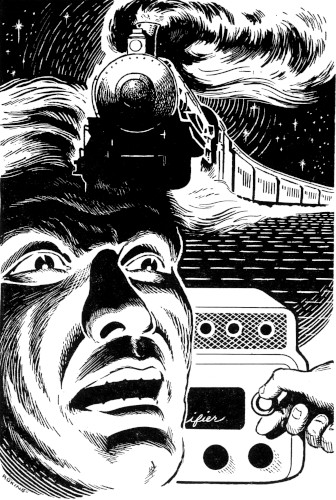

By MAURICE BAUDIN

Illustrated by ADKINS

A quiet concert in the evening by the lake ...

a harmless hi-fi hobbyist ... yet why did Woodard

tremble at the sound, sound, sound.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories November 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Daytimes, Woodard wasted little speech on the other guests at the summer hotel. Biddies and garrulous men—fools one and all, he told himself. They had come to be with nature, they said; but the clear, deep lake with its rocks and pointed firs, and the mountains beyond were merely a backdrop for their inane gabble. They had come for health and renewal, clucking of the ravages of city life. Yet scarcely a one but had acquired some absurd malady. They had turned the small hotel into a hospital for twitches and bor-borygms. As if, because they were paying their way, they must give the climate work to do. As if, thought Woodard, they were hiring the warm sunlight, the cool, sweet air, to mend their palsies, tachycardias, facial tics or rheumatic twinges.

Relishing the fact of being resented and the illusion of being sought after, he kept himself to himself.

But this sort of thing must not be carried too far. Directly after dinner, for fifteen minutes before his evening walk, he mingled with the rest as graciously as their recollections of the day's snubs permitted. He had settled upon this course early in the summer. Circulating, at the breakup of the dinner hour, among as many guests as time allowed, he fell in benignly with all topics, however foolish.

On the last of these fence-mending tours, he tuned in to elderly Mrs. Jenson. "But why," she was asking plaintively, "has poor Mr. Ward's body not risen?"

What a conversational god-send, that presumed drowning! The old girl had stopped circulating romantic rumors about himself. She had relegated her newly developed lumbago to second place. Woodard smiled inwardly. Of course, several times in the past three weeks he had heard her question answered. So, if she listened, had she. How sensible of himself to budget his day's quota of chitchat. Glancing at his watch, he saw that he had two minutes left, enough time for a terse review.

"The lake is very deep in parts, and there the cold would prevent the gas from forming that would raise the body...."

Mrs. Jenson fidgeted. It was one thing to repeat a question; must one listen while someone else repeated the answer? "But no clothes were found, Mr. Woodard!" As he flinched at her corruption of his name, she whimpered: "On the entire shore of this big, big lake—not a stitch of clothing!"

Woodard nodded sympathetically. "Possibly he rushed from the hotel in a state of undress. Was he a frolicsome type?"

"He was a lovely gentleman," she said coldly.

"Ah. Possibly the lake didn't know that." His fifteen minutes were up. He nodded curtly.

But just then, Mr. Nodus joined them. Nodus, who dined at the hotel, was summering noisily with his hi-fi apparatus in a cottage far down the lake. Every guest in the place had spent at least one evening there, hearing the most incredible sound effects music can offer. Every guest, that is, except Woodard. He had known for weeks that the man would invite him. He had known with equal certainty that he would decline. How often, feeling himself watched, had he glanced toward the table where Nodus ate with his two silent house guests? Each time he had met the impassive stare of the large baby face, had stared coolly an instant, had looked away. And now Nodus had the effrontery to grasp his arm.

"Interested in swimming, Woodard?" he said loudly. "Me too! Swimming and music. Well! You're invited to a concert. Works out tonight's the night I can fit you in. You can follow us in your car—about five minutes?"

"Oh but Mr.—Donus, is it?—-Nodus? I'm not—not...." Woodard saw Mrs. Jenson's lips curve in a hateful smile. He lost his nerve. Panicking, he fumbled for words. Fumbling, he was lost.

"Five minutes," Nodus repeated.

Mrs. Jenson sighed spitefully. "Mr. Woodard doesn't know what he has in store!"

