By FRANK HERBERT

Illustrated by FINLAY

The science of language—an overly-neglected field for the extrapolations of science-fiction—is put to brilliant use in this powerful story. Against a background of ultimate peril from a galactic invader, man (in this case, woman) goes back beyond Babel to recall for humanity the places of the soul, where words are not enough.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories October 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Every mind on earth capable of understanding the problem was focused on the spaceship and the ultimatum delivered by its occupants. Talk or Die! blared the newspaper headlines.

The suicide rate was up and still climbing. Religious cults were having a field day. A book by a science fiction author: "What the Deadly Inter-Galactic Spaceship Means to You!" had smashed all previous best-seller records. And this had been going on for a frantic seven months.

The ship had flapped out of a gun-metal sky over Oregon, its shape that of a hideously magnified paramecium with edges that rippled like a mythological flying carpet. Its five green-skinned, froglike occupants had delivered the ultimatum, one copy printed on velvety paper to each major government, each copy couched faultlessly in the appropriate native tongue:

"You are requested to assemble your most gifted experts in human communication. We are about to submit a problem. We will open five identical rooms of our vessel to you. One of us will be available in each room.

"Your problem: To communicate with us.

"If you succeed, your rewards will be great.

"If you fail, that will result in destruction for all sentient life on your planet.

"We announce this threat with the deepest regret. You are urged to examine Eniwetok atoll for a small display of our power. Your artificial satellites have been removed from the skies.

"You must break away from this limited communication!"

Eniwetok had been cleared off flat as a table at one thousand feet depth ... with no trace of explosion! All Russian and United States artificial satellites had been combed from the skies.

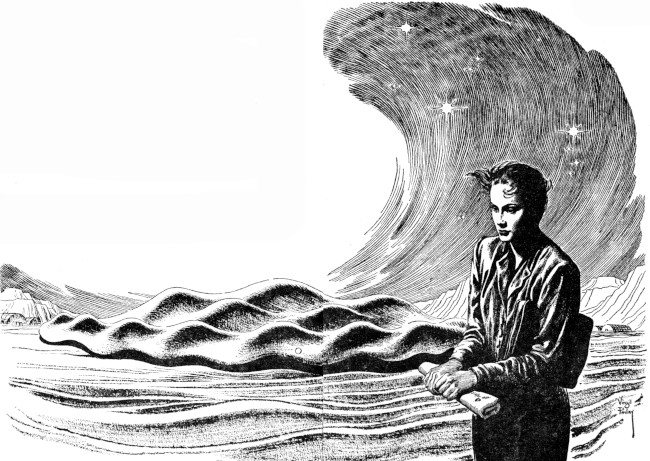

All day long a damp wind poured up the Columbia Gorge from the ocean. It swept across the Eastern Oregon alkali flats with a false prediction of rain. Spiny desert scrub bent before the gusts, sheltering blur-footed coveys of quail and flop-eared jackrabbits. Heaps of tumbleweed tangled in the fence lines, and the air was filled with dry particles of grit that crept under everything and into everything and onto everything with the omnipresence of filterable virus.

On the flats south of the Hermiston Ordnance Depot the weird bulk of the spaceship caught pockets and eddies of sand. The thing looked like a monstrous oval of dun canvas draped across upright sticks. A cluster of quonsets and the Army's new desert prefabs dotted a rough half-circle around the north rim. They looked like dwarfed outbuildings for the most gigantic circus tent Earth had ever seen. Army Engineers said the ship was six thousand two hundred and eighteen feet long, one thousand and fifty-four feet wide.

Some five miles east of the site the dust storm hazed across the monotonous structures of the cantonment that housed some thirty thousand people from every major nation: Linguists, anthropologists, psychologists, doctors of every shape and description, watchers and watchers for the watchers, spies, espionage and counter-espionage agents.

For seven months the threat of Eniwetok, the threat of the unknown as well, had held them in check.

Toward evening of this day the wind slackened. The drifted sand began sifting off the ship and back into new shapes, trickling down for all the world like the figurative "sands of time" that here were most certainly running out.

Mrs. Francine Millar, clinical psychologist with the Indo-European Germanic-Root team, hurried across the bare patch of trampled sand outside the spaceship's entrance. She bent her head against what was left of the windstorm. Under her left arm she carried her briefcase tucked up like a football. Her other hand carried a rolled-up copy of that afternoon's Oregon Journal. The lead story said that Air Force jets had shot down a small private plane trying to sneak into the restricted area. Three unidentified men killed. The plane had been stolen.

Thoughts of a plane crash made her too aware of the circumstances in her own recent widowhood. Dr. Robert Millar had died in the crash of a trans-Atlantic passenger plane ten days before the arrival of the spaceship. She let the newspaper fall out of her hands. It fluttered away on the wind.

Francine turned her head away from a sudden biting of the sandblast wind. She was a wiry slim figure of about five feet six inches, still trim and athletic at forty-one. Her auburn hair, mussed by the wind, still carried the look of youth. Heavy lids shielded her blue eyes. The lids drooped slightly, giving her a perpetual sleepy look even when she was wide awake and alert—a circumstance she found helpful in her profession.

She came into the lee of the conference quonset, and straightened. A layer of sand covered the doorstep. She opened the door, stepped across the sand only to find more of it on the floor inside, grinding underfoot. It was on tables, on chairs, mounded in corners—on every surface.

Hikonojo Ohashi, Francine's opposite number with the Japanese-Korean and Sino-Tibetan team, already sat at his place on the other side of the table. The Japanese psychologist was grasping, pen fashion, a thin pointed brush, making notes in ideographic shorthand.

Francine closed the door.

Ohashi spoke without looking up: "We're early."

He was a trim, neat little man: flat features, smooth cheeks, and even curve of chin, remote dark eyes behind the inevitable thick lenses of the Oriental scholar.

Francine tossed her briefcase onto the table, and pulled out a chair opposite Ohashi. She wiped away the grit with a handkerchief before sitting down. The ever present dirt, the monotonous landscape, her own frustration—all combined to hold her on the edge of anger. She recognized the feeling and its source, stifled a wry smile.

"No, Hiko," she said. "I think we're late. It's later than we think."

"Much later when you put it that way," said Ohashi. His Princeton accent came out low, modulated like a musical instrument under the control of a master.

"Now we're going to be banal," she said. Immediately, she regretted the sharpness of her tone, forced a smile to her lips.

"They gave us no deadline," said Ohashi. "That is one thing anyway." He twirled his brush across an inkstone.

"Something's in the air," she said. "I can feel it."

"Very much sand in the air," he said.

"You know what I mean," she said.

"The wind has us all on edge," he said. "It feels like rain. A change in the weather." He made another note, put down the brush, and began setting out papers for the conference. All at once, his head came up. He smiled at Francine. The smile made him look immature, and she suddenly saw back through the years to a serious little boy named Hiko Ohashi.

"It's been seven months," she said. "It stands to reason that they're not going to wait forever."

"The usual gestation period is two months longer," he said.

She frowned, ignoring the quip. "But we're no closer today than we were at the beginning!"

Ohashi leaned forward. His eyes appeared to swell behind the thick lenses. "Do you often wonder at their insistence that we communicate with them? I mean, rather than the other way around?"

"Of course I do. So does everybody else."

He sat back. "What do you think of the Islamic team's approach?"

"You know what I think, Hiko. It's a waste of time to compare all the Galactics' speech sounds to passages from the Koran." She shrugged. "But for all we know actually they could be closer to a solution than anyone else in...."

The door behind her banged open. Immediately, the room rumbled with the great basso voice of Theodore Zakheim, psychologist with the Ural-Altaic team.

"Hah-haaaaaaa!" he roared. "We're all here now!"

Light footsteps behind Zakheim told Francine that he was accompanied by Emile Goré of the Indo-European Latin-Root team.

Zakheim flopped onto a chair beside Francine. It creaked dangerously to his bulk.

Like a great uncouth bear! she thought.

"Do you always have to be so noisy?" she asked.

Goré slammed the door behind them.

"Naturally!" boomed Zakheim. "I am noisy! It's my nature, my little puchkin!"

Goré moved behind Francine, passing to the head of the table, but she kept her attention on Zakheim. He was a thick-bodied man, thick without fat, like the heaviness of a wrestler. His wide face and slanting pale blue eyes carried hints of Mongol ancestry. Rusty hair formed an uncombed brush atop his head.

Zakheim brought up his briefcase, flopped it onto the table, rested his hands on the dark leather. They were flat slab hands with thick fingers, pale wisps of hair growing down almost to the nails.

