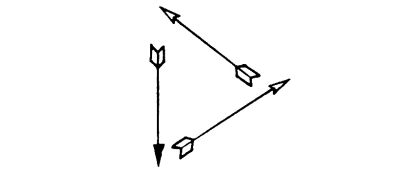

South position corresponding to the note C.

North position corresponding to the note G.

A Handbook for Students

of Conducting

by

Albert Stoessel

With a Preface by

Walter Damrosch

Copyright, 1920, by

CARL FISCHER, Inc., NEW YORK

International Copyright Secured

Copyright, 1928, by

CARL FISCHER, Inc., NEW YORK

International Copyright Secured

Carl Fischer, Inc.

COOPER SQUARE, NEW YORK 3

Boston · Chicago · Dallas · Los Angeles

Conducting is an art, and a difficult one to master.

It requires a special talent, enthusiasm, great nervous vitality; a serious study of the works written by the masters of music; the magnetic power of forcing the executants to carry out the conductor’s demands; infinite patience, great tenacity, great self-control, and absolute knowledge of the technique of the baton.

The last is a complete sign language through and by which the conductor issues his commands and achieves his results.

With the baton and an infinite variety of movements of hand, wrist and arm, the conductor indicates the tempo and its changes, the dynamics, the expression, and in fact all the inner spirit and meaning of the music.

He insures precision and unanimity whether his executants number one hundred or one thousand, and plays upon them as the pianist upon his keyboard or the violinist upon the strings of his Cremona.

Much of this must be inborn, but much can be acquired by study. Mr. Albert Stoessel’s book will be of great help to the earnest student.

Mr. Stoessel was appointed teacher of conducting in the Bandmasters’ School, which I founded during the war at General Pershing’s request at G. H. Q., Chaumont, France.

His book is admirably planned and executed. It is clear, practical and stimulating, and I hope it will be generally used throughout the country.

The lack of routine and the ignorance of even the simplest rudiments of the art of “beating time” is appalling among many of our conductors, organists and choir-masters. Mr. Stoessel’s book should be of great help to them.

July 4th, 1920

“Conducting is the art of directing the simultaneous performance of several players or singers by the use of gesture.” It is thus that Ralph Vaughan-Williams heads his illuminating article on conducting, written for Grove’s Dictionary, and while this rather terse definition is an admirable summing up of the meaning of conducting, it needs to be qualified.

In music the conductor is one, who after assimilating in his own consciousness every phase of a musical composition, becomes the supreme arbiter in the process of bringing that composition into actual being. Music as an art is absolutely dependent on the interpreter. It lives only in the performance, and the interpreter, sensing his importance, is often tempted to place his own personality between the audience and the music itself. It would seem, however, that in ensemble music, (music requiring several or more performers) this opportunity for the glorification of the personality of the virtuoso would be present in a far less degree. And yet, the interpretation by the conductor of the score of such a piece demands a degree of virtuosity transcending by far that which is required in the performance of an ordinary solo composition.

It is the conductor who unlocks the mysteries of the score. Like water that will always rise to its own level, it may safely be said that the actual performance of an orchestral or choral work will only rise to the level of the conductor’s intellectual and spiritual conception. A good conductor can get good results from players of lesser ability, while a poor conductor can throw the finest orchestra into confusion.

Granted that the conductor has a clear and matured mental conception of a musical work, there is still a vast distance between this conception and its final perception by the listener. An enumeration of these obstacles and a description of their overcoming will constitute a complete outline of what the art of conducting is.

A conductor with a definite conception of the musical score in his head is not unlike the commander of an army who has worked out a complete plan of action. Each has to carefully consider the limitation of his forces and equipment, and how best to achieve the objective. Each is working through others and in so doing must make due allowance for the uncertainties of human nature, the capacity and character of each individual as well as that intangible something known as “esprit de corps.” Ceaseless drilling is necessary to achieve that mechanical perfection which forms the foundation of later inspirational and artistic performance.

A survey of the history of conducting will show that the art has evolved through three distinct periods which might be called the “time-beater,” “drill-master” and “conductor” phases. The preparation and performance of any musical score requires the assuming of all three of these roles by the conductor. [Pg 2]

The activity of conducting is doubtless as old as music itself and was probably always employed whenever the musical performance called for several or more participants. The ancient Greeks indulged in two styles of conducting: the conductor indicating the beat by stamping his iron-soled foot or by resorting to what is known as “Chironomy.” This latter was a system of indicating the progress of a musical composition by arm, hand, and finger motions, a definite movement corresponding to every rise and fall of the melody. It was from chironomy, in connection with various speech accents that the notation system of neumes developed.

An interesting feature of this early conducting is the fact that all down beats (accented) were indicated by up strokes of the hand and the up beats (unaccented) vice versa, with downward movements. This is just the opposite to modern practice.

This manner of conducting was probably in vogue in the early Gregorian singing schools, and even a superficial perusal of the Gregorian chants will indicate the intricate rhythmical character of the music taught and sung in these establishments. These early chants, not unlike our modern operatic recitative, had no regular rhythmic scheme and the singing was a sort of musical prose. The singing was lead by a precentor. It was he who gave the pitch and lead with “voice and hand,” that is, he gave the chironomic signs and helped the singers over the rough spots by singing along. The church, however, also knew strict rhythmical hymns and there the leader stamped the beat audibly.

With the advent of polyphony the duties of the conductor increased. He often found it necessary to lead both visibly and audibly. Mendelssohn in a letter to his teacher, Zelter, gives a description of this manifold activity on the part of the conductor, indicating that it persisted even to the rather late date of 1830. Describing the papal choir in Rome, he writes:

“There is a chorus of priests (clericals) who sing only in the presence of the Pope or his representative. It numbers thirty-two regular members but they are seldom all present. The director personally sings with them, helping each part, sometimes singing the deepest bass and again jumping with astounding agility to the highest falsetto soprano.”

With the introduction of the mensural notation the old chironomic system ceased to have a reason to exist and the conductor instead of indicating every fluctuation of the melodic line, merely beat time at certain of the accented divisions of the phrase. This was done usually with a parchment roll of music in the hand, so that the singers and ever increasing number of instrumentalists could keep together.

The transition from the 16th to the 17th century brought about important innovations in music—the accompanied solo numbers of the opera came into being, the figured bass and bar line were introduced generally into choral and orchestral works. And, when in the course of the 17th century the demand that the conductor cease this mechanical beating of the time and give the tempo in a manner commensurate with the effect desired became insistent, the conductor took his place among the performers and lead the music from the clavicembalo. From this [Pg 3] position he not only led the performance but also filled in the harmonies according to the figured bass. When the rhythm wavered, the first violin, whom we call the concertmaster, gave the beat.

Although this method of combined leadership (cembalo and first violin) was the one in general use during the 18th century, there were other modes of leading. Rousseau pokes fun at the Paris opera where much evil noise was made by pounding the floor with a stick in order to keep the musical forces together. It is a grotesque truth that Lully lost his life from an infection of the foot caused by a misdirected stroke of the cane with which he was beating time.

According to Gessner, Bach presided at the organ or cembalo while conducting and this seems to have been the method of Handel and Gluck likewise. Haydn conducted his London Symphonies sitting at the piano, more as a sort of public exhibition than as actual leader. The conducting was done by Solomon, the violinist.

In the meantime another revolutionary change had taken place in music itself. The general or figured bass playing clavier or cembalo was rendered superfluous by the incorporation of the full harmony into the orchestra itself. The only place where it held its own was in the accompaniment to the recitative.

Beethoven conducted his “Eroica” in the house of Prince Lobkowitz, 1804, standing at the conductor’s desk. It is assumed that he used a roll of sheet music, because in Germany the use of the baton was first introduced by Mosel in 1812.

Spohr gives us an interesting glimpse of Beethoven’s conducting methods. He says: “It was Beethoven’s custom to insert all sorts of dynamic markings in the parts, and remind his players of the marks by resorting to the most curious bodily contortions. At every ‘sforzato’ he would thrust his arms away from his breast where he held them crossed. When he desired a ‘piano’ he would crouch lower and lower; when the music grew louder into a ‘forte’, he would literally leap into the air and at times grow so excited as to yell in the midst of a climax.”

From about the year 1812 the use of the baton spread rapidly. We have records of Carl Maria von Weber using the baton in 1817 in Dresden, Mendelssohn in 1835 in Leipzig, and Spohr tells a most amusing anecdote of how the musicians of the London orchestra protested most vehemently when he first proposed to lead them with the magic little stick instead of playing the violin with them.