Scarcely glancing to his right at the lake that lay calm in the hazy twilight, Woodard drove behind Nodus and company. Hi-fi indeed! Torturous device of a science-ridden culture—how had he let himself in for the evening ahead? Why had he permitted this trespass upon his privacy? But when, after some eight miles, the convertible ahead slowed and signalled for a left, he checked the impulse to keep going on around the lake and back to the hotel. Nodus would think him crazy. He would think it aloud in the dining room—ostensibly to the deferential genies, the man and woman who were vacationing with him; but he would think it in a voice that carried.

Woodard pulled up beside the other car in the fir-fringed clearing.

Nodus stood waiting with his two shadows. "Russ will take you to the studio," he said briskly. "The girl and I will be along in a minute." He chuckled, his eyes scanning Woodard's face. "No neighbors here to raise a fuss. No knocking—no kicks or squawks...."

Only from me, Woodard thought, following the leader to a two-car garage some distance from the cottage. Inside, Russ slid shut the door, then flipped a switch that lighted half a dozen table lamps of the beaded fringe variety. Woodard stared in amazement. Heavily carpeted with scatter rugs, the place was walled and ceilinged with fiber-board. On three walls, including the door side, were stuck triple rows of ornamental covers from long-playing records. Running the length of the fourth wall, left of the entrance, a counter rose waist-high, its side hung solid with more record covers. On the left end of this counter was an elaborate system of dialled boxes which Woodard summed up vaguely as player, amplifiers, filters, and so on; on the right, eight open wood boxes of records. On the center of that wall was a large clock with a sweep second hand. Directly beneath, an empty rack of record cover size, beside which a neatly printed sign read "NOW PLAYING".

"Quite amazing," Woodard remarked truthfully. "Well...." He dropped into the center of three chairs right-angling the dial boxes. "Might as well sit."

But Russ, who had been smiling dreamily, was suddenly agitated. He shook his head. He opened and shut his mouth like a fish. As Woodard felt his poise threatened, the door slid open. Nodus entered, preceding Miss—Miss—But her name hadn't ever been mentioned.

Seeing where Woodard sat, he frowned. "No, no," he said. "That won't do. You'll be better off...."

Woodard repeated, "I'm utterly amazed by all this."

Nodus' expression softened. "It's a garage, as you can see. Four hours at the start of the summer to convert it to a sound-room. Three and a half hours, at the end, to reconvert it. On the nose in both instances. Half-hour discrepancy there. We're working on that."

Woodard understood that "we" included the pair, whose life currents evidently flowed from the master's battery.

"Job's all broken down," said Nodus. "I do certain things, Russ does certain things. The girl"—She bridled as he jerked an elbow toward her.—"does her little chores."

The girl! Would she see fifty again? But Woodard felt himself wanting to placate, a sensation both new and unpleasant. "The details must be very interesting," he said weakly.

Nodus' face had gone stern again. "—won't do," he back-tracked curtly. "You'll be better off over there." He indicated a lone chair directly opposite the "NOW PLAYING" sign. "Acoustically speaking, the most effective location in the studio." Clinical and considered, his tone brooked no protest. Woodard stumbled embarrassedly to the chair. "You can see," Nodus stated, "if you look down, all the chalk marks where we've experimented with positions."

And Woodard did see: dozens of white marks on the rug around the chair legs, close together as if fractions of an inch were vital.

As Nodus moved to the dial boxes, Russ and the girl dropped like wraiths into chairs: she nearest Woodard, he in the middle, leaving the place by the apparatus for Nodus. Woodard thought: God, but he has this worked out! He's a tyrant, a baby-faced ogre. And these two goops are in bondage to him.

It came to him that Nodus was curiously untanned for a devotee of swimming.

"What do you weigh, Woodard?"

"Why——oh——one-sixty, I guess...."

Nodus nodded. "Near enough." He selected a record from the box nearest him. "People always like a few effects before the concert," he said. "Preliminaries." His expert hand pressed a switch and turned some dials. The room was filled with a rasping hum. Now Woodard saw what he hadn't noticed before: in the far corner, back of the counter, an unlighted cavernous area; and in its center, black-draped like an oracle of doom, the speaker system.

