| Transcriber's notes: |

| 1. Only one conventional “thought break” (white space between paragraphs) exists in the book (p. 318). Elsewhere, the author uses lines of nine asterisks as thought breaks or to indicate omission. He also uses these asterisks within dialog to indicate omission. These are all duplicated. |

| 2. Footnotes originally appeared at the bottom of each page; they are now placed at the end of each chapter. |

THE STORY OF DON MIFF,

AS TOLD BY HIS FRIEND

JOHN BOUCHE WHACKER.

A SYMPHONY OF LIFE.

EDITED BY

VIRGINIUS DABNEY.

τέκνον, τί κλαίεις; τί δέ σε φρένας ἵκετο πένθος;

ἐξαύδα, μὴ κεῦθε νόῳ, ἵνα εἴδομεν ἄμφω.

Iliad, i. 362-63.

Child, why dost thou weep? What grief hath come upon thy spirit?

Speak—conceal it not—so that we both may know.

PHILADELPHIA:

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY.

1886.

Copyright, 1886, by Virginius Dabney.

It is pretty well understood, I presume, that while books are written for the entertainment of the public, a preface has fulfilled its mission if it prove a solace to the author and an edification to the proof-reader thereof. Yet (however it may be with an author) an editor must, it seems, write one.

Most mysteriously, then, and I knew not whence or from whom, the manuscript of this work found itself in my study, some time since, accompanied by the request that I should stand sponsor for it.

I shall do nothing of the kind. True, the grammar of it will pass muster, I think; and its morals are above reproach; but the way our author has of sailing into everything and everybody quite takes my breath away. Lawyers, military men, professors and students, parsons, agnostics, statesmen, billiard-players, novelists, poetesses, saints and sinners—he girds at them all. I should not have a friend left in the world were it to go abroad that this Mr. J. B. Whacker’s opinions were also mine. If but to enter this disclaimer, therefore, I must needs write a preface.

This author of ours, then, is, as you shall find, an actor in the scenes he describes, and is quite welcome to any sentiments he may see fit to put into his own mouth. He entertains, I am free to admit, an unusual number of opinions; more than one man’s share, perhaps; but not one of them is either reader or editor called upon to adopt.

