THE POISONER OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY

A Romance of Old Paris

By ALBERT SMITH

LONDON

RICHARD BENTLEY & SON, NEW BURLINGTON STREET

Publishers in Ordinary to Her Majesty the Queen

1886

The Mountebank of the Carrefour du Châtelet

The Boat-Mill on the River

The Arrest of the Physician

The Students of 1665

Sainte-Croix and his Creature

Maître Glazer, the Apothecary, and his man, Panurge, Discourse with the People on Poisons—The Visit of the Marchioness

Louise Gauthier Falls into the Hands of Lachaussée

The Catacombs of the Bièvre and their Occupants

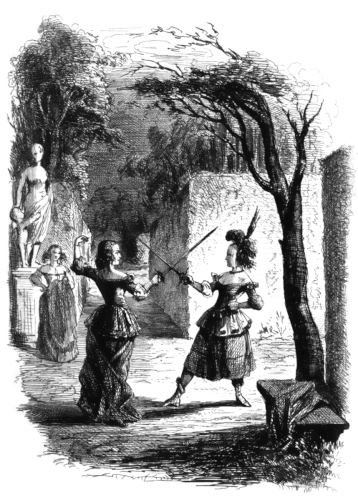

The Revenge of Sainte-Croix—The Rencontre in the Bastille

What further befel Louise in the Catacombs of the Bièvre

Maître Picard Prosecutes a Successful Crusade against the Students

Exili Spreads the Snare for Sainte-Croix, who falls into it

Gaudin Learns Strange Secrets in the Bastille

The Château in the Country—The Meeting—Le Premier Pas

Versailles—The Rival Actresses—The Discovery

The Grotto of Thetis—The Good and Evil Angels

The Gascon Goes through Fire and Water to Attract Attention—The Brother and Sister

The Rue de L’Hirondelle

The Mischief still Thickens on all Sides

Two Great Villains

The Dead-house of the Hôtel Dieu, and the Orgy at the Hôtel de Cluny

The Orgy at the Hôtel de Cluny

Sainte-Croix and Marie Encounter an Uninvited Guest

Louise Gauthier falls into Dangerous Hands

Marie has Louise in her Power—The Last Carousal

Sainte-Croix Discovers the Great Secret sooner than he expected

Matters Become very Serious for all Parties—The Discovery and the Flight

The Flight of Marie to Liége—Paris—The Gibbet of Montfaucon

Philippe Avails himself of Maître Picard’s Horse for the Marchioness

The Stratagem at Mortefontaine—Senlis—The Accident

Philippe Glazer Throws Desgrais off the Scent

Offemont to Liége—An Old Acquaintance—The Sanctuary

The End of Lachaussée

The Game is up—The Trap—Marie Returns with Desgrais to the Conciergerie

News for Louise Gauthier and Benoit

The Journey—Examination of the Marchioness

The Last Interview

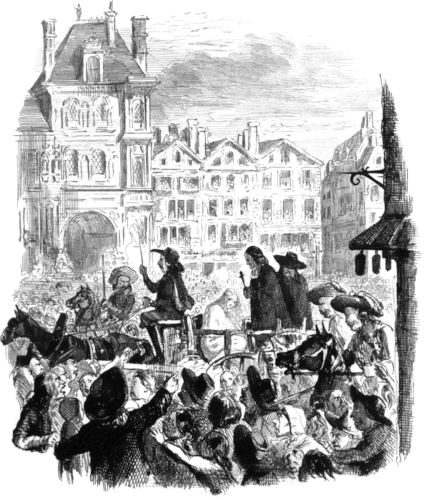

The Water Question—Exili—The Place de Grêve

Louise Gauthier—The Conclusion

WORKED FROM THE ORIGINAL ETCHINGS

By John Leech

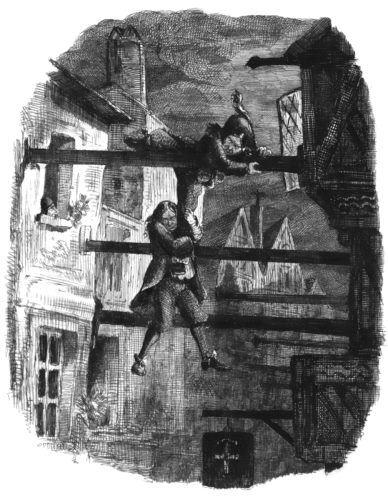

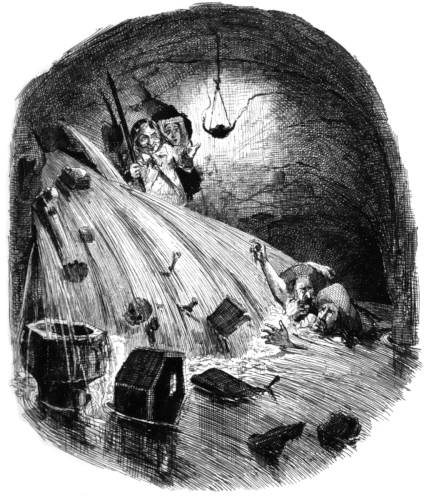

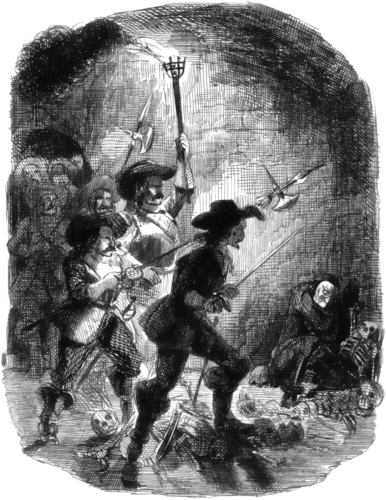

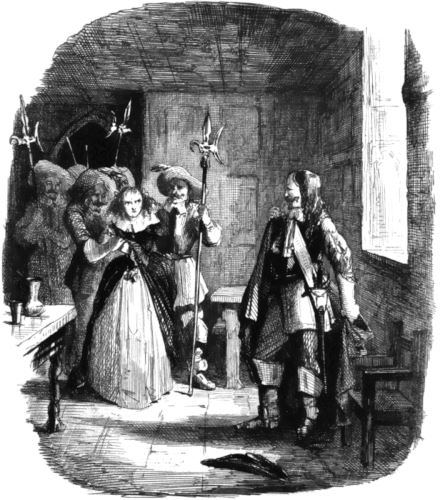

1. The Escape of Lachaussée Prevented

2. The Physician and Mountebank

4. The Students Enlightening Maître Picard

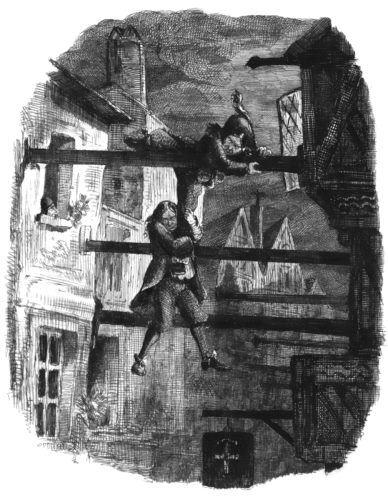

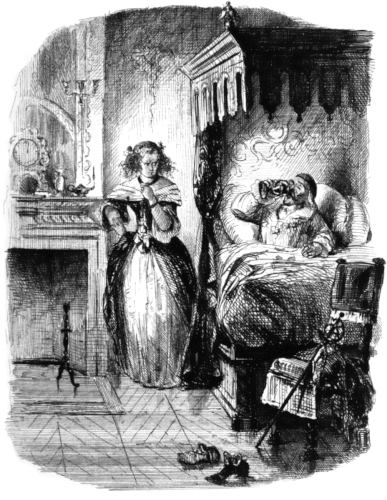

5. Sainte-Croix Upbraiding the Marchioness

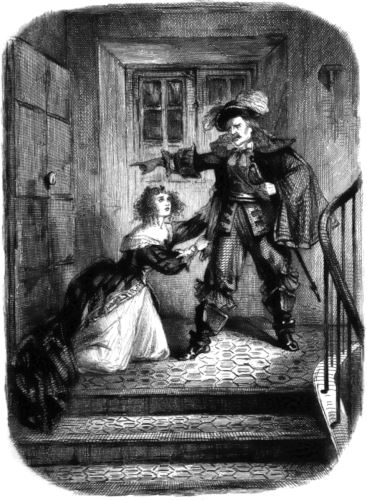

7. Bras D’acier and Lachaussée Outwitted

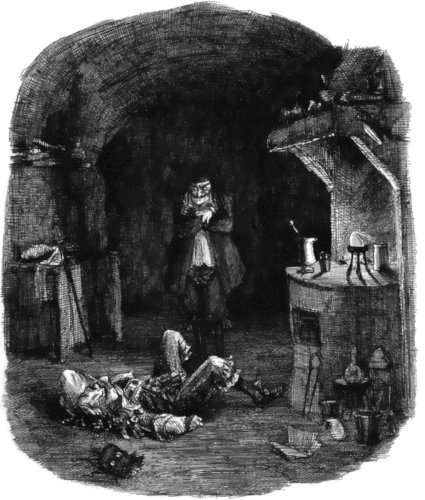

11. Sainte-Croix Surprised by Exili

14. ‘Then, Madame, you are mine at last!’