Russ and the girl looked dismayed even before Nodus snapped, "Oh-oh! Something's not right! Russ—go outside and check the grounding." He pulled Russ to him and whispered. Russ nodded and slipped quietly out.

I could still go, Woodard thought. The hell with any stories he'd spread. I'd.... But the girl was staring at him, serene and knowing as if she read thoughts.

The rasp ceased and the room went still. After a few minutes, Russ entered and took his seat by the girl.

Now Nodus assumed a pedagogical stance, a platform manner. "This," he said, holding the player arm poised above the whirling record, "is the Victoria Falls—Zambesi River—taken at 78 r.p.m., which I still consider the ideal speed. Perfect studio conditions not possible, of course, though the engineer was extremely cooperative." Nodus smiled benignly. "He tried to get rid of the insects. They almost got rid of him. You'll notice a treble hum in the foreground. Giant mosquitoes. Then I'll play it again, filtering out the falls—we can do that—and you'll hear the mosquitoes as if they were primary."

Woodard tried to look intelligently appreciative.

"This will take four and one-half minutes. Precisely. You can check this statement against the clock. The record is longer, but I find that people stop concentrating after four and one-half minutes."

The room filled with the massive roar of a giant river dropping four hundred feet. Woodard clutched the arm of his chair, rejecting the nightmare fantasy of himself taking the falls in a canoe. Nodus too was seated now. Looking impassively straight ahead, like a ceremonial figure on a public stage, he was talking from the side of his mouth to Russ. He played with a pair of horn-rimmed glasses which Woodard had never seen him wear. The girl sat raptly beating a time of her own devising.

It was said—where did one hear these things? Why did one remember them?—that years ago the girl and Mr. Nodus had been in love. That the new era in electronics had alienated Mr. Nodus' affections. Auxiliary priestess now to the monster that had dethroned her, the girl tapped her left wrist with the fingers of her right hand and smiled remotely....

"Four and one-half minutes, as advertised," Nodus said, raising the player arm. "And now, the foreground of mosquitoes. Amplified by—well, no need to be technical. Let's just enjoy it. Two and one-half minutes will do."

Quite so. Higher than coloratura, a whirring, a hum. As if all insect life brought out on the lake by the evening damp had swarmed into that room. And back of the keening shrillness, unending in its behemoth anguish was the muffled roar of the falls. Woodard squirmed. But he wouldn't pay Nodus the homage of warding off the insects. Forcing himself rigid, he watched the clock. His thoughts wandered to the lake, dark and deep outside—and to Mr. Ward, imprisoned by cold in the darkest depth.

Two and one-half minutes exactly.

"Amazing," Woodard said. Antagonized by Nodus' pontifical assurance, he added spitefully, "Of course, nothing sounds like that."

Nodus shrugged aside the irrelevancy. "Hi-fi does," he said, extracting a second record from its case. "We have many requests for that number. Many. And now—an old-fashioned steam train. If you think it's coming toward you—and jump—please try not to displace your chair." About to laugh, Woodard caught himself. The man was not joking. "We don't," Nodus explained, "want to fasten it to the floor till we're perfectly certain that...." He looked for confirmation to Russ and the girl. Both nodded. "We've timed this one at three and one-half—more precisely," he announced, "three minutes and twenty-eight seconds."

It was stupendous, terrifying. Woodard himself vibrated as the colossus approached. But not for anything would he have stirred....

Three minutes and twenty-eight seconds it was, Nodus monologuing from behind his hand to Russ, the girl beating a new time.

In the shattering silence, Woodard laughed tremulously. "This must be the next thing to shock therapy."

The girl tensed. Russ looked wary.

"What makes you say that?" Nodus demanded.

"Why—I just meant...." Woodard was unnerved. He rarely minded giving offense, but he liked to know when and how he was doing it. "I suppose," he placated, "that atomic fission is more what I had in mind...."

Nodus looked at him suspiciously. "There are worse things than atoms," he said. The girl cackled, then looked blankly about as if she hadn't done it. Nodus ignored her. "Not a family man, are you, Woodard?"

"No." Woodard took in Nodus' quick nod. Had the admission somehow worsened his situation?