She tore her attention away from Zakheim's hands, looked down the table to where Goré sat. The Frenchman was a tall, gawk-necked man, entirely bald. Jet eyes behind steel-rimmed bifocals gave him a look of down-nose asperity like a comic bird. He wore one of his usual funereal black suits, every button secured. Knob wrists protruded from the sleeves. His long-fingered hands with their thick joints moved in constant restlessness.

"If I may differ with you, Zak," said Goré, "we are not all here. This is our same old group, and we were going to try to interest others in what we do here."

Ohashi spoke to Francine: "Have you had any luck inviting others to our conferences?"

"You can see that I'm alone," she said. "I chalked up five flat refusals today."

"Who?" asked Zakheim.

"The American Indian-Eskimo, the Hyperboreans, the Dravidians, the Malayo-Polynesians and the Caucasians."

"Hagglers!" barked Zakheim. "I, of course, can cover us with the Hamito-Semitic tongues, but...." He shook his head.

Goré turned to Ohashi. "The others?"

Ohashi said: "I must report the polite indifference of the Munda and Mon-Kmer, the Sudanese-Guinean and the Bantu."

"Those are big holes in our information exchange," said Goré. "What are they discovering?"

"No more than we are!" snapped Zakheim. "Depend on it!"

"What of the languages not even represented among the teams here on the international site?" asked Francine. "I mean the Hottentot-Bushmen, the Ainu, the Basque and the Australian-Papuan?"

Zakheim covered her left hand with his right hand. "You always have me, my little dove."

"We're building another Tower of Babel!" she snapped. She jerked her hand away.

"Spurned again," mourned Zakheim.

Ohashi said: "Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech." He smiled. "Genesis eleven-seven."

Francine scowled. "And we're missing about twenty percent of Earth's twenty-eight hundred languages!"

"We have all the significant ones," said Zakheim.

"How do you know what's significant?" she demanded.

"Please!" Goré raised a hand. "We're here to exchange information, not to squabble!"

"I'm sorry," said Francine. "It's just that I feel so hopeless today."

"Well, what have we learned today?" asked Goré.

"Nothing new with us," said Zakheim.

Goré cleared his throat. "That goes double for me." He looked at Ohashi.

The Japanese shrugged. "We achieved no reaction from the Galactic, Kobai."

"Anthropomorphic nonsense," muttered Zakheim.

"You mean naming him Kobai?" asked Ohashi. "Not at all, Zak. That's the most frequent sound he makes, and the name helps with identification. We don't have to keep referring to him as 'The Galactic' or 'that creature in the spaceship'."

Goré turned to Francine. "It was like talking to a green statue," she said.

"What of the lecture period?" asked Goré.

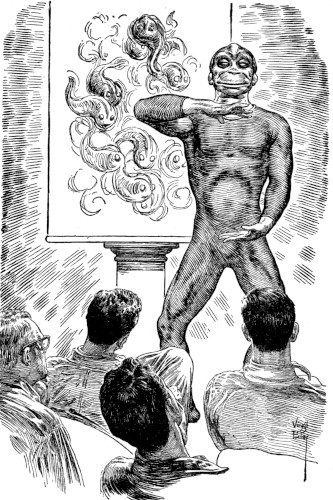

"Who knows?" she asked. "It stands there like a bowlegged professor in that black leotard. Those sounds spew out of it as though they'd never stop. It wriggles at us. It waves. It sways. Its face contorts, if you can call it a face. We recorded and filmed it all, naturally, but it sounded like the usual mish-mash!"

"There's something in the gestures," said Ohashi. "If we only had more competent pasimolgists."

"How many times have you seen the same total gesture repeated with the same sound?" demanded Zakheim.

"You've carefully studied our films," said Ohashi. "Not enough times to give us a solid base for comparison. But I do not despair—"

"It was a rhetorical question," said Zakheim.

"We really need more multi-linguists," said Goré. "Now is when we most miss the loss of such great linguists as Mrs. Millar's husband."

Francine closed her eyes, took a short, painful breath. "Bob...." She shook her head. No. That's the past. He's gone. The tears are ended.

"I had the pleasure of meeting him in Paris shortly before the ... end," continued Goré. "He was lecturing on the development of the similar sound schemes in Italian and Japanese."

Francine nodded. She felt suddenly empty.

Ohashi leaned forward. "I imagine this is ... rather painful for Dr. Millar," he said.

"I am very sorry," said Goré. "Forgive me."

"Someone was going to check and see if there are any electronic listening devices in this room," said Ohashi.

"My nephew is with our recording section," said Goré. "He assures me there are no hidden microphones here."

Zakheim's brows drew down into a heavy frown. He fumbled with the clasp of his briefcase. "This is very dangerous," he grunted.

"Oh, Zak, you always say that!" said Francine. "Let's quit playing footsy!"

"I do not enjoy the thought of treason charges," muttered Zakheim.

"We all know our bosses are looking for an advantage," she said. "I'm tired of these sparring matches where we each try to get something from the others without giving anything away!"

"If your Dr. Langsmith or General Speidel found out what you were doing here, it would go hard for you, too," said Zakheim.

"I propose we take it from the beginning and re-examine everything," said Francine. "Openly this time."

"Why?" demanded Zakheim.

"Because I'm satisfied that the answer's right in front of us somewhere," she said.

"In the ultimatum, no doubt," said Goré. "What do you suppose is the real meaning of their statement that human languages are 'limited' communication? Perhaps they are telepathic?"

"I don't think so," said Ohashi.

"That's pretty well ruled out," said Francine. "Our Rhine people say no ESP. No. I'm banking on something else: By the very fact that they posed this question, they have indicated that we can answer it with our present faculties."

"If they are being honest," said Zakheim.

"I have no recourse but to assume that they're honest," she said. "They're turning us into linguistic detectives for a good reason."

"A good reason for them," said Goré.

"Note the phraseology of their ultimatum," said Ohashi. "They submit a problem. They open their rooms to us. They are available to us. They regret their threat. Even their display of power—admittedly awe-inspiring—has the significant characteristic of non-violence. No explosion. They offer rewards for success, and this...."

"Rewards!" snorted Zakheim. "We lead the hog to its slaughter with a promise of food!"

"I suggest that they give evidence of being non-violent," said Ohashi. "Either that, or they have cleverly arranged themselves to present the face of non-violence."

Francine turned, and looked out the hut's end window at the bulk of the spaceship. The low sun cast elongated shadows of the ship across the sand.

Zakheim, too, looked out the window. "Why did they choose this place? If it had to be a desert, why not the Gobi? This is not even a good desert! This is a miserable desert!"

"Probably the easiest landing curve to a site near a large city," said Goré. "It is possible they chose a desert to avoid destroying arable land."

"Frogs!" snapped Zakheim. "I do not trust these frogs with their problem of communication!"

Francine turned back to the table, and took a pencil and scratch-pad from her briefcase. Briefly she sketched a rough outline of a Galactic, and wrote "frog?" beside it.

Ohashi said: "Are you drawing a picture of your Galactic?"

"We call it 'Uru' for the same reason you call yours 'Kobai'," she said. "It makes the sound 'Uru' ad nauseum."

She stared at her own sketch thoughtfully, calling up the memory image of the Galactic as she did so. Squat, about five feet ten inches in height, with the short bowed legs of a swimmer. Rippling muscles sent corded lines under the black leotards. The arms were articulated like a human's, but they were more graceful in movement. The skin was pale green, the neck thick and short. The wide mouth was almost lipless, the nose a mere blunt horn. The eyes were large and spaced wide with nictating lids. No hair, but a high crowned ridge from the center of the forehead swept back across the head.

"I knew a Hawaiian distance swimmer once who looked much like these Galactics," said Ohashi. He wet his lips with his tongue. "You know, today we had a Buddhist monk from Java at our meeting with Kobai."

"I fail to see the association between a distance swimmer and a monk," said Goré.

"You told us you drew a blank today," said Zakheim.

"The monk tried no conversing," said Ohashi. "He refused because that would be a form of Earthly striving unthinkable for a Buddhist. He merely came and observed."

Francine leaned forward. "Yes?" She found an odd excitement in the way Ohashi was forcing himself to casualness.

"The monk's reaction was curious," said Ohashi. "He refused to speak for several hours afterward. Then he said that these Galactics must be very holy people."

"Holy!" Zakheim's voice was edged with bitter irony.

"We are approaching this the wrong way," said Francine. She felt let down, spoke with a conscious effort. "Our access to these Galactics is limited by the space they've opened to us within their vessel."

"What is in the rest of the ship?" asked Zakheim.

