[p. i]

BY

CHARLES OMAN, K.B.E.

M.A. Oxon., Hon. LL.D. Edin.

FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY

MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

CHICHELE PROFESSOR OF MODERN HISTORY

AND FELLOW OF ALL SOULS COLLEGE, OXFORD

Vol. VI

September 1, 1812-August 5, 1813

THE SIEGE OF BURGOS

THE RETREAT FROM BURGOS

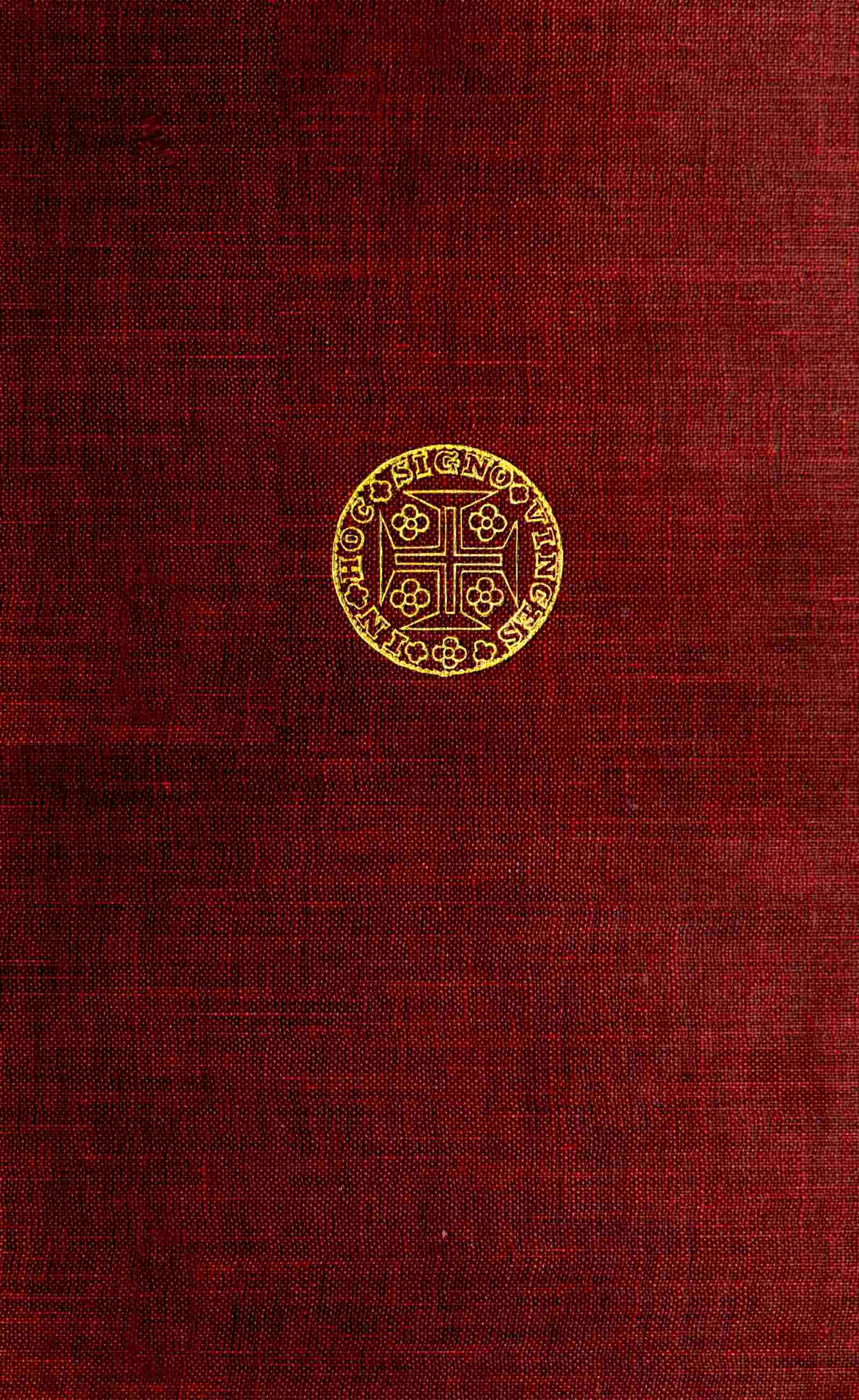

THE CAMPAIGN OF VITTORIA

THE BATTLES OF THE PYRENEES

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1922

[p. ii]

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

London Edinburgh Glasgow Copenhagen

New York Toronto Melbourne Cape Town

Bombay Calcutta Madras Shanghai

HUMPHREY MILFORD

Publisher to the University

Printed in England

[p. iii]

It is seldom that the last chapter of a volume is written seven years after the first has been finished; and when this does happen, the author is generally to blame. I must ask, however, for complete acquittal on the charge of dilatoriness or want of energy. I was writing the story of the Burgos Campaign in July 1914: in August the Great War broke out: and like every one else I applied for service in any capacity in which a man of fifty-four could be useful. By September 4th I was hard at work in Whitehall, and by a queer chance was the person who on September 12th drafted from very inadequate material the long communiqué concerning the battle of the Marne. For four years and six months I was busy in one office and another, and ended up my service by writing the narrative of the Outbreak of the War, which was published by the Foreign Office in February 1919. My toils at the desk had just finished when it happened that I was sent to the House of Commons, as Burgess representing the University of Oxford, after a by-election caused by the elevation of my predecessor, Rowland Prothero, to the Upper Chamber. Two long official tours in the Rhineland and in France combined with parliamentary work to prevent me writing a word in 1919. But in the recess of 1920 I was able to find time to recommence Peninsular War studies, and this volume was finished in the autumn and winter of 1921 and sent to the press in January 1922.

It was fortunate that in the years immediately preceding the Great War I had been taking repeated turns[p. iv] round the Iberian Peninsula, so that the topography of very nearly all the campaigns with which this volume deals was familiar to me. I had marvelled at the smallness of the citadel of Burgos, and the monotony of the plains across which Wellington’s retreat of 1812 was conducted. I had watched the rapid flow of the Zadorra beside Vittoria, marked the narrowness of the front of attack at St. Sebastian, and admired the bold scenery of the lower Bidassoa. Moreover, on the East Coast I had stood on the ramparts of Tarragona, and wondered at the preposterous operations against them which Sir John Murray directed. But there are two sections of this volume in which I cannot speak as one who has seen the land. My travels had never taken me to the Alicante country, or the scene of the isolated and obscure battle of Castalla. And—what is more important—I have never tramped over Soult’s route from Roncesvalles to the gates of Pampeluna, or from Sorauren to Echalar. Such an excursion I had planned in company with my good friend Foster Cunliffe, our All Souls Reader in Military History, who fell on the Somme in 1916, and I had no great desire to think of making it without him. Moreover, the leisure of the times before 1914 is now denied me. So for the greater part of the ten-days’ Campaign of the Pyrenees I have been dependent for topography on the observations of others—which I regret. But it would have been absurd to delay the publication of this volume for another year or more, on the chance of being able to go over the ground in some uncovenanted scrap of holiday.

I have, as in previous cases, to make due acknowledgement of much kind help from friends in the completion of this piece of work. First and foremost my thanks[p. v] are due to my Oxford colleague in the History School, Mr. C. T. Atkinson of Exeter College, who found time during some particularly busy weeks to go over my proofs with his accustomed accuracy. His criticism was always valuable, and I made numerous changes in the text in deference to his suggestions. As usual, his wonderful knowledge of British regimental history enabled me to correct many slips and solecisms, and to make many statements clearer by an alteration of words and phrases. I am filled with gratitude when I think how he exerted himself to help me in the midst his own absorbing duties.

In the preceding volumes of this work I had not the advantage of being able to read the parts of the Hon. John Fortescue’s History of the British Army which referred to the campaigns with which I was dealing. For down to 1914 I was some way ahead of him in the tale of years. But his volumes of 1921 took him past me, even as far as Waterloo, so that I had the opportunity of reading his accounts of Vittoria and the Pyrenees while I was writing my own version. This was always profitable—I am glad to think that we agree on all that is essential, though we may sometimes differ on matters of detail. But this is not the most important part of the aid that I owe to Mr. Fortescue. He was good enough to lend me the whole of his transcripts from the French Archives dealing with the Campaign of 1813, whereby I was saved a visit to Paris and much tedious copying of statistics and excerpting from dispatches. My own work at the Archives Nationales and the Ministry of War had only taken me down to the end of 1812. This was a most friendly act, and saved me many hours of transcription. There are few authors who are so liberal and thoughtful for the benefit of their[p. vi] colleagues in study. It will be noted in the Appendix that quite a large proportion of my statistics come from papers lent me by Mr. Fortescue.