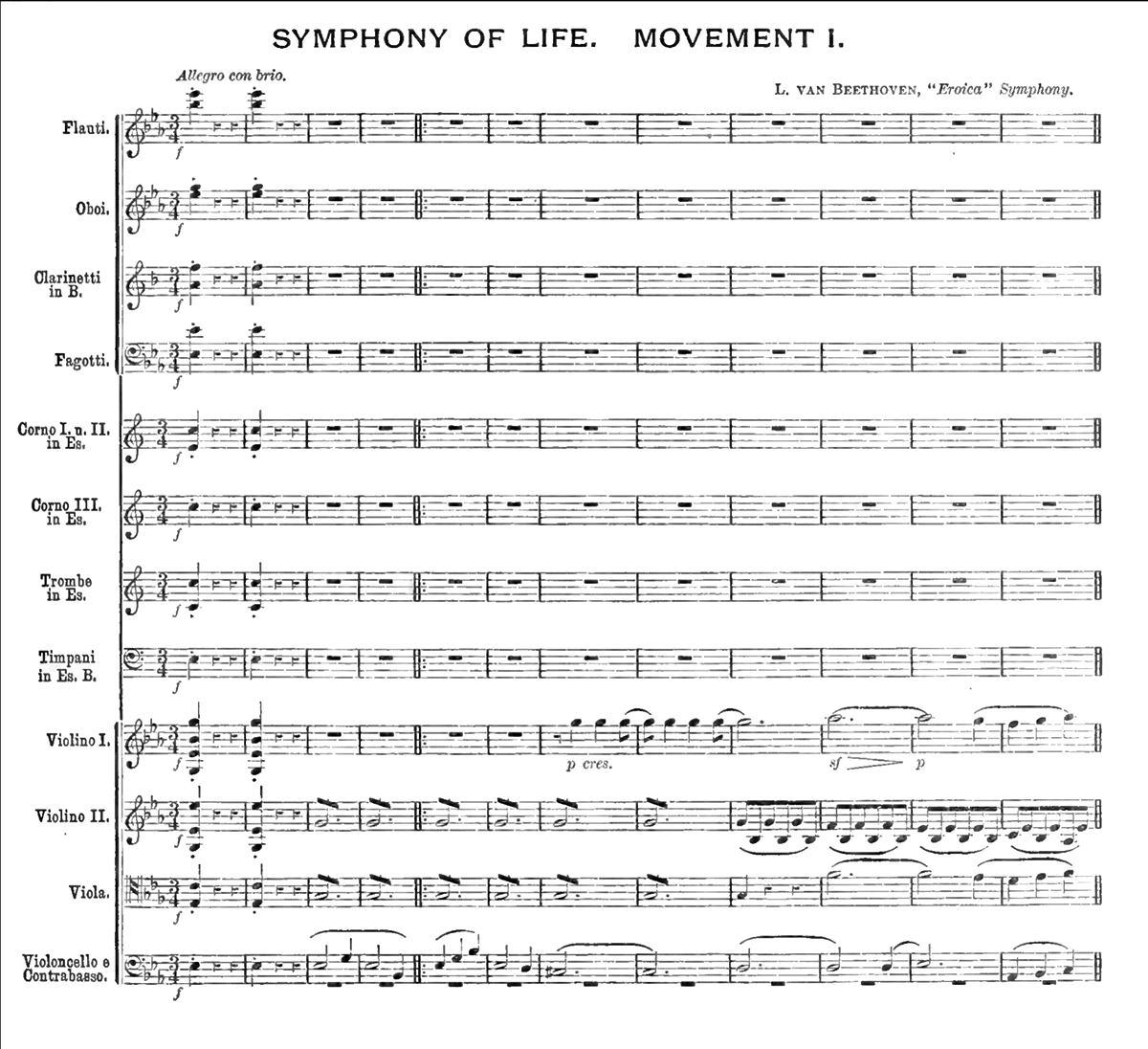

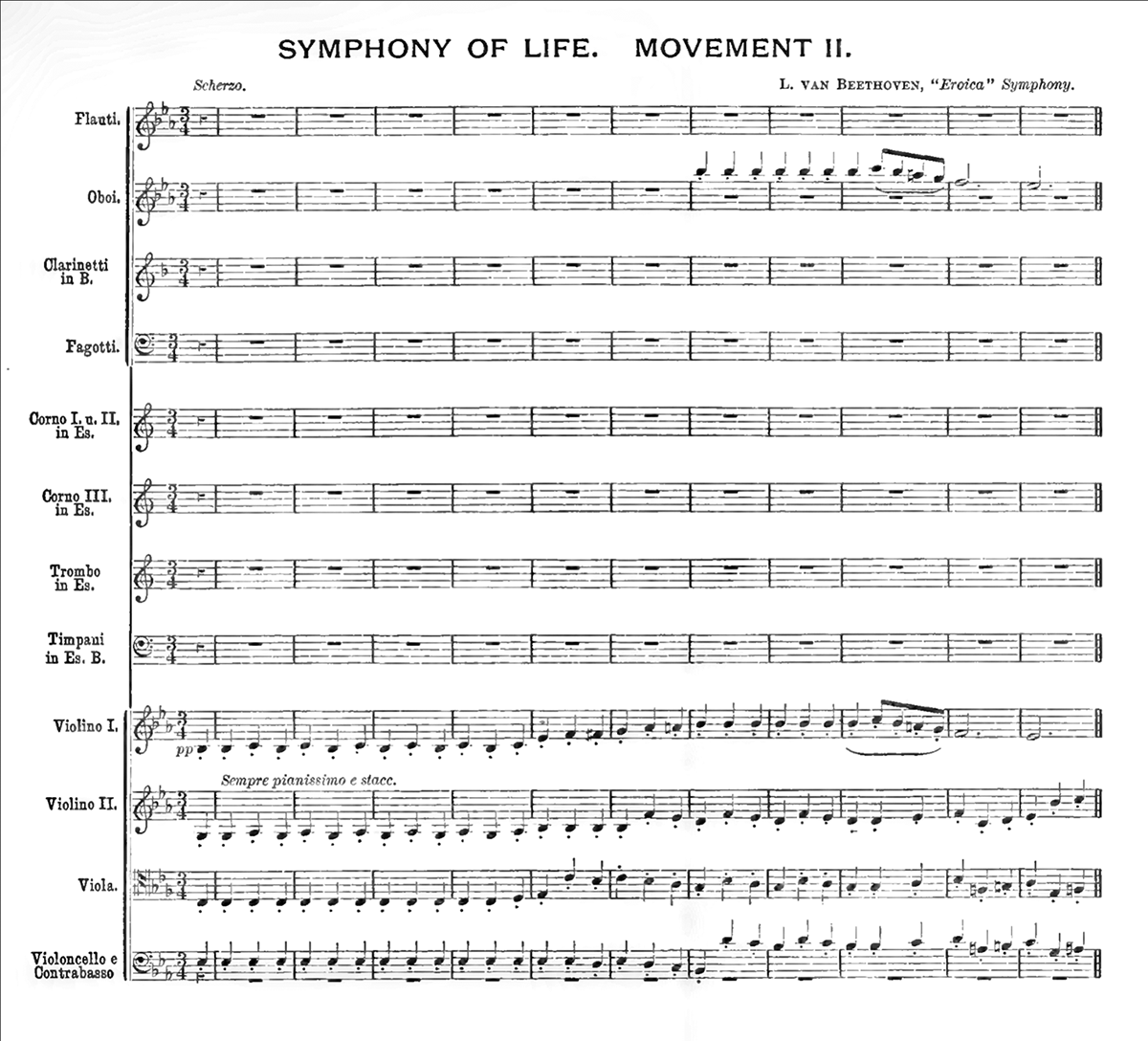

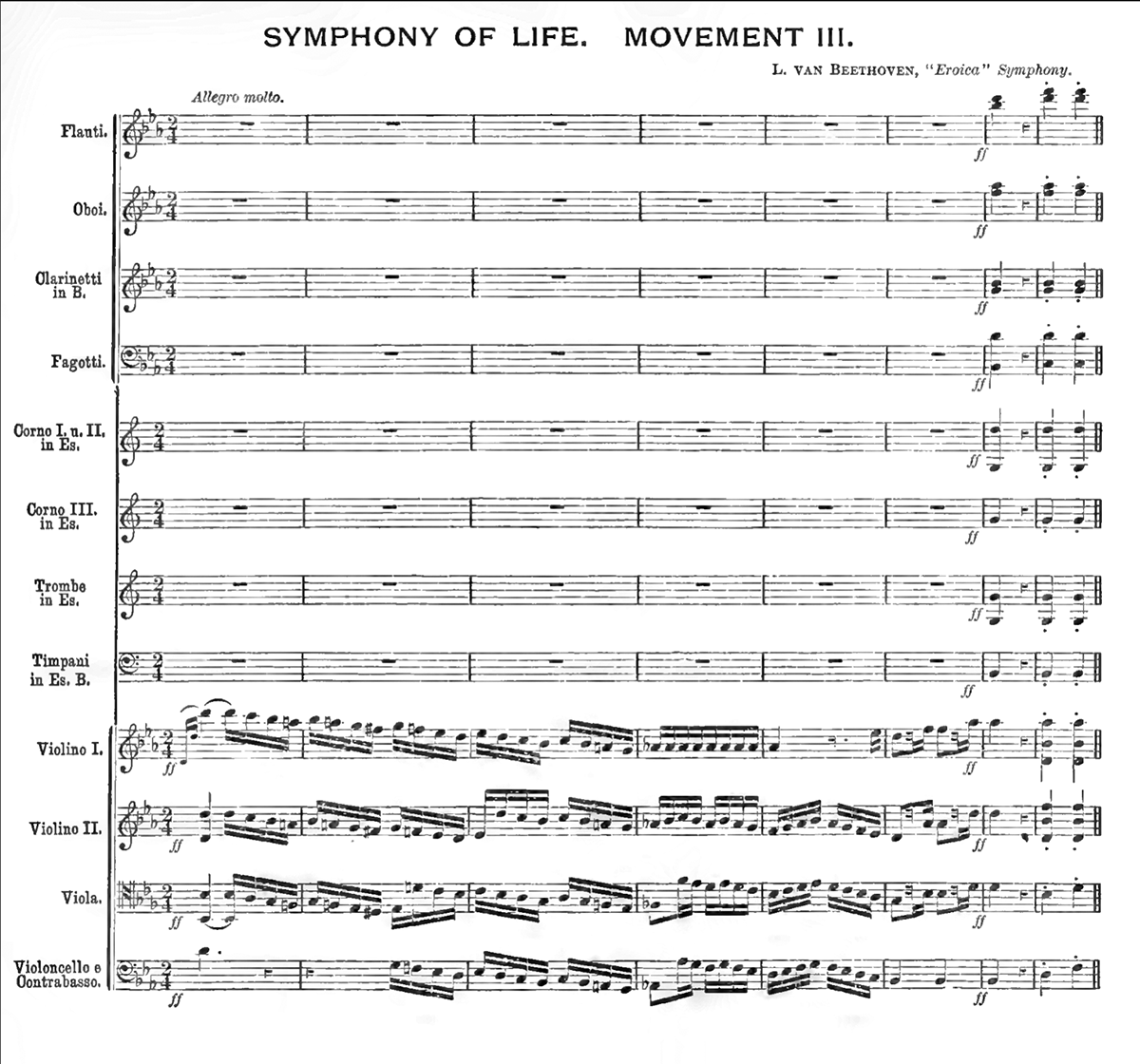

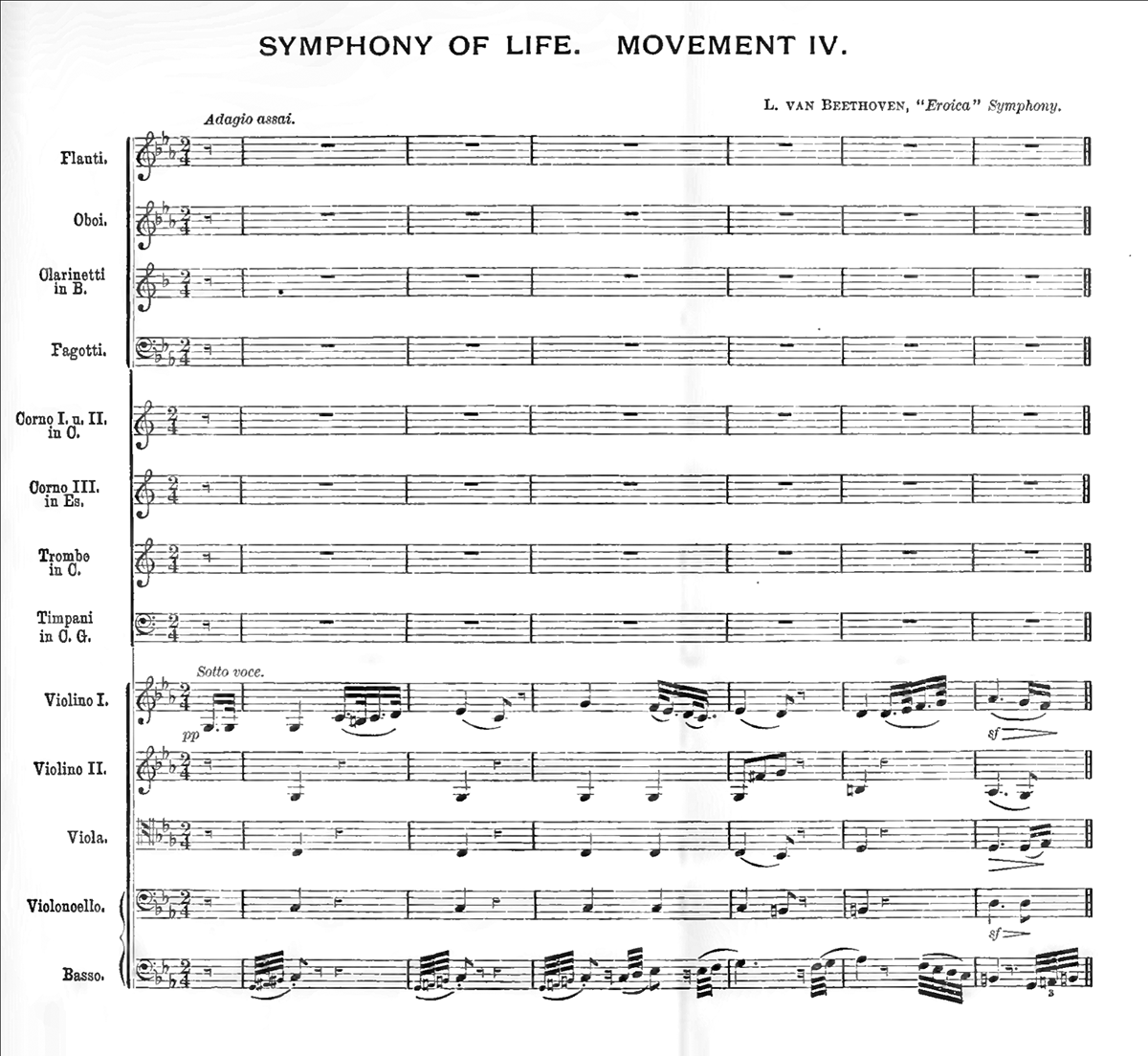

It seems fair, too, to warn the eccentric person who shall read this preface, against putting too much faith in the account Mr. Whacker gives of himself. The astounding pedigree to which he lays claim in Chapter I. may be satire, for aught I know; but when he poses as a lawyer, a bachelor, and a ton of a man, weighing (though he does not give the exact figures) not much less than three hundred pounds, he is counting too much on the simplicity of his editor. For the internal evidence of the work itself makes it clear that he is a physician, ever so much married, and nestling amid a very grove of olive branches. He assures us, too, for example (he is never tired of assuring us of something), that he is entirely ignorant of music; yet divides his work not into books (as a Christian should), but into movements; indicating (presumably) the spirit and predominant feeling of each by the opening page of the orchestral score of one of the four numbers of a famous symphony!

One more word and I am done.

Our author has not seen fit to make any reply to the incessant, and still unceasing onslaughts, from pen and pencil alike, to which the South has submitted, and still submits, twenty-one years after Appomattox, with a silence that has been as grand as it is unparalleled.

His only revenge has been to paint his people and the lives they led.

But it seems to me best to say, once for all, that whenever the necessities of the narrative compel him to show his sympathies on one side or the other (as happens two or three times in the course of the story), they will be found to be with those people among whom he was born, by whose side he fought, and with whom he has suffered. And I feel sure that no man who knows me, in the South, and equally sure that no man who knows me, in the North, would deem me capable of printing this book, had it been otherwise.

V. DABNEY,

108 West Forty-ninth Street,

New York.

April, 1886.

THE STORY OF DON MIFF.

Long, long years before these pages shall meet thine almond eye, my Ah Yung Whack, the hand which penned them for thy delectation will have crumbled into dust. Three hundred years and more, let us say; for thou art (or shalt in due time be) my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandson.

True, I am not yet married; but I intend to be. Nor is there any need of hurry; seeing what a singularly distant and belated relative thou art.

If then, dear, intended Offspring, you will be so anachronistic as to sit beside your proposed ancestor, and so civil as to lend him your ear, he will give you one or two reasons for addressing you, rather than the general public of his own day.

First, then, humanity.

This poor public of his (that is my) day has been, these many years, so pelted with books, that I cannot bring myself to join the mob of authors, and let fly another.

The very leaves in Vallambrosa, flying before the blasts of autumn, cannot compare with them in numbers, as they go whizzing from innumerable presses.

Why, I read, the other day, a statement (by a stater) that if you were to set up, in rows, all the books that are annually published in Christendom (beg pardon, my boy, evolutiondom), and then fell to sawing out shelves for them in the pine forests of North Carolina, the North Carolinians would, when they awoke, find themselves inhabitants of a prairie, provided, of course, our stater goes on to state, the job were completed in one night.