"Rewards, perhaps," said Goré.

"Or weapons to demolish us!" snapped Zakheim.

"The pattern of the sessions is wrong, too," said Francine.

Ohashi nodded. "Twelve hours a day is not enough," he said. "We should have them under constant observation."

"I didn't mean that," said Francine. "They probably need rest just as we do. No. I meant the absolute control our team leaders—unimaginative men like Langsmith—have over the way we use our time in those rooms. For instance, what would happen if we tried to break down the force wall or whatever it is that keeps us from actually touching these creatures? What would happen if we brought in dogs to check how animals would react to them?" She reached in her briefcase, brought out a small flat recorder, and adjusted it for playback. "Listen to this."

There was a fluid burst of sound: "Pau'timónsh'uego' ikloprépre 'sauta' urusa'a'a ..." and a long pause followed by: "tu'kimóomo 'urulig 'lurulil 'oog 'shuquetoé ..." pause "sum 'a 'suma 'a 'uru 't 'shóap!'"

Francine stopped the playback.

"Did you record that today?" asked Ohashi.

"Yes. It was using that odd illustration board with the moving pictures—weird flowers and weirder animals."

"We've seen them," muttered Zakheim.

"And those chopping movements of its hands," said Francine. "The swaying body, the undulations, the facial contortions." She shook her head. "It's almost like a bizarre dance."

"What are you driving at?" asked Ohashi.

"I've been wondering what would happen if we had a leading choreographer compose a dance to those sounds, and if we put it on for...."

"Faaa!" snorted Zakheim.

"All right," said Francine. "But we should be using some kind of random stimulation pattern on these Galactics. Why don't we bring in a nightclub singer? Or a circus barker? Or a magician? Or...."

"We tried a full-blown schizoid," said Goré.

Zakheim grunted. "And you got exactly what such tactics deserve: your schizoid sat there and played with his fingers for an hour!"

"The idea of using artists from the entertainment world intrigues me," said Ohashi. "Some No dancers, perhaps." He nodded. "I'd never thought about it. But art is, after all, a form of communication."

"So is the croaking of a frog in a swamp," said Zakheim.

"Did you ever hear about the Paradox Frog?" asked Francine.

"Is this one of your strange jokes?" asked Zakheim.

"Of course not. The Paradox Frog is a very real creature. It lives on the island of Trinidad. It's a very small frog, but it has the opposable thumb on a five-fingered hand, and it...."

"Just like our visitors," said Zakheim.

"Yes. And it uses its hand just like we do—to grasp things, to pick up food, to stuff its mouth, to...."

"To make bombs?" asked Zakheim.

Francine shrugged, turned away. She felt hurt.

"My people believe these Galactics are putting on an elaborate sham," said Zakheim. "We think they are stalling while they secretly study us in preparation for invasion!"

Goré said: "So?" His narrow shoulders came up in a Gallic shrug that said as plainly as words: "Even if this is true, what is there for us to do?"

Francine turned to Ohashi. "What's the favorite theory current with your team?" Her voice sounded bitter, but she was unable to soften the tone.

"We are working on the assumption that this is a language of one-syllable root, as in Chinese," said Ohashi.

"But what of the vowel harmony?" protested Goré. "Surely that must mean the harmonious vowels are all in the same words."

Ohashi adjusted the set of his glasses. "Who knows?" he asked. "Certainly, the back vowels and front vowels come together many times, but...." He shrugged, shook his head.

"What's happening with the group that's working on the historical analogy?" asked Goré. "You were going to find out, Ohashi."

"They are working on the assumption that all primitive sounds are consonants with non-fixed vowels ... foot-stampers for dancing, you know. Their current guess is that the galactics are missionaries, their language a religious language."

"What results?" asked Zakheim.

"None."

Zakheim nodded. "To be expected." He glanced at Francine. "I beg the forgiveness of the Mrs. Doctor Millar?"

She looked up, startled from a daydreaming speculation about the Galactic language and dancing. "Me? Good heavens, why?"

"I have been short-tempered today," said Zakheim. He glanced at his wristwatch. "I'm very sorry. I've been worried about another appointment."

He heaved his bulk out of the chair, took up his briefcase. "And it is time for me to be leaving. You forgive me?"

"Of course, Zak."

His wide face split into a grin. "Good!"

Goré got to his feet. "I will walk a little way with you, Zak."

Francine and Ohashi sat on for a moment after the others had gone.

"What good are we doing with these meetings?" she asked.

"Who knows how the important pieces of this puzzle will be fitted together?" asked Ohashi. "The point is: we are doing something different."

She sighed. "I guess so."

Ohashi took off his glasses, and it made him appear suddenly defenseless. "Did you know that Zak was recording our meeting?" he asked. He replaced the glasses.

Francine stared at him. "How do you know?"

Ohashi tapped his briefcase. "I have a device in here that reveals such things."

She swallowed a brief surge of anger. "Well, is it really important, Hiko?"

"Perhaps not." Ohashi took a deep, evenly controlled breath. "I did not tell you one other thing about the Buddhist monk."

"Oh. What did you omit?"

"He predicts that we will fail—that the human race will be destroyed. He is very old and very cynical for a monk. He thinks it is a good thing that all human striving must eventually come to an end."

Anger and a sudden resolve flamed in her. "I don't care! I don't care what anyone else thinks! I know that...." She allowed her voice to trail off, put her hands to her eyes.

"You have been very distracted today," said Ohashi. "Did the talk about your late husband disturb you?"

"I know. I'm...." She swallowed, whispered: "I had a dream about Bob last night. We were dancing, and he was trying to tell me something about this problem, only I couldn't hear him. Each time he started to speak the music got louder and drowned him out."

Silence fell over the room.

Presently, Ohashi said: "The unconscious mind takes strange ways sometimes to tell us the right answers. Perhaps we should investigate this idea of dancing."

"Oh, Hiko! Would you help me?"

"I should consider it an honor to help you," he said.

It was quiet in the semi-darkness of the projection room. Francine leaned her head against the back rest of her chair, looked across at the stand light where Ohashi had been working. He had gone for the films on Oriental ritual dances that had just arrived from Los Angeles by plane. His coat was still draped across the back of his chair, his pipe still smouldered in the ashtray on the work-table. All around their two chairs were stacked the residue of four days' almost continuous research: notebooks, film cans, boxes of photographs, reference books.

She thought about Hiko Ohashi: a strange man. He was fifty and didn't look a day over thirty. He had grown children. His wife had died of cholera eight years ago. Francine wondered what it would be like married to an Oriental, and she found herself thinking that he wasn't really Oriental with his Princeton education and Occidental ways. Then she realized that this attitude was a kind of white snobbery.

The door in the corner of the room opened softly. Ohashi came in, closed the door. "You awake?" he whispered.

She turned her head without lifting it from the chairback. "Yes."

"I'd hoped you might fall asleep for a bit," he said. "You looked so tired when I left."

Francine glanced at her wristwatch. "It's only three-thirty. What's the day like?"

"Hot and windy."

Ohashi busied himself inserting film into the projector at the rear of the room. Presently, he went to his chair, trailing the remote control cable for the projector.

"Ready?" he asked.

Francine reached for the low editing light beside her chair, and turned it on, focusing the narrow beam on a notebook in her lap. "Yes. Go ahead."

"I feel that we're making real progress," said Ohashi. "It's not clear yet, but the points of identity...."

"They're exciting," she said. "Let's see what this one has to offer."

Ohashi punched the button on the cable. A heavily robed Arab girl appeared on the screen, slapping a tambourine. Her hair looked stiff, black and oily. A sooty line of kohl shaded each eye. Her brown dress swayed slightly as she tinkled the tambourine, then slapped it.

The cultured voice of the commentator came through the speaker beside the screen: "This is a young girl of Jebel Tobeyk. She is going to dance some very ancient steps that tell a story of battle. The camera is hidden in a truck, and she is unaware that this dance is being photographed."

A reed flute joined the tambourine, and a twanging stringed instrument came in behind it. The girl turned slowly on one foot, the other raised with knee bent.

Francine watched in rapt silence. The dancing girl made short staccato hops, the tambourine jerking in front of her.

"It is reminiscent of some of the material on the Norse sagas," said Ohashi. "Battle with swords. Note the thrust and parry."

She nodded. "Yes." The dance stamped onward, then: "Wait! Re-run that last section."

Ohashi obeyed.

It started with a symbolic trek on camel-back: swaying, undulating. The dancing girl expressed longing for her warrior. How suggestive the motions of her hands along her hips, thought Francine. With a feeling of abrupt shock, she recalled seeing almost the exact gesture from one of the films of the Galactics. "There's one!" she cried.