15. The Marchioness going to Execution

One hundred and eighty years ago, on a sunny spring evening in the year of grace 1665, the space of ground which extended from the front of the Grand Châtelet in Paris to the rude wooden barrier which then formed the only safeguard between the public road and the river, at the northern foot of the Pont au Change, was crowded with a joyous and attentive mass of people, who had collected from their evening promenade to this spot, and now surrounded the temporary platform of an itinerant charlatan, erected in front of the ancient fortress.

Let us rest awhile on the steps of the Pont au Change, to become acquainted with the localities; for little of its ancient appearance now remains. The present resident at Paris, however well versed he might be in the topography of that city, might search in vain for even the vestiges of any part of the principal building, which rose, at the date above spoken of, on the banks of the River Seine. The Pont au Change still exists, but not as it then appeared. The visitor may call to mind this picturesque structure, with its seven arches crossing to the Marché aux Fleurs from the corner of the Quai de la Megisserie. In 1660 it was covered with houses, in common with most of the other bridges that spanned the Seine, with the exception of the Pont Neuf. These were now partly in ruins, from the ravages of time, and frequent conflagrations. Lower down the river might be seen the vestiges of the Pont Marchand—a wooden bridge, which had been burnt down nearly forty years before, some of whose charred and blackened timbers still obstructed the free course of the river. It had stood on the site of the Pont aux Meuniers—also a wooden bridge—to which six or seven boat-mills were attached; and these, in consequence of the flooding of the Seine, dragged the whole structure away in the winter of 1596.

The Grand Châtelet stood at the foot of the Pont au Change; its ground is now occupied by a square, and an elegant fountain. The origin of the Châtelet has been lost in antiquity. It had once been a strong fortress; and its massive round-towers still betokened its strength. Next it was a prison, where the still increasing city rendered its position of little value in guarding the gates; and afterwards it became the Court of Jurisdiction pertaining to the Provost of Paris. Part of its structure was now in ruins; wild foliage grew along the summits of its outer walls, and small buildings had been run up between the buttresses, occupied by retailers of wine and small merchandise. It was a great place of resort at all times; for a dark and noisome passage, which ran through it, was the only thoroughfare from the Pont au Change to the Rue St. Denis, and this was constantly crowded with foot-passengers.

The afternoon sunlight fell upon the many turrets and spires, and quivered on the vanes and casements of the fine old buildings that then surrounded the carrefour. Across the river the minarets of the Palais de Justice rose in sharp outline against the blue sky, glowing in the ruddy tint; together with the campanile at the corner of the quay, and the blackened towers of Notre Dame, farther in the Ile de la Cité, round which flocks of birds were wheeling in the clear spring air, who had their dwellings amidst the corbels, spouts, and belfries of the cathedral. There was not an old gray gable or corroded spire which, steeped in the rays of the setting sun, did not blush into light and warmth. And the mild season had drawn all the inhabitants of the houses who were not abroad to their windows, whence they gazed upon the gay crowd below, through pleasant trellises of climbing vegetation, which crept along the pieces of twine latticing the casements. Humble things, indeed, the plants were,—hops, common beans, wild convolvuli, and the like, spreading from a rude cruche of mould upon the sill; but the beams of the sun came through them cheerfully; and their shadows danced and trembled on the rude tiled floor as sportively as on the costly inlaid parquets of the richer quarters of the city.

The Carrefour du Châtelet was at this period, with the Pont Neuf, the principal resort of the people of Paris, then, as now, ever addicted to the promenade and out-of-door lounging. A singularly varied panorama did the open place present to any one standing at the cross which was reared in the centre, and gazing around him. He might have seen a duel taking place between two young gallants on the footpath, in open contest. Swords were then as quickly drawn forth as tempers; no appointments were made for the seclusion of the faubourgs beyond the walls which occupied the site of the present boulevards; and these quarrels often ended fatally, though merely fought for the possession of some courtesan who, in common with others, blazed forth in her sumptuous trappings on the bridges during the afternoon. But the guards never interfered, and the passengers looked on unconcernedly until the struggle was, one way or the other, decided.

The beggars were as numerous then as now, perhaps more so; for the various Cours des Miracles, the ‘Rookeries’ of Paris, if we may be allowed the expression, which abounded all over the city, offered them a ready colony and retreat. Here were counterfeiters of every disease to which humanity is liable, dragging themselves along the rude footpath; there, beggars of more active habits, who swarmed, cap in hand, by the side of the splendid carriages which passed along the quays, to and from the Louvre. The thieves, too, everywhere plied their vocation; and the absurd custom of carrying the purse suspended at the girdle, favoured their delinquencies; whence certain of them acquired the title of coupe-bourse, as in England the pick-pockets were formerly termed cut-purses.

Crowds of soldiers, vendors of street merchandise, and charlatans of every description filled the carrefour. Looking to the tableau offered by the public resorts of Paris at the present time, the Champs Elysées for instance (in 1665, consisting only of fields, literally in cultivation), it is curious to observe how little the principal features of the assembly have altered from the accounts left us by accurate and careful delineators of former manners.

But, besides all these, the mere idlers, of both sexes, were numerous and remarkable; an ever-changing throng of gay habits, glittering accoutrements, and attractive figures and faces. The license of the age, unbounded in its extent, permitted appointments of every kind to be made without notice. Every kind of dissipation was openly practised, and therefore the world winked at it, as under such circumstances it always does, even if the place of an illicit assignation or conference (and in the reign of Louis XIV. they were seldom otherwise) were a church, as indeed was most frequently the case. The generally licentious taste extended to the dress and conversation; hence, from the crowds of gallants who thronged the carrefour, salutations and remarks of strange freedom were constantly addressed to the handsome women who, in the prodigality of their display of dazzling busts and shoulders, invited satire or compliments; nay, to such a pitch was that negligee attire carried, that some might be seen walking abroad in loose damask robes merely confined at the waist by a cord of twisted silk.

The platform round which the laughing crowd had assembled was formed on a light cart that had its wheels covered with some coarse drapery. There were two occupants of this stage. One of them was a man who might have numbered some forty years; but his thin furrowed cheeks and sunken eye would have added another score to his age, in the opinion of a casual observer. He was dressed entirely in faded black serge, made after the fashion of the time, with full arms, and trunks fastened just above the knee. Some bands of vandyked lace were fastened round his wrists; and he wore a collar of the same material, whilst his doublet was looped together but a little way down his waist. A skull-cap of black velvet completed his attire.

Yet few who looked at him took much notice of his dress: the features of this man absorbed all attention. His face exactly resembled that of a condor, his cap adding to the likeness by being worn somewhat forward; from beneath which his long black hair fell perfectly straight down the back of his neck. His brows were scowling: his eyes deep-set and jet-black: but they were bloodshot, and surrounded by the crimson ridges of the lids. His cheeks were pallid as those of a corpse; and his general figure, naturally tall, was increased in appearance of height by his attenuated limbs. He took little notice of the crowd, but remained sitting at a small table on the carriage, upon which there was a small show of chemical glasses and preparations: leaving nearly all the business of his commerce to his assistant.

This was a merry fellow, plump, and well-favoured, in the prime of life. He was habited in a party-fashioned costume of black and white, his opposite arms and legs being of different colours; and his doublet quartered in the same style. Round his waist he carried a pointed girdle, to which small hawk-bells were attached; and he wore the red hood of the moyen âge period, fitting closely to his neck and head, and hanging down at the top, to the extremity of which a larger bell was fastened His face had such a comic expression, that he only had to wink at the crowd to command their laughter. And when to this he added his jests, he threw them into paroxysms of merriment.

‘Ohé! ohé! my masters!’ he cried, ‘the first physician of the universe, and many other places, has come again to confer his blessings on you. He has philtres for those who have not had enough of love, and potions for those who have had too much. He can attach to you a new mistress when she gets coy, or get rid of an old one when she gets troublesome. And if you have two at once, here is an elixir that will kill their jealousies.’

‘Send some to Louis!’ cried one of the bystanders.

A roar of laughter followed the speech, and the crowd looked round to see the speaker. But, although bold enough to utter the recommendation, he had not the courage to support it. However, the cue had been given to the crowd, and the applause and laugh of approbation continued.

‘Give it to La Vallière!’ exclaimed another of the citizens.

‘Or Madame de Montespan,’ cried a third.

‘Or, rather, to her husband!’ was ejaculated in a woman’s voice.

‘Respect his parents,’ exclaimed a bourgeois, with mock solemnity, who was standing at the foot of the bridge, and pointing to a group of three figures in bronze relief, which adorned a triangular group of houses close to where he was stationed. They were those of Louis XIII., Anne of Austria, and the present King when a child.