The art of conducting as we understand it can be said to date back to this triumvirate, von Weber, Spohr and Mendelssohn. Although all creative musicians of the first water (and who until the era of the modern travelling virtuoso was not primarily a creative musician), these men grasped in the greatest measure the tremendous importance of the proper interpretation of a musical composition and through their personal effort and skill as leaders raised the standard of performance wherever they directed. They realized the important difference between merely beating time and giving the living pulse or tempo of a composition. [Pg 4]

Although Spohr is remembered today chiefly as a composer of violin concerti and duos that all pupils play, in his own time his prestige was equal to, if not greater than that of Beethoven. A man of inflexible character and peculiar critical methods, he was not in full sympathy with Beethoven and von Weber but on the other hand he vigorously espoused the cause of the new German school, even giving a performance of Wagner’s “Flying Dutchman” at a time when Wagner was not at all popular. Wagner never forgot his indebtedness to Spohr, who was the first German musician to recognize him. It was Spohr who introduced the system of marking the score with letters and numbers to facilitate rehearsing.

It is interesting to read Carl Maria von Weber’s directions for time beating. To quote him: “The beat must not be like a tyrannical mill-hammer but must be to the musical composition what the pulse beat is to the life of a human being. There are no slow tempi in which places do not occur which demand a faster movement in order to eliminate the tendency to drag. On the other hand there is no presto which has not contrasting episodes that must be played much slower to avoid the slighting of the expressive passages.—All accelerandi as well as ritardandi must be made skillfully, that is, gradually.” This is only a small example of the reforms brought about by the composer of “Oberon.”

Mendelssohn might be said to have been a living example of the rather worn expression “a born conductor.” Brought up in the most musical of households he was familiar with the orchestra from childhood and in his life time was equally famous as conductor and composer. Although his conducting was not entirely free from certain traits of superficiality and rigid elegance, Wagner’s biting criticism of him must be taken with a grain of salt.

Other prominent conductors of the romantic period were the composers Meyerbeer and Spontini.

It is possible to reconstruct a picture of Hector Berlioz as conductor from his own words. In his little book on the “Orchestral Conductor” he says: “The orchestral conductor should see and hear; he should be active and vigorous, should know the composition and the nature and compass of the instruments, should be able to read the score, and possess—besides the especial talent of which we shall presently endeavor to explain the constituent qualities—other indefinable gifts, without which an invisible link cannot establish itself between him and those he directs; otherwise the faculty of transmitting to them his feeling is denied him, and power, empire, and guiding influence completely fail him. He is then no longer a conductor, a director, but a simple beater of the time—supposing he knows how to beat it, and divide it, regularly.”

“The performers should feel that he feels, comprehends, and is moved; then his emotion communicates itself to those whom he directs, his inward fire warms them, his electric glow animates them, his force of impulse excites them; he throws around him the vital irradiations of musical art. If he is inert and frozen, on the contrary, he paralyzes all about him, like those floating masses of the polar seas, the approach of which is sensed through the sudden cooling of the atmosphere.” [Pg 5]

“His task is a complicated one. He has not only to conduct, in the spirit of the author’s intentions, a work with which the performers have already become acquainted, but he must also introduce new compositions and help the performers to master them. He has to criticise the errors and defects of each during the rehearsals, and to organize the resources at his disposal in such a way as to make the best use he can of them with the utmost promptitude; for, in the majority of European cities nowadays, musical artisanship is so ill distributed, performers so ill paid and the necessity of study so little understood, that economy of time should be reckoned among the most imperative requisites of the orchestral conductor’s art.”

Franz Liszt’s position as composer is too well known to require further elucidation here, but Wagner’s description of his future father-in-law’s conducting is certainly worth quoting. Wagner, passing through Weimar in his flight from the governmental authorities, had an opportunity to attend one of Liszt’s rehearsals of “Tannhäuser.” He tells us: “What I felt when I created this music, he felt in his performance of it; what I wanted to say as I wrote it down, he said in bringing it to performance.” In the directions attached to the scores of his Symphonic Poems, Liszt gives an interesting picture of his ideas on conducting:

“A performance of my orchestral works which measures up to the standard and intentions of the composer and that will give them the proper tone color, rhythm and life, can best be brought about by preliminary sectional rehearsals. With this in mind I respectfully request of the esteemed conductors who intend to perform my symphonic works that they precede the general rehearsal with separate rehearsals for the strings, wood-wind, brass, etc.”

“At the same time I would like to remark that the usual mechanical, cut and dried performance (customary in many cities) be avoided and in its place the ‘new period’ style which stresses proper accentuation, the rounding off of melodic and rhythmical nuances be substituted. The life-nerve of a symphonic production rests in the conductor’s spiritual and intellectual conception of the composition, it being assumed, of course, that the orchestra possesses the necessary powers to realize this conception. Should the latter condition be absent, I recommend that my works be left unperformed.”

“Although I have tried through exact markings of the dynamics, the accelerations and slowing up of the tempo, to clearly indicate my wishes, I must confess that much, even that which is of the greatest importance cannot be expressed on paper. Only a complete artistic equipment on the part of the conductor and players, as well as a sympathetic and spiritually enlivened performance can bring my works to their proper effect.”

It was Liszt’s desire to free the performance of orchestral and choral works from the limitations of bar line rhythm and to effect this change his style of conducting became a sort of modern chironomy in which his gestures expressed the “melos” and underlying spirit of the composition as well as fulfilling their mechanical function.

From Liszt we easily trace the line of growth in the art of conducting to Richard Wagner, and interestingly enough, with Richard Wagner the great line of composer-conductors stops. [Pg 6]

In this day and generation the ever increasing tendency of specialization has brought about an almost complete separation of creative activity from executive activity. Even in the 18th and early 19th century the virtuoso who travelled around was principally a composer who played his own works. The conductor, player, or singer who performs only the works of others is a modern product and was completely unknown until recently.

But, before reviewing the names and accomplishments of the line of purely virtuoso conductors, we must take time to consider Richard Wagner’s position as conductor.

That same unquenchable reformatory fire which manifested itself in Wagner’s composing made him one of the greatest conductors in all musical history. His illuminating performances of Weber’s “Freischuetz,” Gluck’s “Iphigenia,” Palestrina’s “Stabat Mater,” Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony” still cast their echoes down the corridors of time to the influencing of performances that are being given today. Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony” was performed three times by Wagner (in 1846, ’47 and ’49) and not once did his name appear on the program. What a contrast to these days, when often in the advance announcement only the name of the ‘prima donna’ conductor appears!

For years Beethoven’s colossal work was the rock upon which many talented conductors had foundered. Only the Parisian conductor, Habeneck, who conducted from a violin-part, had the patience and character to so drill his Conservatoire orchestra that they mastered to a relatively high degree the difficulties of the work. Wagner tells us in his book on conducting, of the great disappointment that was his when he heard the actual performance in Germany of works which he had come to love through the study of the score. In fact, his book is almost entirely a diatribe against the superficial and conscienceless conductors of this time. Habeneck’s performance of the “Ninth” opened his eyes and he did not rest until he was likewise able to give performances of Beethoven’s immortal work that were to mark a new era and standard of orchestral technic.

He placed little stress on tempo marks, agreeing with Bach that a true musician is able to tell from the character of the music just how fast or slow a composition is to be taken. Taking his cue from Habeneck, he made perfection of ensemble and correct rendition of the notes his starting point and on this solid foundation he reared a structure of the highest poetic beauty and imagination. The melos or spiritual melody of the artwork was sought by him in every measure and when found he caused whichever instrument through which it was expressed to sing it with the utmost intensity and conviction. His fanatical desire to always bring out the “melos” caused him at times to even go so far as to alter the instrumentation of the original, giving notes to the trumpets and horns which they in Beethoven’s time did not possess, and often changing awkward passages in the woodwinds which he considered were dictated more by Beethoven’s deafness than his better musical judgment.

Descriptions of Wagner’s conducting tell us of a man of no more than medium height with a rather still deportment, moderate but decisive [Pg 7] movements of the arms, a great vivacity and a habit of fixing a piercing glance on the players of the orchestra which he ruled imperially. Fürstenau, the flutist, related to Felix Weingartner that when Wagner conducted they had no sense of being led and that each player believed himself to be following freely his own feeling. And yet everything was bound together so powerfully by Wagner’s mighty will that everything went with wonderful smoothness and precision.

Wagner’s epoch-making works demanded a new school of conductors, and gradually he was able to train younger men to carry out his ideas and to spread the message of the new art. Chief among these Wagner apostles was Hans von Buelow, a great pianist and a musician who might have been a creator in his own right had he not heeded the call of specialization, demanded of him as an interpreter. He toured Europe with his small but highly-trained Meiningen Court Orchestra, and completely revolutionized the status of orchestral playing. His conducting of “Tristan” and his beautifully clear piano score of the same, testify of his high understanding of the Wagner spirit. And yet, after his tragic break with the Bayreuth master, he was able to espouse the cause of the classic composers and, what is all the more astonishing, become the chief exponent of the anti-Wagner school, of which Brahms was the symbol.

