Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

By ANNETTE LYSTER

AUTHOR OF "KARL KRAPP'S LITTLE MAIDENS;"

"LIFE STORY OF CLARICE EGERTON;"

"RALPH TRULOCK'S CHRISTMAS ROSES."

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT

SOCIETY LONDON.

56 PATERNOSTER ROW AND

65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

BUTLER & TANNER.

THE SELWOOD PRINTING WORKS.

FROME, AND LONDON.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I. ONE CHANCE BY SEA, AND ONE BY LAND

THE BOY WHO NEVER LOST A CHANCE

ONE CHANCE BY SEA, AND ONE BY LAND.

MANY years ago, when railroads were not quite so common as they are now, and when no one knew how completely they would change the face of old England and the habits and manners of her children, some workmen from Birmingham were employed in laying the rails of a line which was to connect a certain small seaport in Essex with an inland town twenty miles off, which already possessed railroad communication with London. I shall call this tiny seaport—now a considerable place, thanks to this very railway—Sandsea, and the town Kingsmore, though these are not the real names of the places.

The railway was being made for the benefit of the salt trade: there were extensive salt marshes near Sandsea, and hitherto the salt had been sent to London or other places by sea, which was a serious impediment to the trade, as the Essex coast is a very unsafe one.

It was in the month of March, and the weather was bright and dry, but bitterly cold. A north-east wind blew in from the sea and swept over the somewhat level face of the country, nipping any silly little plants which had ventured to show their noses, and nipping too, not only the noses, but the fingers and toes of all who were exposed to its blast.

Several miles of the permanent way had been made, and about two miles of rail, beginning at Sandsea. On these rails the workmen ran a lorry, which carried their tools and the greater part of their own number to the scene of their labour. But the person who brought the men their midday meal had no lorry at her command, and it was a pretty heavy load. She was the wife of the chief workman, who was in command of the party, and except bread, she brought out everything required for a good hearty dinner for the whole gang; the bread they took with them in the morning. This arrangement had worked very well for some time, but one day twelve o'clock passed, and the welcome sight of dinner was not to be seen.

The north part of Essex is not quite so flat as the south; but the hills are low and rounded, and there are no very striking features in the landscape. In a cutting through one of these hills there was a semicircular excavation, where it was intended to build a tool-house presently; but just now it was very useful to the men, as it afforded them shelter from the wind, and for several days they had used it as their dining-room.

"Well, mates!" said Tom Avery, a tall, good-humoured looking fellow, dressed in white flannels, which were wonderfully clean, considering the nature of his work. "Whatever has come to my missis? There's a clock inside of me that says it's past twelve."

"Long past," said another man—a stoutly made surly-looking fellow, with wonderfully black hair. "And I'd like my dinner—I don't deny it."

Tom Avery stood up, shaded his eyes with his hands, and took a good look along the line.

"I see her now!" said he. But a few moments more showed him that unless Bess Avery had turned into a boy, or taken it into her head to put on a boy's dress, this was not his "missis," though it was undoubtedly his missis's basket that the lad carried on his arm, and carried with more ease than its rightful owner ever did.

"Well to be sure! What's up with Bess?" said Tom Avery.

The men all ceased their work, and gazed at the rapidly approaching stranger.

"Blessed hour!" cried a red-headed lad, whose voice proclaimed him an Irishman. "What 'll ye say if he's shoved her into the bog, and made love to the basket?"

A shout of laughter hailed this remark.

"The bog! What's a bog?—You'll mean the marsh, I suppose?" said one.

"And if he stole the basket, he would hardly have come here with it," said another.

"Well, how did he get it, then? Would Bess be very likely to give her basket to the like of he?"

"Look here, Paddy," said Tom Avery, "none of your cheek. My missis has another name besides Bess."

"And I've another name besides Paddy, which isn't me name at all! Larry Deasy, me name is, Mr. Avery."

Here the basket-bearer came within hail, and the matter of the names was dropped for the time.

"Hullo, young chap, where did you get that basket?"

The boy came on, laid down his load on the ground, straightened himself, and drew a long breath. Then he said,—

"Are you Thomas Avery?"

"Mr. Avery; none of your cheek," put in Deasy softly.

"I am; that's me," said Tom, pretending not to hear this.

"Then I'm to give you this basket, and tell you that Mrs. Avery slipped on the rail about half a mile from the town and turned her ankle badly. She couldn't come on, and she didn't know what to do, when I came up to her; and I offered to bring it on for sixpence."

"For sixpence: and who's to give you the sixpence?" said Avery doubtfully.

"She paid me herself, and I lent her my stick to help her home."

"Oh, well, that's a different story. Thank ye, I'm sure it's all right. Come, mates, we must unpack for ourselves to-day."

A little heap of coke and sticks lay ready in the recess to light a fire on which to make some tea, as one or two of the party were temperance men. The basket was quickly emptied and the contents served out: the lad who had brought it had seated himself on the lorry and kept his face turned away, that he might not seem to be wishing for some of the food. The wind swept through the cutting, and he shivered; he was decently dressed, but by no means warmly.

"Come in and sit in the shelter," said Avery, "the wind there is enough to cut you in two."

"Thank you," the boy said, and came in among them, seating himself with his back to the bank.

"Look ye, mate, are ye hungry?"

It was the surly-looking man who spoke. The boy's involuntary glance at the bread and meat answered the question more truly than his tongue did.

"Thank you, sir, I'll do very well."

"Ye know ye're hungry," said the man in a half-angry voice.

"Well, when I'm rested a bit, I'll go back to the village and buy bread."

"Too proud to take a bite with us," was the next remark, in a deep growl.

"Faith, the more fool he!" said Deasy.

"I don't know about pride," the lad said, "but I'd rather earn it, thank you all the same."

"Oh, blessed hour, the like o' that!" Deasy cried, actually ceasing to eat in order to stare. "Musha then, if any one would offer to fill Larry Deasy at their own expense, 'tisn't me that would stand between them and their fancy."

"I'm not a beggar," the boy said shortly.

The surly man pondered a little, and then said,—

"Look ye now. I and two more of us drink tea, and Mrs. Avery, she do make it for us. If you light that fire and make that tea, I'll pay ye in bread and meat. How will that work?"

"That will work well!" the lad said, springing up gaily; "and I'm more obliged than I can say for the chance."

With quick, handy movements, he lighted the fire, and taking the kettle which his employer produced from some hiding-place, he ran to a stream a little way off and filled it. The tea, tied up in a bag, was popped in, and when the water boiled, the tea was made. Tin mugs were now produced, and then the tea-maker was liberally paid in bread and meat, with a mug of tea "for luck," the mail said, with a queer grimace which seemed meant for a smile. If the stranger had been loath to confess that he was hungry, he was by no means loath to eat; he made a splendid meal. And yet so generous was the supply, that he did not quite finish it. Picking up the paper in which the tea had been sent, he made a parcel of what remained, and put it in his pocket. Then he turned to his surly-spoken benefactor and said,—

"May I lie down here for a spell, sir? I'm dead sleepy; and maybe you'd rouse me up before you leave the place?"

"All right. Here's a couple of sacks to cover ye. It's rather cold for sleeping out o' doors."

"I didn't sleep a wink last night or the night before that," the boy said, as he curled himself up near the remains of the fire and covered himself with the sacks. He was asleep in five minutes, and never moved until, at six o'clock, the men came back to collect their scattered belongings.

"Bless the boy! I had nearly forgotten him!" cried Jack Sparling, which was the name of the tea-drinker. "Come, lad, rouse up!"

The boy jumped up, staring, and only half awake for a moment, but he soon remembered where he was and all about it; and while the men piled the tools on the lorry, he very neatly packed up the tins and knives and what was left of the dinner, in the basket. Sparling watched him, and saw that not so much as a crust was kept back for himself, and this gave him a good opinion of the lad, as there could be little doubt that he was in want. The boy brought the basket and laid it on the lorry, saying to Avery—

"If you please, sir, I'm to go to your lodgings with you, for Mrs. Avery took my bundle back with her when I took her basket, and she said I was to come with you and get it."

"All right, get up on the lorry. No, Deasy! not a bit of it, my lad. You rode all the way out this morning and wouldn't help, so you'll just walk, and push all the way in."