Or, to put it in another shape:

The earth, adds Mr. Statisticker, the earth, we will allow, for illustration’s sake, to be twenty-five thousand miles around. Now, says he, suppose all these books to be pulled to pieces [shame!] and their leaves pinned together, end to end, they would stretch ever so (for I cannot, at the moment, lay my hands on his little statistic) they would stretch ever so far.

Shall I add to the already unbearable burdens of my generation? Humanity forbid!

And look at this:

In any given country a certain number of undergarments will be worn out, year by year, producing a certain crop of rags. These rags can be converted into so much, and no more, paper. Hence, as any thinking man would have reasoned (until the advent of a recent invention), the advancing flood of literature was practically held in check. So many exhausted shirts, so many books,—so many exhausted washerwomen, so many (and no more) authors. There was a limit.

That day is gone. Wood-pulp and cheap editions have opened the flood-gates of genius upon the world; and the days of our noble forests are numbered; for one tree is sawn into shelves to hold another ground into paper. And already, through the denudation of the land, the Mississippi grows uncontrollable, taxing even the wisdom of Congress. And many a lesser stream, in which once the salmon sported, or which turned a mill, or meandered, at least, past orchard or corn land, a steady source of fruitful moisture, is now a fierce torrent in spring, in autumn a string of stagnant pools. What the builder began, the builder (for that, I hear, is the Greek for him) and the novelist will end.

Shall I too print a book? Patriotism forbid!

The trouble is, however, that I feel that I have something to say, and a man that has something to say, and is not allowed to say it, is (like a woman or a boiler) in danger. Nor has my native land, when I come to think of it, the right to exact of me that I burst, to save a beggarly sapling or so from purification.

Yes, I have something to say, and I’ll out with it. For I have hit upon a plan whereby I can print my book with the merest infinitesimal damage to the Mississippi and other patriotic streams. It is this. I shall have but one copy printed. This, in a strong box, hermetically sealed, shall be addressed to you. I shall hand it to my eldest son, and he to his; and so it will travel down the stream of time till it reach you; which strikes me as a neat, inexpensive, and effectual way of reaching that goal of all authors, posterity. From father to son, and from grandson to great-grandson.

Provided, of course, they shall all have the courage (as I intend to have) to get married. If not—or what would become of the book, should there be twins?—but I leave these details to take care of themselves. One of them might not live, for example.

On second thought, though, it might be as well to have two copies struck off; yes, and while we are about it, a dozen extra ones, for private distribution among my friends.

And one friend, especially, but for whom this nonsense would not now be bubbling up so serenely from my tranquil soul.

I have just had a conversation with my publisher, which greatly disturbs me.

He tells me that all this talk about limiting the edition to a dozen copies is midsummer madness,—where am I to come in? said he, using the language of the period,—and that he intends to print as many copies as he pleases. So everything is upset. And I shall have to recast my entire work, which, you must know, is already, with the exception of this first chapter, finished and ready for the printer, down to the last semicolon. For, as it stands, my boy, everything I say is addressed to you only; and my book may be compared to a telephone with a private wire three hundred years long. But since my publisher is going to give the general public the right to hook on and hear what I am saying, it is extremely probable that my monologue will be very often interrupted. Whenever, therefore, you find me suddenly ceasing to speak to you personally, and, after a word with my contemporaries, dropping back to our private wire, you may be sure that there has been a “Hello?” and a “Who’s that?” and a “Well, good-by!” somewhere along a cross-line.

And this is the thing that I feel that I have to say:

I would tell you something of the land of your forefathers. Something of Virginia. Not new Virginia,—not West Virginia,—but the Old Dominion and her people, such as they were when Plancus was consul. And, first of all, I will tell you why I have thought it worth while to lay the following sketches before you.

The world, in my day, is full of unrest. Everywhere anxious care and the eager struggle for wealth. Mr. Spencer’s Gospel of Recreation finds few adherents, and the Genius of Repose seems to have winged its way to other spheres.

And I fear matters will be worse in your day; and, just as one, on a broiling July afternoon, looks with a real, though evanescent, pleasure upon pictured polar bears gambolling amid icebergs (in the show-window of a soda-water shop), so I cannot but think that it would be a genuine boon to you could I but lead you for an hour from out the dust and heat and turmoil of your life and bid you cease striving for a little while, while I (I, too, forgetting for a moment that every crust must be fought for), while I reproduce from out the cool caves of my memory certain scenes that I have witnessed.

True, some of them I have not seen with my own eyes, but Charley has, or else Alice, which is just as well.

Yes, my lad, I think the glimpses I am about to give you of the old Virginia life will refresh your tired soul. Just as it refreshes mine to draw the pictures for you. For from me, as well, the reality has vanished. Our civil war (war of the rebellion, as the underbred among the victors still call it) swept that into the abyss of the past; but let me with such poor wand as I wield summon it before you.

In Pompeii, the tourist, looking from blank wall to dusty floor, wonders what there is to see in that little hall; but a native goes down upon his hands and knees; with a few brisk passes of his hand the sand is brushed away, and a Numidian lion glares forth from the tessellated pavement. So I, brushing aside the fast-settling dust, would make you see that old life as I saw it.

And, strangely enough, I, too, have a lion to show you. For, while my real object was by a series of sketches to bring into clear relief the careless ease, the sweet tranquillity, the unapproachable serenity of those old days, I did not see my way to making these sketches interesting. (For not alone in a repast for the body is the serving almost everything.) But the thought occurred to me to stitch them together with the thread of a story into a kind of panorama. For this story I had to find a hero. To invent one would have been, I am sure, quite beyond my powers; and what I should have done I am at a loss to conjecture had I not found one ready made to my hand: a very remarkable young man, that is, who in a very remarkable way suddenly made his appearance upon the boards of our little theatre, upon which were serenely enacting the tranquil scenes in which I would steep your care-worn soul. This is the lion that I have to show you. And when he begins to shake his mane and lash his sides, you will find things growing a trifle lurid in our little impromptu drama. Absolutely none of which was upon the original programme. But dropping from the sky, as it were, in the midst of our troupe, what should he do but straightway fall in love with one of our pretty little actresses. And then the trouble began and the tranquillity came to an end.

As for me, the manager of the show, you will see that I have done my best to relieve the gloom. Between the acts,—between the scenes,—nay, even while they are going on,—you shall find me continually popping out before the foot-lights and interrupting the play, and raking the audience with a rattling rigmarole. All for the sake of keeping their spirits up. And on more than one occasion I go the length (or breadth, as Alice suggests) of standing on my head and making faces at Charley in the prompter’s box. How I should have gotten on had he not sat there, or without Alice in the wings (to superintend the love-passages), I am sure I cannot tell. And if, at the end of the play, I am called before the curtain, I shall refuse to budge unless hand in hand with my two co-workers; who, though content to be for the most part silent partners in this undertaking, have really put in most of the capital.

It is understood, then, between us, Ah Yung, that while this story is composed for your delectation, the injunctions of my publisher force me to recognize the possibility of contemporary readers. The situation is awkward. As though a third person were present at a confidential interview. Ah, I have it.

While I am talking to you, the contemporary reader may nod; and when I turn to her, you have leave to nap it. And small blame to the contemporary reader. For what I shall say to you will seem to her (and especially my didactic spurts) the merest rubbish.

Every school-boy knows that, she will say.

But I am not to be put down by this crushing and familiar phrase of our day, which simply means that the fact in question is known to the Able-Editor, who looked it up in the cyclopædia on his desk an hour since. Every school-boy in ancient times knew, for instance, what kind of a school Aristotle went to, and how he was taught, and what. Aspasia, we may feel sure, knew no German, nor had even a smattering of French; while all conceivable ologies were so much Greek to her. And yet she must have known something. For statesmen and philosophers flocked to her boudoir, and, when she spoke, sat at her feet, silent and wondering. What had she been taught, and how? Every contemporary school-girl knew. What audience could be found now in the wide world that could keep pace with the eloquence of Demosthenes? How had the Athenian populace been taught? For they were more wonderful than their orator. Ah, how much would we not give to know! But no one thought it worth his while to set it all down in a little book; and we know not, and must darkly guess. Else would we rise as one man, and, rushing with torches to all the colleges and universities of the land, incinerate within their costly walls their armies of professors, along with the hordes of oarsmen and acrobats that they annually empty on the world.

A porch sufficed for Zeno.

Ah, there are thousands of little things which they might have told us, but did not. Ah, that Homer, for instance, had described Helen to us as minutely as he did the shield of Achilles. As it is, we must even conjecture that she had a Grecian nose. And as for her eyes and hair—

And the song the Sirens sang, what was the tune of it? How much would I not have given to hear my dear old grandfather play it on his fiddle!

And how did Socrates make out without a pipe after dinner while Xantippe was explaining to him how many kinds of a worthless husband he was?

Ah, we shall never know! Therefore, my boy, I am determined you shall know something about the Virginians in my day. But excuse me for one moment,—my telephone-bell is ringing.

Some stranger has hooked on.

“Hello!”

“Do you claim that Virginia has ever produced a Socrates?”

“Who’s there?”

“Boston.”

“I do not.”

“Ever see a Virginia Xantippe?”

“Well, good-by!”

This is the way I am likely to be interrupted throughout the entire course of my story. True, I shall leave out the hello and good-by part of the business as too realistic, but you will know when they have been hooking on from my stopping to argue with my supposed readers. By the way, if this chapter bears, to your mind, internal evidence of having been composed in Bedlam, you will understand how it has fared with me when I tell you that I had hardly spoken a dozen words when my telephone began to ring like mad. A thousand cross-lines at least must have been connected with our private wire before my first sentence was finished. Heavens, what a jingling they are keeping up even now! I must speak with them.

“Hello! hello! hello!—Good-by! good-by! good-by!”

And why all this clatter, do you suppose?

It is nearly all about these seven words in my opening sentence,—Thine almond eye, my Ah Yung Whack.

I shall analyze the questions and remarks of the first hundred as a sample of the thousands.

Of this number, three announced themselves as authors of English grammars, adding that they could not sustain me unless I changed my ah to ah my; and of the three, one that I should have said Virginian instead of Virginia Xantippe; quoting a rule from his own grammar. Which I was glad he did, seeing that I had never read a line in any English grammar in my born days; and I find that when you are writing a book no kind of knowledge comes amiss.