In Bayreuth Wagner had as his conductors men like Hans Richter, Felix Mottl and Hermann Levi and the names of these men are indelibly connected with the glory that was Bayreuth’s. With the advent of these conductors we stand at the threshold of today.

This brief sketch has led us from the time when the conductor was little more than a time-beater functioning in the most mechanical manner, to our own time when the conductor has achieved an importance in the musical world second only to the creator himself, and in some cases even transcending the position of the mere creator of the music. Did not a great conductor of today recently ask a composer: “Have you ever heard me conduct your opera?” “No.” “You should, you wouldn’t recognize it.”

The conductor of today is not merely the time-beater and drill-master who achieves note-perfection, but he is the genius who frees music from all the imperfections of material limitations, his rhythm is no longer the wallpaper pattern of the bar line, but takes on its original meaning in the stressing of the flowing phrase; his gesture is no longer the mere beat but is the pictorialization and visualization of the music itself.

In the new conductor, Liszt’s ideal of the conductor or time-beater who makes himself superfluous is partially realized, but not in the way Liszt thought. The conductor of today has made the old time-beater-drill-master superfluous by supplanting him with a super-being, one who with his wealth of subtle and interpretative gestures has brought into being a new art of chironomy which does not merely indicate the rise and fall of the melody, but indicates that which no composer has ever succeeded in putting on paper—the living soul and spirit of the artwork.

This chapter is devoted entirely to the physical aspect of conducting. Analysis of the gestures used in conducting has shown that there are four fundamental movements.

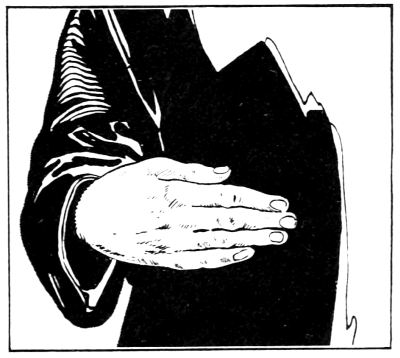

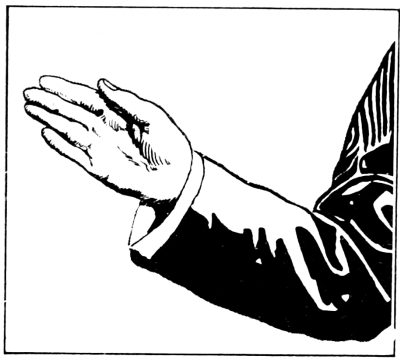

A—Wrist movement in horizontal position. (With palm of the hand facing downward.)

B—Wrist movement in vertical position. (With palm of the hand facing inward.)

C—Fore-arm movement.

D—Full-arm movement.

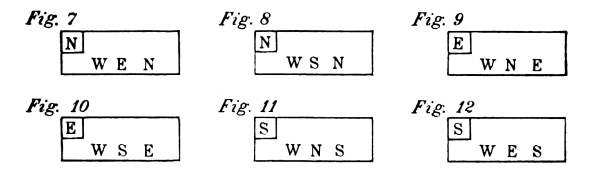

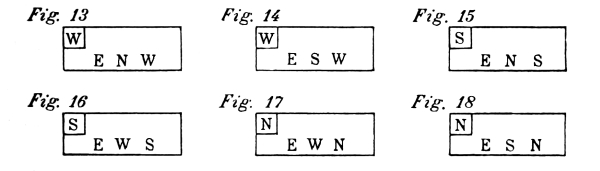

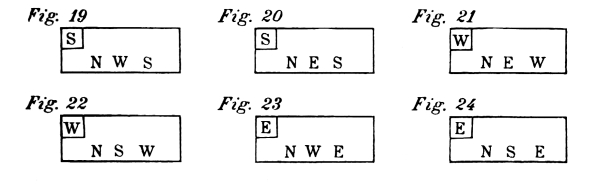

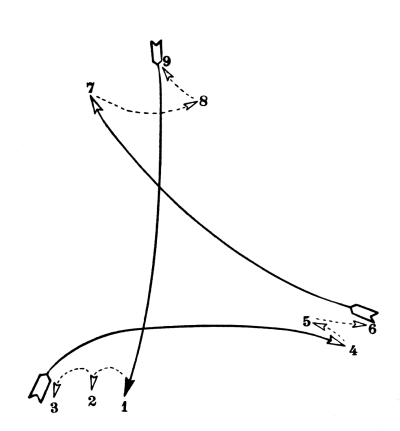

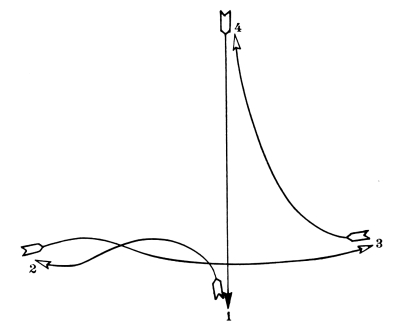

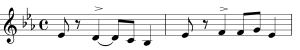

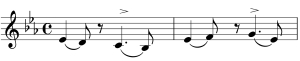

The diagrams on pages 11 and 13 represent a set of exercises for the acquiring of complete control and suppleness of the wrist and arm in all these four movements. On the opposite pages sets of music examples will be found. Each individual note of these examples represents a movement.

The conscientious study and practice of these exercises will not only fully prepare the conductor for the more complicated beating of time-indications, but will give him that poise and confidence which come only with a consciousness of absolute self-control. This physical self-control is one of the greatest essentials in the art of conducting.

There are two series of exercises, each numbering 24 figures. These are to be performed in four different styles, corresponding to the four fundamental movements.

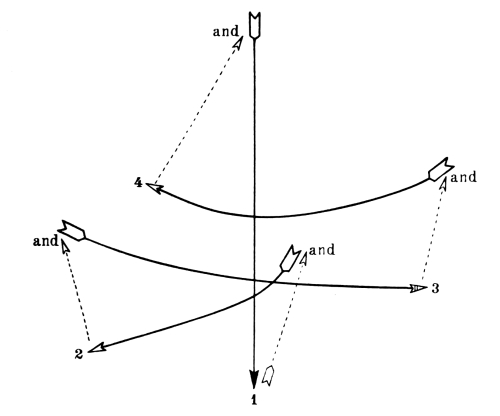

For each style, there are four different positions which, for practical reasons, have been named after the points of the compass; North, South, [Pg 9] East, and West. The drawings contained in this chapter are of the four different positions, for each style of exercise. In the diagram of exercises each of these points is indicated by a letter; N—for North, S—for South, E—for East, and W—for West.

The small letter in the upper left corner indicates the starting point. The other letters indicate the points of arrival.

Each figure is to be executed in time with certain music examples of which each individual note corresponds to a point of arrival.

For instance, figure 1 would be executed with Music Ex. 1 thus:

The sf on a letter indicates a sharp forceful movement as opposed to a more relaxed motion. In the exercises for the wrist, the forearm and upper arm must remain motionless. Likewise, the forearm movement must be executed without moving the upper arm.

Great caution should be taken not to over-tire the wrist and arm, when first practising these exercises.

These exercises are to be practised by the right and left arm alternatively.

It is suggested for the individual practise that the student place the music examples on one side of the music stand and the diagram of the exercises on the other.

Thus he may describe the gymnastic exercises while singing or whistling the music. [Pg 10]

| Ex. 1 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 2 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 3 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 4 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 5 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 6 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 7 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 8 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 9 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 10 |

|

[Listen] |

Apply these exercises to all figures of series 1.

Series 1

| Ex. 1 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 2 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 3 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 4 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 5 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 6 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 7 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 8 |

|

[Listen] |

| Ex. 9 |

|

[Listen] |

Apply these exercises to all figures of series 2

NOTE:—Each individual note corresponds to a gesture indicated in the figures by a N, E, S, W.

Series 2

| The letter in the upper left corner indicates the starting point. |

N—North Position. |

| W—West Position. | |

| S—South Position. | |

| E—East Position. |

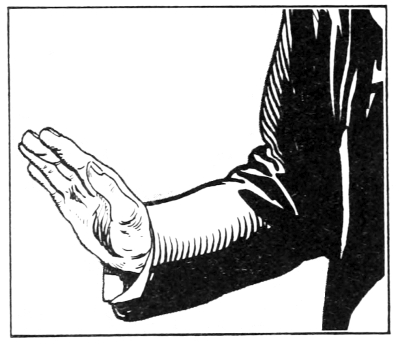

‘N,’ or North position of Style A

1. Drop arm loosely to side.

2. Raise forearm forward until it forms a right angle with the upper arm.

3. Extend hand and fingers; keep the palm facing downwards.

4. Without moving the arm, raise the hand from the wrist-joint until almost at a right angle with the forearm.

Note.—The forearm maintains this position all through the exercises of Style A.