Deasy looked rebellious enough for a moment, but then said, with a laugh, "You may make me walk, but you can't make me push!" And darting forward, he ran away along the line, settling into a kind of trot when he was out of reach, and they saw him no more.

"Lazy young cub!" said Avery wrathfully. "They may well call him Easy Deasy; but I declare, since we began this job, that boy has been the plague of my life! He's got into idle company, that's how 'tis, and he'll lose his place yet."

"What's your name, boy?" said Sparling, who was seated beside the stranger on the lorry.

"Roger Read."

"Where d'ye come from?"

"Last from London, in a ship called the Sandlark."

"And what made them bring ye? For you're no sailor."

"No, indeed!" Roger answered, laughing. "But I was on the wharf looking out for chances, and some boy, the cabin boy they called him, was not to be found, so I offered to go; and another boat belonging to this place is to bring the right boy when it comes after us."

"But what made you come here? Have you no friends in London?"

"I've no friends anywhere. I want work, and in London there are so many looking out for jobs, that a stranger has no chance; so I said to myself, 'Here is a chance,' and so I offered, and they couldn't wait, and didn't like to go without a boy."

"And what are you going to do now?"

"I don't know yet; anything I can get to do."

"What did the sailors pay you?" asked Sparling, after a pause.

"Nothing at all," Roger said, laughing; "and enough, too, for all the work I did. Man, I got sick before we were out of the river, and I just lay like a log the whole way! I would have been thankful to any one that would have thrown me into the sea; and they thought I was shamming! One fellow beat me with a bit of rope—I'm black and blue with bruises; but at the time I didn't feel it, I was so bad. So, of course, they paid me nothing. I got the voyage, you know; and perhaps I may get a chance here."

"You're the lad for chances," said Avery, who was listening to the talk.

"My grandfather told me two rules, and he said if I kept to them I'd die a rich man. One is, 'Never lose a chance'; and the other, 'Earn your dinner before you eat it.' So far, I've minded them both. Why, how fast we've come! I'd no idea we had reached the village."

"The town, if you please," said Avery; "don't let the folk here catch you calling it a village; a seaport town, that's what Sandsea is."

At this the men, who were most of them from Birmingham, set up a laugh; and being now at the terminus, they dispersed, with careless "good-nights."

Sparling lodged in the same house with Avery, and boarded with the Averys, so they went off together, taking Roger with them. They found Mrs. Avery limping about in considerable pain; and she declared that "her man" would have found her sitting crying on the bank when he was coming home, but for "yon lad," who had helped her to her feet, bandaged her ankle with her handkerchief, and lent her his fine, thick stick.

"And there's your stick, my lad, and your bundle too, and I am really obliged to you."

"Keep the stick till you can walk without one, ma'am; it is a good one, for 'twas grandfather's; I'll come to you for it," said young Read, taking his bundle from her.

"Look here, boy," said Avery, "my missis won't carry that basket to the first cutting to-morrow nor yet next day, and if you'll do it, we'll pay you a halfpenny each and give you your dinner."

"Thank you, sir, I will gladly. Why, here's a chance already!" cried Roger, gleefully. "Good-night. Good-night, ma'am; I'll come in good time for the basket."

Sparling followed him out into the passage. "Where are you going to sleep, lad?"

"Well, I don't know yet," Roger answered.

"Come up and sleep in my room; I can lend you a blanket. You needn't be thinking—don't eat the blanket, and then you can face your grandfather."

Roger laughed. "Poor old grandfather!" he said. "He's dead and gone this year past. Well, thank you, sir, I shall be glad to have a roof over me."

But when Sparling shyly offered him a bite of bread and cheese, he refused, and lay down at once, rolled up in a blanket. And if hunger is the best sauce, fatigue is the best sleeping draught; so Roger slept soundly.

THE BEST CHANCE OF ALL.

WHEN Roger awoke the next morning, he found Jack Sparling engaged in his morning ablutions, which were of a rather noisy and vigorous nature. He was offered "a loan of the tub," and gladly accepted it. When he was washed and dressed, he looked round for Sparling, and saw him kneeling beside his low bed, his face hidden in his hands, his whole person perfectly still. Thus reminded of his prayers, Roger knelt down too and said them, watching Sparling all the time. The latter, his prayers finished (Sparling did not merely say his prayers), stood up and opened a little-box which lay on a shelf over his bed. He took out what Roger could see was a picture of some sort, and having looked at it for a few moments, he muttered "My lass!" in his gruffest tones, put the picture into the box, and locked it up. Roger jumped up and went over to the window.

"Another fine cold day," said he. "Well, sir, I'm very much obliged to you, and I shall see you again at dinner time."

"Sleep here till you get good work," said Sparling. "You ain't in my way a bit, and it'll be better for you than sleeping out in such weather."

"Thank you, sir, you're really very kind. If you don't think the people the house belongs too will mind, I am very glad to take your offer."

"No danger. I'm off," said Sparling. Roger followed him down stairs, and Sparling went into the Averys room and said,—

"Tom, ye wouldn't miss what that lad would eat."

"Don't know that," said Tom, "he seemed to have a terrible appetite! Call him in, Bess."

But Roger had vanished, having suspected what Sparling was up to. He ran down to the beach; some fishing boats had just come in, and as he munched his reserved store of bread and meat, he watched the sorting of the fish, and listened with keen interest to the bargainings between the fishermen and the owners of sundry big baskets and small carts, which were soon stored with fish of various kinds and carried away some into the little town, some going off along the country roads.

Not a word was lost on Roger; and he laid up in his excellent memory many useful facts connected with the buying of fish. Then he started off after a woman with a basket, to acquire information about selling it. And he heard that woman sell a fish for two shillings for which he had seen her pay ninepence, and heard her declare stoutly, that "she had just her own money, not a penny more, and no one but Mrs. Parker should get such a bargain, but she had that respect for Mrs. Parker."

"I won't do that," thought Roger; "but I must think about it. It may be a good chance. Any one may sell fish. I must save up my pence."

He then looked about for a shop where they sold milk, and invested a penny in a big mug of skim milk. Thus refreshed, he went to the new railway terminus, and watched the carpenters and painters; getting into conversation with a painter, he so cross-questioned him as to the way he did his work, and his reasons for doing it in one way and not in another, that the man at last said that he never was "good at saying catechiz."

"Well, but you see I really want to know how things are done, it comes in handy."

"Use your eyes then," said the man.

And Roger did use his eyes, not only that day, but very often afterwards, till he longed to take the paint brush and try a bit of "graining" himself.

For three weeks or so, Roger carried the dinner basket every day, and slept in Sparling's room every night. At the end of that time, Bess Avery was all right again, and, as the boy put it, "that chance was over."

But Avery gave him a "bit of a note" to the chief man among the navvies, and armed with this, Roger plodded along the unfinished line until he reached the place where they were now at work. This was nearer Kingsmore than Sandsea, so, when he was engaged by the clerk of the works, Roger was obliged to sleep at Kingsmore. But, in about a fortnight, he was surprised by a visit from Sparling, who had "knocked off" at dinner time and come along the line in search of him.

"Why, Mr. Sparling!" cried Roger. "What brings you here?"

"Came after you. Do you like this chance so well that I needn't tell you of a better?"

"No, sir, I don't greatly like it. They're a queer set, these men."

"Ay, navvies mostly is. Well, Easy Deasy has gone off. Ever since we came here, he's been troublesome, and Avery says he is only in hopes that no boy can be got to come in his place. It's to light the fire, blow the bellows, carry the lead, do Deasy's work all round. It's one and sixpence a day. Will you come?"

"Will a duck swim?" said Roger gleefully. "Are you going back at once? Oh, wait till I speak to Mr. Brown, and if he lets me off at once, I'll go with you, if I may."

Sparling nodded. Roger's arrangements were soon made, for he had found the people of the house in which he lodged so dishonest that he had got the habit of bringing all his worldly possessions, with him, and the load was not a heavy one.

He and Sparling set off at once, Sparling slouching along heavily, always looking down on the path, Roger mighty alert and lively, taking in everything.

"Why, you've reached the second cutting!" said he, when, after a long tramp, they came upon the iron rails in the gathering twilight.

"Ay!" said Sparling.