As to other sources now first utilized in print, I have to thank Mr. W. S. D’Urban of Newport House for the loan of the diary of his ancestor Sir Benjamin D’Urban—most valuable for the Burgos retreat, especially for the operations of Hill’s column. Another diary and correspondence, which was all-important for my last volume, runs dry as a source after the first months of 1813. These were the papers of Sir George Scovell, Wellington’s cypher-secretary, from which so many quotations may be found in volume V. But after he left head-quarters and took charge of the newly formed Military Police [‘Staff Corps Cavalry’] in the spring before Vittoria, he lost touch with the lines of information on which he had hitherto been so valuable. I owe the very useful reports of the Spanish Fourth Army, and the Marching Orders of General Giron, to the kindness of Colonel Juan Arzadun, who caused them to be typed and sent to me from Madrid. By their aid I was able to fill up all the daily étapes of the Galician corps, and to throw some new light on its operations in Biscay.

To Mr. Leonard Atkinson, M.C., of the Record Office, I must give a special word of acknowledgement, which I repeat on page 753, for discovering the long-lost ‘morning states’ of Wellington’s army in 1813, which his thorough acquaintance with the shelves of his department enabled him to find for me, after they had been divorced for at least three generations from the dispatches to which they had originally belonged. Tied up unbound between two pieces of cardboard, they had eluded all previous seekers. We can at last give[p. vii] accurately the strength of every British and Portuguese brigade at Vittoria and in the Pyrenees.

I could have wished that the times permitted authors to be as liberal with maps as they were before the advent of post-war prices. I would gladly have added detailed plans of the combats of Venta del Pozo and Tolosa to my illustrations. And I am sorry that for maps of Tarragona, and Catalonia generally, I must refer readers back to my fourth volume. But books of research have now to be equipped with the lowest possible minimum of plates, or their price becomes prohibitive. I do not think that anything really essential for the understanding of localities has been left out. I ought perhaps to mention that my reconstructions of the topography of Maya and Roncesvalles owe much to the sketch-maps in General Beatson’s Wellington in the Pyrenees, the only modern plans which have any value.

To conclude, I must express, now for the sixth time, to the compiler of the Index my heartfelt gratitude for a laborious task executed with her usual untiring patience and thoroughness.

CHARLES OMAN.

Oxford,

June 1922.

[p. ix]

| SECTION XXXIV | ||

| The Burgos Campaign | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Wellington in the North: Burgos Invested. September 1812 | 1 |

| II. | The Siege of Burgos. September 19-October 30, 1812 | 21 |

| III. | Wellington’s Retreat from Burgos. (1) From the Arlanzon to the Douro. October 22-30 | 52 |

| IV. | Hill’s Retreat from Madrid. October 25-November 6 | 87 |

| V. | Operations round Salamanca. November 1-15 | 111 |

| VI. | Wellington’s Retreat from the Tormes to the Agueda. November 16-20 | 143 |

| VII. | Critical Summary of the Campaigns of 1812 | 167 |

| SECTION XXXV | ||

| I. | Winter Quarters. November-December 1812-January 1813 | 181 |

| II. | The Troubles of a Generalissimo. Wellington at Cadiz and Freneda | 194 |

| III. | Wellington and Whitehall | 214 |

| IV. | The Perplexities of King Joseph. February-April 1813 | 239 |

| V. | The Northern Insurrection. February-May 1813 | 252 |

| VI. | An Episode on the East Coast, April 1813. The Campaign of Castalla | 275 |

| SECTION XXXVI | ||

| The March to Vittoria | ||

| I. | Wellington’s Plan of Campaign | 299 |

| II. | Operations of Hill’s Column. May 22-June 3, 1813 | 313 |

| III. | Operations of Graham’s Column. May 26-June 3, 1813 | 322 |

| IV. | Movements of the French. May 22-June 4, 1813 | 334 |

| V. | The Operations around Burgos. June 4-14, 1813 | 346 |

| VI. | Wellington crosses the Ebro. June 15-20, 1813 | 364 |

| VII. | The Battle of Vittoria, June 21, 1813: The First Stage | 384 |

| VIII. | The Battle of Vittoria: Rout of the French | 413 |

| [p. x]SECTION XXXVII | ||

| The Expulsion of the French from Spain | ||

| I. | Wellington’s Pursuit of Clausel. June 22-30, 1813 | 451 |

| II. | Graham’s Pursuit of Foy. June 22-31, 1813 | 470 |

| III. | The East Coast. Murray at Tarragona. June 2-18, 1813 | 488 |

| IV. | Wellington on the Bidassoa. July 1-12, 1813 | 522 |

| V. | Exit King Joseph. July 12, 1813 | 546 |

| SECTION XXXVIII | ||

| The Battles of the Pyrenees | ||

| I. | The Siege of St. Sebastian: the First Period, July 12-25 | 557 |

| II. | Soult takes the Offensive in Navarre. July 1813 | 587 |

| III. | Roncesvalles and Maya. July 25, 1813 | 608 |

| IV. | Sorauren. July 28, 1813 | 642 |

| V. | Soult’s Retreat. Second Battle of Sorauren. July 30 | 681 |

| VI. | Soult Retires into France. July 31-August 3, 1813 | 707 |

| APPENDICES | ||

| I. | British Losses at the Siege of Burgos. September 20-October 21, 1812 | 741 |

| II. | The French Armies in Spain. Morning State of October 15, 1812 | 741 |

| III. | Strength of Wellington’s Army during and after the Burgos Retreat. October-November 1813 | 745 |

| IV. | British Losses in the Burgos Retreat | 747 |

| V. | Murray’s Army at Castalla. April 1813 | 748 |

| VI. | Suchet’s Army at Castalla | 749 |

| VII. | British Losses at Biar and Castalla | 750 |

| VIII. | Wellington’s Army in the Vittoria Campaign | 750 |

| IX. | Spanish Troops under Wellington’s Command. June-July 1813 | 753 |

| X. | The French Army at Vittoria | 754 |

| XI. | British and Portuguese Losses at Vittoria | 757 |

| XII. | French Losses at Vittoria | 761 |

| XIII. | Sir John Murray’s Army in the Tarragona Expedition | 762 |

| XIV. | Suchet’s Army in Valencia and Catalonia. June 1813 | 763 |

| XV. | Spanish Armies on the East Coast. June 1813 | 764 |

| XVI. | The Army of Spain as reorganized by Soult. July 1813 | 765 |

| [p. xi]XVII. | British Losses at Maya and Roncesvalles. July 25, 1813 | 768 |

| XVIII. | British Losses at Sorauren. July 28, 1813 | 769 |

| XIX. | British Losses at the Second Battle of Sorauren and the Combat of Beunza. July 30, 1813 | 770 |

| XX. | British Losses in Minor Engagements. July 31-August 2, 1813 | 772 |

| XXI. | Portuguese Losses in the Campaign of the Pyrenees | 773 |

| XXII. | French Losses in the Campaign of the Pyrenees | 774 |

| INDEX | 775 | |

| MAPS AND PLANS | |||

| I. | Plan of Siege Operations at Burgos. September-October 1812 | To face | 48 |

| II. | Operations round Salamanca. November 1812 | ” | 130 |

| III. | Battle of Castalla | ” | 274 |

| IV. | General Map of Northern Spain for the Burgos and Vittoria Campaigns | End of volume | |

| V. | Plan of the Battle of Vittoria | To face | 434 |

| VI. | Plan of the Siege of St. Sebastian | ” | 584 |

| VII. | General Map of the Country between Bayonne and Pampeluna | ” | 606 |

| VIII. | Combat of Roncesvalles | ” | 622 |

| IX. | Combat of Maya | ” | 636 |

| X. | First Battle of Sorauren. July 28 | ” | 640 |

| XI. | Second Battle of Sorauren and Combat of Beunza. July 30 | ” | 670 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Portrait of Sir Rowland Hill | Frontispiece | |

| King Joseph at Mortefontaine | To face page | 544 |

[p. 1]

THE BURGOS CAMPAIGN

WELLINGTON IN THE NORTH: BURGOS INVESTED

AUGUST 31st-SEPTEMBER 20th, 1812

The year 1812 was packed with great events, and marked in Spain no less than in Russia the final turn of the tide in the history of Napoleon’s domination. But the end was not yet: when Wellington entered Madrid in triumph on August 12th, the deliverance of the Peninsula was no more certain than was the deliverance of Europe when the French Emperor evacuated Moscow on October 22nd. Vittoria and Leipzig were still a year away, and it was not till they had been fought and won that the victory of the Allies was secure. The resources of the great enemy were so immense that it required more than one disaster to exhaust them. No one was more conscious of this than Wellington. Reflecting on the relative numbers of his own Anglo-Portuguese army and of the united strength of all the French corps in Spain, he felt that the occupation of Madrid was rather a tour de force, an admirable piece of political propaganda, than a decisive event. It would compel all the scattered armies of the enemy to unite against him, and he was more than doubtful whether he could make head against them. ‘I still hope,’ he wrote to his brother Henry, the Ambassador at Cadiz, ‘to maintain our position in Castile, and even to improve our advantages. But I shudder when I reflect upon the enormity of the task which I have undertaken, with inadequate powers myself to do anything, and without assistance of any kind from the Spaniards[1].... I am apprehensive that all this may turn out but ill for the Spanish cause. If, for any cause, I should be overpowered, or should be obliged to retreat, what will the[p. 2] world say? What will the people of England say?... That we made a great effort, attended by some glorious circumstances; that from January 1st, 1812, we had gained more advantages for the cause, and had acquired more extent of territory by our operations than any army ever gained in such a period of time against so powerful an enemy; but that unaided by the Spanish army and government, we were finally overpowered, and compelled to withdraw within our old frontier.’