"The hands on the hips," said Ohashi. "I was just about to stop the reel." He shut off the film, searched through the notebooks around him until he found the correct reference.

"I think it was one of Zak's films," said Francine.

"Yes. Here it is." Ohashi brought up a reel, looked at the scene identifications. He placed the film can on a large stack behind him, re-started the film of Oriental dances.

Three hours and ten minutes later they put the film back in its can.

"How many new comparisons do you make it?" asked Ohashi.

"Five," she said. "That makes one hundred and six in all!" Francine leafed through her notes. "There was the motion of the hands on the hips. I call that one sensual pleasure."

Ohashi lighted a pipe, spoke through a cloud of smoke. "The others: How have you labeled them?"

"Well, I've just put a note on the motions of one of the Galactics and then the commentator's remarks from this dance film. Chopping motion of the hand ties to the end of Sobaya's first dream: 'Now, I awaken!' Undulation of the body ties in with swaying of date palms in the desert wind. Stamping of the foot goes with Torak dismounting from his steed. Lifting hands, palms up—that goes with Ali offering his soul to God in prayer before battle."

"Do you want to see this latest film from the ship?" asked Ohashi. He glanced at his wristwatch. "Or shall we get a bite to eat first?"

She waved a hand distractedly. "The film. I'm not hungry. The film." She looked up. "I keep feeling that there's something I should remember ... something...." She shook her head.

"Think about it a few minutes," said Ohashi. "I'm going to send out these other films to be cut and edited according to our selections. And I'll have some sandwiches sent in while I'm at it."

Francine rubbed at her forehead. "All right."

Ohashi gathered up a stack of film cans, left the room. He knocked out his pipe on a "No Smoking" sign beside the door as he left.

"Consonants," whispered Francine. "The ancient alphabets were almost exclusively made up of consonants. Vowels came later. They were the softeners, the swayers." She chewed at her lower lip. "Language constricts the ways you can think." She rubbed at her forehead. "Oh, if I only had Bob's ability with languages!"

She tapped her fingers on the chair arm. "It has something to do with our emphasis on things rather than on people and the things people do. Every Indo-European language is the same on that score. If only...."

"Talking to yourself?" It was a masculine voice, startling her because she had not heard the door open.

Francine jerked upright, turned toward the door. Dr. Irving Langsmith, chief of the American Division of the Germanic-Root team stood just inside, closing the door.

"Haven't seen you for a couple of days," he said. "We got your note that you were indisposed." He looked around the room, then at the clutter on the floor beside the chairs.

Francine blushed.

Dr. Langsmith crossed to the chair Ohashi had occupied, sat down. He was a grey-haired runt of a man with a heavily seamed face, small features—a gnome figure with hard eyes. He had the reputation of an organizer and politician with more drive than genius. He pulled a stubby pipe from his pocket, lighted it.

"I probably should have cleared this through channels," she said. "But I had visions of it getting bogged down in red tape, especially with Hiko ... I mean with another team represented in this project."

"Quite all right," said Langsmith. "We knew what you were up to within a couple of hours. Now, we want to know what you've discovered. Dr. Ohashi looked pretty excited when he left here a bit ago."

Her eyes brightened. "I think we're onto something," she said. "We've compared the Galactics' movements to known symbolism from primitive dances."

Dr. Langsmith chuckled. "That's very interesting, my dear, but surely you...."

"No, really!" she said. "We've found one hundred and six points of comparison, almost exact duplication of movements!"

"Dances? Are you trying to tell me that...."

"I know it sounds strange," she said, "but we...."

"Even if you have found exact points of comparison, that means nothing," said Langsmith. "These are aliens ... from another world. You've no right to assume that their language development would follow the same pattern as ours has."

"But they're humanoid!" she said. "Don't you believe that language started as the unconscious shaping of the speech organs to imitate bodily gestures?"

"It's highly likely," said Langsmith.

"We can make quite a few pretty safe assumptions about them," she said. "For one thing, they apparently have a rather high standard of civilization to be able to construct—"

"Let's not labor the obvious," interrupted Langsmith, a little impatiently.

Francine studied the team chief a moment, said: "Did you ever hear how Marshal Foch planned his military campaigns?"

Langsmith puffed on his pipe, took it out of his mouth. "Uh ... are you suggesting that a military...."

"He wrote out the elements of his problem on a sheet of paper," said Francine. "At the top of the paper went the lowest common denominator. There, he wrote: 'Problem—To beat the Germans.' Quite simple. Quite obvious. But oddly enough beating the enemy has frequently been overlooked by commanders who got too involved in complicated maneuvers."

"Are you suggesting that the Galactics are enemies?"

She shook her head indignantly. "I am not! I'm suggesting that language is primarily an instinctive social reflex. The least common denominator of a social problem is a human being. One single human being. And here we are all involved with getting this thing into mathematical equations and neat word frequency primarily oral!"

"But you've been researching a visual...."

"Yes! But only as it modifies the sounds." She leaned toward Langsmith. "Dr. Langsmith, I believe that this language is a flexional language with the flexional endings and root changes contained entirely in the bodily movements!"

"Hmmmmmmm." Langsmith studied the smoke spiraling ceilingward from his pipe. "Fascinating idea!"

"We can assume that this is a highly standardized language," said Francine. "Basing the assumption on their high standard of civilization. The two usually go hand in hand."

Langsmith nodded.

"Then the gestures, the sounds would tend to be ritual," she said.

"Mmmmm-hmmmm."

"Then ... may we have the help to go into this idea the way it deserves?" she asked.

"I'll take it up at the next top staff meeting," said Langsmith. He got to his feet. "Don't get your hopes up. This'll have to be submitted to the electronic computers. It probably has been cross-checked and rejected in some other problem."

She looked up at him, dismayed. "But ... Dr. Langsmith ... a computer's no better than what's put into it. I'm certain that we're stepping out into a region here where we'll have to build up a whole new approach to language."

"Now, don't you worry," said Langsmith. He frowned. "No ... don't worry about this."

"Shall we go ahead with what we're doing then?" she asked. "I mean—do we have permission to?"

"Yes, yes ... of course." Langsmith wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. "General Speidel has called a special meeting tomorrow morning. I'd like to have you attend. I'll send somebody to pick you up." He waved a hand at the litter around Francine. "Carry on, now." There was a pathetic emptiness to the way he put his pipe in his mouth and left the room. Francine stared at the closed door.

She felt herself trembling, and recognized that she was deathly afraid. Why? she asked herself. What have I sensed to make me afraid?

Presently, Ohashi came in carrying a paper bag.

"Saw Langsmith going out," he said. "What did he want?"

"He wanted to know what we're doing."

Ohashi paused beside his chair. "Did you tell him?"

"Yes. I asked for help." She shook her head. "He wouldn't commit himself."

"I brought ham sandwiches," said Ohashi.

Francine's chin lifted abruptly. "Defeated!" she said. "That's it! He acted completely defeated!"

"What?"

"I've been trying to puzzle through the strange way Langsmith was acting. He just radiated defeat."

Ohashi handed her a sandwich. "Better brace yourself for a shock," he said. "I ran into Tsu Ong, liaison officer for our delegation ... in the cafeteria." The Japanese raised the sandwich sack over his chair, dropped it into the seat with a curious air of preciseness. "The Russians are pressing for a combined attack on the Galactic ship to wrest their secret from them by force."

Francine buried her face in her hands. "The fools!" she whispered. "Oh, the fools!" Abruptly, sobs shook her. She found herself crying with the same uncontrollable wracking that had possessed her when she'd learned of her husband's death.

Ohashi waited silently.

The tears subsided. Control returned. She swallowed, said: "I'm sorry."

"Do not be sorry." He put a hand on her shoulder. "Shall we knock off for the night?"

She put her hand over his, shook her head. "No. Let's look at the latest films from the ship."

"As you wish." Ohashi pulled away, threaded a new film into the projector.