‘Simon Guillain, the sculptor, was a false workman!’ shouted the bystander who had first spoken. ‘Where is the fourth of the family?’

The mountebank, who had been endeavouring to talk through the noise, found himself completely outclamoured by the uproar that now arose. He gave up making himself heard, and remained silent whilst the crowd launched their sallies, or bandied their satirical jibes from one to the other.

‘Where is the fourth?’ continued the speaker.

‘Ask Dame Perronette, who nursed him!’ was the reply from the other side of the carrefour.

‘Ask Saint-Mars who locked on his iron mask.’

‘Who will knock and ask at Mazarin’s coffin!’ shouted another, with a strength of lungs that ensured a hearing. ‘He ought to know best.’

The name of Anne of Austria was on the lips of many; but, with all the license of the time, they dared not give utterance to it. And, besides, as the last speaker finished, a yell broke forth that drowned every other sound; and showed by its force, which partook almost of ferocity, in what manner the memory of the Cardinal was yet held. The instant comparative silence was obtained a fellow sung, from a popular satire upon the late prime minister—

‘He trick’d the vengeance of the Fronde,—

All in the world, and those beyond.

A bas! à bas le Cardinal!

He trick’d the headsman by his death—

The devil, by his latest breath,

Who for his perjured soul did call,

But found that he had none at all,

A bas! à bas le Cardinal!’

The throng chorused the last words with great emphasis; and then in a few minutes were once more tranquil. The charged cloud had got rid of its thunder, and the storm abated.

The physician, who was upon the platform, took little notice of the clamour. At its commencement, he glared round upon the assembly for a few seconds, and then once more bent his eyes upon the table before him. His assistant continued, as soon as he could make himself audible—

‘Ohé! masters! a philtre for your eyes that will make them work upon others at a distance. Here is one that will infect the spirit of the other with sickness at heart; here is a second that will instil love also by the glance of the eye that is washed with it.’

They were little phials containing a small quantity of coloured fluid. The price was small, and they were eagerly purchased by the multitude. But for every one of the second, they purchased a dozen of the first.

‘Art thou sure of its operation?’ asked a looker-on.

‘Glances of love and malice shoot subtly,’ replied the fool; ‘and my master can draw subtle spirits from simple things that shall work upon each other at some distance. But your own spirits, with the aid of this philtre, are more subtle than they.’

‘A proof! a proof!’ cried a young man at the extremity of the carrefour.

‘The philtre is not for such as you,’ cried the mountebank. ‘You have youth, and a well-favoured aspect; you have a strong arm, a gay coat, and a trusty rapier. What would man require more?’

The crowd turned to look at the object of the clown’s speech. At the end of the carrefour, two young men were gazing, arm-in-arm, upon the assemblage. Both were of the same age; their existence might have reached to some seven or eight-and-twenty years, and they were attired in the gay military costume of the period; with rich satin under-sleeves, and bright knots or epaulettes upon the right shoulder.

One of them, to whom the mountebank had more particularly addressed himself, was of a fair complexion, and wore his own light hair in long flowing curls upon his shoulders. His face was well formed, and singularly intelligent and expressive; his forehead high and expansive, and his eyes deep set beneath the arch of the orbit, ever bearing the appearance of fixed regard upon whatever object they were cast. Still to the close observer there was a faint line running from the edge of the nostril to the outer angle of the lip, which, coupled with his retreating eye, gave him an expression of satire and mistrust. But so varied was the general expression of his face, that it was next to impossible to divine his thoughts for two minutes together.

The other was dark—his face had less indication of intellect than his companion’s, although in general contour equally good-looking. Yet did the features bear a somewhat jaded expression, and the colour on his cheek was rather fevered than healthy. His eyes too were sunk, but more from active causes than natural formation; and he gazed on the objects that surrounded him with the listless air of an idler. His mind was evidently but little occupied with anything he then saw. His attire was somewhat richer than his friend’s, betokening a superior rank in the army.

‘A proof! a proof!’ cried the gayer of the two, repeating his words.

‘Where will you have it then?’ asked the mountebank, looking about the square. ‘Ha! there is as fair a maiden as ever a king’s officer might follow, sitting at the cross. Shall she be in love with you?’

Again the attention of the crowd was directed by the glance of the mountebank towards a rude iron cross that was set up in the carrefour.

At its foot was a young girl, half sitting, half reclining upon the stone-work which formed its base. She was attired in the costume of the working order of Paris. Her hair, different from that of the higher class of females, who wore it in light bunches of ringlets at the side of the head, was in plain bands, over which a white handkerchief, edged with lace, was carelessly thrown, falling in lappets on each side. Her eyes and hair were alike dark as night, but her beautiful face was deadly pale, until she found the gaze of the mob had been called towards her. And then the red blood rushed to her neck and cheeks, as she hastily rose from her seat, and was about to leave the square.

‘A pretty wench enough,’ cried the cavalier with the black hair, as he raised himself upon the step of a house to see her. She was still hidden from his companion.

‘I doubt not,’ answered the other carelessly; ‘but I do not care to look. No,’ he cried loudly to the mountebank, ‘I have no love to spare her in return, and that might break her heart.’

The girl started at his voice, and looked towards the spot from whence it proceeded. But she was unable to see him, for the intervening people.

‘A beryl!’ cried the fool, showing a small crystal of a reddish tint to the crowd. ‘A beryl! to tell your fortune then. Who will read the vision in it? a young maiden, pure and without guile, can alone do it; are there none in our good city of Paris?’

None stepped forward. The fair-haired cavalier laughed aloud as he cried out:

‘You seem to have told what is past better than you can predict what is to come. Ho! sirs, what say you to this slur upon the fair fame of your daughters and sisters—will none of them venture?’

A murmur was arising from the crowd, when the physician, who had been glancing angrily at the two young officers, suddenly rose up, and shouted with a foreign accent—

‘If you will have your destinies unfolded, there needs no beryl to picture them. Let me look at your hands, and I will tell you all.’

‘A match!’ cried the young soldier. ‘Now, good people, let us pass, and see what this solemn-visaged doctor knows about us.’

The two officers advanced towards the platform. As they approached it, the crowd fell back, and then immediately closed after them with eager curiosity. The friends stood now directly beside the waggon.

‘Your hands!’ said the physician.

They were immediately extended to him.

‘You are in the king’s service,’ continued he.

‘Our dresses would tell you that,’ said the darker of the two.

‘But they would not tell me that you are married,’ answered the physician. ‘You have two children—a fair wife—and no friend.’

‘’Tis a lie!’ exclaimed the cavalier with the light hair.

‘It is true,’ replied the necromancer coldly, directing the gaze of his piercing eye full upon him.

‘But our destiny, our destiny,’ said the dark officer with impatience.

‘You would care but little to know,’ returned the other, ‘if all should turn out as I here read it. I have said your wife is fair—a score and a half of years have robbed her of but little of her beauty; and I have said you have no friend. Now read your own fate.’

‘Come away,’ said the fair cavalier, trying to drag his friend by the arm from the platform. ‘We will hear no more—he is an impostor.’

As the soldier spoke a hectic patch of colour rose on the pale cheek of the physician, and his eye lighted up with a wild brightness. He raised his arm in an attitude of denunciation, and cried, with a loud but hollow voice:

‘You are wrong, young man; and you shall smart for thus bearding one to whom occult nature is as his alphabet. We have met before—and we shall meet again.’

‘Pshaw! I know you not,’ replied the other heedlessly.

‘But I know you,’ continued the physician. ‘Do you remember an inn at Milan—do you recollect a small room that opened upon the grape-covered balcony of the Croce Bianca? Can you call that to mind, Gaudin de Sainte-Croix?’

As the officer heard his name pronounced, he turned round; and stared with mingled surprise and alarm at the physician. The latter beckoned him to return to the platform, and he eagerly obeyed. The crowd collected round them closer than ever, hustling one another in their anxiety to push nearer to the platform, for affairs appeared to be assuming a turn rather more than ordinary. And so intent were they upon the principal personages of the scene, that they paid no attention to the girl who had been sitting at the cross, and who, upon hearing the name, started from her resting-place, and rushed to the outside of the throng that now closely surrounded the waggon. But the crowd was too dense for her to penetrate; and she passed along from one portion to the other, vainly endeavouring to force her way through it. Some persons roughly thrust her back; others bade her desist from pressing against them; and not a few launched out into some questionable hints, as to the object of her anxiety to get closer to the two officers.

Meanwhile, Sainte-Croix, as we may now call him, had again reached the edge of the platform. The physician bent down and whispered a word or two into his ear, which, with all his efforts to retain his self-possession before the mob, evidently startled him. He looked with a scrutinising attention, as if his whole perception were concentrated in that one gaze, at the face of the other, and then with an almost imperceptible nod of recognition, caught his companion by the arm, and dragged him forcibly through the crowd.

As the two cavaliers departed, the interest of the bystanders ceased, and they fell back from the platform, except the girl, who glided quickly between them, towards where the officers had been standing. But they were gone; and, after a vain search amidst the crowd in the carrefour, she retired back to where she had been sitting, and covering her face with her hands, was once more unheeded and alone.