I answered him (per telephone) by this question in political economy: whether he thought that by a judicious tariff Massachusettsish enterprise would ever be enabled to raise Indian rubber under glass at a profit and successfully compete with the pauper labor of the sun; and, springing nimbly from political to domestic economy, I trusted that his next Thanksgiving Turkish gobbler would sit light on his stomach. And this I meant, once for all, as a defiance to the whole tribe of grammarians, be they living, dead, or yet unborn.

After the three grammarians come seven spelling reformers, congratulating me on my courage in writing yung instead of young. [How they found this out by tapping my telephone I will explain later, if I have time.] And of these, one, who was also a short-hand writer, thought Whack an improvement on Whacker.

All the remainder of the hundred—that is, ninety—were young ladies.

There is a certain insinuating witchery about the unmarried voice of woman (among males all widowers have it) that is not to be mistaken, even through a telephone. That is, when addressed to an unmarried ear.

Of these ninety, every solitary one asked, “Have you almond eyes?” (for young ladies can underscore, even over a wire), and forty-three of them added, “Oh, how cute!” and forty-seven, “My, how cunning!”

And of these ninety, eighty-nine added that, by a strange coincidence, they, too, were married; the remaining one saying that she was single. She, I take it, was a young widow; especially as she went on to say that she feared that I was a sad, bad, bold, fascinating wretch to speak in my half-frivolous, half-businesslike way of the holy estate of matrimony, which had been commended even of St. Paul. She added that she had often been told that her own eyes sloped a little.

Now you, my boy, know perfectly well that you are called Whack. Nor will it strike you that I have reformed the spelling of your Confucian name, Yung. As to the Ah, you will smile at its being mistaken by a Western barbarian for an interjection. But you do not know, and will be amazed to hear, that you have almond eyes. For you have never seen any other variety. This, therefore, strikes me as a fitting opportunity for explaining to you and the contemporary reader why I began with those seven mysterious words. You, at least, can hardly regret their use, since it was the means of showing you how many candidates there were for the honor of being your great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmother. The aspirants had never seen me, it is true. So that I am not puffed up.

Puffed up? Alas, yes, that is my trouble! Hence my long delay. Woman after woman has admitted that my smile is sweet, my voice low, my ways winning.

His soul is beautiful, they say; then why will he waddle when he walks?

And waddling is mirth-provoking to every daughter of Eve, and laughter is fatal to love.

Not one word of the caballistic seven would I have written but for two very singular dreams which I had. And this is the way, so far as I can make out, that I chanced to dream the first one.

The line of Bishop Berkeley, to the effect that the star of empire is constantly moving west, is naturally a favorite with patriots in this country. It is in everybody’s mouth. I have heard it cited, you could not imagine how often; so often, to put it plainly, that I would undertake to reckon up on my fingers and toes the number of times I have not heard it. Western journalists, especially, see their way to quoting it so frequently that they keep it always in stock, electro-typed and ready for use at a moment’s notice (when a commercial traveller registers at the local hotel, for instance). Not a Weekly is set up as the organ of the pioneerest water-tank of a Western railway, but you shall see this verse figure in the first leader. Now it was this line which, though not the exciting cause of the first of my two dreams, gave direction to it, at least.

A friend had sent me a San Francisco paper, and meeting the familiar line therein, I began wondering to myself, as I lay upon my lounge, where the star of empire could go now, seeing that there was no longer any West left; and, reading on, half awake, after a late supper, and seeing in every column allusions to the glorious climate of California (in worn type), I asked myself, with a drowsy smile, whether it were not to reach this same glorious climate, perhaps, that the star in question had been bending her steps westward throughout recorded time.

If she is to go any further—I dozed—I—she—will have—to—wade—and I fell asleep!

How long I slept I cannot say; but long enough to dream this:

Dream I.—[Welsh rarebit.]

America, at last (so it seemed to me in my vision), is full; and thousands upon thousands of our redundant population are pouring into Asia,—you among the rest; for your day had come,—and you are all as busy as bees, cutting the throats of the heathen, in order to bring them to a true knowledge of the living God, and secure their lands,—as our ancestors have served the treacherous and implacable Red Men.

(When I speak of your cutting their throats, I speak as a man of my time; for it would be the veriest presumption in a mortal of this benighted day to restrict heroes in the blaze of the twenty-third century to such vulgar and ineffectual methods of destroying their fellow-men. Indeed, I must do myself the justice to say that, when I ventured to dream of you as storming the ranges of Thian-Shan and the Kuen-Lun, into which have fled the deluded remnants of the followers of Confucius (of whom, at the date of this dream, you were not one), I did not take the liberty of picturing you to myself, even in a vision of the night-time, as laboriously toiling up those rugged slopes, convincing, as you go, the unregenerate, by the unanswerable suasion of breech-loading cannon and repeating rifles,—lame contrivances of our less-favored age; but)

Before my closed, yet prophetic eye, you float a beautiful, aerial host of missionary heroes and real-estate agents, flecking the sky with innumerable winged craft. There! I see the line halt! A rock-bound fastness lies just ahead! A captain’s yacht—a kind of mechanical American eagle, an ’twere—darts forward through the limpid air, and poises itself just over the enemy, a mile above the earth. A field telephone drops into the fortress, and a parley is held. Unsatisfactory! for an officer in the uniform of the Flying Chemists, leaning lightly over the starboard gunwale, lets fall into the stronghold, with admirable precision, a homœopathic globule of the triple-refined quintessence of the double extract of dynamite. It is finished! Peace on earth, good will toward men! What was, a moment since, a heaven-piercing peak, is now a hole in the ground,—what were, just now, the adherents of an effete theology, in the twinkling of an eye are converted, if not into Christians, at least into almond-eyed angels,—and the victors can read their title clear to mansions near the skies, and to the rice-fields of the Yang-tsi-Kiang, or the tea-orchards of the Hoang-Ho.

I am persuaded that every fair-minded man will allow this to have been a dream that not even Pharaoh need have blushed to own. I feel that it does me credit. But would it have been prudent in me (as a professional dreamer) to see that one vision, and then, as we lawyers say, rest my case? Perhaps I had gone all astray. Who is this Bishop Berkeley, after all? Have men, in their migrations, always followed the sun? Who destroyed the Mound-Builders? and whence came they? and their destroyers? from the East? or from the West?

To certain insects, which live but a single day, the winds may very well seem to blow always in one direction; and there may be in the affairs of men a tide which ebbs and flows in æons rather than in hours. And what is the meaning of this cloud-speck rising along the Pacific coast? Is the nineteenth century, so remarkable in many respects (for instance, brag), to usher in an era as yet unsuspected? Is the tide trembling at its utmost flood,—and is the reflux upon us? Are the “lower orders” the real prophets, as they have ever been before? And is their animosity against the Chinese but a blind feeling of the truth that in these new-comers the European races have met their masters? Can it be that under the contempt expressed for them as inferiors there lurks a secret, unrealized sense of their real superiority?

For wherein do we surpass the Indian whom we are so rapidly supplanting? In two things: endurance under toil and strength to hoard,—industry and self-denial. By force of these traits we have driven the Red Men from their homes. And now, on the Pacific, we meet a race as superior to us in these qualities as we are to the Indian or the negro.

Obviously, therefore, if I would get at the bottom of the business, it behooved me to see another vision. It was not long in coming. The very next day a party of us jurists had luncheon together, and I ate, of all things in the world—

Well, returning to my office, I threw myself upon my lounge, and took up a law-book, stood it upon the bosom of my shirt, and opened it at the Rule in Shelley’s Case. If a man have nothing on his conscience, this justly celebrated rule will put him to sleep in ten minutes.

Before I lay down, therefore, I locked my door; for the spectacle of a sleeping lawyer must ever be a painful surprise to a client.

Dream II.—[Canned lobster.]

Presently I heard a gentle rap. “Come in,” said I. And in there stalked a most surprising figure.

Now, if I had had my wits about me, I should have known it was a dream; for how could he have gotten in with the door locked? So I suppose I must have dreamed that it was not a dream. At any rate, there he was. A Chinaman,—but tall, athletic, and gorgeously arrayed in brocaded silks. A low bow, full of grace and dignity. I rose hastily, without either the one or the other.

“Ah Ying Kee,” said he, with another bow, at the same time lightly touching his left breast with the tips of the fingers of his right hand.

“Be seated, Mr. Kee,” said I, offering him a chair.

“Thanks; I have the honor of addressing Mr. Yang Kee?”

The afternoon was furiously hot. My man had the chest and neck of Hercules. So I contented myself with the haughty reply that my name was Whacker.

“No doubt,—no doubt,” replied he, with a courteous wave of the hand. “In a general way you are quite right; but for the special purpose of my visit permit me to insist that you are Mr. Yang Kee.”

It flashed across my mind that I was dealing with a large lunatic, and my anger cooled.

“Very well,” said I, “if you will have it so. I was never called a Yankee before, that’s all.”

“No doubt; nor have you the least idea that you are one. Still, I venture to remark—with your kind permission—that such is practically the fact. To your eye and ear there are differences between your people and those of Connecticut, just as I have no difficulty in distinguishing an inhabitant of the district of Hing Chang from a dweller on the banks of the Fi Fum. To you we are all Chinese. To us, Americans are all Yankees. Orientals, occidentals. Let Ying Kee stand for the one, Yang Kee for the other.”

“You don’t say Melican man?”

“No; I am not a washerwoman,” replied he, with a smile. “I am a member of the imperial diplomatic corps, and, if you will permit me to say so, a gentleman.”

I gave him to understand that he was more than welcome. (He was six feet two, if he was an inch.)

“Thanks. But my object in calling—”

My retainer would be a stiff one, never fear—

“I call, not as a diplomat, but as a philosopher.”

I sighed the sigh of a jurisconsult.

“I come to discuss with you a dream which I understand you have done us Chinese the honor to dream about us.”

I had not mentioned my dream to a soul. How had he heard of it? I never once dreamt that I was dreaming again.

“You, too, I understand, are a philosopher,—the greatest philosopher, if common fame may be relied on, throughout the length and breadth—”

I gave my hand a deprecatory wave. “Don’t mention it,” said I.

“Throughout the length and breadth of Henrico County,—Hanraker, as the natives call it.”