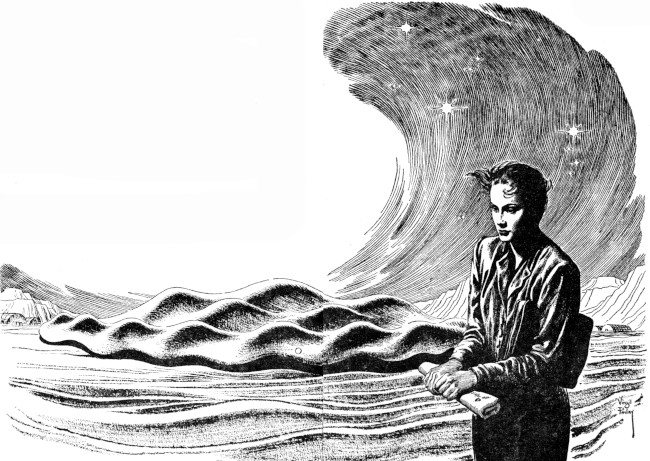

Presently, the screen came alive to a blue-grey alcove filled with pale light: one of the "class" rooms in the spaceship. A squat, green-skinned figure stood in the center of the room. Beside the Galactic was the pedestal-footed projection board that all five used to illustrate their "lectures". The board displayed a scene of a wide blue lake, reeds along the shore stirring to a breeze.

The Galactic swayed. His face moved like a ripple of water. He said: "Ahon'atu'uklah'shoginai'eástruru." The green arms moved up and down, undulating. The webbed hands came out, palms facing and almost touching, began chopping from the wrists: up, down, up, down, up, down....

On the projection board the scene switched to an under-water view: myriad swimming shapes coming closer, closer—large-eyed fish creatures with long ridged tails.

"Five will get you ten," said Ohashi. "Those are the young of this Galactic race. Notice the ridge."

"Tadpoles," said Francine.

The swimming shapes darted through orange shadows and into a space of cold green—then up to splash on the surface, and again down into the cool green. It was a choreographic swinging, lifting, dipping, swaying—lovely in its synchronized symmetry.

"Chiruru'uklia'a'agudav'iaá," said the Galactic. His body undulated like the movements of the swimming creatures. The green hands touched his thighs, slipped upward until elbows were level with shoulders.

"The maiden in the Oriental dance," said Francine.

Now, the hands came out, palms up, in a gesture curiously suggestive of giving. The Galactic said: "Pluainumiuri!" in a single burst of sound that fell on their ears like an explosion.

"It's like a distorted version of the ritual dances we've been watching," said Ohashi.

"I've a hunch," said Francine. "Feminine intuition. The repeated vowels: they could be an adverbial emphasis, like our word very. Where it says 'a-a-a' note the more intense gestures."

She followed another passage, nodding her head to the gestures. "Hiko, could this be a constructed language? Artificial?"

"The thought has occurred to me," said Ohashi.

Abruptly, the projector light dimmed, the action slowed. All lights went out. They heard a dull, booming roar in the distance, a staccato rattling of shots. Feet pounded along the corridor outside the room.

Francine sat in stunned silence.

Ohashi said: "Stay here, please. I will have a look around to see what...."

The door banged open and a flashlight beam stabbed into the room, momentarily blinding them.

"Everything all right in here?" boomed a masculine voice.

They made out a white MP helmet visible behind the light.

"Yes," said Ohashi. "What is happening?"

"Somebody blew up a tower to the main transmission line from McNary Dam. Then there was an attempt to breach our security blockade on the south. Everything will be back to normal shortly." The light turned away.

"Who?" asked Francine.

"Some crazy civilians," said the MP. "We'll have the emergency power on in a minute. Just stay in this room until we give the all clear." He left, closing the door.

They heard a rattle of machinegun fire. Another explosion shook the building. Voices shouted.

"We are witnessing the end of a world," said Ohashi.

"Our world ended when that spaceship set down here," she said.

Abruptly, the lights came on: glowing dimly, then brighter. The projector resumed its whirring. Ohashi turned it off.

Somebody walked down the corridor outside, rapped on the door, said: "All clear." The footsteps receded down the hall, and they heard another rapping, a fainter "All clear."

"Civilians," she said. "What do you suppose they wanted so desperately to do a thing like that?"

"They are a symptom of the general sickness," said Ohashi. "One way to remove a threat is to destroy it—even if you destroy yourself in the process. These civilians are only a minor symptom."

"The Russians are the big symptom then," she said.

"Every major government is a big symptom right now," he said.

"I ... I think I'll get back to my room," she said. "Let's take up again tomorrow morning. Eight o'clock all right?"

"Quite agreeable," said Ohashi. "If there is a tomorrow."

"Don't you get that way, too," she said, and she took a quavering breath. "I refuse to give up."

Ohashi bowed. He was suddenly very Oriental. "There is a primitive saying of the Ainu," he said: "The world ends every night ... and begins anew every morning."

It was a room dug far underground beneath the Ordnance Depot, originally for storage of atomics. The walls were lead. It was an oblong space: about thirty by fifteen feet, with a very low ceiling. Two trestle tables had been butted end-to-end in the center of the room to form a single long surface. A series of green-shaded lights suspended above this table gave the scene an odd resemblance to a gambling room. The effect was heightened by the set look to the shoulders of the men sitting in spring bottom chairs around the table. There were a scattering of uniforms: Air Force, Army, Marines; plus hard-faced civilians in expensive suits.

Dr. Langsmith occupied a space at the middle of one of the table's sides and directly across from the room's only door. His gnome features were locked in a frown of concentration. He puffed rhythmically at the stubby pipe like a witchman creating an oracle smoke.

A civilian across the table from Langsmith addressed a two-star general seated beside the team chief: "General Speidel, I still think this is too delicate a spot to risk a woman."

Speidel grunted. He was a thin man with a high, narrow face: an aristocratic face that radiated granite convictions and stubborn pride. There was an air about him of spring steel under tension and vibrating to a chord that dominated the room.

"Our choice is limited," said Langsmith. "Very few of our personnel have consistently taken wheeled carts into the ship and consistently taken a position close to that force barrier or whatever it is."

Speidel glanced at his wristwatch. "What's keeping them?"

"She may already have gone to breakfast," said Langsmith.

"Be better if we got her in here hungry and jumpy," said the civilian.

"Are you sure you can handle her, Smitty?" asked Speidel.

Langsmith took his pipe from his mouth, peered into the stem as though the answer were to be found there. "We've got her pretty well analyzed," he said. "She's a recent widow, you know. Bound to still have a rather active death-wish structure."

There was a buzzing of whispered conversation from a group of officers at one end of the table. Speidel tapped his fingers on the arm of his chair.

Presently, the door opened. Francine entered. A hand reached in from outside, closed the door behind her.

"Ah, there you are, Dr. Millar," said Langsmith. He got to his feet. There was a scuffling sound around the table as the others arose. Langsmith pointed to an empty chair diagonally across from him. "Sit down, please."

Francine advanced into the light. She felt intimidated, knew she showed it, and the realization filled her with a feeling of bitterness tinged with angry resentment. The ride down the elevator from the surface had been an experience she never wanted to repeat. It had seemed many times longer than it actually was—like a descent into Dante's Inferno.

She nodded to Langsmith, glanced covertly at the others, took the indicated chair. It was a relief to get the weight off her trembling knees, and she momentarily relaxed, only to tense up again as the others resumed their seats. She put her hands on the table, immediately withdrew them to hold them clasped tightly in her lap.

"Why was I brought here like a prisoner?" she demanded.

Langsmith appeared honestly startled. "But I told you last night that I'd send somebody for you."

Speidel chuckled easily. "Some of our Security boys are a little grim-faced," he said. "I hope they didn't frighten you."

She took a deep breath, began to relax. "Is this about the request I made last night?" she asked. "I mean for help in this new line of research?"

"In a way," said Langsmith. "But first I'd like to have you answer a question for me." He pursed his lips. "Uh ... I've never asked one of my people for just a wild guess before, but I'm going to break that rule with you. What's your guess as to why these Galactics are here?"

"Guess?"

"Logical assumption, then," he said.

She looked down at her hands. "We've all speculated, of course. They might be scientists investigating us for reasons of their own."

"Damnation!" barked the civilian beside her. Then: "Sorry, ma'm. But that's the pap we keep using to pacify the public."

"And we aren't keeping them very well pacified," said Langsmith. "That group that stormed us last night called themselves the Sons of Truth! They had thermite bombs, and were going to attack the spaceship."

"How foolish," she whispered. "How pitiful."

"Go on with your guessing, Dr. Millar," said Speidel.

She glanced at the general, again looked at her hands. "There's the military's idea—that they want Earth for a strategic base in some kind of space war."

"It could be," said Speidel.

"They could be looking for more living space for their own kind," she said.

"In which case, what happens to the native population?" asked Langsmith.

"They would either be exterminated or enslaved, I'm afraid. But the Galactics could be commercial traders of some sort, interested in our art forms, our animals for their zoos, our archeology, our spices, our...." She broke off, shrugged. "How do we know what they may be doing on the side ... secretly?"