"No one to care?" cried the girl, her dark eyes gleaming archly. "No one to miss you?"

She was stilled by a flicker of Nodus' eye.

On with the effects. "Now this," Nodus lectured, handling the new record tenderly, "has more surface noise than I consider excusable. I keep it in my library only because...."

He glared at Woodard, who had been unobtrusively removing his jacket and now dropped it hastily to the floor. "That won't do there!" The girl roused and floated over, picked up the offending garment and carried it with abstracted solicitude to a hook by the door.

"—than I consider excusable. I keep it in my library only because the engineer, a really cooperative fellow, learned some very important principles of underwater reproduction from taping these underseas mating calls."

Woodard repressed a smile as the girl, back in her seat, doubled over in silent laughter. Nodus threw her a disciplinary look. "Like to sit in that chair yourself?" he muttered, indicating Woodard's place. Instantly she sobered.

Now what does that mean? Woodard asked himself.

"Nine and one-half minutes will be right for this."

Fantastic that it could be recorded at all, Woodard had to admit, listening incredulously to the beeps and crackles, the yips and squeals and tiny shrieks. Undersea, Nodus had said. Was the lake across the road a similar hotbed of solicitation? Did Mr. Ward's chill presence cast no damper on concupiscence?

Woodard pantomimed astonishment with a wondering nod.

"Now with this one," Nodus recited, "I say nothing. Just mention that it lasts seven seconds. Watch the clock."

Woodard counted seconds so intently that he didn't interpret the four very loud preliminary gasps from the speaker. Suddenly, magnified a hundred times but undistorted, crystal clear and shattering, nearly blowing him off his chair: a monumental sneeze.

His heart stopped, then pounded achingly. He looked furiously at the speaker. It should have been wetly splattered all over the place, but it rested amorphous and unshaken in its dark covering.

"And," said Nodus, "that could have been magnified a thousand times—not in this enclosure—without distortion. An epochal recording." Deftly he switched records, turned a knob or two. "Now here—an old-timer, a real old 78. And if I can find the right groove, a most interesting effect." Leaning over, he whispered something to Russ, who smiled. "I defy anybody to recognize...."

Woodard braced himself to interrupt. "I'd like to be excused for just a minute," he begged nervously, rising. "Have you—do you happen to have...." He fished for words and came up, hating himself, with "Do you have a little boys' room?"

"Can't you wait?"

"Well, I just thought...." Woodard licked his lips. If the next effect were anything like that sneeze, he feared the consequences of delay.

The girl nodded apprehensively at Nodus. "It's the great outdoors," he said grudgingly. As Woodard fumbled with the door, he added very distinctly, "We'll be waiting."

Under the half-moon and the million stars, down the drive and across the road the lake lay darkly glowing. In the cool silence Woodard heard it lapping its shores like the licking of lips. What did happen to Ward? he thought suddenly.

And then he thought, Why don't I—but his keys were in his jacket and his jacket was inside. Now he noticed that Nodus' car had been shifted to stand behind his own. Escape was cut off in any case. He felt a throbbing hollowness, the ache of terror. "I'm being foolish," he said. "I'm going to cut it out." The sound of a human voice, even his own, was oddly reassuring. He would stay just enough longer not to give offense. He would try to make only pleasing responses to Nodus' recital, would act reverential in this shrine to the electronic screech. And when he left, he would point out with the most casual little laugh of well-feigned surprise that his car was cut off—as if it were natural but at the same time comic....

When the garage door stuck, he pulled frantically. After a moment, Nodus opened it from inside. The girl said shrilly "You got locked in the bathroom!" and then shook noiselessly.

"You've interrupted the sequence," Nodus stated. "I'm starting with the last two minutes of the mating calls, then running the sneeze again."

Woodard nodded contritely. The mating calls heard once, it turned out, were heard for all time. But the sneeze, braced for it though he was, retained its power to shake the inner being.

"—defy anybody to recognize this sound," challenged Nodus.

It sent a cold tickling vibration through Woodard, from the soles of his feet to his frontal sinus. When it was over (four and one-half seconds), he needed almost a minute to bring his shuddering to a halt. He saw Russ take a pad and pencil from his pocket. He did not react.