“You are strong on geography.”

“It is made my business by my government to know America. But let’s to our discussion. But is not your office rather close quarters? Might I beg you to walk with me?”

“Where shall we go?” I asked, when we reached the sidewalk.

“What do you say to Rocketts?”

“Rocketts!” I exclaimed; “you are strong on geography!”

“Rocketts?” said he, with a bland smile; “who does not know that it is the port of Richmond, just as the Piraeus was that of Athens?”

I cannot imagine why I put all these fine phrases in his mouth, unless it was because I had read in the papers, not long before, that the Parisians pronounced the manners of the Chinese embassy perfect.

And here I may remark, for the benefit of science, that though the thermometer was at ninety in the shade, I was not conscious of the heat during our long walk. Yet—and it shows that it costs a fat man something even to dream of toil—yet, when I awoke, my brow looked as though I had been earning my bread, whereas a lawyer, as we know, confines himself to earning some other fellow’s.

“And now, Mr. Yang Kee,” said he, as we took our seats in a corner of the docks of the Old Dominion Line, “and now for this very remarkable dream of yours; and permit me to begin by observing that, the central conception of your dream being vicious, the whole business falls to pieces.”

I threw my eyebrows into the form of a couple of interrogation-points.

“You have been at the pains of dreaming that your people are to conquer mine through the instrumentality of armed colonization. Those days, when entire nations—men, women, and children—migrated, sword in hand, are over. Instead of migration we have emigration,—the movement of individuals instead of the movement of tribes; in place of the Helvetii—”

“Mr. Kee, your learning amazes me!”

“It’s all in Confucius,” said he, modestly. “Instead of the Helvetii devastating Gaul, the Swiss waiter lies in ambush against the small change of Christendom. It is no longer warrior against warrior, but man against man. It is not a question of—”

Mr. Kee hesitated, and a subtle smile played over his features.

“Go on,” said I.

“These are the days, I was going to say, of the survival of the fittest, rather than the fightest.”

“Go it, Ying!” cried I; at the same time fetching him a rouser between the shoulders with my rather heavy hand. In my enthusiasm I had forgotten his high rank. I began to stammer out an apology.

“It is nothing,” said he. “It makes me know that you are a good fellow,” added he, at the same time shaking hands with himself, after the manner of his people, with the utmost cordiality.

I do not suppose that a native ever puns without a certain sense of shame; but I confess to enjoying it in a foreigner. He is always as proud as a boy whistling his first tune.

“A Caucasian army is vastly superior to a Mongolian; a Caucasian individual vastly inferior.”

I smiled.

“Oh,” said he, “I know what your politicians say; and I find no fault with them, for they make their living by saying—judicious things. The Chinaman works for nothing and lives upon rice, so that a decent American working-man cannot compete with him. Moreover, he persists in returning to China. He won’t stay, therefore he must go. Moreover, a Celestial is a heathen, while you, dear voters, are all pious and good!”

As he said this, accompanying the remark with a wink of Oriental subtlety, we both, with a common impulse, burst into a laugh so loud that a large rat, which we had observed as he cautiously stole up towards a broken egg which lay upon the dock, precipitately scampered off and down into his hole.

“Oh, I don’t blame your statesmen. They, just as others, have a trade by which wives and children must be fed and clothed. Moreover,”—and leaning forward and confidentially tapping my round and shapely knee with his yellow hand, he whispered,—“moreover, your statesmen are right!” and, straightening up, he paused, enjoying my surprise. “The sentimentality of Pocahontas,” he resumed, with a wave of his hand in the direction of Jamestown, “was the ruin of her people. Opecancanough was a prophet and a statesman. Had the Indians slain the Europeans as fast as they landed—”

Just then the rat thrust his sharp muzzle out of his hiding-place and warily swept the dock with his jet-bead eye. Mr. Kee turned upon him his almond oval and smiled.

“I thank thee, good rat,” he cried; “for thou art both an illustration and a prophecy. Hundreds of years ago, the blue rat held sway on this continent, while you squeaked unknown in the mountains of Persia.”

“’Tis a Norway rat,” I put in.

“No,” said he, quietly, “he is of Persian origin, and migrated to China ages ago, during the reign, to be exact, of Ying Lung Fo. You will find it laid down in Confucius, in his great work, ‘Bang Lie Yu,’—concerning all things, as you would say in English.”

I wonder whether he likes them best broiled or fricasseed? thought I.

“The real Norway rat is little larger than a field-mouse. Your term Norway rat is simply a popular corruption of gnaw-away rat, given him as the most strikingly rodential of rodents.”

“To be found, I suppose,” said I, “in Confucius’s lesser work, ‘Fool Hoo Yu,’ or, concerning a few other things, as we say in English.”

“You have me there!” replied he, with the most winkish of winks. “But we digress. Where is the blue rat now? Perhaps a few specimens might be found, falling back, with the Red Men, upon the Rocky Mountains. And where will the Caucasian race be three centuries [his very figures] hence? Your statesmen are right, but, like Opecancanough, right too late. Your race is doomed; not, indeed, to extinction, for already the despised Mongol begins to find wives among you, but you will be crossed out of existence by a superior and prepotent race. Look at me,” said he, giving himself a slap upon his broad chest; “do I look like an inferior specimen of—there he comes again!”

Looking, I saw the rat, stealthily creeping toward the egg, his larboard eye covering us, his starboard fixed upon a cat that lay dozing in the shadow of a post.

“There he is, that intruder from Persia, and he will remain with you. Housewives may poison, here and there, a score of them,—the survivors take warning; pussy may lie in wait,—he learns to avoid—even to bully her. Terriers may dig down into their hiding-places,—they will bore others. An incautious youngster gets his leg in a trap,—his squeal is a liberal education to the entire colony. He has an infinite capacity for adjusting himself to his environment. He is here for good; and so is the Chinaman. Congress may legislate against him; it will be a Papal bull against a comet. Mobs may assail him, trade-unions damn him; but the Chinaman will not go. And myriads more, the survivors of ages of a fearful struggle for existence at home, will pour in. He will not go. He will come; and between Ying Kee and Yang Kee the fittest will survive.”

“Westward,” began I, “westward the star of empire—”

“Scat!” cried he, leaping from his seat.

Our rat, having, at last, after many advances and retreats, secured the egg, was making off with it to his hole, when the cat, awakening, sprang after him. Down he plunged into his hole, bearing off the egg, but leaving an inch of his tail under pussy’s paws.

“Scat!” cried I, rushing to the rat’s assistance,—and bump! I fell upon the floor.

Ah Ying had vanished. My door was still locked. It had all been a dream.

No, my boy, I am not a candidate for the Presidency. This is no hook baited with the Chinese question. My object is merely to explain how you happen to have almond eyes. And if you don’t, you will understand that it is no fault of mine. The Welsh rarebit dream overcame the canned lobster vision,—that’s all. And having made this clear to you, as I hope, the time has come for me to say a few words about myself.

When this book shall be, on your twenty-first birthday, laid beside your plate, at breakfast, by your thoughtful yellow father, I have no doubt that you will ask him, before even you begin to play your chopsticks, who wrote it. Now, what will it avail you for him to say that it was written by John Bouche Whacker, of the Richmond bar? Who was John Bouche Whacker? And that question means (at least since Mr. Charles Darwin wrote) who was the father and who the mother of J. B. W.; and the father and mother of this pair, and so on, and so on.

Now, I suppose that if I were to push the inquiry into prehistoric times, it would turn out that I was related to the entire Indo-Germanic race; but I shall content myself with indicating to you the three chief strains of blood which mingle in my veins, leaving to you, as you read chapter after chapter, this entertaining ethnological puzzle: Who spoke there? The Dane? or was it the Saxon? As to my Huguenot blood, there will be no hiding that. It will always be on fire, at the merest suggestion of a dogma of theology.

Every school-boy knows that, no sooner had their brave Queen Boadicea perished, than the Britons lost all stomach for fighting, and gave themselves up wholly to roast beef and plum pudding. Nor is it a secret, that when the Roman legions, to whom they had learned to look for protection, were withdrawn from the island, the Picts and Scots, grown weary of oatmeal, began to trouble the more sumptuous feasts of their neighbors. Remonstrances proving fruitless, they sent for the Jutes and the Saxons and the Angles (so called, respectively, from a valuable plant, a fine variety of wool, and a singular devotion to fishing). These sturdy braves crossed the water with their renowned battle-axes, as every school-boy knows. But what even our very learned young friend does not, perhaps, suspect, is that, along with Hengist and Horsa, there sailed, on this historical occasion, two twin brothers, named respectively Ethelbert and Alfred Whacker,—or Hvaecere, as they themselves would have spelled it, had they thought spelling, of any sort, worth their heroic while; which, haply, they did not. Now, from these twins I am lineally descended, as you shall see duly set forth in the Whacker Records, herewith transmitted. You will find in these family annals, too, some details not sufficiently elaborated, perhaps, in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and other authorities for this period. There is the barest allusion, for instance, to the brave death of Ethelbert Hvaecere, the eldest of the twins, which occurred as follows:

When the English (for such recent historians have shown that they were, and not Germans, as they themselves, absurdly enough, supposed themselves to be)—when the English reached the Wall of Severus, they found that earth-work lined, for miles, with Picts and Scots. So, at least, they were named in Pinnock’s Goldsmith’s England, which I read at school. So, too, you will find they are called in the Whacker Records. Recent historical research, however, has demonstrated that the so-called Picts were, in reality, painted Scotchmen, while the alleged Scots were neither more nor less than Irishmen. And I must confess that when I re-read the Whacker Records by these modern lights, I was ashamed that I had not made this discovery myself.

It would appear that the west of Scotland was originally settled by the Irish; and that those who remained at home took so lively an interest in their emigrated brethren, that whenever they got news of a wake or other shindy that was brewing beyond the Channel, they would shoot across in their canoes, or else—so surprisingly low were the tides in those simple days—wade across and join in the fray; as they did on the present occasion.

You and I have no special interest in Hengist’s attack on the tattooed Scotchmen on the enemy’s left; for the two Hvaeceres fought under Horsa, on our left.