"Exactly!" said Speidel. He glanced sidelong at Langsmith. "She talks pretty level-headed, Smitty."

"But I don't believe any of these things," she said.

"What is it you believe?" asked Speidel.

"I believe they're just what they represent themselves to be—representatives of a powerful Galactic culture that is immeasurably superior to our own."

"Powerful, all right!" It was a marine officer at the far end of the table. "The way they cleaned off Eniwetok and swept our satellites out of the skies!"

"Do you think there's a possibility they could be concealing their true motives?" asked Langsmith.

"A possibility, certainly."

"Have you ever watched a confidence man in action?" asked Langsmith.

"I don't believe so. But you're not seriously suggesting that these...." She shook her head. "Impossible."

"The mark seldom gets wise until it's too late," said Langsmith.

She looked puzzled. "Mark?"

"The fellow the confidence men choose for a victim." Langsmith re-lighted his pipe, extinguished the match by shaking it. "Dr. Millar, we have a very painful disclosure to make to you."

She straightened, feeling a sudden icy chill in her veins at the stillness in the room.

"Your husband's death was not an accident," said Langsmith.

She gasped, and turned deathly pale.

"In the six months before this spaceship landed, there were some twenty-eight mysterious deaths," said Langsmith. "More than that, really, because innocent bystanders died, too. These accidents had a curious similarity: In each instance there was a fatality of a foremost expert in the field of language, cryptoanalysis, semantics....

"The people who might have solved this problem died before the problem was even presented," said Speidel. "Don't you think that's a curious coincidence."

She was unable to speak.

"In one instance there was a survivor," said Langsmith. "A British jet transport crashed off Ceylon, killing Dr. Ramphit U. The lone survivor, the co-pilot, said a brilliant beam of light came from the sky overhead and sliced off the port wing. Then it cut the cabin in half!"

Francine put a hand to her throat. Langsmith's cautious hand movements suddenly fascinated her.

"Twenty-eight air crashes?" she whispered.

"No. Two were auto crashes." Langsmith puffed a cloud of smoke before his face.

Her throat felt sore. She swallowed, said: "But how can you be sure of that?"

"It's circumstantial evidence, yes," said Speidel. He spoke with thin-lipped precision. "But there's more. For the past four months all astronomical activity of our nation has been focused on the near heavens, including the moon. Our attention was drawn to evidence of activity near the moon crater Theophilus. We have been able to make out the landing rockets of more than five hundred space craft!"

"What do you think of that?" asked Langsmith. He nodded behind his smoke screen.

She could only stare at him; her lips ashen.

"These frogs have massed an invasion fleet on the moon!" snapped Speidel. "It's obvious!"

They're lying to me! she thought. Why this elaborate pretense? She shook her head, and something her husband had once said leapt unbidden into her mind: "Language clutches at us with unseen fingers. It conditions us to the way others are thinking. Through language, we impose upon each other our ways of looking at things."

Speidel leaned forward. "We have more than a hundred atomic warheads aimed at that moon-base! One of those warheads will do the job if it gets through!" He hammered a fist on the table. "But first we have to capture this ship here!"

Why are they telling me all this? she asked herself. She drew in a ragged breath, said: "Are you sure you're right?"

"Of course we're sure!" Speidel leaned back, lowered his voice. "Why else would they insist we learn their language? The first thing a conqueror does is impose his language on his new slaves!"

"No ... no, wait," she said. "That only applies to recent history. You're getting language mixed up with patriotism because of our own imperial history. Bob always said that such misconceptions are a serious hindrance to sound historical scholarship."

"We know what we're talking about, Dr. Millar," said Speidel.

"You're suspicious of language because our imperialism went hand in hand with our language," she said.

Speidel looked at Langsmith. "You talk to her."

"If there actually were communication in the sounds these Galactics make, you know we'd have found it by now," said Langsmith. "You know it!"

She spoke in sudden anger: "I don't know it! In fact, I feel that we're on the verge of solving their language with this new approach we've been working on."

"Oh, come now!" said Speidel. "Do you mean that after our finest cryptographers have worked over this thing for seven months, you disagree with them entirely?"

"No, no, let her say her piece," said Langsmith.

"We've tapped a new source of information in attacking this problem," she said. "Primitive dances."

"Dances?" Speidel looked shocked.

"Yes. I think the Galactics' gestures may be their adjectives and adverbs—the full emotional content of their language."

"Emotion!" snapped Speidel. "Emotion isn't language!"

She repressed a surge of anger, said: "We're dealing with something completely outside our previous experience. We have to discard old ideas. We know that the habits of a native tongue set up a person's speaking responses. In fact, you can define language as the system of habits you reveal when you speak."

Speidel tapped his fingers on the table, stared at the door behind Francine.

She ignored his nervous distraction, said: "The Galactics use almost the full range of implosive and glottal stops with a wide selection of vowel sounds: fricatives, plosives, voiced and unvoiced. And we note an apparent lack of the usual interfering habits you find in normal speech."

"This isn't normal speech!" blurted Speidel. "Those are nonsense sounds!" He shook his head. "Emotions!"

"All right," she said. "Emotions! We're pretty certain that language begins with emotions—pure emotional actions. The baby pushes away the plate of unwanted food."

"You're wasting our time!" barked Speidel.

"I didn't ask to come down here," she said.

"Please." Langsmith put a hand on Speidel's arm. "Let Dr. Millar have her say."

"Emotion," muttered Speidel.

"Every spoken language of earth has migrated away from emotion," said Francine.

"Can you write an emotion on paper?" demanded Speidel.

"That does it," she said. "That really tears it! You're blind! You say language has to be written down. That's part of the magic! You're mind is tied in little knots by academic tradition! Language, General, is primarily oral! People like you, though, want to make it into ritual noise!"

"I didn't come down here for an egg-head argument!" snapped Speidel.

"Let me handle this, please," said Langsmith. He made a mollifying gesture toward Francine. "Please continue."

She took a deep breath. "I'm sorry I snapped," she said. She smiled. "I think we let emotion get the best of us."

Speidel frowned.

"I was talking about language moving away from emotion," she said. "Take Japanese, for example. Instead of saying, 'Thank you' they say, 'Katajikenai'—'I am insulted.' Or they say, 'Kino doku' which means 'This poisonous feeling!'" She held up her hands. "This is ritual exclusion of showing emotion. Our Indo-European languages—especially Anglo-Saxon tongues—are moving the same way. We seem to think that emotion isn't quite nice, that...."

"It tells you nothing!" barked Speidel.

She forced down the anger that threatened to overwhelm her. "If you can read the emotional signs," she said, "they reveal if a speaker is telling the truth. That's all, General. They just tell you if you're getting at the truth. Any good psychologist knows this, General. Freud said it: 'If you try to conceal your feelings, every pore oozes betrayal.' You seem to think that the opposite is true."

"Emotions! Dancing!" Speidel pushed his chair back. "Smitty, I've had as much of this as I can take."

"Just a minute," said Langsmith. "Now, Dr. Millar, I wanted you to have your say because we've already considered these points. Long ago. You're interested in the gestures. You say this is a dance of emotions. Other experts say with equal emphasis that these gestures are ritual combat! Freud, indeed! They ooze betrayal. This chopping gesture they make with the right hand"—he chopped the air in illustration—"is identical to the karate or judo chop for breaking the human neck!"

Francine shook her head, put a hand to her throat. She was momentarily overcome by a feeling of uncertainty.

Langsmith said: "That outward thrust they make with one hand: that's the motion of a sword being shoved into an opponent! They ooze betrayal all right!"

She looked from Langsmith to Speidel, back to Langsmith. A man to her right cleared his throat.

Langsmith said: "I've just given you two examples. We have hundreds more. Every analysis we've made has come up with the same answer: treachery! The pattern's as old as time: offer a reward; pretend friendship; get the innocent lamb's attention on your empty hand while you poise the ax in your other hand!"

Could I be wrong? she wondered. Have we been duped by these Galactics? Her lips trembled. She fought to control them, whispered: "Why are you telling me these things?"

"Aren't you at all interested in revenge against the creatures who murdered your husband?" asked Speidel.

"I don't know that they murdered him!" She blinked back tears. "You're trying to confuse me!" And a favorite saying of her husband's came into her mind: "A conference is a group of people making a difficult job out of what one person could do easily." The room suddenly seemed too close and oppressive.

"Why have I been dragged into this conference?" she demanded. "Why?"

"We were hoping you'd assist us in capturing that space ship," said Langsmith.

"Me? Assist you in...."