It was with no light heart that Wellington faced the strategical problem. In outline it stood as follows. Soult was now known to be evacuating Andalusia, and it was practically certain that he would retire on Valencia, where he would join King Joseph and Suchet. Their three armies would produce a mass of veteran troops so great that even if every division of the Anglo-Portuguese army were concentrated, if Hill came up from Estremadura and Skerrett’s small force from Cadiz, it would be eminently doubtful whether Madrid could be held and the enemy thrust back. The French might advance 85,000 strong, and Wellington could only rely on 60,000 men of his own to face them—though he might scrape together three or four divisions of Spanish troops in addition[2]. It was true that Suchet might probably refuse to evacuate his Valencian viceroyalty, and that occupation for him might be found by utilizing Maitland’s expeditionary force at Alicante, and Elio’s Murcian army. But even if he did not join Soult and King Joseph in a march on Madrid, the armies of the South and Centre might put 65,000 men into the field.

But this was only half the problem. There was Clausel’s Army of Portugal, not to speak of Caffarelli’s Army of the North, to be taken into consideration. Clausel had some 40,000 men behind the Douro—troops recently beaten it is true, and known to be in bad order. But they had not been pursued since the Allied army turned aside for the march on Madrid, and had now been granted a month in which to pull themselves together. Nothing had been left in front of them save Clinton’s 6th Division at Cuellar, and a division of the Galicians at Valladolid.[p. 3] And now the vexatious news had come that Clausel was on the move, had chased the Galicians out of Valladolid, and was sending flying columns into the plains of Leon. It was clear that he must be dealt with at once, and there was no way to stop his annoying activity, save by detaching a considerable force from Madrid. If unopposed, he might overrun all the reconquered lands along the Douro, and even imperil the British line of communication with Salamanca and Portugal. If, as was possible, Caffarelli should lend him a couple of divisions from the Army of the North, he might become a real danger instead of a mere nuisance.

This was the reason why Wellington departed from Madrid on August 31st, and marched with the 1st, 5th and 7th Divisions, Pack’s and Bradford’s Portuguese, and Bock’s and Ponsonby’s dragoons—21,000 sabres and bayonets—to join Clinton, and thrust back Clausel to the North, before he should have leisure to do further mischief. There was, as he conceived, just time enough to inflict a sharp check on the Army of Portugal before the danger from the side of Valencia would become pressing. It must be pushed out of the way, disabled again if possible, and then he would return to Madrid for the greater game, leaving as small a containing force as possible in front of the Northern army. He summed up his plan in a confidential letter in the following terms: ‘All the world [the French world] seems to be intending to mass itself in Valencia; while I am waiting for their plans to develop, for General Hill to march up from Estremadura, and for the Spanish armies to get together, I shall hunt away the elements of Marmont’s [i. e. Clausel’s] army from the Douro. I shall push them as far off as I can, I shall try to establish proper co-operation between the Anglo-Portuguese detachment which I must leave on this side and the Galician Army, and so I shall assure my left flank, when I shall be engaged on the Valencian side[3].’

Here then, we have a time-problem set. Will it be possible to deal handsomely with the Army of Portugal, to put it completely out of power to do harm, before Soult shall have reached Valencia, reorganized his army, and joined King Joseph in[p. 4] what Wellington considered the inevitable scheme of a march on Madrid? The British general judged that there would be sufficient time—and probably there might have been, if everything had worked out in the best possible way. But he was quite conscious that events might prove perverse—and he shuddered at the thought—as he wrote to his brother in Cadiz.

The last precautions taken before departing for the Douro were to draw up three sets of instructions. One was for Charles Alten, left in command of the four divisions which remained in and about Madrid[4], foreseeing the chance of Soult’s marching on the capital without turning aside to Valencia—‘not at all probable, but it is necessary to provide for all events.’ The second was for Hill, who was due to arrive at Toledo in about three weeks. The third was for General Maitland at Alicante, whose position would obviously be very unpleasant, now that Soult was known to be evacuating Andalusia and marching on Valencia to join Suchet and King Joseph. Soult’s march altered the whole situation on the East Coast: if 50,000 more French were concentrated in that direction, the Alicante force must be in some danger, and would have to observe great caution, and if necessary to shut itself up in the maritime fortresses. ‘As the allied forces in Valencia and Murcia’—wrote Wellington to Maitland—‘will necessarily be thrown upon the defensive for a moment, while the enemy will be in great strength in those parts, I conclude that the greater part of those forces will be collected in Alicante, and it would be desirable to strengthen our posts at Cartagena during this crisis, which I hope will be only momentary[5].’ Another dispatch, dated four days later, adverts to the possibility that Soult may fall upon Alicante on his arrival in the kingdom of Valencia. Maitland is to defend the place, but to take care that all precautions as to the embarking his troops in the event of ill-success are made. He is expected to maintain it as long as possible; and with the sea open to him, and a safe harbour, the defence should be long and stubborn, however great the numbers of the besiegers[6].

With these instructions drawn out for Maitland, Wellington[p. 5] finally marched for the North. His conception of the situation in Valencia seems to have been that Soult, on his arrival, would not meddle with Alicante: it was more probable that he and King Joseph would rather take up the much more important task of endeavouring to reconquer Madrid and New Castile. They would leave Suchet behind them to contain Maitland, Elio and Ballasteros. It would be impossible for him to lend them any troops for a march on Madrid, while such a large expeditionary force was watching his flank. The net result would be that ‘by keeping this detachment at Alicante, with Whittingham’s and Roche’s Spaniards, I shall prevent too many of the gentlemen now assembled in Valencia from troubling me in the Upper Country [New Castile][7].’

Travelling with his usual celerity, Wellington left Madrid on August 31st, was at Villa Castin on the northern side of the Guadarrama pass on September 2nd, and had reached Arevalo, where he joined Clinton and the 6th Division on September 3rd. The divisions which he was bringing up from Madrid had been started off some days before he himself left the capital. He passed them between the Escurial and Villa Castin, but they caught him up again at Arevalo early on the 4th, so that he had his fighting force concentrated on that day, and was prepared to deal with Clausel.

The situation of affairs on the Douro requires a word of explanation. Clausel, it will be remembered, had retired from Valladolid on July 30, unpursued. He was prepared to retreat for any length—even as far as Burgos—if he were pressed. But no one followed him save Julian Sanchez’s lancers and some patrols of Anson’s Light Cavalry brigade. Wherefore he halted his main body on the line of the Arlanza, with two divisions at Torquemada and two at Lerma; some way to his left Foy, with two divisions more, was at Aranda, on the Upper Douro, where he had maintained his forward position, because not even a cavalry patrol from the side of the Allies had come forward to disquiet him. In front of Clausel himself there was soon nothing left but the lightest of cavalry screens, for Julian Sanchez was called off by Wellington to New Castile: when he was gone, there remained Marquinez’s guerrilleros at Palencia,[p. 6] and outposts of the 16th Light Dragoons at Valtanas: the main body of G. Anson’s squadrons lay at Villavanez, twenty miles behind[8]. The only infantry force which the Allies had north of the Douro was one of the divisions of the Army of Galicia, which (with Santocildes himself in command) came up to Valladolid on August 6th, not much over 3,000 bayonets strong. The second of the Galician divisions which had descended into the plain of Leon was now blockading Toro. The third and most numerous was still engaged in the interminable siege of Astorga, which showed at last some signs of drawing to its close—not because the battering of the place had been effective, but simply because the garrison was growing famished. They had been provisioned only as far as August 1, and after that date had been forced upon half and then quarter rations. But the news of the disaster of Salamanca had not, as many had hoped among the Allies, scared their commander into capitulation.