"And what a way you came, losing your half-day too, just to find me. Mr. Sparling, what makes you so kind to me?"

"I'm under orders to be kind," was the answer, given in Sparling's half-surly growl. He did not look up, and Roger stared at him.

"Whose orders, sir?" said he presently.

"My Master's, the Lord Jesus," with a touch of his hand to his cap. "He says:

"'Be kind one to another.' 'Freely ye have received, freely give.'

'Do unto others as you'd like they would do to you.'

"It's in the Bible,—I've no great memory."

Roger walked along in silence for some time. At last he said doubtfully,—

"That's not common talk, sir."

"More's the pity. It's because folks don't know. I wish they did. Look ye here, Roger, you can sleep in my room if you like, and we'll get Mrs. Avery to put in a second bed for you. She won't charge you much. Don't ye go chumming with young Bowles and that set; they mean no harm perhaps, but I doubt they got Deasy into mischief. Bess likes ye, and you'll be safer with us."

"I'm only too glad to get the chance, sir," said Roger.

"You and your chances!" growled Sparling with the queer look that served him for a smile. "And yet I doubt, boy, you're careless about the best chance of all?"

"What's that?" very alertly.

"The chance of going to heaven."

"Oh!" said Roger a little disappointed.

"Ah, just so. You're taking the chance of going—t'other way. A sharp lad like you ought to see to it."

Roger said nothing, but he felt oddly put out. He had been used in old times—they were only a year old, but they seemed far off to him—to go to church and say his prayers regularly; but his lot had never been cast among really religious people, and what Sparling said took him by surprise and puzzled him. Honest, industrious, active, and clever as Roger was, he was very little better than a heathen, as far as any sense of religion went. He knew that it was wrong to steal, and he thoroughly believed that "honesty is the best policy," also that it was wrong and foolish to tell a lie: all this he owed to being the native of a Christian country.

If asked, he would have said that he knew that he would be punished hereafter if he did wrong, and that if he did his best, he would go to heaven: and that was all. But Sparling's words about the "best chance of all" got into his head and stayed there. Only into his head as yet: the boy had no one to care for but himself, and at this time of his life may be said to have been all head and no heart.

He was soon very comfortably settled in the house with the Averys and Sparling, and began saving up money towards a project that was growing in his mind. Presently Tom Avery told him that if he continued to please him as well as he now did, he would take him to Birmingham, and get him taken on permanently in Deasy's place. Even then Roger did not give up his saving ways. Young Bowles laughed at him; but Roger said nothing, until he was asked what he was saving for. "One never knows what chance may turn up," was his answer. He was rather fond of the word "chance," meaning opportunity; and whenever he used it, Sparling would look at him with his grave grey eyes, reminding him always of that "best chance of all."

After a while, Roger took to going to church every Sunday with Sparling: and later in the day they often took a long walk into the country together. Sparling had taken a real liking to the boy, and Roger was not ungrateful. Little by little, he began to love this queer silent young man, ay, and to admire him. And no wonder.

Jack Sparling's life was one that bore looking into. Bess Avery was never weary of telling how, when she and Tom were down with fever, Sparling nursed them and worked for them, as if he had been a brother—though up to that time, they had hardly known him. A purer, holier, more self-denying life no man had ever lived than did this poor rough workman, who could read, but had never learned to write, and who was not even clever at his trade.

The job lasted some time; it was July before the rails were close to the town of Kingsmore, where they would join the rails already in use. And before that time, Sparling and Roger had had many walks and many talks, only one of which we can hear. This took place on a glorious day late in July, and the pair of friends had walked several miles into the country, and were resting under a big beech-tree which stood in the corner of a large field of wheat. It had been a hot summer, and the wheat was ripening early; and the fine full ears and long straw promised a good harvest.

"Where I was born," said Roger, "the ground is red, not black like this."

"This is rare rich soil, they say," answered Sparling; "where was that, Roger?"

"In Devonshire. My grandfather was Sir Carew Shafton's gamekeeper."

"The grandfather that bid ye never to lose a chance?"

"Yes, I never had but one grandfather; at least, I must have had two of course, but I never saw the other. Nor my mother either. She died when I was born."

"What like was your father?" inquired Sparling.

"My father?" said Roger. "My father was a genius. That's what they said of him. Man! There was nothing he couldn't do, except—stick to it. Sir Carew got him a place in a big piano factory; his cleverness lay mostly that way," the boy said vaguely, "but he invented an improvement, and the head folk said they didn't care for it, so he gave up his place and came home. I lived with grandfather, you know. Father walked in,—we were having our tea,—grandfather looked at him,—

"'No. 7,' says he.

"Father laughed. 'Just so, sir,' says he; 'but No. 8 will make my fortune.'

"I didn't understand then; but afterwards grandfather told me that was the seventh start in life he had got, seven places, all different, and gave satisfaction in every one of them, but never stayed long in any. He'd been a clerk in the post office, he'd been in a great chemist's shop, he'd been Sir Carew's—well, it's a long word, and it means he wrote letters for him—Sir Carew is very blind, and likes to have a man to write for him. I forget the rest of the chances, but all were good. Well, in a few days, he went off to London to see who would buy his invention, and soon after that grandfather died quite suddenly. Father wrote for me to go to him, and that he would soon be able to put me to a good school."

He stopped short.

"Well, boy? What next?"

"Next—he died," said Roger. "His invention was no good. He got ill and died."

"Leaving you in London? Why didn't ye go back to Sir Carew?"

"I couldn't, he was very angry with me for going to my father. He'd have been good to me, if I had gone to him when grandfather died; but he was sore angry with my father, and when I said I must go when my father gave me no choice, he said I was not to suppose I could go to him when I was tired of idleness. I never thought of going to him after that. Father was only dead a couple of weeks when I came here. Now, Jack, I've told you all my history, you tell me one thing. I want to know how you came to be—so good?"

"Ain't good."

"Oh, ain't you, though! Jack, were you always like this, ever since you were a boy?"

"No, I didn't get a chance," said Jack with a look at the other. "It's said in the Bible:

"'Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth,—'

"And there's a many promises for those who do that. But I was a wild, idle fellow, and thought nothing of that."

"And what made you think? Jack, do tell me."

"I don't hold by much telling, boy."

"If I guess, will you tell me?"

Jack nodded.

"Was it because of the—person in your picture?"

No answer.

"You know, Jack, I couldn't help seeing you look at it and say, 'My lass!' every night and morning, when you've said your prayers. I did not mean to vex you."

Jack Sparling had turned away his face, but here, he thrust out a big brown fist and gave Roger's a squeeze. He remained quite silent for a long time and then suddenly said,—

"'Twere along of her. I met her when I was just twenty or thereabouts. She was so fair and soft-looking, like a pretty flower, just. Not all kinds of flowers; but, look ye now, I never see a white rose or a June lily, but I feel my heart go sick. It were more than a year before I dared to speak to her. Well, I was to marry her when I could keep her. And I was sent away, as now, on a job—and we was to be married when I came back. But one day I was sent for."

He waited a little to steady his voice.

"She was always delicate. She was too good for this world—not to say for me. She took a sudden weakness of the heart, they said. But I was in time—we had two days together; and we'll have for ever and ever together when we meet again. She gave me her Bible and she says, 'Read it, Jack, my dear, and pray. And I'll be looking out for you.' I began for love of her, and now I love my Master, and would try to serve Him without that. Roger, you have the chance of beginning young and not with a bad youth to remember, as I have. I wish, lad, you'd think serious of it."

"Jack, I will! I'd like to be as you are. I'll buy a Bible to-morrow and begin. You'll have to help me, though."

"You pray for better help than mine, boy. And the sermons, if you put your mind to it, do help wonderful. And the prayers and the hymns. Come now, we must be getting home. Well, it's a long time since I spoke of my lass to any one; though I keep thinking of her. Her name was Mary," he added in a soft voice, not a bit like his usual tone.

This was not the beginning of Roger Read's determination to be a Christian, but it certainly strengthened it, and he kept his word about buying and reading a Bible. He found many difficulties in his readings which Sparling could not explain, always saying,—

"We shall know one day, we know enough for this world."

But Roger, eager and intelligent, could not feel quite content with this, and longed greatly for help and instruction.

A NEW CHANCE.