At last the sun went down, and twilight fell upon the towers and pointed roofs of the old chatelet. The loiterers gradually disappeared from the place and bridge. The rough voitures de place, which clattered incessantly over a pavement so rude and uneven that it became a wonder how they were enabled to progress at all, one by one withdrew from the thoroughfares, carrying a great portion of the general noise with them, not more proceeding from the hoarse voices of the drivers than from the ceaseless cracking of their long whips, which was thus always going on. The cries of those who sold things in the streets was also hushed, as well as the tolling and chiming of the innumerable bells in the steeples of the churches, which until dusk never knew rest, but tried to outclang each other as noisily as the supporters of the different sects, whose hour of meeting they announced. One or two lanterns were already glimmering from the windows of private houses; for by this means only were the streets of Paris preserved from utter darkness throughout the night: and the full moon began to rise slowly behind the turrets of Notre Dame.

There was little security, then, in the most public places, and few cared to be about after dusk, except in the immediate company of the horse or foot patrol, save those who only stalked abroad with the night, so that it was not long before the carrefour was nearly deserted. Two persons alone remained there. One was the assistant to the physician, who had left him in charge of the platform; and he was now occupied in harnessing two miserable mules to the waggon, in which the platform and the apparatus had been stowed away. The other was the girl whom we have before spoken of, and who had remained at the cross in almost the same attitude—one of deep sorrow and despondency.

The fool had nearly finished his labours, and was preparing to leave the square, when the young female quitted her resting-place, and advanced towards him with a timid and faltering step. Believing her to be some wretched wanderer of the carrefour proceeding to her home before the curfew sounded, he took but little notice of her, and was about to seize the mules by the bridle and lead them onwards, when she placed her hand upon his arm and implored him to stop.

‘Now, good mistress—your business,’ said the assistant; ‘for I have little time to spare. A sharp appetite hurries labour more than a sharp overseer; and my stomach keeps time better than the bell of Notre Dame.’

‘I wished to purchase something,’ returned the girl.

‘Ah! you are too late—we have nought left but holy pebbles to keep steeds from the nightmare, and philtres for the court dames to retain their butterfly lovers. Good-night, ma belle. Hir-r-r-r! Jacquot! hir-r-r-r!’

The last expression was addressed to his mules, as they rattled the old bells upon their head-pieces, and moved forwards. Again the girl seized the upraised hand of the mountebank, as he was about to use the whip, and begged him to desist.

‘I am sure you have what I want,’ she said hurriedly. ‘I will pay you for it—all that I have left from my wages is yours. Is not your master the doctor St. Antonio?’

‘Well—and suppose he is?’

‘They talk strangely of his art about Paris, as being able to play with life and death as he chooses. They say that he can enchant medicines; and with a little quicksilver so prepared destroy a whole family—nay, an army.’

‘Were you to believe an hundredth part of the lies they tell daily about Paris, your credulity would find time for nothing else,’ returned the other. ‘What should one so young and fair as you want with poison, beyond keeping the rats from your mansarde?—for to that end alone does my master prepare it, and even then in small quantities.’

‘I wanted it for myself,’ replied the girl. ‘I have nothing left in this world to care about. I wish to die.’

Her head drooped, and her voice faltered as she spoke these words, so that they were almost inaudible; more so than the deep and weary sigh that followed them.

‘Die—sweetheart!’ cried the mountebank cheeringly, as he turned towards her, and raised her chin with his hand. ‘Die!—St. Benoit, who rules my fete day, prevent it! You must not die this half-century. Besides, although the doctors can’t yet find poisons in the stomach, like witches’ nails and pins, yet the stones can whisper, in Paris, all they hear. And what should we get—I and my master—for thus serving you?’

‘All that I possess in the world,’ answered the girl.

‘Ay—that would come first, without doubt; and next, a short shrift, a long cord, and a dry faggot, on the Place de Grêve. No, no, sweetheart: if you brought as much gold as my mules could drag home, we could not do it.’

‘Then you will not let me have it?’

‘Why, you silly pigeon, I have told you so. With that pretty face and those dark eyes be sure you have much yet in store to live for. Or if you must die, don’t make any one your murderer. The Seine is wide and deep enough for all; and, besides, will cost you nothing.’

He spoke these words less in a spirit of levity than the wish to cheer the poor applicant by his good-humoured tones. But the girl clasped her hands together, and looked round with a shudder towards the quays.

‘The river!’ she exclaimed. ‘I have gazed upon it often, but my heart failed me. I shrank from the cold black water as it tore and struggled through those dark arches: I could not bear to think that its foul polluted current would be my only winding-sheet. I would sooner die in my little room; and then in the morning the sun would fall upon me as it does now, but it would not awaken me to another day of weeping—the same sun that shines in Languedoc, only there it is brighter.’

‘Are you from Languedoc, then?’ inquired the man.

‘I was born near Béziers,’ she replied sadly.

‘Mass! why that is my own country. What is your name?’

‘Louise Gauthier.’

‘I don’t remember to have heard it. I ought to have known, though, that you were from the south by your accent. And what brought you to Paris?’

‘There has been much misery and persecution amongst us,’ answered the girl; ‘for we are Protestant; almost all our homes have been broken up, for that reason, and so,’—and she hesitated—‘and so I came up to seek work.’

‘Was there no other reason?’ asked the man. ‘I think there must have been.’

‘I went to the Gobelins,’ continued Louise, avoiding the question, ‘and got employment. I heard that others had gained money there.’

‘And rank too,’ said the fool. ‘My master had a customer this afternoon—an officer in the King’s army, who is better known as the Marquis of Brinvilliers than by his proper name of Antoine Gobelin. The water of the Bièvre has rather enriched his blood; he has besides a fair income, and a fairer wife. And are you there still?’

‘I am not. I was discharged from the atelier this morning for resisting the importunities of the superintendent Lachaussée, and I am now alone—alone!’

She hid her face in her hands, and burst into tears.

‘And why not return to Languedoc, my poor girl?’ said the mountebank, in a kind voice, which associated but oddly with his quaint dress. ‘They would scarcely care to persecute such a gentle thing as yourself—Protestant though you be.’

‘No, no, I cannot leave Paris. There is another object that keeps me here; or rather it did—for all hope is gone. There is now nothing left for me but death. I could have remained unheeded in the country; but in this great city the solitude is fearful: those who are alone, alone can tell how terrible it is.’

Although the duty of the charlatan was to impose upon the public in every fashion that they were likely to bite at most readily, yet there was a kind heart under his motley attire. He threw his whip over the backs of the two mules, and taking the weeping girl kindly by the hands, said to her:

‘Come, come, countrywoman: I shall not leave you to your loneliness this night at least. If aught were to happen to you, I should feel that I myself had brought your body on the Grêve. My wife and myself live in a strange abode, but there is room for you; and you shall go with me.’

The girl looked at him with an expression of mistrust which his calling might well have occasioned; and murmured out a few faint words of refusal.

‘Bah!’ exclaimed the other. ‘You are from Languedoc, like myself, and therefore we are neighbours. I would wager that we have sat under the same trees, within a short half-league of Béziers.’

And he commenced humming the refrain of a ballad in the old Provençal dialect. It was evidently well known to Louise. She shook her head, and pressed her hand before her eyes as if to shut out some sad image that her ideas had conjured up.

‘You have heard that before?’ asked the man.

‘Very often—I know it well.’

‘You heard it from a man, then, I will be sworn; and perhaps a faithless one. He wrote well, long, long ago, who said that those who were gifted with music and singing loved our Languedocian romances, and travelled about the earth that they might betray women. My marotte to an old sword-belt that the tune sang itself in your ears all the way to Paris. Was it not so?’

The girl returned no answer, but remained silent, with her eyes fixed upon the ground.

‘Well, well—we will not press for a reply. But you shall come with me this night, ma bonne, for I will not leave you so. Only let me take you to where our mules’ lodging is situated, and then I will bring you back to my own.’

He scarcely waited for her acquiescence, but lifting her gently in his arms, placed her on the waggon. And then he gave his signal to the mules, and they moved along the carrefour, over which the darkness was now stealing.

They passed along the quays and the Port au Foin, now dimly lighted by the few uncertain and straggling lanterns before alluded to, until the mules turned of their own accord into a court of the Rue St. Antoine. A peasant in wooden shoes clamped forward to receive them, with whom the charlatan exchanged a few words previously to conducting his companion back again, nearly along the same route by which they had arrived at the stables.

‘You may call me Benoit,’ he said, as he perceived that the girl was sometimes at a loss how to address him. ‘Benoit Mousel. Do not stand upon adding maître to it. We are compatriots, as I have told you, and therefore friends. The quays are dark at night, but the river is darker still. You made a good choice of two evils in keeping out of it.’