‘S,’ or South position of Style A

Without moving the forearm, lower the hand from the wrist-joint until at a right angle with the forearm.

‘E,’ or East position of Style A

Without moving the forearm, and always keeping the fingers extended and palm downward, move the hand to the right as far as possible.

‘W,’ or West position of Style A

Without moving the arm, and always keeping the fingers extended with the palm downward, move the hand to the left as far as it will go. [Pg 16]

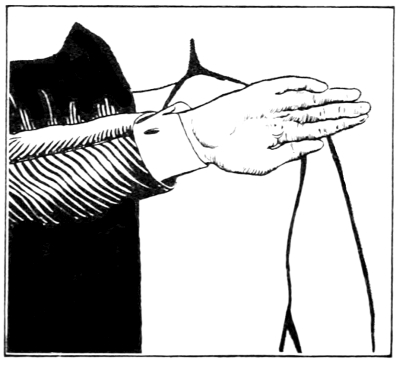

‘N,’ or North position of Style B

1. Drop arm loosely to side.

2. Raise forearm forward until it forms a right angle with the upper arm.

3. The fingers remain extended and the palm is turned so that the thumb is uppermost.

4. Without moving the forearm, raise the hand as far as possible, taking care to keep the fingers extended and palm inward.

Note.—The forearm maintains this position throughout the positions of Style B.

‘S,’ or South position of Style B

Without moving the arm, lower the hand as far as possible, taking care to keep the fingers extended and palm inward (facing to the left). [Pg 17]

‘E,’ or East position of Style B

Without moving the arm, point the hand and fingers to the right until almost forming a right angle with the arm.

‘W,’ or West position of Style B

Without moving the arm, point the hand and fingers to the left until almost forming a right angle. The thumb still remains uppermost. [Pg 18]

‘N,’ or North position of Style C

1. Drop arm loosely to side.

2. Raise forearm forward until it forms a right angle with the upper arm.

3. The palm is turned down.

4. Without moving the upper arm, raise the forearm upwards until the back of the hand almost touches the shoulder.

Note.—The upper arm maintains this position throughout the exercises in Style C.

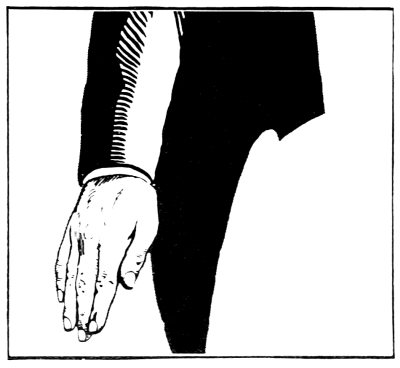

‘S,’ or South position of Style C

Without moving the upper arm, lower the forearm until the palm of the hand is about 3 or 4 inches from the thigh. [Pg 19]

‘E,’ or East position of Style C

Without moving upper arm, turn the forearm to the right about 40 degrees.

‘W,’ or West position of Style C

Without moving upper arm, turn the forearm to the left about 40 degrees, the palm of the hand facing forward. [Pg 20]

‘S,’ or South position of Style D

Lower arm downward until the palm is about 4 inches from the thigh.

NOTE.—All motions in Style ‘D’ are described by the full arm.

‘W,’ or West position of Style D

Turn arm to the left about 40 degrees. [Pg 21]

‘E,’ or East position of Style D

Turn arm to the right about 40 degrees.

‘N,’ or North position of Style D

Raise arm upwards with palm forward and fingers extended.

1. The general attitude of the conductor must be one of quiet, but commanding dignity.

2. He must not only know what he wants, but must be able to convey this knowledge to his musicians by a minimum of gesture.

3. His body must be as firm as the proverbial mighty oak which only sways in the fiercest storm. The head, knees and feet must remain quiet.

4. The length of the arm movement varies necessarily with the length of the individual arm. The increase or decrease in the tempo also calls for changes in motion. A quick tempo is conducted with a smaller motion than a slow tempo. Often the contrast of “fortissimo” to “pianissimo” is indicated by changing from large to small motions.

5. All gestures must be directed by the hand or forearm. Just as the singer is admonished to produce his tones “forward” so should the conductor place his center of energetic motive power as far into the tips of the fingers as possible. This produces the effect of the hand easily drawing the arm after it rather than pushing the dead weight of the arm by a movement that seems to begin in the shoulder.

6. The baton must not be held stiffly as this would effect the suppleness of the whole arm. The gesture must be described by the very tip of the baton, as if an imaginary brush were attached to it and one were painting the gesture on some imaginary surface. As a rule the palm of the hand should be held downward.

7. It is possible to beat time accurately and still use uneven and unrythmical motions. To avoid this, the greatest rare should be taken to move from one beat to another in a measured and symmetrical manner.

8. In a slow movement, accuracy can be obtained by ending each beat with an added sharp wrist movement in the same direction as the beat.

9. The function of the left arm is difficult to describe. Although it plays a more modest part than the right arm, it is nevertheless of much importance. It must ever be ready with preventive motions, indications of instrumental entrances (cues), and to add force to certain gestures of the right arm. But let it here be said that the habit of conducting constantly with both arms describing the motions is only to be condemned.

10. Although all general rules in conducting are dangerous, it is suggested that the principle of indicating each accent, entrance, sudden “forte” or “piano,” one beat in advance be adhered to.

No. 1. Preparatory position. 4/4 time.

Number 2

Position of the first beat in 4/4 time.

Number 3

Position of the second beat in 4/4 time.

Number 4

Position of the third beat in 4/4 time.

Number 5

Position of the fourth beat in 4/4 time.

The music examples are to illustrate the use of the gesture and have been found practical for class work.

In practising these gestures with the music examples, the movement must always be expressive of the character of the music.

Sharp and energetic movements for music of an accentuated character, and moderate, gentle movements for music of a corresponding nature.

The accent is executed by a sharp, quick arm movement. Great care must be taken to execute each movement, even the most gentle pianissimo, clearly and with authority.

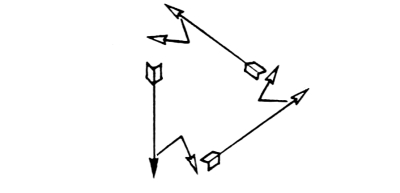

In all the diagrams shown the following principles are adhered to:—

1. The heavy or accented beat is indicated by a dark arrow.

2. The light or unaccented beat is indicated by an unshaded arrow.

3. The semi-accented beat is indicated by a semi-shaded arrow.

4. All subdivisions are indicated by dotted lines.

5. The fundamental beats are described with the arm movement, while subdivisions are performed with the wrist. In this manner, a clear indication of the fundamental beat is always maintained.

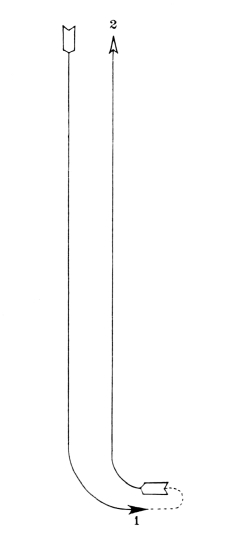

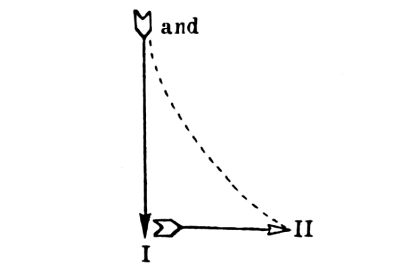

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 1

Fundamental method of beating 2/2, 2/4 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 2

Actual method of beating 2/2, 2/4,

and fast 6/8 and 6/4 time.

| Accented 1st beat:— | [Listen] |

|

| Accented 2nd beat:— | |

[Listen] |

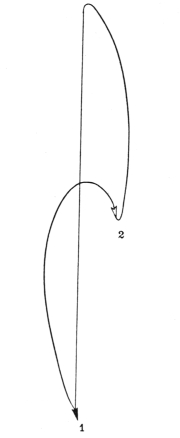

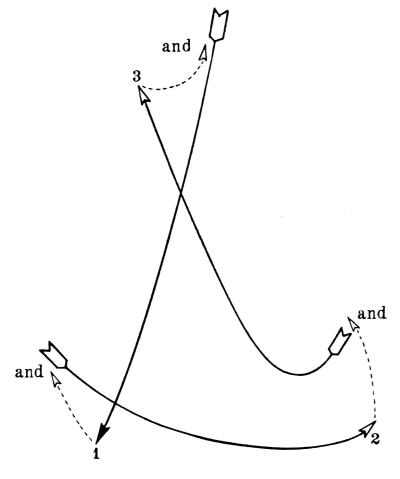

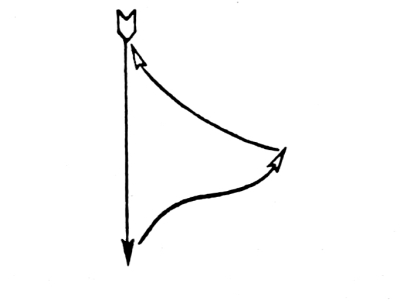

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 3

Normal subdivision of 2/2 and 2/4 time.