A FORTNIGHT or so later, Roger Read was hard at work. The first train was to run the next day. He heard voices raised as if in anger, and standing still for a moment to listen, knew that one speaker was Tom Avery and that the other had a voice that he had heard before, though he did not at once recognise it. Avery was saying,—

"No, I won't, indeed. You were the plague of my life before with your cheek and your idleness. I've got a lad in your place that does his work like a man. I'll have no more to say to you,—" here the speaker and his companion came round some carriages which had hidden them from Roger,—"so be off with you, you needn't say another word."

"Ah, then, Mr. Avery, ye might listen to me. I worked wid ye three whole years, and well you know I was honest and willing—now you say, sir, was I ever in mischief till we came here and I took up with Bowles? In mischief to spake of, I mean."

"You were in too much here to please me."

"Yes, because I took up with Bowles, and you were always down on me; and then I gave impudence, and angered you worse; and then I ran off, thinking to get work on the fishing boats, but they won't have me; and I've tramped the country, and the farmers won't have me, and if you don't take me on again, sir, there's nothing before me but to starve, and that's the gospel truth, so 'tis."

It was Deasy, and his appearance quite confirmed his pitiful tale; he was very ragged, his shoes were in holes, he was very thin, and altogether very unlike the saucy, bright-eyed, Easy Deasy Roger remembered.

"Well, I can't take you on, and you know that as well as I do. You're not able to do a man's work, and I haven't leave to have more than one boy. And Read has the place, and I can tell you he isn't the lad to throw away a chance, as he'd tell you himself."

Roger came forward and drew Avery aside.

"Mr. Avery," he said, "listen to me. Maybe I ought to give it up. Was he really three years with you, and only got idle here?"

"Well, it is pretty true. He never put much into his work, took it easy, he did. But indeed there's no harm in the lad, and I'm sorry for him. He's learned this work, and he's not one that can turn his hand to anything. I was hasty with him too, but you're in your rights, and Deasy must just take his chance."

"And starve," said Deasy, who had drawn near unobserved.

"You can go to the workhouse," said Avery, at which Deasy set up a dismal howl.

"And be sent back to Dublin for me stepfather to kill me! Oh, musha! Thank you, but I won't do that if the water in these parts can drown me. Do you mind the way I was in when you took me on first?"

"I do; but where is the use of talking?" Avery said angrily. "I'm sorry for you, but I can't help you. Roger's got the place, and does the work better than you did."

"But," said Roger, "I'll go, all the same; if you'll take Deasy back, I'll go. I've saved money enough to set me going. I see a real good chance of getting on here; I'd rather go, anyhow, than stand in his way."

Avery looked hard at him—then shouted, "Jack Sparling, come here."

And Jack left his work and came.

"Look here, Jack. Young Deasy has come back, and, as you may see, he hasn't been making his fortune since he left us. He wants to get his place again, and I thought Roger was the lad to stick to it when he had it; but Roger says he will give up and won't stand in Deasy's way. Now the boy learned that kind of talk from you, Jack, so I just called you to see what you'd say."

Jack nodded and looked at Roger, who said,—

"'Do unto others as you would that they should do to you,'

"That's plain enough."

"You may never get such another chance," put in Avery, who looked annoyed.

"That's just it," said Roger, still speaking to Sparling. "I've been all for No. 1 as long as I can remember. I'm never likely to be able to do much, but here's a chance, I may do something. If I don't do it, I suppose it would just show that I'm not in real earnest. And don't be afraid for me, Jack. I have a plan, and I've saved enough to set it going. I shall do very fairly."

"Ay, lad," said Jack. And he stretched out a grimy paw and gave Roger's equally grimy paw a hearty shake, and then turned and walked back to his work.

Avery broke into a laugh, in which there was a queer mixture of unwilling admiration and annoyance.

"It's well for you, Roger, I do believe, that you'll be parted from him, he's making you as great a fool as he is himself; but there, you'll say you wish to be just such another, I suppose. All I have to say is,—Remember, if you give it up, you must stand by what you've done; I won't allow another change."

And Avery walked off.

"You be off now," said Roger to Deasy. "Here's sixpence, go and get some food, and come to work in the morning."

Deasy, who had passed the last ten minutes in staring hard at every one in turn, now stared harder than ever at Roger. Finally, his face began to work, and big tears ran down his dirty cheeks, making strange tracks of whiteness in the grey tint his countenance presented.

"Roger—Roger Read! I'm—not good at saying it—but I feel it, I do! I'll never forget—"

Here Roger was loudly called by half a dozen voices at once.

"Go," said he, "I have no time to talk now;" and when he came back Deasy was gone, to his great contentment.

That evening, when the men left work, Roger unfolded his plan to his friend Sparling, who pronounced it a good one, but said that if it did not succeed, Roger was to write to him at an address in Birmingham, and he would get a friend to answer the letter and send him money to come to Birmingham, where he thought so handy a fellow would surely get work.

Among the other men, particularly the younger ones, Roger's decision about his place was much spoken of, some calling it an act of folly, some admiring it. Avery told his wife privately that he was rather glad, for that one saint was enough! But between Sparling and Roger very little was said on the subject. Very unlike in most things, they were alike in this—they were honestly in earnest in their endeavour to be like their Master. To Sparling, Roger's act seemed natural under the circumstances, though he was sorry that the lad had exchanged a certainty for a chance. In a few days the workmen returned to Birmingham, and Roger was left alone.

At first, he felt very lonely, but he was soon far too busy to think about it, though he missed Jack Sparling very much, and regretted greatly that his friend could not write. He began to carry out his cherished plan at once. In fact, the first day that the train began to run regularly between Kingsmore and Sandsea, Roger, with a huge basket filled with fine fish, was one of the first third-class passengers. He saw with satisfaction that none of the owners of the original baskets and carts seemed to have thought of leaving their old beats.

He had found out that no fish was brought to Kingsmore regularly, and, to use his own words, "to be first in the field was half the battle, and this was a fine chance." First in the field he surely was; and before one o'clock he had sold every fish in his basket at good prices. And he returned to Sandsea, to be ready for the morning boats, a proud and happy lad.

"If I could only tell Jack!" he said.

And now time passed rapidly with Roger for though his work was not exactly hard, it required him to be always on the alert, and to be at the place where the boats came in very early. After a time, others set up baskets to convey fish to Kingsmore, finding the prices there better than at Sandsea. Then, indeed, Roger had a rather anxious time for they tried to undersell him; but after a few days, he found that most of his customers waited for him, saying that he always gave them good fish, and never tried to cheat. He went on making money steadily; in fact, his savings presently amounted to so considerable a sum that his common sense told him he ought not to carry it about with him, even though he had sewed it up in a piece of stout leather, and the leather in a piece of calico, and wore it tied to a piece of cord round his neck.

All this time Roger attended church regularly at Sandsea, where he always slept and spent his Sundays. He now rented the room he had once shared with Sparling; and here he kept his few belongings and his Bible, which he still studied, and still longed to understand better. Many a kind action too, known only to himself and those he helped, Roger did; and Jack Sparling would have felt satisfied if he could have seen how the lad he was so fond of was living.

But Roger, a far more intelligent fellow than Jack, felt his ignorance weigh very heavily on him, and often longed for "a chance" of learning many things—to understand his Bible, to write a fair hand, and to learn arithmetic. He was clever at figures, and could calculate the price of a fish when he sold by weight, well enough; but as he aspired to rise in life, he felt that he ought to know how to keep accounts.

A year and some months went by, and Roger began to feel sure that he could sell more fish than he could carry, even if the basket were yet woven of willow that would contain them: in fact, he knew, to use his own words, that he was losing chances, and to lose a chance went to his heart.

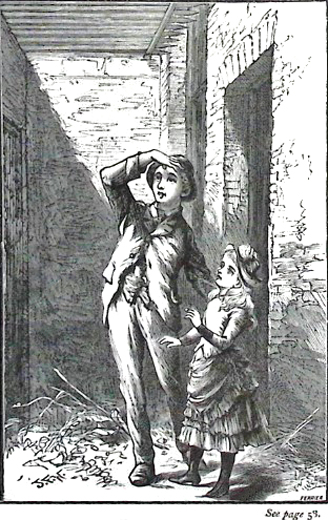

One afternoon he was going up Cecil Street towards the railway station with his empty basket, when an adventure befel him which proved of some importance. He saw a neatly dressed little girl with pretty curly hair, kneeling on the pavement beside a rusty grating which admitted the light to a small window below. The child resisted every effort to get her out of the way, holding on to the bars and screaming dismally. Every one seemed in a hurry, for a train to Sandsea was just about to leave, and many Kingsmore people had lodgings in Sandsea that year, going out there in the afternoon.