Clausel on August 1 had not supposed it possible that he would be tempted to take the offensive again within a fortnight. His army was in a most dilapidated condition, and he was prepared to give way whenever pressed. It was not that his numbers were so very low, for on August 1st the Army of Portugal only counted 10,000 less effectives than on July 15th. Though it had lost some 14,000 men in the Salamanca campaign, it had picked up some 4,000 others from the dépôt at Valladolid, from the many small garrisons which it had drawn in during its retreat, and from drafts found at Burgos.[9] Its loss in cavalry had been fully repaired by the arrival of Chauvel’s two regiments from the Army of the North, and most of the fugitives and marauders who had been scattered over the countryside after the battle of July 22nd gradually drifted back to their colours. It was not so much numbers as spirit that was wanting in the[p. 7] Army of Portugal. On August 6 Clausel wrote to the Minister of War at Paris that he had halted in a position where he could feed the troops, give them some days of repose, and above all re-establish their morale[10]. ‘I must punish some of the men, who are breaking out in the most frightful outrages, and so frighten the others by an example of severity; above all I must put an end to a desire, which they display too manifestly, to recross the Ebro, and get back nearer to the French frontier. It is usual to see an army disheartened after a check: but it would be hard to find one whose discouragement is greater than that of these troops: and I cannot, and ought not, to conceal from you that there has been prevailing among them for some time a very bad spirit. Disorders and revolting excesses have marked every step of our retreat. I shall employ all the means in my power to transform the dispositions of the soldiers, and to put an end to the deplorable actions which daily take place under the very eyes of officers of all grades—actions which the latter fail to repress.’

Clausel was as good as his word, and made many and severe examples, shooting (so he says) as many as fifty soldiers found guilty of murders, assaults on officers, and other excesses[11]. It is probable, however, that it was not so much his strong punitive measures which brought about an improved discipline in the regiments, as the fortnight of absolutely undisturbed repose which they enjoyed from the 1st to the 14th of August. The feeling of demoralization caused by the headlong and disorderly retreat from Salamanca died down, as it became more and more certain that the pursuit was over, and that there was no serious hostile force left within many miles of the line of the Arlanza. The obsession of being hunted by superior forces had been the ruinous thing: when this terror was withdrawn, and when the more shattered regiments had been re-formed into a smaller number of battalions, and provided in this fashion with their proper proportion of officers[12], the troops began to realize that[p. 8] they still formed a considerable army, and that they had been routed, but not absolutely put out of action, by the Salamanca disaster.

Yet their morale had been seriously shaken; there was still a want of officers; a number of the rejoining fugitives had come in without arms or equipment; while others had been heard of, but had not yet reported themselves at their regimental head-quarters. It therefore required considerable hardihood on Clausel’s part to try an offensive move, even against a skeleton enemy. His object was primarily to bring pressure upon the allied rear, in order to relieve King Joseph from Wellington’s attentions. He had heard that the whole of the Anglo-Portuguese army, save a negligible remnant, had marched on Madrid; but he was not sure that the Army of the Centre might not make some endeavour to save the capital, especially if it had been reinforced from Estremadura by Drouet. Clausel knew that the King had repeatedly called for succours from the South; it was possible that they might have been sent at the last moment. If they had come up, and if Wellington could be induced to send back two or three divisions to the Douro, Madrid might yet be saved. The experiment was worth risking, but it must take the form of a demonstration rather than a genuine attack upon Wellington’s rear. The Army of Portugal was still too fragile an instrument to be applied to heavy work. Indeed, when he moved, Clausel left many shattered regiments behind, and only brought 25,000 men to the front.

There was a second object in Clausel’s advance: he hoped to save the garrisons of Astorga, Toro, and Zamora, which amounted in all to over 3,000 men. Each of the first two was being besieged by a Spanish division, the third by Silveira’s Portuguese militia. The French general judged that none of the investing forces was equal to a fight in the open with a strong flying column of his best troops. Even if all three could get together, he doubted if they dared face two French divisions. His scheme was to march on Valladolid with his main body, and drive out of it the small Spanish force in possession, while Foy—his senior division-commander—should move rapidly across country with[p. 9] some 8,000 men, and relieve by a circular sweep first Toro, then Astorga, then Zamora. The garrisons were to be brought off, the places blown up: it was useless to dream of holding them, for Wellington would probably come to the Douro again in force, the sieges would recommence, and no second relief would be possible in face of the main British army.

On August 13th a strong French cavalry reconnaissance crossed the Arlanza and drove in the guerrilleros from Zevico: on the following day infantry was coming up from the rear, pushing forward on the high-road from Torquemada to Valladolid. Thereupon Anson, on that evening, sent back the main body of his light dragoons beyond the Douro, leaving only two squadrons as a rearguard at Villavanez. The Galician division in Valladolid also retired by the road of Torrelobaton and Castronuevo on Benavente. Santocildes—to Wellington’s disgust when it reached his ears—abandoned in Valladolid not only 400 French convalescents in hospital, but many hundred stand of small arms, which had been collected there from the prisoners taken during the retreat of Clausel in the preceding month. This was inexcusable carelessness, as there was ample time to destroy them, if not to carry them off. French infantry entered Valladolid on the 14th and 15th, apparently about 12,000 strong: their cavalry, a day’s march ahead, had explored the line of the Douro from Simancas to Tudela, and found it watched by G. Anson’s pickets all along that front.

The orders left behind by Wellington on August 5th, had been that if Clausel came forward—which he had not thought likely—G. Anson was to fall back to the Douro, and if pressed again to join Clinton’s division at Cuellar. The retreat of both of them was to be on Segovia in the event of absolute necessity. On the other hand, if the French should try to raise the sieges of Astorga or Zamora, Santocildes and Silveira were to go behind the Esla[13]. Clausel tried both these moves at once, for on the same day that he entered Valladolid he had turned off Foy with two divisions—his own and Taupin’s (late Ferey’s)—and a brigade of Curto’s chasseurs, to march on Toro by the road through Torrelobaton. The troops in Valladolid served to[p. 10] cover this movement: they showed a division of infantry and 800 horse in front of Tudela on the 16th, and pushed back Anson’s light dragoons to Montemayor, a few miles beyond the Douro. But this was only a demonstration: their cavalry retired in the evening, and Anson reoccupied Tudela on the 20th. It soon became clear that Clausel was not about to cross the Douro in force, and was only showing troops in front of Valladolid in order to keep Anson and Clinton anxious. He remained there with some 12,000 or 15,000 men from August 14th till September 7th, keeping very quiet, and making no second attempt to reconnoitre beyond the Douro. Anson, therefore, watched the line of the river, with his head-quarters at Valdestillas, for all that time, while the guerrilleros of Saornil and Principe went over to the northern bank and hung around Clausel’s flank. Clinton, on his own initiative, moved his division from Cuellar to Arevalo, which placed him on the line of the road to Madrid via the Guadarrama, instead of that by Segovia. This Wellington afterwards declared to be a mistake: he had intended to keep the 6th Division more to the right, apparently in order that it might cross the Douro above Valladolid if required[14]. It should not have moved farther southward than Olmedo.

Foy meanwhile, thus covered by Clausel, made a march of surprising celerity. On the 17th he arrived at Toro, and learned that the Galicians blockading that place had cleared off as early as the 15th, and had taken the road for Benavente. He blew up the fort, and took on with him the garrison of 800 men. At Toro he was much nearer to Zamora than to Astorga, but he resolved to march first on the remoter place—it was known to be hard pressed, and the French force there blockaded was double that in Zamora. He therefore moved on Benavente with all possible speed, and crossed the Esla there, driving away a detachment of the Galician division (Cabrera’s) which had come from Valladolid, when it made an ineffectual attempt to hold the fords. On the 20th August he reached La Baneza, some sixteen miles from Astorga, and there received the tiresome news that the garrison had surrendered only thirty-six hours before to Castaños. The three battalions there, worn down by[p. 11] famine to 1,200 men, had capitulated, because they had no suspicion that any help was near. The Spanish general had succeeded in concealing from them all knowledge of Foy’s march. They laid down their arms on the 18th, and were at once marched off to Galicia: Castaños himself accompanied them with all his force, being fully determined not to fight Foy, even though his numbers were superior.