They walked on, barely lighted through the obscurity, until they came to the foot of the Pont Notre Dame—the most ancient of those still existing at Paris. It is now, as formerly, on the line of thoroughfare running from the Rue St. Jacques, in the Quartier Latin, to the Rue St. Martin. The modern visitor may perhaps recall it to mind by a square tower built against its western side, flanked by two small houses raised upon piles, beneath which are some wheels, by whose working some thirty of the fountains in the streets of Paris are supplied with water. This mechanism was not constructed until a few years after the date of our story. Before that, the Pont Notre Dame, in common with the other bridges we have mentioned, was covered with houses, which remained in excellent condition, to the number of sixty-eight or seventy, up to the commencement of the last century. They were then destroyed; and now the parapets are covered with boxes of old books ranged in graduated prices; whilst shoe-blacks, lucifer-merchants, and beautifiers of lap-dogs occupy the kerb of the pavement.

Benoit descended some rude steps leading from the quay to the river, guiding Louise carefully by the hand; and dragging a boat towards them, which was lying there in readiness, embarked with his trembling companion, as if to cross the river. But he stopped half-way, close to the pier of the bridge, and then the girl saw that they had touched a long low range of what appeared to be houses, which looked as if they floated on the water. And, in effect, they did so; their continuous vibration and the rushing of the river between certain divisions in their substructure, showing that they were boat-mills.

‘Where are you taking me?’ asked Louise timidly.

‘To our house,’ replied Benoit. ‘You have nothing to fear. I told you it was an odd dwelling. Now mind how you place your foot on the timber. So: gallantly done.’

He assisted her from the boat, which was rocking on the dark stream of the river as it rushed through the arches, on to a few frail steps of wood which hung down from one of the buildings to the water. Then making it fast to one of the piles, he passed with her along a small gallery of boards, and, pushing a door open, entered the floating house.

They were in a small apartment, forming one of a long range which had apparently been built in an enormous lighter; and in one of these the large shaft of a mill-wheel could be seen turning heavily round, as it shook the building, whilst the whole mass oscillated with the peculiar vibration of a floating structure. At a small table in the middle of this chamber, a buxom-looking female, in a half-rustic, half-city attire, was busily at work with her needle, at a rude table. There was little other furniture in this ark. A small stove, some seats, and a few hanging shelves, on which were placed some bottles of coloured fluids, retorts, and little earthenware utensils, used in chemical analysis, completed the list of all that was movable in the room. But the circumstance that struck Louise most upon entering, was the sharp, pungent atmosphere which filled the floating apartment—so noxious that it produced a violent fit of coughing as soon as she inhaled it. Nor was her conductor much less affected.

‘Paff!’ he exclaimed, as soon as he could speak; ‘our master is at his work again, brewing devil’s drinks and fly-powder. Never mind, ma pauvrette: you will be used to it directly.’

The woman had risen from her seat when they entered, and was now casting a suspicious glance at Louise and an inquiring one at her husband alternately.

‘Oh! you have nothing to be jealous of, Bathilde,’ he continued, addressing his better half. ‘Here is a countrywoman from Béziers, without a friend, and dying for love, for aught I know to the contrary. We must give her a lodging for to-night at least.’

‘Do not let me intrude,’ said Louise, turning to the female. ‘I fear that I am already doing so. Let me be taken on shore again, and I will not put you to inconvenience.’

‘Not a word of that again, or I shall swear that your are no Languedocian. A pretty journey you would have, admitting you went to your lodgings, from here to the Rue Mouffetard—for I suppose you live near the Gobelins. There are dangerous vagabonds at night in the Faubourg Saint Marcel; and they say the young clerks of Cluny study more graceless things in the streets than learned ones at their college. A woman, young and comely like yourself, was found in the Bièvre the other morning. I saw them carrying the body to the Val de Grace myself.’

While Benoit was thus talking his wife had been doing the humble honours of their floating establishment towards their new guest. She had placed her own seat near the fire for Louise—for the evening was chilly, the more so on the river—and next proceeded to lay their frugal supper on the table, consisting of dried apples, a long log of bread, and a measure of wine.

‘You will not incommode us, petite,’ said Bathilde. ‘You can sleep with me, and Benoit will make his bed amongst the sacks, where he dozes when he has to keep up the doctor’s fires all night long.’

Bathilde was not two years older than Louise; yet she felt that, being married, she had the position of a matron, and so she patronised her. But it was done with an innocent and good heart.

‘Ay, I could sleep anywhere near the old mill-wheel,’ said Benoit. ‘Its clicking sends me off like a cradle. The only time I never close my eyes is at the Toussaint; and that is because I’ve stopped it. Look at it there! plodding on just as if it were a living thing.’

The charlatan’s assistant looked affectionately at the beam which was working at the end of the chamber; and then wishing to vent the loving fulness of his heart upon something more sensible of it, he pinched his wife’s round chin, and kissed her rosy face with a smack that echoed again.

‘Hush!’ cried Bathilde; ‘you will disturb the doctor.’ And she pointed to a door leading from the apartment.

‘Is there any one else here, then?’ asked Louise.

‘Only my master,’ replied Benoit. ‘He came to lodge here when he first arrived in Paris, because he did not want to be disturbed, as he said. Well, he has his wish. His rent pays ours, and I get a trifle for playing his fool. Mass! think of this attire in Languedoc!’

They proceeded with their supper. Benoit fell to it as though he had fasted for a week, but Louise tasted nothing, in spite of all the persuasions of her honest entertainers. She sipped some wine which they insisted on her taking; and then remained sad and pale, in the deepest despondency.

Her gloom appeared to affect the others. The charlatan looked but sadly for his calling; and every now and then Bathilde turned her large bright eyes from Benoit to Louise, and then back again to Benoit, as if more fully to comprehend the unwonted introduction of her young guest. And sometimes she would assume a little grimace, meant for jealousy, until her husband reassured her with a pantomimical kiss blown across the table.

At last Benoit and his helpmate thought it would be kinder to leave her to her sorrow; and they began, as was their custom, to talk about the events of the day. The interruption of the two young cavaliers was of course mentioned, and was exciting the earnest attention of Louise, when the conversation was broken by the door opening suddenly at the end of the apartment, and the physician of the Carrefour du Châtelet passed hastily out and approached the table.

‘Hist! Benoit!’ he exclaimed, in a low and somewhat flurried tone; ‘some one has gained the mills besides ourselves. Who is that girl?’ he said sharply, as his eye fell upon Louise.

‘A poor countrywoman whom I have given a lodging to for the night. She works at the Gobelins.’

The physician moved towards Louise, and clutching her arm with some force, glared at her with terrible earnestness, as he continued:

‘You know how this has come about. Who is it?—answer on your sacred soul.’

The terrified girl, for a minute, could scarcely reply, until the others repeated his question, when she exclaimed—

‘I do not understand you, monsieur. I have no one in Paris with whom I can exchange a word—none, but these good people.’

‘I do not see how any one could have got to the mill,’ said Benoit. ‘I brought over the boat myself from the quay.’

‘And you have not moved from this room?’

‘Never, since I disembarked with this maiden.’

‘It is strange,’ said the physician. ‘I had put out my lamp, the better to watch the colour of a lambent violet flame that played about the crucible. The lights from the bridge fell upon the window, and I distinctly saw the shadow of a human being, if human it were, pass across the curtain on the outside. Hark! there is a noise above!’

There could be now no doubt; the shuffling of feet was plainly audible on the roof of the floating house; but of feet evidently moved with caution.

‘I will go and see,’ cried Benoit, taking down the lamp, which was suspended from one of the beams. ‘If they are intruders, I can soon warn them off.’

‘No, no!’ cried the chemist eagerly; ‘do not leave the room; barricade the door; no one must enter.’

‘We have nothing to barricade it with,’ replied Benoit, getting frightened himself at the anxiety of his master. ‘Oh dear! oh dear! we shall be burnt for witches on the Grêve. I see it all.’

‘Pshaw! imbecile,’ cried the other. ‘Here, you have the table, these chairs. Bring sacks, grain, anything!’

The women had risen from their seats, and retreated into a corner of the apartment near the stove. The physician seized the table, and, implicitly followed by Benoit, was moving towards the door, when there was a violent knocking without, and a command to open it immediately.

‘It is by the king’s order,’ said Benoit: ‘we cannot resist.’

He reached the door, and unfastened it before the physician could pull him back, although he attempted to do so. It flew open, and a party of the Guet Royal entered the room, headed by the chief of the marching watch of Paris.

‘Antonio Exili,’ said the captain, pointing his sword towards the physician, ‘commonly known as the Doctor St. Antonio, I arrest you in the king’s name!’

‘Exili!’ ejaculated Benoit, gazing half aghast at his master.

The name pronounced was that of an Italian, terrible throughout all Europe; at the mention of whom even crowned heads quailed, and whose black deeds, although far more than matters of surmise, had yet been transacted with such consummate skill and caution as to baffle the keenest inquiries, both of the police and of the profession. Exili, who had been obliged to fly from Rome, as one of the fearful secret poisoners of the epoch, was instructed in his hellish art, it has been presumed, by a Sicilian woman named Spara. She had been the confidante and associate of the infamous Tofana, from whom she acquired the secret at Palermo, where the dreaded preparation which bore her name was sold, with little disguise, in small glass phials, ornamented with some holy image.