Roger stooped over the child and said,—

"What's the matter, you poor little thing? Stop crying and tell me, and I'll help you."

"My shilling, my new bright shilling that father gave me."

"Well, where is it?" said Roger.

"It went down there! Father gave it to me, to buy a wooden spade and a tub, for we're going to Sandsea, you know, and I want to dig like the others; and he bid me keep it in my pocket, but I took it out to look at it, and some one hit my elbow, and it fell, and it rolled along, and I—and it went down there!"

"Well now, you dry your eyes and never fear, we'll get the shilling. Why, it's the shut up house—and the train will be gone. Never mind, I can go by the late one for once. Come along, missy, till I find out who has the key of this house. Your shilling is safe enough, for no one can get at it."

He entered the shop next door, a baker's shop, where Roger was well known; and fortunately it turned out that the baker had the key himself, and he at once handed it to Roger.

With the little girl confidently holding his hand, Roger unlocked the door, and saw before him a narrow passage, with a door at the side which opened into the shop. But the place was so dark that the little girl would not enter it, and Roger could see no way of descending to the basement storey. He groped his way to the window, and, after much fumbling, found that the shutters were outside—a fact which he ought to have remembered, for he was quite familiar with the look of the house. Out he went, and having with difficulty removed the heavy bar, he took down one shutter.

Then the light showed him a small shop, and behind the counter, he found a flight of steps going down to the lower storey. Down he went, groped about in darkness, and found a little door by which he could get out into the area; so he ran back for the little girl, and they went out together.

But at first, the shilling could not be found, and the child was almost in despair, when Roger's keen eyes caught a glimmer from something bright, and with a shout, he pounced upon the coin. The child set up a joyful cry, whereupon a voice from above called aloud,—

"Mary! That's certainly Mary's voice—Where are you, child?"

"That's father. Oh, look, what fun! He's walking over our heads! Father, father—I'm here in this hole."

"Why, how on earth did you get there?" exclaimed the man on the pavement, gazing down at his little daughter in great amazement.

"Wait one moment, and I'll come to you," said the child.

Roger let her go, but he stayed to close up the door and window, and then followed. He found her at the door, telling her story as fast as her little tongue could wag, to a well-dressed man without a hat, who seemed greatly relieved at having found her.

"And I should never, never, have seen my shilling again, only for him. He said he'd find it, and he did find it; and he was so kind, father, and I was just mis'able."

"Why, Read! Is it you?" and Roger recognised Mr. Wilson, who kept the Post Office and had a fine shop, where he carried on business as a bookseller and stationer.

"I am greatly obliged to you. It was very kind of you to waste your time helping my careless little woman here. Her mother missed her from the door, and was so frightened that I had to be off without my hat to search for her. She can't pay me visits in the shop, if she runs off like this."

"I didn't want to run off, indeed! I wanted to look in the window at the spades and pails."

"Well, you came the wrong way, You little goose. Come now, let us get home. Thank you, Read—look in with your basket in the morning."

"Yes, sir," said Roger absently; he was in deep thought, and hardly heard what Mr. Wilson said. As soon as he was alone, he took down a second shutter and examined the shop. It was very dirty, it wanted painting badly, and the woodwork was broken and defaced. Roger looked carefully at everything. Behind the shop there was a tiny room, upstairs there were two rooms, and below there was a good kitchen and a little back yard, all much in need of repair and very dirty.

"I wonder why it is not let; but as it is now, it ought to go cheap," said Roger, standing once more in the shop. "Here's a chance; I can only try."

And having shut up the house carefully, he went back to the baker with the key.

ROGER READ, FISHMONGER.

"IF you please, Mr. Allen, can you tell me anything about the shop next door? It has been empty as long as I've been coming to Kingsmore, and yet it is in a good situation."

"It has been empty longer than that," said Mr. Allen, taking back the key. "Did you find the shilling?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then old Rider's ghost ain't quite as sharp as old Rider when alive," said the baker with a chuckle. "You want to know why that shop stands empty?"

He looked out and saw that no one was coming in just then, so he disposed himself for a chat. Busying himself in arranging the buns on his counter, their fair array having been much diminished since morning, he went on.

"It's a queer story, and many folk laugh at it; and for my part I've lived next door for years and never saw anything. I've heard noises, but laid them to the rats. Rats are restless beasts, and it stands to reason that they'll scamper about an empty house for diversion; when they mean business, they come to me, worse, luck."

However interesting the natural history of rats from Mr. Allen's point of view might be, Roger would much rather have heard the history of the house; but he knew that there was no use in trying to hurry Mr. Allen, who would stand half an hour in discussing the merits of the basket of fish, and end by buying a herring or a small whiting.

Still, the last train to Sandsea must not go without him, so he kept an eye on the baker's clock and waited as patiently as he could.

"They say that it's haunted, you know," resumed Mr. Allen.

"By what?" asked Roger.

"Naturally, by a ghost. Old Rider, the last owner, the last who lived there at least, was found dead in his bed one day. And the servant, a girl from the workhouse, had robbed the till, and off she went, and was never caught to this day. And she won't be now, for that happened fifteen or sixteen years ago. Then a tailor—stop though, I forgot. Old Rider left a heap of money, though I do believe that a shilling a day would have paid his expenses; and his heir was a young lawyer in London, and he didn't want the shop."

"So then a tailor took it?"

"A tailor, a mite of a man, with a face like a half-baked roll," said the baker professionally. "And having been there a month, he gave it up and moved at great expense—said he couldn't stand the behaviour of old Rider, creeping up and down the stairs counting his money all night. He said he heard the chink of the money. Mind you, I say, rats!"

He did say "rats," and that with such energy that his little terrier, peacefully dozing under the counter, sprang up barking like a dog possessed, and flew at Roger, under the impression that he was a rat in disguise. He was ashamed of himself at once, for he and Roger were friends, and retired, with a reproachful glance at his master.

The worst of this incident was, that Mr. Allen had to tell many anecdotes, all indicating Chip's superior pluck and wisdom, before he would return to the next door house. However, Roger at last discovered that a milliner and dressmaker had also given up the house because the old man would go up and down the stairs and count his money; also a fancy stationer. In fact, the shop, after changing hands many times and getting into very low hands, had been shut up, young Mr. Rider giving the key to Mr. Allen, and saying that he would let it no more until these absurd stories were forgotten.

"And I saw it advertised once or twice in the 'Kingsmore Herald,' but no one ever called to see it. It's a ruinous dirty hole, and no one would take it unless it was cleaned and painted; and Mr. Rider won't do that, for he thinks no one will stay in it."

"I wonder what he would ask for it?" said Roger eagerly.

"It was twenty-five in old times. I dare say he'd take fifteen now."

"Mr. Allen, don't tell any one, because may be some one would try to be beforehand with me. But I'd take it at fifteen pounds a year, and do what wants doing myself. I want to set up a fish shop, and am on the look-out for a good chance. Old Rider won't disturb me, for I must sleep at Sandsea!"

The baker was, as he often afterwards declared, knocked all of a heap by the audacity of this proposal. But after some discussion, he promised to write to young Mr. Rider, adding,—

"The father of that little lassie that lost her shilling, if he would write a line in your favour, could do the business. He and George Rider married sisters, and I believe they are good friends."

Roger was in such a state of excitement that he actually started off for the Post Office to speak to Mr. Wilson; but before he was at the end of Cecil Street, he stopped and turned back.

"It would be a bad beginning, to disappoint all my customers and lose my day. One thing at a time, that's a good rule, though my grandfather didn't say so. I'll have time enough to-morrow afternoon."

So he ran back to the station, and was just in time for the train.

Next day, he not only sold a fine haddock to Mrs. Wilson, but was promised the Wilsons' influence and best word with Mr. Rider. And the upshot of the search for Mary Wilson's shilling was, that Roger got the haunted house for fifteen pounds a year.