"Someone has to get a bomb past the force screens at the door—the ones that keep sand and dirt out of the ship. We've got to have a bomb inside."

"But why me?"

"They're used to seeing you wheel in the master recorder on that cart," said Langsmith. "We thought of putting a bomb in...."

"No!"

"This has gone far enough," said Speidel. He took a deep breath, started to rise.

"Wait," said Langsmith.

"She obviously has no feelings of patriotic responsibility," said Speidel. "We're wasting our time."

Langsmith said: "The Galactics are used to seeing her with that cart. If we change now, they're liable to become suspicious."

"We'll set up some other plan, then," said Speidel. "As far as I'm concerned, we can write off any possibility of further cooperation from her."

"You're little boys playing a game," said Francine. "This isn't an exclusive American problem. This is a human problem that involves every nation on Earth."

"That ship is on United States soil," said Speidel.

"Which happens to be on the only planet controlled by the human species," she said. "We ought to be sharing everything with the other teams, pooling information and ideas to get at every scrap of knowledge."

"We'd all like to be idealists," said Speidel. "But there's no room for idealism where our survival is concerned. These frogs have full space travel, apparently between the stars—not just satellites and moon rockets. If we get their ship we can enforce peace on our own terms."

"National survival," she said. "But it's our survival as a species that's at stake!"

Speidel turned to Langsmith. "This is one of your more spectacular failures, Smitty. We'll have to put her under close surveillance."

Langsmith puffed furiously on his pipe. A cloud of pale blue smoke screened his head. "I'm ashamed of you, Dr. Millar," he said.

She jumped to her feet, allowing her anger full scope at last. "You must think I'm a rotten psychologist!" she snapped. "You've been lying to me since I set foot in here!" She shot a bitter glance at Speidel. "Your gestures gave you away! The non-communicative emotional gestures, General!"

"What's she talking about?" demanded Speidel.

"You said different things with your mouths than you said with your bodies," she explained. "That means you were lying to me—concealing something vital you didn't want me to know about."

"She's insane!" barked Speidel.

"There wasn't any survivor of a plane crash in Ceylon," she said. "There probably wasn't even the plane crash you described."

Speidel froze to sudden stillness, spoke through thin lips: "Has there been a security leak? Good Lord!"

"Look at Dr. Langsmith there!" she said. "Hiding behind that pipe! And you, General: moving your mouth no more than absolutely necessary to speak—trying to hide your real feelings! Oozing betrayal!"

"Get her out of here!" barked Speidel.

"You're all logic and no intuition!" she shouted. "No understanding of feeling and art! Well, General: go back to your computers, but remember this—You can't build a machine that thinks like a man! You can't feed emotion into an electronic computer and get back anything except numbers! Logic, to you, General!"

"I said get her out of here!" shouted Speidel. He rose half out of his chair, turned to Langsmith who sat in pale silence. "And I want a thorough investigation! I want to know where the security leak was that put her wise to our plans."

"Watch yourself!" snapped Langsmith.

Speidel took two deep breaths, sank back.

They're insane, thought Francine. Insane and pushed into a corner. With that kind of fragmentation they could slip into catatonia or violence. She felt weak and afraid.

Others around the table had arisen. Two civilians moved up beside Francine. "Shall we lock her up, General?" asked one.

Speidel hesitated.

Langsmith spoke first: "No. Just keep her under very close surveillance. If we locked her up it would arouse questions that we don't want to answer."

Speidel glowered at Francine. "If you give us away, I'll have you shot!" He motioned to have her taken out of the room.

When she emerged from the headquarters building, Francine's mind still whirled. Lies! she thought. All lies!

She felt the omnipresent sand grate under her feet. Dust hazed the concourse between her position on the steps and the spaceship a hundred yards away. The morning sun already had burned off the night chill of the desert. Heat devils danced over the dun surface of the ship.

Francine ignored the security agent loitering a few steps behind her, glanced at her wristwatch: nine-twenty. Hiko will be wondering what's happened to me, she thought. We were supposed to get started by eight. Hopelessness gripped her mind. The spaceship looming over the end of the concourse appeared like a malignant growth—an evil thing crouched ready to envelope and smother her.

Could that fool general be right? The thought came to her mind unbidden. She shook her head. No! He was lying! But why did he want me to.... Delayed realization broke off the thought. They wanted me to take a small bomb inside the ship, but there was no mention of my escaping! I'd have had to stay with the cart and the bomb to allay suspicions. My God! Those beasts expected me to commit suicide for them! They wanted me to blame the Galactics for Bob's death! They tried to build a lie in my mind until I'd fall in with their plan. It's hard enough to die for an ideal, but to give up your life for a lie....

Anger coursed through her. She stopped on the steps, stood there shivering. A new feeling of futility replaced the anger. Tears blurred her vision. What can one lone woman do against such ruthless schemers?

Through her tears, she saw movement on the concourse: a man in civilian clothes crossing from right to left. Her mind registered the movement with only partial awareness: man stops, points. She was suddenly alert, tears gone, following the direction of the civilian's extended right arm, hearing his voice shout: "Hey! Look at that!"

A thin needle of an aircraft stitched a hurtling line across the watery desert sky. It banked, arrowed toward the spaceship. Behind it roared an airforce jet—delta wings vibrating, sun flashing off polished metal. Tracers laced out toward the airship.

Someone's attacking the spaceship! she thought. It's a Russian ICBM!

But the needle braked abruptly, impossibly, over the spaceship. Behind it, the airforce jet's engine died, and there was only the eerie whistling of air burning across its wings.

Gently, the needle lowered itself into a fold of the spaceship.

It's one of theirs—the Galactics' she realized. Why is it coming here now? Do they suspect attack? Is that some kind of reinforcement?

Deprived of its power, the jet staggered, skimmed out to a dust-geyser, belly-landing in the alkali flats. Sirens screamed as emergency vehicles raced toward it.

The confused sounds gave Francine a sudden feeling of nausea. She took a deep breath, and stepped down to the concourse, moving without conscious determination, her thoughts in a turmoil. The grating sand beneath her feet was like an emery surface rubbing her nerves. She was acutely conscious of an acrid, burning odor, and she realized with a sudden stab of alarm that her security guard still waited behind her on the steps of the administration building.

Vaguely, she heard voices babbling in the building doorways on both sides of the concourse—people coming out to stare at the spaceship and off across the flats where red trucks clustered around the jet.

A pebble had worked its way into her right shoe. Her mind registered it, rejected an urge to stop and remove the irritant. An idea was trying to surface in her mind. Momentarily, she was distracted by a bee humming across her path. Quite inanely her mind dwelt on the thought that the insect was too commonplace for this moment. A mental drunkenness made her giddy. She felt both elated and terrified. Danger! Yes: terrible danger, she thought. Obliteration for the entire human race. But something

An explosion rocked the concourse, threw her stumbling to her hands and knees. Sand burned against her palms. Dumb instinct brought her back to her feet. Another explosion—farther away to the right, behind the buildings. Bitter smoke swept across the concourse. Abruptly, men lurched from behind the buildings on the right, slogging through the sand toward the spaceship.

Civilians! Possibly—and yet they moved with the purposeful unity of soldiers.

It was like a dream scene to Francine. The men carried weapons. She stopped, saw the gleam of sunlight on metal, heard the peculiar crunch-crunch of men running in sand. Through a dreamy haze she recognized one of the runners: Zakheim. He carried a large black box on his shoulders. His red hair flamed out in the group like a target.

The Russians! she thought. They've started their attack! If our people join them now, it's the end!

A machinegun stuttered somewhere to her right. Dust puffs walked across the concourse, swept into the running figures. Men collapsed, but others still slogged toward the spaceship. An explosion lifted the leaders, sent them sprawling. Again, the machinegun chattered. Dark figures lay on the sand like thrown dominoes. But still a few continued their mad charge.

MP's in American uniforms ran out from between the buildings on the right. The leaders carried submachineguns.

We're stopping the attack, thought Francine. But she knew the change of tactics did not mean a rejection of violence by Speidel and the others. It was only a move to keep the Russians from taking the lead. She clenched her fists, ignored the fact that she stood exposed—a lone figure in the middle of the concourse. Her senses registered an eerie feeling of unreality.

Machineguns renewed their chatter and then—abrupt silence. But now the last of the Russians had fallen. Pursuing MP's staggered. Several stopped, wrenched at their guns.

Francine's shock gave way to cold rage. She moved forward, slowly at first and then striding. Off to the left someone shouted: "Hey! Lady! Get down!" She ignored the voice.