The French cavalry pushed on to Astorga on the 21st, and found the gates open and the place empty, save for seventy sick of the late garrison, who had been left behind under the charge of a surgeon. It was useless to think of pursuing Castaños, who had now two days’ start, wherefore Foy turned his attention to Zamora. Here Silveira, though warned to make off when the enemy reached Toro, had held on to the last moment, thinking that he was safe when Foy swerved away toward Astorga. He only drew off when he got news on the 22nd, from Sir Howard Douglas, the British Commissioner with the Galician army, to the effect that Foy, having failed to save Astorga, was marching against him. He retired to Carvajales behind the Esla, but was not safe there, for the French general, turning west from Benavente, had executed a forced march for Tabara, and was hastening westward to cut in between Carvajales and the road to Miranda de Douro on the Portuguese frontier. Warned only just in time of this move, Silveira hurried off towards his own country, and was within one mile of its border when Foy’s advanced cavalry came up with his rearguard near Constantin, the last village in Spain. They captured his baggage and some stragglers, but made no serious endeavour to charge his infantry, which escaped unharmed to Miranda. Foy attributed this failure to Curto, the commander of the light horse: ‘le défaut de décision et l’inertie coupable du général commandant la cavalerie font perdre les fruits d’une opération bien combinée’ (August 23rd)[15]. This pursuit had drawn Foy very far westward; his column turning[p. 12] back, only reached Zamora on August 26th: here he drew off the garrison and destroyed the works. He states that his next move would have been a raid on Salamanca, where lay not only the British base hospital, but a vast accumulation of stores, unprotected by any troops whatever. But he received at Zamora, on the 27th, urgent orders from Clausel to return to Valladolid, as Wellington was coming up against him from Madrid with his whole army. Accordingly Foy abandoned his plan, and reached Tordesillas, with his troops in a very exhausted condition from hard marching, on August 28th. Clausel had miscalculated dates—warned of the first start of the 1st and 7th Divisions from Madrid, he had supposed that they would be at Arevalo some days before they actually reached it on September 4th. Foy was never in any real danger, and there had been time to spare. His excursion undoubtedly raised the spirit of the Army of Portugal: it was comforting to find that the whole of the Galicians would not face 8,000 French troops, and that the plains of Leon could be overrun without opposition by such a small force. On his return to join the main body Foy noted in his diary that Clausel had been very inert in face of Anson and Clinton, and wrote that he himself would have tried a more dashing policy—and might possibly have failed in it, owing to the discouragement and apathy still prevailing among many of the senior officers of the Army of Portugal[16].

Wellington had received the news of Clausel’s advance on Valladolid as early as August 18th, and was little moved by it. Indeed he expressed some pleasure at the fact. ‘I think,’ he wrote to Lord Bathurst, ‘that the French mean to carry off the garrisons from Zamora and Toro, which I hope they will effect, as otherwise I must go and take them. If I do not, nobody else will, as is evident from what has been passing for the last two months at Astorga[17].’ He expressed his pleasure on hearing that Santocildes had retired behind the Esla without fighting, for he had feared that he might try to stop Foy and get beaten. It was only, as we have already seen, after he obtained practical certainty that Soult had evacuated Andalusia, so that no expedition to the South would be necessary, that he[p. 13] turned his mind to Clausel‘s doings. And his march to Arevalo and Valladolid was intended to be a mere excursion for a few weeks, preparatory to a return to New Castile to face Soult and King Joseph, when they should become dangerous. From Arevalo he wrote to Castaños to say that ‘it was necessary to drive off Marmont’s (i.e. Clausel’s) army without loss of time, so as to make it possible to turn the whole of his forces eventually against Soult.’ He should press the movement so far forward as he could; perhaps he might even lay siege to Burgos. But the Army of Galicia must come eastward again without delay, and link up its operations with the Anglo-Portuguese. He hoped to have retaken Valladolid by September 6th, and wished to see Castaños there, with the largest possible force that he could gather, on that date[18]. The Galician army had returned to Astorga on August 27th, and so far as distances went, there was nothing to prevent it from being at Valladolid eleven days after, if it took the obvious route by Benavente and Villalpando.

The troops from Madrid having joined Clinton and the 6th Division at Arevalo, Wellington had there some 28,000 men collected for the discomfiture of Clausel, a force not much more numerous than that which the French general had concentrated behind the Douro, for Foy was now back at Tordesillas, and the whole Army of Portugal was in hand, save certain depleted and disorganized regiments which had been left behind in the province of Burgos. But having the advantage of confidence, and knowing that his enemy must still be suffering from the moral effects of Salamanca, the British general pushed on at once, not waiting for the arrival on the scene of the Galicians. On the 4th the army marched to Olmedo, on the 5th to Valdestillas, on the 6th to Boecillo, from whence it advanced to the Douro and crossed it by various fords between Tudela and Puente de Duero—the main body taking that of Herrera. The French made no attempt to defend the line of the river, but—rather to Wellington’s surprise—were found drawn up as if for battle a few miles beyond it, their right wing holding the city of Valladolid, whose outskirts had been put in a state of defence, their left extending to the ground about the village[p. 14] of La Cisterniga. No attempt was made to dislodge them with the first divisions that came up: Wellington preferred to wait for his artillery and his reserves; the process of filing across the fords had been tedious, and occupied the whole afternoon.

On this Clausel had calculated: he was only showing a front in order to give his train time to move to the rear, and to allow his right wing (Foy) at Simancas and Tordesillas to get away. A prompt evacuation of Valladolid would have exposed it to be cut off. On the following morning the French had disappeared from La Cisterniga, but Valladolid was discovered to be still held by an infantry rearguard. This, when pushed, retired and blew up the bridge over the Pisuerga on the opposite side of the city, before the British cavalry could seize it. The critics thought that Clausel might have been hustled with advantage, both on the 6th and on the morning of the 7th, and that Foy might have been cut off from the main body by rapid action on the first day[19]. Wellington’s cautious movements may probably be explained by the fact that an attack on Clausel on the 6th would have involved fighting among the suburbs and houses of Valladolid, which would have been costly, and he had no wish to lose men at a moment when the battalion-strengths were very low all through the army. Moreover, the capture of Valladolid would not have intercepted the retreat of the French at Simancas, but only have forced them to retire by parallel roads northward. At the same time it must be owned that any loss of life involved in giving Clausel a thorough beating on this day would have been justified later on. He had only some 15,000 men in line, not having his right-wing troops with him that day. If the Army of Portugal had been once more attacked and scattered, it would not have been able to interfere in the siege of Burgos, where Wellington was, during the next few weeks, to lose as many men as a general action would have cost. But this no prophet could have foreseen on September 6th.

It cannot be said that Wellington’s pursuit of Clausel was pressed with any earnestness. On the 8th his advanced cavalry[p. 15] were no farther forward than Cabezon, seven miles in front of Valladolid, and it was not till the 9th that the 6th Division, leading the infantry, passed that same point. Wellington himself, with the main body of his infantry, remained at Valladolid till the 10th. His dispatches give no further explanation for this delay than that the troops which had come from Madrid were fatigued, and sickly, from long travel in the hot weather, and that he wished to have assurance of the near approach of the Army of Galicia, which was unaccountably slow in moving forward from Astorga[20]. Meanwhile he took the opportunity of his stay in Valladolid to command, and be present at, a solemn proclamation of the March Constitution. This was a prudent act; for though the ceremony provoked no enthusiasm whatever in the city[21], where there were few Liberals in existence, it was a useful demonstration against calumnies current in Cadiz, to the effect that he so much disliked the Constitution that he was conspiring with the serviles, and especially with Castaños, to ignore or even to overthrow it.

While Wellington halted at Valladolid, Clausel had established himself at Dueñas, fifteen miles up the Pisuerga. He retired from thence, however, on the 10th, when the 6th Division and Anson’s cavalry pressed in his advanced posts, and Wellington’s head-quarters were at Dueñas next day. From thence reconnaissances were sent out both on the Burgos and the Palencia roads. The latter city was found unoccupied and—what was more surprising—not in the least damaged by the retreating enemy. The whole of Clausel’s army had marched on the Burgos road, and its rearguard was discovered in front of Torquemada that evening. The British army followed, leaving Palencia on its left, and head-quarters were at Magaz on the 12th. Anson’s light dragoons had the interesting spectacle that afternoon of watching the whole French army defile across the bridge of the Pisuerga at Torquemada, under cover of a brigade of chasseurs drawn up on the near side. Critics[p. 16] thought that the covering force might have been driven in, and jammed against the narrow roadway over the bridge[22]. But the British brigadier waited for artillery to come up, and before it arrived the enemy had hastily decamped. He was pursued as far as Quintana, where there was a trifling cavalry skirmish at nightfall.

At Magaz, on the night of the 12th, Wellington got the tiresome news that Santocildes and Castaños, with the main body of the Army of Galicia, had passed his flank that day, going southward, and had continued their way towards Valladolid, instead of falling in on the British line of march. Their junction was thus deferred for several days. Wellington wrote in anger, ‘Santocildes has been six days marching: he was yesterday within three leagues of us, and knew it that night; but he has this morning moved on to Valladolid, eight leagues from us, and unless I halt two days for him he will not join us for four or five days more[23].’ As a matter of fact the Galicians did not come up till the 16th, while if Santocildes had used a little common sense they would have been in line on the 12th September.