Six years previous to the commencement of our romance, a number of suspicious deaths in Rome caused unusual vigilance to be exercised by the police of that city, little wanting at all times in detective instinct; and the result was the detection of a secret society (of which Spara was at the head, ostensibly as a fortune-teller), to whose members the various deaths were attributed; inasmuch, amongst other suspicious circumstances, as Spara had frequently, in her capacity of sybil, predicted their occurrence. Betrayed through the jealousy of one of the party, all in the society were arrested, and put to the torture; a few were executed, and others escaped. Amongst these last Exili eluded the punishment no less due to him than to the rest, and, flying from Italy, came into France, and finally established himself at Paris under an assumed name; but his real condition was tolerably well understood by the police, although his depth and care never gave them tangible ground for an arrest. He practised as a simple physician. In this portion of his career little occurred to throw suspicion on his calling; but, driven at length by poverty to sink his dignity in a less precarious method of gaining a livelihood, he had appeared as the mere charlatan, and it was now hinted, that whilst he sold the simplest drugs to the people, poisons of the most subtle and violent nature could be obtained through his agency. Where they came from no one was aware, but their source was attributed, like many other uncertain ones, to the devil. These suspicions were, however, principally confined to the police; the mass looked upon him as an itinerant physician of more than ordinary talents.

Those, indeed, to whom he had administered potions had been known to die; but his skill in pharmacy enabled him to produce his effects as mere aggravated symptoms of the disease he was ostensibly endeavouring to cure. And chemical science, in those days, was so far behind its modern state, that no delicate tests of the presence of poisons—even of those offering the strongest precipitates—were known. At the present time, our poisons have increased to tenfold violence and numbers: yet in no instance, scarcely, could an atom be now administered, without its presence, decomposed or entire, being laid bare on the test-glass of the inquirer.

‘Exili!’ again gasped Benoit, as he drew nearer his wife and Louise; in an agony of fear, also, that the part he bore in the public displays of the medicines would involve him in the punishment.

‘I must have your authority, sir, before I can be arrested,’ replied Exili, as we may now call him, with singular and suddenly assumed calmness. ‘And you must also prove that I am the man of whom you are in search.’

‘I can satisfy you on both points,’ cried a voice from amidst the guard.

The soldiers fell back on either side of the doorway, and Gaudin de Sainte-Croix, the young officer who had held parley with him on the Carrefour du Châtelet, entered the room.

‘I know you to be the same Antonio Exili,’ he continued; ‘you confessed it to me yourself but this afternoon. And here,’ he added, as he held a paper towards him, ‘is the lettre de cachet for your arrest.’

The girl, who had started at the first sound of Sainte-Croix’s voice, now leant anxiously forward as he entered the room; and when she saw him, a sudden and violent cry of surprise burst from her lips. She checked herself, however, whilst he was speaking, but as soon as he had finished, she rushed up to him, and, grasping his arm, cried ‘Gaudin!’

‘Louise!—you here!’ exclaimed Sainte-Croix. ‘I thought you were in Languedoc,’ he added, dropping his voice, whilst his brow contracted into an angry frown. He was evidently ill-prepared for the rencontre, and but little pleased at it.

The Italian took advantage of the temporary diversion afforded by the interview. With the nerve and muscular strength of a young man, he vaulted over the table against which he had been standing, and rushed into his own apartment, closing the door, which was of massy wood, against his pursuers. But this only caused the delay of an instant. Finding that their partisans made not the least effect upon the thick panels, the officer in command ordered them to take a large beam that was lying on the floor—apparently a portion of some old mill-machinery, and use it as a battering ram. It was lifted by six or eight of the guard, and hurled with all their united strength against the door. For the first two or three blows it resisted their efforts, but at last gave way with a loud crash, and the laboratory of the physician lay open before them.

‘En avant!’ cried the captain of the watch; ‘and take him, dead or alive. Follow me.’

The officer entered the room, but had scarcely gone two steps, when he uttered a loud and spasmodic scream and fell on the floor. A guard, who was following him, reeled back against his fellows with the same cry, but fainter; and immediately afterwards a dense and acrid vapour rolled in heavy coloured fumes into the outer chamber. Its effects were directly perceptible upon the rest, who fell back seized with violent and painful contractions of the windpipe; and the man who had kept close upon their commander, was now also struck down by the deadly vapour, which a violent draught of cold air spread around them. But they had time to perceive that a window at the end of the small laboratory was open, and that Exili had passed through it and escaped to the river.

‘It is poison! it is poison!’ cried Benoit lustily, apparently most anxious to give every information in his power respecting his late tenant, and turning fool’s evidence in his eagerness to clear his own character. ‘He has broken the bottle it was in. I know it well. He killed some dogs with it, before the Pâques, as if they had been shot. Keep back, on your lives!’

During this short and hurried scene, Louise had not once quitted her hold of Sainte-Croix, but, in extreme agitation, the result of mingled terror and surprise, still clung to him.

‘Beware! beware!’ continued Benoit; ‘I know it well, I tell you. He has water that burns like red irons; and he pours it on money, which leaves it blue. It will kill you! He has broken the bottle that held it.’

And he continued reiterating these phrases with almost frantic volubility, until one of the guard, at the risk of his life, pulled to the shattered door as well as he was able.

‘Gaudin!’ cried Louise as she fell at his feet, still clinging to his arm and his rich sword-belt. ‘Gaudin, only one word—tell me that you have not forgotten me—that you still love me.’

‘Yes, yes, Louise; I still love you,’ he replied in a careless and impatient tone. ‘But this is not the place for scenes like these; you might, in delicacy, have spared me this annoying persecution.’

‘Persecution, Gaudin! I have given up all for you; I have abandoned everything, even the hope of salvation for my own soul; I have wandered day after day through the heartless streets of Paris, or worked at the Gobelins until my spirits have been crushed to the earth, and all my strength gone, by the struggle to support myself; and all in the hope of seeing you again. Tell me—do you still care for me, or am I a clog upon your life in this gay city?’

‘Not now, Louise; not now,’ returned Sainte-Croix, ‘another time. This is ill-judged, it is unkind. I tell you that I still love you. There, now let me go, and do not thus lower me before these people.’

‘And when shall I see you again?’

‘At any time—to-morrow—whenever you please—at any place,’ continued Sainte-Croix, endeavouring to disembarrass himself from her grasp. ‘There, see! I am wanted by the guard.’

‘Gaudin! only one kind word, spoken as you once used to do, to tell me where I may see you: to show me that you do not hate me.’

‘Pshaw! Louise, this is childish at such a moment. Let go my arm, if you would escape an injury. You see I am wanted. You are mad thus to annoy me.’

‘Heaven knows I have had enough to make me so,’ returned the girl, struggling with the hands of the other as he tried to free himself from her grasp. ‘But, Gaudin! I beg it on my knees, one, only one, kind word. Ah!’

She screamed with pain, as Sainte-Croix, in desperation, seized her wrists and twisting them fiercely round, forced her to loose her hold. And then casting her from him, with no light power, she fell senseless on the floor at the feet of Bathilde, who had remained completely paralysed since the commencement of the hurried scene.

‘He will escape by the river,’ cried the second in command of the night watch. ‘We must follow him.’

Pressing onward with the rest, Sainte-Croix passed from the chamber and stood on the edge of the floating tenements. The boat in which Benoit had arrived was still lying where it had been left fastened by a cord. He directly ordered two of the men into it, and entering himself, divided the cord that held it with his sword, and then put forth upon the river. The others gained the roof of the mill, and they were then joined by some members of the Garde Bourgeois, who had descended, and were still coming down by a rope-ladder, depending from the window of one of the old gabled houses upon the Pont Notre Dame. This was evidently the manner in which they had gained access to the mill, when their feet had first been heard overhead by Exili.

In the meanwhile, the object of their pursuit had escaped by the window, as has been seen, and dropped into the hollow of one of the lighters that floated the entire structure, with the intention of passing underneath the mill-floor to the spot at which another small boat, used by himself alone, was fastened. But it was here quite dark, and the passage was one of extreme caution, being amongst the timbers of the woodwork upholding the mill, between some of which the large black wheels were turning, as the deep and angry water foamed and roared below them, lashing the slippery beams or leaping wildly over the narrow ledges of the lighters.

Supplied with torches by the Garde Bourgeois, the others pervaded every portion of the mill, and at last came upon the track of their object, his lace collar having caught some projecting woodwork in his flight. One or two of them leapt boldly down into the lighters, and the others clung round the structure above upon frightfully insecure foot-room. They were now under the apartment, and entirely amidst the timbers of the works. The light of their torches revealed to them Exili passing onward, at the peril of his life, to gain the boat; but close before them.

A cry of recognition broke from two or three of the guard, and the Italian, as a last chance, caught hold of a beam which overhung the wheels, contriving, at an imminent risk, to pass himself across the channel of the current by swinging one hand before the other. Those who had regarded his general appearance, would scarcely have given him credit for so much power.