"A laugh," Nodus gloated. "A human laugh. More precisely, a chuckle. When Marcella Sembrich produced it originally, in her recording of 'Coming Thro' the Rye', the intent was probably coy, but...."

In his sharp, sudden rage, Woodard forgot tact and caution. "That's so unfair to a singer! To take her voice in one passage and distort it—that doesn't show what she can do!"

"Could do," Nodus corrected coldly. "But it shows what the equipment can do."

"I would never," Woodard began acidly.... A persistent tickle in his throat was making him cough. His post-nasal drip, he recognized grimly.

Nodus glanced at Russ, who was jotting notes. "A few more little effects," he promised, "then the concert."

Woodard nodded, coughing viscously into his handkerchief.

"Now just to give you some further idea...." Nodus looked reproving. "You have a very annoying cough."

"It dries up for weeks," Woodard apologized, "and then...."

"I suggest you control it." Nodus turned to the player. "—some further idea, and no surprises this time, a factory whistle." He chuckled. "No timing. I keep this going till I see the whites of your eyes."

Woodard was sweating copiously before Nodus turned it off. He looked envyingly at the girl. Not enjoying the most effective acoustic location, she had sat through the outrage in a state of catatonic beatitude. "Incredible!" he gasped, coughing again.

And now, in the last lap of the preliminaries, effects came thick and fast. Woodard's sensibilities were still jangled from a rattling, polysyllabic belch (panicking the girl, but unjustifiable otherwise as either art or science) when a powerful soprano, tweetered until it could cut steel, emitted a blood-curdling "Good-bye fo-re-ver!" Tosti rendered by Medea; and as Woodard tried to formulate some idea about unseemliness, he was shaken to his bowels by the agonized shriek of a subway rounding a curve. Next, "Tires Screeching on Hot Asphalt"—not a surrealist poem, and anyway Woodard's critical faculties were pretty well blasted. Then a dentist's drill. Woodard struggled to make sense of Nodus' remarks about a gum cavity and a midget microphone. Finally, perhaps most devastating of all because it suggested evil in bright sunlight, the tender brooded over by the sinister—the excited yelps of girls at play; the bouncing of a ball and the rush of feet across a wood floor; a shrill, drawn-out whistle and the voice of a gym instructress screaming "That's enough, girls!" (The Pepsi-Cola Ladies' Basketball Team: eleven and one-half seconds.)

Woodard peered uncertainly from trauma to learn that the concert proper was at hand.

"I run through a few things, parts of things, interesting sections," Nodus lectured, playing idly with his glasses. "A little program most people seem to like...."

Time was, Woodard would have snapped "I happen not to be most people." But his pulse was pounding, his eyes watering. Racked with coughing, trembling with post-sonic shakes, he could scarcely be called himself. So he tried to nod appreciatively. If he could identify more, really participate—then he might overcome the sensation of being one with three against him. And his sinus might stop dripping.

"The violin," Nodus announced, for the first time placing a record cover on the "NOW PLAYING" rack. "Some unaccompanied Bach partitas."

Woodard laughed hoarsely. "It's been my theory...." He coughed.

"Yes." Nodus held the player arm poised. "Now we'll have nineteen...."

Woodard struggled for recovery. "It's been my theory," he croaked, "that Yehudi makes them up as he goes along."

Russ stared for a moment, then went on writing.

"Do I understand," Nodus asked with cold hatred, "that you refuse to listen to a few unaccompanied Bach partitas?"

Woodard grovelled. The privilege of hearing partitas on this superlative equipment? Refuse? Oh most certainly not—He collapsed in a fit of coughing.

Mollified, Nodus said "I'll wait till you pull yourself together. Meanwhile, you may like to know that of the records my dealer sends me—and he knows my taste, mind you—I keep one in eight. And that one I exchange, on the average, three times before I find a copy I can admit...."

Woodard wanted desperately to concentrate. Here was something solid to work on. Did Nodus keep one record in eleven, or one in twenty-four? It depended, of course, on whether x equalled 8 plus 3 or 8 times 3. Surely one should be able—but he was straining beyond his limit. It was as if some mental spine, which in a past existence had sustained him, were numbed or missing.