N.B.The subdivision of each beat is

indicated by the word “and”.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 4

Method of beating 6/8, 6/4 time when only 2 beats in a measure are required. To be used also for slow 2/4 time. [Pg 35]

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 5

Accented subdivision of 2/2 and 2/4 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 6

6/4 or 6/8 time. (Modern French Method) 6/4 or 6/8 time is a subdivision of 2/2 or 2/4 time. [Pg 37]

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 6a

Old method of beating slow 6/8 time.

The disadvantage of this method is that the 6th beat is out of proportion with the others. In diagram Nᵒ. 6 the long beat comes on the 4th or naturally accented beat of the measure, whereas in 6a the 6th or last beat in the measure is apt to be unduly accented. [Pg 38]

| A—With accent on 1st beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| B—With accent on 2nd beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| C—With accent on 3rd beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| D—With accent on 4th beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| E—With accent on 5th beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| F—With accent on 6th beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| G—With accent on 1st and 4th beat. |  |

[Listen] |

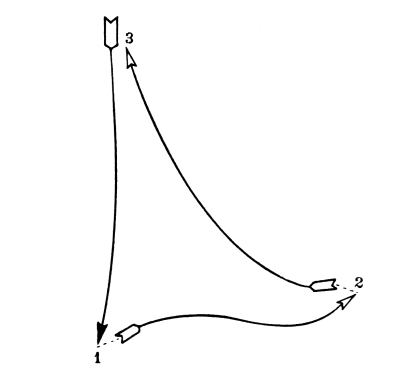

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 7

Fundamental method of beating 3/2, 3/4 or 3/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 8

Actual method of beating 3/2, 3/4 or 3/8 time. [Pg 40]

| B—With accent on 1st beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| C—With accent on 2nd beat. | [Listen] |

|

| D—With accent on 3rd beat. | [Listen] |

|

| E—Accent on 1st and 3rd beat. | [Listen] |

|

| F—Waltz—Accent on 1st beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| Polonaise G—Accent on all 3 beats. |

|

[Listen] |

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 9

Normal subdivision of 3/2, 3/4 or 3/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 10

Accented subdivision of 3/2, 3/4 or 3/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 11

9/8 Time. Only for very slow tempos.

Otherwise, beat 3.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 12

Fundamental method of beating 4/2, 4/4 and 4/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 13

Actual method of beating 4/2, 4/4 and 4/8 time. [Pg 45]

| A—With accent on 1st beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| B—With accent on 2nd beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| C—With accent on 3rd beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| D—With accent on 4th beat. |  |

[Listen] |

| E—With accent on 1st and 3rd beat. |  |

[Listen] |

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 14

Normal subdivision of 4/2, 4/4 and 4/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 15

Accented subdivision of 4/2, 4/4 and 4/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 16

12/4 or 12/8 time.

12/8 time is really a subdivision of 4/4 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 17

5/4 or 5/8 time.

This 5/4 or 5/8 time is a compound rhythm of

(2-3)/4 or (2-3)/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 18

5/8 or 5/4 time.

This 5/8 or 5/4 time is a compound

of (3-2)/8 or (3-2)/4 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 19

Method of conducting slow 5/4 time

when the measure

is not subdivided

into (3-2)/4 or (2-3)/4.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 20

7/4 time.

(3-4)/4 or (3-4)/8 time.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 21

7/8 or 7/4 time.

(3-4)/4 or (3-4)/8 time.

1. “pp” (Pianissimo) is indicated by extending and raising the left arm slightly with the hand at the level of the shoulder, palm downward.

2. “p” (Piano) is indicated by raising the left forearm until the back of the hand is directly in front of the left shoulder.

3. Coda Sign—Raise left arm above the head with one finger extended.

4. Second Ending—Raise left arm above the head with two fingers extended.

5. To stop in middle of strain—Raise left arm above head, with all the fingers extended, and keep it there until halt is desired. At this point, bring it down firmly and quickly.

At the conclusion of this chapter, a word or two on practice in the art of conducting may not be out of place. One might read all about the art of swimming and yet be entirely lost the first time one is actually thrown into the water. The tricky resistance and action of the water is not unlike what the tyro conductor feels when he first takes his stand, baton in hand, in front of the orchestra or chorus.

Of course, when the conductor has even the most amateurish orchestra or chorus with which to practice, no better method need be recommended. But in England and America this is all too seldom the case, and the hapless beginner has to learn his art the best he can, without the aid of this valuable experimental laboratory. [Pg 55]

It is related of Koussevitzky, the great Russian conductor, that in his apprenticeship period he gained his practice of baton technic on an imaginary orchestra which consisted of empty chairs with signs on them representing the various instrumental choirs. It required imagination to do this, and let it be said right here that imagination is one of the first requisites of the conductor.

The beginner in conducting can at least familiarize himself with the feel of the baton, and practice the ordinary gestures until they become as automatic as walking and breathing. Conducting to a phonograph record is most helpful.

After the score has been mastered (see Chapter VI) it is a good plan for the student to conduct an imaginary performance of it, giving the proper gestures and all necessary cues. More great conductors than would ordinarily admit this make a regular practice of this “silent” conducting. Like the great actors whom they strive to emulate, they make a detailed study of every gesture, attitude and, sometimes, pose, which might be expressive of the character of the music they are interpreting.

The “attaque” (start), the “release”, the “fermata” (hold), subdivision, breathing places, phrasing.

One of the most important and difficult results to obtain is a clean cut and united “attaque” or start, on the part of the players. The following suggestions will aid toward an achievement of this result.

When the musical subject begins directly on the first beat of the measure, one beat before, given in the time of the following measures and in the position of the last beat in the measure, will suffice to assure a concerted and clean-cut “attaque.” The following measures, from the PRELUDE TO THE MASTERSINGERS by WAGNER, illustrate this principle.

(B) When the musical subject begins on the last beat of the measure, give the preceding beat, first. This beat should be less marked than those following.

NOTE: Many modern conductors dispense with this preceding beat. However, it is extremely valuable in establishing the rhythm and helpful to less experienced orchestral or band players. [Pg 58]

(C) The principle of the preceding example is also applicable to cases in which the musical subject begins on any fraction of the beat.

(D) In a case where the time is “one” in a measure, and the musical subject begins on a fraction of the measure, beat one whole measure before.

(Hold) and “Release”

Executing the gesture in a rather high position (above the head) beat only the beginning and end of the note.

1—Indicates the start.

2—Indicates the culmination of the chord which must be brought about with a quick, incisive movement to the right, preceded by a short preparatory movement to the left

When the “fermata” (hold) is at the end of the piece, terminate the chord by a sharp second down-beat preceded only by a slight preparatory curve. The second down-beat must be long enough to remove the baton completely from the sight of the audience and to bring it to such a position that definitely terminates all further conducting.

When the “fermata” or hold comes on a note in the midst of a phrase, merely sustain that beat longer than the others.

In example (b) hold the “fermata” on the third beat after beating “one” and “two”.

Employment of the “subdivision” to emphasize and give weight to certain characteristic passages, ritenuti, etc.

By subdividing the beats in the fourth measure of the following example, force and accent are given to the phrase.

The sharply accented beat as a means of obtaining precision in syncopated figures.

By accenting the first and third beats of measures (1) and (2) of the following example, a certain lingering on the tied notes will be avoided.

To secure a firm “attaque” of the horns in the fourth measure, subdivide the second beat of the measure.

To secure precision in the syncopated entrances, subdivide the 4-in-a-measure as indicated by the numbers, using gesture No. 15. (p 47)

To secure precision in the unison pizzicato notes, subdivide the second beat in the first two measures, giving all the beats but this one with a small gesture.

To bring out the climax at letter (C) subdivide the measure at (B) with heavy decisive strokes on each 8th note.

To indicate places for taking breath, conduct in the manner described below. The arm movement must come to a complete stop just before the breathing place.

In his excellent article of “Conducting” in Grove’s Dictionary, Ralph Vaughan-Williams gives the following rule: “As a general rule no more strokes should be used than are absolutely necessary to mark the time”; for instance no bar should be beaten in three strokes that can be beaten in one, no bar should be beaten in four strokes that can be beaten in two.

