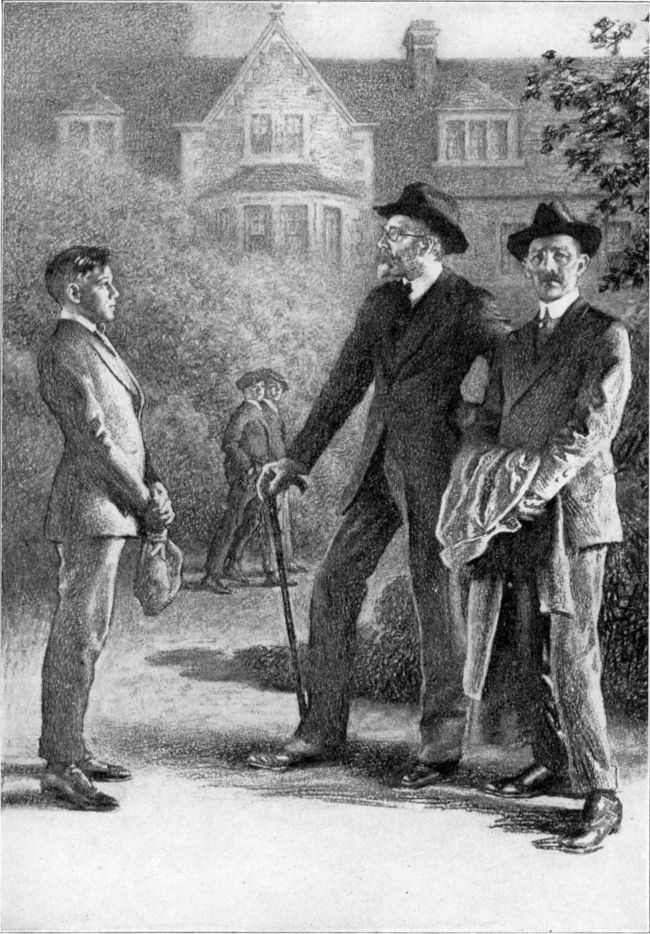

The event justified the handicapping committee’s arrangement. Besides David and Wallace there were only two contestants in the quarter-mile, a fourth-former named Silsbee, who was given twenty yards, and a sixth-former named Heard, who was given ten. It was a chill and windy day, a fact that reduced the number of spectators to a small group who stood near the finish line with their hands in their pockets and their overcoat collars turned up; on the turf encircled by the track the football squads continued to practice, more or less oblivious of the races that were being run;[64] what chiefly marked the day as different from one of trial tests and dashes was the table placed on the grass near the athletic house and bearing an assortment of shining pewter mugs and medals.

It was toward the end of the afternoon that the quarter-mile was called. David and Wallace started together at the crack of the pistol and held together, shoulder to shoulder, halfway round the course. There they passed Heard, and a little farther on they passed Silsbee, and then Wallace forged a little ahead of David. But David had planned out his race; he was not going to be drawn into a spurt until he was a hundred yards from home. So he let Wallace lengthen the distance between them from one yard to five, and from five to ten; and then he set about closing up the gap. It closed slowly but surely—one yard, two yards, three yards gained; then four and then five. For a moment Wallace, who heard David coming up, held that lead, but for a moment only; then David put on all his speed and the five yards’ difference vanished in as many seconds. Twenty yards from the finish the two were racing neck and neck, but David crossed the line a good three feet ahead.

In the athletic house Wallace panted out his congratulations, and David gasped his thanks.

“Handicapped by new shoes, I guess,” David suggested.

“No; you’d have won in stocking feet. Best quarter-miler in school,” Wallace answered. “You wait, though. Lay for you next spring.”

They finished dressing and got outdoors just in time to see the last event on the programme—the finals of the hundred-yard dash, which was won by a sixth-former named Tewksbury. Then the spectators moved over in a body to the table that bore the prizes. David saw Ruth Davenport take her stand next to Mr. Dean, who waited beside the table, ready to speak.