He gained the other side. One of the guard immediately attempted to follow him, and seized the beam; but he had not crossed half-way before his strength failed him, his armour proving too heavy, together with his body, for his arms to sustain; and he fell upon the wheel as it turned, entangling his legs in the float-boards. He was borne beneath the current, and immediately afterwards re-appeared on the wheel, throwing his arms wildly about for help. Scarcely had a cry escaped his lips, when he again passed beneath the surface; the water disentangled him and bore him down the stream for an instant, until he sank, and was seen no more.

Meanwhile Exili was endeavouring to unfasten his boat, and the Garde Bourgeois passing round the other side of the mill had arrived close to where he was stationed, cutting off his retreat in that direction. There was now no chance but the river; and without a moment’s hesitation he plunged into the boiling current, trusting to the darkness for his escape. At the same moment a bourgeois threw off his upper garments, and letting himself down the outer side of the lighter into the river, where the stream was somewhat less powerful, called for a torch, which he contrived to keep above the water in his left hand, striking out vigorously with his right.

It was a singular chase. Both were evidently practised swimmers, and more than once Exili eluded his pursuer by diving below the surface and allowing him to pass beyond the mark. Several times, as they approached, he made a clutch at the torch, or tried to throw back a palm-full of water at its light, knowing if he could but reach any of the houses on the site of the present Quai Desaix, he should be sheltered in some of the secret refuges of the city. And once, indeed, he turned at bay in deep water, locking on to the guard in a manner which would soon have proved fatal to both, when the boat containing Sainte-Croix shot across the river, and came up to where they were struggling. His capture was the work of half a minute, and he was dragged into the boat.

‘So, mon enfant,’ said Gaudin, as the dripping object of all this turmoil was placed, breathless and dripping, in the stern, ‘you thought we stood in somewhat different positions, I will be bound, this afternoon.’

Then addressing himself to the men who were rowing, he added—

‘The Port au Foin is the nearest landing-place for the Rue St. Antoine. And then to the Bastille!’

The stream was violent below the bridge; for the mill-boats obstructed the free course of the river, and the Seine was still swollen and turbid from the spring floods. But the rowers plied their oars manfully, and, directed by one of the guard, who kept at the head of the boat with the torch, were not long in arriving at the landing-place indicated by Sainte-Croix, which was exactly on the site of the present Pont Louis Philippe, conducting from the Place de la Grêve to the back of Notre Dame.

Exili remained perfectly silent, but was trembling violently—more, however, from his late immersion than from fear. His countenance was pale and immovable, as seen by the glare of the torch; and he compressed his under lip with his teeth until he nearly bit it through. Neither did Sainte-Croix exchange another word with any of his party; but, shrouded in his cloak, remained perfectly silent until the boat touched the rude steps of the Pont au Foin.

A covered vehicle, opening behind, and somewhat like a modern deer-cart, was waiting on the quay, with some armed attendants. The arrival of the prisoner was evidently expected. By the direction of Sainte-Croix he was carefully searched by the guard, and everything being taken from him, he was placed in the vehicle, whither his captor also followed him. The doors were then closed, and the men with torches placing themselves at the sides and in front of the vehicle, the cortege moved on.

It was a rough journey, then, to make from the Seine to the Bastille; and it would have been made in perfect darkness but for the lights and cressets of the watch. For the night was advancing; the lanterns in the windows had burned out, or been extinguished; and the tall glooming houses, which rose on either side of the Rue Geoffry Lanier, by which thoroughfare they left the river side, threw the road into still deeper obscurity, their only lights being observable in the windows high up, where some industrious artisan was late at work. A rude smoky lamp hung from the interior of the vehicle, and by its gleam Sainte-Croix was watching his prisoner in silence. At length Exili spoke.

‘You have been playing a deep game; and this time Fortune favours you. But you took her as the discarded mistress of many others; and she will in turn jilt you.’

‘Say rather we have both struggled for her, and you lost her by your own incautious proceedings,’ replied Sainte-Croix. ‘We were both at the brink of a gulf, on a frail precipice, where the fall of one was necessary to the safety of the other. You are now my victim; to-morrow I might have been yours.’

‘And whence comes the lettre de cachet?’

‘From those who have the power to give it. Had you been more guarded in your speech on the carrefour to-day, you might have again practised on the credulity of the dupes that surrounded you.’

‘For what term is my imprisonment?’

‘During the pleasure of the Minister of Police; and that may depend upon mine. Our secrets are too terrible for both to be free at once. You should not have let me know that you thought me in your power.’

‘Has every notion of honour departed from you?’ asked Exili.

‘Honour!’ replied Sainte-Croix, with a short contemptuous laugh; ‘honour! and between such as we have become! How could you expect honour to influence me, when we have so long despised it—when it is but a bubble name with the petty gamesters of the world—the watchword of cowardice fearing detection?’

There was a halt in the progress of the carriage as it now arrived at the outer gate of the Bastille. Then came the challenge and the answer; the creaking of the chains that let down the huge drawbridge upon the edge of the outer court; and the hollow rumbling of the wheels over its timber. It stopped at the inner portal; and when the doors were opened, the governor waited at the carriage to receive the new prisoner.

But few words were exchanged. The signature of the lettre de cachet once recognised was all that was required, and Exili was ordered to descend. He turned to Sainte-Croix as he was about to enter the gate, and with a withering expression of revenge and baffled anger, exclaimed—

‘You have the game in your own hands at present. Before the year is out my turn will have arrived. Remember!’

Night came on, dark, cold, tempestuous. The fleeting beauty of the spring evening had long departed; the moon became totally invisible through the thick clouds that had been soaring onwards in gloomy masses from the south; and the outlines of the houses were no longer to be traced against the sky. All was merged in one deep impenetrable obscurity. There were symptoms of a turbulent night. The wind whistled keenly over the river and the dreary flats adjoining; and big drops of rain fell audibly upon the paved court and drawbridge of the Bastille.

The heavy gates slowly folded upon each other with a dreary wailing sound, which spoke the hopeless desolation of all that they enclosed. And when the strained and creaking chains of the drawbridge had once more lowered the platform, Sainte-Croix entered the vehicle by which he had arrived, and, giving some directions to the guard, left the precincts of the prison.

As the carriage lumbered down the Rue St. Antoine, a smile of triumph gleamed across the features of its occupant, mingled with the expression of satire and mistrust which characterised every important reflection that he gave way to. A dangerous enemy had been, as he conceived, rendered powerless. There was but one person in the world of whom he stood in awe; and that one was now, on the dark authority of a lettre de cachet, in the inmost dungeon of the Bastille. The career of adventures that he had planned to arrive at the pinnacle of his ambitious hopes—and Gaudin de Sainte-Croix was an adventurer in every sense of the word—now seemed laid open before him without a cloud or hindrance. The tempestuous night threw no gloomy forebodings upon his soul. The tumult of his passions responded wildly to that of the elements, or appeared to find an echo in the gusts of the angry wind, as it swept, loud and howling, along the thoroughfares.

The carriage, by his orders, passed the Pont Marie, and, crossing the Ile St. Louise, stopped before a house, still existing, in the Rue des Bernardins, where his lodging was situated. The street leads off from the quay on the left bank of the Seine, opposite the back of Notre Dame; but, at the date of our story, was nearly on the outskirts of the city. Here he discharged the equipage with the guard; and, entering the house for a few minutes, returned enveloped in a large military cloak, and carrying a lighted cresset on the end of a halberd.

He pressed hurriedly forward towards the southern extremity of the city, passing beside the abbey of Sainte Geneviève, where the Pantheon now stands. Beyond this, on the line of streets which at present bear the name of the ‘Rues des Fosses,’ the ancient walls of Paris had, until within a year or two of this period, existed; but the improvements of Louis XIV., commenced at the opposite extremity of the city, had razed the fortifications to the ground. Those to the north, levelled and planted with trees, now form the Boulevards; the southern line had, as yet, merely been thrown into ruins; and the only egress from the town was still confined to the point where the gates had stood, kept tolerably clear for the convenience of travellers, and more especially those dwelling in the increasing faubourgs. Even these ways were scarcely practicable. The water, for want of drains, collected into perfect lakes, and the deep ruts were left unfilled, so that the thoroughfare, hazardous by day, became doubly so at night; in fact, it was a matter of some enterprise to leave or enter the city at its southern outlet.

The rain continued to fall; and the cresset that Gaudin carried, flickering in the night winds, oftentimes caused him to start and put himself on his guard, at the fitful shadows it threw on the dismantled walls and towers that bordered the way. At last a violent gust completely extinguished it, and he would have been left in a most unpleasant predicament, being totally unable to proceed or retrace his steps in the perfect obscurity, had not a party of the marching watch opportunely arrived. Not caring to be recognised, Sainte-Croix slouched his hat over his face, and giving the countersign to the chevalier du guet, requested a light for his cresset. The officer asked him a few questions as to what he had seen; and stated that they were taking their rounds in consequence of the increasing brigandages committed by the scholars dwelling in the Quartier Latin, as well as the inhabitants of the Faubourgs St. Jacques and St. Marcel, between whom an ancient rivalry in vagabondising and robbery had long existed. And, indeed, as we shall see, many high in position in Paris were at this period accustomed to ‘take the road’—some from a reckless spirit of adventure; others with the desire of making up their income squandered at the gaming-table, or in the lavish festivals which the taste of the age called forth.