This rule is unassailable but there are times when it is difficult for the conductor to judge which style of time-beating to use. The Adagio and Allegro of the Overture to “The Magic Flute” are good examples of such a difficulty.

The Adagio is marked ![]() and is usually taken in four moderate beats. The Allegro has no alla breve

and is usually taken in four moderate beats. The Allegro has no alla breve

![]() mark and yet should be taken in two moderate beats.

mark and yet should be taken in two moderate beats.

[Pg 68] To beat the Allegro in four gives it precision but takes away from the light and graceful airiness of the figure by giving undue prominence to the third beat. In any 4/4 or 4/8 gesture the third beat is apt to get almost as strong an accent as the first.

The Allegro Vivace of Mozart’s “Jupiter Symphony” is also taken alla breve instead of in four beats as marked. A number of present day conductors are taking the March in the “Pathetique Symphony” of Tschaikowski in alla breve time with very marked success.

On the other hand there are types of compositions that need the greater energizing power of the four beats. Percy Grainger’s “Molly on the Shore”[2] is a good example of one of these. He requests the conductor to keep four equally accented beats hammering away throughout the whole piece.

[2] Copyright 1911, by G. Schirmer, Inc. N. Y.

In conducting fast moving tempos one-in-a-bar, the conductor will soon notice the individual bars grouping themselves together in phrases and periods, and it is most helpful to the musicians if some slight indication of the groupings be given in conducting. In fast one-in-a-bar movements four single measures often become one large measure of four beats, and if the beginning and termination of this measure group is indicated by a slightly larger beat, the musical composition becomes more intelligible to the player and listener. [Pg 69]

Thus the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

From the sixth measure on

might easily become:

This rearranged phrase grouping should in no way be misunderstood to mean that the tempo should be beaten in 4/4 Andante. Merely, the more compact grouping of faster notes in a slower tempo is often a mental help to both conductor and player in bringing out the proper musical inflection. [Pg 70]

A glance at the following example will show how readily the opening theme of the “Eroica Symphony” falls into groups of four measures each.

On the other hand, the Scherzo of the same work is unevenly divided into phrases of four and two measures.

[Pg 71] With the advent of Stravinsky and other moderns a new problem of time beating has arisen in connection with the attempt to free music entirely from the formal division of the bar line placed at regular intervals. Not that these composers dispense with the bar line completely, but they place it in such disconcertingly irregular places that the conductor’s task is doubly difficult even when he attempts to indicate it merely with a single down-beat.

The two following examples from Igor Stravinsky’s “Petrouchka”[3] illustrate this difficulty. The tempo is too fast to permit the use of regularly divided gestures, and yet it is very difficult to bring in the single beats with such metronomic precision that the musicians can play all of the individual eighth notes evenly and without hurrying.

[3] Copyright by Russischer Musikverlag, Berlin

EXAMPLE Nᵒ. 1

EXAMPLE Nᵒ. 2

[Pg 75]

The author, in his conducting class at New York University has

experimented with several methods, and has finally hit upon the

following system of teaching the intricate baton technic involved in

the conducting of works like Stravinsky’s “Petrouchka.”

The student is made to sit at the piano and play simple five finger figures with a single accent on the first note which is always played by the thumb.

Playing the eighth notes in a rather quick tempo each exercise is to be repeated until the feeling of the recurrence of the down-beat (which corresponds to the accented thumb stroke) becomes entirely automatic. Care must be taken never to vary the speed of the eighth notes and to accent only the first note. [Pg 76]

Translated into terms of this exercise the two examples from “Petrouchka” would be as follows:

The speed of the eighth notes must never vary.

Beat 3-in-a-measure, merely making the third beat one-eighth note longer. [Pg 77]

Beat 2-in-a-measure, merely making the second beat one-eighth note longer.

The Hymn of Jesus:—Gustave Holst (Copyright 1920 by Stainer and Bell, London)

Beat 4-in-a-measure, merely making the fourth beat one-eighth note longer. [Pg 78]

To begin with, a dividing line must be drawn between a waltz played for dancing and the concert waltz. The former is performed in a regular rhythmic manner everywhere, except in Vienna and South America, where the dancers are accustomed to little freedoms of tempo. There is so much really good music written in this form, that it is a pity to hear waltzes “ground out” in the reprehensible one-beat-in-a-measure style of so many of our Military Bandmasters. Portions of Strauss’ “Artist’s Life” Waltzes are given in the following examples, which also contain various modes of beating waltz time to conform with the spirit of the music.

There are many ways of conducting waltz time. Some conductors beat all the beats, others again, only one beat to the measure. Analysis of some of the methods of the great conductors who have not disdained to play the waltzes of composers like Waldteufel or Johann Strauss, has lead us to believe that the three styles of conducting explained in the following diagrams are the ones most generally used.

A—The one-beat-in-a-measure style for passages of flowing melody and great verve.

In order to avoid a monotony of motion, it is best to start the down-beats of each measure, alternately from the left and the right. The dotted line in the diagram indicates the reflex or rebound movement, which brings the hand and arm in a position to start the next beat.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ.1 (Style 1)

(A) Starting the beat from left to right.

(B) Starting the beat from the right.

[Pg 79] B—Following the heavy down-beat of the measure, the second beat will be indicated by a sharp sideward wrist movement and in lieu of the third beat, the hand and arm will be drawn up to the original position in a more relaxed manner.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 2 (Style 2)

Light and delicate rhythmic figures are best indicated by this method.

C—The third method is the regular gesture used in any 3/4 or 3/8 time and indicates each beat.

DIAGRAM Nᵒ. 3 (Style 3)

Same as 3/4 time.

In the following extract from Artists’ Life Waltz by Strauss, the three different styles are applied. The various strains and the manner of beating each measure, are indicated by the Roman Numerals which correspond to the diagrams.

A dilemma sometimes presents itself when certain parts—for the sake of contrast—are given a triple rhythm, while others preserve the dual rhythm.

If the wind-instrument parts in the above example are confided to players who are good musicians, there will be no need to change the manner of marking the bar, and the conductor may continue to subdivide it by six, or to divide it simply by two. The majority of players, however, seeming to hesitate at the moment when, by employing the syncopated form, the triple rhythm clashes with the dual rhythm, require assurance, which can be given by easy means. The uncertainty occasioned them by the sudden appearance of the unexpected rhythm, contradicted by the rest of the orchestra, always leads the performers to cast an instinctive glance towards the conductor, as if seeking his assistance. He should look at them, turning somewhat towards them, and marking the triple rhythm by very slight gestures, as if the time were really three in a bar, but in such a way that the violins and other instruments playing in dual rhythm may not observe the change, which would quite put them out. From this compromise it results that the new rhythm of three-time, being marked furtively by the conductor, is executed with steadiness; while the two-time rhythm already firmly established, continues without difficulty, although no longer indicated [Pg 83] by the conductor. On the other hand, nothing, in my opinion can be more blamable, or more contrary to musical good sense, than the application of this procedure to passages where two rhythms of opposite nature do not co-exist, and where merely syncopations are introduced. The conductor, dividing the bar by the number of accents he finds contained in it, then destroys (for all the auditors who see him) the effect of syncopation; and substitutes a mere change of time for a play of rhythm of the most bewitching interest. If the accents are marked, instead of the beats, in the following passage from Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, we have the subjoined:—

whereas the four previously maintained display the syncopation and make it better felt:—

This voluntary submission to a rhythmical form which the author intended to thwart is one of the gravest faults in style that a beater of the time can commit.

There is another dilemma, extremely troublesome for a conductor, and demanding all his presence of mind. It is that presented by the super-addition of different bars. It is easy to conduct a bar in dual time placed above or beneath another bar in triple time, if both have the same kind of movement. Their chief divisions are then equal in duration, and one needs only to divide them in half, marking the two principal beats:— [Pg 84]

But if, in the middle of a piece slow in movement, there is introduced a new form brisk in movement, and if the composer (either for the sake of facilitating the execution of the quick movement, or because it was impossible to write otherwise) has adopted for this new movement the short bar which corresponds with it, there may then occur two, or even three short bars super-added to a slow bar:—

The conductor’s task is to guide and keep together these different bars of unequal number and dissimilar movement. He attains this by dividing [Pg 85] the beats in the Andante bar, No. 1, which precedes the entrance of the Allegro in 6/8, and by continuing to divide them; but taking care to mark the division more decidedly. The players of the Allegro in 6/8 then comprehend that the two gestures of the conductor represent the two beats of their short bar, while the players of the Andante take these same gestures merely for a divided beat of their long bar.

Bar No. 1

Bars Nos. 2, 3,

and so on.