Now began a busy time indeed. The first thing Roger did, was to take a holiday, and a trip by rail to Colchester. He had seen fishmongers' shops in London, but he wanted to refresh his memory. The glories of the shops in Colchester almost disheartened him—the gold letters, the gilt rails, the marble tables with water always trickling gently down to keep the fish fresh.

"But I'll just do the best I can," he said aloud as he walked back to the station. "To be first in the field is half the battle. I can't afford one of those outside blinds; but then, luckily, I'm on the shady side of the street. I must make a sloping table, though it won't be of stone, and I can keep a watering-pot and trickle water over the fish every now and then. I must make some way for the water to run into a tub, though; I can't have it slopping about the floor. Fishmonger, M O N G E R, not U; now, I'd have spelt it with a U if I hadn't looked! What luck, to be sure."

He went back to Kingsmore and set to work. His savings amounted to twenty pounds and a few shillings; but he had to pay half a year's rent in advance for his shop, Mr. Rider saying that if he were fool enough to be frightened away by the ghosts, he should forfeit his rent. If he employed carpenters and painters, the rest of his money would speedily disappear; so he valiantly determined to clean, mend, and paint for himself.

Every day, as soon as his fish was sold, he shut himself up in the house in Cecil Street and set to work. He bought only what he found he could not do without; a little stock of coal, a big tub, a big iron pot, a water-can, and a scrubbing-brush. Thus provided, he scrubbed and dusted and scrubbed again, until the house was clean from top to bottom.

Then he went to a timber yard and bought wood. The men there were so much amused at the minute accuracy of his measurements and his determination to get exactly enough and no more, that they took pains to suit him; and one of them, who lived in Cecil Street, helped him to carry it home, Roger gratefully making him a present of a fine fish next day. Hammer and nails he purchased, and a ladder he borrowed from Mr. Allen, and, thus provided, he mended and altered the woodwork to suit his purposes, putting a broad sloping table in the window.

Now came the painting. Several pounds of yellow paint and some brushes had to be bought; but the time he had spent in watching the workmen at Sandsea terminus was now proved not to have been wasted, for he made a very good job of his painting. He painted his shutters black and varnished them until they shone again. He removed the glass from the lower part of the window. Finally, he remounted the ladder and painted the board over the window, on which he could discern dim traces of former tenants' names; but he blotted them all out with two or three coats of white paint.

By this time, curiosity was excited in the neighbourhood, and several passers-by asked him, "What sort of shop was this to be?"

"You'll see to-morrow or next day," was all the answer Roger would make.

And when he had devoted a third evening to the white board, he came down the ladder and retired to his shop to consider the state of affairs.

He intended to try to paint his own name and the important word "Fishmonger," for himself. If he failed, he could only put on another coat of white, covering his failure; if he succeeded, it would be a great saving. But if he could only do it unseen, he knew that he would be far more likely to succeed, and besides no one need know of his failure. At last he concluded that as soon as the white paint was perfectly dry, he would sleep in town one night and "have a try," the moment the light would suffice; and as it was still early in August, that would give him a good time.

When the time came for his attempt, he brought his blankets from Sandsea, and at night retired to the little room behind the shop, where he slept soundly and never once thought of the ghost! Perhaps the said ghost was huffed at this disrespectful conduct, perhaps the rats had forsaken the long empty house; at all events, neither then nor ever did Roger hear or see a ghost. I cannot say he never heard or saw a rat, for in the days to come, he was obliged to keep a dog to drive them away.

He was up and at work long before the sun appeared, and when he left off, the whole board bore the inscription—

"ROGER READ, FISHMONGER"

In big capitals. What if the letters were not all the same height? What if the ER at the end had to be compressed into a very narrow space? What if the three words were so close together as to look more like one gigantic word than three ordinary ones? Roger was aware of these faults, yet he thought on the whole it looked well, and would do for the present.

"What a pity I can't open to-day!" he said to himself.

And having further considered the matter, he took his big basket and ran off to the station, to meet the train by which he usually came to Kingsmore himself. His rivals in the trade were by this time reduced to two, a man and a very old woman, to whom Roger had often been very kind. Now the question was,—Would one or both of these persons consent to sell all their fish to him, if they knew why he wanted it? And it would not be fair dealing not to tell them. He accosted them as they got out of the railway carriage, telling them what he wanted, and offering what he knew was a good price for the fish. To his great joy they both consented, the old woman saying,—

"One good turn deserves another, and your shop won't injure my little trade!"

While the man bargained for an extra shilling; but, being a lazy fellow, he was glad to be spared his usual tramp. Roger hurried home, sorted out and examined his fish, arranged it temptingly on the yellow table, tried if his arrangement with watering-pot and tub would work, and at ten o'clock proudly took down his shutters, and began business in his own shop.

"If Jack could only see it!" he muttered.

His first customer was Mrs. Wilson, who was going out for a walk with her children, but stopped to admire the shop and congratulate the new tradesman; also to buy a fish, for which she said she would send in an hour or so.

"Write 'sold' in big letters on a bit of paper, Read, and lay it on the fish; that will look well," said she.

And Roger rather thought it did look well! Though, till his window was empty, he had not much time to think about it.

But after that first day Roger got a little frightened. His customers had no objection to coming to the shop, but they objected to carrying the fish home, and he had no one to send with it. He was obliged to engage a messenger, which did not suit him at all, as he liked to do all his work for himself, and was afraid of the expense. But there was no help for it, and it turned out a very good move—though he was constantly changing his boy, for he expected every one to work as hard as he was willing to do himself; and the boys, alas! had weak leanings towards marbles and tops, and were constantly in scrapes.

In a few months, his custom became so great, that his shop was often cleared before one o'clock, and many people had to go away disappointed.

Roger was now obliged to take another forward step, and again it was a step he did not half like. He was so fully impressed with the truth of the saying, "If you want your work well done, do it yourself," that he hated being dependent on any one for the success of any part of his undertaking. But he thought he would try it for a time, and if he found it did not answer, he could return to his old plan of sleeping at Sandsea and choosing his fish for himself. He made an agreement with the owner of one of the best boats to send him a supply every morning; and, on the whole, this was a good plan and worked well.

But it gave him several hours to himself in the evening, which he at first employed in making the room he inhabited and his kitchen more comfortable. The rooms upstairs he meant to put in good order as soon as he could afford it, and let them. As his notions of comfort were very simple, his work was soon done; and then, indeed, the idle evening hours began to seem long and tiresome.

One evening, strolling along the street in which the church stood, he met a good many boys coming along in haste, and saw that they all ran round the church, to where he knew the Kingsmore schools lay. They were big lads, ranging from fourteen to eighteen, and Roger felt curious to know "what they were up to," so he followed them round the church. They were going into the boys' school-room; and while Roger gazed and wondered, another boy came quickly round the corner and nearly knocked him down.

"Never mind," Roger said, laughing; "you didn't see me, I know. Tell me what is going on in there, if you don't mind?"

"It's the evening school. Mr. Aylmer, the young parson, has begun it, and he teaches us. It's for lads that have to work all day, and who wish to improve themselves."

Roger's eyes actually flashed, so delighted was he.

"Do you think I may go in?" said he. "I'm busy all day, and there are some things I do so want to learn."

"You're the man for Mr. Aylmer, then. Come along; I'm afraid I'm late."

Roger followed him into a long, whitewashed school-room, one end of which was well lighted, and a fire burned cheerily in the grate, for it was winter now, and the evenings were cold. Fifteen boys sat on the benches near the fire; and beside a desk stood a tall young clergyman, just preparing to offer an opening prayer.

The two late arrivals got seats as quickly as they could, and were hardly seated before the prayer began. Then Mr. Aylmer set them all to work, one at one study, another at something else; and when this was done, he came and sat down on the end of the bench on which Roger and his new acquaintance were sitting, to speak to the stranger.

All this time Roger has never been described, nor does the reader know his exact age. He was not very tall, but well-made and strong-looking. He had a sensible, freckled face, not handsome, but remarkably pleasant-looking; honest blue eyes; and brown hair, which he kept cropped very short. It was a bright, wide-awake face, but very pleasant and honest-looking; and Mr. Aylmer felt inclined to like the lad even before he spoke to him.