The pursuit of Clausel continued to be a very slow and uninteresting business: from the 11th to the 15th the army did not advance more than two leagues a day. On the 13th the British vanguard was at Villajera, while the French main body was at Pampliega: on the 14th Anson’s cavalry was at Villadrigo, on the 15th at Villapequeña, on the 16th near Celada, where Clausel was seen in position. On this day the Galicians at last came up—three weak divisions under Cabrera, Losada, and Barcena, with something over 11,000 infantry, but only one field-battery and 350 horse. The men looked fatigued with much marching and very ragged: Wellington had hoped for 16,000 men, and considering that the total force of the Galician army was supposed to be over 30,000 men, it seems that more might have been up, even allowing for sick, recruits, and the large garrisons of Ferrol and Corunna.

The 16th September was the only day on which Clausel[p. 17] showed any signs of making a stand: in the afternoon he was found in position, a league beyond Celada on favourable ground. Wellington arranged to turn his left flank next morning, with the 6th Division and Pack’s brigade; but at dawn he went off in haste, and did not stop till he reached Villa Buniel, near Burgos. Here, late in the afternoon, Wellington again outflanked him with the 6th Division, and he retreated quite close to the city. On the 18th he evacuated it, after throwing a garrison into the Castle, and went back several leagues on the high-road toward the Ebro. The Allies entered Burgos, and pushed their cavalry beyond it without meeting opposition. On the 19th the Castle was invested by the 1st Division and Pack’s brigade, while the rest of Wellington’s army took position across the road by which the French had retreated. A cavalry reconnaissance showed that Clausel had gone back many miles: the last outposts of his rear were at Quintanavides, beyond the watershed which separates the basin of the Douro from that of the Ebro. His head-quarters were now at Briviesca, and it appeared that, if once more pushed, he was prepared to retreat ad infinitum. Wellington, however, pressed him no farther: throwing forward three of his own divisions and the Galicians to Monasterio and other villages to the east of Burgos, where a good covering position was found, he proceeded to turn his attention to the Castle.

This short series of operations between the 10th and the 19th of September 1812 has in it much that perplexes the critical historian. It is not Clausel’s policy that is interesting—he simply retired day after day, whenever the enemy’s pursuing infantry came within ten miles of him. Sometimes he gave way before the mere cavalry of Wellington’s advanced guard. There was nothing in his conduct to remind the observer of Ney’s skilful retreat from Pombal to Ponte Murcella in 1811, when a rearguard action was fought nearly every afternoon. Clausel was determined not to allow himself to be caught, and would not hold on, even in tempting positions of considerable strength. As he wrote to Clarke before the retreat had begun, ‘Si l’ennemi revient avec toute son armée vers moi, je me tiendrai en position, quoique toujours à peu de distance de lui, afin de n’avoir aucun échec à éprouver.’ He suffered no check[p. 18] because he always made off before he was in the slightest danger of being brought to action. It is difficult to understand Napier’s enthusiasm for what he calls ‘beautiful movements’[24]; to abscond on the first approach of the enemy’s infantry may be a safe and sound policy, but it can hardly be called brilliant or artistic. It is true that there would have been worse alternatives to take—Clausel might have retreated to the Ebro without stopping, or he might have offered battle at the first chance; but the avoidance of such errors does not in itself constitute a very high claim to praise. An examination of the details of the march of the British army during this ten days plainly fails to corroborate Napier’s statement that the French general ‘offered battle every day’ and ‘baffled his great adversary.’ His halt for a few hours at Celada on September 16th was the only one during which he allowed the allied main body to get into touch with him late in the day; and he absconded before Wellington’s first manœuvre to outflank him[25].

The thing that is truly astonishing in this ten days is the extraordinary torpidity of Wellington’s pursuit. He started by waiting three days at Valladolid after expelling the French; and he continued, when once he had put his head-quarters in motion, by making a series of easy marches of six to ten miles a day, never showing the least wish to hustle his adversary or to bring him to action[26]. Now to manœuvre the French army to beyond Burgos, or even to the Ebro, was not the desired end—it was necessary to put Clausel out of action, if (as Wellington kept repeating in all his letters) the main allied army was to return to Madrid within a few weeks, to watch for Soult’s[p. 19] offensive. To escort the Army of Portugal with ceremonious politeness to Briviesca, without the loss to pursuers or pursued of fifty men, was clearly not sufficient. Clausel’s troops, being not harassed in the least, but allowed a comfortable retreat, remained an ‘army in being’: though moved back eighty miles on the map, they were not disposed of, and could obviously come forward again the moment that Wellington left the north with the main body of his troops. Nothing, therefore, was gained by the whole manœuvre, save that Clausel was six marches farther from the Douro than he had been on September 1st. To keep him in his new position Wellington must have left an adequate containing army: it does not seem that he could have provided one from the 28,000 Anglo-Portuguese and 11,000 Galicians who were at his disposition, and yet have had any appreciable force to take back to Madrid. Clausel had conducted his raid on Valladolid with something under 25,000 men; but this did not represent the whole strength of the Army of Portugal: after deducting the sick and the garrisons there were some 39,000 men left—of these some were disarmed stragglers who had only just come back to their colours, others belonged to shattered corps which were only just reorganizing themselves in their new cadres. But in a few weeks Clausel would have at least 35,000 men under arms of his own troops, without counting anything that the Army of the North might possibly lend him. To contain him Wellington would have to leave, in addition to the 11,000 Galicians, at least three British divisions and the corresponding cavalry—say 16,000 or 18,000 men. He could only bring back some 10,000 bayonets to join Hill near Madrid. This would not enable him to face Soult.

But if Clausel had been dealt with in a more drastic style, if he had been hunted and harassed, it is clear that he might have been disabled for a long time from taking the offensive. His army was still in a doubtful condition as regards morale, and there can be little reason to doubt, that if hard pressed, it would have sunk again into the despondency and disorder which had prevailed at the beginning of the month of August. The process of driving him back with a firm hand might, no doubt, have been more costly than the slow tactics actually adopted; but undoubtedly such a policy would have paid in the end.

[p. 20]

There is no explanation to be got out of Wellington’s rather numerous letters written between the 10th and the 21st. In one of them he actually observes that ‘we have been pushing them, but not very vigorously, till the 16th[27],’ without saying why the pressure was not applied more vigorously. From others it might perhaps be deduced that Wellington was awaiting the arrival of the Galician army, because when it came up he would have a very large instead of a small superiority of force over the French. But this does not fully explain his slowness in pursuing an enemy who was evidently on the run, and determined not to fight. We may, as has been already mentioned, speak of his wish to avoid loss of life (not much practised during the Burgos operations a few days later on!) and of the difficulty of providing for supplies in a countryside unvisited before by the British army, and very distant from its base-magazines. But when all has been said, no adequate explanation for his policy has been provided. It remains inexplicable, and its results were unhappy.

[p. 21]

THE SIEGE OF BURGOS.

SEPTEMBER

19th-OCTOBER 20th, 1812

The Castle of Burgos lies on an isolated hill which rises straight out of the streets of the north-western corner of that ancient city, and overtops them by 200 feet or rather more. Ere ever there were kings in Castile, it had been the residence of Fernan Gonzalez, and the early counts who recovered the land from the Moors. Rebuilt a dozen times in the Middle Ages, and long a favourite palace of the Castilian kings, it had been ruined by a great fire in 1736, and since then had not been inhabited. There only remained an empty shell, of which the most important part was the great Donjon which had defied the flames. The summit of the hill is only 250 yards long: the eastern section of it was occupied by the Donjon, the western by a large church, Santa Maria la Blanca: between them were more or less ruined buildings, which had suffered from the conflagration. Passing by Burgos in 1808, after the battle of Gamonal, Napoleon had noted the commanding situation of the hill, and had determined to make it one of the fortified bases upon which the French domination in northern Spain was to be founded. He had caused a plan to be drawn up for the conversion of the ruined mediaeval stronghold into a modern citadel, which should overawe the city below, and serve as a half-way house, an arsenal, and a dépôt for French troops moving between Bayonne and Madrid. Considered as a fortress it had one prominent defect: while its eastern, southern, and western sides look down into the low ground around the Arlanzon river, there lies on its northern side, only 300 yards away, a flat-topped plateau, called the hill of San Miguel, which rises to within a few feet of the same height as the Donjon, and overlooks all the lower slopes of the Castle mount. As this rising ground—now occupied by the city reservoir of Burgos—commanded so much of the defences, Napoleon held that it must be occupied,[p. 22] and a fort upon it formed part of his original plan. But the Emperor passed on; the tide of war swept far south of Madrid; and the full scheme for the fortification of Burgos was never carried out; money—the essential thing when building is in hand—was never forthcoming in sufficient quantities, and the actual state of the place in 1812 was very different from what it would have been if Napoleon’s orders had been carried out in detail. Enough was done to make the Castle impregnable against guerrillero bands—the only enemies who ever came near it between 1809 and 1812—but it could not be described as a complete or satisfactory piece of military engineering. Against a besieger unprovided with sufficient artillery it was formidable enough: round two-thirds of its circuit it had a complete double enceinte, enclosing the Donjon and the church on the summit which formed its nucleus. On the western side, for about one-third of its circumference, it had an outer or third line of defence, to take in the lowest slopes of the hill on which it lies. For here the ground descended gradually, while to the east it shelved very steeply down to the town, and an external defence was unnecessary and indeed impossible.