Nodus was staring. So, with an odd, expectant smile, was the girl. To show that his wits had never left him, Woodard blurted out, "The composer never intended the music to sound like this!"

"Like what?"

"The partitas were all wrong!" Now his voice kept breaking. "A composer—and a performer—should have some say—not be fed into equipment like this and—and...." Another paroxysm prevented his concluding: "and used to start sinuses running."

"I haven't played the partitas yet, Woodard."

That stopped the cough. Not played them? Then why did he feel—He found himself thinking with curious gentleness of the guests at the hotel who mocked nature with their complaints. And vast as his sudden pity was for them, it was vaster still for himself. But he tried to latch onto one worthwhile thought: I have nothing to fear but fear itself.

"Nineteen and a half minutes." Relentlessly Nodus lowered the arm.

Woodard tried clinging to the worthwhile thought. But it kept shimmering off in the dissolving world. It wouldn't come right. I have nothing to fear but all mankind, he kept hearing.

And maybe it was better that way; at least he knew.

Finally he asked himself: How did I get into this? I who always kept myself to myself to myself to myself.... Oh he was whirling, whirling, and no one could count his r's p.m. ... myself to myself to....

He slumped unconscious in his chair.

Eleven minutes and thirty-one seconds of partitas had elapsed. Nodus so remarked to Russ, who made note.

And the concert continued. But there is small point in detailing Nodus' accounts, as sensibly delivered as before, of the various selections: how he explained his choice of "Bendermeer's Stream" as a follow-up to the partitas; his apologies for the surface scratches that made the Valkyries' ride sound unlubricated; his cautionings about what to look for in the "Romeo and Juliet Overture"; his meticulous timing of these and the other recordings.

Thirty-six minutes and twenty seconds after Woodard's cerebral disintegration came his impalpabilization.

"Three hours, forty-one minutes, twenty-one seconds," Nodus intoned, and Russ jotted down the melancholy figures. The girl emitted a small shriek of joy and started impetuously for the chair that had been Woodard's. But Nodus raised a preventive arm. "Not yet," he warned. "Not for a few minutes. There may be anarchic sonic residuum. We don't know. And anyway—what's there to see this time? Absolutely nothing left."

"Except his car," said Russ. He spoke with a lisping dreaminess.

"You'll park it by one of the fishing piers. Woodard said as he left here that he'd stop for a late swim."

"Just lovely," sighed the girl. And Russ nodded in slow motion.

Nodus smiled almost reluctantly. Perfectionist that he was, it would be long before he was wholly satisfied. He turned to the girl. "Your idea of substituting the partitas for the Mahler 'Farewell' was very sound. I'm interested in the reasoning."

Her nostrils flaring at the heady draught of his praise, she giggled shyly. "I hoped the partitas would work, because Mahler really fractures me. That 'Farewell' would have finished me—even where I was sitting."

His glance rested on her as if he would bear this in mind. Then he said "It should be safe to look closely now," and he led his technicians to the vacant chair.

"No nasty mess to clean up!" raved the girl. "Nothing like that Ward, with his dreadful post-distillation residuum!" And as Nodus and Russ exchanged smiles at her woman's viewpoint—"Who's next?" she demanded.

Russ was inspired. "That frightful old woman at the hotel!"

Nodus regarded the girl through narrowed eyes. "The one's been spreading those half-wit tales about you and me."

She did not meet his look. "You'd never get Mrs. Jenson here alone."

"Then with her friends," he said expansively. With upturned hand he warded off protest. "I can tell you now that I expect to be ready—before the season is ended—for group therapy." He ignored her little scream of delight, Russ's slow smile of wonder. "Perhaps you don't quite realize—this evening—how important it's been." His voice had begun to tremble, and he rested a moment to steady himself. "After all the years with warts and small excrescences," he said, his eyes misting. "The humiliation of our work with corns...." He raised his head proudly. "But it was to this that it was all leading...." He pointed to the undefiled chair. "And now it begins to look as if we—and with no billions backing us, mind you—would be ready before the no-fallout bomb!"

The girl looked faint with wonder as Russ lisped complacently, "And without the disastrous destruction of priceless commodities."

THE END