Mr. Aylmer was a tall, stalwart young man, a splendid cricketer, and a hard-working clergyman, whose evening school was his own idea and his pet undertaking.

THE EVENING SCHOOL.

"YOU have never been here before, I think?" said Mr. Aylmer. He had a pleasant voice, and, curious to say, it sounded familiar to Roger, though he was sure he had never seen Mr. Aylmer before.

"No, sir; I never heard of it before."

"A stranger here, I suppose?"

"Not exactly, sir."

"Tell me your name, that is, if you wish to attend here regularly. I keep school here for two hours every evening except Saturday."

"Oh, I should like that well! What do they teach here, sir?"

"They, means me," said Mr. Aylmer, laughing. "I have no help as yet. I teach whatever my lads want to know, and some of them have had more education than others. What do you wish to learn?"

"To understand the Bible and to keep accounts," replied Roger, with all the promptitude of one whose mind is made up.

Mr. Aylmer looked curiously at him.

"Tell me your name," said he, "and your age."

"Roger Read, sir; and I'm going on seventeen."

"And your employment? Are you in any of the shops here?"

"No; at least, yes. I keep a shop. I'm a fishmonger," answered Roger with some pride.

Mr. Aylmer at first thought that this was meant as a joke, and was not sure that he liked it. But Roger looked so quiet and grave that he gave up that suspicion, and said gravely,—

"Were you born a fishmonger?"

"Why, no, sir!" Roger said, laughing. "What do you mean?"

"You are so young to be in trade on your own account, that I want to know if it really is so, and how it came about."

"I have a shop in Cecil Street, and there's no one but myself. But I was born down in Devonshire, and my grandfather, Nicholas Read, was gamekeeper at Sir Carew Shafton's place near Bideford town."

Mr. Aylmer looked again at him, and said, "What was the Vicar's name?"

"The Reverend George Aylmer, sir."

"And I am his son, and you are the boy about whom Sir Carew was so unhappy, because, when your poor father's death became known to him, he could not find you. One of my brothers, who is in London, is on the look-out for you still, for all I know. I thought there was a touch of old Devon in your voice. Why did you not write to Sir Carew?"

Roger opened his eyes wide.

"Why, sir, he told me, if I went to my father, he would never have anything to say to me again! And I thought he meant it too. But I've done very well without his help."

"Ah, well! He'll be glad to know that," said Mr. Aylmer drily. "Now I must waste no more time, but when school is over, I must have a talk with you. Do you know anything of arithmetic? I'll set you to work at once."

"And to think you're one of the Vicarage young gentlemen!"' said Roger. "Master George, I'm sure; Master Fred was not so tall."

"Master George it is. Here's a slate and here's a book. Look over the book, and I'll come presently and see how much you know."

"I could tell him that now," thought Roger. "'Nothing' is easy said. I'll just begin at the beginning and learn it right off."

Mr. Aylmer soon found that he had a good pupil in Roger Read—good in a way. Roger spared no pains to learn what he wanted to know; but anything of which he did not see the practical use, he would not learn at all.

History! Of what use would history be to him? Mr. Aylmer said nothing for a long time: all that winter Roger worked away at arithmetic, book-keeping, writing, and his Bible. Before summer came, he could write a fair business hand, was a tolerable accountant, and could write without errors in spelling. His business was thriving, his time was fully occupied, and he was very happy.

No one would ever take Jack Sparling's place in his affections; but he was beginning to regard Mr. Aylmer as a friend, and to love him; and something to love was a great blessing to poor lonely Roger—greater than he knew it to be.

May was a week old, and one Saturday afternoon, Roger was putting up his shutters when some one touched him on the shoulder.

"Oh, Mr. Aylmer! Is that you?"

"It is; and I have come to talk to you. Shall I go down with you to your kitchen, or will you come out for a walk?"

"Whichever you like, sir. If you're not tired, it is pleasanter out than in my kitchen."

"Very good; follow me up to the station. I have a message to leave there."

Roger hastened to finish his work; and having made himself very neat and scrubbed his face and hands until they were crimson, he took his cap and set out for the station. Very soon he and Mr. Aylmer were going along a country road at a great pace.

"There's a wood out here," said Mr. Aylmer, "where I expect to get some primroses. Roger, I think you used to play cricket down in Devonshire?"

"Oh, yes, sir; you see, I had so little to do."

"Well, I'm going to set up a cricket club here, and I count on you as one of my best members. There'll be a yearly subscription, but it will be small. Mr. Dunlop has given us the use of a very nice field. It is easier to find a good flat field here than at home, Roger."

"Well, yes, sir. But don't count on me, Mr. Aylmer, I couldn't spare the time."

"Roger, when I urged you last week to join my English History class, you said the same thing."

"It is quite true, sir. I've got on wonderful, I know; but I have my rent to make up, and I have to put by for the furniture of the two rooms upstairs, and I have to live. And all that won't be done by pleasuring."

"Do you know what the boys call you, Roger?"

"Old Hard-as-nails," said Roger, laughing.

"And you're a little proud of the name? So I see. And they complain that you won't make friends with any of them, but keep altogether to yourself, and work morning, noon, and night."

"So I do, and so I ought! Do you remember my father, sir? He was the cleverest man I ever knew, and yet for want of sticking to his work, see how things went with him. I don't mean to end as he did."

"Very good. But if my dear old father, instead of being a hearty and a temperate old gentleman, bless him! had died, let us say, of over-eating himself, would you advise me to try to live without eating at all?"

"That's not at all the same thing," said Roger.

"I am not so sure of that. Most people divide a man into body, soul, and spirit; but, for my own convenience just now, I divide him into soul, brains, and heart, his body being the house in which these live. And if he doesn't take care of the house, the lodgers suffer for it. Now you, Roger, are neglecting the house, and taking care of only one of the lodgers."

"Which, sir?" said Roger, laughing.

"Your soul; yes, I am sure you are at heart a Christian; and that being the case, I expect you to listen to me when I give you a lecture, which I am going to do forthwith. Here's a very convenient wall, and we'll sit down and have it out. Let me see, how did I mean to begin? Oh, what was Mr. Dunlop's text last Sunday, Roger?"

Roger looked a little surprised and puzzled, but replied,—

"'Seek the peace of the city whither I have caused you to be carried

away captives, and pray unto the Lord for it; for in the peace thereof

shall ye have peace.'"

"Yes. Well, what did he say?"

"He spoke a good deal of the Prophet Jeremiah, and what a sad life he had; and so he had, poor man, though I never thought of it before. Then he told us who the people were who were to seek the peace of the city: what's this he called it?"

"Babylon."

"Yes—and then he said, that if the Jews, being no better than slaves and captives, were to seek the peace of that city, how much more should men seek the peace of England, their own native country, where all have rights and privileges and all are free! And he gave a lot of texts, more than I could remember afterwards, but I know he said that the Lord Himself loved His native country, for He wept over Jerusalem."

"Yes. Now, to whom do you suppose Mr. Dunlop was speaking?"

"He said, to all men. But when he began to talk about votes, I didn't understand him."

"Because of your ignorance, Roger. You know nothing about the past of your native land, nor even what is going on at this present time. But you know what a vote is, don't you?"

"I believe I do, sir. As to all that about my native land, I don't see what business I have with it."

"Well, Mr. Dunlop said that the time is coming when every man, or nearly every man, in England will have a vote. And he said that if people used that power well and conscientiously, it would be seeking the peace of the country. Now, you are sure to be a rich man, Roger; one of these days, you'll have a vote. If you knew something of the history of your country, you'd be in a position to use that vote intelligently and to help others to do the same. If you don't, you'll just be taken in by fine words and false promises, and you'll follow with others like a flock of sheep. Therefore I say that, whether you feel the want of it or not, you are bound as a Christian man to—join my English History class."

Roger laughed.

"I knew that was coming!" said he.

"That's one reason. Another is for your own sake. You have plenty of brains, but you are trying to starve them. You want to learn only what you can turn to immediate use and profit. Now that you have learned all the arithmetic you want, what are you going to do in the long evenings? If you'll learn other things, you'll soon get a taste for reading, and I can lend you books. If you don't care for reading—well, indeed, Roger, I don't like to think what may be the end of those long, lonely, stupid evenings."