The outer line all round (i.e. the third line on the west, the second line on the rest of the circumference) had as its base the old walls of the external enclosure of the mediaeval Castle, modernized by shot-proof parapets and with tambours and palisades added at the angles to give flank fire. It had a ditch 30 feet wide, and a counterscarp in masonry, while the inner enceintes were only strong earthworks, like good field entrenchments; they were, however, both furnished with palisades in front and were also ‘fraised’ above. The Donjon, which had been strengthened and built up, contained the powder magazine in its lower story. On its platform, which was most solid, was established a battery for eight heavy guns (Batterie Napoléon), which from its lofty position commanded all the surrounding ground, including the top of the hill of San Miguel. The magazine of provisions, which was copiously supplied, was in the church of Santa Maria la Blanca. Food never failed—but water was a more serious problem; there was only one well, and the garrison had to be put on an allowance for drinking[p. 23] from the commencement of the siege. The hornwork of San Miguel, which covered the important plateau to the north, had never been properly finished. It was very large; its front was composed of earthwork 25 feet high, covered by a counterscarp of 10 feet deep. Here the work was formidable, the scarp being steep and slippery; but the flanks were not so strong, and the rear or gorge was only closed by a row of palisades, erected within the last two days. The only outer defences consisted of three light flèches, or redans, lying some 60 yards out in front of the hornwork, at projecting points of the plateau, which commanded the lower slopes. The artillery in San Miguel consisted of seven field-pieces, 4- and 6-pounders: there were no heavy guns in it.

The garrison of Burgos belonged to the Army of the North, not to that of Portugal. Caffarelli himself paid a hasty visit to the place just before the siege began, and threw in some picked troops—two battalions of the 34th[28], one of the 130th; making 1,600 infantry. There were also a company of artillery, another of pioneers, and detachments which brought up the whole to exactly 2,000 men—a very sufficient number for a place of such small size. There were nine heavy guns (16- and 12-pounders), of which eight were placed in the Napoleon battery, eleven field-pieces (seven of them in San Miguel), and six mortars or howitzers. This was none too great a provision, and would have been inadequate against a besieger provided with a proper battering-train: Wellington—as we shall see—was not so provided. The governor was a General of Brigade named Dubreton, one of the most resourceful and enterprising officers whom the British army ever encountered. He earned at Burgos a reputation even more brilliant than that which Phillipon acquired at Badajoz.

The weak points of the fortress were firstly the unfinished condition of the San Miguel hornwork, which Dubreton had to maintain as long as he could, in order that the British might not use the hill on which it stood as vantage ground for battering the Castle; secondly, the lack of cover within the works. The Donjon and the church of Santa Maria could not house a tithe[p. 24] of the garrison; the rest had to bivouac in the open, a trying experience in the rain, which fell copiously on many days of the siege. If the besiegers had possessed a provision of mortars, to keep up a regular bombardment of the interior of the Castle, it would not long have been tenable, owing to the losses that must have been suffered. Thirdly must be mentioned the bad construction of many of the works—part of them were mediaeval structures, not originally intended to resist cannon, and hastily adapted to modern necessities: some of them were not furnished with parapets or embrasures—which had to be extemporized with sandbags. Lastly, it must be remembered that the conical shape of the hill exposed the inner no less than the outer works to battering: the lower enceintes only partly covered the inner ones, whose higher sections stood up visible above them. The Donjon and Santa Maria were exposed from the first to such fire as the enemy could turn against them, no less than the walls of the outer circumference. If Wellington had owned the siege-train that he brought against Badajoz, the place must have succumbed in ten days. But the commander was able and determined, the troops willing, the supply of food and of artillery munitions ample—Burgos had always been an important dépôt. Dubreton’s orders were to keep his enemy detained as long as possible—and he succeeded, even beyond all reasonable expectations.

Wellington had always been aware that Burgos was fortified, but during his advance he had spoken freely of his intention to capture it. On September 3rd he had written, ‘I have some heavy guns with me, and have an idea of forcing the siege of Burgos—but that still depends on circumstances[29].’ Four days later he wrote at Valladolid, ‘I am preparing to drive away the detachments of the Army of Portugal from the Douro, and I propose, if I have time, to take Burgos[30].’ Yet at the same moment he kept impressing on his correspondents that his march to the North was a temporary expedient, a mere parergon; his real business would be with Soult, and he must soon be back at Madrid with his main body. It is this that makes so inexplicable his lingering for a month before Dubreton’s[p. 25] castle, when he had once discovered that it would not fall, as he had hoped, in a few days. After his first failure before the place, he acknowledged it might possibly foil him altogether. Almost at the start he ventured the opinion that ‘As far as I can judge, I am apprehensive that the means I have are not sufficient to enable me to take the Castle.’ Yet he thought it worth while to try irregular methods: ‘the enemy are ill-provided with water; their magazines of provisions are in a place exposed to be set on fire. I think it possible, therefore, that I have it in my power to force them to surrender, although I may not be able to lay the place open to assault[31].’

The cardinal weakness of Wellington’s position was exactly the same as at the Salamanca forts, three months back. He had no sufficient battering-train for a regular siege: after the Salamanca experience it is surprising that he allowed himself to be found for a second time in this deficiency. There were dozens of heavy guns in the arsenal at Madrid, dozens more (Marmont’s old siege-train) at Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida. But Madrid was 130 miles away, Rodrigo 180. With the army there was only Alexander Dickson’s composite Anglo-Portuguese artillery reserve, commanded by Major Ariaga, and consisting of three iron 18-pounders, and five 24-pounder howitzers, served by 150 gunners—90 British, 60 Portuguese. The former were good battering-guns; the howitzers, however, were not—they were merely short guns of position, very useless for a siege, and very inaccurate in their fire. They threw a heavy ball, but with weak power—the charge was only two pounds of powder: the shot when fired at a stout wall, from any distance, had such weak impact that it regularly bounded off without making any impression on the masonry. The only real use of these guns was for throwing case at short distances. ‘In estimating the efficient ordnance used at the Spanish sieges,’ says the official historian of the Burgos failure, ‘these howitzers ought in fairness to be excluded from calculation, as they did little more than waste invaluable ammunition[32].’ This was as well known to Wellington as to his subordinates, and it is inexplicable that he did not in place of them bring up[p. 26] from Madrid real battering-guns: with ten more 18-pounders he would undoubtedly have taken the Castle of Burgos. But heavy guns require many draught cattle, and are hard to drag over bad roads: the absolute minimum had been taken with the army, as in June. And it was impossible to bring up more siege-guns in a hurry, as was done at the siege of the Salamanca forts, for the nearest available pieces were not a mere sixty miles away, as on the former occasion, but double and triple that distance. Yet if, on the first day of doubt before Burgos, Wellington had sent urgent orders for the dispatch of more 18-pounders from Madrid, they would have been up in time; though no doubt there would have been terrible difficulties in providing for their transport. It was only when it had grown too late that more artillery was at last requisitioned—and had to be turned back not long after it had started.

Other defects there were in the besieging army, especially the same want of trained sappers and miners that had been seen at Badajoz, and of engineer officers[33]. Of this more hereafter:—the first and foremost difficulty, without which the rest would have been comparatively unimportant, was the lack of heavy artillery.