And things looked so strange to Horsa, as he approached the enemy, that this wily captain called a halt and sent word to Hengist to delay the attack till he could look into matters a little. And this is what he observed, standing a little in front of his line, with the two Hvaeceres (who constituted his staff) by his side.

In the first place, the weapons which these so-called Scots were waving above their heads were not claymores, as he had been led to expect. Instead, they brandished stout, blackish, knotted clubs, and to the accompaniment, not of the shrill bagpipe or the rhythmic slogan, but with fierce and discordant cries. One thing he remarked with grim satisfaction. Standing in dense masses, and whirling their clubs with more fervor than care, it constantly happened that a neighboring head got a tap; and no sooner had this occurred (giving forth a singularly solid sound) than it instantly set up a local internecine fracas of such severity that, at times, considerable spaces of the wall were denuded of defenders; who, tumbling into the transmural ditch, fought fiercely there. In a few minutes, however, they would reappear, smiling, as though they had been seeing fun of some sort, over there beyond the wall. Once, indeed, one of the combatants,—a little bow-legged fellow,—bringing down his shillaleh (which is Celtic for hickory) with a sounding thwack upon the bare head of a burly opponent, knocked him down the slope of the wall on our side, and, standing upon the edge of the wall, with his thumb to his nose, jeered at him.

“Who hit Maginnis?” cried he in Gaelic; and even the Maginnises roared with laughter. Nay, grim Horsa, too, was observed to smile; for he knew their language well, having learned it during his many incursions into Gaul.

But, just at this moment, Hengist riding up, and seeing our men seated on the ground, and laughing, as though at a show, flew into a rage; for, like his maternal uncle, Ariovistus, he was of an ungovernable temper; and asked his brother Horsa what in the Walhalla he meant. “Do you call this business?” added he,—for he was an Anglo-Saxon.

“I am giving them time to knock out each other’s brains,” replied Horsa, in his slow-spoken way.

“Then will you wait till doomsday,” replied the humorous monarch; and galloping back to his lines, well pleased with his sally, he ordered an immediate advance upon the pictured Macgregors in his front.

We charged too. (I have read the account so often that I cannot help thinking I was there.) And it was then that Horsa discovered the meaning of a reddish line along the top of the wall in his front. Observing no signs of missile weapons among the enemy, he had flattered himself that he would easily have the mastery over them, with his terrible battle-axes against their shillalehs. But when we got within thirty feet of them (not before) they stooped as one man and rose again. An instant more and we thought that Thor was raining his thunder-bolts upon our shields. Our men went down by hundreds. A reddish mist filled the air.

’Twas brick-dust!

With such prodigious force did they hurl their national weapon (shamrock is the pretty name of it in the Gael) against our shields, that, where it did not go through, it was reduced to powder.

We stood a long while, stunned, blinded, bewildered; suffering heavily, doing nothing in reply. At last there was a slight lull in the storm of missiles; for as they had each brought over but a peck of ammunition, in their corduroys, the more impetuous among them were beginning to run short; and it was then that our sturdy ancestor showed the stuff he was made of. Assuming command (for Horsa, with Alfred Hvaecere by his side, lay insensible upon the grass), “Men,” cried he, “why do we stand here? Remember Quintilius Varus and his legions! To your axes! to your axes!” And the whole line staggered forward, with Ethelbert well in front and bearing down upon Maginnis. (The same,—though his mother would scarcely have known him, with that blue-black bulge in his forehead.) And it is mainly from an observation that Maginnis made at this juncture that I am inclined to give in my adhesion to the hypothesis of the later historians, who claim that these men were not Scots.

“Erin go bragh!” cried the undaunted chieftain, reaching down into his trousers for a reserve brick,—an heirloom,—black, glistening, hard as flint, mother of wakes—

“Thor smash thee!” cried the Hvaecere; and tossing away his shield, he lifted aloft, in both hands, his mighty axe. It trembled in the air, ready to descend.

Too late,—for the brick of Maginnis landed square between the hero’s eyes,—and you and I had to be descended from the younger brother.

The Whackers, therefore, are not ancestors that one needs blush to own.[1] But I have not meant to boast. Else had I been unworthy of them. They were Anglo-Saxon; and when I have said that, I have said that they had a certain sturdy love of truth, for which this race is conspicuous. And so this book may be absurd, or even wicked, nay, worst of all, dull; but one thing you may rely upon. Every word in it will be true.

|

I sometimes wonder how some people can plume themselves on their descent, though able to trace it back only to the Norman Conquest. J. B. W. |

It did not seem so while I was writing it, but now that my book is finished, it strikes me as one of the oddest works I have ever read. You can never tell what is coming next. Even to me it was a series of surprises. Read the first ten lines of any chapter. Now read the last ten. Heavens, how did he get there! I seem never to know whither, or how far I am going. It has been the same with me all my life. Often, as a boy, I have set out for a neighbor’s on a mule, and not gone all the way.

Another singular trait about this book is what I must be allowed to call its unconscious humor. A strange thing to say about one’s own book; but somehow, when I am reading it, I can’t shake off the impression that some other fellow wrote it, or that I wrote it in my sleep,—so many things do I find in it which I could almost swear I never thought of in my life. And there are a dozen passages in it where I slapped my thigh, crying out, Good! Good! And more than once I caught myself saying, By Jove, I should like to know the old boy who wrote this!

Yet, never in my life was I more serious than when I sat down to write this work; for it was the solemn, theological, Huguenot molecules of my brain that set me to writing; and the book was to be too grave to bring a ripple to the beak of a Laughing Jackass,—that jovial kingfisher whose professional hilarity cheers the lone Australian shepherd.

Now, since man—as every college-boy knows—and it is well to know something—since man is but the sum of his ancestors modified by his environment, whence have I derived this trait of mine, this unconscious humor,—the gift, that is, of making people laugh without intending it? Many persons have it, but where did I get it?

Not from the business-like Whackers, surely. Still less from the Pope-hating Bouches. I must derive it from my Danichester blood. From this source, too, I must get another characteristic,—that of being sad when others are gay. In the midst of piping and fiddling I sometimes ask my heart what is the use of it all. And ofttimes, while I have stood smiling as I looked upon a group of merry children at play, I could feel the tears trickling back upon my heart.

Family traits are generally modified (Darwin, passim) from generation to generation. Thus, the grandson of a painter will be a musician, perhaps; and many literary people are sons of clergymen. There is similarity rather than identity. And so this vein of sadness, which lies so deep in me that few or none of my friends have ever suspected its existence, crops out in one of my progenitors. I allude to Olaf Danichester, Gent., whose daughter Gunhilda was married to John Whacker, merchant, London, in the seventeenth year of the reign of glorious Queen Bess.

Now, from all accounts, this ancestor of ours had a most extraordinary way of saying things that no one else would ever have thought of; added to which was the singularity that, after he had run through the fortune brought to him by his second wife, he was never known to smile. And it is no secret to the Whacker connection (though not generally known in literary circles) that the immortal Shakespeare, who often sat with him over a cold cut and a tankard of ale in the parlor of his prosperous son-in-law (J. W.), has embalmed him for posterity in the melancholy Jaques.

Now, the difference between Olaf Danichester and myself is simply that he gave utterance to his sad thoughts, while I keep mine to myself. I am a mere modification of him, just as he was of his valiant progenitor, Vagn Akason, the Viking. This Vagn, though an eminent waterman in his day, did not come over to America in the Mayflower,—chiefly because he was killed centuries before she sailed, but in part, also, because he felt no wish to make others worship God after his fashion; which was a very poor fashion, I fear, from the account given of him in our Records. At any rate, he was a marvellously handsome fellow, this Viking bold; and when he went forth to battle, a storm of yellow hair, as Motherwell says, floated over his broad shoulders,—so that he looked for all the world like Lohengrin. But I suspect he was not the kind of man we should select, at the present day, as superintendent of a Sunday-school. For one thing, he was a most omnipotous drinker; nor should I ever have admitted that I had a drop of his blood in my veins had it not been necessary for me, as a Darwinian, to account for my unconscious humor. And if these words savor of conceit, let us call it my trick of saying and doing the most unexpected things. Hear the account of the death of this brave young sea-rover, and see whether I do not come honestly by this trait:

He, with seventeen of his companions, had been captured, and had been made, according to the custom of those rude days, to straddle a large log, one behind the other, with their hands tied behind their backs. Up came, then, the victor, Jarl Hakon (after a leisurely breakfast of pork chops), to strike off their heads. This, to us, seems unkind; but having one’s head chopped off was such a matter of course in those days that no one ever thought for an instant of minding it in the least. Give and take was the way they looked at it.

But brave as these men were in the presence of the headsman, they shuddered at the very thought of a barber. They gloried in their long hair. To lose their heads was an incident of war; to lose their locks a disgrace which followed them even into the next world. According to a superstition of theirs, a Sea-Cavalier who lost his curls just before parting with his head was doomed to be a Roundhead ghost and a laughing-stock throughout eternity.

Up strode the fierce headsman, Tharkell Leire, and bade the captive Viking lean forward and lay his golden hair upon the log. He obeyed, but held his calm, sky-blue eye upon the glittering axe, and, quick as a flash, as it descended, covered his fair curls with his fairer neck. And when his seventeen comrades, who sat there waiting their turn, saw how their wily captain had outwitted their enemy, and how he raged thereat, they roared with Sea-King laughter.

Every school-boy knows what the Edict of Nantes was; but philosophers differ as to what was the effect of its revocation upon the fortunes of France. For us it is enough to know that Louis XIV., by recalling it, drove to Virginia our ancestor John Bouche, whose daughter, Elizabeth, completely captivated my great etc. grandfather, Tom Whacker, by her pretty French accent and trim French figure. She was good and wise, too; but the rascal never found that out till after he married her. It must be owing to the Danichester strain, I suppose, that the Whackers, so sensible in many ways, have always sought grace and beauty in their wives, rather than piety and learning; and I suppose I shall be no wiser than my fathers when my time comes.

This Huguenot cross gave the old Whacker stock a twist towards theology. Two of the sons of Thomas and Elizabeth took orders, much to the surprise of their father, who used to say that Reverend Whacker had a queer sound to his ear. So prepotent, in fact, has the Huguenot strain become, that a Whacker is no longer a Whacker. In the old days our eyes were as blue as the sky; now they are as black as sloes. Once we were reserved and silent; now—but enough. As for myself, it has often seemed to me that I was all Bouche,—Bouche et præterea nihil,—as the ancient Romans put it in their compact way.