It will be seen that this is really quite simple, because the division of the short bar, and the subdivisions of the long one, mutually correspond. The following example, where a slow bar is super-added to the short ones, without this correspondence existing, is more awkward:—

[Pg 86] Here, the three bars Allegro-assai preceding the Allegretto are beaten in simple two-time, as usual. At the moment when the Allegretto begins, the bar of which is double that of the preceding, and of the one maintained by the violas, the conductor marks two divided beats for the long bar, by two equal gestures down, and two others up:—

The two large gestures divide the long bar in half, and explain its value to the hautboys, without perplexing the violas, who maintain the brisk movement, on account of the little gesture which also divides in half their short bar.

From bar No. 3, the conductor ceases to divide thus the long bar by 4, on account of the triple rhythm of the melody in 6/8, which this gesture interferes with. He then confines himself to marking the two beats of the long bar; while the violas, already launched in their [Pg 87] rapid rhythm, continue it without difficulty, comprehending exactly that each stroke of the conductor’s stick marks merely the commencement of their short bar.

This last observation shows with what care dividing the beats of a bar should be avoided when a portion of the instruments or voices has to execute triplets upon these beats. The division, by cutting in half the second note of the triplet, renders its execution uncertain. It is even necessary to abstain from this division of the beats of a bar just before the moment when the rhythmical or melodic design is divided by three, in order not to give to the players the impression of a rhythm contrary to that which they are about to hear:—

[Pg 88] In this example, the subdivision of the bar into six, or the division of beats into two, is useful; and offers no inconvenience during bar No. 1 when the following gesture is made:—

But from the beginning of bar No. 2 it is necessary to make only the simple gestures:—

on account of the triplet on the third beat, and on account of the one following it which the double gesture would much interfere with.

In the famous ball-scene of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, the difficulty of keeping together the three orchestras, written in three different measures, is less than might be thought. It is sufficient to mark downwards each beat of the tempo di minuetto:—

Once entered upon the combination, the little allegro in 3/8, of which a whole bar represents one-third, or one beat of that of the minuetto, and the other allegro in 2/4, of which a whole bar represents two-thirds, or two beats, correspond with each other and with the principal theme; while the whole proceeds without the slightest confusion. All that is requisite is to make them come in properly.

Methodical mastery of the full score, mental reading, use of piano. Preparing a score for rehearsal and performance.

To the average layman and even a great many musicians, an orchestral score appears to be about as intricate in appearance as a blue print of a complicated engine. The simile of the blue print and the score is not inapt inasmuch as the blue print represents on paper every detail of the mechanical construction of the engine, and, likewise, the musical score is an exact description on paper of every detail of the musical composition.

No attempt will be made in this book to describe the development of the core from the days of the early Italian opera composers who did not even write out parts for the players, to our own time when hardly anything is left to the imagination of the musician, and everything is written in the music. Likewise, the aesthetic interpretation and evaluation of the musical content of the score will be left undiscussed, to make way for the presentation of the practical aspect of a methodical system of learning to read quickly and accurately the mere notes of the score.

It is related that a celebrated professional magician, in order to train his sense of vision, quickness of mental perception and memory, used to practice looking at a show window for exactly one minute and then writing down from memory the name of every article he saw therein. By practice he was enabled to increase the number of articles remembered from a relatively small number to a total which included everything in the window. Now, what the magician did with his sense of vision, quickness of mental perception, and memory is precisely what the musician must do in learning to read the full score.

Possibly the most confusing thing to the beginner in score reading is the increased demands made upon his vision. Accustomed to reading music in one or two staves, the eye is now called upon to comprehend as many as 24 to 30 staves in a glance. At first this seems an impossible task but like many other seemingly impossible tasks it can be accomplished by patient and systematic practice. Of course, every conductor has his own way of mastering a score and the author can only give his personal method. However, this method has been followed successfully by students, and in practically every case has been found successful. [Pg 90]

It is assumed that the conductor has some ability in piano-playing. Naturally, the more the better, although it is not necessary to be equipped with the highest virtuoso technic. A knowledge of the scales and arpeggios, the ability to play Bach’s Two and Three Part Inventions and Well-Tempered Clavichord might be considered a working equipment for the conductor. Let it be explained here, that while the ideal of score reading is to be able to read and hear every note of the partitur without the aid of the piano, the value of the use of the instrument in the process of developing this ability and as a constant means of checking and proving one’s capacity is unquestioned.

The best exercise for widening or broadening the sense of vision is to practice the playing of three or more part vocal scores. A collection of early church music such as “Musica Sacra,” published by Peters, contains the most practical material. Herein are to be found in two, three, four, five, six, eight, ten and twelve parts and staves, the lovely old polyphonic works of the early Italian masters and the patient practice on these, always adding one more part, will do much toward the spreading of a sense of vision that has become limited by the habitual perusal of just one or two lines. The absolute independence of each individual part makes these polyphonic choruses highly valuable as practice material.

The second difficulty of the full score is the fact that not all of the instruments are written in the familiar clefs and many of them are transposed into different keys because of their peculiar mechanical construction.

Following the method employed in the conducting classes of the High School for Music in Berlin, the author has found the use of Bach’s chorales with each of the four parts written in a different clef, most effective in imparting the ability to transpose. These chorales should be taken from the various two-line editions (Peters, Breitkopf & Härtel, C. C. Birchard) and copied by the student on four separate lines, using the Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass clefs for the respective parts.

| The Soprano clef, |  |

| Alto clef, |  |

| and the Tenor clef, |  |

| are C clefs, i.e., the note on the staff indicated by the clef is |

|

| middle C; |  |

with the Soprano clef this is the first line, with the Alto clef the third, and with the Tenor clef, the fourth. Knowing the position of middle C it should not be difficult to trace the position of the other notes of the scales. The following is an example of the old and new vocal scores: [Pg 91]

Passion Chorale (Bach)

[Pg 92] For variety, the student might make use of ordinary four part hymn tunes in the same manner. These chorales and hymn tunes in the old clefs must not be merely played through a few times, but are to be practiced daily until the process of playing the old clefs has become as automatic as playing in the treble and bass clefs. This will give the student the necessary mental gymnastics and make the reading and playing of the various transposing instrumental parts comparatively easy.

So much for the purely technical preparation in the process of learning to read and transcribe scores.

The following headings are descriptive of a method of score preparation generally used by modern conductors:

1. The Architectural or General Impression.

2. Detailed study of the individual parts.

3. Detailed study of individual sections (strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion).

4. Mental hearing of the composition in parts and as a whole.

5. Piano transcription as a means of checking up and ratifying the mental concept.

When a building is viewed for the first time hardly anything more than a general impression of the type of architecture, size, symmetry, and color is made upon the mind. The details of construction, materials used, number of floors, style of windows and doors are only comprehended after closer study.

At the first perusal of a score, which should always be away from the piano, the impression made is just as general as in viewing the building. Hardly more than the contour of the melody and bass, outstanding climaxes and general character can be grasped at the first reading.

Next, a reading through either with or without piano, of each individual part reveals the details of construction, and the playing on the piano of the various sections gives the harmonic and polyphonic content of the work. A practical knowledge of Instrumentation is most helpful at this stage of the work.

After this detailed study, the work should be read through mentally at about the speed of actual performance, the climaxes noted, the emotional content determined, and a diagram of the form fixed in the mind. There is always a danger of losing the perspective of the work as a whole if too much detailed study is indulged in. The ability to read and hear music without the aid of an instrument is absolutely essential for the conductor. It can be acquired to a degree by proper study. Such works as Wedge’s “Sight Singing and Ear Training” (G. Schirmer) and Robinson’s “Aural Harmony” (G. Schirmer) are invaluable helps. “Musical Form” by H. Anger (Augener) is a most practical treatise on the subject and contains clear instructions for analyzing the piano Sonatas of Beethoven and the Fugues in Bach’s “Well-tempered Clavichord.” [Pg 93]

Upon being questioned as to his opinion of the importance of the conductor’s “ears” or hearing, Wilhelm Furtwängler, the eminent German conductor, made the following reply: “Generally considered, there is no such thing among conductors as a good or bad ‘ear.’ There is only a greater or lesser mastery of the material, that is, the score and its every detail. One can only hear individual mistakes in the complicated mass of sound when one knows completely just what the composer wanted.” (Pult and Takstock, Dec., 1925).

Of course there are conductors who learn the content of a score quickly from listening to the orchestra as they rehearse. But, it matters not how clever the conductor is, his orchestra always senses when it is being used as the means of their leader’s learning the score and their respect for him is lowered. There is a fable of a young conductor who wished to impress himself on his men by a display of sharp hearing. He secretly wrote in a false F♯ in the second bassoon part of a particularly loud and boisterous passage. At the rehearsal in the midst of the orchestral rumpus he suddenly stopped the orchestra and cried out impatiently, “F sharp, F sharp in the second bassoon is wrong,” only to be answered by the first player, “Beg pardon, Sir, the second bassoon is absent today.”