“I am here merely as master of ceremonies,” said Mr. Dean, “and my chief duty and privilege is to introduce to you Miss Ruth Davenport, to whom, of course, you need no introduction. She will hand to each prize-winner the mug or medal to which his efforts have entitled him. As I call off the names each fellow will please come forward. First in the mile run, W. F. Burton; time, six minutes and fifty-one seconds. Second, H. A. Morton.”

Burton and Morton advanced amidst clapping of hands. David saw the smile that Ruth had for each of them as she presented the trophy, and[66] when in his turn he faced her and took from her hand the cup he was aware of a shining eagerness in her eyes; she bent toward him and said, “Oh, I saw you win! It was splendid!”

He went back to his place in the crowd, feeling incredibly happy.

That evening Mr. Dean said to him as he passed him in the dining-room: “It’s all right, David—the matter about which we had our talk. I’m going to have an interview with Wallace to-night, and I hope that he will recognize at once the benefit he is to derive from the arrangement. You and he can have room number nine to yourselves between eleven and twelve each day.”

The thought of the trust placed in him, of the freedom implied, and of the closer association with Wallace was pleasant to David. He hoped that Wallace would not be unfavorably disposed toward the plan. On that point Wallace himself a couple of hours later reassured him. David was getting ready for bed when there was a knock on his door and Wallace entered.

“Mr. Dean tells me that you have me on your back, Dave,” he said. “Pretty hard luck: I don’t see what there is in it for you.”

“Never mind about that,” David answered. “I[67] hope you are going to like the arrangement, Lester.”

“Oh, it’s fine for me. All I can say is, I’ll try not to be any more trouble to you than is necessary.”

In spite of that excellent resolution, in the succeeding weeks Wallace was a good deal of trouble to David. Not only was he naturally dull at Latin, so that even the simplest matters had to be explained over and over to him, but he was restless and impatient. David would get absorbed in his own work and would suddenly remember that he had a duty to Wallace to perform. And a glance would show him Wallace sprawling on a bench with his eyes fixed vaguely on the opposite wall, or fiddling with his pencil or twirling his key ring on his finger, or scribbling the dates of such coins as he found in his pockets. Then it would be David’s part to say: “Buck up, Lester. What’s the matter? Need some help?” Usually Wallace thought that he did, and it would take David five or ten minutes to get him started and prove to him that he really did not.

“You wouldn’t quit at football just because tackling was hard to learn,” David said. “You oughtn’t to be any more willing to quit at Latin or anything else that you have to try.”

“Why aren’t you out playing football, Dave?” Wallace seemed not at all interested in taking the moral to heart.

“Oh, I’m no good at it. I’ve never played very much. Here, start in now.”

“You ought to make a good end or back, with your speed. Why don’t you come out and try?”

“Why don’t you settle down to your job? We’re not here to talk football.”

As a matter of fact, it was David rather than Wallace whose thoughts went straying after that conversation. In view of the episode of the spiked shoes, how was he to tell Wallace that he could not come out for football simply because he had no clothes? Wallace would probably at once play the fairy godmother again and furnish him with an outfit. David was eager to play; he had gained in weight and strength in this last year; there was nothing he would like better than to test his ability and skill, nothing that he hated worse than to be thought soft and timorous. And that, of course, was what most fellows would think.

But his mother’s letters stiffened his self-denial. She wrote that his father seemed preoccupied and worried, and that patients were not paying their bills, and that, though she knew it was selfish,[69] she could not help wishing every minute that David were at home. So he said to himself that he did not care what people thought; he was not going to cost the family a penny more than was absolutely necessary.

Three days after the track meet he was invited to the rectory for supper.

“You’ll get awfully good food,” said Wallace enviously. “I was there at a blow-out last week.”

The rectory was a hospitable house, and on this occasion there were eight other guests besides David, all fifth-formers, who sat down to supper with the family. The food justified Wallace’s prediction; David blushed under congratulations from both Dr. and Mrs. Davenport, and still more under Ruth’s statement from across the table—“It was a corking race.” After supper the rector walked with him out of the dining-room and said a pleasant word, complimenting him on the assistance he was giving to Wallace.