Needless to say, therefore, that this book was to instruct and edify you. You may see that from the very first sentence of it all that I wrote:

“And, now in conclusion, my dear boy, if you rise from the perusal of this work a wiser and better man, the direct author of the book and the indirect author of your being will feel amply repaid for all his toil.”

Such were my intentions. And now read the book, as it stands. Heavens and earth, was there ever such another! Alas, those Danichester molecules, what have they not made me say! Page after page, and chapter after chapter, in which I defy even a mouse to pick up a crumb of edification. Chapter after chapter of feasting, fiddling, dancing, courting,—roast turkeys, broiled oysters, hams seven years old. Bowls full of egg-nogg, pipes full of tobacco, students full of apple-toddy,—everything to make a man feel good, nothing to make him be good. For the heathen Viking in me speaks!

Yet he does not hold entire sway. But as we sit—you and I and the friends you shall presently make—sit joyously picnicking in a fair wood—more than once the trees above us, as you shall find, will seem to moan, as they bend before the gentle breeze. ’Tis the spirit of the melancholy Jaques, perched like a raven, there. To him a sob lies lurking in every laugh; and his weary eyes can never look upon a dimple—a dimple, smile-wrought in damask cheek—but they see therein the sheen of coming tears.

Here I am, then, Whacker-Danichester-Bouche. [Anglicé, Bush.] And, since man is but the epitome of his ancestry, what kind of an author should result? Chemists tells us that it is not so much the molecules as their arrangement. Let us try this: Danichester-Bush-Whacker,—so what else could I be but a Humoristico-sentimental Bushwhacker?

And such I am, ladies and gentlemen, at your service!

And a Bushwhacker, beloved scion, you will rightly divine to be one who whacks from behind a bush. But that this is so is (and that you would never guess) one of those whimsical accidents of which philology points out so many examples. Bushwhackers no more got their name in the way the name suggests than your Shank-high fowls got theirs from length of limb.

How they did get it I must now explain. Not that I may vaingloriously show off my rather quaint and curious philologic lore. I have a better motive. The word has its origin in an incident in our family history; an incident, too, of such interest that it gave rise to a poem, famous in its day, beginning, “All quiet along the Potomac to-night,”—the author of which will never be known. For three hundred and eleven people (two hundred and ninety-nine women and twelve men) went before justices of the peace, when it began to make a noise in the world, and made oath that they wrote it. Which shows, among other things, that there is no lack of justices of the peace in this country. But let’s to the incident.

You must know, then, that the Bouche connection is as numerous as it is respectable. Hardly a county in Virginia where you shall not find a colony of them. And as a rule they are genteel folk, mingling with the best. But (for I shall not conceal it from you) every now and then one stumbles upon a shoot of the original stem that is fallen into the sere and yellow leaf. Still, the motto with us is, that a Bouche is a Bouche, even though he be run down at the heel. But our clannishness has its limits. We draw the line at the spelling of the name,—draw it sharply between Bouche and Bush. Still, I happen to have heard my grandfather say that, though old Jim Bush did not spell the name after the aristocratic Huguenot fashion, his father before him did; and that, consequently, he was one of us.

After all, he was by no means a bad fellow. It covers his case better to say that he was not profitable unto himself. He was, in fact, a kind of Rip Van Winkle, whose hands, though he was desperately poor and owned a farm of a few acres, were more familiar with the rifle than the handles of a plough. For miles around his tumble-down old house he and his gun were a terror to game of all kinds; and it was believed that, of squirrels especially, he had killed more, in his day, than any man within miles of Alexandria. Nor were there lacking those who maintained that upon a dozen of these edible rodents, as a substratum, he could build up a Brunswick stew such as—but I dined with him once, and feel no need of outside testimony. (I suppose it was the French streak in him. He spelt himself Bush, but blood will tell.)

“The main secret, Jack” (everybody calls me Jack, no matter how poor and humble they may be; besides, he was a cousin),—“the main secret is that I put in the brains. When I was a green hand with the rifle I used to knock their heads off; and monstrous proud I was, I remember, of never touching their bodies. Now I save their brains by just wiping off their smellers.”

Yes, my son, he was an out-at-the-elbows Bouche, and his language was low. But let us not sneer at him. He could do two things well. And how many of us can do one! For my own part, when I look at myself and then at my brother-men, I cannot find it in my heart to despise the lowliest of them all. The scornful alone do I scorn. And when I see a little two-legged puff-ball strutting along, with its nose in the air, I long for old Jim Bush and his rifle, that he might serve it as he did the squirrels.

Old Jim’s ramshackle house stood in the zone which lay between the Northern and Southern armies during the winter following the first battle of Manassas, or Bull Bun. He was not young enough to shoulder his musket, having been born in the year 1800. Besides, rheumatism had laid its heavy hand upon his left knee. As scouting parties of the enemy frequently came uncomfortably near old Jim’s little farm, he, dreading capture, spent most of his time in the dense woods which surrounded his house, creeping back, at nightfall, beneath its friendly roof. True, the roof leaked here and there, but it was all he had, and he loved it.

One day the enemy pushed forward their picket-line as far as his house, and established a station there. It was late in the afternoon when they came, and old Jim, who had already returned for the night, had barely time, on hearing the clatter of hoofs at his very door, to rush out by the back way and tumble into the dense jungle of a ravine which skirted his little garden. Very naturally, to a Bedouin like old Bush, the idea of being immured in a noisome dungeon, as had happened to some of his less wily neighbors, was full of horrors; and crawling into the densest part of the thicket, he crouched there pale and hardly breathing, lest the men whose voices he heard so clearly should hear him.

Old Joe—for, while Jim differed from Diogenes in many other ways, he was like him in this, that he owned a solitary slave—old Joe they had caught. No doubt the sizzling (the dictionary-man will please put the word in his next edition)—the sizzling of the bacon in his frying-pan dulled his hearing; and so his knees smote together, when, raising his eyes to the darkened door, he saw a Federal soldier standing upon the threshold.

“Sarvant, mahster!” stammered he through his chattering teeth.

In order to explain his terror to readers of the present day, I must beg them to recall the fact that Lincoln had issued a proclamation that the North had no intention or wish to overthrow slavery in the South. “We come to save the Union,—dash the niggers!” was the angry and universal reply of the Federal soldiers when our women jeered them on their supposed mission. Hence the phrase “wicked and causeless rebellion,” without which no loyal editor could get on with the least comfort in those early days of the war.

Just as a poetess, nowadays, rends her ringlets till she finds a way of working “gloaming” into her little sonnet.

The abolitionists,—to praise them is the toughest task my conscience ever put upon me,—though they brought on the war, were not war-men. They honestly abhorred slavery, and had the courage of their convictions. They would have let the “erring sisters depart in peace” so as to rid the Union of the blot of African servitude, and deserve such honor as is due to earnest men. Later on, they changed their position; but middle-aged men will remember what their views were at the opening of the struggle.

Not recognizing, therefore, a friend in the “Yankee” who stood in his door-way, the glitter of his bayonet was disagreeable to old Joe’s eyes, and the point of it looked so sharp that it made his ribs ache; and his knees trembled beneath him. For old Joe was not by nature bloodthirsty, nor longed for gore,—least of all the intimate and personal gore of Joseph Meekins.

“Sarvant, mahster!”

Perhaps old Jim’s naturally serene temper was ruffled, at the moment, by the fact that the fangs of a blackberry-bush, under which he had forced his head, had fastened themselves upon his right ear. At any rate, I am afraid he muttered, sotto voce, an oath at hearing his old slave and friend call a Yankee master.

“Sarvant, mahster!”

Old Joe’s form was bent low, his teeth chattered, his eyes rolled in terror like those of a bullock dragged up to the slaughter-post and the knife.

The sight of a man’s face distorted with abject fear has always filled me with deep compassion; but I believe it arouses in the average man (which I am far from claiming to be) a feeling of pitiless scorn.

“Sarvant, mahster!” chattered old Joe, writhing himself behind the kitchen table. The soldier was an average man.

“Where is your master, you d—d old baboon?” said he, entering the kitchen.

“My mahster, yes, mahster, my mahster, he—for de love o’ Gaud, young gent’mun, don’t pint her dis way,—she mought be loaded. Take a cheer, young mahster; jess set up to de table” (over which he gave a rapid pass with his sleeve) “an’ lemme gi’ you some o’ dat nice bacon I was jess a-fryin’ for my mahster’s supper.”

At these words old Jim’s teeth began to chatter so that he forgot the belligerent brier.

The soldier, hungry from his march, fell to, nothing loath, but had scarcely eaten three mouthfuls before several of his comrades appeared, all of whom fell foul of poor old Jim’s supper with military ardor, if without military precision.

“Where’s the old F. F. V.?” asked a new-comer, through a mouthful of hoe-cake.

“Yes, where is your master?” put in the first man. “You didn’t tell me. Out with it.”

Joe had had time to repent of his ill-advised admission in regard to the supper.

“You ax me whar Mr. Bush is? Oh, he’s in Culpeper Court-House. Leastways, he leff b’fo’ light dis mornin’ boun’ dar.”

The audacious lack of adjustment between this statement and the facts of the case amazed, almost amused, old Jim. Breathing a little freer, he ventured softly to shake his ear loose from the brier; for he could not reach it with his hand.

“Why, you lying old ape, didn’t you tell me that this was his supper?”

“Cert’n’y, young gent’mun; cert’n’y I say dat, in course.”

“And your master at Culpeper?”

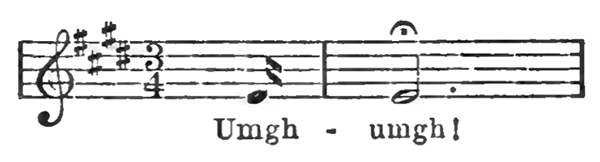

“Yes, young mahster. Dis is de way ’tis. You ’pear like a stranger in dese parts, beggin’ your pardon, an’ maybe you mout’n’ understan’ how de folks ’bout here is. S’posin’ some o’ de neighbors had ’a’ step in, and dar warn’t nothin’ for ’em to eat, an’ mahster hear ’bout it when he come back, how I turn a gent’mun hongry ’way fum de do’. How ’bout dat, you reckon? Umgh-umgh! You don’t know my mahster! Didn’t I try it once! Lord ’a’ mussy!”