To play a full score accurately and fluently on the piano, is an art in itself and in the course of musical history we hear of only a few musicians who really could do this. Saint-Saëns, Liszt, and Von Buelow were said to be proficient in this difficult art, and undoubtedly their marvelous piano technique was a most important factor in their prima-vista score transcriptions. To fluently play a printed pianoforte arrangement of a Beethoven Symphony takes as much technique as to play one of his sonatas. We must not forget the comparative simplicity of even a Wagner score when compared with such a work as Varese’s “L’Amériques” or “The Rites of Spring” by Stravinsky, and it is just likely that any of the three masters just mentioned would have great difficulty in reading Honegger’s “Pacific 231” at the piano.

For the average conductor then, the piano does not become the supreme channel for expressing the score, but is used merely as an aid to his mental and spiritual master of its intricacies.

There still remains for discussion one phase in the work of score preparation, and that is—memory. Just as among concert players the old custom of playing from the printed page has given way to the one of playing and singing everything from memory, so have modern conductors taken to dispensing with their scores in performance.

The increased amount of preparatory work involved in memorizing a score certainly gives one an increased insight into the composition and to be freed from the necessity of reading the printed page gives a much greater authority and command in the whole attitude of the conductor at the performance. We never read of any great military commander leading his troops to battle with his eyes glued on the map, and we have all [Pg 94] heard of the conductors who have their heads in the score when they should have the score in their heads. Arturo Toscanini memorizes every detail of the score before the first rehearsal and conducts even the rehearsals from memory. This, of course, is such miraculous achievement in the mastery of the purely technical that it ceases to be technique and becomes an integral part of the conductor’s being.

The improved gramophone with the new process records of the great orchestral, choral and operatic masterworks can be put to splendid use by the student of conducting. Score in hand, these records should be listened to until completely absorbed and then they should be conducted. The operatic arias are particularly good practice for practising the art of conducting accompaniments.

In concluding this chapter the following paragraph from Adrian Boult’s “Handbook on the Technique of Conducting” is most fitting. He says, “In conducting there is a double mental process. There is the process of thinking ahead and preparing the orchestra for what is to come, that is to say, of driving it like a locomotive. There is also the process of listening and noting difficulties and points that must be altered, in fact of watching the music, as a guard watches his train. At rehearsal the second of these is the more important. Occasionally one must take hold and drive one’s forces to the top of a climax, just as a boat’s crew on the day before the race does one minute of its hardest racing, but takes it pretty easy otherwise. The main thing at a rehearsal is to watch results and to act on them. At a performance it is the other way about—the conductor must take the lead. It is then too late to alter things like faulty balance or wrong expression, but the structure and balance of the work as a whole and the right spirit are the two things of paramount importance.”

There seems to be in the minds of some musicians an idea that a vast difference exists between chorus conducting and orchestra conducting. In fact, it is a very common fact that there are many fine musicians who obtain excellent results from their choruses but who are completely at a loss when it comes to conducting even the orchestral accompaniment of the choral works they are presenting. The tales told by sophisticated orchestral players on their return from music festivals in the provinces about the antics of many choral conductors would be funny if they were not tragic.

Usually, the choral conductor is a good musician and knows his musical subject matter thoroughly. Through the process of much careful rehearsing and teaching, he succeeds in imparting his ideas of interpretation to his chorus, which in turn comes to understand the meaning of his gestures. Up until the first orchestral rehearsal, which is usually the only one, everything goes smoothly; but as soon as the highly trained and sensitive orchestra tries to follow the conductor’s beat, a state of utter chaos ensues. Much time is wasted, the conductor becomes irritable, the chorus demoralized, the orchestra scornful, and in general the outlook for a successful concert begins to look very black. Finally, the more practical side of the orchestra rises above the disgruntled and disillusioned attitude and it rescues the situation by playing more in spite of the conductor rather than because of him. This picture is not exaggerated and has almost a universal application. The author, in his orchestral playing days, has witnessed such scenes not only in the United States but also in France and Germany, and has been told by competent authorities that the same conditions exist in England. In fact, this little tale is one that will be verified by almost every experienced orchestral musician.

The cause of much of this ineffective conducting is a profusion of vague, meaningless (to the orchestral player) gestures on the part of the choral conductor, who has gotten into the habit of making many motions because of certain conditions peculiar to choruses and choral music. First of these conditions is the average chorus member’s rather low standard of musical ability, (in comparison with the professional orchestra) which causes the conductor to lead his charges through intricate rhythmical mazes by indicating every 32d note and beating out the melodic contour rather than giving the basic beats and subdivision of the beats. Secondly, the conductor usually has the assistance of a good accompanist who plays the piano arrangement of the orchestral score so efficiently that the conductor ceases to even think about it, and who provides a firm rhythmical background by crisp and incisive marking of the main beats of the measure. Naturally, the conductor cannot change the habits acquired during many weeks of rehearsal and when he finally finds himself in front of the critical professional orchestra, he is confronted with the task of leading this complicated organization with gestures engendered by the peculiar weaknesses of his choral body and which are totally confusing to the strange orchestra. [Pg 96]

There is only one remedy for this condition. Directors of choruses must remember that essentially there is no difference between orchestral conducting and choral conducting, although there is a vast difference between orchestral and choral training and rehearsing. It is not necessary to give the chorus a special gesture for each 32d note of the melodic line. Chorus members will give a rhythmical performance of a work only when they are made to feel the main pulsations of the movement, and this can be accomplished only by using such established gestures which clearly mark the fundamental rhythm. Naturally, such gestures will easily be understood by the orchestral musicians as well as by the chorus singers. Of course, this refers definitely to the conducting of combined orchestral and choral forces. The conducting of part songs accompanied or unaccompanied calls for a somewhat different treatment.

In A Capella music, the conductor usually dispenses with the baton in order to gain more expressive freedom of both hands. In comparison with a choral-orchestral composition, these part songs and polyphonic choruses have but few individual parts and the conductor is not so much concerned with the actual beating of time as with the subtle indication of interpretative shades and meaning. Nevertheless, the author believes that the fundamental gestures are a sufficiently comprehensive basis for the most expressive type of conducting.

It is not the purpose of this chapter to enter into the details of choral training and interpretation. Those subjects have been admirably treated by other writers and for the chorus master seeking truly authoritative advice in these matters, the following books are recommended:

The last five give invaluable hints on the proper interpretation of the works of their respective subjects.

For teaching a chorus sight singing and proper vocal habits:

This last gives the conductor highly valuable suggestions of methods to obtain correct and effective diction.

A collection of significant paragraphs by various authorities on the Art of Conducting.

“Rhythm. What is rhythm? We all know that music moves in beats or pulses, and at regular intervals—say, at every two, three, or four beats—some of these are stressed or accented. It is these accents which produce rhythm; therefore rhythm may be defined as a pattern of accents, or a phrase of pulses made characteristic by the effect of its contrasted strong and weak accents. Rhythms may be observed even in statuary and architecture. Rhythms may be regular, as when they follow the time-signatures; and irregular, as when many syncopations are introduced.”

“One of the distinguishing features of modern choral technique is what I term ‘characterization,’ or realism, of the sentiment expressed in the music.... Contrasts of tone-color, contrasts of differently placed choirs, contrasts of sentiment—love, hate, hope, despair, joy, sorrow, brightness, gloom, pity, scorn, prayer, praise, exaltation, depression, laughter, tears—in fact all the emotions and passions are now expected to be delineated by the voice alone. It may be said, in passing, that in fulfilling these expectations choral singing has entered on a new lease of life. Instead of the cry being raised that the choral societies are doomed, we shall find that by absorbing the elixir of characterization they have renewed their youth; and when the shallow pleasures of the picture theatre and the empty elements of the variety show have been discovered to be unsatisfying to the normal aspirations of intellectual, moral beings, the social, healthful, stimulating, intellectual, moral and spiritual uplift of the choral society will be appreciated more than ever.”

“The first thing a conductor requires is self-reliance, born of mastery of the subject he has to conduct and confidence in himself. If he is nervous and apologetic, if, when he makes a slip, he feels crushed and would like to sink through the floor, he had better leave conducting alone. It is the confident, not-to-be-daunted man who is fit to be a leader of men.”

“The conductor must take every precaution to make the rehearsals interesting. The test of a society’s success is the popularity of the rehearsals, and the test of the rehearsals is the feeling that if one be not attended something in the way of enlightenment or pleasure has been missed.”

“The man who lacks tact is not fit to be a conductor. Tact is the lubricant that keeps the administrative machinery smoothly working when heat and friction would otherwise arise.”

(From “Choral Technique and Interpretation” by Coward)

Novello