"That's true," Roger admitted. "Before I began to go to the classes, I was almost mad with the long time, and nothing to do."

"I know it. And by degrees, either you must give in and find something to do, or it will be found for you. You know the old hymn,—

"'Satan finds some mischief still

For idle hands to do.'

"And if I had written that hymn, I should have added, 'Also for idle brains.'"

"Well, Mr. Aylmer, I'll come!" said Roger, laughing again. "I won't keep my brains idle."

"Or feed them with only one kind of food, of which of course they would get very tired. And a tired brain, weary with harping on one idea, is no joke. That is what fills our mad-houses, the doctors say. So much for your brain.

"Now for the third lodger. Why don't you make friends with some of my lads? There are a few that I can understand not liking; though, mind you, if you could help them to improve, and don't, you are leaving a duty undone. But Robert Brown and John Meyler, and one or two more, would be good friends for you through life, and you would be the better for their companionship even now."

"But if I get mixed up with a lot of fellows, I shall be losing time, Mr. Aylmer."

"Do you call our walk this evening a loss of time?"

"No! Oh no, sir, I always know I shall get good by being with you."

"That's a great compliment, my dear boy, and a sincere one, I know. But now, are you not aware that what you have said is another proof of what I am trying to make you see—that you want to live altogether for yourself? You think, and plan, and work—all for what? You would get this good at least from making friends with lads of your own age and position; you would find your level, and cease to think of nothing but Roger Read, Fishmonger."

A short silence followed this home-thrust.

"Have I offended you, Roger?"

"No, sir," said Roger in a low voice. "It is true. Jack warned me that I must guard against that. Yet, sir, I do try to be kind to any one that is in want."

"My boy, I know you do. Did I not hear only yesterday that you have taken that poor old Betty Price, the fishwoman, to be your servant, only because she is no longer able to trudge about with her basket? And what I like so much is, that you never speak of these things. But there is something more wanting; you must come out of your shell, and realize that we have duties to our equals and to ourselves. If you don't, Roger, you'll never become more than half a man. And I want you to be a true man—body, soul, and spirit all at their best, so that our Lord may have a trained soldier in His service."

"I'll do whatever you tell me, Mr. Aylmer, I know you are right."

"Then you'll subscribe to my Cricket Club, and come every Wednesday and Saturday evening to help me to teach those who know nothing about it. And that brings me round to my fourth and last head. You know I divided you into four at the beginning, and I have disposed of the three lodgers. Now for the house, Roger, you don't look half so well as you did the evening you astounded me by proclaiming yourself a fishmonger."

"No, I am not; I miss the journey to and from Sandsea, and the pure salt breezes. But I can't go back to the old way now; my business has outgrown that."

"The cricket, and good long walks when you can spare time, will do just as well. By the way, we ought to be walking homewards. No primroses for me to-night; but if you keep your word, Roger, I shall not mind that."

"No fear, sir, I'll keep my word, and I'll try to get out of my shell."

It was not long before Roger felt the benefit to both mind and body which followed upon this determination. He was a clever, thoughtful fellow, and the study of the history of his native land led on to other studies; in fact, he became so fond of reading, that his evenings seemed as much too short as once they had seemed too long. He also took so kindly to cricket that the two evenings in the week were not grudged to it.

But it was a good long time before he succeeded in being on frank and friendly terms with the lads he had so long kept at a distance. They did not like him nor wish for his company. But he succeeded in time, thanks, partly, to a lecture Mr. Aylmer gave to Robert Brown; and he became popular when they knew him better, and he was much happier when he had "got out of his shell."

And his business did not suffer by all these other interests; he attended to it so thoroughly, and was so honest and trustworthy, that when a new fishmonger's shop, with marble slab, gold lettering, and every modern improvement, was opened in Kingsmore, the owner got so little custom that he was obliged to close the shop in a few months.

Now it happened, oddly enough, that this shop also belonged to Mr. George Rider; and Roger at once wrote to ask leave to exchange the house he was in for this far better one, as he was quite able to pay the higher rent.

Having got Mr. Rider's consent to this arrangement, he made a fair offer to the disappointed tradesman for the shop fixtures, and moved into his new premises as soon as his name, in all the glories of gold and scarlet, had replaced that of the original owner.

So it came to pass, that at one-and-twenty, Roger Read was the occupant of one of the best shops in Kingsmore, doing a good business, laying by a little every year, and leading a very healthy, happy life—and all because he attended to his grandfather's maxim, and never lost a chance.

JACK SPARLING.

ABOUT a year had passed since Roger moved into his new shop, and his prosperity had known no check.

Between work, friends, books, and helping Mr. Aylmer in the evening school, his hands, head, and heart were all occupied. There was a junior class in the evening school now, composed of errand boys, crossing-sweepers, telegraph boys, and others whose days were occupied, and Roger and his friend Richard Wilson, son of Mr. Wilson, of the Post Office, taught this class turns about, thus setting Mr. Aylmer free for the elder lads.

The Wilsons were very kind to Roger, and when their eldest boy finally left school, they often asked him to their house, feeling that he was a very safe companion for their boys. Indeed, Roger had used his opportunities so well that he was now a fairly educated man; and a real desire to be kind and courteous to every one made him a well-mannered man too.

All this time, amid all his interests, Roger had not forgotten his first and best friend, Jack Sparling. He had written several times to the address Jack had given him, but his letters were returned, marked, "Gone away and left no address."

Then Roger wrote to Mr. Avery, addressing his letter to the care of Messrs. Waring & Co.; but he got no answer, though the letter did not come back. He often thought of taking a holiday and going to Birmingham in search of Jack; but he was so busy that somehow time slipped away, and this holiday never was taken.

But now something happened which at once stirred up Roger's memory of the time when he had come, hungry and friendless, to the "first cutting" of the Sandsea Railway, and opened to him a chance of hearing something of his dear old friend. The single line of rails to Sandsea was no longer sufficient for the increased traffic, and a second was to be laid down. And soon Roger heard that the contract for laying the rails was undertaken by Waring & Co., the firm in whose service Avery and Sparling had come there some years before. As soon as he knew that the work was begun,—at the Sandsea end of the line, as before,—he went down one evening to Sandsea, and set out to meet the men as they came home from work.

"How well I remember that day!" he said to himself. "It was just here that Mrs. Avery hurt herself—how the town has grown, for there were no houses here then! That sprain of poor Bess Avery's ankle was a fine piece of luck for me, though that is a heathenish way of talking of it. Why, they are collecting their tools in the very same place! There is the lorry, all just the same! Oh! I wonder, shall I have Jack by his strong hand,—such a grip,—in a few minutes? I feel as if I were in a dream, and that presently I shall wake up and find the dinner basket on my arm, and feel the queer sinking that came over me when I saw the food. It was the last time I ever was hungry—more than is pleasant. I mean."

Here he reached the scene of action. The lorry had received its load, and a good many of the men were sitting on it; but seeing a stranger, they waited to see what he wanted. There were many strange faces, one or two who might be acquaintances a little altered, but only two about whom Roger felt no doubt, and neither of these was Jack Sparling. Walking up to the stout man in white flannels, he held out his hand, saying,—

"Mr. Avery, I can't mistake you! And that's Easy Deasy, isn't it?"

Avery looked at him, and said,—

"You have the advantage of me, sir."

While Deasy jumped off the lorry, a fine, tall strapping fellow, with a magnificent red beard, and exclaimed in a voice which had lost none of its brogue,—

"Boys honey! I hope he ain't some one I owed a few pence to when I was here long ago!"

"Not a penny. Larry, don't you know me?" said Roger, laughing. "Mr. Avery, where is Jack Sparling?"

Avery started and looked again.

"You don't mean to say as you—"

"It's himself—Roger Read," shouted Deasy. "And it's meself that's proud to see you, Roger. We were talking of you this very day, and I was wondering if I could find out what was become of you. But, Roger, you're quite a gentleman, now I look at you!"

"Not much of that," Roger answered; "but I've done very well. I have a shop in Kingsmore now. You come over and see me some evening, Deasy. But—"

"A shop!" said Deasy. "Do you mean, a shop of your own?"