But to proceed to the chronicle of the siege. On the evening on which the army arrived before Burgos the 6th Division took post on the south bank of the Arlanzon: the 1st Division and Pack’s Portuguese brigade swept round the city and formed an investing line about the Castle. It was drawn as close as possible, especially on the side of the hornwork of San Miguel, where the light companies of the first Division pushed up the hill, taking shelter in dead ground where they could, and dislodged the French outposts from the three flèches which lay upon its sky-line. Wellington, after consulting his chief engineer and artillery officers, determined that his first move must be to capture the hornwork, in order to use its vantage-ground for battering the Castle. The same night (September 19-20) an assault, without any preparation of artillery fire, was made upon it. The main body of the assailing force was composed of Pack’s Portuguese, who were assisted[p. 27] by the whole of the 1/42nd and by the flank-companies[34] of Stirling’s brigade of the 1st Division, to which the Black Watch belonged. The arrangement was that while a strong firing party (300 men) of the 1/42nd were to advance to the neighbourhood of the horn work, ‘as near to the salient angle as possible,’ and to endeavour to keep down the fire of the garrison, two columns each composed of Portuguese, but with ladder parties and forlorn hopes from the Highland battalion, should charge at the two demi-bastions to right and left of the salient, and escalade them. Meanwhile the flank-companies of Stirling’s brigade (1/42nd, 1/24th, 1/79th) were to make a false attack upon the rear, or gorge, of the hornwork, which might be turned into a real one if it should be found weakly held.

The storm succeeded, but with vast and unnecessary loss of life, and not in the way which Wellington had intended. It was bright moonlight, and the firing party, when coming up over the crest, were at once detected by the French, who opened a very heavy fire upon them. The Highlanders commenced to reply while still 150 yards away, and then advanced firing till they came close up to the work, where they remained for a quarter of an hour, entirely exposed and suffering terribly. Having lost half their numbers they finally dispersed, but not till after the main attack had failed. On both their flanks the assaulting columns were repulsed, though the advanced parties duly laid their ladders: they were found somewhat short, and after wavering for some minutes Pack’s men retired, suffering heavily. The whole affair would have been a failure, but for the assault on the gorge. Here the three light companies—140 men—were led by Somers Cocks, formerly one of Wellington’s most distinguished intelligence officers, the hero of many a risky ride, but recently promoted to a majority in the 1/79th. He made no demonstration, but a fierce attack from the first. He ran up the back slope of the hill of St. Miguel, under a destructive fire from the Castle, which detected his little column at once, and shelled it from the rear all the time that it was at work. The frontal assault, however, was engrossing[p. 28] the attention of the garrison of the hornwork, and only a weak guard had been left at the gorge. The light companies broke through the 7-foot palisades, partly by using axes, partly by main force and climbing. Somers Cocks then divided his men into two bodies, leaving the smaller to block the postern in the gorge, while with the larger he got upon the parapet and advanced firing towards the right demi-bastion. Suddenly attacked in the rear, just as they found themselves victorious in front, the French garrison—a battalion of the 34th, 500 strong—made no attempt to drive out the light companies, but ran in a mass towards the postern, trampled down the guard left there, and escaped to the Castle across the intervening ravine. They lost 198 men, including 60 prisoners, and left behind their seven field-pieces[35]. The assailants suffered far more—they had 421 killed and wounded, of whom no less than 204 were in the 1/42nd, which had suffered terribly in the main assault. The Portuguese lost 113 only, never having pushed their attack home. This murderous business was the first serious fighting in which the Black Watch were involved since their return to Spain in April 1812; at Salamanca they had been little engaged, and were the strongest British battalion in the field—over 1,000 bayonets. Wellington attributed their heavy casualties to their inexperience—they exposed themselves over-much. ‘If I had had some of the troops who have stormed so often before [3rd and Light Divisions], I should not have lost a fourth of the number[36].’

The moment that the hornwork had fallen into the power of the British, the heavy guns of the Napoleon battery opened such an appalling fire upon it, that the troops had to be withdrawn, save 300 men, who with some difficulty formed a lodgement in its interior, and a communication from its left front to the ‘dead ground’ on the north-west side of the hill, by which reliefs could enter under cover.

The whole of the next day (September 20) the garrison kept[p. 29] up such a searching fire upon the work that little could be done there, but on the following night the first battery of the besiegers [battery 1 on the map] was begun on a spot on the south-western side of the hill, a little way from the rear face of the hornwork, which was sheltered by an inequality of the ground from the guns of the Napoleon battery. It was armed on the night of the 23rd with two of the 18-pounders and three of the howitzers of the siege-train, with which it was intended to batter the Castle in due time. They were not used however at present, as Wellington, encouraged by his success at San Miguel, had determined to try as a preliminary move a second escalade, without help of artillery, on the outer enceinte of the Castle. This was to prove the first, and not the least disheartening, of the checks that he was to meet before Burgos.

The point of attack selected was on the north-western side of the lower wall, at a place where it was some 23 feet high. The choice was determined by the existence of a hollow road coming out of the suburb of San Pedro, from which access in perfectly dead ground, unsearched by any of the French guns, could be got, to a point within 60 yards of the ditch. The assault was to be made by 400 volunteers from the three brigades of the 1st Division, and was to be supported and flanked by a separate attack on another point on the south side of the outer enceinte, to be delivered by a detachment of the caçadores of the 6th Division. The force used was certainly too small for the purpose required, and it did not even get a chance of success. The Portuguese, when issuing from the ruined houses of the town, were detected at once, and being heavily fired on, retired without even approaching their goal. At the main attack the ladder party and forlorn hope reached the ditch in their first rush, sprang in and planted four ladders against the wall. The enemy had been taken somewhat by surprise, but recovered himself before the supports got to the front, which they did in a straggling fashion. A heavy musketry fire was opened on the men in the ditch, and live shells were rolled by hand upon them. Several attempts were made to mount the ladders, but all who neared their top rungs were shot or bayoneted, and after the officer in charge of the assault (Major Laurie, 1/79th) had been killed, the stormers ran back[p. 30] to their cover in the hollow road. They had lost 158 officers and men in all—76 from the Guards’ brigade, 44 from the German brigade, 9 from the Line brigade of the 1st Division, while the ineffective Portuguese diversion had cost only 29 casualties. The French had 9 killed and 13 wounded.

This was a deplorable business from every point of view. An escalade directed against an intact line of defence, held by a strong garrison, whose morale had not been shaken by any previous artillery preparation, was unjustifiable. There was not, as at Almaraz, any element of surprise involved; nor, as at the taking of the Castle of Badajoz, were a great number of stormers employed. Four hundred men with five ladders could not hope to force a well-built wall and ditch, defended by an enemy as numerous as themselves. The men murmured that they had been sent on an impossible task; and the heavy loss, added to that on San Miguel three days before, was discouraging. Many angry comments were made on the behaviour of the Portuguese on both occasions[37].

Irregular methods having failed, it remained to see what could be done by more formal procedure, by battering and sapping up towards the enemy’s defences on the west side of the Castle, the only one accessible for approach by parallels and trenches. The plan adopted was to work up from the hollow road (from which the stormers had started on the last escalade) in front of the suburb of San Pedro. The hollow road was utilized as a first parallel; from it a flying sap (b on the map) was pushed out uphill towards the outer enceinte in a diagonal line. The object was to arrive at it and to mine it (at the place marked I on the map). When the working party had got well forward, a point was chosen in the sap at a distance of 60 feet from the wall, and the mine was started from thence. All this was done under very heavy fire from the Castle, but it was partly kept down by placing marksmen all along the parallel, who picked off many of the French gunners, and of the infantry who lined the parapet of the outer enceinte. Sometimes the return fire of the place was nearly silenced, but many of the[p. 31] British marksmen fell. The work in the flying sap was made very costly by the fact that the trench, being on very steep ground, had to be made abnormally deep [September 23-6].

Meanwhile, on the hill of San Miguel, a second battery (No. 2 on the map) was dug out behind the gorge of the dismantled hornwork, and trenches for musketry (a.a on the map) were constructed on the slope of the hill, so as to bring fire to bear on the flank and rear of the lower defences of the Castle. The French heavy guns of the Napoleon battery devoted themselves to incommoding this work; their fire was accurate, many casualties took place, and occasionally all advance had to cease. A deep trench of communication between the batteries on San Miguel and the attack in front of San Pedro was also started, in order to link up the two approaches by a short line: the ground was all commanded by the Castle, and the digging went slowly because of the intense fire directed on it.

Meanwhile battery No. 1 on San Miguel at last came into operation, firing with five howitzers (the 18-pounders originally placed there had been withdrawn) against the palisades and flank of the north-western angle of the outer enceinte of the Castle. These inefficient guns had no good effect; it was found that they shot so inaccurately and so weakly that little harm was done. After firing 141 rounds they stopped, it being evident that the damage done was wholly incommensurate with the powder and shot expended [September 25]. This first interference of the British artillery in the contest was not very cheering either to the troops, or to the engineers engaged in planning the attack on the Castle. The guns in battery 1 kept silence for the next five days, while battery 2, where the 18-pounders had now been placed, had never yet fired a single shot. Wellington was now staking his luck on the mine, which was being run forward from the head of the flying sap.