There on the sand ahead was Zakheim's pitiful crumpled figure. A gritty redness spread around his chest.

Someone ran from between the buildings on her left, waved at her to go back. Hiko! But she continued her purposeful stride, compelled beyond any conscious willing to stop. She saw the red-headed figure on the sand as though she peered down a tunnel.

Part of her mind registered the fact that Hiko stumbled, slowing his running charge to intercept her. He looked like a man clawing his way through water.

Dear Hiko, she thought. I have to get to Zak. Poor foolish Zak. That's what was wrong with him the other day at the conference. He knew about this attack and was afraid.

Something congealed around her feet, spread upward over her ankles, quickly surged over her knees. She could see nothing unusual, but it was as though she had plowed into a pool of molasses. Every step took terrible effort. The molasses pool moved above her hips, her waist.

So that's why Hiko and the MP's are moving so slowly, she thought. It's a defensive weapon from the ship. Must be.

Zakheim's sprawled figure was only three steps away from her now. She wrenched her way through the congealed air, panting with the exertion. Her muscles ached from the effort. She knelt beside Zakheim. Ignoring the blood that stained her skirt she took up one of his outstretched hands, felt for a pulse. Nothing. Now, she recognized the marks on his jacket. They were bullet holes. A machinegun burst had caught him across the chest. He was dead. She thought of the big garrulous red-head, so full of blooming life only minutes before. Poor foolish Zak. She put his hand down gently, shook the tears from her eyes. A terrible rage swelled in her.

She sensed Ohashi nearby, struggling toward her, heard him gasp: "Is Zak dead?"

Tears dripped unheeded from her eyes. She nodded. "Yes, he is." And she thought: I'm not crying for Zak. I'm crying for myself ... for all of us ... so foolish, so determined, so blind....

"EARTH PEOPLE!" The voice roared from the spaceship, cutting across all thought, stilling all emotion into a waiting fear. "WE HAD HOPED YOU COULD LEARN TO COMMUNICATE!" roared the voice. "YOU HAVE FAILED!"

Vibrant silence.

Thoughts that had been struggling for recognition began surging to the surface of Francine's mind. She felt herself caught in the throes of a mental earthquake, her soul brought to a crisis as sharp as that of giving birth. The crashing words had broken through a last barrier in her mind. "COMMUNICATE!" At last she understood the meaning of the ultimatum.

But was it too late?

"No!" she screamed. She surged to her feet, shook a fist at the ship. "Here's one who didn't fail! I know what you meant!" She shook both fists at the ship. "See my hate!"

Against the almost tangible congealing of air she forced her way toward the now silent ship, thrust out her left hand toward the dead figures on the sand all around her. "You killed these poor fools! What did you expect from them? You did this! You forced them into a corner!"

The doors of the spaceship opened. Five green-skinned figures emerged. They stopped, stood staring at her, their shoulders slumped. Simultaneously, Francine felt the thickened air relax its hold upon her. She strode forward, tears coursing down her cheeks.

"You made them afraid!" she shouted. "What else could they do? The fearful can't think."

Sobs overcame her. She felt violence shivering in her muscles. There was a terrible desire in her—a need to get her hands on those green figures, to shake them, hurt them. "I hope you're proud of what you've done."

"QUIET!" boomed the voice from the ship.

"I will not!" she screamed. She shook her head, feeling the wildness that smothered her inhibitions. "Oh, I know you were right about communicating ... but you were wrong, too. You didn't have to resort to violence."

The voice from the ship intruded on a softer tone, all the more compelling for the change: "Please?" There was a delicate sense of pleading to the word.

Francine broke off. She felt that she had just awakened from a lifelong daze, but that this clarity of thought-cum-action was a delicate thing she could lose in the wink of an eye.

"We did what we had to do," said the voice. "You see our five representatives there?"

Francine focused on the slump-shouldered Galactics. They looked defeated, radiating sadness. The gaping door of the ship a few paces behind was like a mouth ready to swallow them.

"Those five are among the eight hundred survivors of a race that once numbered six billion," said the voice.

Francine felt Ohashi move up beside her, glanced sidelong at him, then back to the Galactics. Behind her, she heard a low mumbling murmur of many voices. The slow beginning of reaction to her emotional outburst made her sway. A sob caught in her throat.

The voice from the ship rolled on: "This once great race did not realize the importance of unmistakable communication. They entered space in that sick condition—hating, fearing, fighting. There was appalling bloodshed on their side and—ours—before we could subdue them."

A scuffing sound intruded as the five green-skinned figures shuffled forward. They were trembling, and Francine saw glistening drops of wetness below their crests. Their eyes blinked. She sensed the aura of sadness about them, and new tears welled in her eyes.

"The eight hundred survivors—to atone for the errors of their race and to earn the right of further survival—developed a new language," said the voice from the ship. "It is, perhaps, the ultimate language. They have made themselves the masters of all languages to serve as our interpreters." There was a long pause, then: "Think very carefully, Mrs. Millar. Do you know why they are our interpreters?"

The held breath of silence hung over them. Francine swallowed past the thick tightness in her throat. This was the moment that could spell the end of the human race, or could open new doors for them—and she knew it.

"Because they cannot lie," she husked.

"Then you have truly learned," said the voice. "My original purpose in coming down here just now was to direct the sterilization of your planet. We thought that your military preparations were a final evidence of your failure. We see now that this was merely the abortive desperation of a minority. We have acted in haste. Our apologies."

The green-skinned Galactics shuffled forward, stopped two paces from Francine. Their ridged crests drooped, shoulders sagged.

"Slay us," croaked one. His eyes turned toward the dead men on the sand around them.

Francine took a deep, shuddering breath, wiped at her damp eyes. Again she felt the bottomless sense of futility. "Did it have to be this way?" she whispered.

The voice from the ship answered: "Better this than a sterile planet—the complete destruction of your race. Do not blame our interpreters. If a race can learn to communicate, it can be saved. Your race can be saved. First we had to make certain you held the potential. There will be pain in the new ways, no doubt. Many still will try to fight us, but you have not yet erupted fully into space where it would be more difficult to control your course."

"Why couldn't you have just picked some of us, tested a few of us?" she demanded. "Why did you put this terrible pressure on the entire world?"

"What if we had picked the wrong ones?" asked the voice. "How could we be certain with a strange race such as yours that we had a fair sampling of your highest potential? No. All of you had to have the opportunity to learn of our problem. The pressure was to be certain that your own people chose their best representatives."

Francine thought of the unimaginative rule-book followers who had led the teams. She felt hysteria close to the surface.

So close. So hellishly close!

Ohashi spoke softly beside her: "Francine?"

It was a calming voice that subdued the hysteria. She nodded. A feeling of relief struggled for recognition within her, but it had not penetrated all nerve channels. She felt her hands twitching.

Ohashi said: "They are speaking English with you. What of their language that we were supposed to solve?"

"We leaped to a wrong conclusion, Hiko," she said. "We were asked to communicate. We were supposed to remember our own language—the language we knew in childhood, and that was slowly lost to us through the elevation of reason."

"Ahhhhh," sighed Ohashi.

All anger drained from her now, and she spoke with sadness. "We raised the power of reason, the power of manipulating words, above all other faculties. The written word became our god. We forgot that before words there were actions—that there have always been things beyond words. We forgot that the spoken word preceded the written one. We forgot that the written forms of our letters came from ideographic pictures—that standing behind every letter is an image like an ancient ghost. The image stands for natural movements of the body or of other living things."

"The dances," whispered Ohashi.

"Yes, the dances," she said. "The primitive dances did not forget. And the body did not forget—not really." She lifted her hands, looked at them. "I am my own past. Every incident that ever happened to every ancestor of mine is accumulated within me." She turned, faced Ohashi.

He frowned. "Memory stops at the beginning of your...."

"And the body remembers beyond," she said. "It's a different kind of memory: encysted in an overlay of trained responses like the thing we call language. We have to look back to our childhood because all children are primitives. Every cell of a child knows the language of emotional movements—the clutching reflexes, the wails and contortions, the sensuous twistings, the gentle reassurances."

"And you say these people cannot lie," murmured Ohashi.

Francine felt the upsurge of happiness. It was still tainted by the death around her and the pain she knew was yet to come for her people, but the glow was there expanding. "The body," she said, and shook her head at the scowl of puzzlement on Ohashi's face. "The intellect...." She broke off, aware that Ohashi had not yet made the complete transition to the new way of communicating, that she was still most likely the only member of her race even aware of the vision on this high plateau of being.

Ohashi shook his head and sunlight flashed on his glasses. "I'm trying to understand," he said.