He passed the counterscarp, and had reached the long straggling street of the faubourg, when two men rushed from between the pillars which supported the rude houses, and ordered him to stop. Gaudin was immediately on his defence. He hastily threw off his cloak, and drew his sword, parrying the thrust that one of the assailants aimed at him, but still grasping his cresset in his left hand, which the other strove to seize. They were both masked; and pressed him somewhat hardly, as the foremost, in a voice he thought he recognised, demanded his purse and mantle.

‘Aux voleurs!’ shouted Sainte-Croix, not knowing how many of the party might be in ambush. There was no reply, except the echo to his own voice. But, as he spoke, his chief assailant told the other, who had wrested the light away, to desist; and drawing back, pulled off his mask and revealed the features of the Marquis of Brinvilliers—the companion of Sainte-Croix that afternoon on the Carrefour du Châtelet.

‘Gaudin’s voice, a livre to a sou!’ exclaimed the Marquis.

‘Antoine!’ cried his friend as they recognised each other. ‘It is lucky I cried out, although no help came. It takes a sharper eye and a quicker arm than mine to parry two blades at once.’

The two officers looked at each other for a minute, and then broke into a burst of laughter; whilst the third party took off his hat and humbly sued for forgiveness.

‘And Lachaussée, too!’ continued Sainte-Croix, as he perceived it was one of his dependants. ‘The chance is singular enough. I was even now on my way to the Gobelins to find you, rascal.’

‘Then we are not on the same errand?’ asked the Marquis.

‘If you are out as a coupe-bourse, certainly not. What devil prompted you to this venture? A woman?’ asked Sainte-Croix.

‘No devil half so bad,’ replied Brinvilliers; ‘but the fat Abbe de Cluny. He goes frequently to the Gobelins after dark; it is not to order tapestry only for his hôtel. Since the holy sisterhood of Port-Royal have moved to the Rue de la Bourbe, he seeks bright eyes elsewhere.’

‘I see your game,’ answered Gaudin; ‘you are deeper in debt than in love. But it is no use waiting longer. This is not the night for a man to rest by choice in the streets; and my cry appears at last to have had an effect upon the drowsy faubourgs.’

As he spoke, he directed the attention of Brinvilliers to one of the upper windows of a house whence a sleepy bourgeois had at last protruded his head, enveloped in an enormous convolution of hosiery. He projected a lighted candle before him, as he challenged the persons below; but, ere the question reached them, it was extinguished by the rain, and all was again dark and silent.

Sainte-Croix directed Lachaussée to pile together the embers in the cresset, which the brief struggle had somewhat disarranged; and then, as the night-wind blew them once more into a flame, he took the arm of the Marquis, and, preceded by the overlooker of the Gobelins, passed down the Rue Mouffetard.

They stopped at an old and blackened house, supported like the others upon rough pillars of masonry, which afforded a rude covered walk under the projecting stories; and signalised from the rest by a lantern projecting over the doorway. Such fixed lights were then very rare in Paris; and this was why the present was raised to the dignity of an especial sign: and the words ‘A la Lanterne’ rudely painted on its transparent side betokened a house of public entertainment. Within the range of its light the motto ‘Urbis securitas et nitor’ was scrawled along the front of the casement.

‘I shall give up my plan for to-night,’ said Brinvilliers as they reached the door. ‘The weather has possibly kept the Abbe in the neighbourhood of the Gobelins. You can shelter here: there are some mauvais garçons still at table, I will be bound, that even Bras-d’Acier himself would shrink from grappling with.’

Thus speaking, he knocked sharply at the door with the handle of his sword, which he had kept unsheathed since his rencontre with Sainte-Croix. A murmur of voices, which had been audible upon their arriving, was instantly hushed, and, after a pause of a few seconds, a challenge was given from within. Brinvilliers answered it: the door was opened, and Sainte-Croix entered the cabaret, followed by Lachaussée.

‘You are coming too, Antoine?’ asked Gaudin of his companion, as the latter remained on the sill.

‘Not this evening,’ replied the Marquis. ‘You wished to see Lachaussée, and this is the nearest spot where you could find shelter without scrambling on through the holes and quagmires to the Gobelins.’

‘But I know nobody here.’

‘Possibly they may know you, and my introduction is sufficient. I have other affairs which must be seen to this evening, since my first plan has failed. You will be with us to-morrow?’

‘Without fail,’ replied Gaudin.

Brinvilliers commended his companion to the care of the host, and took his leave; whilst Sainte-Croix and Lachaussée were conducted into an inner apartment in the rear of the house.

It was a low room, with the ceiling supported by heavy blackened beams. The plaster of the walls was, in places, broken down; in others covered with rude charcoal drawings and mottoes. A long table was placed in the centre of the apartment; and over this was suspended a lamp which threw a lurid glare upon the party around it.

This was composed of a dozen young men whom Sainte-Croix directly recognised to be scholars of the different colleges. They were dressed in every style of fashion according to their tastes—one would not have seen appearances more varied in the Paris students of the present day. Some still kept to the fashions of the preceding reigns—the closely-clipped hair, pointed beard and ring of moustache surrounding the mouth. Others had a semi-clerical habit, and others again assimilated to the dress of the epoch; albeit the majority wore their own hair. But in one thing they appeared all to agree. Large wine-cups were placed before each, and flagons passed quickly from one to the other round the table.

They stared at Sainte-Croix as he entered with his attendant, and were silent. One of them, however, recognised him, and telling the others that he was a friend, made a place for him at his side, whilst Lachaussée took his seat at the chimney corner on a rude settle.

‘Your name, my worthy seigneur?’ exclaimed one of the party at the head of the table; ‘we have no strangers here. Philippe Glazer, tell your friend to answer.’

‘My name is Gaudin de Sainte-Croix. I am a captain in his Majesty’s Normandy regiment. Yours is——?’

The collected manner in which the new-comer answered the question evidently made an impression on the chairman. He was a good-looking young man, with long dark hair and black eyes, clad in a torn mantle evidently put on for the nonce, with an old cap adorned with shells upon his head, and holding a knotty staff, fashioned like a crutch, for a sceptre. He made a slight obeisance, and replied—

‘Well—you are frank with me; I will be the same. I have two names, and answer to both equally. In this society of Gens de la Courte Épée,1 I am called “Le Grand Coësre;” at the Hôtel Dieu they know me better as Camille Theria, of Liége, in the United Netherlands.’

At a sign from the speaker, one of the party took a bowl from before him and pushed it along the table towards Sainte-Croix. There were a few pieces of small money in it, and Gaudin directly perceiving their drift threw in some more. A sound of acclamation passed round the table, and he immediately perceived that he had risen to the highest pitch in their estimation.

‘He is one of us!’ cried Theria. ‘Allons! Glazer—the song—the song.’

The student addressed directly commenced; the others singing the chorus, and beating time with their cups.

Glazer’s Song.

I.

Ruby bubbling from the flask,

Send the grape’s bright blood around;

Throw off steady life’s cold mask,

Every earthly care confound.

Here no rules are known,

Buvons!

Here no schools we own,

Trinquons!

Let wild glee and revelry

Sober thought dethrone.

Plan! Plan! Plan! Rataplan!

II.

Would you Beauty’s kindness prove?

Drink! faint heart ne’er gain’d a prize.

Hath a mistress duped your love?

Drink! and fairer forms will rise.

Clasp’d may be the zone,

Buvons!

Even to the throne.

Trinquons!

But full well the students know

Beauty is their own.

Plan! Plan! Plan! Rataplan!

III.

Soaring thoughts our minds entrance,

Now we seem to spurn the ground.

See,—the lights begin to dance,

Whirling madly round and round.

Still the goblet drain,

Buvons!

Till each blazing vein

Trinquons!

Sends fresh blood in sparkling flood

To the reeling brain.

Plan! Plan! Plan! Rataplan!

‘Your voice ought to make your fortune, Philippe,’ said Sainte-Croix, who appeared to know the student intimately.

‘Pardieu! it does me little service. Theria, there, who cannot sing a note, keeps all the galanteries to himself. Ho! Maître Camille! here I pledge your last conquest.’ And he raised his cup as he added, ‘Marie-Marguerite de Brinvilliers!’

Sainte-Croix started at the name; his eyes, flashing with anger, passed rapidly from one to the other of the two students.

‘Chut!’ cried another of the students, a man of small stature, who was dressed in the court costume of the period, but shabbily, and with every point exaggerated. ‘Chut! Monsieur perchance knows la belle Marquise, and will not bear to hear her name lipped amongst us?’

The student had noticed the rapid change and expression of Sainte-Croix’s countenance.

‘No, no—you are mistaken,’ said Gaudin. ‘I am slightly acquainted with the lady. I served with her husband.’