“How was it?”

“You ax me how was it! Go ’long, chile!” (No musket had gone off yet, and Joe began to feel rather more comfortable.) “Go ’long! My mahster was off fox-huntin’ wid some o’ de bloods,—some o’ de bloods,—an’ when he come back an’ find out I hadn’t cook no supper jess ’cause he was away, an’ I done turn a gent’mun off widout he supper, mahster he gimme, eff you b’lieve Joe, he gimme ’bout de keenest breshin’ Joe ever tase in he born days.” And, throwing back his head, he gave a laugh such as these soldiers had never heard in their lives.

And none of us shall ever hear again.

As for old Jim, who had never laid the weight of his finger on the romancer whose imagination was now playing like a fountain, tears of affectionate gratitude came into his eyes.

An instant later, and all kindly feeling was curdled in his simple heart.

Hearing a bustle, he peeped through the briers, and saw the officer in command of the party coming towards the kitchen, bearing in his hand the Virginia flag. He had discovered it in old Jim’s bedroom, where he had tacked it upon the bare wall, so that it was the last thing he saw at night and the first his opening eyes beheld. It was an insult to the Union soldiers, he heard the officer say, to flaunt the old rag in their faces. It was what no patriot could stand. He would teach the dashed rebels a lesson. “Set fire to this house,” he ordered. “The old rattletrap would fall down anyway, the first high wind that came along,” he added, with a laugh.

That laugh had a keener sting for old Jim than the order to burn down the house which had sheltered him for sixty years. The bitterest thing about poverty, says Juvenal, is that it makes men ridiculous.

Late in the night, when the smoking ruins of his house no longer gave any light, Jim crawled stealthily down the ravine. Could the sentry, as he marched back and forth on his beat, have seen the look that the old man, turning, fixed upon him every now and then as he made his way through the jungle, he would have felt less comfortable. As for Jim, half dead with cold, he reached the fires of the Confederate pickets at daybreak. On his way he had stopped at a certain old oak, and, thrusting down his arm into its hollow trunk, drew forth his rifle.

“Bushy-tails,” said he, with grave passion, waving his hand in the direction of the tree-tops above him, “you needn’t mind old Jim any longer. Lead is skeerce these times. You may skip ’round and chatter all you want to. Your smellers is safe. And gobblers, you may gobble and strut in peace now. You needn’t say put! put! when you see me creepin’ ’round. I won’t be a-lookin’ for you. You’ll have to excuse the old man. Bullets is skeerce these days, let alone powder. So, good-by, my honeys. And if you will forgive me the harm I have done you, old Jim won’t trouble you any more.”

And so, with his rifle across his lap, he sat upon a log and warmed his benumbed limbs, and, looking into friendly faces, warmed his heart, too.

“I say, old man,” said a young soldier, chaffing him, “what do you call that thing lying in your lap? Can it shoot?”

“I call her Old Betsey,” said he. “You may laugh at her, but if you hold her right and steady, she hurts. There ain’t anything funny about Old Betsey’s business end, I promise you.” And he tapped the muzzle of his rifle with a grim smile.

Late in the afternoon of the next day (it took him all this day to get thawed) old Jim bade the jolly boys at the picket station good-day. He was going scouting, he said.

“Leave the old pop-gun behind,” cried one.

“No, take it along,” put in another. “Perhaps you may knock over a molly-cotton-tail. Fetch her in, and we will help you cook her.”

Just before sundown the old man reached the summit of a densely-wooded little hill, about three hundred yards from where his house had lately stood. Stopping in front of a tall hickory on its apex, he raised his eyes and surveyed the tree from bottom to top.

“I went up it once, after nuts,” said he, speaking aloud; “but that was many a year ago,—let me see,—yes, forty-five years. Well, I must try—ah, I see,—I can make it.” And, leaning Old Betsey against the huge trunk, he tackled a young white oak.

Old Jim was tough and wiry, and found no great difficulty in climbing this to a point about thirty feet from the ground, where a large branch of the hickory came within a foot of the white oak. This he cooned till he reached the trunk. [I have not time to define cooning. Suffice it to say that, like heat, it is a mode of motion.] Toiling up this till he reached a fork about eighty feet from the ground, he, with a sharp effort, adjusted his own bifurcation to that of the tree, and immediately, without taking time to collect his breath, leaned forward, and fixed his eyes intently upon the little open space in front of the ruins of his house. He gazed, motionless, for a little while, then nodded his head,—“Ah, there he comes.” He sat there for half an hour, watching the sentry come into view and again pass out of sight, as he marched to and fro. “Well, old man,” said he, at last, “I reckon you know about all you want to know.” And twisting his stiff leg out of the fork, with a wry face, he descended the hickory, and took his seat upon a fallen trunk that lay near, throwing old Betsey across his lap. It was growing dark, and every now and then he raised his rifle to his cheek and took aim at various trees around him. Took aim again and again, lowering and raising his rifle, with contracted brows. “I am afraid my eyes are growing dim,” he muttered; “but the moon will rise at a quarter to ten, and then it will be all right, won’t it, old Bet? Don’t you remember that big gobbler we tumbled out of the beech-tree, one moonlight night—let me see—nineteen years ago coming next Christmas Eve? And you ain’t going to go back on me to-night, are you? Oh, I know you will stand by me this one time, if my eyes are just a little old and dim. I know you will help me out, as you have done many a time before, when I didn’t point you just right, but you knew where I wanted the bullet to go. Do you know what’s happened, old gal? Do you know that the little corner behind the bed, where you have stood for fifty years, is all ashes now, and the bed, too? Do you hear me, Betsey? And as the Holy Scripture says, the birds of the air have their nests, and the foxes their holes, but you and I have not where to lay our heads.”

The old man bowed his head over his rifle; and the fading twilight revealed the cold, steady gleam of its polished barrel, spotted with the quivering shimmer of hot tears.

A soldier marched to and fro in the darkness. It oppressed him, and he longed for the moon to rise.

Does the wisest among us know what to pray for?

Tramp! tramp! tramp! tramp! He pauses at one end of his beat and looks down upon his comrades sleeping, wrapped in their blankets, with their feet to the fire. When his hour is up, he, too, will sleep. Yes, and it is up, now, poor fellow, and your sleep will know no waking!

Yet it was not you who burned the nest of the poor old man. Nor even your regiment. Nor had you helped to hound the South to revolution by threats and contumely. ’Twas John Brown dissolved the Union. You hated him and his work, for you loved your whole country,—you and your father, who bade you good-by, the other day, with averted face. And now you must die that that work may be undone. You and half a million more of your people.

The South salutes your memory!

Ah, the moon is rising now. Ribbons of light stealing through the trees lie across his path, and yonder, at the farther end of it, the Queen of Night pours a flood of soft effulgence through a rift in the wood. The young soldier stood in the midst of it, bathed in a glorious plenitude of peaceful light. Such perfect stillness! Can this be war, thought he? He could hear the ticking of his watch upon his heart. But the click! click! beneath that dark old oak,—that he did not hear. And that barrel that glitters grimly even in the shadow,—he sees it not. The tear-stains are upon it still; but the tears are dried and gone.

Click! click!

The muzzle rises slowly; butt and shoulder meet. A head bends low; a left eye closes; the right, brown as a hawk’s and as fierce, glares, from beneath corrugated brow, along a barrel that rests as though in a grip of steel. The keen report of a sporting rifle—not loud, but crisp and clear—rings through the silent wood, and there is a heavy fall and a groan.

And the placid moon, serene mocker of mortals and their woes, floated upward and upward, and on and on. On and on, supremely tranquil, over other scenes, whether of love or hate.

Ah, can it be true that we poor men have no friend anywhere in the heavens above, as some would have us believe? or the ever-peaceful gods, dwellers upon Olympus, have they in very deed forgotten us?

“Where’s your game, grandpa?” asked the young soldier. “We have been sitting up waiting for you and your rabbit.”

“There are two kinds of game,” replied the old man, warming his hands before the fire; “one sort you bring home, the other kind you send home.”

“What! did you shoot a Yankee? One of the boys thought he heard the crack of a rifle.”

“’Twas old Betsey,” replied he, patting her cheek, as it were. “We whacked one of ’em. He won’t set fire to any more houses, I reckon.”

After this, old Jim, thoroughly acquainted with the country for miles around, became a regular scout; and going and coming at all hours of the night and day, he was soon well-known along the line of our outposts. And whenever he had important information to give, he went straight to headquarters; but whenever, after a moonlight night, he stopped at the picket-post, sat down on a log and toyed with his rifle, seeming to have nothing to say, the boys knew that he was waiting for a certain question: “Yes, old Betsey and me whacked one of ’em last night.” And then he would set out for headquarters, and the soldiers, passing the news, and adopting old Jim’s word, would say, “Old Bush whacked another of the rascals last night.” And these two words, so often brought in contact, at last cohered. Bushwhacker did not, therefore, originally, at least, mean a man who whacked from behind a thicket, but one who whacked after the fashion of old Jim Bush.

And I am a Bushwhacker who whacketh after that fashion. So much so, that it seems to me that my parents made a sort of prophetic pun when they named me John Bouche. The difference between me and old Jim is simply this: that he expressed his sentiments with a carnal rifle, I mine with a spiritual one. He hung upon the skirts of the Northern hosts; I go stalking stragglers from the Noble Army of Lies. Every sham the sturdy Whacker molecules of me impel my soul to hate. Yet my Huguenot blood shrinks from martyrdom. Did not they leave France to avoid it? I never attack the main body. But let a feeble, emaciated, and worn-out little lie, or a blustering, braggart fraud, or a conceited, coxcombical sham, stray to the right or left, or get belated on the march! I pounce upon him like an owl upon a field-mouse. It is my nature to. And so the reader must not be surprised, as we journey along together, through scene after scene of my story, to find herself suddenly left alone at the most unexpected times and places. I’ll come back, after a while, bringing a scalp; after which we will jog along together, for a chapter or so, again.